Katja Ehrenberg | Holger Jan Schmidt

Katja Ehrenberg | Holger Jan Schmidt

Mental health and stress behind the scenes of the live music, festival and event industry

Katja Ehrenberg | Holger Jan Schmidt

First Edition: December 2020

© Katja Ehrenberg and Holger Jan Schmidt

Layout

Eva Witten | Köln | info@evawitten.de

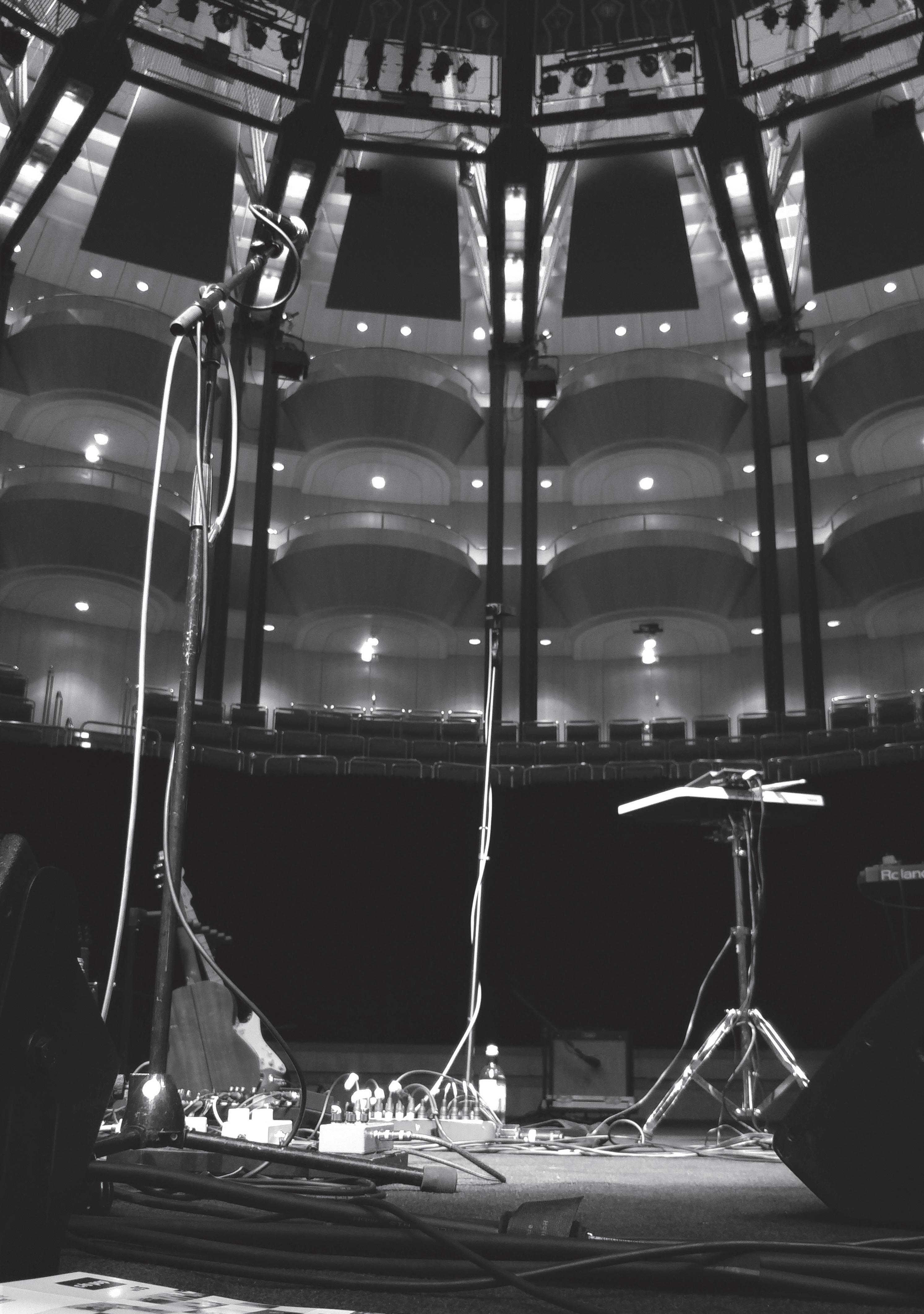

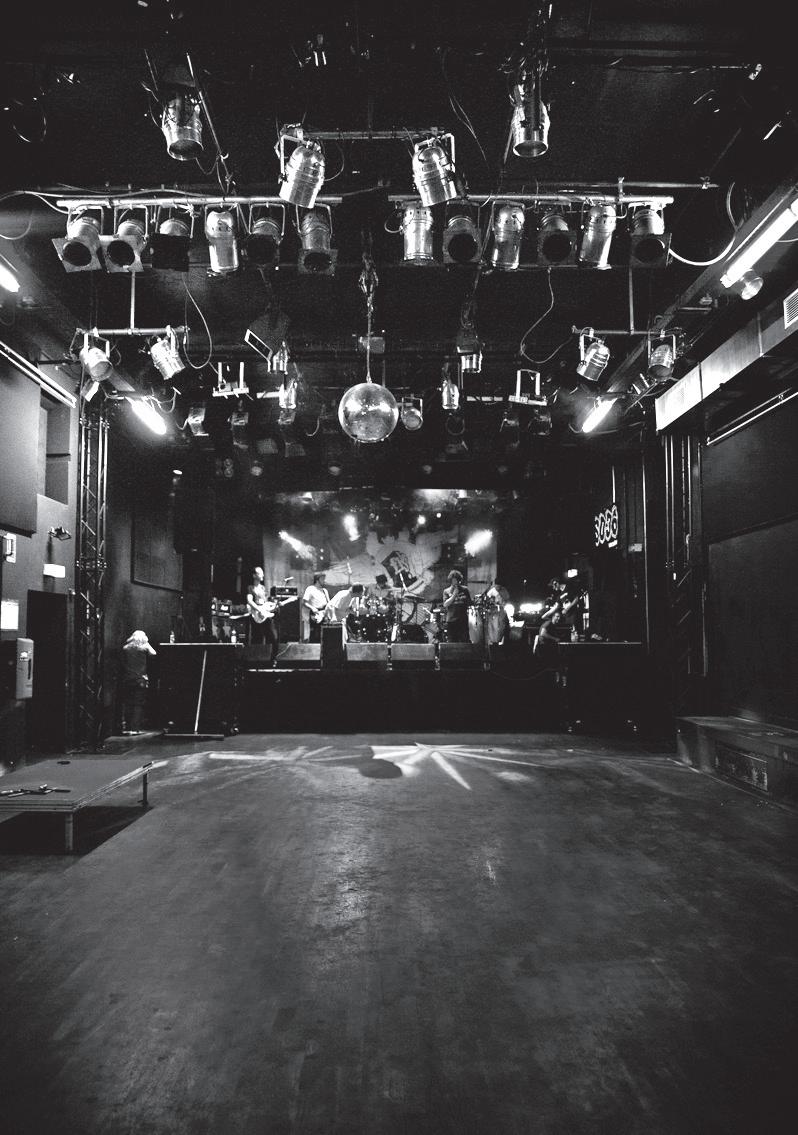

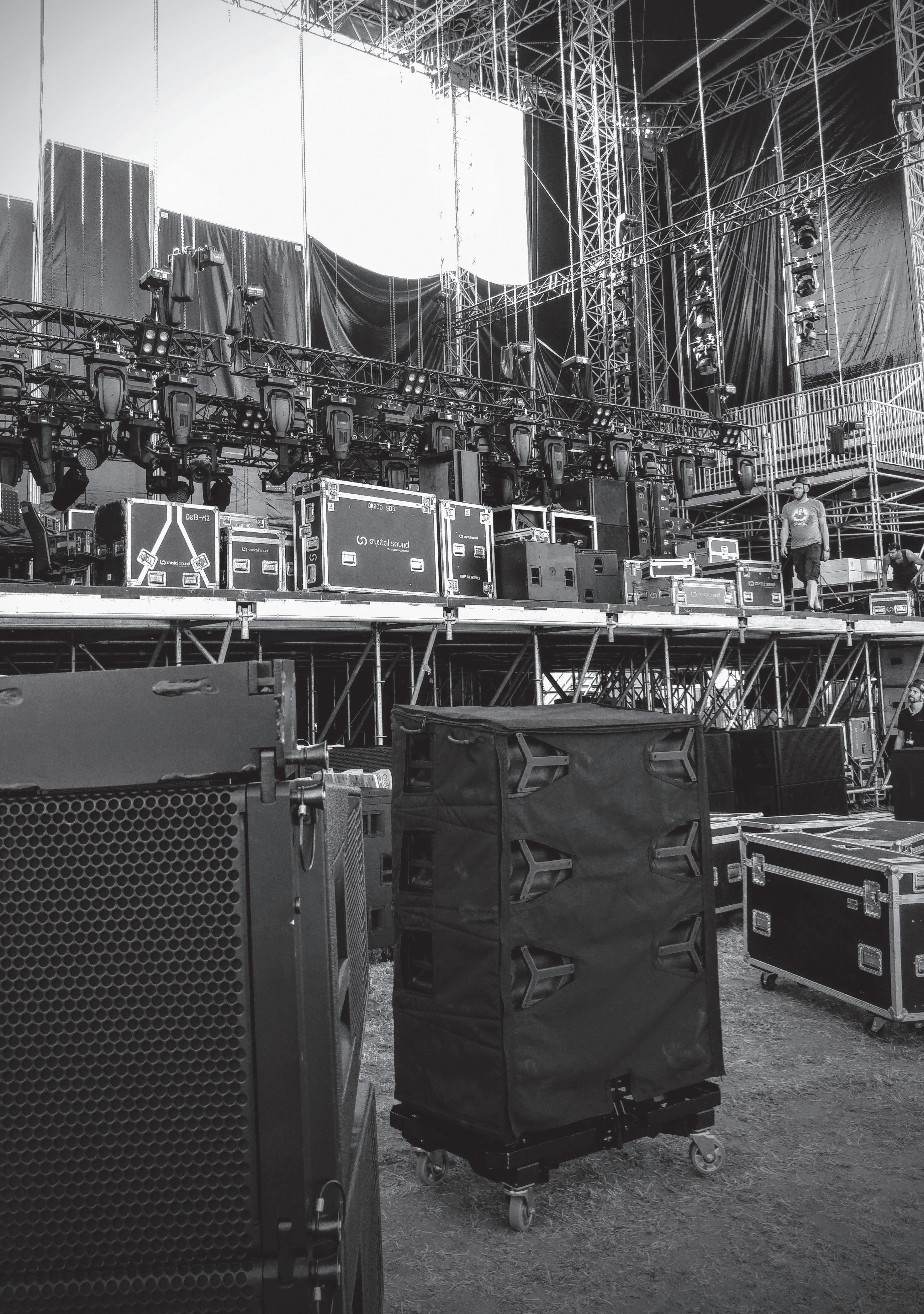

All photos in this book were taken by Svenja Klemp and Holger Jan Schmidt. Please enjoy and keep in mind that the people who can be seen in these pictures are not our protagonists and interviewees. The pictures show the world of festivals, concerts and tours from the inside. Just as we chose to focus on the people behind the scenes for the book, we also decided on a photographic view from rather unusual perspectives for illustration: from behind the mixing desk, at the side of the stage, through empty clubs or across the backstage areas and dressing rooms. We hope to convey a little bit of the special atmosphere of our working habitat in this way.

All authors’ proceeds from the sale of this book will be spent on projects further promoting the visibility of the issue and supportive structures within the sector.

Support

We are very grateful for the kind support of Fresenius University of Applied Sciences Cologne (Business & Media Faculty) who covered a substantial part of the dispenses involved in the entire process, and to YOUROPE - The European Festival Association for supporting print production and inspiring this project in many ways.

This book is dedicated to the innumerable people who you normally cannot see, but without whom the stars could never shine on stage.

Søren Kottal Eskildsen: Implementing a healthier culture around failures.

Annika Rudolph: It is okay not to feel okay.

Fruzsina Szép: I can do things only with passion and love.

Michał Wójcik: How many songs about depression can you actually write?

Philippe Cornu: Discover your passions and live them.

Falco Zanini: If you’re planning a tour, please think about the crew.

Jelena Jung: Just stay in the here and now.

Jovanka Stankovic-Lozo, Marina Kolaric: Someone to talk to for those in need.

This is not the first time the beginning of a book is the last part to be written. But there probably are very few cases when the world has changed so much during the course of a project. We started with the intention to paint a picture of how those active in our beloved industry, who are responsible for making the magic happen that fills millions of people‘s hearts with joy, deal with the challenges of mental health and stress. We wanted to raise awareness by telling personal stories and talking in-depth to various people from all over Europe – people with very different ages, jobs, experiences, approaches, tasks and responsibilities. And that is exactly what we did. But when we were done with all those inspiring, touching and remarkable interviews the biggest stress test for all of us (not only) in the live music, events, festival and creative sector struck as unexpected as it was unprecedented. But let us talk about that later and start with those times when all of this was not even to be expected.

„In the flinty light, it‘s midnight, and stars collide Shadows run, in full flight, to run, seek and hide

I‘m still not sure what part I play, in this shadow play…“

Rory Gallagher (1978)

On November 15th 2016 I was leaving Fresenius University of Applied Sciences in Cologne heading towards its department in Düsseldorf. At that point in time I was 44 and looked back at a history of 25 years with festivals, bands and music. I always did and still do many different things for a living, since I realised that incomprehensibly and brazenly the rockstar career I had envisioned for myself was not going to happen. I worked my way up from stagehand to director and promoter of my hometown festival RhEINKULTUR. Besides that and afterwards I was a booker, agent, stage or production manager, international networker, consultant and marketeer in many different projects and for several festivals and events. One of my jobs was being a lecturer for sustainable festival and event management, and I gave my classes at the universities in the morning and afternoon with enough time in between for my trip along the river Rhine from city to city. Like every week I drove on the nearby Autobahn towards Düsseldorf and sped up with a sandwich in my hand.

A couple of minutes and bites later something strange happened to me. It felt like a spasm in my left chest pulling over my shoulder into my arm and I suddenly felt really hot and somewhat dizzy. I still clearly remember today that I drove at about 130km/h and thought: “Is this a heart attack? If you pass out right now, it’s over…“ Somehow I managed to move correctly from the fast lane to the hard shoulder. There I stopped with hazard lights, racing heart and trembling jaw, let the window down and gasped for air while the other cars were flashing by. Long story short, I slowly went from there to the exit ahead of me, to a close by parking lot and from there to the fire station around the corner. They put me in an ambulance to a hospital where I was tested twice for a heart attack. Negative –instead they asked me whether I was a competitive athlete because the results of all the tests made were so brilliant. I was surprised, because “athlete” is something I never heard anyone say about me before (and after), and went home with a really good new story to tell.

The next week I held my lecture in Cologne again, got in the car and left for Düsseldorf. At the same spot on the Autobahn it happened again, differently though. I felt like a saucepan boiling over. I got hot and cold at the same time and made my way to the university in Düsseldorf, shivering and with air blowing in through an open window. The last part of the way was a tunnel under the old town and I almost freaked out driving through it, but got there safely. Somehow I finished the other lecture and was seriously afraid of going back. I had to stop twice on the way home and when I was almost there my feeling stabilised and I almost decided not to go to the hospital, which was my plan for the whole afternoon when I was feeling disastrous. They checked me and did not find a thing. Again. I was talking to the doctor afterwards when a young assistant passed by. She said from behind the other guy that maybe I should check with a psychiatrist. My first reaction was: „Why? I clearly have something physical. I can feel it.“ The doctor in charge did not react either and so I left not giving any more thought to what she said.

I better should have done that, because it could have meant that I could have realised that I experienced a panic attack that day. Triggered by the shock situation that caused fear of death the week before. Instead I got on an odyssey through all medical departments you can imagine seeing doctors who praised my health and results. The icing on that cake was another panic attack that I had on stage playing with my band in front of a sold out club full of cheering and singing fans. I did not mess up a song, but I was told I looked like a zombie on stage – no wonder, because I was struck where I was feeling safest. That was my natural habitat and it did not feel safe for the next months to come. The medical odyssee had one main advantage though. While I was checked thoroughly on almost every level with the result that I got disappointed, because nobody was able to tell me what was up, I took the chance to find a psychotherapist to address my fear of flying. Which actually is not the best thing to have when you are an international networker visiting festivals and speaking at conferences all over Europe. Being self-employed in that case came in pretty handy, because my flexibility in terms of time was the only reason to get an appointment within a couple of days.

It took almost three months until I was finally redeemed after a time of uncertainty with everything from magnetic resonance imaging to taking muscle relaxants and the joys of physical therapy due to my back being so tense it hurt and caused dizziness. That day I was sitting in the next doctor‘s office, this time it was one of a neurologist who also happens to practice as a psychiatrist, and I heard her say: „We can do the EEG you’re here for of course, but what you told me just sounds like panic attacks.“ When I left the building my back relaxed for the first time in months and when I saw the psy-

chotherapist the next time I said: „There‘s something else on our to-do-list ...“ and we got to work. In the meantime the world did not stand still though. Unsurprisingly, only then do you begin to appreciate the luxury of everything going normally until it is no longer the case – especially when it comes to one’s own health. And it quickly happens that you not only stop functioning yourself, but that exactly that affects everything else. In the months of uncertainty I suddenly was frightened of deadlines approaching. The easiest things that I used to do on the side now took ages and I still remember not securing a very well-paid project because I simply needed the time to deal with myself. It felt unprofessional to me and all of that most certainly is predestined to leave a mark on one’s self-confidence. I found out that it takes a lot of time and effort to address these things.

When asked now what has changed since these days I have to say it is the way stress affects me, how I define stress and how I deal with it today. I definitely feel myself in a different way than before. In a nutshell I found out that I work like a cooking pot and all stress, positive as well as negative, goes in there adding on the heat – and at a certain point it boils over. Crazy enough, the main factor behind what is happening in that moment does not have to be visible at all because it could have happened in the past - you just do not have the resources left to face what is happening and a tiny bit too much causes the eruption.

„And I won‘t know where I‘m going ‘till I get there“

Stu Larsen (2014)

During the following weeks of therapy I learned a lot about stress, the circle of anxiety, breathing and most importantly: myself. I know there are many people hesitating to even think of psychotherapy as an option for themselves. I never had that feeling. The reason probably is that I know my mother saw a therapist when my parents got divorced. The person that always was the stronghold in my life looked for help in a situation that she could not cope with by herself. And that always seemed logical to me although I was still a child. If you break a leg, you do not get the crazy idea of somehow figuring this one out with yourself because it would be a sign of weakness to let a professional fix it. And as I firmly believe the brain is a not too unimportant part of my body I happily took on therapy, although it took some time for me to realise that it worked.

I know that sometimes I scare people by being very honest when answering small talk questions like „How are you?“. But since I do not tend to be a world-class liar, I mostly come out with the truth, which in almost half a century has proven to be quite beneficial. Incidentally, this openness also meant that I soon realised that I was anything but special. I share the exclusivity of a mental health issue with far more people than I have imagined and this can be quite a comforting insight - even if the manifestations of those issues are of course very different and often not comparable at all. But it soon opened a new level of communication even with friends I have known for years, because suddenly there was something else connecting us - namely the experience of dealing with a very personal challenge. At the same time I found out that for others very close to me - even those usually very empathic - it was very difficult to deal with the change that happened to me and the fact that I was reacting differently in certain situations. Some were irritated, others just forgot that there was an elephant in the room that only I could see. I had to learn how to react to this, because I cannot blame them. Yes, sure, I

always considered mental health a very important issue, but of course for those with issues and not for me. That is probably why I never let it get closer to me and why I did not react when the assistant in the hospital raised the subject. I would also not rule out that I have maneuvered through the china shop as effectively as a bull in comparable situations. But now I had my own issue.

I was the best example for the lack of awareness for the subject and its challenges we can find everywhere in our industry. And I found out that there were many situations in my private life but also in my professional life that added up to the point that the pot finally boiled over. To name just a few: The disappointments of a musician who never was able to take the decisive step. The boss who, in passing, launches the wisdom that in our job you cannot have a regular private life, let alone a relationship. The responsibility for all public communication around a tragic death within a festival without being trained in any way for such a case. The effects that a tense working atmosphere on a very personal level leaves behind in the context of a project running for decades. All of this I would have approached or processed differently knowing what I know now. It is of course utopian to think that we can prepare for all possible cases, but I am convinced without any doubt that more knowledge, understanding and acceptance of circumstances make an enormous difference. Somehow we managed to spend centuries of hard work placing the topic of mental health in the taboo corner. Then it is also up to us not to accept that state of affairs as given, but to work on this corner to disappear and deal with the reality. A reality that means that these things happen, that they can happen to everyone, that the responsibility for mental health issues does not necessarily lie within the person experiencing them, and that people simply are different, have different predispositions for whatever reason, and are differently resilient in different situations.

Luckily a main part of what I do is working with wonderful people from all over Europe on subjects like the sustainability of festivals and other events as well as social engagement in our sector. It did not take long until we managed to incorporate the topics of mental health, work-life-balance, responsible working conditions and self-care in our agenda giving us the chance to exchange experiences and raise awareness. It is not possible to suddenly sensitize an entire industry to such a topic with the snap of a finger, no matter how important it is. We have made that experience years ago in the context of environmental sustainability and climate change. It is a process that takes years, but it is a journey worth taking, because this really is about us. We can only perform best when we are at the top of our game and it is our task to create the perfect environment for that performance – together. And we have great opportunities to give the topic the appropriate space and framework. For a good decade, I have been curating conference programs, creating workshop formats and bringing people together so that they can find inspiration and inspire others. So it was only natural that we approach the topic of mental health and stress in our industry in this way too.

As luck would have it, the city of Prague plays an important role in this context, because three events took place there that ultimately led to the idea and the realisation of this book project. As with a number of other international industry meetings and conferences, we have addressed the topic in the Czech capital several times within one year. Let me reflect on two of those. I remember very well how we sat on the stage of Nouvelle Prague in November 2018 and told our stories to the attendees to show that it is possible to be successful in our industry, even though you have to or had to deal with depression, a burnout or panic attacks and the like. On that day, I asked the audience who has ever had an experience with mental health issues personally, in their family or professional environment. It was an unexpected eye-opener when the whole room raised their hand, the importance of the topic was never made more visible for me than in that very moment. The reactions to the session were also incredibly motivating and led to the fact that we came back half a year later to devote a whole day to the topic „work, life & us“ as part of the 8th International GO Group Workshop, an event for the wider festival family to exchange and learn from each other. This is where Prof. Dr. Katja Ehrenberg comes into play.

„And cars speed fast - out of here

And life goes past - again so near There goes the fear again… There goes the fear“

Doves (2002)

Inspirational stories have proven to be one of the best ways to successfully reach people in various contexts and across topics - in addition to well-delivered scientific contributions. Many of my colleagues really appreciate it when an entity from outside the industry presents a cross-industry topic in a way that is industry-specific. Katja can do that. She is a professor at Psychology School of the same university I worked for in Cologne. We got to know each other when she gave a wonderful presentation on group behaviour at another international workshop, which took place on Fresenius University campus in spring 2016 – just a couple of months before the incidents described above. Due to her participation in that event Katja was on my mailing list and frequently received a lot of festival related information not necessarily designed to bother her at all. Nevertheless she seemed to read it and in

early 2019 felt the urge to answer my first promotion mail for the „work, life & us“ day in Prague because this really concerned her true area of expertise. In fact, at this point I was looking for the right person who could explain to us how stress arises, what it causes and how to deal with it. And what could have been better for me than a professor who had already got to know our „weird family“ and despite or because of that offered to take on the part.

We had a special time in Prague, creating a very constructive, personal and intimate atmosphere to talk about general aspects, but also very private stories. At some point it got emotional, at some it was funny. At others it got sad and for some it might have even got a bit intimidating. But it was undeniably inspiring and before we left, Katja came up to me and asked how it would be if we tried to capture this mood and immortalise it in a book. We stayed in touch and soon agreed not to produce another guide on how to behave and deal with those affected or with the focus on the artists, because there are already impeccable offers available. Rather, we had in mind a mixture of basic knowledge and stories from the peer group, those behind the scenes - from festival director to stagehand and social media manager - which make clear that we are not alone with our challenges. Be it because you discover a change in yourself, because you are responsible for employees and colleagues or simply want to contribute to a generally positive climate of awareness and understanding in contrast to dealing with a supposed taboo topic. And we sincerely hope that we have managed to live up to this idea.

I already mentioned in the beginning that we had finished the interviews and a big part of the other chapters when all of a sudden the world was a different place – not only but especially for the live music, festival and cultural sector. Because that meant that our events, tours and concerts could no longer take place at all or only with very little capacity and under extensive restrictions. While we wanted to report on an industry that never sleeps at the beginning of the project, we suddenly found a sector that had almost completely come to a standstill and is put on hold to the day this prelude is written. From one day to another we found ourselves in a whole new situation of stress and pressure. For many, this is associated with a feeling of being lost, one of existential fear and of wanting to work but not being allowed to. There is a major threat to the whole industry and to the mental health of those in it in particular: To be cast on the sidelines without being responsible for it yourself while finding yourself and your profession that you love and identify with exposed to a massive deficit in appreciation. And at the same time to see how your own reserves and resources are dwindling without any concrete positive prospects.

Most certainly we will restart at some point again and our cultural impact and uplifting powers will be needed badly, but today we are in corona‘s second wave and have no idea when there will be a situation comparable to what we previously perceived as „normal“. We wish all our colleagues up and down the supply chain strength, support and the best of luck. Hopefully those who can make it happen will do whatever is necessary and possible to get those who were the first ones to be shut down and last ones to open up again safely through this crisis.

We had to adapt with our book like almost all of us had to do in the past months. Luckily we found a way to include the corona challenge and its effect on the lives of our dear interview partners in our book without overwhelming everything else with a topic that is most relevant today on one hand, but on the other cannot be allowed to dominate the whole project for all times. We are very happy that

we have succeeded in ensuring this additional part of the book in a way that builds on what is currently so often neglected in these challenging days: human connection and exchange. We approached our interview partners again and had them report in group discussions how they are doing, how they are coping with the situation and how things can continue.

It is our firm belief that there will be a day when we will talk about the importance of taking care of mental and physical wellbeing in our industry and personal lives again without the shadow of that virus falling upon us. A time when the „old“ priorities are back on top of the agenda, because they didn’t lose any of their relevance in the meantime. And of course we will also continue to work on ensuring that mental health enjoys a comparable priority as economic sustainability, because the latter is just not possible without the former in the long run. We will also give our best that the conscious handling of the different capabilities, skills and resilience of each individual in our industry becomes the new normal. This book is an important step on that journey at a special point in time and hopefully a helpful and informative one for all those in need and looking for a signpost in the right direction.

„Thoughts run wild, free as a child, into the night cross the screen a thin beam, of magic light Things they just don‘t look the same In this shadow play…“

Rory Gallagher (1978)

To end on a personal note it should come as no surprise that Katja is responsible for specialist knowledge and correct approaches to the sensitive topics in this project and is therefore responsible for the lion‘s share of the book, for which I am infinitely grateful to her. On the other hand, I mainly used my network to find the right mix of people to talk to and it is with greatest appreciation that I bow to the openness and cooperation of our interviewees for their most valuable contributions. I also kept an eye on the process from the target group’s perspective – because this is for you people out there in front, on and behind the stages - and contributed creatively to the book’s final concept and presentation, because that’s what we do for a living: being creative, making things possible and people look and sound good! Let‘s not stop to do so, but please don’t forget to - drumroll! - stay sound and check yourself.

Bonn, Germany, November 2020 Holger Jan Schmidt

Every industry has its highlights, its challenges, and its peculiarities. Every industry is special. For a start, we wish to cast a quick light on “normal” working conditions in the music and event management sector, which may be interesting to those who do not have profound insider knowledge as yet – and maybe also to those who do. In the very first subchapter, we will thus devote a few words to questions such as:

• What defines typical working conditions in the industry and their general context?

• What are the biggest demands and challenges resulting from these working conditions?

• What are sector-characteristic resources that motivate people and could compensate for these demands?

Next, we wish to provide an overview of the functional origin, core symptoms and dynamics of stress. Taking a look at the consequences for body, mind and social interactions as well as from an economic perspective will set the ground for a better understanding of its positive and negative effects. Stress in itself is not a disease and not even necessarily negative. In contrast, occasional stress may contribute to good performance as well as to physical and mental wellbeing. But high amounts of stress for longer periods of time can cause severe problems on different levels, as does also become obvious in the interviews we conducted. In the next subchapters, you will find some concise information on questions including

• In how far are stress reactions evolutionarily functional?

• What happens under stress and how comes that people react so differently to stressful situations?

• What are the most important consequences of chronic stress to our bodies, to our thinking and social behaviour, and at what cost do these consequences come for employers in particular and society in general?

Over and above these “normal”, yet severe consequences, stress may also contribute to serious mental health problems. So-called vulnerability-stress-models suggest that acute environmental stress can act as a trigger when meeting a predisposition. It can lead to anxiety states or depressive episodes, while without such an acute stress experience, the same predisposition may eventually have stayed below a critical threshold for a lifetime with regard to mental disease. Research indicates that people drawn to the creative sector oftentimes bring an enhanced vulnerability in exactly those areas (see chapter 1.5). It thus seems appropriate to cast a quick light on the most frequent and common mental health issues, in particular, as some terms from the field tend to be used in a blurred or inflationary way. The final subchapter of part 1 therefore provides a very basic overview on questions like:

• Which role does stress play in the manifestation of mental health issues?

• What, in a nutshell are typical characteristics of anxiety and panic disorders, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), substance abuse, burnout and workaholism?

• How can I determine if I – or someone close to me – need(s) professional help?

It is an inherent part of the problem that one loses the sense for or may even neglect one’s own health status under severe stress (e.g., when approaching a burnout). The checklist provided at the end of this first part is explicitly not intended for diagnostic purposes or to replace professional assessments, but simply meant to encourage you to regularly do a quick “sound-check” by yourself. This way, you may notice general alarm signs early enough and become less likely to ignore the bigger picture if symptoms co-occur, in which case you should seek professional advice by a help-line, general practitioner, psychologist or psychiatrist. But let us first take a general look at working conditions and their consequences.

Overly high demands at work can result in stress and drainage, eventually ending up in burnout. Too low requirements might also be a problem, eventually ending up in monotony and a so-called bore-out. Ideally, individuals feel moderately challenged and see their tasks as a chance to use, improve and further build their strengths. If demands and skills are in perfect, slightly teasing balance, we are most likely to experience flow. Flow can be described as a state of positive activation yet creative ease, a full immersion into a task while forgetting everything around you and the time seems to fly. Tasks like these typically include immediate feedback during performance, which renders them intrinsically rewarding (Nakamura & Czikszentmihalyi, 2009). Flow has first been described in the context of actively making music, arts, dancing or doing sports, but more recent research indicates equivalent flow experiences can occur at the workplace. Keeping things well-tuned in order to allow for flow actually seems particularly promising, if not vital, to everybody working in the creative sector.

Every job clearly has its demands and energy intense aspects, as well as its rewards and resources which recharge us. Work motivation, job satisfaction and performance outcomes largely depend upon the relative amount of and relationship between these and are subject to a number of popular models in work- and organisational as well as health psychology (e.g. Bakker & Demerouti, 2007; Hackman & Oldham, 1976).

Some classic demands according to relevant models and studies include (cf. Poppelreuter & Mierke, 2012)

• physical demands as a result from lifting heavy items or performing repetitive movements, shift work, exposure to noise, heat or cold, chemicals, etc.,

• emotional demands such as having to hide one’s true mood and feelings, e.g. when dealing with challenging customers or business partners, or being regularly confronted with others’ abuse, suffering or even death (e.g. in a refugee’s rescue, in a children’s cancer clinic, or in a scene where mental issues, substance abuse and suicides are rather frequent),

• very high expectancies and/or workload, insufficient recovery and extreme working hours, as resulting in work-home-conflict and loss of private social support by friends and/or family.

Some classic resources that may counterbalance these are

• autonomy, freedom to create and do things your own way and/or at your own pace,

• social support among colleagues and in teams, as well as social support by friends and family that encourage and value job engagement instead of questioning one’s activity,

• positive performance feedback by supervisors, customers, or significant others,

• inherent feelings of reason and meaningfulness, contribution and efficacy; doing something that has an impact.

Within the festival and event management business, there is by design a huge variety of different jobs. As in every industry, company owners and CEOs face a different level of responsibility up to existential financial threat, compared to employees who are in charge of a particular part, such as artist care and hospitality. Job profiles differ with regard to task-inherent pace, seasonal dynamics and other particular stress factors. However, there are some characteristics that more or less affect most people who take an active part in the live music business, on the negative as well as on the positive side. These are listed in the following Boxes 1 and 2.

Box 1: Risk factors typical to jobs in the festival and event sector.

• extreme work-loads and extreme working hours,

• irregular sleep schedule, sleep-deprivation, bad nutrition and other side-effects of frequent travel and road-life (eventually in addition the low budget = low comfort version),

• high levels of unpredictability (e.g., weather uncertainty for open air, security incidents),

• little opportunity to make up for mistakes or misfortune, bringing extreme performance pressure to deliver on point without delay,

• financial insecurity and risks for owners and freelancers; low wages in some fields,

• very high personal involvement and idealism; readiness to overspend and exploit oneself, a downside of high identification with and passion for one’s profession and known risk factor for burnout e.g. in social jobs, related also to

• emotional demands and strains (e.g. negotiating under high pressure, dealing with other people’s personal issues; difficulty to disentangle professional contacts and private friendships within the “festival family”, e.g. when saying “no” or doing unpaid professional favours),

• permanent availability and difficulty of psychological detachment in spare-time (“relentless business”; “the industry that never sleeps”),

• little understanding from people outside of the industry how “throwing parties” can be a stressful job; lack of empathy and support may eventually lessen social contacts with “outsiders”; friendships increasingly focussing on networks within the sector in turn makes detachment increasingly difficult.

On the positive side, there are at least as many factors which render the field very attractive in terms of job motivation and satisfaction. Likely resources and satisfiers are listed in Box 2.

Box 2: Benefits and resources typical to jobs in the festival and event sector.

• lots of autonomy in creating line-ups, sites and atmospheres according to one’s own personal ideas,

• openness to innovation and creative expression, options for playfully testing entirely new ideas, coming along with chances for personal growth,

• high levels of self-efficacy, i.e. the confidence and belief that one is able to make something happen (“Yes I can”), fostered also by

• strong, immediate and vibrant feedback resulting from successful events, when the concept and the magic work out and everybody enjoys themselves,

• finding meaning in creating cultural impact or setting political impulses, in particular with festivals as catalysts of social change,

• an informal work environment, low hierarchies, coming along with

• high social cohesion and team spirit, feeling of community across the industry,

• being part of something that connects people across borders and music genres,

• positive job image and reputation as resulting from working in the event sector and dealing with celebrities, travelling from one famous venue or festival to another, etc.

To sum up, from a work and organisational psychology point of view, the music and event management business forms a most interesting field. It is on the one hand characterised by quite a number of typical, maybe even some unique demands and stress factors. On the other hand, there are lots of aspects known to contribute to personal and joint fulfilment at work, rendering it largely a matter of passion or “calling” rather than just a job.

Over the last couple of years, public media have started to discuss mental health issues among famous musicians and athletes, slowly taking the subject into the public eye. Awareness is on the rise due to some celebrities’ coming-outs with heavy substance abuse, depression or burnout, and last but not least, sadly, due to a number of suicides. Yet, a look behind the scene is still hardly ever taken. The stress that comes along with making these celebrities’ performances possible in the first place, i.e., with being a production manager, booker, tour manager, roadie or light and sound engineer, with doing all kinds of promotion activities, event security, and so on has very rarely been subject to public awareness, let alone scientific studies (Odio, Walker & Kim, 2013).

One aim of this book is to make a first step towards shedding the spotlight on these crew members and fill this gap. With each band and artist, there are dozens of people working behind the scenes. Considering the relevance of the cultural sector for creating spaces where people can celebrate and enjoy music and arts together and exchange ideas on political and social issues, there is much more to it than feeding the magazines and social media channels or fulfilling a need to party. Events and festivals are most powerful in building positive contacts and overcoming dividing categories such as different languages, nationalities or religions. According to decades of research in social psychology, they therefore represent a most effective way to prevent or overcome prejudice and intergroup con-

flict (see Pettigrew & Tropp, 2008). Moreover, festivals oftentimes very explicitly aim to encourage awareness and responsibility for all kinds of social and environmental issues, which people may take home with them, eventually multiply within their networks, and thus contribute in a “guerrilla” manner to long-term change. Again, this is only possible thanks to all the people devoting their time and energy to the event management business, driven by a very idealistic spirit and lots of voluntary work.

Some say, stress is a modern disease. In a way it is, as stress levels seem to have increased considerably over the last decades. General pace keeps accelerating in many fields, and mutual expectations in business processes rise accordingly. Wherever there was natural turn-taking between more active and more relaxed periods, it seems to become replaced by a more and more relentless rat race. In particular, digital devices brought along the expectation of permanent availability and dissolved borders between work and private life. Helpful as they prove for many especially during corona-related lockdowns, they also contribute to a loss of structure in terms of time and space. Also, over the last decade, most working environments became increasingly complex and dynamically interconnected systems. In such systems, small changes in parameters at one point may have major consequences for a string of other points. Processes and results thus become extremely hard to predict. Teams and individuals are frequently required to shift plans in order to quickly adapt to sudden changes. It does not really matter if these changes emerge from new technology or media (e.g., streaming services), market prices (e.g., disruptively rising artist fees), competitors, shifts in political climate or customer demands, or whatever other, maybe less obvious impulses affecting the field. Taken together, it seems that working conditions in general, and in the music sector in particular, have recently become fairly more demanding and stressful.

From a meta perspective, however, one could argue that stress has always been part of human life. Environmental requirements were hardly any more predictable for our hunting and gathering stone-age ancestors. They did not know in advance either where some wild beast may attack, let alone when, nor whether supplies could feed them throughout the winter or weather breaks may force them to move on with the entire clan (Mierke & van Amern, 2019). These unpredictable incidents were of different quality from, say, a software crash or a headliner cancelling a festival, but not exactly less existentially threatening. Thus, we can assume that our species is evolutionarily well-prepared to deal with unforeseen challenges and the stress they cause. Our genes are the ones of those who survived and reproduced successfully nevertheless, the ones that were resilient and found ways to cope.

A considerable part of our physiological and mental “equipment” has not changed much over the last 40.000 years, in particular when it comes to survival in the face of danger. Yes, the content, shape and maybe also the intensity of stressors have changed, - but how we react and what can help us handle ourselves and the challenges around us in stressful situations has largely remained the same. Based on this reasoning, we believe that although most parts of this book were planned and written in pre-corona times, their message remains valid. The pandemic has shaken the world and the event sector. Concepts such as unpredictability, uncertainty, flexibility et cetera have gained a new momentum, and feelings that result may be overwhelming sometimes. Yet, in general, what helped to cope with stress before will also help to cope now.

What helped our ancestors to handle stress? Research has shown that two major factors matter here:

a) phases of alarm and action readiness must regularly be counterbalanced by phases of full relaxation in order to maintain physical and mental health (Kaluza, 2018), and

b) social support, that is, reliable acceptance and assistance from our “clan”, the ones close to us, which is one of the best known stress-buffers when it comes to maintaining physical and mental health under difficult conditions (Taylor, 2011).

Now what is stress? Back in 1936, stress research pioneer Hans Selye described a “general alarm of the organism when suddenly confronted with a critical situation. Since the syndrome as a whole seems to represent a generalised effort of the organism to adapt itself to new conditions, it might be termed the ‘general adaptation syndrome’.” (Selye, 1936, p. 32). Selye had observed that animals show very similar yet complex physiological and behavioural patterns, regardless whether the particular trigger stimulus was, say, sudden noise, cold, heat or a crowded cage. Another classic in this context is Cannon’s (1929, cited after Kaluza, 2018) early work on the short-term stress reaction, for which he coined the term “fight-or-flight mode”.

The fight-or-flight mode is mainly characterised by a high action readiness resulting from the release of hormones: Adrenaline and noradrenaline are expelled, leading to a rise in heart-rate and blood pressure as well as shallow, but more frequent breathing. Thereby, muscles get supplied with energy and oxygen, and muscle tension increases in order to either run or stand up to whatever attacks you. High activation may also cause sweating. Blood circulation concentrates on large muscle groups and inner organs, so that some people get cold hands and/or cold feet, which even has become a synonym for fear in many languages. Further physiological symptoms of an acute stress reaction are a dry mouth, stomach cramps, nausea or sudden loss of appetite, and/or an urge to go to the toilet. In extreme cases this can even turn into uncontrolled bladder release, the also proverbial “wetting one’s pants”. These latter symptoms are due to a “blockage” of digestion processes in order to fully focus on the situation at hand. Digestion is associated with relaxation, to be done once the threat is over, - after the hunt, so to say.

The interplay between activation- and relaxation-associated reaction patterns in our body is managed by the autonomous nervous system. Compared to the neo-cortex responsible for planning and analytic reasoning as the youngest, and the limbic system responsible for emotions, it is an evolutionarily very old structure of our neural equipment. Autonomous refers to the fact that these reactions are not subject to conscious control. Two main antagonists – the sympathetic and the parasympathetic system – and their interplay steer the complex and still not fully understood processes required for all basic body functions. We usually only take notice of these when they get out of hand (e.g. when blood sugar and insulin level become inappropriate, enzymes lack that are required to digest particular food components, such as gluten or lactose, and so on). It is most important for overall wellbeing that both components are stimulated appropriately, as illustrated in Figure 1.

Nowadays, we hardly ever fight or flight in the ancient meaning of the words. Yet, many people report getting very aggressive under threat, incidentally yelling at others or feeling an impulse to destroy something, to throw their phone against the wall, slam a door or kick something. Others feel an urge to immediately leave the situation, i.e. run out of wherever they are. So, our reactions are not that different after thousands of years, except that they are not very helpful anymore in most cases, in terms of goal-directed coping. A third reaction, freezing, is observed among people who have suffered traumatic events such as severe accidents, repeated (sexual) violence, torture, a lethal or very threatening diagnosis, or other experiences associated with feelings of profound helplessness and loss of control. Freezing or shock is thought to be similar to feigning death, a coping strategy used by some animals when facing predators they can neither flee nor fight.

Only recently a group of researchers criticised that almost all socio-biological stress research has been done with male animals – often rats – because cyclic hormone changes in females were considered a confound variable that could blur experimental results. However, female mammals may show systematically different reactions. As their chance of either being pregnant or caring for young ones is rather high, neither flight or fight seems a very feasible strategy under stress. Taylor and her colleagues (2000) argue that females therefore have developed a different pattern which they named “tend-and-befriend”. It is well-known from a wide range of studies that women increasingly seek social contact and support under stress. Social support, in turn, is well-known to very effectively buffer stress effects on physical and mental health, and the binding-hormone oxytocin provides a physiological basis for this. Studies show that supportive and comforting social contact reduces stress equally well for any gender - it just seems that females are somewhat more prone to seek it (Taylor, 2011).

Taken together, our organism means us well by providing adrenaline-driven energisers for fight-orflight, or by freezing us. The problem is that neither is very helpful when a city council rings to let you know your event cannot take place as planned due to security concerns. Your blood pressure rises, your hands get sweaty, and your mind gets blurry, as planning and reasoning abilities are not part of that ancient stress programme. Maybe you just sit there and stare at the phone (freeze); maybe the overall tension releases itself by yelling at the person calling, or at someone else (fight); or maybe you feel an urge to just run out of the office (flight). None of this will solve your problem, although you’ll probably feel a bit better afterwards. Also, not every stressor triggers the same standard reaction in everybody.

Stress is neither simply a result of particular circumstances, such as high demands, time pressure or multiple tasks. There are people who find this inspiring and who actually claim to need some amount of pressure or stage anxiety in order to perform at their best. Stress is neither a matter of how tough or enduring one is. What seems an interesting challenge on a Monday morning can push you over the edge after a rough week on a Thursday afternoon, though you are basically the same person. In other words, when you are somewhat exhausted already (or maybe just hungry), you are more likely to feel overwhelmed, even if requirements are exactly the same. Thus, things seem to be a bit more complex here. Lazarus and Folkman (1984) took this into account when they defined stress as the negative beliefs and emotions that arise when an individual does not feel able to cope with the demands in a given environment. In other words, stress emerges when the (subjectively perceived!) requirements exceed an individual’s (subjectively perceived!) skills or capacities in a given situation. The process of assessing stressors on the one hand and resources on the other hand is seen as stepwise and iterative (see Figure 3).

First of all, when being confronted with a “stimulus” (e.g., an email informing you about a change in the line-up), we initially classify it as either positive, irrelevant, or as a potential stressor. Positive stimuli may cause joy, pride, excitement, and so on – maybe the new band stepping in for the other one will resonate even more with your audience. Irrelevant stimuli do not do much to us. Maybe that info does not really affect you, if you are the one organising the visitor’s campsite, so you may at most feel empathy for your stressed colleagues. Given that primary appraisal of the situation results in an assessment as “potential stressor”, the next loop starts, in which we assess our coping resources and problem-solving skills or capacities. Even a headliner cancellation is certainly less stressful if you still have a couple of months to go and promotion has not fully started yet, as compared to four weeks before the event, when you are sold out and the social media are buzzing with excited fans looking forward to that particular gig.

Generally speaking, when it comes to that secondary appraisal aspect of “what can I do about it”, we mentally scan all kinds of resources we have at hand to deal with the situation. These may include our own skills, competence and knowledge, technical tools, time, colleagues we may ask for support, and so on. Lazarus and colleagues point out that primary and secondary appraisal are not meant to literally form a first and a second step of a sequential procedure. Rather, while assessing our resources, we may repeatedly take another look at the situation, potentially lower (or raise) our first appraisal of its stressfulness, then re-check what else we could do to deal with it, and so on, as illustrated by the feedback loops.

If we get the impression that we can somehow change matters and actively do something about it, we will usually try. So-called problem-focussed coping strategies aim to control the stressful situation or to influence any parameters relevant to it (Folkman & Lazarus, 1980).

Problem-focussed coping strategies include to

• build skills or knowledge or learn how to use better tools (e.g., a software or a new messenger or platform) which can help to handle the task better,

• seek advice or direct help, e.g. also by delegating some tasks to colleagues or external providers,

• negotiate a new deadline to gain time.

Time-management techniques and transparent, reliable communication within teams can be considered powerful key strategies which may actually proactively prevent many stressful situations from emerging in the first place. They could thus be called a future-oriented variant of problem-focused coping.

If on the other hand we get the impression that we cannot do anything about a situation but basically accept it, it is healthier to do so. Folkman and Lazarus call behaviours that are particularly appropriate in face of an uncontrollable stressor emotion-focussed coping strategies. These do not change anything about the problem. Rather than wasting energy in trying to change the unchangeable, these help to alter the way we feel about it by taking a different point of view.

Emotion-focussed coping strategies include

• acceptance or positive reframing (e.g., as challenge instead of catastrophe),

• humour, and

• seeking social support from someone to talk to, who maybe also gives you a hug or gets you a cup of hot chocolate (or a beer).

• Turning to spirituality may be experienced as consoling when confronted with major incidents (e.g. the loss of a beloved person), another way is to

• seek distraction from one’s emotions, in some cases with the “help” of drugs or alcohol.

Some stress researchers have suggested to further classify coping strategies into functional and dysfunctional ones. Functionality, however, again depends upon the context. It may be goal-directed and helpful to build skills and knowledge when facing a difficult task, but not in face of something that is way beyond your influence, or simply past and gone. After having chosen one or more coping strategies, the process leads to a re-evaluation of the entire experience that will actually feed back into a re-assessment of the same or assessments of future similar events (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). Whether something is within or out of our control again is not just always a matter of objective facts. Some people generally tend to feel helpless and overwhelmed by external requirements. Repeated and strong learning experiences of the unpredictability of events (fate or (bad) luck), or of having been subject to unreliable, arbitrary decisions of powerful others (parents, teachers, …) may result in a generalised expectancy of little internal control, also regarding unrelated situations later in life (Rotter, 1966). The mean effect of such a generalised belief of external control is that it easily becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy, or takes at least a while to be rebutted: If success or failure are just a matter of luck, somebody else’s mood or good-will, investing skills and effort does not seem to be worthwhile. And without such investment, a good result becomes less likely, further supporting the belief of “I am an unlucky person who never succeeds”.

Others may have had many positive experiences of being able to handle things on their own. Though generally appreciated and considered “healthy” in western cultures, the resulting sense of high internal control expectancies may also backfire in some situations. To overestimate control may become dysfunctional in face of events we in fact have little or no control over. People with strong high control beliefs tend to either engage in dead-end endeavours, or dwell on what they should have done differently to prevent what happened, even though they do not carry any responsibility (e.g., an accident they did not cause, becoming a victim to violence, the death of a beloved person). As with any extreme, it will be helpful to question such beliefs of very low or high internal control, and - eventually with the assistance of a professional coach or counsellor -, develop more efficient, fitting coping strategies.

How we assess stressors and coping options heavily depends on our thinking habits, personal beliefs and commitments (Kaluza, 2018). Next to factors like general optimism or perceived internal or external control, internalised doctrines can play a major role in how we experience a stressful situation. Typical doctrines are that one should “never give up”, “handle things by oneself, without bothering others”, that one must always “stay independent”, “be liked by everybody”, or that “things must be just perfect”. These mental stress-enhancers differ between people and can explain further why one and the same situation will never be the same to different individuals. If you are interested in your

personal main stress enhancers and some first impulses on how to “tame” and reframe them in a solution-oriented way, take the self-test in Box 3 as adapted from Kaluza (2018).

Please indicate for each of the following thoughts how often you have it running in your head:

1. I prefer to do everything myself.

2. I cannot go through with this.

3. I hate it when things do not go the way I want or plan.

4. I will fail.

5. I will never make it.

6. It is unacceptable if I fail to complete a task to meet a deadline.

7. I simply cannot stand this pressure.

8. I must always be there for my business.

9. Problems and difficulties are just terrible.

10. It is important that I have everything under control.

I do not want to disappoint the others.

It is awful when others are angry at me.

Strong people do not need help.

16. I want to get along with everybody.

17. It is dreadful when people criticise me.

18. If I rely on others, I will be lost.

19. It is very important that everyone likes me.

20. When making decisions, I must feel 100% certain.

21. I cannot stop thinking about all that could go wrong.

22. It cannot be done without me.

23. I have to do everything the right way.

24. It is dreadful to be dependent on others.

25. It is terrible not to know what is coming.

1 2 0 = never | 1 = sometimes | 2 = often

In order to receive your personal stress profile,

(1) sum up the points marked for thoughts 6, 8, 12, 13 and 23,

(2) sum up the points marked for thoughts 11, 14, 16, 17 and 19,

(3) sum up the points marked for thoughts 1, 15, 18, 22 and 24,

(4) sum up the points marked for thoughts 3, 10, 20, 21 and 25,

(5) sum up the points marked for thoughts 2, 4, 5, 7, and 9.

What do these values mean and what are the first steps to deal with high scores?

Each of these item clusters refers to a basic human need (e.g. for control, or bonding), so there is nothing wrong with having such thoughts in the first place. They may, however, become stress-intensifiers when occurring too strong or too often. As this is not a diagnostic test in terms of serious scientific assessment, and not even faking to be one, we will not indicate critical threshold values such as “below x means this” or “above x means that”. However, you will probably be able to relate to your individual profile, as you may have scored higher on some dimensions as compared to others.

(1) Be perfect! If you score comparatively high on this stress intensifier, this indicates an exaggerated desire for success, self-affirmation and recognition by others, which must be achieved through appropriate performance. A pronounced fear of failure and of making mistakes results in high pressure.

You may want to question yourself: For whom? At what cost? What about health, time for partner, friends, sufficient sleep,…? What may happen in the worst case, if I do not achieve 150%, but 97%, or 80%? Who defines „perfect“ here? What would be „good enough“?

(2) Be popular! High values on this stress intensifier reflect a strong desire for belonging, acceptance and love. This need is entirely human and healthy. When exaggerated, however, it leads to fear of rejection and conflict avoidance at any cost in order to get along.

You may want to reflect on questions like: Do I need to be popular always and with everybody? Do I really risk this person‘s sympathy or respect if I say no to additional demands, utter my own wishes or provide critical feedback? Could it even strengthen our relationship?

(3) Be strong and independent! The stress intensifier mirrors a strong desire for personal autonomy and self-determination. Accordingly, fears to depend on others, to need or ask for help arise, the individuals do anything to avoid showing weakness and rather try to manage everything by themselves.

If you reach high values, you may want to think about: To what aim do I want to be independent, from whom or what in particular? What do I fear if I accept a little less independence? Which advantages may it even have in this particular situation?

(4) Keep control! The stress intensifier expresses a strong need for security and predictability, coming along with a pronounced fear of loss of control or of making wrong decisions, with risk avoidance or avoidance to delegate tasks to others.

To question this stress intensifier, ask yourself: Control of what exactly, and what for? Where could I delegate at least some control? To whom? What would it take to make that easier? Where is control in general possible and where not? What may happen in the worst case?

(5) You will not make it! This stress intensifier is driven by a strong desire for personal wellbeing and a comfortable life, combined with low self-confidence and unrealistic pessimism. Those who reach high values here experience fear of unpleasant feelings and/or failure when facing a challenge, tend to avoid effort and show low frustration tolerance, which in turn may become a self-fulfilling prophecy.

In order to question according thoughts, you may want to reflect on: When did I achieve something similar in the past? Do I know people who succeeded with a similar task? What did they do, how did they approach it? Can I learn from that? What would be a good interim goal, what a good first step towards that? (cf. Mierke & van Amern, 2019)

The above paragraph may suggest it is partly a matter of personality how we assess stress and coping options, which, of course, is not entirely wrong. But we are hardly in the same mood and mind-set 24/7. Rather, we adapt ourselves more or less flexibly to different environments and role contexts, the people we are with, and so on. Such “chameleon behaviour” does not imply that we put on a masquerade or fake to please (Mierke & van Mentzingen, 2016). We rather show differenttrue - sides of ourselves, different faces, or as others put it, send different parts of our “inner team” on stage (e.g., Satir, 1978; Schulz von Thun, 2006). Subjective stress experiences may thus also depend upon which facet of one’s personality is active in – or activated by – the situation at hand. Some may feel stronger than or be less prone to stress-enhancing doctrines such as perfectionism than others. This can alter the way we judge demands and resources, as can factors like daily form (e.g., tiredness), which we may not even consciously be aware of (Bargh et al., 2012).

For all these reasons, it is in a very basic and general sense inappropriate to judge others for being rightfully or not rightfully stressed out. There is no way to objectify stress experiences. Accordingly, there is little use in comparing, let alone competing, when it comes to stress or resilience. To conclude, Lazarus and Folkman’s (1984) model suggests that after all these iterative appraisal processes of stressors, resources and coping, a re-appraisal takes place. Any successfully managed challenge is likely to increase confidence and considerably reduce the subjective threat of similar future events. Thus, experience usually contributes to calmness, and this includes experiences in successfully handling a problem in the outer world as well as experiences with successfully gaining a different perspective on something you could not change, i.e., by taking it with humour and realising that the world somehow kept turning.

Although first-hand experiences can hardly be passed on, you may sometimes wish to have some first aid measures at hand – to deal with acute stress yourself or to support colleagues under acute stress. Some ideas are provided in the following Box 4.

Box 4: How can you help yourself or someone else under acute stress?

Whatever happened, it is usually not a matter of life and death. Still, when someone experiences acute stress, it may feel like a matter of life and death – this is what our body signals, after all. So calming down physically is an important primary intervention:

• Suggest (or do, for yourself) a breathing exercise: Take a really deep breath, inhale for about 5 sec., pause for about 2 sec., exhale for about 5 sec., pause for about 2 sec., inhale again for 5 sec., exhale for about 5 sec., pause briefly, and so on. Repeat that ideally eight or ten times (2-3 min.). This will immediately stimulate your parasympathetic neural system which is responsible for relaxation (see 1.2). It works reliably. And the best thing about it is: You can always do it, as you do not require any specific equipment or particular body position. And you will always have two minutes to spare. You can do it in the car, or on the bike, at a red traffic light, you can do it standing around wherever you are, or sitting on the toilet, actually. Alternatively, you may want to try other breathing or relaxation techniques as available in the links to further resources provided in chapter 4.2.

• Walk around the block or suggest the person that is stressed out to have a quick game of table soccer, pinball, or whatever is at hand to briefly get distracted and let go of physical energy.

• When someone is seeking your support, refrain from any kind of blunt consolation (“everything will look a little brighter tomorrow”, “there is worse, for instance…”, “do not worry, mistakes happen”). Each of these statements is true, and if you manage to make your point with true personal meaning and emotion, it can be very helpful. If you say it just to say something, - do not. Rather take some time to really listen to the person - and if appropriate, offer them a hug.

• Never make (or hasten others to make) important decisions under acute stress. Those will not be good decisions, as explained in the next sub-chapter. Whenever possible, (suggest to) sleep it over.

• Once you have calmed down a bit (or your colleague has), sit down and sketch a crisis plan if applicable. This may include aspects such as: what is most urgent now, what can we still do to turn around things or prevent further damage, what do we need to achieve that, who must be informed now, who can be informed later, who can provide help, and so on. Ideally, you make such plans for hypothetical events (e.g., a thunderstorm, fire or disease outbreak during a festival) “in times of peace”. Having designated responsibilities, crisis-management institutions and well-structured plans turned out as very efficient for governments in saving lives during the corona crisis, and also for festival teams to handle the sudden challenges they were faced with.

1.4 Know your enemy: Symptoms, long-term consequences, costs of chronic stress

In chapter 1.2, we took a look at what is triggered by ancient programmes under acute stress. In chapter 1.3 we elaborated on how people actually determine what is stressful to them, and how to react. When it comes to physical and mental health, or social behaviour and performance at the workplace, we need to complete the picture by taking a more long-term perspective on the issue. Acute stress

may even be helpful sometimes. As pointed out above, it helped our ancestors for tens of thousands of years to overcome obstacles and maybe also fears, to build resilience and foster personal growth. Also, moderate amounts of activation have positive effects on cognition and social interaction - as long as the level of stress does not heavily exceed our resources and limits on a regular basis, and as long as the organism finds its balance again in regular phases of full relaxation. If we lack these pauses, however, we run the risk of getting caught in a chronic stress response cycle, where physiological activation literally piles up over time, and increases sensitivity to additional stress up to a point when a very small incident may cause a total breakdown - physiologically, mentally, socially, or all of them together.

Physiologically, a brief increase in heart rate, a mild elevation in the level of stress hormones and the like actually yields positive consequences. More severe temporary stress responses may still be levelled by social support and other buffering resources. But a prolonged physiological over-activation without such protective factors is detrimental to health. The chronically enhanced levels of cortisol and noradrenaline, chronically high pulse and blood pressure cause heart diseases and damage in inner organs, and raise the risk of a stroke. Typical further outcomes are chronic fatigue or burnout. Oftentimes, people try to counterbalance their state and feelings with regular substance abuse, which in turn gives rise to additional mental health issues – a vicious circle.

Mental consequences of chronically enhanced stress hormone levels are similarly severe. Some of you may have experienced or heard of someone having a black-out during an exam. Regardless of how hard you studied and how much you actually know, all of a sudden you cannot recall any of it any longer. When the brain is flooded with way too high levels of stress-hormones such as cortisol and noradrenaline, the hippocampus, which is responsible for retrieving information from long-term memory, temporarily “shuts down”. High levels of stress hormones narrow our perception and thinking, which may be seen as a protective mode. When over-activated already, the system aims to diminish rather than to enhance further stimulation from fresh sensory or cognitive input in order to protect itself. Simplification and reduction to an elementary minimum are somewhat logical means of self-regulation. This does, however, lead to bad decision making and judgment as complex analyses will be avoided (or simply no longer possible). This is why it is important not to force major decisions, conclusions or actions under stress. Also, this narrowing or closing of the sensory gates to further input makes us more sensitive to noise and other stimuli such as crowded situations, heat, cold, strong unpleasant smells, and we seemingly over-react to these. Some people tend to feel rather weak, small and anxious, accompanied by self-doubts or despair, others might feel irritable, angry or aggressive, or both emotional states may come up and change rapidly.

Moderate amounts of stress, in contrast, come with a positive tone and again have positive cognitive consequences (as does moderate physiological activation). People experience increased attention, concentration and mental speed, they become more open to new thoughts and make remote or innovative associations, which in turn boost creativity. Many artists or sportsmen and –women claim to actually need some amount of stage fever to perform at their best. Emotionally, the distinction between moderate versus extreme cognitive stress may be reflected in the terms excitement versus fright. Sometimes, it even works to rename the butterflies in the stomach from “I am so frightened” to “I am so excited” in order to make them feel less aversive. Feelings that accompany moderate stress include curiosity, eagerness to explore, joy and confidence.

Social interaction does hardly remain unaffected by stress either, and organising cultural events is inherently social – in the making as well as in the outcome. So let us take a look at what happens here under stress. Again, research shows that moderate levels of activation help us to “get going”. We open up, make new contacts more easily and thus expand our network (e.g. Fredrickson & Branigan, 2005), which may again provide us with substantial social or practical support when needed. Also, emotional states of activation and excitement are contagious, so we spread enthusiasm among our group and thus contribute to build a more positive team spirit (Hatfield, Carpenter & Rapson, 2014).

Too high levels of chronic stress, however, again trigger a mode of protection against further stimulation, resulting in reduced openness and empathy for the concerns of others, in social retreat or in aggressive communication styles once retreat is not possible. We become irritable, oversensitive or even hostile. Again, this may lead into a vicious circle, as conflicts consequentially arise at work as well as with partners and friends. These cause additional stress and at the same time cut us off from valuable sources of social and instrumental support, which would be needed more than ever.

Thus, on all three levels, we observe a pattern that can be described as inverted U-shape, as peak performance results from an intermediate level of arousal that neither carries the risk of bore-out nor of burnout. It is illustrated in Figure 4.

Fig. 4: Relationship between level of activation and performance.

Last but not least, stress is economically costly for employers as well as welfare systems, far costlier than to invest in solid prevention and early intervention programmes (see part 4 of this book). Reaching the right-hand, downwards side of the above curve not only affects the individual in terms of physical, mental and social wellbeing and functioning, but society as a whole. Legislation on health and safety at work provides a clear framework on employers’ responsibility and obligations to create appropriate working conditions. Rules that ensure at least some basic standards for workers can be traced back to ancient Egypt (Poppelreuter & Mierke, 2019). We may assume that this

was not only for ethical reasons. In fact, despite legal – or humanistic - concerns, every employer should find stress reduction measures on top of the agenda simply from a financial point of view. Costs emerge from a variety of issues and on different levels. Generally speaking, there are two basic phenomena to be considered: stress-related sick leaves and presenteeism. Sick leaves (e.g. due to psychological or stress related physical symptoms) usually mean extra workload for the remaining team, putting additional stress on them and eventually triggering a chain reaction. Alternatively, one may try to back the team up with temporary replacement workers, which however never deliver the same level of performance as the experienced expert on sick leave. Employees are usually well aware of this, and this gives rise to the second problem, namely presenteeism. Coined as twin-term to absenteeism (the euphemism for skipping work), presenteeism means that people drag themselves to work despite actually being sick. Although largely driven by very honorable motives (e.g., commitment to tasks or not wanting to burden colleagues), this overly loyal behaviour has severe economic consequences. Many studies claim that its costs to organisations actually exceed those of absenteeism (for a review, see Kigozi, Jowett, Lewis, Barton & Coast, 2017).

Economic consequences of stress and presenteeism at work on different levels illustrate that such estimates are complex and may in some cases only represent the tip of the iceberg. They include:

• Suboptimal performance (due to lack of concentration, memory problems, et cetera)

• bad decision making and its follow-up costs

• work accidents and their follow-up costs

• awareness of these issues as further stressor accelerating chronification of symptoms and long-term illness

• Social conflict (due to low frustration tolerance, hostile communication, blaming others)

• bad team climate, emotion contagion within teams

• increase in absenteeism or turn-over within other team-members

• less effective cooperation within the team or between interdependent teams

• less effective, eventually off-turning negotiation style with external partners

• Burnout, sick leave times for rehabilitation, or staff turnover

• losing valuable experience and expertise (let alone human beings and friends)

• vacancies implying an increase in workload and stress for the remaining team

• costs for hiring and training new staff (recruitment and selection process, suboptimal performance in the beginning, time investment for onboarding, …)

• Long-term systemic consequences

• damage to the reputation of a venue or festival among artists, bookers, caterers et cetera, increasing difficulty to build good long-term business partnerships

• damage to employer image (or even industry image) among the next generation of qualified staff and among volunteers

• increased difficulty of recruitment in times of shortage of specialist and managerial talents

It is therefore most sustainable and worthwhile in many ways to invest in stress prevention and stress management training. This is particularly true for an industry whose working conditions are – despite all inherent rewards – inherently challenging and which is, at the same time, inherently attractive to creative and eventually more sensitive, non-normative individuals (Runco, 2014) plus inherently dependent on creative performance.

1.5 Sanity is a full-time job: Talking about and self-checking mental health

Talking about mental health always requires a differentiated perspective. “Sane” and “insane” should rather be seen as two ends of a long, multi-layer continuum than as binary either-or-categories. Similarly, mental disorders hardly ever have one single, obvious or deterministic cause but emerge from a combination of various risk - as well as protective factors. In current research and practice, socalled vulnerability-stress-models offer an integrative approach that regards mental health issues as resulting from the interplay of personal dispositions and situational stress experiences.

The term disposition refers to an individual tendency to act or react in a particular way in face of different situations as may be genetically determined plus emerge from an individual’s psycho-social learning history. Enhanced vulnerability may thus emerge e.g. from hormone imbalance and enhanced sensitivity and/or from early experiences of severe disease, loss or highly unpredictable (social) environments. Accordingly, a more resilient disposition is, among others, characterised by emotional stability and high competence in self-regulation (Okbay et al., 2016) and general optimism (Carver & Scheier, 2014), both again having at least in part a genetic base, as well as being rooted in biographic experiences and resulting cognitive structures (Seeds & Dozois, 2010). An additional important protective factor is perceived social support, one of the best studied buffer variables in health psychology in general (Taylor, 2011). In contrast to dispositional vulnerability, the stress component refers to all kinds of external events or stimuli that require some kind of coping reaction, as already reviewed in subchapters 1.3 to 1.5. These stressors can vary a lot across individuals, depending on whether they resemble and thus re-activate former negative experiences of helplessness or feelings of being excluded from an individual’s biography. A stressor will be particularly impactful if combined with a mind-set of stress-enhancing thoughts (e.g., “Keep control! or “Be popular!”; see chapter 1.3). Vulnerability-stress-models are widely acknowledged in the literature long since, and decades of research in various fields of mental health support their premises (see Seeds & Dozois, 2010). They provide a bridge between a “normal” approach to “normal” stress issues and a more clinical approach to more severe mental health issues by emphasising the complex interplay of the multiple factors that affect human wellbeing.

We consider this perspective as particularly helpful and relevant for the creative sector, whose protagonists oftentimes bring along an increased vulnerability to psychological issues from the start (Bellis et al., 2007; Martindale, 1989). Many professionals as well as volunteers in the event management industry are at the same time (former) active musicians or artists. Artists are known to report mental health problems more frequently than many other professions. For instance, Raeburn, Hipple, Delaney and Chesky (2003) found high rates of depression, anxiety and substance abuse among professional musicians. Others discuss a connection between creativity and affective disorders (Eysenck, 1995; Ludwig, 1995). From a cognitive psychological point of view, such findings do not come as a surprise, as both are characterised by divergent thinking and a preference for remote, intense and/or multi-sensory associations (for a very profound review of these and related findings on creativity, see Runco,