The Were-Writer’s Confession

Gregory Potter remembers the Warren years, Jemm, Son of Saturn, and his Woman of Wonder

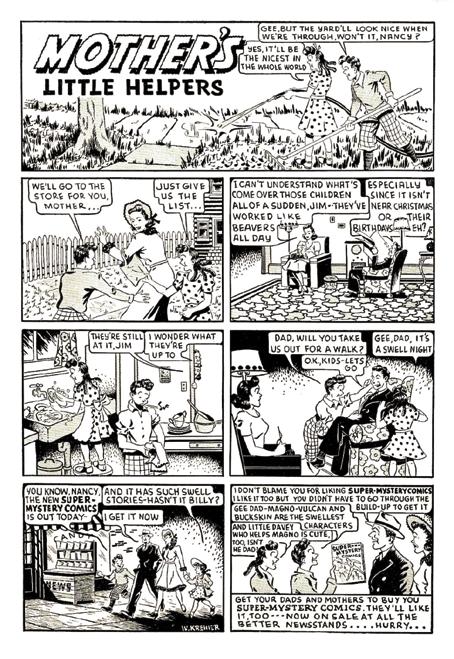

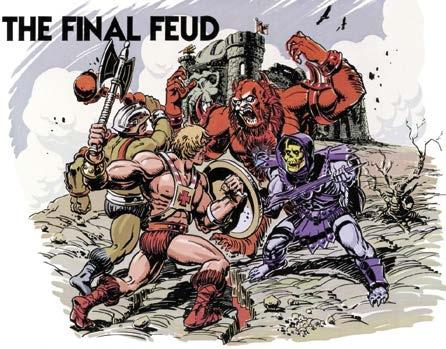

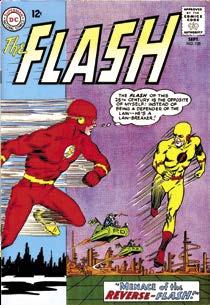

This page: Clockwise from inset right is Greg Potter, age 18, posing for the Providence Journal-Bulletin, a Rhode Island daily newspaper, which included an article about the young comics pro; a panel from “Child” [Eerie #57, June ’74], with art by Richard Corben; and The Flash #139 [Sept. ’63].

by JON B. COOKE

“One cold, windy November evening in Rhode Island, a most curious little child was born,” wrote Gregory Paul Potter in a “Writer Profile,” published in 1972. “It was in the winter of 1953 and the doctors remember it well, for they’d never seen an infant born with a comic book in his hand before. He turned out, oddly enough, to be me!” Then, a dozen years later, in an essay composed for a “Saturnian Salutations” column, the scribe had a similarly weird description of his adolescent years: “I was a teen-age were-writer. While growing up in the unlikely town of Warwick, Rhode Island, I’d constantly metamorphose from a normal, average school kid into a strange, far-from-normal would-be comic-book writer.”

Still, 40 years later, chatting with the sometime comics pro across my dining room table, there sat a pretty normal-looking, average, northof-middle age guy (who, after searching high and low, I discovered was living less than four miles away!). Still, the gent did have an odd, atypical story to share about his experience in the world of American comic books, as a writer for Warren in the ’70s and then, in the ’80s, as scripter for DC.

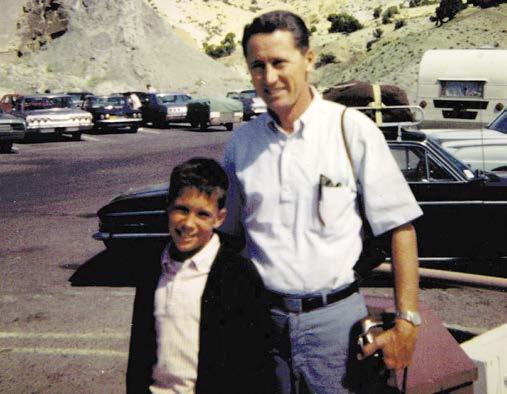

But that strange, far-from-normal trip began back in the summer of 1963, when young Greg selected his first comic book. “I remember it clearly,” he explained, “because we were on vacation with my family up in New Hampshire, at a lake, and it was raining. And my dad, having three young boys, figured, ‘I got to get something to keep these kids busy in a tiny cabin in a rainy day.’ So he took us to a local variety store and said, ‘Pick out something.’ My older brother, Dave, went immediately for MAD magazine. So I figured I had to get something similar. And so I looked around and I saw The Flash [#139, Sept. ’63], the issue introducing Professor Zoom.”

And so, due to that wet afternoon in the Granite State, the journey began. Greg became a devoted DC reader and little brother Jeff called Marvel his own. “He picked up all the Marvel comics and

I’d pick up all the DCs, and we’d have debates about who was better all the time. And, though I would never admit it to him, I secretly loved the Marvel stuff, too. I think Jack Kirby’s Fantastic Four and Thor, and then, especially, Jim Steranko’s Nick Fury, Agent of S.H.I.E.L.D.… God, those were great.”

Outwardly, the middle sibling would profess that Green Lantern was his favorite, when every Tuesday he and Jeff marched down Post Road to Maxie’s Pharmacy, in their Massasoit Terrace neighborhood, to peruse the latest releases on the racks. “Maxie would see us come in and, if the new comics weren’t out, I would ask if they came in and sometimes he’d say, ‘I haven’t put ’em on the rack yet. Come back tomorrow.’ Then he got wise and he’d wait for me to come in and say, ‘If you open the box and you put ‘em on the racks, you can have your pick.’ Maybe he was breaking child labor laws but ,even so, I’d still have happily put ’em on the racks. So I did that for years. I just collected and collected and loved comics.”

The lad also loved to make up stories. “Even way back in third grade, I remember a writing assignment from our teacher, where she basically said, ‘Write a story and make it at least a page,’ which is a big deal for a third grader — a whole page of text! — so I wrote a story kind of based on Puff the Magic Dragon, about a boy and his dragon friend, and it went on and on and on. I was like five pages into it, and everybody else in the class had finished. ‘What’s Greg doing? He keeps writing!’ And the teacher just went nuts about the story. And ever since then, I would write stories just for my own pleasure. I knew from a really young age that I wanted to write. So the comics career started because eventually my brother and I are collecting comics and

because Jeff actually got me into the Warren magazines. He was the one who first bought Creepy and Eerie.”

CB FAN FAIR

By 1968, Greg had been familiar with fanzines and he was inspired to make his own. “I remember Biljo White’s Batmania, and I got all those. In fact, when I was a kid, I did my own fanzine about comics called Comic Book Fan Fair, which I shortened to CB Fan Fair. I did it on a little mimeograph machine out of my dad’s office, which he let me use.” (His father was a founding partner in a top Rhode Island ad/PR agency, Potter-Hazelhurst.) Available copies indicate it was a side-stapled, 24-page effort, with offset-printed covers, which ran between 1968–70, peaked at 100 or so subscribers, and included artwork by Greg,* as well as contributions by Ben Katchor, Arvell Jones, Jim Hanley, Cliff Biggers, Duffy Vohland, and others. Among its contents was an article comparing Will Eisner’s writing to Charles Dickens’ and another titled, “Are the Comics Really Junk?” Issue #14’s cover was graced with art by a rising star in the industry.

”At one point, Jim Aparo did a cover for me… I get this piece in the mail from Jim Aparo! He’s done an original drawing for me of these guys on the moon, astronauts landing on the moon, and one of them is pointing in shock at an Indian totem pole already on the surface. And somebody else was planting a flag saying, ‘We the first come in peace.’ Jim just did it for me for free. I was absolutely shocked.”

Another notable to appear in CB Fan Fair was he who almost single-handedly took down the entire field. “At one point, I was doing an article on Dr. Frederic Wertham and I corresponded with him, so that was fun, too. And he was very friendly and very forthcoming at the time. I actually felt bad for the guy. So villainized (for a lot of good reasons), but he tried to make good.”

According to Greg, his fanzine would be cited in Wertham’s book, The World of Fanzines [1973], a positive, encouraging study of the phenomenon, which including a reproduction of a CB Fan Fair cover. (In contrast to his past disdain for comics, the author of Seduction of the Innocent determined fanzines contain “genuine human voices outside of all mass manipulation.”)

After the fanzine ended in 1970, 16 issues in all, Greg became a DC Comics letter hack, having missives published in (to name but three of his numerous lettercol appearances) Challengers of the Unknown (“Get Rocky a real wow-type female who knows enough judo to throw a big lug like him over her shoulder and into love”), All-Star Western (“I beg, plead, cajole, and demand that you bring back the immortal Bat Lash and Joe Kubert’s Firehair”), and Adventure Comics (“Supergirl’s new look is fantastic!”)**

CON CONCLAVE

Prior to shutting down CB Fan Fair, Greg, with brother Jeff, attended the July Fourth comic con held in Manhattan — officially, the 1969 Comic Art Convention, organized by Phil Seuling.

* Also included were the exploits of Greg’s dystopian character, The Albino, which the Providence Journal described in 1973 as “one of the last individuals and a freedom fighter exist[ing] in a world not unlike that which George Orwell created in 1984.”

** To be fair and to his credit, in that Adventure #423 [Sept. ’72] lettercol, Greg spent most of his communique focusing on Alex Toth’s truly superb “Black Canary” back-up in #419 — “Not since the great Eisner has anyone mastered the art of the moody drawing like Toth.”

Greg had seen an announcement for the gathering some where and made an appeal to his parents. “I begged and pleaded… and I was like, ‘Oh, mom, dad, I have to go to this!’ I just bugged the hell out of them, and they knew I was in love with comics, so they just figured, ‘Okay. Why don’t you invite your friend Mark, too, and we’ll take your brother Jeff and we’ll just make a trip out of it.’” And, despite Greg fearing his parents might yank them away to go sightseeing in the city, “But they never did that. Every day they would let us go to the con, so I think it was kind of their excuse to get away and have a little vacation by themselves. I mean, we were staying at the hotel, the Statler Hilton, where the con was being held, so it was safe. Our parents said, ‘Go downstairs and we’ll see you boys at dinner.’”

Greg was ecstatic. “It was great. I was in heaven! To see all those comics professionals. I was going up to everybody trying to get signatures… and just the smell of the room when you walked in, it was like tables and tables of these comics. I would just rifle through them and get the back issues I needed. And I remember finding Al Williamson’s Gordon, which he did for King Comics. And attending

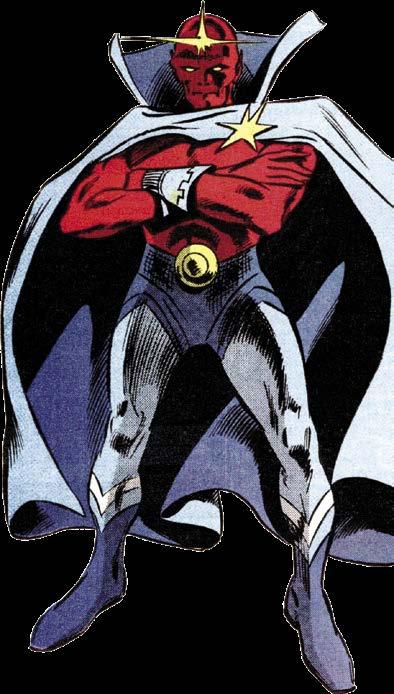

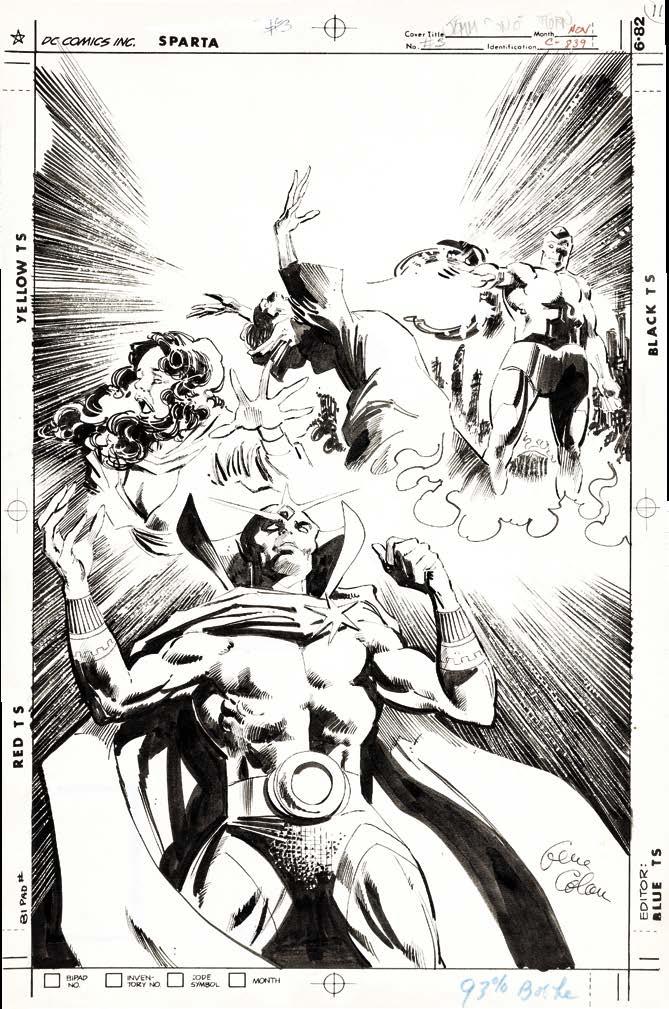

This page: Wonder Woman by George Pérez and Jemm, Son of Saturn by Gene Colan.

Secrets of Haunted House #17 [Oct. ’79], was selected as among the “Year’s Best Comics Stories,” in The Best of DC #5 [June ’80]. In all, Greg had four stories printed in mystery anthologies. In a couple years, Greg mentioned why he stopped with the tame horror stories. “The time needed to do those mystery scripts just never seemed to crop up. And besides — I was ready to do super-hero books. If they would let me do that, then I’d find the time. But, in the days of the ’70s, a non-New Yorker writing DC super-heroes just wasn’t done. So I bided my time… always looking for an opportunity to get back into comics.”

SATURN BY WAY OF MARS

While his association with a certain Amazon super-hero (and superstar artist) would add a certain prestige, Gregory Paul Potter’s most sustained achievement in comics came with his “maxi-series,” Jemm, Son of Saturn [12 issues, Sept. ’84–Aug. ’85], an original character he initially developed as connected to a long-standing second banana super-hero at DC Comics.

In early 1982, Greg reconnected with Levitz, who told him to meet with DC executive editor Dick Giordano. “And I met with Dick,” Greg said, “and I had a portfolio of my Warren and my House of Mystery stuff. Dick looked at it and basically said, ‘Yeah, I can see you can write and put together a story. It doesn’t mean you can do super-hero stuff though… but I want to see how you think as far as the super-hero story, so create a superhero for me; not a story, just a proposal.’ I said, ‘Sure, I could do that.’ So, literally, on the train back from New York, I started thinking about Martian Manhunter, who had disappeared from DC Comics, having left the Justice League of America. So I said, ‘Maybe I can do a story on somebody related to J’Onn J’Onzz.’

“I got home and, maybe three weeks later, I finished up a proposal and sent it into Dick, expecting him to either say, ‘It’s okay,’ or ‘not okay.’ Instead, he calls up and says, ‘We’re going to publish this! This is good!’ So, just like my luck with Archie Goodwin, where I got my first submission published, here was Dick telling me they were going to publish my first proposal.”

Originally called J’Emm, Son of Mars, the tale was to involve “the fate of the Martian race” and J’Emm, the cousin of Martian Manhunter, and was scheduled for a dozen issues, with art by the great Gene Colan and Klaus Janson. The series involved J’Emm crash landing in Harlem and his subsequent bonding with a city kid. The story was set in the ghetto because the writer felt there wasn’t enough Black representation in the medium.

The ’60s had made a big impact on the young Potter. “At the time, I saw this youth movement rising up and it was exciting to me that we were going to change things for the better. It didn’t turn out that way, but that was exciting… But Bobby Kennedy was killed, Martin Luther King, Jr., was killed… I lived in a very white environment. I remember there was only one Black student in my whole school. I was in Massasoit Terrace and it was pretty white, so I didn’t have exposure to anybody else from another race. And to see the racial strife on TV and the protest movement going on, that certainly opened up my eyes.

“I always did feel acceptance of other people and who they are is important. And then, to see on TV, all this racial strife going on, that woke me up big time. I didn’t live in a neighborhood where I was exposed to that, but I did see it on TV. And

This page: Above is Gene Colan (pencils) and Klaus Janson (inks) cover for Jemm, Son of Saturn #3 [Nov. ’84]. Below is cover for Jemm #1 [Sept. ’84]. Inset is DC Releases for September, 1984.

and the art of adventure

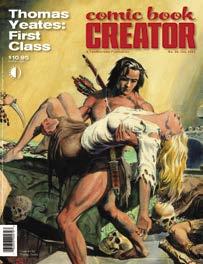

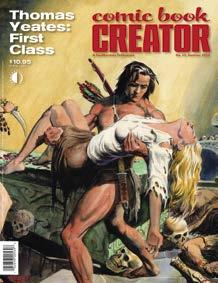

Thomas Yeates’ casual, laid-back demeanor might reflect his mellow Californian origins, but they mask the man’s intense dedication to the art of adventure.

Just look at his work on a pantheon of heroes — Tarzan, Zorro, and Prince Valiant, to name

CBC: Did you have any creative people in your family?

Thomas: I was fortunate, in a lot of ways, because my mother was a stay-at-home housewife in the ’50s, but she was really interested in lots of stuff — other countries and other cultures. When she and my dad got a little bit older and some of the kids were out of the house, they traveled a lot. The house was full of art books, and she bought me oversized, young reader picture books of Call of the Wild, Daniel Boone stories, and all this stuff. I remember we had a really gorgeous large book, Bambi. And they had these great illustrations, paintings, pen-&-inks, and I just was drawing. I felt I drew like every other kid, but I got fascinated by it somehow and kept pushing myself to figure it out.

but three — which reveals his devotion to his predecessors, be they J. Allen St. John, Hal Foster, or Al Williamson. And Yeates is a part of that lineage, deservedly so, and we’re proud to feature the story of his own true-life adventures in the realm of sequential art.

protest, he pretended he didn’t speak English, but he was this great guy who everybody loved.” And he was a really, really cool dude.

I spent time with him playing in the backyard as a little boy, interacting with him. So my take on Pearl Harbor was, “Gee, isn’t it too bad that all these people of Japanese descent got blamed for something?” And there wasn’t much of a backlash against the Germans, of course, because the Germans look like everybody else. And, of course, Pearl Harbor was a big deal, but it wasn’t prominent in their eyes in the late ’50s/early ’60s, in Sacramento. My parents were kind of civically involved. My dad was in the Chamber of Commerce and they were really forward looking. It was the Kennedy Camelot era.

Way later, I found out, going through my mom’s closets, that she had done some pretty impressive art in college or high school. My father could draw a little bit. Once in awhile, I would see something he drew, but he didn’t pursue it. I have three older sisters and the middle sister, Judi, is a very accomplished artist who does watercolors of landscapes and takes classes off and on, and has always had that side of her, although she didn’t pursue anything professionally.

When I was very young and drawing a lot of bad pictures, trying to letter things, my mom gave me some real simple lessons in how to figure out lettering and how to figure out spacing, so you’d have room for all letters. So I knew she had an understanding of art.

CBC: What’s your ethnic background?

Thomas: Both my mother’s parents were born and raised in Point Coupe Parish, Louisiana, and they came to Sacramento at one point and got married. My father’s parents were from Missouri, of Scotch and German and various other Northern European ancestry. After they met, they traveled from Missouri to eastern Colorado before my father was born. Neither of my parents graduated from college, but they came to the capital of California, Sacramento, and did well by their own ambition. My dad had gone to France for a while, toward the end of the war, doing mostly clerical stuff with the troops coming home and then, after the war, he came back to Sac[ramento]. During the war, he married my mom, she joined the Waves and was stationed in Chicago, and then they got married while they were both in the military. My dad worked various jobs until, within 10 years or so, he was in real estate and did well with that. They lived in the old part of Sacramento, which is much more beautiful (in my opinion) and has these really cool old houses, including a lot of Victorians. But they moved out into a house built in ’50s, which was more spacious and modern, but didn’t have as much soul, for my taste. And we had a gardener, who was Japanese and he always spoke very broken English and was very hard to understand. And my mother explained to me that he was born and raised in California. “He is American as you or me, but he was so angry about his family losing everything after Pearl Harbor, when they were put into camps. So, as a

CBC: So, as a kid, you knew about the Japanese internment?

Thomas: Yeah, my mom told me that’s why Robert wouldn’t speak English. We were pretty aware, overall. They watched the news a lot and it was different back then, when we all shared the same news sources. Everybody watched either Huntley-Brinkley or Walter Cronkite.

CBC: When did you start drawing?

Thomas: I always drew, just like most kids, drawing with crayons on the wall in the nursery, standing up in the crib. But my earliest drawing I’ve got is probably from age four or five, a drawing of Peter Pan. My older sister Judi, who’s the artist and eight years older than me, claimed that I always had something extra compared to the other kids’ drawings. I also drew cowboys and Indians… definitely battle scenes. I was your typical blood-thirsty American male, lots and lots of battle scenes, with little tiny figures swarming over a fort. The defenders fighting at the Alamo… The Disney version of American history was real big in my life with the Alamo and the Revolutionary War heroes fighting the Red Coats and Robin Hood. To this day, I really like the historical adventure movies and all the live action films that Disney made in the ’50s. Just watched one the other night I haven’t seen since I was a kid. And they’re real impressive. For some reason, I like them better than more recent ones.

CBC: In retrospect, do you have any opinion about the overwhelming focus on white people that Disney was dishing out? I wouldn’t use the term “white supremacy,” but certainly the predominant point of view was of white people within historical context… I find myself noticing things from the ’50s having really no focus on people of color and women… maybe that’s what Disney’s overcompensating for now.

Thomas: Well, when I was young… there’s a kind of weird philosophical statement or quandary that I’ve heard, that’s kind of bizarre but, in some ways, I understand it: two fish are swimming through the sea and they see each other and one says to the other, “How’s the water?” And a year later, they bump into each other and the other one says, “Well, what’s ‘water’?” When you’re living in it, it’s just the way things are. So, when I was a kid, I wasn’t as focused on that

Photo courtesy of Thomas Yeates.

deeply entrenched racism they were doing by editing people out of the story. I was aware of racism. I heard the N-word all the time growing up, and Martin Luther King, Jr., was on the TV, and we had a very progressive Presbyterian church that my parents joined.

During the civil rights era, the Sunday school teacher would play recordings of Martin Luther King, Jr. So I had this really progressive church and, I found out later, the minister, who my parents were really close friends with, went to the South to march with Dr. King. I didn’t know that, at the time. I would’ve been about eight years old or something. But I do remember that, after Dr. King was shot, that Martin Luther King, Sr., his father, came and spoke at our church. I went to that and saw that sermon when I was 13 or something, when I was pretty much set on my hippie-artist-Berkeley-radical path, at that point. And getting to see that was great. It was like going to a rock concert for me. The guy was just this super-showman, which really worked the audience. I mean, for something that serious, he wasn’t nearly as subtle as his son. He was much more bombastic. But I loved it.

CBC: Was there any generation gap in your family that was so prevalent among young people and their parents of the day?

Thomas: Yes, it was huge. But that didn’t really come about until late. Like I said, my parents were very progressive, very forward thinking. They were part of some Sacramento-based group during the height of the Cold War, when emissaries from other countries — ambassadors, athletes, statesmen, whatever — would visit. In fact, there’s a funny story about this that I don’t really remember, but my sister told me: In 1960, when the Winter Olympics were up at Lake Tahoe, in the Sierra Nevada, there were three or four Russian athletes who came to compete, and they were sent to our home with an interpreter. So me, being

the all American blood-thirsty boy, came out when they’re all sitting around the living room. And I come down the hall with my toy six-shooters and my cowboy hat and everything, and I start shooting them. I’d go, “Bang! Bang!” And everybody was mortified except for the Russians who went, “Ohhh!” and fell over as if they’d been shot. They played right along with me!

So we had a lot of interactions with people from other countries, and my parents were, like I say, pretty progressive. But, by the late ’60s, particularly with the protests against the Vietnam War, the student movement, and the long hair and beards, that really freaked them out. And they switched over to being conservative and supporting Nixon, who’s the enemy to the people who were being drafted into going to Vietnam.

I was always into music. My mother had this fantastic record collection, which she played all the time, and we had great AM radio then that would go from Ray Charles to Chuck Berry to Hank Williams and these great folk singers. And then the Beatles come along, great music, and it was topical… So they tried to be open-minded, but there was definitely a generation gap. I was at home. My sister’s gone off to college by ’68, but I was in the eighth grade and just sucking up all that counterculture stuff and loving it and drawing all the time. And that’s when I got exposed to Wallace Wood, Bernie Wrightson, and Roy Krenkel — all that great stuff, which really fired up my interest in drawing.

CBC: In middle school, were you sociable? Were you athletic?

Thomas: Well, athletic, but not very good at sports. But I was definitely athletic. I loved running around outside and I rode my bike everywhere. I’d go for miles and miles. It’s also typical of that era. Parents just let the kids go. You would just leave

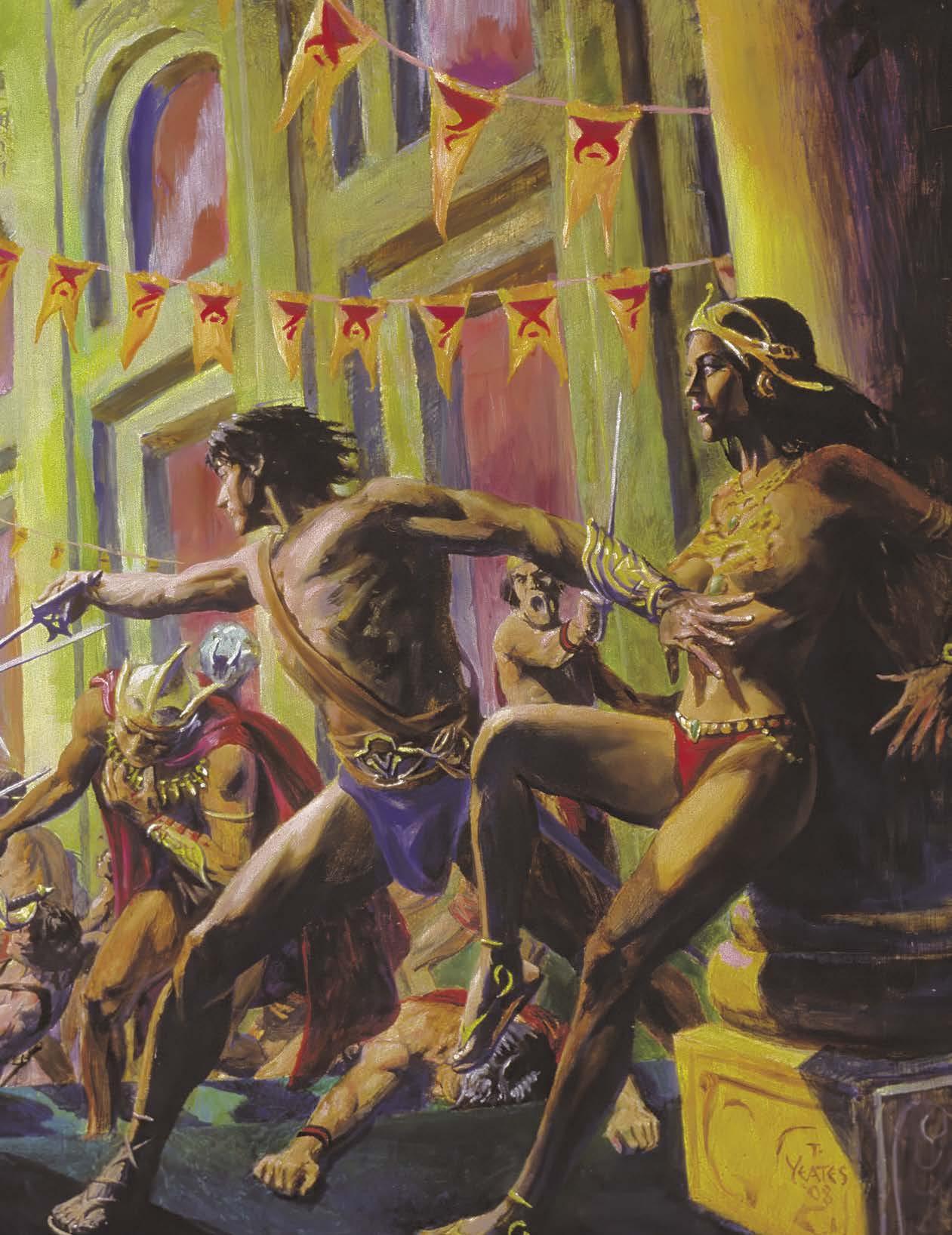

Previous spread: John Carter of Mars painting by Thomas Yeates from 2008.Opposite page: Yeates in the trees, his natural setting, early 2000s. Below: Tarzan of the Apes first edition and J. Allen St. John illo. Bottom: Tarzan painting from 2008 by Yeates.

home and they’d say, “Be back in time for dinner.” And then they’d go play bridge or do whatever they were doing. So I had a lot of freedom and played outside all the time.

CBC: Did you have neighborhood buddies?

Thomas: Oh, yeah. We had a whole ton of kids on our street. The whole baby boom was there in force. Every other house had a couple kids in it, at least. My dad was busy with his business a lot of the time, although he took as much time off for me as he could. There were families that had boys, these overachieving family of boys who got straight A’s and were really good at football. And I wasn’t good at sports. I just couldn’t concentrate or I was always daydreaming, but I played because that’s what everybody did. I was in Little League during grade school.

I was always active and, once I got to be about eight or so, my parents would let me go down to the river, and we had a rope swing, and we went swimming in the river all the time, and it was really cool water in the a hundred-plus Sacramento heat, we’d go down to the river and I was just down there all the time with my friends.

CBC: Did you go off and fantasize about swashbuckling… Robin Hood or…

Thomas: Oh, yeah, all that stuff. We’d play around the neighborhood in our backyards as cowboys and Indians, shooting each other with our toy pistols… All that stuff. And I was the last guy picked to be on the team, and I was a little goofy. I was a nerd, but I loved to run around physically and, the farther I

got into school and got more away from just the kids who lived on my street (who were nice enough), I had a wider range of friends to pick from.

CBC: Were you bullied at all?

Thomas: I had an older sister who bullied me a lot, but it wasn’t too bad in school. As far as the bullies go, I was always kind of drawn to the outlaws a little bit, to the bad kids, and they kind of liked me for… I don’t know why, but they did. So I didn’t really get picked on. The bad kids kind of liked me. For some reason, I related to them better than the A students.

CBC: Did they know that you drew?

Thomas: Yeah, everybody knew I drew.

CBC: Did you get along with girls?

Thomas: Well, I didn’t like girls, like most boys back then, because girls were icky until you get to about age 12, 13, and that changes. Then girls were interesting. And, in high school, though I wasn’t popular and I didn’t have that high self-esteem, I noticed that there were girls who liked me, so then that definitely broadened my horizons, dating and having a girlfriend. And that made a big difference in my self-esteem. And I wasn’t good at relationships at all, but I tried. I was having high school romances, but I floundered through it.

I had a lot of fun in high school. I didn’t like school from first grade until eighth grade. I resented having to go to school. I wanted to be outside playing. But, in high school, it became fun. There was this broader range of people. We had a great art department. I hung out in the art department, drew all the

Family photos courtesy of Thomas Yeates.

time. I had excellent art teachers in high school. Some girls liked me. I became really good friends with some of the cheerleaders, who I did not date, but they liked me. I’d hang out in the art room and draw a lot. I didn’t get that good grades, but I got by.

CBC: Did science fiction or fantasy paperbacks come into play at all during the ’60s?

Thomas: Well, not reading, because I wasn’t a good student. I wasn’t a good reader, although I did read those young reader books, but I wasn’t up for a real science fiction novel. But another real key moment for me was, okay, so I watched the Tarzan movies, the black-&-white ones, on TV.

CBC: The Johnny Weissmuller’s or all of them?

Thomas: Well, various black-&-white. I remember some Weissmuller’s, I remember Lex Barker. I even saw the one with Bruce Bennett. At the NBC affiliate in Sacramento, there was a guy named Henry Martin, who hosted Martin at the Movies in the afternoon. Later in the day, he also hosted a kid’s program which started with a clip of him landing in a jet airplane called “Captain Sacto,” and he would show Tarzan movies once in a while. And I just thought they were so wonderful. I was kind of alienated in a way and this Tarzan guy just had it made. He was hanging out with animals. He was strong. He didn’t have any rules. He had total freedom. He didn’t have to go to school. It was just very attractive life he was leading. And so I loved Tarzan movies. And then when I was in, I was probably about eight, maybe I’d be about ’63, ’64, somewhere in there, I was in a department store with my mom, and there was a spinner rack. And on the spinner rack was the Ace edition of Tarzan at the Earth’s Core with the Frank Frazetta cover. And I had never seen anything like that! I’d never seen a Tarzan who looked like that. I had never seen a drawing like that. I’d never read a title like Tarzan at the Earth’s Core with that weird, edgy lettering. That book was from another place and another mindset, another world. And I just stood there and stared at it and stared at it, picked it up and stared at it, opened it up, looked at the inside, saw the sketch on the inside. It had title page sketch by Frazetta. And my mom came by and said, “Hey, time to go.” And I put it back on the shelf and left. And, that Christmas, it was in my Christmas stocking. So my mom had noticed that her wayward son was interested in a book.

CBC: How neat!

Thomas: I tried reading it, but it was beyond my level, at that point. And then, some years later, I was at a bookstore when I was about 11, with a neighbor and his father, and we went in, and he said, “I’d tell you what, kids: I’ll buy you any book in the store if you promise to read it.” And I went, “Oh, okay.” So I looked around and I wound up in that section where all those Burroughs books were, the Ballantine Tarzan series,

the Ace Pellucidar series, and right next to it were the Lancer Conan books. And the Conan covers were kind of scary, but you were drawn to ’em. But I thought about it a lot, and I said, “Well, I’m interested in Tarzan. The first Tarzan book is Tarzan of the Apes, so I should start there.” So I got that. Even though the cover wasn’t very interesting, I picked up Tarzan of the Apes. I read it and then I immediately went back and bought all the other ones. Throughout the rest of my teen years, I worked my way through Pellucidar series and the Mars series. And then my mother said, “You can’t only read Tarzan stuff.” So I would read In the Shadow of Man by Jane Goodall, which is about real apes. It’s kind of connected (more than I knew at the time) to Tarzan. And I read Louis L’Amour Westerns, which I really enjoyed, and tried to read The Autobiography of Malcolm X. I can’t remember how far I got into it. And I was trying to be well-rounded and try lots of different things. I understood my mom’s concern.

CBC: How far did you get in the Boy Scouts?

Thomas: Well, I didn’t make it to Eagle Scout. I got distracted. I mainly was in Boy Scouts because I loved going camping with the guys, into the Sierra Nevada Mountains, which were real close to Sacramento. There’s a gorgeous mountain range and incredibly beautiful, huge Lake Tahoe up at the top of the mountains there. And skiing is fantastic up there, snow skiing, and the camping in the summertime and swimming in the lakes. And so we’d go camping in the mountains in the

Previous page: Clockwise from upper left is the Yeates family dressed to the nines in 1955. Baby Thomas on his mom’s lap; the clan in a Christmas ’67 Yeates family portrait; Thomas with his dad in the early ’60s; the young hunter with Stanley the dog and feathered victim, ’66; baby Thomas with mom in ’55; and Johnny Weissmuller as the Ape Man, in 1945.

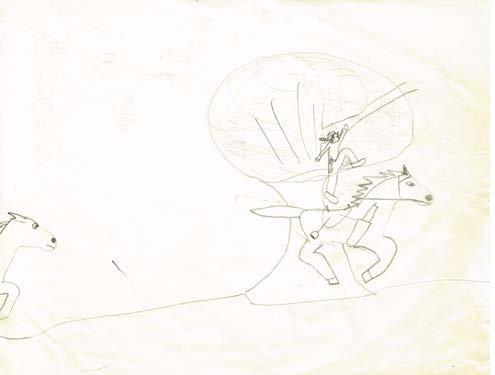

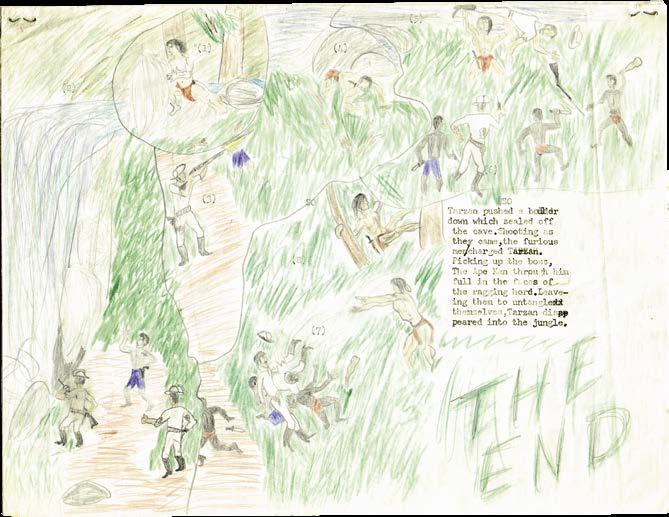

This page: From left at top is Mighty Mouse by five-year-old Thomas; adventure drawing at six; and Peter Pan gets the better of Captain Hook, circa 1961. Below is circa ’68 Tarzan sequence, drawn before his cousin Randy’s comic book storytelling instruction.

the mysteries of love. He was a fantastic personality.)

The classes were a lot of work. Each instructor gave us a week’s work. So, if one teacher gives you a week’s worth, that’s fine. You can do it in a week. But you had four teachers giving you a week’s worth. You can’t do it. And so it was really hard to produce good work, especially for the less experienced artists. So Joe was figuring it out as he went along. It was a lot of work and trial by fire, and some of the students dropped out right away and some of ’em hung in there.

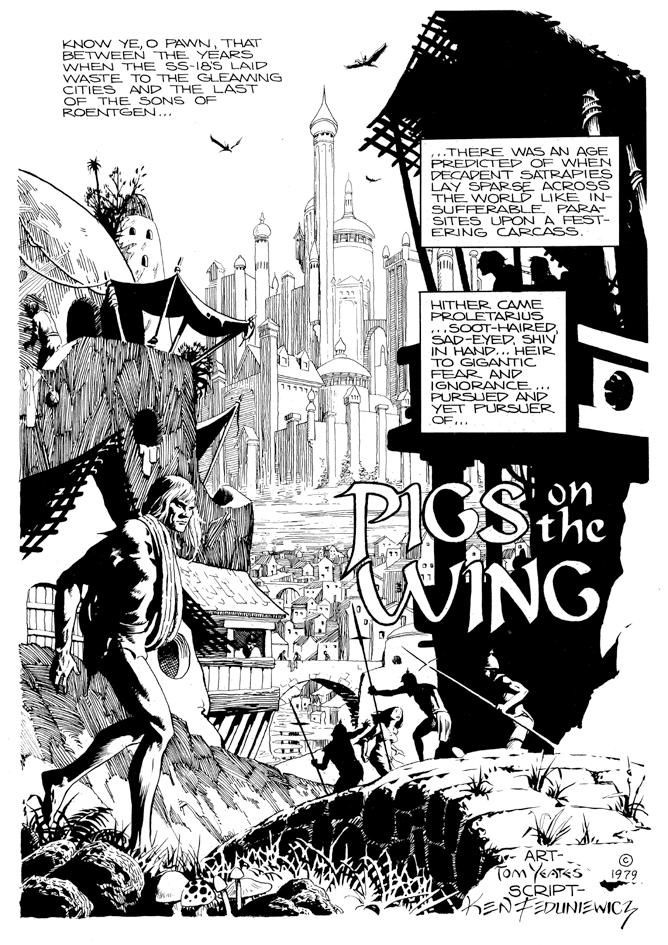

I remember, when I first got there, Joe was reviewing Bissette’s portfolio. Steve’s portfolio was two sketchbooks, full of little drawings and ballpoint sketches of monsters and horrific faces and creatures, and very unique, obsessive work. Totally unlike my romantic heroes and swashbuckling Frazetta-Burroughs kind of things. His was totally different, more Jack Davis-like and Ralph Steadman. Veitch was sort of a Robert Crumb technique over Jack Kirby pencils. The three of us were pretty advanced. We weren’t 18 right out of high school. We were in our 20s. Veitch was probably 24 by then. I think Bissette and I are the same age, so we would’ve both been 21, a couple of years out of high school. So we’ve had some life experience. Vietch had already followed his older brother Tom to California and published a comic book, so his portfolio was that comic book, Two-Fisted Zombies. So we were sort of the three most advanced guys right out of the gate, but there were other students who were pretty good and pretty together — Ron Zalme, Rick Taylor, Ken Feduniewicz, who was a pretty good artist… CBC: You were the associate editor of Third Rail, Feduniewicz’s semi-pro ’zine.

Thomas: That’s correct. So we go to the Kubert School for two years. By the end of the first year, I discovered the brush because Joe gives us each this toolkit in a fishing tackle box and a triangle and a few other tools that were obligatory. And he taught us to use a brush. And I had never used a watercolor brush for India ink. It just never dawned on me. I’d used the watercolor brush when I was a little kid with this little watercolor kit. So that was a huge step forward for me. That’s how those guys did it. So by the end of the first year, Joe gave me a script to do a back-up in Sgt. Rock, and it was written by a local friend.

CBC: Was that Bill Kelly?

Thomas: Yes. Kelly who made an amateur film he’d made that he showed in the basement, and he wrote a couple stories. Bissette got to be friends with him with, he would come hang out at the school. We had great parties at that school. Joe would have an end-of-the-year party, and interesting people would come to that. There was a cartoonist named Jack Binder.

CBC: Otto Binder’s brother.

Thomas: I could never quite figure out who this guy was. I ended up clicking with this guy and I chatted with him quite a bit at one of these parties, and he just was really cool. He reminded me of a smaller Doug Fairbanks, Jr., with this big smile and he liked to joke. And he said he had gone to school and studied art under J. Allen St. John, in Chicago, and that he didn’t really care for St. John because he got the impression St. John wanted everybody to be like him and he wanted to do his own thing. And he said he always had a suitcase with him, and he had a nickname. And so the students nicknamed him “Suitcase Simpson,”* for some reason.

I always gravitated toward the old school guys. I liked the old school stuff, Burroughs, and just the attitude of the old

*Suitcase Simpson, a character with feet the size of suitcases, appeared in Fontaine Fox’s 1908–55 comic strip, Toonerville Folks. It later became the nickname of Major League Baseball player Harry Simpson [1925–79].

adventure stories. I love the work of artists like Dave Stevens and Kaluta. I was just really into the old days, the 1930s….

CBC: So you connected with Williamson over that stuff. Did you sit in on the interview with Al in Third Rail?

Thomas: Yes… [Conversation turns to Yeates going to Mexico during summer break] I come back for senior year and there’s a second class now, with Ron Randall, Jan Duursema, Tom Mandrake, John Totleben, Dave Dorman, Bob Hardin… I’m interacting with all of those guys, particularly Totleben and Randall. So we graduated and the four of us, Rick, John (who quit after the first year), Steve, and myself, decide to rent a house in the area, Nine Berkshire Avenue. Joe was coming up with jobs to do after school, particularly stuff with Ivan Snyder and we would put together these catalogs… so that was great production experience… I helped a little bit, once in a while. And so Joe would come up with these odd jobs, and I remember one was illustrating a book on aliens that Jeff Rovin wrote.

Joe had started going to Europe and he came back from a trip all jazzed up with Arzach and Métal Hurlant and Lt. Blueberry and all this fantastic European stuff. And he was so excited by how much better the printing was in Europe. All this stuff’s

Top: Muriel and Joe Kubert posing on the steps of the Baker Mansion, in 1976. Above: Kubert School instructor Ric Estrada. Below: Kubert School advert.

coming at us and that’s what we wanted to do, the kind of stuff we saw coming out from Europe.

I took my portfolio into New York regularly. I’d make cold calls to various different publishers. I went to Warren magazines… I went to Field and Stream to see if they needed drawings of duck hunters. I went to various places because New York is where everything’s published, but the main target was Heavy Metal. They were doing the kind of comic books we were interested in. So they were very nice to us — we dealt with John Workman and his brother — and they really liked me.

I was usually going up by myself. They said, “Hey, come by anytime you’re in New York, swing by, tell us how it’s going.” But I didn’t get hired. It was very difficult to get hired by them because they bought all their content from Europe. But eventually, after hanging around there, they’d let me use the Xerox machine.

I had created a story with Ken Feduniewicz in the first year, “Pigs on the Wing,” which I drew, and I took it to Heavy Metal, but it was not what they were doing at the time. Their stuff was far more edgy, weird, far-out, sexed up, and creepy, and my stuff was not, but they bought this story and they did run it, but basically, with Heavy Metal, it was because John Workman was so friendly to me and I would just go up there all the time and hang with them.

Then there was an editorial change when science fiction writer Ted White became editor and he was much more

creative, shall we say, and interested in different material. And I had these rock ’n’ roll musicians’ portraits in my portfolio. So they knew I was into rock ’n’ roll and there was an “All Rock” issue Heavy Metal [V4 #7, Oct. ’80] was going to run, so they turned to me. I just lucked out and they said, “Hey, why don’t you just do something really crazy? We got these six pages to fill.” So I was, “Oh boy! It’s time for unsupervised play.” So I did this adaptation of a Jimi Hendrix song, “Voodoo Child,” and I used some experimental techniques with overlays and colors and kind of double-exposure stuff and press lettering. I didn’t get permission for the lyrics. I tried, but couldn’t quite figure it out how to do it (or they didn’t get back to me or something). So we just used the lyrics anyway.

Right around this time, I was taking the bus into New York and I sat with Jack C. Harris and talked. He was amusingly parental toward me and he decided to give me a script to do. He was editing the mystery book called Ghosts and that was the first job I got on my own from DC. (Previous to that, I had done a half-dozen comic stories for DC, but they were all through Joe Kubert.) And that led to another short back-up and another one, and I met Len Wein, and he hired me to do a series of two-pagers. So I got to know Len and he then asked me to draw a one-pager he had written for Heavy Metal.

CBC: So how did Epic happen and when did you first meet Archie Goodwin?

Thomas: I had an interview with Jim Shooter at Marvel, and he goes, “Oh, you’re in the Tarzan and drawing naked ladies. How about this jungle girl character we have?” And he gave me a tryout script for Shanna, the She Devil, but it was the Shanna goes to New York, so I wasn’t doing many jungles or leopards or anything. I did my best and turned it in to Shooter. He said my drawing was too realistic. So I was up there and the guy up at Marvel who liked me was Rick Marschall. He was a total character. I would go up there and hang out with Rick a little bit and he’d throw his telephone across the room at Ralph Macchio, and he was just a nut. So I did some rock ’n’ roll stuff for him. At any rate, I was at Marvel and DC going up to their offices, getting odd little things here and there…

Also, in 1978, Al Williamson was wanting to quit drawing the Secret Agent Corrigan strip, and he called up Joe Kubert and asked, “Are there any young students you think would be a good new assistant for me?” Kubert knew I was a real nut for Al’s stuff. And he said, ”Williamson’s looking for an assistant. Why don’t you give him a call?” So I called and we immediately hit it off on the phone. He drove down with his two adorable kids in this old sedan, and drove me back up to his house where I met his lovely young wife, Corey, who he just married recently after his first wife had passed away from cancer. Archie Goodman and his wife visited the Williamsons regularly, so I may have met Archie there first.

Actually I knew Archie more socially than professionally and then Archie wanted to compete with Heavy Metal. So they decided to start Epic illustrated, see what they can do in this realm. They’re not going to be outdone by these upstarts reprinting the European stuff. They wanted to get in on that. But by then one thing led to another, and I was getting regular work at DC, so I didn’t get on board with Marvel, besides a few spot illustrations purchased by Roy Thomas from my portfolio… but they weren’t that interested in me.

But Marvel did throw me this one bone when the Conan newspaper strip was going down, they needed two more months of dailies and two more Sundays. So they hired me and I did a lot of it in the office because, at the exact same time, I started getting scripts from DC. So I was really overworked at #39 • August

Above: Full page illo by Thomas in Manticore [’76]. Below: Detail from Heavy Metal V4 #7 [Oct. ’80].

that point, and I was sleeping every other night.

I’d do an all-nighter, then sleep the next day, then do an all-nighter and I’d sleep the next day for the period when I had this Conan gig and I’d bring the unfinished dailies to Marvel’s office Monday afternoon. And Ken Feduniewicz had been hired on staff there along with the other Kubert student, Ron Zalme. They were in the production department. And so Ken would come in and see his old buddy, me, when I’d bring in these Conan dailies and he’d letter the unfinished pages while I would ink the other pages and pass ’em back and forth.

I did this in Marvel where there was a side office that was their newspaper department. And sitting in there was Larry Lieber who was doing Spider-Man and he was very quiet and serious. And also sitting in the room was Frank Giacoia inking the Spider-Man strip. Frank was just a kick in the head. I so enjoyed being with Frank Giacoia.

CBC: What was Frank like?

Thomas: Well, he had a little portable TV he would have in front of him while inking. I’m sitting across the table and he’s playing the afternoon movies. I ask, “Frank, how can you draw with the TV on? I’m too easily distracted.” (Today, I would proudly announce that I am “neurodivergent,” a term I love.) He goes, “Oh, I’m not watching it.” And I turned around to look at the movie and it was rolling snow, with no reception, but he knew all these old movies that were on, and he would talk back to the screen and he would wisecrack with Jimmy Cagney (or whoever) in these old movies. So anyway, it was a kick to be with him and then Jack Abel would come in and they’d tell stories and chuckle about stuff. So that was a great experience. My boss was John Romita, although he left me alone. He had more important things to do because the strip was dying anyway. They just needed somebody to fill out the contract for the last few weeks. But I gave it my best shot. It’s not work I’m particularly proud of, but it’s okay, I guess.

CBC: That was your first experience on a syndicated strip?

Thomas: Yes. So I did that strip at Marvel, and this would’ve been the end of ’79, beginning of ’80. But also what was going on then was I started getting jobs regularly, the back-up stories and short stories for the mystery books from DC. And so, from then on, I was at it full time and I learned to say no because I was getting more jobs. Because, at first, you say yes to everything because you don’t have any work and you’re desperate. And then I had too much work, so I had to learn to say no. And I just stuck with DC then because they kept giving me jobs. And it was Jack Harris, Ross Andru, Len Wein, and Karen Berger then. They were editing and giving me books. Paul [Levitz] wrote a fantasy back-up series called “Dragonsword,” in a Ross Andru-edited book, Warlord, which Mike Grell wrote and drew.

CBC: Was “Dragonsword” written with you in mind?

Thomas: Maybe. I don’t know. It started off, I did a two-part “Claw the Unconquered,” the DC sword-&-sorcery character. They wanted to renew the copyright or something, so they cooked up a two nine- or ten-pagers to put in the back of Warlord. It probably wasn’t originally conceived for me, but I really got into that, and it was a really good experience because it was a regular gig, but it wasn’t a whole book. I got into that, and it endeared me to Paul, who I’ve been friends with ever since.

I also did a back-up feature in Jonah Hex, for three or four episodes of a character called Tejano Ranger, which kind of haunted me for a long time. I got Rick Veitch to help me with that. I was supposed to be doing it solo, but I was disobedient and brought Rick in to help. And I’m really happy that I did because it was so great to work with Rick on that job. He just loved doing it with me, which helped both of us to become

professional.

But I didn’t like the end of the story, which is about a white Texas kid who grows up friends with Texan-American Indian. And then it turns out, in the end, the American Indian’s a bad guy and they fight each other and the white kid has to kill his childhood friend. And the climax of the story — I just hated that story — and I really wanted to draw the final battle and have the Indian kill the white kid in the end, and then turn it in at the last minute and hope nobody would notice. But I was new and I didn’t have the guts to do it, so I didn’t. I was a good boy and I did follow the script, but I really didn’t like that storyline.

Top: Yeates page from Heavy Metal V5 #5 [Aug. ’81]. Above: Detail from “Dragonsword” episode by Thomas in Warlord #51 [Nov. ’81].

I’m not as good as any of those guys. So I have to pile time into it to try and get something close to comparable. Then Timespirits ends and Eclipse called, though I did not know the Eclipse people at all. I think right before I moved from New York, either [publishers] Cat or Dean had contacted me about inking a cover of Aztec Ace.

And so I inked the Aztec Ace cover pencilled by Michael Hernandez. And then I moved out to California and it turned out that they were like 20 minutes away. They had relocated to the Russian River, so they said, “Come on over, come hang out. You can use our copy machine.” So I would do an issue of Timespirits, I’d drive over to Eclipse, Xerox all of it… because Williamson had once lost two weeks of Star Wars strips because of FedEx and he had asked me and Brent Anderson to help him redo those two weeks. So I always paid to have Xeroxes of my work before I would send them off by FedEx.

And so I get Timespirits done, and I’m already have this relationship with Eclipse, and Timespirits was not successful, didn’t sell enough books, it didn’t have an audience. All during that time, Steve [Bissette] and Rick [Veitch] are hitting it out the park with Alan Moore doing exactly the radical kind of stuff that we were really into and I was into because I was the one who’s a big environmentalist.

Swamp Thing is an environmental hero, which is very difficult to do, because it’s too politically correct. People don’t want political correctness. But Alan Moore was such an incredible writer and their art so amazing that he could do an environmental hero that was actually sold because it was just so fricking well done and interesting, and Timespirits is really difficult. It also became difficult to work with Steve Perry. He was not interested in what I wanted to do so much, although he catered to my tastes, as most writers will do, as far as what the subject was. But the actual story, he didn’t really want my input.

By this time, Eclipse is working with Tim Truman, who I’m also very close friends with, and he had laid out a whole issue of Swamp Thing for me when he was just getting started. Eclipse was publishing Airboy and I ended up inking some stuff there. Not a lot, but I really enjoyed that. And I did a fill-in issue for Scout, which I really totally love doing that. I love working with Tim and love his artwork. Always have… I was asked back to do six pages of Alan Moore’s very last Swamp Thing. So that was nice. He called me from England and described the page to draw because he hadn’t gotten me anything. It was late. So I had a nice conversation with Alan (and I had met him at the one San Diego he went to) and he’s a great guy.

Around this time, I joined the volunteer fire department.

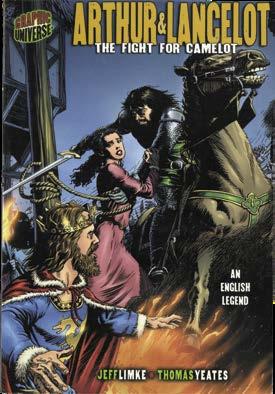

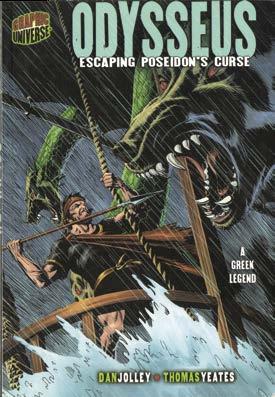

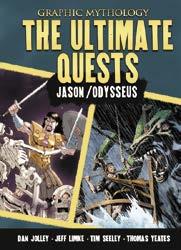

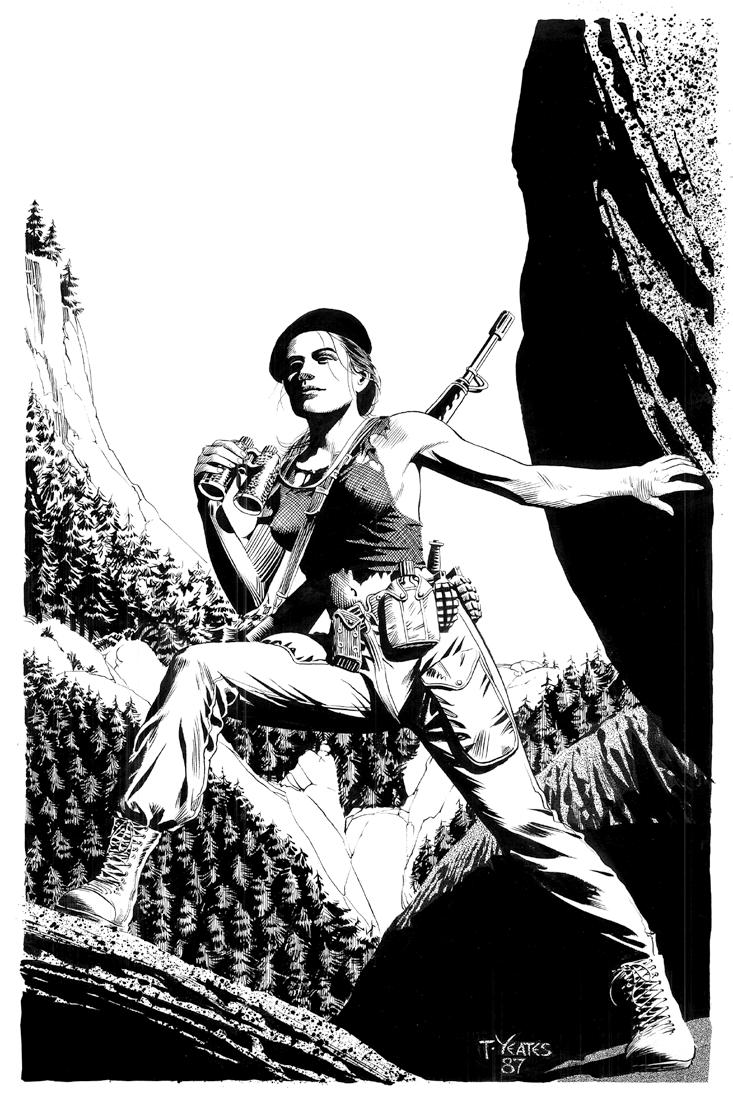

Top of spread: In the ’00s, Thomas worked on a series of graphic novels for the Lerner Publishing Group, all based on mythology and legends (stories, conveniently for the publisher, in the public domain). Produced for readers aged between nine and 14, seven of the run were illustrated by Thomas. Below: Original cover art by Thomas, New America #1 [Nov. ’87], a spin-off of Tim Truman’s Scout series. Eclipse Comics was situated in Northern California, in close proximity to Thomas, who worked on a number of projects for the outfit, including Luger (as inker), Aztec Ace (as cover artist), and Brought to Light (as story artist), a collaboration with writer Joyce Brabner, as well as other titles.

Top: Exquisite Zorro commission piece by Thomas Yeates from 2007.

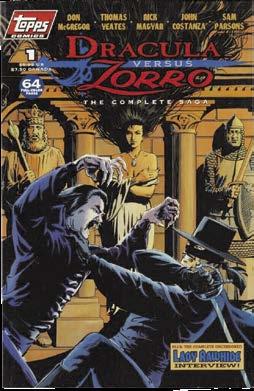

Above: Cover art by Thomas for the Dracula Versus Zorro compilation [Apr. ’94] published by Topps.

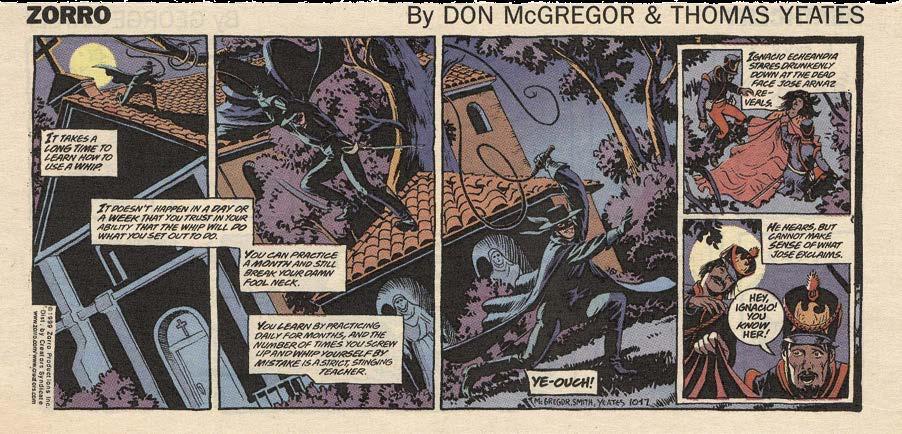

Below: That two-issue mini-series would lead to a daily newspaper comic strip gig for writer Don McGregor and Thomas, who would enlist fellow Kubert School grad Tod Smith to produce the layouts for Thomas to ink. This strip, colored by Thomas, is from Oct. 17, 1989.

TwoMorrows needs your help!

DIAMOND COMIC DISTRIBUTORS

FILED FOR BANKRUPTCY IN JANUARY without paying for our December and January magazines and books, leaving us with enormous losses— and we still have to pay the expenses on those items, and keep producing new ones. Until payments from our new distributors begin in the Fall, we’re staying afloat with WEBSTORE SALES

Every new order (print or digital) and subscription will help TwoMorrows get through this, and emerge even stronger for 2026. Please download our NEW 74-PAGE 2025 CATALOG and order something if you can: https://shorturl.at/gA9Fv

Also, ask your local comics shop to change their orders from Diamond to LUNAR DISTRIBUTION, our new distributor. We’ve had to adjust our release dates for the remainder of 2025 while we wait for orders from our new distributor, so you may see some products ship earlier or later than originally scheduled. We should be back to normal by end of Fall 2025; thanks for your patience!

I was recruited because I was an able-bodied young man who worked at home, so I was always available. If there was an emergency, I could put down my brush and run out the door, run down the firehouse, and respond to the drunk that drove off the cliff into the blackberries. So I was busy and my life was really full… But comics were a challenge. It’s not an easy job to do. It takes an immense amount of time, and the audience is very, very fickle. So you can do a great job and nobody buys it. So anyway, I agreed to do this job for Dungeons and Dragons, and then Karen Berger calls me up and says that a new wonder kid that she really likes, and would I be interested in doing this book called Sandman…?

So then I get a call from Neil Gaman trying to talk me into doing Sandman. And I kind of had an idea that this guy was hot stuff, but he wasn’t that hot yet. And I talked to him for quite a while and I said, “Well, tell me why do you want me to work for you?” I didn’t have that high self-esteem about my work. I mean, sure, Williamson liked it and people liked it, but it wasn’t like it was connecting with an audience at all. I was not a fan favorite. The editors and stuff liked me, and my peers liked me, but… And he said he liked the acting that my characters did when, particularly a scene in a Swamp Thing. I don’t know which one it was. (I did go back and do some more Swamp Things during that period after Alan left and Rick Veitch was writing it, four issues by myself… I helped Karen out when she was in a bind.)

Thomas: Well, it was in the same period or after. That was such a cool gig. I couldn’t bring myself to turn it down. So I had done the Jimi Hendrix in Timespirits and Central American stuff for Eclipse, the Brought to Light political comics for Eclipse. And since I had drawn this stuff with Jimi Hendrix in it, Eclipse got this gig because they were doing 3D comics with Ray Zone and was to do a 3D comic book of Captain EO, that Michael Jackson Disneyland movie-slash-ride at their theme park. And that just was too trippy of a job to turn down.

CBC: Was there an anticipation for Captain EO being a lucrative seller, but sales were a disappointment?

Thomas: The big yes on that. I mean, I really busted my ass on that. I did it on Duo-shade, really detailed, over-the-top stuff. I mean, it was Coppola/Lucas/Disney/Michael Jackson team-up, right? Really high tech. So I was really going for it with detail and composition and everything, and they paid me really well. As I recall, it was an unusually high page rate, so I could put the time into it to really go for it. But, unfortunately, despite the goal to have it on sale permanently in the gift shop and though Ray Zone accomplished this fantastic 3D effect, Eclipse put an ad for Valkyrie, the Golden Age aviation character, on the back cover of Captain EO, featuring Valkyrie with a plunging neckline and Disney wouldn’t put the book in their stores.

IF YOU ENJOYED THIS PREVIEW, CLICK THE LINK TO ORDER THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DIGITAL FORMAT!

So I didn’t take Sandman and I finished the Dungeons and Dragons book, though sword-&-sorcery was far past its sell-by date at that point… But I did make enough money to buy my little two-bedroom, one-bathroom cabin there. That was good.

CBC: Well, how does Captain EO fit into this?

I had this great royalty deal and we were all going to make money forever because our book was going to be sold in the Disney gift store next to the Captain EO ride. But that never happened, though it was a great experience to do it. They wouldn’t give me a script. They were very hush-hush. Michael Jackson was, of course, very touchy about it. I had to redraw Michael’s face as he kept changing his looks.

COMIC BOOK CREATOR #39

THOMAS YEATES career-spanning interview about the Kubert School, Swamp Thing, Eclipse Comics, and adventure strips Zorro, Tarzan, and Prince Valiant! GREG POTTER discusses his ’70s Warren horror comics and ’80s reboot of Wonder Woman with GEORGE PÉREZ, WARREN KREMER is celebrated by MARK ARNOLD, plus part one of a look at the work of STEVE WILLIS, part two of ERROL McCARTHY, and more!

(84-page FULL-COLOR magazine) $10.95 (Digital Edition) $4.99 https://twomorrows.com/index.php?main_page=product_info&cPath=133&products_id=1826

But the way I wrote it was: I went to Disneyland and went to the showing. You sit in a chair that moves, put on glasses, watch this 3D movie, and your chair moves around the universe with Captain EO singing songs and saving a planet with his goofy team. And I took notes. So I had to have scripted it myself while watching it. And I just watched it over and over and over and over and took notes until I had mapped out a coherent (whatever it was) 30-page comic book. And then I took it home and proceeded to draw it. They did give me slides to draw from, though I was sworn to secrecy.

Zorro TM & © Zorro Productions, Inc. Sunday strip courtesy of Ronn Sutton.