Housing & Inclusivity

Tempe-Sorgenfri, Trondheim

Project Course Report, Autumn 2023

Urban Ecological Planning Master’s programme

Department of Architecture & Planning, Faculty of Architecture

Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Trondheim, Norway

AAR4525 - Urban Ecological Planning: Project Course

Autumn 2023

Urban Ecological Planning Master’s Programme

Department of Architecture and Planning, Faculty of Architecture

Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU), Trondheim, Norway

Course Coordinator:

Supervision Team:

Cinthia Freire Stecchini PhD Scholar, NTNU

Cinthia Freire Stecchini PhD Scholar, NTNU

Jarvis Suslowicz PhD Scholar, NTNU

Vija Viese

Research Associate, NTNU

Rolee Aranya

Professor, NTNU

Booklet Layout:

Vija Viese

Research Associate, NTNU

Project Title | Project location | 2

Housing & Inclusivity

Tempe-Sorgenfri, Trondheim

Authors

Sara Sofie Øybakk Gerhardsen Norway

Randa Kalaji Syria

Milena Kisters Germany

Emiliano Muños Espinoza Mexico

This project report presents the results of the extended fieldwork conducted by master students in the first semester of the 2-year international Master of Science Program in Urban Ecological Planning (UEP) at the faculty of Architecture and Design at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU). The extended fieldwork is a key component of the UEP program, allowing students to work in real cases and to learn-by-doing. In Autumn 2023, the fieldwork took place in Trondheim, Norway.

During this semester, the UEP program worked in close collaboration with Trondheim Municipality. This is the first time such a collaboration was established in Norway for the fieldwork, which was planned envisioning mutual benefits for the students’ learning process and the development of plans and programs by the municipality. The location for the fieldwork – Tempe and Sorgenfri, the focus of one the municipality’s ongoing area-based programs – was decided together. From the very beginning, students were provided with official reports and documents about the area as well as contacts for local stakeholders. This was the base information that they had to complement (and challenge!) by conducting their own situational analysis and identification of a problem statement through participatory planning methods.

The students were divided into three groups and worked on one of the proposed broad themes: Housing & Inclusivity, Public Space & Activation, and Mobility & Accessibility. In the final stage of the project, the groups elaborated concepts and proposals for strategic solutions. The collaboration with the municipality made it easier to access stakeholders, who were invited to two mid-term presentations and the final one. Stakeholders commented on the work, validating (and challenging!) the findings and proposals of our students. What you will read in this report, thus, is the work done by UEP students validated and reviewed based on the stakeholders’ involvement in Tempe-Sorgenfri. We hope that this type of collaboration continues, and evolves, in the years to come.

Project Title | Project location | 4

Preface

Another novelty in the Autumn semester 2023 is that the course coordination and supervision was done by three academics in the early stages of their careers. We are two PhD candidates and a research associate from the department, with backgrounds in Architecture, Urban Planning and Design, Psychology, and Geography. Being responsible for the project course and the fieldwork has been an exciting challenge for us and a fruitful learning experience.

As an international master program, students from UEP come from different nationalities. The diversity of backgrounds – also in terms of academic background – is something we take pride in as it allows a rich exchange among students. We understand diversity as a valuable resource in preparing the next generation of conscious planners. To support the broadening of perspectives, particularly establishing relations of North and South countries – something we actively seek at UEP, we also had a study trip to South Africa, during the same semester, as a part of the UTFORSK-NISA project (https://www.nisa-partnership.com/). There, our students were welcomed by our partners at the African Centre for Cities (ACC), at the University of Cape Town (UCT), who introduced them to different realities and projects. The excursion to South Africa also helped the students to contrast the conditions in Tempe-Sorgenfri with those they experienced in communities in Cape Town.

We are thankful for the collaborations with Trondheim Municipality, and our partnerships in South Africa and India through the UTFORSK-NISA project. We are also very thankful for our curious and proactive students, and hope you enjoy reading this report as much as we enjoyed following their process throughout this semester.

Cinthia Freire Stecchini, Jarvis Suslowicz and Vija Viese Fieldwork Supervisors, NTNU, Department of Architecture and Planning

5 | Project location | Project Title

Acknowledgements

We would like to take this opportunity to thank everyone who was involved in completing this research project. Special thanks to our supervisor Cinthia Freire Stecchini for lending us your time and guidance during this process. Without your valuable insight and feedback, we wouldn’t have been able to reach our goal.

We would also like to thank our professors and supervisors: Jarvis Foster Suslowicz, Vija Viese, Mrudhula Soe Koshy, and Peter Andreas Gotsch. Without your knowledge and support we wouldn’t have been able to apply what we learned from you in this report.

We would also like to acknowledge Rolee Aranya; without your suggestion we wouldn’t have been able to see that it was possible for us to approach our problem statement from a different angle.

Furthermore, we would like to thank our interview partners and the municipality for providing us with the necessary date for this project and the residents and workers of Tempe-Sorgenfri whom without, we wouldn’t have been able to get the insight we had to complete this project.

Acronyms and Abbreviations

PBSA

HMO

Purpose-build student accomodationExpansion

Houses of multiple occupation

7 | Project location | Project Title

Housing & Inclusivity

Tempe-Sorgenfri, Trondheim

Contents

Preface

1. Introduction

2. Context

3. Methods & Timeline

4. Situation Analysis and Problem Statement

4.1 Demographic

4.2 Distribution of housing and commercial buildings

4.3 Industry and businesses, restaurants and service offerings

4.4 Housing and living environment

4.5 Education, work and income

4.6 Safety and wellbeing

4.7 Health

4.8 Perception of Tempe-Sorgenfri by its residents

4.9 Development plan for Tempe-Sorgenfri

4.10 Stakeholder Frost Eiendom

4.11 Research in Ola Fost veg

4.12 First intervention

4.13 Second intervention

4.14 SWOT-Analysis - Tempe Sorgenfri

4.15 Problem statement

4.16 Stakeholder Analysis

4.17 Hyblification problem

4.18 Observation walk to identify student houses

4.19 Housing laws Norway

Project Title | Project location | 10

12 16 18 20 20 22 24 26 27 27 27 28 30 33 39 43 48 54 54 56 60 62 63

5. Concept for spatial solutions

5.1 Vision

5.2 Concept for solutions

5.3 Presentation and workshop

6. Proposal for solutions

6.1 Overview

6.2 Densification

6.3 Community-Based Activities

6.4 Common Space

6.5 ModularHousing

6.6 Housing policies to encourage diversity

11 | Project location | Project Title

Contents

7. Conclusion References List of Figures 64 64 67 69 70 70 71 73 79 82 88 100 102 107

1. Introduction

Outline of the report:

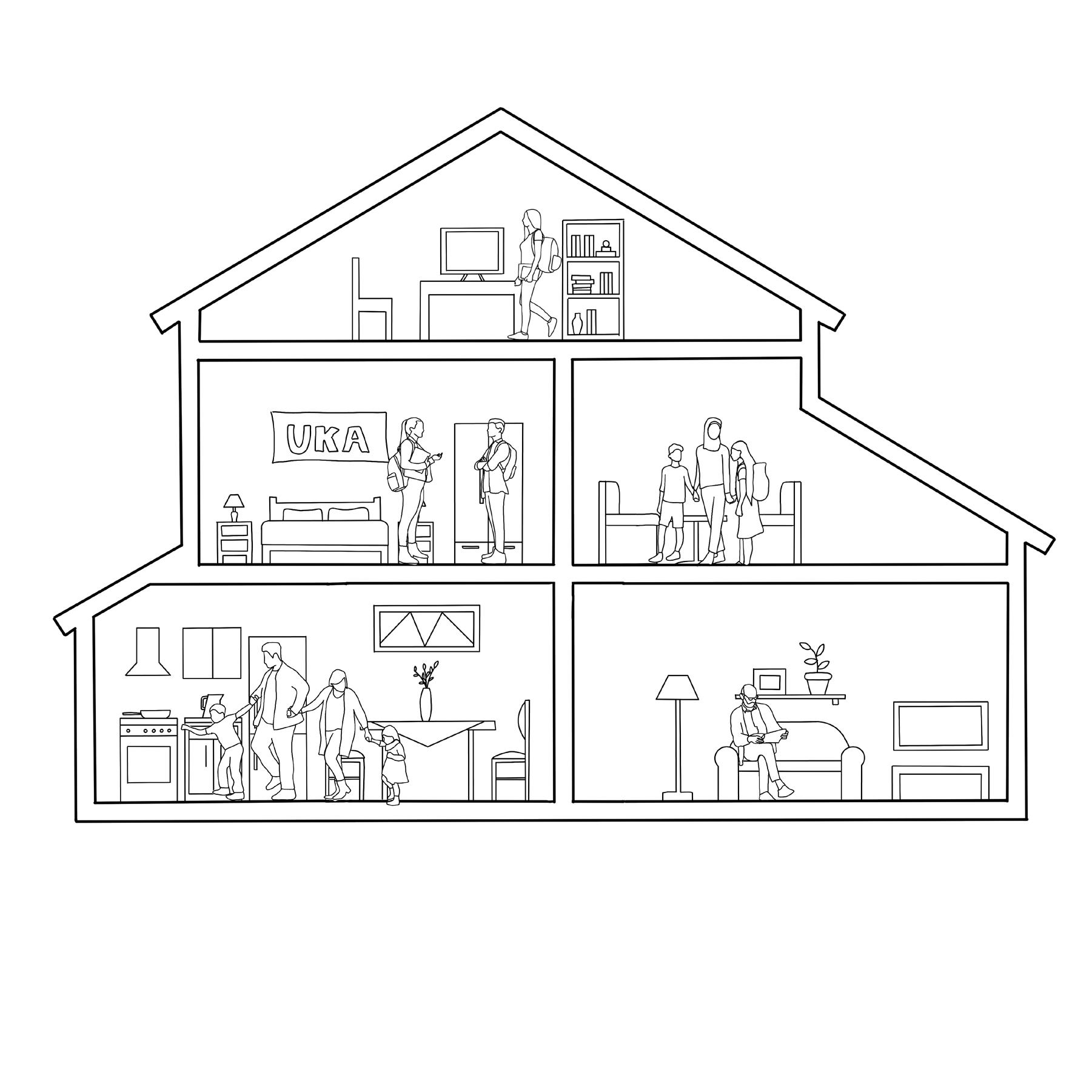

Tempe-Sorgenfri is one of the central districts in Trondheim, Norway. The district consists mostly of residential areas and is under the municipality’s plan for area development within the next 10 years. While most residents are pleased with their living conditions in Sorgenfri, the residents of Tempe express mixed opinions on how their living spaces should be. Some of the challenges that were presented to us were: overcrowded homes where bigger families lived in small apartments, many students living in Tempe and transformation of houses into student housing which leads to families leaving the area, and lack of community sense.

Considering the various challenges, we understood that the challenges are bigger than what we as a student group can tackle and therefore, the report will be addressing inadequate housing and what it means when looking at these challenges. Our group focused mainly on housing and inclusivity. Considering our focus, we came up with proposals for solutions in the form of policies that address the overcrowded homes, studentification, and the lack of community sense.

For the project, our group used different methodological approaches to reach our conclusion. Our approaches included a mix of quantitative and qualitative methods in addition to participatory methods.

The report starts with a short introduction of the area, then follows the analysis which was necessary to identify a problem statement regarding housing. After this part follows the concept on how to tackle the problem statemet and ends with our proposals for a housing progam.

The group:

We are students from all over the world that come from different educational backgrounds. What unifies us is that we have the mission to make the world a better place.

Project Title | Project location | 12

Figures 1, 2, 3, 4: Randa; Emiliano; Sara; Milena

13 | Project location | Project Title

Randa, urban planner

Emiliano, architect

Sara, architect Milena, urban planner

Tempe-Sorgenfri:

Tempe-Sorgenfri is an area located to the south of Trondheim city centre and is one of the two neighbourhoods the Trondheim municipality wants to develop over the next ten years. In this context, the area has been defined geographically: it includes the neighbourhoods of Lerkendal, Tempe, Sorgenfri and Valgrinda (Figure 1). (Loe et al.,2022)

The area is characterised by multiple spatial and cultural sections that stand out, each with its own opportunities and challenges. The Nidelva River, Trondheim’s main river, forms the western boundary of the area and provides a green belt for walking, although access is difficult. To the south, the area is bordered by the E6, from which a main road leads into the city centre, forming a barrier in the middle of the area and separating the neighbourhoods of Tempe and Sorgenfri. A bike highway, less of a destination and more of a section leads hundreds of cyclists through Tempe. The area is also characterised by a wide variety of building typologies, from high-rise blocks to small houses. The Frost Eiendom blocks stand out, providing some of the densest living in the area. About 15% of the population living in Tempe-Sorgenfri is under 18 years old, 41% is between 18-34 years old, 29% is between 35-66 years old and about 15% of the population is over 65 years old. There are plans to develop the bus terminal, one of the larger areas geographically and of little benefit to residents, as an additional residential area. The Lerkendal Stadium is a large sports facility in the area, where football matches attract people from all over Trondheim. In addition, the Nidelv sports area by the river provides a large green and activity area for both residents and non-residents in Tempe. (Loe et al., 2022)

The municipality aims to make Tempe-Sorgenfri a good place to live by improving the neighbourhood environment according to the needs of the residents. (Loe et al., 2022)

Project Title | Project location | 14

Figure 5 : Tempe-Sorgenfri

15 | Project location | Project Title

Tempe

Sorgenfri Valgrinda Lerkendal Holtermannsveg Nidelva

2. Context

Our group chose the topic housing and inclusivity for the project in Tempe-Sorgenfri. The goal was to identify a problem statement that referrs to housing, develop a proposal for solutions by using participatory methods.

The housing areas in Tempe-Sorgenfri are very different from each other. In Tempe is the detached wooden house area and ola Frost veg with its high-rise apartments building. In Sorgenfri accross the Holtermannsveg are very new apartment buildings to find.

Project Title | Project location | 16

High-rise apartment buildings Tempe /

1 Apartment buildings Sorgenfri 2 Detached wooden houses / wooden house area 3

Ola

Frost veg

Figure 6, 7, 8: High-rise apartment buildings Tempe; Apartment buildings Sorgenfri; Detached wooden houses

Figures 9: Map housing

17 | Project location | Project Title 3 2 1

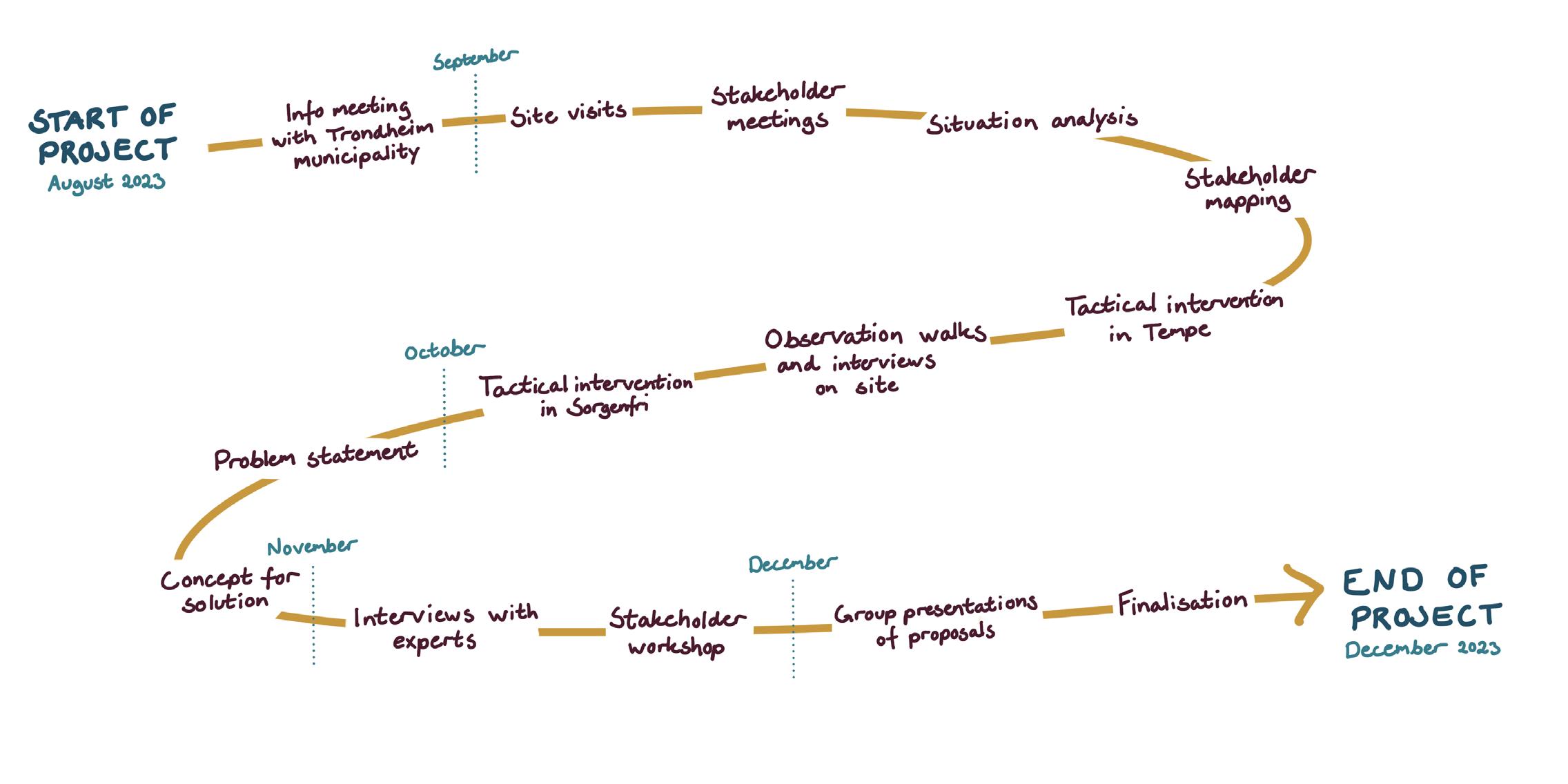

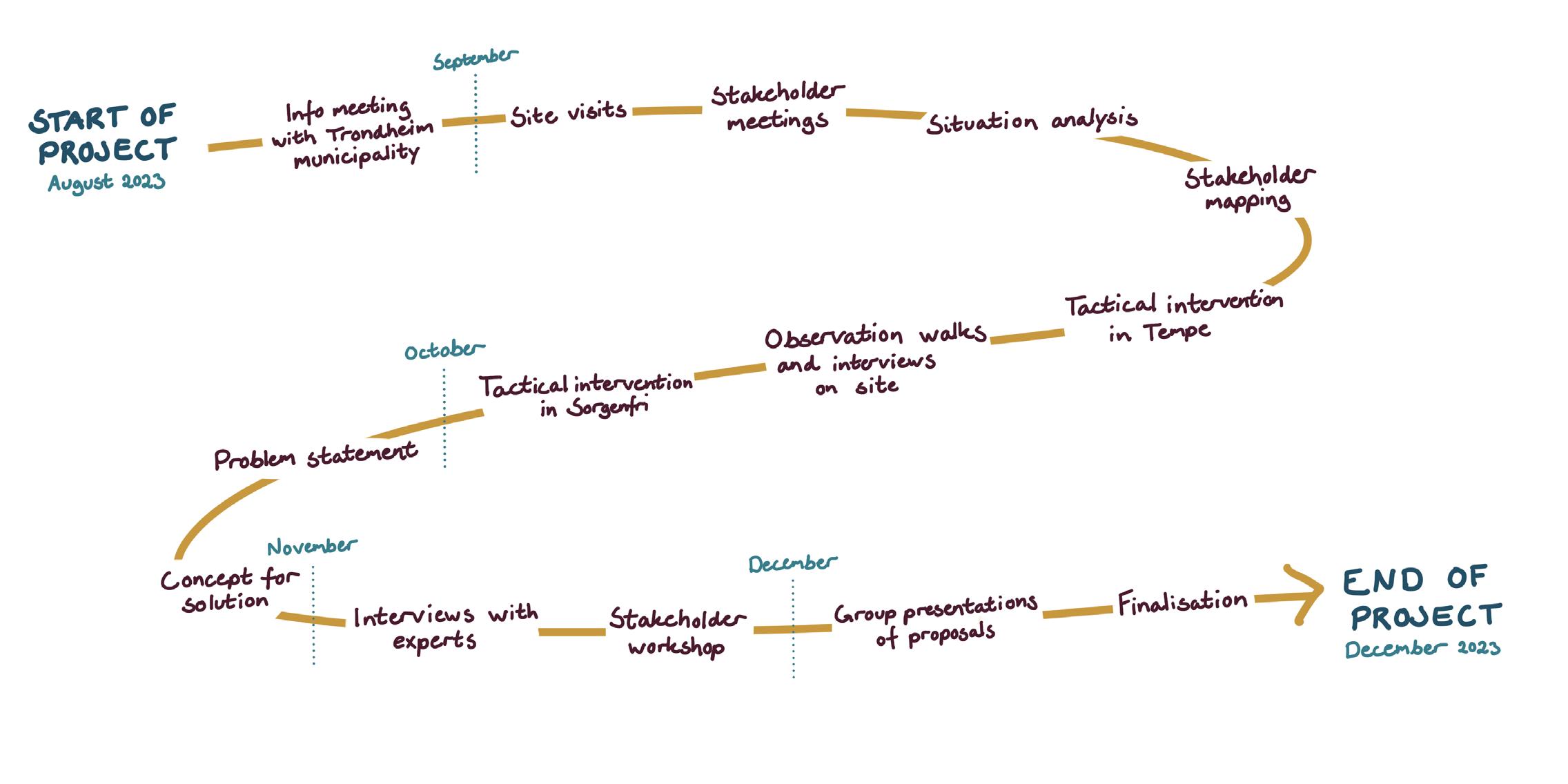

3. Methods & Timeline

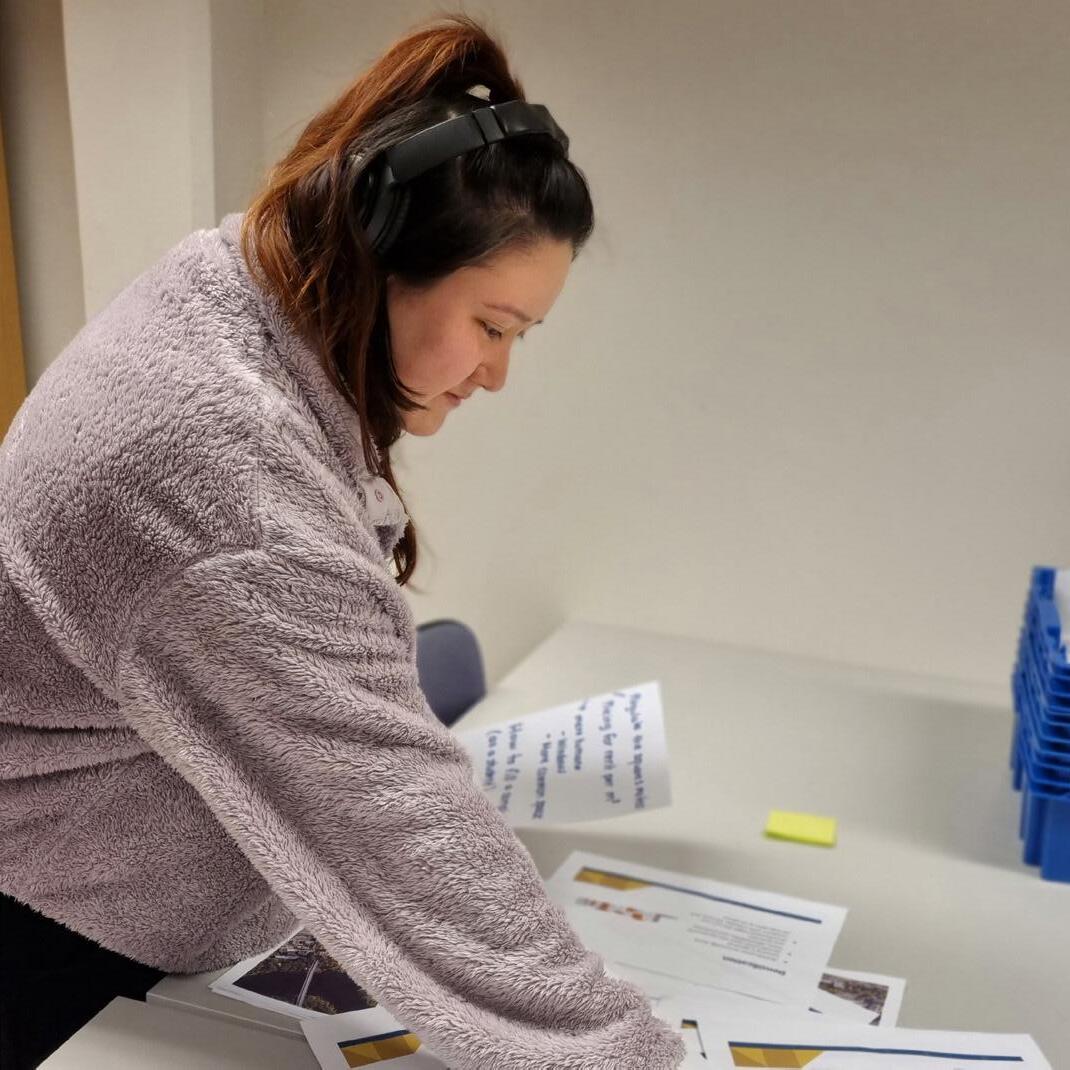

Needs assessment: In order to be able to work on our project regarding housing and inclusivity, different methods were used for data collection and analysis. The purpose of collecting and analysing data specifically connected to our project area and theme was to understand the problems and issues residents have with their neighbourhoods. When understanding the residents’ needs, we can understand what our problem statement is and how to approach it. For this project we used both quantitative and qualitative data methods.

Analysing secondary research: Secondary research are materials that help provide necessary information and background that other methods cannot provide. Secondary research is fact based and requires data understanding. We based our facts on the municipality’s research materials that was provided to us in the beginning of the semester. The research materials included a sociocultural site analysis of Tempe-Sorgenfri that we used to base our situational analysis on.

Interviews: This method is applied by asking relevant actors their opinions and point of views on chosen topics. This helps understand data that might not be found in secondary research. Interviews were conducted with several stakeholders and residents which provided us with new insights to help formulate our problem statement.

Tactical urbanism: Tactical urbanism is a method in approaching neighbourhoods using shortterm, low-cost, and scalable interventions and policies in a public space. It’s a method that can be used by different actors and individuals. The purpose of tactical urbanism is to reclaim or redesign a space for citizens. For planners, it’s a tool that allows for data collection on public opinion of a specific plan. (Lydon, Garcia, 2015). A tactical intervention in the form of “paint your neighbourhood” was carried out by our group in Sorgenfri.

Stakeholder mapping: Stakeholders are different individuals or groups that have different interests that should be considered when developing a plan. Stakeholder mapping is a tool used to help visualise relevant stakeholders in a map. Mapping stakeholders helps organise everyone relevant to the project and understand what influences and power they have. (Olander, Landin, 2005). For our project we present power-interest diagram, stakeholder influence diagram, and stakeholder-issue interrelationship diagram. Each diagram explains further the stakeholders we deemed relevant to each other, our project, and how they influence our problem statement.

Project Title | Project location | 18

Stakeholder workshop: Workshops are useful tools to engage with stakeholders in order to either validate or identify findings relevant to the development of the project. To be able to validate our concepts for solutions, a workshop was conducted where our findings and solutions were presented to stakeholders. The workshop included a discussion of the concepts for solutions where they expressed their opinions on how these concepts should be carried out.

Observation walks: Observation walks help give a better understanding of the area. In addition, walking through neighbourhoods gives a different perspective and context to the observer than just looking at research data. Our group used this method to observe and locate student housing in Tempe.

SWOT-analysis: SWOT is an analysis used to define strengths (S), weaknesses (W), opportunities (O), and threats (T) during the strategic planning phase. For our project, we used this method to identify the different factors that impacts the area of Tempe-Sorgenfri. In addition, this method was used to analyse what impacts our proposals for solutions can have in the future.

19 | Project location | Project Title

Figures 10: Timeline

4. Situation Analysis and Problem Statement

The following data aboutabout “Demographic”, “Housing and living environment”, “Education, work, income”, Safety and wellbeing” and “Health” is from 2018 and therefore does not include the data about the residents from Sorgenfri, as the apartment buildings were not built yet.

4.1 Demographic

In 2018 there were 1892 residents registered in Tempe-Sorgenfri. The area has a high proportion of young adults between 18 to 34 years old compared to the rest of Trondheim, and has a lower population of children, young and older people then other neighbourhoods. There is a high proportion of people living alone compared to the rest of the city (over 60%), especially young people.

While the other population groups are lower compared to the rest of the city, where children and young people are at a percentage of 15% and 35-66 years old at 29%, the percentage of people 67 years and older are higher than the rest of Trondheim at 15%. However this group is declining in the area, while the percentage of children and young people has been rising since 2001.

The percentage of young couples (18-34 years old) living together is at 10,4% and therefore higher than the rest of the city and has increased over time. The other couple-groups are lower and at a percentage of 3,9% (35-66 years old) and 3,2% (above 67 years old). There is a low percentage of single parents households at 3% and couples with children at 9%. (Loe et al., 2022)

Project Title | Project location | 20

Figures 11: Age distribution

Age distribution

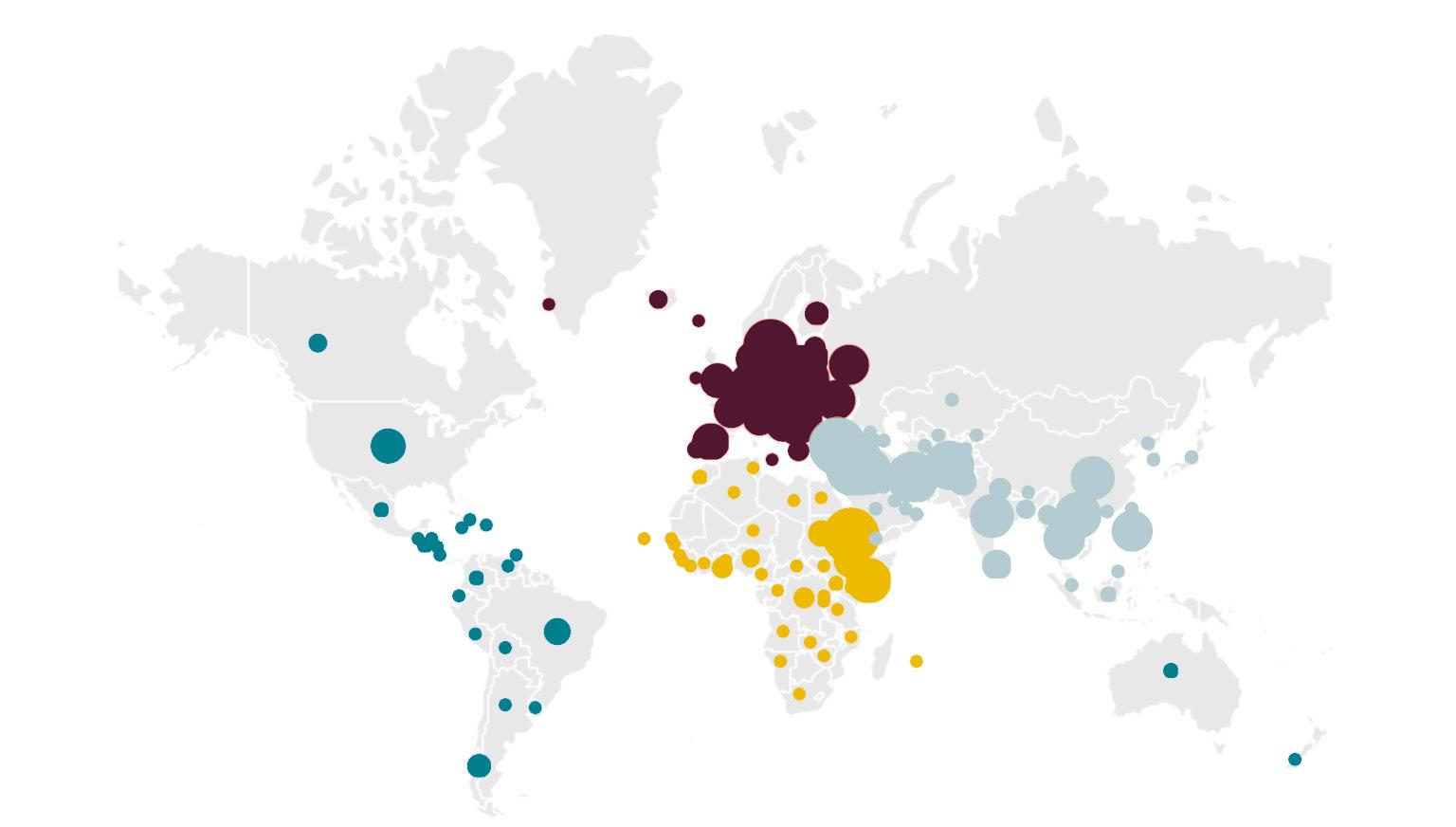

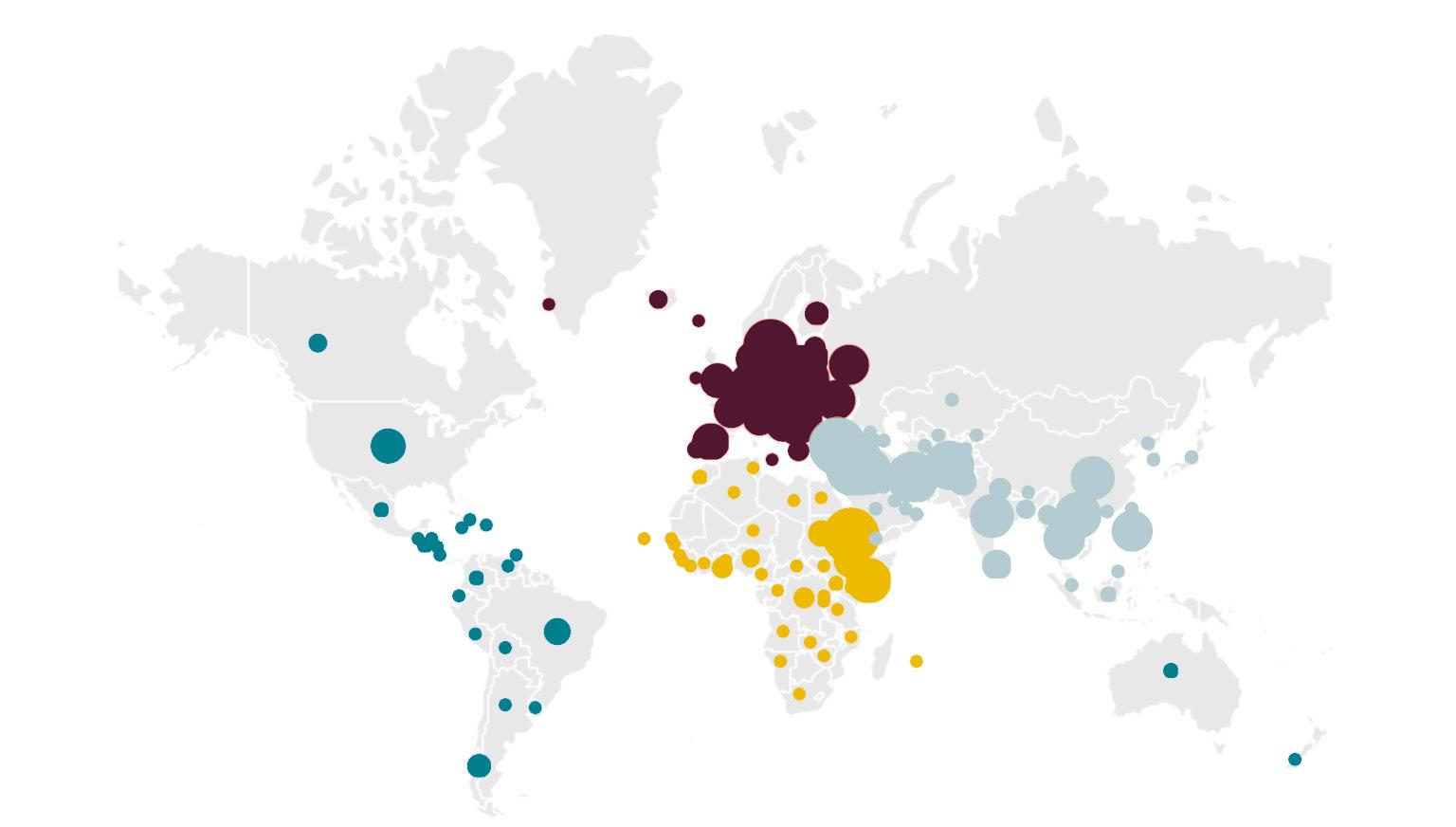

When it comes to ethnicity, the percentage of residents with immigrant background is higher in Tempe-Sorgenfri then in Trondheim as a whole at 31,1%, where Trondheim is at 15.1%. This means that one third of the population in the area belongs to this group. The percentage has risen considerably in the last ten years from 6.3% in 2001, 11,8% in 2009 and to 31,1% in 2018. There is a marginally higher proportion of immigrants from eastern europe then the rest of the city, and one fourth of the residents in the area are immigrants from non-western countries like Africa and Asia. (Loe et al., 2022)

21 | Project location | Project Title

Figures 12: Immigrants in Trondheim

Immigrants in Trondheim: America, Asia, Afrika, Europe, Ozeania

Tempe-Sorgenfri is a mixed-used area. In most of Tempe and Valgrinda/Lerkendal there is more housing, both rental and owned. In this area there is also an industrial area owned by Trondheim municipality near the river, the elderly centre and a commercial building with both offices and stores. Sorgenfri is the part of the area where there are more buildings for industry and offices than for housing. Nærbyen is an area with both rental and owned housing,an office building for Trondheim municipality and offices and parking lots for buses, as the nearest neighbours. By the river there is a blend of industrial- and commercial buildings and offices. (Loe et al., 2022)

Project Title | Project location | 22

Figure 15: Map of uses

4.2 Distribution of housing and commercial buildings

Figures 13, 14: Service; High-rise building

Housing

Industry and warehouses

O ces

Commercial

Social servives

Culture and sports

Research and university

1 : 7500 23 | Project location | Project Title

4.3 Industry and businesses, restaurants and service offerings

In Tempe Sorgenfri are various industrial and commercial businesses like workshops, electricians, car rentals, retailers and a plumbing company. The Bus company AtB is a keyplayer in the area because two big areas are used as a bus parking. Inside the Max building are offices, a grocery store (Coop Extra), shops and pharmacies. The Trondheimsporten-building is an office building for the municipality and the NAV (Norwegian Directorate of Health and Trøndelag County Council). Also the company Siemens has large production and office sites in Tempe-Sorgenfri. In the sub-area there is Max SPILL Tempe, the women’s health centre House of Femme, Klinikk for Alle, and the ticket system company Hoopla. Another big company in the area is the landlord Frost Eiendom. Frost Eiendom is the largest private landlord firm and an important actor in Trondheim, they own four properties with 501 rental apartments in Ola Frosts veg and 157 rental apartments in Sorgenfri. To go out to a restaurant there are only a few options: Kompis and Bartepizza at Sorgenfri and Domino’s Pizza at Lerkendal stadium. In the elderly centre is a district cafe which is open to everyone and the Scandic Lerkendal conference hotel offers food service and a bar but mainly for guests. Moreover there are two more grocery stores in Sorgenfri: Rema 1000 and Kiwi. (Loe et al., 2022)

A kindergarten is located in Tempe-Sorgenfri as well as the SINTEF research centre in addition to some buildings that belong to the NTNU. There are no schools in Tempe-Sorgenfri at the moment, (there are plans from the municipal authorities to build one in the future) so children attend schools in the Nardo and Sunnland school districts. Other public functions and services are the Tempe Health and Welfare centre. The centre houses a nursing home, senior home, a day centre, a community cafe, a party hall, offices for the home care service, physiotherapy, art therapy, a hairdresser, chiropody and a home for people with disabilities. Moreover the Trondheimsporten-building houses adult education and other social, health and welfare services. Moreover there are many facilities for sport and other activities in Tempe-Sorgenfri.There are several soccer fields and sport parks like Tempebanen by the riverbank, the sport club Nidelv IL and the Lerkendal stadium and training pitches dedicated to the Rosenborg club. Also two fitness centres are in the area, a kayak club and a senior dance class at the Tempe health and welfare centre. The centre also offers other activities for the community. Moreover there are studios in the centre that are free of charge and can be rented by artists but they need to contribute to the community. The church in Tempe-Sorgenfri also functions as a meeting point and offers a range of activities. In the area, Bitfix gaming centre offers esports opportunities. (Loe et al., 2022)

Project Title | Project location | 24

Figure 16: Specific uses in Tempe-Sorgenfri

Social infrastructure

1. SINTEF research

2. NTNU buildings

3. SINTEF research

4. Health and welfare centre

5. Tempe Kindergarten

6. Trondheim Kajak

7. Tempe Sports venue

8. Lerkendal Stadium

9. Tempe Church

10. Trondheimsporten

Industry, businnsses, commercial

1. Hotel

2. AtB (parking lot)

3. Max building

1

:

4. Max SPILL, House of Femme, Klinikk for Alle, Hoopla

8 4 2 2 1 2 7 5 9 6 5 3 10 4 3 2 1 1

1. Frost Eiendom Tempe high-rise buildings

2. Frost Eiendom Sorgenfri apartments

5. Siemens grocery stores, gastronomy 7500 25 | Project location | Project Title

4.4 Housing and living environment

The most characteristic housing in Tempe-Sorgenfri are apartment buildings, where almost 85% of all homes are a block, low-rise or high-rise building. Because of this there is a high proportion of 1-2 bedroom apartments. The ownership rate is very low compared to Trondheim, where it lies at 11,4%. 74.4% of the residents in the area are renters. The housing prices are relatively low, but because of the small sizing of the rental apartments, a large proportion of children and young people (two out of three) live in overcrowded households. With the area having a lot of rental housing, the area is characterised by people moving in and out often, which creates instability in the living conditions. This population group is usually students and younger adults who are living in Tempe-Sorgenfri as a stopping place before buying/renting a bigger space or establishing a family (Loe et al., 2022). A good example is how Frost Eiendom explains that Nærbyen in Sorgenfri is an apartment area that is for those who are between finishing studies and establishing their lives forward (presentation).

Overcrowded apartments in Tempe-Sorgenfri

Low income households in Tempe-Sorgenfri

Project Title | Project location | 26

Figure 17: Overcrowded apartments

Figure 18: Low income households

4.5 Education, work and income

In Tempe-Sorgenfri there are more households with annual low income (26.8%) than the rest of Trondheim (14,9%). The proportion of households with low income and children has increased during the years and is now at 40,7%, which is a lot higher than the city which has a percentage of 9,3%. When it comes to education there are 60.2% of the residents that have more than a primary school education, and the unemployment rate is at 34,5% (Loe et al., 2022).

4.6 Safety and wellbeing

There is a lower level of safety and wellbeing in Tempe-Sorgenfri than in Trondheim. The crime statistics from 2017 to 2019 show a higher proportion of perpetrators of violence and threats, whilst there have been no major differences in the rest of the city. But the percentage of violence in Tempe-Sorgenfri is higher than the average in Trondheim. Women and men experience more psychological and physical violence: Women experience more psychological violence, and men experience more physical violence (Loe et al., 2022)..

4.7 Health

According to the HUNT4 health examination in 2019, residents rate their health poorer than the general population in Trondheim. Around one third of those over 18 years old say that they have bad health, which is both for women and for men. Especially for men this is higher than in the rest of the city. For health conditions such as long term limiting illnesses, joint muscle pain and cardiovascular diseases, the proportion of people in the area experiencing this is relatively high. Among men the proportion of diabetes, mental-illnesses, anxiety disorder and depression is prominent (Loe et al., 2022).

27 | Project location | Project Title

4.8 Perception of Tempe-Sorgenfri by its residents

Based on information from surveys and interviews conducted in 2022 the following data was found: There is a broad agreement that Tempe-Sorgenfri is an attractive place to live in (78%). This gives an indication that the residents in the area are satisfied with the neighbourhood they live in. At the same time there are reports that there are dividing lines between the different areas, and that the residents wish to have better connections between them. Because of the areas being divided, there are different opinions about how Tempe-Sorgenfri is perceived by others and they have different wishes on what they want to be improved. (Loe et al., 2022)

Many residents in an online survey state that they think it is positive that there is diversity among cultures in the high rise buildings in Tempe. Refugee families that have been interviewed say that they feel included and that they like the area. One family states that they didn’t feel included in another area of Trondheim, but when they moved to Tempe-Sorgenfri they have made good relationships with neighbours and other families.

Even though many state that they are positive to the diversity of cultures, some state that they think the amount of immigrants in the area could be a problem, and some say that Ola Frosts veg reminds them of a ghetto. Frost Eiendom however states that there are less immigrants than one might think, and based on surnames with international origin, around 20% of the tenants in the high rise buildings have an immigrant background. The statement that Ola Frost veg reminds people of a ghetto can be because the immigrants are more visible then a homogeneous area. (Loe et al., 2022)

The residents state that the reason for living in Tempe-Sorgenfri is because of its geographically central location, and is therefore the most important reason that one might live in the area. Others say that they live in the area because there is good housing for an affordable price and say they have a strong connection to the area. (Loe et al., 2022)

Students living in the area state that they have chosen to live there because that is where they were assigned student housing.

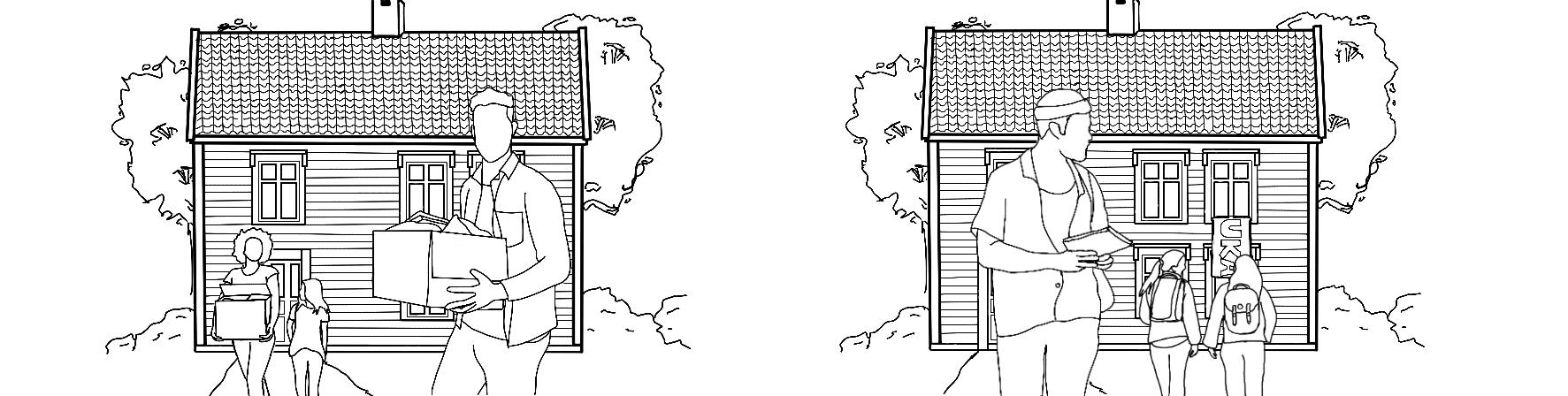

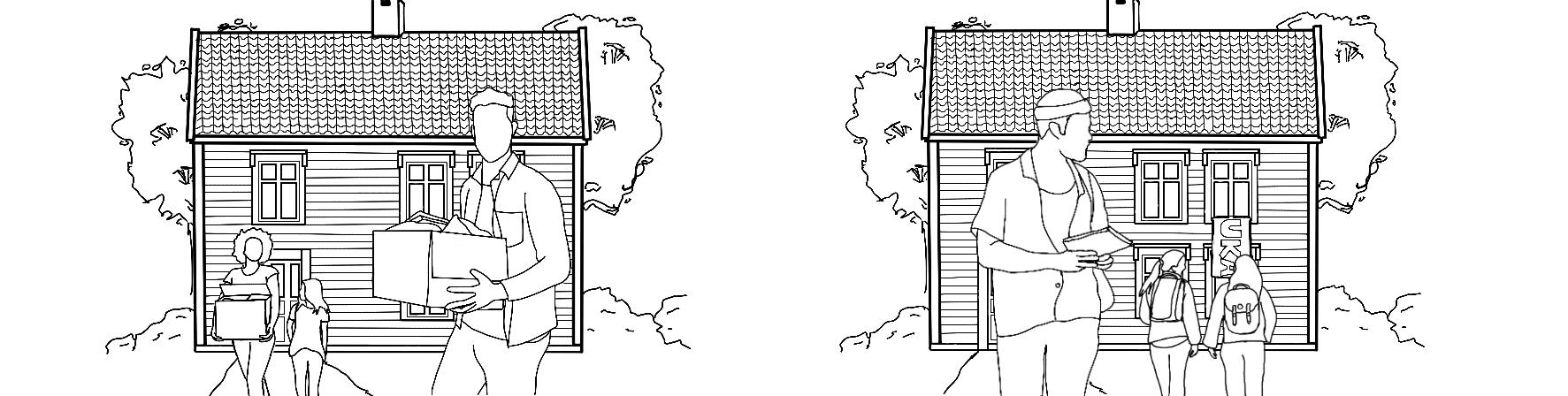

Figures 19: Families moving out, students moving in

Project Title | Project location | 28

Residents observe that there is a decline in families with children in the wooden houses north of Tempe. Many of these houses have been bought and converted to dormitories for students after the families move out. The new residents of the dormitories don’t really get to know their neighbours, and it is reported that there is a lot of noise from different parties in that area.

Residents in the area are worried about their living environment. Because of the amount of students living in the area, together with young adults, many residents only live in the area for a short period of time (Loe et al., 2022).

Only 30% of residents say that they want to stay in Tempe-Sorgenfri the next ten years, one fourth say they don’t know, and 45% say that they don’t see themselves living in the area in a ten year period.

Most people do not know if there are any good kindergartens or schools in the area. The meeting places that children and young use are some playgrounds, parks and Tempe-banen. For the children it is a long way and dangerous to go to school and to visit friends in Nardo because of bad infrastructure and traffic. Especially the underground pedestrian tunnel underneath Holtermannsveien is seen as unsafe because of drug dealing and vandalism. For teenagers there are a few gathering spaces as well, many still go to other areas of the city. There is a wish for more playgrounds and kindergartens and for space to celebrate events like birthdays, baptism and confirmations as many families do not have enough space. (Loe et al., 2022)

29 | Project location | Project Title

4.9 Development plan for Tempe-Sorgenfri

Currently there is a development plan for Tempe-Sorgenfri in the making. The aim of the development plan is to transform an area characterised by commercial and industrial businesses of varying sizes into a modern new urban district. The district will be part of the development of a science-axis, contributing to solidifying Trondheim’s position as a technology and knowledge city. The transformation in Tempe-Sorgenfri is one of the bigger urban transformation areas in Trondheim. The plan will establish the main structure and allow for large building volumes and high-rises that will characterise the district. The biggest challenge is to create an attractive city with multiple functions. There is space allocated for establishing a health and social centre as well as a kindergarten and the plain aims to use the space for housing, offices and services. Currently there are not many areas that classify as “urban”. In the future it is planned that the public facility area by the river side becomes an urban area as well as the area opposite of the Max building. Moreover the number of smaller urban areas shall increase much more in whole Tempe-Sorgenfri. In addition it is also planned to establish a path that follows the Nidelv-River and functions as a link between Tempe and Sorgenfri and the rest of the city on the other side of the river (Trondheim Kommune, 2019; Henning Larsen Architects AS 2023).

Trondheim kommune

Perspektiv

Trafikksystem og parkering

Vegsystem og trafikkfordeling

En utfordring ved stor utbygging i området vil være å begrense økning i biltrafikken som følge av utbyggingen. Det er gjennomført en trafikkberegning for planområdet og store deler av influensområdet for å se på hvordan fremtidig trafikk vil kunne fordele seg som følge av de foreslåtte endringene i trafikksystemet. Selv om det legges opp til lav parkeringsdekning innenfor planområdet vil flere mennesker få området som bosted og målpunkt og flere vil ferdes gjennom området. Dette vil øke det totale transportarbeidet. Området ligger sentralt til med korte gang‐ og

Project Title | Project location | 30

Figure 20: Vision for Tempe-Sorgenfri

Figures 21: development plan

The KPA (Kommuneplan arealdel) is a municipal plan area section document that works as an overarching strategy which determines what the areas in the municipality are to be used for. The strategy determines which areas can be developed and which cannot. The strategy contains provisions on which principles and assumptions are to be used as a basis for the more detailed planning that takes place following the adoption of the area section (Trondheim Kommune, 2022). It is however necessary to mention that the municipality is working on a revised plan for Tempe-Sorgenfri, but it is not available for the public yet.

31 | Project location | Project Title

Findings - sociocultural analysis:

• The residents of Tempe-Sorgenfri experience more violence compared to the rest of Trondheim

• they have more health-related issues

• the unemployment rate is higher

• more households are low-income households compared to Trondheim, especially households with children are low-income households

• area itself is perceived as a fragmented district that has a lack of meeting places and activity areas with no spaces for cultural activities

• decrease in the number of families with children in the wooden house area and that those houses are used more often for dormitories.

• high number of students probably leads to an instability in the living conditions

• the proportion of overcrowded households is comparatively high; there is a large share of children and young people that live in overcrowded homes

• residents like living in Tempe-Sorgenfri

Project Title | Project location | 32

4.10 Stakeholder Frost Eiendom

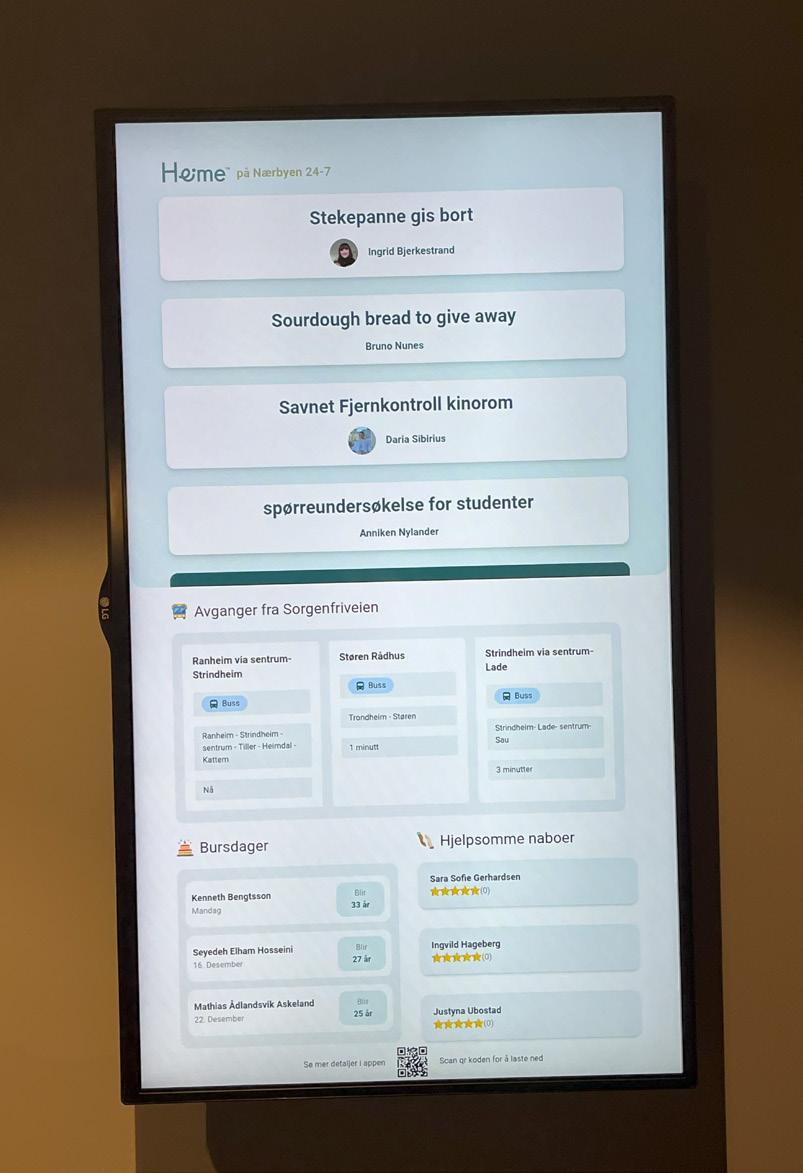

Frost Eiendom is a key stakeholder in Tempe and Sorgenfri. Frost Eiendom is a family owned business, and manages and rents out apartments including Ola Frost veg, Tempe and Nærbyen 24/7, Sorgenfri. Per today they are one of Trondheim’s biggest property managers. Frost Eiendom are in addition to existing buildings, are constructing a new apartment building in the same area (Ola Frost veg 5) (Frost, 2023).

Frost Eiendom’s main vision is “Good for you, good for the city” as they aim for a better understanding of their tenants needs. They also incorporate the UN’s sustainability goals with 3. good health and life quality, 8. decent work and economic growth, 11. sustainable cities and local society and 13. stop climate change, as their main focus. In addition to focusing on life quality and how to improve it, mainly through shared spaces both internal and external (Frost, 2023).

33 | Project location | Project Title

Figures 22: High-rise apartmentbuildings

Ola Frost veg and apartment buildings Sorgenfri

The low-rise building has four levels and 50 apartments. It is the newest and was built in 2006 (Narvestad, 2023).

Ola Frost veg 3was build in 1991 and has the highest number of seniors and no families with children because the building has open balconies (Narvestad, 2023).

Project Title | Project location | 34

Figure 23: Ola Frost veg 1

Figure 25: Ola Frost veg 3 with open balconies

Ola Frost veg 1

Ola Frost veg 3

Ola Frost veg 2

The high rise building in Ola Frost veg 2 has approximately 150 apartments. It was build in 1995. The high-rise buildings have 13-14 levels. The apartments have different sizes. There are two bedroom apartments with 30 to 68 m2, 3-bedroom from 59 to 95 m2 and 4-bedroom from 95 m2. In Ola Frost veg 2 lives a relatively large number of students (Narvestad, 2023).

Ola Frost veg 4

This building was like Nr. 2 build until 1995. In Ola Frost veg 4 lives a significant group of families with children, both Norwegian and non-Norwegians with an immigrant background. They often live in overcrowded conditions (Narvestad, 2023).

35 | Project location | Project Title

Figure 24: Ola Frost veg 2 with wintergardens

Figure 26: Ola Frost veg 4

Common indor and outdoor areas in Ola Frost veg

For Ola Frost veg 4 exists the plan to use one flat on the ground floor as a common flat. Currently the flat is under construction. The apartment is a two room apartment with about 42 m2. Parts of the walls can be removed to open up the apartment so it becomes more spacious and a larger group of people has the option to gather. The apartment will be accessible for all residents of all blocks and the idea is that different activities can take place inside. The new building in la Frost veg 5 will have common areas on the ground level as well.

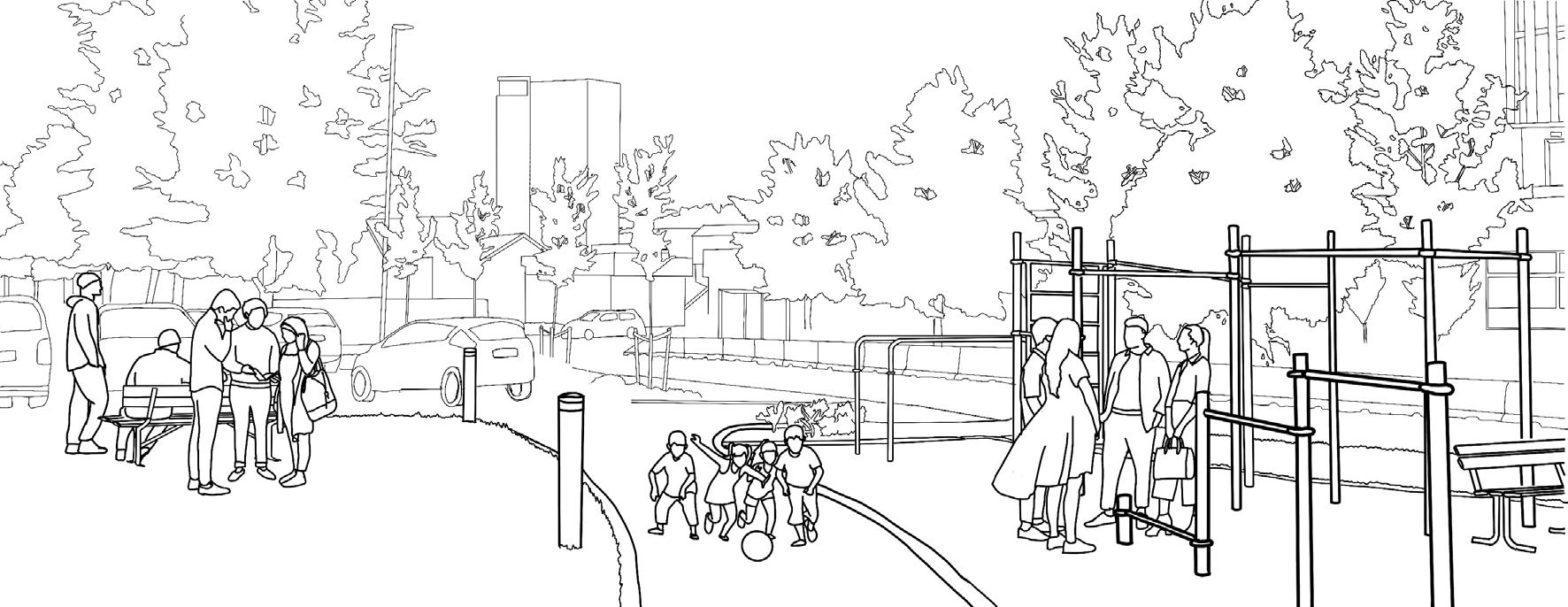

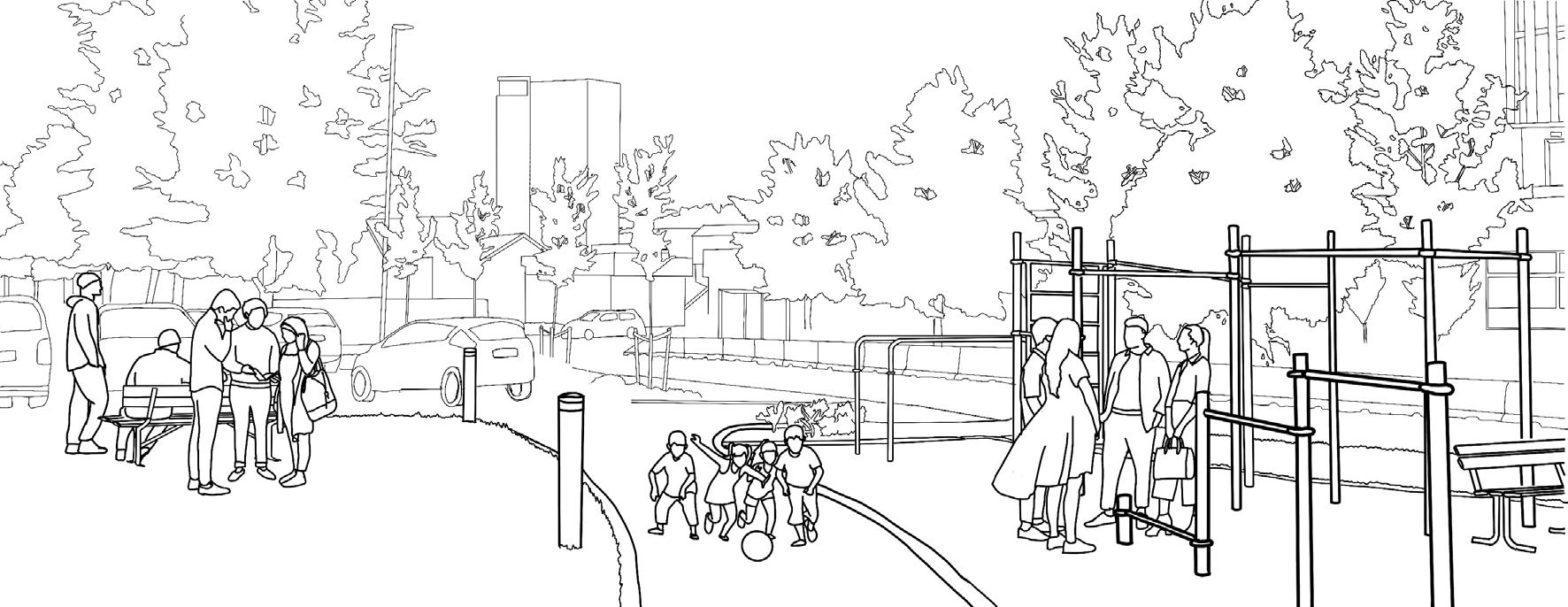

Around the blocks in Ola Frost veg is about 14 450 m2 of outdoor area, that equals about 29 m2 per unit. From 2022 to 2024 the outdoor area gets upgraded and a new parking garage will be constructed in combination with a new 15 level building. Also in the future new projects like urban gardening will be implemented to increase the engagement of the residents. Also Ola Frost wants to change that residents feel excluded in the public space because cliques occupy sites between the high rise buildings (Narvestad, 2023).

Frost Eiendom are also transforming the current parking areas to a green park and will include a café and a community centre on the ground level of the new apartment building. The reason behind this is to address the lack of community spaces at the present time. Frost Eiendom also has the ability to create bigger events to include the community (Frost, 2023).

Project Title | Project location | 36

Figures 27, 28: Common flat; Outdoor area

Sorgenfri buildings

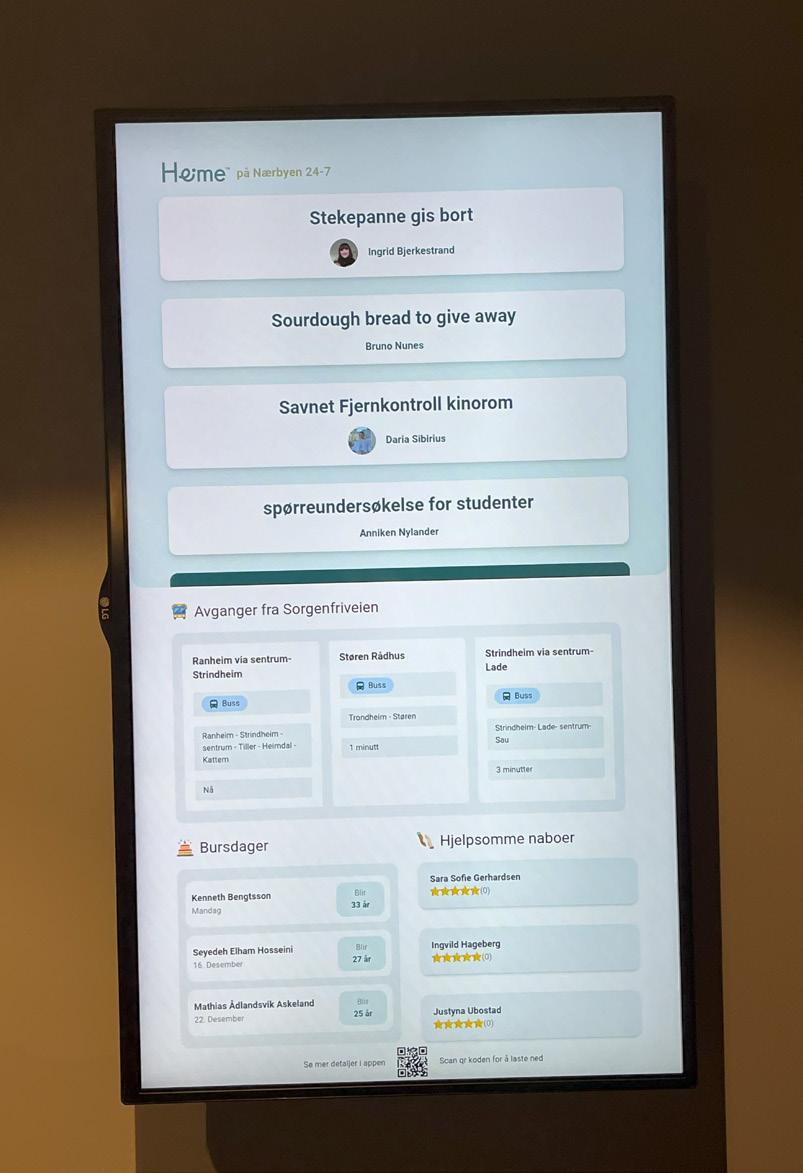

The apartment buildings in Sorgenfri are located around 500 meters from Ola frost veg.. Mainly young people live in the apartment buildings so the buildings have a design oriented for those. (Narvestad, 2023). The apartments were built with the idea of experimenting with co-living in mind. The apartments include more common shared spaces that residents can book or participate in. To communicate with the neighbours the residents can use a digital app, but like in the Ola Frost buildings there have not been any projects initiated that are in residents-control (Narvestad, 2023). It was also mentioned that these apartments were meant to help people who are new to the area build a social network (Frost, 2023).

37 | Project location | Project Title

Figures 29, 30: Sorgenfri apartment building, digital blackboard/community sign

Project Title | Project location | 38

4.11 Research in Ola Fost veg

A case study in Ola Frost veg at Tempe was conducted on “resident participation and common areas in rental housing” in order to understand how to improve the living environment.

The results from the survey in the area showed that the majority of the respondents enjoyed living in the area. But there is also segregation between ethnic-Norwegians and non ethnic-Norwegians identifiable. Another interesting result was that while the majority of residents were interested in using the common flat they were split in wanting to influence the design parts of the outdoor area. The survey had some challenges including not being able to fully get in touch with non-european residents and the demand to create a commitment among them.

The results of the digital survey showed that respondents are happy in Ola Frost veg. The mayority of the people thive well and also the contact between neighbours is quite good even when it is just superficial.

Only 3.6 % plan to move out of the area within the next year and over 30 % live there more than 8 years while almost 52% lived there between 2 and 8 years, that means the living conditions are relatively stable. Especially residents of the oldest age group stated to have a high well being, while younger residents and households with children are less satisfied. (Narvestad, 2023)

39 | Project location | Project Title

Figures 32: How long have you been living in ola Frost veg?

Figure 31: Ola Frost veg 1-4

How long have you been living in la Frost veg?

The interviewed residents underline the general positive impression. The unlimited contract provides predictability, security and ownership and gives the residents the possibility to make their apartments their own by being able to paint the walls for example. There is no uncertainty for the residents that the landlord will sell the building or apartments and use it him/herself. In general the residents are quite happy living in Ola Frost veg and they think the living environment is good. The annual garden parties by Frost Eindom get appreciated and the outdoor areas help the residents to connect and because of many children living in the area children easily play with each other and they have good possibilities to do so. The residents in Ola Frost veg are very diverse when it comes to age groups but also to ethics which is seen as positive. The buildings function as one living environment with different groups that meet from time to time outside, but the contact is informal and non binding but also neighbourly; help was unexpectedly received. Among all these positive things there is a wish for more integration between different cultures. Although the contact between neighbours is mostly positive, some gossiping was mentioned.

It is also mentioned that it is difficult to include foreigners and norwegians and non ethnic norwegians as they do not have much contact with each other, but however there is some informal contact and neighbourly exchange between different nationalities. Cases of racism have also been mentioned and that it is difficult to include non-ethnic norwegians into self-organised activities. Another result from the research is that most residents see students that live in Ola Frost veg as residents that don’t contribute to the living environment. They often live in the building for just a year and then they move somewhere else without engaging and contributing.

Even though the students do not make that much noise in general there are some complaints because of noise in Ola frost veg 2 where more students live then in Ola Frost veg 4. Some residents suggest that students should be invited actively to events so they are integrated better. (Narvestad, 2023) Figures 33:

Project Title | Project location | 40

No engagement between different groups

In the survey 63.5 % of the residents answered that they would be interested in participating in joint activities in the common apartment. Popular suggested activities were a Needlework Group (44.7%), Cooking Group with Communal Dinner (39.5%) and Language café (36.8%). Especially the cooking group and the langage cafe were famous regardless of gender and age.

The residents of the block would not just want common space for each block they prefer it, when it is available for all the residents. The research results show that the residents think it is important that there is something to do in the common space like billiards, table tennis, watch a movie or having space for children playing. Residents thought it would be good to expand the vestibule and to improve it.

From the interviews it could also be found out that there is a segregation between non-ethic and ethnic Norwegians and they do not have much contact using the outdoor area. Language might be a problem but also many non-ethnic norwegians have small children and do not get in touch with norwegians that have a different life reality so easily and some stated that non-ethnic Norwegians have a too high noise level. Even though this is more of an inconvenience than a real problem. Non-ethnic norwegians and ethnic-norwegians stick most often with their “own” group together. But common activities might be the solution to help then get in contact. (Narvestad, 2023)

41 | Project location | Project Title

Findings about Ola Frost veg

• residents in Ola Frost veg 4 live in overcrowded conditions

• indoor common space will be povided in Ola Frost veg 4 (and 5)

• outdoor common space will be provided for the residents of Ola Frost veg and the neighbourhood

• not much exchange between norwegians and non-norwegians

• students move in and out fast in Ola Frost veg and do not contribute much to the area

• residents like their housing but there could be more engagement between neighbours

• people ae interested in common activities like language cafe, needlework gropu, cooking and communal dinner

Project Title | Project location | 42

Figures 34: Ola Frost veg 1

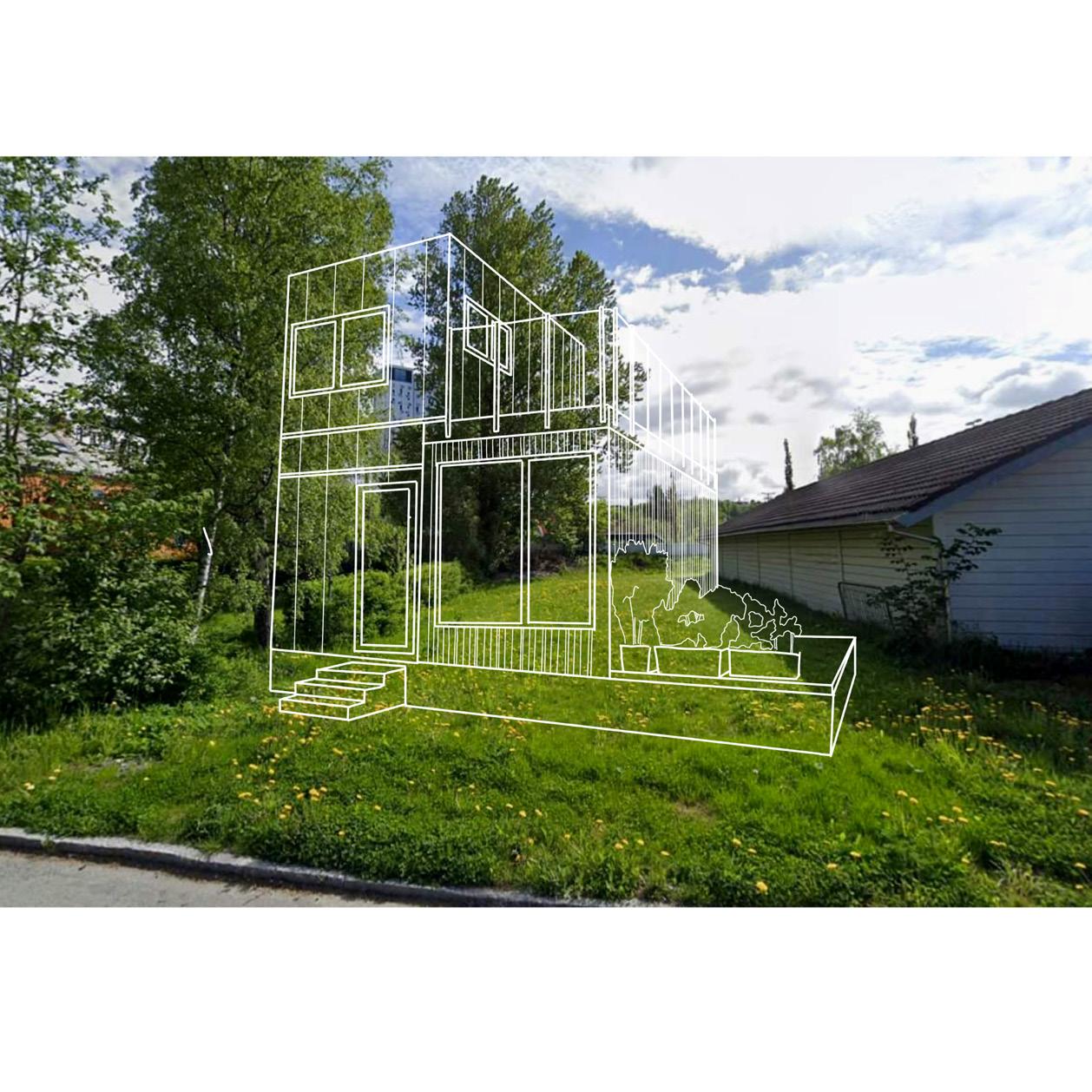

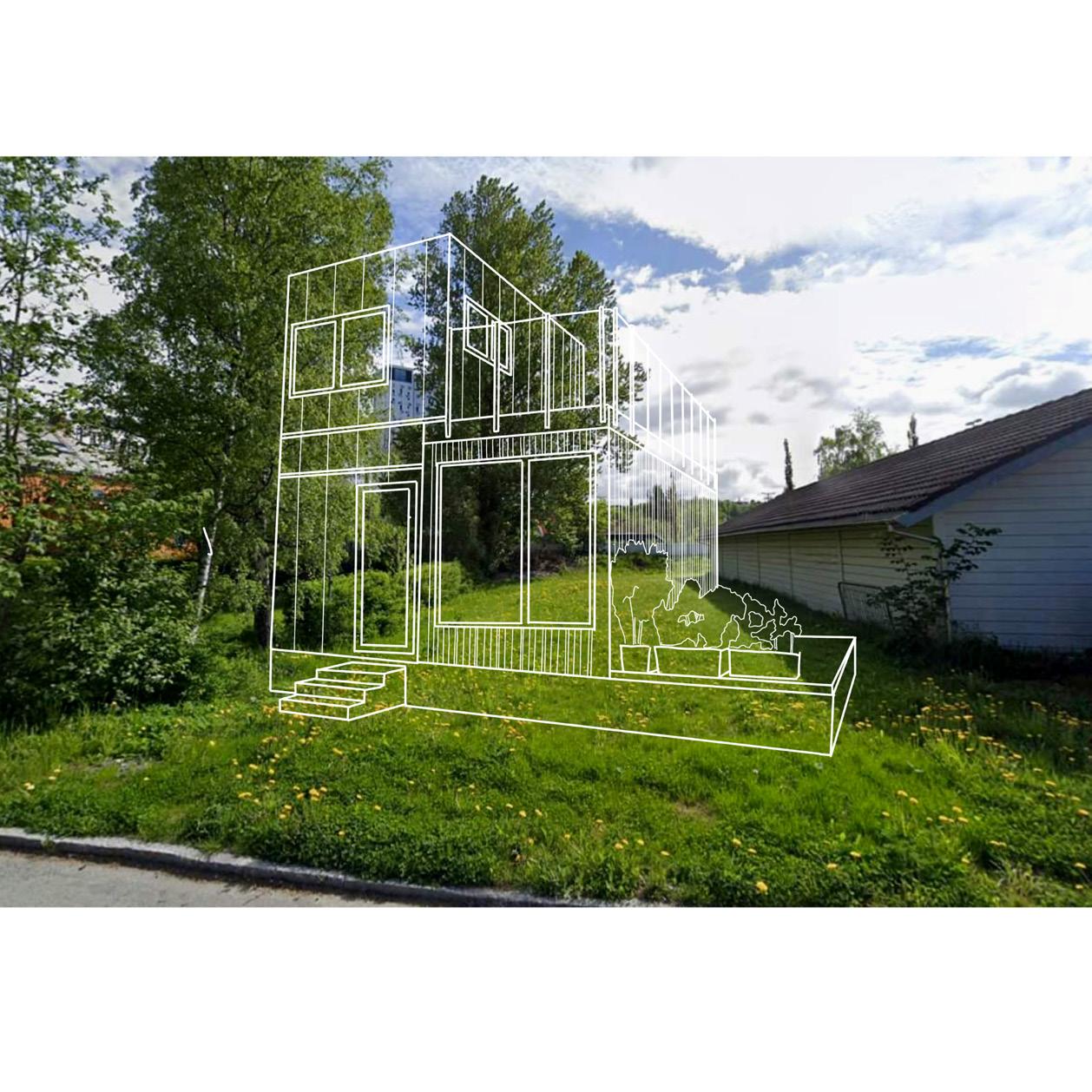

4.12 First intervention

To engage with the community and to understand what they think about housing and the identified problems the first intervention was planned. Therefore the initial idea was to use the common flat in Ola Frost veg 4 for the intervention because most of the available information is about Tempe. The idea was to offer coffee, waffles and activities and make the common flat more visible from the outside by putting some furniture in front of the flat and putting up signs and paint on the ground in the public space to lead the way to the common flat. Inside the flat, several activities were supposed to take place to make people engage and gain a better understanding. of peoples living conditions. Unfortunately the common flat could not be used for the intervention in the end because it is under renovation. Therefore another proposal was worked out.

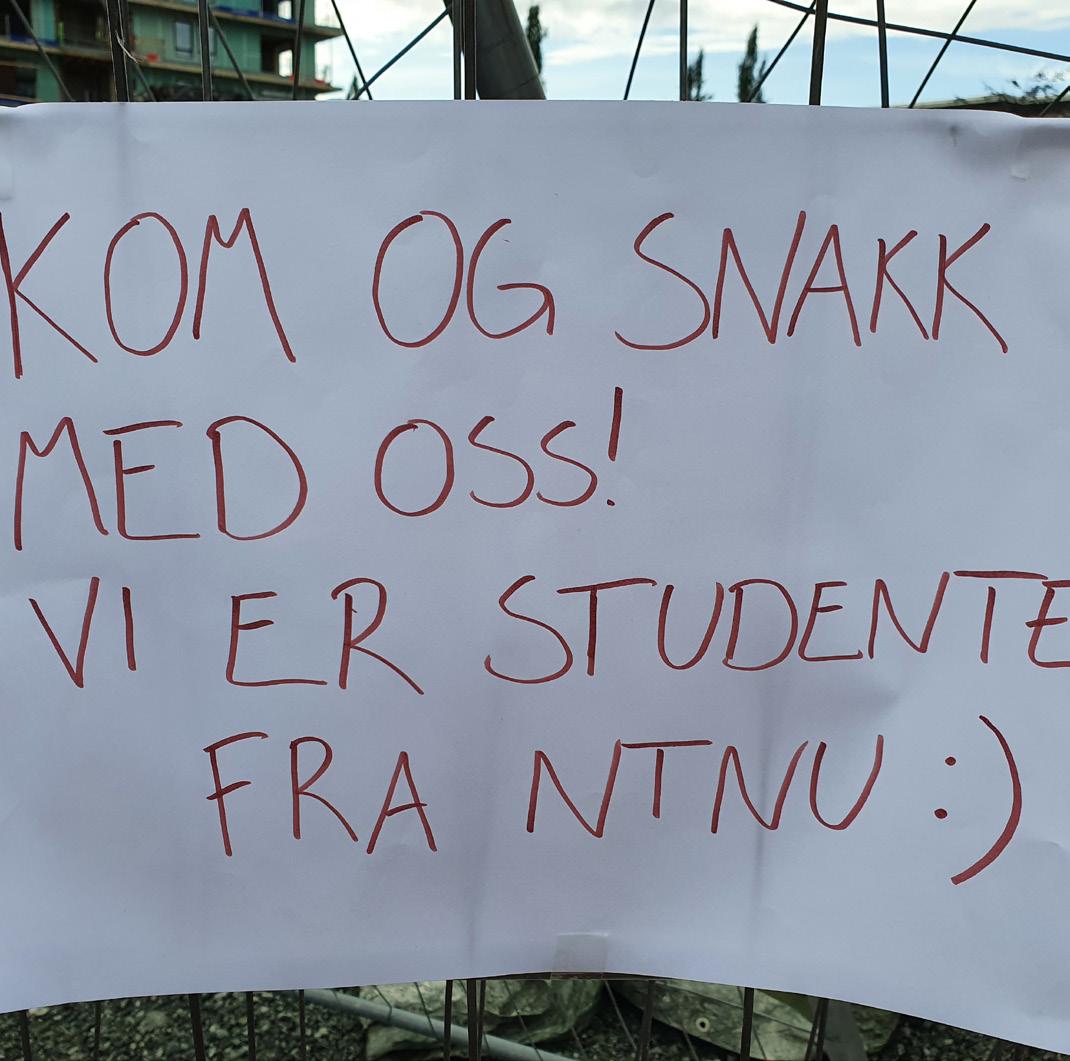

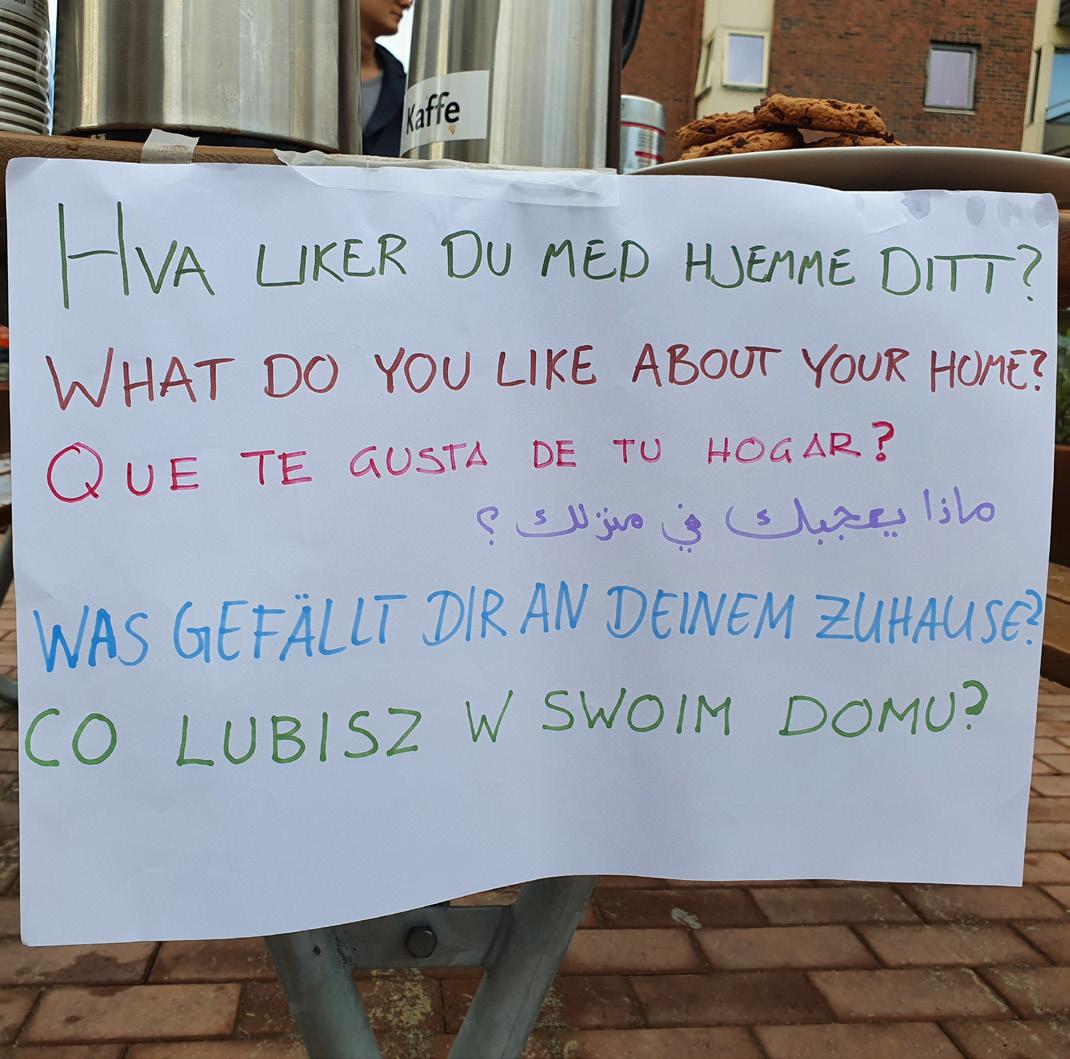

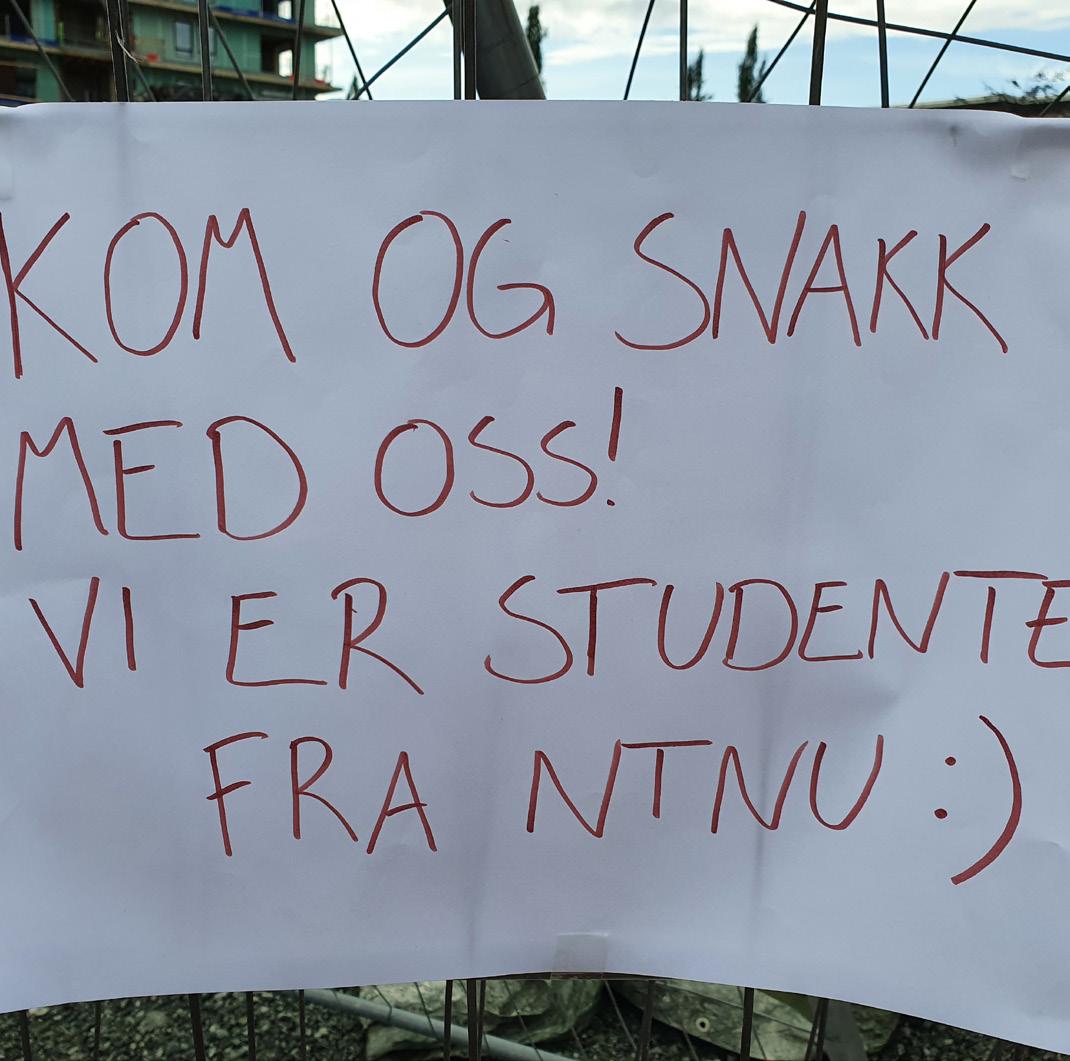

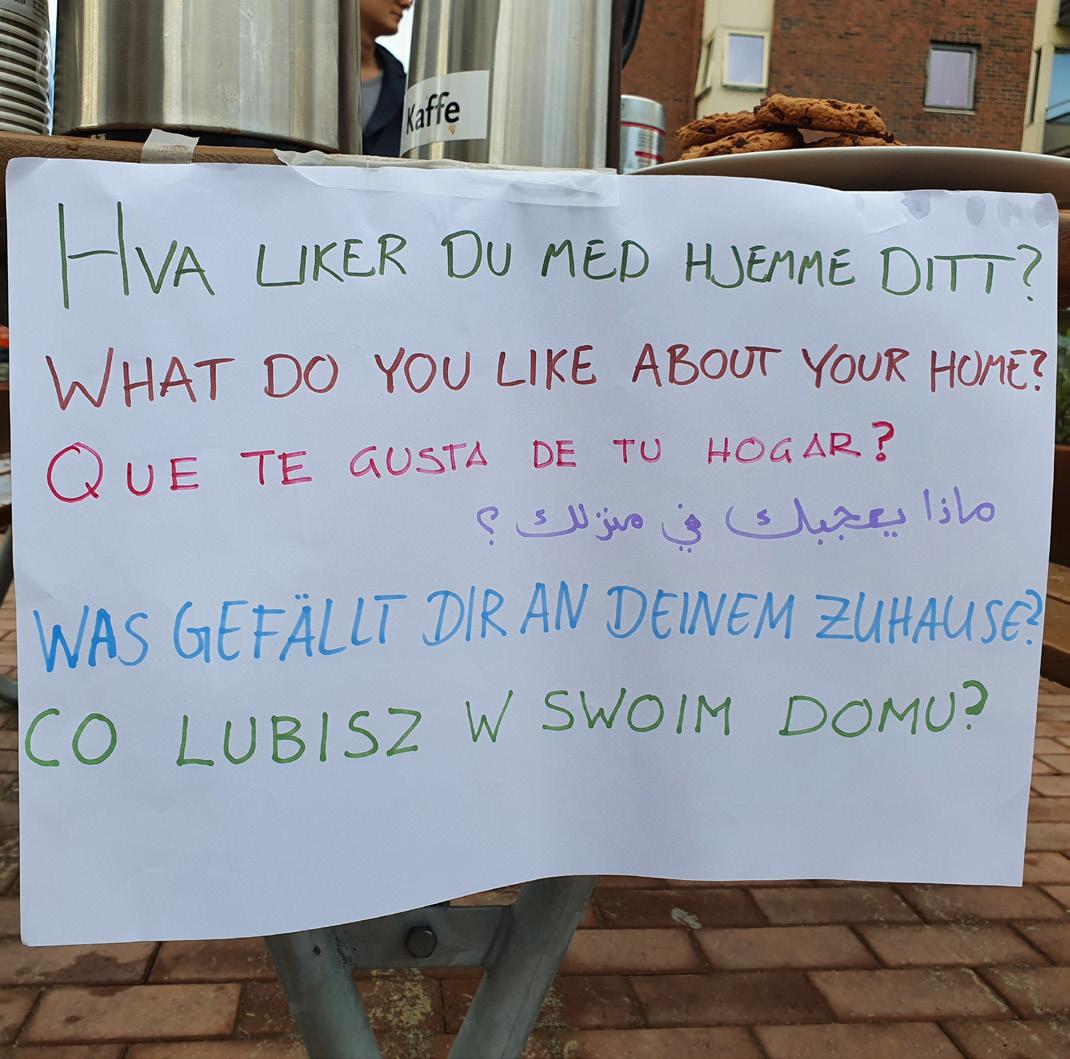

The idea for the new intervention was to bring coffee and cookies to the public space (at Ola Frost veg) and to attract people this way and encourage them to talk about their neighbourhood. To gain more attraction several signs in different languages were made that said “Free coffee”. The languages for the signs were chosen on the basis of the nationalities of immigrants in Trondheim. Finally this first intervention took place in the public space between the high-rise buildings in Ola Frost veg on Saturday the 23rd of September between 11:30 and 16:30.

The beginning was difficult because the group members got rejected when they tried to speak to people. So the strategy on how to approach people was changed because four people were too intimidating: The Norwegian speaking members stayed with the coffee and cookies and the non-Norwegian speaking members walked around in Tempe and Lerkendal and talked to people they met.

The questions that were asked focused on the neighbourhood, the livelihood and housing situations. When some interesting information was found through a conversation, other people were asked what they thought about it. In this way interviewing the locals was successful.

43 | Project location | Project Title

Project Title | Project location | 44

39: People talking

Figures 35, 36, 37, 38: Talking to residents; Coffe; Sign; Sign different languages Figures

We feel like taking the trip on the other side of the road to Sorgenfri to go to a restaurant. So either we they don’t go to a restaurant, or we go into Midtbyen.

Its a long distance to travel to the library in order to borrow books.

For me it is fine but for others it might not work. There are some books at the eldery centre but really few and nearly always loaned by others.

There used to be many more stores in Max-building, now only a hairdresser, grocer store and a pharamcy are left. Since the tax on renting got so high, the shop owners can not afford to rent there.

I am worried the pharmacy will disappear, since there are no doctors offices. There used to be a doctors office and a different pharmacy, but they both got relocated, and the area was without a pharmacy for a time until Apotek1 came.

45 | Project location | Project Title

I like living here and the neighbourhood. Frost Eiendom is a good landlord and they care about us.

The only thing I can complain about is the noisy street and the tunnel for pedestrians

My children like playing here, but I think the playground could be a little bigger and I miss a gym close by.

Since the building behind the footballfield in Tempe got demoloshed there are no issues with drug dealing in Tempe anymore

Families live in overcrowded conditions in Ola Frost veg 2. You can see that they use their wintergardens as additional bedrooms.

It would be nice if all people would use the outdoor areas more to talk to each other and sit together

There will be a new cafe in Ola Frost veg 5, which I am happy about but unfortunately no restaurant.

Title | Project location | 46

Title | Project location | 48 Figures

Project

Project

2: Intervention

In my hometown Froya is used to attend cutural exchange events where they make food and have peformances with different cultures.

I agree! I would be interested in a cultural food “festival”. Therefore it would be nice to have indoor space for gathering and activities.

47 | Project location | Project Title

Figure 40: International food festival

4.13 Second intervention

While the load of information about Tempe, especially about the conditions in Ola Frost veg, is big, there is little to no information about the residents and the living conditions in Sorgenfri. Most of the apartments were built in the last years, that means the building but also the community is very new. To get information about the living and housing conditions and to understand how residents feel in Sorgenfri about living there the second intervention took place in Sorgenfri. It was to find out if the issues in Tempe also apply in Sorgenfri.

1. For the first phase of the intervention a pavilion with a table and chairs was set up. People could get coffee and cake for free and have the possibility to paint wooden boards. Those eventually were put together to create one big picture (mosaic). The idea was that people use the space in the neighbourhood, interact with each other and share information about living and housing in Sorgenfri. The main questions that were asked were:

• How do you like living here?

• Do you want to stay here permanently?

• What do you think about the neighbourhood? Do you interact with your neighbours?

• What would you wish for the neighbourhood?

• The people that painted the wooden boards were guided by these topics questions so the painting refers to this.

2. For the second phase of the intervention the pavilion and the materials stayed there for a couple of days. In this way people had the option to do the painting activity and use the space even when the group was not there anymore.

Project Title | Project location | 48

Figures 2, 3, 4: Intervention; Intervention; Intervention

49 | Project location | Project Title

Figures 41, 42, 43, 44: Intervention; Painting; Gratis Kaffe; Mosaic of Sorgenfri

Second intervention - Findings

During the second intervention much less people wanted to engage with the intervention, were interested or curious. The people that were going in and out of the apartment buildings were a lot younger as well as most of the people that interacted with us. Most of the people talking to the group were probably between 25 and 35, just one man was older than 50 years. Through the first phase of the intervention it was found out that people living in the apartment buildings are very happy with their housing and living conditions. Also the convenient location was mentioned because the apartment buildings in Sorgenfri are located close to the city but also close to commercial areas in the south of Trondheim. One of the residents works close by and applied as soon as possible for one of the apartments so now they are able to walk to his office in 2 minutes.

People also said that they are happy with the apartments even though they have small apartments but they use the common spaces a lot as well for example to work. Others used the common space to watch soccer games together or other kinds of activities that can be done there.

Some also said that there is no real interaction between people from different buildings. A woman told the group that she likes the apartment so much that she wants to buy it soon and live there permanently. Nevertheless that was not stated as an issue that has to be dealt with. Through the second phase of the intervention when the wooden boards were left for a couple of days in front of the apartment buildings, it could be observed that there was interaction with the set up because all of the wooden boards were painted at the end. Based on the paintings the residents seem to be very happy in Sorgenfri but there is a wish for more greenery and someone also painted a picture about a stolen bike.

Based on the second intervention the identified problems so far could not be confirmed in Sorgenfri. In general the people seemed very satisfied with their housing conditions.

Project Title | Project location | 50

Figures 1: Intervention

There are households in the high-rise buildings that have too liitle space in their apartments and are in need of more qualified public space.

The parents from the same nationallity engage more with each other than from different nationalities. The cooperation between the kindergarten and the eldery cente is very successful whereas students do not engage with the kildergarten.

Kindergarten

Not many students interact with the activities in the eldery centre which is probably because there are many activities for students in the city in general but the eldery centre would like to change that. Children meet regualry with residents from the health centre. This activity is very successfull

Families move often because apartments are too small and that there is a need for more common areas where people can meet.

Health and eldery centre

51 | Project location | Project Title Stakeholder interviews

Stakeholder interviews

There are too many students living all together in the wooden house area. I have 68 neighbours in my house that are studnets. There should be more accomodation for them. I will moe out soon.

We see the overcrowded apartments as a topic we have to address as many families live in small apartments with us today. They will probably be defined under what is called cramped living.

Frost Eiendom

Frost Eiendom

Families left the wooden house area in Tempe because there live more and more students.

resdient from the wooden house area Tempe

Students should live in good and healthy living coditions. Moreover students shoudl be in more exchnge with their neighbours and other residents.

Project Title | Project location | 52

Findings from stakeholder interviews and interventions

• people live in overcowded apartments which can be confirmed because people sleep in their wintergardens

• neighbours in Tempe could engage more

• no activities were residents from different cultures and nationalities can come together for exchange, but the indoor common flat could be used for that in the future

• intergenerational exchange is successfull

• some aprtments in the high-rise buildings have too little space

• students do not contribute much to the neighbourhood

• reidents in the Sorgenfri apartments are happy with their housing and living conditions

53 | Project location | Project Title

Figures 45: Mosaic of Sorgenfri

Strenghts:

4.14 SWOT-Analysis - Tempe Sorgenfri

• People in Tempe want more exchange between in age groups and cultural groups

• A good functioning common space housing system in Sorgenfri

• Green areas

• People that are happy with their living environment

• Frost Eiendom as a landlord that cares for its residents

Opportunities:

• Young people with ideas, resources

• Many different cultures and ages

• Public space to make connections possible

Weaknesses:

• Too less connection possibilities

• Too less space for families and students

Threats:

• Residents that might become tired of too many students

• Mobilisering and studentification

• Affecting schools and kindergarten in the future

4.15 Problem statement

Based on the analysis, interventions and interviews there were several problems regarding housing identified. This research will not deal with all of the identified issues from the analysis but focus on the inadequate housing issues in Tempe:

• Overcrowded family households in the high-rise buildings in Ola Frost veg.

• Tempe becomes more and more a student area because apartments are rented out to students, which also leads to instability in the area because they move in and out a lot

• and families leave the area

• to less interaction between different ethnics and students and other groups in Tempe

Project Title | Project location | 54

4.16 Stakeholder Analysis

In Tempe there are many different stakeholders that have been involved, participated and will be affected by future solutions. In our project we will only focus on the ones who will be affected by our topic on housing.

For housing, residents as well as companies and the municipality are the stakeholders in Tempe that are relevant to our project. According to what we have heard from participatory methods, presentations, interviews as well as documents, we have analysed that there are a total of nine stakeholders that are interested in the question about future housing. These are: live in Tempe rent apartments live in the wooden house area

Families

55 | Project location | Project Title

live in the wooden house area

Landlord Ola Frost veg

responsible for student accomodation

landlord that rents out to students in the wooden house area

Renters

Students

Homeowners

Kindergarten

SIT

Frost Eiendom

EngvikInvest

Municipality

Eldery centre

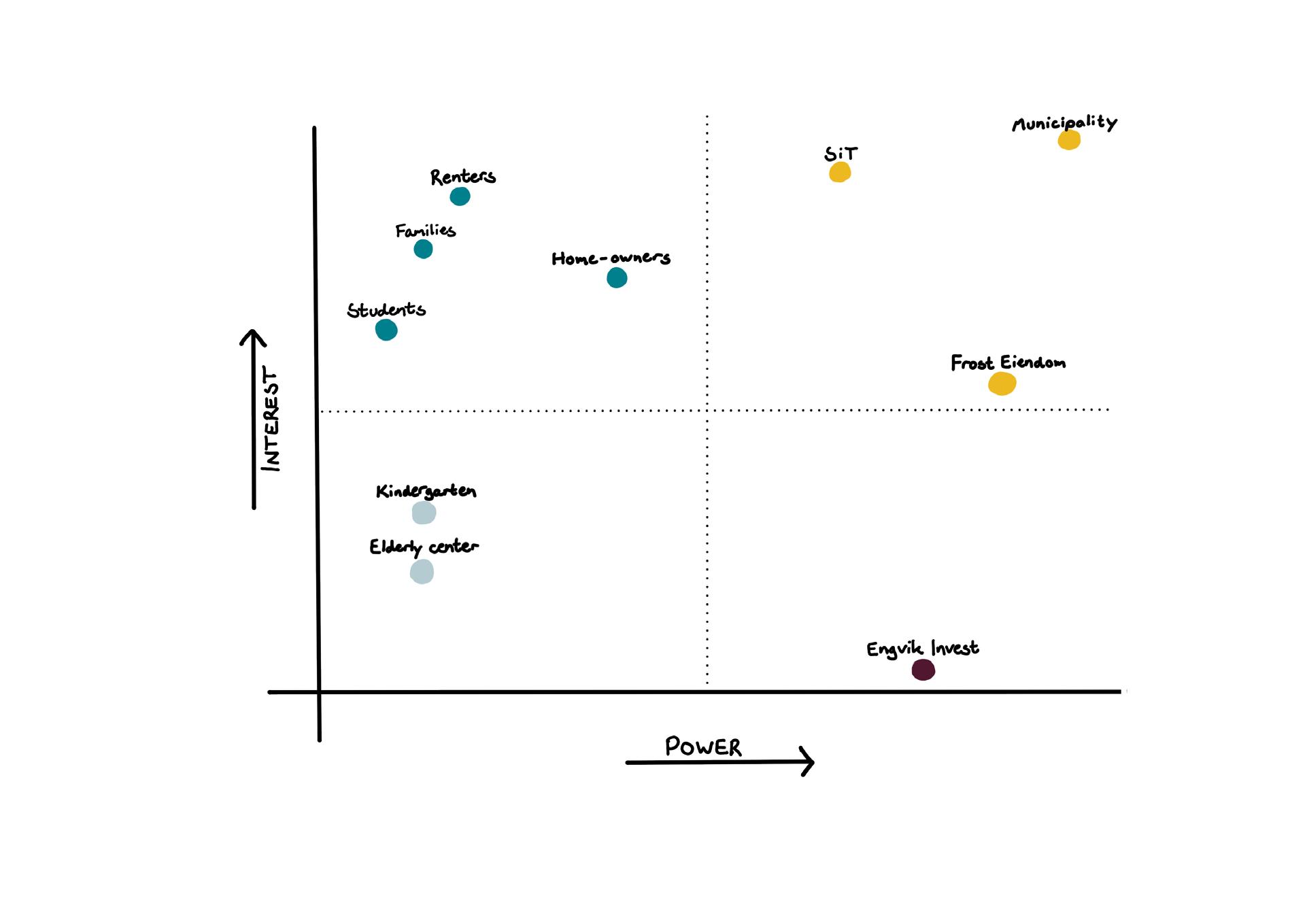

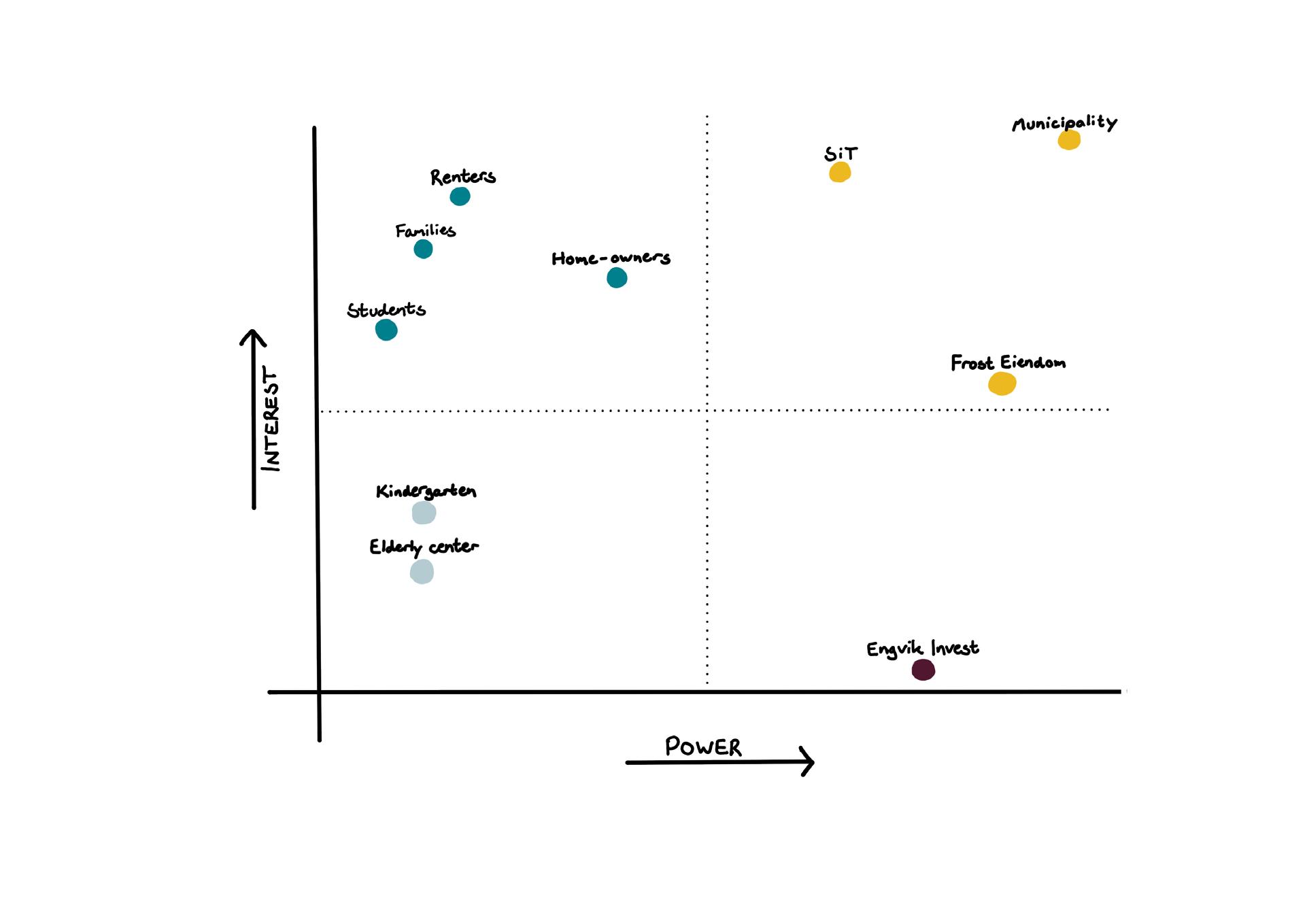

Power-interest diagram

Based on gathered information a power-interest diagram was made to understand and illustrate who is the most interested in the topic, as well as who has the power to make decisions and influence the project process. In the top-left are residents, who we have discovered are very interested in the project, but when it comes to their housing situation they have less power than the bigger companies who own the houses such as Engvik Invest who is in the bottom-right and Frost Eiendom in the top-right. Both of these companies own a lot of rental-housing in Tempe, and have been placed with more power as they are big companies with high income and strong influence. However, they are placed in two different squares in the diagram, as Frost Eiendom, through interviews and presentations, are very interested in developing housing in the area, and seem serious in their claim to be a part of a solution for better housing in Tempe. Engvik Invest may have a lot of power, since they own a lot of houses in the wooden-housing area north of Tempe, but have little interest in future solutions for housing from our interactions we have had with them and tried to have.

Together with Frost Eiendom in the upper-right are Studentskipnaden i Trondheim (SiT) and Trondheim municipality. Both of these stakeholders have expressed a lot of interest in the project, and the municipality were the ones who started the “Områdesatsning” in Tempe-Sorgenfri. Both of them have power, but the municipality is the stakeholder from the analysis that has the most power, as they are a function of the government and have a lot of influence when it comes to housing policies and law.

In the bottom-left is the kindergarten, who has been identified as a stakeholder as they are directly affected by how many families with kids there are in the area.

Project Title | Project location | 56

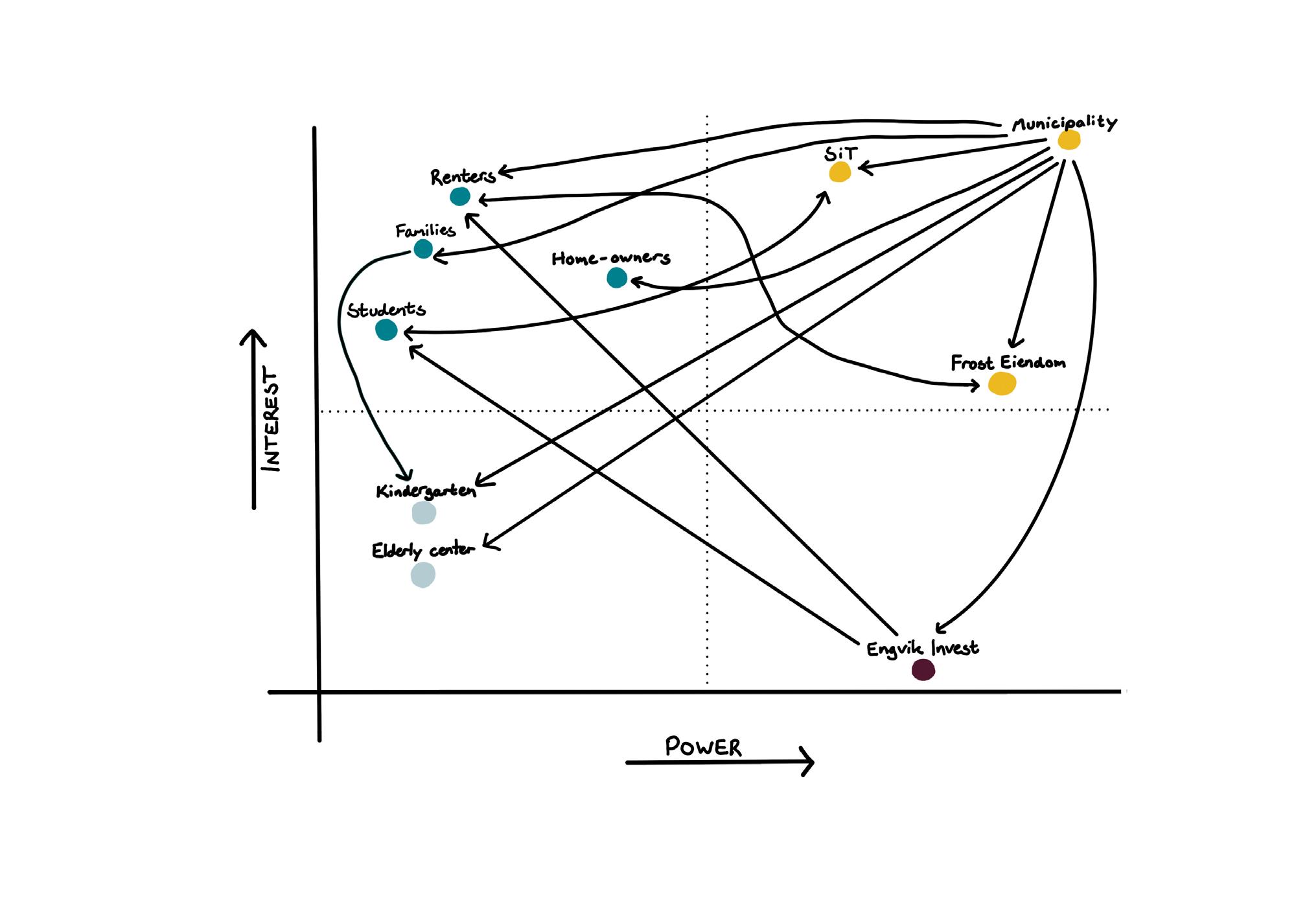

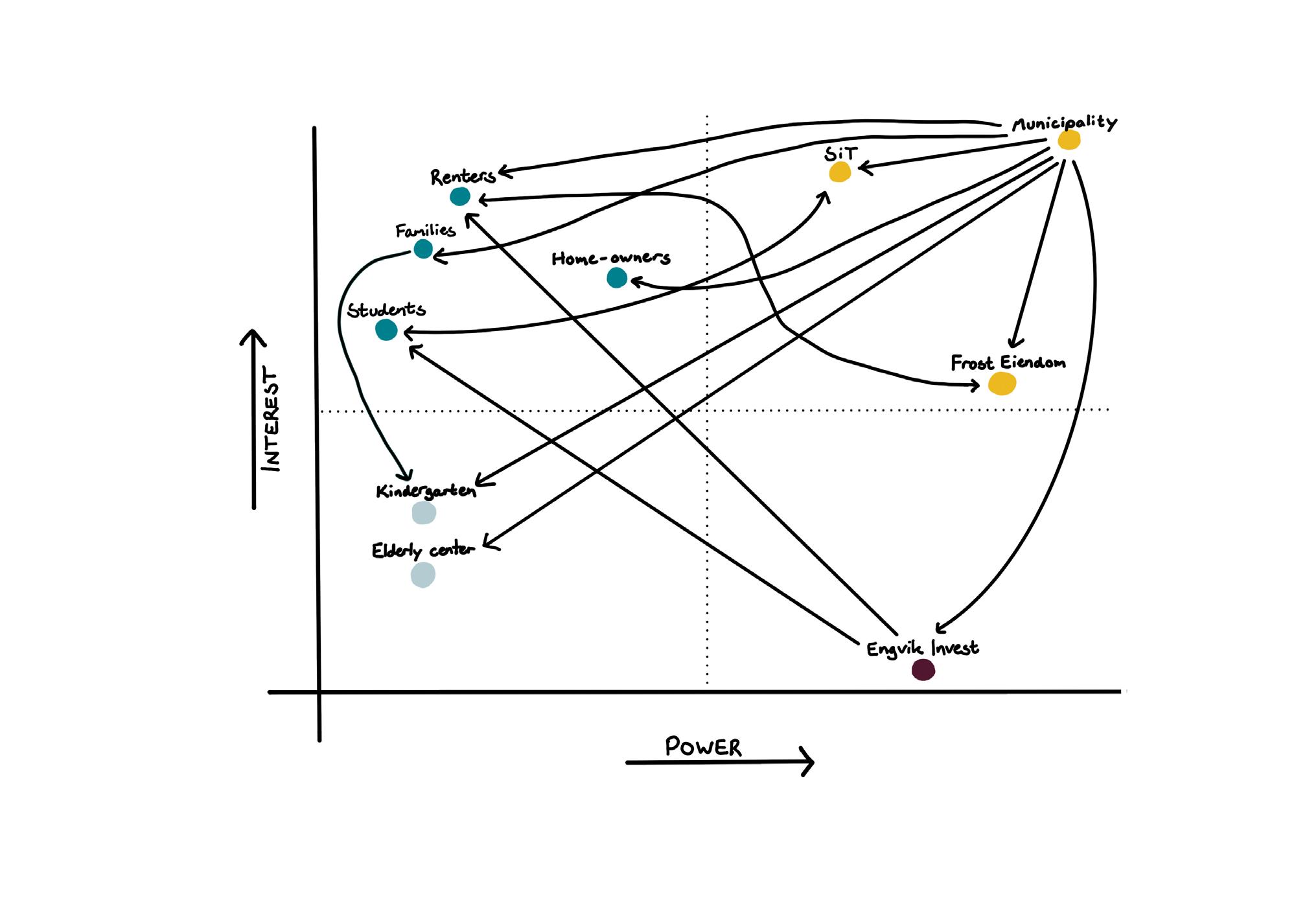

Stakeholder influence diagram

When it comes to influence, the stakeholders who have the most influence over other stakeholders are the municipality, because they are the legislative decision makers when it comes to housing, and can affect every other stakeholders since they have the most power over housing and can affect every other stakeholders since they have the most power over housing laws and landuse. Engvik Invest influences the renters and student, since many of them rent from the company. There is not much influence going back to these two stakeholder (except the municipality has influence over Engvik Invest and Frost Eiendom) as both of them have higher power as seen in the power-influence diagram, and while renters, students and home-owners can express their wishes to them, the municipality and Engvik Invest does not have to follow through.

Some stakeholders have influences that go both ways, such as SiT and students and Frost Eiendom and renters, since they take their residents’ interest seriously and to heart when making decisions.

57 | Project location | Project Title

Figures 46: Power-interest diagram

Project Title | Project location | 58

Figures 47,

48: Stakeholder influence diagram; Stakeholder-issue interrelationship diagram

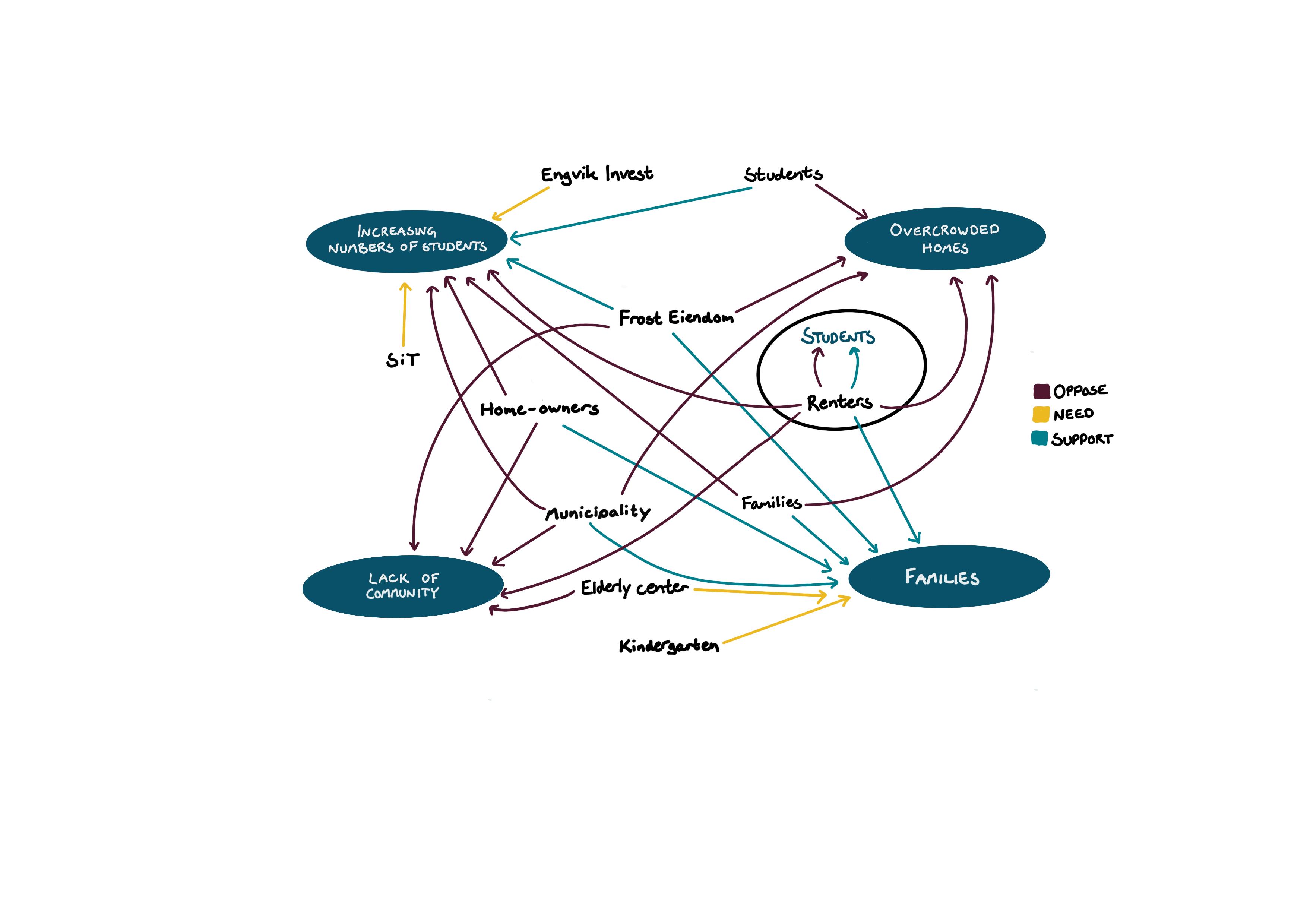

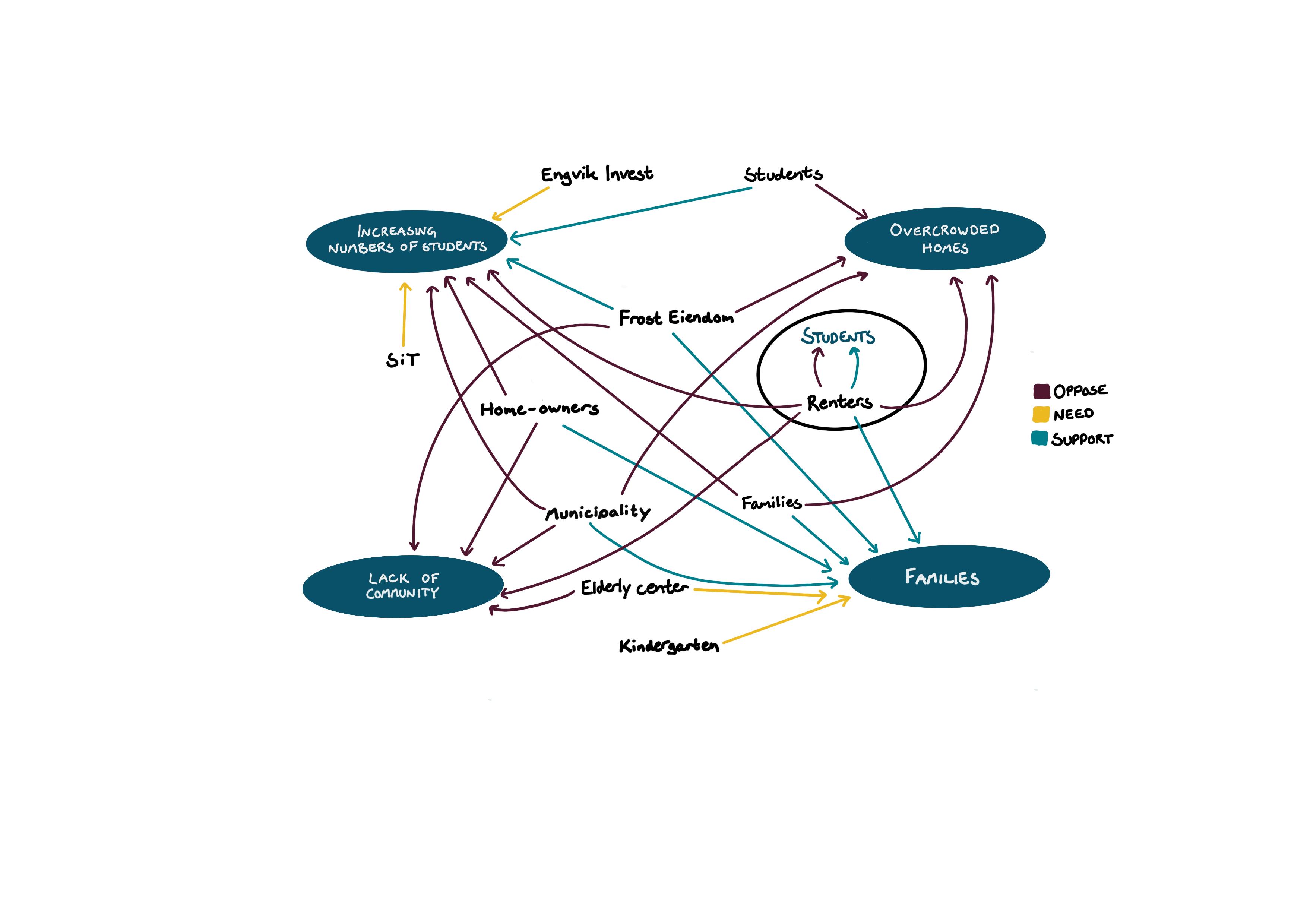

Stakeholder-issue interrelationship diagram

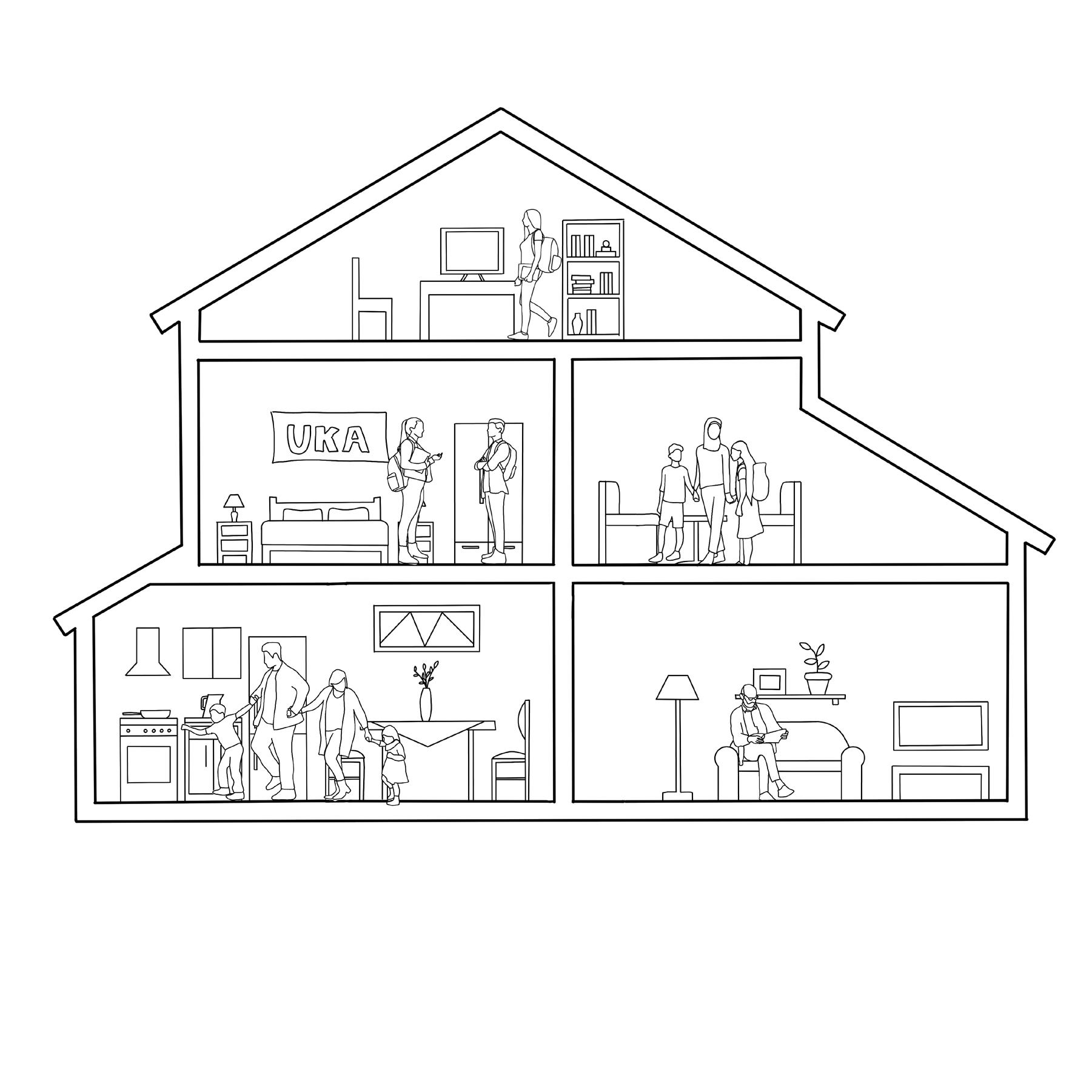

There are four problems related to housing in Tempe. These are increasing number of students and student housing, decreasing of families, overcrowded homes and a lack of diversity. Using the collected data, we have analysed what kind of relationship the stakeholders have to the different issues.

The issue “increasing numbers of students and student housing” has a mix of oppose, need and support. Engvik Invest and SiT’s main objective is to rent out housing to students, and therefore need students in order to maintain their profits, while many others such as renters, home-owners, municipality and families have expressed their worry that there might be too many students in the area, which can affect the diversity of the neighbourhood and cause issues such as nightly disturbances and alienation between groups. Students however do need student housing, and Tempe is located close to the university, and therefore they might support the idea of having more student housing, and Frost Eiendom has expressed that they welcome more students into the area and have interest in renting out student housing in their new high-rise building.

Renters have an internal conflict when it comes to the student situation, as during interviews with residents there have been both residents against having students in the area as they think that they create too much noise and contribute little to the neighbourhood community, and residents that welcome students as they think they bring energy and life to the neighbourhood.

59 | Project location | Project Title

With overcrowded homes and lack of diversity all stakeholders that have a relationship to this problem oppose these problems, and have interest that there will come solutions that can fix these problems.

With the issue of family decreasing, most of the stakeholders express that they support more families in the neighbourhood as it brings more children and life and development to the neighbourhood, while the kindergarten needs families in order to stay operative, which you can see in the stakeholder influence diagram.

4.17 Hyblification problem

What is “hyblifisering”?

“Hyblifisering” is a Norwegian word used for when a house or apartment becomes divided into smaller units called “hybler”. In the Norwegian building law there is no legal definition for what a “hybel” actually is, and there can be several types of living conditions that can fall under the name. The Norwegian Municipal and District Department and the Municipal and Management Committee define “hybel” and “hyblifisering” as:

“The typical example of “hyblifisering” is that lightweight walls are erected to create several smaller bedrooms or dormitories in a larger apartment, detached house, etc. The term can also include a situation where large apartments are split into several, effectively, independent, living units. In other cases, the term “hyblifisering” is used when many people who are not related to each other live in one and the same home, regardless of whether remodelling work has been done inside the house.”

Hyblification is a phenomenon that has for the past years been a frustration and a problem in many Norwegian cities. Residential landlords buy houses that originally are made for partners and families, and turn them into smaller units for single persons called hybler, usually in collectives. These collectives usually get filled by students, who struggle to find student housing as the different student welfare organisations together only have space for 18% of the total student mass in Norway (Statistisk sentralbyrå, 2018). This leads to students having to search in the private market in order to find housing, where there is a shortage of available and low-cost rental housing

Project Title | Project location | 60

in general. Especially in Trondheim who have a student mass of about 37 000 and where every five or sixth person are a student, and they need housing like every other group in society (Statisisk sentralbyrå, 2022). Residential landlords use this as an opportunity to buy and rent out more and more units, and with higher demand each year they continue to buy houses and turn them into hybler. Many of these landlords distribute the apartments into smaller ones, and then they rent them out with higher rent then they get more for the same square metres.

As a neighbourhood gets more and more “hyblifisert”, especially with student renters, family households moves to different parts of the city. The researches at Sintef has found that one of the important reasons for families to live in a neighbourhood is if there are other families there (Furberg, 2023). If families decide to move out because of noise, parties and studentification, more families will follow. A good example of this is Møllenberg in Trondheim, where Møllenberg velferdsforening report that the area has had problems with studentification and a change of age and user from families and elderly to students and young people, to the point that the permanent residents started a movement to change this development so that the neighbourhood could become more diverse, where both families and students can live together (Møllenberg velferdsforening, 2023).

Tempe is an area where a lot of the wooden houses in the north has become hyblifisert, much to the frustration of some residents that we have talked to. Some point out that they make a lot of noise because of parties, and that less and less families have the opportunity to find a house in Tempe of decent size because of the houses being turned into collectives for students. Some of the residents also point out the students also bring life and energy to the neighbourhood, and wish them welcome to stay and live there, however that the total amount might be too much. Therefore we wish to figure out how we can regulate the hyblification so that there can be a diverse neighbourhood consisting of both students as well as families and elderly.

61 | Project location | Project Title

4.18 Observation walk to identify student houses

To identify student housing in Tempe an observation-walk was done by the us. During our walk, signs for students living in the houses like code-locks, key-boxes next to the entrance door, many bicycles in the front garden or mailboxes with many different names were identified. Also typical signs for students like flags from the local student festival could be identified and young people going in and outside to houses could be observed. From the observation wak it can be assumed that already about a third of Tempe is student hosuing.

Project Title | Project location | 62

Figures 49, 50, 51: UKA flag; Mailboxes; Bicycles Figure 52: Student housing

4.19 Housing laws Norway

There are approximately 2,3 million households in Norway with over 2/3 of them owned by the people living in them. This is because owning a house in Norway is a priority, where the desire is for most people to have the opportunity to own. Historically, there has always been a negative attitude towards private actors profiting at the expense of the tenant and because owning a house is seen as a counterweight to the market and a means of combating poverty. Taxes and incentives make it also cheaper to own than to rent. (Sandlie & Sørvoll, 2017)Trondheim municipality is the third most populated city in Norway with 213163 people (Statistisk sentralbyrå, 2023). From those 23.7 % are considered renters and the rest are owners (Statistisk sentralbyrå, 2023). A high percentage of students live in Trondheim. From NTNu’s website it is stated that 85% of overall students who go to NTNU study in Trondheim.

Anyone living in Norway has the freedom of buying a property or renting one. Housing market in Norway can be found online on different websites including finn.no and hybel.no. The rights between landlords and tenants can be found in the Norwegian tenancy act (husleieloven). The Norwegian tenancy act is a law that applies to spaces under consideration for rent. The law itself provides guidelines to landlords on providing adequate housing. The tenancy act also requires all landlords to have approved apartments or rooms to rent out.This does not include hotels and overnighting places. Approved housing follows the rules in TEK17 which includes the regulations on technical requirements for construction works.

When someone rents a space they are allowed to rent for either a defined time or not. Open-ended agreements apply until one of the parties terminates it. Fixed-term housing agreements should not be less than three years as a general rule according to 9-3 of the tenancy act. In addition, fixed-term agreements are to include when the agreement expires. The tenancy act includes what other rights tenants have including that landlords should allow tenants to have their own space without disruption. However, landlords can make changes to the rented space if it can be done “without significant inconvenience for the tenant”, and that change does not cause defects in relation to the home that was originally agreed on between the landlord and the tenant (Husleieloven - husll, 1999, 5-4). Landlords can only increase the rent once a year. The increase is calculated by looking at the consumer price index. For renters, a depositum is usually applied in the tenancy agreement (Husleieloven - husll, 1999, 4-2). The deposit is security in money for the landlord to cover missing rent or any damages that are caused by the tenant. The deposit is placed in a separate bank account and can be a maximum of 6 months rent. The landlord has the right to terminate the tenancy agreement if the tenant breaks their original agreement including not paying rent (Husleieloven - husll, 1999, 9-9).

63 | Project location | Project Title

5. Concept for Solutions

5.1 Vision

The identified problem statement is seen as inadequate housing. Therefore we raise the question what then adequate housing means. Different institutions tried to answer that question:

A professor on housing at NTNU explains that adequate housing goes beyond the physical boundaries. It’s about creating positive impacts for both the society and the individuals. For society, it means adopting diversity and social stability in addition to ensuring accessibility for everyone and adjustability. Adjustability means planning for change, making it flexible to be able to change and adapt over time. For the individual, quality housing provides practical homes with the opportunities for privacy, socialising and improving the overall wellbeing of the individuals.

In Trondheim, Norway social inclusion is not well addressed especially in mixed neighbourhoods where students reside. Therefore it is important to embrace community and include students: One way to include students is to give students tasks within the community, connecting them to refugees through a buddy system, and encouraging understanding between them and the community through organised events.

In order to ensure change, relying on landlords and the private market is not enough. Community commitment and the municipality involvement are important as well as the residents’ opinions for improvements to happen (professor).

United Nations defines being adequately housed as “having secure tenure, not worrying about being evicted or having your home or lands taken away. It means living somewhere where you can keep your culture, and have access to appropriate services, schools, and employment”. (UN, ).

In the Norwegian national strategy for social housing policies ‘We all need a safe place to call home’, it is said that housing is “the fourth pillar of welfare alongside health, education, and work” (Ministry of Local Government and Modernisation, 2020, p.4). It highlights the need to provide suitable housing for everyone under the previously mentioned definition from the UN on adequate housing. The strategy defines those who are at a disadvantage in the housing market as either people “who have nowhere to live, are at risk of losing their homes, and those who live in unstable

Project Title | Project location | 64

housing or living environments” (Ministry of Local Government and Modernisation, 2020, p.4). The document also emphasised that in past strategies it was important to have a good collaboration between different actors to ensure the success of the strategies.

The relevant strategies for social housing that contribute to adequate housing are set as goals for 2021-2024. They are as following:

• “Renting shall be a safe alternative”: Even with a high percentage of homeowners in Norway, there are still many people who cannot afford to buy a house. This makes the renters market as important as the housing market. Yet, the document states that “tenants generally live in poorer and crowded conditions, in addition to that many feel that they live in unstable conditions due to short-term contracts”. (Ministry of Local Government and Modernisation, 2020, p.14)

• “Social sustainability in housing policies”: This goal aims to include housing in the early stages of urban planning. By including housing in all planning stages, the government can predict the population trends and is able to provide a decent and good living environment for everyone. (Ministry of Local Government and Modernisation, 2020, p.22)

• “Clearer roles, and necessary knowledge and competence”: While the responsibilities of each local municipality are equally important it is still a complex topic to consider with each municipality having their own variation in organising their work. This is why the strategy proposes to have a clearer responsibility in a new social housing Act. “A good asset supporting the municipalities is the Norwegian State Housing Bank which provides both financial support and expert advice for many local authorities”. (Ministry of Local Government and Modernisation, 2020, p.27)

In Norway, housing policies initially were created to encourage citizens to own their own homes eventually, but it is challenging for some to be able to own a house and therefore national strategies were implemented for social housing policies. These policies were made to protect those unable to find a place to live.

The Boligstiftelsen in Trondheim, which is a housing foundation that provides affordable housing for its residents, sees adequate housing as community, affordability, and secure tenure. Because it provides affordable housing it is challenging for them to compete with other profit-driven companies.

The foundation owns entire buildings instead of single flats. These buildings include spaces to be used as spaces for community building and connecting neighbours with each other. Moreover

65 | Project location | Project Title

the policies of the foundation are different from social housing in Norway: The foundation doesn’t just take in consideration groups with mental health struggles, addictions, or health challenges as those groups are taken care of by the municipality, but those who struggle to find and afford housing, like low-income families and individuals.However, high rent prices in the city forces people to move out of the city to be able to afford the rent.

While the municipality’s responsibility ends for social housing residents when their living conditions improve which leads to instability in their daily lives, the foundation provides ongoing contracts. Currently the foundation has 200 applications with few available houses for rent. Most of their tenants are single parents, elderly, and middle-aged people. In addition, the foundation takes in refugee students as tenants.

Based on this theoretical background about adequate housing for our project we want to tackle the problem of inadequate housing statement by promoting community, diversity and creating spaces that meet the needs of its residents.

Project Title | Project location | 66

5.2 Concept for solutions

To achieve the vision of adequate housing, tackling the identified problem statement and therefore create community, diversity and creating spaces that meet the need of the residents the following short- , mid-, and long-termmeasures are suggested:

Short-Term Long-Term

Community-Based Activities

Mid-Term

Housing policies to encourage diversity

Modular

Housing

PBSA

Flexible Spaces

Common Space

Densification

Common Space

67 | Project location | Project Title

Figures 53, 54: Vision; Concept for solutions

Prioroty

Measures