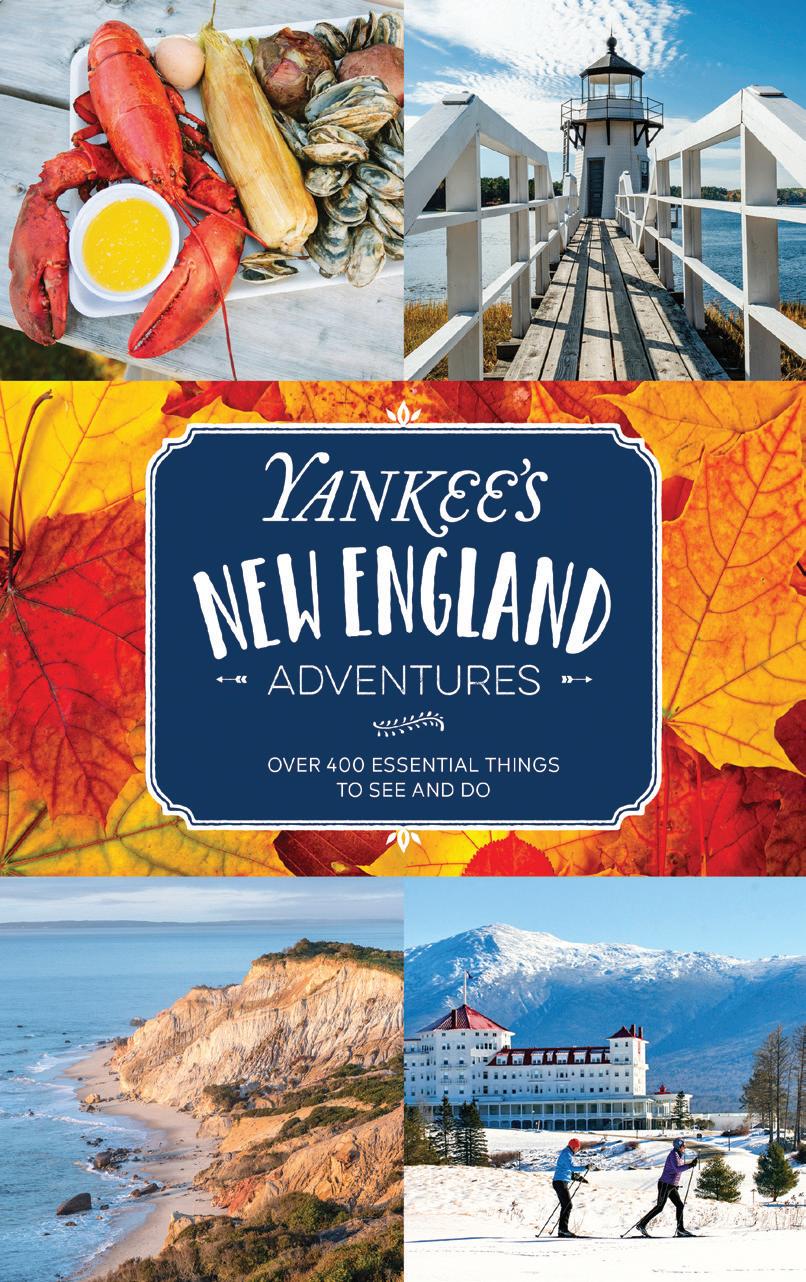

Ultimate Foliage Road Trip

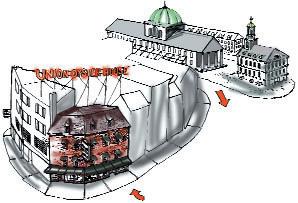

RESTORING THE MAYFLOWER II

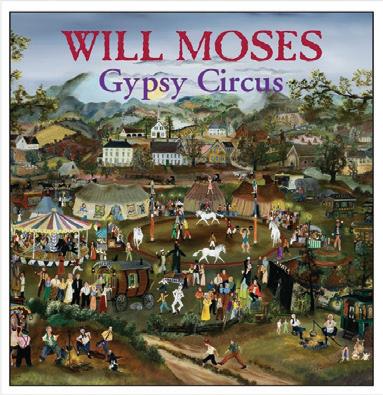

WILL BOSTON EVER GET TIRED OF WINNING? A MOHAWK TRAIL HIDDEN GEM

RESTORING THE MAYFLOWER II

WILL BOSTON EVER GET TIRED OF WINNING? A MOHAWK TRAIL HIDDEN GEM

Cider recipes, fairs and festivals, family day-trips, and more!

We know you want to make your retirement savings last, so it’s important to have an income plan you can feel confident about. Together, we can:

• Navigate the transition from saving to generating income

• Determine if a guaranteed* income annuity is right for you

• Create an income stream that lasts

Set up an appointment with your Fidelity financial professional, or call 866.466.0635 to talk about your retirement income needs today.

To learn more, visit: Fidelity.com/diversifiedplan

Keep in mind that investing involves risk. The value of your investment will fluctuate over time, and you may gain or lose money.

*Guarantees are subject to the claims-paying ability of the issuing insurance company. Certain products available through Fidelity Investments are issued by third-party companies, which are una liated with any Fidelity Investments company. Insurance products are distributed by Fidelity Insurance Agency, Inc., and, for certain products, by Fidelity’s a liated broker-dealer, Fidelity Brokerage Services LLC, member NYSE, SIPC, 900 Salem Street, Smithfield, RI 02917. The Fidelity Investments and pyramid design logo is a registered service mark of FMR LLC. © 2018 FMR LLC. All rights reserved. 853704.2.0

30 /// The Collector

In the antiques-filled home of a globe-trotting Massachusetts teacher, even the upholstery has a tale to tell. By Marni

Elyse Katz

Elyse Katz

40 /// Open Studio

Childhood memories inspire Nicole Aquillano’s architectural pottery. By Annie Graves

44 /// House for Sale

On Maine’s rugged Isle au Haut, we discovered a one-of-a-kind property that’s guaranteed to light up your life. By Joe Bills

50 /// Apples of Their Eye

A family-run orchard in western Massachusetts is making hard cider that can turn any harvest meal into a party of new flavors. By Amy Traverso

61 /// Weekends with Yankee

Warm up a fall evening with the Woodstock Inn’s herbed winter squash tart. By Amy Traverso

68 /// Could You Live Here?

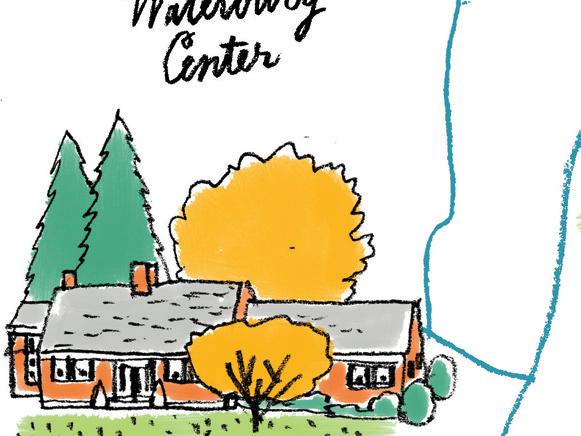

Rural beauty and suburban polish come together seamlessly in a classic but under-the-radar New England town. By Kim Knox Beckius

76 /// The Best 5

These day-trip destinations let families make the most of foliage season. By Kim Knox Beckius

78 /// Out & About

From pumpkin festivals to Halloween hauntings, we round up events that are worth the drive.

8

DEAR YANKEE, CONTRIBUTORS & POETRY BY D.A.W.

14

INSIDE YANKEE

Passion projects show us what happens when work entwines with joy.

16

FIRST PERSON

The act of carving a wooden spoon can yield much more than a humble utensil.

By Nina MacLaughlin18

To lay a foundation for the future, the Hewitt family embarks on a new kind of building project.

By Ben Hewitt24

FIRST LIGHT

How a former trolley bridge over the Deerfield River became a garden in the sky.

By Suzanne Strempek Shea

By Suzanne Strempek Shea

28

KNOWLEDGE & WISDOM

Learning to talk like a cider expert, and getting a science lesson from Family Guy creator Seth MacFarlane.

152

UP CLOSE

In Bennington, Vermont, the venerable Hemmings Motor News motors on. By Joe Bills

Photo: Dave Sarazen, taken at Coast Guard House Restaurant

Photo: Dave Sarazen, taken at Coast Guard House Restaurant

EDITORIAL

Editor Mel Allen

Deputy Editor Ian Aldrich

Managing Editor Jenn Johnson

Senior Editor/Food Amy Traverso

Home & Garden Editor Annie Graves

Associate Editor Joe Bills

Senior Digital Editor Aimee Tucker

Digital Assistant Editor Katherine Keenan

Contributing Editors Kim Knox Beckius, Ben Hewitt, Rowan Jacobsen, Krissy O’Shea, Julia Shipley

ART

Art Director Lori Pedrick

Photo Editor Heather Marcus

Contributing Photographers Adam DeTour, Megan Haley, Corey Hendrickson, Little Outdoor Giants, Michael Piazza, Greta Rybus

PRODUCTION

Director of Production & Distribution David Ziarnowski

Production Manager Brian Johnson

Senior Production Artists Jennifer Freeman, Susan Shute

DIGITAL

VP New Media & Production Paul Belliveau Jr.

New Media Designer Amy O’Brien

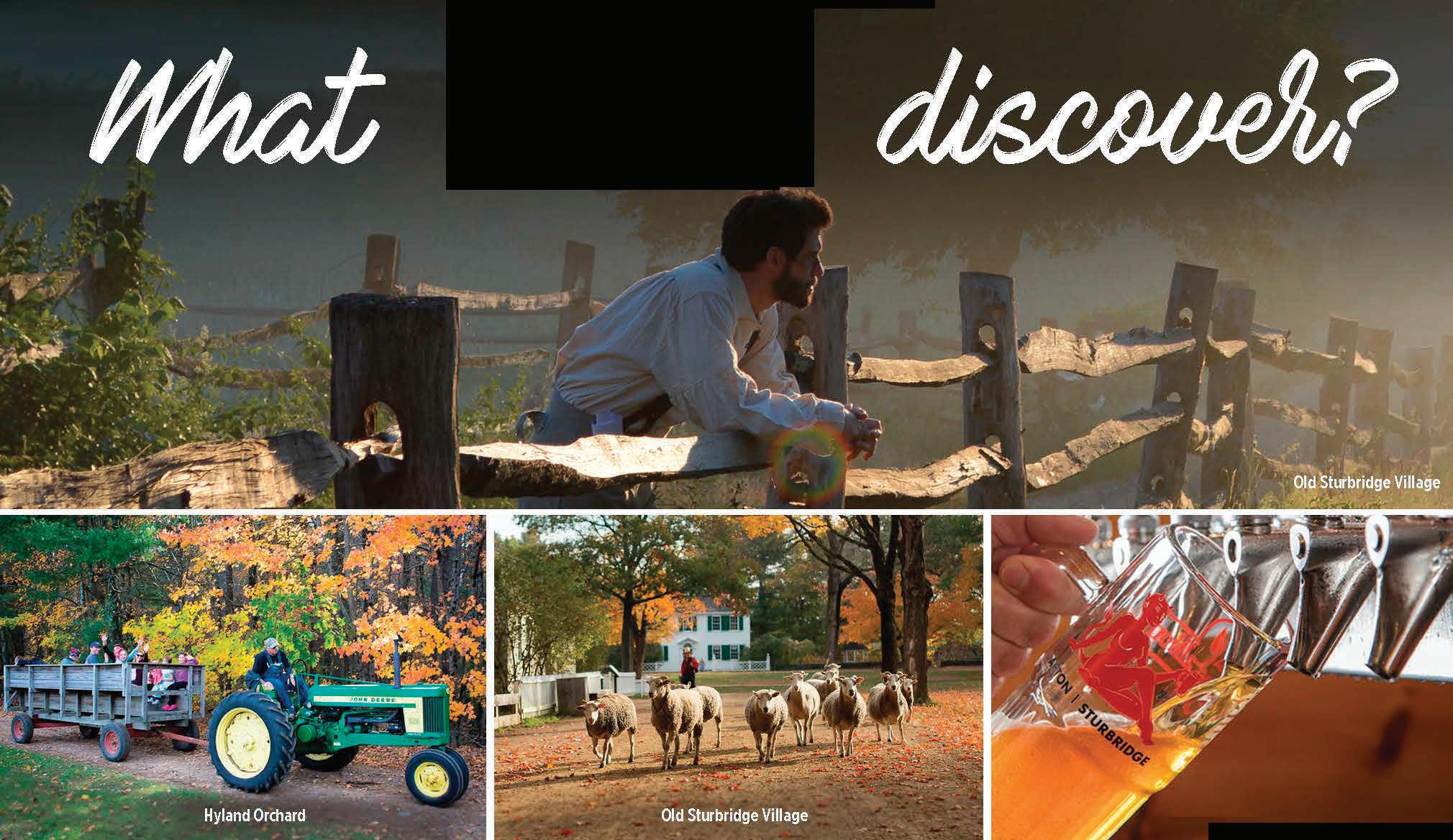

CORPORATE STAFF

Mailroom/Maintenance Supervisor Mike Caron

Receptionist Linda Clukay

Staff Accountant Nancy Pfuntner

Credit Manager/IT Coordinator Bill Price

Accounting Coordinator Sabrina Salvage

Executive Assistant Christine Tourgee

YANKEE PUBLISHING INC.

ESTABLISHED 1935

President Jamie Trowbridge

Editor-in-Chief Judson D. Hale Sr.

Vice Presidents Paul Belliveau Jr., Jody Bugbee, Judson D. Hale Jr., Brook Holmberg, Sandra Lepple, Sherin Pierce

BOARD OF DIRECTORS

Chairman Judson D. Hale Sr.

Vice Chairman Tom Putnam

Directors Andrew Clurman, H. Hansell Germond, Daniel Hale, Judson D. Hale Jr., Joel Toner, Cor Trowbridge, Jamie Trowbridge

FOUNDERS

Robb and Beatrix Sagendorph

Publisher Brook Holmberg

ADVERTISING

Vice President Judson D. Hale Jr.

Media Account Managers Kelly Moores, Dean DeLuca , Steven Hall

Canada Account Manager Françoise Chalifour

Senior Production Coordinator Janet Selle

For advertising rates and information, call 800-736-1100, ext. 204, or email NewEngland.com/adinfo.

MARKETING

ADVERTISING

Director Kate Hathaway Weeks

Manager Valerie Lithgow

Associate Holly Sloane

PUBLIC RELATIONS

Roslan & Campion, 212-966-4600

NEWSSTAND

Vice President Sherin Pierce

NEWSSTAND CONSULTING

Linda Ruth, PSCS Consulting, 603-924-4407

SUBSCRIPTION SERVICES

To subscribe, give a gift, or change your mailing address, or for any other questions, please contact our customer service department:

Yankee Magazine Customer Service

P.O. Box 422446

Palm Coast, FL 32142-2446

Online NewEngland.com/contact

Email customerservice@yankeemagazine.com

Toll-free 800-288-4284

To order additional copies, contact Stacey Korpi at 800-895-9265, ext. 160.

Yankee occasionally shares its mailing list with approved advertisers to promote products or services we think our readers will enjoy. If you do not wish to receive these offers, please contact us.

Yankee Publishing Inc., 1121 Main St., P.O. Box 520, Dublin, NH 03444 603-563-8111; editor@yankeemagazine.com

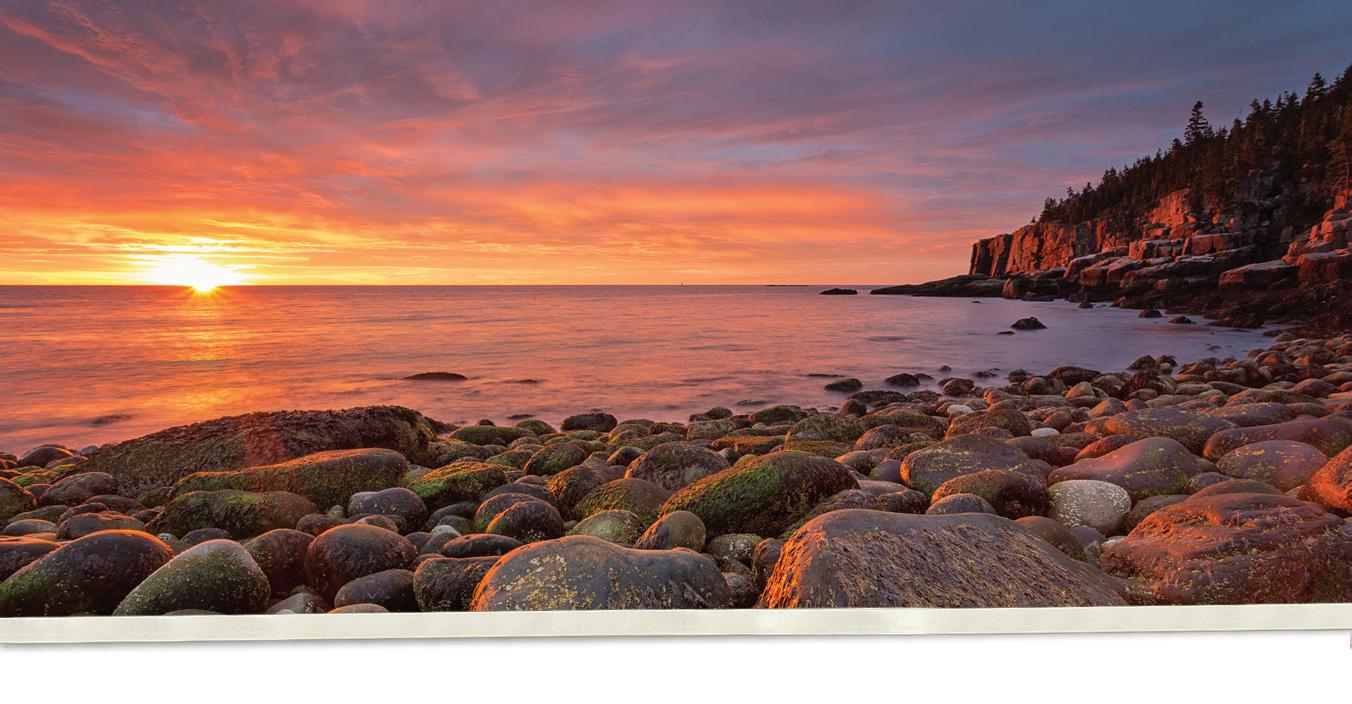

The miles flew by. We didn’t really know where we were headed, but it didn’t matter. Because the longer we drove, the more breathtaking the view became. At one point, we thought we were lost, then we were sure of it. But it’s exactly where we wanted to be. Away from it all and right in the middle of everything. We tried to capture it, but the pictures just don’t do it justice. Nothing beats being there in person, in the right place, at the right time. When nature’s most brilliant exhibition is on full display. This is me.

BE ORIGINAL. BE INSPIRED AT VISITMAINE.COM

14:25 CUTLER 44.6576° N, 67.2039° W

BE ORIGINAL. BE INSPIRED AT VISITMAINE.COM

14:25 CUTLER 44.6576° N, 67.2039° W

A New Hampshire native whose photos have been published in The New York Times, Nature, Boston , and many others, DeTour says he was “in my happy place” while on assignment at Carr’s Ciderhouse for this issue’s food feature [“Apples of Their Eye,” p. 50]. “There’s something uniquely peaceful about being by yourself in an apple orchard on a crisp day waiting for the light to change.”

NINA MACLAUGHLIN

In her 2015 book, Hammer Head , MacLaughlin tells how she left her journalism job to learn the carpentry trade. But a quieter, simpler pursuit—wood carving —has helped her “understand the wordless language of wood,” she says [“Carving Spoons,” p. 16]. MacLaughlin, who lives in Massachusetts, still does plenty of writing, including a weekly column on New England literary news for The Boston Globe

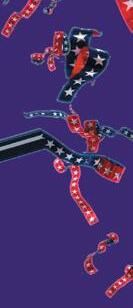

LEIGH MONTVILLE

As a UConn freshman, Montville signed up for the school newspaper in his very first week—and the die was cast. A longtime Globe sports columnist and Sports Illustrated senior writer, this 2009 inductee into the National Sportscasters and Sportswriters Hall of Fame shares with Yankee his take on how Boston teams, for better or worse, have come to rule the 21st century [“When Winning Never Stops,” p. 100].

SUZANNE STREMPEK SHEA

The Bridge of Flowers in Shelburne Falls, Massachusetts, has special meaning for Shea [“A Bridge for Dreamers,” p. 24]. A former newspaper journalist who has written for the likes of The Boston Globe and ESPN the Magazine, she often visits the bridge with her husband on their anniversary, including this year, their 35th. “And we’ll use the bridge as inspiration to celebrate our 90th there too,” she says.

NEIL JAMIESON

The vibrant artwork for the story of Boston’s sports juggernaut [“When Winning Never Stops,” p. 100] comes from this U.K.-born graphic designer, who has worked for Sports Illustrated and People, among others, and now runs his own agency, the Sporting Press. He and his family moved from New York to Connecticut a few years ago, which is when he learned it’s not wise to wear Yankees colors even to Little League games.

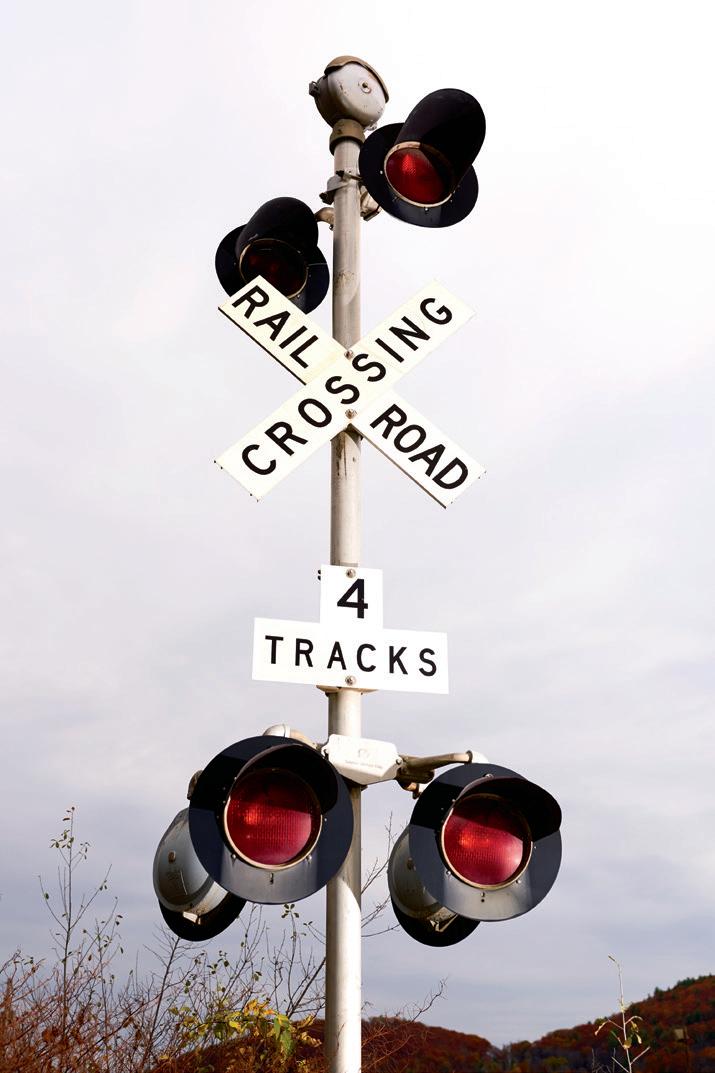

BILL SCHELLER

A veteran freelance journalist and author of 30-plus books, Scheller became intrigued by freight trains a few years ago after he moved to Randolph, Vermont, and began hearing them rumble in the night. “What, I wondered, must it be like to be riding through the dark in those locomotive cabs?” recalls Scheller, who decided to find out—and to bring Yankee readers along for the ride [“Back Tracks,” p. 118].

Judging by the slew of online comments for Howard Mansfield’s article “The Death of Brown Furniture” [July/August], a lot of NewEngland.com readers aren’t ready to give up their antique bureaus and vintage sofas just yet. Here’s a sampling of their views (edited to fit this space):

“‘Brown’ furniture is out of vogue and no one wants it—antiques, history, eek! ugh! We want clean lines and modern, no-fuss living. Understandable, but lamentable. I love my brown furniture with all my heart and the sentiments that make it infinitely more valuable than some glass-and-chrome coffee table.” —Melissa Houston

“As we look to downsize, my wife and I are struggling with what to do with family ‘stuff’ handed down through the generations. Every piece of furniture and glassware has its own story, yet it’s only known by my late parents. They’d be so disappointed knowing their grandchildren and great-grandchildren have no interest in their ‘treasures’ painstakingly collected and cared for over their lifetime. So sad....” —Rob

Cline“The younger generation actually does love antiques. They just don’t know it yet. Their favorite stores—Ikea, Pottery Barn, Williams Sonoma Home— are full of factory-made knockoffs of trestle tables, back stools, blanket chests, and every modern reinvention of ginger jars, Chinese export, and creamware imaginable.... With a few more years under their belts, and a little more of the education and money they’ll accumulate along the

Contrary to the roundup of Rhode Island geography trivia in our July/August issue (“Rhode Signs”), it would take a miracle for the Vatican, at 108 acres, to fit inside any Newport mansion.

way, they’ll want the real thing someday, just the way the rest of us did.”

Mary Kay Felton“When I moved into my first house, my in-laws gave us their dining room set: brown wood painted ‘antique blue.’ I promptly had the entire set stripped and refinished walnut. Now my 30-something children want me to chalk-paint it blue! Everything is cyclical.” —Audrey Mento

I was thrilled to read the article about Maine’s Swedish Colony in your May/ June issue [“Välkommen to Midsommar”]. My great-great-grandparents A.P. and Maria Peterson immigrated to New Sweden in 1871, and when I saw the article’s photograph of the

the poem reads:

THEPOEMREADS:

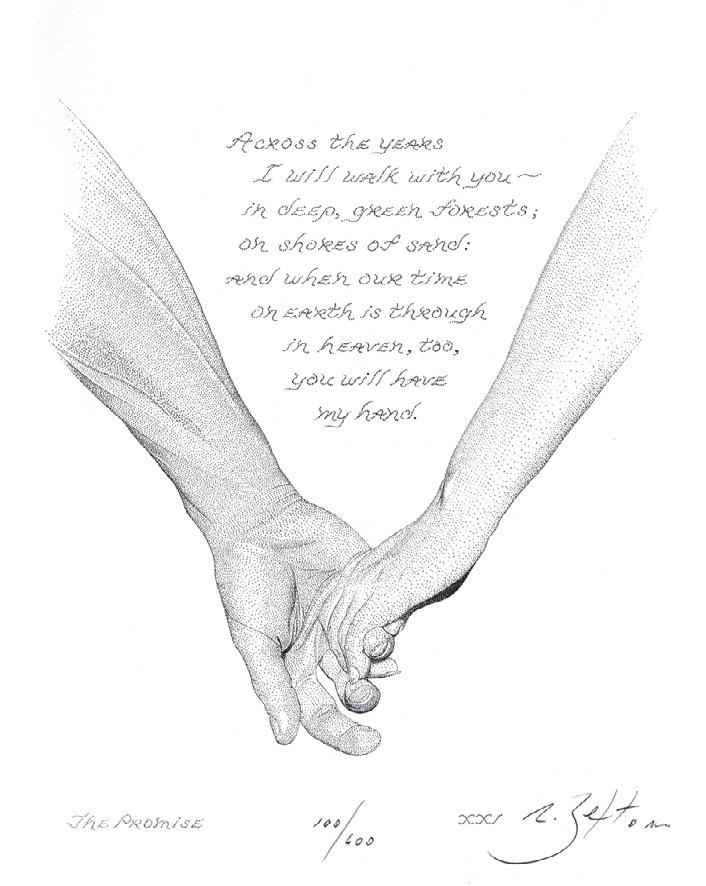

The drawing you see above is called The Promise. It is completely composed of dots of ink. After writing the poem, I worked with a quill pen and placed thousands of these dots, one at a time, to create this gift in honor of my youngest brother and his wife.

Dear Reader,

Now, I have decided to offer The Promise to those who share and value its sentiment. Each litho is numbered and signed by hand and precisely captures the detail of the drawing. As a wedding, anniversary or Valentine’s gift or simply as a standard for your own home, I believe you will find it most appropriate.

The drawing you see above is called “The Promise.” It is completely composed of dots of ink. After writing the poem, I worked with a quill pen and placed thousands of these dots, one at a time, to create this gift in honor of my youngest brother and his wife.

Measuring 14" by 16", it is available either fully-framed in a subtle copper tone with hand-cut double mats of pewter and rust at $145*, or in the mats alone at $105*. Please add $18.95 for insured shipping. Returns/exchanges within 30 days.

My best wishes are with you.

Now, I have decided to offer “The Promise” to those who share and value its sentiment. Each litho is numbered and signed by hand and precisely captures the detail of the drawing. As a wedding, anniversary or Valentine’s gift or simply as a standard for your own home, I believe you will find it most appropriate.

Sextonart Inc. • P.O. Box 581 • Rutherford, CA 94573 (415) 989-1630

Measuring 14" by 16", it is available either fully framed in a subtle copper tone with hand-cut mats of pewter and rust at $110, or in the mats alone at $95. Please add $14.50 for insured shipping and packaging. Your satisfaction is completely guaranteed.

All major credit cards are welcomed. Please call between 10 a.m.-5 p.m. Pacific Standard Time, 7 days a week.

My best wishes are with you.

Checks are also accepted. Please include a phone number.

Apple cider, cold and sweet, Sweeps September off her feet.

Muffins, cobblers, pies, and more

*California residents please include 8.0% tax

The Art of Robert Sexton, 491 Greenwich St. (at Grant), San Francisco, CA 94133

Charm her to the apple core.

Please visit our website at www.robertsexton.com

MASTERCARD and VISA orders welcome. Please send card name, card number, address and expiration date, or phone (415) 989-1630 between noon-8 P.M.EST. Checks are also accepted. Please allow 3 weeks for delivery.

“The Promise” is featured with many other recent works in my book, “Journeys of the Human Heart.” It, too, is available from the address above at $12.95 per copy postpaid. Please visit my Web site at www.robertsexton.com

—D.A.W.

“Across the years I will walk with you— in deep, green forests; on shores of sand: and when our time on earth is through, in heaven, too, you will have my hand.”

“Across the years I will walk with you— in deep, green forests; on shores of sand: and when our time on earth is through, in heaven, too, you will have my hand,”

f abulous j ew elry & g re at p ric es f or mor e than 65 ye ar s

Our gemstone necklace adds a dash of color and fun

This 17.50ct. t.w. multi-gem necklace is at once chic and graceful. The rainbow mix of gemstones shimmers on a 14kt gold chain. The modern way to refine your style with color.

$395

Plus Free Shipping

17.50ct. t.w. Multi-Gem Station Necklace in 14kt Gold 18" length. Bezel-set amethyst, garnet, citrine, peridot and blue topaz. 14kt gold cable chain, springring clasp. Also available in 20" $435; 36" $495

Ross-Simons Item #789469

To receive this special offer, use offer code: STATION48

1.800.556.7376 or visit ross-simons.com/station

Travel: New England’s Best Apple Orchards

We reveal the top spots for picking a peck of autumn’s signature fruit.

NEWENGLAND.COM/ APPLE-ORCHARDS

Recipe: Pumpkin Streusel Bars

Creamy pumpkin pie meets easy-as-can-be cookie bar in this sweet, spicy seasonal treat.

NEWENGLAND.COM/ PUMPKIN-BARS

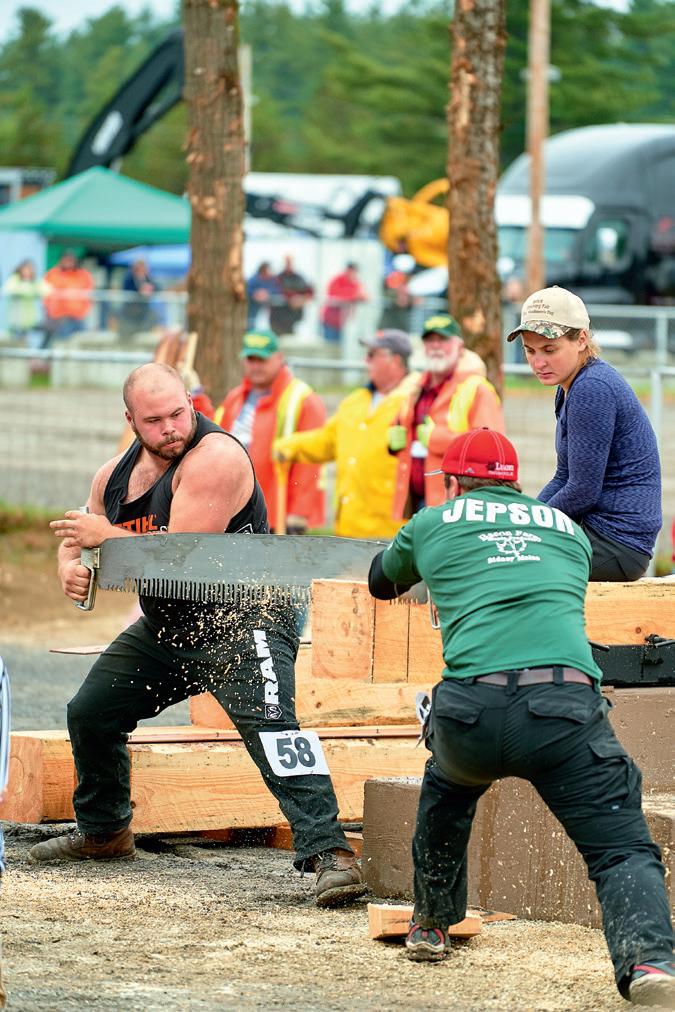

Events: 12 Country Fairs Not to Miss This Fall

Discover the New England fairs that should be on your autumn adventures list.

NEWENGLAND.COM/ FALL-FAIRS

Travel: 2019 Foliage Forecast

Ready to start planning your leaf peeping? Get the scoop on this year’s color with our expert predictions.

NEWENGLAND.COM/ FOLIAGE-2019

two young Peterson girls dressed in Swedish attire, I thought they could be related to me.

I’ve summered in southern Maine for years, and decided to make the five-hour trek north to meet with genealogist Lynn Johnson at the New Sweden Historical Society and Museum. She was as passionate about tracing my ancestry as if it was her own, and was able to tell me about their journey from Gothenburg, Sweden, to Hull, England, then finally to Houlton, Maine, on May 22, 1871. She also traced my great-grandfather Hans Swenson, who homesteaded on 100 acres in New Sweden; I learned he had immigrated to Maine in 1893 and had four brothers and a sister. She even led me to the Petersons’ family headstone, which lies in the cemetery next to the museum.

I intend to go back to New Sweden next year for Midsommar and look up a few of my long-lost relatives!

Carol S. Harvat Lusby, Maryland

Well, did Rye decide to strike out on his own? Did Ben and Penny add new piglets this spring? Does Fin also hunt with a bow? As you can tell, this faithful follower in Connecticut who cannot imagine taking jars of sauerkraut on a camping trip, and marvels at living in a partially finished house, really was disappointed to not find a new “Life in the Kingdom” in your May/June issue.

Barb Francese Madison, ConnecticutEditor’s note: For all those who might be fretting about missing a news fix from the Northeast Kingdom, rest easy. Ben Hewitt’s dispatches resumed in July/August; in this issue, he and Penny embark on new adventures in home building. You can catch up on all of Ben’s columns and features at newengland.com/author/ben-hewitt.

n the summer of 1975, I mailed a story to the Maine Sunday Telegram about my time as a teacher at a Maine treatment center for troubled youths. The center had recently been front-page news because several teenagers had run away, risking the forest over the often-harsh “treatments” I had observed. A few days later, the paper’s features editor called me. His name was Eddie Fitzpatrick, and he wanted to meet. Soon, he was sending me on assignments everywhere in the state, then coaxing me through rewrites, and every few weeks a 3,000-word story with my byline would lead his Sunday features section.

He was the son of an English coal miner, and his infectious excitement about Maine became my own. He loved wilderness adventure, writers, artists, and cooking. In his pages and his life, he brought them all together. So many Portland artists owe him a debt for bringing their work to light. As I do.

Were it not for Eddie Fitzpatrick, gone now two years, I would not be writing this editor’s letter today. Because when I met with Yankee ’s new managing editor, John Pierce, in the fall of 1977, I came with a stack of my newspaper stories—from the tragedy of a child lost at a remote campground to a profile of a young Maine writer whose horror novels were catching fire.

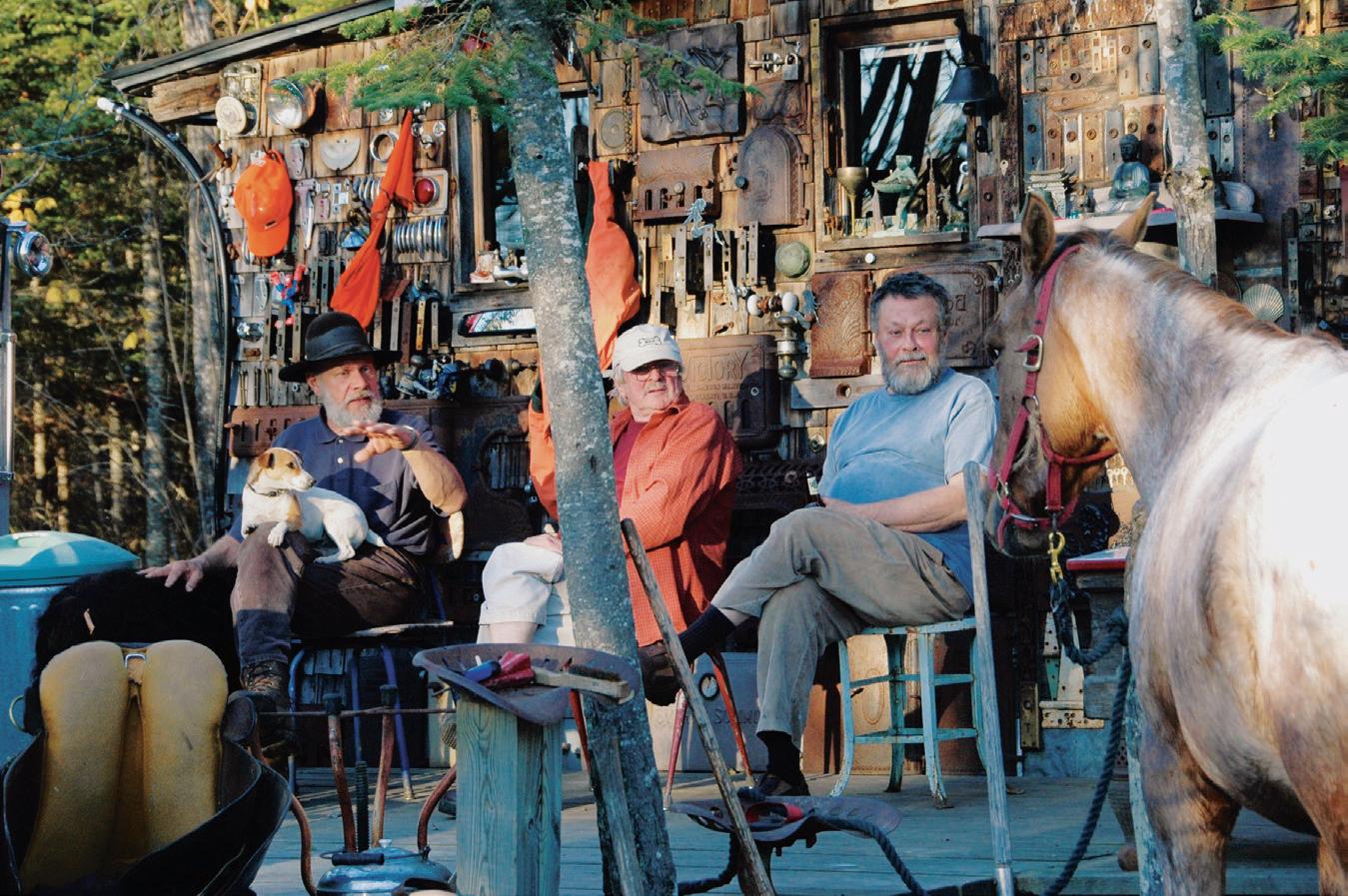

I tell you this because recently I saw a remarkable photo exhibit called “Everyday Maine.” My eyes followed along the procession of 120 photos through several rooms of the University of New England Art Gallery in Portland. Suddenly, I stopped. In a photo titled “Porch Talk,” there was Eddie Fitzpatrick, sitting between two friends at a North Woods cabin, happy, no doubt telling or hearing a story. He had often told his longtime partner, photographer Diane Hudson, “We are the luckiest people in the world.” His passion for Maine and its people now seemed to infuse the gallery. And the more I learned about how the show had come together, the more I wanted to bring even a small part of it to Yankee ’s readers [“Everyday Maine,” p. 104].

Elsewhere in the magazine, you will meet others who have followed their passion. Whether they are tending to flowers that bring thousands to walk among them [“A Bridge for Dreamers,” p. 24], or restoring an orchard to create acclaimed hard ciders [“Apples of Their Eye,” p. 50], or preserving the most famous replica ship in the world [“The Big Question,” p. 116], this issue is an exhibit in itself of what happens when your work entwines with joy. You become one of the “luckiest people.” I know I am, and Eddie Fitzpatrick helped me make that happen.

Mel Allen editor@yankeemagazine.com

Paring away wood can reveal more than a humble utensil.

he birch came down in my dad’s yard, 300 yards from the river. I took some of it home and sat on a stool in my apartment and carved a spoon with a small sharp blade and a small curved blade. Pale wood curls collected on the floor, on my lap. I swept when I was done. Half a dozen more birch blanks—the crude pre-spoon shapes—live now in my freezer, where the cold holds in the moisture. I sanded the spoon smooth and rubbed it with beeswax and flaxseed oil, which smells like soil and honey, which the wood drinks in and raises its grain in thanks. I smoothed my thumb against the soft curves of its bowl, and thought of the pleasure of precision without exactitude. I was astonished, as I always am, at the transformation.

A seed in the soil not far from the banks of a river on the southern coast of Massachusetts … three decades of growth, give or take … sunlight, rain, wind, frost and freeze, thaw and warmth … papery white bark with black gashes like hieroglyphs of blinking eyes … branches that gave perch to cardinals, robins, chickadees … a death, a falling, a lopping … and the rest of the tree decomposes where it fell, returns itself to the soil. Ferns will grow there; mushrooms, maybe. An oak seed might decide to become a sapling. And now a new spoon exists in my kitchen.

“All things change but no thing dies,” writes Ovid in his Metamorphoses , and in holding the section of wood in my hands, running a blade along its length, it felt good to take part in that one tree’s transformation. I was not resurrecting it, not breathing life back into the dead, but involved instead in its changing state. The vibration of its aliveness registers in my hand when I stir the soups and stews, when I raise the spoon to my lips and blow before tasting the tomato sauce.

Taste, touch, sight, smell—what an opportunity spoon-making offers up to the senses. Some months ago, I sat on the floor of my apartment and showed an 11-year-old girl how to carve. She held the blade in her hand and I trusted her, and reminded myself that the hospital is a five-minute walk away, should we need to buy some stitches. But she carved well, a natural. We sat and talked as she carved, blade in her small strong hand, and she paused and asked a good question, a wise one: “At this point, can you tell more with your eyes or more with your hands?” We closed our eyes and felt. We opened them and looked. How do we come to know? What’s the best way to find the truth of things? How do we best sense when something’s right?

She continued to carve and in one fast swipe, plunged the blade deep in, pressed hard, and a tiny pyramid of wood flew and hit the wall. She looked at me with horror on her face, with fear she’d wrecked the spoon, killed it dead. She set the blade on the floor and put the spoon in my hands, as though she couldn’t stand to hold it. I ran my thumb over the divot. “I do this all the time,” I said. “You do?” “I think I’ve gone too deep, but then I find that you can actually go a lot deeper than you think before anything is unfixable.” We could smooth out all the edges, I told her. She picked up the blade again. “Can I keep going?”

The wood forgives. We look and feel and try to get it right. And if, in the end, there is an indentation where once we pressed too deep, so what? Such is how we know we’ve taken part. That is her mark there, the sign that tells that her hands were on this, too.

SEPTEMBER 19-22.....

ST. MARY’S COUNTY FAIR

Celebrate St. Mary’s heritage at this traditional county fair, located at the St. Mary’s County Fairgrounds. www.smcfait.somd.com

OCTOBER 5-6............

RIVERSIDE WINEFEST AT HISTORIC SOTTERLEY

Celebrate the best of Maryland! Tastings from Maryland wineries, live music, local food & craft beer, artisans, and more. www.sotterley.org

OCTOBER 5-6............

BLESSING OF THE FLEET

This family-friendly festival features live music, family entertainment, activities, and much more, with free boat excursions and tours of St. Clement’s Island, Blackstone Lighthouse, and the museum. www.blessingofthefleetsomd.net

OCTOBER 19-20........

53 RD ANNUAL U.S. OYSTER FESTIVAL

Celebrate the opening of oyster season on the Chesapeake Bay and take part in one of the oldest and most popular festivals in the country. www.usoysterfest.com

Outdoor adventure, history, food, culture, and everything in between await you. Find inspiration, adventure, and excitement where the Potomac and the Chesapeake meet. Follow us on Instagram @VisitStMarysMD

Plan your next trip at www.visitstmarysmd.com

t has been a dry summer, and although northern Vermont has been spared the worst of the rainless days gripping the region, we’ve been living for months on the cusp of drought. By early August, even my body feels dry, as if it were a garden in need of frequent watering, or even the occasional relief of a passing shower. So I dive into our pond over and over and over again, grateful that the springs feeding it are prolific and cold; even under the relentless sun, the water level has dropped only a handful of inches, and although the top few feet of water are warm, the depths remain breathtakingly cold.

We have decided, perhaps more impulsively than might be prudent, to build a second house on this property. This, despite the fact that the first house we built—the one we currently inhabit—remains unfinished: The kitchen is but a crude assemblage of makeshift counters, the northwesterly-facing exterior walls remain unsided, and the bathroom patiently awaits a sink of its very own. It seems reasonable to think we might finish this house before starting another, an assumption that is not lost on our friends. “Has anyone ever told you you’re crazy?” a friend says to me when I tell her of our plans. She’s smiling when she says it, but it’s not entirely clear that she’s joking.

There are a number of reasons we’re embarking on this project, all of which are informed by the awakening understanding that at some point in the not-so-distant future, we might do well to have an income stream that is not dependent on our bodies,

nor on the fickle nature of the market for written words. To be sure, both of these have kept us afloat over the years, aided and abetted by our penchant for thrift and (I suppose) a certain prideful recalcitrance: We’ll do it our way. But time marches on, and new aches and pains settle in, and maybe one begins to consider ways in which the burdens of life might be eased by steady income, even something as modest as a monthly rent check. Besides, if there’s one thing we know how to do, it’s building on the cheap, leveraging used materials, lumber sawn from logs harvested on this land, and our still-capable bodies.

So it begins. We hire our neighbor Matt to dig a cellar hole. Matt lives a few miles down the road, and spends his days either working in the woods or running the excavator. It’s not an easy way to make a living, but Matt

is perennially cheerful, in that way of people who seem to have figured out their place in the world. We hire Levi to come with his portable mill and saw the piles of spruce and fir logs I’ve harvested over the winter and spring into 2-by-6s for wall framing. And we hire our friend Mark to help with the framing. We hire Perry and Sons to pour the foundation; they come and are gone so quickly it seems almost like a mirage, except that what remains is literally as solid as concrete.

Meanwhile, Penny and I scour Craigslist and we take a trip to the North Shore of Massachusetts, where we purchase 18 used Marvin windows, a set of French doors, a gas range, a large built-in cabinet, two light fixtures, and probably a few other things I’m forgetting, all for $2,500 cash. The materials are out of a huge waterfront mansion that was

purchased by investors to be gutted and flipped at a substantial profit. “It was perfectly fine the way it was,” the crew foreman tells us, shaking his head in disbelief. “But a house like this, people want everything new, and they’re willing to pay for it.” He helps us load, then offers us three interior doors and a wood stove for free. The stove looks as if it’s never been used.

We drive back through Boston at the height of rush hour, towing our unregistered (but don’t worry, Mom, still perfectly safe!) trailer behind our rusty Ford pickup, me at the wheel, anxious as a long-tailed cat in a roomful of rockers, since it’s one thing to be towing an 18-foot trailer piled high with a menagerie of building materials, and it’s entirely another thing to be towing the same through the late-afternoon melee of Interstate 93 on a workday, sweat beading on my brow, one eye on the truck’s northward-creeping temperature gauge, one eye glued to the brake lights of the car in front of us, and both eyes casting frequent glances at the rearview mirror, where, no matter how often or vividly I imagine it splayed across the road, our load remains secure.

Penny, meanwhile, is cucumbercool. “We’ll either make it or we won’t” is how she replies to my frequent (incessant?) comments pertaining to the truck’s engine temperature, or the risk inherent in the heavy traffic, or even the (moderately) illegal nature of our unregistered (but still perfectly safe!) trailer. Naturally, her composure serves only to agitate me further, and I believe it is no exaggeration to suggest that the five-hour trip shaves at least some period of time from my life. On the other hand, compared with buying new windows, doors, light fixtures, cabinets, and stoves, we’ve saved somewhere in the neighborhood of $15,000. All in all, it is a deal I can live with, particularly

after determining that whatever days/ weeks/month/years the stress has cleaved from my personal allotment, they would have come at the end, when my quality of life would likely be diminished anyway.

In August, a few days after the foundation is poured, Mark and I begin framing the floor system. We’ve designed a modest structure, barely 1,000 square feet, and a roof before winter seems an entirely reasonable goal, even for two men who are committed to working barely 40 hours a week between them. This is to be the third house I’ve built, or at least had a significant hand in building, but only the first that I am not destined to live in, and also the first with no specific move-in date, and thus no pressing deadline. I am enjoying our relaxed approach.

Slowly, the house takes shape: The floor is framed and decked, the first

wall goes up, then the second and third. We set the rafters, then sheathe the roof. The near-drought persists, and thanks to the perpetually sunny skies, we make quick progress despite our short days. For me, the short days are a necessity, in deference to the paying work that is making this project possible in the first place, plus the innumerable homestead tasks that loom in the final approach to winter. For Mark, the short days acknowledge there is firewood to cut and stack, gardens to tend, cars to repair, and his own house to finish. Like me and Penny, Mark and his wife have built their house around them; it’s been 25 years since they broke ground, and he jokes that it might be finished in another 25.

Toward the end of September, the rain comes again. The house is not yet closed in, and our progress slows. I’m still optimistic that we’ll have

it dried in before winter, but that’s only because I have no way of knowing that the first snowstorm will arrive in early November, and that we won’t see bare ground again until the end of April. The snow will bury the pile of roofing I’ve thoughtfully purchased in advance; it will cover the roof deck and make access to the job site challenging. Mostly, though, it will fracture our resolve with its promise of frigid toes and half-frozen fingers, and of hours spent sweeping and shoveling.

But in September, with the leaves on the trees just beginning their annual turn, we know nothing of this, and in our ignorance of what the future holds, Mark and I keep plodding away, joking and laughing through a handful of six-hour workdays each week. As if winter will never come. As if we have all the time in the world.

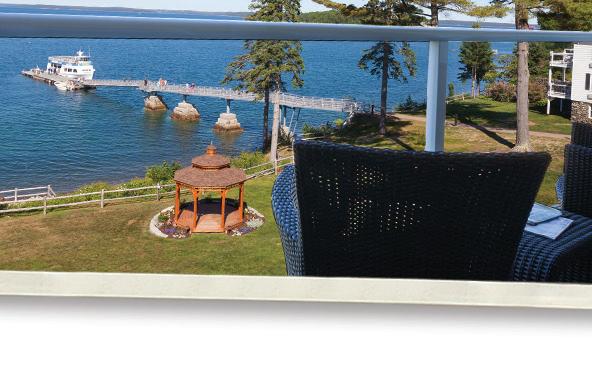

Apartment and cottage living at Piper Shores offers residents fully updated and affordable homes, with all the benefits of Maine’s first and only nonprofit lifecare retirement community. Located along the Southern Maine coastline, our active, engaged community combines worry-free independent living with priority access to higher levels of on-site care—all for a predictable monthly fee.

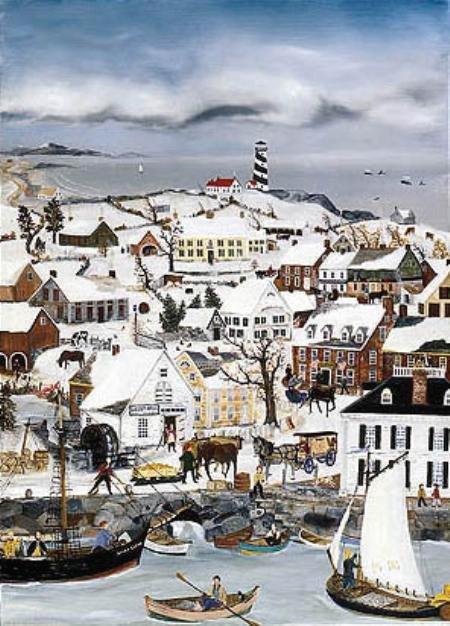

“Herreshoff S” moored in Woods Hole.

It’s late afternoon and our “S Class” sloop sits peacefully in the harbor in Woods Hole, Cape Cod. Designed in 1919 by Nat Herreshoff, this yacht is 27½ feet long and is one of only 103 built between 1919 and 1941. Six of these classic boats are now moored in Woods Hole. Today…about half of these famous wooden boats are still sailing and many are still actively racing. 2019 celebrates the hundredth anniversary of these unique boats. This beautiful limited edition print of an original oil painting, individually numbered and signed by the artist, Forrest Pirovano, captures the majestic appearance of a world famous sailing yacht and gives the subject a sense of time and place.

This exquisite print is bordered by a museum-quality white-on-white double mat, measuring 11x14 inches. Framed in either a black or white 1½ inch deep wood frame, this limited edition print measures 12¼ X 15¼ inches and is priced at only $149. Matted but unframed the price for this print is $109. Prices include shipping and packaging.

Forrest Pirovano is a Cape Cod artist. His paintings capture the picturesque landscape and seascapes of the Cape which have a universal appeal. His paintings often include the many antique wooden sailboats and picturesque lighthouses that are home to Cape Cod.

FORREST PIROVANO, artist

P.O. Box 1011

• Mashpee, MA 02649

Visit our studio in Mashpee Commons, Cape Cod

All major credit cards are welcome. Please send card name, card number, expiration date, code number & billing ZIP code. Checks are also accepted.…Or you can call Forrest at 781-858-3691 …Or you can pay through our website

www.forrestcapecodpaintings.com

Lush foliage on the Bridge of Flowers frames

2½ -year-old Leia, daughter of Carrie Keefe of Turners Falls. Keefe, who is a custom bonnet maker, grew up in western Massachusetts and says the bridge has long been a favorite place to bring friends and family.

Lush foliage on the Bridge of Flowers frames

2½ -year-old Leia, daughter of Carrie Keefe of Turners Falls. Keefe, who is a custom bonnet maker, grew up in western Massachusetts and says the bridge has long been a favorite place to bring friends and family.

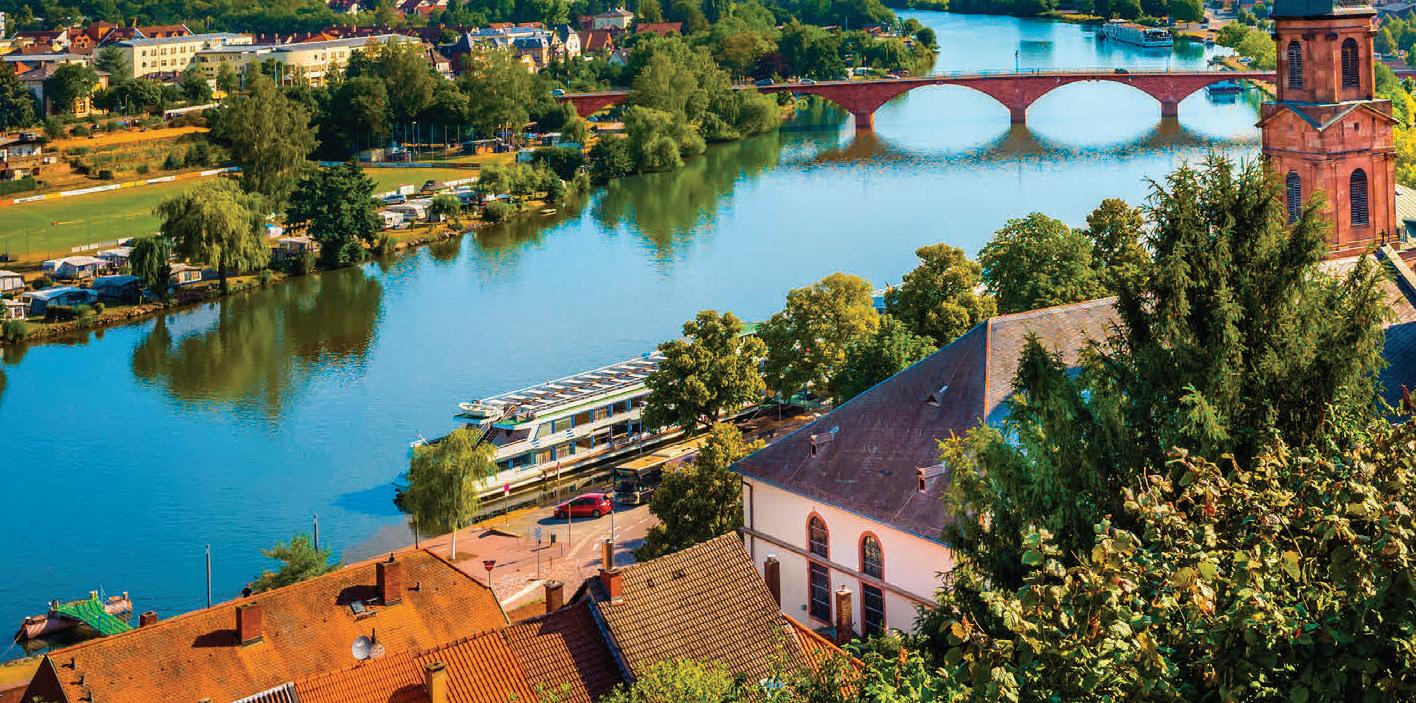

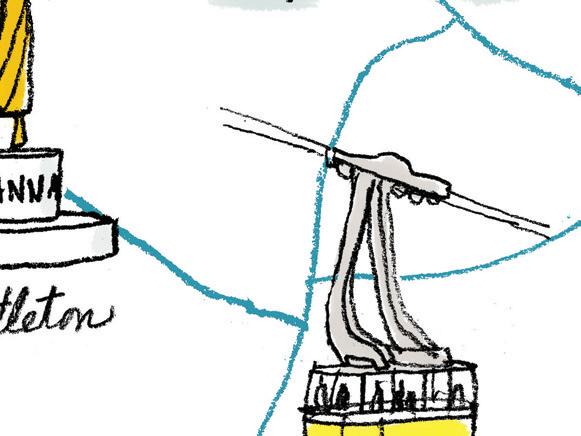

If you’re driving Route 2, Massachusetts’s famed Mohawk Trail, keep an eye out for the sign pointing to the village of Shelburne Falls, about 10 miles west of Greenfield. Make the turn, and soon you’ll forget why you were in a hurry to go anywhere else. From the moment you step onto the 400-foot-long Bridge of Flowers connecting the towns of Shelburne and Buckland, the world will seem to slow.

Black-eyed Susans wink, turtleheads nod. Clematis tendrils reach for the next fence link. Hibiscuses wave frilly skirts against hearty circles of sedum. Flowering kale’s maze of folds look good enough to eat—at least that’s the buzz from the bees zipping past, and the swallows alighting on a nearby bench. Hundreds of flowers, vines, shrubs, and trees edge the path. From early spring to late autumn, some 30,000 garden lovers stroll this former trolley bridge, their senses alive, while the Deerfield River flows past below.

Gardening atop a river wasn’t the goal when the Shelburne Falls & Colrain Street Railway constructed the 18-foot-wide all-concrete bridge in 1908 as a stronger option than the existing 1890 iron truss bridge. The company went bankrupt in 1927, and soon weeds overtook the concrete bridge. But a local homemaker, Antoinette Burnham, saw what others did not. She imagined a gorgeous reuse for a structure deemed too expensive to demolish and, with its water main, too complicated to destroy. The Shelburne Falls Fire District purchased the bridge in 1928 for $1,250 (a steal, given that the $20,000 construction price tag today equals nearly $300,000), and in 1929 the nonprofit Shelburne Falls Area Women’s Club created the Bridge of Flowers Committee to realize Burnham’s dream.

It began with 80 loads of loam that was spread just upriver from Shelburne Falls’ famed glacial potholes and has been nurtured ever since, thanks to local hands and

hearts. The current force is made up of Carol DeLorenzo, head gardener for nearly two decades; Elliston Bingham, assistant gardener for six years; and more than two dozen Bridge of Flowers Committee volunteers (the “blossom brigadiers”).

DeLorenzo was working on an eastern Massachusetts farm when she first noticed a “strong connection” between people and flowers—a bond that now is part of her daily life, and just a six-block bike ride from home.

“The job suits me,” she says as she strides onto the bridge in typical work attire: tank, capris, and sneakers. She puts in 17 hours a week on what she calls “my canvas, my palette,” constantly studying the hundreds of plants, celebrating successes, pondering fixes. “As we go through, we’re looking at the trouble. From our point of view, it’s averting disaster.”

She shops for stock at local retailers and farms and has learned to impulsebuy, grabbing varieties new to the bridge or to herself. Each plant is given a few years to grow and show in soil that ranges from 2½ feet at the top of each of the bridge’s five arches to 8 feet at each pillar, and the sluggish are earmarked for the May plant sale—“like this hydrangea,” DeLorenzo says, bending to touch a leaf. “I can’t wait years to figure it out.”

Adding structure to the flowering plants are vines, shrubs, and trees, including a winding Wisteria floribunda planted in the ’80s that Bingham has pruned into an umbrella shape, and a star-flowered Leonard Messel magnolia that DeLorenzo planted years ago. There’s also a tanand-gray-barked seven-son flower, which is actually a tree and like all the bridge’s trees is monitored for its growth’s effect on the span.

The bridge’s age and its exposure to weather are constant challenges. When the span underwent repairs in 1983, every plant was fostered by volunteers. In August 2011, Tropi-

cal Storm Irene raised the river nearly to garden level, leaving three to four inches of sediment that had to be removed and necessitating reconstruction of the crushed-stone path.

On this September day, beside the bridge’s centerpiece bench and flagpole memorializing the Shelburne and Buckland residents who fought in the two world wars, Vermonters Susan Rosano and Lynn Green are planning a return trip. “It’s like being in the middle of an Impressionist painting,” says Green, while Rosano, a mosaic artist, studies the color combinations. At the Shelburne end of the bridge, Jackie and Dick Maciel rest on a shaded bench before their twohour drive home to Franklin, Massachusetts, where they tend foundation

plantings and a vegetable garden. A nearby box holds donations that, added to Friends of the Bridge memberships and proceeds from the plant sale and other events, fund the two employees’ salaries, plus stock, equipment, and other operating costs.

Lynda Leitner, a Shelburne resident and “blossom brigadier,” doesn’t consider her contributions to be work. “It’s an honor to do this,” she says.

The efforts are appreciated both by the far-flung (just two pages of the guestbook lists visitors from New York, Munich, New Mexico, Turkey, Costa Rica, and Ohio) and by locals, including a man who saw that one plant had been moved and asked DeLorenzo, “What did you do with my garden?”

Donna Gates feels a similar connection. As director and curator at the Salmon Falls Gallery, located up the hill on the Buckland side of the river, she admires the bridge during her 15-minute walk to work. “Who gets a better commute than I do?” she asks. Though she is an artist, Gates says the bridge negates any desire to be creative in soil. “Much better,” she notes, “to enjoy the beautiful garden on the bridge.”

DeLorenzo, whose home garden is a courtyard plot, agrees, her free time going to hiking, playing music, practicing massage, and, inevitably, seeing what the bridge means to others as it heads toward the century mark.

“When I come through town later in the day and see people out here, it just melts my heart to see them looking at everything,” she says, pausing at a mass of pink turtleheads that seem to nod along. “Everybody finds something to love in a garden.”

For more information, go to bridgeofflowersmass.org.

Standing on the bridge, says one visitor, is “like being in the middle of an Impressionist painting.”

From colonial times up to the early 20th century, if you asked for “apple cider” you meant “hard cider,” the alcoholic version, which for decades was the most common beverage in New England. “Cheap and easy to produce … the fermented, sometimes fizzy, juice was more popular than ale, kept longer than milk, and in many places was safer to drink than water,” Yankee once noted.

Thanks to the temperance movement and advances in refrigeration technology, the roles were eventually reversed: Sweet cider became the popular version in the U.S., while hard cider became a specialty item. But craft cideries such as New Hampshire’s Farnum Hill and Shacksbury in Vermont are increasingly reviving this traditional tipple—so why not brush up on a few terms from cider’s heyday?

Apple brandy: Distilled apple cider, with the French Calvados being the best-known example; often used interchangeably with the term applejack .

Applejack: Also called cider oil; often used interchangeably with apple brandy. Originally, applejack referred to the strong drink now known as frozen heart or hollow heart , made by freezing hard cider so that the water is gradually removed and an apple-flavored alcohol remains (the chemical process is called fractional crystallization).

Cider: Originally used to mean a hard, alcoholic drink made from fermenting the juice pressed from apples; in England, hard cider is redundant. Sweet cider refers to unfermented cider.

New England–style cider: A strong hard cider made with a variety of sugars, spices, and raisins.

Scrumpy: A slang term for particularly powerful hard cider; also refers to hard cider to which beefsteak or other meats have been added for flavor.

Stone wall: Hard cider or applejack mixed with rum and spices, and sometimes brown sugar; prescribed for dispelling chills and restoring energy.

—Adapted from “In Search of the Perfect Cider” by Kathy Neustadt with Steven Latorre, October 1996

Seth MacFarlane (born October 26, 1973, in Kent, Connecticut). As the creator of , this Rhode Island School of Design alum may be best known for slapstick and satire. But he’s also into science, helping to briefly revive the classic Carl Sagan show in 2014 and putting his own spin on Star Trek with The Orville , which begins its third season on Fox later this year.

“Evolution doesn’t care whether you believe in it or not, no more than gravity does.”

EVEN THE UPHOLSTERY HAS TALES TO TELL AT THIS GLOBE-TROTTING TEACHER’S MASSACHUSETTS HOME.

BY MARNI ELYSE KATZ

BY MARNI ELYSE KATZ

Specifically, a 17th-century Italian Baroque armchair spotted at an antiques shop in Cambridge, Massachusetts, where Caldarella was attending Harvard. One might think a college student in Cambridge by way of Queens might have better things to spend time, money, and energy on than a dusty piece of furniture, yet Caldarella was fixated. “I was on financial aid with three jobs, but Heidi made it happen,” he says.

He is referring to Cambridge-based interior designer Heidi Pribell, who Caldarella still credits 30 years later for the fearlessness of his collections. And boy, does Caldarella collect. That Italian Baroque chair, which he had upholstered in vintage Fortuny fabric procured from a curator at the Boston Athenaeum, sits in a house chock-full of antiques and vintage finds.

Jagged stone stairs punctuated by vintage pillars lead to the screen door of Caldarella’s Concord, Massachusetts, home: a 1,200-square-foot condo tucked into a clapboard house built in 1872 that was once a manse for the Trinitarian Congregational Church. Transitioning from the lush outdoor gardens is a bit of jolt, since the porch has a Spartan feel, with rickety wooden furniture, a butterfly cage made from found sycamore branches, and casual rows of no fewer than two dozen pairs of shoes.

Step fully inside and the place warms up, revealing itself as a collector’s haven. Caldarella has spent more than 20 years restoring and filling his home—once a hodgepodge of shag carpeting and other 1970s-era remnants—with furnishings collected during his travels, imbuing it with a sense of history and personal meaning. A learning specialist and tutor by profession, he is a self-described teacher, traveler, collector, and recycler to the core, and his home reflects every aspect of this persona.

Heidi Pribell met Louis Caldarella some 30 years ago when she was running her own antiques gallery in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Today she’s an award-winning interior designer who is known for her ability to mix styles and periods to create beautiful but livable homes. Here, she singles out three highlights of Caldarella’s home—and shares a few tips anyone can put to use.

“Each doorknob, window closure, door hinge, and pull has been a vintage purchase that fits timelessly into Louis’s home. An Eastlake sofa, a Biedermeier secretary, an Italian neoclassical bed, and an American Arts and Crafts bookcase—all blend eclectically, like old friends, united by a theme: Boston 19th-century material culture.”

DO: Create a narrative out of objects.

DON’T: Feel obliged to stick to one time period—it’s a home, not a museum.

“We opted for vibrant palettes throughout the home…. In the bedroom we used celery-green trim with peacock-green walls and mostly oxygen-blue ceilings throughout the home. I enjoy using apricot on the ceilings of windowless rooms, like hallways, and lavender ceilings are my favorite.”

DO: Experiment using a bold wall color with contrasting trim to highlight a collection, and always use tinted contrasting color on your ceilings.

DON’T: Wait to change interior finishes until you find the right piece of furniture. Often you’ll spot it later, and it will fit in seamlessly.

“Louis uses early scientific tools and equipment to engage his students’ curiosity. All these items are easily reachable: displayed on the wall, or handy on the dining table. A Victrola phonograph with boxed vintage 78 rpm records sits nearby, always ready to play. What was once ordinary is now fresh and novel to today’s children. Everything is happily used, and things break all the time!”

DO: Use the things you collect.

DON’T: Keep objects stored in boxes or tucked away in the basement.

clockwise from top left : A 19thcentury brass microscope and specimen slides, including “Stinger of a Bee” and “Wing of a Lace Fly”; the very first treasure Caldarella collected, a 17th-century Italian armchair; a painting by Portland, Maine, artist Timothy Wilson amid artifacts including a Makonde water pipe from Africa; vintage brass letters as objets d’art.

In addition to working for a nearby independent school, Caldarella tutors private clients in his living room, where the tools of his trade abound. He says his students learn best with original specimens and primary sources, and that vintage materials can help relieve anxiety around learning. The relics, many picked up at flea markets in Paris (he has a recurring Parisian cat-sitting gig), are as beautiful as they are useful, such as a 19thcentury brass microscope complete with slides (marine algae, eel scales, and an earwig’s head are just a few).

Every step begs a story. Neoclassical dining chairs with horsehair upholstery came from Goodspeed’s Book Shop in Boston, where Caldarella worked as the head of Americana for six years before the store was shuttered in 1995. Also acquired there was a bookcase now built into the basement staircase. The mini library includes an illuminated version of A Christmas Carol, from when he was a rare-book dealer in London, and an 18th-century illustrated folio of Aesop’s Fables

Caldarella’s unyielding attitude toward waste (he believes it is a sin) is evident throughout the house, from the wine closet door covered in more than 7,000 corks sent by friends all over the world, to the Adirondack chairs his father, a carpenter, made with scraps of mahogany left over from a deck they built. And rather than replace the worn floorboards in the upstairs sitting room, Caldarella pulled them up, flipped them over, and refinished them.

Pribell’s influence is also on display. The pairing of a Biedermeier secretary and a midcentury-modern Cherner armchair on the lower level is indicative of her unorthodox-yetsimpatico aesthetic. “These pieces were made almost 150 years apart, but they’re both everyman’s furniture and have complementary curves,” Caldarella says.

In his bedroom, aka the Boar Room (a bit more on that later), the

peacock-green walls were inspired by endpapers of an early 19th-century French book and glazed by Pribell herself, who worked for a time as a decorative painter. “Heidi knew just how to concoct the color using a yellow undercoat, blue glaze, and brown varnish,” he says. “It’s the perfect shade of green, but contains no actual green paint!”

Even the upholstery is woven with tales. Caldarella covered the scrolledarm neoclassical chair, found legless in Maine, with hand-dyed indigo fabric from a textile designer in Amsterdam. “I stumbled upon a house, doors wide open, fabric hanging everywhere,” he says, as though it’s a commonplace occurrence.

The bedroom showcases Caldarella’s largest collection: 50-plus images of wild boars, the symbol of the secret society he belonged to at Harvard. The first one came from a local shop, and then, he says, “the collection took

on a life of its own.” He’s brought boars home from all over the world, from the stalls along the Seine, markets in Rome, and Portobello Road in London, though his favorites were gifts from and made by kids.

Caldarella’s biggest collection may also be his most surprising: He has amassed more than 50 pieces of art and decor that feature boars.

Caldarella keeps smaller collections in the bedroom, too, such as enamel key chains from the 1950s and a pile of Saint Christopher medals. The collections and travels, which are wholly intertwined, seem endless. Last year’s trips, which included Paris, London, New Zealand, Hong Kong, and Rwanda, have yielded antique linens, three Honoré Daumier prints bought for five euros each at the Marché d’Aligre in Paris, and some 19th-century hand-blown, acid-etched wine glasses.

Not everything, however, finds an immediate place. “I have an Ernest Roth engraving of Venice, but as I haven’t been there yet, I don’t feel I have a right to hang it,” he says. “In this case, the art comes before the travel.”

“ We didn’t come to RiverMead to ‘retire’, we came to live full and active lives, secure in the knowledge that we have good choices, good friends, trusted care, and a home for a lifetime.”

I love to watch the surge of water that returns to flood the land twice a day. Water as it flows in and particularly around the edges of docks, creates flow lines. I see the flow lines in this ring, which we call the Returning Tide.

Mountain Laurel

Honest blue. Not pretentious. Rich character and detail. Touring New England this fall … Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Connecticut.

Sitting on the dock of the bay, you start in Boston, with a road trip to New York and Chicago. Grand tour of art museums, then across the country arriving in San Francisco and the great Pacific.

A little piece of summer, autumn blue sky, and ocean too, you get to carry the magic of blue with you every day, wherever you go.

Over two-hundred pieces of blue sapphire jewelry on-line, ready to ship, anywhere U.S.A. Free shipping, as always on all your Cross purchases.

It is never too late or too early to build a collection of treasured objects that your family can enjoy today and for years to come. These could include an amazing auction find, jewelry, a piece of furniture, a serving piece, or even a Christmas ornament. Yankee has partnered with a few New England companies that share our belief that beautifully made objects should be preserved and cared for today so that they can be a part of our lives for generations.

Skinner Auctioneers & Appraisers have helped families in New England and across the country build collections of art, antiques, and objects of value. Skinner knows markets are dynamic and that needs and tastes change. The constant

compelling factor remains the story behind the objects: where and when it was made, who made it and why, and who owned it.

Objects are a window into the history of where we have come from and who we are. Our objects have the power to bind generations together in story and deed; whether you cherish the delicate gold Art Nouveau necklace your grandmother passed down to you or the gay liberation buttons you collected one by one in the 1970s, every object has meaning and holds importance, and together they make visual the story our lives.

Skinner offers a complete range of appraisal and auction services designed to assist you in making decisions to fit your needs, whether you have a question about your collection, are looking to build a new one, or realize that the time is right to deacquisition.

SkinnerInc.com

1. Cape Cod Metal Polishing Cloths

Cape Cod Metal Polishing Cloths are moist, re-usable cloths that clean, polish, and protect all fi ne metals. Easy to use: simply wipe on and bu o with a soft cloth. Also has a pleasant vanilla fragrance! CapeCodPolish.com

2. Wonderland 2019 Annual Ornament

Handcrafted in Vermont, the Danforth Pewter 2019 Annual Ornament is a scene of wintery friends in the woods framed by two white birch trees. A Swarovski blue crystal hangs above the snowy tree like a shimmering star. DanforthPewter.com

3. Walnut BBQ Carving Board

JK Adams has been making quality wood products in Dorset, Vermont since, 1944. The Walnut BBQ Board is an American classic. Personalization is available on many of JK Adams’ products. Lifetime Guarantee. JKAdams.com

4. Oyster Cove Diamonds Grey Blanket

The Oyster Cove Diamonds ChappyWrap (a MA company) is the perfect addition to your home!

O ering comfortable warmth and breathability, it features a reversible, jacquard-woven design and will never pill or fuzz, ensuring that it will last a lifetime. ChappyWrap.com

BY ANNIE GRAVES

BY ANNIE GRAVES

can get homesick pretty easily,” confesses Nicole Aquillano. We are standing in a converted studio/garage in Acton, Massachusetts, as she continues, “I think it’s crazy, for how long I’ve been gone. But it meant a lot to me.” She turns the ceramic mug she’s holding, and I see the drawing of an angular house. The image is hand-drawn onto the clay, tinted blue, and slightly blurred. It is her childhood home in Pittsburgh, and it often appears, like a flash of memory, on the pottery she has been producing since 2012.

Bridges appear, too, alongside brownstones, storefronts, stairways. All rendered in simple graphic lines that say a lot, with a minimum of fuss. Architecture reduced to essence. Images lean and tilt across stacks of platters, tall vases, plenty of mugs, ornaments, even thimbles. They’ve caught my eye for years, populating major craft fairs, galleries, and museums.

When you see this work, it’s not surprising to learn that Nicole was once an

OPPOSITE , CLOCKWISE FROM TOP LEFT : Nicole Aquillano in her studio in Acton, Massachusetts; a selection of her favorite tools for etching designs and applying glaze onto her pottery; Aquillano at work, casting forms; shelves filled with finished pieces, many of which reflect the artist’s flair for architectural drawing.

engineer, with a degree from Carnegie Mellon (though in fact she ended up working for the EPA for eight years, writing industrial wastewater permits, she says ruefully). Yet here we are, in this airy studio off the home she shares with her husband, Sam; their little girl, Rafaela; and, soon, a brand-new baby boy. We’re edged in by the plaster molds she’s created to cast her pots, a potter’s wheel parked beside a small kiln, and every inch occupied by pottery in progress.

Clay was always a passion, from her first class in high school. Even when she worked for the EPA, she was taking classes that allowed 24-hour studio access. “I’d go to work, then to the studio every night—it was like a second job,” Nicole says. “My plan was always to retire and then do clay, because I loved it. But then I realized life goes

by too fast. Now was the time.” She applied to the Rhode Island School of Design and finished the two-year graduate program in 2012, after which she began honing the atmospheric images she’s known for.

“I was looking at architecture, but I didn’t ever really think I could draw,” she says. “But I started to draw my childhood home. That’s the first thing I drew. I drew it over and over and over….”

Then, as now, Nicole etches each drawing, freehand, onto the clay, with a slender knife. It is her main tool, and it has the look of a treasured utensil. Its mate is the small natural sponge used to sop up the blue/black underglaze she applies to the surface of the pottery. As she wipes the color away, it remains in the etched lines. After the bisque firing, she applies a clear glaze

that will blur the drawing, before firing it yet again.

“It took a lot of experimenting to get it to run,” she says. “I wasn’t even necessarily looking for that effect. I pulled out work that I’d fired and wasn’t happy with, so I refired it, and it ran a little bit. And I thought, Oh my gosh, this is what I’ve been trying to say! It gave it that runny look, which I always think makes it look like a memory.”

Which is what it’s all about, to “create a story you can hold in your hand forever.” Most of her custom work, she says, is for people who want a portrait

of their childhood home, although she also does a lot of work for museums.

“People are really connected to place,” she says, as we walk from the studio to the kitchen. Here, she picks up another mug—one of the few that has a second color, glowing yellow. “My childhood home does really well,” she says with a smile. “This is an old, old one of my room. I always put the light on because at the very beginning, my mom asked me to.”

Rafaela is still napping, so we never get to meet, but apparently, according to her mother, she plays with Play-Doh all the time. When her daughter is sleeping, Nicole can pour out a table’s worth of molds. “I’m really happy it’s working out, because I had the most amazing childhood in the world,” she tells me. “My mom raised us, me and my two sisters, and we had a blast, and I want to give that to my kids.” There is a long pause. “So far, so good.”

For more information, go to nicoleaquillano.com.

This work is meant to “create a story you can hold in your hand forever.”

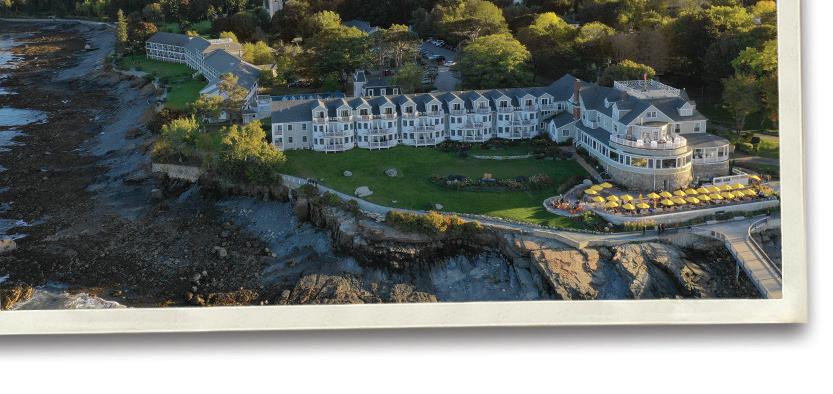

tay awhile on Isle au Haut, and your relationship with time will change. There is something that feels essential, eternal, about this island in Maine’s Penobscot Bay. As I stand on the steps of the keeper’s house at Robinson Point Light, looking toward the rocky shore, the white brick lighthouse, and the blue water of the Atlantic beyond, it’s hard to remember that I have bills to pay or stories to write.

Time passes slowly here, but somehow all history seems recent. The view I’m gazing on is little changed since 1604, when the island’s trio of small mountains led French explorer Samuel Champlain to dub this Isle au Haut (“High Island”). The graceful keeper’s house that I’ve come to see feels like a new arrival, having witnessed only the most recent 112 years of the island’s history.

The lighthouse station on Robinson Point was constructed by the Army Corps of Engineers in the summer of 1907. Comprising the keeper’s house, the lighthouse tower, a small post-andbeam barn, and a boathouse, it was the last full lighthouse station to be built in Maine.

“The person who moves here isn’t just buying an amazing and unique property,” Realtor Jamie O’Keefe had told me as we were motoring toward the island on the twice-daily mail boat. “Island life is its own thing. It isn’t for everyone, and I don’t think you can compare it to anything else.”

In 1934, at the height of the Great Depression, belt-tightening led to the shuttering of Isle au Haut’s lighthouse station. The keeper and his family moved back to the mainland, and the lighthouse was fitted with a batterypowered beacon.

In the years that followed, much of the property was sold back to the heirs of the Robinson family, the original landowners. The federal government owned the lighthouse itself until 1998, when the town of Isle au Haut took stewardship of it.

In 1985, Jeff and Judi Burke saw the keeper’s house for the first time. As the proprietors of the Little River Inn in Pemaquid, Maine, they recognized its potential—or at least Jeff did. He recounts the moment in his 2017 book, The Lighthouse & Me :

I simply couldn’t figure out why all these normally sane people (including my usually rational wife) couldn’t see the guaranteed success of my

Yankee likes to mosey around and see, out of editorial curiosity, what you can turn up when you go house hunting. We have no stake in the sale whatsoever and would decline it if offered.

scheme to create an inn at the old Isle au Haut lighthouse station. Sure, it was an isolated place, devoid of electricity and running water (hence, no bathrooms, not even a place to wash your feet), without a road to access the place nor a safe spot to land a boat. And it had only three rooms. And the islanders detested the tourism threat. And, yes, it would be an outrageously expensive undertaking— and we hardly had a cent.…

In 1986, the Burkes moved in with their youngest son and their dog. When they arrived, water for the kitchen was hand-pumped from a rainwater cistern that filled half the basement. The sewage system was even more basic, consisting of a bucket in an outhouse behind the woodshed. This was just part of what promised to be a daunting challenge, Jeff recalls:

[We’d have to] build a half-mile road and a boat landing, create a sewage disposal system, bring in electricity and plumbing, renovate all the old buildings, and install a commercial kitchen. And then we needed to develop a marketing plan and train a cadre of hospitality professionals, an overwhelming project requiring years to launch. Two months later we opened.

Initially, the Keeper’s House Inn offered an aggressively rustic experience. Guests would hike in, usually with backpacks. There was a makeshift shower in the woods. Water was hauled from the well at a nearby farm. The outhouse remained the only bathroom.

The Burkes improved the property over the next 27 years, helping it gain a reputation as one of the most unusual and beautiful small inns in New England. Today the main house has four bedrooms—all with spectacular ocean views—as well as two bathrooms and an updated kitchen outfitted with a pair of stoves and an industrial refrigerator. The woodshed has been converted into a two-bedroom guesthouse; two other outbuildings are now sleeping cottages.

Although the property remains off the grid, there is electricity, courtesy of solar panels and a generator. The cistern has given way to a reverse-osmosis filtering system that makes seawater drinkable. The indoor plumbing drains to a sewage disposal system that utilizes beds of peat moss and other natural systems to process waste.

When the Burkes eventually decided to retire, Marshall Chapman stepped up to continue what they had started. A geology professor at Morehead State University in Kentucky, he had been a graduate student when he first came to Isle au Haut to study the island’s geology. It was love at first sight. “The island will slow you down and teach you patience,” he says. “It is geologically interesting—and the sunsets are amazing.”

After buying the inn in 2013, Chapman would return to the island

every year in mid-May and stay until August. “Being an innkeeper and a college professor was a lot to juggle, but I had a wonderful chef and a

go of Isle au Haut, but I have to let the keeper’s house go.”

Although he isn’t placing restrictions on how buyers must use the keeper’s house, Chapman would love to see it reopen as an inn. In any case, the new owners should be prepared for visitors.

“This is probably the prettiest two acres on the island, and this property has always been open [to the public],” says Chapman. “The lighthouse is iconic, and people love to see it. I hope the new owners will feel the same dedication to sharing it that past owners have.” —Joe Bills

general manager who made it all possible,” he says.

Chapman’s growing responsibilities at the college, though, forced a tough decision. “I’ve loved having this in my life, but I can’t give it the time it deserves,” he says. “I’m not letting

Including the main house, the guesthouse, two sleeping cabins, a boathouse, and a deepwater dock, this property is listed at $1,975,000. For more information, contact Jamie O’Keefe at the Knowles Company at 207-276-3322 or go to knowlesco.com.

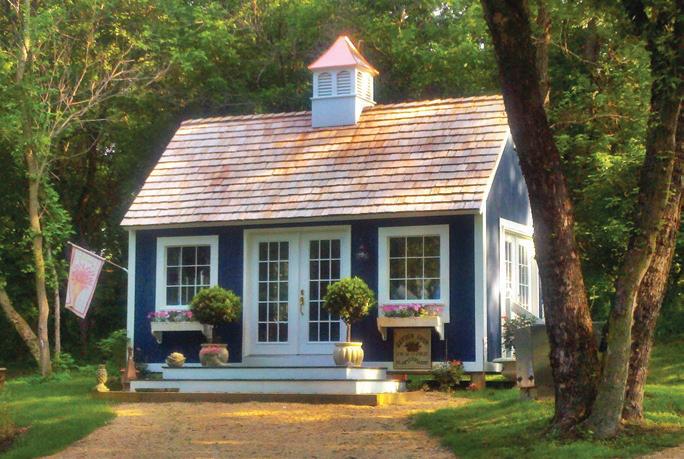

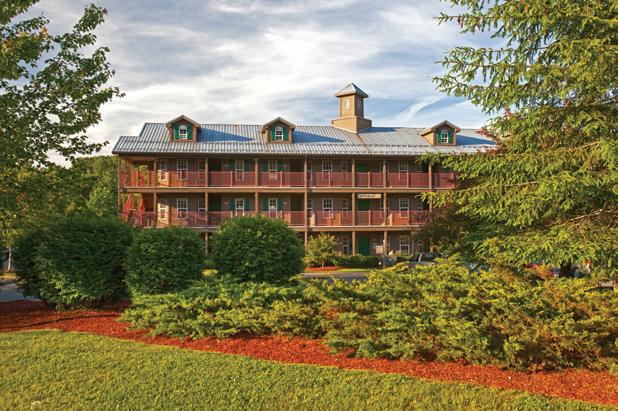

For three generations, the builders, blacksmiths and craftsmen at Country Carpenters have put their hands and hearts into designing and building the finest New England Style buildings available, using hand-selected materials, hand-forged hardware, hand-built and hand-finished by real people. You can feel the difference in your heart.

“The island will slow you down and teach you patience ... and the sunsets are amazing,” Chapman says.

America is growing older, there’s no denying it. The median age in America continues to rise—nearly 10,000 people a day are turning 65. By 2030, one in every five Americans will be of retirement age—more than at any other time in U.S. history.

Thanks to improved medical care, this group has a longer life expectancy than any prior generation. They also have greater expectations of their retirement. After all, Baby Boomers, as this demographic is frequently called, have redefined every other social institution they’ve experienced: marrying or having children later in life, moving more often, women more likely to work outside the home, etc. They are also more active than any previous generation—physically and mentally. They are still eager to travel, start new projects, and often looking for new purpose in life.

Boomers aren’t interested in hearing about the “problems of aging”–everyone is aging! Today’s 60and 70-year-olds may be growing older, but they are far from being “old.” In fact, they’re out running marathons, starting second careers, and generally turning the traditional idea of “aging” on its ear.

Unlike their grandparents, this group can’t count on their children living around the corner. Most adult children are more far-flung than ever—no longer is there the reliable son or daughter living just across town. The traditional 1950s family support model that served the previous generation is no longer applicable.

Given that people are living longer, seeking more from their retirement years, and given that social dynamics have changed, how can someone stay independent and still ensure their future health care needs are covered?

There is one solution that has been quietly operating for the past 100 years in the U.S., and whose structure and practices are uniquely positioned for this generation. Continuing Care Retirement Communities (CCRCs) could be described as “retirement communities with benefits.” With over 1,900 across the country, but just a handful in New England, they are often misunderstood.

CCRCs, also called Life Plan Communities, provide three levels of care: independent, assisted living, and nursing. The critical difference is that people enter the community when they are independent and active, able to live safely on their own. They continue to enjoy their independence, free from the worries and timeconsuming work of home maintenance.

With the addition of housekeeping services, inside and outside maintenance, transportation, dining options, and fitness activities, residents of a CCRC have more time to enjoy life, meet friends, and pursue new interests. They create fast friendships and enjoy the benefits of community living. Meanwhile, they have the assurance that if and when their health needs change, they can transition to assisted living or nursing care without leaving their community.

Although CCRCs look like beautiful retirement communities, complete with gyms, pools, libraries and arts rooms, moving there is not a real estate decision. CCRCs are an insurance product, and they are governed by each state’s regulatory body. Therefore, a percentage of a resident’s entrance fee and monthly service fee is considered a tax deduction as a prepaid medical expense—a real advantage for many.

Most CCRCs in New England are not-for-profit, allowing them to focus on improving the quality of life for older adults rather than shareholder value. Not-forprofit CCRCs are more mission driven, with a longterm view towards the future, serving more, and are dedicated to ensuring long-term sustainability. Their goal is to be around in perpetuity, serving in a broader way rather than chasing a market trend.

Additionally, non-profit CCRCs typically offer a Benevolence Clause, which provides an opportunity for a resident who might have outlived their assets (and has not intentionally impoverished themselves) to apply to the community for benevolence.

Within CCRCs there are contract differences. Some are Type A, which are all-inclusive plans—as you move from one level of care to the next, your monthly fee does not increase (except for two additional meals per day). Type B, or modified contracts, offer targeted insurance, typically providing a portion of your health care fee at a discount from market price, when you need health care. Type C contracts provide independent living at a lower rate, and then offer health care at full market rate.

The solution that CCRCs offer to the next generation of retirees is clear—the independence of living an active, maintenance-free lifestyle, a community full of life-expanding opportunities and friends, and the peace of mind knowing that if anything changes in your health down the road, you have already chosen where you will receive your care.

To learn more about CCRCs, start by investigating these communities.

Concord, NH www.HHHinfo.com 800-457-6833

Keene,

Hanover,

Exeter, NH www.RiverWoodsExeter.org

800-688-9663

Laconia & Wolfeboro, NH www.TaylorCommunity.org

844-210-1400

Nashua,

Shelburne,

802-264-5100

ADAM DETOUR

BY AMY TRAVERSO

ADAM DETOUR

BY AMY TRAVERSO

A family-run orchard in western Massachusetts is making

hard cider that can turn any harvest meal into a party of new flavors.

Carr’s Ciderhouse owners Nicole Blum and Jonathan Carr.

Carr’s Ciderhouse owners Nicole Blum and Jonathan Carr.

The barn at Carr’s Ciderhouse wasn’t built for show. When Jonathan Carr and Nicole Blum took the title to their farm in Hadley, Massachusetts, the chestnut-sided structure was a centenarian in decline, about as old as the gleaming red Mount Gilead cider press that it now houses.

Back when the barn and the press were built, around the turn of the 20th century, cider was already past its heyday as a fizzy, low-proof beverage more popular than beer. When Jonathan found the press for sale in a 2008 classified ad, most people thought of cider only as fresh juice sold in gallon jugs. So when the barn and the press were brought together, the former being rebuilt to accommodate the latter, it was an act of true optimism. Jonathan called it “a hopeful gamble.”

American cider was then in the early days of its current renaissance, dominated by a few syrupy-sweet brands that evoked wine coolers more than apple wine. But the couple stepped into the breach with a clear vision: to grow apples sustainably, to be good stewards of the land, and to make exceptional ciders.

“When we bought the orchard, it was basically going into abandonment,” Jonathan says. “It was unnavigable in a tractor and, frankly, kind of scary, because some of the slopes are pretty severe.” The previous owner had planted the standard New England mix—Cortland, Red Delicious, McIntosh—but most of the trees were weakened by neglect and age.

So the couple began clearing land at the top of the hill, with its sweeping views of the Connecticut River Valley, and planted 1,500 trees in varieties they thought they could grow without pesticides: Golden Russet, Goldrush, and traditional cider apples such as Yarlington Mill and Dabinett.

“The goal was always cider,” Jonathan says. “The table-fruit market is tough, and we wanted to manage the

orchard ecologically. Cider was a great way to not have to worry about the appearance of the fruit.” Plus, having already operated a small market farm together, “we didn’t just want to grow and sell the raw materials,” Nicole says. “We wanted to make something.”

Fast-forward to a crisp day this past November, and the once-humble barn is strung with lights to welcome visitors making their way up the farm’s long, rutted drive, dodging puddles from the previous night’s rain. The sky is deep blue and nearly cloudless, and Carr’s is hosting a cider tasting as part of Franklin County Cider Days, an annual festival that brings thousands to this rural corner of western Massachusetts.

For Jonathan and Nicole, this day comes smack-dab in the middle of a harvest season that ran late, and bins of apples still need pressing. But the old press is quiet today, as Jonathan talks

visitors through the process of turning fresh fruit into the fermented finished product that they’ll be sampling in a moment: how wooden bins, each containing about 600 pounds of fruit, are tipped onto a sorting table and their contents are ferried up a narrow escalator to the third story of the barn, where a grinder breaks them down into the pulp from which their juices can freely flow. Above Jonathan’s head hang the oak and elm pressing racks, burnished with years of apple tannins. “At the end of the day we’re all covered in apple splatter,” he says. “Then we hose the whole thing down and start over.”

What he’s describing is standard cider-making procedure, whether for fresh juice or the hard stuff. But he lights up most when he talks about what they do once all that juice is gravity-fed into stainless steel fermentation tanks. And that is ... as little as possible.

“We don’t add commercial yeast,” he explains. “All fruit has many species of wild yeast that are naturally present on its skin. We found that if you ferment these wild yeasts at cool temperatures, you get good results. And that’s how they would’ve done it in the old days.”

That means letting the juice sit in this uninsulated barn for months at a time, the initial fermentation held in frozen suspense until the warm spring weather can restart the process. It’s a technique that the couple first observed in the cider-making regions of Ireland—where Jonathan was born and

where he and Nicole first tried their hand at farming—and in Normandy and England’s West Country. And it’s the key to producing the well-structured ciders that eschew sweetness but bring forth aromas such as orange, fennel, and rose petals.

“When people who’ve only had mass-produced cider ask what ‘wild fermented’ means, I’ll often use the analogy of sourdough bread,” Nicole says. “You have Wonder Bread, which is soft and squishy, but then you have bread from an artisan baker where there’s so much flavor and structure because they’ve added the element of time.”

Lately, they’ve also been working with their friend Matt Kaminsky, an apple expert, to bring wild apples from the surrounding fields and forests into the mix. “We’re grafting them out in the orchard to see how well they perform in that environment,” Jonathan says. “The idea is to produce a ‘native’ apple cider, rather than just using European varieties.”

And they keep tinkering. Some of the juice they press now gets boiled down, like maple sap, into cider syrup, a rich, caramel apple–flavored sweetener with a long New England history (the product won a Yankee Editors’ Choice Food Award in 2015). And after a trip to Canada during which they met a balsamic vinegar producer using apples rather than grapes, a line of vinegars was born. “We want to figure out ways to preserve everything that we love to do with apples,” Nicole says.

They’ve also been cooking with apples in every form, and that wisdom was recently funneled into Ciderhouse Cookbook: 127 Recipes That Celebrate the Sweet, Tart, Tangy Flavors of Apple Cider, which they cowrote with Nicole’s sister, chef and food writer Andrea Blum.