Vision care team helps youngster see Preventing suicide

Your blood donations help her

How a urologist uses water to relieve prostates

Lessons learned from backyard chickens

Vision care team helps youngster see Preventing suicide

Your blood donations help her

How a urologist uses water to relieve prostates

Lessons learned from backyard chickens

These stories illustrate the special setting of Upstate as the region’s only academic medical university and one of about 180 in the country. Medical universities like Upstate have a medical school, more specialists and expertise, and faculty who pioneer treatments, set the standard of patient care, and teach the next generation.

In Central New York, only Upstate provides the entire range of services. Every hospital in the region sends patients to Upstate for this higher level of expertise. Upstate offers many advantages, whether you are seeking care, education or employment. Recent accomplishments include:

EDUCATION

• Every degree from Upstate improves health, builds a vital workforce, and leads to a meaningful career.

• Essentially 100% of graduating students get a job or enroll in further training.

PATIENT CARE

• Magnet-recognized hospital for its nursing care — the top 9% in the nation

• Upstate has three hospitals; the region’s only Level 1 Trauma Center, children’s hospital, and burn unit; 70 unique clinics; and sees 500,000 patient visits per year.

• Upstate is growing! The Nappi Wellness Institute, Upstate Cancer Center at Verona, and Upstate Center for Children’s Behavioral Health open in 2023.

• Nation’s best COVID saliva test.

• The 80th best scientist in the world, out of 828,030.

• 10% per year research growth; highest royalties in SUNY.

• No. 1 educational institution in NY State. Forbes lists Upstate as a Best Large Employer for the third consecutive year; in the education category, we are No. 1 in NY and No. 26 in the U.S. I am proud of Upstate’s 11,000 amazing faculty and staff whose incredible service improves the health of our community, 24/7, 365 days a year.

Mantosh Dewan, MD

President,SUNY Upstate Medical University

A small fleet of robots ferries everything from medicine to meals around Upstate University Hospital, relying on infrared-light whiskers and a laser that scans for objects for navigation.

Supply-chain challenges and staff shortages during the COVID pandemic prompted administrators to invest in a fleet of 14 TUG robots manufactured by Aethon, which specializes in material delivery in hospitals, manufacturing and hotels. Hospitals across the country are turning to robots to help with staff and nursing shortages, and the medical robot market is projected to grow into a $43 billion industry in the next five years.

Beginning with the transport of critical drugs from the pharmacy within the hospital to the cancer center, Upstate will use the robots to transport medical supplies, meals and, potentially, clinical equipment and linen. Some TUGs can carry items weighing up to 1,000 pounds.

“The possibilities are only bound by what can be safely transported.” says Steve Roberts, director of IMT-autonomous machines at Upstate. “Even now, we are thinking about

how best to integrate these robots with drones.

As our nationally recognized drone program continues to evolve, this handoff will become essential to supporting the transport needs of our remote sites.”

The TUG robot stands about 4 feet high and 2 feet wide and looks like nothing more than a giant storage cart. It’s the technology behind it that makes it impressive. The robot uses lidar (a light-based sensing method), sonar and infrared sensors to navigate. It can get on and off an elevator. When it arrives at its destination, it can let itself in. Each of its seven drawers can only be unlocked at the destination it was programmed for and by the person the delivery is for.

Other types of robots have long been used at Upstate to assist surgeons in performing minimally invasive surgeries, including brain surgery. The addition of TUGs frees up critical time for staff to focus on patient care.

Myron Martin is described as compassionate in his work for Upstate’s environmental services department, with friendly words

for the patients he encounters. He worked the COVID-19 unit of Upstate University Hospital from the beginning of the

pandemic in March 2020. Co-workers nominated him for a Chancellor’s Award for Excellence.

In the first 44 weeks of the pandemic, Martin cleaned 3,657 COVID-positive patient rooms and handled 230 patient discharges. That meant handling a minimum of 3,887 bags of linen and more than 11,000 bags of trash between

patient rooms and common areas.

Martin, who has worked at Upstate for six years, has long been known for his commitment and dedication. While hospitals were extra busy during the pandemic, he was willing to work overtime when needed – and it was needed 34 of the first 44 weekends of the pandemic.

Natalie Baumgartner’s mother, Ryan Earl, remembers the day her daughter smiled at a brightly colored book. “I remember just being overjoyed.” Until that moment, it wasn’t clear that her daughter would ever be able to see.

Natalie was born with cataracts covering extremely small eyes. Additionally, she had a cleft palate, affecting the top of her mouth. “Her eyes were very cloudy,” said Earl. On the second morning of her life, doctors at the hospital where she was born tested her, and they could not see any reflection from the back of her eyes.

The conditions required near-immediate intervention, and so, a few days after birth, Natalie met Upstate’s Stephen Merriam, MD, who would operate on her eyes when she was 6 weeks old and who, six years later, continues to care for her vision.

Merriam was a familiar name to Natalie’s family. When Earl was born, she had cataracts in both eyes, and one of her eyes was small. She was

cared for and operated on by Walter Merriam, MD, the father of Stephen Merriam. Both men are part of the Upstate Center for Vision Care.

Before her first birthday, Natalie’s cleft palate was operated on by Sherard Tatum, MD, at the Upstate Cleft and Craniofacial Center, down the hall from the Upstate Center for Vision Care.

Natalie also developed glaucoma, an excess of pressure within the eye that permanently damages the optic nerve, and has been seen regularly by Stephen Merriam, as well as Upstate ophthalmologists Preethi Ganapathy, MD, PhD, and Robert Fechtner, MD, chair of ophthalmology and visual sciences.

“It’s wonderful that Natalie had such skillful and consistent pediatric care from the beginning. With pediatric cataracts and pediatric glaucoma, time is one of the most important factors that determines how these eyes will do,” said Ganapathy. “The earlier we catch glaucoma, the earlier we can treat it, which translates into better chances for the child to keep meaningful long-term vision.”

The Center for Vision Care at Upstate has assembled a team of ophthalmologists to care for the most complex pediatric eye problems. The center’s specialists work as a team to bring state-of-the-art medical and surgical solutions that previously were only available in major cities. “For Natalie, experts in pediatric cataracts, glaucoma and cleft palate have given her the opportunity to overcome these challenges and have a rich and full childhood,” said Fechtner.

For months after her birth, it was unclear whether Natalie could or ever would see. “She kept her eyes closed a lot,” Earl recalled, and she did not react to her parents’ smiling faces. During one visit, Earl remembers Natalie’s father, Patrick Baumgartner, asking Stephen Merriam, “Just tell me she’ll see – she’ll see something.”

Stephen Merriam could make no promises. Her eyes were so small, maybe 40 percent smaller than one might expect. It wasn’t certain. “We were trying to prepare ourselves for essentially a blind child,” Earl said.

Much of Natalie’s earliest days are a fog to her mother. Still, “everything was so quick.” Something that stuck with her was the struggle to care for Natalie’s eyes. She and Patrick had to work as a team to put contacts in Natalie’s eyes. The task had to be performed every eight days, because the gas-permeable lenses had to be switched out regularly. Natalie reacted as any infant might, loudly and strenuously. One parent would have to hold Natalie tightly while the other changed out the contacts. “We were overwhelmed,” she said of herself and Patrick, “we’d hug each other.”

Then, around the time she was 5 months old, Natalie made what appeared to be eye contact with her mother. Later came the reaction when the colorful book was put in front of her.

“She’s the sweetest kid,” Stephen Merriam said of Natalie. “She has done well with what she has.” He explained that Natalie is considered “low vision” and registered as legally blind. Her continuing eye-pressure issues have required multiple operations, and he says Natalie will be a “lifelong eye patient.” She also has annual visits to the Upstate Cleft and Cranial Center.

Natalie’s vision suffered a setback in April when the retina in her right eye became detached due to glaucoma. Surgery to reattach the retina was not successful. “Ultimately, Natalie only sees out of her left eye now, which appears healthy, and she is still monitored by all the same doctors,” Earl said. “She continues to adapt and thrive, and always amazes us despite any challenges she faces!”

Natalie is now a pupil at Beaver River Central School in Castorland, about an hour and a half northeast of Syracuse. “She’s very smart,” her mother said. She recalled Natalie talking at 10 months and walking at 15 or 16 months.

With the help of glasses — which she started wearing at 8 months,

sparing her parents from having to keep changing out contacts — Natalie can see well enough to watch movies, though she has to be very close to the TV, and enjoys YouTube videos, such as “Ryan’s World.” Three years ago, she welcomed a little brother, Damon Baumgartner, to the family.

“She loves to be challenged,” her mother said. She is careful in getting around. Her limited vision makes it difficult for her to perceive changes in heights but enjoys riding her tricycle and climbing the monkey bars at school. “She’s sassy,” her mother declared with a laugh. “She has come so far.”

“Patrick and I are grateful to all of Natalie’s doctors and all they have done for her over the years,” Earl said. “All of Natalie’s continued successes are a direct result from the care they have provided her, and we couldn’t be more thankful!”

“The Center for Vision Care at Upstate is here to serve our community. In addition to our full-time faculty, we are fortunate to have top ophthalmologists from our community volunteer their time to provide expert care for nearly every eye problem in children and adults,” said Fechtner. “In addition to the clinical expertise, we have an internationally recognized group of scientists at the Center for Vision Research studying the basic mechanisms of vision and the eye. Their leading-edge research is producing discoveries that may, someday, prevent blindness and restore vision.”

The Center for Vision Care, celebrating its 25th year of service, provides a wide variety of eye-care services, from comprehensive eye exams to complex ophthalmic microsurgery. u

It was Aug. 8, and Timothy Carpenter had just returned home from taking his wife, Michelle Angel, to Watertown for her birthday lunch.

He had some copies to make. He was running a page through the copy machine when he started feeling dizzy. He mumbled something.

“What did you say?” his wife called from across the room.

She turned just in time to see him collapse. She called 911.

Prompt recognition, followed by a swift medical response, helped save Carpenter’s life.

Carpenter recalls that his right side was not working. He’d knocked over the chair when he fell. Now he struggled to get up, and he struggled to speak.

Soon, two old friends from the Fishers Landing Fire Department were at Carpenter’s

side. “Mark Baltz was sitting there saying, ‘Will you lay still?’ His nephew, Andy Baltz, walked in, took one look at me, and walked back out to call the helicopter.”

Thousand Islands Emergency Rescue Services arrived to transport Carpenter from his trailer home to the nearby Can-Am Speedway in LaFargeville, where the LifeNet helicopter could land safely.

“It didn’t seem like it took hardly any time at all,” Carpenter says of the flight to Upstate University Hospital in Syracuse. He spent the entire trip trying to communicate that his wallet was in his back pocket. He remembers glancing out the window to see Interstate 81 and the Great Lakes Cheese plant in Adams from above. He remembers landing, hearing the blades of the chopper wind down and his being wheeled into the hospital.

“I remember them taking my shirt off at the

hospital. I remember them saying, ‘We’re going to give you something that’s going to make you feel better,’ and I was out.”

Carpenter’s stroke happened on his wife’s birthday. Fourteen years earlier, he survived a heart attack on her birthday.

“I’m kind of an old bird,” says Carpenter, 58. He worked in a lumber yard when he had his heart attack. At first, he shrugged off the pain as a pulled muscle and continued working. That night he went go-kart racing. The next day, he couldn’t raise his arm above his head, but he worked his entire shift. He returned the next day to load trucks for delivery. Finally, feeling awful, he said he had to go home.

His wife had an ambulance-crew friend stop by to assess him. The man took Carpenter’s blood pressure and turned white. He told Carpenter he was going to the hospital, and he was going immediately. “What scared me,”

Carpenter says, years later, “is that he flat refused to tell me what my blood pressure was.”

Since then, Carpenter has taken an aspirin every day. He said it’s unclear whether his stroke is related to his heart attack.

He awoke Aug. 9 under the care of Timothy Beutler, MD, a neurosurgeon who specializes in critical care at Upstate. A blood clot had totally blocked one of the vessels in his brain.

While Carpenter was out, members of the stroke team gave him a powerful thrombolytic to help dissolve clots, and Amar Swarnkar, MD, a professor of radiology, neurology and neurosurgery, used tools to locate and retrieve the clot in a procedure called a thrombectomy.

“Everything in stroke care is timesensitive,” Beutler explains. “Mr. Carpenter had quite a good outcome. That’s because of a quick recognition of his stroke symptoms, and his quick arrival to Upstate. He was able to get the thrombolytics and to get into the angio suite for the thrombectomy.” The angio, or angiography, suite is where such procedures, involving blood vessels, can be performed.

Beutler says based on the location and size of the clot, if Carpenter had not arrived so quickly, he likely would have suffered a stroke that caused potentially life-threatening swelling. He would have been hospitalized for

weeks. He may have required emergency surgery. He likely would have been left with severe deficits and been discharged to a nursing home rather than to his home.

Because he got prompt care, when Carpenter awoke, he had full movement on his right side, and he could speak. He felt weak on the right side, but he says even that improved by the next day. When he went home from the hospital, his only remaining symptom was a mild facial droop that is barely noticeable. u

• Wear water shoes.

• Gather soaps, cloths and towels before approaching the person.

• Use a shower seat.

• Avoid getting water on the person’s head or face.

• Dim lights that are too bright.

• Play relaxing music.

• Realize there’s no right or wrong time for a bath.

• Sponge baths work, too.

– from the team of nurses in the department of geriatrics at Upstate

Peter Wong was in his early 50s when he had his first stroke. Today, he says, “I remind myself over and over again how lucky I am to be on this side of the earth.”

Through a lengthy journey back to health, Wong has been helped by several experts at Upstate Medical University, including physical therapists, a doctor who oversaw important dietary changes and another who streamlined his prescriptions.

Wong, 60, of Liverpool, loved his job and spent many hours of his life at Syracuse’s Hancock International Airport, where he worked, usually arriving a half-hour early for a shift that started at 4 a.m. He worked for an airline, directing planes into terminals, ticketing passengers, collecting baggage and various other tasks.

One morning in October 2014, just after the last of the passengers were checked in, Wong suddenly leaned against the wall. His words became garbled. His body slid down the wall until he sat on the baggage conveyor belt.

Co-workers helped him into the break room and periodically checked on him. “I wasn’t getting any better. In fact, I was getting worse. So, they got worried.” They called 911. Paramedics wanted to bring him to the hospital emergency department. Wong resisted.

Finally, he agreed to let a co-worker drive him home. She instead drove him to the hospital.

“I got admitted immediately,” Wong remembers. “They found two ischemic strokes had occurred in the pons area of my brain. And they determined it was too late for the medication to break up the strokes.”

At the time, Wong didn’t know anything about the warning signs of stroke or the damage that can result. He soon learned.

An ischemic stroke occurs when a clot blocks blood flow in an artery in the brain. The pons area is the largest part of the brain stem, where information is relayed about motor function and sensation, eye

movement, hearing, taste and more. Medication can be used to help break up clots that are causing strokes, but only if it is administered quickly.

Wong was hospitalized for a week. He was anxious to return to work and feeling better. But the day he was to be discharged, he suffered a third stroke. This one was debilitating. Wong couldn’t swallow, he couldn’t see, and he couldn’t move his left side.

Several weeks later, he was transferred into the department of physical medicine and rehabilitation program at Upstate Medical University. He still struggled physically. “My cognitive, intelligent self was trapped in a world it didn’t want to be in. It was difficult, very difficult, to deal with,” Wong recalls. The therapists and doctors and nurses from rehabilitation “took super care of me. They had to help me through some really, really difficult times. I would spend hours just crying and crying. I felt hopeless. They understood, and they steered me through that.”

He remembers a special “carnival day” that his physical therapist insisted he attend. She wheeled him outside, where food and games were set up, and together they visited every vendor. Wong threw darts and tossed bean bags and came away with a stuffed prize, feeling as if he had won an Olympic medal. “To this day, I have that multicolored fuzzy caterpillar. It stays on my bed. That carnival had a major impact on me. It was unbelievable how much it helped. I applaud these people who help you put your life back together. They give you hope.”

For two months at Upstate and another six months after he was discharged, Wong worked to regain the ability to swallow, and to stand and, eventually, to walk. His goal was to return to work, and he did for a brief time. He continued having transient ischemic attacks, small strokes known as TIAs. He would stumble and injure himself falling. Or he would have a seizure. In four years, he made seven trips to the hospital emergency room. Wong soon realized he would have to go on medical disability.

One of his doctors tried to break his cycle of strokes with a vegan diet. So Wong eliminated animal fat from his diet for an entire year. He says it was torture, but it helped improve his blood pressure. The doctor later allowed that he could have one egg per week, and some yogurt. During a follow-up appointment, Wong’s doctor told him about neurologist Karen Albright, DO, PhD, who had recently joined Upstate. She specialized in pharmacogenetics, how an individual’s genetic makeup affects his or her response to medications.

Wong got an appointment with Albright at the department of neurology’s pharmacogenomics clinic.

Albright told him of an unusual tendency for people from specific regions of Asia to have a genetic variant that could disrupt the metabolism of certain medications including clopidogrel, the blood thinner he was taking to reduce his risk of stroke by inhibiting platelets in his blood. Wong was born in Hong Kong and came to New York City as a preschooler. He was willing to have blood drawn for a genetic test that would reveal how his body was handling the medications he was taking.

Clopidogrel is a prodrug, meaning the body has to convert it after administration. “First, it has to get absorbed,” Albright explains. “Then you have to activate this drug. If you have a genetic variant that makes you a poor metabolizer, you can’t activate the drug enough to adequately inhibit platelets.”

Wong learned that he had a genetic variant that was not allowing his body to fully activate clopidrogel.

Albright discontinued his clopidrogel and replaced it with an alternative antiplatelet medication. Wong has not required emergency medical care since.

“I have not had a TIA or stroke since. It’s unbelievable,” Wong says. “She is amazing.” u

– Are you taking a medication that is not working?

– Have you had bad side effects from a medication?

– Are you taking multiple medications?

– Do you have a family history of adverse drug reactions?

These are some of the reasons people seek help from specialists who understand how genes relate to various medications.

Patients at the pharmacogenomics clinic (PGx, for short), in Upstate’s department of neurology, meet first with a pharmacist and doctor or nurse practitioner to provide a detailed medication history. Pharmacist Danielle DelVecchio says strong evidence does not exist for all medications. But if patients may benefit, genetic testing is offered.

“Our PGx clinic focuses on genes with a high level of

evidence,” Karen Albright, DO, PhD, explains.

“We often tell patients we are not 23 and Me. We cannot predict what diseases you may get in the future. We are not Ancestry.com. We can’t tell you who you are or aren’t related to. We are focused on genes that relate to drugs. We look at genotypes of specific genes that groups like PharmGKB or the Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium have said have a high level of evidence. These groups issue guidelines for clinicians about what they should do with genetic information.”

The federal Food and Drug Administration provides a table of pharmacogenomic biomarkers in drug labeling and says “pharmacogenomics can play an important role in identifying responders and non-responders to medications, avoiding adverse events and optimizing drug dose.”

Health care providers can refer patients to Upstate’s pharmacogenomics clinic by calling 315-464-4243.

A6-year-old Syracuse boy receives infusions of a new medication directly into his brain every other week at the pediatric infusion center, on the third floor of the Upstate Cancer Center.

Julius McClary Jr. – everyone knows him as Juju – has Batten disease, one of a group of rare genetic disorders known as neuronal ceroid lipofuscinoses. His mother, Cristina Rosa, says infusions of the new medication Brineura (cerliponase alfa) have made a tremendous difference.

Soon after his diagnosis, Juju underwent surgery to have a reservoir implanted in his brain, similar to the way some cancer patients have ports implanted in advance of treatment. The medication has to be infused directly into the fluid of the brain. A small patch of his curly hair was cut, and a tattoo on his scalp marks where to access the intraventricular device in his brain.

Each infusion takes about five hours, says Rosa. Her son has been having them every two weeks since May 2021, when they would travel to the University of Rochester and stay overnight in the hospital. She was grateful when Upstate began offering this type of infusion.

Nurse manager Molly Napier says the Upstate team underwent training and collaborated with caregivers at Nationwide Children’s Hospital in Columbus, Ohio, and Golisano Children’s Hospital in

Rochester to transition Juju to Upstate’s infusion center. At the time Juju’s infusions were started, Brineura was being administered only at 75 centers in the United States. Juju was the first Syracuse patient. He prefers to sit in his stroller during the infusion.

Juju was 2 when he began speech therapy for a speech delay. He was 3 when he had his first seizure, at day care. “I knew something was wrong with my son,” Rosa says. Juju was crawling, but not walking, and his balance was off. She pushed for him to see a neurologist who would help them explore genetic testing.

Pediatric neurologist Ai Sakonju, MD, is his Batten infusion team director, with nurse practitioners Stacy Shourt and Meghan Claver and other nurses, including Lauren Wilbur. His primary neurologist is Arayamparambil Anilkumar, MD, and Nienke Dosa, MD, is his developmental pediatrician.

Testing revealed the rare genetic disorder of the nervous system. Children with Batten disease may experience loss of vision, seizures, cognitive difficulties, trouble speaking and problems with coordination, balance and movement. Originally it was believed to be one disease, but experts have discovered more than 100 variants.

Like others with the disease, Juju’s body produces enzymes but not an adequate supply, Anilkumar explains. He says the breakthrough came when researchers developed Brineura, an enzyme replacement therapy.

“The problem is, you cannot put an enzyme into the blood. It doesn’t really work that way,” he says. That is why the medication must be infused directly into the brain.

Brineura is meant to slow the loss of the ability to walk that some pediatric patients experience. BioMarin, the maker of Brineura, estimates 20 children born in the United States each year are affected by this rare, progressive disorder.

“You cannot put the clock back. Whatever damage has happened, you cannot reverse,” says the neurologist. “What you can do is prevent the accelerated loss of brain cells. So you are putting a brake on the progression of the disease.”

Anilkumar says Brineura is helping Juju. He still has his vision, and his seizures are under control.

Rosa is impressed with her son.

“Juju is so strong and resilient. His progress, it just amazes me,” she says. “He’s walking. Now he can walk with assistance. He used to not be able to crawl with a steady balance. Now he’s crawling everywhere.”

He feeds himself, using utensils. He continues to work on speech. Upstate physical therapist Nicole Ramos is helping him get stronger. He started kindergarten this past fall.

“He just makes me so proud. His improvement makes me so happy. He’s got such a big smile. He’s such a happy kid,” Rosa says.

“This was not Juju at the beginning of the diagnosis, so the enzymes are definitely, definitely helping.” u

THE

TPP1 enzyme is missing or not working properly in children with CLN2 disease, one of the forms of Batten disease. This leads to a buildup of storage materials in their lysosomes, associated with cell damage in the brain.When Brineura is delivered to a child with CLN2 disease, it helps replace the missing TPP1 enzyme.

Anyone can hurt their back by lifting something heavy. The resulting pain may come from a herniated disk, also called a slipped or ruptured disk. Some people whose injury does not heal become candidates for a surgery done through a tiny incision, with a quick recovery.

Over the summer, Upstate neurosurgeon Ali Hazama, MD, operated on Julia Blair, 22, now a senior at SUNY Potsdam. Blair was amazed to be so quickly relieved of pain she had since fall 2021.

Blair plays on the college’s women’s varsity lacrosse team. She injured her back while deadlifting during a workout in November 2021. “I must have had the wrong form, or maybe too much weight,” she recalls. “I felt like I pulled something in my back, and a day later, I had shooting pains down my left leg,”

She waited. The pain did not go away. She saw a chiropractor, who had her do some exercises.

The pain persisted as the 2021 autumn

training season gave way to the spring 2022 lacrosse season. Blair only played in a handful of her team’s 16 games. She saw a doctor who ordered an MRI scan of her back and referred her to Hazama for possible surgery.

Since Blair’s pain did not subside on its own, Hazama recommended a procedure called endoscopic lumbar diskectomy (see box). He showed Blair images of the spinal endoscopic tool he would use to remove the disk fragments that were pressing against a nerve and causing her pain.

The tool allows surgery with a tiny incision instead of a traditional, or open, surgery, which would require a much larger incision, then further cutting through large amounts of tissue to get to the problem area, with a lengthier and likely more painful recovery period.

“Endoscopic spine surgery is an ultraminimally invasive technique that really is built around preserving normal body tissue and directly treating the problem without introducing any further damage to the body or

the spine,“ Hazama explains.

“You save the patient the surgical pain, the pain that comes not just from the problem that someone comes in with, but from the actual cutting of normal tissue, that lasts for days to weeks after a traditional surgery,” Hazama says. “That’s why these patients are usually extremely happy with the results of the surgeries.”

Hazama notes that this procedure cannot be used for all spinal problems. But in addition to herniated disks, it can relieve the pressure of spinal stenosis and be used to perform corrective procedures, such as spinal fusions, as well as spinal biopsies.

The thought of surgery scared Blair at first. “I was so nervous, and it ended up being like a piece of cake, and the doctor and all his staff there were incredible. They made me feel so good about having this done,” she says.

The surgery, which took place in May at Upstate, lasted less than an hour, and she went home within a few hours, which is typical for this procedure. She recalls feeling no pain on

minimally invasive procedure usually sends patients home within hours — and withoutJulia Blair underwent an endoscopic lumbar diskectomy at Upstate that relieved the pain of a herniated disk and allowed her to return to her position as attacker for the SUNY Potsdam women’s varsity lacrosse team. The senior from Massena is majoring in psychology.

the three-hour car ride back to her home in Massena, including a stop for dinner.

“I was, like, instantly relieved,” she recalls. As she got up from the table after eating and walked to the car, she was thrilled to realize: “I don’t feel any pain.” Friends and family who had watched her struggle to put on her own socks saw a huge difference.

problems will have their problem resolved without undergoing surgery, a statistic he shares with pride.

But for those whose spinal problem doesn’t resolve by itself, endoscopic spinal surgery offers a route to getting back to one’s normal routine. This surgery has been around for years, but recent advances

This is a minimally invasive operation , a device with a pencil-sized tube, which a surgeon uses to insert tiny tools for cutting, removing and cauterizing tissue. A tiny camera and lights transmit highquality images of the affected area to a refers to the lower back.

is the removal of the damaged portion of a herniated disk. Disks are the rubbery cushions between the vertebrae, or stack of bones making up the spinal column, which surrounds and protects the nerve tissue of the spinal cord. When the outer wall of a disk dries out or weakens with age or injury, the soft, inner part bulges out, resulting in a herniated disk. This can press on nerve tissue and cause pain,

Meet Katrina Hutz. She’s 16, a ballerina, a FayettevilleManlius High School junior. She has a beagle, two cats, two brothers and a mom and a dad.

In February 2022, after mysterious headaches, she was diagnosed with a rare form of leukemia called erythroid sarcoma. Blood products donated by strangers help her get through the treatments.

From February through July, Hutz underwent four rounds of chemotherapy, staying at the Upstate Golisano Children’s Hospital with brief breaks to go home between cycles.

Bone marrow, which makes the body’s blood cells, is sensitive to chemotherapy, and typically blood cell numbers drop after chemotherapy begins. That’s why Hutz and many other cancer patients rely on transfusions of red blood cells and platelets.

“For platelet transfusions, I feel the same during, before and after. But red blood cell transfusions, they give me more energy,” she says. “Usually when my red blood cells are low, I’m really tired, and I can’t really function. After, I can be up and stay awake.”

She completed three weeks of radiation treatment in Boston, “where luckily she did not need any blood products but was closely monitored,” says her mom, Julie Hutz. “Katrina has completed treatment and is now in remission.” u

• Red blood cells — which carry oxygen from your lungs to the rest of your body — are the most frequently used blood component, needed by almost every type of patient requiring transfusion.

A “power red” donation is similar to a whole blood donation. A machine separates red blood cells for collection, and your plasma and platelets are returned to you. The process takes about 45 minutes, about a half-hour longer than a regular blood donation.

• Platelets — the tiny cells in your blood that form clots — are essential for people fighting cancer, chronic diseases and traumatic injuries.

A donation of platelets often results in several transfusable platelet units. The process takes about three hours and takes place at a special donation center. Blood travels from your arm to a spinning machine that separates plasma from the other blood components, which are returned through your other arm.

Find out if you are eligible to donate at www.redcrossblood.org

ALL ARE FREE FOR YOU TO READ, LISTEN, WATCH, ENGAGE.

Record numbers of suicides among young people prompted the creation of Upstate’s Psychiatry High Risk Program in 2017.

“Our mission is very simply to save and transform lives,” says Robert Gregory, MD, a professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences.

This program offers comprehensive outpatient care that includes weekly individual psychotherapy. It may also include medications, and family and group psychotherapy, if appropriate.

“It’s a 12-month program, since it takes a while for transformative healing to occur, enough time for individuals to change lifelong coping patterns and ways of perceiving themselves and others,” Gregory says. The goal is for the person to be well enough to continue their recovery without needing to be in the mental health system.

The weekly individual psychotherapy is a particular style of treatment called “dynamic deconstructive psychotherapy,” which Gregory developed. He describes it as helping someone heal from the inside out.

“It works through a different mechanism than most psychotherapies and feels very different to the patients undergoing it as compared to previous experiences they may have had in counseling,” he says.

Gregory explains that people who are suicidal have an impaired emotion processing system in the brain that renders them unable to process emotionally painful experiences through their prefrontal cortex. So more primitive subcortical areas of the brain are activated, causing them to experience a high state of arousal and distress and a sense of emptiness and disconnection.

Instead of focusing on symptoms or giving

Robert Gregory, MD, explains that the higher-level regions of the brain, shown by the green arrows, either atrophy or become underreactive in response to emotionally charged situations. The lower brain regions, shown by the yellow arrows, become hyperreactive in response to emotion. This leads to a high state of arousal and impulsive pleasure seeking.

advice on how to cope with each crisis that arises, DDP helps patients practice how to connect with and process emotionally laden experiences. This helps activate and remediate the emotion processing system in the prefrontal cortex, much like the way physical

therapy remediates functioning after a stroke.

“As their emotion processing system begins to strengthen and heal, symptoms of anxiety and depression markedly improve, and patients feel more connected with themselves and others, no longer obsessed with thoughts of

learn how to deal with emotional experiences.

Psychiatrist Robert Gregory, MD, says a common indicator of depression is withdrawal from people and difficulty functioning at work or school.

suicide,” Gregory says. “It’s a different way of thinking about treatment, but it really works.”

About two-thirds of the patients in the Psychiatry High Risk Program take psychiatric medication. Gregory says medication may provide symptom relief before the effects of psychotherapy kick in. “What we have found is that the need for medications decreases over time, such that most of our patients are on fewer medications when they leave the program than when they started.”

When the program began in 2017, Gregory and one other therapist handled all of the patients. Today, a dozen staff members are dedicated to the Psychiatry High Risk Program. They’ve treated almost 600 patients between the ages of 14 and 40.

About half of the patients are referred to the Psychiatry High Risk Program through emergency physicians. Self-referrals are also accepted. Call 315-464-3117. u

There may be a lot of expressions of pessimism and negativity.

Be aware that many people who are struggling do not share their pain, and many are very good at hiding depression, he says.

Do not be afraid to ask, “Have you been feeling depressed lately?” and “Have you been having thoughts of suicide?” If the answer is anything other than a definitive “no,” Gregory says, please refer them to the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline, which now has a national three-digit number: 988; or a hospital emergency room.

The Psychiatry High Risk Program in Syracuse can be reached at 315-464-3117.

As a man’s prostate grows, it can impact his urinary tract, causing a variety of troubles when he tries to empty his bladder. Medications and surgery are options to treat the condition, known as benign prostatic hyperplasia, or BPH.

An Upstate urologist offers an alternative treatment.

Hanan Goldberg, MD, offers aquablation therapy, a procedure that requires no incisions. Using robotic tools inserted through the urethra and an ultrasound probe in the rectum, Goldberg maneuvers a tiny water jet to remove excess prostate tissue. This widens the channel, improving the flow of urine.

“The water actually makes the tissue disappear. It is all removed completely because the water jet is so strong,” Goldberg says.

The patient is under anesthesia for the procedure and stays overnight in the hospital

afterward. A catheter, or tube, for urination usually remains in place for up to three days during recovery.

Aquablation was approved in 2018 by the Food and Drug Administration. Urologists have studied how it compares with surgical options. Goldberg says aquablation is as effective as the traditional surgery, called transurethral resection of the prostate, and with fewer side effects.

He says the rate of erectile dysfunction and urinary incontinence after aquablation is zero. The procedure can work on any size prostate, and almost any man who can safely undergo anesthesia would be a candidate.

Aquablation may not be a permanent fix for an enlarged prostate. Goldberg notes that prostate tissue grows back over time.

For details or an appointment, contact Upstate Urology at 315-464-1500. u

Dave Amberg, PhD, Upstate’s vice president for research, was featured in The Post-Standard’s weekly “Conversation on Leadership” series. Here are six takeaways from that conversation:

He considers himself a servant leader, in place to help faculty succeed. “They should be the intellectual drivers of the university,” Amberg says. “I shouldn’t be telling them what they should be working on. They should be telling me what they want to work on, what they think is important and how to support it.”

He isn’t a fan of committee meetings, and the ones he leads tend to be short, maybe no more than 15 minutes. “I’m a very resultsoriented person, and I want to drive every meeting to a set of deliverables and as quickly as possible.”

He is inclusive. “Sometimes leaders want to exclude people that they perceive as being difficult to work with,” he says. “I’ve frequently found that the difficult people to work with are the most passionate about the subject at hand. If you don’t have them in the room when you’re making decisions, if they haven’t been a part of the process, they’re going to undermine it.”

He models good email communication, which he says means never blind copying and never forwarding emails without the sender’s permission. “Those are two aspects of what I call weaponized email. If you’re doing those things, you’re not doing them for a good reason.”

He makes decisions quickly, based on having enough information to be pretty sure it’s the right decision. “In some decisions, the right decisions are obvious immediately. Why not make them right then?”

He values emotional intelligence. “It can be an extremely valuable sixth sense if you can feel and sense how people are responding to what you’re doing or how you’re doing it.” u

Shortness of breath, dizziness, swelling of the legs and chest pain or pressure are symptoms that could indicate a variety of medical conditions, including pulmonary hypertension.

This is different from the hypertension people monitor with blood pressure cuffs squeezing their arms. Hypertension is high blood pressure affecting the vessels of the body. Pulmonary hypertension involves just the vessels that carry blood to the lungs.

“Early diagnosis and more aggressive treatment up front increases the survival,” says Upstate pulmonologist Birendra Sah, MD. “There’s no cure for pulmonary hypertension, but if we diagnose it early and if we treat them with proper drugs, that can lead to increased survival.”

Pulmonary hypertension develops when blood vessels in the lungs become thickened, narrowed, blocked or destroyed.

Krithika Ramachandran, MBBS, is a colleague of Sah’s, specializing in critical care and pulmonary diseases. “Usually the way I explain it to my patients is, I tell them to imagine a balloon with a straw attached to the end. If the diameter of the straw just keeps getting smaller and smaller, that balloon has to be squeezed harder and harder to send flow through the straw.

“That’s essentially what’s happening with the right side of the heart in this situation.”

A diagnosis can be challenging because the first symptoms are generally nonspecific. A person may feel short of breath, or tired. As the disease progresses, legs may swell, or the belly may swell as fluid is retained.

Pulmonary hypertension is dangerous

For help understanding pulmonary hypertension, consider how the blood circulates. The superior and inferior vena cavae feed blood into the right side of the heart, which pumps it through the pulmonary artery into the lungs. That’s where blood releases carbon dioxide and is enriched with oxygen. From the lungs, blood flows into the left ventricle of the heart, which pumps it through the aorta to travel throughout the body – eventually returning through the superior vena cava and inferior vena cava.

because untreated, it leads to congestive heart failure. The chambers of the heart dilate, and their ability to push blood into the lungs diminishes. This reduces the supply of oxygen to the brain and the rest of the body.

To treat pulmonary hypertension appropriately, health providers begin by identifying what type of pulmonary hypertension a patient has.

One type, pulmonary arterial hypertension, occurs when the walls of the artery become stiff. This may develop because of a gene passed down through families, congenital heart disease, use of certain drugs or illegal substances, connective tissue disorders such as lupus or scleroderma, liver disease or infection with the human immunodeficiency virus.

Some people develop this condition without ever learning its cause.

Sah says pulmonary arterial hypertension is typically treated with vasodilator medications, which help the blood vessels relax. In addition, patients may require supplemental oxygen, or medications to thin the blood, or medicine to help the body remove excess water. Another type, chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension, which occurs due to longstanding blood clots in the lung blood vessels, can be treated with surgery to remove the blood clots in select patients, or with vasodilators in patients who are not candidates for surgery.

The other types of pulmonary hypertension are generally treated with supportive care,

he says. That means some patients may need supplemental oxygen. Some may require blood thinners. Some may need inhaled vasodilators. Most benefit from careful measurement of their fluid and salt intake and body weight.

People with pulmonary hypertension are managing a disease that can complicate their lives in multiple ways.

“It’s a very precarious line they toe when they’re trying to keep themselves healthy. So anything and everything needs to be evaluated as a risk-benefit ratio before taking it,” says Ramachandran.

Most patients are taking a medication to help maintain their body’s salt and fluid balance, so they have to be careful about the salt content of their foods and about taking other medications.

If they develop a cold, they may not be able to take a decongestant because it can increase pressure in the lungs and make it harder for the heart to work properly. And the pain reliever ibuprofen can affect liver function and kidney function.

Most of the drugs that treat atrial fibrillation, a common heart rhythm

disturbance, work by slowing the heart rate. This can be a particular concern for someone with pulmonary hypertension because it can depress the heart’s already-impaired ability to pump blood.

Exercise has to be approached with caution, too. Lifting weights above the head is a no-no because of the stress it puts on the heart. Traveling to high altitudes, or on an airplane, may require the use of supplemental oxygen.

The cardiovascular system in a woman with pulmonary hypertension cannot handle the stress of pregnancy and can be life-threatening to her. Also, many of the medications used to treat the disease can cause fetal defects. So women with pulmonary hypertension are advised not to become pregnant.

Pulmonary hypertension caused by left-sided heart disease can be the result of mitral valve or aortic valve disease or failure of the left ventricle because of a heart attack or another disease.

Pulmonary hypertension caused by lung disease can be the result of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases including emphysema and bronchitis, pulmonary fibrosis or obstructive

sleep apnea.

Other health conditions — including inflammatory diseases such as sarcoidosis and vasculitis, blood disorders, metabolic disorders, kidney disease and others – can trigger pulmonary hypertension. And, people with clotting disorders or pulmonary emboli are at risk for developing pulmonary hypertension caused by chronic blood clots.

“The landscape for treating this disease has changed dramatically in the last 10 to 15 years,” Ramachandran says. In the 1990s, a diagnosis of pulmonary hypertension was like a death sentence, with more than half of patients dead within three years. “But now, it can be one of those diseases that you die with instead of die from.”

She explains that multiple medications are available today to help dilate the blood vessels and reduce the pressure, so the heart can pump blood through the lungs.

It’s a complicated disease that requires careful medical management.

Sah says patients with pulmonary hypertension keep in close contact with their pulmonologists, making regular visits for checkups. u

High blood pressure in the blood vessels throughout the body, excluding the lungs.

A person’s blood pressure can be measured through a cuff that squeezes the arm.

If high blood pressure is not controlled, it can lead to dysfunction of the heart and the development of pulmonary hypertension.

High blood pressure in the blood vessels supplying blood to the lungs

In addition to blood tests, chest X-rays and an electrocardiogram to record the heart’s electrical activity, an ultrasound of the heart called an echocardiogram and a procedure called right heart catheterization can help doctors measure the pressure inside the pulmonary artery.

A person can develop pulmonary hypertension regardless of whether they have regular high blood pressure.

Impacting patient care, education, research and community health and well-being through charitable giving.

Helping patients stay healthy after a hospital stay is the goal of an Upstate University Hospital program called Nutritional Support of Heart Failure Patients. The program partners with Off the Muck Market, a local grocery delivery service featuring homegrown fruits and vegetables. The boxes are paid for through donations to Friend in Deed, the hospital’s annual fund overseen by the Upstate Foundation.

Heart failure is a long-term condition that affects the heart’s ability to pump enough blood through the body. Patients are advised to follow a healthful, low-sodium diet, including plenty of fruits and vegetables. For patients who live in a “food desert” — a low-income area where residents do not have easy access to a supermarket — finding these foods after a hospital stay, and even coordinating a trip to the grocery store, often presents a challenge. Food deserts also are associated with a “higher burden of cardiovascular risk factors,” according to the American Journal of Cardiology. About 40% of the city of Syracuse lives in a food desert, and 11% of Onondaga County residents face food insecurity.

To encourage healthy eating, the nutritional support program arranges for a delivery of a box of farm-fresh foods directly to the patients once they are home.

A gift of gratitude is a meaningful way to express appreciation to special caregivers and help patients during their time of great need. To donate, contact the Upstate Foundation at 315-464-4416 or go to www.UpstateFoundation.org/donate.

Initial results of sending the fresh food boxes are good. Of the patients who were provided with boxes, 72 percent did not experience an early readmission to the hospital. Nurse Natasha Zmitrowitz, the heart failure data coordinator at Upstate, says the time for the highest risk of readmission is the first 30 days after discharge. “That is why it is so important to have these healthy foods available during that time.”

Additionally, as representatives from Off the Muck Market educate patients on the foods they receive and how to prepare them, new healthy habits are established to guard against future complications and rehospitalizations.

Jennifer Janes, director of Annual Giving and Donor Engagement for the Upstate Foundation, noted:

“Many times, we think of the care patients receive while they are hospitalized, however, this program gives patients what they need post-care and creates a foundation for a healthier lifestyle. Thanks to financial gifts from grateful patients and families, we can fund programs like this to help other patients during their time of greatest need.”

Off the Muck Market delivers boxes of seasonal fresh fruits and vegetables once patients are back home.

Among participants of the first Central New York Walk for Brain Cancer Research at Upstate were Nneka Onwumere, (center) the medical student who organized the event; neurosurgeon Lawrence Chin, MD, (far left) dean of the College of Medicine; and family members of Debbie Gregg of Cazenovia, for whom the brain cancer research fund is named. They include, left to right, Gregg’s father Gordon Schutzendorf, Stephanie Shutzendorf, Jennifer Hooley, Dennis Gregg and Chip Hooley.

BY JEANNE ALBANESEIt is fitting that the inaugural Central New York Walk for Brain Cancer Research at Upstate Medical University, organized by medical student Nneka Onwumere, fell on Mother’s Day.

Onwumere’s mother, Elsweta Gordon, helped spark her interest in the field of neurology. Later, Gordon’s own health issues solidified Onwumere’s resolve to become a doctor.

Gordon worked as a medical assistant and later as a nurse in the neurology department of a hospital in the Bronx. She died in the fall of 2021, so 2022 was Onwumere’s first holiday without her.

The 1.25-mile walk drew more than 40 participants and raised almost $3,000 for Debbie’s Brain Cancer Research Fund, part of the Upstate Foundation, which supports brain cancer research at Upstate. The fund is in memory of Debbie Gregg of Cazenovia, who died in 2012 from a rare brain tumor. Gregg’s parents, sister and husband were among the people who participated in the walk.

“I was floored by the level of support we received,” Onwumere says of the event. “The weather was gorgeous, and those who walked brought joy to my heart.”

She decided to organize the walk after realizing the Syracuse area had events to support breast cancer and Alzheimer’s, but nothing for brain cancer. Squeezing in event planning around her medical school classes wasn’t easy, but Onwumere had a role model in her mother, who put herself through nursing school while working full time.

Onwumere volunteered doing clerical work during middle school and high school at the VA Medical Center in the Bronx, where her mother worked. On lunch breaks she would visit with patients. One told her she had a good bedside manner and should consider becoming a doctor.

“I really liked talking to patients,” she said. “It helped me learn how

rewarding the doctor-patient experience could be.” She also likes doing things with her hands, which is what pushed her into neurosurgery over neurology.

Upon graduating from college, Onwumere applied to Upstate’s medical school. She was not accepted. Instead, she started to pursue a master’s degree closer to home and took a job as an office assistant for an oncologist at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. She was promoted to research assistant.

Around the same time, her mother started having a series of strokes, furthering Onwumere’s interest in neurosurgery and inspiring her to keep pursuing her dream, despite her initial failure to get into medical school.

Onwumere applied to Upstate again. She was accepted to the Medical Scholars Master’s program, which provides students extra enrichment and a pathway to medical school. She earned that master’s and started medical school in 2020.

“My mother’s experience reminded me of what I could be,” Onwumere said. “It reminded me of what I should be trying to do. It reminded me that I could possibly make a difference instead of giving up. I am very grateful Upstate gave me a chance.”

In addition to her regular schoolwork and responsibilities as a medical student, she has been shadowing doctors in the neurosurgery department. Raising money to boost brain cancer research is a cause that’s important to her, so she was happy to organize the walk.

“My dream is that even after I graduate, this will be a yearly walk. It is something I feel like I can leave as a mark here at Upstate.” She notes that donations and volunteers for the 2023 walk are being handled through the Upstate Foundation. u

Heather Drake Bianchi got her paramedic training at Upstate. At the start of the pandemic, she launched a business that put her skills to work. CineMedics CNY provided medical support on movie sets, which included COVID-19 testing and safety oversight.

Her company has grown beyond movie sets and now provides mobile medical services on site for large events, at the workplace and at home through her company Drakos Clinical Laboratories.

The Syracuse native recently answered some questions about her career.

What is it like, being a paramedic on a movie set?

“You hope that the medic is largely not doing anything, because medics are there primarily to respond to traumatic incidents and illnesses of an acute nature.

“What actually ends up happening is, when you work with the same film crew over and over again, you become their most trusted resource for a number of their medical questions and concerns. A lot of times, people in the movie industry work such long hours that they don’t have the free time to seek out what are much-needed resources for their personal care.

“So a lot of it is not just acute care, but recommendations for who they should go see, why it’s important that they see their primary care physician, helping them to navigate when it’s time to go to the hospital versus when they could go to an urgent care or when they should go see their primary care doctor.

“And then, to a surprising degree, it’s helping them navigate who’s accepting new patients, when they should go and encouraging them to actually be seen, to get their yearly blood work drawn, because otherwise it just doesn’t happen.

“They’re some of the most under-cared-for population that I’ve come across. That was very surprising to me.”

“We’ve been all over the United States and outside of the United States.

“We’re starting a project in London this week. I have another team member right now in Sierra Leone.

“We just wrapped a large project for HBO in Los Angeles, New Orleans and Florida.

“Boston was another big project. We

were the primary medical resource and PCR (a test used to check for COVID infection) testing laboratory for a film called “Don’t Look Up.” It was a large-scale Netflix production.”

What sort of medical equipment do you carry?

“Everything is in a backpack, rather than working out of an ambulance. Everything is collapsible. Everything is portable.

“The most essential things we carry are medications or treatments for injuries and illnesses, where if you don’t solve it within the next five or 15 minutes, you have a real problem. So EpiPens to use for severe allergic reactions, for example. There’s been times that we have supported a film production that’s 40 minutes away from cellphone service, and that’s just cellphone service. That’s not even 40 minutes from help. And so you really need to have an EpiPen and then subsequent Benadryl to treat allergic reactions.

“And then, equipment to be able to treat gross bleeding and trauma. I was working on a sailing ship in the Mediterranean when there was a wave that came up and blew one of the individuals back into the mast. He actually fractured two vertebrae. Now, he was fine; he didn’t have any long-term problems. Managing that acutely was of the utmost importance until we could even get to the point of, not just getting to a hospital, but getting to land. That was a four-hour trip. So you have to think about things a little bit differently than if you were working in a city because when you’re hours or even days away from help, it’s a completely different way of approaching medicine.”

How do you get to a hospital, if you are in a remote location?

“In addition to medical supplies, some of the most important equipment that we have is various types of communication, not just cellphone service but also via satellite. And we recently integrated technology where we could text and communicate via radio waves. There are always safety nets to our initial plan, because if there’s anything that we’ve learned from being a completely self-sufficient logistical laboratory, it’s that you have to have backup plans. That’s just how you operate.

“As an austere paramedic, you’re not just doing the medical, but you’re also overseeing for logistics — that’s transportation, communication, getting in touch with the hospital. And then, you can’t forget about treating the patient in and of itself, which is an entire job.

“An austere paramedic has to be able to multitask better than any field that I can think of.”

Why did you choose a medical career?

“When I started at Rochester Institute of Technology, I was originally a photojournalism major. I switched to medicine, started taking science classes and finished in biomedicine. Later I went on to get my master’s in human anatomy and physiology.

“I got a second master’s from Syracuse University in molecular DNA analysis, the same time I was in paramedic training at Upstate. I chose Upstate because Upstate had a longer and more in-depth, more comprehensive program.

“Choosing to go into medicine comes from wanting to connect with people as much as possible and wanting to help them as much as possible and being advocates for them.” u

He leads Upstate’s urology department now, but 30 years ago, Gennady Bratslavsky, MD, was a 19-year-old immigrant and nursing school graduate from Ukraine who spoke no English. He and his parents settled in Albany, where his uncle lived. Bratslavsky became a U.S. citizen and kept in touch with his friends from Ukraine over the years.

After the Russian invasion began in February 2022, Bratslavsky teamed with Alex Golubenko, a childhood friend from Ukraine who is now a doctor of physical therapy in New York City. They created helpfreeukraine.com and committed to sending 100 percent of donations toward medical supplies for Ukraine.

Bratslavsky’s wife, Katya Bratslavsky, is an artist who is selling her paintings to raise money and has put more than $300,000 toward the medical relief effort so far. She was born in St. Petersburg, Russia, and lived most of her childhood in Moscow until her family moved to Central New York in 1992.

In April, Bratslavsky traveled to Ukraine to deliver first-aid kits, gas masks and satellite phones. Later he and Golubenko shipped a truckload of donated medications and supplies he collected from Upstate, Crouse Hospital, Auburn Community Hospital, Cayuga Medical Center in Ithaca and Mohawk Valley Health System in Utica.

Later, working with World of Connections founder Charita Shteynberg, they secured a large donation of medications from two pharmaceutical companies. Working with several friends, they shipped more than $100 million worth of medications to Ukraine that were distributed to hospitals in every region. World of Connections is a group

that provides liaison services for nonprofits.

Using donations through Help Free Ukraine, Bratslavsky and Golubenko have so far shipped more than a dozen ambulances and trucks to first responders in Ukraine, along with hundreds of pallets of humanitarian supplies including medical supplies and food.

One of the first ambulances went to a cancer center in the western city of Lviv. Another went to a children’s hospital in the capitol of Kyiv, where another of Bratslavsky’s childhood friends now works as a pediatric orthopedic trauma surgeon. Bratslavsky says the Russian invasion “turned my world upside down. I had not realized how deep my roots were in Ukraine and how much I loved the land that brought me up.”

Since early August, he and his wife have hosted three children from Ukraine. Combined with the Bratslavskys’ three children, the house is full. Every dinner “feels like a birthday party,” Bratslavsky says.

His fundraising efforts continue through helpfreeukraine.com u

The medical director of facial plastic and reconstructive surgery at Upstate was part of a medical mission trip to Ukraine in September.

Sherard Tatum, MD, a professor of otolaryngology and pediatrics, was one of eight surgeons who volunteered for the trip that was organized through the American Academy of Facial Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. The academy’s nonprofit group, Face to Face, has arranged similar trips to countries all over the world for the past 30 years.

“From our previous experience in war zones, we knew what kind of civilian and military injuries there would be and that they would be needing help. So we thought we would try to offer that,” says Tatum. He is the academy’s president-elect.

Tatum and other surgeons from New York City wound up operating on 35 Ukrainians during their nine-day trip. About two-thirds were soldiers and the rest civilians with maxillofacial trauma. “That means they were hit in the face with projectiles, either bullets or shrapnel from explosions.” One patient was a child with facial burns.

The surgeons spent the end of the summer reviewing imaging scans of the patients they would see in Ukraine. A Belgian company called Materialise donated 3D-printed titanium implants customized for each patient. Johnson & Johnson donated sutures, and Synthes and Stryker donated screws, brackets and plates needed for putting bone back together, Tatum says.

He packed light, so he had space to carry medical supplies. The group flew into Krakow, Poland, and took a bus across the western border of Ukraine to the city of Ivano-Frankivsk. They coordinated their services with the hospital’s otolaryngology department. After the surgeons returned to the United States, the doctors in Ukraine could confer via videoconference about how individual patients were healing for several days, until all were discharged.

Tatum says the lush, rolling hills and farmland of Ukraine reminded him of Upstate New York. He found the people “incredibly warm and welcoming, and their bravery was standout for me.” Restaurants and hotels were open and operating, with a strict 10 p.m. curfew. They heard air raid sirens a few times but no explosions.

Face to Face — with assistance from nonprofits Razom, Heal the Children Northeast and INgenius — is arranging future medical mission trips to Ukraine.

Similar trips have been a part of Tatum’s career since he began his medical practice. “It just feels right. There are people that need help, and we have the ability to help. We have a lot here in this country, and I think we can share a little bit.” u

In 1825, Thomas Jefferson wrote a letter to Dr. Thomas Sewall of Columbia College of Medicine (now George Washington University) congratulating the doctor on the establishment of the medical school, wishing success that the school “share in the merit of lessening the afflictions of mankind.” That was eight months before the death of America’s third president.

In 1865, Louis Pasteur wrote a note on letterhead stationery from the École Normale Supérieure, the university in Paris where he taught and researched, about a ticket for an upcoming event. Pasteur, a French chemist and microbiologist, is credited with developing vaccines against rabies, cholera and anthrax. He also originated the process of pasteurization.

Both letters recently joined the archives and special collections at Upstate’s Health Sciences Library. Robert Cady, MD, and his wife, Linda Cady, made the donation because they wanted to share these pieces of history. Cady, a pediatric orthopedic surgeon, got his medical degree from Upstate in 1971. u

Among the archives and special collections at Upstate’s Health Sciences Library are a letter penned by Thomas Jefferson, above, and Louis Pasteur, right.

The versatility of this crustless mini-quiche is why Katie Krawczyk, the registered dietitian nutritionist at the Upstate Cancer Center, finds herself sharing the recipe with so many patients.

Eggs are a great source of protein. But if you’re tired of the same scrambled eggs for breakfast, these miniquiches are a good substitute – for meals or snacks any time of day.

BASE:

12 large eggs

½ cup heavy cream

¼ cup milk

2 tablespoons parsley, chopped

2 tablespoons basil, chopped (or other herbs)

¼ teaspoon salt

¼ teaspoon pepper

1 cup shredded cheese (cheddar, mozzarella, Swiss or Gouda work well)

VEGETABLES:

(Note: Feel free to sub in whatever veggies you like or have on hand)

1 cup broccoli, cut in tiny florets

1 cup spinach, roughly chopped

1 red bell pepper, chopped small

¼ to ½ cup onion, diced

1 jalapeño pepper, seeds and veins removed and diced fine (optional)

Preheat oven to 375 degrees. Thoroughly grease a nonstick muffin pan with butter, coconut oil or nonstick spray.

In a large bowl, whisk together the eggs, cream, milk, parsley, basil (or other herbs), salt and pepper. Set aside.

Prepare your vegetables. You can substitute what you like or have on hand instead of broccoli, spinach and peppers. Optionally, you can sauté your onion with a bit of olive oil to soften it up and take away some of its bite. Set aside and allow to cool.

Add all the veggies to the bowl with the egg mixture and stir to combine. Stir in half of the cheese.

Using an ice cream scoop or ¼ cup measure, spoon the mixture into the prepared muffin pan, filling to about ¼ inch from the top. Then sprinkle a small amount of the reserved cheese over each. Place in the oven and bake for 20-25 minutes, or until the egg is fully set and the cheese has just started to turn golden on top.

Remove from the oven and let cool for 5-10 minutes before running a butter knife around each muffin and gently removing from the pan. Enjoy while warm, or let cool completely before storing in an airtight container in the refrigerator. Leftovers can be reheated for several seconds in the microwave or a few minutes in a preheated oven or toaster oven.

Serving size is 2 mini-quiches. Each serving contains 250 calories; 14 grams protein; 11 grams carbohydrates; 1 gram fiber; 16 grams fat; 5 grams saturated fat; and 263 milligrams cholesterol.

“This recipe is very easy and allows patients to really adjust to the flavors that they like,” Katie Krawczyk says.

Upstate physical therapist Caterina

Flatau grew up watching “The Waltons” and “Little House on the Prairie,” television programs that depicted life during the Great Depression and late 1800s, respectively. “I always loved that simplicity,” she says.

She thought about raising chickens. The pandemic created the perfect time to embark on such a project.

Flatau bought a coop and brown wooden henhouse with a green roof and put it beneath trees in her backyard in Fayetteville. Her husband, Ralph, enlarged the coop. A red E, two G’s and an S decorate the side of the henhouse. They doubled the coop wire in spots for more security. The wire extends into the ground to discourage predators from digging under.

Flatau estimates spending 10 to 15 minutes per day caring for the chickens, giving them fresh water and feed, cleaning their living space and collecting their eggs. All four of her remaining chickens – one was killed by a neighborhood husky in late spring – are named Twila, after Flatau’s favorite character on “Schitt’s Creek,” a television series that helped her laugh during the stress of the pandemic. Among them, they produce three or four eggs per day.

Around midday, she lets the chickens out of their coop. They roam the yard, eating bugs and grass. She finds it relaxing to watch them wander. They mostly stay together. On hot afternoons, they huddle in the shade against the house. They have their favorite spots.

“They’re such a joy,” Flatau says.

But in July, she found a new home for

the chickens where they could continue their free ranges lives. “I have new neighbors with new dogs, and I want the dogs to live their best lives enjoying the space,” she said, “but I also want my girls to be safe.” u

• Baby chicks need to be kept indoors until they are several weeks old, and some breeds don’t start laying eggs for months.

• Chickens can live up to 15 years.

• Each chicken has its own personality.

• They make a loud clucking noise when they lay an egg, usually in the morning.

• Frozen corn kernels make a nice treat on a hot day.

• Predators are a continual threat; It’s not “if” you’ll lose a bird, but “when.”

• If your chickens become ill or injured, you’ll need a veterinarian who cares for chickens. Not all do.

• Chickens require occasional bathing, using dish soap and thick gloves in a utility sink.

• Fresh, unwashed eggs do not need to be refrigerated for up to two weeks because they are covered with a protective layer of protein from the hen’s body that seals the otherwise porous shell. Once that “egg bloom” is washed away, the eggs must be refrigerated. In general, hold off washing fresh eggs until just before you eat them. A wash consists of a rinse and rub under warm water.

• Chicken poop makes great fertilizer, but only after it has composted for a year.

• Check whether your municipality allows backyard chickens before following in Flatau’s footsteps. She says to sample the backyard chicken lifestyle, consider renting chickens for a season first.

*A word from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Do not snuggle or kiss your chickens. Even clean, healthy chickens can carry salmonella germs, which spread easily to anything in the areas where poultry live and roam.

A grant from the American Heart Association is funding a researcher’s effort to uncover the role of mitochondria in heart failure — and confirming that his different approach to the question is worth pursuing.

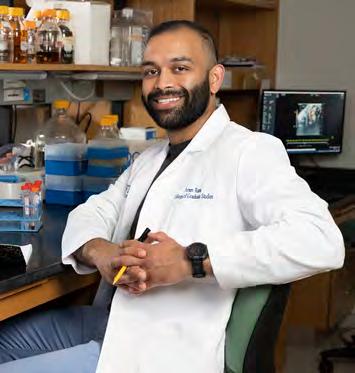

Arnav Rana, a student in his fifth year of Upstate Medical University’s MD/PhD program, is looking at how mitochondria, the so-called powerhouses of the cell, may contribute to heart disease, the No. 1 killer around the world.

Many researchers have considered mitochondria’s possible role in heart disease and heart failure. Mitochondria are organelles that generate most of the chemical energy within the cell. That energy is stored in a chemical called adenosine triphosphate, or ATP.

Most research focuses on the idea that mitochondria can become unable to produce enough ATP. That may weaken the heart so much that it stops doing its job properly. “Each beat requires a lot of energy,” Rana explains. “The thinking is when mitochondria

dysfunction, they can’t produce enough energy.”

Encouraged by Upstate professors Xin Jie Chen, PhD, and David Auerbach, PhD, Rana has pursued an idea that builds on that classic thinking. Rana’s investigation looks at how certain proteins within the cell can build up over time, instead of being absorbed by the mitochondria.

Cells produce more than 1,000 proteins that must transfer into the mitochondria, but if some aren’t transferred, they can build up inside the cell cytosol, the fluid that fills much of the cell’s volume. At high enough levels, the protein buildup can affect the health of the cell and cause “non-bioenergetic stress.”

In the Chen laboratory, Arnav studies whether such non-bioenergetic stress might be a cause of heart failure and the ways in which mitochondrial stress can cause changes to the pumping ability of the heart.

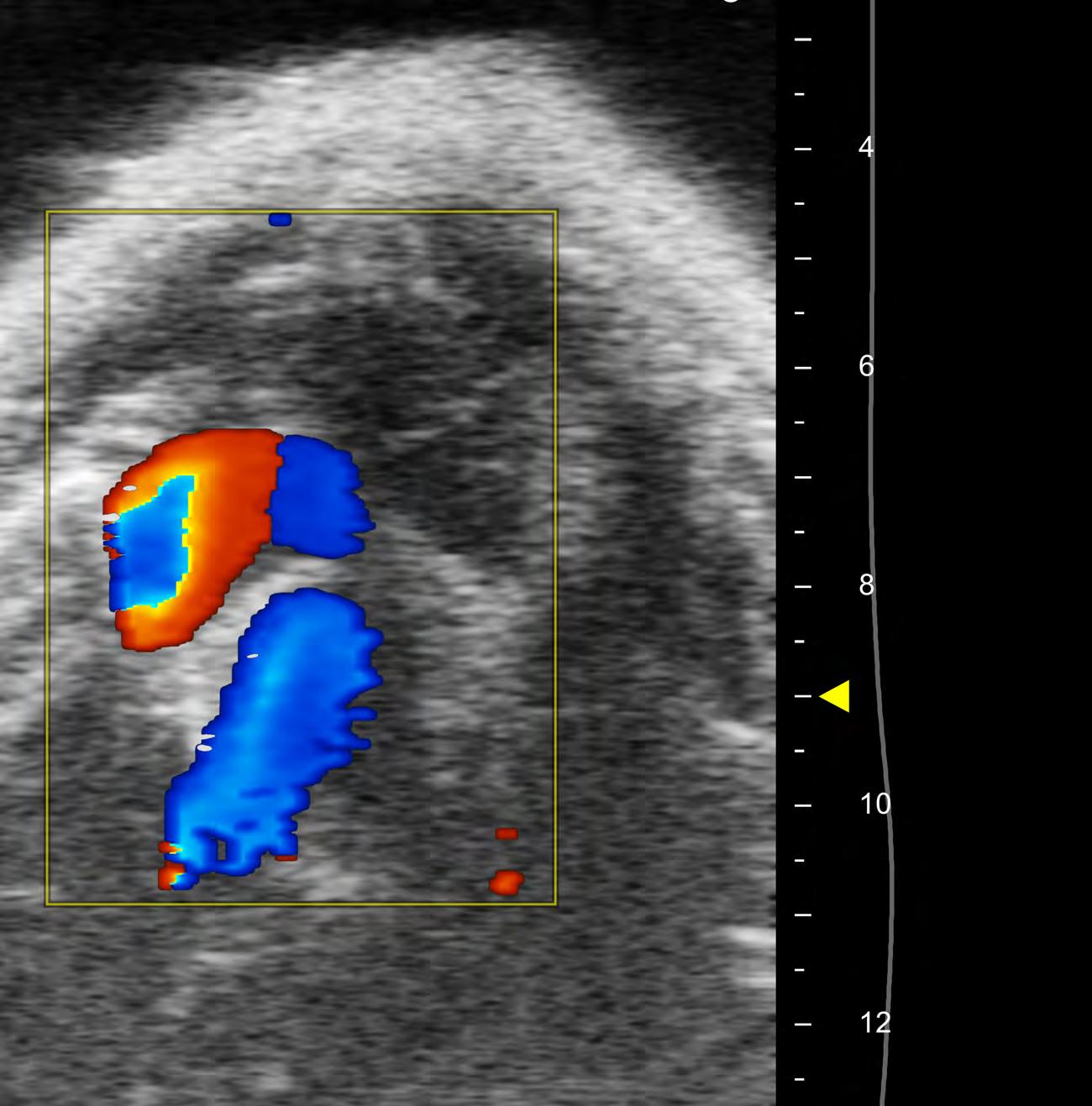

To answer those questions, researchers

use echocardiography, or ultrasound, of sedated mice to determine changes in heart function. Shown in the yellow box is a pulse wave doppler of the flow of blood out of the left side of the mouse heart and through the aortic valve. The red region corresponds to the flow of blood through the aorta and can be used to measure blood velocity as it exits the heart. u