The Tempe Walk: Paving the Path towards Pedestrian Mobility

Tempe-Sorgenfri - Trondheim

Project Course Report, Autumn 2023

Urban Ecological Planning Master’s programme

Department of Architecture & Planning, Faculty of Architecture

Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Trondheim, Norway

AAR4525 - Urban Ecological Planning: Project Course

Executive Summary, Autumn 2023

Urban Ecological Planning Master’s Programme

Department of Architecture and Planning, Faculty of Architecture

Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU), Trondheim, Norway

Course Coordinator:

Supervision Team:

Cinthia Freire Stecchini PhD Scholar, NTNU

Cinthia Freire Stecchini PhD Scholar, NTNU

Jarvis Suslowicz

PhD Scholar, NTNU

Vija Viese

Research Associate, NTNU

Rolee Aranya Professor, NTNU

Booklet Layout:

Vija Viese

Research Associate, NTNU

The Tempe Walk | Tempe-Sorgenfri, Trondheim | 2

The Tempe Walk: Paving the Path towards Pedestrian Mobility

Tempe-Sorgenfri, Trondheim, Norway

Authors

Håkon Haga

Norway

Bachelor of architecture

Master of architecture

Mirkeivan Sayyar Kavardi

Iran

Bachelor of geomatics engineering

Master of urban planning

Mari Tanem

Norway

Integrated master of architecture

Anna Sophia Sokull

Germany

Bachelor of architecture

Master of urban planning

Preface

This project report presents the results of the extended fieldwork conducted by master students in the first semester of the 2-year international Master of Science Program in Urban Ecological Planning (UEP) at the faculty of Architecture and Design at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU). The extended fieldwork is a key component of the UEP program, allowing students to work in real cases and to learn-by-doing. In Autumn 2023, the fieldwork took place in Trondheim, Norway.

During this semester, the UEP program worked in close collaboration with Trondheim Municipality. This is the first time such a collaboration was established in Norway for the fieldwork, which was planned envisioning mutual benefits for the students’ learning process and the development of plans and programs by the municipality. The location for the fieldwork – Tempe and Sorgenfri, the focus of one the municipality’s ongoing area-based programs – was decided together. From the very beginning, students were provided with official reports and documents about the area as well as contacts for local stakeholders. This was the base information that they had to complement (and challenge!) by conducting their own situational analysis and identification of a problem statement through participatory planning methods.

The students were divided into three groups and worked on one of the proposed broad themes: Housing & Inclusivity, Public Space & Activation, and Mobility & Accessibility. In the final stage of the project, the groups elaborated concepts and proposals for strategic solutions. The collaboration with the municipality made it easier to access stakeholders, who were invited to two mid-term presentations and the final one. Stakeholders commented on the work, validating (and challenging!) the findings and proposals of our students. What you will read in this report, thus, is the work done by UEP students validated and reviewed based on the stakeholders’ involvement in Tempe-Sorgenfri. We hope that this type of collaboration continues, and evolves, in the years to come.

The Tempe Walk | Tempe-Sorgenfri, Trondheim | 4

Another novelty in the Autumn semester 2023 is that the course coordination and supervision was done by three academics in the early stages of their careers. We are two PhD candidates and a research associate from the department, with backgrounds in Architecture, Urban Planning and Design, Psychology, and Geography. Being responsible for the project course and the fieldwork has been an exciting challenge for us and a fruitful learning experience.

As an international master program, students from UEP come from different nationalities. The diversity of backgrounds – also in terms of academic background – is something we take pride in as it allows a rich exchange among students. We understand diversity as a valuable resource in preparing the next generation of conscious planners. To support the broadening of perspectives, particularly establishing relations of North and South countries – something we actively seek at UEP, we also had a study trip to South Africa, during the same semester, as a part of the UTFORSK-NISA project (https://www.nisa-partnership.com/). There, our students were welcomed by our partners at the African Centre for Cities (ACC), at the University of Cape Town (UCT), who introduced them to different realities and projects. The excursion to South Africa also helped the students to contrast the conditions in Tempe-Sorgenfri with those they experienced in communities in Cape Town.

We are thankful for the collaborations with Trondheim Municipality, and our partnerships in South Africa and India through the UTFORSK-NISA project. We are also very thankful for our curious and proactive students, and hope you enjoy reading this report as much as we enjoyed following their process throughout this semester.

5 | Tempe-Sorgenfri, Trondheim | The Tempe Walk

Acknowledgements

Throughout this project, the group has received great support both within and outside of the university. The group is grateful for all of this support.

Firstly, the group would like to thank our supervisor, Jarvis Suslowicz. From the beginning till the end, she has helped us with her expertise, her patience, her connections and her general assistance. This project would have never reached its current state without her help, and the group would like to thank her for the time and effort she has given us during this semester.

Secondly, the group wishes to give our thanks to our other course supervisors for their insightful feedback that advanced our work. The feedback and constructive criticism helped take the work in new directions and challenged the group in ways they would not have been able to without their help.

Further, the group wishes to thank Tempe-Sorgenfri’s residents and any stakeholders, interviewees and everyone else who helped provide us with information and experiences within the Tempe-Sorgenfri area, the current project would have never progressed without their input.

The group would also like to thank the Trondheim municipality for their help throughout this project, from workshops and interviews to providing funds for the intervention. The engagement from the municipality helped show strong support from the top-down structures to help Tempe-Sorgenfri, something this report gained significantly.

The group further thanks the University of Cape Town for the support and welcome we received on our academic trip to Cape Town, South Africa. Without their experiences, the report would not have gone in the direction it did.

Lastly, the group are eternally grateful for the support from our friends, family and the other members of the UEP course. Without the support and comradery they provided, the group would have never survived the semester.

Acronyms and Abbreviations

AADF

ADAC

CPRE

DIY GIS

LED

NTNU

NVDB

UEP

Average Annual Daily Traffic Flow

Allgemeine Deutsche Automobil-Club (Common German Car-club)

Council for the Protection of Rural England

Do it yourself

Geographic Information System

Light Emitting Diode

Norwegian University of Science and Technology

Nasjonal vegdatabank

Urban Ecological Planning

7 | Tempe-Sorgenfri, Trondheim | The Tempe Walk

The Tempe Walk: Paving the Path towards Pedestrian Mobility

Tempe-Sorgenfri - Trondheim

Contents

Preface

1. Introduction

2. Context

3. Methods

3.1 Primary data

3.2 Secondary data

4. Situational Snalysis and Problem Statement

4.1 Residents at Tempe-Sorgenfri

4.2 Infrastrcture and accessibility

4.3 Effects on residents

4.4 Intervention

4.5 Major stakeholder

Page

number 12-13 14-17

The Tempe Walk | Tempe-Sorgenfri, Trondheim | 10

4.6 Problem Statement 18-25 20-22 23-25 26-45 28-29 30-35 36-39 40-41 42-43 44-45

Contents

5. Concept for solutions

5.1 Equity and Trondheim’s current goals

5.2 Incorporating stakeholder

5.3 Learning from the workshop

5.4 Enabling change

6. Proposal for solutions

6.1 Short-term solutions for the present

6.2 Additional crossings

6.3 Reduction of speed

6.4 Shared Surface

6.5 Reduction of cars

7. Conclusion and Reflection

7.1 Reflections on methods

7.2 Reflections on problems encountered

7.3 Reflections on strategic interventions

References & bibliography

46-55

52-53

11 | Tempe-Sorgenfri, Trondheim | The Tempe Walk

48-49 50-51

List of Figures 54-55 56-85 58-65

66-68 69-73 74-79 80-85 86-92 88-89 90-91 92-93 94-99 100-103

Tempe-Sorgenfri is an area located to the south of Trondheim city centre and is one of the two neighbourhoods the Trondheim municipality wants to develop over the next ten years. In this context, the area has been defined geographically: it includes the neighbourhoods of Lerkendal, Tempe, Sorgenfri and Valgrinda (Figure 1). (Loe et al.,2022)

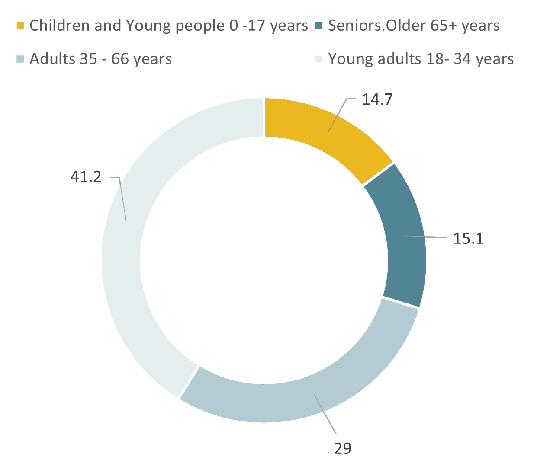

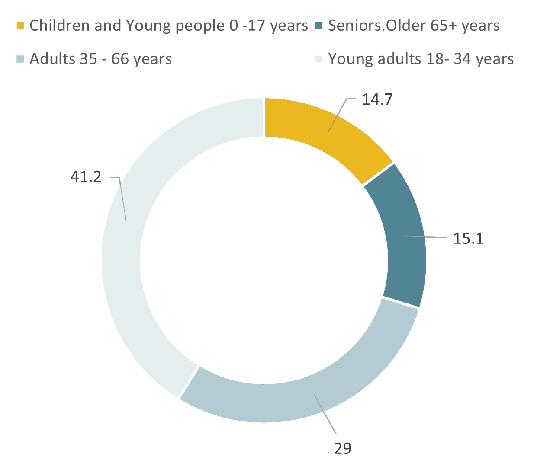

The area is characterised by multiple spatial and cultural sections that stand out, each with its own opportunities and challenges. The Nidelva River, Trondheim’s main river, forms the western boundary of the area and provides a green belt for walking, although access is difficult. To the south, the area is bordered by the E6, from which a main road leads into the city centre, forming a barrier in the middle of the area and separating the neighbourhoods of Tempe and Sorgenfri. A bike highway, less of a destination and more of a section leads hundreds of cyclists through Tempe. The area is also characterised by a wide variety of building typologies, from high-rise blocks to small houses. The Frost Eiendom blocks stand out, providing some of the densest living in the area. About 15% of the population living in Tempe-Sorgenfri is under 18 years old, 41% is between 18-34 years old, 29% is between 35-66 years old and about 15% of the population is over 65 years old. There are plans to develop the bus terminal, one of the larger areas geographically and of little benefit to residents, as an additional residential area. The Lerkendal Stadium is a large sports facility in the area, where football matches attract people from all over Trondheim. In addition, the Nidelv sports area by the river provides a large green and activity area for both residents and non-residents in Tempe. (Loe et al.,2022)

The municipality aims to make Tempe-Sorgenfri a good place to live by improving the neighbourhood environment according to the needs of the residents. (Loe et al.,2022)

The Tempe Walk | Tempe-Sorgenfri, Trondheim | 12

1. Introduction

Figure 1.1: Boundary for the Tempe-Sorgenfri area, consisting of the sub-areas Lerkendal, Sorgenfri, Tempe and Valgrinda

Tempe

Sluppen

Sorgenfri

Lerkendal

Valgrinda

Tempe

Sluppen

Sorgenfri

Lerkendal

Valgrinda

History of Tempe-Sorgenfri

Before the 20th century, Tempe-Sorgenfri was a part of Strinda municipality’s countryside. The first housing in this area was built after 1900. Paulingegård, which used to be a farm before, was divided from Elgeseter in 1971 and it merged with Valgrinden afterwards and was taken over by Den Norske Handelsbank. However, the bank was bankrupt, and the municipality took over the area, making them one of the great influencers of its current condition. The municipality sold part of the area to Frost Eiendom which built the current apartment blocks. (Loe et al., 2022).

In 1864 a railway was built in Trondheim that passed through Prinsens Gate, Elgeseter Gate and Holtermanns Veg and crossed the river at Sluppen. But after the reconstruction, the railway was rerouted in 1884 and since then, the road has been used as a main road for cars towards the city centre (Loe et al., 2022).

The old train and tram lines allowed for great transport options to and from Tempe-Sorgenfri, but did not divide the area as the current road does as its lower traffic volume allowed for pedestrian crossing (Mathisen, 2001).

Several buildings were built in the area during the first half of the 20th century, and the area witnessed a lot of local initiatives to build new recreational and gathering areas such as a football field in Tempe and a grass field in Sorgenfri which became the main football field in Trondheim until the second world war. Lerkendal Stadium was built in 1947 after the war (Loe et al., 2022).

The Tempe Walk | Tempe-Sorgenfri, Trondheim | 14

2. Context

Figure 2.1: Tempeveien & the Frost Eiendom blocks

The Frost Eiendom blocks

The Tempe-Sorgenfri area is dominated by the large Tempe-Sorgenfri blocks. These blocks contain more than 500 apartments and account for a large percentage of the population within Tempe-Sorgenfri.

15 | Tempe-Sorgenfri, Trondheim | The Tempe Walk

A path towards car dependency

Up until the 1900s, any travel within the area was done by foot, or if a person had the means, by one of the horse and carriage drivers found across the city (Mathisen, 2001). This sort of travel allowed pedestrians, bicyclists and carriages to navigate the streets in unison without the hard framework found today (Mathisen, 2001).

With the introduction of the railway, the horse and carriages that used to transport goods into the city center disapeared. The train was used for cargo, and the transportation of people still happened mostly by foot (Kjenstad, 2000).

In 1913 the train line was replaced with a tram with enough space for pedestrians along the side of the Kongsgård Bridge (Kjenstad, 2000). This helped expand Tempe-Sorgenfri as people could easier commute to work within the city itself.

In 1951 the new Elgeseter bridge was built, seeking to replace trams with cars as the main means of transport into Trondheim.

With the widening of the road, the tramline was gradually reduced and Holtermanns Veg was gradually extended, worsening the condition of the road as a barrier at Tempe-Sorgenfri (Mathisen, 2001).

The Tempe Walk | Tempe-Sorgenfri, Trondheim | 16

Figure 2.2: Elgesæter bridge between 1920 and 1930, Photo: (Unknown, 1864)

Figure 2.3: Trondhjem-Størenbanen, Kongsgaard bridge between 1864 and 1884, Photo: (Unknown, 1864)

Størenbanen

The first railway line in Trondheim ran through Tempe, connecting the area to the city centre by providing easy access to the city and an easy crossing of the Nidelva River via the Kongsgård Bridge. Størenbanen helped Tempe-Sorgenfri to become a suburb of Trondheim itself. The bridge was replaced by the Elgesæter bridge.

17 | Tempe-Sorgenfri, Trondheim | The Tempe Walk

3. Methods

As the project encompassed traffic conditions spanning roads across Tempe-Sorgenfri and beyond, the team thought it important to involve and consult stakeholders and residents within the area and beyond. The focus would be on improving the conditions within Tempe-Sorgenfri, without making the conditions worse for any other areas of Trondheim. This chapter will present the methodological path that helped us examine and analyse the conditions.

The chapter is subdivided into primary sources, largely focused on the conditions within Tempe-Sorgenfri itself, and secondary sources, largely focused on the conditions of Trondheim as a whole.

The Tempe Walk | Tempe-Sorgenfri, Trondheim | 18

19 | Tempe-Sorgenfri, Trondheim | The Tempe Walk

Figure 3.1: Timeline of the project report

3.1 Primary data

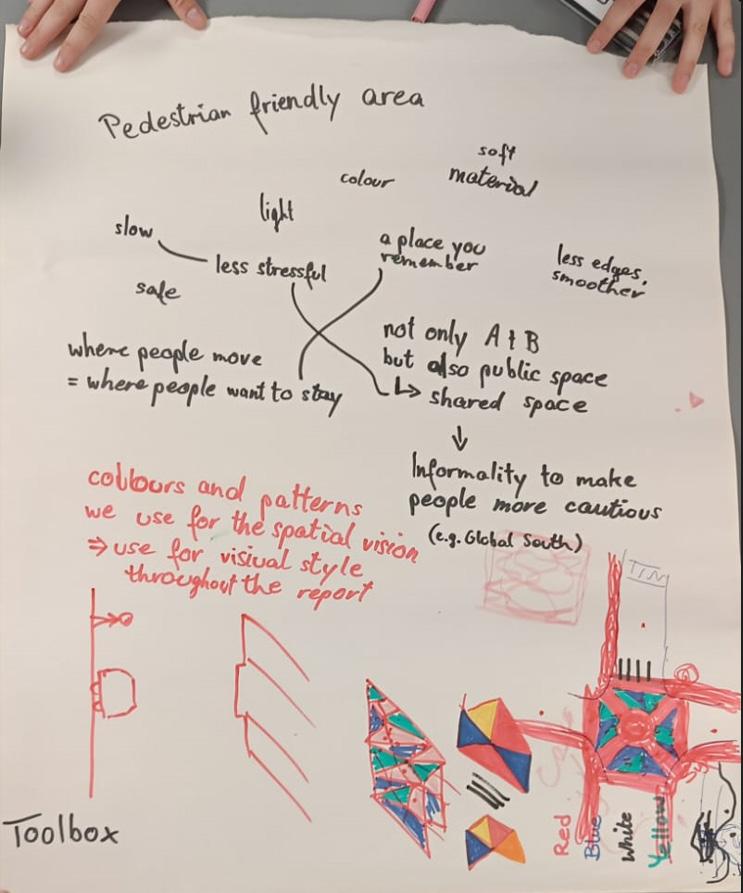

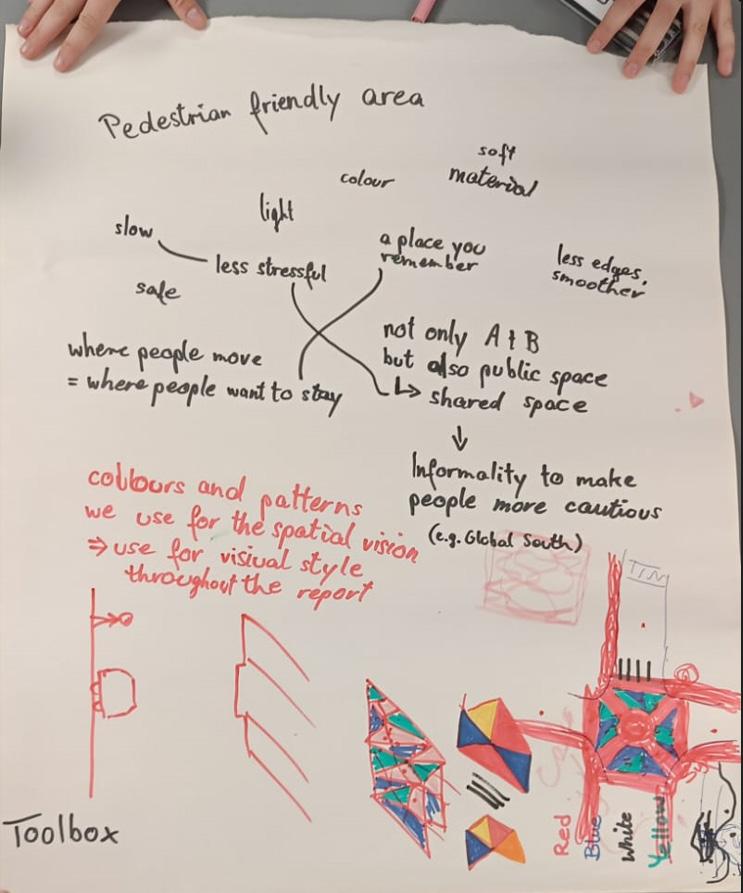

Conceptual brainstorming

Establishing a baseline of expectations between the different group members during the initial stage of the project was considered essential. Different views and ideas were discussed during multiple brainstorming sessions, using both physical and digital idea boards and sticky notes. The focus at this stage was bringing about initial ideas of what topics to address, which people within the area the focus should be on and how the opinions of this community could be best engaged.

Interviews

Group 3 scheduled several formal and informal interviews with both residents and stakeholders within the Tempe-Sorgenfri area. This was done to collect qualitative data on the residents’ own experience of Tempe-Sorgenfri, and the problems they had experienced within it. The informal interviews consisted of interviewing residents and public transport users on the street, while the formal interviews consisted of semi-structured interviews with larger stakeholders and the residents associated with them. These interviews helped confirm or provide alternate viewpoints, to those provided by secondary sources.

Traffic counts

Multiple crossings with potential problems between pedestrians and cars and/or bicycles were found within Tempe-Sorgenfri. Traffic counts were done where the number of near misses between pedestrians and cars and/or bicycles in a 15-minute window was recorded. A near miss was defined as a traffic user needing to swerve, stop or quickly alter their speed to avoid a collision. This helped inform us on which areas of Tempe-Sorgenfri had the most possibility of collisions between users.

The Tempe Walk | Tempe-Sorgenfri, Trondheim | 20

Figure 3.3: Valøyvegen-Tempevegen crossing, an area with high numbers of near misses.

Figure 3.2: An early conceptual map of some of the group’s ideas

Stakeholder analysis

Stakeholder analysis was done to get an understanding of which actors within the area were involved with which issues. Stakeholder power analysis and stakeholder issue analysis were both done to understand how the different actors had complimentary and conflicting interests. This was then used to figure out what dynamics had to be resolved to further develop our schemes.

Internal prioritisation

After feedback from stakeholders, the established concepts for solutions were examined and concepts found unrealistic or undesirable to implement were removed. This step led to the reduction in the focus on road diet as a concept and a greater emphasis on expanded crossings of Holtermanns Veg.

Visual Survey - desire paths

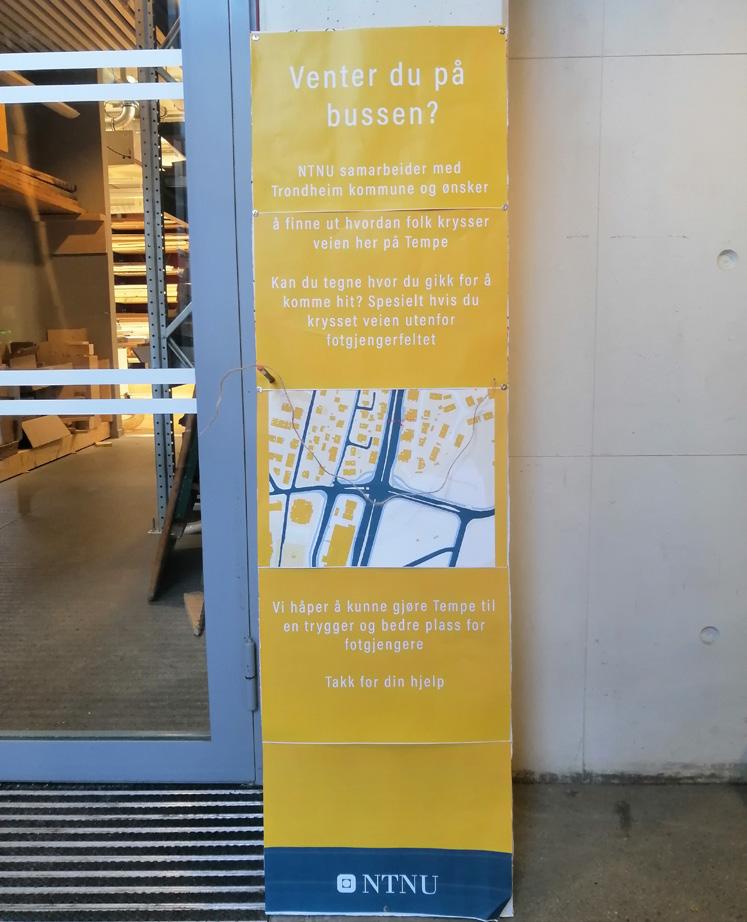

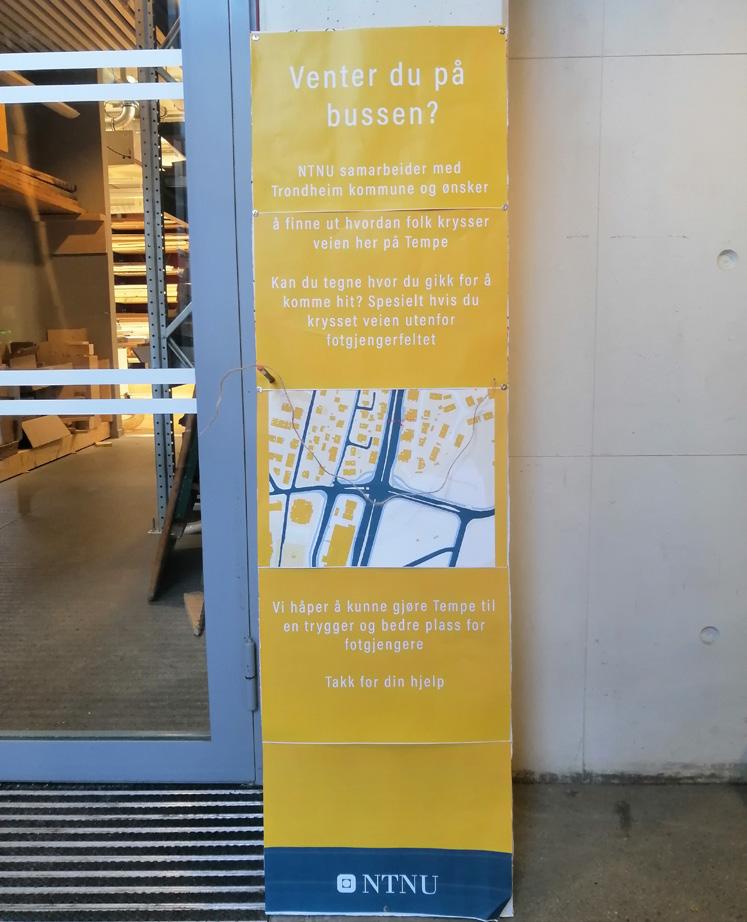

To attempt to gather a wider range of quantitative data, and to engage residents and transport users who did not wish to engage in face-to-face interaction, a visual survey to map desire paths crossing Holtermanns Veg was set up at the bus stop mentioned by residents to be a common destination for informal crossings of the road. This allowed for a better understanding of just how common such crossings were in comparison to formal ones using the established crossings.

21 | Tempe-Sorgenfri, Trondheim | The Tempe Walk

Figure 3.5: Visual survey board posted at the Valøyvegen bus stop.

Figure 3.4: Initial stakeholder interest analysis.

Observation and mapping

To understand how the local community moved around Tempe-Sorgenfri and how these travels interacted with the existing transportation networks, multiple observation and spatial mapping sessions were done on-site. This ranged from mapping the paths taken from residences to key points such as schools or kindergartens, observing how residents sought to cross Holtermanns Veg and seeing when these paths came to a halt when different transportation lanes crossed each other. This was then mapped spatially on maps of the area to better understand the routes and ways the community moved around on site.

Intervention to drive attention

A tactical intervention was done at the Valøyvegen-Tempevegen crossing to bring attention to the unsafe conditions felt by local pedestrians, especially towards bicyclists coming from outside the area. As the intervention led to engagement by multiple residents, this became a good expansion of the opinions held by the local community.

Feedback workshop with local stakeholders

Once the initial concepts for solution had been finalised, group 3 sought more qualitative data as feedback on these concepts. Established stakeholders had more specialised knowledge than the group, and these stakeholders were invited to provide feedback. Through a casual world-cafe discussion session, this was collected to figure out which concepts were the most realistic to implement, and which measures would be needed for them to be successful. Across the different discussions, the overarching conclusion was that a reduction in the number of car users travelling through Tempe-Sorgenfri would be needed for our vision to be realised. This was an invaluable step to finalise our proposal.

The Tempe Walk | Tempe-Sorgenfri, Trondheim | 22

Figure 3.7: Workshop held with local stakeholders for review and consultation regarding the concepts.

Figure 3.6: Intervention in the Valøyvegen-Tempevegen crossing regarding the unclear hierarchy.

3.2 Secondary data

Review of existing second-hand sources

Regarding the history, demographics and plans from the municipality, existing literature proved to be an invaluable resource to provide a baseline understanding. In particular, the data presented by the municipality in their sociocultural area analysis helped create a better understanding of the past, present and future of Tempe-Sorgenfri.

Census data/population data

From the initial stages till the end, it was important to understand the people who lived within the Tempe-Sorgenfri area. This data was largely based on statistics from Statistics Norway and the data gathered from the municipality. This data was used to better understand the age, education and family structures within Tempe-Sorgenfri, which helped inform which groups and what needs might exist within Tempe-Sorgenfri.

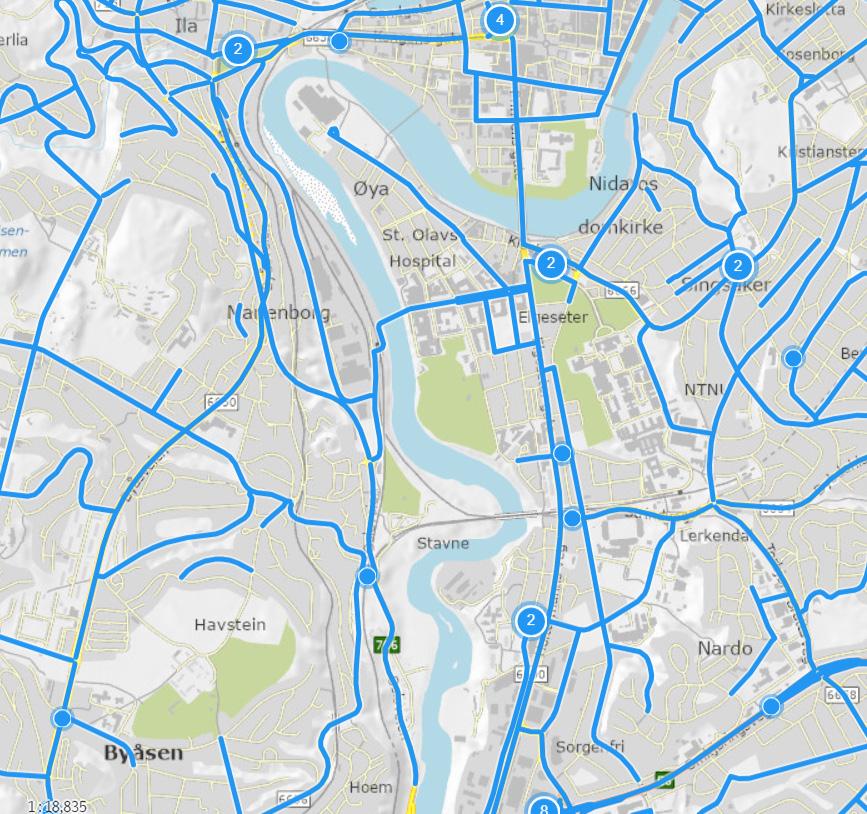

Average Annual Daily traffic Flow (AADF)

The AADF was used as an indicator of streets with high numbers of car flow within Tempe-Sorgenfri and Trondheim as a whole. This AADF data was supplied by Statens Vegvesen Vegkart. The AADF numbers were used to analyse car usage by roads and to find alternative traffic paths into Trondheim outside of Holtermanns Veg.

23 | Tempe-Sorgenfri, Trondheim | The Tempe Walk

Figure 3.9: Statens Vegvesen’s Vegkart was invaluable in the collection of traffic statistics such as AADF.

Figure 3.8: Multiple second-hand sources were reviewed to form a base knowledge about the traffic

Administrative ownership mapping

Due to the overlapping administrative ownership of the roads within and surrounding Tempe-Sorgenfri, mapping of the bureaucratic ownership was done to help establish which administrative stakeholders could help develop which sections of Tempe-Sorgenfri. This also helped map out intersections between municipal and county roads, and county and national roads, which were singled out as needing additional care to be developed.

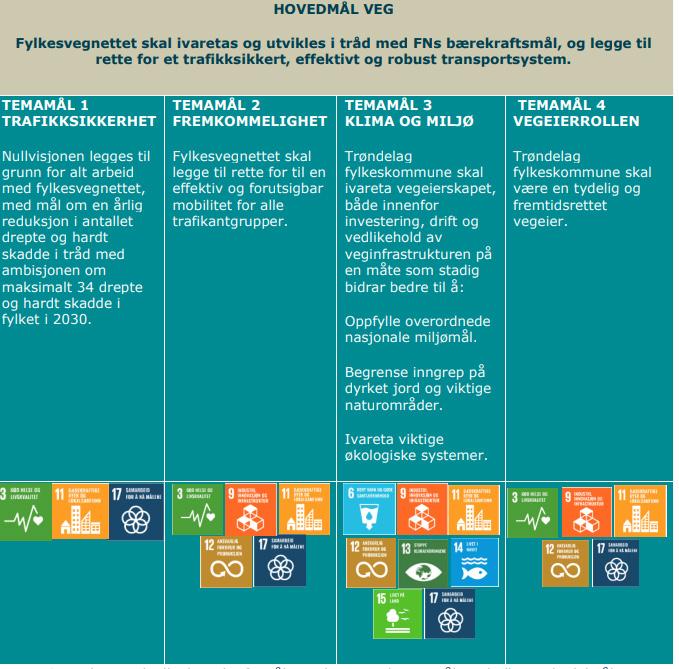

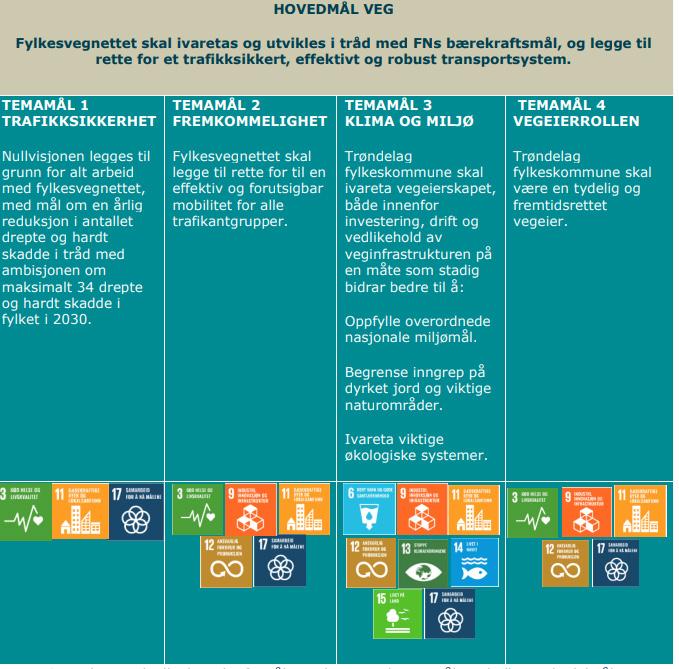

Review of administrative goals

To figure out how the goals held by the group, the municipality and the local community matched up with those of the top-down administrative divisions, a review of existing administrative goals was done. This involved checking what goals were presented by these entities themself, followed by crosschecking these goals against the perception of established stakeholders regarding what these top-down structures sought to achieve at the current time. This helped guide our concepts and helped showcase the differences between de facto goals and de jure goals.

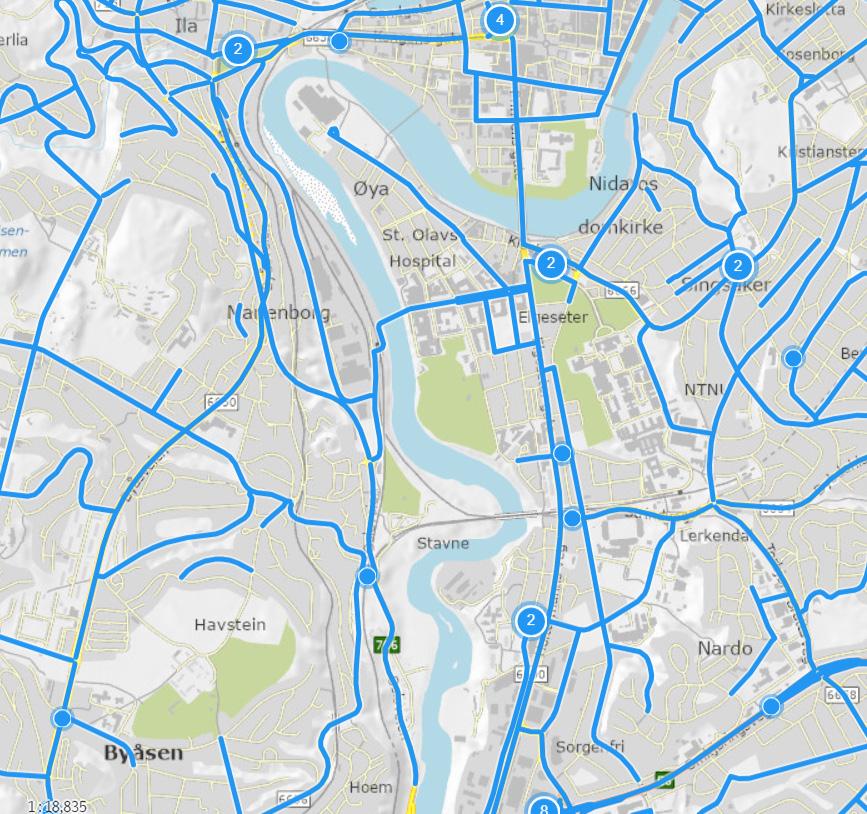

Public transport modelling with GIS

To understand the actual distance travelled by pedestrians to public transportation, GIS coverage area was used to model the pathways to the different bus stops within Tempe-Sorgenfri. This data was used to map out the difference between the availability and accessibility of public transport within the area.

The Tempe Walk | Tempe-Sorgenfri, Trondheim | 24

Figure 3.10: Municipal, county and national goals were constantly reviewed against our work and the public’s perception of the administrative’s work.

Figure 3.11: Modelling of the actual distance needed to be travelled to reach public transportation.

Case studies

As the concepts for what could be achieved within Tempe-Sorgenfri was more finalised, precedents were used to understand what measures were possible, and which ideas led to better results. This helped provide new ideas as well as weed out ideas already proven to not work.

Video Editing

Various aspect of the situational analysis was edited into a short video for easier understanding by stakeholders and the community. Google Earth 3D footage was also used here to better convey the different traffic avenues within the area.

25 | Tempe-Sorgenfri, Trondheim | The Tempe Walk

Figure 3.12: Existing precedences were reviewed and used to bring in successful ideas, while ideas proven to be unsuccessful was removed by the same process.

4. Situational analysis & problem statement

In order to propose meaningful and successful changes to the Tempe-Sorgenfri area, the team first had to understand the area in depth.

As group 3 had been assigned the mobility aspect of Tempe-Sorgenfri, the main transport highway of Holtermanns Veg was a large priority from the beginning. The team also wanted to research and analyse the situations at some of the smaller roads and their connections to Holtermanns Veg to better understand how the people within Tempe-Sorgenfri itself interacted with the transport network.

At this stage it was important to not only use secondary resources, data and reports about Tempe-Sorgenfri, but to also get the opinions, data and problems experienced by the residents themself within the area. Primary sources such as interviews, traffic pattern observations and desire path surveys were invaluable to the team in uncovering these topics. While a lot of the uncovered ideas did match up to the findings within the second hand sources, such as Holtermanns Veg being seen as a barrier by residents, multiple new topics was also uncovered, such as how residents also saw the current bicycle situation as a problem.

The situational analysis presented in this chapter quickly painted a picture of groups of vulnerable road users which had been left behind by the current traffic scheme at Tempe-Sorgenfri. These users felt excluded from the public space as a whole and as a result was secluding themself from it.

As will be shown in this chapter and beyond, improving the situation for these residents became the top priority of this group.

The Tempe Walk | Tempe-Sorgenfri, Trondheim | 26

Figure 4.1: Axonometric view of Tempe-Sorgenfri

27 | Tempe-Sorgenfri, Trondheim | The Tempe Walk

4.1 Residents at Tempe-Sorgenfri

Vulnerable road users

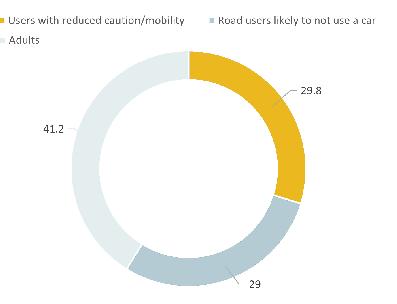

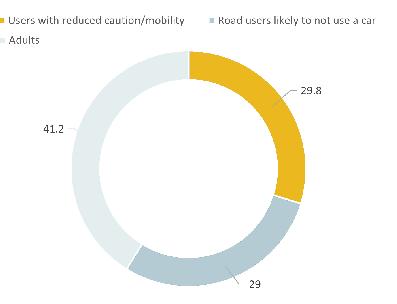

As per the sociocultural site analysis of Tempe-Sorgenfri (Loe et al., 2022), approximately 15% of Tempe-Sorgenfri’s residents are under 17 years old, and an additional 15% are elderly.

The National Travel Habits survey (Grue, 2021) puts forth that these individuals are less likely to own and use private cars. Simultaneously, a substantial portion of the population falls within the 18 to 34 age range, with a significant number being students. Therefore, factors such as financial considerations and short-term stays could contribute to a diminished interest in private car usage among this group.

These demographics show that nearly 60% of Tempe’s total population are individuals with less inclination to use private cars.

This population are then more likely to be pedestrians for part or their whole journey. As per the county’s goals (Trøndelag county, 2022b) these are the most vulnerable traffic users. Therefore, any decision-making and planning processes should consider and involve this vulnerable population, ensuring that the neighbourhood and public spaces are made safe for them.

The Tempe Walk | Tempe-Sorgenfri, Trondheim | 28

Figure 4.2: Population distribution in the Tempe-Sorgenfri area

Figure 4.3: Potentially vulnerable road users

Interview with residents at Tempe

The interviews with the different residents and transportation users within Tempe-Sorgenfri confirmed some of our findings from secondary sources but also brought forth new ideas. In particular, the elderly resident’s experience that the bike highway was as much of a barrier as Holtermanns Veg itself was a surprising realisation. It did, however, strengthen our case that Holtermanns Veg was simply too much of a barrier to the community in its current state.

29 | Tempe-Sorgenfri, Trondheim | The Tempe Walk

Figure 4.4: Quotes from residents at Tempe-Sorgenfri from the group’s interviews

4.2 Infrastructure and accessibility

Public transportaccess and availability

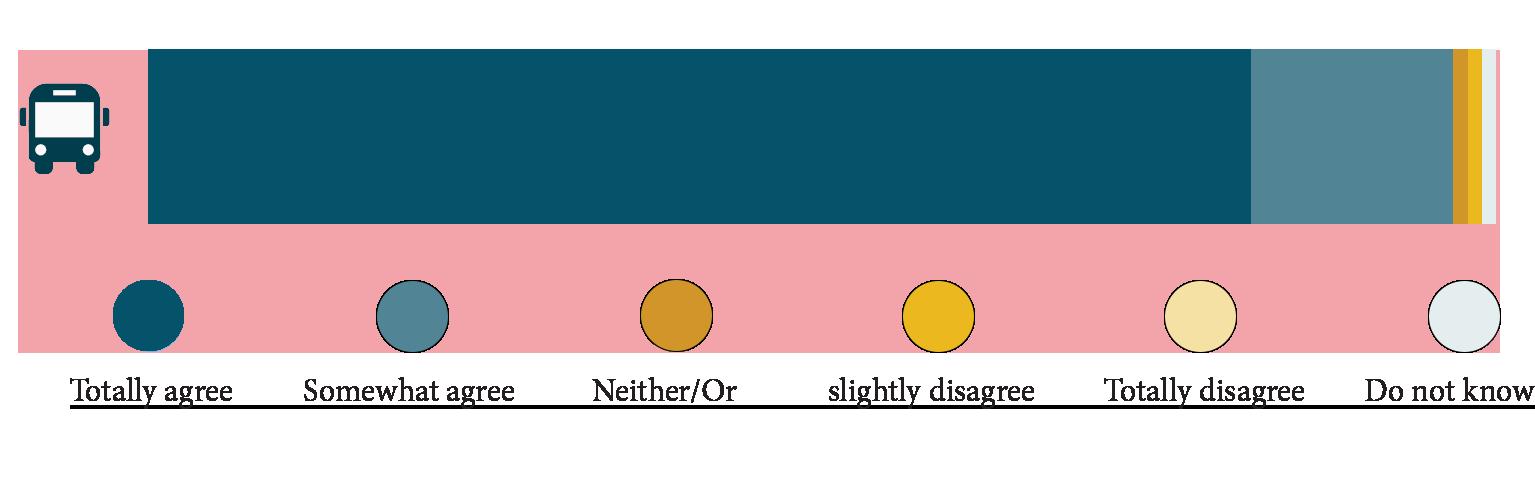

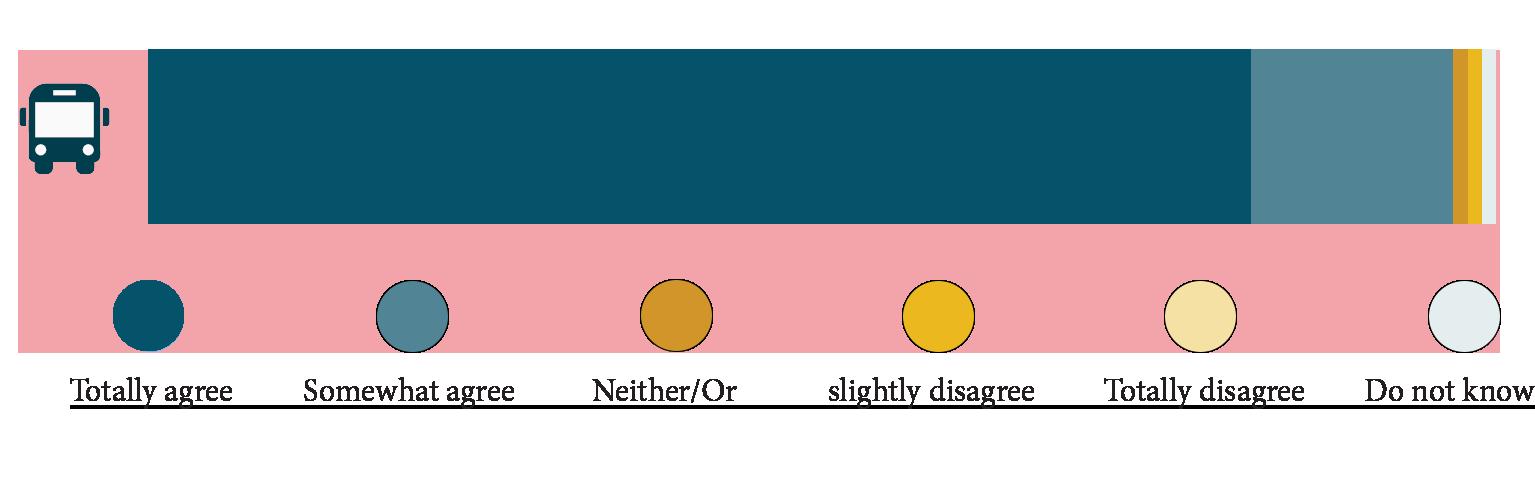

A lot of residents think the best thing about Tempe-Sorgenfri is its central location and good bus connections. According to a survey (Loe et al., 2022), 82% completely agree that there’s good public transport in the area, and when you include those who partially agree, a total of 97% believe the public transport services are good (Figure 4.5). There are frequent bus services to and from the center of Trondheim and other parts of the city.

Despite general satisfaction with availability in the Tempe-Sorgenfri area, there are concerns about accessibility to bus stops. Crossing Holtermannsveg to reach these stops is a challenge due to limited opportunities. Mentioned iin municipal and this group’s interviews, many people prefer crossing the road directly instead of using the underpass or pedestrian crossings due to perceived long distances (Loe et al., 2022).

There is a difference between the availability of public transport and the accessibility of it within Tempe-Sorgenfri. Just because good options exist within the region people may not have access to it.

Availability without accessibility does not lead to good solutions.

The Tempe Walk | Tempe-Sorgenfri, Trondheim | 30

Figure 4.7: People prefer to cross the road rather than use the underpass

Figure 4.5: : Visual results of a survey with the statement “Where

I live there is good public transport”

Figure 4.6: Visual results of a survey with the question “Is Tempe-Sorgenfri suitable for pedestrians and cyclists?”

31 | Tempe-Sorgenfri, Trondheim | The Tempe Walk

Figure 4.8: Walking distance buffer, provided by GIS, towards the bus stops in the Tempe-Sorgenfri area, shows the availability and accessibility to bus stops , as calculated along the available pedestrian network. Scale 1:18 000

Bicycle highway

Trondheim municipality has a strong policy focus on making the city the best cycling city in Norway. A considerable number of cycling paths have been constructed in recent years and are expanding. By 2025, a comprehensive cycling network covering 180 km will be constructed (Kringstad, 2015). This vision was adopted by politicians as part of a long-term strategy to promote cycling. Trondheim municipality notes their goal is to boost daily cycling trips from 34,000 in 2009 to 100,000 by 2025. Currently, a dedicated cycle path with pavement extends the entire stretch from Sluppen to St. Olav’s Hospital (Kringstad, 2015). The cycle path over Tempe, running alongside the E6, is one of the busiest routes for cycling in Trondheim, as well as one of the main cycling links between Trondheim Centre and Heimdal/Tiller (Miljøpakken, 2011).

However, surveys done by the municipality and the interviews done by this group noted the high speed of the bycicles brings about some challenges. Residents put focus on an unclear transition in Tempevegen and its intersection with Valøyvegen. At this crossing point, cyclists frequently approach at high speeds, leading to a perception of confusion and a sense that cyclists pay insufficient attention to pedestrians (Loe et al., 2022). In addition, several parents in the neighbourhood prohibit their kids from going outdoors due to the unsafe conditions caused by fast and careless cyclists passing through the area (Loe et al., 2022).

The Tempe Walk | Tempe-Sorgenfri, Trondheim | 32

Figure 4.10: The bicycle highway in Tempe-Sorgenfri. Scale 1:15 000

Figure 4.9: The contrasting opinions of bicyclists and pedestrians play a key part in the experience of many within Tempe-Sorgenfri.

33 | Tempe-Sorgenfri, Trondheim | The Tempe Walk

Access to school

Children in the Tempe-Sorgenfri area attend Nardo and Sunnland School. In addition to the well-located Tempe Kindergarten within the area, some children also attend Lerkendal Kindergarten to the north of the region. This is another reason why pedestrians need a greater focus within Tempe-Sorgenfri.

The nearest school is roughly one and a half kilometers away, requiring about twenty minutes of walking or taking the bus, as the area lacks local school facilities. This situation can pose challenges, especially in winter. Given that approximately 15 per cent of the population is under 17 years old (See Figure 4.2) (Loe et al., 2022), both the kids themself and their parents are also contending with these circumstances, particularly concerning the accessibility of the elementary school.

During interviews with both the municipality (Loe et al., 2022) and with this group, residents expressed concerns about the safety of the route to school, particularly in the Tempe and Valgrinda areas. Issues include the perceived unsafety of crossing Holtermannsveg and passing through the forest to Nardo, with factors such as darkness in winter, dangerous cars, poorly maintained and narrow roads, and a lack of pavements. The underpass under the main road is considered a connection to school and leisure activities for children, but some residents report instances of vandalism and drunken behaviour, making it intimidating, especially for children (Loe et al., 2022). The underpass is steep and slippery, posing challenges, particularly in winter. Concerns extend to the perceived unsafety of the school route, with mentions of dark sections, dangerous road transitions, and conflicts among different road users, including fears of speeding cyclists. Some residents express fear of cyclists who don’t pay attention and travel at high speeds along Tempevegen. Some characterize the area as “dangerous for pedestrians” (Loe et al., 2022).

Figure 4.11 showcases

Google Maps, to Nardo School, Nidarvoll School, and Klæbuen Childcare for children living in Frost Eiendom buildings. The analysis reveals that the access to the places is long and needs the children to cross Holtermanns Veg at multiple points.

The Tempe Walk | Tempe-Sorgenfri, Trondheim | 34

the access routes, utilizing

Figure 4.11: Showcasing the fastest pathways to elementary schools and childcare shown with the Frost Eiendom blocks as an example of starting location. Scale 1:7500

Minimum distance to

Nardo elementary school

Nidarvoll elementary school

Klæbuen elementary school

35 | Tempe-Sorgenfri, Trondheim | The Tempe Walk

4.3 Effects on residents

Tempe Trouble: a journey towards the bus stop

The Tempe Walk | Tempe-Sorgenfri, Trondheim | 36

Figure 4.12: Comic representation of the common experience of having to rush to one’s bus by running across the road

37 | Tempe-Sorgenfri, Trondheim | The Tempe Walk

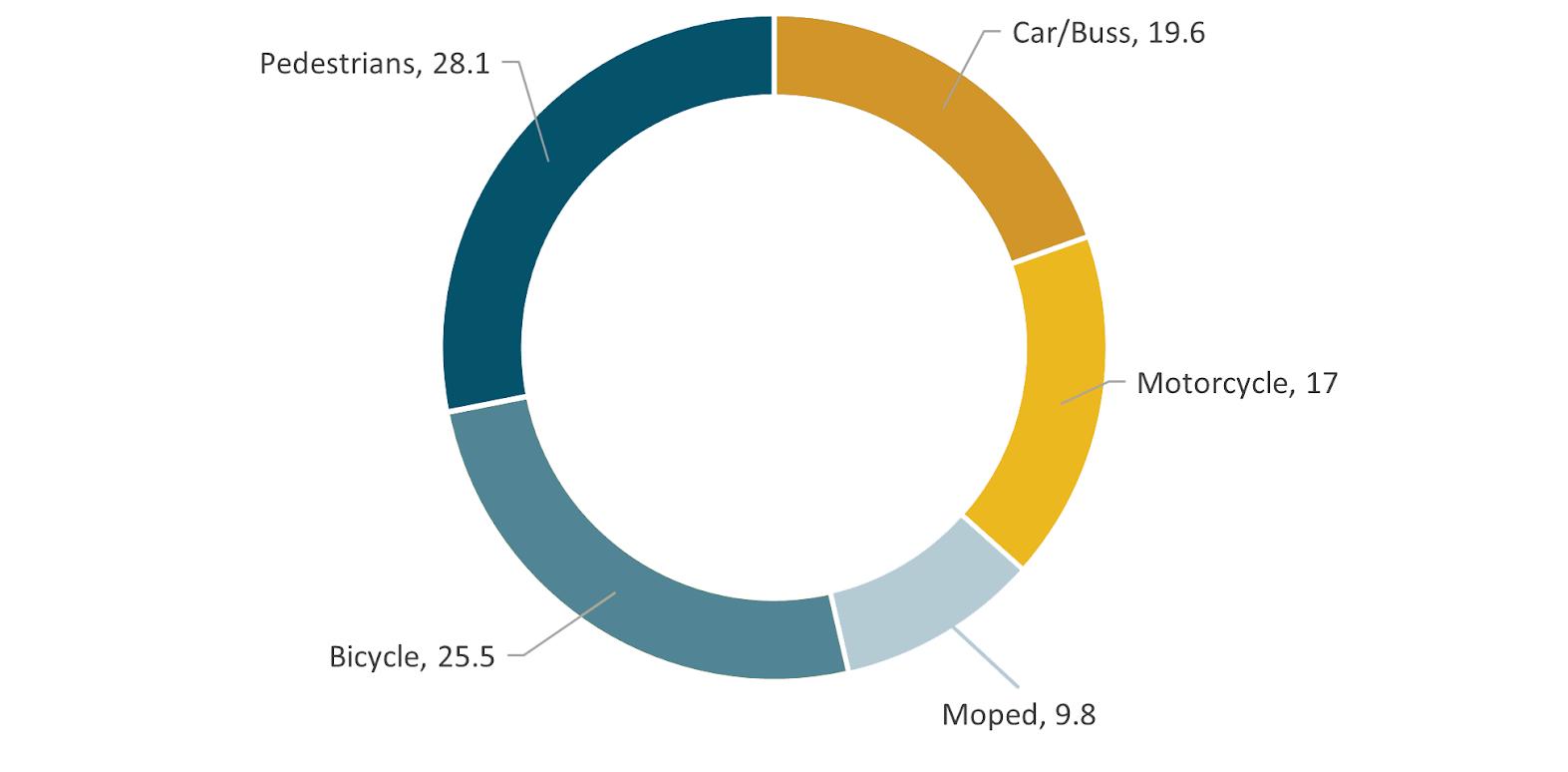

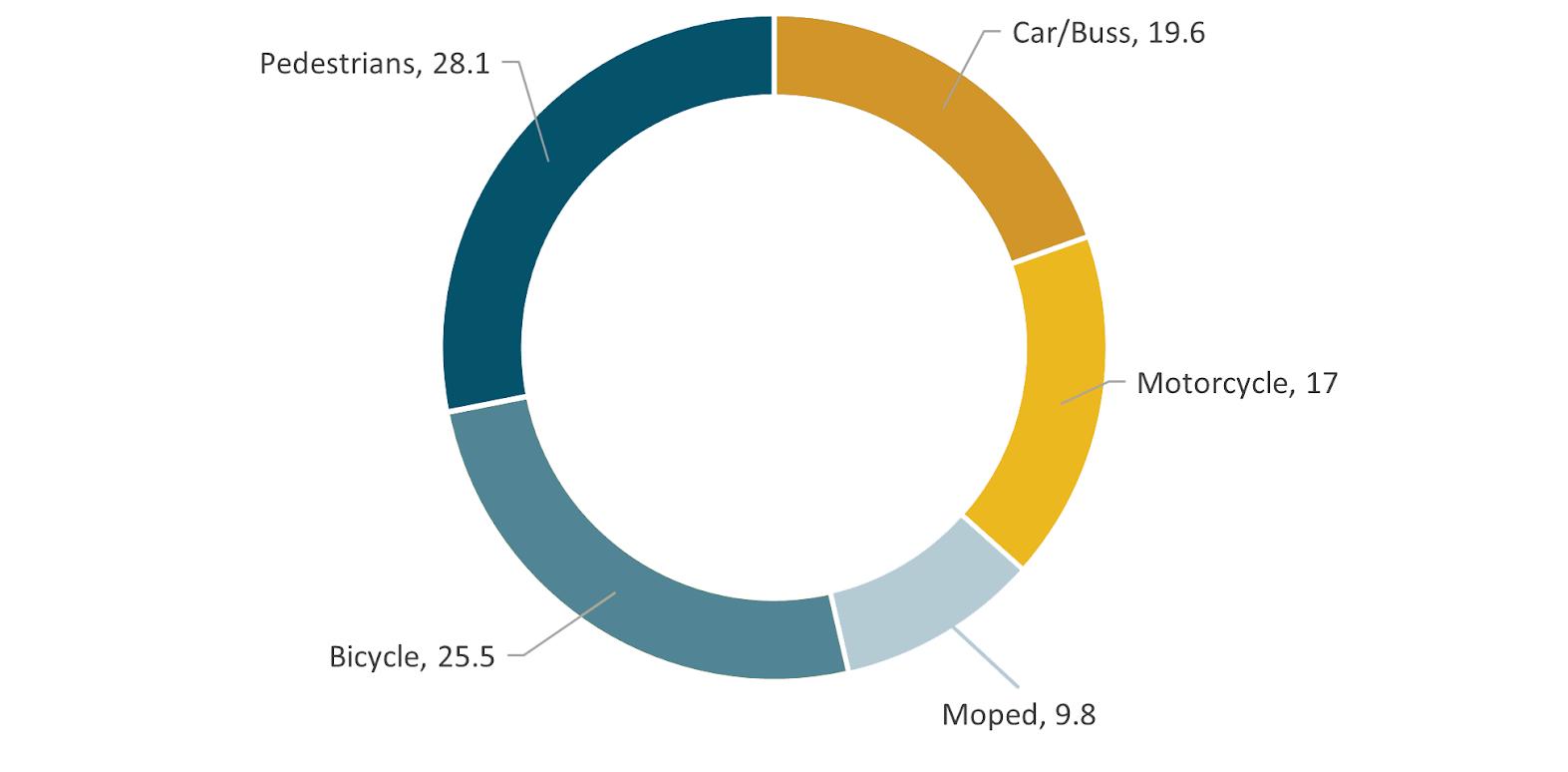

Traffic accidents at Tempe-Sorgenfri

Based on Trondheim municipality’s analysis, from 2008 to 2017, pedestrians were the largest group among the injuries and fatalities. Throughout this period, 322 pedestrians were injured in traffic incidents in Trondheim. Among them, 22 were killed or seriously injured (Trondheim Kommune, 2020b). Despite a 75% reduction in traffic accidents within Trondheim municipality in the last decade, there have been little change in the number of seriously injured and killed at the same time, despite the national average reduction of 40% over the last decade. (Trondheim Kommune, 2020b)

As can be seen in Figure 4.13, pedestrians are the group who have the highest number of severe injuries and fatalities in Trondheim. This strengthened the groups focus on pedestrians as our focus group.

Holtermanns Veg was reported to have had 21 accidents with personal injuries within the Tempe-Sorgenfri area within the last year alone (Solberg, 2023) and have been found to be one of the most dangerous roads within Norway (Sandmo & McDonagh, 2010). Tempe-Sorgenfri also contains one of traffic hotspots marked by Trondheim municipality in need of additional resources (Trondheim Kommune, 2020b).

The Tempe Walk | Tempe-Sorgenfri, Trondheim | 38

Figure 4.13: Proportion of people who were injured/killed by different means of transport Source:(Trondheim Kommune, 2020b)

Desire paths by pedestrians

Many people prefer crossing the road directly instead of using the underpass or pedestrian crossings due to perceived long distances. A survey done by the group at Valøyvegen bus stop confirmed this preference (See figure 4.14). The survey consisted of a map with a pen placed at Valøyvegen bus stop and individuals were requested to mark their daily route to the stop. The map was left at the station for two days. The outcome revealed a significant number of people favoured crossing the street instead of utilizing the underpass. This was verified against the report by Loe et al, based on resident interviews, which supports these observations (Loe et al., 2022).

Due to lack of pedestrian crosswalk, people prefer to cross Holtermanns veg directly rather than use the underpass.

39 | Tempe-Sorgenfri, Trondheim | The Tempe Walk

Figure 4.14: The map placed at the bus stop and routes people drew to depict their daily crossings on the road. Scale 1:2000

4.4 Intervention - how the locals wish to be engaged

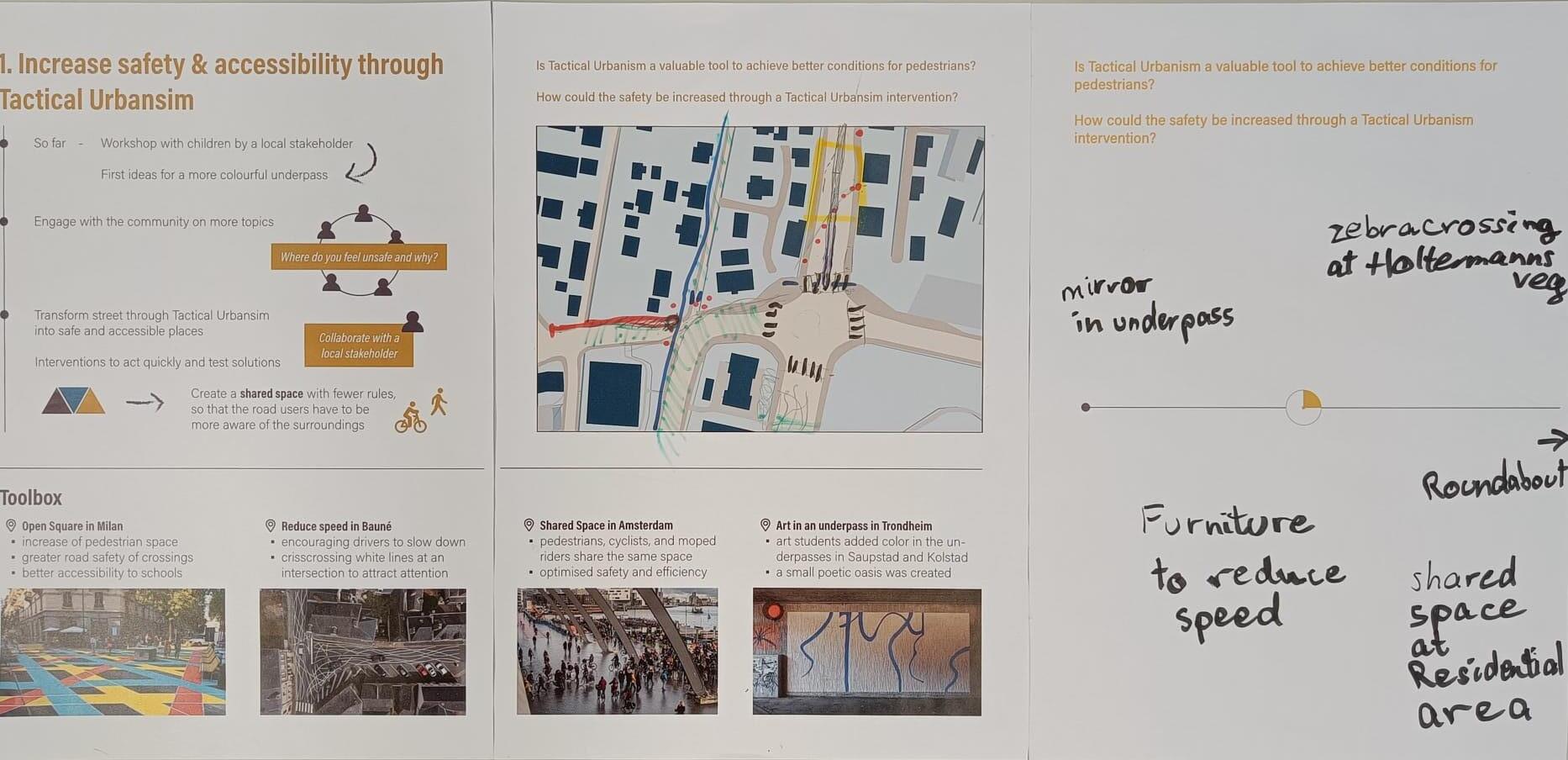

To be able to analyse and experiment with potential long-term solutions, the group experimented with tactical urbanism to see how strategically placed visuals can influence the collective of how to act in the specific crossing between Tempevegen and Valøyvegen.

Intending to draw attention to the spot while also highlighting pedestrian safety, the intervention also had a goal of slowing down the bicyclists and cars. Visually, coloured triangles were spray-painted in the specific space where the majority of uncertain encounters were observed between different road users.

While painting, residents of the neighbourhood showed great interest in the work, despite the intervention being done in the middle of the night. The residents communicated a general frustration with the undefined ownership of the space, and appreciation of any action being taken. Multiple of the residents showed participation fatigue, having felt that they had given feedback to the community multiple times, but nothing had yet to be done. These residents showed great appreciation that something was happening, even if it was temporary.

One of the evocative phrases mentioned regarding the site was:

“I hate this crossing.”

However, the uncertain weather conditions of Trondheim became an obstacle as the coloured spray was affected by unexpected rainfall during the night. This led to a wash-away of the spray paint already before the morning rush. Although some of the colour was still visible, the intervention became somewhat less effective due to its lack of visibility to bypassers at higher speeds. The group noticed little to no effect in the way the residents interacted in the crossing because of this, and reccomends any future interventions use more permanent paint.

Although the desired effect was not achieved, the group notes that the involvement of the residents, some of whom were students, was still a major success of the intervention. By defining a space, the pedestrians were able to imagine the potential of the crossing to improve. The group recommends further tactical interventions be done within the site, both to engage the community in participatory actions and to prevent further residents from experiencing participatory fatigue.

The Tempe Walk | Tempe-Sorgenfri, Trondheim | 40

Figure 4.15: Picture of group 3’s tactical intervention in progress and the local community members that engaged with us because of it in the middle of the night.

4.5 Major stakeholder

One way to understand the site the group is working in is to return to the people within it, but instead of looking at their ethnicity, age etc., we can instead analyse them based on their ability to affect the area, their ability as stakeholders within Tempe-Sorgenfri.

Stakeholder are any group or individual who can potentially affect or be affected by an organization’s objectives (Freeman, 2010). Therefore, they can actively participate or passively be influenced by the outcomes (Marklund-Nagy, 2020).

There are different stakeholder in an area with different needs, powers, and levels of interest. They can be a barrier if they do not agree with the decisions, but they can also provide invaluable information about their area, their living conditions, and the resources available. In order to avoid local conflicts and ensure successful urban projects it is important to understand their interests and their information and to manage the relationship with them, and their relations to each other and the problem (Marklund-Nagy, 2020). To reach that knowledge, a good tool is to use stakeholder mapping. Stakeholder mapping is a valuable tool that helps in recognizing essential stakeholders, understanding their level of influence, and developing a strategy for effective stakeholder management (Kitch, 2023).

Finding stakeholders within Tempe-Sorgenfri is not a quick process. New stakeholder are discovered all the time, and a stakeholder’s level of interest and power changes as the project progresses. While all stakeholder want to improve Tempe-Sorgenfri, and large part even agree on reducing the number of cars in the area, the reality is that each stakeholder has their own vision of what is needed on the site.

When the group analysed the stakeholders, we found that the most interested stakeholder were often the ones with less power. The stakeholder with more power were often complacent with the current stake in the area or had their attention elsewhere. The group found that the more interested a stakeholder was, the more willing they were to engage and the more knowledge they were able to share with the group regarding the situation at Tempe-Sorgenfri, and the context of the road network as a whole.

The Tempe Walk | Tempe-Sorgenfri, Trondheim | 42

43 | Tempe-Sorgenfri, Trondheim | The Tempe Walk

Figure 4.16: Stakeholder Power Interest Diagram and Influence between them

4.6 Problem statement

The group uncovered many findings within Tempe-Sorgenfri through situational analysis.

The population of the area had a high proportion of vulnerable road users.

The site was dominated by cars travelling along Holtermanns Veg and bicycles travelling on the bike highway.

Children and their parents had to walk a long distance to school, which included crossing Holtermanns Veg.

Residents in Tempe-Sorgenfri felt that the existing crossing facilities were unsafe or inadequate.

There was good availability, but no accessibility of public transport on site, often due to the need to cross Holtermanns Veg to access them.

The area had an unclear road hierarchy and had one of Trondheim’s located traffic hotspots within it.

Stakeholder involved in the road had complementary goals in theory, but conflicting needs in reality.

With all this in mind, the group came up with the following problem statements to guide our work going forward:

Holtermanns Veg is a barrier that needs to be overcome. Tempe-Sorgenfri needs to become a more pedestrian friendly area.

The Tempe Walk | Tempe-Sorgenfri, Trondheim | 44

45 | Tempe-Sorgenfri, Trondheim | The Tempe Walk

Figure 4.17: Unequal ownership of Holtermanns Veg between road users.

“5.0 Concept for solutions

A matter of Equity

Based on our situational analysis, we concluded that Tempe-Sorgenfri is not a safe and accessible area for pedestrians, with the main problem being Holtermanns veg acting as a barrier to them.

We found that there are many pedestrians who need access to public transport, but that the spatial distribution of the road currently gives priority to motorised vehicles. In addition, motorised vehicles are still favoured with more power and ability to cause damage than non-motorised road users.

This led us to question the current car-centric design of Holtermanns veg. By redistributing the power in favour of the soft road users, everyone can get a chance to reach their destination safely. That is why the solutions in this report are based on the concept of equity between the different modes of transport in Holtermanns veg.

The route to achieving equity will not be accomplished through treating everyone equally. It will be achieved by treating everyone justly according to their circumstances.

/ Paula Dressel, Race Matters Institute

The Tempe Walk | Tempe-Sorgenfri, Trondheim | 46

Figure 5.1: The current situation and the solution proposed by this report for a more equitable use of the road.

Figure 5.2: The difference in land and resources used for soft traffic users and hard traffic users.

This equity is not about making everyone the same. It is about looking at which groups are currently disadvantaged, and looking at which measures are needed to enable them to have the same potential as other groups.

As the group found in their situational analysis, one disadvantaged group within Tempe-Sorgenfri is the pedestrian. Physically excluded from using public space in favour of car traffic into the city, elderly residents afraid to walk in their neighbourhood because of the speed of bicycles and cars alike, and one of Trondheim’s traffic hotspots, pedestrians in Tempe-Sorgenfri need help to use the area on an equal footing with other road users.

To equalise, vulnerable road users must be treated better, they must be given back the place where they live their lives.

Vulnerable users must be given advantages to compensate their existing disadvantages.

5.1 Equity and Trondheim’s current goals

This focus on equity should not be viewed as an additional goal for the municipality to focus on, but rather as a summary of the transport goals they, the county and the national government have set for themself for the time forward. When this project aims for equity, it will seek to fulfill these goals in line with Trondheim and Trøndelag’s goals.

Norway’s Vision Zero (Trondheim Kommune, 2020a)

“No person shall be killed or grievously harmed using any form of transport.”

“There shall be significant focus on the needs of pedestrians, cyclists and bikers when altering, building or maintaining roads.”

“We shall facilitate for children to be able to travel safely along roads through among other, securing school roads, local environments and other infrastructure, traffic and mobility education and the gathering of relevant traffic knowledge.”

Trøndelag County’s Traffic Security Goal (Trønderlag Fylkeskommune, 2022a)

“The number of accidents involving soft traffic users shall be reduced “

“In urban areas there shall be special focus for facilitation for soft traffic users”

“During prioritization and deciding on the development of new walking and bike roads, the security of traffic users should be one of the primary concerns”

Trøndelag County’s Traffic Accessibility Goal (Trønderlag Fylkeskommune, 2022a)

“The transport offer for soft traffic users shall be improved yearly with the aim all important geographical areas should have options for soft traffic users to get to.”

“In the development of innovative solutions that challenges existing rules and measures, the security of traffic users shall be the primary concern.”

“The number of pedestrian and cyclists in urban areas and on school roads shall be increased”

“There shall be increased cooperation between county and the municipality regarding measures to secure school roads”

The Tempe Walk | Tempe-Sorgenfri, Trondheim | 48

Figure 5.3: The crossing of Holtermanns Veg and Valøyvegen.

5.2 Incorporating stakeholders

A major challenge in transforming Holtermanns Veg into an equitable, pedestrian-friendly area is the layers of bureaucracy regarding the road that need to be navigated in order to implement any changes to the area. As shown in Figure 5.4, these include the national ownership and maintenance of the E6 road, the ownership and maintenance of Holtermanns Veg by Trøndelag County, and the ownership of the municipal roads and services in the area by Trondheim Municipality (Statens Vegvesen, 2001). It is important that all three of these administrative structures are involved in the proposal for Tempe-Sorgenfri, as all three are interrelated and necessary partners if any changes are to be made.

Whether through the national Vision Zero, the county’s traffic safety and accessibility goals, or the city’s commitment to the same goals, all three partners have an existing interest in improving Tempe-Sorgenfri for pedestrians.

A major issue that needs to be addressed before solutions such as those presented earlier in this chapter can be sorted out is to align the priorities of the different levels of government regarding the road through Tempe-Sorgenfri. When the group interviewed municipal employees during one of its workshops, the municipality noted a discrepancy between its efforts to improve conditions for pedestrians and cyclists and the county and national focus on the transport of people and goods to the centre of Trondheim. This is despite the fact that both the county and Statens Vegvesen have specific targets for improving conditions for pedestrians and cyclists as one of their main priorities (Det Kongelige Samferdselsdepartement, 2021) (Trøndelag Fylkeskommune, 2022b).

As Tempe-Sorgenfri is one of Trondheim’s collision hotspots (Trondheim Kommune, 2020b), safety must be the main concern here in order to achieve Vision Zero.

The Tempe Walk | Tempe-Sorgenfri, Trondheim | 50

Another equally important aspect is the involvement of the Tempe-Sorgenfri community itself.

As this group’s intervention has shown, there is a strong commitment from the community to improve conditions in the area. It has been proven that by involving the community in the planning, implementation and maintenance of initiatives that affect their community space, a sense of ownership and responsibility for the project can be instilled within the community (Kinder, 2014; Peeter & Campos, 2022). By engaging the community in this way, hidden talent within the community may be uncovered, and the project may be future-proofed by allowing the community itself to help maintain it.

An investment in the community in the form of stronger community associations (foreninger) with a focus on dugnads would be an invaluable resource for the municipality in this context. This should not replace investment in the area from the municipal, county and national levels, but should be a complementary measure to future-proof the project.

51 | Tempe-Sorgenfri, Trondheim | The Tempe Walk

Figure 5.4: Road responsibility by government level. Scale 1:22 500

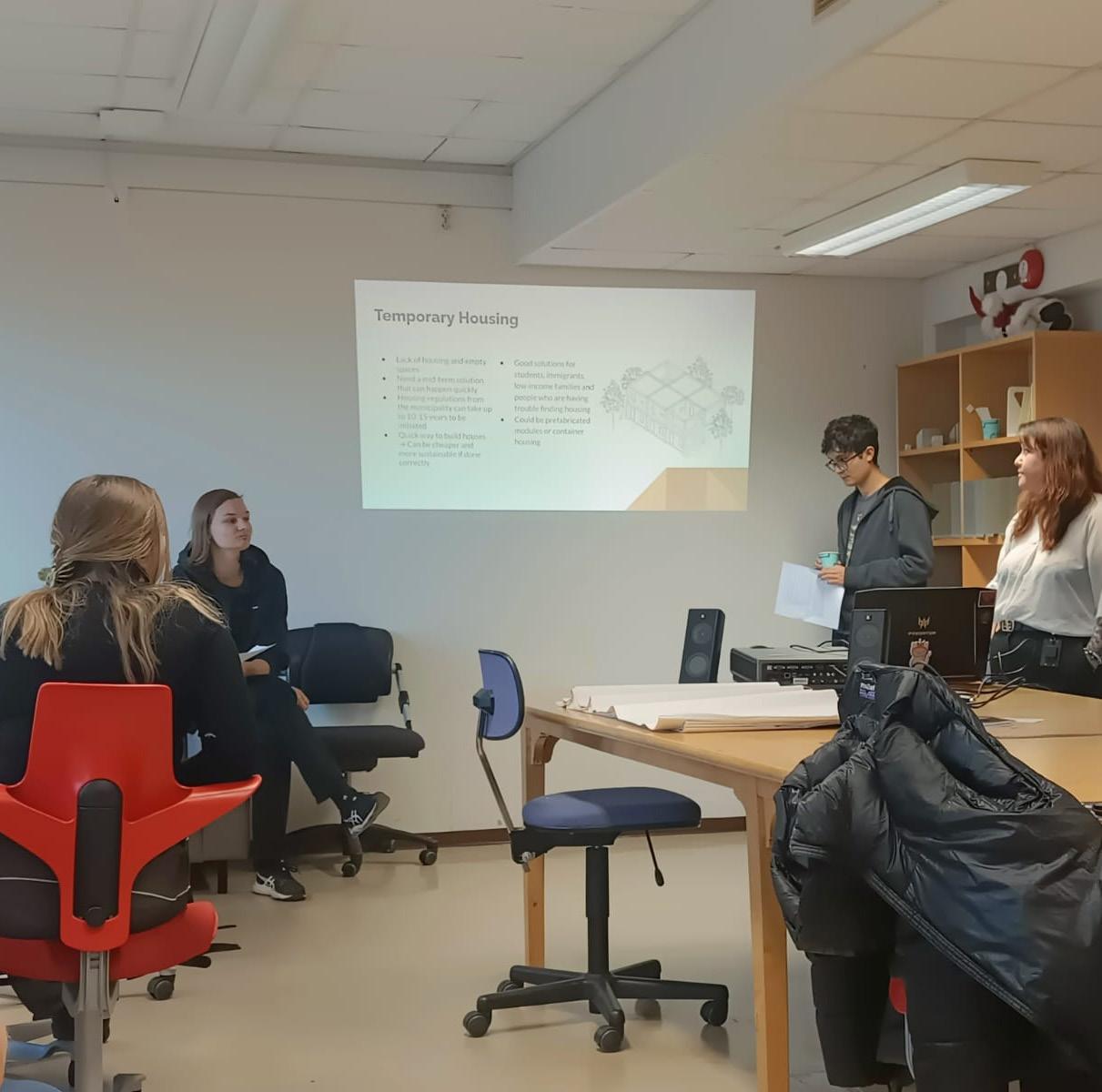

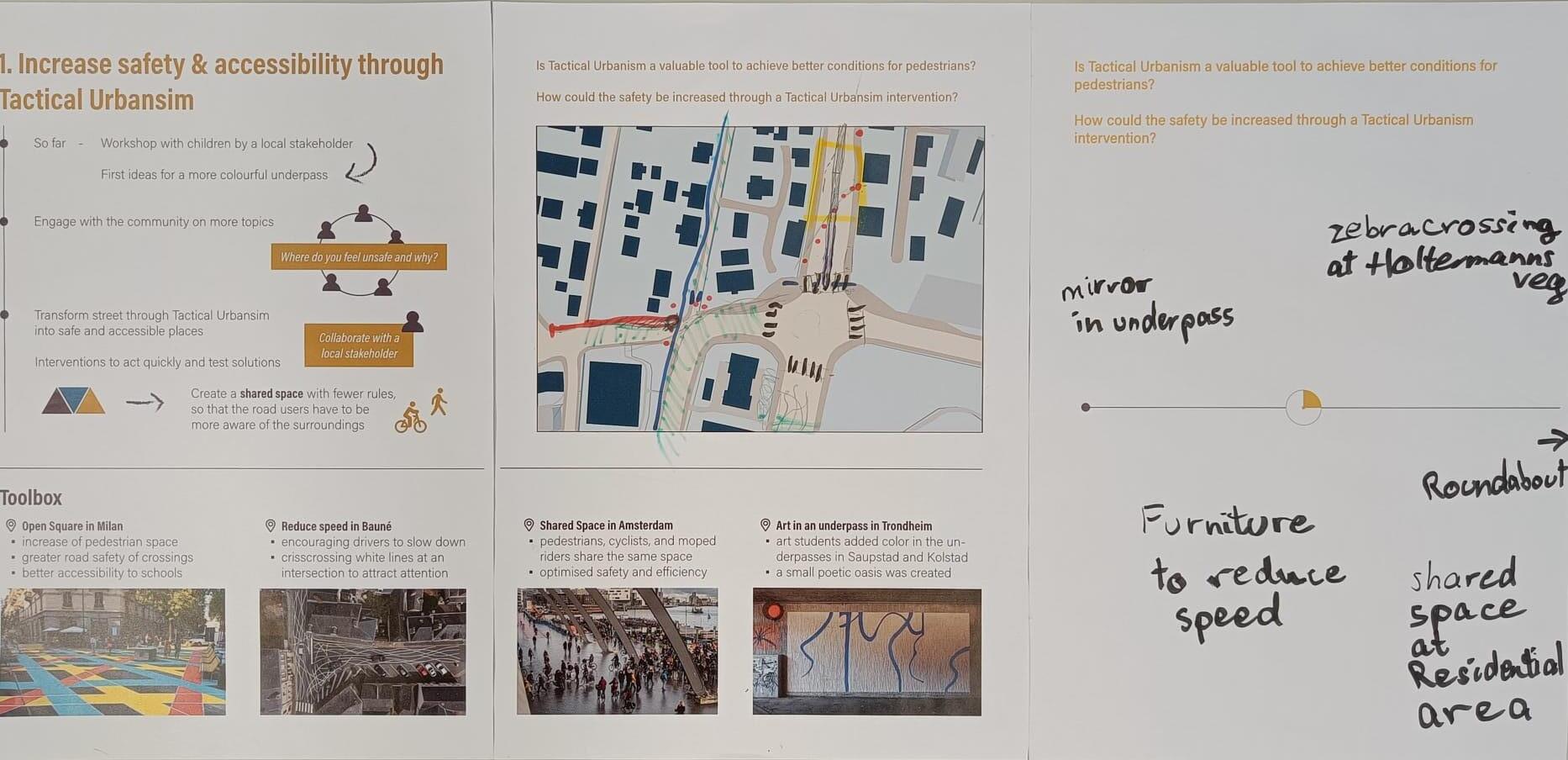

5.3 Learning from the workshop

As part of the process, the UEP course held a workshop where stakeholders were invited to share their opinions about the data gathered about Tempe-Sorgenfri, and the students’ concepts and early proposals.

Group 3 did an initial overview of their findings before splitting into four smaller groups for discussions regarding one of the four concepts for solution that the group laid forth. Feedback was generally positive, but the one theme that kept coming up across all four groups was that for these concepts to be realised successfully, the number of cars on Holtermanns Veg would have to be reduced.

While the number proposed by the different stakeholders varied, all stakeholders agreed that Holtermanns Veg needed less car flow.

This need for a reduction in the car flow on site served as another guiding factor for our proposals. Not only would this reduction help benefit the other proposals to benefit Tempe-Sorgenfri, but this reduction would be beneficial for Trondheim as a whole, helping residents far beyond the initial scope.

The Tempe Walk | Tempe-Sorgenfri, Trondheim | 52

Figure 5.5 & 5.6: Photos from the workshop with stakeholders from Tempe-Sorgenfri.

Figure 5.7: One of the posters produced by the stakeholders to inform future design.

53 | Tempe-Sorgenfri, Trondheim | The Tempe Walk

5.4 Enabling change

There are two types of measures that can be used to reduce traffic flow. One can use enabling strategies, also called pull strategies, to encourage people away from car-based transportation and towards public transportation. The other way is to use deterrent strategies, also called push strategies, to discourage people from using their cars (Piatkowski, 2017). While push strategies are considered more efficient for reducing car dependency in the short term, pull strategies have been found to better increase the resilience of the car independency leading to a smaller chance such positive changes get overturned with future political changes or against public pressure (Piatkowski, 2017). It is worth noting that neither push nor pull strategies work that well by themself. The combination of both measures leads to the best results.

This also ties into the municipal, county and national goals of not only decreasing the number of cars on the road, but also increasing pedestrian and cyclist enabling measures and the availability and quality of public transport (Det Kongelige Samferdselsdepartement, 2021; Trøndelag county, 2022a). This report seeks to focus on proposing encouraging measures over deterrent measures but does propose some deterrent measures to better help the transition.

The Tempe Walk | Tempe-Sorgenfri, Trondheim | 54

Equity must be the guiding hand in proposing change within Tempe-Sorgenfri. County and national priorities need to be shifted back to this focus, as their objectives promise. This equity will be achieved in part by reducing the number of cars on Holtermanns Veg so that pedestrians can occupy the space as they once did.

55 | Tempe-Sorgenfri, Trondheim | The Tempe Walk

Figure 5.8: Push and pull measures are needed to move people away from the car and towards pedestrianism.

6.0 Proposal for Solutions

To achieve an equitable use of Holtermanns Veg, to listen to stakeholders about their needs and concerns, and to redistribute Holtermanns Veg both spatially and power-wise, this group proposes five different proposals for the Tempe-Sorgenfri area that would help to overcome Holtermanns Veg as a barrier and make it a more pedestrian-friendly area.

First, fast solutions in the form of tactical urbanism need to be implemented to help engage the community and prevent participation fatigue.

Second, additional crossings need to be added across the road to help break down the road as a physical barrier and provide alternative crossings.

Third, a speed reduction is needed in the area, both to facilitate the other proposals and to help reduce the dangerous conditions it currently presents.

Fourth, the road needs to be incorporated into a shared space, that can be used by pedestrians, cyclists, public and private transport.

Last, it is necessary to look beyond Tempe-Sorgenfri itself and try to reduce the car dependency of Trondheim’s residents beyond the site, in order to reduce the flow of traffic through the site into the city centre.

The Tempe Walk | Tempe-Sorgenfri, Trondheim | 56

57 | Tempe-Sorgenfri, Trondheim | The Tempe Walk

Figure 6.1: The proposed measures - time & scale

6.1 Short term solutions for the present

One of the most frequently reported complaints within Tempe-Sorgenfri is the underpass under Holtermanns Veg (Loe, et al, 2022). Improvements to this are currently underway. Described as dark, scary and unsafe, a local artist is currently leading an effort to engage the local community in improving the underpass.

The artist is currently working with KIT, the Trondheim Academy of Art and Trondheim Municipality. The aim of the collaboration is to improve the underpass through artistic means. A selection of proposals has already been presented and approved. The proposals included sensor lighting, geometric colouring and participatory processes where local residents are invited into the tunnel to create their own art. The latter proposal aimed to increase the sense of ownership and belonging to the space (Heggdal, 2023).

A general theme for the project was the colouring of the underpass, as it is currently grey concrete, punctuated by occasional graffiti. The artist suggests that the integration of colour and lighting would help alleviate the feeling of the underpass until a more permanent solution can be achieved, but stresses that the short-term solution is still important (Haga, 2023).

The Tempe Walk | Tempe-Sorgenfri, Trondheim | 58

Figure 6.2: The respective underpass, showcasing the unpleasant conditions mentioned by residents.

The Underpass

Coloured statements in graffiti are standing out from the otherwise grey and somewhat depressing public space of the pedestrian underpass. Being the only visual of particularly bright color, the rather unpleasant messages within the graffiti further reduces the feel of the space.

Artistic Illumination

As discussed by both residents and the municipality, the current situation at the crossing does little to encourage safe crossing for pedestrians (Trondheim Kommune, 2012;Loe, et al, 2022). The introduction of artwork, especially one that the community can feel a sense of ownership of, is suggested as a way to increase pedestrian usage of the underpass.

Increased use of the underpass would also improve safety. By improving pedestrian conditions in the underpass, the number of users is likely to increase. An increased flow of people would lead to more eyes on the space (Jacobs, 1961). This passive surveillance would help mitigate some of the unsafe conditions. Increased use of the underpass would reduce undesirable behaviour while using the space.

Strategic placements through tactical urbansim

By introducing art to strategic connecting points of the physical environment, the experience and safety of being a pedestrian at Tempe-Sorgenfri can be elevated (Jacobs, 1961). It is the recommendation of this report that such installations be made within the area to enhance the pedestrian experience.

This report also suggests that such installations should be maintained and only changed for short periods of time in order to better test which locations and installations best improve the experience of local residents. Such a rotation of artwork would also help to prevent spaces such as the underpass from being left untouched for years.

The Tempe Walk | Tempe-Sorgenfri, Trondheim | 60

Community co-production

By engaging the community, the local citizens are more likely to develop a sense of ownership and belonging to their community, by also empowering them to express their perspectives, creating an environment where opinions are valued and acknowledged. Such community led activities promote egality and equity within the community in question (Jacobs, 1961). This would also help the community see clearly what the municipality are doing for their local causes.

Sensor technologies

Another potential approach to elevating the pedestrian experience in the tunnel at Tempe, is using sensor technology for illuminating the space at night and during winter. By using motion activated LEDs installed into the ceiling, this report proposes an energy efficient lit underpass, while still greatly improving the pedestrian experience. This would also help improve navigation, as well as improving accessibility.

61 | Tempe-Sorgenfri, Trondheim | The Tempe Walk

Figure 6.4: The Music Tunnel, Katowice, Poland

Figure 6.3: An example of community-led art, KIT

Prioritising pedestrians in the Tempe Underpass

Another problem identified within the underpass is the unclear hierarchy of ownership of the tunnel between pedestrians and cyclists (Loe, et al, 2022). The current shared situation was described by pedestrians as inadequate. Another use of tactical urbanism here could be to test the best delegation between cyclists and pedestrians for implementation. By using such short-term measures, there is less concern about long-term costs. Two such options are suggested for testing.

Separating pedestrian and cycle lanes within the underpass could contribute to safety and comfort for both. Pedestrians, as the more vulnerable users, would not have to worry about getting out of the way of fast-moving cyclists, while pedestrians could maintain high speeds throughout the tunnel. This approach aims to give pedestrians, who are often the largest population group in urban areas, a dedicated space where they can walk at their own pace, feel safe and enjoy public spaces without having to constantly be aware of oncoming cyclists.

Dedicating the underpass exclusively to cyclists would allow cyclists to continue to use the underpass as a quick crossing of Holtermanns Veg, without having to stop for traffic or pedestrians, which was noted as a benefit for cyclists in the interview with residents. For this to work, there would need to be a greater opportunity for pedestrians to cross Holtermanns Veg in other ways, perhaps by the means discussed later in this chapter.

The Tempe Walk | Tempe-Sorgenfri, Trondheim | 62

Figures 6.5 and 6.6: Showcases illustrated examples of the two proposed versions of the underpass with intended use symbolised with differentiated paths on the ground

Beyond the need for an underpass

As Tempe-Sorgenfri transitions to a more pedestrian-friendly area, the need for the underpass as a mobility element could disappear completely. This report proposes that the underpass then be transformed into performing such a function at this time.

The proposal involves the underpass being transformed into a space for interactive art, allowing local artists a space to interact and showcase to the community. These options would prevent the underpass from falling into disrepair and irrelevance.

As this proposal develops, one could use the prior underpass as a hub to rebrand Tempe-Sorgenfri into a cultural hub within Trondheim, promoting local musicians, artists and performers.

Noted in the interviews from the municipality, the residents at Tempe are currently feeling the need for better community meeting spaces (Loe, et al, 2022). The transformation of the underpass has the opportunity to serve the community as a hub for this and other activities requested by the residents such as bicycle workshops or cafés (Loe, et al, 2022).

The underpass at Tempe has the potential to be transformed into a public space for the local community to fill the void currently felt by the community.

63 | Tempe-Sorgenfri, Trondheim | The Tempe Walk

Figure 6.7: Possible look of the underpass as a public space

Testing of long term solutions

Short term tactical urbanism can also be used as a method to test out the best form of more permanent solutions. One way to do to do this is by reclaiming a car-lane for pedestrians. By temporarily force the cars to take another route, the road can be redistributed between all modes of transport to test more equitable divisions.

During the covid pandemics, Pop-up bike lanes were used as an important measure to redistribute space in cities so that people can cycle safely (Becker et al, 2022). Pop up interventions are a tool to create temporary spaces within the cities’ infrastructure (Becker et al, 2022). Such an approach is also known as DIY Urbanism and is usually created and implemented by single users or small groups and not by municipalities or corporations, and emerge from citizens seeing and responding to some unmet need in urban space (Finn, 2014).

These temporary interventions give the opportunity to try out new street designs, learn from these experiences to improve the designs, and then permanently implement what has been proven the best in practice (Becker et al, 2022).

In Tempe, the intervention can intend to initiate long-term change to respond to the deficiency of safe and accessible space for pedestrians on Holtermanns veg. This could also be implemented by the municipality of Trondheim, leading it towards a rather tactical approach of using short-term and low-cost interventions to test solutions and act quickly (cf. Mike Lydon and Anthony Garcia, 2015). Instead of going through a slow and conventional city building process, such intervention, also known as Tactical Urbanism, can allow the immediate reprogramming of Holtermanns veg as public space. This can be used to demonstrate if or how it is possible to reduce the private motorized traffic.

The Tempe Walk | Tempe-Sorgenfri, Trondheim | 64

Figure 6.8: Proposal for a short-term intervention on Holtermanns veg. Scale 1:2000

Short-term Intervention

By colouring one of the car lanes, pedestrians could reclaim some of the urban space, forcing a reduction of cars on Holtermanns veg. Additional crossings could force the cars to slow down.

This can be used to test where new crossings work best and cause the least disruption, or to test how effective traffic redistribution would be.

65 | Tempe-Sorgenfri, Trondheim | The Tempe Walk

6.2 Additional Crossings

Considering the presence of traffic lights at the intersection of Holtermanns veg and Valøyvegen, along with the existing crossings on the west and east sides, there is a chance to improve pedestrian safety simply by introducing two additional crossings on the northern and southern sides.

Introducing additional crossings on Holtermanns Veg is a relatively fast and cost-effective way to improve pedestrian safety in the area. An example of such a change is shown in Figure 6.10. The crossing at Tempe-Sorgenfri already brings drivers to a stop at the intersection. Adding in a pedestrian crosswalk here therefore demands fewer changes to the infrastructure than the addition of one in another location would need.

The Tempe Walk | Tempe-Sorgenfri, Trondheim | 66

Figure 6.10: Intersection after adding more crosswalks (Standard crossings)

Figure 6.9: Current crosswalks at the intersection

Refuge islands

Given the length of the crossing across Holtermanns Veg, a refuge island would be needed, as shown in Figure 6.11. A pedestrian refuge island is a raised pedestrian area between two lanes in opposite directions of a road. Refuge islands allow people to stop in the middle of the road, so they can split their crossing into two stages (Traffic Choices). It is essential in a broader traffic lane to have a pedestrian refuge island (Ishaque and Noland, 2006; Mukherjee and Mitra, 2022).

Crossing Holtermanns veg, can be time-consuming, especially for elderly individuals or children. To address this issue, it may be beneficial to treat it as a staged crossing. Potential solutions could involve installing a pedestrian mid-block refuge or extending the traffic light duration. However, extending the traffic light time might result in traffic delays. Finding a balance between pedestrian safety and traffic flow efficiency is crucial in implementing the most suitable solution.

67 | Tempe-Sorgenfri, Trondheim | The Tempe Walk

Figure 6.11: Adding pedestrian crosswalks with refuge islands

Additional Crossings

As was found through the desire path survey, there were several areas where residents wished to be able to cross Holtermanns Veg, but where there was simply no way to do so. Another suggestion for improving the pedestrian experience in the area would therefore be to provide additional crossings in these areas, similar to what is shown in Figure 6.12 below.

Based on the survey regarding desire paths (see Figure 4.14), the routes chosen by pedestrians to cross the road suggest a need for additional pedestrian crosswalks along the road in the Tempe-Sorgenfri area.

The Tempe Walk | Tempe-Sorgenfri, Trondheim | 68

Figure 6.12: Examples of locations for additional crossings over Holtermanns Veg based on pedestrian desire paths

6.3 Reduction of speed

A key necessity for returning the streetscape to pedestrian use is the reduction of speed. The current speed along Holtermanns Veg is 60km/h, exceeding the recommended speeds of 40/50km&h (Statens Vegvesen, 2022).

The group found four main arguments behind why a reduction in speed is necessary to help Tempe-Sorgenfri overcome the dangers of the area. Such a reduction would not only work as a measure by itself but would also help to facilitate the introduction of the other concepts proposed in this chapter.

Pedestrian deaths at different speeds

First and perhaps most importantly, the different speeds a car drives directly correspond with the chance a pedestrian has of dying in a car crash (see Figure 6.13) (Pasanen, 1991).

The chance of a crash resulting in death increases exponentially, rising from 10% at 30km/h up to 99% at 80km/h (Pasanen, 1991; Tefft, 2011). By reducing the speed limit down from 60 to 30km/h at Tempe-Sorgenfri, the pedestrian traffic accident mortality rate could be reduced by 68%.

69 | Tempe-Sorgenfri, Trondheim | The Tempe Walk

Figure 6.13: The mortality rate is a direct result of the speed of the car. The rate is known to further increase for the elderly as if the car was travelling at 20km/h higher than its actual speed.

Stopping distance at different speeds

Secondly, higher speeds lead to longer stopping distances (see figure 6.14). Based upon ADAC’s calculations regarding the stopping distances based on different speeds, we found that at ideal conditions, presently a driver would need 54 meters to come to a stop.

By reducing the speed to 40/50km/h the stopping distance could be reduced by 4055%. Such a change would be in line with Statens Vegvesens reccomendations for the existing road (Statens Vegvesen, 2022).

Travel times at different speeds

A reduced speed has the potential to increase travel times. Calculating the expected travel distance from turning off E6 until you reach the Elgeseter Bridge at different speeds (distance / average speed = fastest possible travel time), showing how a reduction in speed across both Tempe and Elgesetergate would affect the travel across this stretch.

To counter this, it is worth noting that when one accounts for reduced traffic flow due to rush hours and time spent at red lights, the time travelled is only reduced by less than 25% when reducing the speeds from 60km/h to 30km/h. (Pasanen, 1991)

The Tempe Walk | Tempe-Sorgenfri, Trondheim | 70

Figure 6.14: The stopping distance includes the stopping distance of the car, as well as a reaction time of 1.2 seconds as recommended by ADAC.

Figure 6.15: Travel distance calculated based on varying speeds showcasing the distance from E6 to Elgeseter Bridge, a journey of about 2.7km.

Death and injury rate at different speeds

Lastly, varying speeds lead to varying rates of injuries. Figure 6.16 shows the rates of Trondheim’s road network which is zoned to different speed limits, and at what rate those speed limits make up the total death and grievous injuries across Trondheim.

These numbers show that not only is the 30km/h speed limit the most common across Trondheim but that these roads cause less death and injury than the 50km/h roads, despite making up more than twice as many roads!

There is a clear correlation between the speed on a road and the deaths & injuries occurring.

71 | Tempe-Sorgenfri, Trondheim | The Tempe Walk

Figure 6.16: Percentage of traffic volume and deaths/injuries at different speeds within Trondheim.

A policy for speed

Overall, the prior arguments show a clear trend that slower speeds reduce the chance of traffic-related accidents and increase the chances of survival when such accidents do occur.

This report proposes the introduction of a 30km/h zone across the Tempe-Sorgenfri area.

Furthermore, this report proposes that as the city of Trondheim continues to progress towards pedestrian-friendly design, the general speed limit across the city should be lowered from 50km/h to 30km/h. This should significantly reduce the amount of deaths and grievous injuries caused within Trondheim.

The Tempe Walk | Tempe-Sorgenfri, Trondheim | 72

Figure 6.18: Location of existing traffic lights along Holtermanns Veg and Elgeseter Gate to be incorporated into the Green Wave. Scale 1:15 000

Figure 6.17: Showcasing an example of a 30 km/h zone road where soft traffic users are able to share the road with hard traffic users.

The need for physical measures

Reducing the speed limit is often not enough to actually reduce the speed of the cars on the road (Pasanen, 1991; Tefft, 2011). It is therefore proposed that physical strategies are introduced together with the policy changes, in order to produce the desired speed (Pasanen, 1991).

One proposal that may be implemented at Tempe-Sorgenfri is the Green Wave. The Green Wave is a traffic system where all intersections along a continuous traffic route are controlled by traffic lights coordinated to swap to green to match the time it takes to drive from one traffic light to another at the speed limit (Wu, 2014; He & Ma, 2019). An optimised traffic crossing at the crossing between Valøyvegen and Holtermanns Vegen would encourage pedestrian crossings such as that mentioned earlier in this report (Wu, 2014). Green Wave are found to be more fuel efficient and safer for both pedestrians and motorised users, leading to less traffic accidents (Wu, 2014). Green Wave systems work best when utilised over longer stretches of road with regular traffic light intersections (He & Ma, 2019). As shown in Figure 6.18, this is very much the case for Holtermanns Veg leading into Elgesetergate and into the city centre. A unified Green Wave system across this stretch would help reduce accidents, lower emissions and tie the road as a whole together (Wu, 2014) (He & Ma, 2019).

73 | Tempe-Sorgenfri, Trondheim | The Tempe Walk

6.4 Shared surface

In the long-term, Holtermanns veg could be transformed into a kerb-less street to encourage equitable use of the right-of-way by all modes of transport. Currently at the Tempe-area, the kerb separates the space for pedestrians and motorized vehicles. With a kerb-less street design, pedestrians, cyclists, and car drivers share the space. Such a design could make the road users more aware of the road conditions, as movement requires negotiation, for example by eye contact (cf. Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission, 2018). A kerb-less stress will slow-down the cars, which makes the space comfortable and safe for non-motorized travel (cf. Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission, 2018). This process would transfer Holtermanns veg from a street you drive through, to one you want to be in. If the municipality of Trondheim succeeds in transforming Holtermanns veg into a kerb-less street, it will probably improve the safety, quality of life and mobility of the residents of Tempe-Sorgenfri.

Benefits of kerb-less streets

Kerb-less streets contribute to road safety as they increase interaction between all modes of transport, reduce vehicle speeds and thus lead to fewer accidents (cf. Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission, 2018).

This improve of safety increases the quality of life. By providing space for social interaction, the street gets a new identity (cf. Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission, 2018).

A street design without kerbs can also improve the streets overall mobility in terms of the efficiency of movement. Sharing road space can improve traffic flow by minimizing delays for both vehicles and pedestrians, by improving interaction between road users and by reducing unnecessary traffic (cf. Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission, 2018).

The Tempe Walk | Tempe-Sorgenfri, Trondheim | 74

Figure 6.19: Benefits of kerb less streets

“If we look at photos from the 1890s and 1900s, it is almost impossible to find a stretch of road where pedestrians aren’t standing or walking around in the middle of the road. The street was for all of us.

/ Eriksen, 2020: Et land på fire hjul. Res Publica, Oslo

The idea of designing streets without kerbs is not new. Before the 20th century, many streets were shared spaces in which all users - bicycles, carriages, and pedestrians – moved through interaction. In Trondheim, in 1864, the Størenbanen railway line opened, running from Prinsens gate, down Elgeseter gate and Holtermanns veg, and crossing Nidelven at Sluppen. After the railway was relocated in 1884, the route was used as a road to the city (Loe et al, 2022).

With the emergence of the motor vehicle and its rapid spread, the understanding of streets was redefined. Roads were modified by marking out areas for different road users, with most of the space allocated to the motorized vehicle and a focus on its efficiency. This was often at the expense of other road users, as it is nowadays clearly visible at the Holtermanns veg. From the 1950s onwards, industry began to establish itself in the area, leading to the demolishment of many residential buildings and the widening of Holtermanns veg in 1966 (Loe et al, 2022). The first law that defined the road as the domain of the cars came only in 1927 (Eriksen, 2020). In recent decades, trends and policies focusing on quality of life have revitalized the concept of the kerb-less street and its importance as a public space.

The questioning of the current car-centred street design of Holtermanns veg leads to the idea of returning to the concept of many early streets serving as community space.

75 | Tempe-Sorgenfri, Trondheim | The Tempe Walk