This issue has a timely focus on several important exhibitions currently showing in galleries nationwide. On 13 April, the 38th edition of Ireland’s contemporary art biennial, EVA International, opened in various venues across Limerick

city. Mary Conlon interviews EVA 2018 curator, Inti Guerrero, for this issue, offering insights into Guerrero’s curatorial research and exhibition-

making strategies. Meanwhile, a number of exhibitions and projects

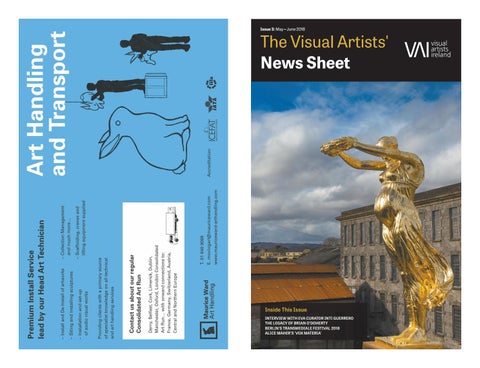

are currently taking place across Ireland to celebrate the diverse career of Irish conceptual artist and critic, Brian O’Doherty, who marks his ninetieth birthday this year. Brenda Moore-McCann’s extended essay outlines some of these events, while reflecting on O’Doherty’s vast artistic legacy. Art Gallery from 7 September to 24 November. Tina Kinsella interviews Maher about her new bronze sculptures and wood relief prints. In other features for this issue, Lily Cahill reflects on the sculptural practice of Hannah Fitz. And much more!