MAGAZINE UVM

DEPARTMENTS

2 President's Perspective

6 The Green

18 Catamount Sports

20 Research Amplified

22 Student Voice

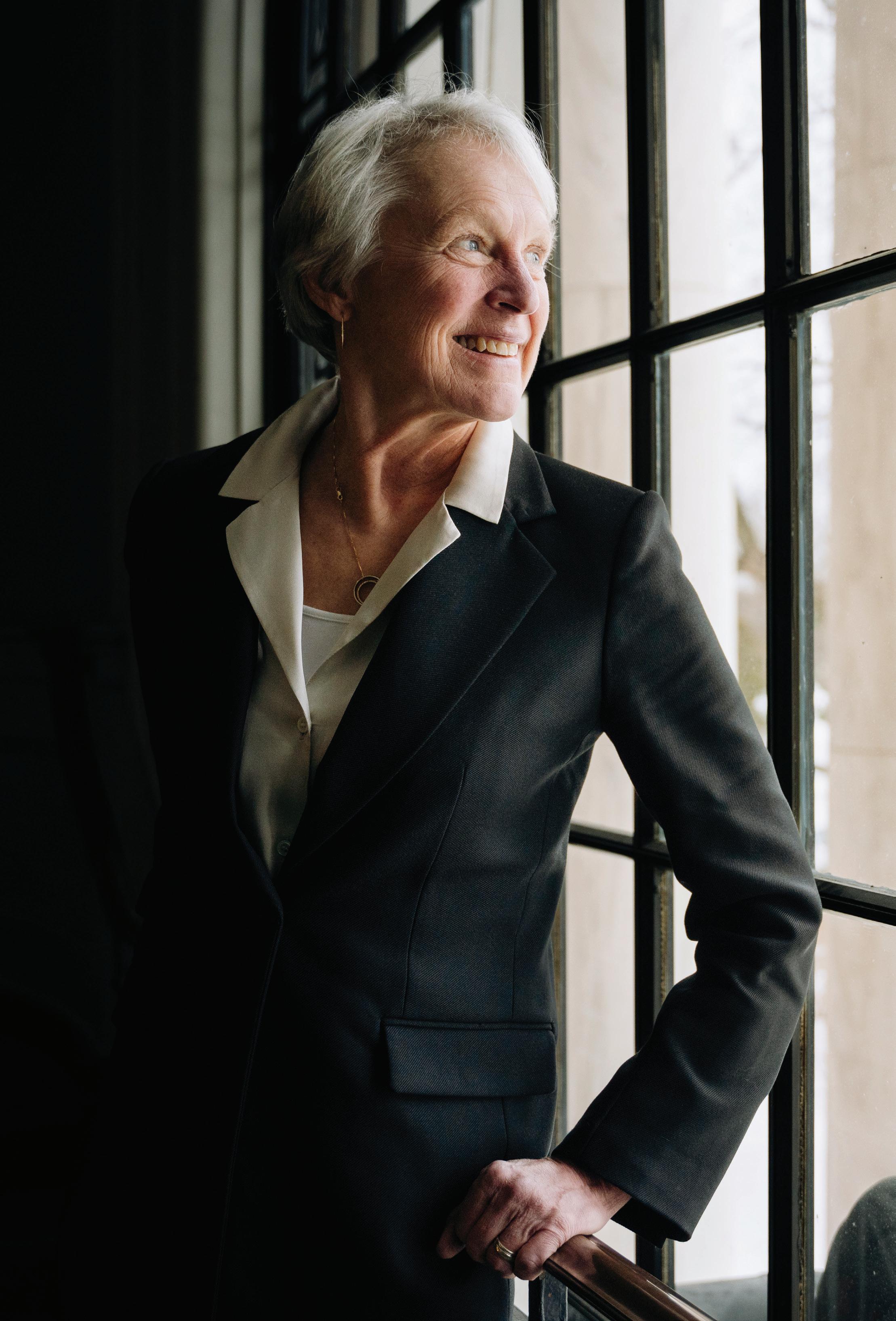

24 UVM People: Katharine Shepherd, Ed.D. Dean, College of Education and Social Services

26 Faculty Books

58 Class Notes

80 Extra Credit

FEATURES

28 TO SAVE THE FOREST, SHOULD WE MOVE THE TREES?

Trees migrate. But with rapid climate change, some can’t move fast enough. UVM researchers are exploring the potential and peril of helping trees to travel.

| BY JOSHUA BROWN38 PARASITE INSIGHT

The bites of kissing bugs transmit deadly Chagas disease. Biologist Lori Stevens is part of an international team working to wall it out—with high-tech tools and low-tech solutions.

| BY JOSHUA BROWN46 WINTER SNAPSHOT

All year, UVM hums with life and meaning. But there’s no denying that most magnificent of seasons: snow season! Here’s a portrait of our place in winter—before sunup to late night.

52 WE, ROBOTS

Three UVM professors, from radically different disciplines, dive into deep conversation about a shared and urgent interest: the meaning of humanity in the era of artificial intelligence.

so fast that “the trees can’t keep pace,” he says. It may be time to help them migrate.

FRONT COVER: On a bluebird day, plant biologist Steve Keller plugs into an iButton data logger on a slope of Camel's Hump. The temperature readings he and his students have been collecting here add to a portrait of the forest begun in 1964 by UVM botanist Hub Vogelmann and his student Tom Siccama. What Keller sees in 2023 makes it clear that the climate is warming Cover Photo: Joshua Brown Back Cover: Bailey BeltramoSPRING 2023

As the sun drops behind the Adirondacks, Lake Champlain puts on a show. When an Arctic blast came through in February, the comparatively warm waters tossed up spectacular columns of sea smoke and steam devils, towering over Burlington.

Photo by Adam Silverman

Photo by Adam Silverman

UVM is Emerging as a Research Powerhouse

As an enthusiastic advocate for American research universities and an active researcher myself, I am especially proud of this spring’s UVM Magazine that highlights some of the exceptional examples of discovery and innovation made possible by my wonderful colleagues at the University of Vermont.

The dividends of university research to society are immense—health, food security, mobility, communication, and many other fields have benefited tremendously. We live in a better world today thanks to the spirit of discovery that has been a critical part of American research universities for over a century.

For students, the appeal of research universities is greater than ever. While few undergraduates may claim research is a top reason for their college choice, they continue flocking to America’s leading research institutions in unprecedented numbers. The reason is clear: students today come to a university to make a difference from their very first day.

That difference is made through research and engagement.

Today’s students recognize that the world needs urgent answers to its most pressing problems—of poverty, new diseases, demographic changes, and climate change. A great classroom education— no matter how engaging—is necessary but not sufficient. Students want to immerse themselves in learning through hands-on research, innovative internships, global engagement, and testing solutions where the problems “live.”

Our undergraduate and graduate students work side by side with groundbreaking scholars who are expanding the boundaries of human knowledge. Their explorations take place in our labs, but as importantly, across the state and around the globe.

With its sometimes purposeful, sometimes serendipitous outcomes, research is a catalyst for fundamental intellectual advances and for growing the economies of our state and nation. We’ve seen remarkable innovations crafted and incubated in UVM labs launch into successful business ventures in recent years—and there are many more to come.

Our faculty invest tremendous effort, creativity, and intellect in expanding UVM’s research enterprise in fields that capitalize on our distinctive strengths –building healthy societies and a healthy environment. Their efforts are being recognized and rewarded more than ever.

Last year, external funding for research at UVM topped a record $250 million and we are on a trajectory to reach even greater heights, cementing our place among the nation’s top public research universities.

While eye-popping numbers capture attention, a subtler improvement is the diversification of research across the disciplines.

The Larner College of Medicine, historically UVM’s top-performer in attracting research awards, continues to win significant new grants for cuttingedge medical research. But over the past several years, the rest of the university has followed Larner College’s lead and achieved even more rapid growth. Today, project funding and awards are in a nearly even split between health sciences and the rest of the university.

Federal agencies, Congress, industry, and the State of Vermont recognize the value of partnering with UVM, and so it’s no surprise that our growth reflects some of the most pressing needs of our generation.

Two new research entities underscore the trend of solving problems through multi-disciplinary research. The Food Systems Research Center and the Institute for Agroecology foster and advance challenges that combine agriculture, economics, sustainability, and international development.

Later this year, we will launch the Institute for Rural Partnerships at UVM, linked closely with the specific characteristics of our state and region, yet capable of finding solutions that can be applied in other parts of the world.

This spring, UVM will recognize the director of the National Science Foundation, computer scientist Sethuraman Panchanathan, with an honorary doctorate when he speaks at our 222nd Commencement. Director Panchanathan’s point of view on the power of “knowledge enterprises” favors the innovation, partnership, and global entrepreneurship culture gaining traction on our campus.

I invite you to share in the pride that accompanies our ascent among the nation’s leading public research universities and to celebrate with us what this means for our students, our state, and our collective future.

—Suresh V. Garimella President, University of VermontPUBLISHER

The University of Vermont

Suresh V. Garimella, President

EDITORIAL BOARD

Joel R. Seligman, Chief Communications and Marketing Officer, chair

Krista Balogh, Joshua Brown, Ed Neuert, Rebecca Stazi, Barbara Walls, Benjamin Yousey-Hindes

EDITOR

Barbara Walls

ART DIRECTOR

Cody Silfies

CLASS NOTES EDITOR

Cheryl Herrick Carmi

CONTRIBUTING WRITERS

Joshua Brown, Beverly Belisle, Enrique Corredera, Christina Davenport, Joshua Defibaugh, Doug Gilman, Rachel Leslie, Rhonda Lynn, Rachel Mullis, Stephen Peters-Collaer, Jeff Wakefield, Basil Waugh

PHOTOGRAPHY

Bailey Beltramo, Joshua Brown, Joshua Defibaugh, Andy Duback, David Seaver, Adam Silverman, Mike Newbry, NordicFocus

PROOFREADER

Maria Landry

ADDRESS CHANGES

UVM Foundation

411 Main Street Burlington, VT 05401 (802) 656-9662, alumni@uvm.edu

CORRESPONDENCE

Editor, UVM Magazine 617 Main Street Burlington, VT 05405 magazine@uvm.edu

CLASS NOTES alumni.uvm.edu/classnotes

UVM MAGAZINE Issue No. 92, April 2023

Publishes April 1, November 1

Printed in Vermont

UVM MAGAZINE ONLINE uvm.edu/uvmmag

instagram.com/universityofvermont

twitter.com/uvmvermont

Because the world’s challenges are not simply complex, they’re existential.

YOU SHOULD KNOW

NATIONALLY RANKED SUPER SCIENTISTS

A new ranking of the top female scientists in the United States conducted by Research.com includes three UVM faculty members in the Larner College of Medicine. Mary Cushman, M.D., M.Sc., professor of medicine, was ranked 124th nationally and 193rd in the world. Jane Lian, Ph.D., professor of biochemistry, was ranked 194th nationally and 305th in the world. Janet Stein, Ph.D., professor of biochemistry, was ranked 265th nationally and 430th in the world. Read more: go.uvm.edu/topscientists

ANNOUNCING UVM'S 5TH CONSECUTIVE TUITION FREEZE AND THE "UVM PROMISE"

This past fall UVM announced freezing tuition and fees for a fifth consecutive academic year, an initiative begun by President Suresh Garimella in 2019 to keep UVM affordable and accessible for students and families from Vermont and across the nation. Also announced—the “UVM Promise,” a new program that guarantees full tuition scholarships to all dependent Vermont students in households with incomes of up to $60,000. Read more: go.uvm.edu/5thfreeze

top 2

TALKING THE TALK WITH THE NEW SCHOOL OF WORLD LANGUAGES

This spring, the UVM Board of Trustees approved the creation of a new School of World Languages and Cultures within the College of Arts and Sciences. Bringing together four departments—Asian Languages and Literatures, Classics, German and Russian, and Romance Languages and Cultures—under the same roof, the new school will open avenues for increased communication and collaboration both within the school and across colleges. Read more at go.uvm.edu/worldlanguages

GROSSMAN'S GREEN MBA GRABS A GOLD STAR, YET AGAIN

For the sixth year in a row, the Sustainable Innovation MBA (SI-MBA) program at UVM's Grossman School of Business was named a Top Green MBA by the Princeton Review’s Best Business Schools rankings— making it the highest ranked green MBA program that is accredited by the Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business. Read more: go.uvm.edu/top2mba

A WEEK OF WORLD-CLASS RESEARCH

NEWEST FACILITY: THE FIRESTONE MEDICAL RESEARCH BUILDING

President Garimella, Provost Patty Prelock, and Larner College of Medicine Dean Rick Page led the Oct. 29 dedication of UVM’s newest biomedical research facility, the Firestone Medical Research Building. Now occupied by more than 40 principal research investigators, the facility accommodates approximately 250 faculty, students, and staff working in the areas of cardiovascular health, brain health, cancer, and lung disease. Its ground floor houses the UVM Center for Biomedical Shared Resources, whose core facilities provide advanced technology for researchers from educational institutions and businesses throughout the state. Joining the dedication was lead donor Steve Firestone, M.D.’69. Learn more: go.uvm.edu/firestoneopening

In celebration of UVM’s recent historic increase in sponsored research—and to celebrate UVM becoming a Top 100 Public Research University—the campus is preparing for the second annual UVM Research Week, a celebration of research, scholarships, and creative works from across the University held from April 17 to 21. Learn more: go.uvm.edu/researchweek23

EDITOR'S CORRECTION

Our fall 2022 issue featured UVM’s Elliot Ruggles, who we described as the “firstever” Sexual Violence Prevention and Education Coordinator at the university. We’re grateful to Heather Hewitt Main, ‘89 G ’96, for correcting the record. She wrote to say that she held a similar position from 1996 to 2002 and there were others before her. “Until we end violence against women it will never be enough, but let’s not forget the work a generation ago by many people who prevented violence at UVM and beyond,” she writes. We fully agree; thanks, Heather.

The new hybrid electric vessel is the first of its kind for research and teaching, fully equipped to expand UVM's cutting-edge world-class research, deliver hands-on education programs to students of all ages, and welcome the public to learn about the mysteries, wonders, and significance of our great Lake Champlain.

— Jason Stockwell Director of the Rubenstein Ecosystem Science LaboratoryTHE LEAHY LEGACY –UVM'S NEW RESEARCH VESSEL NAMED

At an event commemorating the 50th anniversary of the Clean Water Act, UVM President Suresh Garimella revealed the name of the University’s new lake research vessel recognizing Sen. Patrick Leahy’s championing of the Clean Water Act and the many contributions to the University and region by his wife, Marcelle Leahy. The first-of-itskind research boat, a 64-foot hybrid electric aluminum catamaran that will serve as a floating classroom and laboratory, will be named R/V Marcelle Melosira, honoring the senator’s wife, Marcelle Leahy, and the legacy of R/V Melosira, the boat replaced by the new vessel. The vessel is expected to arrive early this year at UVM’s Rubenstein Ecosystem Sciences Laboratory, located in the Leahy Center for Lake Champlain on the Burlington waterfront. Read more: go.uvm.edu/marcelle

Cultivating Meat for A Sustainable Future

scaffolding for cultivating meat.

If this is successful, then perhaps we would have a world where we don't have to kill an animal to get meat.

To cultivate meat, cells from an animal must be acquired, usually through a muscle biopsy. Tahir takes that biopsy—which includes other elements like connective tissue and extracellular matrices—and isolates the cells, growing and multiplying them until their numbers are in the millions. Once enough cells are grown, they’re applied to a scaffold.

“Scaffolding recreates the microenvironment that cells grow on inside an animal's body,” Tahir

“If we want to produce cultivated meat at scale, we need scalable materials,” Tahir said. “Instead of extracting collagen from millions of animals, we need to turn to more sustainable sources such as seaweed.”

While there are overall ethical benefits to cultivated meat, there are some roadblocks in developing and growing cells for consumption. Once cells have been isolated from a biopsy, they’re fed a liquid media to encourage growth.

“The source for the liquid media is called fetal bovine serum, which comes from a calf. But it works so well because it's a soup of nutrients that allows the baby to grow,” Tahir said. “There's a huge movement in the field to try and replace this.”

Cultivated meat is part of an evolving field called cellular agriculture, and

Last year, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) announced that cultured meat was “safe to eat,” which bolstered the field of research around the country and at UVM.

“The announcement cemented the reality of cultivated meat one day appearing on menus nationwide,” Floreani said. “The decision is certainly another motivator for translating our research from the laboratory to cultivated meat producers, and having a real impact on the industry.”

“If this is successful, then perhaps we would have a world where we don't have to kill an animal to get meat,” Tahir said. “We're super far away from that scenario, but doing fundamental research toward that goal is important.”

Transforming Food Systems with UVM's New Institute for Agroecology

FOOD SYSTEMS | Climate change, and longestablished food production practices, have resulted in an unjust and unsustainable system that feeds the world’s population.

“Our food system is in crisis. We can no longer deny that the current model is exploitative of both human and natural resources, and unable to sustain and nourish the world,” UVM Professor of Agroecology and Environmental Studies Ernesto Méndez said. “Agroecology offers an alternative paradigm for food and farming that will build back agricultural biodiversity, confront the climate crisis, address inequity, and activate the power of farmers and citizens through transformations that aim for a thriving society and planet.”

UVM aims to be part of the solution. This spring the University created the Institute for Agroecology (IFA)—based in the Office of the Vice President for Research and the Office of Engagement. Méndez will serve as the IFA’s inaugural faculty director.

The new institute is an ambitious response to the growing calls to transform the world’s food systems in the pursuit of equity, sustainability, and wellbeing through a globally connected, locally rooted approach. The institute will allow UVM to crystalize its research, learning, and outreach in agroecology and food systems transformations through campus-community partnerships and new signature programs, and by providing resources and support for aligned projects. All of this will add capacity to existing initiatives and facilitate processes that will leverage and expand UVM’s land-grant mission.

The institute will integrate over a decade of research and international partnerships established by the Agroecology and Livelihoods Collaborative (ALC), a community of practice

at UVM that works with partners around the world to co-create new solutions to global food systems challenges. Through the strengthening of its wideranging global networks and programs, the institute will also boost UVM’s international reputation for cutting-edge transdisciplinary and participatory research.

For years, the ALC has partnered with local coffee growers in El Salvador, Mexico, and other nations to study their social, economic, and environmental roles in their respective regions. Agroecologists are drawn to coffee agriculture in large part because these shaded agroforestry systems express many social and ecological agroecological principles.

The IFA will benefit from UVM's newly established Food Systems Research Center (FSRC), a collaboration between UVM and the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) Agricultural Research Service, the first USDA research station designed to study local and regional food systems and the farms and processors that contribute to sustainable, healthy environments and people. The research center provides competitive funding that supports researchers in both the IFA and the Gund Institute for Environment.

“UVM’s Institute for Agroecology will be a national and international lighthouse for agroecology and will further revolutionize our growing research enterprise,” Vice President for Research Kirk Dombrowski said. “The Institute will forge new connections between researchers, communities, students, and farmers who will work together to push boundaries in impactful research, learning, and action. These new institutes and centers will synergize and strengthen UVM's collective and distinctive expertise in food systems research both here in Vermont and around the globe.”

New Institute Will Help Vermont’s Rural Communities Thrive

VERMONT | The new Institute for Rural Partnerships at the University of Vermont will help the state’s rural communities thrive in the face of big challenges brought on by climate change and population shifts, thanks to a $9.3-million award from the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s National Institute of Food and Agriculture, with leadership and support from U.S. Sen. Patrick Leahy, D-Vt.

“Vermont, like all rural states, faces unique challenges that affect such important issues as transit, economic and workforce development, water quality, food supplies, infrastructure, and broadband connectivity,” Leahy said. “The Institute for Rural Partnerships will enable the university to continue to be a leader in the studies of rural challenges not only within Vermont, but the nation. As chair of Senate Appropriations, I was proud to support UVM and am excited to see the incredible work that will be done through the establishment of the Institute for Rural Partnerships.”

Under the new institute, UVM will bring the resources and expertise of multiple UVM entities to help find solutions to the most pressing problems rural communities are facing—whether it’s a qualified

workforce, broadband access, clean water, sustainable energy, suitable housing, food production, supporting more welcoming and inclusive communities, or mitigating the stresses placed on the region’s lakes, rivers, and forests.

“The Institute for Rural Partnerships is an ideal realization of UVM’s land-grant mission in service to our state,” said University President Suresh Garimella. “Connecting the university’s talented research and innovation experts with promising, motivated groups with big ideas from across the state will deliver valuable impact in all 14 Vermont counties and beyond.”

“Vermont remains one of the most rural states in the country,” said UVM Vice President for Research Kirk Dombrowski, principal investigator for the project, whose office will house the new institute. “Across the country we have seen significant challenges to rural viability. Part of our land-grant mission is to take what we’ve learned and put it to the service of communities and help meet those challenges.”

Dombrowski said the institute represents a novel approach, a

“spin-in” concept, where partnerships with community-based groups looking for academic expertise will be seeded and fully supported by the University so they are in a better position to find community-based solutions to rural challenges.

“People will deal more effectively with the inevitable change that’s coming if they have the knowledge base, better data, and strong partnerships that the institute will facilitate,” said Dombrowski. “It’s a way to make a path forward and be part of a viable future, rather than resisting change at all costs.”

At the heart of the UVM institute will be an Innovation and Research Incubator seed-funding program to allocate funding and technical assistance to teams of collaborators composed of UVM stakeholders to fund research projects, student internships, and more for early-stage startups and nonprofit businesses working to address rural challenges.

The incubator will focus investment in Innovative Opportunity areas where UVM has deep expertise like regenerative agriculture, connected community schools, transit and housing reimagined, and more.

Senator Leahy Helps Secure Millions in Funding to Support UVM

UVM | Late last year, Sen. Leahy capped his support for UVM with the inclusion of $30 million in Congressionally Directed Spending (CDS) funding in the form of an endowment dedicated to enhancing the experience of its promising and ambitious students, especially through the university’s Honors College, and an additional $50 million in Vermont-focused research funding in the annual appropriations bills that fund the U.S. government.

University researchers will compete for funding from programs supported by Sen. Leahy to address issues important to Vermont, and for which UVM has a track record of research strength. These include U.S. government programs such as $15 million for Institutes for Rural Partnerships, $13 million for food systems research on small and medium-sized farms, $10 million for Rural Centers of Excellence on Addiction, $2 million for unmanned aircraft systems research, and $4 million to establish a new Climate Impacts Center of Excellence.

“On behalf of everyone at UVM, I must express my deepest gratitude for everything we’ve received in this budget,” University President Suresh Garimella said. “It is critically important for the state of Vermont that our university continues to strengthen the richness and quality of our academic offerings and expand the impact of our research enterprise. This funding will help drive those efforts forward for years to come.”

Garimella said the funding would “develop signature programs, support research excellence, and promote leadership and learning opportunities for our talented

students,” particularly those in its respected Honors College. He praised Sen. Leahy’s commitment to the university as integral to its emergence as a premier research institution focused on sustainable solutions with local, national, and global applications and impact.

“Senator Leahy’s impact on the university is incalculable,” Garimella said. “So much of our success over the years can be attributed to his help in securing the necessary resources for our work here at UVM.”

Garimella said the unflagging support of UVM by Leahy and fellow Vermont delegates Sen. Bernie Sanders, Sen. Peter Welch (D-Vt.), and Rep. Becca Balint (D-Vt.) remains centrally important to the success of its mission as the state’s public land-grant research university.

“We are so thankful that our delegation has such faith in the university and will continue to help with securing funding in support of UVM into the future,” Garimella said.

In a UVM lab, scientist Ajit Singh uses a specialized instrument for studying “isothermal titration calorimetry,” he says, “the only one in Burlington.”

AJIT SINGH

In 1953, James Watson and Francis Crick studied remarkable X-ray images made by Rosalind Franklin—and then put their minds together to unpack what Watson called “the secret of life.” Their study “A Structure for Deoxyribose Nucleic Acid,” published in the journal Nature, revealed the geometry of DNA. In the decades since, scientists have discovered many of the details of how DNA works and how genes are turned on and off in both healthy and diseased cells. UVM post doctoral scientist Ajit Singh continues the search. He studies in the laboratory of Professor Karen Glass, a researcher in the UVM Larner College of Medicine’s Pharmacology department and the UVM Cancer Center—part of a team investigating the signals that regulate genes and how alterations in these pathways are involved in cancer and other diseases.

Rhonda Lynn, in UVM's Graduate College, connected with Singh to learn more about his story and his work.

You study DNA and the intricacies of how it works. Where did this interest begin?

AJIT: As an undergraduate, I did some research in human genetics to determine how common features are inherited in humans. I was surprised to see that, although I look physically very similar to my brother, we have many distinct inherited characteristics from our parents and grandparents, such as tongue rolling, straight/curly hair, and so on. This piqued my interest in learning how the information encoded in DNA is controlled.

You grew up in India and are now at the University of Vermont to extend your exploration of DNA. Tell us about that journey.

AJIT: I was born in Uttar Pradesh, a state in India. My father served in the Indian army as a medical officer. He often moved jobs, so I attended seven different schools throughout my studies. Each new home, new place, and the search for new friends made it a typical childhood adventure. This childhood experience has helped me adapt to new environments more quickly. After completing my high school studies, I moved to the southern part of India to attend Bangalore University.

After college, I joined Dileep Vasudevan's team at the Institute of Life Sciences in Bhubaneswar, India, to investigate the riddle of how DNA is packed into cells— eukaryotic cells with a nucleus, which includes all animals, plants, fungi, and many unicellular organisms. I worked in his lab on the structure and function of what are called “histone chaperones” and discovered their role in DNA packaging.

To deepen my understanding of this part of biology, after I finished my Ph.D., I moved to Karen Glass’s lab at the University of Vermont. My research aims to discover how chemical changes in these histone proteins help manage DNA packing and make DNA accessible for translation of the information in its unique sequence. To understand this, I use various cutting-edge structural biology techniques in her lab, such as X-ray crystallography, nuclear magnetic resonance, and cryo-electron microscopy.

Can you tell us more about your research and its wider goals?

AJIT: Many organisms, including humans, plants, and parasites, have their DNA condensed into chromosomes. Each chromosome is, basically, a bundle of linear DNA looped into a complex called the nucleosome, which is composed of histone proteins and DNA. A wide range of biochemical reactions alter how histones interact with DNA—and control how DNA is compressed into chromosomes. I’m interested in a portion of proteins called “bromodomains.” Proteins that have these domains interact with the nucleosome and are often involved in regulating DNA processes, such as replication and repair.

In Dr. Glass’s laboratory, my research focuses on bromodomain-containing proteins in a parasite, Plasmodium falciparum—the main cause of malaria around the world. According to a WHO estimate, there were 409,000 global malaria fatalities in 2019, with children under five being most impacted. There is a pressing need to define the molecular pathways that lead to disease from P. falciparum—due to this parasite's alarming growth in drug resistance in recent years. It's interesting that this parasite’s genome encodes eight bromodomain-containing proteins and that at least one of them is crucial for the development of malaria. My recent publication on the crystal structure of one of these proteins —called PfBDP1—will aid in the development of drugs to fight malaria.

When you're not in the lab, what do you enjoy doing in Burlington?

AJIT: I like to bike, hike, play cricket and tennis, watch American and Indian movies, spend time in nature, and cook. Over the past year that I've been living in Burlington, I've discovered that it is endowed with a wealth of natural beauty, such as the snowfall in the winter. It seems like someone is showering a flower on me. I tried skiing for the first time this winter! The autumn maple tree leaf color shift is really stunning too. UVM has a really welcoming and supportive atmosphere.

As Winters Warm, The Threat of Nutrient Pollution Grows

CLIMATE | “Winter is changing,” says University of Vermont scientist Carol Adair, who recently revealed a significant new threat to U.S. water quality: as winters warm due to climate change, they are unleashing large amounts of nutrient pollution into lakes, rivers, and streams.

Her team’s landmark national study found that previously frozen winter nutrient pollution—unlocked by rising temperatures and rainfall—is putting water quality at risk in over 40 states across the Northeast, the Midwest and Central Plains, the Pacific Northwest, and the Sierra and Rocky Mountains.

Nutrient runoff—from phosphorus and nitrogen in fertilizers, manure, and more—has affected water quality during growing seasons for decades. But cold temperatures and a strong snowpack traditionally kept nutrients in place until spring thaw, when plants can help absorb excess nutrients.

But winter is now the fastest warming U.S. season. Winter rain and snowmelt are increasingly causing large, devastating floods that carry nutrients and soil through watersheds in winter when dormant vegetation cannot absorb them. As a result, winter runoff has transformed from rare or nonexistent to being far worse than other times of the year.

The study, published in Environmental Research Letters, found that “rainon-snow” events affect 53% of the contiguous United States., putting 50% of U.S. nitrogen and phosphorus pools at risk for export by ground or surface water. Where these factors converge, more than 40% of the contiguous United States is at risk of winter nutrient export and soil loss.

“This study is a wake-up call for government agencies and researchers,” says Adair, an ecologist and biogeochemist. “It reveals the existence of winter pollution over 40 states—but we don’t know how much, where it’s going, or the impacts on water quality and ecosystems.”

She says winter floods delivered a massive pulse of nutrients and sediment into the Mississippi River in 2019—far more than growingseason rainfall—contributing to the Gulf of Mexico’s eighth-largest dead zone on record, causing die-offs of fish and other aquatic animals.

To tackle the issue further, Adair has partnered with UVM engineer Raju Badireddy and others to measure changes to winter runoff with printable microsensors. With startup funds from UVM’s Gund Institute for Environment, they aim to transform our understanding of how watersheds work in a warming world—and strengthen our ability to predict and prepare for changing winters.

Researchers Unpack the Complexity of Snow in Vermont

VERMONT | Last summer, in the Jericho Research Forest, Arne Bomblies and his research team were waiting for snow.

“What we’re after is a better predictive model of snow in Vermont and in the Northeast in general,” said Bomblies, associate professor in the College of Engineering and Mathematical Sciences. “The goal is to ultimately understand how things like trees, slope aspect, elevation, rainfall, and cloudiness impact snow and be able to model that.”

“Snow is critically important to the state and the region,” said Beverley Wemple, a professor of geography and geosciences. “Our winter recreation economy depends on our snowpack. Our winters are shifting rapidly and we need more information about these dynamic changes.”

Long-term observations of snow in Vermont come from various sources, including a network of volunteer observers and notably a measurement station near the summit of Mt. Mansfield.

“The Mount Mansfield snow stake is a critical source of high-altitude snow information, but it records only snow depth. We have no idea how much water that corresponds to and what that means for water runoff or how sensitive the snow is to the sun,” Bomblies said. “Compare that to places in the western United States where they have snow-measuring stations monitoring the full range of winter weather dynamics, including the important snow-water equivalent.”

Bomblies and his team installed sensors to measure wind speed, humidity, temperature, snow density, and water equivalent.

“We’ll be able to directly sense all of the

components that make up snow and see how that changes as rain starts to fall or how a particularly sunny stretch affects the snow,” Bomblies said.

The implications of this project are deeply important, not just for snow monitoring but also for snow tourism in Vermont and climate change.

“There’s a growing concern in the Northeast that the warming climate is going to make winter recreation much less available,” Bomblies said. “Vail Resorts has invested money into snowmaking equipment, but sustaining artificial snowmaking in a warming climate will be challenging.”

While overall warming is a worry for snow research, increased weather variability during a winter season has become more drastic and a larger cause for concern.

“It used to be that once it got cold, it stayed cold, with maybe one or two ‘January thaw’ events, commonplace surges in temperature often accompanied with rain,” Bomblies said. “Those have become much more frequent, and it’s one of the features of the changing climate.”

According to the Gund Institute for Environment’s recent Vermont Climate Assessment, the state’s traditional winter season will be shortened by as much as a month in some parts of the state in the future.

“It's certainly a concern around here, what climate change will look like in Vermont, where winter is such an integral component of our identity and livelihood,” Bomblies said. “With data collection starting now, we can improve modeling and follow research projects and help significantly here at UVM.”

Sorry, Celtics. Basketball Star Goes on to Distinguished Medical Career

When Clyde Lord graduated from UVM in 1959, the then men’s basketball all-time scoring leader found himself at a crossroads. He could go to the tryout the Boston Celtics had invited him to. Or he could head to medical school.

It was an easy decision, said his wife of 63 years, Barbara Lord.

“His thinking was that, as a six-feetone center, you’re not going to get that far as a professional,” she said.

His realism about a pro basketball career was only part of the reason Lord opted for med school. From an early age he dreamed of being a doctor. He came to UVM on a full scholarship from Boys High in Brooklyn, at his coach’s advice, because the university had a medical school. Once at the university, he worked as hard at academics as basketball, earning the Wasson Athletic Prize for excellence in the classroom and on the basketball court.

“What sports taught me was discipline,” Lord said in a Vermont Quarterly tribute.

That discipline served him well during his 50-plus-year career.

Lord, who died Jan. 2, made the right call. After choosing historically black Meharry Medical College in Nashville among several schools that accepted him, including UVM, and graduating second in his class, Lord had a long and distinguished medical career.

But not before lighting up Patrick Gym.

Lord might have been small for a center, but he employed “a wide variety of moves, a great deal of speed and unusual rebounding ability,” the Cynic wrote. Those skills enabled him to score 1,308 points over his career, a record that stood for decades. He was elected most valuable player by the student body twice and to the UVM Athletic Hall of Fame in 1974.

After practicing in Okinawa (as a physician with the U.S. Army) and New York, Lord and his family moved to Atlanta, where he started the first anesthesiology group for Southwest Hospital and Medical Center and co-founded the state’s first pain management clinic. He was beloved by his patients, many of whom he called at home after surgery.

Lord never forgot the joy sports gave him. A talented golfer in adulthood, he passed on his love of athletic competition to generations of young people—including his three sons—by coaching youth sports and stressing the importance of academics to all of them. Many of those young people went on to successful professional careers. Three became anesthesiologists.

“They looked up to him and admired him,” Barbara Lord said. “He just prided himself on being a good physician and a caring person.”

They looked up to him and admired him. He just prided himself on being a good physician and a caring person.

Study Shows TikTok Perpetuates Toxic Diet Culture Among Teens and Young Adults

SOCIAL MEDIA | New research from the University of Vermont finds that the most viewed content on TikTok relating to food, nutrition, and weight perpetuates a toxic diet culture among teens and young adults and that expert voices are largely missing from the conversation.

Published in PLOS One, the study found weight-normative messaging—the idea that weight is the most important measure of a person’s health—largely predominates on TikTok, with the most popular videos glorifying weight loss and positioning food as a means to achieve health and thinness. The findings are particularly concerning given existing research indicating social media usage in adolescents and young adults is associated with disordered eating and negative body image.

The study is the first to examine nutrition- and bodyimage-related content at scale on TikTok. The findings are based on a comprehensive analysis of the top 100 videos from 10 popular nutrition, food, and weight-related hashtags, which were then coded for key themes. Each of the 10 hashtags had over a billion views when the study began in 2020; the selected hashtags have grown significantly as TikTok’s user base has expanded.

“We were continuously surprised by how prevalent the topic of weight was on TikTok. The fact that billions of people were viewing content about weight on the internet says a lot about the role diet culture plays in our society,” said co-author Marisa Minadeo ’21, who conducted the research as part of her undergraduate thesis at UVM.

“Each day, millions of teens and young adults are being fed content on TikTok that paints a very unrealistic and inaccurate picture of food, nutrition, and health,” said senior researcher Lizzy Pope, associate professor and director of the Didactic Program in Dietetics at UVM. “Getting stuck in weight loss TikTok can be a really tough environment, especially for the main users of the platform, which are young people.”

Over the past few years, the Nutrition and Food Sciences Department at UVM has shifted away from a weightnormative mindset, adopting a weightinclusive approach to teaching dietetics. The approach centers on using non-weight markers of health and wellbeing to evaluate a person’s health and rejects the idea that there is a “normal” weight that is achievable or realistic for everyone. If society continues to perpetuate weight normativity, says Pope, we’re perpetuating fat bias.

Getting stuck in weight loss TikTok can be a really tough environment, especially for the main users of the platform, which are young people.

“Just like people are different heights, we all have different weights,” said Pope. “Weight-inclusive nutrition is really the only just way to look at humanity.”

Weight-inclusive nutrition is becoming popular as a more holistic evaluation of a person’s health. As TikTok users themselves, UVM health and society major Minadeo and her advisor Pope were interested in better understanding the role of TikTok as a source for information about nutrition and healthy eating behaviors. They were surprised to find that TikTok creators considered to be influencers in the academic nutrition space were not making a dent in the overall landscape of nutrition content.

White, female adolescents and young adults accounted for the majority of creators of content analyzed in the study. Very few creators were considered expert voices, defined by the researchers as someone who self-identified with credentials such as a registered dietitian, doctor, or certified trainer.

“We have to help young people develop critical thinking skills and their own body image outside of social media,” said Pope. “But what we really need is a radical rethinking of how we relate to our bodies, to food, and to health. This is truly about changing the systems around us so that people can live productive, happy, and healthy lives."

“

This is truly about changing the systems around us so that people can live productive, happy, and healthy lives.

Strong Engine, Works Good

By Joshua BrownIn January of 2022, Ben Ogden had a few days back in Vermont. It was his senior year at UVM, and Ogden had been in Europe, ski racing on the World Cup circuit. An engineering major, sometime construction worker, and old car enthusiast who grew up in Landgrove, Vt.—population 177 souls—he’s arguably the most promising American cross-country skier in a generation. Ogden was heading off to China in February to race in the Olympics. So what’s a guy like that going to do with some downtime back on campus? Head up to Sleepy

Hollow Ski Area in Huntington, take a ski—and then get under the hood of a PistenBully snow grooming machine. His friend, the proprietor, Eli Enman, was working to convert the machine from diesel to battery power. “It was in a million different pieces up in his garage and he had the battery pack all assembled. We're talking about thousands of volts, like, this is legit,” Ogden recalls. And he began to wonder how to make this DIY snow groomer work more efficiently. “It's a unique problem—an electric vehicle with a lithium-ion battery pack that’s only

UVM and World Cup skier Ben Ogden ’22 ahead of Norway’s Johannes Klaebo—for the moment—in a 15km race on the sixth leg of the Tour de Ski in Val di Fiemme, Italy. The day before, Ogden blasted ahead of Klaebo—perhaps the greatest skier of all time—in a sprint. In both races, Ogden didn’t beat the Norwegian, but the Vermonter’s gutsy tactics made waves in the world of professional cross-country skiing.

going to be operated when it's cold,” Ogden says. He became so fascinated that “I packed a bunch of these owner’s manuals from all the batteries, that Eli gave me, and I brought 'em to the Olympics,” Ogden says. “I was, like, researching batteries in Beijing”—in addition to leading the United States to a ninth-place finish in the team sprint.

In January of 2023, Ben Ogden ’22—now a UVM graduate student in engineering—stood on the start line of a semi-final sprint in Val di Fiemme, Italy. This was the fifth stage of the World Cup’s grueling Tour De Ski, Nordic skiing’s answer to the Tour de France. (It ends with a ridiculously steep race at an alpine ski area—going uphill.) Between races, Ogden finds slices of time to study the thermal dynamics of electric vehicle batteries. Working, remotely, with Professor Yves Dubief, “I’m modeling how to have them wellinsulated in the cold, without bursting into flame,” he says. Which seems like very useful research, considering that Eli Enman’s homegrown, battery-powered PistenBully met a fiery end. “The controller blew up,” Enman says, ruefully, “and it burned to the ground.”

On this day, to Ogden’s right, was a Norwegian, Johannes Klaebo, perhaps the greatest skier of all time. Winner of five Olympic gold medals, he’s never lost a Tour De Ski sprint. Most World Cup skiers know the conservative thing to do is, um, not try to dust Klaebo. So what’s Ben Ogden—a UVM skier in his final NCAA season, who’s been jetting back and forth between Europe and Vermont to ski for both the Catamounts and the U.S. Ski Team— going to do? “I just took off,” he says. Going into a frenetic overdrive soon after the start, Ogden quickly gapped the field. It was a stunning move that had coaches staring and commentators commenting. Ogden’s goal was to make it through to the finals—using a trick from his youth-skiing days of blasting away suddenly, against faster opponents, in hopes of beating them with surprise. “He was brave,” says Patrick Weaver, the head coach of the UVM Nordic Ski Team, who was watching Ogden on television from Vermont. “I was hoping he was going to go for it—and he did. Ben has this amazing ability to go really fast and hard. He can't do it all day, but when he goes, he’s as quick as anybody in the world.” Finally, Klaebo realized that Ogden was getting away from him and put on the jets. The gamble had failed, Ogden’s engine had burst into flames, and he fell to fifth, one place out of the finals. “Still, that shook Klaebo’s world a little bit; he’s not used to going that hard in the semis,” says Weaver. For Ben Ogden, it was another chance to experiment and look for new ways to succeed. “I’m an entrepreneur of sorts,” he says, pointing to Eli Enman’s exploratory spirit—and the small company his mother and uncle founded, Vermont Maple Sriracha—as inspiration. “They’re not kicking back, waiting for someone else,” Ogden says. “It’s a Vermont thing: get out there and figure it out.”

I was hoping he was going to go for it—and he did. Ben has this amazing ability to go really fast and hard. He can't do it all day, but when he goes, he’s as quick as anybody in the world.

FLOCKING TO WILDFIRE

By Basil Waugh

By Basil Waugh

Are people trading hurricane zones for wildfire areas?

Americans are leaving many of the U.S. counties hit hardest by hurricanes and heatwaves— and moving toward dangerous wildfires and warmer temperatures, finds one of the largest studies of U.S. migration and natural hazards.

The 10 year national study reveals troubling public health patterns, with Americans flocking to regions with the greatest risk of wildfires and summer heat. These environmental hazards are already causing significant damage to people and property each year—and projected to worsen with climate change.

“People are moving into harm’s way—towards regions with wildfires and rising temperatures, which are expected to become more extreme with climate change,” says University of Vermont Ph.D. candidate Mahalia Clark, who led the study.

Published by the journal Frontiers in Human Dynamics, the study—titled “Flocking to Fire”— is the largest investigation yet of how natural disasters, climate change, and other factors impacted U.S. migration over the last decade.

“Our goal was to understand how extreme weather is influencing migration as it becomes more severe with climate change,” Clark says.

‘RED-HOT’ REAL ESTATE

The top U.S. migration destinations over the last decade were cities and suburbs in the Pacific Northwest, parts of the Southwest (Arizona,

Colorado, Nevada, Utah), Texas, Florida, and a large swath of the Southeast (from Nashville to Atlanta to Washington, D.C.)—locations that face significant wildfire risks and relatively warm annual temperatures. In contrast, people tended to move away from places in the Midwest, the Great Plains, and along the Mississippi River, including many counties hit hardest by hurricanes or frequent heatwaves.

“These findings suggest that, for many Americans, the risks and dangers of living in hurricane zones may be starting to outweigh the benefits of life in those areas,” says UVM study co-author Gillian Galford, who led the recent Vermont Climate Assessment. “That same tipping point has yet to happen for wildfires and rising summer heat, which have emerged as national issues more recently.”

One implication of the study—given how development can worsen risks in fire-prone areas—is that city planners may need to consider discouraging new development where fires are most likely or difficult to fight, researchers say. At a minimum, policymakers must consider fire prevention in high-risk areas with growing populations and work to increase public awareness and preparedness.

Despite climate change’s underlying role in extreme weather, the team was surprised by how little the obvious climate impacts of wildfire and heat seemed to factor in migration. “If you look

where people are moving, these are some of the country’s warmest places—which are only expected to get hotter,” says Clark, a Gund Institute for Environment Graduate Fellow from the Rubenstein School of Environment and Natural Resources.

MIGRATION FACTORS

The team analyzed census data from 2010 to 2020 with data on natural disasters, weather, temperature, land cover, and demographic and socioeconomic factors. While the study includes data from the first year of the COVID pandemic, the researchers plan to delve deeper into the impacts of remote work, house prices, and the cost of living.

Beyond the aversion to hurricanes and heatwaves, the study identified several other clear preferences—a mix of environmental, social, and economic factors—that also contributed to U.S. migration decisions.

Top migration destinations shared a set of common qualities: warmer winters, proximity to water, moderate tree cover, moderate population density, better human development

index scores—plus wildfire risks. In contrast, common traits among the counties people left included low employment, higher income inequality, and more summer humidity, heatwaves, and hurricanes.

Researchers note that Florida remained a top migration destination, despite a history of hurricanes—and increasing wildfire. Nationally, people were less attracted to counties hit by hurricanes, but many people— particularly retirees—still moved to Florida, attracted by the warm climate, beaches, and other desirable qualities. Although hurricanes likely factor into people’s choices, the study suggests that, overall, the benefits of Florida’s amenities still outweigh the perceived risks of life there.

“The decision to move is a complicated and personal decision that involves weighing dozens of factors,” says Clark. “Weighing all these factors, we do see a general aversion to hurricane risk, but ultimately—as we see in Florida— it’s one factor in a person’s list of pros and cons, which can be outweighed by other preferences.”

"PEOPLE ARE MOVING INTO HARM’S WAY— TOWARDS REGIONS WITH WILDFIRES AND RISING TEMPERATURES, WHICH ARE EXPECTED TO BECOME MORE EXTREME WITH CLIMATE CHANGE"

To Stay Motivated at Work, I Try to Embrace Curiosity

He didn’t know just how much criticism, science, and communication he was in for. One end product was this essay, published in the journal Science on Jan. 12, 2023, and reprinted here with permission. To get there “took at least eight rounds of edits,” Peters-Collaer recalls. His essay was published in the journal’s “Working Lives” department—a weekly series of strongly personal stories from students and scientists around the world. Bierman’s first assignment for the graduate students in his course was not only modeled on this department—he also invited the department’s editor, Rachel Bernstein, to speak virtually with the students. “After we talked

with Rachel, Paul encouraged us to reach out to her if we felt like we had something worth publishing,” says Peters-Collaer. So, after several rounds of edits of his essay with Bierman— an acclaimed geologist in UVM’s Rubenstein School—and his in-class peers, he sent it in to Science. Bernstein was interested—and she worked with Peters-Collaer “on five more drafts,” he says, asking for better examples, sharper prose, fewer words. “One of the things I learned is that even when a piece of writing needs lot of edits, it doesn't necessarily mean that it’s bad,” he says, “just that it can keep getting better.”

“Hot dog! Looks like you’ve got a Mahonia repens,” Sherel exclaimed in his rural Utah twang. I crouched and gently touched the plant with yellow flowers by my feet. “This one here? How can you tell it’s a Mahonia?” Sherel carefully bent down and adjusted his camo hat to block the Sun. The 75-year-old botanist and leader of our field crew paused briefly to admire the plant before launching into an energetic description of its defining features. That evening, watching the Sun fade behind the mountains, I texted my childhood friend. “Day 1 was actually kind of fun,” I started, “but we’ll see how long it takes before I get bored from just identifying plants in the field all day.”

Up to that point, I had avoided fieldwork. To an undergraduate studying ecology, bending over plants for 10 hours a day seemed a lot less interesting than identifying big-picture trends in large data sets. But I knew potential graduate schools would likely view my lack of field experience as a hole in my resume, and my mother thought I should work for a few years to explore my interests before pursuing further education. So, I applied to field-based summer positions after graduation and landed a job assessing sage grouse habitat in Utah. It felt like a necessary evil before I could move on to bigger, more “intellectual” things.

When the summer was over, I found myself in another field job, this time surveying forest in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. One frozen morning a few weeks in, I came across a strange wasp probing the bark of a decaying beech with what looked like an enormous stinger, 10 centimeters long. Our official duties didn’t extend to insects, but my curiosity was piqued. “Hey, come check this out!” I called to the rest of our field crew, instinctively channeling Sherel’s tireless enthusiasm. Despite the cold, we watched transfixed by this otherworldly insect, which my colleague identified as a giant wasp laying eggs, until it slowly pulled back its ovipositor, stretched, and flew off. As we dispersed back to our tasks, I noticed migrating sandhill cranes flying overhead and thought of their cousins in northern Utah. I sent silent thanks to Sherel for teaching me to approach fieldwork with a sense of wonder— excited to learn, even when my hands are numb.

I’m now a third-year Ph.D. student in forest ecology, and the time I spend leading research crews in the woods of New Hampshire every summer is one of my favorite parts of the year. Our crews typically don’t have previous field experience, and I try to bring Sherel’s excitement to our work. By answering questions with enthusiasm, sharing interesting tidbits, and providing the intellectual context behind our efforts, I hope to show that working in the field can be fascinating and fun.

My younger self would have been surprised: It’s when I’m not in the field that it can sometimes be difficult to remain energized about my work. It’s not just being immersed in nature that I miss. Fieldwork may be buggy, wet, and physically taxing, but collaborating with others helps keep spirits high, and the physical activity helps me stay sharp. Much of my Ph.D. work, on the other hand, is solo and sedentary. So I’ve tried to bring aspects of fieldwork to my day-to-day routine. I take breaks to talk to other graduate students to escape intellectual ruts, and I try to get up from my desk and move for a minute or two throughout the day.

But as the weeks of fieldwork rolled by, the boredom I expected never arrived. I came home from the sagebrush each night with sore legs and a sunburned neck, invigorated by the day’s finds. By picking Sherel’s brain about pronghorn antelopes, aspen groves, and every species of sagebrush, I discovered field days are about much more than rote identification. Each day is an opportunity to learn a little bit more.

I also try to recapture fieldwork’s spirit of discovery by reading a journal article that excites me, regardless of the topic, every Monday. If I’m bogged down by the repetition of analyzing another data set, this helps restore my curiosity and enthusiasm for my work. And when I remember that gleam in Sherel’s eye as he responded to my seemingly mundane, random questions, I remind myself that any task can present an opportunity to learn—as long as I am open to it.

Each day is an opportunity to learn a little bit more.

UVM PEOPLE

BUILDING UPON RECORD SUCCESS KATHARINE G. SHEPHERD, ED.D.

Since joining the University of Vermont as a faculty member of the College of Education and Social Services in 1986, Katharine Shepherd has earned a reputation as a values-driven and facilitative leader.

By Doug Gilman“Katie is a collaborative and servant leader who brings both excellent scholarship and thoughtful leadership to her role,” said UVM Provost Patricia Prelock, who announced Shepherd’s appointment as dean effective Jan. 15. “I look forward to continuing our work together to enhance the success of the college.”

Shepherd is the Levitt Family Green and Gold Professor of Education, who served as interim dean of the college since July of 2021. In addition to her extensive teaching record, she previously held numerous leadership roles including program coordinator of special education, vice chair of the Department of Education, interim associate dean for academic affairs and research, and associate dean for academic affairs.

“I am inspired by the diversity and talent among our faculty, students, staff, and alumni, and the impact of the work that they do within and outside of the college,” Shepherd said. “Together, we prepare outstanding professionals and researchers who engage with our schools, families, and communities to address the most pressing issues of our time. I look forward to advancing the college’s position as a leader in a justiceoriented approach to transforming teaching, scholarship, policy, and service – here in Vermont, across the country, and around the world.”

CESS currently enrolls 720 undergraduate students and 344 graduate students in nationally accredited programs in education, social work, and human services. Strong relationships with school districts, human service organizations, and state agencies yield mutually beneficial partnerships between the college and communities across Vermont. Through their field experiences and internships, CESS students collectively contribute over 190,000 hours annually to the state.

As interim dean, Shepherd supported efforts enhancing the college’s offerings and reputation while contributing to the university’s bid for R1 status. The college's external funding to support research increased by 43% under her leadership. It also established a new Ph.D. in social, emotional, and behavioral health and inclusive education and a new Ph.D. in counselor education and supervision.

During her tenure as associate dean, the college launched an undergraduate certificate in placebased education, certificates of graduate study in education for sustainability and resiliencybased approaches, an undergraduate minor and concentration in computer science education, and a revised individually designed major.

Shepherd’s nationally recognized scholarship focuses on educational leadership and familyprofessional partnerships, collaborative teaming, and state and school-wide implementation of inclusive policies and practices, including Multi-Tiered Systems of Support. She is a recipient of the President’s Distinguished University Citizenship and Service Award, the Higher Education Consortium for Special Education Leadership and Service Award, and the Kroepsch-Maurice Excellence in Teaching Award, among other accolades.

During her career, Shepherd received over $3.6 million in externally funded research grants. Her publication record includes co-authoring two books and authoring or co-authoring 35 peer-reviewed journal articles, 16 book chapters, and 17 additional publications.

Dying Green: A Journey through End-of-Life Medicine in Search of Sustainable Health Care

Christine Vatovec Rutgers University Press, April 2023

Christine Vatovec Rutgers University Press, April 2023

It can cost a lot to die—and not just in money. In Dying Green, UVM scientist Christine Vatovec takes a close look at the care given to terminally ill patients in an acute-care hospice, a cancer ward, and a palliative care unit. Procedures, chemicals, IV tubes, electricity, antibiotics—a vast range of supplies, medical waste, and drugs goes into providing care. Vatovec—an interdisciplinary researcher with faculty appointments in the Larner College of Medicine, the Rubenstein School of Environment and Natural Resources, the College of Nursing and Health Sciences, and a Fellow at the Gund Institute for Environment—analyzes the choices made, the resources used, and the complex interplay between individual health and environmental health. At the foundation of this book is the profound tension between an urgent focus on short-term outcomes in standard health-care practices—and the “slow violence,” she writes, being inflicted from carbon emissions, plastic pollution, and toxic waste that contributes to an expanding public health catastrophe from degrading ecosystems. Vatovec invites the reader to ponder the meaning of sustainability in health care. Through a comparative analysis, Dying Green provides insights and options for reducing the ecological impacts of end-of-life medical practices while also improving care for the dying.

A Female Apostle in Medieval Italy: The Life of Clare of Rimini

Jacques Dalarun, Sean L. Field and Valerio Cappozzo University of Pennsylvania Press, October 2022

In the 14th century, Clare of Rimini lived a technicolor life, including two marriages, two exiles, life as a penitent in a roofless cell in the city’s half-ruined walls, founding a community of like-minded women, accusations of demonic possession, “and finally the writing of her ‘life,’ probably by a Franciscan friar and probably when Clare was still alive, on her deathbed, around 1326,” notes UVM historian and researcher Sean Field. He’s co-author of A Female Apostle in Medieval Italy which interprets the ancient Italian text, in English translation for the first time. Each chapter looks into medieval society—politics, sexuality, religious change, pilgrimages, and heresy—opening a dramatic view onto an Italian city seven centuries ago.

A Woman’s Life Is a Human Life: My Mother, Our Neighbor, and the Journey from Reproductive Rights to Reproductive Justice

Felicia Kornbluh

Grove Press, January 2023

As professor of history and of gender, sexuality, and women’s studies, Felicia Kornbluh knows a lot about the history of reproductive rights. But when she discovered that her mother drafted a law in 1968 that led to New York State decriminalizing abortion, she was surprised and inspired. This revelation motivated Kornbluh to write A Woman’s Life is a Human Life that recounts the push for safe and legal abortion services—and against sterilization abuse— in the 1960s and 70s. It chronicles the national movement for reproductive rights, including guidance for advocacy today. This book “offers insights into how we can form genuine alliances,” a New York Times reviewer wrote, “in order to continue making changes that align with the feminist values of compassion, fairness and care.”

The Progress Illusion: Reclaiming Our Future from the Fairytale of Economics

Jon D. Erickson Island Press, December 2022

UVM economist Jon Erickson stands at the forefront of a reform effort—to tell a new story about the global economy that recognizes we live on a finite globe. “I’m convinced that economics as currently taught and practiced throughout the world is a planetary path to ruin, but there are obvious cracks in the castle wall,” he writes in The Progress Illusion, an exploration of how traditional economics came to believe in the “fairytale of endless growth” and what an ecologically informed economics could aim for instead: enduring prosperity. His approachable and brave book may help let more sunlight in.

AWARDS + RECOGNITIONS

New Book by Paul Deslandes Receives British History Award

Deslandes, associate dean for the College of Arts and Sciences, received the prestigious Morris D. Forkosch Award from the American Historical Association for his book The Culture of Male Beauty in Britain: From the First Photographs to David Beckham. The award recognizes the best book written in English on the history of Britain, the British Empire, or the British Commonwealth since 1485.

Cassandra Townshend

Named Vermont Children's Mental Health Champion

Cassandra Townshend, Ed.D.'21 has been named a Vermont Children's Mental Health Champion for the 2022-2023 school year by the Association of University Centers on Disability and the National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, for her work with Vermont Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports and the Building Effective Supports for Teaching project. Townshend becomes one of only 10 such awardees nationwide.

Fulbright Recipient Antonio Cepeda-Benito to Study in Chile

Over two decades, Antonio Cepeda-Benito has established close collaborations with Spanish-speaking investigators across the world, resulting in new lines of cross-cultural research in food and drug cravings and in body image and eating disorders. The main objective for Cepeda-Benito’s current Fulbright project, "Explicit and Implicit Assessment of Weight Stigma Across English and Spanish Speaking Countries", with the Universidad Adolfo Ibáñez (UAI, Chile) at the Centro de Estudios de la Conducta Alimentaria, is to cultivate and nurture ties with CECA faculty and students. In Cepeda-Benito’s words, “The end goal is to establish a relational foundation that would lead to develop and grow an emerging line of cross-cultural research on the intersectionality of self-stigmas and their impact on health.”

TO SAVE THE FOREST, SHOULD WE MOVE THE TREES?

AS THE WOODLANDS OF NEW ENGLAND FACE A HOTTER FUTURE, UVM RESEARCHERS ARE EXPLORING THE PROMISE AND PERIL OF “ASSISTED MIGRATION”

In a greenhouse at UVM’s Aiken Forest Sciences Laboratory, scientist Peter Clark and lab technician Miriam Wolpert ’20 plant red oak acorns gathered from all over the East Coast. They’re looking for trees that can thrive in Vermont as the state grows rapidly wetter and warmer.

It’s eight degrees Fahrenheit. Off trail, at 2,042 feet of elevation, on the side of Camel's Hump, Professor Steve Keller takes off his gloves, pulls a Dell tablet out of his backpack, unrolls a wire, and plugs it into a scrawny maple tree. Well, actually, into a tiny sensor hanging under a white plastic funnel hanging off the side of the maple. The winter sunshine feels beautiful and the sky glows with a preternatural blue. The trees stand still, a mix of beech and sugar maple, plus a few yellow birches, all silent, their elbows clothed in new snow.

temperatures here are rising. These warmer conditions are, generally, pushing trees upslope and northward. On Camel's Hump, the ecotone—the complex boundary between the mid-slope hardwood forest and the highelevation spruce/fir forest—seems to be caught in a tug-of-war between the recovery of spruce from decades of damage and the rising heat that pushes trees to migrate toward the summit.

Keller has come here to take the temperature of the forest—and to show me the red spruce trees that he and generations of UVM scientists have been studying on this mountain since 1964. At this elevation there aren’t many spruce. “But there’s one—there,” Keller says, pointing to a brave and solitary evergreen tucked into the understory.

“One of the interesting trends that we're seeing is a bit of a rebound in red spruce at these lower elevations,” Keller says. As this forest has recovered from the ravages of acid rain and a long history of land clearing, “we're seeing some spruce come back in—back down the slope—to where they were missing before.”

Keller waits as the data from the sensor downloads onto his tablet—months of temperature and relative humidity readings. He presses the screen and points to a spiking line running across it. “See, it got down to just below zero on Christmas Eve,” he says, tracing his finger down a steep drop in the graph.

Mostly though, it’s up—for both temperatures and trees. Over recent decades, the average

Trees do migrate. If you stood at the summit of Camel's Hump 13,000 years ago, you would have witnessed a bulldozed landscape of rubble and bedrock, left behind by retreating glaciers. Slowly, a treeless tundra grew. Then, at the same time the first Paleoindian hunters were arriving in the Champlain Valley—12,000 years ago—so were trees, wind-blown pioneer species like paper birch and black spruce. Over centuries, a forest formed, dominated by spruce. White pine and hemlock started to show up about 10,000 years ago. Around 8,000 years ago, beech, chestnut, and Vermont’s beloved sugar maples moved in and began to get a foothold. In a drying period 4,000 years ago, the conditions were favorable for oak, which expanded its range. For millennia, trees have marched up river valleys and climbed mountains—their seeds dropped on the ground, carried by rodents, washed by streams, tossed by storms—generation upon generation, chasing a suitable climate.

Now many tree species are losing the race. Historical research estimates that trees in New England, on average, can disperse about onetenth of a mile per year. If they’re booking it, maybe as fast as three-tenths of a mile. But today the climate is warming much faster than that— shifting at four to six miles per year. Under a business-as-usual scenario of greenhouse gas emissions, the climate of Vermont is projected to warm by five, six, seven or more degrees Fahrenheit by the end of the century— becoming like that of, perhaps, West Virginia.

“The trees can’t keep pace,” says Keller, a professor in UVM’s Plant Biology department and an expert on tree genetics. “Climate change is already causing stress. I'm talking about reduced growth, reduced carbon sequestration, more susceptibility to extreme events like drought and heat waves, less ability to fend off pests,” he says. “Our local forests will become more and more maladapted if we don’t do anything. So how do we help?”

"THE TREES CAN'T KEEP PACE. OUR FORESTS WILL BECOME MORE AND MORE MALADAPTED IF WE DON'T DO ANYTHING."

He and other UVM researchers are at the vanguard of a growing number of ecologists, foresters, and land managers who think part of the answer may be “forest assisted migration”—moving the seeds or seedlings of trees from where they live now to where they might have a better shot at thriving in a warmer future. Helping the trees to walk.

Keller tucks the tablet back into his pack and starts his own walk higher up the mountain, kicking up clouds of snow, to look for some more red spruce. The native range for this species stretches from North Carolina to the coast of Newfoundland. Regional modeling suggests that red spruce is especially vulnerable to decline driven by climate change. Isolated “sky islands” at the summit of peaks in the South are at risk of blinking out entirely, and spruce will face stiff competition from hardwood trees in a warmer, wetter Vermont. Plus, they’re especially slow to migrate since they can live 300 years or more.

Keller’s years of research here on Camel’s Hump and all along the eastern United States aims to improve the odds for red spruce. “If you look at red spruce and you assume that all members of the species are alike, you’re missing a lot. The trees differ across their range, across populations,” he says. “There may be unique genetic diversity within the range, pre-adapted to future climates, to future environments. So it becomes a matching problem: if we want to have a healthy spruce forest in New England, where would we look to find the genetic adaptations that will be well matched to the climate of New England in 2100?”

"THE 'LOCAL IS BEST' PARADIGM IS — IF IT ISN'T ALREADY ANTIQUATED FOR A PARTICULAR SPECIES — IT WILL BE WITHIN OUR LIFETIMES. AND CERTAINLY WITHIN THE LIFETIMES OF THE FORESTS WE'RE TALKING ABOUT."

STUDYING SPRUCE

Steve Keller and colleagues collected red spruce seeds along the East Coast. These were germinated in a glasshouse at UVM in spring 2018. A year later, seedlings from all the sources were transplanted to three common gardens—one in Asheville, North Carolina; one in Frostburg Maryland; and one Burlington, Vermont—5100 trees. The seedlings were observed for two growing seasons to see which ones were best adapted to the local climate.

COMMON GARDENS

Experimental outdoor land plots. Into each, 1700 seedlings were transplanted from across the spruce’s native range.

SOURCE POPULATIONS

65 forest sites where red spruce seeds were collected from 340 mother trees.

RED SPRUCE RANGE

The current geographic areas where red spruce trees naturally grow and reproduce.

To find out, Keller and his colleagues and students grew more than 5,000 spruce seedlings with funding from the National Science Foundation. First, they collected seed and genetic information from mother trees at 65 locations throughout the spruce’s range—up the spine of the Appalachians, across New England, and into Canada. Then they germinated the seeds and grew seedlings in a UVM greenhouse for a year. In the spring of 2019, they transplanted the trees to three locations with different climates: Asheville, N.C., Frostburg, Md., and Burlington, V.T.—1,700 seedlings at each place in raised bed gardens.

Then they watched, while the trees went through two growing seasons and one winter, collecting data on survival, growth, bud break and bud set, height, nutrient concentration in their needles, and other measures of whether the seedlings were thriving. They wanted to know how the seedlings were affected by the difference between the climate of their garden site compared to the climate of their mother tree. They discovered that juvenile spruce like to grow in the same climate as their mothers, and their growth trailed off as they got into different climates.

But, of course, the current climate of the mother tree will—very soon—not be its future climate. Using this insight—combined with U.S. Forest Service tree inventories, DNA sequencing, and climate modeling—Keller and his collaborators have developed tools to estimate how far—and from what source—red spruce seed should be moved to give the next generation its best chance of doing well in a warmer future. On a new app that Keller and colleagues created, users can select a period for which they are planting, say the years 2071-2101, dial in moderate or severe greenhouse gas emissions— and then enter a location, say Mount Katahdin in north-central Maine. The app churns away and suggests that red spruce seed with good adaptations for planting might be found on the eastern slopes of Mount Mansfield in Vermont. For Camel's Hump, in 2100, it suggests a spruce forest near the Finger Lakes in New York.

As temperatures rise and Vermont experiences more rain, intense storms, and severe droughts—the conditions will improve for some trees and be worse for others. Forest ecologists expect more southern-adapted trees, like shagbark hickory, black cherry, and red oak, will increasingly find conditions in the state that suit their needs. Other species, including balsam fir, yellow birch, black ash, and sugar maple, “will be negatively impacted,” the 2021 Vermont Climate Assessment reports. But even if the conditions are cozy for a particular species, it must be there to benefit. “The climate might be perfectly suitable for red oak in a given area,” says Professor Tony D’Amato, director of the Forestry program in the Rubenstein School of Environment and Natural Resources, “but it's just not able to get there quick enough to capitalize on that new environment.”

Unlike California or other spots in the West, forests in the eastern United States have the delightful quality of just growing back after they are harvested, or burn, or get knocked down in a hurricane. There is not an extensive tradition of planting trees in the North Woods. Mostly you get whatever trees volunteer to grow—and for areas that are being replanted the adage has been “local is best,” meaning sourcing seed only from nearby. It may become useful, even necessary, for landowners, timber companies, and conservation land trusts to start thinking about how they will introduce genes, trees, and even whole suites of species from farther afield that can keep forests healthy or even forests at all. In some spots, like the invasive-choked, deer-chomped, pest-threatened woods of Chittenden County, there is reason to be concerned that an “alternative stable state”—in the anodyne jargon of scientists— will emerge in the coming decades: the weeds will win and there will be few trees.

“From my perspective as a scientist, the ‘local is best’ paradigm is—if it isn't already antiquated for a particular species—it will be within our lifetimes. And certainly within the lifetimes of the forests we're talking about,” Keller says. “As the climate continues to change, this approach will become less and less viable.”