Margriet Schavemaker Director, Kunstmuseum Den Haag

‘We Should All Be Feminists’: these words are writ large on a T-shirt in the first room in our grand fashion exhibition DIOR – A New Look at Kunstmuseum Den Haag. Maria Grazia Chiuri, the current creative director of Dior, took these words from the famous 2013 TedTalk and subsequent essay by Nigerian writer and activist Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie. This is a sentiment close to my heart. We live in a world where gender inequality is still commonplace at all levels. The fact that Chiuri, the first female creative director at Dior, expresses herself as a feminist in her work and her words, is therefore important. In the exhibition, fashion and costume curator Madelief Hohé explores the layers in her work, presenting it in dialogue with that of the founder of the fashion house, Christian Dior.

Fashion is of course the work of many hands. The hands of people in the spotlight, but above all people behind the scenes. The same is true of a fashion exhibition. I would like to thank everyone – from within and outside the museum – who has contributed to this first, large-scale exhibition on Dior in the Netherlands. I would like to express my deep gratitude to Dior, the team at Dior Héritage and La Galerie Dior for the generous loans and their collaboration, with a special word of thanks for Olivier Bialobos, Deputy General Director of Christian Dior Couture,

Chief Communication and Image for Christian Dior Couture and Parfums Christian Dior. We are delighted with and proud of our pleasant cooperation. I would also like to thank all lenders – fellow museums in the Netherlands and abroad, and many private individuals –for their trust in us and the beautiful and greatly appreciated items they have loaned us.

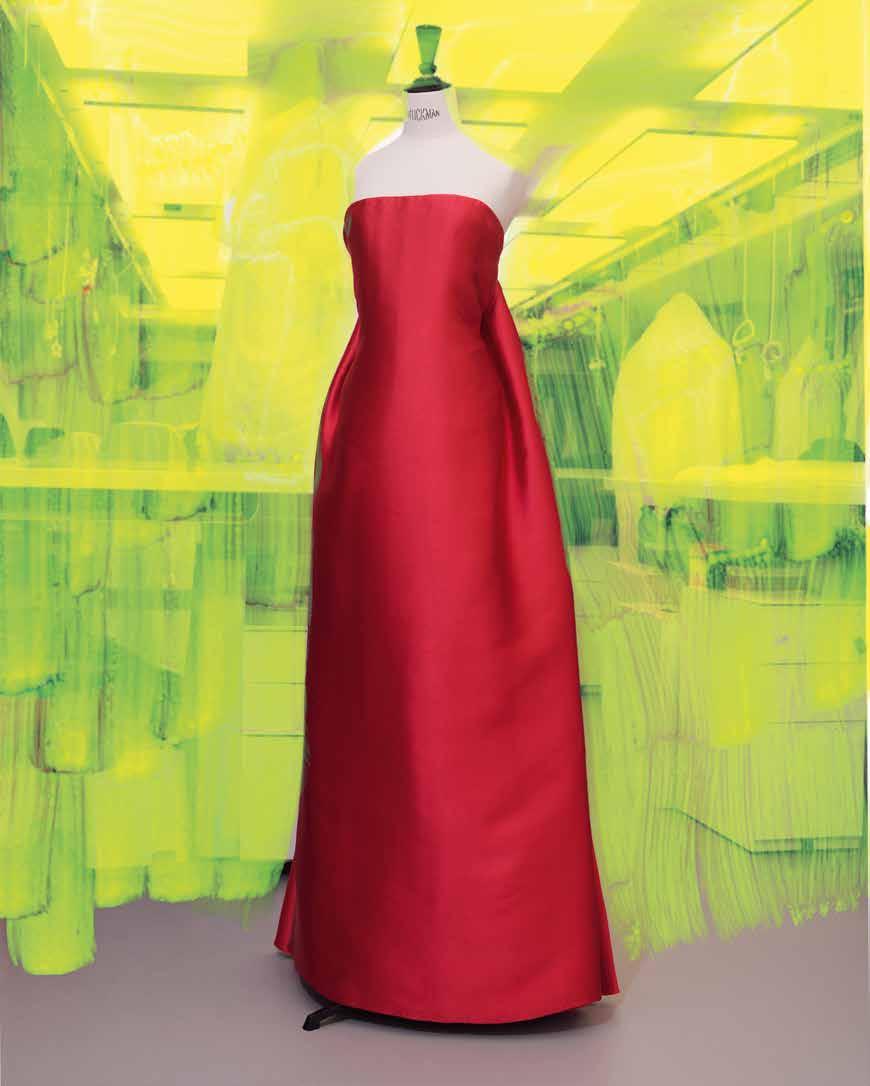

DIOR – A New Look was initiated and conceived by Kunstmuseum Den Haag and will be shown exclusively in The Hague. Thanks to Nationale-Nederlanden, Fonds21 and the Blockbuster Fund for their support for the exhibition. Waanders Uitgevers has published this beautiful catalogue. Many thanks to Marloes Waanders and to Loes Claessens for the design. Maarten Spruyt, the art director for the exhibition, has produced a fabulous design, in collaboration with Tiago Rosaro and Felipe González Cabezas. Finally, a word of thanks to the two photographers who provided the images for this catalogue. Alice de Groot took most of the images of the collection. Kunstmuseum Den Haag also invited leading photographer Viviane Sassen to produce a series of photos of work by Christian Dior and Maria Grazia Chiuri in Paris. She shot this series at the couture ateliers at 30 Avenue Montaigne, the place where Christian Dior most loved to be, and which is still the heart of Dior couture.

Madelief Hohé fashion and costume curator

‘You have to be a curator of ideas’ —Maria Grazia Chiuri

On 12 February 1947 Christian Dior presented his first collection at his brand-new fashion house. It was a huge success. Why? Because Christian Dior had designed a new, feminine look that was completely different from the austere, militant fashion of the time. Dior created a collection with long, full, flowing skirts, brought the narrow waist back and combined it with round shoulder lines and an emphasis on feminine curves. It sparked a revolution. American fashion journalist Carmel Snow dubbed the collection the ‘New Look’. Everyone was talking about it, and the new fashion silhouette was soon imitated –from couture to ready-to-wear.

Christian Dior’s success was unprecedented. Within just a few years he became a household name around the world. Dior worked hard to achieve this, together with his team. He was a modern businessman with a good eye for publicity and a feel for marketing. He travelled the world with his models, giving shows. Every time he launched new lines they not only rocked the fashion world, but also actually became the fashion. Including in the Netherlands. It took

a little time before the Dutch market grew accustomed to the ample shapes of the New Look in 1947, certainly so soon after the war, at a time when textiles were still rationed. But public opinion soon turned, and De Groene Amsterdammer magazine wrote of Christian Dior, ‘He does indeed have his own very unique style, none of the others makes clothes like he does.’ Christian Dior was not able to enjoy his success for long, however, as he died suddenly in 1957. His assistant, 21-year-old Yves Saint Laurent, succeeded Christian Dior as creative director. Within those ten successful years, Christian Dior managed to build a fashion empire that encompassed haute couture, perfume, a boutique range, accessories and worldwide licensing agreements. His successors remained faithful to a number of elements that were key to the work of Christian Dior, such as his New Look silhouette, other distinctive Dior silhouettes, his love of flowers and of strong women, and his ‘Dior dream’, the fairytale creations that were the dream of so many. These elements form the core of this exhibition, in which the work of Christian Dior himself enters into a dialogue with that of his successors. They are, in chronological order: Yves Saint Laurent (from 1957 to 1960), Marc Bohan (from 1960 to 1989), Gianfranco Ferré (from 1989 to 1996), John Galliano (from 1996 to 2011), Raf Simons (from 2012 to 2015) and Maria Grazia Chiuri (since 2016). Chiuri, who is currently at the helm, has the biggest platform in the exhibition. She regards herself as a curator of ideas, allowing the distinctive style of Christian Dior to inform her designs.

The title of this fashion exhibition not only refers to the iconic, feminine New Look, but also to the current era, in which the ideas of the founder live on. Maria Grazia Chiuri has made a thorough study of Christian Dior’s vision and the DNA of the fashion house, but she designs for today’s women. ‘If Dior is about femininity, then it is about women. And not about what it was to be a woman fifty years ago, but to be a woman today.’

DIOR – A New Look takes a fresh look at the couture house, showing designs by Christian Dior himself and by his successors. The central narrative is the dialogue between the work of founding father Christian Dior and Maria Grazia Chiuri. The bold, individual and progressive style of these two designers has impact, and is perfectly in tune with the spirit of their times. They have both given the couture house a fresh ‘New Look’ with their statement looks.

The exhibition also presents Dior stories from the Netherlands. The catalogue highlights Dutch women who wore Dior designs. Who were they? Which designs did they wear? It also considers the makers – men, but also lots of professional women who made Dior designs under licence for their Dutch clients. Many were anonymous, but some were famous names, and the main breadwinners in their families, like Mrs Kruysveldt de Mare and Theresia Vreugdenhil of Amsterdam. They would travel to Paris to choose the Dior designs they regarded as most suitable for their clients, and in accordance with ‘Dutch tastes’. Dutch fashion journalist Constance Wibaut also attended Dior shows in Paris, and would publish illustrated reports on them in Elseviers Weekblad magazine. The exhibition also includes some of her drawings.

Work on DIOR – A New Look has been underway for more than 10 years, involving a large team of people from Kunstmuseum Den Haag and elsewhere. Dior Héritage, the Dior archives, gave us full access to their collection of documentation. The first contacts concerning our research took place when the fabulous Dior archives we know today were still being built, under the inspiring leadership of Soizic Pfaff, director of Dior Héritage. I would like to thank her most sincerely for the years of support as we researched the exhibition, as well as her successor, Perrine Scherrer, who helped us immensely, along with her team. The same is true of Joana Tosta, Senior Manager, Image Projects at Dior Héritage and her colleagues. Our museum colleagues at La Gallerie Dior, including Olivier Flaviano, director of La Galerie Dior, and Hélène Starkman, Cultural Projects Director for Dior, and their teams, proved invaluable throughout the process of creating the exhibition. Our research not only concerned items from our own collection at Kunstmuseum Den Haag, but also encompassed items loaned for this exhibition by other institutions, bringing new information to light that enabled new connections to be identified. I am glad we had the opportunity to work together at international level, and would like to thank everyone who was involved.

A number of fellow curators from the Netherlands and abroad contributed pieces for the catalogue. There are so many lovely books about Dior that our common goal was to add new information wherever possible. Many thanks to all the authors for their input. This English edition was made possible thanks to a generous donation from Dior, for which Kunstmuseum Den Haag would like to express its immense gratitude to Olivier Bialobos, Deputy General Director of Christian Dior Couture, Chief Communication and Image for Christian Dior Couture and Parfums Christian Dior, and Olivier Flaviano, Director of La Galerie Dior.

Christian Dior (1905–1957), who had an indelible influence on the history of fashion in the mid-twentieth century, first spent long years seeking his path in life, before being ‘reborn’ in 1946, when he founded his fashion house at 30 Avenue Montaigne in Paris. Crowned with success from his very first collection, in his autobiography Christian Dior et moi (Dior by Dior)1 published a decade later, he evokes this other Dior, stating that ‘For whether I like the thought or not, my inmost hopes and dreams are expressed in his creations.’2 Today, Dior is heir to this particularly rich history, which those at the helm of the fashion house have continually reinvented.

1 Christian Dior et moi was published in 1956 by Éditions AmiotDumont in Paris. The first English translation appeared in 1957 and a Dutch translation was published in 1958, under the title De mode en ik, by A. W. Bruna & Zoon in Utrecht.

2 Christian Dior, Dior by Dior, translated by Antonia Fraser, London 2012, p. 11.

3 Ibid., p. 215.

4 Ibid., p. 217.

Christian Dior was born in Normandy on 21 January 1905, to a family of industrialists who lived in a villa perched on a cliff in Granville, a seaside resort popular with Parisians every summer for its fashionable beaches. His childhood home, roughcast in a very soft pink mixed with grey gravel, is surrounded by a vast garden overlooking the sea. Dior confides in his autobiography that, ‘In a certain sense, my whole way of life was influenced by its architecture and environment’.3 The young Dior grew up among flowers, for which he cultivated a passion he shared with his mother Madeleine, going so far as to memorize their names and descriptions by poring over the Vilmorin-Andrieux seed catalogues. ‘I could be amused for hours by anything that was sparkling, elaborate, flowery, or frivolous’,4 writes Dior, for whom the ‘magic years’ of his childhood would remain an endless source of inspiration.

In 1910 the Dior family moved to Paris, which had then entered the waning years of the Belle Époque. Lacking any interest in taking over the reins of the family’s business, Christian Dior developed a passion for art in all its forms. The Roaring Twenties, following the end of the First World War, were characterized by an extraordinary effervescence for which the French capital was the nerve centre. Dior’s taste and style took shape in contact with his ‘elective affinities’: ‘We were just a simple gathering of painters, writers, musicians, and designers, under the aegis of Jean Cocteau and Max Jacob,’ he recalls.5 In 1928, at the age of twenty-three, he convinced his parents to let him open an art gallery with his friend Jacques Bonjean, before setting up another one with Pierre Colle. Both galleries exhibited works by famous artists of the time like Picasso, Braque and Matisse, but also by Surrealists and Neo-Romantics, the latter including Dior’s friend Christian Bérard. The premature death of his mother in 1931, and the financial collapse of his father’s business a few years later, forced Dior to close the gallery and find another line of work. Following the advice of his friends, Dior moved into fashion design and illustration. After several months of conscientious apprenticeship, he began selling his sketches of hats to milliners in Paris, while the newspaper Le Figaro commissioned illustrations from him for its women’s pages. In 1938 he was hired as a designer at Robert Piguet’s fashion house. There he was able to witness the entire transformation involved in haute couture, from the fashion sketch to the finished product. After a short period of military mobilization in 1939, Dior lived for a time in Callian, a village near Grasse in the south of France, with his father and his sister Catherine, before returning to Paris in 1941.

5 Ibid., p. 227.

6 Christian Dior, Je suis couturier, Paris 1951, p. 23.

7 Didier Grumbach, Histoires de la mode, Paris 2017, p. 34.

8 Edmonde CharlesRoux, Herbert R. Lottman and Stanley Garfinkel, Théâtre de la Mode. Fashion Dolls: The Survival of Haute Couture, Portland 2002.

He then joined the house of Lucien Lelong as a designer, working alongside Pierre Balmain. Having taken over his family’s fashion house in 1918, which he moved to 16 Avenue Matignon in 1924, Lelong favoured fluid, minimalist and elegant designs. During his time with Lelong, Dior gained greater understanding of dressmaking’s technical aspects, including the importance of cutting as well as the grain of fabric. ‘Creation and execution are the two prerequisites for valid work’, he concluded in 1951.6

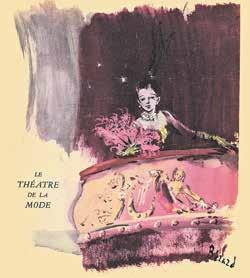

Lelong had chaired the Chambre Syndicale de la Couture since 1936. Founded in its current form in 1911, this association brought together the fashion houses having been officially granted designation as haute couture establishments, for which they had to meet a certain number of criteria, in particular the originality and number of designs made to order for clients by their ateliers. While fine-tuning his skills over the five-year stint with Lelong, Dior also became aware of the economic and cultural importance of French couture, which had been under threat during the war. Indeed, beginning in the summer of 1940, members of the Third Reich with responsibility for the textile industry, who were fully aware of its value, as much for the economy as for a nation’s image, sought to relocate the centre of haute couture to Berlin and Vienna.7 After protracted negotiations, Lelong managed to scuttle this plan. It was also under his leadership that the touring Théâtre de la Mode exhibition was launched in the immediate aftermath of the Second World War:8 forty fashion houses, including prominent names like Balenciaga, Balmain, Rochas, Lanvin and Schiaparelli, were invited to create scaled-down designs to be presented on small wire-frame figurines – as necessitated by fabric shortages – in stage sets designed by artists such as Christian Bérard, Jean Cocteau and Georges Geffroy. The exhibition, featuring more than 200 designs, was organized as a benefit for Entraide Française, whose mission was to coordinate assistance for war victims. After its initial presentation at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris in the spring of 1945, it travelled across Europe and then to the United States, reviving the status of French haute couture on the world stage.

In December 1946, Christian Dior opened his fashion house as an haute couture establish-

ment, with financial support from the textile entrepreneur Marcel Boussac, in a small townhouse at 30 Avenue Montaigne, with just three ateliers in the attic: two flou , or dressmaking, workrooms, and one tailleur , or tailoring, workroom. The spectacular success of the New Look presented on 12 February 1947 would have a considerable impact on the fashion house’s expansion. Seven years later, it extended over five buildings, bringing together twenty-eight ateliers, and employed more than a thousand people.9

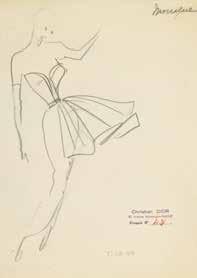

‘Growing up in age and in size, Maison Christian Dior was making its way in the world’, writes Dior in 1956.10 Branches, beginning with Christian Dior–New York, Inc. on Fifth Avenue in 1948, which offered collections adapted to American tastes, were quickly opened around the world and a stream of licences were arranged for manufacturing and reproduction. The scale at which the latter were being created inspired an entirely new business model for French couture, which could thus be distributed rapidly worldwide against the backdrop of strengthened international relations and the rise of new media. Parfums Christian Dior was also founded in 1947 by Serge Heftler-Louiche, one of the couturier’s childhood friends. The first Miss Dior fragrance was launched in December of that year, followed by Diorama in 1949. Soon, these perfumes would be distributed in 87 foreign countries.11 The first lipsticks came out in 1955 and Diorissimo was launched in 1956. The couturier, whose dream was to dress women in Christian Dior ‘from head to foot’,12 also offered a range of ‘colifichets’ (frivolities) – costume jewellery, scarves, gloves, shoes, etc. – as soon as he opened his house, a collection that would be given its own premises from 1955 in the most elegant boutique in Paris, on the corner of Avenue Montaigne and Rue François-Ier. The design of the fashion house’s interiors was inspired by the ‘Louis XVI-Belle Époque’ style so dear to Christian Dior. The pearl grey walls heightened with white mouldings, the medallion armchairs, and the toile de Jouy stretched over the counter of the first boutique and the walls of the fitting rooms expressed the quintessentially French taste he shared with his friend and interior designer Victor Grandpierre. The fashion house turns into a veritable ‘hive of industry’ once the creation of a collection gets under way. Christian Dior would begin by drawing between 600 and 800 sketches over about ten days, infinite variations on several main themes that would define the spirit of the season. He then sent them to the studio, where he would make his first selection, assisted by his small cadre of

9 Christian Dior company brochure produced under the direction of Geneviève Perreau, 1953.

10 Christian Dior, Dior by Dior, translated by Antonia Fraser, London 2012, p. 187.

11 Christian Dior company brochure.

12 Christian Dior, Dior by Dior, translated by Antonia Fraser, London 2012, p. 196.

14 Christian

15 Interview with Christian Dior, L’Aurore, August 1953.

16 Marthe Richardot, André Lacaze and Walter Carone, “Première présentation de la mode d’automne chez Dior”, Paris Match, 12 August 1950.

trusted colleagues: Raymonde Zehnacker, the studio director; Marguerite Carré, the technical director of the ateliers; and Mizza Bricard, the embodiment of French elegance, who also supervised the hat workroom. The contributions of these three women always proved invaluable for the couturier. The sketches were then distributed to the ateliers, where a ‘toile’ (the expression of the design’s volume in cotton muslin) was created, followed by the execution of the design using the selected fabrics. At each stage in the creative process, Christian Dior revised and corrected the 180 designs – afternoon, cocktail and evening dresses, but also suits, ensembles and coats – forming a collection put together in less than two months. The latter was finally presented in the luxurious Avenue Montaigne salons at shows attended successively by the press, professional buyers and private clients. The ‘cabine Dior’, a select group of twelve models, then travelled around the world to present the designs, first in Australia in 1948, as well as other destinations like the United Kingdom and in South America – with the support of KLM, at a time of rapid development in passenger air travel – not to mention Japan.

More than any other art, fashion reflects its time, because a designer must give voice to it through his or her seasonal collections twice each year. As the British photographer and writer Cecil Beaton recalls in The Glass of Fashion, Christian Dior was keen to point out that ‘each age seeks its image’. Accordingly, ‘his New Look [was] merely an expression of what his intuition told him was needed.’13 The ‘clothes for flower-like women’ designed by Dior in 1947 – ‘with rounded shoulders, full feminine busts, and handspan waists above enormous spreading skirts’14 – marked a return to femininity, after the war years when a very masculine silhouette held sway.

The New Look was in truth not entirely new, but inspired by nostalgia for the Belle Époque, whose undulating curves Dior adopted while injecting a distinct modernity in the tailoring. His incomparable success shows just how attuned the look was with the times, which called for going back to the essence of fashion, which ‘is even more about enhancing beauty than merely dressing, more about achieving the perfect look than merely

wearing clothes.’15 This is the tour de force of the fashion house founded by Christian Dior. In just several months’ time, Dior’s reputation had grown by leaps and bounds internationally and by 1952 it accounted for half of the French couture industry’s exports.16 Christian Dior re-established Paris as the preeminent capital of fashion, the only one with access to ‘the best artisans, the best fabric and the best traditions’.17 He continually invented new lines, from Zig-zag and Verticale to Tulipe, A, Flèche and Fuseau. Each season’s collection dethroned the previous one, reflecting a constant desire to be ‘in its style’.

On 3 August 1955, Christian Dior –the ‘Watteau of contemporary dressmakers’18 – was invited to give a lecture on the aesthetics of fashion in the Sorbonne’s Grand Amphitheatre in Paris. He thus became the first couturier to share his insights at this prestigious venue on the ways in which fashion invents and reinvents itself and produces its creations. ‘Your fashion house is renowned worldwide . . . as one of the brightest contemporary stars in the French economy and as an exemplar of the French spirit’,19 stated Jacqueline Capelle de Menou, a professor of French civilization, in her introduction. In his lecture, Christian Dior pointed to the importance of preserving couture traditions and passing them down to future generations. He also confirmed that fashion –beyond the lines created each season and the wealth of techniques involved – had given shape to an entire national economy with the new opportunities opening up in the postwar period. ‘Creation is an ensemble of a thousand and one things’, concluded Christian Dior. ‘It’s a thousand and one skills gathered around the dressmaker. There are fabric manufacturers, silkworks in Lyon, woollen mills in the north of the country, artisanal trades, jewellery, novelties, bags, gloves, frivolities, embroiderers, along with dressmakers, plumassiers and many others, each making their contribution to the collective creation that is Parisian couture’.20

The 24 October 1957, a few months after making the cover of Time magazine, Christian Dior died suddenly of a heart attack in Montecatini, Italy. The event sent shockwaves far and wide. Hundreds of mourners attended the funeral of a man who had become one of the most famous French figures in the world. Carmel Snow, the Harper’s Bazaar editor in chief who coined the phrase ‘the New Look’ upon viewing Christian Dior’s first collection, paid homage to him, while questioning the ability of French haute couture to survive after his passing: ‘To him, there was nothing frivolous about the haute couture. In a machine age, he saw it as one

18

19 Lecture by Christian Dior at the Sorbonne in Paris, 3 August 1955.

20 Interview with Christian Dior by Lise Élina, “Instants du monde”, Radio Télévision Suisse (Geneva), 21 January 1955.

21 Carmel Snow, “Homage to Dior”, Harper’s Bazaar, December 1957.

22 Christian Dior press release, 14 November 1957.

23 Speech by Jacques Rouët, 15 November 1957.

24 “Christian Dior, comment il travaille”, La Femme Chic, 28 November 1950.

of the last refuges of the purely human – that is, the inimitable – and as an important manifestation of the great civilization to which he belonged. The continuing life and energy of the haute couture is vital to France. Christian Dior was vital to the couture. His death at the height of his powers will present it with one of the greatest challenges in its history.’21

Several days later, Dior’s managing director Jacques Rouët confirmed that the fashion house would continue its operations. The company’s press release indicated that ‘its authoritative strength and its reputation have spurred the creation of a school of taste, of the elegance of line, the harmony of colours and the quest for perfection that are fundamental to the techniques of fashion’.22 This ‘École Dior’ would henceforth be responsible for the fashion house’s creative and technical administration, while Yves Saint Laurent, the couturier’s ‘preferred disciple’ who had joined the House in 1955, would create the collections, alongside the small cadre of long-standing studio colleagues already in place.

What is this ‘school of style and taste’23 that Dior has managed to carry into the present day? It is modelled after Christian Dior, its creator, whose influences were expressed in the lines of his dresses as well as his technical prowess. As reported in the magazine La Femme Chic in 1950, this mastery of technique was ‘clearly based on in-depth knowledge of the visual arts (painting, architecture)’. The writer went on to ask, ‘Might it not also be possible to say that, in the construction of his designs, he is following the rules of harmony he learned when he was pursuing an interest in musical composition?’24 Furthermore, Christian Dior always put women at the centre of his art. He wanted

to enhance their beauty, without ever imposing a fashion, which must be defined above all by what they do with it. ‘As couturiers, we record and express, we don’t impose anything’,25 because it is the wearer’s personality that must ‘dominate fashion and the taste of the day’.26 In the rapidly changing post-war world, Christian Dior adapted haute couture ‘to the needs of every modern woman’, while making it ‘easier to wear’.27 His approach paved the way for the invention of the Miss Dior ready-to-wear line, which was launched by Marc Bohan in 1967.

All of Dior’s creative directors succeeding the founder – Yves Saint Laurent (from 1957 to 1960), Marc Bohan (from 1960 to 1989), Gianfranco Ferré (from 1989 to 1996), John Galliano (from 1996 to 2011), Raf Simons (from 2012 to 2015) and, since 2016, Maria Grazia Chiuri – are known for having created elegant fashions anchored in their time while continuing to draw on the Dior style, which ‘is reflected in a spirit more than in a line’, as Christian Dior had already affirmed in 1948.28 Today, Maria Grazia Chiuri adds that it is important for her to ‘translate this heritage in a language that probably is more about now, because I want to speak to a new generation of women.’29

Dior’s key strength as a fashion house is its ability to draw on a repertoire and a heritage both abounding in inspirations whose continual reinvention successfully situates its creations in the contemporary world, all while maintaining a constant and renewed dialogue through and between eras. In this vein, Cecil Beaton reminds us that ‘all artists who, apart from their unique personal gift, are also mediums transmitting the message of the art of the past inevitably are timely as well as timeless’.30 This is perhaps why – once again in the words of Christian Dior – couturiers are ‘the last possessors of the wand of Cinderella’s Fairy Godmother’, making fashion design ‘one of the last repositories of the marvellous’. This may also be what makes them immortal.

25 “La Mode et le Goût”.

26 Conversation between Christian Dior and Alice Perkins of Fairchild Publications at a lunch given by the American Women’s Group in Paris, 10 January 1955.

27 Interview with Christian Dior, L’Aurore, August 1953.

28 Interview with Christian Dior, 18 August 1948.

29 Hamish Bowles, “This Is Not Your Mother’s Dior”, Vogue, 15 November 2016.

30 Cecil Beaton, The Glass of Fashion, ch. 15.

31 Christian Dior, Dior by Dior, translated by Antonia Fraser, London 2012, p. 250.