5 minute read

Rudy Palais by Roger Hill

Eight: Strange Tales of Unusual Comics Tales of the Mysterious Traveler

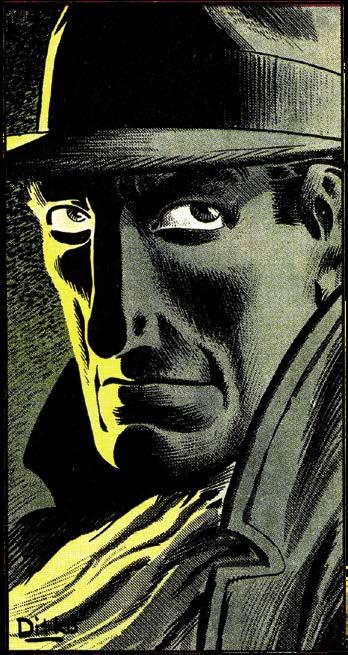

If anyone thinks that the titular host of Charlton’s Tales of the Mysterious Traveler [13 issues, Aug. ’56–June ’59] was a swipe of DC’s Phantom Stranger [six issues, Aug. ’52–June ’53], here’s a little pop culture elucidation: Broadcast between 1943 and ’52, The Mysterious Traveler was a half-hour radio anthology program narrated by the title character and featuring suspenseful dramas in a variety of genres. Produced by the prolific creative team of Robert Arthur and David Kogan, the well-regarded, award-winning show had, like the best of its kind, a evocative opening. “All memorable radio characters had their distinctive entrees. The Whistler came whistling out of the night; Captain Midnight zoomed down from his airplane; the Shadow was just there suddenly, knowing all evil that lurked in the hearts of man. The Mysterious Traveler came on a train.”66 The 370-episode series spawned a one-shot comic book, Mysterious Traveler Comics [Nov. ’48], featuring the art of Bob Powell and Rudy Palais, and included a reprint of a “Famous Tales of Terror” Edgar Allan Poe story that originally appeared in Charlton’s Yellowjacket Comics #6 (perhaps a hint as to how the Derby publisher was initially connected with the property). The character’s creators were closely involved with a short-lived pulp digest that appeared for six issues, The Mysterious Traveler Magazine [Nov. ’51––Nov. ’52], all sporting cover paintings of endangered, scantily-clad women by Norman B. Saunders, listing Kogan as publisher and Arthur as managing editor. Though the radio show had been off the air for over three years, Charlton debuted its Comics Code-friendly series, hosted by a stoic narrator, as Bill Schelly described: “Charlton’s Mysterious Traveler was different from the EC horror hosts in two ways: he was unrelentingly grim and serious (no tongue in cheek humor for him), and he more frequently narrated an entire story, not just its start and finish. He even took an active, if subsidiary, role in the action of an occasional story.”67 Most yarns were written by Joe Gill, and a Steve Ditko in prime form drew an ample number. The writer/artist team also produced stories for the less-horrific second version of This Magazine is Haunted, starring a similar host, Dr. Haunt (who had been initially called Dr. Death in the good ol’ pre-Code days).

BALLANTINE MAGAZINES In mid-1957, famed book publishers Ian and Betty Ballantine went into business with Charlton Press to form Ballantine Magazines, Inc., as well as contracting Capital to distribute the fabled Ballantine paperback line.68 The singular result of that incorporation was a short story anthology digest, Star Science Fiction Magazine, edited by Frederik Pohl and art directed by Richard Powers, itself a periodical extrapolated from the Ballantines’ Star Science Fiction Stories paperback series [#1–6, 1953–59]. Cover-dated Jan. 1958, only one issue of the pulp digest was ever published.

The relationship between the Ballantines and Charlton collapsed when the couple accused Capital of refusing to pay money owed in the amount of $175,000, resulting in a suit filed in federal court.69

OUTER SPACE WAR ADVENTURES Just as Atlas Comics doubled its science fiction line of comics from eight to 16 titles in 1956, Charlton dropped Space Adventures and launched two new ones: Mysteries of Unexplored Worlds [48 issues, Aug. ’56–Sept. ’65] and Out of this World [16 issues, Aug. ’56–Dec. ’59], which joined the similar Unusual Tales [49 issues, Nov. ’55–Mar. ’65]. While still retaining some SF elements, these titles were more in the vein of the quasi-SF/monster/fantasy offerings of the American Comics Group and Atlas, and an occasional DC. The launch of the Russian satellite Ian Ballantine Sputnik 1, on October 4, 1957, signaled the start of the space race between a panicked U.S. and triumphant U.S.S.R., and it also resulted in a mini-boom in science fiction comics. New Cold War-tinged titles included Charlton’s Outer Space [nine issues, May ’58–Dec. ’59] and a revived Space Adventures [36 issues, May ’58–Nov. ’64]. Space War [27 issues, Oct. ’59–Mar. ’64] followed.

Betty Ballantine

Chapter Nine The Launch of Captain Atom

PARANOIA IN THE ATOMIC AGE “We will bury you!” Such was the threat to capitalist nations—the United States of America, in particular—hurled by Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev in late 1956. Whether intended as metaphor or not, the existential fear it would become reality was a preoccupation of the West, and the following year’s development of intercontinental ballistic missiles by the Russians, along with U.S.S.R.’s Sputnik satellite launch, turned the anxiety of the American public into a full-blown panic. At the heart of the national alarm was the atomic bomb, and one federal response was to encourage citizens to, well, bury themselves by building their own fallout shelters, underground living quarters where families would wait out the ill effects of radiation after a nuclear attack. In 1959, to that end, the U.S. Office of Civil and Defense Mobilization published The Family Fallout Shelter, a 32-page booklet of blueprints and instructions for landowners to dig up the backyard and build—and thrive therein—their own subterranean dwelling.

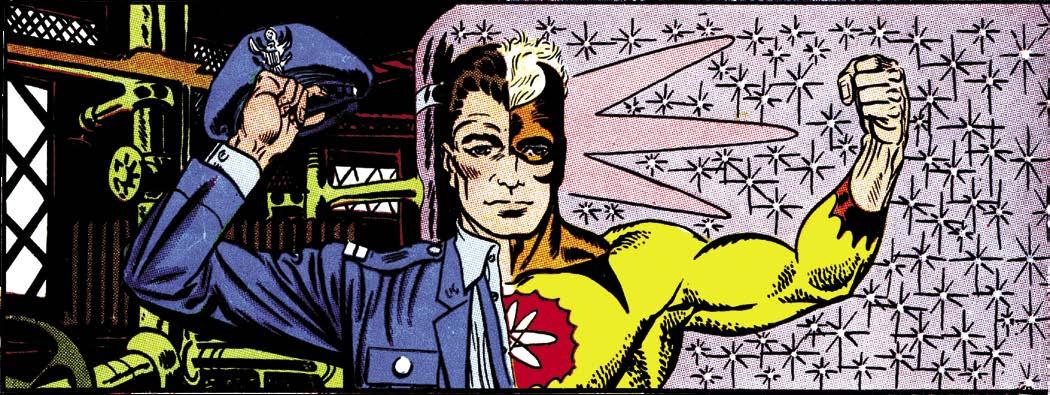

Jazzing it up with an illustrated color cover and expanding contents to 68 pages, in 1960, Charlton reprinted the government publication at no cost to itself, sold Family Fallout Shelter for 50¢, and offered discounted copies for bulk sale. The spectacular cover sported an atomic explosion super-imposed by the outlines of a typical American family. THE COMING OF CAPTAIN ATOM In 1960,* amid the nation’s nuclear hysteria, came Charlton’s first home-spun and enduring super-hero, Captain Atom, the gung-ho all-American character created by Joe Gill and Steve Ditko. Literally a military officer in the U.S. Air Force, Captain Atom’s origin story, with the presence of an approving (though unnamed) President Dwight D. Eisenhower, evokes the origin story starring another super-captain, quintessential patriotic hero Captain America, whose transformation was approved by an (unnamed) President Franklin D. Roosevelt 19 years prior, in Captain America Comics #1. And as anti-Nazi as the star-spangled Marvel character was in his day, the Charlton newcomer was a rabid anticommunist, hellbent on taking the Soviet menace to task. This U.S. patriot wasn’t the first comic book character whose name suggested the nuclear era. After all, Charlton’s own Atomic Mouse, Atomic Rabbit/Bunny, and Atom the Cat preceded him, and he was actually the third Captain Atom to have appeared in comics by that time, one found in mini-comics (which included Tony Tallarico art) and another south of the equator, in Australia.

*Technically 1959, as on the Heritage website, a copy of Space Adventures #33, featuring Captain Atom’s start, includes a newsdealer’s penciled notation of “12/29,” suggesting the character’s newsstand debut was a mere two days before the advent of the 1960s. Space Adventures #36 panel detail courtesy of Nick Caputo.