THEPOEMREADS:

THEPOEMREADS:

Dear Reader,

Dear Reader,

The drawing you see above is called The Promise It is completely composed of dots of ink. After writing the poem, I worked with a quill pen and placed thousands of these dots, one at a time, to create this gift in honor of my youngest brother and his wife.

Dear Reader,

The drawing you see above is called “The Promise.” It is completely composed of dots of ink. After writing the poem, I worked with a quill pen and placed thousands of these dots, one at a time, to create this gift in honor of my youngest brother and his wife.

Now, I have decided to offer The Promise to those who share and value its sentiment. Each litho is numbered and signed by hand and precisely captures the detail of the drawing. As a wedding, anniversary or Valentine’s gift or simply as a standard for your own home, I believe you will find it most appropriate.

The drawing you see above is called “The Promise.” It is completely composed of dots of ink. After writing the poem, I worked with a quill pen and placed thousands of these dots, one at a time, to create this gift in honor of my youngest brother and his wife.

Now, I have decided to offer “The Promise” to those who share and value its sentiment. Each litho is numbered and signed by hand and precisely captures the detail of the drawing. As a wedding, anniversary or Valentine’s gift or simply as a standard for your own home, I believe you will find it most appropriate.

Measuring 14" by 16", it is available either fully-framed in a subtle copper tone with hand-cut double mats of pewter and rust at $135*, or in the mats alone at $95*. Please add $14.50 for insured shipping and packaging. Your satisfaction is completely guaranteed.

My best wishes are with you.

Measuring 14" by 16", it is available either fully framed in a subtle copper tone with hand-cut mats of pewter and rust at $110, or in the mats alone at $95. Please add $14.50 for insured shipping and packaging. Your satisfaction is completely guaranteed.

Now, I have decided to offer “The Promise” to those who share and value its sentiment. Each litho is numbered and signed by hand and precisely captures the detail of the drawing. As a wedding, anniversary or Valentine’s gift or simply as a standard for your own home, I believe you will find it most appropriate.

My best wishes are with you.

The Art of Robert Sexton • P.O. Box 581 • Rutherford, CA 94573

Measuring 14" by 16", it is available either fully framed in a subtle copper tone with hand-cut mats of pewter and rust at $110, or in the mats alone at $95. Please add $14.50 for insured shipping and packaging. Your satisfaction is completely guaranteed.

All major credit cards are welcomed. Please send card name, card number, address and expiration date, or phone (415) 989-1630 between 10 a.m.-6 P.M. PST, Monday through Saturday. Checks are also accepted. Please allow up to 2 weeks for delivery. *California residents- please include 8.0% tax

My best wishes are with you.

MASTERCARD and VISA orders welcome. Please send card name, card number, address and expiration date, or phone (415) 989-1630 between noon-8 P.M.EST. Checks are also accepted. Please allow 3 weeks for delivery.

Please visit my Web site at www.robertsexton.com

“The Promise” is featured with many other recent works in my book, “Journeys of the Human Heart.” It, too, is available from the address above at $12.95 per copy postpaid. Please visit my Web site at www.robertsexton.com

and VISA orders welcome. Please send card name,

“Across the years I will walk with you— in deep, green forests; on shores of sand: and when our time on earth is through, in heaven, too, you will have my hand.”

“Across the years I will walk with you— in deep, green forests; on shores of sand: and when our time on earth is through, in heaven, too, you will have my hand.”

Presenting Yankee ’s picks for New England’s 10 best snow-season destination towns, where warmth is where you find it, both indoors and out. by Steve

Jermanok

Jermanok

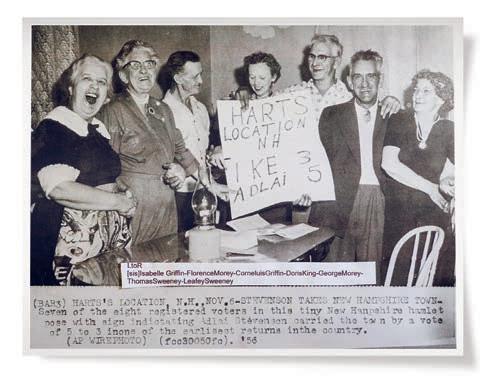

When the citizens of three tiny New Hampshire communities gather at midnight to cast their votes, more than politics is at stake. by Ian

When you fall into a freezing river in the mountains of western Maine, the will to live can be measured by the need to save one you love. by Elizabeth Cooke

First in a new series celebrating New England’s heritage trades: For more than two centuries, lumber from New Hampshire’s Wilkins sawmill has built barns and homes, redone kitchens, and framed additions. Today, Tom Wilkins is keeping his family’s legacy alive. by Ian Aldrich

First in a two-part series on New England’s energy landscape: Citizen activists in Massachusetts and southern New Hampshire take a real-life crash course in engineering and policy when proponents of a natural-gas pipeline stake a claim to their land. by Howard Mansfield

A portrait of a world apart in the heart of Rhode Island’s Narragansett Bay, a hidden place where “time has a different sensibility.”

text by Mel Allen, photographs by Ron

54

54 /// A New Look at Casseroles

Nothing beats the warm comfort of a homey, flavorful, one-dish dinner. by Kathy Gunst

60 /// Local Flavor

Amaral’s Fish & Chips: a family-owned Rhode Island eatery serving irresistible coastal fare and Portuguese American classics. by Amy Traverso

64 /// Could You Live Here?

Uniquely Vermont: Montpelier, smallest state capital in the nation, is quirky, proud, and very much the People’s City. by Annie Graves

70 /// The Best 5

Fireside dining spots: For maximum cold-weather romance, unwind over a satisfying meal beside a blazing hearth. by Kim Knox Beckius

72 /// Local Treasure

Boston’s Nichols House Museum offers an intimate look at Brahmin life on Beacon Hill at the turn of the last century. by Aimee Seavey

74 /// Out & About

Top flower and garden shows, plus 75 other favorite seasonal events. compiled by Joe Bills

departments

8

YANKEE ALL ACCESS

10

DEAR YANKEE

12

INSIDE YANKEE

14

MARY’S FARM

On the Pond by Edie Clark

16

LIFE IN THE KINGDOM

Starting Over by Ben Hewitt

20

FIRST LIGHT

It’s a “Cool Tradition” as folks in South Bristol, Maine, come together every February to harvest the ice from Thompson Pond. by Aimee Seavey

24

64

ONLY IN NEW ENGLAND

Snow Business by Ken Sheldon

26

KNOWLEDGE & WISDOM

Hearty foods, snowy owls, and expert advice on registering your historic property.

29

UP CLOSE

Camden Toboggan Chute compiled by Joe Bills

122

HOUSE FOR SALE

The Bath Sweet Shoppe, in the heart of Maine’s famous shipbuilding city.

126

POETRY BY D.A.W.

140

TIMELESS

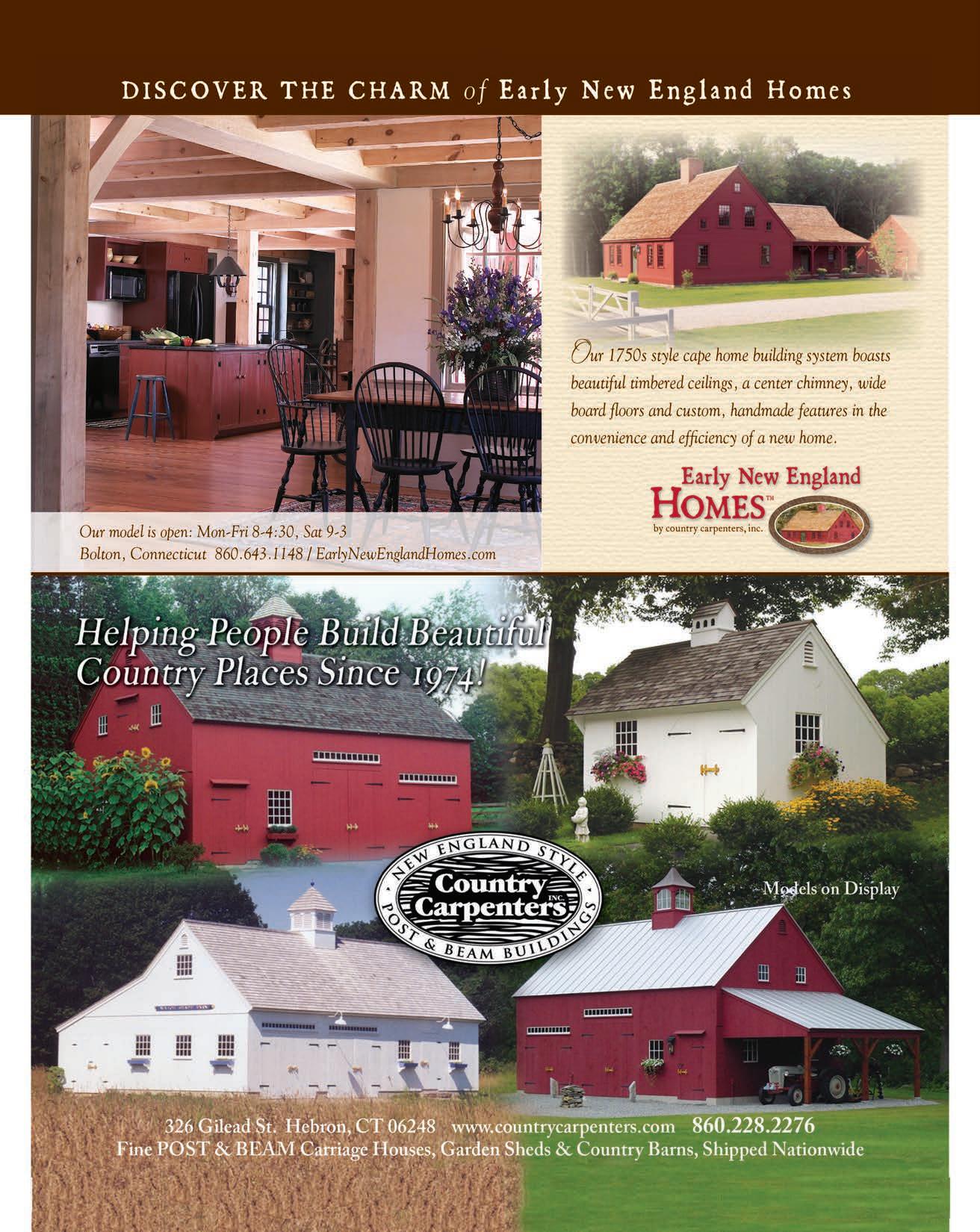

BACK TO BASICS: WHERE TO LEARN CHEESEMAKING, CARPENTRY, BREAD BAKING, WEAVING, AND 26 OTHER USEFUL DIY SKILLS.

by Bridget Samburg, Joe Yonan, and Amy Traverso p. 30

by Bridget Samburg, Joe Yonan, and Amy Traverso p. 30

Kosti

1121 Main St., P.O. Box 520, Dublin, NH 03444, 603-563-8111; editor@YankeeMagazine.com

EDITORIAL

EDITOR Mel Allen

ART DIRECTOR Lori Pedrick

MANAGING EDITOR Eileen T. Terrill

SENIOR LIFESTYLE EDITOR Amy Traverso

SENIOR EDITOR Ian Aldrich

PHOTO EDITOR Heather Marcus

ASSOCIATE EDITORS Joe Bills, Aimee Seavey

VIDEO EDITOR Theresa Shea

INTERNS Michele Hirsch, Heather Tourgee

CONTRIBUTING EDITORS Kim Knox Beckius, Annie Card, Edie Clark, Annie Graves, Ben Hewitt, Justin Shatwell, Ken Sheldon, Julia Shipley

CONTRIBUTING PHOTOGRAPHERS Julie Bidwell, Kindra Clineff, Sara Gray, Corey Hendrickson, Joe Keller, Matt Kalinowski, Joel Laino, Jarrod McCabe, Michael Piazza, Heath Robbins, Kristin Teig, Carl Tremblay

PRODUCTION

PRODUCTION DIRECTORS David Ziarnowski, Susan Gross

SENIOR PRODUCTION ARTISTS Jennifer Freeman, Rachel Kipka

DIGITAL

VP NEW MEDIA & PRODUCTION Paul Belliveau Jr.

DIGITAL EDITOR Brenda Darroch

NEW MEDIA DESIGNERS Lou Eastman, Amy O’Brien

PROGRAMMING Reinvented Inc.

YANKEE PUBLISHING INC. established 1935

PRESIDENT Jamie Trowbridge

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Judson D. Hale Sr.

VICE PRESIDENTS Paul Belliveau Jr., Jody Bugbee, Judson D. Hale Jr., Brook Holmberg, Sherin Pierce

CHIEF FINANCIAL OFFICER Ken Kraft

CORPORATE STAFF Mike Caron, Linda Clukay, Sandra Lepple, Nancy Pfuntner, Bill Price, Christine Tourgee

BOARD OF DIRECTORS

CHAIRMAN Judson D. Hale Sr.

VICE CHAIRMAN Tom Putnam

DIRECTORS Andrew Clurman, H. Hansell Germond, Daniel Hale, Judson D. Hale Jr., Joel Toner, Cor Trowbridge, Jamie Trowbridge

FOUNDERS

ROBB & BEATRIX SAGENDORPH

PUBLISHER Brook Holmberg

ADVERTISING: PRINT/DIGITAL

VICE PRESIDENT/SALES Judson D. Hale Jr.

SALES IN NEW ENGLAND

TRAVEL, NORTH Kelly Moores

(NH North, VT, ME, NY) KellyM@yankeepub.com

TRAVEL, SOUTH Dean DeLuca

(NH South, CT, RI, MA) DeanD@yankeepub.com

DIRECT RESPONSE Steven Hall

SteveH@yankeepub.com

CLASSIFIED Bernie Gallagher, 203-263-7171 classified@yankeepub.com

SALES OUTSIDE NEW ENGLAND

NATIONAL Susan Lyman, 646-221-4169, susan@selmarsolutions.com

CANADA Alex Kinninmont, Françoise Chalifour, Cynthia Jollymore, 416-363-1388

AD COORDINATOR Janet Grant

For advertising rates and information: 800-736-1100 x149 YankeeMagazine.com/adinfo

MARKETING

CONSUMER

MANAGERS Kate McPherson, Kathleen Rowe

ASSOCIATE Kirsten O’Connell

ADVERTISING

DIRECTOR Joely Fanning

ASSOCIATE Valerie Lithgow

COORDINATOR Christine Anderson

PUBLIC RELATIONS

BRAND MARKETING DIRECTOR Kate Hathaway Weeks

NEWSSTAND

VICE PRESIDENT Sherin Pierce

DIRECT SALES

MARKETING MANAGER Stacey Korpi

SALES ASSOCIATE Janice Edson

SUBSCRIPTION SERVICES

To subscribe, give a gift, or change your mailing address, or for other questions, please contact our Customer Service Department: online: YankeeMagazine.com/contact phone: 800-288-4284

mail: Yankee Magazine Customer Service P.O. Box 422446 Palm Coast, FL 32142-2446

We occasionally make our mailing list available to advertisers whose offers we think may be of interest to subscribers. If you would prefer not to receive such offers, please contact us using one of the methods listed above.

New England was the birthplace of the American diner, and these classic establishments still serve as community gathering places. Diner expert Mike Urban dishes up his picks for the best spots in the region:

n O’Rourke’s Diner Middletown, Connecticut

n Agawam Diner Rowley, Massachusetts

n Becky’s Diner Portland, Maine

n Modern Diner Pawtucket, Rhode Island

n Chelsea Royal Diner West Brattleboro, Vermont

For the rest of the list, go to: YankeeMagazine.com/Diners

And DON’T MISS the recipe for the most popular diner dish at: YankeeMagazine.com/Diner-Food

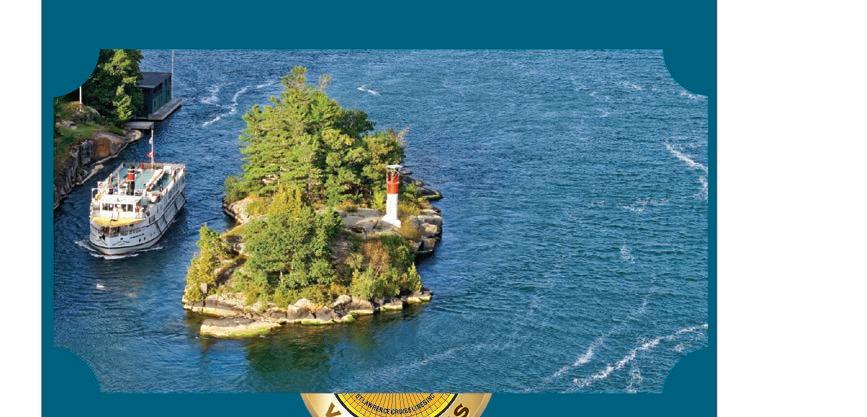

Journey to Cuba in 2016 with Pearl Seas Cruises on an 11-day people to people experience focused on the rich history, heritage, and contemporary life of the Cuban people. The brand new 210-passenger luxury Pearl Mist allows access to more of Cuba’s ports and regions, while providing a relaxed means to interact with Cubans and explore the rich fabric of Cuban culture. These cultural voyages are subject to final government approvals.

We received so many wonderful letters about our special 80th-anniversary issue (Sept./Oct.). Here are a few of our favorites. —Eds.

I grew up in Rhode Island and first read Yankee as a child at my grandparents’ house; I remember being captivated by the cover art. Fast-forward to the early ’80s in Minneapolis, where I was living at the time. I went to an estate sale and found a cardboard box filled with old Yankees from the ’40s and ’50s, which I bought for something like a dollar. I read every one cover to cover, missing my grandparents and my beloved New England. I’ve had a subscription for more than 40 years now and will never stop reading Yankee.

—Steven Thompson

—Steven Thompson

I take exception to your statement in which you supposed that “every person reading these words could get along in the world just fine without Yankee ” [p. 168]. Not true! Thirty-three years ago, this Massachusetts-based Yankee moved to Florida for reasons I’m still trying to fathom. I quickly realized that I’d need a regular dose of New England to keep me at least half sane once I crossed the Mason–Dixon Line.

I used to frame certain Yankee covers that were particularly evocative, so that I could gaze at the beauty of a maple tree in full fall glory while the long fronds of the palm trees just outside the window swayed in the breeze. Though my body resides here, my heart and soul are forever in New England. Each month Yankee reminds me of that truth, and I thank you mightily for it.

Barbara Yoresh Vero Beach, Florida

While sitting here reading the 80th anniversary issue, I just realized that I’ve been looking at the photo of Baxter State Park [p. 102] for almost 20 minutes, and my mind just wandered off to all the places I’ve been to and how lucky I am to have lived in New England. Not everyone can say that they’ve touched Paul Revere’s house or been in the Old North Church or walked the Mohawk Trail. I’m 84 now and have been reading Yankee since I was 12. It made me want to see as much of the world (New England) as I could. My life has been full, and you’ve helped make it so.

Fred Bousquet Shelton, Connecticut

Fred Bousquet Shelton, Connecticut

Many years ago, prior to my daughter’s wedding, I took the family to Boston for a ballgame and to Durgin–Park for dinner. Gina Schertzer was our waitress [p. 124]. She was telling us the lobster

“Quite possibly the best @yankeemagazine ever. 80 gifts #NewEngland Gave to America. Love it!!”

Sarah Beals @JoyFilledDays

prices, and I asked which was the cheapest. She asked why, and I told her about my daughter’s upcoming wedding. And that I was going to be broke. She asked how many daughters I had, and I told her, “One.” In true Durgin–Park fashion, she never let up on my being cheap. When she brought the bill, she sat on my lap and wiped my eyes with a napkin because she said she knew I would cry. I paid, thanked her for the heckling, and left. Afterwards, I found that everyone in my family had slipped her an extra tip because she was so funny. Your article brought back a fond memory.

Earl Cossaboom Springfield, MassachusettsI am very grateful for being included in the commemorative issue [p. 133], proud to be part of the New England region, and appreciative of your thinking of me.

Bill BelichickFoxborough, Massachusetts

Thanks, Coach, but we’re on to March/ April. —Eds.

I noticed two “gifts” that were omitted: Samuel Colt and Wallace Nutting. Whether or not you’re a proponent of firearms, Colt’s invention helped open the West to settlement. Nutting’s work was how folks in the rest of the country became acquainted with New England. His hand-colored photo prints were famous for depicting the region’s beauty. We have multiple ones in our home to remind us of his “eye” and to help us feel as though we’ve never left.

Maria DaBica Dardano Orange City, Florida

I’m disappointed that you didn’t include two of New England’s most famous writers, Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson. Their works exerted great influence during their lifetimes and to this day are widely read.

Joan Chalmers Harris Shrewsbury, Massachusetts

Joan Chalmers Harris Shrewsbury, Massachusetts

Write us at 1121 Main St., Dublin, NH 03444, or editor@YankeeMagazine.com. Please include where you reside. Letters may be edited for length and clarity.

ut there in the land of New Year’s Resolutions, where we promise ourselves that we’ll eat more greens, shed some pounds, walk more, get rid of the clutter, and begin to write in the journal that we received for Christmas five years ago, here’s one more resolution to make. A resolution that can carry you through not only this year but many more to boot, long after that gym membership has languished and the greens have wilted in the fridge: Rekindle the curiosity and desire to learn that we’re all born with. Take those first sometimes-hesitant steps to find new skills, maybe even discover a new passion.

That’s what our special home section is all about. “A Guide to Simple Living: A More Handmade Life” (pp. 30–49) is filled with new chances to test that curiosity. We think that when you read it and consider the 30 different workshops, classes, schools, and learning getaways listed there, it may inspire you to call upon abilities you didn’t even know you could acquire. Skills that know no age boundaries, that require neither wealth nor impressive degrees. The only requirement is wanting to tap into the self-reliant ways in which New Englanders have lived for generations: with resourcefulness, pride in workmanship, willingness to try something new. These are skills that, once learned, can then be passed on to others— friends, children, grandchildren. It’s the way we’ve always learned: teacher to student, who then becomes teacher.

The experts at these workshops differ in what they know but share a love of passing along their knowledge. Then it’s in your hands to enrich your life—as if you yourself become seed, soil, rain, and sun, watching what grows inside. Will knowing how to make a block of delicious cheese or a loaf of wholesome crusty bread, or how to weave a scarf, or how to frame a simple small dwelling, change your life? Probably not. But if these mentors help you to remember what it felt like when you finally got off training wheels and for the first time steadied the bike and shouted, “Look what I can do!” you’ll no doubt add “learn something new” to every list of New Year’s resolutions to come.

Coming back home from a workshop with fresh knowledge is better than a gym, or a bag of lettuce or arugula—as fine as those things are for you. Maybe this is the time to surprise yourself with the gift of childlike enthusiasm. You can learn to ride a bike only once in a lifetime, but there are so many other ways—as the pages ahead will show—to say “Look what I can do now.”

Mel Allen, Editor editor@YankeeMagazine.com

For a child, watching her grandfather skate created a memory where truth and myth lived side by side.

y grandfather, whom we called Bim, loved to skate. He loved to do anything outdoors. He’d climbed the Matterhorn and surfed in Honolulu, and he did back flips off the high diving board until he was in his seventies. But his enduring love was pond hockey. I was little, but going out to the pond near his house to watch him play with the young men of the neighborhood was a clear memory and always a thrill. He was like a magnet—a big man who arrived at the pond with his skates and hockey stick, a puck in his pocket. He wore a cardigan sweater over a flannel shirt, a necktie, and a hat with ear flaps hanging loose, mad-bomber style. His pants were big and roomy, and his leather gloves gripped his stick.

As soon as Bim got his skates laced, the boys would come out of the rushes as if a whistle had been blown. With a shovel, he would skate-clean the ice and then create a couple of goals using bushel baskets. I liked watching him churn down the ice, boys chasing. I got a certain giggly thrill out of seeing him outskate the boys who swarmed around him as he slapped the puck into the goal.

These Saturday games weren’t particularly regular, but once the word went out, a small crowd would gather to watch the competition. A couple of boards balanced on a couple of rocks made good-enough bleachers, and that’s where I’d be, along with my sister and our mother. Teams, I think, were four on four, or, I seem to remember, one boy and my grandfather against four others. I also seem to remember that my grandfather always won. But that could be my untarnished memory of the man.

An early photograph captured my sister and me on either side of our smiling grandfather, skating on the pond. We were probably 5 and 6. Bim is holding his hockey stick, my sister gripping one end of it, with me on the other end; I’m pretty sure this is how we learned to skate. He’d skate between us and coach us as we glided along. We learned to balance on our figure skates and how to stroke the ice with the blades as we moved forward. A better way to learn was just to watch Bim skate. With the grace of a swan, he’d slide forward and then swirl back, creating sprays of ice dust in his wake. He’d skate furiously from one end of the pond to the other, crossing one foot over the other to gain speed. Then he’d turn and skate backwards, his hands clasped behind his back, easy as pie. For Bim, nothing on ice seemed like an effort; it was all sheer joy. Skating was something we could do together on a cold winter’s day. The pond always felt as though it were our own, the ice carved out of the vast frozen tundra just for us.

My grandfather was a modern man, a man who’d likely embrace every innovation of this postmodern age. He owned the first car in his town (a 1908 Buick) and the first pair of skis, and if he were here today, he’d likely have an Apple watch on his wrist, looking up the secrets of the universe while skating backwards. It was only a few years after my sister and I had wobbled around, hanging on to his hockey stick, that Bim died. We were all in disbelief. He’d been everybody’s patriarch, everybody’s hero. We thought he would live forever and continue to teach us and outskate us. Maybe he’s still doing that.

Edie Clark’s books, including her newest, As Simple As That: Collected Essays , are now available at: edieclark.com

y the middle of January, the snow is thigh-deep in the woods, and when I attempt to drive the tractor down to the copse of balsam fir I’ve been eyeing, I make it less than halfway before becoming mired. I shift into reverse and let the clutch out, but the deep-lugged tires churn uselessly, foiled by the sheer accumulation of snow.

Stubbornly, I keep trying to extricate myself, shifting from forward to reverse and back again as quickly as the tractor’s balky transmission will allow, but every rotation of the tires only sinks the machine a little lower into the snowpack. I can feel my spirits sinking with it. In any normal winter, I’d simply wait for a change in conditions—a January thaw, perhaps, or even the inevitable shift of seasons.

But this isn’t a normal year, because just three months ago, we closed on a parcel of land a dozen miles to the north. Within a month of that, we struck a deal to transition our current homestead to friends. This means that as of this very January morning when I find myself unable to reach the trees that will provide the lumber to build our new home, we have less than 10 months in which to erect shelters for our animals and ourselves.

Ten months to fell the trees, skid them, then lift them onto the mill and saw them into the constituent parts of our new home. Ten months

to stack and sticker the green lumber, still redolent of balsam’s earthy sweetness. Ten months to install the septic system and develop the spring I found entirely by chance, tucked into a little hollow at the base of a rock outcropping about 600 feet uphill of the house site, a stroke of good fortune that prompted me to whoop in delight. Ten months to peruse Craigslist for used windows, and then to drive to western Massachusetts

into even fewer, and as I climb down from the tractor to begin the process of extrication, I feel a tentative, licking flame of despair. What were we thinking? That we could build a house and barn in less than a year, each constructed of lumber we’d sawn ourselves? Hah! If there were no other explanation for a winter of recordsetting cold and relentless snowfall,

and the snow too deep, to make plowing it practical. I’ll retreat to the house to stoke the woodstove, set the coffeepot atop it, and revisit the plans Penny and I sketched out on graph paper.

Already, we’ve revisited them a dozen times over, but what else can we do? In the face of everything we must accomplish before the last autumn leaves fall to the ground, inactivity is not an option.

twice in our old Subaru, returning with so many windows strapped to its roof that I can barely hold highway speeds for the wind resistance. Ten months to plan and replan. Ten months to measure, to saw, to hammer. Ten short months.

perhaps the sheer arrogance of our plan would have been reason enough. The gods generally do not let arrogance go unpunished.

I trudge and wallow through the snow, unreeling the winch cable I’ll use to pull the tractor to higher ground.

Our decision to pull up stakes for a parcel of land a dozen miles to the north of here is rooted in a medley of good old-fashioned Yankee pragmatism, and something that is less easily defined but no less meaningful: an evolving understanding of how we want to carry out the latter half of our lives on this earth. For us, that means downsizing and simplifying our lives even further: a (much) smaller house; a lesser array of outbuildings, designed for the ways in which our homestead has evolved, ways that we couldn’t predict 15 years ago.

We did something we never imagined we might do: committed ourselves to another piece of land. “You’re crazy” was the common refrain.

CABOT

Not inconsequentially, we were smitten with the jettisoning of belongings that our new, half-sized home will necessitate, for it’s a homeowner truism that no matter how big you build, you will fill it. Despite taking pains to minimize consumption, we’d filled our first, 2,200-square-foot effort, and our belongings had become our albatross, as if we bore their significant weight on our shoulders.

And so we did something we never imagined we might do, surprising both ourselves and, it’s fair to say, everyone we know (one friend literally had to sit down when she heard the news): We committed our lives to another piece of land. “You’re crazy,” was the common refrain, or some mildly more polite version of it.

And on some level, we couldn’t disagree, because it was crazy. Our home here, the one you’ve seen depicted in photos over the past year, is wonderful. It’s rustically beautiful and, furthermore, sound of structure and spirit. Our children were born under its roof; Penny and I were married at the knobbed height of the land.

What’s more, the land itself is ideal ly suited to our purposes. The pasture is thick and verdant, the garden soil rich and friable. And our neighbors! All winter, three evenings each week, the boys have snowshoed or skied down to Melvin’s barn to help with evening chores. A half-mile over his hayfield, and then down the steep pasture hill, and then back again in the inky winter dark. Sometimes they’ve complained before leaving, for often it’s been below zero and gusting, but always they’ve returned home full of accomplishment and carrying the incomparable odor of cow barn. “You smell barny,” Penny and I say, stretching out the made-up word for full effect.

We considered all of this before we made our decision. We considered, and sometimes we cried. We struggled for months with our decision, and the

odd thing was, the moment we realized how happy we could be if we stayed, that was precisely the moment when we felt as though we could do this: despite our love for this place (or maybe because of it); despite the many ways in which this place is ideal for us; despite everyone who thinks we’ve gone off the rails. (And here’s another thing I’ve learned: One of the best ways to know whether a major change is right for you is if everyone thinks you’re nuts and you still want to go for it.)

The land we’re building on is profoundly beautiful, albeit in very different ways from this property. It’s 96 acres or thereabouts, mostly wooded, with a seven- or eight-acre abandoned apple orchard. There’s just enough pasture to graze our small herd of cows. At the height of the land resides a cathedral-like sugarbush, not large enough to interest a commercial sugar maker, but ideal for our purposes: 100 taps, I’m thinking. A year-round stream bisects the property, and already the boys have identified the most prolific brook-trout holes. Already they’ve found bear and raccoon tracks in the silt along its stony edge.

The next year will be as busy as any we’ve known. We still have this property to manage, gardens to plant, animals to husband, winter stores to put up. Despite spending much of the winter selling and giving away the half or more of our belongings that won’t fit into our new, as-yet-unbuilt home, we’re not there yet. We’ve dispensed with the easy stuff, the unsentimental accumulations of the past decade and a half. Next comes the harder stuff: the boys’ favorite toddlerhood toys, the make-believe kitchen set Penny made them. It even has burner knobs and an oven that opens. But it must go.

Still, I think we’ll hang on to it just a little longer. There’s no reason to be hasty: After all, we’ve got 10 whole months.

Read the rest of this series at:

YankeeMagazine.com/Kingdom

It’s a community gathering every February as residents and visitors in South Bristol, Maine, wield saws, “busting bars,” and pike poles to harvest ice from Thompson Pond.

Its crop is no longer making its way to the Caribbean, but for one Maine town, the passing of another New England winter is marked, as it has been for centuries, by the harvesting of ice.

BY AIMEE SEAVEY

BY AIMEE SEAVEY

oday in Maine, the word “harvest” is most often associated with summer and early fall, when the state’s blueberry and potato crops come in thick and fast—but a century and a half ago, another harvest was equally valuable. Reaching its peak in the dead of winter, this crop wasn’t a grain or a fruit or a vegetable, but cold, hard ice.

In the hundred years before electricity, the same stuff that now comes out of the freezer at the touch of a button was commercially harvested directly from freshwater ponds, many of them in Maine. The resulting blocks were sent not just to neighboring homes, shops, and fishing boats, but as far away as the Caribbean and South America. With the arrival of modern refrigeration during the early 20th century, nearly all of Maine’s icehouses disappeared, but the Thompson Ice House, located on Route 129 in the Midcoast village of South Bristol, remains a rare exception.

After four generations of family ownership and nearly 160 years of commercial cutting, Herbert Thompson knew that the days of profitable ice harvesting on the pond that his great-grandfather Asa Thompson first dammed back in 1826 were over, but he couldn’t bear giving up the tradition. Fortunately, neither could many of his neighbors. After decades of fundraising, the Thompson Ice House Restoration Corporation was formed in the mid1980s, and Thompson officially donated the house and pond for use as a working museum in 1987. From there, it took another three years to build an identical replica of the icehouse, using salvaged materials from the sagging original, complete with a small museum.

of Presidents’ Day weekend, hundreds of locals (plus a smattering of new and returning visitors) turn up at the tiny wooden shack to help keep the ice har vests of South Bristol’s past an active part of its present. Despite the cold, the atmosphere crackles with animated chatter and the rasp and whine of saws. Groups of neighbors talk town news at the ice’s edge, sipping hot chocolate and munching hot dogs from the snack bar, while red-cheeked children play a game of hockey on the one-acre pond’s far side and line up for horse-drawn sleigh rides under bright winter sunshine. Steps away, the surface of the forest-ringed pond is an active work zone, and the plaid-clad volunteers manning the oper ation have the healthy flush to prove it.

Like most harvests, the process of getting the ice from ground to market is straightforward enough, but impossible without a liberal amount of muscle.

The lion’s share of the cutting work is safely done using a sled-mounted circular saw by seasoned volunteers like Thompson Ice House president Ken Lincoln, who’s been cutting here since he was a boy. It’s fun to watch, but questions, and later a helping hand, are encouraged. It’s also a good time to pick up some ice lingo.

In South Bristol, the snow is cleared and cutting lines are marked into a pattern of blocks measuring 22 inches wide by 32 inches long. After the circular saw does its thing, the old-fashioned long saws come out—the kind with sharp, ragged teeth—and novices, including kids, are invited to try their hand at cutting, with guidance from the pros. The ice is first cut into large rafts, or “floats,” made up of the premeasured blocks. Then forked “busting bars” separate the blocks, also known as “cakes,” which float freely in the inky water like a herd of flat, rectangular

icebergs. Each more than a foot thick and weighing as much as 300 pounds, the blocks move awkwardly, so workers wield long-handled “pike poles,” which look a lot like harpoons, to nudge them along toward the channel leading to the icehouse. Arriving at a wooden ramp, the blocks are met by veteran ice men wearing fluorescent, waterproof orange pants—and grins that not even the coldest Maine wind can touch. They position each block into a wooden cradle, where a pulley system (driven now by gasoline horsepower rather than the real thing) hauls it up to the icehouse, where it disappears into the storage room.

There a rugged team receives the new arrivals and uses pike poles to quickly maneuver them (well, as much as you can maneuver a hurtling 300-pound block of ice) into layers. If you can get above the operation and look down, the effect is mesmerizing: a glowing ballet of flannel-clad figures and crusted blocks of ice. To keep the shack cold, its double wooden walls are lined with nearly a foot of sawdust insulation, and hay is sandwiched between each pair of frozen layers.

The Thompson harvest serves a dual role, offering an opportunity not only to reach out and touch a chapter (or block, as it were) of Maine’s economic past, but also to bask in the warmth of honest-to-goodness community camaraderie at its hardiest. And if that’s not enough, in addition to being sold on site via the honor system, a substantial portion of the annual harvest is earmarked for use at the icehouse’s second annual event, an old-fashioned ice-cream social held each July. A bowl of hand-churned ice cream in exchange for the unique pleasure of dragging an antique saw through a foot of natural pond ice? Now, that’s pretty cool.

This year’s ice harvest is scheduled for Sunday, February 14, 2016; the ice-cream social is set for Sunday, July 3, 2016. All are welcome.

For more information go to www.YankeeMagazine.com/clicks.

Route 129, South Bristol, Maine. 207-644-8808; thompsonicehouse.com

Interior & Exerior Real Wood Shutters. Hard-to-find traditional Moveable Louvers all Sizes ~ full Painting family owned ~ Made in USa 203-245-2608 shuttercraft.com

We will custom design a braided rug to meet your needs in any size and over 100 colors. Stop by our retail store and factory at: 4 Great Western Rd. Harwich, MA 03645

888-784-4581

capecodbraidedrug.com

Our rockers, chairs, recliners, and sofas are “made to fit your body.” Visit our showroom at 99 Sadler Street Gloucester, MA 01930

800-451-7247 kleindesign.com

Quality, durability & service guaranteed, Droll Yankees bird feeders were the first and are still the best. Shop for our authentic bird feeders & accessories online.

800-352-9164

drollyankees.com

ome winters are notable for specific storms, such as the Great Blizzard of 1888 and the Northeastern Storm of 1978. Then there are winters remembered for their sheer obstinacy, like last year’s, 2014–15, which went on longer than the Black Death but was more depressing. New Englanders take a variety of approaches to handling all that snow. Here we present Yankee ’s guide to shoveling, mainly so that we don’t have to go out and do it ourselves.

The minimalist’s goal is to clear a space just big enough to park his car, no more. This also gives him the advantage of privacy, since, after about the third storm, the piles of snow on either side of his car make it invisible from the road. Pulling out onto the street involves saying a quick prayer, gunning it, and hoping for the best. He’s met many of his neighbors this way, mostly to share insurance information.

This person actually enjoys winter’s worst chore—even without benefit of medication—which just goes to show that it takes all kinds. If there’s more than an inch of snow, he’s out there shoveling, and he goes back out every two minutes so that he can “keep ahead of it.” As exercise goes, he figures it’s cheaper than a membership at FitnessWorld and doesn’t require him to wear anything involving Spandex.

Woefully unprepared for winter, this type can’t be bothered to zip up her jacket, lace her boots, or put on a hat every time it snows. Her only goal is clearing a path to the mailbox so that she can get her copy of Meditation Monthly to maintain her inner peace. Last year, her inner peace blew a gasket after the fifth blizzard and took off for Bermuda.

Despite the availability of newer, hightech models, this fellow is still using his old metal shovel, which weighs more than the hood of his ’67 Chevy pickup. Also known as “The Heavy Heaper,” he likes to demonstrate what a he-man he is by putting as much snow as possible on each scoop, a practice that over the years has allowed his chiropractor to buy a boat, put braces on his kids’ teeth, and take winter vacations to places where there’s no snow.

This type tosses snow with the care and precision of a Category 5 hurricane, little knowing or caring whether it lands in the street, in his neighbor’s driveway, or on top of passing pedestrians. What he lacks in neatness he makes up for in speed, which leaves him time to get back to more important winter tasks, like staying on top of his fantasy football league team.

This person falls prey to every late-night commercial for “the easy way to remove snow and ice.” Over the years, she’s purchased ergonomically designed shovels (from the Greek ergon, meaning “sillylooking”), electric shovels (essentially, weed-whackers for snow), and even a remote-controlled robotic shovel, which removes snow quietly, neatly, and just in time to haul the grill out for the July Fourth barbecue. None of these gadgets works, but she keeps trying. Note that she’s also been married four times.

By the end of last January, this guy had developed a seriously bad attitude. Determined to put winter in its place, he bought a propane device designed for those who don’t want to remove snow but to destroy it. He wields this tool while shouting, “Die! Die!” When he returns to the house he mumbles, “I’ll be back …” His friends and family are nervous.

An analytical sort, this person approaches shoveling like the Allied landing at Normandy. He has determined the best pattern to clear his driveway in the least amount of time with the fewest strokes. He also has a precise pattern for arranging lights on the Christmas tree, carving the turkey, and loading the dishwasher after dinner. You don’t want to be stuck talking to him at a party.

his is the season to get out that old pair of skates, to take advantage of a solitary woodland pond where the ice groans like a living being, or just to pull on heavy boots and mittens for a walk to the post office, with the snow creaking underfoot and icy branches chattering overhead. Of course a large part of the charm comes from knowing there’s a warm fireside, literal or figurative, to come home to, and perhaps a bowl of chowder and a skillet of cornbread to stoke inner fires. If winter demands a different way of dressing and a different way of moving, it also requires a different way of eating: hearty, wholesome food that sets this season off from the rest of the year. Our traditional foods—chowders, baked beans, steamed puddings, baked pies, and that most maligned but most delicious (when properly made) of dishes, the boiled dinner—all seem made for cold weather.

—“In Praise of Slow Food,” by Nancy Harmon Jenkins, January 1996

—Denis Leary (born 1957). The son of Irish immigrants to Worcester, Mass., this irreverent veteran of the Boston comedy-club scene is now an award-winning actor and producer. Following the deaths of six firefighters in a 1999 warehouse blaze in his hometown, he launched the Leary Firefighters Foundation, which has raised and donated millions of dollars toward emergency equipment and facilities in Worcester, Boston, New York, New Orleans, and elsewhere.

“Racism isn’t born, folks, it’s taught. I have a 2-year-old son. You know what he hates? Naps! End of the list.”

560 snowy owls that Mass. Audubon’s Norman Smith has caught in the vicinity of Logan Airport over the past 32 years

10/22

earliest arrival of a snowy owl at Logan Airport

32 YEARS maximum lifespan of a snowy owl

owls Smith captured at or near Logan Airport in the winter of 2013–14

1700

acres: Logan Airport footprint, resembling Arctic tundra (minus the terminals and

Logan Airport

-81° lowest temperature (Fahrenheit) that a snowy owl can withstand

1000-3500 miles (round trip) snowy owls fly to and from their Arctic breeding grounds

7000 miles (round trip) flown by one snowy owl outfitted with a GPS transmitter at Logan Airport

270° range through which a snowy owl’s neck can swivel, a quarterturn shy of all the way around

ince 1966, when it was created under the authority of the National Historic Preservation Act, the National Register of Historic Places has been identifying America’s historic resources and listing those most worthy of preservation. That list now includes more than 90,000 properties. Inclusion signifies importance but doesn’t guarantee preservation. As the director of the National Register program for the Massachusetts Historical Commission, Betsy Friedberg (RIGHT) has overseen scores of evaluations. She spoke with us recently about the Register and its role.

“In evaluating properties for the National Register, we look at whether a property or district is significant, and whether it retains its ability to convey its significance,” Friedberg says. Connec-

tions to historic events, architectural developments, or significant people are important considerations. In some cases—an archaeological site, for instance—a resource may be included because of its potential

to reveal information in the future. “Most of the properties we list tell a story of their community,” Friedberg adds. “National Register nominations are the vehicle for conveying that story.”

The Register program relies on information from individuals and communities, which is evaluated by the State Historic Preservation Office before a nomination is prepared. “We look to the community to bring forward properties that might have been overlooked but are significant and worthy of preservation,” Friedberg says. “There’s no greater expert on what’s important to a community than the community itself.”

In some cases, properties that don’t qualify for listing on their own may still be eligible as part of an ensemble of buildings, structures, or landscape features: a National Register district. If you believe that your property merits consideration, Friedberg recommends starting at your state historic preservation office, where useful information may already be on file. Each state has somewhat different procedures for evaluation and nomination, but all are based on guidelines from the National Register. “Many property owners love to do research and have done a lot on their own, which is great,” Friedberg says. “But when it comes to the actual nomination, we may still recommend the assistance of a preservation consultant, who understands what it takes to put together a nomination and can focus [owners’] efforts.”

Every once in a while, a request comes in to consider a property that

is already listed. “Before 1980, there wasn’t a requirement that owners be notified about the designation when a property changed hands,” she notes, “so sometimes people contact us and we can give them a happy surprise.”

Don’t expect a speedy process. “We don’t bring nominations forward until we feel that they’re complete,” Friedberg says. Expect several rounds of questions and requests for more information before your nomination is deemed ready to be brought before the state review board. In Massachusetts, there may be as many as 50 properties ahead of yours in the queue, and the board meets four times a year, voting on five to eight nominations per session. Finally, successful nominations are sent to the National Park Service for review and listing. More info at: nps.gov/nr

LEFT : Built c. 1762, the historic Reeves Tavern (now a private home) in Wayland, Massachu setts, is currently under consideration for National Register designation. In his diary, John Adams mentioned stopping here for breakfast in November 1774.

Because they were meant to be pulled down snowshoe trails, early toboggans could be 8 or 10 feet long, but only about 1 foot wide. Toboggans were sometimes pulled by snow dogs, but most often by a man or woman wearing a chest harness.

Early European settlers adopted toboggans for transport, but soon realized that they had recreational value as well.

On February 5–7, the 26th annual U.S. National Toboggan Championships will be held at the Camden Snow Bowl on Ragged Mountain in Midcoast Maine. Last year, more than 425 teams competed in front of thousands of spectators.

Despite its lofty title, the championships are open to anyone who signs up. The event is believed to be the only organized wooden toboggan race in the country, and perhaps in the world.

The Camden chute is one of North America’s biggest, and the only one of its kind left in New England. It’s open to the public on most weekends, holidays, and school vacation days, weather permitting.

For folks who bring their own toboggans, the fee for using the chute is just $5 per person per hour. Or you can rent a toboggan here for $10 per hour.

Rentals are handcrafted by the local Camden Toboggan Company from native ash.

The 440-foot chute is 2 feet wide and has a vertical drop of more than 70 feet, propelling toboggans at speeds of up to 45 mph. Sleds that stay upright stop by plowing through the snow on Hosmer Pond.

Jack Williams, who was 9 when the Snow Bowl first opened, recalls that his 25-cent membership to the Camden Outing Club allowed him to ride his toboggan all winter long.

Camden’s original chute didn’t last long, as the salty Penobscot Bay air caused rapid corrosion.

It had been out of service for many years when it was rebuilt by the U.S. Coast Guard in 1954. By 1964, the chute had once again fallen into disrepair.

The chute sat in ruins until 1990, when Williams, by then a successful businessman and a prominent member of the Camden community, headed up a project to rebuild it. It was dedicated as the Jack R. Williams Toboggan Chute in January 1991. Williams still rides the chute at least once every winter, as the flag bearer and first rider at the championship event.

On February 24, 1991, the first national championships were held at the Snow Bowl, drawing a small but enthusiastic crowd of about 100 Camden folks. The event was conceived by the Parks & Rec department as a winter amusement for locals, but as word spread, people from all over the country started signing up. In recent years, the championships have raised as much as $60,000, which goes toward the Snow Bowl’s operating expenses.

Many participants build their own sleds and design their own uniforms—or costumes. So you might see a toboggan loaded with pirates or Muppets or football players whiz by.

Tobogganing became a popular sport in the late 1880s. Three modern Olympic sports were born out of downhill tobogganing: bobsledding, luging, and skeleton racing.

More information at: camdensnowbowl.com / toboggan-chute

—compiled by Joe Bills

Long before Europeans arrived here, Natives of the northernmost areas of North America used handcrafted toboggans to transport people and goods across the snow. The word toboggan likely originates from the Mi’kmaq (tobâkun) or the Abenaki (udãbãgan) word for “sled.”

FOR THE WOULD-BE DO-IT-YOURSELFER, OUR GUIDE TO SCALING BACK AND SIMPLIFYING, FROM CHEESEMAKING TO RAISING CHICKENS TO BUILDING YOUR OWN (TINY) HOUSE.

Here in the land of Yankee ingenuity, the desire to be more self-su cient is something like a birthright. Conspicuous consumption may be our economy’s primary driver, but the Puritan ethic still holds some sway. And in these times of uncertainty—environmental, financial, political—many of us are shifting toward simplicity, greener living, and self-reliance. It might be as simple as growing and canning tomatoes or learning to knit or dye wool, or it might even mean going o the grid. The collective do-it-yourself ethos is on the rise.

We may not all want to be homesteaders living o the land, but nearly everyone can still find ways to embrace a more handmade life. presents our guide to the simple life in New England—from cheesemaking and weaving schools to beekeeping and chicken farming workshops—plus essential reads and festivals where you can’t help but pick up tips and meet people who are learning by trial-and-error what works. No matter your interest level, there’s a book or a school or a craftmaking vacation that will inspire you to learn something new.

BY BRIDGET SAMBURG, JOE YONAN, AND AMY TRAVERSO • ILLUSTRATIONS BY TWO ARMS INC.

BY BRIDGET SAMBURG, JOE YONAN, AND AMY TRAVERSO • ILLUSTRATIONS BY TWO ARMS INC.

GILL, MASSACHUSETTS

“These are small and intimate classes, and I really make you feel what you’re doing,” says owner Cliff Hatch. Cheesemaking classes are offered in spring and fall. Students with access to milk from their own animals are encouraged to bring it along to Upinngil’s daylong workshops, or Hatch will supply milk from his herd of grass-fed Ayrshire cows. Beginning classes focus on simpler, softer cheeses such as cream cheese, Camembert, Brie, and blue; there’s also an advanced hard- cheese course (cheddar or Monterey Jack). Participants learn about milk quality and which type of bacteria to use as a starter for each kind of cheese. upinngil.com

CRAFTSBURY, VERMONT

Nestled in the beautiful Northeast Kingdom, Sterling College offers a popular and intensive cheesemaking course in partnership with the experts at Jasper Hill Farm. This hands - on, two-week course covers the fundamentals of artisanal cheesemaking, exploring various styles of cheese as well as the science behind the craft. sterling college.edu/academics/continuing-education/ artisan-cheese-program

WARREN, VERMONT

Linda and Larry Faillace offer oneto three - day courses on their farm in the Green Mountains from May to October, using a variety of milks (cow, sheep, water buffalo, goat) and covering the spectrum of cheese styles, from softer cheeses to more challenging, mold-based types. Students range from dabblers to would-be professionals contemplating a career change. threeshepherdscheese.com

SOUTH DEERFIELD, MASSACHUSETTS

Launched in 1978, this school is run by Ricki Carroll, the self- described “cheese queen,” whose home cheesemaking kits are sold online and in gourmet shops around New England. Carroll teaches a one - day, “101” intro workshop as well as a more - advanced

two - day class that will have you pulling mozzarella and turning out your own Camembert- style rounds. cheese making.com

KENNEBUNKPORT, MAINE

“I knew I wanted to do something surrounded by fire and gardens,” says Jill Strauss, a former schoolteacher and Johnson & Wales culinary-school grad. “It engages all of the senses.” Classes, which tend to run three to four hours, are held May through December in Strauss’s kitchen and in the lush gardens where her wood-fired oven stands. Strauss traveled to Italy to study Neapolitan pizza making, and her classes cover a range of subjects, from pizza to pasta to pie-making. jillyannas.com

Small groups allow for plenty of handson experience in these open -hearth cooking classes. Offered year-round in the historic Wheelwright House, the museum’s two-hour courses are rooted in traditional New England cooking, such as bean soup, cod cakes, roasted meats, and hearth-baked bread (stu-

Sterling

offers an intensive two-week course in cheesemaking in

College

partnership with Jasper Hill Farm in Greensboro, Vermont. The operation’s cheese cave, dubbed “The Cellars at Jasper Hill,” includes seven specially calibrated vaults for ripening.

College

partnership with Jasper Hill Farm in Greensboro, Vermont. The operation’s cheese cave, dubbed “The Cellars at Jasper Hill,” includes seven specially calibrated vaults for ripening.

There’s nothing better than the aroma of bread baking in a wood-fired oven.

A selection of New England chefs and instructors can show you tried-and-true techniques for hearth cooking.

dents leave with a printed cookbook). According to Bekki Coppola, director of education, many students come to learn to use their own traditional hearths, but some are simply hoping to become masters of the campfire. strawberybanke.org

WESTERLY, RHODE ISLAND

Using her reproduction 1775-type fireplace, Linda Madison teaches small groups how to cook over an open hearth as well as in a beehive oven. Classes run four to six hours and are offered only in the winter months. Here students can expect to cook a complete meal using a few simple fireplace techniques and antique utensils. Madison offers a blend of historic and modern recipes. “The emphasis is not on Colonial recipes,” she says. That said, Madison’s classes always make Martha Washington’s spiced gingerbread and Thomas Jefferson’s bread pudding. woodyhill .com/cooking

a more handmade life

Shore. “It’s critical to have a hands-on class,” she says, noting that many students are intimidated by canning and worried about safety issues. “If you’ve never done it, it can seem so overwhelming, but it’s so simple.” Grieco’s classes cover pickling, canning, and preserving and use produce from local farms. carolynsfarmkitchen.com

EAST THETFORD, VERMONT

At this “organic farm with a social mission,” you can not only purchase a CSA

subscription but also learn to put up your veggies in classes on preservation and traditional canning. The spring roster includes a session on salt brining (vinegar-free pickling); fall classes include the basics of home fermentation and everyday meal preparation using fermented foods. Free events include Community Cannery Days in July and September, when participants work with kitchen staff to preserve the day’s crop for a share of the goods. The farm’s half-day sessions are small—no more than 15 students each—and are held in an idyllic setting along the Connecticut River about 12 miles north of Hanover, New Hampshire. cedarcirclefarm.org

Making apple butter in your sleep.

keep a stack of aspirational gardening and craft books by my bed, mostly unmolested, occasionally perused. I like the idea of them. I think to myself, Someday, when I’m a completely different person living an entirely different life, I’ll tackle all these projects. But for now, I have a job and a family, a modest 4-by-4 raised-bed garden, and a stack of unsewn quilt squares stashed away in a cabinet. Here’s one thing I can do: make apple butter in my slow cooker at night, while I sleep. It’s a trick I discovered while writing my book, The Apple Lover’s Cookbook (W. W. Norton), and it goes a long way toward delivering the satisfaction of making something by hand, even if you lack Nearing-esque zeal.

The method is entirely simple: Peel and core 5 pounds of apples (any kind) and cut them into chunks. Add 1¾ cups sugar, ½ teaspoon each ground cinnamon and kosher salt, ¼ teaspoon each ground nutmeg and ginger, 2 cups apple cider, and ¼ cup fresh lemon juice. Turn your slow cooker on high, cover, and let cook for about 1½ hours, stirring occasionally. Now set the lid a bit ajar, to let some steam escape.

That’s it. Get a good night’s sleep: 7 to 9 hours. When you wake up, the house will smell like heaven. Stir the apple butter, then refrigerate for up to 3 weeks. Or you might want to can it: Divide the butter evenly among 6 sterilized pint jars (or 12 sterilized half-pint jars), leaving ¼ inch of space at the top of each. Use a pair of tongs to place the lids atop the jars. Then use your hands to twist the bands into place; tighten most of the way. Gently place the jars in a canner with enough boiling water to cover them by at least an inch. Boil 10 minutes; then gently remove and transfer to a wire rack until the jars cool to room temperature. Test the seal: If it’s tight, tighten the bands completely— you’re done. — A. T.

WESTPORT, CONNECTICUT

“The people who used to know how to do this aren’t around anymore,” says owner Ryan Fibiger. He offers singleday basic butchery classes as well as weekend-long courses on slaughtering techniques. “It’s a really important part of the process,” he says. Fibiger says his students include those who are simply curious, others who are devoted

a more handmade life

hunters, and still more who are farmers, seeking to learn more about processing their own animals. fleishers.com

Lynn Coale is nostalgic about a time when people shopped for meat at the local village butcher shop. As director of the Hannaford Career Center, which offers vocational and technical courses to local youth and adulteducation programs to the general public, Coale says that most American beef is processed in one of four plants around the country. But interest in the trade is coming back, and artisan meat cutters are very much in demand. The center offers intensive, multiweek courses in butchering and poultry processing, including instruction in knife skills, anatomy and physiology, food safety and sanitation, and the humane and ethical treatment of animals. hannafordcareer center.org

HARRISVILLE, NEW HAMPSHIRE

The town of Harrisville in southwestern New Hampshire is a designated National Historic Landmark, the only 19th-century mill town that still survives in its original form. The Colony family ran the woolen mills here from the mid-1800s until 1970, and in 1971, John Colony founded Harrisville Designs to keep the town’s textile heritage alive. The center offers workshops in sweater and Japanese knitting; basic, tapestry, and rug weaving; color design and garment construction; and spinning for all levels. Classes run anywhere from two days to multiple weekends. harrisville.com

Norma Smayda has been weaving for nearly 50 years and running her school for 40 of those. She offers two- and three-day workshops year-round, as well as intensive 15-week programs with an emphasis on traditional and Scandinavian weaves for table linens, curtains, towels, wall hangings, and more. Students come with mixed abilities, and Smayda adjusts the curriculum to each. saunderstownweavingschool.com

Sara Parker Strube works at a loom at Harrisville Designs, a restored mill complex in a historic New Hampshire village, offering classes and workshops in the textile arts, including weaving, knitting, and spinning.

Sara Parker Strube works at a loom at Harrisville Designs, a restored mill complex in a historic New Hampshire village, offering classes and workshops in the textile arts, including weaving, knitting, and spinning.

THIS PAGE : A backyard beekeeper inspects a comb from a thriving hive. OPPOSITE : Students from Imagine That HONEY! in Swanzey, New Hampshire, tour a local bee yard.

THIS PAGE : A backyard beekeeper inspects a comb from a thriving hive. OPPOSITE : Students from Imagine That HONEY! in Swanzey, New Hampshire, tour a local bee yard.

GREENVILLE, RHODE ISLAND

a more handmade life

at his first meeting. Now, dozens of people come out to share tips and solve problems. “Interest has skyrocketed,” says Lafferty, who serves as president of the association. He attributes much of the interest to public concern over colony-collapse disorder. The association schedules courses and “Bee School” sessions throughout the year so that newbies can temper their enthusiasm with knowledge. ribeekeeper.org

SWANZEY, NEW HAMPSHIRE

A beekeeper for 15 years, Jodi Turner knows that it’s impossible to learn everything in one workshop or even over a year. Having a mentor to guide you through various stages and questions is invaluable. “I love to see people

thing comes together.” Her workshops typically begin in March and classes are three hours long, once a month, for six months. imaginethathoney.com

HANOVER, CONNECTICUT

Stuart Woronecki, a professional beekeeper for 12 years, welcomes beginners to learn all the beekeeping basics, from hive maintenance, to equipment, to coping with pests and disease, to honey harvesting and processing. His classes run several times per year at locations in Coventry and Mystic, Connecticut, and after four sessions (two and a half hours each), his students are ready to start off on their own. “It’s challenging to be successful,” he admits. But his classes offer a comprehensive foundation and a community of fellow learners. ct-honey.com

A city boy explains the enduring appeal of his sister’s Maine homestead.

TEXT BY JOE YONAN • PHOTOGRAPHS BY MATT KALINOWSKI

TEXT BY JOE YONAN • PHOTOGRAPHS BY MATT KALINOWSKI

ou’re obviously playing the long game,” I tell my brother-in-law, Peter, after we spend an hour strolling around what he and my sister, Rebekah, consider their “forest farm”: a third of an acre of southern Maine woodland on which they’ve planted chestnuts, hazelnuts, black walnuts, and the berry bushes that love to grow in their shade.

Peter smiles. “Well,” he replies, “someone once said, ‘If I knew I’d die tomorrow, I’d plant a tree today.’”

This corner of the farm—affectionately called “the savannah”—is the latest addition to their North Berwick homestead. It’s all part of a life they’ve dedicated to growing food: not for any sort of retail market, but as a way of sustaining themselves, of building a livelihood from the ground up. It’s a far cry from my decidedly more urban existence, busy with a downtown desk job as food editor of the Washington

Post, with restaurant tasting menus and yoga classes. As a journalist, I’ve spent many years getting closer and closer to the source of my sustenance, but my sister takes it to a level that has both intimidated and fascinated me. A few years ago, when work and personal stresses (plus a book contract) had me longing for a retreat, the first place I thought of was the homestead, and I spent a year there learning as much as I could about how they do what they do, and why.

Ever since I started visiting them about 15 years ago, urban friends have asked me to define “homesteading.” It’s tempting to call it the act of growing your own food, but that doesn’t exactly do it justice. “The farmer grows for what sells and must make a living doing it,” Peter says. “The homesteader grows for what the family wants and needs and how they want that to happen.” It’s about frugality; about a close, respectful connection to the land; about using sometimes-

limited resources in a thoughtful way. It’s the antithesis of one-click Amazon shopping, something I engage in just about every week.

But homesteading isn’t about strict self-sufficiency. As Peter points out, why try to do everything yourself when your neighbor is happy to trade his fresh milk for your eggs? When I visited Peter and Rebekah for a week last summer, the first thing I noticed when we pulled onto their road was a huge sign that read, “Leaves wanted.” And sure enough, neighbors were soon dropping off bags of what became a rich mulch for the garden. It’s about interdependence, not independence.

Peter, now 69, bought his five acres for $1,500 in 1976, a little more than a decade after he’d lived for two months with back-to-the-land gurus Helen and Scott Nearing. With a background in construction, he went on to work for many years as a labor activist and writer; in his spare time, he cleared the land and built all the structures himself. When Rebekah, 63, first joined Peter in Maine, the main house was about the size of a trailer, but they expanded it to about 1,200 square feet, brought the garden up to a quarter-acre, and built more sheds, a cold house, even a yoga studio, all powered by solar panels.

My year with them was transformative: It made me much less likely to shy away from physical labor. It taught me the therapeutic value of what I call “mono-tasking”: taking time to immerse myself in one activity rather than toggling among email, Facebook, and the like. It made me into a gardener, too: Upon my return I sold my condo, bought a townhouse farther from downtown, and transformed my 150-square-foot front yard into an abundant source of food. (My first summer harvest included 30 pounds of cucumbers, 50 pounds of tomatoes, and more chile peppers than I could count.)

I continue to be inspired every time I visit. This last time, the two beamed with pride as they pointed out the beachplum bushes, the persimmons, the native chestnuts. It looked supremely organized into a grid, each tree encircled by logs that will feed the soil and the tree’s growing roots as they decompose. They’re watering it all generously, just once a week, but after a year or two they’ll step back and let nature take its course.

At one spot in the heart of the savannah, Rebekah took a seat on a stump that Peter had left in place—and on which he had carved a simple back. “We call it the throne,” she said. She looked up and around and let out a sigh, and I knew exactly what she saw, because if I squinted I could start to see it, too. She was envisioning tomorrow, and next year, and the next decade, and the next century, each year richer and lusher than the one before as the trees grew at different rates and as the grid gave way to nature’s gorgeous randomness. She saw a canopy of greens and browns and reds shading a forest, sundappled and scattered with leaves and moss and twigs, brimming over with food, forever.

It’s about frugality; about a close, respectful connection to the land; about using sometimes-limited resources in a thoughtful way.THIS PAGE AND OPPOSITE : The author’s sister Rebekah and her husband, Peter, at home in North Berwick, Maine; they’ve been homesteading here for 40 years now.

HARPSWELL, MAINE

Farming, logging with draft horses, gardening, animal husbandry, soap making, raising chickens, fiber arts: Jim Cornish covers it all. The school, located on Cornish’s farm, runs yearround on a trimester schedule, with logging, canning, and maple sugaring in the winter; heavy gardening and building projects in the spring and summer; and winemaking, foraging, and butchering in the fall, among other pursuits. Cornish takes four students per trimester (they live on site) and tailors the curriculum accordingly. stone-soup-institute.org

Koviashuvik

TEMPLE, MAINE

Ashira and Chris Knapt have been homesteading and living off the land for about 17 years. In 2008 they started Koviashuvik (Inuit for “a time and place of joy in the present moment”) to help others learn how to incorporate aspects of homesteading into their own lives. The couple teaches a variety of classes, but the most popular is the three-day family sustainability stay. “It’s an educational vacation for families or couples of all ages,” Chris

a more handmade life

n a beautiful clearing in the woods, surrounded by a timber-frame house and rustic cabins, rests one of Maine’s most peac ef ul spots. Chickens cluck, pi gs root for food, and an expansive garden slowly blooms. At the Deer Isle Hostel, hosts De nn is Carter and A nn Carter -S u nd qv ist welcome guests with warm enthusiasm, pl us hand-p um ped water, composting toilets, solar showers, and nightly c ommunal dinners.

For most of us, the idea of living off the land is daunting, not to mention impractical. But to become immersed in the world of the hostel is an opportunity to taste the simple life, if just for a few days. The farm is open to visitors in summer, and guests are asked to just help keep things tidy—no mandatory hard labor. “[Hosting] keeps me connected to the rest of the world,” Dennis says by way of explanation, though he’s hardly isolated; he and Anneli are active community members and do have Internet access. But guests are asked to refrain from cell-phone use, and there’s no electricity from which to recharge anyway. Musical instruments are encouraged. Solar-powered lights illuminate the main guest house “I just want people to know that this is possible,” Dennis says.

Lack of refrigeration means meals are built around fresh produce from the gardens, eggs from the chickens, cured meats, and c anned tomatoes from the prev ious season’s harvest. Guests are also asked to contribute s omething to the meal. One night in the middle of July, we feasted on a rich tomato s oup with lentils and sautéed ramps and che es e brought by another visitor. After dinner, a campfire.

The solar shower pro ved to be an un ex pected highlight of the stay. The water is piping hot, heated by a nearby compost pile. I filled a watering can, hooked it to a boat line, hoisted it to my desired height and presto, a comfortable shower. I went through two bucketfuls, but only because it was too much fun to quit after just one round. —B.S.

Deer Isle Hostel 65 Tennis Road, Deer Isle, Maine. 207-348-2308; deerisle hostel.com. Rates: $25/pe rson/night; $60 private; $15 kids under 14

says. Visitors can tailor their own time and pick and choose the courses that are most interesting to them. Classes include foraging, basketmaking, composting, solar showering, and knife sharpening, to name just a few. kovia shuvik.com

Twelve years ago Margaret Hathaway and her husband, Karl Schatz, left New York City and headed for the hills,

quite literally. “We knew we wanted to get back to the land,” says Hathaway, who had been the manager of the famous Magnolia Bakery. She and Schatz interviewed people all over the country to determine how to best start homesteading and moved in 2005 to a plot in southern Maine. They garden, make cheese, offer poultry-slaughter workshops, and teach classes on chicken raising, bread baking, and more. The farm’s adorable herd of goats enjoy taking hikes with visitors. living withgoats.com

FROM TOP : Margaret Hathaway and Karl Schatz of Ten Apple Farm in Gray, Maine, with their goats Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain and Chansonetta, who happily lead visitors on Sunday hikes into the woods; canning, cheesemaking, and other homesteading workshops are offered here.

FROM TOP : Margaret Hathaway and Karl Schatz of Ten Apple Farm in Gray, Maine, with their goats Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain and Chansonetta, who happily lead visitors on Sunday hikes into the woods; canning, cheesemaking, and other homesteading workshops are offered here.

FROM TOP : Students at The Farm School in Athol, Massachusetts, unwrap haylage for winter cattle feed; the farm’s Red Devon cows are a heritage breed.

FROM TOP : Students at The Farm School in Athol, Massachusetts, unwrap haylage for winter cattle feed; the farm’s Red Devon cows are a heritage breed.

PROVIDENCE, RHODE ISLAND

This one-stop shop for urban growers and gardeners provides tools, feed, supplies, and classes on small-scale food production, backyard animal husbandry, food preservation, and healthy living. Located in a former gas station near Federal Hill, this cute shop even has beehives and a handsome flock of chickens clucking around the demonstration gardens. cluckri.com

ATHOL, MASSACHUSETTS

Crop planning, greenhouse agriculture, root-cellar preparation, and small fruit-orchard management are a few of the skills taught here. The school offers a year-long program beginning in October, preparing students for serious farming. “In order for people to dive in and walk away with confidence and competence, everybody moves through the program and does everything,” says director Patrick Connors. Students run a vegetable CSA, work with draft horses, study animal husbandry (including cattle and poultry management), and learn to weld and build. Some go on to start their own farms, and others work as farm managers. farmschool.org

BURLINGTON, VERMONT

This six-month, full-time experience offers classes in seeds, soil, field care, harvesting, and equipment. Students rotate through area farms, while also running their own fruit and vegetable operation. The program runs May through October and typically includes 20 to 25 new students each year. learn.uvm.edu/program/farmertraining

WAITSFIELD, VERMONT

With more than 100 hands-on courses per year, Yestermorrow is a longstanding destination for beginners and skilled professionals seeking to launch hobbies or further careers. From two-day introductory woodshop classes to multiweek certificate programs, this school can get you started on furniture making, energy efficiency, timber framing, fine finish plastering, net-zero design, small-house design, even skin-on-frame canoe construction in the Celtic and Inuit traditions. yestermorrow.org

BAKERSFIELD, VERMONT

Peter King has been building and living in tiny houses for years. He envisions whole communities of tiny houses, inhabited by people who are working the land, maybe as farmers or maybe as laborers, living on little money and using few natural resources. In the meantime, he’s teaching others to build their own small houses. Intensive, weekend-long workshops, scheduled throughout the year, accommodate four to twelve people each. vermonttiny houses.com

Two recent books from New England authors give you the 101 on all things homegrown, homemade, and do-it-yourself.

The Backyard Homestead Book of Kitchen Know-How

Vermont author Andrea Chesman teaches readers the essentials of jellymaking, fermentation, sourdough, fresh-cheese preparation, even basic butchery, in this easy-tofollow guide. (Storey, 2015)

WASHINGTON, MASSACHUSETTS

“Timber framing is the traditional way of building with timber on your own property,” says program director Will Beemer. And what could be more DIY than building your own home?

Heartwood offers multiday training in timber grading, framing, finish carpentry, even tiny-house construction. Beemer says that many of his students are looking to build their own gardening sheds or guesthouses, while others are traditional carpenters who want to learn timber framing. heartwood school.com

Homesteading: A Backyard Guide to Growing Your Own Food, Canning, Keeping Chickens, Generating Your Own Energy, Crafting, Herbal Medicine, and More

Abigail Gehring, also from Vermont, takes beginners through the essentials of raising vegetables, fruits, and meat, then touches on everything from basketweaving to irrigation-system design. (Skyhorse Publishing, 2014)

Crafted entirely of sterling silver, our simple-but-chic necklace goes just about everywhere. Highly polished beads by the hundreds are gathered in three twisting, turning strands. 18".

Item #784548 $125 FREE SHIPPING

To receive this special offer, you must use Offer Code: TWIST81

Enlarged to show detail.

Students at the Heartwood School in Washington, Massachusetts, keep the craft of timber framing alive using traditional tools and techniques.

Students at the Heartwood School in Washington, Massachusetts, keep the craft of timber framing alive using traditional tools and techniques.

For 42 years, builders and beginners have flocked to Woolwich to learn from the masters. The most popular workshops—an intensive design/build course and a post-and-beam primer—require a multiday commitment. Design/Build covers everything from site planning and foundation basics to insulation selection and alternative energy sources, plus wiring, plumbing, roofing, and more; Purely Post & Beam takes you from designing to cutting to raising a timber frame. You can also sign up for one-time workshops of just a few hours apiece that will teach you useful DIY skills and crafts, such as how to pour your own concrete countertops; sharpen tools; carve wooden spoons, reliefs, or canoe or kayak paddles; wire your home; and make wooden boxes using hand-cut dovetail joinery. shelterinstitute.com

Once a year, Hancock Shaker Village offers a five-day intensive class on timber framing that resembles nothing less than an old-fashioned barn raising. A small, hands-on group—usually no more than 16 students, plus two instructors—builds a timberframe structure and has it in place by the time the workshop ends. The class is always scheduled to coincide with the village’s annual Country Fair in September, making it an especially festive place to spend several days. hancockshakervillage.org

Bridget Samburg is a Boston-based newspaper reporter and magazine contributor. Her recent stories for Yankee include “The New Yankee Craftsmen” (Jan./Feb. 2015) and “The Restorers” (March/April 2015). Joe Yonan is the food and dining editor of the Washington Post and author of Eat Your Vegetables: Bold Recipes for the Single Cook and Serve Yourself: Nightly Adventures in Cooking for One. joeyonan.com

Feeling DIY Curious? Sample a world of new skills at these popular festivals.

third weekend after Labor Day

Unity, Maine

The Maine Organic Farmers and Gardeners Association offers a multitude of apprenticeship, support, and educational programs for new and established farmers. The organization’s annual Common Ground Fair brings it all together over three days, with dozens of workshops on everything from permaculture gardening and seed saving to goat milking and hoof trimming. (Topics also include cooking, parenting, crafts, foraging, and even dogsledding.) It’s the “Big E” for back-tothe-landers—a congenial, family-friendly gathering of thousands. If you’re curious about the farming life, this is the place to get a taste. mofga.org/thefair

Kneading Conference & Maine Artisan Bread Fair

late July

Skowhegan, Maine