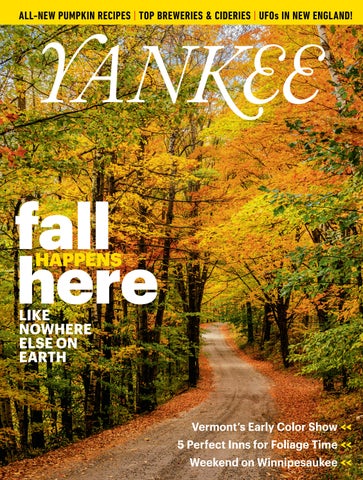

Want to get a front-row seat to the Green Mountain State’s earliest foliage show? Go where the Vermonters go.

By Bill Scheller

By Bill Scheller

76 /// Market Value

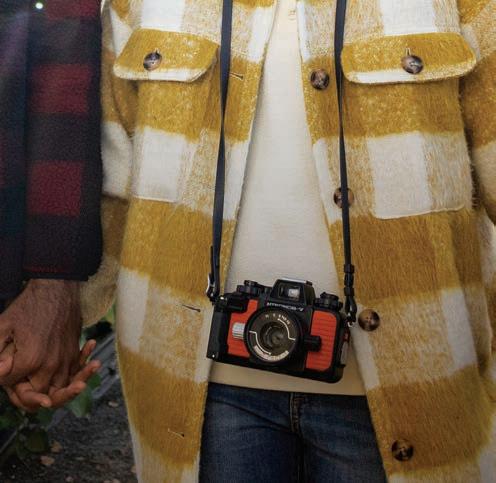

Voices from one of New England’s best farmers’ markets: “We do this for love.” Text by Lissa Goldstein; photos by Ben Stechschulte

///

Discover why a little-known New Hampshire forest is among the most studied and important in the world.

By Nina MacLaughlin88 /// Are We Alone?

A question that has haunted humankind for centuries— and that has deep ties to New England—is closer to being answered than ever before. By Joe

Bills

24 /// Ghost Story

How the stately Victorian mansion became the blueprint for haunted houses.

By Bruce Irving32 /// Open Studio

Vermont artisan Miranda Thomas crafts pottery that holds a world of expression.

By Jenn Johnson

By Jenn Johnson

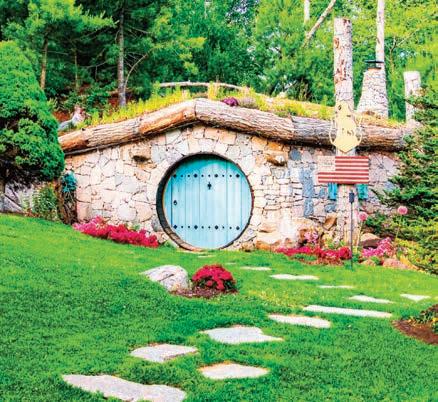

36 /// House for Sale

These turnkey properties can unlock anyone’s dream of luxury farmhouse living.

By Joe Bills40 /// The Great Pumpkin

Sweet and savory recipes showcase one of fall’s most versatile ingredients.

By Amy Traverso

By Amy Traverso

46 /// In Season

A bit of garlic puts fresh autumn produce in a whole new light. By

Amy Traverso50 /// Weekend Away

New Hampshire’s beacon of summer, Lake Winnipesaukee, shines just as bright when the leaves turn. By

Richard Adams Carey58 /// The Best 5

Offering warm hospitality and glorious surroundings, these updated inns are ready for leaf peepers. By

Kim Knox Beckius

Kim Knox Beckius

60 /// Refresher Course

The perfect pairing for a New England fall road trip: top-notch local breweries and cideries. Compiled by Bill Scheller

By Mel

AllenBy Ian Aldrich

Freedom 375

Freedom 375

EDITORIAL

Editor Mel Allen

Managing Editor Jenn Johnson

Senior Features Editor Ian Aldrich

Senior Food Editor Amy Traverso

Senior Digital/Home Editor Aimee Tucker

Travel Editor Kim Knox Beckius

Associate Editor Joe Bills

Associate Digital Editor Katherine Keenan

Contributing Editors Sara Anne Donnelly, Annie Graves, Ben Hewitt, Rowan Jacobsen, Nina MacLaughlin, Julia Shipley

ART

Art Director Katharine Van Itallie

Photo Editor Heather Marcus

Contributing Photographers Adam DeTour, Megan Haley, Corey Hendrickson, Michael Piazza, Greta Rybus

PRODUCTION

Director David Ziarnowski

Manager Brian Johnson

Senior Artists Jennifer Freeman, Rachel Kipka

DIGITAL

Vice President Paul Belliveau Jr.

Senior Designer Amy O’Brien

Ecommerce Director Alan Henning

Marketing Specialists Holly Sanderson, Jessica Garcia

Email Marketing Specialist Eric Bailey

YANKEE PUBLISHING INC.

ESTABLISHED 1935 | AN EMPLOYEE-OWNED COMPANY

President Jamie Trowbridge

Vice Presidents Paul Belliveau Jr., Ernesto Burden, Judson D. Hale Jr., Brook Holmberg, Jennie Meister, Sherin Pierce

Editor Emeritus Judson D. Hale Sr.

CORPORATE STAFF

Vice President, Finance & Administration Jennie Meister

Human Resources Manager Beth Parenteau

Accounts Receivable/IT Coordinator Gail Bleakley

Assistant Controller Nancy Pfuntner

Accounting Coordinator Meg Hart-Smith

Executive Assistant Christine Tourgee

Maintenance Supervisor Mike Caron

Facilities Attendant Paul Langille

BOARD OF DIRECTORS

Ralph Carlton, Andrew Clurman, Daniel Hale, Judson D. Hale Jr., Renee Jordan, Joel Toner, Cor Trowbridge, Jamie Trowbridge

FOUNDERS

Robb and Beatrix Sagendorph

Publisher Brook Holmberg

ADVERTISING

Vice President Judson D. Hale Jr.

Media Account Managers Kelly Moores, Dean DeLuca , Steven Hall

Canada Account Manager Cynthia Fleming

Senior Production Coordinator Janet Selle

For advertising rates and information, call 800-736-1100, ext. 204, or go to NewEngland.com/adinfo.

MARKETING

ADVERTISING

Director Kate Hathaway Weeks

Senior Manager Valerie Lithgow

Specialist Holly Sloane

PUBLIC RELATIONS

Roslan & Associates Public Relations LLC 212-966-4600

NEWSSTAND

Vice President Sherin Pierce

NEWSSTAND CONSULTING

Linda Ruth, PSCS Consulting 603-924-4407

SUBSCRIPTION SERVICES

To subscribe, give a gift, or change your mailing address, or for any other questions, please contact our customer service department:

Yankee Magazine Customer Service

P.O. Box 37900 Boone, IA 50037-0900

Online NewEngland.com/contact-us

Email customerservice@yankeemagazine.com

Toll-free 800-288-4284

Yankee occasionally shares its mailing list with approved advertisers to promote products or services we think our readers will enjoy. If you do not wish to receive these offers, please contact us.

Yankee Publishing Inc., 1121 Main St., P.O. Box 520, Dublin, NH 03444 603-563-8111; editor@yankeepub.com

Want more Yankee? Visit our website, NewEngland.com, for more recipes, travel tips, and the latest foliage updates.

began my life at Yankee on October 1, 1979. The new October issue had just arrived at the homes of tens of thousands of readers. The cover showed a painting of a church with its white steeple pointing toward a blue sky mottled with white puffy clouds, and in the background is a forest filled with the colors that define autumn.

Since then, 44 autumns have come and gone, and now this issue celebrates my 45th. For all these years the question has always been: How does Yankee truly show a foliage season that is unequaled anywhere?

Sometimes I speak to the media about New England in autumn, and a phrase I often use is “this is our Mardi Gras”—a brief, intense time when visitors from all over arrive to be part of something unique, something that feels larger than ordinary life. But I am wrong to say that. Because Mardi Gras is created by people, its roots going back centuries and coated with religious symbolism. It does not really belong to everyone. But fall—these colors, the bracing air, the play of leaves falling into flowing rivers or reflected in tranquil lakes— that happens without us. We play no part except for awestruck observer.

The other day I sat in our office’s small library, where we keep every Yankee since the first one in September 1935. I wanted to see how our covers spoke about fall. Just in recent years: “Autumn Beauty,” “The Best Fall of All,” “The Most Scenic Drive of All,” “Autumn A to Z,” “Chasing Color,” “Fall Comes to the Hill Towns,” “Days of Wonder.” Each cover displayed the most beautiful, most beguiling image we could find. And still, as I turned the pages, year after year sliding by,

I realized we could never do it justice, really. Any more than we could capture the bite of an apple fresh from the orchard, or the sound of leaves underfoot in the forest, or—and this is the point—the look of a hillside in October after a morning rain, and the sun has come out and the color is something you feel and not just see. But we keep trying the impossible.

And looking through those old issues, I was again humbled to read what Ben Rice, then Yankee ’s editor, wrote in the October 1945 issue. To call it an issue is not quite right: The war had just ended. Paper was scarce. He had 12 pages, no photos. But he had something to say on his editor’s page about autumn and what he saw for these all-too-brief weeks, and it came from his heart and to me it has not been equaled. In these pages, we do our best to bring to life what Ben Rice felt, all those years past, about a time when the sounds of war had finally stilled and color slid across the hillsides, and what he saw then is what we see now:

The slow fire spreads from the blazing maples to the gold of the birches on our high slopes. The threat of winter is not yet upon the land, but rather a sense of awakening from the sultry bondage of summer—and the Red Gods call. The smell of burning leaves in the still dusk, the bells of night-wandering cattle, brittle limbs on enormous moons, mists aglow in the valleys— these and a hundred such will always be New England October. And to them even the dullest heart must make some answer.

Mel Allen editor@yankeepub.com

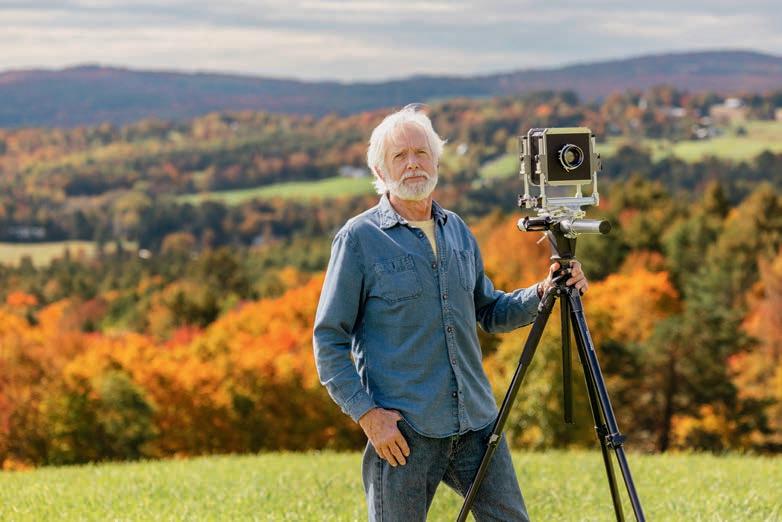

OLIVER PARINI

One highlight of Parini’s latest Yankee assignment [“Fall Comes to the Northeast Kingdom,” p. 64]: getting to meet fellow Vermont photographer Richard Brown. “He’s been an inspiration to me since I first picked up his book, Pictures from the Country: A Guide to Photographing Rural Life and Landscapes, as a budding photographer,” says Parini, whose images have been featured in The New York Times, AARP The Magazine, and The Wall Street Journal

NINA MACLAUGHLIN

“How did I not know about Hubbard Brook before?” marvels MacLaughlin, a Massachusetts-based author and Boston Globe books columnist [“These Tree Say So Much,” p. 82]. “Here is this mighty, buzzing, hugely important experimental forest, with scientists doing research of global importance, tucked into a swatch of woods in New Hampshire. I’m so glad I do know about it now, and glad I get to share some of it with Yankee readers.”

MICHAEL D. WILSON

After moving to Maine nearly a decade ago, this Chicagoarea native has amassed a photography portfolio filled with stunning New England travel images, including a celebration of Lake Winnipesaukee fall foliage for this issue [“Weekend Away,” p. 50]. The assignment not only “rekindled my joy for this particular time of year,” Wilson says, but also introduced him to Moulton Farm’s cider doughnuts—which he’s been thinking about ever since.

CASSANDRA KLOS

To bring visual life to the UFO feature “Are We Alone?” [p. 88], Yankee turned to Klos’s arresting photography project “The Abductees, 1961,” about the Betty and Barney Hill incident. The project aims to “provide an alternative visual library of what the Hills saw,” Klos explains. “The authenticity of a photograph creates a moment bound in truth, building a layer of validity to the Hills’ story that they did not receive during their lives.”

JOE BILLS

With a knack for covering the offbeat, Yankee’s associate editor has written about everything from Silly Putty to roadkill auctions to competitive lobster roll eating. In this issue, he takes readers on a tour of UFO history in New England [“Are We Alone?” p. 88]—which he describes as “trying to wrangle the incredible juxtaposition of sightings, science, and conspiracy theory that all comes smashing together around this subject into a single story.”

LISSA GOLDSTEIN

Interviewing local growers and food artisans for the photo essay “Market Value” [p. 76] was a natural fit for Goldstein, a Maryland native who became interested in farming at an early age. After spending her 20s working on farms in Alaska, California, and Oregon—not to mention British Columbia and Kenya—today she runs a small fruit and vegetable farm in upstate New York called Wild Work Farm with her partner, Steve Wyatt.

After Tropical Storm Irene hit Vermont in August 2011, uprooting countless lives and costing more than $800 million in property damage, the character of the state revealed itself to the world: resilient, rebuilding day by day, neighbor helping neighbor. And it was thought that since Irene was a once-ina-century event, the rivers would not rise that high, that quickly, again.

I write this in mid-July as we are going to press with Yankee ’s fall issue, which happens to celebrate the beauty of Vermont’s Northeast Kingdom. Just this week we have seen “once-in-a-century” devastation return to Vermont after only a dozen years. Photos and videos of the inundated capital, Montpelier, and of bridges washed out and roads like rivers, have touched the nation. But alongside these images, we see reports of Vermont undaunted. Already the largest road reconstruction effort in the state’s history is under way. Vermont will recover.

What this summer’s floods will mean for Vermont’s vital fall tourist season is still unclear (though Yankee ’s expert has some thoughts, below). But in the meantime, there are many ways to help our neighbors in the Green Mountain State. A good place to start is the Vermont Community Foundation, which has established a flood relief fund and compiled additional charitable and informational links on its website: vermontcf.org/vtfloodresponse.

—Mel Allen

—Mel Allen

Looking back on Vermont’s fall color in the wake of Irene, Yankee foliage expert Jim Salge sees signs of hope for this year’s season. “The color was late in 2011,” he says, “but once the show got going, it was good as ever.” He believes that the rains that caused this summer’s flooding may even result in a longer color season. “Red swamp maples always turn earlier when their feet are wet, so they could start as soon as August this year. And on the later end, the foliage lasts longer on trees when there’s been no drought.” To see Salge’s seasonal reports and the rest of Yankee’s foliage coverage, go to newengland.com/fall-foliage.

Who says kids should have all the fun? At The Baldwin — an all-new Life Plan Community (CCRC) — we say this is your time. Make a splash in the pool. Dance, stretch, lift, and box in the tness center. Learn for the love of it. Take to the nearby trails, then top o your day at the local brewery. De ne life on your terms and do whatever you choose — whether that’s everything or nothing at all.

Opening fall 2023!

To learn more, call 603.404.6080 or visit TheBaldwinNH.org today.

My son Dan was born in late September 1985, on the day that Hurricane Gloria howled through southern New England, drenching us on its way north, leaving two million people without power. The windows of the small New Hampshire hospital were boarded up, and no light peeked through from the outside during my wife’s 20 hours of labor. (A nurse wondered if maybe the baby knew a hurricane was afoot.) I crushed ice and drizzled honey over it to keep us going, and then in the early afternoon, Dan’s first cries signaled the storm inside the room had ended. A week or two later, I carried him in the tiny pack I wore on my chest and walked through the tree-lined neighborhood where we lived. The leaves were so scarlet and yellow, it was as if you could breathe the color.

I scooped a handful of maple leaves and held them close to his eyes. This is fall, I said. You will never see it like this anywhere else. You will never forget it.

Dan lives now in Hawaii, and his younger brother, Josh, lives in Colorado. During their childhood they spent summers at a nature camp called Roots & Wings. Like many parents, I wanted them to spread their wings and reach for whatever and wherever their hearts took them. I just never expected it to be so distant.

We had over 20 autumns together, and now nearly as many apart. I think about fall with my boys when the leaves begin to change color seemingly overnight, and then after a couple of weeks, a few fall, then more, and then a cascade, drifting down in their twirling dance, draping the yard. We would rake together in the cool

air, the mounds of leaves becoming a playground, their dog, Scout, leaping in with them. Now when I rake, I drag dozens of acorns along with the leaves. For the chipmunks that dart across the grass, this is takeout service. Many mornings I enter the woodshed to find their hoard tucked between pieces of wood, hidden in corners, filling their pantry against the coming cold.

I think about fall with my boys when the black walnuts drop with a thud in the backyard. The walnuts are green and look like limes; their scent is akin to citrus, and when I scoop them by the dozens to take to the composting heap at the recycling center, my hands are fragrant with walnut. The small stone wall that separates the backyard from the church parking lot next door is littered with broken shells, the aftermath of red squirrel picnics, as if the animals had been shelling peanuts at a ballgame.

Because Dan’s birthday is in late September, every year I send him a gift of home in a box. I buy a quart of maple syrup and a hunk of cheddar and bars of local chocolate, and I lay them on a layer of newly fallen leaves as if they were wrapping paper. My sons’ generation does not hold on to nostalgia and sentiment the way mine does.

I know autumn is a paradox. We love it even more because it is so fleeting. We hold it close, and then it is gone, the trees bare and brown. “A time of good-byes,” my wife once said.

As I write this, I remember a walk after a storm when I carried my son against my chest and showed him flaming red leaves and said, You will never see it like this anywhere else. You will never forget it. It goes so fast, and one day becomes 38 years.

Remember, I remind myself, look at the leaves while they hold on.

For fifteen minutes, for a half hour — sun, orange-yellow-gold — breaks horizon in the East. Light sweeps across hundreds of miles of ocean to strike our shores. The amber light begins to return color to the land as the sun rises. The sun melts the shadows, warms the air, chases fog away, and makes dew drops on spider webs sparkle, then vanish, of course there is darkness six, eight, ten hours while we sleep, dreaming, tossing, turning, reaching for our lover, trusting we are safe, and that a new day will come again. Orange, yellow citrine is pure magic and the promise of a new day.

farewell to summer with a plunge into New England’s premier whitewater rafting scene.

BY IAN ALDRICH

BY IAN ALDRICH

We were a good 10 miles into our pad dle on Maine’s Kennebec River when we decided to abandon ship … sort of. It was really more like departing with aban don. The big rapids were in the rearview mir ror, and before us lay a stretch of calm waters that invited a swim. A couple from Portland were the first to leap in, the boyfriend whoop ing as he plunged underwater repeatedly. That was the only invitation needed for my 11-yearold son, who did his best cannonball, then stretched back in his life jacket to allow the slow currents to float him a good 100 yards from our raft. Now it was my turn.

“What are you waiting for?” my son called out. It was a fair question. I ran a hand through the water, then looked over at our guide, Will Bastian, who from his perch on the back of the raft gave me a grin and a You’re gonna regret it if you don’t jump in expression. A few seconds later, I was floating toward my son. The water was unexpectedly warm in early September, while around us the first tinges of autumn

color had begun to hit the shoreline’s hardwoods. For long stretches it felt as if we had the typically busy Kennebec all to ourselves.

Surprises like that, in fact, framed much of our four-hour trip on the river that morning. We had surfed rapids with names like Big Mama, White Washer, and Taster. We’d stopped at Dead Stream Falls and took turns

sitting behind a rushing flow of water. We’d yelled and laughed, even when it felt as if the whitewater might consume us. And we’d lingered on our backs in the lower river, soaking in what was sure to be the last bit of true summerlike weather.

There are other areas of the Northeast where you can go whitewater rafting, but

nothing truly compares to what you find in Maine. The sport got its start here after the last log drives in 1976, and in the nearly half century since, it has given rise to one of the elite whitewater rafting centers in the United States. The advantages are clear: Maine boasts more whitewater than the rest of New England and New York combined, and on account of

scheduled dam releases, it’s also the only state in the Northeast with guaranteed water flows every day. That means consistent paddling from spring all the way into autumn, when foliage is at its peak.

Much of that fun is based out of The Forks, which sits at the intersection of the Dead and Kennebec rivers. As such, there are seemingly almost as many guides and rafting operators in the region as pine trees. Our outfit was Three Rivers Whitewater, which first started leading trips in 1997 and today boasts a campus that includes a big restaurant and a store, as well as a spread of cabins and tent sites that are within earshot of the rushing Kennebec.

Rafting, of course, is not a passive endeavor. And if you’ve got the right guide it only feels as though you’re riding the edge. In Bastian, a burly Long Islander who found his real home on Maine’s rivers and ski slopes a decade ago, we had the perfect captain. From the moment we put in at the base of Harris Station, the state’s largest hydroelectric dam, we were thrust into the thick of it. Within the first quarter mile we navigated a mix of Class III and IV rapids. As

Bastian yelled out directions like “All ahead!” and “Hold on!” any nerves we had quickly dissipated as we dealt with what was right in front of us.

“We’ll get these families who come here, and it’s not an easy place to get to,” Bastian says afterward. “They’ve probably come some distance, and you can see it in their faces that some of them have really ventured outside their comfort zone. But then they get into it, they get through those first couple of rapids, and they are just beaming. They look and feel like a million bucks.”

That’s certainly how my son and I felt as we floated on the Kennebec on that early September morning. A blue sky hung overhead, and as the currents pushed us forward, we, too, felt part of a river that had powered so many before us.

Come along on a rafting trip down the Kennebec in season three of Weekends with Yankee , at newengland.com/waterwater-rafting, and find out how to watch the latest season of our show at weekendswithyankee.com.

Professionally guided excursions, many of them led by Registered Maine Guides, offer the best and safest way to explore Maine’s whitewater rafting scene. Here are some time-tested outfitters to try.

CRAB APPLE

WHITE WATER, The Forks; crabapple whitewater.com

MAGIC FALLS RAFTING CO., West Forks; magicfalls.com

MOXIE OUTDOOR ADVENTURES, The Forks; moxierafting.com

NEW ENGLAND OUTDOOR CENTER, Millinocket; neoc.com

NORTH COUNTRY RIVERS, Millinocket & Bingham; northcountryrivers.com

NORTHEAST

WHITE WATER, Shirley Mills; northeast whitewater.com

NORTHERN OUTDOORS, Millinocket & The Forks; northernoutdoors.com

THREE RIVERS

WHITE WATER, The Forks; threerivers whitewater.com

More than 40 years ago, a powerful dream came to Vermont sculpture artist Jim Sardonis. “I was standing on a beach looking out [at the ocean] and saw these two whales’ tails emerge from the water,” he recalled in a 2019 interview with Seven Days. “I woke up thinking, I’d like to make that.”

It was a dream Sardonis simply couldn’t shake. He envisioned it as the centerpiece of a proposed project for a museum in Anchorage, Alaska, but as things turned out, it would be in his own hometown of Randolph that the whale tails first came to life.

Sardonis was commissioned to create a grand entrance piece for a planned conference center on a patch of Randolph farmland overlooking Interstate

89. While construction on the center never commenced, Sardonis’s sculpture of two massive whale tails, standing about 13 feet tall and carved from 36 tons of African black granite, was installed on the site in 1989.

Named Reverence, the sculpture of two whales diving into the Vermont landscape was meant to be a symbol of Earth’s environmental fragility. Its grand scale, however, also made it a local landmark—and Randolph residents felt a deep sense of ownership of the whale tails, even after they were sold in 1999 and relocated to a 177acre business park off I-89 in South Burlington.

So it was with considerable fanfare that in 2017 the Preservation Trust of Vermont and the Vermont Community Foundation purchased the original site of Reverence and commissioned Sardonis to make his dream a reality once more.

Installed in July 2019, the 16-foot sculpture is the tallest piece ever completed by Sardonis, whose other work can be seen at such places as the New England Aquarium, Yale University, and Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center. But unlike “Reverence,” this second version, called Whale Dance, is made of bronze. And in his view, that gives these whales a slight advantage over their South Burlington brethren.

“Bronze is strong, so I could make things bend and twist and lean a little more than I could with the stone,” he said. “I could make the whales dance.”

—Ian AldrichTo learn more about Jim Sardonis and to see a short documentary about “Whale Dance,” go to sardonis.com.

For years, drivers on I-89 in Vermont have pulled over to marvel at a sculptor’s outsize environmental vision.ALEXANDER ROYCE/ALAMY STOCK PHOTO Call it double vision: Vermont is home to not one but two massive whale-themed sculptures by Jim Sardonis, the most recent being Whale Dance [SHOWN AT LEFT] in the artist’s hometown of Randolph.

take

Bridge

BY BRUCE IRVING

BY BRUCE IRVING

guarantee that if I asked you to close your eyes and imagine a haunted house, you’d see a Victorian of some sort. Not a cozy little Cape, not an elegant Federal, not a cookie-cutter ranch, but a decaying, turreted, looming Victorian manse.

Why? How did this archetype work itself into the American imagination so thoroughly?

The genesis of the spooky Victorian is an amalgam of technology, fortunes made and lost, fashion, home repair, and the grip of art and popular entertainment on the public mind. The story is at times conjectural, full of generalizations though occasionally specific, and, like the architecture itself, fascinating.

The middle of the 19th century saw an unprecedented growth of industry: Factories cranked out increasingly sophisticated goods, the marketplace encouraged innovation and rewarded the latest-and-greatest, and railroads expanded across the land to deliver

all the new goods. The availability of machine-cut, standard-dimension lumber and wire nails to hold it together brought huge changes to American architecture and construction.

Whereas heavy timber frames once necessitated simple, boxy forms for all but the most opulent structures, this new lightweight “stick” framing eased the construction of corners, making all sorts of overhangs, bays, porches, and other exuberances possible. The availability of factory-made doors and windows, casings, trim, decorative spindles and fretwork, and even roofing and siding meant that the building palette was broader than ever before.

So what to build? As more and more people amassed wealth in the gangbuster capitalist economy, many sought to display it—and what bigger way than through a house? Architects, once a rarity, rose up in their (usually threenamed, always male) multitude, promulgating the latest style, often with European historical roots, that allowed their clients to announce their arrival.

Many were inspired by Andrew Jackson Downing’s 1842 Cottage Residences , one of the first books to endorse several different architectural forms, each with different antecedents—Greek Revival, Gothic Revival,

Italianate—opening the way for a kind of what’s-next mindset in architecture that mirrored the “new and improved” approach of the factories.

Soon enough came the Queen Anne and the Stick styles, with some Tudors, Egyptians, Orientals, and octagons thrown in, and the mansarded Second Empire, straight from the fashionable boulevards of Paris. They were built to be impressive, with tall asymmetric exteriors, towers and wings and off-center porches, and multiple special-function rooms that reflected the social formality of the era. Interiors dripped dark wood paneling and elaborate moldings. In nearly all cases, lavish display overshadowed strict historical precedent, the better to show off what was now technically possible, to take advantage of all the products available,

and, not incidentally, to outshine the Joneses’ place across town.

But fashion has a tortured twin and—over time and through a variety of economic booms and busts—many of these exuberant homes became, alas, unfashionable. In some cases they symbolized past excess; in others, the money that built them evaporated. Often, the times and the occupants simply moved on.

Perhaps there was a fatal flaw lurking in their very facades all along. Aristotle believed that “the chief forms of beauty are order and symmetry,” something borne out in modern research. Interviewed about her 1999 book Survival of the Prettiest, Harvard psychology professor Nancy Etcoff said that regardless of culture or ethnicity, “the more symmetry a body has, the more attractive it is. We find

something ‘wrong’ with even slight asymmetries.” If that’s true, it’s understandable that distaste and unease eventually worked their way into the public perception of Victorians.

And as every homeowner knows, miss a few maintenance cycles and you’ll be sorry. Any lack of upkeep on Victorians—with their vast expanses of articulated wood and abundant corners and seams courting rot and leaks— quickly drags the structures down the road to decrepitude. And if, God forbid, an occupant had not moved on but continued to live in such a decaying pile at the edge of town, its formal gardens now gone to seed … well, therein was a recipe ripe for the baking.

In a delightful online article on the haunted nature of Victorian houses, Archipanic.com describes how the

There are things we feel around us. Crisp air. Warm sunlight. A cozy sweater. And then there are things we feel within us. Curiosity. Exhilaration. Belonging. This is the place to savor the beauty around you. Reawaken your senses, right here in Maine.

Mount Battie

Peaks-Kenny State Park

Scratch to release the scent of Maine.

Mount Battie

Peaks-Kenny State Park

Scratch to release the scent of Maine.

style went “from a symbol of wealth to a symbol of dread.” An early intimation of disquiet came in Edward Hopper’s 1925 painting House by the Railroad , depicting a lonely, eerie, turreted Second Empire in Haverstraw, New York. The great photographer Walker Evans did a series on Victorian houses starting in 1930, including a pair of Gothic Revivals firmly in the grip of desuetude in Dorchester, Massachusetts. In 1938, New Yorker cartoonist Charles Addams published the first view of what would become the Addams Family: a creepy couple being pitched by a vacuum cleaner salesman in the gloomy receiving hall of their Victorian home.

After that, Hollywood and television took over. Starting with 1959’s House on Haunted Hill —which starred Vincent Price and, according to Archipanic.com, “features a mix and match of different styles, including 1890s narrow Victorian corridors, dark furniture, gas chandeliers, and sconces”— and continuing on through Psycho (1960), The Haunting (1963), Dark Shadows (1966), Beetlejuice (1988), It (2017), and season four of Netflix’s Stranger Things (2022), the screen has provided a steady diet of sinister Victorian backdrops. Heck, horror writer supreme Stephen King and his wife, Tabitha, lived for years in an

For those who prefer their Victorians without an overtly spooky vibe, the Park-McCullough Historic Governor’s Mansion in Vermont offers visitors a look inside one of New England’s best-preserved examples of that era, incorporating Second Empire, Gothic, and Italianate styles.

1858 Victorian in Bangor, Maine; they recently repurposed it to house their charitable foundation.

Of course, someone always has to zig when the culture is zagging. In 1979, public television’s This Old House debuted, taking on, as if out of central casting, a c. 1860 Second Empire slowly rotting on a hill in Boston’s Dorchester neighborhood. Over the course of 13 episodes, the crew brought it back to rehabilitated vibrancy, completely erasing its spooky ambiance.

But don’t despair! Those craving their fix of the macabre can head out to Gardner, Massachusetts, where an imposing 1875 Second Empire home, aka the “S.K. Pierce Haunted Victorian Mansion,” awaits. The building was purchased in 2015 by New Jersey dentist Robert Conti. He says the previous owner became convinced that his wife had been possessed by a spirit in the building and wanted to sell. “I learned about it on Facebook, noticed that it was zoned commercial, promised the sellers I’d keep it as original as possible, and bought it sight unseen,” says Conti.

Since it opened to the public in 2022, caretakers of the property have led hundreds of visitors on $25 60-minute tours of the mansion, and Conti is weighing the idea of hosting overnight guests (more than 3,000 are on the waiting list). The staff has counted a total of 14 different ghosts on-site; at least five people died in the house, the last being boarder Eino Sauri, a World War II vet who in 1963 died of smoke inhalation at age 49 when his mattress mysteriously caught fire.

“I wasn’t a believer when I bought the place,” Conti says, “but I definitely have smelled a whiff of smoke when I enter his room.”

EXTERIOR: Decorative belvederes (seen here), cupolas, or towers

ROOF: A low-pitched design with deep overhanging eaves with highly decorative cornices and brackets

Channeling the romance of a rural Italian villa, the Italianate house leaves behind the rigid stuffiness of the past for a rambling and relaxed floor plan with the flair of a low-pitched roof, deep and decorative eaves, arched windows, and decorative cupolas for admiring the natural view.

Time Period: 1840–1885

Characteristics: Low-hipped roof, arched windows

Famous Example: Maine is home to two fine examples: Stephen King’s spooky Bangor residence and the house museum Victoria Mansion in Portland

Where to Find Italianate

WINDOWS: Tall and narrow, with rounded or arched tops

The Second Empire home is like a square Italianate that went to France and came back with a modern and stylish hat. The distinctive dualpitched hipped roof, named for 17th-century architect François Mansart, was enjoying a revival during the reign of Napoleon III (France’s Second Empire), which then spread across the Atlantic.

Time Period: 1855–1885

Defining Characteristic:

Mansard roof

Famous Example: Boston’s

Old City Hall and Providence

City Hall

Where to Find: Throughout the Northeast, as both residences and public buildings

PAINT: House and trim are two shades of the same color, with dark shutters

Homes: In established but still prosperous and growing cities along the northeast coast

ROOF: A classic dual-pitched mansard roof

EXTERIOR: Decorative details including cornices under the eaves and quoins at the corners

Miranda Thomas has a voice made for a good chat. There’s a com plexity to it, with vowels and inflections shaped by both her British parentage and her years spent living in Australia, England, Italy, and America. There’s a warmth, as well, that flows from her love of bring ing things into the world, be they children or gardens or works of art. It’s a voice of someone you could imagine welcoming into your home.

Her pottery has a voice, too. From the blue and white of the Netherlands to the lustrous gold of the Middle East, it carries the accent of many lands; at the same time, its techniques speak of centuries of human culture. But to really hear what it has to say, Thomas believes, you need to touch it.

“Imagine you have a mug, and you’re putting your lips to it or your hands to it or just sort of resting it against your cheek,” she says. “And if it’s been made by hand, you can feel those very slight variances in the surface. It’s just as if you’re having a conversation with it. It’s another form of your senses being coaxed alive.”

Making things by hand—and putting them directly into the hands of others—is a calling that Thomas has long shared with her husband, the furniture maker Charlie Shackleton. After having met at an art and design school in England, the two crossed paths again in Vermont, where they worked for the famed Irish artisan Simon Pearce. Before long they were married and working for

themselves, and today they preside over their joint workshops, ShackletonThomas, which has been headquartered in the same 19th-century mill building in Bridgewater for much of their company’s threedecade-plus history.

The couple’s mediums are different, but their designs are complementary—in the showroom, her quiet, elegant pottery sits alongside his classic wood furniture. And their point of view is a shared one.

“We both love putting life into an inanimate object,” Thomas says. “[Handcrafting] takes a particular sort of mixture of material, observation, skill, many things that culminate from your very hands, and it’s something the machine can’t do.

“There’s a famous saying, I’m pretty sure by Pascal: What is it that puts life into an inanimate object? For is that not what man is? And if you think about it, we’re the same as the rocks and the trees and everything around us, but there’s a little bit of magic that we instill [in the clay and the wood], and that’s what gives them life.”

Thomas first realized her affinity for pottery (which she affectionately calls “cooking with rocks”) when it was introduced at her high school in Australia. “It was the most surprising thing, at the age of 16, to look down and see a bowl just appearing underneath your hands,” she recalls. “I loved it immediately, like I loved surfing. So I just kept doing it.”

She honed her craft with a bachelor’s degree in ceramics as well as learning directly from master potters in

England, notably Michael Cardew. Thomas’s distinctive style emerged early on: strongly decorative but not ornate, with an emphasis on universal symbols of nature, like fish and rabbits, trees and flowers, painted or carved onto the clay.

Thomas was already well into making pottery under her own name—which she had begun doing in 1984—when she found herself taking commissions from, of all places, the White House. In 1998, on a whim, she had sent President Bill Clinton a “rudimentary, really simple little pot” as a gift in appreciation for the country’s recent and notably long stretch of peace. What came back was a thankyou note … and then a request for 16 turquoise and gold pots to be given to Middle Eastern dignitaries … and then a request for a very large white porcelain bowl carved with a peace dove design, to be Clinton’s personal gift to Pope John Paul II.

(About the Pope’s bowl: Because of the tight deadline, Thomas actually made six of them simultaneously in hopes that just one would sit absolutely true, its glaze pristine and incandescent. And just one did. As for the rest, she says, “President Clinton heard about the bowls that didn’t come out perfectly and he wanted them any -

way, because he felt he himself wasn’t perfect. And he gave some of those as gifts as well.”)

Thomas has had several other highlevel commissions since then, including bowls for the United Nations to present to Kofi Annan and Ban Ki-moon, but much of what she makes is meant for everyday people to use in everyday life. And for Thomas, her lasting legacy isn’t about who buys her pottery, anyway. It’s about the next generation who are working alongside her.

“We have this incredible flow of people across our workshops here who want to learn to be either craftsmen or designer craftsmen, and we’ve created a home or a sanctuary for them for a while,” she says. “When you

teach somebody skills, it’s like passing the torch. It’s a wonderful, wonderful thing. And human beings need those skills to be happy. So it’s the one thing I can do for the human race, I think. Working with people and working on those skills and sharing that language—it really places you on a long, long timeline.”

Editor’s note: Like many homes and businesses across Vermont, the historic mill building in Bridgewater that houses ShackletonThomas was flooded by record rainfall as this issue was going to press. As repairs continue, the web store featuring Miranda Thomas’s pottery and Charlie Shackleton’s furniture remains open for orders, via shackletonthomas.com.

For Thomas, her lasting legacy isn’t about who buys her pottery—it’s about the next generation whoare working alongside

her.LEFT: Work in progress on a bowl featuring slip carving, a technique that creates a raised design on the pottery. BELOW: Thomas’s hand-painted limitededition “Imbibe” beakers. BEN FLEISHMAN (POTTER); CLARA FLORIN (BEAKERS)

Harking back to simpler times, farmhouses speak to so much that we love. And while many farmhouses share some basic traits—coziness, functionality, and simplicity of design, all set on spacious acres—each becomes something unique to its place, a compounding of the virtues of the land to which it is inextricably connected. Today, farmhouses still beckon to us, even as they take on new, more upscale lives. Here are five contemporary variations on this classic theme, each ready for the growth of new roots.

Chatham, MA

Once a working farm of the Chatham Bars Inn, this extraordinary estate has been owned by the same family for more than 70 years. Nestled on a south-facing lot with stunning views of Oyster Pond and a mile-long stretch of the Oyster River, the main home, built in 2004, features plentiful windows, a finished basement, a two-car garage, a detached barn, and, best of all, an expansive wraparound deck perfect for watching birds, boats, and sunsets. Price: $9,995,000

• Square Feet: 1,786

• Acres:

1.44

• Bedrooms: 2

• Bathrooms: 2.5 (Rick Smith, Gibson Sotheby’s International Realty, 508-945-0000, rick.smith@sothebysrealty.com)

Turnkey properties that unlock your dream of agrarian elegance.

NOTHING Stops a DR ® Field & Brush Mower

• Up to 2X THE POWER of the competition

• CUT 3" BRUSH & tall eld grass with ease

• WIDEST SELECTION of deck sizes and features

• GO-ANYWHERE power steering and hydrostatic drive options

Devour Brush

Piles with a DR ® Chipper Shredder

PLUS Tow-Behind, Commercial, and

• CHIP & SHRED with power to spare

• BIGGER ENGINES beat the competition

• BUILT USA TOUGH

Tow-Behind

• #1 in vacuum power and capacity

• NEW PRO MAX model holds up to 450 gallons

• All models newly redesigned with up to 20% more capacity

Walk-Behind

• NEW PILOT XT models ll paper leaf bags for curbside pickup

• Collects & mulches up to 50 lbs of leaves

• Includes onboard caddy for extra bags

IRON HORSE SALT FARM

77A Watsons Reach, Sullivan, ME

Is perfection attainable? This bucolic saltwater farm, with panoramic views of both Flanders Bay and the mountains of Acadia National Park, will make you a believer. The sunny four-bedroom farmhouse, which has been extensively remodeled, anchors a gated estate that includes a spacious barn with four horse stalls, an artist’s studio, a boathouse, and multiple garages, as well as the remnants of a seaside manor house. With plenty of space, a half mile of water frontage, and easy access to some of the most beautiful scenery in the world, the possibilities are endless. Price: $3,600,000 • Square Feet: 2674 • Acres: 53

• Bedrooms: 4 • Bathrooms: 3.5 (Jamie O’Keefe, Landvest Real Estate, 207-299-8732, jamieokeefe67@gmail.com)

LEWIS FARM

144 & 232 Town Farm Road, Woodstock, VT

This quintessential Vermont farmstead, which has been in the Lewis family since 1940, offers 130 acres of picturesque hayfields and woodlands along a Kedron Valley hillside near the village of South Woodstock. In addition to the three-bedroom brick farmhouse, the property features a spectacular restored barn, a light-filled twobedroom contemporary house, and a south-facing studio tucked into the hillside. There is also a pond, a riding ring, a tennis court, a smokehouse, and plenty of trails to explore. Price: $2,800,000

• Square Feet: 3,748 • Acres: 130 • Bedrooms: 8 • Bathrooms: 5 (Story Jenks, Landvest Real Estate, 802-238-1332, sjenks@landvest.com)

141 Shearer Road, Washington, CT

This converted dairy barn was relocated to its present location from New York state, but its exposed beams and natural woodwork might well have sprouted from this picturesque property, just an hour and a half from New York City. The farm’s four acres are beautifully landscaped with specimen trees and evergreens, and the land immediately adjacent is protected. The house’s spacious foyer features a grand fireplace, while the great room combines library, living, and dining spaces under a cathedral ceiling. There’s a fireplace in the master bedroom, too. Price: $1,950,000 • Square Feet: 3,146 • Acres: 4

• Bedrooms: 3 • Bathrooms: 2.5 (Maria Taylor, Klemm Real Estate, 860868-7313, ext. 126, mtaylor1800@aol.com)

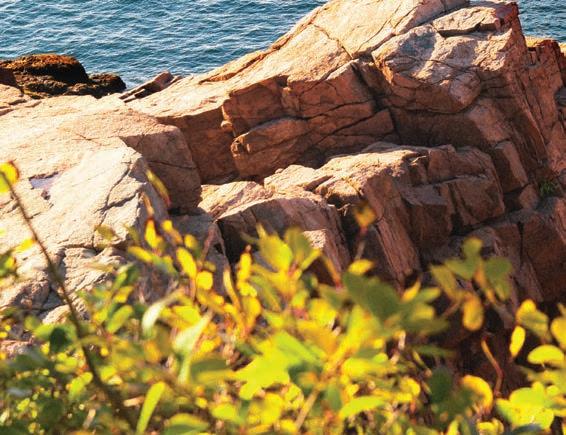

72 Bartletts Landing Road, Mount Desert, ME

Owning this private saltwater farm on the “quiet side” of Mount Desert Island, overlooking Pretty Marsh Harbor, is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. The four-bedroom house, built in 1818, is surrounded by perennial gardens, acres of pasture, and a private shoreline. It boasts wide-plank floors, exposed timber rafters, and plenty of modern amenities cleverly worked in so as not to distract from its rustic charm. Still not convinced? Figure in a heated three-bay garage, an attached barn, and easy access to the wonders of Acadia National Park. Price: $6,295,000 • Square Feet: 3,123

• Acres: 12.28

• Bedrooms: 4 • Bathrooms: 3.5 (Marika Alexis Clark, Legacy Properties Sotheby’s International Realty, 207-780-8900, marika.clark@sothebysrealty.com)

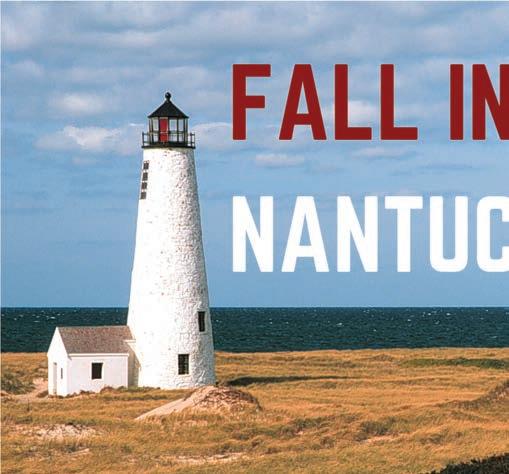

A beloved Nantucket icon

Forrest Pirovano’s painting “Sankaty Head Light” shows a brick and granite cylindrical tower overlooking the ocean

The shoals off the eastern coast of Nantucket have a long history as a hazard to navigation. Sankaty Head Light, on the eastern shore of Nantucket Island was erected in 1849 as an aid to navigation. Situated high on a bluff just north of the town of Siasconset, this red and white striped lighthouse is visible 25 miles out to sea, flashing its light every 7.5 seconds. It was converted to electric in 1933 and fully automated in 1965. The lighthouse is owned by the US Coast Guard and managed by Sconset Trust. This beautiful limited-edition print of an original oil painting, individually numbered and signed by the artist captures the majestic appearance of this world-famous lighthouse.

This exquisite print is bordered by a museum-quality white-on-white double mat, measuring 11x14 inches. Framed in either a black or white 1½ inch deep wood frame, this limited-edition print measures 12¼x15¼ inches and is priced at only $149. Matted but unframed the price for this print is $109. Prices include shipping and packaging.

Forrest Pirovano is a Cape Cod artist. His paintings capture the picturesque landscape and seascapes of the Cape which have a universal appeal. His paintings often include the many antique wooden sailboats and picturesque lighthouses that are home to Cape Cod.

P.O. Box 1011 • Mashpee, MA 02649

Visit our studio in Mashpee Commons, Cape Cod

All major credit cards are welcome. Please send card name, card number, expiration date, code number & billing ZIP code. Checks are also accepted.…Or you can call Forrest at 781-858-3691.…Or you can pay through our website www.forrestcapecodpaintings.com

Sweet and savory recipes showcase one of fall’s most versatile ingredients.

BY AMY TRAVERSO | PHOTOS BY KRISTIN TEIG & LIZ NEILY

BY AMY TRAVERSO | PHOTOS BY KRISTIN TEIG & LIZ NEILY

There are carving pumpkins and there are eating pumpkins and there are squashes that look and act like pumpkins and there’s pumpkin in a can. Most of us stick with the first kind for decorative purposes and the canned stuff for convenient cooking. But in the 300-plus identified pumpkin varieties >>

>> that are grown commercially in the U.S., there’s plenty more good eating to be had.

At the same time, I don’t like writing recipes with ingredients that you have to search high and low to find. The following dishes make ample use of pumpkin puree, which shows up in the cake bars, muffins, snickerdoodles, and chili, a hearty vegetable stew flavored with chili spices and garnished with avocado, sour cream, and cilantro. There’s also a recipe for roasted sugar pumpkin wedges, which are a tasty way to enjoy pumpkin in its prepureed form; you’ll find these edible pumpkins at many supermarkets and most farm stands. Plus, the pumpkin chili also makes delicious use of kabocha, a Japanese winter squash variety with wonderfully sweet, velvety flesh that is also available at most grocery stores. If you haven’t tried kabocha, you’re in for a treat: When cooked, the skin becomes so tender that you don’t even have to peel it. Happy pumpkin season!

For recipes, turn to p. 92

’m playing a bit with the seasonality of this column, because as any garlic grower knows, you harvest bulbs in the summer, not in the fall. But! Garlic takes a few weeks to cure, so homegrown cloves will be ready to eat right now. Also, fall is the season for planting garlic, which is just about the easiest thing you can do in a garden: Take a clove and stick it in the ground, let it overwinter, and watch the scapes come up in the spring. You do want to source your garlic cloves from a local farm, because the bulbs at the supermarket aren’t meant for our climate. And be sure to feed your soil with good compost, as garlic is a hungry plant. But that’s about all you have to do, so get out there and plant your own for next year.

Once you have some ripe garlic on hand, use it in the following recipes. Both are easy weeknight picks. One is a vegetarian take on shrimp scampi made with mushrooms, white beans, spinach, and lots of minced garlic. The other is a sheet pan supper with chicken thighs, cauliflower, shallots, and whole garlic bulbs that you trim and roast until caramelized. Serve the meal with a crispy baguette and smear those silky cloves on your bread. Heaven!

A bit of garlic puts fresh autumn produce in a whole new light.Mushroom, White Bean, and Spinach “Scampi,” recipe p. 48

Book

Earth has seven Blue zones. Seven places where people live longer with vim and vigor. A Blue Zone is not just about more time, it’s more time with a true quality of life. The Blue Zone mindset is about time for discovery, wisdom and work.

Blue Zones are not merely magic places on the globe. Rather, they are places with a population of people who believe in wellness, people who never stop thinking, participating or creating. They subscribe to a lifetime of art and imagination, a lifetime of discovery.

A Blue Zone is not just about place, although these places exist within our world. Blue Zone is really about attitude, belief and philosophy.Yes, it would be nice to live in a place where everyone lived a very long time. Blue Zone living is easier than you might imagine. It’s a decision you make, a decision that exists inside of you. It’s a shift of your consciousness.

Blue Topaz is an amazing gem. It occurs in various shades of blue. At Cross, we choose the prettiest shades of pastel blue, they are the colors in the middle. Our Blue Sky Topaz is the third hardest gem after diamond which means it’s highly resistant to scuffing and scratching. Blue Topaz has a high refractive index (jeweler talk) which means that when a gem is cut properly, it’s the most sparkly bright brilliant pastel blue gem in nature!

Your new Blue Topaz is with you every day to remind you of the guiding principles of what is truly important.

Blue is the color of health and well-being. Blue is the color of youth and vitality. Blue is the color of peace and happiness.

1 teaspoon kosher salt, plus more for the pasta water

1 pound linguine, uncooked

5 tablespoons olive oil, divided, plus more for drizzling

1 pound sliced white mushrooms, oyster mushrooms, or “baby bellas,” or a combination

5 ounces baby spinach

8 large garlic cloves, minced

½ teaspoon red pepper flakes

2 (15 ounce) cans cannellini or other white beans, rinsed and drained

1 cup vegetable or chicken stock

²⁄ 3 cup white wine

2 tablespoons lemon juice

5 thin lemon slices

Minced parsley and freshly grated Parmesan cheese, for garnish

Bring a large pot of water to a rolling boil. Add a palmful of kosher salt, then add the linguine and cook according to package instructions. After the pasta is cooked and drained, do not discard the cooking water.

Meanwhile, in a very large sauté pan over medium-high heat, warm 4 tablespoons olive oil, then add the mushrooms and 1 teaspoon salt. If adding all the mushrooms at once crowds your pan, cook them in batches (when the pan is crowded, the mushrooms will steam rather than brown).

Stir the mushrooms with the salt and oil, then let them cook, undisturbed, until browned on one side, 2 to 3 minutes. Stir, then cook until the mushrooms are browned all over, 2 to 3 minutes more. Remove the mushrooms with a slotted spoon and set them aside. Add the remaining 1 tablespoon oil to the pan, then add the spinach, garlic, and red pepper flakes. Cook, stirring often, until the spinach is wilted. Add the beans, stock, white wine, and lemon juice. Scrape the bottom of the pan with a wooden spoon to pick up any yummy browned bits.

Add the pasta to the sauté pan, along with ½ cup of the cooking water. Add the reserved mushrooms and lemon slices, and toss together in the pan. If the mixture seems dry, add more pasta water. Transfer the pasta to a serving bowl. Garnish with parsley, a generous shower of Parmesan, and a drizzle of olive oil. Yields 6 to 8 servings

ROASTED SHEET PAN CHICKEN WITH SHALLOTS AND GARLIC

2 large heads garlic

3½ tablespoons olive oil, divided

1 large head cauliflower, cut into 2-inch pieces and florets

12 medium to large shallots, peeled and quartered

2 teaspoons fresh thyme leaves, divided

1½ teaspoons kosher salt, divided, plus more for sprinkling

¾ teaspoon freshly ground black pepper, divided

4 large (or 6 medium) skin-on, bone-in chicken thighs

½ teaspoon garlic powder

Fresh thyme sprigs, for garnish Baguette, for serving

Preheat your oven to 425°F and set a rack to the middle position.

Trim the tops of the garlic heads just enough so that most of the bulbs are exposed, about ¼ inch. Set the bulbs on a piece of aluminum foil. Sprinkle with a pinch of salt and drizzle with ½ tablespoon olive oil. Wrap the garlic up with the foil, set on a large rimmed baking sheet, and transfer to the oven for 15 minutes.

Meanwhile, in a large bowl, toss the cauliflower and shallots with 2 tablespoons olive oil, 1 teaspoon thyme leaves, ¾ teaspoon kosher salt, and ½ teaspoon pepper.

When the garlic has cooked for 15 minutes, pull out the baking sheet and arrange the cauliflower mixture in a single layer on it. In the large bowl, toss the chicken with 1 tablespoon olive oil, 1 teaspoon thyme leaves, ¾ teaspoon kosher salt, ¼ teaspoon pepper, and the garlic powder. Nestle the chicken thighs, skin side up, among the cauliflower and shallots and return the tray to the oven. Bake until the thighs are browned and crisp and the cauliflower is nicely browned, 25 to 35 minutes, depending on the size of the thighs. Garnish with thyme sprigs and serve, giving everyone a few garlic cloves to squeeze out and spread on slices of baguette. Yields 4 servings.

Located along the Southern Maine coastline, our active, engaged community combines worry-free independent living with priority access to higher levels of on-site care—all for a predictable monthly fee.

Residents enjoy apartment, cottage, and estate home living in a community of friends, with all the benefits of Maine’s first and only nonprofit lifecare retirement community.

(207) 883-8700 • Toll Free (888) 333-8711 15 Piper Road, Scarborough, ME 04074 • www.pipershores.org

NEW HAMPSHIRE’S CLASSIC SUMMER GETAWAY SHINES JUST AS BRIGHT WHEN THE LEAVES TURN.

BY RICHARD ADAMS CAREY • PHOTOS

BY RICHARD ADAMS CAREY • PHOTOS

BY MICHAEL D. WILSON

BY MICHAEL D. WILSON

OPPOSITE, CLOCKWISE FROM TOP LEFT: The landmark 1950s-era Weirs Beach sign; the historic Busiel-Seeburg Mill in Laconia; exploring the corn maze at Meredith’s Moulton Farm; Shannon Pond at Castle in the Clouds; seasonal treats at Moulton Farm; the town dock in Center Harbor. THIS PAGE: Downtown Meredith takes on a rosy glow in the wake of an autumn thunderstorm.

But it never had to be summer for Lake Winnipesaukee to be a destination. Try it during New England’s fall foliage season, when all the local businesses are still bustling, and the vast lake and its surrounding mountains—the Belknap, Squam, Sandwich, and Ossipee ranges—are never more beautiful.

We’ll start in Wolfeboro, where Mitt Romney keeps a second home. Main Street runs the length of the waterfront, and if you stay at the Pickering House Inn on Main, you’ll find yourself in the newly—and immaculately—restored Federal home of Daniel Pickering, one of the town’s leading citizens in the 1800s. Innkeepers Peter and Patty Cooke offer gourmet breakfasts, sunny rooms that blend the historic and the contemporary, and a wraparound porch overlooking lush gardens, the campus of Brewster Academy, and Wolfeboro Bay.

A 10-minute stroll down Main brings us to Lydia’s Café, where the French toast comes heaped with tiny wild blueberries, sandwiched with cream cheese, and dolloped with whipped cream. Right next door is Made on Earth, a fair trade–certified boutique where naturalfiber women’s clothing is complemented by herb teas, scented smoke bundles, fine jewelry, and shelves of books on Eastern spirituality.

Through mid-October, the 205-foot M/S Mount Washington plies the lake daily between Wolfeboro, on the east shore—and past some of Winnipesaukee’s 300-plus islands—to Laconia’s Weirs Beach on the west. “The Weirs” once hosted a dance hall where the likes of Duke Ellington and Count Basie played; today its boardwalk hums with shops, restaurants, a tavern, a penny arcade, and the bumpbump of bumper cars.

In 1763, New Hampshire Governor John Wentworth built a summer home on the shores of a lake whose name—in one translation from the Abenaki— means “Smile of the Great Spirit.” That home was in the village of Wolfeboro, which on that basis claims the title of “The Oldest Summer Resort in America.”

EAT & DRINK

Canoe, Center Harbor: Five dining areas and a threeseason porch with lake views to enjoy while tucking into lobster mac and cheese, among many other offerings. canoe centerharbor.com

Laconia Local Eatery, Laconia: Dogs are welcome at outside tables at this upscale farm-to-table establishment where all food (organic whenever possible) comes from within 140 miles. laconia localeatery.com

Lydia’s Café, Wolfeboro: A small café with an outsize following for its all-day breakfasts, especially pancakes and omelets, as well as lunch. Facebook Moulton Farm, Meredith: A garden center, a farm stand, a bakery, and an array of homemade foods to take home, all on land farmed since the 1890s. A corn maze and a pumpkin patch round out the all-in-one outing. moultonfarm.com

Trillium Farm to Table, Laconia: Supplied by nearly a dozen local farms and breweries and even a mustard maker, this Middle Eastern/ Mediterraneaninspired eatery is one of the prime lunch and dinner spots in the region. trilliumnh.com

Yum Yum Shop, Wolfeboro: A local bakery landmark for seven decades whose signature frosted gingerbread men, doughnuts, pastries,

OPPOSITE: Passengers congregate on the upper deck of the M/S Mount Washington as it prepares to cast off for a sightseeing cruise. THIS PAGE: The Marketplace at Mill Falls at the Lake, Meredith.If a proper car is handy, drive into Laconia for lunch at Trillium Farm to Table, a bright café that partners with local organic farms in its offerings. Wine, craft beers, and hard cider are available, but for a different take on a nonalcoholic fruit drink, try a cantaloupe shrub.

Your car will also prove handy for the 77-mile loop of roads around the lake and linking its towns. To the north of Laconia lies Meredith, where the League of N.H. Crafts-

men keeps a shop stocked with unique handwrought items made with as much artistry as craft. At the heart of the town lies Mill Falls, with its 40-foot waterfall and an elegant array of shops, restaurants, and lakeside lodgings. Keep going north on Route 25 to the Moulton Farm stand: sustainable agriculture, a corn maze and pumpkin patch, and apple cider doughnuts as light as croissants.

Center Harbor, at the lake’s north end, was a favorite haunt of poet and abolitionist John Greenleaf Whittier. It was also the site of America’s first intercollegiate sporting event: the Harvard-Yale regatta of 1852. Winnipesaukee is surrounded by excellent restaurants, but Canoe is my choice today—say yes to the lobster mac and cheese, or the sweetand-sour calamari—and is as lakeside as the Mount Washington . The Sutton family estate once dominated Center Harbor, and today the Suttons’ refurbished Victorian mansion is a homey B&B beautified by a Lisa Nelthropp mural of town history.

and ice cream have linked generations of sweet tooths. yumyumshop.com

Ames Farm Inn, Gilford: A low-key family resort on 135 acres on Winni’s southern shore, with its own quartermile beach. Open through Columbus Day Weekend. amesfarminn.com

Ballard House Inn, Meredith: At this c. 1784 inn, views of lake and mountains and homemade country breakfasts are enhanced with complimentary wine sipped while sitting on the backyard swing. ballardhouseinn.com

The Inn at Mill Falls, Meredith: Part of a cluster of four inns that helped revive Meredith as one of the main destinations in the Lakes Region, this one is dog-friendly, with designated doggie trails, pet beds, and a treat bag. millfalls.com/stay/ the-inn-at-mill-falls

Long Island Bridge Campground, Moultonborough: Sites for RVs, trailers, as well as pop-ups and tents within a stone’s throw of Winnipesaukee. Canoe and kayak rentals available. Open till midOctober. longisland bridgecampground nh.com

Pickering House Inn, Wolfeboro: A now-restored c. 1813 local landmark, this 10-room inn is made for sitting on the porch overlooking the bay. pickering housewolfeboro.com

Start your journey at the Lexington Visitors Center, now open daily. Check out our revolutionary history room and famed diorama, or shop for unique gifts. Book a Liberty Ride Trolley Tour or Guided Battle Green Walking Tour, and see where it all began on April 19, 1775.

Tours are available seven days per week! All tours depart from the Lexington Visitors Center: 1875 Massachusetts Avenue, Lexington MA GIFT

To book a step-on guide and custom tour scan here

TourLexington.us

Add us to your summer itinerary, and prepare for adventure in the Greater Merrimack Valley! visit merrimackvalley.org

We begin to round back to Wolfeboro through Moultonborough, where the Old Country Store & Museum dates back to 1781. Its floor space and shelves are jam-packed with vintage and contemporary items recalling that name-it-we-got-it ethos of, well, old country stores. Then turn down Route 109 toward a jewel hidden high in the Ossipee Mountains: Castle in the Clouds, which began as Lucknow, a 6,300-acre estate and mansion—no, castle— built in 1913 by shoe magnate Thomas Plant. The builder eventually ran out of luck and went broke, but his restored home provides a window into the human spirit, a taste of a bygone opulence, and magnificent views south over the lake and north to the Sandwich Range. Maybe you prefer to go on foot to where bald eagles soar. Drive through Wolfeboro down to Alton Bay, the lake’s southern tip. Go four miles up Route 11 to the trailhead for Mount Major. A moderate, hour-and-fifteen hike will reward you with a vista no less stunning than Mr. Plant’s. You’ll know how he felt, because you might want to stay forever.

Sutton House B&B, Center Harbor: A pet-friendly Victorian mansion featuring nine guest rooms within a sixminute walk of Lake Winnipesaukee, which you’ll want to take after your sumptuous homemade breakfast. sutton-house.com

Wolfeboro Inn, Wolfeboro: The historic Wolfeboro Inn comes with its own private beach on Lake Winnipesaukee and a pub serving New England comfort food alongside upscale options and an extensive beer list. wolfeboroinn.com

PLAY

Castle in the Clouds, Moultonborough: Autumn is made for chasing views, and one of the best in the Lakes Region is seen from this c. 1914 mansion perched on a mountainside. Tour the estate, and stroll its miles of walking trails. Through October 22. castleintheclouds.org

Mount Major, Alton: The summit of the 1,786-foot mountain provides a stunning photo op—colorful forest, expansive lake, and islands—via a 1½-mile hike that suits everyone. forestsociety.org/ property/mountmajor-reservation

Mount Washington Cruises, Laconia: The M/S Mount Washington departs from Weirs Beach daily and offers a grand tour of Winni, stopping at five ports along the way. Sunset dinner and scenic specialty cruises. Through mid- October. cruisenh.com

Peterborough, NH

Chef-owner Carolyn Hough composes multicourse breakfasts like a jazz improvisationalist. The “notes”? All plucked from her garden and nearby farms. Come fall, homemade yogurt and granola might be followed by caramel-glazed apple hand pies and just-laid eggs topped with Swiss chard pesto. You’ll burn calories on trails that begin right from the 83 acres surrounding this exquisitely nurturing inn. Hike to Cranberry Meadow Pond, then on to the summit of Pack Monadnock. cranberrymeadowfarminn.com

The Old Mill Inn

Hatfield, MA

hospitality and glorious surroundings set these updated properties apart.

BY KIM KNOX BECKIUSs the leaves turn, we’re celebrating New England’s changing lodging landscape, too. These five inns have turned over a new leaf in the past few years—and if you stay at them all, it will be one epic fall-foliage journey.

Camden, ME

Stately trees in fiery fall dress are all that separate this 1886 castle from the sea. Step through the doors and you’ll want to applaud, even if Brett Haynie isn’t singing by the baby grand. His eye for posh, exuberant style and architect owner Will Tims’s desire to preserve this landmark while injecting it with contemporary personality

have transformed The Norumbega into a place ready for its next century. Five of the 11 rooms have fireplaces. norumbegainn.com

Waitsfield, VT

The gentleness here exceeds the sum of the parts assembled by innkeepers Mick and Karen Rookwood, with an assist from Mother Nature. Set on 20 acres, with front-door access to mountain biking and hiking trails that plunge into the Mad River Valley’s bright-hued woodlands, this is a place to feel cared for—from sunup’s elaborate, hyperlocal breakfast until bedtime, when you collapse into a feathery cloud. featherbedinn.com

Arriving after dark? You’ll still be dazzled by color. Not the fall foliage— that can wait until morning, when you sit on the reconstructed covered porch with locally roasted coffee and a secretrecipe biscuit (a specialty the café sells out of daily). At night, sapphire-blue spotlights illuminate the waterfall that once powered this 19th-century mill. It’s a white-noise machine now, ensuring sound sleep for those in riverside rooms. oldmillinn.us

The Kent Collection

Kent, CT

A decade-plus after Yankee named the sophisticated rural town of Kent best for leaf peeping, the Kent Collection’s Garden Cottages, Victorian, and Firefly Inn make this an even more attractive autumn home base. Waterfall and covered bridge photo ops, a scenic stretch of the Appalachian Trail, and the state’s best farm-to-table dining are close at hand, but returning to the spaces co-owner Lulu McPhee has designed, with an eye for both architectural preservation and modern aesthetics, may be your favorite thing of all. kentcollection.com

Local breweries and cideries pair perfectly with a fall road trip in New England—here are 40-plus favorites to get you started.

COMPILED BY BILL SCHELLER

COMPILED BY BILL SCHELLER

ANONYMOUS BREWING, Rowley. There’s micro, nano … and hypernano, which is how Anonymous describes its size ranking in the indie beer world. The North Shore outfit runs a one-barrel brewhouse and keeps its offerings simple and straightforward: single and double IPAs, British ales, and lagers, plus occasional limited editions. The kid-and-dogfriendly taproom (they keep dog biscuits on hand) occupies a rehabbed car-repair shop hung with work by local artists. anonbrew.com

BARRINGTON BREWERY, Great Barrington. This is the home of solar-brewed beer, with PV panels powering the operation. The beer list skews British, with brown ale, stout, and porter, although there’s more than a nod to the citrusy IPAs New Englanders crave. Unlike many bar food–oriented breweries, Barrington offers full lunch and dinner menus, with locally sourced meats and homemade desserts, and a cheddar ale soup that’s sourced, of course, on the spot. barringtonbrewery.net

CAPE COD BEER, Hyannis. The year-round beer garden (indoors in winter) showcases an impressive variety of brews. Tradition is

the watchword here, with all the hallowed bases covered—blond and red ales, IPAs, porter and stout, hefeweizen—though perker-uppers like chilies and coffee make an occasional appearance. A BBQ food truck, along with Dollar Wing Thursdays and Fish Fry Fridays, helps keep patrons off a strictly liquid diet, and there’s plenty of live music. capecodbeer.com

CARR’S CIDER HOUSE, Hadle y. Cider isn’t the half of it at this Pioneer Valley orchard and cidery, which produces hard and soft versions but also supplies apples

(Continued on p. 98)

BY BILL SCHELLER | PHOTOS BY OLIVER PARINI

BY BILL SCHELLER | PHOTOS BY OLIVER PARINI

tI’ve always liked to take what I think of as my “back road” into the Northeast Kingdom, Vermont’s Vermont, hunkered hard against New Hampshire and Quebec. It starts when you turn off Route 100, just south of Lake Eden, and climb into high country on East Hill Road.

My wife, Kay, and I took this back road on a day in early fall, when the Kingdom starts to spill color down into the rest of the state. The still-green woods around the lake gave way to all the hues that autumn brings to red and orange, with yellowing birches for counterpoint. After a crest in the road and the opening of an eastward vista, we came to a well-remembered sign of entry into the Northeast Kingdom: the distant white spire of Craftsbury Common’s United Church.

In a state where settlement generally followed river valleys, Craftsbury Common is unusual. It floats high up on a ridge and clusters around a village green—the eponymous common—out of all proportion to its size. Reaching the village just as its tiny museum was opening, we helped docent Nancy Frohwein mount the flagpole on the porch. Then we headed inside to view relics that dated back to the time of Ebenezer Crafts, who was granted the town in 1780

by the legislature of the Vermont Republic. Ten years later, he and his son Samuel, a future Vermont governor, came to settle here. If it looked on their arrival anything like it did on this luminous autumn morning, they must have thought they’d been granted a morsel of paradise.

Driving down from Craftsbury Common through Craftsbury to East Craftsbury (Vermonters hate to give up a name as a road leaves town), we looked for a turnoff onto a fragment of the Bayley-Hazen Road, that never-completed 18th-century route for a contemplated invasion of Canada. Having driven this portion years ago, I remembered it as an unpaved fall foliage superhighway. But a librarian in East Craftsbury—every village we passed had its library, because this is New England—told us it had been rutted into impassability, probably by ATVs. So, we took a no less lovely blacktop down to Greensboro, on Caspian Lake.

Since it was too early to settle into our quarters at Greensboro’s Highland Lodge, we continued—after a stop at Hill Farmstead Brewery, where it wasn’t too early for a pint—south to Danville, cutting across Route 2 to reach Peacham on the day of its Fall Foliage Festival. Actually, it was day five of a Kingdom-wide celebration of the season, as each year the festival makes the rounds of seven area towns, putting a different spin on “a movable feast.”

Peacham is an anomaly among country towns in Vermont, particularly those in the state’s more hardscrabble corners. The little café at the village crossroads serves cappuccino; the music playing as we ate our homemade blueberry cake wasn’t Garth Brooks, it was Harry Belafonte. And there’s an electric vehicle charger at the library.

We soon saw that Peacham itself was the festival. It’s a pleasantly walkable town, with every event venue just minutes from the crossroads where Church Street meets the local shard of the Bayley-Hazen Road: library and its book sale on one side, café and Peacham Corner Guild craft gallery on the other; historical association a few yards up, past local cooks preparing the evening’s Italian supper at the

Congregational church. We joined locals and visitors alike on the way to the Peacham School, where pupils served an outdoor lunch of homemade quiche, corn chowder, and apple pie. Afterward, we walked up a hill behind the school to the Northern Skies Observatory, where amateur astronomers take advantage of the Kingdom’s dark night skies.

One of the day’s events was an exhibit of prints by local photographer Richard Brown. He started documenting life in the Northeast Kingdom 50 years ago, and his book The Last of the Hill Farms depicts a place where he found “a world of Jersey cows and Belgian work horses, woodburning Glenwoods, and dirt-floored basements full of canned applesauce, mustard pickles and stewed tomatoes in glinting rows on sagging wooden shelves. Autumn mornings, when the sharp fragrance of wood smoke and rotted manure laced the air, when the frost was thick on the land, and the maples began to blaze, I thought I’d died and gone to photographer’s heaven.”

I met up with Brown at the modest headquarters of the Peacham Historical Association, where his prints were on display, and we talked about the town he’d come to in the days when “there was an invasion of people like myself,” back-to-the-landers who “didn’t know what the hell we were doing.” But he and the other newcomers found Vermonters, fifth- and sixth-generation and beyond, who did know what they were doing, and were doing it in the receding twilight of the 19th century. Brown spent years chronicling the lives of his neighbors, having, as he once wrote, “always been drawn to the closeness of Vermont’s past.”

Brown built on the legacy of an earlier photographer who had also been entranced by Peacham: European émigré Clemens Kalischer, who chronicled the town during the 1950s and ’60s. His pictures so poignantly captured the essence of life in a midcentury Vermont village that their appearance in Life magazine, Vermont Life, and a Time-Life book about New England helped establish the state as the quintessence of bucolic Yankeedom, living proof that there really is something the Germans call fernweh —a longing for a place one has never seen. I imagine it must have afflicted more than a few of the folks we sauntered through town with on that festival day.

AFTER PEACHAM, KAY AND I SWUNG UP PAST ST. JOHNSBURY to Lyndonville—where I narrowly resisted killing the afternoon at a favorite spot, Green Mountain Books—and sought out a road we’d never traveled. It runs through deep Technicolor autumn woods to Greensboro Bend via the village-less towns of Wheelock and Stannard, and is punctuated by a marker that states: “In honor of Horace C. Goss who built this road over Wheelock Mountain in 1868.” (We assume Mr. Goss had help.)

Returning to Greensboro, we checked in at Highland Lodge, a rambling and venerable inn that made us feel as

if we’d arrived at Grandma’s big, comfortable house in the country. Our room’s name, though, paid tribute to someone Grandma might not have heard of. It was the Federico Suite, honoring Spanish poet Federico Garcia Lorca, who in 1929 spent time over on Lake Eden with his friend Philip Cummings. Cummings’s family were founders of Highland Lodge. A photo of the two young men hung in our room. I looked at Lorca, in his natty tennis sweater, and wanted to tell him to stay here, instead of going back to Andalusia to be killed by Franco in 1936. The futile warnings of hindsight call to others, as well as to ourselves.

Caspian Lake has long been a quiet summer getaway for people of accomplishment and means, the types who would avoid the Hamptons like the plague. The late U.S. Chief Justice William Rehnquist had a place here, as did author John Gunther, who wrote of the “lollipop” moon shining over Caspian. After a canoe paddle around the east shore, where the lake was a mirror splashed with color, we tucked in too early for moonrise. We woke to a morning of heavy mist over Caspian, the distant call of the loons, and the Dopplered gabble of a southward flock of Canada geese.

The mist cleared during breakfast, and it was time to continue our drive through the autumn Kingdom with a run up Route 16 for stops at two very unusual destinations in the town of Glover. The Museum of Everyday Life occupies a former barn on the roadside, and a quirkier, less formal … well, more everyday museum likely doesn’t exist. Per a note tacked by the door, you turn on the lights when you go in, and turn them off when you leave. What’s inside? Keys and keyholes, alarm clocks, a violin made of matchsticks, a book on how to sharpen pencils, a curtain made of safety pins, toothbrushes, shopping and to-do lists (with a map showing where on the streets of New York they were found), and a collection of notes discovered in library books. The separate Milk House Gallery houses rotating exhibits; when we were there, the theme was bathrooms and their equipage, from replicas of tools the Romans used to wipe away bodily grime, to faucet handles and shower heads, to rubber duckies and a recording of a young Bette Midler singing at a New York bathhouse.