CIVIC DEFRAGMENTATION

CIVIC LANDSCAPE SYSTEMS: LEARNING + RESILIENCE BY DESIGN

2016 LARCH702 Capstone Studio

Department of Landscape Architecture

University of Washington, Seattle

"As cities are now the dominant human habitat, they must be a healthy human habitat. They must be planned, developed, and managed in healthy and sustainable ways—ways that minimize their ecological footprints and maximize health and well-being for their residents. It is important to ensure that the needs of current generations are not being met at the expense of future generations, and to avoid constraining future options. We need to prepare for an uncertain future—there will be shocks and surprises. This requires our environments to be resilient and readily adaptable in the face of change."

– Anthony C. Capon and Susan M. Thompson, in “Built Environments of the Future”. 2011. Dannenberg, Andrew L., Howard Frumkin, and Richard J. Jackson, eds. Making Healthy Places Designing and Building for Health, Well-being, and Sustainability, Washington, DC: Island Press. p.375.

CIVIC DEFRAGMENTATION

CIVIC LANDSCAPE SYSTEMS: LEARNING + RESILIENCE BY DESIGN

DESIGNED AND DEVELOPED BY

Chih-Ping (Karen) Chen

Christel Game

Wenying (Winnie) Gu

Jiaxi (Jessie) Guo

Zhehao Huang

Will Shrader

Seongwon Song

James Wohlers

Led by Associate Professor Julie Johnson

FOREWORD

“Children are a kind of indicator species. If we can build a successful city for children, we will have a successful city for all people.” —Enrique Penalosa1

This book represents the cumulative work of eight graduate students who undertook the University of Washington Master of Landscape Architecture (MLA) 2015-16 Capstone Studio. This talented, and collaborative group developed their designs through research and an iterative, community based process. I greatly enjoyed working with each of them and supporting the realization of design proposals three students developed and others joined in to bring to life.

The quote above by Enrique Penalosa served as a foundation for this MLA Capstone Studio, “Civic Landscape Systems: Learning + Resilience by Design”. Our Autumn Quarter seminar explored theory and precedents of civic landscape systems, and connected these to the position that if we are to create more resilient cities, we need to start with how children may learn from and experience places that define their daily lives. With four students in Rome for a Study Abroad Program, one in Copenhagen for an internship, and three in Seattle, the applications of ideas from literature to local environments afforded varied perspectives. These are revealed in “Section 1: What is Civic Landscape?”.

The seminar concluded with an introduction to Seattle’s Licton Springs-Haller Lake Neighborhood, and the students applied seminar themes to this neighborhood in the Winter and Spring Quarter studio. Students undertook a community based process to learn about neighborhood challenges and opportunities, to identify places and connections that needed attention, and to gain feedback on their evolving design proposals for areas they selected. Analysis revealed this neighborhood is poised for significant change and yet lacks a coherent civic landscape infrastructure. Three of Seattle’s designated “Urban Villages” and a potential fourth, should the North 130th Street light rail station be built, are found here. Its east/west boundaries—North Aurora Avenue North (State Highway 99) and Interstate 5—serve as stark physical and perceptual edges, offering limited opportunities for pedestrians and bicyclists to cross safely. The planned pedestrian bridge over I-5 at Northgate’s light rail station promises a key connection if extended through a network of greenways. And notably, while there are diverse civic landscapes, they are disconnected and merit improvement. Findings from neighborhood thematic analysis, an overview of the studio’s engagement with community members, and introduction of the studio’s “Civic Defragmentation” framework are presented in “Section 2: Analyzing, Engaging, and Framing the Neighborhood”.

Each student developed design that integrate civic landscapes theme (depicted as icons) across spatial scales and with an eye toward strategic development. Three students’ projects involved building and installing particular elements that engaged others in the studio and beyond; these revealed the power of simple design interventions to create opportunities for discourse and learning. Each student’s contextual findings, design, visions, and detailed proposals are described in “Section 3: Project Designs”.

The richness of all this work grows from the tremendous support and engagement of community members, representatives of agencies and institutions, planning and design professionals and faculty, and organizations who are noted in “Acknowledgments”.

I hope this book highlighting the studio’s endeavors—findings, process, design proposals, and built work—may serve as a resource for Seattle’s Licton Springs-Haller Lake Neighborhood, for these eight students who have now graduated, and for others interested in civic landscape systems as a means of enriching children’s learning and lives and of creating more resilient communities.

Julie M. Johnson, RLA, ASLA Associate Professor, Landscape Architecture University of Washington, Seattle 1 Enrique Penalosa, in Jeffries, Duncan. 2014. “Children should be at the heart of future cities.” Green Futures Magazine (April 14). http://www.forumforthefuture.org/ greenfutures/articles/children-should-be-heart-future-cities (accessed February 3, 2016).SECTION 1: WHAT IS CIVIC LANDSCAPE?

SECTION 2: ANALYZING, ENGAGING, AND FRAMING THE

SECTION 3: PROJECT

SECTION 1: WHAT IS CIVIC LANDSCAPE?

WHAT IS CIVIC LANDSCAPE?

CULTURAL SYSTEMS

HEALTHY SYSTEMS OF MOVEMENT

PLAY-URBAN CHILDHOOD

ENGAGING COMMUNITIES

SAFETY

HISTORY IN DESIGN

LEARNING IN PLACE

WELL-BEING AND HABITAT

ECOLOGICAL SYSTEMS

FOOD SYSTEMS

The Civic Landscape Systems seminar addressed themes that frame these systems and supported our goal of engaging communities in the design of civic landscape systems. Most of the icons shown on the left represent the seminar themes; the themes of food systems, history in design, and safety grew from our studio explorations. In the seminar, we studied theory and precedents and reflected on how our findings may be applied. The following pages present a summary of the seminar’s eight themes through a common format. The Rationale introduces why the theme matters. Following this, Main Take Aways summarizes key points from literature we read and discussions we had with each other. The Reflection describes our graphic and written applications of these insights, often through our observations of the three places where we studied during Autumn Quarter—Copenhagen, Rome, and Seattle. And last, Relationship to Studio Site highlights important thematic considerations that our individual projects should address in the Licton Springs-Haller Lake Neighborhood.

CIVIC LANDSCAPES

• SEEING SYSTEMS AND EXPRESSING VALUES

• PLAY—URBAN CHILDHOOD

• LEARNING IN PLACE AND BY DESIGN

• HEALTHY SYSTEMS OF MOVEMENT

• DESIGN FOR WELL-BEING AND HABITAT

• CULTURAL SYSTEMS IN DESIGN

• ECOLOGICAL SYSTEMS IN DESIGN

• ENGAGING COMMUNITIES IN DESIGN

SEEING SYSTEMS AND EXPRESSING VALUES

RATIONALE

Seeing Systems and Expressing Values raises questions about systems and values related to landscape architecture. Design works should be considered not only for beauty, but also cultural, ecological, civic and learning systems and values. Through literature and precedents, we developed some thoughts and studies of how design works how systems and values are represented in landscape architecture.

MAIN TAKE AWAYS

The readings for this theme introduced concepts relating to features and qualities of systems as well as the dynamics of resilience in systems.

In Resilience Thinking, authors Walker and Salt express that resilience thinking provides a framework for viewing a social-ecological system across scales of time and space. Its focus is on how the system changes and copes with disturbance. Resilience enables and responds to change, and so is essential to sustainable systems.1

Capra presents different features of systems, including that they don’t operate in linear ways, but as networks.2

1. Walker B. and Salt D. 2006. “The System Rules: Creating a Mind Space for Resilience Thinking” in Resilience Thinking Sustaining Ecosystems and People in a Changing World.

2. Capra, F. 2005. “Speaking Nature’s Language: Principles for Sustainability” in Stone and Barlow, eds. Ecological Literacy: Educating Our Children for a Sustainable World. San Francisco, CA: Sierra Club Books.

“Systems vs. Objects”

“Systems: Nested networks as a patchwork quilt composed of interdependent fibers.”

“Objects: Singular entities acting in isolation without any relationship to its surroundings.”

REFLECTION

This reflection focused on identifying a local example of inspiring systems. Jiaxi identified Portage Bay Grange in Seattle, which stocks supplies for veggie gardens to local honey to livestock, including chickens, ducks and geese. Kirsten Scott-Vandenberge, who is one of the owners of Portage Bay Grange, notes that through “many layers... that combine to make a working urban farm, backyard agriculturists are designing practical, beautiful opportunities to engage people of all ages in the circle of life.”1 Jiaxi’s diagram shows this quoted “circle of life” as an interconnected system.

RELATIONSHIP TO STUDIO SITE

Many good examples and methods could be applied to the Licton Springs – Haller Lake Neighborhood for developing and creating the neighborhood, but these progressive ideas should be changed and fitted to the existing site conditions. For instance, there are not enough play areas and facilities for children in the neighborhood, thus these spaces should be reconsidered and suggested near the residential areas and also protect children from dangerous conditions. Additionally, all systems of the design proposals should represent spatial functions and values including cultural, ecological, civic and learning.

“Once a year in summer, my neighborhood closes the street and holds a neighborhood party. Families in the neighborhood come out on that day. Kids play together, while their parents chat with each other, having some drinks and snacks.”

PLAY–URBAN CHILDHOOD

RATIONALE

Play serves as an essential human experience across all stages of life, and thus enhances all aspects of a civic landscape system. Playful, urban environments offer learning opportunities, express aspects of local culture, contribute to safety, and enhance the physical and mental health of a community. Creating a playful city enables meaningful interactions and connections to place for all users.

source:

www.kurraltakgn.sa.edu.au/

Design for play in cities requires multiple views on how and where play may occur. With increasingly dense urban areas, planners, developers, and designers must consider not only how spaces afford multiple functions, but also how spaces afford play and accommodate children.1 Play occurs less often when confined to the few small playgrounds in a city. Instead of setting aside spaces for play, cities could integrate play into the places of everyday life--streets, sidewalks, bus stops –making play convenient and spontaneous.2 Using nature for play offers essential opportunities for children to build intimate relationships with place and the natural systems around them. Manipulable elements and multi-sensory experiences characteristic of nature facilitate creativity, and living systems add value with each passing season to teach the regenerative qualities of nature. Through this deep relationship with nature, children may develop ecoliteracy in addition to many cognitive and physical benefits.3

1 London Plan 2011 Implementation Framework “Shaping Neighbourhoods: Play and Informal Recreation”

2 Next City: “For Family-Friendly Cities, Build Play Beyond the Playground” https:// nextcity.org/daily/entry/playgrounds-public-transporttion-cities-family-friendly

Design for inclusion creates an environment accessible for children of various ages and ability levels, while also encouraging social interaction through thoughtful grouping of activities.

REFLECTION

This reflection focused on developing guidelines for design with play integrated in civic spaces. Understandably, play often occurs spontaneously in unexpected places. With the extreme safety regulations in traditional American playgrounds, little is left for children to experiment or manipulate. From the readings, we each developed guidelines for activating play in public, urban spaces.

Guidelines for play in a civic landscape include:

1. Safety – from busy streets and crime.

2. Accessibility – for all abilities and integrated into daily routines such as bus stops.

3. Engaging Physically + Socially –invites collaboration.

4. “Loose Parts”1 – materials that can be creatively manipu lated by users such as natural materials – sticks, leaves, water.

5. Interaction with Ephemeral Elements –qualities that change over time, such as seasonally.

RELATIONSHIP TO STUDIO SITE

Even with the presence of elementary schools and children, the Licton Springs-Haller Lake Neighborhood lacks play opportunities both in quantity and quality. Through design, we hope to integrate play as an underlying feature that attracts people not only to come but also to stay. We will explore how play can be a tool for different types of learning, including cultural, ecological, social, and physical.

Christopher Jobson in “Musical Light Swings on the Streets of Montreal” at http://www.thisiscolossal.com/2012/09/musical-swings-on-the-streetsof-montreal/

LEARNING IN PLACE AND BY DESIGN

RATIONALE

Children are constantly learning, and the landscapes they inhabit offer varied potentials for learning. Robin Moore and Herb Wong provide a useful framework to view different learning contexts: “Informal education includes all learning… that results from children’s daily interactions with the social and physical environment.... Formal education is what we usually associate with schools—lessons delivered to children, in classrooms, by teachers.... Nonformal education provides the bridge between the informal and formal modes of education.”1 These kinds of learning opportunities may involve a mentor or interpreter to a place.

MAIN TAKE AWAYS

The readings for this theme raised several considerations for design that may support learning. Two key insights are seeking relevant learning opportunities and providing the tools for open-ended discovery. Learning happens through meaningful experiences in our local environments. Authors Mannion and Adey wrote, “Through intergenerational place-based education, all participants, places, and the relations among them are co-produced.”1

From Nicholson’s “theory of loose parts” we discovered the importance of natural objects as potential learning tools: “In any environment, both

the degree of inventiveness and creativity, and the possibility of discovery, are directly proportional to the number and kind of variables in it.”2

And he proposed an approach for how we design with this in mind:

“1. Give top priority to where the children are.

2. Let children play a part in the process.

3. Use an interdisciplinary approach.

4. Establish a clearing-house for information.”3

REFLECTION

This reflection focused on critiquing a familiar place that is part of our daily routine, to examine how learning may occur in this place and to suggest what could be changed to improve learning opportunities. Learning opportunities are found in natural areas, artwork, gateways, seating, shade, vegetable gardens, and place-based education.

A well-designed place can engage all types of users. Open spaces are really great “classrooms” for both the children and the community to experience nature, learn about how things work more effectively, and participate in restoring and shaping the future of habitat.

“The bike and pedestrian route along the Tiber offers opportunities for learning about civic landscape systems. The embankment walls contain seasonal flooding of the Tiber. People walking along the river throughout the year cannot miss the dramatic changes in water level. These changes begin to allude to the complex hydrological processes that occur within a watershed.”

Will Shrader

Will Shrader

RELATIONSHIP TO STUDIO SITE

“There are a lot of campos in Italy, but none of them are for children or learning. If any of them were designed for children or even just to take children into consideration, it would be interesting to see how children learn things from daily life. I think this is the goal of edible education: instead of learning from a book, children will be inspired more by learning physical tools of daily life.”

Chih-Ping ChenWhen we design places throughout the Licton SpringsHaller Lake neighborhood, we should think about how can we provide learning opportunities for children from daily life by enabling diverse and engaging experiences and by interacting with others? As the seminar handout for this theme asked, “What might a city look like where everyone can be learning more about the ecological and cultural systems that sustain them?”

HEALTHY SYSTEMS OF MOVEMENT

RATIONALE

Movement seems like the simplest thing for our existence in the world. Our bodies are designed to walk, run, jump and manipulate objects. But in the city we live in, how often do we use our bodies to their full potential? And as the climate changes, forests degrade, and urban development sprawls, what kind of healthy and sustainable movement systems should we propose for our future?

MAIN TAKE AWAYS

Where sidewalks are missing, people experience not only safety issues but basic regard. Janine Blaeloch, who co-leads the Lake City Greenway Group notes, “It’s about dignity.... why should people who are using their feet to get from place to place have to go through such harrowing experiences, feeling they are in danger and also feeling like they’re being disrepected?” 1

Traffic and vehicle control is important to provide safety to pedestrians. This not only requires funding to build the sidewalk, and other safety features, such as crosswalks, lighting and signs, but also to promote education on safety issues.

The construction of infrastructure and the issue of related regulations are both important. When we begin to prioritze modes of transportation besides vehicles, healthy systems of movement will be promoted.

REFLECTION

Different cities have developed their own culture about movement. Copenhagen has developed around biking, so car drivers understand the safety of cyclists, and pedestrians take precedence over their driving convenience.

Seattle and most of the other cities in the United States are car-oriented cities. Efforts to improve the public transit system and to transform the movement system to other healthy and sustainable options of biking and walking are important.

Seongwon Song

L ARCH 590 B: Seminar in Landscape Architecture

Healthy systems of movement seems train as separate not feel Buses are changing broken. It it seems of signal. transportation

This reflection focused on movement systems in our current locations (some of us were in Rome) as well as in childhood. Most of us have good memories of our childhood transportation system, enjoying the convenience and the safe feeling public transportation provided, but also most of us admit that the bikability and walkability in their hometown were not that good, because of the lack of related infrastructure.

November 2, 2015

RELATIONSHIP TO STUDIO SITE

Licton Springs-Haller Lake Neighborhood is located in North Seattle, where there is a lack of sidewalks. We find this evident through data as well as our own experiences in the neighborhood. The neighborhood lacks safe and convenient sidewalks, crossings and bikeways. With the increasing population and density in this area, we need to provide and connect efficient and safe mass transit with walkable and bikable routes for people.

DESIGN FOR WELL-BEING AND HABITAT

RATIONALE

As part of the civic landscape system, design for well-being and habitat refers to landscape design which can promote human health, both physically and mentally, as well as restore the habitat for wildlife. Successful designs are the ones where you can have positive emotions, such as reducing your stress, getting healthy food or socializing with others. Design for well-being and habitat is an essential part of civic landscape design.

“Outdoor spaces for reducing my pressure in my childhood was rooftop of my house. The rooftop was not a pretty garden, but I remember there are some planters and water reservoir. I liked that place because I could feel fresh air and breeze there.”

Seungwon SongMAIN TAKE AWAYS

The readings for this theme provides us the evidence that show the green spaces and natural spaces are important to human beings as well as wildlife.

Urban green spaces have the potential to improve mental wellness. Evidence suggests that city trees or gardens can provide restorative benefits, reduce stress, contribute to positive emotions, and promote socializing.1 Natural spaces afford opportunities and benefits of physical exercise by people of all ages.2 And a study of children having ADHD found that they could focus more easily after taking walks in settings with nature than different kinds of contexts.3

1 Wolf, Kathleen. 2015. Urban Green Space for Mental Wellness: Reflect, Restore, and Heal. CITYGREEN, 2015, Vol.01(11), P.152-159

2 University of Washington Urban Forestry/Urban Greening Research Green Cities: Good Health “Mental Health & Function” http://depts. washington.edu/hhwb/Thm_Mental.html

3 A ‘Dose of Nature’ for Attention Problems. http://well.blogs.nytimes. com/2008/10/17/a-dose-of-nature-for-attention-problems/

“In my current neighborhood, I like the big tree which provide shelter and habitat, I like to enjoy the green there.”

Jiaxi Guo“As a kid, I like to explore the backyard in our community. It has all kinds of insects, flowers and shrubs...I feel free inside.”

Jiaxi GuoREFLECTION

This reflection addressed aspects of our current and childhood landscape that contribute to a sense of well being.

In the neighborhood we currently live in, the aspects that work for our own mental wellness and health are the spaces with nature inside the urban context, like the riverside in a city, the big tree in a yard between buildings, and some urban structure that can attract wildlife.

Childhood experiences we shared to reduce pressure are mainly related to nature, such as natural backyards, parks, wildlife and vegetation, as well as the space for recreation, such as rooftops or playgrounds. We all feel how dramatically life changes, and how our current fast-speed life takes away our childhood habitat places. Creating open spaces in an urban context is essential for our mental wellness and health.

“Elements exist that benefit my mental health. The sound of the starlings that have recently migrated to Rome for the Winter plus the sound of running water from neighborhood fountains is pervasive. As a kid, I would take a magnifying glass wherever I went outside so that I could observe the complexities of natural objects.”

Will ShraderThe Licton Springs-Haller Lake Neighborhood has several natural resources like wetlands and parks. However, most of them lack connections to each other or are in need of restoration. Green spaces are also needed in urban center areas. It is essential for us to create more green spaces to promote human health and improve wildlife habitat.

“My favorite place to reduce my pressure in childhood is the National park with beautiful scenery and great views looking down to Taipei City. Now, I enjoy crossing the bridge with excellent views and the sunset.

CULTURAL SYSTEMS IN DESIGN

RATIONALE

Cultural Systems in Design refers to a design approach that can produce a sense of identity and belonging through personal and cultural lenses, as well as through the lens of justice. Landscape is more than what we see. Successful designs are interpreted with our minds to attribute intangible values and memories to a certain location.

“Chinese gates at Seattle International District. This is an example of how cultural architectonic elements might inspire a sense of identity for many people, depending on their background. “

MAIN TAKE AWAYS

The readings for this topic explores landscape meaning through personal and cultural lenses, as well as through the lens of justice.

People are always looking for a sense of identity and belonging. We find connections in landscape and place and we find identity with different aspects of design. Design in landscapes can support dignity and wellbeing of communities. We ascribe personal and cultural values to landscapes for intangible, or spiritual reasons. 1

Significant places or landscapes reflects on people’s everyday lives, their ideologies, and

1 Taylor, Ken. 2008. “Landscape and Memory: cultural landscapes, intangible values and some thoughts on Asia.” 16th ICOMOS General Assembly and International Symposium: ‘Finding the spirit of place – between the tangible and the intangible’ 29 Sept-4 Oct 2008, Quebec, Canada. Accessed 9 November 2015 at: http://openarchive.icomos.org/139/ Press, pp 4-9.

sequence or rhythm of life over time. This landscapes speak to people, tell stories about their community, relate events and places through history, and offers a sense of continuity and time.2

There are several aspects that will guide a landscape architect to be more decisive and effective in achieving justice through their work. By viewing what we do as having both moral and value-laden dimensions, a democratic approach that engages and empowers people may provide cultural richness to landscape that establishes context, supports moral qualities and values, and calls us to be agents of democracy.3

2 Ibid.

3 Chang, Hyejung. posted September 3, 2015. “Justice Seeking Design” The Field. ASLA online blog. Accessed 9 November 2015 at: http://thefield.asla.org/2015/09/03/aguide-to-justice-seeking-design/

REFLECTION

This reflection focused on each of us thinking about a place that gives us a sense of identity and creating a guideline for designing landscapes with cultural identity.

Designing landscapes with cultural identity requires community engagement as early as possible. Community members know the spaces within their neighborhood the best, so drawing upon their existing knowledge could prove vital to the acceptance of a newly designed space. It is also important to consider future needs of the space.

Guidelines for designing landscapes with cultural identity include:

- Public Accesibility

- Participation

- Education / Interpretation

- Care / Maintenance

“The people’s park in Nørrebro, the most diverse district in Copenhagen, shows a clear link between the space, the place, and the people. Mostly populated by the homeless population, the park lies nestled between two quieter streets and two sets of 4-5 story buildings. When I think of the people’s park I see members of the homeless community spending time there, makeshift tents have been setup underneath tree canopies while metal barrels have been converted into fire pits. The homeless depend on this space to house them and as a result have morphed the park into something that meets their needs and matches their sensibilities.”

James WohlersCultural identity can be reached in different ways, in this case, the park addresses the needs of a vulnerable community, turning this park into a unique place where they can access and enjoy their freedom.

“Getting to know the community members, who they are, what they need and what is it that they envision for the future of their neighborhood is an important step to design meaningful landscapes.”

RELATIONSHIP TO STUDIO SITE

The Licton Springs - Haller Lake Neighborhood is named after existing natural features, but these identity givers are largely hidden. The neighborhood has community groups, who we value learning from, to work with the people from the neighborhood that we choose as our site for the project proposals. Public participation is a way of practicing democracy on landscape projects. We want to address shared problems and common interests that will lead to relevant designs.

ECOLOGICAL SYSTEMS IN DESIGN

RATIONALE

Our designed environments inherently support or interfere with ecological functions and services. In doing so, the built environment is expected to improve its ecological functioning and to be more resilient and adaptive when facing climate change or other local changes. Design for these functions focus on water, and also consider urban forests, and pollinators.

MAIN TAKE AWAYS

With stormwater management in Seattle, designers need to consider what Nina-Marie Lister describes as “the capacity for resilience—the ability to recover from disturbance, to accommodate change, and to function in a state of health.”1 On the other hand, pollinators and urban forest also provide more ecological services and functions for this system. Both of them will increase the adaption and resilience for ecological systems.

Humans rely on ecological systems for living, and it is important to make sure the ecological functioning and services work well because we need biodiversity to sustain us.2

1 Lister, Nina-Marie. 2007. “Sustainable Large Parks: Ecological Design or Designer Ecology?” in Czerniak, Julia and George Hargreaves, eds. Large Parks. New York, NY: Princeton Architectural Press, p. 36.

REFLECTION

This reflection addressed good and bad examples of design with ecological systems.

Seattle offers great examples to improve the city in ecological ways, such as rain gardens, bioswales, and wetlands. These Low Impact Development approaches help the environment to be more sustainable and adaptive to future changes.

In Rome, where four of us were studying, the Tiber River Embankment presents an controversial example. Tiber River Embankment is a great place for people to gather, exercise, and walk. It is also a good habitat for many species. However, it has encountered a serious flooding issue since thousands years ago as the channelized edges do not allow for flood water to settle in ponds to infiltrate easily. With ecological design approaches, the environment would be more adaptive and sustainable in future changes.

“Instead of the tall embankment on two sides, a terraced slope creates room for vegetation and programs for humans. Vegetation will also function as stormwater filtration as well as habitat for other species.”

Will Shrader“Tiber River is an important and historical element. The embankment along the river provides recreation spaces for people. People are using the space for exercising, walking and gathering. Additionally, this embankment functions as green space and open space in the city. The length of Tiber River, and its embankment is long, therefore people could use wherever they want.”

Tiber

Huge trees, following embankment, are function as street trees for both car and pedestrians using embankment. These trees provide beautiful scenery of city. However, these are attacked by starling, especially during fall and winter season. One million of starlings are coming to Rome this season,

RELATIONSHIP TO STUDIO SITE

The Licton Spring- Haller Lake Neighborhood relates with three small lakes: Bitter Lake beyond its western edge, Green Lake to the south, and Haller Lake within. Additionally, there are wetlands in the neighborhood with Ashworth wetland and the constructed Midvale Stormwater Pond. We need to consider how ecological systems can be improved and connected. We need to look at a the whole system through the lens of Low Impact Development. There are forested areas, notably in parks, and areas that lack tree canopy. We also need to identify ways to support pollinators through our design work. Our designs should integrate ecological systems, and not conflict with these process.

River is important and historical element in this city. The embankment following river provides people space for enjoying. People are using the space for exercising, walking and gathering. Additionally, this embankment functions as green space and open space in the city. The length of Tiber River, and following embankment is long, therefore people could use wherever they want.A

bad example of landscape design: Trees (or its species) following Tiber River.

ENGAGING COMMUNITIES IN DESIGN

RATIONALE

Design does not occur in isolation. It impacts many different groups of people and so should incorporate their voices. In order to fully comprehend the issues at hand, we need to engage with community members and work together to solve problems. This process empowers participants, forms relationships across different groups and builds ownership of a space.

MAIN TAKE AWAYS

The literature for this theme provided insights on how to successfully engage communities, including developing strategies for communicating; listening to understand the concerns, goals, and resources of the community; and identifying what changes are needed.

Randolph Hester describes the role of landscape architects in community design, writing, “We can point out landscape resources previously untapped. We can show how to use those resources in ways that benefit the community members most in need. We can strike a balance between consumption and conservation so that resources sustain the community over time.” Shaping space is one of many skills that landscape architects possess. We work with communities, educating them on how to care for a space and raising awareness of critical issues such as stormwater management.1

REFLECTION

To better understand community engagement, we reflected on our readings and discussion by diagramming an idealized model of community engagement and re-examining a place through others’ perspectives. Some of us were studying or working abroad, so the places we examined ranged from Seattle to Copenhagen to Rome.

“From the perspective of the fruit and vegetable vendors, the crowds of tourists that I find overwhelming represent potential customers. The empty crates and trash mean the vendors have had a successful day and earned money to sustain themselves and their families. Without the ability to sell food here everyday, the vendors may not have another option for work. Therefore this place has significant value both economically but also socially in the relationships and community the vendors build with each other.”

Will Shrader“Appealing: open space, children’s playground, fresh markets, green space, responsible for pocket park.

Unattractive: homeless at night, not safe, exposed to traffic (not good for easily access). Findings: need more space for public or children’s playground around this neighborhood. Viewing the place through others’ eyes: children from playground, they might feel that staying more or coming this playground many times. This is because there are not enough playground for them. However, it is not appropriate walking from their home due to traffic, even the walking distance is not long.”

RELATIONSHIP TO STUDIO SITE

People living in the Licton Springs-Haller Lake Neighborhood come from a diversity of backgrounds and cultures and are vocal in their protest of the lack of pedestrian and bicycle infrastructure across much of North Seattle. Groups like Feet First, Aurora-Licton Urban Village (ALUV) and the Licton-Haller Greenways Group advocate for these changes to the built environment. As students and designers, we engage in a dialogue with these different groups to help us understand their neighborhood and incorporate their feedback into our designs.

SECTION 2: ANALYZING, ENGAGING, AND FRAMING THE NEIGHBORHOOD

1. NEIGHBORHOOD ANALYSIS

• LAND USE

• MOBILITY

• OPEN SPACE

• ECOLOGICAL SYSTEM

• DEMOGRAPHICS

• CULTURAL DIVERSITY

• EDUCATION + PLAY

• COMMUNITY

The Licton Springs-Haller Lake Neighborhood is located in North Seattle. Interstate-5, and Aurora Avenue (State Highway 99) , serve as east/west neighborhood edges. The north/south boundaries are the north City Limits at North 145th Street and North 85th Street. The studio explored the neighborhood and undertook thematic analysis. Additionally, throughout the studio, engagement with the community was prioritized in order to hear concerns about the neighborhood and receive design feedback. The combination of analysis with valuable insights from community members revealed several challenges and opportunities within the neighborhood. Moving into conceptual development, the studio proposed a neighborhood-scale framework plan branded Civic Defragmentation to re-envision transportation networks and provide a strong foundation for individual design work.

2. COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT PROCESS

3. FRAMEWORK PLAN

Image Sources:

1. http://www.rolludaarchitects.com/?p=1751

2. https://tipspoke.com/northacres-park/t9110

3. http://cosfrontporch.wpengine.netdna-cdn.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/HallerLake-photo.jpg

4. http://www.tristarteamre.com/Blog/Archive?tag=Haller%20Lake%20Real%20Estate

5. https://www.seattleschools.org/directory/elementary_schools/northgate/

7. http://www.uwmedicine.org/locations/multiple-sclerosis-center

9. http://yourfuturein.it/ctc/northseattle/

12. http://bex.seattleschools.org/bex-iv/cascadia-es-and-robert-eagle-staff-ms/

14. http://frontporch.seattle.gov/2014/08/04/haller-lake-p-patch-12th-annual-opengarden-celebration/

LAND USE

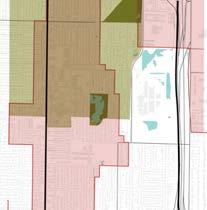

Licton Springs – Haller Lake Neighborhood includes portions of three different urban villages: Northgate (Urban Center), Bitter Lake Village (Hub Urban Village) and Aurora-Licton Springs (Residential Urban Village). According to Seattle 2035, the city’s Draft Comprehensive Plan, Urban Centers are characterized by their high percentage of commercial and mixed-use development, which accounts for over half of the land use in each urban center. The main land use types in Hub Urban Villages are commercial / mixed-use, multi-family residential and single family residential. In the Residential Urban Villages, the main land use types are single family residential, multi-family residential and commercial / mixed-use.

Legend

Bitter

Aurora-Licton

Licton

Source: Seattle 2035, http://www.seattle.gov/dpd/cs/groups/pan/@pan/ documents/web_informational/p2273587.pdf

Types of Urban Villages

Urban Center

Hub Urban Village

Residential Urban Village

Land Use Categories

commercial mixed-use

single family multi-family industrial

orthgate

major institution public facilities utilities parks, open space cemeteries

reservoirs

water bodies

vacant

unclassified

master planned community

Source: Seattle 2035, http://2035.seattle.gov/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/aurora-licton-springs-sf-zones.pdf

Existing land use distribution

Comprehensive Plan Future Land Use Map (FLUM)

Source: Seattle 2035, http://www.seattle.gov/dpd/cs/groups/pan/@pan/documents/web_informational/p2273587.pdf

According to Seattle 2035, commercial and multi-family residential uses would be increased, but parks and open spaces are not except in the Hub Urban Village designation. Another urban village may be created around N. 130th Street and I-5 where a light rail station may be built.

Source: Seattle 2035, http://2035.seattle.gov/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/bitter-lake-sf-zones.pdf

Source: Seattle 2035, http://2035.seattle.gov/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/NE-130th-St-and-I-5-Residential-and-Potential-New-Urban-Village.pdf

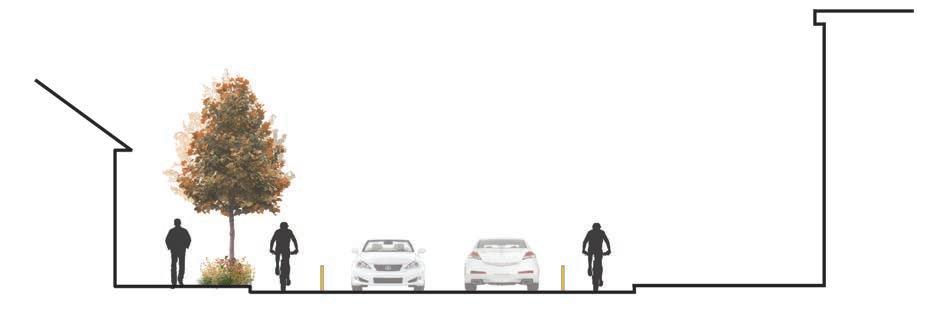

MOBILITY

The Licton Springs-Haller Lake Neighborhood is bounded by Interstate 5 to the east and by Aurora Avenue N. to the west. These car dominated streets foster unsafe conditions for people on foot and bike, and serve to separate the neighborhood from its surrounding context. The challenge here is to reclaim some of this space for pedestrians and bicyclists in order to create a better connected, safer, and more livable neighborhood.

Commuting North and South

I-5 and Aurora Avenue North are high traffic North-South streets for commuters and so prevent greater East-West connectivity. How can we design safe crossings for pedestrian and cyclists along these busy corridors?

Opportunities to Connect

The pedestrian network is not well connected from north to south, while the bicycle network is not very developed in general except along the Interurban Trail west of Aurora. Within the next 5 years, however, the city has planned to implement more bicycle lanes.

Human Health and Well-Being

A dearth of dedicated bike lanes and safe pedestrian infrastructure discourages biking and walking. As a result, cars take up much of the roadways while physical activity and social capital are diminished.

Transit and Networks

In terms of bike and transit infrastructure, the City has much planned or being constructed. Metro’s bus lines traverse parts of the neighborhood. Metro’s RapidRide along Aurora provides frequent bus service, and a light rail station is under construction at Northgate, with a pedestran bridge planned across I-5 enabling access to and from the neighborhood. Additionally, a light rail station may be built at I-5 and NE 130th Street and another is planned at I-5 and NE 145th Street. From these hubs, a network of safe walking and biking routes are needed to connect with civic and other neighborhood destinations.

Source: Seattle Department of Transportation

Pedestrian Flow

Streets in orange are designated walking routes. These designated routes, however, lack overall connectivity. Some walking areas even appear as isolated patches, as if they are islands surrounded by a sea of automobiles. Yet again, busy streets like Aurora Avenue and highways like I-5 sever the walkability of this area. East-west connections across these busy routes should be increased in order to attenuate the power that cars hold over the area.

Source: Seattle Department of Transportation

Traffic Flow

Over 15,000 cars/day travel on streets marked red. The high frequency and speed of cars on these roads create unsafe conditions for those on foot or bike. Conditions on these streets should be redesigned to balance the space among all modes of transportation in addition to creation of public gathering space. In this way, we can foster an inclusive environment where all travelers can safely move and spend time in these corridors.

BICYCLE NETWORK

The Interurban Trail, running north-south, serves as an extensive bicycle route. However, such facilities don not yet exist within the neighborhood beyond the designated bike lanes along College Way North. A green way is planned for North 100th Street, to connect with the pedestrian bridge across I-5 to the Northgate Light Rail Station. North 130th Street is being planned for improvements, which will be an important resource for a light rail station at NE 130th Street and I-5.

Citywide Network

Existing

Local Connectors

Existing

Recommended Recommended

Off street

Cycle track (protected)

Neighborhood Greenway

2016 Implementation

Off street

Cycle track (protected)

In street, minor separation

Neighborhood Greenway

Shared street

Source: Seattle Department of Transportation

OPEN SPACE

Licton Springs-Haller Lake Neighborhood contains different forms of open space, including Licton Springs Park, Mineral Springs Park, Northacres Park, Bartonwood Wetland, cemeteries and Haller Lake. These open spaces provide opportunities for biking, dog walking, playing frisbee golf, wandering, fishing, gardening, and being in nature.

While there is a diversity of open spaces and recreational activities in and around the neighborhood, they are not evenly dispersed, nor are they easily accessible. The “Gaps” map developed by Seattle Parks and Recreation illustrates the lack of open spaces near Aurora Avenue within the two urban villages. As these areas are designated to increase in population, there is an increased need for viable open spaces.

WALKING DISTANCE OPEN SPACE DISTRIBUTION RECREATION ACTIVITIES

Source: WAGDA, https://wagda.lib.washington.edu/data/geography/wa_cities/seattle/index.html

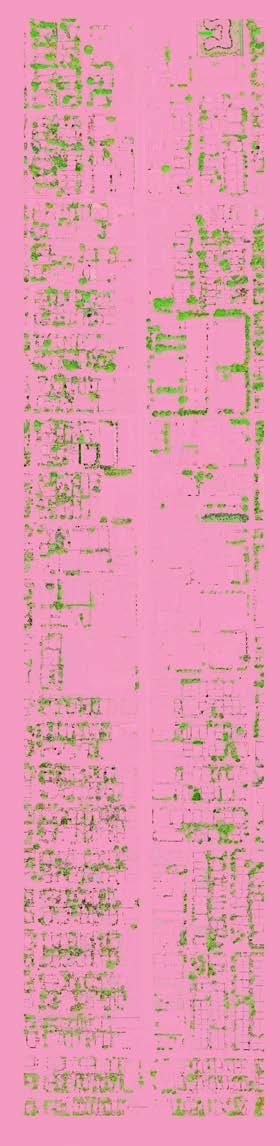

ECOLOGICAL SYSTEMS

Ecological systems of particular focus are Tree Canopy, Water and Critical Areas in the Licton Springs-Haller Lake Neighborhood. Seattle established a goal in 2007 to reach 30% tree canopy cover in 30 years.1 It is important to look at the existing conditions and try to fill the gaps. Water is also an important issue for Seattle. In Licton Springs- Haller Lake Neighborhood, the major receiving water body is Lake Union and flooding has occurred in this area before. We should consider how to treat stormwater in this area. Some critical areas like peat area and wetlands are found near North Seattle College.

1. http://www.seattle.gov/trees/docs/Tree_Canopy_Assessment_Council_EEMU.pdf

Canopy cover is the percent of the city that is covered by trees as seen in an aerial view. Seattle has about 23% canopy cover. However, many spaces lack tree canopy along Aurora Ave. We should consider how to plant more street trees in this area.

Source: http://web6.seattle.gov/DPD/Maps/dpdgis.aspx, Seattle Street tree map http://web6.seattle.gov/SDOT/StreetTrees/

STORMWATER

The major receiving water body for the Licton SpringsHaller Lake Neighborhood is Lake Union, and the majority of the stormwater system is a separated stormwater sewer. Additionally, a stormwater facility, Midvale, is located south of the cemetery.

MAJOR RECEIVING WATER BODY

Source: http://www.seattle.gov/util/cs/groups/public/@spu/@ drainsew/documents/webcontent/1_037857.pdf

CRITICAL AREAS AND WATER RESOURCES

The neighborhood is surrounded by two major creek systems in Seattle: Piper’s Creek and Thornton Creek. Seattle contains three small lakes: Green Lake, Haller Lake and Bitter Lake. All of them are located near or within our neighborhood. Regarding flooding issues, we should be mindful of wetlands, soil types and some steep slopes in the neighborhood. Wetlands are found in Licton Springs Park, cemetery, north west of Haller Lake along Ashworth Avenue North, within North Seattle College campus, and on existing police station site just northwest of the college.

CRITICAL AREAS

SEATTLE SMALL LAKES

Source: WAGDA, https://wagda.lib.washington.edu/

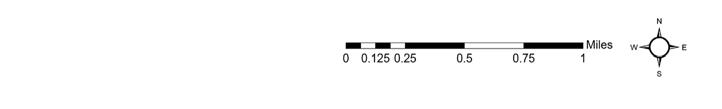

This Licton Springs-Haller Lake Neighborhood has a medium density population compared to the city, and has experienced increasing population and increasing housing during the last decade. The diversity of the neighborhood is high compared to much of North Seattle.

POPULATION CHANGE

Source: U.S. Census Bureau Decennnial Census 100% Count data 2000, 2010

HOUSING DENSITY

The Licton Springs-Haller Lake Neighborhood has a relatively lower income (darker blues indicate higher income) and higher crime rate compared to other parts of the city (lighter shades indicate higher crime). There is a high percentage of immigrants in this neighborhood compared to much of North Seattle.

INCOME AGE UNDER 18

Source: http://www.weichert.com/

FOREIGN BORN CRIME RATE

Source: http://www.seattletimes.com/seattle-news/data/a-spike-in-king-county-foreign-born-populations/

Source: http://www.neighborhoodscout.com/wa/seattle/crime/

Mixed: non-Hispanic mixed race people

Other: American Indian, Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander

CULTURAL DIVERSITY

HIGHLIGHTS

Image Source: Google maps

Aurora-Licton Springs population: 9.682

These graphs represent the different races that exist in the City of Seattle as a whole and the Licton Springs-Haller Lake Neighborhood. According to 2006 - 2010 US Census, we can see how all three graphs are dominated by White (depicted in orange) followed by Asians (depicted in brown), but then the group that follows changes. In Seattle the third major ethnic group is Black (depicted in purple), but in Licton Springs-Haller Lake Neighborhood is Hispanics (depicted in light blue). This means that there is a higher percentage of this population in both neighborhoods. Spanish is also represented in the percentage of languages spoken other than English. Much of the Licton Springs-Haller Lake Neighborhood has over 30% of the population as non-English speakers at home, more than the average 21.3% of Seattle overall.

Data Source: http://statisticalatlas.com/place/Washington/Seattle/Overview

Haller Lake population: 9.746

SEATTLE, WA

LICTON SPRINGS

9,682 POPULATION

Graphs Data Source:

HALLER LAKE

9,746 POPULATION

Data Source: http://seattlecitygis.maps.arcgis.com/apps/StorytellingTextLegend/index.html?appid=92ef6933d46f4c9786c8e8f09515284f http://seattlecitygis.maps.arcgis.com/apps/StorytellingTextLegend/index.html?appid=92ef6933d46f4c9786c8e8f09515284f http://statisticalatlas.com/place/Washington/Seattle/Overview

Data Source: http://statisticalatlas.com/place/Washington/Seattle/Overview

Data Source: http://statisticalatlas.com/place/Washington/Seattle/Overview

PERCENTAGE OF POPULATION SPEAKING A LANGUAGE OTHER THAN ENGLISH AT HOME RELEVANT LANGUAGES IN THE AREA

PERCENTAGE OF THE POPULATION SPEAKING A LANGUAGE OTHER

Data Source: http://statisticalatlas.com/place/Washington/Seattle/Overview

PERCENTAGE OF MOST REPRESENTATIVE LANGUAGES IN THE AREA:

Image Source: http://www.seattle.gov/dpd/cityplanning/populationdemographics/aboutseattle/raceethnicity/default.htm

Source: http://www.seattle.gov/dpd/cs/groups/pan/@pan/documents/web_informational/dpdd016861.pdf

Image Source: http://www.seattle.gov/dpd/cityplanning/populationdemographics/aboutseattle/raceethnicity/default.htm

Image Source: http://www.seattle.gov/dpd/cityplanning/populationdemographics/aboutseattle/raceethnicity/default.htm

CHINESE

CHINESE:

PERCENTAGE OF MOST REPRESENTATIVE LANGUAGES IN THE AREA:

CHINESE:

PERCENTAGE OF MOST REPRESENTATIVE LANGUAGES IN THE AREA:

CHINESE:

SPANISH:

SPANISH

SPANISH: african languages:

SPANISH: gov/dpd/cityplanning/populationdemographics/aboutseattle/raceeth-

african languages: gov/dpd/cityplanning/populationdemographics/aboutseattle/raceeth-

AFRICAN LANGUAGE

Image Source: http://www.seattle. gov/dpd/cityplanning/populationdemographics/aboutseattle/raceethnicity/default.htm

EDUCATION + PLAY

PUBLIC SCHOOLS

1. INGRAHAM INTERNATIONAL H.S.

2. BROADVIEW THOMSON K-8

3. NORTHGATE ELEMENTARY

4. CASCADIA ELEMENTARY

5. LICTON SPRINGS K-8

6. ROBERT EAGLE STAFF MIDDLE

7. GREENWOOD ELEMENTARY

8. DANIEL BAGLEY ELEMENTARY

9. NORTH SEATTLE COLLEGE

10. OLYMPIC VIEW ELEMENTARY

PRIVATE SCHOOLS

11. LAKESIDE HIGH SCHOOL

12. LAKESIDE MIDDLE SCHOOL

13. BISHOP BLANCHET HIGH SCHOOL

source: google earth

source: seattleschools.org

source: google earth

A range of centers for education exist in the neighborhood from elementary schools to higher education. Three new schools will open in the fall of 2017, serving over 1600 elementary and middle school students1 in close proximity to Licton Springs Park and the local community college. North Seattle College draws over 14,000 students2 and offers wonderful potential for outdoor learning in its biodiverse Barton Wood Wetland.

1. http://bex.seattleschools.org/bex-iv/cascadia-es-and-robert-eagle-staff-ms/ 2. https://northseattle.edu/about-north

WHO ARE THE KIDS?

There are many elementary and middle schools within and near the neighborhood; however, there is a lack of safe bike and pedestrian routes connecting to them. Northgate Elementary, a focus of our studio, is a highly under served school with 86 percent of the students receiving free or reduced lunches. The diversity at the school is quite high. Latino students comprise the highest percentage and over 20 languages are spoken by the students.

CHILDREN QUALIFYING FOR FREE & REDUCED LUNCH | 20093,4

86%

40%

Source: northgatees.seattleschools.org

NORTHGATE ELEMENTARY | 20093

39%

LICTON K-8 | 20094

Total: 259 students

Total: 189 students

Total: 53,872 students

3. “Northgate Elementary 2009 Annual Report.” online: https://www.seattleschools.org/UserFiles/Servers/Server_543/File/Migration/Schools/School%20Directory/Departmental%20 Content/siso/anrep/anrep_2009/257.pdf

4. “Alternative School #1 at Pinehurst 2009 Annual Report.” (former name for Licton K-8) online: https://www.seattleschools.org/UserFiles/Servers/Server_543/File/Migration/Schools/ School%20Directory/Departmental%20Content/siso/anrep/anrep_2009/955.pdf

COMMUNITY

Within the Licton Springs-Haller Lake Neighborhood, we discovered community groups who bring different civic focuses:

• Licton-Haller Greenways Group

• Aurora Licton Urban Village

• Aurora Commons

• Haller Lake Community Club

• Licton Springs Community Council

• Aurora Avenue Merchants Association

LICTON-HALLER GREENWAYS GROUP

Licton-Haller Greenways Group has monthly meetings and is focused on improving street safety and comfort for all travelers, especially children, older people, pedestrians and bicyclists. The group’s webpage notes: “Since the spring of 2014, we have been engaged in community building, advocacy, and action-based projects to make streets safer for all people, particularly for children and elders and people who are walking and bicycling.”1

1 Seattle Neighborhood Greenways. http://seattlegreenways.org/neighborhoods/ licton-haller-greenways/

AURORA LICTON URBAN VILLAGE

Source: http://seattlegreenways.org/neighborhoods/licton-haller-greenways/

Logo and Image Source: https://www.facebook.com/ Aurora-Licton-Urban-Village-1503087143342417/photos_stream?ref=page_internal

The mission of this group is stated on its webpage: “Build a pedestrian-safe, visually vibrant, economically sound, liveable and welcoming urban village using sustainable-growth principles.”1

1 Aurora Licton Urban Village. http://www.auroralictonuv.org/about/

AURORA COMMONS

“Aurora Commons, located along Aurora Avenue, provides a welcoming space for our unhoused neighbors to rest, prepare a meal, connect to resources and collectively create a healthy and vibrant community.”1

1 Aurora Commons. http://www.auroracommons.org/#about-marquee

Source: Aurora Commons. http://www.auroracommons.org/#about-marquee

HALLER LAKE COMMUNITY CLUB

The Haller Lake Community Club is a non-profit organization that serves as the neighborhood community council. It aims to support communication and foster neighborhood enhancements.1

1 Haller Lake Community Club. http://www.hallerlakecommunityclub.org/about/

The Licton Springs Community Council holds monthly meetings and communicates activities in its newsletter.1

1 Licton Springs Neighborhood. http://www.lictonsprings.org/council/council.html

AURORA AVENUE MERCHANTS ASSOCIATION

Aurora Avenue Merchants Association is an organization whose multi-pronged mission include: “encourage the growth of existing business activities... promote public safety, support activities believed to be beneficial to the community... offer friendship and assistance to the surrounding residential community”1

1 Aurora Avenue Merchants Association. http://auroramerchants.org/about-us/mission/

Source: Haller Lake Community Club Photos, https://picasaweb.google.com/ hallerlakecc/EggHunt2015#6211960825496813698

Halloween Party

Source: Licton Springs Neighborhood Annual Events, http://www.lictonsprings.org/ action/events.html

Source: Aurora Avenue Merchants Association Galleries, http://auroramerchants.org/ galleries/

http://auroramerchants.org/galleries/

2. COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT PROCESS

JANUARY 14, 2016 | COMMUNITY MEETING

The Licton-Haller Greeways group hosted a community meeting for the studio to learn about the neighborhood as the studio was getting underway. Those who participated included community members involved in greenways, the Licton-Springs Community Council, Aurora Licton Urban Village group, Feet First, and Northgate Elementary. The studio met at tables with community members using maps of the neighborhood to guide discussion of five major themes. Community members also created postcards of their visions for the neighborhood. A summary of findings is presented here.

SAFETY

Transportation related safety

• Not enough sidewalks in the neighborhood

• Not sufficient lighting

• High speed car traffic

• Difficult for bikers and pedestrians to cross arterial streets (no infrastructure)

Crime related safety

• Car break ins

• Stolen packages from homes

• People doing drugs; needles left on the ground

Relevant places mapped by community members

• Many community members focused on Aurora because of both transportation and crime related concerns.

PICTURES FROM THE COMMUNITY MEETING

• The area behind Home Depot makes people feel unsafe due to drug use.

• Many intersections are unsafe because there is not sufficient infrastructure for pedestrians and bicyclists.

TRANSPORTATION

• Aurora Avenue is not safe and not walkable.

• Sidewalks are not enough wide for pedestrians.

• Cars and buses are running too fast.

• People get scared at night, because there are not enough street lights.

• If people want to walk in their neighborhood, they usually drive to Green Lake and walk there.

• Students ride in their parents’ car, so there will be lots of traffic given school attendance zones.

OPEN SPACE

Likes:

• Quite a few participants like going to Licton Springs Park for jogging and dog walking.

• Most participants know about the Licton Springs.

• The P-Patch at North Seattle College is a favorite space.

• Green Lake is one of the most popular places in the Northwest Neighborhood District.

• Some go to the cemetery; however, few consider it an attractive open space.

PICTURES FROM THE COMMUNITY MEETING

SOCIAL CAPITAL

• Community members wish there were more amenities like community centers, outdoor movie theaters, P-Patches, and small convenient stores. They also wish there were more activities such as block parties, cultural festivals, and farmers markets.

• Just north of our focus area, Shoreline represents a precedent for an attractive area that features many amenities.

COMMUNITY IDENTITY

Dislikes:

• Most participants don’t like going to Aurora Avenue because it is unsafe.

• Most adjacent streets are also unsafe for walkers and cyclists.

• Participants consider Haller Lake a private place, though there are two public access points.

• Amenities that participants noted as missing were: convenient shop / market, farmer’s market, sidewalks, and library.

• The neighborhood lacks a sense of identity. Aurora Avenue, a busy arterial, and Highway I-5 bound the neighborhood but also cause fragmentation.

• Assets exist within the community, like The Lantern, a popular bar and gathering place for people just off of Aurora Ave. on N 95th St. Other places like Larry’s Market used to provide valuable services but no longer exist. Oak Tree Village represents an opportunity for community gathering space.

• The Evergreen-Washelli Cemetery and Licton Springs Park represent part of the area’s history as the cemetery houses monuments from the late-19th century while the spring at the park is a sacred Native American site.

FEBRUARY 3, 2016 | DESIGN CONCEPT DISCUSSIONS

This early design concept presentation, attended by community members, design and planning professionals, and faculty allowed our studio to present bold ideas based on the wealth of information learned from the community meeting and thematic analysis of the neighborhood. Following an overview of the studio and analysis findings, reviewers met at tables to discuss individual design projects. Our concepts were grounded in community needs and analysis, and pushed the boundaries of convention.

FEBRUARY 24, 2016 | SCHEMATIC DESIGN PRESENTATION

Using feedback from our concept discussions, we developed schematic design proposals. A variety of returning and new reviewers attended, including: a planning faculty member, design and planning professionals, and community members. Feedback from these presentations raised challenging questions to explore in design refinement.

MARCH 14, 2016 | WINTER QUARTER – FINAL DESIGN PRESENTATION

Each of us further refined and represented our design proposals for the end of Winter Quarter presentations. Reviewers included: faculty, design and planning professionals, and community members, some of whom had participated in prior presentations.

APRIL 18, 2016 | OPEN HOUSE – NORTHGATE ELEMENTARY

The Community Open House held at Northgate Elementary offered the opportunity for community members to see and discuss our latest iterations of design from the previous quarter. We had a good turn out with several new people eager to see and discuss visions for the future of the neighborhood.

MAY 9, 2016 | SPRING QUARTER – FINAL DESIGN PRESENTATION

The final presentation for Spring Quarter, held in UW’s Gould Hall, revealed the culmination of the studio’s design and graphic work. A combination of faculty, design and planning professionals, and community members attended to give us feedback.

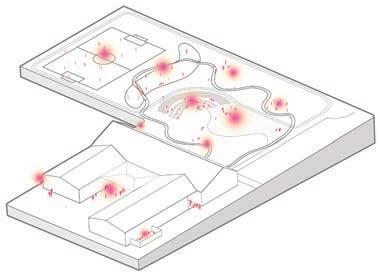

FEBRUARY 2016 | NORTHGATE ELEMENTARY SURVEY

FEBRUARY 25 + APRIL 24, 2016 | SCHOOL ADMINISTRATION MEETINGS

Two of us chose to focus on Northgate Elementary. We wanted to learn from the students and teachers what features they would like in an ideal schoolyard. We developed the poster below. One copy was placed out for students, one was placed for teachers to mark their preferences. The posters for students received enthusiastic support for nearly all elements. Teachers’ responses were more varied, with particular interest expressed for a stage, sculpture, and movable play parts. The two of us used this feedback to help determine the programming for the school site. We also presented schematic and refined design proposals to the school’s Principal and Administrative Secretary for feedback and to develop ideas for building elements for the school. The April 24th meeting included the Seattle Public Schools staff member who reviews proposed school projects. We developed a Seattle Public Schools Self-Help Project Application for construction of outdoor movable planters and mural installation, which was approved.

We are UW Landscape Architecture graduate students exploring outdoor play and learning opportunities for Northgate Elementary.

We would like to know what you want at your school. Please draw a check mark in the white box below the images that you would like here! If you have other ideas, feel free to write or draw them in the open space.

You can email us at: larchstudio702@gmail. com

Please provide your input by FRIDAY, FEBRUARY 26TH.

Thanks for your help!

3. FRAMEWORK PLAN CIVIC FRAGMENTATION

For us, the disconnection, or fragmentation, of civic spaces in the Licton Springs-Haller Lake Neighborhood limits the resilience of vibrant community life and ecological systems. We found the concept of “habitat fragmentation” representing this condition, and thus “habitat defragmentation” serves as model for change, drawing from the characterizations by the firm Van Bommel FAUNAWERK:

“For many animals the network of roads, whether fenced or not impose a serious barrier. Habitat fragmentation due to human development is an ever-increasing threat to biodiversity. Fragmentation of species’ habitat in smaller or isolated patches increases the risk of local extinction.... Habitat defragmentation can be reached by creating habitat or wildlife corridors to reconnect isolated patches of species’ suitable habitat. This may mitigate some of the effects of habitat fragmentation.”1

http://www.vanbommel-faunawerk.nl/pages/habitatdefragmentation.php

CIVIC DE FRAGMENTATION

Building from this, we define our design framework as “Civic Defragmentation”. Civic Defragmentation connects and revitalizes civic spaces with a network of safe and engaging pathways and activities for ecological and cultural learning and resilience.

SECTION 3: PROJECT DESIGNS

COEXISTENCE OF OPPOSITES: ALONG AURORA AVENUE

NORTHGATE ELEMENTARY: CELEBRATING CULTURE AND WAYS OF LEARNING

ECO-PEDAGOGICAL LANDSCAPES

BUILDING A HABITAT CORRIDOR

COMMUNITY NETWORKS

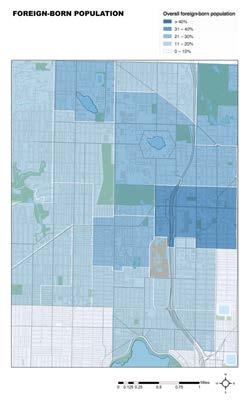

In this studio, each of us chose particular sites to design, drawing from the themes of civic landscape systems we studied, our neighborhood analysis findings, and community feedback. These proposed designs include: streets designed for pedestrians, bicyclists, and transit while contributing to ecological systems and identity; parks serving community life, habitat, ecological learning, and green infrastructure; temporary street art installations calling attention to how space is used and what is missing and permanent installations to improve pedestrian experiences; and redesign of a schoolground to support ecological learning and celebrate cultures. The map on the left illustrates our projects spatially, and indicates the potential network of connections among the neighborhood’s diverse civic landscapes towards achieving civic defragmentation.

CIVIC DEFRAGMENTATION PROJECTS

• 130TH SONATA | CHIH-PING (KAREN) CHEN

• ECO-PEDAGOGICAL LANDSCAPES | WILL SHRADER

• NORTHGATE ELEMENTARY: CELEBRATING CULTURE AND WAYS OF LEARNING | JAMES WOHLERS

• COEXISTENCE OF OPPOSITES: ALONG AURORA AVENUE | SEONGWON SONG

• BUILDING A HABITAT CORRIDOR | CHRISTEL GAME

• HEALING LICTON SPRINGS | JIAXI GUO

• COMMUNITY NETWORKS | WENYING GU

• MOVE, STAY, ENGAGE | ZHEHAO HUANG

130TH SONATA

N 130th Street is an important east-west commuting route for the residents who live in the Bitter Lake/Haller Lake area. However, N 130th Street is not safe nor comfortable to walk along. The planned light rail station at NE 130th Street and I-5 will create even greater need for safe and engaging pedestrian and bicyclist movement along N 130th Street. In this design, I focus on creating a more interesting route for residents and school kids. I weave together fragmented civic activities, transit, bicyclists and pedestrians through different tempos of design qualities that relate to their immediate context.

SITE ANALYSIS

HYDROLOGY

OPEN SPACE

TREE CANOPY

Bitter Lake and Haller Lake are located in this area as well as Ashworth Wetland.

Data Source: https://wagda.lib.washington.edu/

Northacres Park and Bitter Lake Playground server this area.

Data Source: https://wagda.lib.washington.edu/

There is a lack of tree canopy rate along the street, especially around Aurora Avenue North, while significant tree canopy is found at Northacres Park.

Data Source: http://web6.seattle.gov/DPD/Maps/dpdgis.aspx

Many people live in the area near Aurora Avenue N, as the Bitter Lake Urban Village extends along either side of Aurora Avenue N. Most of them will rely on the public transportation to go to work and school.

Source: http://www.seattletimes.com/opinion/sound-transit-must-add-north-seattle-light-rail-station/

CONCEPT “THE SONATA”

The concept of Sonata grows from the existing conditions and qualities of the street tempo. As I identified certain walkable destinations and features, the character of each movement emerged.

UNSAFE AND BUSY STREET

N 130th Street is a car oriented street. There are 2 traffic lanes in each direction. The sidewalks have little planted buffer to protect pedestrians from the fast moving traffic. It is not sate for people to walk. Lack of tree canopy is another reason make this street not comfortable to walk.

PEDESTRIAN |BICYCLIST |GREEN INFRASTRUCTURE

The future light rail station will make N 130th Street an important route for students and residents to go to work and school along. Green infrastructure can improve N 130th Street and make a safer corridor from Northacres Park to the Bitter Lake Playground and places in between for pedestrians and bicyclists.

STREET CHARACTER

Furthermore, the civic features that currently are fragmented along N 130th Street will influence the street’s character. It will make this street more fun, with connecting destinations for people to go easily from place to place.

The district fragments of civic spaces define different character along N 130th Street just like a sonata1, which is a continuous composition with different characters and tempos in each movement. Spatially along N 130th Street, each movement has its own theme. People can participate in different activities along this Sonata, so they will not feel bored or unsafe on N 130th Street.

1 http://home.earthlink.net/~dbratman/sonata.html

green infrastructure

bike lane

car lane

green infrastructure

sidewalk sidewalk

N 130th Street is composed of four key movements between Bitter Lake and Aurora Avenue on the west and Northacres Park and the Light Rail Station on the East. It is designed as a safe route for pedestrians and bicyclists interspersed with green infrastructure that links with particular civic features. Based on the theme and character along the street, N 130th Street shows different appearances on each movement.

PROBLEMS AND OPPORTUNITIES

huge parking lot

VISION

lack of seating area for the bus stop

steep and tall wall unmarked crosswalk beside high school

Map Source: WAGDA, https://wagda.lib.washington.edu/data/geography/wa_cities/seattle/index.html

potential entrance to Haller Lake, but currently blocked

uncomfortable bus stop

potential space for expand the P-Patch

unclear entrance to Northacres Park

Urban Plaza

Map Source: WAGDA, https://wagda.lib.washington.edu/data/geography/wa_cities/seattle/index.html

Urban Water Journey

CIVIC FRAGMENTS SYSTEM

Civic fragments are woven together along N 130th Street make this route safer and more appealing to pedestrians and bicyclists, and more ecologically healthy. In addition, based on different rhythms, the street exhibits a different character for each movement. People will use this route more often and come to know their neighborhood better as well.

Rondo

1 http://home.earthlink.net/~dbratman/sonata.html

parking lot

CONNECTION IN GREEN DEVELOPMENT

The overpass provides a new landmark for N 130th Street which offers pedestrians and bicyclists another option to across Aurora Avenue N. In the future, the commercial center is expected to increase gathering places, with mixed use developments increasing. The new Police Station will also give N 130th Street a safer image. This greener commercial area will function as a lively, fun, and healthy community hub.

Urban Water

Journey

SCHERZO

1 http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/scherzo

7’ sidewalk

flowering trees raised crosswalk

Looking west on N 130th Street towards Ashworth intersection and proposed raised crosswalk

PROPOSED SECTION

Ingram High School

WATER JOURNEY AND PLAYFUL BUS STOP

This design relocated bus stop along N 130th Street from the west side of the Ashworth intersection to the east side of the intersection, along the edge of Ingraham High School. The design provides a space to connect the community and school kids. People can dance and listen to the music, hang out with friends at this terrace bus stop. The raised crosswalk increases safety to start on the water journey.

44’ travel

14’

12’ sidewalk + variety green sidewalk + variety green Private Property

Ingram High School

EXISTING SECTION

raised crosswalk for school kids

Ashworth wetland education sign

Haller Lake public access

Map Source: WAGDA, https://wagda.lib.washington. edu/data/geography/wa_cities/seattle/index.html

1 http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/andante

HABITAT CORRIDOR

PROPOSED SECTION

P-PATCH HABITAT REDESIGN

People can grow their own food in the expanded P-Patch which is considered a “slow food” concept instead of fast food idea. The P-Patch is an important habitat along the habitat corridor extending from Northgate Elementary School to Lakeside High School and extending along N 130th Street as well. Decoration on the pavement will be digitally linked signs to guide people and help them learn about their neighborhood.

Map Source: WAGDA, https://wagda.lib.washington. edu/data/geography/wa_cities/seattle/index.html

Urban Forest

ALLEGRO

Allegro is a piece of music that is a swift tempo that is animated.1

1 http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/allegro

With a new Urban Village surrounding the N 130th Street Light Rail Station, more people will be living in this area. Northacres Park becomes a treasured urban forest. A new pedestrian entrance is proposed at 3rd Ave NE with a raised crosswalk across N 130th Street and pedestrian axis path connecting to the dog off leash area and children’s playground. Residents can walk to enjoy a baseball game in Northacres Park. Along N 130th Street, a meandering path takes visitors along a series of habitat rich bioswales.

ECO-PEDAGOGICAL LANDSCAPES

Will ShraderEco-pedagogical landscapes explores design solutions at Northgate Elementary, an under served school in North Seattle with a highly diverse immigrant population as well as high rates of poverty. The current national education standards create a barrier especially for EngIish language learners through its inflexible curriculum and standardized test-based model. Students at Northgate would benefit from an outdoor space that facilitates learning opportunities for all abilities and supports cultural diversity.

I propose short term and long term design solutions for a readily implementable framework for Northgate Elementary to shift the paradigm of education to a more dynamic pedagogy accessible to every child and customized to local context. This is achieved through interactive outdoor learning spaces throughout the neighborhood that highlight natural processes, facilitate cultural exchange, and invite play.

CRITICAL STANCE : SHIFTING CULTURAL PERCEPTIONS OF NATURE

UNMITIGATED RESOURCE USE

POPULATION GROWTH

CULTURAL PERCEPTIONS OF NATURE

INCREASING ENVIRONMENTAL DISTURBANCES

DEGRADATION OF NATURAL SYSTEMS

UNINHABITABLE PLANET

STANDARDIZED TEST BASED EDUCATION

FUNDAMENTAL SHIFT IN EDUCATION SYSTEM

CONTEXT ECO-PEDAGOGICAL LANDSCAPES

ACTIVATED CITIZENS

PEDAGOGY

SUPPORTING

ECOLOGICAL LITERACY

CULTURALLY RELEVANT EDUCATION

COLLABORATIVE PROBLEM SOLVING

BUILDING

RESILIENT URBAN SYSTEMS

For the last 20 years ecologically-focused, pedagogical theory has cited the importance of prioritizing human conservation of the environment for long term heath of the planet. David Orr’s seminal writing on ecological literacy in the early 1990’s emphasized the connection between the environment and education, stating: “built on the recognition that the disorder of ecosystems reflects a prior disorder of mind, making it a central concern to those institutions that purport to improve minds. In other words, the ecological crisis is in every way a crisis of education.... All education is environmental education… by what is included or excluded we teach the young that they are part of or apart from the natural world”. 1 To improve and maintain environmental health, we must have individuals and communities that intimately understand and connect with it. Ecopedagogy, a theory that emerged from Paulo Freire’s ideas of critical pedagogy, calls for “an alternative global project” concerned with making changes in economic, social, and cultural structures ultimately for the wellbeing of the environment.2

2

DESIGN GOALS :

TO SUPPORT...

CULTURAL DIVERSITY & LEARNING

ECOLITERACY

COLLABORATIVE LEARNING

+

COMMUNITY

source: http://www.seattle.gov/transportation/sidewalkrepair.htm

Sources: http://2035.seattle.gov/draft-urban-village-maps/ and Google Maps

NORTHGATE ELEMENTARY: EXISTING CONDITIONS

The outdoor spaces connected to Northgate Elementary present several opportunities and constraints important to my design decisions. The grass field (blue) is shared with the community as ball fields and open space; however, the public is restricted from using the space during school hours for safety reasons. The 10’-16’ retaining wall adjacent to the field and asphalt play court aggressively fragments the space and inhibits sight lines. Unifying these spaces creates grading challenges; however, it is a great opportunity to better connect the school and the community and expand children’s everyday play and learning experiences. In terms of the spaces immediate to the school, there are also several opportunities (shown in red) to improve play spaces and provide infrastructure for learning.

STUDENTS AT NORTHGATE ELEMENTARY

CULTURAL DIVERSITY