roots

You may notice many administrator quotes are absent from this issue of the Tufts

has concerns with the accuracy of fairness of reporting towards the administration from the

concerns, Tufts Media Relations has declined to comment on pending

understands the importance of these stories and intends to meet with the Observer soon. The Observer, like many other student publications around the country, has

Observer is disappointed with Tufts Media Relation’s decision to decline to comment to

ministrators to do the same. The Observer commits itself to telling stories of marginalized voices on

hopes our readers cherish the writing of our staff and value the student perspectives enclosed in this issue.

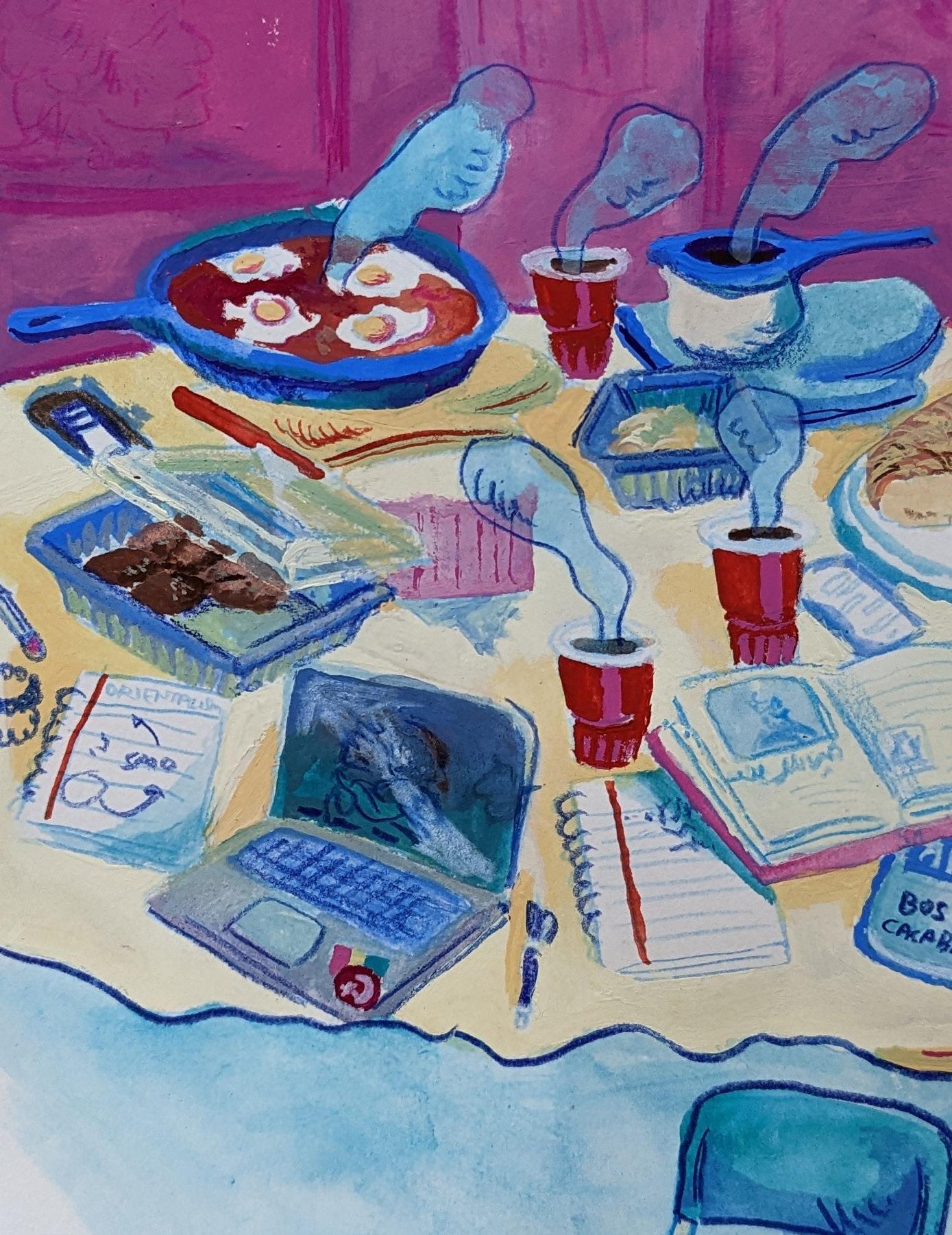

By Lily Feng and So a Valdebenito

By Lily Feng and So a Valdebenito

In 2017, an Equality of Opportunity Project study put Tufts among the top 10 elite colleges with families from the highest income brackets. In fact, more Tufts students come from the top 1 percent of earners than the bottom 60 percent. The lack of socioeconomic diversity at Tufts impacts students who are firstgeneration—those who are the first in their family to attend college—and/ or low income (FGLI). Furthermore, it calls to question Tufts’ written commitment to Diversity and Inclusion, to “embrace those at the margins of society” and fostering “an environment that encourages open dialogues across many different perspectives.”

Increased access to higher education across class divides leads to greater socioeconomic diversity on college campuses and more dialogue about class consciousness. At Tufts, the conversation among institutions and their students has expanded to encompass the lived experience of low-income students on elite college campuses and how the university can support these students once they arrive.

Breaking down the socioeconomic distribution of Tufts’ student body, 18.6 percent of students are from families of top 1 percent earners, or those with a total household income of $630 thousand per year, which is almost 10 times more than the bottom 60 percent of earners. Contrastingly, only 11.8 percent of Tufts’ student body comprises the bottom 60 percent of income earners, or those who make $65 thousand per year or less. 77 percent of the student body comes from the top 20 percent of the income earners, and the median family income of a student at Tufts is $224,800. Investigating Tufts’ socioeconomic diversity—or a lack thereof—exposes a student body stratified by wealth and class.

Associate Professor of Sociology Helen Marrow pointed to studies within social psychology and sociology that show evidence where having, generally, greater exposure to people with different backgrounds and histories can

help break down stereotypes. This exposure, “increased understanding of [diverse] experiences and… perspective-taking,” she said. These new perspectives can actually “create empathy and drive empathy, and drive crossgroup sharing.” However, Marrow said, “[Tufts has] an overrepresentation of people from families in the top income category compared to the lower one. So [is Tufts] class diverse? By income? I mean, no, the data shows no.” To this end, opportunities for cross-sharing and expanding perspectives on class

are lost because of the overrepresentation of the higher income brackets at Tufts.

According to Marrow, the relationship between elite colleges and the socioeconomically homogenous populations that inhabit them can be framed in terms of a long-standing debate that asks, “Do [elite institutions] reproduce class stratification in the surrounding society? Do they reform it [or] do they transform it?” Marrow offered, “There’s some of both. Higher elite institutions kind of both chip away and transform some of the surrounding class stratifications.” However, at the same time, “they reproduce class inequality.” Tufts’ lack of socioeconomic diversity, then, implicates the institution and the ways it reproduces class inequality.

Just last year, Tufts received a $25 million challenge grant to expand the number of Pell Grant recipients. Pell Grants—funding that the government allocates to undergraduate students who demonstrate exceptional need and students with undocumented status—are linked to increased accessibility for lowincome students to obtain professional degrees. 12 percent of the class of 2026 was eligible to receive Pell Grants, compared to the class of 2025 where only 12.1 percent of students received Pell Grants along with 11.7 percent of the class of 2024. These efforts to promote socioeconomic diversity fall short when compared to other private colleges and universities. Currently, 20 percent and 19 percent of the undergraduate student population receive federal Pell Grants at MIT and Harvard University respectively.

Students feel the impacts of the lack of socioeconomic diversity at Tufts when they arrive on campus. For sophomore Paola Ruiz, an FGLI student, the lack of socioeconomic diversity within the student body has been a constant part of her experience since attending Tufts. She said, “[The lack of socioeconomic diversity] is something that I became so hyperaware of when I came to Tufts that I wasn’t aware of before. I feel like that’s something that I can’t unsee in every single space [at Tufts].”

An anonymous FGLI sophomore commented on the difficulties of accessing basic resources and necessities at Tufts. In a written statement to the Tufts Observer, she said, “[Tufts] needs to reevaluate how it is currently treating its first-generation, low-income students, especially when it comes to basic necessities like food, housing, and course materials. I don’t appreciate that Tufts continues to accept students without the proper resources to support them.”

To sophomore Nicolas Cordova, being a low-income student affects what resources are available and when. “Being low income does affect your resources that [in turn] affect your educational life… I have to reach out to [professors saying], ‘as a low-income student I can’t afford this’ and ‘is there any way for me to get an access code [for the textbooks]?’And having to do that for every single class is a little

bit cumbersome because there’s a stigma having to disclose that.” Tufts’ Division of Student Diversity and Inclusion states methods for where students can obtain access codes for their textbooks, but asks for students to consider “creative solutions” to ensure they have the required material for their courses, despite their reassurance of providing any materials necessary.

Ruiz finds that the lack of access to resources plays a deeper role in her sense of belonging. She said, “I feel like I’m not equipped to be in these spaces. I feel like I don’t have all the tools that everybody else around me has because I don’t have access to all the things people [have] had access to.”

Furthermore, Cordova brought up the difficulties of his transition to Tufts. “Coming here,

it made me realize that a lot of people who did come from all these private schools had access to so many resources to prepare them with skills necessary to succeed at higher education.”

Because of this, he believes that he must put in additional effort to succeed at Tufts. He said, “That’s something I’ve currently been struggling with, because my school did not have those resources that equipped us with the necessary skills to be able to succeed in higher education.”

Kevin Pham, an FGLI sophomore, also finds that he did not have access to the same opportunities afforded to other students before they arrived on campus. “Seeing everyone go and have [funding for a] debate team, or seeing people who were able to travel for competitions… having these opportunities [prior to college], that is a privilege by itself.”

Within the broader Tufts student body, however, this experience can create a degree of separation and alienation for FGLI students. The anonymous sophomore explained that some students can be inconsiderate about problems significant to her and other FGLI students “because they are not significant

to them. These are small costs from laundry to textbooks, to going out, to getting clothes for formal events, and overall just being at Tufts and wondering if my financial aid will be enough the next year for me to comfortably stay here.”

Because of the social divide these FGLI students experience, some feel there aren’t enough open conversations between FGLI students and the broader student body. Ruiz said, “We talk a lot about how race and ethnicity shape how people find spaces to belong in at Tufts. But I think we [as Tufts students] don’t talk about socioeconomic status and how that also shapes how you show up and how you feel in those spaces.” While wealth plays a role in a students’ social orientation, socioeconomic diversity can work to bridge the divides between students’ various backgrounds. In Ruiz’s experience, an environment that lacks socioeconomic diversity, such as Tufts, further socially divides the student body.

The anonymous sophomore described experiencing, “a lot of implied biases [about the FGLI experience] that students come into Tufts with and implied knowledge that makes the experience and path to success really tumultuous at times.” This student finds that while she is proud to be first-generation, she wonders, “if people outside the community can move past it and consider other things that I bring to the table.”

Concerns over socioeconomic diversity have been a historic battle for Tufts’ students, but the institution has been receptive in implementing programs that facilitate the transition to college for FGLI students. For example, BLAST, or Bridge to Liberal Arts Success at Tufts, began operating in 2012 and consists of a six-week summer program prior to students’ first year at Tufts. Tufts also offers BEAST, Building Engagement and Access for Students at Tufts, which is a free, four-day pre-orientation program for FGLI students.

Pham found his way to navigating Tufts as an FGLI student through BLAST. “For me and other members of my cohort,” Pham said, “we were really well supported.” However, Pham recognized, “There are so many other students who didn’t have these opportunities because of the limited number of people allowed into these bridge programs.”

The FIRST Resource Center serves as a primary support system and is available for all FGLI students. Created in 2018, the FIRST Center provides necessary financial knowledge and access to opportunities to empower FGLI students and works to foster communities through Tufts’ partnership with Questbridge and on-campus groups like the First-Gen Collective FIRST Advising Seminar, and United for Immigrant Justice Organization.

Sophomore Ayomide Olyede, a Peer Leader at the FIRST Resource Center, said, “I love working with the First Resource Center… It is really nice being around people who have had similar experiences to you, especially at an institution like Tufts, where you can feel kind of on the outs.”

The anonymous sophomore said, “[The FIRST Center] was actually one of the reasons I applied… I thought it was really cool to have a physical space on campus.”

Cordova feels Tufts has succeeded in creating a comfortable social environment to help connect FGLI students because the FIRST Center excels at curating events, “to get to know the [FGLI] community.” Cordova finds that he has had relatively good experiences at Tufts being low-income, and “80% of [my good experiences] come from the FIRST Resource Center. I’m very grateful that that’s something that we have on campus, and it’s something that a lot of schools don’t have.”

Additional monetary resources for FGLI students can be found through student-managed programs and funds. For example, student organizations have the option to call upon the Tufts Community Union for financial support for club-sponsored events that require members to pay to participate.

Within the university, there is an ongoing conversation as

to how they can be better supported by Tufts. The anonymous sophomore said, “There’s a lot more that institutionally could be done with the FIRST Center… I would say that the students in the community are most responsible for providing that support to each other and less and less Tufts is [the one providing support].”

Pham similarly acknowledged that, “if you’re not actively seeking [resources available to FGLI students], it’s really hard to be aware of the resources that the FIRST Center offers.” This places an additional burden on FGLI students to seek out scarce resources. Pham adds that he’d like to see more support for staff members at the FIRST center. He said, “staff members at DSDI centers such as FIRST [have seen] a lot of turnover lately in this regard, which harms everyone involved, especially when you don’t feel represented at Tufts, facultywise.”

Oloyede said, “The FIRST Center has so many ideas and ways to help students… [but] they do not always get the opportunity… There is not enough outside funding dedicated to bridging the gap and giving these students the college experience they deserve.”

Beyond improving the efficiency of the FIRST Center, there are other approaches that would better the FGLI experience. The anonymous sophomore hopes to see Tufts commit to more well-rounded support for their FGLI community and students. She suggested, “Tufts [should] do very specific things

like [having] a match grant up to $25 thousand from a foundation for accepting FGLI student enrollment, and I would want to know what Tufts is planning on doing with the grant, how it’s going to better the FIRST Center and support it at a time of transactional leadership.”

Tufts could also dedicate more resources for mental health that are intended specifically for FGLI students. Pham said Tufts can improve the experiences of its FGLI students by providing “more support for CMHS. Hire more staff, make booking an appointment more accessible, as many FGLI students struggle with the transition [to college].”

In general, more transparency from Tufts on issues pertaining to the FGLI community would benefit students. “Trying to be less performative in their actions is something I’d like to see. Being more transparent in their decision-making process,” said Pham.

Improving the FGLI student experience at Tufts can aid in establishing a stable foundation in which their academic and social lives are supported and made equal with everyone on campus. Ruiz said it “is such an embodied experience that other people don’t experience,” thus change must be enacted by centering the perspectives and experiences of FGLI students that must be lived to truly be understood.

Scanning the empty check-boxes of racial and ethnic groups on the Tufts application or in surveys sent out by the administration, students will find a diverse mix of identities listed as options. However, Middle Eastern and North Af rican, or MENA, is almost never included among them. Currently, there is neither data collected on MENA students at Tufts nor an identity center or other commu nity space specifically dedicated to their community. Tufts’ identity centers are im portant sites for people of marginalized identities to find joy, community, and a space to explore their identity and cul ture. Without such a space, many MENA students at Tufts feel they have been left without essential resources afforded to other campus communities.

In the United States, the Middle Eastern community has experienced in creasing rates of discrimination, espe cially after 9/11. Despite their specific experiences of ethnoracial oppression, the US federal government classifies people from the MENA regions as white. However, many people with MENA ori gins do not identify as white, and many non-MENA, non-Latine whites also do not perceive MENA people as white.

Senior Omayma Dalal, a Moroccan and Syrian student, said, “Whiteness… comes with the white privilege. And obvi ously, there’s a lot of [Middle Eastern and North African people] with darker pig mented skin. So no one will stop us in the street and be like, you’re white.” Sabrina Rangwani, co-president of the Persian Stu dents Association, echoed this sentiment, and said, “I have yet to meet someone who feels that a white label is adequately repre sentative of us. We are forced to officially label ourselves as white while receiving none of the benefits of whiteness.” With a majority of the MENA community not identifying with or benefitting from white ness, it begs the question as to why they

By Liani Astacio

have not been given resources specifically dedicated to them at Tufts and beyond.

Dalal feels that the lack of a MENA representative on the Tufts Community Union Senate and the absence of an iden tity center for MENA students “makes [MENA students] feel like we’re invis ible minorities that no one’s acknowledg ing.” Additionally, Ragwani commented on the role of a MENA identity center in promoting recognition of the Tufts MENA community. She said, “Hav ing staff at this identity center that are ‘on our side’ might help us get further in our efforts with [the] admin[istration].”

Dean James Glaser, a member of the Diversity and Inclusion Leadership Coun cil, described the current institutional sup port Tufts provides for MENA students in a written statement to the Tufts Observer. “There is a Muslim chaplain and there are prayer rooms available for MENA students who practice Islam. There is a Muslim House on campus as well,” he wrote. Dalal described how Muslim spaces at Tufts are not replacements for a community space for MENA students, noting “most Arabs [at Tufts], even in [the Arab Student As sociation], identify as Christian, atheist, or of a minor[ity] religion,” despite the conflation between the two communities.

Other Division of Student Diversity and Inclusion centers have been consid ered options for some MENA members to find community; however, they are not a total replacement for having a dedicated MENA identity center. Dalal elaborated on how some North African students have ac knowledged that while they are part of the African diaspora, the Africana Center is not always the best fit for them. Dalal said, “We’re not part of the Black identity, and we don’t share Black history, so it makes us feel uncomfortable trying to integrate into a space like that because we know that that’s not our space, and we do not want to disrespect it.” Dalal noted some MENA

students she knows also question their belonging in the Asian American Cen ter, despite many Middle Eastern coun tries being geographically located in Asia.

The primary spaces in which MENAidentifying students can find community are through student-run clubs. Nessren Ourdyl, a Moroccan student, said, “We have a lot of student-made spaces. For example, there’s the Arab Student Association. A lot of students are in Muslim Student Asso ciation obviously, and there’s also another student group that’s MENA-based called Taqadum.” The ASA and MSA are groups dedicated to providing communities for the Arab and Muslim student populations, and Taqadum is a student group dedicated to MENA students who would like to dis cuss issues related to gender and sexuality.

Due to MENA students’ ethnic and religious diversity, some of these clubs do not provide space for all identities within the community. Dalal, who is president of the ASA, said, “There are a lot of people who are North African who do not iden tify as Arab, and there are a lot of people within the Middle East, like the Turks and the Kurds, who do not identify as Arab as well.” She continued, “ASA tries to include as many MENA individuals as we can, [but] a lot of people at the end of the day do not identify as Arab. Everyone else who’s not Arab and doesn’t want to be part of the club [doesn’t] have a community to go to.”

Another roadblock to expanding sup port for the MENA community is the lack of data on the number of MENA students at Tufts. Historically, census data on a minority group can help funnel resourc es, such as an identity center, to them. Without these statistics at Tufts, it is dif ficult for students to receive the resources and funding they need. Glaser cited this as a reason there is not a MENA student center. In a written statement, he said, “Identity centers and physical space are expensive, so we have to have a critical mass of students to justify that expense.” However, he also acknowledged that Tufts does not collect data on the number of MENA students besides the number of in ternational students by country of origin.

Associate Professor of Anthropology Amahl Bishara wrote in a statement to the Observer, “Those from the MENA region

have been underrecognized by the univer sity, in part, I think, because the US census has not been set up to recognize those from the MENA region, and thus we have tended not to be recognized in standard measures of racial and ethnic diversity on campus, as on the Diversity Dashboard.” The Diversity Dashboard displays data on racial and eth nic diversity in the Tufts student, faculty, and trustee population. According to Da lal, Bishara has collaborated with student groups in the past to collect this data; how ever, these efforts were not able to replace a university-wide count. Bishara stated, “It is certainly incumbent on the university to do all it can to recognize all the forms of diversity on campus, despite the shortcom ings of those federal systems currently.”

The creation of identity centers at Tufts has historically been a struggle. Tufts opened its Indigenous Center as recently as March of this past year after years of effort. Many of the Tufts DSDI centers were created out of student activ ism and initiative; similarly, many MENA students have acknowledged student and faculty efforts to expand institutional sup port. Ourdyl noted that there has been “a huge push for an Arab or MENA house.”

However, according to Dalal, turn over in the Office of Diversity, Equity, In clusion, and Justice and in DSDI has been an obstacle to obtaining this space. Jared Smith, the most recent Director of the FIRST Resource Center, left his position at Tufts this semester. Robert Mack, the previous Chief Diversity Officer at Tufts, left the university last semester for a posi tion at the New School. Dalal said, “Chief Mack was our point person. He wanted us to fight for a MENA-identifying center… But unfortunately, he also had to leave. And Jared also left the FIRST Center and Jared was also someone who I was al ways talking about how to establish this.”

Reflecting on her past four years at Tufts, Dalal said, “I’ve seen abso lutely no change from the Tufts insti tution when it comes to recognizing and resourcing MENA students. And I wanted to see it happen because I do feel like we had people in positions of power [such as Chief Mack and Jared Smith] who tried to advocate for us.”

“WE ARE FORCED TO OFFICIALLY LABEL OURSELVES AS WHITE WHILE RECEIVING NONE OF THE BENEFITS OF WHITENESS.”

(AARW) which has showcased movies to the Boston audience for the past 40 years. AARW is a “political home for pan-Asian communities in Greater Boston [and is] a member-led organization committed to building grassroots power through political education, creative expression, and issuebased and neighborhood organizing.” Mat thew Cho, a Korean-Indian member of the Tufts Asian Student Coalition, reflected on his experience working at AARW and at tending the festival. He said being part of AARW helped him “develop a better under standing of what grassroots community or ganizing entails,” the BAAFF being a prime example. The BAAFF tends to play films that do not receive mainstream attention in order to support and showcase underrep resented artists. The selection is broad and non-homogenous, just like the Asian Amer ican experience. The festival showcases im migrant, queer, and dark-skinned Asians who are often not portrayed in popular narratives. Some films showcasing these narratives at BAAFF are Free Chol Soo Lee, Crossings, and In Search of Bengali Harlem.

The BAAFF attracts a large and broad range of guests, within and outside of the diaspora. Through the BAAFF, tradition ally neglected Asian American narratives are shared with others to be seen and un derstood, especially in a political and racial context. Junior Arnav Patra, who attended the festival, commented on the role In Search of Bengali Harlem played in provid ing representation. He said, “[I appreciated] hearing language on screen that’s similar to my own… because that’s very rare, espe cially in the theater, because I think most times when I hear South Asian languages, I can understand it at home or from fam ily.” In Search of Bengali Harlem is a docu mentary that follows Aladdin Ullah as he discovers his mixed ethnic heritage over two continents—first in East Harlem where his ancestors found a home in its Hispanic community, and then in South Asia. Ullah created the film with Vivek Bald, an MIT scholar, and discovered much of his own

tance of representation, especially of those who are often marginalized even within the Asian American community. He said, “In Asian American context, it sometimes feels that South Asian voices play second fiddle. So I think having the BAAFF high light South Asian and then also South Asian cross-racial solidarity as such, in one of their main showings, was really im portant to see that there’s a recognition of our community within the broader Asian American [community].”

Tufts’ Asian American Center Director, Aaron Parayno, raffles off BAAFF tickets at no cost to students to encourage them to at tend the festival. Parayno said, “I think it’s a good opportunity for students who might not be from the Boston area to interact with folks who… live here… and our communi ties that have been here for generations.” Pa rayno continued to talk about the festival’s importance in the realm of representation, stating how rare it is for Asian Americans to be represented in “mainstream” media. He said, “Even when Asian Americans are [rep resented], it often pushes stereotypes of the

while watching these films that they are just one step on the long journey to racial equity. The BAAFF is a great first step though, as Chinsen said, because it makes uncom fortable issues easier to talk about. It opens a door to some of the more serious issues Asian American communities face, while si multaneously building a community around its viewers. The BAAFF will run again in 2023 as a co-project with ArtsEmerson, highlighting its continued commitment to ensuring Asian American film representa tion thrives in Boston.

DESIGN BY CARINA LO

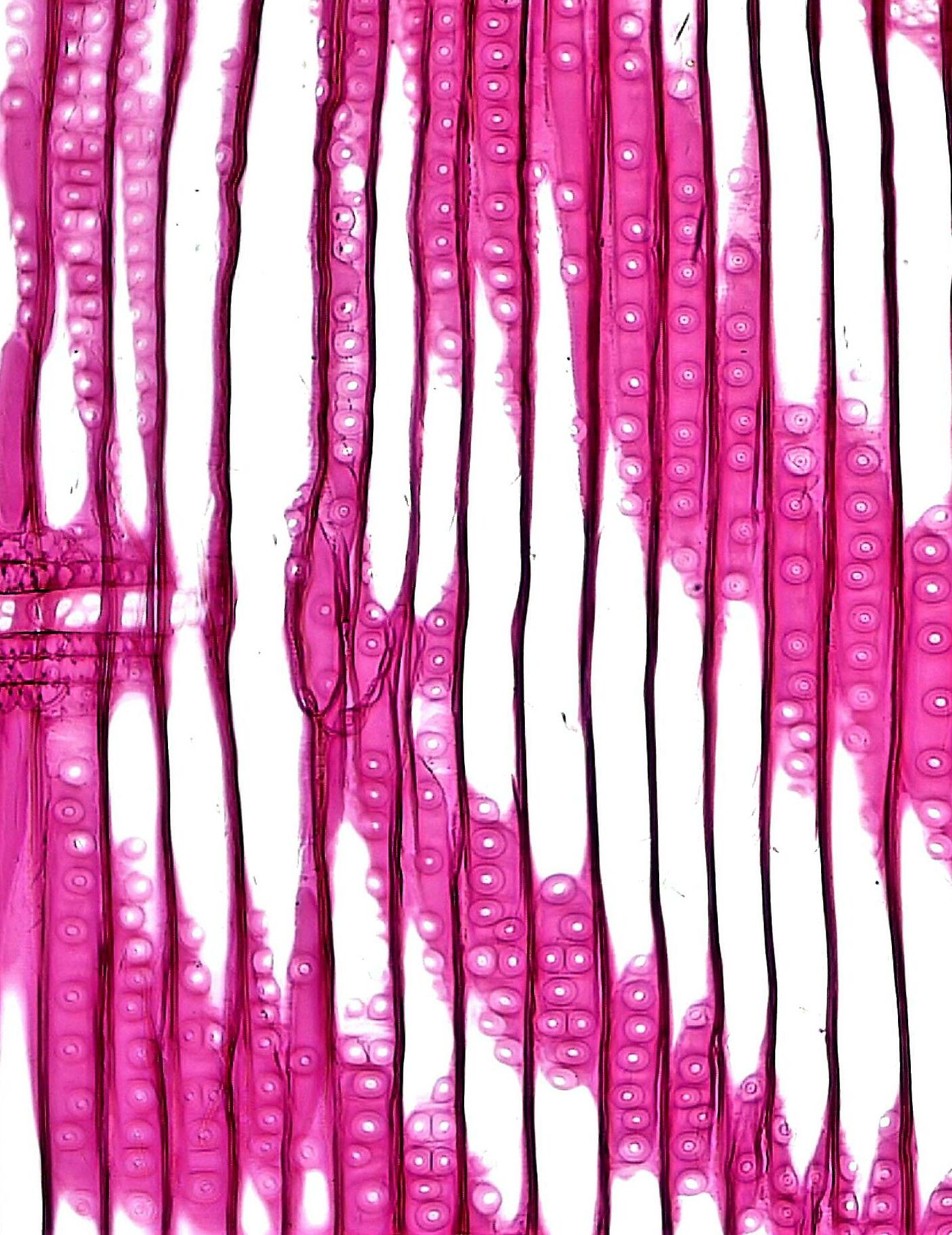

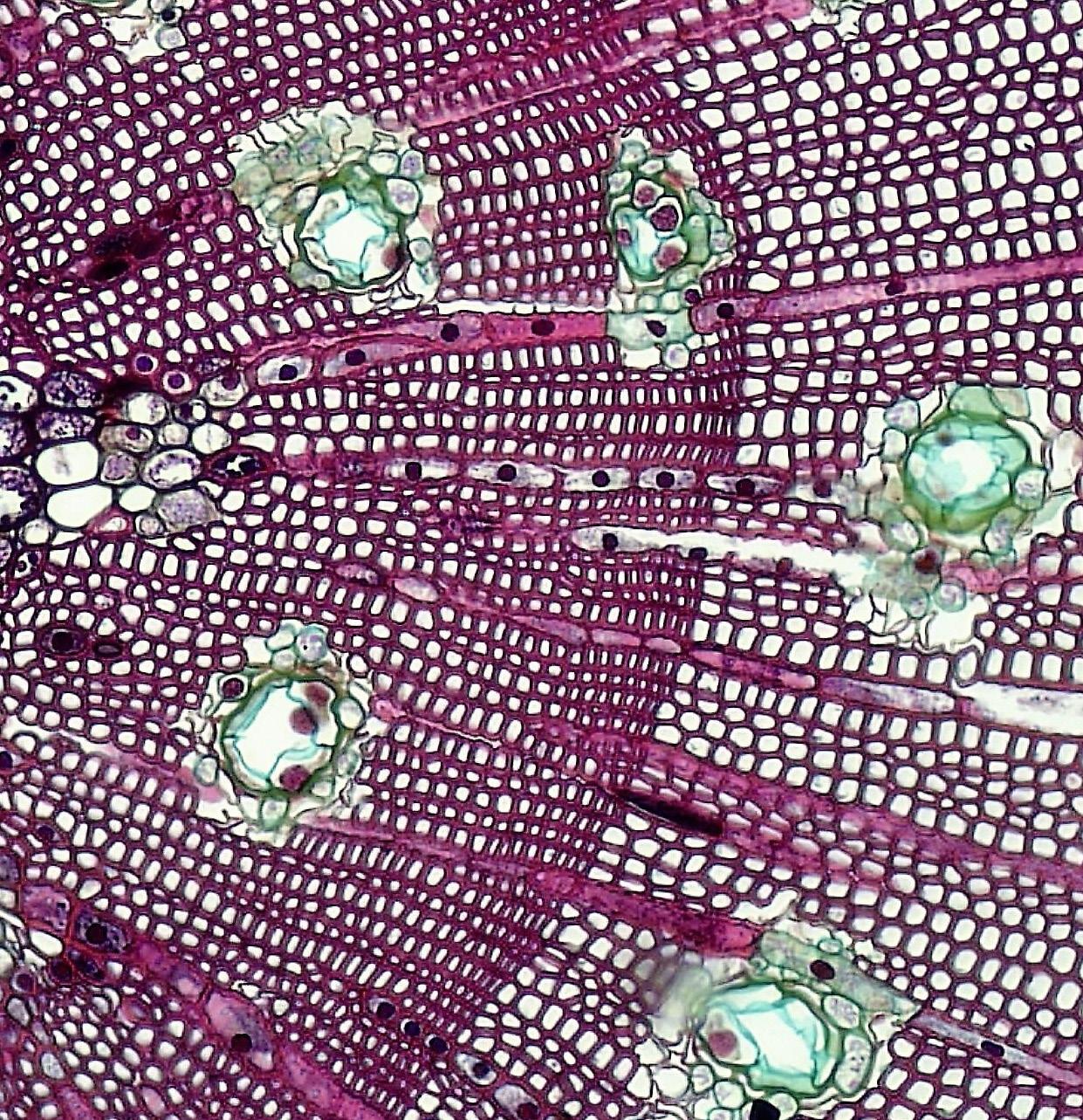

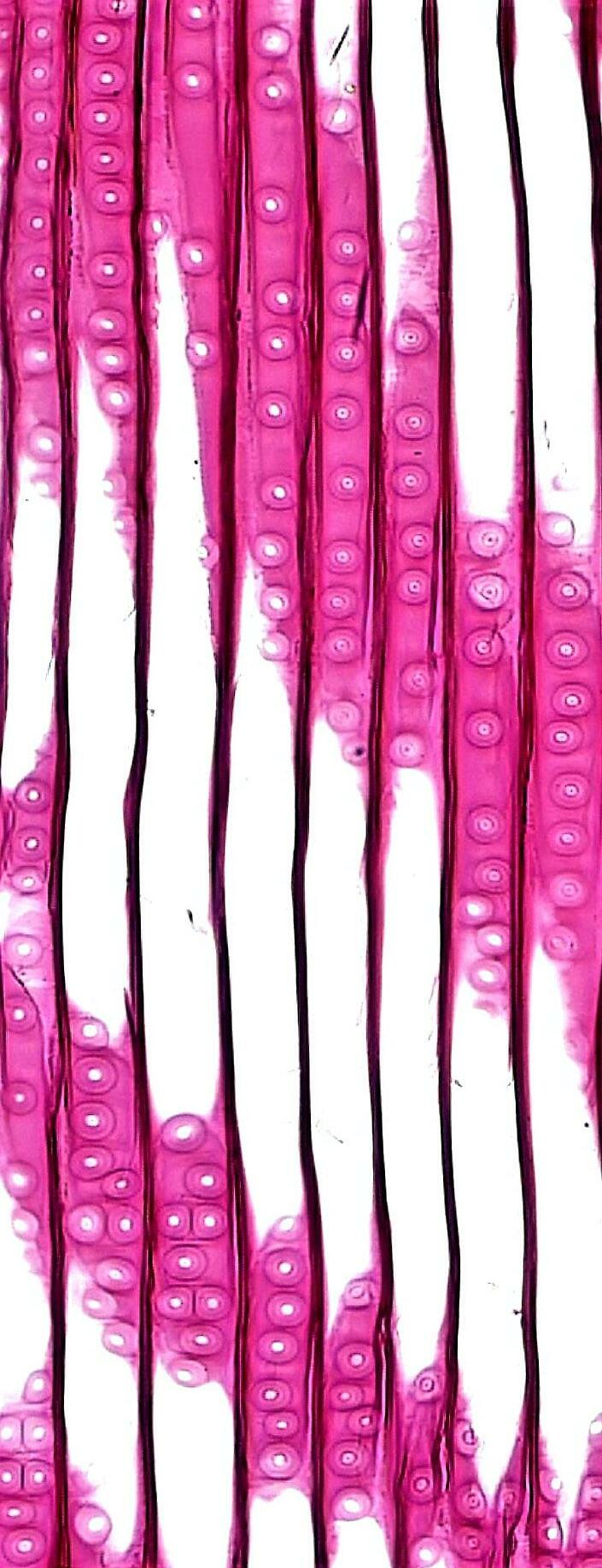

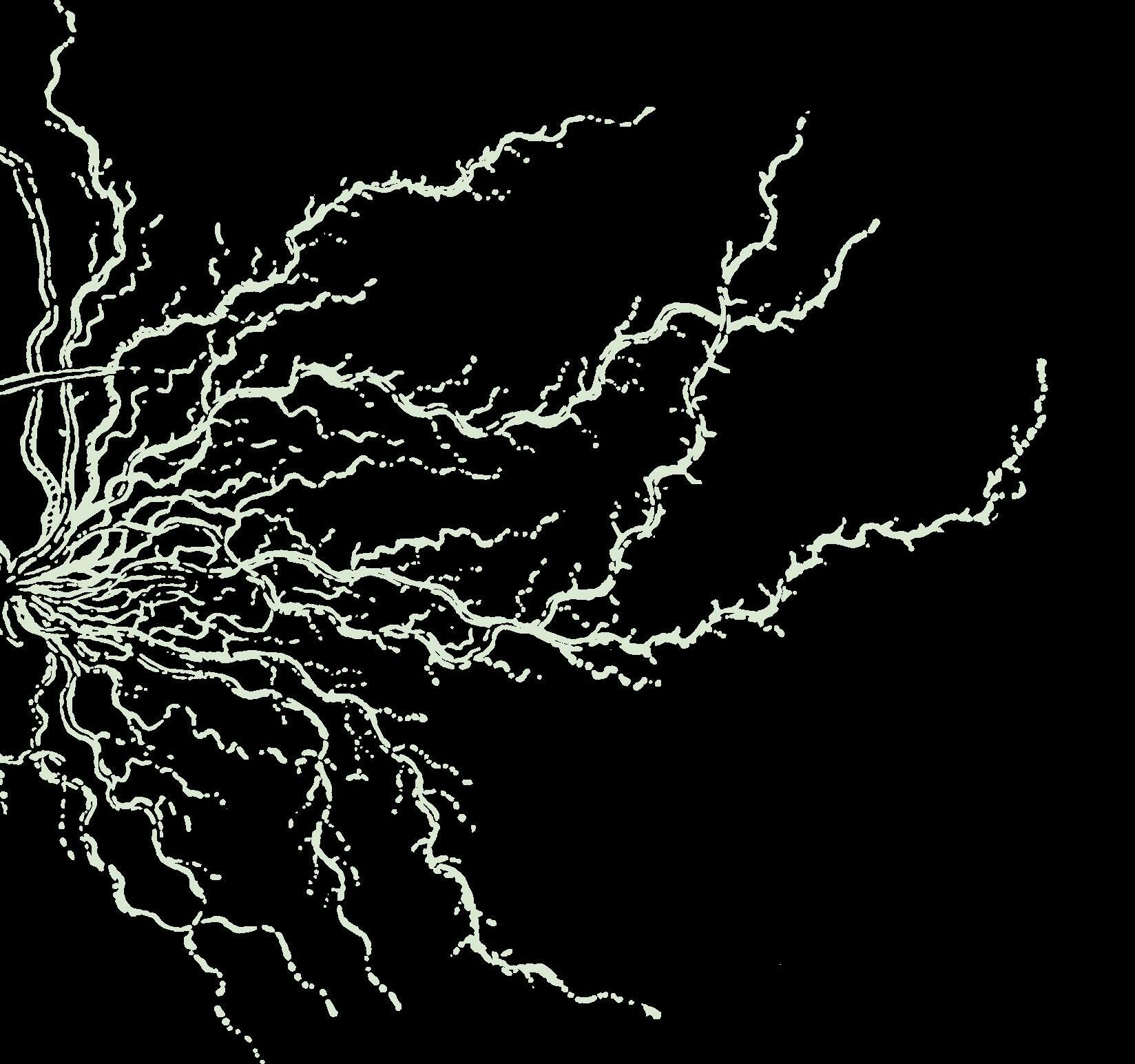

ERIN MCCHESNEY, ENTANGLED, MURAL

DESIGN BY CARINA LO

ERIN MCCHESNEY, ENTANGLED, MURAL

As a child in China, I was pretty much only exposed to tattoos through movies. More specifically, action movies about classic gangster-police rivalries. At the end of every one, there was almost certainly a righteous-looking, severely injured police man (the protagonist) standing over a mob boss (the antagonist) dying of blood loss. Red liquid would gush from the side of his mouth onto his tattoo-covered neck, usu ally of a colorful dragon or feline, mouth open, sharp teeth showing. They’d have one last solemn dialogue on evil’s inability to defeat the righteous before the mob boss turned his head limply, and the policeman was picked up by the ambulance, which al ways arrived dramatically late. There he re united, oxygen mask on, with his beautiful, sobbing bride. Only then did the credits roll, and as the lights turned on, the whole cinema filled with applause.

Here’s the catch, though, I was most definitely too young to be let into the theater for these R-rated movies. How ever, since Chinese cinemas weren’t as strict as the US about age regulations, these violent blockbusters made up the majority of movies I watched. By the time my mom promptly tucked me into bed

at 9 p.m., my mind would be plagued by the bloody scenes I witnessed with her just hours ago. As she kissed my forehead and flipped the light switch, the shadowy figures of ruthless mob sters appeared in the window’s glow, the machetes in their hands clinking loudly against the wooden floor. The tigers and dragons detached from the mobsters’ bare, sweaty skin and flew across my bedroom as I struggled to breathe quietly under the blanket. In the apartment’s drowsy silence, even the faintest noise from the heating pipes sent my eyelids snapping open as if from the tension of elastic springs. Soon, I would find myself tiptoeing across the hallway, eventually landing on my mom’s queen-sized bed. Instead of interrogating me, she would in stinctively pull on the blanket’s corner so I could slide under. And as soon as I reached this new fortress, I would drift soundly asleep, as if my 5’2 mother could effortlessly defend us against an army of tatted mobsters. When I was in elementary school, my mom dated a guy who lived in our apartment building. He drove a Lexus convertible, and sometimes when my mom was too busy at work, he picked me up from school with its top off. Under the envious gaze of my classmates, he would swerve out of the school lane at outra geous speed (I later learned how much money he lost on speeding tickets each year, but that is irrelevant to this story). Even more heroically, he taught me how to “properly” punch someone if I was ever bullied at school. I was only forced to use this technique once in the fourth grade when a much bigger kid decided to kick me during an intense recess bas ketball game, and it got me sent to the principal’s office. Still, it felt pretty sweet being a rebellious child for once. Need less to say, this man got on my good side fairly easily, until I caught him shirtless in our living room one day, smoking a cigarette and drinking hot tea. Over his stomach was a gigantic tattoo of a tiger perching itself in the middle of a green mountain path. I was petrified. In a mo ment’s time, all the dots seemed to con nect: the loud convertible, the fighting tu torial, and now the tattoo… Though my

mom repeatedly denied the possibility of him being a gangster, I tried diligently to find evidence to prove otherwise during the remaining years of their relationship. After all, as suggested by seemingly cred ible sources, only bad people get tattoos. This perception drastically changed after I began studying abroad in the US almost a decade ago. Here, tattoos seem to be far less exclusive. Uber driv ers have them, Starbucks baristas have them, pediatricians have them, and even my teachers have them! I also learned, through their prevalence, that tattoos aren’t limited to the flagrant, colorful beasts I grew up fearing. It turns out, people get fine-line drawings of birds and branches, whole arm sleeves of One Piece characters and Pokémons, or tiny, illeg ible stick-n-pokes of hearts and fruits. Eventually, it only seemed natural for me to begin envisioning myself with tattoos. Every once in a while, a new idea that seemed unbelievably edgy to my teenage self would cross my mind, and I would rush to record it on my notes app before it slipped out of my head. I imagined my body as a gallery of memories and im ages, a mystery box filled with my most prized possessions. These thoughts made me reflect on what I wished to keep clos est in this gigantic world, the times and people that were worth the commitment of temporary pain and eternal commem oration. Over time, I was able to curate a whole list of unthinkable things I could do to my skin, and the idea of being in control of “customizing myself” felt like a comfort in this tsunami of a world.

I got my first tattoos in China the summer before college, just a few months after my 18th birthday. Over the course of eight hours, the artist conjured a skeleton on each of my thighs, one of a person in a contemplative position, the other of a dog, which was in honor of my childhood pet, Ci Lang. On the train home, I rolled my shorts up a whole three times, hoping for everybody to witness the lifelong de cision I had just semi-impulsively made at the wise age of 18. Despite the over whelming exhilaration, though, I found my new acquisitions to be a simultaneous source of self-consciousness.

Every day since then, I increasingly find myself fearing others’ sharp gazes.

My mom said my tattoos would give my grandparents a heart attack, so I put jeans and khakis on for every family function, even if it is August and 90 degrees out. On the subway, I pull my shorts lower when there are children sitting next to me, assuming my tattoos will affect them the same way the ones in action mov ies affected me. Whenever I meet with an authority figure like a friend’s parent or a professor, I watch where their eyes are going and whether their brows begin to furrow in disapproval. When posting updates on social media where I’m con nected with people back home, I delib erately select images where none of my tattoos are showing. Though I have seem ingly shed my prejudice against tattoos, I feel myself continuing to look through the perspective of those who think oth erwise, repeatedly undermining the free dom I have tried to define for myself.

These days, it seems tattoos are only getting more stigmatized in China due to the government’s efforts. They are no longer allowed to be shown on television, forcing certain celebrities to incorporate long-sleeved turtlenecks or a thick layer of concealer into every outfit. Athletes are prohibited from getting new tattoos and are “strongly encouraged” to laser off the ones they already have. As a part of the entrance screening for civil servants, one of the most sought-after professions in China, tattoos are specifically checked for, and those who are found with them automatically fail. In the place I call home, tattoos are still something unspeakable, a taboo to be shunned and erased. These regulations communicate the narra tive that for someone to be respected by their communities, they must forgo the free expression of their individuality to fit into the boundaries of law and order. Under these pressures, many have chosen to conform. Yet for me, this pill some how seems far harder to swallow. I want to be valued and trusted by those around me, as a family member or a profession al alike, just as I long to be accepted for simply expressing my internal currents to the world. So here I am, finding myself at odds between two perceptions: one of the constraints of my roots, the other of my desire to be free as an inked bird, so real it could fly right off the skin.

By Amari Turner

By Amari Turner

When you find a burning cross on my front lawn know that it’s too late. I’ve already been marked by the holiness of the white man’s burden. My heaven was stripped away by the whitehood, Taken by the prideful wizard next door.

Don’t let Kanye speak at my funeral. He’ll tell you I was hanged peacefully, That there was no resistance in my capturing That it was my choice to sway in the tree. He’ll let the choir sing over my body until it decomposes Becoming nutrients to feed the hanging tree. We can’t let him save sinners with tickets to heaven. We won’t find God in a pair of Yeezys on a Calabasas mountain top.

Please don’t let a “cultured” Chad weep over my casket Though it wouldn’t be the first time a self-proclaimed woke white boy cried over my pain to turn his hate crime into a campaign speech. His great-grandfather took those night rides in Alabama because he wanted to. Wore that robe with honor.

Lit every fire under the guidance of WWGWD, What Would the Grand Wizard Do? The only difference between Chad and his grandfather is that Chad apologizes Like the ashes on his grandfather’s hands don’t still stain his skin, Like it’s a coincidence we have the same last name.

When I die, reincarnate my blood into the Confederate flag. Isn’t that the real heart of America? Its deepest pride and embarrassment A woven image of this country’s secrets.

This wasn’t an accident.

When I find a burning cross on my front lawn, know that I set the fire. Used Chad’s tears and bones as fuel. Know that it’s a warning to Kanye That his services are no longer needed. When I die, take my casket to the ocean. I’d rather drown with my ancestors than burn in their image.

On long Sunday afternoons, we hold each other to pass the time. After the bitter taste of stale crackers and cranberry juice We shed the skin of burning church clothes, and slide into fresh white Nikes. Heartbreak waves and all being hand over our bodies. The O’Jays and Marvin Gaye sing us into memory.

My brother is in the living room holding a glass of courage. The words of Stairway to Heaven are pouring out of him Spilling onto the carpet.

When the courage runs out, he throws the glass onto the floor and lets the tears chase it. My mother tries to clean up the mess. He shakes her off and keeps singing.

The music stops.

We can’t keep crying over the same songs, Listening each time like the outcome will be different. The repetition is driving us insane.

My brother is angry. Lost melodies flow misplaced adrenaline until Closed eyes cry glass into the lyrics. He rocks to the beat to keep from falling over. This is how time keeps us.

My aunt refuses to accept the mourning from the kitchen. Washing the beans from the plates is her dying wish The music is too loud for her to focus. Her voice gets lost in unison with ours, Forcing obedience into the air.

It’s time to remember.

Instead of pouring one out, We bless our bodies with ice-cold heaven. Our tongues split silence until we get tired of wasting our hard-earned money on grass.

It takes the whole bottle, before we’re coherent enough to have a conversation. Hennessy touches the lips of “I love you” We mix it with half a cola to remember it’s okay to cry. Break bread on gravestones so on Monday mornings we can starve forgiveness. I can hear your voice when they take shots to the head, “Sunday is our home.”

By Billy Zeng and Rohith Raman

By Billy Zeng and Rohith Raman

AAC grow to its full potential.

Historically, student activism within the Asian American community has been focused on advocating for physical space and visibility to better connect Asian students. Student activists pushed for the creation of many of the Tufts’ Division of Student Diversity and Inclusion (DSDI) centers in light of targeted violence against minority groups. The Asian American Center (AAC) is one of eight identitybased centers on campus, and, tradition ally, it has struggled to receive the neces sary administrative financial support and resources to support the Asian American community. Many student interns took matters into their own hands to ensure the longevity and future of the AAC. According to a 2018 Tufts Observer article, AAC interns took the initia tive to launch fundrais ers that would help the

“[The administration] almost took away the AAC and the DSDI Centers, and the Mural Room [at the AAC] is to com memorate that and say this is our space,” said junior Nacie Loh, a member of the Tufts Asian Student Coalition (TASC).

Prior to the establishment of the Asian American Center, there was a robust Asian American community that created affinity spaces on their own. Voices, a literary and visual arts magazine, serves as a space for the Asian diaspora to have a sense of iden tity and belongingness. A group of Asianidentifying students that eventually formed TASC spearheaded this initiative accord ing to a 1976 Observer article titled Asian Lit Magazine. TASC’s current mission is “to educate and mobilize toward progres sive social change, [and aspire] to foster a safe space within which the Tufts commu nity can learn and discuss Asian American issues.” Similar to TASC’s Voices, the

Tufts Association of South Asians (TASA) produced a South Asian literary and arts magazine titled S.A.L.A.A.M in the early 2000s. Around the same time, student activists formed the South Asian Political Action Committee (SAPAC) to advocate for a Hindi/Urdu language program and a South Asian center separate from the AAC.

Three years ago, when inaugural AAC Director Linell Yugawa retired, the Tufts administration initially had no inten tion of filling her position. This decision sparked frustration across the Tufts stu dent body. On March 21, 2019, a group of concerned Asian and Asian American students wrote in a Tufts Daily op-ed, “[The Asian American community] can not let the university define [their] reali ties and possibilities.” Students from the Asian American community then took the initiative to open a dialogue with the administration to meet their demands for institutional resources and support.

After this student mobilization, the Tufts Administration sent out a univer sity-wide email announcing Aaron Pa rayno had been named the new direc tor of the Asian American Center—six months after the release of the op-ed.

In recent years, Asian student activ ism has shifted toward advocating for in tellectual resources to study Asian Amer ica. With Tufts’ addition of the Race, Colonialism, & Diaspora (RCD) Stud ies Department in 2018, Asian Ameri can student organizers have shifted their energies to advocating for institutional investments and support for ethnic stud ies scholars as well as the growing ethnic studies community as students can declare majors and minors in various RCD tracks.

Academic discourse can provide an other avenue for like-minded individuals with shared experiences to come together and think about their identities critically.

Junior Anneke Chan, a member of TASC,explained, “It [is] really nice to be in spaces where there are other students who [share Asian] identities.” She continued, “There’s a certain solidarity when you understand that you’re learning about things that af fect you together.” For Chan, these class es become “a community space where there [is not] one necessarily built-in.”

These academic spaces for Asian American students often create a social network of students with similar experi ences and political motivations. “When you are doing [organizing work]… you can uplift certain things that your club is working on and [it is] going to be received well [and] critically thought about and talked about,” said junior Saira Mukher jee, a member of SAPAC. “If I need com munity support, these are people and fac ulty that I can come to, which is valuable.”

However, many Asian American stu dents, like those in TASC and SAPAC, have struggled to find this community in aca demic spaces because of a lack of courses within the field of Asian American studies.

Senior Matthew Cho, a member of TASC, spoke about his experience tak ing the ExCollege class Asian Ameri can Boston, “That was a semester where there [weren’t] any Asian American studies [classes]… I think that it’s im portant to note that ethnic studies have come out of student protest and resis tance and that there is resistance [from] the university to teach these classes.”

This institutional inertia extends be yond the classroom, affecting not only those within academia but also activ ist groups. For student organizations like TASC and SAPAC, which focus on political advocacy on campus, it is of ten difficult to reach their goals. As they work on projects like adding caste to Tufts’ discrimination policy, these groups face a constant uphill battle to overcome barriers erected by the administration.

Last spring, SAPAC began advocat ing for the addition of adding caste to the Office of Equal Opportunity’s (OEO) discrimination policy. SAPAC circulated a petition that amassed 571 signatures from Tufts students, faculty, and staff; however, caste has yet to be explicitly added to the OEO’s discrimination policy. Sophomore Sristi Panchu, a member of SAPAC’s caste discrimination working group, revealed the challenges that their

group has faced with the Office of Equal Opportunity. She said that “[the OEO] makes [changing anti-discrimination policies] sound like such a smooth and streamlined [process], but it’s really not”.

Loh expressed her frustration at the degree of the Tufts administration’s coop eration in responding to student claims. “[Tufts often waits] for students [calling for change] to graduate so that they can move on from it,” she said. “I’m think ing about the AAC and how, in 2019, they almost took [it] away.” As the ad ministration fails to recognize students’ needs, the burden falls on other facets of the community to pick up the slack.

Departments like RCD Department rely on the labor of faculty members to continue to function. In fact, there has recently been much controversy over

However, a relationship between stu dents and faculty who experience this provides an avenue to pursue more criti cal academic work and accountability on campus. “Every four years, students cycle through, and the administration knows that. [Tufts] will do these very performa tive things like talk about making task forces… to placate until students gradu ate,” Mukherjee continued. “A lot of the time, professors end up being the only living memory of movements that want ed to get off the ground, but [couldn’t].”

For Courtney Sato, an Assistant Pro fessor within the RCD Department, this collaboration captures the essence of criti cal scholarship and dialogue within Asian spaces. “At a place like Tufts, students and faculty are often able to work in tan dem to showcase the kinds of research that are possible through departments like the RCD Department… Similarly, I aim to offer students the kind of mentor ship that reflects my own commitments to working not just in conventional uni versity spaces, but through work and ac tivism that goes beyond the bounds of the university,” Sato explained in an email to the Tufts Observer. “Often, students are some of the best collaborators for such work as they’re often already integrated and engaged with such communities.”

the treatment of faculty of color, with the Admissions Dean being accused of workplace discrimination on racial grounds. This has brought to the forefront the long-lasting concern that the com munity has had for these faculty mem bers and the resources they are given.

When asked about the role faculty and staff play in the struggle for representation, senior Malvika Wadhawan, co-director of SAPAC, explained, “Professors and faculty do have a lot of power at this university… Professors of color generally can’t even get to that point of having tenure… A lot of how organizing on campuses works is through student and faculty collaborations… [Uni versity of California faculty made a plea to] add caste to their anti-discrimination policy.” Wadhawan continued, “[Howev er], it [feels] like, if [those faculty] weren’t there, [nothing] would be happening.”

Bringing together academics, stu dents, and community members, student activist groups have created momentum in realizing some of the Tufts Asian American community’s goals. For the future, TASC and SAPAC want to continue to push Asian students at Tufts to critically engage with their identities. Wadhawan said, “A lot of Asian American students on this campus are not political and pride themselves in not being political… I think there’s a lot of room [for] the Asian American com munity at Tufts to grow in terms of think ing about their own identities critically.”

“THERE’S A CERTAIN SOLIDARITY WHEN YOU UNDERSTAND THAT YOU’RE LEARNING ABOUT THINGS THAT AFFECT YOU TOGETHER.”

By Leah Cohen

By Leah Cohen

This Halloween, the greatest fright was a terrifying, bonechilling pack of ghouls—the United States Supreme Court—receiving oral arguments for two cases poised to decimate the barest semblance of equity in college admis sions across the nation: affirmative action. The most con servative Supreme Court bench in 90 years has had a mara thon two years and this year it’s tackling some of its most controversial social-policy-oriented cases yet. In this case, lawyers from the organization Students for Fair Admissions presented their case for why af firmative action—the use of race as a factor in college admissions—is a violation of Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Tufts joined 32 other colleges and universities in submitting amicus briefs in support of our neighboring university down the red line, Harvard, and of affirmative action as a practice.

As oral arguments began in Washington, D.C. this year, Tufts students received an email from the Office of the President titled, “Statement on Supreme Court Cases regarding College Admissions.” Tony Monaco wrote, “At Tufts, we celebrate diversity and recognize its power to enlighten, teach, and bridge differ ences. Indeed, it is foundational to our mission to provide transformative experiences for students, faculty, and staff in an inclusive and collaborative environment.”

Obviously, this is a sentiment we can all get behind, generally speaking. But in the face of recent news about discrimination in the Tufts Admissions office, as well as the data available on the university’s “diversity dashboard,” these words ring hollow. For an institution such as Tufts—famous ly need-aware in their admissions—this case presents a mo ment for reflection: Do we accurately practice the principles of affirmative action?

The phrase affirmative action was first used by former President John F. Kennedy to describe a directive for federal agencies to intentionally and proactively diversify their employee base by ensuring applicants are treated equally without regard to race, color, religion, sex, or national origin. This directive also established the Committee on Employment Opportunity. Following this, colleges began to implement this tactic of affir matively assessing their admissions standards and structuring them to include race—and the impact of structural racism—in their assessment of prospective student applications.

The prime driver of the war on affirmative action is a conservative activist named Edward Blum, also famous for being a key architect in Shelby County v. Holder, the 2013 SCOTUS case that decimated the Voting Rights Act. Blum is the frontman of a vast network of far-right donors, litigants,

and politicians. These two cases are Blum’s second attempt to end affirmative action, the first being the failed 2016 chal lenge Fisher v. University of Texas at Austin, in which Blum sought out and celebritized Abigail Fisher, a white Texan woman who claimed she was not accepted to UT Austin because her spot was claimed by someone benefiting from the university’s affirmative action policies (though she did not actually meet the benchmarks for automatic acceptance to the university as a graduate of Texas public schools). A common theme in anti-affirmative action cases is this phe nomenon of imaginary white grievance—that if it were not for this policy, the spot would’ve been claimed by a white student. The 2022 cases make for a stunning example of multiculturalist white supremacy, a term coined by Ameri can Studies scholar Dylan Rodriguez. In these cases, the plaintiffs are non-white but still operate within the dynam ics of American white supremacy, which has reconstructed whiteness around capital and proximity to racial dominance as opposed to purely the phenotype of the body.

According to Tufts University’s own data, as of fall 2021, 47.9 percent of Tufts undergraduate students self-identified in their application materials as white, and 68.4 percent of Tufts faculty identified as white. Only 5.2 percent of under graduates identified as Black or African American. Despite the implementation of and renewed support for affirmative action, Tufts’ own admissions statistics bring under scru tiny whether Tufts actively recruits, accepts, and represents diverse communities.

Several articles from on-campus publications reveal that Tufts’ admissions diversity issue extends well beyond need-aware policy and insufficient aid grants. There is cur rently an ongoing investigation into Director of Admissions JT Duck for discriminatory practices against his employ ees in the admissions office. A September report revealed massive dysfunction, exclusionary practices, and failures of the Office of Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Justice in the Provost’s office. The people in charge of making deci sions about who gets to attend this institution are currently under inves tigation for racism and discrimination. does that make for an “inclusive and collaborative environment?”

The issues of racism and lack of commitment to diversity trick le down from the administra tion. A stunningly low 3.4 per cent of Tufts faculty identified as Black or African American in fall 2021. A recent Tufts Observer article took a deep dive into the

“mass exodus” of faculty of color from the univer sity, driven away by a lack of financial resources and a “cli mate of hostility.” How can the universi ty expect pro spective students of color to feel confi dent about enrolling in this institution given these circumstances?

consider when I selected Tufts. When I visited campus be fore enrolling, I mostly saw faces that reflected my own. As a Jewish woman, I was doubly affirmed I’d be cared for on campus by Tufts’ vibrant and multi-faceted Jewish life, which included space for progressive, anti-occupation Juda ism that had become integral to my religious practice in my teenage years. Now, as I watch the white ethno-nationalist takeover of the Supreme Court manifest itself in attacks on diversity on college campuses—led by a Jewish man—I feel dismay and anger that someone who claims to share my re ligious and cultural values would feel compelled to attack affirmative action. I can think of no better example of tik kun olam—healing the world—as a praxis than affirmative action: the intentional and proactive effort to mitigate the harm of systemic racism and historical exclusion by factor ing in race in admissions to elite institutions.

With all of the university-wide blatant failures to cul tivate a diverse campus—evident in its lack of student and staff racial diversity and its inequitable need-influenced admissions practices with respect to financial aid—the question of whether or not Tufts truly practices principles of diversity feels inevitable. With the likely overturn of the practice impending, it is time for Tufts to reassess its admis sions policies and potentially overhaul the whole process. In order for Tufts to be a truly anti-racist institution that cultivates sincere diversity and cultivates an “inclusive and collaborative environment,” a lot has to change.

By Neya Krishnan

By Neya Krishnan

“you don’t get rid of the pain, you just make room for it” shares a six-year-old girl as she narrates the way she placed her small hands on her mother’s flailing chest, how she pumped life into her mom’s frail frame and failed, how she resented her hands for not being enough. how she carried the memory like an anchor around her ankle and fell into a “deep depression.” and I wonder how a child comes to learn depression how she could so intimately know the cruel enormity of that sensation, that painful existence. but I suppose these are the casualties when a child becomes rootless.

“she was killed at home, cooking dinner with her cats, by a Russian missile” a journalist confides in an audience of undergrads at 10:30 a.m. on a Saturday morning; they sit in cushioned auditorium seats, munching free bagels and muffins from the lobby outside, eager to feast on his words too— but grief traces his tongue and caresses his words as he aims to fossilize his friend’s memory. I try to picture the mundanity of the moment, this woman pacing around her kitchen in search of ingredients in her cabinets, her cats carefully tracing her steps, and the precise second a monster missile erased the scene in an act of violence. is that all it takes to remove a legacy?

“it’s important to have a long-term commitment to places” I heard a woman say once— I’m not sure that’s true but it makes me question what makes a place worth the long-term commitment— the same woman spent six years of her life documenting a village in the Congo where three-year-old girls were viciously violated by men who believed a baby’s blood would offer them supernatural protec tion. what rooted her there? how do we decide to stay in a place that isn’t safe? I’m not sure I know.

“if he was here, he would...” my mom’s best friend whispered as we spoke about the loss of her husband over strawberry margaritas— and I realized then there is nothing more painful than the series of possibilities that are born and simultaneously die within that singular conditional “if.” mom’s best friend is family, and I think that status change happened after the loss— she is the kind of family that waits outside the airport, plans the surprise party, drives to the middle of the highway when our car breaks down. and I find it sort of strange and wonderful how roots can burn, blister, break, and still, still remain ever-growing.

in my most hormonal years, my best friend melissa told me every pimple is an angel’s kiss, and I clung to her words as every monstrous spot emerged and collapsed, leaving dark whispers on my face as I scraped and scarred. and now I am 20 and mostly they have faded— all but the two on my cheeks from you

Don’t forget to set your clocks back!” is a phrase most Americans have grown accustomed to when day light savings time (DST) hits. While many groan and complain about this seemingly trivial process, others de light in getting to wake up to the extra hour of sunshine. As DST continues, it receives more controversy each year. Many wonder how this archaic practice is still beneficial to modern society. Just recently, the US federal government proposed the Sunshine Protection Act, a bill that would make DST perma nent so that the time would no longer change twice a year, and American so ciety would operate under one standard time.

Many people are in support of this bill as DST can cause disruption in the

schedules and life balances of many Americans, including college students within the Tufts community. The Sun shine Protection Act provides unique benefits for these students.

DST is a practice that began over 100 years ago when English construc tor William Warnet proposed that the idea of daylight savings would prevent the British Government from wasting daylight. His idea was that DST would give more light in the daytime during working hours, allowing for laborers to have more energy and therefore be more productive. This idea continued to become popular until it was adopted by England following the end of World War I and several more countries, in cluding the United States, in 1918.

By Siona WadhawanToday, DST continues to reinforce toxic notions of productivity and hustle culture through distorting daily sched ules and limiting how we can practice self-care outside of work. Its very in ception, rooted in the idea of produc tivity and maximizing labor, is just the first indication of this. Because Tufts is an elite university, many students are already under a large amount of pres sure to be constantly productive to earn good grades, build strong resumes, and have successful careers. Low income and first generation students are also especially burdened by this, as they are dealing with added stressors of student loans, and for some, pressure from fam ily members to work hard to receive high paying jobs to provide for their families back home.

The process of DST distorts stu dents’ lifestyles when they are already balancing academics, extracurriculars, jobs, as well as the looming pressures of internships and career paths. As a freshman this year, it has been difficult to adjust from having an organized day to day schedule to having lots of unstructured time which I have the sole responsibility of managing. Being at a smaller, liberal arts university like Tufts, the “girlboss” culture is definitely real. I often feel like I am putting a lot of pressure on myself to complete as many tasks as I can in order to maximize my time as much as possible. Having the sun set by 5pm, often when I am just getting out of class, can heighten these feelings, as it gives me the sense that I have less time in the day to get work done. When it becomes dark that much earlier, I feel a sense of shame that I have wasted time and not been as pro ductive as I “should” have been during the day.

Additionally, DST limits the amount of down time students have to spend outside and decompress. The time limit constrains students’ ability to practice self-care and make time for themselves outside of academics and work. Students who may be on workstudy programs, hold off-campus jobs, or participate in research have even less free time they can prioritize and may not get to experience sunlight at all throughout the day. While one could argue that people can still exercise selfcare indoors, there is a lot of value in being outside that we are losing due to daylight savings. Being out in fresh air and sunlight is a critical way that many students including myself can ground themselves amidst hectic schedules and feel connected to the present.

In fact, spending time outside has been proven to increase our mental and physical health. A lack of exposure to sunlight can result in seasonal depres sion for many people, a phenomenon in which the brain responds to changes in daylight hours. The amount of day light one receives affects melatonin and

serotonin chemicals in the brain which influences mood and sleep cycles in an individual. This is why the loss of sunlight earlier in the day as a result of DST can be especially harmful. When students have less time to be in the sun and outdoors, they are more likely to feel tired and experience mood chang es. Having darkness fall so early in the evening has been shown to increase levels of melatonin while decreasing levels of serotonin in the brain result ing in experiences of depression for many people. A research paper pub lished in 2017 indicated an 11 percent increase in depressive episodes during the switch from daylight saving to stan dard time.

The mood, sleep, and schedule changes associated with DST all work to exacerbate these pressures and emphasize a negative relationship to time and productivity. By continuing to practice DST, America enforces a negative prioritization of productiv ity over physical well-being which is passed down to younger generations. This emphasis on grind culture can result in students creating very high expectations for themselves and feel ings of shame and failure when they are unable to meet these goals. Studies indicate that this ultimately results in people being less productive and leads to burnout. Even more worrisome, this can lead to serious mental health issues including anxiety and depression.

These toxic relationships to work and productivity can also affect the way we see ourselves. When the work we produce becomes the marker of vali dation for us, our self-worth as human beings becomes intrinsically tied to the work we produce and our contribu tions to society rather than our quali ties as individuals.

Ultimately, the issue of DST raises an important question surrounding the kind of standards that are reinforced for college students regarding time and productivity. We need to critically ex amine the impact of grind culture in

our society and the ways in which it affects our mental and physical health.

There is a lot more that can be done at universities to lessen the strains of academia. For example, the govern ment should ensure all universities are equipped with proper mental health and counseling services to improve stu dent well-being. Within the Tufts com munity itself, Counseling and Mental Health Services can be expanded to account for seasonal depression, espe cially as it coincides with the busiest exam season for most students.

In terms of academic workload, more networks of communication could be established between academic departments so that different disci plines can work with one another to ensure that big assessments and dead lines do not fall on similar dates. For example, there have been periods this semester where I have felt really over whelmed by the amount of tests and projects I have that fall at the same time. Creating a system around this is a major way student stress levels could be minimized. This could be addressed through implementing more flexible timelines so that students can adjust as signment deadlines depending on their workload in other classes, rather than receiving late penalties or not being able to dedicate enough time to prepare for their different subjects.

The administration can oversee actions such as these as a way to be gin rethinking how hustle culture and toxic productivity are embedded in our academic institutions. Lastly, all of us as individuals have a part to play when it comes to dismantling grind culture for good. This can look like checking in with ourselves and others frequently on stress levels and physical well-being. Take breaks, go outside, spend time with friends, and most importantly re mind yourself your value is not defined by the work you do. You can only be your most meaningful and authentic self when you put your well-being first and foremost.

After just 44 days in office, Prime Min ister Liz Truss resigned from her posi tion in late October. Rishi Sunak, Brit ish billionaire and previous chancellor of the Exchequer, in assuming the role after Truss, made British history by becoming the first Asian prime minister. Truss left her position due to an incredibly turbu lent and unsuccessful start politically and financially, which can be attributed to a failed economic strategy meant to restore UK markets. Many have been left wonder ing why the United Kingdom’s leadership has been so unstable and what’s to come for its future.

Truss’ start took a turn when her eco nomic plan was met with backlash and disagreement, undermining her authority and resulting in Conservative Party MPs (Members of Parliament) revolting against her. Truss’ team believed markets would give the country the ability to restructure the economy with 45 billion pounds ($50 billion) of unfunded tax cuts.

This resignation left Truss as the shortest-serving PM in British history. However, she isn’t the first PM to receive widespread dislike. Predating her office, Prime Ministers Gordon Brown, Theresa May, and Boris Johnson had also been met with disdain from the British public.

Boris Johnson led a much longer path than Truss, but was also forced to step down after members of his Cabinet quit

and one of his closest allies, Treasury Chief Nadhim Zahawi, publicly asked him to re sign for the good of the country. Johnson’s infamously brash personality allowed him to execute Brexit—which many politicians believed an impossible feat.

Johnson won the 2019 election with the most considerable conservative major ity since 1987. David Art, a political sci ence professor and scholar on European comparative politics, noted that at the time of Johnson’s election, he was fairly popular and promised to get Brexit done, leading to a resounding victory.

The sudden lack of public support that contributed to his resignation stemmed from several elements of inadequate lead ership. “What happened to Johnson was that a series of scandals sapped almost all of his support,” Art said. “When Donald Trump would have a scandal, voters dip by about 5 percent, but what’s special about British politics is once the confidence in the leader goes, it all crashes.”

Since David Cameron announced that he would implement Brexit in 2012, it has been a major destabilizing factor in Brit ish politics to which many other woes in British leadership can be connected. Art explained David Cameron was forced to resign when he lost the Brexit referendum, which he called himself. “[Cameron] could have been a long-standing prime minister, but Brexit cut his career short,” Art said.

By Megan ReimerTheresa May’s inability to get Brexit done also cost her the prime ministry.

After all the political instabil ity—mainly from tensions surrounding Brexit—Tufts students and faculty con nected to British affairs are hoping for a leader who understands the people’s needs while following through on their responsibilities.

With the UK on the brink of a reces sion, economic turmoil has left many peo ple worried. Ruhama Mulugeta, a sopho more from London, said, “It’s so extremely costly to live in London right now, because of inflation and tax increases, and on top of that there are minimal job opportuni ties available now.” She also described how inflation has caused the value of the Brit ish pound to dip to record lows against the US dollar. “You need someone who under stands the economy and the financial side of it,” she said.

Mulugeta also feels the UK needs a prime minister for the people. “[The UK needs] someone who has the interests of the public. I feel like [past prime minis ters] didn’t take into account all the com munities, like the working class, as much as they cared for people trying to get their money up,” Mulugeta said. “A good prime minister [is one who benefits] ev eryone, which is hard because how can you benefit everyone?”

“The new prime minister, Rishi Sunak—no one re ally likes him,” Mulugeta said. She values representation in politics, but, despite Su nak being a person of color, she said, “[He] is worse than some. He’s all about making the rich richer and the poor poorer.”

Sophomore Ishika Gupta is also wary of Sunak. “Sunak is similar to Boris John son, and Johnson was all talk, no walk,” she said.

Like Mulugeta, Gupta also thinks that Sunak may not have the best intentions when it comes to alleviating poverty. “Su nak was basically evading his taxes and he and his wife got away with millions of pounds for nothing. He’s a billionaire.”

In April 2022, it was found that Sunak’s wife, Akshata Murty, had potentially evaded up to £20 million in UK tax by being non-domiciled and paid £30 thou sand a year to keep the status.

In addition to economic matters, Gupta was dis satisfied with the past prime minis ter’s treatment of her home country of India. She is look ing to Sunak to follow through on his word.

Past prime ministers like Johnson “did nothing that he said, absolutely nothing,” Gupta said. This inaction with India con tributed to Johnson’s low public approv al at the time of his departure—which Art stated as 20 percent—already unheard of in American politics. Liz Truss’ rating was half of that when she resigned.

Sunak’s public approval rating is going to be guided by his han dling of the British economic state. “Hopefully, Sunak just helps restore the economy,” Mulugeta said. “I think that’s what the future of British politics should look like because there’s a lot of classism in the UK, and I feel like that’s some thing that needs to be fixed.”

Sunak is con sidered politically left of Liz Truss, but they are both right-leaning, free-market con servatives. “The main difference between the two is that Sunak criticized Truss’ economic plan as a ‘total fantasy and unrealistic,’ that would result in a market crash. [Her budget plan] was called ‘trus sonomics,’” Art said. This moniker was coined by critics, who

pointed out that the current state of the fi nancial market would not be able to make Truss’ supply-side and trickle-down-eco nomics-based plan a success.

Sunak is a member of the Conserva tive Party. The opposing party, the Labour Party, hasn’t been in power since 2010. In November 2022, nearly 50 percent of Brit ish voters intended to vote for the Labour party in the next general election, com pared with only 24 percent for the Conser vative party. Prior to Boris Johnson’s res ignation in July 2022, 29 percent of voters said they would go Conservative, with less than half, or 40 percent, voting Labour.

These results indicate a change may be coming in the next presumed election in 2025. “The Labour Party sometimes has dreamy, nice intentions; they are all about helping people, but it can be unrealistic,” Mulugeta said. “I feel like sometimes people think the reason why they vote conservative is that it seems more realistic, and it’s more focused on the economy, so it’d be nice to find a middle ground between both of them because I feel like [Labour Party] is more concerned with people, and the other one is more concerned with money.”

Mulugeta is looking to the UK for a leader who acts with the interests of ev eryone in mind. “Prime ministers don’t always take everybody into account, and that’s when things get messy. I hope that the future of Britain involves a means to support all walks of life in our diverse communities.”

With extremely low public opinion polls about conservative support in Brit ain, Sunak needs to rally support for the party through his leadership by the time of the next election in 2025. For the Tufts community, students like Mulugeta and Gupta are hoping for a better and brighter future in the UK that includes everybody, not just the rich and powerful.

“[SUNAK] IS WORSE THAN SOME. HE’S ALL ABOUT MAKING THE RICH RICHER AND THE POOR POORER.”

“& now back to massachusetts,” I captioned an Instagram post of myself and friends in New York in late June 2022. While scrolling through the comments, one stuck out to me. Someone had com mented, “Where we all definitely live,” to which I replied, “home?”

“Home?” is the way I still feel about Massachusetts. Not Medford/Somerville, MA, but Western Massachusetts, where my family relocated during our crosscountry move from Los Angeles in June 2021. It’s been over a year now since the city I grew up in has no longer technically been home, yet even after all that time, my search for a feeling of home remains.

Since June 2021, I’ve been able to visit California three times. In theory, I wouldn’t have visited Los Angeles much more than that given I’m in college, but the action of going home over breaks to

by Adeline Grimmett

by Adeline Grimmett

somewhere that was never “home” creates a big difference. I knew my family would move someday, but I hadn’t expected my world to shift locations immediately after high school. There were three days be tween donning a cap and gown and get ting on a plane to North Carolina to be a sleepaway camp counselor. Could three days have ever been enough?

In only three days, I hugged my best friends goodbye, drove circles around the streets I called home, and laid in my twin bed, just as I had since I was two years old. It was my goal to memorize the pressure of my friends in my arms, glue the sights of Los Angeles in my brain, and suck in the air of my bedroom in hopes I could remember these things forever while fighting the knowledge they would never be the same again. It is one of my greatest blessings that I left California prior to my childhood home being packed into boxes; I remember it just as it was all my life. I lived 92 percent of my life in that home. How could it be possible to replace that in

the 8 percent of my life, only 18 months out of 227 total, I’ve lived since then?

It has been 18 months of self-discov ery in many ways, but at the top of the list comes the answer of where to call home. Well, an in-progress answer, but one that is much clearer now than a year ago. In November 2021, if asked, I would have said my home was in Western Mas sachusetts where I have a physical house. Today, I’m no longer sure that home re quires physicality. In the past year and a half, each day has come with a new question of home. Questions like: What does the physicality of home mean? Is it only one place? Does the amount of time you’ve spent in a place affect its classifica tion as home? Can home be people? Can it be a thing? An idea?

Part of my process of moving on from losing a place so important to me is pondering the answers to these ques tions. Home, of course, doesn’t have to be a place, but sometimes it is. I smiled over my Tufts admissions email while sitting on my living room couch, I cried about the death of my first dog on the hardwood hallway floor, and I whispered my deepest secrets during sleepovers in the guest room bed that got smaller each year I grew up. And sometimes it’s not. Looking back, there was no place that I felt mentally safe and free in Los Angeles. There was always the worry of expecta tion and conformity—who my parents wanted me to be, who others in LA were, and who I thought I should be.

Home is a feeling of safety—a place where I don’t have to hide my emotions— which I found in my car, where blasting music drowned out the world. Home is where I can be unabashedly myself and not have to try to fit in. Like in the the atre where I can hide in the shadows of someone else’s story. On the T, where I am a stranger to everyone for just a few minutes. Home is with like-minded people. People like my friends and room mates at Tufts that allow me to be my messiest, just-woken-up self and love me anyway. There is a sense of belonging one should feel when they arrive at the end of the day. I felt a semblance of this for the first time in my lumpy bed at sum mer camp right after I moved, and then again as I returned to the halls of Metcalf

after classes. Home allows you to experi ence life without worrying about perfec tion. Something I get to experience with my girlfriend who wipes away my tears when I cry. Home takes each moment of life and stores it, sans judgment, to remember at another time. Just like my memories tucked away in books and in music. Home is a manifestation of your heart, found in a million little moments and meaningful people.

While seeking a singular replace ment for home, I found it in a jumble of people, places, and ideas. Though these experiences may not be forever, they’ve all been places of comfort for the mo ment. Home is not just one place—some thing I knew long before moving, but didn’t comprehend until the discovery of my (potentially infinite and still in-prog ress) mixture of residences and residen tial feelings.