Public Space

Tempe Sorgenfri - Trondheim

Project Course Report, Autumn 2023

Urban Ecological Planning Master’s programme

Department of Architecture & Planning, Faculty of Architecture

Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Trondheim, Norway

AAR4525 - Urban Ecological Planning: Project Course

Executive Summary, Autumn 2023

Urban Ecological Planning Master’s Programme

Department of Architecture and Planning, Faculty of Architecture

Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU), Trondheim, Norway

Course Coordinator:

Cinthia Freire Stecchini

PhD Scholar, NTNU

Supervision Team:

Cinthia Freire Stecchini

PhD Scholar, NTNU

Jarvis Suslowicz

PhD Scholar, NTNU

Vija Viese

Research Associate, NTNU

Rolee Aranya Professor, NTNU

Booklet Layout:

Vija Viese

Research Associate, NTNU

Public Space | Tempe-Sorgenfri | 2

Public Space

Creating functional and social spaces

Trondheim, Norway

Authors

Mariana Aguirre Garcia Mexico city - Mexico

I am Mariana Aguirre García from Mexico and I am currently pursuing my Master’s degree in Architecture at the Universidad Autónoma Nacional de México. I am an exchange student at NTNU. My interest lies in the process of project design, and I strongly believe in creating humane and livable spaces as a fundamental goal in any design effort. I believe that participatory processes enrich the final results.

Moos Timmers

Hengelo - The Netherlands

I am Moos Timmers and I completed my bachelor’s degree in Urban Planning at Saxion University in Deventer. I chose to do a Masters in Urban Ecological Planning (UEP) in Trondheim. My interest lies in understanding how cities function and how we can make them more liveable for everyone. I strongly believe in giving the voice to the people and want to emphasise its importance in urban projects.

3 | Tempe-Sorgenfri | Public Space

Preface

This project report presents the results of the extended fieldwork conducted by master students in the first semester of the 2-year international Master of Science Program in Urban Ecological Planning (UEP) at the faculty of Architecture and Design at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU). The extended fieldwork is a key component of the UEP program, allowing students to work in real cases and to learn-by-doing. In Autumn 2023, the fieldwork took place in Trondheim, Norway.

During this semester, the UEP program worked in close collaboration with Trondheim Municipality. This is the first time such a collaboration was established in Norway for the fieldwork, which was planned envisioning mutual benefits for the students’ learning process and the development of plans and programs by the municipality. The location for the fieldwork – Tempe and Sorgenfri, the focus of one the municipality’s ongoing area-based programs – was decided together. From the very beginning, students were provided with official reports and documents about the area as well as contacts for local stakeholders. This was the base information that they had to complement (and challenge!) by conducting their own situational analysis and identification of a problem statement through participatory planning methods.

The students were divided into three groups and worked on one of the proposed broad themes: Housing & Inclusivity, Public Space & Activation, and Mobility & Accessibility. In the final stage of the project, the groups elaborated concepts and proposals for strategic solutions. The collaboration with the municipality made it easier to access stakeholders, who were invited to two mid-term presentations and the final one. Stakeholders commented on the work, validating (and challenging!) the findings and proposals of our students. What you will read in this report, thus, is the work done by UEP students validated and reviewed based on the stakeholders’ involvement in Tempe-Sorgenfri. We hope that this type of collaboration continues, and evolves, in the years to come.

Another novelty in the Autumn semester 2023 is that the course coordination and supervision was done by three academics in the early stages of their careers. We are two PhD candidates and a research associate from the department, with backgrounds in Architecture, Urban Planning and Design, Psychology, and Geography. Being responsible for the project course and the fieldwork has been an exciting challenge for us and a fruitful learning experience.

Public Space | Tempe-Sorgenfri | 4

As an international master program, students from UEP come from different nationalities. The diversity of backgrounds – also in terms of academic background – is something we take pride in as it allows a rich exchange among students. We understand diversity as a valuable resource in preparing the next generation of conscious planners. To support the broadening of perspectives, particularly establishing relations of North and South countries – something we actively seek at UEP, we also had a study trip to South Africa, during the same semester, as a part of the UTFORSK-NISA project (https://www.nisa-partnership.com/). There, our students were welcomed by our partners at the African Centre for Cities (ACC), at the University of Cape Town (UCT), who introduced them to different realities and projects. The excursion to South Africa also helped the students to contrast the conditions in Tempe-Sorgenfri with those they experienced in communities in Cape Town.

We are thankful for the collaborations with Trondheim Municipality, and our partnerships in South Africa and India through the UTFORSK-NISA project. We are also very thankful for our curious and proactive students, and hope you enjoy reading this report as much as we enjoyed following their process throughout this semester.

Cinthia Freire Stecchini, Jarvis Suslowicz and Vija Viese

Fieldwork Supervisors, NTNU, Department of Architecture and Planning

5 | Tempe-Sorgenfri | Public Space

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to the residents of Tempe-Sorgenfri who generously shared their time and insights with us, and to the children who participated in our intervention. Special thanks to the Health and Welfare Center and Barnehage S.A. and other institutions that welcomed us and engaged us in meaningful and productive discussions.

Our appreciation extends to the municipality for giving us the opportunity to work in this neighborhood. We are grateful for their openness in answering our questions and their involvement in our work.

We extend our sincere thanks to our supervisors, Vija Viese, Cinthia Freire Stecchini, and Jarvis Suslowicz, as well as the lecturers who provided valuable guidance throughout the process. We would like to give a special thanks to Vija, who provided us with encouragement throughout the semester.

We would also like to thank our classmates and friends for their unwavering support. Their input, suggestions, and uplifting spirits were essential to our journey.

Finally, we would like to thank our family and friends for their continued and unwavering support.

Public Space | Tempe-Sorgenfri | 6

Acronyms and Abbreviations

PPS Project for Public Spaces

UEP Urban Ecological Planning

WS Workshop

7 | Tempe-Sorgenfri | Public Space

Public Space

Public Space | Tempe-Sorgenfri | 8

Tempe-Sorgenfri, Trondheim

Mariana Aguirre Garcia

Moos Timmers

9 | Tempe-Sorgenfri | Public Space

Public Space | Tempe-Sorgenfri | 10 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION 12 2. CONTEXT 13 3. Methods 14 3.1. Data analysis: 14 3.2. Observation: 14 3.3. Participatory Activities 14 4. SITUATION ANALYSIS 16 4.1. First impression 16 4.2 Tempe-Sorgenfri from above 18 4.2. Statistics Tempe Sorgenfri 20 4.3 Observations 22 4.4 Participatory activity 26 4.6. Semi structured interview 31 4.7. Problemstatement 33 4.9. Tactical Urban Intervention 38 5. Concept for solutions 41 5.1. Low voices 41 5.2. Criteria of exclusion 44 5.3. Profiles 45 5.4. Case study area Tempe 45

11 | Tempe-Sorgenfri | Public Space 5.5 Mapping analysis Tempe 46 5.5.1 Functional analysis 46 5.5.2. Public space analysis 48 5.5.3. Green analysis 50 5.5.4. Property and green 52 5.6. Opportunities Tempe 54 5.7. Profiles in Tempe map 56 5.8. Defined low voices Tempe 58 6. Proposal for solution 58 6.1. The low voice method 58 6.2. The Stage-Scale Matric 61 6.2.1. Tempevegen 63 6.2.2. Football field 65 6.2.3. Nidelva river 67 7. Conclusion 68 7. 1. Recommendations 68 8. Reflection 69 8.1. Reflection on methods 69 8.2. Reflection on problems encountered 69 8.3. Reflection on strategic interventions 70 Bibliography 72 List of Figures 74

“In a well-designed and well-managed public space, the armor of daily life can be partially removed, allowing us to see others as whole people. Seeing people different from oneself responding to the same setting in similar ways creates a temporary bond.” Carr et al. (1993, cited in Amin 2008, p. 5)

The history of urban planning involves designing public spaces to construct social places and promote citizen participation through interactions among strangers. Vibrant public spaces are essential for a healthy and democratic society, as they provide a safe A healthy and democratic society requires vibrant public spaces (Amin, A. 2008). However, cities and societies are complex and diverse, as Jane Jacobs famously observed: “The point of cities is multiplicity of choice.”

The Municipality of Trondheim initiated this project to enhance the neighbourhood environment of Tempe-Sorgenfri, based on the requirements of its residents (Loe et al., 2022). Tempe-Sorgenfri is a diverse neighbourhood, with a varied population and a wide range of available facilities. The Urban Ecological Planning approach, which prioritises human-centred solutions through participatory methods, was utilised to determine the role of public space in Tempe-Sorgenfri and its contribution to neighbourhood improvement.

What do the residents of Tempe-Sorgenfri think about public space, how do they experience their environment, how does this differ from individual to individual, and do they feel a sense of community? Through various forms of engagement with residents, we obtained answers to these questions. This has allowed us to devise a methodology that guarantees the involvement of residents in the participation process, with the objective of creating public spaces. We then proposed different engagement strategies for three selected opportunities in Tempe by implementing the methodology in the residential area of Tempe.

Public Space | Tempe-Sorgenfri | 12

1. INTRODUCTION

Figure 1. Baseball field Sorgenfri (Source: Authorship of Team PS - UEP 2023)

This report is based in Trondheim, Norway, specifically within the county of Trøndelag. Trondheim is the country’s third-largest city with a population of 212,660 as of 2023 (Trondheim Kommune, s.d) and is known as a student city, in part due to the presence of NTNU University (NTNU, s.d). The study focuses on the Tempe-Sorgenfri neighborhood, which is currently undergoing renovations by the municipality. The objective of this endeavour is to enhance the quality of life in response to a low score identified in the land use plan/ zoning plan (Trondheim Kommune, 2023).

The neighbourhood has potential for densification due to its location near the city centre and accessibility via public transport, making it an attractive area for private developers. The most recent zoning plan proposal was in 2019, and a new proposal is currently being developed to prepare the neighbourhood for upcoming changes. The aim of this plan is to develop Tempe-Sorgenfri into a highly populated and pedestrian-friendly neighbourhood with exceptional public spaces and urban features. (Trondheim Kommune, 2023)

According to the socio-cultural analysis report (Loe et al. 2022), the neighbourhood has a negative reputation among Trondheim citizens. A digital survey showed that most respondents do not find it appealing as a place to live, although two-thirds believe it is a good environment for raising children. Many feel that public spaces in the neighbourhood are unattractive and inaccessible. However, a significant number of respondents expressed uncertainty on this matter. The responses regarding areas for leisure activities were mixed, with some participants indicating a lack of knowledge and others expressing positivity.

13 | Tempe-Sorgenfri | Public Space

2. CONTEXT

Norway

Trondelag

Trondheim

Tempe Sorgenfri

Figure 2. Location Tempe-Sorgenfri (Source: Authorship of Team PS - UEP 2023)

3. Methods

To become acquainted with the area, we began with secondary data analysis and observation.

3.1. Data analysis:

The municipality provided us with access to various reports regarding the neighbourhood, including the Tempe and Sorgenfri Land Use Plan/Zoning Plan, the Tempe and Sorgenfri Public Spaces and Connectivity Strategic Plan, and the Tempe-Sorgenfri Socio-Cultural Site Analysis. The purpose of this study was to collect data on the community’s demographics, opinions on public spaces, and the municipality’s future plans and goals for the area. Additionally, map analysis was conducted to understand the spatial data and relationships between different areas.

3.2. Observation:

As Shveta Mathur (s.d., 5:50 - 6:16) explained, this is a passive method of gaining knowledge by absorbing the sights and sounds of a settlement, site, or community. It provides a preliminary understanding of the spaces that can be worked with.

The initial approach involved a meeting with the municipality, during which they presented a summary of the content of numerous reports, followed by a walk around the neighbourhood.

After becoming familiar with the secondary data, our focus shifted to actively engaging with the community to gather primary data.

3.3. Participatory Activities

Small talks: We went to the neighborhood and engaged with the residents in casual conversations to get to know their opinion about the public space and what changes they would like to see in the

neighborhood. This form of dialogue is effective because people tend to engage in informal settings, enhancing communication and obtaining more genuine data (Swain, Jon & King, Brendan, 2022).

Discussions: We held formal meetings with several stakeholders from the neighbourhood to gather their input and perspective on the situation, as well as their desires or recommendations.

Tactical Urbanism: As defined by Mike Lydon, is “a city, organizational, and/or citizen-led approach to neighborhood building using short-term, low-cost, and scalable interventions to catalyze longterm change” (cited in Gökçe Tuna, 2022). Used as a way to raise awareness and learn knowledge about the residents willingness to form part in participatory processes.

Semi- estructured interviews: As defined by Participatory Learning And Action (PLA), this refers to “checklist of questions that need to be covered during each interview. But they also allow for discussion around areas of interest that emerge over the course of the interview” (INTRAC, 2017. p 2).

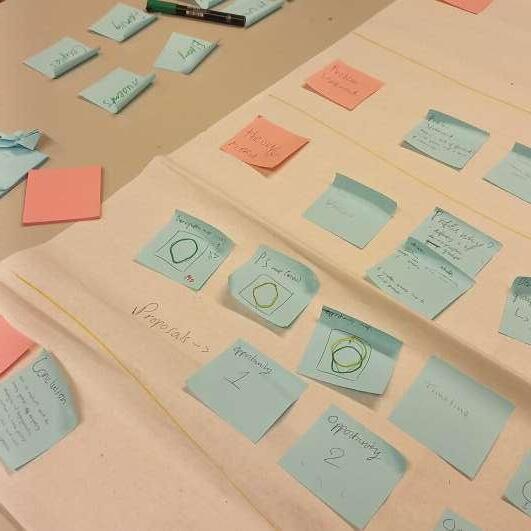

Stakeholder workshop: This method igathers information from key stakeholder institutions and academics who are knowledgeable about the issue. The aim is to gain valuable insights from their perspectives.

Tools such as mind mapping and map analysis were used to organize ideas, concepts, and processes throughout the entire process.

Public Space | Tempe-Sorgenfri | 14

15 | Tempe-Sorgenfri | Public Space

Figure 3.0. Mapping the process of the project (Source: Authorship of Team PS - UEP 2023) Figure 3.1. Stakeholder workshop (Source: Authorship of Team PS - UEP 2023)

Figure 3.3. Tactical Urban Intervention on the football field in Tempe (Source: Authorship of Team PS - UEP 2023)

4. SITUATION ANALYSIS

4.1. First impression

On Monday, 21st August 2023, the municipality organized a Kickoff event. The event was attended by various stakeholders, including different departments of the municipality such as Biodiversity, Mobility, and Urban Development, as well as PhD students and a local artist. The objective of the event was to facilitate networking and information sharing. This meeting also provided us with an opportunity to gain a first impression of the Tempe-Sorgenfri neighbourhood.

The municipality provided an introduction to Tempe-Sorgenfri, describing the area, its residents, past developments, and future plans. During the tour, various locations were highlighted, including the underutilised football field and the poorly connected pilgrim’s path. Following the tour, presentations were delivered by the municipality’s departments and other stakeholders. The

presentations covered a range of topics, such as the conservation of biodiversity in the Nidelva nature reserve, a future zoning plan for Tempe-Sorgenfri, friluftsliv (outdoor life), the significance of children’s voices and child-friendly environments, the results of a participation study in Ola Frosts veg in Tempe, and Tactical Urbanism.

Public Space | Tempe-Sorgenfri | 16

Figure 4.1. Kickoff presentation 21/8/23 (Source: Vija Viese, 2023)

Figure 4.2. Walking tour 21/8/23 (Source: Vija Viese, 2023)

Figure 4.3. The football field (Source: Authorship of Team PS - UEP 2023)

17 | Tempe-Sorgenfri | Public Space

4.2 Tempe-Sorgenfri from above

Tempe-Sorgenfri is situated south of Trondheim city centre. The area is bordered by the Nidelva river to the west, the railway to the north, the Nardo neighbourhood to the east, and the E6 highway to the south.

The area comprises a diverse range of facilities, including the nature reserve ‘the Nidelva river’ on the west side, Valgrinda’s green structure, a significant portion of industrial areas, commercial spaces, and offices such as the NTNU headquarters and MAX center, as well as scattered recreational spaces like Tempebanen and several residential areas.

The residential areas can be divided into four sub-areas: Tempe, Sorgenfri, Lerkendal, and Valgrinda. (see figure 4.4)

Tempe and Sorgenfri consist mainly of residential buildings, including high-rise buildings and detached houses. In Tempe, there are several large facilities, including the Tempe Barnehage SA, the Tempe Health and Welfare Center, and the MAX Center. Additionally, there is the Nidelva corridor and a playground/football field that residents report is underutilized. Holtermanns veg is a significant boundary that separates Tempe from other sub-areas.

Sorgenfri is primarily occupied by students and features various public spaces between the highrise buildings, as well as nearby convenience stores and office buildings.

Lerkendal stands out due to its identifiable football stadium, surrounded by sports fields and the Scandic hotel. The area also includes a church and a combination of high-rise buildings (mainly student housing) and detached houses.

Public Space | Tempe-Sorgenfri | 18

Facilities Tempe-Sorgenfri

19 | Tempe-Sorgenfri | Public Space

Figure 4.4. Map with the main facilities in Tempe-Sorgenfri (Source: Authorship of Team PS - UEP 2023)

4.2. Statistics Tempe Sorgenfri

Population

Based on the 2018 census, Tempe-Sorgenfri has a population of 1,892 residents. The accompanying graph (see figure 4.5) illustrates that 41.2% of the population falls within the 18-34 age group, with a significant number of university students, “which is related to the fact that Trondheim as a university city attracts young people who want to study and younger people of working age due to the large labour market” (Levekår og folkehelse i Trondheim kommune 2021 - Folketall og alderssammensetning, s.d.). The 35-66 age group is the second largest, comprising 29% of the population. The elderly population accounts for 15.1%, while the younger generation makes up the remaining 14.75%.

It’s worth mentioning that since the last census, it is reasonable to infer that there may be additional people (mostly students) residing in the area who are not formally registered.

Over the recent years, the construction of new residences, known as ‘Nærbyen,’ has taken place in the Sorgenfri area, adding 157 rental homes (Forsiden - Nærbyen 24/7, 2022).

Immigrant population

Tempe-Sorgenfri has a significant foreign resident community, including international students and regular residents. According to the 2018 census, 31.1% of the population has an immigrant background, while the remaining 68.9% are native residents. Among those with an international background, 24.75% are primarily from Africa and Asia, with only 3.45% originating from EU countries. The countries of origin for the remaining 2.95% are unspecified. (see figure 4.6)

Rental houses

In Tempe-Sorgenfri, the proportion of rented houses is 74.3%, which is significantly higher than the 31% in Trondheim (Levekår og folkehelse i Trondheim kommune, 2021). The same source indicates that home ownership is less common among people with lower incomes than among those with higher incomes.

Age distribution Tempe-Sorgenfri in 2018

Immigrant poputation Tempe-Sorgenfri 2018

Rental houses 2018

Public Space | Tempe-Sorgenfri | 20

Figure 4.5. Chart with the age distribution in Tempe-Sorgenfri in 2018 (Source: Levekår og folkehelse i Trondheim kommune, 2021)

Figure 4.6. Chart immigrant population Tempe-Sorgenfri in 2018 (Source: Levekår og folkehelse i Trondheim kommune, 2021)

Figure 4.7. Amount of rental houses Tempe-Sorgenfri & Trondheim in 2018 (Source: Levekår og folkehelse i Trondheim kommune, 2021)

Small homes

Small homes are defined as those with one to two rooms. In Tempe-Sorgenfri, the percentage of small homes is 65.9%, which is significantly higher than the 31.2% in Trondheim (Levekår og folkehelse i Trondheim kommune, 2021). This may indicate that many people are living in flats, or it may be due to the phenomenon of ‘hyblifisering’.

Hyblifisering

When houses are often divided into multiple rooms that can be rented out by homeowners to increase their profits. However, this practice has become problematic in several neighbourhoods in Trondheim, as it has led to families moving out of their homes. Families are essential for creating vibrant neighbourhoods (Adresseavisen, 2023).

We engaged with a resident of Tempe who lives there with her family. She mentioned that the house she lives in is now hyblificated as well. Before it gave home to four families and now to 69 students. She plans to move out of the house.

Cramped houses

A house is considered cramped if the number of rooms is less than the number of people living in it, or if one person lives in one room, and if the number of square meters per person in the household is less than 25. In Tempe-Sorgenfri, the percentage of cramped houses without children is 13.6%, which is slightly higher than the 9.9% in Trondheim. The percentage of households with children living in cramped houses is 69.1% in Tempe-Sorgenfri and 21.5% in Trondheim, indicating a significant difference (Levekår og folkehelse i Trondheim kommune 2021 - Boligstørrelser, antall rom, s.d).

Given the high percentage of small and cramped houses in Tempe-Sorgenfri, it is crucial to ensure sufficient outdoor spaces are available. According to the social cultural analysis, it is crucial to design and facilitate flats and limited green areas well, especially when many families live in cramped quarters. The analysis states, ‘When a large proportion of residents live in flats, many families live in cramped quarters, and there are limited green areas, it becomes extra important to design them well and facilitate them for several user groups’ (Loe, et al., 2022, p. 48).

Socio-cultural site analysis report

According to the 2022 Socio-cultural site analysis conducted in Tempe-Sorgenfri, residents in the neighbourhood generally report a lower sense of security compared to Trondheim

Small houses 2018

Cramped houses (without children) 2018

Cramped houses 2018 (with children as proportion of all households with children)

21 | Tempe-Sorgenfri | Public Space

Figure 4.8. Amount of small houses Tempe-Sorgenfri & Trondheim in 2018 (Source: Levekår og folkehelse i Trondheim kommune, 2021)

Figure 4.9. Amount of small houses Tempe-Sorgenfri & Trondheim in 2018 (Source: Levekår og folkehelse i Trondheim kommune, 2021)

Figure 4.10. Amount of cramped houses (with children as proportion of all households with children) Tempe-Sorgenfri & Trondheim in 2018 (Source: Levekår og folkehelse i Trondheim kommune, 2021)

overall. Nearly 75% of individuals in Tempe express a strong sense of security in their immediate surroundings, low compared to the 85-88% of Trondheim. Regarding well-being, 62.6% of women and 58.2% of men in Tempe report feeling comfortable, which is lower than the corresponding figures for Trondheim, where 72.4% of women and 69.6% of men report feeling comfortable. It should be noted that the crime rate in Tempe-Sorgenfri is 7.4%, which is slightly higher than the overall rate of 6% for Trondheim (Loe, et al., 2022).

4.3 Observations

After reading the official reports, our initial actions involved taking several walks through all areas of the neighbourhood. We specifically focused on observing public spaces without attempting to engage with residents yet. Interestingly, we rarely crossed paths with other people during our walks.

The route (see figure 4.11) we took visited all of the sub areas of Tempe-Sorgenfri and through the green areas we were able to access.

This project uses the Project for Public Spaces diagram to evaluate the public spaces in Tempe-Sorgenfri.

Project for Public Space

Project for Public Spaces

Project for Public Spaces (PPS) is a nonprofit organization that has been in existence since 1975. PPS applies William H. Whyte’s ideology on the elements of vibrant public spaces. The organization provides a resource that can be used to understand what makes a great public space and to evaluate them. A great public space can exist when considering four aspects: sociability, uses and activities, access and linkages, and comfort and image (PPS, s.d.). Each of these aspects is divided into subcategories to enhance understanding.

Public Space | Tempe-Sorgenfri | 22

Figure 4.11. Observation route Tempe-Sorgenfri (Source: Authorship of Team PS - UEP 2023)

Figure 4.12. PPS diagram, What makes a great space? (Source: PPS, s.d.)

Observations route Tempe-Sorgenfri

Tempe

At first glance, the Tempe appears to have abundant green areas, primarily in the gardens of detached houses. However, it is important to note that these are not public spaces. The expansive grey streets are the prominent feature of Tempe. Our exploration of the area revealed several public spaces, including the football field, the green area between the Ola Frost buildings, and the corridor along the Nidelva River. While not strictly public, residents have access to spaces such as the kindergarten playground and the healthcare center. Upon closer inspection through the lens of the four qualities considered by the Project for Public Space (PPS), these areas appear less promising due to a lack of activity and undefined use. Specifically, the PPS criteria reveal that the areas are not meeting the necessary standards.

Sorgenfri

In Sorgenfri, there are public spaces located between the student housing. These spaces are officially open and accessible to everyone. However, due to the large housing blocks surrounding them, they may feel less welcoming to outsiders. The spaces are well-maintained and include amenities such as benches, a basketball hoop, a small playground, and a real-life chess board. Despite the variety of equipment, there is a limited amount of greenery.

23 | Tempe-Sorgenfri | Public Space

Football field

Playground Ola Frost

Detached houses street

Park Ola Frost

Facilities

Meeting areas

Figures 4.13. Photos made for the observation analysis pp. 23-25 (Source: Authorship of Team PS - UEP 2023)

Lerkendal provides facilities that cater to a wider audience than just its residents of the area. These include the Lerkendal stadium, its surrounding sports fields, and the Scandic hotel.

There is also a church which can be considered as semi-public, because it is not owned by the government but further it is open to everyone. While it serves as a green space, it may not be suitable for non-reli-

Valgrinda

Valgrinda is a residential area comprising apartment blocks and other large buildings from NTNU and various companies. On the outskirts of the area, there is a prominent green structure that is not easily accessible. Additionally, Valgrinda provides some green public spaces, including a playground located between the apartment blocks.

NTNU headquarter

gious recreational activities or gatherings. Trondheim Studenthage is a semi-public space primarily intended for students.

Most of the other green spaces in the area are private or lack functionality as suitable gathering spaces.

Public Space | Tempe-Sorgenfri | 24

Lerkendal

Housing blocks Church

Various playground equipment

Apartment blocks

Student housing

Between the residential areas

There are various other functions between these living areas. The Nidelva river is a nature reserve that offers a walking track. Tempe Banen, with football fields and the opportunity to kayak, is also nearby. Additionally, there is industry in various scales and office buildings, resulting in a more grey and car-based area. The Holtermanns veg has a big impact on Tempe Sorgenfri. The busy traffic road stands out in the area and is a dangerous barrier. Individuals are crossing the road at their own discretion. The street reduces safety and negatively impacts accessibility for pedestrians.

25 | Tempe-Sorgenfri | Public Space

Scandic hotel and football fields

Nidelva river

Holtermanns veg

Tempebanen

4.4 Participatory activity

A series of informal and semi-structured discussions and an interview were conducted with the objective of engaging with residents and stakeholders of the area. The discussions were named ‘Waffle Day’ and ‘Small Talks’. Representatives from the Tempe Barnahaga SA and the Tempe Health and Welfare Center were also consulted.

4.4.1 Small talks

Waffle day - 17 September 2023

The intention of the Waffle Day was to have a first engagement with the residents and discuss Tempe-Sorgenfri. To facilitate communication with residents, we were handing out waffles. Our focus was on gathering opinions about living in Tempe-Sorgenfri, with particular attention to public spaces. We chose the site between the OlaFrost buildings in Tempe because it is relatively busy for Tempe-Sorgenfri.

We engaged with a diverse group of individuals, including elderly residents, parents with children, and a group of elderly friends socializing.

The families we spoke to had an immigrant background. When asked about the sense of community in the neighborhood, they expressed agreement, stating that they feel part of the community. However, they mentioned that, overall, they interact less with people who do not have an immigrant background. They noted occasional gathering events for neighbors, but these are typically scheduled on weekdays, making it challenging for many residents to attend. As most of the interviewed families were parents with small children, they collectively highlighted a lack of activities for kids. The limited options in the playground, situated close to Tempevegen, which they considered unsafe for children. They also missed an indoor area to gather in the colder season.

A middle-aged man from Syria lives in Tempe with his wife and child. He appreciates the diverse community in Tempe and finds it easier to connect with non-ethnic Norwegians than with Norwegians themselves. He believes that there is a clear social divide

between non-ethnic Norwegians and Norwegians.

A mom (who lives 20 years in Tempe)with her child was telling us that she likes it to live in Tempe. It is easy to make friends here, especially in the summer. There are distinct groups between ethnic Norwegians and non-ethnic Norwegians. Due to time constraints, she does not attend gatherings hosted by Frost Eiendom. She expressed concern about the safety of the bicycle lane for children and suggested adding more games to the park for children.

Another group we interviewed consisted of elderly individuals, with limited English except for two people, a woman in a wheelchair and a man. The woman, who does not reside in Tempe but visits friends there regularly, expressed a favourable opinion about the neighbourhood, stating that she prefers it over her own.

The men in the elderly group agreed with her positive opinion, citing the well-organized environment and reasonable rental prices as reasons for their preference. Regarding the sense of community, he acknowledged the friendliness among residents but agreed that there is a tendency for people to form groups based on similar backgrounds, which can result in limited interaction with foreign residents.

We engaged with a third group of adults who were chatting. They appreciated the friendly atmosphere of the community and valued the presence of students and children for the vitality they bring to the neighbourhood. They expressed a desire for more comfortable open spaces that can be used throughout the year.

Public Space | Tempe-Sorgenfri | 26

Figures 4.14. Waffle day 17/10/23 quotes participants (Source: Authorship of Team PS - UEP 2023)

“Easy to make friends here, especially in summer when people are outside. The bicycle lane is a bit dangerous for children”

“Norwegians tend to only to talk with other norwegians”

“We don’t interact much with foreign residents, they stay in their group”

Tempevegen - 23 September 2023

At this event, we positioned ourselves along Tempevegen to engage with the students more effectively. They were harder to reach in Ola Frost veg. Our objective was to gain insight into their perspective on living in Tempe-Sorgenfri, their use of public space, and identify any areas that they feel are lacking.

Given the temporary nature of student residence during their studies, most of those interviewed expressed a lack of inclination to get to know their neighbors or to actively form a community. Similarly, spending their free time in public spaces within Tempe-Sorgenfri wasn’t a priority for them; instead, they preferred other locations outside the area. One student mentioned utilizing the football field for picnics during spring, but overall, the usage of public spaces was limited.

However, there were two friends who had been residing in the area for more than a year and a half. They had not only acquainted themselves with their neighbors but also established strong relationships, considering that many in the neighborhood are fellow students. They are open to join some ‘special’ events like lighting the christmas tree in the neighborhood. While they agree that public spaces lack diverse activities, they do engage in activities like taking walks and grocery shopping within the area.

We also had conversations with two other women. One has been a resident for over 40 years and holds a highly positive view of Tempe, affectionately stating, “This is my home.” She cherishes the community and the connections she has formed over the years, regularly utilizing public spaces through daily walks.

Conversely, the second woman, despite living close to her family and enjoying her role as a caregiver to her granddaughter, has a less favorable opinion of Tempe. She expressed concerns about the area having a negative reputation for drug and alcohol-related activities. Due to this perception, she prefers not to engage in any community activities, “if there’s even one”, as she emphasized.

“We often hear the students partying late in the night”

“I don’t have any contact with my neighbours”

Public Space | Tempe-Sorgenfri | 28

Figures 4.16. Small talks in the Tempevegen (Source: Authorship of Team PS - UEP 2023)

Discussions

Tempe Health and Welfare Center - 26 September 2023

Our aim in meeting with the Health and Welfare Center was to gain an understanding of their role in the community. Additionally, we sought to gather the perspectives of elderly residents of Tempe regarding their use of public spaces, including accessibility and whether these spaces meet their needs and preferences.

The Health Center serves as the residence for 70 individuals, encompassing both the elderly and those with disabilities. The health center plays a crucial role in community engagement through the organization of various events. These include the Tempe Festival, pop-up exhibitions featuring local artists, and activities that facilitate interaction between elderly residents and children from the kindergarten. Additionally, the health center provides shared spaces, such as a hairdresser and a café, that are accessible to all community members.

The Health Center is an important indoor communal space that is available for year-round use, particularly during the winter months. The centre has strong ties with the local community and relies on volunteers, many of whom are community members, along with students who work there during weekends and holidays. The centre is diverse, with a workforce representing 18 nationalities, with the majority residing in Tempe. The administrator highlighted the success of activities that promote intergenerational connections. However, she expressed a desire for more interaction between families and children, as the elderly enjoy spending time with the kids. The cafeteria is a significant social space where community members can buy items, settle in, and converse with others (Public Space team, 2023).

The community members express a desire for more accessible outdoor areas, such as the Nidelva corridor. Although it currently serves as a prime location for birdwatching, communing with nature, and socializing, the absence of seating and wheelchair accessibility is noted. The football field, on the other hand, is easily accessible to all community members and has significant potential as a venue for

“we would like to have an indoor space, so we can stay inside in the colder season”

“A pub would be nice”

4.4.2.

Figures 4.17. Tempe Health and Welfare center (Source: Authorship of Team PS - UEP 2023)

diverse activities.

Additionally, they expressed a wish for the inclusion of amenities like a pub and a doctor or general practitioner closer to the area.

The kindergarten - 27 September 2023

We aimed to gather information about the kindergarten’s role in the neighborhood, the location where children play, and the opinions of both parents and children regarding Tempe-Sorgenfri.

The kindergarten in Tempe predominantly enrolls children from the local community, though some come from neighboring areas such as Sorgenfri or more distant locations like Sluppen and Kolstad. Typically, children walk to school, unless they reside in another part of the city. In Tempe-Sorgenfri, the diversity is also reflected in the kindergarten. The staff notes that the children’s interactions within the kindergarten are not affected by ethnic or cultural differences. However, some parents express reservations about their children playing with kids from different nationalities outside of the kindergarten setting.

According to the kindergarten staff, Norwegian families tend to utilize outdoor spaces more frequently than non-ethnic Norwegian families. When non-ethnic Norwegian families do venture outside, they often engage in activities within the outdoor area of the kindergarten. The kindergarten organizes trips to various locations, including the park near Birkebeinervegen, Finalebanen by St. Olavs, the park on the opposite side of Stavne Bridge, the trail along Nidelven, and the Tempe sports facility. Additionally, the kindergarten occasionally explores parks in other neighbourhoods.

When asked about public places and parks, the kindergarten staff stated that there are limited options in Tempe-Sorgenfri and expressed a desire for more. They specifically mentioned that the football field would be more appealing with additional activities and seating options (Public Space team, 2023).

“There are not really good playgrounds in Tempe, we take the kids to other neighbourhoods to play”

"Parents often bring their kids to our playground because there aren't many good public spaces around here."

Public Space | Tempe-Sorgenfri | 30

Figures 4.18. Barnahaga SA (Source: Authorship of Team PS - UEP 2023)

4.6. Semi structured interview

Municipality of Trondheim - 6 November 2023

Participants: Sigrid Topsøe-Strøm Gilleberg (landscape architect) and Carolina Berg Hagen

Objective

The semi-structured interview questions were prepared and sent to the municipality beforehand. They were categorized into two sections: questions related to the football field case and general questions related to participation and public space. The objective was to comprehend the municipality’s management of participation projects in public spaces, with a specific emphasis on the current process for the football field. The meeting consisted of a back-andforth discussion. Notes were taken, and the municipality subsequently provided us with additional relevant information resources to support our project research.

Current method of participation processes by the municipality

The municipality does not use a single method for all participation projects. Instead, they have an instruction guide that provides various methods. Before starting a participation process, the municipality can choose the method(s) it considers useful.

the actual process for the football field (see figure 4.20):

1. Defining stakeholders: The municipality is using stakeholder mapping to identify and prioritise stakeholders. In this case, the municipality aims to engage with students from Nardo School, Sunnland Ungdomsskole (high school), children from Barnahaga SA Tempe, and an architecture consultant. To gain a better understanding of students’ preferences, the municipality is considering meeting with Sit Bolig, a student housing organization.

The municipality receives a budget from the government’s finance department, which requires them to consider the participation process carefully. The municipality has stated that investing more money in the participation process would leave less money for design.

2. Reaching stakeholders: The municipality engages with students from Nardo School by initiating a dialogue with them and the person in charge of area renewal in Tempe (områdeløft). The students are then provided with information about the area and the case. This is followed by a student council election where they can vote for their class representative.

No participatory activities are planned with the children from Barnahaga SA Tempe. However, they will have conversations with the caretakers and parents.

3. Meeting and designing with consultant: The municipality meets with the architect and class representatives to discuss the football field case. The representatives speak on behalf of the students and express their wishes and preferences. The municipality has discovered that children can be effective advocates for their peers, including those in kindergartens, due to their experience with younger siblings and their own childhood preferences. Additionally, Sunn-

31 | Tempe-Sorgenfri | Public Space

Figures 4.19. Statens Hus Trondheim (Photo: Entra ASA, s.d.)

land ungdomsskole’s older students have been invited to contribute to the proposal for the football field’s design. Typically, a consultant is responsible for this stage, as the municipality lacks the capacity to design playgrounds.

4. Execution: During this stage, the final design is constructed.

5. Evaluation with stakeholders: The municipality will evaluate the process and outcome with the involved stakeholders. After completion, the municipality frequently receives feedback from other non-involved residents as well.

Hard to reach people

During the meeting, a significant topic of discussion was the municipality’s challenge in engaging with ‘low voices’ - individuals who are difficult to reach when it comes to participation. To initiate a participation project aimed at engaging with residents, the municipality sends out letters. Unfortunately, the municipality only has the address of the property owner, which means that the owner is responsible for forwarding the letters to the renters. Additionally, the letters are only available in Norwegian. However, this process is not always successful, resulting in the exclusion of some individuals. The municipality is making an effort to be more aware of the low voices in society. For example, in Trondheim, an adult representative is selected to amplify the voices of children.

The municipality also recognizes the challenge of engaging individuals who may not express their opinions during a project but may express dissatisfaction with the end result. In Thornæsparken, situated in the Møllenberg neighbourhood, a shelter was removed after the park was built. This was due to concerns from previously quiet residents about noise nuisance caused by people hanging around. How can we involve individuals who may not have a strong opinion in the initial stages of a process?

Communication

Another challenge in the participation process is maintaining communication with participants from the beginning, through the middle, and after the project’s completion. How can investment in the participation process bring long-term benefits?

Temporal interventions

When asked about the use of temporal interventions to engage with residents, the municipality responded that they have no plans to implement such interventions. The reason for this decision is the extensive paperwork required to justify the necessary materials and ensure safety. The municipality believes that it would be more beneficial to invest the project funds elsewhere.

Public Space | Tempe-Sorgenfri | 32

Figures 4.20. Diagram of the actual process for the football field carried out by the municipality (Source: Semi-structured interview municipality, 2023)

Actual participation process football field

The situational analysis indicates that Tempe Sorgenfri is a highly diverse area with four distinct sub-areas, each with their own unique characteristics. Our participation activities and conversations with the community are primarily focused on the Tempe sub-area. While there are public spaces available, residents have expressed a desire for additional or improved facilities. Residents of Tempe enjoy living there, but there is a lack of connection between ethnic Norwegians and non-ethnic Norwegians. Furthermore, some public spaces do not meet the needs of all residents. For instance, the park in Ola Frost is mainly used by apartment residents, particularly the elderly and parents with children. Other areas in the detached house district are rarely used, such as the football field. As discussed with the elderly center, the Nidelva River is difficult for the elderly to access, and there is a lack of seating in the neighbourhood. This is also confirmed by kindergarten Barnahaga SA, who would like to see more playgrounds and play equipment, for example on the football field.

While students find living in Tempe acceptable, there’s a perception that they are somewhat isolated from the neighborhood. Simultaneously, there are concerns about students partying, contributing to noise nuisance. Connecting with students poses a challenge, as they are notably absent from public spaces like Ola Frost Park. This absence may be related to a misalignment between the offerings of these spaces and the specific needs and preferences of the students. It suggests a potential gap between the interests and requirements of students within the existing public spaces.

and when they are most effective.

When does public space function?

To understand this question, it is important to first understand what public space is and why we need it. There are various interpretations of public space. Madanipour (1996, p. 144) describes it as “space that is not controlled by private individuals or organizations, and hence is open to the general public”. This mostly refers to the ownership of public space. Carr et al. (1992, p 50) explain it as “publicly accessible places where people go for group or individual activities”, referring more to accessibility for everyone. While Mark Francis (1989) described public space as “the common ground where civility and our collective sense of what may be called ‘publicness’ are developed and expressed.” Emphasizing ownership by all and the importance of a sense of collectivity. Jan Gehl also quotes on the subject.

“In a Society becoming steadily more privatized with private homes, cars, computers, offices and shopping centers, the public component of our lives is disappearing. It is more and more important to make the cities inviting, so we can meet our fellow citizens face to face and experience directly through our senses. Public life in good quality public spaces is an important part of a democratic life and a full life” (Gehl, J. 2011)

Gehl emphasises the significance of public space as a reflection of democratic values. There are various perspectives from which to view public space, all of which emphasise inclusivity and accessibility as key concepts, it is a space for everyone.

This leads us to the problem statement:

“In Tempe-Sorgenfri there is a lack of (functional) social spaces and a sense of community” (Public Space team, 2023).

Addressing these challenges is paramount to creating a more cohesive and inclusive community in Tempe Sorgenfri. In order to develop a plan, it is important to understand the function of public spaces

33 | Tempe-Sorgenfri | Public Space

4.7. Problemstatement

How does a public space look?

There are various public spaces where people can gather, including outdoor spaces like parks, squares, and playgrounds, as well as indoor spaces like libraries and cultural centres. Streets and roads are also open and accessible to everyone, but they serve a more universal function, including mobility and accessibility to public spaces. Safety is a crucial aspect of public spaces, encompassing both accessibility and the prevention of crime and violence. It should be emphasized that safe spaces are spaces that are accessible to everyone (UN-Habitat, 2018). To understand exactly how a well designed public space should look, we can use the PPS analysis as explained in the section 4.3 Observations.

Democracy and participation

The Charter of Public Space (INU), developed by the Istituto Nazionale di Urbanistica, aims to promote better cities by improving public spaces. The document explains how public spaces should be creat ed, emphasizing the importance of inclusivity and innovative prac tices that align with contemporary methods of communication and urban engagement. Urban residents have the right to participate in

transparent decision-making processes, ensuring their involvement in shaping and creating public spaces. The charter of public space emphasises the importance of democracy in public spaces, stating that “public space is the gymnasium of democracy” (2013, p. 3).

In conclusion, it can be stated that public spaces can be created through participation. Firstly, participation promotes democratic values. Secondly, effective participation processes can improve the aspects that contribute to great public spaces, as identified by PPS. Finally, participation can bring about numerous other benefits. According to Nabeel Hamdi, a prominent figure in participatory planning, participation is essential for identifying neighbourhood needs, establishing partnerships, building community, promoting equity, and achieving ownership and efficiency (UN-Habitat Worldwide, 2014). Therefore, participation is necessary to create more functional and social public spaces in Tempe Sorgenfri. An effective participation process can be achieved when it is fair, meaning that everyone

Public Space | Tempe-Sorgenfri | 34

4.8. Stakeholders mapping

Power-Interest diagram

Based on our findings and analysis, we used the power-interest diagram to map stakeholders. In this context, ‘interest’ is defined by which individuals or entities have more to lose. Tempe residents have some power due to the municipality’s commitment to participatory methods. However, it’s important to note that their influence is not as extensive as the municipality’s, as the latter retains the financial and decision-making authority to shape policies.

The kindergarten and the health center occupy a middle ground in terms of power, as they have influence within the area. Frost Eiendom (owners of the Ola Frost buildings) have considerable power and are less directly affected when conditions are not optimal. They differ from other landlords, particularly those who own detached houses, as they are responsible for the park between their buildings and, according to residents, maintain constant communication with their tenants. Landlords do not have a significant interest in the condition of public spaces. However, they can benefit financially from improvements that enhance the area’s image and attract more people.

The researcher and the artist derive their position on the interest scale from their work in Tempe. However, they lack the authority to determine what is implemented. Industries and offices own significant land in the area, but their primary interest is in the convenience of the public space for their

35 | Tempe-Sorgenfri | Public Space

Figures 4.21. Power Interest diagram public space Tempe (Source: Authorship of Team PS - UEP 2023)

Power-Interest diagram public space Tempe

workers during lunch breaks, with limited overall interest. For now, outside visitors remain spectators, viewing Tempe-Sorgenfri as a transit area rather than a destination.

Influence diagram

Residents have a significant impact on stakeholders as their opinions and well-being are of utmost importance, and they are major users of services provided by stakeholders such as kindergarten, health centre, artists’ work, and researcher. This influence also extends to their impact on the municipality. Similarly, the municipality influences residents through its methods of communication and involvement, as well as through its control over taxes, services, policies, etc. The municipality and Frost Eiendom have a positive relationship, with Frost representing the interests of the residents.

The kindergarten and health center have a constant interaction that influences each other. Landlords have an impact on residents by controlling housing conditions and shaping opinions about the area. Additionally, the opinions of residents shape how Tempe is perceived by outside visitors.

Influence diagram public space Tempe

Public Space | Tempe-Sorgenfri | 36

Figures 4.22. Influence diagram public space Tempe (Source: Authorship of Team PS - UEP 2023)

Stakeholder-issue interrelationship diagram

In analyzing public spaces, our primary categories align with the four qualities outlined by the Project for Public Space in “What Makes a Great Place?” (s.d): Access and Connections, Uses and Activities, Sociability, and Comfort and Image (see for further explaining 4.3. Observations). The diagram illustrates that residents who live in the area and experience the space on a daily basis prioritize all of these qualities as essential needs. The municipality supports all these needs with its efforts to involve the community in the design of the renovation of public spaces. Frost Eiendom prioritises the comfort and image of its properties, as well as accessibility, supporting activities, and sociability. These aspects have less direct impact on Frost Eiendom if they are not functioning optimally.

37 | Tempe-Sorgenfri | Public Space

Figures 4.23. Stakeholder-issue interrelationship diagram public space Tempe (Source: Authorship of Team PS - UEP 2023)

Stakeholder-issue interrelationship diagram public space Tempe

4.9. Tactical Urban Intervention

HYNDERLØYPE - 01 October 2023

What is Tactical Urbanism and why?

To begin, it is important to understand the concept of Tactical Urbanism. While there are similar concepts such as DIY urbanism and Urban Prototyping (The Street Plans Collaborative, 2016), we will be focusing on Tactical Urbanism. According to Mike Lydon, Tactical Urbanism is “a city, organizational, and/or citizen-led approach to neighborhood building that utilizes short-term, low-cost, and scalable interventions and policies to catalyze long-term change” (cited in Gökçe Tuna, 2022). A tactical urban intervention has the potential to provide new insights, be part of a transformation, and create new opportunities in a given situation. It can be likened to an experiment that guides the process or an event with significant impact. As Nyseth et al. (2010) state, “events present something becoming.”

Institutional and citizen-led

There are two ways to execute tactical urbanism. The first is institutional tactical urbanism, which is carried out by planners, businesses, researchers, policymakers, and organizations. This approach aims to encourage active involvement and participation, create consensus, provide immediate access to expertise and resources, and reduce risk for stakeholders and planners. To clarify how to reduce risk, the municipality can delegate the execution of the tactical urban intervention to a third party. This includes transferring the responsibilities of the intervention, which reduces risks for the municipality. Delegating the task to a third party can also save a significant amount of time in terms of paperwork and justifying expenses for purchasing materials. Tactical Urbanism takes on another form through citizen-led initiatives, which are carried out by citizens, local community organizations, and businesses. As the process develops, more influential players may become involved. Citizens may use tactical urban interventions to protest, illustrate practicality, express alternative perspectives, or react against bureaucracy (Suslowicz, 2023).

To clarify, we are students from NTNU and can be classified under

Figures pp. 38-40. Tactical Urban Intervention 01/10/23 (Source: Authorship of Team PS - UEP 2023)

the institutional form of Tactical Urbanism. Our intervention was conducted in response to prior discussions and interviews. The purpose of our intervention was to engage with residents and gain knowledge from them, particularly regarding their willingness to participate in Tempe.

The location & announcement

The football field was chosen as the location due to its spaciousness and lack of a specific function. It was frequently mentioned during conversations and semi-structured interviews with the community. According to the municipality (see 4.6. Semi-structured interview with municipality), a participation process has been initiated for the transformation of the football field. The intervention may offer new insights for this process.

The football field is somewhat hidden within the neighbourhood and is not visible from the main roads, which posed a challenge in attracting enough participants. To overcome this, we promoted the event within the community by distributing posters and making announcements in the Tempe-Sorgenfri Facebook group.

Obstacle course!

In response to feedback from residents and stakeholders, we have decided to construct an obstacle course. Barnahaga SA and the Health and Welfare center expressed a need for play equipment for children and more activity on the football field. The obstacle course can also complement the municipality’s future plans to build a playground. This intervention aims to gather information about the residents’ opinions and their awareness of the municipality’s plans. Additionally, it provides an opportunity to engage with children and gather their feedback on the football field. Do they use it? What changes do they suggest? What type of playground do they prefer?

To create a playground or the obstacle course, we collected objects with no defined purpose that were easy to move around, allowing people to reorganize the playground themselves. We collected 30 pallets, an industrial cable reel, spray paint (green, blue, and yellow),

markers, and cardboard.

To increase the difficulty of the obstacle course, a stopwatch was added. The site was occupied from 12:00 to 17:00, and the materials were left in place when we departed. After a week, the materials were removed.

Results

The obstacle course results were satisfactory, despite the rainy weather and the low amount of people being outside. Every child who passed by, attempted the course, with some initially hesitant but gaining confidence with parental support. Upon inspection, we noticed that the pallets were consistently being rearranged, suggesting that they may be used frequently by the children.

Findings

The people that were attracted to the obstacle course were mainly children and parents or grandparents. Students passed by but were not interested in engaging. Elderly (except for grandparents with their grandchildren) were not passing by, so we have no indication about what their opinion is.

Some people are interested in participating in the improvement of the public space.

A great number of the residents aren’t aware of the future plans of the municipality about the area.

The temporal intervention worked as a way to raise awareness. People came to the event and gave their support to the project and expressed a wish to participate.

For the playground, objects with no defined purpose works well since children can move them as they want.

By having the choice to reorder the object, it gives them ownership of the place, therefore activating it.

Even though we mainly aimed at activities for kids, it’s important to have spaces for everyone, like a sitting area for the parents and elderly. Some neighbors also suggested an ice rink and a fire pit, making the space enjoyable for both summer and winter.

Public Space | Tempe-Sorgenfri | 40

5. Concept for solutions

5.1.

In a participatory process, reaching certain demographics proves challenging. In previous studies conducted in Tempe, such as the research titled “Resident Participation and Common Areas in Rental Housing” focused on the Ola Frost Veg by an NTNU researcher, a survey aimed to “develop suitable participation models for professionally managed rental housing” (Narvestad, 2021).

The survey (see figure 5.1) had 56 participants, including 6 respondents aged 18-30 (none of whom were students) and 20 respondents aged 60-70. The results indicate that the elderly group (60-70) is more receptive to participation compared to the younger generation (18-30). Furthermore, certain groups, such as ‘foreign-cultural immigrants,’ provided minimal responses (Narvestad, 2021).

“Marginalized voices” and “noise”

The groups that lack representation often consist of marginalized voices, defined as “when groups or individuals are pushed to the edge of society and are not afforded an active voice or place in the community” (Bradshaw, R. 2020). Another case of ignored voices occurs when they are categorized as noise, defined as “when people raise their voices to challenge existing discourses and the status quo”, and are decided to be ignored by those in power, “since it tends to be loud, unpleasant, and causing disturbance” (Refstie & Brun, 2016. p 137).

Marginalized voices, defined as “when groups or individuals are pushed to the edge of society and are not afforded an active voice or place in the community”

(Bradshaw, R. 2020

Noise, defined as “when people raise their voices to challenge existing discourses and the status quo” (Refstie & Brun, 2016. p 137)

41 | Tempe-Sorgenfri | Public Space

Figure 5.1. Amount of responses survey Ola Frost Veg in Tempe distributed by age (Source: Narvestad, 2021)

Amount of responses survey Ola Frost Veg in Tempe distributed by age

Low voices

We define low voices as:

“Those who are not reached or engaged throughout the design process. Consequently, their opionions and needs are either unheard or assumed.”

Public Space | Tempe-Sorgenfri | 42

Both of these cases are too extreme for the situation in Tempe. The municipality is doing the effort to make participatory processes for the renovation of some areas but all the projects are driven by budget so defining the level of participation in any project is strongly influenced by money and time. It is in debate within the municipality if it’s worth it to talk with the residents in an area when it is already in their knowledge what they want and other groups are hard to reach as stated in our earlier interview findings (Semi-structured interview. Municipality of Trondheim). The former sentiment was more focused about the elderly population.

“Low voices”

Since these hard-to-reach people do not fit the description of marginalized or noisy voices, we propose the term ‘low voices’. This term can be seen as a softer form of ‘marginalized’. Low voices refer to “those who are not reached or engaged throughout the design process. Consequently, their opinions and needs are either unheard or assumed.” The term low voice was also used by the municipality while having the interview.

The actual process the municipality is implementing, as it is in the case of Tempe, consists of establishing communication with Nardo school, where students actively participate in the decision-making process. The students elect representatives to form a council that attends meetings with the municipality’s consultant and project manager. Then, the municipality collaborates with an architecture consultant to develop a design based on the conclusions drawn from these interactions. (see 4.6 Semi-structured interview Municipality)

According to Arnstein’s Ladder of Citizen Participation (Sherry R. Arnstein, 1969), the current level of participation in this process falls under the categories of placation or tokenism. This implies that while the municipality acknowledges the voices of the representatives (in this case, the students), their input may not be fully integrated, as the ultimate decisions are made by the municipality.

43 | Tempe-Sorgenfri | Public Space

Ladder of Arnstein

Figure 5.2. Ladder of Arnstein, 8 levels of participation (Source: Sherry R. Arnstein, 1969)

Every case is unique and may be more accessible to a specific group. How can we ensure inclusivity for as many people as possible? To identify these low voices, we investigate each group for exclusion criteria in each specific case. This criteria is based on interviews and an analysis of the actual process.

Language: The actual process of informing residents at the start of a participation process is by sending an email in Norwegian. This is a problem because not everyone in Tempe speaks Norwegian.

Considering that more than 31% (see 4.2. Statistics) of the residents are international, language can be seen as a barrier and can make people feel and be excluded.

Interests: If the process only addresses one type of issue and the activities proposed are not inclusive, this can lead to disengagement.

Age: By having limited representation with a particular group giving importance to a particular one, or well, by assuming incompetence, underestimating the capabilities of certain groups.

Gender: As explained in HER City, “research shows that girls and women do not use a city’s public spaces to the same extent as boys or men” (Andersdotter Fabre, et al., 2023, p. 9). This can happen when assumptions are made about stereotypical gender roles, when one activity is more appropriate for one gender than another, and when the diversity of gender identities is not taken into account.

Cultural differences: Given that Tempe is home to people from many different cultures, a lack of awareness of cultural norms can lead to exclusion; this adds to the friction between some nationalities, as explained in the discussion with the Barnahaga

Schedule: Meetings and gatherings typically take place on weekdays, which may make it difficult for certain groups to attend due to work and childcare responsibilities. This was previously explained in the Waffle Day section (see 4.4.1. Small talks).

Educational or professional background: It is important to take in consideration the background of the people. When applying a par-

ticipation method or explaining a participation case, it is necessary to use a way of speaking that everyone can understand. ‘‘User participation is meaningless if participants cannot understand what is being proposed’’ (Kheir Al-Kodmany, 2000, p. 220).

As mentioned before, these criteria of exclusion are based on our findings in the neighborhood, depending on the case it can be added more or changed to suit the situation.

Criteria of exclusion

Public Space | Tempe-Sorgenfri | 44 5.2. Criteria

exclusion

of

Figure 5.3. Criteria of exclusion defined through the analysis and interviews (Source: Authorship of Team PS - UEP 2023)

5.3. Profiles

To understand a community, it is useful to profile its citizens into groups that share similar characteristics, as explained in Tools for Creating a Community Profile, a guide prepared by the University of Hawaii at Manoa (2021). A community profile provides a comprehensive understanding of the demographic and social characteristics of a particular group of people in a particular place. This information is essential for professionals to assess needs, secure funding, allocate resources, and develop strategic plans; in our case, to develop specific strategies for engaging each group in participatory processes.

In order to create profiles for the development of public spaces, it is crucial to conduct a thorough analysis of demographic data. It is essential to draw conclusions from observations, interviews and discussions with different stakeholders in the area. This process should actively involve residents to understand how they identify within the community.

Profiles should start with broad information and then become more detailed to provide more accurate results and better representation. For example, the UNESCO definition of youth is 15-24 years old. Because people between these ages don’t necessarily share the same interests, there are different ways to approach and engage them. The same applies to individuals who speak the language of the country and those who do not, families with young children versus families with teenagers, people with limited mobility and so on. There are these sub-categories that can be applied to any profile, but depending on the case, only those that can be addressed will be taken into account.

5.4. Case study area Tempe

To apply the profiling and exclusion criteria to define the low voices, we decided to choose a case study area. Tempe-Sorgenfri is a very large neighbourhood as a whole. It can be divided into four sub-areas with different characteristics. As a case study we will focus on Tempe because it is the area with the most people, the largest area spatially and the most diverse in terms of stakeholders.

Tempe as case study area

45 | Tempe-Sorgenfri | Public Space

Figure 5.3. Map of Tempe as case study area (Source: Authorship of Team PS - UEP 2023)

5.5.1 Functional analysis

The functions shown in this map can be classified as either formal or informal. The concept of formality and informality is very complex. In the context of the functional analyses, we want to talk about the informal social factors, which “include the relationship between an individual and other individuals or groups, and the resources available to individuals that may influence their social interactions with others (for example, financial resources, time and health, etc.)”, and the formal social factors, which “comprise organizational policies and structures (decision-making processes, social structure and organization of activities, etc.) (Williams, 2005).

We talk about ‘informal functions or activities’ (such as friendship groups) and ‘formal functions’ (such as supermarkets). The formal functions are easy to discover, they are public and official, so they are visible. Informal functions can be harder to recognise because they are less visible. However, they can be valuable in defining the needs of an area. These unregistered activities can refer to a need that people have created for themselves, which can lead to a sense of ownership and pride. In Tempe we have recognised student groups as formal activities, on Google Maps some student residences mark themselves on the map and add information. One example is ‘Holters bar og Klub’ (Google Maps, 2023).

These activities can help to understand the people who live in the neighbourhood, which is helpful for a participation process. Informal activities can often be related to hobbies, sports or other activities that bring people together.

indoor hall that is used weekly, especially during the winter season. There is also a cafeteria that is open to people outside the health centre.

Economic:

2. The MAX centre includes an Extra supermarket, hairdresser, pharmacy, bicycle shop, Trondheim Bydrift (municipal administration) and offices.

3. Transport company run by the same family for several generations

4. Pest control shop

5. Clothing web shop

6. Photo studio

7. Petrol station including a Seven Eleven

Social functions:

8. The football field, which is now rarely used.

9. Ola Frosts Park, a small park with some play equipment for children and several places to sit and enjoy the surroundings. Overall, the area is popular with the residents and is used more in the summer than in the winter.

10. Kindergarten Barnahaga SA, most of the children enrolled in the kindergarten are from Tempe. They play an important role in the community. The kindergarten also has a playground

Informal

Formal

Healthcare:

1. Tempe Health and Welfare center: This centre for the elderly plays an important role in Tempe as they have strong links with the community and help to organise various events such as the Tempe Festival and activities that bring the elderly together with children. They have an

11. There are three student groups that have identified themselves, but it is important to note that there may be other similar groups that have not been identified.

Informal groups, such as those based on friendships and family relations, can be more difficult to recognise. Additionally, the Facebook group Tempe-Sorgenfri is an example of such a group.

Public Space | Tempe-Sorgenfri | 46

5.5 Mapping analysis Tempe

47 | Tempe-Sorgenfri | Public Space

Facilities Tempe-Sorgenfri and the surrounding

Figure 5.4. Map of facilities in Tempe and surrounding (Source: Authorship of Team PS - UEP 2023)

5.5.2. Public space analysis

There is a clear division between public and private spaces in the area.

The northern half of Tempe, which is primarily composed of detached houses, occupies a significant portion of the neighbourhood. Public spaces in this area are limited to the roads and the football field, with no direct access to the Nidelva river.

The southern half, on the other hand, has more public spaces than private ones, including two indoor spaces that are not explicitly defined as public or private: the MAX centre and the cafeteria in the Health and Welfare centre. The marked outdoor public spaces in this area include the Ola Frost park, the playground, and the Nidelva river.

Public Space | Tempe-Sorgenfri | 48

49 | Tempe-Sorgenfri | Public Space Public and private spaces Tempe

Figure 5.5. Map of the public and private spaces in Tempe (Source: Kartverket, s.d. )

5.5.3. Green analysis

Tempe features a prominent green structure that gives rise to smaller interconnected green areas weaving through the neighbourhood.

The municipality classifies nature into four categories based on “factors such as the occurrence of red-listed species, rarity, continuity, important biological function, size, etc.” (Trondheim kommune, s.d.). The four categories of nature are:

Value A - Very important

Value B - Important

Value C - Very locally important

Value D - Locally important

The football field is considered as D - locally important. This “applies to areas that have a certain biological diversity, but are not rare or particularly valuable in terms of particular species/nature types.” (Trondheim kommune, s.d.). In areas with value D, the ecological functions must be maintained.

The Nidelva river is a highly valuable nature reserve, with different areas designated as A, B, or C. The football field in Tempe has been designated as value D.

The pilgrim path along the Nidelva river is part of a larger network and has interregional significance. However, it is difficult to access, particularly for elderly and disabled individuals (see 4.4.2.

Discussion Tempe Health and Welfare centre). Improving the connection with Tempe would enhance accessibility. In addition, much of Tempe is covered in grass, which limits ecological diversity, and the Holtermanns veg acts as a barrier, blocking the expansion of greenery. There is no green structure along the bicycle path except for one next to Ola Frost park. This presents an opportunity.

Public Space | Tempe-Sorgenfri | 50

51 | Tempe-Sorgenfri | Public Space

Green analysis Tempe

Figure 5.6. Map of the green analysis of Tempe (Source: Authorship of Team PS - UEP 2023)

5.5.4. Property and green