It has been an honour to produce Tusaayaksat magazine for the Inuvialuit society. What began as a newspaper in 1983 is today a full-fledged magazine in color, filled with pictures and words of Inuvialuit. This process of change in the magazine is also a reflection of the Inuvialuit society as a whole. Defined by growth and progress, Inuvialuit society seeks to preserve its cultural values within a dominant Canadian culture. Living in the cold isolated Canadian North is part of the Inuvialuit’s identity that cannot be separated when taking into consideration its culture. Our ancestors, with their experiences on the land, have developed a systematic foundation for us in terms of shelter, gathering food, and clothing ourselves using basic skills and tools. Such practices have been passed on from

one generation to the next, allowing for the preservation of our social traditions. However, in the midst of regional, national and global change, many facets of our existence have been challenged. At such times, the Inuvialuit overcame many of these challenges and continue to strengthen the community from the roots. This issue of Tusaayaksat represents the Inuvialuit’s determination in building a strong and prosperous future by intertwining the past and the present and forging an authentic identity for generations to come.

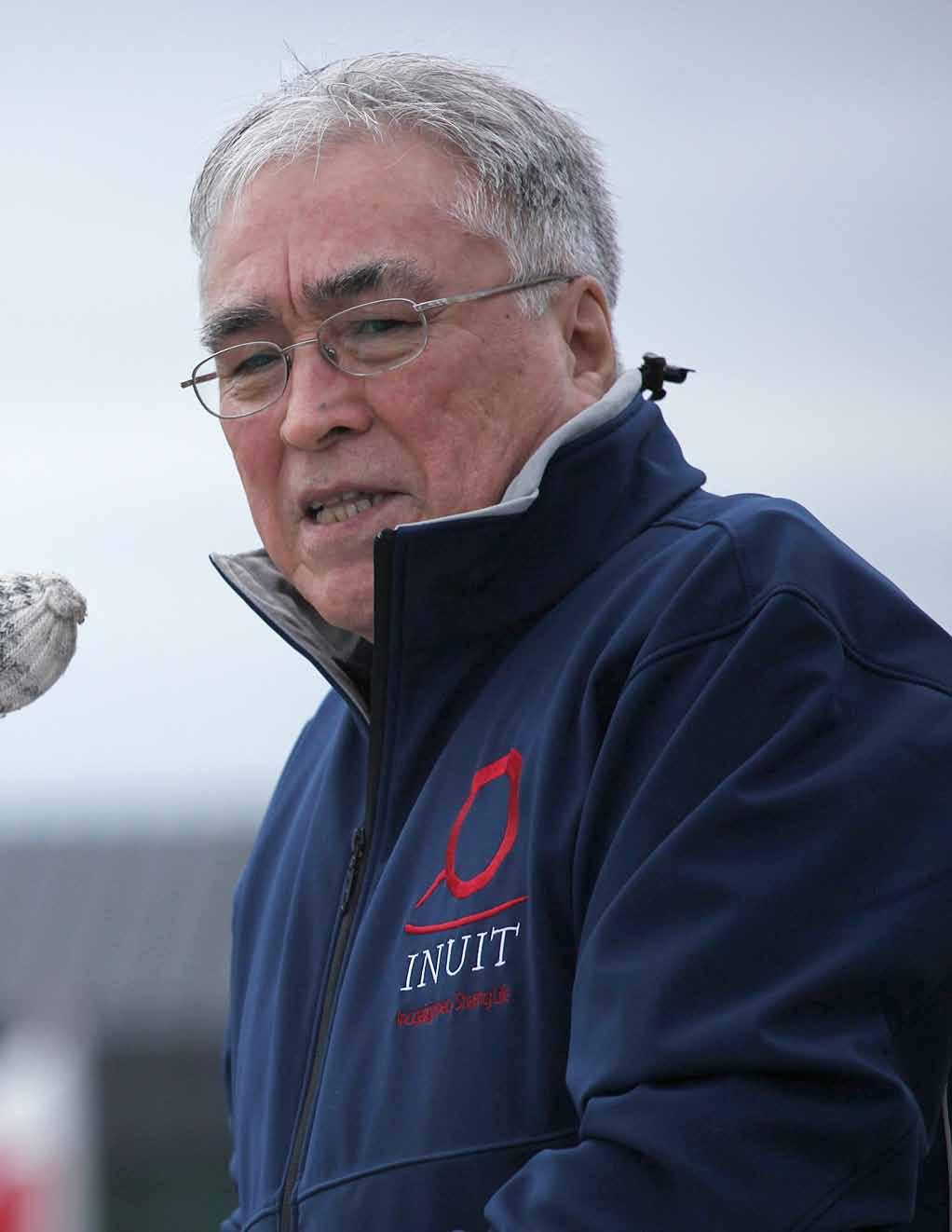

Topsy Cockney

Topsy Cockney

Tusaayaksat is Inuvialuktun for “something new to hear about.”

Published quarterly by Inuvialuit Communications s ociety at 292 Mackenzie Road, Inuvik, northwest Territories, Canada. Please note starting this issue we have changed the method of labeling by volume and number to being just a number. number 28 accounts for the very first issue of the magazine to this current one. For advertising and subscription inquiries: please email us at ics@northwestel.net or call (867) 777-2320.

Publisher Inuv I alu IT Co MM un IC aTI ons s o CI e T y

Editor in Chief To P sy Co C kney

Managing Editor Maun G T I n Assistant Editor a h M ad s yed

Contributors

Ja MI e Bas T edo. a l B e RT e l I as. Tyee Fellows. k ev I n Floyd. Mel I nda G I ll I s. l e TITI a Pok I ak. Maun G T I n

Contributing Photographers

h ans Bloh M s hannon C IB o CI n oel Co C kney. e dwa R d e as Tau G h. Tyee Fellows. l an C e G R ay. Fa IT h Go R don. Te RR y h al IFax. Pe GG y Jay. Tessa Ma CI n T osh. Bo B Meshe R lI nh nG uyen. l e TITI a Pok I ak. d av I d sT ua RT s us I e s ydney. Maun G T I n. d ev I n Tu R ne R wanl I w u

Designer d av I d lIM o Production a ukus TI Med I a d es IG n sT ud I o

ICS Board of Directors

President Je R o M e Go R don (Aklavik)

v ice President d onna k eo G ak (Sachs Harbour) Treasurer d e BBI Radd I (Tuktoyaktuk) Directors d elo R es h a R ley (Inuvik) M I ll I e Th R ashe R (Paulatuk) Ma RG a R e T k anayok ( Ulukhaktok )

The title says it all. The beaming faces of uvunga atiga – “real people” – clearly show it. Their words shout it. This book’s take-home message leaps off every page: Proud to Be Inuvialuit.

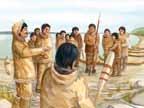

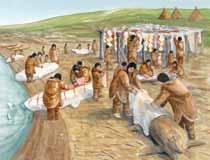

“This story is about my family, my community,” writes Tuktoyaktuk outfitter and author James Pokiak, “and the importance of keeping our traditions and teaching them to the young in our ever-changing world.” Central to those traditions is the annual beluga whale harvest, the featured adventure in this book.

Having set the stage which celebrates local home and town life – from swinging on monkey bars under the midnight sun to visiting the famous ice house deep under streets of Tuktoyaktuk – Pokiak’s story really takes off when he invites his daughter, Rebecca on an adventure to harvest her first beluga whale. “She’s a bit nervous,” writes James, explaining that years ago, women were not allowed to hunt. But times have changed and he has trained her well. “When she’s sure of a good shot she throws the harpoon.”

What follows is a unique and very sensitively portrayed description of how the Pokiak family and friends process a harvested whale. “It was the most respectful hunt I have ever been on,” says co-author Mindy Willet, a Yellowknife based educator and

Published by Fifth House Grades 4 – 8, 32 pages

ISBN: 978-1-89725-259-8

former teacher in Kugluktuk. “To see the building of community that goes on around the processing of the meat is so encouraging. I hope it continues forever!”

One of northern Canada’s foremost photographers, Tessa Macintosh, contributed over fifty sparkling images to this project. “The Pokiaks were so generous with their hospitality and so sharing of their lives for the book,” Tessa told me from her Yellowknife home. “I felt honoured to be part of the team and to share my enthusiasm for the place, the culture, and family life with young readers.” Captivated by the rich coastal landscape and whaling culture, Tessa described Tuktoyaktuk as “a photographer's heaven”. She hopes that readers find the book’s photographs mamaqtuq. “That's how I think a good photo should be – delicious!”

Pokiak’s narrative of the good life in Tuk and on the land is enriched by interesting sidebars with Inuvialuktun word games, traditional stories, and songs. The book also includes a fascinating depiction of harvest strategies from the days when people pursued belugas in sealskin kayaks, as well as a close-up look at contemporary whale-hunting technology. The back of the book includes additional vocabulary plus details on the Inuvialuit Settlement Region, related literature, beluga facts, and how traditional and scientific

knowledge have been blended to help protect beluga populations. All of this material provides a treasure trove for potential class discussion and followup projects.

This is the fifth book in “The Land is Our Storybook” series about the diverse lands and cultures of the Northwest Territories. Like all the other titles in this series, Proud to Be Inuvialuit is aimed at kids, but will appeal to young and old readers everywhere who have an interest in northern lands and aboriginal cultures.

This book can be read in less than ten minutes. But its warm, cheerful photos and engaging, multi-layered text will entice you to curl up and linger in the glow of a proud and vibrant northern culture.∞

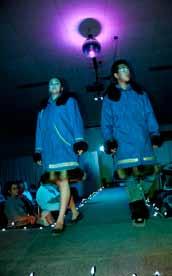

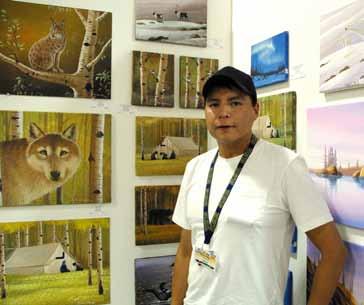

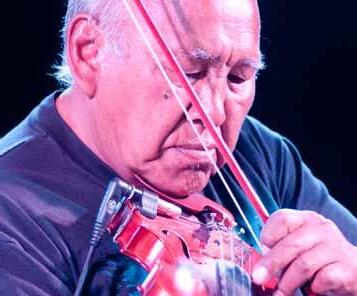

The opening ceremony of the 22nd annual Inuvik Great Northern Arts Festival (GNAF) took place on July 9, 2010 at the recreational centre inside the Midnight Sun Complex. The night was made memorable with Inuvik drummers, dancers, and singers, whose music, dance and song brought liveliness and filled everyone’s eyes and ears with excitement. Bright flashes from cameras illuminated the entertainers from all sides. As time elapsed, the sounds and movements became more intense drawing the audience onto the stage to unleash the rhythm in their body.

From July 9th to the 18th, creative works of over 60 different Northern artists and of artists across Canada were displayed filling every corner. From carvings, paintings, sewing, beading, leather works, metal works, to handcrafted jewellery were on display throughout the Festival. For many established artists, the Festival has become a place they call home and where they return each year. For new artists, it is a

place where they can introduce their works to a wider audience and promote their craft. The Festival also allows them a chance to interact and grow in the artist community.

During the Festival, spectators from across Canada and around the world poured in to the center looking for a unique purchase, others simply wanted to be part of the experience in enjoying artwork that translates the culture of the Canadian North.∞

Inspiring to make you look bold, feel smart and be beautiful.

Olivia Lennie

Sarah McNabb and baby Alianna Gruben

Delanie Elias

Jennifer Cockney Mathew Nuqingaq Delaney Arey

Tara McNabb and Brian Kowichuk

Karis Gruben

Brian Francis

Alicia Lennie

Alicia Lennie

Koomuatuk Curley

Nicole Collison

Alicia Lennie Jenny Kalinek

Jennifer Cockney

Nicole Collison

Olivia Lennie

Sarah McNabb and baby Alianna Gruben

Delanie Elias

Jennifer Cockney Mathew Nuqingaq Delaney Arey

Tara McNabb and Brian Kowichuk

Karis Gruben

Brian Francis

Alicia Lennie

Alicia Lennie

Koomuatuk Curley

Nicole Collison

Alicia Lennie Jenny Kalinek

Jennifer Cockney

Nicole Collison

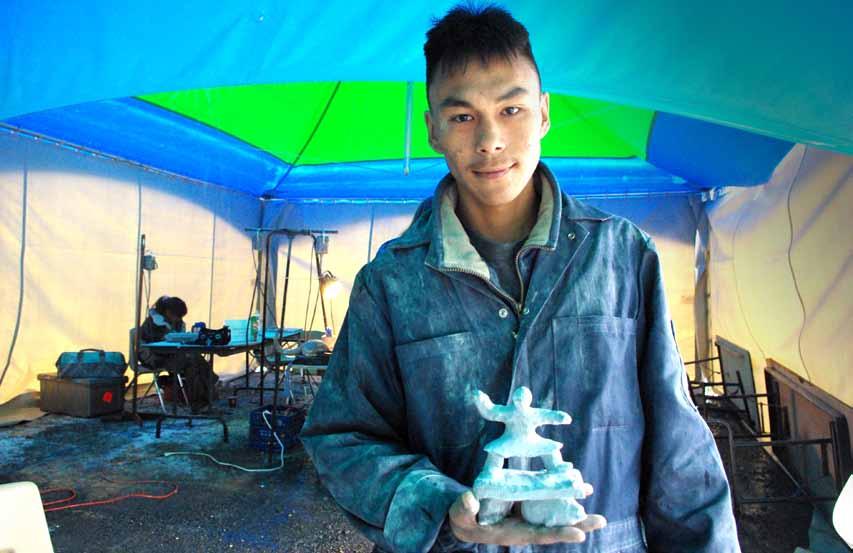

CURTIS TAYLOR, CARv ERTUKTOYAKTUK, NT

At the age of twelve inspired by his father, Curtis Taylor began carving with caribou antler like his father and later moved on to carving with soapstone. Today at twentythree, Taylor has become a well-known artist in the Northwest Territories. People from all across Canada, U.S., Japan and China appreciate Taylor’s sculptures.

MARY ANN TAYLOR, CARvER - TUKTOYAKTUK, NT. Mary Ann was born in Tuktoyaktuk and began carving nine years ago, learning from her father and her brothers. She has exhibited her work locally and at previous festivals.

H AOGAK , EAMSTRESS - S ACHS ARBOUR , NT

Haogak has been a seamstress for years. Her fine creations include fancy shoes embroidered with colorful flowers; from concept to finished product crafted by her own hands.

Growing up in Northern Canada is not easy. Inuit Youth living in isolated communities face social problems such as suicide, poor housing, school failures, violence, alcohol and substance abuse, and sexual abuse almost on a daily basis. These are heavy issues for Inuit Youth to grapple with on their own. But gather them together from all over Canada, give them a safe haven to explore such issues together, stir in a healthy measure of Elder wisdom plus a good dose of fun – and watch a magic power grow. That’s what happened in Inuvik last August at the second National Inuit Youth Summit.

“The summit gives Inuit youth the opportunity to participate fully and to be engaged in the issues that most directly affect them, and create solutions for youth by youth,” said Jesse Mike, past president of the National Inuit Youth Council (NIYC). Sponsored through a combination of grants from over 15 different organizations, the Summit was organized by the NIYC with huge support from Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami (ITK) and the Inuvialuit Regional Corporation (IRC).

The 68 conference delegates included elders and youth from every Inuit region across Canada representing 29 communities. Staff from ITK, IRC, the National Aboriginal Health Organization, National Aboriginal Role Model Program, Canadian Rangers, and many helpful volunteers from the Inuvik community were among the other participants.

The first youth summit of this scale was held in Kuujjuaq, Quebec, back in November 1994. This conference was an important stepping stone in creating a national voice for Inuit youth, aged 13 to 30, and marked the creation of the National Inuit Youth Council. This organization is made up of young

representatives from land claim organizations in Nunatisavut, Nunavik and the Inuvialuit Settlement Region, as well as the three regional land claims organizations of Nunavut.

In the 16 years since NIYC’s creation, it has helped many regions to develop innovative youth programs such as holding regular culture camps, in which elders share their land skills, and sending youth advocates to the United Nations to lobby for implementation of its Convention on the Rights of the Child. With NIYC’s support and guidance, Inuit youth across Canada’s North have developed a much stronger role in their parent organizations, making them a true force for positive change.

This force was definitely in the air at the Inuvik Summit, though you might not have felt it right off the bat. “First of all, everybody was very shy and didn't know anybody,” 17-year old Inuvik delegate, Alicia Lennie told Tussayaksat. “But they got us to sit at different tables, with four or five different communities at each. After about an hour we had to switch to other tables and be with different people. We had »

to ask each other questions like, What is your favorite colour? Your favorite food? At the end of the day everybody became friends.” In summing up what she learned at the Summit, Alicia said it was “having confidence in who you are and presenting yourself. Don't be ashamed of who you are, and have fun.”

The fun stuff at the Summit included an Out-on-theland Day where everyone could take part in traditional Inuit games, canoeing, swimming, kayaking, and the biggest excitement of all, the blanket toss, where at least 25 people hold a canvas blanket and fling someone – often kicking and screaming – high into the air. Evening entertainment included a special performance of the Inuvik Drummers and Dancers and an OldTime Dance. These fun activities were fueled by all kinds of tradtitional foods such as smoked fish, chowder, dried caribou, and musk-ox burgers and were accompanied by much laughter, dancing, and singing.

The work revolved around a very full agenda based on youth input from across Canada gathered by the National Inuit Youth Council. That input called for practical sessions that would directly benefit all participants, both young and old, while inspiring them to take new ideas and knowledge back to their communities. The Summit offered a series of daily workshops and discussion forums that delegates could choose from depending on their particular interests. Topics included health and fitness, mental health, early childhood development, fetal alcohol syndrome, addictions, education priorities, and the Canadian Rangers. The promotion of traditional knowledge, Inuit language and culture, Inuit history, and leadership were strong undercurrents that flowed throughout all of these workshops.

While the Inuit youth were rolling up their sleeves to work on National Priorities, a special guest dropped in on their Summit. “Have big dreams,” NT Premier Floyd Roland told the entire delegation just before boarding a plane for a meeting in Aklavik. “Enjoy everything to the fullest.” The Premier drew on his own experience to inspire everyone to aim high, to become whatever they want. He told them how, in his day as an Inuvialuk youth, he had far fewer opportunities than today’s kids. “Being a young boy from Inuvik, I never thought I’d become the Premier of NT”, he said. But, through a combination of steady, hard work and supportive parents and elders, he realized his dreams and scaled the heights of political power. Though brief, his words of encouragement gave the youth much to think about.

With the success of this year’s gathering and revitalized funding support for NIYC, we won’t have to wait another sixteen years for the next National Inuit Youth Summit. One of the delegates’ last duties was to pick a site for the 2012 Summit. Congratulations to the community Kangiqsujuaq in Nunavik, northern Quebec. That’s where Inuit youth can take stock of the significant progress and positive ripples set in motion at this year’s summit. It is at these summits where, according to past NIYC President, Jesse Mike, “members pass on knowledge and responsibilities to the younger members to maintain the forward movement toward a better life for Inuit youth.”

All at the Inuvik Summit would likely agree that this journey forward will be challenging, with many closed doors and rough stretches along the way. “We will go through changes, and ups and downs,” said NIYC’s new president, Jennifer Watkins, in reflecting

on what’s next. “But we will reach our goals together, as friends, as a community, regionally, locally and nationally.” Thanks to the new friendships, a common vision, deepened cultural pride, and boosted self-esteem spread by the Inuvik Summit, Inuit youth now have a shared reservoir of power to draw upon to move to a better life, one small step at a time.

Take this example. “There was a girl who was never able to speak out in public, who was very shy and nervous a lot of the time,” said Sarah Jancke, the Kitikmeot Regional Board member for NIYC. “Today I saw her get up and speak into a microphone about what she would like to see in education with Inuit youth. That alone made the entire summit worth it. I have at least one person going back with self-confidence.”

Besides bolstering everyone’s sense of self-worth, the summit reinforced the central importance of education in realizing one’s dreams. “This summit in Inuvik has been very empowering,” Jennifer Watkins said. “It has been a chance for us to learn from each other and from our elders. Learning can take us a long way. They say education is the key to success and I believe in that.”

“From the summit, I learned that I must go back to school and not avoid it like the plague,” said Inuvik delegate Douglas Price. “That my people, the Inuit of the North, can take control of their future by putting ourselves through school. The government is there trying to help us with an open hand. We must reach out and grab onto it, and embrace ourselves for the things to come ahead.”∞

The Inuvik Community Greenhouse is an extraordinary place. A place where your senses come alive. As you swing open the front door, your sight immediately fills with a world of greenery, ranging from large tall plants to small shrubs, vibrant colorful flowers to vines climbing wooden arbors. It smells fresh and alive as a hint of wetness in the air captures the aromas of different herbs.

The structure of that is now a greenhouse has undergone tremendous changes over the years. In the beginning it resembled a Quonset hut and housed hockey arena. Now, with its roof replaced with Plexiglas, the sun penetrates into this vast space and nurture growth. Today, the Inuvik Community Garden is known as one of the largest and most northern

community greenhouses in North America. Over a decade ago the Community Garden Society of Inuvik (CGSI) with the support of Aurora College brought the project together in hopes of community development. The greenhouse consists of two components: the main floor houses 74 raised plots for Inuvik residents. Some of these plots are sponsored for elders, group homes, children’s groups, the mentally disabled, as well as local charities. The second floor totals 4000 square feet and is designed for commercial purposes, this space is designated for bedding plants; as well, hydroponics vegetables are grown to cover operation and management costs. With the objective of being environmentally friendly, gardeners adhere to the goals of recycling, reusing, and reducing. In fact, the »

... the Inuvik Community Garden is known as one of the largest and most northern community greenhouses in North America.2010 greenhouse coordinator Ashli-Lisa McCarthy.

greenhouse encourages gardeners to bring their own biodegradable waste from their kitchens for compost and encourages them to utilize organic fertilizer, to ensure chemical free soil.

The organizers take innovative measures to promote the greenhouse. This year Ashli-Lisa McCarthy, who managed the day-to-day operations of the facility, organized the Fall Fair, which has become an annual event. The Fall Fair “allows for a chance to get community members that don’t have a plot to come in and see what it is all about”, explains McCarthy. For those that had a plot in the greenhouse, the Fall Fair was an added perk to celebrate and display their beautiful gardens to the public.

In order to truly enjoy gardening you have to experience the stages of growth, states Lucy Kuptana.

Seven years ago Kuptana had little knowledge about gardening, but she decided to start her plot in the greenhouse. Today, her beautiful garden consists of mint, cucumber, rhubarbs, gladiolas, nasturtiums, peas, tomatoes, peppers and rosemary. “When it is time for harvest enjoying the fruits of your labor is the most satisfying feeling because you nurtured it yourself day-in day-out, you know what you put in it and because of these reasons you are comfortable eating it” says Kuptana. It has also become a place where she and her boys spend time together seeding and watering the plants.

Social interaction among gardeners is another major component of the greenhouse that allows for getting to know the community better. For newcomers there is plenty of help and knowledge that can be gained

from the long-term members. Three years ago, for Melinda Gillis, the greenhouse was a stepping-stone into gardening. Her husband wanted to build her a greenhouse at home but she is hesitant to take that step because of the many friends she may have to leave behind and the many tips she gains from them. She explains “being part of this has been beneficial because so many people here know so much about growing from fertilizing to pollination using methods I was unaware of.” Gillis who has one full-plot is going to add another one next season to make available more produce for her family of seven.

Given the geographic remoteness, Inuvik depends on the more southern parts of Canada for all its produce. By the time transportation costs are taken into account, the prices of produce jump almost three-fold

on cost of buying vegetables. Hundred dollars for a full plot and fifty dollars for half a plot plus a membership fee of Twenty-five dollars per season is a small price to pay compared to the benefits gained for fresh, locally grown produce. Moreover, members can thoroughly enjoy many other benefits such as having a key to access the greenhouse at their leisure to having access to flower and vegetable sales a day prior to the public sales. Near the end of September the greenhouse wraps up its operations for the year and reopens in March. For many growing in the greenhouse is cyclical; but for others it is a new found hobby that adds a little green in life to warm their hearts.∞

By Agnes Nigiyok

By Agnes Nigiyok

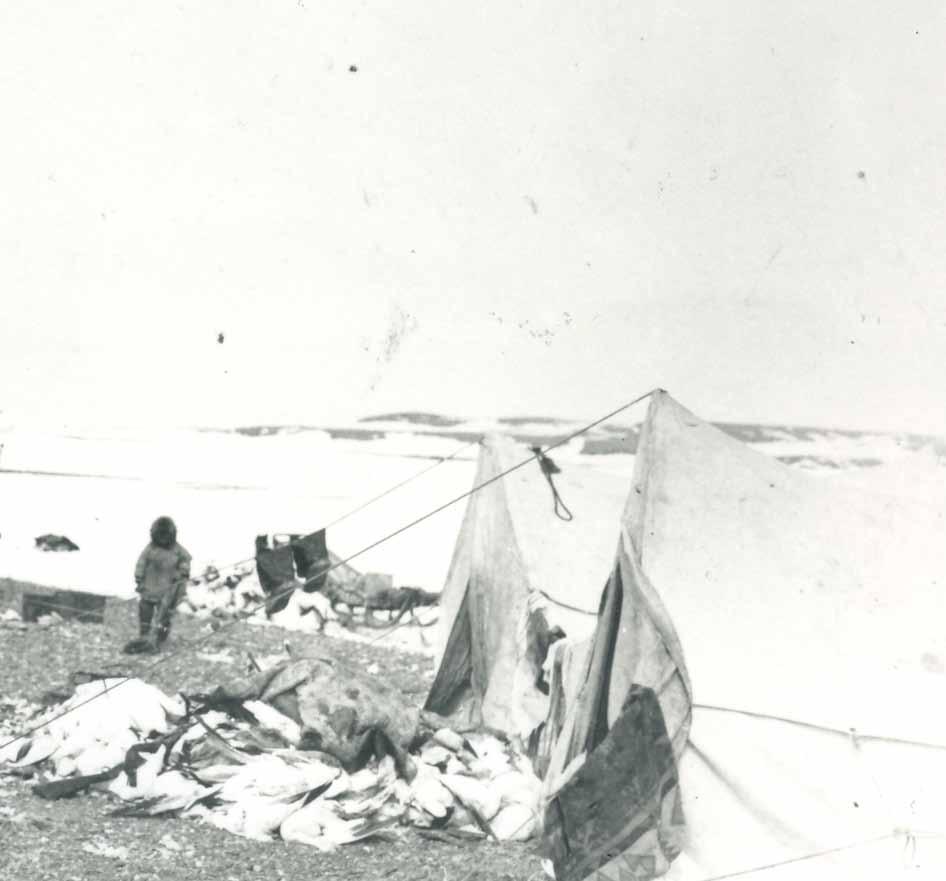

“I will tell about the time we were just married. We got only one child. This was about the time we were in a shipwreck. This is an actual life story. Now I am getting old. We went on a schooner from around Cape Perry area. The boat had no engine. It only had sails to make it go. My husband and I did not really know how the land was. Even though it is my land around the Holman area, the reason I did not know it so well was because I did not grow up around there.

Day after day, we travelled across from the mainland. They took turns to pilot the boat. Every time we looked out on top of the boat, it had ice on it. Also, we had only new dogs with us on the ship and they too had ice on their fur.

Sometimes I got tired of lying down below. I would go out to look, but there was no sign of land anywhere. Oh yes! The ship we were on belonged to Tokluk and his wife. I was told that my relatives were still alive. My husband had wanted to bring me to see my

relatives. Day after day passed. I would sleep or lay down from being seasick. I barely got up.

One of the times my husband came to check on me, he woke me and said, “Wake up. We can see some land but I don’t know what land it is.” So I got up because I really wanted to see land. I looked out. The land was really white with snow. I did not really realize how late it was. This land was to be our home. I wondered how we were going to get to the land fast enough because the ship we were on had no engines. We kept sailing. Soon we were closer to the land. Maybe the current had helped some. Again my husband came down and looked in towards me and said, “We are very close to the land but we are very near a long cliff bank.” I suddenly felt afraid. I only thought of my husband’s aunt. Her name was Banigabluk. She hardly ever got up.

She started shouting and saying, “You should put the sail outward to the sea. That way we won’t »

In this story elder Agnes Nigiyok (1909 – 1994) shares her experiences of being in a shipwreck. At times, the tale is dark yet moving depicting the struggles and hope of individuals in search of land they can call home. Nigiyok’s words are filled with vivid images of people and landscape reflecting a past for all to remember.

hit against the cliff.” But no one heard her for they were so busy. There were three men. They had cut the ropes off the sails. We drifted to the shore. I was still down below deck. Only when my husband started to call me saying, “Agnes, put all our blankets and bedding on top deck”. Our ship started to tear from rocks. There were very large waves, and water started to rock back and forth inside the ship. By this time, everyone had gone on top deck. There were just a few of us. Tokluk, the ship owner, stared at my husband, Jacob Nipalayok, and David Bernhardt. They started to lower the little boat to the water. After they did that they started to throw down bags of sugar, tea, and coffee into the little boat. The waves overturned it with all the stuff in it. After a while, they decided to put a long pole from the ship down to the shallow area so that we could try and go down and get to the shore. David tried to fix it so that we could try to go down to

safety. Before my husband’s auntie could go down, the long pole broke in half. They put another pole down into the water hoping that this time it wouldn’t break. The men kept telling the women not to be afraid although it was very hard not to be scared. We could be really wet right up to our waist down, but the men said, “We have to get to safety”.

So, before the second pole could break, we started to try to get to the shore. The old lady was first because we wanted her to be first to get to safety. So, after her, we all got to the shore. There was a lot of snow on the land. By the time we all got to the land, we had lost almost everything. All we had was our clothing that we were wearing. When they were on the pole, sometimes a big, huge wave would go over David Bernhardt as he was trying to fix the pole. I think that’s how we got to the shore. Only my husband was left alone on the ship. He was planning

David Bernhardt, 1938.

David Bernhardt, 1938.

“We are very close to the land but we are very near a long cliff bank.”

to save his dogs – even though there was no food for them. After a while we all wrung out the salt water from our clothes. Then we put them back on because that’s all we had.

My husband had six dogs. He threw them all into the water. The dogs kept trying to go back to the ship. We would call the dogs to the shore but they just tried to swim back to the ship so my husband, Jacob, had to save himself because by this time the ship was starting to break, all he had to carry with him was his small little suitcase. Inside it was his tobacco and matches. Long ago there were no cigarettes around. Oh yes, he had his hunting knife inside also. This knife was to become very handy later on.

The place on the shore we had gone into had quite a bit of wood. I gathered wood together so that I could start a fire to dry our mukluks and clothes. The Tokluks were crying because they lost all of their tea, sugar, coal, and other things.

All of the things that were on the ship, we could see them on the bottom of the ocean floor, some of them shining. The ship also broke up into pieces. Among

some of the things that were on the ship – one of them was a tent and it came to shore. So we all got it untangled and the men put it up. At least now we had shelter. It was a four bar tent. I gathered wood and made fire and dried up all our socks and mukluks.

Tokluk and his wife were still very quiet and very unhappy. But David and Jacob were talking and laughing by themselves. We had nothing to eat – not even tea.

By now it was getting little daylight. Our daughter, Elizabeth, was two years old. I would breastfeed her when she got hungry. She was still lively. There was lots of snow for tea, but no pots and tea leaves.

Evening was upon us. I kept lots of wood near the fire so it wouldn’t go out. I was the only person who kept the fire going. The rest were inside the tent. After breastfeeding my daughter, I put her on my back. I started to go for a walk along the shore where the ship had broken up. It was evening time. I could not see too far.”∞

Agnes Nigiyok with baby girl. David Bernhardt with a young bear. DeSalis Bay, 1934. Fred and Andy Carpenter, David Bernhardt, and Jim Wolki. Egg River, Banks Island; Spring 1933.

By Agnes Nigiyok

Elias

By Agnes Nigiyok

Elias

Uvani, Agnes Nigiyok (1909-1994) quliarimaya taimani umiiyaramik. Ilaanni nanginaqtuq atuqlugu tajva nunamun tulangniaqsimagamik nunamun, ukiiviksaqtik qiniqllugu. Nigiyom uqausiit nalunaivialuktut, inuit nunagaluat takumayuuyarnaqtut.

Puiguqungiluta tamapta.

Quliaqtuarniaqtuami aipaniklungalu taimani. Atautchimik nutaruaqtuguk. Taimani umiiyarapta. Una quliaqtara ilumuuqtuq. Qangma aaquaqsimaakiqtuami. Umiaqpauyamun ikiyuanni Cape Parry-m qaningani. Umiaq ingniqutaittuq. Tingilrautilikkun aulavaktuq kisian. Aiparalu nuna tamana nalugikpuk. Nunagigaluariga tajva Ulukhaktuum qaninga, ilisimaluangitkiga inugukvingingilugu manna.

Ubluni qapsikalungni tajva aulayugut. Ikayuqtigiiklutik aqutpagaat umiaq. Nasitaraangapta umiam qaanganin , siku takunaqtuq. Tajvaptauq qimmiaryuit qimmivut umiami, mitquit sikutat.

Ilaanni yaravaktuami, nalanguliqlunga umiam iluani. Aniblunga qiniriaqpaktuami aglaan takusinaittuq sumik, nunamik takunaittuq. Oh Eh! Tokluk aipanilu umiaqpauyangak una. Tusaayuami ilatkaguuq ilangit inuuyut suli. Aiparma ilatka uvamnun takutqublugit.

Ublut kapsikaluit qaangiutiyut. Sinikpaktuami nalauyaqlungalu malittaraangama. Makilluayuittunga.

Ublut ilanganni aiparma takuyaqtugaani, tupaaqlunga uqalautiyaani,”Makittin. Nuna takunaqiyuaq ilitarisuitkiga aglaan. Takuyaqtugara aniblunga. Nuna qatiqsinigaa, apiblugu. Nalugiga sumuktilaanga. Nuna takumayaqput nayuqtaksaqput. Isumayuami qakuguta nuna tikitcharnirikput umiaqput ami ingniqutaittuq. Aulayugut. Nuna qaglimaakitqaikput. Sarvamluuniin ikayuraatigut. Aiparma upakkaminga qiviagaani uqallaqlunilu uvaguuq “Nuna qaglivialukaqput aglaan sivunnaptingni imnaqpak takiyukaluk” Tajvani iqsisaktuami. Aiparma atchanga, Banigabluk makiluayuittuq. Angami ququakihlaqtuq, “Tingilrautit tarium tungaanun ililugit. Imnanun apulaitugut taimaligupta”. »

Tusaangitqaraat sakukpalaaqsimablutik. Angutit pingsut. Tingilrautit aklunaangit kiblurnigait. Sinaanun tipiyuanni. Umiam iluani ittunga suli. Tajva kisian aiparma ququakirmanga, “Agnes, qipiutivut tamaita umiam qaanganukkit. Umiaqput uyaqat siqumisimaakigaat. Ungiulikpait. Imaq iluanukluni umiaqput uviqiitaakiqtuaq.

Tajvani taima tamapta qaanganuktuanni. Inukittugut. Umialik, Tokluk, qivialakamigik ipara, Jacob

Nipalayoklu taamnalu

David Bernhardt umiuyaq imamun atqagaat. Taima aasiin niqikalungnik usilliqlugu. Umiuyaq mikimiyuaq. Malikpait kinngutaat, usiangit taima. Qiyuk takiyuq iliyaat umiamin sinaanun ikkatumun timmungniarukluta. David qiyuk

taamna tutqiqsiniakiga isumagiblta ami. Aiparma atchanga timugataqtinnagu qiyuk navihlaqtuq qitqagun. Alamik illiqihlarmiut navilaiturluuniin una. Angutit iqsitqungitkaluaraatigut tajva aglaan iqsisungitkaluaqtuni sapirnaqtuq. Kinitkaluarluta tajva uqautigaatigut, “Annaksaqtuksauyugut”

Taima aasiin qiyuk naviktinnagu, timungniakiutiyuanni. Aaquaksaq isumagiblutigu sivuliuyuaq. Tamapta aasiin timmuktuanni. Nuna apilluarnigaa. Nunamuktainarapta suralivut tamaitakapsak ulapitavut.

Anuraatualuvut tajva atimayavut. Malikpaum ilaanni qulautpagaa David Bernhardt, qiyuk atuqtaqput uva munarimagaa. Taimanakiaq timmuktuanni. Aipara

David Bernhardt, 1938.

David Bernhardt, 1938.

“Nuna qaglivialukaqput aglaan sivunnaptingni imnaqpak takiyukaluk”

kisimi tajva umiami suli ittuq. Qimmini annautisuklugit, uva niqiksaitkaluaqtut. Taima anuraavut tariitat sivvuqtupaluakikavut tamapta. Atipsaaqlugit aasiin ami anuraatualuvut.

Aiparma qimmiit 6nguyut. Imamun miluruutiyait. Umiamun utiruktut aglaan. Ququaqpakaluaraptigit timmulainirmata aipara Jacob annaksaqtuaq. Umiaq ami siqumisimaakiqluni tajvani. Ikpiaryuni ikutiniklu taugaaqiniklu imalik tigumiaqlugu. Ingilraan “cigarettes” takunaittut. Savinilu iluani inniqtuaq. Taamna savik quyallitauvialuktuksauniqtuaq.

Tulakvikput qiyuunirman nuatiakikatka nanialiuruklunga anuraavut ami paniqsiaksat. Toklutkut tamaita suralitik ulapitait. Qiayuk. Tamaita niqautitik, aluaq, suliqaa.

Tamaita suralgit umiam qaangani ittuat tajva takunaqtut kiviyat. Ilangit saligaittut, qibliqtut. Umiaq siqumavialuktuaq. Qulaani ittuanin tupiq

tipiman sinaanun angutit isivinamijung napagaat. Uqqipalukluta tajvani. Tupiq angiaqtuq. Qiyungnik nuatchiblunga naniaqlunga paniqsikavut anuraavut. Tokluklu aipanilu nipaittuk quviasungituk. Davidlu Jacoblu aglaan nipaiyuittuk iglaqpaktuk. Niqaitugut, tea-ngutaitugut.

Tajva qaumaksimaakiqtuaq. Panikpuk, Elizabeth, malrungnik ukiuniklunilu. Kaaliraangan miluktitpagara uvamnin. Qipilraituq. Aputauyuraluaq aglaan qattaruangitugut tea-ngutaitugut.

Unnuguutiyainni. Qiyuutitka inugiaktut qanini, qamitqungilugu naniaq. Uvanga kisian tajva naniaq munarigiga. Ilatka tupqum iluani. Paniga miluktitqaaqlugu amaakigara. Taavunga sinaanun pisuuyaakiqtuami umiam siqumijvianun. Unnuklunilu, ungavanun takunaittuq.∞

Agnes Nigiyok with baby girl. David Bernhardt with a young bear. DeSalis Bay, 1934. Fred and Andy Carpenter, David Bernhardt, and Jim Wolki. Egg River, Banks Island; Spring 1933.Aplaneload of Inuit leaders celebrated Canada Day this year in Nuuk, Greenland. While most of us took a day off to celebrate summer, they had been working long hours, through that whole week, to tackle some of today’s most pressing issues facing Inuit society. They had gathered for the 11th General Assembly of the Inuit Circumpolar Council (ICC), the organization that fosters political and cultural strength among 150,000 Inuit from across Canada, Alaska, Greenland and Russia.

Make no mistake, this meeting was a big deal, requiring a major investment of time, money and resources by several nations and lots of very important people. This special forum happens only once every four years. Delegates included Inuit leaders from all levels of government, federal Ministers, United Nations diplomats, ambassadors, plus renowned scientists, educators, sociologists and economists. The Honorary Patron for this esteemed Assembly was none other than His Royal Highness Frederik, Crown Prince of Denmark.

Still, as high-powered as this meeting was, organizers gave it a simple name that evokes images of good times at home with family and friends: “Inoqatigiinneq, Sharing Life”. Mary Simon, President of the Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, captured this practical, back-tobasics tone of the Assembly in her opening remarks. “These meetings demonstrate that of the many complex international issues we discuss, most issues in the end are basic human issues affecting the well-being of our families.”

The meeting’s agenda was dominated by these five issues:

• Economic development in a fast-changing Arctic and global economy;

• The Arctic environment and the many stresses it faces due to contaminants, climate change, and threats to biodiversity;

• Hunting and food security, with a focus on the effects of animal rights groups on traditional activities;

• Governance of Arctic regions, particularly in light of sovereignty questions that are heating up as sea ice thaws and development pressures mount;

• Health and well-being, with a focus on community wellness and the importance of language and culture in supporting youth. »

Chair of ICC

Chair of ICC

“Most of these issues are ongoing,” Duane Smith told Tusaayaksat a few weeks after the Assembly. Born and raised in Inuvik, Smith is a veteran advocate of Inuit rights and Vice Chair of ICC. He feels that each issue has many levels and, as the Assembly’s theme suggests, ultimately reaches back to touch all Inuit homes. In fact, for Smith, housing itself is a big issue that deserves much more attention. “I don’t think this issue will ever go away primarily because the Inuit population is recognized as one of the fastest growing, where population is rising much faster than housing can keep up. Therefore you have overcrowding issues, poor living conditions, the re-emergence of certain health diseases such as tuberculosis, poor air quality, dietary issues. Health is a broad issue and relates closely to the quality of housing and the standards that are set.”

Tusaayaksat asked Smith how he saw our federal government responding to such issues. “The present Conservative government has it’s own way of operating and delivering,” he said, “and we have to try to work out a process where the Inuit nationally can have a relationship with them to raise issues of concern. Unfortunately it always takes time, with any government, be it the federal or regional level. When we see an issue of dire need for attention right then and there, it’s not always their first priority. Hopefully we can develop some kind of mechanism to deal with these pressing issues in a more immediate manner. To some degree I believe this federal government has been trying to do that. In other areas like housing they are definitely lagging.”

Smith stressed that, in dealing with the kinds of

issues addressed by the ICC Assembly, governments need to deal with them more directly, “instead of through standard processes that have been in place for the past fifty years.”

Smith was one of the nine international delegates who signed the Nuuk Declaration, the Assembly’s flagship document that will steer ICC’s work over the next four years. It is an inspiring and practical assertion of Inuit values and priorities shared around the circumpolar world.

The Nuuk Declaration begins by recognizing that “the respectful sharing of resources, culture, and life itself with others is a fundamental principle of being Inuit.” It encourages all Inuit, in the spirit of the Assembly’s theme, “to share their life’s experiences and Inuit knowledge with each other and with those who live beyond the circumpolar region.”

The Declaration highlights youth as “the key to a sustainable future” and calls for more meaningful engagement of children, youth and elders in the work of ICC. Further, it strongly encourages all Arctic states to fully implement the provisions of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child.

Heightened threats to the Arctic marine environment were also highlighted, with the Declaration making specific mention to the Gulf of Mexico’s recent offshore oil disaster. It calls for increased recognition of the fragility of Arctic waters and of the fact that “any significant oil spill would be catastrophic for Inuit”. It points to the “significant concern and measured fear” shared by Inuit people over shrinking sea ice but also to their history of successfully “finding resources within their communities and elsewhere to adapt and

Inuit Translator Martha Flaherty.meet challenges created by change.”

True to ICC’s core mandate, the Nuuk Declaration calls for putting Inuit issues, concerns, and rights at the centre of all Arctic policy initiatives and decisionmaking. In this spirit, it makes special mention of the UN’s 2007 Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and encourages all Inuit to learn about this important affirmation of their rights and how it applies to their particular situation. It also directs the ICC to “strongly encourage all Arctic states to fully implement its provisions”.

The entire text of this document is definitely worth reading. To find it, just search “Nuuk Declaration 2010” on the Internet. You’ll see that a lot of its directives are aimed at preparing for a looming storm of change, most of which is arising outside of Inuit homelands.

Keynote speaker, Marie Greene, President of Alaska’s NANA Regional Corporation, spoke eloquently on this subject. “As the Arctic becomes more accessible to the Outside world – as the world creeps closer to our borders, our waters, our lands – we must work together to protect them. We must stand together, for we face strong Outside influeneces and we will need each other to remain steady when this impending storm comes. If we are united, we will succeed. I urge

us, as Native peoples of the North, to make a pledge to consult not only with our own people but with each other. To make every effort to work through our differences so we can face the world in strength of unity... We will show the world that though we speak different languages, we are one people, we are the Inuit, and this land is ours.”

In reflecting on the impact of the Nuuk gathering, Mary Simon stated that, ”I have always used events such as these ICC meetings as a marker to evalutate our progress on the most pressing issues of the day. It is my hope that the 2014 Assembly looks back at this week’s event as the beginning of a renewed emphasis and effort towards positive social change for Inuit.” Simon spoke passionately of the responsibility of Inuit leaders to move governments beyond statements of good intentions into “a new era that will look at the health and education of Inuit as a measure of our entire country’s well-being.”

In a typically punchy closing to her talk, Simon declared that, “Inuit have never accepted the status quo as anything other than the starting point for change. Let the 2010 ICC General Assembly be that point in time for a new era in social change for the Inuit. Nakurmiik.”∞

ITK President Mary Simon and Makivik President Pita Aatami.

From left: Chucky Gruben, Charlie Evalik, Cathy Cockney and Carol Arey.

Western Artic Drummers and Dancers , LoriAnne Elanik and Lorna Elias.

ITK President Mary Simon and Makivik President Pita Aatami.

From left: Chucky Gruben, Charlie Evalik, Cathy Cockney and Carol Arey.

Western Artic Drummers and Dancers , LoriAnne Elanik and Lorna Elias.

Have you ever wondered, “What if this didn’t happen, what if one thing went differently?” It is a question that perpetually comes back to me, always looking for an answer.

Where to begin? Before we jump into any adventure or story, I want to share a little about my background as both an Inuvialuk and a student. For as long as I can remember, my home has been Vancouver, British Columbia. I grew up in Vancouver and experienced the busy urban backdrop, for better or worse. I have always considered Vancouver my home, but after this summer I’ll have to think twice about that statement.

I entered this world on March 22nd 1990 as the son of my mother, Topsy Cockney, and father, Terence Fellows. I am the only son in the family, with three outstanding sisters: Melinda Gillis, Christina and Terri Fellows. Terri is my twin, and no, we don’t look alike. I graduated from West Vancouver Secondary School and I am carrying on my education at the University of British Columbia. Living in Vancouver, my ties with my Inuvialuit roots have been strained at times. However, with frequent visits of friends and family, I have always been reassured of where I came from. This is my story.

In the spring, I was just finishing up another school

By Tyee Fellowsyear. I was informed of an open position at Parks Canada in Inuvik for an Ecological Scientist Assistant. The position called for a person who is currently attending post-secondary school and whose studies are geared towards biology. At the time I didn’t think much of it. However, both friends and family thought otherwise. They insisted that I apply for the position. Sceptical at first, I went ahead and did so. Within weeks after applying, I found myself on the next flight to Inuvik. It turned out to be a decision I will never regret.

Before I could settle into my office, I was scheduled to assist in an ecological monitoring project led by doctors Linh Nguyen (Ecosystem Scientist with Parks Canada) and Erica Nol (Trent University) in the forest and tundra ecosystems surrounding Sheep Creek in Ivvavik National Park. Among this group was Jason Straka, a graduate student attending the University of Victoria, and Devin Turner, a recent graduate at Trent University. They will spend the next 71 days pursuing studies in the Canadian North made possible by NSERC Northern Research Internships with Parks Canada (Western Arctic). I, along with Jay Frandsen, a volunteer who soon became a Park patrol-person for Parks Canada, got a glimpse of field monitoring and research by assisting in inventorying over 16,000 insects, 10,000 plants, and 93 nesting birds.

“When patterns are broken, new worlds emerge.”

– Tuli Kupferberg

Our journey began on a brisk spring morning with a flight by Twin Otter to the remote location of Ivvavik National Park in the northern Yukon. It’s hard not to get goose bumps when the otter is packed to the brim with people and cargo, and the landing strip at Sheep Creek is neither regulation size nor paved. Half-way through the flight, turbulence became a minor concern. I peered out the square-foot window watching grizzly bears and Porcupine caribou while at the same time having my head in a ‘Sic-Sac’. The trip as a whole was a success. Observing the changing landscape from the vast Mackenzie Delta to the coarse British Mountains was something I’ll never forget.

Both Jay and I were the first of many volunteers and Parks Canada staff to assist in the science at Sheep Creek. Although our stay seemed far too short, I made the most of every day. Each day I spent there was worth a story of its own. One event that still resonates occurred during the trip; it was the hike to ‘Halfway to Heaven’. The peaks of the British Mountains possess an atmosphere where everything collides simultaneously into a single unforgettable moment. Eyes wide with infinite views, ears filled with the sound of blistering winds, instead of the grating sounds of traffic and ringing phones is something everyone should have the opportunity to experience at least once.

My expedition did not stop there; my next trip was to Aulavik National Park, a place with undulating hills, meandering rivers, and musk oxen. I spent the next 15 days assisting in several ecological monitoring projects, which were supported by Polar Continental Shelf Program (Natural Resources Canada) and Parks

Canada, led by Dr. Linh Nguyen in the tundra and freshwater ecosystems. I helped to establish 27 soil profile sites with Dr. Wanli Wu (Ecosystem Scientist with Parks Canada in Winnipeg), John Lucas Jr. (Site Manager for Aulavik National Park), and Joe Kudlak (Park patrol-person for Aulavik National Park). As well, I helped inventory over 10,000 plants with Amanda Joynt (Habitat Biologist with Department of Fisheries and Oceans) and Craig Brigley (Ecosystem Data Technician for Parks Canada). Finally, we surveyed 42 lemming winter nests, sample water quality in the Thomsen River, and establish 12 sites along the Thomsen River for freshwater invertebrate sampling. Our means of transport was by canoe over water, by twin otter and helicopter over air, and by hiking over land.

Aulavik has a natural beauty all its own with wildlife and a landscape that is unique to the Western Arctic. Every day was something new, ready to be discovered. Early into the trip, we were approached by an intimidating but friendly arctic wolf that approached within 10 metres of us. Later that week, while we were out in the field, a herd of 28 muskoxen surrounded my colleagues during one of our lunch breaks. During the course of our trip, fishing was a personal highlight. I watched Joe Kudlak fillet multiple fish and learned to do it myself. He demonstrated to me what it took to live on the land and what tools and skills are needed. Being a part of the ecological monitoring program and working in the field, I gained invaluable experience and knowledge that no book or classroom could teach.

Looking back on my journey, I can’t help but to thank my family, friends, and Parks Canada for giving me this once in a lifetime opportunity. The time spent in the field and here in Inuvik has been a remarkable experience. Anyone that I failed to mention, please know that you are not forgotten.∞

On board Her Majesty’s Ship Investigator, Captain Robert McClure and his crew of 66 men set out in 1850 to find Sir John Franklin, who had gone missing during his search for the Northwest Passage five years earlier. Instead of finding Franklin’s lost ship, McClure and his crew found the Northwest Passage, and narrowly avoided the same fate as Franklin. As the winter of 1851 approached, the Investigator’s crew sought refuge in what McClure called “the Bay of God’s Mercy”, not knowing they would be stranded there for two arctic winters. They survived on meagre rations and whatever wildlife they could hunt. The crew suffered from scurvy and was near starvation. Three of McClure’s men: John Boyle, John Ames and John Kerr perished. Members of another English ship named HMS Resolute eventually rescued the Investigator’s crew. The HMS Investigator was abandoned at Mercy Bay, which eventually sank to the bottom of the ocean floor. In July of 2010, approximately one hundred and fifty years later, the ship was rediscovered by Parks Canada.

Having an education background in anthropology, I was invited to join the Parks Canada 2010 Archaeological Survey, which was successful in both discovering the sunken ship and in locating the graves of the three sailors. It was exciting to be given the opportunity to be part of this momentous project, which gained international attention and a visit from the

Minister of Environment, Jim Prentice.

There were nine members in our crew, consisting of two teams: the land team set out to find the three graves and to record known archaeological sites; and the underwater team set out to locate the Investigator in the waters of Mercy Bay. We also had three valuable Inuvialuit guides from Parks Canada, who assisted in both the land and water surveys.

The land crew included Henry Cary, Edward (Ed) Eastaugh and Me. Henry Cary was responsible for coordinating the logistics of the entire trip, which ran smoothly and successfully. Ed Eastaugh, from the University of Western Ontario was in charge of the geophysical survey. From them, I learned a lot about what’s involved with field equipment and procedures. They are very knowledgeable about the history of Arctic peoples and were great to work with.

The underwater team consisted of Ryan Harris, Jonathan Moore and Thierry (Terry) Boyer. Ryan Harris was head of the Underwater Archaeology crew, whose discovery of the location of HMS Investigator made headlines around the world. Jonathan Moore assisted the land crew when the marine team was unable to go out on the water due to bad weather or ice. Thierry Boyer, the optimist, would look at things on the bright side and make light-hearted jokes.

Halfway through our expedition, Minister Jim Prentice and a Canadian Cable Public Affairs Channel (CPAC) documentary crew joined us on the shores

of Mercy Bay. Minister Prentice was very impressed with the entire project. During his stay he was treated to bannock, fresh char, unbelievably warm weather, and a dive in Mercy Bay for a close up look at the Investigator.

The Inuvialuit members of the expedition, John Lucas Jr., Mervin Joe and Joe Kudlak, contributed greatly to camp operations and safety. Aulavik National Park Site Manager John Lucas Jr., had a wealth of knowledge regarding the weather, animals and safety. Mervin Joe was great to be around, as he was always whistling or had positive comments or quotes. Their keen eyes for finding artifacts were very helpful. Joe Kudlak, the avid fisherman was very knowledgeable of plants and animals. No matter what the weather was like, we would often see him exploring and enjoying his time on the land. On our very first night at Mercy Bay, we were treated to a fresh char dinner, caught by Joe at Polar Bear Cabin while we were on our way to Mercy Bay. At times, I would sit with Mervin, John and Joe and we would tell stories, talk about our families and share our experiences. Being in Mercy Bay made me wonder what it would have been like for our ancestors who had lived in the area so many years ago.

It was an awesome experience to actually be walking and camping in the area where our ancestors had traveled, hunted and camped.

Parks Canada is a great organization I was fortunate to work with in exploring beautiful Aulavik National Park. My favourite part of the trip was visiting and recording the Paleo-Eskimo site, situated on the south shores of Mercy Bay, dating back as far as 2400 years. It is not very far from the infamous cave in Gyrfalcon Bluff that elders warn people not to visit.

We were graced with great weather and a successful expedition. However, once August came around, the weather quickly turned to fall. On the way back, we were forced to stay at Polar Bear Cabin for one night. Foggy weather in Sachs Harbour forced us to take a detour to Ulukhaktok. It was a huge contrast to our smooth trip up to Aulavik National Park. Unpredictable weather and extreme conditions are some of the many characteristics of the north. Nevertheless, the Inuvialuit and Inuit in general have adapted to the weather conditions and managed to survive. The project was an amazing experience, and I would do it again in a heartbeat.∞

In July of 2010, approximately one hundred and fifty years later, the ship was rediscovered by Parks Canada.

This year I was fortunate enough to witness six incredible artists spend their summer traveling, creating and being inspired by one of the most beautiful places in the world: Ivvavik National Park.

Each summer, Parks Canada hosts a program called “Art in the Park,” which gives artists of the Inuvialuit Final Agreement and the rest of Canada a once-in-alifetime opportunity to travel to a remote Northern park and find inspiration for their art. This year, the program was held for ten days in July, when all the flowers of Ivvavik National Park were in full bloom. The artists’ were based at Sheep Creek, alongside the mighty Firth River and the spectacular British Mountains.

Three participant places are always set-aside for Inuvialuit beneficiaries in the program. This year, Print-maker, Roberta Memogana; sketch artist, Micheal Payne; and seamstress, Sheila Nasogaluak were the three successful Inuvialuit artists that contributed to the success of the program and to their personal growth as artists. With much excitement, Sheila Nasogaluak traveled out to the park carrying her sewing machine in her arm. In the past the Inuvialuit wore their art and created spectacular articles of clothing to showcase their skills. Today, visitors to the North are always looking for a beautiful pair of slippers or a stunning parka as a souvenir to complete

their northern travel experience. To reflect this, the Art in the Park program is allowing for a broader definition of “art” in order to include other traditional art forms and engage more Inuvialuit artists in the future.

My time with the artists was an unforgettable experience. Their enthusiasm for art was contagious; I could not help but put my own hands to use as an artist. To spend time with a small group of people in a remote place bonds you as a community. You get to learn and teach one another and that is extraordinary.∞

Early in the New Year, Parks Canada will be accepting applications for the 2011 Art in the Park program. For application information, please email us at inuvik.info@pc.gc.ca or visit Parks Canada at www.pc.gc.ca

A smiling seamstress Sheila Nasogaluak working away at her Ivvavik Studio.

Participants of the 2010 Artist in the Park program; from left: Roberta Memogana, June Hill, Lori Waters, Sheila Nasogaluak, Leslie Sharpe and Michael Payne.

Melinda Gillis

A smiling seamstress Sheila Nasogaluak working away at her Ivvavik Studio.

Participants of the 2010 Artist in the Park program; from left: Roberta Memogana, June Hill, Lori Waters, Sheila Nasogaluak, Leslie Sharpe and Michael Payne.

Melinda Gillis

By Maung Tin

By Maung Tin

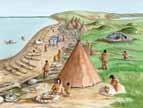

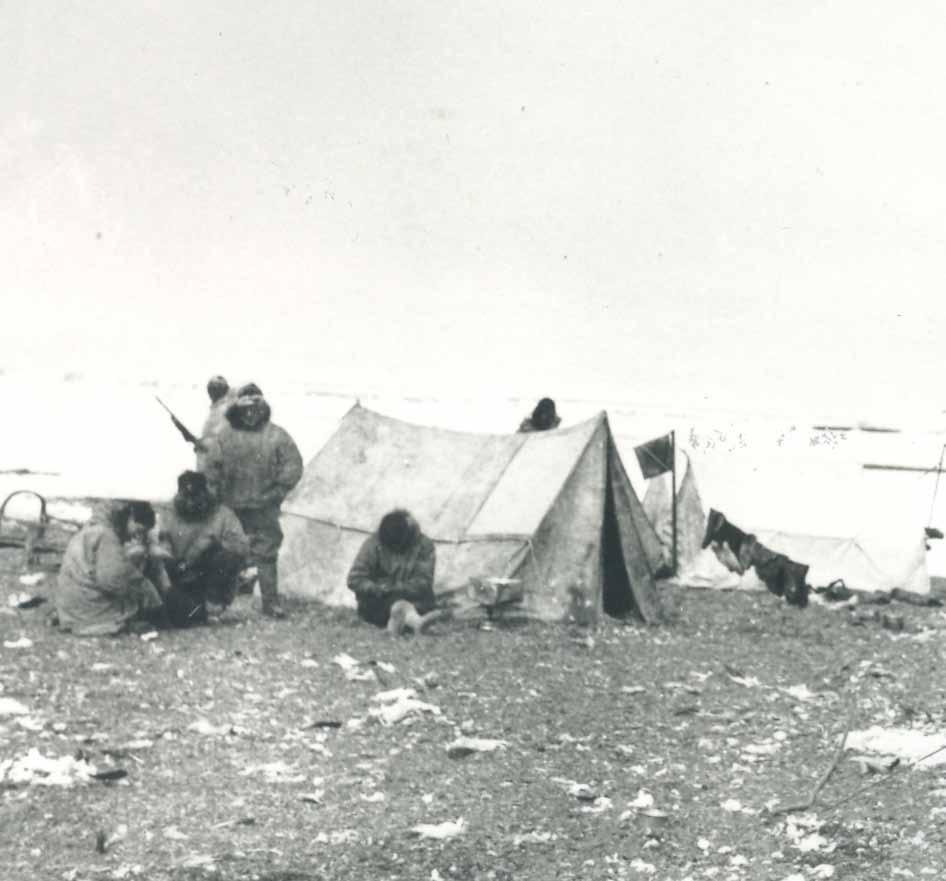

For many generations, Shingle Point has been a place for whaling, hunting and fishing. This seven-mile stretch of gravel off the Yukon’s picturesque Artic Coast has also had a significant history of a settlement and society that survived despite many colonial hardships that it encountered. It was this very place where The Hudson’s Bay Company thrived in its commercial success; a place where the DEW Line sat on 2682 acres of the coastal plain providing advance warnings of potential hostility; and most importantly a place where missionaries established “experimental” residential schools. The fragmented past is now a place of beauty that seeks to recapture culture and tradition.

today, Shingle Point has become a summer destination for families to enjoy and practice harvesting of beluga whales, fish, birds and land mammals. In 1997, the notion of family gathering expanded with the establishment of Shingle Point Summer Games. This all began one evening when a handful of friends and a few families sat around listening to elder stories. Amongst them were Carol Arey and her colleague Annie B. Gordon who became fully absorbed in the excitement; after the stories, they were left to contemplate, “why not make this a yearly event?” An event that could involve a cookout, fun games and skill competitions, which will bring the community closer together. With much preparation, organization and gathering of funds, they inaugurated the event, the Shingle Point Summer Games.

The first year of the event was a tribute to the memory of those that passed on. The event was a great success with planes chartered and boats commissioned, bringing in people from Inuvik, Aklavik and Alaska. Excitement was at its peak “which included

drum dancing, singing, arctic sports, games, Kipotuk (ring-toss) and cooking food around the clock… and everyone volunteered,” says Arey. The tradition continues from that point on, bringing in more people and new faces including tourists, keeping the folklore alive.

This year the event commenced with fierce wind and heavy rain. Little children, youths and adults joined in on the scavenger hunt, lining up to hand in their findings. As the weather became more forgiving the games and the cookout took their natural course bringing everyone to rejoice in mouthwatering foods ranging from muktuk to freshly grilled hamburgers.

Given the turbulent history of Shingle Point, culture and tradition is revitalized through great support and devotion year after year by community members. They are trying to maintain an identity for present and future generations. Arey conveys it is these positive aspects of “sharing, caring, respect for the land and animals that needs to be continued to keep the tradition going…and only than we can enjoy the land we have been blessed with”.∞

From right: Karlyn Mcleod, Trisha Greenland, verna Arey and Cecilia Greenland take part in ring-toss competition. From right: Kendall Archie, Holly Archie, Riley Furlong and Desiree Arey. Sam Mcleod and his daughter Sydney. Ricky Selamio, Dean Arey and Eddy Greenland having a laugh. Liz Gordon dizzy sticking.This year marks the 7th successful journey on the Horton River as part of the Inuvialuit Development Corporation (IDC) run Arctic Youth Leadership program (AYL). The AYL expedition program has the goal of integrating Inuvialuit and Inuit youth. Eleven youth, five Inuvialuit and six Inuit, participated in the second fully integrated program, with two of the youth acting as peer leaders, while undertaking their second journey, and receiving advanced leadership training. The IDC and Nunasi Corporation greatly values’ integrating the two groups as it provides an opportunity for cultural exchange and diversity to leadership training. The program

enabled Inuvialuit and Inuit youth to work together in developing effective solutions for mutual challenges, as well as supporting the emergence of an arctic network for future leaders.

The Horton River as a site to conduct a leadership development program is very appropriate, as it is a historical place and is rich in resources. In the past, it catered to the Thule, whalers and traders. Various archeology sites remain along the river and reflect the variety of inhabitants across time. Today, the Inuvialuit continue to be human presence in the area.

The Horton River itself is a 250-kilometer waterway that allows for remote white-water canoe expeditions. The River snakes through the upper canyons,

past tundra plains, and along the Smoking Hills. The name Smoking Hills was gained when searchers were looking for Franklin and his men, when they saw smoke rising hoping that it was the lost men; instead, the smoke turned out to be sulphur, lignite and other minerals oxidizing in a slow burn. The River ends up near the mouth of Franklin Bay. The setting blends natural scenery and a variety of wildlife has become the ultimate destination, drawing in people from all over the world for paddling.

The AYL expedition begins at the second half of

Horton River; which is the lower section of the river that passes through the tree line, the tundra, rolling hills and the Smoking Hills near the ocean, and finishes next to the river’s mouth close to the end of Cape Bathurst. The two-week expedition begins with a flight with Aklak Air from Inuvik to a gravel bar close to where the Whaleman River flows into the Horton. After assembling the folding Ally canoes, participants break into both tent and food groups and canoeing partners. After this, the students then head off to the white water sections of the Horton River. »

“We did a little activity where we organized ourselves based on what we thought, or how we got through some situations I guess on sort of a grid; and depending upon where were on the grid we were told what animal we would represent, and what things we would be good at, like the pros and cons of our style of leadership. It was really good.”

– AYL Graduate 2010v ideographer and photographer David Stuart cooking up a storm. Shannon Ciboci and Haley Smith.

Along with the canoeing adventure, the students learn aspects of wilderness living that compliment their conventional knowledge, leadership skills, communication skills, conflict-resolution skills, risk management skills, and backcountry cooking skills. These arrayed categories of skills all meet the primary goals of the AYL program set by IDC, that of being primarily to

teach leadership skills in the participants.

By the end of the expedition, the participants are able to understand the intricacies involved with being a part of a team, as well as learning to work as a team member, to plan and achieve goals, and to initiate progressive actions towards achieving their goals. Upon successful completion of the AYL expedition,

The program enabled Inuvialuit and Inuit youth to work together in developing effective solutions for mutual challenges, as well as supporting the emergence of an arctic network for future leaders.

individual students earn up to four credits towards their high school transcript.

Each of this year’s eleven participants has developed a broader understanding of the natural environment and their relationship with it; and the appreciation for the complexity and diversity contained in the natural world.

In the seven years of providing this leadership opportunity, the Arctic Youth Leadership program has produced one hundred and two young Inuvialuit and Inuit graduates. With this well-earned success the youth are learning new skills to navigate their exciting futures and meet challenges in their lives. ∞

Participants – Arctic Youth Leadership Program 2010

Zakkery Kudlak Ulukhaktok

Haley Smith Inuvik

Lance Gray Inuvik

Shannon Ciboci Inuvik

Paulou Ittungna Inuvik

Caine Akukujuk Pangnirtung

David Kullualik Iqaluit

Tera Yarema Rankin Inlet

Martha Arnarauyak Rankin Inlet

Hope Makpah Rankin Inlet

Swen Ugyuk Taloyoak

If you are an Inuvialuit youth living in the Inuvialuit Settlement Region, between the ages of 15 to 19, possess leadership potential, are active in school and community, and want to participate then ask your school Principal for an application or visit the a rctic Youth l eadership website at: www.arcticyouthleadership.ca

“When you first get out there, you don’t know what you are going to do, you don’t know what to expect, you sort of miss home at first, then you get through the trip, and get used to the lifestyle. You really enjoy it, and then when you are told that you have to come back, and the plane lands and it all flashes past, you know, it is such a quick trip. When you get back you enjoy all of it you really learn to love it out there, you have just a different appreciation for what is out there.”

“Everyone began to feel like family as the trip went down and when we had to leave it was kind of hard to leave the whole group”

AYL Graduate 2010

_Swen Ugyuk David Kullualik Kevin Floyd and Noel Cockney uopn arrival at Horton River. AYL Graduate, Lance Gray Shannon Ciboci