13.1121.02

SUMMER EXHIBITION 2024

The Summer Exhibition 2024 Catalogue is dedicated to Voula Kaplanis. The UWA School of Design farewells Voula at the end of an extraordinary 25 years of service to the University. Thank you Voula for keeping us all in line and taking care of us, you will be missed. We wish Voula all the best for her next adventure!

A selection of projects from semester two, 2024 at The University of Western Australia, School of Design.

The University of Western Australia acknowledges that its campus is situated on Noongar land, and that Noongar people remain the spiritual and cultural custodians of their land, and continue to practice their values, languages, beliefs and knowledge.

Designed and edited by Lara Camilla Pinho, Andy Quilty and Samantha Dye.

156 ARCT3040 Advanced Design Thinking

160 ARCT2001 Design Studio 2

172 ARCT1001 Architecture Studio 1

192 ARCT1010 Drawing History

196 ARLA1030 Structures and Systems

200 Landscape Architecture

202 LACH5511 Independent Dissertation by Design Part 2

206 LACH5422 Landscape Design Studio – Making

214 LACH4421 Australian Landscapes

220 LACH3003 Design Through Landscape Management

222 LACH2050 Plants and Landscape Systems

228 LACH3001 Landscape Resolutions Studio

236 LACH2001 Landscape Dynamic Studio

244 LACH1000 Landscape Groundings Studio

252 Urban Design

254 URBD5802 Urban Design Studio 2

Foreword by Dr Kate Hislop

The student reflections published in this Catalogue speak powerfully about what it is that propels us in the School of Design to gather, routinely, in celebration of the work of our students. The digital catalogues provide an abridged and accessible record of the larger exhibitions that bring hundreds of students together with their friends and families to wrap up another semester.

Daniel Glover’s Foreword to the Fine Arts & History of Art section in this edition notes the fundamental connection with the world achieved through the act of creation. The making of art – of various kinds – is resistance and antidote to the mindless scrolling now a mainstay of daily life. Active immersion in the reality surrounding us, through the interrogating and creating of art, replaces the hours otherwise devoted to the passive (sometimes damaging) consumption of an endless digital stream. Art necessitates interested engagement with ideas, practices, places, people. It offers us pause to be connected in the here-and-now.

In the Foreword to the Architecture, Landscape Architecture & Urban Design section, Eugene Tiong reflects upon the critical relationship between ‘choice’ and ‘growth’ that characterises creative endeavour. It is an aspect not often enough understood or discussed about these disciplines, that at every step there is a choice to be made: about ideas, options, interpretations, directions, tools, materials. There is always a fork in the road and a path that wasn’t taken. Learning and maturity come with the recognition that choice – whether deliberate or instinctive – represents opportunity gained, and foregone. All part of the journey, the finding of a voice.

And on the work published here, I can only say what a privilege it is to see such quality work emerge from students’ commitment to their studies, and to the central relationship between ideas and expression. I continue to enjoy working in a School that foregrounds the pursuit of independent thought, the production of creative work, the building of dynamic and purposeful lives.

My congratulations to everyone in the School community for another successful year, and farewell and good luck to those graduating or moving on at the end of 2024. As always, I acknowledge and thank the School of Design staff who led units, guided projects and supported students. And again, I extend my gratitude to the team of Lara Camilla Pinho, Andy Quilty and Samantha Dye for producing another excellent exhibition catalogue.

Dr

Kate

Hislop, Dean/Head of School, UWA School of Design

Image: First Year student pinning up work in progress during the mid semester Design Jury Week, 2024.

FINE ARTS & HISTORY OF ART

Foreword by Daniel Glover

To create is to connect with the world we exist in. Artists draw from the body, the natural, or the artificial to explore and engage with the social culture that surrounds them. This is an important aspect of art, particularly within our current digital age. We are constantly connected to one another through the online realm, yet we are paradoxically separated by the intangible space that it creates between us. This digital sphere encourages us to drift in a timeless realm of endless entertainment, training us to passively view and receive streams of dialogue.

Without a space for thoughtful discussion, we are free to reject or accept views – both new and old – without a second thought as to why we agree or disagree. Instead of recognising their broader implications, we instead continue to scroll past in search of something that distracts us from our surrounding reality. In this context, art becomes a counterbalance, fostering a space that allows us to critically engage with the transforming realm of dialogue. Whether they harness digital or physical mediums – or both – contemporary artists, as with their historical counterparts, hold the tools to amplify critical and emotional responses to global concerns.

Within the discipline of art history, emotion is often (though certainly not always) treated as a lesser part of creating. In this field, we look to sources and text – the facts – to understand why an artist created the thing we perceive. We compare objects with one another to determine the context and purposes of composition, and to understand what exactly is being said by a work. Alternatively, we employ the writings of cultural theorists to conjure within artworks new meanings previously not considered. This is an invaluable process, as it allows us to determine – through tangible testaments of change – where our political and social cultures now stand. Yet, despite the factual specificity tied to historic lives, we are often drawn to observe material culture through the connections we see between ourselves and those who came before us. We are connected to them by a collective feeling they capture.

Good art emerges when an artist chooses to embrace the inherent vulnerability that the process of creation demands, pushing themselves to intentionally think through why they create. Across my degree, particularly this past year, I have continually been inspired by the Fine Arts and History of Art students and faculty that surround me. Each of them, fuelled by their individual experiences and beliefs, are engaged with art and its capacity to help us understand and interpret the tumultuous world that surrounds us. To see such sentiments fostered within the works of early-stage artists reminds me that art is not just a discursive return to the ‘greats’ of the past. Art is about being in a specific place – temporally and spatially – and reflecting on the world that it exists in. With image and video media saturating every corner of our lives today, art allows us to stop, if only for a moment, and reconnect with this point in time we possess.

Daniel Glover

Bachelor of Arts, History of Art and minor in Curatorial Studies, 2024

Marilène Oliver, I Know You Inside Out, silver ink screen printed onto clear acrylic, stainless steel rods, 2001, 200 x 70 x 50cm, Beaux Arts London.

FINE ARTS

Master of Fine Arts by Research

Supervisors: Dr Ionat Zurr & Dr Vladimir Todorovic

JIMI DE PRIEST

‘Biomimetic Autonomous Weapons: Experiments in Tactical Media’

Fusing inspiration drawn from Tactical media and soviet propaganda posters, this body of work combines DIY electronics, film, cell culture and robotics into sculptural automata which critically digest the imperialist war machine. Through rendering anti-war ideologies into symbolic 3D forms, the works address social tensions in the imperial core which abstract and normalize the ongoing atrocities committed through automated weapons systems. Probing the deflated revolutionary spirit which proliferates throughout the imperial west, reflections on the material reality forged by fascist appropriations of automation technology beckons towards a communist dismantling and reimagination of its implements.

ARTF4005 Fine Arts Honours

Unit Coordinator and Supervisor: Dr Vladimir Todorovic

RICHARD JORDAN

‘Counterfactual Crustacea / Ant Food / Elemental Fish, Curiosities from the Depths & Sensory Scales’

Wet Synthesis. Using taxidermy techniques, the artist recombines body parts from 4 animals (Panulirus cygnus, Corvus coronoides, Thenus orientalis, Portunus pelagicus) into 4 new fictional composite beasts or chimeras of Counterfactual Crustacea –each complete with biographies of speculative ecology. This creative approach is then inverted into using synthetic materials to make sculptural works inspired by real animals. From sculptural facsimiles of marine life presented together – Curiosities from the Depths – to more abstract artworks including Sensory Scales, Ant Food and Elemental Fish. Collectively these artworks are expressions referencing Australian fisherman folk-art and the European kunstkamer (cabinet of curiosities) tradition.

Image: Richard Jordan, Counterfactual Crustacea, 2024, taxidermy.

ARTF3050 Advanced Major Project

Unit Coordinator: Sarah Douglas

Teaching Staff: Sarah Douglas & Annie Huang

GERMAINE CHAN

‘Woe Woe Woe!’

Positioned between historical religious painting and contemporary urban art, Woe Woe Woe! presents a world where flesh and spirit collide. This series highlights tensions between freedom and suppression within the context of spiritual and existential conflict. Drawing inspiration from the Book of Revelation, the works explore themes of faith, morality, and humanity’s relentless search for meaning.

…I heard an angel flying through the midst of heaven, saying with a loud voice, “Woe, woe, woe to the inhabitants of the earth, because of the remaining blasts of the trumpet of the three angels who are about to sound!” Revelation 8:13 (NKJV)

Image: Germaine Chan, Fight-time, 2024, acrylic paint and oil pastel on board, 120 x 90 cm.

ARTF3050 Advanced Major Project Unit Coordinator: Sarah Douglas

Teaching Staff: Sarah Douglas & Annie Huang

ISABELLE REITZE

‘Walking on Eggshells’

In our post-industrial society, environmental pollutants permeate our bodies. Heavy metals, microplastics and synthetic chemicals have been permitted to leach into our environment; wreaking havoc on our hormonal function and DNA. In the face of a historically low national fertility rate and growing anxiety of depopulation, these toxins pose an immeasurable threat to human fecundity. Due to systemic negligence and challenges observing oogenesis, research into the effect of pollutants on female fertility is lagging in comparison to their effects on sperm count and quality.

Walking on Eggshells offers an imagined representation of a molecular process. The objects belong to an evolving body of work investigating the impacts of contemporary life on female reproductive structures, gametes, and maternal lineages. These corrupted cultural artifacts are at once hostile and fragile, materialising the wrath and vulnerability of female bodies at the whim of corporate greed and bureaucratic negligence.

ARTF3050 Advanced Major Project

Unit Coordinator: Sarah Douglas

Teaching Staff: Sarah Douglas & Annie Huang

WILLOW ARMITSTEAD

‘ULTIMATE FANTASY’

ULTIMATE FANTASY draws on desire, dreams, connection, and identity. Whose fantasy is it: the subjects, or a fantasy that is projected onto the subject? Dim lighting, purple hues, and esoteric symbols refer to ideas of ‘glamours’ within witchcraft; illusionary spells and (false) aesthetics of opulence. This body of work questions the truth of our own identities within the context of relationships; how gestures of care exaggerate, stretch, and expand. Alongside discomfort there is joy and humour in this series; I do not mind overextending myself for those I love. Everything in moderation, remembering to warm up and stretch after.

ARTF2054 Drawing, Painting & Print Studio

Unit Coordinator: Andy Quilty

Teaching Staff: Andy Quilty & Leyla Allerton

DAVID WILKINSON

‘An exploration of the interaction of print marks made by ink monotype and a selfportrait drypoint from a polycarbonate plate’

My prints are made from a single drypoint self-portrait drawing scratched into a polycarbonate plate. The variations of each image have been made via a layer of ink monotype above the drypoint grooves. This layer of ink created unique possibilities to reveal the underlying self-portrait. The interaction of the drypoint beneath and ink monotype created opportunities to interweave between figurative and abstractive image making.

My self-portrait prints represent a journey of self-discovery through the creative process of making and subtracting marks. Through this unit, I was encouraged to experiment and extend my mark making knowledge through a process of trial and error. I found this approach very refreshing, allowing me to be more spontaneous and explorative. I transitioned from being apprehensive and restrained in my mark making attempts to embracing an approach of taking risks and making mistakes as a creative process. With this experimental approach in mind, I made 200 prints to explore the interaction of ink marks made by monotype and my self-portrait drypoint.

Image: David Wilkinson, An exploration of print marks made by ink monotype and a self-portrait drypoint from polycarbonate plate (detail), 2024, monotype and drypoint on paper, 21 x 29.7cm (each).

on paper, 21 x 29.7cm (each).

ARTF2054 Drawing, Painting & Print Studio

Unit Coordinator: Andy Quilty

Teaching Staff: Andy Quilty & Leyla Allerton

JONTY CLARK

‘Worker’s Compensation’

An article on PerthNow detailed a construction worker who died as a result of a “freak machinery accident” on a construction site on the Mitchell Freeway. The article emphasised that the off-ramp, close to where the man had died, remained closed and that commuters should prepare for delays. Disregard the father, husband, friend who has died and let your family know that you are going to be late for dinner because your commute is inconvenienced. As a labourer on construction sites around Perth, this article reaffirmed my feeling of being disposable as a worker, because it was never meant to be about me, it is about what is being built. My project Worker’s Compensation contains a series of artworks that capture my feeling of being a piece of plaster, waiting to inconvenience someone as soon as I am damaged.

ARTF2054 Drawing, Painting & Print Studio

Unit Coordinator: Andy Quilty

Teaching Staff: Andy Quilty & Leyla Allerton

NOA WILLIAMS

‘HOLIDAY”72 (Aunty Sheila)’

HOLIDAY”72 (Aunty Sheila) is a collection of 16 prints inspired by postcards written by a stranger named Aunty Sheila during her travels around the world between 1972 and 1976. Combining transfer printing, ink, and found photographs, the series reimagines these postcards, blending nostalgic imagery with faded, dreamlike elements.

Influenced by artists like Ed Templeton and Robert Rauschenberg, the work focuses on imperfection and the feeling of distant memories. Alongside the prints, a handmade photo album showcases the original postcards, inviting viewers to read Sheila’s story and feel nostalgia for a stranger’s memories.

Image: Noa Williams, Resort, 2024, monoprint, ink monotype, solvent transfer, found photographs, cartridge paper, 21 x 29.7 cm.

ARTF2021 Animation & Video

Unit Coordinator: Dr Vladimir Todorovic

LUCINDA TASSONE

‘Dead Cat’

The film is centred around an unnamed black cat whose fate is ultimately doomed. This life of a dead cat is explored in multiple scenarios- sometimes escaping death as an onlooker, but most remarkably at the unforgiving tracks of a high-speed railway. Feline anatomy and natural movements are studied in both static and dynamic sequences. Close-ups where line weight is enhanced reflect heightened states of emotion.

Image: Lucinda Tassone, Dead Cat, 2024, animation, dimensions variable.

ARTF2021 Animation & Video

Unit Coordinator: Dr Vladimir Todorovic

EVA HAJIGABRIEL

‘More’

My animation, More, delves into the tumultuous process of getting ready. This was inspired by the many societal pressures placed on people, especially women, to look and appear a certain way. I was inspired by my experiences of this feeling to make this animation.

“…as the character continues to feel distaste towards their appearance, they make changes that become more drastic as they go on. Chopping and dyeing their hair, such desire for a drastic change is expressed through the intense sharp contrast between the electric green and the muted purple background. The character’s descent of sanity becomes most prominent as they begin to pursue more extreme acts, and the surroundings begin to change. As they begin to violently give themselves at-home piercings, the video aesthetics begin to divulge into high contrast, high-impact visuals.”

Image: Eva Hajigabriel, More, 2024, animation.

ARTF1053 Digital Art and Object Making

Unit Coordinator: Dr Vladimir Todorovic

Teaching Staff: Dr Vladimir Todorovic, Donna Franklin, Samuel Beilby, Leyla Allerton, Esther Forest & Julie Ziegenhardt

JANELLA NICOLI

‘Class of 3034’

Class of 3034 is an abstract installation comprised of a short montage and a sculptural swarm of futuristic ants constructed with aluminium flashing, nuts, rivets, and wire. Amplifying the evolution of natural processes to robotic systems, Class of 3034 conflates Amazon warehouse transportation robots with ants. In this way, the installation critiques anthropomorphic perceptions of robots whilst tracking the evolution of human warehouse workers to automated robots through biomimicry, an engineering process that relies on natural systems to inform human constructions.

Image: Janella Nicoli, Class of 3034, 2024, mixed-media installation, dimensions variable.

ARTF1053 Digital Art and Object Making

Unit Coordinator: Dr Vladimir Todorovic

Teaching Staff: Dr Vladimir Todorovic, Donna Franklin, Samuel Beilby, Leyla Allerton, Esther Forest & Julie Ziegenhardt

BELLA LINDSAY

‘MADE 4 U’

MADE 4 U is a mixed media installation that explores themes of overconsumption, idolization, and the potential for human/AI relationships. My piece was inspired by Japanese pop culture and portrays the study space of someone obsessed with their AI girlfriend, addressing the theme of an “automated future” by examining how loneliness and intimacy are commodified through digital products.

HISTORY OF ART

Shipwrecks Museum in Fremantle, 2024.

HART3276 Prints from Durer to Toulouse-Lautrec

Unit Coordinator: Dr Susanne Meurer

Teaching Staff: Dr Susanne Meurer & Daniel Dolin

NALINIE SEE

‘Contemporary Landscapes: Baumgartner and Lichtenstein’

Landscapes in art are often reflections of the time and cultural context in which they are created, offering more than just a depiction of nature.

Christiane Baumgartner’s Schkeuditz II (2005) and Roy Lichtenstein’s Landscape I (1967) present landscapes in unconventional ways, yet both works embody the essence of how time and space were experienced during their respective eras. Baumgartner’s blurred, fleeting woodcut captures the transient nature of modern life, while Lichtenstein’s bold, graphic pop art reduces nature to simplified, commodified forms. Despite their differing approaches, both prints reveal how landscapes can act as vehicles for exploring the shifting cultural contexts of their times, reflecting the evolving engagement with time, space, and perception.

From Wood to Screen: Mediums and Their Impact on Landscape Representation

To understand how each artist engages with landscape, examining how their chosen mediums— woodcut and screenprint—shape their artistic vision and reflect the cultural zeitgeist is essential. Christiane Baumgartner’s use of woodcut in Schkeuditz II is a striking fusion of traditional printmaking with contemporary digital imagery.1 By translating a video still into the slow, labour-intensive process of woodcut, she captures the contrast between the rapid, fleeting nature of modern landscapes and the

permanence of traditional techniques. The blurred lines in the print evoke a sense of speed and motion as if the viewer is witnessing the landscape from a moving vehicle. Relief printing allows Baumgartner to emphasize the transience of contemporary life, where landscapes are often experienced in passing, mediated by technology.

In contrast, Roy Lichtenstein’s Landscape I employs the screen-printing technique, a hallmark of his Pop Art style, to offer a different interpretation of landscape. Lichtenstein utilises flat, graphic shapes and bold, primary colours to transform the natural world into a highly stylised and simplified form. By incorporating elements from commercial art, such as Benday dots and bold black outlines, Lichtenstein critiques the commodification of nature and the influence of mass media on artistic representation.2 The screenprint technique, known for its ability to produce precise and reproducible images, mirrors the mass production of commercial imagery and reflects post-war America’s fascination with consumer culture.3 Lichtenstein’s landscape is not an attempt to capture the natural beauty of the environment but rather to present it as an altered, reproducible object that comments on how media and advertising have reshaped our perceptions of nature. Through this approach, Lichtenstein challenges traditional notions of the landscape by presenting a version that is both visually striking and critically reflective of contemporary culture’s engagement with mass media.

Geometric Abstractions: Baumgartner’s Lines and Lichtenstein’s Dots

Both artists, despite their vastly different approaches, rely on simple geometric forms to construct intricate, layered representations of landscapes, showcasing how abstraction can reveal deeper truths about nature and perception. This formal approach ties into broader explorations within

their respective oeuvres, where each artist continually revisits the complexities of time, media, and representation. In Baumgartner’s Schkeuditz II, the landscape is rendered through a repetitive sequence of straight, parallel lines that shift in weight and density. These lines, derived from the interlace technique of video imagery, create an effect that is both mechanical and organic, mimicking the rhythm and motion. By stripping the landscape down to its most basic visual components, Baumgartner emphasises the fleeting and ephemeral nature of modern life. The process of meticulously carving and printing these lines from a video still contrasts with the rapid, transient nature of her subject matter. The viewer is presented with an image that feels in constant motion, yet frozen in time —an illusion created through the repetition and precision of geometric forms. This dynamic interaction between movement and stasis reflects Baumgartner’s exploration of how technology mediates our experience of landscapes in the contemporary world. Furthermore, Schkeuditz II is part of a broader series in which Baumgartner repeatedly addresses themes of motion and time, often using the same video-towoodcut technique to explore how fleeting moments can be captured in a fixed medium. The Schkeuditz series exemplifies her continued interest in how technology alters our perception of the natural world.

In a similar fashion, Roy Lichtenstein’s Landscape I reduces the natural world to its elemental forms, using Benday dots, flat planes of colour, and bold outlines to construct his vision. The simplification of shapes in Lichtenstein’s landscape abstracts nature into a format reminiscent of comic strips and advertisements. His use of primary colours and geometric precision not only flattens the image but also challenges the viewer’s expectations of what a landscape should be. While Baumgartner’s work engages with the technological mediation of landscapes, Lichtenstein’s print directly confronts the

commodification of nature, turning a traditional scene into something manufactured and mass-produced. His employment of geometric forms—particularly the uniform Benday dots—creates depth and vibrancy, yet the overall effect is detached, reflecting the growing sense of artificiality in the way landscapes were consumed through media in post-war America. This print is also part of a larger body of work in which Lichtenstein repeatedly explored the ways mass media and consumer culture shape visual experience. His landscape series continues his ongoing critique of the manufactured nature of modern visual culture, echoing themes of repetition and standardisation that run throughout his oeuvre. Both artists, through their use of simple geometry, invite us to reconsider how landscapes are constructed and perceived in a modern, media-saturated world. Their works, as part of a larger series, reveal an ongoing investigation into the relationship between nature, technology, and consumerism, capturing how these forces shape our contemporary experience of the landscape.

Abstraction and Detachment

To deepen the analysis of how these artists manipulate landscapes, it is crucial to explore how their use of abstraction not only redefines the visual but also introduces a profound sense of detachment from the natural world. Abstraction in both Christiane Baumgartner’s Schkeuditz II and Roy Lichtenstein’s Landscape I introduces a form of detachment from the natural world, transforming familiar landscapes into something more ambiguous and artificial. In Schkeuditz II, the blurred lines obscure the clarity of the scene, creating a sense of uncertainty and distance. This abstraction not only alters the viewer’s perception but also introduces a feeling of alienation as the landscape becomes a fleeting memory rather than a concrete reality. The image, fractured by motion and technology, seems elusive – both present and

absent – mirroring the fleeting way in which we often experience landscapes in contemporary society, filtered through screens or glimpsed from moving vehicles. Lichtenstein, on the other hand, takes this sense of alienation to an extreme with Landscape I. By reducing natural elements to bold outlines, flat colour fields, and Benday dots, he strips the landscape of its organic qualities, presenting a version of nature that feels almost industrial. His use of primary colours to depict earth, sky, and water departs so far from their natural hues that the landscape loses its connection to the real world. Lichtenstein’s abstraction turns nature into a mass-produced object, distancing the viewer from the emotional or sensory experience typically associated with natural landscapes. The result is a landscape that is less a depiction of nature and more a critique of how mass media reduces and simplifies complex realities into digestible, commodified forms. Both artists, though working in different mediums, use abstraction to explore how the increasing mediation of nature through technology and consumer culture leads to a loss of direct engagement with the landscape. Whether through the blurred ambiguity of Baumgartner’s lines or the synthetic construction of Lichtenstein’s forms, their works encourage a reflection on how modern life has distanced us from the natural world, leaving us with representations that feel strangely distant and manufactured.

Conclusion

In examining Christiane Baumgartner’s Schkeuditz II and Roy Lichtenstein’s Landscape I, we uncover how each print offers a distinct commentary on its era’s interaction with landscapes. Baumgartner’s use of woodcut and digital imagery in Schkeuditz II introduces a landscape that shifts with every glance, reflecting the fragmented and transient nature of modern experience. The blurred lines of her print capture the disjunction between rapid technological

advancements and static visual representations, emphasizing the fleeting nature of contemporary landscapes. In contrast, Lichtenstein’s Landscape I employ the screenprint technique to transform nature into a commercial spectacle of flat colours and graphic precision. His use of Pop Art conventions critiques how media and consumer culture have commodified the natural world, presenting a landscape that is both visually striking and critiqued for its superficiality. Lichtenstein’s print reduces nature to digestible, mass-produced forms, challenging the authenticity of traditional landscape representation. While Baumgartner’s blurred, transient scenes and Lichtenstein’s geometric, colour-saturated forms approach abstraction differently, both prints reveal how their respective cultures grapple with the evolving dynamics of technology and commercialization. Their works, through their distinct printmaking techniques, not only highlight how abstraction can distance us from reality but also offer insights into how modern and mid-20th-century societies have navigated their changing environments. This comparison underscores how each artist’s print serves as a lens through which we can better understand the impact of technological and commercial influences on our perception of landscapes.

Endnotes

1. Jasper Kettner, “Woodcut in Motion: Time in the Prints of Christiane Baumgartner,” Print Quarterly 24, no. 1 (2007): 24.

2. Diane Waldman, Roy Lichtenstein (New York, N.Y: Guggenheim Museum, 1993), 129.

3. Susan Lambert, Prints: Art and Techniques (London: V&A Publications, 2001), 84.

HART2223 Modernism and the Visual Arts

Unit Coordinator: Dr Darren Jorgensen

ROSIE ANDA

‘Hybrid Origins and Transformation: Surrealist

Photography in 1930s Japan’

Surrealism emerged in Japan during one of the most chaotic moments in the country’s modern history, as the social and political climate of the prewar period provided fertile ground for it to take root. Surrealism’s embrace of unconventional and ambiguous modes of expression gave artists the ideal visual idiom to obliquely respond to ongoing political oppression, critique the social structure, and express personal dreams and anxieties. Internal and external social pressures and changes, as well as criticism and debate regarding the nature of Surrealism, led to multiple interpretations of the movement in Japan.1 The fragmentation of various strands of Surrealist art and the absence of collective activity meant that the movement existed outside of a central, unified group, and thus its political goals were never explicitly formulated. Practices such as literature, painting, and photography developed and operated mostly independently from one another, with imported trends being adapted to suit the Japanese context. This terminological and aesthetic fluidity underscored the movement with an idiosyncratic ontology that challenges the hackneyed conventions of a Eurocentric interpretation of Surrealism.2 Rather than merely echoing a European avant-garde, Surrealism in Japan – particularly in its photographic expression – operated in a unique way that was relative to the country’s own modernity and development.

Into the Dreamscape

The term Surrealism first appeared in Japan

around the same time as the publication of André Breton’s 1924 Surrealist Manifesto, with literary and poetry groups emerging throughout the 1920s.3 Western influences in Japanese art and the enthusiasm for Western trends and styles can be traced back to the Meiji period (1868-1912) and the Westernisation policies enacted as Japan emerged from its isolation (sakoku) and began engaging in international trade. The desire of Japanese artists to consolidate their position within a global artistic modernism conflicted with anti-Western and antimodernist sentiments that were arising as Japanese society became increasingly nationalistic.4 By the time Surrealism arrived on Japanese soil in the 1920s, artists and intellectuals were privy to Western art practice and thus possessed the selfawareness and self-confidence to produce art that was simultaneously commensurable to and distinct from European Surrealism.5 Despite the proliferation of Western theory and ideas, Japanese artists and writers did not yet share a common definition of Surrealism, as no European Surrealists knew Japanese. Mistranslations of Breton’s theory could not be corrected, meaning that some of the most crucial elements were entirely absent from the Surrealist discourse in Japan.6 The lack of definitional clarity led to debate about the true nature of Surrealism and its role in the Japanese art world, further complicating efforts for Japanese artists to define this new style.

Breton’s ideas contrasted greatly with the increasingly repressive political climate in Japan, particularly as Surrealism’s arrival coincided with the Proletariat Art Movement which insisted that art should be accessible to and support the masses, creating an ideological clash with the individualistic and introspective nature of Surrealism.7 Surrealism’s emphasis on the mind and fantasy led supporters of the Proletariat Art Movement to view it as an indulgent engagement with pure art that reflected

only bourgeois sensibilities and overlooked social and political realities.8 It was believed that art should reflect the struggles of the real world, so perhaps the Surrealist desire for transformation was viewed as a serious threat in a political environment increasingly wary of dissent.9 By the 1930s, Surrealism was more widely accepted, and its influence was particularly notable among painters and photographers. The Paris-Tokyo League of Emerging Art Exhibition was held in Japan in 1932 and included Surrealist works by many European artists – amongst them Max Ernst, André Masson, Man Ray, Joan Miró, and Giorgio de Chirico. The exhibition toured Tokyo, Osaka, Kumamoto, and Dalian, and by the mid1930s, an increasing number of European Surrealist writings were translated and disseminated around the country.10 With greater access to European art and theory, ideas such as automatism, unconsciousness, madness and dreams began to be widely and seriously discussed in Japan.11 However the term itself remained open to individual interpretation, allowing artists to adapt Surrealism to convey their personal struggles with the conflict between the self and the nation, as well as their desires and anxieties regarding modern life.

Surrealist Aesthetics and Social Critique

As Chinghsin Wu writes in Reality Within and Without: Surrealism in Japan and China in the Early 1930s, “Behind these seemingly scattered and divergent views of surrealism, there lies a shared, quintessentially modernist understanding of surrealism as an art form with the potential to develop and progress while both echoing and contributing to parallel progress in science, technology, and society”.12 This potential is particularly evident in photography, which balances the objective and subjective by leveraging its unique status as both an indexical and pictorial form of representation.13

Photography’s deeply embedded association with modernity, when situated within a Surrealist context, illustrates how the medium can illuminate new visual realms by presenting life in a new way. By merging the scientific with the artistic and the real with the imagined, photography both captures moments that evoke the uncanny and reveals aspects of reality that might otherwise go unnoticed, challenging conventional perceptions. This dynamic creates a dialectic between the current and future moment – the familiar and the unfamiliar – that positions photography as the ideal medium for producing Surrealist images while aligning with the desires and goals of a society undergoing transformation in the wake of modernity. After Tokyo was nearly destroyed by the Great Kanto Earthquake in 1923, the reconstruction of the city fostered a new urban culture captivated by the idea of modern life (modan raifu). Photography was deeply entwined with this emerging metropolitan culture, as new forms of expression were essential to addressing the demands of urban living and modernity.

With a smaller market for it than other forms of visual art, Surrealist photography was only exceptionally featured in photographic magazines, rendering the medium less prone to censorship as these were not yet subject to the same scrutiny as other types of publications.14 Photographers often imbued everyday objects with symbolism and metaphorical meaning, making their critiques more challenging to decipher. Yamamoto Kansuke, a prominent figure in Japanese Surrealism, created the series Birdcage at a Buddhist Temple starting in 1940. The most well-known image from this series features a telephone encased in a birdcage, alluding to the growing limitations on free expression in the lead-up to war.15 Yamamoto’s work exemplifies the trend of “photo objects”, which emphasised the exploration of objects beyond their normal utilitarian

function to question photography’s capacity to render a true representation of reality.16 Other photographers experimented with techniques that aligned more directly with the original Surrealist texts. A notable example is Ei-Kyū, whose first collection of works Nemuri no riyū (The Reason for Sleep) (1936), evokes a quintessential Surrealist ontology through its allusion to dreams and the unconscious as the origin of production. Through experimentation with automatism and combining photogram production with Surrealist collage, the indexical boundaries of photography and it’s medium-specific limitations are transcended.17 As censorship escalated throughout the war, works were infused with elements of patriotism. It became a common strategy for Surrealists to blend motifs and aesthetics from traditional Asian belief systems, such as Buddhism, with classical imagery from Western culture, including Greek-style architecture and statues. This allowed to continue avant-garde practice while appearing to support the war efforts, balancing both national and international demands and highlighting the ingenuity of Japanese Surrealists.18

Postwar Encounters

Arguably, framing Japanese Surrealism as intriguing and ‘unconventional’ still rolls the dice in favour of a European avant-garde. The integration of Surrealism into the fabric of Japanese cultural history cannot be reduced to the determinants of European Surrealism, as each was informed by their own unique circumstances within modernism.19 Perhaps this construction arises from the lack of obvious core or defining features of Japanese Surrealism, further complicated by the destruction of much of the material necessary for understanding its early formations during the war. A considerable number of negatives and original prints were lost in Allied bombings and the atomic attack on

Hiroshima, making it nearly impossible to establish a straightforward continuity of work. As a result, the achievements and significance of the Surrealist photographers of the 1930s have been largely underrepresented.20 What remains clear, however, is the profound scope of Surrealism and its role in reflecting a new, modern Japan, which stimulated artists, intellectuals, and critics to question the function and purpose of art within society.21 By embracing and adapting Surrealist principles, Japanese photographers developed a unique way of interpreting their reality, one that resonated deeply within their localised context whilst simultaneously engaging with global artistic movements.

Endnotes

1. Chinghsin Wu, “Surrealism in Japan”, The Routledge Companion to Surrealism (Taylor & Francis Group, September 1, 2022), 252.

2. Jelena Stojkovic, Surrealism and Photography in 1930s Japan: The Impossible Avant-Garde (Taylor & Francis Group, February 20, 2020), 4.

3. Wu, Surrealism in Japan, 252.

4. Chinghsin Wu, “Reality Within and Without: Surrealism in Japan and China in the Early 1930s”, Review of Japanese Culture and Society: 26 (University of Hawai’i Press, December 2014), 189.

5. Ibid.

6. Wu, Reality Within and Without, 191.

7. Wu, Surrealism in Japan, 253.

8. Ibid.

9. Michael Richardson, “Charting an Amorphous Past: Surrealism in Japan”, Communicating Vessels: The Surrealist Movement in Japan, 1923-70 (The Enzo Press, 2012), 999.

10. Wu, Surrealism in Japan, 255.

11. Ibid.

12. Ibid.

13. Stojkovic, The Impossible Avant-Garde, 6.

14. Ibid., 20.

15. Wu, Surrealism in Japan, 256.

16. Ibid., 257.

17. Stojkovic, The Impossible Avant-Garde, 25.

18. Wu, Surrealism in Japan, 259.

19. Richardson, 1000.

20. Stojkovic, The Impossible Avant-Garde, 168.

21. Wu, Reality Within and Without, 205.

HART2274 Introduction to Museum and Curatorial Studies

Unit Coordinator: Dr Susanne Meurer

Teaching Staff: Dr Susanne Meurer & Isabel Di Lollo

CRUZ DAVIS-MARTINEZ

‘“Look, look”: An Exploration of the Cultural Construction of “America” for Australian Audiences’

Anna Park’s exhibition Look, Look at the Art Gallery of Western Australia (AGWA) offers Australian audiences a unique perspective on American culture through a powerful collection of large-scale charcoal and ink drawings. This exhibition, Park’s first museum show outside the United States, runs from April 20 to September 8, 2024, and challenges viewers to reconsider narratives that shape their understanding of sexuality, identity, and power within the context of society.1

Upon entering the exhibition, visitors are confronted with a full-body mirror, forcefully emphasising their role as viewers of Park’s work and her cultural commentary. On the other side of the mirror lies the titular work Look, look (Image 1). The drawing sets the tone for the rest of the exhibition as the rest of the exhibition explicitly lacks color. The sheer scale of the pieces in tandem with the dynamic energy adds to their impact, with figures and forms that seem to leap off the paper, capturing the viewer’s attention and pulling them into their world.

The exhibition is spread across several rooms, each meticulously arranged to guide visitors through the nuance themes of Park’s work. Upon entering, viewers are immediately struck by the scale of the drawings. Aside from being traditionally formatted for a gallery, this orientation was likely done to continue the narrative of people outside of American

culture to merely glimpse into a different culture, as if standing outside looking in through a window. The high ceilings and open spaces of the gallery enhance the impact of these large-scale pieces, allowing the viewer to step back and take in the full composition or move closer to appreciate the fine details of Park’s charcoal work. The lighting is deliberately subdued, focusing attention on the stark contrasts of Park’s black-and-white drawings. This choice of lighting creates an intimate yet isolating atmosphere, drawing viewers into the world Park has created while exemplifying the discomfort she had faced as she processed the formation of her identity. The shadows cast by the frames add to the sense of depth and movement, making the figures in her work appear even more dynamic.

The first of two rooms introduce visitors to Park’s critique of gender norms and beauty standards. Here, her drawings of distorted female figures are juxtaposed with text from mid- 20th-century advertisements, challenging viewers to understand how their outward appearances directly impact how they are perceived akin to an advertisement of a product. In the second room, the exhibition shifts to explore the impact of mass media on identity formation. This section is designed to feel more chaotic, with the artworks drawn in a seemingly haphazard manner, thus reflecting the overwhelming nature of contemporary media consumption. The proximity of the works to each other creates a sense of hallucination,2 mirroring the constant barrage of images and information that Park critiques. This is in large part due to the walls of the room being much closer in proximity to each other, enunciating the feeling of claustrophobia. The use of collage in these drawings is mirrored in the layout, with works overlapping and crowding the space, forcing viewers to navigate through almost indistinguishable visual noise. The gallery uses this spacing (or lack thereof)

to emphasise the fragmented nature of memory and the selective way in which we remember the past. The room’s design encourages visitors to linger, to connect the dots between the different cultural references in Park’s work, and to consider how these fragmented memories shape our present understanding of identity. Park’s use of charcoal is masterful, creating a range of textures and contrasts that add depth and complexity to her compositions. The drawings are at once chaotic and controlled, with swirling lines and overlapping forms that convey a sense of disorientation and fragmentation. This visual language

is particularly effective in conveying the themes of the exhibition, which revolve around the overwhelming nature of contemporary life and the constant bombardment of images and information that define our media-saturated society.

Park’s exploration of identity is deeply personal, informed by her own experiences as an immigrant from South Korea to the United States.3 Her work reflects the complexities of identity formation in a media-saturated society, where cultural perceptions and stereotypes play a significant role in shaping how individuals see themselves and are seen by

others. By utilising the notoriety of the Art Gallery of Western Australia, the artist employs a practical joke of sorts on the audience, cunningly perpetuating the same feeling of how she felt as a United States immigrant onto her Australian audience. In addition to the gallery’s notoriety, she utilises mirrors at every opportunity throughout the exhibition to evoke those same feelings of being an outsider – from the entryway of the exhibition to the tabletop used to display her thumbnail sketches.

A recurring theme in Look, look is the idea of “perpetual visibility”—the sense that one is constantly being seen and judged in a society obsessed with appearances and social media.4 Park’s drawings capture the alienation and self-awareness that come with this constant scrutiny, using fragmented images and disjointed narratives to convey the psychological impact of living in such an environment.5 The interplay between text and image in Park’s work is particularly effective in conveying this theme. The speech bubbles and captions she incorporates often contain clichéd expressions and stereotypes, which she then distorts or decontextualises to highlight their absurdity. This technique encourages viewers to reconsider the validity of these expressions and the role they play in reinforcing societal norms. By utilising only white walls in the gallery with minimal label texts, the exhibition forces viewers to face what it is that Park has had to face throughout her life: identity.

Park’s work and by extension, the ways in which her works take up the museum’s space, is also a commentary on the nostalgic way in which we consume and remember media. The use of blackand-white drawings creates a timeless quality, evoking a sense of nostalgia that draws the audience into a reflection on the past. The absence of color strips away any distractions, allowing the focus to remain on the form, composition, and the raw emotion embedded in Park’s work. This is in reference to

the monochrome imagery prevalent in mid-20thcentury media, from classic advertisements to early television, reinforcing the theme of media’s historical influence on identity. The minimally blank walls of the gallery further amplify this sense of nostalgia. With the absence of vibrant colors or elaborate displays, the gallery space itself becomes a canvas, mirroring the simplicity and directness of Park’s drawings. The white walls, unadorned and free of excess embellishment, create an almost clinical environment that heightens the viewer’s awareness of the artwork. This setting emphasises the contrast between the past and the present, encouraging viewers to engage deeply with the memories and cultural references embedded in the work. The gallery does more than just complement Park’s drawings; it actively participates in the narrative, creating a space that is both reflective and unsettling, drawing the viewer into a deep contemplation of the themes of nostalgia, identity, and media.

Anna Park’s Look, look is a powerful and thought-provoking exhibition that challenges viewers to reconsider the narratives that shape our understanding of identity, gender, and media. Through her dynamic and chaotic drawings, Park invites us to engage with the complexities of contemporary life, offering a critique of the societal pressures and cultural constructs that influence how we see ourselves and others. The thoughtful layout and sensory experiences all contribute to making this exhibition a profound exploration of the complexities of contemporary life, identity, and media. The exhibition is a significant milestone in Park’s career, marking her emergence as a major figure in contemporary drawing. Her work resonates on multiple levels, combining technical skill with a deep understanding of the psychological and cultural issues that define our time. Look, look is not just a visual experience, but an intellectual and emotional journey that prompts reflection on the narratives that shape our understanding of the world.

Through her powerful drawings and the carefully crafted exhibition space, Park offers a compelling critique of the societal norms and media influences that define our lives, making this exhibition a must-see for anyone interested in contemporary art and culture.

Endnotes

1. Look, look. Anna Park. Simon Lee Foundation. 2024, July 8, https://slficaa.artgallery.wa.gov.au/program/look-look-anna-park/

2. Look, look. Anna Park. Simon Lee Foundation.

3. Watson, Graeme & Hill, Leigh Andrew. Rising art star Anna Park will have her first Australian exhibition. OUTinPerth. 2023, December 11, https://www.outinperth.com/rising-art-star-annapark-will-have-her-first-australian-exhibition/

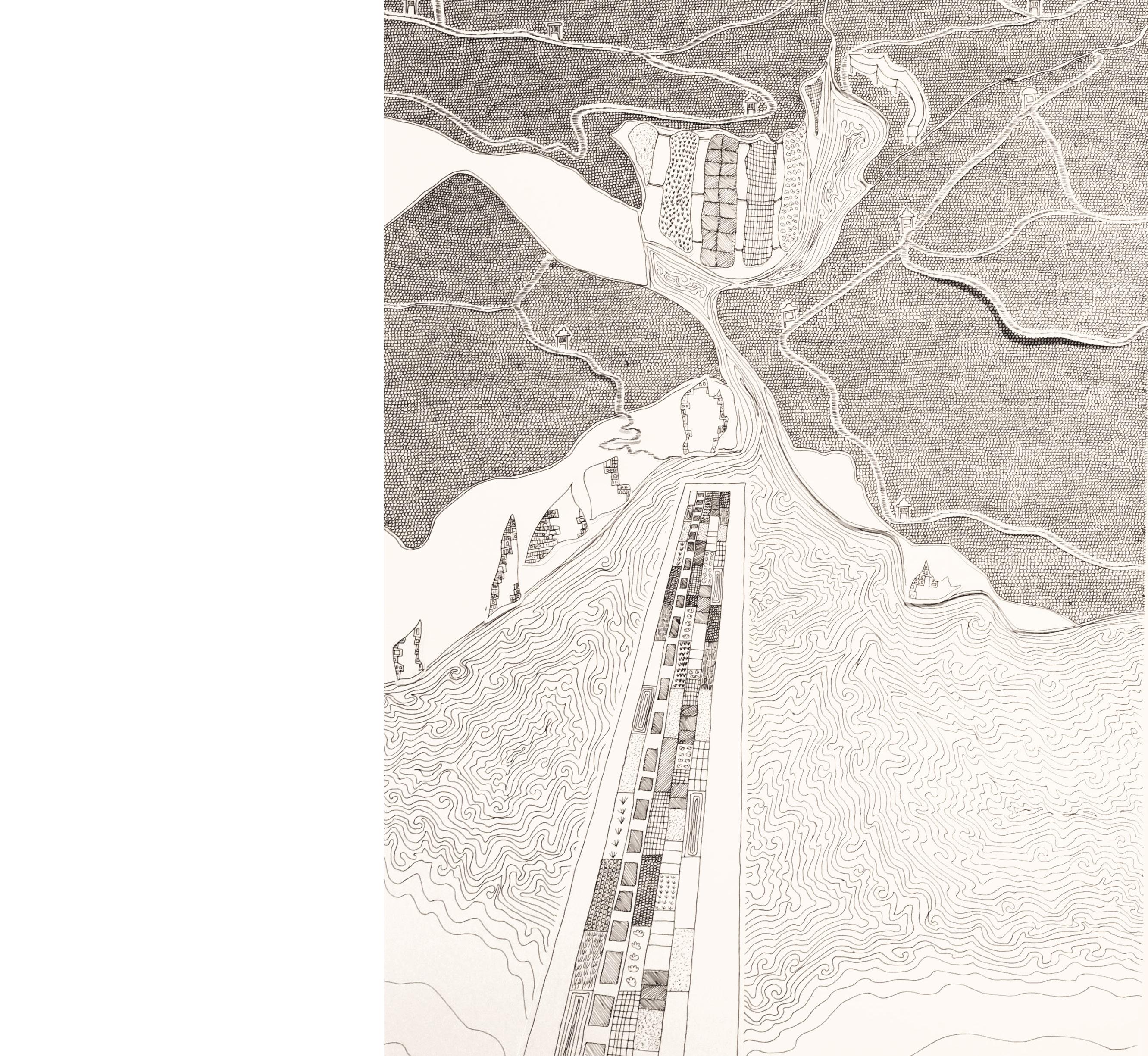

4. Look, look.: Anna Park in Perth. Juxtapoz Magazine. 2024, July 23, https://www.juxtapoz.com/news/installation/look-look-annapark-in-perth/

5. Look, look. Anna Park in Perth. Juxtapoz Magazine.

ARCHITECTURE, LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE & URBAN DESIGN

ARCHITECTURE

Foreword by Eugene Tiong

In 2019, I arrived in Perth, stepping into unfamiliar territory with a clear purpose: to pursue my dream of architecture. I began this path with hope and determination, confident I could overcome any challenge. Over time, I learnt that growth is neither swift nor easy. It is a continuous process of learning, marked by challenges, discoveries, and moments of reflection.

The past five years have been a journey of resilience. Creative blocks, technical hurdles, and sleepless nights tested my resolve. Moments of frustration, including unexpected computer failures, adapting to a global pandemic, and the relentless pressure of deadlines, became opportunities for growth. Each challenge taught me valuable lessons and prompted deeper reflection on my aspirations and the life I envisioned.

Through these experiences, I discovered that growth comes from choice: what to learn, what to value, and who to become. Failures became opportunities to improve, and collaboration with peers and mentors turned individual struggles into shared victories. Together, we brainstormed, refined ideas, and pushed creative boundaries, discovering that the heart of design lies in connection and teamwork.

As my skills grew, so did the opportunities. From sharing knowledge with younger students to participating in internships, competitions, and receiving awards, each milestone affirmed the value of persistence and passion. These moments served as reminders that challenges are not barriers but pathways to growth and discovery.

This journey is not mine alone. Each student here has faced their own challenges and found their unique voice through design. Each year’s exhibition represents the culmination of countless hours of effort and showcases the intersection of creativity, functionality, and sustainability. Each project, whether displayed or not, is a testament to the dedication and talent of its creator. Special congratulations to all whose work is featured in this year’s Summer Exhibition and Catalogue. Your achievements are truly recognised and celebrated.

As I graduate, I look to the future with gratitude and optimism. Questions about the future remain, but perhaps the answers are less important than the journey itself. The road ahead is uncertain but filled with promise. Let us approach it with courage, creativity, and a commitment to shaping a better world.

To my fellow graduates in Architecture, Landscape Architecture, and Urban Design, congratulations on this remarkable achievement. To those continuing this journey, embrace it with passion, curiosity, and resilience. To everyone reading this, I wish you success in your own endeavours.

Finally, I extend my heartfelt thanks to the UWA School of Design for its support and guidance. I am deeply grateful to those who encouraged me along the way and to my younger self for taking that first brave step.

Eugene Tiong, Master of Architecture, 2024.

Image: X.01 CHAIR designed and crafted by Eugene Tiong, finished in Vic Ash (L) and Jarrah (R), 2024.

ARCHITECTURE

ARCT5011 Independent Research Part 2

Unit Coordinator: Dr Kate Hislop

Supervisor: Dr Beth George

KATHERINE DOWNIE

‘Accessible Commonplace / Commonplace Accessibility’

This thesis identifies the limitations of merely complying with accessibility standards, such as Australia’s National Construction Code, and argues for a shift towards designing for the full spectrum of human diversity. It proposes that accessibility should move beyond being an afterthought or a regulatory checkbox and instead become a core design principle that inspires creativity and innovation in architecture. Through engagement with literature, case studies, and conversations with architects and users, the research investigates how inclusivity can be embedded into every stage of the design process.

The research explores the emotional and sensory dimensions of architecture, considering how design impacts wellbeing and the lived experience of space. It integrates ideas from Universal Design, embodied cognition, and interdisciplinary approaches to provide practical frameworks for architects. The outcome includes conceptual diagrams, suppositions, and design strategies that go beyond compliance to create accessible environments.

By addressing the disconnect between architectural education, practice, and diverse user experiences, the thesis envisions a built environment that reflects and celebrates the multifaceted nature of human existence. It aspires to make accessibility commonplace in architecture, shifting the discipline towards a more inclusive and inspiring future.

Image: Diagrams illustrating inclusive design principles and embodiment in architecture.

Image: Conceptual frameworks redefining accessibility in architectural practice.

ARCT5011 Independent Research Part 2

Unit Coordinator: Dr Kate Hislop

Supervisor: Lara Camilla Pinho

JADE RICOURT

‘Lessons Learned’

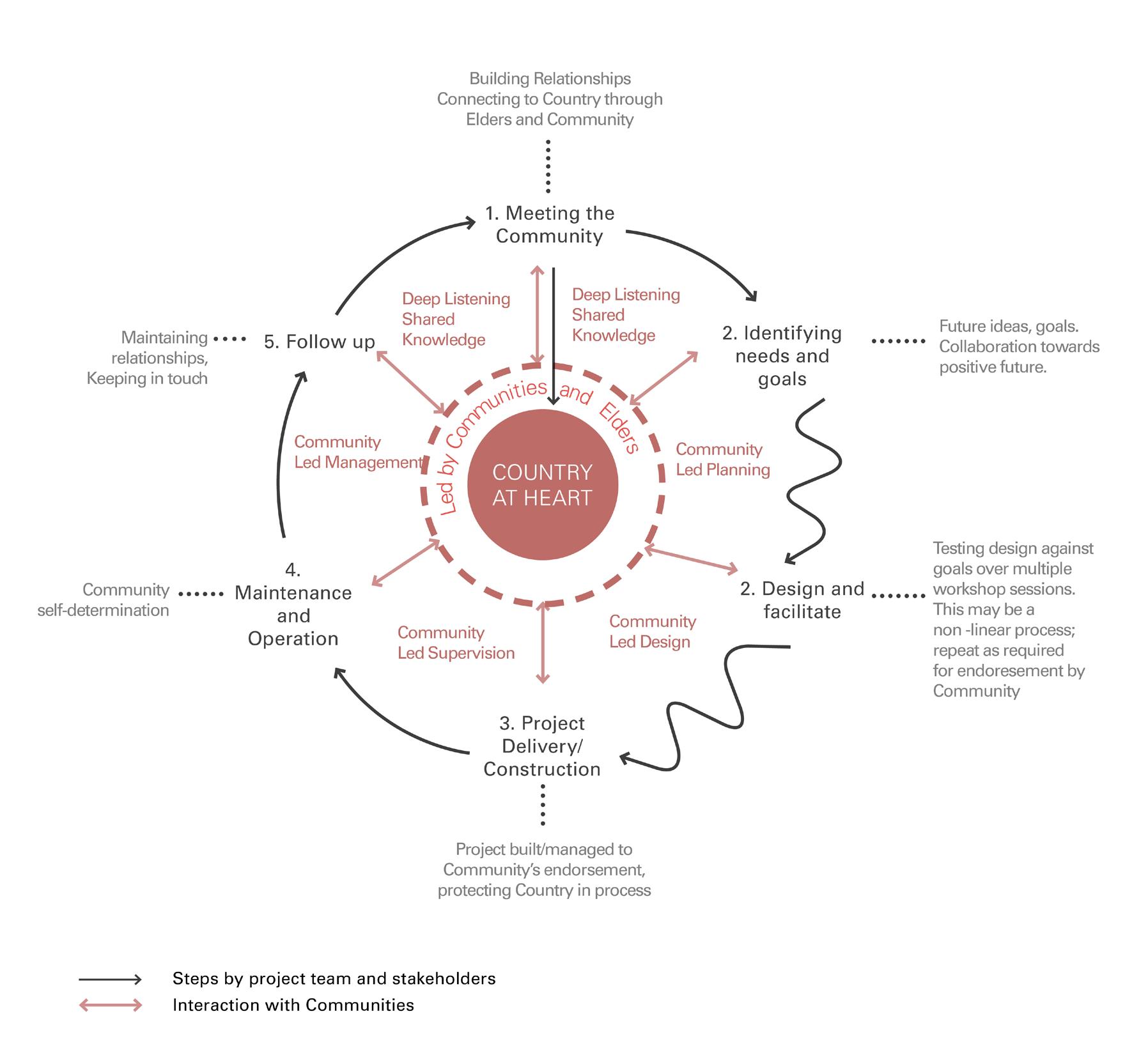

The built environment plays a vital role in shaping our daily lives, influencing the cultural, social, and physical landscapes of the places we inhabit. Yet, it often falls short of understanding the communities it serves, as seen in remote Australian communities where significant living disparities remain. In these remote communities, the disconnect between design and culture has far-reaching consequences. Inappropriate housing solutions, shaped by cultural irrelevance, have deepened health disparities, with cultural incompetency emerging as the root cause of these misaligned designs. In response, this research seeks to foster cultural competency among built environment professionals, including educators, students, practitioners, and academics, to bridge this disconnect and support the creation of designs that honour and reflect the communities they serve.

At first glance, there appeared to be a significant lack of documentation on community engagement processes specific to built environment projects. However, as the research progressed, valuable insights began to emerge, with new publications continuing to surface throughout the year reflecting the industry’s ongoing shift toward reconciliation and designing with and for Country. Creating a platform to strengthen cultural competency by curating and expanding access to these resources emerged as a logical progression. To support this vision, a vast array of resources, including books, thesis projects, frameworks, guidelines, podcasts, webinars, courses, and reports, have been incorporated to educate and empower the integration of Indigenous cultural protocols into design practice. The Lessons Learned repository serves as a central platform to organise, share, and enhance access to these resources, amplifying their reach and impact.

While information on the subject has grown, it remained crucial for the research to gather insights from practitioners experienced in cross-cultural and multi-disciplinary contexts. Through conversations with nine built environment professionals, the study explored cultural awareness, protocols, and engagement strategies.

Envisioned as an evolving platform, the repository encourages users to contribute new and relevant content which would undergo a review process, guided by a panel that includes First Nations representatives, ensuring that the contribution reflects the diverse voices and needs of First Nations communities. This research is part of a broader industry movement dedicated to honouring cultural identities and the profound connections to land through design.

Image: Lessons Learned Repository Website.

Interactive Map Navigation explanation diagram;

Concluding diagram informed by the Lessons Learned from Perspectives.

ARCT5011 Independent Research Part 2

Unit Coordinator: Dr Kate Hislop

Supervisor: Joely-Kym Sobott

CARINA VAN DEN BERG

‘Finding Common Ground: A dissertation on the formation of national identity in coffee spaces of Australia’

“Social space tends to be translated, with more or less distortion, into physical space…”1

“The most successful ideological effects are those that have no words, and ask no more than complicitous silence…”2

Ideology exists within an assured social reality that is entered through mutual agreement; a common ground. It is thus manifested through the lived relations between an ‘imaginary lived relation’ and the conditions of the relation.3 Imaginary pertains to an “image” like a mirror where individuals play a role in producing the framed image. Culture gives the ideology tangibility, by informing the practices that frame the image, thus a kind of image making. And so, as culture is underpinned by ideology it also legitimates nationalism by the means to be practiced within social reality.4 Bourdieu’s theory on habitus explains how the image making is a result of “regulated improvisations” within the cultural field of production. Coffee spaces provide the common ground for these improvisations, or image making, to be practiced and regulated.

Benedict Anderson sees that the behaviours surrounding cultural artifacts are what construct the ‘imagined political communities’ of national identity.5 Imagined communities inform and define a nation state, but in the difference between behaviours surrounding

the cultural artifact it defines the limits of national identity. Yet, as a stagnate object cultural artifacts don’t encapsulate the evolving nature of culture and thus of national identity. Thus, in conjunction with habitus it is a better indication not only how nationalism informs cultural practices but how it may evolve and adapt to new regulations and behaviours.

Behaviours in the space inform how the ideology takes hold. So, it is through participating in the cultural system that form a collective identity. Participation from individuals derive from an innate desire to feel important and appreciated.6 As participants become regularly satisfied, the repetition paradoxically starts regulating them. Cultural spaces like coffee shops become a training ground for behaviours that define national identity to be practiced and regulated.7 As the performance is repeated by a mass of individuals, it collectively constructs a congruent experience. This collective experience is what defines a national identity, as it not only groups multiple experiences but it defines the boundary from other identities. National identity is thus not in the cultural commodity but in the behaviour surrounding it, the habitus.

The coffee spaces themselves have been regulated to becoming a common ground for multiple nationalities. These spaces are largely a result from immigration, first the English with their coffee palaces that exert an enclosed and insular coffee space. Then the Americans who had no spatial infrastructure but introduced coffee drinking to Australians homes making it accessible to all individuals. The two extremes were mediated but the southern European immigrants post World War 2. Here the Italians and Greeks opened spaces that mimicked American style dining within luxurious and modern cafes, coffee bars and restaurants.8 This builds civic nationalism providing the means for different nationalities to share similar practices and form community. The flat white was born from one of

these Italian owned coffee bars.9 As of this year, the flat white has become Australia’s greatest culinary export and maintains recognisable as Australia’s coffee beverage.10 As Australian owned cafes and coffee shops appear world-wide, it supports Benedict Anderson’s observation that national identity’s limit is defined not by boarders of a country nor the cultural commodity. But defined by the behaviour surrounding the commodity.

In the media and newspaper, a prevailing theme attaches coffee spaces with the threat of economic disparities plaguing different socioeconomic groups within Australia.11 Despite rise in cost-of-living in Australia, the coffee space industry’s profits are still rising.12 Indicating that many Australians aren’t willing to sacrifice this daily routine and have fostered symbolic capital on the coffee spaces. Cultural spaces like coffee shops serve as arenas where social conflicts, such as those stemming from the cost-of-living crisis, are navigated through collective identity and nationalism. Bourdieu’s theory suggests that ideology is used to build symbolic capital of a cultural commodity in turn motivating customers to return. Symbolic capital changes the transactions in coffee spaces from being purely transactional over a commodity to being racked with meaning.13 Agents in the field who compete for dominance in the coffee space field, make use of nationalism to draw upon customers’ perceived value for the commodity. Hence coffee spaces do not form national identity but use the ideology to promote their space and attract more customers. Cultural mediators, including media and political figures, further reinforce this identity by promoting the spaces as social, egalitarian hubs. Though this primarily fuels attendance rather than solving socioeconomic divide. Ultimately, while ideology in these spaces can mediate cultural conflict, it doesn’t fully address larger societal conflicts like the cost-of-living crisis.

Despite imagined communities not able to resolve conflicts within social reality, coffee spaces still serve an important role that allows people to gather. As such, coffee spaces house a sense of community to build that informs the basis of social capital. Social capital, according to Robert Putman in Bowling Alone, is used to build general reciprocity which is a key social characteristic of what underpins public trust in a democratic system of government. Public trust is crucial to enable democratic governments make policies that effectively work at closing socioeconomic divides.14 In this way, the theory of Bourdieu, Eagleton and to an extent Anderson, may be extended to include associative democratic ideology. Putman’s research emphasises the importance community clubs at helping to build public trust and an effective democratic government.15 This would also be founded on principles of Associative Democracy outlined by Paul Hirst, as democracy founded on free, communal gatherings.16 Therefore, future research could analyse how coffee spaces could help inform public trust in a democratic system. Coffee spaces, like other spaces, are places to gather and meet people. When individuals have the space to gather, ideologies can be practiced and play out, such as nationalism, democracy, egalitarianism, and so on.

As designers of the built environment, it is our responsible to help facilitate these spaces. People need spaces to gather, spaces to talk and community to build. This dissertation aimed to highlight the connection between spaces and the role it has at building ideologies but also constructing social reality. Although the role of the architect is not actively dictating what ideologies and social structures play out in their spaces, they provide the means and space for them to take hold. Paradoxically architects are as much the designers of these spaces as they are, at times, inhabitants. With their own social, symbolic and cultural capital architects exert their ideologies, at perhaps unknowingly, when designing these spaces.17

The symbolic capital of an architect is reflected in his client and occupants. However, spaces the architect designs when they work on more public commissions should, in theory, be open to a broader social and cultural capital, to allow for more inclusivity. This will in turn allow for larger groups of people to gather and congregate, cultivate new ideologies.

According to Michel Foucault, this is only possible if the architect cultivates and symbolises the needs of the occupants, mediating between the community and the built environment. “I think [architecture] can and does produce positive effects when the liberating intentions of the architect coincide with the real practice of people on the exercise of their freedom.”18 And so, the responsibility for an architect is to work with the client and design good spaces for communities to gather. To liberalise and realise the ideology, architects work with the people that occupy the space. Finding common ground to better design spaces for the community.

14. Join or Die, directed by Pete Davis and Rebecca Davis (March 12 ,2024) Netflix.

15. Join or Die, directed by Pete Davis and Rebecca Davis (March 12 ,2024) Netflix.

16. Paul Hirst, “Associationalist Ethics and the Logics of Collective Action,” in Associative Democracy. Cambridge: Polity Press, 1994.

17. Pierre Bourdieu, Outline of a Theory of Practice, pg 78.

18. Michel Foucault, “Space, Knowledge, and Power,” interviewed by Paul Rabinow. Skyline, 1982.

Endnotes

1. Pierre Bourdieu, p. 2000 Pascal Meditations, Cambridge, Polity Press, pg 134.

2. Pierre Bourdieu, p. 1977, Outline of a Theory of Practice, London, Cambridge University Press, pg 188.

3. Terry Eagleton, ‘What is Ideology?’, pg 142.

4. Terry Eagleton, ‘What is Ideology?’, pg 14.

5. Benedict Richard O’Gorman Anderson, ‘Introduction’ in Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism (London: Verso, 2006), pg 6.

6. Anderson, ‘Introduction’, pg 12.

7. Pierre Bourdieu, Outline of a Theory of Practice, pg 77.

8. Emma Felton, 78.

9. S. J. Wills, “The Sydney History of the Flat White” Origin of the Flat White. 2015. http://www.flatwhitehistory.com.au/.

10. N.a. “Flat white are Australia’s greatest culinary export.” The Economist. April 11th 2024. https://www.economist.com/ culture/2024/04/11/flat-whites-are-australias-greatest-culinaryexport; IBIS World.

11. Gabrielle Chan.

12. IBIS World.

13. Pierre Bourdieu, ‘The Production of Belief’, pg 78.

ARCT5011 Independent Research Part 2

Unit Coordinator: Dr Kate Hislop

Supervisor: Dr Beth George

SASKIA DAALE-SETIADY

‘Kevin Lynch’s Image of the City as a tool for critiquing contemporary planning practises’

This thesis contributes to a critique of contemporary urban planning in Western Australia. It is an account that utilises cartographies over time, historical photographs, various urban study methods and personal encounters within the suburb of Scarborough, Western Australia. Through the guidance of past urban principles drawn from urban theorist Kevin Lynch and his seminal work Image of the City (1960), this is an advocation for a revival of experiential planning approaches as essential tools for understanding the relationship between design and the experience of our contemporary cities. This thesis presents a critical question: How may the application of Kevin Lynch’s theory of Image reveal the anomalies of spatial experience in a contemporary Perth suburb governed by controlled frameworks?

Image: Map showing development of Scarborough districts in 1915 – Good Bathing, Good Surf, Good Beach.

Image: (Left) Paths – Scarborough’s most memorable routes; (Right) The Snake Pit, Spiritland.net, n.d, accessed 12 September 2024, https://www.spiritland.net/snakepit-wa.html

https://www.spiritland.net/snakepit-wa.html

ARCT5101 Architecture Studio

Unit and Studio Coordinator: Kirill de Lancastre Jedenov

‘Popo Islands’

RAMONA ZARE

‘Popo Island – A Populated Paradise’

This imagination of Popo Islands is inspired by the dream of living a long, healthful life in the paradise of an untouched natural landscape while surrounded by thousands of friends and extended family.

The project is an unconventional exploration of the concept of creating a sustainable high-density living that does not cut down trees, push out animals, or disturb current habitats. The buildings will also encourage population longevity despite their high density. Every building or landscape choice will be no more than a light touch to the earth’s surface.

To create a highly populated paradise, existing tactics from previous projects such as Kowloon Walled City, will be used to develop a self-sustaining island that has no major negative impacts on the environment.

Stilted buildings, floating food production pontoons, and vertical farms are among the ideas that hold the foundation of sustainable living on this island. A high-density building will be hidden with the natural caves of the island so individuals have a place to retreat in the evening and can call it their home. All of this will be inspired by blue zone living the islands design will encourage moving naturally, fostering positive outlooks, eating wisely, and creating human connection to foster this high-density ageing population that can live successfully in paradise.

Image: Elevated hiking trail.

ARCT5101 Architecture Studio

Unit Coordinator: Kirill de Lancastre Jedenov

Studio Coordinator: Peter Tibbitt

‘Place of Origin’

THALE URKEDAL BIERING

‘In Between Dunes’

The aim of the project is to create something timeless and constant in a forever evolving landscape. Set among the red sand dunes of the Simpson Desert in the Pilungah Reserve, the field station provides accommodation for two caretakers, who reside there for six months at a time, and accommodates up to eight visitors for shorter, two-week periods. In addition to living quarters, the field station features a shared common area, and a workshop designed for learning and discussion.

Positioned in between the shifting sand dunes, the field station functions as an observatory. Rather than simply offering a view of the dunes, the architecture itself measures their gradual movements. A long concrete wall, extending far beyond the field station, serves as a record of the sand’s passage. As the dunes move alongside it, the movement will be visible on the wall. But as the landscape moves, so must the field station.

The field station is a timber construction which is designed to be both assembled and disassembled, allowing it to be periodically relocated along the concrete wall as the dunes move closer. Rather than relocating the entire station at once, individual parts are moved in stages, reshaping the relationships within the station’s program and offering an adaptive approach to its layout. The timber structure connects to the concrete wall through beams that fit securely into notches, creating a flexible yet enduring base that allows the station to respond to the landscape’s changes over time.

Image: Elevation and section.

Detailed plan.

ARCT5101 Architecture Studio

Unit Coordinator: Kirill de Lancastre Jedenov

Studio Coordinator: Craig Nener

‘We are Water’

JACK CONNOLLY

‘Sunken Baths’

Sunken Baths explores water’s profound influence on landscapes – both natural and cultural – translating its transformative presence into a sculptural intervention within the hillside. The architecture emerges as a subtle incision carved into the terrain, reflecting how rivers shape valleys over time. Its form is an interplay of fluid topography and spatial design, tracing a gentle, undulating ramp that meanders through the space like a natural watercourse. By rejecting conventional steps or terraces, this continuous gradient fosters a seamless, accessible journey, evoking the quiet persistence of flowing water and inviting visitors into an immersive environment of movement and reflection. Each turn along the path reveals shifting perspectives of earth, sky, and water, reinforcing the dynamic interplay that defines the space.

The project draws inspiration from the Balinese Subak system, a centuries-old tradition of water management that demonstrates a harmonious relationship between people, land, and resources. Within the design, concrete columns evoke the rhythmic, geometric order of terraced fields. Carefully imprinted textures recall the undulating patterns of rice paddies, conveying a sense of cultural continuity. References to agricultural rhythms and communal stewardship reaffirm the intricate relationship between built form and the living environment. This material dialogue grounds the architecture in a narrative of innovation and collaboration, where water’s presence underpins both subsistence and spiritual life.

In combination, these strategies yield a spatial experience that synthesizes geological forces and cultural adaptation. The carved hillside, fluid pathways, and textured surfaces coalesce into a sanctuary where water’s power and meaning are celebrated. Geological and anthropological elements offer visitors a direct encounter with elemental processes. By engaging memory, tradition, and the primal allure of moving water, this architecture transcends mere functionality, offering a narrative that resonates with place. The interplay of water, terrain, and crafted materials transforms these baths into an immersive landscape, encapsulating an essence of place.

Image: Elevation.

ARCT5201 Detailed Design Studio

Unit Coordinator: Dr Rosangela Tenorio

Studio Coordinator: Andrea Quagliola

‘Surf Resort on Rote Island, Indonesia’

HARVEY RUPP

‘Surf Resort on Rote Island, Indonesia’

Through analysis of ‘Suti Solo do Bina Bane’, a poem of spiritual significance to the Rotenese – the importance of palm shade and border stone architectural features have been felt for generations and act as the backbone of the public/private material logics driving the design.

Private units take on a monumental and inward facing stance, offering reliable and intimate escape from the outside world during the day.

Public program shifts focus to mimic the palm forest trunks and filtering of light, accentuating the powerful golden hour silhouettes on the ocean side of the site.

By allowing penetration of light and views Eastward, visitors are drawn towards the ocean at a time of gathering, performance and storytelling.

Image: Worms-eye isometric view of family unit, showing earth pillars and courtyard features.

ARCT5202 Detailed Design Studio 2

Unit Coordinator: Dr Rosangela Tenorio

Studio Coordinator: Lara Camilla Pinho with Bradley Millis and Jess Gibbs

‘Normalising Unconventional Materials in Local Contexts’

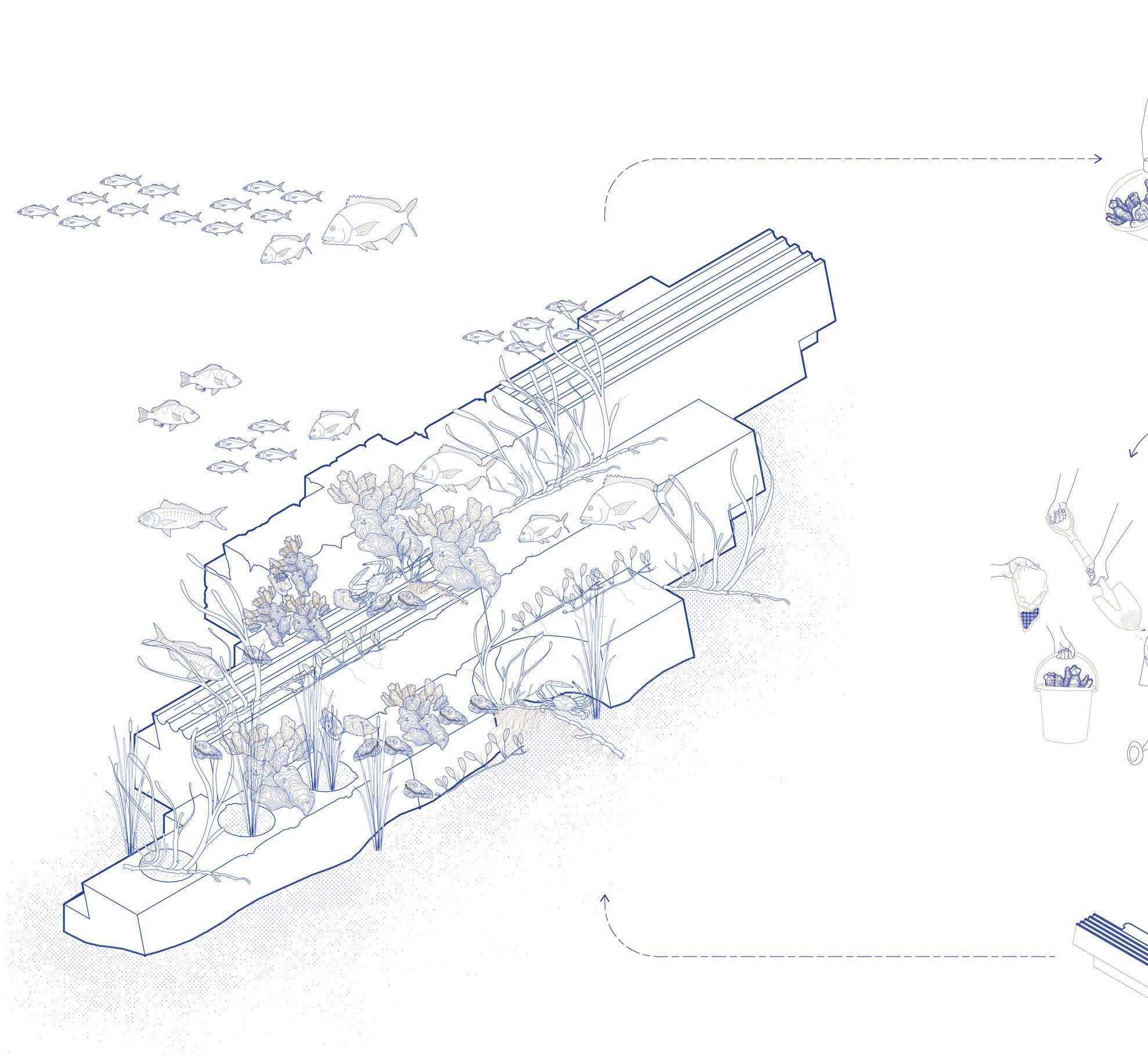

SAVANNAH KELLY

‘Tidal Threads’

What if the tides not only shaped our shores, but reshaped how we live in harmony with nature?

The Tidal Threads project envisions a revitalised Fremantle foreshore, reconnecting the city with its natural waterfront by synthesising multi-species interactions and ecological design.

By reclaiming and extending the harbour, the project establishes a continuous landscape network that seamlessly interconnects social-ecological relationships between terrestrial and marine environments. Preserving the functionality of Fremantle’s working port, the design anticipates the city’s growth as a hub with expanding residential opportunities. To balance this, Tidal Threads introduces protected marine areas and leverages the brackish waters at the confluence of the Indian Ocean and Swan River to restore natural abundance of biodiversity within the heavily industrialised Fremantle Port.

Tidal Threads centres around three key intervention strategies that integrate multi-species habitats to enhance ecological restoration and flood mitigation. The ‘Sea Slabs’, a living seawall, serves as a conduit to the waterfront, supporting marine biodiversity, particularly oyster reefs, whilst promoting human interaction. Tidal marshes are reintroduced to boost productivity and biodiversity, aiding in phytoremediation. Meanwhile, the Intertidal Promenade embraces the dynamic, littoral relationship between land and water, responding to the natural ebb and flow of the tides and transforming the challenges of flooding into opportunities for ecological enhancement and public engagement.