20 minute read

Artist Spotlight: Clint Harmon Losing His Appeal; Of Catholics and Comic Books

BORN OF FISSION, FUSED BY FIRE Calling Charlton’s new super-hero of the ’60s, “the symbolic Cold War-Hero of America,” Lou Mougin opined, “He epitomized the atomic might that put us one step ahead of the unspeakable Commies (at least, the editors hoped he did). Atom’s strip combined science fiction themes with simplistic red-baiter theology not quite as unrestrained as [Joe Simon and Jack Kirby’s other patriotic hero] Fighting American, but certainly more committed than the apolitical DC heroes.”1

Charlton stalwart Rocke Mastroserio drew a pair of tales, but historian Lou Mougin pointed out that the character’s main artist was worthy of distinction: “Ditko’s work for Charlton and Marvel in the very early 1960s ranks as his most technically virtuous, but it didn’t save Captain Atom from the comic-book scrap heap. The strip was removed from Space Adventures after a total of only nine issues.”2

Describing the character’s origin as “rather than being merely irradiated, was actually incinerated at the epicenter of a thermonuclear explosion in which his body was reconstructed with added super-powers,” James Wright noted that Captain Atom was a harbinger of sorts, as the character “signaled a change in how superheroes were forged. The combination of nuclear excitement and Cold War paranoia led to a host of new characters being dreamed up in the years that followed. [Marvel’s] The Fantastic Four, The Hulk, Spider-Man, The Sandman, and Daredevil were all created as a result of radioactive experiments.”3 THE DITKO MYSTIQUE The final issue of Captain Atom’s maiden run, Space Adventures, #42 [Oct. 1961], would have likely shared spinner rack space with a title that launched the so-called “Marvel Age of Comics”: Fantastic Four #1 [Nov. ’61]. And perhaps it was Steve Ditko’s art on the Charlton super-hero series that ignited in Stan Lee a spark that led to the notion, a few years hence, that the artist would be a perfect match for the Amazing Spider-Man series (probably not, though). Regardless, while Ditko had been primarily known for drawing supernatural stories at both companies, he proved an intriguing and idiosyncratic choice to illustrate a super-hero book.

Ditko’s approach to super-heroics was utterly unique, with limbs twisted into odd, almost grotesque angles, bodies hurtling through the void in bizarre fashion that somehow worked. “He was a powerful draftsman,” Gerard Jones and Will Jacobs observed, “but he had an independent mind and a strange, almost baroque style—simultaneously looking back to the Golden Age and forward to some world no one had imagined yet—that was nowhere near the slick clarity that DC… demanded. He picked up a few jobs from the low-paying Martin Goodman line, but mainly had to subsist on even lower pay from Charlton. The good side to all this was that no one was trying to make him draw the ‘right’ way.”6 In furthering their study, The Comic Book Heroes authors referenced the artist’s work in Space Adventures #33: “There’s a definitive Ditko moment on Captain Atom’s very first page. It’s a six-panel page plunging us straight into the story, not the full-page ‘symbolic splash’ excerpting a highlight of the story to follow, customary at DC. The hero is trapped inside a missile as it’s about to be launched, and Ditko brings us closer, closer, closer in on him, until all we see is his eye, opened wide with horror and ringed by sweat. In a field that liked its heroes cool and preferred the objectivity of classical composition and the Hollywood medium-shot, this was a riveting focus on the individual and his most intimate reactions to a moment of crisis.”7 Simply put, Ditko was well on his way to becoming a superb, much-admired super-hero artist and one of the truly great comic-book storytellers.

MERCURY RISING… AND FALLING Only a few months after Captain Atom was dropped from Space Adventures, the title gave super-heroics another go with decidedly second-rate Mercury Man, “the Fluid Man of Metal from Outer Space,” who appeared in two issues with a pair of adventures drawn by Rocke Mastroserio. The character, sole survivor of the planet closest to our sun (Mercury), had been transformed during an experiment into a chemical element (mercury) and sprouted winged feet (and ears) like a certain Roman mythological figure (Mercury). He was dedicated to eradicating warfare on Earth. The writer is unknown, though as Dan Hagen wryly noted, “This super-hero was created by somebody who really knew how to underline a theme.”8

The Other Captains Atom

The first character sporting the name Captain Atom was an Australian series published by an outfit from Down Under called Atlas, debuting in Jan. 1948, and running for 64 issues, until 1954. “Drawn in a crude but fascinating style by Arthur Mather,” Aussie comics expert John Ryan wrote, “the character combined the ’magic word’ (Exenor!) gimmick from Captain Marvel and the twin brothers ploy from [Quality’s] Captain Triumph and shrouded it with the mystique of the atom bomb explosion of Bikini Atoll, still fresh in people’s minds.”4 The Captain Atom Club boasted some 75,000 Australian members. Another sharing the same moniker— this one an American super-hero— emerged in 1950, in mini-sized issues published by Nation-Wide. “Captain Atom was a scientist-adventurer who used gadgets to investigate the unknown and fight various menaces,” writes @FKAjason on his blog.5 “His gadgets and vehicles included a uranium amplifier, a spectrascope, an atom submarine, a walkie-talkie television, atom-powered noiseless ram rocket, and an auto-gyro parachute. The stories he appeared in were written to teach kids lessons about science.” Captain Atom lasted for seven issues, ending in 1951. Previous spread: Family Fallout Shelter [1960] and panel details from Space Adventures. Art by Ditko. This page: Clockwise from left is Australia’s Captain Atom #1 [1948], back cover detail from Nation-Wide Publishing’s Captain Atom #1 [1950]; and cover detail from Space Adventures #44 [Feb. 1962].

SUPER WESTERN HEROES Little noticed during the early ’60s, perhaps, was the fun taking place within Charlton’s lineup of Western comics. For instance, the mysterious PAM was stretching the bounds of genre in his Kid Montana assignment, a title which he effectively rebooted in #32 [Dec. 1961] with an new origin story and revised look. Within a few issues, PAM had the gunfighter encountering “The Snow Monster”—the spitting image of The Heap—and visiting a “prehistoric dawn world” populated with dinosaurs! Soon enough, the aging gunslinger was also battling Killer Apes and the Frank Frazetta-inspired Black Arrow, yet though the artist-writer gave it his all, the renamed Montana Kid was cancelled by #50 [Mar. 1965].

Another lively shoot-’em-up series was “The Gunmaster,” which embraced the super-hero trope of masked crimefighter, launching in Six-Gun Heroes #57 [June ’60]. As Don Markstein relates, “The character got even more super-heroey a few years later, with the introduction of a Robin-like sidekick, Bullet the Gun Boy. Bullet was Bob Tellub, whose name even the dullest child was probably bright enough to spell backward and thus divine the Secret Meaning.”39 The duo received their own title in the mid-’60s—twice!—with the first lasting four issues [’64–65]; the second going for six [’65–67].

Charlton’s very first incognito Western hero was Masked Raider, and his crime-fighting partner was a golden eagle named Talon. By 1960, Morisi was handling the art chores, but even his considerable talents—which lent an enthusiastic super-hero-like verve to the stories—were not enough to save the feature, one that had started with #1 [June ’55] and ended with a second series, Masked Raider #30 [June ’61].

By the mid-’60s, Westerns were on the wane at Charlton, though a few titles did survive into the next decade: Billy the Kid and Cheyenne Kid, and two barely squeaked in, Outlaws of the West and Texas Rangers in Action, both gone by 1971.

The New Ways of the Old Blue Beetle

Unseen since the indignity of last appearing as back-up in Nature Boy #3 [Mar. 1956],* Charlton’s adopted super-hero, The Blue Beetle, was revived and refigured as a ’60s costumed character in spring 1964, with the release of his own title’s #1 [June 1964]. The blue-clad crime-fighter’s resurrection was likely prompted by the rise of the Marvel super-hero line, as well as DC and Archie’s profitable forays into the genre. But writer Joe Gill made some tweaks to the character’s background and abilities, as author Christopher Irving related in The Blue Beetle Companion: Rather than a patrolman, Dan Garrett (now with two “t’s,” perhaps so they could trademark his name from the possibly public domain “Garret”) was now an archaeologist who discovered a magic scarab in an Egyptian tomb. Speaking the phrase “Kaji

Dha,” Garrett magically transformed into the red-goggled, super-powered Blue Beetle. This new Beetle was a far cry from his 1939 pulp counterpart. However, like the later ’40s and ’50s versions, the 1964 model was also a generic Superman with a sliding scale of super-powers. The stories were fun at their best, laughable at their worst, and a step back from even the [Ted] Galindo stories of the ’50s.40

Irving also explained that the type of adversary had changed: “Gone were the generic gangsters and racketeers of the Fox Blue Beetle—they were traded in for science-fiction oriented adventure stories that involved mad bug men and atomic red knights. Being a super character, this new Blue Beetle needed super-powered villains, such as the Giant Mummy, Magnoman, Mr. Thunderbolt, and the laughable Praying Mantis-Man (literally a green-skinned man in a mantis costume).”41 This initial fiveissue run ended with a cover-date of Mar. 1965, with all issues written by Gill and drawn by penciler Bill Fraccio and inker Tony Tallarico. Faccio told Jim Amash that he enjoyed penciling the title (and was glad his oft partner was inking). “I liked it,” he said, “because it had plenty of action.”42 *No, consideration is not given to Israel Waldman’s Human Fly #10 [1963], reprinting B.B. tales.

This page: At top is Masked Raider #27 cover detail, by Pete Morisi, and Gunmaster from Six-Gun Heroes #57 [June ’60] by Dick Giordano, as well as two Kid Montana covers, #35 [July ’62] (top) by Charles Nicholas and Vince Alascia and #36 [Sept. ’62] by Morisi. Above, maybe penciled by Bill Fraccio, definitely inked by Frank McLaughlin, Blue Beetle #1 [June ’64] cover detail.

Nine: The Launch of Captain Atom The Fightin’ 5

It was Archer St. John’s comics publishing house which first used the appellation “Fightin’” (dropping the last letter—g) in the title of a comic book. In fact, St. John had two separate comics, Fightin’ Marines and Fightin’ Texan, a Western series, that employed the colloquialism. But it was Charlton who let loose with the word after acquiring the war series. By 1956, the Derby imprint had no less than four war books utilizing the g-droppin’ abbreviation for the title.

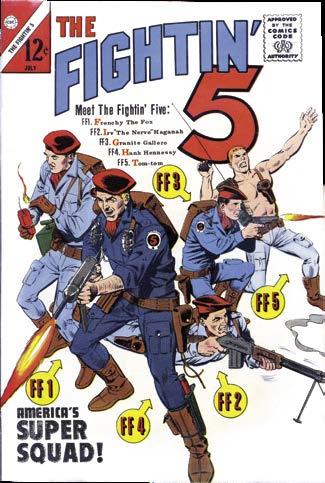

So it was natural, when Charlton wanted to add some super-hero team verve to a new title, that editor Masulli and company would select the alliterative Fightin’ 5 for the July 1964 debut.

What exactly prompted the new book isn’t clear, but there was definitely a sense the series was a Charlton version of the classic Blackhawk team, then still being published by DC Comics. As John Wells pointed out: “With their matching blue uniforms and red [berets], the military squad was something of a scaled-down version of the Blackhawks, but without a membership comprised of many nations. The Fightin’ 5 was ‘America’s Super Squad,’ and its men were all U.S. citizens. Naturally, they took on Communist threats to Uncle Sam, though usually overlaid with nods to older menaces ranging from Nazis to Aztec warriors.”43 The jingoistic series, lasting 14 issues, was written by Joe Gill and drawn by the able Montes and Bache.

LOSS OF (QUALITY) CONTROL As John Korfel noted, the year 1960 bore witness to a startling number of printing and binding errors coming from the Derby publishing company. He wrote, “Approximately 65 issues of 36 different titles with cover dates from Mar.–Oct. 1960 were misprinted. These errors included contents not matching covers, blank inside covers, contents stapled upside down, and covers printed with only partial color. Several hundred of these error books which found their way out of the Charlton printing plant have been discovered. It is unknown how many of these titles were eventually republished without the errors, and all books over those dates are scarce to rare.”44

Evidence of such pitiful attention to detail can be seen at the Comic Book Plus website, which reproduces the guts of Secrets of Young Brides #21 [Sept. ’60] stapled over with the cover of 10 Minute Crossword Puzzle Magazine #13!45 Such a sustained collapse of quality control begs questions like: was the preponderance of outrageous mistakes due to the plant’s labor woes and worker opposition to an anti-union publisher, with disgruntled employees sabotaging the publications? Or could it have been because of an influx of poorly managed, unskilled immigrant workforce—many who couldn’t communicate in English—maybe unintentionally messing things up. Did anybody care at all? Answers, alas, are lost to eternity. COVER STORIES Perhaps it was editor Masulli who introduced a frequent Charlton habit that persisted over the decades, one instituted as a cost-cutting measure yet came across to readers as frankly third-rate and cheap. Regardless of instigator, the outfit, rather than incur the expense of commissioning new cover art for certain comic titles, would instead make stats of interior artwork and cobble together a slapdash cover at no cost.

As for original covers, Dick Giordano shared, “At one point in time, I did every Charlton cover, including not only the artwork, but I wrote whatever copy there was, and [specify] the type… Some of it was as a freelancer, some of it was on staff. When Pat Masulli was in charge, I had a studio in Ansonia—the next small town over from Derby—and Charlton gave me samples of the type fonts they had, logo stats, and the finished art for each title, and I had to comp a layout for a cover, including book and/or story titles, write any copy that was needed, and the I would spec the type and send it in to them. Some were montage covers, paste-up photostat covers. I drew all the original artwork.”46 (Upon ascending to Masulli’s position, Giordano enjoined Rocke Mastroserio as main cover artist, “If you go through the entire run,” Giordano explained, “you’ll find a lot of my layouts on his covers. I did tight layouts and he finished them.”)47

Nine: The Launch of Captain Atom “Thank You and Good Afternoon!”

The above headline? That was his trademark sign-off phrase, one he used after appropriating it from a Charlton music mag editor, a closing salutation he’d employ on his public pronouncements, starting as Charlton’s incoming comics editor in 1965 and ending with his 1993 retirement as a top executive at DC Comics. His name was Richard Joseph Giordano, born on July 20, 1932, in New York City’s Bellevue Hospital, and he was the only child of Graziano (“Jack”) and Josephine, sweethearts since their early youth. Dick Giordano was a sickly kid—health issues would plague him all his life—and was bedridden for much of his tender years. “My father used to read me the Sunday funnies, and the week between was a long wait for me,” he said. “He happened to find Famous Funnies on the newsstand one day and brought it home. He read me that whole book for the rest of the week, instead of just on Sundays—it was the Sunday funnies all wrapped together in 64 pages. Yeah, that’s when I got started, and in fact, I started drawing from some of those issues.”98

Early on, young Dickie encountered a new comic book masked adventurer— an action hero, if you will—that made an impact. He told Michael Eury, “Batman was the character that made me think seriously about finding a way to make comics my life’s work.”99 Elsewhere he explained the character’s appeal: “One of the reasons why Batman is my favorite super-hero is because he’s not really a super-hero,”100 an apparently contradictory statement that would make sense when Giordano got the opportunity to create his own super-hero universe.

His goal to become a professional artist became an early pursuit, one encouraged by instructors and family. “I went to an elementary school where I had a great art teacher who impressed me,” he said. “My mother (who was a very good artist when she was younger) was delighted that I was able to draw. I think my ability was inherited. The teacher encouraged me, and when I was ready to graduate, she suggested I try getting into the School of Industrial Arts, which was a vocational high school in New York City available— free—to anybody who could get in. I took the test, passed, and spent four-and-a-half years there (the extra half-year was because I got sick with the illness that always plagues me, and lost about a half-year).”101

During that near half-decade at SIA, the young artist learned a valuable lesson about deadlines, when one particularly strict instructor brooked no excuse when an assignment was late. “I learned something from that: that, if something’s due on Friday, it’s due on Friday. You don’t argue about whether it’s really necessary to get it in on Friday; you just do it. I learned that from him. So that’s how I learned about making deadlines. That’s something that stands with me today, I have a reputation for making deadlines, no matter how dumb they are—I make them. Sometimes I get help, but I make deadlines. This situation was the reason why. At SIA, there were a wonderful bunch of instructors, and I learned how to be a professional from them.”102 Graduating in 1951, Giordano had attended SIA with a stellar crew of fellow future pros, including Angelo Torres, Tony Tallarico, Ernie Colón, and some guy named Anthony Benedetto (later more commonly known as legendary crooner Tony Bennett). Giordano found work with Iger Studios, starting at the ladder’s bottom rung as a gofer, page-eraser, and delivery boy of finished work to Fiction House. Increasingly, the nascent professional learned on the job and proved increasingly skilled with the pen and brush.

“Anyway,” Giordano said, “I enjoyed working at Iger. I started out with inking backgrounds and, in nine months, I was inking figures—just the figures— and that’s as far as you could go in nine months. Then, I heard from my father that Charlton was looking for artists. So, my dad and I, on New Year’s Day, went up to fellow cabdriver Harold Phillips’ house, where his brother-in-law Al Fago was visiting. Fago was the managing editor at Charlton. He thought I was good enough to work for them and, of course, I grabbed it, and left my staff job at Iger.”103 The year was 1952.

This spread: Clockwise from upper left is a close-up of Dick Giordano’s parents posing for their wedding portrait; Giordano illustration from Fantastic Science Fiction #1 [Aug. 1952]; charming portrait of Giordano inscribed to “Baby”; Giordano’s cover art adorns Teen Confessions #28 [May 1964]; and 1970s Batman painting credited to Bob Kane.

Giordano continued, “To give you an idea of what we’re talking about, even though the rates were terrible, Fago promised me seven pages a week to pencil and ink, at $20 a page… $140! I was making $40 at Iger’s. You really can’t argue that. The $40 a week at Iger’s was not enough, so I was also working on weekends in a soda shop as soda jerk, which actually I enjoyed. I delivered newspapers and I loved that, because it was all outside.”

He added, “I really don’t remember what work I was doing for Charlton, but for two or three years I had the world’s best set-up: Al Fago lived in Great Neck and he had a Chrysler and, each week, he would drive to my studio, pick up my assignment from the previous week, and hand me a new one. I didn’t even have to leave the house!”104

It was the artist’s Hot Rods and Racing Cars assignments that fostered an early appreciation for automobiles. “As a result of my working on the Hot Rod comics,” he said, “I really got into cars. I had a 1953 Dodge, which had the first V-8 engine I ever owned, and we put straight-through pipes on it, turned it into a dual exhaust, which means rbrmm brmm-brmm-brmm… instead of ssssssssssshhhh. I took all the chrome off the car, filled in the holes, and we painted it, customized it, and put skirts on the back wheels… it didn’t look like a ’53 Dodge anymore. You know… you get caught up in it.”105

Soon, Fago moved to Connecticut and grew fond of the fine young man who also joined the in-house staff. “I met Al in my 20s, and it was sort of like a father-son relationship in a lot of ways,” Giordano said. “As a matter of fact, I found out later Al had two daughters and he kind of had plans for me, when I was still single, to marry me off to one of his daughters. I didn’t know about it until years later when his wife told me.”106

After the Fagos quit Charlton, incoming editor Pat Masulli hired newly married Giordano as an assistant and the young artist, now a Connecticut resident, learned about the editorial side of the business. By 1959, he went freelance, though remained appreciative of his overall Charlton experience.

“At the time,” he said, “to get into the business, you had to start at one of the farm clubs, so Charlton was the ideal place for me to start, because it was the minor leagues. The company wasn’t going anywhere at the time, but on the other hand, they were allowing me to experiment and learn my craft, by giving me one job after another after another. There wasn’t any slowdown in my income. I was penciling and inking everything I got in those days. So, I had what I wanted out of it.”107

As the mid-’60s approached, Giordano began to suffer an existential conundrum. “I was going through a period in my life where I was having problems working,” he said, “where I was trying to figure out why am I here, why are we doing these things. I was dealing with my mortality, all those things, and I thought, ‘This type of staff job—the editorial position—would be better for me than to get by freelancing. I’ve got a family to support.’ So, essentially (though not in a physical way), I kept throwing myself at John’s son and then publishing head Charlie Santangelo’s feet until he offered me the job. I had to let him know I was available, and when they decided to move Pat Masulli out of the comics and into the music business end, I was the only one they considered, and I got the job.”108

Asked if being Masulli’s assistant clinched the gig, he replied, “Not necessarily. Because I made myself available for the job, really. Because I said, ‘I don’t want to freelance anymore; I want to get a staff job and I want to run this.’”109

And run it he did. Though Dick Giordano would hold the position for only a few years, his reign would prove to be the most significant in the entire history of the Charlton Comics Group.