NCAD FIELD as ‘taskscape’, Hempcrete structure by Helen McLoughlin; photograph © and courtesy Gareth Kennedy.

6. Roundup. Exhibitions and events from the past two months.

8. News. The latest developments in the arts sector.

9. Notes on Grammar. Joanne Laws outlines the conversation surrounding gender-neutral pronouns. Reading Time and Infrastructure. Christa-Maria Lerm Hayes reflects on Brian O’Doherty’s social practice legacy.

10. The Heavenly Order of Humble Materials. Cornelius Browne considers the salvaged and the handmade. Molecular Revolutions. Shannon Carroll discusses her recent curatorial projects including a show at The LAB Gallery.

11. Fully Whole. Iarlaith Ní Fheorais responds to Holly Márie Parnell’s latest film, made with her brother David. Grief Weaving. Donegal-based artist Emily Waszak considers recent developments in her textile practice.

In Focus: Field Work

12. Drawn With Nature. Lisa Fingleton, VAI Member Glossaries for Forwardness. Marie Farrington, VAI Member

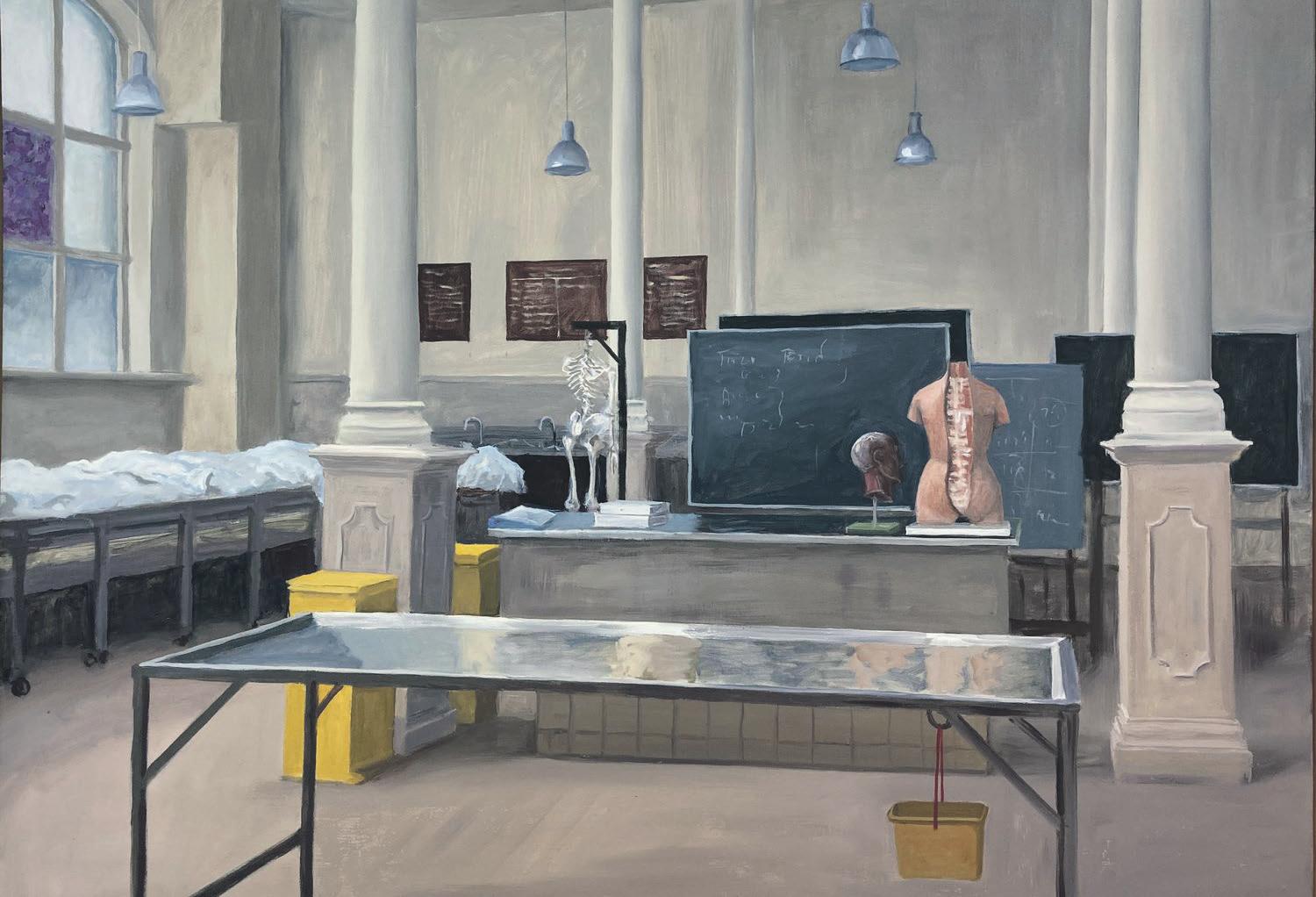

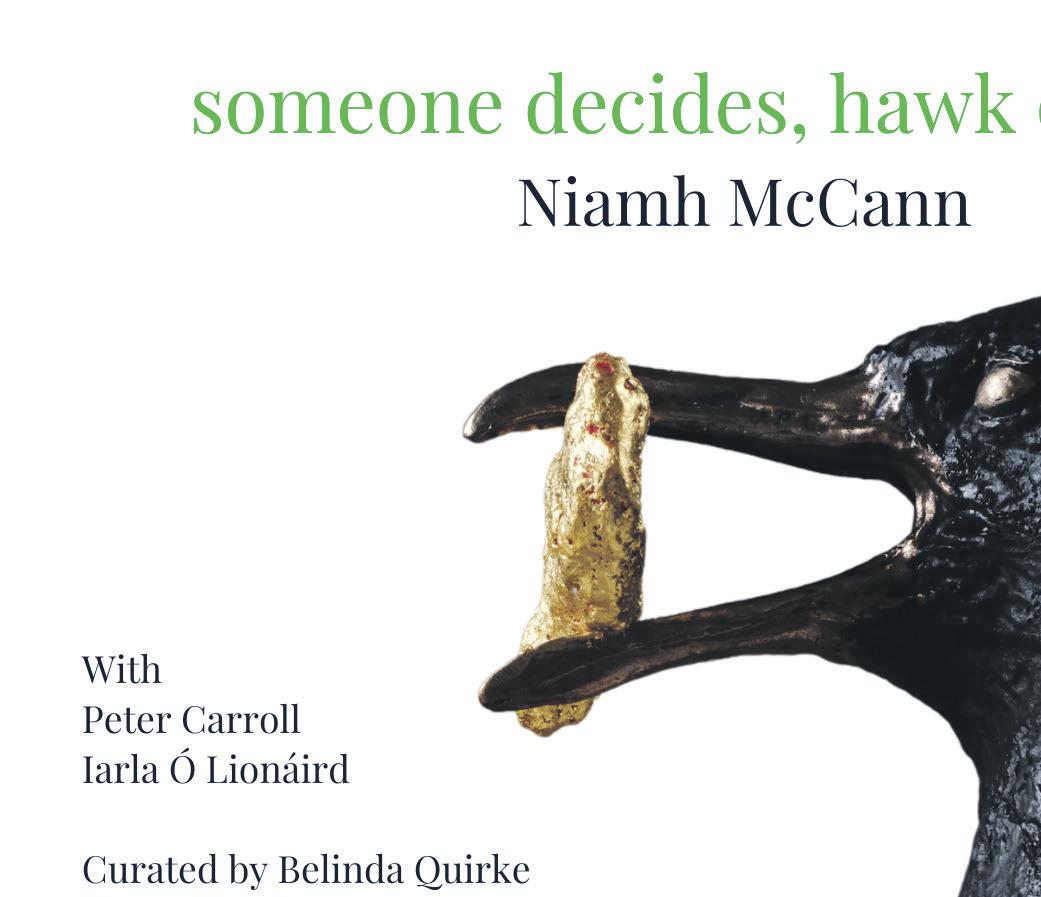

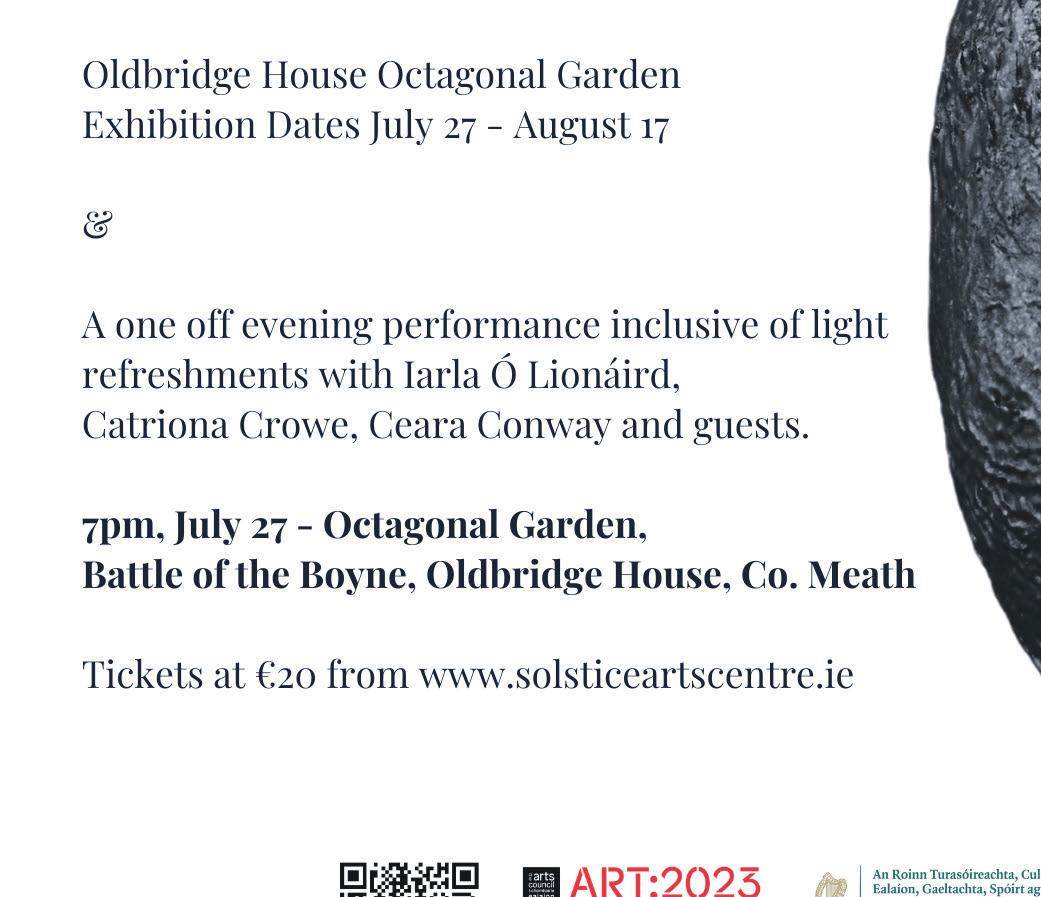

13. Holdings. Belinda Quirke, Director of Solstice Arts Centre

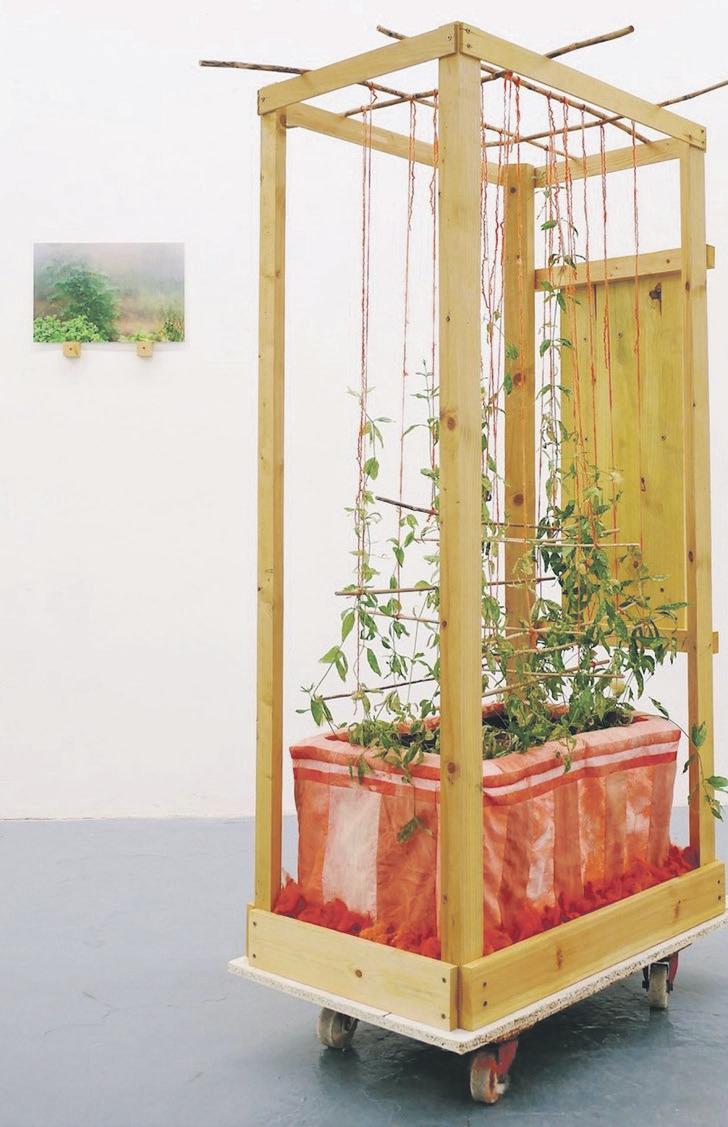

14. The Green Cube. Sandra Murphy, IMMA Biodiversity Tours Tracing a Lightning Path. James Kelly, VAI Member

15. Living Sculptures. Katerina Gribkoff, VAI Member

16. NCAD Field. Gareth Kennedy, Artist and Lecturer

17. Sustainment Feasts. Deirdre O’Mahony, VAI Member

Seminar

18. Collective Space. Sarah Long reports from Cobh in Cork on the SIRIUS Summer School 2023 programme.

19. Dragana Jurišić, Hi, Vis 3 from the series ‘Hi-Vis (2020-21); photograph © the artist, courtesy of Crawford Art Gallery.

20. Sarah Pierce at IMMA

21. ‘Bodywork’ at Crawford Art Gallery

22. Ellen Harvey at Butler Gallery

23. Dorje de Burgh at South Tipperary Arts Centre

24. Roseanne Lynch at Photo Museum Ireland

26. Say What You See. Ian Wieczorek outlines his involvement in organising a retrospective of the art of Gus Lynott. Loading Bay. Frank Wasser discusses a new project for artists’ writing commissioned by the National Sculpture Factory.

27. History of the Present. Eoin Dara interviews Maria Fusco about her new opera-film about Belfast, class, and conflict.

28. Post-extractivist Landscapes. Judy Carroll Deeley discusses her collaboration with UCD Humanities Institute.

Exhibition Profile

29. Aftermath: Perpetrator Trauma. Mary Flanagan considers Dominic Thorpe’s exhibition at the Linenhall Arts Centre.

30. This Rural. Selina Guinness reviews a recent exhibition at Lismore Castle Arts focusing on photographic practices.

32. Shelter. Anne Hodge discusses an exhibition by the Shell/Ter Artist Collective at the National Gallery of Ireland.

34. Extinction Beckons. Frank Wasser reviews Mike Nelson’s recent survey exhibition at the Hayward Gallery in London.

35. Twilight Zone. Alannah Robins outlines the involvement of Interface at Supermarket Art Fair in Stockholm.

36. The Grammar of Clouds. Martin Finnin discusses the evolution of his painting practice.

37. Expanded Painting. Amy Higgins outlines the development of her artistic practice.

The Visual Artists’ News Sheet:

Editor: Joanne Laws

Production/Design: Thomas Pool

News/Opportunities: Thomas Pool, Mary McGrath

Proofreading: Paul Dunne

Visual Artists Ireland:

CEO/Director: Noel Kelly

Office Manager: Grazyna Rzanek

Advocacy & Advice: Elke Westen

Advocacy & Advice NI: Brian Kielt

Membership & Projects: Mary McGrath

Services Design & Delivery: Alf Desire, Emer Ferran

News Provision: Thomas Pool

Publications: Joanne Laws

Accounts: Grazyna Rzanek

Board of Directors:

Michael Corrigan (Chair), Michael Fitzpatrick, Richard Forrest, Paul Moore, Mary-Ruth Walsh, Cliodhna Ní Anluain (Secretary), Ben Readman, Gaby Smyth, Gina O’Kelly, Maeve Jennings, Deirdre O’Mahony.

Republic of Ireland Office

Visual Artists Ireland

The Masonry

151, 156 Thomas Street

Usher’s Island, Dublin 8

T: +353 (0)1 672 9488

E: info@visualartists.ie

W: visualartists.ie

Northern Ireland Office

Visual Artists Ireland

109 Royal Avenue Belfast

BT1 1FF

T: +44 (0)28 958 70361

E: info@visualartists-ni.org

W: visualartists-ni.org

MA: ART & PROCESS is an intensive and stimulating taught

Masters in Fine Art that is delivered over three semesters through the calendar year from end of January to December.

Each semester focuses on a different function of the course:

• CRITIQUE

• RESEARCH

• PRESENTATION

MA:AP offers innovative approaches to learning, individual studio spaces, access to college workshops and facilities, professional experience through collaborative projects, peer-to-peer exchange and a bespoke visitor lecture series.

Now taking applications for start January 2024

MTU Crawford College of Art & Design

Cork Ireland

Information and online application details: https://crawford.cit.ie/ courses/art-and-process/ ccad.enquiriescork@mtu.ie 00 353 021 4335200

12.08.23–08.10.23

Opening Sat Aug 12 (16.00–18.00)

Including works by: Josh Begley / Charles Brady / Paul Carroll

17–30 July 2023

Vincent Cianni / Michael Craig-Martin / Dorothy Cross / Vanessa Daws

Rineke Dijkstras / Andy Fitz / Jona Frank / Marcus Harvey

Nicolai Howalt / Nevan Lahart / Louis le Brocquy / Jeannette Lowe

Colm MacAthlaoich / Colin Martin / Fearghus Ó Conchúir

Kenneth O’Halloran / Mandy O’Neill / Tony O’Shea / Julian Opie

Martin Parr / Paul Pfeiffer / Luis Alberto Rodriguez / Amelia Stein

Sarah Walker / Elinor Wiltshire

Julian Opie Running women., 2016Fingal County Council Arts Office in partnership with Graphic Studio Dublin are offering two Fine Art Print Residencies for professional artists at any stage of their career, working in any discipline, who are interested in exploring print processes.

The two-week long residencies will provide an ideal environment for the development of a creative project in printmaking, working with a master printer.

To be eligible to apply, applicants must have been born, studied or currently reside in Fingal.

Closing date for receipt of applications: Thursday 27th July 2023 at 4.00pm

Visit www.graphicstudiodublin.com to download an application form.

For further information please contact Graphic Studio Dublin by email at info@graphicstudiodublin.com

www.fingalarts.ie

www.fingal.ie/arts

Fingal County Council Arts Office in partnership with the RHA are offering an opportunity of a funded studio space for a professional artist for a period of one year, commencing in September 2023. The award is open to practising artists at all stages in their professional careers working in visual art.

The award offers an artist the opportunity to develop their practice within the institutional framework of the RHA and covers the cost of studio rental and administration.

To be eligible to apply, applicants must have been born, studied or currently reside in Fingal.

Closing date for receipt of applications: Monday 24th July 2023 at 4.00pm

Visit www.rhagallery.ie to complete an application form.

For further information please contact the RHA by email at annie@rhagallery.ie

www.fingalarts.ie

www.fingal.ie/arts

Fingal, A Place for Art

Fingal, A Place for Art

The Arts Council’s Artist in the Community (AIC) Scheme, managed by Create, offers awards to enable artists and communities to work together on researching, developing, and delivering projects.

Closing Dates

Round One: 27 March, 2023

Round Two: 25 September, 2023

www.create-ireland.ie

Dublin

Douglas Hyde Gallery

The Douglas Hyde Gallery presented the first institutional exhibition in Ireland by renowned artist Uri Aran. Titled ‘Take This Dog For Example’, Aran’s exhibition was on display from 31 March to 25 June. In ‘Take This Dog For Example’, materials and the language of learning trace through multi-faceted works, from Sesame Street’s Ernie (without his Bert) and study desks, to blackboards, slide projectors and projection stands, alongside a library of composed letters.

thedouglashyde.ie

Kerlin Gallery

Kerlin Gallery presented ‘Repeating Song’, an exhibition of new work by Aleana Egan, from 14 April to 27 May. Across painting and sculptural arrangements, the works in ‘Repeating Song’ foster an ambient space in which to convey sensations through looking. Traces of interactions and experience are harvested and expressed through material objects, colour, and form, presenting a rhythmic installation rooted in the blending of inchoate interior visions and sources from the world at large.

kerlingallery.com

SO Fine Art Editions

‘Dreams of Reality’ by Yoko Akino was on display from 6 May to 3 June at SO Fine Art Editions. The fine art prints in this exhibition reflected the influence of the world around Akino, lived experiences and feelings of wonder for nature and all that life offers. The physical landscape of mountains and islands seem unchangeable, as if they have been there forever, yet their contours and colours are altered constantly by passing clouds and rain showers that appear and disappear in unfolding dramas.

sofinearteditions.com

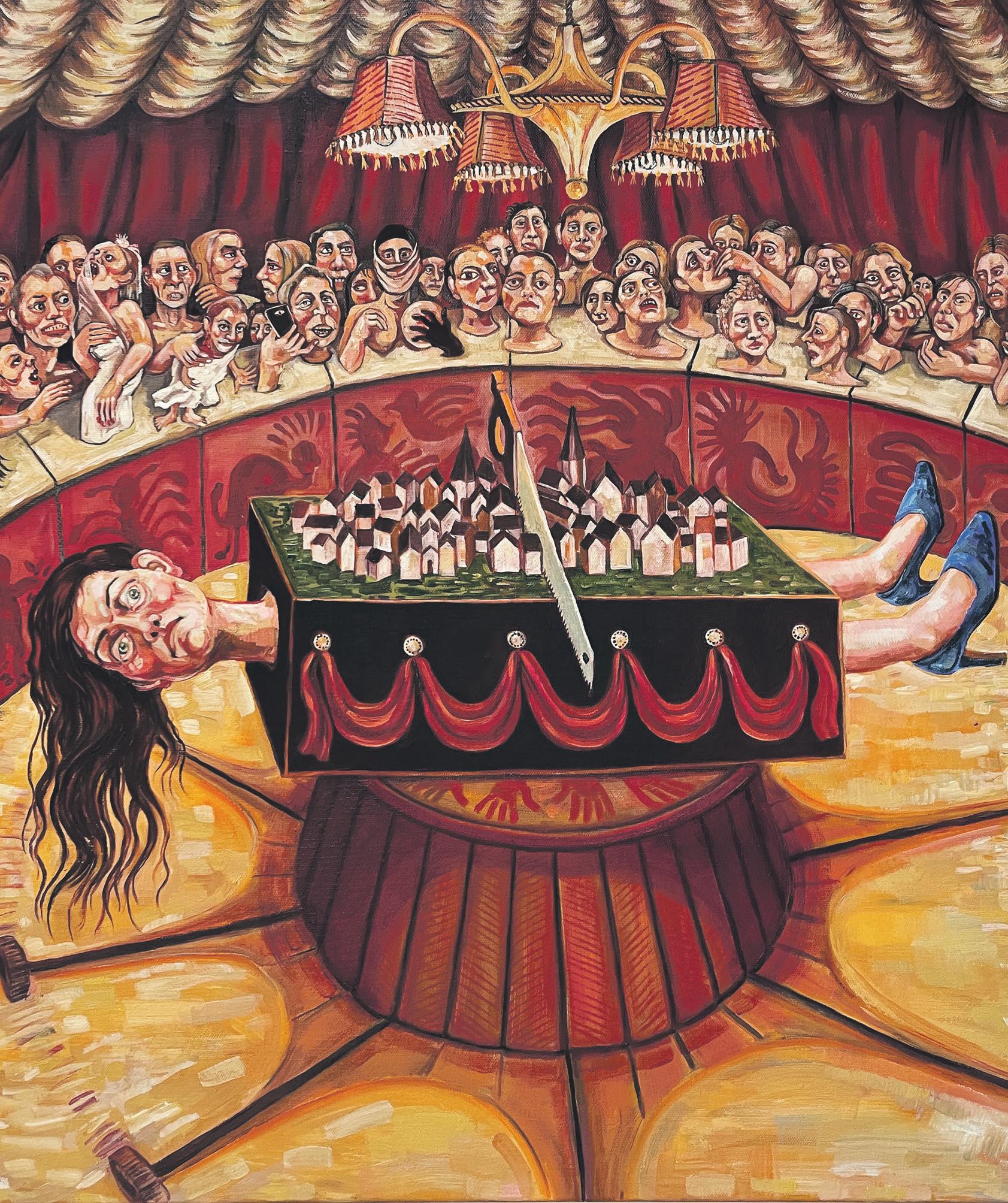

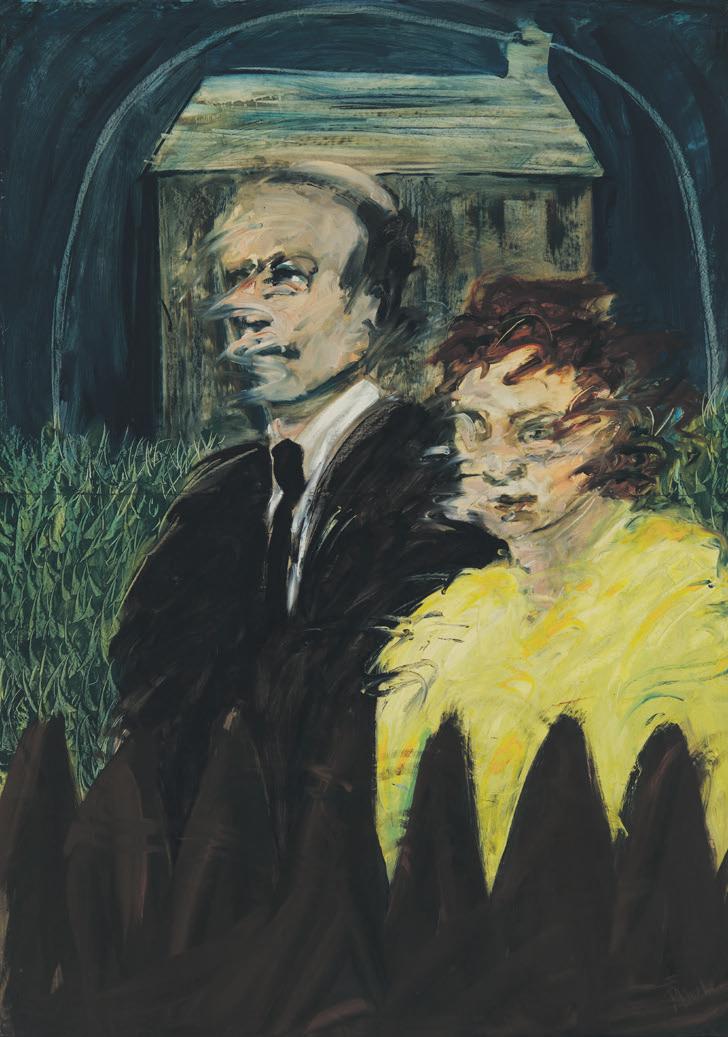

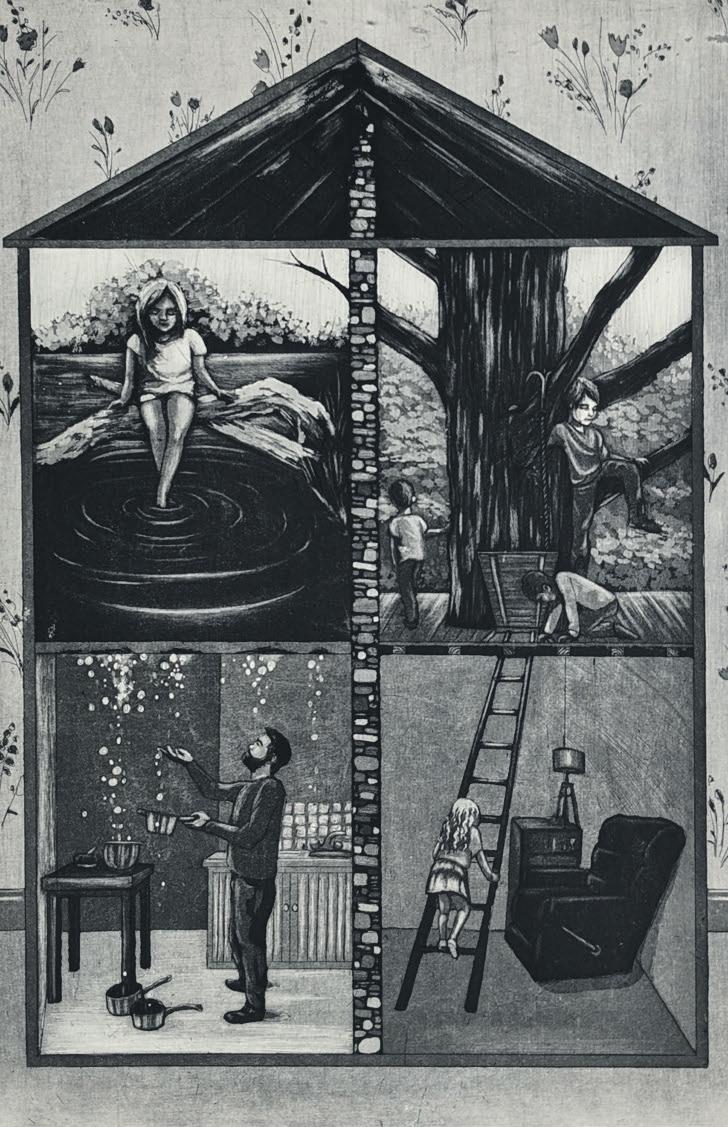

IMMA

IMMA presented ‘Irish Gothic’, a major retrospective exhibition by one of Ireland’s most accomplished and respected artists, Patricia Hurl, from 10 February to 21 May. Hurl’s work is of its nature, political and traverses the disciplines of painting, multi-media and collaborative art practice. The exhibition was the first major exhibition of Hurl’s work spanning more than 40 years and features over 70 of the artist’s paintings and drawings.

imma.ie

Rua Red

From 5 to 16 May, NCAD MFA students presented ‘Bigger Than Us’, which aimed to demystify the creative process and transcend the boundaries of difference. Individual endeavours took on a life of their own and exceeded the walls of the studio to allow insight into the chaos and uncertainty that corrals our contemporary and artistic experience. With works by Walker Shaw, Tallon McGinn, Fiona Somers, Marco Di Sante, Stephanie Rowe, Katie Whyte, Irina Mc Auley, Tammy Quane, Kate Hynes, Evan Dow, Justyna Doherty and Mia Shattock. ruared.ie

The LAB Gallery ‘Molecular Revolutions’ (30 March – 27 May) was curated by ARC LAB Curatorial Scholar, Shannon Carroll. ‘Molecular Revolutions’ was a multi-disciplinary group show presenting work by Bassam Al-Sabah, Mark Clare, Clodagh Emoe, Jennifer Mehigan, Erin Redmond, Rosie O’Reilly and Trevor Woods. Inspired by the French Philosopher and life-long eco-activist Félix Guattari, and his concept of molecular revolutions, this exhibition aimed to draw attention to our relationship with the natural world, one that has for so long been marked by disproportion.

dublincityartsoffice.ie

At Cathedral Quarter Arts Festival (27 April – 7 May), Dan Shipsides presented ha ha – syzygetically speaking, 2023 – a public artwork, deployed throughout the Cathedral Quarter area, featuring twinned flags that play with and celebrate the expanding communicative beauty and potential of the spaces between laughter and language. Shipsides’s photographic series, Summit Stammers – ha ha (Bearnagh), which documents the flags installed in another location, was also exhibited in the Black Box.

cqaf.com

Golden Thread Gallery

Golden Thread Gallery hosted Irish artist Niamh O’Malley after the hugely successful national tour of ‘Gather’, Ireland at Venice 2022. ‘Gather’ was the national representation of Ireland at the 59th International Art Exhibition of La Biennale di Venezia, curated by Temple Bar Gallery + Studios. The solo exhibition at Golden Thread Gallery, titled ‘Gather Belfast’, was informed by O’Malley’s work for ‘Gather’ while also exploring the breadth of her current practice. The exhibition ran from 29 April to 24 June.

goldenthreadgallery.co.uk

The MAC

On display from 7 April to 2 July, ‘At The Table’ brought socially and politically engaged practices into The MAC’s core gallery programming. It is the museum’s first major exhibition developed from MACtivate, the work they do with their five Associate Partners – The Rainbow Project, Participation and the Practice of Rights, Alliance for Choice, Action Mental Health and Extern. ‘At The Table’ aims to challenge who is and isn’t invited to ‘the table’ where decisions that determine our lives are made.

themaclive.com

The photographs in Lane Shipsey’s first solo show ‘ABHAILE | HOMING’ take an idiosyncratic, personal, and sometimes humorous look at home, homing, and ways we think about home. What do we mean when we say we feel at home? How do we feel when the place we live in could easily be someplace else? And when we wake not knowing where we are? These questions are posed in Shipsey’s photographs, made on a journey to find home. On display 1 June to 27 July.

culturlann.ie

‘FAKE BODY’ refers to a TikTok hashtag used to trick algorithmic moderators in order to avoid videos becoming flagged for containing partial nudity. The need to circumvent the automation and commodification of desires and personas through networked technologies is a shared concern for artists Lana May Fleming and Luke van Gelderen. Their work contrasts contemporary masculine identities, celebrity culture, and the modified female body with the pressure of unattainable perfection. On display 13 to 27 May.

platformartsbelfast.com

QSS Belfast presented ‘Future Works’, a collection of curated work from participants in the recently established HND in Product Design with Ceramics, a two-year full-time course in Belfast Metropolitan College. At the latest COP Climate Change Summit, world governments further committed to achieving ‘net zero’ carbon emissions. Each of us, as individuals and members of communities, has a part to play in changing our own behaviours. As creative practitioners we may also play a role in influencing the behaviour of others. On display from 4 to 25 May.

queenstreetstudios.net

36 Gallery presented ‘Openness’, a solo show by Irish artist Noel Hensey, from 9 to 18 June. The exhibition had two main elements: a large site-specific sculpture, inspired by the visual humour of the 1980s American television series, Police Squad! (1982); and a video work concerned with emotional openness. Hensey’s objective was to show that openness isn’t just the act of disclosing something personal; rather it’s about the all-inclusive spaces that can open up. Supported by the Arts Council of Ireland and Culture Ireland.

36limestreet.co.uk

‘A Sphere Of Water Orbiting A Star’ features significant new work by the Turner Prize-nominated The Otolith Group, co-commissioned by Galway Arts Centre and Hangar Artistic Research Centre, Lisbon. The exhibition features unreleased recordings of conversations between Gerald Donald of Detroit Techno duo Drexciya and Kodwo Eshun, along with films made in Galway at the mouth of the River Corrib as it enters the Atlantic Ocean. On display 13 May to 1 July.

galwayartscentre.ie

‘PORTALS’ was a group exhibition that delved into playful dreamscapes and journeys across fictional realms. The artists featured in this exhibition offered pathways into speculative fictions and alternate worlds. ‘PORTALS’ embraced the potentiality of technology, fantasy, and the unconscious mind in providing us with portals of escape. The exhibition incorporated newly commissioned and existing works including a site-specific outdoor sculptural installation by artist Daire O’Shea. On display 29 April to 22 June.

athloneartsandtourism.ie

Crawford Art Gallery

Anna Furse’s ‘muscle: a question of power’ is an immersive experience that takes visitors on an audio-guided journey through Crawford’s Canova Casts collection and culminates with a new video work exploring the muscularity of professional women. The exhibition engages with society’s contemporary obsessions with beauty and perfection, strength and power. It raises specific awareness of women and muscle, and how the ‘weaker sex’ gains agency through the acquisition of physical strength. On display 28 April to 20 August. crawfordartgallery.ie

The Glucksman

‘Hollow Earth: Art, Caves and The Subterranean Imaginary’ is a group exhibition that brings together a wide range of responses to the image and idea of the cave. It includes painting, photography, sculpture, sound, installation and video, as well as archives and architectural models, alongside works from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Featuring works by contemporary artists and collectives, ‘Hollow Earth’ descends into the depths to explore questions of prehistory and myth, ritual and the future. On display 10 April to 9 July.

glucksman.org

In Hanne Nielsen and Birgit Johnsen’s exhibition ‘Particles’, they perform as birdlike figures beamed down from somewhere in the universe. Together, they wander through Tarkovsky-inspired scenes. Drones are deployed to provide the vertical perspective they need to travel through time and space, unfolding a machine-vision, flying in abrupt movements, watching, searching, monitoring, and disappearing into the sky. On display from 28 April to 24 June.

ormstonhouse.com

‘Breath Variations’ by Christopher Steenson used sound, video, and transmission-based methodologies. ‘Breath Variations’ aimed to explore the materiality of time, its permanence and evanescence. By manipulating and extending the sonic dimensions of Flat Time House, Steenson investigated the capacity of breath as a ‘least event’–Latham’s term for the shortest departure from a state of nothingness – to punctuate linearities of time and space. On display 12 to 14 May.

flattimeho.org.uk

Rachel Parry and Cormac Boydell showed ‘Drawings on paper and ceramics’ at Grilse Gallery, Killorglin, between 1 April and 7 May. Parry and Boydell have been making art of a very high order for decades. Parry is primarily known for her intricate and haunting assemblages of ‘nature’s debris’; Boydell for his unique ceramics which are often a development from his notebook sketches. For the exhibition Parry showed a series of large-scale drawings of the human senses, while Boydell presented a selection of his many travel notebooks and drawings. grilse.ie

The inexpressibly precious and fast-diminishing craft of building wooden boats was celebrated in an exhibition of photographs by West Cork-based photographer, Kevin O’Farrell. ‘Hegarty’s Boatyard: Last Surviving Traditional Wooden Boatyard in Ireland’ ran from 13 May to 10 June at Uillinn: West Cork Arts Centre. Over the past 25 years, O’Farrell has created a body of work focused on three generations of the same family working in Hegarty’s Boatyard, Oldcourt, Skibbereen, County Cork.

westcorkartscentre.com

The F.E. McWilliam Gallery presented ‘Catherine McWilliams: Selected Work 1961 – 2021’ from 4 February to 3 June. For over six decades, McWilliams produced original and compelling images of life in Northern Ireland. Her work ranges from the domestic to the surreal and prioritises the experiences of women and children. McWilliams lives in North Belfast, in the shadow of Cavehill, and taught in a local secondary school during the worst years of the conflict.

visitarmagh.com

Lavit Gallery

‘Cork Printmakers Members Exhibition’ at Lavit Gallery featured new work by members of Cork Printmakers. The exhibition celebrated the diverse practices and approaches to fine art printmaking. With over 100 members, Cork Printmakers artists work across traditional and contemporary fine art printmaking techniques, including lithography, etching, screen-printing, and relief printing, as well as expanded print practice, which incorporates video, sculpture, and installation. On display 18 May to 10 June.

lavitgallery.com

‘Re_sett_ing_s’, a collaborative exhibition between Locky Morris and Jaki Irvine, was expanded upon with new filmic, digital and sound elements for Void Gallery and beyond. The artists were approached separately by Mark O’ Gorman, speculating on ‘hidden connections’. Unbeknownst to him, they had a close friend in common, the artist Anne Tallentire, whose Setting Out 3 (2021), with its yellow builder’s string and hints at musicality, acted as a touchstone for the development of the work. On display 4 March to 3 June.

derryvoid.com

Minister for Tourism, Culture, Arts, Gaeltacht, Sport and Media, Catherine Martin TD, and Dr Caroline Campbell, Director of the National Gallery of Ireland (NGI), unveiled Ireland’s first public Cézanne painting (the National Gallery owns a drawing by the artist, acquired in 1954). The painting, La Vie des Champs, was created between 1876 and 1877 upon the artist’s return to Provence, in southern France, from Paris.

Translating to “Life in the Fields”, the oil painting depicts an imaginary, idyllic scene inspired by the country life of Cézanne’s native Provence. The painting, made when Cézanne returned to Impressionism, offers a window into the evolution of the artist’s career with his employment of a lighter colour palette and sensational

IMMA (Irish Museum of Modern Art), Hugh Lane Gallery, and Culture Ireland are delighted to announce a new threeyear pilot named ‘IRELAND INVITES’, aimed at showcasing Irish visual art to the international biennale circuit.

IRELAND INVITES seeks to enhance international exposure for Irish visual artists by hosting biennale curators to undertake visits to studio and art institutions in Ireland. During their visit, curators will have the opportunity to enhance their understanding of contemporary art practices in Ireland, availing of the curatorial expertise of IMMA, Hugh Lane Gallery and Culture Ireland, who will facilitate research and create bespoke hosted trips for each visiting curator.

Commenting on the new initiative, Annie Fletcher, Director, IMMA, Barbara Dawson, Director Hugh Lane Gallery and Sharon Barry, Director Culture Ireland said: “An analysis of biennales over the last 20 years shows an opportunity to develop the representation of Irish visual artists internationally and IRELAND INVITES seeks to address this in a joint initiative between IMMA, Hugh Lane Gallery and Culture Ireland. Over the next three years, we look forward to welcoming curators from around the world to see the very best Ireland has to offer in terms of visual arts.”

Inti Guerrero, Artistic Director of the Sydney Biennale, 2024 is the first visiting curator as part of IRELAND INVITES. Later in the Summer, Miguel A. López and Dominique Fontaine, co-curators of the Toronto Biennale, 2024 will also visit Ireland to coincide with EVA International showcase taking place in Limerick. Further curator visits will be confirmed later in the year.

New Director at Void Gallery

Void Gallery in Derry is delighted to announce the appointment of Viviana Checchia as Director. Viviana Checchia is a curator, programmer, and researcher active internationally and joins Void Gallery from her recent roles as Residency Curator at Delfina Foundation, London, and Senior Lecturer on the MFA at HDK-Valand, University of Gothenburg.

brush strokes that are characteristic of his later, more famous works.

Originally owned by Cézanne’s renowned Parisian art dealer, Ambroise Vollard (1866-1939), this marks the first public display of La Vie des Champs since 1996, when it featured in a touring exhibition at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

It is hoped by the NGI as well as the Department that the acquisition will help in the Gallery’s recovery from the Covid lockdowns, and serve as a beacon of creativity and expression in Ireland. The painting is on display in the National Gallery’s Millennium Wing, Rooms 1-5, as part of the national collection and is open, free of charge, to the public.

Viviana brings with her long-standing experience as Co-Director of ‘Vessel’, an international curatorial platform based in Puglia, South of Italy, for the support of social, cultural, and economic development through and with contemporary art. Previous to these roles she was Public Engagement Curator at the Centre for Contemporary Arts, Glasgow, and has produced and contributed to a range of international projects, including the Young Artist of the Year Award, Ramallah, and the 4th Athens Biennale.

Welcoming the appointment, Void Board member and Curator at IMMA Ireland, Seán Kissane, said: “The Board of Void is delighted to welcome Viviana as the new Director. She has a fantastic record of achievement in many fields, including the co-founding of ‘Vessel’ with its focus on socially engaged practice, public programming, commissioning, and writing. Viviana has set out a very exciting vision for Void, and we eagerly anticipate seeing how this will evolve and develop in the coming years. The Board would like to sincerely thank the outgoing Director, Mary Cremin, for her extraordinary work at Void. Among the highlights were Helen Cammock’s winning of the Turner Prize; bringing Eva Rothschild to the Venice Biennale; and moving the gallery to its new home in Waterloo Place. We wish her the very best with her future endeavours.”

Responding to her appointment, Viviana said: “I am really looking forward very much to taking on my new role at Void and to working with the team and the board. Art and its relationship with society is one of the catalysts that has informed my work to date and I am excited to see what we can do at Void by way of this catalyst, with the locale and with the wide array of artists, curators and organisations connected to Void. Engagement and commoning have been very important aspects of my practice and I hope to share some of this approach as we shape a future for the organisation with Void’s creative ecosystem that is responsive to the urgent socio-environmental issues of our time and imaginative with the ways in which contemporary art can drive that ambition.”

The Minister for Tourism, Culture, Arts, Gaeltacht, Sports and Media, Catherine Martin TD has announced the selection of artist, Eimear Walshe, with Sara Greavu and Project Arts Centre as the curator, to represent Ireland at the 60th Venice Art Biennale in 2024.

The Venice Biennale is one of the most important international platforms for the visual arts, attracting over half a million visitors, including global curators, gallerists, art critics, and artists. The selection of the team to represent Ireland was made following an open, competitive process, with international jury members.

Eimear Walshe's pavilion for Venice 2024 will offer a new cultural synthesis that links our contemporary moment to the past, particularly to gendered and sexual legacies related to the history of land and housing. Working with a range of deeply talented collaborators, their work proposes a relationship with land and shelter driven by collective agency and community. This work will return to Ireland on a national tour, supported by the Arts Council, in a variety of venues across the island.

The selected artist, Eimear Walshe said: “I’m very proud to be representing Ireland at Venice this coming April. My practice is deeply enriched by being embedded in Ireland, in a place, and with people, so beloved to me. At the same time, my work emerges from the context of a nation in escalating crisis; this is the subject of my work. With Sara Greavu as curator, we aim to make a pavilion in tribute to those who persist, against the odds, in being shelter for each other.”

On 22 June, Lord Mayor of Dublin Caroline Conroy and Minister for Tourism, Culture, Arts, Gaeltacht, Sport and Media, Catherine Martin TD, announced details of €3 million in match funding for ‘Space to Create’. The initiative will provide up to 60 artist workspaces in the capital, in partnership with Dublin City Council.

Space To Create sees Dublin City Council (DCC) identify buildings which can be refurbished to create new artist workspaces. The shortage of workspaces is particularly

acute in Dublin and Space to Create will see a further €3 million invested by DCC so that artists will be provided with turnkey workspaces as well as opportunities to use performance and gallery space and flexible office spaces. More than half of the spaces will be in use before the end of 2024 and the remainder in early 2025.

DCC is also collaborating with Xestra Asset Management to develop artist workspaces at Artane Place in Dublin 5. In 2022, 14 artists, many of whom live or work locally in Artane, were awarded spaces following two rounds of shortlisting and interviews through an open-call process. This is a unique scheme where Dublin City Council and the Department support the capital refurbishment of buildings in Artane Place and DCC will then lease and manage the buildings to provide artists’ studios, helping professional artists to be able to live, work and create art in their local area.

The artists cover a range of art forms, from visual arts, performance, literature, design and dance. The first artists, Ella Clarke and Alan Mongey, will be moving into their new workspaces in the coming weeks, while the remaining 12 artists will be in place by December 2024. Ella Clarke commented “this new studio is five minutes from my home in Artane and will transform my practice as a dancer, teacher, and choreographer. As well as giving me time back, the quality and size of the space will be an inspiration and a step change in my career.”

In addition to the Curved Street building, where the announcement was made, and Artane Place, DCC is working to open up further unused sites. These include the Council-owned 8 and 9 Merchants Quay, which will also undergo a refurb to provide 21 artists workspaces and the former Eden restaurant in Temple Bar which will accommodate six artists. It is expected that artists will be in place in 2024. In addition, a vacant site on Bridgefoot Street will house 20 new temporary units for artists. 2 Curved Street (the former Filmbase) itself is currently in negotiation with new tenants after a year-long open call process conducted by the City Arts Office and Temple Bar Cultural Trust.

TO MY SURPRISE, the general public suddenly seems to care intensely about grammar. As an editor, I can confirm that the average person is not especially committed to the nuances and particularities of the English language; yet these things are currently being hotly debated in the media.

The language we use is important, particularly in relation to identity, since language is fundamental in shaping cultural expectations and perceptions of ourselves. The growing recognition of gender diversity1 is increasingly framing the usage of gendered pronouns (such as ‘he’ or ‘she’) as exclusionary, in certain contexts.2 It’s worth emphasising that this pertains specifically to the English language, since there are many widely spoken languages that contain no gendered pronouns. In English, conventional pronouns have the effect of assigning a binary identity,3 which excludes nonbinary people.4 It is also important to stress that this critical debate does not hinge on eliminating feminine or masculine pronouns, but on normalising the use of at least one gender-neutral pronoun5– namely, the ‘singular they’.6

My own learning on this subject began around six years ago, when a group of artists were writing an article for VAN. One of the artists referred to themselves as ‘they’ – which at first felt unusual, slightly cumbersome, and to my mind, grammatically incorrect. After an informative conversation with the artists (as well as some research, courtesy of The Oxford Compendium of English), I proceeded with the article using ‘they’ as a singular pronoun, while committing to learning more about the convention.

Certainly, the ‘singular they’ has been around for centuries and is widely used today in everyday conversation, as in: “Someone left their bike outside.” It is commonly used in situations where a person’s identity is not known. However, more pressing is its use in scenarios where a person does not wish to specify or disclose their gender, or actively states their preference for nonbinary pronouns.

We can see how historical resistance to the evolution of language might act as a cipher for some thinly-veiled moral code – one that serves to uphold societal order, lest it be plunged into existential chaos by syntax. For example, the usage of Ms – as opposed to Miss (used to denote a girl) or Mrs (referring to a married woman) –extends back to the seventeenth century, but it was revived and popularised in the twentieth century in response to a perceived need in the English language for a more general term, untethered to a woman’s domestic situation. Nevertheless, Ms was contested well into the twenty-first century, by those who felt it was variously bland, problematic, or even, as described by one Tory MP, “political correctness gone mad.” Nowadays, Ms has become so nor-

malised that many publication style guides stipulate its default use, unless the subject has expressed a specific preference for Miss or Mrs.

In the semantics of this debate, my own particular position is that I use gender-neutral singular pronouns and related adjectives out of respect for those who prefer it, but I acknowledge that its usage can lack linguistic precision or clarity in certain circumstances. [As a side note, many have argued that this perceived deficit requires the invention of a completely new non-gendered singular pronoun, and some have accordingly proposed suitable remedies; however, ‘they’ has gained the most traction, due to its historical precedence]. Often, I will seek alternative solutions, such as reconfiguring a sentence, where appropriate, to avoid the need for pronouns at all.

Crucially, there is a need to balance any pragmatic difficulties of using the singular they against what is at stake in the refusal to employ inclusive language. This may include actively or inadvertently aligning with homophobic and transphobic rightwing factions that are fuelling hostility and violence against already marginalised and othered communities. Research suggests that using non-gendered pronouns actually helps to reduce unconscious bias and gender stereotyping, while also enhancing positivity towards women and the LGBT+ community.7 Moving the conversation beyond whether or not gender-neutral pronouns are ‘legitimate’, to one of solidarity and empathy, is a small but proactive step in creating a more inclusive and accepting society.

Joanne Laws is Editor of The Visual Artists’ News Sheet.

1 Gender diversity describes gender identities beyond the Western binary framework of male and female. Many indigenous communities recognise multiple gender identities and societal roles, which are not assigned according to biological sex. This was commonplace in pre-colonial tribal communities.

2 Gendered or gender-specific pronouns reference someone’s gender: he/him/his or she/her/hers.

3 Binary identity refers to the classification of gender into two distinct, opposite forms of masculine and feminine.

4 Nonbinary describes genders that don’t fall into the categories of male or female.

5 Non-gendered, gender-neutral, or nonbinary pronouns are not gender-specific.

6 The singular ‘they’ is officially listed in the Merriam-Webster and Oxford dictionaries as a singular pronoun.

7 Summary report: Margit Tavits and Efrén O. Pérez, ‘Language influences mass opinion toward gender and LGBT equality’, PNAS, August 2019, Vol. 116, No. 34.

CHRISTA-MARIA LERM HAYES REFLECTS ON BRIAN O’DOHERTY’S SOCIAL PRACTICE LEGACY.

INSTALLING THE EXHIBITION, ‘Brian

O’Doherty: Reading Time’ at SIRIUS in Cobh, four months after the artist’s passing, and holding a Summer School there in his memory gives ample opportunity to engage with this polymath’s legacy.1 It is expected that O’Doherty’s US-based institutional activities – including his National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) directorship, Art in America editorship, Long Island University professorship of film, and so on –would be rather distant for Irish audiences to have figured much in an appraisal of his achievements here. It has been the visual art realm, after all, that has led his critical reception, with Brenda Moore-McCann, Christina Kennedy, Lucy Cotter, Yvonne Scott, and I, having done our bit from an Irish perspective. And if this ‘realm’ – for my students’ generation, at least – now exceeds what could once neatly be pinned down as art practice, art history, theory, curating, or criticism, then it is already clear that the category-defying artist would have a good chance at resonating more with current, expanded, rather than more rigidly disciplined, historical categories. He may even have something to contribute to artistic research, art writing, social practice, art activism, infrastructural critique, and decolonial work.

These connections are what I explored with the participants of the SIRIUS Summer School (6 – 10 June). It was poignant to do this at SIRIUS – the site of the former Royal Cork Yacht Club in Cobh, which overlooks the spot from where Brian O’Doherty emigrated in 1957, along with untold numbers of other Irish people. I was again ‘in residence’ in that building, as were the O’Dohertys in 1995-96, just before I got to know them. Walking in the footsteps of Brian and Barbara, holding the same keys, had quite an affective charge for me. Knowing that O’Doherty was a medical doctor and researcher in the field of perception, attention to materials and physical situatedness, feels particularly relevant there. It is this attentiveness and thoughtfulness that his work appears to value and foster in many different ways.

When planning the exhibition with Brian and Barbara in New York last July, I received his blessing to establish a material connection. I suggested not just to remake a rope drawing (HCE Redux, 2004) in the building but also to span the same kind of rope from the Classicist columns of the yacht club’s balcony to the dock below, showing in subtle, yet unambiguous ways how the leisurely, ‘civilized’ life of one group had necessitated the departure of others on coffin ships. This rope now reaches from art to the water, to address the global military complex’s presence in Cobh, questions of migration in Europe today, and the ecological issues on the doorstep of the exhibition space, too. That rope may be a fairly limp

little gesture that doesn’t do anything on its own, but it is there for all of us to stumble upon when admiring the sheer beauty of the location. Without it, we would have just borrowed from the ice cream-hungry attractiveness of Cobh to draw audiences and remained quiet. We know that silence about violence is also violence. O’Doherty didn’t remain quiet vis-à-vis Bloody Sunday. For 36 years, he signed perfectly well-behaved Ogham-derived prints and multi-coloured drawings responding to James Joyce with “Patrick Ireland” in an open invitation to remember and to act.

How plausible and connected in the here and now the social practice side of Brian’s work would be has been truly surprising to me – even me, I should say, as I’m the person who turned him into a bit of a Beuys in the introduction to my edited volume, Brian O’Doherty/Patrick Ireland: Word, Image and Institutional Critique (Valiz, 2017). He was happy about that. His ‘helicopter view’ on the spheres of art and writing had both a strategic and tactical side that the world today appears to need. I’m not suggesting that anything quantifiable was altered in the peace process on the island of Ireland because of the Name Change (1972), or that the art sector in the US is now without its problems because Brian marched through the institutions and made the funding landscape more inclusive for conceptual practices and artists from marginalised groups. His is a pioneering institutional critique (initiated in his book, Inside the White Cube, University of California Press, 1986) but it is also a foresighted, critical and infrastructural investment of considerable time, energy, and leadership qualities (namely thoughtfulness and kindness).

This is why my curating of O’Doherty’s exhibition at SIRIUS now surprisingly fits neatly with a very special EU-funded project on spatial practices for empathic exchange (SPACEX) and why ‘Cork Caucus’ – Art/Not Art’s Cork City of Culture programme, curated with Charles Esche and Annie Fletcher in 2005 – could feed into my Summer School programme as a local legacy of social practice. Even Patrick Ireland’s large, near-psychedelic, now MDF-covered wall painting from 1996 in the central space at SIRIUS may yet break down walls, starting (hopefully) with its own MDF. I think it should convince locals that in 1996, the old yacht club was turned into something special: rather than putting on show the ‘civilized’ side of oppressive power, it became theirs.

Christa-Maria Lerm Hayes is an art writer, researcher, and curator working at the University of Amsterdam.

1 Many friends and colleagues have done this recently. See: Brenda Moore-McCann (ed.), ‘A Tribute to Brian O’Doherty (1928–2022)’, The Brooklyn Rail, May 2023 (brooklynrail.org)

CORNELIUS BROWNE CONSIDERS THE SALVAGED AND THE HANDMADE IN THE EVOLUTION OF HIS PAINTING PRACTICE.

SHEETS OF HARDBOARD flung from a delivery van onto damp grass by the roadside –the beginning of a new body of work. My sawing is flagrantly amateur. Years ago, I gave up on achieving straight lines. For a long time, exhibiting my paintings left me feeling exposed. Most things I observed on gallery walls looked neat and professional. So, when the Regional Cultural Centre in Donegal recently purchased three landscapes for their collection, and selected examples of my worst DIY – speaking approvingly of visible blade-marks and knobbly edges as though they were part of the pieces, which of course they are – I felt momentarily uplifted.

Growing up, as the walls were perennially damp and we possessed no camera, there were few items of decoration in our home. Much of the ornamentation, however, had been blessed, and thus raised into the spirit realm. One of my chores was to keep holy water fonts replenished. Each room had its own crucifix. In plastic, darkening frames, miracles of apparition and beatification glowed amid fungal manifestations that no amount of scrubbing could halt.

Dad was a chronically unemployed oddjob man. Atop a stepladder, he radiated happiness as he lavished care on other houses, and, along as little helper, it stung me that our own walls repelled paint. Dad is now gone from the world, but I pass intricate stone buildings into which he poured hours of his life, nudging uneven segments into place, and he is standing there within the walls of resplendent properties. When time grew heavy and work was scarce, dad made cottages and bird houses from scrap wood on the kitchen table, painting onto them little wildlife scenes using leftover gloss. Mum, a lifelong hand-knitter, spun yarns as another jumper for an upmarket shop in Dublin materialised on her lap.

When I began painting seriously, around the age of ten, I also became a dedicated scavenger of wood and household paint. When I started painting outdoors, a couple of years later, the act of transferring sunrise from sky onto rough board appeared miraculous, gelling in my mind with our sacred

pictures. In lieu of learned technique, after long familiarity with patterns emerging from mum’s hands, I often felt I was knitting with paint.

In 1983, as I was beginning to modestly blossom as a young painter, distinguished economist Professor John Kenneth Galbraith delivered a lecture to the Arts Council of Great Britain at the National Theatre in London: “It is only when other wants are satisfied that people and communities turn generally to the arts; we must reconcile ourselves to this unfortunate fact. In consequence, the arts become a part of the affluent standard of living. When life is meagre so are they.” This conflating of the arts with affluence ignores the wealth of expressive work made by low-status people. Working with common or everyday waste material across generations has encouraged a distinctly autobiographical strain of creative energy, inventively linking art and craft. By the late eighties, installed in art college and struggling to function within the artistic, social and aesthetic environment of a culturally dominant class to which I did not belong, I found myself cut off from that energy. It was a long walk back to where I started from.

In 2016, the Douglas Hyde Gallery held a posthumous exhibition of paintings by Bill Lynch. The American artist had died three years earlier, aged 53, having never had a single exhibition in his lifetime. After studying art at Cooper Union in New York’s East Village, Lynch worked intermittingly as a house painter and carpenter. He started painting on salvaged wood because he was skint and eco-conscious. These hard and resistant materials – old plywood, used planks, a tabletop pocked with woodworm – underpinned paintings of insect-wing delicacy. We know little about Lynch, but we know that he said this, in a letter to a friend in the 1990s: “I realised that the art of the twentieth century is the fruit of personal revelation, while ancient art is the product of mystery initiation.”

SHANNON CARROLL DISCUSSES HER RECENT CURATORIAL PROJECTS INCLUDING AN EXHIBITION AT THE LAB GALLERY.

GROWING UP IN the Dublin mountains, I developed a deep affinity for our natural landscape, which has informed my values and motivations as a curator. With a background in History of Art and Philosophy from Trinity College, and an MA from UCD in Art History, Collections and Curating, I have a strong traditional research element to my practice. Reading and writing informs my thinking, and situates my research within broader contexts. Conversations are also a big influence on my practice. Talking with other artists and peers over coffee and studio visits, leading group discussions and nature walks, all inspire me to further develop my thinking whilst building relationships with other like-minded artists and researchers.

The outcomes of my research are project dependent. To date that has included curating exhibitions, commissioning work, creating installations, hosting events, interviewing artists, writing, and collaborating.

In 2021 I was awarded the ARC LAB Curatorial Scholarship, working alongside Curator Sheena Barrett at The LAB Gallery in addition to completing the MA in Art & Research Collaboration (ARC) with IADT. This scholarship gave me the opportunity to deepen my research on ecological art practice, develop my curatorial practice, and realise this research in the form of various projects and events.

For our MA graduate exhibition in January, I hosted a Climate Café at The LAB Gallery. This free event brought artists and the public together to discuss the intersections of art and ecology amid the climate crisis. I facilitated a group discussion with the artists Vanya Lambrecht Ward, Catherine McDonald and Rosie O’Reilly, exploring the practicalities of working as ecologically focused artists. This was followed by a lecture by artist Cathy Fitzgerald on eco-literacy for creative practice. Using the lens of art to create a relaxed space for people to come together and navigate difficult conversations around climate change, can help inspire action out of eco-anxiety and make people feel more connected.

My MA research led me to develop other projects and exhibitions. As a part of the inaugural Earth Rising eco art festival at IMMA last year, I collaborated with artist and friend Rosie O’Reilly, to create Tréimhse (2022), a deep listening, audio soundwalk in the formal gardens. Using field recording, sound and storytelling to lay down new pathways, the walk places Irish language with its close ecological observations at the heart of its storytelling. Tréimhse grew out of conversations between Rosie and I on the power of Gaeilge as a cornerstone of a new ecological era. As a native Irish speaker, I believe in the power of Irish words to offer us more complex and meaningful insights into the natural landscape, helping us to bridge the distance

between the human and more-than-human world.

My 18 months at The LAB culminated in planning and curating an exhibition based on my research. Inspired by the French Philosopher and eco-activist Félix Guattari (1930-1992), I curated ‘Molecular Revolutions’, which presented work by Bassam Al-Sabah, Mark Clare, Clodagh Emoe, Jennifer Mehigan, Rosie O’Reilly, Erin Redmond and Trevor Woods. Guattari saw an answer to the environmental crisis in ‘molecular revolutions’ and proposed re-examining everyday life, finding solutions through small acts of revolution that provide a counter argument to capitalist culture, and have the potential to bring about social transformation. The works in this exhibition question and challenge current structures in society. Working within the parameters of ecological art in Ireland, these artists softly subvert the status quo and make us question our place in the world. The exhibition drew attention to our relationship with the natural world, exploring how we got to this point and inviting us to think about what happens next.

In the spirit of connecting with our landscape and local ecologies, artist Suzanne Carroll and I curated ‘Barnavave – Tread Softly’, a one-day outdoor exhibition that brought people out of the traditional gallery space to a deserted hillside village known as Barnavave. Situated on the edge of the Cooley Mountains with many links to Irish mythology, the exhibition featured works from ten artists installed within the walls of the village ruins. The artists used ecological art practice to engage with this intriguing site, whilst working within the parameters of sustainable exhibition-making and the concept of ‘leave no trace’.

Other upcoming projects include curating a programme of exhibitions and public events with Kilkenny Arts Office, to coincide with Kilkenny Arts Festival and Culture Night. This is part of the Emerging Curator Development Programme, through which I will continue my research into ecological art practice and connections to place, with a specific focus on Kilkenny.

Art has always been at the forefront of cultural upheaval and social change. By engaging with local histories and ecologies, highlighting themes of responsibility, and acknowledging loss and waste, we can focus on shifting perspectives. Using the lens of art, we can uncover the deeper layers of our relationship to the more-than-human world, paving the way for alternative futures.

Shannon Carroll is an emerging curator of ecological art, whose practice explores the role that that art can play in climate change.

@shannonmariacarroll

IARLAITH NÍ FHEORAIS RESPONDS TO A RECENT FILM BY HOLLY MÁRIE PARNELL AND HER BROTHER DAVID.

DONEGAL-BASED ARTIST EMILY WASZAK CONSIDERS RECENT DEVELOPMENTS IN HER TEXTILE PRACTICE.

I TURNED TOWARD ritual through grief –profound grief in isolation – and desperation, which I imagine is a common enough path. When the sudden, unexpected death of my husband during the first Covid-19 lockdown left me completely alone in the extreme pain and sheer panic that grief brings, I looked for something to contain my grief. Ritual practice became that container. The only activities that could bring me back into my body were ritual chanting and weaving. During this time, unable to engage the future in any meaningful way, I began a series of small, automatic weavings, expressions of love and pain, which I called ‘Grief Weaving’.

tive labour. My practice is material and embodied, interacting with waste, found and natural materials collected from sites of industry, abandonment, and the natural landscape. These materials and objects have an active interiority that I seek to engage through making and installation processes. Repetition is also a key element of my work, from the repetitive under/over rhythm of weaving, and the making and remaking of object forms, to the daily practice of ritual acts.

CABBAGE (2023), A FILM by Holly Márie Parnell and her brother David, is an intimate portrait of a family and a journey home. David, Holly and their mom, June, moved to Canada from Ireland, following severe cuts to disability services under austerity in 2011. The film joins the family as they prepare to move back to Ireland after a decade away and chronicles the barriers they face in doing so. It is an intimate portrait of David’s life, his voice, and his relationship with his family, but we also experience a sense of a place, with contemplative shots of landscapes.

As well as offering a tender glimpse of a family experiencing the bitter sweetness of returning home, the film also considers the expectations we hold for human life, bodily autonomy, and how we care. It raises critical questions on the barriers disabled people face in living a full life and the right to home. The film features David’s writing, created using eye tracking technology, through which he asks “Does my body surprise you? Does my body inspire you? Does my body scare you?”

The film feels warm and familiar, with scenes of June gathering seaweed at dusk, David bathing in brilliant sunlight surrounded by lush foliage and bird song, watching YouTube, buying Aran jumpers, or speaking to Holly. In an early scene, June is shuffling through vast piles of medical papers, recanting the low expectations medical professionals had for David when he was going through the diagnostic process. She responds to this by saying: “I don’t know how you can measure the essence of being human.”

These reports, that can determine the outcome of a life, detail David’s condition and doctors’ opinions, many dismissive of David’s chances in life, which June says convey a “sense of just writing him off.” In a later scene, June is filling out a questionnaire as part of a new wave of paperwork, aimed at getting David the services he needs to

return home. It is clear that these questions are limited in scope and fail to grasp the full breadth and potential of disabled life.

Cabbage offers an account of the displacement of disabled people and their families due to austerity; but the film is also an account of ‘access intimacy’ between David and his family, despite this dispossession. According to disability justice campaigner, Mia Mingus, access intimacy is “that elusive, hard to describe feeling when someone else ‘gets’ your access needs, the kind of eerie comfort that your disabled self feels with someone on a purely access level.”1 The deep knowledge of access needs is so tied up with feelings of home. David and June share an intimacy around what he needs and wants on a foundational, affective level. When June is filling out a report detailing David’s care needs to service providers in Ireland she says: “It’s hard to get that all across in a little bullet-point form.” She notes that one of his care needs is “being outside, even late in the night looking at stars.” That’s what it’s all about –the dignity and freedom to go outside and look at the stars. This is how we will build a world in which disabled people don’t just exist but are allowed, as June describes, to be “so fully whole.”

Cabbage (2023) was screened as part of Berwick Film & Media Arts Festival in early March, where it received a Berwick New Cinema Award. The film was also presented at SIRIUS (18 March – 15 April) and is included in aemi’s 2023 Irish national and international tour, Súitú (aemi.ie).

Iarlaith Ní Fheorais is a curator and writer based between Ireland and the UK.

@iarlaith_nifheorais

1 Mia Mingus, ‘Access Intimacy: The Missing Link’, 5 May 2011, leavingevidence.wordpress.com

Mirroring the way grief moves and shifts through the body over the passage of time, the scale and trajectory of my work has also evolved. My work is concerned with building ritual imaginaries as anti-capitalist resistance, weaving thresholds to the unseen worlds of our loved ones and our ancestors. Reclaiming ritual requires a slowing down and contemplation of other, better worlds. The first step in building is imagining. To this end, I have been making objects of imagined rituals, starting from archetypal object forms. When assembled, these ritual objects activate the space, creating ritualised environments through which to view traces of the unseen.

During my time as Artist-in-Residence at Dublin City University (DCU), I developed a workshop called ‘Ritual Objects, Ritual Imaginaries’ in which the participants create ritual objects from found materials. Through the creation and use of these objects, participants examine what ritual can tell us about the kind of world we want to build. Ritual acts are prefigurative acts. My practice is a sculptural practice, grounded in the soft logic of textiles. With a background in industrial weaving, I use textiles as a medium through which to reframe and revalue feminised, reproduc-

As a migrant artist of Japanese descent living in Ireland, I have long struggled with how to present my work to a predominantly white Irish audience while remaining true to myself and my artistic vision. I do not want to perform my cultural identity for the white Irish gaze, nor do I want to hide it away. My work is deeply informed by my Japanese heritage, but it is not a literal performance of it. It is the lens through which I understand the world. I am inspired by my Japanese culture, even as I am situated in the wild, rural landscape of Donegal. In ‘Shadow and Fold’, a recent exhibition at Arts Itoya in Takeo, Japan, I incorporated small stones from my local beach in Donegal alongside the ceramic and textile objects I created using traditional Japanese materials.

Later this year I will present a new body of work at the Regional Cultural Centre in my husband’s hometown of Letterkenny. This solo exhibition opens on 22 September and marks the beginning of a supported relationship with the RCC, which will unfold over the next three years. I am so grateful for the kindness, patience, and artistic support I have received from so many people, while struggling to come to terms with loss and grief.

Emily Waszak is a Donegal-based textile artist.

@emily.waszak.art

FOR OVER 20 years, my eco-social practice has focused on exploring deep-rooted connections between art, food, farming, social justice, and resilience. My projects incorporate socially engaged, collaborative and performative processes, participatory moving image, large-scale drawing installations, as well as creative and autobiographical writing.

Grounded on a 19-acre organic farm with native woodland and meadows near Ballybunion in County Kerry, my partner Rena Blake and I run a project called The Barna Way. From here we engage with diverse communities of place and interest through social farming as well as live food and cultural events, while protecting habitats for wildlife. This 17-year project is propelled by an accelerated sense of urgency around food insecurity, the climate crisis, biodiversity loss, and forced migration. In 2020 we planted 10,000 native trees on our land and have developed a woodland walk.

Our aim is to create cultural spaces where communities, artists, food producers, and farmers can come together to resist industrial food systems and the fallacy of ‘cheap food’ by thinking global and acting local. Through the prism of eating and growing local food, communities are invited to create a vision for transformative food ecosystems. Projects include an annual 30-day Local Food Challenge, The Portlaoise Pizza and The Sandwich Project, which recently featured on the new RTÉ series, Food Matters (2023). My book, The Local Food Project (The Barna Way, 2018), explores the power of growing and eating local food in the context of climate change and biodiversity loss.

Thanks to Dr Cathy Fitzgerald and other artists involved with the Haumea Ecoversity training programme (haumea.ie), I am trying to spend more time embedded in the land and really listening to, and learning from, the nature around us. Earlier this year, I received the Creative Work Development Award from Kerry Arts Office for a project called ‘Dyeing Earth’, which involves creating natural dyes, charcoals, and drawing materials from the land outside my studio.

I was recently the embedded artist with ‘Corca Dhuibhne Inbhuanaithe / A Creative Imagining’, one of 15 pilot projects funded by the Creative Climate Action Fund. Over 18 months, I worked in partnership with the Dingle Hub, Green Arts Initiative of Ireland, and MaREI Research Centre for Energy, Climate and Marine, to support farm families on the Dingle Peninsula to creatively look at ways in which they can respond to climate change.

One of the main issues identified by farmers was that they felt their voices were not being heard, so we decided to co-create a film. Voices From the Field / Guthanna ón nGort (2023) gives a powerful insight into the communities that work on the Dingle Peninsula to rear animals and grow produce so that our wider society may be fed and nourished. With humour, diligence, and passion, the ten farming families provide an urgent overview of the real-time consequences of climate change affecting our local ecosystems and our lives today. The film is being screened at the Crawford Art Gallery until 23 July.

As part of the Climate Action Project, we were also invited by Creative Ireland to create a 100-foot interactive drawing project at the National Ploughing Championship last September. The Creative Climate Wall was a live response to the solutions for climate change offered by hundreds of farmers in sometimes challenging weather conditions. After the Ploughing Championships, the wall was transported by the OPW to IMMA for the Earth Rising Festival, where it was installed in the Garden Galleries and carried with it traces of rain and earth from the fields of Laois. As artists, we are being asked to move “beyond the ego to the eco”. We are being asked to respond to the climate crisis and work in collaboration with nature. The Creative Climate Wall was literally drawn with nature herself.

‘GLOSSARIES FOR FORWARDNESS’ is a multi-platform project examining convergences between landscape and memory through the architecture of the Museum Building in Trinity College Dublin (26 April – 23 September). This project arose from my artist residency at Trinity Centre for the Environment (2021-22) where my research approached geological sampling methods as ways to explore our interpretation of landscape, and how land can participate in its own representation and display.

Built in 1853 by Cork architects Deane, Son & Woodward, the Museum Building is a seminal work of Ruskinian Gothic architecture. The building itself can be thought of as a geological collection; it is constructed from a vast catalogue of stone types, indexing examples of Caen Stone, Armagh Limestone, Cork Red Limestone, Kilkenny Black Limestone, and Connemara Marble. My practice employs casting to construct sculptural archives that capture residual aspects of sites, mapping how materials are coded and transformed over time. The works in ‘Glossaries for Forwardness’ were developed by repurposing and inverting analysis procedures used by the Department of Geology, translating processes such as thin-sectioning, microscopic imaging, and resin-mounting into modes of making in the studio. This was informed by research into philosopher Isabelle Stengers, who proposes the scientific method as a practice to negotiate new ways for human and non-human relations to cohabit. The reality-generating potential of scientific field study emerges as a way to enable landscape to direct images and imaginations of itself. This became an important methodology for me to question how the interpretation, appropriation, and conservation of landscape can be reckoned with collectively in light of climate change.

‘Glossaries for Forwardness’ is curated by Rachel Botha, whose curatorial approach to the exhibition and its visual identity referenced the building’s materiality and design, the geology and geography departments housed within the building, and its existing displays. Site-responsive sculptural and textile interventions, installed throughout the foyer of the Museum Building, perform a reflexive sampling of the building’s interior, through an extensive material glossary which includes volcanic olivine dust, bio-resin, anthracite, acid-etched glass,

muslin, drafting film, and cast ink. In collaboration with Stanisław Welbel, a six-channel spatial audio installation emanates from the building’s ventilation system, composed on a synthesiser by assigning sounds to the various stone types to build a layered soundscape.

Exploring geology’s links to memory and visibility, ‘Glossaries for Forwardness’ offers an invitation to reimagine human relations to land. Just as the geological research that underpins this project is co-determined by the natural processes it attempts to represent, the presented works make space for the active agency of landscape to emerge. As deep-time materials intersect with momentary human gestures, ‘Glossaries for Forwardness’ activates the Museum Building to engage in a co-creative process whereby the geological actions that formed its architecture – layering, folding, stacking, accumulation, and erasure – become concentrated in the act of making. The exhibition is a call for forwardness, a linear push across one state of being and into another –solid to liquid, inner to outer – encouraging a critical engagement with the representative frameworks through which the climate crisis is mediated.

‘Glossaries for Forwardness’ is supported by the Arts Council, Trinity College Dublin, Trinity Centre for the Environment, Adam Mickiewicz Institute, Dublin City Council, and Fire Station Artists’ Studios. The exhibition is accompanied by a programme of talks, screenings, listening sessions, and a publication, with texts by geologist Dr Quentin Crowley, writer Anneka French, and me. A collaboration with the Department of Ultimology in September will include a talk exploring a range of visual and written resources, where stones signify endings, followed by a participatory workshop with artist Anaïs Chabeur.

Marie Farrington is an artist based in Dublin. She is artist-in-residence at Dublin City Council’s Residential Studios, Albert Cottages, and is currently presenting work in ‘Hammerheads’ at Solstice Arts Centre (1 July – 16 September). Forthcoming projects include a residency at SEA Foundation, Tilburg, and a solo exhibition, ‘Relics in Reverse’, at PuntWG, Amsterdam in 2024.

mariefarrington.com

OVER THE LAST two years, the agri-technology company, Devenish, kindly granted Solstice Arts Centre access to the Lands at Dowth in Meath. The multi-layered 552acre holding includes Netterville Manor, Dowth Hall, and significant Neolithic edifices. By means of systematic, material and field study, invited artists have shaped a rich and insightful arc of site occupation. The term ‘holdings’ is a word that epitomises the complexity of Ireland’s land use, referring to both tenure and human dominion, but also to the haptic touch, embodied labour, and connection to the land.

Maria McKinney traverses both traditional belief and cutting edge agri-tech. In Cairn mycorrhiza root blanket (2021), she cites the highly sophisticated communicative and shared roots systems between plant and fungi. The artist’s splayed form is contoured in hand-sewn glass beads and 3D-printed biopolymer mushrooms, hybridised with the earth. McKinney’s animal feed crafted dissenting mantra Need, Feed, Greed (2023) in punk pink gouache juxtaposes corporate interests with the nutritional demands of an escalating global population. In Goatherd (2022), the horns of the near-extinct Old Irish Goat, hang

at the neck of a woman’s coat, adorned in reclaimed SNP array chips – DNA microarrays used to detect genetic polymorphisms.

Cliona Harmey examines the future past of solar significance through experiments in light reactive substances. Harmey trials the nineteenth-century anthotype, in which images, derived from photosensitive plant material – in this instance the multispecies grass research swards of Dowth – develop in sunlight. An invisible stream of photons continually shifted Harmey’s Quadrat I and II (2023) throughout the exhibition. In Beam (2023), Harmey signals climate emergency via a common survival SOS mirror onto the steps of Dowth Hall.

Seoidín O’Sullivan’s practice is that of activism and commoning. A sandbag circle invites visitors to the exhibition to sit and exchange, chiming with the use of sandbags in both archaeological and flood fortifications. O’Sullivan correlates the quadrat, a key grass measurement device, to the ancient apparatus of sator, rebus and mathematical magic square, in complex material layering – from greenhouse tiled floor, farm apparatus and neolithic relief. In Settlement (2023) O’Sullivan arranges soil from the multi-sward seed in chequered floor outlay.

The sator acrostic word square, appears particularly appropriate if read as a horticultural care system:

R O T A S to rotate

O P E R A to aid, work

T E N E T to hold

A R E P O (meaning is uncertain)

S A T O R to sow

Martina O’Brien queries our failing hubristic control of nature and the duality of natural and technological networks in Throughout Outlier’s Stage, Mammalian Eye (2023). Animal and earth are bound by a multitude of natural and interweaving biological, migratory, climate and planetary systems, surveyed and quantified by manmade technological and methodical systems. O’Brien acts as citizen scientist, manually and systematically collecting feral night-time footage via animal tracking cameras. O’Brien alludes to sci-fi author Kim Stanley Robinson’s fictional technology – the ‘Internet of animals’ – that allow animals to communicate with humans and other animals via a network of sensors and devices. The footage is intermingled with ‘how to’ found internet footage of taxi-

dermy, querying humankind’s detachment from, and dominion over, the natural world.

Rachel Doolin and Anne Marie Deacy speak to ancient soundings and the use of white quartz stones known as Clocha Geala at neolithic burial sites. Quartz is a ‘triboluminescent’ material, which when rubbed together, creates a luminous glow. Quartz is also piezoelectric (an electrical converter of mechanical stress) utilised in various technologies, particularly in sound and time instrumentation. In Oscillithic (2023), a birch ply table physically vibrates with sounds of Dowth stone. Upon the rippling grain lies photographic research and chunks of quartz that glisten under the gallery lighting. Quartz as neolithic site signifier, ritual tool, and ancient instrument, criss-crosses millennia in the tiny crystal oscillator of Oscillithic II (2023), in which captured soundings trail up through deer antler antennae to shortwave radio transmission.

‘Holdings’ ran at Solstice Arts Centre from 6 May to 17 June. solsticeartscentre.ie

NATURE AND ART create the perfect daisy chain; the rhythms, colours, and textures are all a discovery for our senses. We love the excitement and anticipation of an exhibition opening, just as ornithologists and nature lovers hold their breath in anticipation of the sighting of the swifts and swallows, or the sounds and smells of the changing of the seasons.

Unfortunately, our anticipation of the delights that nature brings can no longer be taken for granted. The melancholic and beautiful song of the blackbird on a late summer evening is precious. Yet, taking the time to stop and listen has almost become non-existent for some people in their busy everyday lives.

Since 2021, IMMA has been hosting the wonderful IMMA Outdoors programme from June to September. Events have included workshops on weaving, botanical drawing, and printmaking, in addition to historical walks along with a host of evening events, as well as talks for all ages featuring guest artists. All of these events are facilitated by our Visitor Engagement Team.

This new programme of educational events provides an opportunity to design and develop a biodiversity tour, which I named The Green Cube Biodiversity Tours. The tours give participants possibilities for looking, listening, and learning about the flora and fauna that is particular to the 48-acre site at IMMA. The tours also allow a natural slowing down for people – it just happens that way, it’s human nature!

To date, there has been a very positive response to the biodiversity tours across a broad demographic. For example, older adults from the Mercer’s Institute for Successful Ageing (MISA), Bealtaine, and younger art students in IADT, TU Dublin, and UCD’s Department of Architecture have all engaged enthusiastically with the tours. I have also provided tours for primary and post-primary schools. In addition, I have collaborated with some of the artists in our Artists’ Residency Programme, facilitated by Janice Hough. Artists now more

than ever focus on strengthening the link between art and ecology. I was lucky to have the opportunity to work with the artist Clodagh Emoe in her development of the Seed STUDIO at IMMA (2021-22).

We celebrated International Women’s Day in March, beginning with an early morning Green Cube tour, followed by a workshop, facilitated by Brigid McClean, on eco dyeing, using natural plant dyes and home-spun wools. Finally, a tour led by Trish Brennan of Patricia Hurl’s exhibition ‘Irish Gothic’ completed the day. These three events united the Green Cube with the White Cube of the gallery space, bringing together the outdoors and indoors of the museum.

IMMA celebrated Earth Day on 22 April by organising a day of biodiversity tours which involved a walk and talk tour of the outdoor sculptures, located throughout the grounds of the museum. In September, we will once again host the Earth Rising Eco Festival. Earth Rising will provide a focus on the most exciting innovators in the field of eco citizen science, design, and creativity. It is hoped that this will give rise to greater awareness of how audiences can become agents of ecological change.

The social benefits of the biodiversity tours at IMMA are also important to highlight. The tours for older adults, in particular, have had a very positive effect, allowing people to see nature with fresh eyes and enjoy the outdoors in a relaxed and safe environment. Participants often arrive as strangers and leave as fellow nature lovers. We regularly enjoy a coffee and chat together in the Courtyard Cafe at IMMA, sharing a favourite nature poem, story, or even a song.

IMMA Biodiversity Tours will take place on: Friday 7, 14 and 28 July; Friday 4, 11 and 25 August; and Friday 15 and 22 September. All tours begin at 2pm. For booking details see IMMA website.

imma.ie

James Kelly VAI MemberI CREATE SCULPTURAL objects and videos that are concerned with non-waking realities and especially explore a rare type of dream in which is felt the tone and flavour of another reality – one that seems external to my own subconscious. I seek release from the mundane through forms of magical thinking, the making of tools, shrines, and charged objects, reminiscent of game pieces, glyph-like alphabet forms, or ritual items. Agreeing with Derek Jarman’s assessment that film is an inherently magical medium that transforms matter into light, I use Super 8 and photography as thought processing vehicles.

A great portion of my video work between 2009 and 2012 imagined an intuited state between the nomad and the agriculturist. For example, in the digital video, Glimpse of the Matter (2010), a figure digs laboriously by hand a series of deep holes, searching for something essential within. I believe that early farming must have commenced our questionable sense of ownership of land, seeding our tendency to look at the earth as a resource while cutting that symbiotic umbilical cord with our environment, more intrinsic with herd-following, nomadic behaviour. In They Could Not Have Known What They’d Eaten (2012), a great journey is made through the farmlands of continental Europe into North Africa, encountering seasonal festivals, such as May Day in Cornwall and the Vendemmia wine harvest parades in Italy.

As James Frazer hypothesised in The Golden Bough (Macmillan and Co., 1890), a need to influence the outcome of the seasons developed a ‘sympathetic magic’, accessed through ritual and resulting in the beginnings of religious practice. Through this sympathy, the practitioner hopes to have an effect upon the world. In the Irish context, rural folk customs, piseógs, and superstitious practices evolved to enact symbolic control over the landscape.

During my residency at Leitrim Sculpture Centre last year, I created a series of works which slowly evolved from my encounters with a narrow belt of the Glenade Valley in north Leitrim. Beside Eagles Rock to the west and above Gle-

nade Church to the east, are two fading zigzagged paths, which climb the sheer stony faces of the valley. Once the routes of wheelless carts bearing turf, they are now for me gateways to the unpeopled upper lands of dark lake waters and heather-beds – spaces readily populated by the imagination. My encounters with this dramatic, shapeshifting landscape infused my new work with otherworldly dimensions.

A particular kind of dream gave rise to the objects and assemblages displayed in my recent solo exhibition, ‘Lightning Path’, at LSC (5 May – 10 June). Far from the everyday unconscious, there occasionally comes visions of another parallel world, provoked by external forces, encountered directly in the land. These dreams are super charged and remain in the memory clearly for long periods. I find myself in the setting of vast, ruined, or abandoned spaces, cities, rock-cut temples, portals, or shrinelike structures. The remains of such portal sites, naturally formed or archaeological, are widely dispersed across the north-Leitrim landscape.