Explorers Lewis & Clark followed an epic course along the Columbia and Snake Rivers. Discover these iconic rivers for yourself aboard the elegant paddlewheeler, Queen of the West. From the high desert canyons of the interior to the dense mountain forests of the Pacific Coast, the dynamic landscape is filled with history and natural beauty. This fabulous 8-day cruise features the finest cuisine, regional entertainment, and exciting land excursions. Call today for information about this incredible experience.

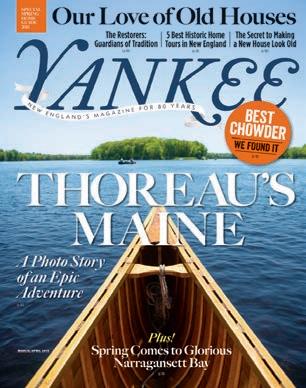

A s that little banner just under our Yankee cover logo proclaims, we think of ourselves, proudly, as “ N ew England’s M agazine.”

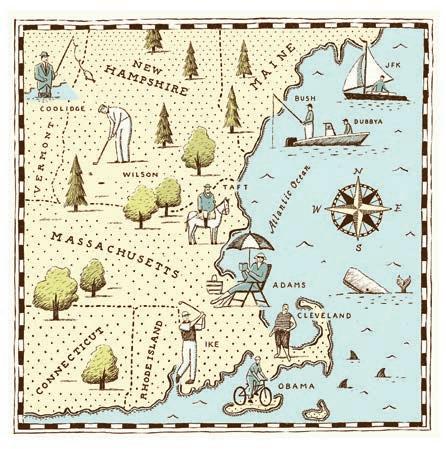

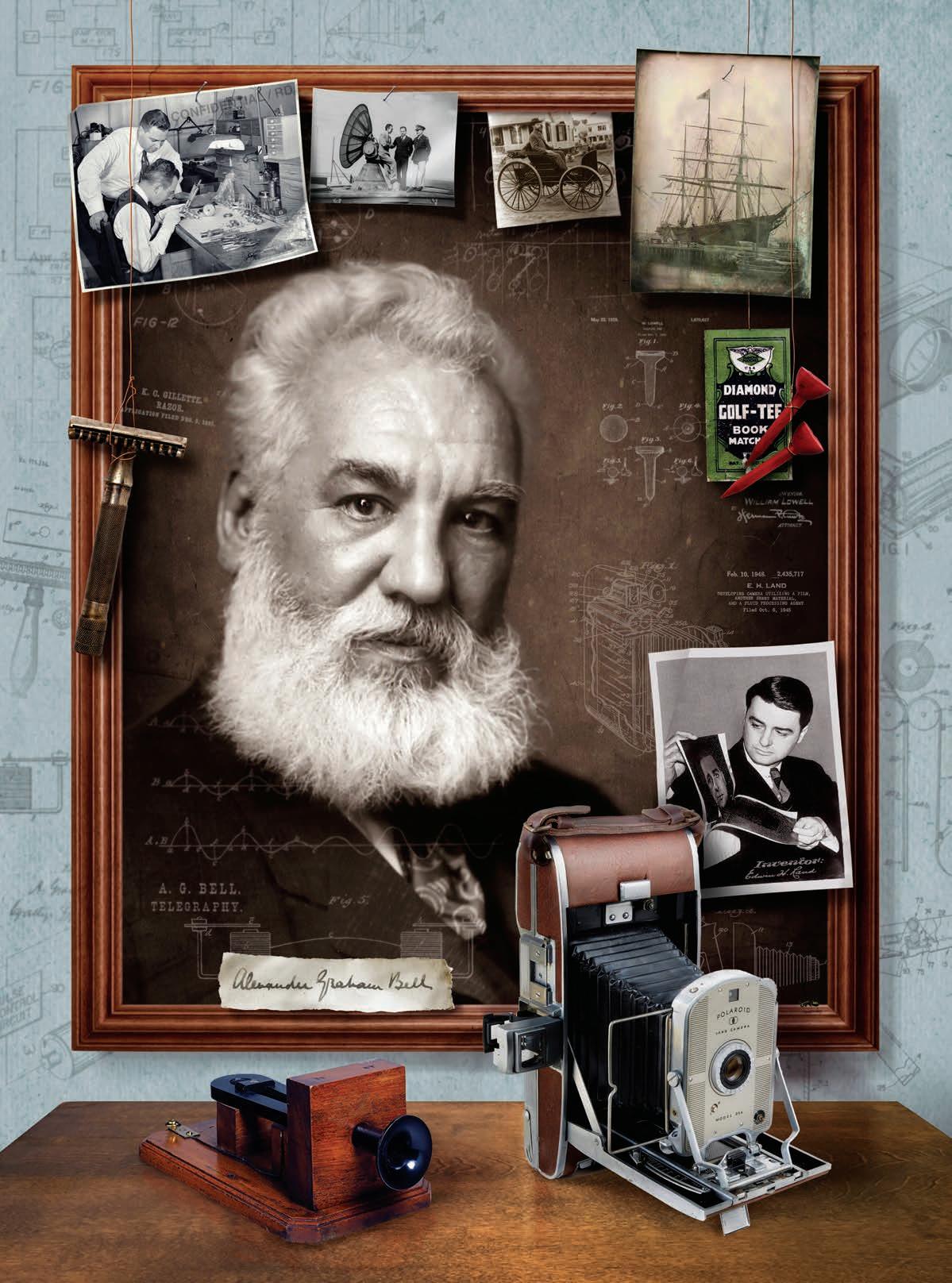

To celebrate this special 80th-anniversary issue, we’re shining a bright light on the extraordinary gifts that N ew England has given to A merica. For eight decades now, Yankee has been the caretaker of those gifts and of the tradition they represent. The pages that follow will highlight 80 of the gifts we treasure most, arranged without regard to rank or chronology. For additional content and more information on each gift, be sure to turn to our “Resources” section, pp. 156–158.

PAGE 90

America’s last wooden whaleship, the Charles W. Morgan , sets sail once again. Plus: Stories of Civil War heroism and tragedy, and one man’s determined mission to save New England’s covered bridges. # 38–44

PAGE 100

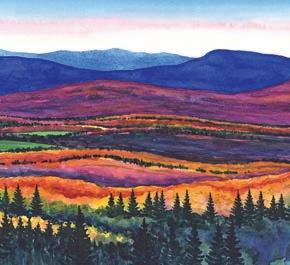

Photographer Richard Brown captures the brilliant hues of a New England autumn. Plus: Percival Baxter’s extraordinary gift to the people of Maine, and the biggest “braggin’ wind” in the world. # 45–48

PAGE 104

Yankee ingenuity has produced hundreds of innovations that have transformed our lives. Plus: New England’s environmental and civil-rights leadership, literary genius, sports heroes, and more. # 49–79

PAGE 38

7 Wonders of Fall # 13–19

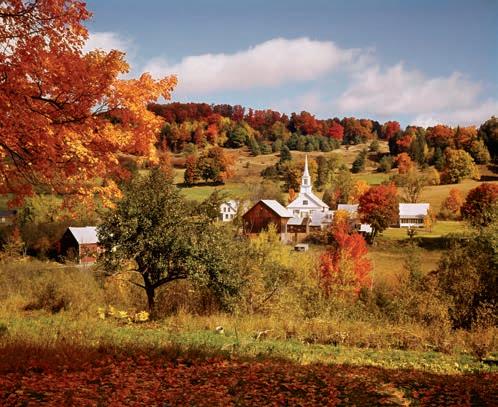

Why we love Jenne Farm, the Conway Scenic Railroad, “the Kanc,” the Northeast Kingdom, Vermont’s Route 100, apple orchards, and cranberry bogs.

PAGE 54

The Cape Cod House # 20

Early New Englanders invented the classic Cape out of necessity, but its charm and practicality made it a favorite American style. by Bruce Irving

PAGE 60

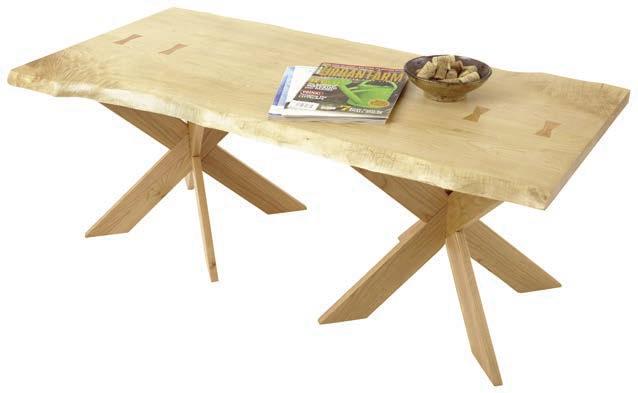

Home & Garden Sampler # 21–24

Why we love wicker, flea markets, Tupperware—and the magnificent “library of trees” that is Harvard’s Arnold Arboretum.

PAGE 66

The Mother of Good Cooking # 25

Fannie Farmer’s Boston Cooking-School Cook Book created the modern recipe and changed forever the way Americans ate.

PAGE 72

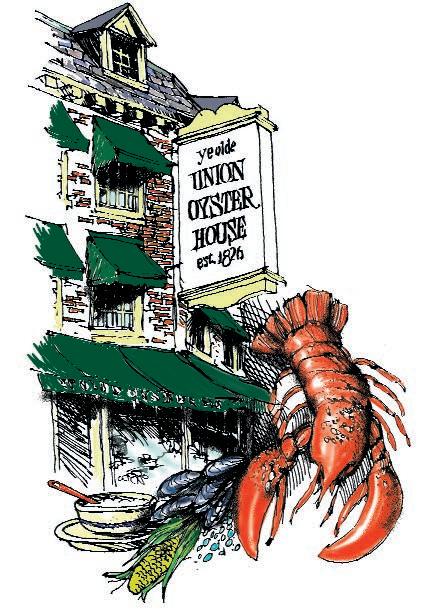

A New England Food Sampler # 26–35

Why we love Toll House cookies, health food, gourmet ice cream, New England’s best seafood, and more. Plus: New England’s heirloom fruits and veggies, and Julia Child’s beloved Cambridge kitchen, now at the Smithsonian.

PAGE 82

Local Flavor # 36

Louis Lassen’s lunchtime brainstorm, the “hamburger sandwich,” made New Haven, Connecticut, famous for more than just pizza. by Amy Traverso

PAGE 84

37

Boston’s venerable Durgin–Park restaurant serves up a winning version of Indian pudding, the region’s most iconic dessert. by Aimee Seavey

PAGE 8

YANKEE ALL ACCESS

PAGE 10

DEAR YANKEE

PAGE 12

INSIDE YANKEE

PAGE 14

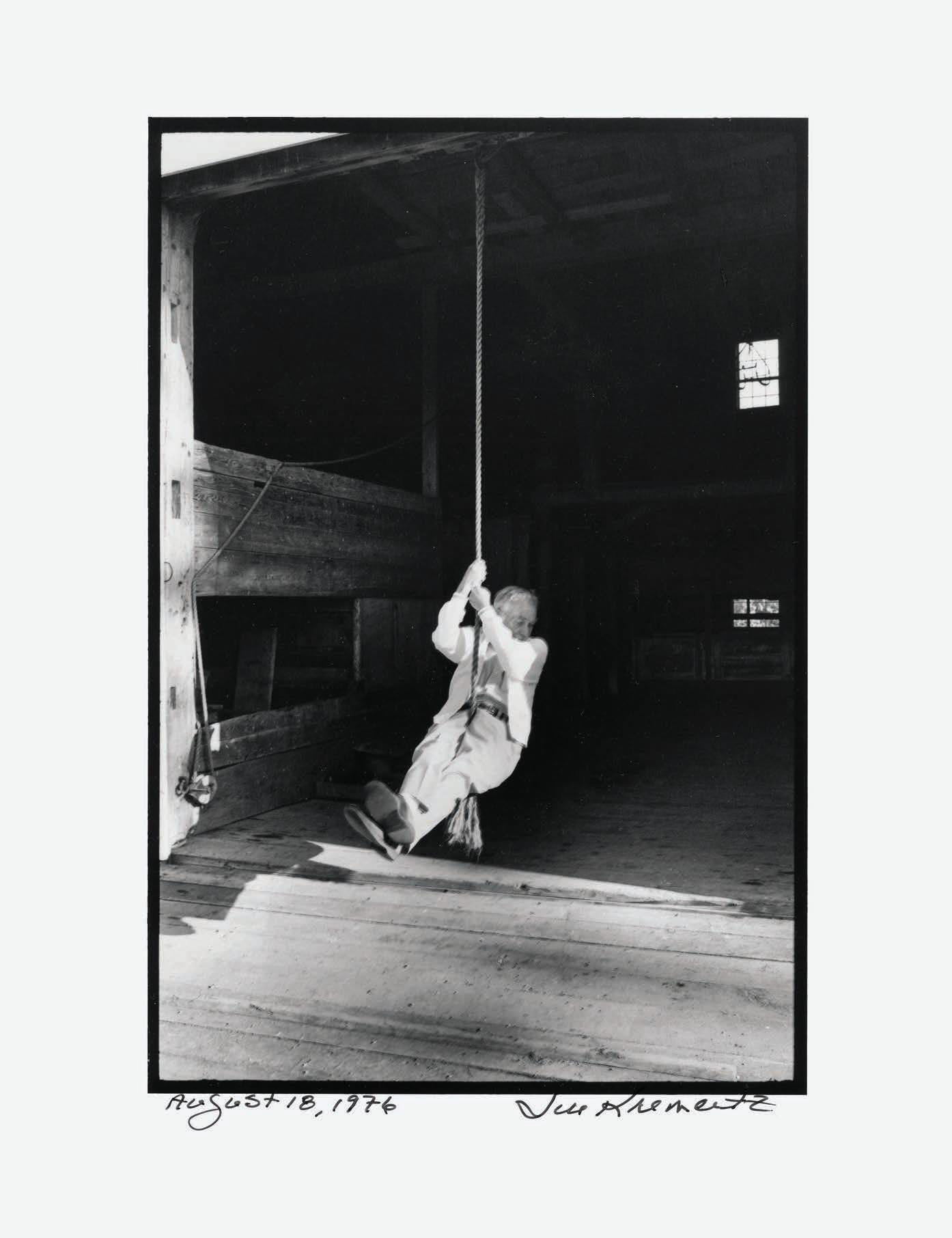

A MOUNTAIN OF A MAN

Yankee ’s founder, Robb Sagendorph # 1 by Judson D. Hale Sr.

PAGE 16

MARY’S FARM

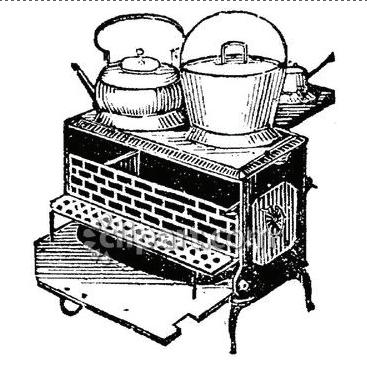

The Mighty Glenwood # 2 by Edie Clark

PAGE 18

LIFE IN THE KINGDOM

Eating the Sun # 3 by Ben Hewitt

PAGE 22

FIRST LIGHT

The country store, Yankee humor, Beacon Hill, Revolutionary firebrands, Frisbee frolics, fall photos, writers’ homes, Nubble Light, “Fly Rod” Crosby # 4–12

PAGE 140

HOUSE FOR SALE

The Yankee Moseyer visits a five-barn New Hampshire farmstead. # 80

PAGE 146

EVENTS CALENDAR

PAGE 152

CORRECTIONS

PAGE 156

RESOURCES

PAGE 168

JUDSON D. HALE SR.

Yankee ’s Yankee # 81 by Mel Allen

DIGITAL CONTENT! For quick and easy access, just download our free Yankee Connect app to your smartphone. Then look for this symbol in our pages, launch the app, and scan the marked photos to get videos, slide shows, or audio files.

1121 Main St., P.O. Box 520, Dublin, NH 03444. 603-563-8111; editor@YankeeMagazine.com

PUBLISHER Brook Holmberg

EDITORIAL

E DITOR Mel Allen

ART DIRECTOR Lori Pedrick

MANAGING EDITOR Eileen T. Terrill

SENIOR LIFESTYLE EDITOR Amy Traverso

SENIOR EDITOR Ian Aldrich

PHOTO E DITOR Heather Marcus

A SSOCIATE E DITORS Joe Bills, Aimee Seavey INTERNS Bethany Ann Bourgault, Theresa Shea

C ONTRIBUTING E DITORS Annie Card, Edie Clark, Annie Graves, Ben Hewitt, Kim Knox Beckius, Justin Shatwell, Ken Sheldon, Julia Shipley

CONTRIBUTING PHOTOGRAPHERS Julie Bidwell, Kindra Clineff, Sara Gray, Corey Hendrickson, Joe Keller, Matt Kalinowski, Joel Laino, Jarrod McCabe, Michael Piazza, Heath Robbins, Kristin Teig, Carl Tremblay

PRODUCTION

PRODUCTION D IRECTORS David Ziarnowski, Susan Gross

SENIOR PRODUCTION ARTISTS Jennifer Freeman, Rachel Kipka

DIG ITAL

VICE PRESIDENT/PRODUCTION & NEW MEDIA Paul Belliveau Jr.

DIGITAL E DITOR Brenda Darroch

NEW MEDIA DESIGNERS Lou Eastman, Amy O’Brien

PROGRAMMING Reinvented Inc.

ADVERTISING : PRINT/DIG ITAL

VICE PRESIDENT/SALES Judson D. Hale Jr. (JDH@yankeepub.com)

SALES IN NEW ENGLAND

TRAVEL, NORTH (NH North, VT, ME, NY) Kelly Moores (KellyM@yankeepub.com)

TRAVEL, SOUTH (NH South, CT, RI, MA) Dean DeLuca (DeanD@yankeepub.com)

DIRECT RESPONSE Steven Hall (SteveH@yankeepub.com)

CLASSIFIED Bernie Gallagher, 203-263-7171 (classified@yankeepub.com)

SALES OUTSIDE NEW ENGLAND

NATIONAL Susan Lyman, 646-221-4169 (susan@selmarsolutions.com)

C ANADA Alex Kinninmont, Françoise Chalifour, Cynthia Jollymore, 416-363-1388

AD COORDINATOR Janet Grant

MARKETING

CONSUMER

M ANAGERS Kate McPherson, Kathleen Rowe ASSOCIATE Kirsten O’Connell

ADVERTISING

DIRECTOR Joely Fanning

ASSOCIATE Valerie Lithgow

COORDINATOR Christine Anderson

PUBLIC RELATIONS

BRAND MAR K ETING DIREC T OR Kate Hathaway Weeks

NEWSSTAND

VICE PRESIDENT Sherin Pierce

DIRECT SALES MAR K ETING MANAGER Stacey Korpi

SALES ASSOCIATE Janice Edson

YANKEE PUBLISHING I NC.

established 1935

PRESIDENT Jamie Trowbridge

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Judson D. Hale Sr.

VICE PRESIDENTS Paul Belliveau Jr., Jody Bugbee, Judson D. Hale Jr., Brook Holmberg, Sherin Pierce

CHIEF FINANCIAL OFFICER Ken Kraft

CORPORATE STAFF Mike Caron, Linda Clukay, Sandra Lepple, Nancy Pfuntner, Bill Price, Christine Tourgee

BOARD OF DIRECTORS

CHAIRMAN Judson D. Hale Sr.

VICE CHAIRMAN Tom Putnam

DIRECTORS Andrew Clurman, H. Hansell Germond, Daniel Hale, Judson D. Hale Jr., Joel Toner, Cor Trowbridge, Jamie Trowbridge

FOUNDERS

ROBB & BEAT RIX SAGENDORPH

Printed in the U.S.A. at Quad Graphics

SUBSCRIPTION SERVICES: To change your address, subscribe, give a gift, renew, or pay online: YankeeMagazine.com/subs

Yankee Magazine Subscriptions, PO Box 422446, Palm Coast, FL 32142-02446; 800-288-4284

ADVERTISTING RATES & INFORMATION: 800-736-1100 x149; YankeeMagazine.com/adinfo

Our region includes miles of pristine beaches along the Atlantic – many with small-time charm, magical ocean views, savory cuisine, unique boutiques, and lively entertainment. Miles of forests, wildlife preserves and conservation areas offer unspoiled nature walks and hiking trails. Paddling by canoe or kayak through scenic inland waterways that flow directly into the Atlantic Ocean may charm you, or perhaps 17 public golf courses will challenge you and South County’s rich history will surely come alive at our 15 museums.

Our August 1973 issue contains a letter regarding the supposed dearth of sentiment in Maine men. Apparently, this applies to all New Englanders:

My New Englander is of doubtfuller-than-Maine origin, being he’s from Massachusetts, and he nearly choked on the marriage vows that he recited, being’s they contained the word love . “You look all right,” is the highest compliment I ever get, and once when I bawled (all right, so I was younger then) and said he never said he loved me, he muttered darkly, “I show it in other ways,” and went back to whittling on his woodcarving.

There is some evidence that he may be mellowing, however. One night last winter he got out of bed to go to the bathroom, and I think he must have thought I was asleep, which I almost was, being barely aware he was up, because when he came back to bed he said out loud, “I love you!” It startled me awake, so’s I got up and wrote down the date and time (1:10 a.m.), but I’d appreciate if you’d omit to print my name and address if you print this letter, as I’d hate for his relatives back in Massachusetts to get the idea he’s become maudlin.

As an avid Yankee reader (and New Hampshire native), I must make haste to correct an inaccuracy in Jane and Michael Stern’s “Traveler’s Journal” in the March 1982 issue!

Is it because fame is fleeting? Is it because I moved to California? Or is it because I lost 250 pounds and with it my chances of repeating my recordbreaking eating marathons? Whatever the case, the so-called record that pro

wrestler André the Giant supposedly set of eating 40 lobsters at Custy’s restaurant in North Kingstown, Rhode Island, is a mere two-thirds of my record: a record that hung proudly in Custy’s until their unfortunate fire last year. André’s socalled record was an average day for me, and my record was 61 lobsters!

If I go back to Custy’s it will be a moderate visit “for old time’s sake.” Gone will be the dozens of lobster shells left behind, but I do ask in the interest of journalistic accuracy, and in memory of Tom Shovan, who broke eating records coast to coast and sent buffet proprietors across New England into shudders and cold sweats for 40 years, that Yankee print a correction to this gross misstatement, which would lead the naïve reader to believe that a mere 40 lobsters are enough to satisfy a truly voracious appetite.

Tom Sullivan Woodland Hills, California 1982Yankee is well known for its lasting appeal. It was recently brought to my attention just how lasting some issues can be. In January 1980, our old farmhouse was featured in “House for Sale.” When the issue hit the streets, we received more than 200 phone calls and letters. The house was sold, and since that time we’ve moved to two other homes in the same town. We’ve kept the same phone number.

Imagine my surprise when I recently received a phone call from a woman asking if the house was still on the market. She had seen it in her doctor’s waiting room and hadn’t noticed that the magazine was 15 years old. She was so disappointed that I wished I still had the house to sell her.

Virginia Feeney Sunapee, New HampshireApril

1995H AN D SOME H OME , EQU I P T FARM—110 acres, about 55 miles from Boston; 190 fruit trees, 50 acres field, on improved road: splendid 2-story 10-room Colonial, electricity, marvelous views; good barn, 4-car garage; catalog price $5000 cut to $4400, part down, including 13 cows, heifers, bull, machinery, 1½-ton truck, milk route, etc. Here is grand value. Free 100-page catalog. Strout Realty, 810-A P Old South Bldg., Boston, Mass.

May 1939

85 acres. 1000 cords wood. Near large town. Good markets. New house, barn for 18 head, other buildings. Orchard, $2650. Terms. 4 acres. On lake. Good buildings. $2250. Easy terms. A.H. Knight, West Warwick, R.I.

May 1939

Schoolkids frown as if to say, ‘So how did summer slip away?’

Ecstatic mothers click their heels: ‘So this is how vacation feels!’

— D.A.W.

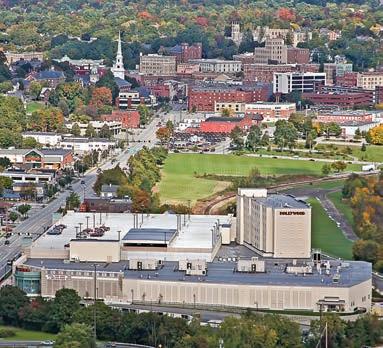

illions of words reside in Yankee ’s library, across the hall from where I sit—80 years of bound magazines crammed onto the shelves—and each sentence, each story, is different from any other, except for this: Every story connects in some way to the words Robb Sagendorph, Yankee ’s founder, wrote inside the cover of that first issue in September 1935. “ Yankee is born today,” he wrote, as if his magazine were flesh-and-blood. “His destiny is the expression and perhaps, indirectly, the preservation of that great culture in which every Yankee was born and by which every real Yank must live … Give him your care, your interest, your heart …”

When Sagendorph began his magazine, he felt that New England was losing its identity. He feared that the modern world would overwhelm its towns and villages and a way of life that remained apart from anywhere else. The world

of 1935 around him was electric with change and tension: America was still gripped by a Depression with 20 percent unemployment; Europe was feeling the prophetic tremors of Hitler’s and Mussolini’s reigns of terror. Whatever lay ahead for New England, Sagendorph hoped that his new magazine could be a part of it and could capture the feel and mood and character of a region so deeply connected to America’s roots.

Now, 80 years later, the towns and villages of New England still resist being folded into the endless indistinguishable American landscape of strip malls and superhighways. Historic preservationists and nature conservancies have saved buildings and landscapes so that you can wander city streets and rural hillsides and see with the eyes of two centuries past. New England still possesses a singular culture, one that is still connected to its roots. And Yankee still searches for the stories that rise from those roots.

Inside these pages are stories about the places and the people who have lived here and how they’ve inspired us, no matter where we come from. We call these places and people and deeds “gifts” because they’ve made our lives better, more interesting; they’ve made us want to be better ourselves. We could have filled 20 special issues with a different set of gifts. These are not the only gifts; we chose these particular ones because we liked the way they blended together to show the depth and breadth of New England’s reach into American life.

Our collection is a mixture of freshly brewed stories and adapted excerpts from Yankee favorites along the way. They’re not arranged in order of importance; we don’t possess the wisdom needed to judge where Julia Child or clam chowder ranks in comparison with the Cape Cod house or the grace of a single E. B. White paragraph. I know that many of you will wish that a favorite New England person or place or food or moment in history were included here, but the choices were so many and the pages, alas, too few to hold all that we wished. But write us, via old-fashioned mail or at editors@yankeepub.com. You can also get our ear on Facebook. Whenever you let us know what you think, you give us the gift that all editors seek: an attentive, caring reader.

Mel Allen, Editor editor@YankeeMagazine.com

THE

Dear Reader,

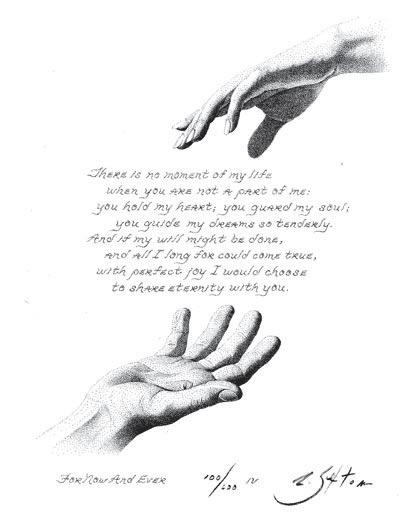

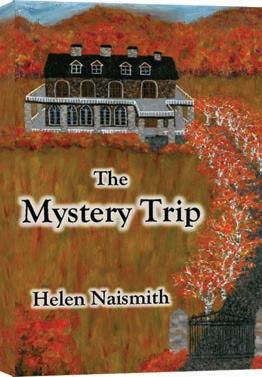

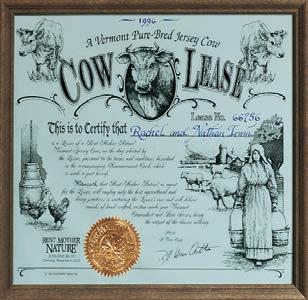

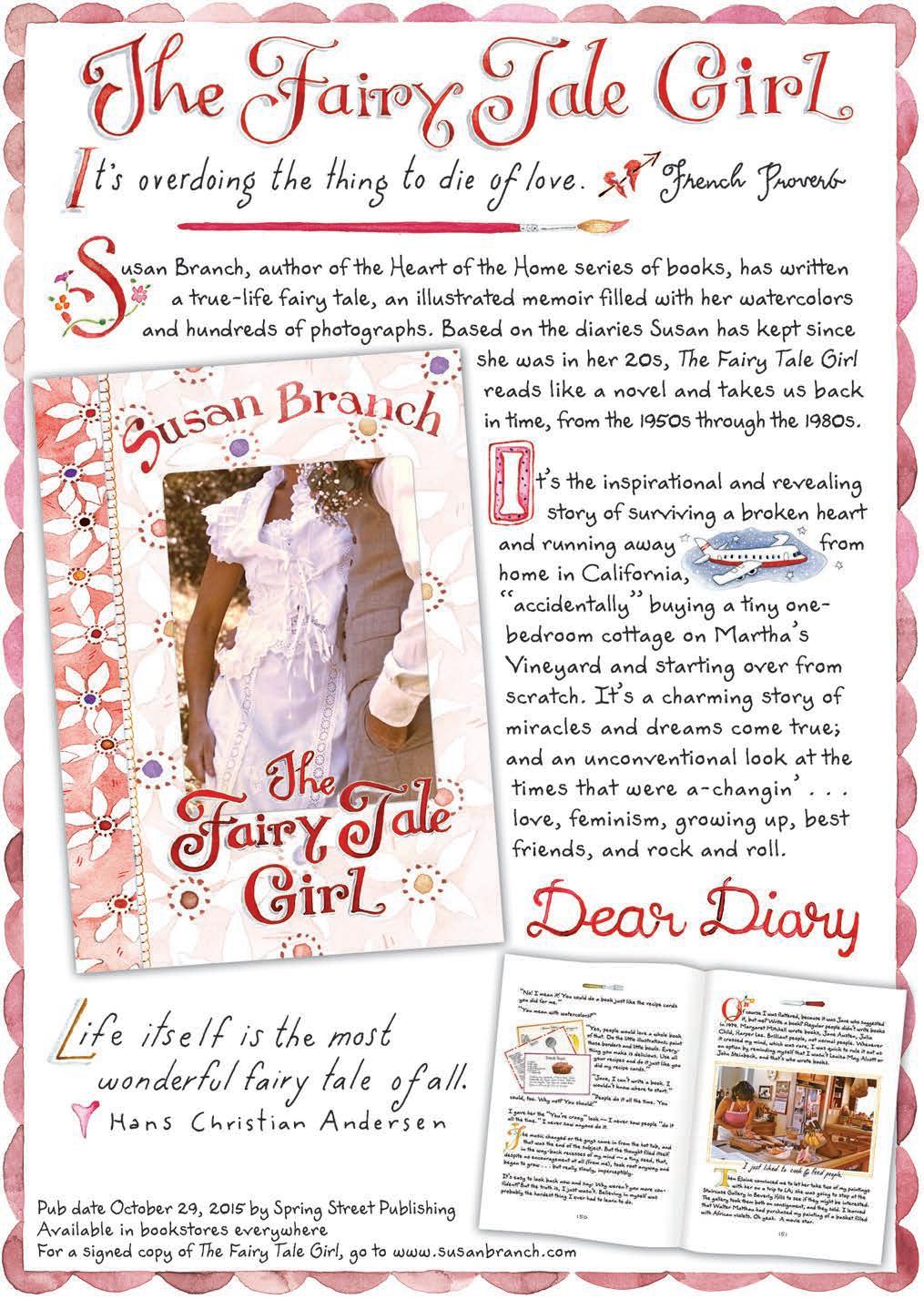

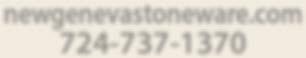

The drawing you see above is called For Now and Ever It is completely composed of dots of ink. After writing the poem, I worked with a quill pen and placed thousands of these dots, one at a time, to create this gift in honor of the the love of two of my dearest friends.

Now, I have decided to offer For Now and Ever to those who have known and value its sentiment as well. Each litho is numbered and signed by hand and precisely captures the detail of the drawing. As an anniversary, wedding, or Valentine’s gift for your husband or wife, or for a special couple within your circle of friends, I believe you will find it most appropriate.

Measuring 14" by 16", it is available either fully-framed in a subtle copper tone with hand-cut double mats of pewter and rust at $135*, or in the mats alone at $95*. Please add $14.50 for insured shipping and packaging. Your satisfaction is completely guaranteed.

My best wishes are with you.

The Art of Robert Sexton • P.O. Box 581 • Rutherford, CA 94573

All major credit cards are welcomed. Phone (415) 989-1630 between 10 a.m.-6 P.M. PST, Monday through Saturday. Checks are also accepted.

Please allow up to 2 weeks for delivery.

*California residents- please include 8.0% tax

Please visit my Web site at www.robertsexton.com

“There is no moment of my life when you are not a part of me; you hold my heart; you guard my soul; you guide my dreams so tenderly. And if my will might be done, and all I long for could come true, with perfect joy I would choose to share eternity with you.”

BY JUDSON D. HALE SR.

BY JUDSON D. HALE SR.

uring every Fourth of July, my mind turns to Robb Sagendorph, founder of Yankee Magazine, who died 45 years ago, on July 4, 1970, but whose presence I still feel within the pages of every issue, including this one. He was my first boss and mentor—and, oh yes, he was my uncle, too. That long-ago July Fourth was a very sad day, but my most vivid memories of him are happy and wonderful to recall. Take, for instance, my very first morning …

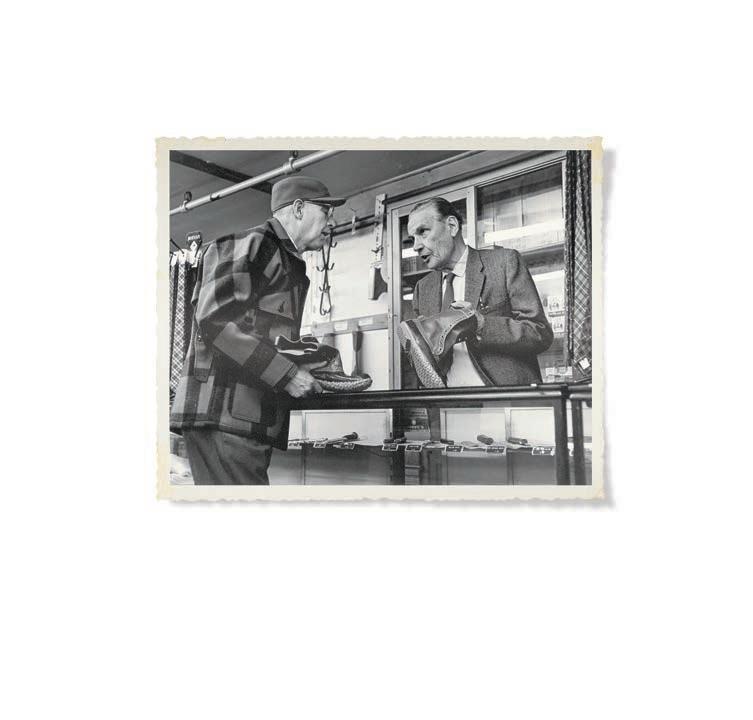

“Look at this, Jud,” Robb said as I walked for the first time into the room on the second floor of the red-clapboard building in Dublin, New Hampshire, where I’m still to be found today, 57 years later. He was holding up a small, extremely old almanac. His battered old desk was in one corner of the room. Mine, newer and bigger, was in another, and there were three other people. My presence that first morning increased the Yankee editorial and advertising staff by 20 percent.

“It’s an original copy of the 1793 Old Farmer’s Almanac ,” he said, carefully leafing through the delicate, brittle pages for me to see. His hands, I noticed, were extraordinarily large, like the rest of him. He wore a bright-red bow tie and red suspenders; the sleeves of his white Brooks Brothers shirt were rolled back to the midway point of his long forearms, and a lighted cigarette was hanging from his mouth. Most noticeable to me, however, were the deeply etched lines on his face. They were placed perfectly, as if by a sculptor. Over subsequent years, people often told me they thought Robb Sagendorph looked like New Hampshire’s Old Man of the Mountain.

“Very valuable,” he muttered while continuing to carefully turn over the pages of the 1793 almanac. (Robb had acquired the title from Little, Brown in 1939, four years after starting Yankee.) “Probably fewer than a dozen of these exist, and I have three.”

I noticed the ash on his cigarette was becoming long. As time went on over our subsequent 12 years together, I grew familiar enough with him to often cry out, “Robb, your cigarette!” and he’d search for an ashtray, during which time the long ash usually fell off anyway. But on that first morning, meeting him for only the third or fourth time in my life, I couldn’t do that.

“Life holds more meaning,” he went on, “when the past ties into the present,” and with that he picked up a copy of the brand-new edition of The Old Farmer’s Almanac lying on his desk and held it up next to the old one. “When that happens, one gains the assurance the present will tie into the future,” he said, looking directly up at me with a smile made somewhat crooked by the continued presence of the cigarette.

The smile dislodged not only the long ash but the lighted head as well. I watched in some alarm as it fell directly onto the 1793 almanac and began smoking its way through the first few pages. My expression alerted him to the crisis, and in the next instant we were both galvanized into action, blotting, slapping, and finally blowing away burnt pieces of almanac from his desk.

“Perhaps not quite as valuable now, Robb,” I said laughingly, conscious that I had omitted the word “Uncle” for the first time. He laughed, too. My mother and others had warned me that he was stern, serious, imposing, and, as they put it, “difficult.” Yet in less than five minutes I felt close to this complex mountain of a man. It was the beginning of a bond between us that would outlive him by many years.

He’s been gone for 45 years. But I can vividly picture him perusing this 80thanniversary edition of his beloved Yankee Magazine, his enduring gift to us all. No doubt he’d have a few details to criticize—he wasn’t always easy to please. But I know he’d be proud. He’d have that smile on his face that I remember so well, and, sure, in my mind there’d be a lighted cigarette dangling from his lips.

Some things never change.

So thanks, Robb. Thanks and ever thanks.

NUMBER 2

BY EDIE CLARK

BY EDIE CLARK

hat was to become my stove was jammed into a freight car on the sidelines of the old train station in Littleton, Massachusetts. The stoves were pushed together willy-nilly, wherever space could be found. From this amazing jumble, Dave Erickson urged me to select one that most appealed; he would extract it and restore it to its former splendor. Outside, among the grasses, dozens more, mostly in pieces, awaited rescue. In the darkness of that freight car, I found what I was looking for: a diamond in the rough, no rust, the stylish legs and warming shelf still smooth and even a little shiny. And, like almost all the stoves in this vast yard, it had a story: It had belonged to an old lady in Fitchburg who hadn’t used it to burn wood, but instead had run gas pipes through it. As a result, the stove was in remarkably good condition. Dave reminisced a bit about the day he took it out of her kitchen. Then as now, no one can rhapsodize about a cookstove like Dave, who has kept his love affair with these beauties for some 35 years. He’s been an evangelist for old cookstoves almost as long as I.

The stove I chose was to replace one that my first husband and I had bought 10 years earlier from a hardware store in Brattleboro, Vermont—an antique sold “as is.” A Glenwood C manufactured in 1890 , it was like new. That stove became the heart of our house and, most painfully, had to be sold with the house when we divorced some years later. A multitasker, the Glenwood burned wood, so it heated the house and its oven baked our bread and the stovetop cooked or heated just about anything. The oven door proclaimed Glenwood C in ornate, embossed lettering, and in the center of the name was the thermometer gauge for the oven. Beneath the oven door was a little pedal (beautifully decorated as well); if I pressed it with my foot, the door swung open so that I could easily put the turkey or whatever into the oven, not needing three hands. The various warming shelves not only kept dishes hot but at different temperatures: some warmed just a little, others almost cooked. Gradually, very gradually, I learned that I could do many things on this stove that I couldn’t do on a modern stove. I could even grill

steaks. That stove turned me into a believer, a believer in the Glenwood, a believer in wood heat and wood cooking, and a believer in form and function, which these stoves displayed in spades. Now I needed a replacement, and I turned to stove restorer Dave Erickson in my search.

Almost everything I know about Glenwood stoves came to me first through trial-and-error but then through Dave.

From him, I learned about dampers and draft slides, finials and footrests, towel racks and trivets, nickel plating, scrollwork, and side cars. I’ve listened to him sermonize about the brilliance of butter warmers, clock shrines, and simmer burners and explain the physics of draft and the intricate and ingenious path the heat takes around the oven on its way up the chimney.

The one thing he’s never told me is that the Glenwood was America’s first home appliance. Stoves like mine came out of the massive fiery furnaces of the foundries of Taunton, Massachusetts, then known as “Stove City.” The Glenwood quickly replaced the hearth as a way to cook, distinguished by its ability to heat and bake with far more precision than an open fire.

Literally thousands of other foundries turned out cookstoves of all varieties in that booming era between the 1850s and World War I (when iron became more valuable for waging war than for cooking dinner). The Glenwood was simply the first and, in the opinion of many, including Dave, the best. “They’re the most durable, most reliable, and most beautiful, and they have an indestructible design,” he says. “They’re the Cadillac, the Eldorado, of stoves.”

The stove that Dave pulled out of that freight car back in the 1980s has followed me through the many phases of my life and now sits in my kitchen here at Mary’s Farm, facing another stove, also a Glenwood. That one cooks with gas and is clad in green- and- cream enamel, the name Glenwood also proudly shown on the oven door. The two stoves, one from the 19th century and the other from the 20th, rest on their graceful legs and catlike feet. Facing each other as they do, it sometimes seems as though they’re speaking to each other, and if they are, it’s a conversation I would love to hear.

Edie Clark is the author of As Simple As That: Collected Essays and What There Was Not to Tell: A Story of Love and War. Order your copies, as well as Edie’s other works, at: edieclark.com

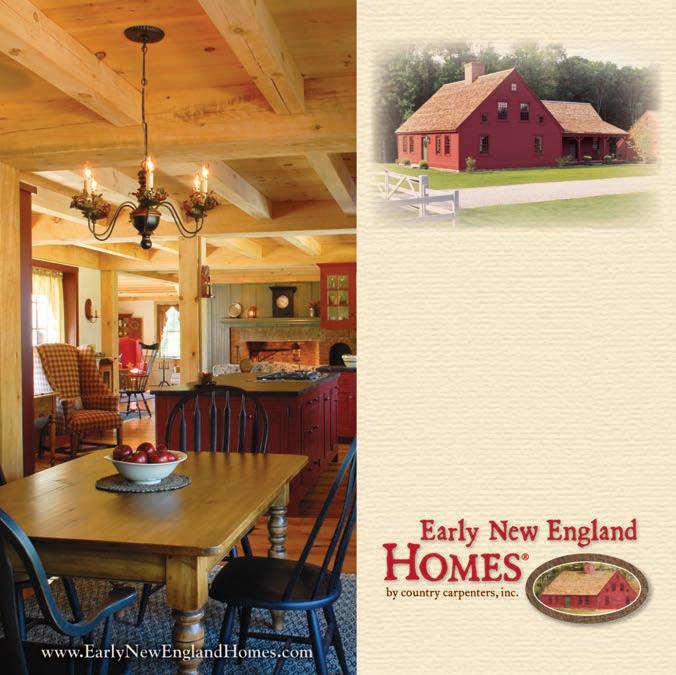

Our 1750s style cape home building system boasts beautiful timbered ceilings, a center chimney, wide board floors and custom, handmade features in the convenience and efficiency of a new home.

Our model is open: Mon-Fri 8-4:30, Sat 9-3

NUMBER 3

n any four-season climate, on any farm, September and October are the months when the truth becomes known. If the farm is one that relies on the harvest for income, the truth is expressed in the infallible language of numbers, of profit and loss. If the farm is like ours, instead relying on the harvest to feed its inhabitants, the truth is expressed in the slow accumulation of burlap bags filled with the root crops that will see us through the winter.

First, we pull the onions. It’s been a perfect onion year—they’re huge, leviathan things, almost a parody of themselves. We spread them on the porch to dry atop screened frames; after a few days, the outer skin begins to peel and flake, and gossamer slips of copper-colored onionskin drift into the house on the breeze.

Then we dig the potatoes, row after row of them, nine rows in total. Everyone loves digging potatoes—in part because it’s not difficult work, but mostly because no matter how many years you’ve dug potatoes, it’s impossible not to feel a small sense of giddy discovery every time your hands find those subterranean orbs, smooth and cool under the soil.

The potatoes go into bags, and we carry the bags to the root cellar. Some of the bags are so heavy I can lift them only a few inches off the ground, and it feels as though my shoulders might be pulled from their sockets by the weight of all that starch. Every few steps, I pause to rest, the lumpy bag at my feet.

The beets are next out of the ground: red ones, gold ones. Too many, if you ask

me; I’m not much of a beet guy. Then we bring in the squash, the sun-yellow ‘Delicata’ and the beige-orange ‘But ternut’; from a distance, their whimsi cal shapes remind me of ukuleles.

Down in the woods, the boys and I pick the last flush of chanterelle and hedgehog mushrooms. It’s been an amazing mushroom year—cool-ish, neither too wet nor too dry—and the season seems as though it will never end. “There are more over here! There are more over here! …” the boys keep calling, as they rush from one patch of mushrooms to another. They never pick even a fraction of what they find; as with the potatoes, they’re drawn to the discovery as much as to the mush rooms themselves, and I can’t blame them. I follow behind and fill my basket. Once that’s full, I remove my shirt, fold it into a pouch, and fill that. We’ll have fresh mushrooms for lunch and dinner; the rest we’ll dry in the greenhouse for long-term storage.

We slaughter two beef cattle—a shaggy Scottish Highland cow and a big Shorthorn/Jersey steer—and as always, I pause for a moment before pulling the trigger. There’s something that feels both profoundly right and entirely unfair about the act. The rightness, I suppose, is the ownership of the process, the acceptance of our role in the tangled and imperfect web of relationships between my family and the animals we depend on.

But I can’t quite get over the trust these creatures have placed in us, how when I approach them with the gun, the .410 slug chambered and ready to do its bidding, they look at me the same way they’ve looked at me for each of the past 700 or so mornings, probably expecting the back-of-head scratching they’ve become accustomed to. It’s my habit to stand with them for a minute or two each day, scratching them absentmindedly, looking out over our land and feeling

OPPOSITE : The Hewitt boys, Fin and Rye, haul the squash harvest home from the field. THIS PAGE ,

TOP : Beef cattle graze the farm’s rich grass.

OPPOSITE : The Hewitt boys, Fin and Rye, haul the squash harvest home from the field. THIS PAGE ,

TOP : Beef cattle graze the farm’s rich grass.

as though maybe I know my place in the world.

This morning is different, and when the animals are on the ground, bled out and stone still but for the occasional involuntary twitch of muscle fiber, I think of how it’s become popular to talk of “harvesting” animals for meat, and I think I don’t agree. The day before, we’d dug those potatoes, everyone on hands and

knees moving down the rows—except for Fin, who kept stopping to juggle potatoes, if dropping two for every one he caught can be called “juggling.” The bushel baskets filled fast, enough potatoes to last us all winter and into the spring. Enough potatoes to last us until the day we’ll wish we never have to eat another. We were happy filling those baskets, maybe even joyful. That felt like a harvest.

Taking the lives of animals feels different to me. It feels like something that shouldn’t be diminished by euphemism, however much we might want to soften the language of killing, perhaps to make it more palatable to those who disagree with our actions. Or perhaps we do it to make it more palatable to ourselves. But words can’t change the truth: You harvest a potato; you kill an animal.

Later that day, after we’ve skinned and gutted the beef and transported the sides 30 minutes north to a small custom meat-cutting shop where the

700-pound carcasses will be reduced to steaks and burgers and roasts, Penny and the boys take the silky, longhaired Highland hide down below the house and begin the arduous process of “fleshing.” Fleshing involves the vigorous scraping of the hide’s interior to remove the extraneous fat and flesh that would otherwise spoil. It’s the first step in turning the fresh hide into usable material; in this case, the boys want to make simple sandals called huaraches.

While Penny fleshes, Fin and Rye take axes and extract the brains from the animals’ skulls; the brains contain lecithin, which is essential to proper hide tanning. The boys will make a slurry of brain and water, which they’ll rub into the hide before drawing it tight in a simple frame and leaving it to dry.

Later, I place the heads into plastic buckets with holes drilled in them to allow the ingress and egress of flies,

We’re doing something that seems no less than magic: We’re eating the sun.

which will lay millions of eggs on the decomposing flesh. Our chickens will eat the resulting maggots. We’ll eat the eggs the chickens lay, and when they stop laying, we’ll eat the chickens themselves. If it’s true that you’re not merely what you eat but also what the animal that you eat eats, then we’ll eat the maggots that themselves ate the flesh of the cow we killed, the very same cow that fed itself for two years on the verdant grass of our pasture, grass that was full of the sugars produced by photosynthesis, essentially the conversion of sunlight into the energy stored in carbohydrates.

What I’m saying is: If it’s true that you’re not merely what you eat but also what the animal that you eat eats, then we’re doing something that seems no less than magic: We’re eating the sun.

Finally, the first fire in the cookstove, the return of the morning ritual: Crumple the newspaper, lay the kindling, strike the match; fill my stovetop coffeemaker while the kindling catches; then insert the first sticks of stovewood through the small enameled door. I pull a chair up close to the stove and rest my feet atop the warming iron, slowly moving them away from the firebox as the temperature increases.

In three minutes, the entire stove will be too hot for my feet. In seven or eight minutes, if the wood is dry and I’ve built the fire right, my coffee will begin to perk. In 20 minutes or maybe a little less, my family will begin to rise. In 30 minutes, it will be light enough to begin morning chores.

When people comment on our life, it’s often to say something about the work involved, the small discomforts of labor and weather. Or maybe about the minor material deprivations—the things we don’t own, either by choice (we don’t want them) or circumstance (we can’t afford them). Or, often it’s about the commitment, the simple fact that we can’t leave on a whim for longer than a few hours; we don’t take vacations, and there are no overnights to the city for a nice meal and a show.

When people say these things, I nod. I say, yes, all these things are true.

We’re often cold, hot, hungry, sore, tired, wet. There’s much that we don’t have. Can’t have. There are many places we don’t go. Can’t go. It’s true, all of it.

matters to me, how it’s worth forgoing anything I must forgo to enable and protect it. But I’m too self-conscious. I worry that they’ll think me smallminded, too easily amused, incurious.

Yet, every morning beginning in the fall of the year and lasting until mid-spring, I rise and kindle a fire in the cookstove. I set a chair before it and my coffee atop it. I place my feet on the warming iron until it becomes too warm, and then I cross my legs and wait for light to come into the sky. I drink my coffee.

There’s a part of me that wants to try and explain to these people how much the privilege of this small ritual

Just a rural fool living an insular life by his woodstove as the day comes to life around him.

So I just nod again, say yes again. And keep my mornings to myself.

The first fire in the cookstove, the return of the morning ritual: Crumple the newspaper, lay the kindling, strike the match, fill my stovetop coffeemaker while the kindling catches; then insert the first sticks of wood.

When the townspeople of Craftsbury, Vermont, hang out at the general store, the line blurs between “store” and “story,” a scenario little changed since America’s first country store opened in Adamsville, Rhode Island, in 1788.

ittle more than a century has passed since folks hitched horses off the porch and rambled into the Craftsbury General Store to pick up lamp wicks, a pinch of snuff, and perhaps a new cowhide whip. But scarcely 20 minutes have passed since Bruce Urie, whose ancestry goes back to some of the town’s first settlers, stopped into the store for two handy items still available since the beginning: a newspaper and a hunk of cheese. True, Bruce rode in via his Subaru Legacy, as opposed to dismounting from his best bay mare, but he crossed the exact same threshold—where the green paint is scuffed to bare wood—as his ancestors did at the store’s opening, circa 1855–1860, just before the dawn of the Lincoln administration.

This old store with a tiny bit of everything serves as the keystone of Craftsbury’s civic life. The town, founded in 1781, is a swerve off the beaten track, but boasts nice libraries, pretty churches, a pint-size college, and a handsome community lawn called “the Common.” Home to about 1,000 people (down from an all-time high of 1,400 back in the mid-1800s), the village is either an arduous horseback ride or a 30-minute car drive to the nearest major grocery store, movie theatre, or restaurant. Hence the General Store stands in for all these things—the original fulfillment center—where you can dash over to pick up a carton of eggs, a DVD, and a pulledpork pizza. And if you park yourself over by the coffeepot

any given morning, you’re sure to witness an unofficial roll call, as in comes Barb from the Academy, followed by Paula who works at the Flower Shop, then Sarah, who runs the Art House, then Jeremiah from the Jones farm, then Sam, our district representative in the state legislature, then Rick, who teaches agriculture at the college, then Norma, who’s delivering the newspapers … taking cup after cup.

Here, a talented eavesdropper can learn who bought the inn, what the crew at Pete’s Greens is harvesting, where your neighbor’s daughter has been accepted to college, when the Fire Department is having its BBQ, and why the guy you buy fenceposts from has decided to run for governor—all illustrating the kinship of “store” and “story.” Furthermore, over the course of a day, customers take part in what I call the “ecology of watchfulness,” an upshot of busybody-ism, as Emily asks after Margie’s health, and then Margie

asks about my chickens, and then I query Stuart about his plant nursery, and Stuart asks Emily about her renovation plans. “Some former elected official named Vance who currently lives in Derby forgot his earmuffs,” reads an entry in the store’s staff journal. “Never mind. He came back.”

Twenty years ago, Andy Humphrey, grandson of the store’s owners from 1972 to 1995, sought to understand the meaning of the store for its citizenry. The then-16-year-old spent a weekend at the store, keeping track of who came in and what they bought.

Over a weekend in March, he counted 83 customers “of all shapes and sizes,” and discovered their most common purchases were newspapers, milk, and candy. But he also counted the chips, cheese, bananas, ice cream, minced clams, and frozen apple turnovers that were rung up at the register, as well as sandpaper, paint rollers, videos, bags of ice—all prompting Andy to comment that “most people seemed to be there for only a few specific items or simply something to do to pass the time,” and that his grandparents had known almost every person who came in by name.

Yet what interested Andy most was the “talk of the town.” A day or two before, a local house had burned down and “two-thirds of everyone who came in had something to say about the fire.”

Two decades later, everything the former proprietors’ grandson observed is ongoing, and the store is like a classic play with new actors. Its current owner,

Emily Maclure, a 34-year-old Vermont native, plays the lead, and with her best supporting staff, Rene Orzolek and Marie Royer, they greet customers by name as they stop in: 83, 90, sometimes 200 shoppers a day, to pick up newspapers, milk, and candy. This past March, when another local house burned to the ground, instantaneously the store’s counter sported a plastic jug that began greening up with 1s, 5s, and 20s for the neighbor left with nothing but the clothes on his back.

Although Emily doesn’t carry hardware supplies, she’ll stock minced clams and frozen apple turnovers upon request. The General Store receives 15 big truck orders a week, in addition to 15 little deliveries (local bread, local milk, local eggs, and so on), and anyone perusing the inventory is bound to enjoy these rich juxtapositions, which in many ways mirror the mix of folks who

shuffle, swagger, or stride through the door. The soda-cap earrings made by a grade-schooler dangle next to a display of cigars, which are next to the baseball bats signed by our local retired Red Sox/ Expos pitcher. Shelves abound with organic Vermont-made baby food and Duncan Hines cake mix.

And it all has a story behind it: from the flannel shirt draped on a chair (left by the Sterling College work crew who volunteered to wash windows) to the heating vent decorated with a mural of local sights (like Pete’s red truck and Mark’s yellow house); from the new picnic table (came from Emily’s brother) to even the newest beer Emily is stocking.

The store’s 12th proprietor in 150 years decided to carry it just because of its name, a name that summarizes the feeling of this provident place: “A Tiny Beautiful Something.”

Cottage residents at Piper Shores enjoy spacious, private homes while realizing all the benefits of Maine’s first and only lifecare retirement community. Our active, engaged community combines affordable independent living, with guaranteed priority access to higher levels of on-site healthcare—all for a predictable monthly fee.

Call today for a complimentary luncheon cottage tour.

Two decades later, everything the former proprietors’ grandson observed is ongoing, and the store is like a classic play with new actors. Anyone perusing the inventory is bound to enjoy the juxtapositions, which mirror the mix of folks who come through the door.

“Humor can be dissected, as a frog can,” E. B. White famously said, “but the thing dies in the process.” Nevertheless, throwing caution to the wind (along with some lint picked off an old sweater), we examine here the contributions made to the field by Yankee humor, which was anaesthetized using extracts of Town Meeting reports prior to the procedure, and which we hope it will survive.

BY KEN SHELDONThe cornerstone of New England humor is the tightlipped Yankee farmer, invariably rocking on his porch or leaning against a fence as he matches wits (or half-wits) with a person from away. This reticent character is so popular, we even sent him to the White House once: Calvin Coolidge, who famously said, when a woman bet she could get him to say more than two words, “You lose.”

Closely related to the Taciturn Farmer (second cousin on his mother’s side), the Country Bumpkin tells tall tales, usually in a Yankee accent thicker than 40W maple syrup on a winter morning. By a centuries-old agreement among the six New England states, the Bumpkin must be from Maine (or pretend to be). The most notable member of the tribe was Marshall Dodge of Bert and I fame, who, like most bumpkins, was a lot smarter and better educated (Yale) than he let on.

Over the ages, the Rustic Wit has dispensed homespun advice and topical commentary, usually under a pseudonym in case victims chafed under the topical ointment. His grandfather was Ben Franklin, who begat the once howlingly funny (and now largely forgotten) Seba Smith, who begat Josh Billings, who begat Titus Moody, and so on. Franklin may also have originated the one-liner in his Poor Richard’s Almanack.

Like some medications, Yankee humor is often time-release: It may take some time after hearing a Yankee joke before you actually get the punchline. If this occurs while you’re driving, it’s best to pull over until you regain control. Safety first.

Take the old Mainer who ran a stoplight and broadsided a Cadillac with New York plates. The New Yorker screamed bloody murder until the Mainer pulled out a flask of whiskey and encouraged the other guy to take a swig to calm himself. As the Mainer put the bottle away, the New Yorker said, “Aren’t you going to have some?”

“Nope,” the Mainer said. “I’ll wait till after the police come.”

Stand-up comedy owes an equal debt to 19th-century lecturers such as Maineborn Artemus Ward, who kept audiences in stitches by wandering onstage as if lost and standing for several minutes in dead silence. Of course, the king of the orators was Mark Twain, who made his home in Connecticut. Twain was at the top of his form when picking on New England’s fickle weather, which he speculated was made by “raw apprentices in the weather-clerk’s factory who experiment and learn how … and then are promoted to make weather for countries that require a good article, and will take their custom elsewhere if they don’t get it.”

A recurring theme of Yankee humor is the “not from around here” category, based on the belief that anyone not born here is, at best, lacking in the rudiments of common sense. Woe betide those who try to pass, like the fellow who claimed that his children were natives because they were born here and was told, “Just because a cat has kittens in the oven, that don’t make ’em biscuits.”

Another oft-repeated motif of Yankee yarns is “The Project,” in which a woefully inept handyman attempts to build or repair some object that anyone with tartar sauce for brains would walk away from. Adding to the drama is the congenital cheapness of the protagonist, ensuring that “The Tale of the Boat” (or outhouse, or sugar shack) will invariably end up a tragedy.

New England has contributed more than its fair share of mirthmakers to American culture: radio stars like Fred Allen; dynamic duos like Bob and Ray, or Car Talk ’s Tom and Ray Magliozzi; Jay Leno, king of the late-night TV hosts; and stalwarts like Tim Sample, keeping the Yankee storytelling flame alive. The heart of Yankee humor, according to Sample, is a calm sense of the way things are, which may go right over the hearer’s head. “It ain’t that it ain’t funny,” Sample says. “You just don’t get it.”

One must walk, not ride, to really savor the character of Beacon Hill. One of the finest times to complete a tour is at dusk—along narrow, cobbled Acorn Street perhaps, or Branch, softly illuminated by gaslamps below, while overhead the building tops are still caught in the glow of the setting sun. It is an appropriate time of day to reflect on the generations of scholars, builders, statesmen, and seafarers who made Beacon Hill their home.

—“Beacon Hill: Hub of the Universe,” by Paul Darling, May 1979

—Sam

One of the “Founding Fathers” of the Revolution, upon hearing the sound of musket fire at Lexington, Massachusetts, April 19, 1775

A

“Taxation without representation is tyranny.”

—James Otis (1725–83)Colonial lawyer and member of the Massachusetts provincial assembly

“What a glorious morning is this!”

Adams (1722–1803)

“Don’t one of you fire until you see the whites of their eyes.”—William

Prescott (1726–95)Commander of American troops at the Battle of Bunker Hill

“Tonight the American flag floats from yonder hill or Molly Stark sleeps a widow!”—John

Stark (1728—1822)Commander of New Hampshire troops at the Battle of Bennington

“I only regret that I have but one life to lose for my country.”—Nathan

Hale (1755–76)young Connecticut schoolteacher turned soldier, executed by the British for spying on September 22, 1776

1871

year when Frisbie P ie C ompany was founded in Bridgeport, CT

3 disc toys invented by Fred Morrison before the Frisbee (Whirlo-Way, Pluto Platter, Flyin-Saucer)

SEVEN players on an Ultimate Frisbee team

cents offered to Fred M orrison for the cake pan he was tossing on a S anta M onica beach in 1938

1920 year when Yalies began flinging their pie plates to one another

221 pages in Frisbee: A Practitioner’s Manual and Definitive Treatise

100,000,000 Frisbees manufactured 1957–1994

80+ countries in which Ultimate Frisbee is played

74 mph fastest Frisbee throw, according to Guinness World Records

65 dollar price on eBay for an original Frisbie pie plate

1100 unique flyingdisc specimens in R ichard Pancoast’s basement collection in Stratford, CT

443 FEET farthest Frisbee toss, according to Guinness World Records

NUMBER 9

Photographer

N A LD RIC H

rowing up in New Hampshire’s Connecticut River Valley, Kindra Clineff fell in love with photography and autumn. Thousands of images later, the adoration continues. What goes into capturing the iconic fall foliage shot? We caught up with Clineff at her Topsfield, Massachusetts, home and studio to find out.

the best,” she says. “For a recent Yankee assignment in northern New Hampshire, I made repeated trips to specific locations just to get the moment when the mist was coming off the Androscoggin River, with the foliage in the background.”

Backlight, that is. Bright sunlight can wash out foliage color, so Clineff avoids shooting with the sun at her back. Instead, she aims her camera in its direction. Backlighting her subjects, she says, makes the leaves and grass look more vibrant. But shooting this way requires finding something with which to shade your lens (more than just a lens shade) so that there’s no sun glare. Clineff’s foolproof method: “I’m a master at finding and working with the shadows cast by trees, signs, and even telephone poles,” she jokes.

Morning, Sunshine

Sundown can be magical, but Clineff prefers early morning. Often, she’s out before the sun is up—for a story in northern Maine she was hiking a trail at 4:30 a.m.—but the payoff is extraordinary. The light is gorgeous, and “if you get that fog or mist, that’s

Keep in mind that fall foliage isn’t a singular moment. A pretty image may be a tree that’s topped with color but still green below. A week later, that same tree may be bare at the top but vibrantly colorful closer to the ground. Also, autumn color is about more than just the maples. “Look at everything around you,” Clineff says. “I find blueberry fields unbelievable. Their rich crimsons are unearthly.”

Thanks to the Web, Clineff can scout out areas before she visits, for conditions and for color. Her favorite tool? The webcam: “It’s great for weather, and you can see what the foliage is looking like.”

When Clineff was shooting in Boston one morning early in her career, a stranger gave her some advice that has remained with her, whether she’s shooting foliage or not. Don’t forget to consider the shadows, he told her. “I’ve never forgotten that,” Clineff says. “He was talking about shadow as a graphic element but also much more. Be aware of everything; don’t narrow your field of vision.”

For more on Clineff and her work, visit: kindraclineff.com

Kindra Clineff has been shooting foliage for Yankee since 1989. She knows that each fall brings a unique gift to anyone with a camera and an eye for unrivaled beauty.A maple tree in all its glorious fall color towers over a meadow in Johnson, Vermont.

September 27

Plymouth, Massachusetts

Yankee Magazine this summer, telling the stories behind some of our favorite New England experiences through a series of editorial features, social media and events. See what we’ve been up to.

On Yankee’s social media channels, our editors kicked o the 2015 ea market season by noting trends and their favorite nds at the Brim eld Antique Show.

Celebrate the crafts of the 17th century with more than 50 artisans, musicians, and foodies (including Yankee associate editor Aimee Seavey) as Plimoth Plantation staff and visiting “makers” demonstrate historic skills ranging from furniture making to beekeeping. plimoth.org

October 3

South Deerfield, Massachusetts Yankee Magazine’s senior food & lifestyle editor Amy Traverso will be on hand to sign her Apple Lover’s Cookbook and host a cooking demo as Yankee Candle Village hosts fruit and cider tastings, live music, hayrides and more. Meet local orchardists and sample seasonal flavors.

yankeecandle.com

Associate Editor Aimee of the Tanglewood Music Center was celebrated with two days of events.

backdrop, as Yankee set sail with the July/August issue.

How many high-schoolers turn to Nathaniel Hawthorne’s Mosses from an Old Manse for their yearbook quote? Kim Knox Beckius did, and “dreams have condensed their misty substance into tangible realities” since the author of books like New England’s Historic Homes & Gardens (Union Park Press, 2011) began producing About.com’s New England Travel site in 1998. Even if literary luminaries failed to inspire your teenage dreams, visit these homes where Kim strongly senses their presence, and you’ll grasp how passion and place shaped phrases that still stir hearts and minds.

Inside the family homestead where Emily Dickinson was born in 1830, died in 1886, and, notoriously, holed up for most of her adult life, she’s less enigmatic. Yes, mysteries remain, and the headless form at the top of the stairs may startle you. But look closely: This replica of the poet’s famed all-white attire isn’t ghostly garb but a sweet, lace-trimmed house dress. Strict parents, the ravages of disease and the Civil War, a secret love, family scandal … Dickinson’s tiny desk was her refuge; her 1,800 poems, therapy. You’ll leave having “met” a woman who chose to “dwell in possibility”—rather than in a judgmental world not yet ready for her rule-breaking verse. Amherst, MA. 413542-8161; emilydickinsonmuseum.org

Samuel Clemens became the Mark Twain we cherish during 17 happy, productive years in Hartford. Within this 1874 brick Victorian, Twain isn’t merely the witty, quotable satirist who dreamed up Tom Sawyer’s and Huckleberry Finn’s adventures in the thirdfloor billiards room. He’s a local guy with neighbors like Harriet Beecher Stowe (tour her house, too) and a fam-

ily he loved. Tales you’ll hear of Twain’s financial and personal losses will tug at your heart. Hartford, CT. 860-2470998; marktwainhouse.org

How did a California boy become the beloved, melodic voice of rural New England? Answer: Robert Frost’s grandfather bought him a farm. Although there are other Frost houses to visit in New England, here in Derry, New Hampshire, a young man scratching out a living became a keen observer of the wisdom that lies in nature’s first green or a snowy evening. As you stroll the path through a landscape that appears even in poems Frost wrote long after selling the farm in 1911, you’ll spy the “ Mending Wall” and “Hyla Brook,”

which, says site manager Bill Gleed, “does exactly what Frost says it does in the poem—every year.” Derry, NH. 603-432-3091; robertfrostfarm.org

Edith Wharton’s Berkshires estate, where she lived and wrote from 1902 to 1911, is New England’s most autobiographical home, the embodiment of all that she and coauthor Ogden Codman Jr. preached in her first book, The Decoration of Houses. This nonfiction treatise on design railed against Victorian fluff in favor of more balanced, harmonious interiors. How conducive to creativity was this thoughtfully conceived mansion and its manicured gardens and grounds? Wharton wrote some of the most celebrated of her more than 40 novels here, including The House of Mirth. Readings and themed tours ensure that the property is perpetually inspiring. Lenox, MA. 413-551-5111; edithwharton.org

If Nathaniel and Sophia Hawthorne had owned smartphones, their endearments would have been lost to us. Luckily for romantics, they’re etched into the window glass at the Georgian clapboard house that the newlyweds rented from the Emersons in 1842. Concord, Massachusetts, is rife with writers’ homes, but none is more iconic than the Old Manse, overlooking the North Bridge, where the “shot heard ’round the world” plunged local militiamen into a battle with long-lasting reverberations. The upstairs study is ground zero for America’s second revolution: the Transcendentalist shift in thought. Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote his landmark essay, “Nature,” while gazing out at the Concord River. Hawthorne installed a desk, condemning himself to stare, undistracted by nature, at the opposite wall. Says site manager Tom Beardsley, “It’s the room people come from all over the world to see.” Concord, MA. 978-3693909; thetrustees.org/places-to-visit/ greater-boston/old-manse.html

• 200 wooded acres: cozy cottage clusters, 65 acre preserve

• Easy access to the Eastern Trail

• 850 to 1350 square foot cottages

• 7 models and many optional upgrades

• Clubhouse, pools and many other amenities

• 9 minutes to Dock Square, Kennebunkport

• 8 ft x 10 ft sheds available

• Pre-construction prices starting at $204,500

NUMBER 11

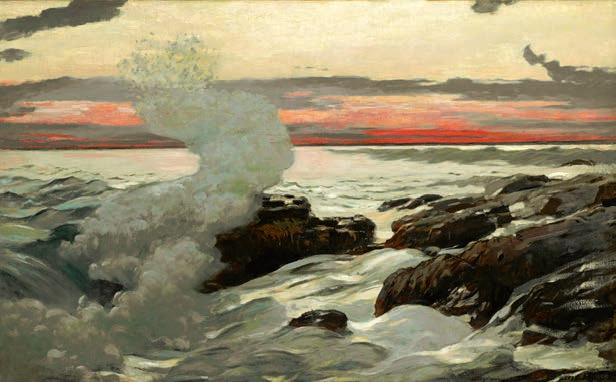

arely 200 feet from the shallows of Maine’s Long Sands Beach, the Cape Neddick Light Station perches so handsomely on its bony 2.8-acre nest of Nubble Island that we call it simply “Nubble Light.” Maine boasts more than 60 standing lighthouses. Nubble Light, Maine’s southernmost light, may well be the one we love most.

In 1977, when Voyager 1 and 2 blasted off for Jupiter and beyond in search of possible alien life, their capsules carried photos to show what we revered here on Earth. Among those photos: the Great Wall of China, the Grand Canyon, Nubble Light. The lighthouse and the keeper’s house are on the National Register of Historic Places, and their likenesses are

engraved on York’s town seal, as if to say: Nubble belongs to the country, but here is its home.

The keepers of the light who lived here from 1879 until the last Coast Guardsman left in the summer of 1987 felt that this was their calling. They tended the French-crafted Fresnel lens as if it were a child, polishing its light until it shone like gold. Sometimes winter blew fog that blanketed the knoll for weeks at a time. The keepers knew that the safety of ships depended on their keeping Nubble’s red light glowing 13 miles out to sea. At dawn, they’d extinguish the light, watch the sun creep over the water, and start their chores.

Nubble Light is at its finest on a blue-sky day when the ocean scent makes mere breathing worth the trip. Stop at tiny Sohier Park on Nubble Road. Ahead you’ll see the gleaming white tower reaching 41 feet high, and beside it the trim red-roofed keeper’s house, a few outlying sheds, and a white picket fence, as if the lighthouse is standing on a shady neighborhood street.

Lighthouses have become icons of our yearning, speaking to us of lives spare and romantic at the same time. We wish we lived there; we know we cannot. So we carry the light inside, no matter where we live. —Mel

AllenNUBBLE LIGHT

Nubble Road (off U.S. Route 1A), York Beach, ME. nubblelight.org

Off the coast of York, in southeastern Maine, the Nubble and its lighthouse are off-limits to the public, but visitors can catch a great view from Sohier Park on the mainland. This area saw many shipwrecks before the lighthouse was constructed. The wreck of the Isidore in 1842 is the most famous; her crew all perished. Since then, legend has it that a phantom ship continues to haunt the seas around Cape Neddick.

NUMBER 12

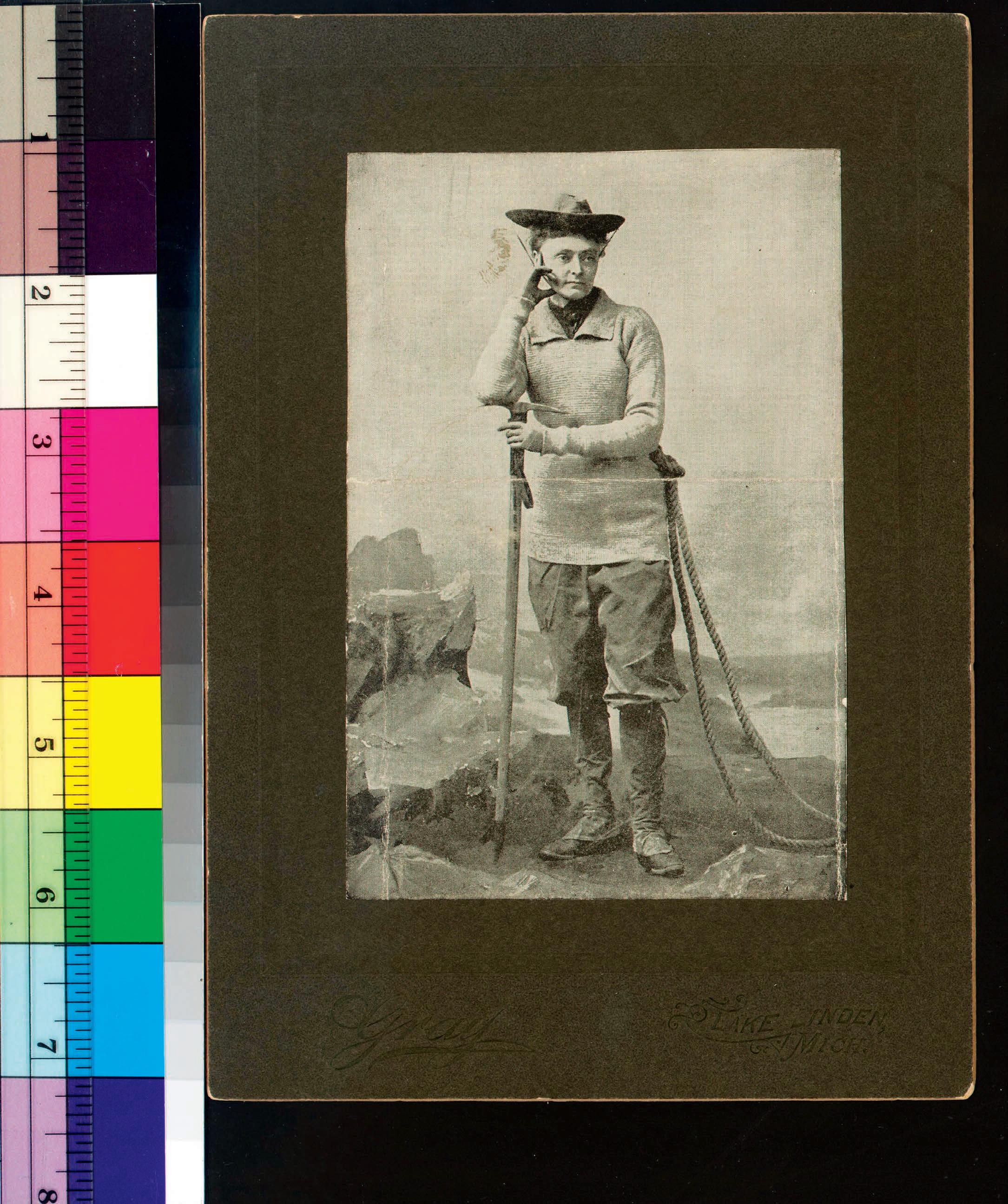

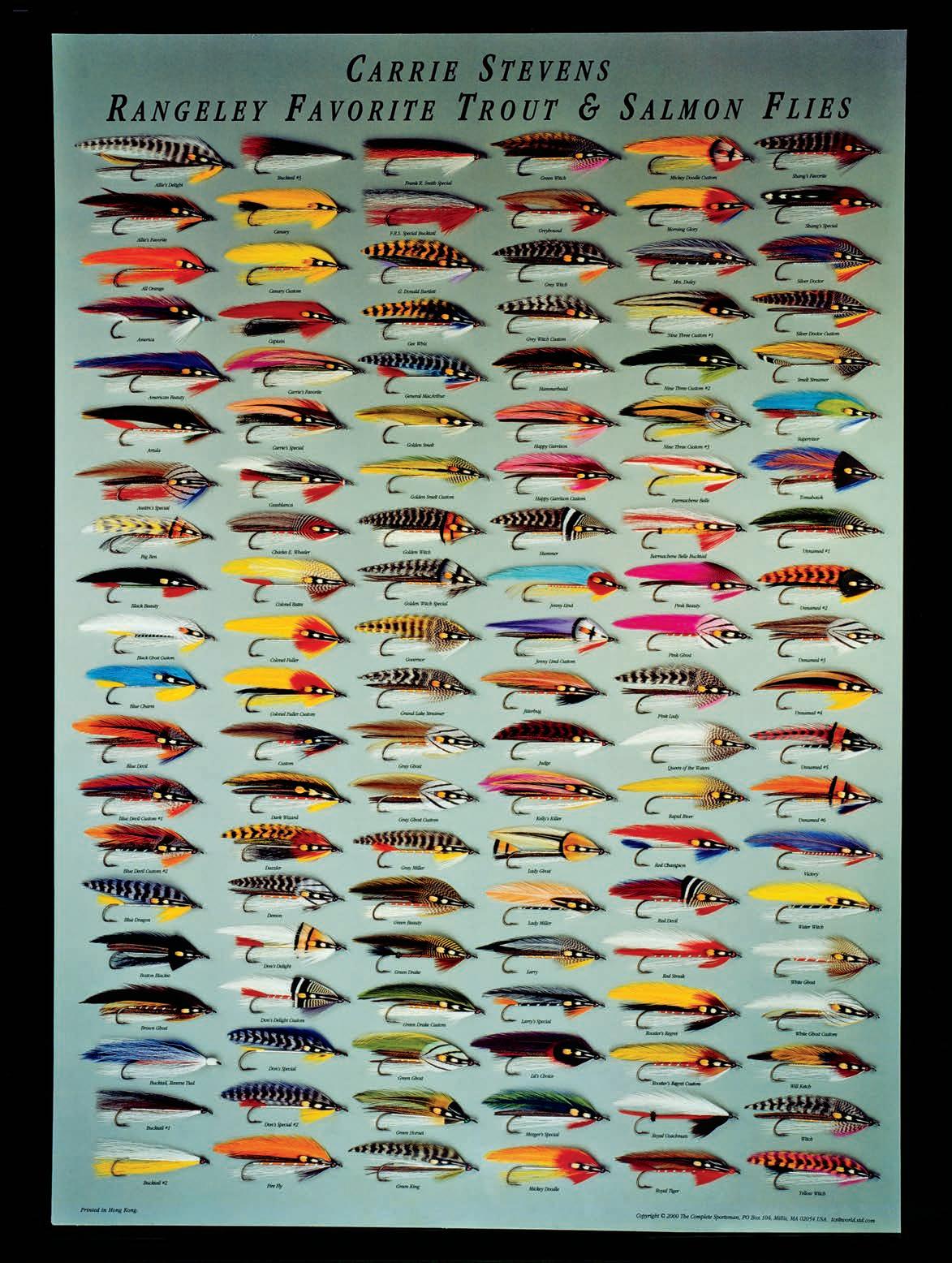

Crosby visited Round Mountain Pond, west of Ashland, Maine, in the summer of 1891, and while there caught 52 trout in 44 minutes of fishing. At the time, she claimed that the feat was unmatched by any woman and had been accomplished by only five men.

Cornelia Thurza Crosby was born in Phillips, Maine, on November 10, 1854. Her father,

In 1886, a friend presented Crosby with a five-ounce bamboo rod. She became so adept at fly fishing that friends called her “Fly Rod,” a nickname she started using as an outdoor writer in 1889. “Fly

Rod’s Notebook” ran in Maine newspapers and in publications as far away as Boston, New York, and Chicago. Starting in 1901, she wrote regularly for the national magazine Field & Stream

An early proponent of catch and release, Crosby is said to have caught more than 200 fish in a single day, and some 2,500 trout during the summer of 1893.

Crosby helped create Maine’s popular exhibit at the first New York Sportsmen’s Exposition, held in May 1895 at Madison Square Garden. The display, called “Camp Maine Central,” featured a 10x13-foot log cabin and dozens of mounted animals and fish. For the 1896 show, Fly Rod added tanks of live trout and salmon and decked herself out in a daring calf-length doeskin skirt, rifle in hand.

As her fame grew, Crosby was hired by the Maine Central Railroad as its first publicity agent. Her job was to write about things that would attract people to Maine, not necessarily about the railroad.

Although initially opposed, Crosby came to support the issuance of hunting and fishing licenses, with proceeds funding Maine’s Department of Fish & Game (now Inland Fisheries & Wildlife). She was a vocal advocate for game preservation, catch limits for fish, kill limits for deer, and closed seasons for big game.

According to a newspaper account, Crosby returned to Rangeley Lake to fish when she was in her eighties, staying two weeks at Bald Mountain Camps.

Crosby died in Lewiston on Armistice Day 1946, just a day after her 92nd birthday.

—compiled by Joe Bills

When Maine passed an 1897 bill requiring hunting guides to register with the state, the first license issued went to ‘Fly Rod’ Crosby, a sportswoman and journalist whose natural flair for public relations had helped establish western and northern Maine as outdoor-sports destinations.

“Fly Rod” Crosby,photographed in Edwin Starbird’s studio, c.

1890. “I would rather fish any day than go to heaven,” she once wrote. Her friend Louis Sockalexis, a Penobscot Indian and pro baseball player, said, “Her face is white, but her heart is the heart of a brave.”

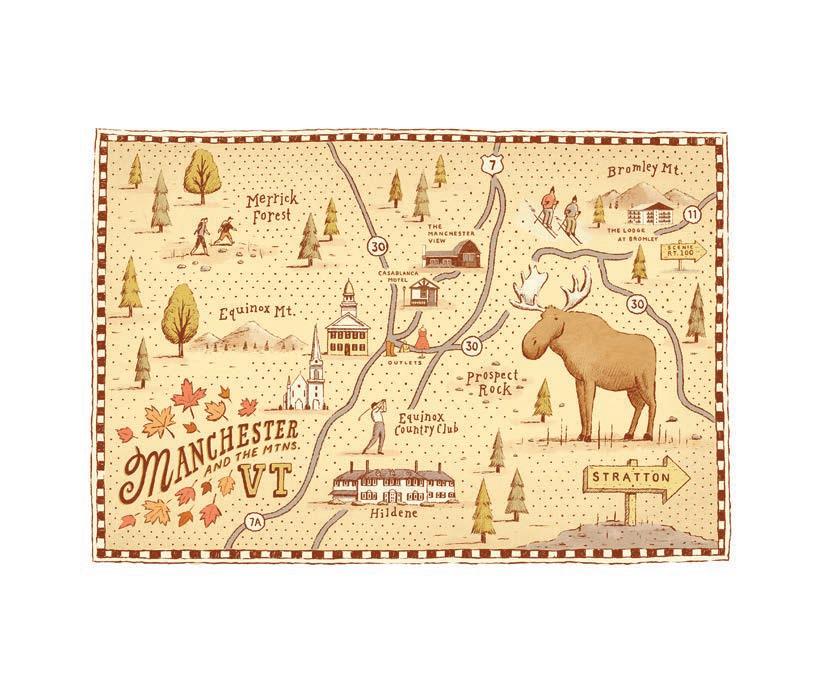

The Lodge at Bromley If being near the mountains just isn’t close enough, stay on the mountain at The Lodge at Bromley. Remarkably family-friendly with a special kids’ lodge, this slope-side resort is just feet from Bromley Mountain and a short drive to Manchester’s museums and designer outlet shopping. Located in the charming village of Peru, enjoy breathtaking vistas of the West River Valley from your window, or hop onto one of Vermont’s nearby scenic byways for a relaxing, beautiful drive.

The Peru Fair Approximately 100 exhibitors will converge on the tiny village of Peru, Vermont to sell their arts at this year’s 36th annual Peru Fair. The parade of whimsical characters officially opens the Fair as music and the smell of food fill the air. Highlights include a pig roast, art demonstrations, artisan crafts, music, dancing, and foods of all tastes. Date: September 26. 9-4 p.m.

boasts charming village centers, historical museums, outdoor adventures, and designer outlet shopping – all within three hours from Boston and less than four hours from New York City. Gas up, get on the road and head to southern Vermont

Manchester View Fine Lodging If you’re looking for a cozy and luxurious room with sweeping mountain views outside a private balcony, this is the lodge for you. Cradled by mountains from almost every direction, Manchester View’s elegant, rustic rooms and family-size suites make for an authentic mountainside vacation. Be sure to enjoy the outdoor heated swimming pool (in-season) before curling up to one of the property’s nineteen working fireplaces. Located close to town, you can’t miss the area’s shopping,

experience at these quaint storybook cottages. Charmingly restored, Casablanca’s cabins offer modern amenities with a vintage vibe, in the heart of Manchester Center. The real stars of this pet-friendly, retro escape are the grounds –complete with gardens, grills, a screened in gazebo and lawn games that transport you back in time to a simpler way of life. Toss a few horseshoes or relax around a fire pit for an evening of songs and s’mores.

32nd Annual Weston Craft Show Don’t miss the opportunity to visit one of the most prestigious exhibitions of contemporary crafts in Vermont. The Weston Craft Show features exceptional Vermont artisans through a carefully juried array of arts and crafts. This show offers discerning collectors high quality, diversity and beautiful displays.

Dates: October 9 -11. 10-5 p.m.

7

OF FALL

Two centuries old, the Jenne Farm nestles amid the rolling landscape around Reading, Vermont.

Two centuries old, the Jenne Farm nestles amid the rolling landscape around Reading, Vermont.

he story goes that years ago, when Floyd Jenne Sr. traveled from Reading, Vermont, to New York City—a distance that can’t be measured merely in miles—he arrived at Grand Central Terminal, looked up, and saw a massive photo of his farm spread across the walls. His surprise couldn’t have been greater than the awe that a first-time viewer experiences standing on the rising hillside above Jenne Farm—except that few who venture out here are completely unprepared. Most come with a purpose. Most know exactly why they’ve come. And some even know precisely where they’re going to stand.

Jenne Farm is the most photographed farm in New England, possibly in all of North America. And maybe even, as Rebecca Gibbs in Thorton Wilder’s play Our Town might say, in the Western Hemisphere. Chances are, you’ve seen it, too—been there, in a sense.

Especially in fall, photographers descend like cows coming down from pasture. Cameras click, documenting the

rise and fall of light on the idyllic scene. But despite the hundreds, maybe thousands, of calendars and postcards and bits of advertising and star turns in films like Forrest Gump and Funny Farm , nothing prepares you for the downward sweep of land and the tidy cluster of tumbledown red buildings burrowed into pillows of hills. In a landscape brimming with farms, Jenne Farm rises to the top, like cream on fresh milk.

Linda Jenne Kidder has been a trustee of the 460-acre spread since 2003. She remembers when the photographers began to descend, in the mid-1950s, after students at a local photography school started snapping shots of the 1813 farm, built by her forebears. The photogenic setting soon caught the eye of Life magazine, Vermont Life , and, of course, Yankee. “It was pretty overwhelming,” she recalls. Her eyes linger over a landscape that lives in her blood; Jennes have been on this land since 1790.

“[People] would come by the busload,” she recalls. “We always had beagle puppies, and they’d ask me to hold one of

A Conway Scenic Railroad train heads through New Hampshire’s Crawford Notch, amid dramatic scenery, on tracks that were laid in the 1870s.the puppies, take my picture, and give me nickels, dimes, and quarters.”

In her late teens, when all the postcards began appearing, Linda realized what a special place the farm was. In the face of entreaties from developers, she keeps it going with a herd of beef cattle and a maplesugaring operation. “I’m glad we can keep it,” she muses, “but it needs a lot of work. It’s still a beautiful place.” Hundreds of photographers click their cameras in agreement each year, as the sugar maples burst with color.

And somewhere out there, tucked into a photo album, hanging on a wall, or hidden away in an old shoebox, are photos of a 10-year-old Linda Jenne, holding a beagle pup, against this backdrop of simple beauty. The world’s moved on since then, but there’s still a little corner of peace and tranquility at the top of Jenne Road that feels as though you’ve just drifted back in time, to a piece of heaven on earth. You can even take a picture of it.

—“J Is for Jenne Farm,”

by Annie Graves, September/October 2012

by Annie Graves, September/October 2012

From Woodstock, drive south on Vermont Route 106, through South Woodstock; then follow the road up Reading Hill. There will be a small sign on the right-hand side and a sign for Jenne Road.

he Conway Scenic Railroad runs vintage equipment from the old round house in North Conway, New Hampshire. From late spring to mid-December, some of the trains go south down the valley to Conway. The other trains run north to Glen and Bartlett through what

(continued on p. 44)

A fiery autumn sunrise greets travelers pausing at the C. L. Graham Wangan Grounds Scenic Overlook along “the Kanc,” in White Mountain National Forest. A century ago in the old logging days here, a wangan was a supply storehouse (sometimes on wheels).

Up and up you go, to 2,860 feet, with a scattering of lookouts where you can pull over to photograph views near and far.

(continued from p. 41)

an 1890 edition of Sweetser’s White Mountains described as “the broad intervales of the Saco River.”

I live five miles north of Glen and I’ve been through those intervales 10,000 times or more, but I’d never seen them this way until I rode the Scenic Railroad up the valley. I’d seen them from the road or from the tops of the mountains, but now I was a tourist on my home ground. I was riding the train through the backyards of people I knew. I was seeing their woodsheds and their children’s swings as landscape.

The serious work of another age began at Bartlett. The long climb through Crawford Notch to Bretton Woods and Fabyan Station was the most famous grade in the Northeast; it was so steep that when steam locomotives ruled the rails, as many as five helper engines were put on in Bartlett. Our train was a lightweight by those heroic standards: just a coach, a first-class car, and an observation car with open sides and outward-facing bench seats. Now I easily remembered the slight posting motion when seated, matching the bump-thump bump-thump of the rails, and the swaying sailor’s gait when negotiating the aisles. I also remembered, with some slight difficulty, how to stay calm while crossing a trestle 94 feet above a rushing stream, and so narrow that it seemed to have no visible means of support.

“When we entered the Notch, we were struck with the wild and solemn appearance of everything before us.”

Crawford Notch pinches tighter and tighter, and the railbed climbs steadily up its west wall. The ornate language of Sweetser’s day strikes us as quaint and improbable, but his description of the ride through Crawford Notch still rings true: “When we entered the Notch, we were struck with the wild and solemn appearance of everything before us.” Sweetser’s elevated cadences have retired to the archives, but I was grateful to the Conway Scenic Railroad for giving me a new view of the place where I live.

—“Good Grade,” by Nicholas Howe, September 2001

Conway Scenic Railroad, 38 Norcross Circle, North Conway, NH. 603-356-5251; conwayscenic.com

he Kancamagus Highway, which opened in 1959, may be the most scenic 34.5-mile drive in New England. The popularity of this paved mountain pass—Route 112—between Lincoln and Conway, New Hampshire, ensures that you’ll have company in October, so you’ll want to wake up early to explore it. Up and up you go, to 2,860 feet, with a scattering of lookouts where you can pull over to photograph views near and far, and here and there you’ll find picnic spots where you can linger above the foliage. It’s a drive to take with the windows open, eyes peeled. Don’t be surprised if you come upon a line of cars pulled over, waiting for the moose to shuffle back into the forest.

—“K Is for Kancamagus Highway,”

by Ian Aldrich, September/October 2012

Enjoy the wonderful Blackstone River Valley National Heritage Corridor at more than 80 exciting experiencesmany are free!

Contact us for a free, color brochure or download it: Blackstone Heritage Corridor, Inc.

One Depot Sq., Woonsocket, RI 02895 401-765-2211 • www.BlackstoneHeritageCorridor.org

A Wee Faerie Village is back!

The return of our popular faerie house walking trail this year highlights over twenty faeriesized castles, towers, and palaces celebrating fiction’s greatest royal tales.

It’s the Vermonter’s Vermont … the loneliest and loveliest corner.

Whenever my wife, Kay, and I want to visit Vermont as though we didn’t already live here, we head for the Northeast Kingdom. It’s a name that fits a world apart, and it comes with a story of its origins. Local newspapermen used it in the early 1940s, but it was Vermont’s legendary Senator George Aiken who first gave “Northeast Kingdom” widespread currency.

As for the region’s true boundaries, who wants to split hairs? Some offer a neat delineation, drawing a line around the three counties of Orleans, Caledonia, and Essex, but the eastern reaches of Franklin and Lamoille counties ought to be tossed in as well. The Northeast Kingdom begins where most people would sooner do their big-ticket shopping in Newport or St. Johnsbury than in Burlington. It’s the Vermonter’s Vermont.

—“The Vermonter’s Vermont,” by William Scheller, September/October 2011

oute 100 is a restless road. As it salamanders its way through the mountainous middle of Vermont, it seems perpetually on the verge of decision, only to change its mind in a mile. One minute, it’s slaloming along a rocky riverbed through dense cover of birch and maple; the next, it’s soaring up to a sudden vista as though God has suddenly pulled away a curtain. There’s a reason that this stretch of highway—some 200 miles, from Massachusetts to Lake Memphremagog in Vermont—has been called the most scenic in New

England. In some circles, it’s known as the “Skiers’ Highway,” since it connects Vermont’s giants—Snow, Okemo, Killington, Sugarbush, Stowe, Jay—like knots on a whip.

But the road really comes into its own in autumn, hitting the peak of fall

foliage not once but many times as it traces an up-and-down course along the unspoiled edge of Green Mountain National Forest. When civilization does break through, it’s in the form of some of Vermont’s most quintessential villages.

Leaf peeping, after all, is about more than just leaves. It’s about the foliage experience—farmstands and country stores, craft galleries and hot cider. And Route 100, with its many off-thebeaten-path side trips, offers all of that in one long, winding package. Because the road never makes up its mind, you don’t have to, either.

And when it finally ends, some 10 miles short of Canada, your most difficult decision is the one to turn the car around and head home. The only comfort is that you get to see the whole show over again in reverse.

—“Driver’s Delight,” by Michael Blanding, September/October 2009

Vermont’s Route 100, with its many off-the-beaten-path side trips, offers all the different elements of the foliage experience in one long, winding package.

If it tastes good in your glass, it will probably taste great in your marinade. And when you’re feeling creative, the New Hampshire Liquor & Wine Outlets stock thousands of potential ingredients to experiment with. Stop by any of our 78 convenient locations throughout the state for outstanding selection, legendary prices, and no sales tax.

shmead’s Kernel’, ‘Roxbury Russet’, ‘Belle de Boskoop’, ‘Pink Pearl’, ‘Winter Banana’ … The names of antique and rare apple varieties are part poetry, part history lesson. Many go back centuries, some as far as the Renaissance. Most of the old varieties we know today, though, sprang up around the turn of the 19th century, when John Chapman (a.k.a. “Johnny Appleseed”) departed Massachusetts for the nascent Northwest Territory of Ohio and points west, planting nurseries as he went. By 1905, when the U.S. Department of Agriculture

Please

Liquor

commissioned a report on all known American apple varieties, researchers counted some 14,000 unique types. Today, only about 100 are grown commercially in any volume, but after decades of ‘Red Delicious’ dominance, the old apples are finding a new audience—especially here in New England, where savvy growers are swapping some of their ‘Cortland’ trees for ‘Calville Blanc d’Hiver’ and ‘Cox’s Orange Pippin’. These antique stunners have flavors and aromas that run from toasted nuts to honeyed champagne to lemonade, and tasting them is like discovering an entirely new fruit species.

—“O Is for Orchard,” by Amy Traverso, September/October 2012For a list of New England orchards that feature not only beautiful settings but also heirloom apples, turn to p. 50.

These antique stunners have flavors and aromas that run from toasted nuts to honeyed champagne to lemonade.

Paul and Jo-Ann Desrochers grow vegetables, peaches, plums, and nectarines, but they have a special love of heirloom apples—nearly 90 varieties, all grown without pesticides. You’ll find ‘Westfield Seek-No-Further’ (a Massachusetts native), ‘Newtown Pippin’, and the wondrous ‘Hidden Rose’, whose bland green-brown skin gives way to bright fuchsia flesh that tastes of raspberries. Open Saturday afternoons in the fall. 156 Plainfield Pike Road, Plainfield, CT. 860-564-2154; facebook.com/pages/18thCentury-Purity-Farms/1145617086 17136

At this hilltop orchard in southwestern New Hampshire, you’ll find more than 50 apple varieties in neat rows, drawing your eye toward sweeping views of the Connecticut River Valley. Manager Homer Dunn adds more old breeds each year; the roster now includes ‘Belle de Boskoop’, ‘Reine des Reinettes’, and ‘Hudson’s Golden Gem’. Bring a picnic and top it off with pie from the orchard’s store. 57 Alyson’s Lane, Walpole, NH. 800-856-0549, 603-756-9800; alysons orchard.com

Possibly the most beautiful orchard view in New England, with vistas as far as the White Mountains. When you turn your attention back to the trees, you’ll find 80-plus apple cultivars tended by owners Tim and Amy Bassett. One variety especially worth noting: ‘Hampshire’, a tree that sprang up from seed on this very farm; with its abundant juice and rich flavor, it makes a great pie. 656 Gould Hill Road, Contoocook, NH. 603-746-3811; gouldhillfarm.com

Steve Wood and Louisa Spencer operate two businesses on their land in westcentral New Hampshire: Poverty Lane Orchards, where they grow dozens of antique and unusual apple varieties, and Farnum Hill Ciders, where they make complex ciders from the aforementioned apples. Both are worth exploring for their nuance and quality. 98 Poverty Lane, Lebanon, NH. 603448-1511; povertylaneorchards.com

In the heart of America’s first fruit bowl, this beautiful winery and restaurant is also home to a spectacular antique-apple orchard stocked with rare finds, such as ‘Pink Pearl’, ‘Ashmead’s Kernel’, and ‘Esopus Spitzenberg’— nearly 100 in all. (Call ahead to make an appointment.) Tack a wine tasting and dinner onto your day and you have a make-your-own harvest festival. 100 Wattaquadock Hill Road, Bolton, MA. 978-779-5521, 978-779-9816 (dinner reservations); nashobawinery.com

Landmark Trust USA manages these 626 pristine acres in southern Vermont, where a team of orchardists tends some 90 varieties of low-spray heirloom and unusual apples. This beautiful property served as the location for the orchard scenes in The Cider House Rules. There’s a farm stand, plus classes on pruning and grafting, pie baking, and cider making. Great bonus: You may rent either of two of the many historic structures here for a weekend getaway—or the adjoining Rudyard Kipling estate, Naulakha, where he wrote his Jungle Book series. 707 Kipling Road, Dummerston, VT. 802-254-6868; landmark trustusa.org —A.T.

CRAFT: BEERS + TRADES | SEPT. 19 & 20

DIG IN: A FIELD-TO-TABLE FESTIVAL | OC T. 17 & 18

BOUNTY: A NEW ENGLAND THANKSGIVING NOV. 7 & 8, 14 & 15, 21 & 22 AND 26

WINTER MARKET | NOV. 27 – 29

CHRISTMAS BY CANDLELIGHT | DEC. 4

A worker rakes cranberries at harvest time in Duxbury, Massachusetts.