NET.SIM digital simulation of tension-active cable nets for design investigation of material behaviours on structure and spatial arrangement

Architectural Association Emergent Technologies and Design Masters of Architecture Dissertation 2007-2008

ring ring

Sean Ahlquist

Moritz Fleischmann

Tutors: Michael Hensel

Achim Menges

Michael Weinstock

OUTLINE

ABSTRACT

1 PRECEDENTS & PRIMARY RESEARCH

1.1 Precedents

1.1.1 Physical Form-Finding

1.1.2 Computational Form-Finding Engineering-Based Software for Form-Finding Software Using Spring-Based Solvers

1.1.3 Articulation of Computational Form through Fate Map

1.1.4 Cable Nets as Space-Making Devices

1.2 Computational Networks

1.2.1 Network and Geometric Topology

1.2.2 Spring-Based Particles Systems

1.2.3 Springs in Processing Hooke’s Law

1.2.4 Cylindrical Net Topology

2 EXPERIMENTS & DEVELOPMENT

2.1 Embedded Fabrication

2.1.1 Cylindrical Transformations

2.1.2 Mapping of Computational Cylindrical Net

2.1.3 Data Mining for Fabrication through Node ID

2.1.4 Spatial Articulation of Net

2.1.5 Evaluating Cable Net Installation

2.2 Topologically Defined Net Components

2.2.1 Component Systems for Form-Found Structures

2.2.2 Subdivision Algorithm for Cellular Framework

2.2.3 Single Cell Net Parameters

2.2.4 Multiplication and Association of Net Components Hierarchies and Meta-Spring

2.2.5 Evaluating Cab le Net Installation

2.3Threshold Conditions

2.3.1 Comparing Actual Density and Perceived Density

2.3.2 Computational Threshold Analysis

2.3.3 Extended Vector-Based Analyses

3 APPLICATION & OUTLOOK

3.1 Contextual Inputs

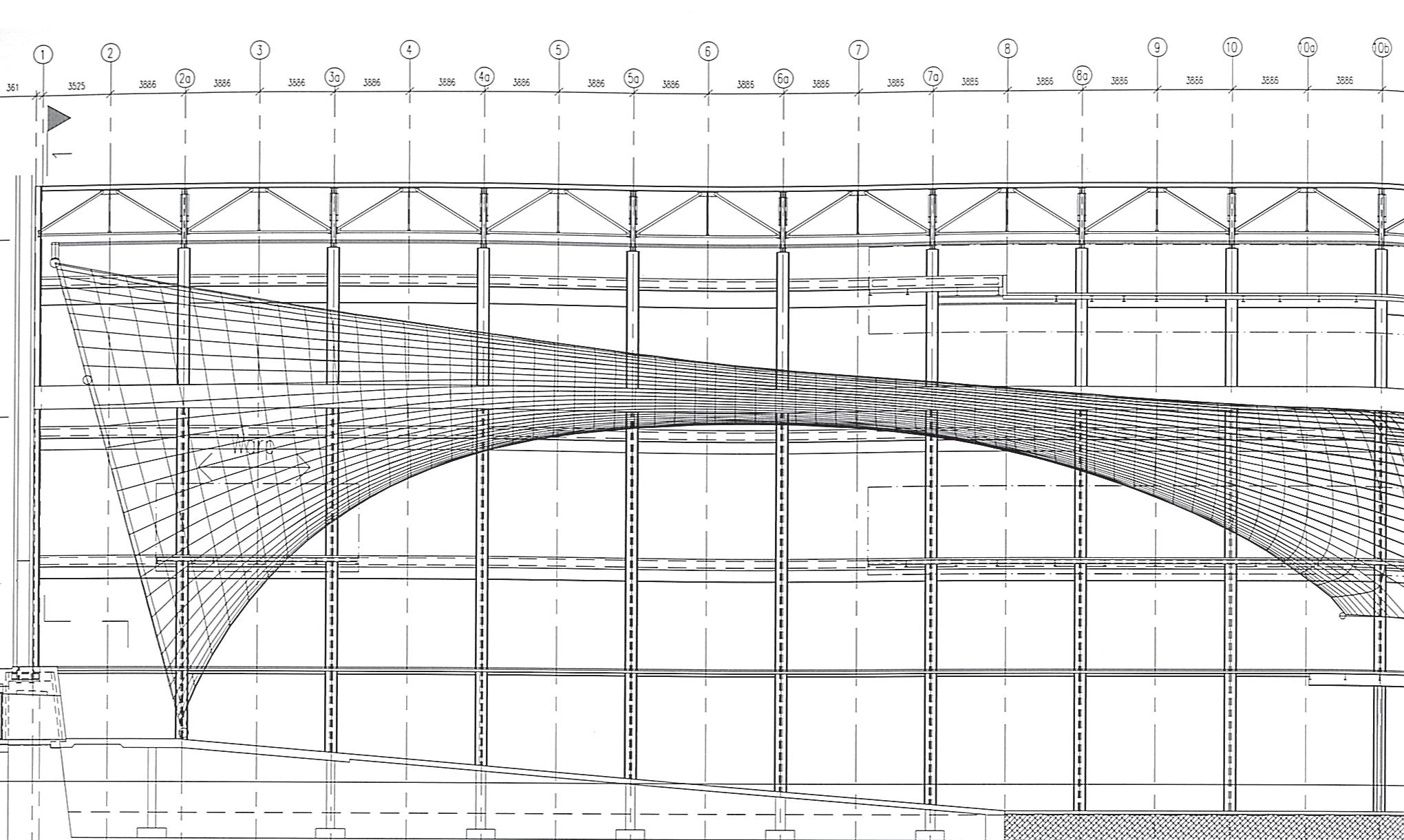

3.1.1 In-Situ: Turbine Hall of Tate Modern

3.1.2 Comparison to Marsyas Installation

3.2 Conclusion

3.2.1 Elemental Processes

3.2.2 Architectural Emergence

3.2.3 Embedded Feedback

3.3 Outlook

4 REFERENCES

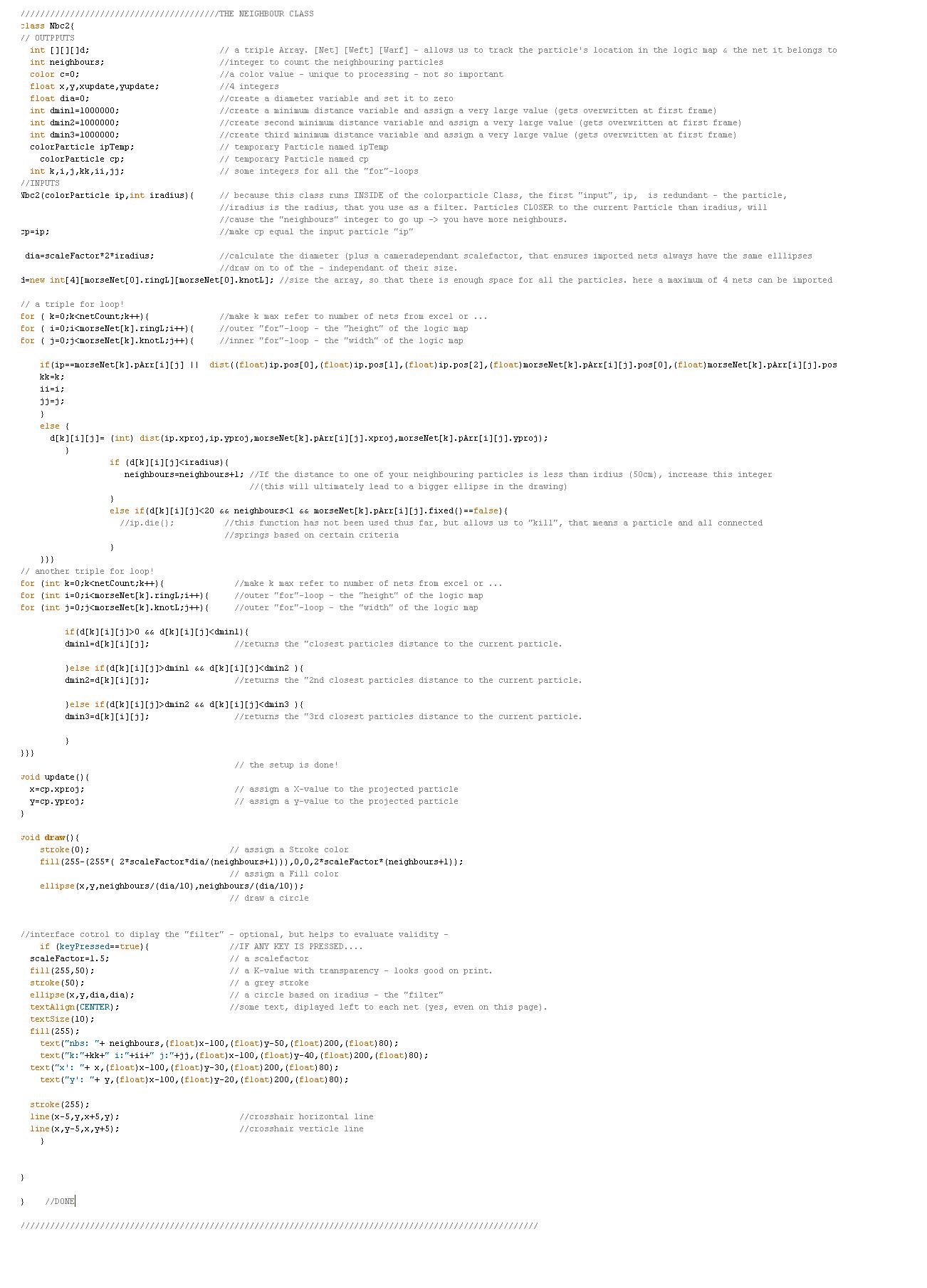

5 APPENDIX

3.3.1 Translations to Material and Fabrication

5.1 Apendix A: Rhino Scripts

5.2 Apendix B: Processing Scripts

5.3 Work Map

5.4 DVD

NET.SIM digital simulation of tension-active cable nets for design investigation of material behaviours on structure and spatial arrangement

ABSTRACT

Tension active systems are compelling architectural structures having an intimate connection between structural performance and the arrangement of material. The direct flow of structural forces through the material makes these systems attractive and unique from an aesthetic point of view, but they are a challenge to develop from a design and an engineering perspective. Traditional methods for solving such structural systems rely on both analog modeling techniques and the use of highly advanced engineering software. The complexity and laborious nature of both processes presents a challenge for iterating through design variations. To experiment with the space-making capabilities of tension active systems, it is necessary to design methods that can actively couple the digital simulation with the analog methods for building the physical structure. What we propose is a designer-authored process that digitally simulates the behaviors of tension active systems using simple geometric components related to material and structural performance, activated and varied through elemental techniques of scripting. The logics for manufacturing and assembly are to be embedded in the digital generation of form. The intention is to transform what is a highly engineered system into an architectural system where investigation is as much about the determination of space and environment as it is about the arrangement of structure and material.

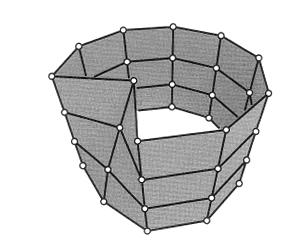

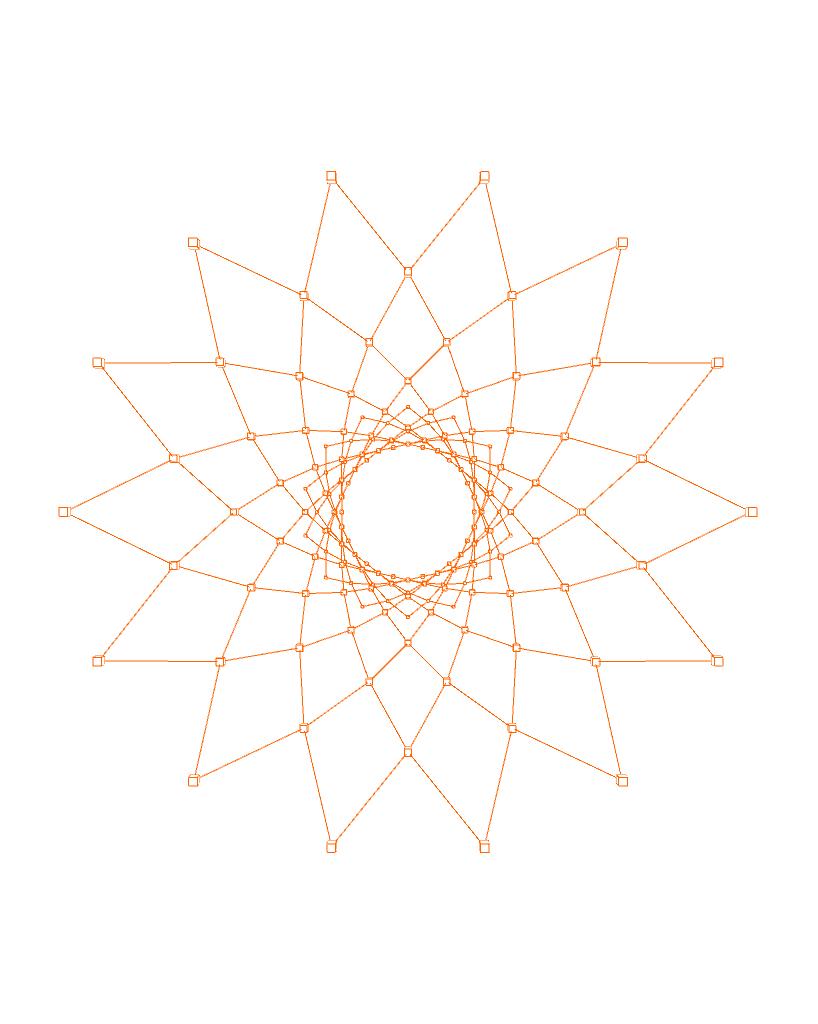

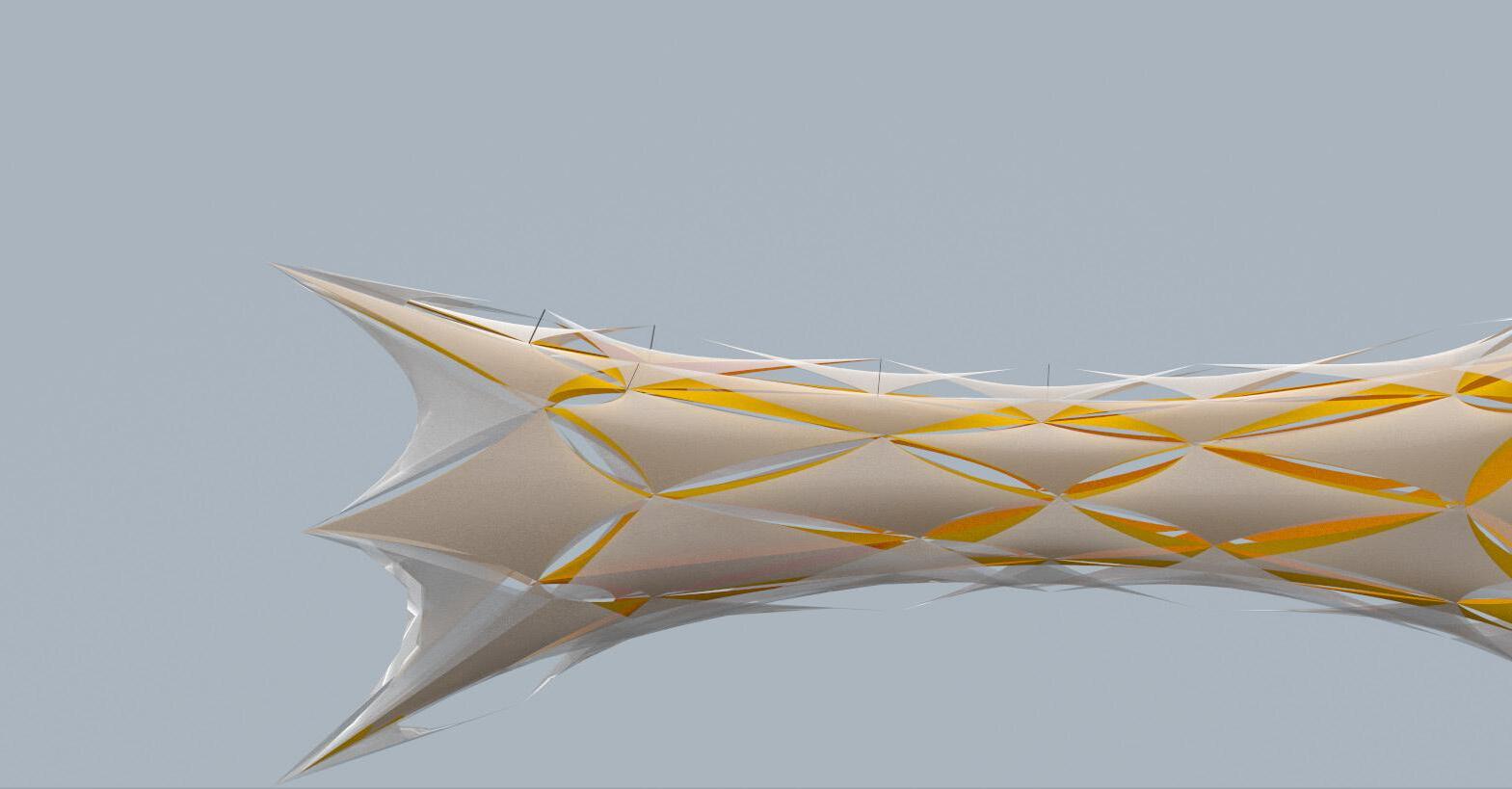

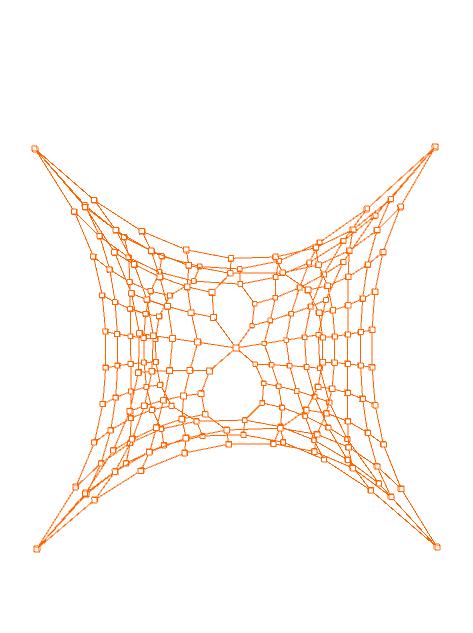

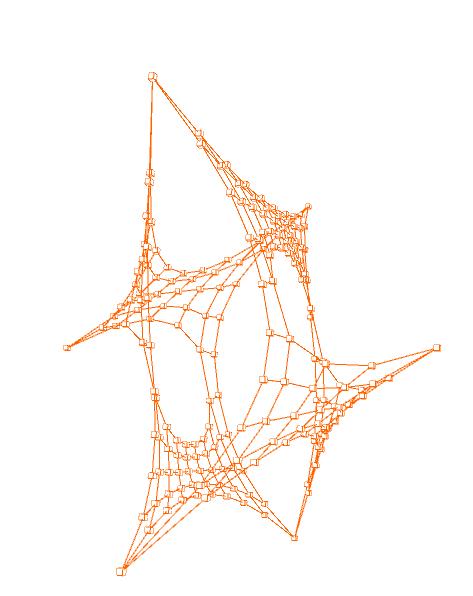

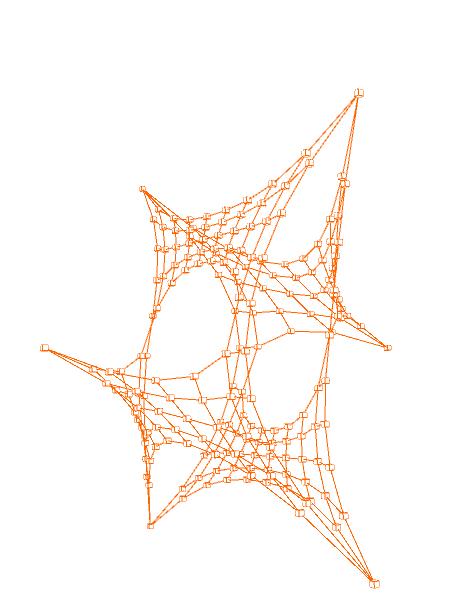

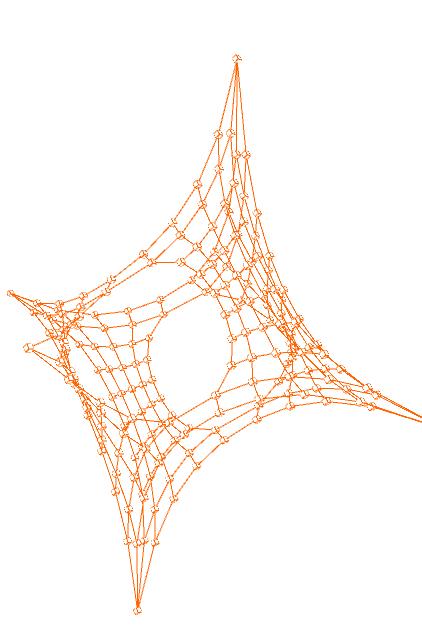

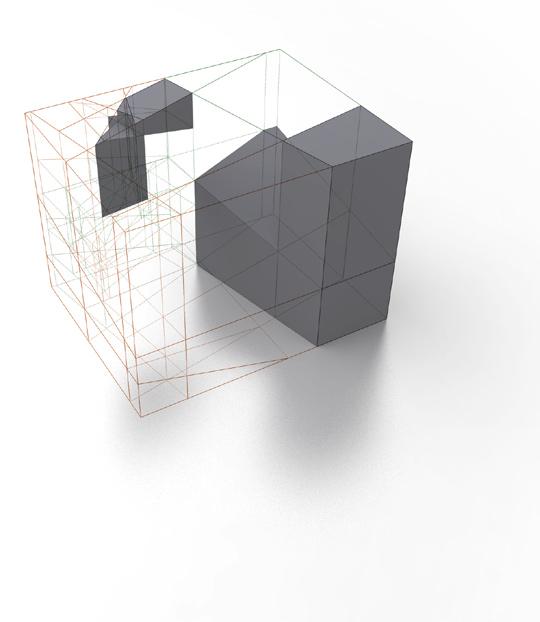

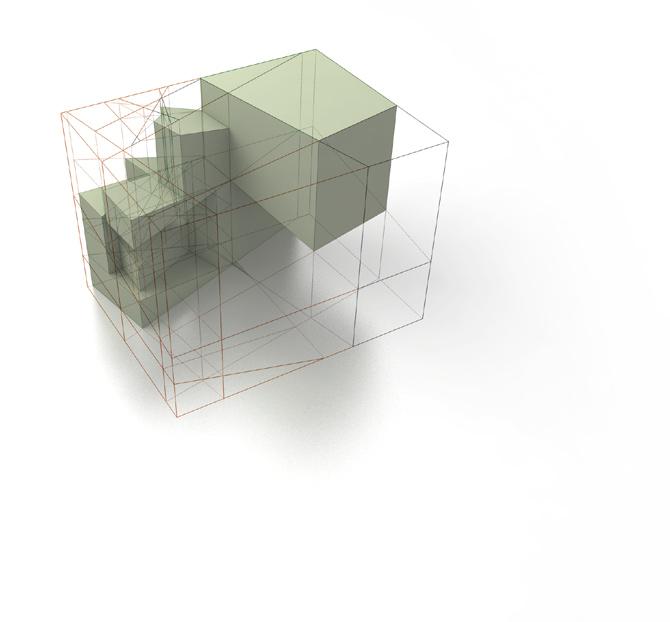

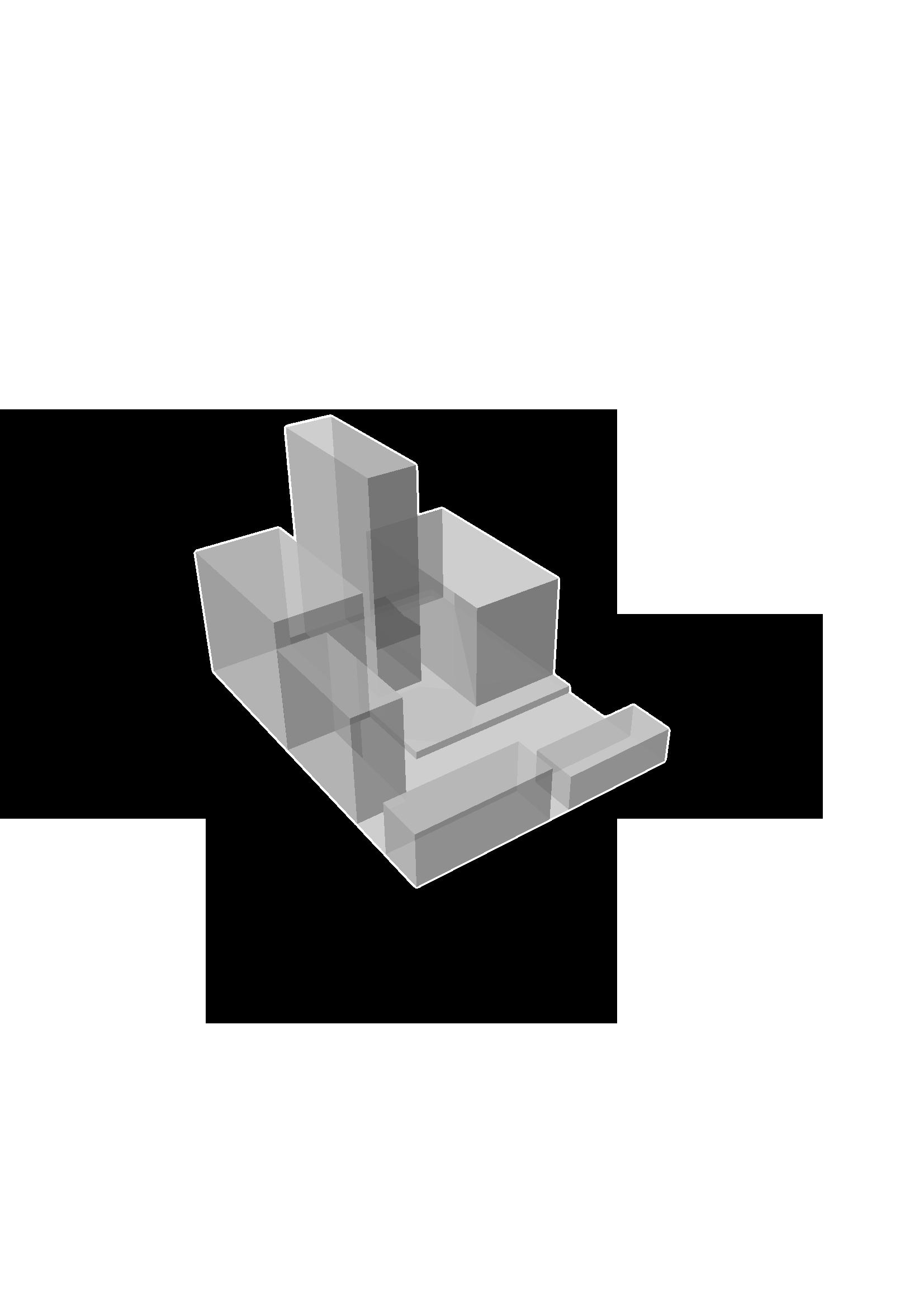

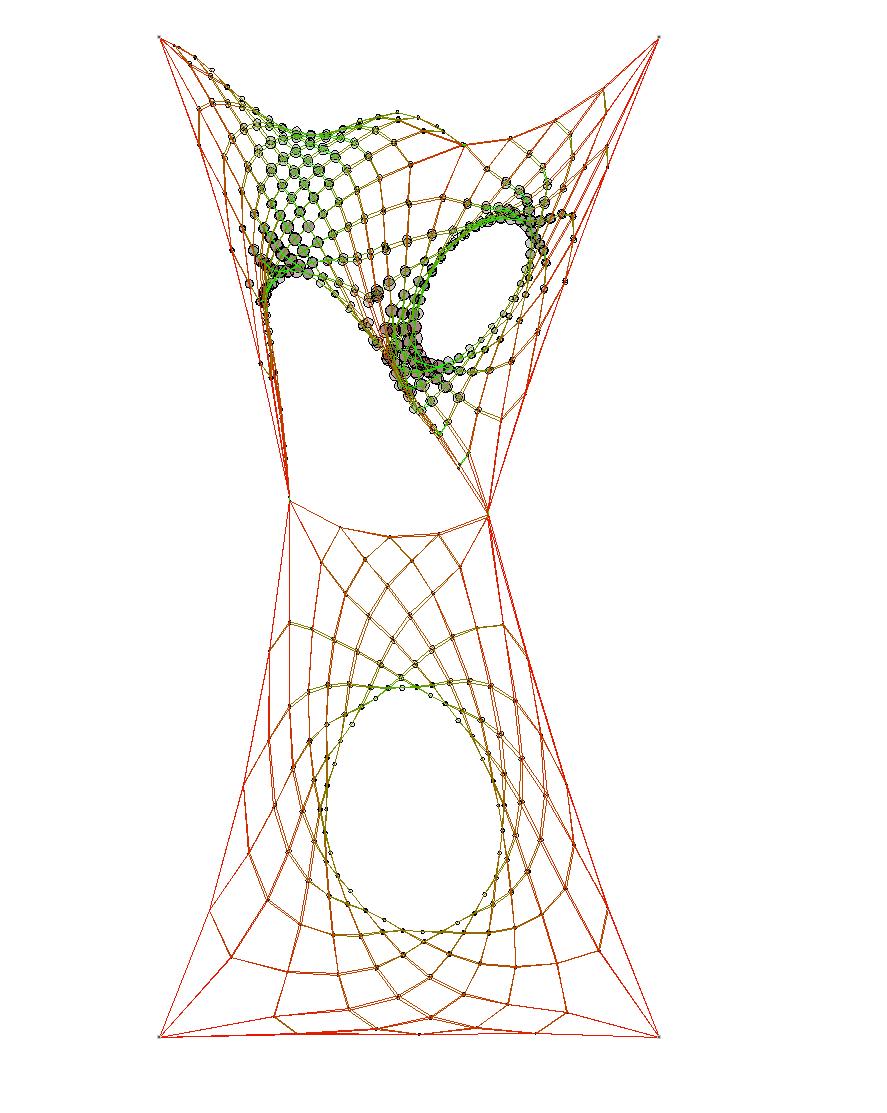

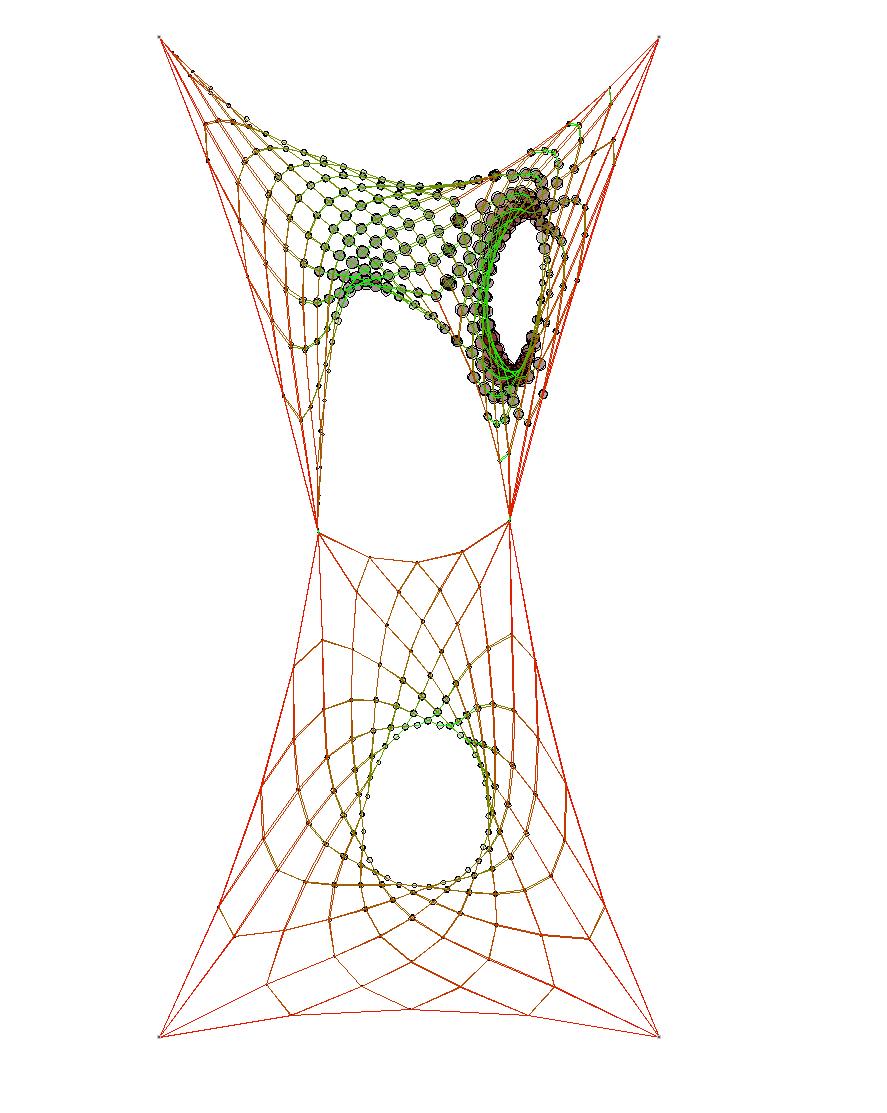

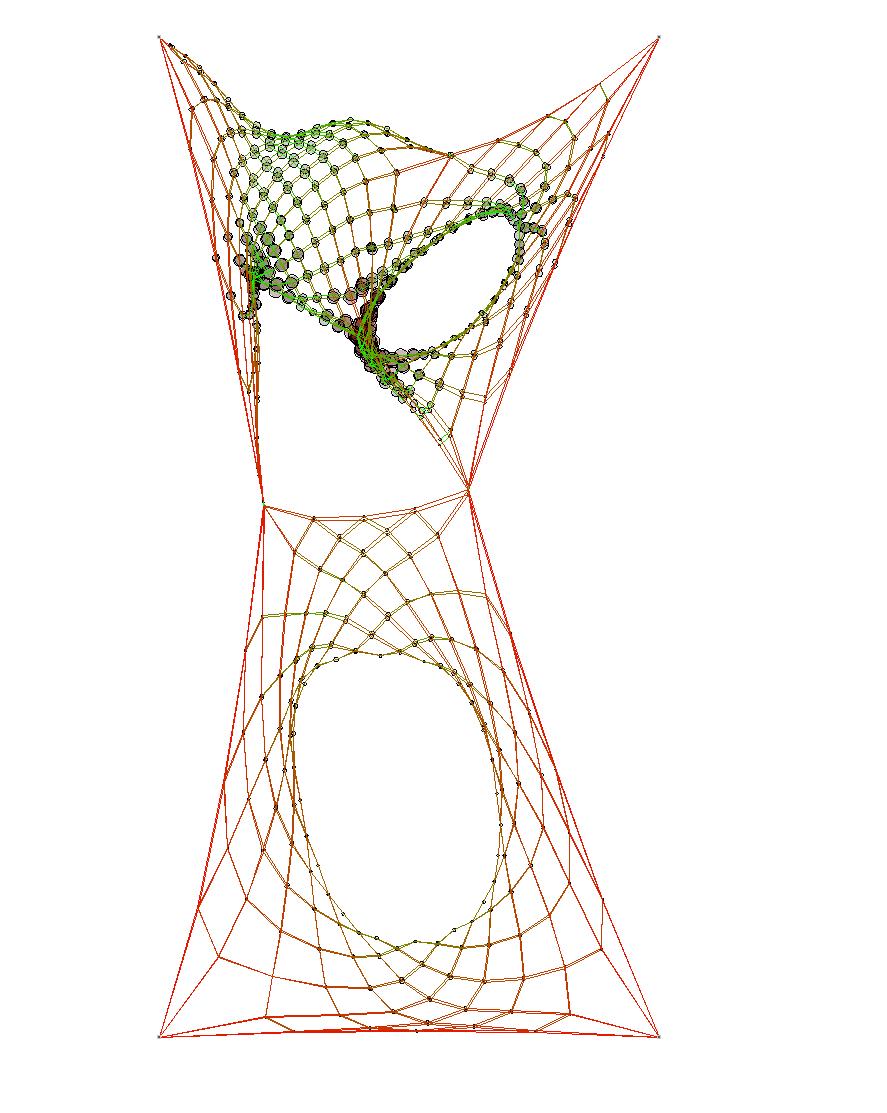

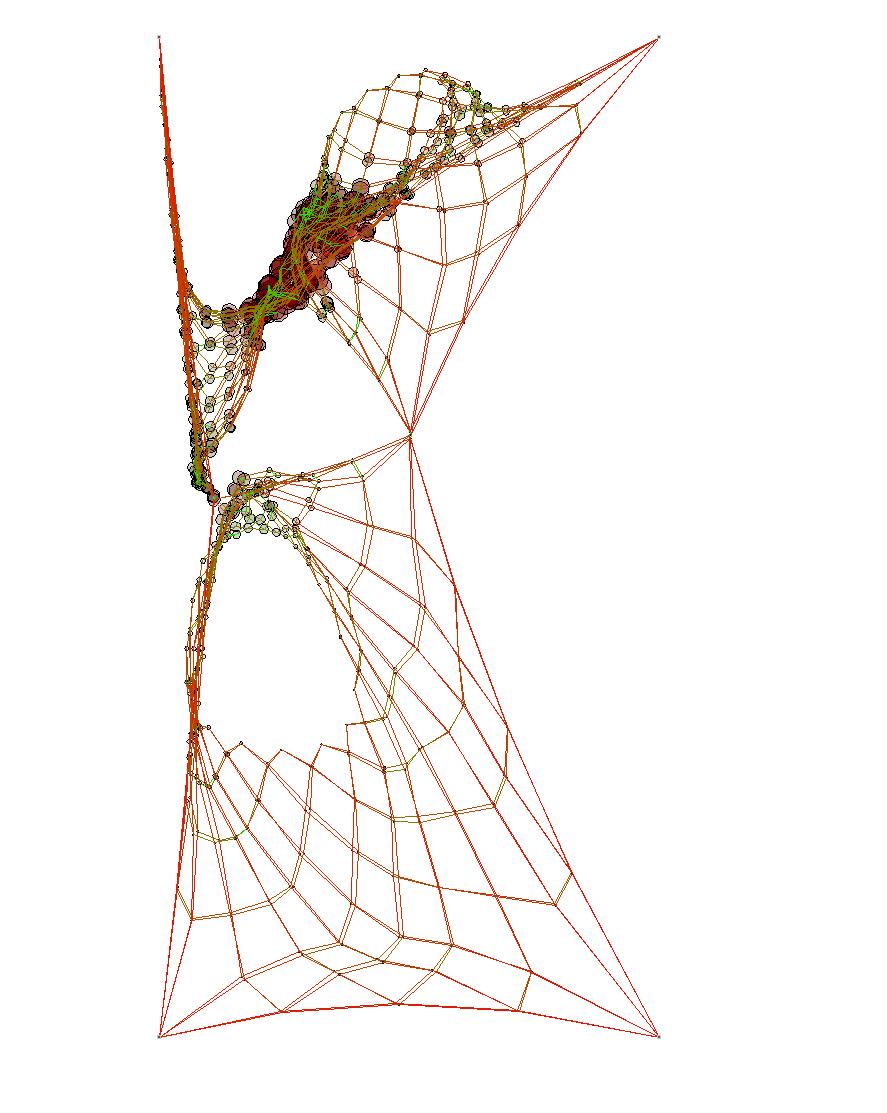

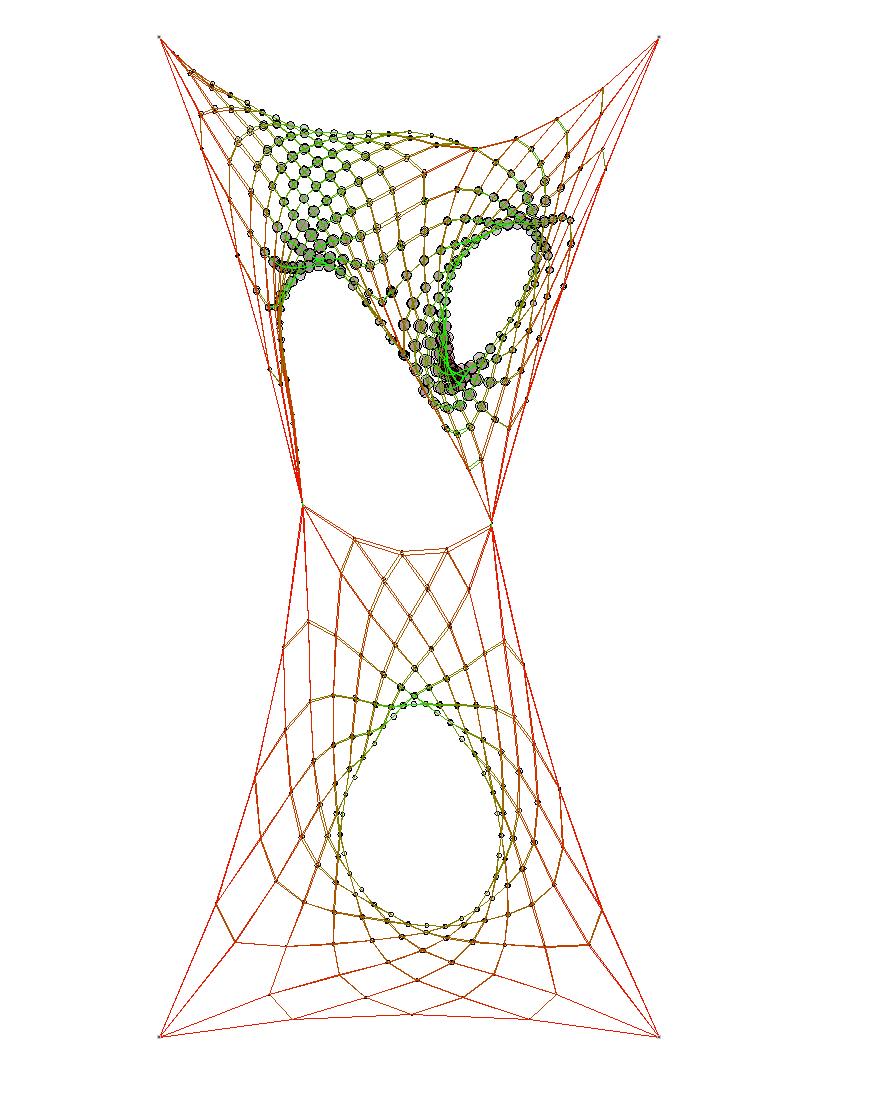

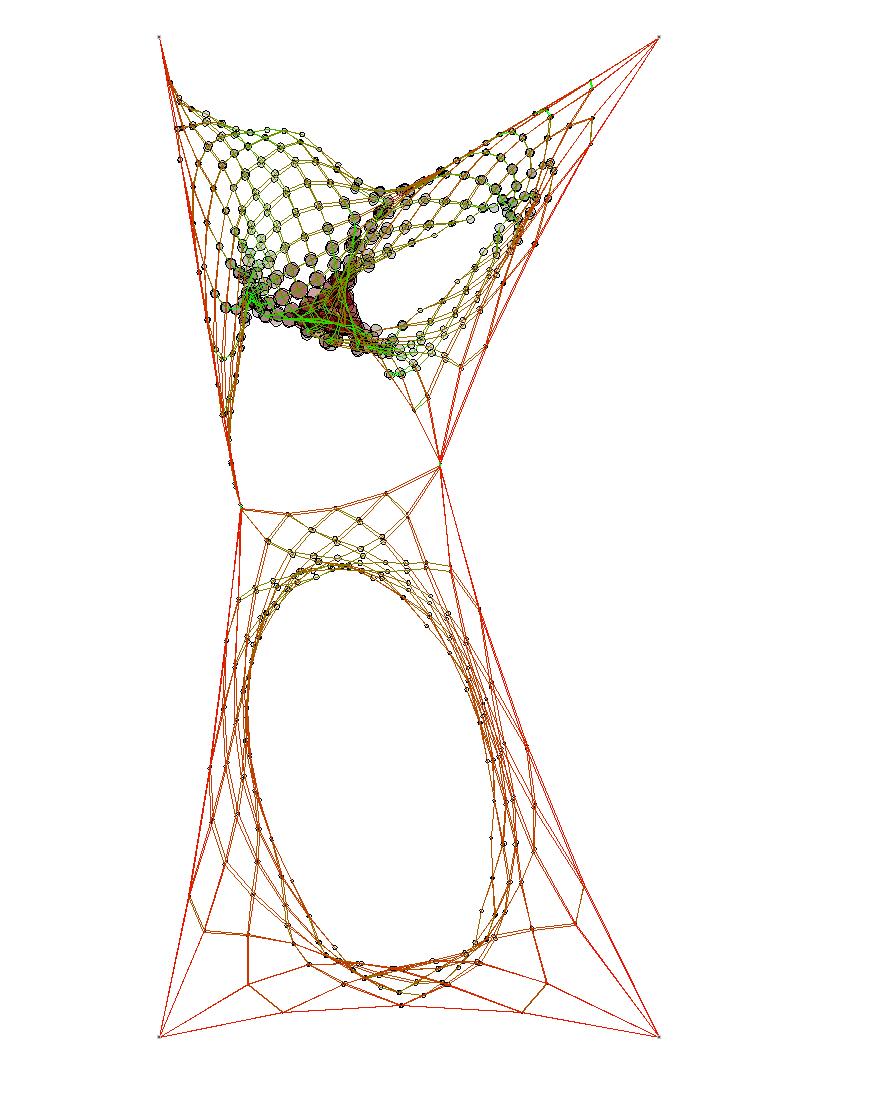

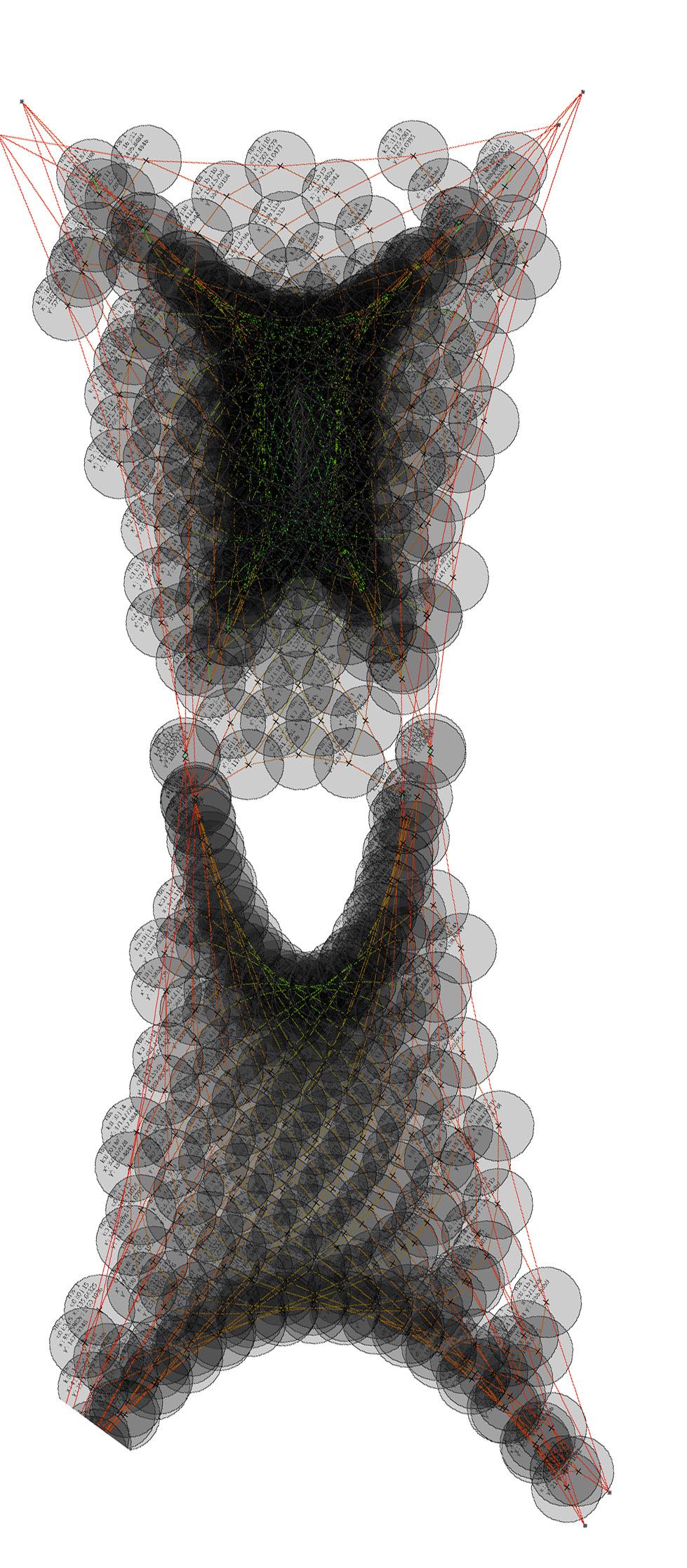

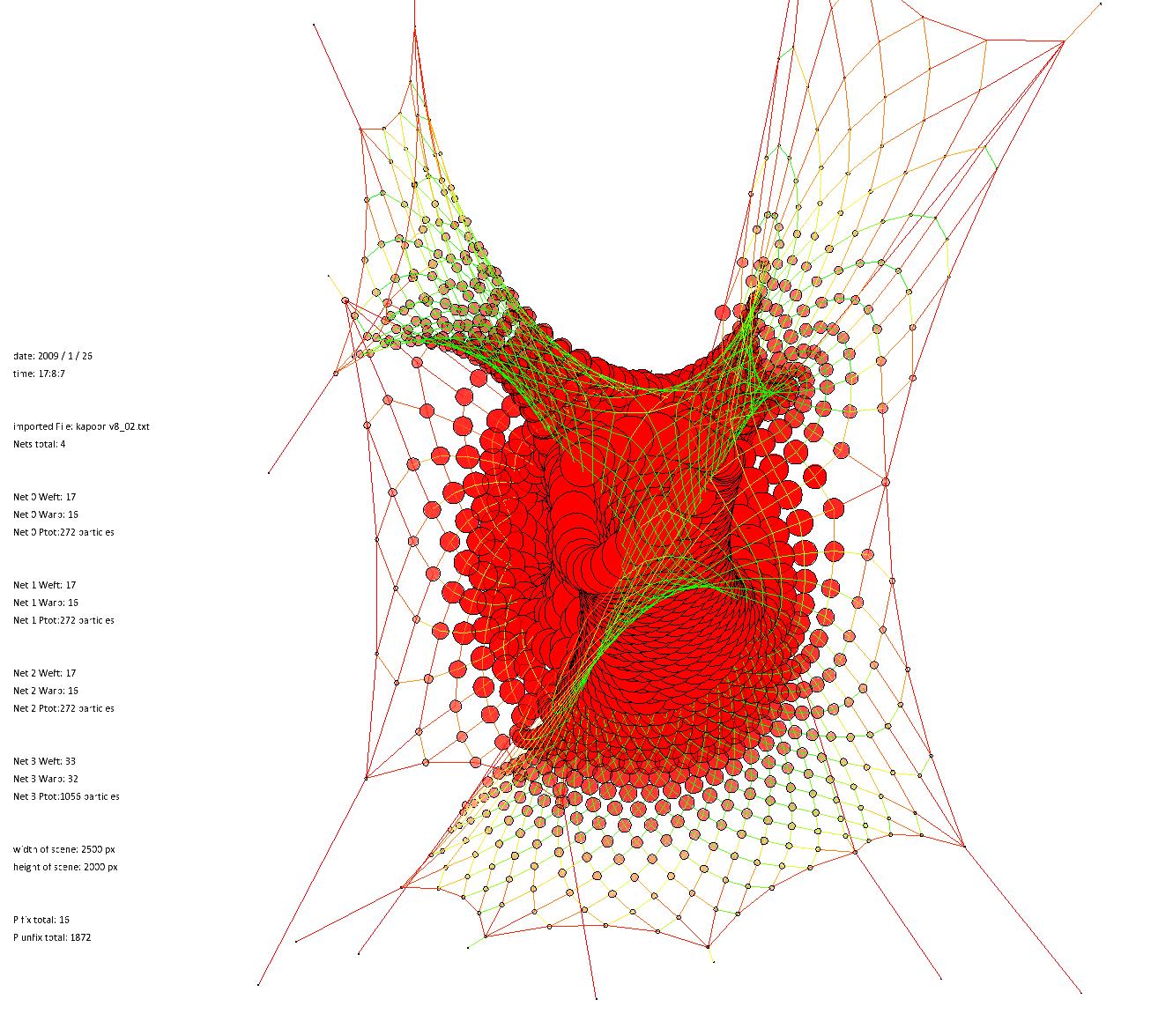

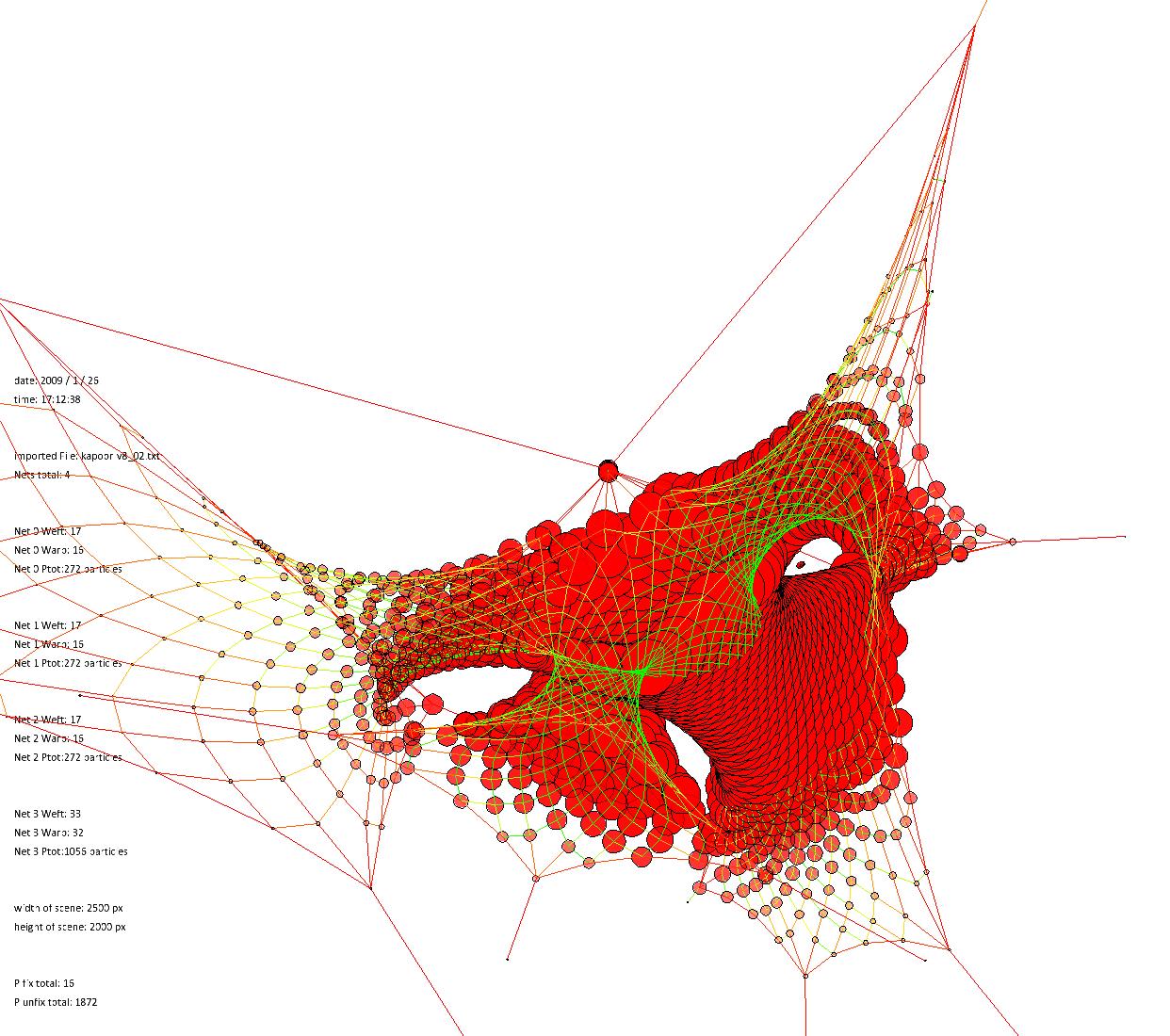

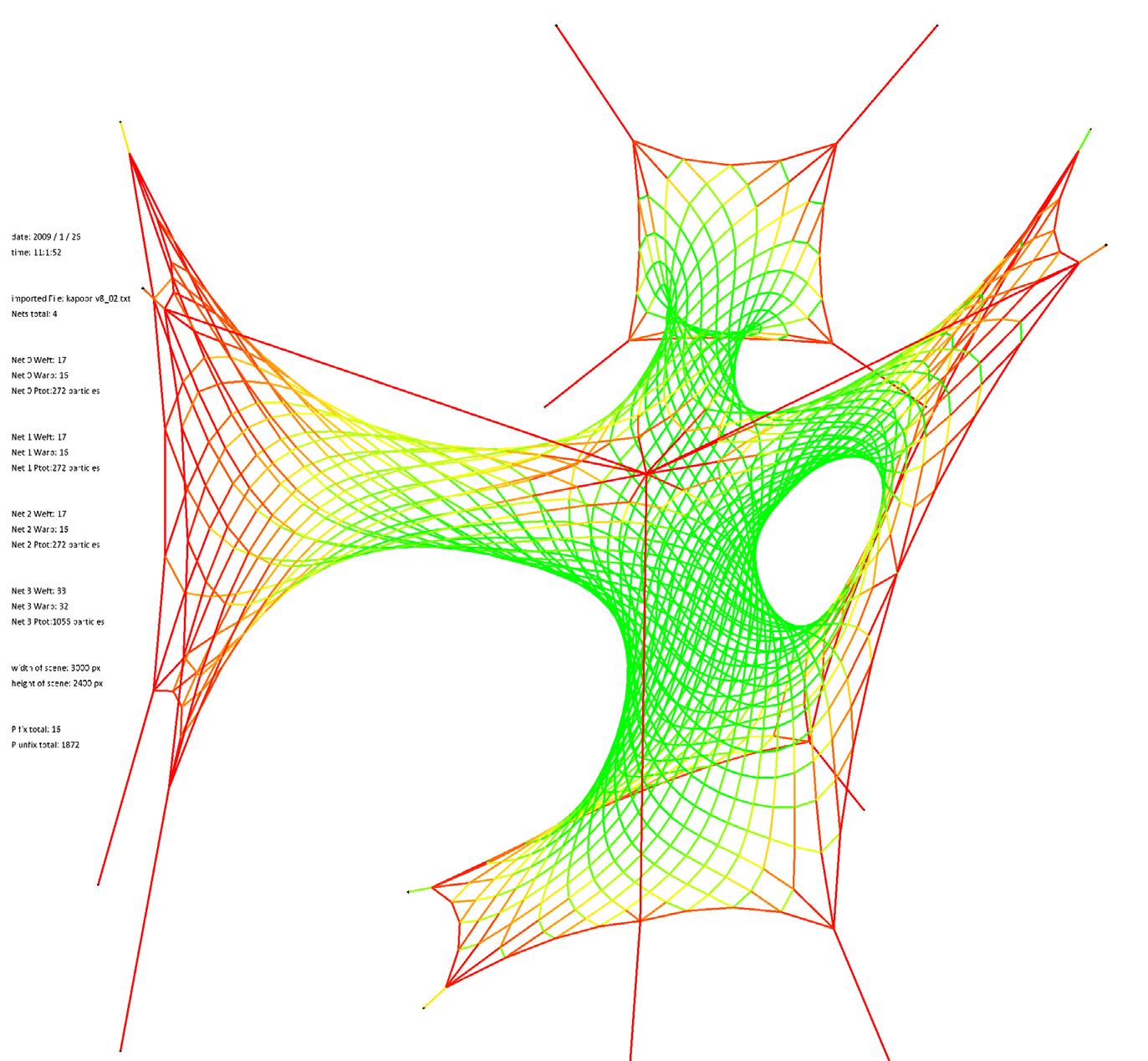

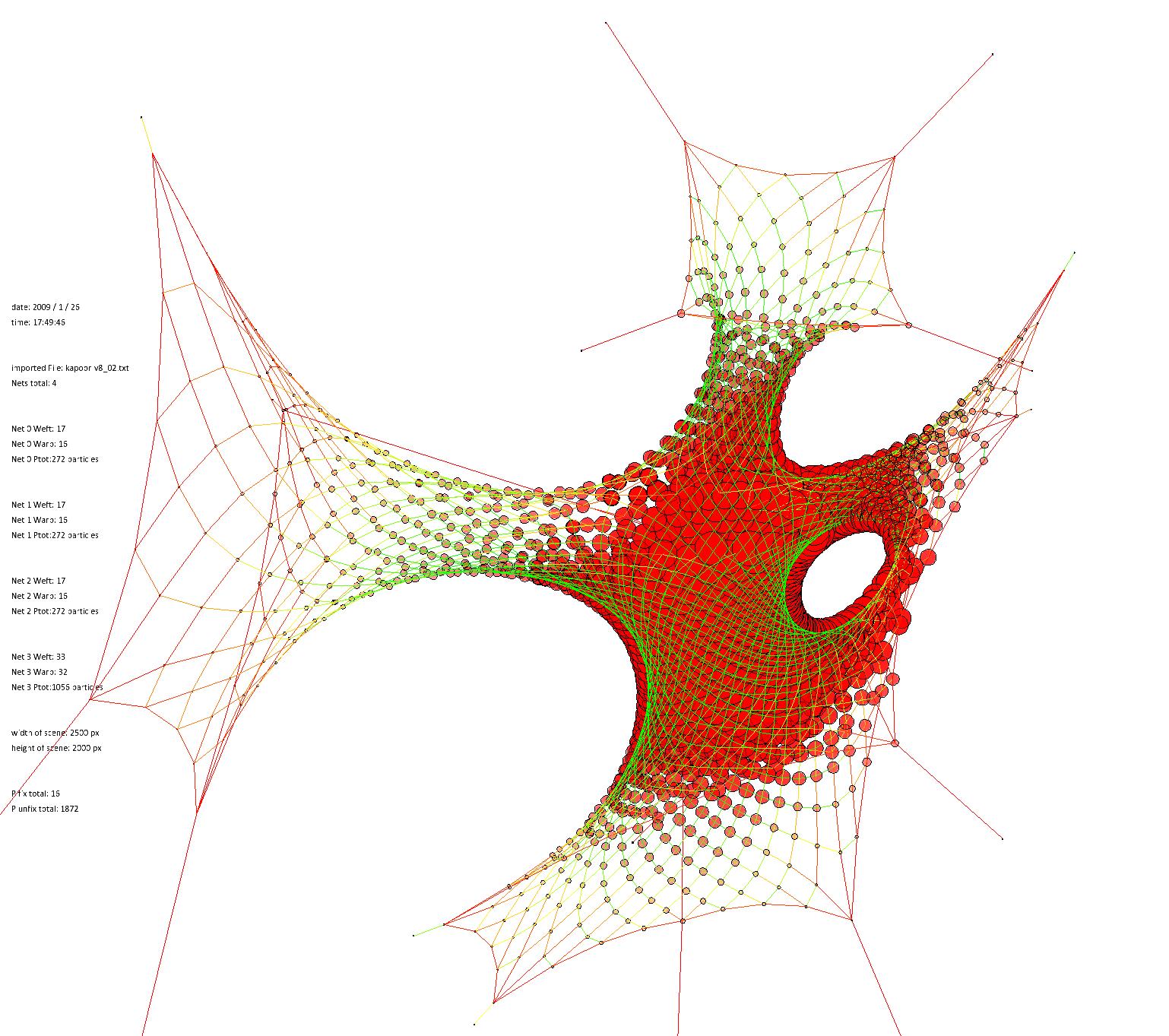

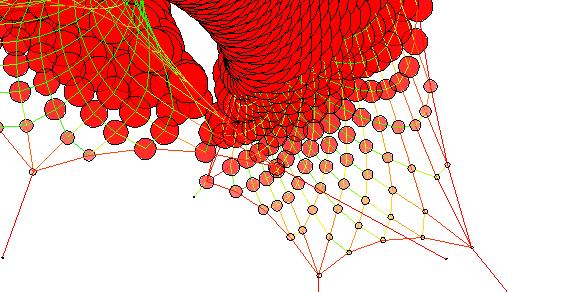

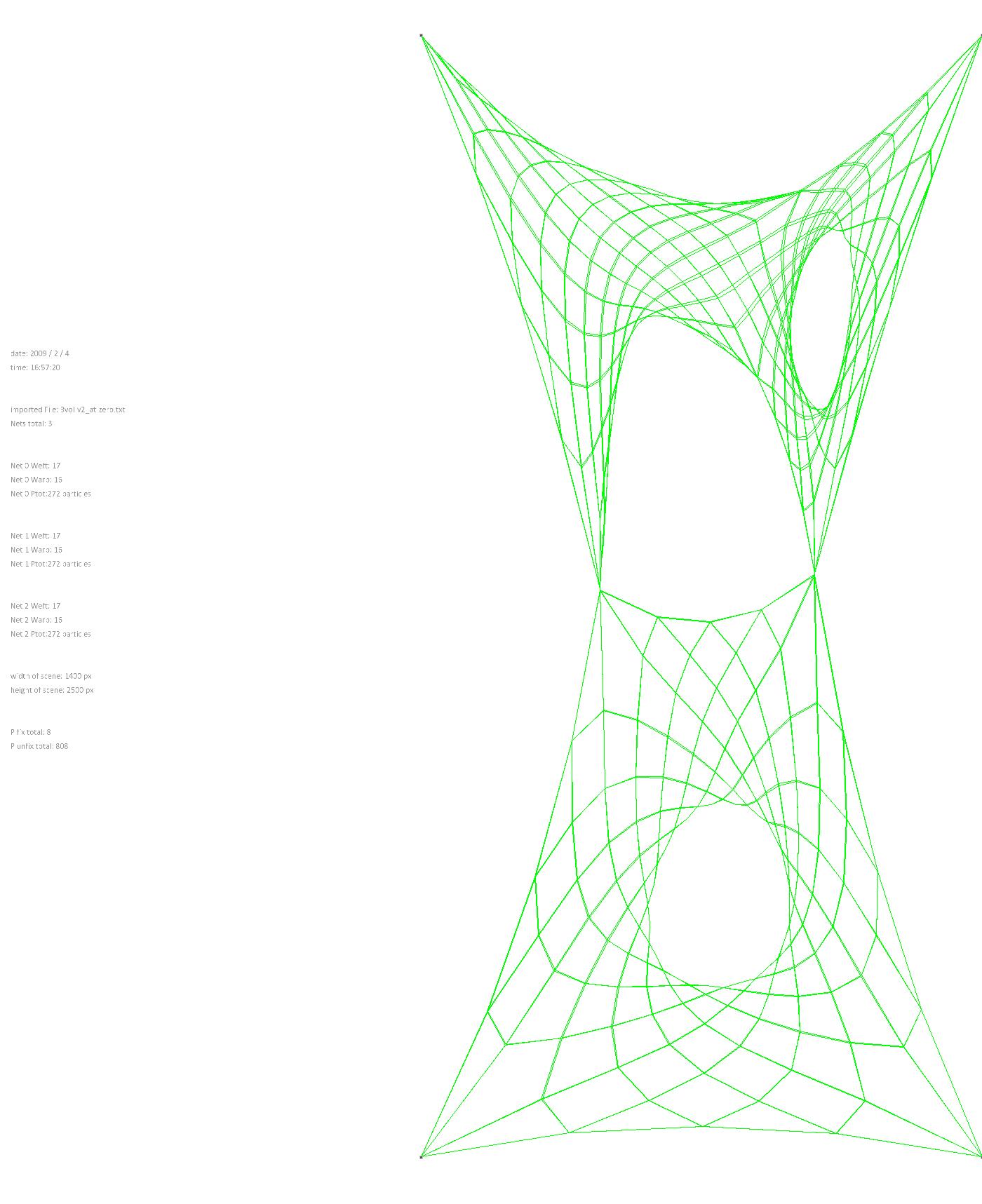

1 Computationally form-found structure. Branched, volumetric structure formed with 4 topologically cylindrical net components.

1 PRECEDENTS & PRIMARY RESEARCH

1.1 Precedents

1.1.1 Physical Form-Finding

1.1.2 Computational Form-Finding Engineering-Based Software for Form-Finding Software Using Spring-Based Solvers

1.1.3 Articulation of Computational Form through Fate Map

1.1.4 Cable Nets as Space-Making Devices

1.2 Computational Networks

1.2.1 Network and Geometric Topology

1.2.2 Spring-Based Particles Systems

1.2.3 Springs in Processing Hooke’s Law

1.2.4 Cylindrical Net Topology

1.1 Precedents

A common method for digital design generation is to separate the shaping of form from the application of a structural strategy. While this process allows for freedom in form and space experimentation, it often leads to problems when coordinating a structural system with the forms that have been established. In comparison, with tension active systems the overall form and position of materials are driven directly by the flow of forces through the system. This presents a certain degree of efficiency in the relation of material to structure and enclosure of space. The lightness of these structures in relation to the amount of force that they can withstand is attractive. It presents an opportunity to directly link design generation with the material and structural strategy. But, the complexity of this type of structural system poses a challenge for the architects, particularly those who wish to explore non-standard spatial and material organizations.

1.1-1

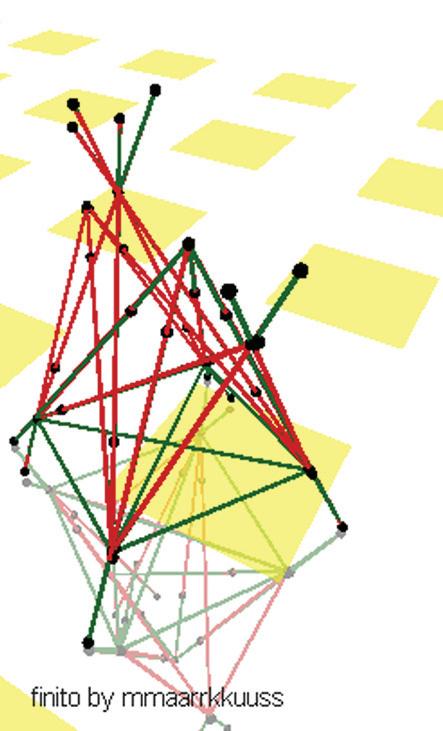

Computational spring-based model built in Processing, describing the elements of a kinetic structure and whether they are acting in tension or compression. Simulation by Sam Joyce, Bath University of the Heatherwick Studio Rolling Bridge project.

Defining architecture in a digital environment is a matter of manipulating geometries. Geometries without structural or material constraints have a vast solution space. The first step for narrowing the solution space is in defining the most basic geometric element and charging it with properties (constraints) based on physical behavior. The next step is addressing the network by establishing a solver for the behavior of the whole system (aggregation of geometric units). In the case of simulating cable nets, a simple digital element that can simulate flow of forces is a computational spring which follows Hooke’s Law of elasticity. This is represented by a simple unit of geometry (a line), yet dynamic and extensible in that it can be realized as an element under tension force or compression force, with direct implications into material definition. Solving the network happens through the method of dynamic relaxation, iterative steps for finding the balance of force flow through the system.

To fold this into a system for iterative design and structural behavior simulation, there has to be variability and accessibility within the system. The mathematics and programming for computational spring systems and dynamic relaxation are advanced, but their processing load is quite light. The number of variables for a single spring is limited but can be connected to material properties such as elasticity. The organization of a network of springs, though, is completely flexible and independent of the individual spring properties. Accessing variables of individual springs

and defining the protocol for connectivity of the network are straightforward and done through basic scripting.

This mode of realizing extensibility through simple material units and techniques for transformation fits with the process of biological growth. Examining these methods aid in understanding the need for simple design mechanisms to generate high degrees of variation and specification in form. Activating all of the options for spring parameters and network association provides for vast arrays of forms, each of which are structurally valid. But, considering this tool as a system for exploration, validity could be expanded to consider forces of arrangement, function, atmosphere, and other spatial characteristics. These particular traits would be realized through a well-managed catalog of elements and variables.

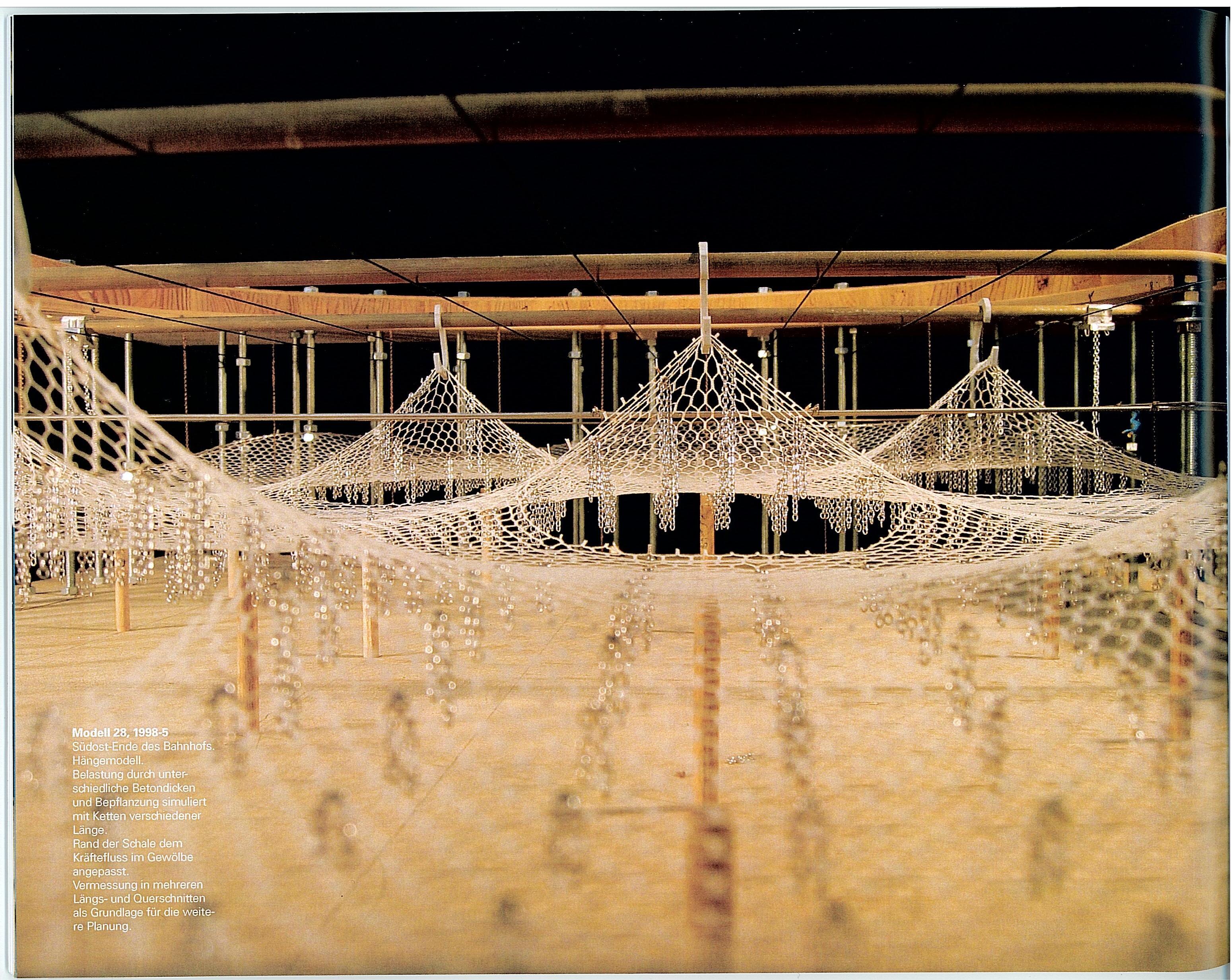

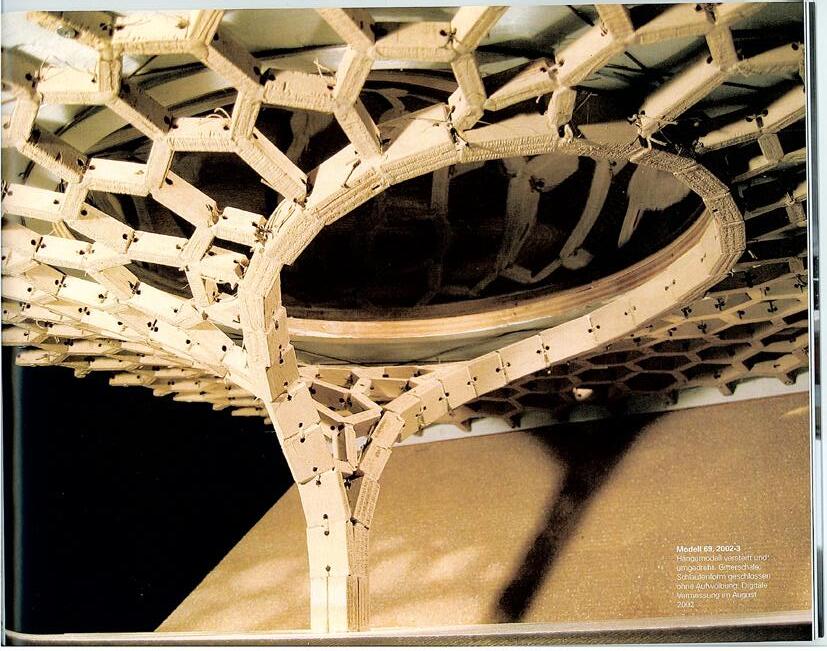

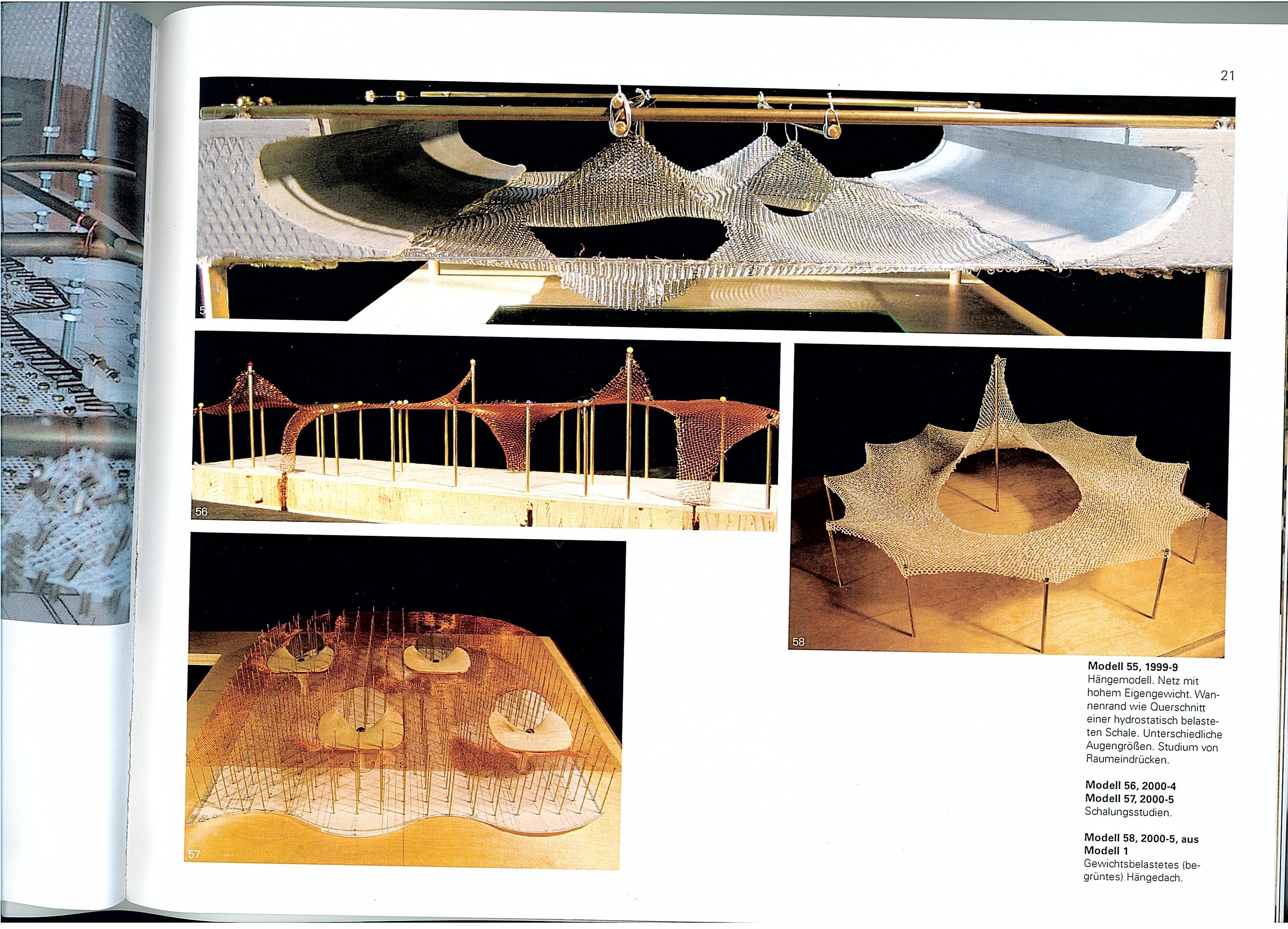

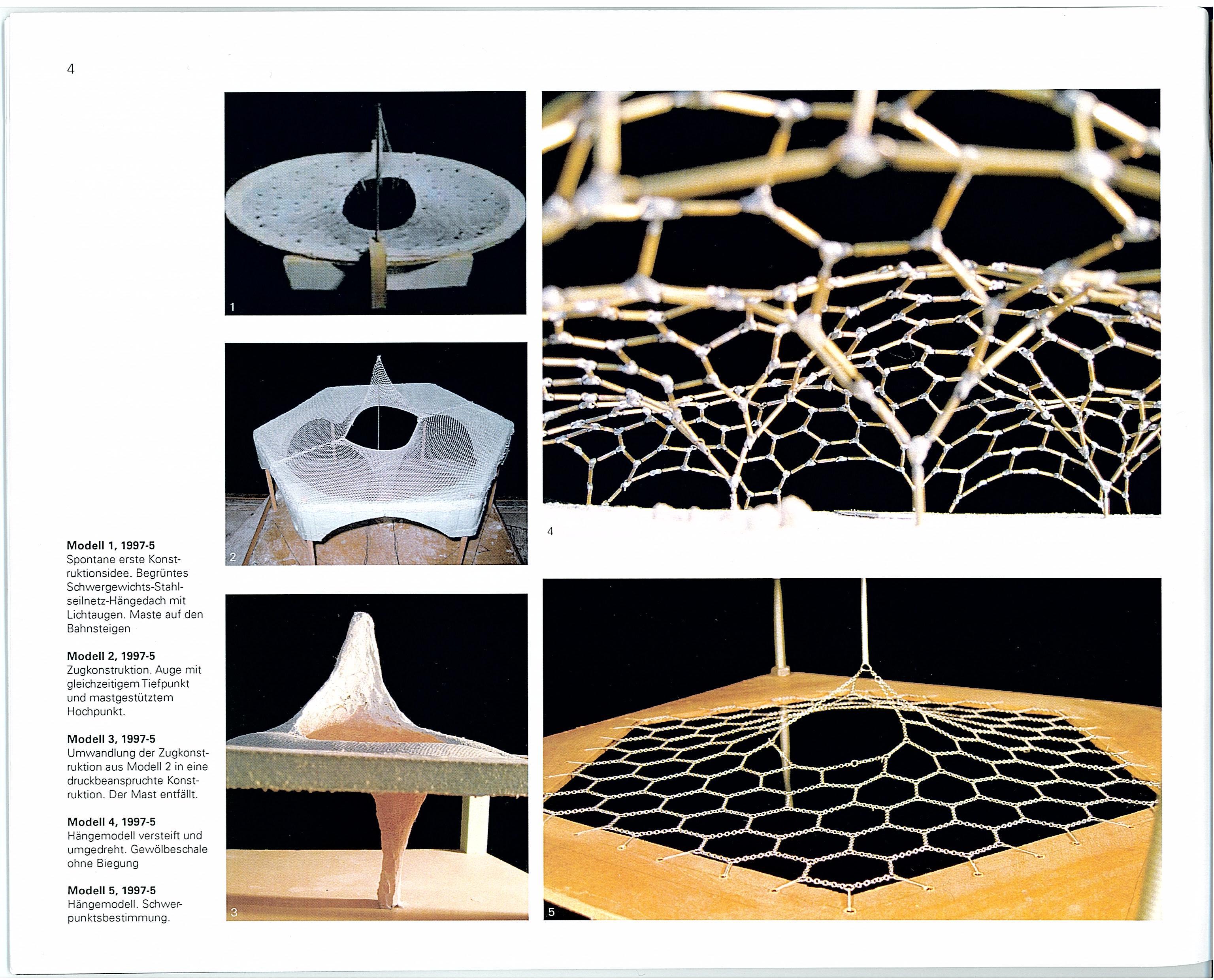

1.1.1 Physical Form-Finding

The study of cable net structures falls into the more general category of form-finding, structural systems where material and structure have very strong interdependencies. Form-finding, in contemporary methods, is done through two sets of procedures: physical simulation with scale models, and digital simulation through advanced engineering software. These two modes are often not directly related, and both, independently have impedances to a quick, iterative design-oriented process. The resolution and optimization of material to structure is often the singular mode of

intention for both of these processes.

Physical modeling as the method for designing with form-finding structures is done at a particular scale where there can be a connection between the materials in the scale model and the materials to be used in construction. This often means models are built at a scale as close to 1:1 as possible. Where the flow of force is dependent on the properties of the material, “scaling” the performance of the model to full-scale means there has to be a link in material make-up between the different scales. There is a translational process not only in size but in material properties, structure, and performance of the overall system. This transition if often not easily accomplished. Factors of material and structure can scale at different rates when moving up in size.

To study the analog model, understanding the transitions in scale, means an almost scientific examination of its behavior, purely within the scope of structural performance and how the materials can withstand those forces. This knowledge and method is outside of the realm of the architect as a designer. To understand the behavior of the system, the entire system has to be constructed. This is embedded in the nature of structures based on form-finding. Structure and material are interdependent; therefore all material parts play a role in the shaping of form. Where the architect wants to investigate various possibilities of the effects of the structure on physical environment and its influences on inhabitation, changes to parts of the system

are inevitably necessary. This means a cost in the physical adjustment of the scale models, and the re-analysis of the relation of material and structure for the entire system. Iterative design changes are a challenge in this mode of design investigation. When basing process and analysis on physical modeling methods, the transition to information for construction is cumbersome as well. It means another layer of incredibly precise examination to determine dimensions for material and methods of assembly.

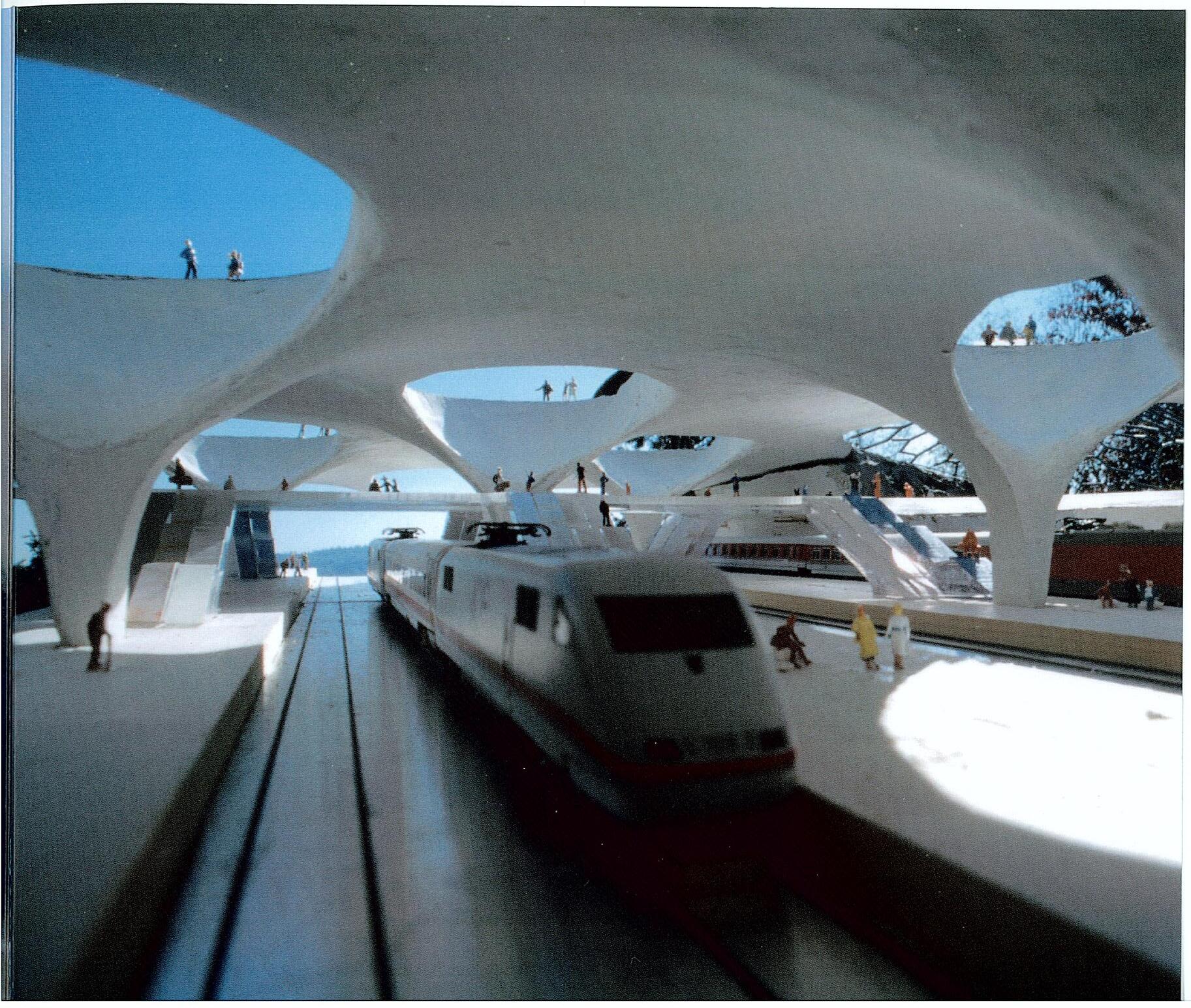

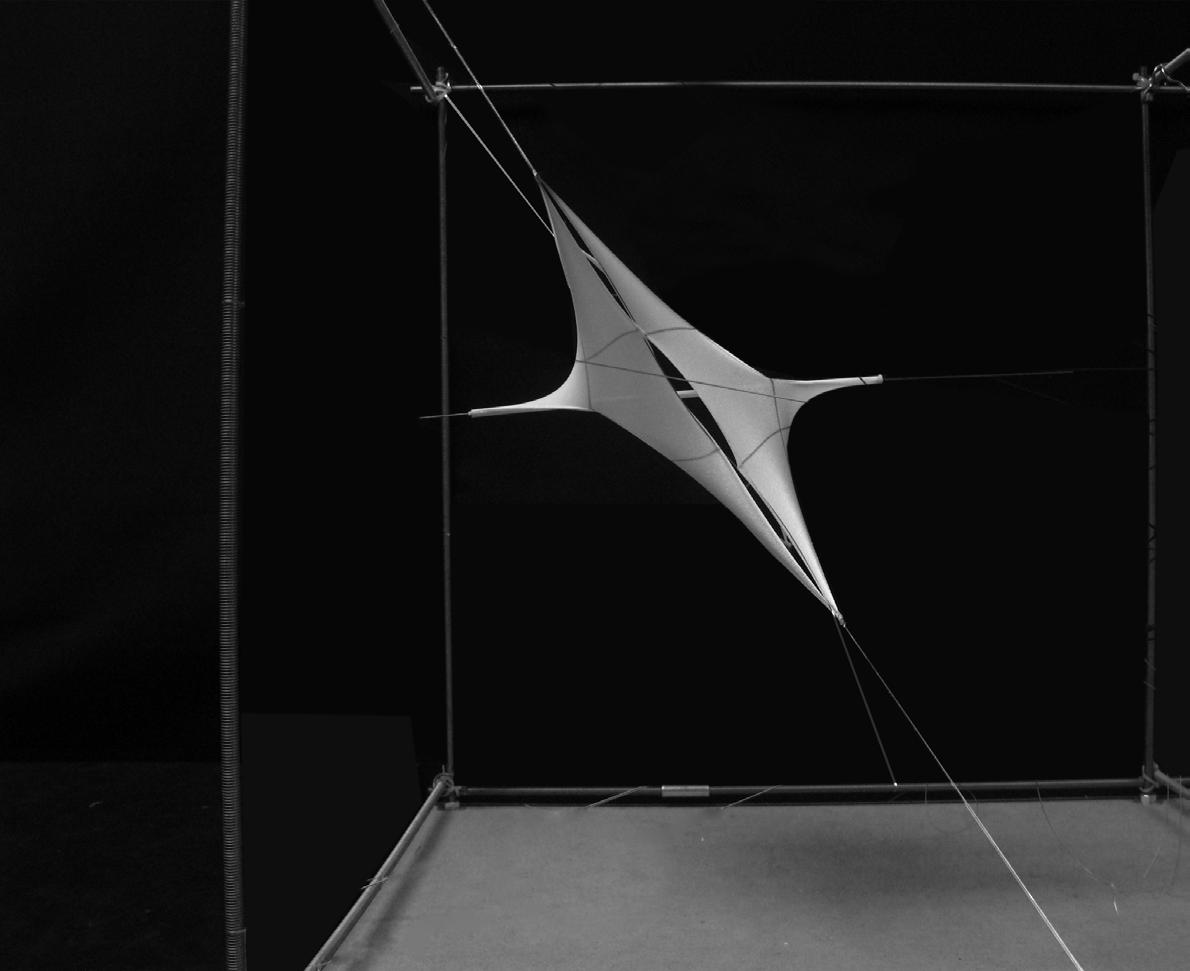

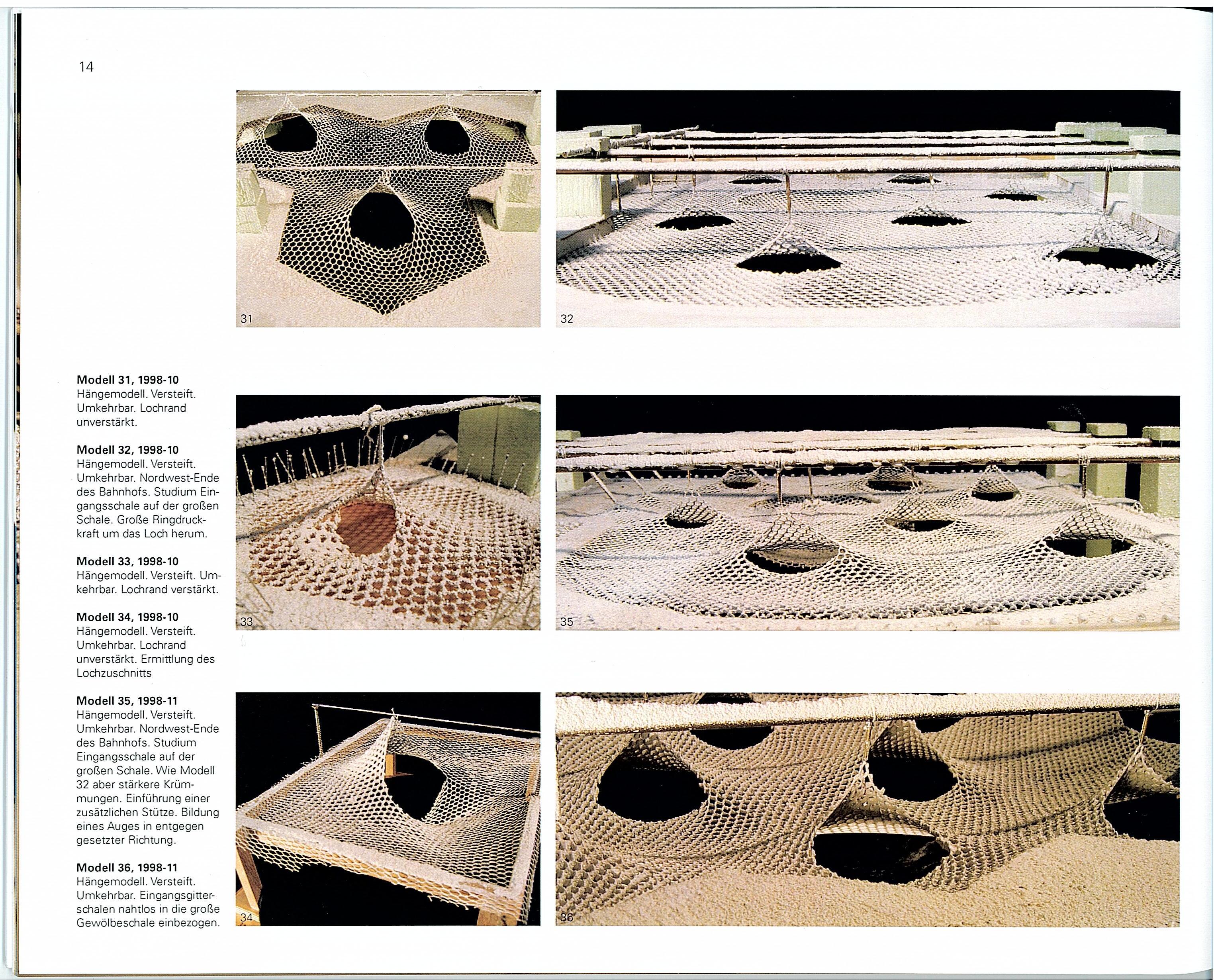

1.1-2

Tension-active

1.1-3

Proposal

1.1-4

1.1.2 Computational Form-Finding

The process of developing form-found tensionactive structures is highly technical and exhaustive. The primary methods are through either analogue modelling and analysis techniques or in specialised engineering software. The breadth of knowledge necessary to utilise these methods and their highly prescriptive nature are impediments to a design process investigating variation in form of this structural type and its potential for non-standard spatial and environmental conditions. The development of computational spring algorithms has provided an avenue for efficient studies of tension active structures. Accomplished through a programming language such as Processing, the design environment is also accessible and variable. Tracking through examples of spring systems generating hybrid tension/compression structures, a design process can be formed with elemental means of geometry and programming, making possible iterative investigations of complex tension-active systems.

Engineering-Based Software

Digital simulation alleviates some of the issues around translation in terms of physical forces and information for construction. But, the accessibility of these programs, such as Forten 3000, from a design point of view is limited, and the use does still demand expertise in the structuring of tensile systems. RhinoMembrane, by TSI, is a plug-in for Rhino that simulates tensile membrane

structures, and attempts at bridging the gap between design and engineering for tension-active systems. In testing the software, though, there is still a limitation to design investigation. Because of the demanding setup and the prescription of certain elements to their part in the form-finding process, defining edge cables and pre-stress for instance, being able to control and vary the system is difficult. Also, this works with a “black box” algorithm meaning the computation and mathematics at play are not being fully exposed to the designer therefore not utilized in the design investigation process. These engineering-based software packages and plug-ins do not offer a light or low-resolution analysis within the architects grasp to provide intuition in form-making that can later be fully examined.

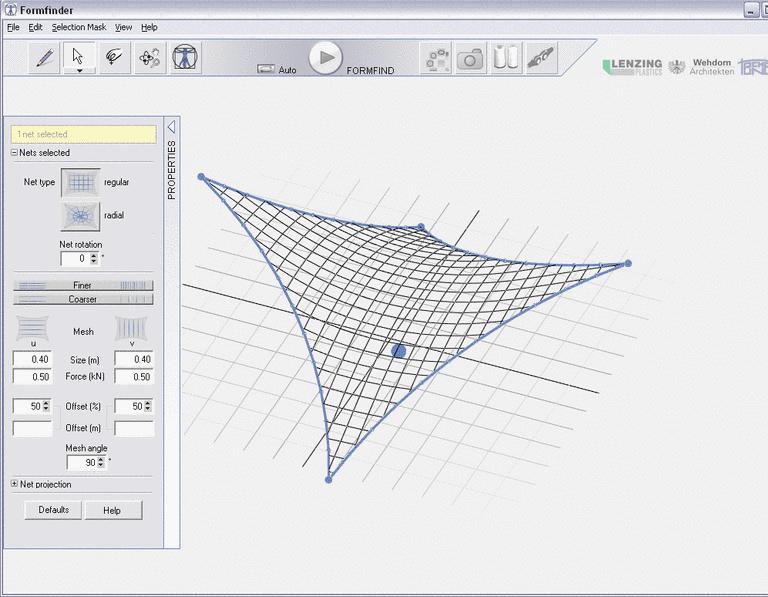

Relatively new packages have emerged that are oriented towards architects, where it is considered that the architect is more interested in design than technical specification and analytical feedback. To provide design accessibility, though, these softwares have to minimize the range of geometric options, while still demanding a specification of elements during the setup of the design. For the Formfinder software, the base geometric components to start with either a “regular” or “radial” mesh description. These particularly topologies will have limits to the type of geometries that can be produced. The software also only deals with “open” surfaces (sheets). The Rhino Membrane plug-in does allow a large range of meshes as the initial input. The geometries are

“relaxed” based on rules for defining a surface with equilibrium tension. But, the relxation solver highly depends on the specification of the “edges” of the membrane. The edges define where the rest of the geometry will relax towards. What this means is that the definition of the edge gives a strong indication of what the general position of the relaxed geometry will be. It minimizes the concept of form-finding, and leaves design to the configuration of the edges and the strength to which the hold the shape when tension forces run through the geometry. This is a challenging parameter to control when there is no understanding of the exchange between initial shape, edge definition, and relaxed geometry.

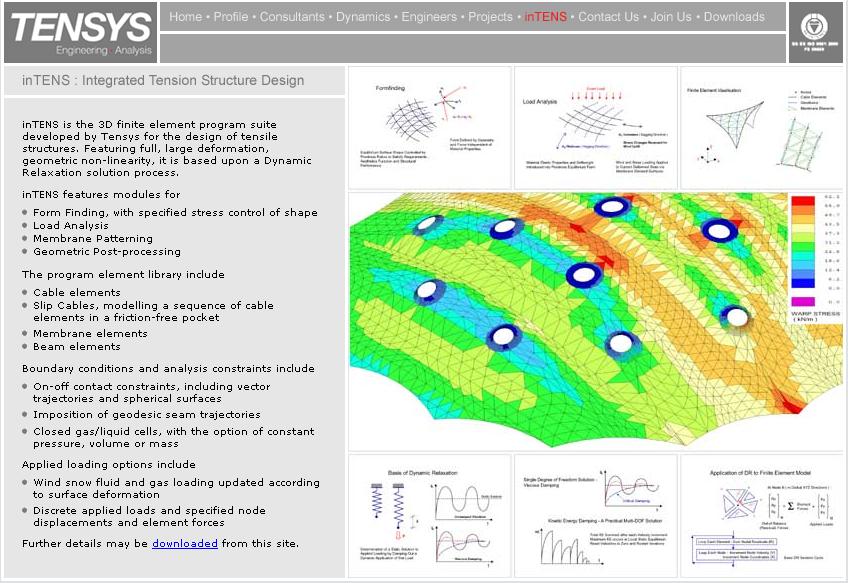

1.1-6

inTens software by Tensys. Finite element analysis is integrated in the program for creating tensionactive structures.

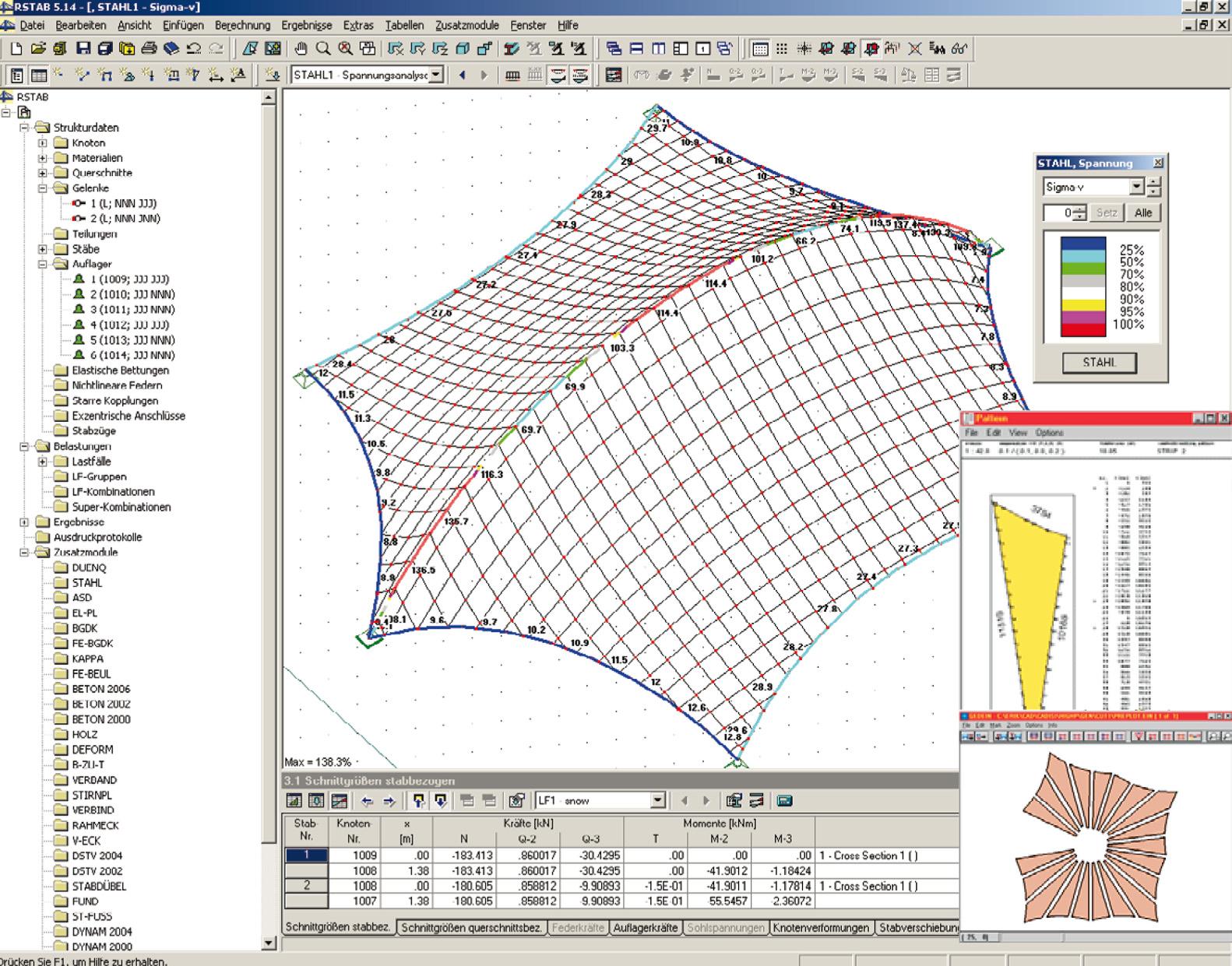

1.1-7

RSTAB software connected to Easy membrane design software, by Dlubal. Together, the software packages can produce models, provide analysis, and produce data for fabrication.

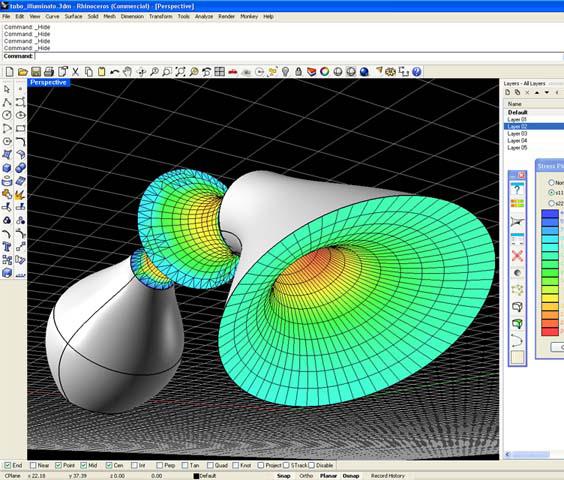

1.1-8 Formfinder software. The software is defined as a sketching tool of membrane design for architects.

1.1-9 Rhino Membrane plug-in by TSI for Rhino3d. Finite element analysis is included in this plug-in that relaxes any mesh to a stressed (tension) surface.

Software Using Spring-Based Solvers

Various experiments in developing digital algorithms mimicking form-finding methods have led to the creation of an efficient computational method for simulating tension-active systems based on springs. In 2004, Prof. Ochsendorf and Simon Greenwold, through a workshop at MIT, conducted digital form-finding experiments based on Gaudi’s analog form-finding experiments with catenaries. One product of this workshop was an algorithm built for the Processing language based on the physics of springs. Axel Kilian, as a part of his PhD research at MIT, utilized this algorithm to digitally form-find linear catenaries. He extended the application to solve for tensile surfaces by using a network of springs. Springs are a part of a computational physics model where their force, generally, is connected to the distance at which the two ends of the spring sit apart from each other. Hooke’s Law specifies the amount of force through the degree of difference between a spring’s actual length and its rest length. A spring-based computational system serves as an efficient solver for tension-active systems. The particular system by Greenwold is placed within the programming environment of Processing (a Java based language) allowing it be lightweight, flexible, and openly accessible.

Spring systems become effective design experimentation tools when they are computationally efficient and openly accessible. Visually, responsiveness is necessary to understand the relation-

ship between the outcomes emerging from the process and the input parameters. Accessibility is necessary from a programming standpoint, so that the algorithms necessary to run the system can be developed and controlled by the designers themselves. A design system developed by Soda shows how a complex structure can be understood and refined visually through interactive engagement and immediate feedback. Sodaconstructor is a web-based construction kit for spring systems, developed through an interest in dynamic systems where behaviour could arise through the feedback between the user and the computational rules of the system.1 What emerges is an understanding of how particles and springs interact in the context of gravity and movement. What this poses for a design paradigm is that spring systems can be very lightweight computationally allowing for configurations to be developed, varied and reconfigured while structural forces are solved instantaneously.

Connecting the dynamic nature of spring systems and the affects of mapping particular associations of springs is expressed in a model that describes the Rolling Bridge by Heatherwick Studio. By configuring the truss network with springs, the simulation, written in Processing, is able to describe tension and compression forces, and the switching in between. The experiment seeks to understand the physical behaviour of the constructed bridge through the conceptual nature of the computationally based spring system. This offers interesting possibilities in describing valid structures through a computational component that has specific

structural properties but not absolute material properties.

The simulation of the Rolling Bridge offers a different approach from the Sodaplay website in that it is not interface driven. Both are based on computational springs, but the Rolling Bridge simulation is defined and controlled within the script. For the designer of the script, it offered the best option for establishing the structural concept (computational springs with a dynamic relaxation solver), testing it through a very specific concept and understanding all the inter-relationships between parameters.

1.1-10

CarefulSlug by Soda from Sodaplay. com. Web environment allows for the construction of tensioncompression structures that undergo influence of gravity and friction. Underlying solver is based on computational springs developed in Java.

1.1-11

Structure developed in SW3D (sw3d. net). Using the Sodaconstructor library, SW3d, created by Marcello Falco, expands the functionality into three dimensions creating an environment where kinetic structures can be interactively generated and edited.

1.1-12

Heatherwick Studio, Rolling Bridge, Paddington Basin, London, 2004. The kinetic steel-framed bridge transforms through the hydraulic expansion and contraction of various struts in the truss-like structure.

1.1-13

Sam Joyce, Rolling Bridge simulation, School of Architecture and Civil Engineering, University of Bath, 2008. The program simulates the physical behaviour of the Rolling Bridge, comparing the abstracted physics of the spring system with the actual performance in the bridge

1.1-14

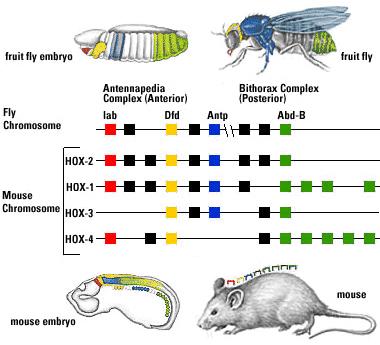

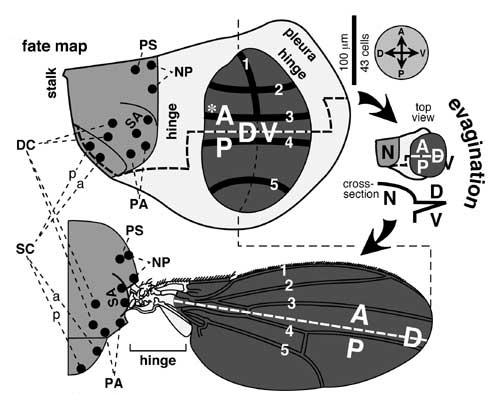

Description of the shared homebox genes between a fruit fly and a mouse.

1.1-15

Fate map for the development of the fruit fly wing. Diagram A depicts the layout of genes. Diagram B shows the related morphological development.

1.1-16

Initial layout of particles with double-array ordering system.

1.1-17

Fate map describes the specification of geometry (springs) and association (various connection types between particles).

1.1-18

Morphological description of fate map described in Figure 1.16.

1.1-19

Samples of the toolkit (scripted functions in Processing) which develop and specify form. Most functions simply address the ordering system in various waysassociating particles within a single network of springs and/or across two networks of springs. Additional variables such as spring-strength provide for further specification and adaptation of form.

precedents

1.1.3 Articulation of Computational Form through Fate Map

1.1.3 Articulation of Computational Form through Fate Map

Michael Hensel hypothesizes about a computational process “extending the concept of the material system by embedding material characteristics, geometric behavior, manufacturing constraints and assembly logics.”1 This is the goal of a computational design process for cable net structures. An examination of the field of evolutionary biological development offers models for how integration of a high number of components and functions can be realized through simple, repetitive means.

Evolutionary Developmental Biology explains growth and development through the following: modularity, repetition, switching, and geography.2 The interconnection of these is what gives the process its robustness and extensibility. The functioning of the homeobox presents clear processes for how variation can be generated with the same set of tools.

Moving through the stages of development, the challenge is how to track and control variation from the initial setup through to the final form. Abstracting processes described in evolutionary developmental biology provide the logic for proceeding through the steps of geometric form development. In defining the base geometric unit, extensibility is primary. Embryological development works with several primary materials to realise multiple structural types (both tension and compression systems). Instead of prescrib-

ing multiple context-independent components, a single unit should be able to develop into various material types.

The fate map, a representation technique for tracking cell development, is a helpful concept in managing form specification in complex systems. The control of articulation can only be gained when the initial setup can be connected to the final form. In the spring-based system, the network arrangement is akin to the fate map, the particle being equivalent to the cell. A logical ordering system for the components of the map allows for easy determination of where particular articulations in form occur, in what contexts, and which transformation functions are applied.

1 Hensel, M and Menges, A, Inclusive

Performance: Efficiency versus Effectiveness, Versatility and Vicissitude: Performance in MorphoEcological Design, 2008, Volume 78 No 2, 54-63.

2 Carroll, S, Endless Forms Most Beautiful: The new Science of Evo-Devo and the Making of the Animal Kingdom. London, Orion Books Ltd, Phoenix, 2007.

1_precedents

Architects have the ability to alter our perception of a space (environment) through the use of physical material.

Often the relation between the geometry and the material is not immediate. Especially in the current state of fabrication a lot of materials are “standardized”. Not only in performance, but also dimension, geometry and size. Shape and material property are highly determined by industry standards and fabrication methods. These are treated as an additional layer. Sometimes this choice is based on certain material characteristics (transparency etc.) or a specific performance criteria (high isolation, high strength etc.). In rare cases does the material choice feed back into the actual geometry a significant degree. “Structural Analysis” operates as a re-dimensioning process (widen beam, thicken floor plate, re-dimension column) altering a very limited set of input parameters (thickness, width etc.) of the initial, individual element. The agglomeration of these elements make up the “architecture”. A current trend is the design of Information systems that help managing the vast amount of elements (BIM), but the process becomes very elaborate and problem of detached geometry and structure remain. This ultimately leads to a very limited way in which we, as architects, allow ourselves to manipulate an individual’s perception of a certain space.

Tensioned nets are one example of a basic material system. Their shape is determined, by the forces acting upon the whole structure and each element

used within the net contributes to this behavior. The physical process in which a net takes shape under the application of external forces is usually referred to as form finding.

Not only is this process interesting for architects to look at, because of the fact that the resulting form / net geometry has a certain degree of validity or inherent truth, which other models that are not based on form finding methods lack.

A fascinating aspect of these design investigation systems is the amount of inputs needed to re-define the shape of the model. Moving one anchor point of a net to another location in space can have significant repercussions on the form. This means, that the architect / designer can actually explore different shapes, of the same validity (regarding the distribution of physical forces) with very little effort. At least in a model.

But the model has to be able to account for these alterations intended by the designer. A certain material’s elasticity might prevent one from exploring a certain configuration of anchor point locations. The only intervention left for the designer in this case (besides disregarding the idea) is to either change material (with more elasticity) or add material. Both options result in the rebuilding of the net (model), which is a time-consuming procedure. Something that we experienced during our first form finding investigations of tensionactive nets during EmTech’s core studio in the fall of 2008.

Without being specialists in the construction and

dimensioning of nets we were able to observe during this important period of time of our studies, that all nets have certain similarities. Their tendency to take shape into what would mathematically be described as a minimal surface was particularly interesting, as this was a property inherent to the material system, but never “intended” by us, the designers.

It was our interest to expose the drivers / actuators for these common properties amongst nets and membranes in order to explore net configurations that would expand the vocabulary of spatial perception of these architectures thus far.

In order to use nets as space-making devices we focused on net topologies that are not very common and rarely used for projects at an architectural scale. Usually architects and engineers investigate the use of planar net topologies. These nets are, by nature, “flat”. Their inherent capability to circumscribe a space is limited. These planar nets have multiple boundaries (equivalent to “sides” of a polygon in geometry) and are mostly used to define form-active roof structures - which is logical, if the underlying topology is understood.

By “closing” the net in 1 dimension, or in simpler terms, by transforming the planar topology into a cylindrical one, the boundary conditions are reduced to only 2. Furthermore a directional of the net is generated that was previously not present. Whereas the planar nets (objects) allow the spectator (subject) to define his position in relation to the object (“I am under / above the net”), the cylindri-

cal net topology generates spatial conditions that can be described as being “inside” of the net. This new characteristic led to a search for ways of emphasizing or alleviating degrees of enclosure enforced by a cylindrical tension active net system.

In order to pursue this exploration of spatial effects of cylindrical nets on their environment it was necessary to develop a digital form finding method. Embedded into this method needed to be information about structure, performance and characteristic of each element augmenting the system. Implementing a method for accessing all data for fabrication was necessary, as our intention as architects was not to develop hypothetical computational mesh geometries, but actual physical architecture manifested through a digital method of form finding.

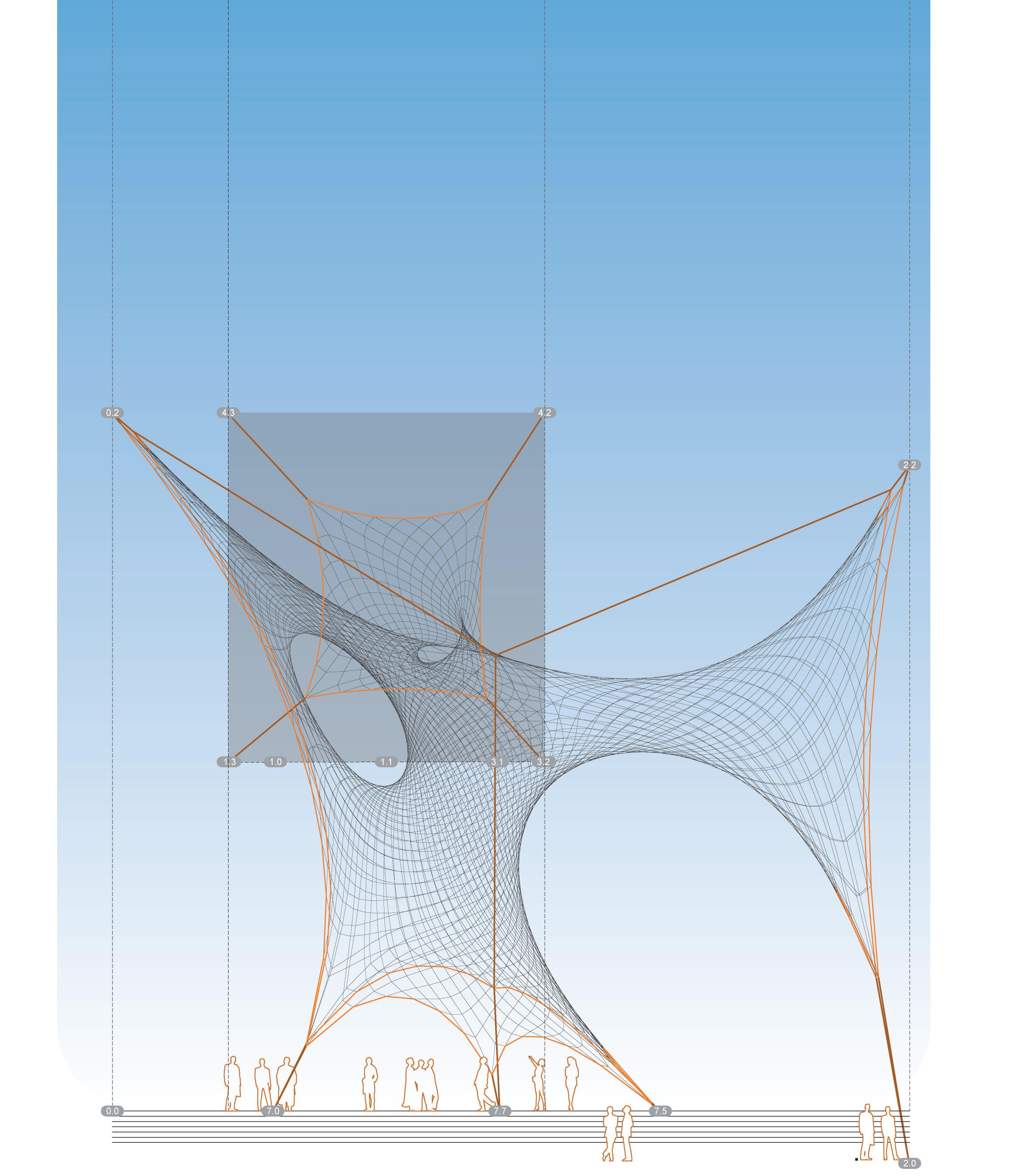

A lightweight vector-based analysis tool simulating the perception of a net’s density from different points of views was developed. By measuring degrees of enclosure of cylindrical nets this analysis tool aims at a computational method for defining a net’s space-making capacities as well as its potential to serve as a protective shield against external forces (simulated through vectors) such as sun, rain or wind.

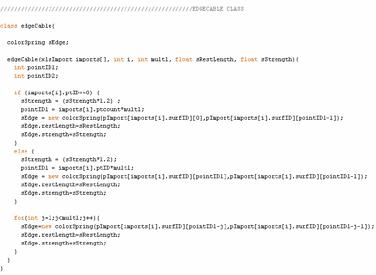

1.10

cable-net structure for a cooling tower for Balcke in Germany built in 1972. Consulting by Schlaich engineers. 142 meters in diameter, 181 meters pylon height.

1.11 fishing net in China. an example of a net with a medium mesh size.

1.12 membranes can be considered very tight nets. As tension-active elements they are used for tents to protect against wind, rain and sun.

1.13

net installation at the Johann Wolfgang von Goethe University of Frankfurt by Hannes Schewertfeger. 90 squaremeter area.

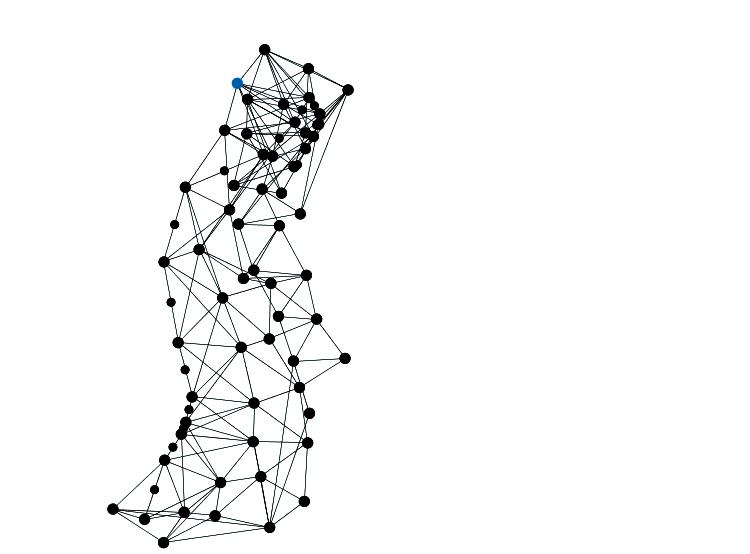

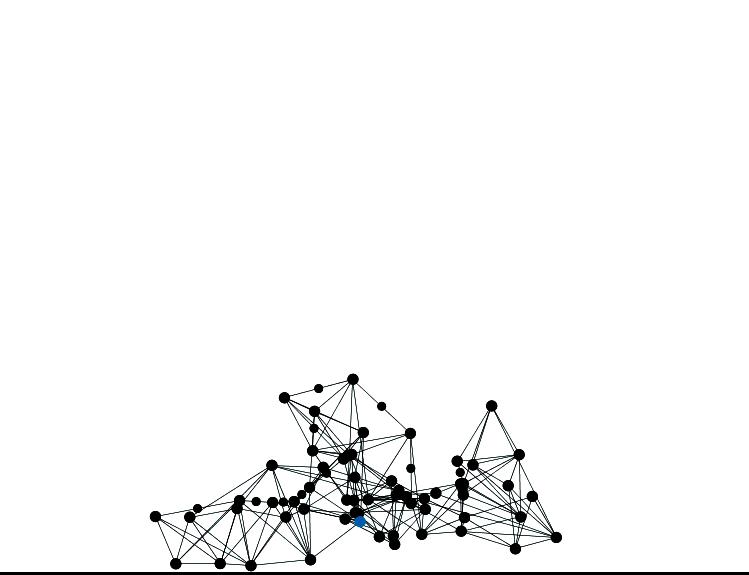

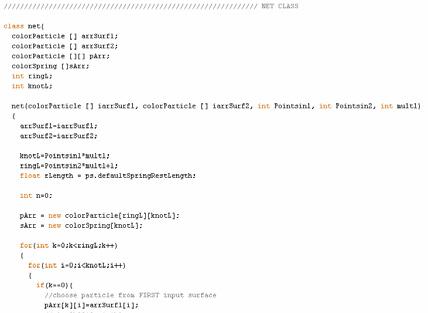

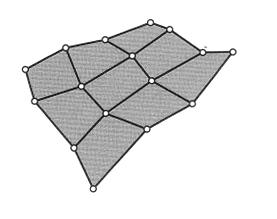

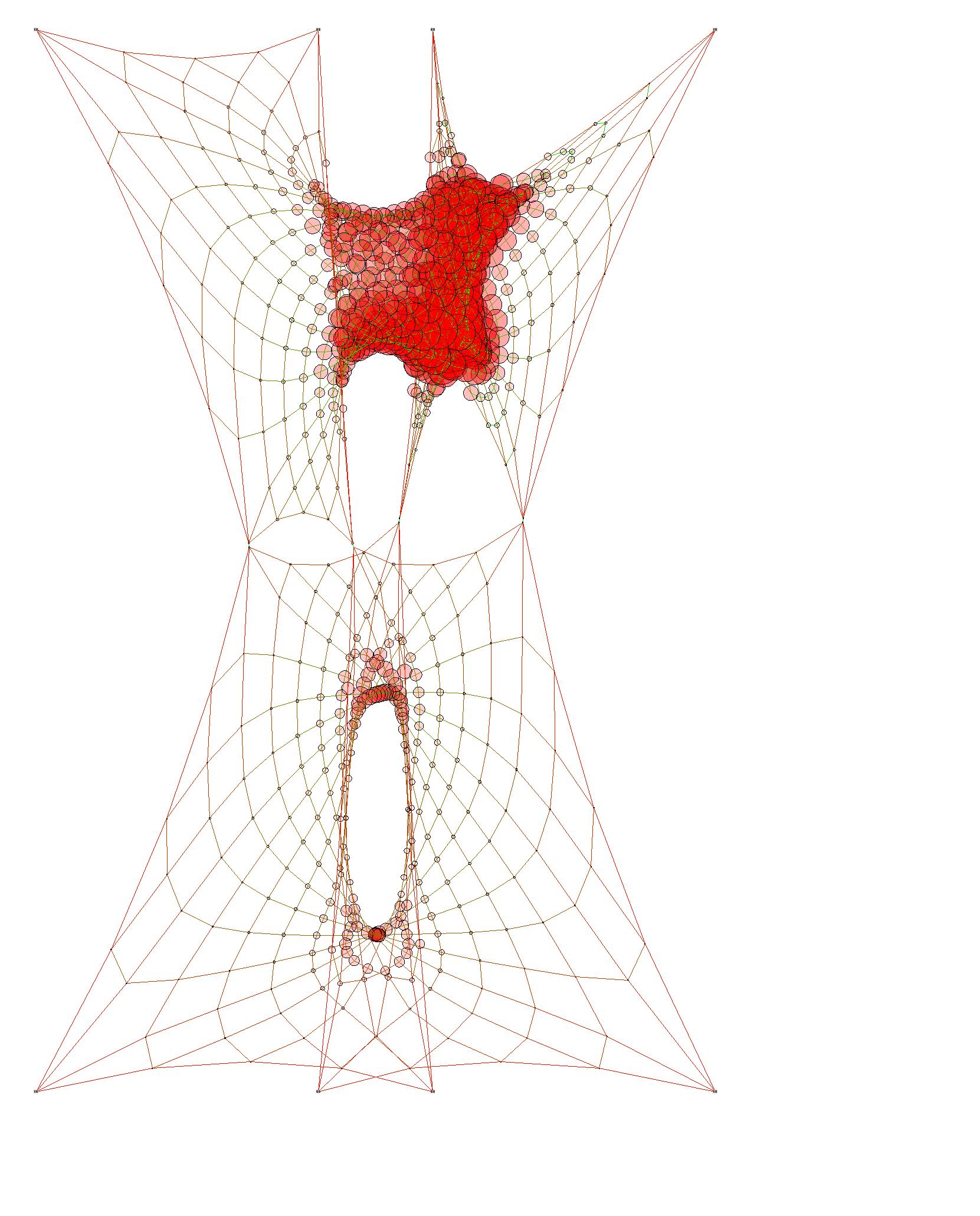

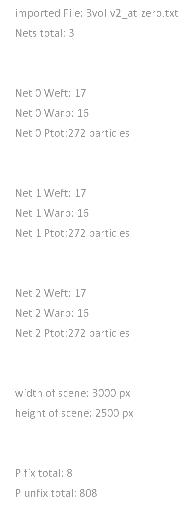

A spring-based particle system simulates the tension and compression within a network of connected springs. The overall connectivity between the elements forms the net-topology. In order to simulate multiple net configurations quickly a method derived from the investigations in evo-devo was developed.

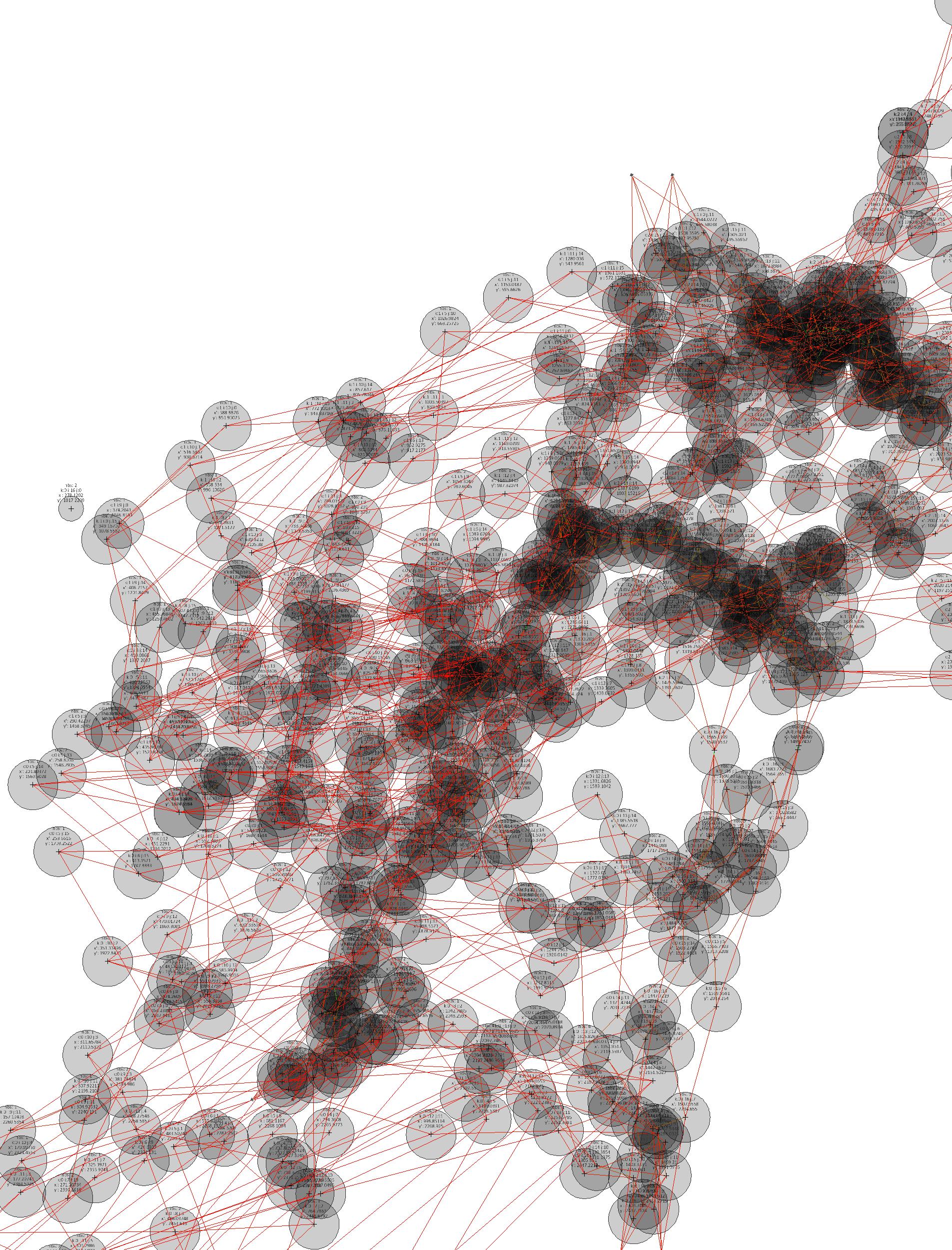

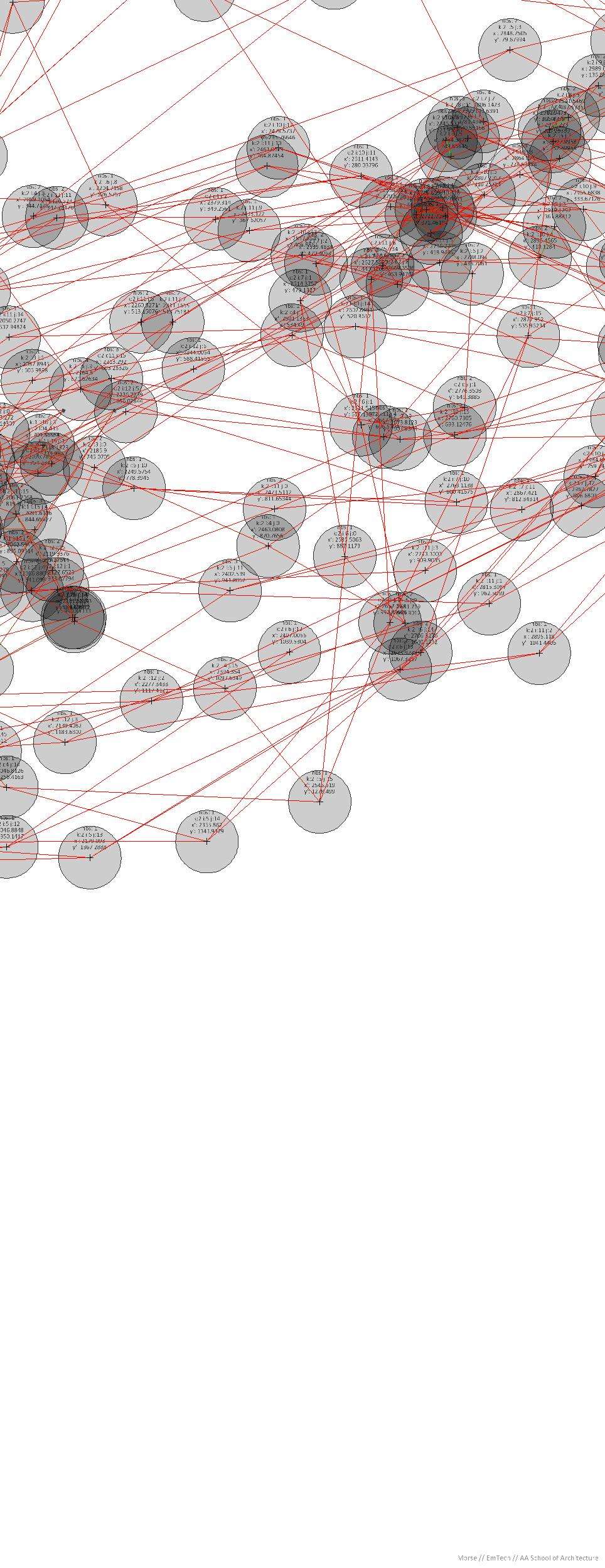

Every computational net is built through a logic map (2-dimensional array), which determines potential size & density of the net through its dimensions.

In processing Springs are inserted based on the logic map, that determines Particle-to-Particle relations, connectivity and the overall net topology.

Switches are accessed to fix or unfix the boudaries of the nets. The combined use of these switches and the logic map allows to simultate multiple net variations easily and quickly, while the method of how they were constructed maintains absoluetly transparent and accessible (see chapter 2.1. embedded fabrication). In the process of dynamic relaxation the predetermined network topology takes shape through the simulation of the forces within the system.

1.2.1. Network and Geometric Topology

The mapping of nodes describing pathways for communication and data transfer is the basic definition of network topology, where nodes are considered as devices constituting a computer network.

Examples of base network topologies are shown in Figure 1.2-2. This is a useful description for how a particular pattern (or a systematic hybrid of multiple patterns) for the association of nodes can be constructed to form an interconnected continuous network. It is also important to clarify that network topology does not consider position. It refers only to the strategy for arrangement of the devices that are engaged in the network environment. This explains the difference between a logical topology (of associations) and physical geometry (of position).

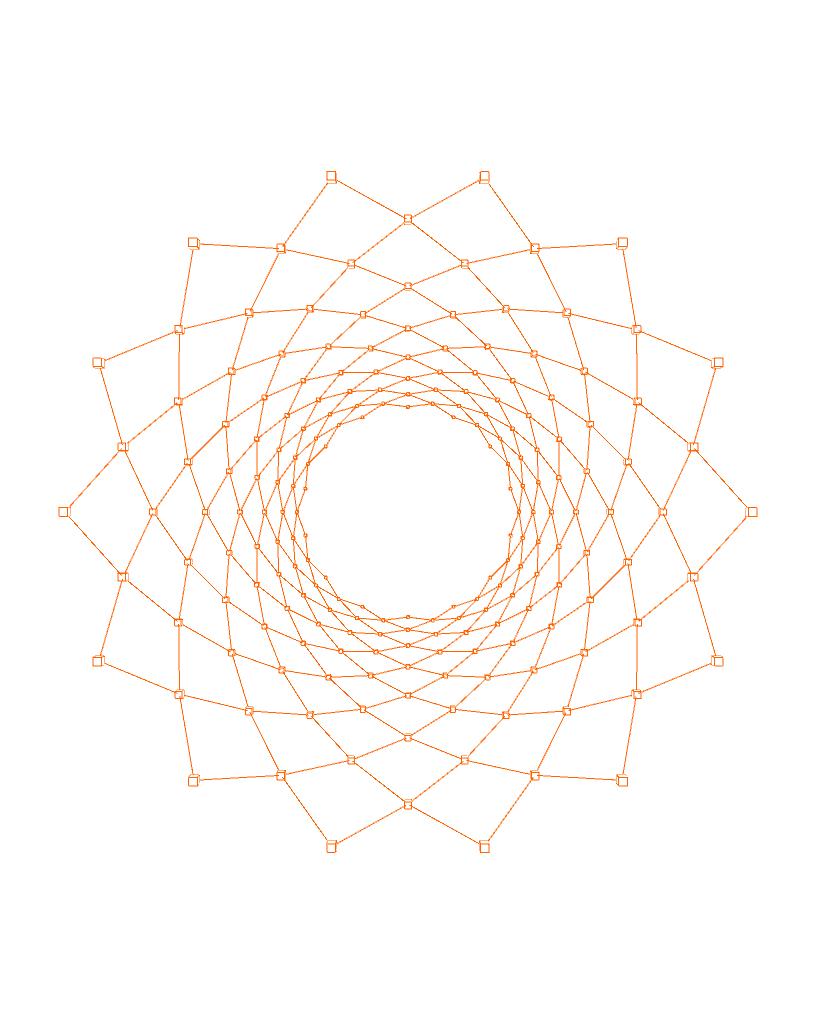

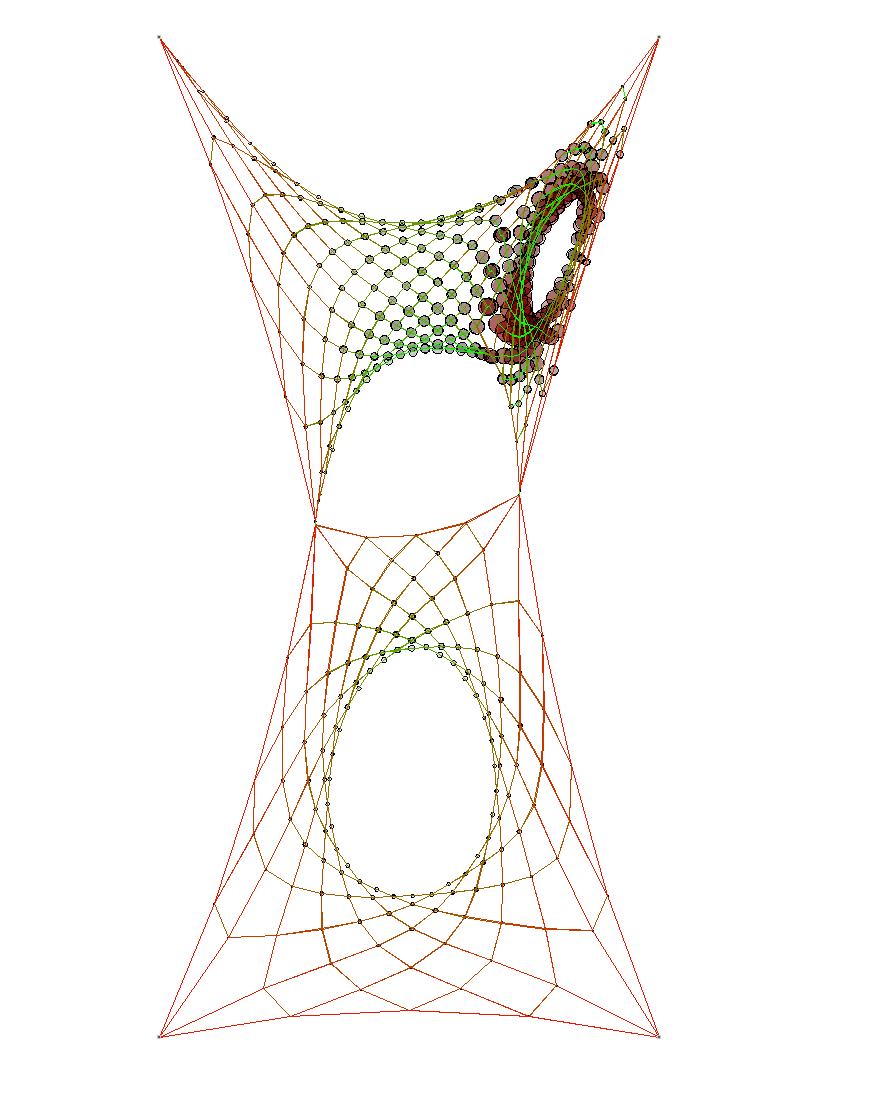

Geometric topologies have limits to the types of geometries that they can construct. The repercussions are examined here both in terms of geometry performance and in connection to its potential for the definition of the boundaries of architectural space. In the cable net experiment, selecting the logic akin to the “ring” topology, when transformed into 3 dimensions, means for a continuous surface that can define various degrees of bounded space.

The appropriateness of the “ring” topology is evident when compared to other network topology types. It makes sense that the “line” topology expands to an open surface defined by 4 edges, where the “ring” topology easily transforms to a 1-dimensional continuous surface, bounded by 2 edges. (Figure 1.2-4) It would seem that forming space through a series of open surfaces involves more effort, physically and computationally. Surfaces are either transformed to define a continuous boundary (with subsequent geometric issues as mentioned earlier) or coupled with multiple surfaces to eventually have a clear delineation of space. The other topologies, cylindrical and torus based, more quickly and clearly begin to define the boundaries and orientation of a particular space (Figure 1.2-4), and all with a single strategy.

1.2.2 Spring-Based Particle Systems

Particle systems are simple physics models that only deal with point-masses and forces. That means that - as opposed to rigid-body models - objects in particle systems do not occupy any volume. Their behaviour is quite simple, but powerful. (Figure 1.2-8)

Particles

A particle is an object with a location and a mass. It is acted upon by any number of forces. The greater a particle’s mass, the more is required to accelerate it.

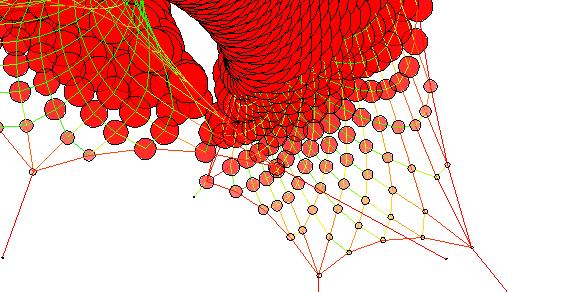

A particle’s location in space is determined by the forces acting on it, unless the particle’s position is declared as “fixed”. This boolean value indicates whether a particle’s position is being controlled manually or by the forces in the system. A fixed particle can be attached to a single point in space, or the mouse, or may be moved simply by (re-) setting its position. Often a whole system of particles will be attached to a single fixed particle and will move with it. In order to be a solvable system from a structual point of view the particle system needs to contain fixed particles. Springs Springs are forces that exist between 2 particles. The force enacted by the spring pulls or pushes the 2 particles together or apart with a force proportional to the distance of their separation. A spring’s performance is defined by the variables of rest length, spring strength, and damping.

Rest length is considered to be the length of a spring at which it no longer pulls or pushes. The strength of a spring determines how hard it pulls / pushes when it is stretched / compressed. The amount of Damping controls the energy absorbed by the spring as it bounces (dynamic relaxation) Damping is necessary in order to prevent the spring from oscillating for too long.

Hooke’s Law

Hooke’s Law is a solver for the forces in computational springs. It determines the forces on two particles connected by a spring. If the spring’s current length during the process of dynamic relaxation is greater than its Rest length then the force of the spring acts to pull the two particles together. If the spring length is less than the rest length, then the force acts to repel the two particles. Both of these forces act along the vector defined by the two particles. The force on a particle “a” due to particle “b” is given by:

Where ks is the spring’s strength, kd is the damping constant and r is the Rest length.

To solve the accumulation of vector forces such as in a network of interconnected springs, the RK Solver or Euler Solver is typically used.

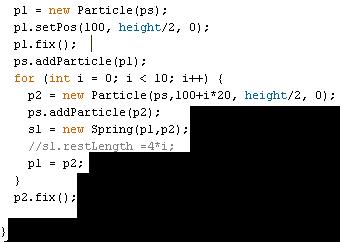

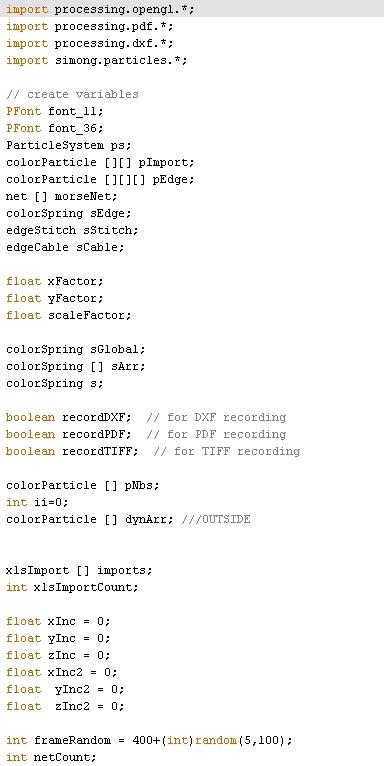

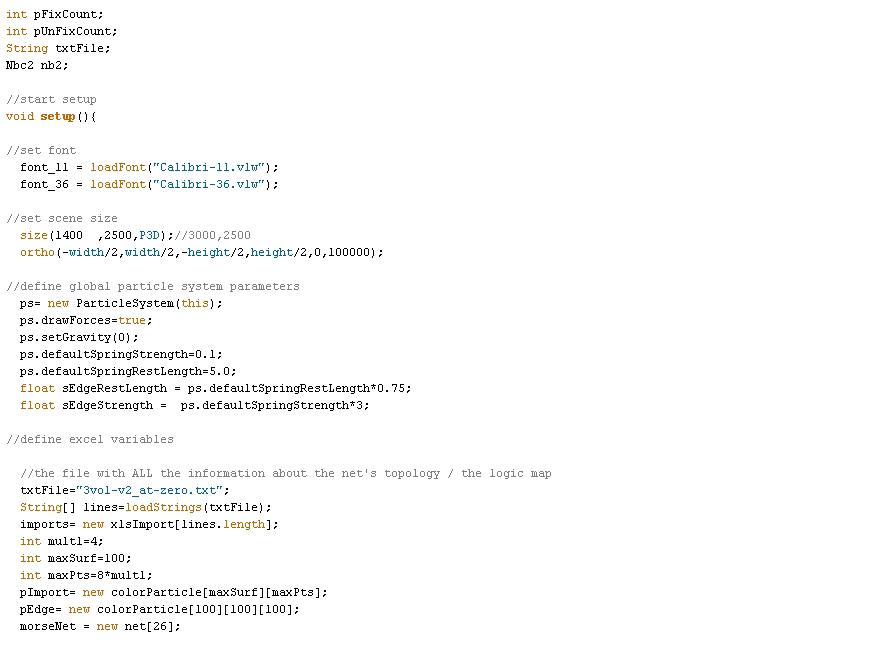

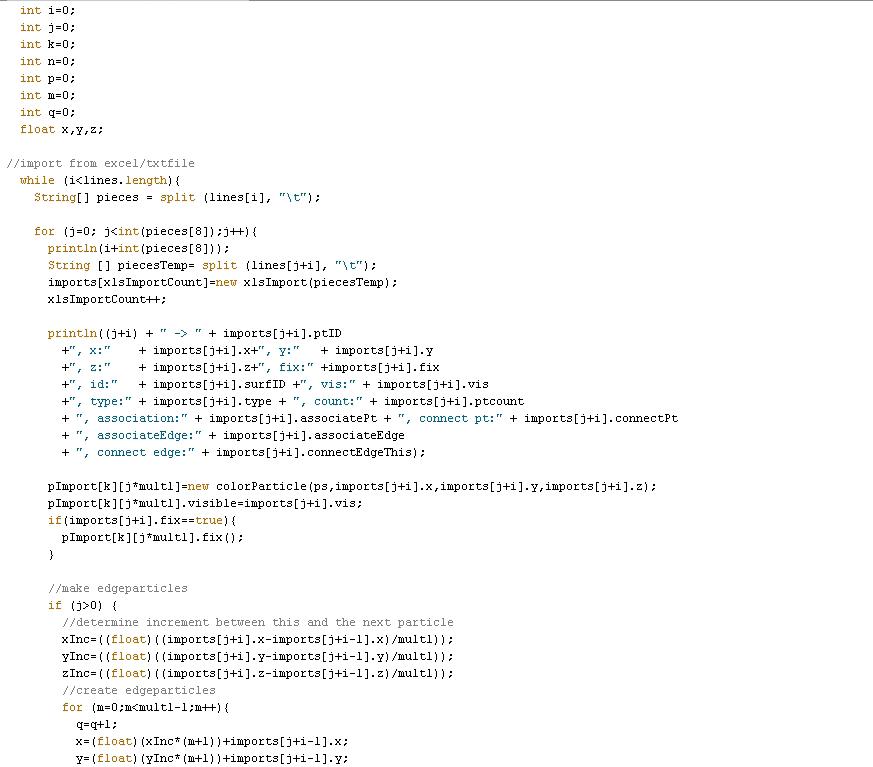

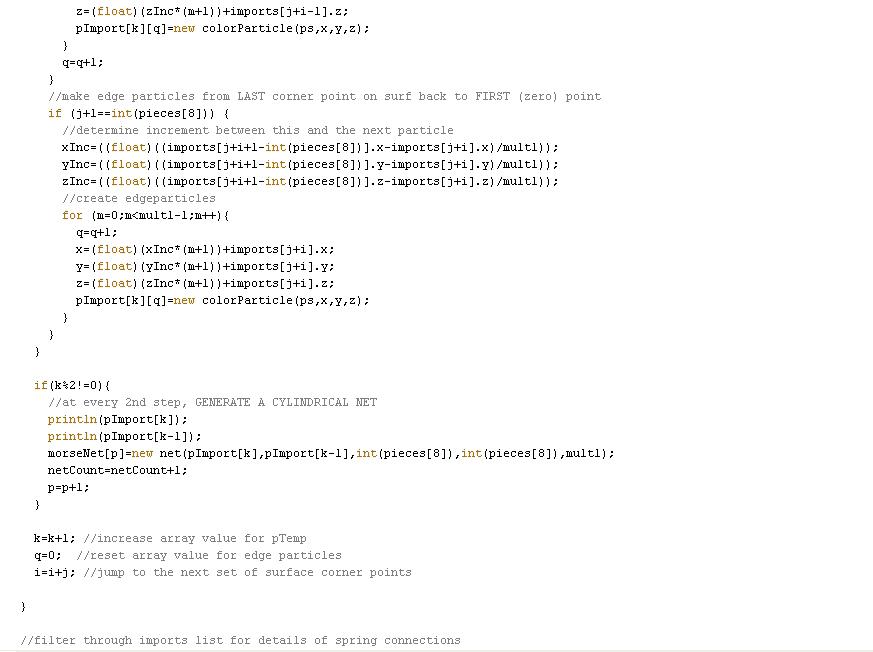

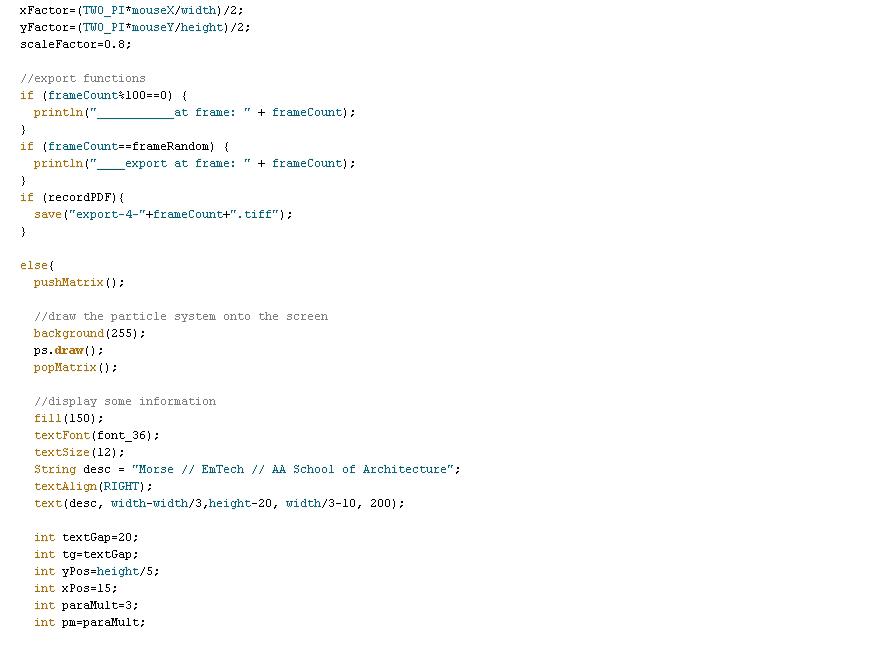

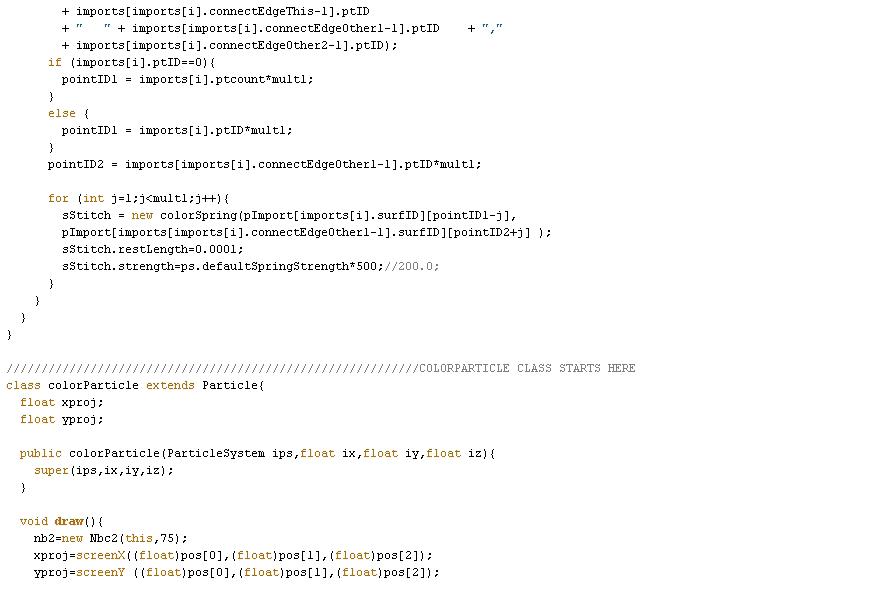

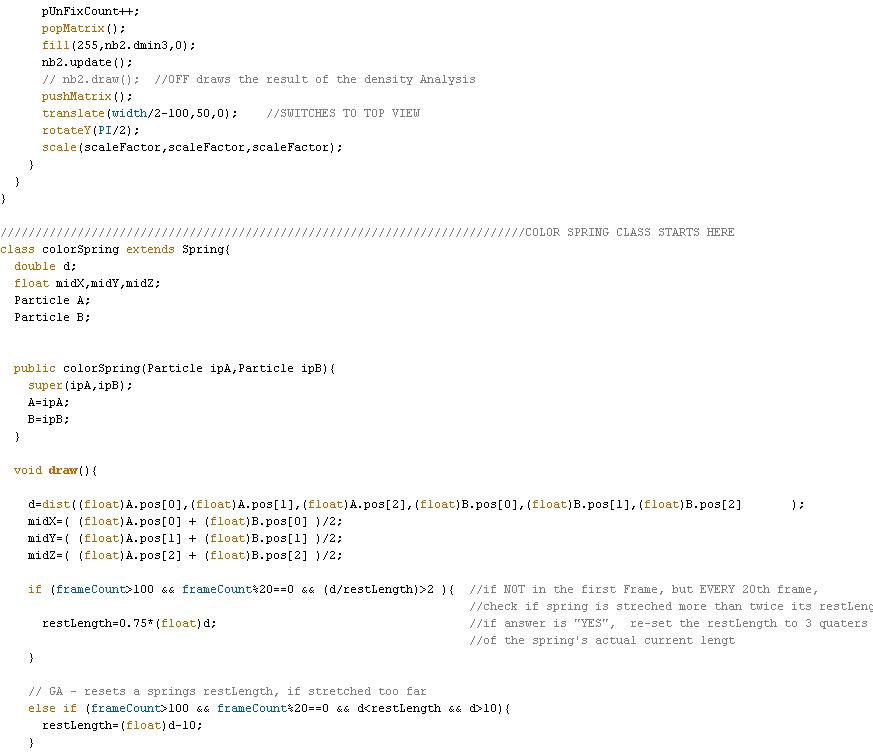

1.2.3 Springs in Processing

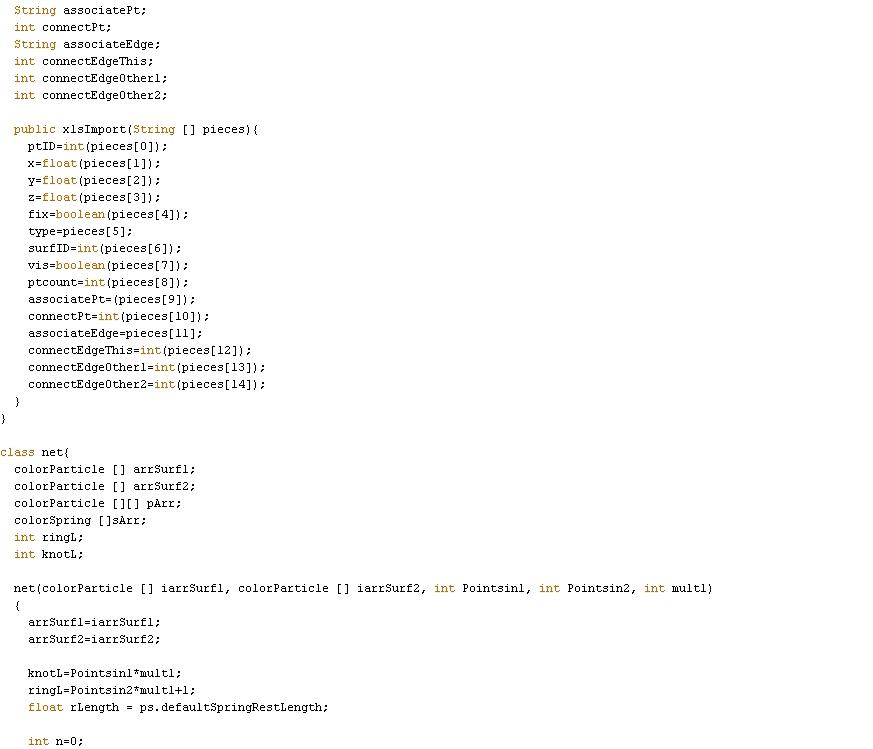

For the “Form-Finding and Structural Optimization: Gaudi Workshop” at the MIT in 2004 conducted by Prof. Ochsendorf, Simon Greenwold developed a Particle System written in the Processing - a Java-based computer programming language

This programming language, which is available for free download at www.processing.org, has gained a high degree of popularity far beyind the initially targeted community of artists. The software is used by engineers (for example: Chris Williams) and by

architects at workshops like Smart Geometry. Axel Killian, who took part in MIT’s workshop, provided the particle system library for processing and helped in getting started with the first particle systems.

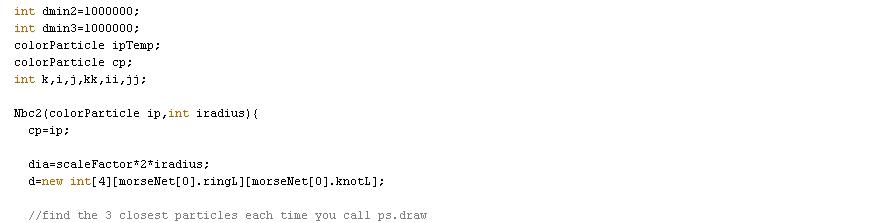

When using the Particle System, the initial setup is developed through the creation of an array of particles. Each particle carries values for mass and position, where force can acts to negotiate the particle’s final position. Force, in this case, comes from a linear network of springs. The position of a particle can be calculated through the simple equation of force (f) = mass*acceleration, where f is the vector sum of all forces.

The step of enacting external forces and resolving the internal flow of forces drives the final positioning of the particles. With the spring system, this happens through the combination of the spring solver and the resulting computational process of dynamic relaxation. Dynamic relaxation is the current standard for realizing the equilibrium state of tension active systems through iterative steps of vector oscillation. It is important to see the distinction between the physical topology defined through dynamic relaxation and the user-defined network topology defined through the 2-dimensional array of particles: the logic map.

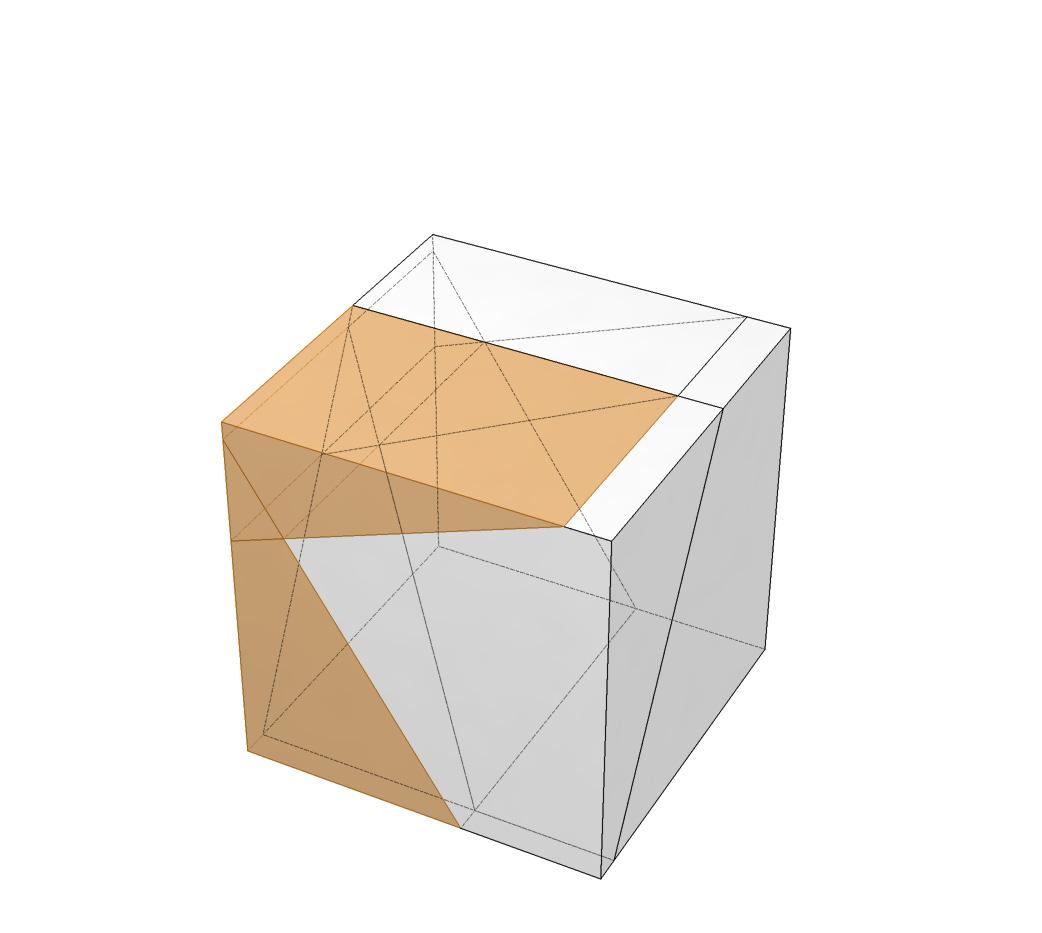

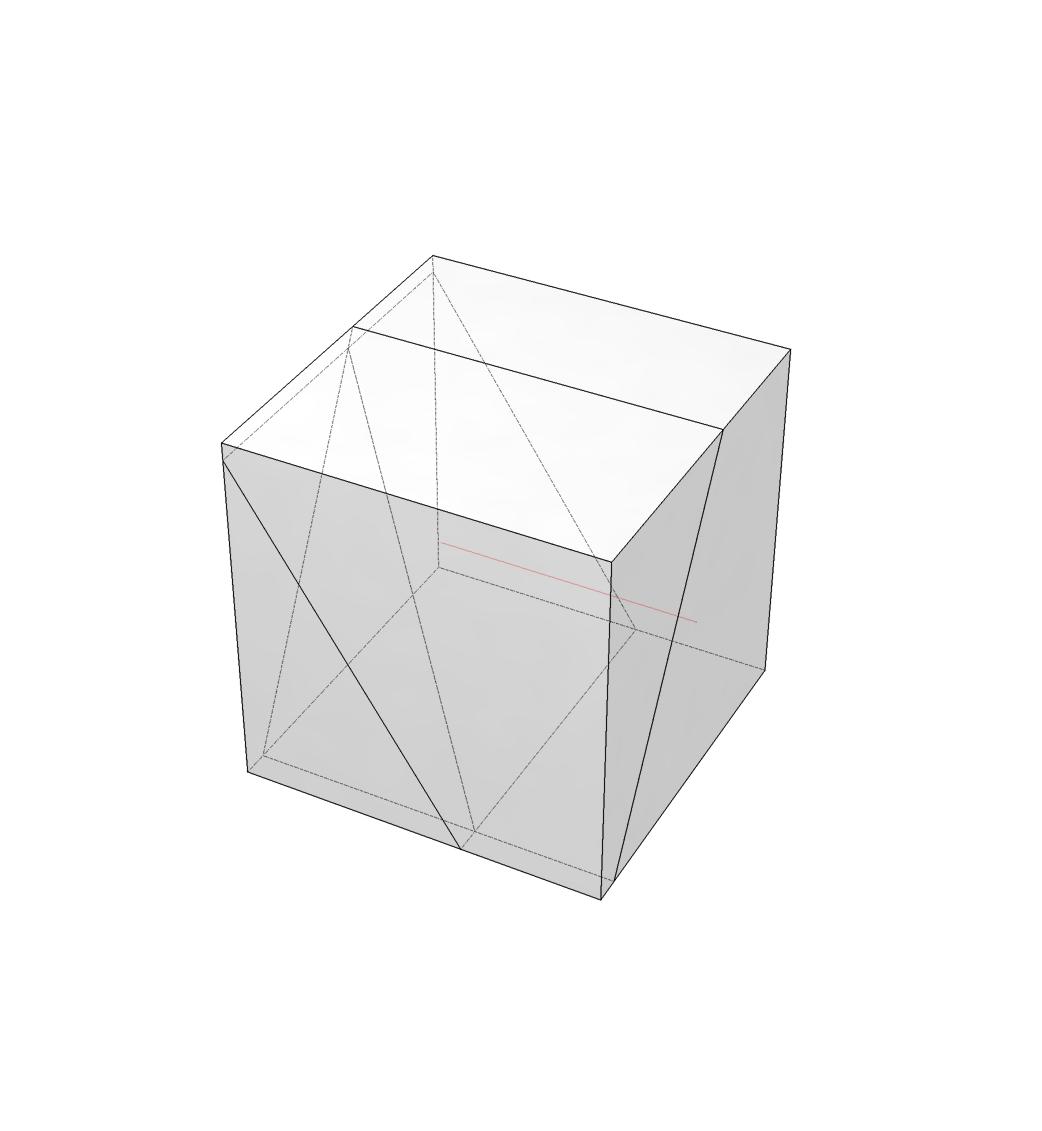

Network Topologies

Examples of logical network topologies depicting various patterns for connecting network devices. Logical topology describes association not spatial position.

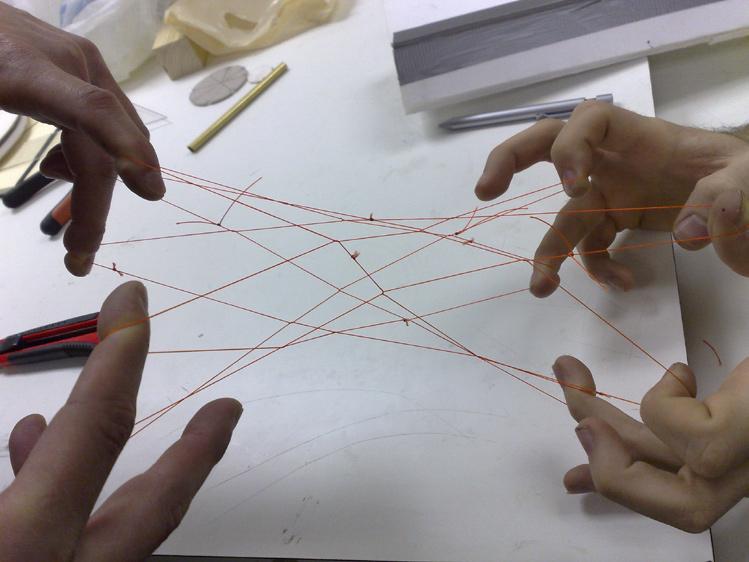

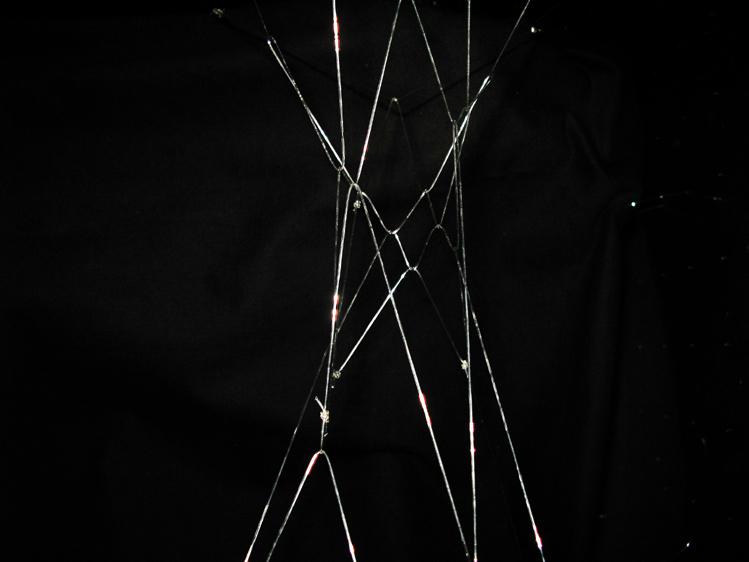

1.2-3 various physical prototypes of cylindrical nets were built. The development of a spatial network topology is shown through a series of physical modeling experiments with tensioned net structures. With the intention of forming a system that when translated into its physical topology arranges surface, structure, and space, this model is an example of a typical “formfinding” process. The interesting aspect is in the link between the inherent geometric logic of the initial loop, as a closed “ring” (bottom left), and the spatial form constructed when activated into a physical topology (top middle). This connection between material and space in the most rudimentary components of the design system is a primary necessity in the design process that solves for integrated conditions of surface, space, and structure.

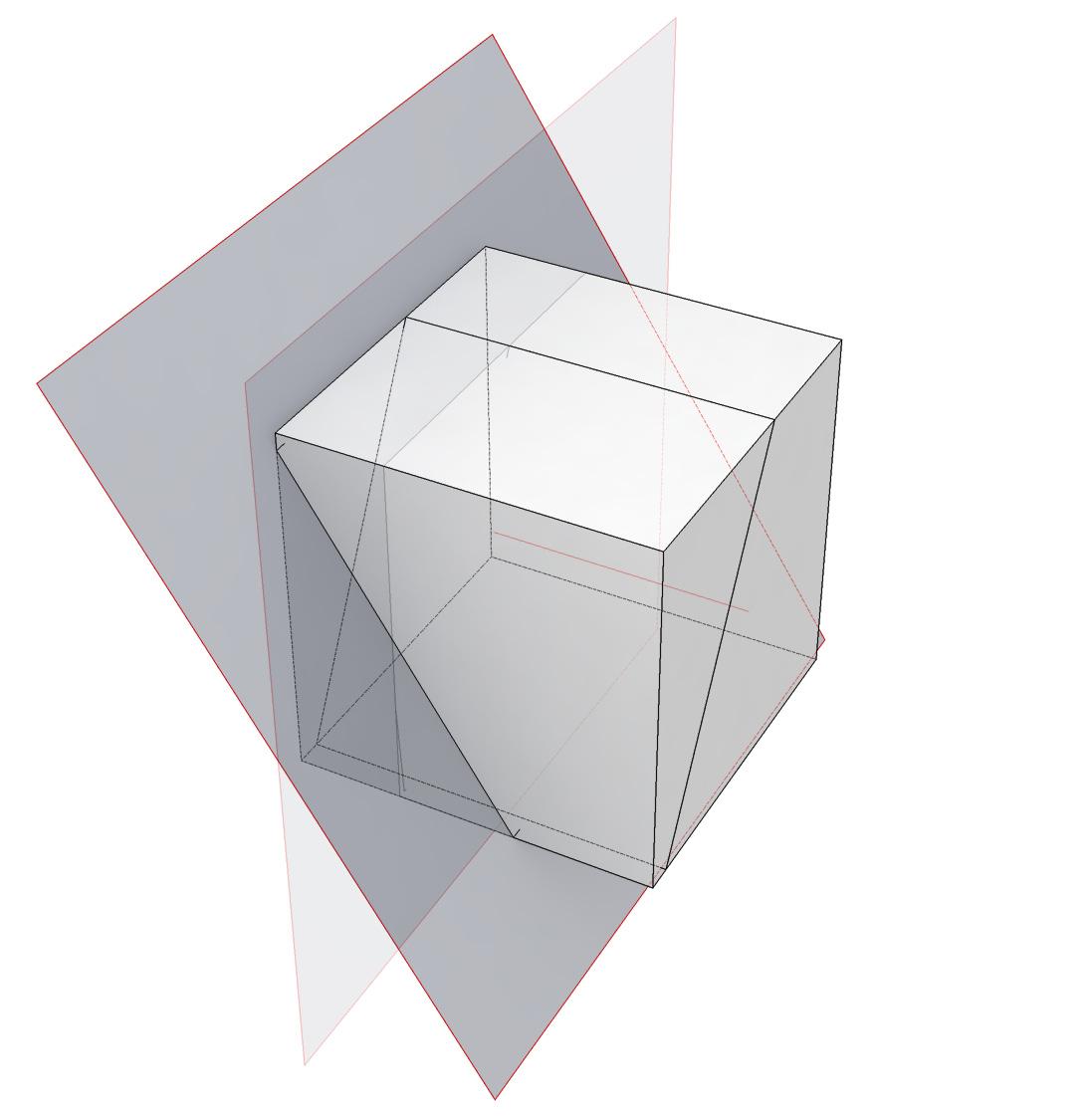

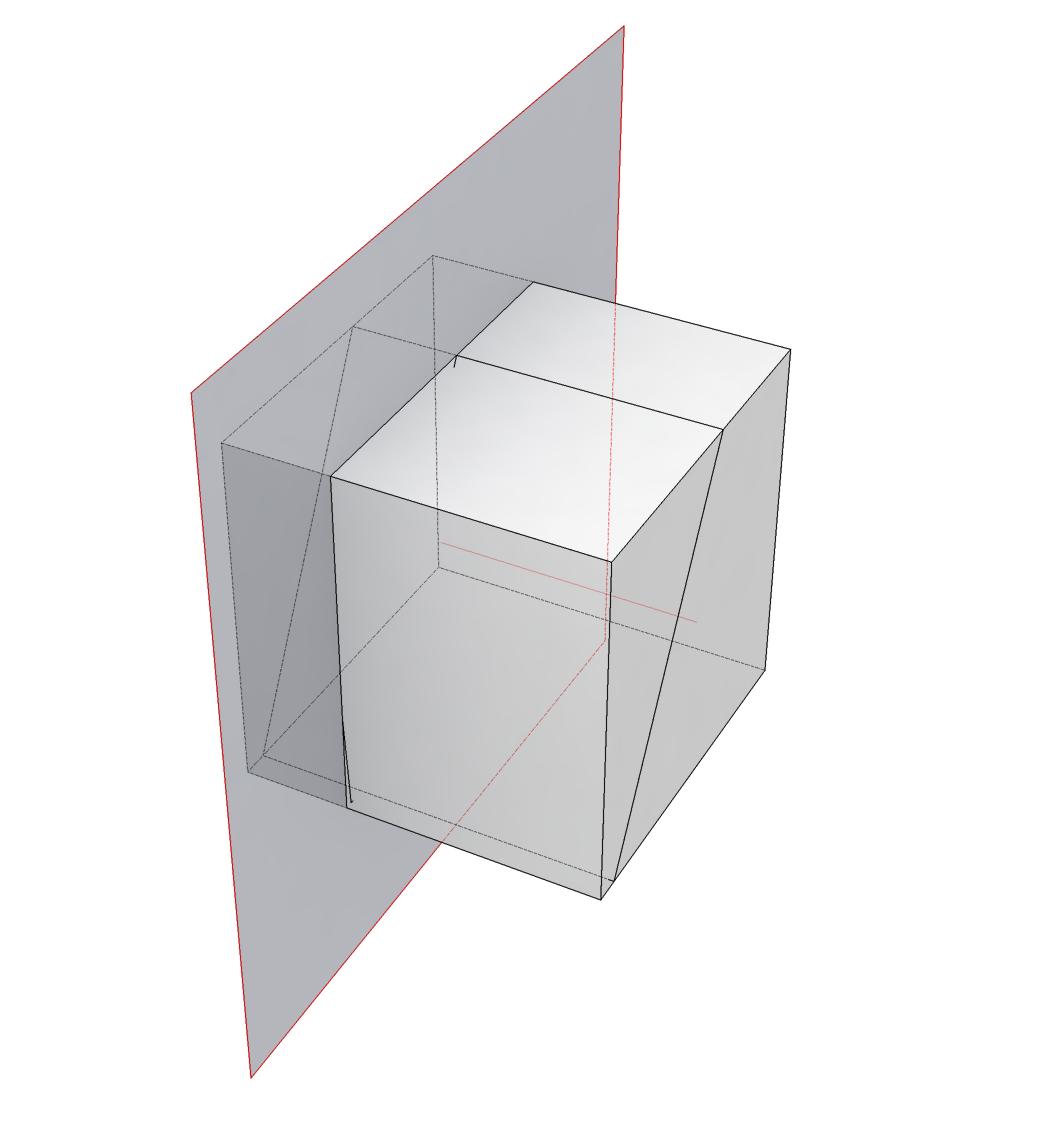

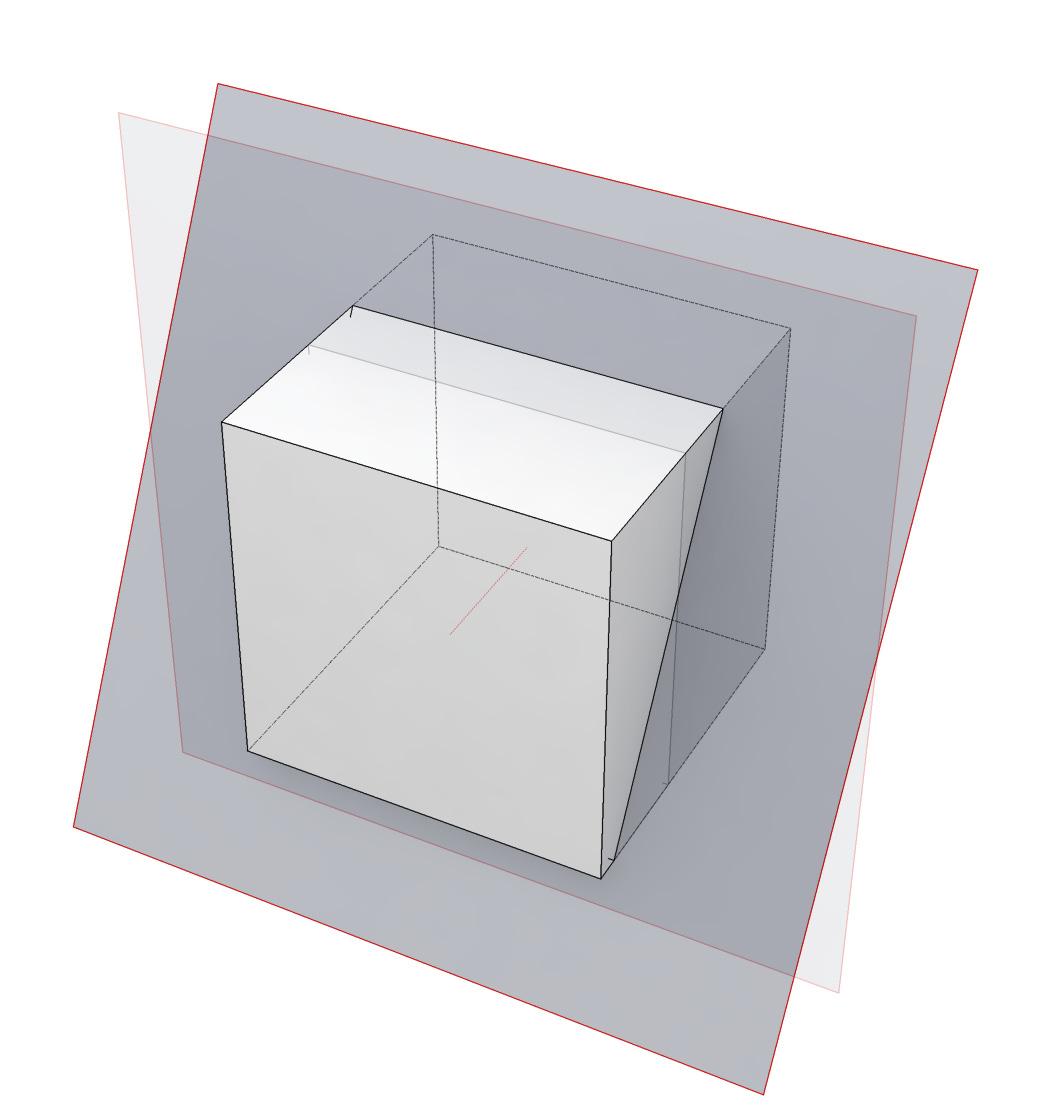

1.2-4

Geometric Topologies by increasing in topological dimensionality (curves have 1-dimension, usually described by the parameter “t”, surfaces are 2-dimensional, UV-space) of a network of nodes as shown on the vertical axis, different geometries can be formed. By closing their open ends, respectively edges, higher degrees of enclosure can be achieved. In 3-dimensional geometry the sphere / torus have the highest degree of enclosure. Based on experiments with cylindrical nets, a topology that introduces directionality and a certain degree of enclosure to the planar topology by very simple means (closing 1 edge) was chosen as a component for the construction of different net morphologies.

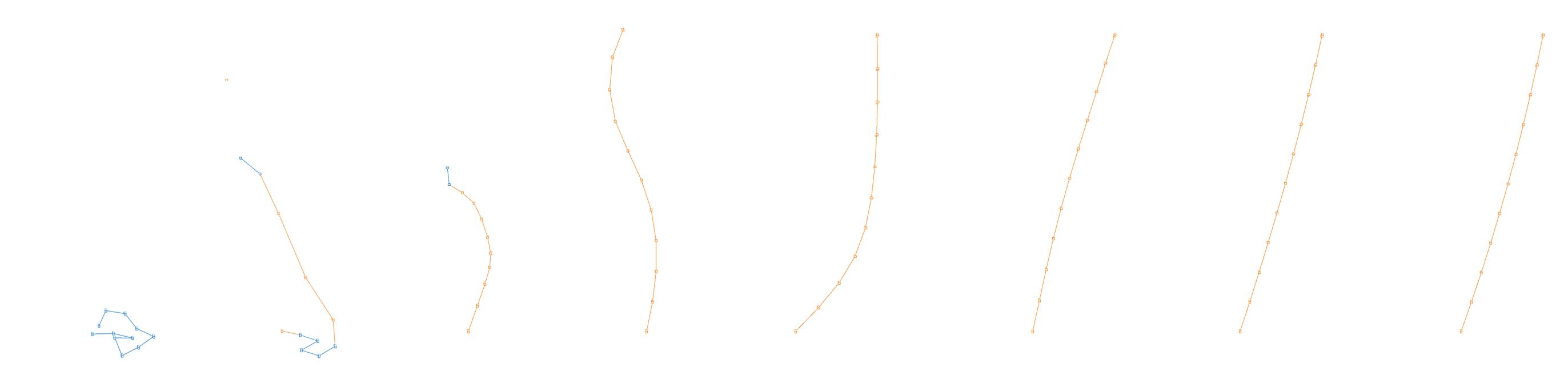

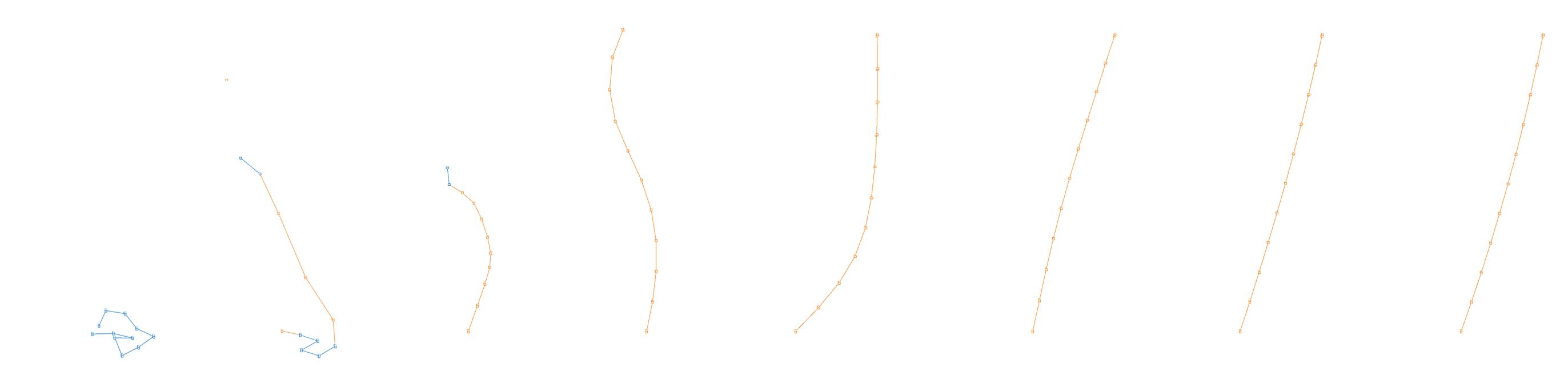

1.2-5 programming a computational chain through the linear connection of multiple (10) particles in a singular (1D) “for”-loop a chain between particles is formed. By inserting computational springs between the particles, the behavior of a physical chain can be simulated (in real-time). One end of the chain (p2) is fixed to a specific location in Cartesian Space whereas the other end of the chain is controlled via a particle that is directly connected to the user’s mouse position (ScreenX, ScreenY). The visual result of this small script displayed here is shown in

1.2-8

Computational Chain Model

Dynamic Relaxation of Spring system in Processing. A linear network of springs connects 10 particles. The last particle’s position in the chain, is controlled via the position of the user’s mouse in the processing interface (dashed circle). The first particle is fixed (orange circle). Dynamic Relaxation resolves system to equilibrium state of forces. The system is able to track which spring is in tension (blue) or compression (orange) within the system. With increasing distance between the fixed particles, the springs increase their tension force.

1.2-9

particle system diagram besides rest Length, a spring has 2 other parameters: strength and damping. Particles, the other important part of a Particle system besides forces, can be fixed to a specific location in space (XYZ), but in computationally simulated nets, most particles negotiate their position through the forces acting upon them. In order to simulate the behavior of tension-active systems, only Particles and Springs are necessary - even though a Particle System consists of more parameters. Boolean values equal “switches” of a “fate map” in biological models in function.

particle system

F

1.2-7

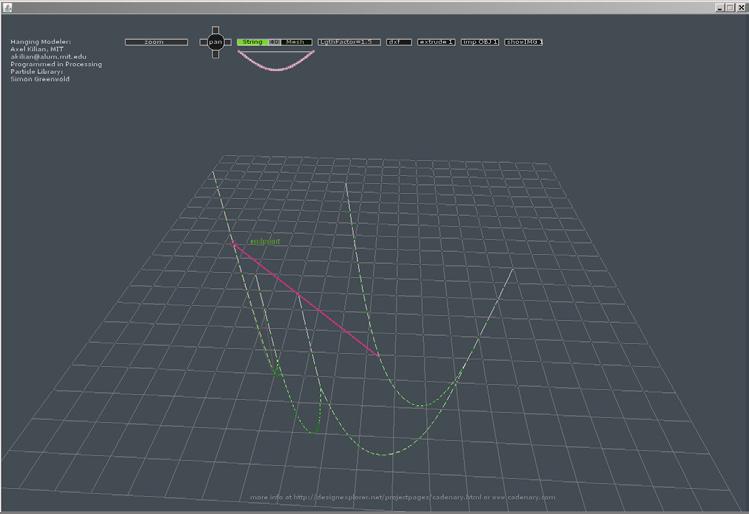

CADENARY software

A software programmed and developed by Axel Killian at the MIT during a workshop for digital formfinding experiments based on Gaudi’s hanging chain models. The software was written in processing and utilizes Simon Greenwold’s particle System written for this workshop. The software focusses on real-time user interaction through an interface for the digital simulation of linear and planar networks of hanging chains. It can be downloaded and explorer at www.designexplorer.net/

1.2-10

Hooke’s Law

a law in physics which calculates the forces within a spring.

The 2 most important stages in which an active spring can be observed, are shown in this diagram: tension and compression. If a spring is stretched beyond its rest Length, it will act as a tension element (top / orange). If the spring is forced into a length below its rest Length, it acts as an compression element. The mass of the particles connected to each end of the spring cause it to oscillate past its rest Length until a final position / length is determined with regards to all other forces in the network (computational form finding).

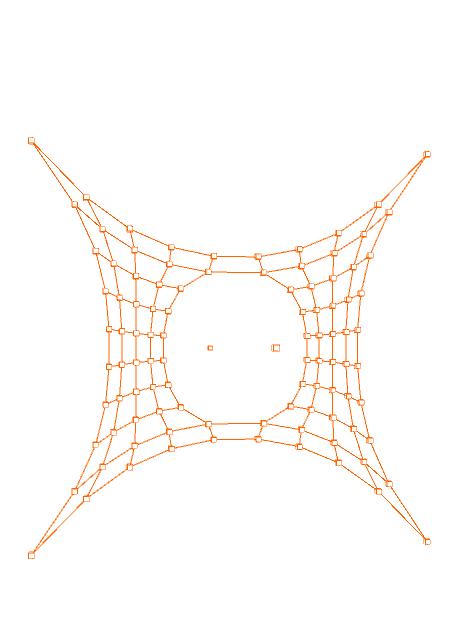

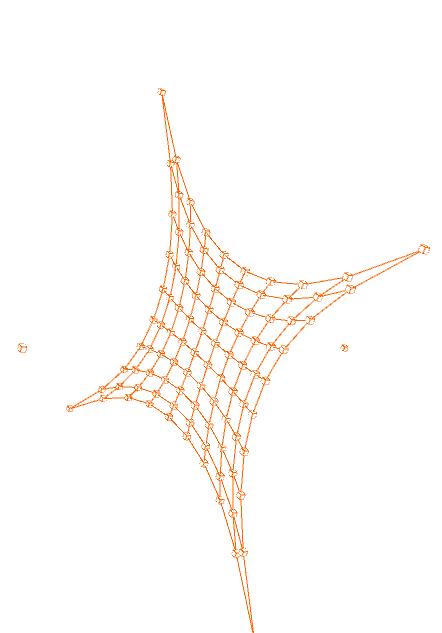

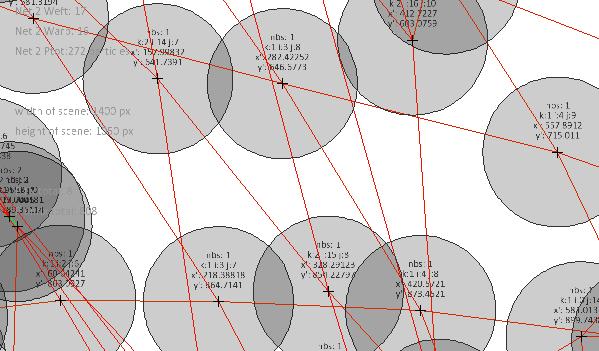

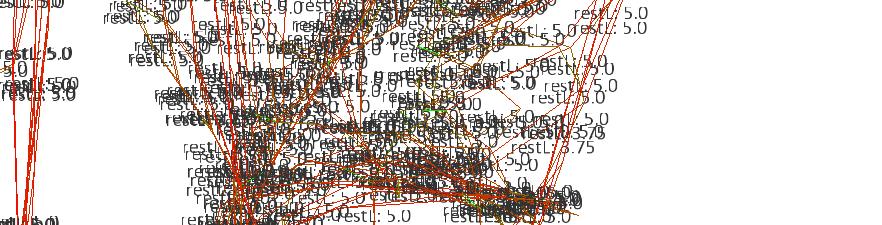

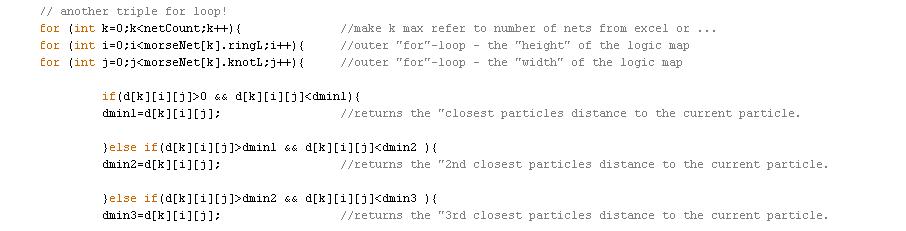

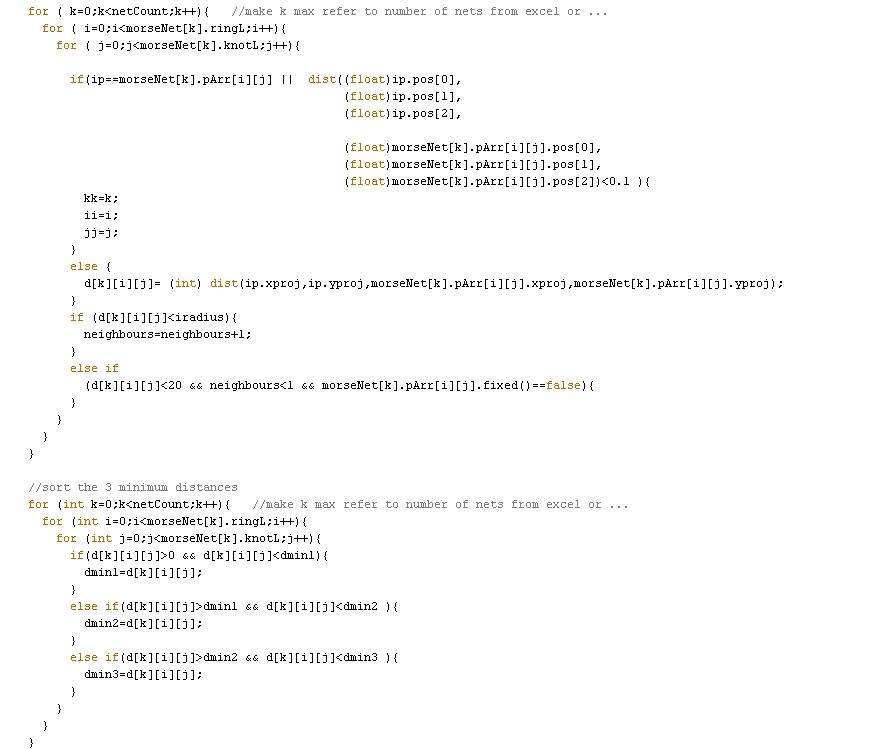

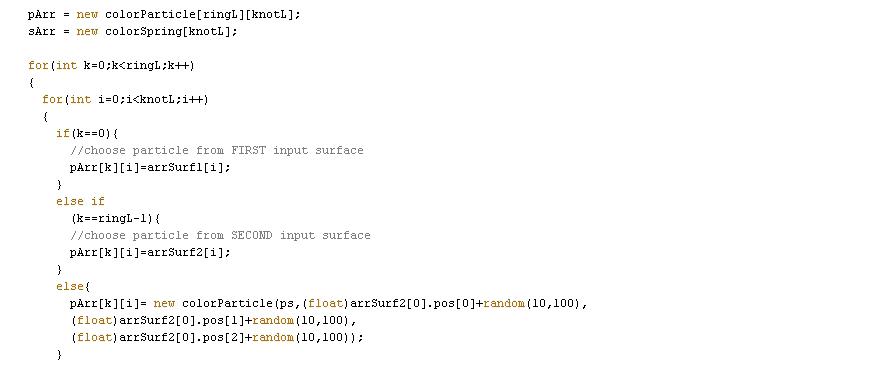

1.2-11 logic map

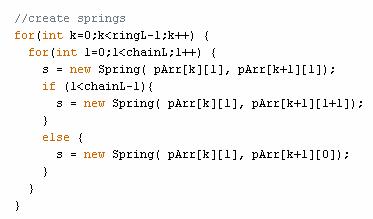

The logic map is a 2-dimensional array in processing. 2-dimensional arrays are a very common programming device and can be seen as simple ordering systems. Technically they are most efficiently generated through the use of a double “for-loop” in the script, where the outer “for”-loop determines the “height” of the logic map (even though it is a nongeometric , topological map) and the inner “for”-loop controls the width” of the logic map. The logic map can be used for multiple purposes and the method of generating it is common to all the experiments undertaken as a part of the research - not only in this chapter, but throughout the entire dissertation.

In this basic example, the logic map is used to create particles and assign them a unique ID based on their location on the logic map (top diagram). Furthermore, the map is used to determine which particles are fixed particles (middle diagram - orange particles are fixed). In this case, Particles at the bottom (i=0) and top (i=4) of the logic map are, through a simple “IF”-statement, declared as “fixed” parts of the net. In a third and last step, springs are inserted into the logic map. The method in which particles are connected via springs needs to be determined once and is then automatically repeated throughout the net (like most things with a “for”-loop). The particles a at the sides of the 2-dimensional array, were connected back to the beginning in order to build a cylindrical as opposed to planar net. Computationally , all these events take place in 1 double “for”-loop.

A 2-dimensional cylinder is difficult to draw (1.2-11 - bottom) and can be easier understood as a 3-dimensional geometry (see next figure).

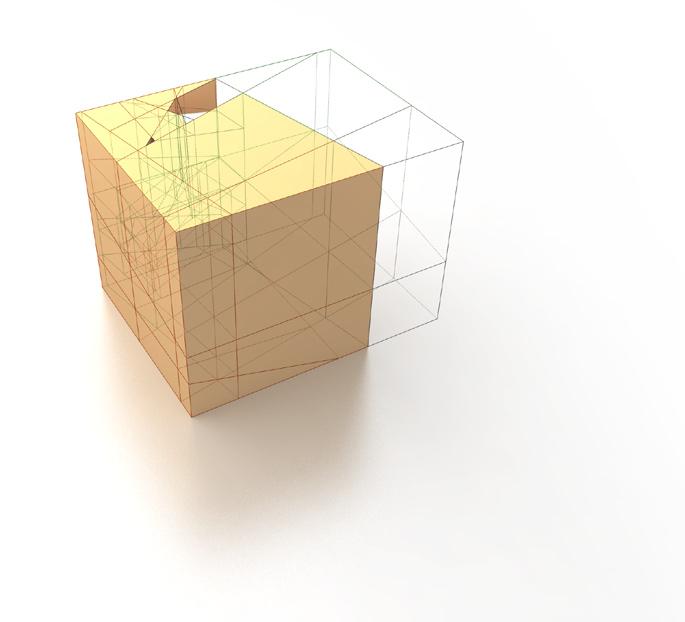

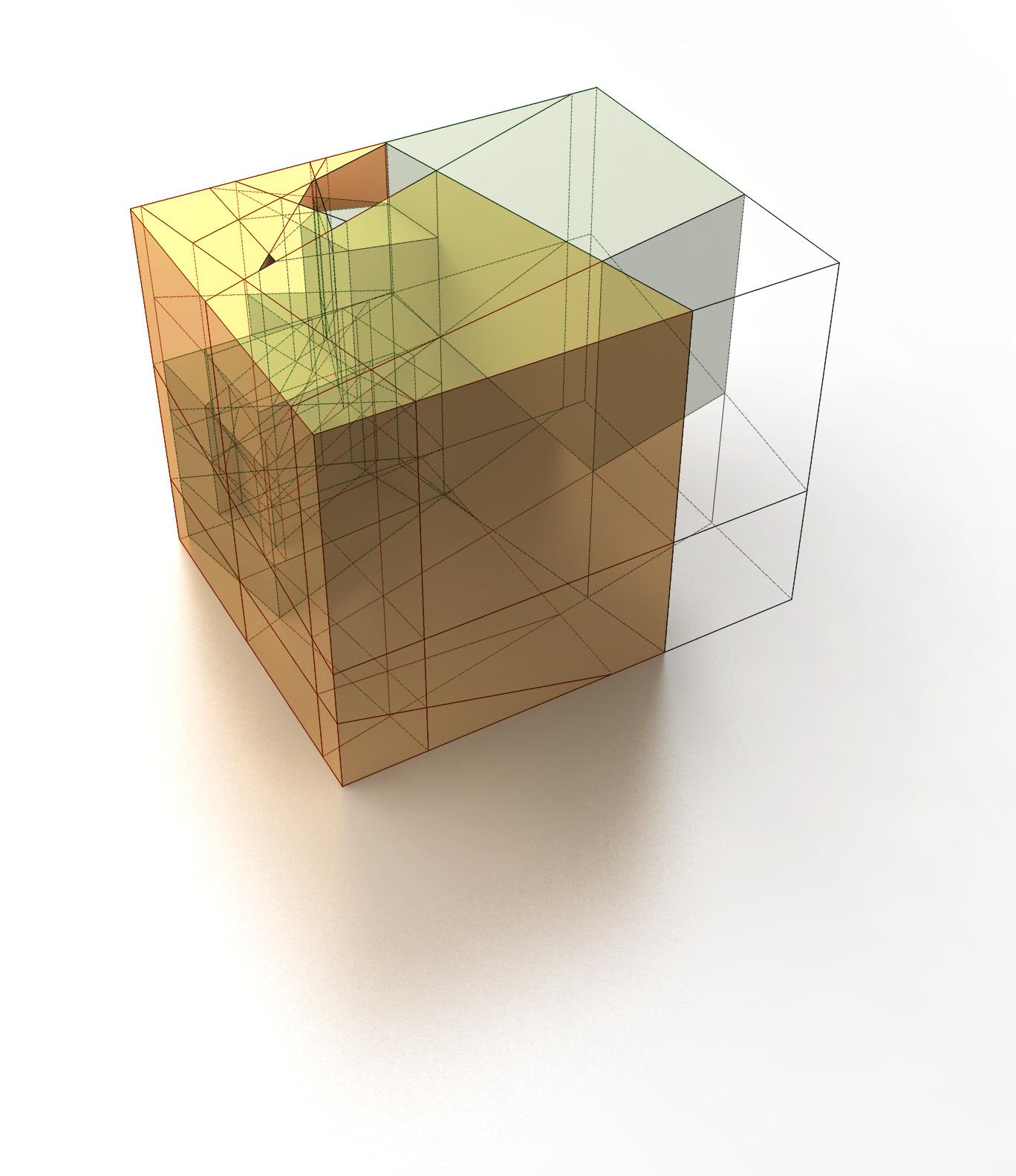

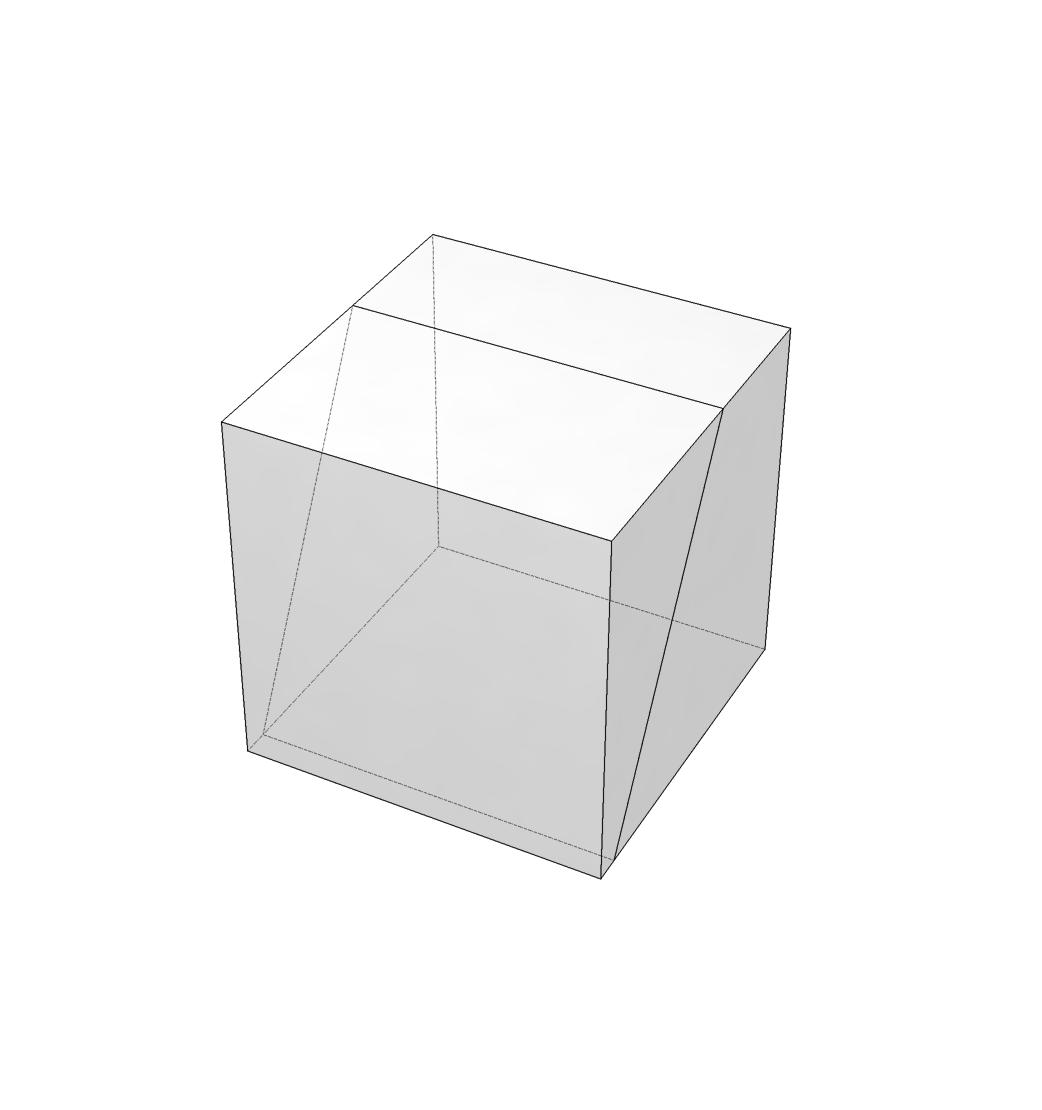

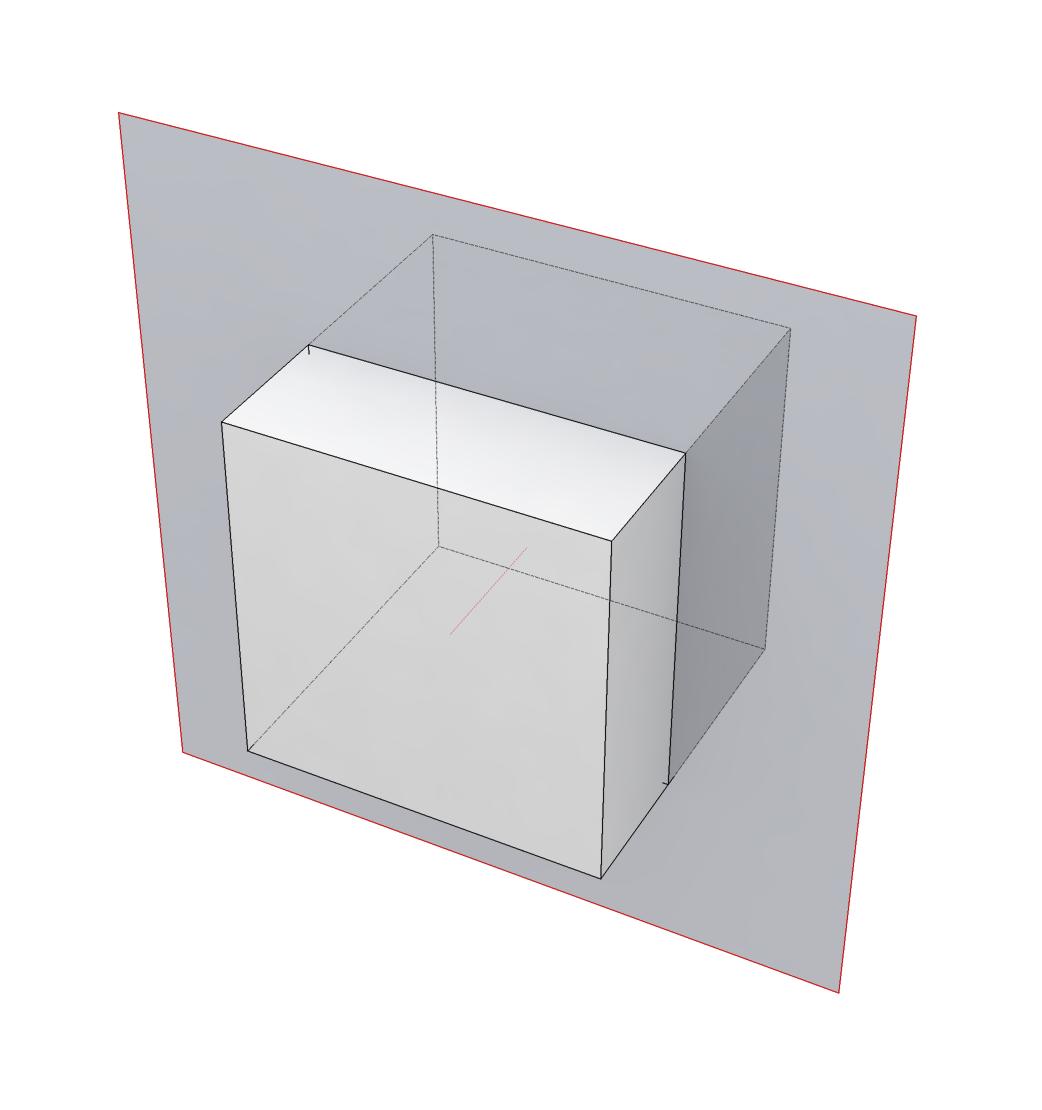

1.2-12

Shows the geometrical output of the combined inputs of the logic map in diagram 1.2-11 . The additional information as opposed to the logic map is, that every particle has been assigned to a specific XYZ-location in space. At this point it could be anywhere, but for purposes of readability we created a “cylindrical mesh”. Highlighted is the edge condition of the logic map

1.2-13 topological symbols are used to identify the underlying topology of a cylindrical net geometry, because it becomes more and more difficult to identify the inherent topology of a net, once the process of dynamic relaxation has started. In this case, all the characteristics of the net (size, connectivity, edge connectivity) built through the logic map in 1.211 are maintained

particles & ID

particles & ID

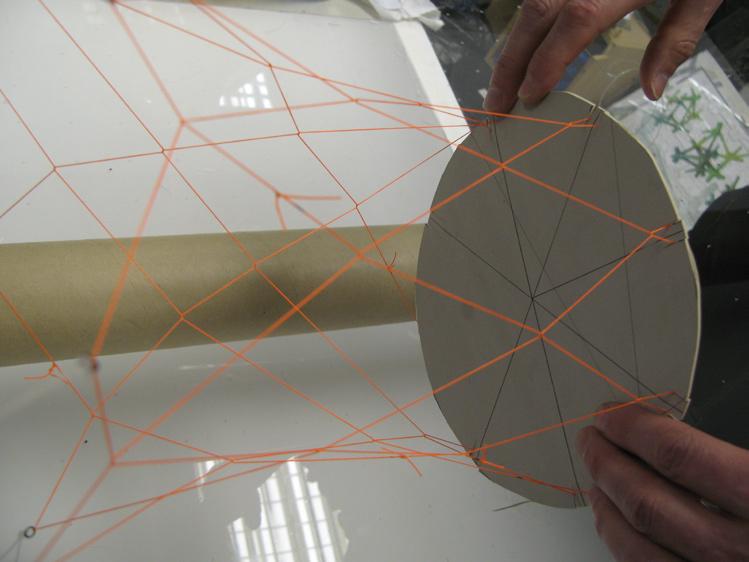

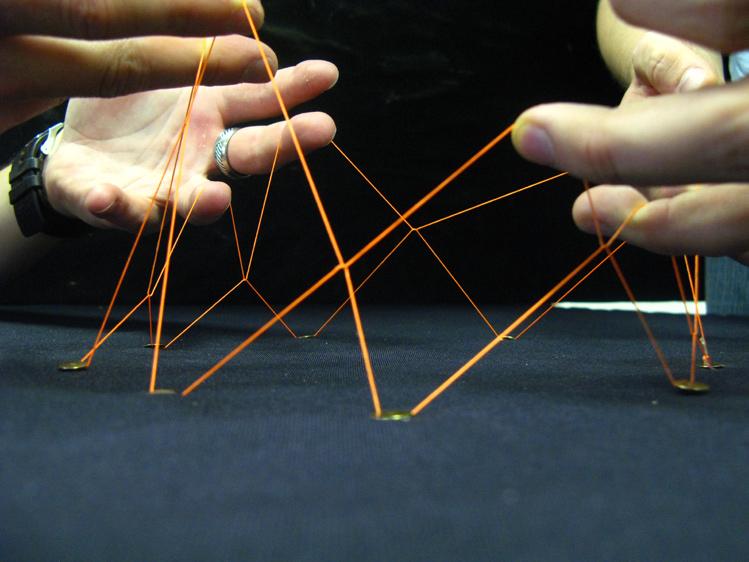

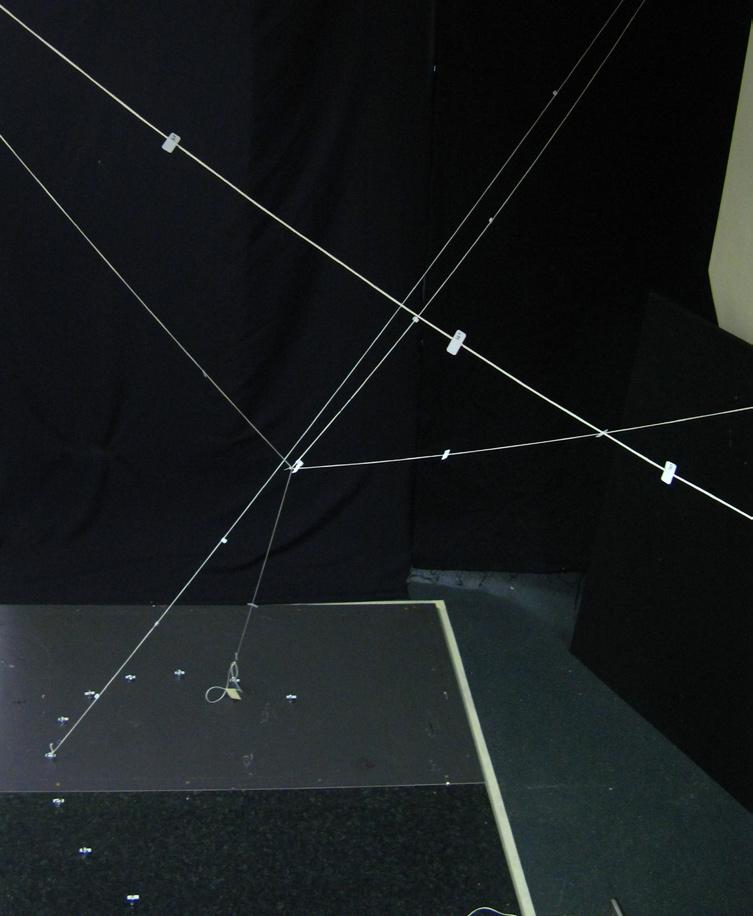

Spatial Networks

This initial experiment is based on physical experiments undertaken with cylindrical nets. A cylindrical network topology has a certain potential for enclosing and orienting space where the geometric units that construct the network have a direct correlation with a material strategy. The development of a spatial network topology is shown through a series of physical modeling experiments with tensioned net structures (figure 1.2-16) , preceding the design of the Cable Net Installation in the next chapter. With the intention of forming a system that when translated into its physical topology arranges surface, structure, and space, the “ring” network topology is translated into a 3-dimensional network. In figure 1.2-16, the system is defined by 5 closed loops, where each loop is 30 cm in perimeter and each pair of loops are interwined 5 times. This experiment delineates clearly the translation from a simple network topology into a physical topology. The loop dimension and number of “intertwinings” describes the variables for the system. This model is an example of a typical “form-finding” process. But, the interesting aspect is in the link between the inherent geometric logic of the initial loop, as a closed “ring”, and the spatial form constructed when activated into a physical topology.This connection between material and space in the most rudimentary components of the design system is a primary necessity in the design process that solves for integrated conditions of surface, space, and structure.

1.2-16

formfinding cylindrical nets

In this physical experiment, the Initial network topology is transformed into a tensioned net structure.When tension is added, the location of the nodes is determined and also descriptive of the flow of forces through the entire array of loops. Computationally-based Spatial Networks

1.2-14

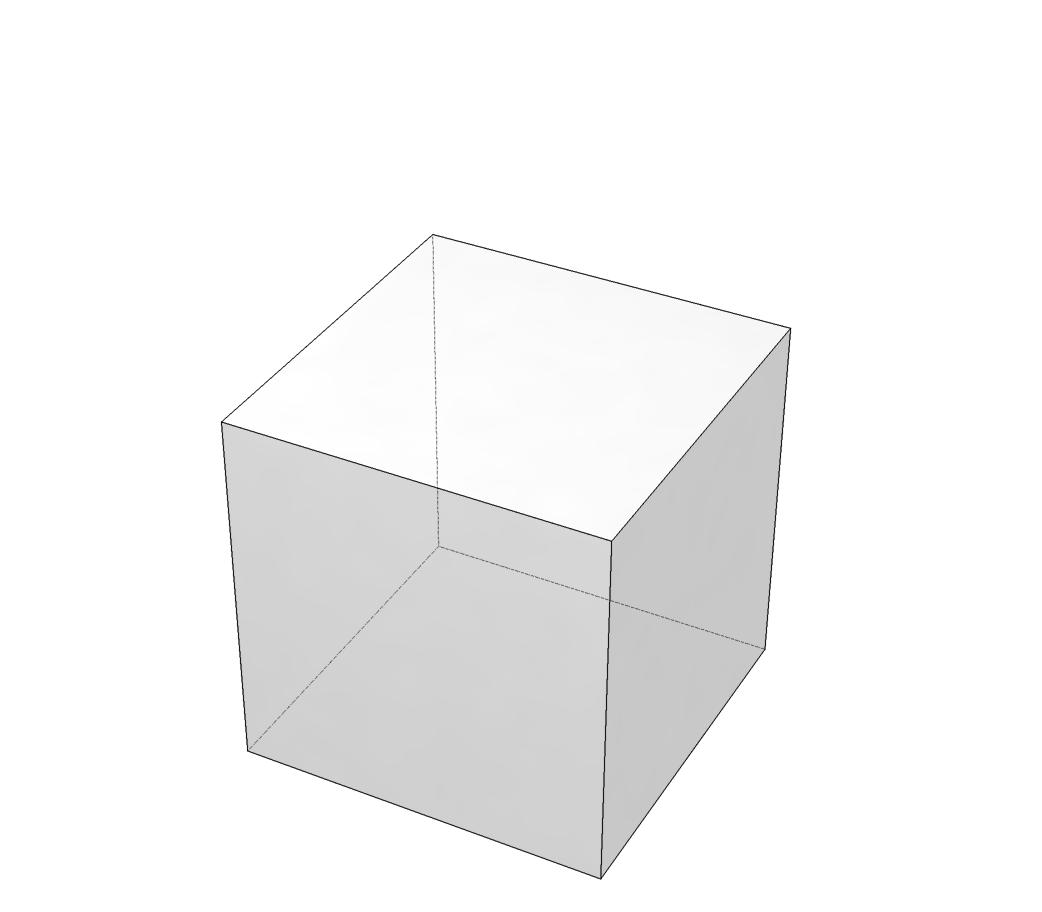

net geometry

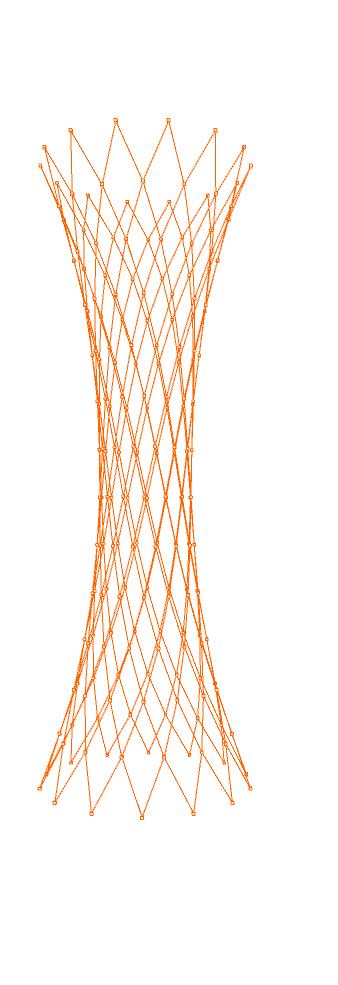

the depicted cylinder uses a larger logic map, but maintains all characteristics desribed previously. The image shown is comparable to 1.2-12, with the significant difference, that the lines draw in 1.2-12 for diagrammatic reasons are now substituted by actual, computational springs. The images shows the cylindrical net at frame 0 of the dynamic relaxation process from the out- and inside.

1.2-15

net morphology at frame 1000 the springs have shaped the net into its final form. Geometry is altered / Form is found. Both through the application of forces implied by springs, that shape the now tension-active system.

1.2-17 logic map for planar net

Through a simple alteration of the logic map, a different type of net can be simulated. In this case a planar net with 4 fixed particles at its corners and a slightly different way of building the network of springs through particle associations (bottom): The springs are now running from left to right and top to bottom (of the map). This has repercussions on the behavior of the net, which, if simulated with a high density (in this case “9”) resembles that of a membrane. The chosen network is more closely related to the Weft and Warp of a membrane (different structural behavior in different directions, because of weaving manufacturing process).

1.2.4 Cylindrical Net Toplogy

These first sets of experiments were conducted in order to intially understand how computational springs are effective solvers for the simulation of physical forces. Beyond that. the main interest was that of connecting these simple elements into larger networks to simulate the behaviour of physical, cylindrical nets. By utilizing a two-dimensional array of particles as a logic map for building the topological network of springs, a simple underlying method was achieved. This model could be accessed at later stages of the design of cylindrical nets (see chapter 2.1.”embedded fabrication”).

Understanding how the topological associations between particles, through the connectivity defined in the logic map, affect the overall geometry in the process of dynamic relaxation to simulate the behaviour of physical nets made the rebuilding of physical prototypes for every new investigation redundant.

Spatial Networks

These first physical experiments use a cylindrical network topology. The nets resulting from these topological conditions have a certain potential for enclosing and orienting space where the geometric units that construct the network have a direct correlation with a material strategy

The development of a spatial network topology is shown through a series of physical modeling

experiments with tensioned net structures, preceding the design of the Cable Net Installation. With the intention of forming a system that when translated into its physical topology arranges surface, structure, and space, the “ring” is translated into a 3-dimensional, cylindrical network. This model is an example of a typical “form-finding” process. The interesting aspect is in the link between the inherent geometric logic of the initial loop, as a closed “ring”, and the spatial form constructed when activated into a physical topology.This connection between material and space in the most rudimentary components of the design system is a primary necessity in the process that solves for integrated conditions of surface, space, and structure.

Computationally-based Spatial Networks

Other types of systems can be engaged working with the same directness, responding to inputs of space, material and structure. Considering fabric (membrane) materials as a part of the cylindrical net morphologies provides for further definition and articulation of space, while also working reflexively with the structure of the system.

It is through these types of tools and the understanding of their underlying logics through which we intend to realize architectures of multiple, specific, and interrelated concerns of material and space.

Surfaces, Boundaries, and Continuity

In the Cable Net Installationshown in the next chapter, the main characteristic of architectural space is one of continuity. Continuity, as we choose to further characterize it, is that of a series of spaces that are both interconnected yet distinct described by the most minimal means of material and structure.

The purpose for these initial experiments is the establishment of parameters in the computational system (the geometric topology, the springs, the material, the structure, and the fabrication) that allow a simulation of physical behaviour of cylindrical nets.

This is achieved by validating the computationally generated (logic map) nets through comparisons to physical prototypes. Valdation is not achieved through the simulation of highly specific (structural) conditions, but through the observation and modelling of the behaviour of these tension active systems.

Once the capabilities are understood, the computational process can be expanded to test and evolve relationships that include these more specific characteristics of space. It could be argued that in the design possibilities of this type of material system, examination in built form is necessary to evolve the method, the pressures on the system, and the outcome.

1.2-18 membrane component

Based on physical experiments with membranes a component consisting of 2 minimal-hole membranes rotated by 180 degrees was developed. The comprehension of the mechanisms at work led to the development of a similar computational net component.

1.2-19 computational planar net (type1, type 2 & type6) by accessing the logic map, a catalogue of 6 different palar net components was developed. Even though never used, these elements show the potential of understanding the logic map as a device for building, accessing and altering net geomentries.

1.2-20 logic map of type 6 by deleting / not generating particles in specific locations, interesting spacial conditions, such as minimal holes can be achieved / articulated.

1.2-21 meta nets understanding the potential for the articulation of space through the use of different net topologies is a important challenge for the designer. Shown is a cylindrical meta-net, with planar components, that feed back into the shape of the architecture.

2 EXPERIMENTS AND DEVELOPMENT

2.1 Embedded Fabrication

2.1.1 Cylindrical Transformations

2.1.2 Mapping of Computational Cylindrical Net

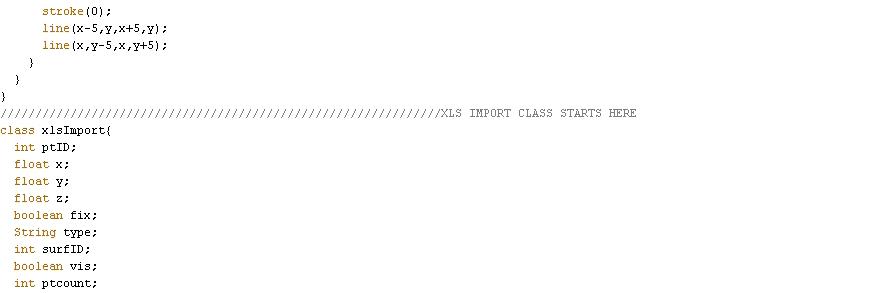

2.1.3 Data Mining for Fabrication through Node ID

2.1.4 Spatial Articulation of Net

2.1.5 Evaluating Cable Net Installation

2.2 Topologically Defined Net Components

2.2.1 Component Systems for Form-Found Structures

2.2.2 Subdivision Algorithm for Cellular Framework

2.2.3 Single Cell Net Parameters

2.2.4 Multiplication and Association of Net Components

2.3Threshold Conditions

2.3.1 Comparing Actual Density and Perceived Density

2.3.2 Computational Threshold Anaylsis

2.3.3 Extended Vector-Based Analyses

2.1 Embedded Fabrication

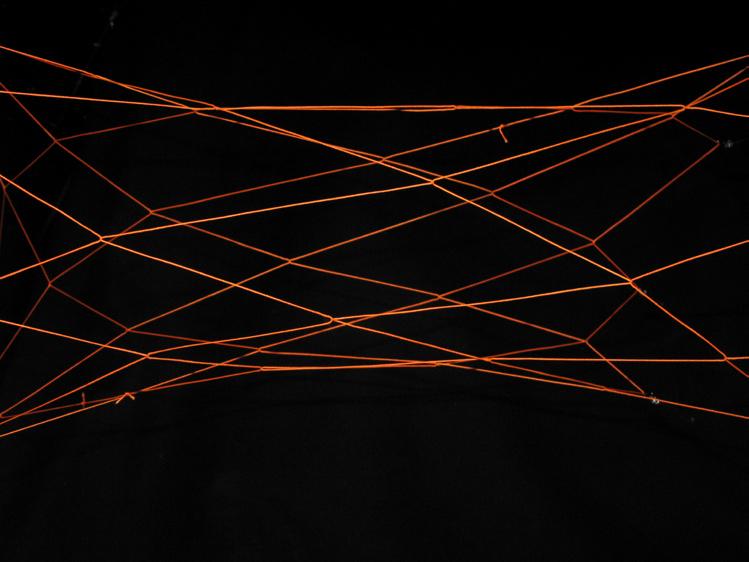

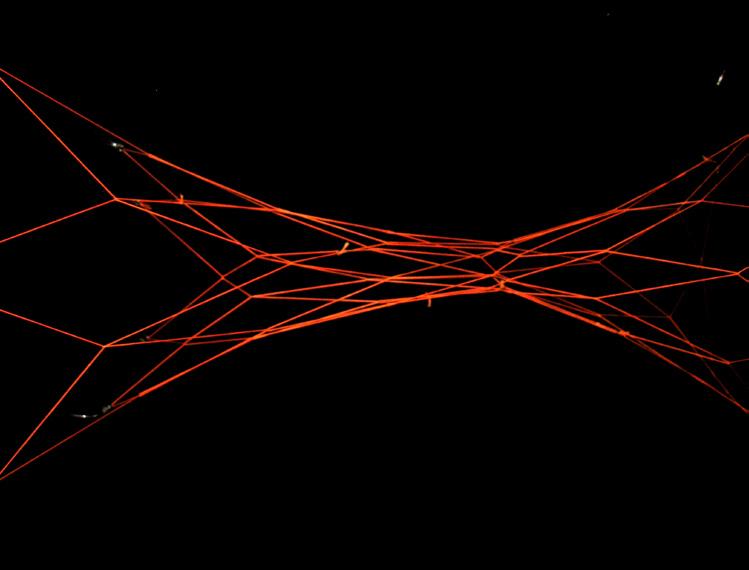

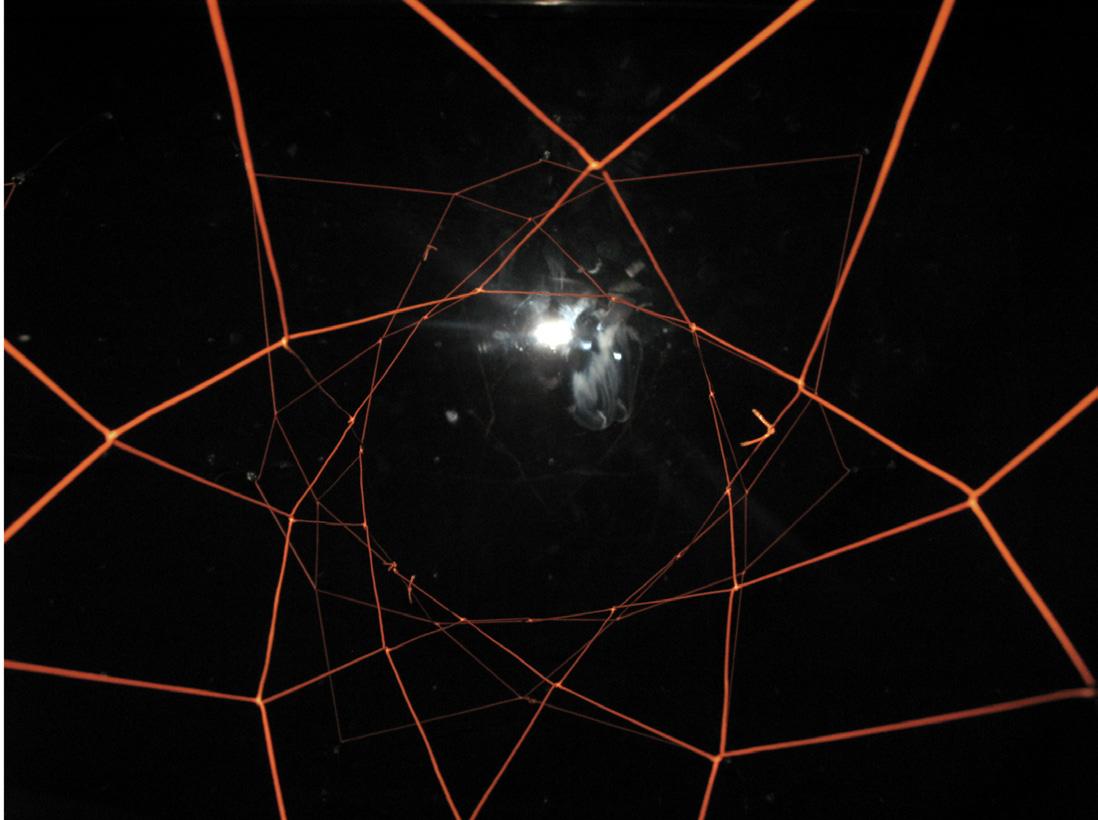

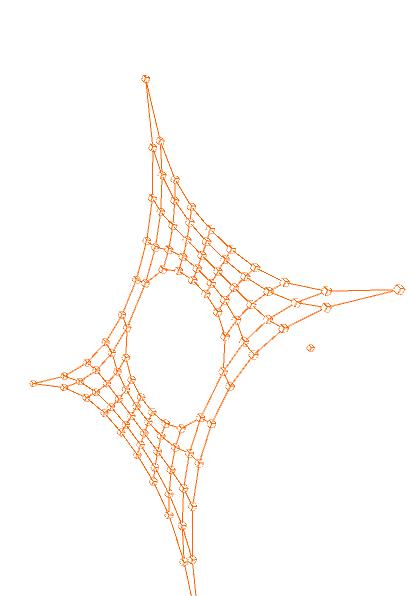

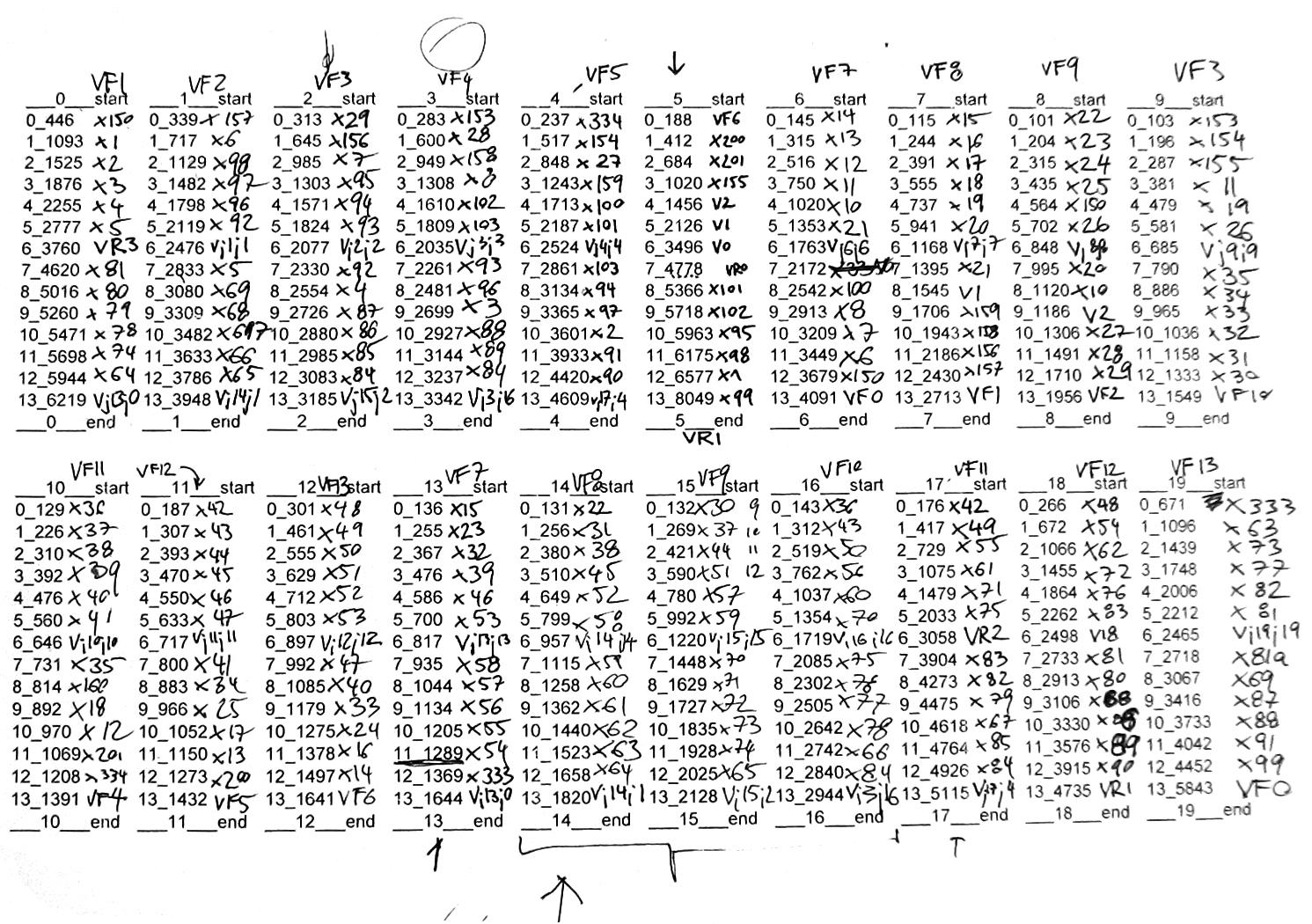

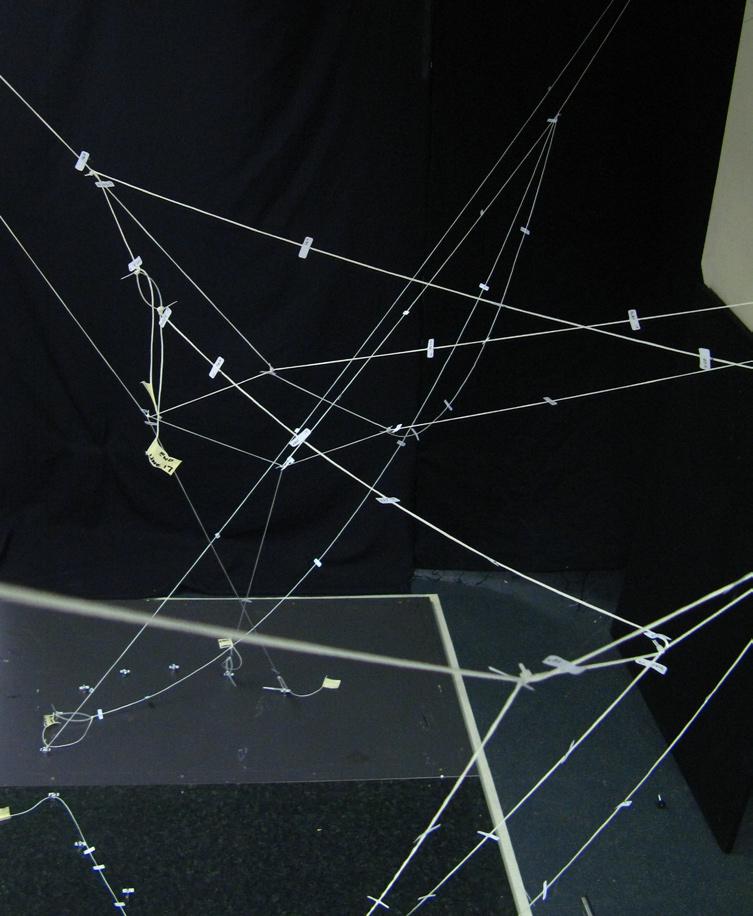

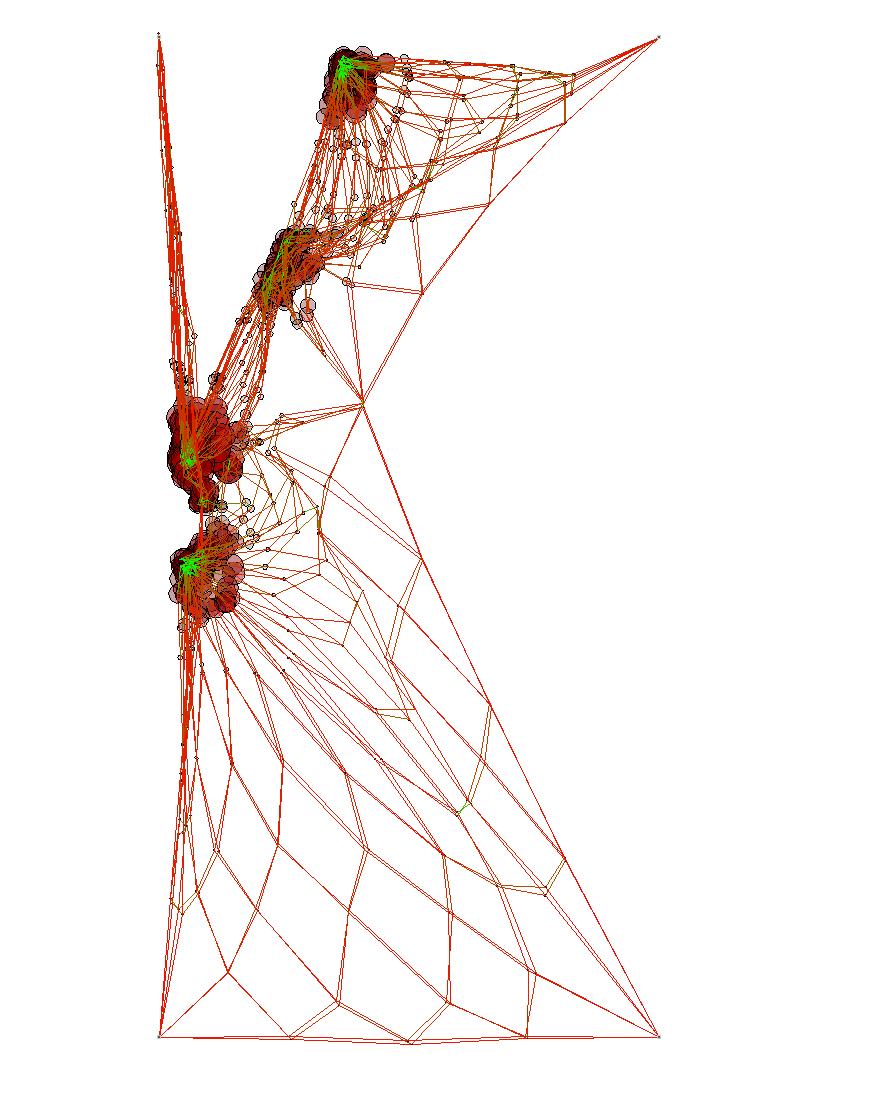

The Cylindrical Net Morphologies cable-net installation is an experiment in synthesizing processes of digital simulation and fabrication into a design system allowing for experimenting with associations between material arrangement and spatial effects.

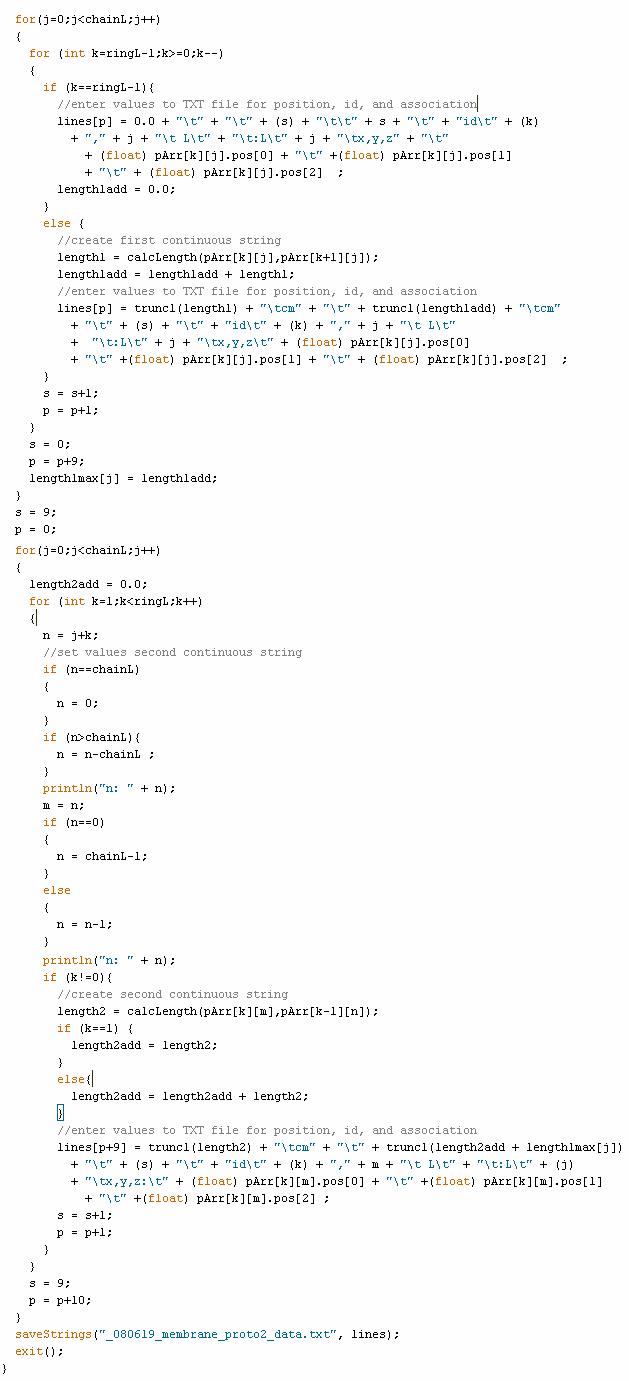

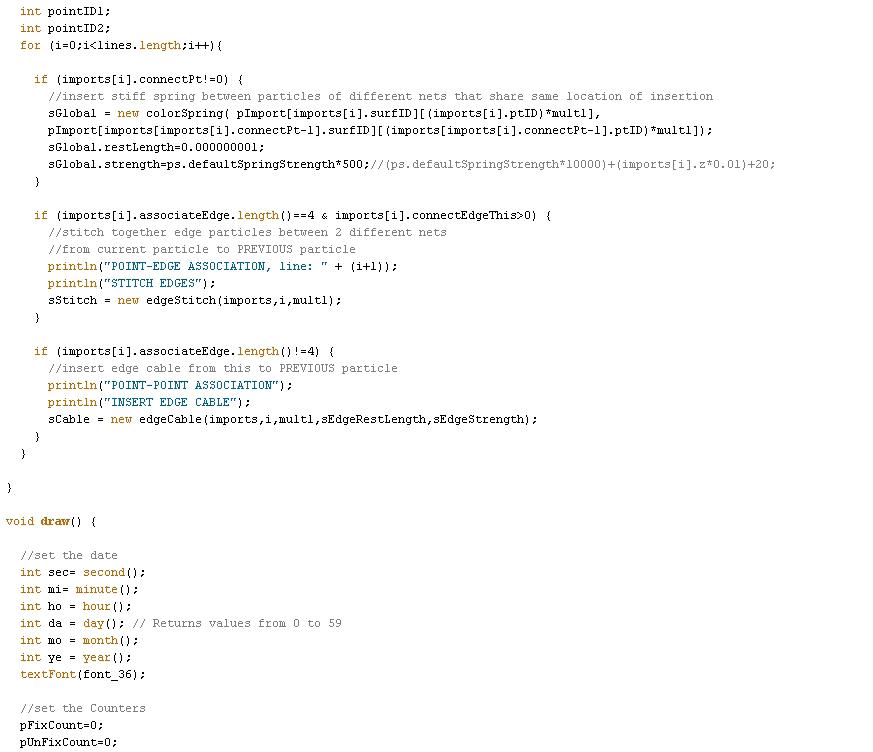

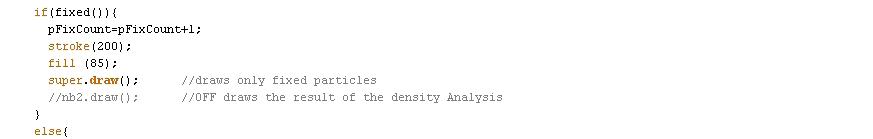

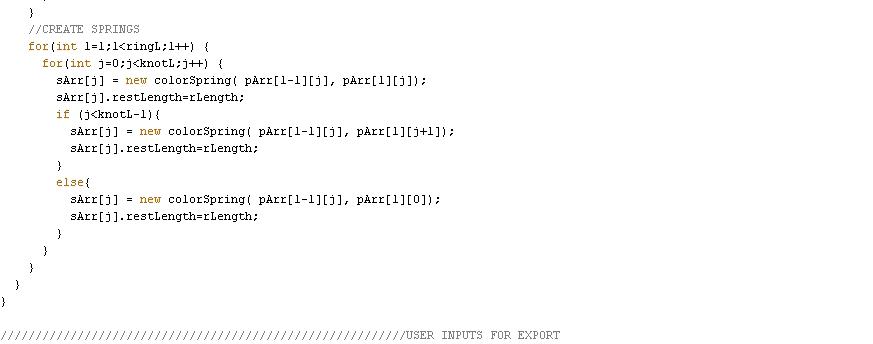

Considering the computational system in a more direct application to architecture, the questions of material and assembly arise. The spring, once relaxed into a state of force equilibrium, has implications for the type of material that it may represent in the constructed form. Being in tension or compression has obvious influences on material specification. The fate map planning of the system provides the opportunity to link between initial setup, materiality and fabrication. In the Cylindrical Net Morphologies installation at the Architectural Association, the method of inscribing a logical identification system to the particles in the spring system allowed for ease in fabrication. Re-tracking through the network meant re-accessing the identification system through different looping protocols. The iterative for-loop mechanism was the fundamental programming method to accomplish this degree of control and production.

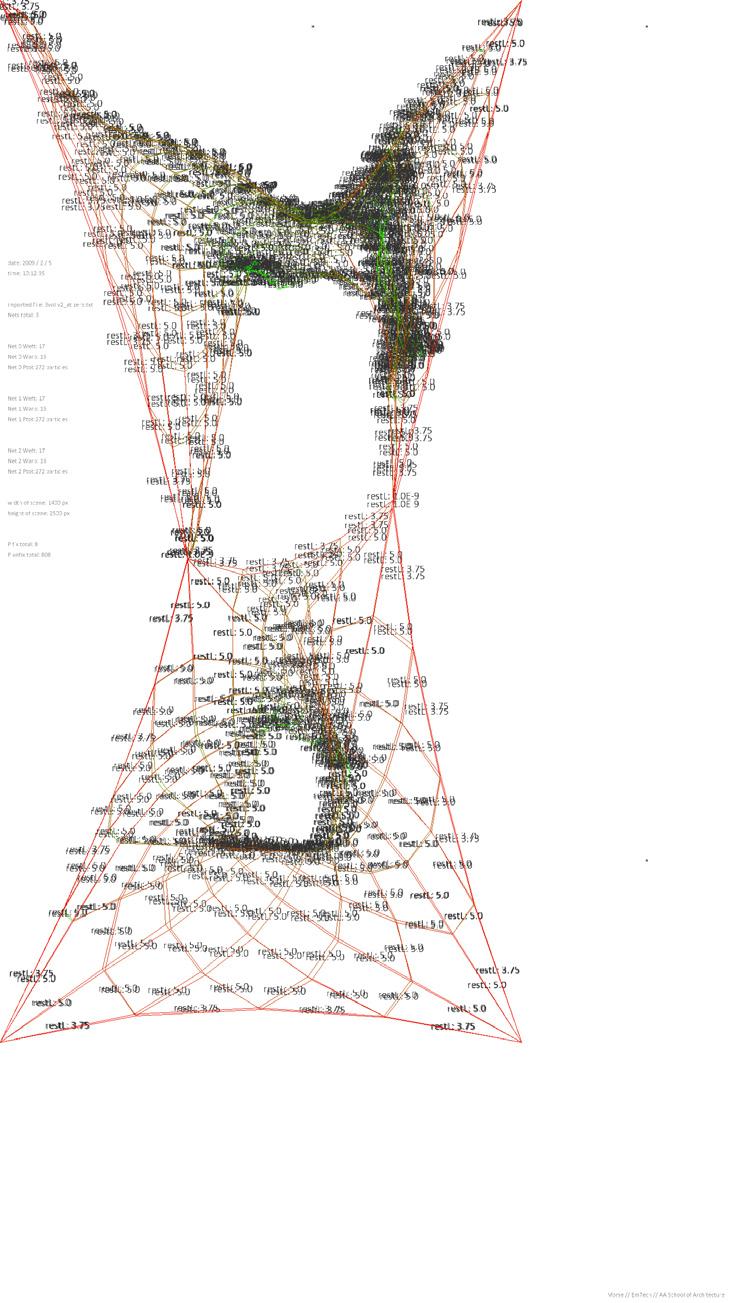

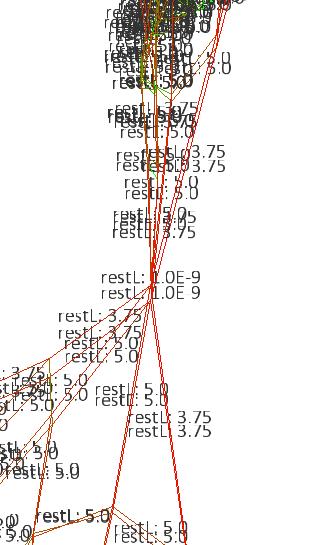

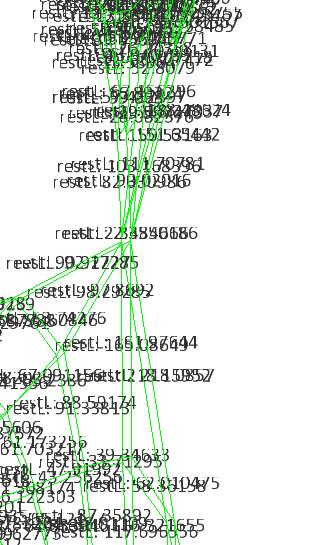

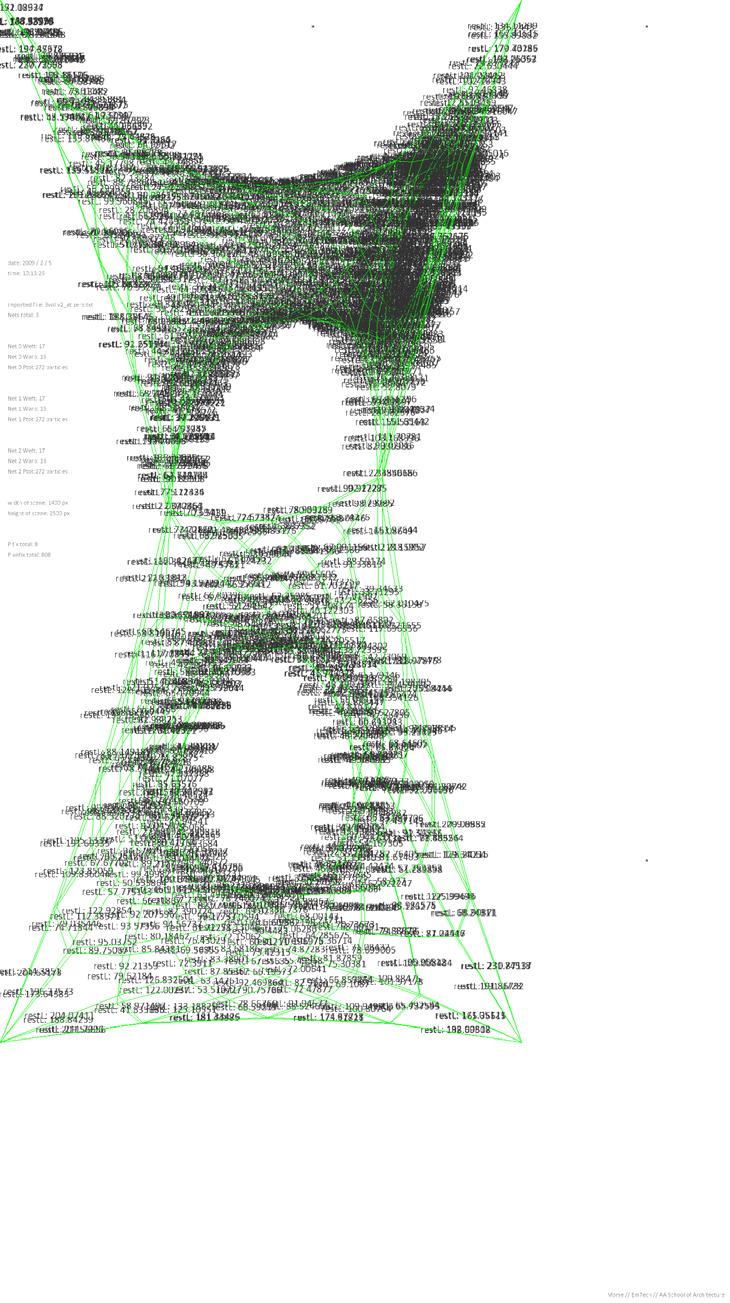

2.1-1

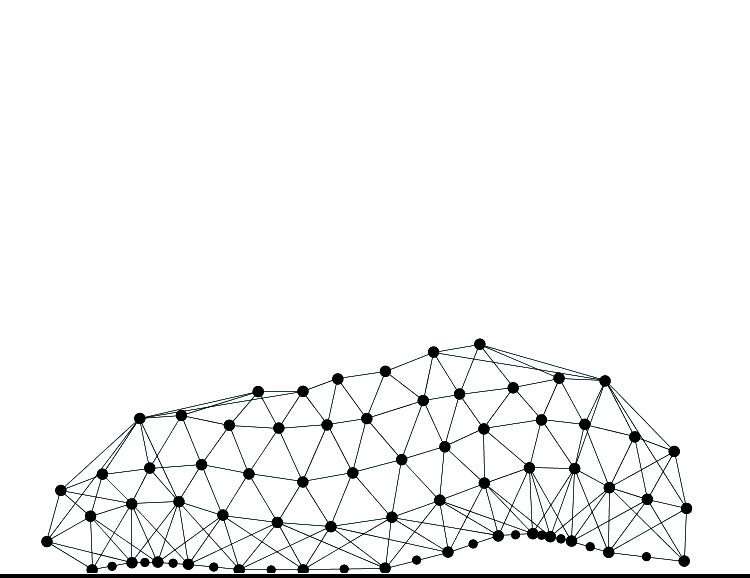

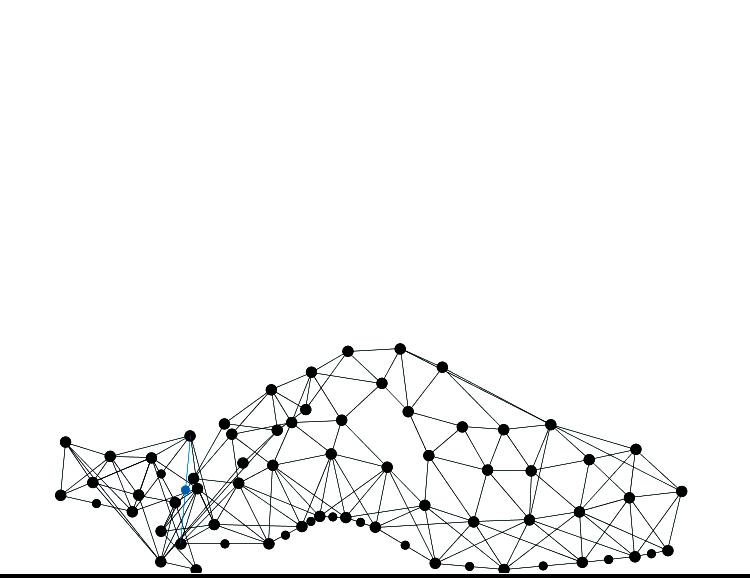

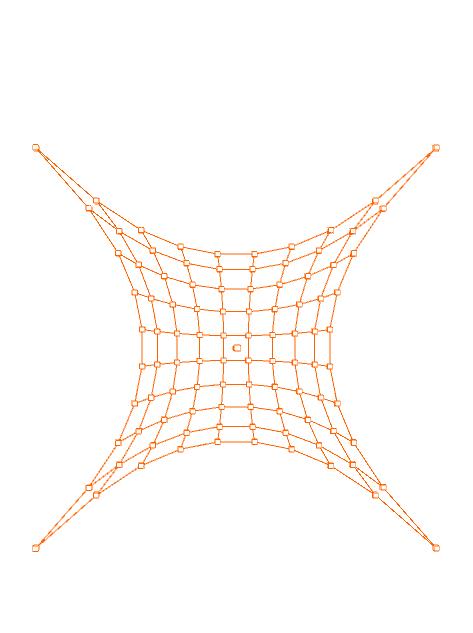

Computational model of form-found net with mapping of nodes and associations for use in fabrication

The Cylindrical Net Morphology is defined by the user-generated network topology consisting of computational springs where form is generated through finding an equilibrium of tension forces. The network topology is based on the 1D continuous surface (“ring” network) method of association. Embedded in this strategy is a comprehensible logic for manufacturing and assembly of any form that the system produces. Part of the potential for the network topology is to realize a specific architecture of multiple spaces defined by a single continuous boundary. Prior to all particles positions being realized, there is the opportunity to embed certain surface performance characteristics, beginning to narrow the solution space.

2.1.1 Cylindrical Transformations

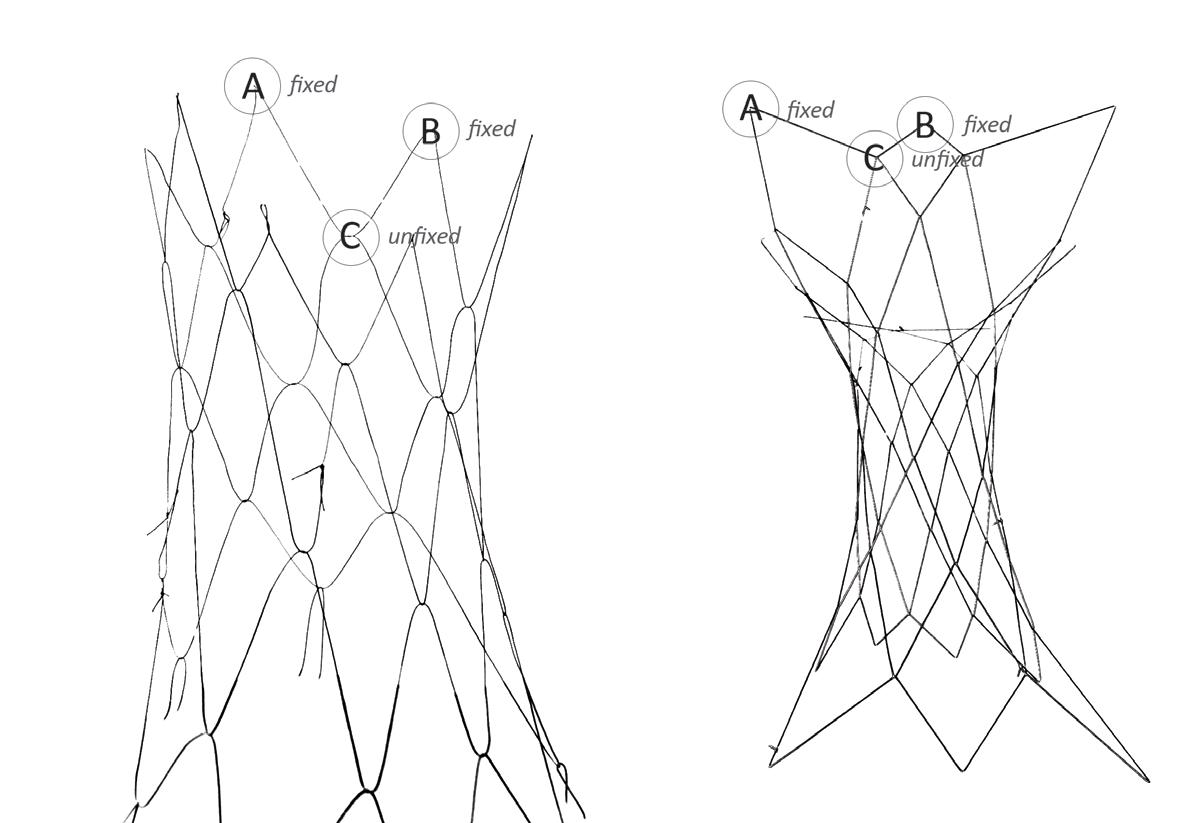

The initial experiments focus on establishing the list of parameters available in the system using symmetry to test the process. Considering the context of the exhibition space, the symmetrical arrangement is transformed into an involuting cylinder through the variation of two basic functions. (Figure 9) The circular array of anchor points undergoes an anisotropic transformation into an elliptical array. It is then varied and tested to determine which end-nodes of the system attach to points along this elliptical array. This function drives the basic involution of the cylinder when an end-node from one end is transformed to the other end. The variable of switching nodes from being fixed (anchored in physical terms) to un-fixed is tested in various locations. This investigates the ranges of density in the resulting mesh and the number of anchor points to the existing exhibition space. Attachments points for the net are minimized in the ceiling and evenly distributed in the floor.

2.1.2 Mapping of Computational Cylindrical Net

One of the simplest components of the design system is the double array assignment identifying each particle. The double array is created through a simple nested for-loop. Each step of assembling (defining the network topology), refining, and extracting information from the particle array simply means re-accessing the double array. The identification for each node remains constant through every transformation of the form. The methodology (the for-loop) remains constant as does the data inserted into the for-loop (the double array values for each particle/node). The ability to address different issues and manipulate

form generation in various ways is simply through the shift in how the for-loops move through the double array. These varied methods are described in Figures 12 and 13. It is a quite sophisticated capability in controlling, localizing, and accurately locating transformation, but accomplished through simple for-loop mechanisms.

The ease of fabrication is in the direct relationship of the initial components of the computational system to the parts of the physically constructed form. The particle is the identifier of a node in space, the point at which the springs connect. The spring, in the relaxed model, defines a physical distance between the nodes. Fabrication is a matter of coordinating this information and qualifying it to the characteristics of the material being used for construction. This logic is universal in the system. No matter what the formal outcome is the method for sorting through the nodes/particles for fabrication is the same for each result.

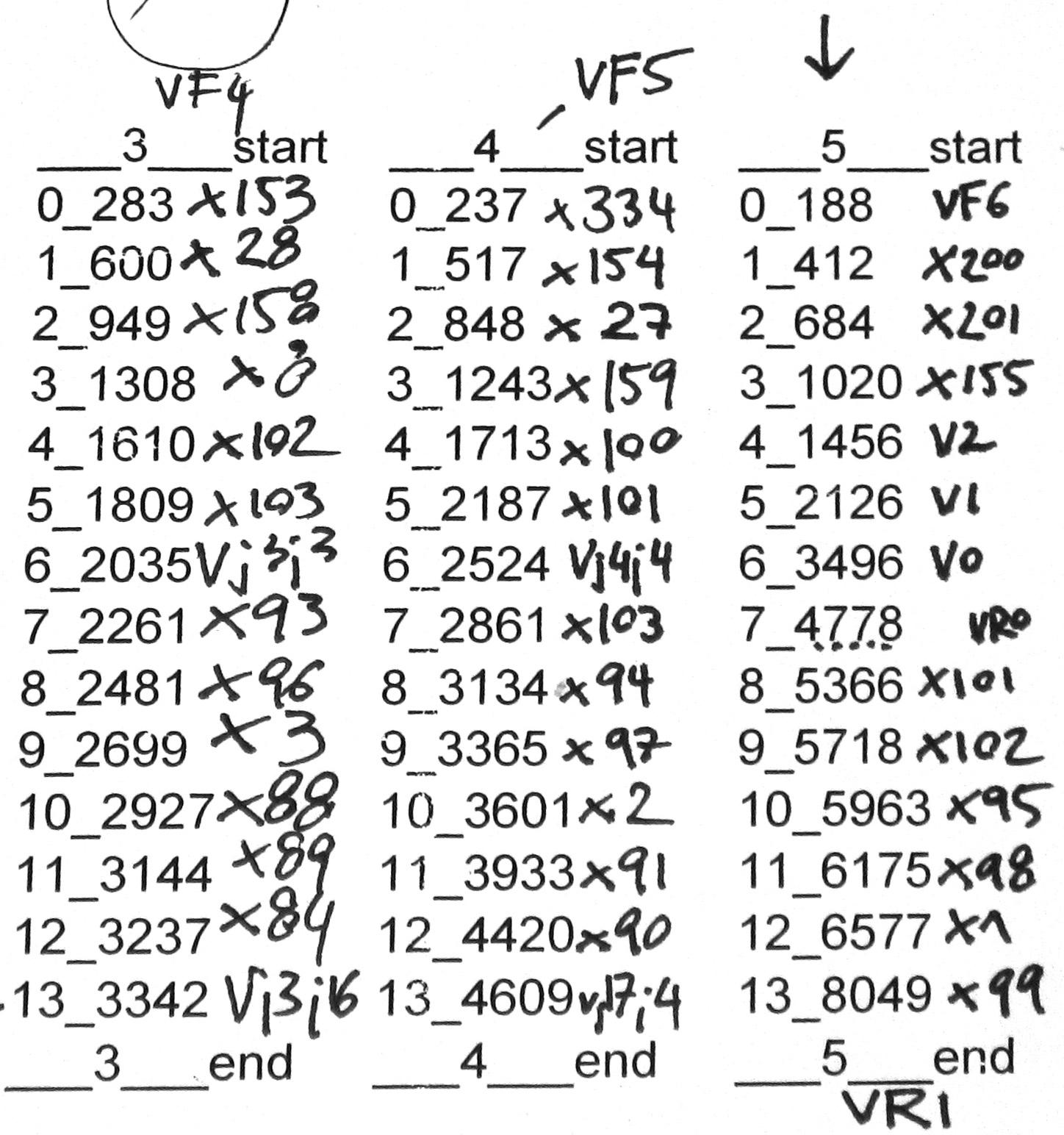

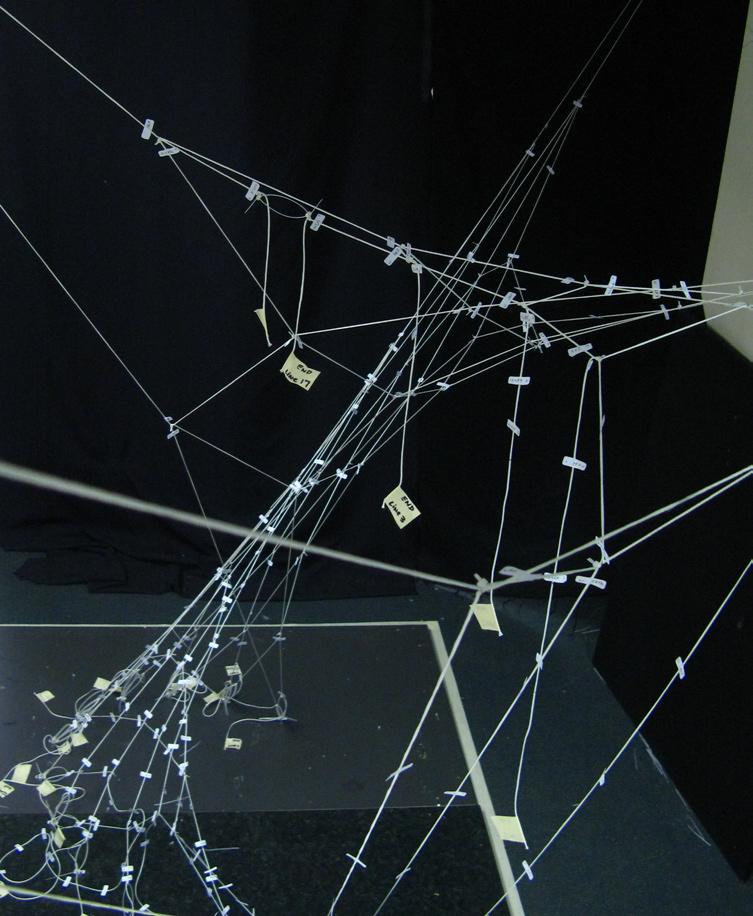

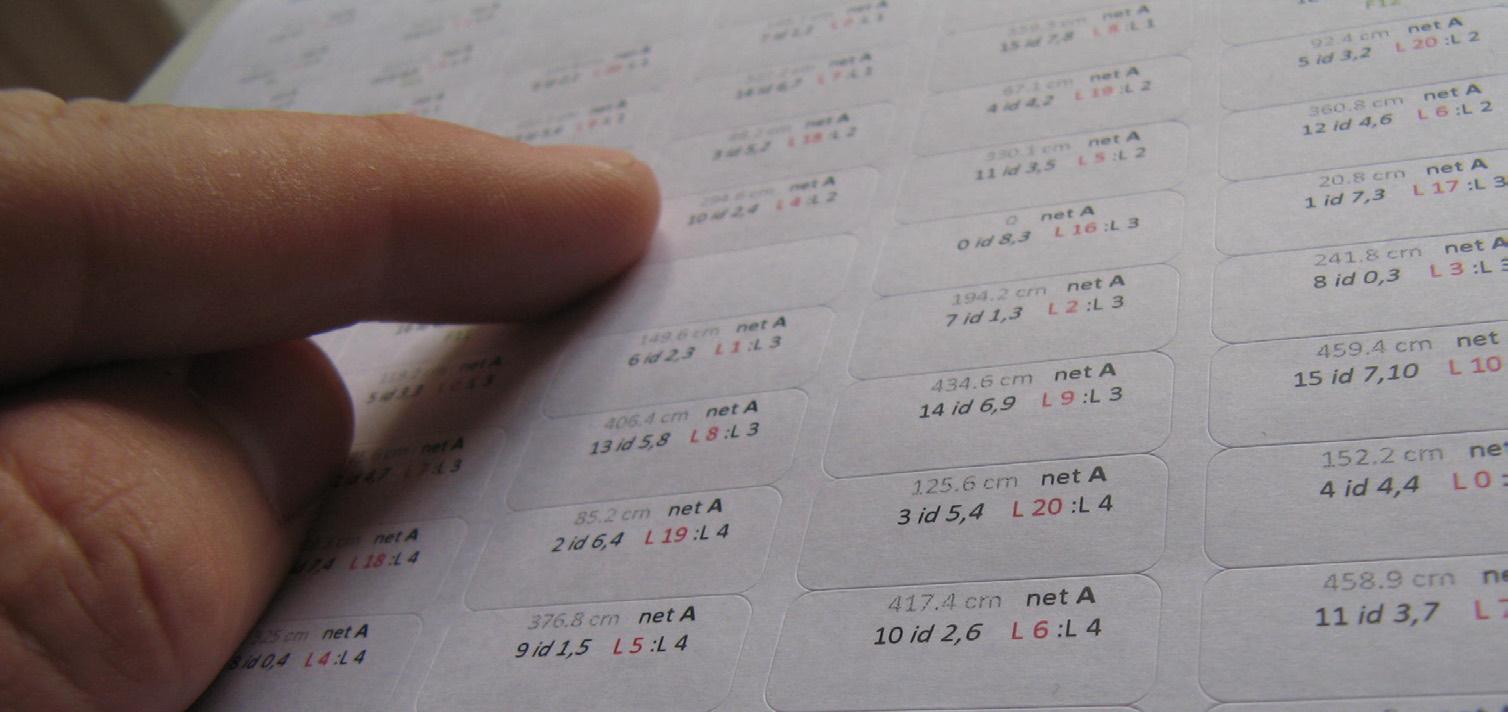

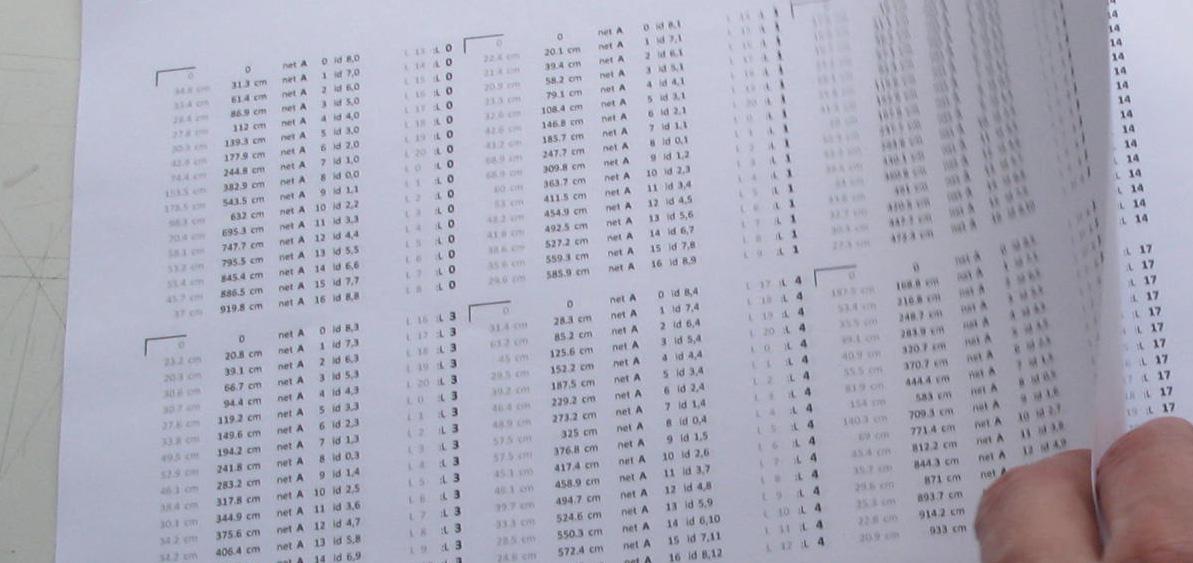

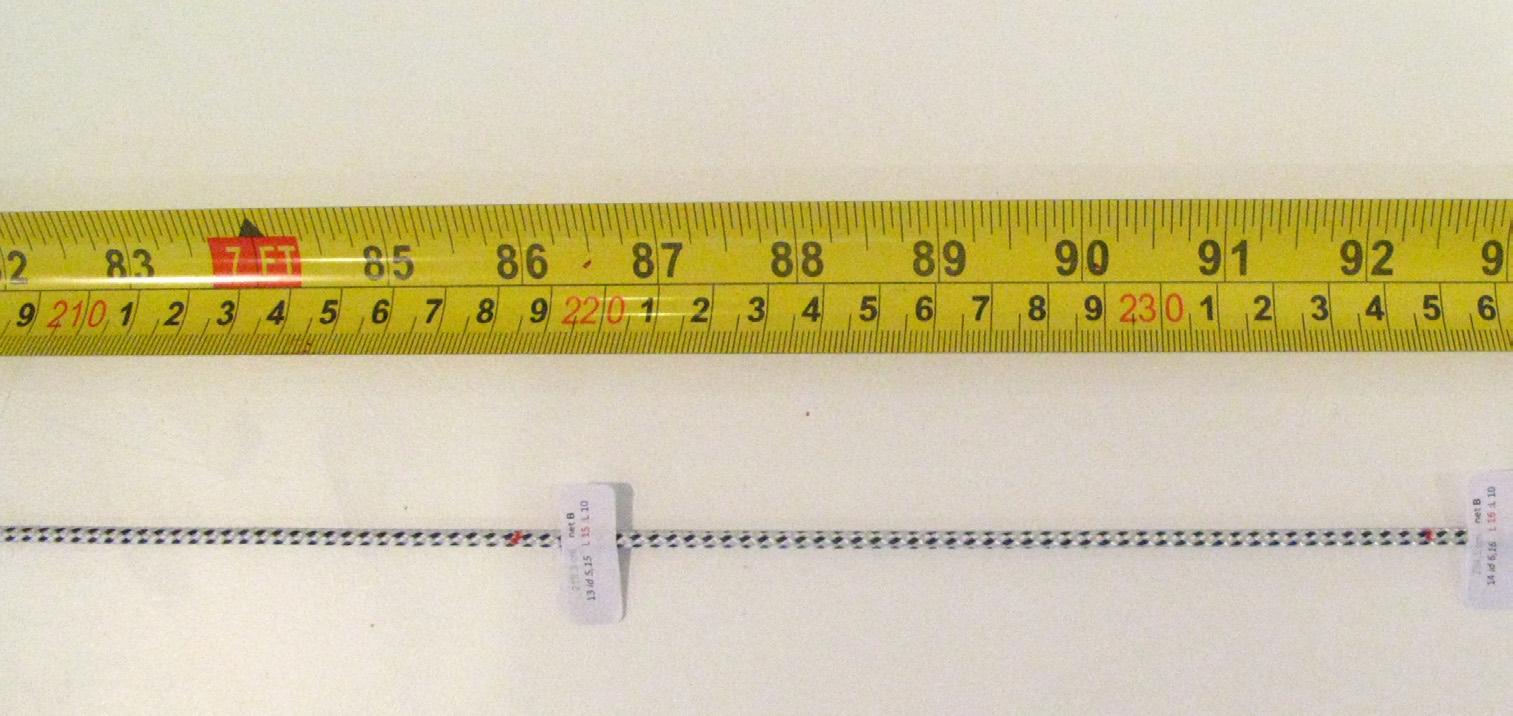

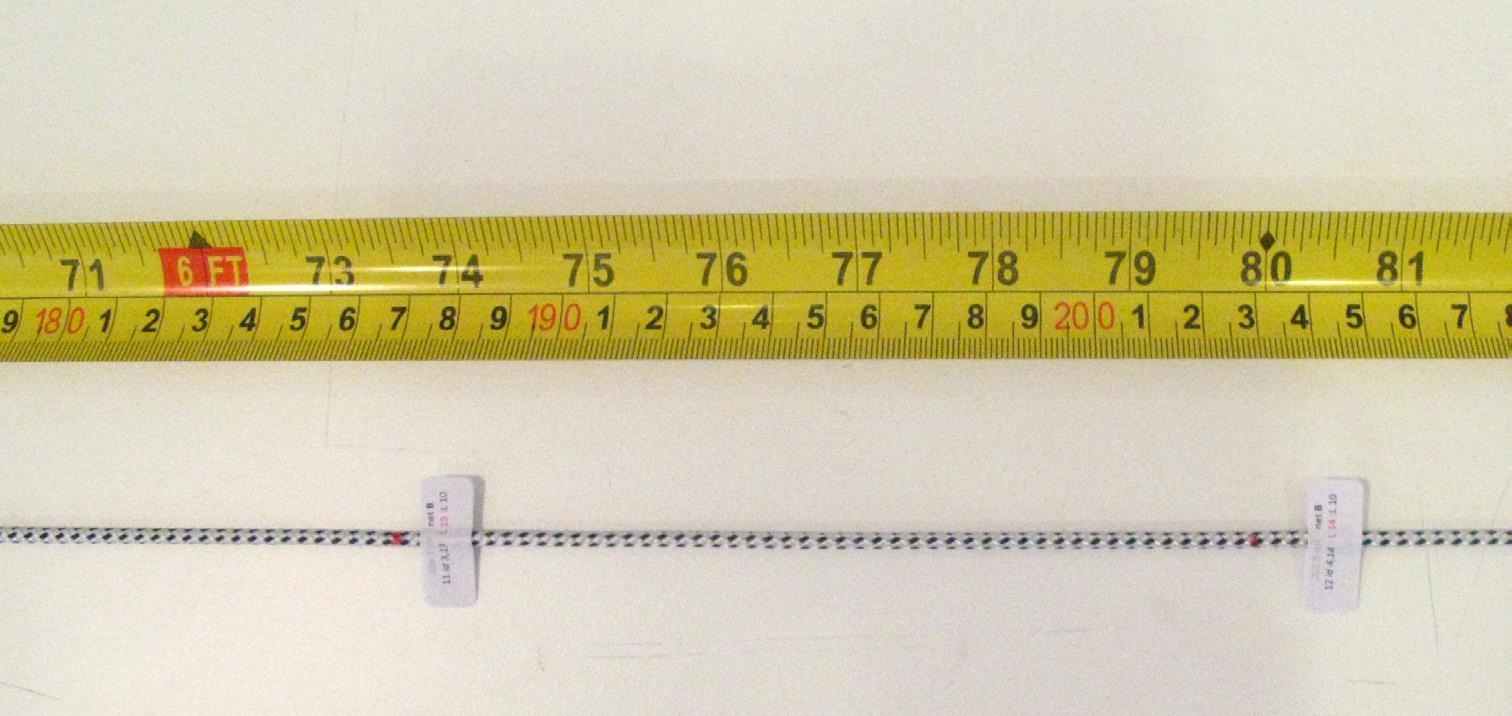

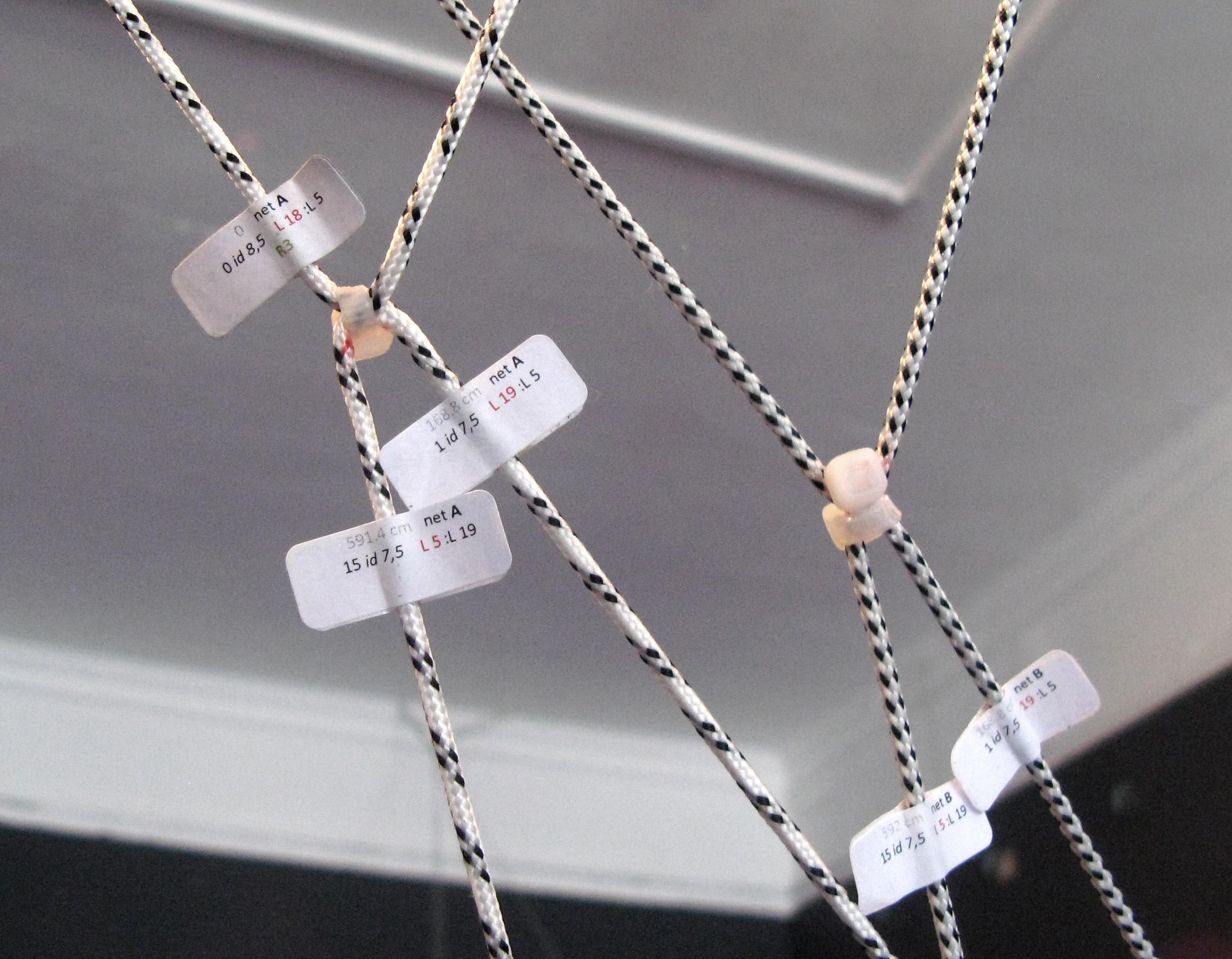

2.1.3 Data Mining for Fabrication through Node ID

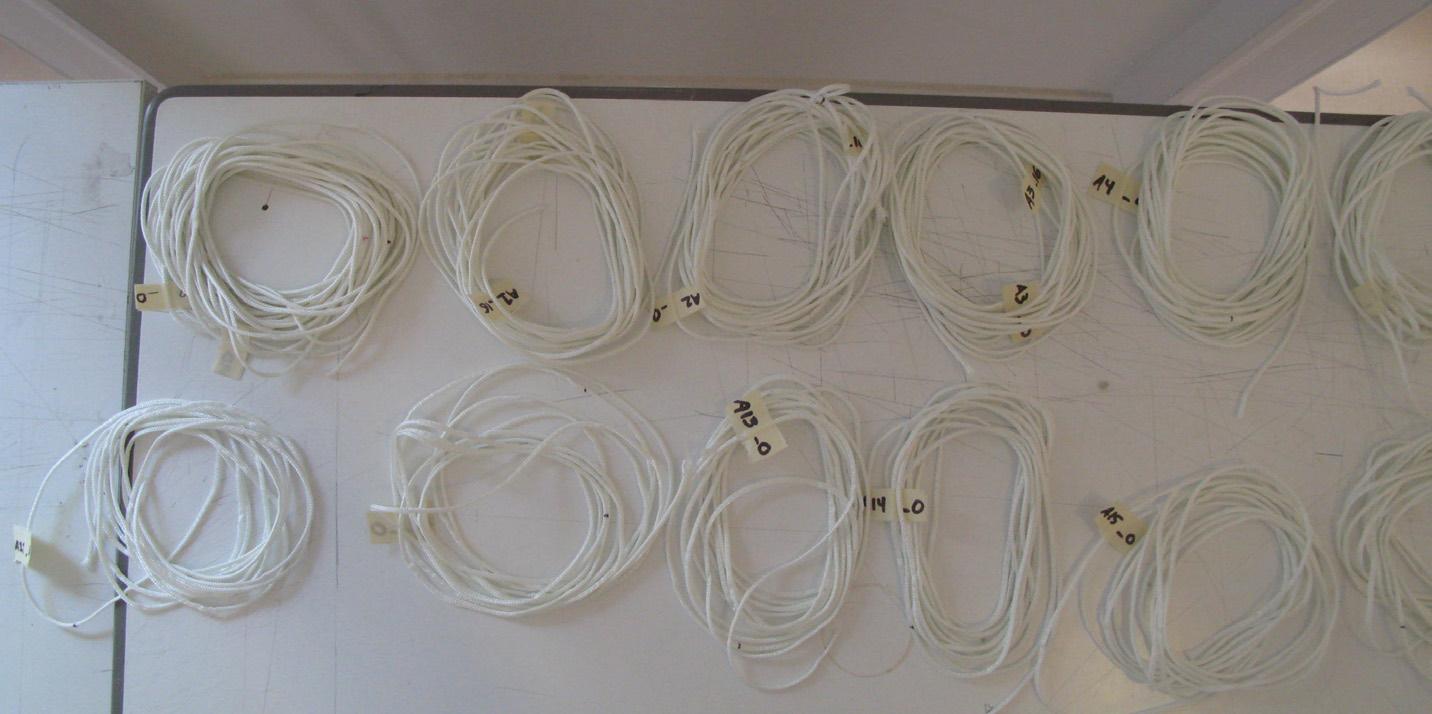

The node identification is the most valuable information of the entire system. This is generated in the very first step of the process, where each node is defined by a unique double array value. The next step is in understanding the sequence of connecting the nodes. Rather than translating one spring to one length of material (in this case, 2.5mm diameter string is used), an array of springs is connected (Figure 3.5) so each net is broken down into only 20 individual lengths of material. The connection sequence for nodes is shown in Figure 3.XX. For construction, tags are generated to locate the nodes along the lengths of line and indicate which lines connect at each particular node. (Figure 3.XX) This data is then further filtered to define the specific distances between nodes and the overall lengths of the lines for construction. In calculation, the stretch of the 2.5 mm diameter string is considered and the distances between nodes are adjusted to respect material as opposed to their finite locations in digital space.

2.1.4 Spatial Articulation of Net

The “ring” topology eludes to certain types of geometries, in a rudimentary way: the cylinder. The cylinder is of particular interest because it describes a boundary and a directionality. In a form-finding process, this spatial capability can

be taken further to investigate directionality while simultaneously arranging structure. This combination of organizing space simultaneously with structure is intended to carry into the articulation of the Cylindrical Net Morphology installation.

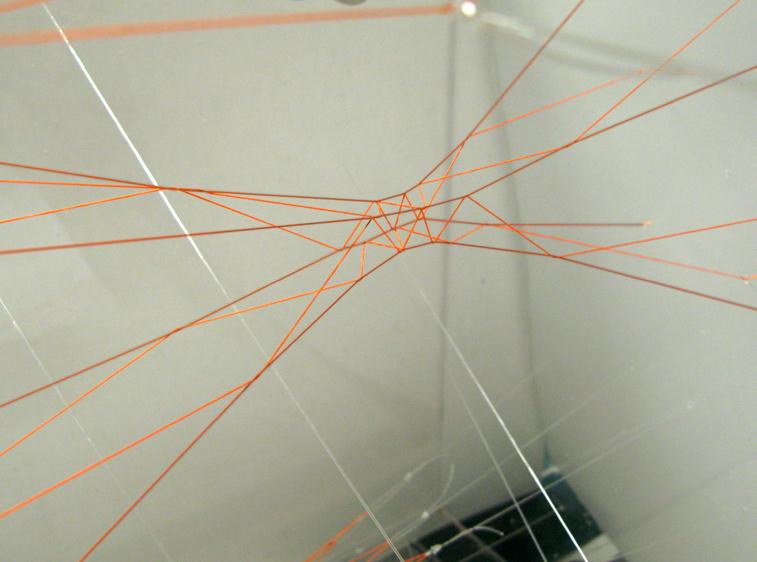

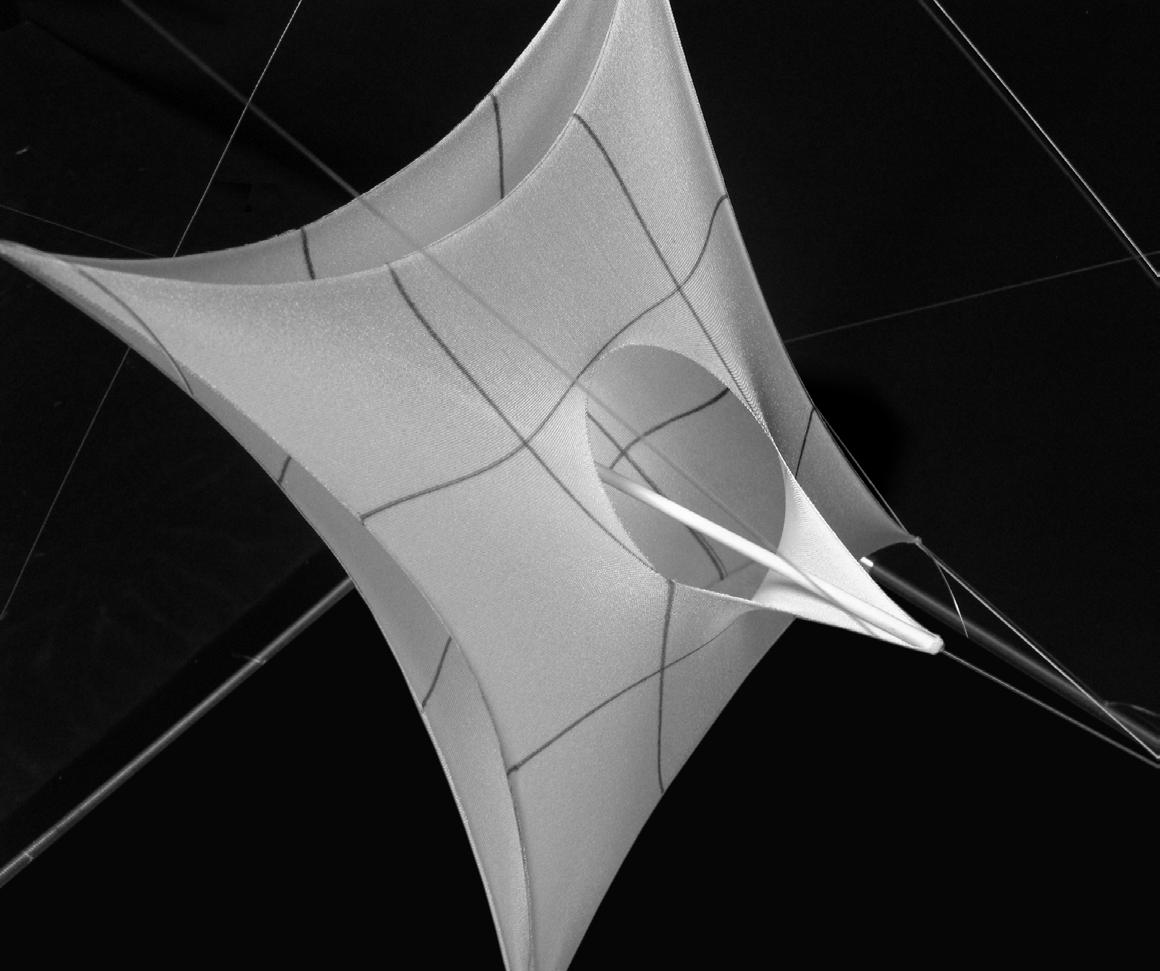

A membrane component which combines tensionactive surfaces with an internal compression element serves to articulate the flow of view and space between the 2 surfaces of the net installation (Figure 2.1-33). Using the net surfaces for anchor points of the component, it becomes a lower-hierarchy element within the whole system. Though, visually, it becomes more apparent and registers the space between the two nets more distinctly.

Compression elements exist in the computational model to push the surfaces of the net apart in certain regions. In construction, they also serve as a device for post-tensioning. Computationally, the compression element is a spring whose actual length is shorter than its defined rest length. The nature of the force, tension or compression, can only be realized in the dynamic relaxation process, when all the spring forces are acting against eachother. This introduces another scenario where situations of both structure and space are solved simultaneously in this computational form-finding process.

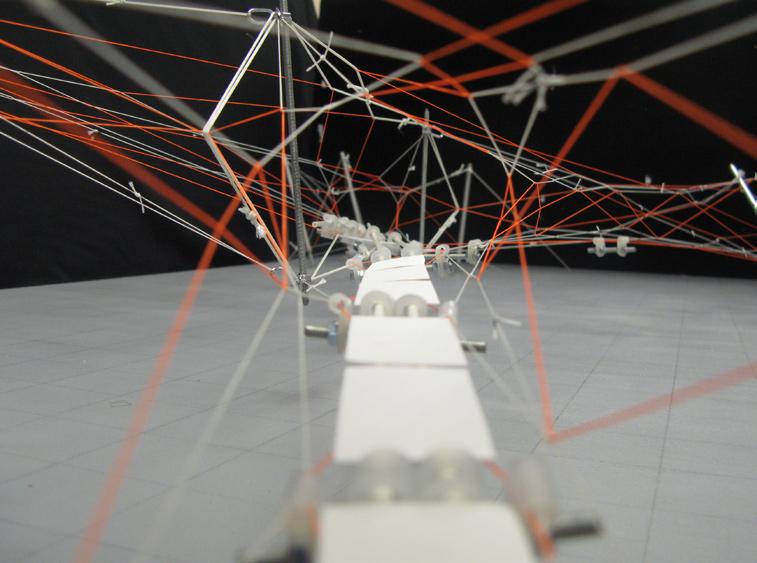

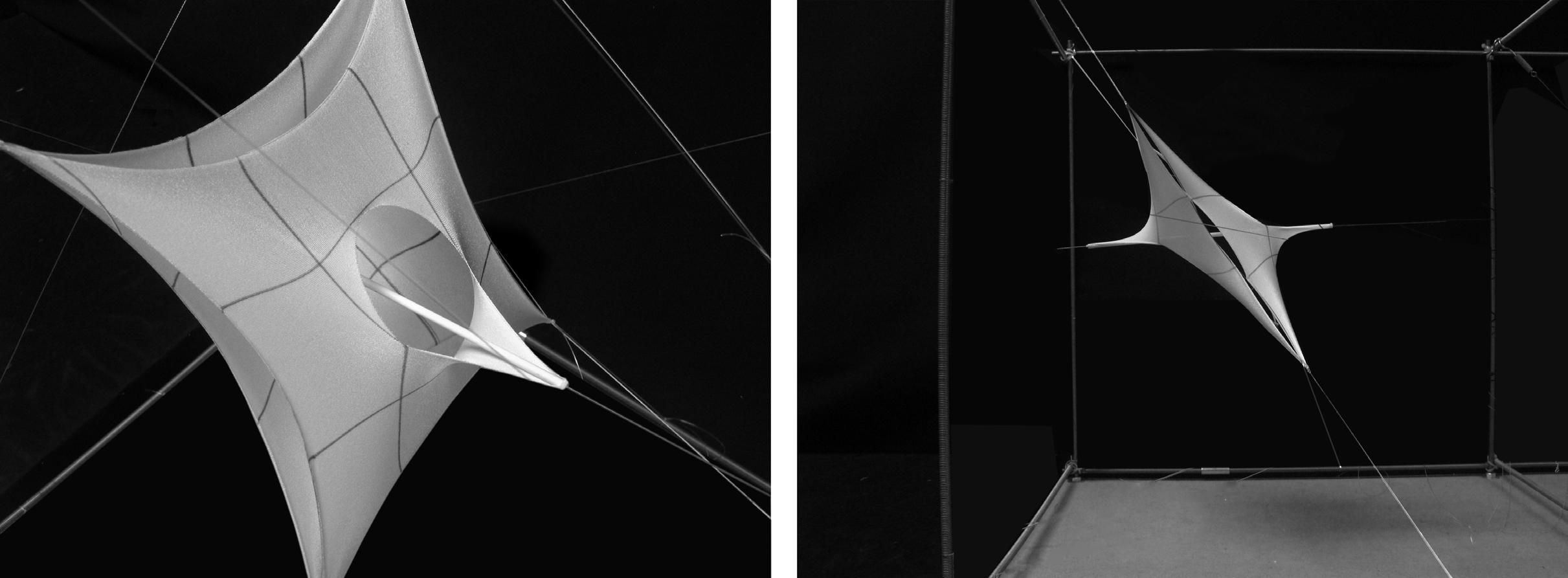

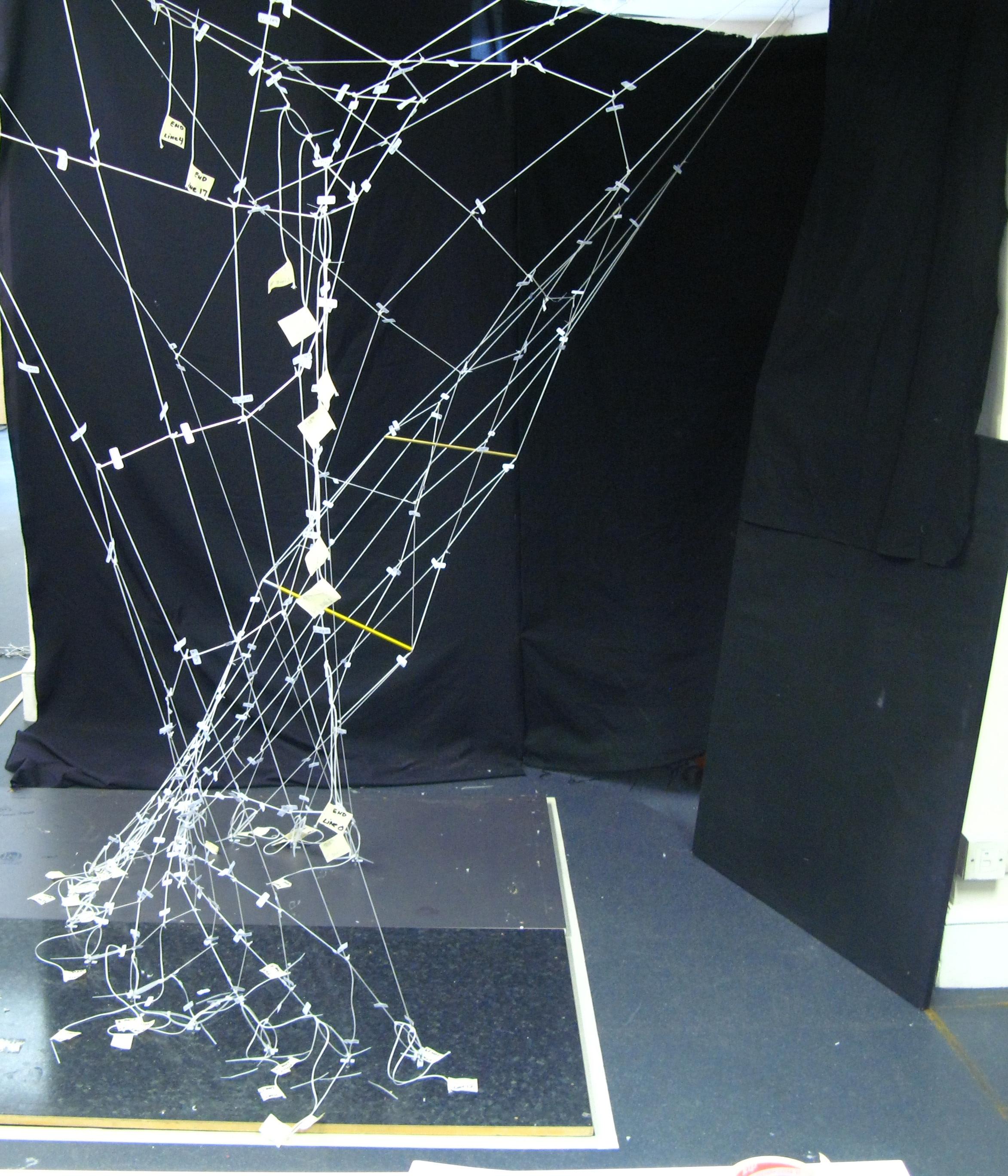

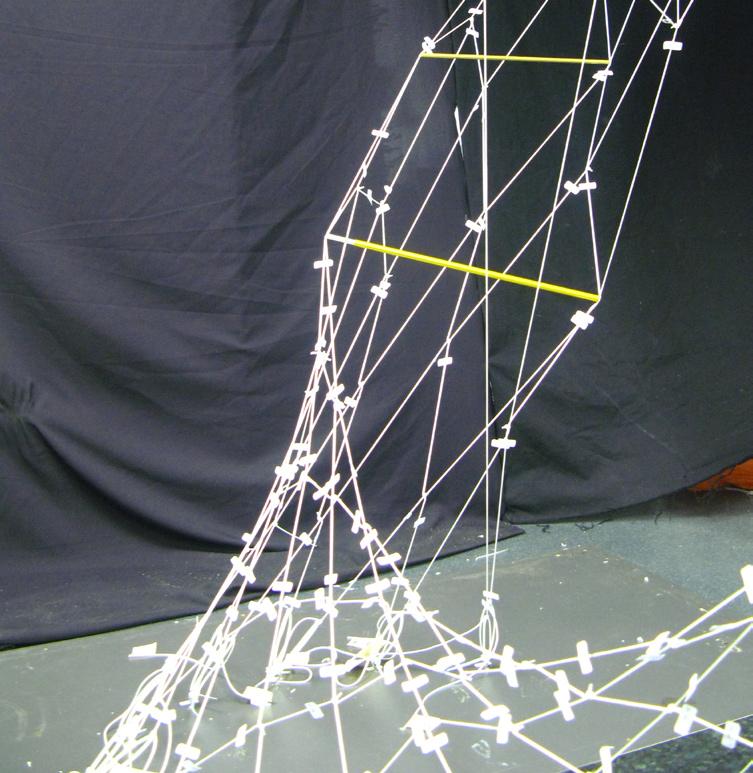

Cylindrical Net Morphologies

cable-net installation for AA

Project Review Exhibition, spring 2008. the tensioned net, compression elements and membrane components for this installation were developed through the computational spring system in Processing. a cylindrical network topology of springs was transformed to produce the complex physical arrangement. the installation was built in the Studio 2 space at Bedford Square, june 2008.

2.1-3 transformation from symmetry. the initial spring model is based on a pair of circular arrays of anchor points. to adapt to the studio space for the installation, the two sets of anchor points are scaled eccentrically.

2.1-4 the transformation to the final net arrangement for fabrication utilizes 3 variables. 1- the anchor points are scaled assymetrically, 2-various edge particles in the net are unfixed, and 3- one fixed particle is relocated from its native location along the bottom array of points to a location along the top array. the red line indicates the relocation of a fixed particle from it original location to that on the upper boundary.

2.1-5 initial design for experiment of translating digitally form-found model in Processing to physical construction. the design was extracted as linework from Processing into Rhino.

2.1-6 manual placement of node tags. nodes were identified in the digital model at the intersections between individual springs. the IDs were done manually, so there is no clear convention nor a specific pattern in the naming.

2.1-7 length measurements from Processing. the distances between particles (meaning the length of springs) was calculated digitally and compiled directly into an Excel spreadsheet. the lengths were compiled in a way to create continuous lengths of material. the translation was 14 individual computational springs = 1 length of string with individual lengths measured along that line.

2.1-8 and 2.1-11 full-scale mockup for design of tensioned net installation. this mockup tests the translation from computational data and the method for assembling the cable net. the white tags are the node identifiers. the larger tags identify the start or end of the major line elements. gold elements compression elements. inserted into the net testing their affect for post-tension and spatial articulation.

2.1-9

sequencing of fabrication. lines were installed and locked together, using cable ties, where they crossed per the information in the digital model. one node ID exists on 2 lines. this indicates the crossing point and where the two seperate lines would become locked together. the only positional information (x,y,z coordinates) that was necessary was for the anchor points on the floor and ceiling of the space.

2.1-10

compression elements were installed into the net after it was fully assembled. these acted as devices to add tension to the system and see how local posttension would effect the overall arrangement. these elements also allowed to spatially articulate the net - expanding certain areas by pushing apart the surfaces of the net. the compression element were aluminum tent poles with a diameter of 8mm. in future experiments, the simulation of compression elements was added as a capability of the computational process.

2.1-12 and 2.1-12a unique double array values. simple particle map which describes the unique ID for each particle. the ID is created through a simple , logical double for-loop in Processing.

2.1-13 and 2.1-13a installing of springs, connecting all particles. this is an example of how the double array ID method becomes useful. for inserting the network of springs, it is a simple computational method of stepping incrementally through the list of particles.

2.1-14 and 2.1-14a moving through node network for fabrication. while we want to track the springs in the network, we want to move through it in a fashion that connects springs across the entire network. for fabrication, as opposed to translating one spring into a single length of material. this method assembles multiple springs, accumulating the length and association data, and creating longer, but fewer continuous lengths of material. the computational method for extracting this information is more complex. though, the complexity is primarily due to tracking across the ends of the computational boundary. the incrementing has to be adjusted when hitting the maximum boundary of the array - setting is back to zero 0 to then continue incrementing upwards.

2.1-15

final design of cable net for installation. the orange line highlights multiple springs to be connected for fabrication as a single length of material. each spring length is tabulated and logged into the associated node information. nodes and the static spring model is reconstructed through a script in Rhino. this version of the net is designed for installation in the AA Studio 2 space.

2.1-16

ID tag for specific node/particle. the ID for the tag originates from the double-array value assigned to the particle during the initial creation of the array of particles and spring network.

2.1-17

particle map for computational net. the hilighted springs describe the movement through the double-array of particles to describe the a single continuous line for fabrication. this method is embedded in the computational process in Processing. because it describes a movement through the topological particle map, any geometry can be analyzed in this same manner., and thus fabricated as well.

A2_id6,20 L14:L20

A2_id6,20

L14:L20

L14:L20

A2_id6,20

L14:L20

2.1-18

description of complete net with all node IDs. the installation consists of 2 nets (net A and net B, as shown in excel data Figure 3.19). They grey and orange lines depict the 2 different nets. At moments, they are pushed apart by springs acting in compression in the computational model.

2.1-19 sample of excel data extracted from computational model.

a distance in computational model from current particle to the previous particle

cummulative distance for physical string material. value is reduced by 10% to account for material stretch

c net A or net B

d node number alond current line and unique ID for current node

e other line which crosses at current node

f current line

2.1-20 list of Excel sheet printed for fabrication. these “mappings” laid out all the lengths and node locations for the strings to fabricate the entire net. for net A and net B, there were a total of 8 sheets necessary to build the entire installation.

2.1-21 printed tags. from the Excel file, tags were printed to be affixed to the strings. this allows for the physical node to be seen in space. data on the tag would indicate which lines should cross at any given node.

2.1-22 sample of Excel spreadsheet showing the data for construction of 2 seperate lines. data is extracted directly out of the Processing model.

b

1 : 1/30/2009 : _080625_membrane_proto4_data_pArr1_stretch10_formatted.xls

: _080625_membrane_proto4_data_pArr1_stretch10_formatted.xls

2.1-23 digital layout of lines for fabrication of net. the values above and below the line represent that actual distance computationally (below) and the adjusted distance reduced to consider stretch in the string material used for fabrication. the reducing the lengths, this insured that we would be construction a tensioned net without adding further tensioning mechanisms.

2.1-24 detail of one of the lines for fabrication. the ‘x’ indicates an anchored point for that end of the line.

2.1-25 measuring and location of nodes on string material. the material is 2.5mm nylon string.

2.1-26 setup for measuring overall line length and location nodes along line.

2.1-27 series of strings measured and tagged with node locations.

2.1-28 node and ID tags in completed installation. the node is fixed with a cable tie, connecting the two lines that cross at this particular node. the node is “form-found” through the procedure of locking the two lines together (line 19 and line 17 in the photo). the node is not determined through the input of a coordinate (x,y,z) position. the arrangement of the net is derived through the connecting of the nodes - by tracking common node IDs across different lines, and locking them together.

2.1-29 anchors for the ceiling. the extension bolts allowed for some degree of post tension in the installation.

2.1-30 node at which 2 nets are locked together. an 8-way node is generated when the nodes of nets A and B are locked together.

2.1-31 nodes for nets A and B. the two different string patterns signify the difference between net A and net B. this distinction is also noted on the tags.

2.1-28 node and ID tags in completed installation. the node is fixed with a cable tie, connecting the two lines that cross at this particular node. the node is “form-found” through the procedure of locking the two lines together (line 19 and line 17 in the photo). the node is not determined through the input of a coordinate (x,y,z) position. the arrangement of the net is derived through the connecting of the nodes - by tracking common node IDs across different lines, and locking them together.

2.1-29

comupational compression member. the function for generating compression elements exists within the dynamic relaxation process in Processing. a compression element is a spring that exterts a pushing force (its actual length is shorter than it rest length). in this scenario the size and amount of force is parametric to the distance between neighboring particles. therefore, the size of the compression member has to be solved during the dynamic relaxation process. the spring incrementally expands and gains strength to eventually meet the criteria set for it - in this case, a length that equals 1/2 the distance between 2 neighboring particles.

2.1-30 connection element for compression member. at certain nodes an additional spring element was introduced to simulate a compression member and push the nets apart in certain places. this pin is located at those nodes and anchors the insertion of an aluminum rod.

2.1-31

compression members in installation. the compression members provide secondary, local post-tensioning for the net. they also articulate the spatial characteristics of the overall structure. as the installation is created of two nets (one inside the other), there are moments where the nets are pushed apart from eachother by the compression members, creating gaps between the two surfaces.

2.1-32

compression member spanning across networks. there are also instances where a compression element (signified by the gold rods) spans across the entire installation. at each end they connect to both nets A and B, spanning across the entire interior of the installation. these act primarily as devices for expanding the gross spatial characteristics of the net. they add a minimal amount of posttensioning.

if (length(local) < distance * 0.5) then { springRestLength(local) = springRestLength(local) * 1.5; springStrength(local) = springStrength(local) * 1.5; }

2.1-33

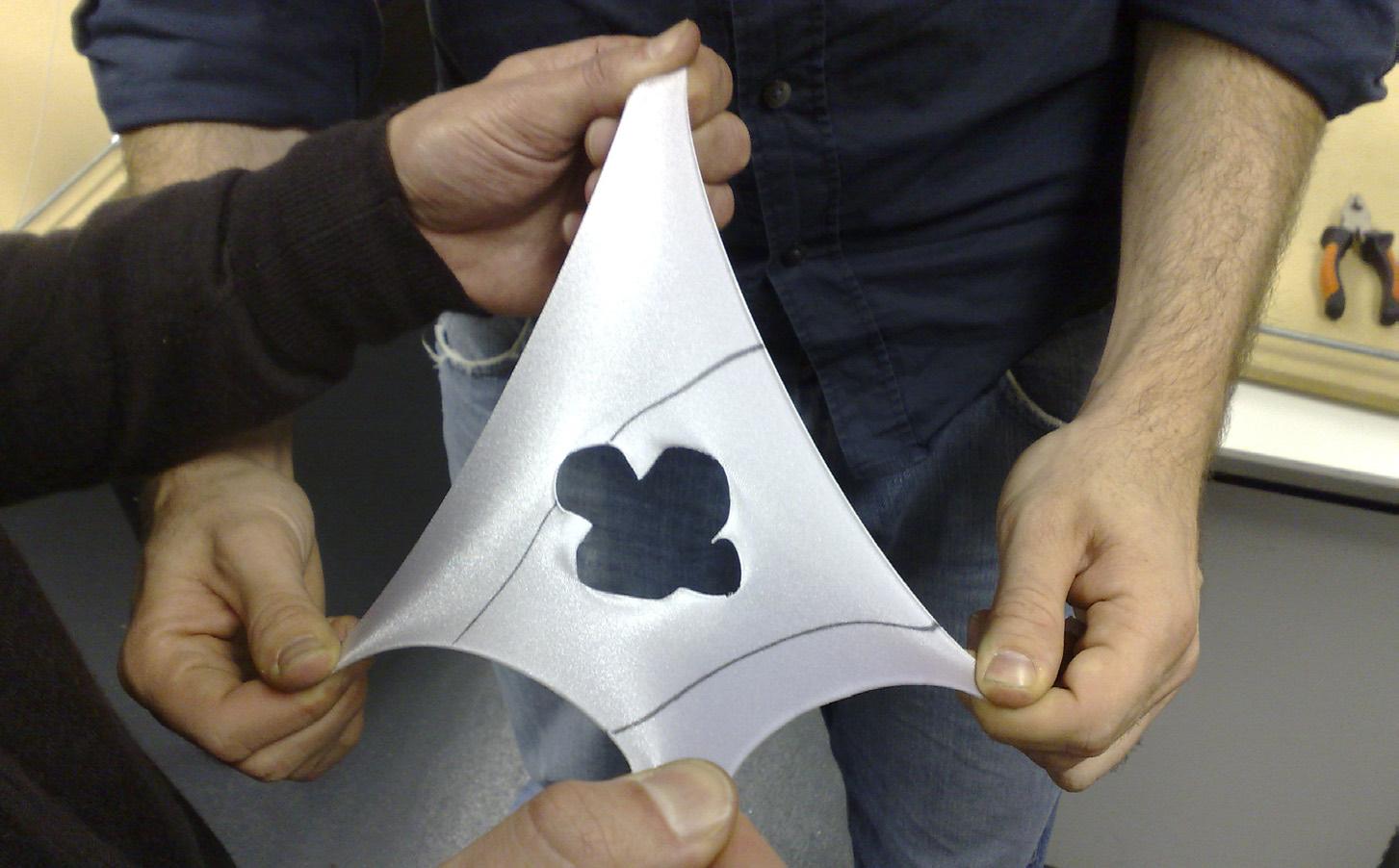

experiment with tension and compression active component. the membrane is anchored (via strings) at 4 corners with an internal compression element. when tension is activated in the component, the compression element finds it position and simultaneously opens up minimal holes on both membranes surfaces.

2.1-34 membrane component installed into net. membrane components were added to the net after it was completely installed. they did little to affect the overall tensioning. they acted primiarily as visual devices emphasizing the gap between net A and B.

2.1-35 computational membrane component. this component was simulated computationally, though it was not utilized for the fabrication of the installation. it was not clearly understood how to translate the computational geometry to a physicall material.

2.1-36

mambrane fabrication. the caluclations, sizing, and fabrication for the membrane components were all done manually.

2.1-37 array of membrane components. the compression element is not present in the membrane component for the installation. the connection of the minimal holes between components provided the same effect spatially.

38

embedded fabrication

ITERATION.05

chain.count:

ring.count:

rest.length

x.parameter

20 12 5.0 (pow(i,2.6)*r*sin(a)*0.006)+60-0.8*i (pow(i,2.0))*(r*(cos(a))*0.01)

The most interesting result from the experiment is that the digital process is transformed from structural simulation to a design simulation with embedded structural and material constraints. In engineering software packages dedicated to cable net structures, the setup demands high specificity of material and positional details. In this environment where demands are many and mostly related to predetermined material and structural matters, the ability to connect variables with design intent is quite minimal. The ability to perform multiple iterations can be even more difficult.

ITERATION.01

chain.count:

ring.count:

rest.length

x.parameter

y.parameter

20 8 5.0 (pow(i,2)*r*sin(a)*0.006)+60-0.8*i (pow(i,2))*(r*(cos(a))*0.01)

ITERATION.02

chain.count:

ring.count:

rest.length

x.parameter

y.parameter

20 20 1.0 (pow(i,1.7)*r*sin(a)*0.006)+60-0.8*i (pow(i,1.7))*(r*(cos(a))*0.01)

FRONT TOP SIDEITERATION.05

chain.count:

ring.count:

rest.length

x.parameter

20 12 5.0 (pow(i,2.6)*r*sin(a)*0.006)+60-0.8*i (pow(i,2.0))*(r*(cos(a))*0.01)

2.1-39

ITERATION.01

chain.count:

ring.count:

rest.length

x.parameter

y.parameter

20 8 5.0 (pow(i,2)*r*sin(a)*0.006)+60-0.8*i (pow(i,2))*(r*(cos(a))*0.01)

ITERATION.02

chain.count:

ring.count:

rest.length

x.parameter

y.parameter

20 20 1.0 (pow(i,1.7)*r*sin(a)*0.006)+60-0.8*i (pow(i,1.7))*(r*(cos(a))*0.01)

ITERATION.03

chain.count:

ring.count:

rest.length

x.parameter

y.parameter

30 20 5.0 (pow(i,1.1)*r*sin(a)*0.006)+60-0.8*i (pow(i,2))*(r*(cos(a))*0.01)

ITERATION.04

chain.count:

ring.count: rest.length x.parameter y.parameter

24 6 5.0 (pow(i,2.6)*r*sin(a)*0.006)+60-0.8*i (pow(i,2.0))*(r*(cos(a))*0.01)

2.1-38 and 2.1-39 examples of design variation from the same computational process that generated the Cylindrical Net Morphologies installation. these examples utilize only a minimal set of variables to produce very different formal outcomes. each design, though, has the same topological strategy, and can therefore be fabricate in the same manner and with the same ease as the Net installation. the design would be in the scale of the network. as the chain.count (num. of particles in the lateral direction) and ring.count (num. of particles in the longitudinal direction) increase, the number of elements to be fabricated will also increase.

ITERATION.05

chain.count:

ring.count:

rest.length

x.parameter

y.parameter

20 12 5.0 (pow(i,2.6)*r*sin(a)*0.006)+60-0.8*i (pow(i,2.0))*(r*(cos(a))*0.01)

ITERATION.06

chain.count:

ring.count:

rest.length x.parameter y.parameter

40 12 7.0 (pow(i,2)*r*sin(a)*0.006)+60-0.8*i (pow(i,1.6))*(r*(cos(a))*0.01)

FRONT TOP SIDEExamining visually the installation, it is apparent in how the density of the mesh (frequency of lines and nodes within a certain sized area) plays a part in comprehending the shape of the net and its possible implications as a threshold. A regularized pattern, one which has a certain frequency of repetition, aids in reading the continuity of the surface and thus reading the form. With this installation, the pattern is more typically irregular as the two nets connect and disconnect, and the compression element push the patterns of the two nets out of sync. This is an interesting aspect in being able to produce and fabricate, in a heavily methodical way, such irregularity. But, there is also an interest in producing readable forms; ones

which can serve as thresholds or boundaries to clearly defined areas of space.

Figure 3.41 begins to show how the cylindrical net can form boundaries to shape areas other than typical centralized cylinder form. In the design, this is generated through the involution of the cylindrical form (see Figure 3.4). These types of spaces, generated from the cylindrical topology are compelling. Further experiments will focus on how to locate such conditions, and how these conditions can control or indicate certain types of movement through spaces defined by these cylindrical net morphologies

2.1-40 regularity in pattern. the mesh is organized in a way that present a relatively regular pattern. the membranes accentuate the pattern. these 2 conditions, the pattern and the membranes, help to more clearly define the shape of the overall form.

2.1-41 bounded area. the involuted cylinder, from this perspective, begins to define a bounded area. the membranes serve to enhance the clarity of reading this bounded space.

2.1-42 movements indicated by different net arrangements. net densities can begin to elicit certain types of movements through the nets.

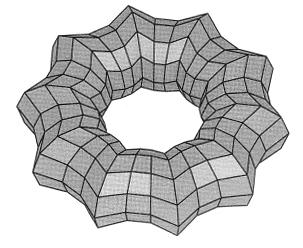

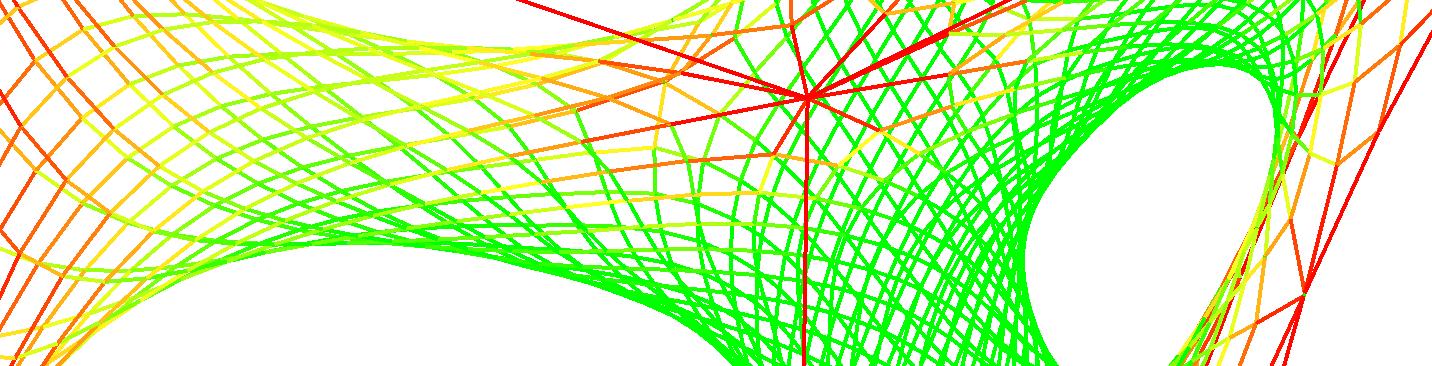

2.2 Topologically Defined Net Components

As the Cylindrical Net Morphologies installation worked with a pair of layered cylinders, this experiment focuses on how to construct and associate a series of interconnected cylinders. With the installation, the two nets were relatively autonomous. They connected at moments, but the moments were more about pattern than they were about following a particular reasoning and design / structural strategy for why they should connect or disconnect at particular moments.