Dynamic television 44 Adam West 46 Burt Ward 50 Yvonne Craig 54 Supporting players 56 Extracurricular television 57 Rogues’ gallery 58 INITIUM ORIGIN STORY HOLY RATINGS!

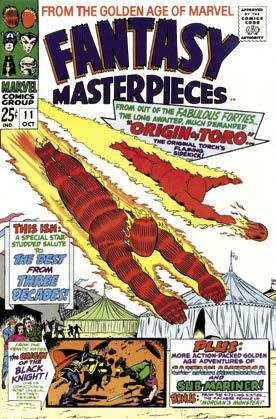

ANIMATION 2

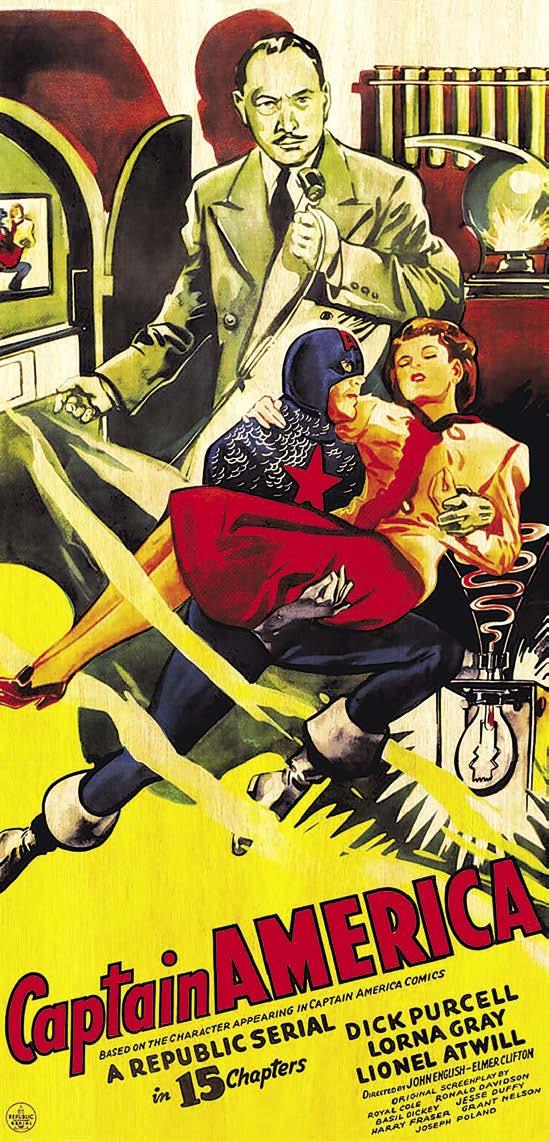

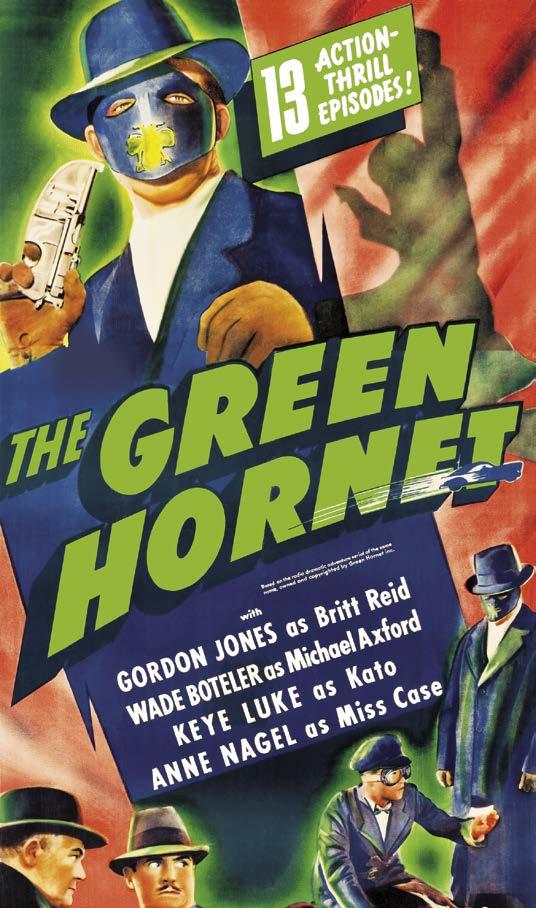

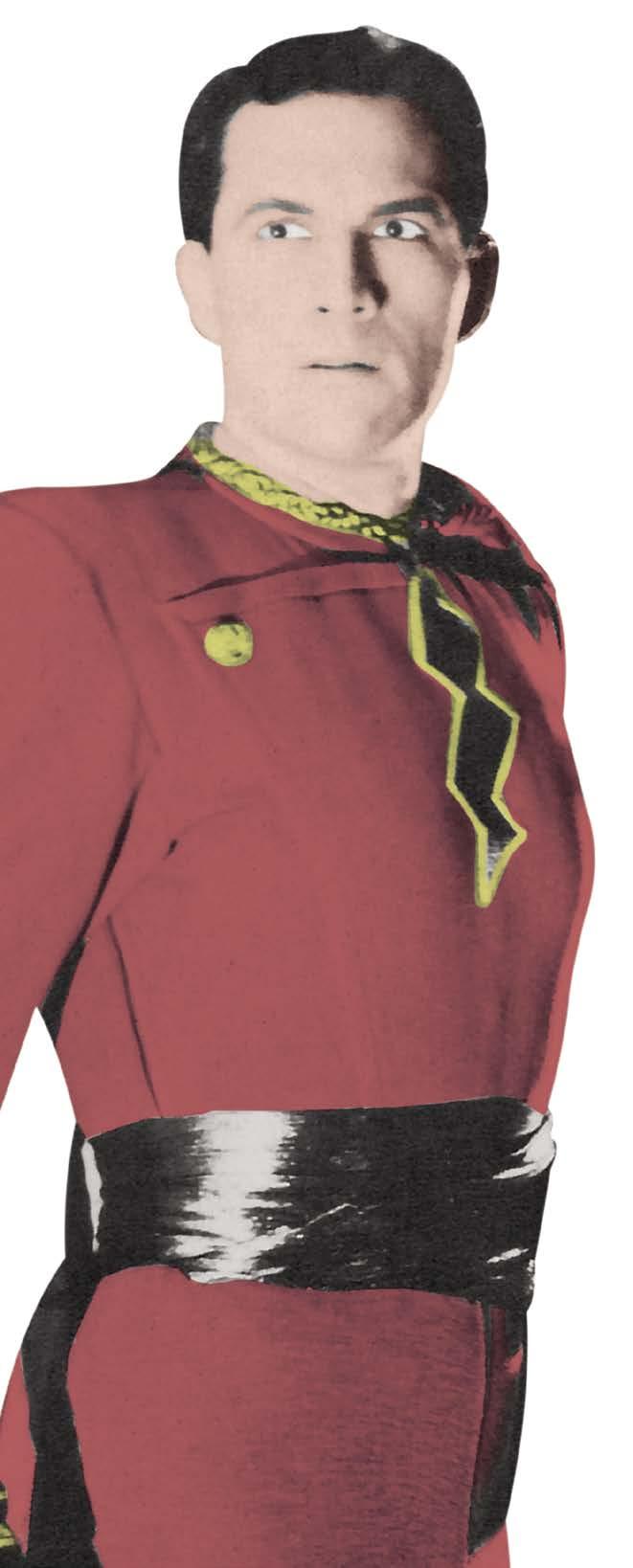

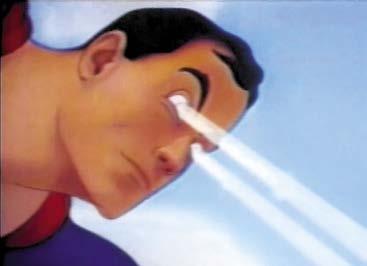

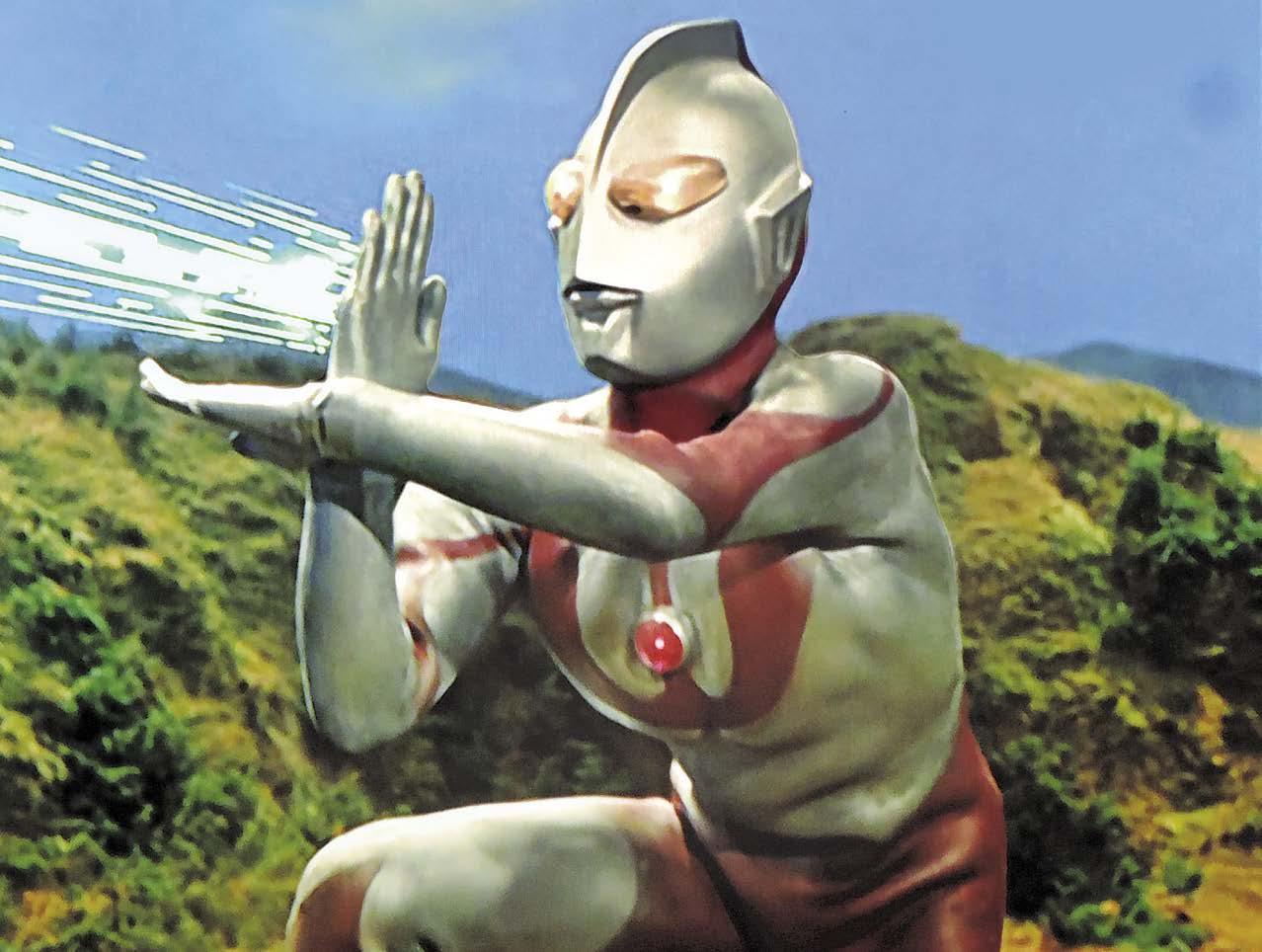

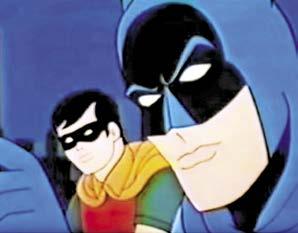

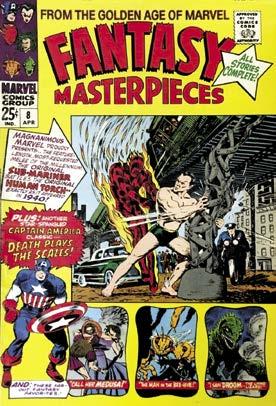

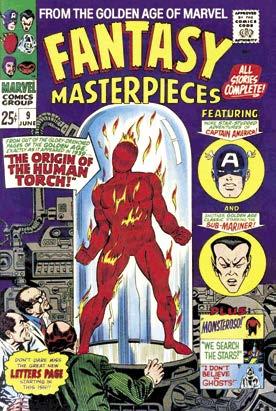

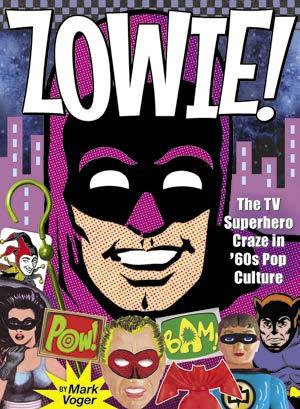

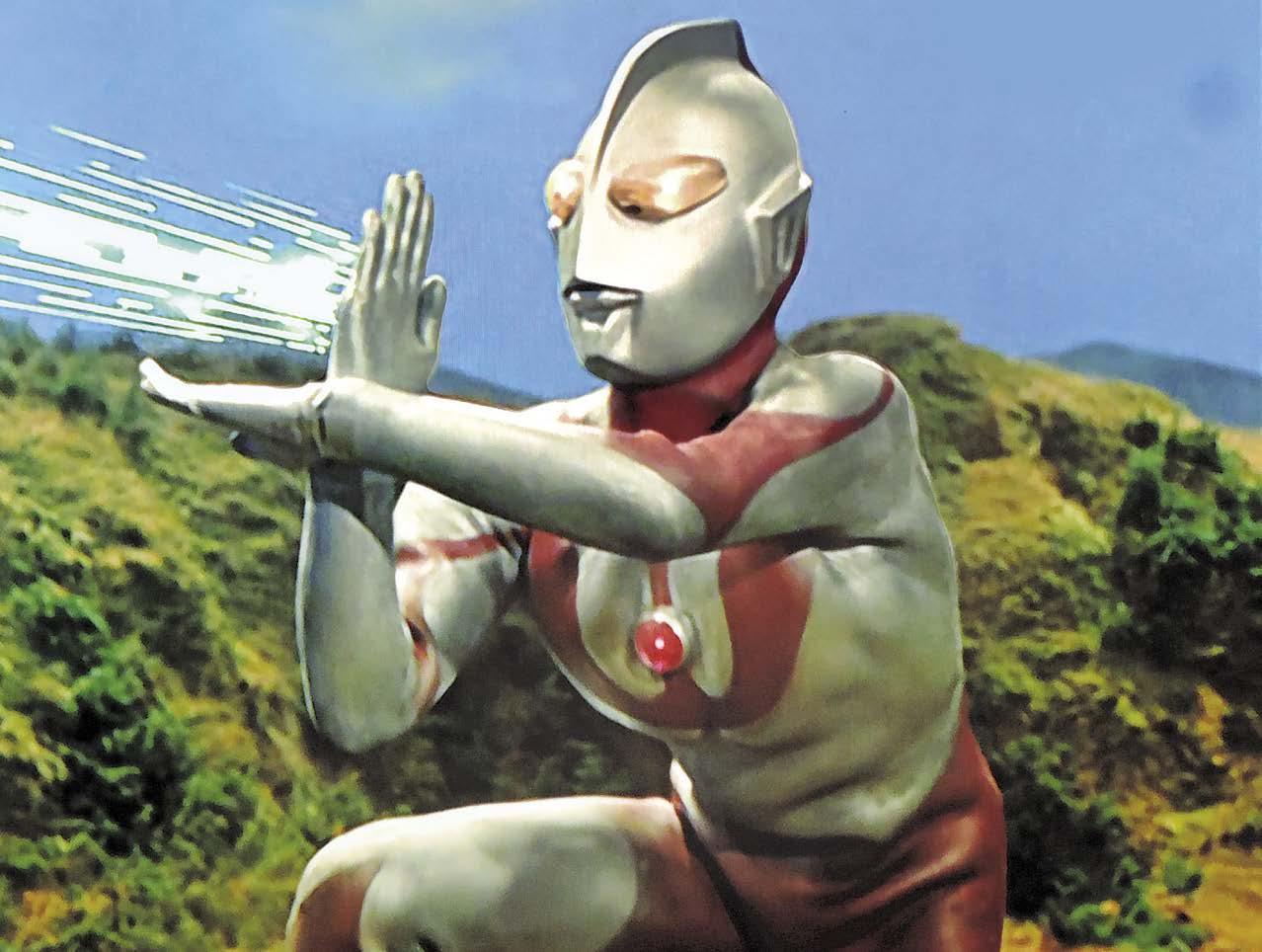

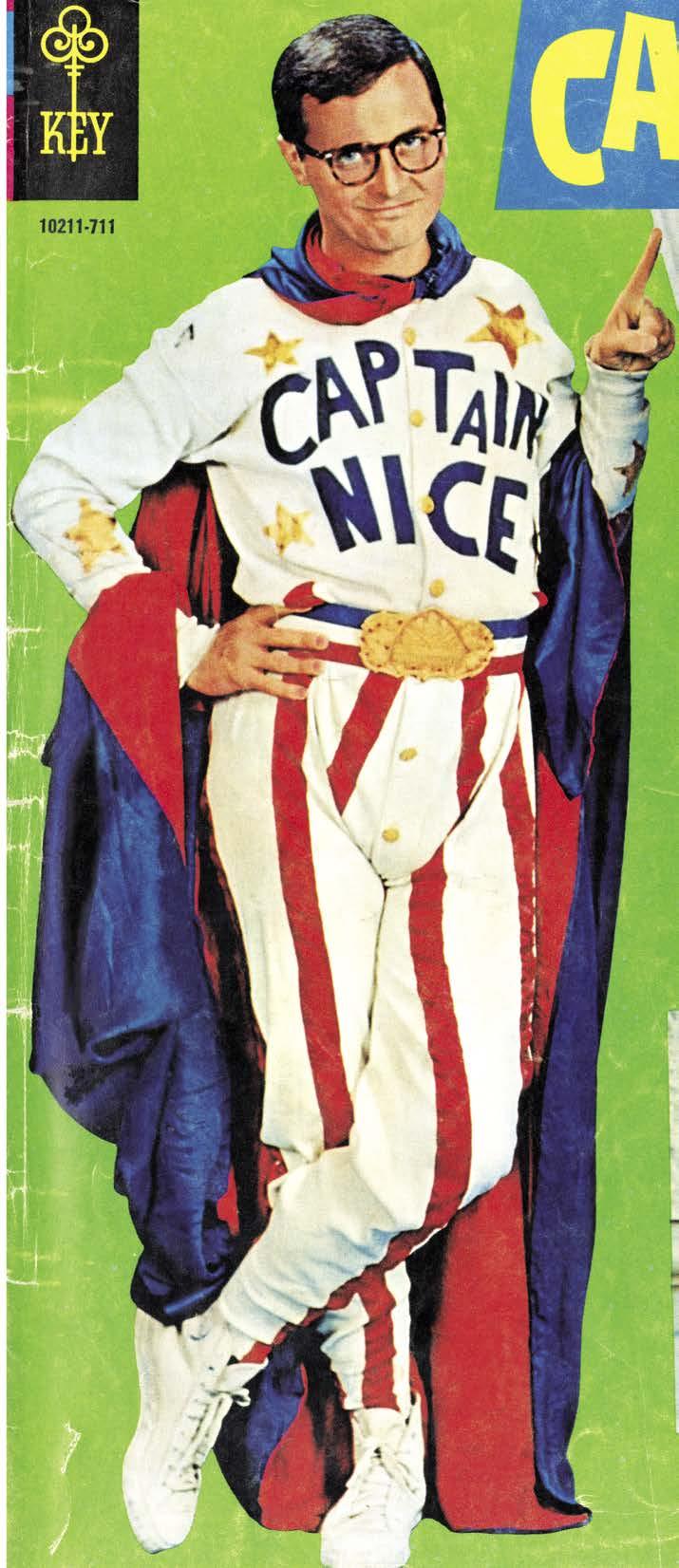

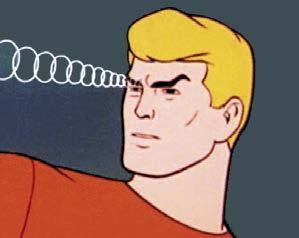

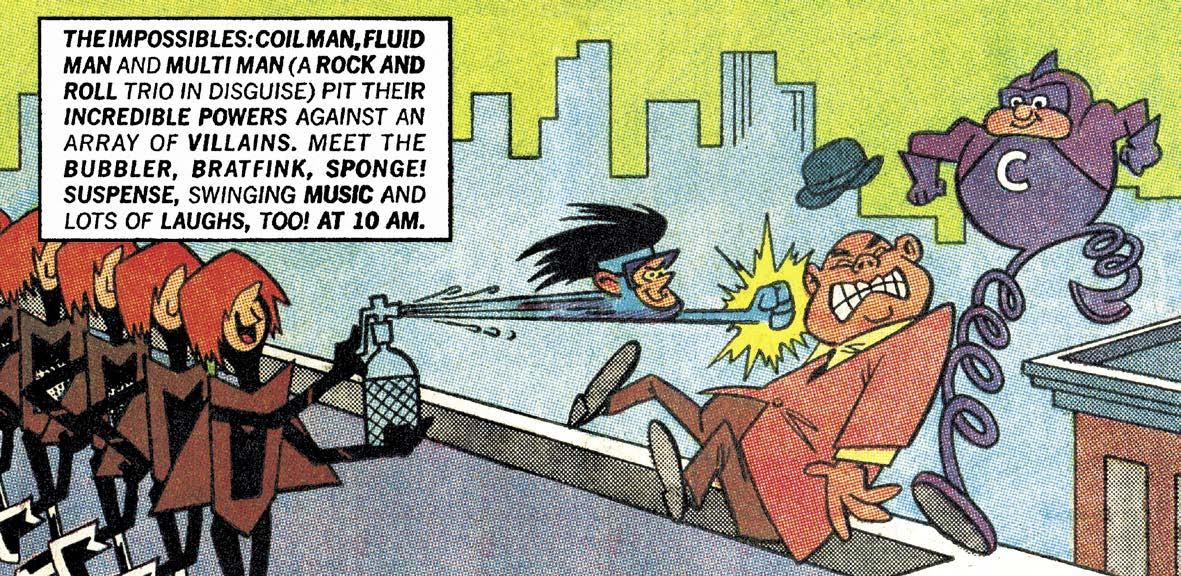

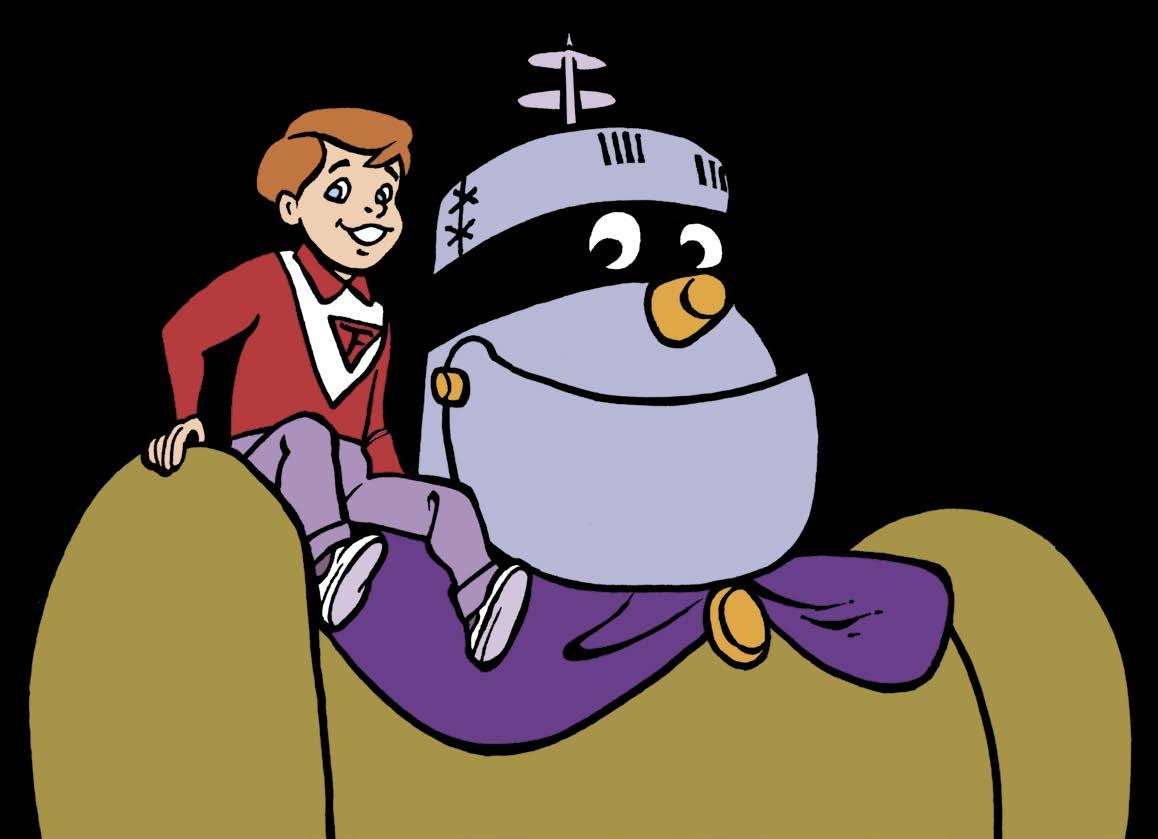

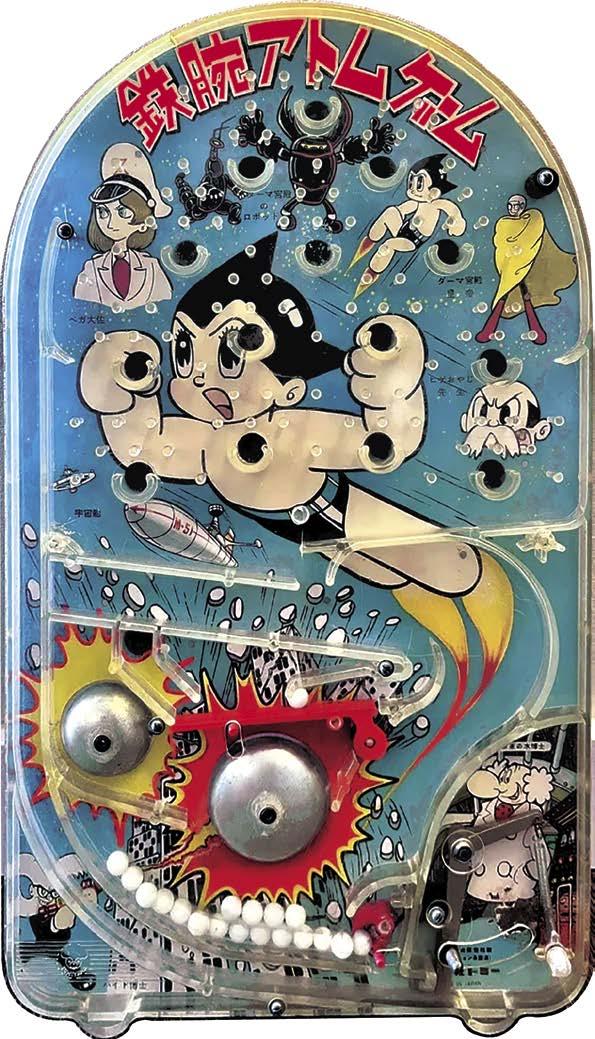

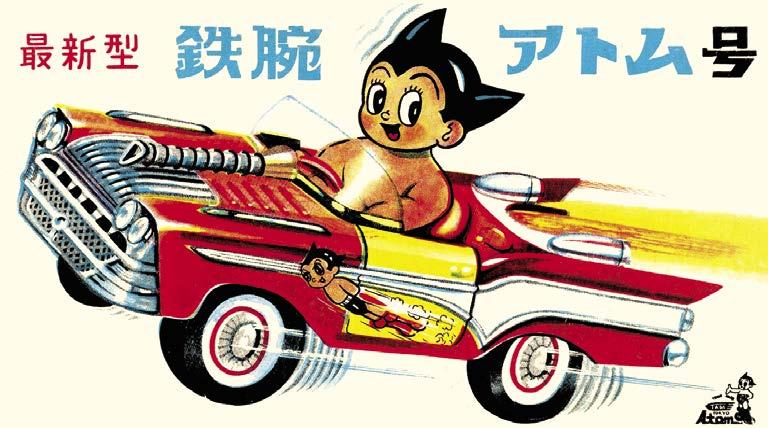

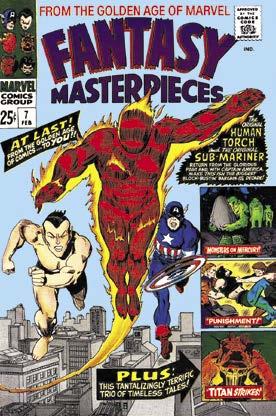

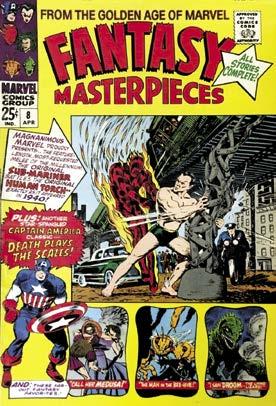

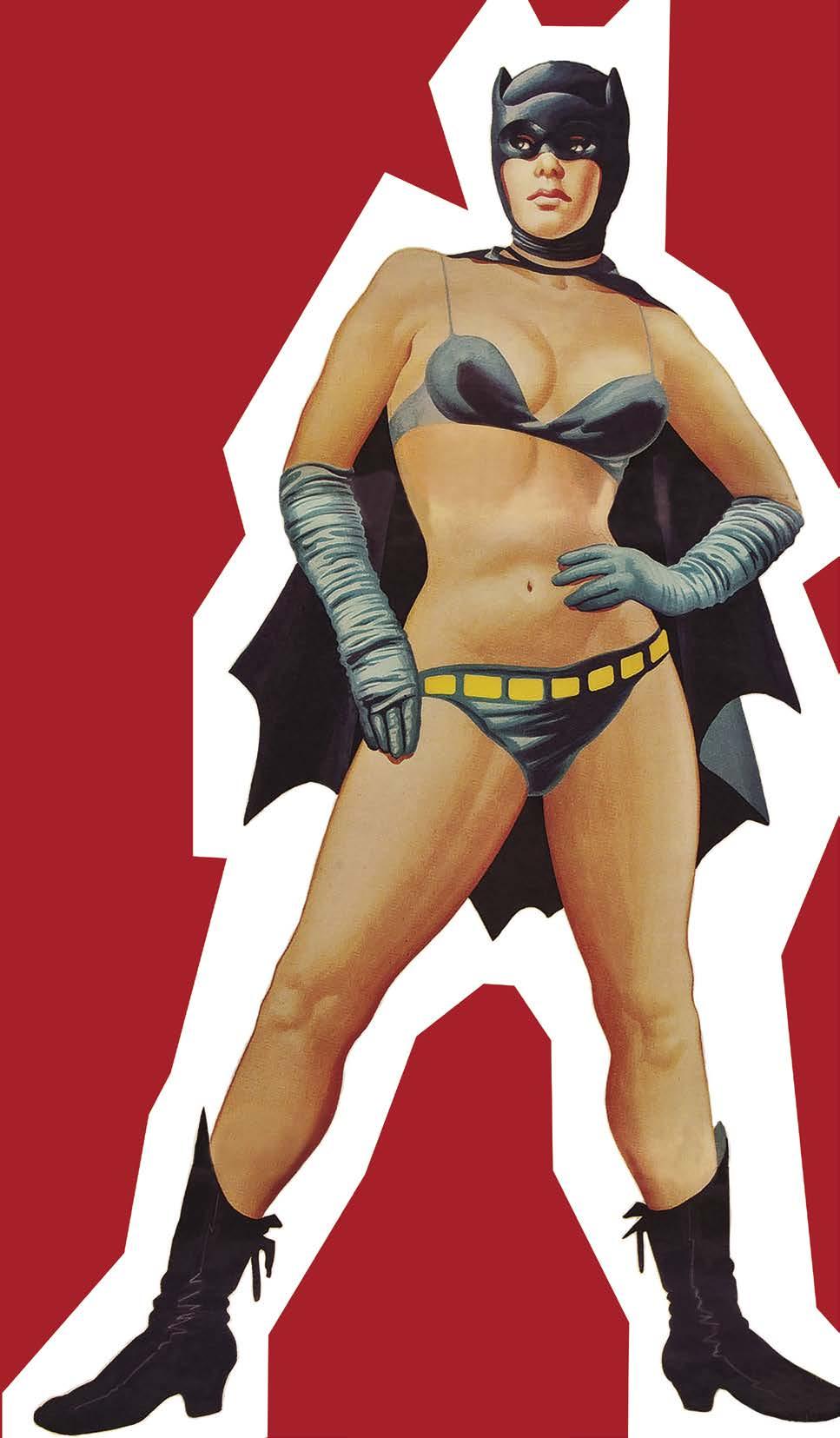

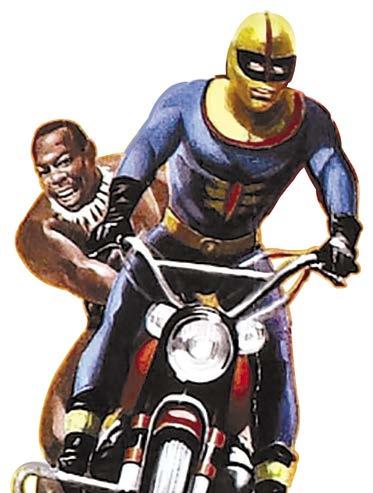

Insets: Bat lady by Margaret Brundage © Weird Tales; “The Detectives” © NBC Television; Eartha Kitt publicity photo; “Johnny Sokko” © TV Tokyo; “Space Ghost” © Hanna-Barbera Productions Introduction 4 Overview 8 Timeline 10 Roots of superdom 12 Batman begins 16 Jerry Robinson 20 George Roussos 23 Dick Sprang 24 Sheldon Moldoff 25 Birth of a film genre 28 Green Hornet serials 30 Captain Marvel serial 32 Fleischer Superman shorts 33 Batman serials 34 The Phantom serial 35 Captain America serial 36 Superman serials 37 Clayton Moore 38 ‘Adventures of Superman’ 39 Noel Neill 40 ‘The Green Hornet’ 74 Van Williams 76 Bruce Lee 78 ‘Ultraman’ 80 ‘Starman,’ ‘Johnny Sokko’ 82 ‘Captain Nice,’ ‘Mr. Terrific’ 83 Ron Ely 84 Frank Gorshin 62 Burgess Meredith 64 Cesar Romero 65 Julie Newmar 66 Eartha Kitt 69 Malevolent memories 70 ‘Pow!’ went the pop stars 71 The Batmobile 72 ‘Marvel Super Heroes’ 86 Filmation 88 ‘Space Ghost’ 90 Comic book worthy 91 Funny and furry 93 Japanimation 94

EARLY FILM & TV

MORE TV HEROES

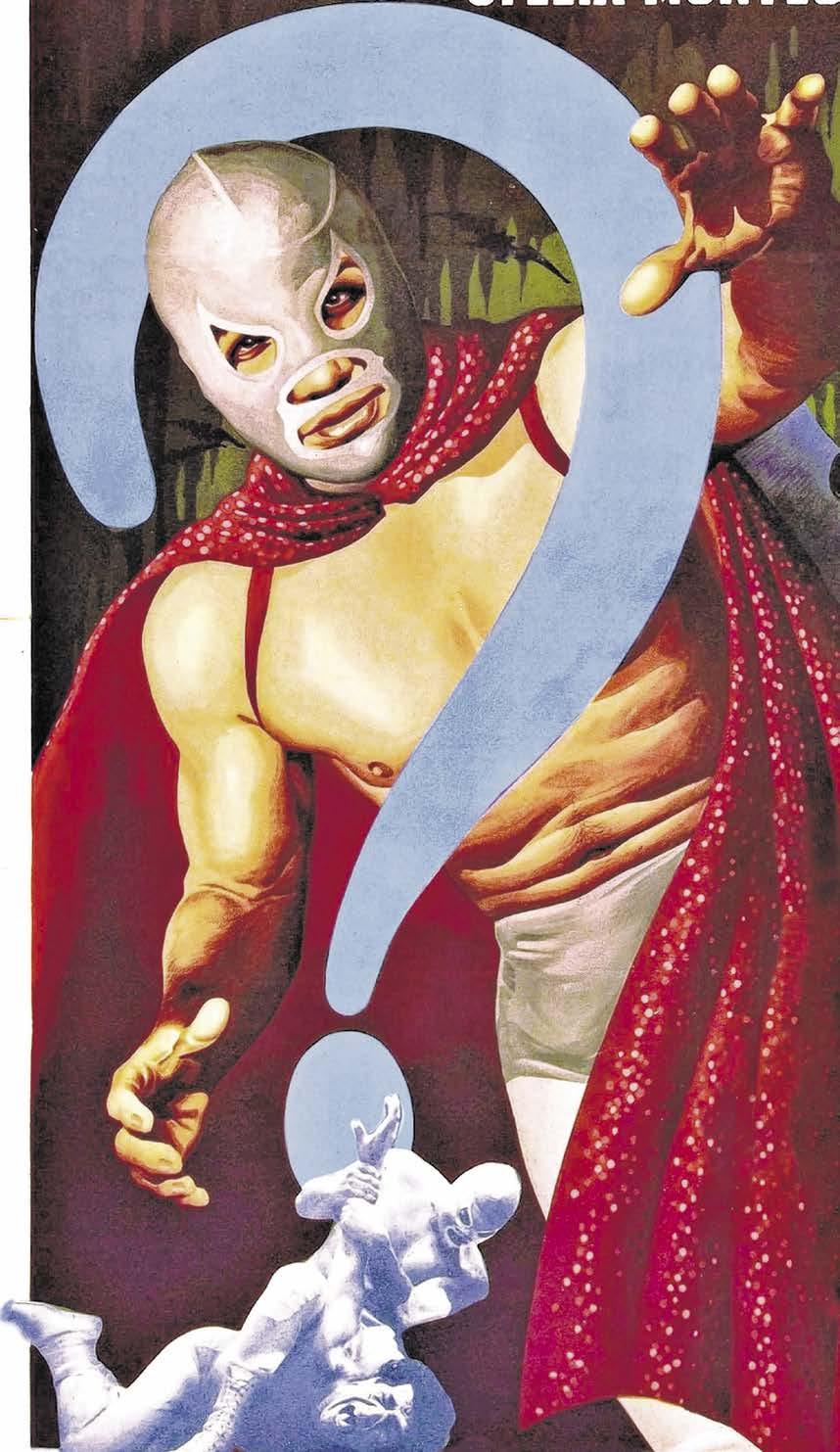

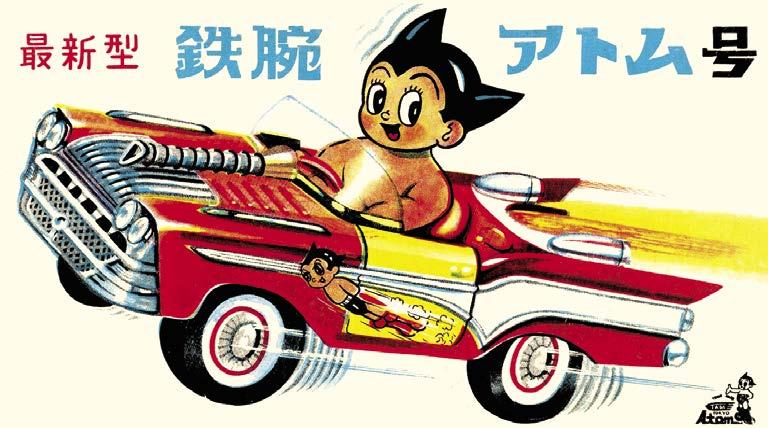

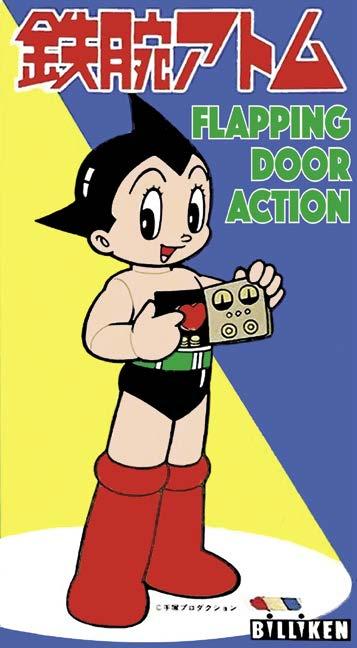

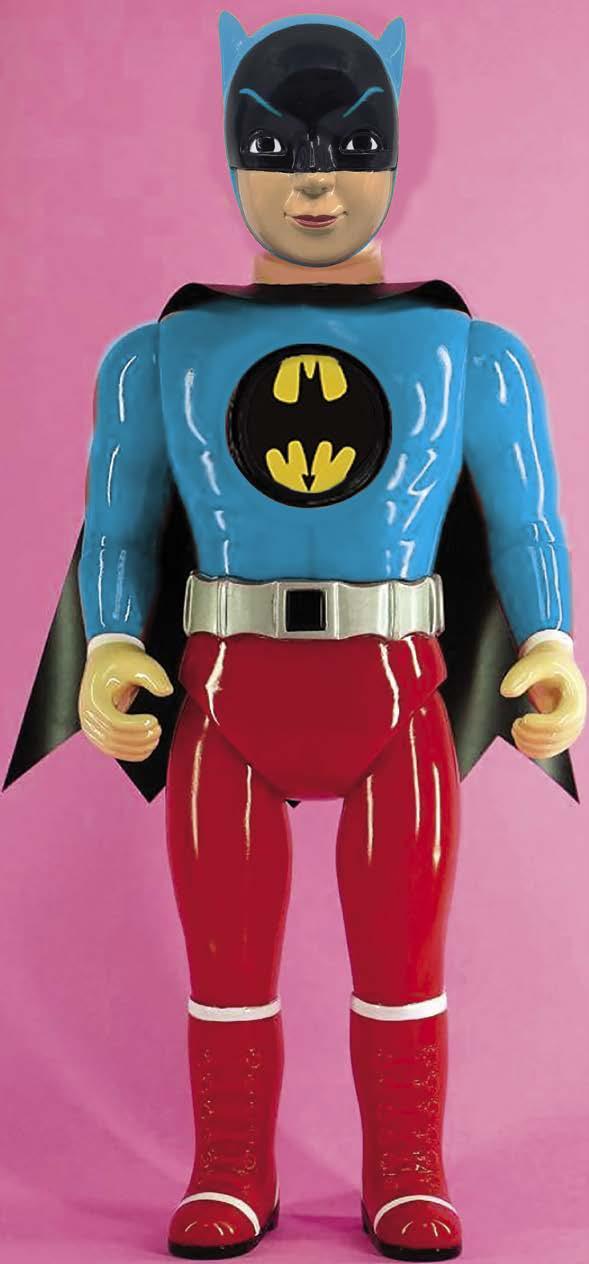

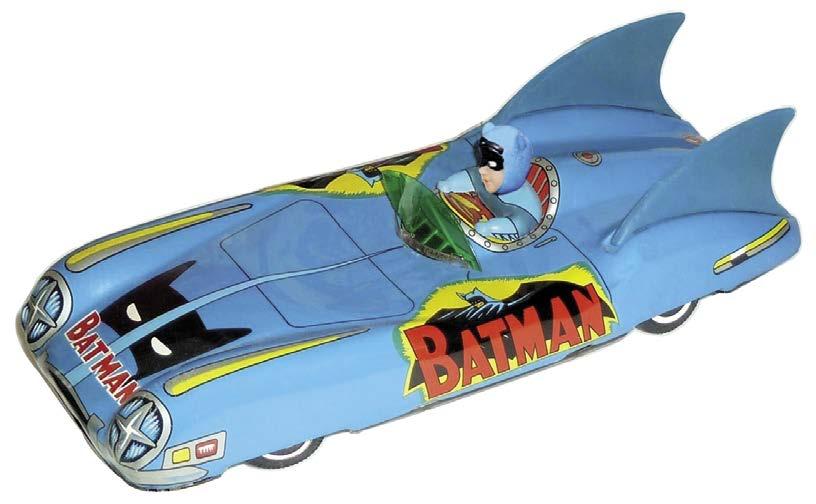

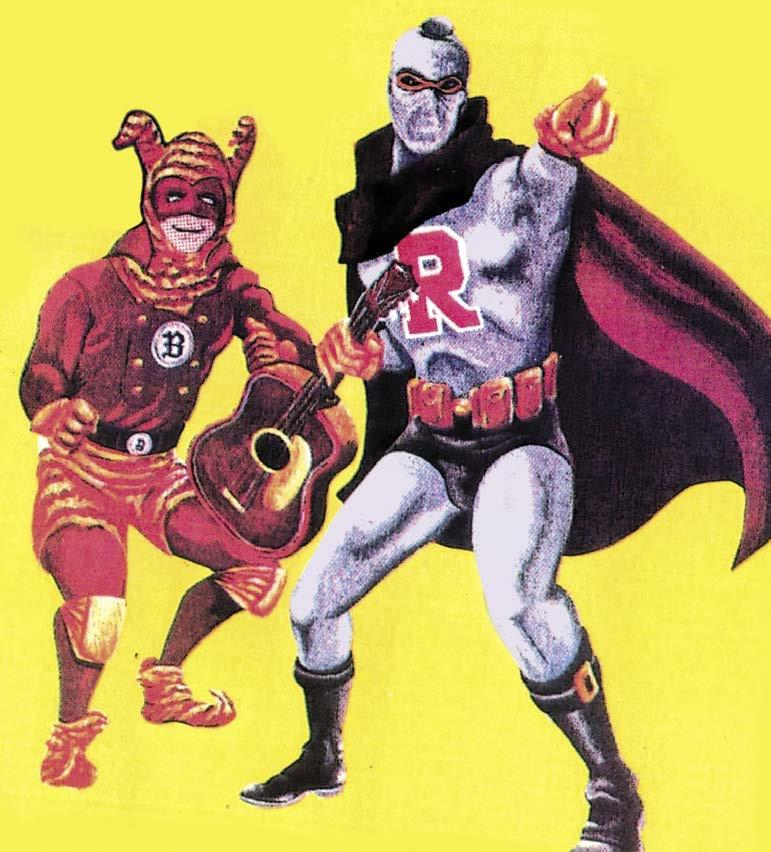

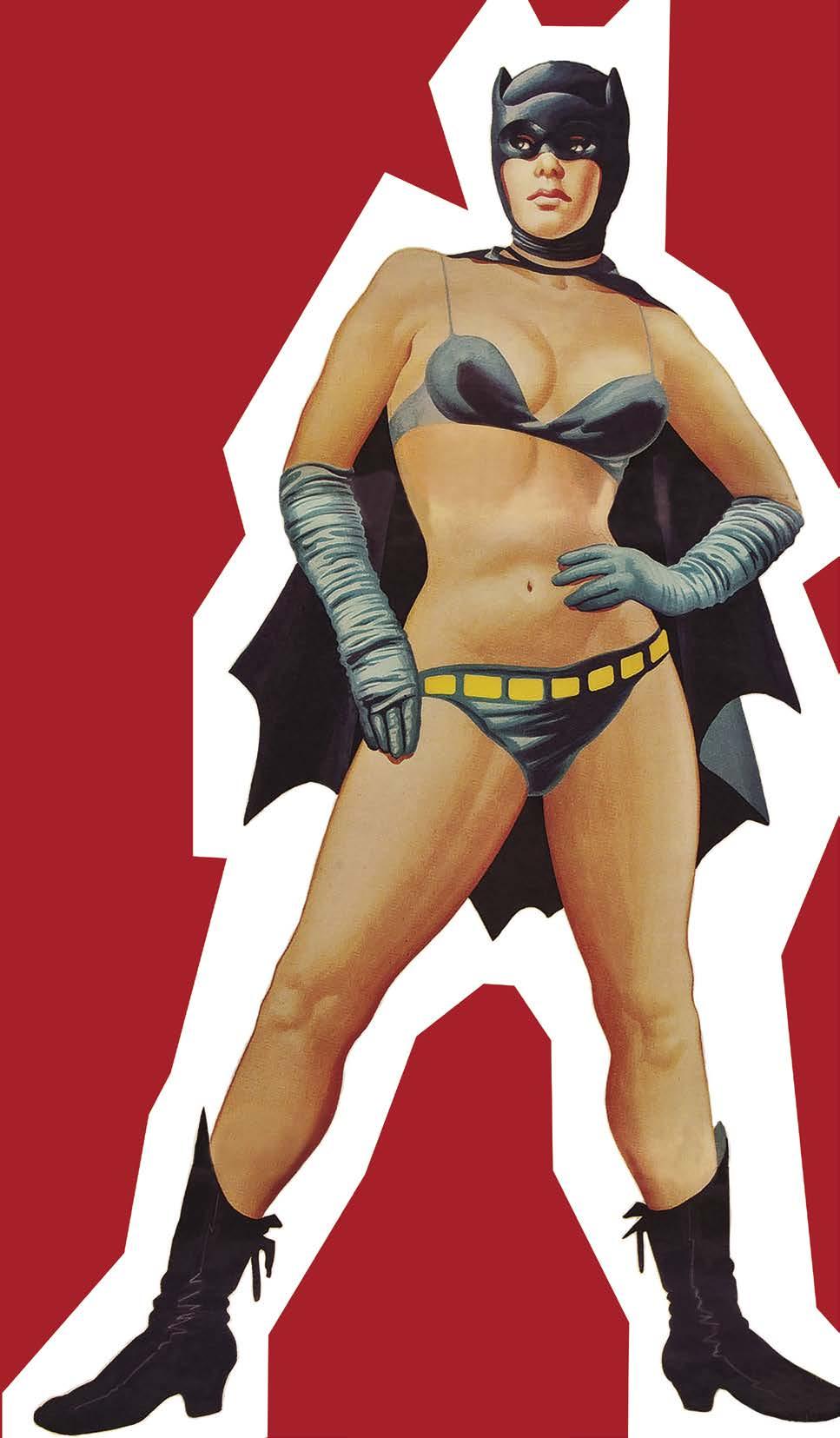

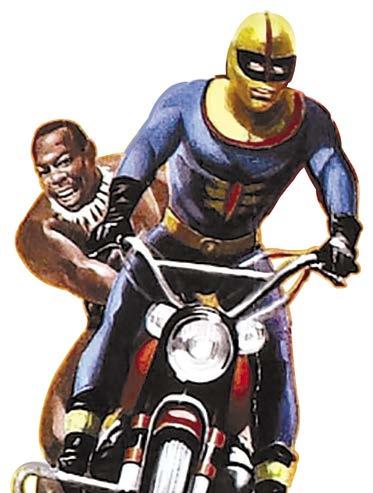

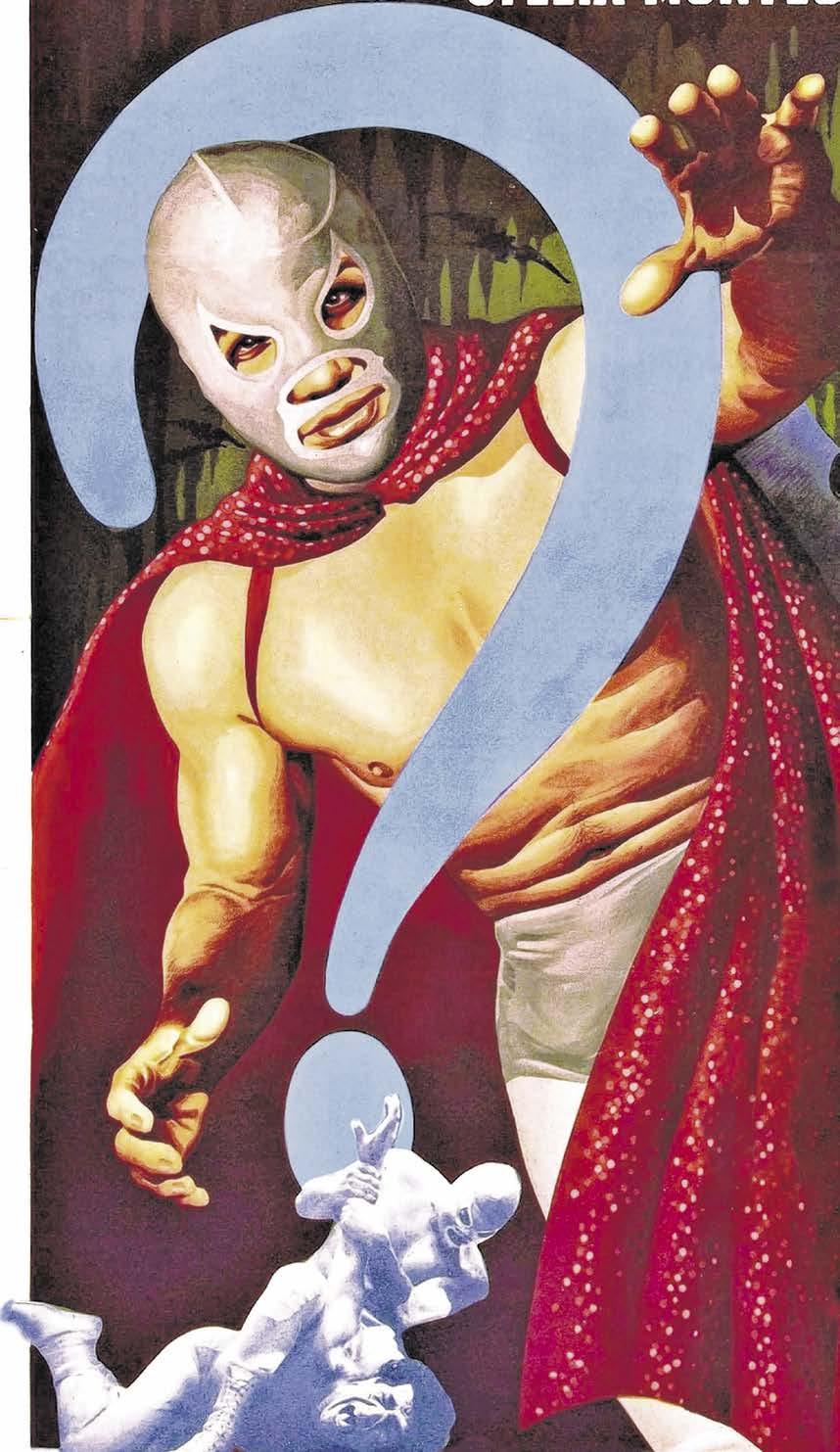

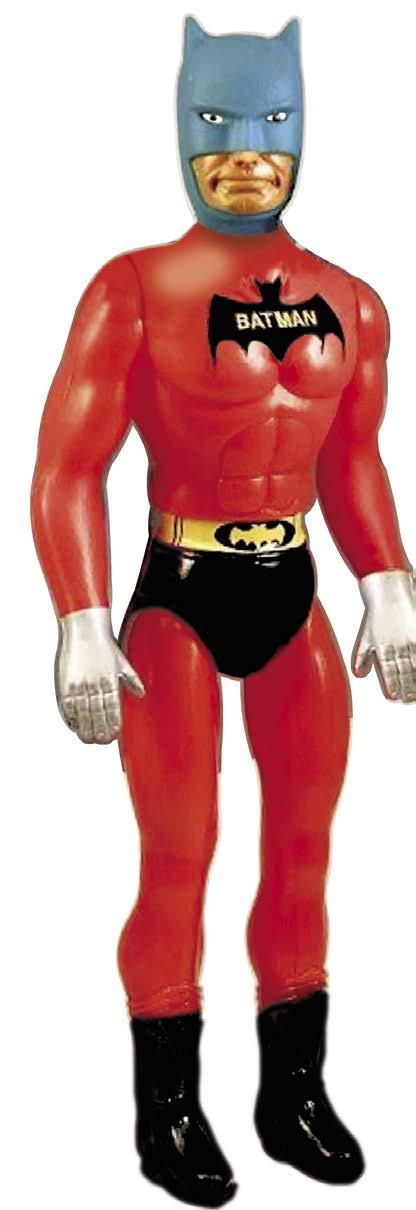

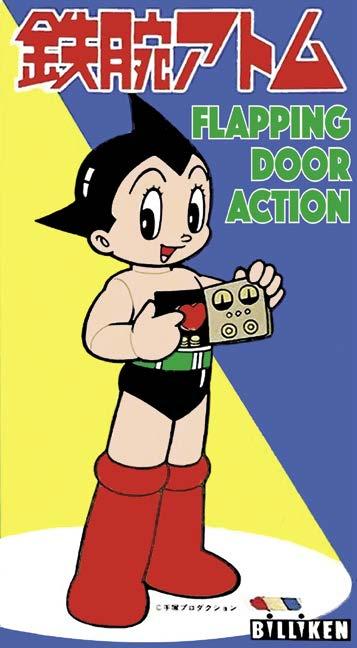

Tights, camera, action 162 ‘Batman’ the movie 164 Lee Meriwether 166 ‘Rat Pfink and Boo Boo’ 167 A tale of two Batwomen 168 Superhero imports 170 Medium in flux 138 Carmine Infantino 141 Joe Giella 142 Batman comics vagaries 143 Creating Batgirl 145 The Marvel bump 146 TV character comic books 150 Parody panels 153 The superhero glut 154 3 All rights reserved under international copyright conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from Mark Voger, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review. Address inquiries to Mark Voger c/o: TwoMorrows Publishing. Photos credited to Kathy Voglesong © the estate of Kathy Voglesong Written & designed by: Mark Voger Publisher: John Morrow Proofreader: Kevin Sharp “Zowie! The TV Superhero Craze in ’60s Pop Culture” © 2024 Mark Voger ISBN-13: 978-1-60549-125-7 First printing, July 2024 Printed in China Front cover: Ka-Pow © Amalgamated Superheroes; playing card and Punchboy toy © current copyright holders; “Wild World of Batwoman” poster detail © ADP Productions; Aquaman mask © Ben Cooper & © DC Comics Inc.; Super Dracula by Tony Tallarico © Dell Publishing; Riddler cane and Batphone replica © Warner Bros. & DC Comics Inc. Frontispiece: Detail from “Rat Pfink and Boo Boo” movie poster © Morgan Picture Corp. Back cover: Captain Art Director and Zok! button © current copyright holders; Fly Girl © Archie Comics; Courageous Cat © Trans-Artists; Flash Gordon © King Features Syndicate; “Las mujer murcielago” poster detail © Cinematográfica Calderón Published by: TwoMorrows Publishing 10407 Bedfordtown Drive Raleigh, North Carolina 27614 COMICS PRINT MEDIA Insets: Toy box art © Captain Action Enterprises; Polly © Dell; “Las Mujer Murcielago” © Cinematográfica Calderón; “Argoman” © Fida Cinematografica; Julie Newmar photo © Kathy Voglesong MOVIES CRASH & COMEBACK COLLECTIBLES For Nairb AFTERMATH Rise of an industry 96 Games people played 97 Heroes of Halloween 98 Batmabilia 104 Japanese visions 108 Green Hornetabilia 111 Marvelous merch 113 Hanna-Barbera stuff 114 Captain Action in action 116 Super Soakys 120 Masked on magazines 122 Book ’em 128 Trading cards 130 Norman Saunders 132 Death of the Dozierverse 172 1989: Twice upon a time 173 Modern superhero movies 177 Bruce Wayne in Gotham 178 Respect at last 182 Detective story 184 Epilogue 186 ‘The Super Zero Awards’ 188

Everything was Batman in 1966. You had to be there.

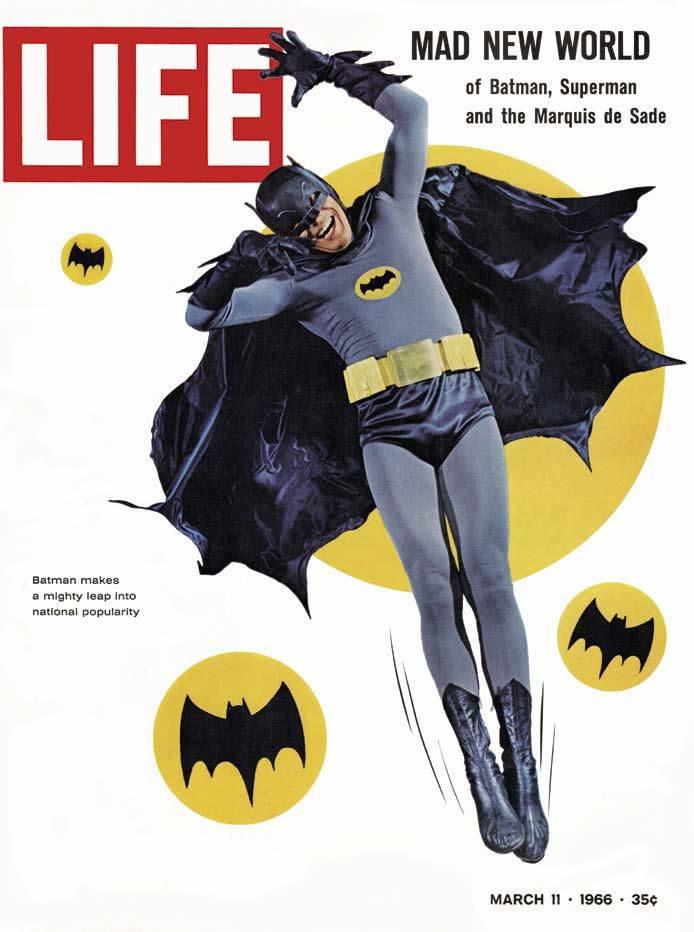

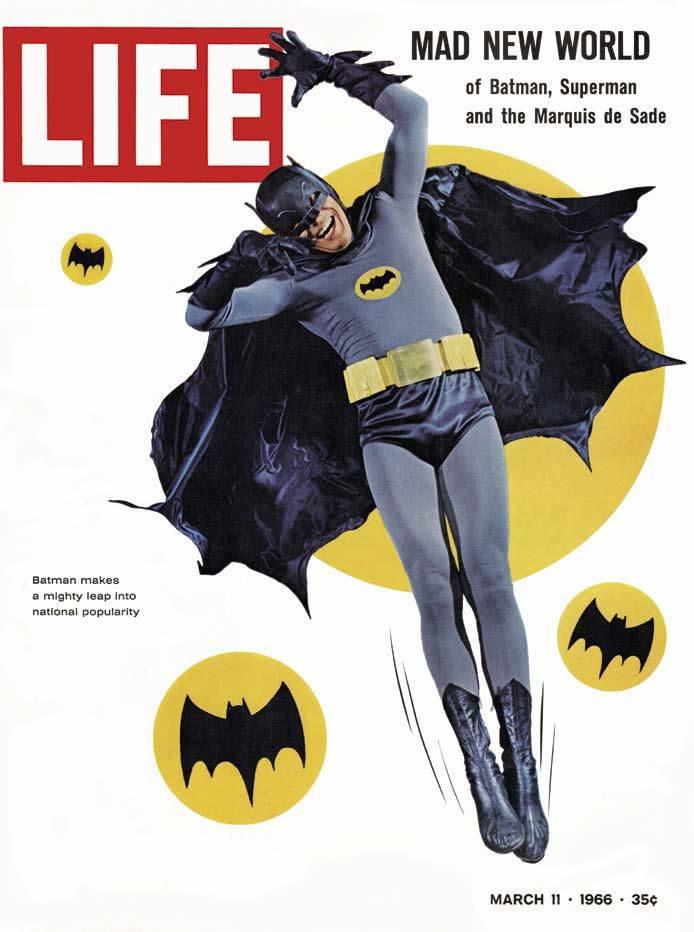

Can you name an actor who landed on the cover of both Life and Mad magazines in the same year? Adam West, the star of TV’s “Batman,” had that honor. West was also granted a papal audience, and learned that Pope Paul VI was a bat-fan. Hollywood elite clamored for roles as “guest villains” on the TV show.

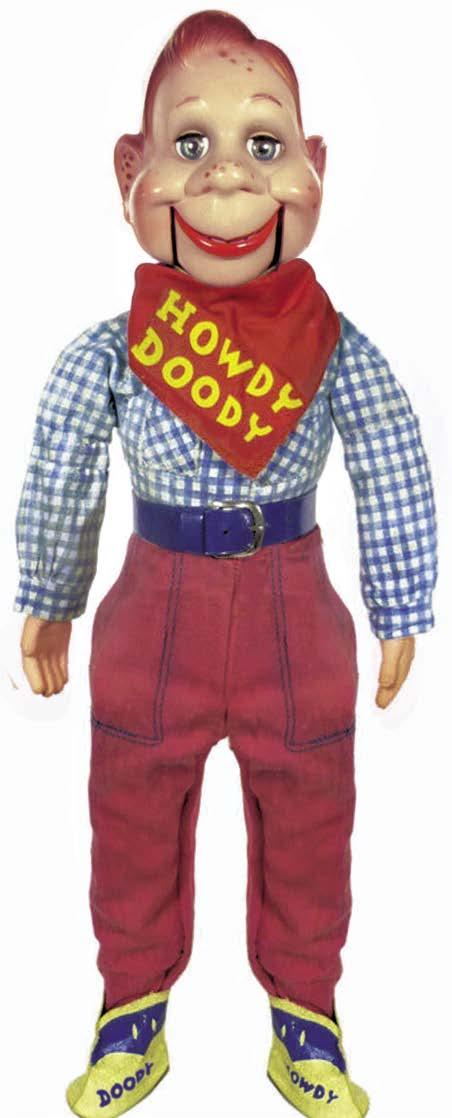

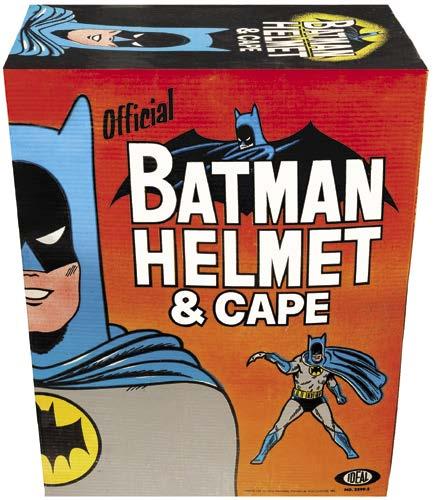

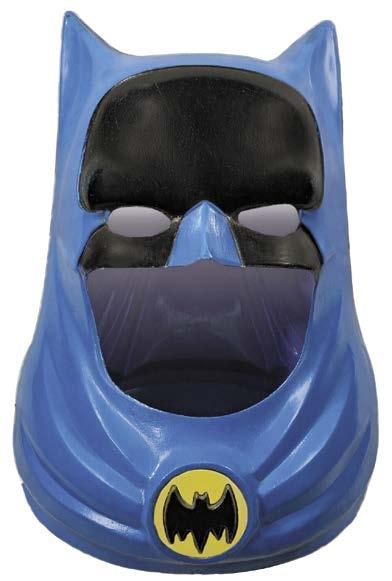

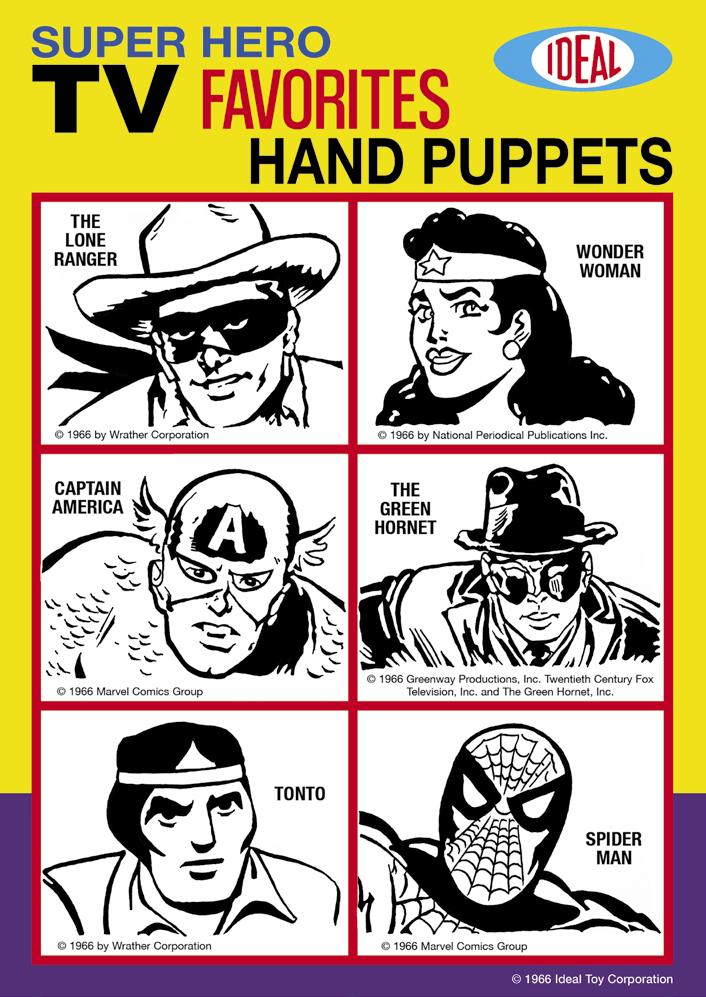

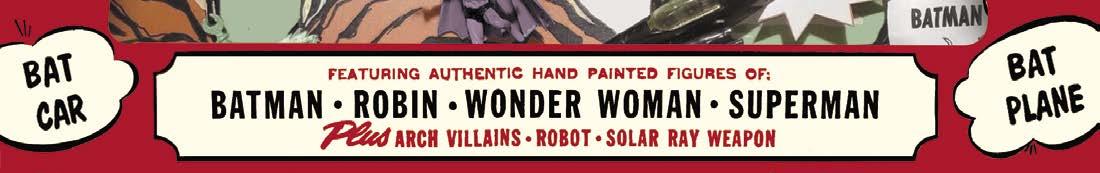

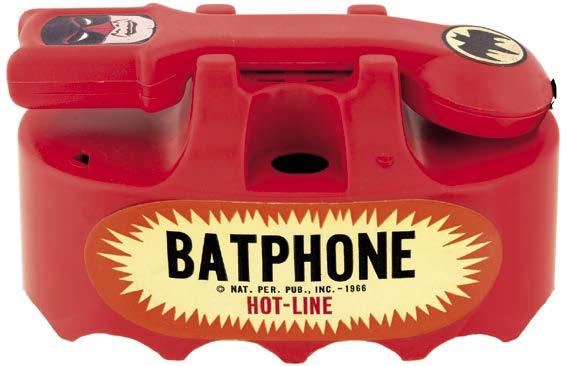

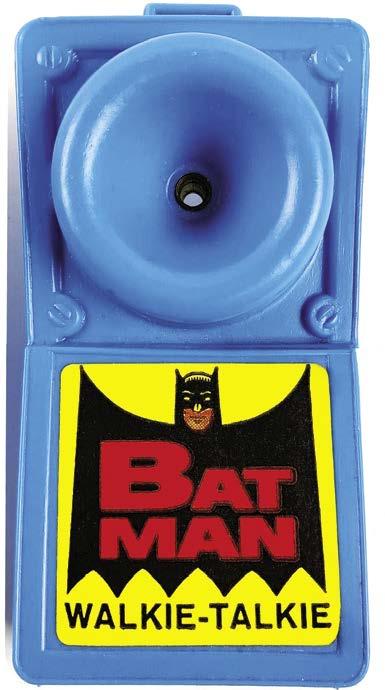

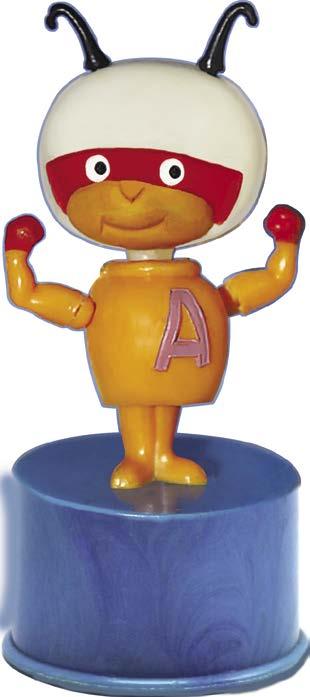

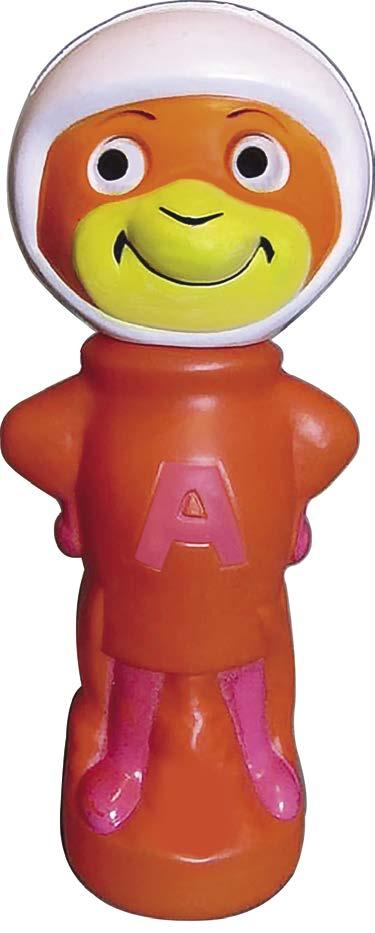

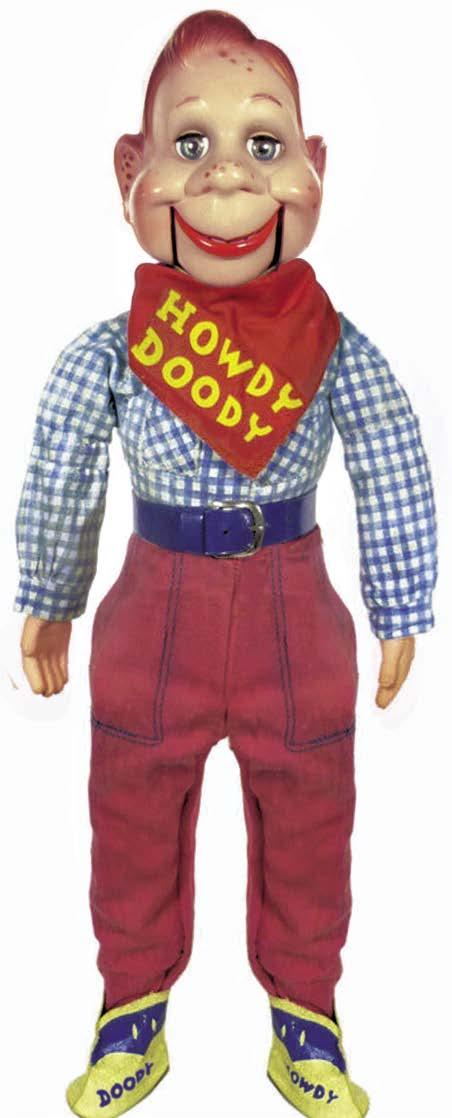

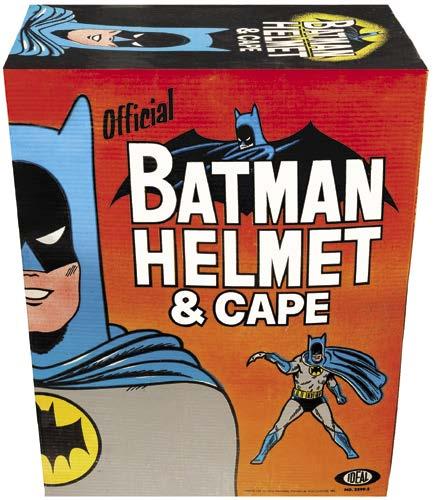

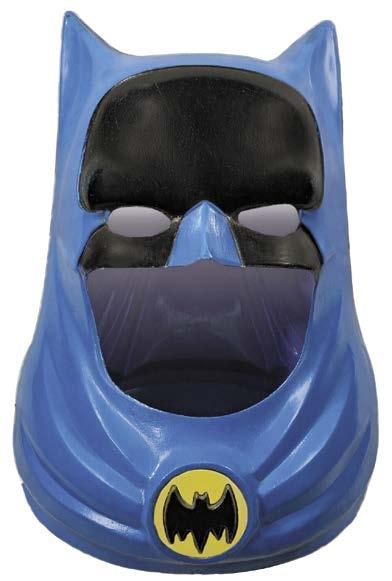

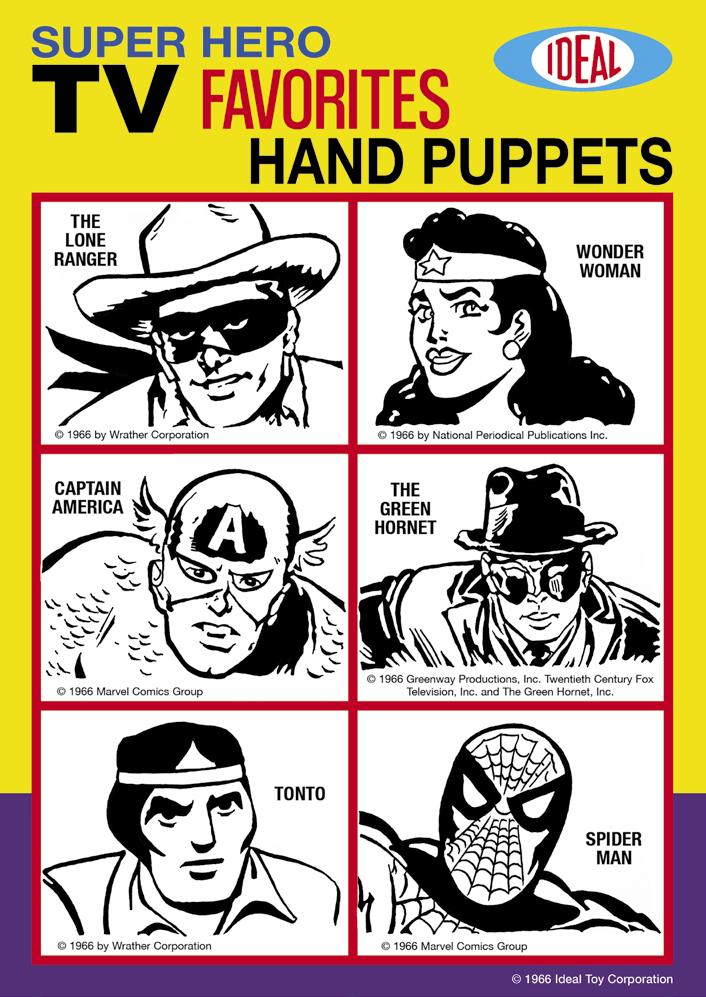

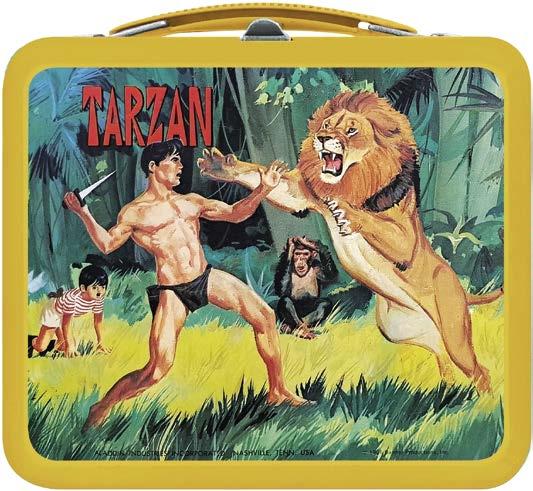

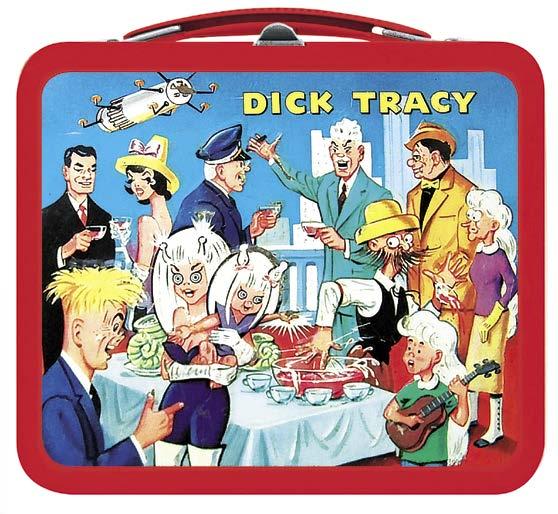

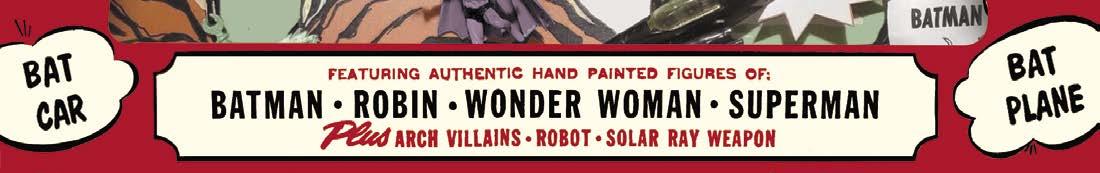

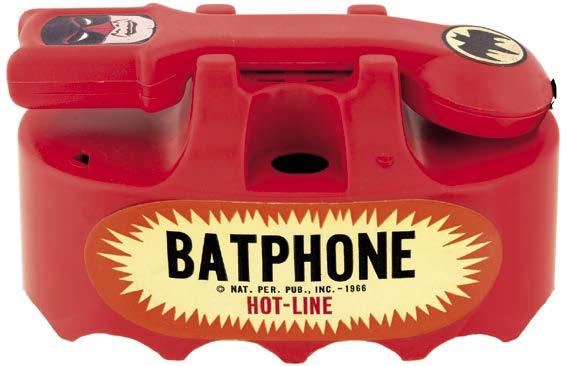

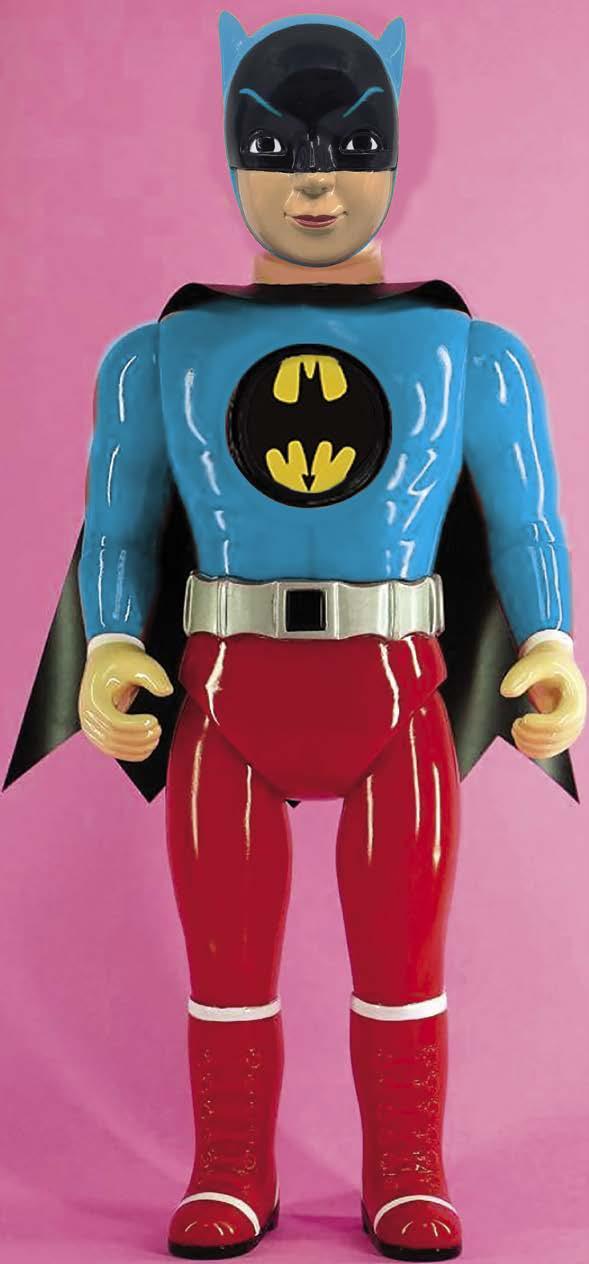

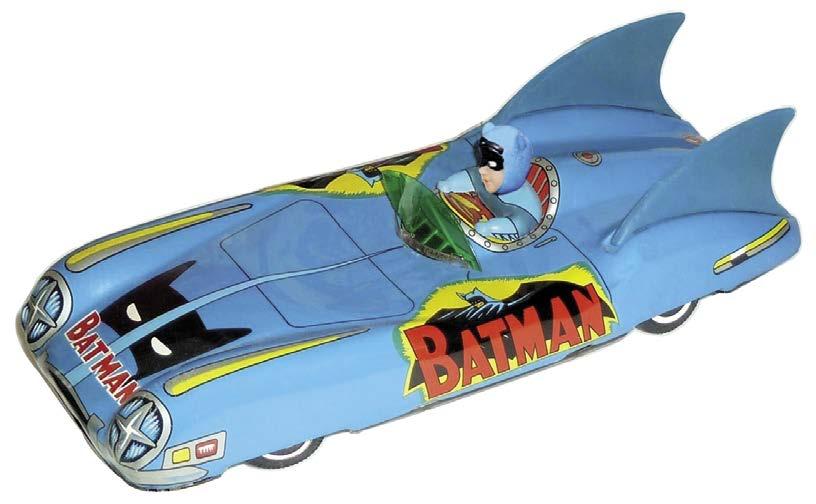

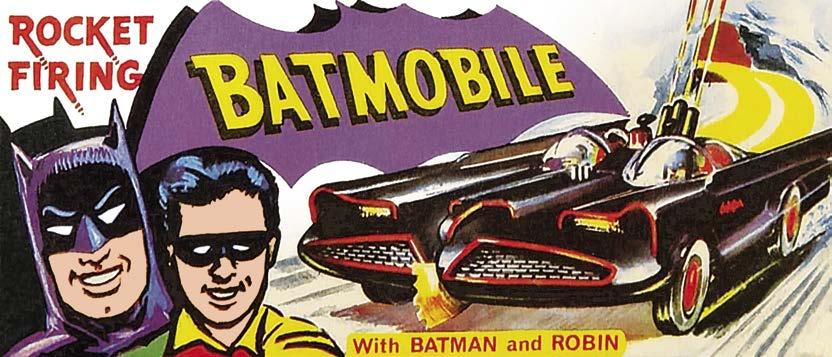

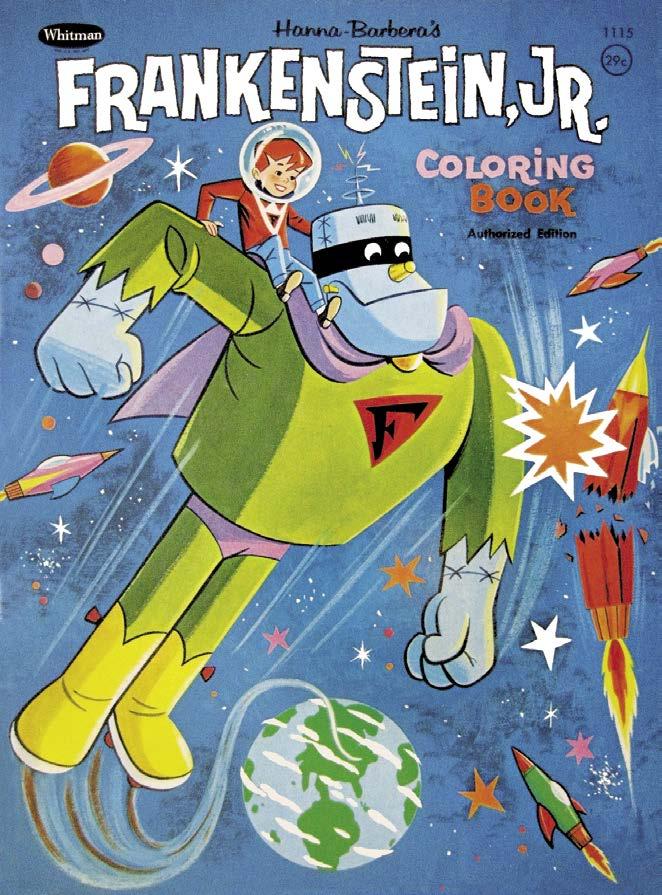

Wherever you turned, you saw the wholesome faces of Batman and Robin smiling on every kind of merchandise: lunch boxes, puppets, bubble-bath toys, model kits, trading cards, Halloween costumes, comic books (of course), paperbacks, record albums, coloring books, play sets, board games, buttons, Big Little Books. Miniature Batman comic books were inserted as premiums inside boxes of Kellogg’s Pop-Tarts. So, yeah, Batman always taught you to be a good citizen, but he also sold Pop-Tarts.

AS THE GIDDY BLUR GOT GIDDIER IN ’66, YOU

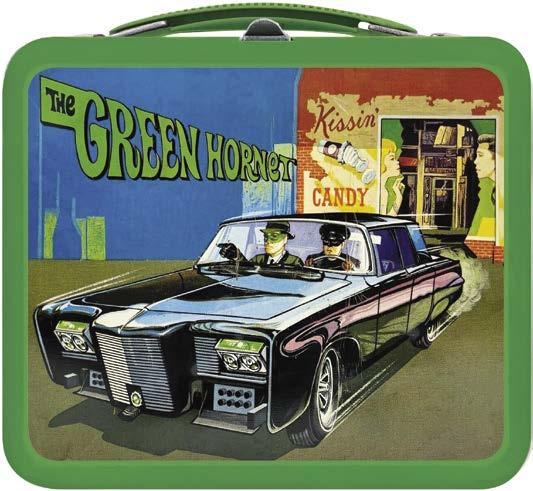

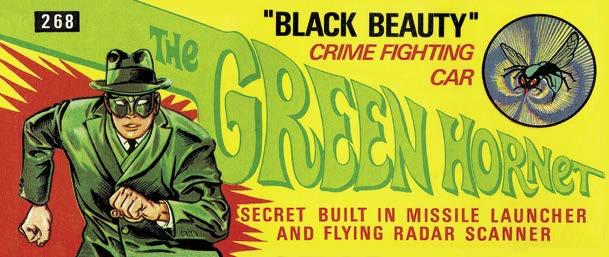

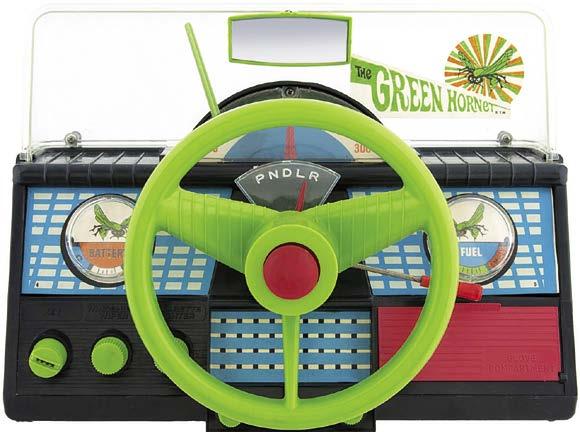

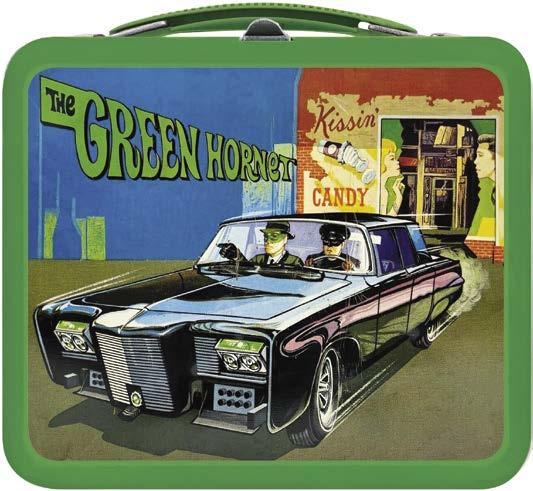

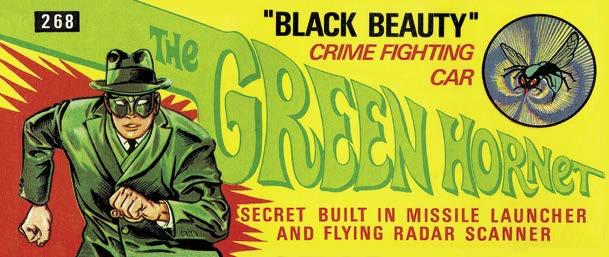

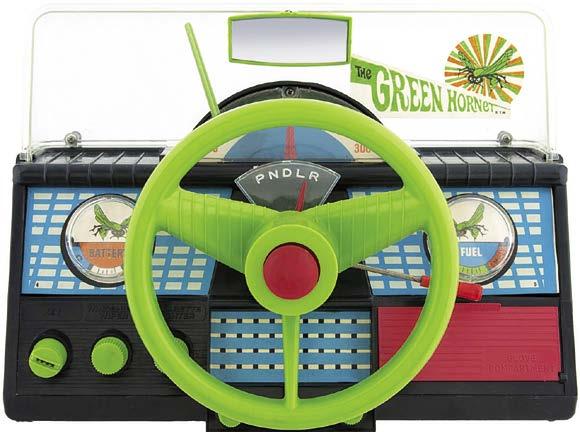

began to notice that beyond Batmania itself, an overarching mania for superheroes in general was creeping into the culture. “Batman” showrunner William Dozier followed up with “The Green Hornet” starring Van Williams and Bruce Lee. Like Batman, the Hornet had a trusty sidekick and a sweet ride, but the similarities ended there. “The Green Hornet” was a bit more serious, more adult, which may account for its status as a one-season wonder.

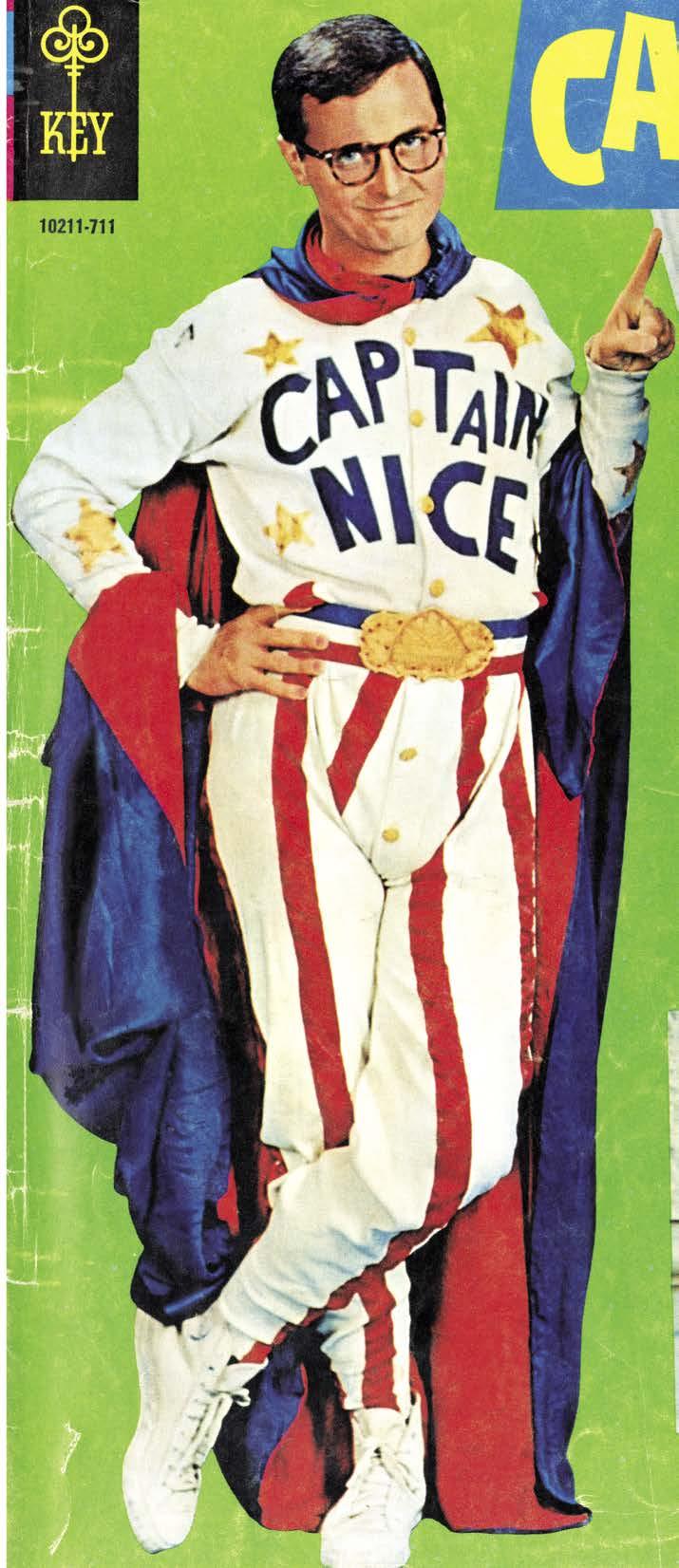

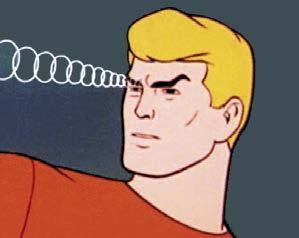

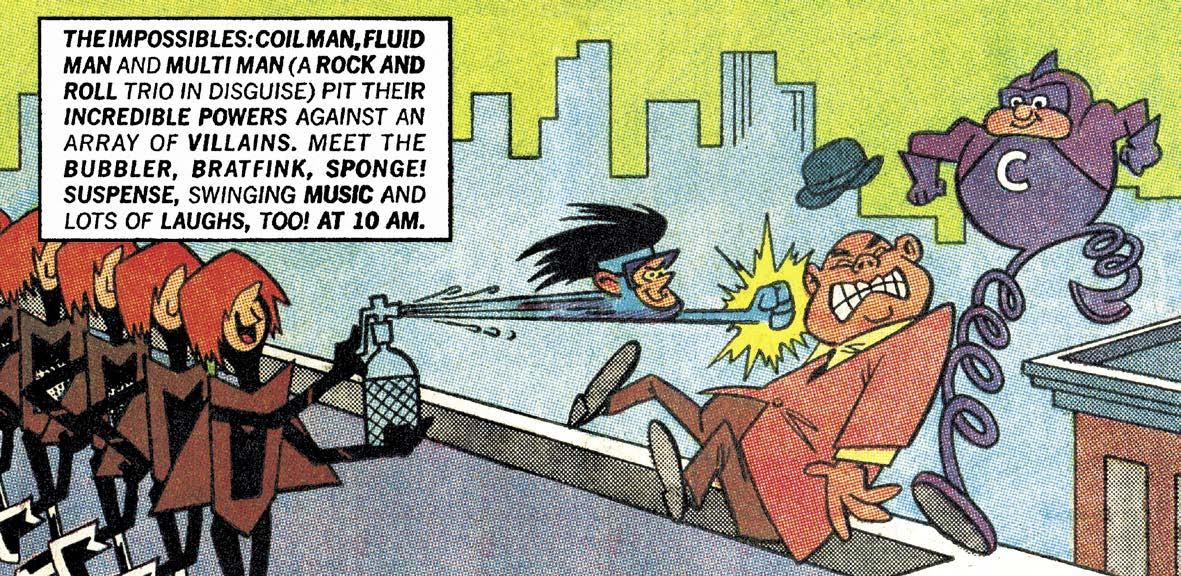

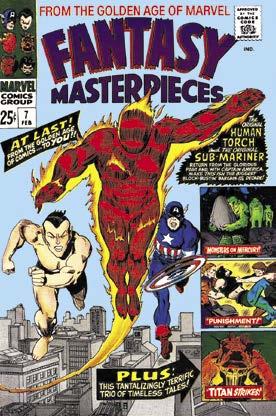

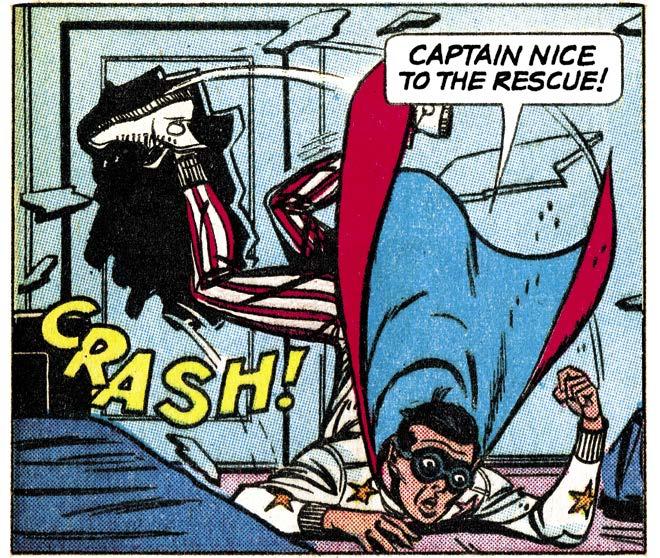

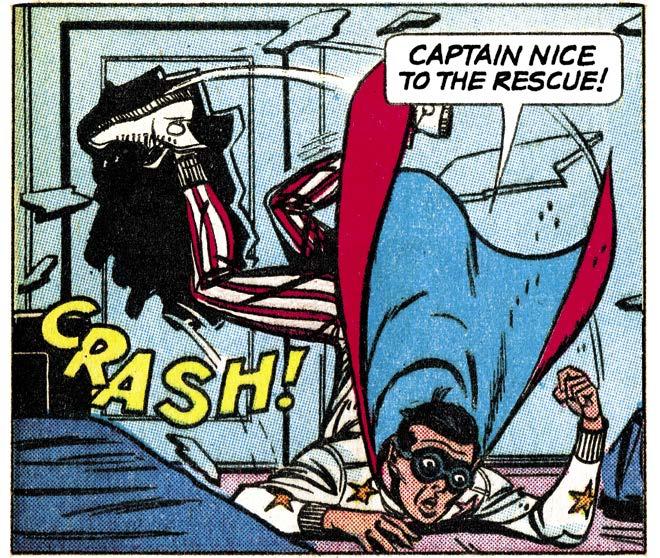

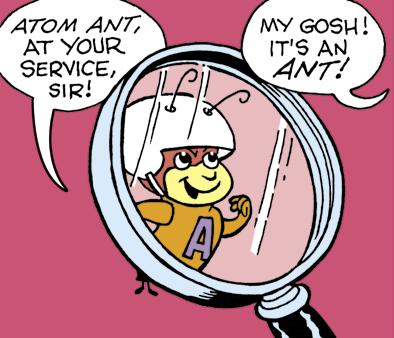

Networks greenlit not one, but two superhero sitcoms: NBC’s “Captain Nice” and CBS’s “Mr. Terrific.” Grantway-Lawrence’s threadbare but charming “The Marvel Superheroes” recycled actual comic-book art in “limited animation” at its most limited. But, hey, it introduced many of us little ones to Jack “King” Kirby.

The medium of comics — birthplace of the superhero genre — itself became obsessed with capes and cowls once the craze hit. Publishers who’d given up on the genre a decade earlier (Charlton, Harvey, ACG, Archie Comics) were suddenly dusting off old heroes or cooking up new ones. Meanwhile, the “Big Two” — DC and Marvel — pulled some wacky genre stunts during the craze.

BUT WHEN THE TV “BATMAN” CRASHED IN ’68, IT really crashed. The once-hot series had entered into a death cycle of sinking ratings and production values. Did the lackluster ratings trigger the lower budgets, or vice versa? Either way, West’s final flap of the cape happened just in time for the hippies, with their marijuana and their Nehru jackets, to commandeer the culture. Overnight, the ’66 Batman became an anachronism. The “Camp Age” (as author Michael Eury termed it) was receding fast.

To those who grew up watching the TV show, and generations thereafter who saw it in reruns, “Batman” became a pleasant memory. But in the comic books, the words POW! and BAM! were summarily banned. Something akin to a rehabilitation took place over the ensuing decades, with the character facing increasingly less fanciful, more reality-based threats. In the comics milieu, this trend wasn’t unique to Batman. Overall, creatives strived to make superhero characters more “relevant.” Alas, Batman comic books were no longer suitable for 8-year-olds.

It all led to writer-artist Frank Miller’s influential (to say the least) revisionist miniseries Batman: The Dark Knight Returns, which was collected into a buzz-magnet trade paperback in 1986. Miller set his story in a future in which Bruce Wayne had retired his Batman costume, and now dulls his post-traumatic stress with alcohol. Circumstances force Wayne to suit up once again, of course, or there wouldn’t be a miniseries.

Tim Burton’s 1989 blockbuster “Batman,” likewise not for the

This detail from an Aurora ad encapsulates the trend. Opposite: Superheroes (and villains) invade newsstands. © Aurora Plastics Corp.; On the Scene © Warren Publishing

Little Ones, soon followed and ignited a new wave of Batmania.

For the first time since West’s day, Batman was being discussed in the mainstream. The 1966-68 series became something of a scapegoat, an object of derision among a new breed of devout Batman geeks who believed West’s portrayal strayed too far from the dark avenger who hunts criminals from the murky shadows of Gotham City. This oversimplified view became the consensus among said geeks, but rates further discussion.

Though the “returning-Batman-to-his-brooding-roots” narrative makes for a sanctimonious sound bite, it ignores the fact that prior to the ’60s TV show, the comic book Batman only really brooded for about a year, his first. (Co-created by artist Bob Kane and writer Bill Finger, Batman debuted in 1939 in, all together now, Detective Comics #27.) Robin — a smiling lad in a colorful costume — was introduced in 1940 expressly to make Batman a less scary, more relatable figure to small-fry readers.

So here’s another way to look at the whole 1966 thing: The TV show “Batman” was, we can all agree, a comedy. West’s Batman was never intended to be “the” Batman. Over generations, the character had wildly differing iterations, and this was one more. The TV “Batman” was a lark, see? It was a comedy — and a clever, colorful, delectable one at that, one that happened to dominate the culture for a year or two before crashing and burning.

Not that the 1966 Batman ever really went away.

9

Roots of superdom

There were always superheroes. Some of them even wore tights.

Before streaming, before handheld devices, before the internet, before home video, before television, before moving pictures, before radio, before print, what did you have?

Word of mouth. (And Corinthian pottery.)

Folklore and legends, parables and myths, fables and old wives’ tales … these were “mass communication” in ancient times. To understand how the TV superhero craze of the 1960s came into existence, we must first establish where the notion of the “superhero” originated. Looking back — way back — it’s clear that humans have always needed heroes and, more to the point, heroes with special powers who operate on the side of good.

In short, better versions of ourselves.

Is Superman really all that different from Hercules, a legendary hero from Greek and Roman mythology of decidedly mixed lineage (god dad, mortal mom) and super strength?

Prometheus anticipated the Human Torch. Hammer-swinging thunder god Thor anticipated hammer-swinging thunder god Thor. Pegasus belongs in the League of Super Pets, yo!

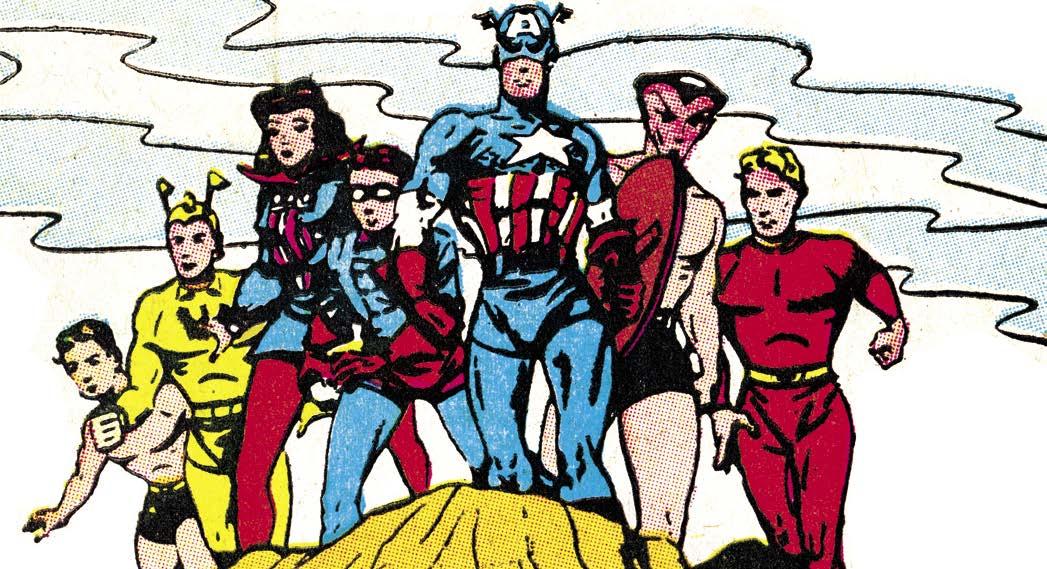

Were Jason and the Argonauts the first-ever superteam? Jason was the great grandson of a god; was raised by a half-man, halfhorse; married a sorceress; and went on a quest to find the fleece of a winged ram. (I could have sworn there was a Saturday morning animated series by Filmation titled “The Argonauts,” with Ted Cassidy as the voice of Jason and Casey Kasem as Acastus.)

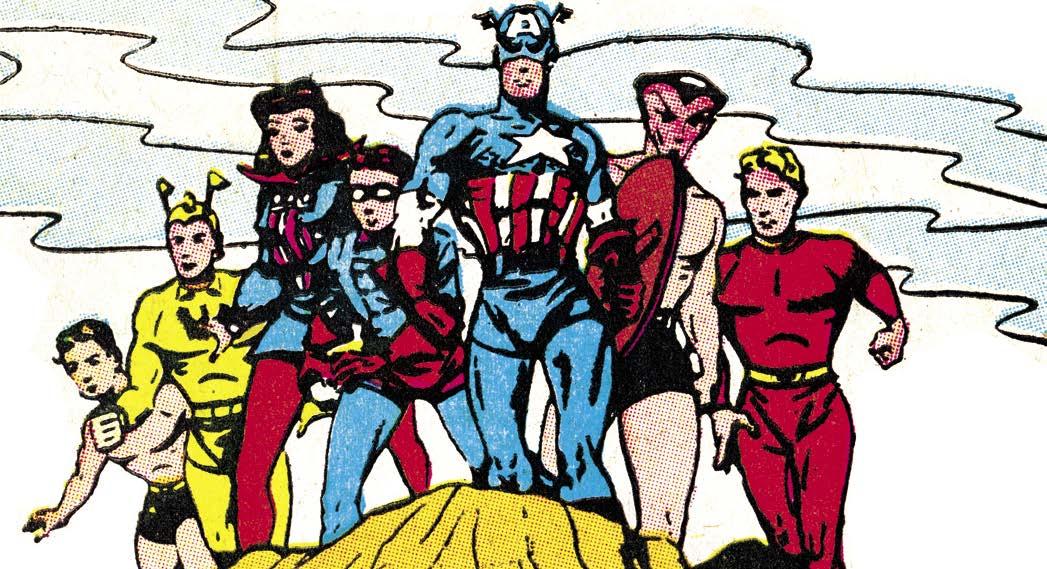

If the Argonauts were the original Justice League, doesn’t that make King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table the original Avengers? Robin Hood was an altruistic vigilante who “robs from the rich and gives to the poor.” His prowess with a bow and arrow were rivaled only by ... Green Arrow and Hawkeye.

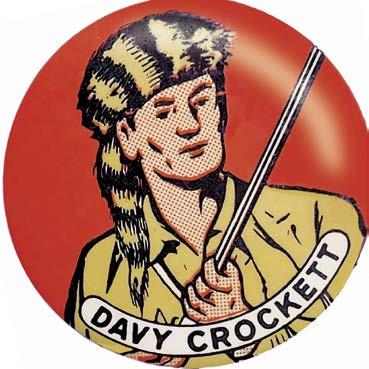

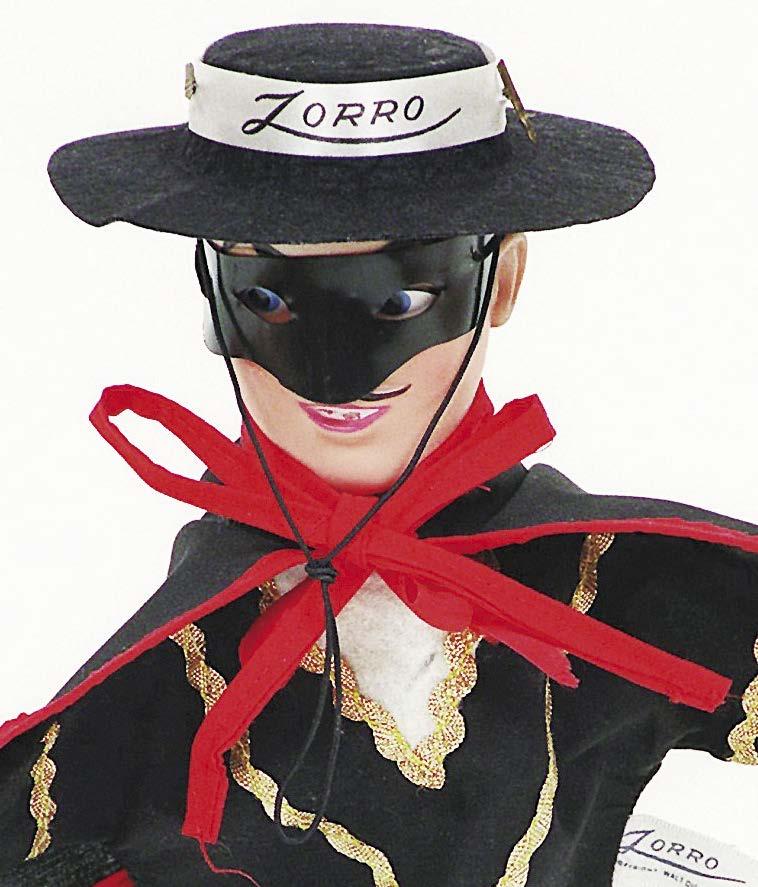

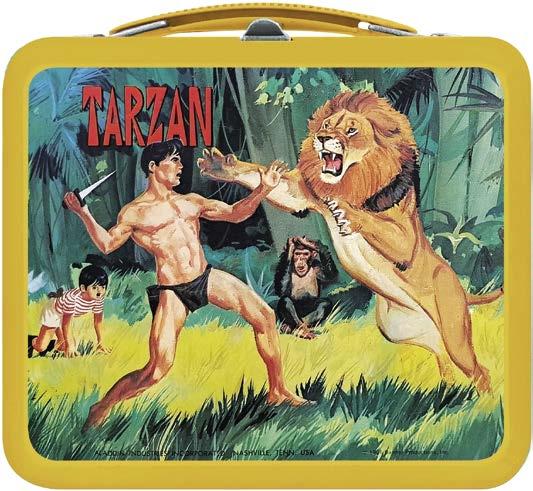

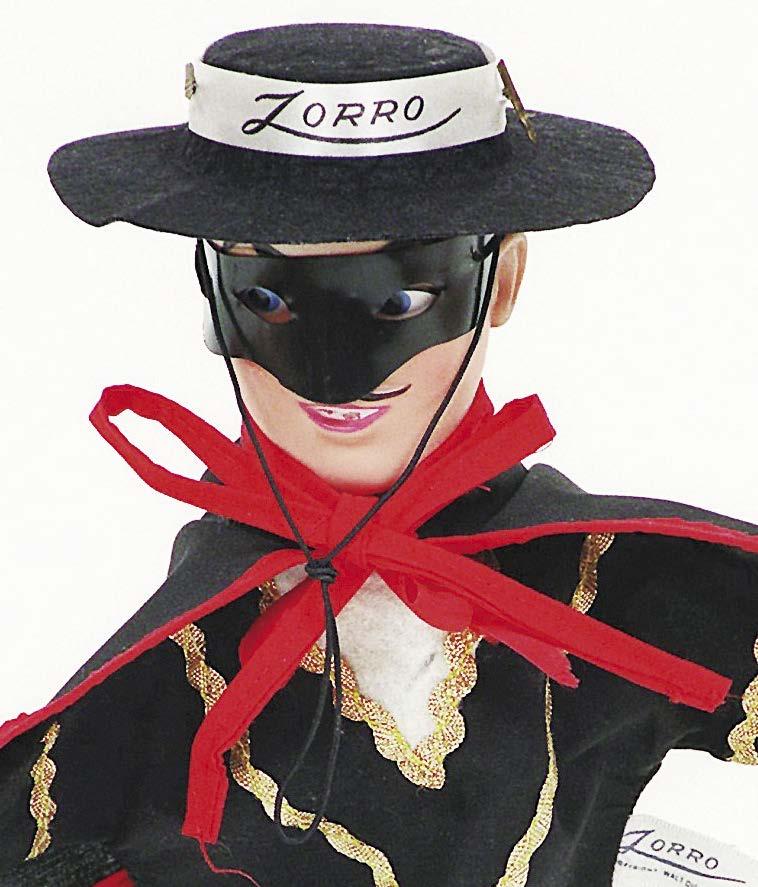

IN (RELATIVELY) MODERN TIMES, THE PULP fiction magazines of the late 19th century through the 1950s brought about many masked avengers and sci-fi heroes, some of whom influenced the creators of Superman and Batman. The Shadow, the Spider, the Black Bat, Tarzan, Zorro and a lot of deeper-cut characters (who have long since faded from collective memory) sprang forth from the pulps. Many of these characters were adapted to other media such as radio, movie serials and comics.

The jungle hero Tarzan debuted in The All Story (Oct. 1912) in “Tarzan of the Apes” by Edgar Rice Burroughs. The masked avenger Zorro debuted in All-Story Weekly (Aug. 1919) in “The Curse of Capistrano” by Johnston McCulley. Artist Margaret Brundage’s sexy-creepy lady with the vampire-bat headdress on the Oct. 1933 Weird Tales cover would upstage Batman or Catwoman. (Hot tip: Investigate Brundage’s work!)

Another prototype, Japan’s Ôgon Bat (or Golden Bat), debuted in 1931 in the quaint old medium kamishibai (or “paper theater”). Bold, acrobatic masked heroes pervaded the silent era of film.

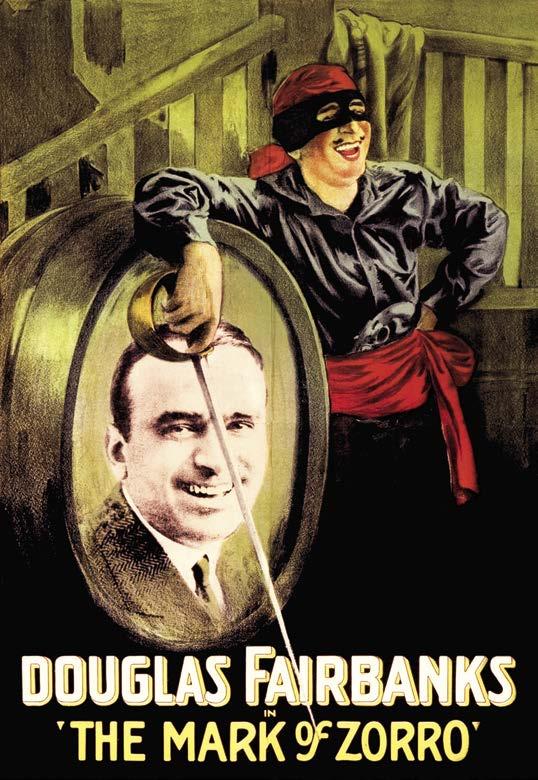

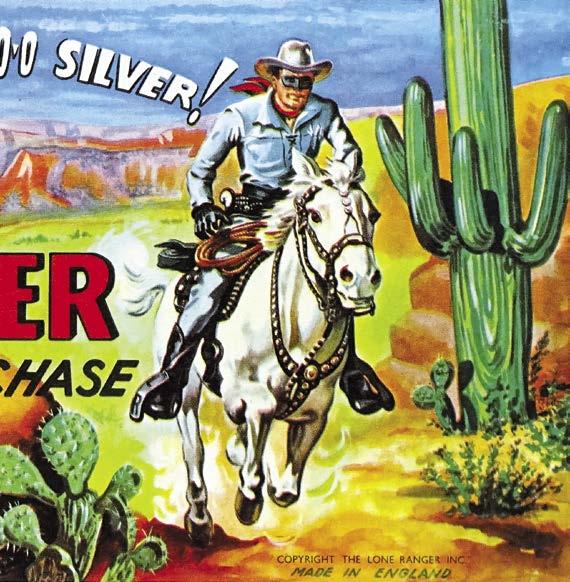

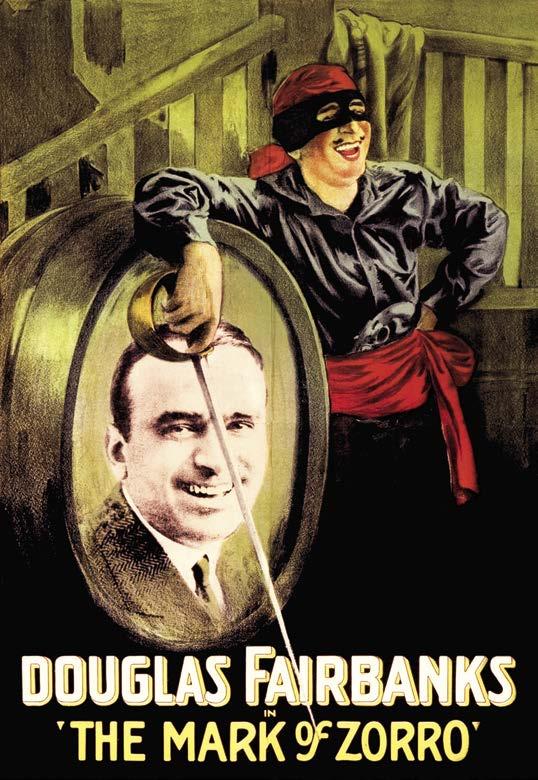

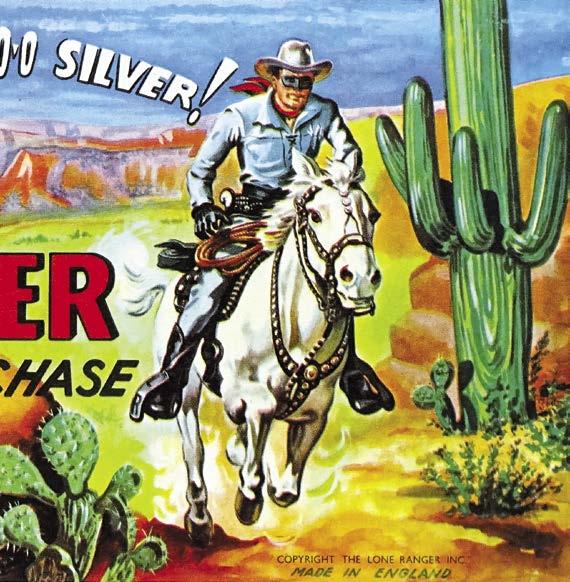

Zorro was only a year old when Douglas Fairbanks Sr. donned the mask in Fred Niblo’s 1920 swashbuckler “The Mark of Zorro.” Radio gave us heroes like the mysterious Shadow (in 1930). The Old West vigilante the Lone Ranger (in 1933) and his great nephew the Green Hornet (in 1936) were introduced by George W. Trendle and Fran Striker. Radio also provided a new venue for existing characters Superman (in 1940) and Batman (in 1945).

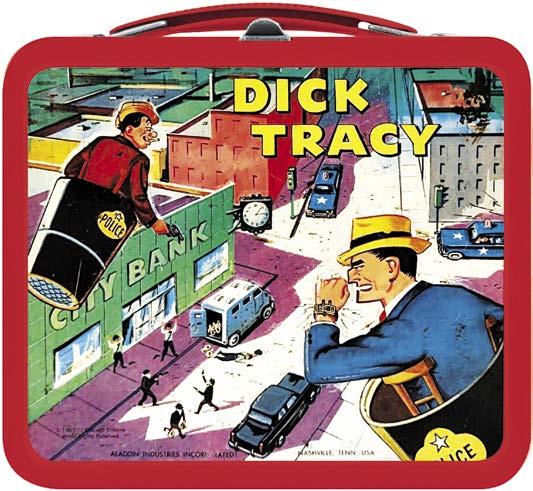

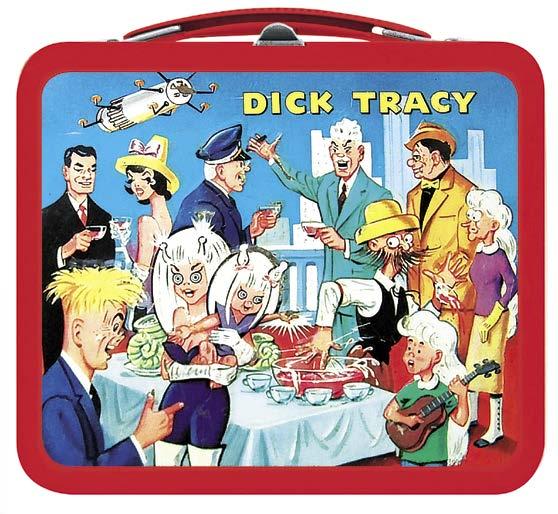

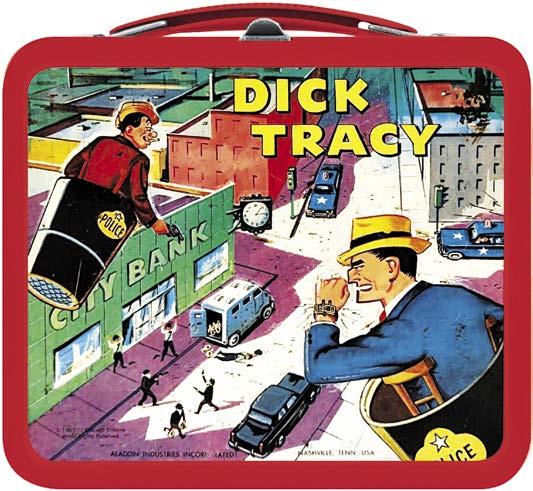

The newspaper comic strips brought us heroes that still seem timeless today. Such strips include Philip Francis Nowlan’s “Buck Rogers” (in 1929); Chester Gould’s “Dick Tracy” (in 1931); Alex Raymond’s “Flash Gordon” (in 1934); Lee Falk’s “The Phantom” (in 1936); and Hal Foster’s “Prince Valiant” (in 1937). Of these, Falk’s Phantom, “the Ghost Who Walks,” seemed most simpatico with the comic book superheroes who were soon to follow.

ORIGIN STORY

13

“Mark of Zorro” (1920) gave us an early masked avenger on film. Opposite: Genre thrills on pulp fiction covers. © United Artists; magazine covers © current copyright holders

“The Phantom, as you may know, is the first masked hero in the comics,” said Lee Falk. “He came before Batman, before Superman.”

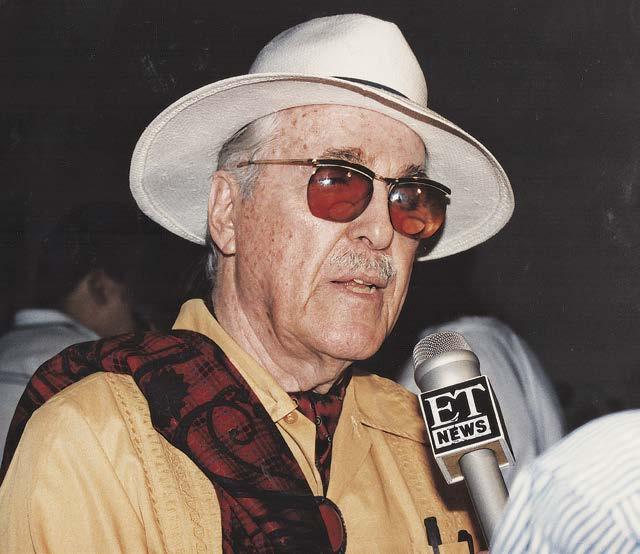

St. Louis native Falk (1911-1999) created the comic strip heroes Mandrake the Magician (in 1934) and the Phantom (in 1936) for King Features. “The Phantom” — for which Ray Moore was the founding artist — presented a jungle hero in a lavender “union suit” who was descended from a 400-year line. The Phantom wore a mask and skull ring passed down from father to son ever since pirates murdered the original Phantom’s father. Each Phantom has taken the “Oath of the Skull.” Like Batman, the Phantom possessed no super powers, just brains and brawn.

“I had the idea for a man of justice, a crimefighter in sort of a mask going through the jungle,” Falk once told me. (I interviewed the writer in 1991 and 1996.)

“Kind of odd. I had nothing to do with the color process. I didn’t even think about color until the Sunday page (which debuted in 1939). We made him purple. A man in purple going through the jungle — he should have been camouflaged, in green.

“Anyhow, I worked from the heroes of antiquity, of Asia, Greece, Rome, the great heroes of Western Europe, Spain, France, Ulysses, all the heroes. So the Phantom was sort of a combination of those heroes. He’s a hero, a jungle-man hero. I was certainly influenced by what I read as a kid. I grew up with Tarzan, and the Phantom was sort of like a modern Tarzan swinging through trees. I didn’t have a horse for him in the beginning; he had to swing like Tarzan. But he was quite different from Tarzan. He was a college graduate and so forth.

Some of these aspects — the murdered parent, the oath, the tights, the cave — were soon echoed in Batman and Superman.

“And also, some of it might have been from ‘The Jungle Book’ by (Rudyard) Kipling. That story fascinated me as a kid. In fact, if you remember, in ‘The Jungle Book’ there was the Bandar-log, the monkey who befriends the boy. So I called my tribe — the group that sort of protects the Phantom — I called them the Bandar, which is my homage to Kipling.”

BUT THE IDEA OF THE LONG

LINE

OF PHANTOMS,

and even the jungle setting, came along after the strip’s 1936 debut.

“Actually, when I started him, he was a playboy named Jimmy Wells,” Falk pointed out. “He was a friend of Diana’s, who was the heroine. Well, it turns out that at night, the playboy is the Phantom. She gets in some trouble with some gang. Unbeknownst to her, he’s trying to help her. He comes in the night, this masked man, very romantic. She sort of wonders who this mysterious masked man is, not realizing that it’s Jimmy Wells, who is an old friend of the family and wants to marry her.

“So I began with the idea of Jimmy Wells, who was like Superman’s Clark Kent. Where I adopted the idea from, I have no idea. The idea I had first was just the Phantom. In a story, I took the Phantom to the jungle, and then I left him there. So I actually adopted a whole new legend about the Phantom, bit by bit, over the first year. He became the 21st generation of a whole line of Phantoms dedicated to the destruction of piracy — which stands for criminality of all kinds — piracy, cruelty and injustice.

“This was passed down from father to son. And that became the legend of the Phantom. That became the whole idea. It was very developed. There was a Skull Cave, which looked like a big skull, which was created by nature. And we went on from there.”

“The Phantom was, in part, the inspiration for them,” Falk said. “Batman has a Batcave like the Phantom’s Skull Cave. They (Batman and Superman’s creators) weren’t being plagiarists; they were just inspired by the first thing they saw.

“The Phantom inspired a whole lot of costumed superheroes, as they became known. But the Phantom was never a ‘super’ hero. He wasn’t like Superman. He wasn’t immune to being hurt. He would get hurt; he’d be wounded; he’d bleed. So he was more like Batman in that respect. That kept him very interesting.”

At the time Falk and I spoke, “The Phantom” was the longestrunning comic strip still being written by its creator.

“I’ve always kept control,” Falk said. “I still do storyboards, composition. My storyboards are like film scripts. My scripts first show the action, with a description of that, and characters, dialogue. And then you go on to the next panel and so forth. That way, I’ve kept control of the feature. But my artists are excellent. The artists usually improve on what I give them.”

As for being the longest-running writer: “Well, most of them are dead. I started when I was 19. Most of the other guys were in their 30s and 40s, which was still kind of young. But I was very young. That’s why I’ve been doing it for 60 years.”

Said Falk of his other comic-strip creation: “Mandrake has good foreign circulation, because he translates well. There’s a lot of humor to him, but it’s not jokes. It’s humor out of the situation.

“Mandrake and (his sidekick) Lothar were the first Black and White partners, so to speak, in a comic strip. In fact, Lothar was the first Black character in comics, ever. The Phantom and Mandrake translate much better in foreign languages, because they’re not particularly American. They’re just men of the world.”

14

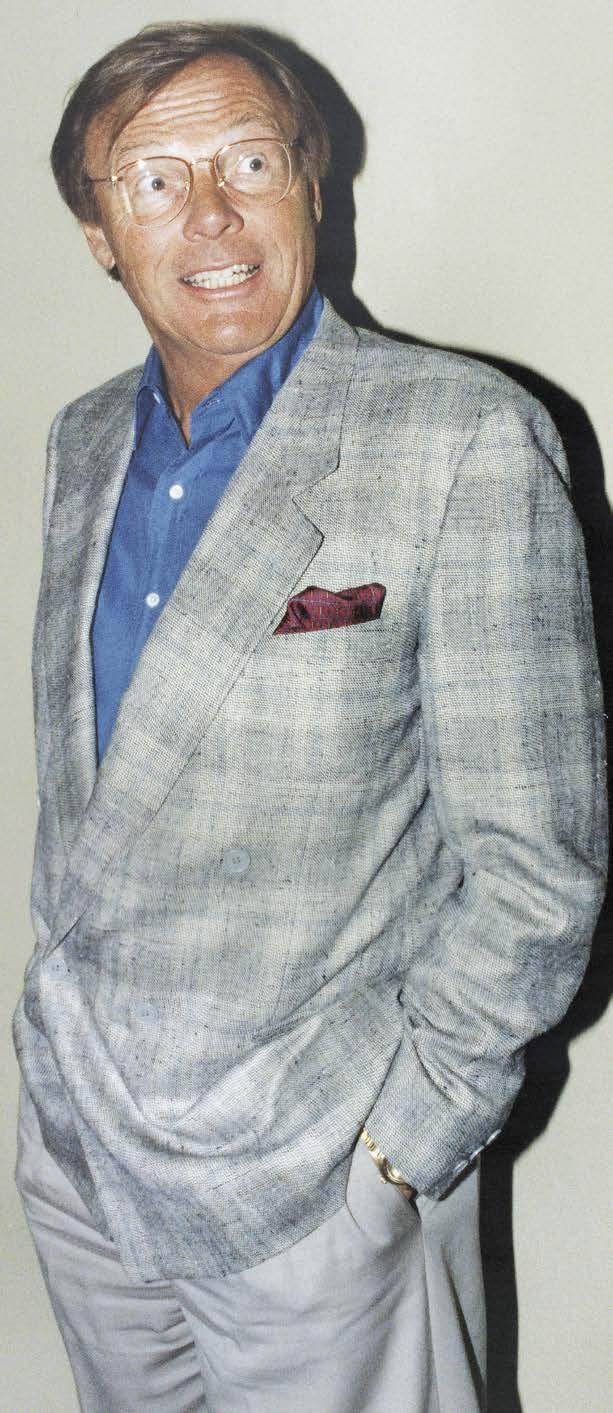

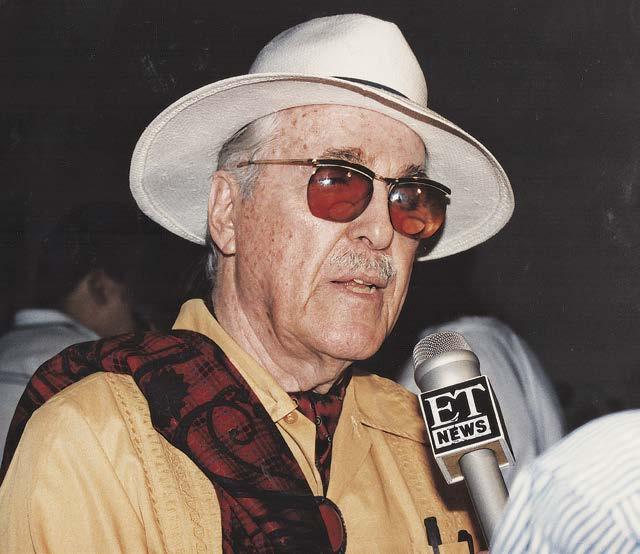

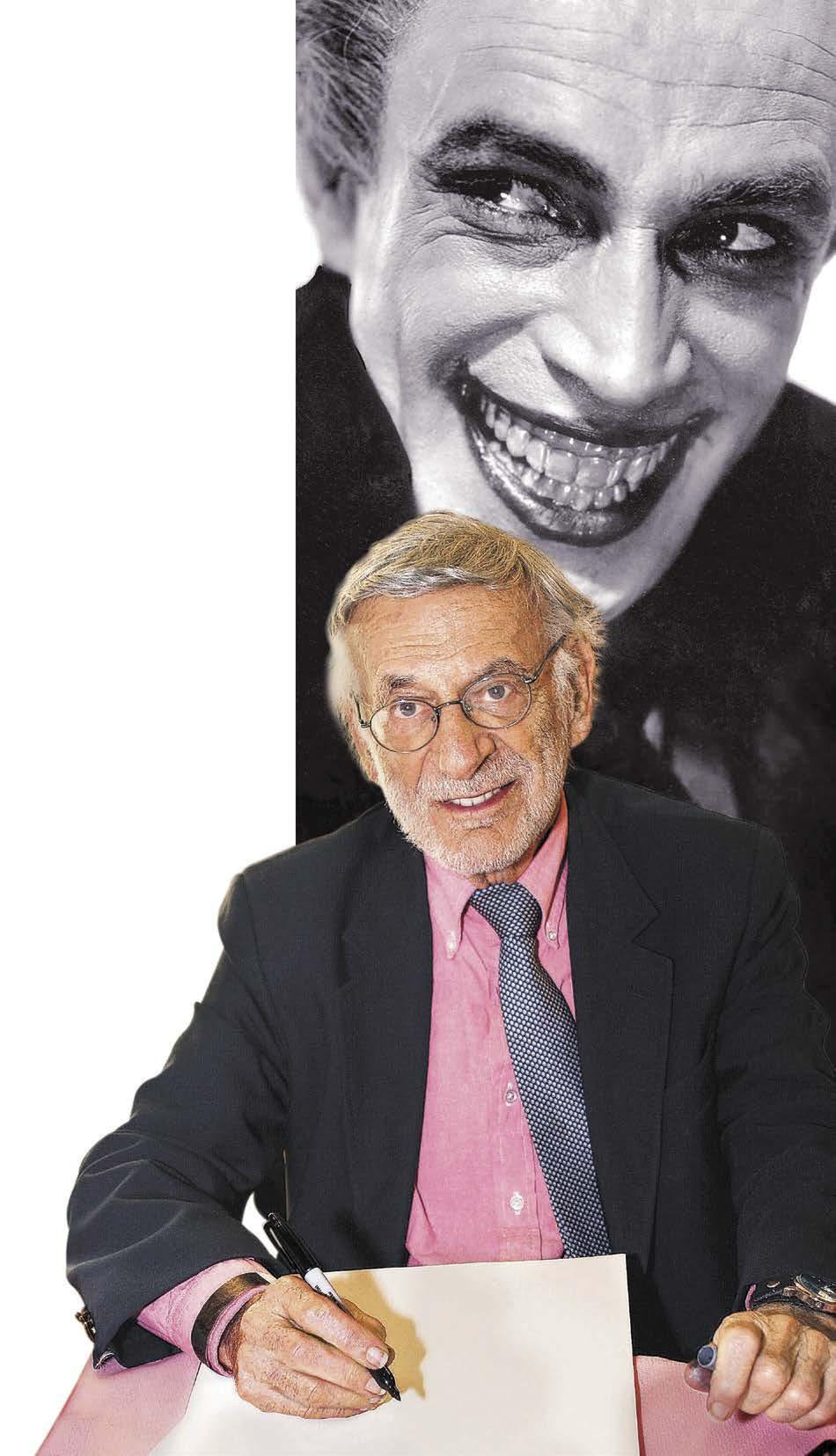

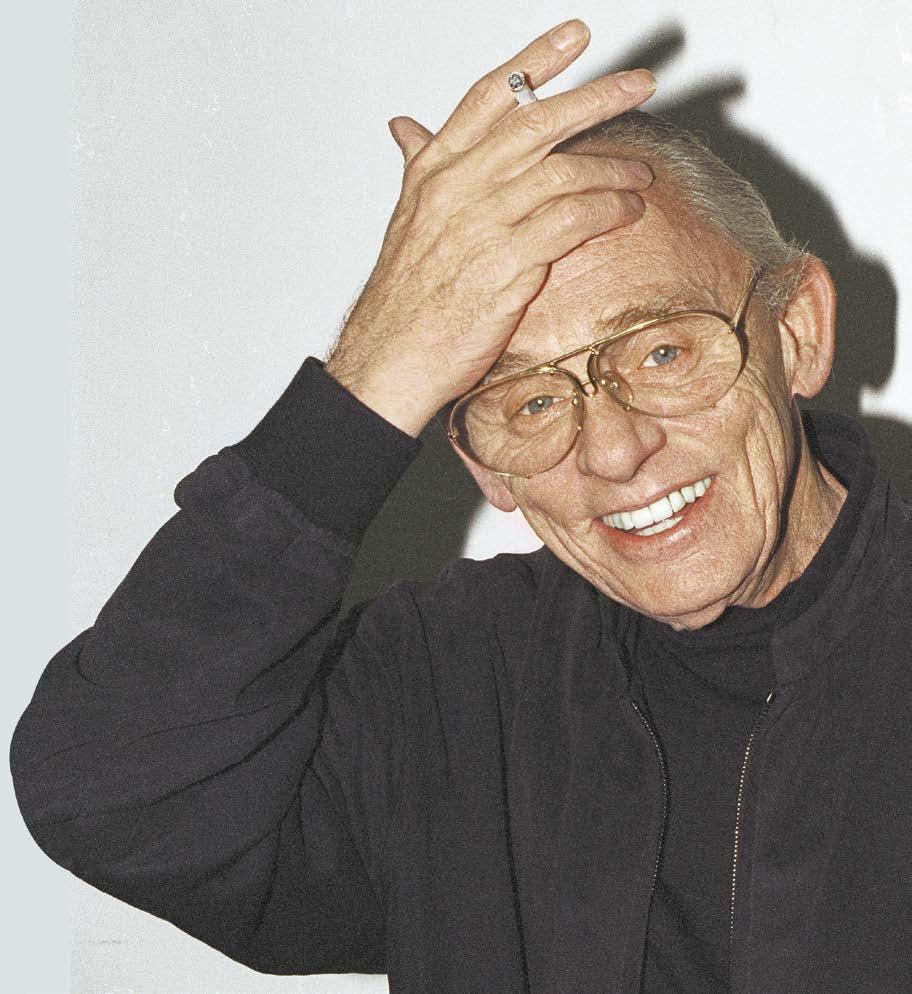

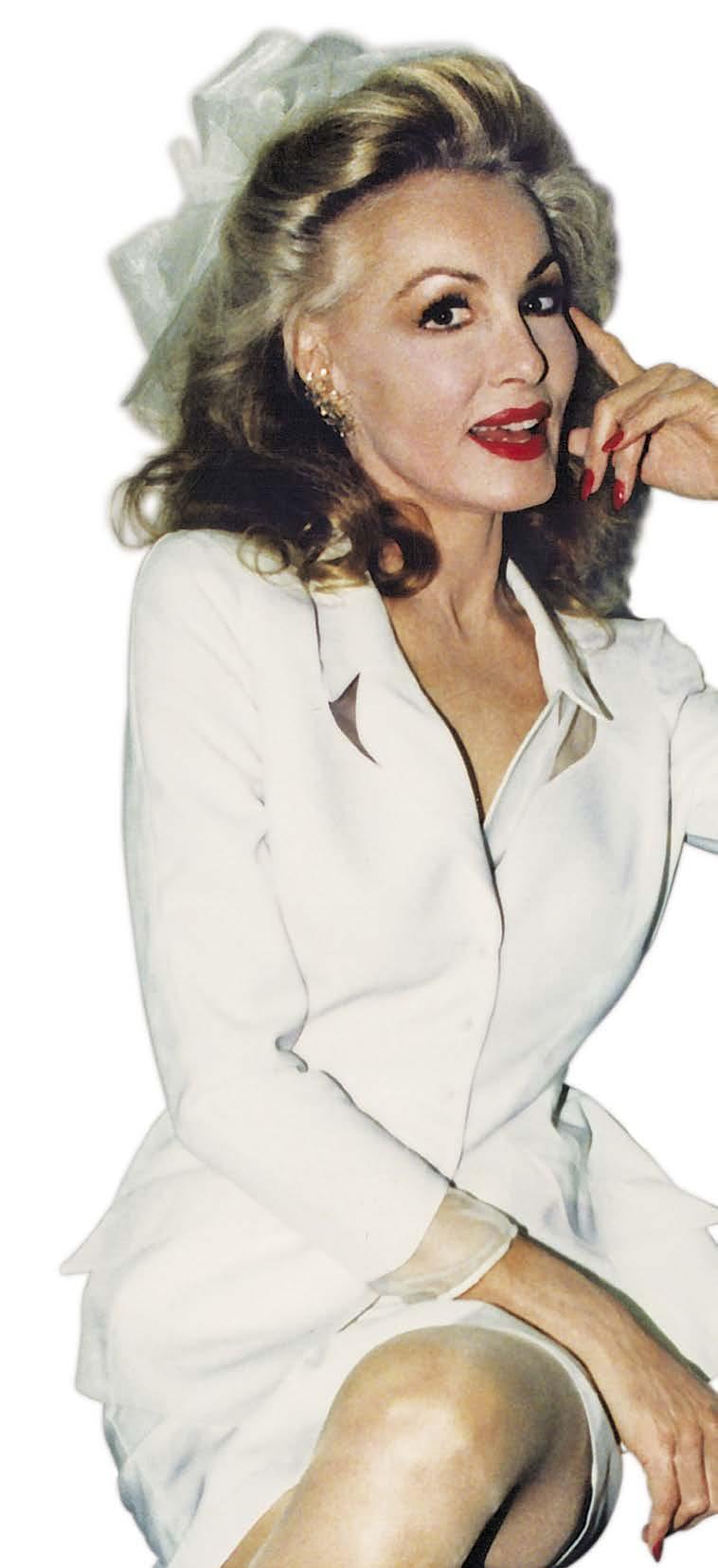

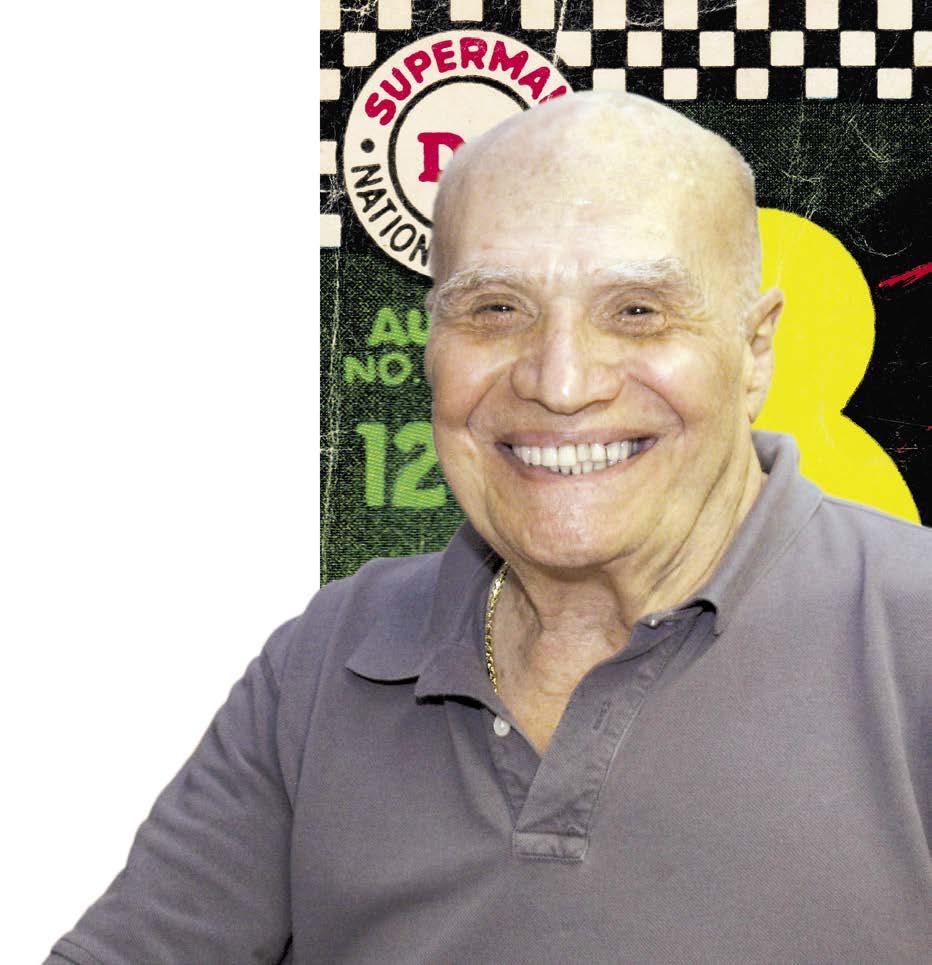

Writer Lee Falk, creator of the Phantom, met the press in 1991.

Photo by Kathy Voglesong

Batman begins

From his first flap of the cape, Batman was breaking the rules of a genre in its infancy. Superman wore bright colors. Batman wore black.

The two seminal superhero characters, introduced within a year of one another, were inexorably linked from the start. What they had in common — both were orphans with secret identities who took a vow to protect the innocent — wasn’t nearly as interesting as their contrasts. Superman was smiley; Batman was brooding. Superman had super powers; Batman was a mere mortal. Superman played by the rules; Batman possessed the ruthless heart of a vigilante.

WHEN ACTION #1 SCORED NEWSSTAND gold, its editor Vincent “Vin” Sullivan (1911-1999) sought a followup superhero. He mentioned this to Bronx native Bob Kane (1915-1998), a cartoonist who had been drawing humorous fill-in pages for Action. These were often written by Denver native Milton “Bill” Finger (1914-1974), Kane’s fellow alum of DeWitt Clinton High School in the Bronx. Kane had a wisp of an idea — just the name Bat-Man and a vague sketch — and turned to Finger to help flesh it out.

Both men loved adventure-genre fiction and films, and put those influences in their proposal. (Kane would later cite Roland West’s 1930 mystery “The Bat Whispers” starring Chester Morris as an influence, even if the masked Bat of that film was the bad guy.)

Kane pitched the Batman concept to Sullivan, apparently neglecting to mention Finger’s contribution.

Batman debuted in Detective Comics #27 in 1939, an anxious time in America. Folks were still reeling from the Great Depression, and a war was looming.

The first Batman story — illustrated by Kane and written by Finger — bore the unsexy title “The Case of the Chemical Syndicate.” (This was Detective Comics, not Action Comics, so mysteries were de rigueur.)

What aspects of the Batman mythos were present from the start? In the first panel, we meet Bruce Wayne (identified as a “young socialite”) and Commissioner Gordon. That, and the costume, are about it.

Or was it a purple-throated calliope? From Detective Comics #33 (1939). Opposite: “The Bat Whispers” (1930). © DC Comics Inc.; © Atlantic Pictures

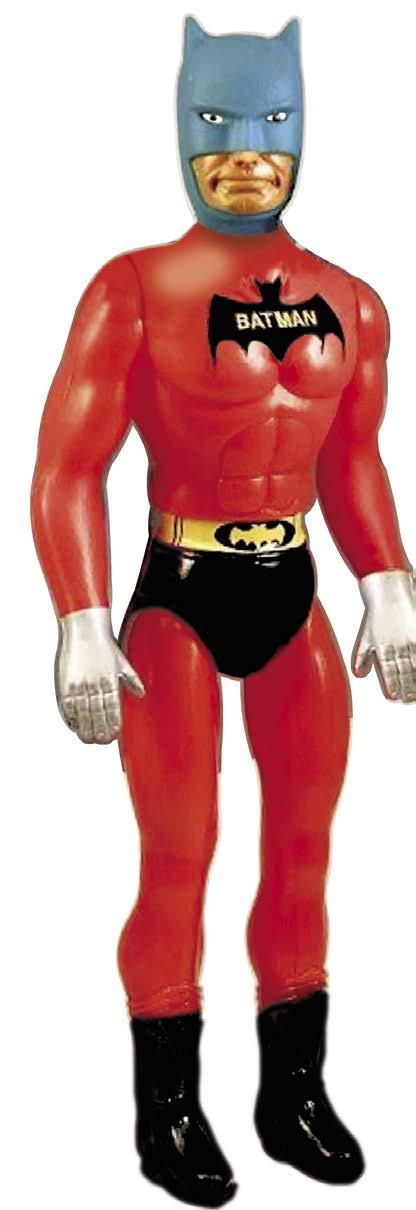

Otherwise, the earliest Batman is a punisher who has zero empathy for lawbreakers. When he sends a gangster into a vat of acid with a punch, Batman brusquely remarks: “A fitting ending for his kind.” Batman drives a car (colored red, at least in DC’s 1990 reprint), but it has no bat-like modifications yet. His dialogue is 100 percent pun free.

Fun facts: The character name is actually spelled with a hyphen (“Bat-Man”) over the first three stories, often in quotes and preceded by the article “the.” And Batman fires a gun (!) in ’Tec #32.

In the first 11 Batman stories through Detective #37 (1940), it’s plain how the character was influenced by the movie serials and pulp fiction stories of the day. Batman was so simply drawn and unambiguously written, you’d swear he was dreamt up by a couple of kids. Which he was. Kane was 22; Finger was 21.

So Batman was a boyhood fantasy not only for millions of readers, but also for his co-creators.

17

Without Bob Kane, there’d be no Batman. Without Bill Finger, we wouldn’t remember Batman. A guy in red with no cowl, no bat-ears?

For many years, the origin story of Batman — the real life origin story, not the bat-flies-in-the-window one from the comic book — was as cloaked in mystery as the character himself.

For 76 years following Detective #27’s newsstand debut, sole creator credit was ascribed to Kane, despite many indelible contributions to the character made by Finger from the very first story.

And, owing to the misleading (and no longer practiced) tradition of “ghosting” in comics, even the artwork credit went to Kane. As a result, the dynamic art of Dick Sprang, Sheldon Moldoff, Win Mortimer, Jack Burnley, Lew Sayre Schwartz, Stan Kaye and others was credited to one man, disregarding stylistic variations — and keeping fans in the dark.

Yet, by Kane’s own account in his memoir “Batman and Me” (1989, Eclipse Books) written with Tom Andrae, Finger overhauled Kane’s initial sketch of Batman in what sounds very much like an act of co-creation. As Kane described it in his memoir:

“One day I called Bill and said ‘I have a new character called the Bat-Man and I’ve made some crude, elementary sketches I’d like you to look at.’ He came over and I showed him the drawings. At the time, I only had a small domino mask, like the one Robin later wore, on Batman’s face. Bill said, ‘Why not make him look more like a bat and put a hood on him, and take the eyeballs out and just put slits for eyes to make him look more mysterious?’

At this point, the Bat-Man wore a red union suit … Bill said that the costume was too bright: ‘Color it dark gray to make it look more ominous.’ The cape looked like two stiff bat wings attached to the arms. As Bill and I talked, we realized these wings would get cumbersome when Bat-Man was in action, and changed them into a cape, scalloped to look like bat wings when he was fighting or swinging down on a rope. Also, he didn’t have any gloves on, and we added them so he wouldn’t leave any fingerprints.”

It may seem odd that a writer, not an artist, would have so much to say about a character’s look. But Finger thought visually, and often put Batman in predicaments based on optical appeal. Dick Sprang was a Batman artist during the ’30s-’40s period called the Golden Age of Comics. “The scripts were never signed, but I could always tell a Bill Finger script,” Sprang told me in 1993. “I’d instantly recognize his unique approach to comic writing.

“I always enjoyed working on his scripts, because they were not only extremely well-written and perfectly visualized, but the guy would supply me with background. He would always send a handful of ‘scrap’ (printed visual references) from his own files to help illustrate, to help convey his viewpoint, what he wanted illustrated in his script. And then, of course, I would carry on with other research from my own files, and try to make it authentic.”

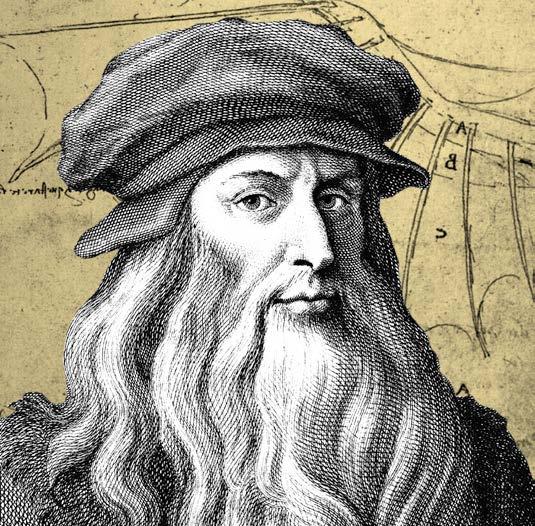

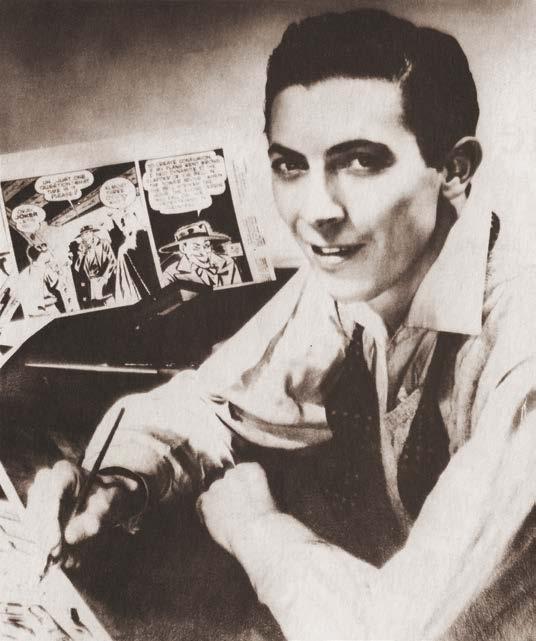

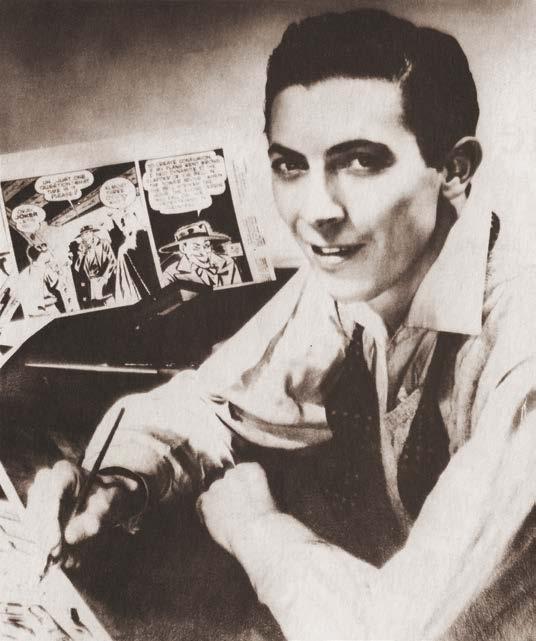

Bob Kane at the drawing board (1944). Below: Two inspirations were Leonardo da Vinci and the 1931 film “Dracula.”

© McClure Newspaper Syndicate; © Universal Pictures

Bob Kane at the drawing board (1944). Below: Two inspirations were Leonardo da Vinci and the 1931 film “Dracula.”

© McClure Newspaper Syndicate; © Universal Pictures

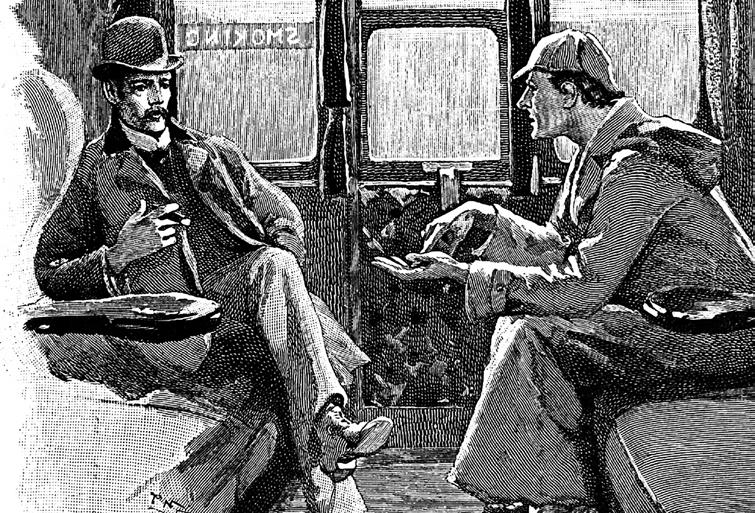

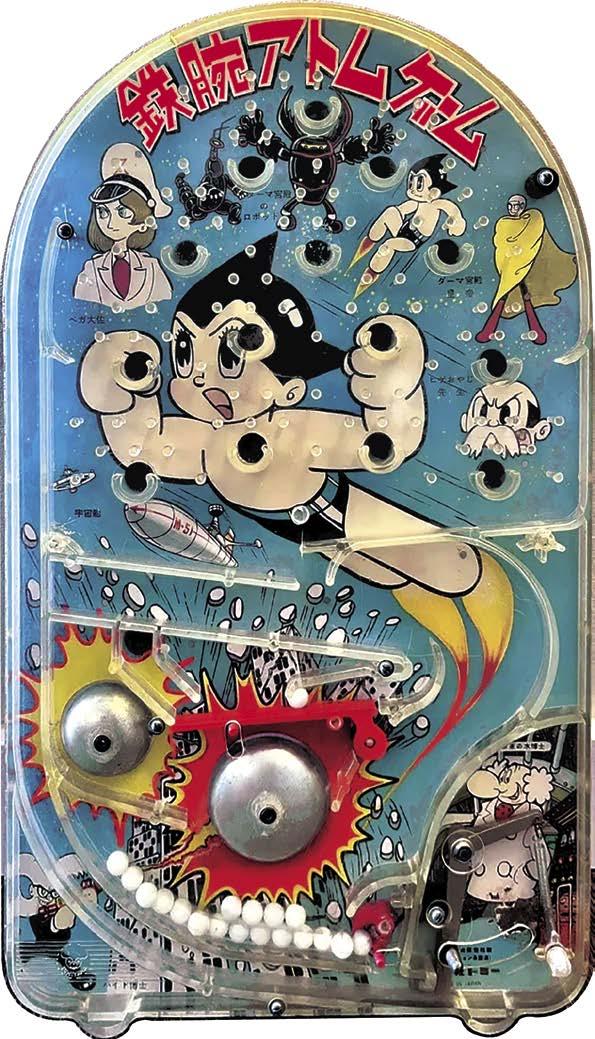

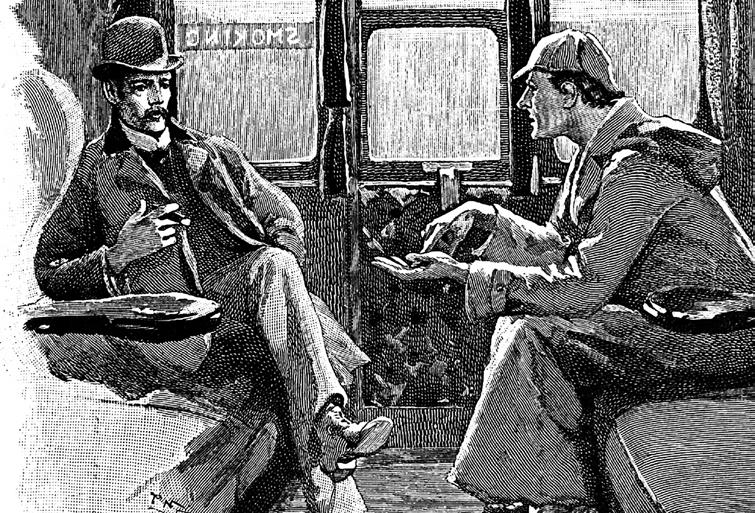

When Bill Finger decided Batman needed a Dr. Watson, Jerry Robinson pitched in. Left: Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson

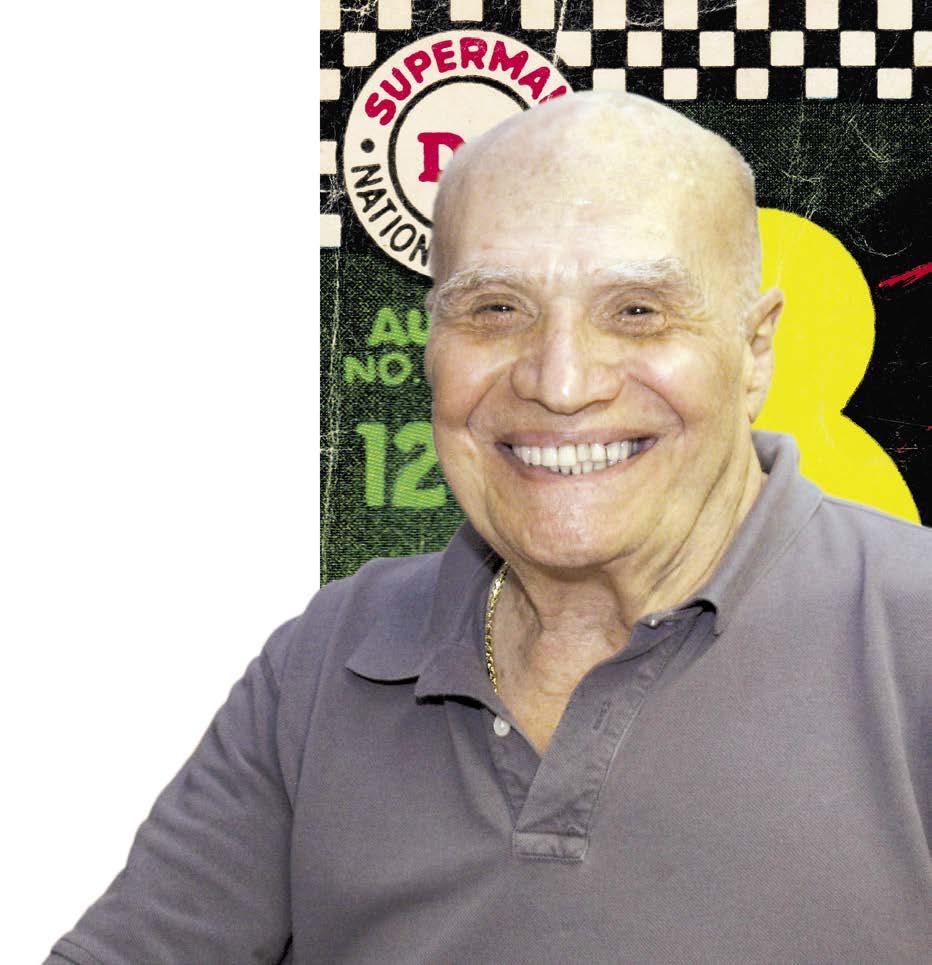

Jerry Robinson

It was the summer of 1939. Batman was a thing, but only just.

A 17-year-old journalism student at Columbia University named Jerry Robinson had a chance encounter with someone he’d never met before, Bob Kane, at a tennis resort in Pennsylvania.

Kane, then 23, paused and engaged Robinson in conversation after taking note of the jacket the teenager was wearing.

“I went out to play tennis and I wore a jacket that I had decorated with my cartoons,” Trenton native Robinson (1922-2011) told me during an interview conducted in 1989.

“And Bob Kane, who had just started Batman shortly before that, saw it and asked who did the cartoons. A friendship developed, and he said that if I came to New York, I would be able to assist him on Batman.”

Bat-what? By summer ’39, a few Batman stories had been published in Detective Comics, not that Robinson had seen them.

“I had never heard of it,” he said. “In fact, Bob took me down to the local magazine store to find a copy of it.”

Robinson bit, and the decision changed the course of his life.

“I came to New York and started work in the fall,” he said. “In fact, I didn’t even go back home. I went right from the resort.”

Robinson reckoned he debuted in “one of the fall issues of 1939,” initially as a letterer and background inker. (For non-geeks: “Pencillers” draw the artwork in pencil, “inkers” finish it in black ink.) As an artist, Robinson grew in leaps and bounds over the next couple of years. He graduated to inking main figures, and eventually began pencilling outright. Robinson’s contributions marked a turning point for Batman. He retained Kane’s cartooniness, but added a much needed fluidity that Kane’s stiff figures lacked.

HERE’S WHERE THE STORY GOES SOUTH.

Today, Robinson is acknowledged as a co-creator of two important characters in the Batman canon that both debuted in 1940: Robin and the Joker. But for many years, Kane denied Robinson’s credit. (Sound familiar?)

Batman’s co-creator, writer Bill Finger, decided that Batman needed a sounding board, a Dr. Watson to his Sherlock Holmes. Partially based on Robinson, Robin debuted in Detective Comics #38, touted as “The Sensational Character Find of 1940!”

Recalled Robinson: “I was a kid at the time — I was only 17 — and they would call me ‘Robinson the Boy Wonder.’ I didn’t like that at the time because I wanted to be thought of as older.

“In fact, I did name him, but my concept was from Robin Hood. If you look at the costume, it’s kind of an update of Robin Hood.”

Regarding the Joker, Robinson didn’t mince words.

“The Joker was my creation,” the artist stated.

“Batman was growing more popular with each succeeding issue, and they decided to publish the Batman quarterly, Batman #1, for which we needed a lot more stories. My idea was to create a new villain, because there weren’t supervillans in the comics at the time. From my studies in literature, I learned that all the great heroes from Biblical times on had an antagonist. Even Sherlock Holmes had Moriarty. But we never had one for Batman.

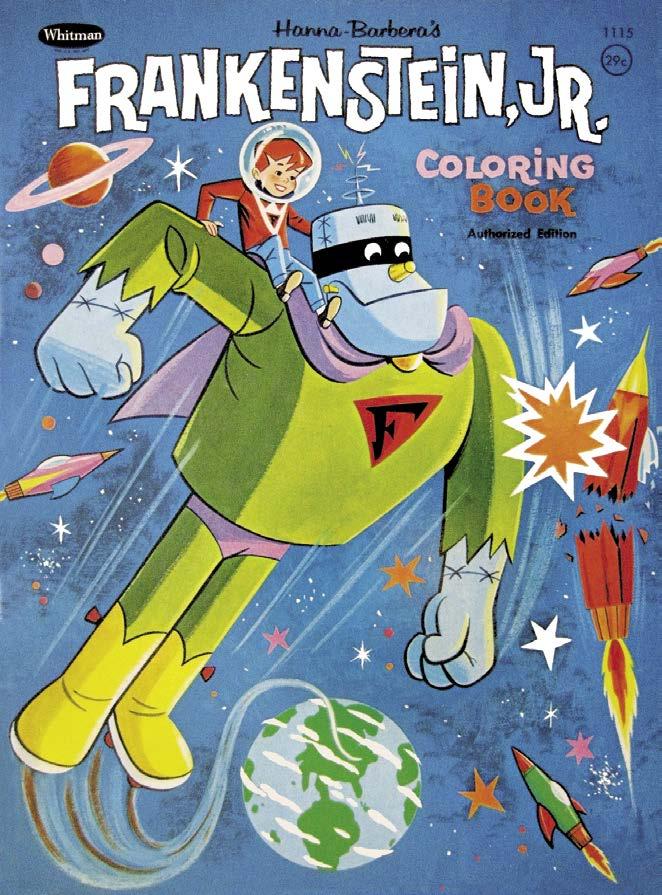

“I had written a lot of humor pieces in my courses at Columbia. I wanted to create a villain that had some sense of humor. That would be a contradiction in terms, a villain with a sense of humor. That is the essence of a good character: It has contradictions.”

20

artwork by Sidney Paget (1890s). Robinson named Robin for Robin Hood. Right: Errol Flynn as the fabled hero (1938). © Strand Magazine; © Warner Bros.

A NAME FOR THE CHARACTER THEN PRESENTED itself. As Robinson told it: “Once I’d decided on his sense of humor, in searching for a name, the Joker came to mind. I immediately associated it with the joker playing card. That’s where the visual image of his head came from. That’s where we started from.”

Robinson’s playing card concept was used in the Joker’s debut story (and occasionally thereafter). But Kane’s Joker design was more influenced by a reference supplied to him by Finger: German actor Conrad Veidt in the silent adaptation of Victor Hugo’s “The Man Who Laughs” (1928). The Joker debuted in Batman #1.

Kane recollected the Joker’s genesis differently in his memoir: “In a number of interviews, Jerry Robinson has claimed that he created the Joker. At this time he was an 18-year-old kid just out of high school. He came in with a drawing of a joker playing card, with a joker that looked like a court jester. … Jerry claimed that this card was the original inspiration for the Joker. ... I do not doubt that my ex-assistant is sincere in believing that he did, in fact, create the Joker, but time has eroded his memory.”

BACK THEN, NO ONE KNEW HOW MUCH MONEY would change hands over characters like Robin and the Joker.

“In those days, and being so young, we never thought of that,” Robinson told me. “That was a long time ago. Since then, we’ve become a little more aware of our creative rights.

“In fact, (Superman co-creators) Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster are good friends of mine. I don’t know if you remember the story a few years ago, but they were left penniless. Myself and another artist (Neal Adams) renegotiated that deal for them, and I represented them. Finally, I did get at least some justice for those two.” (Shuster died at age 78 in 1992; Siegel at age 81 in 1996.)

Said Robinson of his old collaborators on Batman: “I haven’t talked to Bob in some years. He moved to the coast. I’d occasionally speak with him or see him in New York. Bill passed on some years ago (in 1974). It’s really a shame he didn’t get credit for his contributions in his lifetime. It’s only now that they’re starting to know his name. It was never signed on the strip, which it should have been. I used to sign his name myself to stories I drew.”

ROBINSON WAS NO FAN OF THE TV SERIES.

“I didn’t like the concept of that TV thing, because they really had camped it up so much that I knew it wouldn’t last more than a couple of seasons,” the artist said. “It didn’t do justice, I don’t think, to the initial concept, which I think is very strong and could have been a long-lasting series, just as Tarzan has been and James Bond has been. Or a strip like ‘Peanuts,’ if it’s handled properly, can go on. But if you parody it, it wouldn’t have the longevity. That’s what I objected to.”

But Robinson had no objections to the show’s portrayal of the Joker. “I liked the selection of Cesar Romero. In fact, I met him out in Hollywood. I kidded him at the time that when I created the Joker, I didn’t know I was reviving his whole career.”

Said Robinson of the casting of Jack Nicholson in the 1989 film: “He didn’t fit my idea visually – the Joker is tall and slim — but I think he’s an excellent choice.”

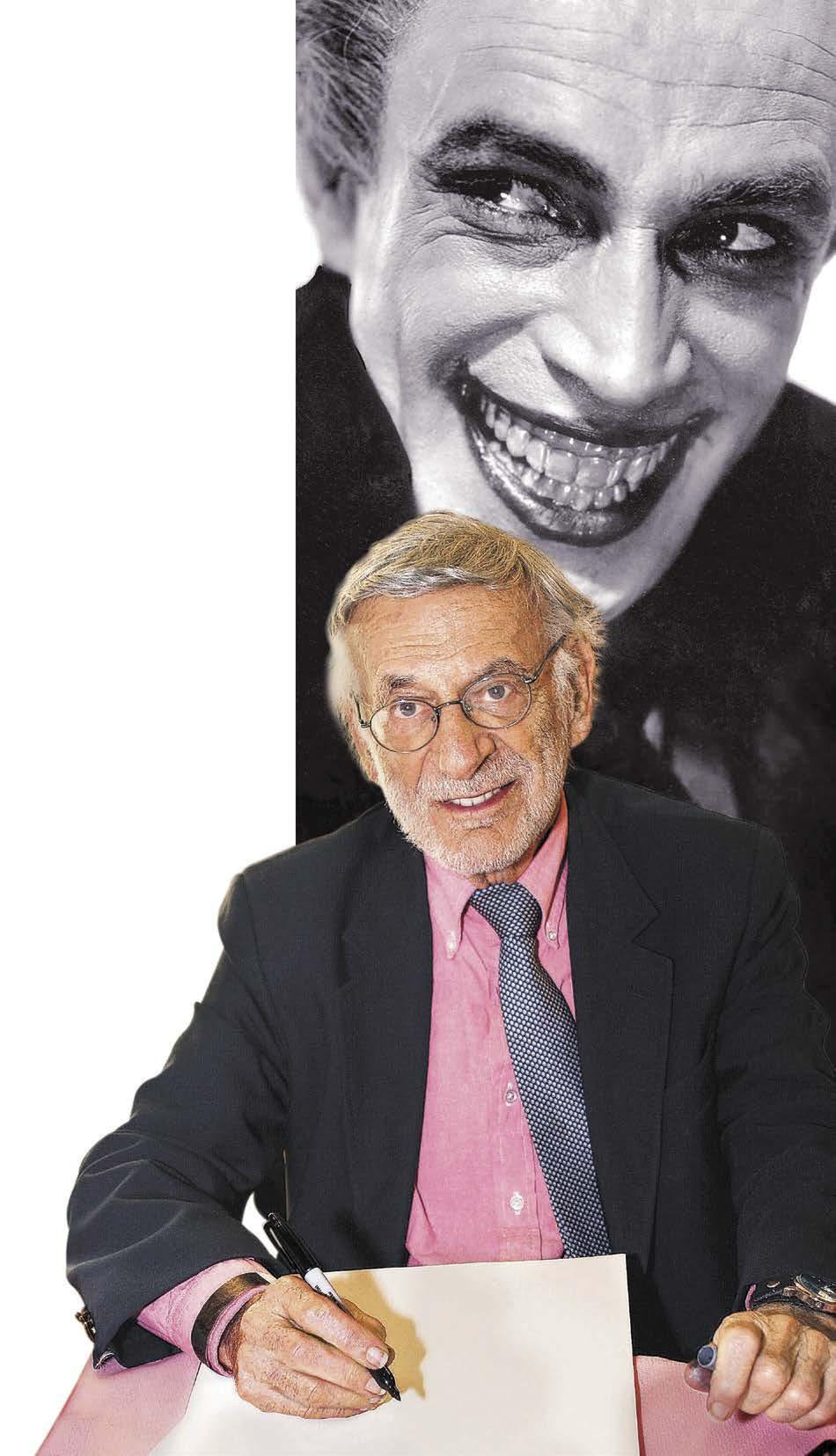

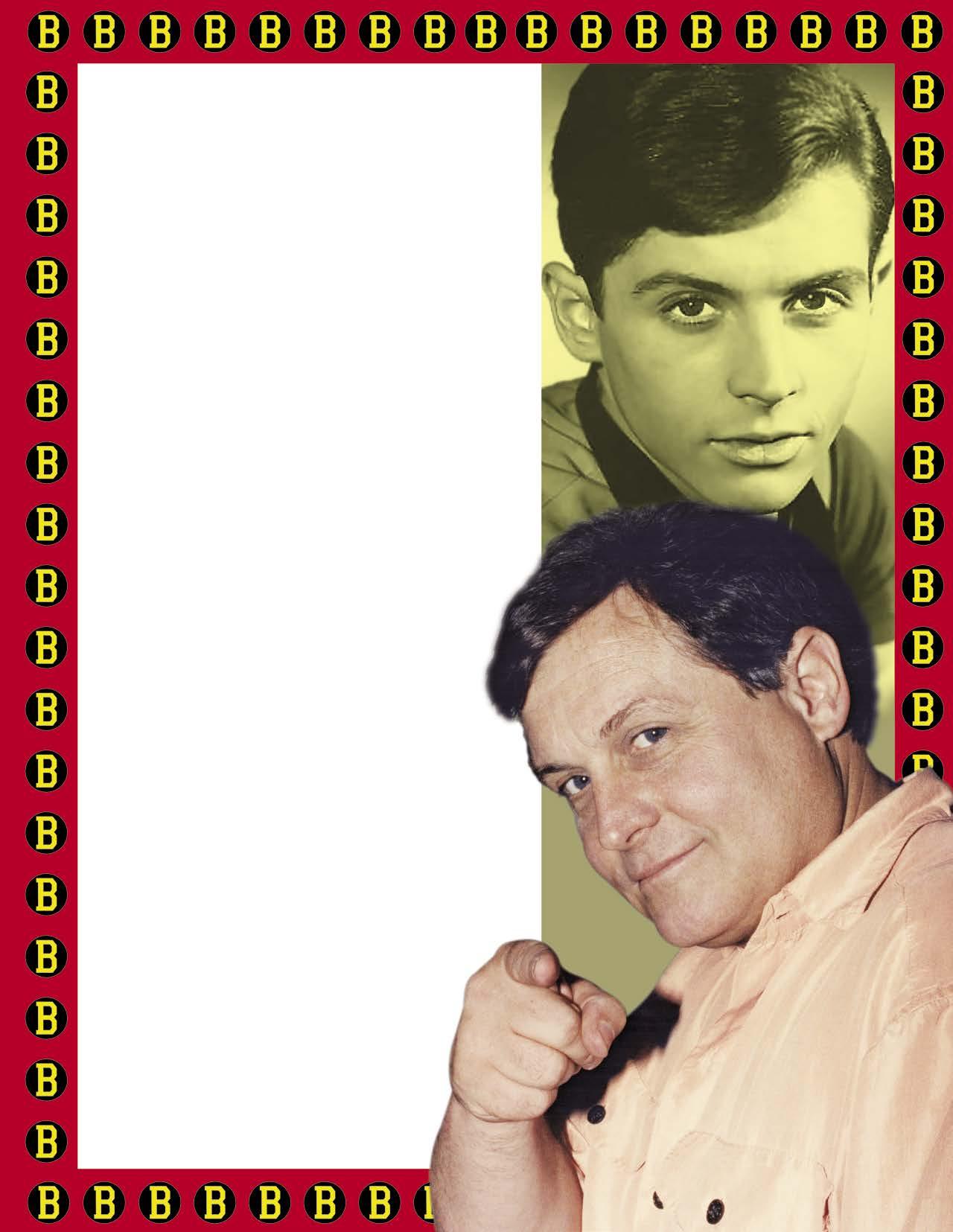

Jerry Robinson in 2003.

Background: Joker influence Conrad Veidt. 2003 photo by Kathy Voglesong

Jerry Robinson in 2003.

Background: Joker influence Conrad Veidt. 2003 photo by Kathy Voglesong

Dick Sprang

(1915-2000)

HE REFASHIONED THE CHARACTER, AND THE villains, as his own.

The most distinctive Batman artist of the Golden Age of Comics, Dick Sprang gave Bruce Wayne a square jaw and Dick Grayson an oval head. He played with perspective, sometimes imbuing his panels with a prescient trippiness. His villains could be garish, even grotesque. Sprang’s Joker, wearing a face that never quite adhered to the laws of human proportion, was a deformed, twisted nightmare. His Two-Face was like something dreamed up by Lon Chaney Sr. His Catwoman was sexy, but there was larceny and murder behind those alluring eyes.

The art of Dick Sprang was never equaled or duplicated. When that art was initially published, his byline didn’t appear. Savvier fans certainly recognized his work when they saw it. Some may have even wondered: Who is this mystery artist?

SPRANG WAS BORN IN

Ohio and turned pro when he was a teenager. Before seeking work in comics, the self-taught Sprang wrote and illustrated for pulp fiction magazines, doing western and detective stories.

“I saw that the pulps were just about being crowded out by the comic books,” Sprang told me during an interview in 1993. “This was a trend. Now, you can’t change a trend, but you can try and manage it. I saw opportunity in the comics.”

One day, Ellsworth paid Sprang the ultimate compliment. Said the artist: “Later, after some years, Whit told me, ‘Look, go your own direction with Batman. Do what you want to do with him.’ I took this as quite an endorsement. But analyzing it, I couldn’t see any dramatic changes to be made in this highly popular character.”

Regardless, Sprang’s Batman evolved over the years: “I widened Batman’s waist a bit. I made his figure a little more fluid in action. I shortened his bat-ears. But I retained Kane’s basic concept.”

As for Robin: “He was a little tough, that kid Robin,” said Sprang. “You know how a kid is. His head is very deep at the back. The skull is very round at the back. Sometimes I flattened him out a little bit. So (editor) Jack Schiff or one of the boys would suggest, ‘Hey, make his head more round!’ ”

“I made his figure a little more fluid in action,” said artist Dick Sprang of modifying Batman in his art. Photo illustration

At DC, Sprang was seen by editor Whitney Ellsworth. “Of course, I had no idea that I’d ever be put on Batman,” Sprang said. “Whit handed me three script pages of a Batman story that had already been drawn and published. He said to me, ‘Take ’em home.’ He said, ‘By the way, I hope you won’t look for the book in which these pages have appeared.’ I said, ‘Don’t worry, I won’t. I understand why you’re doing this.’

“He said, ‘Pencil it all, ink about half of it, do some lettering, put the balloons in, but get it out as quick as you can. I’d like it back in four days.’ Like he told me, I brought it back in four days.

“Whit went through it, squared it up, picked up the phone, and asked for a check. He turned to me and said, ‘What was your name again?’ He gave me a page-rate check for a story that had already been published! Well, this impressed me to no end.”

Initially, Sprang kept his drawing style on Batman more or less consistent with that of Kane — both artists were cartoony — but Ellsworth did not direct Sprang to mimic Kane outright.

“Of course, he told me to stay with the character,” Sprang said. “Naturally, I assembled a bunch of Bob Kane stuff and drew him as best I could. I followed that for quite some time.”

Sprang was directed to strive for authenticity in illustrating a series of whimsical back-in-time stories written by Finger in the 1950s.

The artist recalled: “Whit Ellsworth was quite insistent on this point. He said, ‘Look, kids read this stuff. When they see ancient Rome, ancient France, ancient Greece, I want them to see those countries as they existed — the architecture, the costuming, the horse gear, everything. Let it be somewhat educational for the kids.”

Sprang inked his own pencils until 1945, after which he was teamed with Charles Paris, who became Sprang’s exclusive inker for the duration of his career with DC Comics. “Charlie told me once that he enjoyed my stuff because there was no question what I intended,” Sprang said. “My pencils were not sketchy.”

SPRANG RETIRED FROM DRAWING BATMAN IN 1961, though he later produced special commissions for fans.

“So I still draw the character a lot,” he said. “But I must tell you, when I began to do the recreations in about ’84 or ’85, it was tough to get the character back. I found I’d lost a lot of facility.”

Was Sprang at all bothered about the fact that during all those years, he never received a byline for his Batman artwork?

“I know it annoyed some people to be ‘ghosting,’ but not me,” the artist said. “Only in the later ‘giants’ (reprint issues) did they start to give me a credit. That was just fine.

“Bob Kane had a contract; I think he owned the title. His name did appear on Batman, as you may recall, in that boxed signature of his. Whit had asked me if that would bother me when I first worked for him. I said, ‘Look, as long as my name appears on that oblong, green piece of paper.’ ” (Namely, the check.)

24

Cinematic

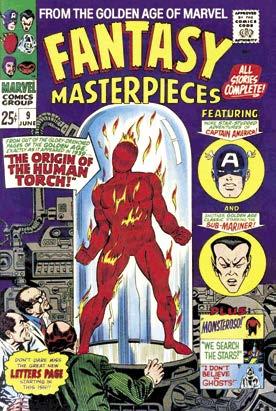

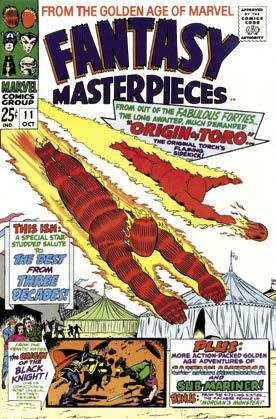

“MOVING PICTURES” WERE FIRST SCREENED IN Superhero comic books were first published in 1938. This leads to a simple question: What was the first superhero movie? Well, as with many burning topics, the answer is not as simple as the question.

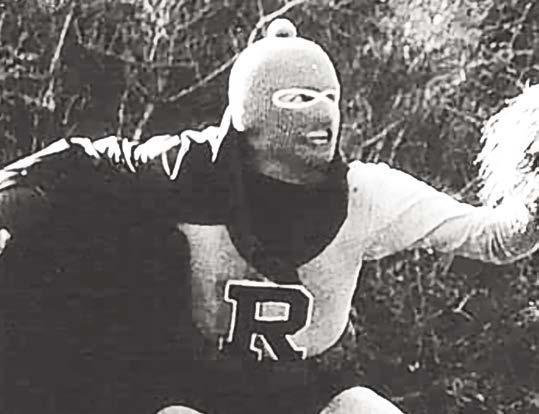

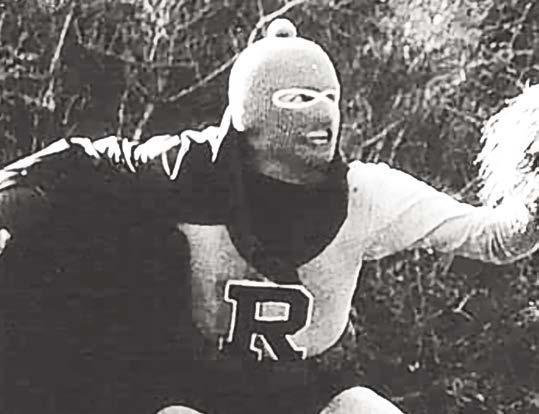

The earliest live-action depictions of superheroes on film were called “serials” or “chapter plays.” These were not full-length movies, but a succession of short films (typically 12 to 15) that played theaters in weekly installments. Yeah, they were low-budget, low-tech, and formulaic, but their influence is still being felt. The TV Batman’s cliffhangers and periodic fight scenes were torn from the serials.

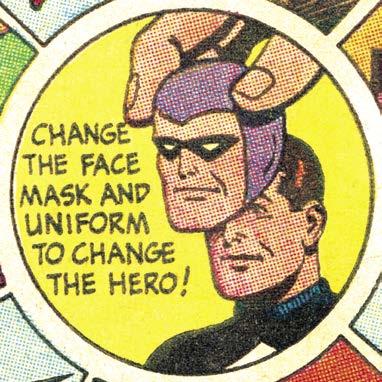

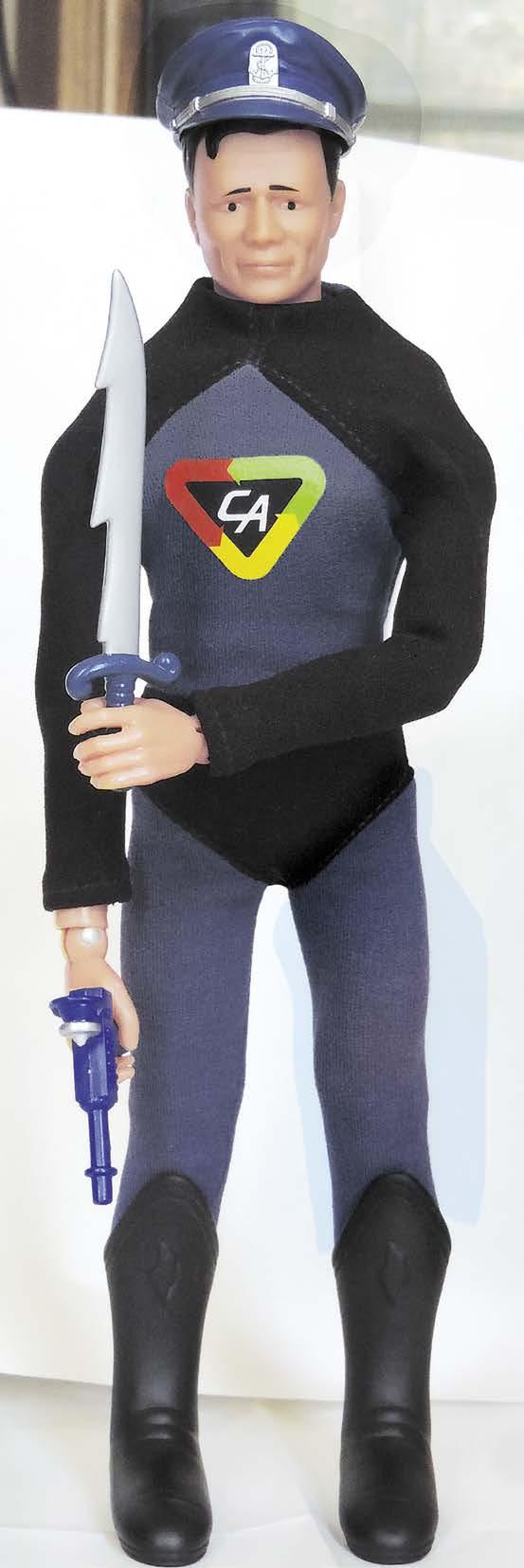

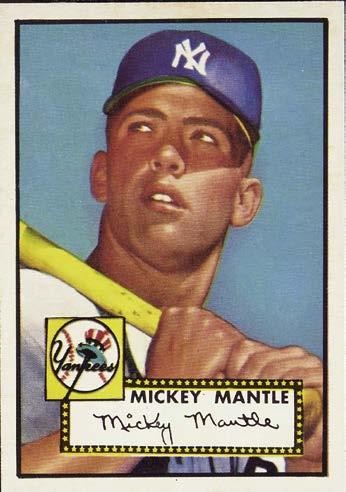

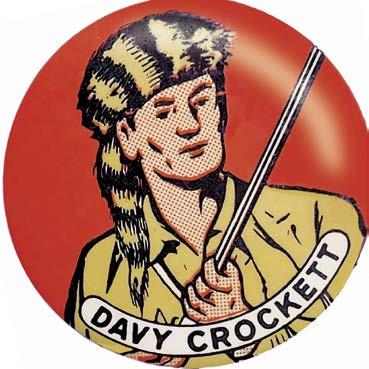

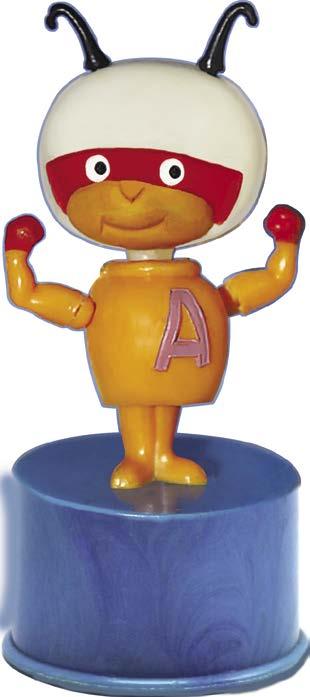

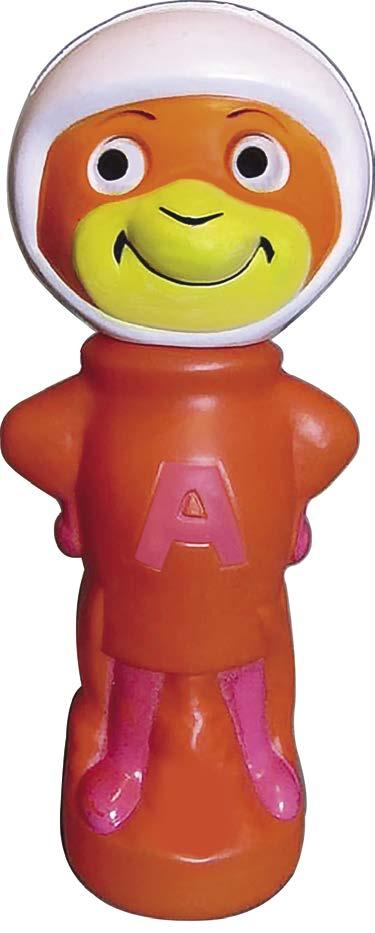

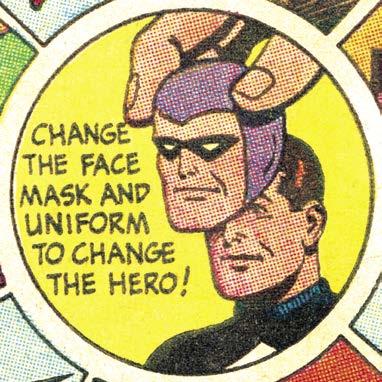

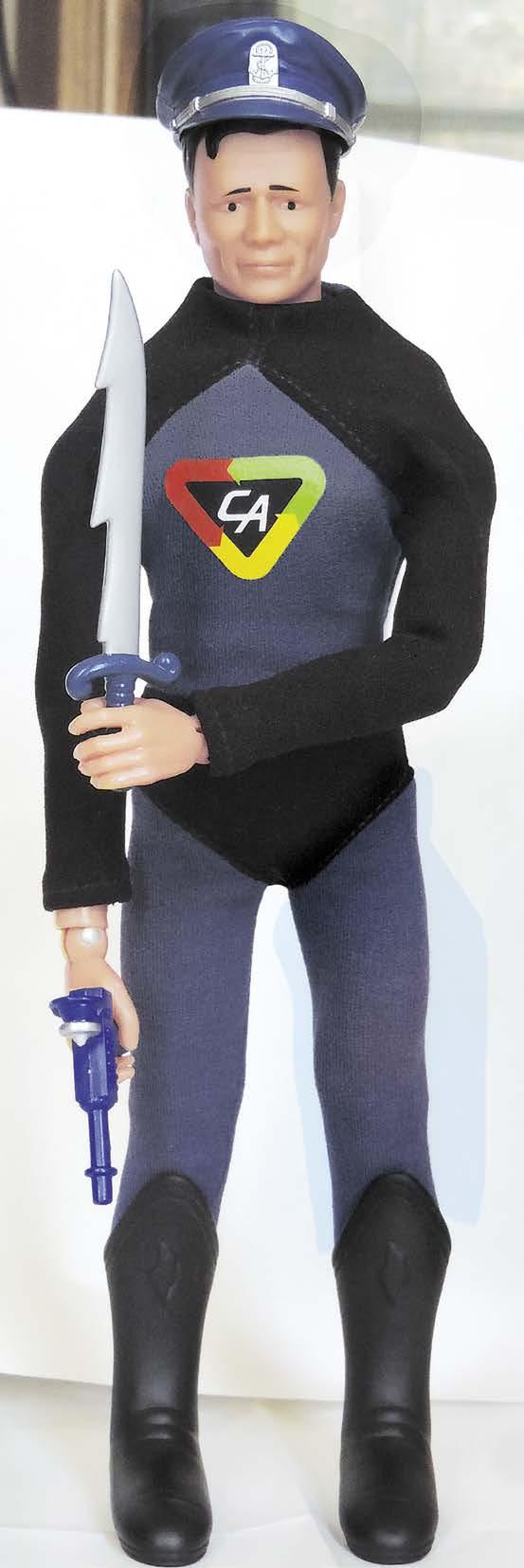

Universal’s serial “Flash Gordon” (1936) starred Olympic-gold-metal swimmer Buster Crabbe as Alex Raymond’s comic strip hero. Flash was not a superhero per se, but he resonated during the 1960s Batmania craze as one of nine characters that Captain Action — “the Amazing 9-in-1 Super Hero” — could change into when the toy was introduced by Ideal in 1966.

The serials also gave us masked avengers (some of whom originated in fiction and radio) who looked and acted a lot like superheroes. These include the Spider in “The Spider’s Web” (1938); “The Shadow” (1940); “The Masked Marvel” (1943); and mander Cody in “Radar Men From the Moon” (1952).

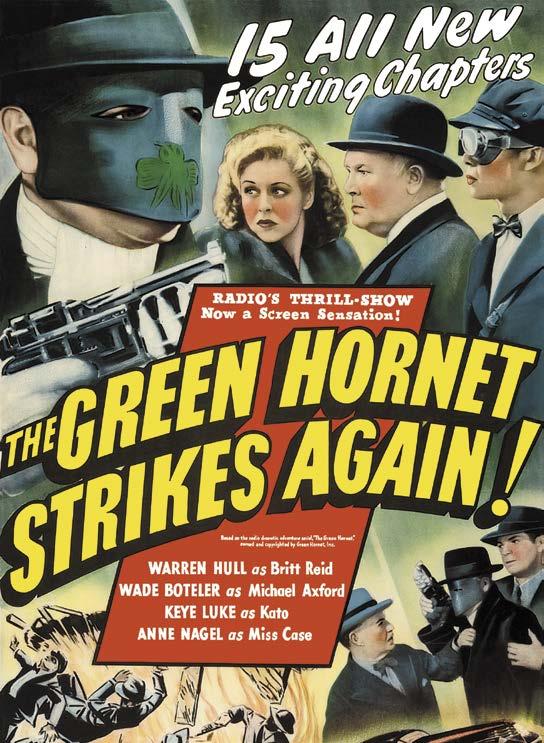

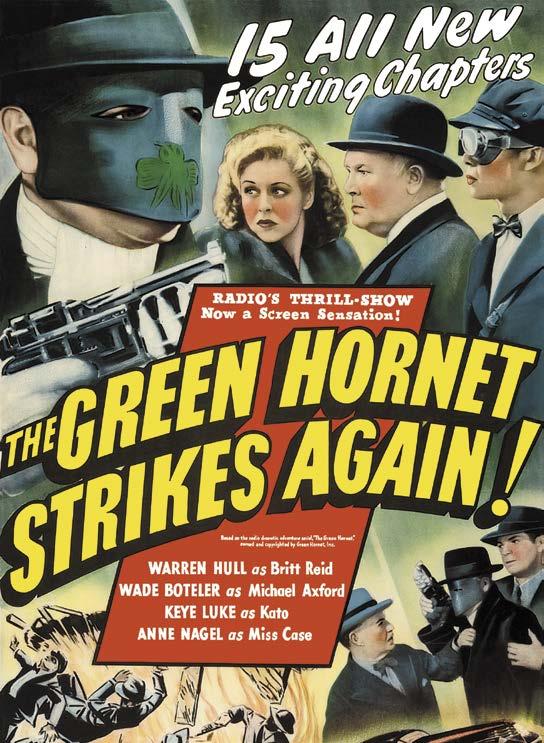

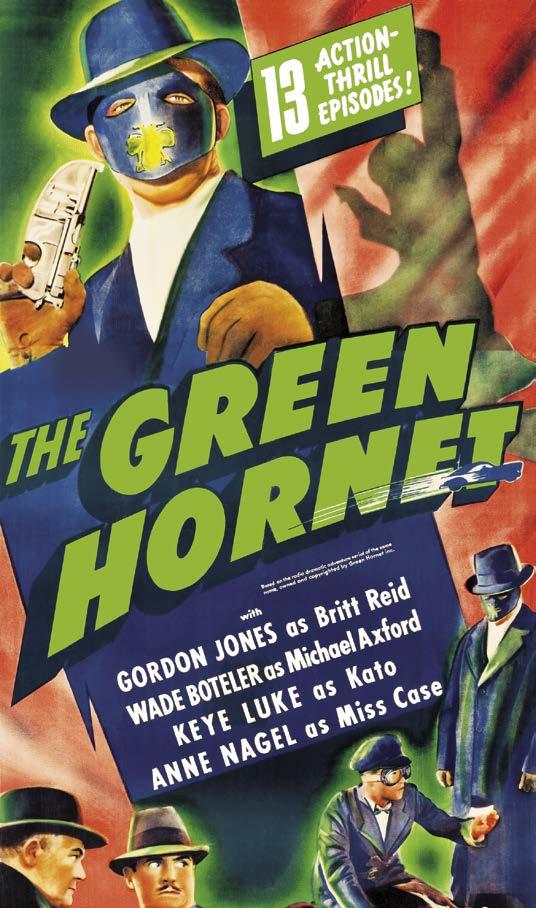

LIKE BATMAN, RADIO’S GREEN HORNET wore a mask but had no super powers. He, too, resonated during Batmania for a special reason: “Batman” executive producer William Dozier’s followup TV series “The Green Hornet” (1966-67). This makes the Hornet as much a super hero as Batman, and therefore worthy of the distinction First LiveAction Superhero on Film for his 1940 serial of the same title.

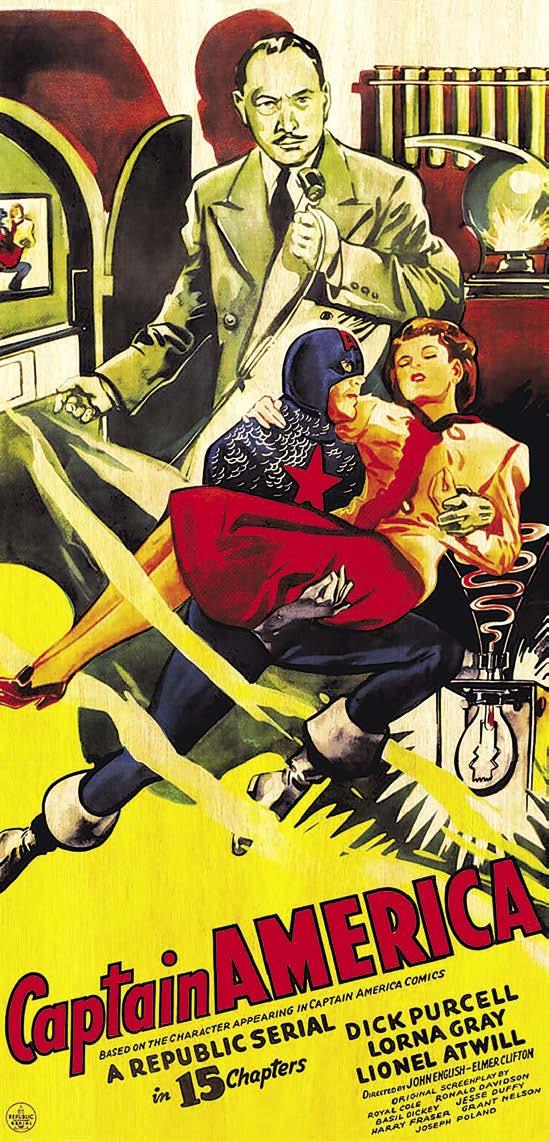

Cutting it finer, the First Live-Action Comic Book on Film was played by Tom Tyler in “The Adventures of Captain Marvel” (1941). The important qualifier in the previous sentence is the term “comic book,” as opposed to newspaper funnies, pulp fiction, radio, etc. (Yeah, it’s gettin’ geeky up in here.)

More comic book superheroes like Batman, Captain America and Superman would follow in their own serials. But 10 years would pass before a superhero finally top-lined a feature film as opposed to, yep, a serial. That film was “Superman and the Mole Men” (1951) star ring George Reeves, the First Live-Action Superhero Movie. It led to the First Live-Action Superhero TV Series — lots of “firsts,” eh? — “The Adventures of Superman” (1952-58) also starring Reeves.

Elsewhere in TV land, a series based on another of Captain Action’s original nine alternating characters, the Lone Ranger, aired from 1949 until ’57, with Clayton Moore wearing the mask.

Main image: Buster Crabbe with large space gun as Flash Gordon. Insets from top right: The Masked Marvel, Commander Cody, the Spider and the Shadow. © Universal Pictures;

EARLY FILM & TV

© Republic Pictures; © Columbia Pictures

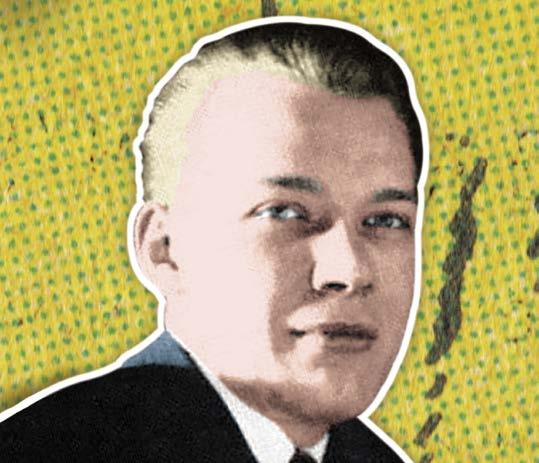

Gordon Jones and Keye Luke as Green Hornet and Kato. A lifetime later, Luke played Master Po on TV’s “Kung Fu.”

© Universal Pictures; © The Green Hornet Inc.

‘The Green Hornet ‘ (1940)

HOW’S THIS FOR TRANSPARENT EXPOSITION:

“It was a lucky day for me when I rescued you from that native in Singapore.”

That was Britt Reid (Gordon Jones), who had yet to adopt his Green Hornet persona, to his “houseboy” Kato (Chinese-American actor Keye Luke). Many Asian actors in old Hollywood movies were cast as houseboys. The white jackets were compulsory.

“He tried to kill me because I was Korean,” answered Kato, insuring that nobody in the World War II-era audience would think he was Japanese. “You shall never be sorry you saved my life.”

Ford Beebe and Ray Taylor’s “The Green Hornet” — the first of two back-to-back Hornet serials from Universal Pictures — is a classic origin story. But in keeping with the breakneck pace of the serial format, that origin is swiftly spelled out in dialogue and a bit of visual business. Britt and Kato’s transformation into masked crimefighters takes up a mere 11 minutes in Episode 1 of 13.

Britt — a “playboy” (just like Bruce Wayne!) who inherits a newspaper from his father — commends the “scientific knowledge” of Kato, who has developed a superfast car motor, a gas gun, and a buzzing siren that “sounds like the giant green hornet we encountered in Africa.” These spiffy accessories have been invented in secret, awaiting the day when Britt will finally put them to use, though he’s not yet sure how. “I’ll prove to that skeptical old dad of mine that I’m not just a playboy,” he tells Kato, leading us to suspect deep-set daddy issues are to blame.

AT THE SENTINEL (LOVE THAT STOCK FOOTAGE of a newsroom and a printing press), Britt is visited by a judge (Joseph Crehan) and the police commissioner (Stanley Andrews), who tell him they miss the anti-racketeering editorials his pappy used to write. “It was my father’s privilege to run this paper as he saw fit. I think the same applies to me,” is Britt’s pithy comeback.

He asks his visitors about their response to the current wave of racketeering activity: “What are you waiting for? A modern Robin Hood to lead you out of the woods?”

“Yes, Reid,” says the judge solemnly. “That’s just what this city needs, a Robin Hood.” Hmmm ...

So Britt dons a mask, Kato dons goggles, and the two take to the streets in that buzzing car. Posing as an underworld figure himself — something The Sentinel is only too happy to promulgate — the Hornet investigates, and smashes, one racket after another.

These include the building of a dam and tunnel with substandard materials; profiting from murder via a life insurance scam; sabotaging competing busing and trucking companies; a chop shop that sells parts from stolen cars; extorting “protection” money from launderers; and voter intimidation. (These guys do it all.)

Sourpuss Cy Kendall, who had a face made for gangstering, is perfectly cast as Munroe, the unseen racket boss’s enforcer.

The Sentinel’s watchful receptionist Lenore Case (Anne Nagel) is one of the few people to realize that the Hornet is really a good guy. “They ought to pin a medal on him instead of trying to catch him and put him in jail,” she says. Horror buffs remember Nagel from two Universal classics: She played the ingenue in the Boris Karloff-Bela Lugosi vehicle “Black Friday” (1940), and Lon Chaney Jr.’s kind-of love interest in “Man Made Monster” (1941).

Luke played Lee Chan, “No. 1 son” of Charlie Chan, in the film series about Earl Derr Bigger’s Chinese detective. Luke also played blind Master Po in TV’s “Kung Fu” starring David Carradine.

30

‘

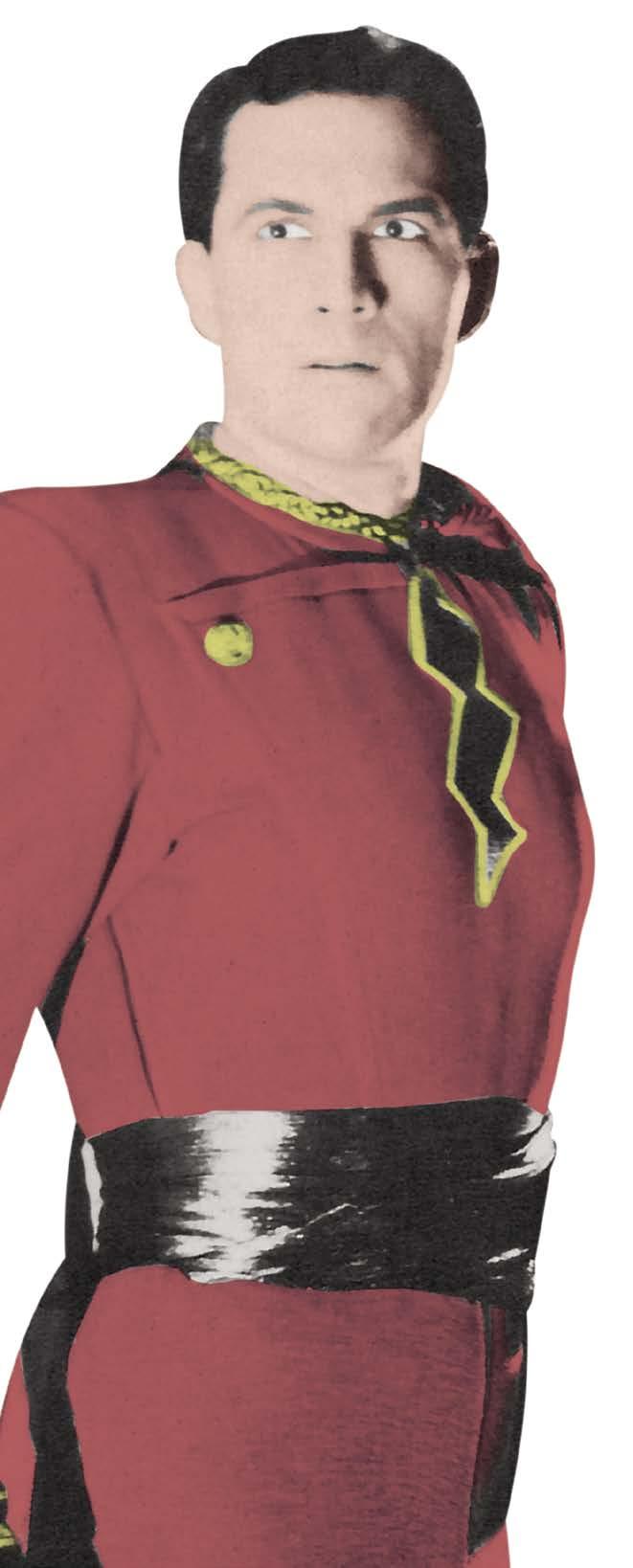

The Adventures of Captain Marvel ’ (1941)

A MASKED CRIMINAL MASTERMIND WHOSE identity is unknown to his own flunkies seeks to obtain a superweapon with which to rule the world, all the while being pursued by a costumed avenger.

That could be the plot of any serial based on a comic book superhero. In this case, it happens to be the very first one: Republic Pictures’ “The Adventures of Captain Marvel” co-directed by William Witney and John English.

While not exactly capturing the humor and whimsy of the Fawcett Publications comic books, the serial may well be the best of the wide 1940s field. Tom Tyler cut a dashing figure in the Captain Marvel getup, moving gracefully and playing the character straight — no winking, no barely concealed humiliation.

IN A “VOLCANIC LAND” CHEERLESSLY called the Valley of Tombs, an archeological expedition discovers an ancient tomb containing a golden idol in the form of a scorpion. Accompanying the expedition is radio journalist Billy Batson (Frank Coghlan), who encounters a robed, bearded wizard named Shazam (Nigel de Brulier).

The idol must not fall into the wrong hands, Shazam warns Billy. To prevent this, Billy is granted the power to transform into a superbeing. Says the old man: “All that is necessary is to repeat my name … Shazam!”

The golden scorpion is outfitted with five special lenses which, when positioned correctly, emit a destructive beam that can melt a mountain. A hooded fiend who calls himself the Scorpion — even the actor who plays him is listed only as “the Scorpion” in the credits — wants that idol. “Whoever controls the device will have power that men have dreamed of since the beginning of time,” he roars.

But expedition members cleverly divide the lenses among themselves in an attempt to keep things honest. (The real reason, savvy viewers know, is to give the flunkies a reason to pursue said expedition members for 12 chapters.)

Joining forces with Billy are Betty (Louise Currie), who is unafraid to get her dainty hands dirty, and Whitey (William Benedict), Billy’s kinda goofy wingman. Benedict’s Bowery Boys character was likewise called Whitey. Typecasting? Or “othering” just ’coz the actor’s pallor bordered on translucent?

Legendary stuntman David Sharpe put his gymnastic training on display, effortlessly executing a standing back flip in costume. For the flying sequences, a dummy gliding along a wire is sometimes utilized. Though not 100 percent convincing — the face is clearly that of a mannequin — seeing the dummy “fly” through actual environments (not rear screen) with cape flapping is so darned cool, you gladly overlook the deceit. On those occasions when Tyler’s face is visible, he achieves credible takeoffs and landings.

This Captain Marvel can be a badass. One of his signature moves is to lift a bad guy over his head and throw him. At one point, Marvel cavalierly tosses a baddie from atop a tall building. There’s nary a scream, but it’s a cinch the guy doesn’t survive the plunge. Judge, jury and executioner — it wouldn’t happen in a Fawcett comic book.

Tom Tyler moved gracefully and played it straight.

© Republic Pictures; © Fawcett Publications

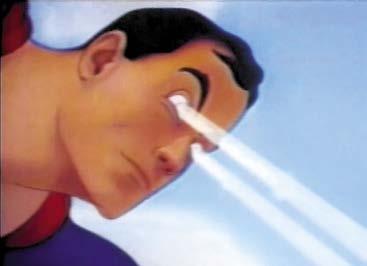

‘Superman ’ shorts (194 1 - 4 3)

THE FIRST CINEMATIC DEPICTION OF SUPERMAN, AND the first time the endless possibilities of the superhero genre were fittingly explored on film, happened in cartoons.

Fleischer Studios — the animators behind those fantastically strange Popeye and Betty Boop shorts — kicked off a series of seven-minute sci-fi masterpieces that comprise the Superman shorts. The Technicolor cartoons (most directed by Dave Fleischer) did what live action and even comic books could not, by demonstrating Superman’s super strength, speed and flight in imaginative and realistically executed scenarios. The Fleischers achieved a sweeping scope in their heavily storyboarded sequences of crackling laboratories, gleaming superweapons, giant robots, lumbering monsters, and teeming Metropolis itself.

Lois Lane (initially voiced by Joan Alexander) was a rare protofeminist character in the genre. She never flinched in her pursuit of The Big Story, despite sexist attitudes of the era. Lois’s snooping invariably resulted in her being lowered into a bubbling cauldron; or suspended over an active volcano; or stuffed into a torpedo awaiting launch. This is where the Man of Steel (initially voiced by radio’s Superman, Bud Collyer) came in.

The episodes typically wrapped with a Daily Planet headline (over Lois’s byline) summarizing the adventure. Lois would deflect compliments on her reporting by adding, “ . thanks to Superman!” Clark Kent then winked at the viewer.

The debut short, “Superman,” was nominated for an Oscar. The shorts popularized (but did not outright introduce) the concept that Superman can fly; previously, he “leaped.” Superman’s co-creators Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster were billed in the opening credits. The “faster than a speeding bullet” intro narration originated in these shorts, and was retained for the 1950s TV series.

FLEISCHER STUDIOS’ NINTH SUPERMAN

short, “Terror on the Midway,” was its last. It’s commonly reported that Paramount Pictures “absorbed” the Fleischers’ operation after two costly features underperformed at the box office. But in “The Fleischer Story” (Da Capo Press, 1988), author Leslie Cabarga suggests a more concerted takeover by Paramount.

Not helping was the fact that the Fleischer brothers — Max, Dave and Joe — often butted heads, to put it mildly, over remuneration, credit, workplace ethics and morale.

Despite greatly reducing the number of drawings, Paramount’s new animation arm Famous Studios maintained a degree of quality in the remaining eight shorts. Two key Fleischer refugees, Seymour Kneitel (Max’s son-in-law) and Isadore Sparber, were hired as production chiefs.

Five of the eight Famous Studios shorts are World War II-themed. In “Japoteurs,” the “world’s largest bomber plane” (an American invention) is hijacked during its maiden voyage. In “The Eleventh Hour,” Superman commits acts of sabotage in Japan. In “Destruction Inc.,” Lois investigates a munitions plant suspected of enemy infiltration. “Jungle Drums” ends with an Adolf Hitler cameo. In “Secret Agent,” a beautiful undercover agent embarks on a desperate mission to deliver a dossier detailing enemy plans.

Some shorts present regrettable stereotypes. We’ve been here before. Such cringe-worthy scenes can really ruin the party for classic movie buffs.

Superman’s sci-fi roots were visualized in the animation medium. © Paramount Pictures; © Fleischer Studios; © DC Comics Inc.

Superman’s sci-fi roots were visualized in the animation medium. © Paramount Pictures; © Fleischer Studios; © DC Comics Inc.

Clayton Moore

THE LONE RANGER WAS — NO PUN INTENDED — A straight shooter who never took a drink or killed indiscriminately, unlike some movie cowboys. “Well, the show started on radio in 1933. We, on the television series, lived up to the rules and regulations of the radio show,” said Clayton Moore (1914-1999), who portrayed the masked western hero on TV alongside Jay Silverheels (19121980) as Tonto. “It was a good moral program. Great for the kids. Great for the grownups, too. We need it today.”

Moore played in 169 of the 222 episodes of “The Lone Ranger,” which aired on ABC from 1949 through 1957.

“We pioneered the TV business,” Moore told me in 1992. “We started in 1949. We worked pretty fast, believe me. The budgets were very low in those days. We kept pretty active. And, of course, we had the fights going. Jay and myself were very careful. We rehearsed the stunts quite a bit. We made sure that nobody got injured. There was a tremendous amount of horse work. We did all of the horseback work, too. I love horses.”

SAID MOORE WHEN ASKED HIS THEORY ON on the enduring appeal of the Lone Ranger: “Well, I don’t think it’s only the Lone Ranger. I think it’s the fair play and the honesty that the cowboys showed, fellas like Roy Rogers, Gene Autry, and the Durango Kid, Charlie Starett. We had great heroes in the early days, too — Ken Maynard, George O’Brien, Colonel Tim McCoy, Tom Mix, Hoot Gibson, Buck Jones.

“I was quite a western (movie) admirer when I was a kid. It was Americana, the trials and tribulations the pioneers went through in the early days across the desert and the mountains with the storms and the snow. A tough life. They survived. They gave us what we have today: America.”

Said Moore of his costar Silverheels: “He was a wonderful man to work with. We were certainly good friends off the screen as well as on the screen. We shook hands for the first time in 1949. “Jay was a full-blooded Mohawk Indian. He was born on the Six Nations reservation in Brantford, Canada. Good sense of humor. Very quick study. Good athlete. Wonderful horseback rider. He was quite a gentleman. We kept in touch constantly. We did a lot of personal appearances together years ago.”

Said Moore of another co-star, the white thoroughbred horse Silver: “A beautiful animal. Very fast horse. Never got injured. Was very calm. Well kept. He was bathed every day. You know, with a white horse, you’ve got to keep him nice and clean, so he’ll look nice.”

Did Moore wish to reprise his role in Universal’s “The Legend of the Lone Ranger” (1981)?

“I would have liked to have done the feature that they made at that time, of course,” the actor said. “Anything pertaining to the Lone Ranger, I was always very eager to participate in.” The role instead went to a relative unknown named Klinton Spilsbury, and the movie bombed. I asked Moore if he thought he would have done a better job as the Ranger. There was a brief pause. “I think everybody tried real hard to make a nice picture,” he finally said. “I got out of that one, didn’t I?”

Clayton Moore, then 78, again wore the Lone Ranger’s mask in 1992.

Photo by Kathy Voglesong

Noel Nei ll

THE FIRST ACTRESS TO PLAY LOIS LANE, GAL PAL of Superman, never read Superman comic books as a girl.

“I don’t think girls were into comic books,” Neill (1920-2016) told me during a 2002 interview. “They were into dolls and things like that. I think the boys were into Superman.”

Neill originated the role in 1948 in the first of two Superman serials starring Kirk Alyn. When Phyllis Coates quit the TV series “The New Adventures of Superman” after one season as Lois, Neill was hired to replace Coates without auditioning.

She explained: “Mr. (Whitney) Ellsworth — who had been with National Comics for many years in New York and was one of the top dogs — was sent over to watch over the show. He and his wife moved out there. So I didn’t interview, because they knew that I had done the serials with Kirk Alyn. I had done those 30 chapters with Kirk. The producer just called my agent and said, ‘Does Noel want to play Lois Lane again?’ And he said, ‘Well, obviously, she will.’ And that was that.”

NEILL WORE MUCH FASHIONABLE ATTIRE IN THE serials, including some wacky-in-retrospect hats. But not on TV.

“I had three suits, all alike,” she said with a laugh.

“We would shoot 26 episodes in 13 weeks. First, we would do all of the scenes with the ‘heavies’ (villains), as we called them in those days — you know, the character actors — for several weeks, and then get rid of them. In the last two weeks of filming, the four of us (Neill, Reeves, Jack Larson as Jimmy Olsen and John Hamilton as Perry White) would get together at the Daily Planet and do all of our stuff for the 26 episodes. Of course, this was all difficult to keep track of. The poor little script girl!

“That’s why we wore the same outfits all the time. Because there’s no way the script girl could possibly keep track of what we were wearing. So we just wore the same thing.”

Cast members, too, found it hard to keep track of continuity.

“We just kind of winged it,” Neill said. “Of course, wearing the same outfit all the time, we didn’t have to think too much. But we would get the call sheets every afternoon telling us what we’d be doing the next day. So we would collect that and put it in our daily book and give it a quick rundown. We used to say, ‘All the dialogue is the same; they just change the name of the heavies.’ ”

THE PACE WAS EASED BY CAST CAMARADERIE.

“It was fun just working together,” Neill said. “We were so used to each other after doing — what? — 70-some episodes together. Jack was a very good actor and George was a fabulous actor and Mr. Hamilton was just hysterical. He was a riot.”

Being a superhero series and all, “The Adventures of Superman” had more special effects than the average show. The FX were overseen by Thol “Si” Simonson.

“One morning, Jack and Mr. Hamilton and I were at the cave. It was the first shot of the morning. The night before, Si had built the wall that George was to come through. They would let it set for a certain amount of time. But something happened; it set just a little harder than it should have. And so the director, George Blair, yelled, ‘OK, everybody! One take! One take only!’

Noel Neill in a glamor shot circa the late 1940s. Opposite: Neill, then 83, showed her Superman colors in 2003.

“Then he yelled, ‘Action!’ And so there we were, waiting for George (Reeves) to come through the wall. And the next thing we knew, we saw one hand and one foot in the wall! And there was dead silence. Everybody just stood there staring. And finally, somebody yelled, ‘George (Blair)! Cut the film! Cut the film! George (Reeves) is stuck!’

“And he was, bless his heart. George Reeves pulled himself back out of this wall and took a very courtly, Southern bow to everybody and said, ‘I will see you all tomorrow.’ So there was a mad scramble to redo the day’s filming. ‘What do we do?’ ‘Help! Help! Help!’ Scatter, scatter, scatter. But bless his heart, George (Reeves) didn’t scream and yell or anything.

“Mr. Simonson was so upset. But it was just the timing — a little bit too long, and the wall hardened. But he was so effective with all of this. Jack Larson always said that he put himself in Si’s hands because, you know, fire shots were coming up out of the stage and off the walls and everything. But we trusted him.”

The way the production was structured, there were long stretches of inactivity for the cast.

“Everybody would be pretty well scattered,” Neill said. “See, we shot 26 shows in 13 weeks. According to our contracts, which were laughable, they could give us two and a half years off and still get us back again if they wanted us. So we wouldn’t see each other for two and a half years! Everybody went their own way. It was kind of strange. But it made for a lot of happy reunions.”

40

2003 photo by Kathy Voglesong

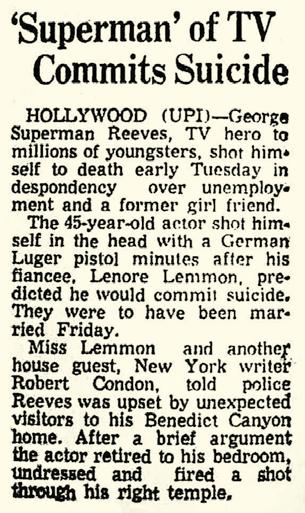

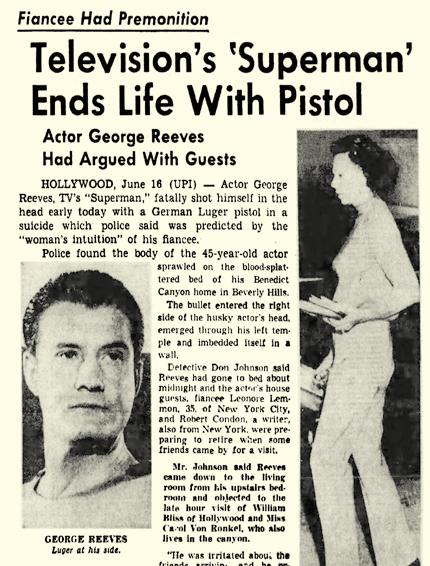

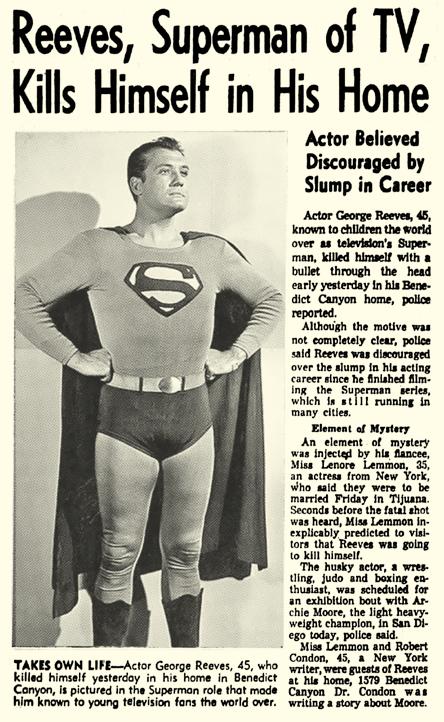

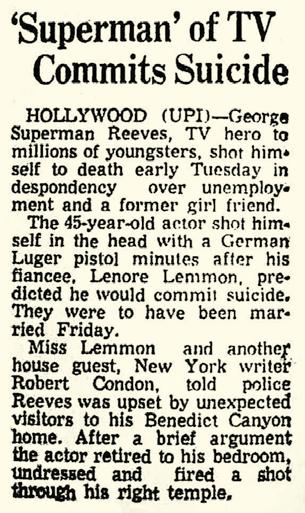

Mourning Superman

We didn’t know he was dead. We only knew he was Superman.

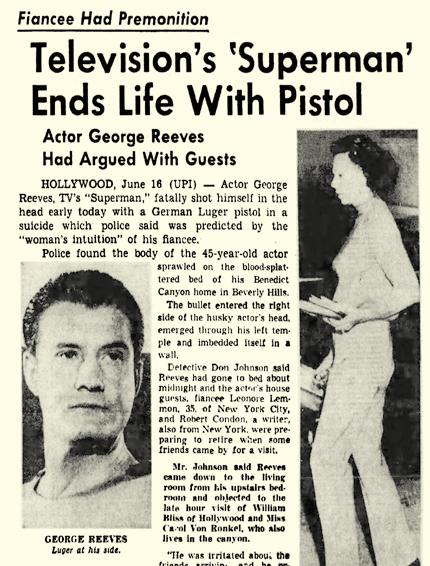

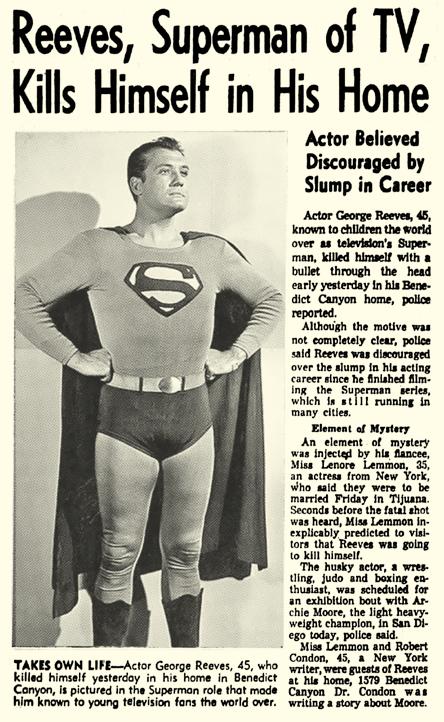

The 1952-58 TV series “The Adventures of Superman” starring George Reeves received a nice boost from 1966-era Batmania.

“Watch Superman on Television!” proclaimed a 1966 full-page advertisement that ran in comic books, the medium of Superman’s birth. “America’s favorite adventure character comes right into your home in thrilling super action!” The ad featured a list of 83 stations that carried the show. (To this day, when I see the ad, I look for my local station: WKBS, Channel 48 in Philadelphia.)

The rub: The Batmania generation had to learn — in a slow, protracted process — that the star of the series was long dead. We didn’t typically get the news from parents or teachers. More likely, it was reported via the kid grapevine in the schoolyard or around the neighborhood. This was, in its own way, quite traumatizing.

Reeves’ co-star, Noel Neill, told me spirits were high among the cast in June 1959, when they were informed by producer (and DC editor) Whitney Ellsworth that 26 more episodes were ordered.

As she told me in 2003: “I said, ‘Gee, that’ll take us almost into Christmas, and give us a little Christmas gift.’ Mr. Ellsworth said, ‘Come on by. We’ve got the same offices. Come see if your old costume still fits.’ So I stopped by a few days later. George Blair, the director, and George Reeves were together playing their usual gin rummy game, happy as little bugs. Everything was fine.

“George (Reeves) was going to direct a movie. Anyway, he was very happy. We had those 26 shows to look forward to.”

A few days later, on June 16, 1959, Reeves was found dead of a gunshot wound to the head in his Benedict Canyon home. The death was ruled a suicide, despite irregularities in witness statements and some evidence. Neill learned the tragic news in an odd way. She received a call from Reeves’ fiance, socialite Leonore Lemmon, but initially misunderstood who Lemmon was talking about.

Recalled Neill: “His girlfriend called and asked if I’d heard what happened to George. I thought she was talking about her husband. I said, ‘No. What happened to him?’ We had this idiotic conversation. She finally said, ‘No! Not my husband! George Reeves!’ I said, ‘Oh, my gosh!’ So that was the first I heard of it.

“There was no talk of making any more (‘Superman’) shows, because the gentlemen in New York had said, ‘Well, we’ve got 104, so we’ll just run ’em forever. We don’t need any more.’ Which was good for them, bad for us.”

Neill said the tragic news was under-reported, but not because of some coverup or conspiracy. “Everything was quickly hushed up, shall we say, any publicity,” the actress said. “Because, well, it was a children’s show, and they didn’t want all the children in the world to realize that Superman was human after all.”

Dynamic television

EVERYTHING CAME TOGETHER. THE MOON was in the seventh house. A perfect thing happened in 1966, and that thing was “Batman.”

Producer William Dozier — not a comic book guy — and writer Lorenzo Semple Jr. created what seemed, to a world of mostly non-comic-book people, like a comic book brought to life. (Only true comic book people, then a marginalized demographic, knew better.)

The production became Dozier’s baby, but it didn’t start that way. ABC had the rights (and a hole in its schedule), and made an overture to Dozier, who agreed to a meeting. Never having read Batman, Dozier bought “seven or eight copies of the vintage Batman comic books” for crash research.

“At first, I thought they were crazy,” Dozier (1908-1991) told Joel Eisner in “The Official Batman Batbook” (1986).

“I really thought they were crazy, if they were going to try to put this on television. Then I had just the simple idea of overdoing it, of making it so square and so serious that adults would find it amusing.”

DOZIER MOUNTED A COLOR-SATURATED production fueled by Semple’s hip scripts (with subsequent writers taking his comedic cue). The casting gods, too, were with “Batman.” Adam West’s Bruce Wayne was a human mannequin and a grown-up Boy Scout. Burt Ward’s Dick Grayson was the last gasp of well-behaved pre-hippie youth.

They were bolstered by veterans Madge Blake (fidgety Aunt Harriet); Alan Napier (stalwart Alfred the butler); Neil Hamilton (no-nonsense Commissioner Gordon); Stafford Repp (stereotypical Irish cop Chief O’Hara); plus the many stars who gleefully hopped onto the roller coaster as guest villains.

Without West, would “Batman” have rocked our world? Also considered for the role were Lyle Waggoner, Mike Henry and Ty Hardin. Fine professionals all, but come on. Dozier already had his amazing, colorful production built and the first scripts written. In the 11th hour, all he needed was for the perfect Batman to stroll through his office doors.

The show kept things light, though there was one reference to Batman’s violent origin story — the one in which Bruce Wayne’s parents are shot dead in the street in front of young Bruce, triggering his vow to fight crime.

In West’s very first words as Bruce, he addresses a group whose anti-crime program he supports financially. Bruce speaks of the time “when my own parents were murdered by dastardly criminals.” This was the first — and last — instance of the TV “Batman” getting real like in the comics.

Burt Ward and Adam West (shown in 1992) weren’t household names when first cast in “Batman.”

Opposite: SOCK! POW! It’s the opening credits!

HOLY RATINGS!

45

1992 photo by Kathy Voglesong; opposite © DC Comics Inc., © Warner Bros.

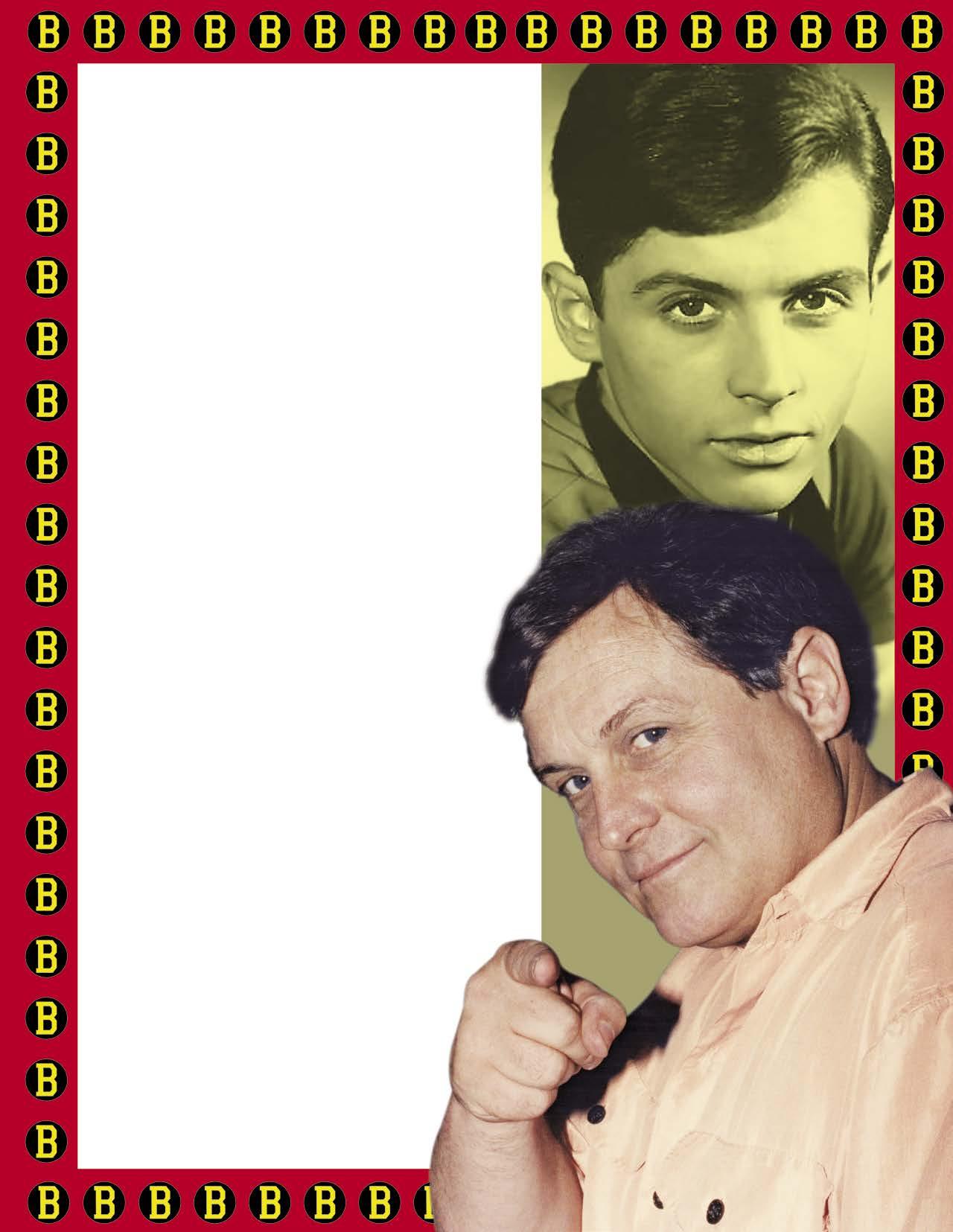

Adam West

HE WAS THE RIGHT (BAT) MAN FOR THE JOB.

An actor who could be both leading man and clown, Adam West (19282017) was born Billy West Anderson in Walla Walla, Washington. In his 1994 memoir, he was candid about his mother, Audrey, an alcoholic who West knew, even as a youngster, was not faithful to his father. Audrey had dreams of stardom, and once told West that but for his birth, she could have been Joan Crawford. Armchair psychologists might point to these events as the roots of West’s own issues with intimacy and commitment.

West worked as a radio disc jockey in Walla Walla … spent a year with the McClatchy news agency … worked in an embryonic television facility at Fort Monmouth, N.J., while in the Army … migrated to Hawaii, where he made his film debut in the Boris Karloff movie “Voodoo Island” (1957) and hosted “The Kini Popo Show” on local TV … migrated to Los Angeles ... and won promising early roles in “The Young Philadelphians” (1959), TV’s “The Detectives” (1961-62), “Robinson Crusoe on Mars” (1964) and “The Outlaws is Coming” (1965).

In the end, a silly little TV commercial for Nestlé’s caught the attention of producer William Dozier, leading to the role of a lifetime.

I interviewed West on six occasions between 1992 and 2010.

Q: Is it ever painful for you to talk about “Batman”?

WEST: Not at all. I have no rancor, no bitterness. I don’t cry over all the money I’m missing.

Q: When did you realize that you had become irreversibly famous?

WEST: It was when I got home from the studio on the night “Batman” was scheduled to go on the air. I stopped at a market in Malibu, where I lived at the time, to grab a steak and a six-pack of beer for dinner. I was in a hurry and overworked. And I heard, at the checkout, “Come on! Hurry up! We’ve gotta get home to watch ‘Batman’! Faster!” And I thought, uh-oh, this could be the start of something.

Q: When “Batman” premiered, us kids tried to stay faithful to “Lost in Space” on CBS. But once we saw you and Burt in those costumes …

WEST: That’s very funny. See, that’s how we grabbed the kids. And then as adults, they watch it later and then they get the jokes.

Q: You grew up during a great time for Batman comic books; you were 11 when the character debuted. Did you read them as a child?

WEST: Yes, I did. My education was elective, not selective.

Q: Did you bring anything from the comics into your portrayal?

WEST: Well, you know what you do? You grab a little from something and something else, and you scratch it out. What I called on there was not so much the comic book, literally, but the sense memories of having read it and what it did to me. You know what I’m saying? As a kid. How it affected me, to call that back.

Adam West (shown in 1994, opposite, and 1992, right) was constantly reminded that the public equated him with Batman.

Who else could have worn the cape and cowl?

Photos by Kathy Voglesong; “Batman” © Warner Bros.; character © DC Comics Inc.

Photos by Kathy Voglesong; “Batman” © Warner Bros.; character © DC Comics Inc.

Q: What were your other injuries on that first episode?

WARD: On the same show, there’s a scene where Batman breaks through the subway. This is the Frank Gorshin one, the first one. I was on the table, and Batman breaks through the tunnel in the subway to rescue me. The special effects men were to have built a “breakaway” set, so that when they put in these light explosives, it would just break away and Batman could come through. Well, the people that built the set, in their infinite wisdom, didn’t make it a breakaway set. They built a regular set with 2x4s. There wasn’t time to cut it all up and redo it. So again, the special effects people, being the geniuses that they were, planted three sticks of dynamite and nearly blew the entire sound stage down! I had 2x4s landing on my head! I went right back into the emergency ward.

Then — on the same show — I’m climbing out of a burning car and Batman, being the main character, gets to come out first. So I’m down there in this flaming car while Adam stands there, taking quite a while in front of the camera before coming out. And just as I start to jump out, the car accidentally blew up and threw us both to the ground. I got scorched and went back in the emergency room.

So that was three (laughs). Anyway, quite a lot of things like that happened. I thought I wasn’t going to survive it.

Q: As a show-biz newcomer, were you aware of the legendary status of many of the guest stars who appeared as villains?

WARD: Oh, sure. I was like a kid in a candy store. Every one of these superstars shows up, and here I am, just a kid working with them, you know? I was just a 20-year-old kid brought up in a sheltered life. So for me, all of this stuff was so much of a change. It was really a treat to work with so many greats. I don’t have one complaint about one person on “Batman.” They were all terrific. It was like a learning experience for me, working with people like Tallulah Bankhead and George Raft. Great, great actors and actresses. They were fabulous. Each one brought something different to the show. I just had the greatest time.

Q: Were there any guest villains who didn’t “get” it?

Tallulah Bankhead was, first and foremost, a stage actress ...

WARD: No, she was wonderful. “Batman” was such a success that everybody wanted to do the show. Everybody wanted to kind of let go and be crazy, and that’s what they did.

Q: It seemed that the top four villains on the show were Riddler, Penguin, Joker and Catwoman. The movie supported this view.

WARD: Well, they may have been the four who were selected for the movie, but I’ll tell ya, I really enjoyed working with a lot of the others, too. Victor Buono, who played King Tut, was incredible. I think Vincent Price, who played Egghead, was great.

Q: Adam said Otto Preminger was the most difficult guest.

WARD: I had heard stories about the horror, the terror of this man Otto Preminger. But he was very nice to me.

Q: How about his fellow Mr. Freeze, George Sanders?

WARD: George Sanders had an elegance and a class. He just reeked of class. He kind of reminded me of Cesar Romero. Very classy man. Just totally professional. Totally sophisticated. He was just terrific. The fact of his suicide (in 1972) was such a surprise. It really stunned me, the tragedy of his death.

“It was the first thing I ever tried out for,” said Ward (shown in 1992) of auditioning for the role of Robin.

Photo by Kathy Voglesong

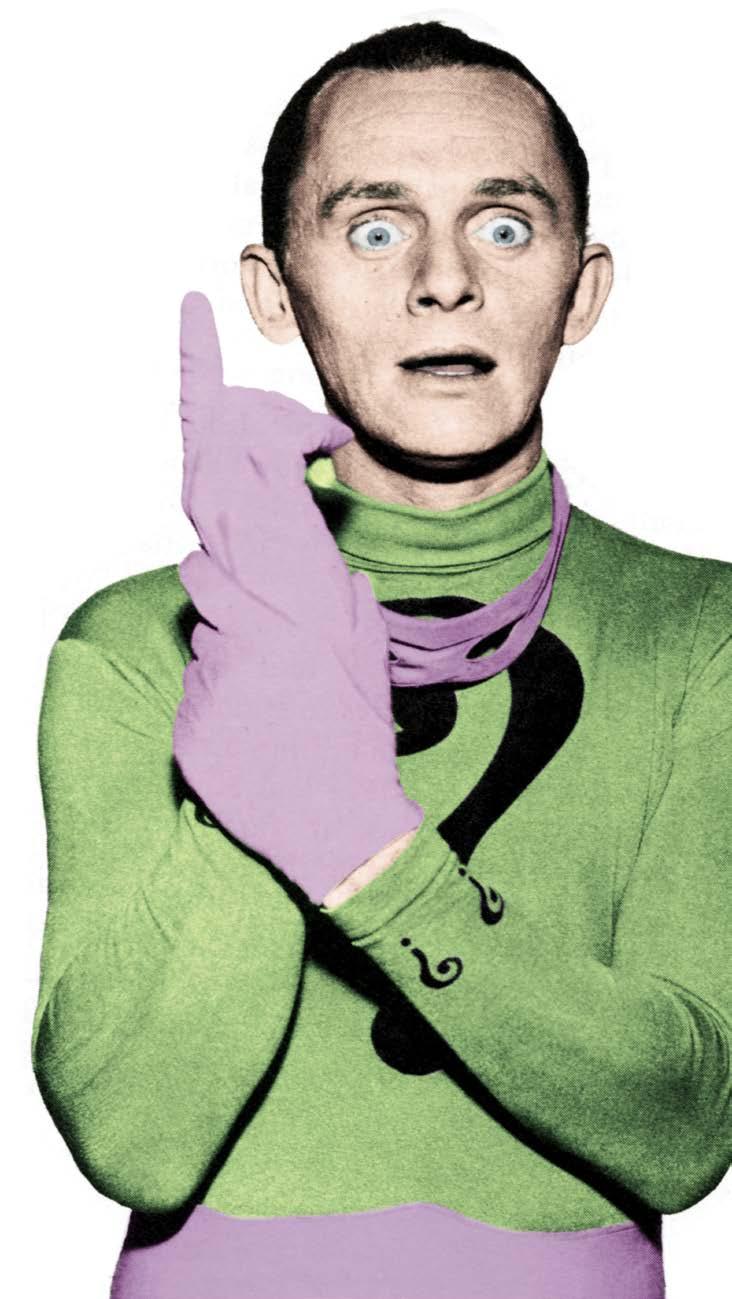

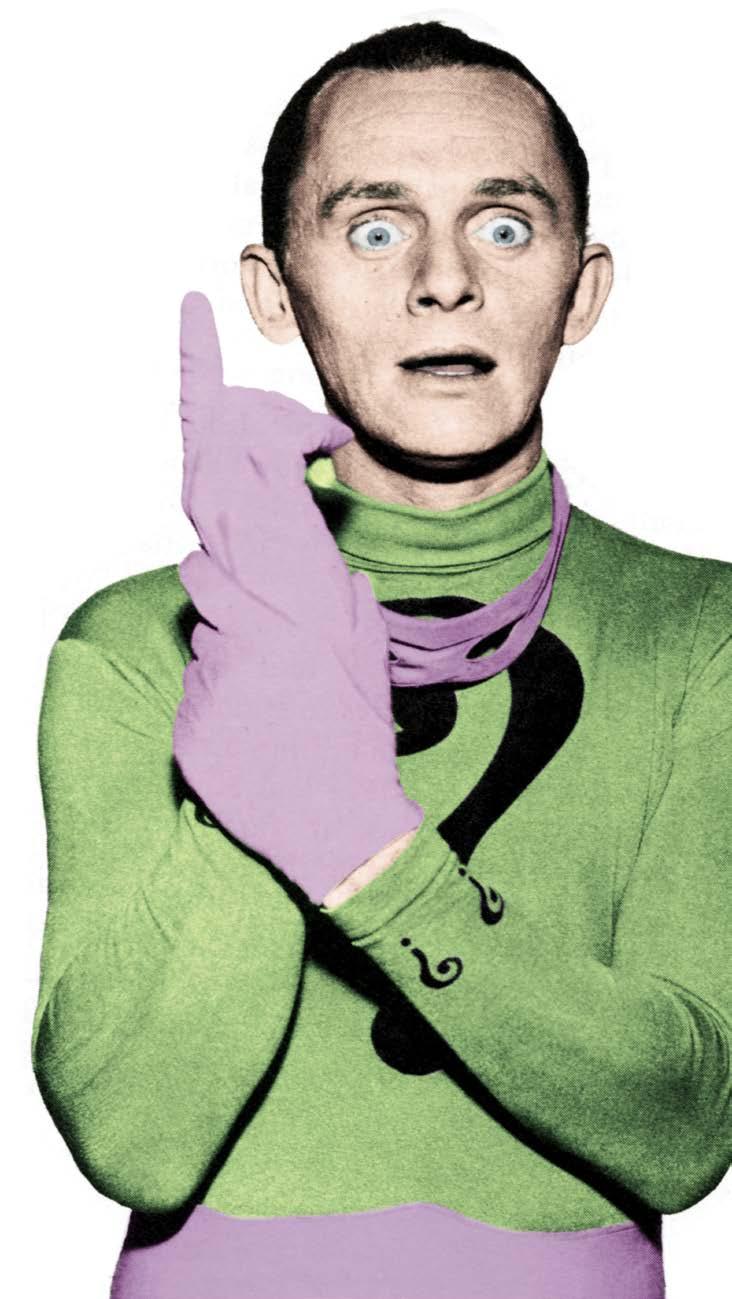

Q: The outfit you wore as the Riddler was unforgivingly form-fitting. Did you have to lay off the pasta in order to squeeze into it?

GORSHIN: I love pasta (laughs). I always eat pasta. But that’s not fattening. It’s what you put on that pasta that’s fattening. No, at the time, I was pretty trim. I only weighed 155 pounds, as opposed to now. Now, I’m between 175 and 180. The costume was dictated by the comic book. That’s what the comic book was. If you look at those old comic books, he wore the same skin-tight outfit. The same one I wore, the same one Jim Carrey wore (in “Batman Forever”).

Q: Adam and Burt said they got pretty banged up while shooting “Batman.” Do you have any dangerous stunt anecdotes?

GORSHIN: When I came down that slide in that first episode, I had a tough time doing that. When I’d get down to the bottom of the slide, I always ended up on my can. That was embarrassing, to have everybody watching. But then after a few tries, I got it.

Q: As the Riddler, sometimes you wore the mask, sometimes not. Did you do this unconsciously, or was it in the script?

GORSHIN: Well, the Riddler wasn’t worried about being recognized. But he would feel, from time to time, that the mask made him more attractive (laughs).

Q: Burt Ward has called Adam West, with affection, the world’s greatest upstager. Did he upstage you?

GORSHIN: No. It was Burt Ward who upstaged me. He’s the world’s greatest upstager (laughs).

Q: What was the main difference between making “Batman” the TV show and “Batman” the movie?

GORSHIN: Really, there was no difference, although on the show, each episode would be dedicated to one particular villain. On the movie, we all got to work together — Cesar and Burgess and Lee Meriwether. In that respect, it was different. And it took more weeks to shoot than an episode, of course.

Q: Before “Batman,” you did those wild impressions of Kirk Douglas and Burt Lancaster on “Ed Sullivan.” Did you ever hear from those guys?

GORSHIN: I heard they were flattered by what I did. Kirk Douglas himself told me he loved to watch me do it. He said that if he ever forgot how to do himself, he would call me (laughs).

Q: Are there ever times when you regret being so identified with the Riddler?

GORSHIN: No! How could I resent it? It was really an important part of my career. I like to think that people are aware that I do other things too. I can’t resent it, because it did a lot for me. Even now, I get kids who are 10, 11 years old who know me because they’ve seen me as the Riddler. So it’s kept me alive, so to speak, my career.

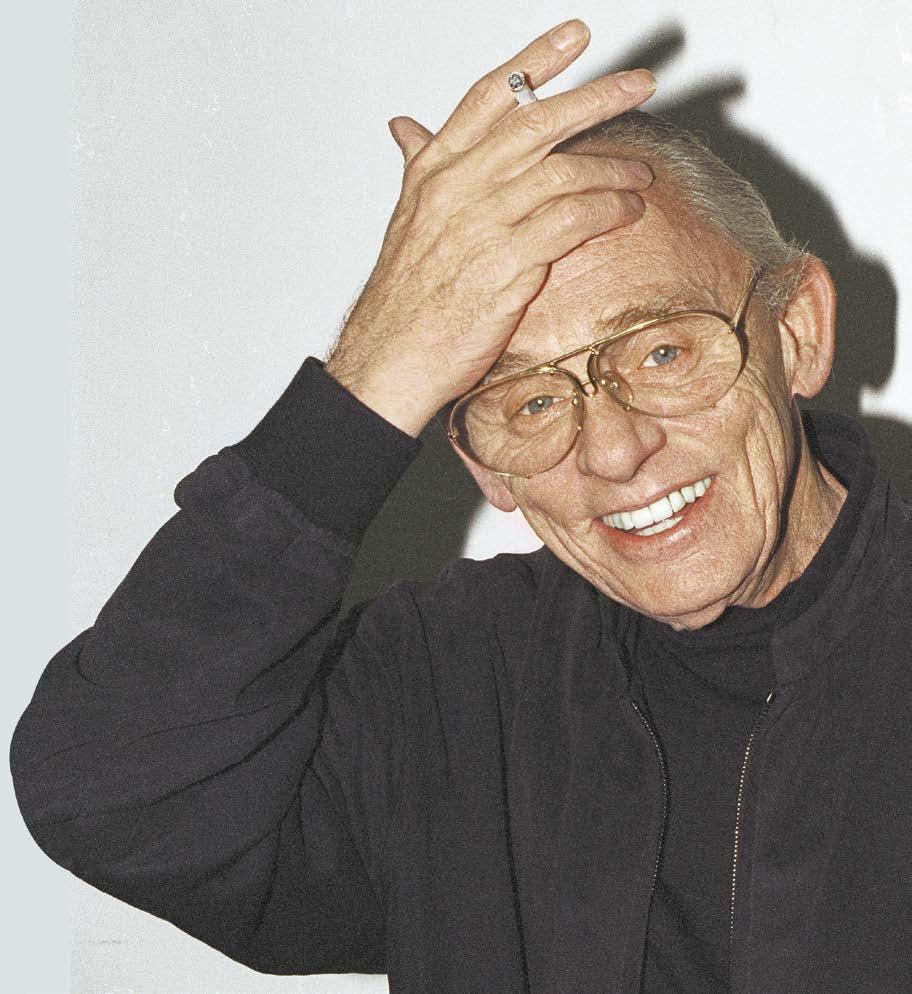

Gorshin (shown in 2001) compared the Riddler to Shakespeare.

Photo by Kathy Voglesong

Gorshin (shown in 2001) compared the Riddler to Shakespeare.

Photo by Kathy Voglesong

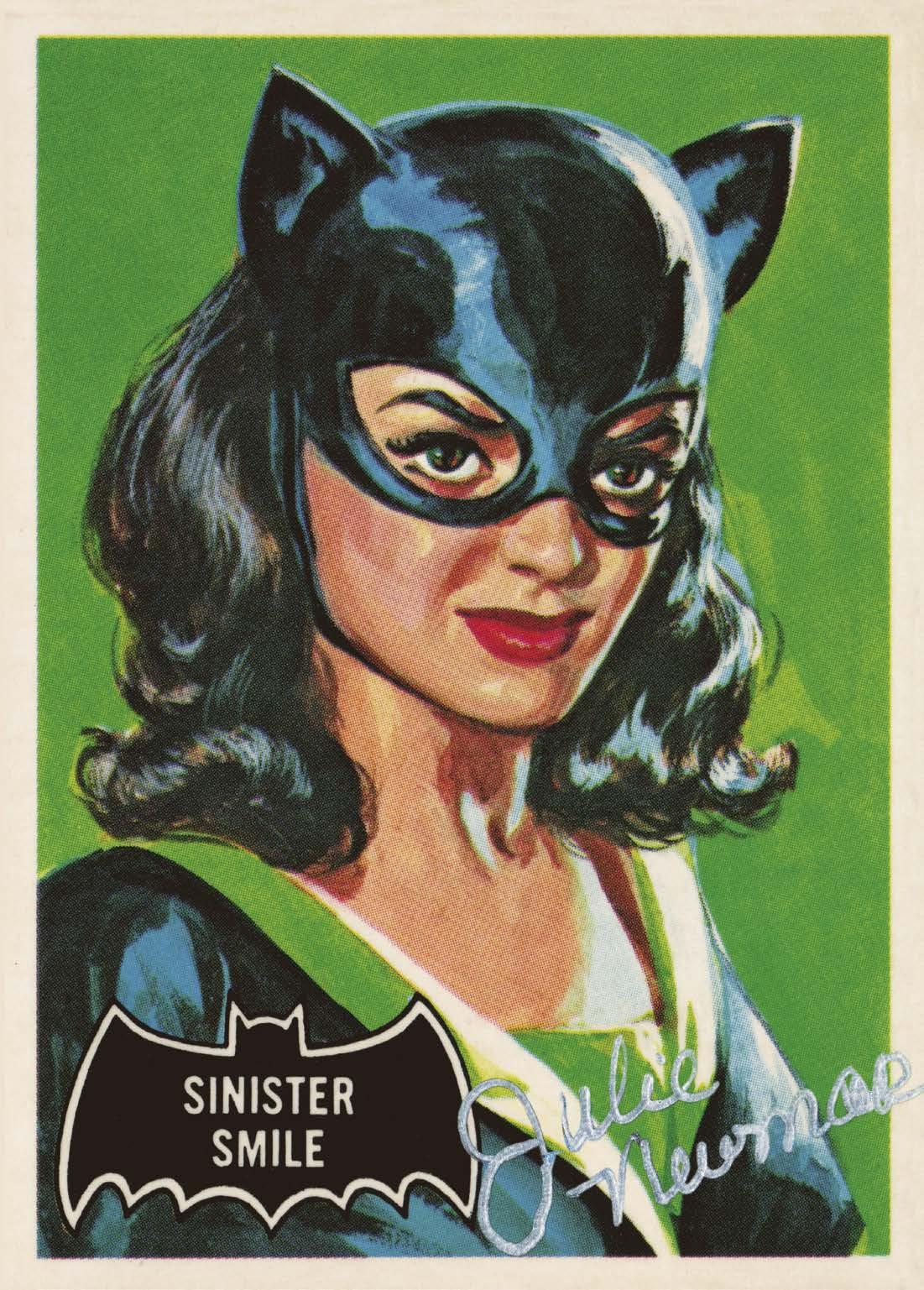

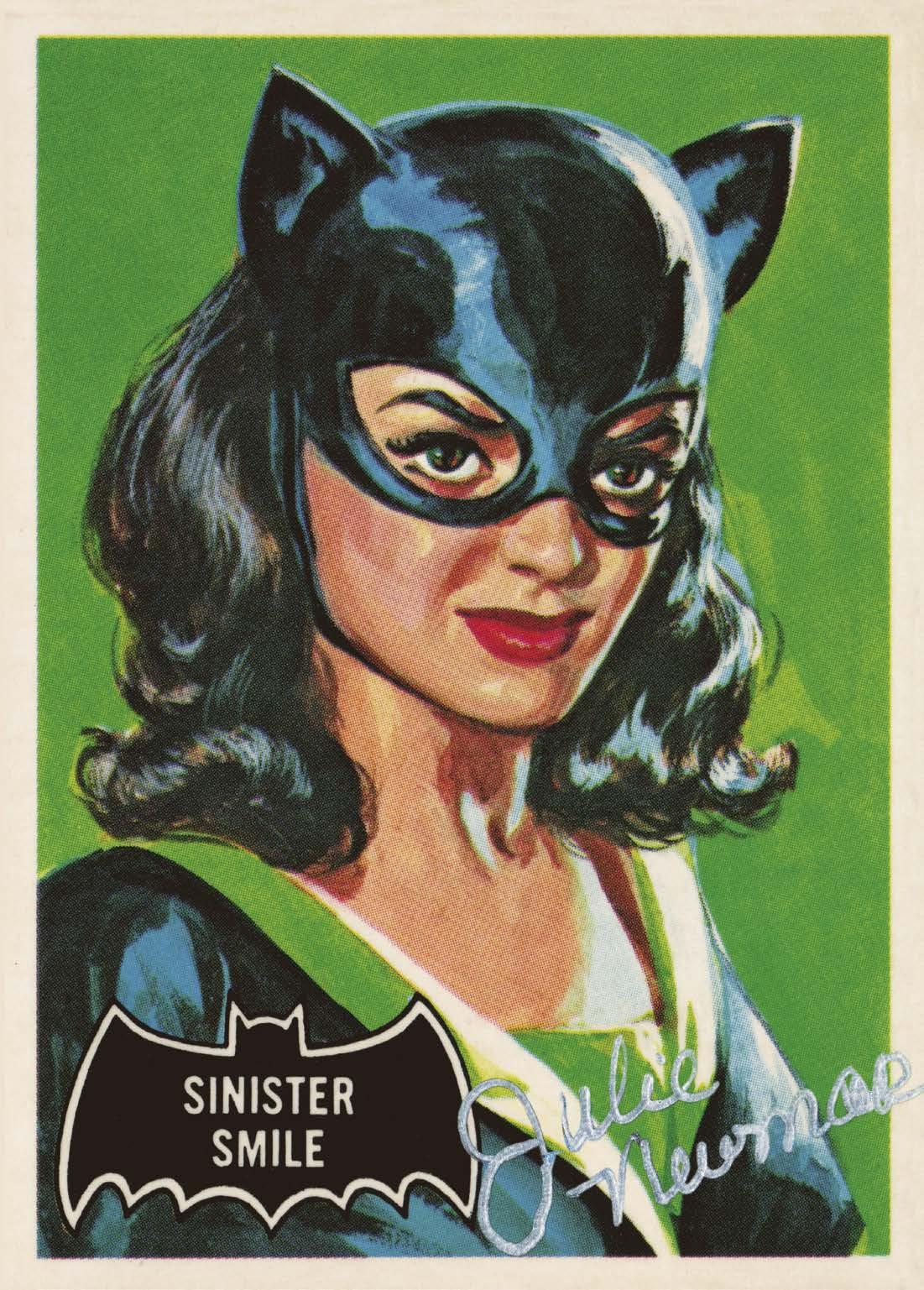

Q: Of course, Stanley Ralph Ross wrote all of that delicious dialogue for the Catwoman, which you ran away with.

NEWMAR: If it hadn’t been for Stanley’s brilliant dialogue — all I had to do was just physicalize the words. When you have gorgeous dialogue like that, all you have to do is get in the right costume and show up.

Q: You make it sound like anyone could’ve done it.

NEWMAR: No, it’s true. There’s a lot of details in that, so that the end result is that everything looks easy. But, yeah, I owe my career to Stanley Ralph Ross (laughs).

Q: But you certainly brought something of yourself into the Catwoman, something that wasn’t in the scripts.

NEWMAR: I’m sure that with the Catwoman, as any role, one offers one’s gifts. If it works, it works. If the part is wrong or the editing or whatever goes into all of our magicmaking, if the other guys didn’t do their jobs, then we all suffer, you see. But I think they all did their jobs on the “Batman.” I give the producer (William Dozier) the top star for that. They prepared the ground for me to dance on. They gave me the clothes to shine in.

Q: The Catwoman costume stood out in a show in which every other actor was swathed in colorful fabric. It looked like someone literally measured every inch of your body.

NEWMAR: It was me. See, I have the secret of making zingy clothes, form-fitting clothes. It’s almost as if licorice was poured over the body, and then they zip you into it. It’s very easy to wear. It’s secret is in the seams. The whole secret is in the seams, and I’m the only one who knows how to do it.

Q: Catwoman was once teamed with the Sandman, played by Michael Rennie, who was so wonderful and mysterious as Klaatu, the Christ-figure space alien in “The Day the Earth Stood Still” (1951). How was it, working with Rennie?

NEWMAR: Oh, my. Yes, that’s right. That was a bizarre sequence. Forgive me for not having a splendid story about him. Stanley probably does. And Stanley didn’t write that show. So, we were kind of ... not working together. We were working shoulder-to-shoulder in that. Stanley wrote five out of the six shows (featuring Newmar), but he didn’t write Michael Rennie’s show. You know, these things happen very fast. And I’m not a big-time socializing actress.

Q: What do you think of the other actresses who’ve followed you in the role of Catwoman, such as Lee Meriwether, Eartha Kitt and Michelle Pfeiffer?

NEWMAR: Personally, Lee Meriwether is a dear and beloved friend of mine. I love her. Eartha Kitt has a far better “purr” than I do, and Michelle Pfeiffer has a far better “meow” than I do. So, I look up to them. Well, not really. They look up to me — but that’s only because I’m 5-foot-11 (laughs).

“It’s almost as if licorice was poured over the body,” said Julie Newmar, shown in 1995, of the customized costume she wore as the Catwoman.

Photo by Kathy Voglesong

Photo by Kathy Voglesong

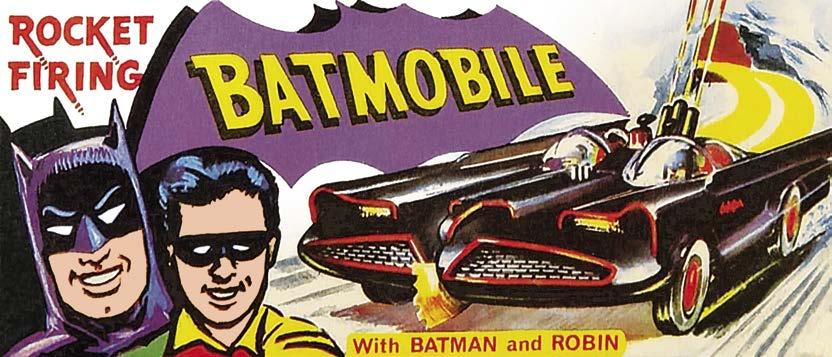

Righteous wheels

HE WAS DESIGNING A CAR FROM A COMIC BOOK.

But George Barris, Hollywood’s “King of the Customizers,” didn’t design a comic book car.

“As you know, in the comic book, Bob Kane had an old Zephyr,” Barris (1925-2015) told me during a 1997 interview.

“The bat-face was just cut out of metal and stuck on the front. Of course, this was an artist’s rendition. When they (ABC TV) came to me — this was in 1966 — they said, ‘We want to get a 20th-century Batmobile, something that would be for a crimefighter with the crimefighting equipment of today.’ Immediately I thought, ‘If I’m going to build a Batmobile, I want to incorporate the bat-features into the car, and not have it be just a ‘paste-up.’

“That’s why, when I designed the car, I designed it off the Futura. The original car was a Futura Lincoln-Mercury Ford ‘concept car.’ A concept car is not a production car or a year model. It’s not sold to the public. It’s a concept car like you see at a new car dealers’ show. You see special ‘idea’ cars or futuristic cars.

“Because we had three weeks to build the car, I had to have a basic car that I could work with. That one (the Futura) already had some of the characteristics that I wanted. It had the double basic bubbles. It was only a two-passenger. It was 20 feet long. I could use that to effect the length and the wheel base.”

With the Futura as a suitable “skeleton” for the Batmobile, Barris set about customizing the vehicle.

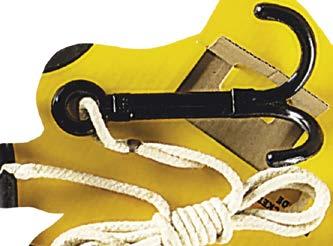

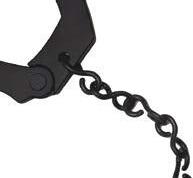

“Of course, I changed the basic fins around so that I could get the bat-fins,” Barris said. “I took the headlights and made them into bat-ears. I took the scoop and made it into a nose. We had the chain slicer coming out of the nose. The grills on each side, I made out of cavities; they became the mouth.

“In painting the car black, we outlined all of the characteristic lines in a fluorescent reddish-orange, which is a ‘glow’ color, so that it would glow at night. That meant the bat-face and the batfins and the bat-figures would illuminate at night on camera or wherever we had it. That’s the effect we wanted.”

What did the TV folks mean when they said the car should have the “crimefighting equipment of today”?