Winter in Vermont january/february 2015 A Special Way of Life in the Northeast Kingdom (p. 14) The Farmer Who Made Winter Magical (p. 92) A Town That Loves Covered Bridges and Artists (p. 110) KeepiNg TiMeLeS S Cr AFTS ALive (p. 48) New e N g la N d’ s Ma ga zi N e fo r 80 y ea r s A Classic Winter Trip Steps Back in Time (p. 34) Boston Cream pie: New england’s Dessert (p. 72) Warm Up to This pe rfect Comfort Food (p. 60) Inside the Coldest Town How t H e c itizens of a small m a ine town survive winter in “t H e c ounty” (p. 80) SpeCiAL reporT: Maple Sugar Makers at a Crossroads (p. 100)

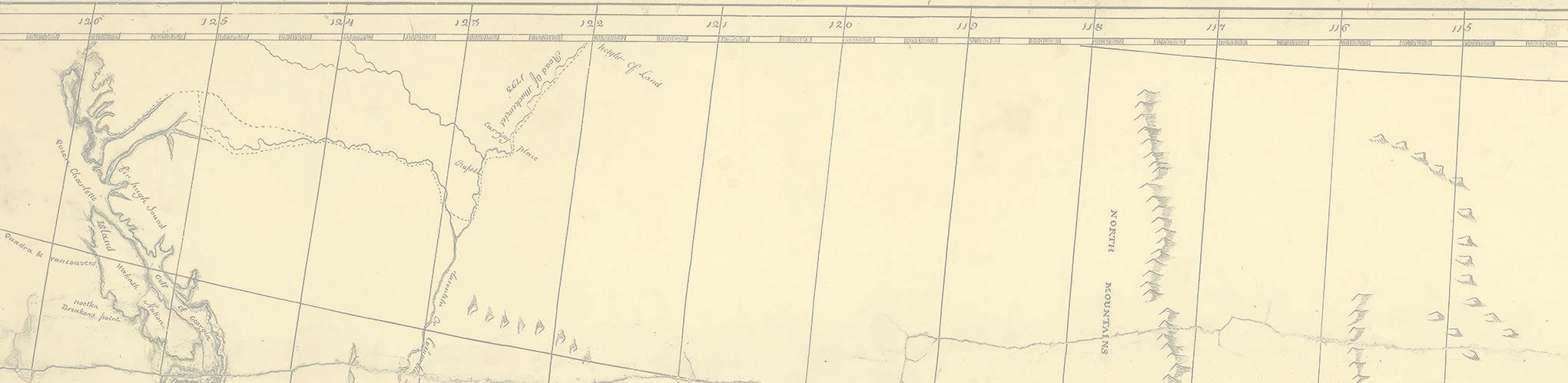

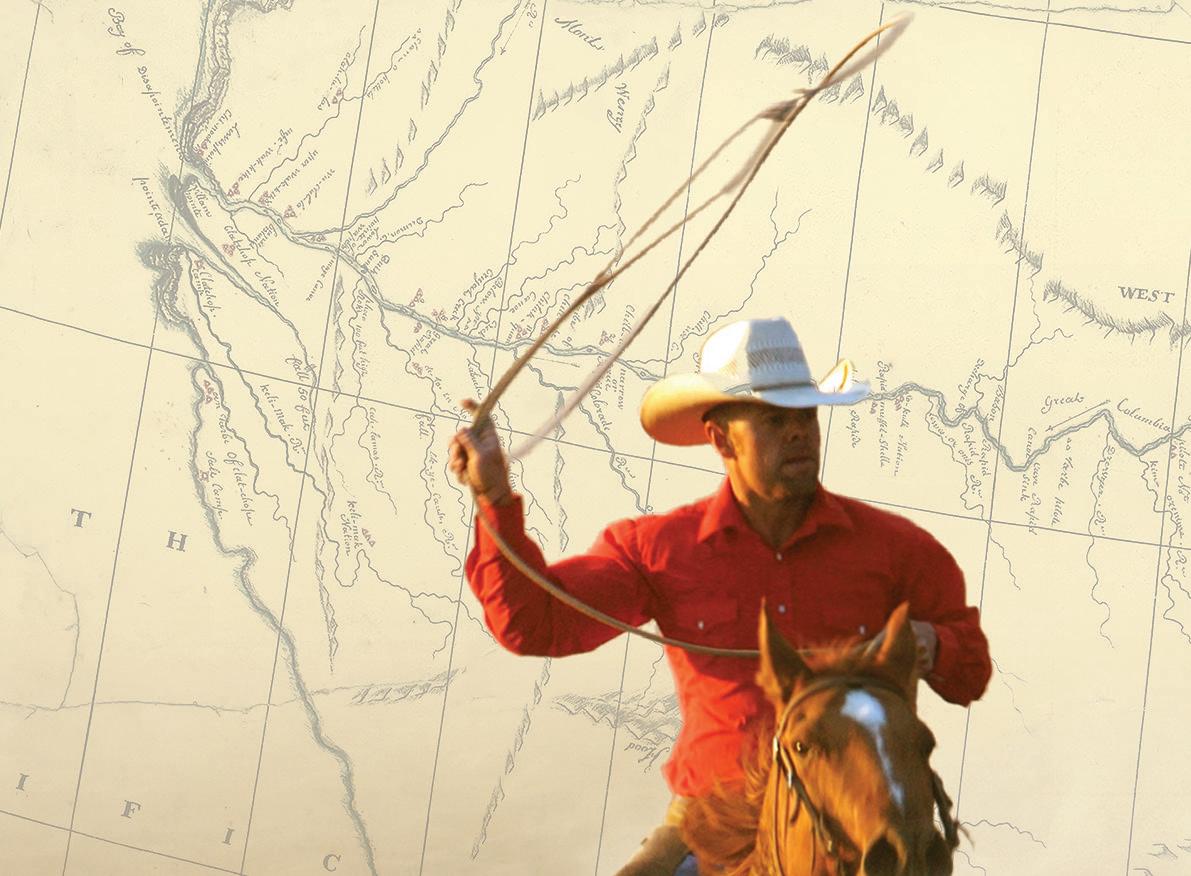

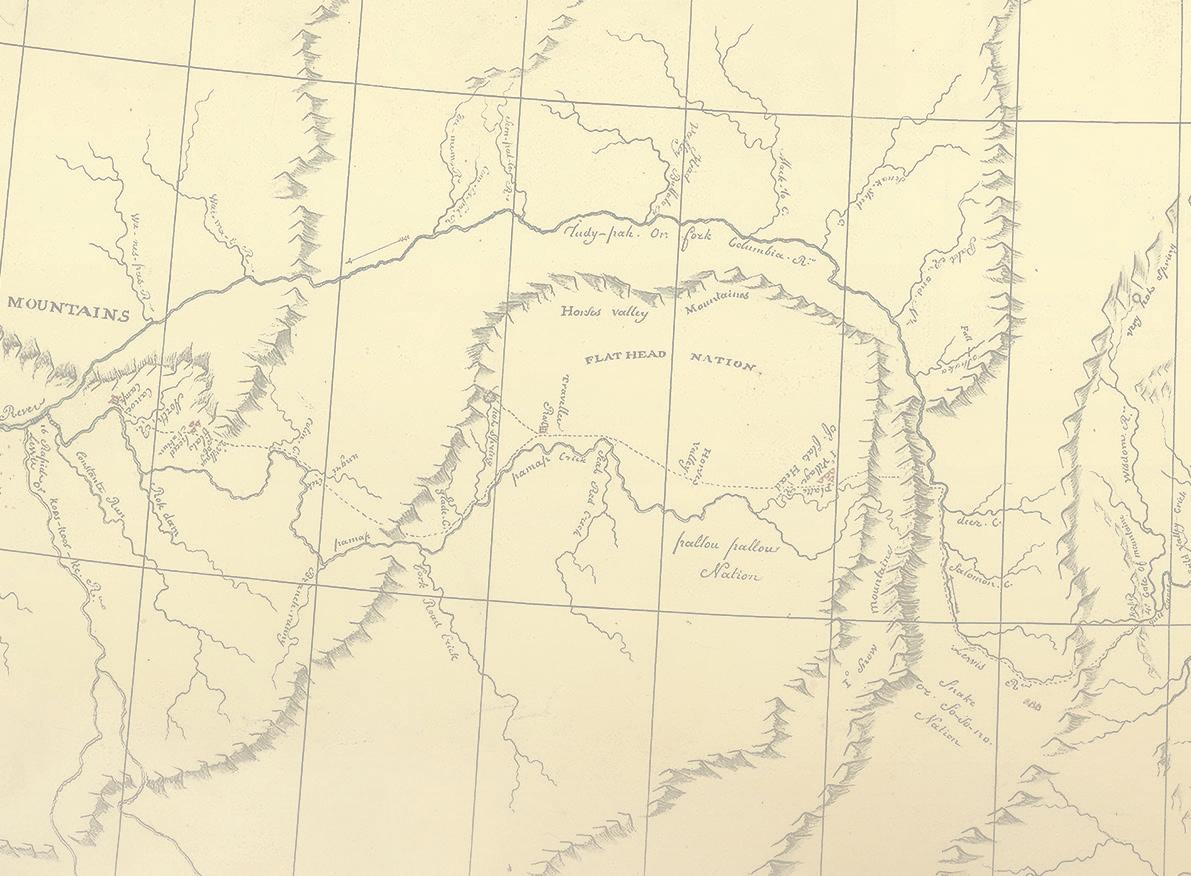

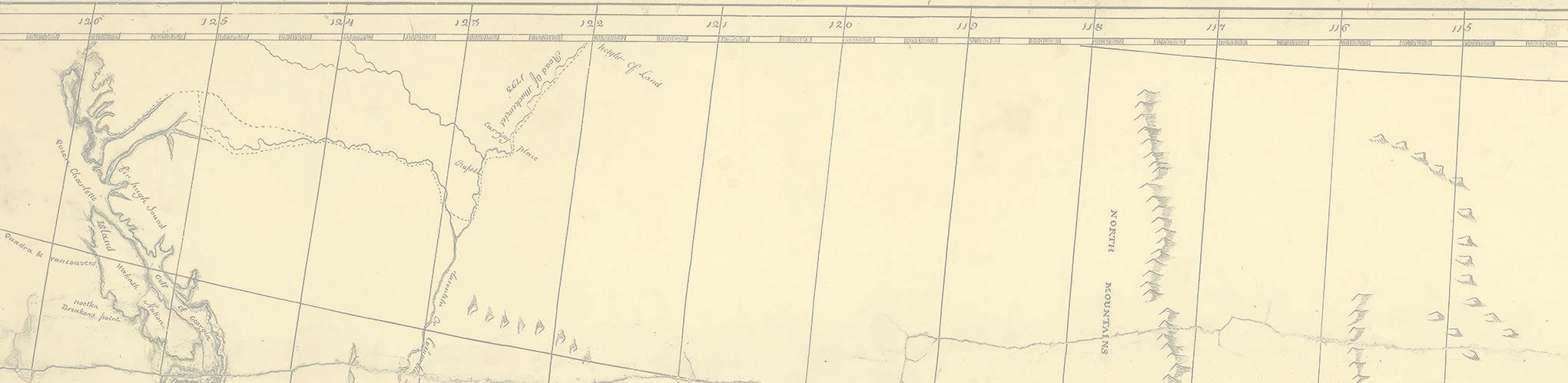

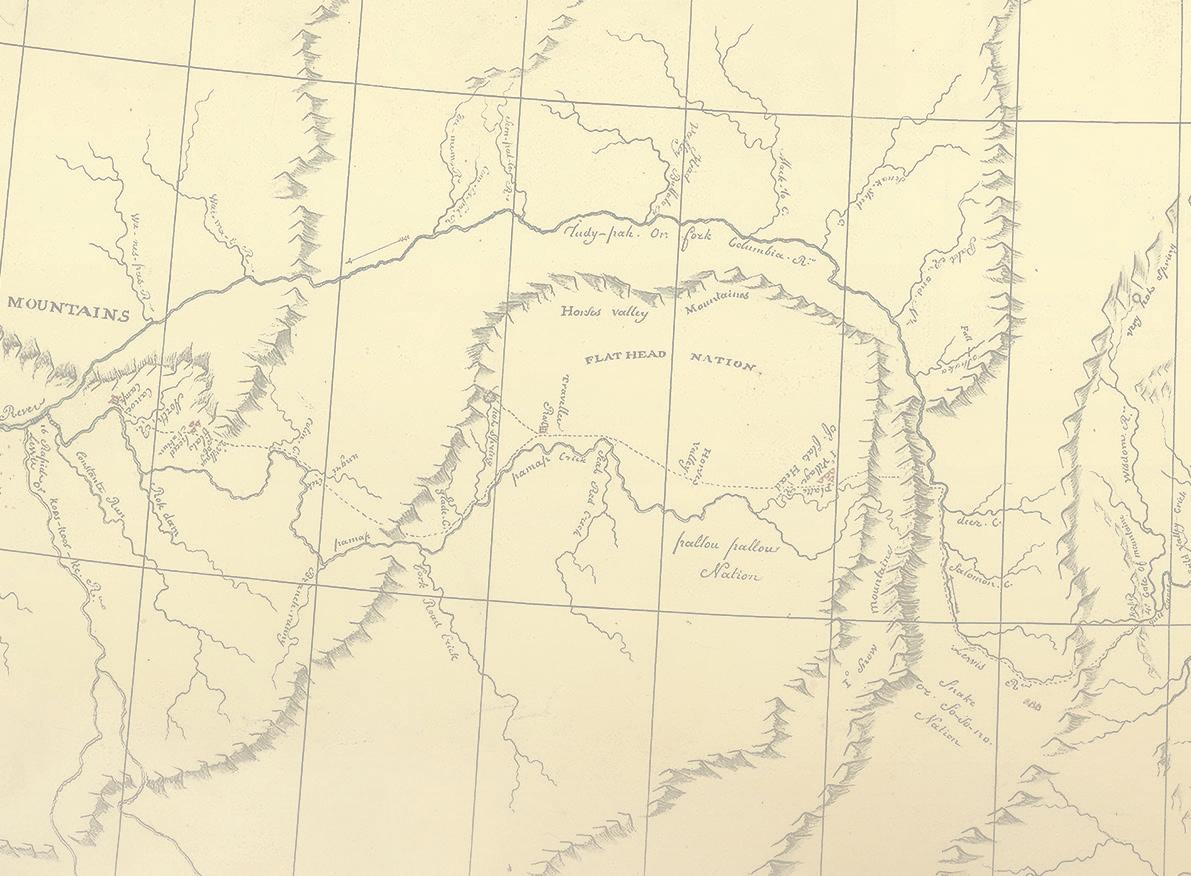

1-800-230-7029 Columbia River ver Snake River Astoria Portland Clarkston Spokane Pendleton Stevenson Multnomah Falls The Dalles Umatilla Richland Fort Clatsop Mt. Hood P a c i fi c O c e a n Washington Oregon Idaho Eight days cruising the spectacular Columbia and Snake Rivers in the Northwest Discover the Western frontier of the cowboys Enjoy the finest cuisine with locally-sourced ingredients Unparalleled personalized service is the hallmark of American Cruise Lines All American destinations, ships, and staff

5 Reasons to Cruise with American Cruise Lines Wild West Cruise the www.americancruiselines.com Small Ship Cruising Done Perfectly™

Top

80

In far-north Aroostook c ounty, Maine, where subzero temperatures often linger for days, local folks live by one winter rule: “If you can’t embrace it, you’re never gonna like it.” by Jaed Coffin

90 ///

Nanny, Rose, and I

A painting showed a young woman what love looked like. And then it came to life. by Naomi

Shulman

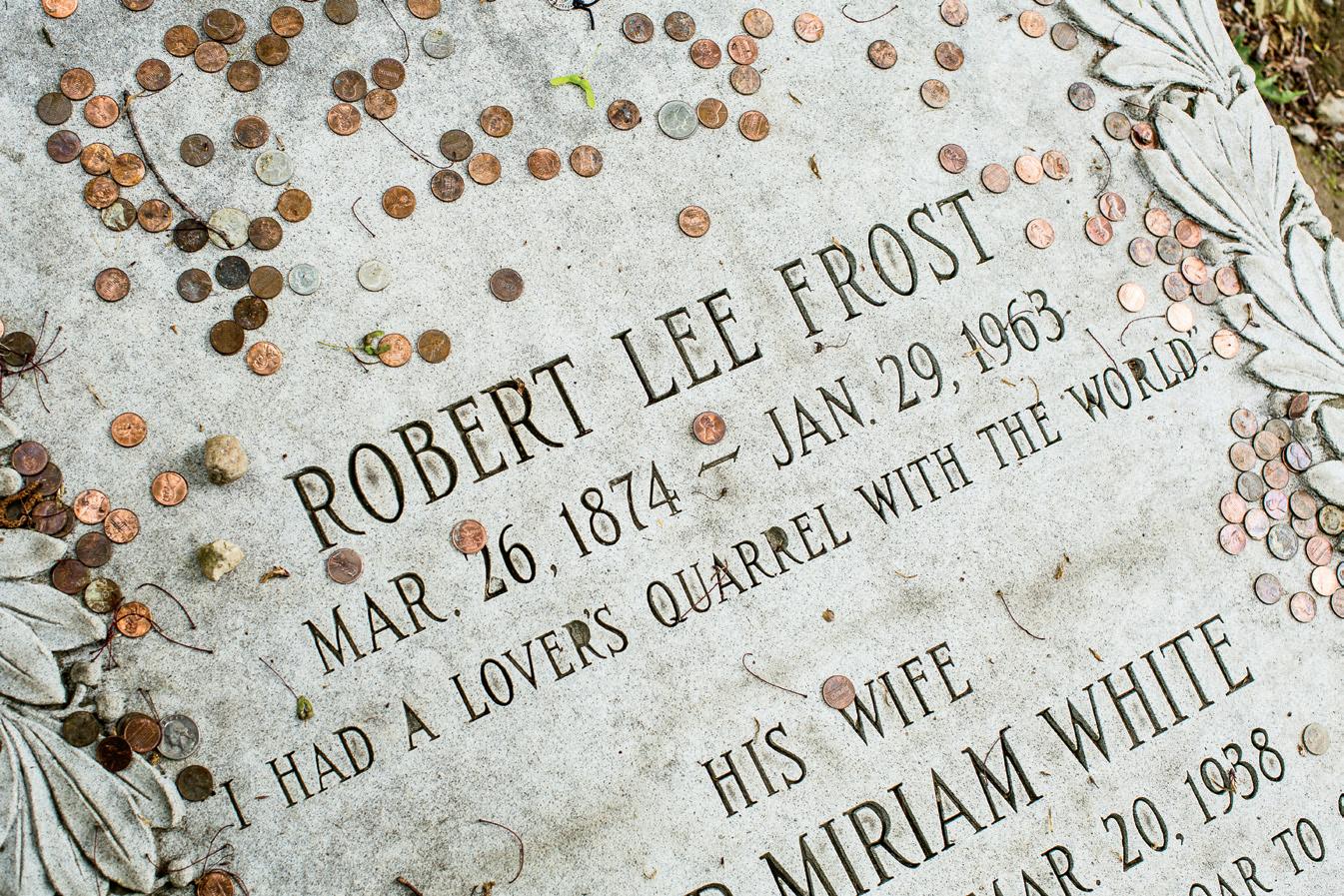

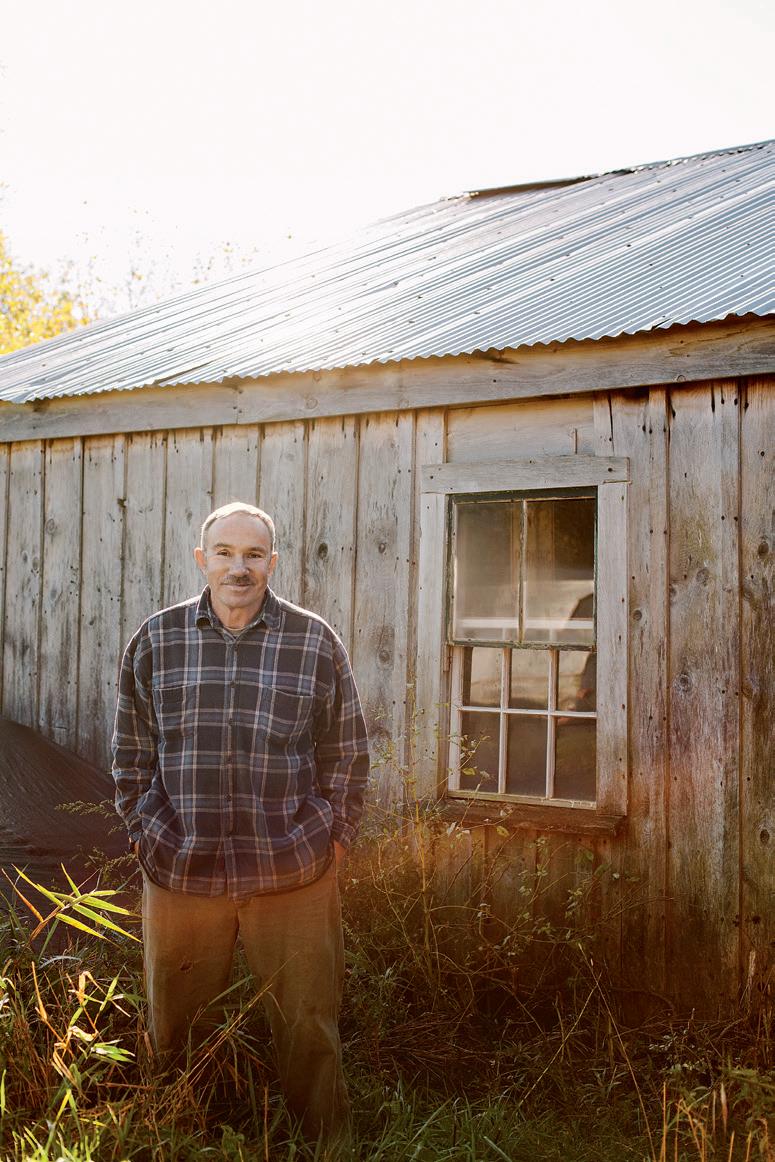

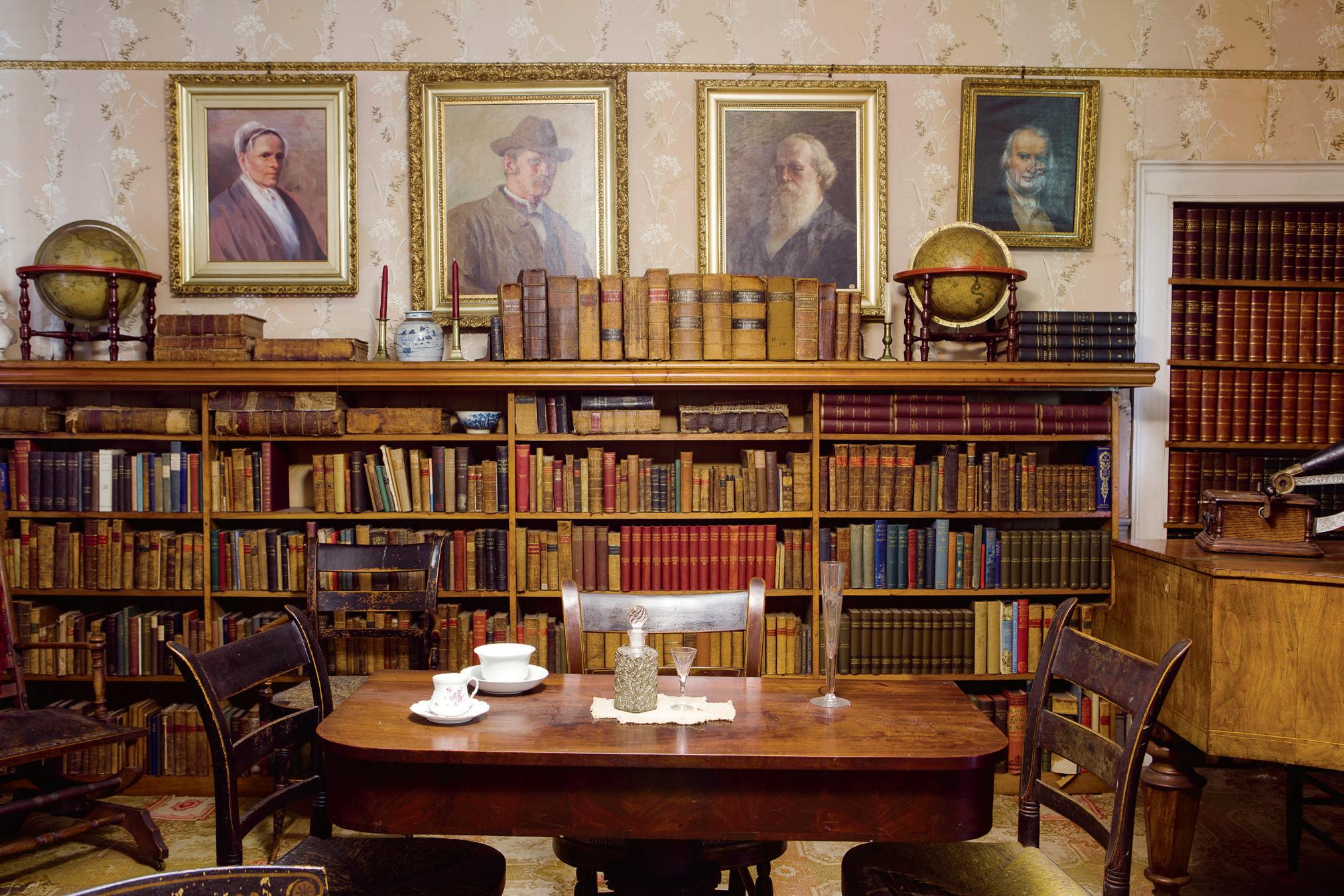

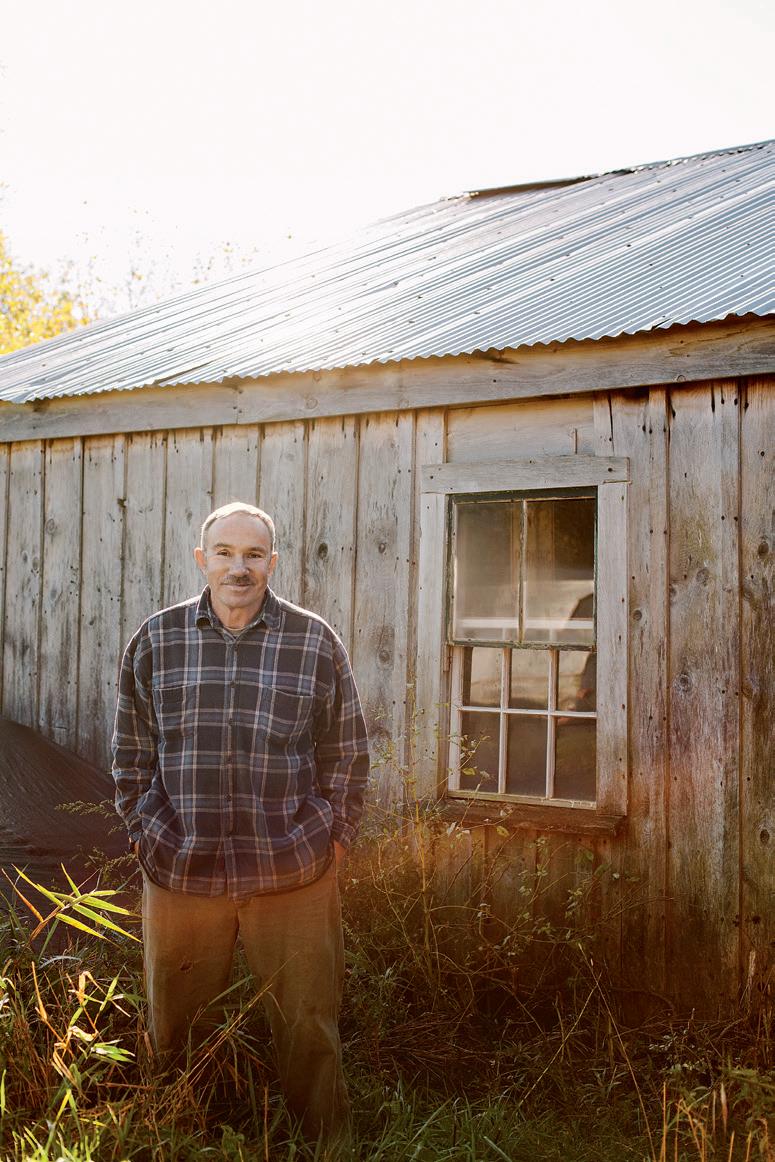

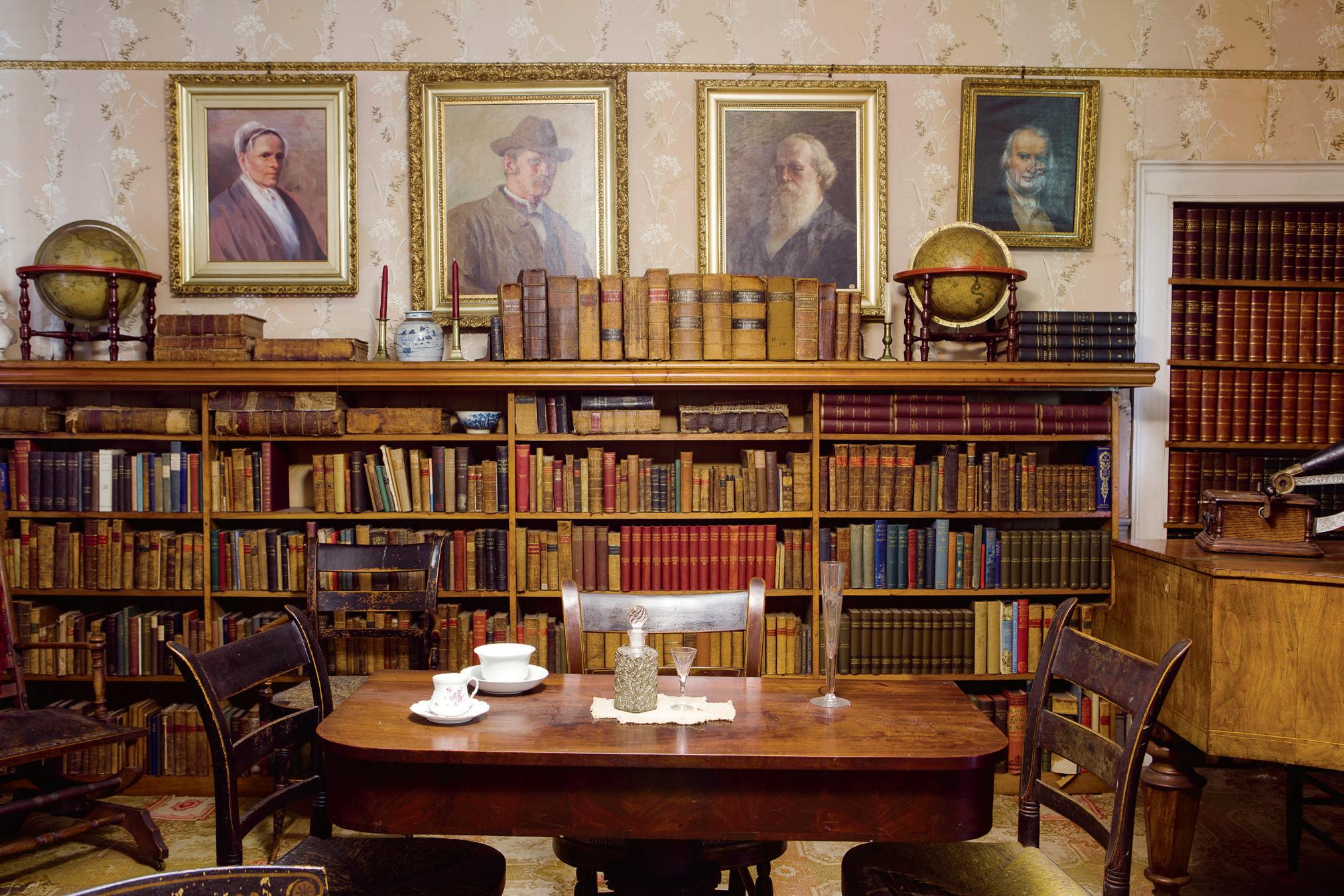

92 /// Return to Silver Fields

From his farm in Ferrisburgh, Vermont, naturalist and historian robinson produced 14 books of stories and essays celebrating New England’s timeless beauty. today, a new generation of readers is rediscovering his graceful, poetic prose, a paean to the mystical power of the landscape around us. by

Leath Tonino

98 /// The Big Question

Ski-resort snowmaker Doug Fichera explains the art of beating Mother Nature to the punch. interviewed by Ian Aldrich

joel laino (barn); corey hendrickson (sugarfields) 2 | yankeemagazine.com yankee (issn 0044-0191). bimonthly, Vol. 79 no. 1. Publication o ffice, dublin, nh 03444-0520. Periodicals postage paid at dublin, nh, and additional offices. copyright 2014 by yankee Publishing incorporated, all rights reserved. Postmaster: send address changes to yankee, P.o box 420235, Palm coast, fl 32142-0235.

Amid the rolling landscape of north-central Vermont, the barn at Mountain View Farm in Morrisville has weathered nearly two centuries of New England winters. photograph by Lori Pedrick January/February 2015 contents

o N th E coVE r

80 /// Culture of the Cold

A storage barn on a potato farm in Presque Isle, Maine, hunkers down under a blanket of fresh snow.

features

Eastport Prince Edward Island Pictou Lunenburg Campobello Island Bar Harbor CanadaUSA Rockland BOSTON Call today 1-888-890-3732 www.pearlseascruises.com PEARL SEAS ®Cruises Harbor Hopping Cruising from Boston makes visiting the most unique towns in Maine and Atlantic Canada easier than ever before. Experience the 11-day adventure in supreme comfort aboard the brand new Pearl Mist. Call for your free cruise guide today. Round-trip from Boston

the guide

travel

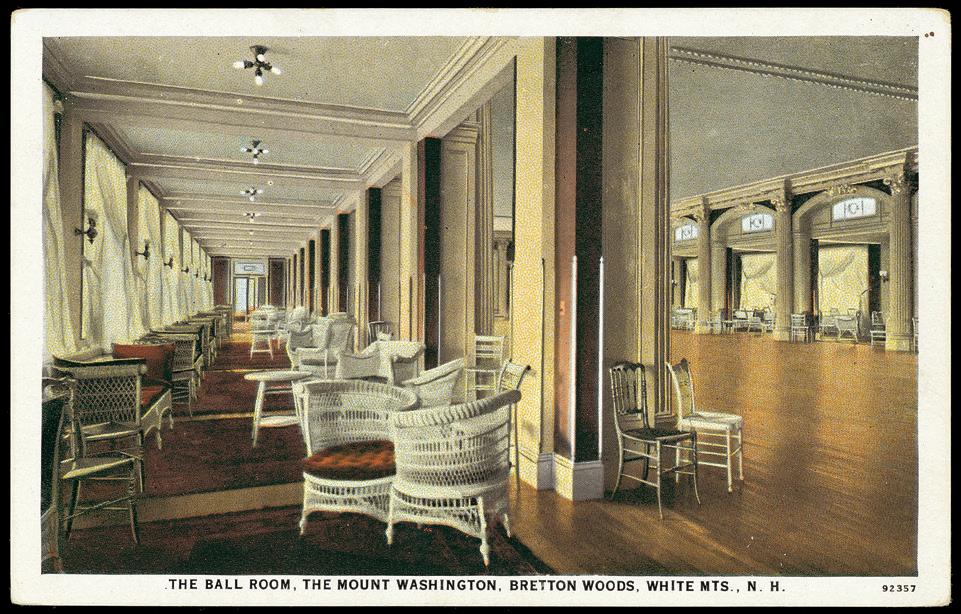

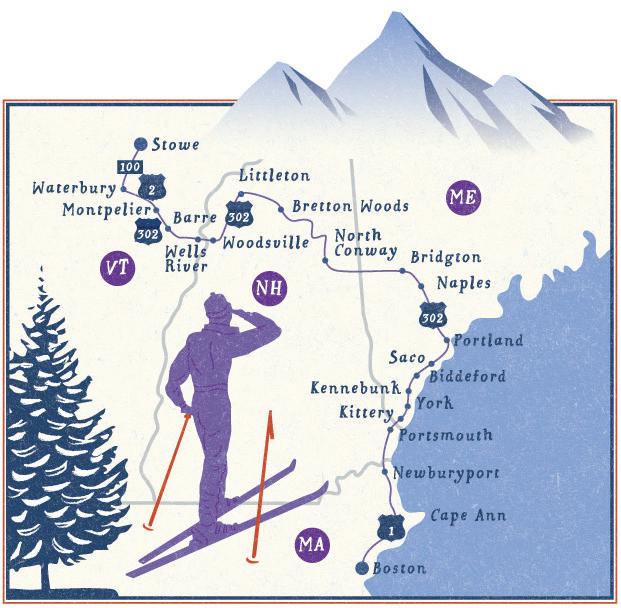

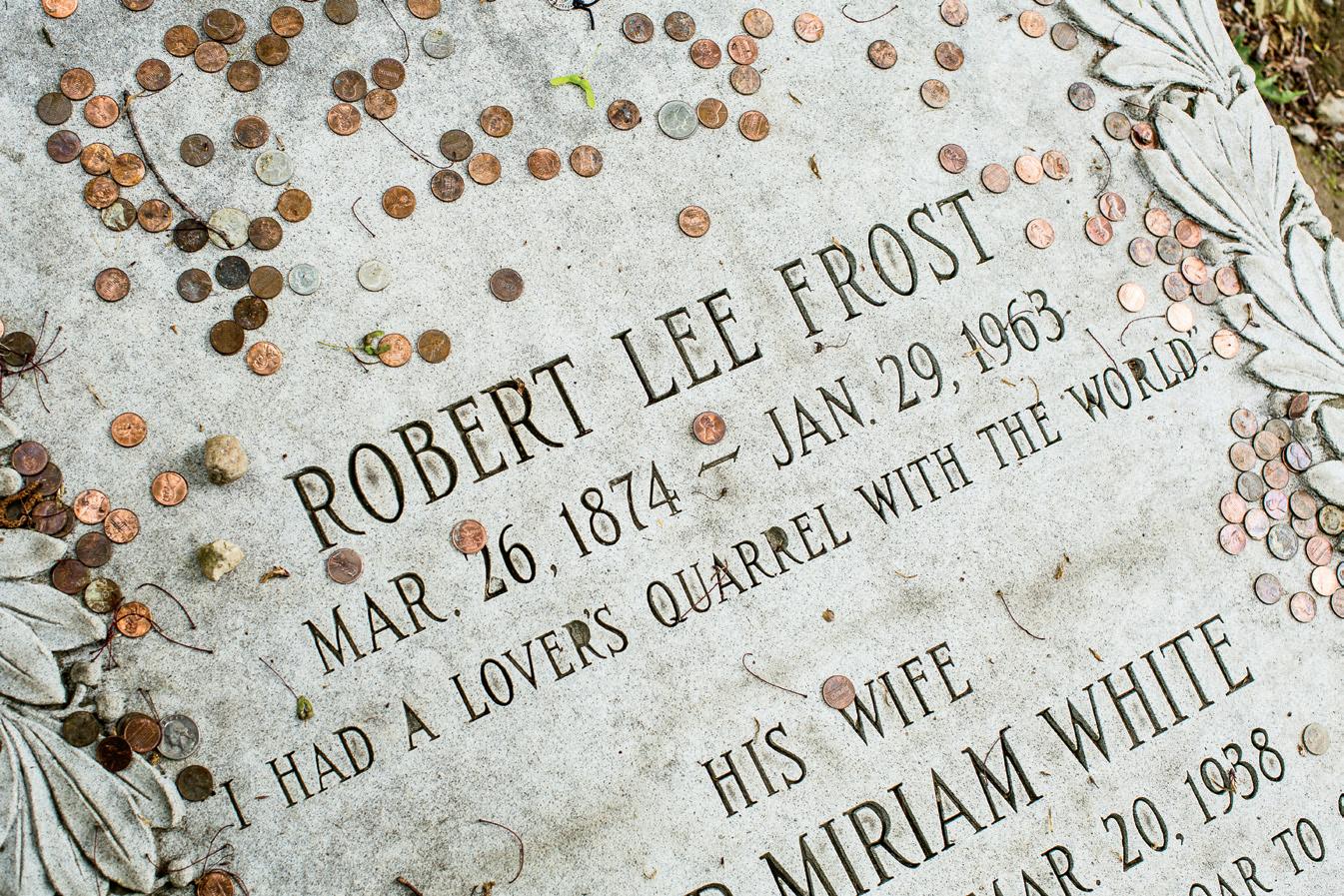

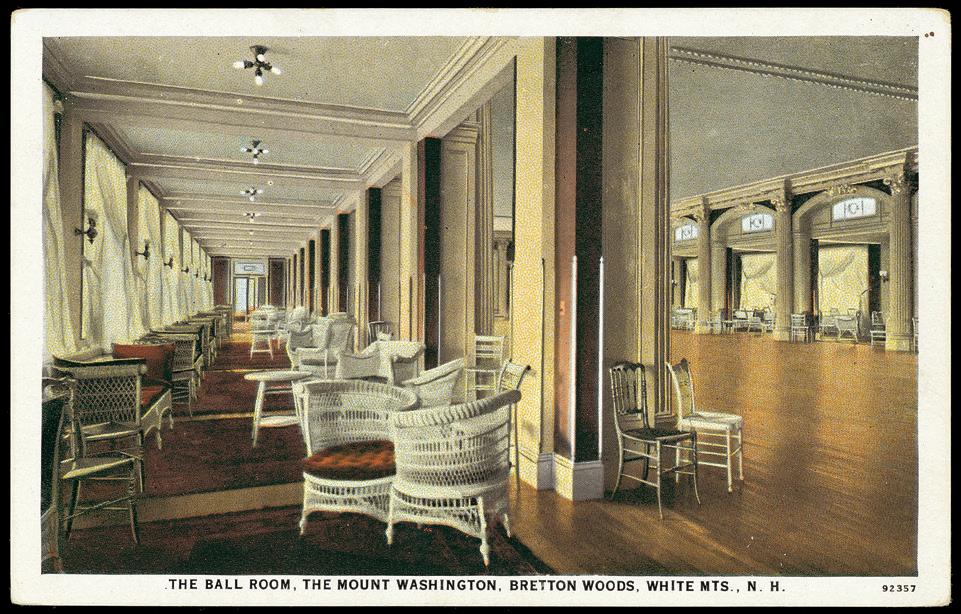

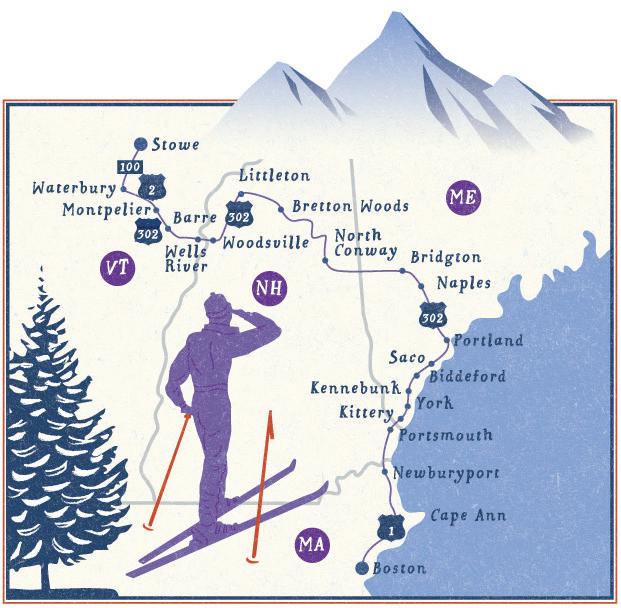

34 /// Finding the 1930s

Across the high country of Vermont and New Hampshire and down the coast from Portland to Boston, our time-travel adventure takes you from ski slopes to cities where classic New England endures. by Bill Scheller

48 /// The New Yankee Craftsmen

From letterpress printing to boatbuilding to stone-wall construction, these determined New Englanders are keeping our region’s traditional arts and trades alive. by Bridget Samburg

food

60 /// Franks & Beans Revisited

Inspired by an heirloom-bean farm in southern Maine, Yankee finds five new ways to celebrate a favorite New England pairing. by Molly Shuster

68 /// Local Flavor

Our food editor visits Olneyville New York System, an old-style Providence diner where the banter is as distinctive as the wieners. by Amy Traverso

70 /// Best Cook in Town

From her kitchen in Arlington, Mass., home chocolatier Denise Eckhardt creates rich, delectable gifts for friends and family. by Edie Clark

72 /// Recipe with a History

Beantown’s venerable Parker House was the birthplace of Boston cream pie, a chocolate-glazed wonder of a cake, thanks to that yummy, gooey filling beloved by generations of New Englanders. by

Aimee Seavey

8

On the Web

9 dear yankee

10 inside yankee

12 mary’s farm

The Art of the Trades by Edie Clark

14

Life in the kingdOm

A Hard Winter: First in a new series, the story of a homesteading family making their way in northern Vermont. by Ben Hewitt

20 first Light

Yankee rescues a cache of precious photos of old-time New England … 5 best easy ski trails … and more …

110 cOuLd yOu

Live here?

Bennington, Vermont by Annie Graves

116 hOuse f Or sa L e

The Yankee Moseyer visits a White Mountains home with plenty of pastureland and spectacular views.

118 events ca L endar

122 p Oetry by d. a .W. 128

from top: mark fleming; jarrod m c cabe;

detour 4 | yankeemagazine.com

adam

home

48 60 34 departments

Rocky

a d r es O urces Yankee Insider .................. 13 Winter in Vermont........... 32 Home & Garden ............. 51 Retiring to the Good Life 76 Marketplace 124 More Contents

up cLOse

Marciano

I Love You Signal Flag Bracelet #X3098 $495 00 Lobsterman’s Wife’s Sea Glass Bracelet #X2593 $285 00 Watermelon Patch rmaline Collection 285 00 - $985 00 Compass Rose Pendant from $75 00 Sailor ’s Valentine Pendant from $125 00 Scallop Shell Pendant #X3116.....$145.00 French Daisy Pendant #X2542 $345 00 Racing Star Pendant #X2996 $135 00 Snow Opal Pendant $195 00 - $495 00

Sea Glass Pendant #EX3093 $235 00 Perfect Wave Pendant #X2820 $835 00 All Hands On Deck Bracelet #EX3201 $365 00 New England Snowflake Bracelet #X2871 $385 00 Valentine’s is coming birthdays and anniversaries too and someone you know can hardly wait. Cross Jewelers 570 Congress St , Portland, ME www.CrossJewelers.com 1-800-433-2988 Always Free Shipping more details about this jewelry on-line

Lighthouse

publisher : Brook Holmberg

editorial & production

e ditor: Mel Allen

art director: Lori Pedrick

managing editor: Eileen T. Terrill

senior lifestyle editor/

f ood, home & g arden: Amy Traverso

senior editor: Ian Aldrich

photo e ditor: Heather Marcus

a ssociate e ditor: Joe Bills

a ssistant e ditor: Aimee Seavey

intern: Taylor Thomas

contributing lifestyle e ditor: Christie Matheson

c ontributing e ditors: Annie Card, Edie Clark, Tim Clark, Jim Collins, Annie Graves, Ben Hewitt, Justin Shatwell, Ken Sheldon, Julia Shipley, Caroline Woodward

c ontributing photographers: Julie Bidwell, Kindra Clineff, Sara Gray, Corey Hendrickson, Matt Kalinowski, Joe Keller, Joel Laino, Jarrod McCabe, Michael Piazza, Heath Robbins, Kristin Teig, Carl Tremblay

production d irectors : David Ziarnowski, Susan Gross

senior production artists : Lucille Rines, Rachel Kipka

diGital

vice president/production & new media : Paul Belliveau Jr.

digital e ditor: Brenda Darroch

designer : Lou Eastman

e-commerce manager : Alan Henning

web design associate : Amy O’Brien

programming : Reinvented Inc.

The Quality Choice for Weather Products. 508.995.2200 www.maximum-inc.com Contact us for a FREE catalog LEON LEVIN R SHIPPING USE CODE: NEW15 L E O N L E V I N . C O 1.866.937.5366 Our New Collection h Arrived free Sign up for e-mails and be the first to see our newest styles. 6 | yankeemagazine.com 1121 Main St., P.O. Box 520, Dublin, NH 03444 603-563-8111, editor@YankeeMagazine.com

Printed in the U.S.A. at Quad Graphics subscription services To change your address, subscribe, give a gift, renew, or pay online: YankeeMagazine.com/subs Yankee Magazine Subscriptions, P.O. Box 422446, Palm Coast, FL 32142-02446. 800-288-4284 new england’s magazine

advertising: print/digital vice president/sales: Judson D. Hale Jr., JDH@yankeepub.com

sales in new england travel, north (NH North, VT, ME, NY): Kelly Moores, KellyM@yankeepub.com

travel, south (NH South, CT, RI, MA): Dean DeLuca, DeanD@yankeepub.com

direct response: Steven Hall, SteveH@yankeepub.com

classified: Bernie Gallagher, 203-263-7171, classified@yankeepub.com

sales outside new england

national: Susan Lyman, 646-221-4169, susan@selmarsolutions.com

c anada: Alex Kinninmont, Françoise Chalifour, Cynthia Jollymore, 416-363-1388

ad coordinator: Janet Grant

For advertising rates and information: 800-736-1100 x149

YankeeMagazine.com/adinfo

marketing

consumer

m anagers: Kate McPherson, Kathleen Rowe associate : Kirsten O’Connell

advertising

director : Joely Fanning associate : Valerie Lithgow

coordinator : Christine Anderson

puBlic relations

B rand mar K eting direc t or : Kate Hathaway Weeks

newsstand

vice president: Sherin Pierce

direct sales mar K eting manager: Stacey Korpi

yankee publishing i nc. established 1935

president: Jamie Trowbridge

editor-in-chief: Judson D. Hale Sr.

vice presidents: Paul Belliveau Jr., Jody Bugbee, Judson D. Hale Jr., Brook Holmberg, Sherin Pierce

chief financial officer: Ken Kraft

corporate staff: Mike Caron, Linda Clukay, Sandra Lepple, Nancy Pfuntner, Bill Price, Christine Tourgee

Board of directors

chairman: Judson D. Hale Sr.

vice chairman: Tom Putnam

directors: Andrew Clurman, H. Hansell Germond, Daniel Hale, Judson D. Hale Jr., Joel Toner, Cor Trowbridge, Jamie Trowbridge

founders

ro BB & B eat rix sagendorph

100% Made in USA Quality Solid Wood Call 1-800-660-6930 New! Solid Cherry Folding TV Tray Tables Elegant and built to last... our sturdy solid Cherry hardwood tables with contemporary contoured styling are easy to fold and store. Backed by our Quality Guarantee. SETS OF 2- 4 WITH STAND: $199.95 - 299.95 Shelving, Desks, Media Stands, Tables, Cabinets, Small Space Solutions, Adirondack Chairs www.manchesterwood.com FREE Shipping always AMERICAN MADE FURNITURE J14I007 Riley MW Y26:MW 11/10/14 6:35 AM Page 1 come see it made! from our hands to yours in BENNINGTON, VERMONT and homestyle store 800.205.8033 | benningtonpotters.com | 324 county street making pottery locally for 66 years | 7 january | february 2015

Social

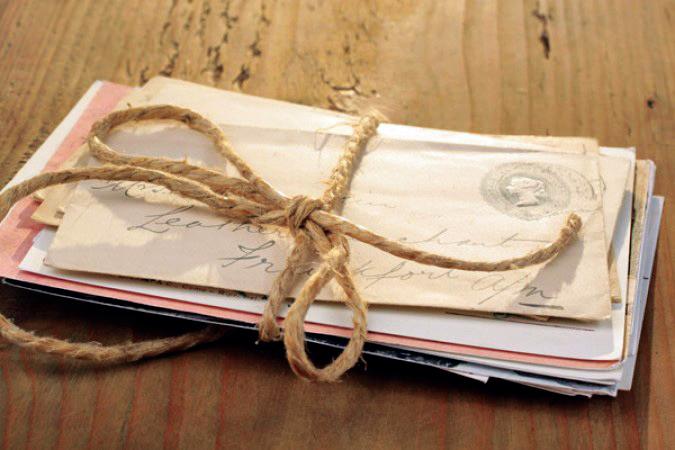

Have you heard the tale of Room 9—the honeymoon suite—at the Waybury Inn in East Middlebury, Vermont? In 1987, newlyweds discovered a secret drawer hidden behind a bit of fretwork on the room’s quirky antique desk. Read the story of how that discovery sparked a tradition that has spanned almost three decades! Go to: YankeeMagazine.com/Spotlight

How well do you know New England? Test your knowledge every Wednesday when we post a new mystery photo at: Facebook.com/YankeeMagazine

Pinterest.com/ YankeeMagazine

Comfort-Food Recipes Church-supper dishes Soups & chowders Casseroles Photographs Winter in Vermont Featured photographers Maine barns Don Shall (inn); D ream S time (letter S ); aimee S eavey (turtle S chop S uey); lori pe D rick (barn) 8 | yankeemagazine.com On the Web | thi S i SS ue Valentine’s Day Gifts Turtle candy Lavender hearts Tissue-paper valentines YankeeMagazine.com/more Content from this issue of yankee will begin appearing online after January 1, 2015

YankeeMagazine

connect to ne W en G lan D D i G itally In

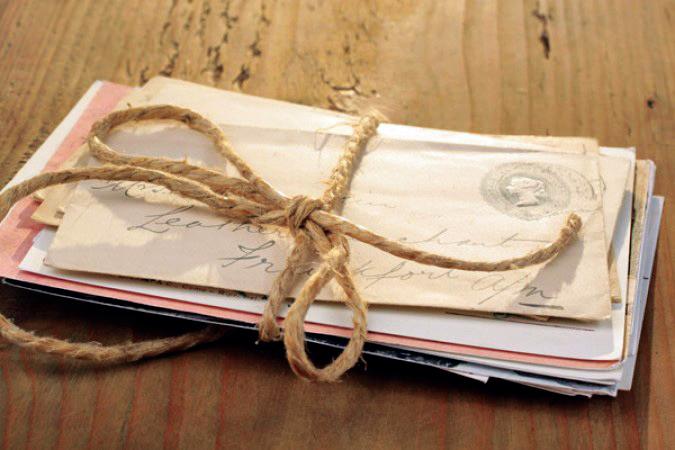

SpotlIght: love letters at the Waybury inn

Sites Comment on classic Yankee articles at: Facebook.com/

View photos of New England at: Instagram.com/ YankeeMagazine Tweet us at: Twitter.com/ YankeeMagazine Pin your favorite recipes at:

the

Bonus Content More “Life in the Kingdom” photos Make the perfect Olneyville wiener Check out our new food podcast, The Chowder Pot

Digital Edition

‘A Real New England Christmas’

I want to extend my gratitude for the way you truly captured a New England Christmas on the cover of the November/December issue.

A couple of years ago I e-mailed you stating my utter disappointment in the November/December issue. Last year was better, but this year was spot-on. I also like the way you included the food issue as its own mini-magazine.

Overall, the issue was surprisingly in keeping with what I had grown to love about Yankee Magazine and, frankly, what had been lacking in recent years. This year you really got it right—well done.

Victoria Sullivan Manchester, New Hampshire

‘Ask the Expert’

I’ve been roasting chickens for at least 50 of my 72 years, most times with success, but not always. Today, we tried the recipe in “Cooking the Perfect Roast Chicken” [November/December, p. 24]. I don’t think we’ll ever roast a chicken any other way again—it was the best! Thanks to you and to Marjorie Druker.

Bob White Caribou, Maine

‘First Light’

Your otherwise superb November/ December issue was marred for me by a single word, the author’s choice of “lumbers” in the story on Stockbridge, Massachusetts (“Home for the [Norman Rock well] Holidays,” p. 14), in the sentence: “A pale turquoise ’55 Studebaker lumbers [emphasis mine] into place.” Believe me, ’55 Studebaker beauties did not “lumber.” They slunk, glided, or slid smoothly into parking spaces.

Peter Kushkowski Portland, Connecticut

‘Most Controversial Animal in New England’

I read with interest Richard Conniff’s article about gray seals [September/ October, p. 106]. My brother, a friend, and I have fished for stripers out of Provincetown for 15 years. Over the last five we’ve been seeing more and more seals. The article stated that no striper was found in seal scat. I don’t know very much about seals, but this past June we were running our boat between Long Point Light and Woods End Light when a large seal surfaced near us and proceeded to wolf down a striper. I can say for sure that one seal ate one striper in early June 2014.

Bill Garrison Maurice River Township, New Jersey

‘The Mohawk Trail Turns 100’

Your September/October issue was one of the best ever, especially since I grew up in Greenfield, Massachusetts, and still live and work nearby. I was, however, disappointed that you left out Waine Morse in your story about the Mohawk Trail [p. 84]. He’s the proprietor of Old Greenfield Village, which sits at the base of the Trail. Over his lifetime, Waine and his lovely wife, Peg, have put together a wonderful “old town” reminiscent of what this area was like in the 1800s. An old-time stagecoach and horse greet visitors; there’s a general store, a blacksmith shop, an ice-cream parlor complete with marble soda fountain, a drygoods store, and so much more. You can feel the Morses’ passion and desire to educate folks about the past.

Cindy Hunter Gill, Massachusetts

Open weekends and holidays from May 15 to October 15. More information at: mtdata.com/~mmwm33/ —Eds.

| 9 january | february 2015

Write us at 1121 Main St., Dublin, NH 03444, or editor@Yankee Magazine.com. Please include where you reside. Letters may be edited for length and clarity. Dear Yankee | letter S from our rea D er S

Follow along with two intrepid photographers who, in the most ambitious photo project in Yankee’s 80-year history, documented Maine’s re-creation of Thoreau’s epic canoe expedition into the state’s northern wilderness. Then get cozy with a special issue devoted to New Englanders’ love of old homes.

Opening the Attic Door

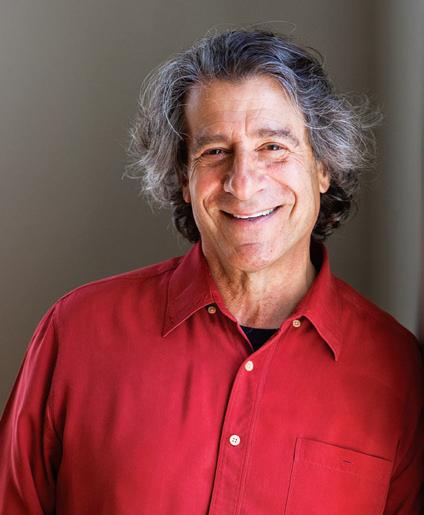

hen I came to Yankee 35 years ago last October, the magazine was so ingrained in the life of the region that it was sometimes hard to know whether New England was shaping Yankee or the magazine was somehow defining how people saw New England. Probably a bit of both.

Yankee exists because of New England, but I also think it’s fair to say that many people’s vision of New England has come from our pages—because even though New England’s landscapes and lifestyles have changed over the decades, Yankee ’s heart has stayed faithful. Capture the voices and the distinctive character of six states and bind it between covers. Let readers know the people who work here and play here. Let readers see how the four seasons shape not only the landscape but how we live.

When Robb Sagendorph began Yankee in September 1935, he created a blend of country wisdom, stories of people ignored by glossy publications, and photos that invited readers inside and into a way of life. Now, 80 years later, we kick things off with “Finding the 1930s” (p. 34), an ode to the time when Robb would have traveled New England finding stories for his fledging magazine, and likely stayed in the same places that our writer, Bill Scheller, did last winter. “Life in the Kingdom” (p. 14) portrays the enduring Yankee character: self-sufficient, hardworking, independent, tied to the land. “The Right Home” (p. 20) introduces a priceless collection of early-20thcentury photographs that had drifted deep into oblivion in Yankee ’s offices—until rescued, so that future generations can now share the bond between past and present. “Return to Silver Fields” (p. 92) does what Robb always wanted to do: find people long forgotten who should be remembered, especially when they have timeless things to pass along. “The New Yankee Craftsmen” (p. 48) shows that even as technology propels us forward, there remain people who still practice ancient arts and trades, whose work possesses rare beauty and stands the test of time.

As 2015 unfolds, check in at YankeeMagazine.com and follow our Facebook page for a variety of bonus content that comes along with our 80th year. All year, I’ll be opening an attic door where hidden treasures await. When I find them I’ll want to share them. I’m reading through hundreds of stories, and in time my editors and I will choose our 10 all-time most unforgettable Yankee stories. I want all of you to come along when that door opens.

This issue begins a year-long series we call “Life in the Kingdom” (p. 14), about Ben Hewitt’s daily life with his family on their 40-acre homestead in northern Vermont; photos by his wife, Penny, complement the text. The turning of the seasons on the Hewitt land means ever-changing work and play—and, as readers will discover, the two blend seamlessly in the family’s life.

Ben’s 2014 book, Home Grown , tells how the couple’s two sons are learning about the world—not inside a classroom, but in the woods, among animals and their own unfettered imaginations.

Mel Allen, Editor editor@YankeeMagazine.com

Ben’s new book, The Nourishing Homestead, comes out this winter.

JARROD M c CABE (ALLEN); JESSE BURKE (HEWITT); LITTLE OUTDOOR GIANTS (THOREAU) 10 | YANKEEMAGAZINE.COM

PEEK INSIDE OUR NEXT ISSUE

SNEAK

Inside Yankee | BY MEL ALLEN HOW THE STORY HAPPENED

Mel Allen

ORIGINAL VIDEOS: JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2015 U.S./CANADA $5.99 YANKEEMAGAZINE.COM Yankee on Your Tablet THIS ISSUE’S TABLET EXTRAS INCLUDE ORIGINAL VIDEOS, BONUS PHOTOS & AUDIO TRACKS Subscribers Get Free Access Subscribers get FREE access to Yankee’s tablet edition. For more information, or to subscribe, visit: YankeeMagazine.com/tablet Now on Ipad, Kindle Fire, GooglePlay and Nook New England for a slideshow of additional images from Alton Blackington. Yankee editors Amy Traverso and Aimee Seavey serve up a heap of delicious advice in our all-new monthly food podcast, The Chowder Pot

The Art of the Trades

ast New Year’s Eve, I bought a new car, something I do every 10 years or so. Two days later, I had to drive three hours north, to the White Mountains, to teach a workshop. In a blizzard. Baptism by fire. The car charged through it like a filly heading for green pastures. I passed accidents along the way, but I arrived without incident and felt lucky to be only a couple of hours late. The hotel was a grand historic structure from the Victorian age, restored to keep the feeling of the old while offering the luxury of the new. The car was whisked from me on arrival and put into a valet parking lot. In the morning, I took in the breathtaking view of the Presidential Range, which seemed to advance outward in every direction. Two or three days later, temperatures were forecast to plummet as low as 30 to 40 below zero. Maintenance men were on their knees in the hallways, applying blowtorches to frozen pipes. I called a friend at home to ask her to please check on my house. Her report was what I feared: The pipes were frozen. I called Glenn, my plumber, who has always been there for me at times like this. This time was no exception. He went right over. Yes, he told me by cell phone, the pipes were frozen and cracked and needed to be replaced. He set right to the task, and by the end of the day, everything was in order.

People know that this isn’t what usually happens when temperatures fall below zero. Finding a plumber then who might be available is like looking for a ripe, sun-warmed tomato in the dead of winter. Over the years, I’ve had two plumbers. The first one was Dan, whose wife was a friend of mine. They’d met in college, both of them art majors. While in college, Dan worked as a plumber’s assistant to help pay his way through school. When he got out of school, he kept on plumbing. The pay was good. He never returned to the art, but his work became his art, pipes aligned and plumb and tidily labeled. People noticed. After a while, he was in such demand that I couldn’t get him, so I switched to Glenn, who once worked for Dan and whose work was just as lovely. But I wonder what it’s like for an artist to labor in obscurity like that, the result of his work hidden behind a wall. Eventually, Dan’s wife, who had a career as a graphic artist, joined Dan in his business and now goes out on calls with him, leaving her art behind the way Dan did. Apparently, art is a dangerous profession.

A friend of mine, who once taught English and drama to high-school students, tells me that he used to counsel his students to be able to find a job in the trades, even despite high aspirations. “Something to fall back on,” he says.

Is there a lesson here? Arriving home from the White Mountains in my eager new car, I managed to back into my porch, a sickening crunch in the dark of a moonless night. In the morning, I called Michael, another artist in the trades who’s there to help when I need him. In time, the porch, too, was fixed: an erasure of the fact of my late-night miscalculation.

At the time, it all felt catastrophic, a lightning bolt from God, but in retrospect, everything has been restored, as if nothing had ever happened. I don’t know whether there’s a lesson here, but certainly a reason for me to be grateful.

Edie Clark’s latest book is What There Was Not to Tell: A Story of Love and War

Order your copy, as well as Edie’s other works, at: YankeeMagazine.com/store or edieclark.com

12 | yankeemagazine.com illustration

clare owen/ 2

by

art

Mary’s Farm | edie clark

When pipes freeze and other calamities occur, a hero is someone with a wrench and knowhow.

Garden Adventures

RHODE ISLAND FLOWER SHOW

FEBRUARY 19–22, 2015

THURS. - SAT. 10 AM–8 PM • SUN. 10AM–6PM

The 2015 RI Flower Show promises to be the best ever! Our theme Garden Adventures delivers plenty of excitement and fun for the whole family! Speakers and demonstrations will provide valuable, cutting edge information. Visit flowershow.com for more information or call Karen Brol, Ticketing Coordinator, 401-253-0246

Enter sweepstakes at YankeeMagazine.com/Giveaway LOOK AT WHAT PAST WINNERS HAVE WON! Gerlinde S., won a Contemporary Tray Table set of 2 from Manchester Wood Deborah K., won a 2-night stay at Meadowmere Resort Facebook.com/YankeeMagazine Instagram.com/YankeeMagazine Pinterest.com/YankeeMagazine

INSIDER {Events, Giveaways, Special Offers & Promotions}

RI CONVENTION CENTER

PROVIDENCE, R I

•

FlowerShow.com Feb 19 - 22, 2015 THUR - SAT ~ 10 AM - 8 PM SUN ~ 10 AM - 6 PM RI CONVENTION CENTER ONE SABIN ST. PROVIDENCE Presented By

RENÉE FLEMING WED., FEBRUARY 11 7PM • HISTORIC THEATER HISTORIC THEATER/BOX OFFICE: 28 Chestnut St., Portsmouth, NH LOFT: 131 Congress St., Portsmouth, NH TheMusicHall.org (603) 436-2400

A Hard Winter

A homesteading family creates a world unto itself in northern Vermont. First in a year-long series.

iven that this is our first column together, I suppose it makes sense to begin with a description of our place, its features both natural and manmade, the folds and hollows of field and woodland, and the hard, etched lines of house and barn and outbuildings. Probably, too, I should introduce myself and my family, whose faces (especially those of my children, so often the subject of my wife Penny’s photography) will undoubtedly be a commonplace sight in these pages.

I am Ben Hewitt, and I live with Penny and our two sons, Finlay, 12, and Rye, 9, on a 40-acre hill farm in Cabot, Vermont, just a few miles from the traditional boundary of the Northeast Kingdom. You’ve probably heard of Cabot; it’s where Cabot Creamery cheese comes from. Fin and Rye are unquestionably products of their environment. They know how to milk a cow. They know how to butcher a hog and wield a splitting maul. They can identify at least six different edible wild mushrooms in our woods. They can shoot a gun and drive a tractor and erect a watertight shelter of twigs and leaves. They know many of the things most children their age once knew in this country.

14 | yankeemagazine.com Life in the Kingdom | by ben hewitt

photographs by penny hewitt

CABOT

My family and I don’t farm for our income, at least not in the common understanding of income as being composed solely of money. That’s not to say we don’t sell some of our farm products, because we do. But the majority of what we produce stays in our home, or finds its way to the homes of our immediate neighbors and family, often via informal barter. Meanwhile, the bulk of our moneyed income is earned via my writing, both in these pages and elsewhere.

I once heard a writer describe his craft as a poor living but a great life, and I can find little to disagree with in that sentiment. Come to think of it, I once heard a farmer say the same thing. He was right, too.

On our farm we currently have six cows, two of which are in milk, the rest of which will become beef at some later date. We have a small flock of sheep, usually a half-dozen or so; we raise them for meat and for wool. Each year, we fatten a few hogs on waste milk from our cows and from the dairy farm located a quarter-mile up the road. There’s a flock of laying hens, of course, and the boys husband a small herd of goats. Every summer, we raise a batch of broiler chickens for the freezer.

We have 100 mature blueberry bushes, which means there’s a day every summer that one or both of the boys come running down the field, clutching the season’s first ripe speci-

mens in a grubby fist. It also means that we eat blueberries all winter long: over pancakes, in yogurt, straight out of the bags we freeze them in. There’s a small orchard, which is really more like two small orchards, though we’re slowly filling the space between them with more trees. Every spring, we hang 60 or so sap buckets, enough that we don’t buy much maple syrup, or even sugar, for that matter. There are gardens, three of them totaling perhaps a quarter-acre, and from these we harvest enough vegetables to satisfy our annual produce needs.

opposite : When you heat only with wood, it helps if splitting and stacking count as a family outing. From left, Penny, Rye (age 9), Ben, and Fin (age 12) Hewitt. this page , bottom : The Hewitt farmhouse amid snowcovered ever greens. above : A greenhouse projects from the front of the house; at left is a multipurpose shed and workshop; at right in this shot are solar panels for generating electricity.

My family and I live in a house we started to build in the late ’90s, although, truthfully, it’s still not quite finished. This is because we built the house around us, like a crustacean growing its shell, sleeping and working in a construction zone for years. That’s not a bad way to make a home, but it does become tiresome, and as it becomes tiresome, “done enough” thinking begins to take root. The unfinished trim along the stairwell is done enough. My office, with its windows still in primer, is done enough. That temporary heat shield behind the stove? You guessed it: done enough.

Still, it’s a proud house, simple, sturdy, and tight. It’s a humble house, too, which might seem a contradiction, but isn’t. It’s proud of its humility. It knows what it is, and it doesn’t pretend to be anything else. House or human, I think that’s not a bad way to be.

| 15 january | february 2015

This is a hard winter. I know this because Rye has just returned from morning chores. “It’s warm out,” he says, shrugging out of his sweater and hanging it on a peg by the woodstove. It’s 7:25 a.m.

I glance at the thermometer: three degrees above zero. “Warm out,” says my son. Three degrees above zero is warm only when it’s the first morning in nearly two weeks when the temperature can be measured in positive numbers. Three degrees above zero is warm only if the day before it never got above three degrees below zero and you had to break the ice on the cows’ water four times between morning and evening chores. Three degrees above zero is warm only if the mind and body have come to understand that cold is subjective: What is cold can feel warm. Presumably, what is warm can also feel cold, though it’s hard to imagine that now.

And I know this is a hard winter because we’re burning through our firewood at an alarming rate. “Half your wood and half your hay by Ground hog Day” is what the oldtimers say, speaking from a reservoir of experience that eclipses my own by decades, if not generations. As of yesterday, a bit more than two weeks until this traditional midwinter measure, the empty portion of our woodshed comprises at least half the available space, and no matter which angle I choose, or how determinedly I squint my eyes, the emptiness remains, the wood it once contained having literally gone up in smoke.

We put up about six cords of firewood each year. This generally leaves us with a half cord or maybe a bit more to carry over into the following autumn. I don’t mind passing that remaining row of wood during the muggy days of early June, when the unfilled portion of the woodshed serves as a quiet admonishment. Every year we plan to have all the coming winter’s firewood under cover by the end of May, and every year, we don’t.

16 | yankeemagazine.com

Life in the Kingdom | by

clockwise from top left : Rye collects eggs from the family’s dozen or so hens; the Hewitts raise a few hogs each year for meat; Rye and Fin take a break from clearing the roof.

ben hewitt

We cling stubbornly to a self-imposed deadline that we know months in advance will be broken—a deadline I can already see breaking by the end of February, when we still don’t have enough logs hauled from our woodlot—because relinquishing it feels like a slippery slope; we might fall even further behind. And in a way, I’ve come to understand that if we have all our firewood under cover by the fourth of July, we’ve actually hit our deadline. This is damaged logic, I concede, but it’s damaged logic that keeps us warm year after year.

I used to think we burned a lot of wood, until I told our neighbor, Melvin. He didn’t merely chuckle; he flatout laughed. “Six cords?” he said. “Try 15.” Melvin is a dairy farmer in his mid-sixties; his farm abuts the southern and western boundaries of our land. He still puts up most of those 15 cords himself, one tractor-bucket load at a time, typically gathered only a handful of hours before he’s to feed it to his furnace. Melvin has deadlines for putting up firewood, too; they just happen to be a bit more pressing than ours. I often see him on his way to the woods, high in the cab of his big New Holland. He always waves and smiles; he doesn’t seem to mind the work, nor does the lack of a shed full of dry wood seem to cause him consternation.

I try to remember this now, with our wood disappearing into the hungry maw of our big Elm stove one precious wedge at a time. Three degrees above zero may seem warm to my son, but it’s not warm enough that we

w w w r i v e r w o o d s r c o r g | 8 0 0 6 8 8 9 6 6 3 LIVE

Choose a life that gives you more time to enjoy what you love, new friends who share your interests and peace of mind for your future.

| 17 january | february 2015

RiverWoods in Exeter, New Hampshire. A retirement community that is more than you’d expect.

Sunday is our day to work on firewood as a family. Some families go to church; we cut and split wood. Sometimes I think there’s not much difference between the two.

can stop stoking the fire that is all that stands between us and frozen water lines. We have no backup heat; it’s not as if we can just decide to stop burning wood when the shed is empty, and I suspect it may not be long before Melvin and I are passing each other on our tractors on our way to our respective woodlots. I resolve to wave and smile at least as broadly as I know he will.

With the exception of two winters in my early twenties when I inhabited rental properties, I’ve been warmed by wood for the entirety of my 42 years. When you become accustomed to the particular heat of wood—dry, contained, and forceful in a way that somehow seems to embody the labor required—you develop partial immunity to other heating fuels. I can never be truly warm in a house heated by electricity or oil; the heat they produce is like a ghost heat to me, and no matter the temperature, I find myself always looking for the source, the place where I can stand, rotating front to back like a rotisserie chicken.

Sunday is our day to work on firewood as a family. Some families go to church; we cut and split wood. Sometimes I think there’s not much difference between the two. Both are expressions of faith in forces beyond our control. At the landing where I’ve deposited the lengths of beech, maple, birch, cherry, and ash, Penny and I use chainsaws to buck the wood into stovelength rounds. We split by hand; this is everyone’s favorite chore, because the satisfaction of watching a piece of wood cleave beneath a wedge of steel propelled by your own muscles is one of those distinctly rural charms, like snitching the season’s first almost-ripe tomato straight off the vine before the boys get to it. Such charms don’t wane with the passage of time.

When we split, Fin and Rye hoard the rounds of ash, which seem almost to fall into perfect wedges at the mere threat of being struck. At their ages, it’s fair enough for the boys to get the

18 | YANKEEMAGAZINE.COM

Life in the Kingdom |

BY BEN HEWITT

CLOCKWISE FROM TOP LEFT : Fin (left) and Rye head out across a snowy field; Rye splits a log for firewood; “Apple” is in the lead as Rye brings some of the herd in. The Hewitts keep six cows, most of them Jersey/Milking Shorthorn crosses.

easy-splitting wood, though it occurs to me that at some point in the nottoo-distant future, this arrangement will reverse itself. “Here, Papa,” they’ll say, “you take the ash.” I’ll pretend to be

etition, thousands upon thousands of swings, until it’s unquestioned. Split enough wood and you don’t need to think or hope you’ll hit the target; you needn’t even plan to hit it. You will hit

Just as we could buy so many of the things we produce on this land, we could buy our firewood. It wouldn’t be prohibitively expensive, and I suspect that were I to calculate the moneyed returns on our efforts to fill the woodshed, I’d come to view minimum wage as something to aspire to. I’d come to see that putting up our own firewood is illogical.

offended, and perhaps I will be, just a little. But mostly, I’ll be grateful.

For now, though, I’m vigorous enough to revel in the labor necessary to reduce even the most recalcitrant logs to stove-size pieces. I love the way swinging a maul quickens the pulse, limbers the muscles, and raises beads of sweat across our brows before falling to melt divots into the snow. And I love the unheralded skill splitting wood requires, a skill that’s acquired only through seasons of countless rep-

it, and you know you will hit it, and this knowledge is quietly pleasing in a way that says something about what it means to have mastered a task so essential to your well-being.

For all its abundance and convenience, the modern world offers precious few opportunities to cultivate these skills, and I sometimes wonder if that’s what truly draws Penny and me to this life. It’s an attraction that’s not easily explained in terms of logic and reason.

But when I’m in the woods taking a break, and the tractor and saw are shut off, and it’s so quiet I can hear a pile of snow slough off a spruce bough and whump to the ground 30 feet away, I’m reminded that one of the greatest measures of wealth is the freedom to decide for oneself what makes sense. And what makes sense, in this particular moment, is that I get off my butt and haul a pile of logs back to the house so we can keep on splitting.

Ben Hewitt’s fourth book, The Nourishing Homestead: One Back-to-the-Land Family’s Plan for Cultivating Soil, Skills, and Spirit, will be published this winter by Chelsea Green.

New England’s and Maine’s premier 55 Plus Active Lifestyle Community 635-acre Oasis Conservation & Nature Convenient Location Near College Town Neighborly Ambience & Activities Low-maintenance Living Custom Homes A Masterpiece of Maine Living HighlandGreenLifestyle.com 7 Evergreen Circle, Topsham, Maine | 866-854-1200 28 States and Counting... The Coles: all the way from Los Alamitos, California to Highland Green

Split enough wood and you don’t need to think or hope you’ll hit the target; you needn’t even plan to hit it. You will hit it, and you know you will hit it.

First LIGHT

Chewing the fat around the woodstove in the Cilley General Store, Plymouth Notch, Vermont, February 1926. President Calvin Coolidge’s father, John, owned the building from the late 1860s until 1917. Son Calvin was born in 1872 in the house attached to the back of the store, and as president used the store’s second-floor hall as his office during summer breaks from Washington.

Chewing the fat around the woodstove in the Cilley General Store, Plymouth Notch, Vermont, February 1926. President Calvin Coolidge’s father, John, owned the building from the late 1860s until 1917. Son Calvin was born in 1872 in the house attached to the back of the store, and as president used the store’s second-floor hall as his office during summer breaks from Washington.

The Right Home

A priceless collection of 2,000 glass-plate negatives that captured New England life from the 1890s through the 1930s had been forgotten in a box in the cellar of Yankee’s offices. Then they were rescued.

hey’ll often start, ‘I have a funny question. You may not be interested, but …’” As the senior curator of Historic New England’s archive, Lorna Condon fields countless phone calls from people concerned about the future of their most personal treasures. Family Bibles, paisley shawls, albums of vacation photos—Condon has welcomed them all into her collection. Although the reasons for the donations vary—a death in the family, or the selling of a home, perhaps—she says it usually boils down to one common sentiment: “I really want to find the right home for it.”

The photos you see on these pages come from Yankee ’s own donation to Historic New England, the Boston-based preservation society. Like Condon’s other petitioners, we just wanted to find a better place for them than their previous home, which until the 1980s was a box, forgotten and molding in the cellar of Yankee ’s offices in Dublin, New Hampshire.

The collection—around 2,000 glass-plate negatives dating from the 1890s through the 1930s—is a relic from this magazine’s early days. In the 1960s the editors bought up vintage negatives to use as stock photography. In the collection you’ll find idyllic landscapes and portraits alongside documentary news photos, many taken by early New England photojournalist Alton Blackington, for whom the collection is named. Most of these photos were packaged into nostalgic coffeetable books with titles like Yankees Remember: Stories and Pictures of Good Old Days in New England as Remembered by Old-Time Yankees. But by the 1970s, they had fallen out of use and were bundled away into a dark corner, lost for a decade until stumbled upon by our then-archivist, Lorna Trowbridge, daughter of Yankee ’s founder, Robb Sagendorph.

| 21 inside first light: only in n ew england : Yankee Zodiac … pp. 24-25 knowledge & w isdom : Facts, stats & advice … pp. 26-27 The bes T 5 : Green-circle ski trails … p. 28 local T reasure : Yiddish Book Center … pp. 30-31

b y jus T in sha T well Alton h . Bl A

A phs from Y A nkee p u B lishing c ollection/ h istoric n ew e ngl A nd

ckington photogr

She catalogued and cared for the negatives, but in terms of publishing, they received little more use than they had in the cellar. (By the 1980s, Yankee wasn’t printing that many photos of Calvin Coolidge.) Like most things kept for sentimental reasons, they were, to us, effectively useless, but we couldn’t just get rid of them. Some things don’t go in the trash.

Condon notes that although Historic New England doesn’t take everything it’s offered, she always ends up thanking callers: not for the donations, but for being conscientious about finding a proper home for their collections, for stopping to consider that someone else might be interested in their stories and objects, and for not just throwing them away.

You see, this is the first step in building an archive. There are climatecontrolled rooms in every museum and library across the country filled with things that someone, somewhere,

h aying in t homaston, Maine, 1928. t his image and the one opposite at bottom were part of b lackington’s collection but might have been shot by another photographer.

Who Was alton Blackington?

a lton Blackington (1893–1963) was a yankee after our own heart. Remembered by his son as “a barefoot boy from Rockland, m aine, who never forgot his roots,” he built his career—and a fair amount of fame—by chronicling and celebrating the stories of n ew englanders. He began his career as a photojournalist for the Boston Herald, rising to prominence with his on-the-ground reporting of the Hurricane of ’38. By that time, he’d also branched out into radio, in 1933, with his long-running program Yankee Yarns, on which he regaled his audience with the lore and history of n ew e ngland, accompanied by as much folksy charm as you’d expect. He later produced a book with the same title and its sequel, More Yankee Yarns . Blackington’s close friendship with Yankee founder and editor Robb Sagendorph facilitated the donation of his photos and papers to the magazine after his death. a t the time, Sagendorph wrote that the acquisition represented “one of the finest collections of n ew e nglandiana in existence.” —J.S.

sometime, decided not to chuck into a dumpster. Preservation starts at home. Every one of us is a frontline archivist, each time we hold something back from a tag sale, explaining to our spouse, “No, no, I think I want to keep this,” or, on moving day, when we stand in decisively over a box of mementos, still sealed from the last move, but, with a sigh, finally set our creaking back to hoisting it onto the truck, bound for some new attic to haunt.

i n n ew h ampshire’s White Mountains, a lton b lackington films the sunrise from the summit of Mount Washington.

There are reasons why some things survive the countless purges of our lives, and it is exactly those reasons that Lorna Condon is most interested in hearing. She recalls one seemingly bizarre donation, a bundle of 250 greeting cards. With it came a memoir from the woman who’d kept them, explaining what each had meant to her when she and her family received it. And just like that, a story elevated into history something that many would consider rubbish. “If we can put the story with the objects, that’s really what’s important to us,” Condon explains. “It’s the story of why these things are saved.”

But for some artifacts, that’s just the beginning. They continue to tell us tales long after those who donated

First Light | the blackington collection 22 | yankeemagazine.com

them are gone. That can be especially true of photographs. Though the pictures remain the same, their meanings have a tendency to shift over time. “We bring our own sensibilities, our own perceptions, to images,” Condon says. “It’s an ongoing revelation when you work with a photographic archive.”

She produces two photos of the same building as an example. It’s an impressive, cupola-topped house in Dorchester, Massachusetts. In the first image, shot in the 1870s, the foreground is filled with people in country finery, genteelly enjoying a game of lawn tennis. In the second, shot in the 1960s, the lawn is replaced by a bleak street. Steel fire escapes rudely bolted to the home’s façade indicate that it has been divided into a boardinghouse. “When you put those two photographs together, the story becomes so much

more complex,” Condon says. “What happened to that neighborhood in the 90 years between the first photograph and the second? There’s a tremendous amount of history and story there.”

And what story do Yankee ’s photos tell us? They remain an immersive window into New England life in the early 20th century, but perhaps their most interesting tale is the one they tell about the changing tastes of the magazine’s editors. Those coffee-table books left out many of the images from

the 1920s and ’30s, presumably because they weren’t “old-time” enough. Why show a Model T when you can show a horse and buggy? But those same images neglected by our 1960s progenitors are the very ones that make 21stcentury editors swoon, which I suppose is evidence that not even nostalgia is immune to the changing hand of progress. Our sentimental connections to the past keep marching along beside us: our constant companions and baggage. That is, of course, until they aren’t. Until the day comes when we just can’t justify lifting that box onto yet another moving truck, or when we really do need that extra space in the cellar. Until that day when we decide to unburden ourselves of the responsibility of being the only one who remembers, and we place a call to someone like Lorna Condon to see whether it’s time for our personal history to become part of everyone’s history. It may seem like a funny question, and she may not be interested. But …

Historic New England holds a vast archive of images from across the region, many of which are accessible online at: historic newengland.org/collections-archivesexhibitions/collections-access/highlights/ photography. See more archival shots from HNE’s Yankee Publishing Collection at: YankeeMagazine.com/historic-photos

| 23 january | february 2015

Former Yankee associate editor Justin Shatwell recently returned to New England after working as a reporter for the Virgin Islands Source.

right : Calvin and Grace Coolidge with their chow, Blackberry, at Vermont’s Plymouth Cheese factory (founded by John Coolidge), 1931. Although the Coolidges made Northampton, Mass., their primary residence, they returned often to their home state. Blackington’s collection included more than 250 images of the former president and first lady. below : Boston’s North End, c. 1925; Engine 6 of the city’s firetruck fleet is in the foreground.

Yankee Zodiac

Babylonian astronomers created the first zodiac, a division of the year into 12 sections, each represented by an animal or other symbol. The Greeks used the zodiac to develop a system of astrology. The Chinese zodiac can be used to determine a person’s destiny based on his or her birth date. Not to be outdone—and feeling it’s high time we New Englanders had a stake in this game—we proudly present the Yankee Zodiac. (Or semi-proudly.)

By ken sheldon

JANUARY: moose

You are reserved and somewhat aloof, but people still seek you out. When you do let others get close to you, they may find you a little scary. You never throw anything away, and you have enough return-address labels in your desk to last you for the next 27 years. Avoid Black Flies.

febRUARY: beANs

You have a hearty, wholesome nature that appeals to many people, but not all. You enjoy being with people and are often seen at potlucks and church suppers. You make friends easily, but often find later that they’re gone with the wind.

mARch: mApLe sYRUp

Your sweet personality makes you well-liked, but you do have a dark side, which some people actually prefer. Others find your taste too expensive. You are compatible with most other types, especially Beans. You will find success in culinary settings, but may want to branch out into new areas.

ApRiL: bLAck fLY

You are strong-willed and quick-witted, with a biting sense of humor that people don’t always appreciate. In fact, almost never. You have a vast collection of resealable plastic containers and lids, none of which match. Avoid Loons.

mAY: Loo N

Devoted to family, you are otherwise standoffish and complain loudly when upset, giving you an undeserved reputation for being crazy. Thrifty by nature, you bring home unused ketchup packets from restaurants. Choose partners carefully; you are compatible only with other Loons, and sometimes not even them.

24 | yankeemagazine.com First Light | only in n ew e ngland JANUARY eNUJ YAm RpA i L mARch febRUARY

decembeR: cRANbeRRY

People find you cranky and somewhat bitter, but they do appreciate your straightforward honesty, even if they tend to string you along. You don’t mix well with other types, except for Turkeys. The last weather person you trusted was Don Kent.

NovembeR: tURkeY

Unlike many Yankees, you are gregarious by nature and prefer to flock with friends rather than go it alone. You’re also a bit flighty and can lose your head if you’re not careful. Your ancestors met the Mayflower when it sailed in. Avoid Stoves.

octobeR: stove

Your natural warmth draws people to you, though you can sometimes get overheated. Even then, you have a glow about you. You have a reputation for being frugal and have been known to get three cups of tea out of a single teabag. You are very compatible with Beans.

septembeR: cANdLepiN

You like to think you stand alone, but when the ball gets rolling you have a tendency to fall in with the crowd. A true homebody, you’re rarely seen outside of New England. You hate waste and always bring home those little bottles of shampoo and conditioner from hotels.

AUgUst: LighthoUse

You are known for your steadfastness, your reliability, and your extensive collection of Moxie memorabilia. Although you prefer a solitary existence, you are nevertheless quite popular and very photogenic. You don’t necessarily like meeting new people, and your relationships are often rocky.

JULY: cLAm

A true New Englander, people think of you as quiet and taciturn, although your real personality sometimes bubbles up, giving you away. In your opinion, the novel Ethan Frome was a laugh riot. Avoid Turkeys.

Rebmetpes

JUNe: LobsteR

Yours is a shy, somewhat prickly personality, and you have a tendency to snap at people. It’s sometimes hard to get you out of your shell, but when you’re on a roll you can be delightful. You are most compatible with Clams. Lucky numbers: 2 and 4. Don’t ask why. Some people think you’re paranoid, but you simply avoid social situations for fear you might get trapped and couldn’t get out.

| 25 january | february 2015

illustration by mark brewer

decembeR NovembeR octobeR

tsUgUA YLUJ

USEFUL STUFF FROM 80 YEARS OF YANKEE

What Readers Asked Yankee in 1938

Q: What would an ingenious Yankee do if he were caught out without an auto defroster?

Scene: cold, sleety night.

—Robert Carson, Iowa City, Iowa

A: An ingenious Yankee would pour some salt into a handkerchief and wind it around the windshield wiper. Or he would possibly cut an onion in half and rub one of the halves over the windshield to form a frost-resisting film. And if he were very ingenious, he would not only do that but would also take home the remaining half (or even both halves!) as a donation to the weekly boiled dinner.

Q: When should Christmas greens be taken down?

—Avis Adams, St. Johnsbury, Vermont

A: January 7, in the morning, or the fairies decree bad luck.

Q: How may winter squashes be kept all winter without rotting?

—Mrs. T. T. Rolph, Littleton, New Hampshire

A: Store them in the old brick oven of a used chimney. They’ll keep firm and fresh well into the next summer.

—excerpted from “I Want to Know,” a column of questions from readers with responses from Yankee contributors, January 1938

WE WERE RIGHT ALL ALONG

“Under the microscope, I found that snowflakes were miracles of beauty; and it seemed a shame that this beauty should not be seen and appreciated by others. Every crystal was a masterpiece of design and no one design was ever repeated. When a snowflake melted, that design was forever lost. Just that much beauty was gone, without leaving any record behind.”

—Wilson “Snowflake” Bentley (1865–1931), farmer and photographer. Growing up in Jericho, Vermont, young Bentley had many winters to observe snow. His fascination with the budding field of macro photography led him to capture his first snow-crystal image in 1885. His legacy became a collection of more than 5,000 images of snowflakes, showing that no two were alike.

NEW

ENGLAND

By the Numbers

100-200

postcards sent by retired Maine newsman Edgar Comee (1917–2005) to media outlets decrying use of the term “nor’easter”: “a pretentious … practice of landlubbers”

1837

earliest use of “nor’easter”

TWO

nor’easters dubbed “Storm of the Century”: Eastern Canadian Blizzard of 1971 and Blizzard of March 1993

48 inches of snow fallen on Bennington, Vermont, in the Blizzard of 1888, “America’s Greatest Snow Disaster,” prompting Boston to develop the first subway in the U.S.

44,000,000

volume in acre-feet of water dropped by the Blizzard of 1993, which if converted strictly to rain would have drenched 44 million acres in 1 foot of water

3,500

cars buried on Boston’s Route 128 during the Blizzard of 1978; total of 10,000 cars buried on Northeast roadways

500 width of average nor’easter in miles

TWELVE months of the year when nor’easters can occur

ZERO

nor’easters counted by the National Weather Service on a monthly, annual, decade, and century basis (NWS counts only hurricanes)

COURTESY OF JERICHO HISTORICAL SOCIETY, JERICHO, VERMONT (BENTLEY); BOSTON GLOBE /GETTY IMAGES (BLIZZARD OF 1978). OPPOSITE: HEAD SHOT COURTESY OF CRESCENT DRAGONWAGON; EISING STUDIO/STOCKFOOD (BEANS) 26 | YANKEEMAGAZINE.COM First LIGHT | KNOWLEDGE & WISDOM

NOR’EASTERS

COMPILED BY JULIA SHIPLEY

How to Cook Boston Baked Beans

Baked-Beans Basics

Simmer your beans in water for an hour; then drain them and layer them on top of a chopped onion. Next, Dragonwagon says, cover your beans with “some form of fat, sweet, and savory.”

(For the traditionalist route, she recommends a melted mixture of brown sugar and molasses with pork or bacon tossed in.) Next, let the dish bake six to seven hours, “long enough for everything to permeate each other,” she says. Dragonwagon takes the lid off for the last hour of baking, “for crustiness on top.”

Buying Your Beans

Standard baking beans are Maine yellow eye or navy beans. Dragonwagon stresses the importance of finding recent-crop beans, because old beans won’t get tender or creamy. She frequents farmers’ markets, where the growers know how old their crops are. If you’re shopping at the grocery store, check the bag for a harvest date.

The Bean Pot

“There’s no logical reason why beans in a bean pot should be any better,” Dragonwagon says. But bean-pot loyalists believe they are, and you can usually find one at a good secondhand store; any pot with a tight lid, though, will work. Dragonwagon recommends ceramic, because it heats slowly. She also has no qualms about using a slow cooker.

Soaking the Beans

so that they cook evenly. Dragonwagon soaks her beans overnight or does what’s called a “quick soak,” in which she brings the water to a hard boil. Here’s an added benefit: Soaking reduces cooking time, and as Dragonwagon points out, that’s crucial for the economical Yankee.

Pork or Veggies?

Traditional baked beans use salt pork, but for vegetarians (including Dragonwagon), that’s not an option. When replacing any ingredient, Dragonwagon asks, “What role does that ingredient play?” Salt pork lends smokiness and saltiness and is a source of fat. For vegetarians, a good alternative is butter or vegetable oil. To get that smoky flavor, Dragonwagon adds chipotle pepper or smoked paprika.

The Complete Meal

Dragonwagon serves baked beans with cabbage salad or slaw. Instead of carrots and mayo, she suggests diced apples and a slightly sweet vinaigrette with a touch of honey or maple syrup. The full traditionalist route, of course, calls for steamed Boston brown bread, which is surprisingly easy to make. (Find it at: YankeeMagazine.com/ recipe/boston-brownbread-steamed ) Together, the beans and bread can be made in advance, for “the perfect cold-weather dish.”

rescent Dragonwagon finds baked beans comforting, relaxing, and fragrant. “It’s very much a Yankee preparation,” she says, “because they cook really slowly, so you get the residual heat, and you get the aroma of the beans cooking that whole time.” For beginning cooks, especially, they’re ideal. They’re straightforward, Dragonwagon notes, “and don’t need fussing. Beans are very forgiving.”

Soaking your beans in water is like “putting on your underwear before you get dressed,” Dragonwagon says. It’s the important first step. Why? Because soaking lets the beans absorb moisture slowly during baking

More beans! For a traditional New England–style franks-and-beans supper, plus four other hearty recipes, see p. 60 in this issue.

For a vegetarian baked-beans recipe, go to: YankeeMagazine.com/ veggie-beans

| 27 january | february 2015

ASK THE EXPERT

Writer and cook Crescent Dragonwagon is the author of Bean by Bean She lives in Westminster West, Vermont. B Y zinni A SM i TH

Beginner’s Luck

Lifelong skier and longtime ski journalist Moira McCarthy spends her winters skiing trails everywhere. And sure, she loves the steeps, but here’s a secret McCarthy can share: Some of the most beautiful moments on a mountain can be found on … wait for it … the green-circle trails. Here’s a list of her favorite easy trails in New England.

Toll Road, Stowe Mountain Resort

Stowe is famous for its gnarly brotherhood of expert trails called the “Front Four,” but skiers in the know head to the four-plus-milelong, tree-lined beauty of a green that personifies the word “meandering.” Cruise along the winding curves of Toll Road to a clearing with a delightful stone chapel you can ski to. (And reflect in. It was built in memory of a young girl who loved to ski but lost her life to cancer.) Turn past thick woods, open vistas, and sometimes even a peek at some wildlife. Toll Road was cut in the mid-1800s as a natural way to the top of the mountain, and hasn’t been changed—because good things happen when you let nature lead the way. Stowe, VT. stowe.com

Wild Kitten, Wildcat Mountain

This being Wildcat, you might have expected Polecat as the favored green. Not so. Wild Kitten is on the opposite side of the mountain and is even better. As you glide along this long yet gentle trail, you look right into the belly of Tuckerman Ravine and at the greatness that is Mount Washington. Like all good old-school Eastern trails, the Kitten isn’t wide, but it’s forgiving enough to let the skier feel at ease while taking in that incredible beauty. From top to bottom, it gives every skier a chance to experience all the awesomeness that is Wildcat. Breathtaking and gentle, all in one mellow run. Pinkham Notch, NH. skiwildcat.com

Hudson Highway, Saddleback Ski Area

One of the original trails cut at classic Saddleback, Hudson Highway sweeps you out wide from the top of the mountain to the bottom, allowing you varied views of the Rangeley Lakes, which seem to go on forever. At 9,800 feet, it’s long enough to make you feel worthy, with a drop of a gentle 2,000 vertical over that length, keeping you moving just enough. It’s the only green circle from the top of the Rangeley lift and is known as a “must ski” by even the hardiest locals. As an early-day warmup or a late-day cruise to take in the distant alpenglow, Hudson is true green-circle goodness. Rangeley, ME. saddlebackmaine.com

West Meadow—Drifter Link—Old Log Road, Stratton Mountain Resort

Sure it has three names, but this long, pretty, varied trail flows from top to bottom as one. As you wind out with a view to the east, you take in majestic Mount Equinox. Then, as it turns you to face the west, the distant Adirondacks take up your view. This long run (8,000 feet total) swings you by all that is Stratton: lovely homes, thick woods, open views, past the mogul hill where you can watch World Cup–level bump skiers (and dream!), and yes, right into the base area, where you can ski up, grab a homemade empanada at a booth, and catch the lift to do it all again. Stratton, VT. stratton.com

Bear Claw, Loon Mountain Resort

Bear Claw is a great green for group skiing. Not only is it fun enough to stand on its own (this winding trail is almost like a gentle roller coaster), but it also offers quick jumps onto more challenging trails—and then empties them back out onto Bear Claw. That means you can ski along and make choices as you cruise, always coming back to green again (or meeting up with those who veer off for a bit). It’s the longest run on Loon and is serviced by the comfortable gondola. It also has access to the resort’s Lil’ Stash, where nature meets park skiing—and where you can take a selfie with a statue of Paul Bunyan. Lincoln, NH. loonmtn.com

C

( W ild C

28 | yankeemagazine.com First l ig H t | the best 5

Courtesy of Wild

at Mountain

at); illustrated portrait by Martin Hargreaves

Wildcat Mountain’s W ild Kitten trail, pin K ha M notch, n e W h a M pshire

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2015 | 29 GLIDE UPSTAIRS ON A STANNAH STAIRLIFT. The safest and easiest way to go up and down your stairs is on a Stannah Stairlift. At the touch of a button, your Stannah glides you smoothly between floors. A Stannah will fit most types of stairs, straight or curved, comes in a choice of colors to match your decor, and may be purchased or rented. For a FREE Information Pack or to request a FREE survey of your stairs call 1-800 UPSTAIR (1-800-877-8247) today. Learn more online at www.StannahStairlifts.com The Stairlift People Showrooms: 20 Liberty Way, Franklin MA 02038 and 45 Knollwood Rd, Elmsford NY 10523 MA HIC #160211 • CT Elevator Limited Contractor License # ELV.0475333-R5 FlowerShow.com Feb 19 - 22, 2015 THUR - SAT ~ 10 AM - 8 PM SUN ~ 10 AM - 6 PM RI CONVENTION CENTER ONE SABIN ST. PROVIDENCE Presented By Garden Adventures

The Collector

When people come to the Yiddish Book Center in Amherst, Massachusetts, they gaze at the volumes and say, “Who ever knew such a literature existed?”

By justin shatwell

By justin shatwell

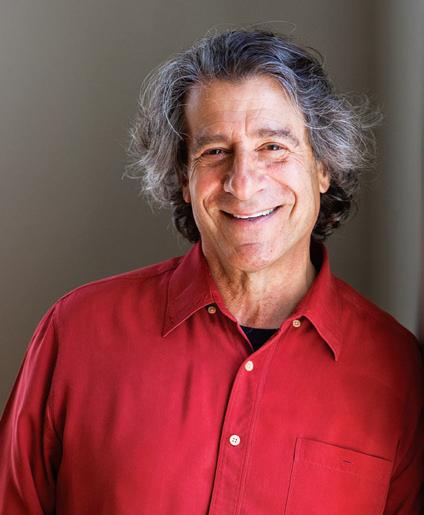

on’t you know Yiddish is dead?” When Aaron Lansky (inset, top), then a graduate student of Yiddish literature, first proposed saving the world’s Yiddish books in 1980, many scholars were pessimistic, and with reason. Just 40 years earlier, Yiddish—a 1,000-year-old language that blends Germanic, Hebrew, Romance, and Slavic tongues—was spoken by more than 11 million Jews, but within a single generation it had almost vanished. With it, the key to the community’s books was slipping away as well—an entire canon of Jewish literature perilously close to being forgotten.

In 1939, Yiddish was spoken by three-quarters of the world’s Jews, but the horrors of the Holocaust combined with the pressure of assimilation forced the language out of the mainstream. (There are only around 155,000 speakers in the U.S. today.) Except within some Orthodox communities, Yiddish simply wasn’t being passed down, and Lansky feared what would happen to the older generation’s books when left to the children who couldn’t read them. He founded a grassroots organization of volunteers to scour basements and attics across the globe in search of forgotten tomes. When he began, academics were estimating that there were only some 70,000 Yiddish books left

First Light | LOCAL TREASURE 30 | yankeemagazine.com

justin shatwe LL

L g

L ey ( L

a

g

(interior and book); Michae

rin

ansky);

ndrew

reto (vintage type)

outside of libraries. So far, Lansky and his team have found 1.5 million.

A sliver of that collection is on display at the Center’s home in Amherst, Massachusetts, on the campus of Hampshire College, Lansky’s alma mater. Row after row of books stand sentinel, their titles, written in goldleaf Hebrew letters, glinting in the sprawling, sunlit hall. “When people come here,” Lansky says, “they stand on the balcony, look over the books, and say, ‘Who ever knew such a literature existed?’”

And what a literature it is. On the Center’s shelves you can find everything from memoirs and modernist poetry to potboilers and detective novels. Yiddish presses from Warsaw to New York to Buenos Aires pounded out titles in every conceivable genre, a cacophonous symphony of creativity that’s now gone almost silent.

The Center is filled with displays and programs to make the story of this literature accessible to the estimated 99 percent of visitors who don’t read Yiddish, but perhaps its most important and exciting work is its effort to give these books new voice. Like excavating a pyramid one grain of sand at a time, the Center’s translators are revealing these stories to the English-speaking world, page by page.

opposite : Main exhibit area, with children’s corner, foreground, and Yiddish literature on shelves, background. this page , from top : Vintage type from the Center’s re-created Yiddish print-shop display; Dos kluge shnayderl (The Clever Tailor) , by Solomon Simon, 1933.

13 Yiddish Words We All sAY

Chutzpah: nerve, extreme arrogance, brazen presumption. In english, chutzpah often connotes courage or confidence, but among yiddish speakers, it’s not a compliment.

glitC h: Or glitsh. Literally “slip,” “skate,” or “nosedive,” which was the origin of the common a merican usage as “a minor problem.”

klutz: Or better yet, klots. Literally “a block of wood,” so it’s often used for a dense, clumsy, or awkward person.

kosher: Something that’s acceptable to Orthodox j ews,

especially food. In english, when you hear something that seems suspicious or shady, you might say, “That doesn’t sound kosher.”

kvetsh: In popular english, kvetch means “complain, whine, or fret,” but in y iddish, kvetsh literally means “to press or squeeze,” like a wrong-size shoe.

maven: Pronounced meyven a n expert, often used sarcastically.

nosh: Or nash. To nibble; a light snack, but you won’t be light if you don’t stop noshing.

It is incredibly slow work (to date, only 2 percent of the estimated 40,000 individual titles have been translated), but the mystery of it is infectious. What sleeping masterpiece is just waiting to be awakened?

“Is there a Moby-Dick on our shelves? It’s too early to know,” Aaron Lansky says. “We’re waiting to see what will emerge.”

Yiddish Book Center

1021 West St., Amherst, MA. Sunday–Friday 10:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m. 413-256-4900; yiddishbookcenter.org

(adapted from The y iddish Handbook: dailywritingtips.com)

sC hloC k: Cheap, shoddy, or inferior, as in “I don’t know why I bought this schlocky souvenir.”

shlep: To drag, traditionally something you don’t really need; to carry unwillingly. When people “shlep around,” they’re dragging themselves, perhaps slouchingly.

shmaltz Y: e xcessively sentimental, gushing, flattering, over-the-top, corny. This word describes some of Hollywood’s most famous films. from shmaltz, which means chicken fat or grease.

shmooze: Chat, make small talk, converse about nothing in particular. but at Hollywood parties, guests often shmooze with people they want to impress.

shtiC k: Something you’re known for doing, an entertainer’s routine, an actor’s bit, stage business; a gimmick often done to draw attention to yourself.

spiel: a long, involved sales pitch, as in “I had to listen to his whole spiel before I found out what he really wanted.” from the German word for play

| 31 january | february 2015

winter in vermont

REBECCA AND

Comfort, pure and simple.

Comfort, pure and simple.

Comfort, pure and simple.

Comfort, pure and simple.

Comfort, pure and simple.

Comfort, pure and simple.

Comfort, pure and simple.

Comfort, pure and simple.

Comfort, pure and simple.

∙ “Having stayed at many a New England inn, I simply cannot remember any place as lovely and welcoming as the Snapdragon.” Robin, Massachusetts

∙ “Having stayed at many a New England inn, I simply cannot remember any place as lovely and welcoming as the Snapdragon.” Robin, Massachusetts

∙ “Having stayed at many a New England inn, I simply cannot remember any place as lovely and welcoming as the Snapdragon.” Robin, Massachusetts

∙ “Having stayed at many a New England inn, I simply cannot remember any place as lovely and welcoming as the Snapdragon.” Robin, Massachusetts

Stowe, Vermont 800-729-2980

brasslanterninn.com

∙ “Having stayed at many a New England inn, I simply cannot remember any place as lovely and welcoming as the Snapdragon.” Robin, Massachusetts

∙ “Having stayed at many a New England inn, I simply cannot remember any place as lovely and welcoming as the Snapdragon.” Robin, Massachusetts

∙ “Having stayed at many a New England inn, I simply cannot remember any place as lovely and welcoming as the Snapdragon.” Robin, Massachusetts

“Having stayed at many a New England inn, I simply cannot remember any place as lovely and welcoming as the Snapdragon.” Robin, Massachusetts

“Having stayed at many a New England inn, I simply cannot remember any place as lovely and welcoming as the Snapdragon.”

∙ “Having stayed at many a New England inn, I simply cannot remember any place as lovely and welcoming as the Snapdragon.” Robin, Massachusetts

Windsor, VT - 802-227-0008 - www.snapdragoninn.com - innkeeper@snapdragoninn.com

Windsor, VT - 802-227-0008 - www.snapdragoninn.com - innkeeper@snapdragoninn.com

Windsor, VT - 802-227-0008 - www.snapdragoninn.com - innkeeper@snapdragoninn.com

Windsor, VT - 802-227-0008 - www.snapdragoninn.com - innkeeper@snapdragoninn.com

Windsor, VT - 802-227-0008 - www.snapdragon inn.com - innkeeper@snapdragoninn.com

Windsor, VT - 802-227-0008 - www.snapdragoninn.com - innkeeper@snapdragoninn.com

Windsor, VT - 802-227-0008 - www.snapdragoninn.com - innkeeper@snapdragoninn.com

Windsor, VT - 802-227-0008 - www.snapdragon inn.com - innkeeper@snapdragoninn.com

Windsor, VT - 802-227-0008 - www.snapdragon inn.com - innkeeper@snapdragoninn.com

www.VermontVacation.com

“Our trip has far surpassed any expectations we had. From the delicious breakfast to the roaring fire, we were captivated by your charming Inn.”

JESSE, PENNSYLVANIA

∙

Robin, Massachusetts Discover St. Johnsbury’s Arts & Culture Campus catamountarts.org • 888-757-5559 stjacademy.org • 802-748-8171 fairbanksmuseum.org • 802-748-2372 stjathenaeum.org • 802-748-8291 Catamount Arts is your cultural and entertainment headquarters! Inside the renovated Masonic Temple, you’ll find independent and international films, one of the largest art galleries in the Northeast Kingdom, and concerts and activities. Explore your universe in northern New England’s Museum of natural history! Collections include animals and artifacts, shells and tools, gems and fossils and Vermont’s only public planetarium under a great Victorian arch. St. Johnsbury Athenaum is a public library and art gallery in a National Historic Landmark building – a monument to the nineteenth-century belief in learning. It is a lively site for public readings and events throughout the year. St. Johnsbury Academy is an independent, coeducational day and boarding school for students in grades 9 through 12 and a post-graduate year. We serve students from 50 Vermont and New Hampshire towns, 15 states, and 28 countries. A Southern Vermont Country Inn Luxurious Lodging Award-Winning Dining Relaxed Ambience 800-532-9399 • threemountaininn.com Winter Packages STARTING AT $78.00

1-800-VERMONT winter in vermont Liberty Hill Farm Inn A Vermont Farm Vacation A family friendly B&B • 511 Liberty Hill, Rochester VT 05767 802-767-3926 • www.libertyhillfarm.com kids, cows and kittens! Cross-country skiing and the best breakfasts around make for a vacation to delight! Liberty Hill Farm Inn A Vermont Farm Vacation Winter fun in the heart of the Green Mountains Info at: rikertnordic.com • 802-443-2744 Stylish, secluded lodging. Exquisite farm-to-table cuisine. Authentic Vermont hospitality. 7 WoodWard road, Mendon, VerMont 802-775-2290 • www redcloverinn com Red Clover Inn The RESTAURANT & TAVERN

The GUIDE TRAVEL

THIS PAGE : In Stowe, Vermont, skiers of the 1930s take to Mount Mansfield’s slopes on the Nosedive Trail, newly cut by the Civilian Conservation Corps and soon to become a world-class racing trail. Mansfield’s ski patrol, founded in 1934, was the first such group in the U.S.

OPPOSITE : Skiers at today’s Stowe Mountain Resort on the Sunrise Trail. Mount Mansfield and neighboring Spruce Peak together are now crossed by 116 trails.

34 | YANKEEMAGAZINE.COM

Finding the 1930s

A time-travel adventure from ski slopes to cities where classic New England endures.

by Bill Scheller

Contemporary Photographs by Mark Fleming

by Bill Scheller

Contemporary Photographs by Mark Fleming

| 35 JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2015

’ve spent the past couple of days skiing at Stowe, riding the rope tow and hitting the handful of trails cut over the past few years by the Civilian Conservation Corps. I’ve been spending nights in the village, at the Green Mountain Inn, where I bumped into Lowell Thomas. The renowned globetrotter and radio pioneer was broadcasting his show from the inn, talking up the skiing on Mount Mansfield and signing off with his signature “So long, for now.” So long, Mr. Thomas. I’m going to hop into the Packard and head east on the next leg of my journey.

The rope tow? A scant few trails?

Lowell Thomas? A Packard?

Only in my imagination. I’m in Stowe, Vermont, all right, and I have been skiing at Stowe Mountain Resort , which today sprawls across Mount

Mansfield and Spruce Peak. I’ve done those early trails— Nosedive, Chin Clip, Lord, and a few others—that still thread Mansfield, although I rode chairlifts and the gondola instead of that infernal rope tow. And I’m checking out of the Green Mountain Inn , still Main Street’s only place to stay. But Lowell Thomas said his last “So long” more than 30 years ago, and I’m traveling by Subaru instead of Packard. Still, my reverie this week isn’t going to wander far from reality. I want to recreate the sort of trip a winter traveler might have taken in the late 1930s, skiing in the North Country and then meandering down the coast to Boston. I’ll drive no Interstates, stay in no motels, and mostly eat in places where FDR’s voice once came across the radio behind the counter … a counter where a

thumbed-through copy of that new magazine, Yankee , might lie next to the cash register.

“New England is a finished place,” wrote historian Bernard DeVoto in 1932, three years before Yankee made its first appearance. Well, we now know that our region was still a few shopping malls shy of completion in DeVoto’s day. But the remarkable thing is that so much of what was “finished” in the ’30s is still with us today.

I drove south from Stowe on Route 100, the road that 1930s skiers would have traveled by bus on their way north from the train depot at Waterbury, Vermont. From Waterbury, I took old two-lane U.S. Route 2 to Montpelier.

36 | YANKEEMAGAZINE.COM THE GUIDE | travel

PREVIOUS PAGE: GREG DIRMAIER COLLECTION; BETTMANN/CORBIS (LOWELL); COURTESY OF GREEN MOUNTAIN INN (GMI)

A classic Vermont town, Stowe sits by the Little River, just east of Mount Mansfield State Forest. Home to both a lively arts scene and year-round outdoor adventure, it has hosted travelers since the mid-19th century. INSET : Writer, broadcaster, and world traveler Lowell Thomas, 1934.

LEFT, FROM TOP : At Stowe Mountain Resort, modern amenities keep visitors returning to this venerable New England ski area. Here, a gondola rides high over the slopes; guests relax by the fire in a common room at Stowe Mountain Lodge, a rustic alpine-style hotel that opened in 2008.

ABOVE RIGHT, FROM TOP : Welcoming visitors since 1833, Stowe’s Green Mountain Inn hosted many of Lowell Thomas’s radio broadcasts in the 1930s; Yankee’s January 1937 issue featured a special “Winter Sports” section, with cover art by Beatrix Thorne Sagendorph, wife of the magazine’s founder, Robb Sagendorph.

| 37