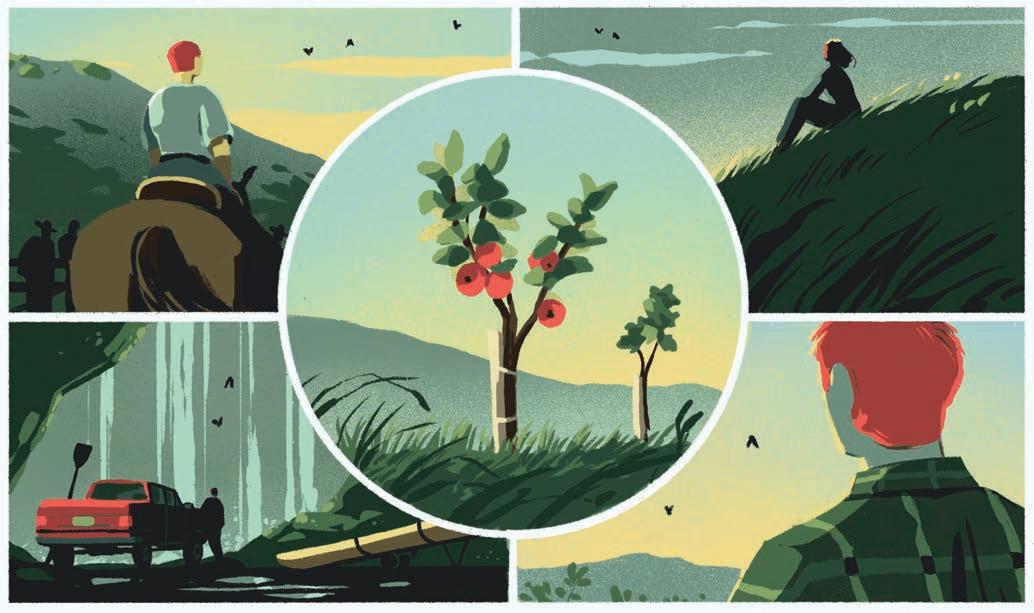

Go leaf peeping in one of New England’s last undiscovered foliage spots

Go leaf peeping in one of New England’s last undiscovered foliage spots

62 /// Small Towns, Big Color

This little pocket of rural New Hampshire just might be the best and least-crowded foliage destination in New England. By Mel Allen

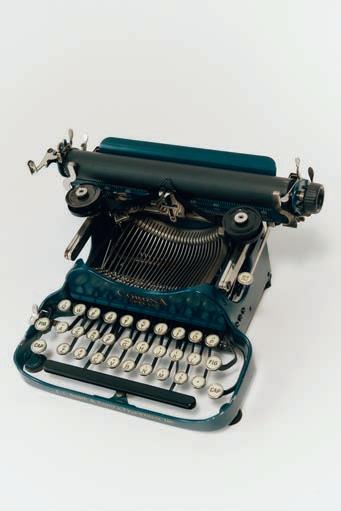

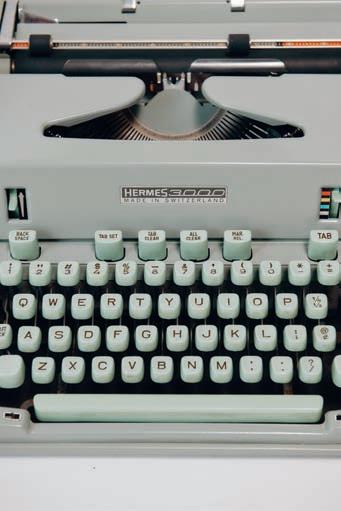

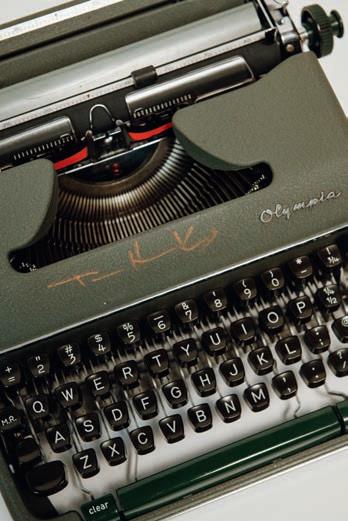

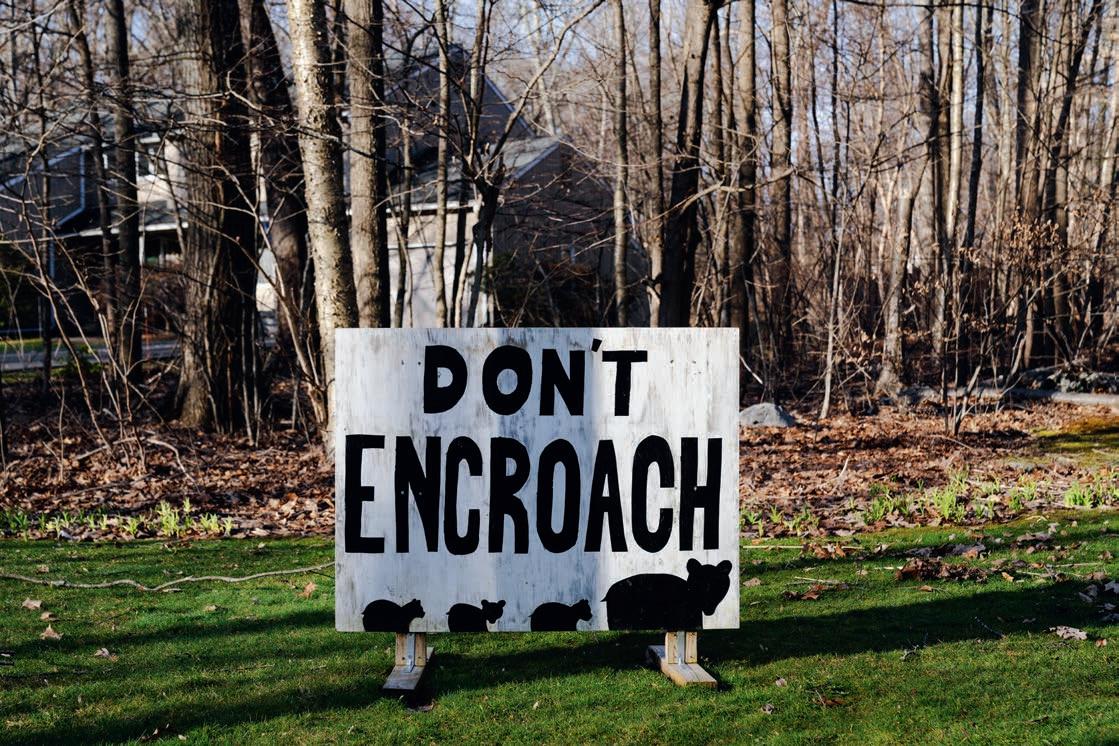

76 /// Keys to the Past

In a modest workshop in the Boston suburbs, Tom Furrier preserves history one typewriter at a time. By Ian Aldrich

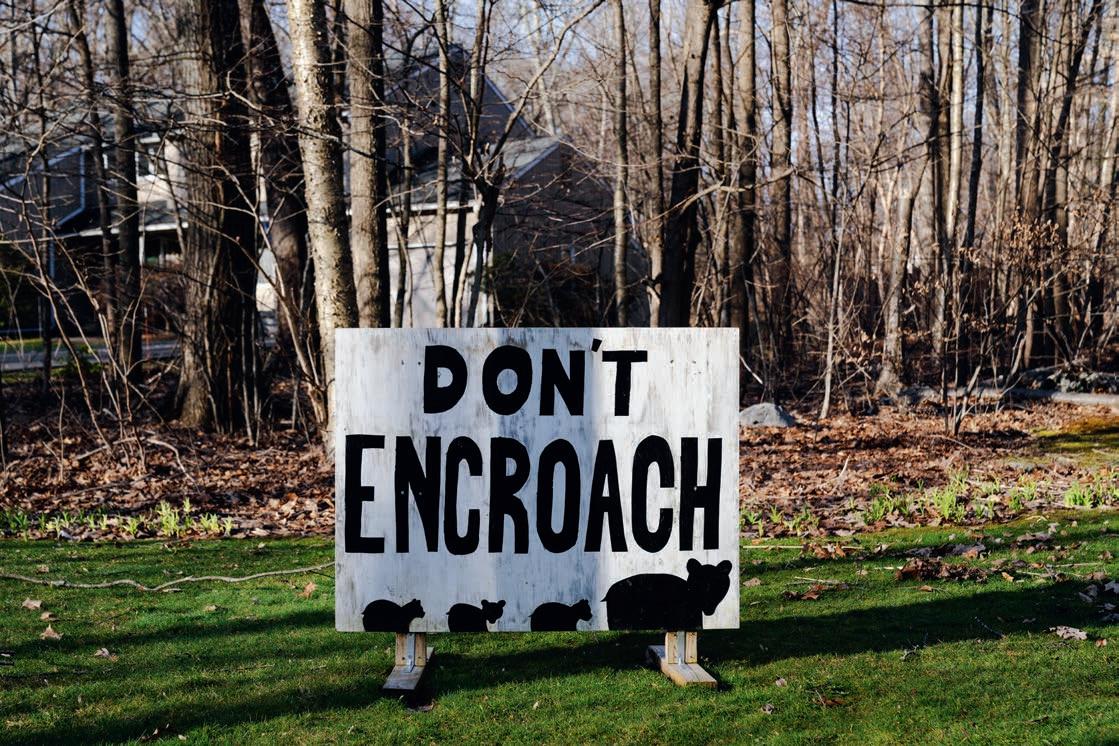

82 /// The Bears Next Door

Wild animals need to be left alone—but in the small, densely populated state of Connecticut, that’s an increasingly tall order. By Christine Woodside

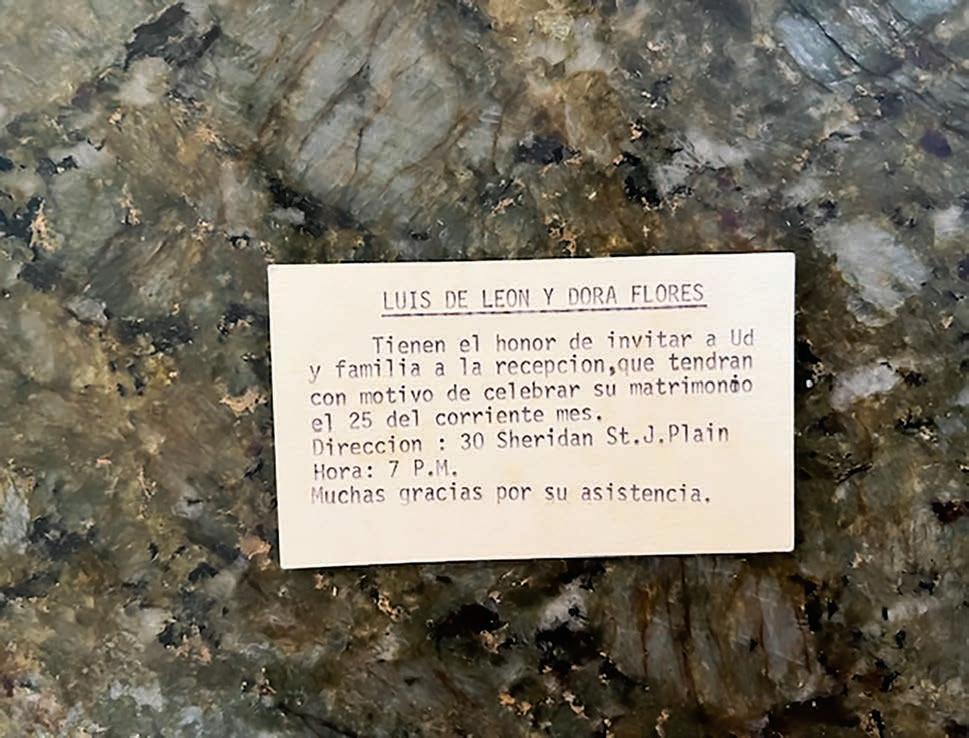

86 /// Days of Our New Lives

A family trip leads back to the crossroads of past and future. By Jennifer De Leon

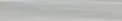

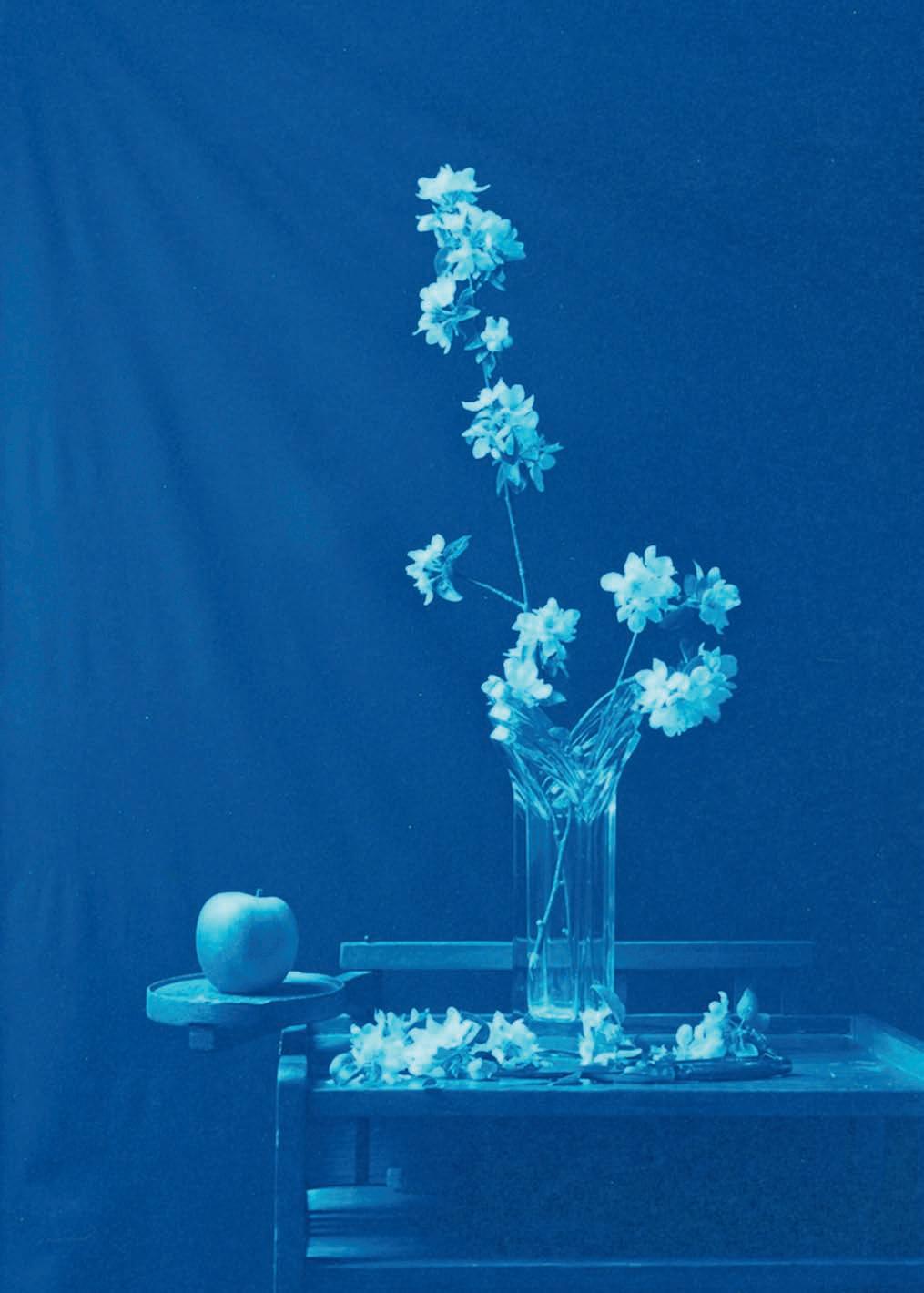

90 /// View Finders

One of the nation’s oldest camera clubs has seen everything about photography change—except for its hold over us.

Explore the mighty Mississippi River aboard the newest fleet in the country. With itineraries ranging from 8 to 23 days, enjoy an intimate cruising experience with fewer than 200 guests. Indulge in delectable cuisine and delve into America’s rich heritage, from bustling cities to serene landscapes, on this unforgettable journey.

28 /// ‘Standing in the Old Ways’

At this tranquil, minimalist home carved into a Vermont forest, less is truly more. By Annie Graves

34 /// Made in New England

Maine seamstress Katrina Kelley’s handcrafted linens balance everyday utility with uncommon artistry. By

Courtney Hollands

40 /// Baked-In Ease

Simple, delectable recipes from cookbook author Jessie Sheehan make home baking a breeze.

44 /// In Season

Step aside, apples: Another flavorful fall fruit is ready for its star turn. By Amy Traverso

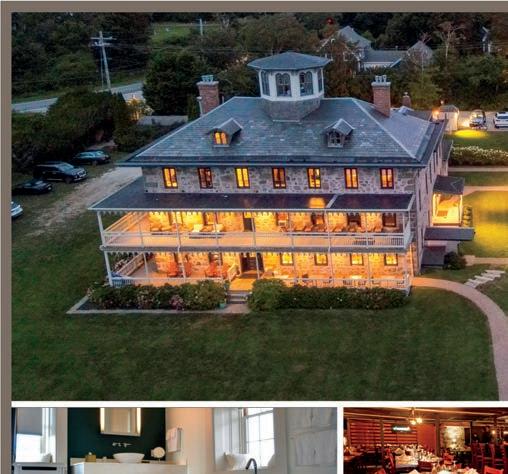

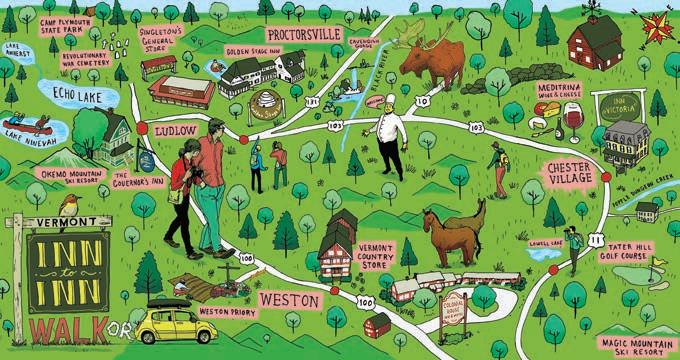

50 /// Weekend Away

Youthful energy mixes with a legacy of poets and scholars in Amherst, Massachusetts, one of New England’s most eclectic and invigorating towns. By

Katharine Whittemore

60 /// Playing the Markets

Among the best fall drives are the ones that lead to a colorful, bountiful New England farmers’ market.

Compiled by Bill Scheller

BEHIND THE SCENES

18

FIRST PERSON

Nature’s lamplight calls us to see things in a new way. By Edie Clark

20

For nearly a century and a half, B.F. Clyde’s Cider Mill has kept one of autumn’s sweetest traditions alive. By Amy Traverso

24

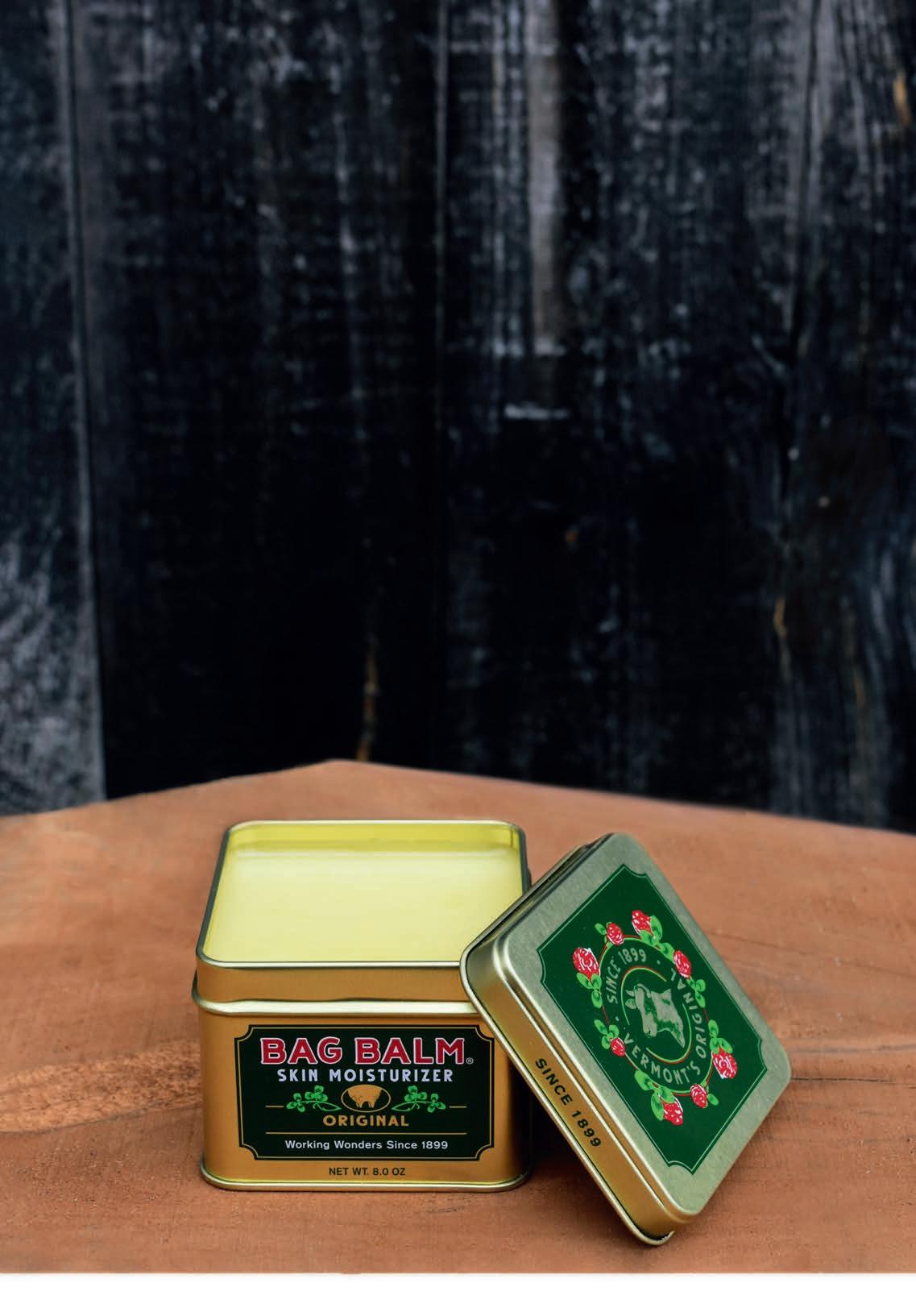

How a salve created for dairy farmers became a skin-care sensation. By Alyssa Giacobbe

128

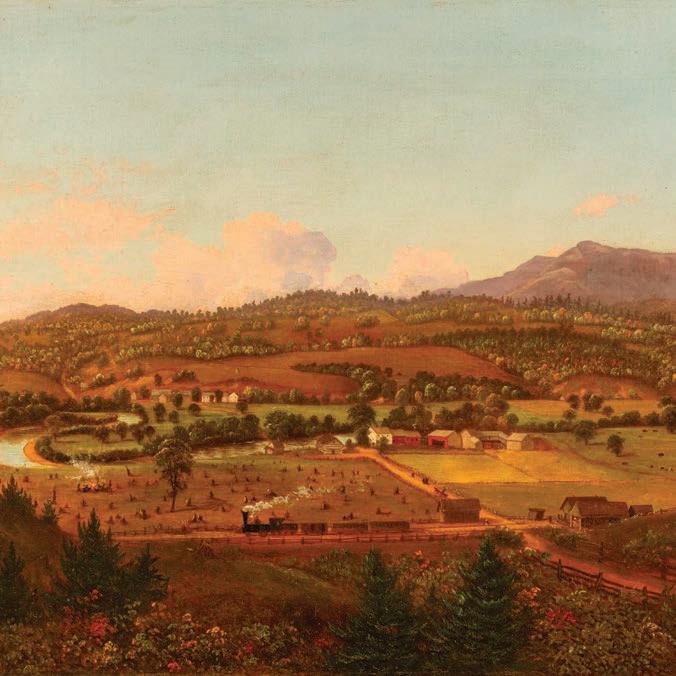

LIFE IN THE KINGDOM

When change happens, what stays constant is the love of the land. By Ben Hewitt

Share Your Love For Acadia. Start a Family Tradition.

Immerse yourself in the heart of Acadia. Our locations offer the perfect launchpad for your adventures in Acadia National Park.

Editor Mel Allen

Managing Editor Jenn Johnson

Senior Features Editor Ian Aldrich

Senior Food Editor Amy Traverso

Senior Digital/Home Editor Aimee Tucker

Travel Editor Kim Knox Beckius

Associate Editor Joe Bills

Associate Digital Editor Katherine Keenan

Contributing Editors Sara Anne Donnelly, Annie Graves, Ben Hewitt, Rowan Jacobsen, Nina MacLaughlin, Bill Scheller, Julia Shipley, Kate Whouley

Art Director Katharine Van Itallie

Senior Photo Editor Heather Marcus

Contributing Photographers Adam DeTour, Megan Haley, Corey Hendrickson, Michael Piazza, Greta Rybus

Director David Ziarnowski

Manager Brian Johnson

Senior Artists Jennifer Freeman, Rachel Kipka

Vice President Paul Belliveau Jr.

Senior Designer Amy O’Brien

Ecommerce Director Alan Henning

Digital Manager Holly Sanderson

Marketing Specialist Jessica Garcia

Email Marketing Manager Eric Bailey

ESTABLISHED 1935 | AN EMPLOYEE-OWNED COMPANY

President Jamie Trowbridge

Vice Presidents Paul Belliveau Jr., Ernesto Burden, Judson D. Hale Jr., Brook Holmberg, Jennie Meister, Sherin Pierce

Editor Emeritus Judson D. Hale Sr.

CORPORATE STAFF

Vice President, Finance & Administration Jennie Meister

Human Resources Manager Beth Parenteau

Information Manager Gail Bleakley

Assistant Controller Nancy Pfuntner

Accounting Associate Meg Hart-Smith

Accounting Coordinator Meli Ellsworth-Osanya

Executive Assistant Christine Tourgee

Maintenance Supervisor Mike Caron

Facilities Attendant Ken Durand

BOARD OF DIRECTORS

Andrew Clurman, Renee Jordan, Joel Toner, Jamie Trowbridge, Cindy Turcot

FOUNDERS

Robb and Beatrix Sagendorph

Publisher Brook Holmberg

Vice President Judson D. Hale Jr.

Media Account Managers Kelly Moores, Dean DeLuca , Steven Hall

Canada Account Manager Cynthia Fleming

Senior Production Coordinator Janet Selle

For advertising rates and information, email sales@yankeepub.com or go to newengland.com/adinfo.

ADVERTISING

Director Kate Hathaway Weeks

Senior Manager Valerie Lithgow

PUBLIC RELATIONS

Roslan & Associates Public Relations LLC

Vice President Sherin Pierce

NEWSSTAND CONSULTING

Linda Ruth, PSCS Consulting

SUBSCRIPTION SERVICES

To subscribe, give a gift, or change your mailing address, or for any other questions, please contact our customer service department:

Yankee Magazine Customer Service P.O. Box 37900 Boone, IA 50037-0900 Online newengland.com/contact-us Email customerservice@yankeemagazine.com Toll-free 800-288-4284

Yankee occasionally shares its mailing list with approved advertisers to promote products or services we think our readers will enjoy. If you do not wish to receive these offers, please contact us.

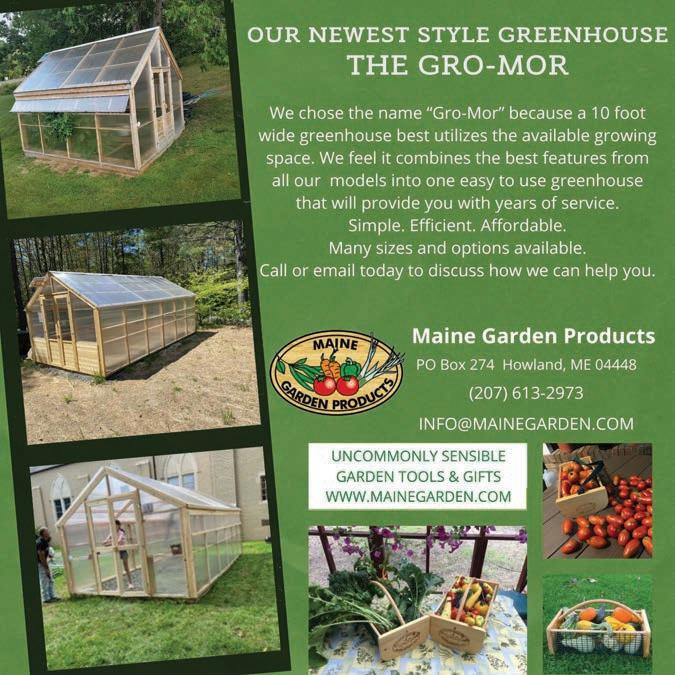

What to Plant Before the Frost Fall is the perfect time to prepare for next year’s growing season. Check out our top picks for fall planting in New England! newengland.com/fallplanting

Harvest Pumpkin Chili

Brimming with flavor, this hearty stew makes for a perfect fall warm-up. newengland.com/pumpkinchili

Everything You Should Know Before Driving the Kanc This Fall

New Hampshire’s famous foliage route is always worth experiencing—but our savvy tips will make your drive even better. newengland.com/kanctips

Best Foliage Brews and Views

Our guide to New England breweries that offer gorgeous views of autumn color alongside top-notch beers. newengland.com/brewsandviews

Want more Yankee? Follow us on social media @yankeemagazine and scan the code below to read bonus content!

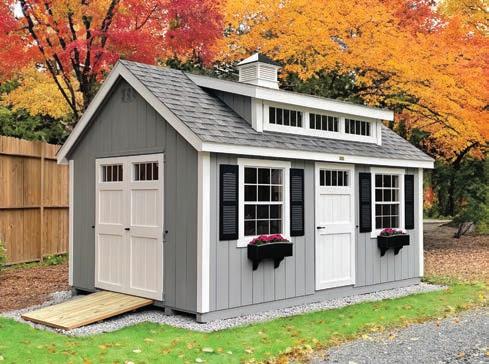

To understand the allure of colonial New England, you can begin by taking a look at the work of Country Carpenters, whose handcra ed home and barn kits are inspired by the timeless architectural s les at the heart of this region’s identi . Founded in 1974, the family-owned Connecticut company o ers everything from saltboxes to bigger designs—traditional structures that clients o en put to innovative use. Here, Chief Operating O cer Josiah Loye shares more of the Country Carpenters story.

Country Carpenters is celebrating its 50th year. How did it begin, and how has it grown? Our founder, Roger Barre Sr., had a strong love for post-and-beam barns. With his son, Roger Jr., he started disassembling old tobacco barns and reusing the timbers to build post and beam homes. Inevitably, the owners would want a small garage or barn, too, so the business evolved to the point where we put our focus on those

outbuildings. In 2006, we went back to the roots of our business and started o ering reproduction 18th-century-s le homes. This year, to distinguish the two sides of the business, we created Post and Beam Barns to join Early New England Homes, two distinct companies under the Country Carpenters umbrella.

What do you see as the special appeal of historic New England architecture? It’s really part of the heritage of America as a whole. Many of the first Europeans to come here were boatbuilders, and they took their skills and transferred them to actually building the barns we have here today. They launched a new art form—an American art form. Today, we have a lot of New England clients, of course, but we also ship around the country and other parts of the world. We’ve sent kits to Canada, Ireland, England, and all the way to Australia.

How are clients using Country Carpenters’ barn spaces these days? We

have a lot of car collectors among our clients. People have built breweries out of our barns, or used them as wedding venues. We had one client put a tennis court in his barn; others put in a climbing wall for their kids. Then there’s the whole barn home, which has really taken o the last few years. “Barn-dominiums”—they’re a real thing.

Why is handcra ing such an important part of the Country Carpenters process? Representing New England s le goes beyond design. When you buy a building from us, you’re ge ing a unique piece of art. When they see our buildings, people can really sense that. You’re not just ge ing some mass-produced product—you’re ge ing something that’s beautiful and well made, and will stand the test of time.

To read more of our interview and to see a varie ofCountryCarpenters’o erings,go to:newengland.com/country-carpenters

SAVE THE DATE! Country Carpenters hosts its annual Hebron Colonial Days celebration on Sept. 21 at its headquarters in Hebron, Connecticut. Visitors can see the working life of 1750s New England, including blacksmithing and textile work demonstrations, while also ge ing an up-close look at some of the company’s signature buildings. countrycarpenters.com/colonial-day

would not be writing this column were it not for two people: John Pierce and Judson Hale. In 1977, I had been writing freelance features for the Maine Sunday Telegram for two years. My first story paid $40; I eventually rose to a lofty $150 for a 3,000word story (travel expenses on me).

Still, that hardscrabble time gave me the robust portfolio of work that I would bring to my first meeting with John Pierce. I was 31, and to my surprise John, the new Yankee managing editor, was even younger. As he looked at my clippings, we talked easily, and I left with an assignment that would not only pay $400 but also include expenses. And I felt I had made a friend—something I never forget when I meet hopeful writers today.

Soon after, John asked me to come to Dublin, New Hampshire, to meet Yankee ’s editor, Jud Hale. I gave Jud a typed list of 28 story ideas and he accepted 25, something he told me had never happened before. I was offered a retainer contract, meaning $600 for each story would arrive each month, prepaid. For a freelancer, this was like finding a door that opened onto a new life.

A year later my dad, who had retired to Florida, discovered that the back pain he thought was related to golf was actually lung cancer that had spread to his bones. When his doctor told me the prognosis—three to six months—I put all my reporter’s skills to work.

Soon we were at an alternative cancer clinic on the island of Jamaica. Then an alternative heat-therapy clinic. And finally we were with a doctor who came to the house to inject paindeadening serum deep into my father’s back.

I flew down from Maine every few weeks to help Dad. When a story deadline loomed while I was in Florida, I dictated the article to a Western Union operator, who relayed it to John in New Hampshire. Even as Yankee ’s retainer

checks kept me afloat, I fell what seemed hopelessly behind on my end of the deal. One day John phoned to tell me that Jud agreed to retroactively boost all my previous story fees to $800. I was caught up. I never forgot that.

Shortly before my father died, John and Jud asked me to join Yankee as a senior editor. I would start October 1, 1979. I flew south and sat beside my father’s bed. Having been a young man during the Great Depression, he had long fretted that my freelancing was a precarious way to live.

“I’m going to Yankee full-time,” I told him. He looked at me with painkiller-glazed eyes. “Benefits?”

“Yes,” I said. He smiled, one of the last I can remember. “Good,” he said, then closed his eyes and slept.

I thought about all this as I sat on the deck of a boathouse on the edge of Dublin Lake last week. It was a windswept afternoon, with small sailboats scudding over the waves. The boathouse belonged to the family of my colleague Ian Aldrich, who was hosting a gettogether for my upcoming birthday. On the dock with us were seven other Yankee staffers who help create the magazine you are reading now.

Dublin Lake rests in a curve of the road less than a mile from our office, with Mount Monadnock rising to the south. And it is here, the Monadnock Region, that we showcase in our cover story, “Small Towns, Big Color” [p. 62]. People come from far away to soak up what we find here every day.

Sometimes on my early-morning walks, I say hello to my dad. I usually tell him about the two grandsons he never knew and what I’ve been up to lately. Today I said, Pop, remember when you asked about benefits? And I told him about a gathering at a boathouse, with my friends, by the lake.

Mel Allen editor@yankeepub.com

Meet South County’s New Residents!

South County Tourism Council is proud to present two new troll sculptures by renowned recycle artist Thomas Dambo. Head to Ninigret Park to meet Erik Rock and Greta Granite. Admission is free. Find out more at SouthCountyRI.com.

In the 10 years that this native Vermonter has been writing his “Life in the Kingdom” column, much has changed for him and his family—something he pauses to consider in this issue [p. 128]. But his inspiration remains the same: the small stories and minor events of rural life. “It always feels as if they contain so much more than it seems at first glance,” he says. “I think a lot of my work revolves around attempting to unearth the bigger stories hiding inside the smaller ones.”

An indelible moment in reporting “The Bears Next Door” [p. 82] came when Woodside was allowed to watch up close as wildlife biologists performed a checkup on a sedated wild bear. “After waking up she would, I hoped, never remember any of us … but I would never forget her,” says Woodside, a Connecticut writer and longtime editor of the AMC’s biannual journal, Appalachia Her most recent book is Going Over the Mountain: One Woman’s Journey from Follower to Solo Hiker and Back

A freelance photographer whose work has appeared in The Atlantic, The New Yorker, and Wired, among others, Luong lives in Arlington, Massachusetts—just a few miles from Tom Furrier’s typewriter shop, as it turned out [“Keys to the Past,” p. 76]. Another pleasant discovery? “Learning that Tom and I shared an affinity for thoughtful and functional design, so getting to learn about which typewriters were manufactured when, and which models became popular, was very fulfilling.”

In writing about the literary town of Amherst, Massachusetts [“Weekend Away,” p. 50], Whittemore was reminded of just how accessible its writers can be—as when Norton Juster gamely agreed to meet with a book club of grade school boys, including her son Will. “It was a big hit,” recalls Whittemore, senior editor of Amherst magazine. “And a decade-plus later, Will had a job at the assisted-living facility where Juster spent his last years. They happily continued the conversation.”

Growing up in the small town of New Haven, Vermont, Estey discovered his love of photography in capturing beautiful landscapes throughout the Green Mountain State. So it was a “full-circle moment” to photograph the rural Vermont home of Matt and Britt Witt [“‘Standing in the Old Ways,’” p. 28], founders of Red House bags and his close friends. This is the first Yankee assignment for Estey, whose client list also includes Food & Wine, Vermont Tourism, and Downeast Cider.

A photographer whose work has graced such publications as The Wall Street Journal and Garden & Gun, Haley turned her lens on Amherst, Massachusetts, for this issue’s “Weekend Away” [p. 50]. “One thing I love about my job is that occasionally it calls for my family to tag along, which was the case when we explored the Eric Carle Museum and a few other spots. Editorial photography can feel much like going on a field trip, so it’s extra special to experience that with them.”

Six years ago Yankee readers learned that a series of small strokes had forced Edie Clark to end her long-running “Mary’s Farm” column, and the response was as though a beloved family member had been taken from them. The letters and cards came flooding in, most of them carrying the same message: Your column was always the first thing I looked for.

Since then, letters for Edie have continued to flow to us at Yankee , and also to the nursing care facility where she lived until she passed away on July 17, 2024, at the age of 75. In her final years, Edie was unable to write, and even reading was difficult, but she kept that special essence that shone through in her writing: a love for friends who filled her life with happiness, and for the natural world she glimpsed from an outdoor patio where hummingbirds hovered.

I know Edie’s passing will deeply affect all who knew her, just as I know that her timeless columns and stories will endure into the future.

—Mel Allen

We at Yankee will publish a tribute to our friend and colleague Edie Clark in the November/December issue. Readers are invited to share their remembrances of her, too, by writing to editor@yankeepub.com. We will publish a selection of what we receive—Edie would love that.

On this amazing 15-night cruise, explore picturesque waterfront towns and admire the stunning natural landscapes that stretch out before you. In the comfort of your private balcony, bask in the beauty of the Thousand Islands region, adorned with stately mansions, fairytale castles, and historic lighthouses.

Explore Well ™

As the seasons transition from summer to fall, Maine ingredients and produce items to enjoy, and Maine is one of my favorite places to gather culinary inspiration! When the weather starts to cool, I’m always eager to break out my trusty Dutch oven and get to work on a big pot of soup. This Maine Cheddar, Potato & Corn Soup recipe starts with a variety of potatoes from a local farmstand for hearty autumnal flavors, and fresh sweet corn adds bright notes and color to the dish. The soup also features a sharp Maine cheddar cheese for a creamy richness, while the fragrant onions and leeks are caramelized and deglazed with a splash of Maine-cra ed beer. Save the rest of the beer to sip as you serve this comfort-food dish celebrating the seasonal flavors of Maine. —Kate Bowler

Kate Bowler is the creator of the award-winning food and lifestyle website Domestikatedlife.com and the author of the entertaining cookbook New England Invite: Fresh Feasts to Savor the Seasons. You can follow her @domestikateblog.

Hungry for More?

Looking to get inspired and try some delicious local Maine cheeses? The Maine Cheese Guild hosts this year’s Maine Cheese Festival on September 8 in Pi sfield, and Maine Open Creamery Day on October 13. For more culinary inspiration and seasonal flavors of Maine, check out VisitMaine.com.

SIGN UP HERE! Scan this QR code to subscribe to Bountiful: Maine’s Seasonal Food Journal, a culinary email from the Maine Office of Tourism.

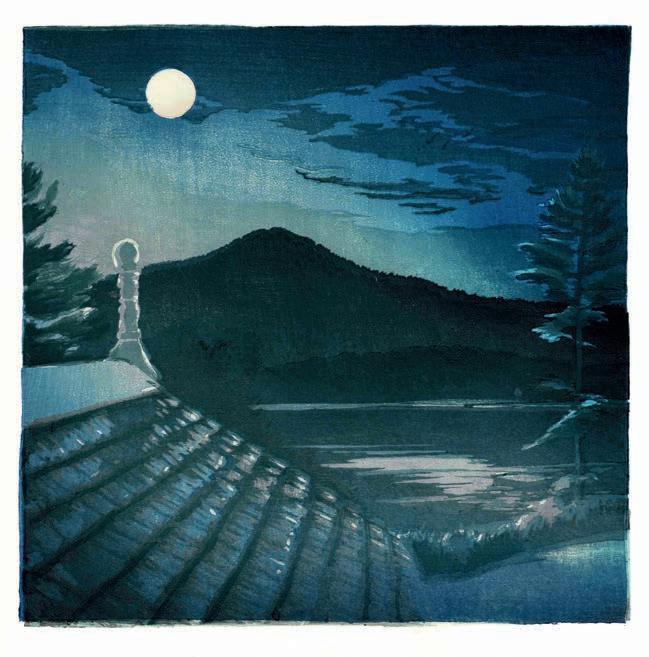

A call to see things anew by nature’s lamplight.

On a cold, clear October night, clouds race across the sky as if on a summer’s day. The clouds are full, billowing, with the full moon reflecting off them, creating a light almost as brilliant as that of the moon’s. The sky itself is a midnight blue, and the stars are as sharp as steel points. I have rarely seen such a dramatic sky.

On nights of a full moon, we are often inside our snug homes, asleep, or stashed in the connected rooms of the city, unable (even if the desire exists) to see past the blazing lights of the metropolis. But here, in the stillness of an autumn night, there are no distractions or interferences, and the event of a full moon can exhibit a pull similar to a tide or an appetite.

The moon rises, a big pink disc or creamy yellow, blood red—the color always slightly different as it inches up from behind the pines that edge the field. I go to the window as if called. The moon at the horizon is huge, an orb bearing down on us. As it moves higher in the sky, the color drains, fading to a bright white.

Early Native Americans devised their calendar around the phases of the moon. To them the moon was one of the most important aspects of their lives, around which everything that mattered to them revolved. They planted and harvested according to its phases, calculated their

days and nights according to its wisdom. Each month was the length of the moon’s cycle. Each month the name of the moon identified what mattered most that month. There were many variations. March was the Full Sap Moon, referring to the sap rising in the trees at that time of year. December was sometimes the Full Long Nights Moon, referring to the short days of that month. According to The Old Farmer’s Almanac , the October moon I see is the Full Hunter’s Moon.

I am reminded of all of this that night as the moon creates a scene of singular beauty and awe. Soft moonlight spills onto the floor and creates still, silent shadows across the room. From my window, the outline of my house spreads across the lawn below in dark moon shadow. The light is bright enough for a walk without a flashlight, and so I go out. Standing there, I realize that many people around the world are blind to this moon, the light of their television sets providing a strange parallel. Among other reasons, Native Americans revered the moon for the light that it gave them. Now we have so many sources of illumination, who needs the moon?

Whether or not we watch it or even see it, the moon still affects us deeply, the architect of our seasons, our tides, our storms. The Blue Moon, of course, is the occurrence of more than one full moon in a single month. But maybe we could borrow this and call all the moons from now on the Blue Moon—a sad moon, trying as it does to get our attention and remind us of what really matters.

This essay was originally published under the title “Blue Moon” in the October 2005 issue of Yankee.

Note: The author of this essay, beloved Yankee columnist Edie Clark, passed away the week that this issue went to press. You can find a remembrance by editor Mel Allen on p. 14, and look for a special tribute to Edie in the November/December issue of Yankee

A contraption so rare it’s been designated a National Historic Mechanical Engineering Landmark, the 19th-century steam-powered press at B.F. Clyde’s Cider Mill puts the squeeze on as much as 100 tons of apples a week.

For nearly a century and a half, B.F. Clyde’s Cider Mill has kept one of autumn’s sweetest traditions alive.

BY AMY TRAVERSO

PHOTOS BY ALLEGRA ANDERSON

ucked into the village of Old Mystic, Connecticut, B.F. Clyde’s Cider Mill looks like a vintage model railroad station inflated to life-size proportions. You half expect to see a locomotive pull up and unload a crowd in top hats and hoopskirts. A white Victorian with wine-colored trim, scalloped shingles, and a cupola, the mill even has a whistle that looks and sounds exactly like that of a steam train. Its high-decibel shriek signals to staff and visitors that the old-fashioned work of pressing apples into cider is about to begin—and everyone comes running.

Inside, the air is almost sticky with the aroma of apples, but underneath it there’s wood, leather, and oil, a blend unique to this place. “We are the last steam-powered cider mill in the United States,” says Josh Miner, a fifthgeneration member of the family that has owned Clyde’s since it was founded by Benjamin Franklin Clyde in 1881. Josh is shouting to be heard over the rhythmic clanking of the mill’s press, whose technology hails from the Garfield administration: pulleys and ropes, leather belts, wooden frames, cast iron gears. There’s no plastic in sight, save for the polypropylene pressing cloths and the bins they’re stored in.

On pressing days during the mill’s operating season, which runs from September through November, you can follow the whole process from the moment the truck pulls up filled with apples from the Hudson Valley. It tips its bed to send fruit on a conveyer belt to the basement, where the apple washer scrubs the fruit clean (a well-placed window offers a view). After washing, the apples climb two stories to the grinder, which sits right above the press. With the pull

of a wood lever, the grinder roars to life, churning the fruit into juicy pulp, which is then pressed between fabriclined wooden racks until the juice flows thick and sweet into the wooden gutters and down to a well.

The press is a thing of beauty, a mid-1890s Boomer & Boschert from Syracuse, New York. Josh’s great-great-

CLOCKWISE FROM LEFT: The tasting room at B.F. Clyde’s; sorting a fresh load of apples for the mill, which uses varieties ranging from Red Delicious and Empire to Ginger Gold; a detail of the 15-horsepower steam engine, built circa 1890 by Ames Iron Works; the fifth generation of family owners, Amy Harrison with her brothers, (FROM LEFT) Josh and John Miner.

great-grandfather bought the press and built the Victorian surround from a kit. “Some would have put the machinery in a barn,” Josh says, “but this is special.” Over the years, as more and more cider mills went out of business, his grandfather would travel around and buy any parts on offer. This library of spares allows B.F. Clyde’s to make repairs without needing to order custom parts.

The mill is still a family operation, with the current staff including the fourth, fifth, and sixth generations of B.F. Clyde’s descendants. “We still speak most of the time,” jokes John Miner, Josh’s brother. And the mill’s long history is visible in details like the old stoneware cider jugs hanging from the ceiling, and a post marked with the heights of grandchildren and greatgrandchildren dating back to 1978. But the family has also embraced change, adding flash pasteurization, a tasting room, and an underground pipe that

transports the freshly pressed juice to the mill’s store, where two doughnut robots and a cider slushie machine are continually in operation. (As you walk around the property, beware of influencers who may stop short in front of you to snap a photo of a doughnut perched on their slushie cup—a pairing so delicious-looking even Yankee ’s photographer couldn’t resist.)

The mill is also a magnet for the school-age set. “Every so often, I go around and see families, and it just grabs you by the heart,” says Amy Harrison, John and Josh’s sister. “We give them that place to make memories— the ones who come on opening day every year, and the ones who have been coming for 60 years.” She got her nursing license years ago and has worked in the field on and off, “but even when I was a nurse, I always wanted to be here,” she says. “This is where my heart is.” clydescidermill.com

Located along the Southern Maine coastline, our active, engaged community combines worry-free independent living with priority access to higher levels of on-site care—all for a predictable monthly fee.

Residents enjoy apartment, cottage, and estate home living in a community of friends, with all the benefits of Maine’s first and only nonprofit life plan retirement community.

(207) 883-8700 • Toll Free (888) 333-8711 15 Piper Road, Scarborough, ME 04074 • www.pipershores.org

How a salve created for Vermont dairy farmers became a viral skin-care sensation.

When it was launched in rural Vermont more than a century ago, Bag Balm was made for cows, a remedy for udders chapped by blustery New England winters. These days, apparently, it’s also made for TikTok.

The jelly-like salve concocted with lanolin and petroleum jelly is famously adaptable: Over the years, Bag Balm has been used as everything from diaper-rash cure to rust protectant to a paw conditioner for dogs. But it also was cruising under the radar as something of a beauty secret, with hereand-there mentions from celebrity fans like Shania Twain and Oprah—until a TikTok “skinfluencer” named Alix Earle helped make it a viral sensation

in 2022. After Earle touted it to her followers (now 7 million and counting) as a favorite remedy for facial dryness caused by harsh acne medication, other fans chimed in, with some even recommending Bag Balm for “slugging,” a trend involving slathering the face with Vaseline to seal in moisture.

“I was like, this sounds gross,” admits Libby Parent, president of Vermont’s Original Bag Balm, based in Lyndonville. “Are we sure we want to be part of that?”

Turns out: Yes, they did. Online sales tripled within a month of Earle’s post, and it soon became clear that the 125-year-old brand had achieved a marketing coup—getting the attention of the coveted Gen Z shopper—without

even trying. “It just sort of happened,” Parent says.

The company now uses its social media channels (including, as of 2022, TikTok) to tell Bag Balm’s origin story to a whole new audience. And to celebrate Bag Balm’s 125th anniversary this fall, there will be gold and other color variations on its iconic green tin, which has remained largely unchanged for generations.

Yet there’s only so much that one can, or would want, to do with a product that’s been living up to its promise since 1899. “There’s a lot of trendy ingredients in skin care, and there’s been consumer burnout,” says Parent. “At the end of the day, we’ve just got a super-versatile product that works.” —Alyssa Giacobbe

If you’re widowed, divorced, or single-by choice, you owe it to yourself to discover how Edgewood can help you live a longer, healthier, happier life. Nearly half the residents here are just like you, and they’ll tell you: Edgewood is the best of all worlds.

You’ll find new friends around every corner while still enjoying all the privacy you want, when you want it. Learn something new or discover a hidden talent with a variety of classes and lifelong learning opportunities. And rest easy with a built-in support network, financial predictability, and priceless peace of mind.

“THE

Imagine a community built for freedom and choice. Where everything is within easy reach and friendships happen naturally. Imagine opening your life to new experiences, unexpected adventures, and myriad opportunities to focus on your well-being. Add in peace of mind with convenient services, amenities, and guaranteed priority access to innovative health care. Now imagine it’s all right outside your door, with a home that works for you, not the other way around.

Could The Baldwin be everything you’ve hoped for? Maybe it’s more. Choose one of the few brand-new apartment homes available before the waitlist becomes your only option. Call 603.699.0100 or go to TheBaldwinNH.org.

Less is more in this minimalist, tranquil home carved into a Vermont forest.

BY ANNIE GRAVES

BY CHADWICK ESTEY

Thanks to their home’s secluded location, Britt and Matt Witt chose not to put curtains or blinds on the large windows and glass doors that are central to the building’s design. “I much prefer the view of nature as a constant,” Britt says. OPPOSITE: Britt in the kitchen, whose stone floor tiles bring a “lived-in” feel to the space.

he house stands alone, in the center of a clearing: a simple white structure with dark window eyes, open to the sunny glade.

Behind, a mossy rock face, several feet high, creates nature’s own version of a stone wall, and the woods fan out for miles. The steep roof rises like prayer hands. Birdsong drops all around.

“I had this vision for so long about how I wanted this house to look,” says Britt Witt. “All the white, very reminiscent of the white steepled churches all over Vermont. We thought about it for what felt like years.”

The last time I saw Britt and her husband, Matt, was seven years ago, when they were ensconced in an expansive brick studio in Burlington, Vermont, making ruggedly beautiful waxed canvas bags under the name

Red House. Since then, the former Arizonans have weathered Covid; cleared the land they bought in 2016 on this precipitous ridge in Weybridge, Vermont; built their elegant, spare home on 23 acres; and finally moved in full-time, in 2022. They’ve also (just) sold their namesake “Red House,” in Shelburne, where they raised their kids, half an hour north of here.

“This is the Vermont we longed for when we moved here,” says Matt. “We were always looking and pricing, but it was insanely expensive—totally out of our grasp. So we ended up in a little house in Shelburne Village, which worked out great, with the kids walking across the street to the school.”

When they expanded their search beyond Chittenden County, this was the first property they looked at: affordable, nothing but dense woods, with a treacherous driveway winding skyward, and a sharp, lunging turn

ABOVE RIGHT: The couple’s love of the outdoors inspired the addition of a shower in the side yard. “Starting out our days here all spring and summer long is a true gift,” Britt says.

OPPOSITE: A high ceiling was another must-have feature, says Britt—“just giving us tons of space to let our energy and imaginations rise in.” The large open space is kept impressively toasty in winter by a woodstove, even though the home also has radiant floor heating.

they dubbed Dead Man’s Curve near the top. They eventually bought three of the five lots, and “dreamt on it, for four years,” says Matt. “We would come up here and have little gatherings with friends and set tables in the middle of the woods.” Britt points past the double glass doors, leading from the kitchen. “We homed in on that mossy rock wall. It was like Lord of the Rings, like Shire country.”

With a tight budget, they began talking to builders, getting quotes. “We drew this building on a piece of computer paper,” says Britt. “There was no architect. We had this vision of what we wanted. Then Matt called me one day, and he’s like, ‘Britt, I don’t think it’s going to work.’ The quotes weren’t in our budget, or if they were, they didn’t include electrical. Or a roof.”

And then, they found their guy; met him in Middlebury, over bagels and coffee. “We were sitting there,” Britt remembers, “and I asked, ‘So is the roof included?’ Yes, it’s turnkey. ‘ Can we do marble counters?’ Yeah, no problem. ‘Cabinets?’ Turnkey. ‘Toilet?’ Yes, guys, it’s turnkey. And it’s like, yes, yes, yes.”

Their budget helped keep the design simple. Two or three interior walls. No closets. “It keeps you honest in what you possess,” Matt says. “Everything has to have a place or a function. If it doesn’t, it’s not necessary.”

For inspiration, they drove around, literally. “Britt wanted to create this great room to mirror all of the churches we were driving by. Three to four windows on each side, big double doors. And she’s like—let’s make our church out in the woods.”

So how exactly did they design a great room? They found houses that inspired them. They had to learn what a pitch was. “We just picked one and held our breath,” Britt laughs. “We had no idea what we were doing. But that’s never stopped us before.” The ceilings are nine feet high in the kitchen; 22 to the peak in the living room. They settled on six lights for the Marvin casement windows, but agonized over whether it should be 12. Or two. They studied other people’s windows, roof pitches. And hand-flagged the boundary of their future home in the woods, tracking the sun, figuring out where the front of the house would go.

They broke ground on June 1, 2019. The house was “done” by November. Hundreds of details were decided in those months. And that, they emphasize, is the crux of everything.

“We decided to be really intentional with the fixtures, with the finishes, with the trim and the molding, and the doors we picked out. To take this simple space and just give it an energy that almost doesn’t belong,” Matt recalls.

“It’s the details that make all the difference,” Britt says. But nothing was more important than the gooseneck sink fixture, its brass now aged, sitting proudly at the center of the kitchen island. It was the first thing the couple bought, before they even broke ground. The whole house is built around it.

Britt’s dad lives in England, and that’s where she first learned about DeVOL Kitchens, makers of gorgeous bespoke kitchens. The bathroom lights are

also from DeVOL, but it’s this specific DeVOL faucet that sets the entire tone for a simple, elegant workspace, with a decidedly Shaker feel.

The kitchen floor is just as intentional. “I wanted something that looked like you brought in stones from outside, and that’s your floor,” Britt says. “Old, old English. I found a piece of quartzite, and knew this was it. When you’re building new, you need to have character. That’s why we did unlacquered brass on the kitchen faucet. The marble countertop gets a patina, too, and with the floor sometimes pieces chip off.”

ABOVE: Handcrafted by Vermont artisans, the wood shelving throughout the house was repurposed from the couple’s former Red House studio in Burlington.

ABOVE LEFT: Bath taps by Waterworks and pendant lighting from DeVOL Kitchens are among the thoughtfully chosen fixtures for the minimalist bathroom.

LEFT: At the heart of the Witts’ home is this DeVOL brass kitchen faucet, which they say helped inform all their other design choices.

Matt sees a connection to their Red House waxed canvas bags. “They age, too. A handbag that’s five years old looks totally different from when it was new. All this stuff as well. That was a shiny faucet; now it has character on it.”

Other details? The bathtub taps on a sprawling tub are from Waterworks, inspired by the Marlton Hotel in New York City, where they once stayed. And someday there will be an indoor shower, but meantime Matt has installed and hardscaped an outdoor hot/cold shower. “Shower season” runs May to November.

“It’s exactly what we wanted when we first came here,” Matt says softly, looking around the glowing space. It’s easy to imagine the seasons moving past these windows in a kaleidoscope of colors and images. Deer and birds. Foliage and snow. Light and more light. They’ve planted fruit trees and blueberry bushes, built raised garden boxes. “We want to stand in the old ways,” says Matt. Then he grins. “We’re going backward. We’re not going into the future, into the meta. We’re standing in the old ways. Our end goal—we jokingly say—is that we want our whole life to become projects and chores, all the time.”

Last winter, Britt says, she gave up artificial light at night. “We had candles and oil lamps all winter.” Matt muses, finishing the thought: “It’s like we have 150-year-old people inside of us, trying to get out.”

seamstress

Kelley’s

BY COURTNEY HOLLANDS

The fact that Katrina Kelley has a tattoo of a needle and thread snaking up the inside of her left forearm isn’t that surprising. She is, after all, the designer and sole seamstress behind the buzzy Newcastle, Maine–based Amphitrite Studio.

What is surprising is that she did the ink herself. “I got the tattoo machine as a gift for my 30th birthday,” says Kelley, 44, perched on a chair amid antiques and sewing equipment in her cozy home studio. “The focus on the art took away from the pain. It was a weird cancellation of properties, so it became just like drawing on myself.”

The more you get to know Kelley, however, this act of visceral self-expression starts to make sense. She has a relentless need to create, a need that drove her to launch Amphitrite Studio as an Etsy shop selling women’s linen clothing in 2012. Over time, Kelley shifted her focus to linen napkins, towels, tablecloths, and other

LEFT: Kelley uses two trusty machines to create her Amphitrite Studio textiles: for the inside seams, a Bernette serger, and for the finishing work, a Juki sewing machine ( PICTURED). “They are both workhorses and can easily put up with full sewing days,” she says. “I couldn’t make half as much as I do if I didn’t have them by my side!”

TOP: The Amphitrite Studio linen tea towel in dusty rose, one of Kelley’s favorite tones to work with.

home and kitchen textiles, a metamorphosis that became complete the December day in 2019 when restaurateur Erin French from the Lost Kitchen—yes, that Erin French—called to order aprons for her shop.

As luck had it, Kelley had been working on a café apron prototype. “I was like, Shut the front door,” she says, with a laugh. “They found me, called me, and wanted me to make something because they saw what I was trying to do … that was a big confidence-booster.”

Since then, the Amphitrite Studio aprons— long or short half aprons or full length with a cross-back in saturated earth and jewel tones— have become Kelley’s calling card. They’ve also helped put her on the map: The 2022 design book Remodelista in Maine included her studio in a who’s who of the state’s artisans. “The aprons are the biggest hit, but also the biggest pain to make,” Kelley says, explaining that they

require her to switch between multiple sewing machines, plus iron between each step. Still, she says all this with a twinkle in her eye, as if she always knew her meandering path would lead her here.

Kelley grew up in the Catskills, the youngest of four children. Her parents were hippies turned Jehovah’s Witnesses. Her mother, Kathlyn, retained an artistic streak and a homegrown ethos, making the family’s clothes, leading craft time, and teaching Kelley to sew at age 4. “My nursery was her sewing room,” she says. “I like to think that’s where I got my start.”

LEFT: “I love a chef who’s not afraid to wear white and truly use it! A wellused linen can remind you of all the memories and meals you’ve created,” says Kelley, whose apron designs took off after a nudge from top Maine chef Erin French.

RIGHT: Another Amphitrite Studio standout is this teal-striped tea towel made from sturdy 9-ounce “rough” linen. It was featured in the recently published design book Remodelista in Maine as one of 30 must-have Maine products for the home.

When Kelley was 14, she relocated with her mom to southern Maine, where the family had often spent summer vacations. She did homeschool and then trained to be a hairdresser, working as a colorist and also as a florist in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, before moving to a cabin in Damariscotta, Maine, in 2005. There, Kelley landed a job at a natural pet food store, which is where she met her nowhusband, Jeff, a customer, who encouraged Kelley to start her sewing business in 2012 and get her online associate degree in business.

The name Amphitrite—the goddess of the sea and the wife of Poseidon in Greek mythology—was a no-brainer from day one, she says. “I originally chose it for the strong feminine vibe with ties to the sea,” she says. “I’ve always been drawn to the sea. When I was a kid, I actually drowned and was out for over a minute at Old Orchard Beach…. Ever since then, I’ve had a healthy fear of the ocean that’s turned into a reverence for its strength.”

It’s no surprise, then, that Kelley counts nature among her inspirations. Her art is also shaped by loss—including the loss of her brother Kieth Napolitan, an accomplished Portsmouth chef who died from an overdose in

2014. “My grief threw me into making things that other chefs could use,” Kelley says. “It was this natural progression of, this is where my heart already is. I’m going to keep making more kitchen-inspired things.”

Kelley spends her days measuring, cutting, sewing, ironing, and packaging her wares for shipping. She creates fresh patterns when inspiration strikes, like the vintage-leaning apron with thinner ties she’s currently working on. Looking to repurpose the fabric scraps and elastic left over from making masks during the pandemic, she designed one of the newest additions to her line: linen dish covers that are not only stylish, but also a sustainable alternative to single-use plastic wrap.

And in warmer months, Kelley opens her showroom—a solar-powered camper parked in her Newcastle driveway—to visitors. That’s also where she styles and shoots photos for her website, newsletter, and social media.

Amphitrite Studio is truly a one-woman show, and Kelley says she wouldn’t want it any other way. “I’m sure you can tell by looking around that I’m not a simple person,” she says. “This is what I live and breathe. I have no idea how to be anything but creative.” amphitritestudio.com

Feather your nest with these New England–made textiles.

AMERICAN WOOLEN COMPANY: In 2014, American Woolen bought Warren Mills, the last U.S. mill capable of producing both woolen and worsted fabrics. Today, it not only sells these textiles to domestic designers, but also sews them into preppy throws. Stafford Springs, CT; americanwoolen.com

ANICHINI : Local craftspeople stitch fabrics from Portugal, Italy, Turkey, and other farflung places into shower curtains, meditation pillows, and kitchen linens for this Green Mountain State company’s “Made in America” collection. Tunbridge, VT; anichini.com

BATES MILL STORE/ MAINE HERITAGE WEAVERS: When the 151-year-old Bates Manufacturing Company shuttered in 2001, its former president, his daughter, and a few employees formed Maine Heritage Weavers to continue making the venerable manufacturer’s shabby-chic matelassé cotton bedspreads and coverlets. Monmouth, ME; batesmillstore.com

BRISTOL LOOMS: Set a sunny table with Maya Cordeiro’s coordinating brightly colored placemats, table runners, and napkins. Beyond the dining room, her handwoven baby blankets are especially sweet. Bristol, RI; bristollooms.com

MATOUK: One of the last vestiges of Fall River’s textile-making past, the Matouk factory turns out crisp sheets and plush towels favored by celebs, high-end interior designers, and luxury hotels the world over. Fall River, MA; matouk.com

• Chip and shred with power to spare

• Bigger engines that chew up the competition

• Built USA tough for smooth, reliable operation

DR® is the Leader in Leaf Vacs

• #1 in vacuum power and capacity

Stops a DR® Field and Brush Mower

• New PRO MAX model holds up to 450 gals.

• Up to 2X the power of the competition

• Walk-behind models available

• All tow-behind models newly redesigned with up to 20% more capacity

• Cut overgrown brush, tall field grass, and saplings up to 3" thick

• Commercial, Electric, Walkand Tow-Behind models available, including the NEW PRO MAX60T!

PHOTOS BY NICO SCHINCO

’ve baked professionally for 20 years, but over the past decade

I’ve made it my mission to make home baking easier and more accessible. My specialty is what I call the “snackable bake,” an easy-peasy sweet or savory treat that can be assembled in 20 minutes or less with nothing more than a whisk, a bowl, and a spatula. Recipes for snackable bakes call for just a handful of pantry-friendly ingredients, and the simple instructions always fit on a single page. I’ve published more than 200 such recipes in my most recent books, Snackable Bakes and my latest, Salty, Cheesy, Herby, Crispy Snackable Bakes , from which these recipes are excerpted.

While these recipes may be effortless to throw together, they’re just as delicious and celebration-worthy as their time-consuming brethren, the “project” bakes—those fussy dishes that require at least one trip to the grocery store, take hours to assemble, and often have several components. Project bakes are impressive and tasty, but for busy, hungry folks, “snackable” really is the name of the game. So, whether it’s Jenny’s Egg Puffs with Prosciutto Bottoms or Herby Yogurt Biscuits for breakfast, Black Bottom Cupcakes with Cream Cheese Filling for an after-school snack, Better-ThanApple-Pie Bars for a fun twist on a dinner-party dessert, or Spiced Pumpkin Snacking Cake with Fluffiest Chocolate Buttercream for a unique addition to the Thanksgiving spread, these recipes will (quickly!) satisfy all your baking needs no matter the day, time, or occasion.

JENNY’S EGG PUFFS WITH PROSCIUTTO BOTTOMS

I’ve known Jenny since I was a little kid, as our parents are old friends, and she makes a mean cheesy egg situation that I am obsessed with. I love that it calls for Muenster cheese and cottage cheese and cream cheese. And I also love that I thought to make it muffin-sized and to line each cavity with a slice of prosciutto. If you’re not a meat eater, you can bake the puffs in cupcake liners for a truly portable snack experience, or bake them directly in the greased tin for an extra-crispy bottom. Go to town with green chilies, chives, herbs, bacon bits, etc.

Cooking spray, for the muffin tin

12 slices prosciutto

4 large eggs, lightly beaten

½ cup whole milk

¼ cup unsalted butter, melted and slightly cooled

½ teaspoon baking powder

¼ teaspoon kosher salt

½ teaspoon freshly ground black pepper

¼ cup (33 grams) all-purpose flour

2 cups (200 grams) shredded Muenster, Monterey Jack, or low-moisture mozzarella

1 cup cottage cheese, 2 percent fat or higher

2 ounces full-fat cream cheese, cubed

Preheat your oven to 350°F. Generously grease a 12-well muffin tin with cooking spray. Line each well with a slice of prosciutto, folding it to make it snugly fit the bottom and sides of each cavity.

Whisk together the eggs, milk, and melted butter in a large bowl. Sprinkle the baking powder, salt, and pepper over the egg mixture and whisk to combine. Whisk in the flour and then the shredded cheese, cottage cheese, and cream cheese. Evenly pour the batter into the prosciutto-lined wells of the prepared tin (each will be pretty full).

Bake for 30 to 35 minutes, rotating at the halfway point, until a wooden skewer inserted in the center comes out clean.

Remove the tin from the oven and let cool briefly on a wire rack before running a knife around the edge of the muffin wells and removing the egg puffs. Let the puffs cool for at least 10 minutes and serve warm or at room temperature. Yields 12 puffs.

HERBY YOGURT BISCUITS

Looking for a simpler way to do biscuits, I tried making them with melted butter. They worked! The yogurt here adds wonderful tang and tenderness, resulting in a biscuit that splits easily (thanks to the website Serious Eats for the inspiration). A combo of woody herbs (such as thyme) and soft herbs (such as dill) works best here.

2 cups (260 grams) all-purpose flour, plus more for sprinkling

1 cup (130 grams) cake flour

1½ tablespoons granulated sugar

1 tablespoon baking powder

½ teaspoon baking soda

1 teaspoon plus ¹⁄ 8 teaspoon kosher salt

¼ cup finely chopped mixed fresh herbs, such as thyme and dill, plus 9 dill sprigs for decorating the biscuit tops

1 cup full-fat yogurt (regular, not Greek)

½ cup (1 stick) unsalted butter, melted and cooled slightly

1 large egg

Preheat your oven to 425°F. Line a baking sheet with parchment paper.

Whisk together the all-purpose flour, cake flour, sugar, baking powder,

baking soda, 1 teaspoon salt, and chopped herbs in a large bowl. In a 4-cup measuring cup or medium bowl, whisk together the yogurt and melted butter (don’t worry if the butter solidifies a little while you do this). Pour the yogurt mixture into the flour mixture and stir with a flexible spatula until no loose flour remains.

Turn out the dough onto a lightly floured work surface and sprinkle just a bit of flour on top. Pat out the dough into a 6-inch square, about 1½ inches tall. Using a bench scraper or a chef’s knife, cut the dough into nine square

biscuits and evenly space them on the prepared baking sheet.

In a small bowl, whisk together the egg and the remaining ⅛ teaspoon kosher salt. Brush each biscuit with this egg wash and decorate its top with a dill sprig.

Bake until the tops and bottoms of the biscuits are nicely browned, 17 to 20 minutes. Remove from the oven and let cool on the baking sheet for about 5 minutes before placing the biscuits on a serving plate. Enjoy with loads of softened salted butter. Yields 9 biscuits.

Apple pie is great, but apple pie bars are, well, better. I like Honeycrisp and Pink Ladies in these bars, but I won’t lie: Granny Smiths are my go-to. The crumb topping and crust can be made old-school style with your hands (always the best tools in the kitchen), but if you use your food processer, you will save time. The crumb topping and crust soften a bit on day two, and that is hardly a bad thing.

FOR THE TOPPING AND CRUST

Cooking spray or softened unsalted butter, for the pan

2 cups (260 grams) all-purpose flour, plus more for flouring your fingers

¾ cup granulated sugar

¼ teaspoon kosher salt

10 tablespoons cold unsalted butter, cubed

1 large egg

1 teaspoon vanilla extract

FOR THE FILLING

¼ cup plus 2 tablespoons granulated sugar

1½ tablespoons all-purpose flour

¾ teaspoon ground cinnamon

¼ teaspoon kosher salt

4–5 medium apples (about 1½ pounds total), peeled, cored, and thinly sliced (about ¼ inch thick)

1½ tablespoons fresh lemon juice

Confectioners’ sugar, for dusting

Preheat your oven to 375°F. Grease an 8-inch square cake pan with cooking spray or softened butter. Line the pan with a long piece of parchment paper that extends up and over two opposite sides of the pan.

To make the crumb topping and crust by hand, whisk together the flour, granulated sugar, and salt in a large bowl. Rub the butter into the dry ingredients using your fingers, until

(Continued on p. 102)

Step aside, apples: This flavorful fall fruit is ready for its star turn.

BY AMY TRAVERSO

STYLED AND PHOTOGRAPHED BY LIZ NEILY

Okay, pumpkin spice. Yeah, yeah, cider doughnut. This fall, let’s instead remember the versatile wonder that is the humble pear. I say “humble” because to say “things went pear-shaped” isn’t a compliment. To be described as “pearshaped” isn’t really one, either. But looks aside, this fruit has few equals when it’s ripe, exploding with flavor and dissolving into a nectar-like syrup on the tongue.

The following two recipes can make use of any variety of pear (since there are only about a dozen being grown in any volume in this country, you won’t be overwhelmed by options). And the pears you choose don’t even have to be ripe. The higher acidity of unripe fruit works better in many baked dishes, especially those with a sweet sauce, such as the sticky toffee puddings, or savory dishes like the sheet pan chicken. Plus, most supermarket pears are rock-solid and take days to ripen. Who wants to plan ahead for fruit? Enjoy it now, as is.

Walnuts, pears, and blue cheese: This classic combination is the perfect marriage of flavors. Here, I take the trio from the cheese tray to the sheet pan, using it as inspiration for an easy and delicious fall meal.

Now Airing on Public Television Stations Nationwide

4 bone-in, skin-on chicken thighs

1½ teaspoons fennel seeds, crushed (optional)

1 teaspoon plus ½ teaspoon kosher salt

½ teaspoon plus ¼ teaspoon freshly ground black pepper

3 large pears, unpeeled, cored, and cut into ½-inch-thick slices

1 medium red onion, cut into ½-inch-thick wedges

1 tablespoon olive oil

½ cup walnut halves

8 cups arugula or baby spinach leaves, washed and dried Juice of ½ lemon

2 ounces crumbled Gorgonzola or other blue cheese

Preheat your oven to 450°F and set a rack to the middle position. In a medium bowl, sprinkle the chicken with the fennel seeds, 1 teaspoon salt, and ½ teaspoon pepper. Toss to coat. Arrange on a large rimmed baking sheet. Add the pear slices, onion wedges, olive oil, and remaining salt and pepper to the bowl and toss to coat. Arrange the mixture around the chicken and transfer to the oven. Bake for 25 minutes. Scatter the walnuts around the baking sheet and cook for 5 more minutes. The chicken should be nicely browned and crisp. If not, bake a few

minutes more. Remove from oven. Arrange the arugula or spinach on a serving platter. Top with the pears, onions, and walnuts, and sprinkle lemon juice over all. Then top with the chicken thighs, sprinkle with blue cheese, and serve. Yields 4 servings.

The British use “pudding” to describe a variety of desserts, but by American standards, these little treats, which are baked in a muffin tin, are cakes. Sweet and moist (thanks to pureed dates), topped with pear slices and soaked in a rich toffee sauce, they’re the perfect finale to any meal.

2 medium unripe pears, peeled

³⁄4 cup chopped pitted dates (about 7 large dates)

½ teaspoon baking soda

¹⁄ 3 cup boiling water

¹⁄ 3 cup firmly packed light brown sugar

3 tablespoons unsalted butter

1 large egg

½ cup plus 2 tablespoons (80 grams) all-purpose flour

³⁄4 teaspoon kosher salt

½ teaspoon baking powder

FOR THE SAUCE

½ cup (1 stick) unsalted butter

1 cup firmly packed light brown sugar

¼ cup heavy cream ¼ teaspoon kosher salt

Preheat your oven to 350°F and set a rack to the middle position. Take a standard 12-cup muffin tin and spray 8 wells with nonstick baking spray (you won’t be using the rest). If you don’t have baking spray, you can grease them with butter and then dust with flour.

Stand a pear upright on a cutting board. Slice down each side so that you have four ¼-inch-thick slices of pear. Repeat with the second pear. Lay each slice, rounded-side down, into the center of a muffin cup. Set aside.

Put the dates in a small bowl with the baking soda. Pour the boiling water on top and stir so that the dates are submerged, then let the mixture sit for about 10 minutes while you make the batter.

Using a stand or handheld mixer, beat the brown sugar and butter on medium-high speed until creamy, about 1 minute, scraping down the sides of the bowl regularly. Add the egg and beat until blended. Sprinkle in the flour, salt, and baking powder and mix on low speed until evenly combined.

Puree the date mixture in a blender or with an immersion blender, then add it to the batter and mix on low speed until evenly combined.

Using a tablespoon, drop the batter into each of the prepared muffin cups, dividing it evenly. It will settle around the pear slices. Bake until the cakes are fragrant and spring back lightly when poked, 18 to 20 minutes. Let the cakes cool in the pan for 5 minutes before turning them out onto a cooling rack (hold the rack against the muffin tin, then flip).

Meanwhile, make the sauce: In a small saucepan, melt the butter. Add the brown sugar, cream, and salt and whisk until smooth.

Serve the puddings when they’re still a bit warm, spooning a generous amount of the sauce over them. Yields 8 servings.

Alive with both youth and a legacy of poets and scholars, this college town ranks among the most eclectic and invigorating in New England.

BY KATHARINE WHITTEMORE | PHOTOS BY MEGAN HALEY

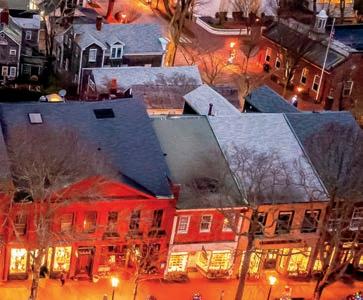

CLOCKWISE FROM TOP LEFT, OPPOSITE: The Eric Carle Museum of Picture Book Art; scratch-baked whoopie pies at Atkins Farms Country Market; an aerial view of the town common and the Amherst College campus; strolling through the rows at Mike’s Corn Maze; grilled filet mignon with a green peppercorn demi-glace at Sunderland’s Blue Heron Restaurant.

Amherst, Massachusetts, is a wonderfully wordy sort of place. Peppered with professors giving lectures and students furiously writing papers, this small city of about 38,000 (you pronounce it without the “h”: Am-urst) is home to three of the schools in the “Five College Area”: UMass Amherst, Amherst College, and Hampshire College. And if you mill around Amherst’s eclectic, brickand-maple-tree-lined downtown or cross the various campuses, you’ll likely overhear conversations stippled with words like particle physics and Kafka and gender studies—or, for that matter, TikTok.

Plenty of famous wordsmiths have lived in Amherst, too, most notably the em dash–admiring poet Emily Dickinson, but also Norton Juster, author of The Phantom Tollbooth , and Noah Webster, of Webster’s Dictionary fame, who helped found Amherst College. (A faded verdigris statue of the lexicographer, pompously arrayed in Roman senatorial garb, sits on the North Campus. Students like to adorn it with beanies and event fliers; during the pandemic, Noah wore a mask.)

This is a town, then, of academics and authors—but also activists. They regularly gather at Amherst’s busiest intersection, holding signs next to one of the electrical boxes painted by local artists. I’m partial to the turquoise-and-red box showing Emily Dickinson, with a line from one of her letters: “Pardon my sanity in a world insane.” These days, protesters sometimes march on Amherst Common when they, too, deem the world insane, and the results can go beyond words: Amherst is the second U.S. city, for instance, to start a reparations fund for Black residents. Still, verbosity is the town’s hallmark: Its 240-representative town meetings grew so notorious for their endless opining that, in 2018, the governing structure was streamlined to a 13-member board.

So now you get the joke stamped on coffee mugs sold in town: “Amherst, MA: Where only the ‘h’ is silent.”

LEFT: At the Emily Dickinson Museum, a pinecone is a polite reminder for ardent poetry fans to not actually sit at the writing desk in her bedroom. OPPOSITE: Trees dressed in turning leaves shade a North Pleasant Street sidewalk.

My office looks right onto Amherst Common, and when I tire of banging out my own words, I like to stroll the Amherst Writers Walk, which spirits pedestrians to the lovely, mostly clapboard homes of 12 writers, including Robert Frost, who taught at Amherst College for a spell. The tour’s apogee is the Emily Dickinson Museum, and this fall is a prime time to take in its two properties: The Homestead, where the poet dwelled in possibility, was restored in

2021, and The Evergreens reopened just this year—it’s the impressive Italianate home of Emily’s brother, Austin, and his wife, Susan, who was Emily’s great love.

While Amherst is a fine place for rambling (both the walking and talking varieties), it’s a fine place for eating, too. One thing that sets it apart from other Pioneer Valley towns is the large number of international students who live here, which has translated into a longer-than-average roster of cuisines, including eclectic pan-Asian (try Fresh Side for its terrific tea rolls), Vietnamese (there’s fetching pho at Miss Saigon), and Tibetan (as in MoMo Tibetan Restaurant, with its tasty MoMo dumplings with chili sauce).

But wait—“Brown Bear, Brown Bear, what do you see?” I see the Eric Carle Museum of Picture Book Art looking back at me. This light-filled modern venue, located right by Hampshire College, displays work by not only Carle but also fellow children’s book authors and illustrators, such as Mo Willems (Don’t Let the Pigeon Drive the Bus! ), who lives in nearby Northampton. It is part of Museums10, a collaboration started by the Five College Consortium to highlight area museums on campuses and off. Two are

The Archives: Amherst’s best-kept secret is a modern speakeasy that opened in 2022 with a faux-studious vibe (among the cocktail options: the Study Abroad). The address is 30 Boltwood Walk, but it’s intentionally tricky to find—dare yourself to try. Facebook

Atkins Farms Country Market: Here’s where to satisfy that seasonal hankering for fresh cider doughnuts—not to mention pumpkin whoopie pies and caramel apples. Plus: Look for the monthly tastings of wines, beers, and ciders. atkinsfarms.com

Blue Heron Restaurant:

The longtime owners of Blue Heron, set in the 1867 Old Town Hall in Sunderland, were 2022 James Beard Award semifinalists for Best Restaurateurs. The culinary results of their expertise (such as the irresistible truffled mushroom risotto) speak for themselves. blueherondining.com

Fresh Side: This Asian fusion cuisine—Thai, Korean, Vietnamese, and more—is innovative and healthy. Try the signature tea rolls or Five Spicy Beef Noodle Soup. There’s sidewalk dining in good weather. freshsideamherstma.com

Protocol: Opened in 2023, Protocol puts a cosmopolitan spin on farm-to-table, with a gleaming bar and copious greenery. Seasonal fare and great bar-food staples fill a menu that the chef calls “high-end and low-brow.” protocol-amherst.com

STAY

Inn on Boltwood: Stay in the heart of it all at this 1926 Colonial Revival hotel, where each of the 49 rooms has a view of either Amherst College or the town center. Its eco-friendly initiatives have earned Silver LEED status, a rare honor for a historic inn. innonboltwood.com

Returning Tide, Large Blue Sapphire Ring

Returning Tide, Medium Blue Sapphire Ring X3898...$1,950

Returning Tide

Pink Maine Tourmaline Ring G3972...$1,450

Returning Tide, Small Blue Sapphire Ring X4010...$1,350 The Gull Honey Gold Citrine & Diamond Ring G3950...$2,650

X4012...$2,650

From Sea to Shining Sea

Sunset Citrine & Diamond Ring X4516...$2,250

Crew West

SparHawk Maine Tourmaline & Diamond Ring G3650...$2,485

The Schooner

Blue Sapphire & Diamond Ring CMT2240...$3,138

Sea Sense

Burma Ruby & Diamond Ring CMT2189...$3,450

Fair Winds & Following Seas

Blue Sapphire & Diamond Ring CMT2269...$3,934

The Gull Blue Sapphire & Diamond Ring CMT2248...$6,000

To see 100 more Clipper Ship Trade Wind pieces of jewelry. Visit our website.

As you enter a room you move with ease. You’re silent, you turn, there is music to your fluidity.

Grace draws us closer. It is the move of the world class gymnast. It is the curve and curl, the twirl at your landing with a smile. The ring you wear is a touch of heaven. It is reaching up to the whisper of an angel.

As you chose to wear this ring your presence is the soul of the artist. Your ring is pure poetry.

To see more of our Clipper Ship Trade Wind Collection go to www.crossjewelers.com/collection/trade-wind or scan this QR Code with your smartphone camera to go directly to see The Clipper Ship Trade Wind Jewelry Collection.

at Amherst College, both free to the public: The Beneski Museum of Natural History has the skeleton of a Columbian mammoth, plus eerie casts of hundreds of dinosaur footprints from the banks of the Connecticut, while the Mead Art Museum displays 5,000 years of artworks and boasts an entire 1611 manor room (stained glass, walnut, lots of crests) brought here from England.

It’s surprising that a town this owlish (Amherst Books, by the way, is an excellent indie bookstore) can also work for night owls.

You’ll find live music, dance, comedy, story slams, and more at The Drake, a recently debuted performance venue named for a long-gone local hotel. Just around the corner is Amherst Cinema, one of the best independent movie theaters in New England. And the UMass Amherst Fine Arts Center hosts top live acts such as the Peking Acrobats, the Mingus Dynasty jazz band, and, coming this October, Dropkick Murphys.

Amid all its culture, Amherst also has a high nature GPA. There are lots of easy walking options and hiking destinations, including Hadley’s Skinner State Park, where the Summit House on Mount Holyoke features the most beautiful panoramic view of the area. In Amherst, the Hitchcock Center for the Environment offers looping paths through the woods and a great educational visitors center. Then there’s the Amherst College Wildlife Sanctuary, with trails through 500 acres filled with forest, wetlands, and nearly 100 student-monitored nesting boxes occupied by wrens, bluebirds, and more. On one trail, you’ll stumble across a mailbox, as oddly marvelous a sight as, well, a phantom tollbooth. The box is marked “Free Poetry.” Read the words inside, then leave some of your own. That’s the Amherst way.

Amherst Cinema: Offering classics, indies, and National Theatre Live films, this movie house urges you to “See Something Different!”— which could mean bellylaughing at 1959’s Some Like It Hot or quietly weeping at Wim Wenders’s 2023 Perfect Days. Oh, and they serve wine and beer at the high-end snack bar, too. amherstcinema.org

The Drake: Partly funded by the town, this music venue opened in 2022 and quickly drew crowds with such acts as Dinosaur Jr., Regina Carter, and Roomful of Blues. thedrakeamherst.org

Emily Dickinson Museum: Apart from tours, the museum also hosts engaging events such as September’s “Tell It Slant ” poetry festival, which features a group reading of all 1,789 of Dickinson’s poems. Bonus: The creators of the TV series Dickinson recently gave the museum a number of the show’s costumes. emilydickinsonmuseum.org

Eric Carle Museum of Picture Book Art: Carle’s beautiful illustrations from The Very Hungry Caterpillar and other childhood classics share the spotlight with rotating exhibits (this fall, look for the work of Brazilian illustrator Roger Mello), as well as kid-friendly art projects and storytelling sessions. carlemuseum.org

Mike’s Maze: Wagon rides, pedal carts, potato cannons, a playground, a petting zoo, and a wildly inventive eight-acre corn maze are this Sunderland attraction’s ingredients for cooking up a perfect autumn play day. mikesmaze.com

Skinner State Park: Hike or drive to the top of Mount Holyoke, crowned by a former 19th-century hotel, and soak up the summit views of jewel-toned foliage and the Connecticut River Valley. mass.gov/locations/ skinner-state-park

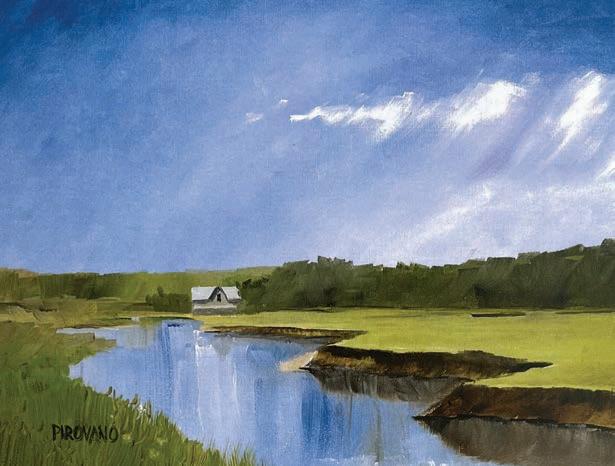

This Forrest Pirovano painting is of a salt marsh on Cape Cod

While the sandy beaches of Cape Cod often get all the attention, a natural beauty lurks in the background that often gets overlooked. Cape Cod’s salt marshes provide miles of natural beauty while offering a safe habitat for several wildlife species and protecting the shores from erosion. Fish, turtles, and birds, including rare species like the eastern box turtle, least tern, and river herring come to the marshes for nesting and feeding. For people, these coastal areas provide not only picturesque views, but also a welcome buffer against stormy weather and a natural filter for pollutants. Next time you are exploring Cape Cod, take a minute to appreciate the beauty and importance of the local salt marshes.

This exquisite print is bordered by a museum-quality white-on-white double mat, measuring 11x14 inches. Framed in either a black or white 1-½ inch deep wood frame, this limited-edition print measures 12-¼ inches high x 15-¼ inches wide and is priced at only $149. Matted but unframed the price for this print is $109. Prices include shipping and packaging.

Forrest Pirovano is a Cape Cod artist. His paintings capture the picturesque landscape and seascapes of the Cape which have a universal appeal. His paintings often include the many antique wooden sailboats and picturesque lighthouses that are home to Cape Cod.

FORREST PIROVANO, artist

P.O. Box 1011 • Mashpee, MA 02649

Visit our studio in Mashpee Commons, Cape Cod

All major credit cards are welcome. Please send card name, card number, expiration date, code number & billing zip code. Checks are also accepted.…Or you can call Forrest at 781-858-3691.…Or you can pay through our website www.forrestcapecodpaintings.com

Among the best drives you can take this fall are the ones that lead you to a colorful and bountiful New England farmers’ market.

COMPILED

BY

BILL SCHELLER

COVENTRY FARMERS’ MARKET:

Tucked between Willimantic and Storrs, Connecticut’s largest farmers’ market takes place Sundays at the Hale Homestead, the 1755 birthplace of patriot Nathan Hale. Locally grown produce and homemade treats abound, and the schedule is packed with special events including a pumpkin harvest celebration, a holiday market, and Dog Day, which features pup-related events and treats—and even rescue dogs to adopt. Depending on when you visit, you might also learn about 18th-century hearth

cooking and the games Nathan Hale played here as a boy. coventryfarmersmarket.org

DANBURY FARMERS’ MARKET: Danbury might have earned renown as the “Hat City” in its manufacturing heyday, but farming still looms large in southwestern Connecticut. A cornucopia of local produce spills onto Danbury Green on Saturdays, with heritage growers such as South Glastonbury’s Killam & Bassette Farmstead and the ninth-generation Mitchell Farm being joined by newcomers offering microgreens, CBD salves, and fresh-ground coffee. Check the website for recipes using the latest harvests. danburyfarmersmarket.org

GREENWICH FARMERS’ MARKET: Yes, it’s a commuter parking lot, and yes, that’s I-95 across the way, but the countryside comes to Greenwich on Saturdays, bringing fresh produce, artisan breads, organic raw cold-pressed juices, microgreens and edible flowers, lamb and chicken, and—offered throughout the season as they ripen—stone fruit and berries from South Glastonbury’s Woodland Farm. The apple pie from Oronoque Farms Bakery has been voted best in Connecticut. greenwichfarmersmarketct.com

(Continued on p. 108)

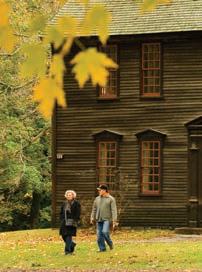

This little pocket of rural New Hampshire just might be the best and least-crowded foliage destination in New England.

BY MEL ALLEN | PHOTOS BY OLIVER PARINI

New Hampshire’s Route 101 is the main east-west highway through the Monadnock Region, but it can still feel like a country road when it rolls through an unspoiled autumn vista like this one, at

n my 45th autumn in the Monadnock Region since I first arrived here one October, I ask myself: Where would I take a friend who has never been to this beguiling place tucked into southwestern New Hampshire? And this is my answer. Here is where we’d go.

Let’s begin on high, looking for hawks. We drive up a twisting 1.3-mile road at Miller State Park to reach the 2,290-foot summit of Pack Monadnock, the little sibling of the mountain for which this region is named. The park lies four miles east of downtown Peterborough, and we will soon stop there—but now, on a brisk fall morning, we look outward and upward.

The wind swirls, the air cools, and color sweeps across the landscape below us, visible through summit clearings. A sign points to an outcropping where on clear days you can see all the way to Boston, 75 miles distant. Another sign leads you to a view of Mount Monadnock itself. “The mountain that stands alone” looms to the west, in the town of Jaffrey; for two centuries, the stark bald summit of this signature peak has enticed hundreds of thousands of visitors to climb to the top.

Another day, we might join them on one of Monadnock’s many trails, but this morning we’re headed for the “hawk watch” observation deck. The thermals above Pack Monadnock make this a key point in a raptor migration highway, attracting crowds of hawks as they wing their way southward each autumn. A few years ago, watchers counted more than 5,000 on a single day. Naturalists from the Harris Center for Conservation Education in nearby Hancock often will be on hand to identify and talk about the soaring hawks, falcons, and eagles that keep our eyes skyward.

And this is how many people first come to know the Monadnock Region: from mountain summits with sweeping views that take in forests and lakes and distant villages. But those of us who live here know it for the intimacy of small towns with waterways too numerous to name. We know it for slow drives in fresh air. And for the country lanes where we walk and bike, the trails we hike, the ponds and rivers we paddle. But we also know it for sitting, for taking our ease by town greens and stone walls and at cafés, watching the business of a

town unfold; and for driving endless curves, ever alert for the unexpected. We know it for the artists and musicians and chefs and artisan bakers who have settled here, giving travelers new reasons to visit out-of-the-way places that once were all but forgotten.

So come meander with me. We will start from Peterborough, my hometown, and loop southward and then north and west before returning. The next day we will set off from Keene, the region’s only city, with some 23,000 residents. On each drive we’ll stop often, and as day passes easily into twilight, we will wonder where the time went.

For me, Peterborough defines the Monadnock Region more than any other of its nearly 40 towns. Just before you reach the town from

the east, the road opens up to a view of Mount Monadnock that is both an invitation and a promise. Here is the peace and beauty that for more than a century has inspired thousands of writers, painters, filmmakers, and other art ists to create masterpieces in their cabins at MacDowell, one of the oldest artist residency programs in the country. You can feel that inspiration as you stroll among Peterborough’s shops, restaurants, and parks, accompanied by the music of two rivers coursing through town. To my mind, the most memorable kind of foli age display is a single tree erupting with color, and the tall maple in Depot Square will stop you cold. You will know the one I mean—right by the walking bridge next to Bowerbird & Friends, a gem of an antiques and decor shop. We could pass hours exploring in town, but instead a sweet drive takes us through villages that connect one to the next like a ribbon

through forest and farmland and old homes fronting country roads. We first come to the center of Temple, home to America’s oldest town band, and pause to visit the Old Burying Ground, where the early settlers lie in the most bucolic final resting place you could imagine. Next comes a slight detour to Ben’s Sugar Shack and the Maple Station Market, after which you’ll never think of maple syrup (and fresh maple doughnuts) the same way again.

The road climbs on the way to Hilltop Café in Wilton; at times it feels as if we are driving into the clouds hanging over the meadows. The risk of stopping at the café is that with a setting so lovely and peaceful, and food so satisfying, we’ll be reluctant to leave. But leave we must, so we follow the Souhegan River to the turn to visit Frye’s Measure Mill, a historic Wilton landmark where Shaker- and colonial-style wooden boxes have been made since 1858.

We pass through Lyndeborough and Greenfield before stopping in Francestown. If you can’t come here for foliage season, visit on Labor Day, when Francestown puts on a celebration unlike any I know, with parade floats