Climate Sensitive Design and the Urban Morphology

Integration of Morphological Parameters in Bio-Climatic Urban Planning

Architectural Association

Emergent Technologies & Design 2010

MArch Phase II, Thesis

Radhika Radhakrishnan, Sebastian Nau

Integration of Morphological Parameters in Bio-Climatic Urban Planning

Architectural Association

Emergent Technologies & Design 2010

MArch Phase II, Thesis

Radhika Radhakrishnan, Sebastian Nau

We would like to thank,

Mike Weinstock for his guidance and support throughout the entire year and for his relentless advice throughout the development of this thesis. His experience and precious assistance was the catalyst for achieving progress and for acquiring knowledge and experience.

Toni Kotnik, our studio master. His commitment and steady support enabled us to constantly explore new directions in the design and allowed us to take maximum advantage of the course. Especially, his help with mathematical problems enabled us to push the boundaries of the project and to develop it in ways we did not anticipate.

George Jeronimidis and all EmTech teaching staff, as well as all guest lecturers and consultants; the knowledge and experience we gained during the first phase of the course provided us with the tools and skills necessary to progress on this project.

Qibing Jiang, our friend and peer, who was always at hand to assist us with problems related to computation and scripting.

Fazia Ali-Toudert, who, as an urban climatologist, provided us with valuable insights into the field.

Janet Barlow, who assisted us with any questions related to the urban microclimate.

Finally, we would like thank our families, friends and peers for constant moral support and encouragement.

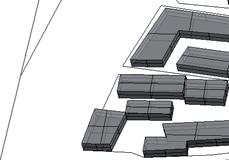

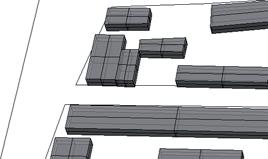

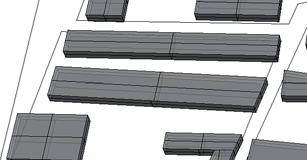

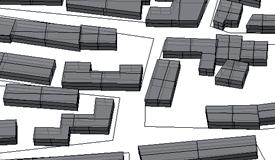

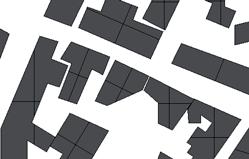

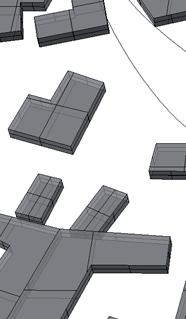

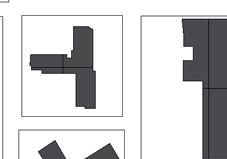

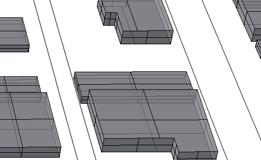

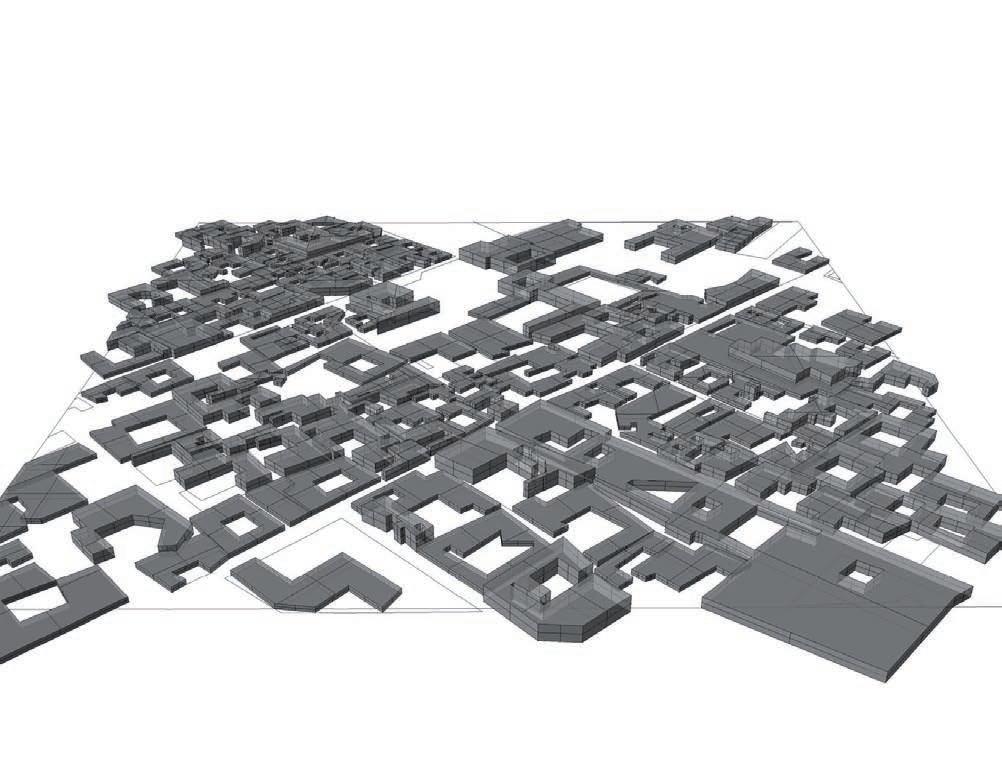

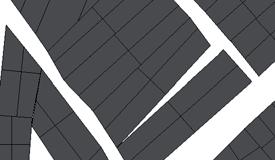

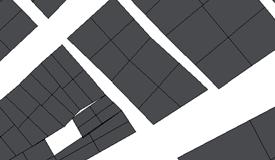

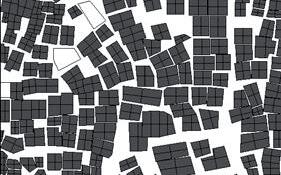

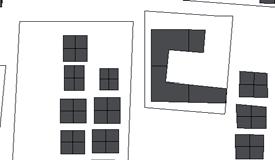

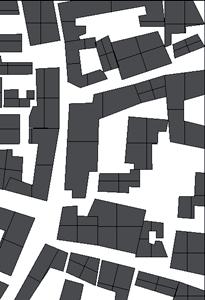

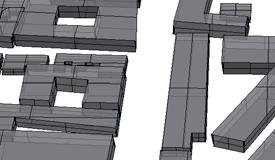

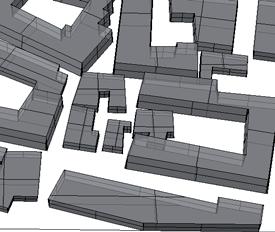

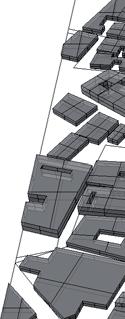

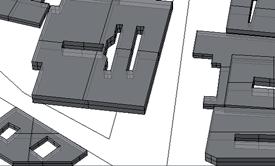

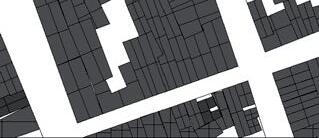

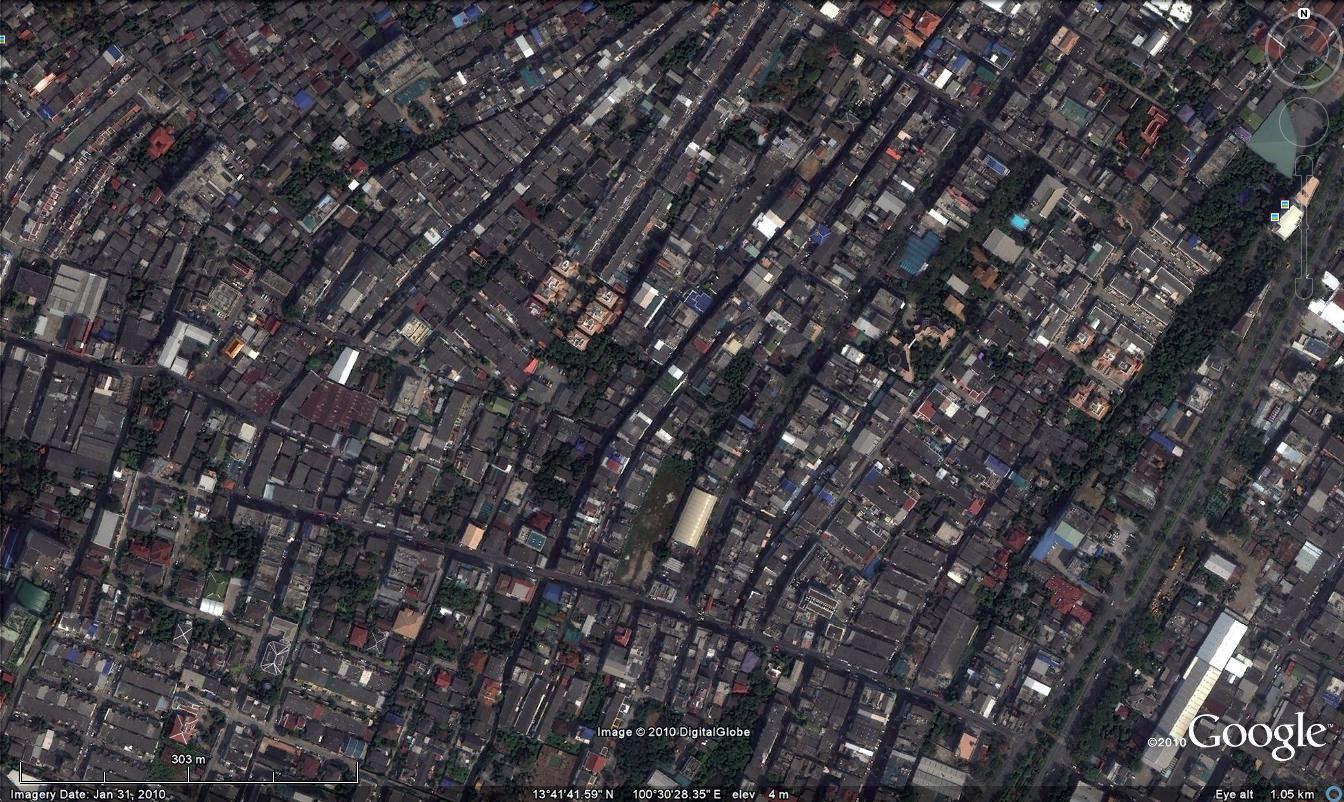

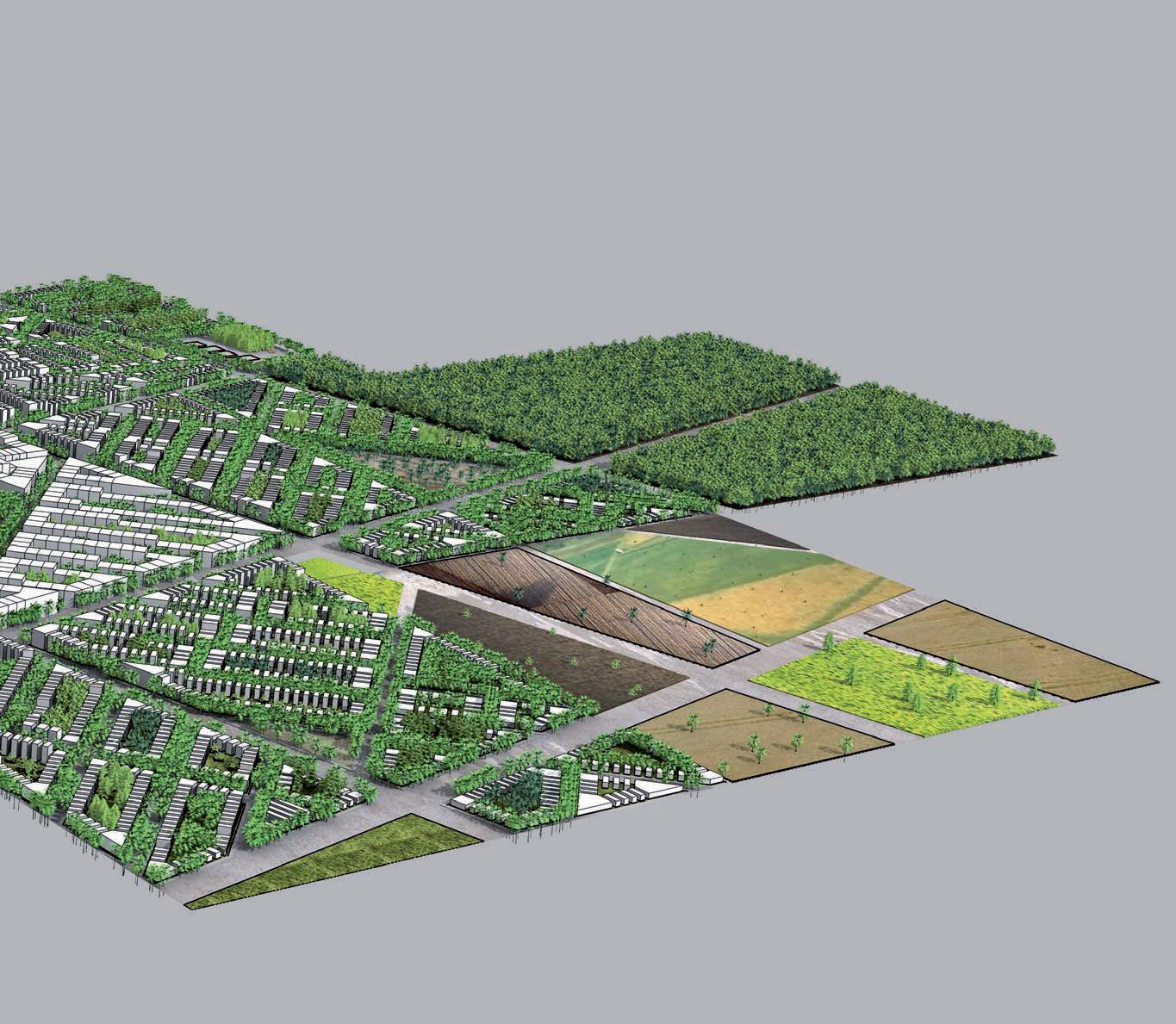

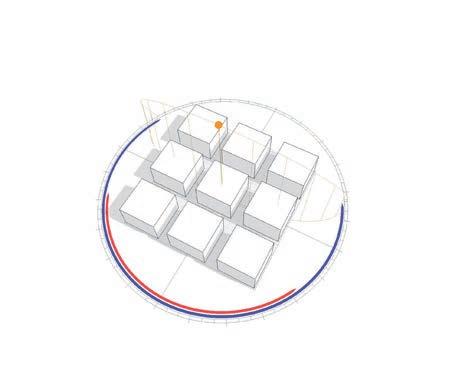

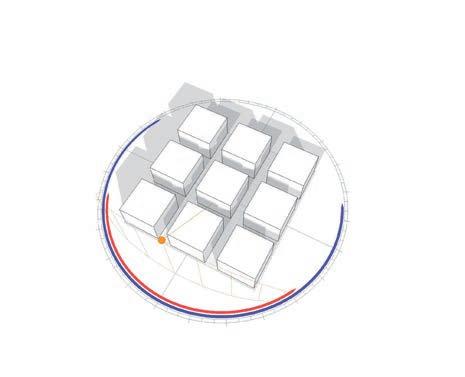

Morphological indicators: The diagram depicts approximated travel routes to parks along the street network. These can be evaluated and used as latent design information to draw conclusions about the performance of the fabric.

Reducing the energy demands of cities will be one of the biggest challenges for architects and urban planners in the coming decades. Tackling the urban microclimate, by addressing the urban morphology in design processes, could play a crucial role in this process; it is likely the most suitable way to enforce means of passive energy saving onto urban agglomerations.

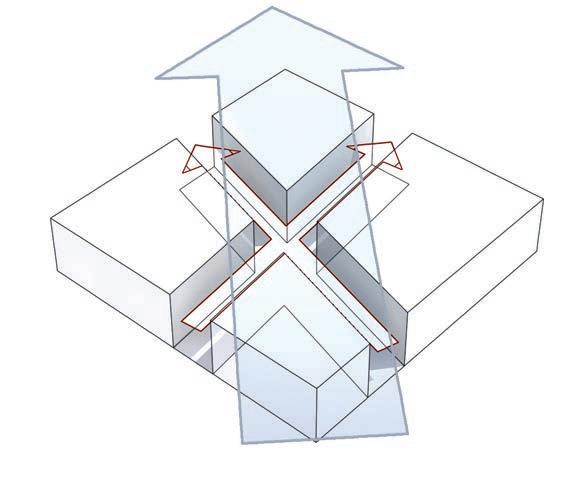

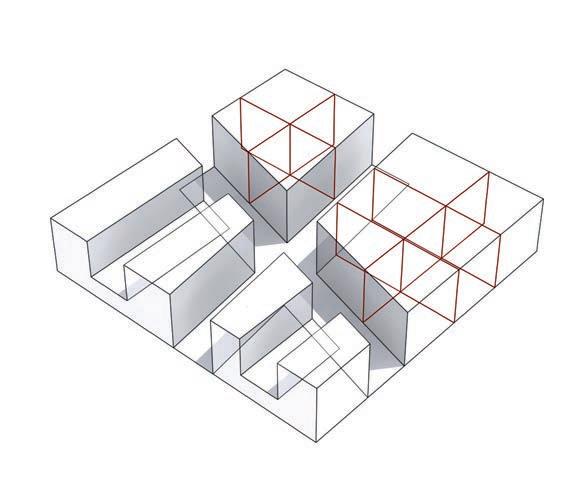

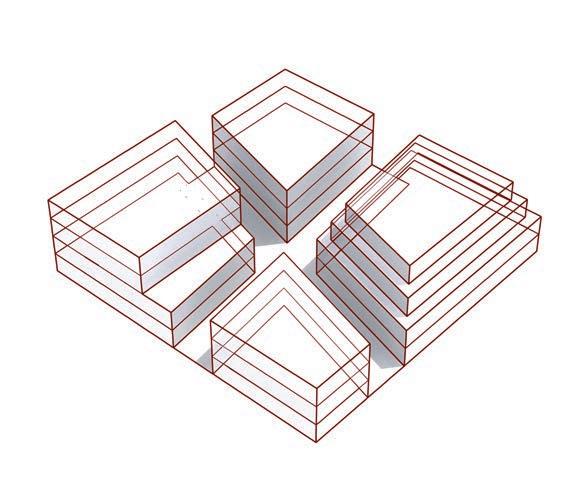

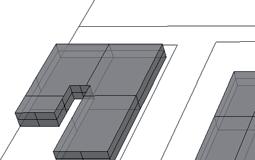

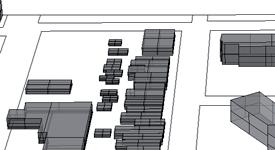

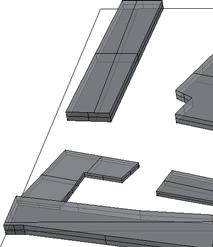

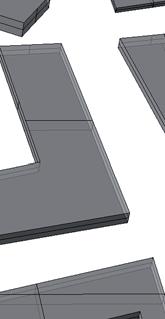

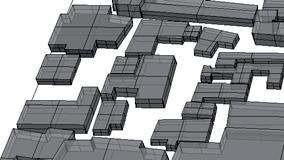

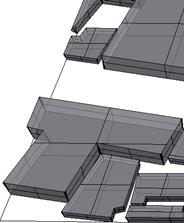

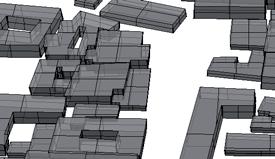

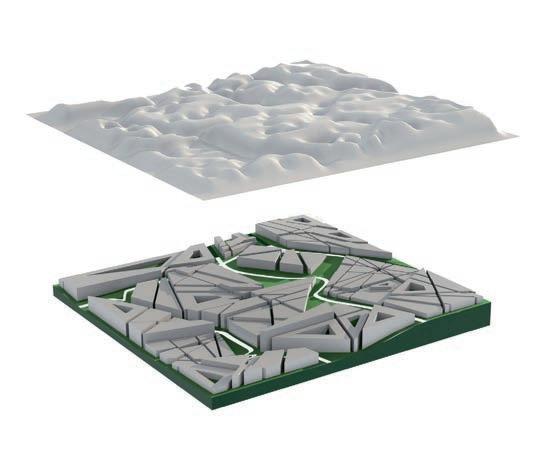

The design research project presented in this thesis investigates the current methods in microclimatic research and proposes how such strategies, which so far have only been used in urban analysis, can be implemented in design processes. The complex interaction of physical processes that result in urban microclimates leads to the adaptation of simplified morphological indicators. Such indicators that reveal latent microclimatic characteristics of urban morphologies will be analysed and further explored. Coupled with a genetic algorithm it is subsequently shown how they can be utilized to simultaneously generate and evaluate urban layouts as part of generative design processes.

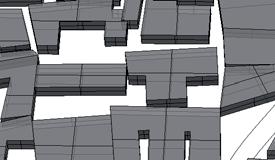

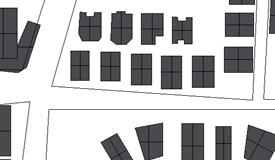

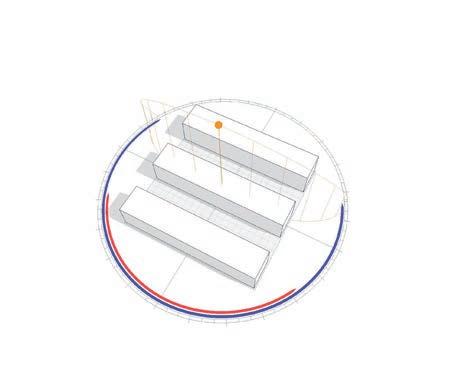

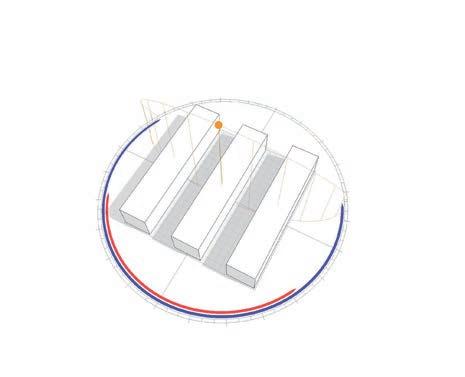

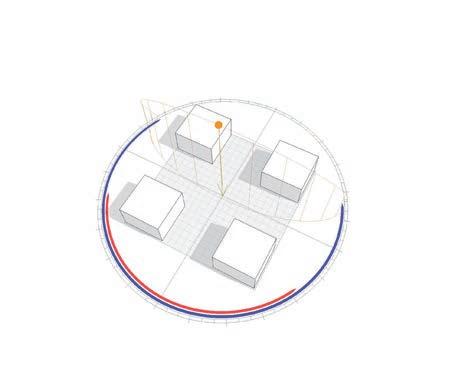

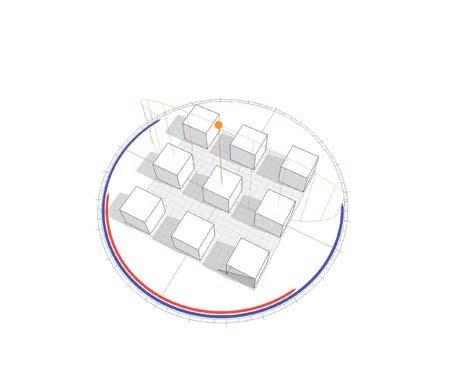

The project thus introduces a bio-climatic approach to urban planning that incorporates microclimatic considerations. Throughout the project strategies are developed that approach urban design from the patch/block level. It will be shown how patch morpholo-

gies can be optimized according to microclimatic considerations and how such patches may aggregate to form coherent urban structures. By implementing different indicators at different stages of the design it is revealed how different parameters for evaluation might come into play at different stages of the project. The result is a hierarchical planning approach from schematic urban patches all the way down to the building level.

In addition, the method of using morphological indicators will be extended to draw conclusions about urban qualities inherent to patch morphologies. Together with microclimatic considerations it will be shown through a series of design experiments how these can be utilized as latent information within urban planning.

Computational methods, like Fractals, Cellular Automata, Genetic Algorithms, etc., have become common tools in order to simulate and understand the underlying complex patterns and processes in urban morphologies. Whereas mostly such tools are used for analysis and prediction of possible urban developments they are rarely implemented in urban planning. The reason for this is that with most of such techniques only selected aspects of the complex overall urban organization/structure can be evaluated, isolated from other relevant factors that need to be considered when planning urban space.

The logics of computation imply that only quantitative data can be evaluated, whereas social and aesthetic factors, which are not measurable, remain untouched. Important human considerations, like the perception of space, remain un-computable. The problems with too rational approaches to urban design have become evident through the mistakes that evolved out of ‘Modernism’ during the last century where the re-organization of urban space has often resulted in ‘sterile’ arrangements that completely failed in social terms.

The problems with using digital methods as generative design tools nowadays often results in processes of post-rationalization where the outcome of conventional urban planning is justified through the use of computational analysis. Such approaches leave the impression of optimized design solutions that are gen-

erated from the bottom up by evaluating and assessing ‘all’ design parameters. The notion of ‘evolutionary methods’, where all possible scenarios are evaluated against each other mimics the diversity that can be observed in evolved cities.

The following chapter introduces some of the most acknowledged computational methods that are currently utilized in urban analysis; in addition, environmental and microclimatic software packages are introduced. Frequently used by architects and climatologists they allow to draw conclusions about the environmental performance of buildings and urban fabrics. Some of them, nevertheless, imply complex calculations as they couple Computational Fluid Dynamics with energy balance models; this is necessary in order to reflect complex processes of energy exchange and interaction that constitute urban microclimates. It will be shown that, at least at the urban scale, limits exist in terms of computation and that calculations are generally time consuming and currently more suitable for analysis than design.

Arithmetic strategies such as Fractals, Cellular Automata and Genetic Algorithm are increasingly used in understanding urban models of growth in terms of organizational patterns with respect to time. Thus when applied on computational models, predictions of future growth can be achieved.

Computational methods, like Fractals, Cellular Automata, Genetic Algorithms, etc., have become common tools in order to simulate and understand the underlying complex patterns and processes in urban morphologies. Whereas mostly such tools are used for analysis and prediction of possible urban developments they are rarely implemented in urban planning. The reason for this is that with most of such techniques only selected aspects of the complex overall urban organization/ structure can be evaluated isolated from other relevant factors that need to be considered when planning urban space. The logics of computation imply that only quantitative data can be evaluated, whereas social and aesthetic factors, which are not measurable, remain untouched. Important human considerations, like the perception of space, remain un-computable. The problems with too rational approaches to urban design have

become evident through the mistakes that evolved out of ‘Modernism’ during the last century where the re-organization of urban space has often resulted in ‘sterile’ arrangements that completely failed in social terms.

The problems with using digital methods as generative design tools nowadays often result in processes of post-rationalization where the outcome of conventional urban planning is justified through the use of computational analysis. Such approaches leave the impression of optimized design solutions that are generated from the bottom up by evaluating and assessing ‘all’ design parameters. The notion of ‘evolutionary methods’, where all possible scenarios are evaluated against each other mimics the diversity and that can be observed in evolved cities.

Evolutionary concepts are highly associated with this where it is argued that through computation all possible scenarios can be simulated and evaluated to find the most suitable one.

Artificial processes for locating urban activities based on simple rules pertaining to local circumstances give rise to complex global patterns that mirror the spatial organization of cities. These systems are called Cellular Automata (CA). They provide a useful means of articulating the way highly decentralized decision-making can be employed in simulating and designing robust urban forms. 1

Simulations of existing urban fabric and providing solutions as potential design strategy were two separate areas of work, the combination of which has only been done in recent times. Rulebased procedures were used to replace mathematical functions thus striping the integrated tissue to the most basic, yet complex in its approach to optimization.

1 Batty, Michael; Cellular Automata and Urban Form: A Primer; Journal of the American Planning Association, Vol. 63, No.2, Spring 1997. “American Planning Association, Chicago, IL.

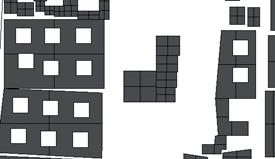

Cellular Automata is one such tool in this discipline. Using a system of pixilation or adjoined cell system, wherein the transition of one cell to the next and its state is dependent on rules. These rules of growth or decline are determined by the neighbourhood cells and their state. This thus is a dynamic growth model, often applied on a two dimensional grid to portray in an Urban setting, the growth or decline of a city in relation to the neighbour and neighbourhood.

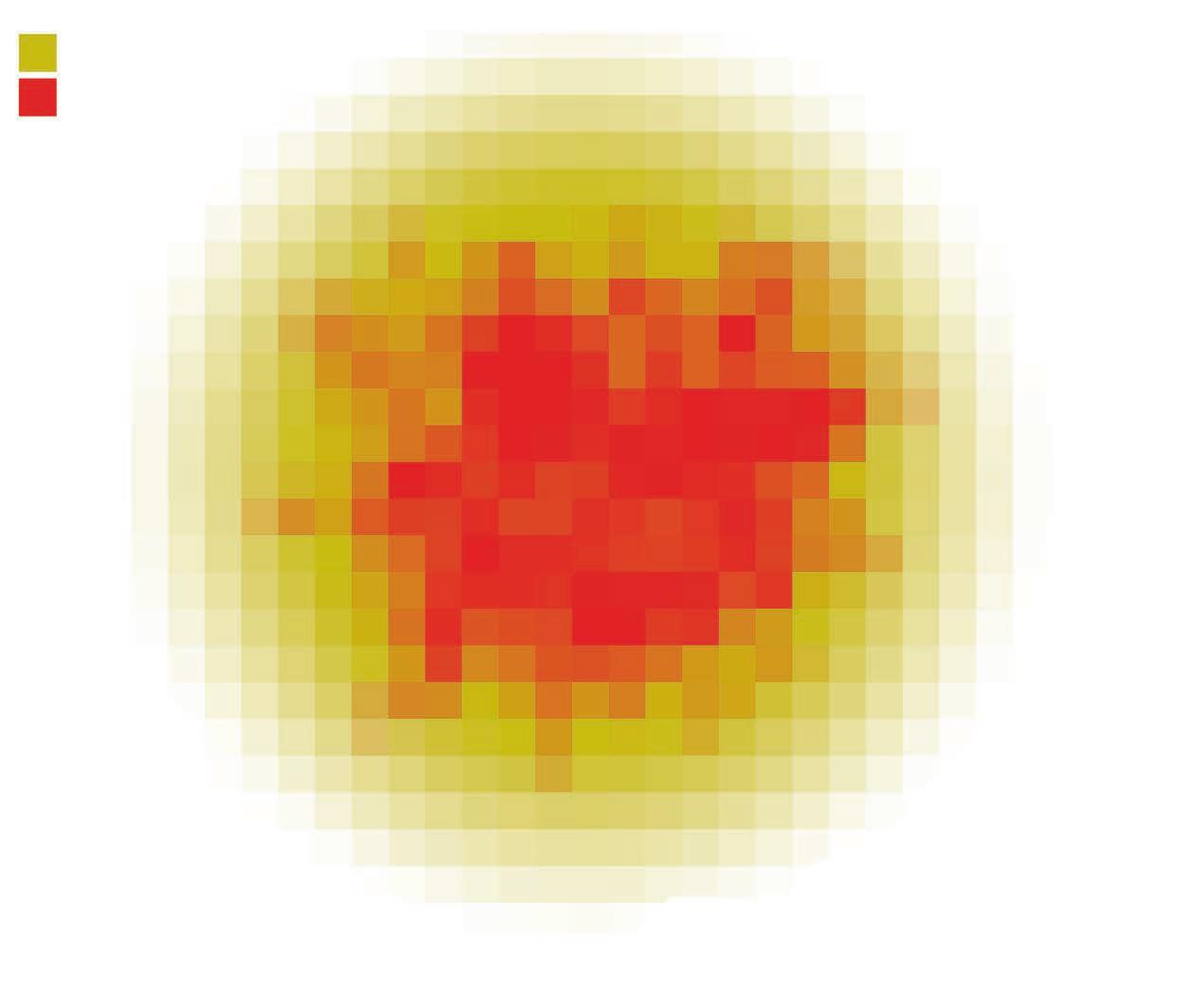

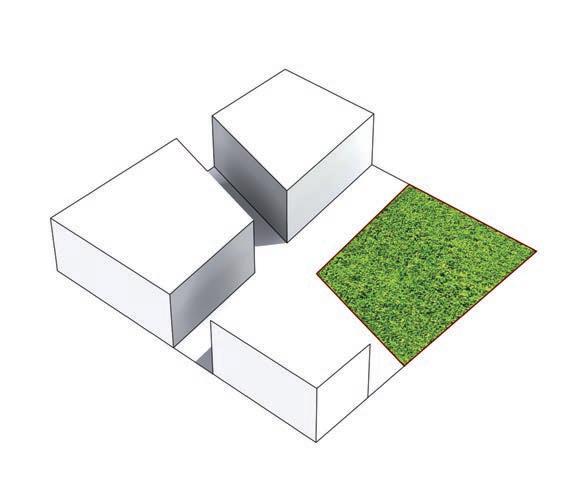

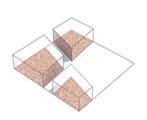

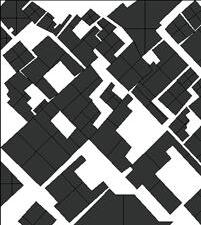

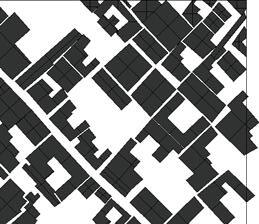

Diagrams above: Envi-Met analysis run on an urban patch sample measuring 250 x 250m. The left hand diagram depicts the surface temperature (k) at 10.00am; built areas are shown in black. The right hand diagram depicts the ‘sky view factor’ in form of isopaths or contour lines. The Envi-Met model allows to calculate a multitude of different parameters that relate to the urban microclimate. It is highly accurate, however, calculation times are considerably long.

< 301.16K

301.16 - 303.79K

303.79 - 306.42K

306.42 - 309.05K

309.05 - 311.67K

311.67 - 314.30K

314.30 - 316.93K

316.93 - 319.56K

319.56 - 322.19K > 322.19K

Artificial processes for locating urban activities based on simple rules pertaining to local circumstances give rise to complex global patterns that mirror the spatial organization of cities. These systems are called Cellular Automata (CA). They provide a useful means of articulating the way highly decentralized decision-making can be employed in simulating and designing robust urban forms.

Simulations of existing urban fabric and providing solutions as potential design strategy were two separate areas of work, the combination of which has only been done in recent times. Rulebased procedures were used to replace mathematical functions thus striping the integrated tissue to the most basic, yet complex in its approach to optimization.

Cellular Automata is one such tool in this discipline. Using a system of pixilation or adjoined cell system, wherein the transition of one cell to the next and its state is dependent on rules. These rules of growth or decline are determined by the neighbourhood cells and their state. This thus is a dynamic growth model, often applied on a two dimensional grid to portray in an Urban setting,

the growth or decline of a city in relation to the neighbour and neighbourhood.

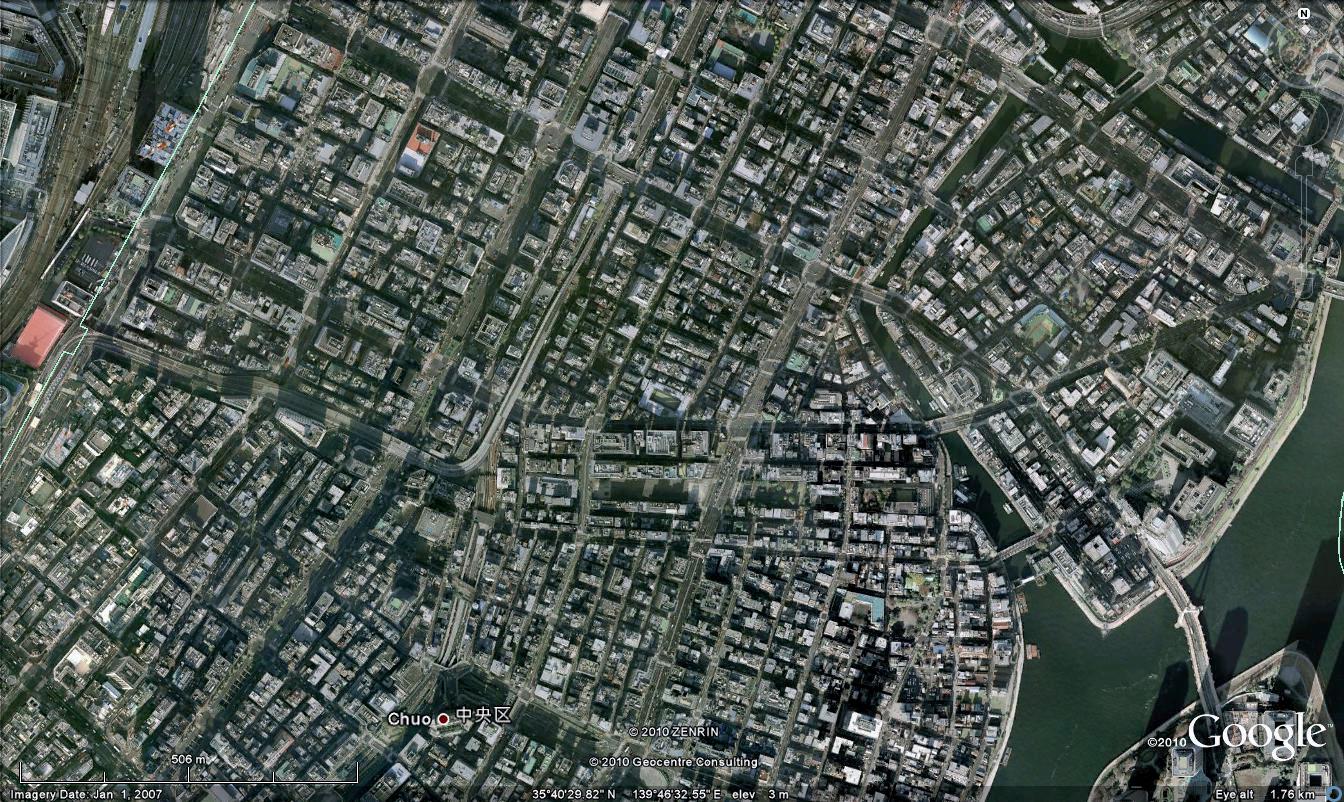

Eni-Met is one of most advanced computational softwares for urban microclimatic analysis. Developed by the University of Bochum, it is a freeware package that allows to analyse urban patches in their microclimatic performance. Envi-Met does not allow to import 3D model data (e.g. In DXF format); the Envi-Met ‘area input file’ is drawn from plan and height information is subsequently assigned by numbers (see diagrams above). To test Envi-Met an example file was set up using one of the early patches created with a genetic algorithm (refer to First Experiments chapter for more information); for all grid cells the soil is set to asphalt; a park (right hand corner) is assigned ‘grass’ as surface material.

Area Input File:

Dimensions: 105x105x25 Grids

Horizontal Grid Size: 2.00m

Vertical Grid Size: 2.00m

Rotation out of North: 0.00

Location:

Latitude (+: Northern Hem.,-: Southern Hem.): +51.31

Longitude (-: Western L., +: Eastern L.): +0.05

Time Zone GMT

Time interval for Output (min): 60

Simulation Timing:

Start Date (DD.MM.YYYY): 23.06.2001

Start Time (HH:MM:SS): 06:00:00

Simulation Time (h): 24

Sun heights for changing dt: I: 0to40.00°,II:40.00 to 50.00°, III: above 50.00°

Time steps assigned: I10.00s,II: 5.00s, III: 2.00s

Basic Meteorology:

Wind Speed in 10 m (m/s): 3.00

Inflow Direction (180=South): 90

Initial Temperature Atmos. (K): 293.00

Spec. Humidity in 2500m (g/Kg): 7.00

Relative Humidity in 2m (%): 50.00

Cloud Cover (low/mid/high): (/8) 0/0/0

Adjustment Factor for Solar Input 1.00

Boundary Condition Type T,q: Open (Default)

Boundary Condition Type TKE: Forced (Default)

Turbulence closure 3D model: TKE Model, Normal Model

Building Properties:

Inside Temperature (K): 293

Heat Transmission Walls: 1.940

Heat Transmission Roofs: 6.000

Albedo Walls: 0.200

Albedo Roofs: 0.300

Soil Properties:

Temperature:

Upper Layer (-20cm): 293.00K

Middle Layer (20-50cm): 295 K

Deep Layer (below 50cm): 293 K

Relative Soil Humidity:

Upper layer (-20c,): 50.00%

Middle Layer (20-50cm): 60.00%

Deep layer (below 50cm): 60.00%

Calculation/Duration:

Time (HH:MM:SS): 17:05:06

Above: Input information for Envi-Met analysis; in order to return data Envi-Met requires a large range of input parameters for calculations. Precise site information about e.g. wind speeds, humidity or soil characteristics are therefore required in order to obtain usable results. Factors such as location, date and time can be set; calculation times are, however, long: it took just over 17 hours to calculate a 24 hour cycle for the test patch shown above. There are also limitations to size, i.e. the urban area that can be analysed: The largest urban patches that can be currently calculated measure 250 x 250m.

Wind Speed (m/s); 10.00am

0.20 m/s

0.40 m/s

0.60 m/s

0.80 m/s 1.00 m/s

Variables for Atmosphere (calculated during simulation):

Classed LAD and Shelters

Flow u (m/s)

Flow v (m/s)

Flow w (m/s)

Wind speed (m/s)

Wind speed Change (%)

Wind direction (deg)

Pressure Perturbation (Diff)

Pot. Temperature (k)

Pot. Temperature (Diff K)

Pot. Temperature Change (K/h)

Spec. Humidity (g/Kg)

Relative Humidity (%)

TKE (m2/m2)

Dissipation (m3/m3)

Vertical Exchange Coefficient Impulse Km (m3/s)

Horizontal Exchange Coefficient Impulse Km (m3/s)

Absolute LAD (m2/m3)

Direct SW Radiation (W/m2)

Diffuse SW Radiation (W/m2)

Reflected SW Radiation (W/m2)

LW Radiation Environment (W/m2)

Sky View Factor Buildings (/)

Sky View Factor Buildings and Vegetation (/)

Temperature Flux (K*m/s)

Vapour Flux (g/kg*m/s)

Sensible Heat Flux (W/m²); 10.00am

W/m²

W/m²

W/m²

W/m²

W/m²

Water on Leaves (g/m2)

Wall Temperature on Cell border x (K)

Wall Temperature on Cell border y (K)

Wall Temperature on Cell border z (K)

Leaf Temperature (K)

Local Mixing Length (m)

PMV Value

PPD Value

Mean Radiant Temperature (K)

Gas/Particle Concentration (mg/m3)

Gas/Particle Concentration (mg/s)

Deposition Velocity (mm/s)

Total Deposed Mass (mg/m2)

Deposed mass Time averaged (mg/(m2*s)

TKE normalised 1D

Dissipation normalised 1D

Km normalized 1D

TKE Mechanical Turbulence term of the E/eps equation

Stomata Resistance of leafs (m/s)

CO2 (mg/m3)

CO2 (ppm)

Plant CO2 Flux (mg/kg*m/s)

Div Rlw Temp change (K/h)

Local Mass Balance (mg/(s*m3)

Envi-Met analysis allows to extract large quantities of data from urban sample sites; the range of parameters that was calculated during the test run, introduced on the previous page, is depicted above. Data can subsequently presented graphically in form of 2D maps or 3D models. The diagrams at the top of the page show such representational diagrams for wind speed and sensible heat fluxes at 10 o’clock in the morning.

Tools for Modelling the dynamic urban microclimate system can become challenging in terms of calculations and strategizing apart from mere computational limitations. However, recent developments in the area seek to perform dynamic simulations of the coupled surface-plant- atmosphere system on regular computers. This can prove to be extremely useful in terms of urban and architectural planning aiming at a balanced environmental model.

Ecotect is a conceptual design tool that couples an intuitive 3D design interface with a comprehensive set of performance analysis functions. It can help in terms of vizualising the effect of the sun and shadow patterns. However in terms of using this as a real time analysis tool, it does not provide with a very strong base.

Of the most advanced available tools for fluid flow simu-

lation models is ENVI- met. It is much advanced and accurate as compared to tools like ECOTECT, in terms of giving a more complete diurnal cycle including all the heating and cooling processes taking place in the urban environment. ENVI –met is a3D coupled computational fluid dynamics and energy balance model.

It can be used to calculate the wind flow around different urban forms as well as all the parameters associated with energy balance and atmospheric transfer processes(shadows, reflections, turbulence, transfer, plant evaporation etc). The results have been proven to be fairly accurate when tested on models used in the design experiments.

The input model is however requires a largely pixilated version to be read. This is setback in terms of using this as part of a design tool. Another setback maybe the time involved in the completion of a single simulation, thus increasing the time of a feedback loop within evaluation and design.

Image references :

Fig1 : http://1.bp.blogspot.com/_gss1sFcUYg4/RlMGxrPFgBI/ AAAAAAAAAHQ/UM8fejIrD8s/

Fig. 2 : http://29.media.tumblr.com/tumblr_kzeli4H6cU1qaqm2ao1_500.jpg

Fig. 4 : http://www.dlr.de/caf/Portaldata/60/Resources/images/2_dfd_la/2_dfd_la_sl/temp_wind_e

Figs. 5-8 : Peeters, Aviva ; Etzion, Yair; Israel, Sept 2010; GIS Based Object Recognition Model for Analyzing the Urban Form

Fig 9 : http://www.casa.ucl.ac.uk/andy/blogimages/helsinki2050. jpg

It is predicted that the global population will increase to just over 9 billion by the year 2050. This exponential growth will, however, not be the same in all parts of the world and it is especially African and Asian countries, which will encounter rapid increase in population numbers in the next decades. Godfray reports that Europe’s population will decline, Africa’s will double, while China’s will peak in 2020 to be overtaken by India’s population at around 2030 (Godfray, 2010). It is especially the young average age of people (under 30) in these countries that leads to exponential growth and enormous space requirements; while demographic changes will require cultural adaptations it is especially the vast expansion of such societies that will put enormous pressure on architecture and urbanism.

The world’s population today is over 50% urban (Kennedy, 2009). This trend of urbanization is certain to continue and the last few decades have seen the rise of megacities in developing countries such as Mumbai, Sao Paulo or Mexico City that all peak 16 million inhabitants (Godfray, 2010). Mills (Mills, 2006) points out that the highest rates of urbanization are occurring in poorer parts of the world and Arnfield (Arnfield, 2003) adds to this that

most of such areas are located in the tropical world (Population Reference Bureau, 2001b; United Nations, 2001). It can therefore be assumed that most of the expected urban growth is happening in regions with rather extreme climates; Golany describes the most sensitive ones as the hot-dry, the cold-dry and the hothumid ones (Golany, 1996). Urban development in such regions will likely enforce high environmental pressures that will affect local economies and the exploitation of natural resources. It is therefore necessary to come up with innovative urban concepts that address the metabolisms of cities; such concepts need to be tailored to the specific regional settings and must in particular respect the prevailing climatic conditions.

Average Increase in 10 Years

The Global population reached the first billion in 1804. Until 1900 there were 1,6 Billion people on the earth, growing to 2 Billion in 1927 and 3 Billion in 1960. Fourteen years later there were 4 Billion and in 1987 5 Billion people were counted. In 1999 the global population reached 6 Billion people. As a result the global population almost quadrupled during the 20th Century. Future growth is expected to exclusively happen in third world countries. (Source: DeutscheStiftungWeltbevoelkerung/United Nations World Population Prospect: The 2008 Revision, 2009)

Global Population: Distribution per Region/Area 2009 & 2050. Source: United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, Prospect 2009

Africa

Europe

Latin America and the Caribbean

Nothern America

Asia Oceania

100 - 280%

80 - 100%

60 - 80%

40 - 60%

20 - 40%

0 - 20%

-30 - 0%

Global Population Increase/Decrease in per cent per country; 2009 - 2050. Source: United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, Prospect 2009

Distribution of Urban Population by Size of Urban Settlement (Global). Diagram adopted from United Nations (2009)

Percentage Distribution of Urban Population by Development Region. Diagram adopted from United Nations (2009)

Percentage Urban by Development Region. Diagram adopted from United Nations (2009)

Percentage Urban by Major Area. Diagram adopted from United Nations (2009)

Source: United Nations, Department of

Los Angelos

30-40 million Sao Paulo Mexico City New York-Newark

20-30 million

10-20 million

Kennedy points out that the metabolism and the greenhouse gas emissions of a city are strongly dependent upon its location (Kennedy, 2009). Local temperatures, wind conditions as well as humidity and radiation have a direct impact on the energy requirements of urban areas. They directly influence the indoor energy demands in terms of heating and cooling but indirectly also have an effect on the urban energy consumption related to transportation. It is the outdoor comfort as well as travel distances that determine how people commute; both are directly related to the morphology of a city. Salat points out that there is a strong correlation between population density and energy consumption (Salat, 2007). Other authors agree with this (Kennedy, 2009) and regard densification as one of the key strategies in order to create ‘sustainable’ cities.

As much as high urban densities might mitigate high energy demands related to urban sprawl it needs to be mentioned that most studies do not take into account the energy demands related to vertical transportation in high-rise conglomerations. It also needs to be pointed out that energy requirements for buildings in the domestic and non-domestic sector exceed those for transportation and industrial processes. Salad points out that in urbanized countries like the UK buildings represent half of the energy consumption and together with transportation cities represent more than three quarters of the energy consumption (Salat 2007).

Largest (25) Urban Agglomerations in 2025. Source: United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, Prospect 2009

Appropriate adaptation of the morphology of a city is therefore clearly necessary in order to mitigate high-energy requirements; the urban geometry not only affects the density and related travel behaviours but also alters urban climatic conditions, which in turn affect energy demands related to indoor and outdoor climatic conditions. It is the interaction of geometries, surface materials and local weather conditions that determine whether an urban fabric is heating up or cooling down; whether it is desirable to lower or rise temperatures in urban areas hereby clearly depends on the location. Golany therefore argues that each climatic region necessitates a distinct urban form and configuration in order to make a city or neighbourhood cooler or warmer and that urban designers should borrow knowledge from other disciplines such as urban climatology, botany, geography, etc. in order to enhance urban comfort (Golany, 1996). Currently Urban Microclimates often evolve uncontrolled through the interaction of the local climate and geography in relation to the urban morphology. As microclimates develop at various levels and scales within an urban fabric it is mainly due to the poor inter-disciplinary work between architecture and urbanism that microclimates are not addressed in urban planning. Ali-Toudert points out in this context that there is a clear lack of guidelines that can help planners and architects in the process of improved microclimatic urban design (Ali Toudert, 2001).

Largest Urban Agglomerations (millions) in 2025 (2009 projections); Source: United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, Prospect 2009

*incl. Long Beach-Santa

Source: United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, Prospect 2009

Percentage Urban in 2009. Source: United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, Prospect 2009

Percentage Urban in 2050. Source: United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, Prospect 2009

600-700%

500-600%

400-500%

Urban Population: Size of Urban Population per country; increase in percent from 2009 to 2050. Source: United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, Prospect 2009

Percentage Urban; increase in percent from 2009 to 2050. Source: United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, Prospect 2009

Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division *(thousands)

**(as percentage of urban population)

In terms of absolut numbers mostly African and Asian countries are projected to show the largest increase in per cent from 2009 to 2050

The diagrams on the previous pages confirm that much of the world’s increase in population over the next forty years is expected to happen in the poorer parts of the world (refer to appendix 01 for additional information); especially Asian and African will encounter massive increases in population. This is also true regarding urbanization where especially African countries are expected to go through a massive shift as people migrate to cities. As the diagrams, which were drawn from data provided by the United Nations (United Nations, 2009), illustrate graphically the tendencies for future urbanization additional information is provided by the United Nations:

“The world urban population is expected to increase by 84% by 2050, from 3.4 billion in 2009 to 6.3 billion in 2050. By mid-century the world urban population will likely be the same size as the world’s total population was in 2004. Virtually all of the expected growth in the world population will be concentrated in the urban areas of the less developed regions, whose population is projected to increase from 2.5 billion in 2009 to 5.2 billion 2050. Over the same period, the rural population of the less developed regions is expected to decline from 3.4 billion to 2.9 billion. In the more developed regions, the urban population is projected to increase modestly, from 0.9 billion in 2009 to 1.1 billion in 2050.”

(United Nations, 2009)

“The sustained increase of the urban population combined with the pronounced deceleration or rural population growth will result in continued urbanization, that is, in increased proportions of the population living in urban areas. Globally, the level of urbanization is expected to rise from 50% in 2009 to 69% in 2050. The more developed regions are expected to see their level of urbanization increase from 75% to 86% over the same period. In the less developed regions, the proportion urban will likely increase from 45% in 2009 to 66% in 2050.” (United Nations, 2009)

“The world urban population is not distributed evenly among cities of different sizes. Over half of the world’s 3.4 billion urban dwellers (51.8%) lived in cities or towns with fewer than half a million inhabitants. Such small cities account for 53.2% of the urban population in the more developed regions and for 51.3% of that in the less developed regions. Between 2009 and 2025, small urban centres with fewer than half a million inhabitants are expected to account for 45% of the expected increase in the world urban population.” (United Nations, 2009)

“Over the next four decades, Africa and Asia will experience a marked increase in their urban populations. In Africa the urban population is likely to treble and in Asia it will almost double. By mid-century, most of the urban population of the world will be concentrated in Asia (54%) and Africa (20%).” (United Nations, 2009)

“The increases in the world urban population are concentrated in a few countries, with China and India together projected to account for about a third of the increase in the urban population in the coming decades, Between 2009 and 2025, the urban areas of the world are expected to gain 1.1 billion people, including 231 million in China and 167 million in India, which account together for 36% of the total increase. Nine additional countries are projected to contribute 26% of the urban increment, with increases ranging from 16 million to 52 million. The countries involved are: Nigeria and the Democratic Republic of the Congo in Africa; Bangladesh, Indonesia, Pakistan and the Philippines in Asia, Brazil and Mexico in Latin America, and the United States of America. Among them, those in Africa and Asia will experience high rates of urban population growth, usually surpassing 2% or even 3% per year.” (United Nations, 2009)

Ouagadougou:

Expeceted growth

81% until 2020

Climate Zone

Sahel Zone

Countries within Sahel Zone

Largest four African Megacities in 2020

Fastest growing cites in Africa (average growth rate 51%)

Sub

Urbanization prospects for Africa; largest Megacities and fastest growing cities. Source: World Urbanization Prospects: The 2009 Revision; United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division

City 2010-2020* Absolute Growth (000s)

Kinshasa 4,034

Lagos 3,584

Luanda 2,308

Dar es Salaam 1,754

Nairobi 1,669

*Projections

City 2010-2020* Absolute Growth (000s)

Ouagadougou 1,548

Cairo 1,539

Abidjan 1,375

Kano 1,100

Addis Ababa 1,051

*Projections

Africa’s 10 Fastest Growing large Cities (2010-2020). Source: World Urbanization Prospects, The 2009 Revision

According to the UN Habitat report, with an urban growth rate of 3.41 per cent, Africa is the fastest urbanizing continent in the world and will in 2030 cease being predominantly rural. The increase in urban populations will lead to an exponential increase in the demand for shelter and services. But as the authors point out African cities are already inundated with slums; a tripling of urban populations could spell disaster, unless urgent action is initiated today. (UN Habitat 2010):

• “Cairo, with 11 million inhabitants is still Africa’s largest urban agglomeration. But not for much longer. In 2015, Lagos will be the largest with 12.4 million inhabitants. In 2020, Kinshasa’s 12.7 million will also have overtaken Cairo’s then 12.5 million population. Luanda has recently surpassed Alexandria and is now Africa’s fourth largest agglomeration. It is projected to grow to more than 8 million by 2040.” (UN Habitat 2010)

• “Up to 2020, Kinshasa will be the fastest-growing city in absolute terms, by no less than four million, a 46 percent increase for its 2010 population of 8.7 million. Lagos is the second-fastest with a projected 3.5 million addition, or a 33.8 per cent increase. Dar es Salaam, Nairobi, Ouagadougou, Cairo, Abidjan, Kano and Addis Ababa will all see their populations increase by more than one million before 2020.” (UN Habitat 2010)

• “In the case of some African cities, projected proportional growth for the 2010−2020 period defies belief. Ouagadougou’s population is expected to soar by no less than 81 per cent, from 1.9 million in 2010 to 3.4 million in 2020. With the exception of the largest cities in the Republic of South Africa and Brazzaville in Congo, from 2010 to 2020, the populations of all sub-Saharan million-plus cities are expected to expand by an average of 32 per cent.” (UN Habitat 2010)

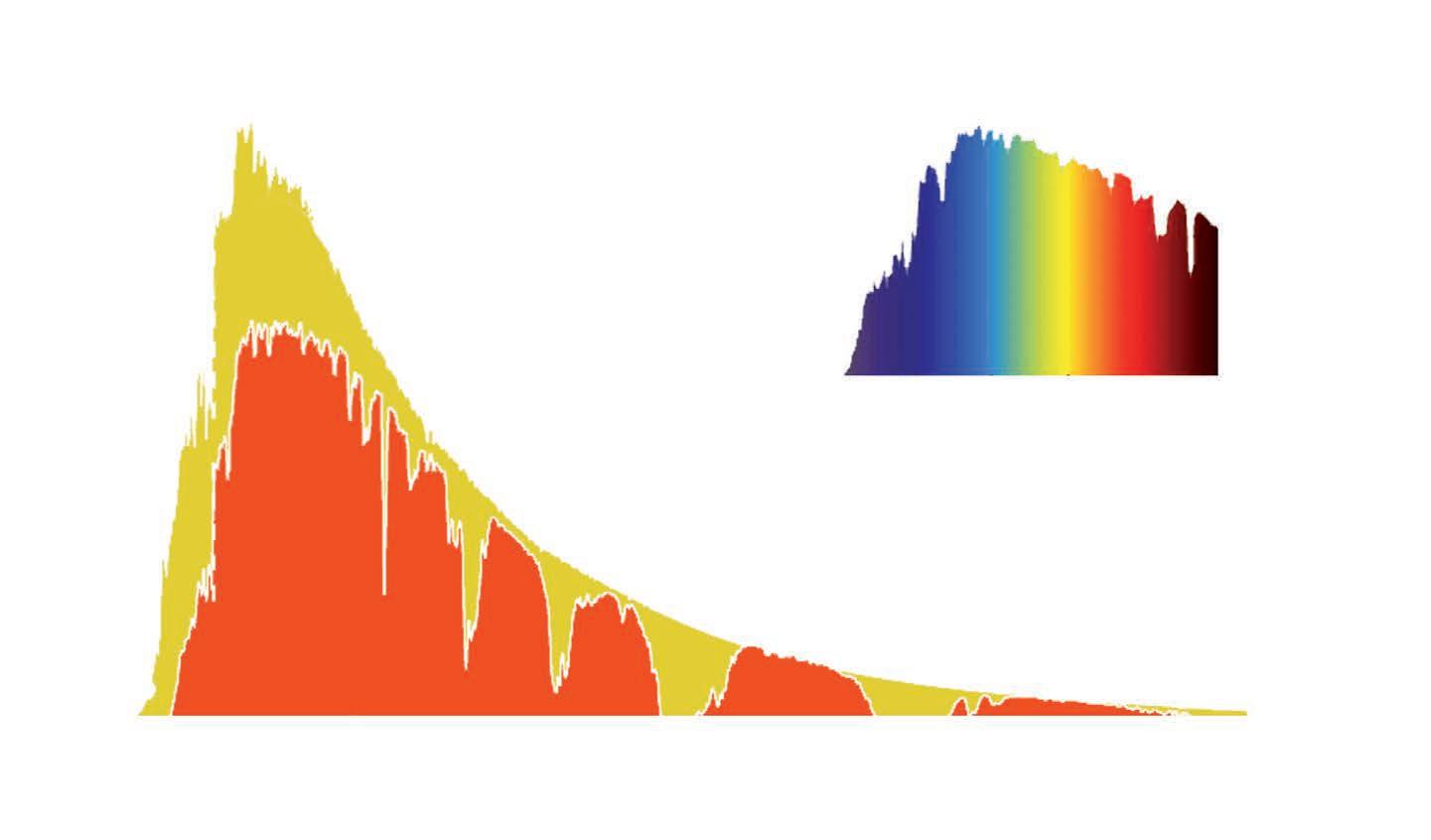

The energy content of the atmosphere is constantly driven towards equilibrium, occurring as a natural phenomenon. This includes factors such as solar radiation in the upper atmosphere; albedo, or reflection of the radiation from clouds, snow, ground and water surfaces; distribution of water and landmasses; and topography including the elevation and distribution of land features. The regional or macroclimate is a resultant of the net effect of these factors.

Climatic classifications:

One of the most wide used and popular climatic classification is the Koppen climate classification , later the Koppen- Geiger climate classification system. The same is widely used also as reference to predict the shifts in the climate in the future. This system of classification is primarily based on the vegetation prevalent in the area (biomes) 1

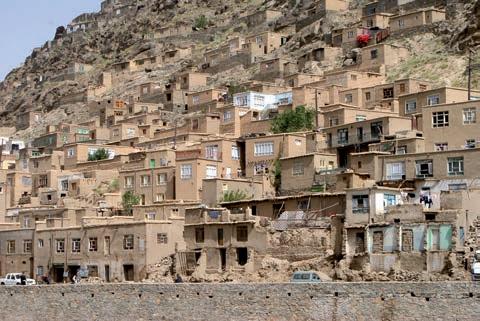

In terms of the architecture, characteristics right from the ancient civilizations through Vitruvius to Cerda’s Eixample indicated the considerations of select climatic parameters as design determinants. This sensitivity found in vernacular architecture towards climate, and the apparent consequences of the same contributing to the micro climate have been used as a basis for identifying regions or macroclimate. It considers the climate, location in terms of distance from the edge of the continent, and topography.

1 Köppen climate classification. (2011). In Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved fromhttp://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/322068/Koppen-climateclassification

For the distinction of vernacular architectural regimes, the world climate zones have been divided into the 9 zones, namely:2 3 (i)

Arctic and Sub Arctic:

- All areas north of the Arctic Circle at 66.33 °N belong to this zone. The region immediately south of this is the Sub- arctic. Although no human settlements prevail in the Antarctic, the conditions are similar to the Arctic.

- There are 4 distinct biomes found inthis zone: the polar seas and the glaciers, the coasts and islands, the treeless tundra plains, the taigathe large coniferous forests of most parts of Canada, Alaska, Scandinavia and Siberia.

- Air temperature and radiation are key factors to human habitation: outgoing radiation takes away much of the incoming solar energy because of clear air and water vapour.

- Winters are long and cold with incoming solar radiation at very low angles. The presence of sea or Ocean has major climatic influence on the temperature.

Observed Vernacular Responses:

- Continuity in blocks.

2 Oliver, Paul; Encyclopedia of Vernacular Architecture 3 http://www.worldclim.org/

- Orientation

(ii) Continental:

- Large flat, open terrain : subject to exposure of winds and major storm systems..

- Major difference between the seasons.

- Between the Taiga region , through the mid latitude grasslands and hardwood forest; from semi arid mid latitude areas towards the hot deserts to subtropical edge.

- Southern Hemisphere: 20 °S to 40 °S

Observed Vernacular responses:

- Protection against wind : use of trees and earth.

- Planted landscapes as windbreakers

- Low profile, earth embraced and aerodynamic in form to reduce surface exposure

- Lowered floors in pit houses with earth covered walls, airtight fabric or skin construction to avoid wind and also use thermal capacity of earth.

- Entrance facing east. Steeper rear side braced against prevailing westerly winds.

- Continuous wind breakers , also usually tall (10 ft )

- Insulation in walls

(iii) Desert:

- Extreme differences in the temperatures

between night and day.

- Evapo-transpiration is the major factor of concern.

- Strong sun and high temperatures.

- An average of 3000hrs of sunshine annually.

- Due to the low water vapour presence in the atmosphere, both incoming solar radiation and the outgoing radiation are high, thus causing rapid air temperature changes as much as 3 ° C per hour. Resulting from this are sunny hot days and rapidly cooling nights.

- Rainfall occurrence is erratic. The sparse vegetation also leads to flooding.

- Erratic winds, with speed between 15 and 30 mph; dust haze, sand storms.

Observed Vernacular responses:

- Massive defensive built structures; blank walls , shuttered openings, courtyards, narrow streets to baffle winds.

- Heavy construction material to delay thermal flux.

- Intensive solar heating reduced by reflective surfaces/ ventilated double construction.

- Vaulted or domed roofs better than flat roofs as they can reradiate heat better at night.

- Shade roofs, Arbors, Armadas

- Cross ventilation is not the usual summer cooling strategy because of the high temperature of winds( more than skin temperature). Instead the use of wind towers is common, made to capture winds

and diffuse into the building.

(iv) Maritime:

- Most maritime climates are restricted by coastal climates with the exception of Western and Central Europe, leaving the mainland open to wind and moisture effects of the Atlantic. Europe: continuous westerly and northwestern winds

- Four distinct seasons are characteristic of this region.

Observed Vernacular responses:

- Built forms are made sensitive to dampness.

- Pitched roofs are common. Large roofs of insulated material and limited wall areas to reduce thermal loss and maximize the internal heat are a common feature.

- Maritime effects from the North and West.

- Entrance is most commonly places on the South side.

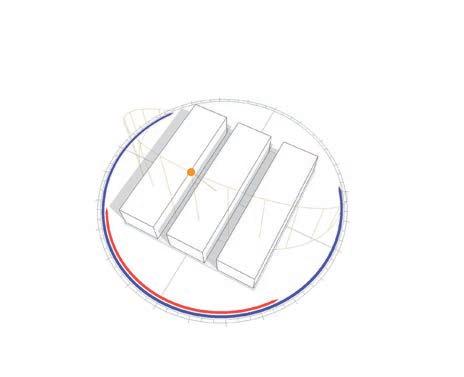

- Linear pattern of blocks in a single row, with broadside to the sun.

- No openings in the northern walls as protection against winds.

(v) Mediterranean:

- Moderate and coastal with sunny, dry, warm summers, and mild or cool, damp winters.

- Latitude: 45 ° N to 30 ° N; west coast of all the continents.

- Area around the Mediterranean sea; deep, thermally stable water surrounded by land and mid latitudes.

- Warm water stabilizes air temperature and reduces diurnal swings.

- The rugged terrain and broken surrounding highlands leads to the rise of many a microclimate.

- Sirocco, Mistral and Bora are some of the local winds- the warm dry blowing in from the Sahara, the cold northerly winds from in France and Greece respectively.

Observed Vernacular responses:

- Heavy masonry for insulation

- Conical roofs

- Entrance and small openings in the south, very small opening to the north.

- Reflective white surfaces

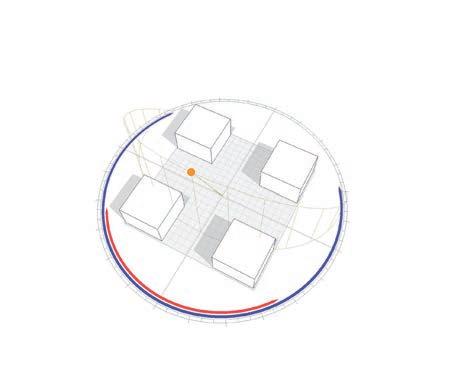

- Courtyards

- Narrow streets

(vi) Monsoon:

- 3 seasons

- Wind that reverses itself seasonally , blows continuously between land and adjacent water body

- Prevailing winds from north east .

- High humidity during most parts of the year.

- Increased precipitation during most parts of the year.

Observed Vernacular responses:

- One storey design typically on raised floor

- Deep, well sheltered porch at least on one side, deep overhangs on all sides encouraging ventilative cooling and convective dissipation of the attic heat from gabled roof.

- Hot dry season: massive walls on the ground floor, with a storey of light weight construction above.

- Elements such as porches provide shade and also rain protection

- Shared perimeter walls thus only narrow front wall exposed to weather facing narrow streets.

- Rugosity increased to reduce solar gain and also as options for thermal control.

- Fresh air allowed only when air is cooler than the building.

- Lower levels are cooler.

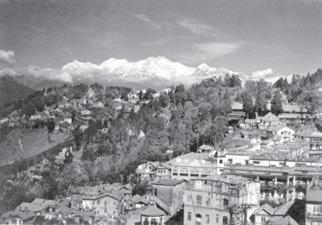

(vii) Montane:

- The altitude of land and orientation of slope is an influential factor on the local climate, irrespective of the latitude.

- Frequent precipitation, dominant diurnal wind patterns , distinct seasons, many local microclimate and seasonal flow.

- Impact of large mountain ranges to the global climate is profound. They act as barriers to the flow of winds and this causes climatic shifts on both the windward and leeward regions.

- The interrelated mountain and valley systems are important to human settlement due to the resulting microclimate.

- The altitude primarily causes a drop in the air temperature. Also the rainfall and snowfall is much higher.

- Uplift of airstreams on the windward sides causes condensation of moisture and increases precipitation. Gaps in mountains causes strong flow of winds.

Observed Vernacular responses:

- Aerodynamic form

- Multi-storied

- Expansive roof with generous overhangs

- Raised porches

- Relatively shallow roofs.

- Massive tapering external walls

(viii) Subtropical

- Humid warm coastal; warm but outside the tropics.

- Multiple seasons

- Cool or mild winter is short and damp with rain, but seldom snows, and the frost free period is at least nine months.

- Humid summer is long, warm and muggy.

- Considerable humidity throughout the year

- Similar conditions with variable seasons also characterize the uplands and plateaux within the tropics including at the Equator.

- Large lowland areas with humid warm climates are on the east and southeast coasts of four continents, between latitudes 25 ° and 38 °

- Average monthly temperature is above 25 ° C

- Cool humid winters with average monthly temp below 10 ° C

- Continuous humidity provides a narrow annual range of temp

Observed Vernacular responses:

- Well spaced buildings with generous garden and large canopy shade trees.

- White lime plastered on thick rammed earth walls tempers summer heat.

- Few windows towards the sun. Windows are places deep and high in the walls.

- Full solar penetration in the winter is desirable.

- Incoming and outgoing radiation are stronger so there is an increased use of thick walls for thermal mass.

(ix) Tropical:

- Warm and wet throughout the yr with little variation.

- No distinct seasons

- Slight difference between day and night conditions

- High humidity continuously; high precipitation throughout the year.

- 10 ° of the equator; 23 ° North at the Tropic of Cancer to 23 ° S at the Tropic of Capricorn

- Trade winds affect these regions

- Stable conditions, with narrow range of temperature daily and annually. Mean temp for year is around 18 ° C

- Max air temp between 27 ° and 32 ° C

- Relative humidity : 55 %- 100%

- Lack of wind or strong storms

- Skies normally clear

- Atmospheric turbidity due to high relative humidity which prevents solar heat from dissipating.

- Frequent rain storms can be accompanied by thunder and lightning

Observed Vernacular responses:

- Extensive roofs for shading, well sloped for the rain.

- Increased natural convection including stack ventilation by the use of gable vents.

- Frame construction adopted, to maximize the cross ventilation with the slightest breeze.

- Lightweight construction

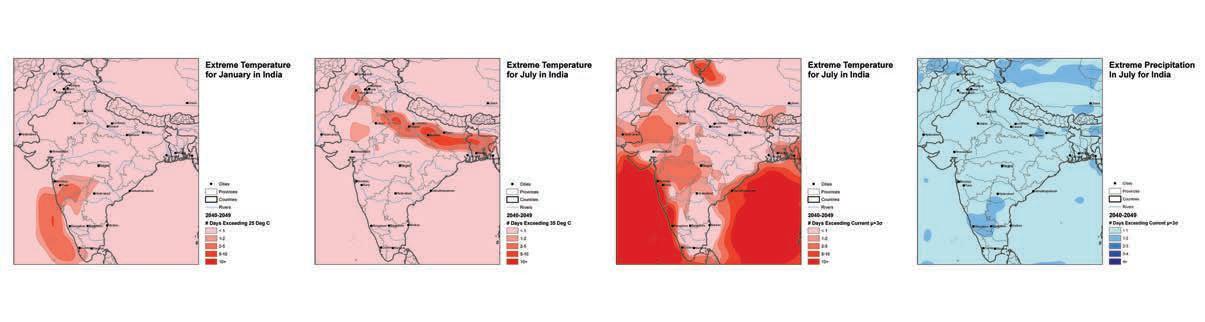

A Bio-Climatic design approach to urbanism requires a thorough analysis of all relevant climatic parameter; this not only with respect to current climatic conditions but also with regards to potential future changes and shifts.

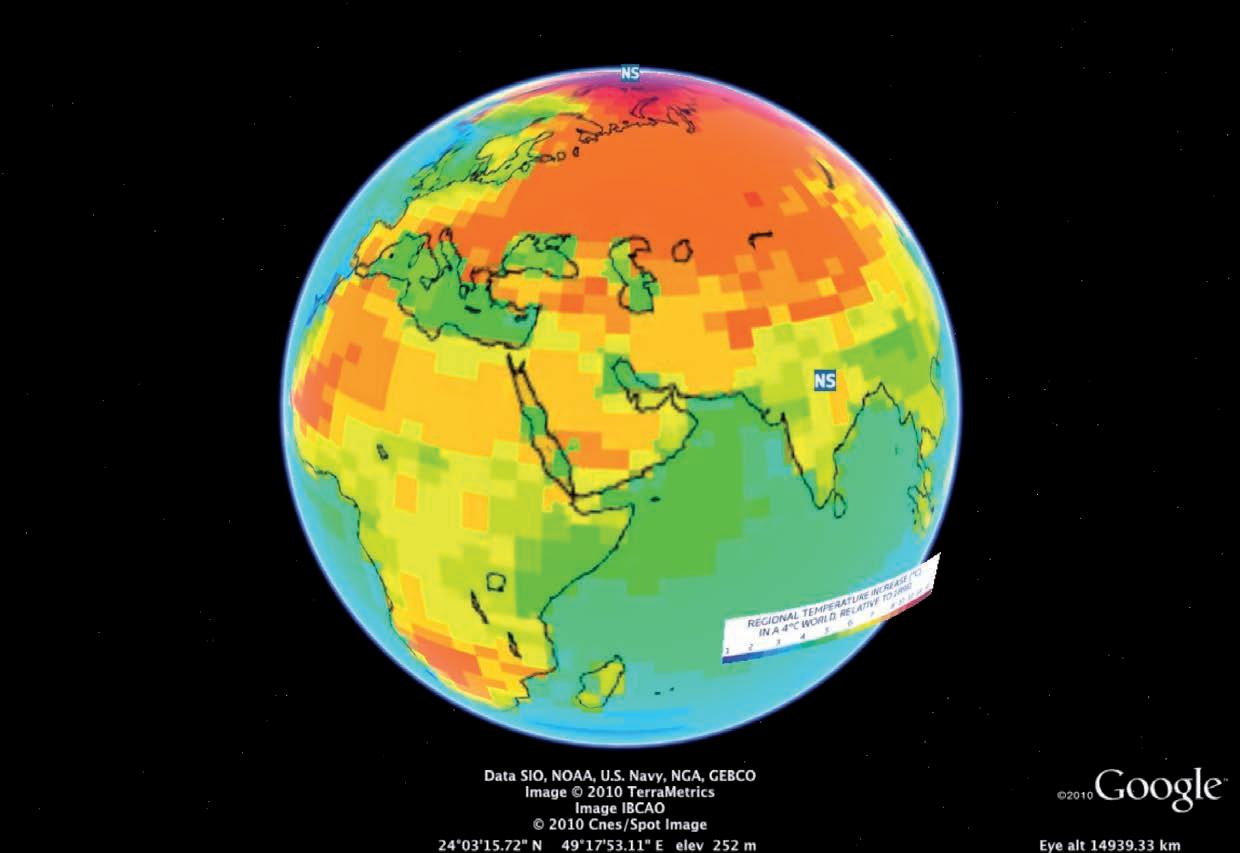

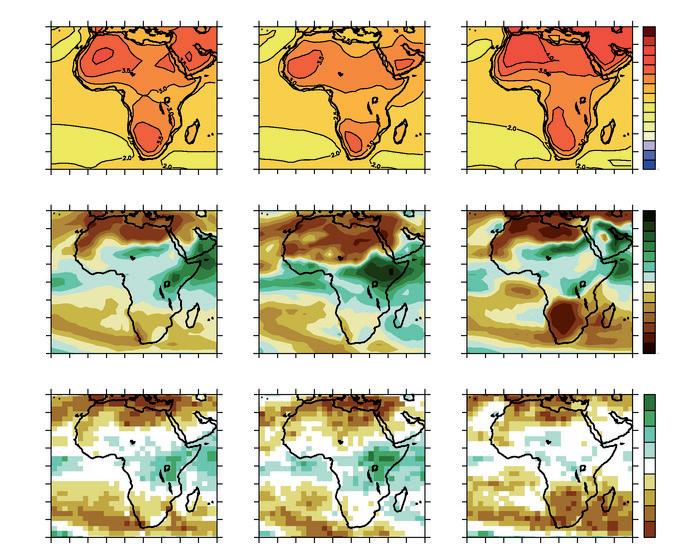

Today different climate models and theories exist that predict changes to the global climate over the next 50 to 100 years. As much as there is disagreement, whether the earth will warm up, cool down, or whether the global climate will remain static, it seems that the concept of global warming is the most widely accepted. Van Esch (Van Esch) reports that according to an IPCC 2007 report heat stresses will generally increase due to a global temperature rise between 1.1°C and 6.4°C. A joint study conducted by the UK Met office in cooperation with Google Earth (2009) predicts even more radical changes in temperature until the year 2050; here temperature increases are predicted to be in average at around 5°C, however some of the polar regions are projected to experience a rise in temperature of up to 12°C.

Projected increases in global temperature will have a drastic effect on the fossil fuel consumption of cities and urban agglomeration; as much as higher energy consumption due to increased cooling loads could result in massive problems, it is the change in weather patterns and the associated problems that impose a real threat to urban (and rural) societies. According to the UK Met Office changes over the next 40 years will include extreme temperatures, that in certain regions will lead to shortages in terms of crop production and water availability; as most urban develop-

ment is predicted to take place in regions with already extreme climates, continuous urban growth could result in the literal starvation of cities. Extreme temperature rises in polar regions, on the other hand, could further accelerate the already rapid decrease of the polar ice caps; associated rises in global sea levels could likely result in permanent flooding and in this way have an impact on many coastal cities. Overall, shifts in temperatures will have an impact on current climates. Williams reports that key risks associated with projected climate trends for the 21st century include the prospects of future climate states with no current analog and the disappearance of some extant climates (Williams, 2007). Climate shifts projected by the Met Office include the shift of monsoon regions and increased occurrence of tropical cyclones. The effects of such weather phenomena on human settlements can already be witnessed today.

Cities that are planned today therefore need to respond to such scenarios and need to incorporate strategies that can mitigate the effects of climate change. Future climate projections should therefore be studied by urban planners and urban strategies need to be deployed that allow for careful planning and adaptation over time.

Permafrost:

• Almost complete disappearance of near-surface permafrost from Nothern Siberia. Reduction of Permafrost in Canada and Alaska.

Water Availability:

• Water resources affected by up to 70% reduction in run-off around the Mediterranean, southern Africa and large areas of South America.

• Complete disappearance of glaciers from many regions in South America. In Peru’s Cordillera Blanca summer run-off from glaciers reduced by up to 69% as the glacial area falls by 75%.

• Half of all Himalayan glaciers significantly reduced by 2050. The Indus river basin obtains 70% of its summer flow from glacial melt. In China, 23% of the population lives in the western regions where glacial melt provides the principal dry season water source.

Crops:

• Maize and wheat reduced by up to 40% at low latitudes.

• Soybean yield could decrease in all regions of production, including North and South America, southern and eastern Asia.

• Decrease in rice yield of up to 30% in China, India, Bangladesh and Indonesia.

Drought:

• Drought events occur twice as frequently across southern Africa, South-East Asia and the Mediterranean basin.

Sea Level Rise:

• Sea levels could rise as much as 80cm by the end of the century. Longer term, 4°C would result in a much higher rise in sea level. Sea level increases are likely to be even greater at low latitudes, disproportionately affecting tropical islands and low-lying regions such as Bangladesh.

• For the population at 2075, a mean sea-level rise of 53cm means that up to an additional 150 million people per year would be flooded due to extreme sea levels. Three-quarters of these people live Asia. Up to 56 million people would be flooded along the Indian Ocean coast, 25 million along the east Asian coast and 33 million people would be flooded along the South-East Asian coast. Other vulnerable regions include Africa, Caribbean Islands, Indian Ocean Islands and Pacific small Islands.

• Greenland Ice Sheet has a 60% likelihood of irreversible decline. This would result in a very long-term sea-level rise of up to 7 meters globally.

• It is not known how stable the West Antarctic Ice Sheet is, or whether a 4°C global temperature rise will send it into irreversible decline. If this ice sheet did melt it would contribute a further 3.3 metres to long-term sea-level rise globally. Sea-level rise combined with storm surges could pose a serious threat to people and assets in the Netherlands and south-eastern parts of the UK.

Tropical Cyclones:

• Tropical cyclones could be more intense and destructive. Global population increases, particularly in coastal areas, and sea-level rise mean greater cyclone and hurricane related losses, disruptions to infrastructure and loss of life as a result of storm surges. For major cyclone disasters flooding from storm surges has been the primary cause of death.

Extreme Temperature:

• Hottest days of the year could become as much as 10-12°C warmer over the eastern North America, affecting Toronto, Chicago, Ottawa, New York and Washington DC.

• Hottest days of the year across Europe could be as much as 8°C warmer

• Hottest days of the year could be as much as 6°C warmer over highly populated areas of eastern China.

The impact of a global temperature rise of 4°C - Projected for 2055. Diagram adopted from UK MET Office/Google Earth, 2009

In recent years there has been growing public awareness for the need of ‘sustainable urban design’ in order to mitigate energy consumption and waste production of cites. The US Environmental protection agency concluded in 2001 that ‘…the urban form directly affects habitat, ecosystems, endangered species, and water quality through land consumption, habitat fragmentation, and replacement of natural land cover with impervious surfaces. In addition, urban form affects travel behaviour, which, in turn, affects air quality; premature loss of farmland, wetlands, and open space; soil pollution and contamination; global climate; and noise’ (Jabareen, 2006).

As much as it is attempted to develop and implement concepts for ‘environmental-friendly’ cites, there is disagreement of what appropriate solutions are. As a result, different concepts for sustainable urban forms exist. In the 1960’s Jane Jacobs was at the forefront to argue for diversity and against urban sprawl. As a result, a variety of different urban movements evolved that criticise the monotony and lack of urban qualities that were in many cases linked to modernistic ideas; the ‘Neo-traditional Movement’, as well as other concepts, such as ‘Urban Containment’, the ‘Compact City’, or the ‘Eco-City’, can be seen as an reaction to urban planning that was implemented in the 1960s and 1970s.

They all argue for alternative ways in order to improve urban qualities and to mitigate energy consumption.

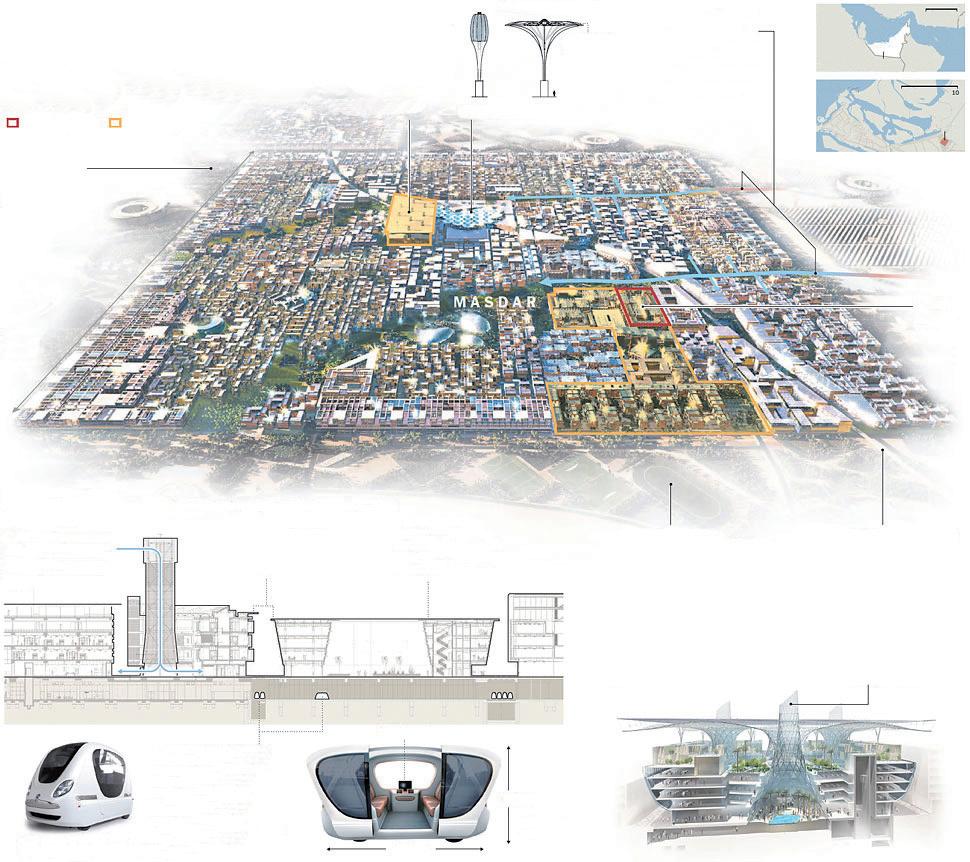

Nevertheless, with growing environmental awareness and energy prices soaring, recent concepts for ‘sustainable cities’ focus much more on the metabolism of cities; i.e. the reduction of energy consumption via renewable energies and the mitigation of waste produced. Currently, the most well known example for such a zero-carbon/zero-waste ecology is the proposed master plan for the city of Masdar in the United Arab Emirates. In the following chapter different concepts for ‘sustainable’ urban development will be introduced. In addition characteristics of urban sprawl, densification and satellite towns will be explained.

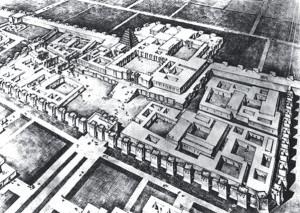

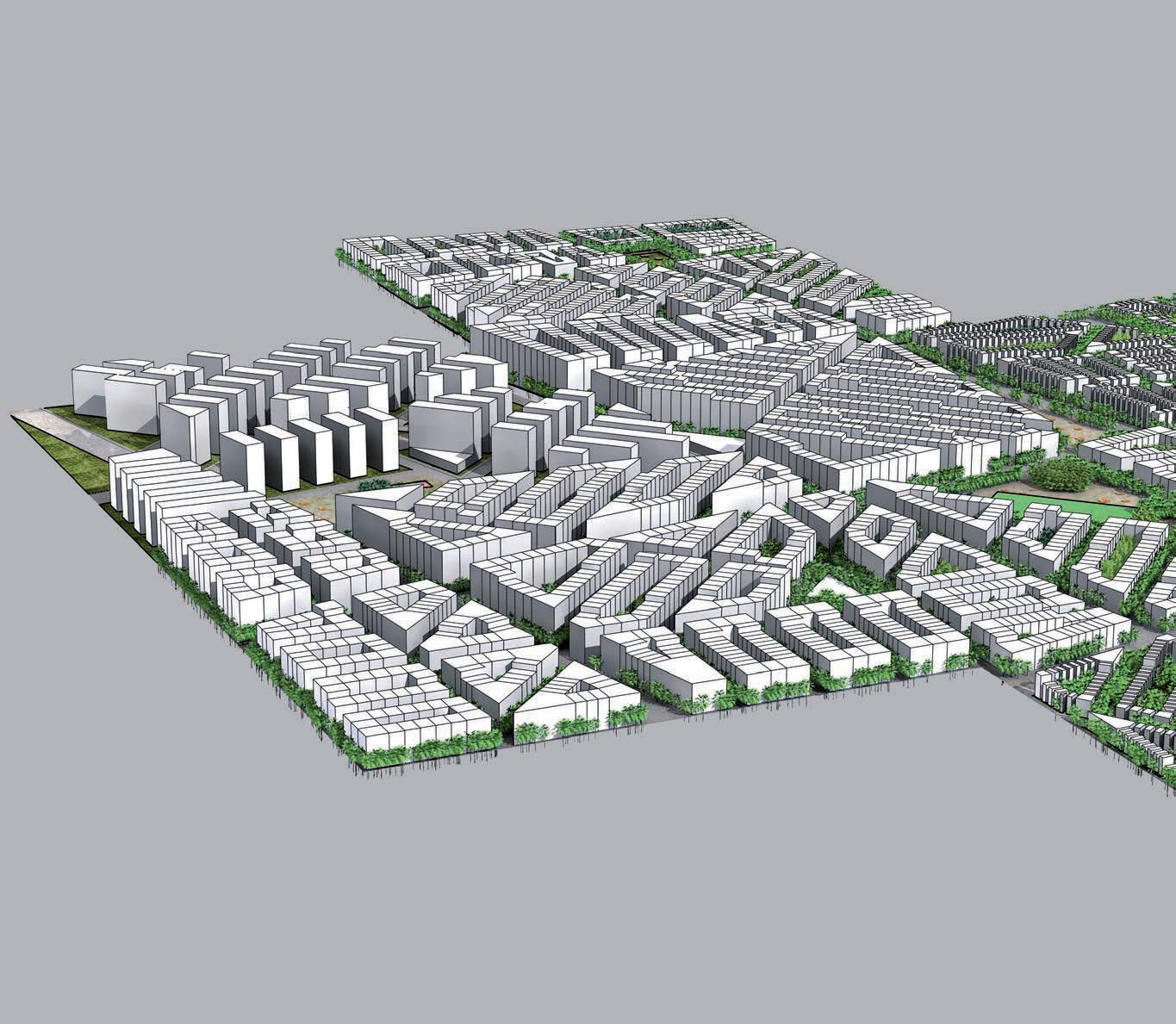

Images above: Masdar City, United Arab Emirates. The master plan is advertised a paradigm for sustainable urbanism. Designed by Foster & Partners, the city will rely entirely on solar energy and other renewable energy sources, with a sustainable, zero-carbon, zerowaste ecology (Source: Wikipedia). Located in the desert, 17km outside Abu Dhabi, the design is currently executed. Once it is completed it will have to proof its high ambitions (Diagram: www.nytimes.com).

As the urban population is predicted to drastically grow over the next four decades cities will encounter a rapid increase in size and number. This tendency has massive implications on energy demands that are related to infrastructure, heating and cooling. The development of appropriate design strategies that take the reduction of energy consumption into account should therefore be the main challenge for architects and urban planners.

Poor urban qualities of cities that were developed in the post war area have resulted in new approaches to urbanisms that include e.g. the eco city or the neo-traditional development. As much as these strategies try improve urban living conditions strategies are lacking that incorporate geography and climate into urban design. Key to establishing a bio-climatic urban approach is to identify the parameters that need to be considered for mitigating the energy demands of an urban fabric. In this context Jabareen (Jabareen, 2006) points out seven factors that should be considered for any ‘sustainable’ urban planning approach:

Compactness of urban form is for many planers one of the key strategies in the approach to sustainable urban design. It can help to prevent urban sprawl and can help to minimize transport of energy, water, materials and products. (Jabareen, 2006). For example, Dumreicher et al. argue that a sustainable city should be compact, dense, diverse, and highly integrated. Compactness goes hand in hand with the goal of livability and works to prevent commuting, one of the most wasteful and frustrating aspects of city life today.

The size of contemporary cities is only possible because of modern means of public transportation, including buses, subways and elevators. Such infrastructures allow cities to expand in the horizontal as well as in the vertical extent and allow for a separation of living and working. The form of the city thus reflects the transport technologies that were dominant at a specific time.

Infrastructural networks and technologies have enabled urban agglomerations to reach unprecedented sizes; nevertheless they impose enormous energy demands and put enormous strains on the environment. Jabareen suggests that a restructuring of the urban and metropolitan transportation system can help conserve energy in several ways as compact and transit orientated development shorten trips and encourages non-motorized travel.

Density is an important measure that allows to draw important conclusions about, e.g. the compactness of an urban fabric; in this way it is highly related to sustainability. Dense urban morphologies suggest shorter travel distances and, depending on a city’s geographic location, density can be used as an indicator regarding the energy requirements of a fabric; in cold climates shared party walls can reduce heat loss whereas in hot and humid areas isolated buildings can improve the ventilation potential of a fabric und thus reduce cooling needs.

Different concepts of measuring density exist, though. In general density can be defined as a ‘numerical measure of the concentration of individuals or physical structures within a given geographic unit.’ (Ng, 2010)

According to the above definition a common concept of measuring density is to look at the ratio of population to land area. Density can, nevertheless, also be expressed in other ways. Planners often look at the relationship between occupied land (or floor area) to un-built land. The later method is often used as a way of measuring building density; the plot ratio or floor area

ratio combined with site coverage can thereby give indications about the morphology of an urban fabric: High plot ratios combined with low site coverage tend to suggest tall and free standing buildings, whereas lower plot ratios and high site coverage might indicate urban sprawl (compare diagrams on page 180).

As much as density can be associated with sustainability it needs to be stressed that there is different opinions among scholars whether high or low densities are beneficial in terms of reducing energy consumption.

Many scholars and planners believe that concepts of mixed land use should be (re-) introduced into cities in order to reduce travel distances and to enhance social activities. The classic model of live-work, where residential and commercial activities are intertwined within the same neighbourhood or block has in the past often been replaced by rigid zoning structures that separate such activities. Jabareen argues that imposed zoning reduces the diversity in local areas and results in increased traffic and less safe streets; he resumes (Jabareen, 2006): “For a sustainable urban form, mixed uses should be encouraged in cities, and zoning discouraged.”

Car orientated post-war urban planning has often resulted in monotonous urban landscapes with poor neighbourhood qualities. The paradigms of modernity have therefore let to new planning approaches, such as ‘new urbanism’, ‘smart growth’ or ‘sustainable development’. In the early 1960s Jane Jacobs was one of the first to challenge current planning regimes by advocating urban strategies that are formed around the central idea of diversity. Diverse development thereby implies a mixture of land uses, building and housing types, architectural styles, and rents; by introducing diversity it is hoped to break with the homogeneity and monotony of urban form and to enhance social interaction and activities.

According to Jabareen passive solar design is central to achieving sustainable urban form. He argues (Jabareen, 2006): “…architects have a larger share of responsibility for the world’s consumption of fossil fuel and global warming gas production than any other professional group.”

As pointed out earlier the morphology of an urban fabric has large implications on its ability to absorb or reflect solar radiation. In other words, the capacity of an urban structure to store or release heat is highly dependent on its morphological characteristics. Jabareen points out that the reduction of energy demand due to heating or cooling should be central to an urban design; passive solar design can therefore be achieved by specific design measures that relate to the constitution of the urban fabric. Orientation of buildings as well as densities should be carefully considered when planning an urban fabric. Factors such as built form, the street canyon, building design as well urban materials should also be added to this.

Greening is an important consideration towards improving the qualities of an urban fabric. Besides it’s social and recreational values it has important implications on the microclimate of an urban area. Compared to hard surfaces vegetation has the ability to store water; this can help mitigating sewer systems in areas with a lot of rain and prevent surface water run-off. In warmer climates parks and green areas can act as cool islands as they release heat through evapo-transpiration and shade can be provided through vegetation. Urban pollution and smog can also be acted against by appropriate green planning.

Hot-Humid

Equatorial Zone

Cold-Humid

U.S.A and souther Canada

Hot Diurnally and Seasonally with minor temperature Range.

Heavy rain

More Comfort at High Elevation

Exessive Heat

High Humidity

Hot-Dry

Middle East and North Africa

Snowy

Windy, Blizzard Condidtions

Very Cold Nights

Low Temperature

Winter and Summer

High Precipitation

Windy

Cold-Dry

Inland Plateau

Intense Solar Radiation

Large Temperature

Amplitude between Day and Night

Dusty Storms

Torrential Rain

Low Cloudy Days

Intense Dehydration

High Salinization

Evaporation exceeding Precipitation

Excessive dryness

combined with high day temperature

Dusty and Stormy

Ventilation: Open Ends and Dispersed Form

Widely Open Streets to support ventilation

Combined vatiation of Building Heights

Wide, yet shadowed open Spaces

Shadowing, planned tree zones

Heating (Passive & Active):

Mixture of open and enclosure forms

Protected Edges at Winter Windward Side (with structures or trees)

Uniformed Building Heights

Medium Dispersed Open Space

Circumfernetial and Intersecting Tree Strips

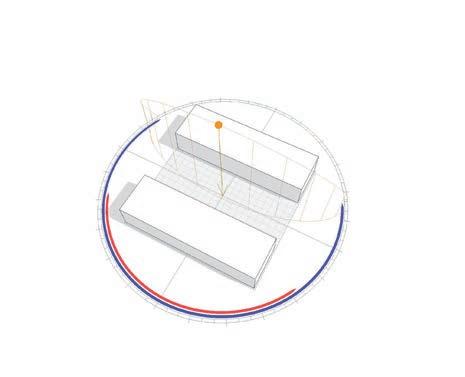

Compact Forms:

Shadowing

Evaporative Cooling

Protected Urban Edges from Hot Winds

Windward Location near a Body of Water

Narrow Winding Neighborhood Roads and Alleys

Mix of Building Height to Shadow the City

Small Dispersed, and protected public open Spaces

Cicumferential and Intersecting Tree Zones

Use of Geo-Space City Concept

Dispersed Form with open ends to support ventilation

Stressful and Uncomfortable Strong Dry and Cold Wind

Excessive Low Temperature associated with Dryness

Stressful Wind

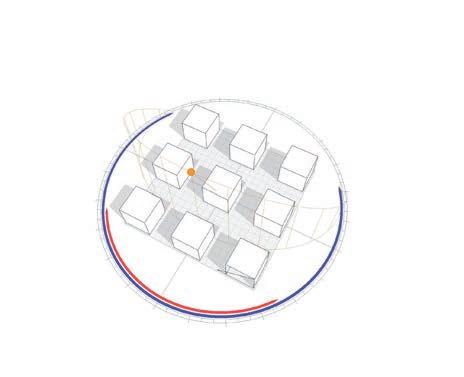

Compact and Aggregate Forms, Clustered Forms

Protected Urban Edges

Narrow Winding Neighborhood Roads and Alleys

Uniformed City Height

Small, Dispersed, and Protected Public Open Spaces

Circumferential and Intersecting Tree Zones

Use of Geo-Space City Concept

Classification of Major Climate Types and Urban Morphologies, adopted from Golany (Golany 1996)

Mix of Open and Controlled Enclosure Forms

Compact Form

Compact and Aggregate Form, Clustered Forms

Seashore Strips Desert Coasts

Windy and Stormy Breeze System High Humidity Erosive

High Humidity Windy

Mountain Slopes Lower, Middle and High Slopes

Windy and Increasing Windy Air Circulation Higher relative Humidity than the Lowland

Provide Healthy and Moderate Climate

Enhance attractive View

Windy

In Humid Region: Moderately dispersed Form

Open Urban Edges

Wide Streets perpendicular to the Shore to receive the Breeze

Dispersed High Rise

Buildings to receive Ventilation

Variety of Building Heights

Wide Public Open Space

Shadowing, Planned Tree Zones

In Dry Regions:

Open Towards the Sea, Compact and Protected toward the Inland

High Rise Buildings mixed with low Height

Small protected and dispersed Public Open Spaces

Shadowing, planned tree zones

Semi-Compact Form: Mix of Compact and Dispersed

Horizontal Stress and Alleys to enhance the view

Low height Buildings

Small Dispersed Public Open Spaces

Non Obstructive Protected Tree Zones

Use of Geo-Space City Concept

Classification of Major Climate Types and Urban Morphologies, adopted from Golany (Golany 1996)

In Humid Regions: Moderately Dispersed Form

In Dry Regions: Compact and Protective toward the Inland

Semi-Compact Form: Mix of Compact and Clusterd Forms

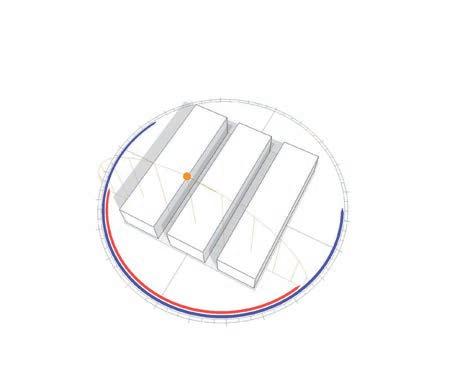

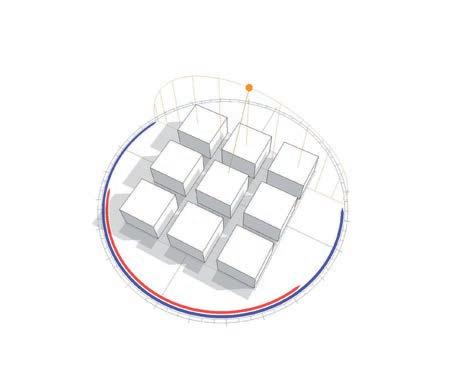

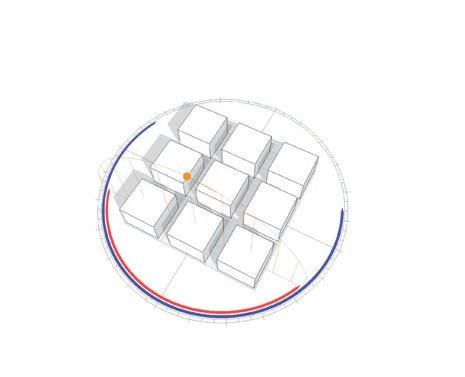

Golany argues that different climate zones require specific urban forms in order to best respond to the environment. The diagrams above and on page 34 provide a catalogue of environmental criteria and corresponding design responses (Golany, 1996).

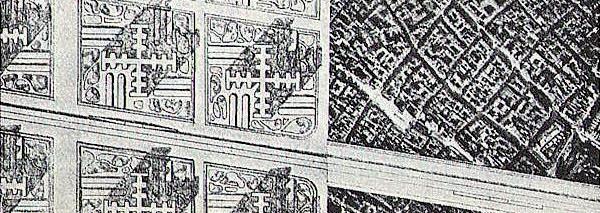

The beginnings of cities may be thought of as agglomeration points of peoples where in there were material exchanges coupled with some kind of administrative structuring. Chronologically, they may be classified into two broad categories as before and after the Industrial Revolution in the 18th and 19th centuries.

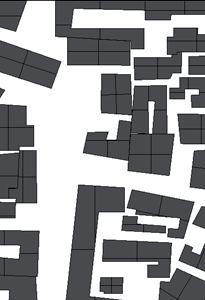

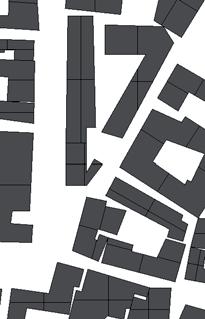

The ‘Evolved city’ of ancient civilizations to the pre industrial era came about into being over long periods of time, developing in patterns under the influence of various factors, such as climate , culture and political confinements through time. The ‘Planned City’, of the post industrial, post-war and till date, on the contrary, was an implementation of detailed land use strategies and plans laid out directly aiming at building centers of economic foci by governments in collaboration with urban planners. However both cases reflect are emergent phenomena due to the dynamic flows of people and energy.

The determinant factors of location and persistence of a polis have in all cases been in relation to Mercantile, Governance and/ or Microclimate pertaining to the geographic location (mainly in the case of evolved cities).

City forms are material constructs that are composed of a spatial array of dwellings, a pattern of street and public spaces together with differentiated buildings of varying sizes associated with the regulation of energy and material flow, and the extension of metabolic network across the surrounding territory.[MW, The Architecture of Emergence].

‘Urban Microclimates’ evolve locally through the interaction of the built environment and the local climate. There is no clear delineation for the size and extent of Microclimates; they can range from individual facets of the urban environment, through streets and city blocks to neighbourhoods. In this sense the city consists of a patchwork of microclimates. All local microclimates together comprise the overall microclimate of the city.

The control and optimization of Urban Microclimates is currently not addressed in design.

We argue that the only way to optimize the ‘Urban Microclimate’ in a design process is by using simplified parameters; in other words we believe that the use of complex computational analysis tools like e.g. Fluid Dynamics are currently still too time consuming to be used in generative design processes. We therefore believe that simplified Urban Parameters (Morphological Indicators, such as e.g. Rugosity or Porosity) should be used to rapidly extract indicative results.

These urban parameters are set in different proportions against the global factors of climate and topography. In order to set these proportions, the performance of an evolved city against that of its planned counterpart, in each of the 9 global zones, is assessed with respect to the morphological indicators. We believe these results reveal key information to feed our optimization tool to respect the needs of not just the local built environment, but their overall setting in any given geographic location.

We however do acknowledge that apart from the above mentioned quantifiable morphological indicators, there exist certain other non- quantifiable factors of culture, and social preference and identity related to an urban setting . Kevin Lynch describes this attribute as “a sense of place”. Lynch specifically describes how to achieve a sense of place regardless of the purpose and structures. [Lynch: What Time is This Place? And Site Planning] Often culture and familiarity are associated with these ideas.

At present, 2% of the world’s land surface is covered by cities and yet the people living in them consume 75% of the resources consumed by mankind. The ‘ecological footprint’ of cities is many times larger than the areas they physically occupy (Rees, 1999).

Sprawl is the spreading out of a city and its suburbs over more and more rural land at the periphery of an urban area. This involves the conversion of open space (rural land) into built-up, developed land over time.

From the standpoint of urban planning institutions, the style of that conversion can sometimes be more important than the amount of the conversion. Organizations whose chief concerns involve urban planning goals may tend to emphasize qualitative attributes of sprawl -- such as attractiveness, pedestrian-friendliness and compactness.

However, the effect of sprawl on the natural environment and agricultural resources, the more important overall measure of sprawl is the actual amount of land that has been urbanized. Knowing the actual square km of urban expansion (sprawl) provides a key indicator of the threat to the natural environment, to the nation’s agricultural productivity and to the quality of life of people who live in cities and in the small towns and farms that are near cities

Precendent: US cities:

Between 1982 and 1997 America converted approximately 25 million acres (39,000 square miles) of rural land — forests, rangeland, pastures, cropland, and wetlands — to developed land: that is, sub-divisions, freeways, factories, strip malls, airports, and the like.

Over a 20-year period (1970-1990), the 100 largest Urbanized Areas in the United States sprawled out over an additional 14,545 square miles. That was more than 9 million acres of natural habitats, farmland and other rural space that were covered over by the asphalt, buildings and sub-divisions of suburbia. And that was just for the half of Americans who live in those 100 cities. This strategy of urban plan has now become a topic of concern.

[Source: NumbersUSA]

Instead of expanding the boundary, cities often respond to development pressure by setting targets for increased urban densities. The result is reflected by the establishment of high rise cityscape and compact urban settings. The effects of urban density on the total energy demands of a city are complex and conflicting ( Givoni,1998). Highly concentrated load centres and compactness of land use patterns will bring benefits to energy distribution and transport system design, buut crowded conditions may create congestion and undesirable local microclimate.

Precedent: Hong Kong

Satellite cities are usually conceived as new developments or major expansions to existing settlements that are separated from metropolitan core by belts of rural land. Planners argued that restrictions should be placed on central growth, and the development of separate centres within the metropolitan region encouraged.

The Greater Plan of London, 1944 was one of the pioneers of the type.

Precedent: Tokyo

The rapid sub urban expansion from the WW1 to the mid 30s combined with the setting up extensive railway networks saw the development of satellite towns to Tokyo. This was advanced rapidly with the involvement of the private sector.

A lot has been published about sustainable architecture in recent years. Whereas most of such publications look at buildings as single entities, less is known about the mutual interactions of buildings within an urban context. It is certain, however, that the complex arrangement of urban surfaces and materials has an effect on the local micro-climatic conditions and that energy demands of buildings can be reduced by appropriate urban design. Studies by various authors have shown that the urban morphology strongly affects a building’s solar accessibility and it’s capacity to absorb and reflect radiation (Oliveira Panao, 2008). The arrangement and distribution of urban entities further influences wind speeds and directions; Golany points out that the configuration of the city can ease wind velocity and can support the increase or decrease of temperature (Golany, 1996).

The morphology therefore not only has clear implications on the energy budget of buildings but also on the comfort levels of the surrounding streets and public places.

Radiation, Wind, Temperature and Humidity are important factors that change the climate at a local scale through the interaction with the complex urban morphology. The Urban Microclimate can therefore be described as small-scale mutual interactions of the built urban elements with the regional climate:

‘An urban microclimate may be defined as the distinctive climate in a small-scale urban area (neighbourhood) or space, and is constituted by the influence of the built environment on the larger scale climatic conditions of solar radiation, temperature, humidity, precipitation (type, frequency, and amount), atmospheric pressure, and wind (speed and direction). In other words: the spatial layout of a city and its neighbourhoods sets the conditions for their microclimates (Van Esch).’

Urban Microclimate

Urbanism

Local Climate & Geography

Architecture

Urban Microclimates evolve, mostly uncontrolled, out of the interaction of three key components: Architecture, Urbanism and Local Climate & Geography; microclimates occur at different scales and hierarchies. The lack of inter-disciplanary work between urban planning and architecture means that micro-climatic aspects are not addressed in design and that urban fabrics are rarely set out to respond to local climatic conditions. In addition clear guidelines are lacking that allow designers to optimize urban morphologies according to the regional context; the complexity of the topic makes it difficult for designers implement design strategies that address the urban morphology, mineralization as well as building materials in order to reduce the energy demands of cities.

Urban Microclimates clearly have an effect on the energy consumption of cities. With energy resources becoming more and more precious and an increasing awareness for sustainability the Urban Microclimate is therefore central in reducing the energy requirements of cities. Addressing the Urban Microclimate can be seen as one of the key strategies in reducing the energy budgets of urban agglomerations.

Urbanization is correlated with both, economic growth and increased resource consumption (Mills, 2006). Jack points out that one-third of the total energy and two-thirds of the US’s petroleum consumption are directly related to settlement patterns (Jack, 1981). Steemers adds that the use of air conditioning and artificial light can typically double a buildings energy use and that buildings account for half of our total energy budget. He further points out that poor urban microclimates have significant implications on energy use as well as health (Steemers, 2000). In this sense the Urban Microclimate is not only responsible for the amounts of energy used for indoor heating, cooling and artificial lighting but it also controls the comfort levels outdoors and thus the tendency

to use outdoor spaces. In this sense the Microclimate affects also peoples’ likeliness to walk, cycle or use public means of transportation. Christopher Kennedy points out that urban form has also a strong impact on the urban metabolism (Kennedy, 2009): ‘As previous researchers have shown, transportation energy use is inversely correlated with urban population density’.

Incorporating the Urban Microclimate as design parameter within Urban Planning should therefore be one of the key strategies to tackle future urban problems.

Microclimates evolve at different scales and hierarchies; scales of influence range from individual buildings and materials to regional conditions such as bodies of water or winds. An urban fabric therefore is characterized of a multitude of small-scale climatic zones that respond to the characteristics of the local fabric. Fazia Ali-Toudert therefore describes the city as a patchwork of individual microclimates (Ali-Toudert 2007).

As mentioned previously the Microclimate of an Urban area is the result of many complex processes, most importantly the interaction between the urban morphology and the local climate. Golany states that on the urban scale, natural, passive methods and the urban morphology are almost the only urban tactics available for improving the thermal performance of cities (Golany, 1996). Reduction of the energy budget of cities can therefore only be achieved by smarter ways of urban planning that are based on a better understanding of how the urban geometry reacts with the local climate. It can only be achieved by altering the urban fabric in ways that optimize the use of natural resources, like e.g. wind and sun, in the best optimal way.

Currently, microclimates evolve uncontrolled as a consequence of decisions that are taken at different scales within different disciplines. Especially architecture and urbanism need to work closer together in order to better control microclimates, which are a product of discipline-specific decisions. In this sense decision taken at the building scale (surfaces, materials, etc.) and urban decisions made at the metropolitan level (e.g. zoning) should be

coordinated in a coherent and homogenous way. Golany also points out that it is necessary for the urban designer to borrow knowledge from other disciplines such as urban climatology, botany, geography, etc. and to bring them into urban design in order to enhance urban comfort (Golany, 1996). Ali-Toudert summarizes (Ali Toudert, 2001):

‘The research done in urban climatology shows that the urban geometry is responsible of the global urban climate; particularly the appearance of the urban heat island and local wind systems due to the effects of heat storage in the urban fabric, modified energy balance and obstruction effects to sun and wind.