George Bolster, ‘Communication: We Are Not The Only Ones Talking...’, installation view; photograph by Tomasz Madajczak, courtesy the artist and Uillinn: West Cork Arts Centre.

6. Roundup. Exhibitions and events from the past two months.

8. News. The latest developments in the arts sector.

9. Guerrilla Painting. Cornelius Browne considers connections between underground filmmaking and plein air painting. Turning Towards a Rupture. Fiona Hallinan discusses the demolition of Ireland’s second largest catholic church.

10. Intrinsic Models of Accessibility. Iarlaith Ni Fheorais outlines a forthcoming access toolkit for curators and producers. The Fabric of Nostalgia. Belfast-based artist, Anushiya Sundaralingam, reflects on her multidisciplinary practice.

11. Unruly Forms of Care. Cecilia Graham and Grace Jackson discuss their curatorial residency at PS² in Belfast. To Huddle. Saidhbhín Gibson outlines an informal art discussion group she has been convening since 2017.

12. An Art to Grief. Day Magee reflects on the significance of losing their father and the profound art of human grief. How to create a fallstreak. Neva Elliott discusses her recent solo exhibition at Linenhall Arts Centre.

Organisation Profile

13. Greywood Arts. Jessica Bonenfant outlines the evolution of a multi-disciplinary artist’s residency and hub in Cork.

Career Development

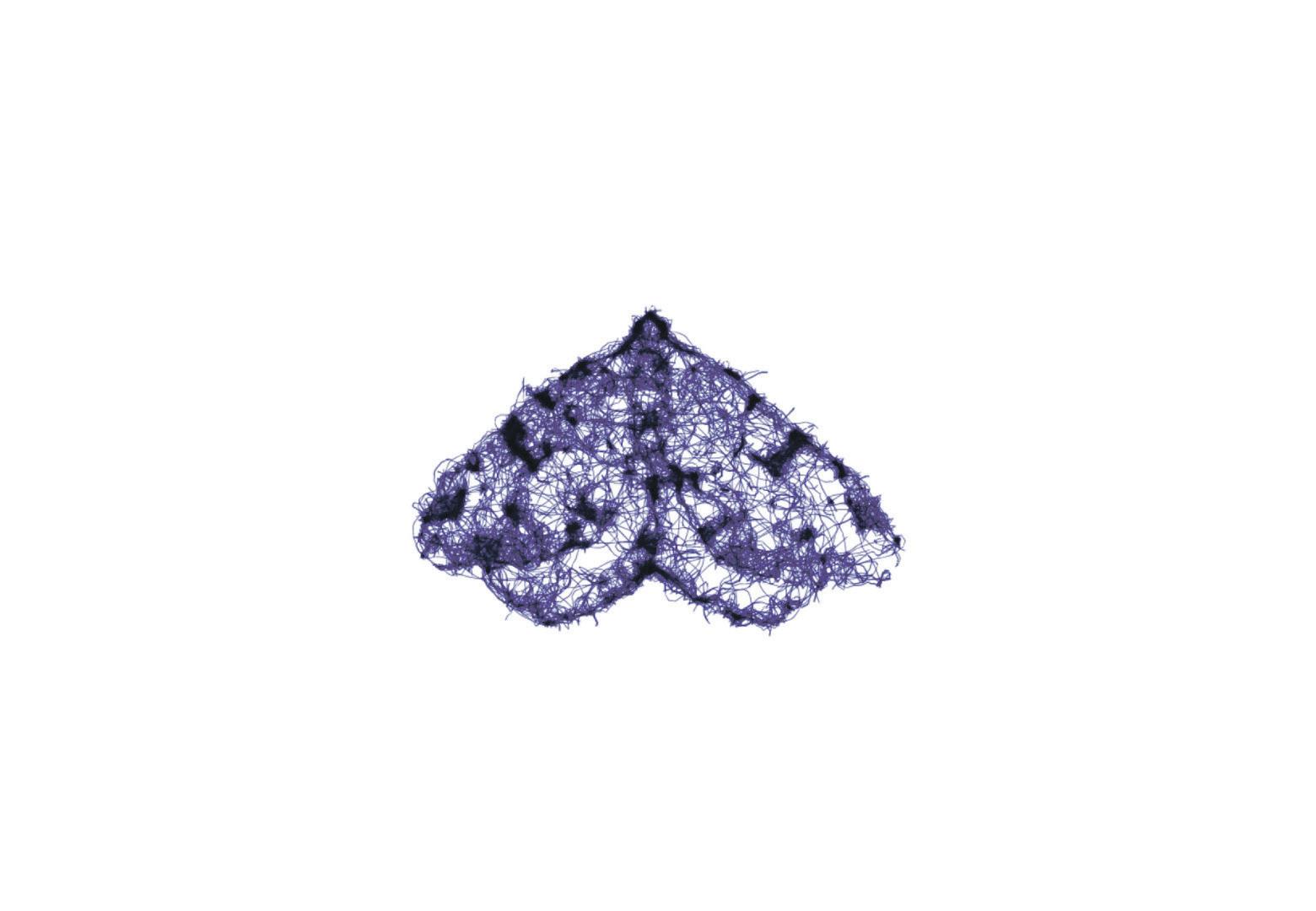

14. Older Than Our Gods. Brian Curtin interviews artist George Bolster about the evolution of his practice.

16. Home, Architecture, Territory. Miguel Amado interviews Alice Rekab about evolving thematic concerns in their practice.

19. Fiona Kelly, No Such Thing as Away #3, 2023; photograph by Kate-Bowe O’Brien, courtesy of the artist.

20. John Beattie, ‘Reconstructing Mondrian’, Hugh Lane Gallery

21. Anthony Luvera, ‘She/ Her/ Hers/ Herself’, Belfast Exposed

22. Fiona Kelly, ‘A Demarcation of Time’, RHA Ashford Gallery

23. Raymond Watson, ‘Apis Mellifera', ArtisAnn Gallery

International

25. Leaking Lands. Miguel Amado and Georgia Perkins outline a solo show by Ofri Cnaani presented at Rampa in co-production with SIRIUS.

26. Image as Protest. Varvara Keidan Shavrova reviews an exhibition by Joy Gerrard and Paula Rego, currently showing at Cristea Roberts Gallery in London.

Exhibition Profile

28. Xenophon: Making Oddkin. Michaële Cutaya reviews Siobhan McGibbon’s recent solo exhibition at Galway Arts Centre.

Project Profile

30. The Invisible Museum. Curator Brendan Fox outlines recent and forthcoming projects from the Museum of Everyone.

31. Centre Becomes Margin. Léann Herlihy reflects on their recent performance at Project Arts Centre.

32. Systemic Crisis. Maximilian Le Cain reviews Doireann O’Malley’s new 3D theatre play, Conversations on a Crosstown Algorithm.

VAI Member Profile

34. Shetland: An Archaeology of the Unknown. Jackie Flanagan outlines a recent body of tar paintings made in Shetland.

35. Vision Over Visions. Pat Boran reflects on a recent exhibition by VAI and Aosdána member, Sean Fingleton.

36. Rural Mythologies. Shane Finan discusses some of his recent site-responsive projects.

Last Pages

37. Public Art Roundup. Art outside of the gallery

38. Opportunities. Grants, awards, open calls and commissions.

The Visual Artists' News Sheet:

Editor: Joanne Laws

Production/Design: Thomas Pool

News/Opportunities: Thomas Pool

Proofreading: Paul Dunne

Visual Artists Ireland:

CEO/Director: Noel Kelly

Office Manager: Grazyna Rzanek

Advocacy & Advice: Elke Westen

Membership & Projects: Siobhán Mooney

Services Design & Delivery: Alf Desire

News Provision: Thomas Pool

Publications: Joanne Laws

Accounts: Grazyna Rzanek

Board of Directors:

Michael Corrigan (Chair), Michael Fitzpatrick, Richard Forrest, Paul Moore, Mary-Ruth Walsh, Cliodhna Ní Anluain (Secretary), Ben Readman, Gaby Smyth, Gina O’Kelly, Maeve Jennings, Deirdre O’Mahony.

Republic of Ireland Office

Visual Artists Ireland

The Masonry

151, 156 Thomas Street

Usher’s Island, Dublin 8

T: +353 (0)1 672 9488

E: info@visualartists.ie

W: visualartists.ie

Northern Ireland Office

Visual Artists Ireland 109 Royal Avenue Belfast

BT1 1FF

T: +44 (0)28 958 70361

E: info@visualartists-ni.org

W: visualartists-ni.org

Patricia

10 Feb — 21 May

A major retrospective by one of Ireland’s most accomplished and respected artists

Admission: Free Book Now at imma.ie

IMAGE: Patricia Hurl, The Kerry Babies Trial, 1985 / oil on canvas, 155 x 109 cm / Drogheda Municipal Art Collection, Highlanes Gallery / Courtesy The Highlanes Gallery / Photographer: Jenny Callanan

IMAGE: Patricia Hurl, The Kerry Babies Trial, 1985 / oil on canvas, 155 x 109 cm / Drogheda Municipal Art Collection, Highlanes Gallery / Courtesy The Highlanes Gallery / Photographer: Jenny Callanan

The Arts Council’s Artist in the Community (AIC) Scheme, managed by Create, offers awards to enable artists and communities to work together on researching, developing, and delivering projects.

Closing Dates

Round One: 27 March, 2023

Round Two: 25 September, 2023 www.create-ireland.ie

Daniel Tuomey

Venus Patel

Tanad Aaron

Dublin Black Church Print Studio

Black Church Print Studio presented ‘Love you my sweaty’, curated by Sara Muthi, winner of Black Church Emerging Curator Award, at The Library Project. The often discarded aspects of daily life can reveal poignant realities and important commentaries about the human condition, class structures, and lived experience. With this exhibition, Ella Bertilsson, Susan Buttner, An Gee Chan, Michelle Malone and Alison Pilkington look to restage inner dialogues ranging from the silly to the existential. On display from 13 to 28 January. blackchurchprint.ie

Hang Tough Contemporary

Hang Tough Contemporary in collaboration with Ceadogán Rugs presented the ‘Island’ exhibition in aid of the Peter McVerry Trust. ‘Island’ was an ambitious undertaking in which Ceadogán invited 12 of Ireland’s leading artists to collaborate on creating a unique one-off rug or wall hanging based on each artist’s designs. The work was exhibited at Hang Tough Contemporary from 26 January to 5 February and was then auctioned by Whyte’s Auctioneers on Sunday 5 February.

hangtoughcontemporary.com

The Irish Architectural Archive and Askeaton Contemporary Arts presented ‘Little Republics: Preparations and Elements’, a solo exhibition by Adrian Duncan. This extensive presentation of artworks and interventions is the culmination of a yearlong artist residency scheme situating the artist between Dublin and Askeaton. During this time, Duncan has researched and developed a new series of sculptures, displays and printed matter, each related to the cultural impact of the housing phenomenon ‘Bungalow Bliss’. On display from 13 January to 3 March.

iarc.ie

Draíocht

Pushing into space is the first solo show by Ellen Duffy, Draíocht’s resident artist 2022/2023, commissioned by Draíocht and curated by Sharon Murphy. Duffy works across sculptural assemblage, expanded painting, mixed media collage and drawing. Her process is playful and seeks the building of dialogue between the objects and materials used in her work. For this new body of work, Duffy has adopted and retranslated found and sourced materials during her year-long residency at Draíocht. On display from 1 March to 29 April.

draiocht.ie

IMMA

‘Xenogenesis’ brought together a selection of works by The Otolith Group, the London-based artist collective founded in 2002 by Anjalika Sagar and Kodwo Eshun. The Otolith Group’s pioneering artworks address contemporary social and planetary issues, the disruptions of neo/colonialism, the way in which humans have impacted the earth, and the influence of new technology on consciousness as well as “a science fiction of the present” through images, voices, sonic images, sounds, and performance.

imma.ie

‘Time Sensitive: Leeward’ presented a series of reflections and observations rooted in the artists’ lived experiences. Artists Anne Vetter, Frank Abruzzese, Karl Logge & Marta Romani, Laurence O’Toole, Rosie O’Gorman, Sarah Ellen Lundy and curator Karla Sánchez, have all resided for long periods in both city and countryside, the latter being the place where, in the last several years, they have spent most of their time. The Rural is not a unified and defined space; it is hybrid, it is complex. There are, also, multiple discourses of rurality. On display from 28 January to 10 February. mart.ie

Bbeyond

Bbeyond celebrated the 80th birthday of one of their founding members, trustee and current committee member Alastair MacLennan on 3 February. MacLennan has been an inspirational, seminal figure in the Northern Irish, Irish and UK performance art world. He continues in his 80th year as a vibrant practicing artist whose openness draws many not only to his work but to him as a person, his practice and life intertwined. ‘Art in life, life in art’, the Bbeyond motto, is certainly true of MacLennan.

bbeyond.live

Naughton Gallery

Featuring a range of local and international artists, ‘NGXX’ spanned a broad variety of processes and practices. Painting, photography, drawing, sculpture, illustration, tattoos, and textiles are all represented. The 20th anniversary of the Naughton Gallery is commemorated through a visionary, panoramic survey of a truly exciting roster of artists at various points in their careers, from established names to emerging talents. On display from 13 October 2022 to 29 January 2023.

naughtongallery.org

QSS

QSS presented the 2022 graduates from Belfast School of Art as part of ‘Emergence VI’. Now in its sixth year, the annual ‘Emergence’ exhibition provides a professional platform for recent graduates at a transitional stage in their career. The exhibition featured work by: Adam Skinner, Brea Freeburn, Darcy Patterson, Deborah Adair, Emma Stewart, Eva Perrott, Katie Ballentine, Louise Kennedy, Luke Foster, Melissa McKee, Miles Smith, Natalie Gibson, Reuben Brown, Rhys Murphy and Tomas Antunes. On display from 12 to 9 February.

queenstreetstudios.net

Golden Thread Gallery

Golden Thread Gallery presented Phillip McCrilly’s first solo show in the project space of the gallery titled ‘I Can Never Nail the Days Down’. Curated by Mary Stevens, the exhibition explores “gender socialisation, considered ideas around home, as well as the potential for a fulfilled queer life in a rural Irish context.” The work questions McCrilly’s own relationship with the post-conflict period, intimacy and research into the connection of people and place. On display from 7 January to 18 February.

goldenthreadgallery.co.uk

Pollen Studio and Gallery

Aoibhin Maguire is an artist from Belfast, who now lives and works in London. ‘This Earth is Alien to me’ was Aoibhin’s first solo exhibition. Interested in emotion, place, home, storytelling, diaries, chaos and daydreaming, Aoibhin contrasts her complex subject matter with her use of bright colour – something which she has always been drawn to. The title alludes to her experiences of imposter syndrome throughout her time on earth. On display from 2 to 4 February.

pollenstudiobelfast.com

Ulster Museum

‘The Druithaib’s Ball’ is the 2021 Turner Prize-winning installation by the Belfast-based artists known as Array Collective. They are the first artists from Northern Ireland to win the prestigious Turner Prize. The group of eleven artists from the north and south of Ireland, England and Italy all live and work in Belfast creating collaborative actions in response to socio-political issues affecting them and their communities. The exhibition continues until 3 September.

ulstermuseum.org

Backwater Artists Group presented ‘Tonnadh // Fuaim an Toinne’, an exhibition of work by Bríanna Ní Léanacháin, which ran from 26 January to 17 February. Bríanna is the recipient of the Backwater Artists Group Ciarán Langford Memorial Bursary 2021. The exhibition consisted of a video-based installation, exploring the changing relationship to the landscape and inspired by research into folklore and ancient Irish history. It addressed the overwhelming anxiety born from the current climate crisis through Irish folklore. backwaterartists.ie

‘Catherine McWilliams: Selected Work 1961 – 2021’ runs until 3 June. For over six decades, McWilliams has produced original and compelling images of life in Northern Ireland. From a self-portrait painted when she was 21 to recent compositions exploring the threat of climate change, her work ranges from the domestic to the surreal and prioritises the experiences of women and children. McWilliams lives in North Belfast, in the shadow of Cavehill, and taught in a local secondary school during the worst years of the conflict.

femcwilliam.com

‘At The Gates of Silent Memory’, is a solo exhibition of photography by Clare Langan, curated by Eamonn Maxwell. Known for her expansive and award-winning film projects, which have been seen in galleries and festivals across the world, Langan has a parallel photography practice using digital SLR and the unique Hasselblad XPan cameras. These images are taken in locations around the world including Dubai, Iceland, Kerry, and Monserrat reflecting Langan’s practice and environmental concerns. Exhibition continues until 20 April.

athlone.ie

The PhD exhibition ‘Re-Cover’ ran from 19 January to 24 February. There was also a symposium on 25 January at the BCA Lecture Hall and online via Zoom. ‘Re-Cover’ included the work of nine current PhD students – Fadwa Bouziane, Qi Chen, Kat Cope, Kate Collyer, Katerina Gribkoff, Joseph Hendel, Kelly Klaasmeyer, Robbie Lawrence, and Ling Liu – who collectively covered ground through artistic research. The artists are searching and re-searching for new understandings: both un-covering and re-covering systems.

burrencollege.ie

glór

Due to the ongoing war, contemporary artist Yevhen Svitlychnyi was forced to flee Ukraine for Ballyvaughan and the Burren. In Ukrainian, painting is called obrazotvorche mystetstvo, literally the art of creating images. In the works presented in this exhibition, the images of the unspeakable tragedy of the war are created through the prism of thousands of years of biblical history, and culture: war – death – life – image – myth. ‘The Burren – Ukrainian Chronicles: Part III’ was on display from 27 January to 25 February.

glor.ie

‘Lined Out’ is an exhibition by Emma Roche, recipient of the 2021 Wexford Arts Centre EMERGENCE Award. With an idiosyncratic approach to painting encompassing weaving, knotting and knitting, Roche’s unorthodox textural paintings are accompanied by a new large-scale commission of hand-screen printed works on paper by ‘Small Night’ by James Merrigan. Roche’s preparatory drawings, made quickly and obsessively, are informed by the humdrum of repetitive daily tasks. Exhibition continues until 11 March.

mermaidartscentre.ie

Niamh McCann’s ‘Hairline Crack [a dialogue]’ is a new multimedia body of work that responds to the 100th anniversary of a North-South border. Metaphorically mining the deep seams of colonialist atrocities and plundering, it combines sculpture, collage and video to question the vestiges of dominant power structures. McCann cuts through well-devised spectacles to subvert landscapes, material histories as well as the dominion humans have held over earth. On display from 3 February to 26 March.

centreculturelirlandais.com

GOMA

‘I brought the dream of flying…’ was a new exhibition by artists Corina Duyn and Caroline Schofield, that took place at GOMA Gallery of Modern Art, Waterford, from 14 January to 11 February. Inspired by a broken-winged bird puppet which accompanied Corina when she moved to a full-time nursing home care last year, the exhibition features work made in response to this move and illustrates the new collaborative creative process Corina has developed with Caroline as a result of her increasing disability.

gomawaterford.ie

There is nothing like a period of enforced isolation to remind us of the deeply human (and non-human) need to come together. ‘If We Could See Ourselves As Others See Us’ by Brian Irvine and John McIlduff (Dumbworld), is a sound, video and living installation inspired by a journey through moments of assembly across Meath. Choirs now able to join and sing together, swimmers taking the cold plunge together, gravestones repurposed as picnic tables for gatherings, trees connecting under the earth in a network of support. On display from 14 to 27 January.

solsticeartscentre.ie

‘Inverts on the castle wall, Perverts in the tall grass below’ by Kian Benson Bails, presented a body of work produced through investigations into rural Ireland, aesthetic language associated with rural and regional art spaces and queer communities. Using historical canon to construct alternative narratives around Irish queerness, the title of the exhibition frames language, and anglicisation of queer academia and asks how this written and documented theory is engaged in Irish culture. On display from 1 December 2022 to 15 January 2023. customhousestudios.ie

Lavit Gallery presented Helen Cantwell and Bernie Hennessy, with the 2022 Roberts Nathan Student of the Year Award. This is an annual award given to one or more graduates of MTU Crawford College of Art & Design. In addition to an exhibition at Lavit Gallery, both artists receive a cash prize of €500 sponsored by Roberts Nathan Accountants, Cork. This exhibition marks the beginning of Lavit Gallery’s 60th anniversary programme. On display from 26 January to 18 February.

lavitgallery.com

The Model presents Niamh O’Malley’s ‘Gather’ – the critically acclaimed exhibition that represented Ireland at the 2022 Venice Biennale. Works from Ireland at Venice are brought into an expanded dialogue with a larger selection of O’Malley’s artwork. This exhibition also reveals and considers the influence of the west of Ireland on her work.

Born in County Mayo, O’Malley uses many materials including steel, limestone, wood, and glass. She shapes and assembles objects to create a purposeful landscape of forms. On display from 3 February to 9 April. themodel.ie

Uillinn: West Cork Arts Centre and the Crespo Foundation are very pleased to announce visual artist Dominic Thorpe as the recipient of the inaugural Uillinn: West Cork Arts Centre Residency Award 2023 supported by the Crespo Foundation. The Frankfurt-based foundation, originally established by the photographer, psychologist and philanthropist Ulrike Crespo (1950-2019), carries out operational projects in the fields of art, education and social affairs.

The Uillinn/Crespo Residency is a residency opportunity open to contemporary visual artists based outside the county of Cork and encompasses a purpose-built studio at Uillinn, accommodation in Skibbereen, travel costs and a weekly stipend of €350 over an eight-week

PhotoIreland announced the five Irish artists selected to join the FUTURES Photography Platform in 2023. They are: Aindreas Scholz, Emilia Rigaud, Niamh Barry, Phelim Hoey, and Ryan Allen. In joining the platform, now in its sixth year, they not only enter a growing list of talent from across Europe, but also benefit from a growing range of opportunities supported by Creative Europe and the 18 platform members planned throughout the present year, culminating in an annual networking event at the Robert Capa Contemporary Photography Centre in Budapest.

PhotoIreland continues its role as the Irish member of the platform, supporting contemporary artists and bringing international practices to Ireland. Currently, PhotoIreland is working closely with FOMU, Fotodok, and Robert Capa Contemporary Photography Centre co-curating the annual travelling FUTURES exhibition and co-editing the annual publication. The exhibition will travel to Fotodok and then to Dublin in July 2024, in the context of the FUTURES Meet Up event, and will be accompanied by a busy networking and educational programme for audiences and artists in addition to the exhibition.

Former tenants of Belfast’s Cathedral Buildings, which was devastated by fire last year, are set to benefit from £154,696 of funding support to sustain their work.

The Arts Council of Northern Ireland announced that 13 former tenants of Cathedral Buildings are set to receive £154,696 of exchequer funding, supported by the Department for Communities (DfC) and Belfast City Council, as part of the Cathedral Buildings Fire Support Programme.

On Monday 3 October 2022, the Old Cathedral Buildings on Donegall Street, Belfast, was devastated by fire severely impacting the livelihoods of the many creative businesses, sole traders and practicing artists based there.

Following an initial exercise to gauge the former tenants’ needs, the Arts Council of Northern Ireland, in partnership with the Department for Communities and Bel-

period from 22 July to 16 September 2023. The open call for the residency received 167 applications from all over the world. The selection panel noted the exceptionally high standard of proposals received.

Dominic Thorpe works in performance art, as well as drawing, video, photography, installation and relational processes. Dominic’s work has addressed a range of critical content, most recently focusing on collective memory and perpetrator trauma. He has regularly engaged with artist-run initiatives as well as inclusion and education-based projects and organisations.

fast City Council, launched the Cathedral Buildings Fire Support Programme in December 2022. The programme offers former tenants funding to counter the costs incurred as they relocate and seek to re-establish themselves.

Dr Suzanne Lyle, Head of Visual Arts, Arts Council of Northern Ireland, added, “The Arts Council of Northern Ireland welcomes this good news and is grateful to the Department for Communities for making this vital funding available to those whose livelihoods were devastated by the Cathedral Buildings fire. This funding is absolutely critical in helping these artists and arts organisations reactivate their work, sustain their artistic practice and manage existing projects.”

John Ball, Head of DfC’s Arts Branch said: “The Department’s support to those impacted by the fire in the Cathedral Buildings is a signal of the importance placed on the people and organisations who work to make our arts sector what it is. We were pleased to be able to work together with the Arts Council, Belfast City Council and Libraries NI to provide this practical and much needed help.”

Councillor Ryan Murphy, Chair of Belfast City Council’s City Growth and Regeneration Committee said: “The impact of the fire has been devastating for the former tenants of Cathedral Buildings. As well as providing funding, we’ve worked in partnership with the Destination CQ BID, to support tenants to relocate, to navigate their insurance policies where possible, and to offer business support services. I’m glad that we’ve been able to collaborate with the Department for Communities and the Arts Council of Northern Ireland to give these businesses and cultural organisations vital support and I wish them all every success in their new locations.”

Another recipient of the Cathedral Buildings Fire Support Programme is Digital Arts Studios (DAS), a non-profit organisation that provides artists’ residencies, equipment hire, training, outreach and exhibitions. DAS is a space for artists and creatives to work, learn and advance their careers and the organisation aims to support and encourage visual artists whose innovative work merges with digital technolo-

gies. DAS will use their funding to replace equipment that will be used by visual artists on the DAS residency programme and by participants in their in-studio workshops, training and support hub services.

Dr Angela Halliday, Director, Digital Arts Studios, commented, “Digital Arts Studios is delighted to have received funding from the Cathedral Buildings Fire Support Programme. This funding will help purchase essential equipment for artists to use to develop skills and create new work. Digital Arts Studios is grateful to the Department for Communities, Arts Council of Northern Ireland and Belfast City Council for this much-needed assistance, and we look forward to welcoming artists to our new premises at 1 Exchange Place, Belfast, where they can make use of the new equipment and resources.”

All those set to receive funding through the programme include:

• Aidan Mulholland T/a Mulholland Violins (£45,280)

• Dermot Gibson (£600)

• Digital Arts Studios (£21,100)

• Ellen Blair (£829)

• Elly Makem (£607)

• Excalibur Press Ltd (£21,851)

• Form Native Limited (£11,461)

• Hazel Alderdice T/A Perfect Fit (£5,045)

• Jennifer Mehigan (£11,405)

• Nicholas J Larkin T/A Roscio Films (£4,207)

• Oranga Creative Ltd (£12,804)

• Suzanne Magee (£1,573)

• Timothy Farrell (£17,934)

Pallas Projects/Studios and its Board of Trustees are delighted to announce that the organisation has been granted Charitable Status by the Charities Regulator. This hugely significant development, a key objective of their long-term strategic planning, is the culmination of several years of dedicated work. It helps ensure that the organisation is best placed to continue their role as a leading exponent of artist-run practices on the island of Ireland, and to provide and develop opportunity for Irish artists to make and exhibit cutting-edge and experimental work.

In addition, and in line with recent organisational and programmatic developments and in tandem with their Charitable Status, they wish to announce a restructuring of roles at Pallas Projects/Studios. They are delighted that their long-standing assistant curator Eve Woods is to take on the role of Curator/Programme Producer, with Mark Cullen and Gavin Murphy acting as joint Artistic Directors.

Pallas Projects/Studios and its Board of Trustees would like to thank all those involved in the organisation, their staff, studio artists, exhibiting artists and those who visit, engage with their exhibition and education programmes. In particular they wish to thank The Arts Council for their continued support.

Pallas Projects/Studios look forward to continuing their role in advocating for increased supports for artists workspaces in 2023 and beyond, and in delivering artistic and educational programmes to ensure the best emerging and early career artists can have every opportunity to thrive and produce new, exciting and meaningful work, now and into the future.

Eight artists awarded studios at TBG+S Temple Bar Gallery + Studios is pleased to announce the awarded artists from the open call for Three Year Membership Studios and Project Studios.

Three Year Membership Studios have been awarded to Clodagh Emoe, Lisa Freeman, Jaki Irvine, and Jesse Jones. Project Studios have been awarded to Tara Carroll, Maïa Nunes, Mandy O’Neill, and Luke van Gelderen.

Three Year Membership Studios at Temple Bar Gallery + Studios offer a long-term tenure to artists who have developed an established, professional practice. Project Studios offer a one-year tenure to artists who are developing exciting emerging practices and demonstrate talent and potential.

The artists were awarded their studios by a selection panel following an open submission application process. The panel included current TBG+S Studio members and established curators based in Ireland and internationally. The artists are representative of the high-quality and rigorous contemporary art practices in Ireland today.

CORNELIUS BROWNE CONSIDERS CONNECTIONS BETWEEN UNDERGROUND FILMMAKING AND PLEIN AIR PAINTING.

FIONA HALLINAN DISCUSSES THE DEMOLITION OF IRELAND’S SECOND LARGEST CATHOLIC CHURCH.

“To demolish is to obliterate, to eradicate, to erase, to destroy. Informally, the verb is used to describe an overwhelming defeat. It is the end.” – Ellen

Rowley, Making Dust (2023)IT COULD BE a catharsis to watch a building come down. Indeed, many demolitions have been presented as spectacle; as opportunities for gathering and celebrations in themselves. Watching a church come down could represent a purge – a way of starting over from a failed plan. ‘Emotional residue’ is a term in social psychology that describes how buildings and objects contain real, tangible traces of events in the lives of their inhabitants that can be sensed by other people over time.1

at VISUAL Carlow until 14 May. It will also be presented at the Irish Architectural Archive later this year (14 September – 20 October). The project includes a film, Making Dust (2023), that maps the research and writing of architectural historian Ellen Rowley on to the process of dismantling the church, and a table made from fragments of the demolition. At a symposium in May, the table will be activated with a meal, gathering different perspectives on the project. Rowley notes that a swathe of buildings, including the large-scale churches of Catholic Ireland, will be threatened with demolition. Built within the last 50 years or so, they don’t seem old enough to be considered of historic virtue.

TWENTY YEARS AGO this spring, I was part of a skeleton crew in Leitrim, shooting Ireland’s first indigenous horror movie. Dead Meat (2004) was also the first film completed under the Irish Film Board’s Micro-budget initiative, which provided funds for projects budgeted at €100,000. In the credits, my name appears under Production Designer. However, we had so few hands and so little money, that roles were, by necessity, fluid. Over that Easter weekend, we shot some of our most exhilarating scenes in a cottage belonging to novelist John McGahern. I was introduced to McGahern on Good Friday, wearing a weighty crucifix around my neck, brandishing a fake axe, and doused in fake blood. To stretch our budget, we frequently filmed en plein air. I cherish memories of freewheeling days and nights scouting locations.

Our next film planned as a company was Chiaroscuro, a psychological horror I had written about disintegrating relationships within an artists’ colony, which I was also slated to direct. To attract funding, I created an elaborate storyboard, comprising hundreds of drawings. This was the first artwork I had produced since graduating from NCAD twelve years earlier. Despite positive feedback, Chiaroscuro languished in development purgatory, but it reignited my passion for drawing.

My original intention had been to make Chiaroscuro as a Dogme 95 film. Lars von Trier’s avant-garde manifesto proposed a new way of producing films with extremely low budgets, adhering to strict rules that he provocatively termed the ‘vow of chastity’. Dogme films had to be shot on location, using hand-held cameras without any special lighting, with direct sound recording, and no music, optical work, or filters. The manifesto attacked illusory cinema and promoted a naturalistic alternative.

During my early childhood we had no television set, and I was 19 before setting foot in a cinema. In between, we had a black and white telly, our aerial erratically

picking up signal, meaning the picture was often snowy. Graveyard slot screenings of old or disreputable films turned me into a teenage insomniac. My inclination was towards guerrilla filmmaking, the ultralow budget underground work of directors operating on the margins. One night in deepest winter, I caught the only film written and directed by Barbara Loden. Wanda (1970) was shot by a crew of four people for $100,000 on grainy 16 mm film, usually reserved for documentary work. That freezing night, I experienced a snowfall of feelings about working-class art. I recollect Loden’s ideas on mainstream filmmaking: “I hate slick pictures, they’re too perfect to be believable. I don’t mean just the look. I mean in the rhythm, in the cutting, the music – everything. The slicker the technique is, the slicker the content becomes, until everything turns to Formica, including the people.”

Ten years ago, I returned to painting. Not one of my pictures has been slick. As a painter, I have taken a ‘vow of chastity’: all paintings are created entirely outdoors in a single session, with no preliminary drawing, underpainting or photographic reference, no retouching in the studio afterwards, and no varnishing. I have vowed to paint in the open across every season, at all times of day and night, continuing to work through whatever the weather throws my way, which is unpredictable on the Donegal coast. Painting a picture like Looking at Snowy Mountains, my fingers numb with cold, I have no idea that two strangers in a boat are about to drift into view. When I call out to them to please stay where they are for a few minutes, and look towards the snow, I recall that a long time ago, I had hoped to direct a film.

Cornelius Browne is a Donegal-based artist. His current solo exhibition, ‘All Nature Has A Feeling’, continues at the RCC, Letterkenny, until 25 March.

regionalculturalcentre.com

There is an ongoing international movement to ‘de-monumentalise’ due to the reckoning with colonialism and imperialism, documented by Nicholas Mirzoeff in ‘All Monuments Must Fall’.2 Buildings, however, are not monuments. They are functional spaces that provide shelter, but which extract large amounts of natural resources in their construction. To knock a building down and build a new one is often an economic decision; but in a climate crisis, can we afford to make decisions based on the arbitrary index of financial cost? Perhaps we should pay attention to the traces left in buildings, in materials.

Finglas West’s Church of the Annunciation, by architect David Keane, was a landmark building in the area – the tallest thing around except for the mountains. Designed to hold gatherings of over 3000 people, it opened in 1967 as part of a series of giant churches built around Ireland for a decidedly Catholic society. The 1961 Census records 94.9% of the country’s population identified as Catholic; however, as this percentage continues to decrease, there are fewer reasons to justify exclusive use of a building on this scale.

‘We Turn Towards an Ending and Pay Attention’ is a project currently showing

Over the blue hoardings that concealed the demolition site, we asked passers-by what they thought about this building coming down. There was no major dissatisfaction about its dismantling; I noticed instead a distinct ambivalence. This project was not an act of protest or memorialising, but a way to mark a moment we describe as a ‘rupture’. It considers issues of land ownership, the agency of materials, sustainability, the built environment, and the legacy of the Catholic church’s power in Ireland; it asks what do we value, where do we gather, what should we keep and, in the context of a climate crisis, what should we discard?

Fiona Hallinan is an artist and researcher based between Brussels and Cork, and co-founder with Kate Strain of The Department of Ultimology. departmentofultimology.com

1 Krishna Savani et al., ‘Beliefs About Emotional Residue: The Idea That Emotions Leave a Trace in the Physical Environment’, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Vol. 101, No. 4, 2011, pp. 684-701 (krishnasavani.com) 2 allmonumentsmustfall.com

IARLAITH NI FHEORAIS OUTLINES A FORTHCOMING ACCESS TOOLKIT FOR CURATORS AND PRODUCERS.

MANY ARTS ORGANISATIONS and curators are eager to create more accessible spaces for art workers, audiences and artists, but struggle to find the right advice. Numerous artists have self-organised in response to inaccessible environments, creating toolkits and resources to help fellow artists advocate for themselves. Recent examples include: Access Docs for Artists, an online resource to “help disabled artists communicate their access needs with galleries, art organisations and other employers”, developed by Leah Clements, Alice Hattrick, and Lizzy Rose in 2019 (accessdocsforartists.com); and Accessibility in the Arts: A Promise and a Practice, an accessibility guide commissioned by Recess, New York, and written by Carolyn Lazard in 2019, which is “geared toward small-scale arts non-profits and the potentially expansive publics these organisations serve” (promiseandpractice.art).This has resulted in a long-awaited increase in artists sharing their access needs. Unfortunately, many curators and art organisations are still unprepared for supporting these requests.

With this in mind, I applied for Arts Council England funding to produce an access toolkit for curators and producers in late 2021. The aim of the toolkit is to provide key information on how to work, make and display accessibly in the visual arts, from fundraising and budget planning to working with artists. As a disabled curator myself, I also wanted to create a resource for disabled art workers to use to advocate for their own access needs.

I began by interviewing four disabled and/or chronically ill artists, alongside four curators and producers who either work in disabled-led art organisations, have disabilities themselves, or produce particularly accessible programmes. The artists have diverse practices with varying access needs, and all predominantly work in the UK and Ireland. For interviewees to speak openly about their experiences, their contributions have been anonymised. I asked artists about their experiences of working with institutions, curators and producers, what their access needs are, how they’ve been met in the past, and crucially, what their practice would look like if all their access needs were met. Curators and producers were asked questions on planning, policy, funding, current access provision, management, and their own access needs.

Firstly, all of the curators and producers I spoke with called for an intrinsic model of accessibility – one which centres access from the very first planning conversations, thus taking account of access needs of art workers, artists and audiences at every stage. This is opposed to the most common model, which often considers access an add-on at the end of a project. Key to making the intrinsic model work is gathering the access needs of the team, having

those early conversations with artists and colleagues, and building that into a plan. This could include people needing flexible working patterns, support workers, assistive devices or technologies, easy-to-read documents, flagging flare-ups, caring obligations, upcoming surgeries, or more time to complete tasks. A valuable way of collecting this information is an access rider – a simple document allowing artists or freelancers to share their relevant access needs, which could be requested as part of a contract.

Once access needs are assessed, their provision can be included when fundraising. It is recommended that 10% to 20% of a project budget should be ringfenced for access, therefore ensuring that if access costs arise, there is a budget in place. Many awards allow access costs to be requested above the award amount, where needed. It can be more difficult to account for access in regular organisational funding but this percentage guide is a useful metric when building access into an organisation longterm. Many artist respondents highlighted the need for access budgets to support their own access needs in the production period, and not just the display of their work. Artists also state that flexible approaches to production schedules, project outcomes, and ways of communicating are vital.

In terms of display, most interviewees advocated for a creative and intersectional approach to access. There are many ways to make an artwork accessible, but those tools should be considered alongside creative ones, as part of a holistic approach. You can’t be accessible to everyone all of the time, and there is no such thing as ‘fully accessible’. Access is a conversation and a process that will look different in every project. An intersectional approach can make working and witnessing art accessible for everyone. This may include: flexible working supports for parents or trans people undergoing care; quiet spaces for older people or those who are breastfeeding; paying people to attend meetings; or sliding-scale ticket prices for disabled people, students, pensioners, unemployed people, and those on low incomes. And everyone appreciates comfortable seating, no matter who they are.

As we consider the impact of the Arts Council of Ireland’s Equality, Diversity and Inclusion (EDI) Toolkit, it is essential that organisations provide the supports necessary to include disabled art workers, artists and audiences, beyond our own commitment to disability justice. Later this year, I will publish a free online toolkit, intended as a practical guide, outlining ways we can create more accessible practices, organisations, and ways of working across the sector.

BELFAST-BASED ARTIST, ANUSHIYA SUNDARALINGAM, REFLECTS ON HER MULTIDISCIPLINARY PRACTICE.

MY FIRST MEMORY of making art is sitting outside my classroom in the warm, open air, drawing banana and coconut trees. Growing up in Sri Lanka, I watched the making of many traditional, handmade creations for everyday cultural and religious life including crafts, textiles, and weaving. I saw patterns, colours and textures used everywhere, in all aspects of life, from births and weddings to funerals. Patterns were even made while sweeping the sandy floor of our house.

Since graduating with a degree in Fine and Applied Arts from Ulster University, I have been working as a full-time artist and arts facilitator in Belfast. While I initially trained as a printmaker, my practice has since become more diverse, working in both two and three dimensions, creating installations, paintings, prints, and mixed-media works. As a multidisciplinary artist and collector, I like to incorporate different materials and textures in my work, and frequently use less traditional materials such as thread, encaustic, flax, metal, and bamboo. Experimentation and exploration of ideas, subjects, materials and effects drive my practice and continually challenge and motivate me.

My current work reflects on challenges of identity and the nature of belonging. I am concerned with how our relationship with natural and cultural environments shape our sense of self and place, particularly if one’s surroundings change through displacement, whether by choice or not. When I left Sri Lanka in 1989, I left behind my roots, culture, identity and tradition. Over the years, my work has evolved, and I have been influenced through many different aspects of living in Northern Ireland; however, the sights and sounds of my childhood regularly influence and inspire my work, enabling me to reconnect with some of the things I have lost.

My next solo exhibition runs from 9

March to 6 April at Island Arts Centre, Lisburn, and is entitled ‘Rip it Up and Start Again’. It is kindly supported by a grant from Lisburn & Castlereagh City Council. This exhibition takes the sari, a traditional item of Sri Lankan clothing, and reworks metres of cloth to tell a new story of the generations of women who wore this fabric. Collected saris from the Sri Lankan diaspora, many passed down in families, have been ripped and reworked to create new works. Fabrics that come from everyday settings to special occasion wear have been imbued with meaning, perhaps sadness, joy, sentimentality and nostalgia. This exhibition speaks of Sri Lankan communities throughout the world yet reflects on a very basic human sense of identity, and what that means.

Depending on my practice, I can work from my home studio, at Belfast Print Workshop, or at Queen Street Studios, where I am a member. Sharing creative practice is important to me, and I have facilitated many short and long-term projects for all ages and abilities. I enjoy giving something back. I come from a society where art is not valued as a profession, and although my family has always been supportive, I have had to fight to be respected as an artist. I have recently been awarded the 2022 Artist’s Career Enhancement Scheme from the Arts Council of Northern Ireland for a project with the Ulster Museum, titled ‘தப்பிஓடு TappiOdu (Flee)’.

Anushiya Sundaralingam is a multidisciplinary artist based in Belfast. anushiyaartist.co.uk

The Angelica Network amplifies the voices of women and non-binary artists of minority cultural and ethnic backgrounds. angelica.network/home

CECELIA GRAHAM AND GRACE JACKSON DISCUSS THEIR CURATORIAL RESIDENCY AT PS² IN BELFAST.

SAIDHBHÍN GIBSON OUTLINES AN INFORMAL ART DISCUSSION GROUP SHE HAS BEEN CONVENING SINCE 2017.

I WAS LIVING between Carlow and Kilkenny around 2014. At the time, I felt there was limited opportunity in the immediate area to engage in discourse around contemporary art. I wanted to develop an event which had the potential to bring people together to have critical conversations and to share knowledge. I also wanted to create an inclusive event for a community to interact, socialise and be visible to one another. I imagined a group of us, huddled over hot cups of tea. I think the fact that I was renting a very cold apartment influenced this Dickensian image.

“Terms like serious and rigorous tend to be code words [...] for disciplinary correctness; they signal a form of training and learning that confirms what is already known according to approved methods of knowing, but they do not allow for visionary insights or flights of fancy.”

– Jack Halberstam, The Queer Art of Failure (Duke University Press, 2011)

WHEN WE STARTED collaborating, we were approaching the end of our curatorial master’s programme, both exhausted, disappointed, and heartbroken. We had hoped for a discursive programme that encouraged conversations about dismantling patriarchal and hierarchical structures within the institution. Instead, we felt that the university perpetuated those institutional structures, requiring a rigid professionalism that treats artists as tools to uphold curatorial discourse and power.

Care was, and still is, at the centre of discussions about the future of institutions and curation. How can we care for one another when the institutional structures are, themselves, hostile? How can we build something new from these structures? The answers to these questions came not from our formal education, but from the nourishing conversations we had in the park, or over a pint in the pub. These chats built the foundation of our approach, which estranges itself from professionalism, slickness, and rigidity within curation.

It is freeing to be directly responsive to the artists we work with, and we encourage artists to explore their own interests. For this reason, there is no logic or linearity to our work. Sometimes common themes emerge between projects; however, this is not always the case. One thing that does run through many of our collaborations is a desire to experiment or create collectively. In 2022, our first two projects as Curators-in-Residence at PS² – ‘Handycam Gifts’ by Mark Buckeridge and ‘Queer na nÓg’ with Bog Cottage – upheld the importance of collaboration and collective labour.

At the time of writing, Tara McGinn’s ‘A Change in the Cells’ currently occupies the gallery space at PS2, reimagining the static

exhibition structure as something that can accommodate both rest and slow working. We are looking forward to a threeday collective video workshop with Lillian Ross-Millard and a site-specific installation with Christopher Steenson and a project with Nollaig Molloy. Each project has taken a different form, and accommodating this flexibility ensures that we are putting the artist at the centre. Our goal is simple: we intend to collaborate with each artist and celebrate their individual interests.

Throughout this residency, we have been keen to dismantle hyper-productive and linear ways of working, giving artists the opportunity to return to thoughts that feel incomplete, or create work that has the potential to shift and grow based on their changing interests. The ‘flights of fancy’ that Jack Halberstam refers to are important to experimental art practice, and as curators we seek to accommodate the changes that come up through our collaborations.

Friendship is important too, and we count all our collaborators as friends. Through a welcoming and responsive approach, we hope to foster a different type of artist-curator relationship that prioritises camaraderie and vulnerability with ample space for failure. We wish to create a comfortable and safe space for artists to follow the life of an idea, rather than imposing hierarchical or bureaucratic procedures that equate curatorship with control.

The team at PS2 have shown us true generosity, advocating for our experimental practice, and showing flexibility and understanding when sudden change occurs – a rarity within art institutions. We have learned to navigate deadlines in a way that leaves room for our malleable approach, even though this often goes against the standards imposed by funding bodies. For the first time in a long time, we feel excited about curatorial practice and what we can accomplish with it.

Cecelia Graham & Grace Jackson are a curatorial duo who value kind-hearted and vulnerable approaches to artistic-curatorial relationships.

ceceliagraham.cargo.site gracejackson.ca

I began getting a sense of the demand for such a bespoke event. I considered who it was for, what the objective was, and where it would take place. After completing my MFA, I had more time to put the idea into motion. The first H U D D L E took place at Arthouse in Stradbally in January 2017.

With each ‘huddle’, a prescribed piece of text is emailed beforehand. The chosen writing might be influenced by an exhibition in the host venue, or it might be a seminal text that will spur interesting dialogue. For the first event, I chose a text from Failure (2010, The MIT Press) – a book edited by Lisa Le Feuvre, as part of the anthology series, ‘Documents of Contemporary Art’. Jörg Heiss’s interview with Swiss artist duo, Fischli/Weiss, prompted discussions around notions of failure, permission to fail, and art that uses failure as its core concept.

H U D D L E No. 11 took place in the main gallery at VISUAL Carlow, where we deliberated the late Brian O’Doherty’s essay, ‘Notes on the Gallery Space’. O’Doherty’s book, Inside the White Cube – first published in 1976 as a series of three articles in Artforum – asserted many salient observations about the influence of white cube spaces on art, artists, and the reconstituted audience.

In 2019, I had work in the exhibition, ‘A

Vague Anxiety’ at IMMA, and convened a huddle in one of the studios. We unpacked Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2010) by Jane Bennett, whose writing resonates with aspects of my visual art practice. We discussed the chapter ‘Vitality and Self-interest’, arguing the proposal that if all matter was to be viewed by humans as having its own tendencies, this could be of political and ecological benefit to the environment.

The first outdoor huddle took place during the pandemic in 2021 under Covid guidelines. Donnelly’s Hollow in The Curragh, County Kildare, was the perfect setting, since a sloped depression in an otherwise flat plane acts as a natural amphitheatre. We looked at Virginia Woolf’s essay, ‘On Being Ill’, which first appeared in The Criterion in 1926. Nearly a century after the piece was published, Woolf could have been writing about “the great experience” of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Huddles are nomadic and ephemeral. The emphasis is on the time we are together, face-to-face, responding to the prescribed text, and any periphery topics that arise along the way. Electronic communication and screen time is kept to minimum. To date, 21 huddles have taken place in numerous venues across Ireland, including Temple Bar Gallery + Studios, Butler Gallery, Kilkenny Arts Office, National Design & Craft Gallery, and Riverbank Arts Centre. My thanks to Laois, Kildare and Kilkenny County Council Arts offices, and to the huddlers who attend these events.

Saidhbhín Gibson is a visual artist currently based in County Kildare.

DAY MAGEE REFLECTS ON THE SIGNIFICANCE OF LOSING THEIR FATHER AND THE PROFOUND ART OF HUMAN GRIEF.

NEVA ELLIOTT DISCUSSES HER CURRENT SOLO EXHIBITION AT LINENHALL ARTS CENTRE.

THE ETYMOLOGY OF bereavement is to “deprive or rob of.” At root, it is something enacted upon us. So too is bereavement’s progeny, grief, arriving not just for the person who is gone but also for ourselves. After my husband Colin died from cancer at 40, I entered a period of grieving, both for him and my lost self.

In my time and culture, without the black parramatta silk or bombazine dress of the Victorians, or Jewish observation timelines, I found I lacked a defined process of mourning. So, I went back to work a week after the funeral and carried on until, after further unexpected and traumatic deaths close to me, I was no longer road worthy. I left my job and returned to my practice. Within death, a part of me was reborn.

This return to making was markedly different from my previous practice. Then, my gaze turned outwards to contemporary society; now, I looked inwards to my own experience. Through my work, I bore witness to my grief in what had become a chaotic, uncontrollable world. Living as material, I began working from a place of transparent vulnerability.

the vast expanse of ocean and sky.

Making acted as a tether to the departed – a way to hold them close – so much so, that I found it difficult to finish pieces. Only when the Linenhall Arts Centre invited me to show with them in January did I finalise the body of work and realise that this was not a letting go. My solo exhibition, ‘How to create a fallstreak’, continues in the gallery until 4 March. The fallstreak of the title is a meteorological term for holes that can appear in cloud formations, referencing the proverbial gap in the clouds I was attempting to create.

While writing the exhibition wall panels, I found myself repeatedly returning to re-work these ‘tombstones’. While demonstratively focused on my own experience, I was also attempting to expand autobiography, to go beyond personal memoir and speak to others about shared human experience. I wanted to create honest, open narratives beside my pieces to enable conversation rather than hide behind distancing art-speak.

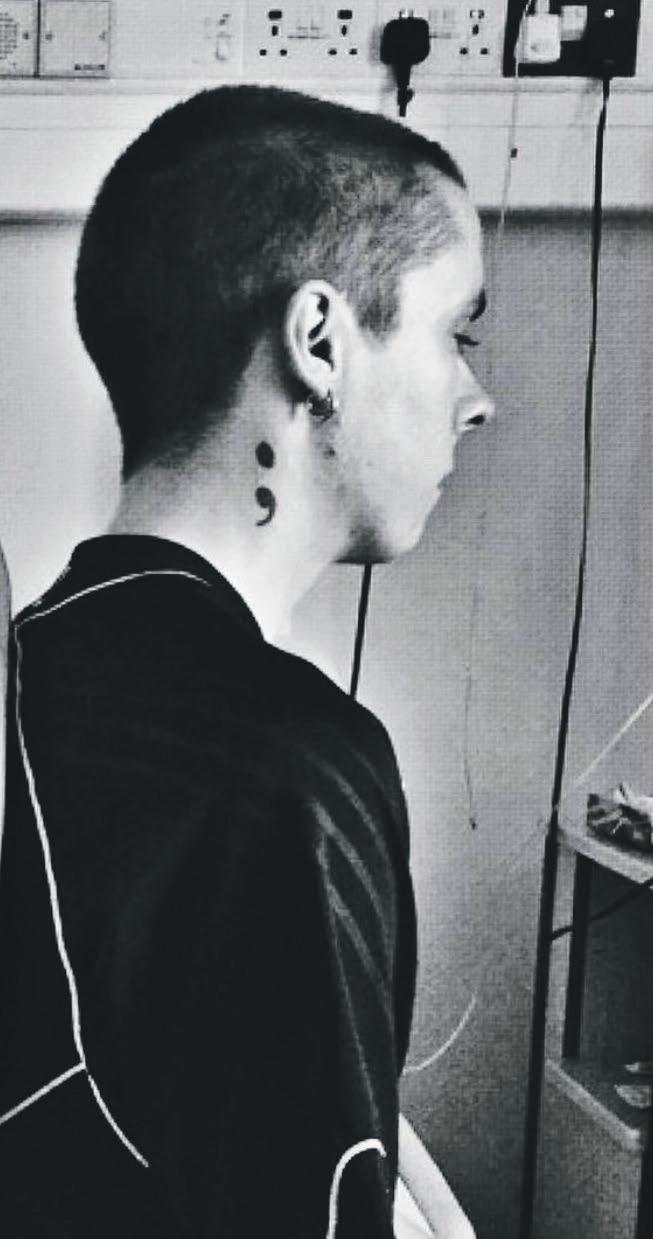

FOUR ANNUAL UNITS of temporal measurement; four terms under the bodily condition of grief. Grief is a map of itself that loads in anything but ‘real-time’. All previous conceptions of self crystallise and shatter. This is the cost of love. You were rare in ways that grow evermore apparent as I live on. You were good in ways I still come to terms with; I will likely never be as good. Not that I have to be anything but what I am, I’m sure you’d say. But you deserve to be relived – re-enacted – through me. I am, after all, impossible without you. I live the continuation of the information that lived through you. Whether there is a heaven or not, only that which we enact upon the world – the gyroscopic balance of our deeds and motivations – is what sustains it, and what it sustains. To that end, I won’t let you die any more than you have to.

Childhood is the belief in adulthood itself. The child scries the face of its elder for surety, not realising that it is another child staring back, bigger on the outside. The secret to adulthood is that there is no secret – yet it’s one that must somehow still be kept. I see now why you were a bus driver – you got people to where they needed to go. Bus driving was but one emergent form of your doing so, in the same way that art is mine. You understood this in your final moments, foreseeing my grief process, telling me to ignore the nurses and document whatever I wanted. Pictured are our two bodies: yours unable to breathe lying down, nor able to hold itself up; mine improvising with itself and a pillow to prop you up, breathing for you rhythmically, unknowingly performing the image then captured by your sister. Even now I am documenting. I often say I do what I do out of fear as

much as out of love – for ultimately, ours is the creative material of life itself.

Bodies are the holy sites through which life takes its pilgrimage. Your faith was both what dealt our mutual wound, and what continues to heal it. We are forced to reconcile with where our parents’ beliefs end and ours begin. Bodies are belief systems; systems that are believing. Self-fulfilled prophecies, distinct from our own; phenomenological algorithms simulating themselves, until their every probability in space and time has been enacted.

I look for you everywhere. The most meaningful way to do so, I have found, is to deign to look at the world through your eyes. This is how we keep people alive –even those still living – to try to see life from their perspective. In order to see, we must live as they do, according to the self-mythographies they inhabit. We must conceive of the indignations they overcome as they, like us, try to communicate to others the terms on which they might be loved. It is not just how we sustain them, but also ourselves in self-compassion, as we grow from self to self.

We love not only towards a future, but towards a past. We are them now, and they are now us. We are the material. We are the crest of their lives’ incline, just as they were to those before them, in radial waves of living information, emanating outward in every temporal direction.

Day Magee is a performance-centred multimedia artist based in Dublin. daymagee.com

What emerged was a lyrical conceptualism blurring art and life, externalising emotion, responding to relationships and the situation I found myself in, and forming presence that manifested absence. This is a lived archaeology of loss involving people, objects, place and story. Physically, it formalised across photography, text, object, video, sound, and documentation of performative action, such as Sending messages to the sea (2021-22), inspired by lighthouse keepers’ wives, signalling to their husbands from the shore, where I used semaphore flags, the language of the sea, to communicate: “I am here my love, where are you?” to

My practice has become a memorial, a transitional object, a communication and a salve. As I embodied loss, so did my work. To fill a void of absence, to find a way back to myself, to heal and come to a new understanding of my loss, I made art. This allowed me to access a space of mourning and, with it, a restoration of self.

Neva Elliott is a contemporary artist based in Dublin. After ten years as CEO of Crash Ensemble, Elliott returned to her art practice in 2021. Last year she was made an Irish Hospice Foundation signature artist. nevaelliott.com

THE SOUND OF hammering echoes from a Georgian house in the village of Killeagh, County Cork. Passers-by stop to pull a book from the free library. In the evening, a glowing circle appears above the river. Inside the house, artists from Ireland and abroad meet for dinner.

This is Greywood Arts. Nestled at the foot of Glenbower Wood, just beside the Dissour River, we aim to position creativity at the heart of East Cork. We are passionate about creating a warm and welcoming space where artists and the community can come together to explore creative processes, to learn and to grow. We do this by hosting artists-in-residence from all over the world, organising community art projects, programming cultural events and offering educational workshops. Our hope is that participants discover a sense of belonging, broaden their perspectives, and deepen their sense of empathy.

Five years ago, Greywood Arts opened its doors as a multi-disciplinary residency space. Located in the main house, it is an artist-run space that attracts those working in the visual, literary and performing arts. We welcome as many residents from Ireland as we do from abroad. We accept applications for our self-funded Creative Process residency on a rolling basis. We frequently support individual artists’ grant applications that include a residency with us, and we are working to broaden our own funded opportunities. We anticipate an open call for a funded residency co-hosted with the National Space Centre this summer. The visual art studio has drafting table and sink, with high ceilings and wooden floors. The Big Studio suits many visual artists, as well as performers, and our cosy writers’ room overlooks the river and is perfect for desk-based creatives. Residencies range from three nights to three months, and we love to support engagement between visiting artists and the local community. Once a week, we have dinner with all of the residents. Outside, two goats and a flock of hens preside over half the old walled garden, alongside newly planted fruit trees and raised beds.

In November 2022, we launched a spectacular light installation at our annual Samhain parade. Villagers carried willow lanterns made during workshops facilitated by Caoimhe Dunn, a member of ISACS (Irish Street Arts, Circus and Spectacle Network). Then, with everyone gathered on the bridge, Circle of Light (2022) was illuminated. Created by VAI member artist Aoife Banville, it brightens the darker winter months; it is a small yet powerful way to lift our spirits and remind us that our community is strong and united in difficult times.

Last November we partnered with the nearby National Space Centre (NSC) to deliver the first Space Fest – a celebration of art and science for Science Week. We hosted accomplished filmmakers Valerie Van Zuijlen (NE) and Emilia Tapprest (FI) who further developed their docu-fiction work, Our Side of the Moon (2022). This story of ‘moonbouncers’, who communicate by bouncing satellite signals off the moon, explores the complexities of modern technology, connection, synesthesia and embodiment. Emilia filmed a stunning movement scene beneath the NSC’s 32-metre satellite dish with Japanese Cork-based dancer, Haru. The exhibition also showcased photographic works made by nearly 100 young people, who learned about morse code and how light travels, during workshops with artist and educator, Róisín White.

We have a busy spring ahead as we grow by leaps and bounds. In April we plan to launch a new multi-disciplinary network for artists in East Cork and West

Waterford. We understood how many artists live in the region, often isolated and unaware of each other. We piloted the project last autumn with the support of both Cork County and Waterford City and County Council arts offices. Members will have access to monthly meetings, half of which will be salon-style sharing events. These will be complemented by talks, workshops and skill sharing. The artists involved in the pilot connected immediately, sharing support and building collaborations. In May, they will have an exhibition and event at Greywood Arts during the May Sunday Festival, which will travel to the Old Market House Arts Centre in Dungarvan later in the year.

May Sunday has been Killeagh village’s festival day for nearly 200 years. Music and dancing on the local landlord’s estate became an annual tradition that shifted to the village centre in the 1920s. The festival had lapsed since 2001, but many locals told us how much they missed the celebration. In 2018, we invited a small team of artists to research the festival and capture local memories, to create a new offering. We moved the fes-

tival back to its point of origin, which is now the community owned Glenbower Wood. In 2021 we created a pandemic-safe art trail throughout the wood with the support of Cork County Council. This year, we are once again incorporating an art trail into the festival, thanks to support from the Arts Council’s Festival Investment Scheme. It will run for two weeks, from 29 April to 14 May, featuring both local artists and four more selected by national open call.

Our most thrilling endeavour this spring is the opening of a new venue, The Coach House at Greywood Arts. For the past year we have been overseeing the renovation of a derelict outbuilding into studios for local artists, an arts education space and a flexible 50-seat event and exhibition space. Supported by LEADER, Cork County Council, and a Fund It campaign, it will be a perfect community resource for the small village.

Jessica Bonenfant is Artistic Director of Greywood Arts. greywoodarts.org

CORK-BORN ARTIST GEORGE Bolster is based in New York City, with a studio just south of the historic Prospect Park in Brooklyn. Establishing a formidable career since the days of art school in his native city in the 1990s, Bolster’s resume speaks as much to how artists now function professionally as to his particular gifts. His profile is transnational with regular exhibitions in Europe as well as the US; when we spoke, he had just opened a solo at Uillinn: West Cork Arts Centre. Bolster’s work has become increasingly interdisciplinary and collaborative, and he is resolutely involved in theories and ideas – a concern with research that has come to underwrite much contemporary art. The artist has also has completed a number of important residencies and a major monograph of his practice, When Will We Recognize Us, will be published by Hirmer Verlag this year. Our paths first crossed at art school back in the day. I am interested to know how Bolster became the artist he now is, and what he thinks about the influences that shaped him.

Brian Curtin: What was your experience of art education in the 1990s – for example, the emergence of the influence of theoretical writings and a shift towards research-based practice?

George Bolster: I studied painting at Crawford and Chelsea colleges, and it is telling that I didn’t do any painting at the latter. In Cork the teaching was formalist and there seemed to be a fear of talking about art. But in London there was much more interest in art discourse. When I began at Chelsea, I was defensive because of my earlier experience, to the point that tutors took me aside and told me they were there to help me! I relaxed and taught myself to be supportive and constructive not dismissive. I was nicknamed Tristram Shandy, a figure of eccentricity.

I initially encountered theory through reading publications by Zone Books and this led me to conceptual art. But, with conceptualism, I felt there was a flattening of the poetic with a dry language and execution. Ideas of research-based practice became more appealing and a lot of my work has consequently been collaborative, whether working with musicians or scientists. With conceptualism, I felt restricted, though that may just be me!

BC: What was the London art scene like when you graduated?

GB: It was the time of the YBAs (Young British Artists) who had come from Goldsmiths as I was finishing my MA at Central Saint Martin’s. Goldsmiths’ graduates got most of the attention, with art dealers at their graduation shows, but I did exhibit at smaller, alternative venues including screenings at Chisenhale Gallery. I never felt like a British artist, which was the brand, and had a problem with the term being celebrated due to colonial history. I didn’t try to fit in.

BC: A longer interview could unpack that. But at what point did you shift from ‘recent graduate’ to professional?

GB: I curated an international group exhibition ‘Multiplicity’ at Fota House in Cork in 2004 with Arts Council funding. This project continued for over a year because the final venue was Derry’s Context Gallery. Through this experience, I developed practical skills in all aspects of art administration, including pre-emptive problem-solving. ‘Multiplicity’ gave me a sense of being proactive and building community – something I had always yearned for, as being an artist can be lonely.

BC: How did your move to the US in 2008 play out in this respect?

GB: I initially moved to San Diego and responded to the sharp change by curating TULCA Festival of Visual Arts in Galway, which I titled ‘i-Podism: Cultural Promiscuity in the Age of Consumption.’ I worked with artists whose work had impacted me during my move, with the iPod as a metaphor for a personal digital library of important sights. It was also an auto-critique of the figure of the curator by removing any implicit sense of objectivity and embracing subjectivity – again, being proactive while pushing against expectations of who or what we are. Moving to the US was also important because I began the shift away from the deconstruction of Christian imagery in my early work.

BC: Was there a catalyst for that?

GB: I completed the Robert Rauschenberg Residency and then a residency at the SETI Institute – an organisation that investigates extraterrestrial life. I discovered Rauschenberg’s environmental activism in the 1960s and how, alongside Warhol and others, he created the ‘Moon Museum’ which was attached to Apollo 12 in 1969. I then visited NASA to research a project that digitises pre-Apollo mappings of the moon and began to further wonder about the conservation of artworks for the future. This project was housed in an old McDonald’s building because the ventilation system was perfect for archival storage. Essentially, I became interested in the need for us to evolve less damaging forms of technology for our cultural longevity in the universe.

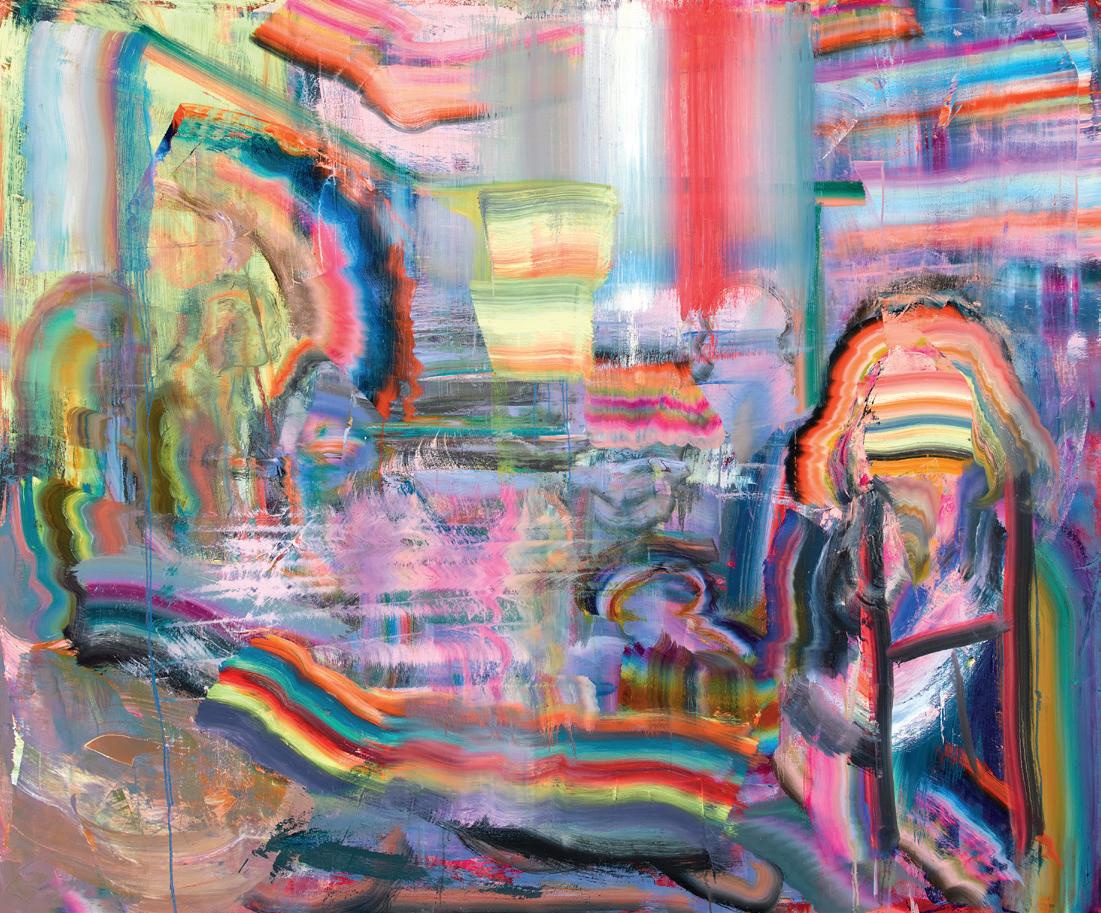

BC: The installations you recently showed at Uillin: West Cork Arts Centre use large Jacquard tapestries with epic landscape imagery.

GB: I began with Jacquard in 2014 but the early experiments failed, and I returned to the medium in 2017. Back to your question about research, during the time

of the residences, I met a scientist who spoke about the importance of failure in experiments. The concept of failure as a requirement for discovery gave me a more profound insight into, say, da Vinci than any study of art history ever could.

The Jacquard machine was the basis of computational language, a process of programming resulting in something akin to an analogue/digital image. I am interested in making a virtue of glitches, staging a sort of dysfunctional relationship between myself and the machine which is analogous of human relationships to the environment.

BC: Finally, how have your evolving interests affected you personally? During your introductory talk with Seán Kissane at Uillinn, you looped back to religion.

GB: I grew up in an atheist household. Religion depoliticises how you interact with the environment. If you think you’ll go to heaven, why care about the planet now? Belief, or unquestioned knowledge, causes us to stagnate, to exist in stasis. And, let’s face it, humans are a lot older than their gods.

George Bolster’s solo exhibition ‘Communication: We Are Not The Only Ones Talking…’ ran at Uillinn: West Cork Arts Centre from 7 January to 11 February.

georgebolster.info

Brian Curtin is an Irish-born art critic based in Bangkok. He is the author of Essential Desires: Contemporary Art in Thailand (Reaktion Books, 2021). brianacurtin.com

Miguel Amado: In your projects, you seem equally invested in enabling reflection about your own identity and bringing different people together. Would you agree?

Alice Rekab: I think that’s really astute. In the Ireland I grew up in, I was very much in the minority in a lot of ways. I didn’t have any mixed-race friends at all, even when I went to college. It was only when I moved to London to do my PhD that I met other artists of various heritages who were making work – or even just looking at the world – through the lens of being mixed race.

MA: Ireland was very culturally homogeneous in the 1990s.

AR: I distinctly remember being 12 or 13 years old and suddenly seeing other Black people in Ireland for the first time – for example, a woman at the back of the bus that I couldn’t identify. I recall wanting to speak about that, but also feeling this strange sense of alienation, because obviously there aren’t that many Sierra Leonians in Ireland, and I had no way of knowing which part of Africa the woman was from or had connections with. Navigating all the nuance of difference and African-ness was a learning process, particularly as a young person growing up in a mono-racial society.

MA: Your recent project, ‘Family Lines’, which included an exhibition at The Douglas Hyde and multiple events in and beyond the gallery during 2022, engaged with this inquiry in two ways: conceptually, through your works, and practically, at grassroots level, as you facilitated encounters with others.

AR: ‘Family Lines’ was about an internal, subjective conversation

MIGUEL AMADO INTERVIEWS ALICE REKAB ABOUT EVOLVING THEMATIC CONCERNS IN THEIR PRACTICE.

that happens through clay, the paintings, the images, the albums. It constituted a place of self-discovery, something deeply personal that then becomes political. But it was also about making a space to share my experience, specifically of intergenerational migration, as much as enable its examination with and through multiple voices. Thus, it also allowed me to reach out to a community with whom I wanted to connect and enable the public to engage with.

MA: It is as if the project operated as a platform not only for your works, which engage with underrepresented narratives, but also for Black Irish creatives, who are still part of those same underrepresented narratives.

AR: My aim was for them to be heard by others and to be heard by one another, showing that one’s voice isn’t the only voice – that one is not alone – and understanding that the conversations we have with one another are a way of dealing with invisibility or erasure. When you are raised in the West, a lot of ignorance is ingrained in you, because we’re not taught otherwise. I didn’t learn anything about my father’s family, or what Sierra Leone was, or about West Africa through school. And if who one is does not matter, that has an impact on one’s sense of belonging.

MA: This is why you often talk about the emotional and intellectual impact of your first visit to Sierra Leone in 2009.

AR: I always knew I was Irish Sierra Leonian because I had a close relationship with my grandmother, but that was in the vacuum of mono-racial Ireland, and thus I only understood my heritage in relation to her. The first time I went to Sierra Leone, I was in her company, and that was the moment I realised I was Irish Sierra Leonian in relation to her within a Black majority context. That was revelatory yet difficult, as I became aware of the complexity of my light skin tone. When people there looked at me, they didn’t see a mixed-race person, even if I spoke Creole or understood the nuances of local behavior. And I also became aware of the privilege I had, just from having been born in Ireland. So that trip was the catalyst for the consciousness of being myself, appearing to me in a mirror larger than the borders of my inner world.

MA: You seem to translate this experience into your works, whether they are 3D pieces, paintings, or digitally collaged lens-based imagery, and particularly when you use materials such as clay.

AR: The use of clay emerges directly from my body and from the subconscious as something that is almost impossible to articulate verbally. The material enables that which feels outside of language to manifest physically, as it has this kind of primeval quality. The animals I sculpt are my interpretations of the souvenirs that were in my home, objects that had been brought over by my father’s family in the 1960s as symbols of their culture. They allow me to critically examine mainstream Western representations of Africa as a place where wild and unknown things live, as I play with the emergence of an African tourist industry for the Western gaze and the need for immigrants to connect with their geographies of origin through material culture.

The idea of mapping ways of understanding – that’s where the paintings come in. I use boards, sometimes reclaimed, as the surfaces onto which I apply a mixture of clay, images, and oil stick, and there’s a lot of cutting and texturising, which in a way operates like a sort of fractured, temporal diagram of life. For instance, Our Common Ancestor: Five Panels of Enmeshed Historical Narrative (2022), which was on view at The Douglas Hyde, suggests a quantum timeline in which different times are superimposed on one another and create meshes that get read through in different ways; they are a short-circuiting of human history and personal and cosmic histories. There are these master stories, but

there are also intimate ones – for example, a miniature picture of my grandmother sitting solitary at a table next to a vast depiction of a fossil and a stellar explosion. Certain stories are valued differently, depending on your proximity to them.

The digital collages reconfigure all the elements. They often feature family photographs, which I may bring together with other images. And then there’s a digital drawing aspect that creates the links – both literally and symbolically – as well as areas of intensity through mark-making of what seem like coronas around certain figures or objects, as a means to bring to life dear people or beloved animals that are dead.

MA: Your latest exhibition, ‘Mehrfamilienhaus’, is on view at Museum Villa Stuck in Munich, and features works that, while speaking to the core of your concerns, look at new areas of interest.