22 minute read

Santangelo’s Songsheet Shuffle

Forgotten Golden Age super-hero Yellowjacket was a curious character who, despite being named for a wasp genus, had supernatural control over bees, able to direct the flying insects to attack the criminals he was fighting. In a hero history, Stacy Baugher designates him as an “orphan character.”2 His origin is roughly thus: Crime writer Vince Harley has a beekeeping hobby. A hoodlum unleashes a beehive on Vince, who is a person who cannot be stung, and he decides to become costumed crimefighter. The origin, Baugher states, “became a sort of framing sequence for the Yellowjacket stories. Vince Harley would find himself in some sort of sticky-wicket and, as the Yellowjacket, would save the day. He would write the adventure as a fiction story, and his editor would give him a check.”3 Subsequently, Vince’s origin is modified a tad by actually having him, in fact, stung and then gaining superhuman strength. Vince is briefly made editor-in-chief of Dark Detective Magazine (certainly a title that would fit nicely with the Charlton-related pulps, such as Dramatic Detective), and the character starred in all ten issues of Yellowjacket Comics, with stories elsewhere appearing in TNT Comics #1 [Feb. ’46] and Jack-in-the-Box Comics #11 [Oct. ’46], the latter a new title taking over Yellowjacket’s numbering. Yellowjacket

A TIMELY MYSTERY One true curiosity in the early history of Charlton is the odd inclusion of Marvel Comics material in two issues of Jack-in-the-Box Comics, #12 [Dec. 1946] and #13 [Apr. ’47]. The most glaring evidence of Charlton purchasing inventory from Marvel is certainly the best-looking: Basil Wolverton’s marvelous “Flap Flipflop” seven-pager in JITB #13, as it retains its Marvel job number, SL-847. (Could “SL” stand for the initials of Marvel editor Stan Lee?)

In JITB #12, “Squat Car Squad,” itself a long-running series at Martin Goodman’s outfit, even references Marvel’s Super Rabbit in its opening panel! (Also in JITB is Marvel’s Tubby Pig.) TRIPLE-THREAT ’N’ TNT Two one-shots from the mid-1940s appear to have some kind of association with Charlton, if not being outright products of the outfit. Triple Threat Comics [Winter 1945], which is listed as published by Special Action Comics, Inc., 49 Hawkins Street, Derby, Conn., and printed in Holyoke, Mass. (The “Duke of Darkness” story therein—possibly written by Richard Hughes—is speculated to maybe have inspired Steve Ditko in the creation of his Marvel character, Doctor Strange.) TNT Comics [Feb. 1946], which features a Yellowjacket story, was published by the Charles Publishing Company, of 49 Hawkins Street, Derby.

ANTHROPOMORPHIC FUN Another Charlton shell company using the very same Hawkins Street, Derby, address was Children’s Comics Publishers (initially sans apostrophe), a guise only used for the second comic book series

At right: Well before horror was all the rage in the industry, Yellowjacket Comics included a series that briefly featured an EC-like host, “The Ancient Witch.” Yellowjacket #7. Art by Alan Mandel.

shopping center not far from Charlton Press.

While serving his sentence in a New Haven jail cell, Santangelo had also been given five years probation by a New Jersey court after a conviction for conspiracy, a charge related to his bootleg capers. “On September 5, 1944, in requesting an Order Terminating Probation,” author Barry Kernfeld explained, “Santangelo’s probation officer wrote: ‘Subject has made a very satisfactory adjustment for a period just short of four years; he has been regularly employed; has fulfilled prohibition requirements, and is felt deserving of this consideration.’”24 As Kernfeld mused, the onetime “songlegging kingpin” hadn’t so much been vanquished by authorities, but rather assimilated to claim victory, having bested all rivals.

BURTON NORRIS LEVEY, ESQUIRE An important addition to the early Charlton years was Ed Levy’s cousin, Burt Levey, who served as the company’s general manager for over two decades before leaving in 1967 to start his real estate brokerage. Born March 22, 1917, Burton Norris Levey graduated the University of Alabama, passed the Connecticut bar in 1940, and joined the U.S. Army Air Corps during World War II. Before serving in England, he married Diane Goldman, on February 20, 1943, and together the couple would have two children and settle in Woodbridge, a bedroom community just a few miles from Derby.

Diane shared, “My husband had been an attorney and had been practicing for a short time after graduating law school before he enlisted in the Air Corps. When he came home [from the war], his cousin Ed, who was just starting a publishing company with his friend John Santangelo, suggested that Burt come and join them instead of going back to practicing law. And so he did [in 1945]. He was instrumental in running the business and was in a very important position and also part-owner. He ran the publishing side of the company.”25 Burt was also a vice-president of Charlton Press. He passed away in Florida, on Sept. 28, 2012, at the age of 95.

In a 2011 interview, Diane discussed a photo featuring Burt and some engravers at 49 Hawkins Street, the facility used before the Charlton Building was constructed on the outskirts of Derby. Describing it as a “small little printing factory,” she added, “I recall it very well on Hawkins Street, in Derby, and they were doing practically hand-set presses. I remember my husband learning the business from the bottom up and learning how to set the presses with the press man.”26

One question persists: was the Pepe and Co. Building, at 49 Hawkins Street, referred to as the “Charlton Building” for the period before the Division Street plant was completed?

Photo courtesy of Shaun Clancy. Previous page: At top left is a 1947 editorial cartoon by Chad Kelly published in the Saturday Review of Literature [Mar. 20, 1948], commenting on an anti-comics radio show episode aired earlier that month. The caption read, “Cartoonist Chad Kelly, author of ‘The Babcocks,’ was inspired by John Mason Brown’s broadcast to produce this drawing: ‘I was so impressed by your version of the ill effects of cartoons on little children that I pictured myself as a fire-breathing dragon with pencils and pens for horns that gobbled up infants’ brain cells and left them in a state of insomnia.’” Bottom right is Billboard’s Dec. 24, 1949, announcement of Charlton’s acquisition of competitor Song Hits magazine and the cover of the Oct. 1951 edition of that mag. This page: Likely a late ’40s pic of a rare glimpse inside Charlton’s 49 Hawkins Street printing operation, featuring general manager Burt Levey (in necktie) and three company engravers.

Four: The Coming of Charlton Comics Of Catholics and Comic Books

In 1956, the Catholic Church had conflicting views of John Santangelo—or, at least, St. Mary’s pastor Father John Quinn did. Reporting to Monsignor Wycislo of Catholic Relief Services, the Derby-based priest said he was quite familiar with the publisher, “his background and his business,” and praised the Italian immigrant for his generous charitable contributions. But Father Quinn was blunt: “Santangelo is living in a bad marriage, a divorce situation, and never goes to church; though his wife attends church daily and his children attend St. Mary’s School.”27

It’s curious that those church records uncovered for this book make zero mention of the fact that Charlton, under its Catholic Publications, Inc., imprint, laudably published 29 issues of Catholic Comics, between Oct. 1946 and July ’49. Plus, it appears Santangelo even did work for the Vatican itself. “Shortly after the war, when there was considerable fear that Italy would drift into Communism,” the publisher’s profile in New England Printer and Lithographer related, “Santangelo was commissioned to print a foreign language anti-Communist comic sheet for the Vatican. In 1950, also in association with the Vatican, he printed the official guide for the Holy Year Jubilee pilgrims to Rome.”28

Perhaps that “foreign language anti-Communist comic sheet” was Record! Italian author Armando Ravaglioli, editor of conservative Italian comics weekly Il Vittorioso, negotiated a deal with Santangelo to reprint portions of Catholic Comics in Record! #1–3. Alfredo Castelli reported that Carlo Peroni, who worked at Vittorioso at the time of Record!, told him the short-lived comic book was actually printed by Charlton in the U.S. and exported to Italy. Castelli added there is proof enough that Record! was a Charlton job: pick up an actual copy and note the similarity. “In addition to the format, it shares the same unmistakable paper, screening, coloring, printing, and characteristic smell (perfume?)” of Charlton’s comics of that era.29 (And, of course, the fact that Derby-based Catholic Publications is actually referenced in Record! is more than enough evidence.)

Catholic Comics #5 [Oct. 1946] (the title’s first issue, as numbering continued from recently cancelled Marvels of Science, #4 [June ’46]) followed the far more successful Catholic comic title, Treasure Chest of Fun & Fact, which had debuted on March 12, 1946, running until July 1972. Still, CC’s one issue shy of 30 is a good run, with vol. 3, #10, the last issue of CC proper, dated July 1949.

The credited editor of Catholic Comics was William K. Bennett, once corporate counsel for the neighboring city of Ansonia and, at that time, an attorney representing Charlton Press, with John J. Henry listed as business manager (from Arlington, Virginia, as noted on CC V.1 #7 Statement of Ownership).

Before the war, Notre Dame alumni “Jack” Henry had been program director for a Waterbury, Conn., radio station, where he met Dan Gentile and became the high school student’s mentor. After the war, Henry joined up with Catholic Publications, and Gentile (no relation to future Charlton editor Sal Gentile) freelanced for Henry while attending Notre Dame. “The feature article of each issue [of Catholic Comics] was ‘Bill Brown of Notre Dame,’ and that was Jack’s idea,” Gentile told Shaun Clancy. “He created this fictitious character named Bill Brown, a four-letter athlete, and I would write the [script] to present an anecdote of Bill Brown’s athletic prowess for each issue. I would send him the [script]—his office was in Derby. He would forward [it] to the artist in New York City.”30

During summer break, Gentile worked on commission selling Catholic Comics subscriptions to parochial schools in the New York City vicinity, and he described the Funnies, Inc., crew working

This spread: Some contents of Catholic Comics were adapted for the Italian sports comic book, Record! On this 1946 newspaper pic of a kid at a comics display at right, note the presence of Catholic Comics (along with Zoo Funnies). Next page features rare Catholic Action Comics covers, 1949 Notre Dame Scholastic pic, and the Catholic Comics letterhead.

Chapter Five The Go-Go Fifties

LAST MAN STANDING Having peaked 1945–47, the heyday of the songsheet periodical business was in the magazine industry’s rear-view mirror, and into the new decade, after buying out Song Lyrics, Inc., and demise of D.S., Charlton was last man standing. The Derby publisher was still deriving a neat profit with their six songsheet publications, two which specialized in “hillbilly” and “cowboy”music (later collectively known as country western). And the ’50s transformed the Charlton songsheet mags themselves as, while many pages were still devoted to song lyrics, others increasingly featured profiles and articles that often contained solid writing, insight, and pertinent information instead of just hype. Plus, new genres were being visited, including the music of the much-ignored mainstream Black audience, with Rhythm and Blues and Rock and Roll Songs (serving an entirely new music category) debuting in 1956.

By New Year’s Day, 1950, Charlton had, by appearances, all but abandoned its comics line, publishing a mere pair of titles, Cowboy Western Comics and Pictorial Love Stories, the latter a romance series that would be defunct by spring, drowned by the “love glut” on newsstands that very same year. Comics were curtailed despite the fact that, a few years prior, the company had incorporated their Colonial Paper Company, achieving yet another goal in Charlton’s quest to have all publishing operations under one roof. At that stage, the all-in-one designation was figurative, not literal, as Colonial was off-site and much of the editorial work was being done at their satellite Fifth Avenue office, in New York City. And, though it contradicted Santangelo’s vision, the comic division’s work was still being farmed to outside contractors. Soon enough, it would be time to bring it all home to Derby.

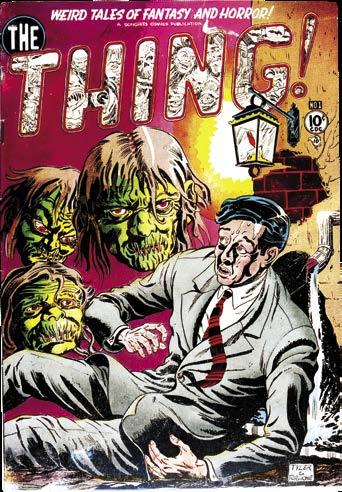

This page: Above is The Thing! #1 [Feb. 1952], Charlton’s particularly gruesome entry into the then exploding horror comics scene. Right is 1954 pic of John Santangelo and pressman reviewing uncut press sheet.

FIRST COMES LOVE Charlton had entered the romance genre in 1949, debuting Pictorial Love Stories exactly two years after Joe Simon and Jack Kirby invented the hugely successful category with their Young Romance #1 [Sept.–Oct. 1947]. By the end of the 1950s, Charlton would produce 21 separate romance titles (a few being carry-over purchases from other publishers), ranking the outfit as the most prolific producer of love comics in the entire industry. (By the time Charlton Comics closed for good in the mid-1980s, it had released an estimated 1,428 individual romance comic books, which accounted for about one-quarter of all love comics ever published in America!)1 Their debut effort, Pictorial Love Stories #22 [Oct. 1949] (which continued the numbering of Western title Tim McCoy), improbably credited then-14-year-olds Charlie Santangelo and Charles Levy as editors, was an interesting title in its short five-issue run. It was unusual in the genre—unique even—as romance comics historian Michelle Nolan observed: the title featured series starring regularly appearing characters issue to issue, including the idiosyncratic artist and text-heavy writer Fred Bell’s “Hotel Hopeful” series, Mrs. Lucinda Michael’s—the boarders called her “Aunt Mike”—boarding house for young ladies, whose anecdotes provided an episode’s drama; “Me–Dan Cupid,” a cute series of a winged cherub armed with (you guessed it) bow and arrow and plotting to hook up lads with lasses and vice versa; and “Catharine Carter’s Casebook,” the lovelorn advice columnist of a “famous chain of newspapers” who broke the fourth wall to directly inform us readers about the hapless advice seekers she found herself involved with.3

For those more accustomed to the relatively benign and nonviolent Comics Code-approved love comics of 1955 and thereafter, a read of the Charlton pre-Code romance titles can be an eye-popping experience. There’s a startling amount of gunplay and violence taking place in the stories—stabbings, murders, catastrophes, face-slapping, girls thrown from cars, a dame who kills to protect her man, and even the smitten Janey and Ken who kiss and make up standing over the body of a machine-gunned, bleeding-out adversary. And that’s just in the first three issues of Pictorial Love Stories!

Above: Michelle Nolan said early issues of True Life Secrets [#1, Mar. ’51–#29, Jan. ’56] “had some of the worst art ever to appear in comics.”2 Cover to TLS #23 [Nov. ’54]. Inset top: Details of various Pictorial Love Stories continuing features.

The Distribution Racket

History will probably never reveal the precise business arrangement between retailer and distributor regarding Charlton’s comic book offerings, but rumors have abounded over the decades. Having their own distribution network—a crucial part of Charlton’s fabled all-in-one set-up—presented the opportunity for a direct-market style arrangement. In a scathing missive to The Comics Journal in 1986, Ted White, legendary science fiction and Heavy Metal editor, shared all sorts of Charlton rumors, with one having an authentic ring: “The product was distributed in a crude but effective method,” White wrote. “News dealers were shipped large quantities of every title and told that they could keep the receipts on everything sold over a basic number. Say they sent 20 copies of a comic. After the dealer had sold ten, he could sell the remaining ten for 100 percent profit.”4 A similar rumor had it that retailers paid deliverymen upfront for Charlton’s share of half the copies upon arrival, conveniently eliminating burdensome paperwork and any follow-up, increasing cash flow and maybe creating incentive for profit-sharing truckers.

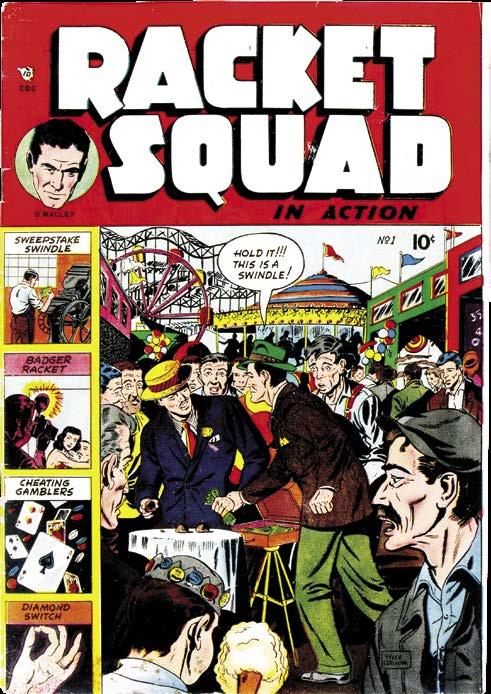

CRIME DESCENDS ON CHARLTON The boy editors continued to be credited in two new Charlton titles released with March 1951 cover dates, Crime and Justice and Lawbreakers, the first two of the publisher’s entries into the crime category, a lucrative genre pioneered by Lev Gleason’s Crime Does Not Pay, which had premiered nearly a decade before. The Charlton offerings were relatively nondescript, with Crime and Justice containing continuing features—”Len Rawson, F.B.I.”; Thin Man knock-off “Mr. & Mrs. Curtis Chase”; “Radio Patrol,” etc.—but, try as it might with “Art Anderson, Automobile Detective” and “Sergeant Force’s Murder Mysteries,” regular characters just didn’t catch on in Lawbreakers. (To tell the truth, that title wouldn’t make it out of 1952, as it became the horror-infused Lawbreakers Suspense Stories for six issues in 1953.) Crime and Justice, which continued until #26 [Sept. 1955], when it transformed into Rookie Cop, might be best remembered for its remarkably bland covers once the Comics Code Authority stamp appeared on them. The third crime title coming out of Charlton, this one in 1952—when the publisher invested heavily in their comics line—was the longest-lasting of their “law and order” line, ending with #29 [Mar. 1958]. Racket Squad in Action—#1 [May 1952]—was actually first conceived by one of the greatest of all pulp magazine writers.

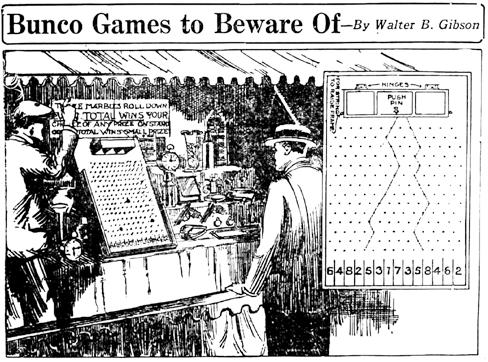

THE SHADOW OVER DERBY Walter Brown Gibson [1897–1985], best known as creator of famed fictional crimefighter The Shadow, didn’t merely scribe over 300 novel-length adventures of the pulp/radio hero and thus become a major figure in the history of pulp magazines. He was actually also an important presence in the comic book field. Historian Will Murray wrote, “Gibson’s comics career was as breathtaking in its sheer prolific sweep as it was in its astonishing anonymity. He did a little bit of everything––and a ton of certain genres––for just about everyone. He scripted Batman for Mort Weisinger. Crime and Punishment for Charles Biro. Magic comics for four different publishers. Even the lowerrent publishers like St. John and Ajax-Farrell made use of his skills… Walter Gibson was the chief writer for numerous long-running comics titles for several houses, but hardly anyone ever knew it. And he scripted a ton of commercial comics.”5

In addition to his Street & Smith comics work, Gibson— also an amateur magician who once worked for the great Harry Houdini—scripted comics for a certain Derby, Conn., publisher. “After launching Racket Squad in Action for Charlton,” Murray shared, “he bailed out of their The Thing! one issue before Steve Ditko climbed on board, thus averting one of the great potential comics collaborations of all time.”6

Indeed, Gibson had started Charlton’s Racket Squad in Action, where he was credited as co-editor alongside Al Fago, and the title lasted for 29 issues, between mid-1952 and 1958. The writer told Murray, “Oh, I did one that was dandy. That was called Racket Squad in Action. I took all kinds of rackets that I knew, that I’d done in The Bunco Book and various other things, and put them all in that book.”7

The Bunco Book, first published in 1927, was a collection of Gibson’s newspaper columns from the 1920s, a feature titled “Bunco Games to Beware of,” which was syndicated by Public Ledger Company. The book was reprinted in 1946 and ’86. (Gibson, as will be seen, remained an vital player in those early Charlton years.)

Walter Gibson

This page: Shadow creator Walter Gibson briefly edited at Charlton Comics, making use of his knowledge of scams and cheats for his Racket Squad in Action—he wrote a newspaper column on the subject (illo from one at far left), later collected in his oft-reprinted Bunco Book [1927].

RISQUÉ BUSINESS Entering the new decade, Charlton continued expanding into new directions, one being the time-honored field of racy “girly” magazines. Peep Show featured black-&-white glamour shots of scantily-clad burlesque performers and short biographical text, and it was launched in Winter 1950 under the N.E.W.S. Publishing Corporation banner. It lasted for 34 issues, ending in mid-1958. Notably, Peep Show #18 [Fall ’54] featured famous pin-up model Bettie Page on the cover and in a five-page photo essay therein.

In its mid-’50s feature on John Santangelo, New England Printer and Lithographer relayed, “Some years ago, as an avid art-lover, he acquired the 86-year old French magazine La Vie Parisienne, which so greatly aided the Yanks to maintain their morale during the war years of this century. La Vie Parisienne is still published in Paris, with its American edition, carefully edited to suit American tastes and customs—Paris Life—regularly published and distributed in this country.”12

In essence, Paris Life had much the same content as Peep Show—photo essays of curvaceous, nude young women accompanied by brief copy, albeit conveyed not without a certain continental charm, and, like its French cousin, it also contained mildly suggestive short stories. Whether Santangelo was the actual publisher of the French edition is unclear, though 1950s editions of La Vie Parisienne appear to still be the product of publisher Georges Ventillard, suggesting Santangelo obtained from Ventillard the license to use the name and logo (the latter which appeared beside the American logo on early issues). Paris Life #1 was cover-dated April 1951, and the last issue was #35 [Dec. 1958]. The French version, founded in 1863, shuttered its doors in 1970.

In 1956, Charlton published two issues of Pin-Up Photography, the first cover-featuring the notorious Miss Page and also spotlighting “advice from industry veteran Charles Kell on the nuances of cheesecake photography.” (Kell, by the way, lensed what has been called the rarest of all pin-ups, Bettie Page’s centerspread in Satan #2 [Apr.1957], a men’s magazine not published by Charlton.)

One May 1956 visitor to the Derby plant shared this critical observation about Charlton’s saucy offerings: I visited the printing plant where millions of copies of the most scandalous magazines and publications are produced. This printed material deals with vice, corruption, and sensational stories about theatrical stars and well-known people. The accompanying photographs were partly pornography, containing semi-nude girls in seductive and suggestive poses. I glanced through these magazines as they came off the presses: Paris Life, Hush-Hush, Top Secret, Peep Show magazine,

Secret Stories,* all banned by religious organizations, Catholic and Protestant clergymen, and by many leading newsmen.13

In late May, within a few weeks of that eyewitness account of a stroll through Charlton’s press room, the company faced charges by Brooklyn District Attorney Edward S. Silver—“In our fight,” the D.A. vowed, “to stop the dissemination of obscene and lewd publications to our teenagers.”14 Charlton was among 36 persons (21 of them retailers) and nine corporations who faced accusations of disseminating dirty magazines. But a greater threat facing the publisher probably wasn’t from the skin mags, but because of the burgeoning field of “exposé” magazines—two of them name-checked in the visitor’s quote above—yet another category Charlton had started exploiting in the ’50s.

*No such title Secret Stories was apparently published by Charlton, but the visitor may refer to Secrets of Love and Marriage #1 [Aug. 1956].

Five: The Go-Go Fifties Charlton Comics’ Haunted Things

It’s no surprise that Charlton was late getting in on comics’ horror craze sweeping the field in 1951 (though one could argue their “Famous Tales of Terror” short stories in Yellowjacket Comics between 1944–46 made them an industry vanguard!), as the outfit was all too often late to the dance when it came to exploiting popular trends. But to say its take on the subject could be sublime— specifically in the pages of The Thing! [#1–17, Feb. ’52–Nov. ’54]—and even holds its own somewhat when compared with EC’s Tales from the Crypt, et al.… well, that might be stunning to hear. [See Steve Bissette’s in-depth look for a detailed analysis.]

And what’s also surprising is that Charlton’s first honest-to-goodness managing editor—a cartoonist known primarily for his funny animal material —was so bloody good at packaging these notorious funnybooks! In fact, the Al Fago-edited material proved so infamous that the crusading Dr. Frederic Wertham in his anti-comics screed, Seduction of the Innocent, made mention of The Thing! #9’s “Mardu’s Masterpiece,” about which the good doctor describes: “A painter ties the hands of his model to the ceiling, stabs her, and uses her blood for paint. (Flowing blood is shown in six pictures.)”19

Among the illustrations in SOTI is a panel from that same issue of The Thing!, featuring a robot in a second story, “Operation Massacre,” crushing a poor chump’s head, which is spurting blood and emitting a skull-cracking sound effect— “CRUUNCH!” Wertham’s caption reads, “Stomping on the face is a form of brutality which modern children learn early.”20 (That same panel was actually used as the cover illo of the British book, Ghastly Terror! The Horrible Story of the Horror Comics [1999].)

In his assessment of the non-EC horror comics publishers, Lawrence WattEvans, shared about the Charlton titles in the category: “They were a bit slow to pick up on horror,” he wrote, “but when they did they went at it full-force.

“The Thing! began in 1952 and lasted 17 issues, featuring a narrator named The Thing (who was never seen clearly). Although there was an obvious EC Comics influence, the stories got wilder than anything the tightlycontrolled EC crew ever produced.

“Their other horror titles were relatively secondhand. A crime title, Lawbreakers, was transformed into Lawbreakers Suspense Stories and, as such, lasted six issues, some of them with truly bizarre covers; the one where a maniac’s holding a handful of severed tongues is particularly memorable [#11, Mar. ’53], though the woman being eaten alive by moths is also striking [#12, May ’53]. Then Charlton bought the name Strange Suspense Stories from Fawcett, and gave it to Lawbreakers Suspense Stories for its remaining seven issues. (When the Code came in, it was retitled This Is Suspense! for four issues, then switched back to Strange Suspense Stories.)

“They bought This Magazine Is Haunted outright, continuing the numbering from the Fawcett version.” Watt-Evans then opines, “This Magazine Is Haunted and Strange Suspense Stories lacked the over-the-top charm of The Thing! and Lawbreakers Suspense Stories; I really don’t know why.”21

Charlton horror of any consequence wouldn’t reappear until after the Code’s revision in the early 1970s.

This page: Items from the Charlton horror titles—Steve Ditko’s striking cover for This Magazine is Haunted #21 [Nov. 1954] and The Thing! #1 [Feb. 1952] title page by Albert Tyler and Bob Forgione.