TWO MORROWS PUBLISHING

KING-SIZE BULLPEN TRIBUTE

ROY T H OMAS’

COLLECTORS’ ITEM CLASSICS

THREE GREAT ISSUES!

EACH MOVIE-LENGTH COLLECTORS' CLASSIC IS GUARANTEED TO BE... AMAZING! ASTONISHING!

EACH MOVIE-LENGTH COLLECTORS' CLASSIC IS GUARANTEED TO BE... AMAZING! ASTONISHING!

AS FANTASTIC AS THE DAY IT FIRST APPEARED!

AS FANTASTIC AS THE DAY IT FIRST APPEARED!

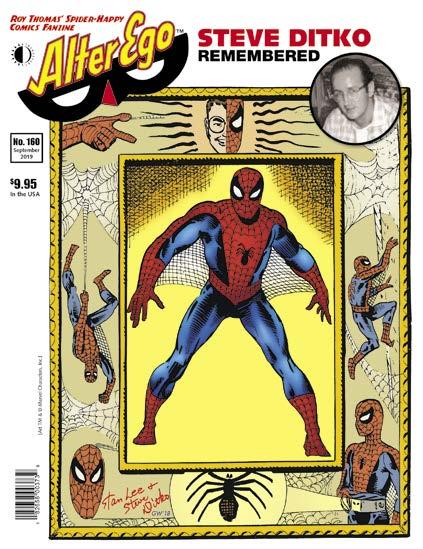

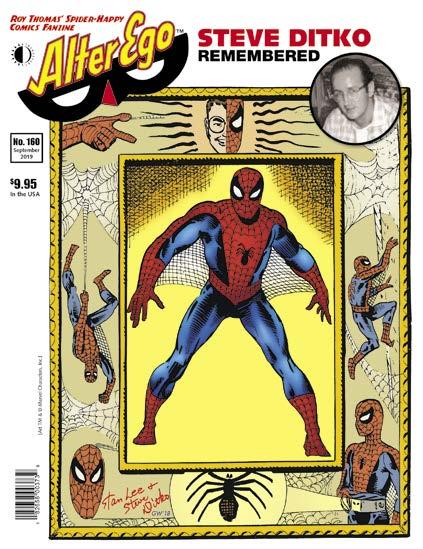

THE NEVER-TO-BE FORGOTTEN SOLD-OUT ISSUES FEATURING: STEVE DITKO!!

THE NEVER-TO-BE FORGOTTEN SOLD-OUT ISSUES FEATURING: STEVE DITKO!!

JACK KIRBY!! AND STAN LEE!!

JACK KIRBY!! AND STAN LEE!!

PLUS: OVER 30 NEW PAGES ON THE FOUNDERS OF THE MARVEL BULLPEN!

ALTER EGO COLLECTORS’ ITEM CLASSICS

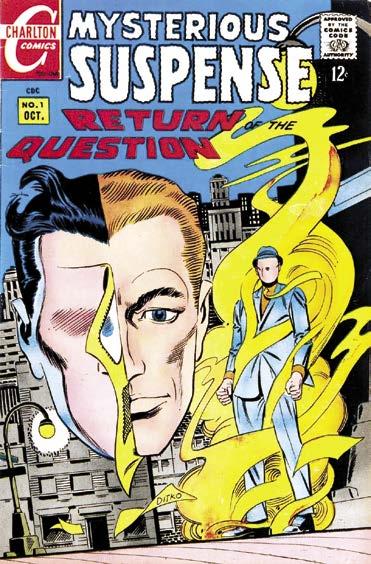

ALTER EGO #160: The Amazing Steve Ditko Issue Writer/Editorial: Steve D., We Hardly Knew Ye! .................... 5 Steve Ditko: A Life In Comics .................................. 7 A brief bird’s-eye view of a remarkable artist—and storyteller—by Nick Caputo. Steve’s Secret ............................................... 28 Paul Levitz remembers collaborating with—and knowing—Steve Ditko Steve Ditko Interview—1968 .................................. 29 Mike & Richard Howell and Mark Canterbury, from the pages of Marvel Main #4. “A Very Mysterious Character” ................................. 35 An essay on Ditko by Yancy Streeter Barry Pearl. A Life Lived On His Own Terms ................................ 39 Bernie Bubnis tells of his personal encounters with Spider-Man’s co-creator, 1962-2017. Two Visits to Steve Ditko’s Studio/Sanctum Sanctorum ............ 47 Russ Maheras on meeting the elusive artist. Steve Ditko ................................................. 55 Craig Yoe on Ditko, himself, and the Muppets. Mr. Monster’s Comic Crypt! First Love ........................... 57 Michael T. Gilbert examines the very first art and stories by the great Steve Ditko. NEW! Mark Ditko Interview ................................... 64 Steve Ditko’s nephew speaks to Alex Grand. FCA [Fawcett Collectors Of America] #219 ....................... 83 P.C. Hamerlinck presents Brian Cremins’ look at Ditko in This Magazine Is Haunted.

EGO

Astounding

Lee

Writer/Editorial: The Last Gathering ............................. 93 Guest editorial by John Cimino, about Roy T. & himself visiting Stan on Nov. 10, 2018. An Interview With Stan Lee –Conducted On-Air By Carole Hemingway ....................... 95 In 1975, junketing to plug a book, Stan had a great time with one talk-radio lady. Tributes To A Titan .......................................... 111 Marvel minions Thomas, Wolfman, Shooter, Isabella, Kraft, & Englehart on Stan Lee. Stan Lee & Moebius ........................................ 132 Jean-Marc Lofficier on bringing two legends together to produce Silver Surfer: Parable Stan Lee, Al Landau, & The Transworld Connection ............... 138 Rob Kirby spotlights the man who succeeded Stan as president of Marvel Comics. Comic Fandom Archive: My (Admittedly Minor) Encounters With Stan Lee ................................... 148 Bill Schelly showcases his few (but meaningful) contacts with The Man. NEW! Stan Lee In 1968 ..................................... 153 A vintage interview for Rutgers University’s radio station. FCA [Fawcett Collectors Of America] #220 ...................... 162 P.C. Hamerlinck presents a multitude of Fawcett collectors—remembering Stan Lee! TABLE OF CONTENTS

ALTER

#161: The

Stan

Issue

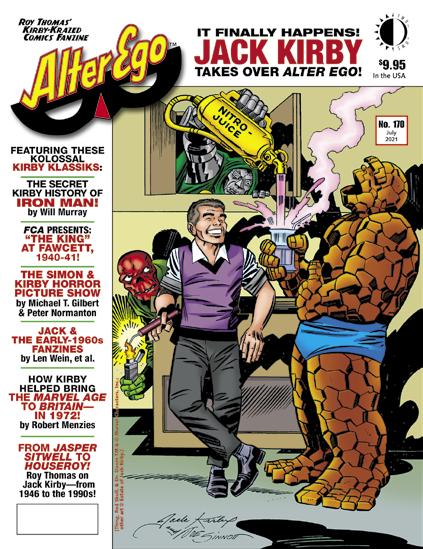

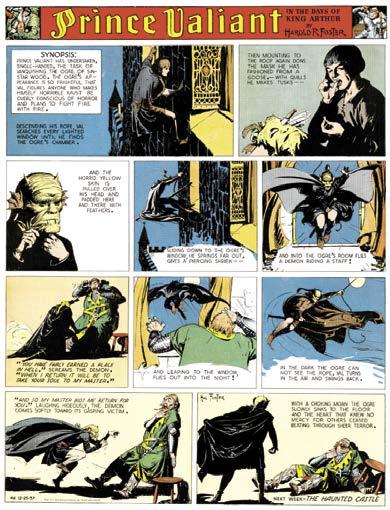

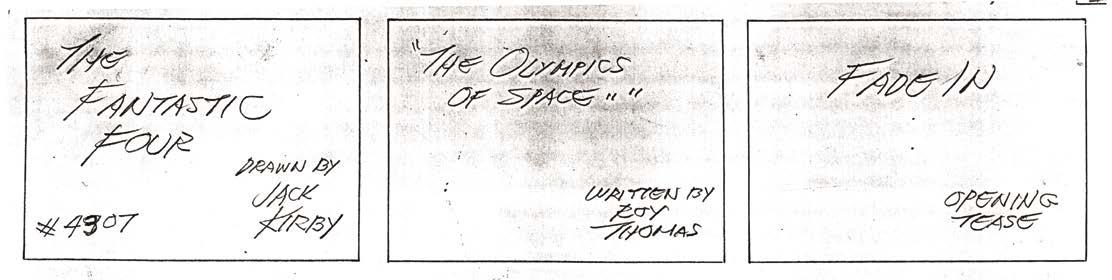

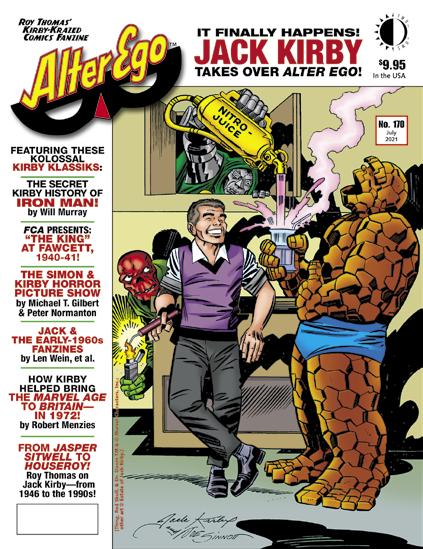

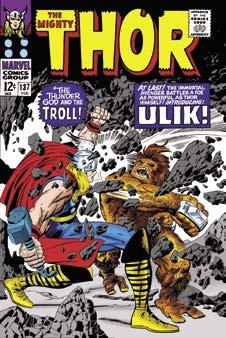

ALTER EGO #170: The Fantastic Jack Kirby Issue

Will Murray on how Kirby, Heck, Lee—& even Ditko—shaped Ol’ Shellhead in the 1960s.

The ultimate Marvel artist in the Golden Age of Comic Fandom, compiled by Aaron Caplan.

Not Stan Lee’s Soapbox, But Stan Lee’s Jack-In-The-Box! .......... 191

The Man talks about The King, 1961-2014—as gathered by Barry Pearl, with Nick Caputo.

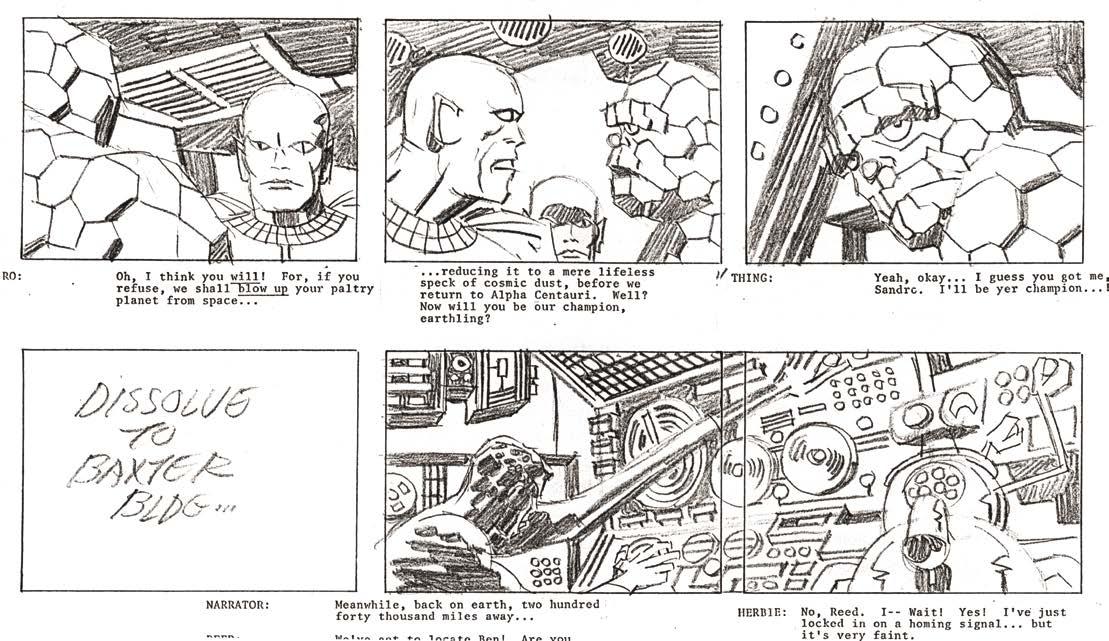

The Top 10 Jack Kirby Marvel Slugfests (1961-1970) .............. 203

Fantastic Four, Hulk, Thor, Captain America—even Spider-Man—selected by John Cimino.

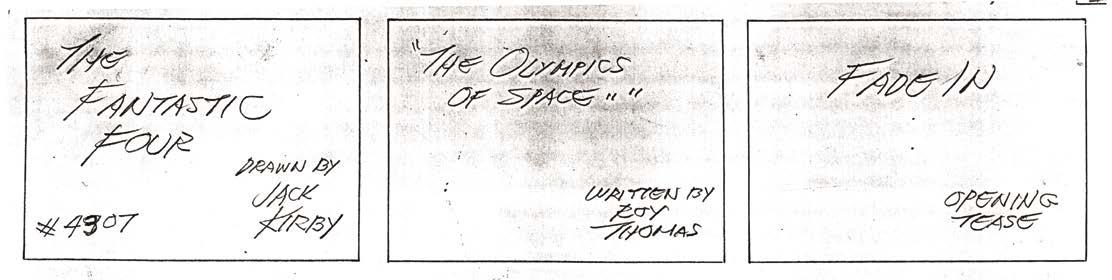

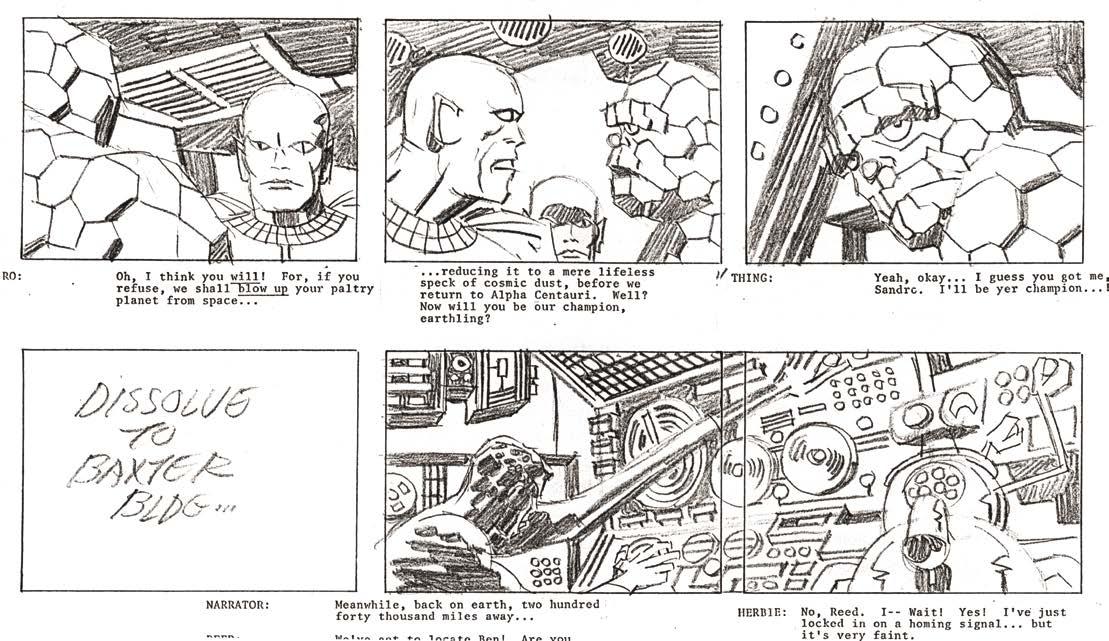

NEW! Jack Kirby 1976 Interview .............................. 209

Peter Smith quizzes Kirby for a college dissertation.

NEW! Discovering Kirby In The ’60s! ........................... 215

Shane Foley takes us on a dynamic trip down Memory Lane.

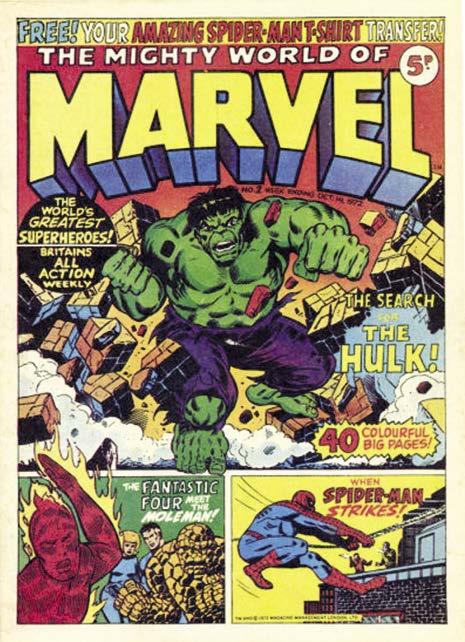

“The Marvel Age Of Comics Started On September 30, 1972!”......... 218

That’s definitely true—if you were in the UK and hanging around with Robert Menzies.

From Jasper Sitwell To Houseroy—& Back Again! .................

Roy Thomas on being a Kirby fan, colleague, and foil, from 1947 till last week!

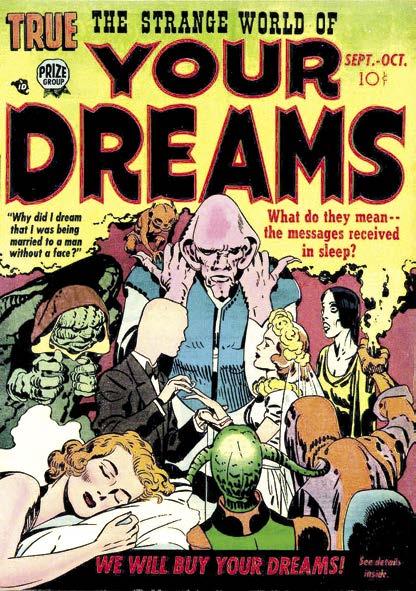

From The Tomb: The Jack Kirby Macabre .......................

On his own or with Simon or Lee—Peter Normanton salutes Kirby as a master of horror!

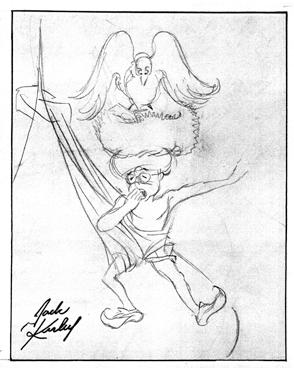

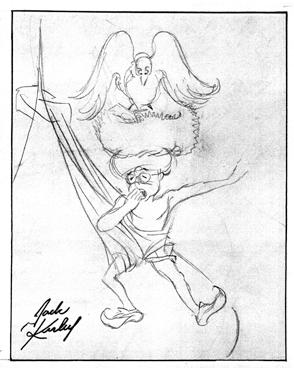

Mr. Monster’s Comic Crypt!: Simon & Kirby’s Recycled Masterpieces ...

Jack & Joe tried never to waste a drawing—and so does Michael T. Gilbert.

FCA [Fawcett Collectors Of America] #229 ......................

P.C. Hamerlinck presents Mark Lewis presenting Kirby’s Captain Marvel & Mr. Scarlet!

225

235

241

247

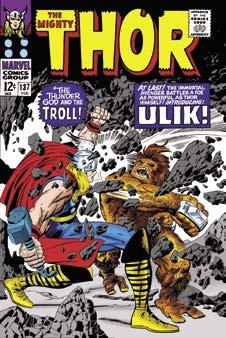

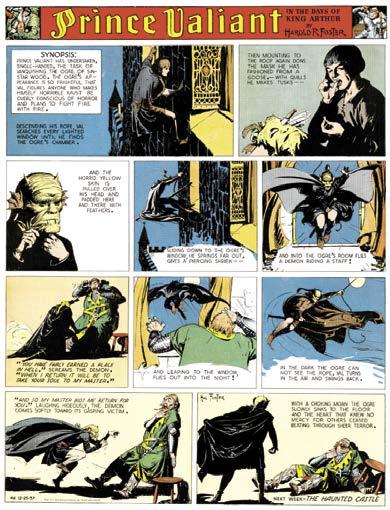

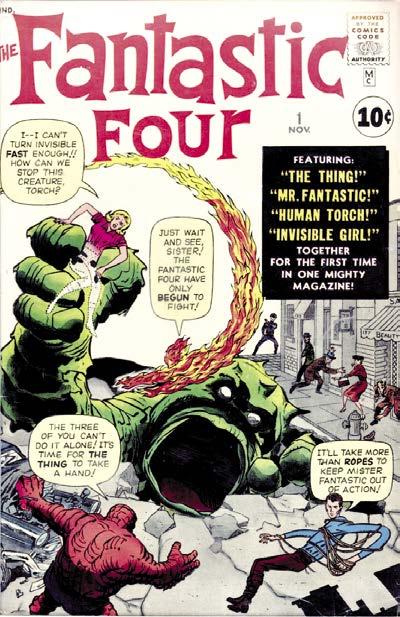

Above: Since it was Benjamin J. Grimm who made Ye Ed fall in love with The Fantastic Four and Stan Lee’s writing (I already was a Jack Kirby art fan since the age of five or so) in that Nov. 1961-cover-dated #1, Roy T. figured there was no better illustration for this page than the world’s first full frontal look at the guy Stan would soon dub “the ever-lovin’ blue-eyed Thing.” Inks by George Klein, if Dr. Michael J. Vassallo’s researches are correct—and they probably are! Reproduced from Roy’s bound volume. [TM & © Marvel Characters, Inc.]

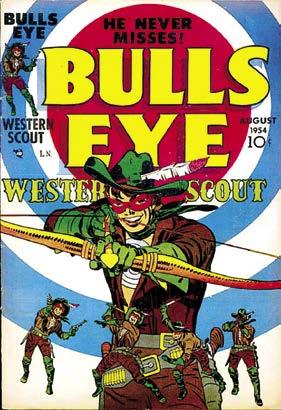

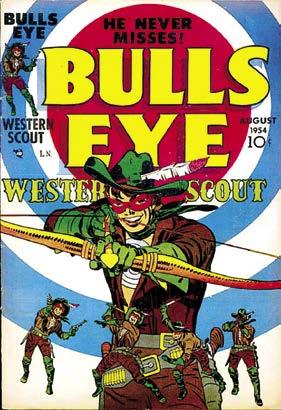

Above: One of the great (and last) co-creations of the deservedly legendary Joe Simon & Jack Kirby team was the hero of Bullseye #1 (July-Aug. 1954), who began life at the pair’s own doomed Mainline imprint, but whose final two issues were published by Charlton after Mainline went under. Bullseye and Boys’ Ranch are rightfully considered classic Western comics of the late Golden Age. [TM & © Estates of Joe Simon & Jack Kirby.]

Jack For All Seasons ......................... 172 The Secret Kirby Origin Of Iron Man ...........................

Writer/Editorial: A

173

Jack Kirby & The Early-1960s Fanzines ......................... 185

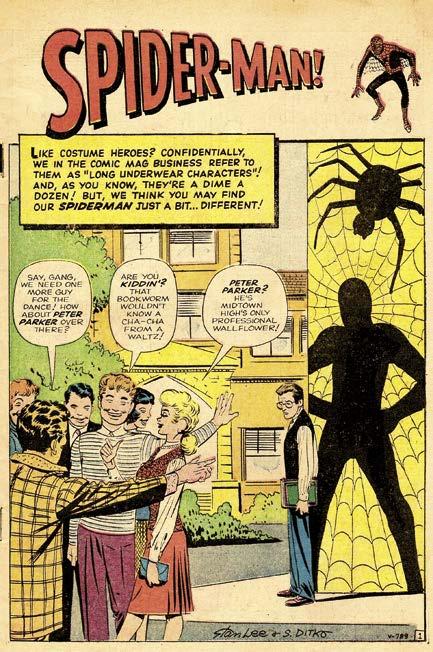

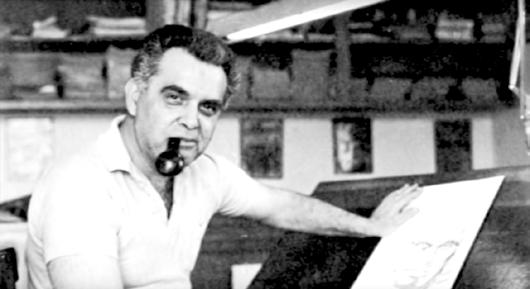

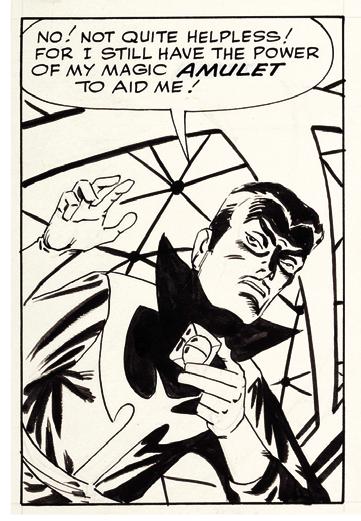

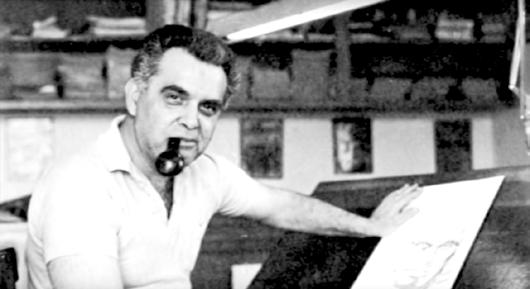

STEVE DITKO: A Life In Comics

A Brief Bird’s-Eye View Of A Remarkable Artist

by Nick Caputo

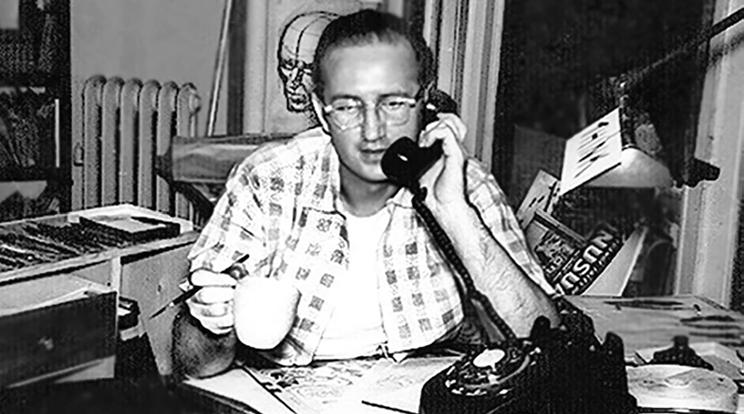

Steve Ditko was born in Johnstown, Pennsylvania, on November 2nd, 1927, where he spent his childhood and teenage years. After high school he joined the post-World War II Army, and upon his return to civilian life became a student at the Cartoonist and Illustrators School in New York City. There he was taught by comicbook artist Jerry Robinson, one of the early (and renowned) contributors on “Batman.” Ditko was greatly influenced by Robinson, along with many other comicbook and strip artists, including Mort Meskin.

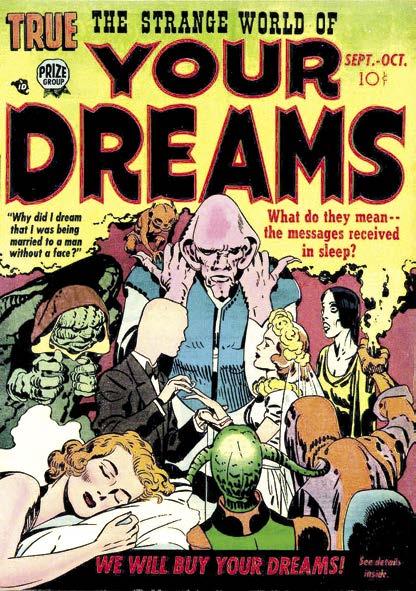

Ditko’s entry into the comicbook field began with a number of small publishers. While his first sale, scripted by Bruce Hamilton (“Stretching Things”) for Ajax-Farrell, appeared in Fantastic Fears #5 (Jan. 1954), his first full-art published

story was “Paper Romance” in Daring Love #1, cover-dated Sept.Oct. 1953, for Stanmor. Other 1953-executed stories include the even earlier “Hair Yee-eeee” (signed “SS,” likely a collaboration with fellow student Sy Moskowitz) in Strange Fantasy #9 (Dec. 1953; Farrell) and at the Simon & Kirby studio, assisting on Captain 3-D # 1 (Harvey) and the unpublished second issue (primarily as background inker) and as full artist on “A Hole in the Head,” a 6-page thriller in Black Magic, Vol. 4, #3, for the Prize group.

In addition to more Black Magic stories and Ditko’s first Western for Timor [A/E EDITOR’S

NOTE: See p. 35], 1954 launched a long and creatively rewarding association with Charlton Press. In his first year with the company, Ditko produced

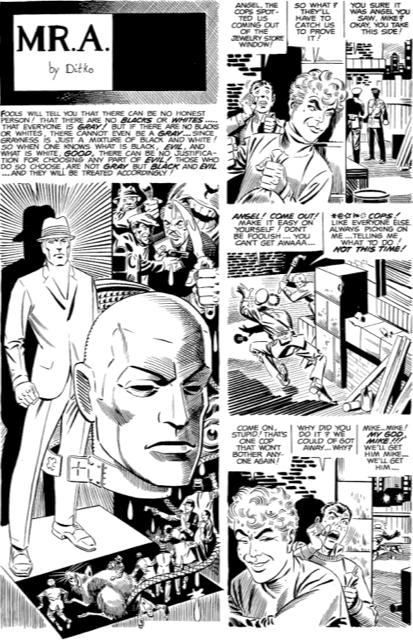

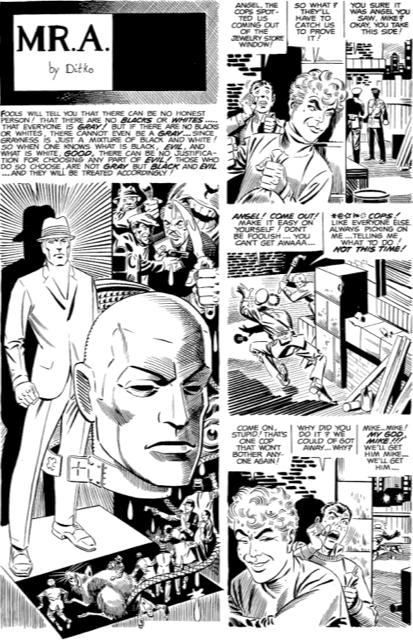

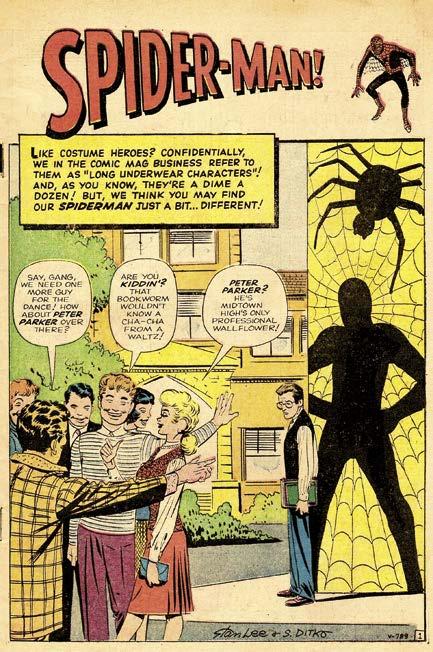

Steve Ditko in one of the most-reproduced of the relatively few photos of him known to exist—flanked by the splash page of the most famous story he ever drew, the origin of “Spider-Man” from Amazing Fantasy #15 (Sept. 1962), scripted by Stan Lee— and a splash featuring his most personal creation, “Mr. A,” from witzend #3 (1966). Thanks to Bob Bailey and Jim Kealy, respectively, for the two art scans. [Amazing Fantasy page TM & © Marvel Characters, Inc.; “Mr. A” page TM & © Estate of Steve Ditko.]

7

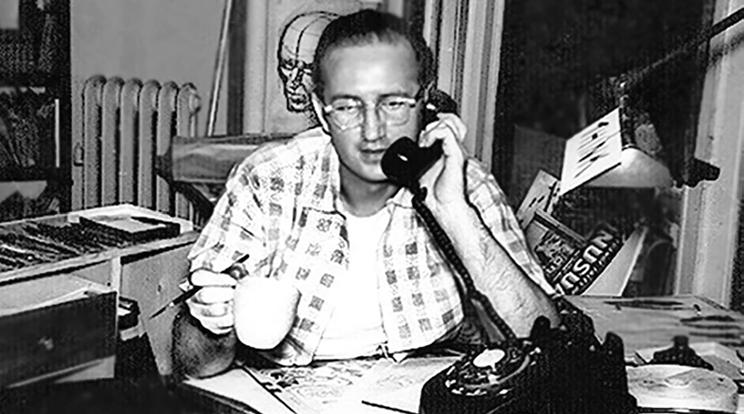

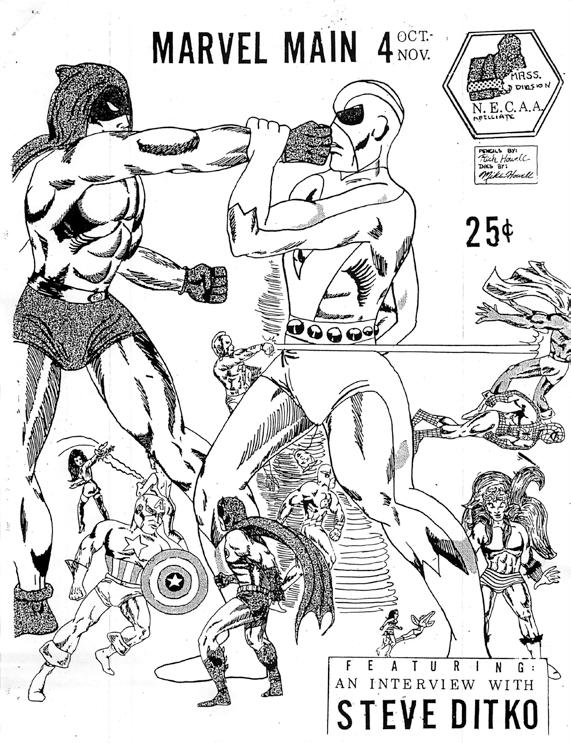

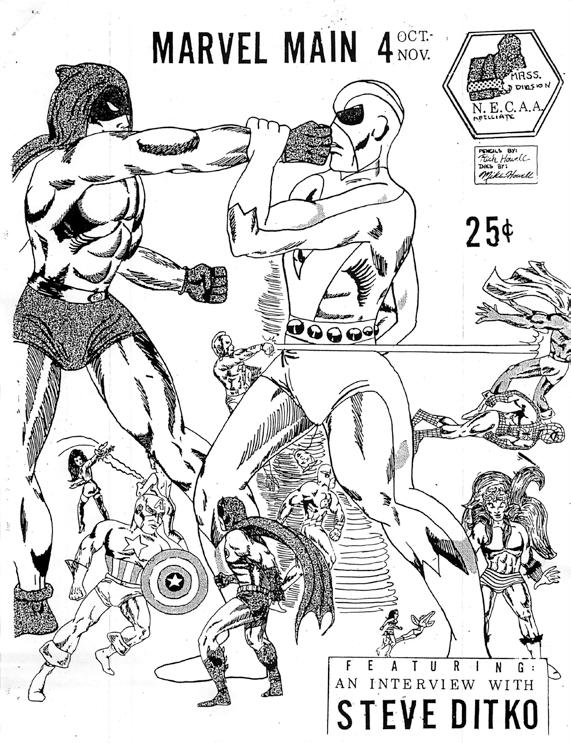

STEVE DITKO Interview–1968

Conducted by Mike & Rich Howell and Mark Canterbury

Conducted by Mike & Rich Howell and Mark Canterbury

A/E

EDITOR’S NOTE: This interview, which was conducted by mail, first appeared in the fanzine Marvel Main #4 (Oct.-Nov. 1968). It has been reprinted with the permission of Mike & Rich Howell. At our request, Mike wrote the new introduction below, which immediately precedes the interview. Alas, Mark Canterbury, who asked a few questions of his own, passed on several years ago. The interview was retyped for Alter Ego by Eric Nolen-Weathington.

Part I - Introduction

How Steve Ditko Talked To Marvel Main

by Mike Howell, founding editor of Marvel Main

The summer of 1968 was one of the most historic in American culture. Along with assassinations, demonstrations, and presidential elections, another, quieter, bit of upheaval was taking place: Steve Ditko was bringing out new characters and often-polarizing stories.

News of this tectonic change in the national comics industry was spread by the Blue Blazer Irregulars who made up the nascent comic fan community through their network of choice: the fanzine.

Through a combination of idle determination, sincere respect for Ditko’s work, and an elevated sense of mission, I directed my self-published mimeographed fanzine, Marvel Main, toward trying

The former, on left, in the mid-1960s—and the latter, on right, in a more recent photo (though, alas, we have none of his brother Michael or of Mark Canterbury). Above them is Rich’s cover for Marvel Main #4. [Heroes TM & © Marvel Characters, Inc.]

to get a “big name” interview. And we got a beauty, from Steve Ditko.

How difficult was that? you might wonder. Well, if you were a sheltered, suburban 14-year-old it was really quite a challenge. To start, I had no idea where (although New York City was a starting guess) or how to locate Ditko. My trips to the big city of Boston helped me learn the subway system and become familiar with Filene’s Basement and its automatic markdown policy that was catnip to my mother. When my brother Richard and I accompanied her there, we almost always were rewarded with a Tintin book, so braving the crowds had its perks, but that didn’t get us any closer to Steve Ditko.

A bit of background. Our core fan group was very tightly held: myself, my brother Richard, and our next-door neighbor, Mark Canterbury. We shared a delight in comics and absurdist humor and quirky corners of what would grow into America’s pop culture. The fact that we all sucked at sports and that dating, etc., seemed decades away helped with our hermetic association. Our impulse to keep ourselves amused led each of us to found a self-published

29

Steve Ditko & Richard Howell

“A Very Mysterious Character” An Essay On STEVE DITKO

by Barry Pearl

“You never really understand a person until you consider things from his point of view…until you climb in his skin and walk around in it.”

Atticus Finch, Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird.

One day a man will ring your doorbell and offer you CELEBRITY! He will offer you fame and fortune and recognition. He will fight your battles for you and gear up the troops to go after your perceived enemies.

And all you have to do is give him everything you have… your privacy, your intimate moments, your private thoughts, your old artwork, your new artwork, and details from events fifty years old. You’ll be expected to show up at conventions and sit and autograph comics that someone will sell tomorrow on eBay and sit in on panel after panel examining your work from fifty years ago and dismissing what you are working on now.

There are those who accept the offer, love the money and attention, but then complain about the lack of privacy and the wave of criticism.

Those who don’t take it are called eccentric, outsiders, has-beens, and hard to work with. With their subject out of the limelight, people can write newspaper articles and books saying outrageous things that bring publicity onto themselves, knowing

their subject will not bother to respond. They will tell you that they tried to get Ditko to cooperate with them, but it is never unconditional. They want something from him: his opinions, his personality, and most of all his approval. They will have people who never meet him write about him, make claims about him, and, by keeping him out of it, they seem to validate their own absurd remarks. This is not journalism; in fact, it is not even common sense.

Some people’s work speaks for itself. In the world of serious comicbooks, no one’s work speaks more for itself than Steve Ditko’s.

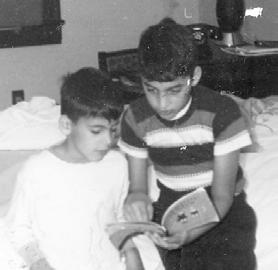

Here’s a rare photo of the artist in 1963 with his nephews Mark (on the left) and his older brother Steve—yep, another Steve Ditko! With thanks to Mark Ditko, via John Cimino. This pic came in just before we went to press.

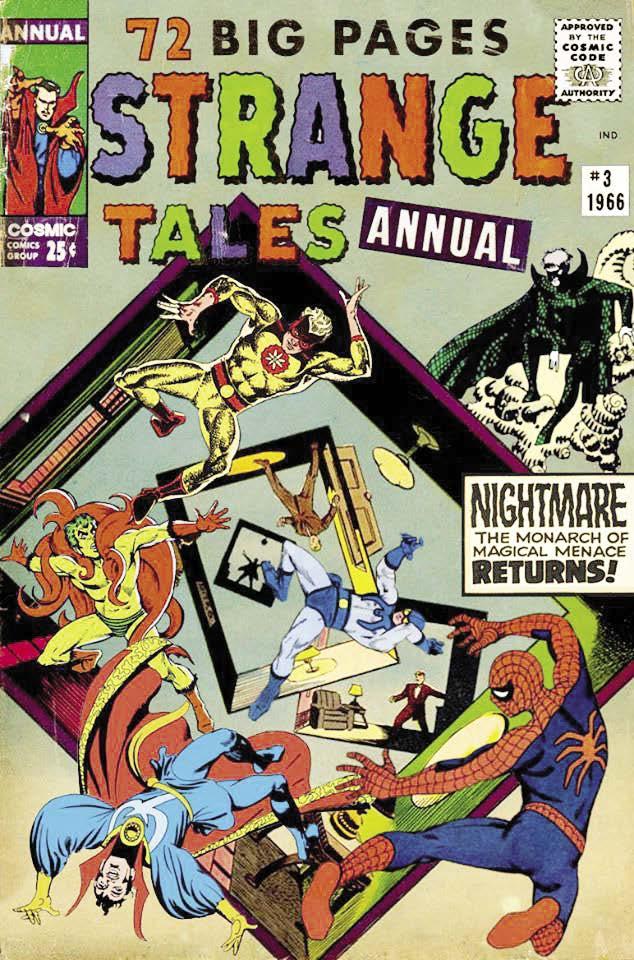

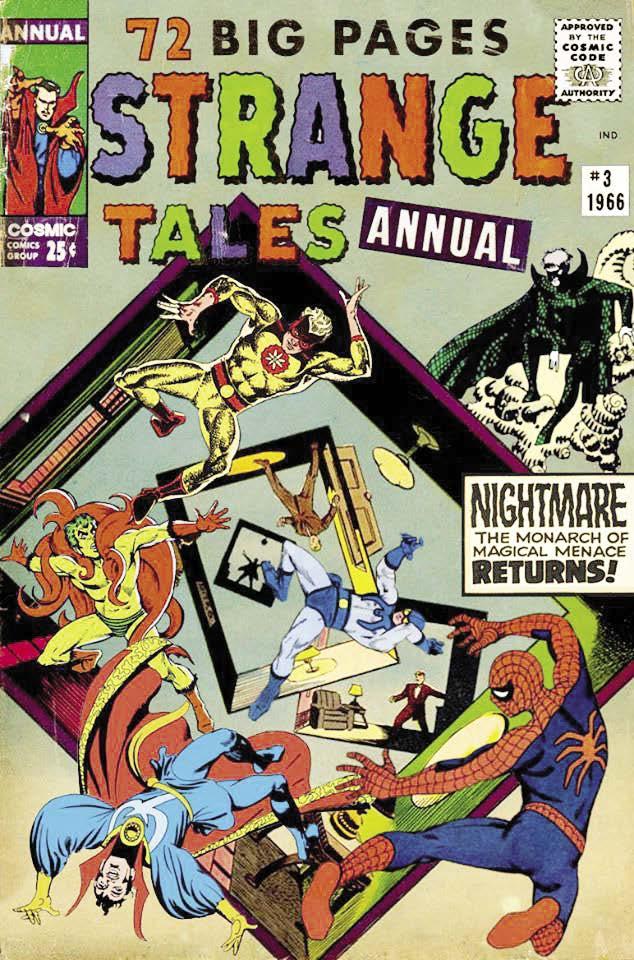

The Marvel Age of Comics was built on Jack Kirby’s creativity, Steve Ditko’s ingenuity, and Stan Lee’s continuity. Jack Kirby gave wonder to the Marvel Universe. Steve Ditko gave it awe. Kirby externalized the quest for knowledge, Ditko internalized it. On a journey to the Infinite, Kirby took us to the outer reaches of the universe. On a journey to find Eternity, Ditko took us into the minds of the Ancient One and Doctor Strange. In Doctor Strange’s first adventure in Strange Tales #110, Ditko introduces us to Nightmare, a villain that personifies an anxiety that we all share. Ditko places us in another dimension, one that exists in all of us, where the laws of physics are not relevant or even observed. Soon, this will be developed into the intangible home of Dormammu and all that follow.

The Hulk is a great example of Ditko recognizing what made a character work and what didn’t. When Kirby introduced him, his change was caused by external factors, dusk and dawn, and later a machine. Ditko’s Hulk changed that to an internal issue, uncontrollable anger. This made the Hulk unique among

He Rode A Blazing Western!

The Rawhide Kid (as re-conceived by Stan Lee and Jack Kirby in the early 1960s) and Peter Parker/Spider-Man may indeed have had similar origin stories as Barry suggests. But Steve Ditko never drew Rawhide Kid, so we’ll just toss you the splash page of a Ditko-illustrated “Utah Kid” story from Timor Publications’ Blazing Western #1 (Jan. 1954). Barry’s buddy Nick Caputo, who supplied it, says that the “Utah Kid” references are “crudely lettered” (like, the “H” looks ready to fall off!)—and he does bear more than a passing resemblance to Timely/ Atlas’ Ringo Kid—so could this have been an art sample that went astray and wound up at another company? We’ll doubtless never know. [© the respective copyright holders.]

35

Steve Ditko

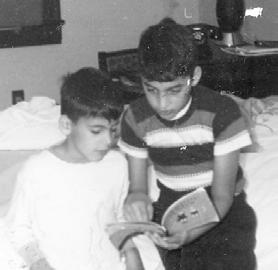

Barry Pearl seen some years back, when his older brother Norman was teaching him to read. Thanks to BP.

A Life Lived On His Own Terms

Encounters With Spider-Man’s Co-Creator, 1962 to 2017

by Bernie Bubnis

Ifirst met Steve Ditko in 1962. The last time I saw him was October 2017, and that is where this story begins.

The New York Comic Con at the Javits Center was a circus of people. I was flipping through some original artwork stacked on two tables. Every other second, someone bumped into me, and it was getting crowded. So crowded that it started to bother me. A guy in a Spider-Man costume offered to climb onto my shoulders so my wife could get a better photo. Just take the photo with him next to me, please. I was ready for lunch.

My wife and I left Javits and headed to a restaurant on West 52nd St. that we remembered from years ago (please, please make it still be there). Victor’s Cuban Cafe was, and it brought

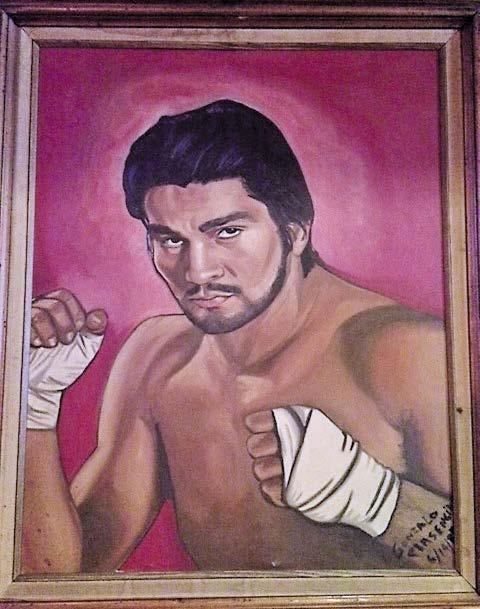

back memories of joining a conga line led by Roberto Duran (Victor’s boxer cousin) and dancing into the night. Honestly, remembering a good moment in your life is a magic pill, and that led me to start remembering a lot of good moments with artist and writer Steve Ditko. Wasn’t his studio just around the corner?

I had corresponded with him over the years, but those letters were too few and far between. My last in-person meeting with him had been in August 1964. I was growing up, and life’s responsibilities took control of my time. Our correspondence became more consistent in 2014, the year the NYCC would host a panel called “Survivors of the 1964 Comicon.” I knew he would want to be there... hey, what do I know... I’m a dreamer. He didn’t, but his handwritten letters would make me wait patiently for the next envelope from him to arrive in my mailbox (please, please make him answer his phone).

His hearing is bad and he admits it. Mine is bad and I don’t admit it. My wife took the phone and let him know we would be coming by. His studio/ apartment was located at 1650 Broadway, and the entry was from West 51st Street. A guy at the front desk asked if we had an appointment and pointed us to the elevators. Before his floor, the doors opened and in steps someone I knew. “Steve, it’s me, Bernie!“ He looked confused, so my wife increased the volume, “IT’S BERNIE BUBNIS FROM THE 1964 COMICON!” He stared and said, “You look different.” I didn’t know if he was kidding, and I started laughing, “It’s been

39

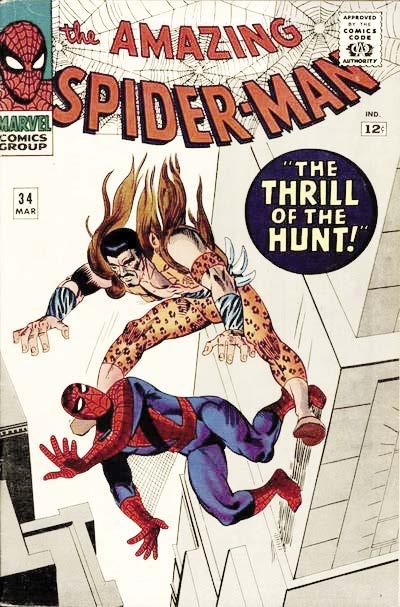

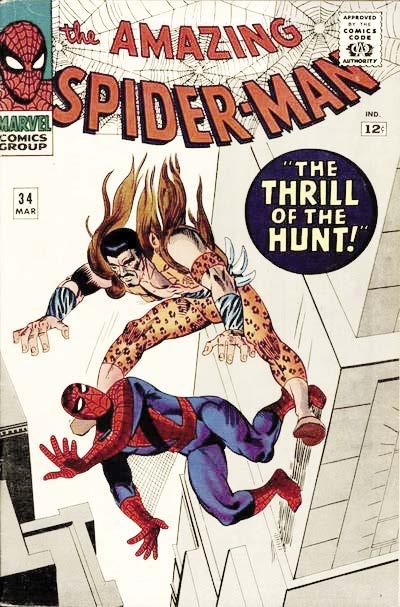

Bernie Bubnis with a cosplay Spidey at the New York Comic Con in October 2017—and, because this article is partly the story of Bernie’s long “hunt” for essence of the elusive Steve Ditko, an image of the iconic cover of Amazing SpiderMan #34 (May 1966). Thanks to Bernie for the photo, which was taken by his wife Lucille, and to the Grand Comics Database for the cover scan; note his “Comicon 1964” button. [Cover TM & © Marvel Characters, Inc.]

Boxed In

Up Close & Personal With Steve Ditko!—Part 2

Bernie and Lucille Bubnis at Victor’s Cuban Cafe that 2017 day—and a portrait of boxer Roberto Duran that hung there. Bernie recalls joining the fighter there in a conga line years earlier. Thanks to the Bubnises for both photos. We’re informed by Bernie that Roberto Duran “is still an icon to a lot of people. This portrait was in the bar area of the restaurant, and they were redoing the floors. When I showed interest in taking the photo, two workers built a shaky platform and then stood on it to take this photo for me. That is true love.”

Up Close & Personal With Steve Ditko!—Part 3

Two Visits To STEVE DITKO’s Studio/Sanctum Sanctorum

by Russ Maheras

Iwrote my first letter to Steve Ditko in early 1973, while I was still in high school. It was the typical letter a budding fan-artist might send a seasoned professional comics artist back then— full of effusive praise, capped with a request for some secret kernel of artistic knowledge that would magically transform overnight a fan’s crude artistic efforts into professional-level artwork. Ditko did his best to answer, giving what was, in retrospect, a solid list of advice.

Two years later, I wrote him again, and this time I asked if I could stop by his studio for a visit when I was in New York City later that year. He politely declined, and I pushed that idea into the dustbin of history—not realizing that 28 years later my request would become a reality.

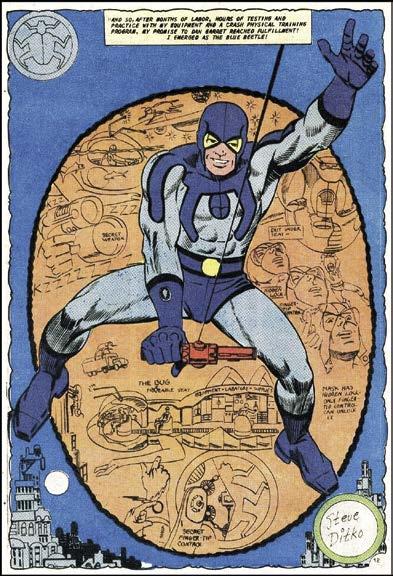

appeared online shortly after the artist’s passing: Charlton’s Captain Atom and Blue Beetle—Marvel’s Spider-Man, Dr. Strange, and Nightmare—and DC’s Creeper. Thanks to Russ for the photo, and to Michael T. Gilbert for sending the homage. [Captain Atom, Blue Beetle, & The Creeper TM & © DC Comics; Spider-Man, Dr. Strange, and Nightmare TM & © Marvel Characters, Inc.]

work,

More than two decades passed before I wrote Ditko again, in 1997. In the interim, I joined the Air Force, learned to be an aircraft avionics technician, got married, had kids, opted to be a career Airman, traveled and lived abroad for nearly a decade, earned a bachelor’s degree, retrained into public affairs during the early 1990s military drawdown, kept drawing, and kept publishing my fanzine, Maelstrom. In fact, my third letter to Ditko was a request for what I knew was an extreme longshot: an interview for an upcoming issue of my zine. Again, he politely declined.

I wrote a few more letters during the next two years about nothing in particular—including a couple while I was stationed in the Republic of Korea in 1998. In one of them, I included some terrifically supple Korean-made brushes that were ridiculously cheap, but feathered ink like a Winsor & Newton brush costing 30 times as much.

In 1999, I retired from the Air Force, published Maelstrom #7, and dutifully sent Ditko a copy. Our correspondence continued off and on until 2002, when I started preparing a Steve Ditko article for Maelstrom #8—along with a cover I drew that featured many of his more notable characters. When the issue was published, I sent him

a copy, and something about it must have struck a chord, as he sent me several letters of comment. Suddenly, our correspondence was a regular back-and-forth, and as my letters got longer, so did his. Some of his letters were 10, 12, or even 16 pages long.

So when I found out I had a business trip to New York City in mid-August 2003, I figured it couldn’t hurt to call ahead of time and ask if it I could stop by his studio on the 11th. To my surprise, he said yes. What follows are the notes I made in my hotel room immediately following visit #1, followed by notes I made after my second studio visit on Feb. 11, 2005.

Visit #1

At about 2:50 p.m., Aug. 11, I knocked on Steve Ditko’s studio door. He opened it and said without introduction, “Hello, Russ,” and reached out and shook my hand. I went inside and gratefully thanked him for seeing me. I asked him where I could set down my laptop carry case and he pointed to a spot; then I asked him if he minded if I took off my suit coat, and he said, “Here, let me take that from you,” and he took my coat and hung it up on his coat rack.

47

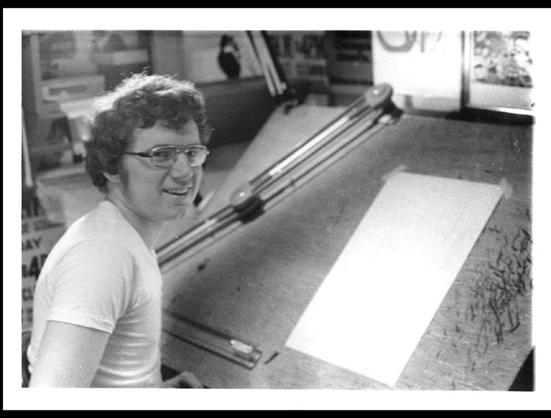

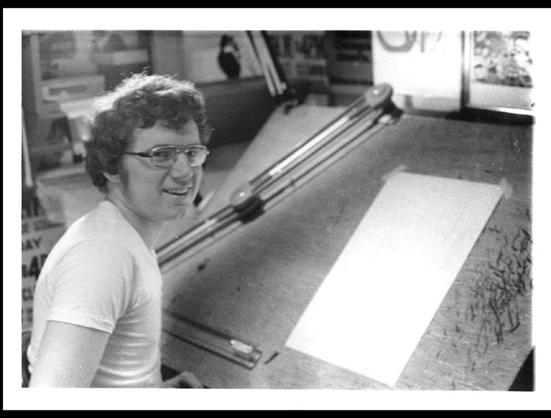

Russ Maheras circa 1973, around the time he first met Steve Ditko— juxtaposed with an anonymous but skillfully done homage composed of samples of Ditko’s 1960s super-hero

which

(Above:) Ditko’s “Stretching Things” from Farrell’s Fantastic Fears #5 (Jan. 1954), recolored by Bernie Mireault in 1991. This story, scripted by Bruce Hamilton, was one of Ditko’s first! [© Farrell Publications.]

(Above:) Ditko’s “Stretching Things” from Farrell’s Fantastic Fears #5 (Jan. 1954), recolored by Bernie Mireault in 1991. This story, scripted by Bruce Hamilton, was one of Ditko’s first! [© Farrell Publications.]

57

(Above:) Gilbert’s “Revenge Of The Boneless Man,” drawn in 1991 for Hamilton’s Grave Tales and published in 2005 in Atomeka’s Mr. Monster: Who Watches The Garbagemen? Color by Bernie Mireault. [© Michael T. Gilbert.]

Monster’s Comic Crypt!

First Love…

by Michael T. Gilbert

Hooked on Ditko!

1959 was the year Grandma Nurock gave me a beat-up copy of Marvel’s Tales to Astonish #1. Jack Kirby’s lead story featured a mutated turtle, roughly half a zillion feet tall. Wow! Tales illustrated by Jack Davis and Carl Burgos followed. But the story that really hooked me was “I Know the Secret of the Poltergeist!”— illustrated by you-know-who!

I was seven years old. And so began my sixty-year love affair with Steve Ditko.

Ditko’s art was direct and powerful, the storytelling wildly inventive and compelling. Moody black areas gave the stories solidity. Ditko’s characters were warm and ethnic-looking—a stark contrast to the cool, WASPy heroes drawn by DC mainstays like Carmine Infantino and Mike Sekowsky.

By contrast, the hero of Ditko’s “Poltergeist!” tale looked like a Polish peasant. In this story an investigator devoted to debunking the supernatural comes to a young couple’s house—a house apparently haunted by mischievous spooks called Poltergeists.

58 Mr.

“I’ve Got A Secret!”

(Above:) Ditko’s splash and final panel for “I Know the Secret of the Poltergeist!” from Tales to Astonish #1 (Jan 1959). Scripter unknown. [TM & © Marvel Characters, Inc.]

Steve Didn’t Put All His “X” In One Basket!

(Above:) “The Thing from Planet X” from Tales of Suspense #3 (May 1959). Scripter unknown. [TM & © Marvel Characters, Inc.]

MARK DITKO Interview

STEVE DITKO’s Nephew Speaks To Alex Grand

PUBLISHER’S NOTE: This interview originally aired on August 2, 2021, on the Comic Book Historians podcast. ©2021 Comic Book Historians. It was transcribed by Alex Grand and copyedited by John Morrow.

ALEX GRAND: Let’s kind of start off with, first, tell us your exact relation to Steve Ditko. Your dad is his brother, right? Basically that’s the relation.

MARK DITKO: Yep, yep. Steve Ditko is also my godfather. So I’ve known him since I was born, pretty much; obviously he was around when I was a kid, but then he and I kind of connected up after I moved out of Johnstown, in the early ’90s—’90, ’91. We kind of connected up through written correspondence. I mean, I would go back every now and then and see him over Christmas or something when I was visiting. But we pretty much started a written correspondence around ’90, ’91, and then that continued for the decades beyond that.

ALEX: So then it sounds like when you were a kid, he would come and visit on holidays. And then as you grew up and you moved out of Johnstown, your connections were through letters. And then if in person, it’d be back at Jonestown again on a holiday or something like that.

MARK: Yeah, exactly. When I was a kid he always popped in at least two or three times a year. He was always there. I remember him being around obviously [at] Christmas and then he would come in the summer sometimes, because we would always have a family barbecue and get-together in the summer. And he was always there flipping burgers or something. So I always saw him around then. I don’t know when he stopped doing the kind of the summers or the multi-visits, but he always maintained his holiday Christmas visit. So sometimes I would go back over Christmas and I would see him then. But early on as a kid he was always around multiple times a year. You know what? I didn’t even really realize that he didn’t live there because as a kid, he was around, we

would have family get together and he’d be around. He was just there.

ALEX: So what, he was driving to Johnstown from New York then?

MARK: No, he would take the train in.

ALEX: The train. There you go.

Upon his passing, DC Comics ran this memorial tribute. For a creator who’s largely thought of as a Marvel and Charlton artist, Steve certainly made his mark at DC. [Characters TM

MARK: Yeah. He was always on the train. In fact, he wrote to me one time that [when] he was on one of his train visits, on the way back, he wrote multiple issues of a certain character he was working on. Because he’d work on the train.

ALEX: First, so the audience knows—you’re an engineer by trade, you’ve written books on it, you’ve managed big projects. From what I’ve understood and the way I’ve analyzed Steve Ditko’s work, he approached everything analytically. Like for example, he would see the Jack Kirby version of what could be Spider-Man and then Stan kind of scrapped that and said, “Steve, you come up with something.” And then he analyzed what would be a Spider-Man better than anyone in history ever has before or since, with webs coming out of the wrist and the weird body movements—the web costume, which is the best costume, I think, in history. It seemed to me like he analyzed what would make a proper Spider-Man and then hashed it out. And if that’s correct, would you say that you share a similar analysis of the environment around you?

MARK: You know what? You mentioned it earlier; to me, it’s just analytical thinking; you’re not getting lost in some kind of emotional something. You’re creating a fantasy. I actually thought

Honoring Ditko

& © DC Comics]

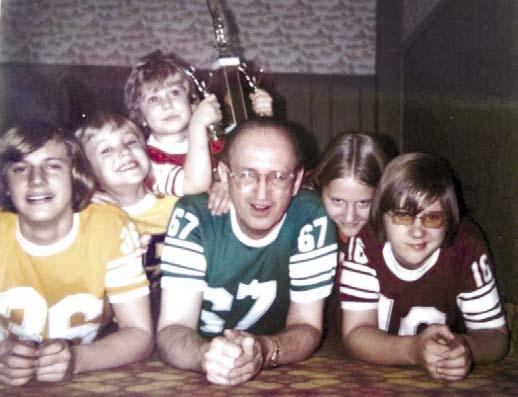

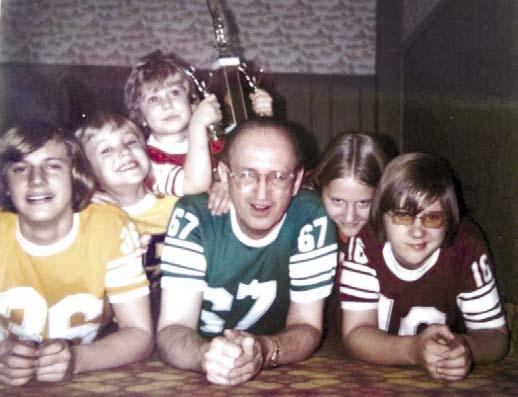

Uncle Steve Ditko with his nephew Mark (right).

about what you just said when he was creating Dr. Strange, and he was creating this alternate universe, what would it be like now if you... when we went to clean out his studio and his apartment, I ended up taking his library, and you look at what he read or what he studied and the magazines that he had subscriptions to, he was taking all of that into account when he was creating something. And yeah, I would say, okay, art, we know art is a... I don’t want to say a subjective type thing... let me rephrase that, because really art is subjective from the observer, but from the creator’s perspective, I think the creator does have a thought process that obviously goes into [it], especially panel layouts and things like that, and then the imagery. So yeah, he was very, I’ll say, scientific. I mean, as a kid, I know my dad told me that in the barn, he had his own little place that he had built that was kind of the secret room where he had all of his collections and chemistry sets. And he was, I would say, a mad scientist of sorts. He needed that just in his thought process.

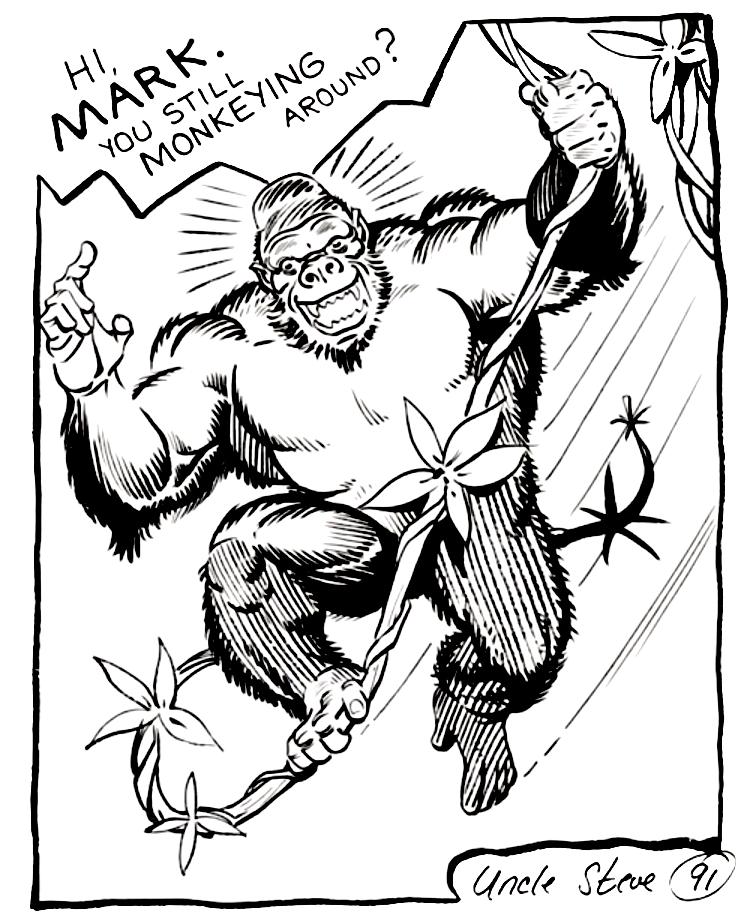

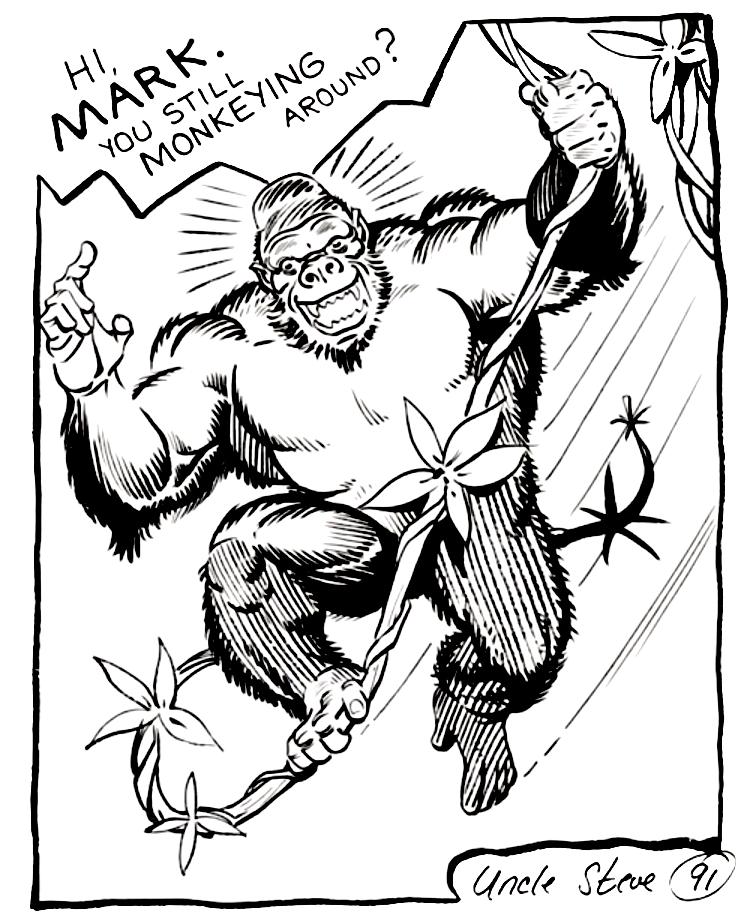

MARK: I probably remember Konga around the 1963, ’64 era, maybe ’65 or so. So I’m loving Konga as a kid, it was just a great storyline. It was very upbeat, it was fun and playful, but then my uncle would come in—I remember some Christmases, my older brother who was two years older than me, he would draw, he was always sketching and drawing stuff. We all drew, but he was older. He took that first leap into there and I remember that he would show my uncle and my uncle would give him pointers. He would put a piece of tracing paper over it and kind of comment on it and stuff. But when I found out that he could draw, I would say, “Uncle Steve, can you draw me a gorilla?” Because I loved Konga. So I’d say, “Hey, can you draw me a gorilla?” And he’d just whip out this gorilla and I’d be like, “Man...”. It was so fun so I was like, “Man, can you draw!” I had no idea he was drawing the comics that I was reading. I had no idea. So it really wasn’t until—I don’t know when the cat got out of the bag, but it wasn’t something that the family talked about. My dad didn’t talk about it, my aunts and uncles didn’t talk about it. When my uncle Steve came home, it wasn’t like, “Oh, here’s what I’m working on now, look at me.” It wasn’t like that. So it probably wasn’t until I was maybe 14, 15 or something that I realized what he had created.

ALEX: That’s great. What a cool revelation too, huh?

MARK: Yeah, I know. It was just like, “Whoa, uncle Steve, you

Taking One For The Team

ALEX: So when did you find out that he was the same Steve Ditko that co-created Spider-Man?

MARK: That probably really wasn’t until I was in maybe my mid-teens, because as a kid, he was just another one of my uncles, my fun uncle that we would goof around with and he would play, he would goof around and wrestle with us. And as I got older, he taught us how to throw knives and hatchets and just playful type stuff. But early on, as a kid, there were always comics around the house. And at some point I probably need to ask my dad, “Where did those come from?” Because, they just appeared. I’m a kid, I’m four years old, I don’t know where this stuff just appears from. I don’t know if my uncle was sending it to the family. I’d have to not believe that my dad was buying it. I think my uncle probably was sending it to everyone, but they just appeared around the house. So I started reading Konga; that was kind of my earliest recollection of reading comics.

ALEX: And what year would you say you started reading comics?

Still Swingin’

Mark Ditko Interview

The allegedly camera-shy Ditko was anything but with family around (that’s young Mark Ditko at far right in 1975). Photo courtesy Mark Ditko.

65

Mark’s early love of Konga (top) was rejuvenated in this 1991 sketch by his uncle. [Konga TM & © the respective owner.]

rock, man.”

ALEX: Why do you think he wasn’t telling everybody that... was he just keeping stuff close to the chest? Is that something in the mind of his generation, and being a Ditko of that generation, that they just didn’t verbalize their achievements so much? What was the source of his, let’s say, aversion to soaking in the limelight on his achievement with Spider-Man and Dr. Strange?

MARK: No, I think you kind of hit on it—and this is just my opinion, because I don’t know why he did what he did, really, other than I know what we wrote together. I know what we talked about. And a lot of this stuff I kind of have to extrapolate from the family because, hey, the kids are similar. My dad obviously has similar characteristics as my uncle and my aunts, and even my grandparents, his parents. They were just, I want to say, with that kind of immigrant mentality. For second generation Americans, they... in fact, Zack Kruse, in his book Mysterious Travelers, he mentions a book in there, and I talk about it all the time: For Bread with Butter, the history of the immigrants in Johnstown. And it talks about their attitudes and how education was not the highest priority. It was a priority, but doing something, having a good work ethic and buckling down and doing a job, was actually the highest priority. Because look, you’re an immigrant, you got to get paid. You just got to have that work ethic. So he had that, my parents have that, my aunts and uncles have it, all of them. I saw that in my family, which was really probably something that was just a general immigrant mentality. But I’d say not everybody could be successful, because they have to have a certain talent. They have to have a certain intelligence and mindset.

My grandfather on my mom’s side—there was Grandma and Grandpap, on my dad’s side it was Poppy and Bubba, so that was how we kind of referred

to them. So I’ll say they were geniuses, learning the language themselves, learning their own skillset, become a master carpenter by himself and just learning and learning. They were sponges and they had the intelligence to do that. So I think that that work ethic is what I saw in my uncle, that he had that capability to just put his mind to something that was a real passion, and commit and be able to really be successful.

ALEX: So I know that there are basically two layers to every question about Steve Ditko to you, right? There is what you learned from him about that particular topic, and then there’s also the subjective of your impression, of why something could be.

MARK: Yeah.

ALEX: And I know that interplay exists anytime anyone asks you about your uncle, but I wanted to ask you a couple of things. Was he religious or atheist or agnostic?

MARK: Well, I would say that he was born into a religion; we’re Byzantine Catholic. So we were born in that. But no, that wasn’t something that he really followed. He believed that this was one lifetime and when it was done, it was done, and make the best of it. So that was kind of his attitude.

ALEX: Did he ever mention any childhood comics influences? It’s said that he loved Jerry Robinson’s Batman.

MARK: Yup.

Fighting Americans

ALEX: Will Eisner’s Spirit. And then also, Mort Meskin had made an impression on him when he worked under him at the Simon & Kirby Studio. Did those discussions ever come up about his childhood comic collection, and as a budding comic artist?

Mark Ditko Interview

Dearly Beloved

Steve & Mark in 1992 at a church ceremony for Mark’s youngest daughter Stefanie.

(Left:) Detail from original art for Strange Tales #117 (Feb. 1964), page 3. [Dr. Strange TM & © Marvel Characters, Inc.]

66

Steve (far left and inset) during his Army service.

as a creator? They weren’t really close friends, right? But they worked at the same place around the same time. Was that the full extent of it? Were they mainly acquaintances with respect for each other? What’s your impression of that?

MARK: Yeah, I think that’s all that it was. They weren’t buddies, they didn’t hang around. They were just acquaintances. They clearly knew of each other and they were just two ships passing in the night on certain comics, because they didn’t necessarily collaborate all that much. He inked Jack’s work on the covers and stuff like that, but I never really talked to him about that. I wrote to him when I had met Jack and Jack and I had talked. I can’t really recall what the response was on that, but it wasn’t that they were buddies connected at the hip. It wasn’t like that.

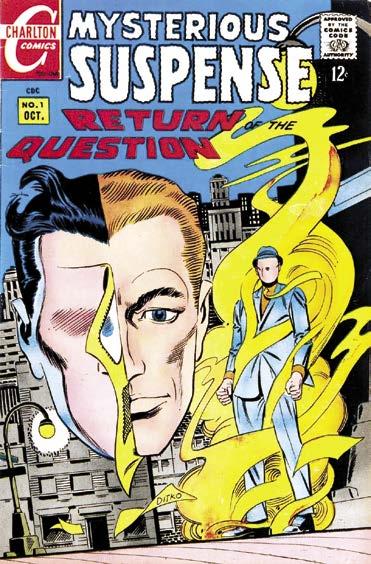

ALEX: As far as some of his post-Marvel characters, you can see some elements of objectivism within Blue Beetle and most certainly The Question and Mr. A. Just from your impression of it, is that probably the direction he was going to take Spider-Man, or do you think he looked at those characters as, “These are different concepts and I’m going to do this with them”?

MARK: This is really covered in Zack’s book, Mysterious Traveler, that I think there was an evolution going on with the way he created characters. So I think, to me, Spider-Man would have evolved in that direction to where early on—in fact my spin on [how] he created this flawed Peter Parker character. He didn’t build these flaws into him and expect them, in my opinion, to be maintained.

The reality is all of a sudden you have super-powers and you’re going, “Whoa! What the...?” And then you’re trying to get

your head wrapped around that until you figure out where you’re at, and it’s a microcosmic life that you’re learning. Like, how do I function now with this? And then eventually you start to sort it out. You start to have more experiences and you start to just get more of a focus, and little by little you evolve. So I think Spider-Man would have gone that way.

No other character is more closely associated with Ditko than Mr. A—but while the strip focused on absolutes of right and wrong, Ditko was much more philosophically nuanced than fandom’s legends about him would lead us to believe.

ALEX: It was because he was a 15-year-old that he had those flaws in that...

MARK: You would expect it.

ALEX: That you would expect it. And then when he lifted that large weight in that later issue, overcoming a lot of his mental anxieties, that was a metaphor of a growth moment where he was going to achieve a more final, more adult worldview of what he would think would be more appropriate. And that’s why I think a lot of people feel that when he left, it wasn’t really the Spider-Man that was intended, at least from his perspective anymore, that it became more of an anxious mascot for Marvel Comics.

MARK: Yeah. I mean, look, he was a storyteller, and he mapped and plotted those things out. He knew where he wanted to go with that, because it’s almost like Harry Potter. How many volumes is that? Do you think she just kind of made it up as she went, the author? I think there was a master plan.

74 Mark Ditko Interview

The Man, The Myth

[TM & © Estate of Steve Ditko]

ALEX: Yeah. There was probably an A to Z on this.

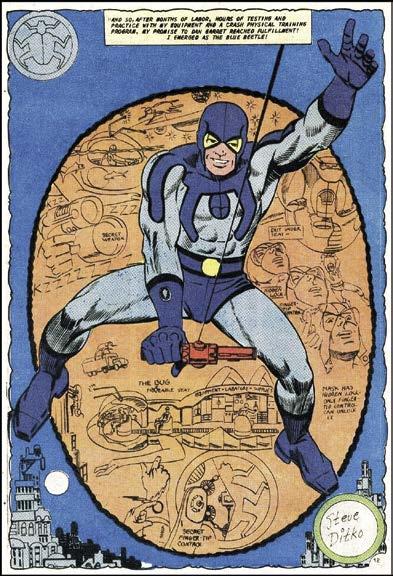

MARK: Exactly. So I think he saw where it was going to evolve, he just jumped ship before he could complete that evolution. So he goes, and now he’s doing Blue Beetle, and it is sort of an extension of that. I mean, the artwork of Blue Beetle, to me, is just mind-blowing. It’s very SpiderMan-ish kind of, but that’s what he’s known for, that action, integrating that action into static panels. So I think it was all an evolution, and Spider-Man, Peter Parker, would have eventually kind of gotten there. And that’s why I think later on he was like, “Okay, you know what? I’m done with that. I could actually set that aside, because it’s not going where I would have taken it. So I’m not going to sit here and whine about it. I’m going to move on to my next character and I’m going to do what I’m going to do.”

ALEX: A lot of people don’t put these two characters together. Knowing what you know of your uncle and your discussions and just studying the guy as well, the concept of The Chameleon who is faceless, and then The Question and Mr. A—at Charlton, he did a Chameleon-type character before the Marvel one, and then even later, he did a character that was kind of similar. What do you think it is about the faceless character that seemed to appeal to his artistic sensibilities?

MARK: I’ve never thought about that. And that’s something where I think I’m deficient; in my knowledge of his characters and their personalities and all that stuff. I know the main characters, but I am by no means a comic historian. I watch your show

and you talk about stuff, and I’m just like, “Whoa, that is over my head.” I mean, I had no idea of any of that stuff. So I don’t know. My thoughts on it now are that it was just a way to make that imagery stand out.

ALEX: Like a vehicle. More like a storytelling vehicle, maybe.

MARK: Exactly. Yeah.

ALEX: Some people will say that The Question is him, just like some people want to say Peter Parker is him. But is The Question more him, or is that another construct that he analyzed and put together, do you think?

MARK: I don’t think any of those things are him. He wrote to me at one point and he said that he thinks comics should have evolved to be more of an educational medium. So I think all he was doing is telling a story. And he’s trying to get a moral across.

ALEX: Yeah, teach a lesson of some kind.

MARK: Exactly. And, to me, a lot of that stuff he’s doing, he’s just trying to do it in what he sees as an entertaining way of trying to get some life, whether it’s ethics or morality or integrity, some point across, and getting them to try to look at something in a medium that maybe they wouldn’t otherwise have seen. So I don’t think he was trying to tell his life story or create an image of himself.

Next Steps

And even with Mr. A—the black and white. He says everything is black and white. People go, “Oh, that’s harsh. It’s ridiculous. You can’t have that attitude.” Well, you know what? Maybe it can’t be applied across the board, but in some instances, he’s getting you to process life through maybe a different lens. I’ll just make a strange analogy. My dad has this saying sometimes, which I don’t really agree with, but he says it: “All things in moderation.” And I get what he’s saying. And in a certain frame, that actually makes sense. Don’t overdo. Don’t eat four gallons of ice cream every single night. That’s not going to be a good thing. So all things in moderation.

And so my uncle had this sort of, okay, black and white. But that doesn’t mean everywhere, because for example, I could tell my dad I only did a little bit of heroin tonight. Look, I’m moderating it. I only do so much a week. It’s like, no. To me, that is a black and white. No, don’t do that. So my uncle, in this sort of black and white mentality, could say, “Look. Do you think it’s okay to just steal, oh, I don’t know, maybe just pads of paper? Because look, it’s not like you’re stealing bills. You’re not taking a computer or something. You’re just taking some paper.

Mark Ditko Interview 75

If the Blue Beetle is the logical evolution from Spider-Man, is The Question a direct descendant of Spidey villain The Chameleon? [Blue Beetle, Question TM & © DC Comics; Spider-Man, Fantastic Four, Chameleon TM & © Marvel Characters, Inc.]

One Life, Furnished In Early DITKO

An Imaginary Story Featuring Charlton Comics, Ibis The Invincible, Doctor Strange, & The Great Connecticut Flood Of 1955

by Brian Cremins for Harlan

by Brian Cremins for Harlan

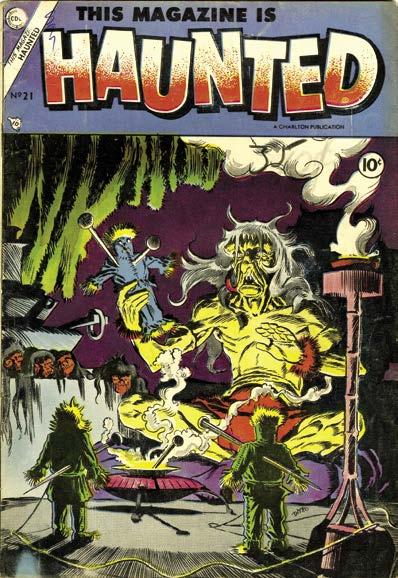

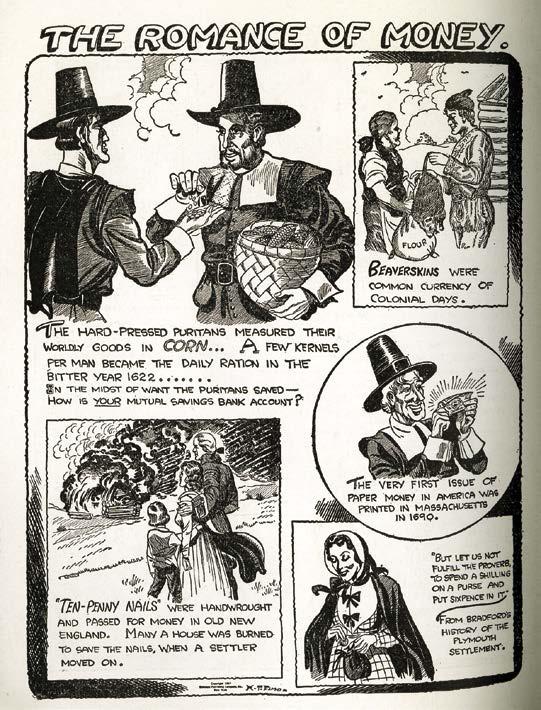

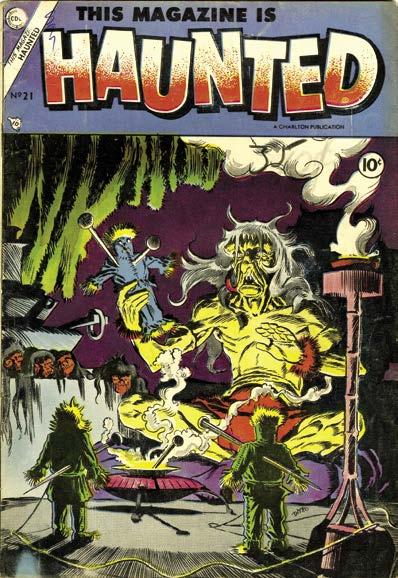

These are the facts as I know and understand them: The late Steve Ditko, legendary co-creator of Spider-Man and Doctor Strange, never worked for Fawcett Publications.

He was a few months too late. By the time he began drawing covers and stories for This Magazine Is Haunted, a title introduced by the Fawcett comics line in 1951, Charlton Comics from Derby, Connecticut, had taken over the title. In 1954, Ditko drew five covers for the series, along with four stories. Then, by early 1955, This Magazine Is Haunted ceased publication. Sort of. It carried on as a comic called Danger and Adventure, which, as the Grand Comics Database points out, picked up where This Magazine Is Haunted left off with issue #22. On the cover of that issue of the series is none other than Fawcett’s Ibis the Invincible. Unlike the members of the Marvel Family—which Fawcett, as part of its settlement with National, had promised never to publish (or allow to be published) again—Ibis

still had some life left in him, even if the story Charlton published had first appeared in Whiz Comics #45 a decade earlier. (And, just for the record, This Magazine Is Haunted returned to the Charlton lineup in 1957-58 for five more issues, though sporting a butchered numbering system that can confuse the unwary reader—and Ditko contributed heavily to the revised series’ covers and interior artwork.)

Those are the facts. But we’re all friends and comicbook fans here. We love our What Ifs? and our Imaginary Stories (many of which Otto Binder himself wrote for DC’s Superman comics after Fawcett’s settlement with that company). When I began working on this article, P.C. Hamerlinck urged me to explore one of these alternate histories: What if Charlton had hired Steve Ditko to draw “Ibis the Invincible” for Danger and Adventure? What if Ditko had gotten a head start on ideas he later introduced with Stan Lee

in his studio in the 1960s, flanked by his cover for This Magazine Is Haunted #21 (Nov. 1954), that comic’s final issue in its initial Charlton, pre-Comics Code incarnation—and the cover of Danger and Adventure #22 (Feb. ’55), which continued the TMIH numbering but cover-featured Ibis the Invincible, a sorcerer-hero, in an Alex Blum-penciled story reprinted from Fawcett’s Whiz Comics. Charlton had recently purchased many of Fawcett’s effects after the latter publisher left the comicbook business in 1953. Alas, this was far too early for Ditko get the opportunity to work his own particular brand of magic with the potent Ibistick! [Ibis the Invincible TM & © DC Comics; other cover TM & © the respective trademark & copyright holders.]

84

Steve Ditko

A 1975 Radio Interview With STAN LEE

Conducted On-Air By CAROLE HEMINGWAY, KABC-Talk Radio, October 1975

Transcribed by Steven Tice – with Additions by Rand Hoppe

EDITOR’S INTRO:

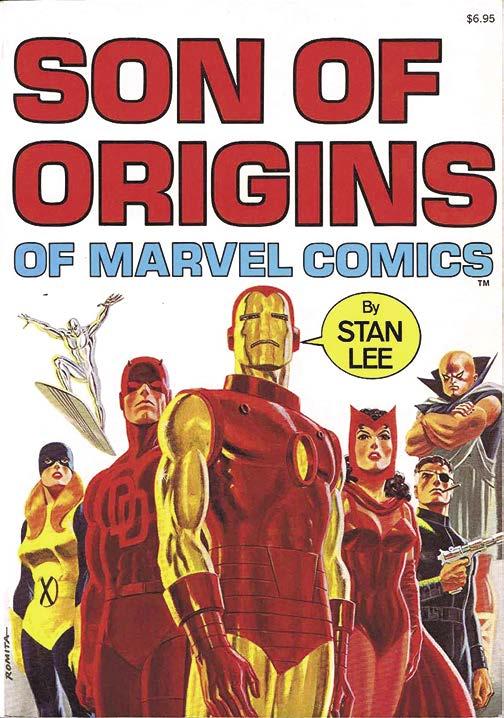

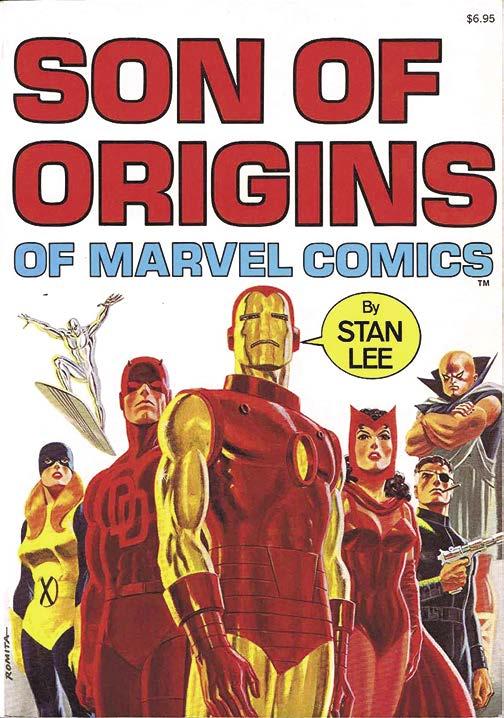

In October 1975, Stan Lee, then still living on the East Coast and serving as Marvel Comics’ publisher, made one of his periodic trips to Los Angeles—in this case, to help promote the new Simon & Schuster/Fireside hardcover Son of Origins of Marvel Comics, the sequel to 1974’s Origins of Marvel Comics. Both books were composed of stories he had scripted in the 1960s for the early days of Marvel, with Lee also providing new prose introductions to each tale. One of his most memorable appearances was on talk-radio station KABC in L.A., where the nighttime hostess was Carole Hemingway.

Hemingway had begun on the station a year earlier, and had quickly become a very popular presence on the nighttime air waves, remaining there until 1982, and later having another such radio gig (though in the afternoon) from 1986-93. She also later owned a media consulting firm operating out of Beverly Hills, California, and for some time wrote a nationally syndicated newspaper column of social commentary.

When I first read a transcription of some of the latter part of this hour-long interview with Stan Lee, I thought—as, apparently, did a few other readers as opposed to listeners— that Carole and Stan had gotten off on the wrong foot and were hostile to each other. However, after the entire talk was transcribed, it was apparent that it was nothing but a good-natured verbal “love & insult fest,” perhaps a welcome aperitif to all the radio shows on which Stan did little but plug product. He and Hemingway made a good match—and when I discovered that none other than the legendary Jack Kirby had called in near the end of the show to toss in his 2¢ worth (at a time when he had only recently returned to Marvel for what would become, alas, merely a three-year stay), I decided that it had to be spotlighted in this celebration of Stan the Man….

LEE: I love The Silver Surfer.

CAROLE HEMINGWAY: Hi, everybody. The time is 9:05 at KABC-Talk Radio… this is ridiculous! Why did I invite you here? [chuckles; Lee laughs] Who can talk about comicbooks? Nobody can talk about comicbooks for an entire hour. They’re boring and violent… bloodshed!

STAN LEE: Just ask me some questions. Just introduce the thing. There is violence, there is bloodshed, but these are Marvel Comics, which are a model of decorum.

HEMINGWAY: No, no, no… I’ve been reading this…

LEE: You lucky devil…

HEMINGWAY: No, no, no… you’re the devil.

LEE: The introductions that I wrote, did you know…

HEMINGWAY: No, they are pretty bad, actually.

LEE: Well, it’s been nice seeing you! I’m glad the settings are not turned on or anything. [chuckles]

HEMINGWAY: This is Stan Lee, by the way. He originated Marvel Comics and all those people with some sort of extra-fantastic power. We have Marvel Girl, Cyclops, Iceman, Iron Man, Magneto, Wasp, Silver Surfer, Ant-Man…

HEMINGWAY: He’s mean and cruel.

LEE: No, he’s sweet and adorable—almost Christ-like in his aspect and demeanor, and the college kids are really into The Silver Surfer.

HEMINGWAY: They’re into The Silver Surfer…

LEE: There’s a lot of philosophy… Your problem is…

95

A/E

Carole Hemingway & Stan Lee bookend the cover of the brand new 1975 Simon & Schuster/Fireside hardcover book that Lee had come west to ballyhoo: Son of Origins of Marvel Comics, with its dramatic painted cover by John Romita. [Cover art TM & © Marvel Characters, Inc.]

Tributes To A Titan A Few Of Those Who Worked For & With Him Remember STAN LEE

Assembled by Roy Thomas

A/E

EDITOR’S INTRODUCTION: Because another issue of Alter Ego (#150, to be exact) was dedicated to Stan Lee in conjunction with his 95th birthday, just under two years ago, I felt freer than I otherwise might have in setting up the precise contents for this one, which will be on sale nearly one year after his passing on November 12, 2018. I invited a handful of key people who worked editorially for Marvel Comics in New York City when Stan was on the scene as editor and/or publisher to share their thoughts about working with him. I realize I could have approached any number more, and perhaps I should have. Maybe some of those folks will share their thoughts with us for a future issue.

The first tribute-payers below are three of the surviving gents who served under publisher Stan as his editor-in-chief, presented in the order in which they served: myself, Marv Wolfman, and Jim Shooter. Two others, Len Wein and Archie Goodwin, sadly, have left us—and Gerry Conway, who served for a few weeks in early 1976, sent his apologies but did not at present feel up to putting his thoughts on paper. Others accepting our invitation were Tony Isabella, who came on staff in the early 1970s; David Anthony Kraft, who signed on a year or so later; and Steve Englehart, only briefly a staffer but another of Marvel’s top writers of the 1970s.

Here are their thoughts, in roughly the order in which they were piped aboard, beginning with myself, because I came to work for Stan in July of 1965 and served as the company-wide editor (Stan and I agreed on the hyphenated title “editor-in-chief”) from 1972 to 1974… a period of a few months over two years….

A Trio Of Tributes by Roy Thomas

Because I’ve written at length about Stan in many places, including in Alter Ego #150 and in the sizable Taschen book The Stan Lee Story (not to mention in 2014’s 75 Years of Marvel: From the Golden Age to the Silver Screen), I’ve decided to mostly limit my thoughts to those related to my final face-to-face meeting with him—on November 10, 2018—as it would turn out, less than two days before he passed away.

First, though, I thought I’d reprint the few paragraphs I wrote in 2017 as an “Afterword” for the first, 1200-copy edition (counting 200 “artist’s proofs”) of The Stan Lee Story, which by sheer coincidence would go on sale at bookstores around the time of Stan’s death. That page would be replaced in the general edition of the book (published in July 2019) by a truncated account of our final encounter. Here is my original “Afterword,” by courtesy of copyright-holder Taschen:

Stan Lee is a whirlwind I first encountered in the pages of Marvel Comics in 1961… then in person four years later. Ever since the latter day, he has been a dominant presence in my life, whether I was employed by Marvel at the time or not. For the next several years after 1965, he was for me a one-man course of instruction on the way to write—and to edit—thrilling yet humanized comicbook heroes.

Beyond “Bullpen Bulletins”

Until I met him, I’d had other comics writers and editors after whom I might have patterned myself; but standing on his right hand, morning after weekday morning for years, mostly swept those other influences away, much like those rivers that Hercules channeled through the Augean stables. For here, I quickly realized, was a man who was very clearly in command of what he was doing as both writer and editor… and who knew how to get the best, the very best, out of writers and artists (and other editors) alike.

This book, as was surely apparent long before you reached this page, is not and never was intended to be a biography. It is, rather, the story of one man’s—of Stan the Man’s—journey through the vine-encrusted jungles of 20th- and 21st-century popular culture, both reacting to what had come before and greatly influencing what has come after. In harness with some of the finest action and humor artists ever to wander into the mad, mad world of comicbooks, and working from his own personal and commercial instincts, only rarely with a preconceived road map, he charted a course that has been a pathway for all who have come since, whether they know it or not. (And mostly they do.)

Working with and for him, in one capacity or another, for much of the past 50-plus years has been a privilege and good fortune of which a boy in the trans-Mississippi Midwest could scarcely have dreamed when first reading the four-color exploits of Captain America, the Human Torch, and the Sub-Mariner in the latter 1940s.

Once, when it had abruptly occurred to him that there was an 18-year age gap between the two of us, Stan squinted at me and said, “You know, I could have been your father!”

In many ways, Stan… you damn near were.

My manager/pal John Cimino gave his POV of the events of November 10, 2018, in this issue’s guest editorial on pp. 93-94 of this issue. Here is my own, an expansion of the necessarily brief remarks that appear in the “Afterword” of the general edition of The Stan Lee Story. Both versions are based on notes I wrote on November 12th of last year— the day after I’d flown back from L.A. to South Carolina and the very morning I learned of Stan’s passing:

The cover of the New York Daily News for Nov. 13, 2018, the day after Stan Lee’s passing. With thanks to Michael T. Gilbert. [TM & © the respective trademark & copyright holders.]

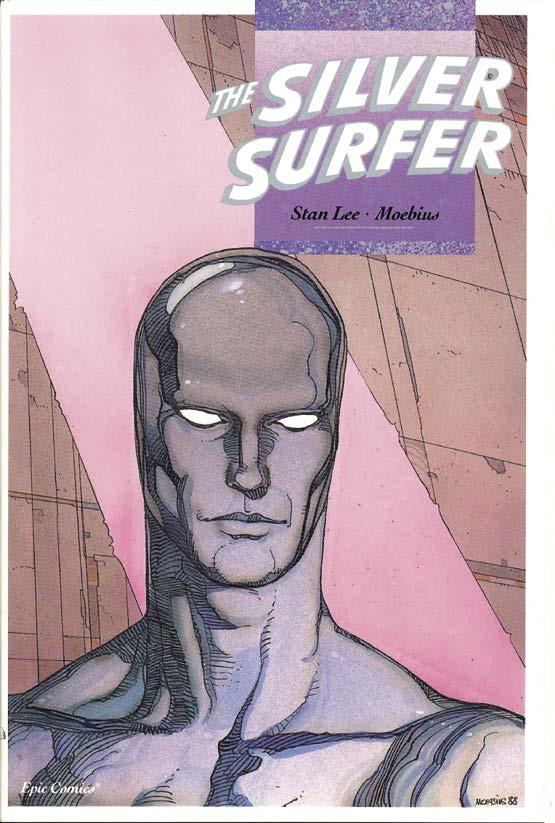

STAN LEE & MOEBIUS

When Titans Clashed—Together!

by Jean-Marc Lofficier

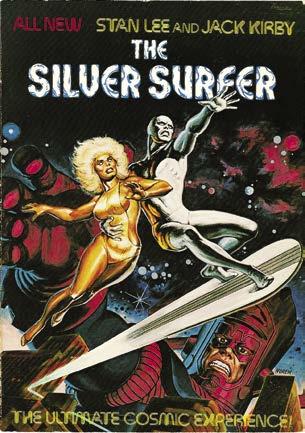

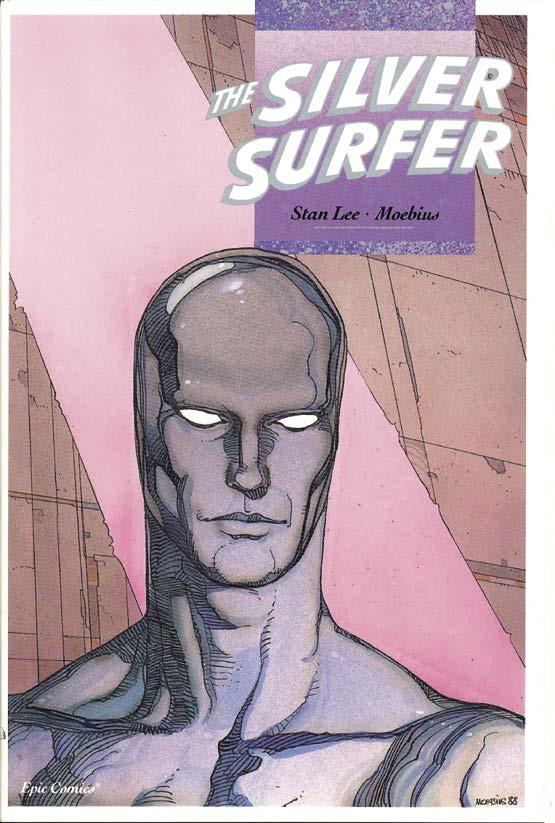

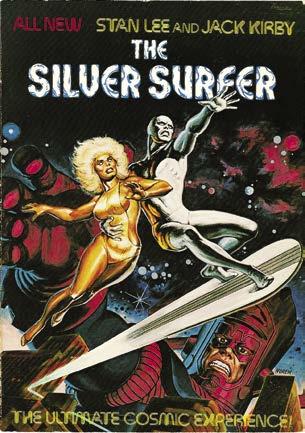

Ionly worked with Stan once—on the Silver Surfer graphic novel he did with Jean “Moebius” Giraud in 1987-88.

Jean and I, who were then business partners, first met Stan in a one-on-one at the American Booksellers’ Association convention in May 1987 in Anaheim, California, then again at the San Diego Comic-Con a couple of months later. Stan was very eager to find a way to work with Jean, and the feeling was reciprocated. The problem was that Jean was unfamiliar with most of the Marvel characters. He had first discovered them in their French editions in 1969 in the magazines Fantask, then Strange, published by Editions Lug, the current successor of which is Hexagon Comics, of which I am today editor-in-chief.

The one series that had most impressed him was Stan and John Buscema’s glorious Silver Surfer of 1968-70, which had garnered much praise from French writers and artists, and had even been wonderfully parodied by top cartoonist Marcel Gotlib

in his humor magazine Fluide Glacial (which also published Carmen Cru, which my wife Randy and I translated for the US market under the title French Ice).

So, when we had lunch at Comic-Con, I suggested the Surfer as the best “candidate” for a collaboration. This was greeted enthusiastically by Stan, since it was his favorite character. I also suggested to Stan that he should write a stand-alone story, with just the Surfer, without a plethora of other Marvel guest-stars, like the other stand-alone he had done with Jack Kirby to try to sell a Surfer movie, which had ended up being published by Simon & Schuster in 1978. This was, he said, something that fit his vision perfectly, and he wouldn’t have dreamed of doing otherwise.

Jean was very intent on having his name on a “real” American comicbook, one printed on newsprint, colored with the Ben Day process. Archie Goodwin, who was then Epic’s editor, came up with the concept of publishing the story as two comics first, reusing the original Surfer logo from the ’60s, then collecting it in a jacketed hardcover with some additional features six months later.

Stan went home to write the plot, almost suffering from stage fright, which I thought was both surprising and endearing. After all, if Moebius was Moebius, he was Stan “The Man” Lee. And Jean was not an intimidating figure; he and Stan had visibly clicked during the lunch and had found much in common in their philosophies of life.

I genuinely don’t recall how long it took Stan to write the plot

132

Jean Giraud (aka “Moebius”) & Jean-Marc Lofficier

That’s “Moebius” on the left, around the time of his and Stan Lee’s Silver Surfer: Parable graphic novel—while Jean-Marc is seen (on right) walking his dogs in the countryside earlier this year. Jean Giraud, of course, drew and colored the cover of the Marvel/Epic graphic novel. The two separate issues won the 1989 Eisner Award for “Best Finite/Limited Series.” Thanks to Jean-Marc for the photo of himself; the pic of Moebius was found on the Internet. We figure you know what Stan looks like by now—and alas, we have no photos of him and Moebius together. [Parable cover TM & © Marvel Characters, Inc.]

STAN LEE, AL LANDAU, & The Transworld Connection

by Rob Kirby

by Rob Kirby

While greater knowledge and insight into comics’ history has been accumulating in print during recent decades, both in book form and in magazines such as this one, there are undoubtedly many other tantalizing secrets still waiting to be uncovered and deciphered. One such mystery has long surrounded a company known as Transworld Feature Syndicate, Inc., and how exactly it became involved with Marvel’s global expansion. Through my researches into the origin and development of Marvel’s own line of British comics, it’s now clear that, despite Transworld Feature Syndicate being involved with the comic giant’s overseas activities until the 1980s, it was never owned by Marvel, or indeed by any of the companies that later bought Marvel. This discovery is somewhat at variance with what, for example, Roy Thomas seems to have assumed when writing 75 Years of Marvel: From the Golden Age to the Silver Screen (p. 494), but as you’ll discover in these pages, Transworld initially operated in quite a different area altogether.

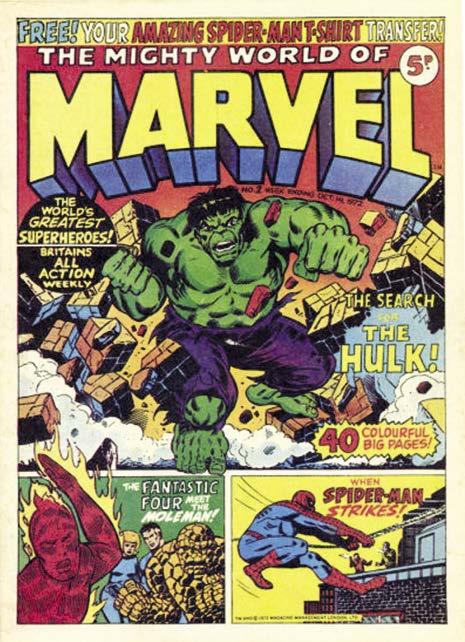

Mighty World Of Marvel #2 (Oct. 14, 1972)

We showed you the cover for MWOM #1 (Oct. 7, 1972) in conjunction with Robert Menzies’ article on Marvel UK in Alter Ego #150—so here’s the Jim Starlin/Joe Sinnott cover for issue #2, which spotlighted the ever-Incredible Hulk. Thanks to the Grand Comics Database. [TM & © Marvel Characters, Inc.]

possibly have become aware of the Transworld name. The same holds equally true for those aficionados of the many and varied reprint comics published in Australia, New Zealand, and on mainland Europe—likewise the products of a variety of local publishers—where the Transworld name would again often be displayed somewhere within their copyright information. Beyond that, there was little to go on.

Who, and what, exactly, was Transworld? The puzzle seemed unsolvable.

Read All About It!

If you’ve ever read any of Marvel’s own British reprint comics from the first half-decade or so of their existence—or indeed any of the earlier licensed comics pre-1971, which used material from the Marvel/Atlas vaults, hailing from companies such as Thorpe and Porter, Alan Class, Odhams, and IPC—you might

The origins of the Transworld family were equally a mystery to me when I first began research for a history of Marvel UK after a decade-long search to index every single story published by Marvel in Britain since 1972—not an easy task, pre-Internet. There was next to nothing to be found about who Transworld were; and. after the birth of the web… actually, there still wasn’t that much extra to go on. I would eventually find out more, but only after widening my purview to take into account all those licensed comics referred to above that preceded Marvel’s creation of The Mighty World of Marvel in 1972, a lineage that went as far back as 1951.

In looking back right to the beginning, there were hints that

138

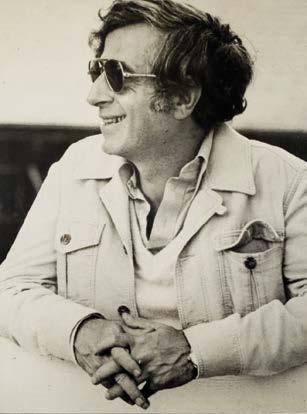

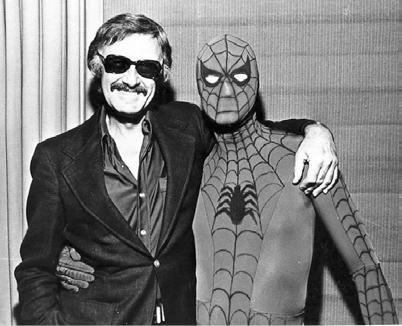

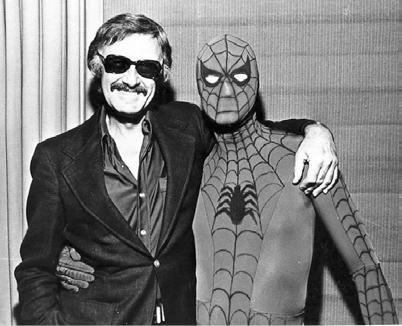

Stan Lee and web-headed friend in a photo taken in 1974, during the period when Lee and Landau were publisher and president of Marvel Comics, respectively. Thanks to Ger Apeldoorn.

Al Landau in a photo taken sometime in the 1980s. Courtesy of his grandson, Robert Landau. Albert Einstein Landau was the godson of Albert Einstein... named after the renowned physicist in honor, Rob Kirby discovered, of his having helped to raise funds to keep The Jewish Telegraphic Agency going between the world wars.

My (Admittedly Minor) Encounters With STAN LEE

by Bill Schelly

If there hadn’t been Stan Lee, then someone would have had to invent him.

Wait—that’s exactly what happened: A Jewish kid from New York City named Stanley Martin Lieber invented “Stan Lee,” the character most of us grew up admiring—the fun-loving uncle who shamelessly bragged about Marvel Comics, who wrote many of them, who loved comicbooks and, yes, who loved us, his fans.

I first heard of Stan Lee in the fall of 1963, when I pulled a copy of Amazing Spider-Man #7 from the dark recesses of a giant magazine rack at my local drugstore. The first cover blurb by Stan that I read was: “Here is Spider-Man as you like him… Fighting! Joking! Daring! Challenging the most dangerous foe of all, in this—the Marvel Age of Comics!”

I thought: that’s different. DC comics didn’t have cover blurbs like that, except maybe putting the title of the story on the cover –certainly nothing so seemingly personal, addressing me, the potential reader (“as you like him…”). Intrigued, I opened it and read: “Never let it be said that the Marvel Comics Group doesn’t respond to the wishes of its readers!” And then, outright bragging: “A tale destined to rank among the very greatest in this… The Marvel Age of Comics!”

“What’s ‘The Marvel Age of Comics’?” I asked myself. “It sounds like there’s a whole bunch of different comics being published that I’ve never heard of!” By the time I finished reading Spidey #7, I was thoroughly bowled over by the fabulous Ditko artwork and Stan’s deft, humorous script.

Turning to the letter column, “The Spider’s Web,” I found letters that were fairly typical of a Green Lantern or The Flash letter column, but the answers were “straight from the shoulder” responses that seemed to take me inside the comicbook business. The “Special Announcements Section” began: “Here it is, the section we like best! A place for us to get together, relax a while, and chew the fat about comic mags.”

It then went on to talk about the two newest Marvel comics, The Avengers and The X-Men, and the changes in a couple of their other titles: “Don’t delay in letting us know how you like the big changes in Tales to Astonish and Tales of Suspense.” Ant-Man had become Giant-Man, and Iron Man had a new suit of armor. “Hope you like it!” Stan said, adding, “That’s probably the most unnecessary phrase ever written! If you don’t like the mags we edit for you, we’ll shoot ourselves!”

The column ended with: “Okay, time to close shop for now. So let’s put away our little webs till next ish, when we’ll bring you another book-length epic which all you armchair critics can tear apart to your heart’s content! Till then, keep well, keep happy, and keep away from radioactive spiders!”

Suddenly I realized I had a grin on my face. I really

148

Fandom Archive

Comic

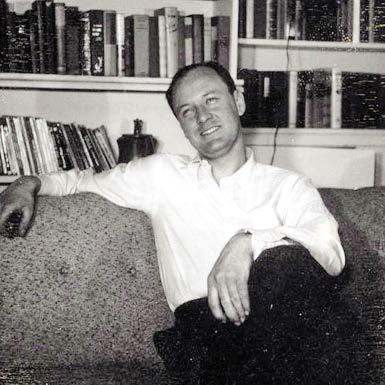

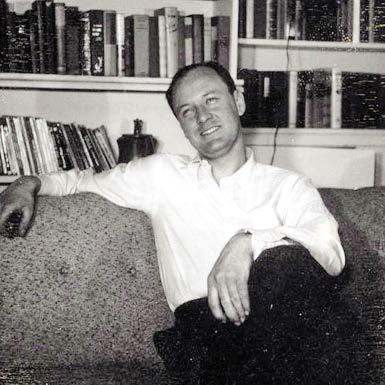

Bill Schelly & Stan Lee\

That’s Bill on the left in a recent pic, and Stan Lee “at home in the early 1960s” on the right, not long before he and artist/co-plotter Steve Ditko produced the superb Amazing Spider-Man #7 (Dec. 1963). This was the first Marvel comicbook that Bill ever bought, drawn in by Steve’s excellent artwork and Stan’s seductive verbiage. [TM & © Marvel Characters, Inc.]

STAN LEE In 1968

Transcribed by Steven Tice

This interview was conducted in the Marvel Comics offices on either February 8 or 18th, 1968, for WRSU, the radio station broadcasting from the campus of Rutgers University in New Brunswick, New Jersey, and serving the greater Central New Jersey area. Further specifics are lost to time, but enjoy this conversation with the face of Marvel Comics, speaking to his beloved college audience.

STAN LEE: Ladies and gentlemen, allow me to welcome you to the home of Marvel Comics, the Batty Bullpen. And now, as I look at this sea of happy, smiling faces and contented readers… I hope we’re not on.

ANNOUNCER: That was Stan Lee, editor of the Marvel Comics Group. Over the past few years, Marvel comics have become some of the most popular reading matter on virtually every college campus in America today. WRSU went to New York to discuss the success of, and future plans, of Marvel Comics with Stan Lee. Here’s what he had to say to our panel of experts.

INTERVIEWER #1: I was wondering, there may be some people who have maybe just seen them on the stands and figured they were another one other comicbook, or another brand of comicbooks, and I wondered how exactly you got started, and how did you revitalize some of the new characters that have been floating around, or how did you create your new ones?

LEE: Well, actually, I think, for the first twenty years of our publishing history, it would be honest and fair to say that we were just another group of comicbooks. And then, about six years ago or

The School Of Hard Rocks

whenever, when we first brought out the premier issue of The Fantastic Four, we were kicking around ideas and wondering what to do, and it occurred to us, as I say, “Let’s try and do the kind of books that we would enjoy if we read comics. Let’s not try to do something that we think a ten-year-old will buy.” And we introduced the Fantastic Four, and our objective there was to violate all the rules, and to violate all the clichés. Heretofore, any books involving teams of superheroes had heroes who got along beautifully with each other, and were always successful, and always acted and reacted in very predictable ways. So we thought, “Why don’t we get a team of super-heroes who argue among themselves, and fight occasionally, are dissatisfied, want to quit, maybe they have money troubles, and so forth? They won’t wear costumes.” The first two issues of the FF, they didn’t even wear costumes. I learned that was a mistake. When the mail started coming in, the readers said, “Gee, that’s the greatest book in the world! Oh, we love it! You gotta get a lot more like it! But give them costumes. They gotta have costumes.” That was one of the little rules I learned that I wouldn’t have suspected: in a super-hero strip, you just need costumes, because the avid fans can’t really relate to them or something unless they’re

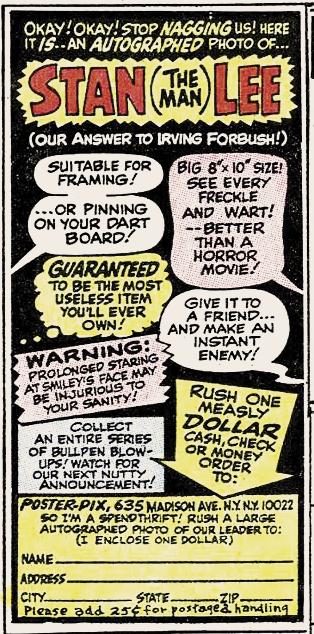

Photo Synthesis

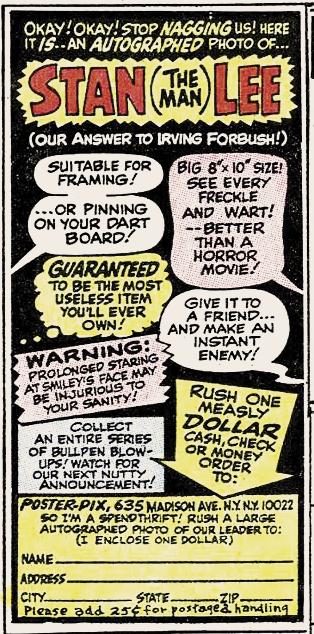

1968 Marvel comics sported a house ad (above) where, for a measely $1, you could order an autographed photo of Marvel’s fearless leader. A planned series of pix of other Bullpenners never materialized. [TM & © Marvel Characters, Inc.]

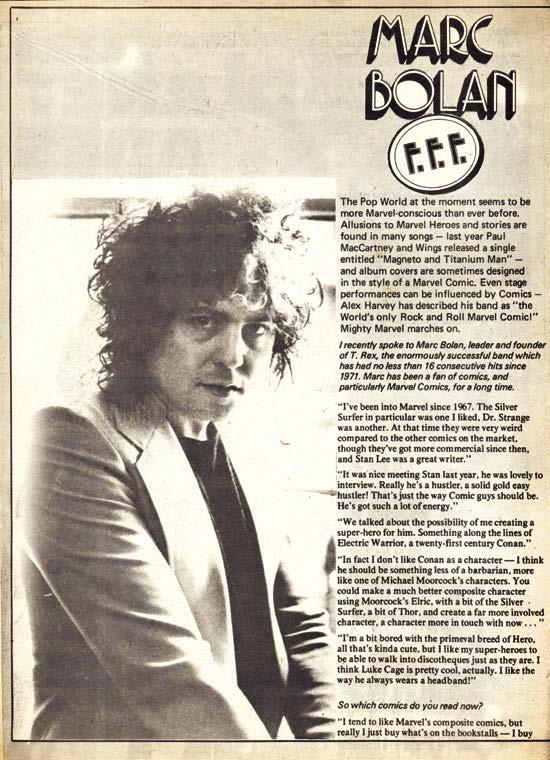

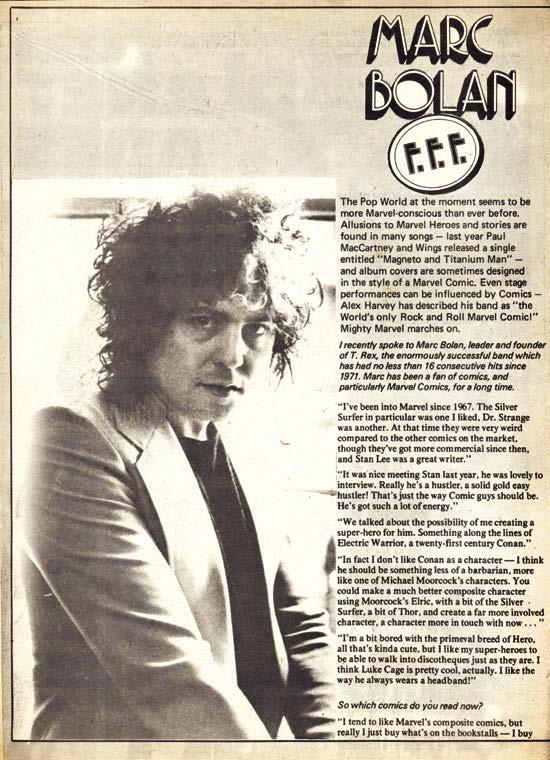

English guitarist, singer, and songwriter Marc Bolan (frontman for the group T-Rex) began following Marvel Comics around age 20— and Stan played up their meeting in the Bullpen Bulletins page, in an onging effort to court the college-age audience. Above is Bolan’s interview from the UK’s Mighty World of Marvel #199 (July 21, 1976). Thanks to Robert Menzies for the scan. [TM & © Marvel Characters, Inc.]

153

Meat On Their Bones

wearing colorful costumes—the characters, that is, not the fans. We then learned another rule. We learned that what we have to do with these characters is treat them like fairy tales for grown-ups. They all have some super-power, because that’s sort of the shtick. That’s the hook we hang the plot on. One fellow can walk on walls, or can burst into flame, or whatever. But if we can accept the fairy tale quality of the super-power, then we try to write everything else as realistically as possible. We sort of added another dimension to comicbook characters, and the college kids were the first ones to realize this, and to become fanatically fond of them. Thank goodness.

INT #1: One thing that I noticed, I’ve never seen in any comicbook, and very rarely in a comic strip, whereby the main character, or one of the head characters, in the Fantastic Four, referring to getting married, and now Sue Storm is pregnant, and how the whole thing has just given a whole new dimension, family life. When they take off their costume, they’re still a character you can follow.

LEE: Well, I would say that’s a key word, the unexpected. If we could make a reader feel that he doesn’t quite know what he’s going to get, that a character might die, or might get married, or—I’d love to have Sue have a miscarriage, but I dasn’t, because we announced earlier to some fans that they would have a baby this

year, and I don’t want to—. Really, the reason I’d like her to have a miscarriage is that I don’t have any idea what kind of baby to have, or what to do with him once she has the baby. I’m sorry we ever started this darned thing, although we’re going to have to go through with it. We and Sue are going to have to go through with it.

INT #1: I’ve noticed that a lot of the characters have been developed athletically since they first came out, referring mostly to Spider-Man, The X-Men, and Johnny Storm. Do you want to keep bringing them out until they look more and more like regular comicbook characters, but they look less and less like people?

LEE: Well, I’m sorry to hear you say that, because that was not my intention, and I think the artists, the different artists, just get a little overzealous. We have that trouble. Jack Kirby is so good at drawing muscular people, and he loves to do it so, that we have continuing arguments about it every month. He’s making Reed Richards look like Thor now, and, you know, originally Reed was sort of a slim, scientific type of guy. Marie Severin very often does that with the Hulk. She has—when the Hulk turns to Dr. Bruce Banner, he doesn’t look much less strong than he does when he’s the Hulk. This is just something that we try to catch. We’re not doing it intentionally, but, unfortunately, I guess the artists are so used to drawing muscular people that it’s hard for them to—now, you’re right about Spider-Man, and I have to talk to John Romita about that. He should look like just an ordinary, slender fellow, but he has been getting kind of stronglooking, himself. That’s our fault. It’s an oversight on our part. Not intentional.

INT #1: But it looks like, just lately, they’ve been getting more and more handsome and muscular.

LEE: Well, I’m glad to hear you mention that, and I’m going to make a note to go over this with a lot of the artists as soon as you leave, because this is a failing on our part.

INT #1: Where would the ideas come from for a particular story?

LEE: Well, I’d love to say they all come from me, but, actually, you never know. I’ll talk to an artist, or I’ll talk to one of our other editors or writers, and—you know, it’s a funny thing. Most of the ideas—people usually say, “How do you get your ideas? How do you think these things up month after month?” I sometimes wonder if the ideas are as important as the execution, because I think the ideas are about the easiest thing. Some of our best stories had ideas that were fairly simple and commonplace, but I feel, more than the idea, it’s the way you tell it, the way you present it. We’ve done stories that were quite successful with the readers, judging by the sales we’ve had and the mail we get, and then, after rereading the story, I would say to myself, “Well, the story was really nothing. It was just the hero meets a villain, fights him, defeats him, and then goes off into the night.” But I suspect it was the little subplots, and the little asides, and the little things and

1968 Stan Lee Interview

154

As Kirby’s work got more impressionistic over time, even his scrawny, bookish Reed Richards packed on some serious muscle. From The Fantastic Four #83 (Feb. 1969), inks by Joe Sinnott. [TM & © Marvel Characters, Inc.]

depth, the characterization, and so forth, that we throw in that, if anything, makes our books a little better than some others. I think it’s those extra little touches rather than the basic ideas, because I think most of our ideas are pretty much the same from issue to issue. It’s practically the same plot all the time, just tackled from a different direction.

INT #1: I noticed that you switch from writer and artist and everything, but they still manage to keep the same continuity of character from month to month.

LEE: Well, I, of course, in the beginning, I tried to set the pace and to set the style, and now we’ve sort of got that established. The dialogue I have always felt is the most important thing. Just as in a radio show, certainly the dialogue is the most important thing, I think in a motion picture, or in a television show, it’s what the person says that matters. Good dialogue can make a very banal plot seem very important and very profound, and I think bad dialogue can make the greatest plot in the world seem corny and hackneyed. The one thing that everybody seems to go for is realism. It seems the more realistic you can be, the more successful you are, in any media. Now, to me, the thing that gives a story

realism is having the characters talk and react, and, of course, you can only tell their reactions by what they’re saying, like real people. Therefore, the thing that we spend, I guess, about 99% of our time on is the dialogue. I will rewrite one sentence a dozen times if I don’t feel I’ve got it right. Now, I’m sure nobody else, certainly nobody at any other comic company, does this or worries about this. They’re—many of them are still writing these things the way they were being written twenty years ago. The hero sees the villain running down the street, he says, “There goes the monster! Let’s get ‘im!” That’s it, and it doesn’t matter what character it is, they all speak the same. They don’t have any different speech mannerisms. So we’re really hung up on this business of everybody has to talk in his own distinctive way. We wouldn’t have Daredevil really speak the way Captain America speaks, and we wouldn’t have Spider-Man speak the way Iron Man would speak. We try to get a shade of difference in each one, and we feel we know the characters that way.

INT #1: There was a Captain America, and he’s not the same character now. What exactly made you bring him back instead of a new character.

LEE: Oh, he’s really the same character. We’ve just tried to treat him like a real, living, breathing, rational human being instead of a cardboard figure. No, I felt, again, by reading the fan mail, and seeing how the readers liked costumed characters and the type of characters they liked, I felt that they would like Captain America. They would like his costume, they would like the concept behind Captain America, and we felt, well, let’s try it. And we proved to be right, because he’s terribly popular now.

INT #1: I was wondering if there were any plans in the future to bring back Bucky?

LEE: No. I think—this is my own feeling, but I’m not crazy about teenage sidekicks for heroes. To me, there’s something a little corny about it. I’ve never even been able to sink my teeth into the whole Rick Jones, or Rick—you know, I never can remember his name, if it’s Rick Jones or Rick Brown. But in the relationship between the Hulk and Rick—somehow a teenage kid running around with an adult, to me this belongs with Batman and Robin, and it belongs with the old time comics. Unless they are really needed, unless it fits in with the characterization and with the plot. To just bring it

1968 Stan Lee Interview

Silent Stan

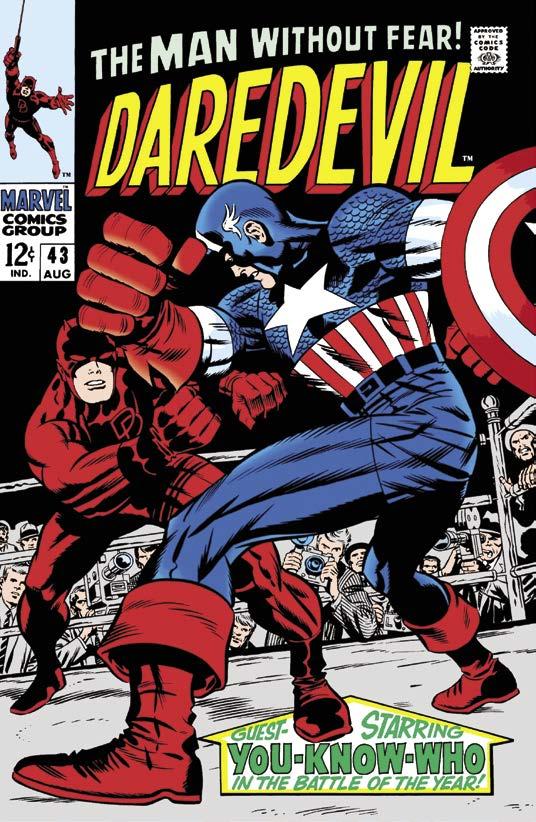

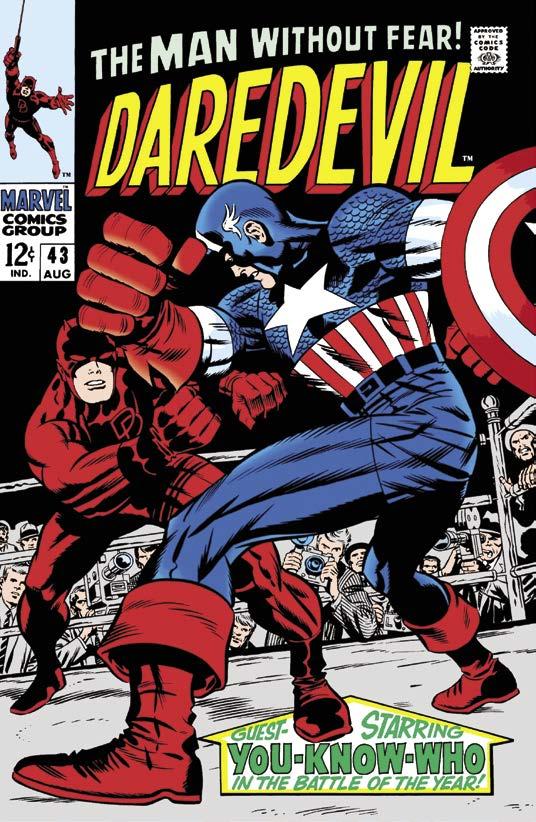

When you’ve got a cover as powerful as this Kirby/Sinnot beaut from Daredevil #43 (Aug. 1968), no need to clutter it up with word balloons. [TM & © Marvel Characters, Inc.]

Just For (Side) Kicks...

155

(Left:) Writer Roy Thomas likewise didn’t feel sidekicks were needed, and instead morphed Rick Jones into a modern Billy Batson who could “become” Captain Mar-Vell in 1968’s Captain Marvel #17 (Oct. 1969, with art by Gil Kane and Dan Adkins). (TM & © Marvel Characters, Inc.]

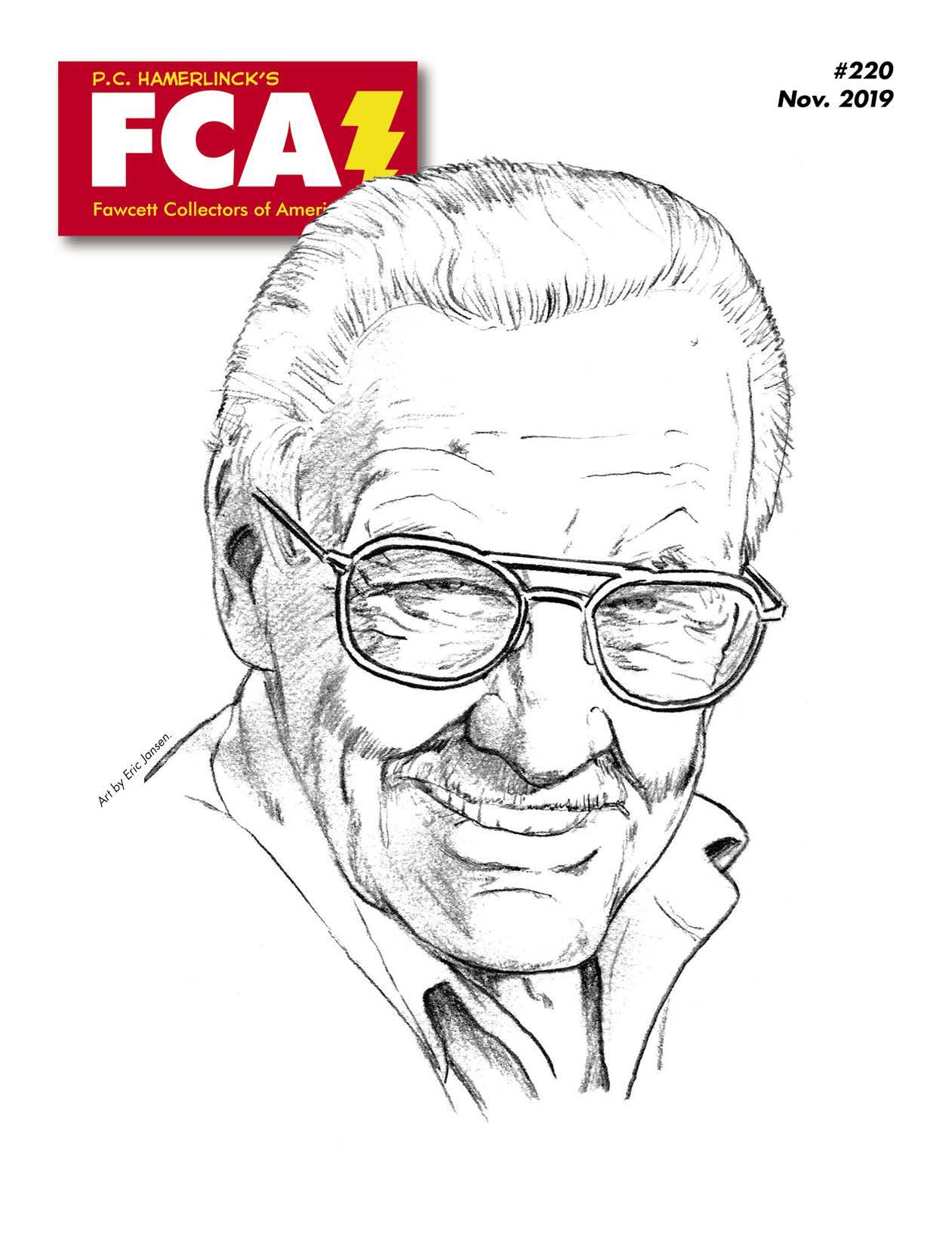

Art©2019byEricJansen.

STAN THE MAN

Fawcett Collectors Remember Marvel’s Smilin’ Leader

Edited by P.C. Hamerlinck

P.C. Hamerlinck

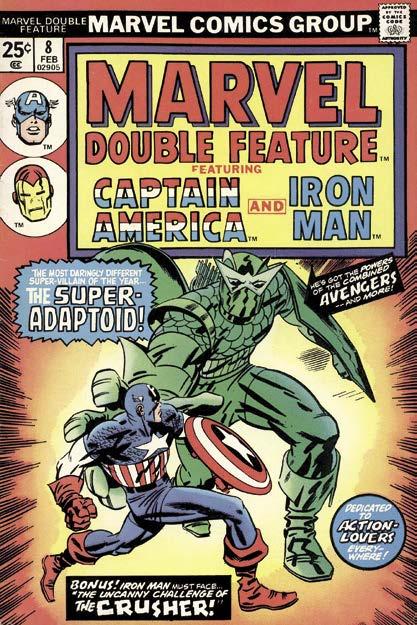

Idiscovered Stan Lee’s work when I began reading super-hero comics in 1973 at the age of 11. I was absorbing his often-profound “Soapbox” installments (where it became clear that Stan was just as much a hero as The Mighty Thor or The Invincible Iron Man) before stumbling across Lee and company classics within the pages of indispensable reprint titles for us newcomers like Marvel Tales, Marvel’s Greatest Comics, Marvel Double Feature, and Marvel Triple Action