International School Aut | 2019 | Volume 21 | Issue 3

Winter

Summer |

The magazine for international educators

A model for differentiation techniques Education in Silicon Valley | Focus on mental health and wellbeing | Balancing sport with school

BACHELOR PHILOSOPHY, POLITICS AND ECONOMICS (PPE)

MULTIDISCIPLINARY STUDY IMPROVE YOUR WORLD

THE VIBRANT CITY OF AMSTERDAM

MODERN CAMPUS UNIVERSITY SMALL-SCALE

HIGHLY INTERACTIVE CLASSES

VU INTERNATIONAL STUDENTS VRIJE UNIVERSITEIT AMSTERDAM INTERNATIONAL STUDENTS #VUAMSTERDAM #VUAMSTERDAM_INTERNATIONAL

WWW.VU.NL/PPE

We should always remember that innovative educational methods and trends will only function with real human connections. We can only improve our education when we teach with our heart and mind. Doruk Gurkan, page 44

in this issue... comment Your magazine, your views, Mary Hayden and Jeff Thompson

35

39

5

responses Growth and the emerging supply-side concerns, Tristan Bunnell 7 Interpreting the ‘international school’ label and the theme of identity, Heather Meyer 11

features Balance and belonging: a recipe for wellbeing in international schools? Angie Wigford and Andrea Higgins 15 Home teachings, abroad, Stephen Spriggs 18 Is the IB meeting the needs of our times? Mikki Korodimou 19 ‘So did your Daddy cry when the car died?’, Natalie Shaw and Lauren Rondestvedt 21 The important role of senior leaders in mentally healthy schools, Margot Sunderland 23 Pupils with autism are twice as likely to be bullied – what can teachers do? Tania Marshall 25 Looking through the Crystal Ball, Naaz Fatima Kirmani 27 Will my son be a global citizen? Hedley Willsea 29 Are we able to slay the educational Leviathan? Andrew Watson 31 Pressure cooker education in Silicon Valley, Sally Thorogood 33 What global educators need to know about teacher wellbeing, Mitesh Patel 73

curriculum, learning and teaching

46

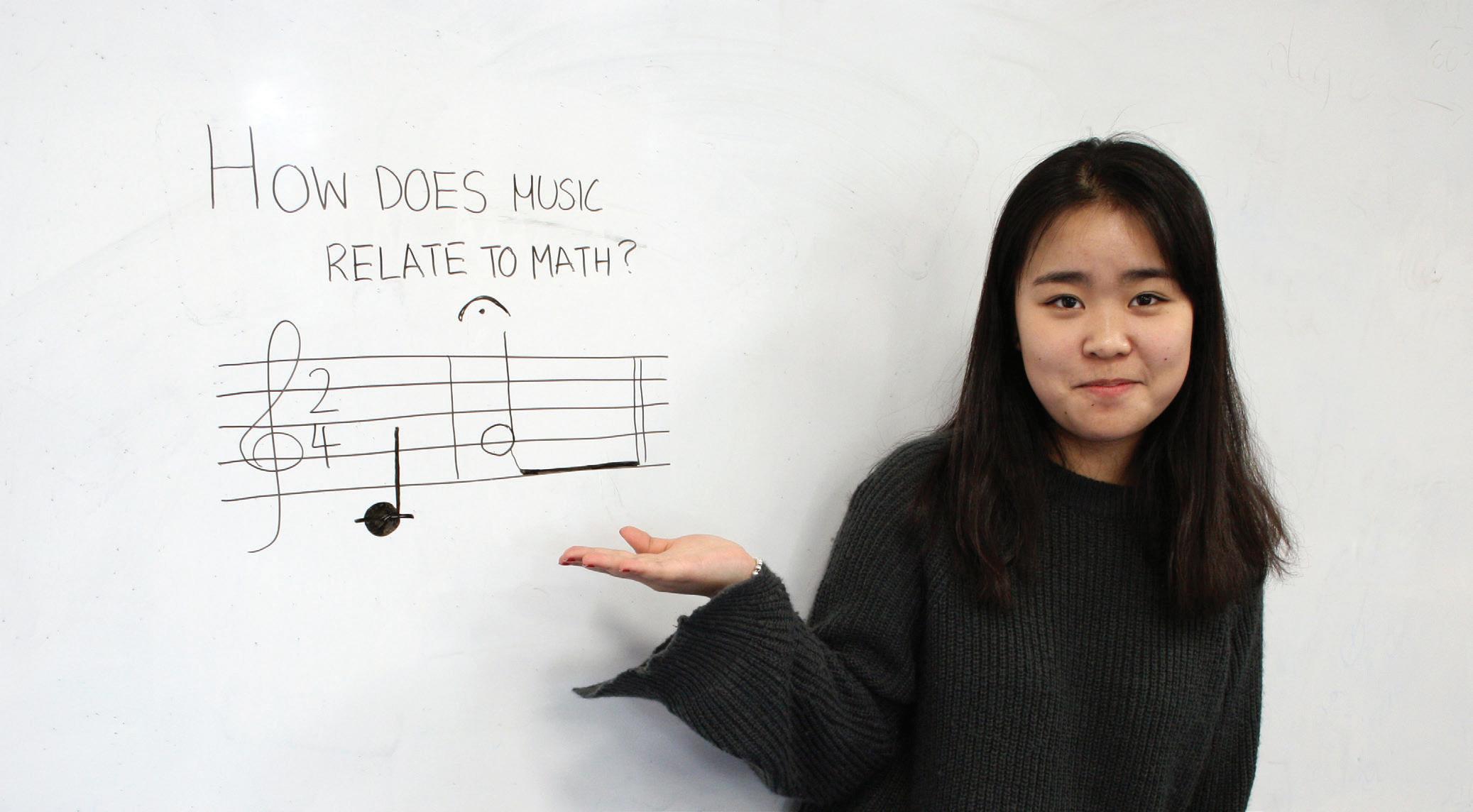

Is education the answer to the biggest challenges facing the planet? Ivan Vassiliev 35 The thesis sits smugly on the shelf, Adam Poole 37 How do student-athletes balance sport and education? Anne Louise Williams 39 Inquiring together: student and teacher collaboration Victoria Wasner 42 Lost in education, Doruk Gurkan 44 Meaningful and holistic integration of mathematics content in life, Stefanos Gialamas and Angeliki Stamati 46 Are IB students prepared to defend against ‘fake news’? Shane Horn 49 Different strokes, Nicky Dulfer 51

regulars Fifth column: Dr Neely’s dilemma, E T Ranger 55 Science matters: Bad science and serious consequences! Richard Harwood 57 Forthcoming conferences 58

people and places The IB turned 50 in 2018! This is how we celebrated, Mickie Singleton 59 Sister schools and study tours – a passport to the world, Brendan Hitchens 61 Striving to serve our island community, Daniel Slevin 63

book reviews

Winter

Summer |

61

| 2019

Sage on the Screen, by Bill Ferster, reviewed by Tim Metcalfe 67 Teaching and Learning for Intercultural Understanding, by Debra Rader reviewed by Gustavo M Lanata 69 The Learning Rainforest, by Tom Sherrington, reviewed by Wayne Richardson 71

Comment

Your magazine, your views Editors Mary Hayden and Jeff Thompson invite contributions on mental health and wellbeing One of the pleasures of editing International School magazine, we have found, is not only the interaction it brings with the many authors and potential authors who make contact with ideas for contributions, and the opportunity for us to read so many accounts of the interesting and exciting things that are happening around the world in international schools (and indeed in internationally-minded schools in national systems), but also the reassurance afforded by such communications that our Comment column itself finds a readership. That this is the case has been evident most recently from the responses received – both positive and negative – to our suggestion in the IS58 Comment column (volume 20 issue 1) that the term Third Culture Kid is outdated and in need of replacement. We have been pleased to include such responses in subsequent issues of IS, and are happy to see that the points made are still in readers’ minds: in this issue, for instance, Hedley Willsea makes reference to it in his article speculating on what the future might hold for his young (TCK) son. More recently, our invitation to comment on the term international school (IS61, volume 21 issue 1) has led to further contributions – in one case somewhat controversially in respect of the anonymity granted to our contributor to Comment (IS62). We are pleased to be able to include in this (IS63) issue two further articles on this topic, from Tristan Bunnell and Heather Meyer. Do please keep them coming! Although we did not set out to identify a specific theme for the current issue, two articles coincidentally draw attention to a topic that is of increasing relevance and concern in systems of education nationally and also, it is now clear, in the international school sector. The issue can broadly be described as mental health and wellbeing, and the article by Andrea Higgins and Angie Wigford (the latter an experienced international school teacher now working as an educational psychologist) raises many issues with which teachers and leaders in international schools will identify. Mary Hayden and Jeff Thompson Editors Jonathan Barnes Editorial Director James Rudge Production Director Alex Sharratt Managing Director For Editorial enquiries contact Mary Hayden and Jeff Thompson Email: editor@is-mag.com Website: www.is-mag.com International School© is published by John Catt Educational Ltd, 15 Riduna Park, Melton, Woodbridge, Suffolk IP12 1QT, UK Company registration 5762466

Winter

Summer |

| 2019

Margot Sunderland’s article on the role of senior leaders in what she describes as mentally healthy schools provides further food for thought with respect to similar concerns. For future issues of IS magazine, we encourage contributions relating to mental health and wellbeing from those who are facing the challenges of supporting students in international schools to cope with the pressures they encounter in their formative years. While there may be little doubt that young people face growing pressures as the 21st century progresses, the issues are complex and the means of addressing them no less so. Media reports of suicide in university students, recent data showing the doubling in a decade of antidepressant prescriptions (across age groups) in England, increasing awareness of the pressures on school and university students arising from social media and the negative as well as positive uses to which it is put, all set against a backdrop of political uncertainties on a global scale, make clear that these are challenging times in which to be moving towards adulthood. Amongst the many uncertainties of today’s world, however, what is certain is that teachers in international schools will not only be increasingly aware of the growing pressures on students, but will also be developing support systems to accommodate and alleviate them. We hope to be able to share with readers of future IS issues suggestions, ideas, and examples of good practice – please do get in touch if you can help us to do so.

We’d like to hear your thoughts on this and any other articles in this magazine

John Catt Educational Ltd is a member of the Independent Publishers Guild. No part of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted in any form or by any means. International School is an independent magazine. The views expressed in signed articles do not necessarily represent those of the magazine. The magazine cannot accept any responsibility for products and services advertised within it.

Email: editor@is-mag.com

The following enquiries should be directed through John Catt Educational Ltd. Tel: 44 1394 389850 Fax: 44 1394 386893 Advertising: Madeleine Anderson, manderson@johncatt.com Circulation: Sara Rogers, srogers@johncatt.com Accounts: accounts@johncatt.com International School© 2019 ISSN 1461-395 Printed by Micropress Printers, Reydon, Suffolk.

5

It’s our birthday! Ten years old. That’s ten years of supporting IB World Schools with flexible digital solutions that address key educational challenges. To celebrate, we’re offering new IB DP courses. And if that’s not enough, we’re also launching iGCSE and A Level courses. Happy birthday to us.

Find out more and join the party at pamoja.courses/birthday

Responses

Growth and the emerging supplyside concerns What does a surge in school numbers mean for the historic and traditional values of the international school sector? asks Tristan Bunnell The K-12 English-medium ‘international school’ market is set for unprecedented growth. Figures released by ISC Research (Glass, 2018) suggest that the number of schools will double by 2027. Further, the number of students and staff, and fee revenue, is expected to more than double. It is predicted that between 2017 and 2022 there will be an extra 3,150 schools and 2.35 million children. The decade up to 2027 will involve an extra 7,200 schools and 5.6 million children. These figures show that we are witnessing what have been described (Machin, 2017) as ‘gold rush’ conditions, with the forces of demand (led by globalisation) and supply (led by neo-liberal policy-making) being historically aligned. The eventual lifting (Marsh, 2017) of the cap on ‘locals’ attending schools in Vietnam is testament to that, as the government there attempts both to attract foreign investment and to reduce the talent brain-drain. But such levels of growth inevitably bring forward concerns. It was stated in the previous Comment section of this magazine by editors Hayden and Thompson that ‘the social and political contexts in which the [international] school exists may pose strong challenges to the values underpinning the nature of the education that it promotes’. An accompanying piece, written by an anonymous educator, was provocatively titled The rise of ‘illiberal international schools’? and addressed the thorny issue of schools ‘which receive significant funding from national entities whose political discourse, action, and impact is in conflict with the humanitarian values that the international school movement has long championed’. This is a relatively new and under-explored narrative. Previously, discussion has tended to focus on the demand-

side of growth. Who are the ‘new consumers’? Are there still ‘Third Culture Kids’? What can we call the new types of forprofit, branded schools that have emerged constituting what I previously termed (Bunnell, 2014) the ‘post-ideal’ mode of operation? What is the ‘institutional primary task’ (Bunnell, Fertig and James, 2017) of these schools? Such issues are still important, and need more discussion, but the lens of inquiry has now begun to turn to the supply-side of growth. Who is funding the growth? Why are governments relaxing regulations? Where is the profit going? The location, and indeed the political context, is clearly a growing concern as our anonymous writer points out. That discussion resonates with discussion a few years ago about ‘international aid’ being given by nations such as Denmark to overseas nation-states that helped politically to prop-up illiberal governments; the term ‘Dead Aid’ was coined to reflect this issue (a cynical play on the ‘Live Aid’ concerts of the 1980s). However, other dimensions that have been largely overlooked are slowly emerging from the dark. The recent sale of UK-based Cognita, which in 2018 was operating 68 schools in eight countries, offers a useful real-world example. The company was bought in August 2018 by Jacobs Holdings, a Swiss-based firm with a wealth partly derived from the manufacture of coffee and cocoa. What was arguably even more significant was that two potential bidders for Cognita were Temasek Holdings, a major Singapore ‘Sovereign Wealth Fund’ with assets worth USD 200bn, alongside another Singaporean wealth fund, GIC (formerly known as Government of Singapore Investment Company) with assets of USD 360bn (Kleinman, 2018). The entry into the

What we have here is a complex situation where the assets of one nation-state are being used to fund the growth and development of private schools in another nation-state. Winter

Summer |

| 2019

7

GREAT SCHOOLS have

GREAT BENEFITS Be great ISM International Student Insurance is A+ protection you can offer your international students— athletes and scholars alike. Our plans provide coverage for J-1 and F-1 visa-holding international students studying in the United States and domestic students studying or traveling outside the United States. With three tiers of coverage to select from, our plans fit family budgets of all sizes.

Greatness starts here. Tascha Gorley | 302-656-4944 | tascha@isminc.com

Protect your students. Protect those who protect your students. isminc.com/insurance

ismfanpage

#ISMINCinsurance

Responses

international school market of ‘Sovereign Wealth Funds’ is not entirely new, with Bahrain’s Mumtalakat Holding Company being probably the best known. Assets come primarily from surplus revenues from Bahrain’s oil and gas reserves. What we have here is a complex situation where the assets of one nation-state are being used to fund the growth and development of private schools in another nation-state. In my latest book (Bunnell, 2019) I refer to this situation as a form of ‘Inter-National Education’. Moreover, we also have a problematic situation where the origins of the funds may compromise the values of the schools in which they are invested. I now see this as a form of ‘post-ethical’ activity, adding depth to my ‘post-ideal’ model. Wealth derived from oil and coffee production do not sit easily with the mission statements of many traditional ‘international schools’, committed to promoting the sustainability of the planet. This adds considerably to the notion of the ‘illiberal’ school. Put simply, it seems timely to start considering the supply-side of growth. It involves a complex set of forces, some of which undermine and contradict the values for which the field of international schooling traditionally and historically stands.

References Bunnell T (2014) The Changing Landscape of International Schooling: Implications for Theory and Practice. Routledge: Abingdon Bunnell T (2019) International Schooling and Education in the ‘New Era’: Emerging Issues. Emerald Publishing: Bingley Bunnell T, Fertig M and James C (2017) Establishing the legitimacy of a school’s claim to be ‘international’: The provision of an international curriculum as the institutional primary task, Educational Review 69(3), 303-317 Glass D (2018) International school students considering a wider range of study abroad destinations, ICEF Monitor, 21 February. Available via http://monitor.icef.com/2018/02/international-school-studentsconsidering-wider-range-study-abroad-destinations/ Hayden M and Thompson J (2019) Comment, International School, 21(2), 3 Kleinman, M (2018) Swiss family office snaps up £2bn British schools giant Cognita, news.sky.com, 31 August 2018 Machin D (2017) The great Asian International School gold rush: an economic analysis, Journal of Research in International Education 16(2), 131-146 Marsh N (2017) Vietnam: local enrolments at foreign schools expected to grow after cap removed, The PIE News, 17 May 2017

Dr Tristan Bunnell is a lecturer in international education at the University of Bath Email: t.bunnell@bath.ac.uk

Winter

Summer |

| 2019

9

Education ready. University ready. Work ready. Ready for the world. Cambridge Pathway inspires students to love learning, helping them discover new abilities and a wider world. To learn more, visit cambridgeinternational.org

Responses

Interpreting the ‘international school’ label and the theme of identity Heather Meyer explores what we actually mean by established terms and boundaries In the most recent issues of International School, there has been an interesting debate on terminology and rhetoric commonly used within international school communities. The interest in the use of the label Third Culture Kid in these issues also highlights the ongoing significance of identity and belonging within international school communities. The popular Third Culture Kid label and the title ‘international school’ have both become increasingly ambiguous as they become distanced from their contexts of origin. The term ‘international school’ today can be interpreted in a variety of ways, and holds varying meanings for different people around the world. I see this as a positive direction, however, as schools may become increasingly responsible for defining the term for themselves – weighing in on the extent to which they intend to interpret the label ‘international school’ literally or symbolically with respect to their individual ideological direction, and according to the requirements and expectations arising from the context in which the school is situated. As schools move towards an increasingly ‘global’ outlook, it is ever more vital to consider the extent to which locality plays a role in such ‘global’ frameworks and ultimately in the institutional identity of each international school. While literal interpretations of the term have led to a degree of homogenised practices and definitions, I argue here that employing a symbolic interpretation of the term encourages customised approaches towards establishing and cultivating institutional, community and individual identity. The term ‘international school’ in a literal sense foregrounds the culturally diverse community of individuals who represent different nationalities at the school, and who ultimately are the basis for the international school system. It reminds us of a world comprised of national boundaries which largely work to reinforce our similarities and differences – linguistically, culturally, ideologically, politically, socially, and so on. Thus when entering international schools, we see (and have seen for decades) similar imagery: a collection of national flags flying high representing many nationalities present at the school, and a conglomeration of national symbols beautifully showcased to demonstrate and support the title of the school. These visuals also hold a sense of cultural value to community members who identify with them. It is also not Winter

Summer |

| 2019

uncommon to find events within international schools that work to celebrate the inter-national makeup of the community – the literal coming together of many different nationalities. ‘Intercultural’ days for example have allowed members to represent and perform their nationalities – waving national flags, producing and consuming an assortment of national dishes, and dressing up in national colours and dress. These events not only contribute to the identity of the school as ‘inter-national’, but also help affirm a sense of belonging to (a) national culture(s) for participants. These overt displays of national representation also come in more subtle forms, such as asking a child how they celebrate particular festivities in ‘their’ country, or creating nationality groups within parent-teacher organisations. While these opportunities are geared to empower community members and facilitate a sense of belonging, they also encourage ‘groupism’, which is a form of boundary-drawing and classification. In order to have groups, there needs to be an in-grouping (inclusion) and out-grouping (exclusion) process, even if it is subtle. Nationality-based groupism reinforces a sense of national belonging and, by extension, a sense of nostalgia – it allows us to tap into our past and/or engage with culturally-relevant things with which we can identify and, even for just one moment, feel ‘less foreign’. At the same time, it provides a relatively ‘easy’ means to classify and group oneself and others: those who belong, and those who do not. Socially, it fortifies the habit of classifying others according to national background, and holds students, staff and parent community members responsible for cultural representation – reinforcing the notion that nationality is a central feature of ‘identity’. However as we all know, the cultural backgrounds and trajectories of international school students can be quite complex, fluid and particularly unpredictable. There are therefore some significant tensions between establishing the school in the literal sense as an ‘inter-national’ learning space in which community members represent an array of identifiable nationally-oriented cultures, and in the symbolic sense – as a ‘global’ institution (however the term ‘global’ is to be defined). While the literal interpretation of the term ‘international school’ may lead to practices of groupism,

11

Responses

with all its positive and negative implications, taking more of a symbolic approach may push boundaries further on how ‘culture’ and ‘identity’ are conveyed, understood, and expressed in the school community. Challenging the community to find cultural similarities with others that go far beyond national orientations is a way to encourage a more ‘global’ approach to identity and belonging: that individuals can be a part of many other cultures – football cultures, musical theatre cultures, educational cultures, business cultures, etc. This means continuing to create activities that encourage in-grouping across diverse social fields, and facilitating opportunities which encourage students to conceptualise their own identities as individual, unique, flexible, and thus ‘global’. This can be achieved through increased intercultural engagement with the host society in spaces outside of the international school, with charitable, sport, cultural and social (etc) events and activities. By engaging with this form of cultural diversity, students are able to conceptualise their world in a more complex and fluid manner. On an institutional level, perceiving and defining each international school as a ‘global’ learning space and community situated within a uniquely ‘local’ setting is beneficial to the positionality and identity of the individual institution. Localities can provide ample amounts of intercultural dialogue and exchange that extend beyond nationally-oriented frameworks. Engagement can be beneficial in establishing a sense of belonging and identity in relation to the host society on an individual level, but also on an institutional level.

Winter

Summer |

| 2019

Schools play an important role in the development of a child’s perception of the world: how they perceive themselves, how they perceive others, and the extent to which they draw boundaries between themselves and others. By extension, these practices of boundary production impact the ways in which students see themselves on a global scale – their aspirations towards future mobility; their perception of their own access to different cultures; and the conception of their position within the world as a ‘global citizen’. Encouraging and facilitating opportunities for students, staff and parents to establish a sense of belonging to cultures that are specifically not rooted through nationality-based groupism or representation does not entirely fit the literal sense of the title ‘inter-national school’. It does, however, follow closely the ideological or symbolic orientation for which schools are currently striving: that of creating global citizens. Dr Heather Meyer is a researcher of international schools, based at Coventry University, UK. Email: hmeyercoventry@gmail.com

13

IB PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT DEVELOPING LEADERS IN INTERNATIONAL EDUCATION

IB online workshops help you upgrade your teaching practice Open to all educators in dozens of relevant, timely topics: • Four-week workshops allow pacing that you control. • A fresh engaging module is introduced each week. • Collaborate with IB educators worldwide. • An experienced workshop leader guides your learning experience.

better student outcomes

deeper understanding of IB pedagogy

stronger confidence in your teaching practice

greater ability to manage your teaching load

Features

Balance and belonging: a recipe for wellbeing in international schools? Angie Wigford and Andrea Higgins reveal the findings of a survey of 1,000+ teachers What does wellbeing mean to the international school community? What promotes wellbeing and what are the barriers to it in this particular sector? Those were the initial questions upon which we based a survey entitled ‘Perceptions of international school teachers and leaders on their wellbeing and that of their students’. Over 1000 international school teachers from more than 70 countries responded to an online questionnaire which was followed up with 18 individual interviews. The overwhelming response was positive. For example, 90% of the international school teachers who responded said they found their work full of meaning and purpose for most, or all of the time; they were proud of their work and also proud of their ability to support their students’ general wellbeing. At first glance we were very excited by these results. When we delved deeper, however, a more complex picture emerged. We found it helpful to use the balance model of wellbeing (Dodge et al, 2012), whereby wellbeing is achieved when a person has sufficient resources (psychological, social or physical) to successfully address challenges in each area. This idea of balance is commonly

Winter

Summer |

| 2019

reflected in the literature on resilience and coping strategies (eg Lahad et al, 2013) which are closely related to wellbeing. Key resources identified in our research were: supportive relationships, effective school support systems, robust communication and strong leadership. The challenges that stood out were the pressures of teacher workload, student workload, academic pressure and mobility (mainly in terms of transitioning between schools for both teachers and their students). Teachers really valued positive relationships with their colleagues, their students and even with parents. They talked about enjoying a sense of achievement, being able to make a difference and contribute to the community. Another key aspect of wellbeing for teachers was professional autonomy and being supported to explore creative and innovative approaches to their work. Teachers also reported high levels of student engagement, with friendships, belonging and being included as key features of their students’ wellbeing. Challenges to wellbeing for teachers were around high levels of emotional pressure, and just under half reported ongoing frustration in their work. Many said that their school

15

iP

iLS

Integrated. Individual. International.

NEW for 2019

iPrimary and iLowerSecondary Computing programme. Just like our English, Maths and Science programmes, our new Computing programme has been developed with leading education and industry experts to ensure that it gives students the knowledge and skills for lifelong learning.

Are you in? Find out more at qualifications.pearson.com/iprimary qualifications.pearson.com/ilowersecondary

Features

was not concerned about their personal wellbeing. Teachers reported that their students’ challenges included: friendship problems, language issues, lack of sleep and high levels of stress (often due to academic pressure from school and parents). Interestingly there were some indications of a consistent 10% difference in the perception of leaders to that of teachers, with the leaders being more positive. When this research was presented to a group of headteachers at a conference recently, there was an acknowledgement that it is the leaders who set the culture in a school, but in terms of wellbeing one group said ‘the behaviours and skills (around supporting relationships) are challenging to develop even if the knowledge and philosophy are aligned’. This recognises that enhancing wellbeing through promoting better relationships is something easier said than done. Transitions in international schools have an impact and this came up as a key aspect of wellbeing, with experiences of induction and first impressions having a lasting effect. Teachers reported that their students were often significantly affected by moving school, leading to some students giving up on trying to fit in and not wanting to make friends for fear of losing them again. This factor in the wellbeing of students in international schools was identified long ago (see Fail et al, 2004) and continues to be a key challenge with varying levels of recognition, from some schools reporting pre- and postmove contact with annual follow-up to next-to-no support, as noted by one interviewee: ‘At this point we don’t have a strategy. We say ‘Welcome, here’s your uniform, here’s your timetable, let us know if you have any questions’’. Also of concern to us has been an increased awareness, through recent discussions with school counsellors, that there is anecdotal but real evidence of self-harm becoming a common coping strategy for distressed students. There is a risk of self-harm becoming normalised and accepted by students. Schools need to address this but to do so is to necessitate talking about it, something many are reluctant to do. In summary, we would argue that wellbeing for staff and students in an international school can be enhanced by Winter

Summer |

| 2019

a focus on the concepts of belonging and coping. Many schools talk about having a caring community, and we would suggest that approaches that enhance belonging and develop emotional coping skills are an important part of that. In a place where a person feels that they are valued and part of a community, their ability to tolerate stress is enhanced and therefore their wellbeing more in balance. A community which supports individuals to develop good relationships and effective coping strategies is similarly more likely to demonstrate resilience at an individual and organisational level. It would be unrealistic to suggest that any one person or organisation can always have ‘good’ wellbeing; stress is a part of life and is often a helpful prompt. Our survey indicated that there are high levels of wellbeing in many international school communities and that a large part of this is based on the fact that there are high levels of psychological, social and physical resources helping to balance out the challenges. References Dodge R, Daly A P, Huyton J & Sanders L D (2012) The challenge of defining wellbeing. International Journal of Wellbeing, 2(3), 222-235. Fail H, Thompson J & Walker G (2004) Belonging, Identity and Third Culture Kids: Life histories of former international school students. Journal of Research in International Education, 3(3), 319-338. Lahad M, Shacham M & Ayalon O (2013) The BASIC Ph Model of Coping and Resiliency: Theory, Research and Cross-Cultural Application. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers. Wigford A & Higgins A (2019) Wellbeing in International Schools, Available via www.iscresearch.com/resources/wellbeing-ininternational-schools

Angie Wigford is the Lead Educational Psychologist with International Educational Psychology Services Ltd. Email: angie@internationaleps.com Andrea Higgins is Academic Director of the Educational Psychology Doctorate at Cardiff University, Wales. Email: HigginsA2@cardiff.ac.uk

17

Features

Home teachings, abroad Stephen Spriggs on the transition from national to international school teacher

18

the class hold up a hand to answer. Yet teaching in the Far East can see this fall flat as a result of the group culture often found in the region, where individuals avoid being singled out by choice and alternative strategies should be employed. Whether it’s something as simple as pulling names out of a hat or creating groups with a ‘team leader’ who is nominated to present their answer to the class, the open back and forth nature of education is one thing to maintain. For first-timers abroad the initial settling-in period may be much rougher, devising a teaching plan with little experience to draw on. If there are more experienced staff around, use them. Every teacher making the decision to move away from their home country is likely to have been through a similar sort of experience: currency exchanges, new cities to explore, new cities to get lost in, new languages and nuances to pick up. Having someone around to learn from whilst also seeing first-hand what aspects of delivery they stuck with may help tremendously. Dealing with classroom management can also be testing to start with. Particularly in countries with rambunctious personalities where the conversation between students is non-stop, you may need to learn a new way of doing things. When it comes to managing the students, behaviour is usually deeply ingrained within the system, meaning a sudden change can result in either a spectacular positive or a damaging negative. Stop/starting a class not only wastes time but can end up harming students not participating in the disruptions by restricting their time to take in what is being taught. Contributing to the development of the future of the next generation is a tough task no matter where you’re doing it, and moving away from the familiarity of home to a destination where the ins and outs of how teaching works can be completely different to what you’re used to presents challenge after challenge. Within the context of your new school, its policies and the advice of your new colleagues, implement what you think is appropriate from your previous training and methods, eliminate what is clearly incompatible with the new culture, and adapt what remains. No matter how you do it, the next generation is in your hands. Stephen Spriggs is Managing Director of William Clarence Education (williamclarence.com). Email: info@williamclarence.com

Summer |

Winter

Making the decision to teach abroad, most teaching professionals will take it upon themselves to study their new environment carefully to pick up on the norms and standard techniques applied to their classrooms. Yet, as an international teacher, you bring something new, exotic, and unknown into the class – so how much should you adapt to the situation, and how much of your home country’s system should make the trip overseas with you? The initial culture shock of a new country may wear off for seasoned travellers, accustomed to making moves across continents in search of their next challenge, but it’s always nice to maintain some creature comforts from home. Why would this be different for your work life? It wouldn’t. In fact, maintaining some semblance of the methods picked up at home can go a long way in facilitating a smoother transition period than attempting to take on everything at once. In addition to the stress of physically moving your life, there’s also the psychological impact of a new classroom of students from a different culture all looking at you for guidance; it can be testing if there’s a period of total loss as the year begins. As an international teacher, you do not need to adapt to all the norms of the country, but adapt what you can and stay mindful of avoiding any cultural fauxpas. Indeed, the curriculum can differ wildly across different regions; take South Korea for example where the education business is a big deal with hagwons at night and a great academic focus in the day. Finding a balance to start with is key to success. Upon first arrival take the time to absorb what is happening, who is dealing with whom, how are the students responding to the existing staff, and where do you fit in with the new system? If you’ve been teaching in England and you’re moving to an international school teaching the English national curriculum, the amount of change may be minimal; after all the parents have sent their children to the school specifically for a British-style education which you provide with aplomb. In this instance, not totally adapting to an overseas style of teaching can work in your favour; there will be less necessity to change the way you work if the class you deliver to are there specifically for your style of teaching. One aspect that you may take with you is the position of the teacher within the classroom; how do you and the students interact? A sure fire home-run from back home may fall flat in a new cultural setting. Question and answer sessions, for example, are common in many Western-style classrooms. They’re hard to get wrong; simply ask and have

| 2019

Features

Is the IB meeting the needs of our times? We must acknowledge the ‘certainty of uncertainty’, writes Mikki Korodimou Practising education that ‘meets the needs of our times’ (the founding principle of the Atlantic College project in 1962 (Jonietz and Harris, 2012)) requires an in-depth personal, communal and global exploration to understand what exactly these needs are. Answering this pertinent problem means taking a step back. It demands a critical reflection of where we are at in terms of our educational practices and the world we call home. It asks of us to think about how we have arrived here and perhaps most importantly to reflect upon where we wish to go. Coming into teaching for the first time in January 2018 at UWC Atlantic College was invigorating. It was challenging and it was adrenaline-filled. Learning early on that saying ‘I don’t know’ was OK, I started to feel like the possibilities for exploration in the classroom were infinite. Despite the evident engagement and curiosity ignited in the students, however, when we delved into the unknown the stress of moving away from the security of the syllabus, textbook and marking criteria quickly became apparent. The word Winter

Summer |

| 2019

‘assessment’, the dreaded 45 points maximum of the International Baccalaureate Diploma Programme, and the question ‘is this going to be in the exam?’ crept in. Boundaries of time and space for experiential, personal and contextuallybased learning materialised. The focus of education, it seems, is increasingly on the end goal, rather than on the means used to get there. We are turning what should be a learning journey (synonym for life) into a process of accumulation. Whether it be IB points, experiences, or CAS (Creativity, Activity, Service) hours in the IB Diploma, we are collecting, without necessarily engaging with value in the process or the interconnected nature of all that we do. The success of the IB over the past 50+ years has been phenomenal; there are numerous benefits of the education provided by the IB Diploma Programme, and countless examples of how the programme can be moulded, tailored and contextualised by passionate and engaged educators. Yet there are also downsides which must not remain in the shadows of our contentedness. In his recent book, David

19

Features

As you set out for Ithaka, hope that your road is a long one, full of adventures, full of knowledge. Extract from Ithaka by Cavafy Gleason (2017) explores the ways in which competitive educational environments are impacting young people. We are over-scheduling, over-burdening and over-pressuring students. The drive for 45, and to excel, is causing high levels of anxiety and stress. This troubling observation is echoed by young people, parents and educators alike. If (albeit somewhat problematically) we are telling our bright young people that it is up to them to fix the issues in the world today, then we need them to be well in order to do so. We live in a world characterised by uncertainty. In times of uncertainty, we need flexibility and creativity to react. What’s more, we need to have the space to see the connections between all that we do, as only then will we even have a glimpse at the larger picture. So how do we ensure that we create room for space, systemic thinking and flexibility in the rigid and long-engrained systems within which we currently educate? What do we want at the core of education? How do we put wellbeing at the centre of all that we do? Where are we succeeding in our educational approaches and where is there room for additions or improvement? These are all questions which our team of students and staff at UWC Atlantic College have begun to engage with over the course of the past year. The Land and Sea Stewardship project at UWC Atlantic College is a collaboration between students and staff to design a new programme of education that is relevant to the needs of the world of today and its future. Our learning UWC Atlantic College

journey so far has brought about several important lessons. Young people need to have space in which to reflect, to play and to exist without the requirement of making all their time ‘productive’. It is within this space that they will be able to absorb, process and reflect upon the ways in which the things they are learning relate to them. Wellbeing cannot be an addition to the education we currently provide; it must be central to the design of the system. By thinking about education as process and journey, we are able to take a step towards extracting it from the silos that grades and subject disciplines have put it into. Unlike the structured framework in which we currently operate, a more processual journeylike approach could help us to overcome the rigidity of disciplines and groups, and challenge dichotomies such as curricular and extra-curricular education. Learning from place is also extremely valuable. We are beginning to see that as we delve into the depths of the ‘global world’, the ‘local’ is in danger of becoming part of a mythological past. International education is perhaps especially guilty of this. Yet, in international schools across the world, where we revel in the glory of our communal ‘multiculturalness’, perhaps we are at risk of missing out on the lessons we can take from making hosting spaces into places attached to meaning. By attempting to engage in place-based learning, we hope to remedy this, and allow for international education to have space for contextual connections. Where do we go now? Perhaps thinking about what the needs of our times are is the wrong starting point. We should be thinking about designing systems of education (and all other types of systems which hang from it) that are flexible enough to adjust to the needs of the times, both today and beyond. Acknowledging the certainty of uncertainty could allow us to place wellbeing, flexibility and values at the heart of educational design, thus giving space for education to mould to changing climates (political, economic, atmospheric and more). There is a long learning journey ahead for us in this monumental task, but in the same way that Cavafy urged travellers to Ithaca to hope that their road be a long one, we too welcome the lessons and experiences coming our way. References Gleason, D L (2017) At what Cost?: Defending Adolescent Development in Fiercely Competitive Schools. Concord, MA: Developmental Empathy. Jonietz P L & Harris D (2012) World Yearbook of Education 1991: international schools and international education. London: Routledge.

Mikki Korodimou is the Land and Sea Stewardship project leader at UWC Atlantic College. She came into the role having been a student at Atlantic College between 2009 and 2011, and later a Geography and Environmental Systems teacher. Email: mikki.korodimou@atlanticcollege.org Summer |

Winter

20

| 2019

Features

‘So did your Daddy cry when the car died?’ Natalie Shaw and Lauren Rondestvedt write about preparing pre-service teachers for supporting children through experiences of bereavement From supporting children through the loss of a pet to framing the death of a family member, the experience of being a significant presence during a time of bereavement is one that all teachers inevitably encounter at various points in their career. As Chadwick (2012) notes, teachers’ appropriate responses towards loss, and their ability to accompany a child or group of children on the journey of coming to terms with death, directly relates to the quality of our schools as places of emotional security and inclusion, as well as places where challenging human experiences can be explored intellectually. At ITEps (International Teacher Education for Primary Schools: the first full bachelor’s programme to train students to become teachers in international primary schools), the topic was approached with Year 1 student teachers in conjunction with a design-based education book project, during which the experience of death was one possible focus for students to address in their children’s book. However, the issue clearly has wider significance, with regards to general pastoral responsibilities as well as with a view towards the inherently intercultural teaching and learning situations that students will encounter throughout their careers. Familiar with the caution regarding narrow narratives about human experience (Atrey, 2016), students were invited to a workshop about bereavement, where the topic was explored from a broad perspective, whilst reflecting the plethora of understandings of death that are present in our schools. Negating attempts to classify children’s understanding of the concept of death in stages related to age (Chadwick, 2012), the session explicitly drew on approaches that focus on the agency of children (Mahon, 2011; Esser et al, 2016) and acknowledged that a myriad of factors contributes to children’s expertise with regards to the concept of death. Students heard that intellectual, personal and cultural aspects equally contribute to a child’s expertise: intellectually, an accurate understanding of core bodily functions enhances a child’s scientific understanding. On a personal level, prior experience with loss provides a child with expertise through lived experience, whereas the prevalence of death and metaphysical ideas present in a particular culture shape the Winter

Summer |

| 2019

child’s exposure to and acceptance of death as a part of life (Mahon, 2011). Language was identified as a key factor in providing honesty and accuracy. Grollman (2013) warns of the danger of framing death in ways that may instil fears in children with regards to regular experiences of life: the idea that death may be explained as ‘having gone to sleep’ may lead to children avoiding bedtime for fear of ‘disappearing’ overnight. In particular, communication was explored with regards to attachment theory, and the necessity to enable children to conceptualise the experience in ways that facilitate continued secure attachment. Attachment theory as a method of framing a child’s experience of grief was introduced broadly to students, and the three main styles were outlined: secure, anxious and avoidant. Research regarding attachment styles and grief has suggested that the attachment style of a child has an impact on that child’s coping styles and needs, as explored by Stroebe (2002) which has provided a model for categorizing adaptive or

Understanding children’s grief is a complicated process that began on the assumption that children’s grief mirrors that of adults.

21

Features implications of both ethnic and religious culture on the perception of death and the grieving process, while also highlighting the influence of popular culture (PenfoldMounce, 2018) and family culture (Thieleman, 2015). The real-life example in a Middle-Eastern teaching context of a mismatch between a well-intended, Western teacherinitiated grieving session and local children’s surprise at the expectation that they should be sad about a community death enabled students to reflect on the intersection of these influences. In conclusion, students were invited to draw on all aspects that had been discussed in the session as ‘diagnostic tools’, assessing every situation they might encounter in practice as a new and unique manifestation of a universal experience, and to use their newly gained insight flexibly to determine the best possible course of support. References

22

Chadwick A (2012) Talking about Death and Bereavement in School. How to Help Children Aged 4-11 to Feel Supported and Understood. London: Kingsley. Dyregrov A & Dyregrov K (2013) Complicated grief in children: the perspectives of experienced professionals. OMEGA-Journal of Death and Dying, 67(3), 291-303. Esser F, Baader M, Betz T & Hungerland B (2016) Conclusion: potentials of a reconceptualised concept of agency. In Esser F, Baader M, Betz T & Hungerland B (eds) Reconceptualising Agency and Childhood: New perspectives in Childhood Studies. Abingdon: Routledge. Grollman E (2013) Explaining Death to Children and to Ourselves. In Papadatos C & Papadatou D (eds), Children and Death. Philadelphia: Hemisphere. Konigsberg R D (2011) The truth about grief: The myth of its five stages and the new science of loss. New York: Simon and Schuster. Kübler-Ross E (1969) On death and dying. New York: The Macmillan Company. Mahon M (2011) Death in the Lives of Children. In Talwar V, Harris P & Schleifer M (eds), Children’s Understanding of Death: From Biological to Religious Conceptions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Packman W, Horsley H, Davies B & Kramer R (2006) Sibling bereavement and continuing bonds. Death Studies, 30(9), 817-841. Penfold-Mounce R (2018) Death, The Dead and Popular Culture. Bingley: Emerald. Stroebe M S (2002) Paving the way: From early attachment theory to contemporary bereavement research. Morality, 7(2), 127-138. Stroebe M, Schut H & Boerner K (2017) Cautioning health-care professionals: Bereaved persons are misguided through the stages of grief. OMEGA-Journal of Death and Dying, 74(4), 455-473. Thieleman K (2015) Epilogue: Grief, Bereavement and Ritual Across Cultures. In Cacciatore J & DeFrain J (eds) The World of Bereavement: Cultural Perspectives on Death in Families. New York: Springer.

Dr. Natalie Shaw is a lecturer in Educational Studies at Stenden University, The Netherlands Email: natalie.shaw@stenden.com Lauren Rondestvedt is a Masters student in Educational Sciences at The University of Groningen, The Netherlands Email: l.rondestvedt@student.rug.nl Summer |

Winter

maladaptive coping. However, understanding children’s grief is a complicated process that began on the assumption that children’s grief mirrors that of adults (Dyregrov & Dyregrov, 2013). Historically, ‘letting go’ or ‘moving on’ from grief was seen as the means to closure. Packman et al (2006) explored the concept of continuing bonds as a means to support ongoing attachment, specifically related to children. Based on research and personal stories, students heard ways in which children could maintain a healthy relationship with the deceased individual in a way that supported secure attachment while clarifying to the child that the person was no longer physically present. The overall goal in supporting children in grief through attachment is not to confirm children’s fears of abandonment (anxious) nor to suggest that they should never expect attachment in the first place (avoidant). With a view to promoting secure and healthy attachment, students were provided with the concept of resilience, and the importance of fostering resilience in children in a multitude of ways. In this way, they can support children in overcoming small challenges and changes in an effort to equip them with tools for coping. To outline the manifestation of grief, the 5 stages of grieving (Kübler-Ross, 1969) were presented as a broad framework for understanding. At its conception, these stages were believed to occur in sequence, and unsuccessful resolution of one stage prevented movement to the next. Recently, these stages as a sequential process have been ‘debunked’ (Koningsberg, 2011) but have remained as descriptors of possible phases. As Phyllis R Silverman (principal investigator of the Harvard Child Bereavement Study) suggested, grief does not end at a particular time. Stroebe et al (2017) emphasized that grief is a system of complex emotions and processes, and that individual factors should be considered. The takeaway message for students was to use the stages as possible manifestations of grief, but be aware that each individual will vary in the way grief is experienced. Relating both to the manifestations of grief and to the general concept of death, cultural influences were further explored. The facilitators took care to examine the different

Atrey S (2016) “The Danger of a Single Story”: Introducing Intersectionality in Fact-Finding. In Alston P & Knuckey S (eds), The Transformation of Human Rights Fact-Finding. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

| 2019

Features

The important role of senior leaders in mentally healthy schools Margot Sunderland offers some guidance to help support students and teachers Heads and senior leaders keen to ensure their school is a mentally healthy environment really do have their work cut out. Research on international school wellbeing conducted by Cardiff University School of Psychology and International Educational Psychology Services (Wigford and Higgins, 2019), flagged that supportive relationships, healthy communication, effective support systems and clear, strong leadership are the most important factors for positive staff and student wellbeing in international schools. For headteachers, such a responsibility may appear a Herculean task, especially as senior leaders’ own emotional requirements also need to be met. Many senior leaders are overwhelmed by heavy workloads and the need to constantly improve attainment, making it difficult for them to provide mental health support for teachers and students – a point they must inevitably address. So what can be done? Here are our top six tips: Senior leaders need to prioritise their own psychological support Counselling brings down toxic stress (which is dangerous to the immune system and a key factor triggering mental ill-health) to tolerable stress – heads should attend twice weekly therapy sessions where they can off-load, weep, howl, rage in front of someone who truly understands. ‘Psychological hazards’ health checks for teachers and a shift to psychologically aware, warm and empathic whole-school cultures This involves putting in place a system of valuing teachers and removing the psychological hazards of shame and blame. Research shows that feeling valued is key to mental health, whereas shame triggers the same reaction in the body as physical injury (Dickerson et al, 2014). To this end, one head adopted the ‘I wish my headteacher knew’ intervention. It’s a simple written note exercise for teachers (which can be anonymised) – a derivation of the intervention ‘I wish my teacher knew’ used by teachers keen to really understand the issues that students were facing. Unsurprisingly the teachers wrote back: ‘We don’t feel valued’. This was a wake-up call for the head and senior leaders who then began to focus on Winter

Summer |

| 2019

making time to acknowledge and appreciate members of staff. This head also started and ended the week with several small talking circles for staff at which they could express their feelings about school and home (led by a teacher trained in group facilitation). A shift from a culture of blame regarding test results to a culture of support for teacher-student relational health will also have a positive impact on students’ mental health. Research shows that the more securely attached children are to teachers, the better their behaviour and the higher their grades (Bergin and Bergin, 2009). Bringing down toxic stress to tolerable stress for teachers Heads have a responsibility to find ways of bringing down teachers’ toxic stress to tolerable stress levels. A quick ‘therethere’ chat in the corridor before the teacher’s next lesson is not sufficient to reduce toxic stress levels. Rather, it’s important to ensure that staff have access to an oxytocin (anti-stress neurochemical) releasing environment on a daily basis e.g. a work-free sensory staff-only zone with time to use it built into the school timetable. It needs to include some of the following elements which we know from neuroscience triggers oxytocin and opioids: • Warm lights (uplighters) • Colour • Soothing music • Lovely smells • Comforting fabric • External warmth heating the body (e.g. electric blankets) • Open fire DVD (Uvnas-Moberg, 2011) Bringing down toxic stress to tolerable stress for students Many children arrive at school in an emotional state not conducive to learning – this could be due to troubled home

23

Features

lives or other external factors. There are many neuroscience research-backed interventions designed to bring down stress levels in vulnerable children from toxic to tolerable. These are best implemented at the beginning of the school day and include:

clearly to ensure that they have got the message, coupled with a formal valuing of each individual child in terms of their special qualities: eg kindness, generosity, perseverance, explorative drive.

• Replacing detention room with meditation room (research shows improved learning and less bad behaviour)

Conclusion Responsibility for mental health in schools should not simply rest on the shoulders of headteachers. What is required is international recognition of the importance of monitoring the mental health culture of every school –a governing bodies, trust boards and directors need to make staff wellbeing, as well as student wellbeing, key performance indicators for our schools.

• Sensory play

References

• Time with animals or time outside

Bergin C & Bergin D (2009) Attachment in the Classroom. Educational Psychology Review, 21, 141-170.

• Tai chi • Mindfulness

All of these interventions support learning and protect against toxic stress-induced physical and mental illness. Train key members of staff to become ‘emotionallyavailable adults’ for vulnerable children There is a wealth of evidence-based research showing that having daily and easy access to at least one specific emotionally-available adult, and knowing when and where to find that adult, is a key factor in preventing mental illhealth in children and young people – it’s called social buffering. If the child does not take to the designated adult, an alternative person should be found. Create a policy around testing and exam stress Heads need to ensure students understand that their selfworth and the worth of others cannot be measured simply by tests and exams. This needs to be communicated very

24

Dickerson S, Grunewald T & Kemeny M (2004) When the Social Self Is Threatened: Shame, Physiology, and Health, Journal of Personality, 72(6), 1191-1216 Uvnas-Moberg, K (2011) The Oxytocin Factor, London: Pinter and Martin Ltd Wigford A & Higgins A (2019) Wellbeing in International Schools, Available via www.iscresearch.com/resources/wellbeing-ininternational-schools

Dr Margot Sunderland is Director of the Centre for Child Mental Health (www.childmentalhealthcentre. org), a non-profit organisation that provides mental health training in schools, and CoDirector of Trauma Informed Schools UK (www.traumainformedschools.org). Email: info@childmentalhealthcentre.org

Summer |

Winter

• Accompanied drumming

| 2019

Features

Pupils with autism are twice as likely to be bullied – what can teachers do? Tania Marshall considers a nuanced approach Primary pupils with special educational needs are twice as likely as other children to be bullied, according to the University College London (UCL) Institute of Education (2014), while according to the World Health Organization, 1 in 160 children have an autism spectrum disorder (WHO, 2018). Learning and socialising with neurotypical children can pose a challenge for pupils with autism who find it hard to read facial expressions and body language, and have difficulties understanding the intentions of their peers. They may also prefer to play alone, which sets them up as targets in the playground, with other children finding it easier to pick on them as they do not have a support structure around them. Individuals with autism are more likely than their neurotypical peers to be victims of bullying. They can, however – usually unintentionally – bully others due to their high sense of justice, misinterpretation of social cues or their rigid belief that they are right. In these situations, it is likely the autistic pupil did not intend to bully, or was unaware she/he was behaving in such a way. Looking specifically at girls with autism, females on the spectrum are set up by the very nature of a combination of their traits to be taken advantage of and vulnerable to the ill intentions of others. These traits include:

outer edges or have a boy as a friend), teachers often do not recognise that the girl is having difficulties. There are a few ways in which teachers can counteract the likelihood of a pupil with autism being bullied. It is extremely important to educate all pupils about autism and tolerance of difference. Pupils with autism could also be assigned a ‘neurotypical buddy’ who makes sure the pupil is safe and supported. Friendship skill acquisition, from as young an age as possible, is crucial for pupils with autism to learn. The best basis for this is through interests held in common with peers. Pupils with autism should also be provided with alternatives to the less structured parts of the school day such as break times and lunchtime. Some examples are lunchtime clubs or library activities. This is important because allowing a child on the spectrum out into the playground is akin to placing a person in a literal minefield. A ‘social bomb’ is going to go off; it’s just a matter of when, where, how, and who is involved. Those who are being bullied often hide it due to their fear of it getting worse, so it can be challenging to spot signs of a pupil with autism being bullied. Outward signs usually include crying, refusing to go to school, hiding in certain areas of the school, and/or clinging to the teacher or other staff member.

• high sympathy or emotional empathy • social naivety • misinterpreting other people’s intentions • being less able to read facial expressions and body language • not understanding the unwritten social rules • being overly idealistic about relationships • social immaturity Socially, in primary school, girls with autism tend to be included in groups by neurotypical girls and taken care of. Neurotypical girls may take a girl with autism under their wing and the girl with autism will mimic and copy them. Boys with autism, on the other hand, tend to spend time alone and are more likely to be bullied in primary school. Due to the fact that girls with autism appear to be part of a group (although they often flit between groups, stay on the Winter

Summer |

| 2019

Those who are being bullied often hide it due to their fear of it getting worse, so it can be challenging to spot signs of a pupil with autism being bullied.

25

Features

Schools also have an important role to play in teaching pupils with autism about hygiene, independence and resilience, self-esteem, managing bullying, and career planning.

• understanding the social world • understanding instructions • being misunderstood and misunderstanding others • being bullied for being different (whether that be because they are ‘odd’, ‘quirky’, ‘eccentric’, ‘out of the box thinkers’, or ‘weird’ – as described by neurotypical pupils) There are also many misconceptions about autism which result from stigma about what autism should look like and a lack of research, books, training programmes and interventions for females. One such misconception is that autistic girls do not have any strengths, and this is inaccurate. Many girls with autism have a multitude of strengths, some of which can include: attention to detail, perfectionism (a

26

double-edged sword), perfect or near-relative perfect pitch, acting skills, artistic and creative skills, writing skills, caring skills, great skills with animals, loyalty, determination and tenacity, high IQ, dance and athletic ability, and many more. It is important for teachers to take a strength-based approach to teaching pupils with autism to offset their tendency towards self-deprecation, alongside instilling values of acceptance, inclusion and tolerance among all pupils. The type of teacher a pupil with autism has can make or break their school experience – teachers who are patient, creative, accepting and intuitive can help children with autism to thrive in the school environment. References UCL Institute of Education (2014) Children with Special Educational Needs Twice as Likely to be Bullied, Study Finds, Accessed via https:// childnc.net/children-with-special-educational-needs-twice-as-likelyto-be-bullied-study-finds/ World Health Organization (2018) Autism Spectrum Disorders, Accessed via www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/autism-spectrumdisorders

Tania Marshall MSc is an author, psychologist, AspienGirl Project lead for girls with Autism or Asperger Syndrome, and Autism Ambassador for Education Placement Group. Email: admin@centreforautism.com.au

Summer |

Winter

If the pupil is selectively mute, try having them write or draw about the issue. This is important because the pupil may not understand the difference between teasing, nasty behaviours and bullying. Schools also have an important role to play in teaching pupils with autism about hygiene, independence and resilience, self-esteem, managing bullying, and career planning. Another very important factor is training that focuses on reducing vulnerabilities and increasing safety and self-advocacy. In terms of the cyber world, while girls with autism are intuitively skilled at using the internet they are socially naive and vulnerable to internet predators, so online safety teaching is a must. Some of the other major challenges young people with autism face in the school environment are:

| 2019

Features

Looking through the Crystal Ball Naaz Fatima Kirmani offers a glimpse of the changing educational landscape and the impact of new technologies The unprecedented digital transformation of recent years has ushered in an intense technology-driven world. We now live in an increasingly diverse, globalised, complex and media-saturated society. Technology and its effect is by far the most popular topic concerning 21st century learning and education. The rapid advancement in educational technology calls for radical changes in the way we think about intelligence, education and human resources, in order to meet the extraordinary challenges of living and working in the 21st century. While we may not be able to peer into the future to ascertain what skills will be important 10 years from now, it is possible to examine trends that have changed the demands of work and life in the recent past and continue to do so today. In both developed and developing nations, young people have become increasingly reliant on social networking technologies to connect, collaborate, learn and create – while employers have begun to seek out new skills to increase their competitiveness in a global marketplace. Education, meanwhile, has changed much less. Schools are faced with perhaps one of the greatest challenges – engaging students and creating excitement about learning. With few exceptions, school systems have yet to revise the way they operate in order to reflect current trends and technologies. The future growth and stability of our global economy depends on the ability of education systems around the world to prepare all students for career opportunities and help them to attain higher levels of achievement. However, despite numerous efforts to improve educational standards, school systems around the world are struggling to meet the demands of 21st century learners and employers. When we actually reflect on educational experiences, it’s difficult not to conclude that few schooling experiences teach job skills which are needed in the present world. Seldon (2018) describes the first education revolution as having focused on organised learning from others through family units, groups or tribes, while the second education revolution related to the coming of institutionalised education in the form of schools and universities. The third education revolution, which started in the 1950s, gave rise to issues related to inequity in access to educational opportunities, administrative workload for teachers, lack of training and pedagogical support. It continued to support a capitalist model of education, with the privatisation of education and in various contexts the limiting of access to a privileged class. These issues can be well managed, Winter

Summer |

| 2019

leveraging the technology positively to economise time and effort, and reaching out to the disadvantaged group of students in society. A recent report by the World Economic Forum (2018) states that, by 2022, today’s newly emerging occupations are set to grow from 16% to 27% of the employee base of large firms globally, while job roles currently affected by technological obsolescence are set to decrease from 31% to 21%. In purely quantitative terms, 75 million current job roles may be displaced by the shift in the division of labour between humans, machines and algorithms, while 133 million new job roles may emerge at the same time. All this indicates that we have reached a ‘tipping point’ in education that requires us to explore a new and broad model which bridges the gap between formal education and vocational skills needed for a future world. It’s time to reimagine this educational model in order to create a fairer and broader system for young people which promotes a combination of skills such as critical thinking, collaboration, communication, problem-solving and resilience, along with the requisite knowledge of subject disciplines. Mobile and assistive technologies have brought in a fresh approach to creating learning opportunities and making it possible for learners to access digital content in a more personalised manner than ever before. Such technology can be a powerful partner for assisting changes

With few exceptions, school systems have yet to revise the way they operate in order to reflect current trends and technologies.

27

Features

28

learners. As Sir Ken Robinson has aptly remarked (2011), ‘Our task is to educate their [our students’] whole being so they can face the future. We may not see the future, but they will – and our job is to help them make something of it’. Sir Ken reminds us that education is about more than just learning facts and feeding them back through tests; it is about learning how to think, how to apply difficult concepts, how to create something meaningful or provocative, and how to contribute to the growth of the individual and that of society. References Robinson K (2011) Out of Our Minds: learning to be creative, Chichester: Capstone Publishing Ltd. Accessed via www.fredkemp.com/5365su12/ robinsonchpt123.pdf Seldon A with Abidoye O (2018) The Fourth Education Revolution – Will Artificial Intelligence Liberate or Infantilise Humanity? Buckingham: University of Buckingham Press World Economic Forum (2018) 5 Things to Know about the Future of Jobs, Accessed via www.weforum.org/agenda/2018/09/future-of-jobs-2018things-to-know/

Naaz Kirmani was IB Diploma Coordinator and Head of Senior School at Indus International School, Pune, India before becoming in 2018 a full-time PhD student at the University of Bath. Email: N.Kirmani@bath.ac.uk

Summer |

Winter

in teaching and assessing methods. The time has come to make a shift to a more autonomous model of learning – and Artificial Intelligence promises the transformation. It is envisaged that the Fourth Education Revolution – driven by new technologies such as Artificial Intelligence – will create unique challenges and opportunities for educators and learners in the coming decade. The use of Artificial Intelligence is often misinterpreted as robots taking over classrooms and replacing teachers, but Artificial Intelligence actually involves many assistive tools and platforms to facilitate enhanced learning environments, quality and quick feedback, personalised learning, and support for administrative tasks. It creates and supports self-directed and autonomous learning opportunities for young learners who prefer to acquire knowledge in a more informal and unstructured manner. New and assistive technologies can be used effectively to reassess, redesign and remodel formal education, laying more emphasis on individual skills and dispositions. Some aspects which would require immediate focus include continuing professional development of teachers, and what professional skills or competencies are required to equip teachers to deal with the changing paradigm of teaching and learning in the 21st century. Our attention is also drawn towards some of the key issues related to access and accountability such as data access and protection, current assessment standards, and learning environments in different contexts. While we continue our attempts to envision the uncertain and ambiguous future, let’s look forward to all the positive changes the future holds for educators and young

| 2019

Features

Will my son be a global citizen? How early should I be thinking about this, wonders Hedley Willsea... ‘Ladies and gentlemen, parents and graduating students of the class of 2032, it strikes me that children are the most precious asset of any society. And looking back at my own childhood I see, in fact, that school and hospital visits are the only times in your life when every adult in the building is unconditionally committed to your wellbeing…’ In 2032 my son is due to graduate from high school, so I’ve started drafting my guest-of-honour speech fourteen years early. Well, there’s no time like the present and – as you can see – it still has a long way to go. As does my son, who began school this academic year. On his first day of term I was probably the most nervous adult in the school building, and as I spent the preceding evening frantically ironing name tags into his uniform, I realised that his first day would mark his first formal step into society. Even now, months after the hurdle of the first day, I brood over the prospect of him spending the next fourteen years being measured against a series of social and academic norms. I shouldn’t be losing any sleep over this – as a professional educator I am one of the people laying down the measuring sticks, and I’ve spent almost two decades doing this very same thing to other people’s children. So why does it trouble me now? Ridiculous as it may sound, it has taken my son’s first day of school to force home the realisation that schooling is citizenship; there are rules to follow, even at four years old. And while in a perfect world education is a right, the reality is that it remains a privilege. For example, after visiting my son’s classroom on his first day I searched online for ‘third world classroom’ and the stark visual contrast still resonates. To put it another way, my son is lucky to attend an international school – but he doesn’t know it yet. If all goes well he will eventually study the IB (International Baccalaureate) programme, the aim of which is to ‘develop internationally-minded people who, recognising their common humanity and shared guardianship of the planet, help to create a better and more peaceful world through intercultural understanding and respect’ (IB, 2019a). As a teacher who has spent eighteen years in international schools I have repeatedly questioned what it really means to be ‘internationally-minded’ and this has led me to peruse back issues of this (IS) magazine. In volume 15 issue 2 (2013), the main theme of which was international mindedness, Richard Harwood and Katharine Bailey offered the following definition of international mindedness, which they also called global consciousness: Winter

Summer |

| 2019

‘A person’s capacity to transcend the limits of a worldview informed by a single experience of nationality, creed, culture or philosophy and recognises in the richness of diversity a multiplicity of ways of engaging with the world’. In another article from the same issue, Ian Hill (previously IB deputy director general) defined education for international mindedness as: ‘the study of issues which have application beyond national borders and to which competencies such as critical thinking and collaboration are applied in order to shape attitudes leading to action which will be conducive to intercultural understanding, peaceful co-existence and global sustainable development for the future of the human race.’ According to the IB Learner Profile (IB, 2019b), internationally-minded students are, among another things, caring, principled and open-minded. But as I read all of the above, I cannot help but ask: is it all simply an ideal? What of the ‘real world’ back home in public sector schools? As David Wilkinson in IS magazine volume 19 issue 2 (2017) notes: ‘[T]he question of access to the IB programmes needs to be addressed and acted upon, particularly in the developing world where the cost of the programmes is prohibitively expensive for all except the international schools that serve the local elite and the transient expatriate communities.’ Admittedly the IB is viewed by some in the UK (Middleton, 2010) as for the more privileged independent sector but, according to www.ib-schools.eu, as of 2014 there were 155 schools in the UK offering the IB, only 83 of which were independent. The IB has also been criticised for its frontloading of the IB Learner Profile; non-IB adherents, for example those schools favouring A-levels, may ‘prefer character-building to

It has taken my son’s first day of school to force home the realisation that schooling is citizenship; there are rules to follow, even at four years old. 29

Features

30

References IB (2019a) www.ibo.org/globalassets/digital-tookit/brochures/ corporate-brochure-en.pdf IB (2019b) www.ibo.org/benefits/learner-profile/ Middleton C (2010) IB or Not IB? That is the Question. Accessed via www.telegraph.co.uk/education/secondaryeducation/8125719/IB-ornot-IB-That-is-the-question.html Mitchell Institute (2017) www.mitchellinstitute.org.au/wp-content/ uploads/2017/03/Preparing-young-people-for-the-future-of-work.pdf PISA (2019) www.oecd.org/pisa/ Schleicher A (2017) http://oecdeducationtoday.blogspot.com/2017/12/ educating-our-youth-to-care-about-each.html UN (2019) www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainabledevelopment-goals/

Hedley Willsea is Head of English at the Anglo-American School of Moscow Email: hedley.willsea@aas.ru

Summer |

Winter