HUMBERSTON FITTIES

the story of a Lincolnshire Plotland

ALAN DOWLING

Taken in September 2007, on the Civic Trust Stand at the Fitties Heritage Weekend.

Please note headline on newspaper article (behind Alan), ‘Very Nearly Heaven’. in 2007, the Civic Trust Stand at the Weekend. Please note headline on newspaper article (behind Alan), ‘Very Nearly Heaven’.

HUMBERSTON FITTIES

the story of a Lincolnshire Plotland

by ALAN DOWLING

Dedicated to Alan Dowling (15th September 1932 to 27th August 2018) and all those past and present who made the original book and this 2022 edition possible.

This reprint was made possible by his loving wife and daughter, Dorothy Dowling and Ann Smyth.

‘The sea pinks and the sea lavender covered the marshy areas with masses of colour and later, when the Autumn tides caused the drain to overflow, the marsh turned to a lake and the dune area became a virtual island.

What a paradise Humberston was then!’

Cleethorpes 2001

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system of transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise without the prior permission of the author.

Copyright © Alan Dowling, 2001

First printed in 2001

Reprinted in 2022 and 2023

Printed by Waltons Publications

46 Heneage Road, Grimsby waltonspublications.com

Publisher: Independent Publishing Network

Publication Date: Monday 15th May 2023

ISBN: 978-1-80352-732-1

Author: Alan Dowling

Email: annie.smyth@ntlworld.com

Please direct all enquiries to the above.

3 CONTENTS Foreword 5 Acknowledgements 6 List of Maps 8 Abbreviations 9 1. Introduction: Plotlands 10 2. Tents and Troops: 1900-1918 17 Under Canvas on the Fitties 17 The First World War 22 3. The Simple Life: 1919-1939 25 Bungalow Beginnings 26 Humberston Fitties and Fitties Field 32 Relaxation and Play 33 Food and Drink 37 Services 39 Privies and the Dilly Cart 40 Transport 42 Health 43 Growth and Public Health 44 A New Owner 45 4. War and Peace: 1939-1949 47 Land Reclamation 48 Post-War Recovery 48 Potential Purchasers 52 The Fitties in 1949 54 5. Holidays for All: 1950-1974 55 New Campers, New Bungalows 57 Planning and Development 59 Caravans 62 Management 64 Removal of Anthony’s Bank Bungalows 65 Condition of Bungalows 66 Private Facilities and Public Services 69

4 CONTENTS Daily Life 72 More Facilities 77 The End of an Era 78 6. Controversy and Conservation: 1986-1996 82 First Leisure Corporation, 1986-1987 82 Cleethorpes Borough Council Proposals, 1987-1989 85 Whitegate Leisure, 1989-1990 92 Bourne Leisure, 1991-1995 93 Becoming a Conservation Area, 1995-1996 100 Postscript 103 Appendix A: First Camp and Second Camp 107 Appendix B: Other Camping at Humberston 108 Appendix C: Defending the Fitties Against the Sea 111 Bibliography 117 References 119 Index 126

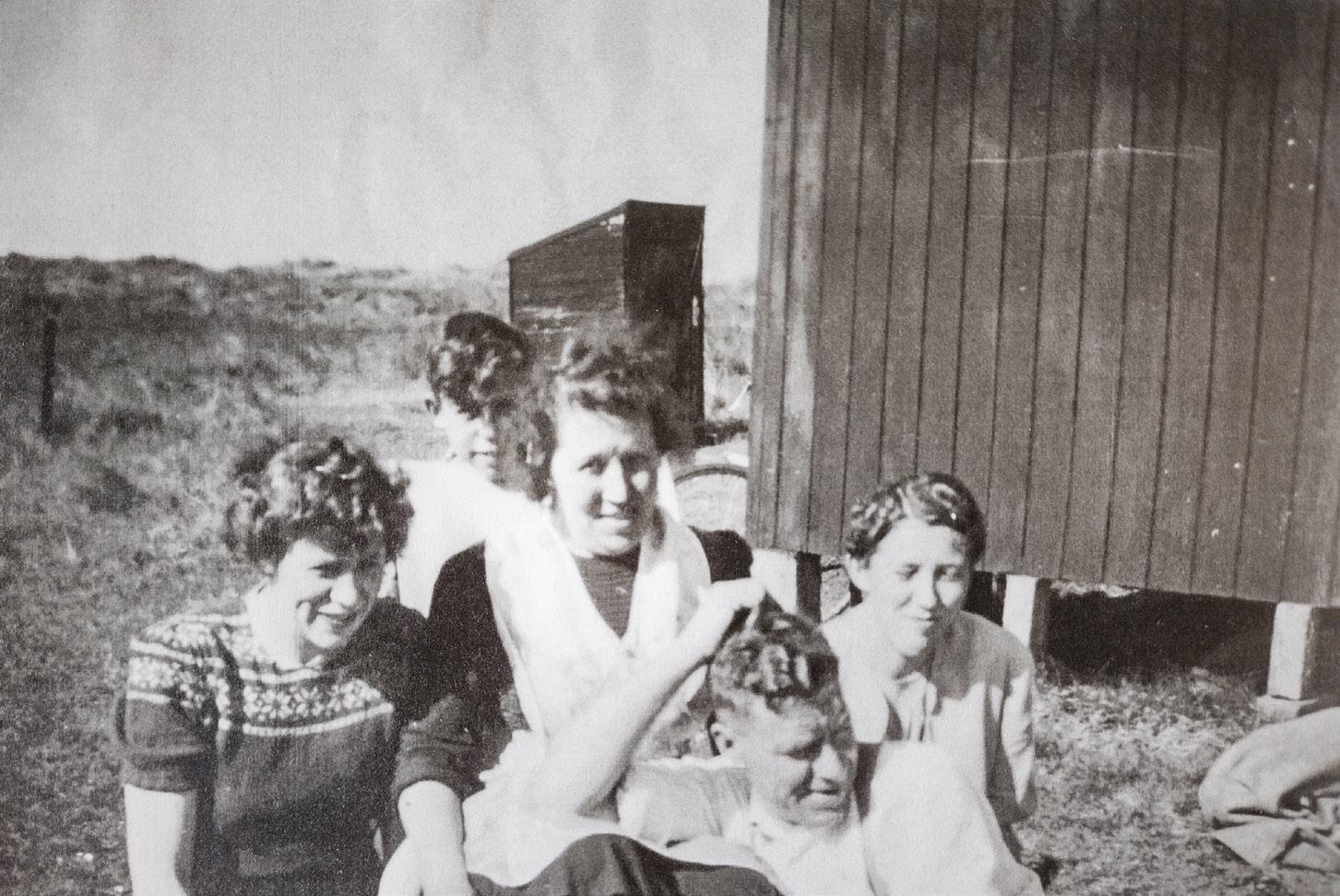

Superlatives are the order of the day when people talk about their life on the Humberston Fitties bungalow or chalet camp on the Lincolnshire coast: ‘paradise’, ‘magical’, ‘the best years of my youth’, ‘idyllic’, ‘blissful freedom’, ‘very happy days’, ‘lovely and relaxed’, ‘we didn’t want to go abroad’, ‘years full of sun and happiness’, ‘the beach was like lying on the Riviera’, and so on.

This affection for ‘the Fitties’ is widespread and many people have happy memories of family holidays on the camp, whilst others still enjoy its relaxed lifestyle.

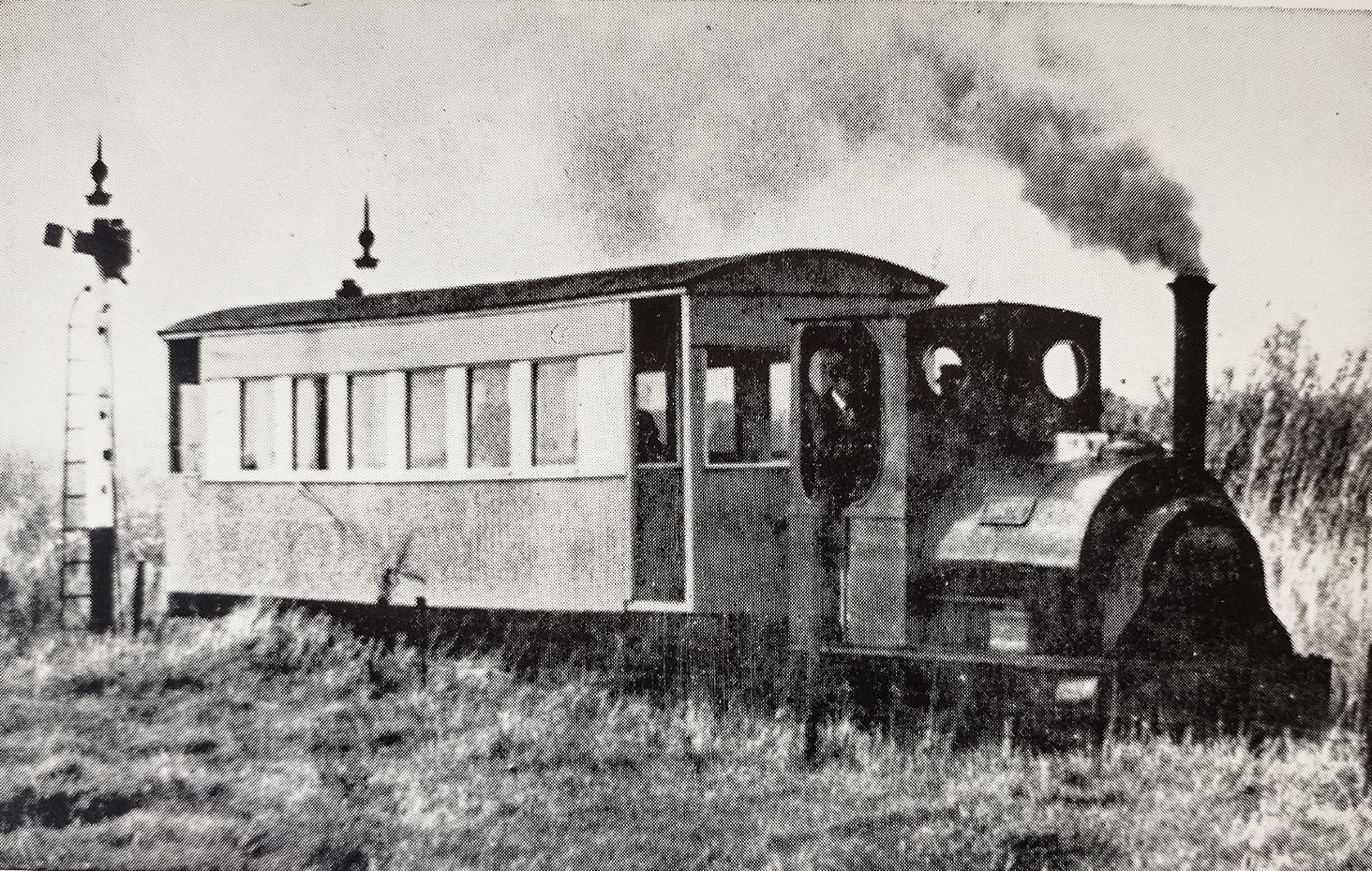

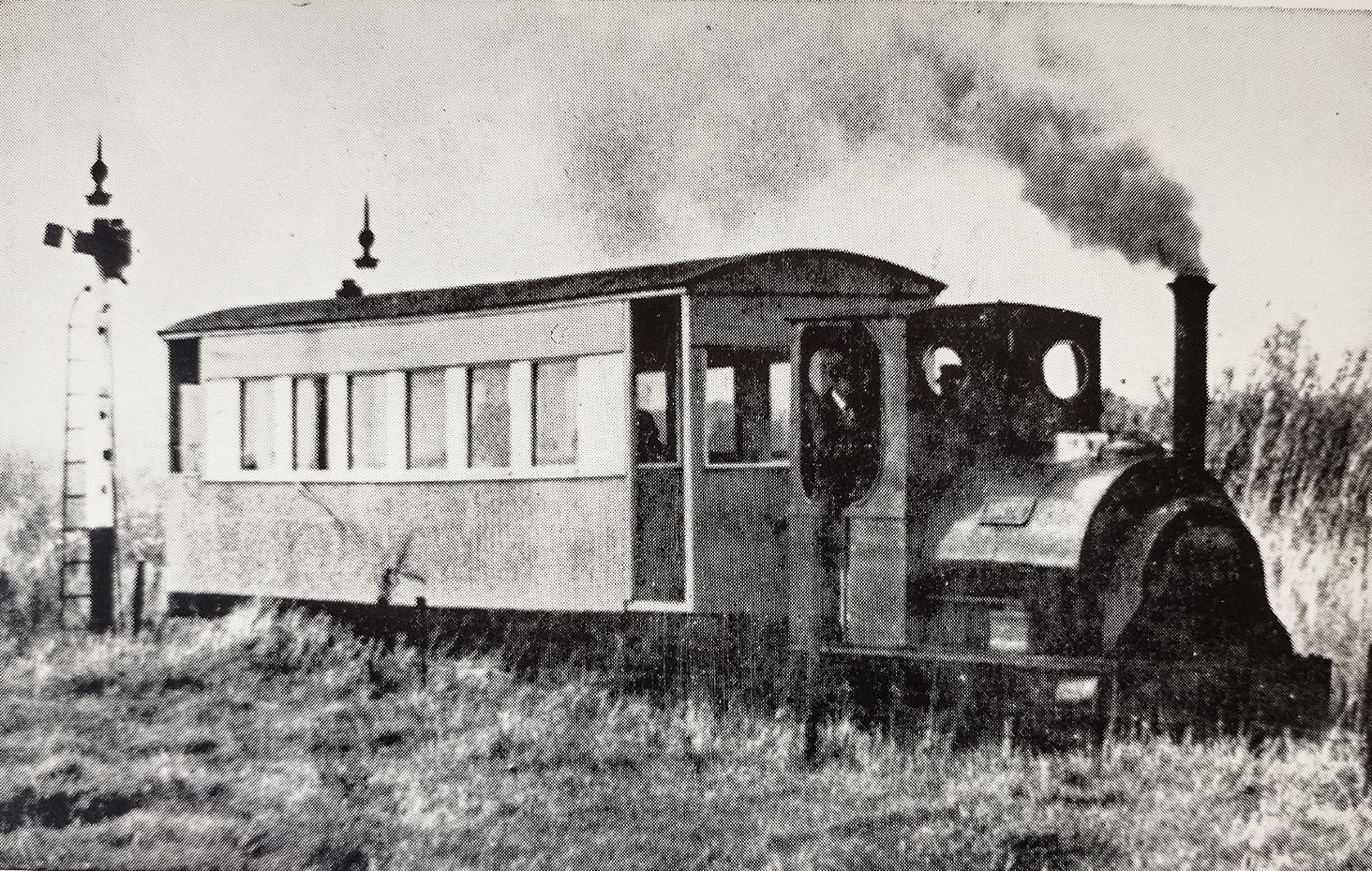

Apart from its personal importance to its many supporters, the particular significance of the Fitties camp is that it is a surviving example of the many ‘plotland’ developments which were once to be found distributed throughout the country. These informal developments of holiday and residential chalets, bungalows, huts, converted buses, railway carriages, etc., grew in a haphazard manner on coasts and in the countryside, mainly in the period between the two world wars.

This book sets out to tell the story of one of these plotland camps, the Humberston Fitties. It recounts how the Humberston coastal sand dunes accommodated the tents of summer campers in Victorian and Edwardian times and how the bungalow camp began in the dunes in the years immediately following the First World War. It then blossomed in the 1920s and 1930s as part of the general spread of holiday chalet provision along the Lincolnshire coast. During the Second World War it was used for military purposes and returned to holiday use with the restoration of peace and the post-war expansion of the holiday industry. It was subsequently overshadowed locally by the rapid increase in the provision of static holiday caravans. More recently it experienced a troubled period during which its character and existence were threatened. It survived and was created a conservation area in 1996 on the grounds of its historical significance.

A couple of points should be made about the use of certain words. The first point is, should the buildings on the Fitties be called bungalows or chalets? Regardless of the dictionary definitions, both words are used on the camp for the same type of building and I have used both terms indiscriminately with no implied difference in meaning. Early campers tended to use ‘bungalow’ and many still do so. In recent years, ‘chalet’ has been favoured in official documents and, consequently, features more in later chapters. The second point is that because of its origins and lifestyle I frequently refer to the Fitties as a ‘camp’ and the bungalow owners or tenants as ‘campers’. It is now officially termed a ‘park’, so this term also figures in the book’s later chapters.

5

FOREWORD

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Although I have never owned or rented a Fitties bungalow, for many years I have been a fan of this unusual and varied conglomeration of buildings devoted to the carefree life.

I frequently thought about looking into the history of the camp and in 1996 I was spurred into action when I saw an appeal in the Grimsby Evening Telegraph from Alfreda Ellidge asking for help in compiling a history of the Fitties. Alfreda and her husband Robert had been in the forefront of the campaign to protect the camp’s future by gaining conservation area status in 1996, and were also keen to record the history of the Fitties. I contacted Alfreda and we decided to start working together on the project. Other very important commitments soon arose for Alfreda which made it difficult for her to continue with the joint venture. However, I still regard the book as the product of a joint enterprise because it would probably never have been written without the enthusiasm of Alfreda and Robert for the Fitties and their continued help, support, and encouragement. They in turn wish to make their own acknowledgement, as follows: ‘We simply could not have got this far without the dedication and energy of Marlene and Dennis Weltman. Dennis died just before the dreams for which he and Marlene had worked so hard (particularly the electrification of the Fitties) the last great project of his life here, came true. We all owe Dennis and Marlene an unrepayable debt of gratitude - Alfreda and Robert Ellidge’.

My initial research was amongst documentary records relating to the Fitties. Subsequently, I made numerous appeals for further information at every opportunity, including appeals through local newspapers, local radio and the internet. I am particularly grateful to those people who responded with accounts of their life and holidays on the Fitties. They gladly gave of their time and memories and trustingly lent family photographs and other documents for copying. Accordingly, this publication is an amalgamation of my researches amongst documents and my interviews with these people. As a consequence, those aspects of Fitties life for which records survive, or upon which people have contacted me, will have been dealt with more fully than other aspects. Further information to help fill gaps in the story of the Fitties will be welcome.

Those who have helped me and to whom I am indebted include Bob Arkley, Sybil Bacon (nee Goodhand), Hadyn Baker, BBC Radio Humberside, Mrs. Butts, Betty Card and Eileen, Norman and Pat Carter, Wilton Cobley, John Conolly, Mrs. Coulbeck and Sue, Alan Coxall, Rex Critchlow, ‘Roly’ Curtiss, Edward Drury, Eric Drysdale, Bruce and Peter Edge, Dave and Kath Edwards, Alfreda and Robert

6

Wyatt Ellidge, Eileen Emptage, Rachel Fazey, Major Clixby Fitzwilliams, Mrs. Gaunt, Cyril Gloyn, Dennis Goodhand, Peter N. Gough, Grimsby Telegraph, Derek Hallam, Carole Harman, Margaret Hart, Frank Hill, Steve Hipkins and Grimsby Central Library staff, Anne Howe, Dot Huckin, Roger Hunter, Anne Jackson (nee Gordon), Lincolnshire Archives, Horace McDonald, Rod Marchant, Roger Martin, Patricia May (nee Grantham), Stan Meakings, Ken Moriarty, Beryl Morriss (nee Goodhand), Colin Newton, North East Lincolnshire Archives Office (John Wilson and Carol Moss), Mrs. Pitson, Frank Priest, Mrs. M. Roberts, David N Robinson, Elsie Robson (nee Drewry), The Sheffield Star, Mr. and Mrs. Sissons, Annie, John and Roannah Smyth, Cllr. (Mrs.) Margaret Solomon, John Storey, Tameside Local Studies Library, Mariette Thorpe, Edward Trevitt, Ken Turner, Geoff Wagstaff, Jean Wales, Welholme Galleries (Andrew Tulloch), Janet Wilmott, Colin Wright, and the Yorston family. I am also grateful to Gary Cooper and the staff of Waltons Publications in Grimsby, who have been most helpful, good-natured and professional in seeing to the printing of the book.

The photographs which illustrate the book have been provided as follows: Alan Coxall, p.53 (both photographs); Peter Edge, pp.29 (both) and 38 (below); Dave Edwards, p.63 (above); Rachel Fazey, p.60 (both); Cyril Gloyn, pp.31 (both) and 45 (above); Grimsby Telegraph, pp.67 and 70; Anne Howe, pp.76 (above) and 91 (above); Lincolnshire Coast Light Railway, p.63 (below); Horace McDonald, p.17; Rod Marchant, p.50 (both); Patricia May, p.38 (above); Colin Newton, pp.34 (below) and 80 (below); Tameside Local Studies Library, p.23; Welholme Galleries, p.34 (above); Yorston family, p.73 (both), p.81 (2022) relatives of the Butler Family, p.46. (2022). danwhitbyphotography, p.41 (below) and p.80 (2022). All other photographs are by the author. My final thanks are to my wife Dorothy, who has given practical help and has also cheerfully accepted the years I have spent researching the subject and crouching over a word processor keyboard. Fortunately, we share a liking for ‘noseying’ around the Fitties and have had many enjoyable walks there together at all times of the year.

Additional Acknowledgements Reprint 2022

Adrian Wilkinson from North East Lincolnshire Archives Office, for his unwavering support enabling this book to be reprinted.

Stuart Turnbull at Waltons Publications for his professionalism in overcoming obstacles encountered and always being available to us.

Lisa Cutting and Julie Connell for their interest, encouragement and support towards reprinting this book.

Grateful thanks to our daughter Ann Smyth for taking on such an onerous yet rewarding task with me, Dorothy.

7

LIST OF MAPS

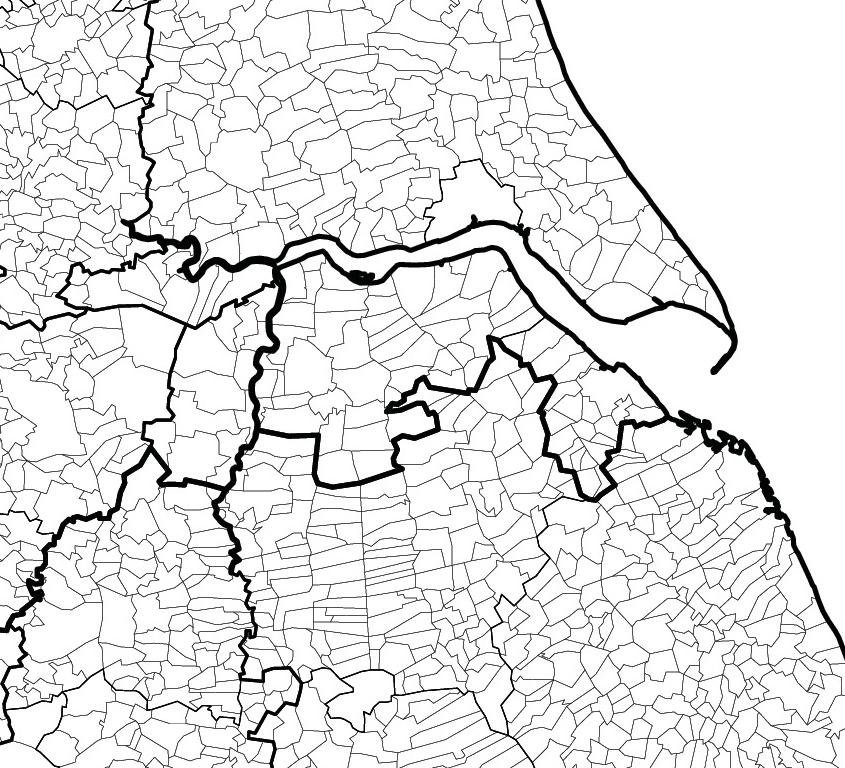

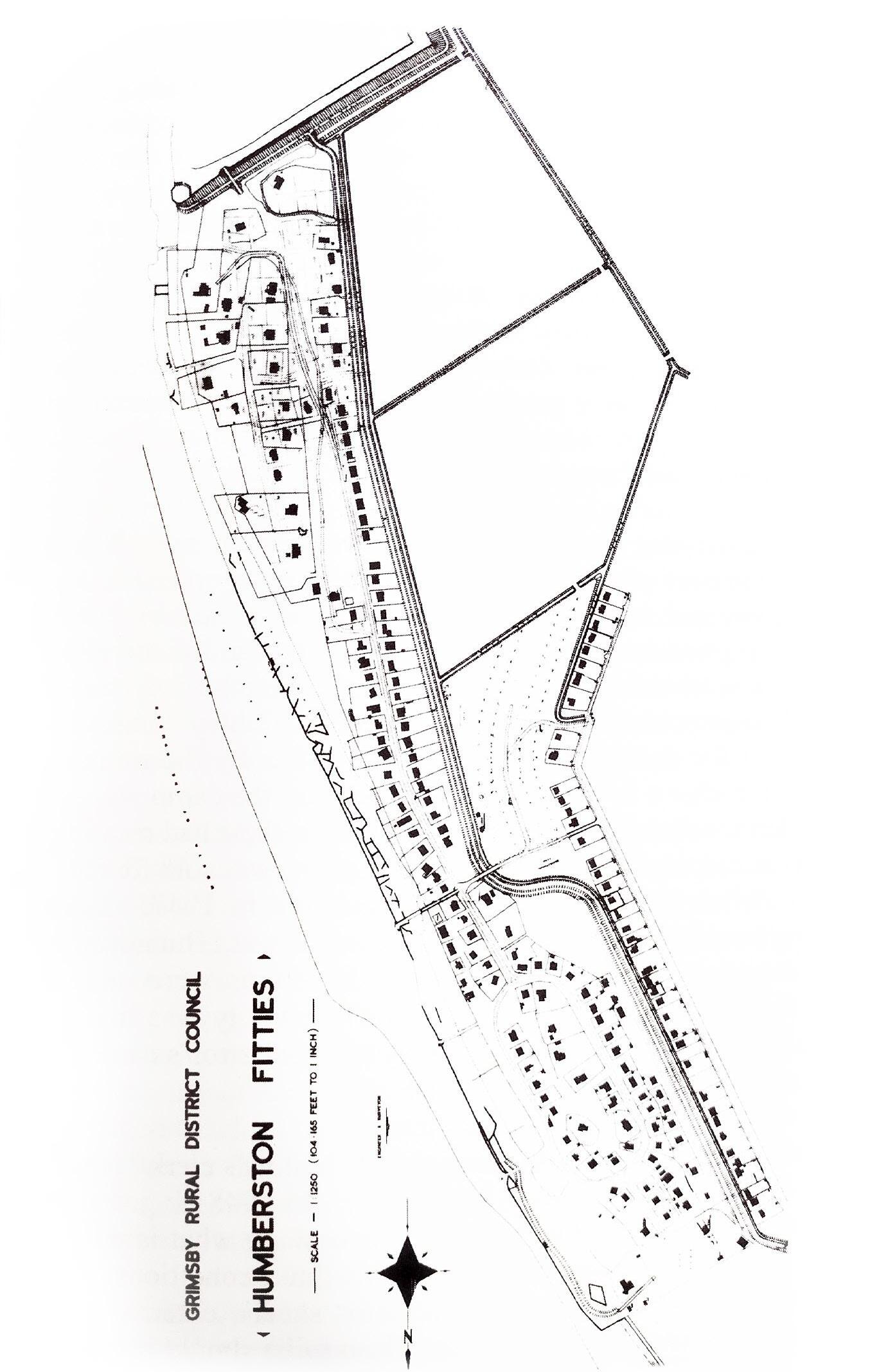

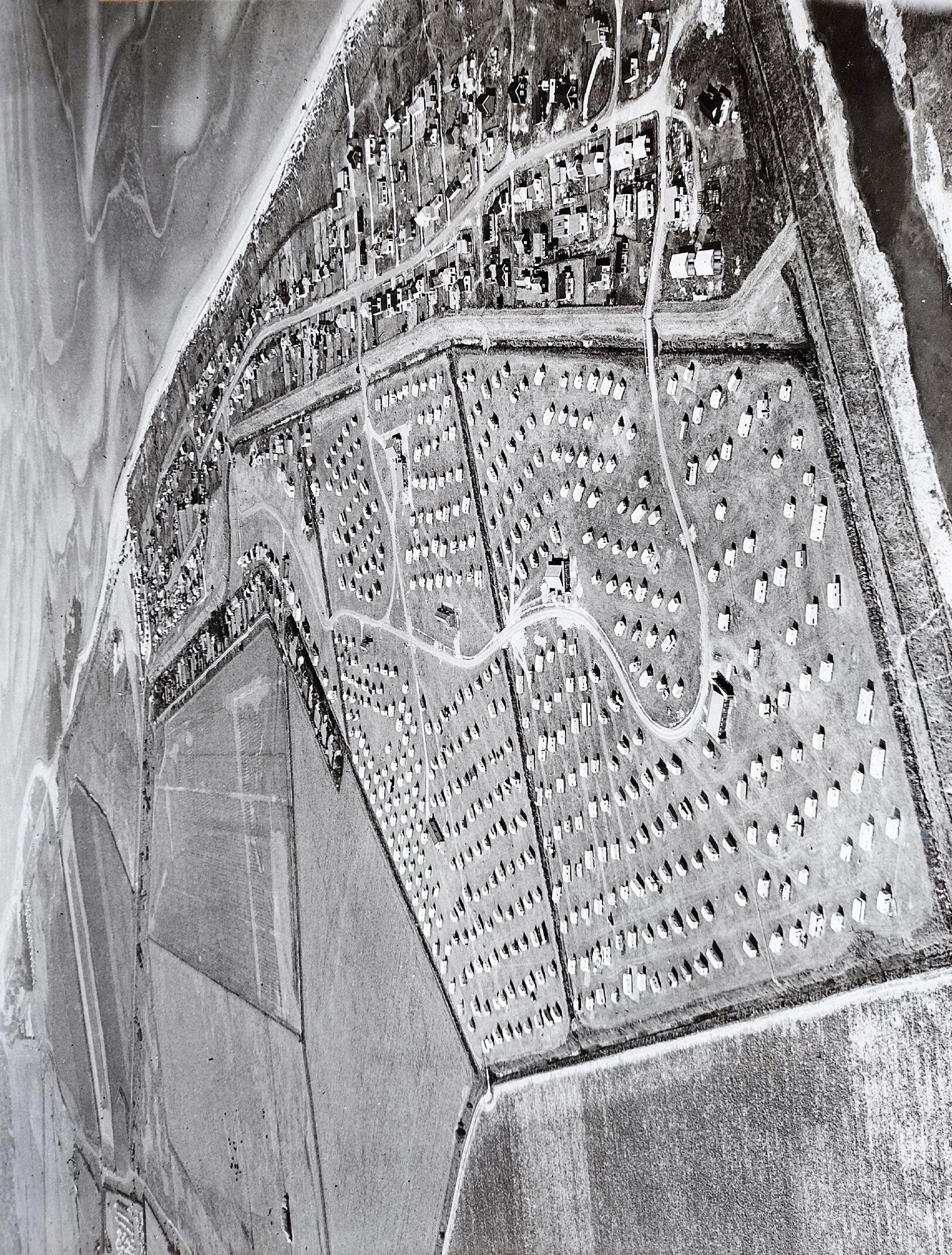

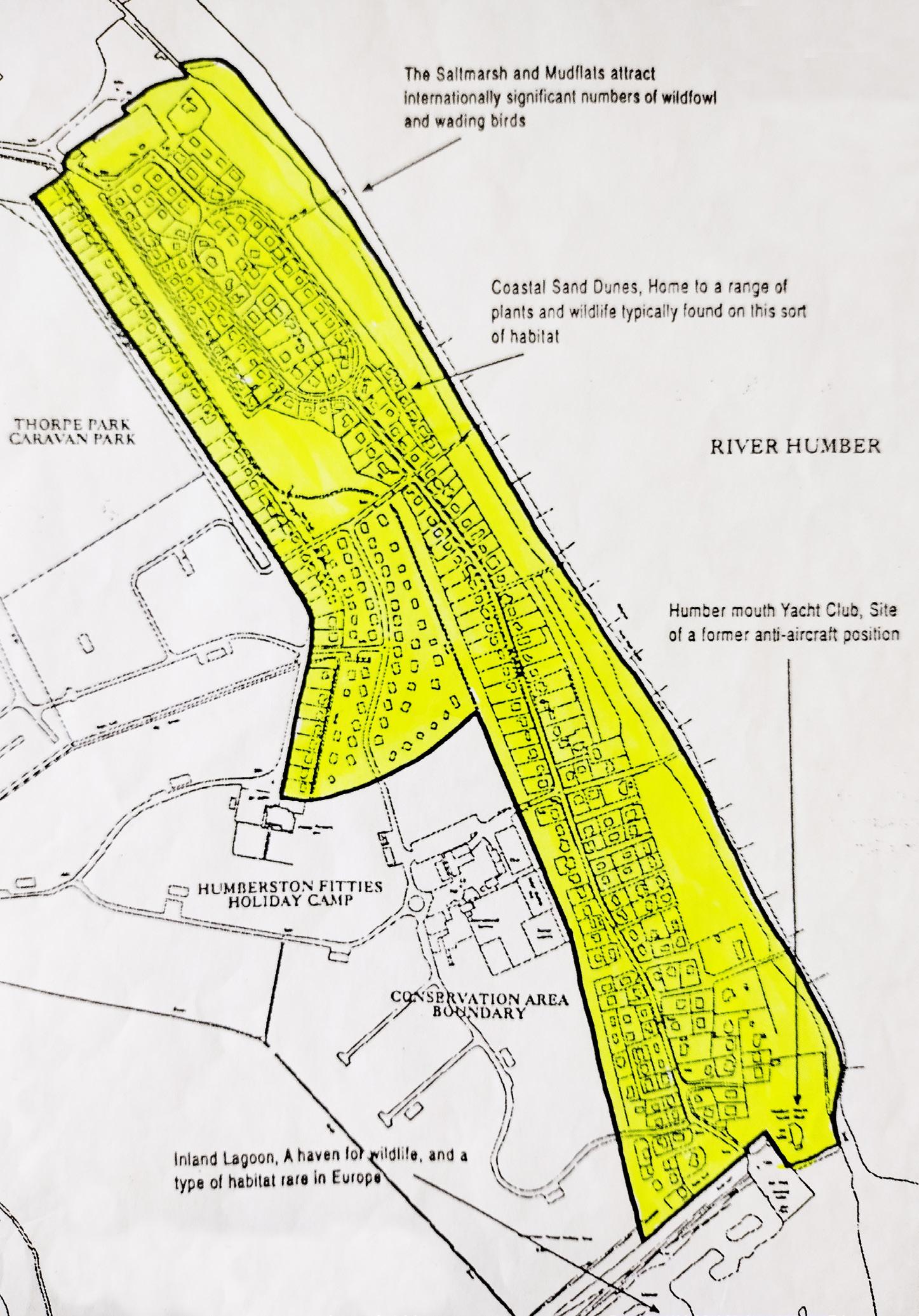

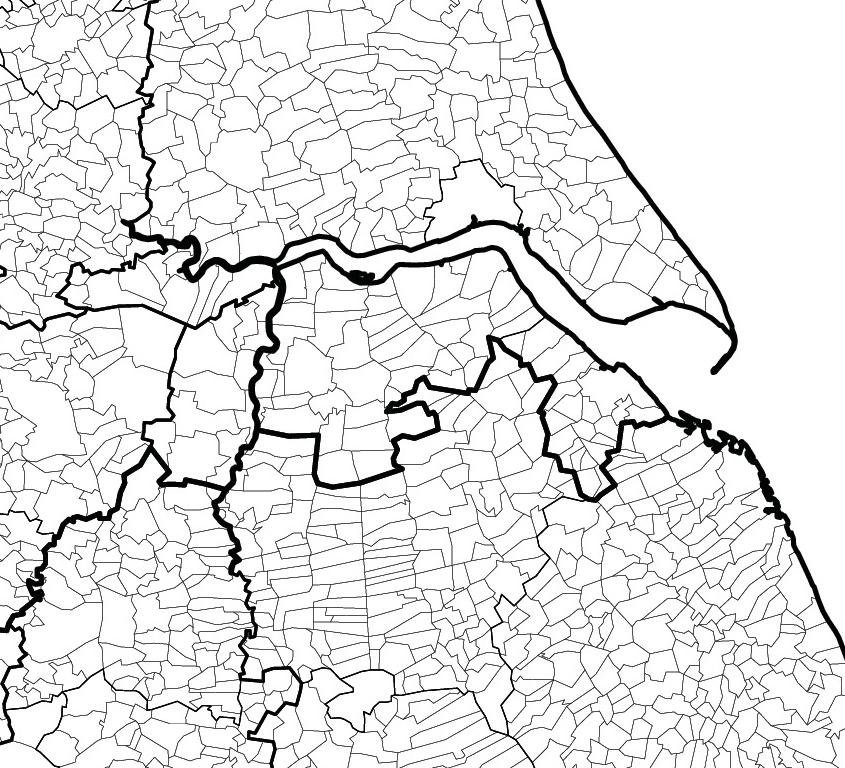

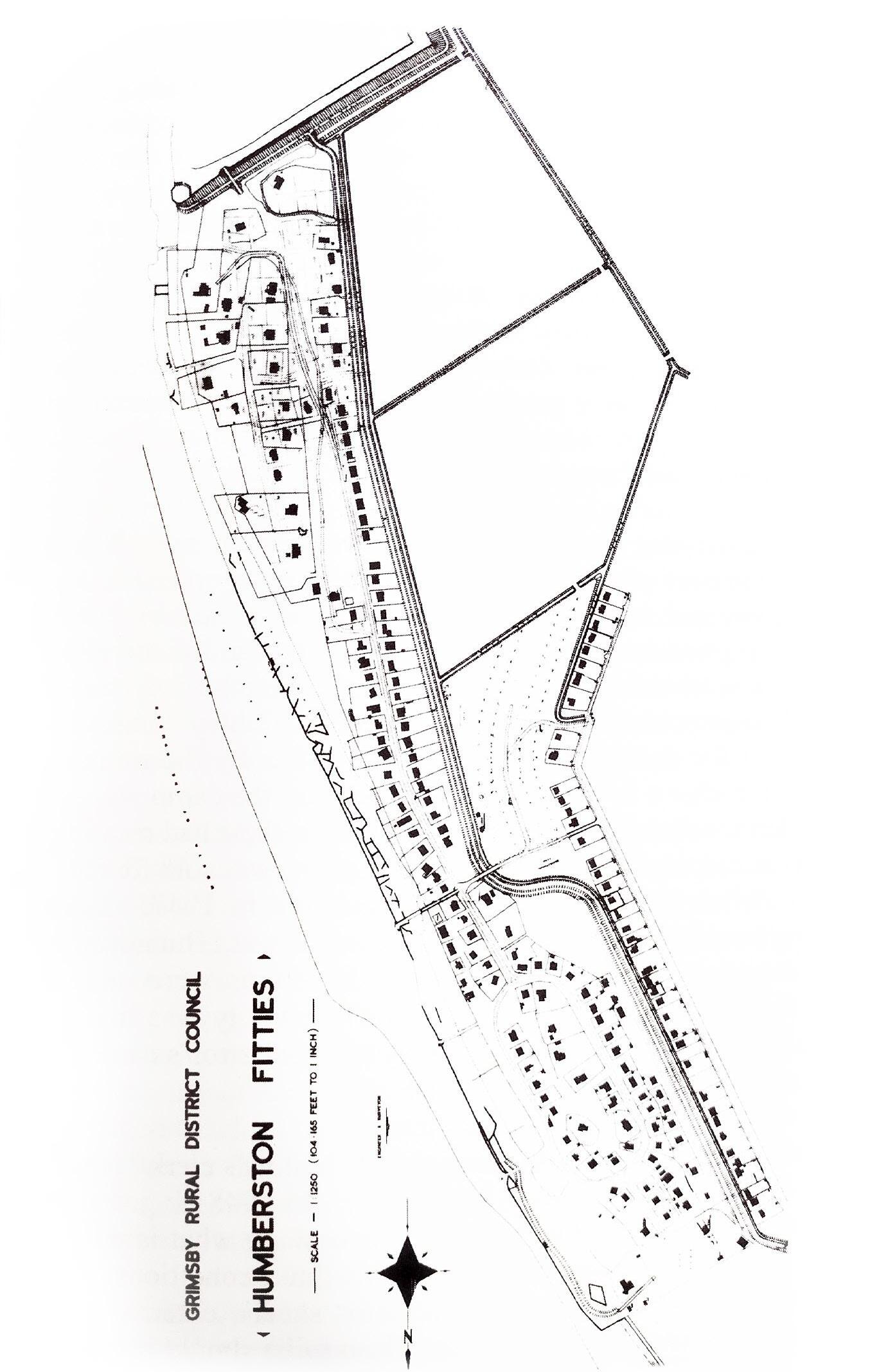

1. Location of the Humberston Fitties.

© Crown copyright 2022 OS 100065902. You are permitted to use this data solely to enable you to respond to, or interact with, the organisation that provided you with the data. You are not permitted to copy, sub-license, distribute or sell any of this data to third parties in any form.

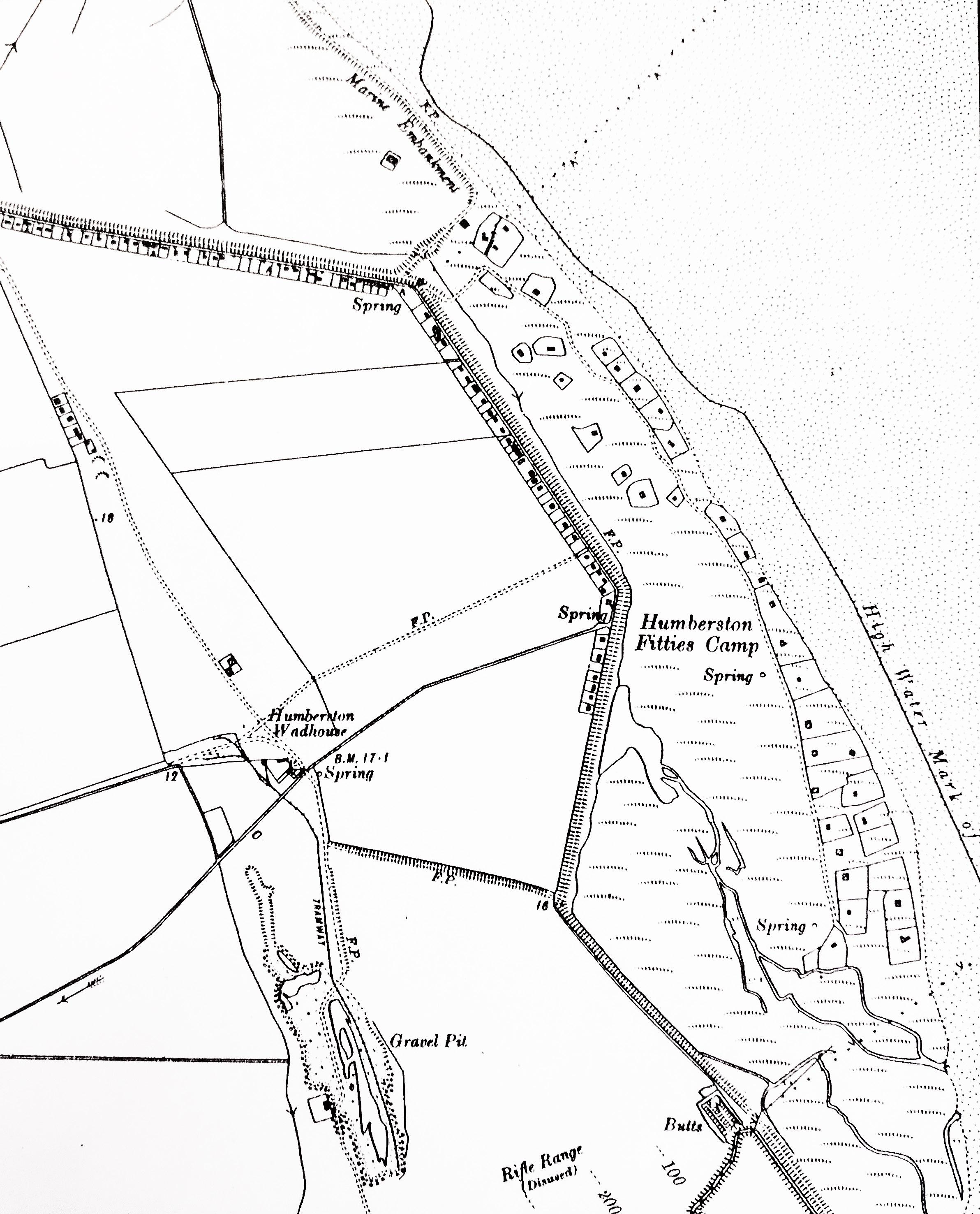

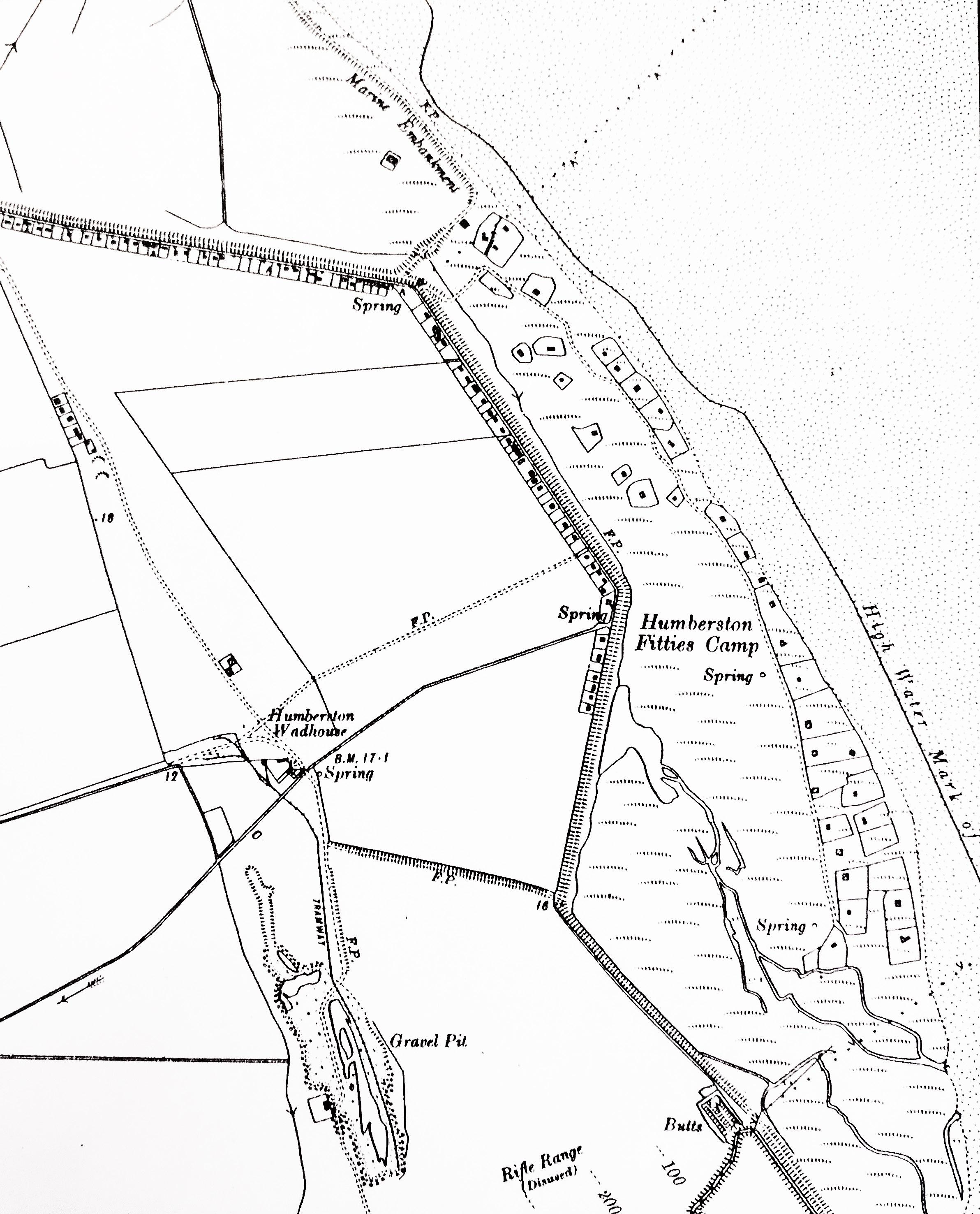

Humberston Fitties, 1907.

(Extract from: Lincolnshire (Parts of Lindsey) Sheet XXXI NW. Ordnance Survey, 1907. Scale of original map: six inches to the mile).

© Crown Copyright. All Rights reserved. Ordnance Survey.

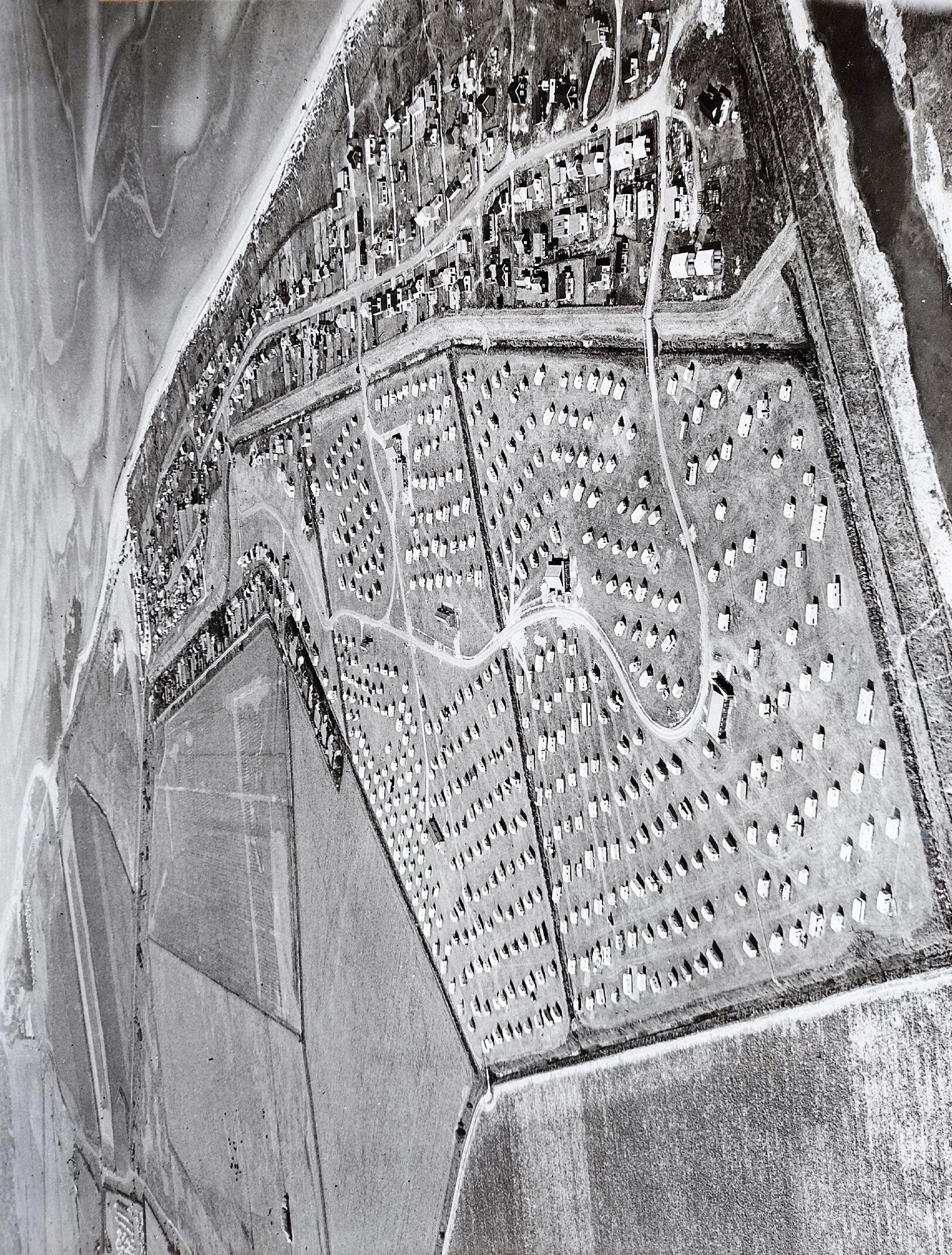

3. Humberston Fitties, 1932.

(Extract from: Lincolnshire (Parts of Lindsey) Sheet XXXI NW. Ordnance Survey, 1932. Scale of original map: six inches to the mile).

© Crown Copyright. All Rights reserved. Ordnance Survey.

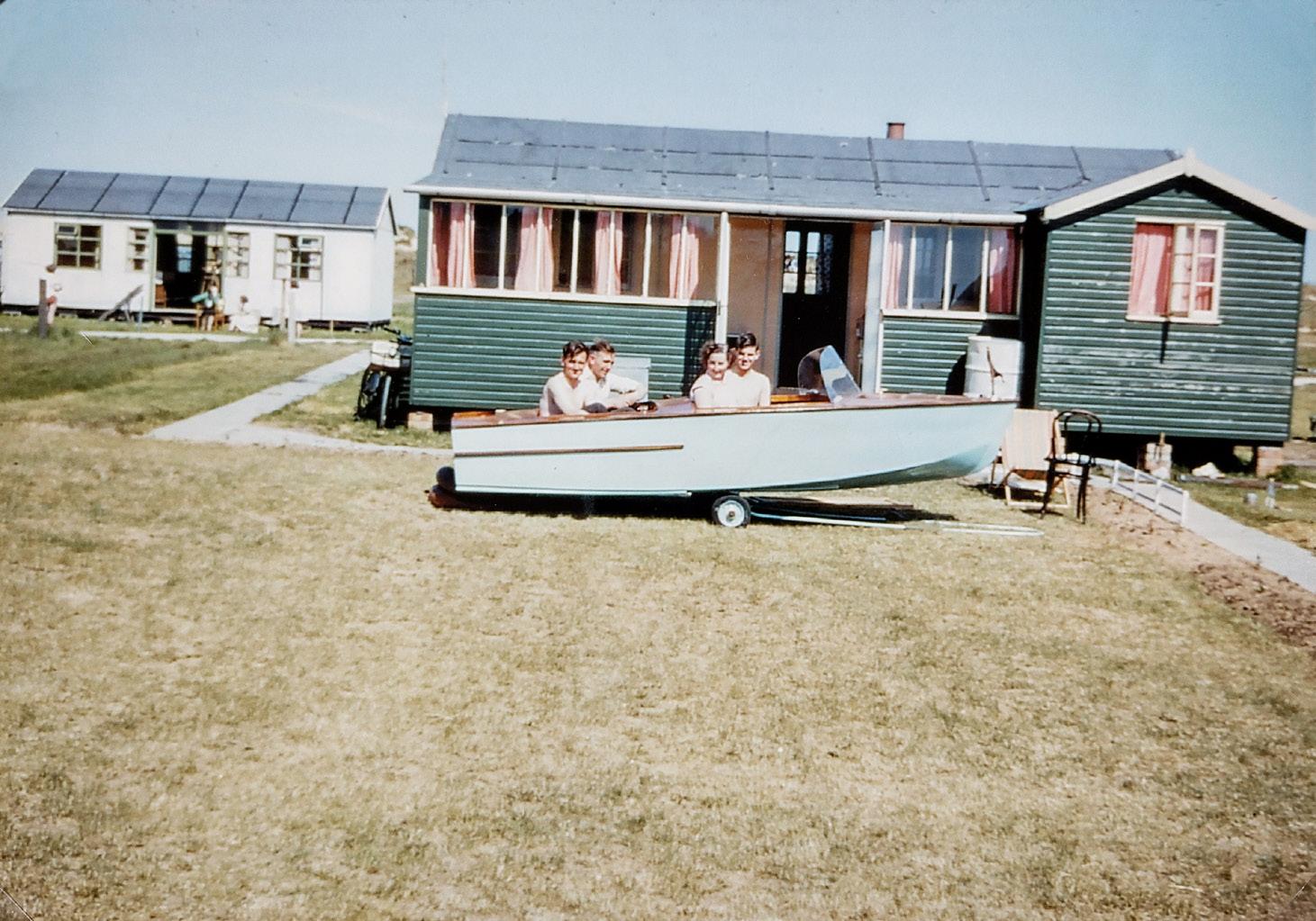

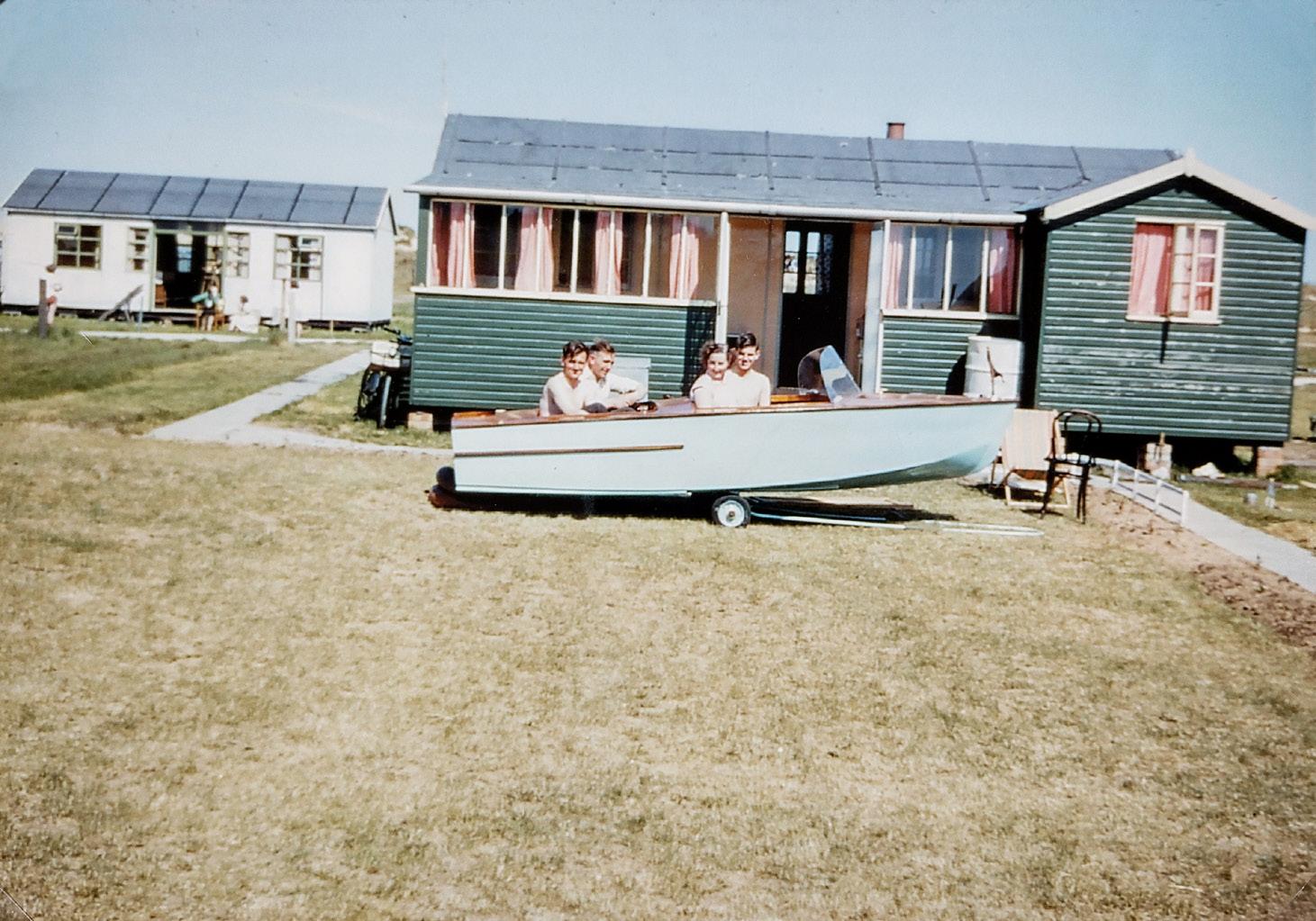

08

2.

19

24

56 LINCOLN

4.

Humberston Fitties, 1955.

BOSTON

GRIMSBY

HULL CLEETHORPES SCUNTHORPE

HUMBERSTON FITTIES

ABBREVIATIONS

ABBREVIATIONS

BC Borough Council

BC Borough Council

FC Grimsby Rural District Council Fitties Committee

FC Grimsby Rural District Council Fitties Committee

FORA Fitties Owners Residents’ Association

FORA Fitties Owners Residents’ Association

FORAB Fitties Owners Residents’ Association (Bungalows)

FORAB Fitties Owners Residents’ Association (Bungalows)

GDT Grimsby Daily Telegraph

GET Grimsby Evening Telegraph

GDT Grimsby Daily Telegraph GET Grimsby Evening Telegraph

GN Grimsby News

GN News

GT Grimsby Telegraph

GT Grimsby Telegraph

HFCA Humberston Fitties Campers’ Association

HFCA Humberston Fitties Campers’ Association

NELA North East Lincolnshire Archives

NELA North East Lincolnshire Archives

RDC Grimsby Rural District Council

RDC Grimsby Rural District Council

1. INTRODUCTION Plotlands

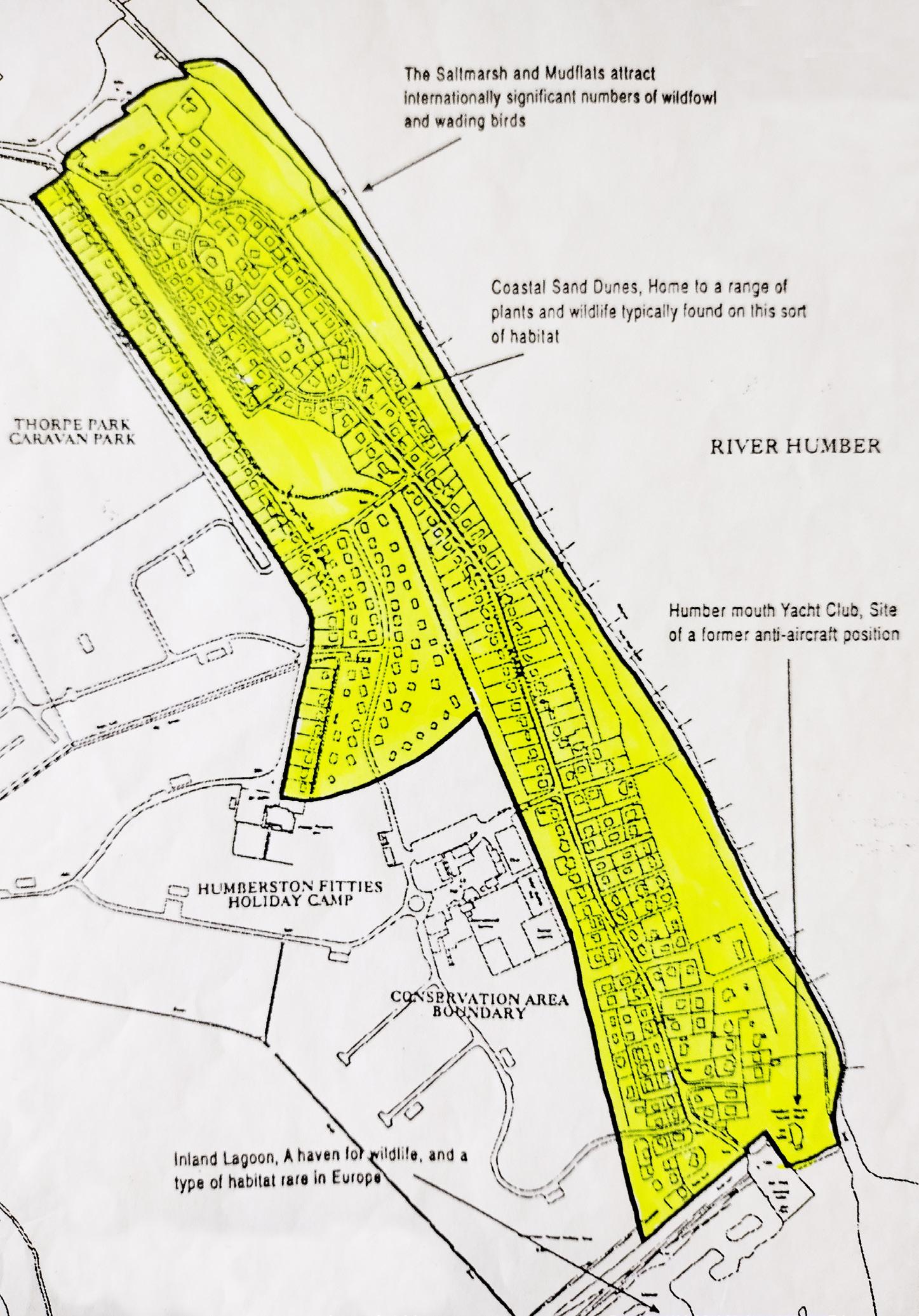

‘Humberston Fitties’, or simply ‘the Fitties’, are the customary local ways of referring to what is currently officially termed the Humberston Fitties Chalet Park. The park, or camp, contains about 300 chalets or bungalows and lies on the Lincolnshire coast in the parish of Humberston immediately to the south of the resort of Cleethorpes.

The land upon which it lies was once salt marsh and ‘Fitties’ is a Lincolnshire term signifying salt marsh, hence its name.1 The expressions ‘Humberston Fitties’ and ‘the Fitties’ are used to describe both the camp (and its later caravan extensions) and the general area of reclaimed salt marsh in which it lies. The interpretation is usually clear from the context within which the expressions are used.

In 1707 there were reckoned to be 391 acres of ‘outmarsh or Fitties’ in the Manor of Humberston.2 In 1795 part of the marsh was enclosed within a sea bank known as Anthony’s Bank* as a preliminary to turning it over to agricultural use. The present Anthony’s Bank Road which leads to the seafront follows the line of the bank, which then turns in a southerly direction near the camp entrance and runs through the camp. Sand dunes built up in front of the bank and eventually these became the location of the first bungalows on the Fitties.3 Subsequently, the area to the landward side of the bank was also used for bungalows. This type of bungalow development came to be called ‘plotlands’ and the rest of this chapter will outline briefly the growth of plotlands in this country.

The authors of a well-known book on plotlands provide us with the following introduction to the subject:

In the first half of the twentieth century a unique landscape emerged along the coast, on the riverside and in the countryside ... It was a makeshift world of shacks and shanties, scattered unevenly in plots of varying size and shape,

*Some people refers to this as Saint Anthony’s Bank. The author is not aware of any evidence of the historical use of a saintly prefix but would be pleased to hear of any relevant evidence. All historical records which have been refer simply to Anthony’s Bank. The portion of marsh at the southern end of the Fitties between Anthony’s Bank and the sea was known as Anthony Water. There was an Anthony Farm in Humberston which was known later as Cottagers Yard Farm. The question yet to be answered is, who was Anthony?

10

with unmade roads and little in the way of services ... To the local authorities (who dubbed this type of landscape the ‘plotlands’) it was something of a nightmare ... But to the plotlanders themselves, Arcadia was born ... ordinary city-dwellers discovered not only fresh air and tranquillity but, most prized of all, a sense of freedom.4

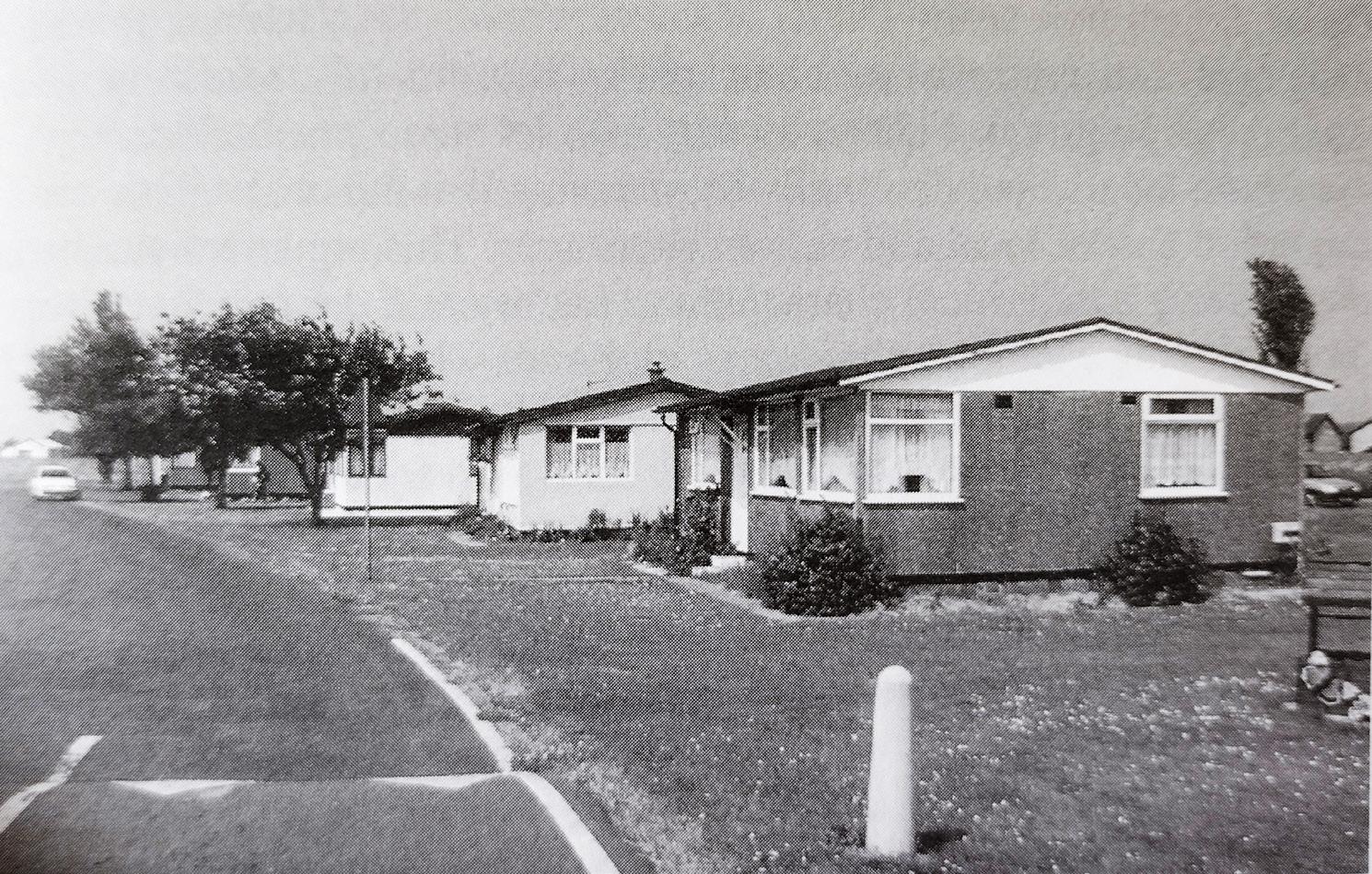

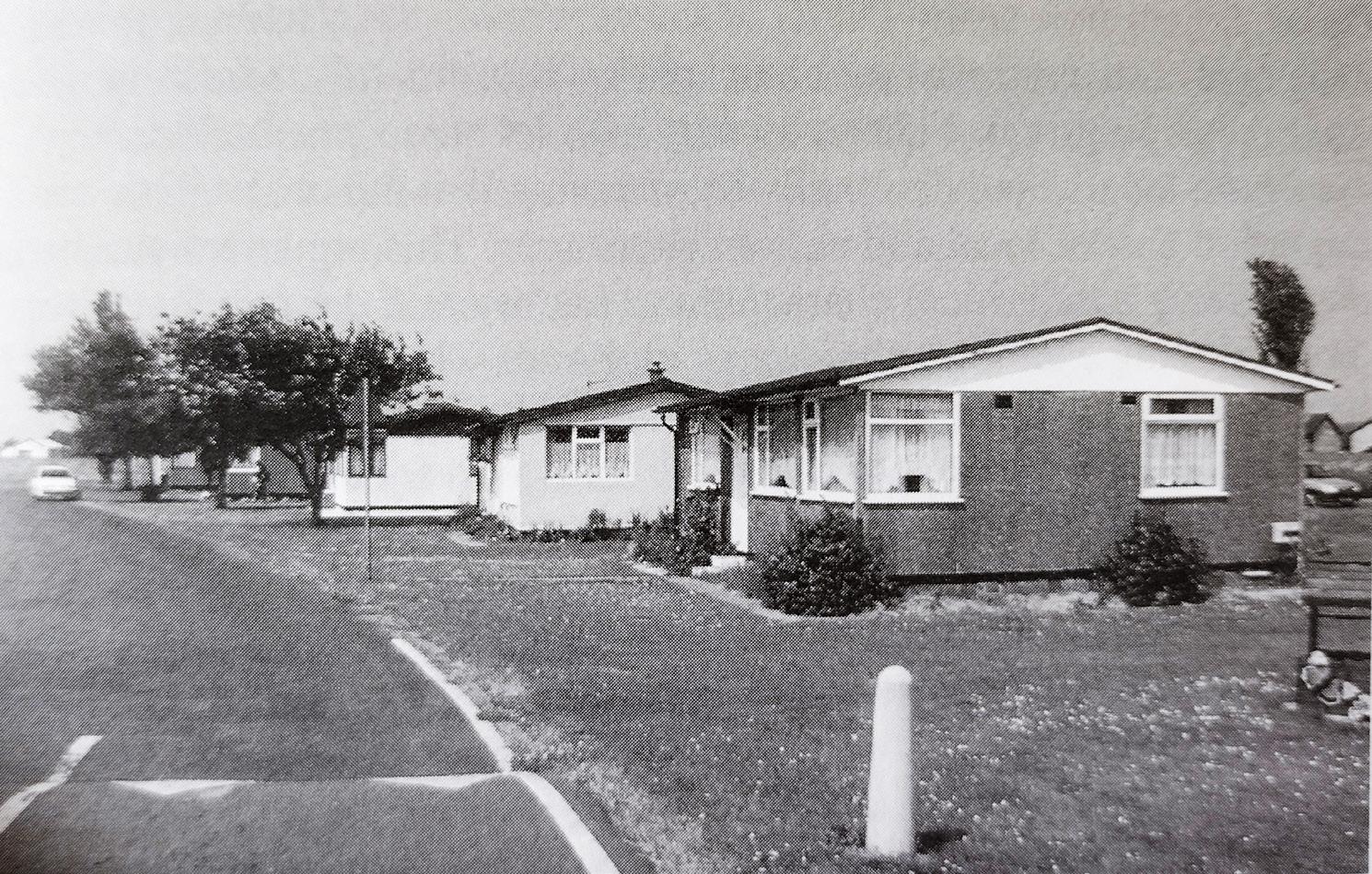

The growth of such plotlands was concentrated within a fifty-year period from the 1890s to the end of the 1930s, with a peak during 1919-1939.5 The Humberston Fitties is a surviving example, even though any ‘shacks and shanties’ which it may have had, have now evolved into, or been replaced by, chalets and bungalows. The Fitties has its own distinctive appearance and history, which have been shaped by local factors. But how did plotlands arise and become a countrywide phenomenon? What were the circumstances which led to the creation of numerous similar ‘camps’?

It is certainly a common human characteristic to wish at times to ‘get away from it all’ and retreat to that day-dream country cottage with a thatched roof and roses round the door. For many centuries, wealthy people could achieve this, on a grander scale, by virtue of having a country house and a town house, not to mention a hunting lodge, and spending an appropriate part of the year in each establishment. With growing industrialisation and the rapid growth of towns, the idea of having access to a bolt-hole or a place for fresh air and relaxation started to have a wide appeal.

In the 1720s Daniel Defoe commented on merchants of the City of London who had summer houses in the surrounding countryside ‘whither they retire from the hurries of business, and from getting money, to draw their breath in a clear air, and to divert themselves and families in the hot weather’, before returning ‘to smoke and dirt, sin and seacoal’ in the winter. Epsom was the City businessmen’s spa where they could relax with their families, but some had to ride daily into the City to attend to business matters.6

In his novel Oliver Twist, Charles Dickens extolled the virtues of a temporary change of residence and at the same time painted an idealised picture of a country retreat:

After another fortnight, when the fine warm weather had fairly begun ... they departed to a cottage at some distance in the country ... Oliver, whose days had been spent among squalid crowds, and in the midst of noise and brawling, seemed to enter on a new existence there. The rose and honeysuckle clung to the cottage walls; the ivy crept round the trunks of the trees; and the garden-flowers perfumed the air with delicious odours ... It was a happy time. The days were peaceful and serene.7

11

One forerunner of plotlands may be seen in the collections of ‘gardens’ which were frequently found on the outskirts of early nineteenth century towns. Although they can be likened to our current system of garden allotments they had a much wider use than growing produce and had a greater affinity with continental ‘leisure gardens’. Many town dwellers acquired outlying gardens as places for evening or weekend relaxation. On the outskirts of Nottingham in the 1830s such gardens accommodated a wide variety of summerhouses, owned by all classes from workpeople to substantial tradesmen.8 Grimsby had similar gardens in the East Marsh area, which were leased or purchased from the Grimsby Corporation. In 1834, one which was put up for sale included:

A Brick Summer-House covered with slate containing two rooms, the one above commanding extensive Views of the River Humber and the Country around Grimsby. The garden, etc., was formerly in the occupation of Mr. John Richmond, Surgeon, deceased; [and] will be found a very desirable acquisition for any Gentleman, Merchant, Gardener, or other resident inhabitant of Grimsby.9

The nineteenth century also saw a growing interest in a form of dwelling which would become particularly associated with plotlands, the bungalow. This had been introduced into the country from India, and came to be regarded largely as a place for leisure and relaxation. In 1819, Sir Walter Scott had one of his characters, Guy Mannering, talk of his ‘bungalow, with all convenience for being separate and sulky when I please’.10 Towards the end of the century there was a growing interest amongst the middle classes in having a countryside or seaside vacation bungalow. At the same time, the concept of ‘the weekend’ as a time of recreation at a cottage or bungalow became popular.11

Something which may be said to have helped form a plotland ‘ideology’ was the ‘return to the land’ movement which developed towards the end of the nineteenth century. When some contemporaries considered the squalor and disease of Victorian towns, they thought that possibly it was the industrial system itself that was at fault and that a solution might be a return to the rural economy and village life and crafts. Cities and towns were seen, by some, as physically and morally corrupting and, consequently, health and happiness could only be found in the countryside. They also argued that the elaborate social conventions of town life, the formal clothing, the houses and their heavy furniture and furnishings needed to be replaced by a plainer, simpler style of life. They believed that this was more possible in the country than in the town, and, consequently, a ‘return to the land’ was necessary.12 There is little doubt that the growth of plotlands was bound up with the idea of ‘the simple life’ - the idea of escaping and abandoning town life for a simpler, freer, rural life.

12

The ‘return to the land’ enthusiasts found vindication of their beliefs in the ‘garden city’ movement of the late nineteenth century.13 Some philanthropic manufacturers had become disturbed at the unhealthy working class living conditions in towns and, consequently, started building their own estate villages. Later examples, such as Bournville and Port Sunlight, had spacious layouts, with wide roads, green spaces, and gardens. These were contemporary with the emerging ‘garden city’ movement, which came to be popularly understood as meaning new towns or suburbs with informal low-density layouts, tree-lined roads, gardens and various designs of houses. The first garden city, Letchworth, was inaugurated in 1903 and a major plotland development, Peacehaven, later advertised itself as ‘a garden city by the sea’.14

Because of motivations such as these, there had been a steady increase in the development of plotlands around the country since the 1890s. However, the great surge occured after the First World War. There was a post-war decline in farming and farm incomes, and a surplus of land. Consequently, farmers and others were able to take advantage of a new source of income and land use by renting out plots for chalets. There was also a major housing shortage and an absence of effective controls on the use of land. To these factors were added the expansion of road transport and the increasing use of the motor car in providing a means of easy access to the countryside and seaside. A widespread increase in leisure time and annual paid holidays was also relevant. In the early 1920s only one and a half million people had paid holidays; by 1939 this had risen to over eleven million. Seaside holiday resorts in particular boomed during the inter-war period. Camping by the sea had had devotees for many years but became increasingly popular. The coast saw an increasing number of camp-sites, including organised holiday camps. By 1939, one and a half million holiday-makers took some sort of camping holiday. This appeared to register a need for informal family holidays, for which plotland sites were well suited. Consequently, ideal conditions were created for the formation, or expansion, of plotlands for holiday or permanent occupation.15

Plotlands appealed to a wide range of society. Because they were frequently on marginal land, or on wind-swept sand dunes, plots were available cheaply or possibly at no cost at all. Accordingly, they could suit the poor who wanted a permanent home or a weekend hut. If need be, building materials could be carried out a plank at a time by bicycle. The sense of freedom for which they stood also attracted ‘Bohemians’ such as artists, writers, musicians, actors and entertainers, and also professional and business people. Buildings ranged from small huts to large bungalows and incorporated a wide range of materials, particularly timber, corrugated iron and sheet asbestos. Conversions were widespread, including railway carriages, bus bodies, trams, garden sheds and surplus army huts.16 There would normally be a haphazard distribution of buildings, frequently in an irregular

13

and scattered development, with little overall planning or provision of services. Around the country ‘within reach of major towns, a proletarian colonisation of the land was taking place’.17 Some of these ‘colonies’ went on to become large-scale permanent settlements, such as Peacehaven in Sussex, and Jaywick and Canvey Island in Essex. During the years 1921-26, Peacehaven grew from having a handful of inhabitants to housing a population of 3,000.18

The expansion of plotlands went in tandem with a boom in the building of bungalows. Although the latter were being built increasingly for permanent occupation they had retained their wide appeal as places for relaxation or holidays. ‘Simplicity’ was the recurrent theme of bungalow living, with a belief in sunshine, fresh air and the merits of the open-air life.19 Such ideas became increasingly popular and in 1923 it was commented that:

Young married people of the middle class flock to bungalow towns. There they can live a sort of aboriginal existence for a time. There is always a great attraction in a primitive existence, and it is here that the bungalow craze comes in. The demand is increasing very rapidly [and] there are very large developments in bungalow buildings - for instance, at Shoreham. The enormous demand for tents and bungalows is far ahead of the supply, and a bungalow city, where a sort of ‘Swiss Family Robinson’ existence can be lived for a few weeks in the year, is a demand which town planners must direct their attention to very seriously.20

This mention of town planners highlights the fact that the delight of a generation enjoying its newly-found access to coast and countryside was not shared by all. Bungalows, weekend shacks and converted coaches created Arcadia for some, yet threatened to destroy it for others. For many contemporary commentators, the coastal plotlands amounted to a string of ‘seaside slums’, which presented major sanitary problems and damaged the natural scenery: ‘No part of England seemed immune from this new invasion ... among the worst is Flamborough Head where a whole town of hutments has completely ruined the scenery of that fine chalk headland ... [and] miles of the Lincolnshire and Norfolk coasts are disfigured’.21 Winifred Holtby’s fictional representation in the 1930s of a coastal plotland illustrates vividly this body of opinion:

Two miles south of Kiplington between the cliffs and the road to Maythorpe stood a group of dwellings known locally as The Shacks. They consisted of two railway coaches, three caravans, one converted omnibus, and five huts of varying sizes and designs. Around these human habitations leaned, drooped and squatted other minor structures, pig-sties, hen-runs, a goathouse, and, near the hedge, half a dozen tall narrow cupboards like upended coffins, cause of unending indignation to the sanitary inspectors.

14

A war raged between Kiplington Urban District Council and the South Riding County Council over the tolerated existence of The Shacks.22

In 1937, George Orwell described a caravan plotland in Wigan and criticised the way in which poorer people were being obliged to live in squalid conditions because of the shortage of working class housing:

The majority are old single-decker buses (the rather smaller buses of ten years ago) which have been taken off their wheels and propped up with struts of wood. Some are simply wagons with semi-circular slats on top, over which canvas is stretched. Water is got from a hydrant common to the whole colony, some of the caravan-dwellers having to walk 150 or 200 yards for every bucket of water. There are no sanitary arrangements at all. Most of the people construct a little hut to serve as a lavatory on the tiny patch of ground surrounding their caravan, and once a week dig a deep hole in which to bury the refuse.23

Others feared that England would become one vast built-up suburbia:

When England’s multitudes observed with frowns That those who came before had spoiled the towns, ‘This can no longer be endured’ they cried, And set to work to spoil the countryside.24

In view of such observations and arguments, conservationists and others called for greater governmental control over the use of land.25 Since the nineteenth century, local authorities had had powers to approve or reject plans for streets and buildings. However, a growing appreciation of the need to control the type of building development which showed little concern for the provision of amenities and a healthy environment led to the passing of several acts of parliament in the twentieth century which were concerned with the control of land use and the prevention of unsuitable development.

Several reports during the Second World War emphasised the need for comprehensive planning, including the necessity of maintaining good agricultural land and preserving natural amenities. The result was the Town and Country Planning Act of 1947 which introduced an overall planning framework for the entire country.

All land and its development were brought under a unified system of planning and changes in the use of land had to be approved by local planning authorities. Possibly the contemporary comment of The Times best summed up the need for the act:

15

The people of Britain are too numerous, their cultures too complex, their wants too diverse, for them to be able to live, work, move about and enjoy themselves satisfactorily without some regulation of the nature and distribution of their settlement and workplaces, and of the uses to which they put the limited land in their small island.26

Local authorities had opposed plotlands partly on account of costs, i.e. for the provision of services and roads in the future, and also on grounds of public health. The 1947 act now provided effective means of controlling the development and creation of plotlands.27 We shall see that the workings of the act and the concerns of local authorities were reflected in the development of the Humberston Fitties.

From the foregoing survey it is evident that there were many types of plotland, from the idyllic to the squalid, and their creation led to the evolution of two fundamental and opposing views. On the one hand they were seen as arcadian retreats to nature, the simple life and freedom. This was balanced by the opinion that, even discounting those that were dangers to public health, they spoilt those very natural surroundings which had attracted the plotlanders in the first place.

Whatever the strengths may have been of the opposing arguments, the latter half of the twentieth century certainly saw a fall in the number of plotlands. In addition to the effects of new legislation, some plotlands on the coast suffered clearance as part of military defence schemes during the Second World War. Others were subject to flooding by the sea, particularly during the devastating floods along the east coast of England in 1953. Others developed into permanent settlements and were ‘improved’ as temporary buildings were replaced by permanent bungalows. Those that have survived, such as the Humberston Fitties, have acquired a new status as part of the nation’s social history and ‘heritage’.

Regardless of what the planners and public health officials may have thought, there is no doubt that those who were fortunate enough to be inhabiting plotlands by choice were confident that they had discovered a sort of heaven on earth. Accordingly, the last word in this introduction should be left to plotlanders themselves, such as the early pioneers of Jaywick who said ‘They thought they had found a kind of Robinson Crusoe island, where they could be quiet and peaceful’.28 Or one of the early ‘colonisers’ of Humberston who wrote:

The sea pinks and the sea lavender covered the marshy areas with masses of colour and later, when the Autumn tides caused the drain to overflow,

16

the marsh turned to a lake and the dune area became a virtual island. What a paradise Humberston was then!29

the marsh turned to a lake and the dune area became a virtual island. What a paradise Humberston was then!29

17

17

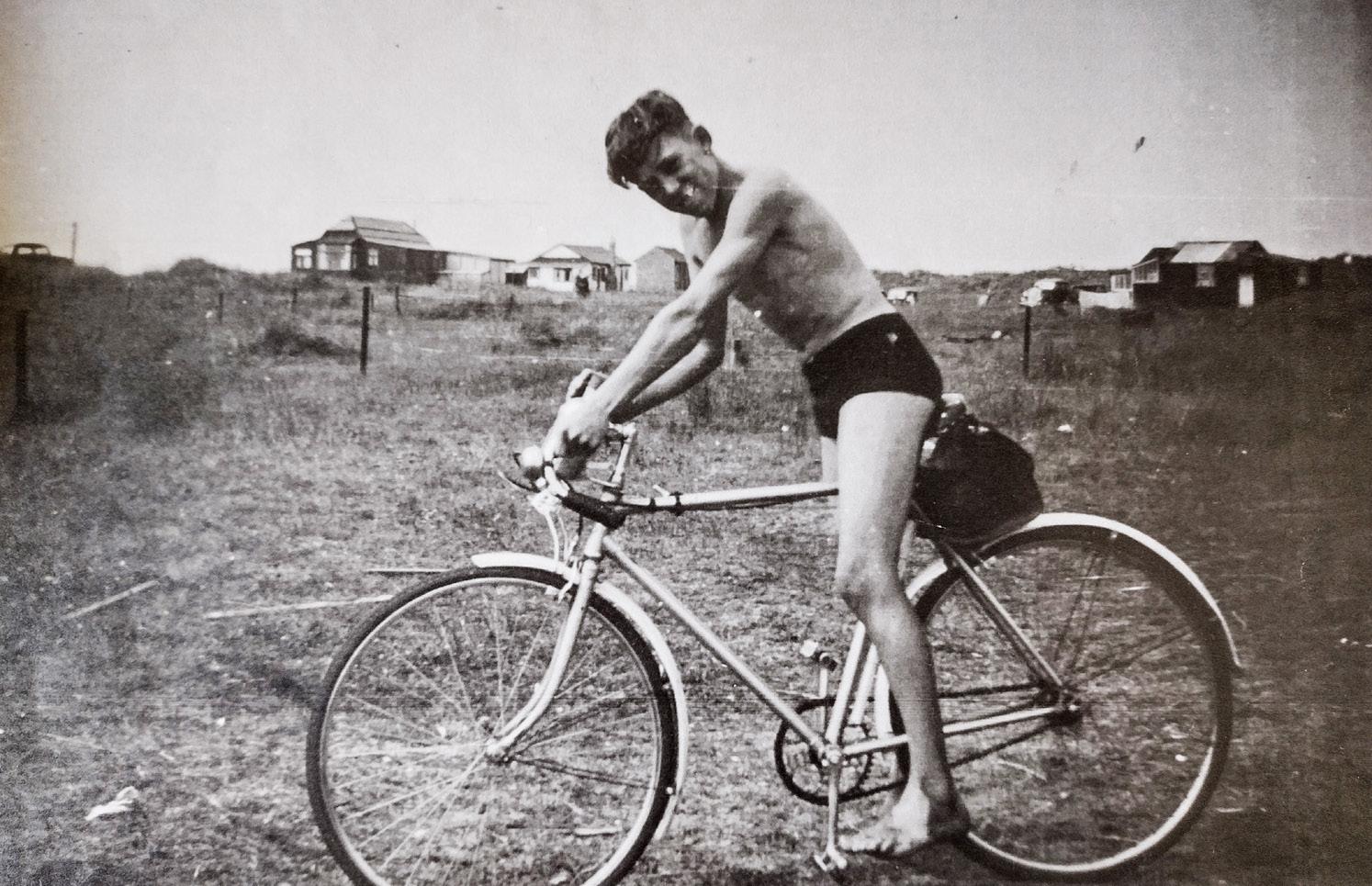

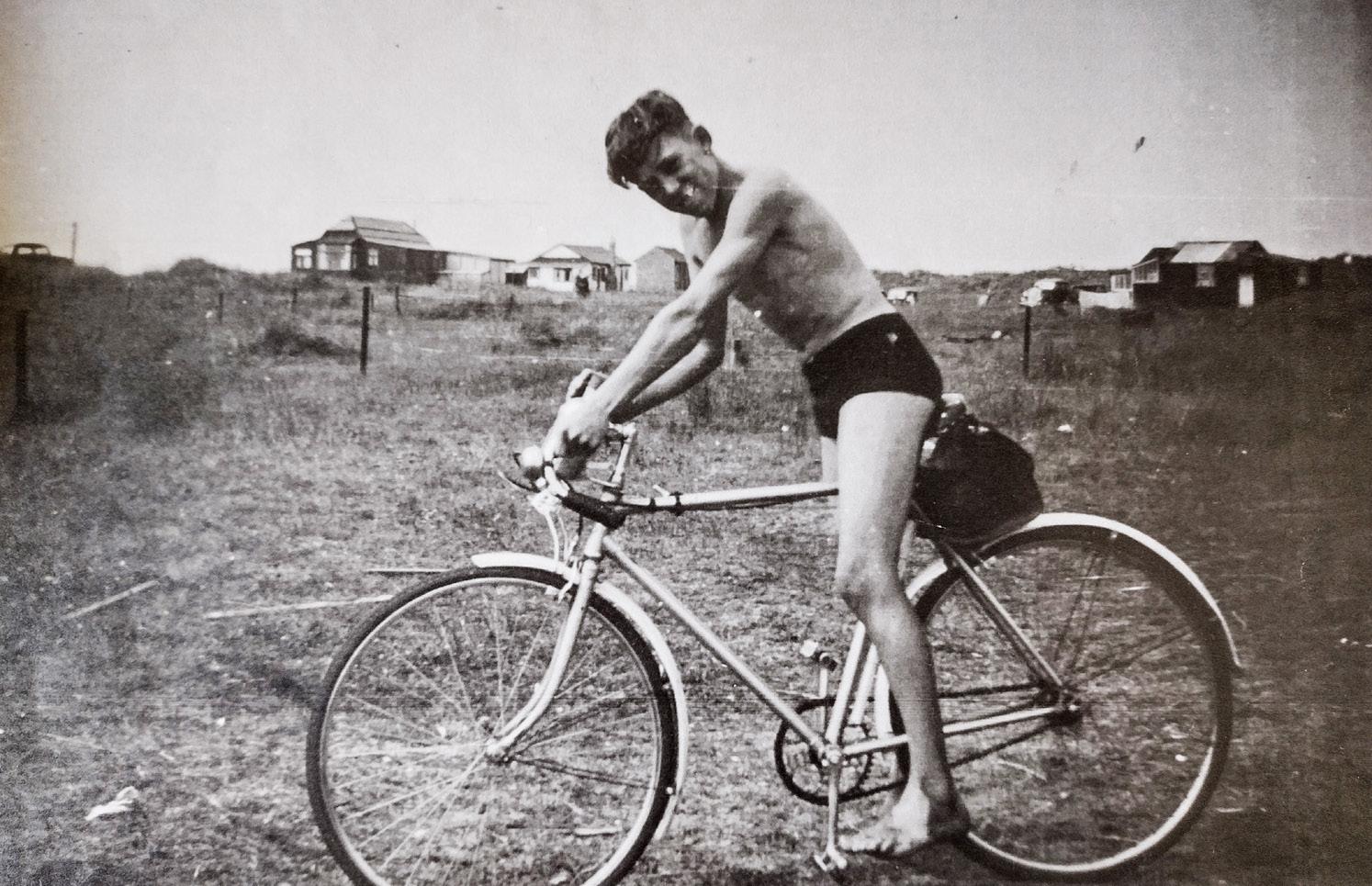

Len Reaney and Horace McDonald on the Fitties Beach, 1930s.

Len Reaney and Horace McDonald on the Fitties Beach, 1930s.

2. TENTS & TROOPS 1900-1918

The first known reference to a bungalow on the Humberston Fitties is in 1920 but long before then the foreshore sand dunes were being used for summer camping in tents. This came to an end with the First World War when the foreshore was taken over by the military.

The troops had huts there for shelter and it appears that some of them were used as summer camping bungalows after the war.

Under Canvas on the Fitties

We can trace the antecedents of the Humberston Fitties bungalow camp back to the year 1900. As the Victorian period drew to a close, tent camping was a popular activity on the Humberston coast and the area that would later become ‘the Fitties’ was a regular location for camping under canvas. We are indebted to a local newspaper for reports of camping on the Humberston Fitties at the beginning of the new century. The first report describes the camp site in August 1900:

The camping ground at Humberston presented a scene of unwonted animation on Thursday evening. There are in all about thirty tents there, and they accommodate about forty people. Of course there are married as well as bachelor quarters but we are assured that the camp is a highly civilised community, and that there is a very respectful distance between the different quarters. Camp life in itself is full of attractive incident. The married ladies of the camp invited the other occupants of the camp and their friends to a social evening. They were assisted by the gentlemen of the little community who accumulated a mass of driftwood and placed it in a convenient position in the sandhills, where it was lit and a camp fire made that gave to the encampment a truly Bohemian aspect. The party first engaged in the game of forfeits after which there were vocal selections and recitations. The next item on the programme was a very bountiful repast which had been provided by the married ladies. The site of the al fresco nocturnal fete was illuminated by Chinese lanterns, the acetylene light, hurricane lamps and candles. After supper the festivities were resumed and a most enjoyable evening concluded with the rendering of ‘The ladies are jolly good fellows’.1

A reporter returned a year later. Much of his report anticipates the lifestyle which would be described by bungalow owners later in the century:

18

19 Humberston Fitties, 1907. © Crown Copyright. All Rights reserved. Ordnance Survey. 19 Humberston Fitties, 1907. © Crown Copyright. All Rights reserved. Ordnance Survey.

The pleasures of camping out appeal to a considerable number of people in this locality and they eagerly look forward to the change summer by summer. At the present time the Humberston foreshore presents quite a gay appearance with its tents dotted here and there ... at the time of visiting there were between twenty and thirty of these portable residences there. There are married quarters and also a plot reserved for the bachelors. Everything is conducted within the precincts of the camp in that free and easy style and with that freedom from restraint that appeals so much to the hearts of some English people.

The delights of the informal open-air existence are then praised, and we have possibly the first mention of a holiday building (a portable wooden shed) on the Fitties:

On the camping ground the meals may be al fresco whenever the weather permits. Of course, considerable difficulty occasionally attends the commissariat arrangements, and it is perhaps this matter that prevents a much larger number betaking themselves of the Humberston foreshore during the summer months. If one has his own trap it is much more convenient than having to bring victuals by hand or through the carrier. Then, when the raw food gets there it must be cooked before it is fit to be eaten. Wood must be found with which to light the fire, and water must also be procured for the kettle. Plenty of wood is obtainable from the shore, etc., whilst there is an excellent supply of water in a spring adjoining the camping ground. There are some who bring their food already cooked and for those who like to lay in a small stock of tasty trifles a portable wooden shed fitted up with shelves admirably suits their purpose.

The writer anticipates again the later Fitties family lifestyle as he emphasises that families are camping there:

Besides the young men who go for the ‘fun of the thing’ there are families who avail themselves of the opportunity afforded them purely for health’s sake, and sometimes people go there with their children during the school holidays ... For the most part the male inhabitants of the camp follow their respective vocations during the day and return to the bosoms of their families at night.

And he illustrates how the families pass the day:

While the men are away there are many ways in which the ladies can employ their time. Besides reading and walking, and enjoying pleasant chats with their neighbours, it is also necessary for them to prepare for

20

the homecoming of their husbands and occasionally a game at croquet or tennis serves to while away a pleasant hour. As to the children, they have glorious times at their games, wading, and gathering cockles, etc. By the time the husband arrives at his tent he often finds that his dutiful wife has been to the Shepherd’s Hut, which is close by, and has procured him some fresh milk - condensed milk is kept in reserve - new laid eggs and farm house butter, whilst the other members of the family bring their freshly gathered shell fish, with their possibly hidden typhoid germs, to add to his creature comforts.

Further mention is made of temporary wooden structures:

Readers will doubtless be interested about the sleeping arrangements. Some of the very hardy gentlemen content themselves with rugs alone in the shelter of their tents, whilst others have the ordinary bedstead. In one instance a summer-house has been transformed into a snug little bedroom, and in another case a small wooden erection serves as a dormitory and also as the family wardrobe. The experience certainly possesses many attractions. There is a novelty about it that is something out of the run of everyday life.

And finally, the reporter emphasises the communal nature of the camp:

There have been occasions in the past when a minister [of religion] has happened to make one of the community and then he has conducted divine service on a Sunday. The Union Jack proudly floats from one of the tents in token of the loyalty of the little community who, judging by their happy and healthy looking countenances, are enjoying to the full the benefits of the outdoor life.2

The seashore camp was vulnerable to action by the sea, as was demonstrated in January 1905, when fierce storms affected the area:

The high tide not only dashed over the lower parts of the sand hills near the camping ground, but effected a breach in the sea wall, opposite the shepherd’s house. There was formerly a clough through that place, which once broken into soon caused a large gap. At 10.30 [a.m.] the water was still pouring through into the Fitties, but soon after that time carts began to arrive with sand bags, etc., and

*The Shepherd’s Hut was the term used by campers for the shepherd’s house which used to lie near the seaward end of the South Sea Lane. The name was still being used by some bungalow families in the 1920s and 1930s. One Fitties family was even using the term in the 1960s to refer generally to the camp shop.

21

by working hard under the direction of Mr. Marshall some 18 men with horses and carts managed, before the darkness fell, to make the place secure against another tide.3

The camp must have continued to be patronised because in 1907, the local Medical Officer expressed concern at the sanitary arrangements and advised the Grimsby Rural District Council that they ‘should notify the party letting the plots that formed the camp that before next season he should submit a scheme of sanitation and water supply’. In 1910, an organisation tersely referred to as the ‘Camping Club’ was renting land for camping on the Fitties. Another user of land was the Grimsby Rifle Club which rented land for a rifle range along the very southern edge of the Fitties.4

The First World War

Civilian camping at Humberston was disrupted by the outbreak of the First World War. By 8 August 1914, the 3rd Battalion of the Manchester Regiment were on their way to Cleethorpes. The battalion had two main functions. Firstly, to train recruits for active military service and get wounded men fit again for action. Secondly, to guard the coastline between Cleethorpes and Tetney Lock. The headquarters was in Cleethorpes and troops were billeted ‘all over the district’. The battalion history carries several references to troops being stationed on the foreshore at Humberston. In 1914, H Company were on ‘outpost duty’ there in huts. In 1915, a picket at Humberston was situated ‘on the sandy strip of land occupied by the Holiday Camp’. The picket consisted of fourteen men by night and seven by day, although as all fit and trained men were rapidly drafted to the battle front it was difficult to maintain the pickets at full strength. Men were ‘billeted’ on the foreshore in 1916. 1917 saw H Company ‘in camp in the Sand Hills’ and in 1918 the company was still ‘at Foreshore Camp’.5

During the winter of 1914, trenches were dug on a line from the foreshore to Holton-le-Clay and training included bayonet fighting and musketry practice. In contrast, the battalion band gave sacred concerts on the Cleethorpes Pier on Sunday evenings. Relaxation included football, hockey, gymnastics and crosscountry running. The battalion’s hygiene must have been of concern to the military authorities because during 1915:

An attempt was made to have a bathing parade in the Humber once a week

*In default of evidence to the contrary, the expression ‘holiday camp’ in context presumably refers to the tent camp site, and not what would be implied by the words’ modern usage.

22

but it was discontinued, as when, after a lengthy march across the sands, one did reach the sea, the water was so full of foreign and decaying matter from Grimsby and Hull that the cleanliness of the men was not increased by the performance.6

but it was discontinued, as when, after a lengthy march across the sands, one did reach the sea, the water was so full of foreign and decaying matter from Grimsby and Hull that the cleanliness of the men was not increased by the performance.6

Despite such difficulties, the men presumably managed to keep clean and healthy and the battalion comprised 4,000 men in 1916. In the same year there occurred the battalion’s tragic loss of life in Cleethorpes when a bomb which was dropped by a Zeppelin hit the Baptist Chapel where a batch of incoming recruits were temporarily billeted; thirty-one soldiers were killed in the incident.7

Despite such difficulties, the men presumably managed to keep clean and healthy and the battalion comprised 4,000 men in 1916. In the same year there occurred the battalion’s tragic loss of life in Cleethorpes when a bomb which was dropped by a Zeppelin hit the Baptist Chapel where a batch of incoming recruits were temporarily billeted; thirty-one soldiers were killed in the incident.7

When the war was over, the battalion commander noted that:

The chief work of the Battalion consisted now of dismantling our fortifications, and as the Battalion had nearly seven miles of front, even allowing that the trenches were not continuous, it was not a job that could be done in a few days. All the barbed wire entanglements had to be taken, trenches, redoubts and strong points filled in again and made level. 8

When the war was over, the battalion commander noted that: The chief work of the Battalion consisted now of dismantling our fortifications, and as the Battalion had nearly seven miles of front, even allowing that the trenches were not continuous, it was not a job that could be done in a few days. All the barbed wire entanglements had to be taken, trenches, redoubts and strong points filled in again and made level. 8

It was some time before this work was completed and several campers remember playing amongst trenches and dug-outs in post-war years.

It was some time before this work was completed and several campers remember playing amongst trenches and dug-outs in post-war years.

Members of the 3rd Battalion Manchester Regiment at Humberston ca. 1915 (above) and 1918 (below). The battalion guarded the local coastline during the First World War. This included stationing men on the Humberston sand dunes in huts - some of which were thought to have been used by campers after war.

Members of the 3rd Battalion Manchester Regiment at Humberston ca. 1915 (above) and 1918 (below). The battalion guarded the local coastline during the First World War. This included stationing men on the Humberston sand dunes in huts - some of which were thought to have been used by campers after war.

23

23

24 Humberston Fitties, 1932. © Crown Copyright. All Rights reserved. Ordnance Survey. 24 Humberston Fitties, 1932. © Crown Copyright. All Rights reserved. Ordnance Survey.

3. THE SIMPLE LIFE 1919-1939

The two decades following the war saw the Humberston dunes and adjacent land transformed into the Fitties camp with a wide variety of ‘bungalows’ from the custombuilt holiday home to shacks and superannuated commercial vehicles, such as old buses and railway carriages or old gypsy caravans. Campers’ recollections of the early days of the camp reinforce the distant view from the beginning of the twenty-first century that the 1920s and 1930s were halcyon days for the Fitties, even if we discount the rosy hue of nostalgia.

Located well away from populated areas and having no mains services, it was possible to live ‘the simple life’ and enjoy the open air, beach, marshes, flowers and wildlife.

Even as the Great War had been drawing to a close, events were taking place further down the Lincolnshire coast which would encourage the growth of holiday plotlands such as the Fitties. Owners of land adjacent to the coastline had claimed that they also automatically owned the sandhills and beach above high water mark and, accordingly, could place bungalows and huts thereon. A legal judgement in 1918 regarding sandhills at Mablethorpe ruled that whilst such ownership was not automatic, it could be acquired if ownership had been exercised over a period of at least twelve years. The effect of the judgement was to enable long-standing landowners along the coast to enclose and build on the dunes. Consequently, ‘Bungalows, shacks, caravans and old bus bodies and railway carriages appeared wherever a track gave access to the sandhills and seashore’.1

The Humberston land which was to become involved in this Lincolnshire coastal plotland development formed part of the estate of the Marquess of Lincolnshire. In 1920, the Marquess sold his Humberston estate.

At some point, the land upon which the camp would grow came into the ownership estate agents and auctioneers (Maslin). Others included Arthur Drewery, trawler owner; Stanley Robson, organist and choirmaster at Grimsby’s St. James’ Church; of the Humberston Fitties Company Limited.* This land lay within the Grimsby

*Little is known about this company. It was engaged in sand and gravel extraction from what is now the private nature reserve near the end of the South Sea Lane. It was possibly formed for this purpose and later went into the leasing out of bungalow plots. Any information on it would be welcome by the author.

25

Rural District, whose local authority, the Grimsby Rural District Council (RDC), were to play an increasingly important role in the history of the Fitties.2

Bungalow Beginnings

The post-war re-birth of civilian camping on the Fitties took place in 1919. Mrs. E. E. Scully has given an account of how this led to the beginning of the bungalow camp in the dunes. She and her brother and their parents were at a low ebb after the effects of the 1919 influenza epidemic and other illnesses, when:

During a long walk, to blow away some of the weariness and despair, Mrs. Bunker fell in love with a stretch of sandhills and dunes, in what was then the remains of Humberston army camp. The solitude (not a house or human being in sight) and the restfulness of it all was just the tonic she needed. Her husband decided to move his frail and weary family from Dudley Street [in Grimsby] to ‘The Fitties’ for the summer to see if the air would bring back their lost health. Thus what was the first summer-living family set up home at Humberston, making the journey on a horse and cart, complete with chest of drawers, a tent and the essentials of daily living, pots, pans, bedding, etc. ... However, though the Bunker family enjoyed their solitude and their tent, the next summer father bought a small bungalow, and no doubt unwittingly, began the organised colonisation of Humberston that we are familiar with today. After the bungalow was installed, others had the same idea. Soon there was quite a community, and lots of children, for whom the whole area was a paradise of wood-fires, free donkey rides and ‘dabbing’ - catching dabs at low tide with a pronged stick and cooking them over the open fire for supper.3

Mr. Bunker had been a keen camper before marriage so presumably needed little prompting to resort to the Fitties. He was also a banker and the 1920s and 1930s saw the evolution in the sand dunes of a microcosm of local business and professional life. In addition to banking, bungalow owners were representative of the fishing industry (Edge), building and contracting (Goodhand), household furnishers (Gordon), hairdressers (Cripsey), butchers (Hibbit), joiners and furniture makers (Cobley), general practitioners (Drs. McKerchar and Burnett), shoe shop proprietors (Powell), fruiterers and florists (Drewry), photographers (Burton) and estate agents and auctioneers (Maslin). Others include Arthur Drewery, trawler owner; Stanley Robson, organist and choirmaster at Grimsby’s St. James’ Church; Lionel Chatterton, manager of boat builders and fitters W. H. Thickett; and Hadyn Taylor, dentist and swimmer of the English Channel. 4

Early pioneers Mr. and Mrs. Tom Edge lived in Cleethorpes and in 1923 took possession of their new holiday bungalow, Lingalonga. Mr. Edge was a director

26

of Atlas Steam Fishing, a partner in Letten Bros. and a well-known fish auctioneer. The bungalow had been built in sections at the premises of W. H. Thickett and then assembled on site. Like several other bungalows it was raised on old trawler ‘bobbins’.* Thus began many happy years on the Fitties for Mr. and Mrs. Edge and their grandsons Peter and Bruce Edge, and maid Doris. The boys had most of the comforts of home, including a hot bath every night, in a tin bath in front of the stove. Initially, out of choice, the bungalow had no bedrooms. An extremely large tent accommodated grandparents in a ‘bedroom’ compartment at one end and children in their ‘bedroom’ at the other end. The maid had a separate large bell tent. Later on the bungalow was extended and had three bedrooms - one for the grandparents, one for the maid and one for the two boys. Tents were then kept for visitors who would come at the weekends or for longer periods.

Other pioneers included Mr. Hibbit, a Cleethorpes butcher, and his family. The Hibbit’s converted horse-drawn furniture removal van was one of the first ‘bungalows’ you saw as you turned into the camp. Wilton Cobley describes it as ‘huge’. It had four bunks at the back, whilst the front part was the living room and kitchen; it was all one big living and sleeping area. Windows had been fitted and its wheels had been removed but it was still recognisable as a furniture removal van. It was high up and the tailgate was lowered to make a slope which gave access into the van.

Joseph Drewry, local fruiterer and florist, had a bungalow in the dunes in the 1920s. His daughter recalls that it was near the present camp entrance with only five other bungalows in the vicinity, including Dr. McKerchar’s which was as far out in the dunes as he could get it. The Gordon family bungalow was also in the dunes. Daughter Anne remembers that the bungalow was ‘the second one on the dunes’ near to the present Anthony’s Bank car park. It bore the name It’ll Do, on the basis that anything not required at home would ‘do’ for the bungalow. It was raised on bricks, leading to sleep being disturbed by rabbits thumping about under the floorboards, a problem solved by the installation of wire netting to prevent access under the bungalow. Many bungalows had garden rollers in an attempt to flatten the rough ground, presumably for the playing of games.

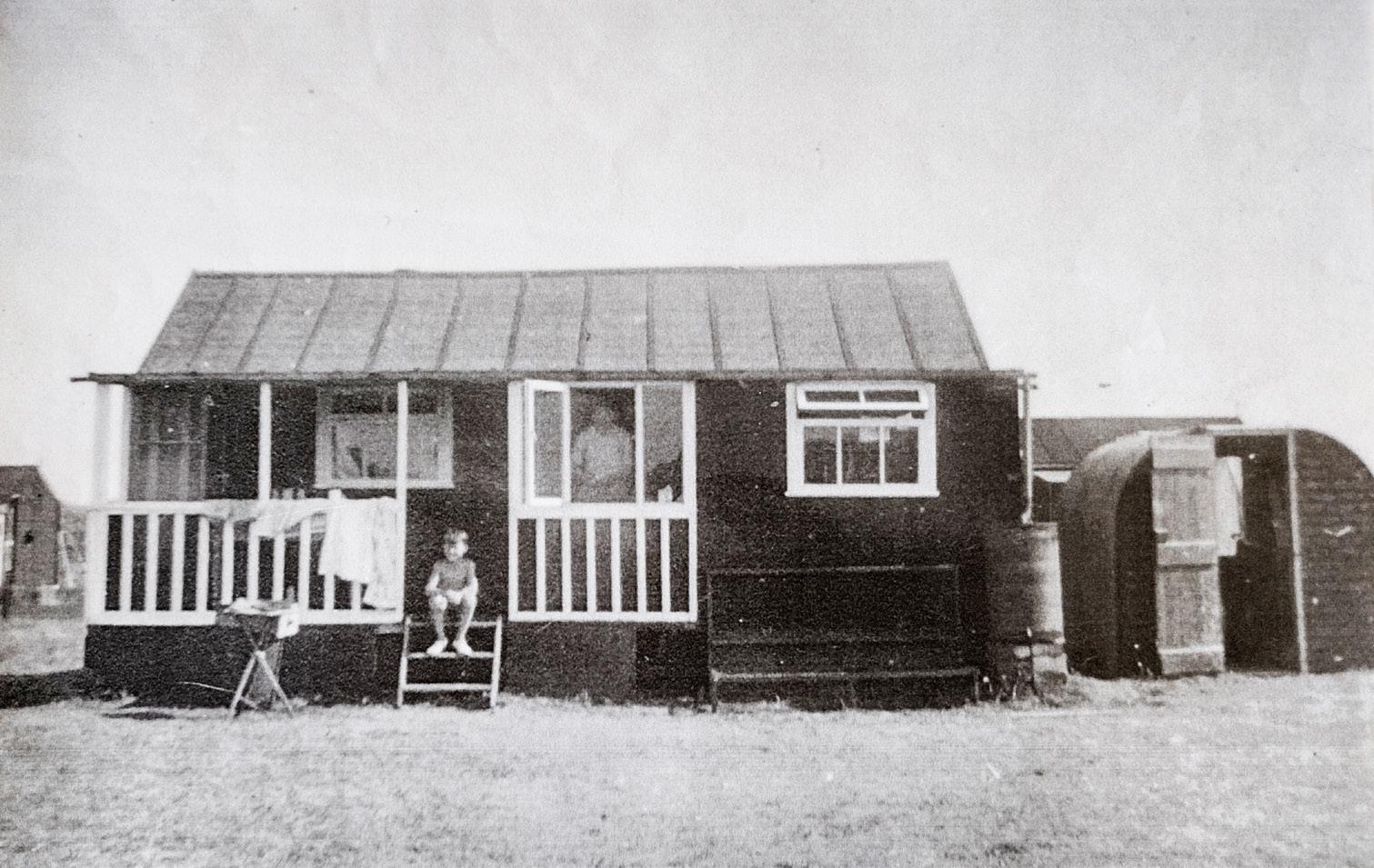

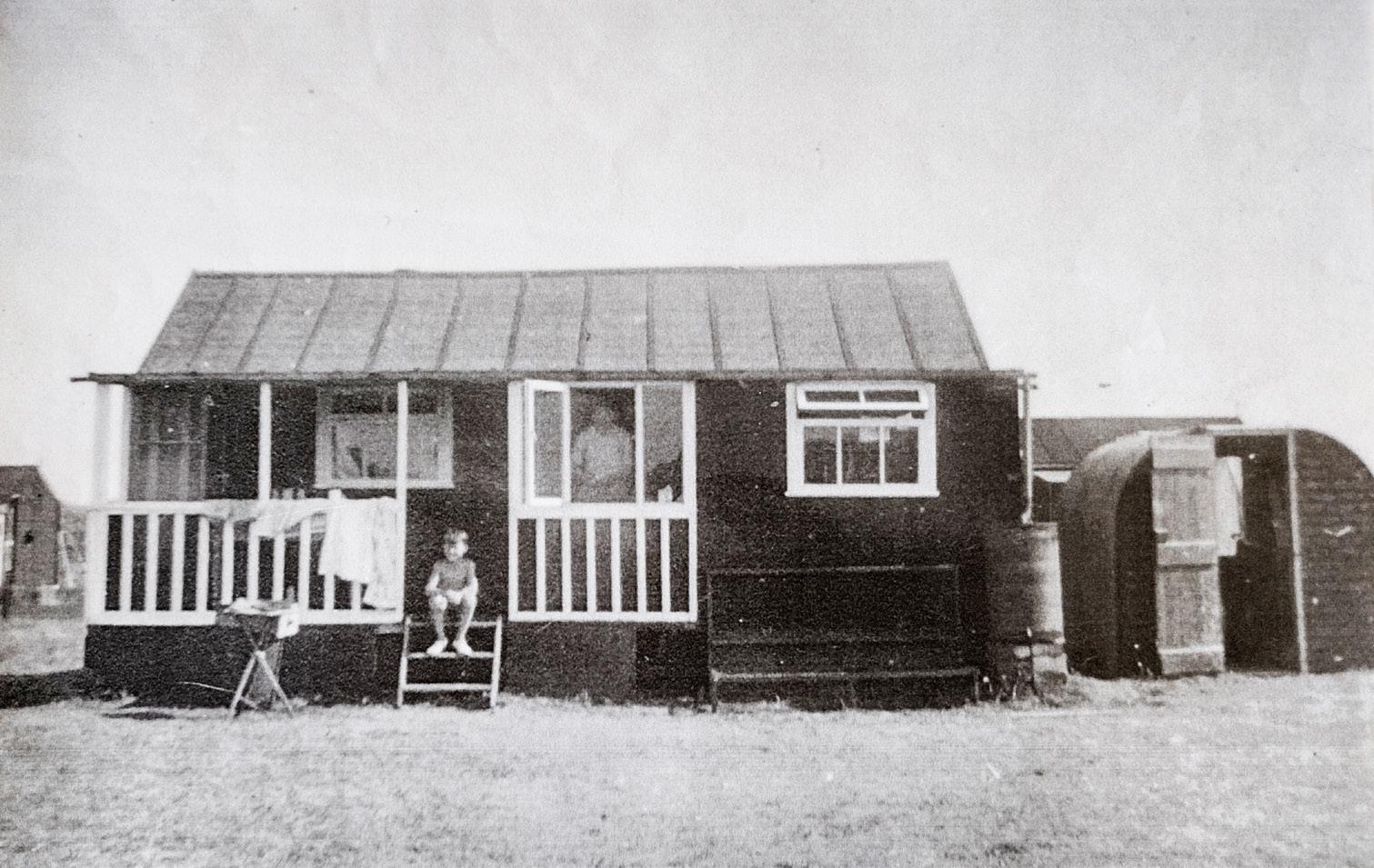

Mr. and Mrs. Carl Cobley and sons Wilton and Frank lived in Heneage Road, Grimsby, and had their holiday home on the edge of the dunes by the early 1920s. Mr. Cobley was a joiner, furniture maker and retailer and built the bungalow himself. It was made of horizontal weatherboard and was creosoted, except for the window frames. It was called Sunglow and had two double bedrooms, two

*These are large round thick slices of wood which were used by several owners to raise their bungalows above ground and, hopefully, above the flood level.

27

or three single bedrooms, a large living room, a kitchen and verandah. Raised on trawler bobbins, it stood twelve or eighteen inches above the sand.

It was in 1930 when the Goodhand family settled into their new holiday bungalow. The family’s permanent home was in Dudley Street in Grimsby and Mr. Harold Goodhand was joint managing director of the builders and contractors Hewins and Goodhand. He had a bungalow built on the dunes by employees of the firm. His children, Dennis, Sybil and Beryl, have happy memories of their time on the Fitties during the 1930s. It was a large bungalow with three, later converted to four, bedrooms, to accommodate mother and father, five children, a maid and, initially, a nanny. There was also a large sitting room, a kitchen, front and rear verandahs, a shed and, near the boundary of the plot, the privy. A bell tent or two on the plot served to accommodate visitors.

The bungalow was made of timber with a felt roof. It was raised on blocks; this made a hideaway for those children who needed privacy for a quiet, and illicit, cigarette. The space was also used by wild rabbits. A council employee would come round at times and put out snares, which the children would then pull up. The bungalow was on a large plot with a post and wire fence to indicate the boundary. A flagpole marked the southern extent of the pitch. Neither the Goodhands nor their neighbours attempted to turn their plots into gardens. They were looked upon as camping pitches and the Goodhands always called their plot a ‘pitch’, with all that term’s redolence of camping. The bungalow was named The Limit because of its location as the ‘last ‘ bungalow at the limit or southern boundary of the camp (on land which is now part of the Humber Mouth Yacht Club site). Family members also reckon that the name summed up the fact that there were so many children at the bungalow at times.

In 1932, another bungalow, named The Olde Log Cabin, was built by employees of W. H. Thickett for the firm’s manager, Lionel Chatterton. It was built on the sand dunes and raised on trawler bobbins, many of which are still in perfect condition. The bungalow was extended during its early years; part of the verandah at the front was incorporated into the house to enlarge a bedroom; the back bedrooms were extended and sunroom, balcony and kitchen were added.5

Edward Drury recalls that in the 1930s his employer, who was engaged in the port’s coal trade, took a liking to the dunes:

Mr. Ernest William Nickerson the father of the late Sir Joseph Nickerson had a bungalow on the Fitties. It was called Waving Marram and used simply as a holiday residence. When Ernest Nickerson purchased the bungalow during the 1930s ... the area was full of similar buildings all privately owned, and used during the summer holiday season only.6

28

The Edge family bungalow, Lingalonga, ca. 1930. The large tent on the right was used for sleeping by Grandpa and Grandma Edge and grandsons Peter and Bruce Edge. Doris the maid slept in the bell tent on the left. Dunes can be seen in the distance on the right.

The Edge family bungalow, Lingalonga, ca. 1930. The large tent on the right was used for sleeping by Grandpa and Grandma Edge and grandsons Peter and Bruce Edge. Doris the maid slept in the bell tent on the left. Dunes can be in the distance on the right.

Edge bungalow, Lingalonga 1930. was sleeping by Grandpa and Grandma Edge and grandsons Bruce Edge. the maid slept in the bell tent on the left. Dunes can be in the distance on the right.

29

Grandpa Tom Edge, Alec, Uncle Ernest Noble and Peter Edge relaxing on the Fitties at Lingalonga, ca. 1930.

29

Grandpa Tom Edge, Alec, Uncle Ernest Noble and Peter Edge relaxing on the Fitties at Lingalonga, ca. 1930.

Edge, Uncle Ernest Noble Edge on the Lingalonga 1930.

The colonisation by the better-off is illustrated by Mrs. Scully:

Servants were brought along if anyone had them. My mother allowed ours to do without her cap when camping. I was never allowed to present anyone with a cup of tea unless it was on a small tray. A regular trouble was clocks stopping due to the sand. If a maid was sent to ask the neighbour the time she had to say ‘Mrs. X sends her compliments and could you please tell her the time?’ When silver teapots appeared my father thought it was the beginning of the end. Silver was not a particularly expensive item in those days but he considered it unsuitable for camping.7

All the bungalows referred to so far were built in or near to the dunes. Other bungalows were built along the landward side of Anthony’s Bank and also along the track running from the North Sea Lane end of the bank in the direction of the present Tertia Trust camp at the seaward end of South Sea Lane. As with the dunes bungalows, most of the families were from the immediate locality and included representatives of local businesses and trades. In 1929, Charles Henry McDonald, a master joiner and undertaker living on Alexandra Road in Grimsby’s West Marsh, built a small bungalow on Anthony’s Bank. His son, Horace, describes it as like a little one-roomed shed with a couple of bunks and a stove. For foundations, Mr. McDonald used a dozen old trawler bobbins. A few years later, the RDC required bungalows to have separate sleeping quarters so he added a bedroom and at the same time made the bungalow roof higher. It was named Mac’s Rest. The annual ground rent is believed to have been about 11s.0d. (55p.)

The bungalow was about the sixth one from the North Sea Lane end of the bank. At that time there were still vacant plots nearby but neighbours included an artesian well borer (Smith), a baker (Hockney), a clothing outfitter who had a big bungalow built (Norris), two well-known dancing teachers and shopkeepers (the Hawley sisters) and retired fish and chip shop proprietors (Mr. and Mrs. Cox of the popular Pea Bung in Freeman Street, Grimsby; their bungalow was No.1 on the bank). The proprietor of the Sheffield Arms public house in Grimsby had a bungalow and would hire a taxi and send his barmaids down for two or three hours during the afternoon for a break before their evening shift.

The McDonald bungalow was quite distinctive in the way it was used. Although Mr. and Mrs. McDonald had eight sons and one daughter, it was two of the sons, Horace and Cyril, who made most use of it. The parents spent time at the bungalow but never slept in it. Horace and Cyril were given parental permission to sleep in it and it became a home-from-home from 1929 to 1937 for the two brothers and their close friends. Other friends who were camping in tents on a nearby camp site ribbed them for not sleeping under canvas and not being ‘proper outdoor lads’. Accordingly, two army surplus bell tents were purchased for 7s.6d. (37.5p.)

30

Winter on the Fitties, ca. 1932/33. The notice on the van below reads ‘To let. Apply... Brereton Avenue, Cleethorpes.’

Winter on the Fitties, ca. 1932/33. The notice on the van below reads ‘To let. Apply... Brereton Avenue, Cleethorpes.’

Winter on the Fitties, ca. 1932/33. The notice on the van below reads ‘To let. Apply... Brereton Avenue, Cleethorpes.’

31

31

31

each and erected on the bungalow plot. From then on, Horace and two friends slept in one and Cyril and a friend in the other.

One of Horace’s friends, Len Reaney, subsequently bought his own bungalow, which is still on the camp. He was living in Granville Street in Grimsby when he bought the bungalow for £45 in 1938, two years before he got married. It had been built in 1933 on plot number forty-two Anthony’s Bank by local joiner C. H. Thompson. It had a living room, two bedrooms and an open verandah which served as a kitchen. A third bedroom was added later. At one time it was given the name That’ll Do. This arose from the frequent remark ‘That’ll do for the bungalow’.

Some bungalow owners would rent them out for holidays. Edward Trevitt recalled:

I was living in lodgings in Grimsby in the 30s, and my landlady had one of the huts on this site. It had cost about £40 to build and the accommodation consisted of a living room, three small bedrooms and a kitchen, with a small detached toilet hut. It was let for a couple of weeks in the summer to cover the annual maintenance cost, but we spent many happy weekends there.8

The Grantham family rented a bungalow in the mid-1930s. As we shall see below, the family were advised to take young Pat Grantham to the Fitties in order to recuperate from illness. They rented a bungalow on Anthony’s Bank called Homefield and enjoyed their stay so much that they had an annual fortnight’s holiday there until the outbreak of war in 1939. Mr. Grantham was a post office clerk and the rent for Homefield, as far as daughter Pat can recall, was thirty shillings (£1.50) per week. This rent would be saved up week by week ‘for that fortnight of simple delights’. The bungalow had three bedrooms and a cupboardsized ‘cookhouse’. On the verandah there was a let-down table for the preparation of food, washing up, and so on.9

Humberston Fitties and Fitties Field

During the 1920s and 1930s, the bungalows in or near the dunes and those along Anthony’s Bank came to be regarded as two distinct camps. Those in or near the dunes were referred to as the ‘Humberston Fitties’ bungalows.* Those which stretched along Anthony’s Bank were known as the ‘Fitties Field’ bungalows; this was because their plots were located on the edge of the large field of that name which lay behind Anthony’s Bank. With the exception of those bungalows which

*This area was also known as Second Camp. See Appendix A regarding the use of the name.

32

still lie on Anthony’s Bank Road, this field is now part of Thorpe Park. Several campers have confirmed that they were effectively two separate camps and the RDC distinguished between the two areas, possibly for administrative convenience.

The dunes bungalows were frequently built for the more well-off local business and professional people, some of whom had servants in residence. Possibly because the Fitties camp began in the dunes, the bungalows there had plots which were generally much larger than most of those along Anthony’s Bank. This difference is demonstrated by respective rateable values. An average rateable value for a dunes bungalow in 1939 was £7, whereas an average for one on Anthony’s Bank was £4.10 One camper recalls that when he first went to the camp in the 1920s there were no bungalows on the bank but it quickly filled up over a couple of years.

The two camps were separated geographically and the dunes bungalows were more secluded and off the main track. Some dunes campers from the inter-war years have said that they simply never saw the people from the other camp, whilst a camper from an Anthony’s Bank bungalow remembers that they hardly ever went amongst the dunes bungalows because they were out of their way. They had no reason to go there. Their main interest was in getting to the beach as quickly as possible.

This lack of contact between the two camping areas may have been merely a reflection of the small-scale ‘grouping’ which occurred on each camp. It will be seen that bungalow families frequently formed close relationships with families from a few neighbouring bungalows. They would socialise mainly within this group and their children would tend to play together. Beyond that ‘group’, there could be another ‘group’, and so on. Whether in the dunes or on Anthony’s Bank, regular socialising might be with only a few neighbouring families. Although a campers’ association, the Humberston Fitties Campers’ Association, was formed in the 1920s, there is no evidence that the campers of this period felt a need to come together as a large-scale social or recreational community. Such an idea may have been contrary to what they were there for, personal freedom and individuality.

Relaxation and Play

Between the wars, most of the families on the Fitties were from the Grimsby and Cleethorpes area and it was quite usual to spend the entire summer on the camp with father travelling to work daily from the bungalow. The Edge boys joined their grandparents annually for the whole period of the school summer holidays and grandfather Edge travelled to work from the bungalow. Mrs. Edge and the maid stayed at the bungalow with Peter and Bruce. The Goodhand family would go down to the bungalow after the Easter weekend and come back at the beginning of September. Mr. Goodhand used to sleep there at night and travel to work each

33

Views of Anthony’s Bank looking towards North Sea Lane.

Views of Anthony’s Bank looking towards North Sea Lane.

Views of Anthony’s Bank looking towards North Sea Lane.

ABOVE: ca. 1930. The path to the right is on the Cleethorpes side of the bank.

ABOVE: ca. 1930. The path to the right is on the Cleethorpes the bank.

ABOVE: ca. 1930. The path to the right is on the Cleethorpes side of the bank.

BELOW: Bungalows Anthony’s bank Road and, in the left distance, along the path leading to the Tertia Trust camp, mid-1950s. All these bungalows removed at the behest of the local planning authority in the late 1950s

BELOW: Bungalows along Anthony’s bank Road and, in the left distance, along the path leading to the Tertia Trust camp, mid-1950s. All these bungalows were removed at the behest of the local planning authority in the late 1950s

BELOW: Bungalows along Anthony’s bank Road and, in the left distance, along the path leading to the Tertia camp, these were removed at the behest the local planning in the 1950s

34

34

34

day. He had a car and used to take the children to school each morning until the start of the summer school holiday. The Gordon family also spent the summer at the bungalow, with Mr. Gordon leaving the bungalow for work in the morning and returning in the evening.

Mr. and Mrs. Cobley were both engaged in the family business in Freeman Street, Grimsby, and stayed in town during the week. After closing the shop about 9.00 p.m. on Saturday they would drive to the bungalow to relax for the rest of the weekend; this was probably their main reason for having a place on the Fitties. Their sons Wilton and Frank spent the whole of the summer at the bungalow and were looked after during the week by maid Vera. Horace McDonald and his friends stayed at the bungalow, sleeping in a tent, from Whitsuntide to the third week in September and cycled to work daily. During the winter, when overnight stays were not permitted, they would go down just for the day.

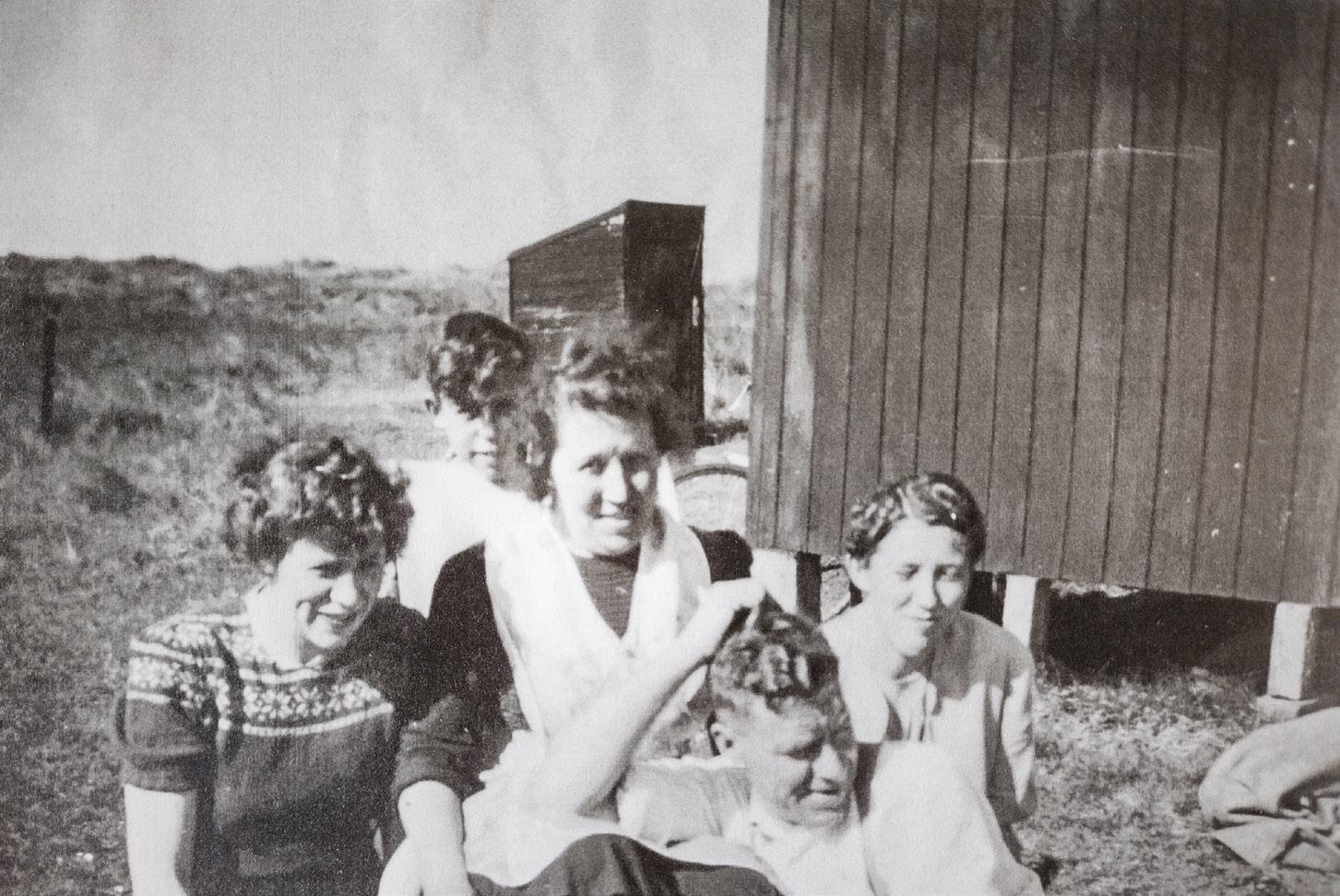

For children in particular the Fitties was an outdoor delight, with a degree of freedom to play and roam which was not available to their peers who were confined to the towns. Those who were children on the camp in those days remember playing in groups with children from neighbouring bungalows, with whom they passed blissful summers, playing and exploring the camp, beach and fields in all weathers. Neighbouring families in the northern area of the camp included the Hibbits, Cobleys, Edges, Maslins, Powells, Robinsons, Burnetts, Drewerys, and Harrisons. Beach games, swimming, tennis, football and cricket were popular.

Starting from the tideline, ‘golf’ was played out to the Haile Sand Fort, counting the number of strokes to hit the fort and the number to come back.* This was an activity also looked forward to by visitors, both adults and children. Peter Edge was a member of the Cleethorpes Golf Club from the age of eight and every day on the Fitties he would ‘drive’ a fish basket full of golf balls. His grandfather would stand by and correct his swing. Their ‘course’ stretched south over the rough ground from their chalet to the southern end of the camp. After bank holidays or weekends the children would go ‘bottling’, which entailed searching for bottles left by the trippers. The camp shop would give a penny for every bottle which was returned.

The Goodhand bungalow was at the other, southern, end of the camp but the children have similar happy memories of leisure activities. A favourite game was

*This fort is situated in the Humber about a mile from the Humberston shore. It is a well-known local sight and features prominently in people’s memories of the fitties. It and its partner, the Bull Fort, which lies about a mile from Spurn Point, were constructed during the First World War.

35

trap, bat and ball, using a rounders-type bat. Games were played with members of several neighbouring families, and included rounders, cricket and tenniquoits (a fast game played over a net). A putting green was laid out between neighbouring bungalows. The Goodhand family had what is recalled as ‘a complete friendship’ with the three neighbouring families of the Chattertons, the Robsons and the Abbotts. The adult members of the families sometimes joined with the children for group activities. These took place on an irregular basis, according to the weather. A suitable time was on long hot summer evenings, after the men had returned from work. Games competitions were held between the ‘old folks’ and the youngsters. Lionel Chatterton even had a presentation cup made and a special cricket match was held at the end of the summer.

The beach and sea were obvious attractions. It was normal to walk out to the Haile Sand Fort. This could be dangerous but the children on the camp were brought up to know the tides. ‘Dabbing’ was a popular pastime. The Goodhands used a piece of wood like a broom handle with a cross bar at the bottom which had sixinch nails in it with the ends made into barbs. They would then walk along a creek plunging the nails into the sand. Dabs are small flat fish which they recall as being not very enjoyable to eat. ‘Cockling’ produced buckets of cockles. These were washed and put into a bucket with some flour (to make them less sandy) before being cooked.

Swimming was popular but only when the tide and other conditions were suitable. There was a strong current in a creek which ran along the foreshore. So strong, that if it was chest high it was difficult to stand up in it. Beryl and Sybil Goodhand recall the occasion when they were swimming once at night and were suddenly surprised at being fully illuminated by a searchlight which was being shone on them by the ‘boys’ who were manning the Haile Sand Fort. The estuary could be dangerous for boats and the Goodhands recall that in the 1930s hardly anyone went sailing. The Burton family had a canoe but used it only in the dikes on the marsh.

Indoor games included playing cards and a new game, Monopoly. The wireless provided poor reception but the Goodhand’s wind-up gramophone accompanied dancing on the verandah or in the sitting room. Unfortunately, the sitting-room linoleum had to be polished afterwards. The Goodhand ladies and friends used to do embroidery; a favourite place for this was on Chatterton’s bungalow ‘jetty’ - a verandah that faced the sea.

The Fitties bungalows received many visits from family and friends. Peter Edge recollects that at weekends and other holidays there could be as many as four or five Rolls Royces, etc., parked by their bungalow, with perhaps twenty people there altogether. Some family members would travel from Fleetwood, complete

36

with chauffeur. One uncle would bring not just a bunch of bananas but a whole ‘stick’ - and was very popular with the children! The Goodhands also had many visitors. Mrs. Goodhand’s only stipulation was that they must bring an egg for their breakfast. A lot of children used to visit them and people of various nationalities such as French, Danish and German. It was the novelty and simplicity of camp life which seemed to attract friends and relations.

Several groups of families combined to have bonfires to mark the end of the season in September; collecting the wood on the beach was a regular summer occupation. This was another opportunity for visitors to come and perhaps sleep overnight in a tent. The Cobleys found that the bungalow attracted many visitors, who would generally bring their own food. A bell tent would be erected to provide extra accommodation. Mrs. Cobley’s sister had a draper’s shop in Scunthorpe and would bring all her ‘girls’ from the shop for a week’s summer holiday, whereupon the two boys would be ‘bunged outside’ to sleep in a tent.

Horace McDonald and his friends were young men in the 1930s and their means of passing the time included Sunday morning parades along the foreshore showing off their tan. ‘In our white shorts with blue stripe down the sides, ankle socks with blue tops and white sand shoes we thought we were the Charles Atlases* of those days’. They kept up with current fashions, including plus-fours and widelegged Oxford ‘bags’. The latter were soon discarded because when they went dancing and swung their partners round, the trousers wrapped round their legs and tripped them up. They would walk from the Fitties to the Cleethorpes Pier and Cafe Dansant for dances. After dancing on a Saturday night, they might have a midnight swim at Humberston, at times under a full harvest moon. Sometimes they were joined by perhaps a dozen friends who were camping nearby in tents. In the winter they might be on the beach playing football, including at least one match which took place on Boxing Day.

Food and Drink

Cooking for the pioneering Bunkers in their first year on the Fitties was an outdoor event:

Although we had a primus stove, mother was rather nervous of it at first, so everything was cooked on an open fire outside. This included steaming a pudding, and I remember her struggling to keep the fire going, but she did. We were always gathering driftwood.11

*Charles Atlas was an internationally-famous body builder whose correspondence courses were supposed to transform seven-stone weaklings into real ‘he-men’.

37

ABOVE: Grantham family and friends, and the dog ‘Peter the frog eater’. at Homefield on Anthony’s Bank, August 1939. Money was saved throughout the year for the family’s annual ‘fortnight of simple delights’ at the rented bungalow.

ABOVE: Grantham family and friends, and the dog ‘Peter the frog eater’. at Homefield on Anthony’s Bank, August 1939. Money was saved throughout the year for the family’s annual ‘fortnight of simple delights’ at the rented bungalow.

ABOVE: Grantham family and friends, and the dog ‘Peter the frog eater’. at Homefield on Anthony’s Bank, August 1939. Money was saved throughout the year for the family’s annual ‘fortnight of simple delights’ at the rented bungalow.

BELOW: Lingalonga ca. 1930. Front: Grandpa Tom Edge, Alec. Middle: Grandma Edge with brush and dustpan, Aunt Mabel Noble with bottle, Doris the Maid with bottles, Uncle Ernest Noble with water buckets. Back: Uncle Ernest’s chauffeur, Wilson.

BELOW: Lingalonga ca. 1930. Front: Grandpa Tom Edge, Alec. Middle: Grandma Edge with brush and dustpan, Aunt Mabel Noble with bottle, Doris the Maid with bottles, Uncle Ernest Noble with water buckets. Back: Uncle Ernest’s chauffeur, Wilson.

BELOW: Lingalonga ca. 1930. Front: Grandpa Tom Edge, Alec. Middle: Grandma Edge with brush and dustpan, Aunt Mabel Noble with bottle, Doris the Maid with bottles, Uncle Ernest Noble with water buckets. Back: Uncle Ernest’s chauffeur, Wilson.

38

38

38

Mrs. Edge and the maid cooked on a paraffin stove and Mrs. Edge would run a flag up their tall flagpole to let the boys know that it was lunchtime. The flag could be seen for a great distance and a lot of the bungalows had flag poles. Mrs. Goodhand and the maid also did the cooking. Their coal/coke-burning stove had to be black-leaded. Cooking was also done on a primus stove. Mrs. Goodhand would go into Grimsby weekly and do the shopping for the forthcoming week. A lorry would then deliver these supplies to the bungalow every Friday. It would also bring a large block of ice, which used to go in the top of the ice-box. The Cobley’s maid Vera did the cooking during the week and the boys were expected to fetch water and occasionally peel potatoes. Another job they had was to collect wood from the beach for the wood-burning stove.

At the McDonald bungalow, perishable food such as milk and fish was kept in an outside food safe. As far as cooking was concerned, the primus stove became the maid of all work. Horace McDonald was the breakfast cook and recalls ‘Breakfast on a Sunday morning; bacon, eggs, fried bread, and tomatoes, all cooked on the old trusty primus stove’. He also remembers the trifles that never set, which they finished up by drinking.