5 minute read

The Grand Jury

A CRITICAL STAGE IN THE CRIMINAL JUSTICE SYSTEM

At one time, grand juries functioned as a buffer between the people and the state. Today, they function as a weapon of the prosecution. T he grand jury is an independent body of citizens who decide whether an accused must stand trial for a felony. Its origins can be traced to a decree by England’s King Henry II in 1166. It was later guaranteed by King John in Magna Carta of 1215. Four centuries later, it was brought to the American colonies and the first regular grand jury was convened in Massachusetts Bay in 1635.

No other nation has grand juries except Liberia, and only half the states in this country still have them. New York is one of them. The grand jury is mandated by the Fifth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution and Article I, § 6 of the New York State Constitution. Both provide that, “No person shall be held to answer for a capital or otherwise infamous crime, unless on ... indictment of a grand jury.”

35 The U.S. Supreme Court said the grand jury “belongs to no branch of the institutional government, serving as a kind of buffer or referee between the government and the people.” Courts convene grand juries, but do not oversee them. A judge is not present. Instead, the prosecutor runs the proceedings. The grand jury has two functions. As a sword, the grand jury functions as an investigative arm of prosecutors to gather evidence against a suspect by issuing subpoenas for witnesses and documents. As a shield, grand jurors decide if the government has sufficient evidence for an indictment.

A trial jury is called a petit jury because it has 12 members for criminal cases, and as few as 6 for civil cases. Judges and lawyers determine who sits on a petit jury. In contrast, a grand jury has 16 to 23 members selected randomly from the public.

Trials are open and anyone can attend, but grand jury proceedings are conducted entirely in secret. With limited exceptions, only the prosecutor, stenographer, and witnesses can be in the presence of grand jurors. The prosecutor selects which witnesses testify and the questions put to them. The prosecutor drafts the indictment and instructs the grand jurors on the law.

The prosecutor is not obliged to inform a targeted suspect that a grand jury has been impaneled to indict him. The prosecutor can present constitutionally tainted evidence to grand jurors. The prosecutor is not obliged to inform grand jurors a witness is cooperating with the government in exchange for a deal. A prosecutor is not required to present evidence showing the suspect may be innocent. The prosecutor is not even required to tell grand jurors the targeted suspect wants them to hear specific evidence the suspect insists will exoner

Sol Wachtler, New York’s former Chief Judge, told the Daily News “any prosecutor worth his salt can indict a ham sandwich.” In the public mind, an indictment carries a presumption of guilt.

ate him. As the U.S. Supreme Court said, “The grand jury can hear any rumor, tip, hearsay, or innuendo it wishes, in secret, with no opportunity for cross-examination.”

Rules of evidence and procedure differ somewhat in state and federal cases. A suspect has no right to appear before a federal grand jury. In a New York state case, if a defendant has been arrested and arraigned, then he has a right to appear and testify, but this is rarely advisable because his testimony can be used against him at trial. A defendant has no right to know the grand jury’s reasons for its decision to indict, nor the identity of witnesses against him unless such witnesses testify at trial.

Targeted suspects are rarely subpoenaed before federal grand juries because they can invoke their right against self-incrimination and refuse to testify. Targeted suspects are never subpoenaed to appear before New York state grand juries because all witnesses have automatic immunity. For that reason, witnesses cannot invoke their right against self-incrimination.

A witness may have a lawyer present – waiting outside the grand jury room in federal proceedings, inside the room in New York state proceedings – but that lawyer may not object to a prosecutor’s questions or speak to the grand jurors.

Grand juries retain some independent power to question witnesses, and subpoena witnesses and documents not sought by the prosecutor. Most importantly, a grand jury can refuse to indict suspects targeted by the government. In practice, however, this rarely happens.

If the grand jury finds probable cause the government has a case, it votes a “true bill” signed by the grand jury foreman. Only a simple majority is required, i.e., 12 votes out of 23.

Double jeopardy does not bar another federal grand jury from indicting a suspect after a prior grand jury refused to do so. In a New York state case, the district attorney need courts approval to get a second bite at the apple before a different grand jury, but such approval is relatively easy to obtain.

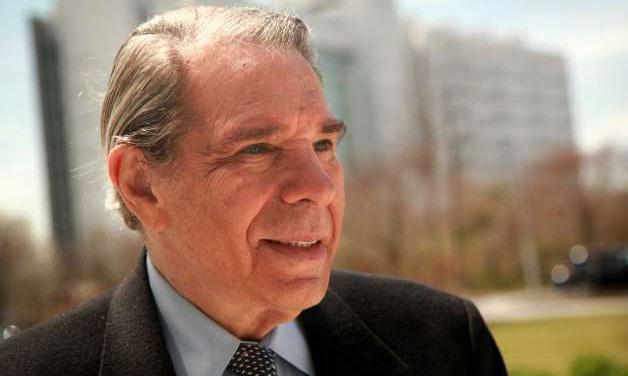

Francois Annabi, Esq Criminal Defense Attorney Contributing Writer

Life experiences, both in childhood and adulthood, shaped Francois Annabi’s destiny to become a criminal defense attorney. He was only an infant when his parents were convicted of selling narcotics. His father was sent to federal prison for sixteen years, and his mother, dragged down by the father, served two years. Many years later, Francois would once again have his life impacted by the criminal justice system. His sister, a popular elected official, was wrongfully convicted of bribery and sent to federal prison for six years. His sister’s wrongful conviction, in addition to his parents’ convictions, were key factors in Francois Annabi’s decision to become a criminal defense attorney. He interned for a renowned defense lawyer and volunteered for a non-profit organization that educates the public about wrongful convictions. He went on to start his own law practice in White Plains, New York. To quote Annabi, “Overall, the system works, but when it fails, it fails hard and lives get torn apart.” He can be contacted at: