19 minute read

Charlton’s Jailhouse Compact

Thinking About

by STEPHEN R. BISSETTE

The Charlton Comics pre-Code legacy had been left to rot until the 1980s, when authors/comics scholars Lawrence Watt-Evans38 and Will Murray began the first English-language autopsies for The Comics Buyer’s Guide of the plethora of EC’s predecessors and competitors. (Watt-Evans serialized “Reader’s Guide to Pre-Code Horror Comics,” in his regular “Rayguns, Elves, Skin-Tight Suits” column, and Will Murray’s comprehensive “Ditko Before the Code,” Nov. 23, 1984.) In Part 15 of his “Pre-Code Guide,” Lawrence tore into the Charlton lineup: “These comics are sick. Warped. Disgusting. I love ’em.”39

Launched from their bedrock of “Famous Tales of Terror” comics stories published in Yellowjacket Comics (beginning with #1 [Sept. 1944]), Charlton’s The Thing! ran 17 issues [Feb. 1952–Nov. ’54], borrowing its title from the 1951 hit science fiction/horror film, The Thing from Another World. The Thing! series didn’t take its title from a licensed radio program, but it presented itself as if it had; the named-but-essentially-unseen host was a definite nod to the popular radio mystery-suspense programming of the 1930s, ’40s, and early ’50s.

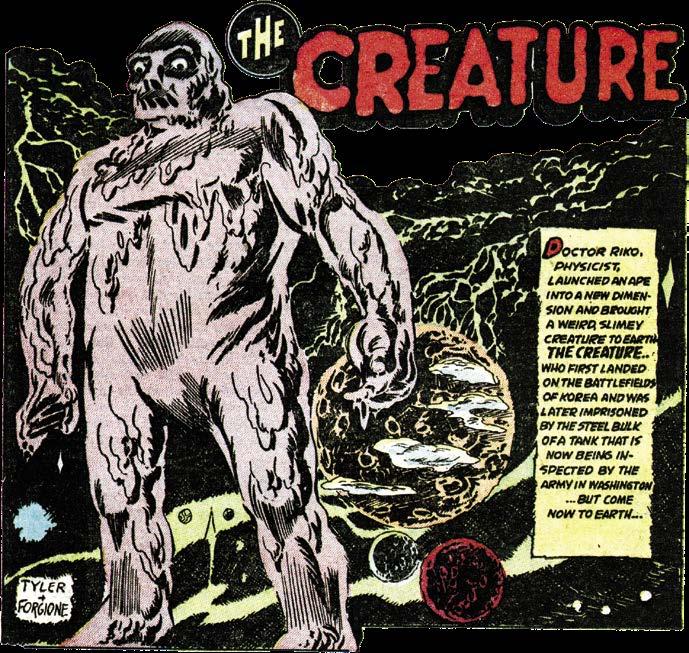

The Charlton pre-Code horrors were all packaged by the Al Fago Studio, and, despite the fact horror wasn’t Fago’s cup of tea, he didn’t flinch. Assembled with Charlton’s usual formula of low page-rates offset by minimal editorial restrictions or oversight—a mercantile laissez-faire—amid the mediocrity and crude work, Charlton published a lot of really quite extraordinary horror comic stories. A mad, scattershot approach to storytelling was typical of The Thing!’s first issues—manifest in #1’s “The Creature from Dimension 2-K-31,” concluding with “The Creature,” in #2— settling down by its third issue into more traditional horror comics motifs (ghosts, mummies, vampires, werewolves, zombies, etc.) and comfortably linear scripts. There’s scant evidence as to who might have scripted these stories, but both chapters of the Creature’s saga were signed by Albert Tyler and Bob Forgione, who continued to contribute work to the series as more familiar Charlton contributors joined in (John Belfi, Dick Giordano, Tex Blaisdell, Lou Morales, etc.). Tyler’s solo art was a noticeable cut above the Tyler/Forgione efforts (and just about every other contributor’s) until Steve Ditko’s arrival in #12 [Feb. 1954]. No longer collaborating with Tyler on art duties after #2, Forgione stayed on as the primary contributor to the title, and his bold, blunt inking and drawing style suited the title and the genre well enough.

Initially, there were lots of vengeful ghosts—and I mean lots of ghosts. From its second issue onward, The Thing! was (like all the pre-Code horrors, including EC Comics) busily plundering story material from available sources: fairy tales, folk tales, short stories, the pulps, genre radio plays, movies, etc. Sometimes the writers brought their own spin to the material, sometimes they’d just go with straightforward (albeit uncredited) adaptations. As with their competitors, vampires, zombies, and the walking dead were key ingredients of the Charlton pre-Codes. Vampires in The Thing! were typically in the traditional caped, cowled, and fanged forms, but there were some attempts at invention. A still-hungry severed vampire head was fed in the cautionary parable “Mark of Violence” in #10, and T. Collier had some fun with the Cuban sugar plantation bloodsuckers in “Haunt of the Vampire” in #7, mixing and matching capes, fangs, sombreros, bolo ties, blood-fattened bellies, bat-like faces and wings, before the final panel’s payoff of a human-headed bat-boy flying toward the reader worthy of the Weekly World News. Reanimated mummies popped up more than once, but The Thing! brought novel spins to the archetype: John Belfi crafted a partially-unwrapped female macrocephalic jumbo mummy in #12’s “The Mummy’s Curse,” while for #5’s “Curse of Karnak,” Bob Forgione drew the humanoid “living gods”—the animal-head-

Charlton Comics’ Forgotten Artists

When poring over the names of artists who produced a good chunk of Charlton Comics’ output between 1952–54, one is struck by the relative unfamiliarity of so many of those creator names: Bob Forgione, John Belfi, Frank Frollo, Lou Morales, Dennis Laugen, Albert Tyler, Stan Campbell, Ray Osrin… And a cursory glance at the Grand Comics Database makes clear that these artists seemed to have vanished from the Derby publisher’s line by mid-decade—and from the entire industry altogether!

Of course, it’s no surprise that hundreds left the field for good in the aftermath of the mid-’50s anti-comics campaign—about 900 by David Hajdu’s count44—but Charlton provided safe harbor for other (to fans, more recognizable) names of the outfit’s regular lineup: Dick Giordano, Tony Tallarico, Vince Alascia, and Sal Trapani, to specify a few.

As with those just-mentioned who stayed in comics, it is remarkable that so many of those in the Charlton fold were of Italian descent. Maybe Naples-born Al Fago had a preference for young artists with family names connected to his motherland, or maybe it’s just that a preponderance of Italian youngsters had graduated the art schools of New York City and theirs was the talent available. We can only speculate, but, in an effort to showcase talented artists too long ignored and some sadly forgotten, what follows are biographical sketches of a select, mostly Italian group of artists:

Bronx-born Frank Frollo [1915–1981] is a name that goes back to the early years of comics, when he joined up with the studio of packager Harry “A” Chesler, producing strips for the Centaur line. Initially, his art evoked a certain Alex Raymond vibe, and Frank Joseph Frollo would improve over time. He left Chesler in 1939 and joined up with the Eisner and Iger Studios. In 1940, he associated with Funnies, Inc., and 14-year-old neighbor John Belfi became his assistant. Frollo worked a day job as advertising manager of a Brooklyn corrugated paper plant until joining the U.S. Army as T/5 Corporal, where he served in Europe as the 63rd Regiment headquarters artist. Frollo returned to comics, again working for packager Funnies, Inc., as well as illustrating pulp magazines. In 1952, he found steady work with editor Al Fago—and Walter Gibson, with whom he had collaborated on “Blackstone,” circa 1945. At Charlton, he toiled on their crime and science fiction titles. By 1955, Frollo exited comics and established what would become a long career in advertising, first employed as art director in various firms, and eventually founding his own outfit, FAA Advertising. In 1940, he married Emily Bongiorno and they had two sons together.

John Belfi, perhaps better known due to his interaction with fanzines, was born in Suffern, N.Y., in 1924, and, at 12, he had artwork published in a local newspaper. Upon turning 14, John William Belfi and family moved to the Bronx. Near Mint related, “There he learned that the cartoonist Frank Frollo lived some five or six blocks away. Belfi met Frollo and began assisting him after school and on weekends in Frollo’s studio.”45 Within six months, the youngster completed full pages. He then attended the School of Industrial Arts and also assisted a number of artists, including Jack Cole, Mac Raboy, Reed Crandall, Will Eisner, Lou Fine, Dan Barry, and others. In 1943, Belfi enlisted in the U.S. Army Air Corps, was stationed in Asia, and discharged in ’46, when he returned as art assistant, for instance inking on DC’s Green Lantern. In 1950, he joined with penciler Joe Certa and writer Gardner Fox to produce the daily comic strip, Straight Arrow. Between 1952–55, he worked on Charlton assignments, then left comics and “drifted” into advertising. He founded the John Belfi School and Workshops and labored at numerous newspapers as writer and cartoonist. “Married at 19, I had three children, divorced after 30 years, remarried…”46 He died in 1995.

Belfi cousin Albert William Puglucio [1924–1983]—known as Al Tyler— lived in the Bronx and presumably entered the comics world with an assist from Frollo, whose work appears alongside Tyler’s in Centaur’s Super Spy #1 [Oct. 1940]. Despite Norman Rockwell advising him to attend the Pratt Institute, Tyler (who officially changed his name— as did his entire family—after his father died in 1947) studied at the High School of Industrial Arts and the Art Students League. His credit reappears in 1952, on work published by Charlton. Dick Giordano remembered, “I found somebody who had a studio, and they were looking to rent space. His name was Al Tyler. (The artist who just moved out was Bob Forgione, a name you may not know, but he worked with Jerry Robinson back in those days, as Jerry’s assistant,

John Belfi

The 1954 Revival of the Blue Beetle

Galindo and Osrin photo courtesy of Shaun Clancy. There’s little doubt that Atlas Comics— later known as Marvel—sensed the gathering threat regarding the war against “crime comics” and thus sought to get some distance from the horror books that had so dominated their output. Wholesome Superman adventures proved popular as a TV show, so why not revive their super-hero books and refresh a once tried-and-true genre? Then, for a few brief months, innocuous costumed characters replaced the horrific fare on stands and, naturally, Charlton jumped (tardy yet again) into the fray.

Any overt connection between Victor Fox, whose Fox Comics had owned Blue Beetle, and John Santangelo has yet to be found—though the Charlton publisher once sharing a Manhattan office with onetime Blue Beetle publisher Sherman Bowles certainly intrigues—so why BB was chosen remains a mystery.

But, in mid-1954, revive the azure-attired character Charlton Comics did, reprinting mostly 1950 Fox exploits, unfathomably in the science fictionthemed Space Adventures #13 and 14 (with editor Al Fago literally tracing BB #60’s cover for the former and yet signing his own name to the appropriation!) and—taking the numbering from cancelled horror title The Thing!—the new BB title lasted four issues, though only two contained a majority of new work.

“The Golden Age Blue Beetle was going nowhere,” Dick Giordano, who drew the covers for the character’s 1954 run, griped to Christopher Irving. “[We] were putting out something akin to the Golden Age, which had no place in the marketplace that existed.”64

In general, the reprint material was poorly drawn stuff, but the new work was quite handsome, rendered by Pratt Institute-educated Ted Galindo, whose memory of freelancing for Al Fago was hazy when discussing his Charlton days with Shaun Clancy. “The only work I did with him was with [inker and friend] Ray Osrin. We did about three or four Blue Beetle stories for him and that was about it… I only saw Al Fago maybe three or four times. If I remember correctly, it was Ray that was working with them as an inker and, once Al saw my pencils, he wanted me to work with him and have Ray ink my work, but I don’t remember how we met, but we did become good buddies, Ray and I… I think Ray would get the script and I would go over his house and talk about it. Then I would take it home and do the penciling and bring it back to Ray. So, almost all the business was done at his house.”65 In the 1950s, Theodore Louis Galindo [1927–2020] also worked out of the studio of Lone Ranger artist Tom Gill and freelanced for numerous companies, from Atlas to Prize, all the while producing a good amount for Charlton, where he also drew “Rocky Jones, Space Ranger,” in Space Adventures. Deconstructing Roy Lichtenstein blogger David Barsalou wrote of the artist, “One of Galindo’s strengths was his adept characterizations. The post Comic Code Prize crime comics often included sequences of talking heads. With less talented hands, these sequences could become rather boring, but Galindo’s carefully handling of the viewing angle and his effective emotional portrayals keep his stories interesting. While Galindo could handle emotional portrayal, he was no slouch when it came to action.”66

This page: Space Adventures #13 [Nov. ’54] cover swiped Fox’s Blue Beetle #58 [Apr. ’50] cover. Ted Galindo penciled/ Ray Osrin inked Blue Beetle #21 [Aug. ’55] page. Galindo, Lea Osrin, and pal.

Five: The Go-Go Fifties Ascent of the Artist Named Ditko

If not for Stephen John Ditko [1927–2018], Charlton would be an even more under-appreciated comic publisher. It was the artist’s arrival at the comic book company, in the pages of their 1950s horror line, where Ditko produced his first brilliant work, thus beginning an association that prevailed for much of the next three decades.

Born in Johnstown, Pennsylvania, Steve Ditko was attracted to comic strips and, in particular, the comic book art of Jerry Robinson (and, to a lesser extent, Will Eisner), so much so that, after a stint in the U.S. Army, he moved to New York City in 1951 to receive instruction from Robinson at the Cartoonists and Illustrators School.

His drawing talent blossomed just as horror comics were in their prime. As related by Ditko biographer Blake Bell: Ditko’s penchant for drawing graphic horror scenes was apparently driven by an unbridled work ethic and by an interest in the trends of the day: when a publisher shifted in a particular editorial direction and said,

“this is what we need,” Ditko geared all his imaginative powers toward producing the best work he was able to within those parameters.67

In 1954, after a brief time on Joe Simon and Jack Kirby’s Black Magic title, Ditko found his longtime home. In a letter to Mike Britt, he wrote, “I had been around to Charlton Press on my earlier rounds and now they had an opening and I went to work for them. At this point, I quit looking for work. The old Charlton Press was very good to me. I had all the work I could handle and a free hand in any way I wanted to do the story. Since I was still going to [C&I] school in the evenings, I figured it would be better to stick strictly with them and try to develop myself.”68

Looking over Ditko’s early Charlton work in The Thing! and This Magazine is Haunted, one is amazed at the quality of the artist’s rendering and overall sophistication in the storytelling. But, just as the excellence of his Charlton work was reaching a fever pitch, illness struck.

Blanche Fago remembered Ditko from those early days, as she told Jim Amash, “He was a very good artist. A very nice, quiet person. He didn’t want anyone to know what he did in his private life. He was ill for a while, and didn’t want anyone to come and visit him. We never knew what was wrong with him. We lost track of him when he left Charlton. I often wondered what he had done, because he had so much promise!”69

The malady Fago refers to was an infectious disease Ditko had contracted. Fran Matera, an artist sporadically freelancing for Charlton, revealed the ailment to Amash: “I remember watching Steve Ditko draw comics in the [Derby] office. He had tuberculosis. A woman named Angie who worked there said, ‘He’s not long for this world.’”70

But, while it took a year, Ditko did recuperate and, with his TB in remission, he came back to the tri-state region, intent on a Charlton homecoming. But the man’s plan proved ill-timed. The Derby publisher had been devastated by the Connecticut floods of 1955 and so, for the time being, it was in retrenchment. He found work at Atlas, the company soon to become Marvel Comics, where Ditko later established his greatest legacy as one of the founding architects of the so-called “Marvel Universe.” With editor Stan Lee looking over his shoulder, Ditko would co-create Spider-Man and, on his own, originate Doctor Strange, both billion-dollar properties for Disney today.

This spread: Top is one of the few existing photos of enigmatic Steve Ditko. This snapshot was taken in the late 1950s by a studio mate. A panel from Ditko’s story in Crime and Justice #18 [May 1954]. On next page is Ditko’s horrifying cover for Strange Suspense Stories #19 [July 1954] and This Magazine is Haunted #16 [Mar. 1954] “Dr. Death” cover detail by Ditko. Crime and Justice #18 panel courtesy of Frank Motler.

Chapter Six American Comic Book Factory

A LETTER FROM LEVY Less than two weeks before Christmas 1954, former Fawcett Comics artist Marc Swayze received a (very tardy) missive from co-publisher of Charlton Press Ed Levy, replying to Swayze’s letter of August. Levy informed the Louisiana-based artist (co-creator of super-hero Mary Marvel, Captain Marvel’s sister) that the Connecticut company didn’t have a department devoted to comics per se, as work was farmed out to an “independent contractor”—presumably meaning Al and Blanche Fago. “However,” Levy added, “we can use a satisfactory artist of comics experience here in Derby,” suggesting Swayze send samples, references, and salary requirements.1

Swayze would take Levy up on a subsequent job offer and, into the new year, he and his family came north and settled into their new home on Roosevelt Drive, in Ansonia, and the artist started commuting the short ride to the ever-expanding Charlton plant. Swayze had freelanced for Fawcett between 1941 and ’53, and now his job wasn’t only to draw stories, but also “make presentable” inventory material Charlton had purchased from defunct comic book publishers who had abandon the business due to the anti-comics hysteria, which gave rise to the Comics Code Authority. “My responsibility was to clean up the material to conform to Code Office guidelines… replace nasty words like ‘cop’ and ‘babe’ with ‘police officer’ and ‘young lady’… and raise necklines, lower skirts, cover midriffs, and anything else that needed it.”2

In the wake of a crushing settlement with DC Comics, Fawcett, once publisher of top-selling Captain Marvel Adventures, broadsided its staff and freelancers (including Swayze) when it quite suddenly decided in fall 1954 to quit its comics line. The company immediately went about shopping its properties—sans the Marvel Family characters, which were all thrown into legal limbo—and inventory (of which there was plenty, given the abrupt cancellation of its numerous active titles). Charlton quickly snatched up the offerings and, before the year was out, material produced by Fawcett was coming off the presses at the Derby plant. Charlton acquired at least 17 titles and numerous characters, including Ibis, Golden Arrow, Don Winslow, Nyoka, Lance O’Casey, and Hoppy, the Marvel Bunny (who, to avoid legal entanglements with DC, was ultimately renamed Happy, the Magic Bunny).

Photos courtesy of Frank Romano and the Museum of Printing.

SPENDING SPREE With the comics industry reduced to tatters in the aftermath of Wertham, Kefauver, et al., Charlton was in remarkably good position compared to other second- and third-tier publishers, doubtless due to not being wholly dependent on its comic book line. So the outfit was in an enviable position to go bargain hunting and find deals they did, snatching up material from St. John (“Mopsy” stories and Fightin’ Marines, the first of Charlton’s extensive line of war comics containing the abbreviated word, “Fightin’,” in their names), Toby Press (Captain Gallant, Li’l Genius, Ramar of the Jungle, Soldier and Marine, plus “Monty Hall of the U.S. Marines” stories), and Fox (Blue Beetle, and tidbits that include “Rocket Kelly” and Pete Morisi’s “Skipper Hoy”), as well as some random items from Star Publications and Ziff-Davis.

Aside from the Fawcett haul, Charlton’s marquee acquisitions were Code-worthy leftovers from Allen Hardy’s Comic Media, including “Noodnik” humor stories, Death Valley, and Pete Morisi’s tough guy, Johnny Dynamite, from Dynamite. There also was the créme de la créme: four titles from the legendary creative team of Joe Simon and Jack Kirby.

Gabby… Gabby… Nay!

“Extended, uncontradicted testimony” from two former Charlton employees confirmed to the Federal Trade Commission that (gasp!) Gabby Hayes #55 [Aug. 1955] contained a reprint of “Gabby Hayes and the Human Porcupine,” first printed in 1951 by Fawcett. Weirdly, the FTC found Charlton committed “unfair and deceptive acts”7 for not informing buyers that stories in Gabby Hayes, Lash LaRue, Rocky Lane, and Atomic Mouse were reprints. Even stranger, the publisher’s defense was that Charlton Press, Inc., didn’t start producing comics until Aug. 1955(!), “when it purchased the assets of… Derby Color Press, of Derby, Conn.”8 The FTC didn’t agree and ruled in 1959 that Charlton had to “clearly and conspicuously” note on covers if any reprints appeared therein. SIMON & KIRBY GO TO DERBY In the end, Joe Simon said, “It was better than nothing.”9 Up until that time, the most popular team of comic book creators in history—with names better known to readers than even those of the creators of Superman—was, after a phenomenally successful decade-and-a-half run, on the skids.

Simon and Jack Kirby’s self-publishing enterprise, Mainline Publications, was formed in 1954, “only to find the business climate suffocating,” wrote David Hajdu in The TenCent Plague, and the historian continued: Although the titles they created… were tame, the major comics distributors declined to take them on. “We couldn’t get a decent distributor, because all the laws about selling comics had all the news dealers scared out of their wits—they were afraid to put comics on the newsstands,” said Joe Simon. “So our own choice was to go with Leader News, which was the distributor of Bill Gaines’s [EC] comic books, and with all the protests going on and the parents groups and the educational groups raising hell and the laws and the hearings and so forth, Leader News was in shambles. Our books weren’t being sold. They never even got on the newsstands.

Jack and I were pulling our hair out, and finally we couldn’t take it anymore, and we couldn’t afford to keep producing comics that never got unwrapped, and we had to pull the plug on our own company.”10

As the end arrived for Mainline, and as Simon and Kirby simultaneously partnered with Charlton to produce the ambitious Win A Prize (see sidebar), the two negotiated with the Derby publisher to print their remaining Mainline inventory. “I met with the owner, John Santangelo, and we struck a deal,” Simon said. “As a result, the final issues of all four Mainline series [Bullseye, In Love, Foxhole, and Police Trap] were published by Charlton, at times supplemented by stories from the Charlton stable of writers and artists. The production standards weren’t what Kirby and I had maintained on our own, but at least the stories would see the light of day. And we would receive a small amount of income.”11

Calling it “the last port of call,” Simon shared some insight into the Charlton set-up: “We made frequent trips to their plant in Connecticut, where the highlight of the day was a tasty Italian lunch at the executive table of the employees’ spacious cafeteria. When the noon whistle blew, the printing