The Visual Artists’ News Sheet

September – October 2023

Mark Joyce, Heliocentric 2, 2019, pigment on raw linen; photograph © and courtesy of the artist.

First Pages

6. Roundup. Exhibitions and events from the past two months.

On The Cover Columns

9. Hide and Sing. Cornelius Browne reflects on his ongoing artistic collaboration with Sara Baume. The Anatomy of Art Making. Manal Mahamid outlines her journey as a multidisciplinary Palestinian artist.

10. ACNI Collection. Joanna Johnston outlines recent acquisitions to the Arts Council of Northern Ireland Collection . Earth Rising. Siobhán Mooney outlines the forthcoming eco art festival taking place at IMMA this September.

11. Wicklow Artists Salon. Philip St John and Joanna Kidney reflect on a year of the Wicklow Artists Salon. The Ocean and The Forest. Frank Golden draws on European Modern Art to reflect on Timothy Emlyn Jones’s exhibition.

Festival

12. The Gleaners Society. Frank Wasser interviews Sebastian Cichocki about his guest programme for EVA International.

In Focus: Artist-Led

14. An Altering Rhythm. Inter_site.

15. Welcome to the Neighbourhood. ACA. relocation / reaction / response. Catalyst Arts.

16. A Basic Need for Space. Basic Space.

17. Grass Roots. Muine Bheag Arts.

Critique

19. Ruby Wallis, ‘Whistling in the Dark’, installation view, Galway Arts Centre; photograph by Tom Flanagan, courtesy of the artist and Galway Arts Centre.

20. Fiona Mulholland, Artlink, Fort Dunree.

21. Katherine Sankey, The LAB Gallery.

22. ‘Then I Laid the Floor’, Triskel Arts Centre.

23. ‘On Earth We are Briefly Gorgeous’, glór.

24. Galway International Arts Festival, Various Venues.

Exhibition Profile

26. Red Illuminates. Adam Stoneman considers Jialin Long’s current body of work which uses AI processes.

27. Bending Light. Catherine Marshall reflects on Mark Joyce’s recent solo exhibition at Damer House Gallery.

28. Empathy Lab. Colin Martin discusses current themes in his painting practice and forthcoming show at CCI Paris.

Postgraduate

29. Getting to the Heart of Practice. Laurence Hynes discusses his experience of the MA Creative Practice at ATU Galway. Daughter(s) of Danu. Nina Fern outlines her artistic journey as part of the MA Creative Practice at ATU Sligo.

Project Profile

30. The Agri-Cultural Summer Show. Ciara Healy interviews Orla Barry about evolving thematic concerns in her practice.

32. The Ninth Muse. Frank Wasser interviews Aoibheann Greenan about her current body of work.

33. Supernatural Bureau. Kate Strain interviews Sonia Shiel about current and forthcoming projects.

Member Profile

34. Twilight Time. Ann Quinn, VAI Member.

35. You Begin. Margaret Fitzgibbon, VAI Member.

36. Stacks. Mary O’Connor, VAI Member. Give Me A Ring Tomorrow. nerosunero, VAI Member.

The Visual Artists’ News Sheet:

Editor: Joanne Laws

Production/Design: Thomas Pool

News/Opportunities: Thomas Pool, Mary

McGrath

Proofreading: Paul Dunne

Visual Artists Ireland:

CEO/Director: Noel Kelly

Office Manager: Grazyna Rzanek

Advocacy & Advice: Elke Westen

Advocacy & Advice NI: Brian Kielt

Membership & Projects: Mary McGrath

Services Design & Delivery: Emer Ferran

News Provision: Thomas Pool

Publications: Joanne Laws

Accounts: Grazyna Rzanek

Board of Directors:

Michael Corrigan (Chair), Michael Fitzpatrick, Richard Forrest, Paul Moore, Mary-Ruth Walsh, Cliodhna Ní Anluain (Secretary), Ben Readman, Gaby Smyth, Gina O’Kelly, Maeve Jennings, Deirdre O’Mahony.

Republic of Ireland Office

Visual Artists Ireland

First Floor 2 Curved Street Temple Bar, Dublin 2

T: +353 (0)1 672 9488

E: info@visualartists.ie

W: visualartists.ie

Northern Ireland Office

Visual Artists Ireland 109 Royal Avenue Belfast BT1 1FF

T: +44 (0)28 958 70361

E: info@visualartists-ni.org

W: visualartists-ni.org

Online – 29 September 2023 (10am-4:30pm)

In Person (Tullamore) – 2 October 2023 (11am-5pm)

Programme highlights include:

• Imogen Stidworthy: How We See Work

• Cristina da Milano: Nothing About Us Without Us

• In Conversation: Lindsey Mendick and Helen Pheby

• Panel: Exploring Our Intrinsic Interconnection with the Natural World

• Panel: Working with AI in Contemporary Art Practice

• Launch: The Hedge School Project

• Artists Speak, Speed Curating & VAI Café

Information & Bookings: visualartists.ie

Taispeántas Ealaíne Comhaimseartha

Casino Marino, Baile Átha Cliath

An 1 Iúil go dtí an 6 Samhain 2023

An Exhibition of Contemporary Art

Casino Marino, Dublin

1 July to 6 November 2023

casinomarino.ie

Christopher Banahan, Alana Barton, Mónika Bögyös, Becks Butler, Celie Byrne, Joanne Clerkin, Joanne Betty Conlon, John Cooney, Laura Cronin, Vivienne Dick, Amanda Doran, Samantha Ellis Fox, Philip Flanagan, Owen de Forge, Carol Graham, Charles Harper, Ciaran Harper, Anthony Haughey, Beverley Healy, Jessica Hollywood, Stephen Johnston, Merve Jones, Vanessa Jones, Garry Loughlin, Maitiú Mac Cárthaigh, Connor Maguire, Alice Maher, Paddy McCabe, Kim Montgomery, Kevin Mooney, Daniel Nelis, Eva O’Donovan, Nuala O’Sullivan, Tolu Ogunware, David Quinn, Alex de Roeck, Vera Ryklova, Dáibhidh Stiúbhard, Éva Anna Szántó-Nádudvari, SÍle Walsh.

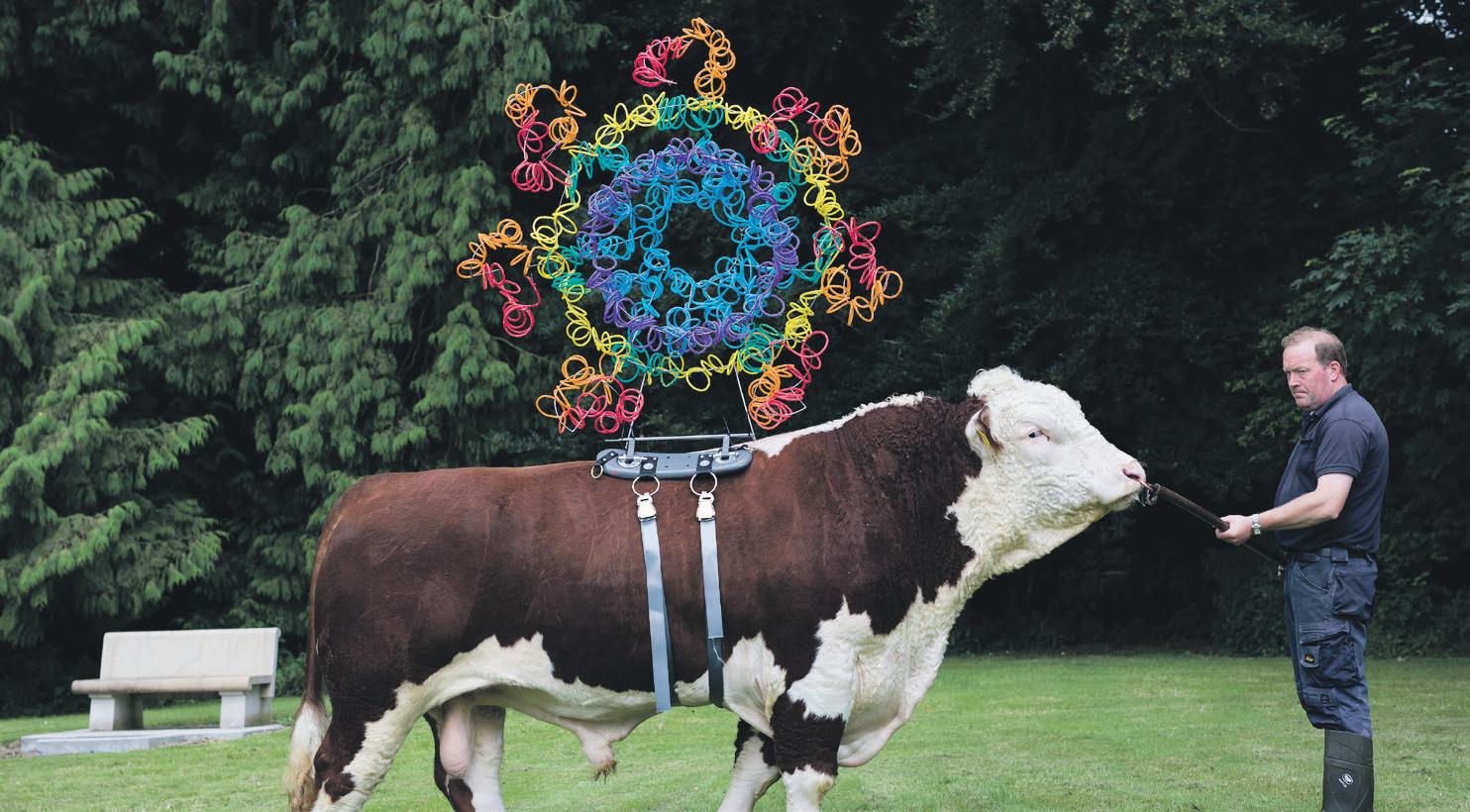

Image features detail of Amanda Doran’s Beast Mode

Image features detail of Amanda Doran’s Beast Mode

MA: ART & PROCESS

is an intensive and stimulating taught Masters in Fine Art that is delivered over three semesters through the calendar year from end of January to December. Each semester focuses on a different function of the course:

• CRITIQUE

• RESEARCH

• PRESENTATION

MA:AP offers innovative approaches to learning, individual studio spaces, access to college workshops and facilities, professional experience through collaborative projects, peer-to-peer exchange and a bespoke visitor lecture series.

Influence and Identity Twentieth Century

from the Bank of America Collection

26

Now taking applications for start January 2024

MTU Crawford College of Art & Design Cork Ireland

Information and online application details: https://crawford.cit.ie/ courses/art-and-process/ ccad.enquiriescork@mtu.ie 00 353 021 4335200

Dublin

Project Arts Centre

Project Visual Arts presented ‘Culchie boy, I love you / Grá mo chroí thú, mo chábóigín féin’, by Kian Benson Bailes, from 22 June to 12 August. Showcasing sculpture, collage, musical instruments, ceramics, textiles, woodwork, and live sound elements, Bailes’s work delves into rural queer experiences, intertwining Irish folklore and craft traditions. The show was accompanied by an essay from Iarlaith Ní Fheorais. Bailes’s creations, inspired by the essence of rural Ireland, challenge perceptions, and evoke a sense of purpose and local identity. projectartscentre.ie

Temple Bar Gallery + Studios

On 2 September Léann Herlihy presented With Everything We’ve Got! [warm-up], a one-hour performance as part of the group exhibition ‘Reflex Blue’ at Temple Bar Gallery + Studios. Herlihy takes stylistic reference from alt text/image description, and utilises frameworks of coalition building. This body of work moves against common understandings of sporting bodies and situates itself as a warm-up for an expansive project that realises an active state of losing/ falling as an embodied response to systemic injustice.

templebargallery.com

Walter’s Bar

ArtNetdlr presented ‘PERSPECTIVES’, an exhibition of new work by Maria Ginnity at the Upstairs @ Walters, Dún Laoghaire. The exhibition was opened on 29 June by artist and Head of RHA School, Colin Martin, and was on view until 23 July. Focused primarily on figurative art, Maria’s work captures a moment in time, drawing the viewer in through the use of cropped images and unusual perspectives. The overall result is rhythmic, bold and intriguing.

artnetdlr.ie

Rua Red

Candice Breitz’s exhibition, ‘Love Story’, delves into cultural diversity, confronting social barriers hindering connection and belonging in South Dublin County. ‘Love Story’ spotlights personal stories of displaced individuals, like Syrian escapee Sarah Ezzat Mardini, and former child soldier José Maria João. Breitz weaves their narratives into an emotive montage, raising powerful questions about the impact and representation of human suffering. On display from 25 August to 11 November.

ruared.ie

The Complex ‘MOVE – SET – MOVE’ was a newly commissioned group exhibition by Lucy Andrews, Andy Fitz, and Katie Watchorn. The artists engaged in detailed discussions about sculptural processes, materiality, and the interplay of objects. The exhibit ran from 19 August to 2 September and showcased their explorations into the transformative qualities of materials, the strive for authenticity, and the peculiarities of handcrafting. Glass emerged as a common material thread, while the artists’ interconnectedness resembled a “love triangle” of ideas. thecomplex.ie

Zoological Museum

‘Anthropomorphia’ was a two-site Dublin exhibition by multidisciplinary Visual Artists Mel French and Celine Sheridan. The Complex Gallery, curated by Mark O’Gorman, and the Zoological Museum in Trinity College both exhibited work that stems from a collaborative research engagement within the fields of Zoology and Psychology. Both French and Sheridan’s artworks reflects on and engages with the psychosomatic of both human and animal. On display from 7 June to 23 August.

tcd.ie

Belfast

ArtisAnn Gallery

‘The Name of the Water’, an exhibition by Karen Daye-Hutchinson and Déirdre Kelly, is a fusion of Venice and Belfast. Their artworks, inspired by cartography, depict the intersection of these two locales. Karen’s prints and bookworks, a product of her Scuola Internazionale di Grafica residency, converse with Déirdre’s shifting collages from her Ballinglen Arts Foundation experience. Lagoons surround and define the shape of Venice, in the same way that the ocean characterises the wild Irish coastline. On display from 5 July to 26 August. artisann.org

Belfast Print Workshop

Belfast Print Workshop celebrated art and heritage at the Linen Biennale 2023, fusing art, culture, and heritage. From 3 to 31 August, the studio and gallery showcased the intricate beauty of linen, captured by talented artists. The opening reception on 3 August immersed attendees in the world of linen artistry. The event featured guest speakers and demonstrations throughout the month, offering insights into the creative process behind this remarkable medium.

bpw.org.uk

Naughton Gallery

The Naughton Gallery presents ‘Neue Palette’, a solo exhibition by multidisciplinary artist Gianni Lee from 10 August to 1 October. Hailing from New York and Los Angeles, Lee’s work spans fashion, fine art, and music, showcasing his mastery of diverse media like painting, drawing, and photography. Lee’s art transcends boundaries, often featuring his signature skeletal graffiti figures or focusing on alien-like subjects to address societal challenges. The exhibition delves into Lee’s creative process, exploring completion in artistic creation.

naughtongallery.org

Belfast Exposed

Belfast Exposed hosted the British Journal of Photography’s exhibition, ‘Portrait of Humanity Vol. 5’, from 3 August to 23 September. Deirdre Brennan’s portraits of Dublin streets were selected, including her portrayal of Elizabeth and Edward O’Brien. When Brennan encountered the couple, their glamour and love prompted a spontaneous street photoshoot. The exhibition celebrated 200 portraits worldwide, with 30 overall winners displayed at Belfast Exposed and The Indian Photo Festival. belfastexposed.org

Golden Thread Gallery

‘Objects in Time’ by artist Anne Butler ran from 3 August to 2 September. Butler’s exhibition featured intricate Parian porcelain vessels, wall pieces, and sculptures, all of which aimed to delve into the concept of the material and the passage of time. Her art was inspired by both natural and manmade structures, revealing connections between cultural and personal memory, while juxtaposing strength and fragility, permanence and loss. The exhibition was presented in collaboration with Craft NI as a part of August Craft Month. goldenthreadgallery.co.uk

Ulster Folk Museum

‘Gintlíocht’ was an exhibition of contemporary art on the theme of heritage skills and crafts, as part of August Craft Month and the Linen Biennale 2023. Supported by PSsquared, the exhibition brought together Susan Hughes, Dorothy Hunter, Tara McGinn, Emma Brennan, artist collaborators Sinéad Bhreathnach Cashell, Jayne Cherry and Alice Clarke, Grace McMurray, Gerard Carson and collective Soft Fiction Projects, who showed work on the theme across the site, for the month of August. On display from 1 August to 1 September. ulsterfolkmuseum.org

Regional & International

Athlone Civic Centre

‘The Weight Of It All’ by Mariza Halliday was on display from 31 July to 1 September. This confronting exhibition showcased a series of paintings that delved into the artist’s personal struggle with mental health. Born out of a period of grief following the loss of a close friend, these artworks have evolved into a poignant representation of a journey with mental health over the years, offering viewers a visual glimpse into the intricacies of the artist’s mind.

marizahalliday.com

GOMA

‘An Instinct, A Continuance’ is a new video installation by Sandra Johnston based on physical movements that are interconnected with archival material and textual forms referencing colonial residues of WWII. Developed with GOMA, this project furthers Johnston’s long-term experimentation with non-verbal communication, looking at how we move and express ourselves as emotional conductors, being incessantly changeable – both sociable and insular in our patterns of self-construction. On display from 22 July to 26 August. gomawaterford.ie

Live Art Ireland

Convergence festival, presented by Live Art Ireland with Livestock, ran from 25 to 27 August and aimed to celebrate and promote diverse artistic talents from around the world. It served as a platform for artists to showcase their innovative works and foster cross-cultural exchange. Artists included: Kira O’Reilly, Satadru Sovan Banduri, Selina Bonelli, Erica Felicella, Topiy Volodymyr & Mariya Hoyin, Marina Barsy Janer x Isil Sol Vil, Slavek Kwi, Mads Floor Andersen, Una Lee, Robbie Maguire, Venus Patel.

live-art.ie

Ballina Arts Centre

Sligo artist Sarah Ellen Lundy named her exhibition ‘Géag’, the Irish word for the limb of a tree or human arm, because her varied installations draw on the parallels between human and non-human forms. Sarah’s work has been selected for the Chicago Underground Film Festival 2023, and this show includes her filmic work, Every Woman Is An Eyeland, an eco-feminist exploration of the connections made between women and nature in culture and religion. On display from 15 July to 26 August.

ballinaartscentre.com

KAVA

‘A Moment of Joy’ by Kathryna Cuschieri was on display from 25 August to 3 September. Kathryna uses the flexible potential and properties of hot glass to explore the emotions that carry the inner world of visions, dream images and fairy tale. She envisions her work as an alchemical process that brings the ordinarily hidden into the light. Some of her works entail creating a body-cast. This cast is first taken in plaster and silica of the person whose story she is working with.

kava.ie

National Sculpture Factory

The festival ‘CLAY : holding/transforming/ performing’ ran from 25 to 27 August and involved a mould making workshop with Kate O’Kelly, a live raku bench for audience participation throughout the month of August, and a live performance by Florence Peake. This festival was curated by artist Clare Twomey, artist Nuala O’Donovan, and NSF curator Dobz O’Brien. Featured artists were Linda Sormin, Florence Peake, William Cobbing, Simon Kidd, Kate O’Kelly, Bernadette Tuite and Nuala O’Donovan.

nationalsculpturefactory.com

Clare Museum

‘Dúlamán na Farraige’ by Marie Connole features new work that expands on her previous exhibition at the Irish Arts Center in New York. Sublime figures of hybrid sea creatures, informed by scientific research and folklore, dwell in an aquatic underworld. The merging of their bodies with Kelp seaweed conveys the intensity and range of human emotion. Dúlamán is the Irish word for a type of seaweed. On display from 1 August to 1 September.

marieconnole.com

Lavit Gallery

‘Into the weave’, was a group exhibition of artist and makers using textiles, with a wide variation of experience with the medium. Exhibiting artists included Laura Angell, George Bolster, Ceadogán Rugs (designs by Deirdre Breen and Shane O’Driscoll), Myra Jago, Allyson Keehan, Richard Malone, Evelyn Montague, Ailbhe Ní Bhriain, Helen O’Shea, Caroline Schofield, Margo Selby, Matt Smith, Jennifer Trouton and Leiko Uchiyama.

lavitgallery.com

R-Space Gallery

R-Space Gallery and artist Jill Phillips presented an innovative interactive exhibition, ‘Connected Emotions’, from 28 July to 26 August. The exhibition brought together art, design and science, to create a textile installation and explore connections between emotions and different types of design. Visitors had the opportunity not just to view but interact and contribute to this installation, and thus explore their very own emotional connections with design.

rspacelisburn.com

Custom House Studios + Gallery

‘Stack’ by Sinéad Ní Mhaonaigh was on display from 6 to 30 July. Sinéad Ní Mhaonaigh is innately concerned with the material qualities of paint, and the physical act of painting itself. Resisting the confinements of allegory, she earnestly engages with painting as its own autonomous language. Much like a poet, Ní Mhaonaigh is interested in ambiguity and in anachronisms. It has been said that she is a painter who suggests rather than represents. Ní Mhaonaigh has become known for deriving titles of her shows from the Irish language. customhousestudios.ie

Linenhall Arts Centre

‘Attitude of a Plane’ by Julie Merriman was an exploration of women’s contributions to aviation and Irish female pilots. In a series of large-scale composite drawings, mimeograph prints and book art, various aspects of flight was explored. The show examined the design and construction of the first aeroplane, built by an Irish female aeronautical engineer, and the experience of a contemporary Aer Lingus female pilot, flying an Airbus A330-200 from San Francisco to Dublin. On display from 21 July to 26 August.

thelinenhall.com

University Hospital Galway

As part of the Galway International Arts Festival visual arts programme, the ‘Salthill Reverie’ group exhibition was a celebration of place, viewed through the eyes of the Hare’s Corner Collective; artists Sacha Hutchinson, Hilary Morley, Ursula Murry and Geraldine O’Rourke. Using paint, collage and photography, they expressed what Salthill means to them as individuals. Their images reflected the sights and sounds: the sea, the shelters, and people of all ages, swimming, diving, walking, and chatting. On display from 17 July to 30 August. giaf.ie

Hide and Sing

CORNELIUS BROWNE REFLECTS ON HIS ONGOING ARTISTIC COLLABORATION WITH SARA BAUME.

Angelica The Anatomy of Art Making

MANAL MAHAMID OUTLINES THE EVOLUTION OF HER PRACTICE AS A MULTIDISCIPLINARY PALESTINIAN ARTIST.

I AM CURRENTLY in the final stages of completing my thesis for an MA in Cultural Policy and Art Management at University College Dublin. Concurrently, I am thrilled to be actively engaged in a captivating residency, hosted by Leitrim Sculpture Centre.

As an artist, I believe that identity goes beyond conventional categories like nationality, religion, or gender; that’s why I find a great fascination in exploring the diverse conceptual aspects of identity. My current focus lies particularly on examining the lives of Palestinians who reside under Israeli occupation. In my artistic practice, I delve into themes that are part of my daily reality, particularly the intersection of landscape and identity.

ture, video, installation, drawing, photography, printmaking, and collage are all essential artistic processes. However, moving image has emerged as a powerful medium for me in the Palestinian gazelle project, to depict the visually divided and geo-politically fragmented Palestinian landscape. This takeover of the landscape is an act of decolonisation. It monitors the physical barriers, checkpoints, and cultural divides imposed on our people, allowing me to tackle these pressing issues, challenge prevailing norms, and break through forbidden boundaries.

WRITER AND ARTIST, Sara Baume, and I are on the lookout for a gallery to host our two-person exhibition, ‘North & South: A Conversation in Words, Objects, Pictures’. By nature, all my life, I have been reclusive, and to show work I must scale inner walls. Considering this, beginning to collaborate, particularly with one so brilliant as Sara, has been as invigorating as a summer spent painting by the sea.

‘North & South’ is a relaxed conversation between two artists working at opposite ends of this island. Of course, I was in communication with Sara long before we had exchanged a word. Her debut novel, Spill Simmer Falter Wither, published in the spring of 2015, alerted readers to the arrival of an exciting new literary talent. While I grew up in a house without a single book, my children are growing up in a house overflowing with thousands. The book as physical artefact has, for this once bookless child, never lost its enchantment. I find magic in the communion that exists between writer and reader over the stillness of the printed page.

Once we began talking, outside of Sara’s books, affinities between our work patterns and responses to the world quickly came to light. Sara in Cork, myself in Donegal, unknown to one another, we have been walking our same local roads, fields and beaches year after year, often within earshot of our respective stretches of the North Atlantic. The art we make grows out of this repetition. Sara constructs the same object over and over with small, yet significant, changes. I paint in the same locations across seasons and years, building such local knowledge that I’m versed in which buds on which branches will open earlier than others on the same tree. Although the works are primarily engaged in this scrutinisation of place, they are also driven by wider-world anxieties. In answer to consumerism and climate change, I have woven a simple existence that harmonizes with the life and art cultivated by Sara. In this, we are both artists of this present hour of crisis.

The great essayist, William Hazlitt, insisted that no one should approach an artist at work, for something sacred is happening in that moment. Sara, as both author and visual artist, locates divinity in the everyday, and I hope I tread a similar path. We have each invented art-related rituals as a form of substitute for organised religion. To varying degrees, at various times, we have retreated from the world, to renew wonder.

We talk about art, finding, to our mutual delight, that we are drawn to the same outsider, folk or visionary artists: Hilma af Klint, Alfred Wallis, Maud Lewis, and John Craske, among others. Echoing af Klint, we never accent individual paintings or sculptures; rather, they become droplets in a hidden stream. Such kinship do Sara and I feel with our forebears – mostly mavericks, whose work was neglected or unseen during their lifetimes – that we share a keen sense of continuity in our day-to-day experiences of making art. Sometimes, one must converse with the dead to unearth what is still alive.

After words, we are now conversing in objects and pictures. Responding to my paintings, Sara has been creating cotton appliqué and silk floss on linen landscapes, capturing the beauty of her southern walks. My new northern landscapes will occupy the same dimensions as my well-thumbed copies of Sara’s non-fiction debut, handiwork, and its fictional companion piece, Seven Steeples. Both books concern withdrawing from society, finding sanctuary in remote places, and living as an artist in harmony with nature.

In his poem, The Botanist’s Walk, John Clare says of the nightingale, “she hides and sings”, which might well describe the poet himself. Hazlitt also hid, beginning in childhood when he would read all day in the long grass, his whereabouts unknown. Art is often created in secrecy but thrives by communication – we hide and sing.

Cornelius Browne is a Donegal-based artist.

For example, during a family visit to a zoo in Kiryat Motzkin, in the Haifa District of Israel, I discovered that in the signage, an animal was described as a ‘Palestinian gazelle’ in English and Arabic, but as an ‘Israeli deer’ in Hebrew. To my surprise, I also discovered that the Palestinian gazelle was amputated. This scene struck a deep emotional chord in me, as metaphorical image of the gazelle’s struggle and the challenges we face as Palestinians under the oppressive occupation. It also triggered childhood memories of a picture of a deer, which hung in my parents’ living room, and set me on a path of research and exploration.

Through my research, I discovered the deep-rooted importance of the gazelle in Palestinian and Arab culture. The animal permeates various aspects of daily life, from food, tea, and sweets to folk music, literature, and placenames. I also found that the Arabic term, ghazal, carries connotations of beauty and flirtation, and has close connections with the Palestinian landscape, history, and culture.

I set no limits when it comes to choosing the right medium for each project. Sculp-

My artistic exploration delves into the ecological consequences of colonialism on the Palestinian landscape. Growing up amidst the breathtaking hills of my rural village, I witnessed the displacement of Palestinian communities, replaced by Israeli settlements. The fragmented landscape, with its checkpoints and barriers, acts as a metaphor for the fractures within our society. Through my art, I aim to shed light on the impact of political forces on our concept of home, and the profound interconnectedness between our land and its people.

Since I moved from Haifa to Dublin in 2020, amid restrictions due to the Covid-19 pandemic, I have been exploring the artistic scene in Ireland, and have gained momentum, particularly as I approach the end of my master’s studies. I have been engaging in the art scene in Dublin, working on some projects, undertaking a residency in Leitrim, and planning an exhibition that I will be announcing soon. Additionally, I am working on a project to participate in the Dubai International Art Fair. Currently, one of my works is on display at the Qattan Foundation in Ramallah.

Manal Mahamid is a multidisciplinary Palestinian artist currently based in Dublin. manalmahamid.com

Collections

Ecologies

ACNI Collection

JOANNA JOHNSTON OUTLINES RECENT ACQUISITIONS TO THE ARTS COUNCIL OF NORTHERN IRELAND COLLECTION.

THE ARTS COUNCIL of Northern Ireland (ACNI) holds over 700 works in its public collection and supports contemporary visual arts practice across Northern Ireland by purchasing from artists living and working in the region. The ACNI Collection has a long history dating back to 1943. By the late 1990s, ACNI had amassed some 1,200 artworks, which were subsequently, for the most part, gifted to the permanent collections of museums across Northern Ireland between 2012 and 2013.

The collection of works currently held covers a new collecting period from 2002, which represents the practices of artists at different career stages and is illustrative of a wide range of disciplines including painting, sculpture, drawing, craft, printmaking, photography, video and digital media works.

The ACNI Collection has always prioritised public lending, with a remit to provide the public access to the visual arts. Our aim for the collection is to continue to exhibit as much of it as we can, and as widely as possible, which we do through a free Art Lending Scheme. This loan scheme is open to galleries, museums, and a wide range of public venues across the island of Ireland and further afield, to borrow a full exhibition of works, or a single loan, as part of a larger exhibition.

Over the past year, ACNI has lent works to institutions both within and outside of Northern Ireland, including Birmingham Open Media Gallery, PhotoIreland, Crawford Art Gallery, Centre Culturel Irlandais, Craft NI, and the Golden Thread Gallery. To further increase the reach of the ACNI Collection to younger audiences, in 2019 we launched a Schools Lending Programme, which has successfully grown to 12 participating schools spread across Northern Ireland, positively connecting the work of contemporary artists to the school arts curriculum and allowing young people to engage with the visual arts in non-tradi-

tional settings.

ACNI recently published a brochure, Arts Council of Northern Ireland Collection Acquisitions 2021-22, outlining the purchase of 35 new works by 22 artists during this timeframe. These acquisitions are innovative and challenging and contribute to the development of visual arts practice in Northern Ireland. For the artist, having their work held in a major public collection can really help raise their professional profile and is an important institutional endorsement that can open doors with curators and galleries, as well as interest from other collections. Artworks are acquired for the collection in a number of ways throughout the year, including from current exhibitions, directly through visits to artists’ studios, and also through an open-submission scheme, which ACNI operates every two to three years.

Among last year’s purchases, pieces were largely drawn from significant exhibitions taking place that year, with artists ranging from recent graduates to those with established practices. A number of themes can be observed, including an interest in the spaces we inhabit in a physical and abstract sense, an exploration of process and materiality, and a representation of past and present cultural narratives.

New pieces to join the ACNI Collection include a large-scale ink on canvas work by Joy Gerrard, photographic works by Paul Seawright, Golden Fleece Award-winning sculptural and photographic work by Maria McKinney, a video piece by Myrid Carten, and a sculptural installation by Nina Ołtarzewska. Full details of works purchased can be viewed on the ACNI website and Instagram page.

Joanna Johnston is the Visual Arts & Collections Officer at the Art Council of Northern Ireland.

artscouncil-ni.org

@artscouncilni_collection

Earth Rising

SIOBHÁN MOONEY OUTLINES THE FORTHCOMING ECO ART FESTIVAL TAKING PLACE AT IMMA FROM 21 TO 24 SEPTEMBER.

IN LATE OCTOBER 2022, IMMA presented a pilot eco art festival, Earth Rising, celebrating people, place, and planet. The festival hosted practitioners tackling climate change, a showcase of citizen science, and an artistic programme drawing on themes of environmentalism, eco-activism, and environmental art. Over three days, this vibrant event showcased more than 70 projects, consisting of workshops, sound, film, talks, installation, and performance.

For this inaugural event, IMMA sought to give a platform to as many creative voices as possible working, and to provoke, inspire, and empower audiences to become agents of change. The huge response to and success of the festival reflects the pressing need for people to get together to discuss possibilities, exchange ideas, and engage critically and artistically with this urgent global issue. Over 9,000 people attended the festival last year.

Earth Rising 2023 will run over four days from 21 to 24 September. The festival will feature exhibitions, screenings, workshops and talks led by innovators and thinkers in the fields of science, design and creativity.

Earth Rising Presents: Through an open call, IMMA has provided funding to support over 50 artists, who will showcase their work during the festival weekend. Events include an outdoor film screening; nest-making workshops with the Oikos Artist Collective; cheesemaking workshops with David Beattie and Michelle Darmody; a live cinema indoor performance from Colm Higgins; an outdoor Gaelic ritual immersive theatre piece by Sadbh Grehan; a community smokehouse by William Bock and Max Jones; a Woodland Symposium presented by Interface; a wind activated clay pipe installation by Brandon Lomax; and an interactive moss-pit from RE-PEAT; to name a few.

Earth Rising Talks: Presented in partnership with the DCU Centre for Cli-

mate and Society, this programme will bring together voices from diverse fields to explore creative solutions for environmental and societal change. Eminent author and activist, Dr Vandana Shiva, Irish inventor and environmental advocate Fionn Ferreira, Irish broadcaster and ecologist Anja Murray, and best-selling author Eoghan Daltun are among the notable speakers. On Culture Night, Friday 22 September, the festival will host a special Seanchoíche storytelling evening, exploring the theme of Creativity for Change.

Earth Rising Field Kitchen: Curated by Jennie Moran and Gerry Godley, this dedicated food-themed site within the festival aims to demonstrate and provoke, while fostering a spirit of convivial debate and discussion. Bright minds, young activists, creative thinkers and skilled hands from Ireland and elsewhere will walk us through the new food landscape. With an empowered and positive stance on our shared food future, this space promises a richly diverse programme throughout the four-day event.

Earth Rising Future Generations Tent: Curated especially for children and young adults by ECO-UNESCO, this will host a vibrant programme of exhibitions, workshops, and discussions, exploring themes of biodiversity, sustainability, and agency for change, involving younger generations in the crucial conversations.

As a space for dialogue and understanding, IMMA recognises the significance of the climate crisis as one of the greatest challenges of our time. Earth Rising aims to be a catalyst for creative thinking, imagination, and individual agency in tackling this urgent issue, to reimagine a more sustainable future for generations to come.

Siobhán Mooney is an independent curator, co-director of Basic Space, and co-curator of Earth Rising.

Art Practice

Wicklow Artists Salon

WRITER PHILIP ST JOHN AND VISUAL ARTIST JOANNA KIDNEY REFLECT ON A YEAR OF THE WICKLOW ARTISTS SALON.

IN 2019, WICKLOW County Council Arts Office held a funding seminar in Mermaid Arts Centre. Afterwards, we were talking about how much we had learned from listening to artists from other disciplines. We were surprised that, although there is a lot of emphasis on cross-practice collaboration now, there are few opportunities to meet people working in other artforms. Wouldn’t it be useful to have regular get togethers in an informal but structured setting?

As far as we knew, there was no model for an event like that in Ireland. There are arts festivals, of course, and these mix different art forms, but are aimed at a more general audience. Our event would be for all disciplines and would address issues of particular concern to artists and cultural practitioners.

After a lot of discussion, we devised a format. Each event would have a facilitator and a panel of two or three artists. The panellists would begin the evening by sharing some of their work. After the panel discussion, the rest of the gathering would join in with questions, comments, and suggestions. This would be followed by tea and coffee and an invitation to continue the conversation in a nearby bar. Crucially, the Arts Office supported the venture, and both Mermaid and The Courthouse arts centres agreed to host the event. So, after four salons, what have we learned about the realities of being an artist in Ireland today?

Surviving as an artist is tough

Even our most high-profile guests are finding the creative life a struggle. One performer memorably described a moment on stage when they realised that everyone else in the room was earning more than they were. Others talked of banks refusing to give mortgages and rent increases forcing them to move out of urban centres, where performing artists, in particular, are most likely to find work. Income is sporadic, unpredictable, and rarely enough. Resilience seems to be as vital as talent in this career. One guest told us they hadn’t earned more than €20,000 in any year, across two decades. Another became so frustrated with earning a living in low-paid jobs in the service industry, that they ingeniously blended creative work into their paid time: they now create art on the job.

Money matters

All of our guests were generous with financial advice. One wisely advised us to put aside a percentage of any income, however small, and to keep rigorous written records of incomings and outgoings. Others praised such innovative schemes as Mermaid’s Transform, which buys the practitioner time to develop and sustain their career. And of course, the Basic Income for the Arts Scheme would go a long way to easing the financial pressures on artists

if it becomes permanent. Finally, we were struck by how younger and older artists differed in their attitudes towards income. A couple of older artists said that no one had asked them to be an artist, and that whatever hardships they were experiencing were of their own making, whereas some younger artists expressed a stronger expectation of financial support: art is important, and you can’t have art without artists, so fund them!

Art can take a long time

Many of the projects our guests discussed were years in the making. This is especially the case with collaborative art, where different opinions and visions have to be integrated. Then there is the need for funding; however, finding adequate support can require patience and persistence.

We need to look after ourselves

All of our guests had suggestions about how to deal with the stresses of the lifestyle. Two are regular sea-swimmers; another finds escape in playing in a band and roller-skating. Another centres himself through playing music to the tick of a metronome for an hour each day. Many guests stressed the need for breaks from work, the benefits of taking the weekend off, sticking to office hours, and also setting limits for time spent on admin. Yet, however individual a practice might be, and however strongly felt the need for time alone, all agreed that creative buddies are essential for support, advice, and solace.

Ireland is alive with creativity

One exciting aspect of the salons has been the opportunity to bring together such a dazzling array of vision and skill under the same roof. During the introductory sections, we’ve experienced a bodhrán solo, a novel extract, theatre images, a poem, insights into an artwork critiquing surveillance technology, a brain-imaging self-portrait, dance visuals, and a video of a collaborative arts sea swim project. Our most recent salon, Taking the Initiative, took place at The Courthouse Arts Centre in Tinahely on 24 June. An exciting range of artists and cultural practitioners shared their experiences of creating a new theatre festival, an internationally acclaimed literary magazine, and two art centres. It is really heartening and inspiring to experience such powerful, adventurous works side by side.

Philip St John is a writer and Joanna Kidney is a visual artist. Both are based in Wicklow. The Wicklow Artists Salon will reconvene with a new programme of topics in autumn. For further details about the salon, see the websites of Wicklow County Council Arts Office or Mermaid Arts Centre.

Art Practice

The Ocean and The Forest

FRANK GOLDEN DRAWS ON EUROPEAN MODERN ART TO REFLECT ON TIMOTHY EMLYN JONES’S RECENT EXHIBITION.

WHEN I CAME to Ballyvaughan in the late 1980s, I used to run into the noted installation and video artist, James Coleman, who had a summer cottage on the Green Road in a little kind of Dingley Dell, surrounded by apple and beech trees. He used to tell me that he could spend hours just sitting in his chair, mindfully gazing out of the window, alert to the plenitude of the natural world surrounding him. He used to speak of these periods of immersive observation as being critical to his process.

There’s a similar story relating to the great Austrian poet, Rainer Maria Rilke, who, in the early part of the twentieth century, worked as secretary to the sculptor, Auguste Rodin. Rodin was Rilke’s first mentor and when Rilke was at an impasse in his work, Rodin advised him to go to the zoo and sit in the presence of an animal. Rilke was only 24 or 25 at the time, and the animal he chose was a panther. He sat for hours with the panther in immersive contemplation and the poem he produced was a seminal work that set him on course to become a poet of great power.

Dean of the Burren College of Art since 2003, Timothy Emlyn Jones is a prolific artist with a similar disposition of mind; namely, that the phenomenal world is the ultimate subject. Tim’s magisterial drawings are the result of a kind of contemplative and meditative indwelling in the landscape. But as Tim himself would say, every painting is in a way incomplete; we the viewer, with our attendant experiences and histories, complete each work, and it is through this relationship that the painting achieves its ultimate destiny.

Every artist, no matter what their discipline, is aware of a state of pure immersion. This is the point of self-forgetfulness, in which the ego and its attendant stresses are sublimated, and one enters a state of ecstatic flow. Time seems suspended and passes without any real consciousness, and the work appears to complete itself by some kind of magical artifice. It is a kind of ecstasy. As Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi says, in his lecture on flow, the word ‘ecstasy’ derives from Greek and means ‘to stand to the side’. It was only later that it became analogous to a mental state. Mihaly argues that ecstasy is essentially about stepping into an alternative reality, where one’s identity disappears from consciousness. Obviously, this will only happen if you have the established skills and technique to accomplish whatever it is you’re doing – be it realising a drawing or writing a novel. Tim is a master of flow and the serenity his works exude is a reflection of that.

Tim’s latest exhibition, ‘The Ocean and The Forest’, ran at The Gallery Café in Gort from 9 July to 31 August. As the exhibition title implies, Tim’s artworks were divided neatly into ‘the ocean’ and ‘the forest’, as two parts of a whole that sit easily together

because they derive from the same contemplative enquiry. When I asked Tim, during a studio visit, if his birch drawings had an affinity to any other artist, I was surprised when he said Gustav Klimt. Klimt, whom many consider principally as a figurative artist, also composed landscape paintings during his summer stays at Lake Attersee in Austria. It is only when you see his beech and birch paintings that the link becomes obvious. There are also traces of Egon Schiele’s more metaphorical landscape paintings, and philosophical alliances with yet another Austrian artist, Friedensreich Hundertwasser, who founded the transautomatism art movement. These connections with Austria go back to Tim’s first visit to Vienna in 1982, where he first encountered the Jugendstil work of Charles Rennie Mackintosh at The Secession. As a professor at Glasgow School of Art, Tim would later develop an intimate understanding of Mackintosh’s secessionist aesthetic, which is tacit within the works on show in Gort.

There has always been something of the rebel about Tim, and this goes back to his membership of the Free International University (FIU), established by artist Joseph Beuys and writer Heinrich Böll in the mid-70s, and which focused, in part, on interdisciplinary work and cooperation between the sciences and the arts at a time when that was far from fashionable. Tim played a very active part in the FIU. That rebel note is struck in Tim’s work, through his use of artist Stuart Semple’s pigment, Black 3.0 (the original of which Anish Kapoor tried to buy exclusive rights to) and Semple’s limited edition pigment, Incredibly Kleinish Blue. Black is central to Tim’s oeuvre because, for him: “Black emphasises the nature of the mark. It is unquestionably itself before it is anything else.”

Given the contemplative and meditative nature of his work, I asked Tim if he has a ritualised set of actions prior to engaging with a drawing. He spoke of centring, and of the Alexander Technique and of breath. For his ocean drawings in particular, each line was delivered on the outbreath, which gives power to the lineation. An important question for every artist is knowing when to stop; knowing when a work has realised its particular destiny. For Tim, the conclusion of a work is “the point at which you can no longer find the correct place for the next mark.”

Frank Golden is a County Clare-based poet, novelist, and visual artist. frankgolden7.com

The Gleaners Society

CONTINUING UNTIL 29 October, the 40th edition of EVA International centres around the theme of citizenship, and comprises the EVA Platform Commissions, Partnership Project initiatives, and a special Guest Programme, ‘The Gleaners Society’, curated by Sebastian Cichocki.

Frank Wasser: Sebastian, it’s an incredibly busy time for you, so thanks for agreeing to talk with me. I wanted to start by asking you about your own practice. Can you tell me about your research methodologies, and how you arrived at the curatorial framework for the EVA Guest Programme?

Sebastian Cichocki: Where to start? I’m very much into assemblies, summer camps, and gatherings. I’m interested in people, and so I work with movements and organisations who are eager to apply artistic strategies in their daily work. My background is in sociology, and I’ve always been fascinated by the social potential of art. I like to think of art as an apparatus that can bring people together and change things, to open our eyes to new possibilities.

FW: Where or how do these possibilities unfold? What are the contexts that your practice operates within?

SC: I work in the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw, a public institution which is under construction, and it is just about to open in its final configuration. I’ve been working with different formats. For me, curating is a lot about usefulness, agency, and doing things with art. This is much more interesting than defining something as art or not art. My natural environment is to be among people who represent different skills, competences, and backgrounds. They are chefs, gardeners, therapists, climate activists, social workers, or biologists, but what is characteristic is that most of them graduated

from art academies. Climate and anti-fascist activism, feminist movements, these are all close to my heart. I’m part of the Sunflower community, an anti-imperialist think-tank and emergency centre, working mainly with the large Ukrainian diaspora and its queer community in Poland. Environmental struggle is something I’ve been working with a lot recently, which evolved from a fascination with land art practices as a possible way of escaping the traditional configuration of the museum. Needless to say, the museum might be an outmoded apparatus, but it is undergoing radical changes.

FW: You have previously spoken and published widely on the invisible histories and ideological frameworks of museums. How does the context of the art biennial differ from that of the museum?

SC: It’s fascinating how we can do things in a different way. I love museums and global biennials, but I do feel that they are operating in separate galaxies. It’s quite unusual how they are restricted by very specific ways of doing things; the singularity of an artwork, the cult of the authorship, all these

obsessive ways of separating art from notart. Many regulations, which were kind of petrified in the nineteenth century, are still determining what art is. The biennial model follows these protocols; it is mostly novelty that is fuelling this system. The expectation is that you have to present something which is new and unusual, the unknown, the forgotten, the overlooked. In a way, a contemporary focus on ‘the marginalised’ has replaced the dominance of dead white men in the western art canon. This is quite an insatiable and exploitative system. But actually, this novelty is the last thing I am interested in.

FW: So, does this refusal of ‘novelty’ underpin the thematic framework of ‘The Gleaners Society’, your Guest Programme for EVA? Gleaning was originally a farming term, denoting the act of collecting or gathering that which already exists.

SC: Yes, exactly, gleaning is about picking up stuff, the leftovers; it has specific legal and ethical connotations in different languages. The act of gleaning is the opposite of over-production and extractivism, because as you know, we do generate a lot

of objects and ideas. The standard biennial is like a potlatch ritual, with the necessity to constantly commission and produce – it’s quite a monstrosity. It’s hard to believe how time-consuming and exhausting the model is, and I seriously question its sustainability. So, I was thinking about this unique opportunity in Limerick, working with such an open and generous organisation. I was told “you don’t even have to do an exhibition!” This was so liberating. Paradoxically, in the end we might end up with a quite conventional exhibition. EVA has such a rich history, albeit hardly visible in the city, but there are small traces of previous editions. It’s like a myth, something immaterial and fleeting, that is also treated as a piece of public property. For example, the person who works in the local flower shop will tell you what should be done for an exhibition!

FW: I guess the idea of gleaning also implies crisis. Is this something you’re considering?

SC: Yes, the planetary crisis; ecocide, fossil fuel wars, loss of biodiversity. In this sense, it is all about saving the resources that exist. There are so many contemporary versions of gleaning; for example, foraging, free shops, dumpster diving. For me, gleaning is not only a metaphor – it is a methodology. Let’s look at the leftovers of the past. There have been 39 editions of EVA. What are those stories, invisible traces, or unfinished businesses? One of the unwritten rules of the biennial format is that you are obliged to invite mostly new names, but what if you work with what is already established in this unique environment of collaboration and trust? One of the first things I did was scan through the incredible artists who had already contributed, such as Orla Barry and Deirdre O’Mahony, with a view to working with them again. What would it mean to bring back Janet Mullarney’s sculptures, which were exhibited in Limerick in the

1990s? There are artists who know the local context deeply, so why not engage with them and continue these conversations, in spite of expectations and fetishisation of the new?

FW: Your approach is reminding me of conversations I had with the curators of documenta fifteen last year. They had this idea of harvesting ideas over the course of the event. Is there a connection here?

SC: Yes, this is interesting because I just came back from Korea, where I worked with local collectives, including ikkibawiKrrr, who will participate in EVA. They were also one of the core members of documenta fifteen. While drinking rice wine, and spending a lot of time with each other, we spoke about the particularities of what gleaning meant in European history and what might be the Asian parallels, like the lumbung concept. Our conversations are ongoing and will grow over the following months. In this sense, gleaning is also about my resources, recent projects, existing collaborations, and network of friends in the Baltic States, South Asia, Ireland, Ukraine and Poland. As the hero of my teenage years, Robert Smithson, once wrote: “Nothing is new, neither is anything old”.

Frank Wasser is an Irish artist and writer based in London. frankwasser.info

Sebastian Cichocki lives and works in Warsaw, where he is the chief curator at the Museum of Modern Art. artmuseum.pl/en

The 40th edition of EVA International opened on 31 August and continues until 29 October, spanning various locations in Limerick city and beyond. eva.ie

In Focus

Artist-Led

An Altering Rhythm

INTER_SITE

Collective Members

INTER_SITE IS AN artist collective based in Cork City, and was established in 2021 by Pádraic Barrett, Deirdre Breen, Aoife Claffey and Kate McElroy, amidst the restrictions of the Covid-19 pandemic. A collective desire was established as isolation was enforced. As four students undertaking the MA in Art & Process at MTU Crawford College of Art & Design, we gravitated towards one another, pulled together by commonalities in our individual practices. Pressing themes include the agency of body and materials, non-spaces, the potentiality of place, and the particular presentation of research-driven media.

2021 proved to be a precarious period for exhibition-making, production, and dissemination. It was the perilous nature of the exhibition at this time that spurred us to consider alternative sites outside of the traditional white cube space. This ultimately led us to the Marina Warehouse, the former Ford Factory in Cork’s Docklands. With the success of our MA show behind us, we approached the industrial site during the first window of tentative re-openings in May 2021. The decision to exhibit and make work in an industrial space provided an open and autonomous platform where our ideas, processes, and subsequent artworks, could expand and breathe.

It was here that we began our distinct collective formula, which lends towards ephemeral, large-scale, artist produced exhibitions and events in non-traditional art spaces. In the intervening years, we have had seven more site-responsive collective exhibitions, including ‘Oileán’ on Spike Island, ‘Pulsating P(l)ace’ in Wandesford Quay Courtyard, PADA (an international residency and exhibition in Portugal) and most recently, ‘Oscillation: An Altering Rhythm’ in the newly renovated Counting House, as part of STAMP Festival of Creativity in Cork last May. Our exhibitions lead the viewer through a carefully considered kaleidoscope of media, including video projection, sound, sculpture, performance, and installation. We aim to activate the environment and the encounter, reimagining spaces, and re-presenting them, using art as a tool to question structures of power.

Embedding art in non-traditional settings challenged us to respond to specific historical and conceptually loaded sites that affect our mechanism of production and display. Audience engagement is integral to our thinking and informs how we plan and stage the work. By activating these kinds of spaces, we hope to reach beyond traditional art audiences to reconsider the environment and the present moment.

Support from the community of Cork has been foundational in our development; Cork City and Council Arts office, Sample Studios, MTU Crawford, Backwater Artists Group, The Living Commons, and the general public have all greatly encour-

aged us. We look forward to exhibiting our work in Dublin for the first time at Pallas Projects, from 5 to 21 October, as part of their Artist-Initiated Projects programme. The exhibition will allow us to reflect on our trajectory so far and help us orient towards what is to come. We will embrace the gallery setting and consider how we can stretch the boundaries of this format. In developing this work, we are considering durational, time-based media and how we can probe the tension between permanence and impermanence. As a collective working against standardised modes of presentation, we are interested in disturbing the white cube format and recovering connections to reality from inside those walls.

Alongside the exhibition will be a publication, designed by collective member Deirdre Breen, who is currently on maternity leave with twins. Deirdre has used her design skills to create a dynamic book which chronicles INTER_SITE’s progress so far. Divided into sections, like multiple sites, the publication catalogues six Corkbased site-responsive exhibitions from 2021 to 2023.

Through shared concerns and artistic approaches, INTER_SITE aims to shed light on the paradoxical nature of current systems. Ultimately, we believe more can be achieved together. The individual within the collective can bring experience and expertise that can be distributed and synthesised within the group. As artists, our responsibility is to make visible different perspectives, often through a process of challenge and consensus. Our practices remain independent but share a common language and objective. We wish to disrupt the ordinary and create space for reflection where alternative narratives can emerge.

As its core, through collaboration and cooperation, INTER_SITE is founded on the ethos of care. By refusing to work in competition and instead choosing participation and co-creation, the collective itself becomes a site of resistance, potential, and world-making.

INTER_SITE is a Cork-based artist collective, established in 2021 by Pádraic Barrett, Deirdre Breen, Aoife Claffey and Kate McElroy. Our forthcoming exhibition runs at Pallas Projects/Studios from 5 to 21 October.

@inter_site

Welcome to the Neighbourhood

Askeaton Contemporary Arts

Michele

Horriganrelocation / reaction / response

Catalyst Arts

Husk Bennett

TRANSITION, RELOCATION, AND precarity swarm artist-led spaces such as Catalyst Arts. Catalyst was founded in 1993 by a group of MFA graduates from Belfast School of Art, who felt the city lacked exhibition spaces and opportunities. Born as a harbour for experimentation, live art, production, and curation, the ecologies and processes within Catalyst have developed over time, shaped by the various artists who have passed through the rolling board.

Niamh Seana Meehan, and Tanad Aaron, and was curated by Catalyst Co-Director, Kate Murphy. Aspects of the exhibition remain in the gallery, almost as a lingering question, through Weir and Aaron’s permanent installations, and the remnants of Meehan’s window vinyls.

SINCE 2006, ASKEATON Contemporary Arts has commissioned, produced, and exhibited contemporary art in our small town in County Limerick. An artist residency programme, titled ‘Welcome to the Neighbourhood’, situates Irish and international artists in the midst of Askeaton each summer, while thematic exhibitions, publications, and events occur throughout the year.

There are no ‘white-cube’ gallery spaces or arts centre infrastructure in Askeaton. Instead, artists work in public spaces throughout the town and hinterland – from petrol stations and hair salons, to medieval castles and uninhabited islands. This form of engagement focuses on the existing dynamics of the locale, intending to bring forward the diverse layers of daily life and create a rich framework for subjective encounter. Generally, the artists we work with have a vested interest in placemaking and context, and the local community is often actively immersed in the development of projects through sharing their specialised knowledge, assistance, and participation. This approach is built on a belief that contemporary art can be a form of critique, investigation, and celebration, in which artists play a primary and fundamental role at the centre of social dialogue.

For our recent summer programme, Robin Price delved into a murder mystery narrative with the local Tidy Towns committee; Chris Kallmyer arrived from Los Angeles to investigate the sounds of holy wells (a pertinent topic, considering the high levels of water pollution here); while Bryony Dunne made bricks from river clay, stamping them with goat footprints to remember the devilish legacies of the ruined Hellfire Club, seen in the centre of Askeaton. In addition to the artist residency, a public programme featured, amongst other events, the premiere of Michael Holly’s short film, Lily of the Valley (2023), exploring an esoteric body of artworks by Flemish-Irish artist Lily van Oost (193297), evoking the intrinsic relationship

between sculpture, inhabitation, and nature. Reassessing Van Oost’s work today, Holly’s video – one of many commissioned since 2020 for our online media channel – delves deep into the memories, documents, and artworks that make up her legacy, made in close collaboration with film artist, Mieke Vanmechelen.

Our programme and relationship with artists, while primarily based in Askeaton, often stretches to elsewhere; many artworks made here have been subsequently presented throughout the world in exhibitions, art biennials, and film festivals. For several years, we’ve worked with the Irish Architectural Archive in Dublin, placing artists to research and produce works in direct relationship to their holdings. In early 2023, Adrian Duncan’s Little Republics (The Lilliput Press, 2022) was realised in this context, examining the history of bungalow building in Ireland, and utilising resources made available to him in Dublin and Askeaton towards an extensive exhibition and publication project. Over the next year, we are planning public programmes with partners in New York, Chicago, and Helsinki.

Another aspect of ACA has been the commissioning and realisation of artist publications, and we recently worked with Camden Arts Centre in London to launch Adam Chodzko’s new publication Ah, look, you can still just about see his little legs sticking out from it all! (2023). The book emerged out of lockdown conversations with Adam around his lifelong relationship with Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s sixteenth-century painting, Landscape with the Fall of Icarus (1560), and is richly illustrated with his many multimedia artworks, made over the last thirty years.

Michele Horrigan is a curator at Askeaton Contemporary Arts. An archive of artist projects, news updates, media channel, and publications is available on the ACA website. askeatonarts.com

In January 2021, Catalyst moved from a monolithic building in College Court, to a hive of creativity at 6 Joy’s Entry – marking our fifth premises within Catalyst’s 30 year-history. Re-structuring thoughts and processes have been integral to the success of our programming and curation in the new venue. Recent programme highlights include ‘it feels hairy to start again from nothing’– our re-imagined Catalyst Members Show 2022, featuring Reuben Brown, Niamh Seana Meehan, Peter Glasgow and Sun Park. The limited floorplan of Joy’s Entry meant we needed to take a more considered approach and exhibit selected members’ works. The 2023 Members Show, running from 17 August to 15 September, has once again been re-imagined, in the hope of accommodating more members in the space.

Cecelia Graham’s recent director show, ‘Ornaments of Prospect’ (2 March to 1 April 2023) saw Beau W Beakhouse and Sadia Pineda Hameed transform our gallery into a think-tank of speculative futures, through examining tools and their history. “Tools and their use can also redefine hierarchies and create a foundation for considering anti-colonial strategies of resistance, whilst acknowledging the complex role of tools in capitalist and western hands that utilise their designs as instruments of progress.”1 By re-contextualising and examining ways of working and power structures, we can conceptualise new strategies and dialogues within the artist-led space.

Another cumulative show came with ‘core is concrete’ (3 October to 6 November 2023) which spotlighted a series of site-orientated responses, questioning the function of the space. The show featured Ben Weir,

Catalyst Arts began as a response to the arts and cultural landscape of Belfast, against a backdrop of violence and unrest, prior to the Good Friday Agreement. Belfast remains a challenging and somewhat turbulent city; however, Catalyst Arts continues to offer opportunities, supports, and community for emerging and established artists. The organisation persists at the forefront of contemporary art, and remains critical within the arts ecology on the island of Ireland. Whilst we rely on funding from the Arts Council of Northern Ireland, we remain autonomous in certain aspects, through our independent publishing, fundraising, and membership. We have also established a number of independent events and workshops, such as OFF-Site*, Propagate, and FIX.

The Catalyst board is constantly in flux – an organisational model aimed at preventing stagnation and catalysing new ways of thinking, collaborating and working. At its core, Catalyst Arts has a community-centred approach to contemporary art and curation. It’s hard to conceive of the organisational structure, which has been maintained over the last three decades; yet its legacy of ‘anchored unsteadiness’ continues to produce new discoveries, connections and methodologies.

Husk Bennett is a current Co-director of Catalyst Arts, along with Sean Ward, Dominic McKeown, Silvia Koistinen, and Rachael Melvin. The Catalyst Arts Members Show 2023 continues until 15 September, while our forthcoming exhibition, featuring Charys Wilson and Hazel O’Sullivan, will be presented from 5 to 31 October. catalystarts.org.uk

A Basic Need for Space

Basic Space

Siobhán MooneyBASIC SPACE IS an independent, voluntary-led art organisation, founded in 2010 by Kari Cahill, Hannah Fitz, Greg Howie, and Hugo Byrne, while they were students. Basic Space was established during the recession and from frustration at the lack of exhibition spaces for emerging artists in Dublin. A vacant warehouse was secured just behind Vicar Street and a studio and exhibition space were set up. The venue became an essential testing ground for creative dialogue and risk-taking for a wide range of artists.

Providing a space for ‘things to happen’, and a place to experiment for a community of artists, was the driving force for Basic Space in these early years. Important collaborations and connections were made with other artist-led spaces in Ireland and across Europe at this time. In 2012 Basic Space took part in IMMA’s Residency Programme, which was followed by a move in 2013 to Eblana House in The Liberties.

From 2016 onward, Basic Space occupied a number of locations in Dublin. As the years progressed, empty space around the city increasingly got swallowed up by development. The logistics became almost impossible and it was no longer viable for Basic Space to exist in a physical location. This new nomadic presence led to increased collaborations with established art institutions. Basic Space programmed residencies, staged exhibitions, and held events under an ethos of exploring new and alternative ways of programming without a dedicated base. It became a flexible site for collaboration and engagement, and as different iterations emerged and co-directors came and went, these core principles allowed Basic Space to evolve and adapt to changing socio-economic and political circumstances, while continuing to provide a supportive and safe platform for a diverse range of artists.

Over the past 13 years, Basic Space has initiated over 50 projects through the dedication of 19 different co-directors, who have striven to maintain the organisation as a vital and useful space for the creation and dissemination of contemporary art. Basic Space have collaborated with 126 Artist-Run Gallery, Ormston House, Gallery Eight, CCA Derry~Londonderry, TBG+S, Galway Arts Centre, and ONONO Rotterdam, to name a few. More recent projects include: inviting Diana Bamimeke to curate the exhibition ‘On Belonging’ in the Library Project; a Basic Space commissioned t-shirt from the artist Emma Wolf-Haugh, with proceeds going to support MASI; a solo show by Cara Farnan, hosted by Backwater Artists Group in Cork; and a self-improvement table quiz fundraiser, devised by David Fagan and John Waid.

In the summer of 2020, Basic Space hosted a series of Instagram conversations with various practitioners in response to and in support of the Black Lives Matter movement. In December 2022 Basic Space were invited to be co-selectors, along with Gavin Murphy and Mark Cullen, for Periodical Review 12 in Pallas Projects/Studios. Most recently, in collaboration with MART Gallery, Basic Space invited Kasia Kaminska and Samuel Arnold Keane to run an urban foraging and anthotype workshop.

Basic Space also curates Basic Talks, a monthly series of informal talks with leading contemporary practitioners, in partnership with the Hugh Lane Gallery. This crucial activity provides steady funding for Basic Space while offering an open platform for artists, curators, writers, and collectives to present their practice in the form of lectures, workshops, presentations, and performances to new audiences. This relationship with the Hugh Lane was forged in 2016 by the directors at the time and, so far, 45 Basic Talks have taken place. Francis Fay, Manal Mahamid, Vanessa Daws, and Venus Patel are among the most recent speakers.

Basic Space is currently funded on a project-by-proj-

ect basis. While this affects our ability to make longterm plans, it also affords us a degree of flexibility and receptivity that is at the core of how we engage with the artists, audiences, and institutions that we work with. Ireland is well out of recession, but there are still not enough spaces for artists to work. Back in 2010, when Basic Space was founded, artists could just about afford to rent a studio and live in the city; however, this has now become almost impossible.

A lot has changed in the intervening years, but the ethos on which Basic Space was founded – collaboration, inclusivity, experimentation, engagement and providing space for artists – remains as relevant and important as ever. We hope to keep evolving and producing dynamic and valuable events with a strong focus on underrepresented communities within the art world. As an artist-led space in a world increasingly dominated by profit-driven forms of expression, Basic Space exists solely for artists.

Upcoming events include Basic Talks from Laura Fitzgerald, Jonathan Mayhew, and Ciara Roche; an event with Conor Nolan, based on a residency borne from a collaboration between Basic Space and VOID Gallery in Saskatoon; and some exciting fundraising events in autumn.

Grass Roots

Muine Bheag Arts

Mark Buckeridge and Leah Corbett

MUINE BHEAG ARTS is an artist-run organisation based in County Carlow. Set up by Mark Buckeridge and Leah Corbett in 2020, the organisation grew out of a need for better arts infrastructure outside of the city context, and a wish to create a space for experimental programming in a local setting. Our aims are to promote contemporary art and artists in collaboration with the community.

Muine Bheag Arts presented its inaugural programme, Grass Roots, in 2021, followed by the second edition in 2022. Grass Roots refers to the self-organising approach of the programme and how working at a local level facilitates ideas and dialogue. Grass Roots begins in the community, inviting artists and contributors to respond to the town of Muine Bheag as a site for artistic production, research and collaboration. In this way, growth is cultivated by and for everyone involved.

Rather than operate from a fixed space, Muine Bheag works remotely to host exhibitions and events in the public realm, providing opportunities for artists to make work that may not be possible in a gallery setting. In 2022 we worked with Marian Balfe, Angela Burchill, Colm Keady-Tabbal, Gemma Kearney, Niall McCallum, Cillian Moynihan and Quantum Foam to present a series of public sculptures and events that unfolded in green spaces throughout the town, as well as in the Community Centre, along the river, and in St. Andrew’s Church.

Niall McCallum presented New Versailles turning over and over (2022), an earthwork that guided visitors through a labyrinthian structure, referencing the town’s history and surprising links to Versailles. Descent of Waves (2022), an audio-based performance by Quantum Foam, incorporated environmental sounds from the River Barrow. The performance took place onboard the local community boat, Bád Keppel, and spilled out across the riverbanks.

The town’s architecture, infrastructure, and history provide the backdrop for each of the projects we undertake. Working in this setting requires ongoing dialogue and negotiation with members of the public. We rely on the community for essential local knowledge, for use of spaces, and for tangible support. Having grown up in Muine Bheag, Mark’s connection to the area is key to building a strong relationship to the community.

The third edition of Grass Roots takes place from 11 August to 10 September and includes contributions from Cóilín O’Connell, Mollie Anna King, Niamh Seana Meehan and Holly Pickering. The artists spent time together as part of a short residency in June, which has led to a rich and meaningful programme, whereby the artists have each developed new site-specific works in response to their time in Muine Bheag. A series of public sculptures is accompanied by a programme of events including a film screening, ceramics workshop, performance, and zine-making workshop.

Looking ahead, we want to continue to promote experimental programming and to champion art in the public realm. We

are committed to supporting artists and to building our relationships and networks within the community. It’s important for us to continue asking questions, challenging how and why we do things. Rather than expanding our programme for the sake of expansion itself, our priority is to create a sustainable model which will allow Muine Bheag Arts to continue our work.

Despite the difficulties faced by the sector, and especially artist-run initiatives, we are hopeful for the future, having seen over the past three years how community and communication have supported the development of Muine Bheag Arts so far.

Mark Buckeridge and Leah Corbett are founding directors of Muine Bheag Arts. muinebheagarts.com

The Visual Artists' News Sheet

Critique

Edition 69: September – October 2023

Ruby Wallis, ‘Whistling in the Dark’, installation view, Galway Arts Centre; photograph by Tom Flanagan, courtesy of the artist and Galway International Arts Festival.

Ruby Wallis, ‘Whistling in the Dark’, installation view, Galway Arts Centre; photograph by Tom Flanagan, courtesy of the artist and Galway International Arts Festival.

Critique

Fiona Mulholland ‘In Search of Pearls & Future Fossils’ Saldanha Gallery, Artlink, Fort Dunree 24 June – 23 July 2023

AS OBSERVED BY American writer, Ray Bradbury, in his dystopian novel, Fahrenheit 451: “We need not to be let alone. We need to be really bothered once in a while. How long is it since you were really bothered? About something important, about something real?”1 If we imagine the future, does it provide a sense of comfort or a feeling of terror that is nearly the stuff of Science Fiction? Looking directly at a crisis such as climate change does not seem to have produced the lessons that might bother society; it is necessary to take a more oblique perspective. Artists are ideally placed to probe important issues as their sensory approaches can often communicate to the individual on a different register. Art is immediate, subjective, and often jarring, with messages persisting in the mind longer than any news report.

Fiona Mulholland’s recent exhibition at Artlink, ‘In Search of Pearls & Future Fossils’, integrates natural materials and handcrafts while dwelling on reconfigurations of manmade materials and their detrimental impact on nature. The setting for this exhibition is deliberate, as Mulholland wanted to reference the coastal landscape as a dramatic and constantly evolving environment. Fort Dunree was strategically built in 1813 on a hillside overlooking the natural harbour of Lough Swilly. A military museum now occupies the original fort which leads to the Saldanha Gallery. The gallery is named after the HMS Saldanha that sheltered in Lough Swilly from a heavy storm in 1811 but was later wrecked off Fanad Head with over 250 lives lost. The fact that Artlink occupies the former military hospital building interestingly connects with Mulhol-

land’s hopes that through meditation on detritus and found objects, we can consider avenues for renewal and repair of our surroundings.

The exhibition is laid out across three spaces, which lead the viewer from the present, through the past, and into the future. In the Mezzanine Gallery there are 17 works, including a series of small, square photographs, titled Land and Sea essence | Sites Unseen, which document the shore, plants and sea life, including dandelion seedpods, underlining a sense of ephemerality. For Mulholland, these photographs act as preparatory sketches for her larger photographs and sculptures, and are her means of “studying, listening and reflecting”. The artist notes that “it is an effort to capture the essence of things and conduct an almost microscopic study of their energy.”2

Presented along the glass corridor is the ‘Donegal Ringfort Series’, comprising eight pieces of digital embroidery on tweed and linen. These works feature individual mapped ringforts with a scale indicator, suspended against the glass backdrop within their embroidery hoops. This makes a direct connection between the archaeology of the past and the landscape around the fort. These works are felt by the artist to be “the perfect way to capture the theme of comfort and repair and a return to simpler ways, yet the contradiction is that they are machine-made rather than handmade.”3

The main gallery features extensive artworks, including wall-based photographs and silk hangings, combined with freestanding sculptural pieces, shelf-based works, and a vitrine of cast objects. There is a dramatic interplay between the thin grey metal roof beams of