Angela Cartwright and Bill Mumy’s Lost (and Found) in Space book was issued in 2015 on the 50th anniversary of Lost in Space. It was a delightful romp through the pair’s personal history of work and friendship that resulted from the series that ran from 1965 to 1968 (and forever in reruns). Along with rare photos and behind-thescenes tidbits, the book was an archive of memories small and large that made an impression on the young actors.

After the book went out of print and on the recommendation of producer Kevin Burns, their friend who kept Lost in Space in the public eye, Mumy and Cartwright commenced work on an expanded edition

that includes a new bounty of unseen photos and memorabilia: Lost (and Found) in Space 2: Blast Off into the Expanded Edition

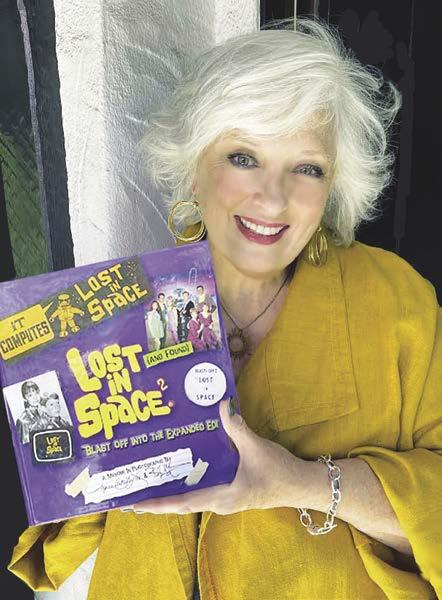

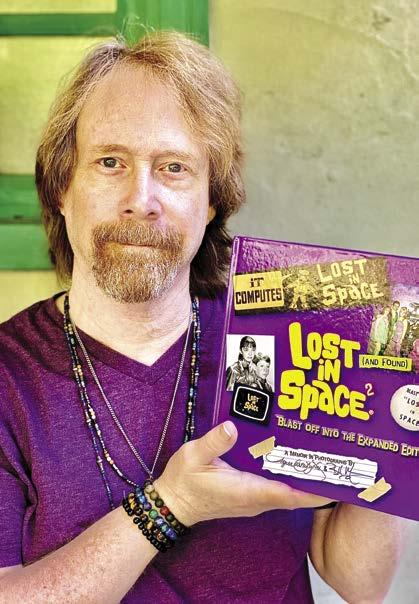

In an interview conducted for RetroFan through Zoom, Cart wright and Mumy discuss the bounties available in the updated edition. “This book is more than twice as long as the first,” explains

(ABOVE) This issue’s cover stars Angela Cartwright and Bill Mumy, and their new book, the crowd-pleasing Lost (and Found) in Space 2: Blast Off into the Expanded Edition. “I feel like this book is a very fitting look into everything we’ve experienced so far in the last 57 years,” Bill Mumy tells RetroFan. Lost (and Found) in Space 2: Blast Off into the Expanded Edition Published by Next Chapter Publishing, a division of Next Chapter Entertainment LLC. Licensed by Synthesis Entertainment. © 2021

Bill, known as “Billy” during his childhood. “It’s 352 pages with 925 photographs. And a lot of the photographs were never seen before because Kevin Burns acquired a cache of unpublished CBS photos.”

Cartwright was equally excited and challenged by the new book. “Kevin said, ‘Oh, my God, you definitely have to update your book because there’s so much that people haven’t seen.’ We had his blessing to use any pictures that we wanted. I think a picture does tell a thousand words or even ten thousand words. They trigger many memories to me. There were piles and piles of proof sheets, and we poured over them and tried to find things that hadn’t been released. There’s also items that my parents had collected, and they’re both passed now, so it took me a couple of years to actually get through a lot of it. My dad took photos when he came to the set. Bill’s mom took Polaroids. Those kinds of things have not been seen and shared. This new book really delves into what was going on when we were shooting and then our lives afterwards.”

Thumbing through the expanded edition is a revelation for fans of Lost in Space. The candid photos, studio memos, scripts, and promotional materials take the reader right onto the set. Angela, Bill, and their cast mates led extraordinary lives that the home viewers could never imagine. For Bill, it was an uplifting experience. “There’s quite a lot of detail and remembrances in the new book where we discuss what was happening in front of, behind, and to the sides of those photos. And for the most part, it’s been a very positive and emotional experience to go back there because [20th Century] Fox was our home for ten months a year for three years.”

In just one example of the unique nature of filming a TV series, the actors all had stand-ins, with exact replicas of their colorful ward robes. The duplicates, whose heights had to match the featured players, saved wear and tear on them while the crew was setting up the camera and lighting the scene. The director used that time to block the stand-ins and coordinate his camera placement, while special effects men planted their explosives or positioned pull-

wires to guide the Robot’s motion. Because of their young ages, Bill and Angela were required by law to spend a certain amount of time at the studio’s school, so stand-ins provided them the time to learn their lessons. For scenes that included explosions or violent action, stunt doubles were brought in… even though Mumy really wanted to do it all himself. “Jonathan [Harris, Lost in Space’s Dr. Smith] once told me, ‘Never deny a stunt person a paycheck, Billy-Person.’ He was right, and I’ve always remembered that.”

After nearly going out of business due to the cost overruns of Elizabeth Taylor’s 1963 epic Cleopatra, 20th Century Fox had rebounded and was going full-steam by the mid-Sixties. The studio’s renaissance was due to the mega-successful The Sound of Music (co-starring Lost in Space’s Angela Cartwright) and soon-to-be released feature hits Our Man

Flint, Fantastic Voyage,

(TOP) Angela and Bill in

studio classroom, October 1965. © 2021 Synthesis Entertainment. (RIGHT AND INSET) Angela Cartwright’s Penny Robinson parka, from Lost in Space Season One and shown in the photo on the following page, sold for an astounding $10,625 on a Heritage auction on November 7, 2021!

Courtesy of Heritage.

personal note to Angela from Irwin Allen on the first day of shooting the pilot. Bumper stickers and promotional pins made only for television publicists are shared along with something extremely personal to Bill, his name imprinted on the fabric backrest of a director’s chair. Of particular interest to fans are call sheets attached to scripts, behind-thescenes photos of Irwin Allen and his associates making magic, and rare press releases from the network run. Angela’s collection predates Lost in Space with several issues of the Linda Williams doll from The Danny Thomas Show. She also has collectible dolls in the image of her characters from The Sound of Music and Lost in Space.

The updated book features original costume drawings by the Irwin Allen’s wardrobe designer, Paul Zastupnevich. “Paul was great,” says Bill. “He was like the [The Simpsons ’] ‘Smithers’ to ‘Mr. Burns’ in terms of his relationship with Irwin.” Zastupnevich was a showman himself when it came to designing the costumes of Lost in Space. Angela’s thirdseason outfit was especially wild. “Paul came up with that whole pop look and the combination of those colors, which worked so well,” she recalls to RetroFan “Bill and I were both growing because we were young kids, and they had to keep extending the pant legs. That’s why I think Paul eventually ended up putting me in a skirt because I just kept growing and growing. I changed quite a bit from that first season to the third season.”

By the end of Season Three, ratings were holding up well enough for Lost in Space, with an average of 15 million viewers a week. NBC’s The Virginian was more popular in the time slot, but considered a much different demographic to the CBS bean-counters. In the days of only three networks (no cable or satellite channels), 15 million sets of eyeballs was good, but nevertheless, Lost in Space ’s potential renewal was on the bubble. Adding to the woes was economic inflation eating into the show’s profits. Actor’s raises and the increased costs of sets had already taken its toll on the show’s production quality. Despite that, Lost in Space pulled off some stunning episodes such as “The Anti-Matter Man,” set in a strange mirror world of living rocks and trans-dimensional walkways. On top of that, CBS had asked Fox for a lower budget if the show would be renewed for another year. It all came to a head after the wrap party for Season Three as the cast headed out for a few weeks of relaxation before resuming production in the fall of 1968.

“We had been verbally assured that there would be a fourth season,” recalls Bill. “As you know, that suddenly changed, and there was no fourth season. I was shocked. I even cried. Angie and I didn’t have anywhere to go to school for the balance of semester, so we stayed there on the lot for quite a while. Our attachment to the lot and our perspective of experiencing all that entailed between the ages of ten and 16, by the time we wrapped things up, was a very wide spectrum of experiences and memories.”

Lost in Space ended its CBS run in the summer of 1968, and immediately went into syndication for local televisions station to schedule as they wished. Many channels wisely put reruns of the show on five days a week between the end of school hours and prior to the six o’clock news, gaining a whole new generation of fans. Lost in Space was a hit in syndication and ran in many markets for over a decade.

Ah, Mayfield. Quintessential suburbia. You can almost smell the flowers in the town square. You can almost see the gentlemen tipping their hats to the ladies. And you can almost hear the rustle of the newspaper as neighborhood dad Ward Cleaver turns the page, relaxing on the couch after a hard day at the office while his wife June knits by his side, wearing her omnipresent pearl choker.

Mayfield is a real place—at least, as real as Mayberry, Gotham City, or Bugtussle.

It is the hometown of Theodore Cleaver, a.k.a. “the Beaver,” an inquisitive, baseball cap-wearing, freckle-faced everykid played by Jerry Mathers on the sitcom classic Leave It to Beaver (1957–1963). Also starring were Barbara Billingsley as protective mom June; Hugh Beaumont as sage dad Ward; and Tony Dow as Beaver’s good egg of a big brother, Wally.

Leave It to Beaver was one of several comedies from the period built around family life, such as Father Knows Best, Make Room for Daddy, The Donna Reed Show, and The Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet. But Beaver was different. More true-to-life. Funnier, even.

How so? There’s an outmoded expression that encapsulates much of the parenting style of the Fifties and Sixties: “Children should be seen, not heard.” TV fathers from the era weren’t what you’d call demon strative. They generally wore suits, and left the messier aspects of childrearing to the missus. So Leave It to Beaver was, for its time, a trailblazer.

Though the show has a reputation for being about a dopey kid with a knack for getting into hot water—the famous soup-bowl-billboard episode of 1961 is a handy metaphor for this view— Beaver was really about parents having thoughtful conversations to decide how to discipline their children without trampling their feelings.

Ward often reminisced about growing up on a farm under a father who was quick to dish out corporal punishment. June was always there to remind Ward not to allow history to repeat itself. Their boys were a study in contrasts. Wally was a top athlete, a good student, and popular with boys and girls. Theodore was a klutzy dreamer who hated “yucky” girls and had few ambitions beyond reading comic books or skipping stones.

Beaver wasn’t a bad kid so much as a gullible one. When he messed up, his ne’er-

Gee, Wally! Stars of Leave It to Beaver recall the making of a sitcom classic

do-well pals were usually near the crime scene. It was Larry (Rusty Stevens) who insisted Beaver take the go-cart for a spin; it was Gilbert (Stephen Talbot) who convinced him to fly the ornate kite before the glue was dry; it was Whitey (Stanley Fafara) who goaded him into climbing that billboard.

That’s another difference between Wally and Beaver. Wally usually knew better than to listen to his pals, two-faced Eddie (Ken Osmond) and sad sack Lumpy (Frank Bank).

Mathers and Dow created believable chemistry despite their vastly different backgrounds in the acting field. Mathers was, at age eight, a show-biz veteran when Leave It to Beaver began, while Dow was a TV tenderfoot.

‘HELL o, MR. MATHER s’

While shooting Leave It to Beaver, Mathers was occasionally greeted by a formidable filmmaker: Alfred Hitchcock. Prior to Beaver, Mathers had a role in Hitch cock’s The Trouble With Harry (1955) as Shirley MacLaine’s pint-sized son who finds a body in the woods.

“When I was doing Leave It to Beaver on the Universal lot, Hitchcock was doing [the series] Alfred Hitchcock Presents same time,” Mathers once told me. (I interviewed the actor in 1993 and 1998.)

“He would always come by in his chauffeur-driven Rolls, and he’d roll down the window and say, ‘Oh, hello, Mr. Mathers.’ It was kind of interesting to have somebody like that—who was a very imposing figure—call me Mr. Mathers. I was about eight or nine at the time.”

According to Mathers, the Leave It to Beaver scripts were often based on experiences in the families of the producer-writer team

(INSET) Director Alfred Hitchcock cast Jerry Mathers in The Trouble With Harry (1955). (RIGHT) Mathers in a scene from the film (and, hey, how about that swell toy raygun?).

© Paramount Pictures.

that created the series. Joe Connelly and Bob Mosher, who cut their teeth in radio, had nine kids between them—plenty of comic fodder for plotlines.

“All of the stories from the original Leave It to Beaver were from real life,” Mathers said. “They may be a combination of 50 things that happened to 50 different kids in just one episode, but the main storylines in most of the truly funny episodes

“I think that’s what makes them so timeless. You know, things that really happened to kids in the Fifties—you can still relate to them.”

A lot of Mathers’ funniest lines derive from irony; Beaver didn’t always realize what he was saying.

Bing Crosby, and Lou Costello. Her Beaver role was a reunion; Washburn earlier played Billingsley’s daughter in the short-lived series Professional Father (1955).

“I had stayed in touch with Barbara,” Washburn told me in 2003. “I was so fond of her—one of the nicest, sweetest ladies in the world. After that, she got Leave It to Beaver

“So when I went on the audition to read for that part, I really wanted it for two reasons. One was because I wanted to work with Barbara again. And two, because I always had a crush on Tony Dow. He’s darling. He and I have remained friends all these years.”

In a subtle way, Washburn’s role as a teenage girl in an unfa miliar environment who is ostracized was ahead of its time.

“It really was,” the actress agreed. “It’s certainly different from the shows that are on TV now. They were all so innocent then. The storylines were just so simple. I mean, the father would always come in with his suit and tie on. Today, it wouldn’t really work. It’s a different era.”

Most of the surviving cast members reunited for the TV movie Still the Beaver (1983) and its spin-off, the syndicated series The New Leave It to Beaver (1984–1989). Mathers, Dow, Billingsley, Osmond, and Bank effortlessly slide back into their roles as series regulars. The TV movie was dedicated to Beaumont (who died in 1982), and contained a flashback to Ward’s 1977 funeral, which ended with a close-up of his gravestone marked: “Beloved Father and Husband.”

Casting directors for the Eighties shows were diligent in digging up old Beaver players for cameos: Stevens as Larry Mondello (now a religious convert in a turban who calls himself Ivishnu); Brewster as Miss Canfield (now the school principal); Deacon as Fred Rutherford (smarmy as ever); Cornell as Richard; Tiger Fafara as Tooey; even George O. Petrie (a mainstay on The Honeymooners) as Eddie’s dad.

In an episode set at Wally’s high school reunion, Holdridge returned as Julie Foster, now trying to seduce her (happily married) old flame. Baird returned for a cameo in the same episode, laying a smacker on the suddenly popular Wally. Best of all—Weil who hadn’t been on TV since the original series—returned in 1987 to cameo as Beaver’s old nemesis Judy Hensler, for a hilarious scene in which she and Mathers traded insults once again. When Judy brags that she married a doctor known as “Mr. Proctology,” Beaver comments, “Then I’m sure you make a perfect couple.” Nice one!

Noticeably absent from the Eighties shows was Stanley Fafara as Whitey. (The role was filled by Ed Begley, Jr.) Sadly, Fafara drifted into heroin addiction after Beaver, though he was clean for the last eight years of his life. Fafara died in 2003 at age 54.

Billingsley, Osmond, and Bank made cameos in the 1997 movie adaptation, also titled Leave It to Beaver. (Dow, who later became a director, had thrown his hat in the ring to direct the movie, to no avail.) Cast reunions continue on talk shows and at fan conventions. Billingsley died in 2010; Bank in 2013; Osmond in 2020; and Dow in 2022.

Children’s book author Beverly Cleary wrote three Leave It to Beaver paperbacks for Berkley Medallion, including (RIGHT) Leave It to Beaver (1960) and Beaver and Wally, interior pages seen here (BELOW). ©

NBC Universal Television.

(ABOVE LEFT)

The Little Golden Book Leave It to Beaver (1959).

(ABOVE RIGHT)

The Golden Record release presents “The Toy Parade,” which is the Leave It to Beaver theme song with winceinducing lyrics like “fiddledee-dee” and “rum-tee-tum.”

Leave it to Beaver © NBC Universal Television.

BY s C o TT s AAv EDRA

BY s C o TT s AAv EDRA

Gift-giving is one of humanity’s oldest activities. Not as important as finding food, shelter, and avoiding predators, but we’ve been doing it a long while, that’s all I’m trying to say. Fast-forward many thousands of years, and we’ve evolved so much as a species that not only do we give gifts to others, but to ourselves as well.

The opportunity to gift ourselves is, in part, due to the abundance of inexpensive goods and the ease with which we can make our purchases. This easy access came from the rise of shopping through the mail as exemplified by the thick Sears Roebuck catalogs (not the first, but the most important) and at brick-andmortar five-and-dime stores like the once mighty Woolworth chain.

Mail order was a very attractive option for hard-working entrepre neurs. It didn’t require the start-up costs a large retail business did, and if you could find your niche market you didn’t need to compete head-on with the giants of the business.

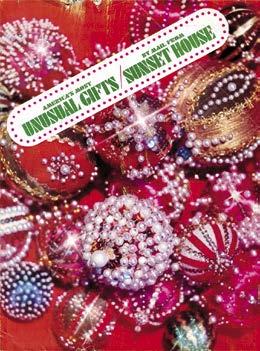

(TOP LEFT) The 1969 Hanover House catalog and (BOTTOM LEFT) the 1967 Sunset House catalog. Both Christmas-time catalogs were full of many of the same types of inexpensive (some would say unnecessary) merchandise. (INSET) A 1965 mail-order ad touting an easy entry into the mail-order business.

Lilli Menasche, as Lillian Vernon, began a mail-order business out of her kitchen, ultimately becoming the first female-led company traded on the New York Stock Exchange. Originally, she placed ads in Seven teen magazine for personalized items, her specialty. She soon issued a regular catalog full of goods waiting to have your name or initials placed on them.

Other notable mail-order retailers include Harriet Carter Gifts (another business originally based in the kitchen), Walter Drake, Spencer Gifts, Miles Kimball, Hanover House, Carol Wright Gifts, and Sunset House. These retailers presented merchandise of modest value squarely aimed at everyday Americans of modest means. They reached their potential customers through catalogs and small ads placed in popular mid-level magazines like Family Circle, Coronet, Better Homes & Gardens, etc.

The really fun mail-order companies sold gleefully dopey stuff that was probably more entertaining to read about than own (I’m looking at you, X-Ray Specs). Johnson Smith and Honor House had ads in cheap magazines and comic books. The busy Johnson

A helpful booklet for shoppers, It’s Fun to Shop Mail Order, from

Smith ads were iconic and just packed with the smallest type and illustrations. Johnson Smith used to produce the “Sears Roebuck catalog” of novelties, which you could even get in hardback for a time. Hundreds of pages of the strangest, most wonderful things (and, to be fair, many cringers, too).

As a kid, I often sent away for catalogs for things I couldn’t afford to buy, but the “window shopping” aspect was fun. I think I got at least as much enjoyment from going over the Captain Company ads in Famous Monsters of Filmland for monster masks, posters, and Super 8 films as I did from the editorial material.

What follows is a beauty pageant of sorts for items you might see for sale in the catalogs and small ads from our youth. The focus is on the more offbeat stuff, because that’s the most fun. [And “offbeat” is RetroFan’s middle name!—ed.]

“Folks will be clock-eyed when they see this on your bathroom wall.” It’s a reminder that “time’s a-wasting, it helps get you to the office, train or school on the dot!” Like a clock. COST: $6.60 and maybe your standing in the community.

The Johnny Clock was probably my introduction to the wonderful world of screwy mail-order items. It was a gift from my late motherin-law and fellow novelty shopper, Virginia. She was a devoted thriftstore diver, and I benefited greatly since she loved to find homes for her treasures. Not every item was a winner, but the Johnny Clock is one of my prized pieces. The top seat was indiffer ently outlined in a classy gold tone, and the numbers were decorated by equally classy plastic “diamonds.” It was on the wall of every home office I’ve had until it finally stopped working.

This Johnny Clock was in use for years in the author's office. The faux diamonds make this model clearly superior to the one seen in the ad detail (RIGHT) from a 1957 issue of House Beautiful.

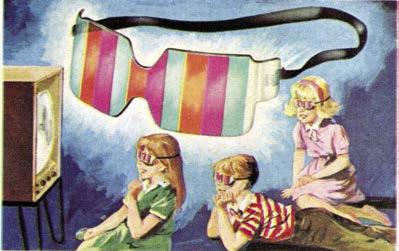

These modest glasses allow you to watch black-and-white television program ming in, and I quote, “livid color.” I’m pretty sure this is a typo, but I admit to being intrigued by the notion of watching angry color TV. Red, green, and orange stripes are supposed to create a “fantastically life-like optical illusion.” I’m pretty sure that’s a typo, too. COST: $1.49

Johnny Clock was pretty popular as toilet-lid novelties go, making its way up the mail-order ladder to be included in the 1981 Montgomery Ward catalog. By then it was available in four different colors (such as Rust and Brown) for only $15.99 each.

I was very lucky to be born in 1951 and to have grown up in San Diego, California. Beyond being a tourist town (and a great place to throw a convention about funnybooks), it was a surfing community long before surf culture achieved national attention. I loved listening to the Beach Boys and Jan and Dean. I read Surfer magazine because it featured Rick Griffin’s “Murphy the Surfer” comic strip, which taught me how to draw surfers for both my classmates and my junior high newspaper. I even got in trouble with my parents for using the local thumbs-up surf-term “bitchen” too often. (Yeah, elsewhere it’s spelled “bitchin’,” but in San Diego, it was definitely “bitchen.”)

The only time I ever actually surfed was when I was a scholar ship student at Point Loma’s Cal Western University and lived in a dorm that was located less than 100 yards from a surfing beach. I waded in with a friend’s surfboard and was about to mount when a wave hit me, and I lost the board, as well as my swim trunks. At least we found the board—if not my trunks—which was also lucky because I needed it to cover myself while doing the Walk of Shame to my dorm room.

A bit farther up the coast from where my embarrassment occurred was where—a few years earlier—one of my favorite elements of surf culture was created by a local cartoonist named Michael Dormer. In fact, Mike was much more that that, creativitywise, but in 1963, I didn’t know his name.

But “Hot Curl the Surfer”?

Bitchen!

Being born in 1951 also allowed me to be in the front row for the popularity of monsters in entertainment, publications, and merchandise from the mid-Fifties to the mid-Sixties. The first time

I ever saw Mike’s name was on a hilariously weird afternoon kids’ show hosted by a cute li’l monster and his kookie mad scientist creator who aired The Marvel Super Heroes cartoons. The show’s name?

Sooo, who was this Michael Dormer guy, anyway? Whoever he was, he was a very big deal to me.

Born in Hollywood in 1935, Michael Henry Dashwood Dormer was welcomed into a family of writers and musicians. Apparently, they needed an artist because li’l Mike was learning how to draw at the age when most children are learning how to walk. When he reached the age of five, his folks enrolled Mike in a Del Mar school in San Diego County to take art classes focusing on sculpture and ceramics. He was also mentored by a then-popular fine artist, Louis Geddes.

At 12, Mike took first prize in a National Fire Prevention poster contest. By the time he was 15, his interests shifted from art to music. While attending San Diego’s Mission Bay and San Dieguito High Schools, Mike was a guitarist with an experimental jazz band, performing music that he also wrote and arranged. Once he reached age 18, he refocused on art, juggling a number of different clients and assignments.

By this time, Mike had honed his graphic skills to the point that he was working as a pro illustrator and cartoonist across the spectrum of his profession. He contributed to men’s maga zines ranging from Esquire to nudie magazines and drew editorial cartoons for San Diego’s Independent, a longtime weekly newspaper. Michael’s first illustration for San Diego Magazine, the first of hundreds over the next 50 years, was created in 1954.

But as many teens approaching the age of 20 do, young Mr. Dormer decided to hit the road to see America, financing his journey by painting murals or playing piano in saloons and barrooms around the United States.

Mike’s attempts at “fine art” in 1955 have been described as “beatnik-style canvases, replete with splashes of paint, expres sionist figures and bendy, twisty tropes.” Soon, by concentrating on commercial art, he got much better. In the mid-Fifties, Michael relocated to Los Angeles, where he attended the legendary Chouinard Art Institute thanks to a scholarship. While in L.A., he co-founded a small business that his family has described only as an “off-beat novelty product featuring his cartoons.” (I’d sure like to know what that was!)

When sales began to ebb, Mike moved north to San Francisco. He considered the city’s art scene to be more enlightened than that of the Showbiz Capitol of the World. As a San Franciscan, he hung out with noted Fifties outsider writers such as Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Allen Ginsberg, and Jack Kerouac. It’s also where Mike sold his first fine art paintings.

(BOTTOM) Dormer, circa early Sixties, and with some of his non-surfer work. (TOP) An untitled Dormer painting from the Masterman Gallery. Facebook.

Around this time, Mike and his new bride moved to Bucks County, Pennsylvania, where he won painting contests and exhib ited and sold his paintings. Dormer signed a publishing contract that enabled him to write and illustrate a half-dozen humor books. But after 18 months, his marriage dissolved, and he moved back to SoCal.

A few years later in 1957, Mike returned to San Diego County to set up his own painting studio, but this time he settled in La Jolla, the seaside town where Theodor Geisel, a.k.a. “Dr. Seuss,” and his wife resided. The Pour House, a hip coffeehouse in La Jolla’s neighborhood of Bird Rock, became a second home to Mike, who was hired by its owner Lee Teacher to be his unique part-time nightclub comic and jazz poet. Lee and Mike hit it off, and eventu ally co-created an art gallery in the Pour House that featured early works by avant-garde artists of the time. Dormer also published The Scavenger (1959), an innovative art and poetry zine that premiered a

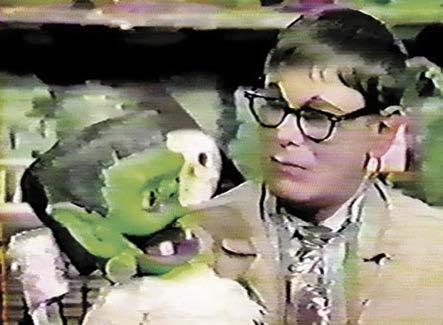

The other aspect was that Shrimpenstein! was live, so when things when wrong, the viewers received more entertainment than they planned.

“We had a script for the first two or three shows,” Jim Thurman once told the Los Angeles Times. “They were kind of dopey little kid things, and we kind of ad-libbed around it, and [due to that] the show became hip and wasn’t for kids any more.”

Gene Moss admitted to the Times, “I didn’t think the show would last a week since it was a put-on. The networks hardly ever accept a kids’ show that’s funny. The meatballs behind the network desks, usually guys who don’t understand children, won’t buy anything they don’t like. But Channel 9 is different from networks; they’ve been great with us—no restrictions, and they have promoted the show.”

My favorite moment-gone-wrong is when Gene as Von Schtick had to enter the set while riding a mini-cycle. The “walls” of the set were just strung-up butcher paper decorated with paint and markers. Von Schtick had no control of his mini-cycle, which suddenly sped up and plowed right through the paper wall, with the doctor still hanging on! After it crashed against a real wall, Gene checked himself over to make sure he wasn’t hurt. The crew was going wild and laughing like crazy as things cut to a commercial. At age 15, I thought it was the funniest thing I’d ever seen on television. It’s still up there.

Shrimpenstein! had a huge following among high school and college students all over Southern California. There were also older fans, such as The

“I remember the time Channel 9 was literally off the air for many hours due to problems with their transmit ter. Shrimpenstein! didn’t air that day, and on the next show, Dr. Von Schtick tried to explain how it was not one of his experiments that caused the outage. To prove it, he replicated the ex periment… and the station went off the air again, this time for 20 seconds or so. And I remember Wilfred the Wie ner Wolf—a puppet, but you only saw his paw the way you only saw White Fang’s paw on Soupy Sales’ show. He was there to sell Hormel Wieners, which was a major sponsor, and one time he explained that they were made by throwing kitty cats into the vat. I think that was the end of that sponsorship.”

MARK EVANIER editor, writer, panel moderator, and cheese-dipper

Lyrics written by Mike Dormer

Late one night

(ABOVE) Dr. Rudolf Von Schtick on Shrimpenstein! ’s literally paperthin set. (RIGHT) Shrimpy, voiced by Jim Thurman, frequently confounded Von Schtick.

Shrimpenstein © Michael Dormer and Lee Teacher.

and Lee Teacher.

In the laboratory

There began the story Lightning flashed And something missed A poor old crazy scientist Had dropped his bag of jellybeans Into his Frankenstein machine And SHRIMPENSTEIN Was created In just half the time That takes to make a Frankenstein Because, you see, He’s half the size of you and me, And just because he isn’t mean He’s just a tiny walking jellybean.

Welcome back to Andy Mangels’ Retro Saturday Morning, and prepare for a visual feast! Saturday morning television was appointment viewing for anyone growing up from the Sixties to the Nineties. From 8am to Noon, while their parents slept in from the workweek, kids could sit in front of the television and enjoy a time just for them. Cartoons—and later, live-action

series—were produced by studios like Filmation Associates, DePatie-Freleng Enterprises, Total Television, Jay Ward Productions, Hanna-Barbera Productions, Sid and Marty Krofft, D’Angelo Produc tions, Marvel Productions, Sunbow Produc tions, Ruby-Spears, DIC, Film Roman, and others. But how could the networks best reach kids to let them know when the new

shows would be airing? Enter the television ads that ran in comic books, touting new and exciting Fall seasons! It made sense, since many shows were adapted from comic books! For most kids, those two-page spreads were their first looks at future TV favorites. In the first of a semi-regular series, we’re offering you a rare look at every Saturday ad we can find!

The first comic-book ads for Saturday animation appeared in Harvey comics cover-dated May 1962, showcasing Casper and other Harvey stars on ABC. Here is that first ad (LEFT), and two later ads from 1966. Characters © Classic Media, LLC.

BY ERNIE MAGN o TTA

BY ERNIE MAGN o TTA

Any child of the Seventies recognizes those opening lyrics. They were written by Linda Laurie (“Ambrose (Part 5)”) and belong to the memorable theme song of the Sid and Marty Krofft live-action, Saturday morning television classic, Land of the Lost, a children’s sci-fi/adventure series in which the Marshall family—teenage Will (Wesley Eure, TV’s Days of Our Lives), younger sister Holly (Kathy Coleman, TV’s Adam-12), and their father, Rick (Spencer Milligan, TV’s General Hospital )—are transported to an alternate universe after their raft plunges down a waterfall and they are sucked through a time doorway. The Marshalls awaken in the primitive Land of the Lost, a place inhabited by dinosaurs, ape-like bipeds called Pakuni, and the

“Marshall, Will, and Holly, on a routine expedition, met the greatest earthquake ever known”… and look where it got them! Title card for Sid and Marty Krofft’s Land of the Lost, starring the dino-fighting Marshalls: (LEFT TO RIGHT) Wesley Eure as Will, Kathy Coleman as Holly, and Spencer Milligan as Rick. © Sid & Marty Krofft Productions.

“Marshall, Will, and Holly… on a routine expedition…”

terrifying, lizard-like Sleestak. The resourceful family quickly makes a nearby cave their home base. Will and Holly befriend the youngest Paku named Cha-Ka (Phillip Paley, Beach Balls) while their father seeks out the only civilized Sleestak, the intelligent Enik (Walker Edmiston, H. R. Pufnstuf ). The kids give nicknames to many of the dinosaurs they encounter, most notably an angry T. rex named “Grumpy” and a baby Brontosaurus named “Dopey.” Each week, the Marshalls, who are later joined by their Uncle Jack (Ron Harper, TV’s Planet of the Apes), do everything in their power to escape the Land of the Lost while simultaneously dodging deadly dinosaurs, hostile Sleestak attacks, and many other fantastic threats.

Created by Sid and Marty Krofft (Sigmund and the Sea Monsters), David Gerrold (TV’s Star Trek), and Allan Foshko (April in the Wind ), Land of the Lost aired every Saturday morning on NBC between 1974 and 1976. The enter taining show, which is made up of 43 half-hour episodes and lasted for three seasons, benefitted greatly from scripts written by very well-known science-fiction writers such as Larry Niven (Ringworld ), Theodore Sturgeon (More Than Human), and Star Trek veterans D. C. Fontana and Walter Koenig.

The well-loved and influential show has spawned a remake series that aired in the early Nineties and lasted for two seasons, and a 2009 theatrical film starring Will Ferrell. As of 2018, the Kroffts have been hard at work preparing a new television version that they hope to produce as an hour-long series.

Recently, I was lucky enough to inter view Will Marshall himself, Wesley Eure. In addition to being a talented actor, former teen idol, and an extremely nice guy, Wesley has written several books for both kids and adults, including the classic children’s tale The Red Wings of Christmas He has also raised funds for important charities; co-created the Emmynominated, educational TV

show Dragon Tales; and is a gifted singer. The multi-talented Wesley took time out of his hectic schedule to chat with me about his adventures in Saturday morning television, happily speaking about a variety of subjects such as working with fellow cast members, performing the show’s iconic theme song, and the dynamic duo: Sid and Marty Krofft.

RetroFan: Tell me about how you got into acting. Was that always a dream of yours? Wesley Eure: Oh, yeah. I grew up in Hattiesburg, Mississippi, and when I was five years old, I stood up and said, “I want to be an actor.” My family were all educators. None of them were in the entertainment industry, so they all looked at me like I was from another planet. [laughs]

My dad left when I was two and never came back, so I think I

Wesley as Land of the Lost ’s Will Marshall was a teen heartthrob, profiled in teen mags like Tiger Beat and 16. © Sid & Marty Krofft Productions.

just needed attention. I started by doing school plays and community theater. Then we moved to Las Vegas because my mom was heading a drug abuse program for the state of Nevada. I was supposed to go to college, but I decided to go on auditions instead, and I eventually got a role on Days of Our Lives, which was amazing to me.

RF: When did you first hear about Land of the Lost?

WE: I met Sid Krofft at a party, and he asked me to audition, which I did. Not long after, I got a phone call saying that I got the part. I was 20, I think, and I was going to be playing a 15-year-old. I wasn’t sure if I wanted to do that, but thank God I said yes because it’s been a wonderful journey with Land of the Lost Sid’s 92 now. He calls me all the time, and he recently told me that they never saw anyone else for the part of Will. He said they knew they wanted me and they cast the rest of the show around me. First, they had to find a guy who looked like my dad. And then I auditioned with Kathy and some other actresses. But he said I was the only choice they ever had for Will. I never knew this. Sid just told me like, two weeks ago. It was very flattering.

RF: You also sang the show’s theme song. How did that come about?

WE: They actually came to me and asked me to do it. I was in a band with a guy named Michael Lloyd, who is now one of the top music producers in the business. We went to his studio, and I recorded it. And then when we got to the third season and Uncle Jack joined the cast, there were new lyrics to the opening song, so we went back and recorded that. I also did the end credits theme, which is my favorite.

RF: I like that one, too. Cool song.

WE: Yeah, and a lot of big bands do covers of both the theme song and the end

In October 1964, I was 11 years old and a huge fan of Marvel Comics, having graduated from being a DC Comics reader just a few months before. In those days, super-heroes were hard to find outside of comic books. On TV, reruns of the Adventures of Superman TV show and occasional showings of the 1940s Max Fleischer Superman theatrical cartoons dominated. Batman creator Bob Kane’s Courageous Cat and Minute Mouse was in reruns. Mighty Mouse was a familiar face, but not a television original. That was it.

But the Saturday morning network television block was undergoing renovations. New cartoons were being commissioned to satisfy growing

Baby Boomers, of which I was one. The networks had yet to discover the ratings potential of serious super-heroes, but they would soon tap that golden geyser.

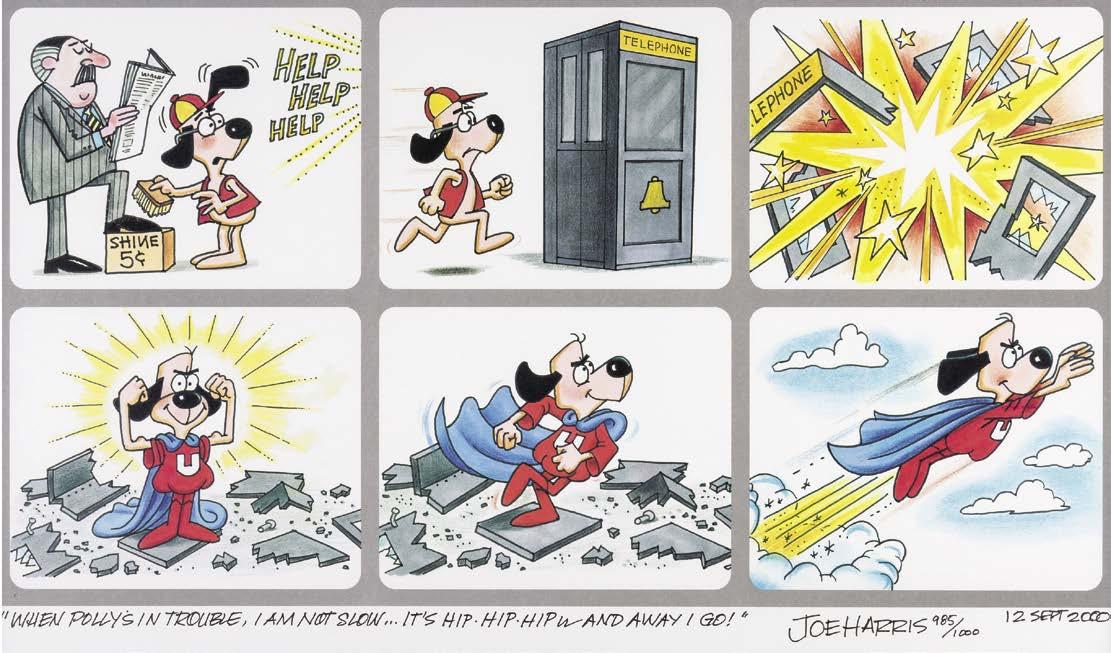

An early effort in that direction was Total TeleVision productions’ [those aren’t typos—it’s a capital “V” and lowercase “p”—ed.] Underdog, which debuted on Saturday, October 3, 1964. With its stirring theme song and clever writing, it became an instant hit, running for three years on two networks and jumping into syndication seemingly forever.

While Courageous Cat and Minute Mouse [see RetroFan #19] were a gentle takeoff on Batman

(ABOVE) There’s no need to fear! From Shoeshine Boy to Underdog, in a 2000 limited edition print signed by Underdog cartoonist Joe Harris. © Classic Media, LLC. Courtesy of Heritage. (LEFT) The men behind Underdog: co-creators Buck Biggers and Chet Stover, from their Seventiesvintage TV Tinderbox letterhead, and cartoonist Joe Harris. Courtesy of Mark Arnold.

and Robin, Underdog was nothing less than an off-center satire of Superman. If I had still been reading the Man of Steel, I might have been mildly offended. But I had moved beyond that cardboard character.

Underdog was an anthropomorphic dog that possessed all of Superman’s signature powers: super-strength, super-speed, flight, invulnerability, X-ray vision, and others. To these were added an amazing array of super-duper powers, including cosmic vision, atomic breath, and atomizing vision. Underdog obtained these by taking a Super Energy pill, which not only transformed his true mutt self, but demolished the phone booth into which he ducked to conceal the explosive change.

Eventually, I outgrew TV cartoons, and all but forgot about the Pup of Steel, except for that rousing theme song, which latter-day bands covered with enthusiasm.

In 2006, Disney announced a live-action Underdog film. When my Starlog editor asked me to interview the character’s creators, I pounced on the opportunity. A planned set visit to the nearby Providence, Rhode Island, filming location never materialized, but that didn’t matter. I boned up by reading a recently released book, How Underdog Was Born; rang up its authors, Underdog’s still-living creators; and got the backstory in detail.

Before they concocted the indefatigable cartoon canine, W. Watts “Buck” Biggers and Chester “Chet” Stover were working at an advertising agency called Dancer Fitzgerald Sample (DFS). Biggers was Vice President of Account Supervisors. Stover was Creative Director and had a tobacco account, which he felt guilty about.

“In advertising in those days almost everyone that I knew was doing something to get out,” Buck Biggers admitted. “When you went to lunch—and those were the days of three-martini lunches—what you talked about was this guy’s working on a movie, this guy’s working on a book, another guy’s starting a hardware business. Everybody was doing something. And they were going to get out. Now, most of those people never did get out. But it was something to talk about. Because the business was in those days extraordinarily pressure-driven. You could be fired overnight. And I wanted to get out. And so did Chet.”

“I didn’t want to get out as badly as Buck did,” Chet Stover said. “I always sort of liked the advertising business. Advertising was exciting. There was no such thing as seniority. You went ahead on your own, as far as competition was concerned, for jobs. I got paid very, very well. It was stimulating.”

In 1960, DFS agency head Gordon Johnson challenged Biggers to create an original cartoon series to promote General Mills cereals for Saturday morning TV.

“I leaped at the chance,” Biggers recalled. “Of course, I had to beat Chet over the head, but I finally got him to join me.”

Biggers and Stover formed Total TeleVision to produce King Leonardo and His Short Subjects Tennessee Tuxedo and His Tales followed in 1961. Both were modest successes, but they sold tons of Cheerios, which was the bottom line.

Working from their respective Cape Cod and Connecticut homes, the collabora tors rendezvoused for weekly conferences every Thursday at a motel in Framingham, Massachusetts. Their long, tedious days in the pressure-cooker world of advertising were over.

Cox? Photograph by Philippe Halsman, from the Van Every/Smith Galleries at Davidson College. (BELOW) Barney Fife himself, Don Knotts, was briefly considered for the role. Knotts, of course, was immortalized as a Sixties toon in the wonderful family film, The Incredible Mr. Limpet. © Warner Bros.

“There was no pressure at all,” Biggers remembered with pleasure. “We met one day a week in our inn, then we would go our separate ways and write our scripts that we had outlined together. Then the following week we would look those over and plot new ones. I can’t tell you how great it was. Chet and I just laughed our way through every meeting we had. We just enjoyed it tremendously. We ate a lot of shrimp and drank a lot of martinis. We have said many times—and we meant it—all things considered, we should have paid them to let us do it.”

“We just had a lot of fun doing it,” agreed Stover. “It was just fun. It wasn’t like a nine-to-five job.”

Underdog came about when two Saturday morning time slots opened up.

“I had a meeting with Gordon Johnson,” Biggers explained, “and he said that the agency had purchased for General Mills two new time slots, one on ABC and one on NBC, for the coming year. For those, they needed two new series. And Jay Ward and Bill Scott— who we knew very well and had done Rocky and Bullwinkle —had been asked to create one series. Assuming that the agency and General Mills liked both series, the one they preferred would go on NBC, and the other would be relegated to ABC. The only two things

(LEFT) Who better to portray Shoeshine Boy and Underdog than the humble and loveable Wally

The Christmas riots of 1983. Do you remember them?

Those of us who survived this mass hysteria don’t much talk about it anymore, weighted down by the shame of the season the world went mad. The media was there, broadcasting the carnage, its cameras trained on the scowling faces of the obscenity-spewing rioters. Some of us sat safely on the sidelines, transfixed by the images flickering on our television sets. And some cheered on the dissidents and their frantic fits of pushing, shoving, and eye (and price) gouging. These rebels were moms and dads, formerly docile, civilized providers, now teetering on the brink of barbarism. They fought not for a compelling social or political cause… but for a doll.

In a simpler time, before parents felt their children were prepared to handle the truth about the facts of life (human reproduction, not the Eighties TV show), the question “Where do babies come from?” was answered by either “The stork drops them off on the doorstep” or “They’re plucked from a cabbage patch.” This issue’s RetroFad borrowed from the latter to coin its name, “Cabbage Patch Kids,” which is arguably a better brand than “Stork Droppings” would have been.

The original Cabbage Patch Kids® are 16-inch dolls made of fabric bodies. Their plastic heads have hair woven from yarn, in many different hairstyles, with some being babybald. Cabbage Patch Kids’ cherubic faces have lovable, wide-open eyes that beg you to be their “mommy.” They’re all a bit chubby (it’s baby fat!), engendering irresistible huggability. Cabbage Patch Kids are undeniably adorable.

The marketing of the dolls is a twofold stroke of genius. Each Cabbage Patch Kid is said to be unique, with no two dolls possessing the exact same facial features, eye colors, and hair. And Cabbage Patch Kids aren’t sold (although money does

change hands), they’re “adopted,” with a birth certificate/adoption papers issued with each doll.

Coleco Industries, a Hartford, Connecticut–headquartered toy company, began manufacturing Cabbage Patch Kids in 1982. But it was the adoption angle that propelled Cabbage Patch Kids beyond the toy sensations of the previous few years (Star Wars action figures, the electronic memory game Simon, and Atari’s Video Computer System, among them) into becoming the third bestselling toy of all time (after Hot Wheels and the Rubik’s Cube). Coleco tugged at heartstrings (as well as Daddy’s credit card) by sponsoring a Cabbage Patch Kids “adoption event” at the Children’s Museum in Boston, Massachusetts, in June 1983. A fairy tale–like origin story printed onto each Cabbage Patch Kids’ box revealed that the dolls’ creator was a “ten-year-old boy” named Xavier Roberts. A “BunnyBee” lured Roberts to a cabbage patch secreted behind a waterfall. There he found the birthplace of the Cabbage Patch Kids, and dedicated himself to helping adopt out these cute li’l darlings to new homes.

Who could resist a backstory like that? The media sure couldn’t, providing Coleco’s new product no end of publicity, including a Newsweek cover feature and network television

This charming cover photo for the December 12, 1983 edition of Newsweek belied the violence going on at department stores selling the in-demand doll. © Newsweek.

In 1968, Rankin/Bass Productions’ landmark TV special Rudolph the Red-Nosed Rein deer [see RetroFan #12—ed.] was appearing on NBC’s The General Electric Fantasy Hour for the fifth time! Rudolph’s unusually high annual ratings had given producers Arthur Rankin, Jr. and Jules Bass some clout at the NBC television network.

In 1966, on Thanksgiving Day, Rankin/ Bass followed up their original hit with The Ballad of Smokey the Bear, which, like Rudolph, was filmed in their trademark “Animagic” stop motion. Smokey, too, appeared on the NBC General Electric Fantasy Hour.

During 1965–1968, Rankin/Bass Produc tions released five feature films! Three were in Animagic: Willy McBean and His Magic Machine (1965), The Daydreamer (1966), and Mad Monster Party? (1967) [see RetroFan #17]; while The Wacky World of Mother Goose (1966) was filmed in cel animation, and King Kong Escapes (1968) in live-action.

This was the busiest Rankin/Bass had ever been! They were also developing, for ventriloquist Edgar Bergen, a pilot called The Charlie McCarthy Show (which would not see the light of day) and off-Broadway musicals A Month of Sundays (1968) and Huck (which would ultimately be handled by another production team). Jules Bass and music composer Maury Laws were even on the set of Jerry Lewis’ 1967 film comedy, The

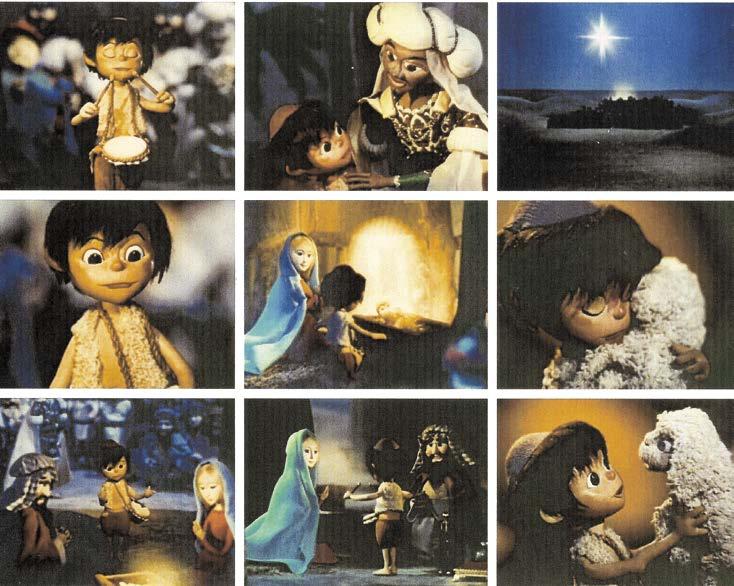

(LEFT) Miscellaneous scenes from Rankin/Bass Productions’ Animagic classic The Little Drummer Boy, first seen on NBC-TV in 1968. The title’s illustration of Aaron, the drummer boy, is by MAD cartoonist Paul Coker, Jr., who passed away on July 23, 2022. Unless otherwise noted, all images accompanying this article are courtesy of Rick Goldschmidt. © 2012 Miser Bros Press/Rick Goldschmidt Archives.

Big Mouth, discussing and working on preliminary elements of Hey, Bellhop!, a proposed Animagic version of the comedian’s Bellhop movie character. (Shortly after my book The Making of the Rankin/ Bass Holiday Classic: Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer pictured the Jerry Lewis figure made for this unproduced project, Lewis wanted to resurrect Hey, Bellhop! I connected Jerry with Arthur Rankin, but nothing came of it.)

In 1967, Rankin/Bass produced another NBC special, based on Charles Dickens’ Cricket on the Hearth, in cel animation, at Toei studios, which aired as part of The Danny Thomas Show. Thomas hosted it in live-action, and it also starred his daughter Marlo Thomas, as the voice of Bertha. This led to another cel-animated production, Thanksgiving 1968’s The Mouse on the Mayflower, starring Tennessee Ernie Ford (Rankin/Bass originally planned for Bing Crosby to narrate the special, but the deal fell through). This special would not be sponsored by General Electric, but instead by Your Gas Company (a.k.a. American Gas Association).

“After we made the deal with our sponsors, [Your] Gas Company, I had another meeting with the NBC executives in early 1968,” said producer Arthur Rankin, Jr., who died in 2014. “This was on a Friday, and I told them we had another Christmas special, which could be filmed in Animagic like Rudolph, based on The Little Drummer Boy, which of course was another big Christmas song.

“At the time, I actually had nothing,” Rankin confessed. “I needed to keep our Animagic studio in Japan, MOM, working, so I had hoped to rush another Christmas special into production. They said, ‘Get us a script by Monday, and maybe we could fit it into our holiday schedule.’ I went back to the office with my secretary and rang up our writer, Romeo Muller, in High Falls, New York!”

According to Romeo Muller’s brother, Gene Muller, “I remember this very clearly. Romeo got a phone call from Arthur Rankin, and I was there. He needed a story about The Little Drummer Boy right away. Romeo actually came up with the story over the phone conversation and dictated it to Arthur’s secretary. This is how fast it all came together, and I was amazed at the talent of my brother!”

“I went back with the script on Monday,” said Rankin. “We got the green light, so instead of having just one TV special on NBC sponsored by [Your] Gas Company, we had two. It was essential that I keep our studios in Japan working, and now we were working with several. Toei worked with us on the Saturday morning TV series in 1966, the [animated cartoon] show, so we did Cricket and with them; but eventually we would work with Mushi Studios, too, on the Snowman, which we’ll cover in next year’s Christmas edition of RetroFan —ed.], etc. Since the stopmotion Animagic became our trademark, we had to keep MOM going, and Santa Claus Is Comin’ to Town would follow Drummer Boy in short order.”

The quality of these productions during this period is amazing. Even though Boy was rushed, it is one of Rankin/ Bass’ finest moments, and should have been nominated for and received an Emmy! Actually, its 1976 sequel, The Little Drummer Boy, Book II, is the only Rankin/Bass production to be nominated for an Emmy. (More on the sequel later.)

The production designer of the Little Drummer Boy special is listed as Charles Frazier, not Rankin/Bass regulars Paul Coker, Jr. or Jack Davis. Strangely enough, no one seems to know anything about Charles, and this is his only credit as a designer. I am

This early promo for the 1968 Thanksgiving special The Mouse on the Mayflower —featuring art by Jack Davis— reveals Rankin/Bass’ original choice for the special’s narration and songs. Instead, Tennessee Ernie Ford provided those roles. © 2012 Miser Bros Press/Rick Goldschmidt Archives.

wondering if this was a made-up name for this production. (Jules Bass used the phony name Julian P. Gardner as writer for many of the productions. According to Maury Laws, the P stood for “Phony.” Gardner is the first name of Arthur’s second son.)

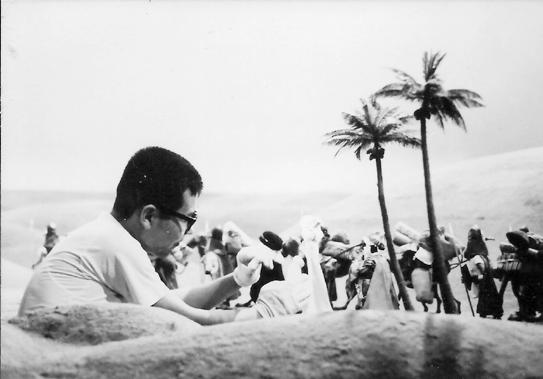

By this time, Tad Mochinaga, the father of stop motion in Japan and the person in charge of that country’s MOM studios, was handing over the reins to animator Hiroshi Tabata (seen in the production photos pictured here). Hiroshi felt that The Little Drummer Boy ’s Animagic didn’t live up to Tad’s animation in Rudolph