10 minute read

Taxation of Ganja

At this point we all know of at least one state or jurisdiction that allows for at minimum the use of marijuana for medicinal or recreational use. As of January 8, 2018, the following states have legalized marijuana for recreational use: California, Colorado, Hawaii, Maine, Massachusetts, Nevada, Oregon, and Washington. Even though these states and several other states (when you bring medicinal marijuana into the equation) have relaxed or completely decriminalized the possession of marijuana, the federal government still treats cannabis as a scheduled narcotic. A scheduled narcotic is a drug or other substance that has a high potential for abuse. Marijuana is currently listed as a Schedule I narcotic.

In recent years, the United States Congress passed a law, which must be renewed annually, that prohibits the United States Justice Department from interfering with state medical cannabis laws. As of January 4, 2018, the United States Attorney General, Jeff Sessions did not renew this law and therefore, federal prosecutors can pursue marijuana cases in states where marijuana is legal. This is currently an ongoing issue in Congress right now so I will be keeping a close eye out on future legislation or changes within the current legislation. I can tell you this, Congress is not taking this lightly and several states, including Colorado and California are ready to fight as this industry has provided for or has the potential to provide for a surplus of the kind some of these states have never seen.

Even before a state decides to legalize marijuana, the taxation of marijuana begins to form. Let’s start with the federal taxation of cannabis. The Internal Revenue Code (Code) governs federal taxation in this country. Generally speaking, gross income is what we are taxed on less any deductions or specific items that are not considered gross income. Gross income according to the Internal Revenue Code “means all income from whatever source derived…” then the Code allows for exceptions to this general rule. So reading it literally, all income from whatever source derived includes both legal and illegal activity. So while our federal government treats the cannabis industry as an illegal activity, certain portions of the Code are applied regardless of the industry in question and that is when the complications begin.

All businesses are required to pay federal taxes on their gross income under the Code, even if the income arises out of an illegal activity. The return of capital is not subject to tax. Return of capital occurs when an investor receives a portion of his original investment and these payments are not considered income. So in this context, a business’s gross receipts (or sales) must be reduced by the cost of goods sold (COGS) in order to determine gross income before income tax can be assessed. For a business producing cannabis, COGS is calculated by taking inventories at the beginning of the tax year, adding current year production costs, and finally subtracting year-end inventories. For resellers, COGS is calculated by subtracting year-end inventories from current year purchases. In all other illegal businesses, the taxpayer may deduct all ordinary and necessary business expenses, as long as the expenditures themselves are not illegal under the Code. Still, under Code Section 280E, this section specifically precludes individuals or business trafficking in certain Schedule I and II drugs (recall, marijuana is a Schedule I drug) from claiming those deductions. Under Code Section 280E, taxpayers are prohibited from claiming deductions or credits in the trade or business of illegal trafficking of drugs listed in the Controlled Substances Act. Under this section of the Code businesses are also unable to deduct ordinary and necessary expenses that are not illegal such as salaries, rent, utilities, etc. Recall as discussed above that this section of the Code does allow businesses to recover their investment in cannabis and also allows the reduction of gross receipts by cost of goods sold.

After a business satisfies their federal taxation requirement, the state requirements need to be fulfilled as well. Taxation by the states varies from one state to the next, but we will discuss some of the more popular ways the states derive revenue from the cannabis industry. First, sales and use tax which generally speaking is a percentage of the amount of the sale. In some states, medical marijuana is exempt from sales and use tax, in other states it is taxed. Second, some states subject recreational marijuana to an excise tax, cultivation tax, privilege tax, and/or a special sales tax. In addition, cities and counties within the state may also impose a specific taxes on retail marijuana. Finally, states impose fees for sales tax licenses, producer’s licenses, processor’s licenses and seller’s permits.

The same way there is a tax return required to be filed with the federal government, states also impose some taxation reporting requirements, such as retail sales tax returns, retail marijuana sales tax returns, and state personal and corporate tax returns. Any non-compliance on your part would result in heavy penalties and fines, as well as the potential for loss of license or permits. If you make a decision to join this industry in any capacity, just ensure that you obtain professional advice from organizations and personnel who specialize in this industry. The cannabis industry is growing and firms are finding new opportunities to serve this industry as more states slowly legalize marijuana.

Cannabis dispensaries and recreational stores are currently about a $3 billion a year industry. This industry is known to have the highest percentage of companies with seven figures of revenue in Year 1. If you are thinking about diving into this industry that’s great I would love to welcome you, but this industry is constantly changing and evolving so you must always stay on top of all legislation including state regulations and federal regulations. That is where having an attorney or advisor to consult on state and federal changes comes in. My recommendation for anyone who decides to enter this industry is to remain compliant. Compliance includes paying and remitting all taxes on all levels, including city, county, state, and federal. Being compliant allows you to continue to make money and that is the whole point. If you don’t remember anything from this article, remember this one thing: All income from all sources derived, generally speaking is gross income regardless of the legality of the business.

Jeneria Rhodes

Contributing Writer

J. T. Maxwell, CIA, EA, CFE, CPA, Esq.

is the CEO of BayShore Tax & Consulting Group. The firm specializes in full accounting, business consulting, tax preparation and planning, tax resolution, and our newest division, cannabis accounting, where we specialize in providing accounting, tax, and advisory solutions to cannabis businesses.

AN OVERVIEW OF THE FEDERAL SENTENCING GUIDELINES

How the Sentencing Guidelines Work

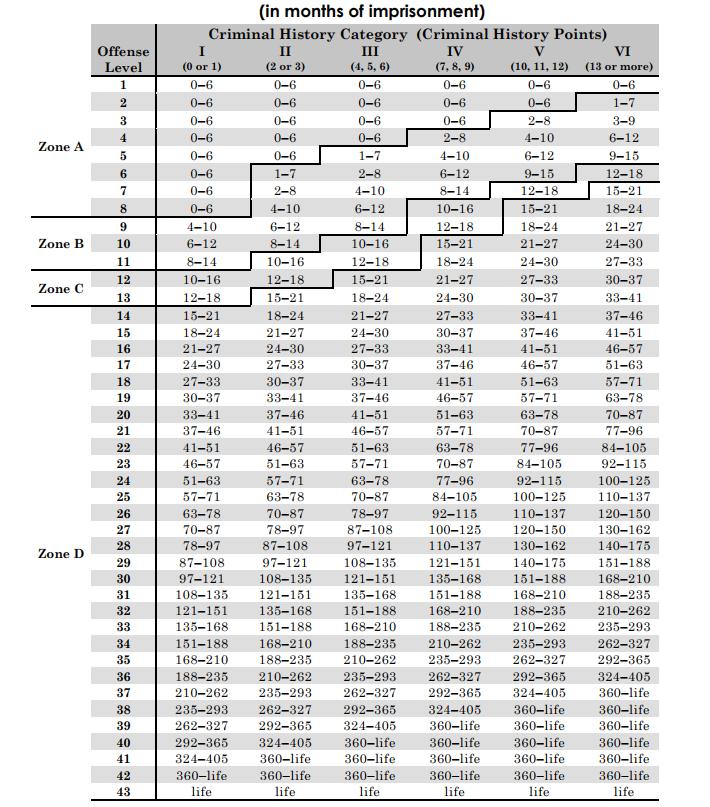

The sentencing guidelines take into account both the seriousness of the offense and the offender’s criminal history.

Offense Seriousness

The sentencing guidelines provide 43 levels of offense seriousness - the more serious the crime, the higher the offense level.

Base Offense Level

Each type of crime is assigned a base offense level, which is the starting point for determining the seriousness of a particular offense. More serious types of crime have higher base offense levels {for example, a trespass has a base offense level of 4, while kidnapping has a base offense level of 32).

Specific Offense Characteristics

In addition to base offense levels, each offense type typically carries with it a number of specific offense characteristics. These are factors that vary from offense to offense, but that can increase or decrease the base offense level and, ultimately, the sentence an offender receives. Some examples:

• One of the specific base offense characteristics for fraud (which has a base offense level of 7 if the statutory maximum is 20 years or more) increases the offense level based on the amount of loss involved in the offense. If a fraud involved a $6,000 loss, there is to be a 2-level increase to the base offense level, bringing the level up to 9. If a fraud involved a$50,000 loss, there is to be a 6-level increase, bringing the total to 13. •One of the specific offense characteristics for robbery {which has a base offense level of 20) involves the use of a firearm. If a firearm was brandished during the robbery, there is to be a 5-level increase, bringing the level to 25; if a firearm was discharged during the robbery, there is to be a 7-level increase, bringing the level to 27.

Adjustments

Adjustments are factors that can apply to any offense. Like specific offense characteristics, they increase or decrease the offense level. Categories of adjustments include: victim-related adjustments, the offender’s role in the offense, and obstruction of justice. Examples of adjustments are as follows:

• If the offender knew that the victim was unusually vulnerable due to age or physical or mental condition, the offense level is increased by 2 levels. • If the offender obstructed justice, the offense level is increased by 2 levels.

Multiple Count Adjustments

When there are multiple counts of conviction, the sentencing guidelines provide instructions on how to achieve a “combined offense level.” These rules provide incremental punishment for significant additional criminal conduct. The most serious offense is used as a starting point. The other counts determine whether and how much to increase the offense level.

Acceptance of Responsibility Adjustments

The final step in determining an offender’s offense level involves the offender’s acceptance of responsibility. The judge may decrease the offense level by two levels if, in the judge’s opinion, the offender accepted responsibility for his offense.

In deciding whether to grant this reduction, judges can consider such factors as:

• whether the offender truthfully admitted his or her role in the crime, • whether the offender made restitution before there was a guilty verdict, and • whether the offender pled guilty. Offenders who qualify for the 2-level reduction and whose offense levels are greater than 15, may, upon motion of the government, be granted an additional 1-level reduction if, in a timely manner, they declare their intention to plead guilty.

Criminal History

The guidelines assign each offender to one of six criminal history categories based upon the extent of an offender’s past misconduct. Criminal History Category I is the least serious category and includes many first-time offenders. Criminal History Category VI is the most serious category and includes offenders with serious criminal records.

Determining the Guideline Range

The final offense level is determined by taking the base offense level and then adding or subtracting from it any specific offense characteristics and adjustments that apply. The point at which the final offense level and the criminal history category intersect on the Commission’s sentencing table determines the defendant’s sentencing guideline range.

Sentences Outside of the Guideline Range

After the guideline range is determined, if an atypical aggravating or mitigating circumstance exists, the court may “depart” from the guideline range. That is, the judge may sentence the offender above or below the range. When de- In January 2005, the U.S. Supreme Court decided United States v. Booker, 543 U.S. 220 (2005). The Booker decision addressed the question left unresolved by the Court’s decision in Blakely v. Washington, 542 U.S. 296 {2004): whether the Sixth Amendment right to jury trial applies to the federal sentencing guidelines. In its substantive Booker opinion, the Court held that the Sixth Amendment applies to the sentencing guidelines. In its remedial Booker opinion, the Court severed and excised two statutory provisions, 18 U .S.C. § 3553 (b) (1), which made the federal guidelines mandatory, and 18 U.S.C. § 3742(e), an appeals provision.

Under the approach set forth by the Court, “district courts, while not bound to apply the Guidelines, must consult those Guidelines and take them into account when sentencing,” subject to review by the courts of appeal for “unreasonableness.” The subsequent Supreme Court decision in Rita v. United States, 551 U.S. 338 {2007), held that courts of appeal may apply a presumption of reasonableness when reviewing a sentence imposed within the guideline sentencing range.

For additional information about the United States Sentencing Commission, contact:

Office of Legislative and Public Affairs United States Sentencing Commission One Columbus Circle, NE, Suite 2-500

Washington, DC 20002-8002 (202) 502-4500 • FAX: (202) 502-4699 E-mail: pubaffairs@ussc.govIIwww.ussc.gov

14 Disclaimer: The characterizations of the sentencing guidelines in this overview are presented in simplified form and are not to be used for guideline interpretation, application, or authority.