A SPECIAL REPORT ON THE NEW ENGLAND ENVIRONMENT, STARTING ON P. 83

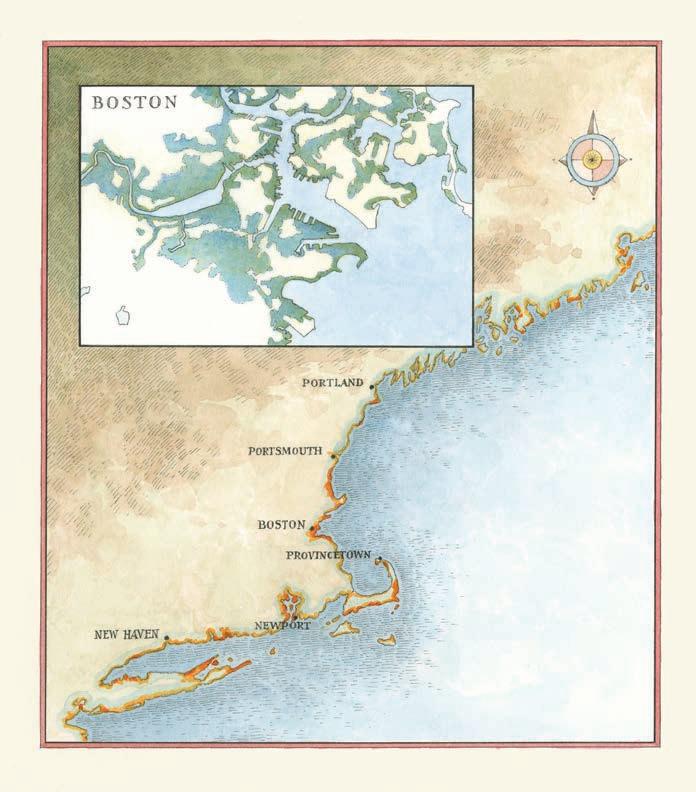

New England was built on the coast. Its fate will depend upon how well we adapt to a future that can no longer be denied.

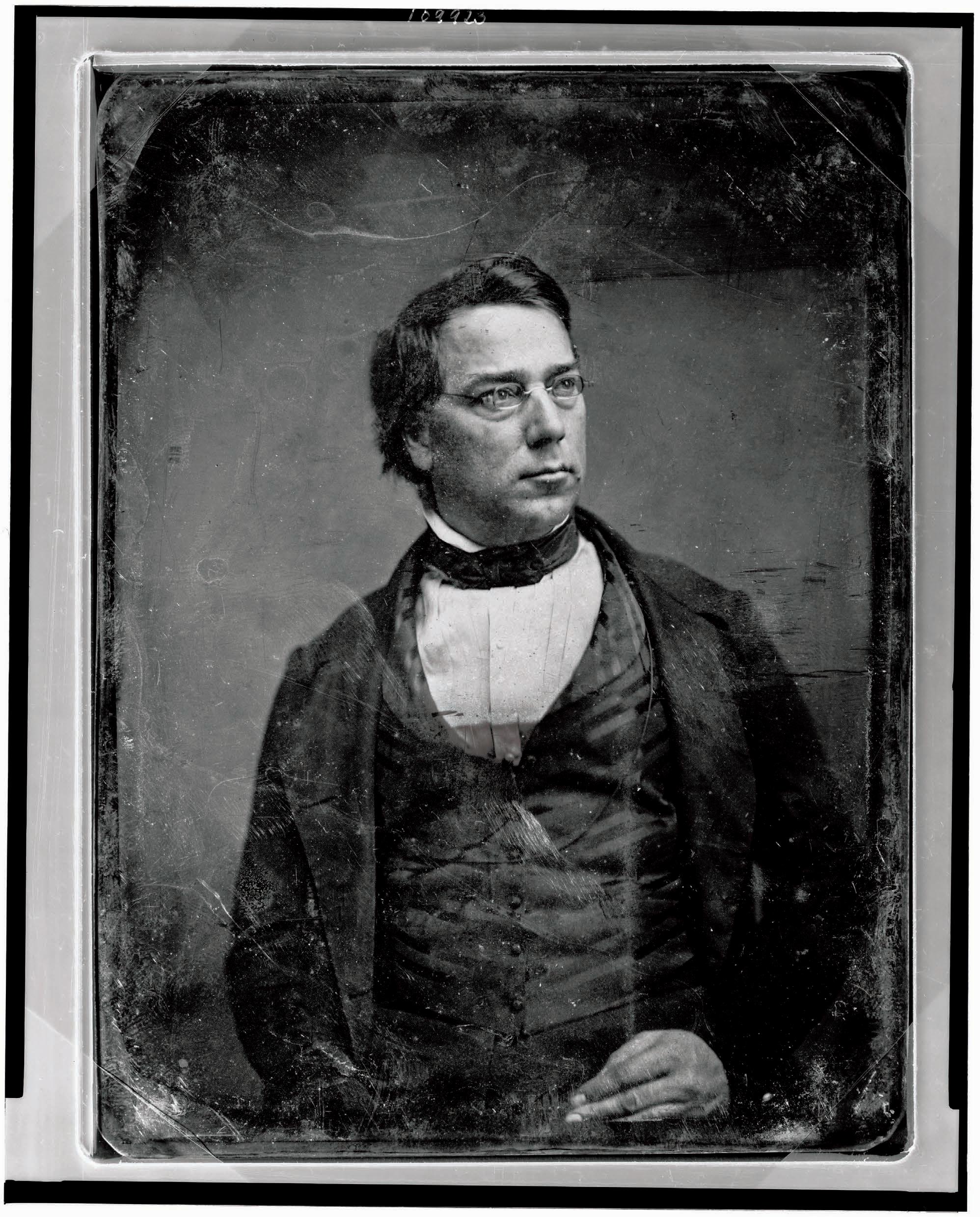

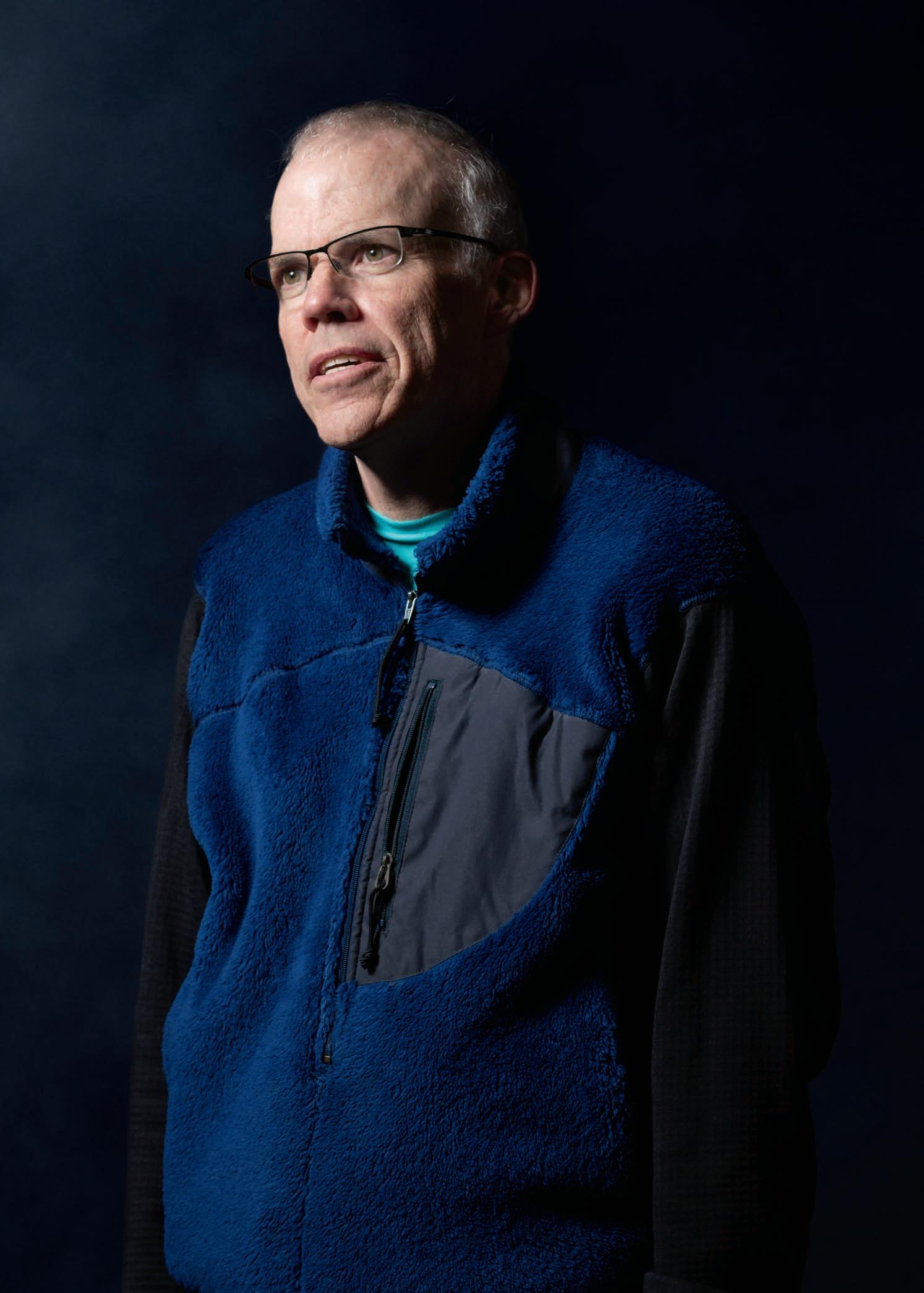

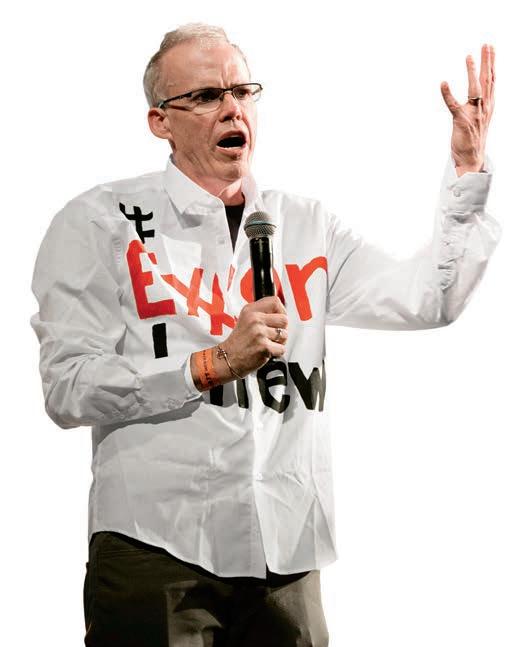

As Vermont scholars from very different eras, George Perkins Marsh and Bill McKibben share common ground in trying to save the planet.

By Leath Tonino and Richard ConniffA look at some of New England’s most memorable contributions to the conservation movement, from Walden to Project Puffin.

From the heart of moose country, a story about who wins and who loses in our rapidly changing climate.

By Cheryl Lyn DybasNature photographer Jerry Monkman creates art that’s also a call to action.

Meet the women of the most dominant college athletic program in the nation, which has galvanized the state of Connecticut for two decades. By

Mike Stanton

Mike Stanton

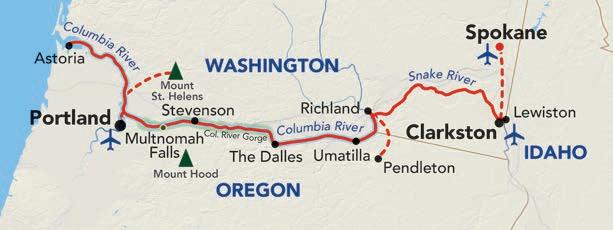

Travel along the epic route forged by Lewis & Clark in complete comfort aboard our elegant new riverboats. Each stop along this captivating journey has its own story, embodied in the history, culture, and beauty of the region. Enjoy award-winning onboard enrichment programs. Small Ship Cruising Done Perfectly®

departments

10

12

INSIDE YANKEE

32 ///

New Hampshire’s Bre Doucette finds interior design solutions outside the box. By Annie Graves

40 /// Open Studio

Creativity takes wing in the colorful bird carvings of Maine artist Roland LaVallee. By Annie Graves

46 /// House for Sale

On Maine’s Blue Hill Peninsula, a pondside cottage holds a century of family memories. By Mel Allen

50 ///

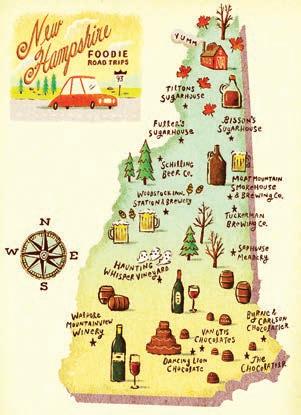

Senior food editor Amy Traverso gives a sneak peek at the delicious destinations featured on season 2 of our TV show, Weekends with Yankee.

60 ///

In her debut column for Yankee, contributing editor Krissy O’Shea celebrates spring on her family farm with a pickled rhubarb and farro salad.

64 /// Could You Live Here?

Small but sophisticated, the river town of Exeter, New Hampshire, feels like a crowd-pleasing coastal retreat ... without the crowds. By Annie Graves

74 /// The Best 5

Visiting these lush indoor gardens will banish the last of your winter blahs. By Kim Knox Beckius

78 /// Out & About

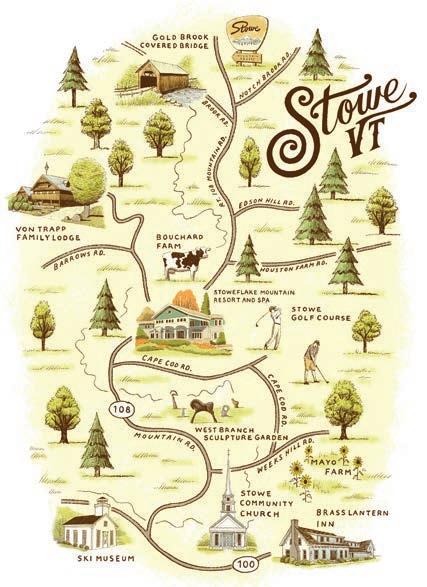

From maple sugaring to sheepshearing, we round up New England’s signature events of the season.

It’s high time to channel our inner Paul Revere.

14

MARY’S FARM

Praying for an ancient barn at winter’s end. By Edie Clark

16

Where the local camaraderie is as important as crossing off your shopping list.

By Ben Hewitt22

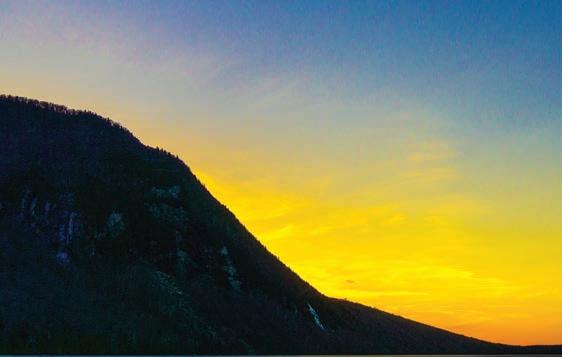

FIRST LIGHT

Embracing spring in an armload of fresh-picked tulips. By Steven Slosberg

28

KNOWLEDGE & WISDOM

A primer on racking up “Yankee Points,” life advice from novelist John Irving, and marathon legend Joan Benoit Samuelson’s eye-opening stats.

30

ASK THE EXPERT

How to find joy in Mudville.

144

TIMELESS NEW ENGLAND

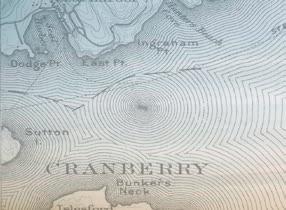

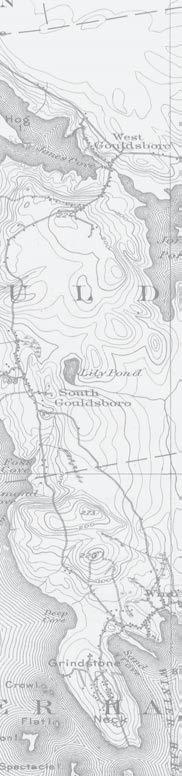

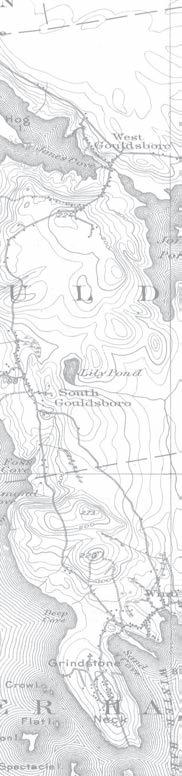

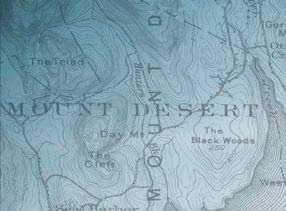

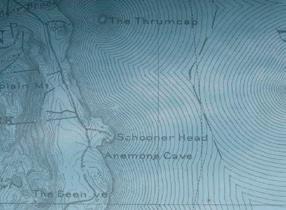

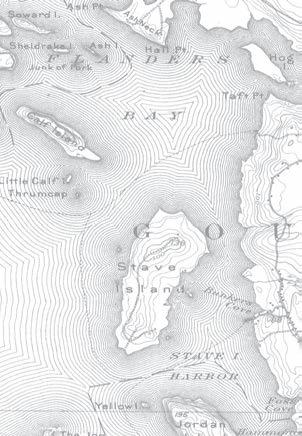

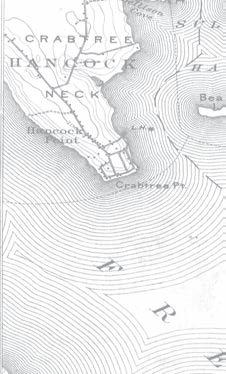

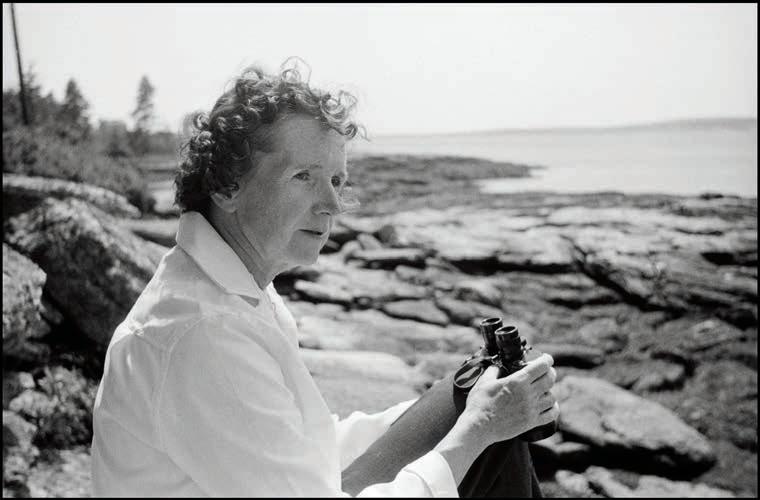

Rachel Carson’s love affair with the Maine coast.

1121 Main St., P.O. Box 520, Dublin, NH 03444. 603-563-8111; editor@yankeemagazine.com

EDITORIAL

EDITOR Mel Allen

ART DIRECTOR Lori Pedrick

DEPUTY EDITOR Ian Aldrich

MANAGING EDITOR Jenn Johnson

SENIOR EDITOR/FOOD Amy Traverso

HOME & GARDEN EDITOR Annie Graves

ASSOCIATE EDITOR Joe Bills

PHOTO EDITOR Heather Marcus

SENIOR PHOTOGRAPHER Mark Fleming

DIGITAL EDITOR Aimee Tucker

DIGITAL ASSISTANT EDITOR Cathryn McCann

CONTRIBUTING EDITORS Kim Knox Beckius, Edie Clark, Ben Hewitt, Krissy O’Shea, Julia Shipley

CONTRIBUTING

PHOTOGRAPHERS Julie Bidwell, Kindra Clineff, Sara Gray, Corey Hendrickson, Joe Keller, Joel Laino, Jarrod McCabe, Michael Piazza, Heath Robbins, Carl Tremblay

PRODUCTION

PRODUCTION DIRECTORS David Ziarnowski, Susan Gross

SENIOR PRODUCTION ARTISTS Jennifer Freeman, Rachel Kipka

DIGITAL

VP NEW MEDIA & PRODUCTION Paul Belliveau Jr.

DIGITAL MARKETING MANAGER Amy O’Brien

YANKEE PUBLISHING INC.

established 1935

PRESIDENT Jamie Trowbridge

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Judson D. Hale Sr.

VICE PRESIDENTS Paul Belliveau Jr., Jody Bugbee, Judson D. Hale Jr., Brook Holmberg, Sherin Pierce

CONTROLLER Sandra Lepple

CORPORATE STAFF Mike Caron, Linda Clukay, Nancy Pfuntner, Bill Price, Sabrina Salvage, Christine Tourgee

BOARD OF DIRECTORS

CHAIRMAN Judson D. Hale Sr.

VICE CHAIRMAN Tom Putnam

DIRECTORS Andrew Clurman, H. Hansell Germond, Daniel Hale, Judson D. Hale Jr., Joel Toner, Cor Trowbridge, Jamie Trowbridge

FOUNDERS

ROBB & BEATRIX SAGENDORPH

PUBLISHER Brook Holmberg

ADVERTISING: PRINT/DIGITAL

VICE PRESIDENT/SALES Judson D. Hale Jr.

SALES IN NEW ENGLAND

TRAVEL, NORTH Kelly Moores KellyM@yankeepub.com

TRAVEL, SOUTH Dean DeLuca DeanD@yankeepub.com

TRAVEL, WEST David Honeywell Dave_golfhouse@madriver.com

DIRECT RESPONSE Steven Hall SteveH@yankeepub.com

SALES OUTSIDE NEW ENGLAND CANADA Françoise Chalifour, 416-363-1388

ADVERTISING: TELEVISION

NATIONAL WNP Media, 214-824-9008

AD COORDINATOR Janet Selle

For advertising rates and information: 800-736-1100, ext. 204 NewEngland.com/adinfo

MARKETING

ADVERTISING

DIRECTOR Kate Hathaway Weeks

MANAGER Valerie Lithgow

ASSOCIATE Holly Sloane

CONSUMER

MANAGERS Kate McPherson, Kathleen Rowe

ASSOCIATE Kirsten Colantino

NEWSSTAND

VICE PRESIDENT Sherin Pierce

MARKETING MANAGER Stacey Korpi

SALES ASSOCIATE Janice Edson

SUBSCRIPTION SERVICES

To subscribe, give a gift, or change your mailing address, or for other questions, please contact our customer service department:

Online: NewEngland.com/contact

Phone: 800-288-4284

Mail: Yankee Magazine Customer Service P.O. Box 422446 Palm Coast, FL 32142-2446

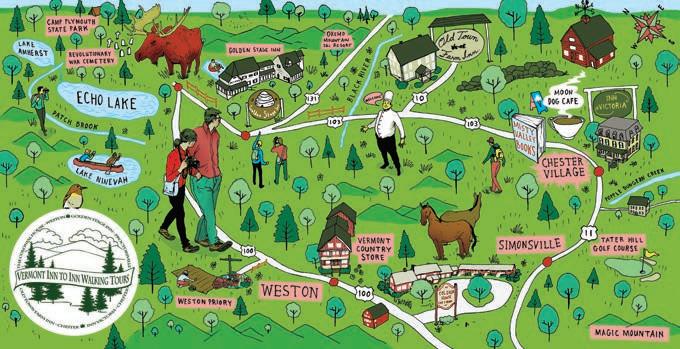

Travel: Best Spring Events in New England

From maple sugaring in March to antiquing in May, here’s what’s worth the trip.

NEWENGLAND.COM/ SPRING-EVENTS

Holidays: Classic Easter Dishes

We round up great brunch, lunch, and dinner ideas for your Easter table from the Yankee archives.

NEWENGLAND.COM/ EASTER-RECIPES

Recipes: Easy Corned Beef and Cabbage

Our go-to recipe is simple, flavorful, and full of Saint Patrick’s Day tradition.

NEWENGLAND.COM/ CORNED-BEEF

Food: Guide to New England Pancake Houses

Favorite regional eateries serve up the pancakes and maple syrup you crave.

NEWENGLAND.COM/ PANCAKE-HOUSES

This is, well, I’m not sure I have the words for what this is. I’ve never been on a ship like this before. The world looks so different from here. But it’s awesome. And the crew is showing me all kinds of stuff — how to raise the sail, read a map, sing songs. They call the songs sea shanties, or something like that. One of the guys told me I had a great voice. Hmmm. This ship will always be a part of who I am. This is me.

TRISTAN SPINSKI

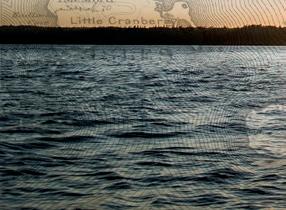

In creating photographs for “Rising Seas” [p. 84], Spinski veered away from the “mythic, ominous landscapes” that usually illustrate climate change. Instead, he looked for scenes with a more familiar, everyday feel—because “if we can recognize these places,” he says, “we realize what’s at stake.” A regular , Mother Jones, and The New , Spinski lives in South Portland, Maine.

LEATH TONINO

George Perkins Marsh [“Two Voices, One Message,” p. 92] was a natural fit for Tonino, who’s long been obsessed with the history of environmental thought. “To look at how we understand our relationship to the planet, you’d best look at Marsh. And the fact that he’s a Woodstock boy—well, that’s just awesome,” says the Vermont-born Tonino, whose first book, The Animal 1,000 Miles Long, is out this summer.

MAAIKE BERNSTROM

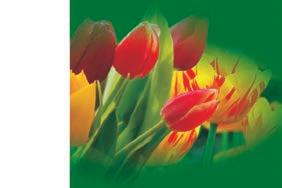

Bernstrom’s photographs of a pick-your-own tulip farm [“Plucky Sorts,” p. 22] represent something of a family affair: Her father wrote the accompanying story, and her daughter tagged along on the shoot (“The biggest challenge was keeping her from picking all the tulips!”). From her home in Rhode Island, Bernstrom stays busy shooting for everyone from Vineyard Vines to Rhode Island Monthly.

JERRY MONKMAN

“My job is simple: I like to play outside, taking videos and pictures that help conserve wild places in New England,” says Monkman, who’s based in New Hampshire. Trying to distill his 25-year career into a handful of images [“Beyond Beauty,” p. 110] was, in a word, “painful.” But he says it was enlightening, too: “It was interesting to see how my work seems to reflect the different periods in my life over that time.”

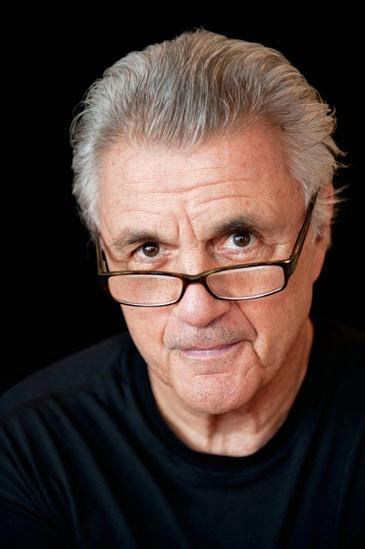

Shown, from left, with photographer Steven G. Smith, Stanton brings a champion’s pedigree to the story of UConn women’s basketball [“Team for the Ages,” 120]. He shared in a Pulitzer for investigative reporting while working at The Providence Journal and penned the best-selling book The Prince of Providence, about ex-mayor Buddy Cianci. These days, he teaches journalism at UConn and lives outside Providence.

CHERYL LYN DYBAS

A veteran ecologist and science journalist, Dybas may reside in Washington, D.C., but she left her heart in New England, where she lived for over a decade. In addition to “walking a mile in their hoofprints” for her feature about New England’s moose [“Ghosts of the Northern Forest,” p. 104], she’s written widely about science and nature for the likes of National Geographic, Smithsonian , and The Washington Post.

On opening your January/February issue, I was brought to tears reading “Leaving Mary’s Farm” [about columnist Edie Clark’s good-bye to her New Hampshire homestead]. I then turned to Edie’s essay “Night Sky.”

I remembered an event from a few months ago, a severe storm that knocked out power for all of Cape Elizabeth—something that hadn’t happened even during the infamous ice storm. At one point, I opened the front door and was dumbstruck by the brilliance of the stars in the night sky. In the 30 years I have lived here, I had never seen the cape completely dark.

How lucky for Edie that she was able to have so many nights with that blessing just outside her front door. God bless Edie and Yankee for sharing Mary’s Farm with us for all these years. Ann Patch Cape Elizabeth, Maine

I live in South Portland, Maine, and my mother, who lives in Connecticut, sends me a subscription to Yankee every year. I called to talk to her on her birthday this week, and she asked if I had seen the new issue and if I’d ever been to the Holy Donut in Portland (of course I have!). I decided to bring her a few samples for her birthday, and we thought you’d like to see the results.

Stephanie and Barbara McSherry

Stephanie and Barbara McSherry

April showers get our goats, Launching everything that floats.

Even gators in the moats

Purchase plastic overcoats.

I thoroughly enjoyed reading “A Movable Forest” [November/ December] by Julia Shipley and Joe Keohane. My mom gets your magazine on a regular basis and passed this article over to me when I came home for Sunday dinner a few weeks ago. Life has been a little crazy recently, but I just got around to reading it this morning and couldn’t put it down.

I’m a native New Yorker who has spent every summer since birth in Spofford, New Hampshire. I recently purchased an apartment in Ditmas Park, Brooklyn, and have lived here for the past year and a half. When I read the story of the Christmas tree farmers and their connection to my current neighborhood, it made me feel all of the warm, fuzzy holiday feelings. It also connected with me on a spiritual level. As a Christian woman, I appreciated the sharing of the farmers’ personal faith story. Thank you!

Rebecca Wells Brooklyn, New York

y son Josh was born on Earth Day 1988, and he grew up with a love of natural places seemingly imbued by fate. I mention him here because it is his generation and the ones that follow that will judge how we have treated this planet. This year Earth Day will be observed on Sunday, April 22, in nearly 200 countries, and we will watch on our TVs and on our computer screens the scenes from rallies warning of a carbon-heavy climate future that seems to become more real by the day.

I write this a week after a “bomb cyclone” in early January battered coastal Massachusetts with frigid waves. We saw gripping photos of firefighters nearly waist-deep in water on Boston’s Long Wharf; we saw images of cars at Gloucester High School encased in floodwaters and ice. Last fall we watched hurricanes lash Texas, Florida, and Puerto Rico and felt relieved we lived here, untouched—and now we were confronted with our own vulnerability. Nobody should be surprised. The climate scientists have warned that over the coming decades, stretching into the next century, New England is poised to suffer some of the biggest temperature increases, the most precipitation, the fiercest storms. So what do we make of it, when it feels as if we just had an unwelcome preview?

I know our readers look to Yankee for beauty, for love of the land, for this region’s traditions and history, and also to meet people from all walks of life who enrich the six states we call home. Yet sometimes the stories that may shake us a bit demand their due—and these are the kinds of stories you’ll find in our special report “Our Land, Our Sea, Our Future” [p. 83]. They show how New England has earned a historic place in the conservation movement [“Two Voices, One Message,” p. 92, and “Green Milestones,” p. 102]; caring about the planet is in our DNA. But they also lay out a cautionary tale in which we all play a part. “Rising Seas” [p. 84] will give you pause. It is meant to. New England was shaped by the sea, and it now must find a way to adapt to what a changing sea may bring.

I believe New England is a place where the world will look for answers to what can seem like unsolvable problems, because many of the greatest minds and innovators live here. They are already designing ways to make a livable future. But we all own a stake in what happens today, tomorrow, 20 years hence. We need to get astride our horses and, like Paul Revere, ride hard and fast, fearless in our warning, driven to spread the truth. Earth days depend on us.

Mel Allen

Celebrating the annual survival of the kind of barn they don’t build anymore.

’ve been told that the barn behind the house here is older than the house, which dates to 1762. Usually a family builds the house before the barn, though I suppose there are always exceptions, and no one was recording what Benjamin Mason did when he came here from Massachusetts in that forbidding, pre-Revolutionary year. Whatever happened with the house, I know for sure that the barn is older than this nation.

The building is tall, 30 by 45, and built on the ground. Inside, the timbers that support the structure are blond, wide at the top and tapered toward the bottom: gunstock posts made of chestnut. The tenons that connect the posts and the beams are big as corncobs, and they, too, are still light-colored, as if they were hammered in there yesterday.

Stepping into this barn is like stepping into an American history book. In there, I cannot help but think of the men who carved these posts out of trees, which grew, undoubtedly, very near to where the barn now sits. On the ground floor, there are two big windowless box stalls on one side and three smaller ones, each with a window looking east, on the other. In the center is a wide aisle that runs the length of the building—at the ends are doorways broad enough to drive a wagon through, which I’m sure was what happened most every day, the horses harnessed and hitched in the shelter of the barn and then driven out into the field, where hay or corn was picked up and brought back in through the other side. In this barn, roosters strutted, hens pecked, horses snuffled, cows were milked, and hay was thrown aloft. Generations of farmers stamped snow off their boots or wiped sweat from their brows, entering the building where their business took place, every day of the year.

It’s quiet now. Leaning as it does to the north and east, the barn has taken on a poetic profile, the sort that photographers and painters love to capture. Inside, the stalls harbor many things. One stall is piled with a collection of shutters and windows, likely saved from the last renovation, which I believe was in the 1950s. Another has boxes of saved magazines, all of them yellowed and swollen with years of sun and moisture, and yet another has a hodgepodge of old wooden kitchen chairs and an enamel kitchen stove, missing the lids.

Since I bought Mary’s Farm five years ago, I’ve managed well with the house, some months counting out my last nickels in order to get done what needs to be done. But the barn has suffered. I’ve been able to take only two swipes at saving it, more triage than repair: When the wide expanse of the back doorframe began to sag, a metal bar was hastily wedged underneath. And in the corner afflicted with dry rot, we cinched the buckled post back upright using a chain and a come-along, which remain in place. These measures may buy time until I can afford more.

Winters are what bring these structures down. The winds and the heavy snows combine to defeat their heritage. All winter, I look out my window to the barn and say silent prayers. In April, I watch the snow retreat and whisper thanks for another year of mercy.

Because of what the barn has to say, I want it to live another century. I dream of sheep in the stalls, the fragrance of lanolin and hay and manure scenting the aisle, and red-backed chickens in the coop, muttering and squawking and flapping when I walk in with the grain.

This essay first appeared in Yankee’s April 2003 issue. Edie Clark’s books are available at edieclark.com.

A great country store offers far more than just things to buy.

e live exactly six miles from what I believe to be the best country store east of the Mississippi. It’s called Willey’s, and it is right in the center of Greensboro, Vermont, a town of 750-ish residents on the eastern shore of Caspian Lake. Willey’s is housed in a rambling white clapboard building, with goods located on three floors (if one includes the basement, which I do, since I’m down there on at least a weekly basis, pawing through bins of plumbing apparatus). There’s a single gas pump on the building’s north side, and a bulletin board that runs almost the entire length of the front wall’s exterior.

Greensboro is one of those rural towns that have carved out a niche for themselves as destinations for affluent second-home owners. Credit goes in part to the lake, which is surrounded by tastefully remodeled “camps” that often run north of $500,000 and are, in most instances, far more commodious than the homes occupied by year-round residents.

But I imagine Willey’s doesn’t hurt, either. Were I in the position of choosing where to invest in a Vermont vacation home, being within a short hop of Willey’s certainly would be a factor in my decision. Amid the store’s fully stocked grocery, hardware, building supply, and household departments, one can procure a very nice bottle of wine, a pair of rubber barn boots, jumper cables,

a box of 12-gauge shotgun shells (and the gun to load them into), a length of two-inch schedule 40 PVC pipe, a wedge of Jasper Hill Farm’s Bayley Hazen Blue (which is made barely two miles from the store), a can of cream of mushroom soup, and a toilet plunger.

It is a rare week that I do not find ample reason to visit Willey’s. And while some of these expeditions do fall under the heading of legitimate need, there are—if I’m being entirely honest—just as many that fall under the heading of “just enough need to be considered legitimate but in truth more an excuse to visit Willey’s.” I know I’m not the only one: Around here, the acronym BTW is understood to stand for “Back Ta Willey’s,” which is what happens when one returns home with a ½-inch copper elbow only to realize that the line one is cutting into is actually ¾-inch. (This is a hypothetical scenario, of course.)

I like visiting Willey’s because I like the drive: the first three miles on a winding gravel road that traces a fastmoving mountain stream; the second three on a secondary paved road that often compels me to brake for meandering chickens. And I like visiting Willey’s because I can never be sure who I’m going to run into, though it’ll probably be someone I know, which means Willey’s is the backdrop for a goodly percentage of my social life. Too, I like visiting Willey’s because I can trade heckles with Rob Hurst, who is quick of wit and chuckle, and whose family has owned Willey’s for 118 years. Once, Rob tried to up-sell me on a branded drill bit intended to bore pilot holes for concrete screws (it didn’t work—I bought the cheaper, nonbranded bit, which did just fine), and ever since then, I like to accuse him of padding his retirement account with

each nut, bolt, and screw I carry home. Which leads me to another thing I like about Willey’s: the prices. I’m not sure how they do it, because the store is too small to have the bulk purchasing power of its larger competitors. For instance, I recently bought a metal electrical junction box for less than half what the exact same box cost me at a local building supply store. Such drastic disparities are not the rule, but in my experience, a 10 to 15 percent discount relative to the competition is common here. And the gas at the single pump is always at least a dime cheaper than anywhere else.

The truth is I’d shop at Willey’s even if the prices weren’t so good, because it is my fervent belief that the world is a better place with stores like Willey’s in it. In my view, these stores offer much more than merchandise; they offer community and kindness and decency, along with a sense of camaraderie and connection to a particular place. It’s no original thinking on my part to wonder if, despite all the convenience it provides, online and big-box shopping sells us short on a whole lot of less tangible—but no less important—benefits.

For my own amusement as much as anything else, I thought to compile a month’s worth of my purchases at Willey’s. I have not edited this list in any way, shape, or form; what you see is what you get. I offer commentary relating to some purchases but not all, because many of the items are too mundane to deserve elaboration.

On October 3, 2017, I buy:

• One tank of gas for our Kia Soul, which is maybe the slowest, ugliest car on the road in 2018, but which I love for precisely that reason.

• Two Chessters frozen custard sandwiches, the empty wrappers of which will end up wadded under the front seats of the aforementioned vehicle. (PS: My older son was with me. I would never buy two for just myself. Never.)

• One schedule 40 90-degree elbow.

• One scrub brush, for cleaning the buckets I use to collect and transport waste milk from a friend’s dairy farm for our pigs.

At the register, I run into our neighbor Andy, who is on his way home from work (he’s a builder). He’s buying a single Otter Creek Backseat Berner, which is one of the beers I favor, and I briefly consider picking one up, too. But there’s something about the combination of beer and Chessters that feels too decadent, so I don’t. Andy and I discuss the weather, which has been dry and warm to the point of peculiarity. But truth is we’d probably discuss the weather no matter what.

and now the lines ran smack-dab across it. And if you’re wondering why I cut the doorway before I rerouted the lines, so am I. Later, I go BTW and buy:

• One cylinder of MAP gas to replace the propane I used to sweat two of the copper elbows before it ran dry. This is actually a blessing in disguise, as switching to MAP gas for the remaining joints, in comparison to propane, is sort of like upgrading from a moped to a Ferrari.

• One ½-inch copper coupling. I don’t want to say why I buy this, because it would reveal what a lousy excuse of a plumber I am.

On October 10, I buy:

• One three-inch paintbrush for applying finish to a set of shelves that I’m building from the spalted maple logs I pulled out of the woods last autumn, and which David down at Lamoille Valley Lumber in

Greensboro Bend was kind enough to saw into live-edge boards for me (since, nearly two years after moving it from our old home, our sawmill isn’t set up yet—a fact of life I’m trying to accept with more than my usual equanimity).

• One box of 1¾-inch trim screws for assembling said shelves.

• One package of Frito-Lay salted peanuts. A weakness, I admit.

• Four 15A duplex outlets. I pass Dave at the hardware counter, but he’s deep into conversation (something about guns, from what I gather), so we just nod hello.

On October 13, I buy:

• One ½-inch-by-3 5/8 -inch hitch pin for the left telescoping sway bar of the tractor’s three-point hitch. The previous pin went missing at some point over the past week or two and, now that I have purchased a replacement, is sure to be found any day.

• Two pints of heavy cream from Butterworks Farm in Westfield, Vermont, to make ice cream for my son Rye’s birthday. Although we are milking a cow, she is late in her

Our pearl necklace is layered with elegance

We’ve suspended three sizable cultured pearls from three polished sterling chains to bring you this clean, minimalist design. A fresh and modern way to add the elegance of pearls.

f abulous j ew elry & g re at p ric es f or mor e than 65 ye ar s

$69 Plus Free Shipping

Cultured Pearl Three-Layer Necklace

18" length. Three 9-9.5mm cultured freshwater pearls. Sterling silver box chain with springring clasp. Shown slightly larger for detail.

Ross-Simons Item #870331

To receive this special offer, use offer code: LUSTER179

1.800.556.7376 or visit www.ross-simons.com/LUSTER

BY STEVEN SLOSBERG

BY STEVEN SLOSBERG

n an early May morning under high blue skies, I am suddenly done in, seduced by an exultant impressionist’s landscape of almost every blooming color under the sun. I am not alone. Crowds of day pickers, arriving with the animated air of county-fair bustle, are only just beginning to make their way down the long dirt road to Wicked Tulips, New England’s only pick-your-own certified organic tulip farm, where 800,000 tulips are blossoming.

They have come here, to the grounds of historic Snake Den Farm in Johnston, Rhode Island, to disappear into color: pale pinks and blush pinks; purples cupped in yellow, purples dipped in ink; oranges richer than any citrus; reds bruised by violet; whites rinsed in apricot, lemon, and magenta. Petals like satin, petals like silk, all bunched in voluptuous rows of knee-high blossoms across five acres.

I take a breath of air scented by earth, flower, and straw-strewn pathways. Tulip lovers are here from seemingly every city, town, and village in Rhode Island; from the far reaches of Connecticut to the west, and well north into Massachusetts. They’ve arrived with children, with spouses, with parents and siblings. They are chatting, en masse, as garden clubs; they are in wheelchairs and in strollers; they are wearing broad-brimmed hats and ball caps; and they’re carrying buckets big and small. They’re here by the hundreds, patiently checking in at the entrance tent and looking about in wonder, as morning nears noon.

I chat with a seasoned gardener from Connecticut who happens to be Dutch. She has come to the farm with her daughter and 4-yearold granddaughter. “I picked exotics, French parrot tulips. They reminded me of a Dutch painting,” she says. “Everything here is a picture. In Holland, you cannot pick at Keukenhof [the world-renowned spring garden in Lisse]. Here, you can take some of this beauty home.”

As the light of sunset begins to spread across the fields at Wicked Tulips in Johnston, Rhode Island, a pair of bucket-toting youngsters pick their favorite blooms from the hundreds of thousands on offer at this one-of-a-kind organic farm.PHOTOGRAPHS BY MAAIKE BERNSTROM

An encounter with Jeroen Koeman, the tall and lean native of the Netherlands who owns Wicked Tulips with his Massachusetts-born wife, Keriann, embodies the frenzy of day picking and daily demands of a farm in its brief window of profitable harvest. With cap slightly askew and his “Wicked Tulips Farm” T-shirt ablaze with the national color of his homeland (orange), Jeroen has dismounted from his tractor to talk tulips with a dozen ladies from the Barrington Garden Club. Shortly into his talk, as he faces the group amid the picking fields, Jeroen is approached by Keriann, also in an orange T-shirt, who gently informs her husband that he’s left the tractor running.

Farming in New England, Jeroen tells the women in Dutch-accented English, is farming in New England weather. Wicked Tulips had hoped to open for the season in April, but a cold March left plants weakened, and this first week of May became the peak week for picking. Tulips are among spring’s most brilliant harbingers, and as neighboring farmers are still out preparing the soil and planting, and the oaks and maples rimming the farm are beginning to leaf out, Wicked Tulips and its customers are having their moment. For tulip lovers, there is no place like it, certainly not in these climes. Wicked Tulips, Jeroen tells his group of listeners, is the only source for certified organic tulip bulbs in the country.

Wicked Tulips evolved from the Koemans’ initial endeavor, EcoTulips, in Madison County, Virginia. Keriann was a mortgage broker and Jeroen was working for a large Dutch bulb wholesaler that had its U.S. base in Virginia. After several years running EcoTulips, however, the couple found the Virginia climate too hot too soon, and the local deer too ravenous, and began looking along the eastern seaboard for more favorable conditions. They briefly tried the

North Fork on the eastern end of Long Island, and they eyed Maine. Then they heard about Snake Den Farm: Located just west of Providence, it’s part of the 1,000-acre Snake Den State Park and home to a handful of small farmers who lease land from the state.

“It’s best to be within 10 miles of the coast,” says Jeroen. “We thought Rhode Island might be the best climate for growing bulbs: cold in the winter, hot in the summer. Bulbs need dry and warm over the summer.”

In October 2015, they began planting the first of what would be 250,000 bulbs in “u-pick” fields, utilizing a Dutch-built planting machine—a Koningsplanter (“King’s Planter”)—shipped from the Netherlands. “In the past we planted up to 60,000 bulbs by hand,” Jeroen says. “[The machine] can plant all the bulbs in one day. By hand it would take almost two months.”

For the first pick-your-own season the following spring, they welcomed some 17,000 visitors to the

tulip farm over three weeks, from late April to early May. The farm has also cultivated what it calls show gardens—meant only for ogling and strolling—as a respite for pickers and a sensory delight for all.

Buckets in hand, the pickers meander among the tulip rows, isolated from the world beyond the fields, carefully selecting blooms. From the picking fields, they head toward the wrapping station. Here, on long work tables outfitted with large rolls of brown paper, farm workers help them lay out the tulips and wrap them in paper bundles. Vases also are available for purchase.

For the record, Keriann says her favorite tulip is “Angelique,” a widely popular white-and-pink variety. Jeroen’s favorite, at first thought, is “Princess Irene,” an orange tulip showcasing the national color of the Netherlands and its royal House of Orange. Then he reconsiders and pronounces “Lalibela” his tulip of choice. “It is orange-red and super-strong. A classic tulip,” he says.

Although tulips are not perennials, Jeroen says, they do have perennial traits. “Whatever you plant will die, but the plant creates a few baby bulbs.” In summer, Jeroen digs up all the bulbs planted in the fall. “These bulbs double in quantity.” But, he adds, only about 10 to 20 percent of those bulbs are big enough to grow a flower in the spring.

The crowds of pickers are blissfully oblivious to the history and farming methods. Tulips are why they came, and tulips, carried by the bundle and armful as they make their way to their parked cars, are why they will return.

For up-to-date information on ticket prices and business hours, go to wickedtulips.com. This year would-be pickers also will be able to use the farm’s website to buy advance tickets, which are required for entry on weekends.

If you’re tired of having your outdoor enjoyment rained on...baked out...or just plain ruined by unpredictable weather...

At last there is a solution! One that lets you take control of the weather on your deck or patio, while saving on energy bills! It’s the incredible SunSetter Retractable Awning! A simple...easy-to-use...& affordable way to outsmart the weather and start enjoying your deck or patio more...rain or shine!

The SunSetter is like adding a whole extra outdoor room to your home giving you instant protection from glaring sun...or light showers! Plus it’s incredibly easy to use...opening & closing effortlessly in less than 60 seconds!

So, stop struggling with the weather... & start enjoying your deck or patio more!

For a FREE Info Kit & DVD email your dvd@sunsetter.com

Yankee was recently in Edgartown, MA, for the Martha’s Vineyard Food & Wine Festival, the annual celebration of the island’s rich food traditions and ingredients. In an event inspired by her recent Yankee feature “The Great Lobster Roll Adventure,” senior food editor Amy Traverso hosted a tasting of three types of lobster rolls with the Lighthouse Grill’s executive chef, Richard Doucette. The festivities led into the Grand Tasting, held on the Great Lawn of the island’s historic Harbor View Hotel.

Yankee was recently in Edgartown, MA, for the Martha’s Vineyard Food & Wine Festival, the annual celebration of the island’s rich food traditions and ingredients. In an event inspired by her recent Yankee feature “The Great Lobster Roll Adventure,” senior food editor Amy Traverso hosted a tasting of three types of lobster rolls with the Lighthouse Grill’s executive chef, Richard Doucette. The festivities led into the Grand Tasting, held on the Great Lawn of the island’s historic Harbor View Hotel.

The MVF&W festival puts a spotlight on local chefs and the farmers, fishermen, oyster producers, and artisans they work with. The festival, which Yankee sponsors, is four days and three nights of unique-to-the-island experiences and dinners with some of the region’s most notable and award-winning chefs, such as Jeremy Sewall (Island Creek Oyster Bar, Row 34), Mary Dumont (Cultivar), and Colin Lynch (Bar Mezzana).

The MVF&W festival puts a spotlight on local chefs and the farmers, fishermen, oyster producers, and artisans they work with. The festival, which Yankee sponsors, is four days and three nights of unique-to-the-island experiences and dinners with some of the region’s most notable and award-winning chefs, such as Jeremy Sewall (Island Creek Oyster Bar, Row 34), Mary Dumont (Cultivar), and Colin Lynch (Bar Mezzana).

Celebrating the people, destinations, and experiences that make the region and Yankee Magazine so unique. Follow along @YANKEEMAGAZINE

Plan ahead and join Yankee at this year’s Martha’s Vineyard Food & Wine Festival. Enjoy access to top chefs from Martha’s Vineyard, Boston, and beyond. October 18-21 For more information go to mvfoodandwine.com

t was my wife who first discovered Yankee Points. One morning not long after we moved to New Hampshire, as she was hanging wash on the front porch, she discovered that wooden clothespins counted two YPs each. From that moment on, we learned new things every day. We learned that you get points for stopping by the dooryard instead of using the telephone. You get points for warming up cold coffee, for going to the dump in a rustedout truck, and for giving misdirections to people with Massachusetts plates.

It’s 100 points a month for each junker visible from the road and 400 points for an apostrophe misplaced in public, as in Fresh Egg’s. Newcomers often garner unexpected points: 1,200 for not posting their property, 1,000 for down-trading a Porsche to a pickup, 100 for a macaroni

and cheese casserole baked for church supper, 50 for staying awake through town meeting, 400 for losing in a tightly contested race for Trustee of Graveyards….

Attitude points may be the hardest to explain. For instance, there are large awards for generosity and for selfishness. If your neighbor’s house burns down, you get 500 points for giving him a blanket and 500 more if it has holes in it.

It takes 75 years, according to reliable authorities, to get the hang of Yankee Points—by which time you might even qualify for the 50,000 terminal points awarded for an open coffin in the parlor for the funeral.

—Adapted from “How to Pile Up Yankee Points,” by Donald Hall, November 1990

John Irving (born March 2, 1942, in Exeter, New Hampshire). The quote comes from Irving’s breakthrough novel, The World According to Garp , published 40 years ago. Since then, he has won a National Book Award and a screenwriting Oscar, seen his books translated into 35-plus languages, battled back from prostate cancer, become a grandfather of four, and been inducted into the National Wrestling Hall of Fame. Next up: fi nishing his 15th novel, Darkness as a Bride

“Everybody dies. I’m going to die too. So will you. The thing is, to have a life before we die. It can be a real adventure having a life.”

Compiled by Julia Shipley

5/16/57

Date that Joan Benoit was born in Cape Elizabeth, Maine

One

Number of marathons that she ran before winning the Boston Marathon in 1979

1983

Year she set a women’s world record (Boston, 2:22:43)

11

Number of years before any woman would beat her worldrecord pace

Number of days after knee surgery that she won the 1984 Olympic trials

Twenty-seven

Age when she took gold in the first women’s Olympic marathon, in 1984

8 Size of Benoit’s running shoes

3:12:27

Time in which she ran the 2017 Sugarloaf Marathon, winning her age group (women 60-64)

146,000 Estimated miles she has run in her career

71

Number of minutes between Benoit and the next Sugarloaf finisher in her age group

Nineteen

Percentage of 180,000 U.S. marathon finishers in 1984 who were women

Percentage of 541,000 U.S. marathon finishers in 2013 who were women

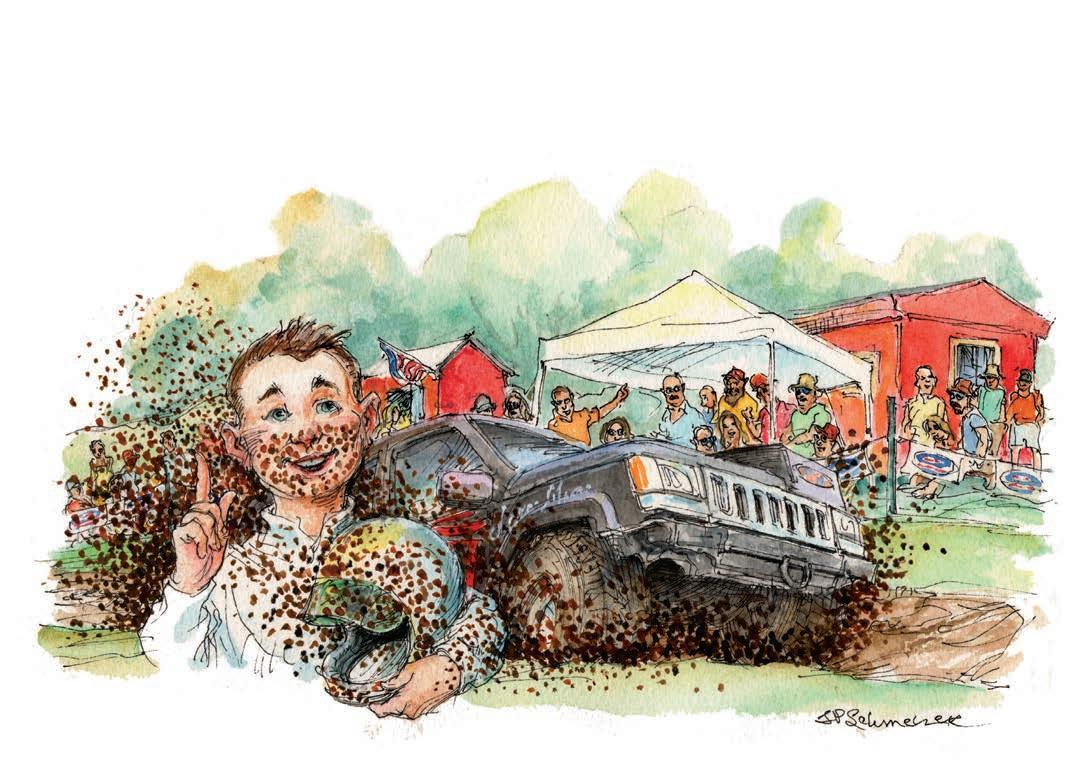

ILLUSTRATION BY J.P. SCHMELZER

BY JOE BILLS

ILLUSTRATION BY J.P. SCHMELZER

BY JOE BILLS

asily overlooked by city dwellers, mud season is all too real for the rest of us in New England. Consider that in Vermont, for instance, more than half of the nearly 16,000 miles of roadway is unpaved. For tips on keeping one’s vehicle moving through the muck, we visited Gilsum, New Hampshire, to chat with 16-year-old mud racer James Munroe. He began competing when he was 13, not long after being diagnosed with non-Hodgkin lymphoma. “[Racing] was something he was excited about, and he needed the distraction,” says his mom, Jessica. “He loved it right away.” Here’s some wisdom we gleaned from this young master of the mire.

“It’s important to know the clearance of your vehicle and how deep the mud is,” says Munroe, who has raced in up to two feet of the stuff at Monadnock Speedway in Swanzey, New Hampshire. “Smaller cars will literally be down in the mud, while larger truck tires kind of skim over the top.” If you don’t know what you are driving into, get out and look.

Traction is key when driving in mud. If your vehicle has four-wheel drive or other tractioncontrol equipment, mud season is exactly what it’s meant for. “Lock in the four-wheel drive, and don’t forget to lock the hubs,” Munroe says, and laughs. “You never want to find out you aren’t in

four-wheel drive once you’re already in the middle of things.”

When it comes to mud, you’re better off blazing your own trail if the ruts have gotten too deep. “It all depends on what is already there,” Munroe says. “Sometimes the ruts can be good and will keep you on track, but I’m always ready to cut a new path if I have to.”

Your goal should be to get through the mud with as steady a hand as possible. Maintain momentum, and avoid stomping on the gas or the brakes. Keep moving in as straight a line as possible to minimize steering. If you start to slide, ease off the gas and turn the wheels slightly into the skid. Don’t worry about the tires spinning so long as you are moving forward. If you start

losing forward momentum, ease off the gas until the tires start to grab again.

When you’re driving in mud, the No. 1 thing to avoid is coming to a full stop. If you do lose all momentum, turn your wheels from side to side, to see if traction can be gained in another direction. You can also reverse out, or rock the car from forward to reverse in an attempt to get it moving. “On the track, I only got stuck once, and it was bad,” Munroe admits. “Embarrassing. I was suspended on the mud, with all four tires off the ground. If I had it to do over again, I would have stayed up on one of the banks, to give the tires something hard to chew on.”

Mud gets everywhere, and it can be as hard as cement when it dries. As soon

as possible, wash the mud off your car and check carefully for any damage. “I use a pressure washer after a race, and even with that, cleaning can take a long time,” Munroe says. “And it isn’t just the mud. Rocks can get thrown up and lodge in the springs or in the brakes. It isn’t fun, but the longer you wait, the worse it gets.”

As for keeping all that mud out of the house, we checked in with Munroe’s mother, Jessica. “Luckily, his clothes don’t get nearly as dirty as the truck does,” she says. But sometimes it’s unavoidable. In those cases, it’s a problem to be dealt with outdoors. “Mainly it’s his boots that get the worst of it. Thankfully, we can let the mud harden up and hit them together. If it’s really bad, the power washer will do the trick.”

By ANNIE GRAVES

Photographs by KELLER + KELLER

By ANNIE GRAVES

Photographs by KELLER + KELLER

re Doucette’s farmhouse, built in 1846, would be scarcely recognizable to its original family, but its breezy style and witty design solutions have become familiar to more than 100,000 monthly online visitors. “I started decorating when I was 13,” says Bre, smiling, as she stands in the kitchen of the Candia, New Hampshire, home. “Sometimes I would change the look of my bedroom three times in the same afternoon. I just had to get it out.”

These days, an avid audience regularly checks out Bre’s blog, Rooms for Rent, along with her Pinterest and Instagram postings, to see what she’s changing next, and how she’s doing it. Is she repainting the kitchen island? Adding bold pillows to the slipcovered couch? Tweaking the flowers on the dining room table that her husband, Jesse, built and that she stained to beachy perfection? Or building an outdoor patio to offset their newly shingled barn?

“I was always creating vignettes on my dresser,” says Bre, now 32, “always drawing room sketches at school.” When her parents bought an early Gateway computer and told each of the kids they could pick one game for it, Bre chose interior design software. “My parents said, ‘It’s not really a game,’ and I said, ‘Well, it is for me.’”

The game became reality in 2011, when Bre and Jesse bought the Candia farmhouse. It had been updated by a contractor who wanted to flip it, so the basics—including new plumbing and electrical—were in place. And with two acres abutting 100 acres of conservation land, there was plenty of room for the couple’s two young children, Carter and Dannika. “When we found this, we just knew,” she says.

But while they loved the character of the house, “at the time it was a lot of brown, mustard brown, and more brown inside,” she says. “The house felt covered up. I wanted to use colors that would complement the interior, instead of just being something to put on the walls.”

A year later, Bre started blogging about the details: the colors she was

trying out, the bargains she was find ing, the fun of it all. “With the blog, all of these dormant ideas were coming out. All the dreams I had as a kid could be expressed, and there was a commu nity that soaked it up.” The beautiful results—a style that Bre calls “clean farmhouse”—brought both subscribers and sponsors.

Today, the first thing you notice upon entering the light-soaked kitchen is a floor-to-ceiling dish rack filled with white ironstone platters and weathered cutting boards. “It was just a blank wall, bowed out because the chimney behind it had settled,” Bre recalls. “It drove me crazy because we had three doors lined up on that one wall: bathroom, basement, and back hallway. I wanted to do something that felt like it had always been there, and to distract from the

wall of doors. It took a year to convince my husband—it was a big job. We had to cut out the chimney!”

The rack is backed with beadboard; thin strips of wooden screen strapping create the rails. “I didn’t want anything too heavy,” she says. “The wall felt heavy enough, with all those doors.” Beadboard wraps the kitchen island, too, and repeats as the backsplash. And to make the stock cabinets seem less “stocklike,” the couple attached corbels—which

1 Bre made the kitchen’s “Bakery” sign from a barn board that had been squirreled away down in the basement. It proved to be the perfect solution after everything else they tried on top of the dish rack looked wrong. “It’s nailed to the wall, and it’s staying with the house!”

2 This dining room dresser, which had belonged to Bre’s mother, was the first piece of furniture Bre and Jesse tackled together. After sanding it down to look like weathered oak, they applied an “Early American” stain for the first layer and put a “driftwood” stain on top of that. A light sanding blended the two stains together.

3 The dining room is painted in Glidden’s Wood Smoke, a Better Homes & Garden 2012 top pick for paint colors.

also brace the open shelving added near the back entry after every other attempt at placing furniture there blocked the doorway.

An entire wall of gray chalk paint, which Bre mixed herself, evolved as a solution to another problem: The wall abutting the dining room bumps out, creating a wall on two planes. “I wanted to turn this quirky thing into something that looked purposeful and was pretty as well,” she says. “I’ve grown tons in figuring out how to disguise unsightly things.”

With each lesson Bre has learned, her readers have gained insights into thinking outside the box. Even clutter offers creative opportunities. Vintage wooden crates stashed under Jesse’s hand-built kitchen bench hide the kids’ boots and shoes; in the kitchen’s back entryway, hooks are hung at two distinctly different heights, with numbers stenciled beside them. “I wanted it to

feel like an old schoolhouse,” Bre says. “Every day, the first thing my son does when he gets home is hang up his jacket and backpack and put his shoes away.”

The kitchen flows effortlessly into the dining room, which is the only room that hasn’t been repainted more than once. “It feels like it’s the color it was always meant to be!” Bre exults. But she points to a once-problematic jog that Jesse retrofitted with a woodstove, hearth, and mantel. “It was a funky corner in the dining room—we always thought that somewhere down the road, we’d have to square it off. But a few months after we moved in, he decided we needed a woodstove, and it was the perfect place to put it.” That first winter they lost power eight times, so the solution was pretty and practical.

Bre indicates the half walls topped with columns that divide the dining and living rooms. “This was the selling point for me,” she says. The feeling

of open space, the uncluttered style … it’s an oasis of calm. “Weathered wood, white, and anything slipcovered—it’s what I’m known for.”

Yet we’re also in the presence of a wealth of how-to projects and low-cost fixes. Bre sanded and restained the coffee table (built by Jesse’s grandfather), stenciled a faded Union Jack flag on the corner table (made by Jesse), fashioned a coatrack from a piece of driftwood, and even painted the two dreamy abstract landscapes beside the

couch (“I’m not a painter, but I think I just found a new hobby”).

And yes, the tutorials appear on her blog. You, too, can affix barn boards to the wall behind your bed to create a headboard. Paint stripes on drop-cloth curtains. Make a farm table from two-by-sixes. Bre’s advice, widely applicable, is “Keep going until you see what you like.”

She points to the master bedroom’s “Rooms for Rent” sign, the one that inspired the name of her blog. Made by Pottery Barn, the sign was originally priced at $229. Bre kept an eye on it until it landed in clearance for $30. “Anyone can decorate, and it doesn’t have to be expensive,” she says. “It’s knowing where to look and what to find. That sign represents my passion: decorating rooms with ideas that people can ‘rent,’ in a manner of speaking. This house, with its dilemmas, forced me to look outside the box for solutions—that’s been my journey with it.”

She pauses, and looks around the airy farmhouse kitchen. “I wouldn’t change one thing about that.”

Flat-finish latex paint, mixing container, unsanded tile grout, paint stirrer, roller or sponge paintbrush, 150-grit sandpaper, chalk, sponge

(1) Start with flat-finish latex paint in any shade. For small areas, such as a door panel, mix 1 cup at a time. Pour 1 cup of paint into a container. Add 2 tablespoons of unsanded tile grout. Mix with a paint stirrer, carefully breaking up clumps. (2) Apply paint with a roller or a sponge paintbrush to a primed or painted surface. Work in small sections, going over the same spot several times to ensure full, even coverage. Let dry.

(3) Smooth area with 150-grit sandpaper, and wipe off dust. (4) To condition, rub the side of a piece of chalk over entire surface. Wipe away residue with a barely damp sponge.

—From Martha Stewart Living , January 2007

The wood carvings of Maine’s Roland LaVallee bring springtime inside when we need it most.

hen I first arrive in the coastal town of East port, Maine—practically in Canada—fields of wild lupine are blooming across the countryside, bursting into pink and purple spires. But by the time this story appears, we’ll be staring down winter’s long white spyglass, look ing to glimpse the first signs of spring.

Regardless of the season, an uncommon number of birds can be found roosting just blocks from the center of this artsy-vibe town, population 1,300. While Roland LaVallee’s Crow Tracks home and studio might look like any other charming gray clapboard 1860s New Eng lander, behind its laid-back façade there’s avian anar chy—albeit the carved-wood sort.

The front room flaunts the evidence, floor to ceiling. An imposing pileated woodpecker guards the heights over the fireplace. A white heron crouches low on the mantel. Seabirds stalk along hunks of driftwood, and crows clasp folded dollar bills in their beaks. Shelf upon shelf of tiny golden birds cling to stumps of polished wood, and chickadees sidle up to phoebes. It’s the quiet est bird sanctuary you can imagine.

With his neatly carved brown moustache and care fully whittled beard, Roland resembles some of his more human sculptures, although most of these reflect his humorous side—which bubbles up easily when asked what brought him to Maine.

“Connecticut was too full of people,” Roland says with a dry twinkle, recalling why he moved here in 1977, then worked in Eastport’s textile mill for the next 20 years. All the while, he carved wood, a pastime since childhood, when he would create spears, decoys, and “little faces out of pine—the same things I carve now.”

But in Maine, there was an additional incentive. “There was always the chance you’d get laid off at the textile mill,” he recalls. “I had books on making decoys—I thought I should make some and see what happens, see about selling them in the gift shops on Route 1.” He smiles, remembering those early carvings. “My decoys were funky as can be. I was using house paints, learning as I went along.”

We walk to the adjacent room, where Roland cuts raw chunks of pine into rough bird shapes, then shaves more and more wood away until the bird within emerges. The workshop is warm with the colors of wood, the smell of sawdust. “Pine spins in my hands easy,” he says. “I work with stuff that works well with me.”

This includes a jumble of favorite tools housed in a battered trunk in the kitchen, where Roland sits to paint birds at a glass-topped table looking toward Passamaquoddy and Cobscook bays, across to Franklin Roosevelt’s summer place on Campobello Island. (The view is breathtaking; this is “where the light is,” he says.) Roland lifts the trunk lid: X-Acto knives, delicate chisels, small paintbrushes, and a refined wood-burning tool for adding feathers and other details, bought in the late 1980s. “I’ve kicked out about 8,000 birds with it,” he says.

The evidence is all around: There are currently about 435 birds in the front room, Roland estimates. Some years he turns out lots of chickadees; other years he’s busy working on big

It’s a long winter. We’re surrounded by cold water. Spring doesn’t come until maybe the last week in May.”

When spring does finally arrive, Roland will work outside under the apple tree, carving on a chopping block that overlooks the terraced back garden that he tends with his wife, Barbara Barrett. He’ll move around the yard with the sunshine, following the light. “We get a lot of wind,” he says. “But the good weather is nice … when it comes.”

commissions. Regardless, he says, “fall and winter I work on my inventory. I know, for example, that I’ll need six puffins, six herons. January comes, and I start doing the weirder stuff—clams, mermaids, monsters.

Back in the studio, Roland cradles a snowy owl in his hands, pointing out details of paint and carving. “I get up every day, carve a different bird.” His face lights up with this bird in hand. “I’m having a good time.”

Prices range from $40 for a small crow sculpture to $700 for a custom bird piece. For more information, call 207-8532336 or go to crowtracks.com.

“Pine spins in my hands easy. I work with stuff that works well with me.”

BEST-SELLING STYLE

FIND YOUR PERFECT FIT

US sizes 5-11 with half sizes 5.5-9.5

Three width fittings: Hotter Comfort Fit a US Medium/wide/D-E fit

Extra Wide Fit US Wide/EE fit + Triple E fitting a US Extra Wide Fit

Styled for ultimate comfort, with its supple leather and nubuck uppers, cushioned foot bed and plaited touch-close strap, it’s easy to see why Shake is one of our best-selling casual styles.

Every single pair of Hotter shoes is designed around a host of signature comfort features, so that from the moment you slip them on in the morning to the moment you take them off at the end of the day, every step will be a pure delight. Using only premium materials such as butter soft leathers and super-soft suedes, combined with sumptuous cushioned insoles, collars and tongues, plus extra wiggle room for toes, we guarantee a perfect fit straight out of the box.

We would love to offer you the opportunity to sample our Comfort Concept© features for the very first time with Shake, one of our best-selling favorites, at an unbeatable price. Experience true comfort, carefully designed and crafted in Britain, with free tracked shipping direct to your door.

are handmade using the finest quality ingredients,and are fully cooked before packaging. One dozen delicious pierogi are nestled in a tray, making a one pound package of pure enjoyment!

are HANDMADE using the finest quality ingredients, and are fully cooked before packaging. One dozen delicious pierogi are nestled in a tray, making a one pound package of pure enjoyment!

You can get Millie’s Pierogi with these popular fillings:• Cabbage • Potato & Cheese

• Farmer’s Cheese • Blueberry • Prune

• Potato & Cheese with Kielbasa • Potato & Onion

Turns any day into an occasion – order today!

Box of 6 trays-$42 • Box of 10 trays-$63

Box of 6 trays-$46 • Box of 10 trays-$69

Polish Picnic-$45 • Polish Party Pack-$69

Polish Picnic-$43.50 • Polish Party Pack-$66

Kapusta & 5 trays–$45.50 • Plus Shipping

Kapusta & 5 trays–$49

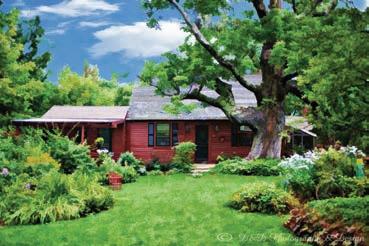

Kill Kare, in the words of one recent guest: “What a jewel of a house, floating on the lake ... a place of daydreams and tranquility.” BELOW : The wraparound porch, looking out on Walker Pond.

Perched on the shore of a pond on Maine’s Blue Hill Peninsula, a family cottage holds a century of memories.

Yankee likes to mosey around and see, out of editorial curiosity, what you can turn up when you go house hunting. We have no stake in the sale whatsoever and would decline it if offered.

hile most of us live in a house, a few of us—the luckiest ones—know that sometimes a house can live inside us as well. On this day in late June, we are sitting on an expansive porch alongside Walker Pond in Sedgwick, Maine, hearing the story of a summer home that has been a part of Catherine Larson’s life as long as she can remember. Her husband, Dan, joins us and sprinkles the conversation with anecdotes about his own relationship with the cottage that Catherine’s grandfather built and named Kill Kare because, Catherine explains, “you came here and felt all your cares melt away.”

There is a hint of salt air on the breeze; the bay is only a few hundred yards distant through the woods. Roses line the porch. Catherine tells about her many summers here, fishing and picking blueberries and paddling canoes, rowing boats, learning to swim and then testing to see how far her endurance could take her. There were campfires and watching the sun setting and the dark settling into the quiet and the stars filling the sky.

The story of Kill Kare begins in the humidity and heat of the Baltimore–Washington, D.C., region, from which Catherine’s grandparents, Wilbur and Catherine Smith, followed other wellto-do families to Maine’s Blue Hill Peninsula in the early 1900s. There, they found bracing, clean air in a cluster of cottages in Brooklin that came to be known as the Colony.

Wilbur Smith built his cottage by the sea in 1915, but he was passionate about freshwater fishing, too. One day he rowed his boat to the middle of Walker Pond, one of the very few clear and deep freshwater ponds around, and saw two great boulders along the shore. He decided he would build on those boulders a getaway from his ocean getaway, and he’d sit on a wraparound porch and feel as if he were all but floating. He built the shingle-style cottage in 1917.

His wife scoured flea markets, antiques shops, and local farms for the rustic furnishings that gave the pond cottage a personality that remains, even as electric lights replaced candles and kerosene lamps, and showers were added and a bedroom became a dining room. “My grandfather called my grandmother ‘the hostess to the coast,’” says Catherine, and she recalls it was rare for the cottage not to be filled with family and friends.

All that was before Catherine’s mother, Grace Hooper McNeal, started a girls’ camp called Four Winds in 1946 on nearby farmland that Wilbur owned. Then came the summers that worked their way into Catherine’s life, first as a young child, then coming of age surrounded by campers and counselors. The camp became both home and family, and Kill Kare became a place to rest, to host reunions, to house campers’ parents. Camp Four Winds ran for 57 seasons before closing in 2002. The family sold it to a neighbor, an avid environmentalist who, Catherine says, “has cared for the land.”

Catherine and Dan take us on a stroll through the cottage, which becomes a tour through generations of family memories: the framed menu from a gathering in 1932; the fish mounted above the great stone fireplace, which leads to stories about bass that seemed to leap from water to net to frying pan. There’s a photo of Catherine’s son as a boy; he’s now in his early

30s. “We talked long and hard with him about selling,” Catherine says. “He only comes now for one week. And we’re not getting younger.”

The six bedrooms speak of the carefree days of summer, when friends and family seemed to arrive in a happy stream; the lack of closets speak of the casualness of it all, of unpacking and simply hanging clothes on hooks. Catherine points out the kerosene lamp her grandmother designed, how she wanted it homey but also with a hint of the wildness that attracted them in the first place.

When we return to the porch, a loon splashes down in front of us. The sun slants across the water. The quiet is everywhere. “How many family discussions have we had here?” Catherine muses. “This has always been a place for healing with nature. It’s where we came when we lost loved ones. It’s where we have always felt at peace.” Then she adds, “It is heartbreaking, but it’s time.”

“We want to leave on a high note,” Dan says. “We hope we find a family with kids who can grow up here and be careful with the environment. Someone who will want to be here for many generations.” With shorefront building regulations today, he says, a cottage like this, perched on boulders, can never be replicated. “You can buy many places on the water, but the soul that this house has speaks to some people. That’s what we hope.” —Mel

AllenThe Larsons’ property is priced at $1.2 million and includes 40-plus acres, 350 feet of waterfront, and—in addition to Kill Kare—a modern two-bedroom carriage house apartment just up the road. For more information, contact Jill Knowles of the Christopher Group in Blue Hill, Maine, at 207-248-2048.

VERMONT CHEDDAR-ALE DIP (RECIPE, P. 54)

VERMONT CHEDDAR-ALE DIP (RECIPE, P. 54)

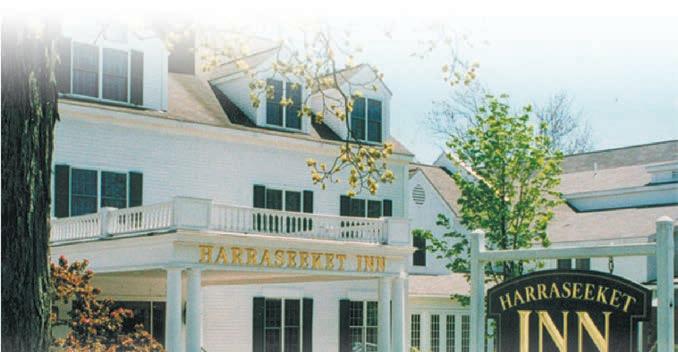

Join food editor Amy Traverso for a delicious behind-the-scenes tour of the places and people featured on Weekends with Yankee our WGBH television series, now in its second season.

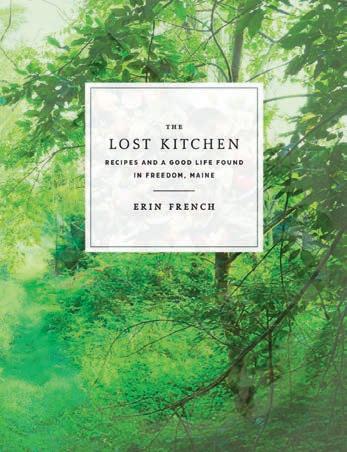

he drive from midcoast Maine to the Lost Kitchen is a northwesterly trek through woodsy back roads punctuated by stone-walled fields and a glimmering string of lakes and ponds. In a van loaded with camera equipment, we’re racing to reach New England’s most sought-after restaurant before diners arrive. As we head inland, the towns’ names turn from Rockport and Northport to abstractions: Liberty, Hope, and, finally, Freedom.

Finally, Freedom could be the title of chef Erin French’s memoir, should she ever write one. She was a young kid here, flipping burgers in her dad’s diner, before leaving for bigger adventures in Boston and California. After having a child, she returned to Maine and picked up baking and catering jobs, mastering wedding cakes and dinner for 50. In Belfast, she drew together those skills, all her courage, and a preternatural talent for making things beautiful—dishes, table-

scapes, rooms—and opened the original Lost Kitchen with her husband, first as a semisecret weekly supper club in her apartment and then as a real restaurant in a flatiron building on Main Street. The menu was dictated by whatever was local and in season; the seafood, vegetables, fruit, cheeses, and meats all came from Maine. Her avid customer base was only partly local, as word quickly traveled far beyond midcoast Maine. But then everything fell apart: Her marriage imploded and took the restaurant with it. French and her son came home to Freedom in 2013 to figure out what to do next.

The answer that seemed so unlikely five years ago looks inevitable now, in light of her success: to take over the first floor of Freedom’s newly renovated 1834 gristmill and turn it into a restaurant. To see if those adoring crowds would drive 17 miles inland to taste her food again.

Freedom is a tiny place. There were 716 inhabitants here in 1870, and that number has barely ticked up since. But once

word got out about a seemingly magical restaurant in middle-of-nowhere Maine, the diehards came back—and then the world came calling. The new Lost Kitchen opened on, appropriately enough, Independence Day 2015, and soon everyone wanted in. By 2017, demand had reached the point that when the reservation line opened for the season at midnight on April 1, the town’s phone system became so logjammed that it set off alarms at the fire station. Thousands of people were hitting redial, redial, redial. At about 1 a.m. French posted on Facebook, sounding like an eyewitness to a flood: “This is bigger than us ... thousands of calls pouring in. Doing our best to keep up ... please bear with us....”

French knows that those who are lucky enough to nab these coveted spots are expecting the meal of a lifetime. They’ve worked hard to get here, and she’s fiercely protective of their experience. So when a stranger walks into the restaurant with a tall tale about a phone message left by ... he can’t remember the chap’s name, but he said there might be a cancellation tonight ... a staffer politely sends him on his way. “We don’t have cancellations,” she tells me, “and we’re all women here.” (There is one male dishwasher, TJ, but he mostly sticks to the basement prep kitchen.)

Our small TV crew knows that getting permission to film here is the proverbial golden ticket, so we all do our best to remain unobtrusive, sticking to the edge of the room as diners make their way through the cheese, salad, sorbet, and lamb courses. I watch the

careful choreography as French’s team arranges little bouquets of herbs and edible flowers, a French signature, atop beds of greens while she works the stove in the open kitchen. With each course, she takes a break to mingle with guests or tell a story, or dance. She says she wants the dining room to feel like an extension of her home, so every object is curated to her taste, from the jadeite sorbet dishes shaped like hens to the commanding floral arrangements that she composes from whatever is growing locally: sawedoff birch branches, amaranth, dahlias. Her staffers—mostly farmers who also supply the restaurant when they’re not waiting tables—move around the room with practiced ease. As dusk turns to night, they bring out a new round of candles, because French likes how it refreshes the eye. This may be rural Maine, but there’s an element of High Church in the ritual tranquility.

As I watch dinner unfold, director of cinematography Alan Weeks and sound engineer Christoph Gelfand weave among the tables to get closeups while Rennik Soholt, our director, keeps an eye on a monitor in the lobby. Every shoot day on Weekends with Yankee is an attempt to capture something essential about New England via the extraordinary experiences we’ve curated into a 13-episode season. When guests step out for a break— from arrivals to final toasts, this is a four-hour experience—we grab interviews with the willing. They emerge from the dining room with the radiantly transfigured look of converts.

“Was it worth the trouble getting here?” I ask. “Oh yes,” they say. “Oh my God, yes.”

A visit to the Lost Kitchen was just one adventure that my cohost, Richard Wiese, and I filmed for this new season of Weekends with Yankee. The following stories and recipes offer a taste of the show’s food segments, with behindthe-scenes insights into how we bring Yankee to life onscreen.

In her 2017 cookbook, The Lost Kitchen: Recipes and a Good Life Found in Freedom, Maine, Erin French writes: “My Gram wasn’t the best cook, but pies were her thing. I can still taste the sugary graham cracker crust she’d press into the tins and then top off with creamy vanilla pudding. We’d sell them at the diner, finished off with a mountain of whipped cream and a maraschino cherry. I dress up my version with a spray of Johnny-jump-ups or any other edible flower I can find.”

We adapted French’s recipe to put the deliciousness of a perfectly made graham cracker crust front and center, We love how she elevates a simple dish with attention to presentation and technique. It’s typical of French’s approach

to food: Start with great ingredients, distill the flavor, make it beautiful.

45

11 graham crackers

¼ cup granulated sugar

7 tablespoons salted butter, melted

3 cups whole milk

1 vanilla bean, split lengthwise, seeds scraped out with a spoon

½ cup granulated sugar

Pinch of salt

¼ cup cornstarch

3 large egg yolks

2 teaspoons vanilla extract

Whipped cream and edible flowers, for garnish (optional)

Preheat oven to 350° and set a rack to the lower-third position.

Make the crust: In a food processor, pulse the graham crackers, sugar, and butter until well ground. Press the crust mixture into a 9-inch tart pan with a removable bottom. Bake until the crust is set but not browned, about 10 minutes, then allow it to cool.

Make the filling: Heat the milk, vanilla bean and seeds, sugar, salt, and cornstarch in a medium saucepan over medium heat, whisking constantly, until it thickens, 6 to 8 minutes.

In a large bowl, lightly beat the egg yolks. Slowly whisk 1/3 cup of the milk mixture into the yolks to gradually raise their temperature. Slowly whisk in the remaining milk. Return the mixture to the saucepan and whisk over medium heat until just bubbling. Remove from heat, let cool slightly, and stir in the vanilla extract. Remove the bean.

Pour the filling into the crust and let it set in the refrigerator, at least 5 hours and up to overnight. Slice and serve topped with whipped cream and edible flowers, if you like. Yields 8 servings.

Some of the best food we tasted while filming season 2 was in the aging rooms of Grafton Village Cheese and Jasper Hill Farm, two award-winning cheese makers located in small Vermont towns. Following the process from fresh vats of milk to fully aged wheels, then being able to pull samples of Grafton’s clothbound cheddar and Jasper Hill’s Bayley Hazen Blue, was the kind of behind-thescenes access that made filming such a delight.

Then, just up the road from Jasper Hill, we tasted why Shaun Hill’s remote brewery, Hill Farmstead, has been named the best in the world for the past three years by influential craft beer site RateBeer. With dozens of ales, stouts, porters, and pilsners on offer, this is the only place where Hill’s fans can access the full range of his products. People come from all over the country to visit this windy hilltop, a former dairy farm that has been in Hill’s family for more than 200 years, and their enthusiasm is as irrepressible as the bold IPAs that make this place famous.

In honor of these three locations, I developed a recipe for cheddar-ale

dip that combines all the Vermont flavors that still remain so vivid in my

VERMONT CHEDDAR-ALE DIP

In choosing an ale for this recipe, know that the darker brew you choose, the stron ger the flavor will be. Also, avoid using preshredded cheddar, which is coated with an anticaking agent that will make the dip very thick.

Melt butter in a big skillet over medium heat. Whisk in flour until smooth. Cook, whisking continuously, about 1 minute (don’t let mixture brown). Add ale very slowly, still whisking, then add

per to taste. Cook over medium heat, whisking continuously, until mixture is thickened and bubbly, about 5 minutes.

ing until melted. Top with scallions, if desired, and serve with tortilla chips or

On a clear blue August day, we arrived at the Farm at Chatham Bars Inn, an eight-acre property that turns out thousands of pounds of tomatoes, cucumbers, beans, squash, carrots, and other produce for the inn’s three restaurants and the local community. It’s been a work in progress since 2012, when the inn purchased this former berry farm. “With a lot of work, you can turn Cape Cod soils into productive soils,” says farm manager Josh Schiff, explaining how his crew enriched the sandy earth with layer after layer of compost. It took a lot of investment, courtesy of inn owner Richard Cohen, a New York–based real estate investor, but there was a precedent here: In its earliest days, the inn was a hunting lodge for wealthy Bostonians that boasted an on-site dairy and vegetable farm—so Schiff’s efforts complete a circle.

When we visited, Chatham Bars Inn’s executive chef, Anthony Cole, was hosting a farm-to-table dinner with guest chef Colin Lynch of Bar Mezzana in Boston. Part of a weekly summer dinner series that is open to the public, the meal featured Schiff’s produce, local seafood, and a great ocean view. We sat at a long communal table, passing plate after plate of roasted carrots with dates and herbed yogurt; sweet tomato salads; striped bass; and roasted sweet peppers with raisins and burrata. Fellow diners told me about their favorite new eateries: Sunbird and Vers in Orleans, Snowy Owl in Brewster. My list of must-try

Cape restaurants kept expanding. It’s a good problem to have.

For a prettier presentation, you can buy small (½-inch-thick) carrots with their tops attached. Trim off all but an inch of the stems, then pick and wash some of the delicate leaves for a garnish. Also, for the dinner at Chatham Bars Inn, Lynch used fennel pollen in the seasoning, but this can

be difficult to find. Freshly crushed fennel seeds are a great substitute.

20 small carrots with tops, peeled and left whole

3 t ablespoons olive oil, plus more for drizzling

¾ teaspoon kosher salt

¼ teaspoon freshly ground black pepper

Juice and zest of ½ medium lemon

2 t ablespoons chopped fresh dill ( optional)

1 t ablespoon minced fresh chives

1 t ablespoon minced fresh mint

½ medium garlic clove, minced

1¼ cups plain whole milk Greek yogurt

1 tablespoon fleur de sel or Maldon sea salt flakes

½ teaspoon finely crushed fennel seeds

5 dates, pits removed, cut into strips Carrot leaves, for garnish

Preheat oven to 375° and set a rack to the middle position. Toss the carrots with the olive oil, kosher salt, and pepper. Arrange on a baking sheet and roast until tender and caramelized, 40 to 50 minutes.

In a small bowl, combine the lemon juice and zest, herbs, and garlic with the yogurt; stir to combine. In another small bowl, stir together the sea salt and crushed fennel seeds.

Once the carrots are roasted, assemble the dish: Smear equal amounts of the yogurt mixture on four to six plates. Arrange carrots on each plate and sprinkle with date strips, carrot leaves, and fennel salt. Finish with a drizzle of olive oil. Yields 4 to 6 servings.

During our trip to New Hampshire’s Lakes Region, chef Brendan Pelley of Boston’s Doretta Taverna and Raw Bar took me foraging for henof-the-wood mushrooms and sumac berries in a novel way: by golf cart. We were at his family’s cabin at the Arcadia Campground Association, a close-knit community of seasonal

homes and campsites. Pelley grew up coming here, fishing and playing in the woods. When his chef training sparked an interest in foraging, he began finding edible treasures everywhere, including the little patches of ground between campsites. “People see me out here and think, What’s that Pelley kid up to now? ” he said as he piloted the golf cart around the property. Once we had loaded up on edibles like sweet fern and goldenrod, he cooked up a delicious meal over a campfire, including this recipe for trout with wild mushrooms.

TOTAL TIME : 40 MINUTES

H ANDS- ON TIME : 40 MINUTES

A little advice on substitutions here: If you can’t find trout, swap in branzino. Wild mushrooms can be pricey, so feel free to substitute regular button mushrooms—just be sure to build flavor by browning them well over high heat. And if you can’t find ramps, you can use scallions instead.

4 wild or farm-raised trout fillets

½ teaspoon plus 1 teaspoon

kosher salt

¼ teaspoon plus ¼ teaspoon

freshly ground black pepper

1½ tablespoons plus 2 tablespoons

olive oil

½ teaspoon plus 1 teaspoon roughly

chopped fresh thyme leaves

12 ounces wild mushrooms (e.g., hen-of-the-wood, chanterelles),

cut into bite-size pieces

2 cloves garlic, minced

2 tablespoons salted butter

2 ounces whole ramps or scallions, cut into 3-inch lengths

Fresh lemon juice, for drizzling

Pat the trout fillets dry with a paper towel and season all over with ½ teaspoon salt and ¼ teaspoon pepper.

Set a large nonstick skillet over medium-high heat and add 1½ tablespoons oil; swirl to coat. When the oil begins to smoke, add two trout fillets, skin side down, and gently shake the pan to keep them from sticking.

Reduce heat to medium and cook until the skin is golden brown, 2 to 3 minutes. Sprinkle the tops of the fillets with some of the ½ teaspoon of chopped fresh thyme, then carefully turn them over and cook for 1 minute. Transfer to a paper towel–lined plate. Repeat with remaining fillets.

Return the pan to medium-high heat and add 2 tablespoons olive oil. When it begins to smoke, add the mushrooms and remaining salt and pepper. Cook, stirring occasionally, until mushrooms turn golden brown at the edges, then add the remaining 1 teaspoon thyme and garlic. Cook, stirring, for 1 minute, then add the butter. Transfer the mushroom mixture to your serving plate.

Return the pan to high heat and cook the ramps in the residual fat until slightly charred, about 3 minutes.

To assemble the dish, arrange the mushrooms on each plate, add a trout fillet, skin side up (to show off the crispy skin), and garnish with the ramps. Finish with a drizzle of lemon juice. Yields 4 servings.

For more information about Weekends with Yankee or to check local TV listings, go to weekendswithyankee.com. Electric

SEASON 2 PREMIERES APRIL 2018 ON PUBLIC TELEVISION STATIONS NATIONWIDE

(CHECK LOCAL LISTINGS)

CATCH UP ON SEASON 1 AT WEEKENDSWITHYANKEE.COM FUNDED BY: