September 24, 2021–January 29, 2022

Marjorie Barrick Museum of Art

University of Nevada, Las Vegas

September 24, 2021–January 29, 2022

Marjorie Barrick Museum of Art

University of Nevada, Las Vegas

Published by UNLV Integrated Graphics Services

Integrated Graphics Services

University of Nevada, Las Vegas Box 1028

4505 S. Maryland Pkwy.

Las Vegas, NV 89154

Copyright © 2022 Marjorie Barrick Museum of Art

Marjorie Barrick Museum of Art

University of Nevada, Las Vegas Box 4012

4505 S. Maryland Pkwy. Las Vegas, NV 89154

Artworks by Catherine Angel, Tomoko Daido, Claudia DeMonte, Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Carla Jay Harris and Dr. Brenda E. Stevenson, Chase R. McCurdy, Krystal Ramirez, Heidi Rider, and Jay Sarno, et al. © 2012 by Catherine Angel, 2013 by Tomoko Daido, 1983 & 1984 by Claudia DeMonte, 1991 by Felix Gonzalez-Torres, 2021 by Carla Jay Harris and Dr. Brenda E. Stevenson, 2018, 2020 by Chase R. McCurdy, 2020 by Krystal Ramirez, 2020 & 2021 by Heidi Rider, and c.1966 by Jay Sarno, et al.

Catalog designed by Chloe J. Bernardo

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or used in any manner without the prior written permission of the copyright owner, except for the use of brief quotations in a book review.

September 24, 2021–January 29, 2022

Marjorie Barrick Museum of Art University of Nevada, Las Vegas

CATHERINE ANGEL

TOMOKO DAIDO

CLAUDIA DEMONTE

ASHLEY HAIRSTON DOUGHTY

JUSTIN FAVELA

FELIX GONZALEZ-TORRES

CARLA JAY HARRIS

CLARITY HAYNES

BRENT HOLMES

CHASE R MCCURDY

KRYSTAL RAMIREZ

HEIDI RIDER

JAY SARNO et al

LANCE L SMITH

MIKAYLA WHITMORE

I Am Here invites us to think about what it means to use art as a vehicle for personal narratives. What stories do artists choose to tell about themselves, and who is invited to talk? These artworks manifest their creators’ “heres” in a variety of ways, reflecting a multitude of individual backgrounds and historical choices.

Luxor, Las Vegas, 2012

Toned gelatin print

17.5 x 17.5 in Marjorie Barrick Museum of Art Collection

Gift of the artist

2020.08.001

“I got lost within the creative process of photographing the objects in front of me, so I decided to be a photographer. Photography gave me an avenue to immediate expression of what I was going through, if you think of art as an expression of self. Photography has an element of truth: This happened that day, that time, that month I made [my first] photograph.”

Raegen Pietrucha, “Balance Through Contrast.” (UNLV News Center, February 22, 2017)

Tomoko Daido

Hoover, 2013 Black and white photograph 7 x 7 in Marjorie Barrick Museum of Art Collection

Gift of the artist 2020.04.001

“The figure in the shadow is not me. That is you. That is all.”

Tomoko Daido, email to Alisha Kerlin, August 12, 2020

Claudia as Whistler’s Mother, c. 1983

9.5 x 9.5 x 0.5 in Claudia at Doubleday Field, c. 1984

13 x 14 x 1 in Claudia Watching TV, c. 1983

Acrylic and glitter on pulp paper

8 x 8 x 0.5 in Courtesy of the artist

Claudia in Riyadh, c. 1983

Acrylic on pulp paper

14 x 11 x 1 in Courtesy of the artist

“I started to make the doll figures be about me, but more universal. I was interested in all the things we do every day as women that art is never made about. It’s very different today. But, again, this is a long time ago. It was considered craft and not appropriate. You had to be serious; you couldn’t use certain materials. I mean the idea that you would use pulp paper, which is like a children’s clay material, and then make things about a woman’s daily life. Not the “important things” but the things we all spend hours a day doing that nobody honors.”

Claudia on the Telephone, c. 1983

9 x 8 x 1 in Claudia Bowling, c. 1984

Acrylic and glitter glue on pulp paper

10 x 10 x 1.5 in Marjorie Barrick Museum of Art Collection

Gift of Alessandro Figueroa

2020.10.01

2020.10.02

Felix Gonzalez-Torres

Untitled (L.A.), 1991 Green candies individually wrapped in cellophane, endless supply, overall dimensions vary with installation, original weight: 50 lb (22.7 kg). Jointly owned by Art Bridges and Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art © The Felix GonzalezTorres Foundation.

“Above all else, it is about leaving a mark that I existed: I was here. I was hungry. I was defeated. I was happy. I was sad. I was in love. I was afraid. I was hopeful. I had an idea and I had a good purpose and that’s why I made works of art.”

Felix Gonzalez-Torres was interviewed by Tim Rollins at his New York apartment on April 16 and June 12, 1993. Felix Gonzalez-Torres. Edited by William Bartman. (New York: Art Resources Transfer, Inc., 1993)

“

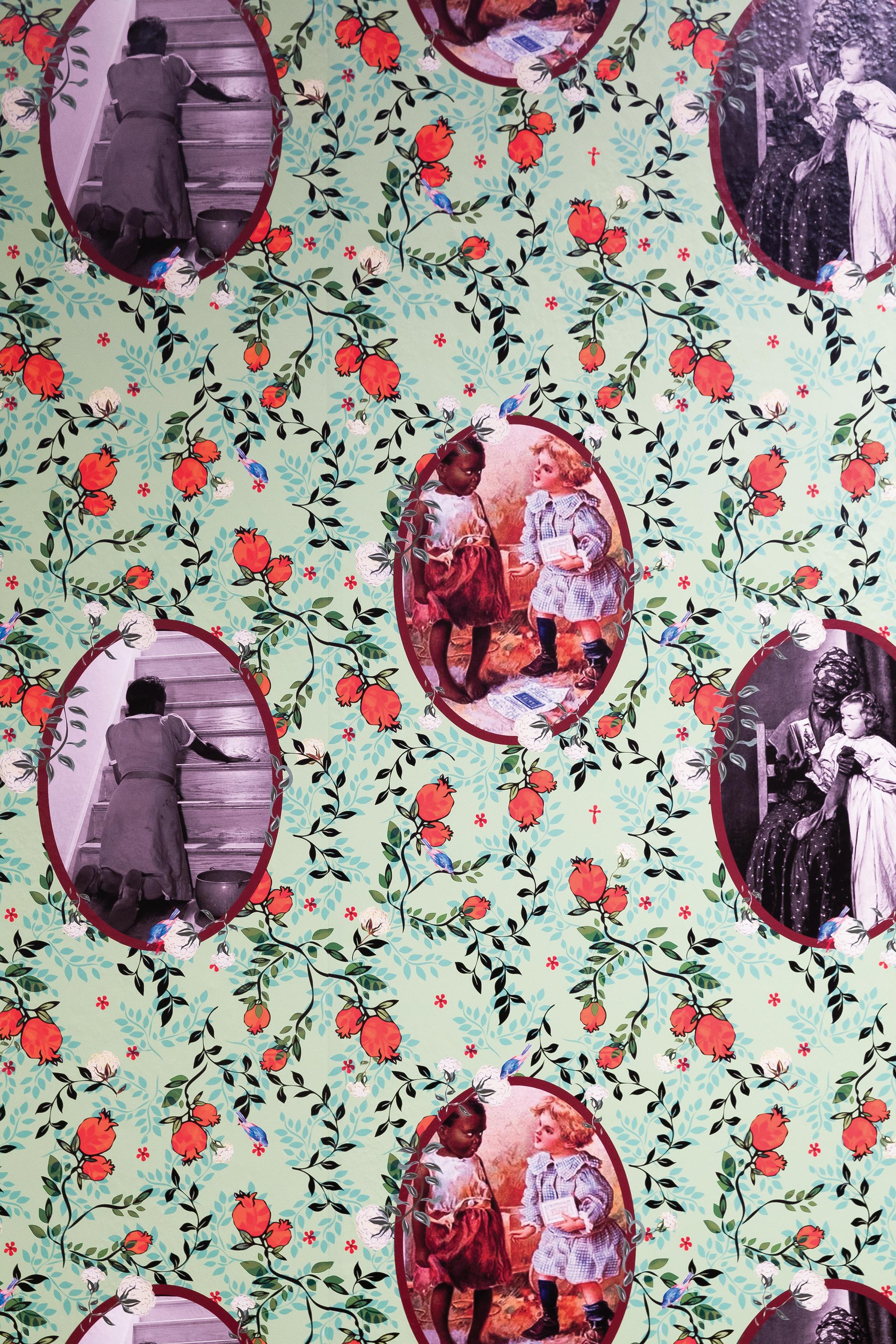

Bitter Earth is a collaborative project. I think that’s a key piece of information. Because that’s how the project started—with myself and Brenda Stevenson, who’s my aunt. She’s also an historian and an educator. We’ve been wanting for a while to come together on a project because there’s just so much overlap between what she studies and what I am interested in. I often deal with works that have to do with memory, ancestral memory, as well as Black experience and her work is very much about the experience of Black women as well. Bitter Earth is the genesis of her world and my world coming together.”

“We got together with the idea of Jim Crow. We came up with the idea of a five-part piece and she wanted to have a room. I thought, “Great,” because at the end it will be like a house. We’ll have various rooms dedicated to time periods. We started with the living room […] And that’s how she came up with the notion of taking my idea and putting it into something that was visually appealing and that was also symbolic in many ways and really captured this notion of living with your history. Because we can’t escape the history. We can come home and close the door but the history lives with us, in our spaces where we are.”

“An art gallery or a museum is a place where you can feel comfortable, feel excited, you can feel provoked, feel angry, and you can feel comforted by the fact that we’ve had some positive change in our society. Some problems still linger but some problems have largely disappeared. I’m hoping people will learn that’s what history is about and that’s what art is about too. History and art are ways of coming to terms with our society and wanting to make our society more beautiful than it already is, more comforting than it is, and in some ways more challenging.”

D.K. Sole spoke to L.A. artist Carla Jay Harris about Bitter Earth, an installation she created in collaboration with her aunt, UCLA historian Dr. Brenda Stevenson. The work confronts Black history in the United States during the Jim Crow era. Harris “evolved” the work for Las Vegas when it was exhibited in I Am Here

DKS What were your thoughts about I Am Here when we were describing it to you at first?

CJH I heard about the show initially from an artist I did a studio visit with during a residency I was doing in ACRE, which is in Wisconsin. When I was talking to her about my installation she mentioned the show that you-all were working on. As soon as I heard the description, I thought, “Oh, well, this is a really good fit.” Some of the themes of the show and the other artists were very much in alignment with themes I’m working on and the kind of work that I do.

It’s always tricky when I do something remotely. I hadn’t seen the space in person in advance. But I do think you guys gave me a good idea of what it was going to look like. And hopefully I did a good job describing the piece, and how it should come together. So in terms of logistics, it was a successful collaboration.

The piece is meant to be site-specific. Every time I show it, I change it a little bit. I like specifically catering it to the environment and the community it’s going to be shown in. For the show at the Barrick, I created a new panel in the wallpaper that talks specifically about Black women in the West and in Las Vegas. Jim Crow is a massive thing, and there’s so much that happened that it’s impossible to ever encapsulate everything. But having it site-specific

EVERY TIME I SHOW IT, I CHANGE IT: A CONVERSATION WITH CARLA JAY HARRIS

gives me more freedom to show different aspects of what occurred during that era. And I got to do some more research specifically about the West. I’m from the East Coast, so that’s more my background than the West.

My producing partner Dr. Stevenson was a major help. She did a lot of help with the research, and identifying the images and keeping the piece accurate. That, I think, is one of the best benefits of partnering with a historian. She knows where to look, and she knew what was accurate and what wasn’t. It helped tailor the piece and drive it forward in that way.

CJH A lot of the information came from the Library of Congress, but I don’t know specifically where she pulled the information about Las Vegas from. She’s in the History Department and there are people there that focus on the West and African Americans in the West. So my guess is probably from colleagues and literature.

It’s always kind of a back and forth. I was describing what I thought would make sense for the new panel. She did some research, and came back with some information and an array of images. Then we talked through what we wanted to represent, and how it should all come together. In the end we settled on two new images that would be the best fit both aesthetically and thematically for the piece.

In all of the panels we like to dabble with the dichotomy of the images speaking to each other. I think the Las Vegas panel did that particularly well. And the new images were both a good addition and an extension of the other images in the piece.

CJH I think we started out with eight, although I don’t remember specifically what they were. Some of them were images of protest, some were entertainers, and then we had a lot of images of cowgirls as well. They’re all close to the same themes, but were ultimately cast aside because there was a lack of clarity or they didn’t fit well into the wallpaper. The two we chose were definitely the best fit.

We got it down to a science by the time we did the Las Vegas panel, but it was tricky when we were making the original piece. The original has like fifteen different panels in it, and coming down to the final images took a lot of time and thought to make sure everything worked, not just from the conceptual point of view, but also aesthetically, because it had to be both for the piece to be successful.

It was something we both had to learn along the way, about what images would work best. It was challenging in the sense of making up our minds, but there wasn’t conflict about it. I think you have to go into a collaborative project with the right attitude. You know, if you only want something your way then don’t partner with someone. But for me, I enjoy the collaborative process. And I have my own independent solo art practice separate from that, so if I ever had anything that I had to have or had to do, I could always do it in my solo practice.

CJH There’s an image of Jim Crow, who was an actual character. She felt that was something important and needed to be in the piece. In terms of design, I did my own, but we did discuss the overall look of it so that we were both on the same page. The design and the drawings needed to match up to the themes of the images and they had to work together. So we did have conversations about those, but, at the end of the day, it was my design.

This was the first time I had shown it remotely. I had to give a lot of thought about how the piece can travel, and there are some good lessons there about how to package it, how to show it, and evolve it for different spaces. I also feel like creating the new panel taught me some things. I learned a lot from that process; how to streamline my process of making the piece site-specific, not just in terms of shape, but also in content.

This piece in particular works so very well in university environments and museums. I feel there’s so much that can be learned about the era from it. I’m hoping to be able to continue to show it in similar environments in the future.

Don’t Say I Didn’t WARN You..., 2018 Print 2020

“It’s a reflection in the work of my contending with the everyday realities of this world. So, there are those days and moments and times when it feels as though things are about to come down. And there are those moments, admittedly, a lot of the time when I’m making the work, where I feel as though I’m somewhere else and I’m transported elsewhere.”

Black and white photograph 3 x 3.75 in Marjorie Barrick Museum of Art Collection

Gift of the artist 2020.07.001

I’mFineI’mFineI’mFine, 2020 Git meee., 2020

You should be ashamed of yourself., 2021

I didn’t mean to., 2020 U ain_t The One., 2021 Good baby., 2020 Tryin’ so hard., 2020 peripatetic daddy., 2021 SHUT UP., 2020

The last day of Four Godddamned Yearz., 2021 OhBoy, 2020

Don’t look at me., 2020 NO., 2020 2020, 2020 1 (888) GET-YURZ, 2020

Fuck this shit., 2020 Hesitant., 2020

Lil’_darlin’_, 2020 get off my life., 2020

Tell me I’m pretty., 2020 Be my daddy., 2020

Deflated., 2020 C’mere., 2020 U used 2 want me., 2020

“I started working on my face after I got the Coronavirus. I wanted to continue with my drawing practice. But I work standing. I couldn’t do it. I was just too weak. And I was starting to feel really crazy inside ‘cause I couldn’t make anything. ‘Face painting is a part of my [clowning] practice, but it’s usually not something I think of outside of doing a performance. [By printing my face on handkerchieves] I was able to move into another body of work that I was actually able to do. So that’s been the main thing that I’ve been doing. During and after the virus. It’s part of my practice to make something every day. The truth is this is an emotion-based practice that allows me to process whatever I’m feeling. In a creative way. And then wash it off. And send it down the drain. I print it to preserve it. I take a photograph of it as a way to remember. And to share [on social media]. Because I feel like not everybody turns to creative expression when they’re struggling. Or when they’re emotionally exhausted. Or lonely. Or any other kinds of feelings. But I know that some people who don’t do that themselves, turn to other people’s creative practices to help them.”

Oil based face paint on men’s fabric handkerchiefs 15.5 x 15.5 in Courtesy of the artist

Krystal Ramirez (she/her)

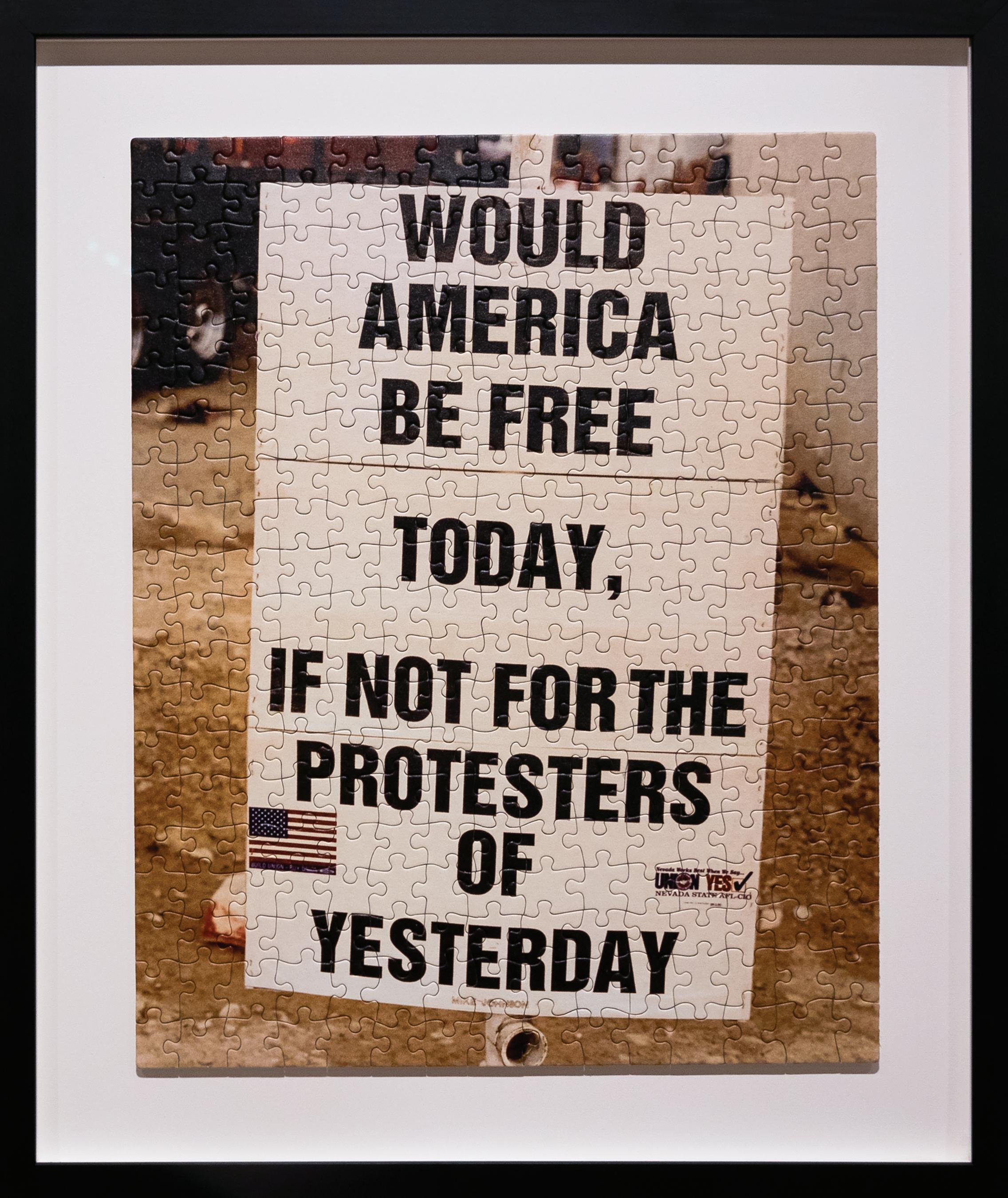

Protest Puzzle, Untitled #1, February 2020 Paperboard, adhesive, printed reproduction of a photograph 20 x 16 in Marjorie Barrick Museum of Art Collection

“Las Vegas was built by people of color but not made for people of color. Nevertheless, I love Las Vegas and all the people who fought for my family to be here and to live a healthy and prosperous life. My mother has been a part of the Culinary Union for 25 years, and this undoubtedly changed the course of my family’s life. These signs are from protests held by the Culinary Workers Union Local 226, primarily in the ‘90s, to unionize Las Vegas casinos. The idea to make the photographs into puzzles is inspired by Felix Gonzalez-Torres. As has been said about Gonzalez-Torres’s work:

Gift of Nancy J. Uscher This artwork was purchased with funds dedicated to supporting womxn artists of color 2020.11.01

Photograph of Frontier Strike rally, Culinary Union, Las Vegas (Nev.), 1991 September 21. From the series, We Get What We Take. A collaboration with a division of UNLV Special Collections, Latinx Voices of Southern Nevada

‘The puzzles suggest a nostalgic movement coming from the disheartened intention of reviving a past time’s intensity.’”

Text by Krystal Ramirez. “The puzzles suggest …” is quoted from: Francesco Dama, “The Open Works of Felix Gonzalez-Torres.” (Hyperallergic, 2016)

Krystal Ramirez (she/her)

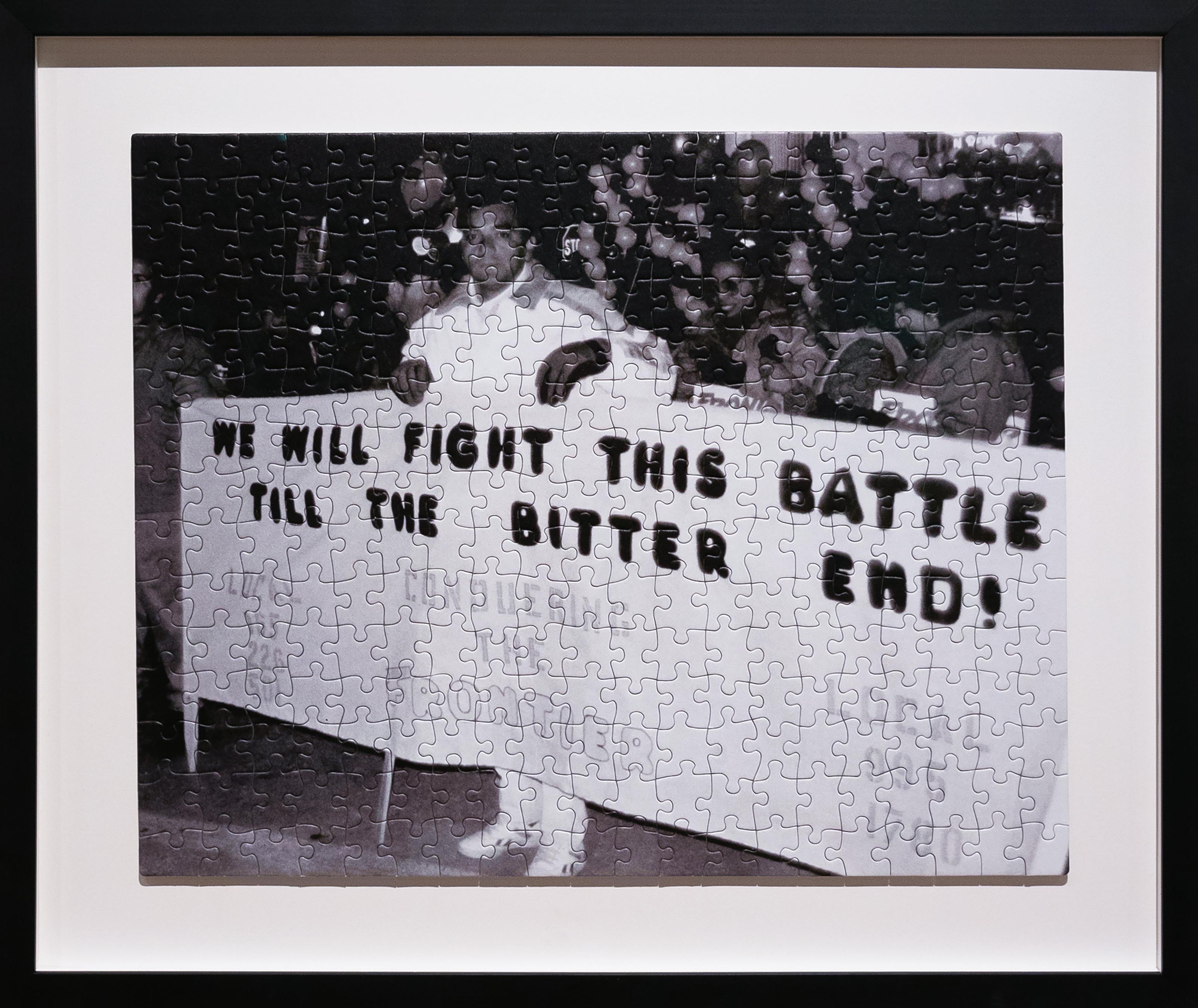

Protest Puzzle, Untitled #2, February 2020

Paperboard, adhesive, printed reproduction of a photograph 16 x 20 in

Marjorie Barrick Museum of Art Collection

Gift of Nancy J. Uscher

This artwork was purchased with funds dedicated to supporting womxn artists of color 2020.11.02

Photographs of MGM Grand rally, Culinary Union, Las Vegas (Nev.), 1994 May 26. From the series, We Get What We Take.

A collaboration with a division of UNLV Special Collections, Latinx Voices of Southern Nevada

Protest Puzzle, Untitled #3, February 2020

Paperboard, adhesive, printed reproduction of a photograph 16 x 20 in

Marjorie Barrick Museum of Art Collection

Gift of Nancy J. Uscher

This artwork was purchased with funds dedicated to supporting womxn artists of color 2020.11.03

Photographs of Desert Solidarity march, Culinary Union, Las Vegas (Nev.), 1992 December 05. From the series, We Get What We Take. A collaboration with a division of UNLV Special Collections, Latinx Voices of Southern Nevada

Sarno Block, Caesars Palace Latticework, c.1966

Concrete

12.5 x 10.5 x 6.75 in Marjorie Barrick Museum of Art Collection

Gift of Heidi Sarno Straus

2020.03.001

“In your opinion, do I look like any designer you ever met? I would rather hang up by my thumbs! So I don’t look like a designer, but see that block outside there through the window, that design that covers the front of the building? That’s the Sarno Block, I’ve had it patented and anybody wants to use it, they got to come to me! See this office? It’s elliptical. An ellipse, in my opinion, is the friendliest shape. The new convention hall we’re building will be my version of the Roman circus— elliptical. I dreamed up the idea for this whole place, and I designed or supervised everything.”

“I’m Form and Function. Stack me up end to end, I make the letter “S”. Illuminate me from behind, I am architectural continuity. As a façade, my breezeway keeps unwanted heat out. My S curves have been gazed through by the best of them as well as the worst. From rags to riches and vice versa, I’ve seen it all. From lovemaking to lives ending. I hold secrets…”