Turn Up the Color!

HOP ABOARD the best

FOLIAGE TRAINS

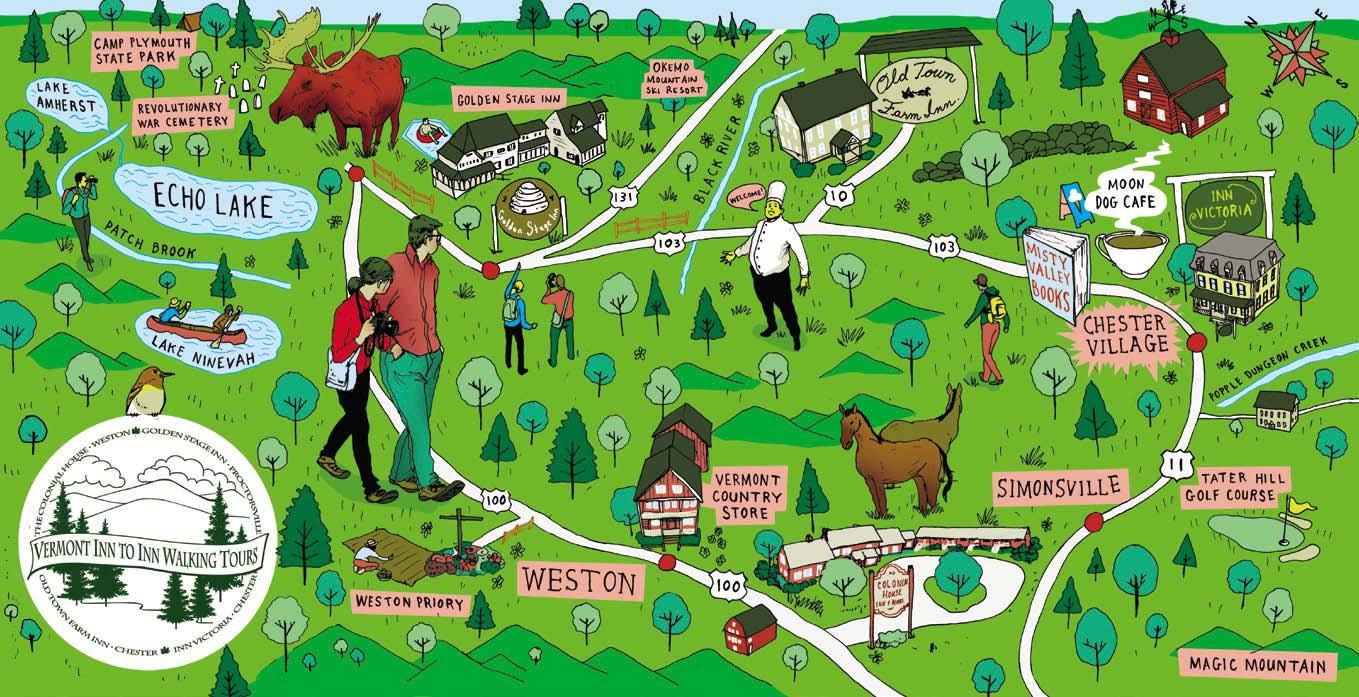

DISCOVER

VERMONT’S hidden HOT SPOTS

ROAD-TRIP with fellow LEAF PEEPERS

HOP ABOARD the best

FOLIAGE TRAINS

DISCOVER

VERMONT’S hidden HOT SPOTS

ROAD-TRIP with fellow LEAF PEEPERS

///

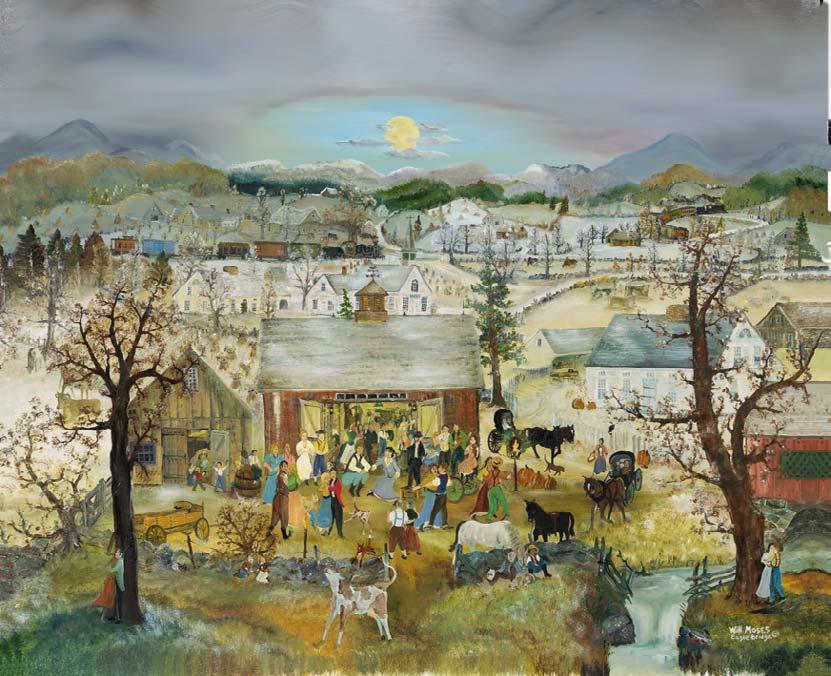

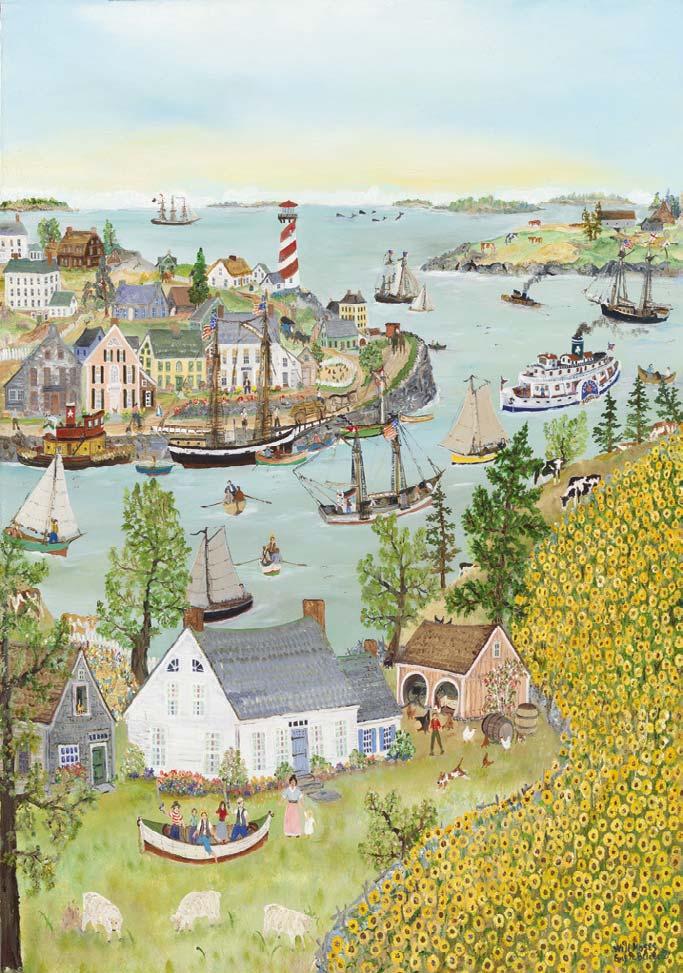

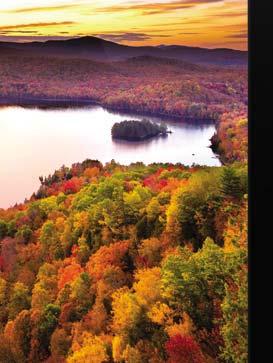

As crowds flock to Vermont’s top foliage towns this fall, there’s plenty of prime color to be found in surprisingly little-known spots, too. By Bill Scheller

110 ///

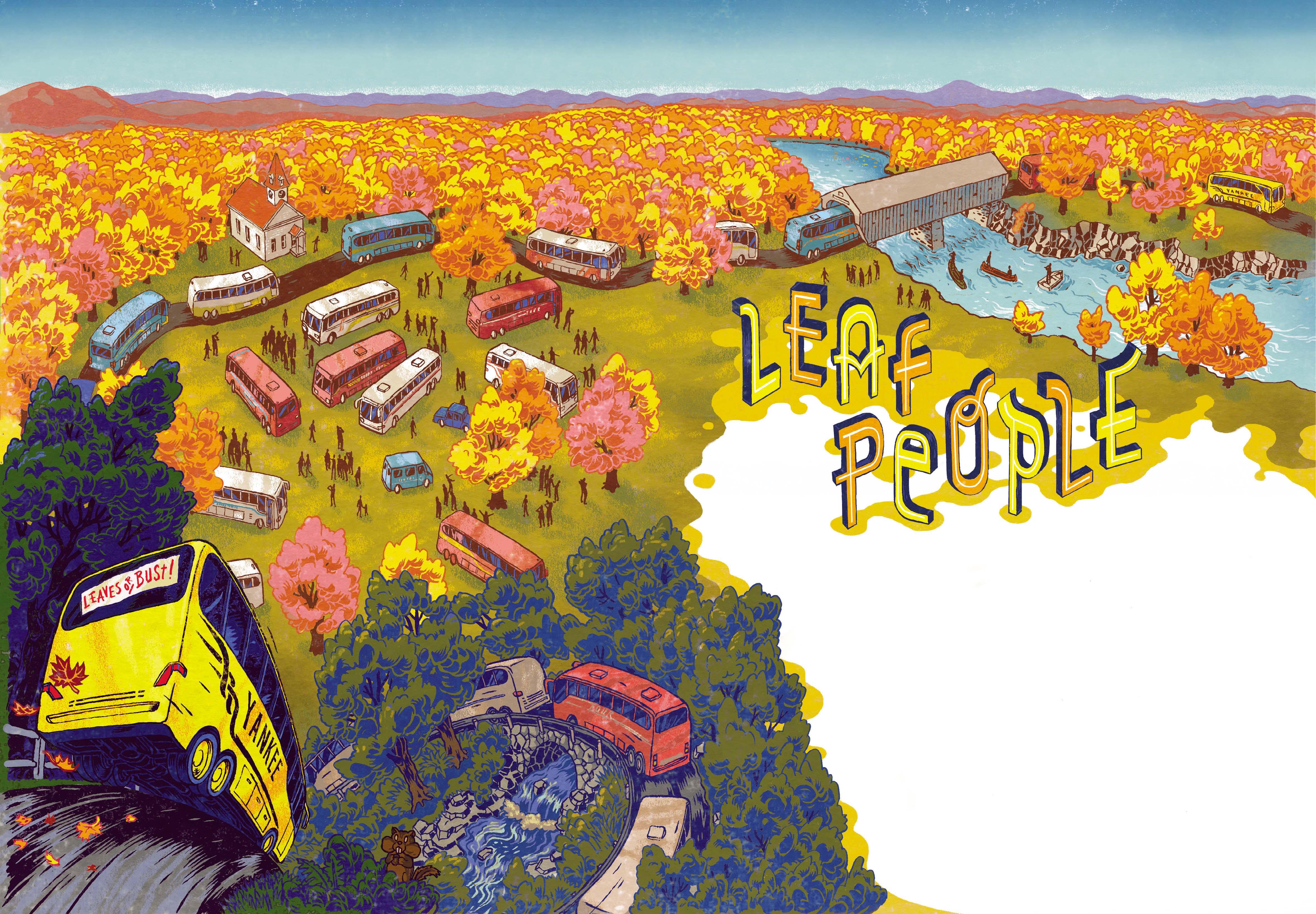

After years of watching foliage bus tours rolling past in autumn, a Yankee editor hops aboard to see his home through a leaf peeper’s eyes. By Ian Aldrich

///

Meet New England’s “grainiacs”: the farmers, millers, and bakers who are right now creating some of the best breads in the country. By Rowan Jacobsen

///

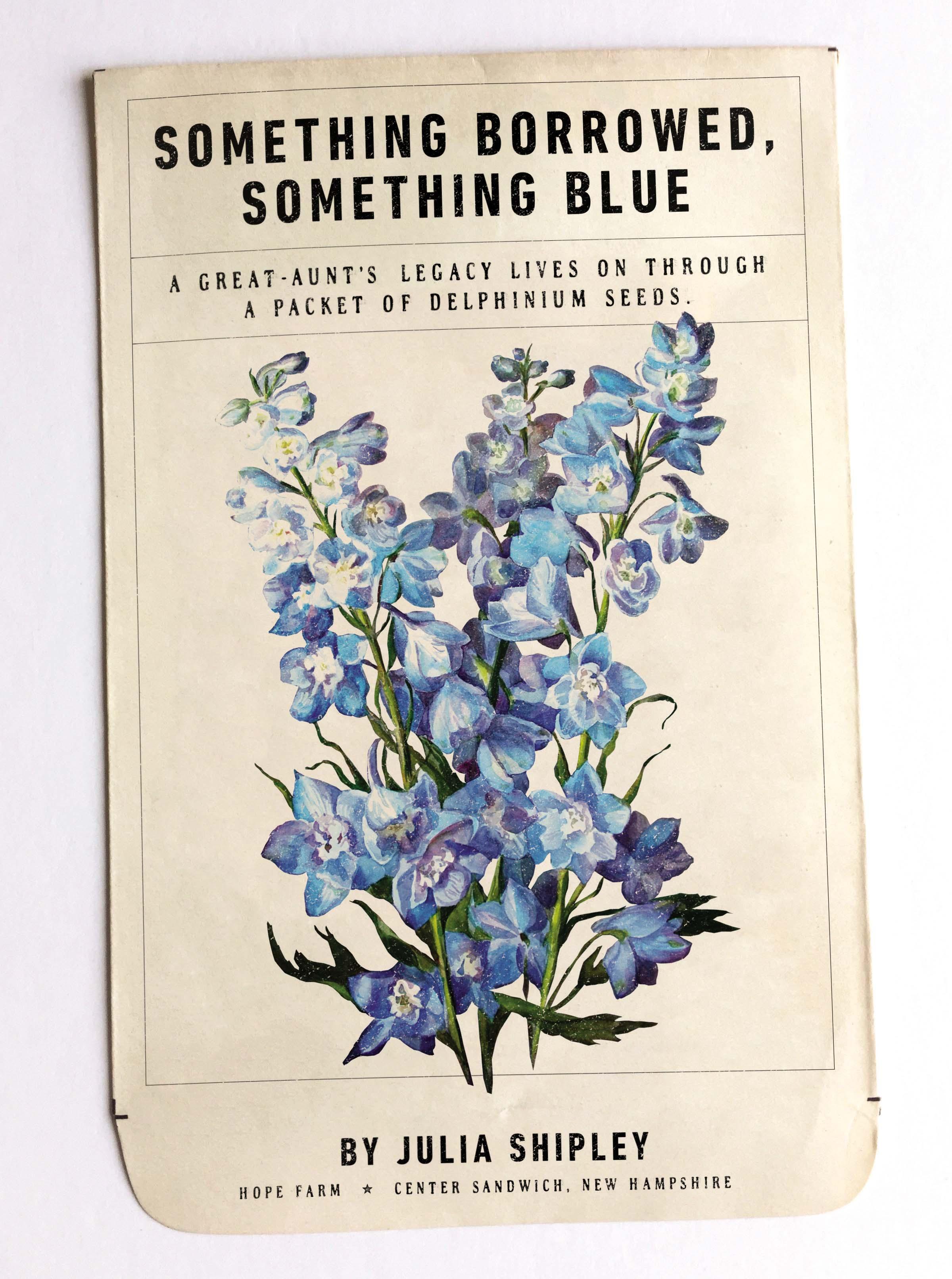

A decades-old packet of seeds holds the promise of remarkable blooms—and the memory of the equally remarkable woman who collected them. By Julia Shipley

128 ///

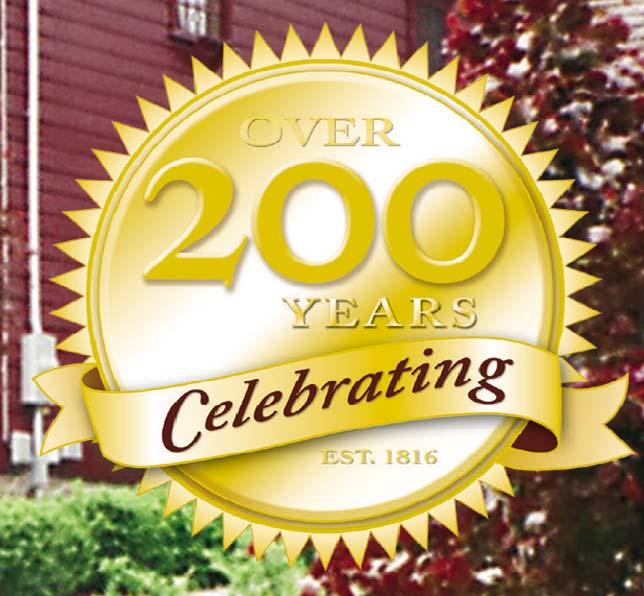

The granddaddy of New England country fairs may be turning 200 next year, but its appeal never grows old.

Photographs by Mark Fleming

///

How Ken Burns’s documentary on the most divisive event in America since the Civil War came to life in a quiet New Hampshire village. By Mel Allen

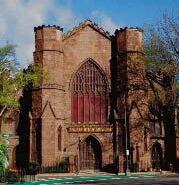

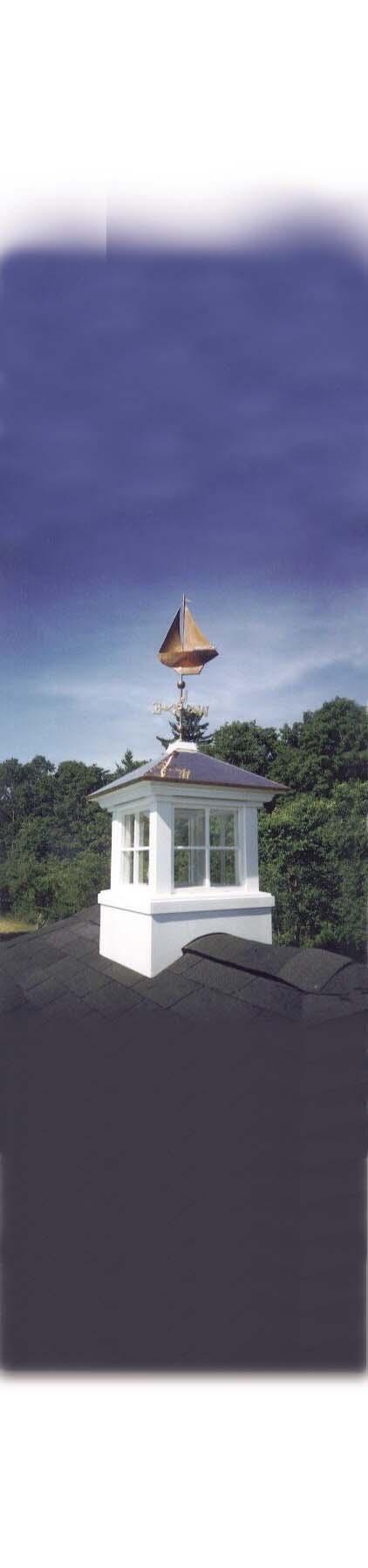

32 /// An Ideal Setting

Rhode Island jewelry artist Carolyn Morris Bach transforms an overgrown 18th-century Cape into a polished work-and-living space. By Annie Graves

40 /// The House at Allen Cove

A legendary American writer. A stunning Maine saltwater farm. This just might be Yankee ’s ultimate House for Sale. By Mel Allen

58 /// Fruits of the Forest Photographer turned forager Jamie Salomon sets his sights on wild mushrooms. By Keith

Pandolfi

Pandolfi

64 /// Local Flavor

10

DEAR YANKEE, CONTRIBUTORS & POETRY BY D.A.W.

12

INSIDE YANKEE

In praise of unexpected encounters.

14

MARY’S FARM

Drawing strength from an extraordinary family friend.

By Edie Clark16

LIFE IN THE KINGDOM

As the days get shorter, the list of chores grows longer.

By Ben Hewitt20

FIRST LIGHT

A bike trip into the heart of Maine’s famous landscape and the lives of its people.

By Peggy Grodinsky26

68 /// New Vintage Cooking

TraversoBaked in a farmhouse and sold on the honor system, these pies are a Vermont slice of life. By Amy

Re-creating a recipe from memory ... when the memory isn’t yours. By Amy Traverso

70 /// Could You Live Here?

Find maritime history and witchy lore side by side in one of the most idiosyncratic towns in the country. By Annie Graves

76 /// The Best 5

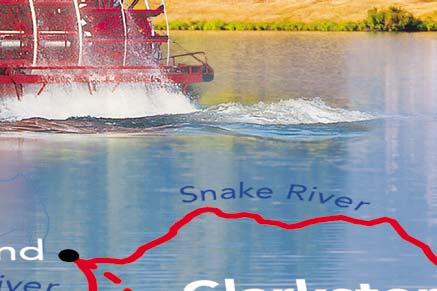

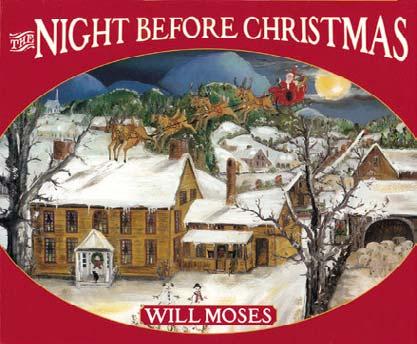

Ride the rails to autumn color on New England’s top foliage trains. By Kim Knox Beckius

80 /// Local Treasure

Paying tribute to the Maine lumbermen who felled the trees that built a nation. By Ian Aldrich

82 /// Out & About

From Oktoberfests to country fairs, we round up regional events that are worth the drive.

KNOWLEDGE & WISDOM

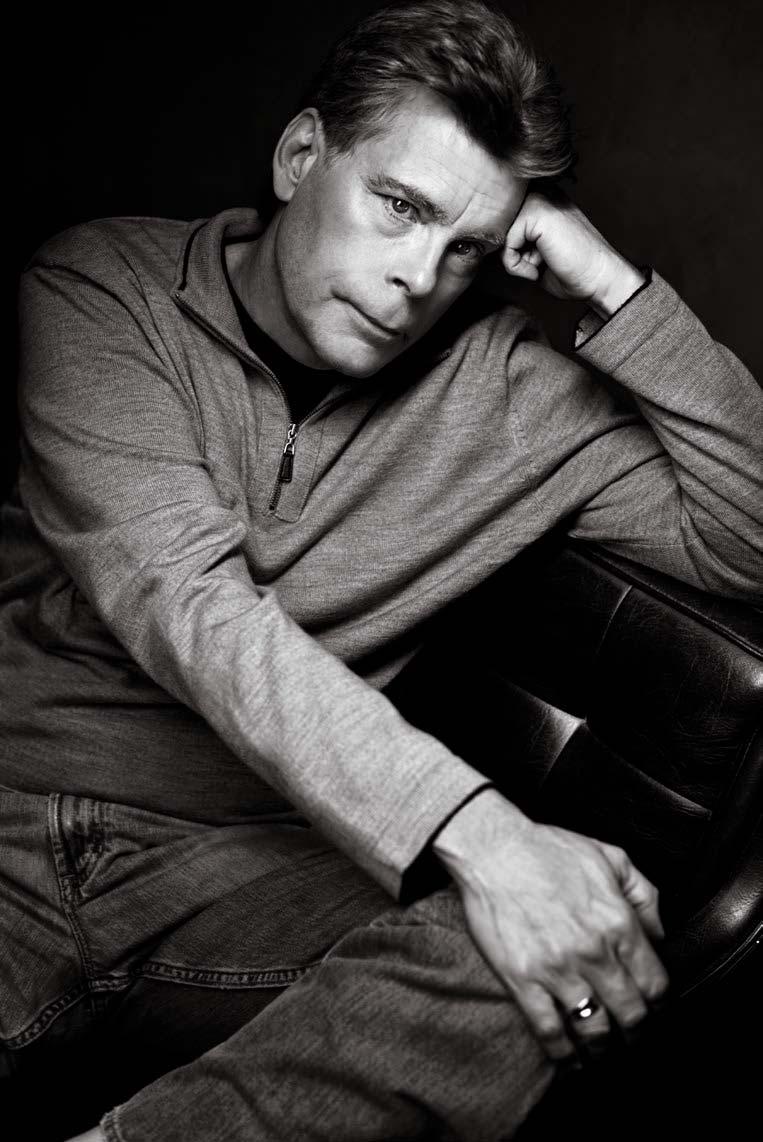

Taking the measure of a country mile, revisiting Philip Johnson’s iconic Glass House, and scary insight from Stephen King.

28

ASK THE EXPERT

Pro tips on winning a wife carrying championship.

156

TIMELESS NEW ENGLAND

Remembering the quirky shopping paradise that was “the Basement.”

1121 Main St., P.O. Box 520, Dublin, NH 03444. 603-563-8111; editor@yankeemagazine.com

EDITORIAL

EDITOR Mel Allen

ART DIRECTOR Lori Pedrick

DEPUTY EDITOR Ian Aldrich

MANAGING EDITOR Jenn Johnson

SENIOR EDITOR/FOOD Amy Traverso

HOME & GARDEN EDITOR Annie Graves

PHOTO EDITOR Heather Marcus

SENIOR PHOTOGRAPHER Mark Fleming

DIGITAL EDITOR Aimee Tucker

DIGITAL ASSISTANT EDITOR Cathryn McCann

ASSOCIATE EDITOR Joe Bills

INTERN Heather Tourgee

CONTRIBUTING EDITORS Kim Knox Beckius, Edie Clark, Ben Hewitt, Julia Shipley

CONTRIBUTING

PHOTOGRAPHERS Julie Bidwell, Kindra Clineff, Sara Gray, Corey Hendrickson, Joe Keller, Joel Laino, Jarrod McCabe, Michael Piazza, Heath Robbins, Carl Tremblay

PRODUCTION

PRODUCTION DIRECTORS David Ziarnowski, Susan Gross

SENIOR PRODUCTION ARTISTS Jennifer Freeman, Rachel Kipka

DIGITAL

VP NEW MEDIA & PRODUCTION Paul Belliveau Jr.

DIGITAL MARKETING MANAGER Amy O’Brien

YANKEE PUBLISHING INC.

established 1935

PRESIDENT Jamie Trowbridge

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Judson D. Hale Sr.

VICE PRESIDENTS Paul Belliveau Jr., Jody Bugbee, Judson D. Hale Jr., Brook Holmberg, Sherin Pierce

CONTROLLER Sandra Lepple

CORPORATE STAFF Mike Caron, Linda Clukay, Nancy Pfuntner, Bill Price, Sabrina Salvage, Christine Tourgee

BOARD OF DIRECTORS

CHAIRMAN Judson D. Hale Sr.

VICE CHAIRMAN Tom Putnam

DIRECTORS Andrew Clurman, H. Hansell Germond, Daniel Hale, Judson D. Hale Jr., Joel Toner, Cor Trowbridge, Jamie Trowbridge

FOUNDERS

ROBB & BEATRIX SAGENDORPH

PUBLISHER Brook Holmberg

ADVERTISING: PRINT/DIGITAL

VICE PRESIDENT/SALES Judson D. Hale Jr.

SALES IN NEW ENGLAND

TRAVEL, NORTH Kelly Moores KellyM@yankeepub.com

TRAVEL, SOUTH Dean DeLuca DeanD@yankeepub.com

TRAVEL, WEST David Honeywell Dave_golfhouse@madriver.com

DIRECT RESPONSE Steven Hall SteveH@yankeepub.com

SALES OUTSIDE NEW ENGLAND

NATIONAL Susan Lyman, 646-221-4169 Susan@selmarsolutions.com

CANADA Alex Kinninmont, Françoise Chalifour, Cynthia Jollymore, 416-363-1388

AD COORDINATOR Janet Selle

For advertising rates and information: 800-736-1100, ext. 204 NewEngland.com/adinfo

MARKETING

CONSUMER

MANAGERS Kate McPherson, Kathleen Rowe

ASSOCIATE Kirsten Colantino

ADVERTISING

DIRECTOR Joely Fanning

ASSOCIATE Valerie Lithgow

PUBLIC RELATIONS

BRAND MARKETING DIRECTOR Kate Hathaway Weeks

NEWSSTAND

VICE PRESIDENT Sherin Pierce

DIRECT SALES

MARKETING MANAGER Stacey Korpi

SALES ASSOCIATE Janice Edson

SUBSCRIPTION SERVICES

To subscribe, give a gift, or change your mailing address, or for other questions, please contact our customer service department: Online: NewEngland.com/contact

Phone: 800-288-4284

Mail: Yankee Magazine Customer Service P.O. Box 422446 Palm Coast, FL 32142-2446

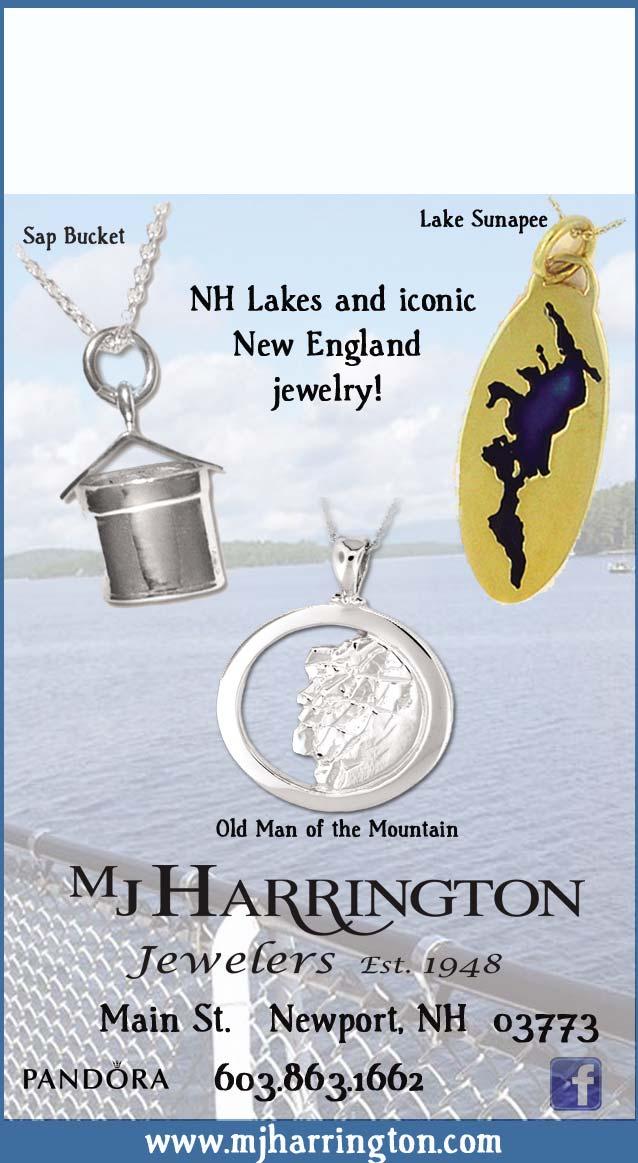

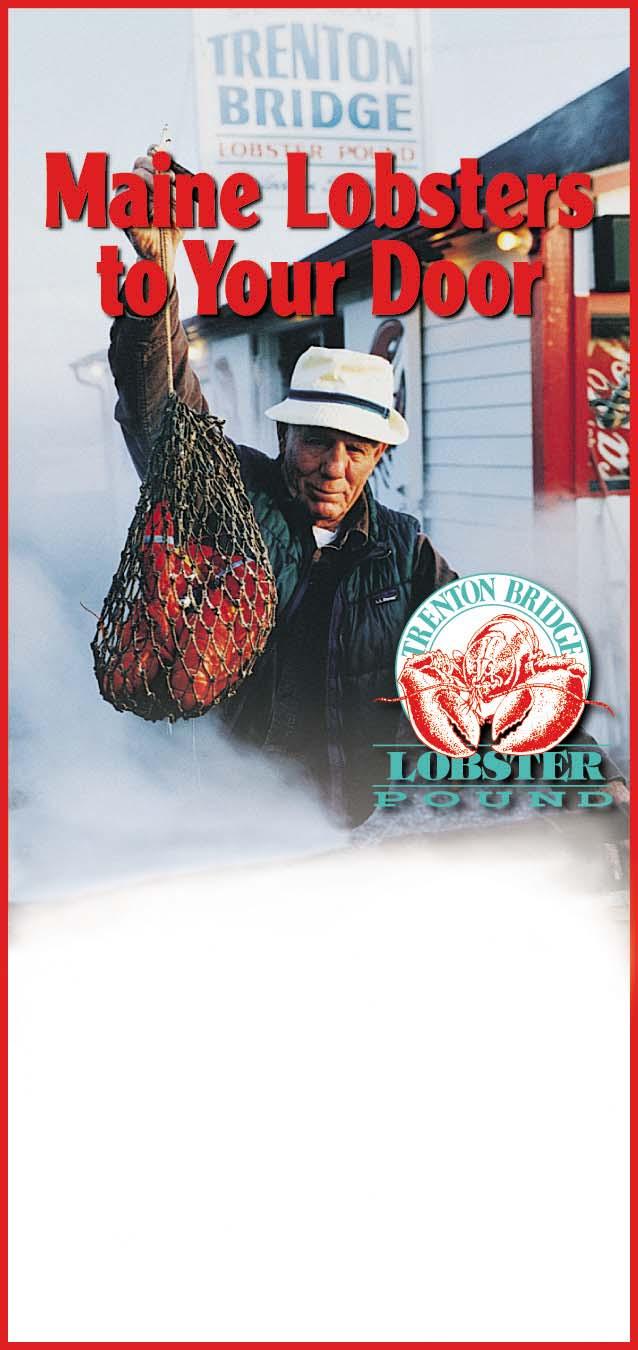

Like his great-great-grandfather, (a clipper ship sea captain), Keith travels every two years to the Far East to acquire gems at the source and then he designs and makes the jewelry for us.

The Clipper Ship Trade Wind Jewelry Collection is again in the port of Portland for 2017. Over one-hundred pieces of luscious sapphire, ruby, and emerald jewelry. Sneak peek preview on-line. Call or click to buy, or to experience the real thing, visit us in downtown Portland.

Check it out on-line. Come visit us Monday - Friday 9:30am - 5:00pm

Travel: Ultimate Foliage Weekend Planner

A weekend-by-weekend guide to the best seasonal color in New England.

NEWENGLAND.COM/ FALLWEEKENDS

Events: Biggest Fall Fairs

We round up our favorite places to go for deep-fried whoopie pies, tractor pulls, concerts, and more.

NEWENGLAND.COM/ FALLFAIRS

Recipe: Apple Cider Doughnuts

Enjoy the ultimate flavor of fall with this easy recipe you can make at home.

NEWENGLAND.COM/ CIDERDOUGHNUTS

Travel: Best Pumpkin Festivals

Celebrate October’s signature crop at these five great gatherings.

NEWENGLAND.COM/ PUMPKINFESTIVALS

IAN ALDRICH

Yankee ’s deputy editor admits he usually avoids groups when he can—and especially group travel. But joining a weeklong fall foliage bus trip turned out to be a surprisingly good time [“Leaf People,” p. 110].

“Part of that was the people, all of whom were from outside New England, including some who’d never been here before,” he says. “Their excitement about the region made me appreciate my home even more.”

PEGGY GRODINSKY

For Grodinsky, the toughest part about reporting on her BikeMaine ride was having to write up detailed notes by flashlight every night while the other tired cyclists went blissfully to sleep [“Tour de Maine,” p. 20]. The Portland Press Herald food editor didn’t even learn to ride a bike until she was 10 or 11; these days, the chain grease marks on her legs much of the summer prove that she’s making up for lost time.

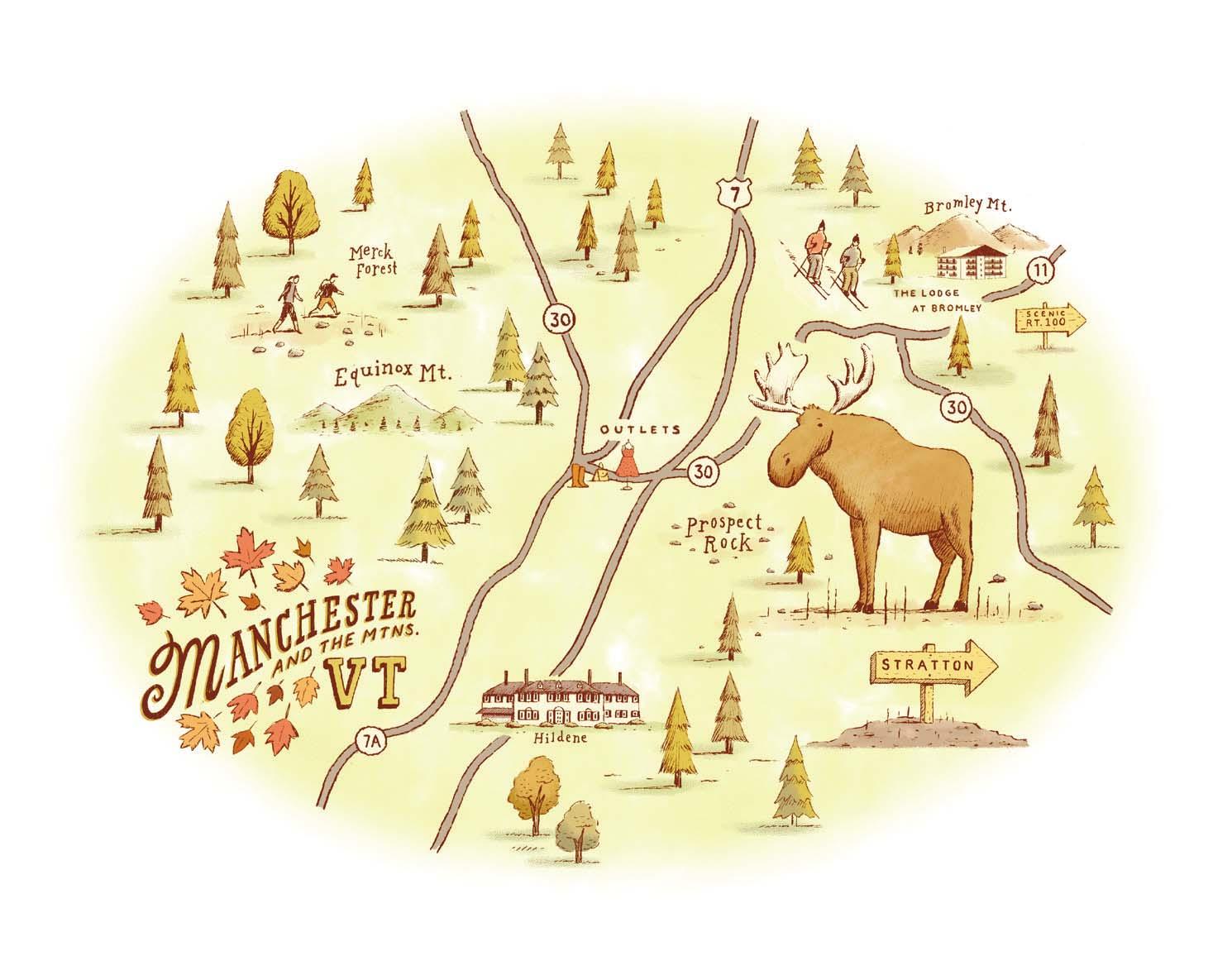

ANDREW DEGRAFF

Having just returned to the East Coast after two years in California, this Maine-based artist enjoyed the chance to illustrate his home turf [“Leaf People,” 110]. “While I was trying to access the impressions, colors, and feel of a visitor to New England,” he says, “this assignment was also a sort of homecoming for me. It’s nice to be back.” DeGraff’s second book, Cinemaps: An Atlas of 35 Great Movies, is out this fall.

SARA GRAY

Though today she’s a photographer living in Maine, Gray was born in Vermont and actually grew up on a Morgan horse farm in Shelburne. She says she was thrilled to shoot a foliage story in Vermont [“Hidden Gold,” p. 96] that focused on four different parts of the state—three of which she’d never visited before. “Vermont is such a small state, and I love the fact that I am still discovering new areas!”

ROWAN JACOBSEN

Recently named a Knight Science Journalism fellow at MIT, this Vermonter got a master’s in creative writing and then never wrote fiction again, instead penning seven nonfiction books as well as articles for the likes of Outside and Mother Jones. Of this issue’s story about New England bread [“On the Rise,” p. 118], he says, “It contains my favorite line I’ve ever written. Just four words. Can you guess?” [Ed. note: See bottom of p. 11.]

JULIA SHIPLEY

This year Shipley was a national award finalist for “The Farmer’s Life,” her column for Yankee ’s digital issue. Her latest dispatch also appears in these pages [“Something Borrowed, Something Blue,” p. 126], which yields “some amusing irony,” she says. “There were six people at our wedding (including us), because we wanted a really private occasion. But by writing about it here—well, that’s kinda the opposite, isn’t it?”

Just wanted to send a quick message about Weekends with Yankee on PBS. The “Icons of New England” episode is the first I’ve ever seen, featuring segments on Olneyville New York System wieners and Philip Johnson’s Glass House. I look forward to many more episodes, but this was a great one to catch for my first time….

I am a born-and-raised Southerner; however, beginning before college I would take a yearly trip to New England for either snowboarding and skiing in the winter/spring or a summer/fall trip for all the other amazing activities, food, people, and scenery. I would love to have a vacation home in New England; at the very least, I would like to resume my yearly excursions to New England for my family, so they can experience all of the sights and sounds that I fell in love with many, many years ago. All of this reignited by one episode of Weekends with Yankee . Please keep up the great work, and I can’t wait to get back.

Josh Escue Acworth, GeorgiaWhen I saw the words “How Many Lobster Rolls Can You Eat in 10 Minutes?” on your cover, I immediately turned to the story inside [“Feeding Frenzy,” July/August]. In 2010, my son, Matt “Megatoad” Stonie, won the Hampton Beach Lobster Roll Eating Contest, stuffing down 24½ lobster rolls in 10 minutes. To this day, although “Gentleman” Joe Menchetti and Teddy Delacruz came very close, Matt still holds the record. I wish that fact had been included in the article.

Matt, who is now 25, lives in California but spends his summers with his grandparents, the Rev. Henry Stonie and Mary Jo Stonie, in Hampton, New Hampshire. His eating escapades are eagerly covered by the

Behind the couch, two crickets play A back-and-forth duet all day

Convinced that summer’s here to stay

And tunes have kept the cold at bay.

—D.A.W.

Cathy

StonieSan Jose, California

I expect you will get many notes thanking you for publishing “Hometown” [July/August]. I was drawn into every photograph and lingered over them and returned to them again and again. That is the very thing every photographer, amateur or pro, seeks to make happen, and few do. Not in the way Barbara Peacock has managed…. I have never felt so uplifted by anyone’s work as I do seeing these moments from a hometown.

Diana Hayes

South Woodstock, Vermont, and Bedford, New Hampshire

in “On the Rise,” is “I met a maltster.”

Jacobsen’s favorite line ever, from p. 148

We are not making this up: Rowan

henever I take to the road, the stories I tell when I return are always about what I stumbled upon when I wasn’t following a plan but just casting about to see what might be waiting for me if I looked around. The turnoffs leading to country lanes, for instance, that might bring me to someone’s art studio or woodworking shop standing nearly out of sight, so when I step inside it feels as if I have discovered a secret known only to locals. There are few more satisfying pleasures of leaving home than that. This is what readers tell me: They look to Yankee to guide them to the tucked-away places where their own adventures can take shape. This issue’s stories do just that.

Rowan Jacobsen’s “On the Rise” [p. 118] began when he took a bite of fresh bread made by a small Vermont bakery using wheat grown right down the road, and he realized it might be the most satisfying, most wholesome he’d ever tasted in his career as a food writer. Yankee ’s food editor, Amy Traverso, found two women who sell home-baked pies in one of the most “look what I discovered” places imaginable: a pie shed on the lawn of their farmhouse in a New England village [“Poorhouse Pies,” p. 64]. And for our travel feature, frequent contributor Bill Scheller sought out not the familiar, high-traffic leaf-viewing spots but instead the towns where you’ll find plenty of room at the inn, at the dining table, and on the hillsides in this season of beguiling foliage colors [“Hidden Gold,” p. 96].

“The Making of The Vietnam War ” [p. 136] had its start when I was dining at the Restaurant at Burdick’s in Walpole, New Hampshire, and happened to glance at a poster on the wall for an upcoming movie by the town’s most famous resident, Ken Burns; the premiere was still more than a year away, and I had not known about it. And “The House at Allen Cove” [p. 40] happened just two weeks before this issue went to press. I was traveling in Maine, and someone I was chatting with said, “Did you know E.B. White’s former house might be for sale?” A tour of the property ensued—and in my four decades doing stories here, I can’t recall a more time-stopping moment than entering White’s studio and seeing what he saw when he wrote some of the most elegant prose of our time.

There is yet another journey of unexpected discoveries that awaits you, dear reader, in Yankee ’s digital issues. The mere tap of a finger on your mouse or keyboard will bring you to many additional stories and columns, including Julia Shipley’s “The Farmer’s Life,” which also appears in this issue as “Something Borrowed, Something Blue” [p. 126]. The pages may be electronic, but the heart and soul is all New England. All Yankee. So take the turn off the main road, and go see what you’ll find at newengland.com/yankee-digital.

Mel Allen editor@yankeemagazine.com

In troubled waters, it helps to remember the courage of a remarkable family friend.

almost drowned three times before I turned 5. The first near-miss happened when I was only 3 and my father was carrying me out to the big surf, as I had begged him to do. An enormous wave tore me from his arms and into the crashing sea. It felt as if I had been propelled into the spin cycle of my mother’s washing machine, hitting the ocean floor and then bouncing upward again, over and over. My father tried to grab me, but a lifeguard got there first and pulled me to safety. It took my mother weeks to get the sand out of my scalp and my bathing suit.

Then came the riptide incident at Shelter Island. I was paddling in the shallows when I realized that the shore was drawing farther and farther away from me. How could that happen? I wondered. As hard as I tried, I could not change direction. My mother was on the shore, waving her arms and calling me to come in. Another lifeguard was on the way, and pretty soon we had joined my parents on the beach, where they hovered over me anxiously.

Finally, there was the time when we were all swimming in my aunt’s pool, and I was in a plastic ring meant to keep me safe. But while the adults were standing knee-deep in the water, talking intently, I slipped through the ring—so easily, as if it was meant to be. All the grown-ups rushed to my rescue. I coughed and spat out the taste of chlorine, everyone patting me on my back and later taking me out for ice cream.

You’d think I would fear the water after that and never again go swimming. But then we moved to a house next door to a neighbor who had a large pond. My sister and I called this neighbor Uncle Jack, even though we were not related. The pond was spring-fed and 16 feet deep, and the water had a beautiful green color to it. All summer we could be found swimming in the big circle of its embrace. No waves threatened us.

Uncle Jack was the local sheriff, which gave him some distinction. When on duty, he wore a badge and a special broad-brimmed hat, which sat on his head at a tilt, as well as a stern look that could be fearsome. He had grown up in rural Georgia and had only one arm, with just a stump sticking out from his other shoulder. As a boy, Uncle Jack had taken lunch to his father at the cotton mill and, while walking past the spinning wheel in those pre-OSHA days, gotten his sleeve caught in the big machine. He was young, maybe not yet 10, so he had many subsequent years in which to teach himself to do things with one hand, one arm.

During Uncle Jack’s workday, the stump was hidden by the sleeve of his jacket or shirt, but when he swam with us it was unavoidable—just a swirl of underarm hair and the results of what must have been a primitive surgery in the early 1900s. It took me two years before I could look directly at it.

I used to watch Uncle Jack from the kitchen window as he worked on his little “plantation,” as he called it. What he could do with one arm was incredible in my eyes. He could cut down trees, drive his tractor, and rake leaves like a well-oiled machine. There was no mention of handicapped or disabled . He was not, he seemed to be saying, any different from anyone else. Sometimes I would hold one arm behind my back and try to do even the smallest tasks with the other. There was no way. When difficult times come and riptides pull me in the wrong direction, I think of Uncle Jack the sheriff. I know that some feared him, but I loved him, because of what he could do.

Introducing the ridiculously comfortable Hubbard Fast. High performance cleverly cloaked in style.

he shortening of the daylight hours takes me by surprise every autumn, perhaps in part because it comes at precisely the wrong time for us. In no other season is there more urgency in the air; September and October offer the last chance for reliably good (or at least not horrendously bad) weather in which to check off the list of tasks we’ll never reach the end of. Indeed, it often seems as if we add new tasks faster than old tasks are completed, and it occurs to me that were I a mathematician, I could probably develop an equation to demonstrate the precise disparity between the rate of adding tasks and the rate of completing tasks. For some reason, this depresses me.

Truth be told, I am not much of a list maker. I find them an unwelcome reminder of all that remains undone—and besides, does not the list itself become yet another chore demanding my attention? Must I now add “make a list” to my list? And oh, how many lists have I lost, how many precious hours of my too-short life frittered away frantically searching until the list is finally plucked from the wallet pocket of my rainsoaked Carhartts, the ink having succumbed to the moisture so that Finish cow gate looks something like Fin is sow mate. (My son Fin does not find this nearly as humorous as I do.)

My wife, Penny, on the other hand, is a list maker of unequaled commitment and expertise. She could teach university-level list making. Her lists never stray: They are like perfectly trained dogs, always at her beck and call. Furthermore, they are reliably legible, printed neatly onto the backs of junk mail envelopes pulled from the recycling bin (selection of proper list-making materials would come in week two of her class).

In an effort to stockpile enough snacks to last their boys through winter, the Hewitts slice and dry foraged apples in autumn.

Most amazing to me, Penny has an uncanny sense of the proper lifespan for a list; she knows when to give up on one and begin another, even if this means transferring tasks between them. Me, I just keep halfheartedly scrawling on the same old list, my printing growing smaller and smaller as I run out of space, until I give up and cram the damn thing into the back pocket of my work pants, where it is forgotten until I am afflicted with the nagging sense that there was actually something important on that list, something I really need to accomplish before the cold settles, something I cannot quite recall, but if only I could find … ah, there it is. Fin is sow mate. Now what could that have been?

At least the weather is on our side. Indeed, it transcends superlatives: day after day after day of azure-blue skies speckled with lazy drifting clouds, a pattern that is interrupted by showers just often enough to keep us from falling into the same drought that’s afflicted much of the Northeast.

On these halcyon mornings, I milk in a T-shirt just as the sun is clearing the copse of spruce to the east. Milking outdoors, kneeling on the ground, we are subject to the vagaries of weather. Halter, fence post, cow, bucket. Sometimes I wish for more commodious infrastructure, but not as often as I’m glad to not have it, because if I had it I’d use it, even on mornings as fine as these—the early slanting light, the smell of sun on cow, the laying hens gathering around me

Since 1996, Good News Garage has provided more than 4,600 refurbished donated vehicles to New England families in need.

“Thank you for this opportunity to help myself. This car makes it easier for me to get to the babysitters and to work. Thank you for helping my family!” FREE TOWING & TAX DEDUCTIONS

Donate online: GoodNewsGarage.org

Donate toll-free: 877.GIVE.AUTO (448.3288)

And oh, how many lists have I lost, how many hours of my too-short life frittered away frantically searching for them?

as if this might finally be the morning I do something other than shoo them away. Forever hopeful, those hens. A guy could learn a thing or two.

On the days I’m not checking off tasks on the list I can’t find, I work at a farm a mile down the road, alternating between running our small excavator and laboring on a variety of building projects. The farm is owned by our friend Tom; we drive past it almost every day. It’s situated precisely where the road narrows and curves through a stand of old mother maples. The narrowness of the road, the corner, and the proximity of the big trees compel me to ease off the gas, but truth is, I would do so anyway because there’s almost always an excuse to crane my neck: the muscle-bound draft horses, grazing a roadside paddock; or Tom on the tractor, flipping

a towering pile of compost; or the big flock of hopeful laying hens, clucking and pecking and scratching their way around the barnyard. Sometimes Tom’s younger daughter and her friend sell lemonade at the side of the road, and I stop and give them a dollar for a 25-cent cup because I’m a sucker for a lemonade stand on a scarcely traveled gravel road run by a couple of 8-year-olds who wave their arms frantically and shout, “Stop! Ben! Stop!” when I approach.

I like working at Tom’s farm. In part, I like it because I often work with the young man who lives there, in a single room adjacent to the haymow of the barn. His name is John, and he’s 24, and when he’s not working on the farm he logs with the horses grazing that roadside paddock. He smokes hand-rolled cigarettes and keeps a bushy beard that goes smashingly with the grease-

stained suspenders holding his pants in place. John is young enough to be my son but seems to already have found his place in the world. He tells me he does not aspire to have a farm of his own; he is happy with his life as it is, the day-in, day-out labor of the farm, the single-room apartment, his team of horses, and the occasional logging job. He thinks of finding a woman who can be similarly content with these modest circumstances (and if she, too, rolls her own, all the better). He realizes this might be a challenge, but he can be patient.

John and I work well together; we are silly and somber in equal measure, and we both like listening to classic rock on the radio. Never, ever underestimate the value of a workmate who likes the same music as you do—though in all honesty I really like classic rock only in particular circumstances, such as when I’m installing

‘hoo-guh’) means “a sense of being cozy or comforted.” Chilton’s Hygge table is designed and built in Maine from solid ambrosia maple, known for its rich, distinctive wood grain. What could be cozier?

clapboards on the gable ends of an old barn, and it’s raining a bit and just cold enough to make me wish it weren’t raining, and I can smell the smoke spiraling off the lit end of my workmate’s hand-rolled cigarette.

I like working at Tom’s farm also because I like the work itself. I am not an especially skilled builder, but I’m competent enough to imagine that I know the pleasure a skilled builder must feel when driving a nail into a piece of wood that fits just so . And though I’m a tad loath to admit it, I sort of like working with machinery, and in particular the excavator, which is a remarkable piece of equipment, capable equally of destruction and production. I take satisfaction in operating the excavator with maximum precision, and sometimes I find myself calculating how many hours it would have taken to do the job by hand, and I marvel anew at the ingenuity of our species.

I do not normally worship at the altar of efficiency, and I understand all too well the ways in which laborsaving devices undermine the sheer pleasure of manual work, along with the experiences and knowledge it confers—not to mention the relationships cultivated around shared work. My time on the excavator is always solo, absent the jobsite banter I value so much. It’s just me and the steady thrum of the diesel engine. Yet it is truly impressive what the machine can accomplish, and to spend less than an hour excavating a water line trench that would have taken me three or more days (and an extra-large bottle of Tylenol) to dig by hand seems worthy of acknowledgement.

Finally, toward the end of October, the fine weather breaks, and on the 23rd we awaken to wind-driven snow, four inches on the

ground and mounting, the cows on the wrong side of their sagging fence, browsing the garden for remnants. It’s not yet daylight as we drive them back to their paddock, but the accumulated snow lends its particular luminescence, and we do not need head lamps.

Later, I lay flakes of hay to kneel on for milking, a little prayer mat upon which to repent my sins one squirt at a time. Locked my sister in the closet. Squirt. Snitched one of my father’s Lucky Strikes. Squirt. Snitched another. The snow melts into the heat of Pip’s flanks and the sleeves of my wool jacket. No T-shirt today. No early sunlight falling across my cow and me.

I milk fast, fingers cold, until the bucket is full and my hands ache from the effort. I release Pip from her halter and drape it over the fence post. She ambles back to her mates. I pick up the bucket and walk back through the new-fallen snow to mine.

Apartment and cottage living at Piper Shores offers residents fully updated and affordable homes, with all the benefits of Maine’s first and only nonprofit lifecare retirement community. Located along the Southern Maine coastline, our active, engaged community combines worry-free independent living with priority access to higher levels of on-site healthcare—all for a predictable monthly fee.

atch out! Sand!” I hear the woman I’m riding with warn me at the very moment my bike slides out from under me. Even as her words float into my ear, I’m down. Luckily, I’m more shocked than hurt, and it’s only later at our (astonishingly beautiful) oceanside campsite that evening that my brain truly registers the fall. The car behind me didn’t hit me, and the merging road immediately in front of me was empty. My bike is intact and— discounting a scraped knee—so am I.

It’s Sunday, day 1 of BikeMaine 2016, and I have started with a bang, or at any rate a splat.

The annual seven-day ride is organized by the nonprofit Bicycle Coalition of Maine as a way for participants to “explore the people, places, culture, landscape, and food of Maine.” This is the third consecutive year that my sister Carolyn and I have signed up. I’ve lived in Maine just three years, but my job as a newspaper editor requires that I know the place like an old-timer. The appeal of getting to know it at the leisurely pace of a bicycle outweighs my ever-present anxiety about my ability to ride 60-plus miles a day.

A day earlier, Carolyn and I and 398 other cyclists from across the country and around the world congregated on a sunny September afternoon on the Schoodic Peninsula, the less-traveled part of Acadia National Park. We were surrounded by iconic Maine scenery: scraggy pines, crashing waves, rock-strewn beaches. Also hundreds of

bicycles, piles of gear, and many rangy, muscular 50- and 60-somethings. More than a third of us are repeat riders—which tells you something. The youngest rider, I later learn, is 26; the oldest is 79.

Each year, BikeMaine focuses on a different area of the state. In 2016 the route zigzags from the Schoodic Peninsula to Eastport and back again, covering 354 miles in one of Maine’s more remote, impoverished, and—I am about to discover—ravishing regions. Though I live in Portland, I’ve never been here before.

The Bicycle Coalition of Maine launched BikeMaine in 2013 to promote bicycle tourism as a path to local economic development. Staffers work with the communities along the route, plotting the off-the-beaten-path rides and integrating everything local: food and drink, farms, libraries, historical societies, conservation organizations. By the time we bikers arrive, these villages are as intrinsic to the experience as the cycling.

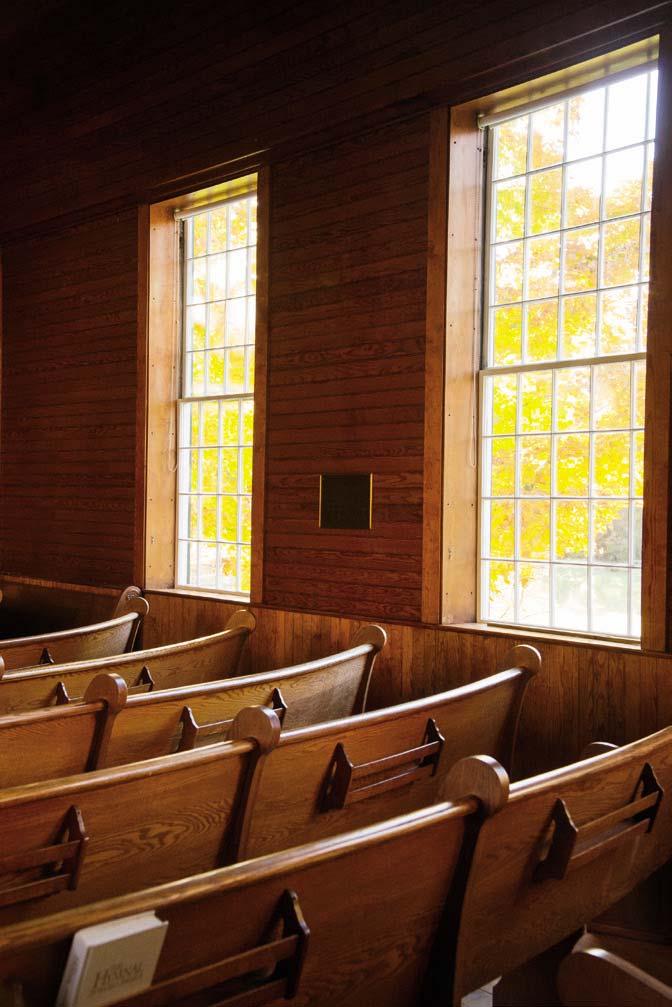

Day 1 brings a breathtaking ride, despite the scary tumble and an even scarier fast-moving storm, the only bad weather in a week of blue skies. Before I know it, I’m in Jonesport, the day’s destination. Sawyer Memorial Congregational Church—a church of the elegantly simple, white-steepled New England sort—has opened its doors to us. Carolyn and I snack on homemade molasses cookies in the church basement and check out a craft fair on the lawn. Then a member of the congregation steers us to the sanctuary, where the church organist sits at the big pipe organ previewing the Christmas service by candlelight just for us. Joy to the world indeed.

On my desk as I write this sits a miniature lobster trap, a souvenir given to each and every rider by the town of Machias, where we camp on day 2. The town manager itemizes the trap components as we polish off barbecued chicken, kale salad,

green beans, baked potatoes, and hermit cookies (all meals and snacks are included in the $875 price). She explains that inmates from the Downeast Correctional Facility made the traps from Maine balsam wood, while she herself made the blue soap lobsters, which smell like blueberries, a nod to the region’s signature crop. The traps also hold dollhouse-sized scrolls that tout Machias’s attributes, summarizing the town as “unique as a rare blue lobster.”

BikeMaine can feel like a happy roving summer camp for grown-ups, and, as at camp, we quickly settle into a routine: There are blueberry bogs and blueberry crisps, and many (sometimes too many) short, steep hills with many (sometimes too many) Maine-made Bixby bars to fuel the climbs. There are waving schoolchildren along the road, then ringing cowbells and applause when we reach camp. The lines for hot showers, post-ride beer gardens, and communal teeth-brushing under the stars are reliably sociable. Bedtime is early—“Nine p.m. is biker midnight,” a rider tells me—and we rise early, too. Because I am slow, a passing cyclist’s “On your left” becomes the rhythm and refrain to which I ride.

The Down East beauty, though, is never routine. On the days when my back aches, my legs protest, my lungs huff, and I am wondering what I could have been thinking to spend my vacation like this, I remind myself to look

There’s a lot of harmony between what I make every day and where I live. I need a place to stretch out, feel relaxed. Fuel my passion. Here, you can be open to new ideas and are completely free to explore them. I couldn’t do this in a big city anymore. There are too many distractions. But here, in this fantastic place, I can be creative and follow my own way. It’s a place where I proudly proclaim every morning, this is me.

JOURNEY NO.21 BEACHES REGION

JOURNEY NO.21 BEACHES REGION

around. Spectacular! Miraculous! Magical! Awesome! I write all these words, with all these exclamation points, in my trip diary. Our campsite on private land at Kelley Point is so beautiful that I consider staying there and abandoning the ride. The stunning route into Eastport has me contemplating a move Down East. Awesome in the true sense of the word , I scribble by flashlight in my tent after we pedal to Reversing Falls Park in Pembroke.

We snap out of our collective routine one evening in Eastport. Two riders in cycling shirts and shorts who have lived together for years casually stand up in the big communal tent where we’ve been eating a tasty salmon dinner. A rabbi materializes and, before a cheering congregation of bicyclists, they pledge their love. The most stress-free wedding ever, the bride tells me later.

On day 5, we ride through blinkand-you’ll-miss-it Dennysville, one of many villages in which the cyclists outnumber the residents. I hop off my

bike to take in the Audubon exhibit at the Academy Vestry Museum, quite possibly the most charming museum in Maine. It has opened specially to accommodate us, and inside I learn that John James Audubon preceded us Down East by almost two centuries.

The next day, in even-smaller Whitneyville, a 70-something gentleman named Skip happens to hear me ask about the local library, a former schoolhouse. Skip locates the library key and gives me a private tour, spinning tales of the school it had been in his boyhood, when there was no plumbing or electricity and the reward for good behavior was getting to ring the big cast-iron school bell. The money the town has raised by feeding the cyclists will go toward renovating the building, he says.

BikeMaine 2016 ends with an exhilarating ride on perfectly paved

park service roads into Acadia. There’s one last excellent lunch, then I’m lugging dirty gear to the car, loading up my bike, and hugging new friends good-bye. When I get home, flush toilets and cotton sheets briefly turn my place into the poshest of four-star hotels. It’s nice to wake up without worrying about rain. Still, for a week or two I struggle to make the transition from two wheels. In the car, I find myself fixated on hills and fretting over cratered road surfaces. And then, gradually, my BikeMaine adventure recedes. My days shift from sweating hills to sweating deadlines. Though I sit for hours, it’s on a swivel-tilt office chair, and the glow comes from a computer screen and not incandescent skies. Another year will pass before I am on a bicycle saddle again, riding BikeMaine, with the state unfolding and revealing itself inch by inch and mile by mile as I roll by.

For more information on the BikeMaine tour, go to ride.bikemaine.org.

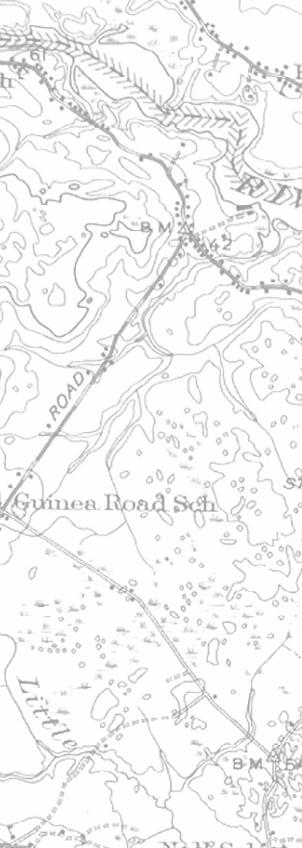

n our last trip through southwestern New Hampshire, we had many opportunities to ask directions in both the larger towns and offthe-beaten-track hamlets. Out of curiosity, we checked our odometer against the local estimates in hopes of establishing the exact distance of that old chestnut, the country mile.

We found that the average country mile is more than twice as long as the standard mile: 2.3 standard miles to the country mile, to be precise. But as this figure is subject to change without notice, we postulate the following:

1. Country miles get shorter as they increase in number. One country mile may equal three standard miles, but three country miles will be closer to six miles than nine. If you’re lucky.

2. The smaller the town, the larger the mile. In Manchester, a mile is a mile is a mile. In Rindge, a mile is two miles or probably three or four. Usually.

3. A winding line is just as short as a straight line between two points in the country. No one needs to know how far it is to the next town “as the crow flies,” and the shopkeeper giving you directions knows this. The road he sets you on is The Road, if not The Best Road, and is therefore the shortest way, regardless of what the crows are doing.

—Adapted from “How Long Is a Country Mile?” by David N. Wyman, October 1975

Stephen King (born September 21, 1947, in Portland, Maine). Following on the heels of his 70th birthday this year—and the release of the big-screen adaptation of his novel It—Halloween seems a fitting time to celebrate Maine’s horror master. Just don’t do it at his Bangor mansion, please: To cut down on holiday crowds at their gate, King and wife Tabitha have been known to publish ads in the local paper saying they would not be home on Halloween night.

“We may only feel really comfortable with horror as long as we can see the zipper running up the monster’s back.”

11

Number of acres bought in New Canaan, CT, by architect Philip Johnson in the mid-1940s

1949

Year that Johnson completed his so-called Glass House, which became his second home after his New York City residence

Three Number of years he spent designing a transparent home for his property, inspired by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s Farnsworth House in Plano, IL

$60K

Cost of the Glass House project (including a brick guesthouse)

1,792

Size in square feet of the Glass House, comprising one bedroom, one bathroom, and a kitchen/living area

1997

Year that the Glass House property earned National Historic Landmark status

Ninetyeight Johnson’s age when he died in his sleep at the Glass House, in 2005

14

Number of Johnsondesigned structures on the now-49acre property, including a studio, sculpture and painting galleries, and a “ghost house”

130,000

Estimated number of visitors who have toured the Glass House property since it opened to the public in 2007

n some level, the success of every relationship is dependent on the couple’s ability to pick each other up when they are down. Westbrook, Maine’s Elliot and Giana Storey, winners of the 2016 North American Wife Carrying Championship at Sunday River Resort in Newry, Maine, have taken this to something of a literal extreme.

“When I first met Elliot, he would talk about this ‘wife carrying’ thing and I had no idea what it was,” Giana recalls. “Then we married and eventually gave it a shot, and it was fun.” For the uninitiated, a wife carrying contest is an obstacle course run by a male competitor while carrying his female partner. The official rules state that “the wife to be carried may be your own, or the neighbor’s, or you may have found her further afield.”

The official course is 278 yards long, with two dry obstacles and a water obstacle. There is no set way in which

the wife must be carried, but the most common is the so-called Estonian carry, in which the wife clings upside down to the husband’s back. “When he runs, he needs his arms,” says Giana. “My goal is to be a good jockey. They call it saddling up—the girls just need to be fit and hold on, but that’s not as easy as it sounds. My sister says I have good koala bear skills.”

Elliot is a big, powerful guy who competes in strongman events. Giana is an aerobics instructor and cake maker— professions that may sound as if they shouldn’t go together, she admits, “but I’ve always loved baking and I needed to work from home.” Elliot’s leg strength is a major reason for their success. “He can lift anything,” says Giana, who acknowledges that her own biggest strength, cardiovascular fitness, isn’t much use in the race. “I always want to take over the cardio section for him. He has the power, but I’ve got the wind.”

“See how this woman has her arms locked in around his chest?” Elliot says, pointing to a photo. “That’s right around his heart and lungs. As soon as he starts to run, she’s going to be choking him out.” When Giana is in position, she locks in by using her hands to grip her own legs. “I’m barely touching him at all. My goal is to stay tight like a backpack, so he has mobility, and I can shift and compensate if he stumbles.”

In the championship race, Elliot cleared the giant log hurdle at something close to a full run. (Most competitors sacrifice their momentum to clamber over, for reasons that become obvious when we watch a video of his leap. “That was so close to my face!” Giana marvels.) “We talked about it and practiced,” Elliot says, “but you don’t know how it will go until you do it. You get one chance. We needed that

edge, because on the straightaways I’m not the fastest guy.” Indeed, Team Storey opened a big lead coming out of the log hurdle, but the second-place team, from Virginia, closed strong and was just 3.5 seconds behind at the finish.

“The whole race lasts about a minute,” Elliot says. “It’s amazing how spent you can be after a minute of going 100 percent.” Giana takes a beating, too. “My quads slam on his shoulders, and it really hurts,” she says. “But Elliot is really spent. Two years ago he wouldn’t even speak to me after. This year he was so cranky that I couldn’t stop laughing.”

“It’s a crazy thing to do,” says Elliot, “but our kids think it’s awesome.” For winning, the Storeys took home Giana’s weight in Goose Island Oktoberfest beer (11 cases) and five times her weight in cash ($665). Normally a very fit 145 pounds, Giana gets down into the 130s for the race; even so, she was the heaviest woman ever to be part of a winning team, making theirs the competition’s biggest prize ever. “I’ve never been one to be precious about my weight,” she says, and laughs. “I guess that’s a good thing.”

Team Storey’s win earned them a berth in the world championships, held in Finland every July. Though they had hoped to be the first Americans to bring home the title, they missed a spot on the podium by fractions of a second, finishing fourth overall. They were, however, the top-finishing “actually married” team. “We aren’t disappointed,” Giana says, “because now we’ve been through the course, and we can strive to be better next year.”

This year’s annual North American Wife Carrying Championship will be held at Sunday River in Newry, Maine, on October 7.

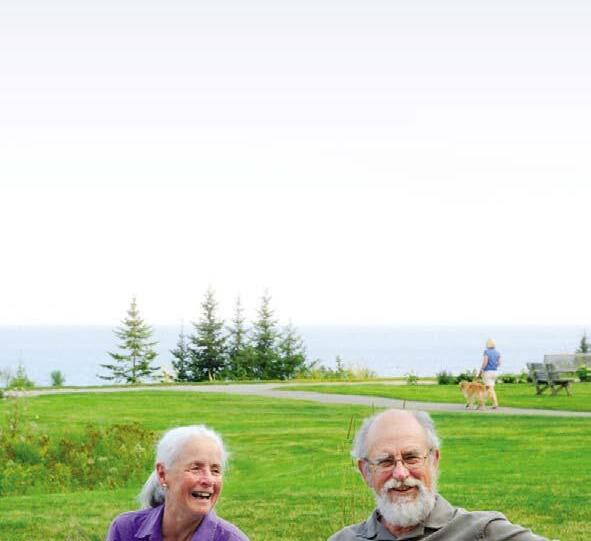

When was the last time you considered “60” as old? Today’s 60- and 70-year-olds are running marathons, starting second careers, and generally bashing the traditional idea of “aging.” Yes, it’s finally happening —our youth-focused culture is acknowledging that there is a lot of life in what many call “the third chapter,” or retirement.

Part of the reason for this trend is the “silver tsunami” that is closer every year. By 2030, we will have more 65-year-olds than any other time in U.S. history. In addition to the sheer magnitude of people, this group has a longer life expectancy than any prior generation —and will live longer with more complex diseases,

thanks to improved medical care. This means their medical costs will be greater.

Not only that, but this group of retirees has greater expectations of their retirement than any prior generation. After all, boomers have redefined every other social institution they experienced; from marrying later, having children later, moving more often, etc.

Today’s retirees are significantly more active than any previous generation. They are physically and mentally more active, and they want to travel more, start new projects, and find new purpose in life.

To learn more about CCRCs, start by investigating these communities.

Unlike their grandparents, this group can’t count on their children living around the corner. Most adult children are more far-flung than ever, sometimes living across the country. No longer is there the reliable daughter across town—today she may be heading up a company in California. So the traditional 1950s family support model that served for the previous generation is becoming defunct.

Given that people are living longer, and seeking more from their retirement years, and given that social dynamics have changed, how can someone stay independent, and still ensure their health care is covered?

There is one solution that has been quietly operating for the past 100 years in the U.S., whose structure and practices are uniquely positioned for this generation. Continuing Care Retirement Communities (CCRCs) could be described as “retirement communities with benefits.” There are 1,900 across the country, but just a handful in New England, and they are often misunderstood.

CCRCs, which are also called Life Plan Communities, provide three levels of care: independent, assisted living, and skilled nursing. The critical differentiator is that people enter the community when they are independent, and can live safely on their own. They enjoy active, independent lives, free of the worries and time consuming work of home maintenance.

With the addition of housekeeping services, inside and outside maintenance, transportation, a meal program, fitness activities, and 24-hour emergency call service, residents have more time to enjoy life, meet friends, and pursue new interests. They create fast friendships, and enjoy the benefits of community living. Meanwhile, they have the assurance that if

and when their health needs change, they can transition within the community.

Although CCRCs look like beautiful retirement communities, complete with gyms, pools, libraries and arts rooms, moving there is not a real estate decision. CCRCs are an insurance product, and they are governed by each state’s regulatory body. Therefore, a percentage of a resident’s entrance fee and monthly service fee are considered a tax deduction as a prepaid medical expense—a real advantage for many.

Most CCRCs in New England are not-for-profit, and offer a Benevolence Clause, which states that if a resident has outlived their assets (and has not intentionally impoverished themselves) they will not be asked to leave due to lack of funds. The pricing varies by organization, but on the whole, the larger apartment or cottage you prefer, the more costly the entrance fee and monthly service fee.

Within CCRCs there are contract differences. Some are Type A, which are all-inclusive plans, meaning that as you move from one level of care to the next your monthly fee does not increase (except for two additional meals per day). Type B or modified contracts offer targeted insurance, typically providing a portion of your health care fee at a discount off of market price, when you need health care. Type C contracts provide independent living at a lower rate, and then offer health care at full market rate.

The solution that CCRCs offer to the next generation of retirees is clear—peace of mind for you and your family, a home where you can be as independent as you like, where you can build a community of friends, secure in the knowledge that if anything changes in your health down the road, you have chosen where you will receive your care.

TRANSFORMS AN OVERGROWN 18TH-CENTURY CAPE INTO A POLISHED WORK-AND-LIVING SPACE.

he house sits in a cup of sunlight at the end of a two-mile dirt road that winds past old sheep meadows. It sits with assurance and composure, a fact of the landscape. In 1784, this postand-beam Cape in Richmond, Rhode Island, was built on the road to the mystical-sounding village of Usquepaug, about 10 minutes away; today it is Carolyn Morris Bach’s home and studio. The house has sat here, in this clearing, longer than almost anything around it. It is a world unto itself, defined by clusters of birches and red sugar maples and a 200-year-old chestnut tree that leans toward the sunroom like an old friend. The corncrib, also c. 1784, was reclaimed by Carolyn from a raucous tribe of red squirrels. Graceful walls of Connecticut flat stone meander around the blueish-gray home; elsewhere, indigenous-stone walls trail off into the woods. “I call them Fred Flintstone stone walls—round and lumpy,” says Carolyn, a slender artist who moves through the house like a dancer on a familiar stage.

Near Bach’s workbench you’ll find this collection of “things of inspiration,” which includes, on the top shelf, a brush she made from a deer antler found on a walk in the woods.

OPPOSITE : An owl pendant Bach created from cow bone and detailed with sterling silver and gold.

She sparkles when we talk about the house, “only 20 minutes from the raw Atlantic.” It is ideally sited for someone who makes intricate, beautiful jewelry that is sensitive to the natural world: “To be able to have the woods, and to know that the ocean is out there—I don’t know if you can improve on that.” At the same time, it fulfills the needs of an artisan whose work appears in the Boston Museum of Fine Arts and is cherished by the likes of Madeleine Albright (who featured one of Carolyn’s brooches in her book Read My Pins). T.F. Green, in Warwick, is “an amazing airport,” and Richmond is less than 15 minutes from Amtrak, offering an hour’s ride to Boston or three hours to Manhattan.

I originally came to see Carolyn for “Open Studio,” Yankee ’s regular series of portraits of New England artists. I was prepared to enter the tiny world she inhabits, a world of images that are mysterious and elemental. Foxes, ravens, moon goddesses; creatures made of carved bone, moonstones, and golden twigs. Miniature works of art that her collectors often refer to as talismans. As a matter of course, most studios reveal something of artists and their craft. But in this case, Carolyn’s entire home, where she’s lived since 1991, breathes with the same sensibility imbued in her jewelry. “My life as an artist and this place are completely interwoven,” she agrees.

As we walk through the old Cape and into the newer ell, arcing behind like a scorpion tail, nature appears everywhere. Deer antlers picked up on walks through the more than 65 acres that she owns. Barred owl feathers parading like exclamation points atop a doorway. Shells displayed

OPPOSITE : Melding the antique with the artistic, the dining room features primitive furniture from the early 1800s lit by a wrought-iron chandelier.

LEFT : In one of the front rooms, an original granite hearth becomes an eyecatching display space.

BELOW : A 19th-century apothecary case holds bird’s nests of all shapes and sizes that Bach has collected over the years.

in a bathroom, tucked into the slots of an antique wooden fixture that once held room keys in an old Italian hotel. “I look at things literally—bathroom, water, shells,” she says with a smile. She’s always been fascinated by things with wings; there are bird’s nests in every nook. “When I’m out walking, the property gives me gifts.”

Carolyn’s life as an artist began even before she attended the Rhode Island School of Design. “I studied ceramics at a progressive high school in Michigan,” she says. “I really had no interest in jewelry, but my art teacher suggested I try it. It was as if I was meant to make it. That’s something that people say about my work, too—it looks effortless. And in a way, it is. I don’t make mistakes. It’s usually right the first time.”

Clear vision is important when you’re working with precious stones and metals. But every homeowner knows it’s absolutely vital in renovation, where second-guessing can demolish a bank account. By the mid-1980s, Carolyn had begun to hit her stride as a crafter of tiny talismans. Her interest in Inuit artwork, sparked by a 1981 show at the Smithsonian Institution, had evolved into fashioning her own mystical little creatures. “And once I started doing figurative work, it just took off,” she says.

She and her then-husband were living at the time in a spacious Greek Revival in the center of Carolina, Rhode

Island. “I wanted to be able to look out of my window and see no houses, only nature,” she says. “We saw a little blurb about this house in the local paper and came to look at it. It was so overgrown, a real wreck. I didn’t know if I had the heart to renovate another house, but really, I fell in love.”

Love begat labor. The original center-chimney Cape is dominated by three massive granite fireplaces on the ground floor, one of which was hidden beneath vinyl paneling. The stones are staggering in size. In the low-slung dining room, a square bread oven punctuates a fireplace blackened by centuries of use. Particleboard ceilings were removed to reveal old beams, beautifully preserved under the layer of ugliness. “I wanted to cry some days, it was just such a mess,” Carolyn remembers.

The dark kitchen—an addition from the early 1900s—was gutted to the studs and opened to the peak. Velux skylights now overlook a peaceful blend of pale pine cupboards and terra-cotta tile floors. High shelves display baskets, teapots, and doll-sized Adirondack chairs. The effect is masterful: Where many collections feel cluttered, this is pared down, painterly. A still life everywhere you look. “You don’t really notice they’re there, but when you do, it’s like, ohhhh,” Carolyn says, looking up. “I don’t know anyone who isn’t enamored of little chairs.”

As for the Mexican floor tiles: When she asked her tile man about the pile of accumulating rejects, he showed her their dog and chicken tracks. “He thought they were flawed,” she says. “And I said, ‘No, no, I want them in the floor.’” She points to an espadrille print. “Apparently as the clay was drying, all sorts of stuff was walking by. What could be better than dog paws?”

“THERE IS NOT ONE INCH OF THIS HOUSE THAT HASN’T HAD MY DESIGN AND MY MARK ON IT.”

Italian and Portuguese pottery lends a splash of color to the kitchen, which is anchored by a floor of handmade Mexican tile.

Italian and Portuguese pottery lends a splash of color to the kitchen, which is anchored by a floor of handmade Mexican tile.

Meanwhile, as the beauty of the old house was emerging, there was new construction going on just a few steps away. Two studio rooms—one for storing materials and the other outfitted with tiny tools, like a fairy-tale workshop—were designed and built specifically for Carolyn’s furniture. “This is my paint box,” she says, opening a long drawer in an old printer’s cabinet to reveal a tumble of stones. Petrified sycamore looks like barred owl feathers. Flares of petrified manganese oxide in quartz resemble minuscule leaves. And rutilated quartz—“Each of those lines is a different mineral,” she explains, pointing at the golden filaments in the stone. “Doesn’t it look like spun straw?”

In the adjacent workroom, Carolyn hammers slender gold twigs, carves tiny fox faces from cow bone supplied by a dairy farmer in Little Compton, and fashions wings for a deer goddess. “This is where I spend most of my life,” she says. Here, too, the surroundings are spare and tranquil. “I couldn’t work in an ugly space. Ever since I was a little child, things that are ugly upset me.”

A few years after she moved in, Carolyn joined the house to the studio with a long, angled room that she calls her office. Paid for with “gold scrap,” it is flooded with natural light, thanks to the bank of windows running along each side, and filled with design books, Japanesestyle sculptures from her days at RISD, and a few choice pieces of furniture, like the 1840 partner’s bench from Ireland. “Can you imagine trees being that big?” she asks, stroking the massive width of the desk.

LEFT : Modern additions complement the house’s historical charm, as do the classic stone walls and mature hardwoods.

BELOW : Bach in her studio, where she blends her love of the natural and the mystical with jewelrymaking skills honed over the past three decades.

“You know,” she says, “I’ve touched every square inch of this house. There is literally not one inch that hasn’t had my design and my mark on it.” As we stand in the office, with views into the old Cape one way, a glimpse of her studio the other, Carolyn’s clear vision is apparent on all sides.

It’s there in her jewelry, too. “I thought I would reinvent myself last year by focusing on gemstones,” she confesses. “People loved the work, but one woman came up to me at a craft show, pointed to a pair of opal earrings, and said, ‘You know, these are really beautiful, but any jeweler could do this.’ And then she walked over to one of my weirder goddess pieces, and she goes, ‘Only you can do that.’”

Carolyn nods slowly. “And that was like ... the universe sends me messages when I need it. I just needed to hear that.”

Prices range from $400 for a pair of simple silver earrings to $12,000 for a major necklace in gold. For more information, call 401-364-0623 or go to carolynmorrisbach.com.

E.B. White wrote some of the most enduring words in American literature while living on this

Though chickens and sheep have given way to flower gardens, this North Brooklin, Maine, farm still looks much as it did when its most famous occupant lived here.

40-acre-plus saltwater farm in Maine. For the past three decades, the Gallant family have made it their own. Now, they hope a new family will love it the way they have.

BY MEL ALLENLEFT : E.B. White, shown in Maine in 1977, loved the privacy that small-town life afforded him. For a series of New Yorker essays he filed from North Brooklin, he used only the dateline “Allen Cove.” That way, he said, “no one will be able to find [me] except by sailboat and using a chart.”

BELOW : The rope swing made famous in White’s 1952 children’s classic, Charlotte’s Web

he swing still hangs by the barn doorway. There may or may not be a spider spinning her web in the darker corners of the rafters on this early July afternoon in North Brooklin, Maine. Allen Cove, a small inlet in Blue Hill Bay, sparkles in the sunlight. There are gardens of flowers so beautiful that the eye goes to them even before settling on the sturdy white clapboard farmhouse that has stood here for more than 200 years.

I knock on the farmhouse door. No answer except for the bark of a dog. A man who I soon learn has been the caretaker here for over 15 years is working in a shed by the barn and calls out, “Just walk on in, they know you’re coming.”

Robert Gallant is waiting inside, and I follow him to a breezy sunlit room that looks out on a patio, gardens, a pond, and a sweeping view of the bay and the distant mountains of Acadia National Park. He and his wife, Mary, have been married nearly 60 years, and for more than half of those years they have traveled from their South Carolina home to spend summer and fall on their 44-acre saltwater farm, one of the loveliest and best preserved in Maine. They arrived here only a few days earlier, and Robert greets me in a voice with the slow, easy inflection of the deep South. He’s led a vigorous life, with a highly successful business career as a managing partner of the GallantBelk department store chain and a property developer. But he’s on the back end of his eighties now, and lately he’s had a rough go of it. His right wrist is heavily wrapped after a recent fall, and he’s reluctantly coming to terms with what he can and can’t do anymore. I learn all of this over the next few hours as I hear Robert’s and Mary’s stories, which speak to a deep love for everything my eyes can see—as well as those things that undoubtedly only theirs can. There is a bittersweet feel to

our time together. It’s clear they do not want to leave. They know they should. It is time, they say, to downsize to one home and live closer to their four children and seven grandchildren, who remain in the Carolinas.

Mary enters the room. Within moments she connects the threads of their story with those of the previous owners, E.B. and Katharine White, who bought the farm in 1933 and moved here full-time four years later. Katharine died in 1977, her husband in 1985. “I’m sure you want to do the Charlotte’s Web thing,” Mary says, and quickly ushers me to the barn and sheds that once housed the Whites’ hay, sheep, geese, chickens, pigs and (of course) spiders, and probably a rat or two. The barn itself also provided the setting for one of the most beloved children’s books of all time.

We walk from room to room in what is possibly the most impressive and well-kept barn I have ever seen. There is that rope swing, immortalized in Charlotte’s Web as the one from which Fern and her brother launched themselves from the loft. Here’s where Wilbur’s trough would have been, Mary says, and “right here”— she points—“is the hole where I tell children Templeton the rat would scurry back and forth.” Light pours into the barn from massive windows the Gallants found in a salvage yard. “We think we have changed the barn for the best,” she says. Many of the

improvements, she notes, had to do with “opening rooms up to more light.”

Every spring, Mary would arrive to open the house and ready the gardens for planting. For many years, in midJune, a teacher from a school 90 miles away would bring her class to visit. “They sit on hay bales in the barn,” Mary says, “and we play the recording of Mr. White reading Charlotte’s Web They swing on the same rope swing that they knew Fern had; they sit on the milking stool where Fern had sat. I wanted them to grow up remembering this day. I hoped one day they’d want to find Mr. White’s other writings.”

The tour of the barn and its sheds reveals a river of belongings flowing from one family to another—a collection of worn work gloves, an icebox from the Whites’ New York apartment, and also pieces the Gallants picked up as they canvassed flea markets and antiques shops. “I’ve been here all these years and I keep finding things,” Mary

says, showing me a newly discovered stack of empty grain sacks.

We go back into the house, where the tour continues. There is much to take in: 12 rooms, six working fireplaces, three and a half bathrooms, 19th-century stenciling on the stairway walls, a wood cookstove in the kitchen. Here is the sunny study used by Katharine White, a revered New Yorker editor and avid gardener, now an office for Mary. Next we look in on the darker, north-facing office that belonged to E.B. White, now Robert’s. Upstairs, Mary opens the door to a bedroom that was once heated in winter by a small woodstove set into a fireplace. “This was Mr. White’s room,” she says. “He was afraid of fire,” and she points to the rope ladder squeezed into a corner of the closet.

After the tour, we rejoin Robert in a room that was formerly the old woodshed. They floored it and shined it up, and it’s become their summer

sitting room, where the breeze flows through open doors and a day can slide by as you simply look out to the sea and mountains. They take turns telling me how they found this farm—a story Robert clearly relishes.

In 1939, his family came to the Maine woods. “Can you imagine how happy a 10-year-old boy could be sleeping in a log cabin?” he says. “I woke up to the smell of my mother frying bacon. The memory stayed with me.” He had always loved sailing, and “Maine has the finest sailing in the world. I wanted to have a sailboat in Maine.” In the early 1980s, he flew to Bangor, rented a car, and gave himself 10 days to find a place to put that sailboat. “The woman at the rental counter told me, ‘Don’t go lower than Bucksport,’” he says. “‘Lower than that is too close to Boston.’” Off he drove, and eventually he found his way to the Blue Hill Peninsula. “I said to Mary, ‘We have to go up there.’”

And two years later, that’s what they did. It was Mary’s first time in New England, and they found what she calls “the perfect spot,” a cottage on 12 acres overlooking Eggemoggin Reach, famous among sailors. It was perfect, and they bought it—except now Robert had also seen the prettiest saltwater farm on the entire peninsula, the one owned by E.B. White. Months after White’s death, Robert learned that his son Joel was interested in selling it privately. They met on the farm. “I walked all over,” Robert says, “thinking like a developer, and I came up with a figure I was willing to pay. Joel quoted a price and it was almost the same, to the nickel. We shook hands. I took out a checkbook to leave a deposit. He said, ‘We don’t need that. We shook hands.’”

“And now,” Mary says, smiling, “we suddenly had two houses on the Maine coast.” For the next few years, before they sold it, they rented out the cottage or loaned it to friends; in the

The drawing you see above is called Legacy. It is completely composed of dots of ink. After writing the poem, I worked with a quill pen and placed thousands of these dots, one at a time, to create this gift in honor of the love shared by two of my dearest friends.

Now, I have decided to offer Legacy to those who have known and value its sentiment. Each litho is numbered and signed by hand and precisely captures the detail of the drawing. As an anniversary, wedding, or Christmas gift for your husband or wife, or for a special couple within your circle of friends, I believe you will find it most appropriate.

Measuring 14” by 16”, it is available either fully-framed in a subtle copper tone with hand-cut mats of pewter and rust at $145, or in the mats alone at $105. Please add $16.95 for insured shipping and packaging. Your satisfaction is completely guaranteed.

My best wishes are with you.

The Art of Robert Sexton • P.O. Box 581 • Rutherford, CA 94573

All major credit cards are welcomed through our website. Visa or Mastercard for phone orders. Phone (415) 989-1630 between 10 a.m.-6 P.M. PST, Monday through Saturday. Checks are welcomed; please include the title of the piece and a contact phone number on check. Or fax your order to 707-968-9000. Please allow up to 2 weeks for delivery.

*California residents- please include 8.0% tax

Please visit my Web site at www.robertsexton.com

“This, I will remember, when the rest of life is through: the finest thing I’ve ever done is simply loving you.”

meantime, they made the farm their own. Robert laid out an allée of trees that led like a magical pathway to the trim boathouse where, when the weather was right or there was too much going on in the house, E.B. White would retreat with his black Underwood typewriter. There he built a simple table and bench, placed a barrel for waste and an ashtray by his side, and with the sea breezes for company typed some of the most elegant and memorable sentences in the English language. For their part, the Gallants brought in some extra furniture and added fresh paint and curtains, helping to make the boathouse, like the entire farm, what E.B. White had wanted: a place for families to love.

The Gallants’ children grew up and brought their own children here, where they found a sturdy dock for launching boats and brave bodies into the chill water, and trees bursting with ripe peaches, pears, and apples. There were berry bushes, endless pasture to run through, clams to dig and fish to catch, evening campfire cookouts, and lazy days for reading.

And as the Gallants were putting down roots, they had a guide: Henry Allen, who had worked for the Whites for 37 years. “I said, ‘Henry, we will need someone to look after this place,’” Robert says. “Henry said, ‘I’ll stay on for 30 days. See if you like me, and I’ll see if I like you.’” Allen stayed on for seven more years before finally retiring in his late sixties. “Oh, it broke my heart when Henry left,” Mary says. “He was the spirit of this place. He was our connection to the personal side. Henry said people tried to encourage Mr. White to name the house, which he thought pretentious, but he said if he had to, he would call it ‘Two Big Chimneys and a Little One.’”

Whoever comes after the Gallants will soon learn that E.B. White simply wanted to be left alone, to write and to farm and to be a member of the community. He did not want his

Set back from the clamflats is the boathouse where White often did his writing when the weather was fine. Though the Gallants updated the decor a bit, they left in place his handmade bench and desk ( BELOW )—and even added his original liquor cabinet, moved here from the farmhouse.

home to become a shrine, a museum, a writers’ retreat; he wanted it to stay just a family home. His granddaughter Martha White, a staunch defender of her grandfather’s wishes, told me she believes the Gallants have made it their own, which is how it was meant to be. She hopes it will forever be that way.

“I feel I’ll always want to come back to Maine,” Mary says. “But I will miss just settling in, the way you do when it’s home.” Robert’s voice grows a bit huskier as he chimes in, “This house, this barn, this property is very dear to our hearts. These have been the best summers of our lives.” Mary says she will miss the sunrise over the cove, and the full moon rising “right there”—she gestures toward Harriman Point—adding, “You can read a book by its light.”

E.B. White never knew the Gallants, but he’d know what they’re feeling. He told one of the few interviewers whom he welcomed to the house, “This place doesn’t fit me since Katharine died. The only thing is, I really had to live here. Also, I love the place, and it’s my home.”

The property is priced at $3.7 million. Serious inquiries only, please. For more information, contact Martha Dischinger at Downeast Properties in Blue Hill, Maine, at 207-266-5058 or by email at msd@brooksvillemaine.com.

welcome to the seventeenth century

Readers of this non-fiction narrative have the opportunity to sail across the Atlantic Ocean on Winthrop Fleet ships, learn about dramatic events which led to Harvard College’s establishment, and to go into battle during the English Civil War. Visit early farms, mansion houses and orchards in colonial New England and manor houses and modern-day museums in England. Enjoy unforgettable encounters with early colonial men and women and their Native American contemporaries.

theforgottenchapters.com

Our Cheese Lover’s Gift Box, a sampling of some of our favorites $49.99

Our Cheese Lover’s Gift Box, a sampling of some of our favorites $49.99

15% OFF

Check

Use the code YANKEE to receive 15% of your purchase.

Use the code YANKEE to receive 15% of your purchase.

A truly memorable CHRISTMAS GIFT. First, we’ll send each person on your list a personalized parchment document — a copy of an authentic 1890 TREASURY DEPT. lease, plus a GIFT CARD from you. During the harvest each lessee receives PROGRESS REPORTS full of facts & folklore, thus sharing in the adventure of sugaring. In Spring, when the sap has been processed, each Tree Tenant will get at least 60

SYRUP in decorated jugs (30 oz. guaranteed to Bucket Borrowers) – even more if Mother Nature is bountiful. We do all the work, your friends get the delicious results, and you get the raves! Tree Lease $69.95 + S/H Bucket Lease $59.95 + S/H

It might be hard to believe that one person feeding birds in their yard can help restore the balance of nature. But it’s true. Because in nature, everything is connected. And everything matters.

Enjoy

BY KEITH PANDOLFI

BY KEITH PANDOLFI

Well, not too deep, really: We were on the outskirts of Portland, Maine, the scatterings of discarded beer cans and cigarette butts indicating the most recent wildlife in the area was likely a herd of drunken teenagers.

It was late October, and aside from the scrunch of our boots in the leaves there was barely a sound as we walked along steep cliffs rising from the Saco River and made knee-cracking jumps over shallow creek beds. Along the way, we talked a little—about our children, about the unsettling number of New Yorkers relocating to Portland—but our minds were only half-focused on these conversations. We were hunting, you see. Hunting for wild mushrooms.

Jamie Salomon, the photographer, declared that conditions weren’t great. Maine was experiencing a drought, which was making the fruits of the mycelium—aka mushrooms, which are drawn to the surface by moisture— hard to come by. And this was the tail end of the fall season, a last window of opportunity before deep frosts would put an end to any new growth. The spring morel season was long behind us; the slower, drier summer season expired. We hoped that a recent bout of rain would bring us some frilly brown

hen of the woods, black trumpets, fragrant porcini, egg yolk–colored chanterelles, or bright red lobster mushrooms.

I’d driven from Brooklyn, New York, to join Jamie and his friend Pierre Janelle, the innkeeper, on my first-ever foraging mission. Jamie, who’s always had a taste for wild mushrooms, started foraging after taking a class with a local mycological society. He met Pierre, an avid home cook with a shared love of mushrooms, a few years back, and they’ve been at it ever since, spending weekends searching Maine’s forests— or sometimes just their neighbors’ yards—for their quarry.

On this day, Jamie was on the lookout for king boletes, the meaty American cousins of the Italian porcini, identifiable by the spongy bottoms of their caps. If lucky, he would also stumble upon some pungent matsutakes, the firm white mushrooms that are nothing short of sacred in Japanese cuisine and can fetch around $25 per pound from the Portland restaurants to which he occasionally sells his bounty.

The first lesson Jamie and Pierre shared with me is that there are certain signs, or “setups,” that’ll tell you which woods are conducive for foraging and which ones are a waste of time. “You want mature forests that are open, not full of thickets,” Jamie said. “Scrubby woods are no good.” The forest we’d chosen was perfect: It was rife with hemlocks and oaks, both of which have a symbiotic relationship with the mushrooms we sought. The mushrooms’ mycelia—fine underground networks of fungal threads—seek out tree roots, tapping their nutrients. In turn, the mushrooms help absorb water and minerals for the trees.

The second lesson: Mushroom foraging can be a tricky business. Ingesting the wrong kind can lead to anything from the mild (an upset stomach) to the hallucinatory to the downright deadly. “You’ll want to rule out any Amanita Jamie told me, referring to a genus of potentially toxic species that are identifiable by the small, egglike bulb seen

once they’re picked from the ground. “I try to collect mushrooms that don’t have look-alikes, like black trumpets and hen of the woods.”

While none of the specimens we came across that day were deadly, some did have the potential to send us to bed with gastrointestinal distress. Case in point: On our drive to the woods,

It took only 10 minutes in the woods with Jamie and Pierre until I was hooked. The longer we walked, the more my focus shifted away from the trees and creeks and rocks, and toward the forest floor and the fungi below. Before long, that was all I could see.

I was electrified when I came across a huge outcropping of bright yellow fungi on a fallen log, thinking they

It was just the three of us that day—a writer, a photographer, and a third-generation innkeeper—a trio of middle-aged men heading deep into the Maine woods.WILD MUSHROOM CHOWDER

were chanterelles. But when I called Jamie and Pierre over to have a look, they were unimpressed. “Honey mushrooms,” Jamie proclaimed. He later told me that while a lot of people love eating honey mushrooms—they’re a popular filling for pierogi in Ukraine—he’s never given them much thought. “It’s like fish. There are hundreds of species out there, but there are only a few that most people are interested in eating.” He had the same reaction when we stumbled upon a crop of inky caps. “I don’t collect those,” Jamie said. “If you

eat them with alcohol, they’ll make you sick—and I like to drink.”

After an hour and a half of hunting, we left the woods empty-handed. But when we got to Jamie’s car, he opened the trunk to reveal a magnificent 35-pound hen of the woods that looked to be the size of a small asteroid. “I found it in front of a house in Kittery, right along Route 1,” he said. And while I’d never had this sort of reaction to a 35-pound heap of fungi before, my mouth began to water. He told me that he was going to sell it to a chef he knew,

but that he’d already shaved a bit off and pickled it.

Back at his house, Jamie shared some of that pickled mushroom with me—which made me realize I needed to make more room in my life for pickling mushrooms. As I was leaving, I asked what he was up to for the rest of the weekend. He said he’d seen a chicken of the woods (not to be confused with a hen of the woods) growing on a neighbor’s tree; he was going to drive over with a ladder and cut it down.

Heading back to my hotel, I could hardly keep my eyes on the road. All I could see were mushrooms. A few days later, the jar of pickled mushrooms in my refrigerator was ready to eat, a memory of the Maine woods kept alive in my city kitchen.

The following recipes can all be made with mushrooms commonly found in supermarkets: button, portobello, shiitake, oyster, and “mixed wild” varieties. If using wild mushrooms, be sure to source them from a reputable forager. Better yet, enroll in a mushroom identification course through your local extension program or mycological society.

TOTAL TIME : 2 HOURS, 25 MINUTES

H ANDS- ON TIME : 25 MINUTES