RESPONSIVE GROWTH SYSTEM

RESPONSIVE GROWTH SYSTEM

Emergent Technologies and Design

RESPONSIVE GROWTH SYSTEM

M. Arch. Dissertation

Radhika Amin

Samidha Kowli

Rachelle Spiteri

EMERGENT TECHNOLOGIES AND DESIGN

Michael Weinstock Director

George Jeronimidis Director

Evan Greenberg Studio Master

Mehran Gharleghi Studio Tutor

Wolf Mangelsdorf Visiting Professor

ARCHITECTURAL ASSOCIATION, SCHOOL OF ARCHITECTURE

GRADUATE SCHOOL PROGRAMME

COVERSHEET FOR SUBMISSION 2013-14

PROGRAMME:

Emergent Technologies and Desgn

TERM:

2015 Term 4

COURSE TITLE:

M.Arch. Dissertation

COURSE TUTORS:

Evan Greenberg, Mehran Gharleghi

SUBMISSION DATE:

February 6, 2015

DECLARATION:

SUBMISSION TITLE:

STUDENT NAMES:

Michael Weinstock, George Jeronimidis, “We certify that this piece work is entirely our own and that any quotation or paraphrase from the published or unpublished work of others is duly acknowledged.”

Responsive Growth System

Radhika Amin, Samidha Kowli, Rachelle Spiteri

SIGNATURE OF STUDENTS:

Radhika Amin

DATE:

February 6, 2015

Rachelle Spiteri Samidha Kowli

We would like to thank our families, tutors and friends for their support and encouragement throughout the project.

A special thanks to:

Em.Tech. staff: Michael Weinstock

George Jeronimidis

Evan Greenberg

Mehran Gharleghi

Fellow colleague: Antiopi Koronaki

CONCLUSION 8.1 Overview 8.2 System refinements 8.3 System Potentials APPENDIX Finite element analysis Surface Variation

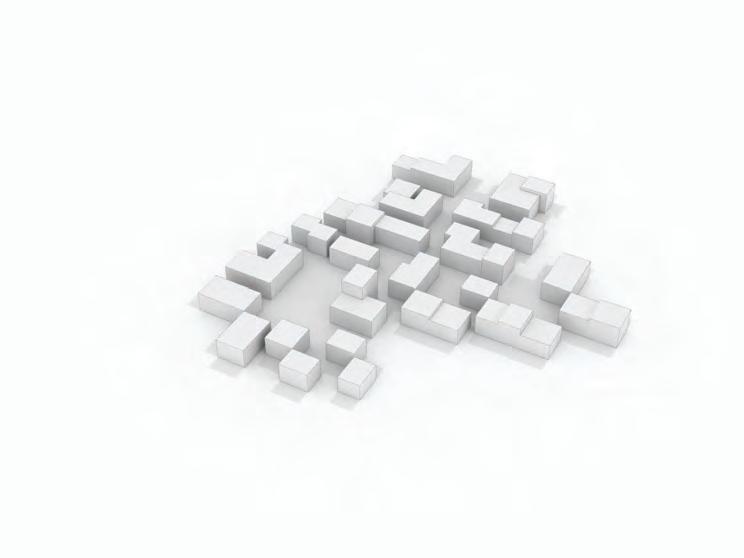

Logic Growth Simulation SYSTEM DEVELOPMENT 6.1 Overview 6.2 Residual Sites 6.3 Urban Growth Negotiators 6.4 Site Strategy SYSTEM IMPLEMENTATION 7.1 Overview 7.2 Strategy Implementation on site 7.3 Sequential Occupation 7.4 System Evaluation

INTRODUCTION THE DOMAIN 2.1 Overview 2.2 Informal urban settlements 2.3 Dharavi: Existing Urban Fabric 2.4 Precedents 2.5 Ambition METHODS 3.1 Overview 3.2 Techniques 3.3 Tools MATERIAL SYSTEM 4.1 Overview 4.2 Material techtonics 4.3 Geometry Exploration 4.4 Material System Development 4.5 Material System Potentials 4.6 Conclusion URBAN GROWTH STUDIES 5.1 Overview 5.2 Urban Character Analysis 5.3 Urban Growth Simulation 5.4 Conclusion 1. 4. 8 10 20 28 38 1 3 126 128 134 146 56 58 60 66 72 74 80 82 98 120 156 158 160 176 190 194 198 202 44 46 48 180 182 184 6. 8. 2. 5. 7. 3. CONTENTS

Combinatorial

ABSTRACT

Abstract

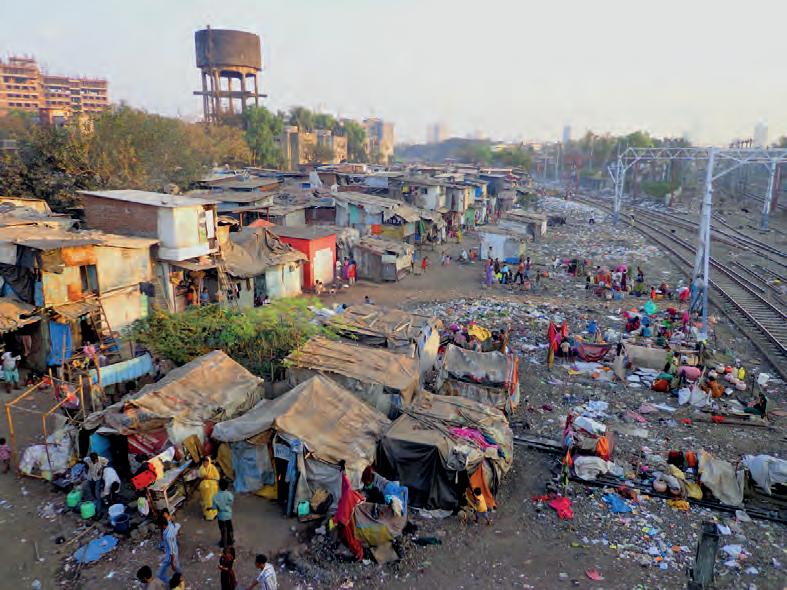

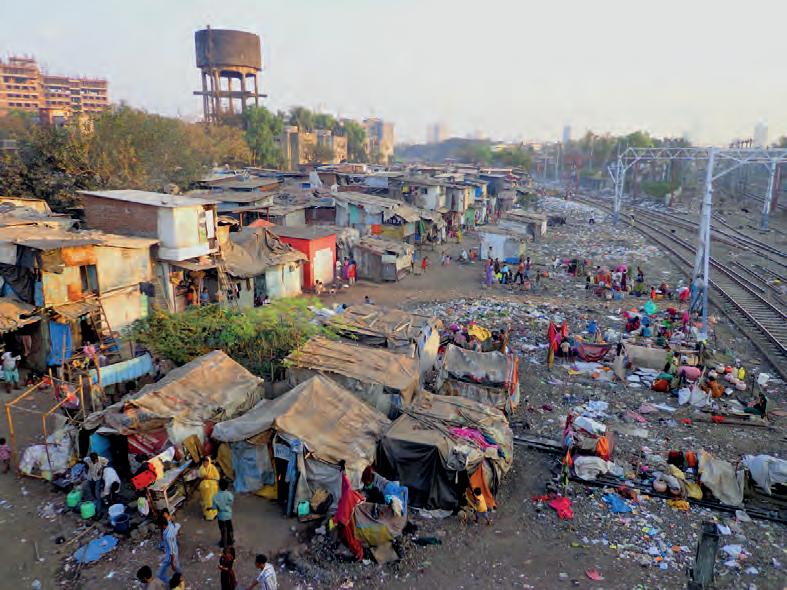

Located in the metropolitan city of Mumbai in India, the informal settlement of Dharavi with its dense population and scarce resources highlights a condition commonly encountered in developing countries, of rapid urbanisation. The potential of Dharavi lies in its numerous household industries which shape the existing urban fabric through social clustering of dwellings. Their contribution to the economy of the city makes them integral to the city’s development, however a lack of infrastructure provision results in an unhealthy, polluted living environment with high cases of waterborne diseases. The existing rehabilitation efforts of relocation into high-rise apartments disregard their social organisation and income generating means, resulting into failure of the typology.

Characterised by rapid growth and fluctuating population, a lowtech, fast assembly material system supplemented with social and sanitation infrastructures, is developed for urban growth deployment in Dharavi. Sensitive precedent approaches incorporate incremental growth of a unit, however there is no consideration of the temporality of land occupation and flexibility of clustering demanded by a variable user group which is very important in the context of high density informal settlements.

The focus of the research is on developing a strategy for urban growth moderation driven by sociocultural context and environmental comfort. The interventions both at the material scale and urban scale are non-prescriptive such that they are adaptive to different aggregation scenarios and enable a permanency and consolidation of the fabric with time.

1 ABSTRACT

1. INTRODUCTION

The social and economic success, and the resilience of informal settlements can be traced back to their self-built character, which allows them to accommodate increasingly high populations. In the case of Dharavi, this character has encouraged the formation of work-based communities which have become major contributors to Mumbai’s economy. So while these communities are successful for their social organisation, the issue of overcrowding has brought about problems of poor health and sanitation.

By understanding self-building as an enabler of community values and adaptive urban growth (in terms of spatial extension and structural temporality), but also identifying the limitations it has beyond a certain scale of self-organisation, the challenge for any intervention in this context, to address the issue of health and sanitation, is to negotiate with the self-built character across different scales of the built fabric.

The research will concentrate on addressing this issue at three scales: developing a material system for self-building, distributing community open space backed-up with structural elements and infrastructure plug-ins for growth initiation as well as mediation and providing a skeleton of underground infrastructure.

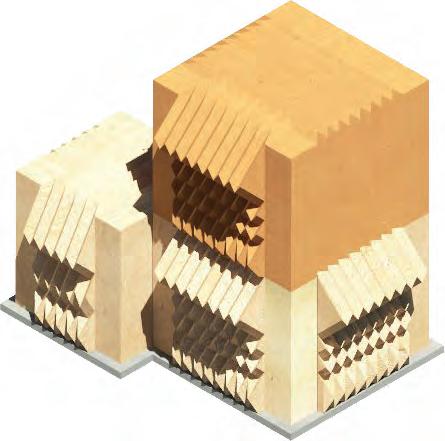

The material system will need to deal with the issue of unsafe, non-ventilated dwellings resulting from poor quality and knowledge of construction techniques. In order to accommodate the variation inherent in the social structure of Dharavi, the material system will be developed as a ‘kit’ of component surfaces informed by structural and environmental performance. Materiality of the components will be developed such that it enables an increased permanency with time.

At the urban scale, a strategy for implementation of open spaces and access to infrastructure will be developed. The open space

insertions will be informed by and inform the potential for selfbuilt agglomerations, to provide an adequate open-to-built space ratio and porosity for environmental comfort and households’ access to infrastructure. An underground infrastructure network enables individual plug-in connections relative to an emergent cluster formation and will have the potential to be reconfigured with incremental growth of the fabric.

A site specific strategy through the study of existing context conditions will be devised in order to integrate the different scales of urban interventions. This will be informed by a detailed analysis of the existing urban fabric to understand the physical organisation and existent diversity; critical evaluation of the developed material system through simulation of growth for its ability to enable the existing variant aggregation characteristics and potentials for improved habitability in terms of environmental comfort for the outdoor space.

The research is carried out through the following stages.

The Domain sets out the current scenario of informal settlements focussing on specific values and issues in Dharavi, taking into account its potential as a craft-based settlement. A detailed investigation of the built and open spaces in Dharavi and related precedent approaches are studied to outline the ambition of the research

This Methods establishes the various stages of the development of the strategy to moderate urban growth in the context of informal settlements. It also discusses the various tools used in the process of the system development.

The development of research is conducted through two chapters.

The Material system chapter focuses on developing a structurally sound, fast assembly material system informed by the social and environmental parameters. The adaptation of the material system for a low-tech fabrication and permanency of the dwelling unit with respect to its lifespan will also be discussed.

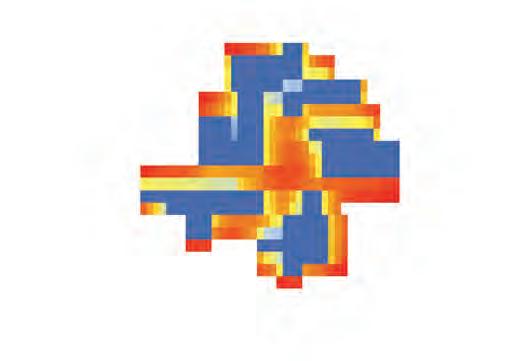

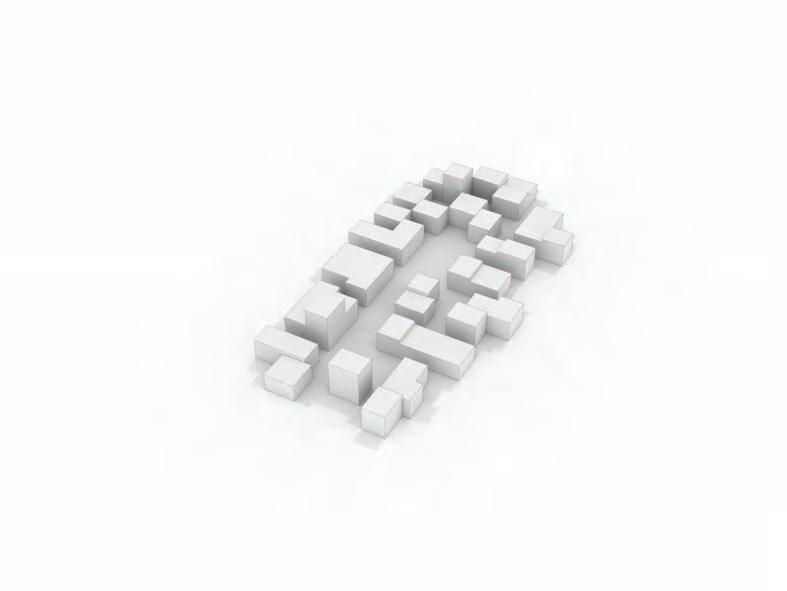

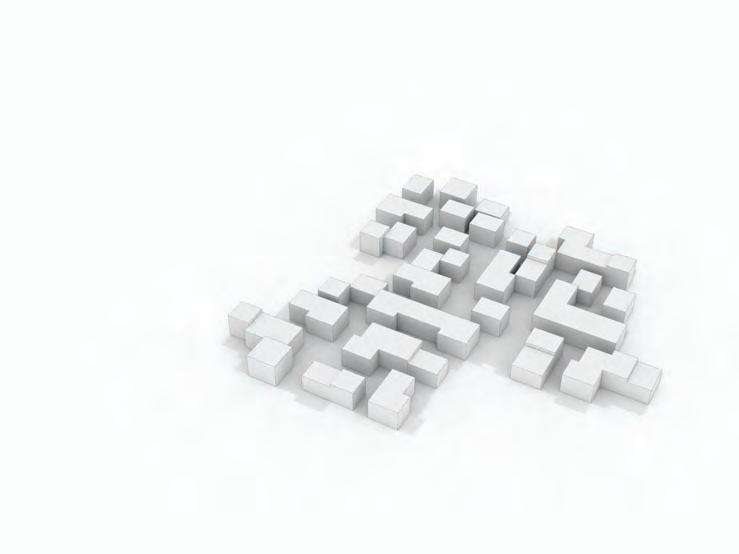

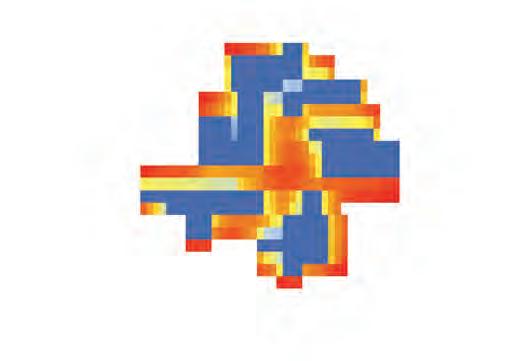

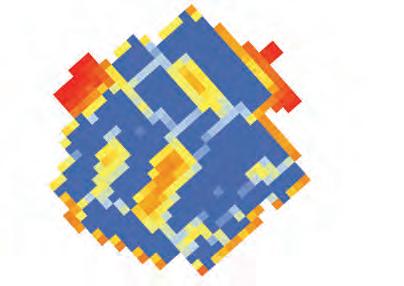

In Urban growth studies, an in-depth analysis of the different existing urban spatial characters is carried out. Following these studies, an algorithm for urban growth simulation will be set up, with existing spatial logic informed with inputs from the material system. Through climatic analysis, conclusions will be drawn which will inform the spatial characters required for community open spaces.

The System development will establish the program with respect to the existing community structure. The urban growth moderators will be detailed out in terms of their geometry variation for environmental comfort. The site strategy for urban deployment will be developed relative to the existing context conditions and detailed out for three different scenarios.

In System implementation, the strategy developed will be tested on a site by simulating a pseudo scenario for urban growth. The emergent cluster formation will be studied to contrast with the existing fabric. The urban growth will be studied across a time scale by recording specific instances in terms of the permanency of the fabric. The underground infrastructure as well as materiality of the architecture will be detailed out.

The Conclusions chapter critically analyses the developed system in context of Dharavi and discusses the future potentials of the system in terms of future scope for the material system as well as the value of the project in other relevant scenarios.

4 5 INTRODUCTION RESPONSIVE GROWTH SYSTEM

2. THE DOMAIN

The chapter begins with a discussion on informal settlements, recognising the positive aspects of a self-organised social structure and its potentials. Many of the fastest growing informal settlements are in South Asian countries, such as India. The informal settlement of Dharavi, in Mumbai, is taken into consideration, particularly for the relationship between its social structure and built urban character, and the positive effect this has on the community. There are however, also problems which arise from the informality of the settlement, these are outlined followed by discussion of precedent examples of interventions on informal settlement, which address infrastructure and sanitation on the one hand and incremental growth on the other. The ambition is outlined for the need to address the problem of an unsafe and unhealthy environment at two scales: the introduction of a material system for a low-cost selfbuilt housing typology that works in a context such as Dharavi’s, together with a strategy for an urban intervention which provides open spaces and infrastructure in derelict or vacant sites within Dharavi for their integration into the urban fabric so that these may contribute to the generation of safer and healthier urban growth.

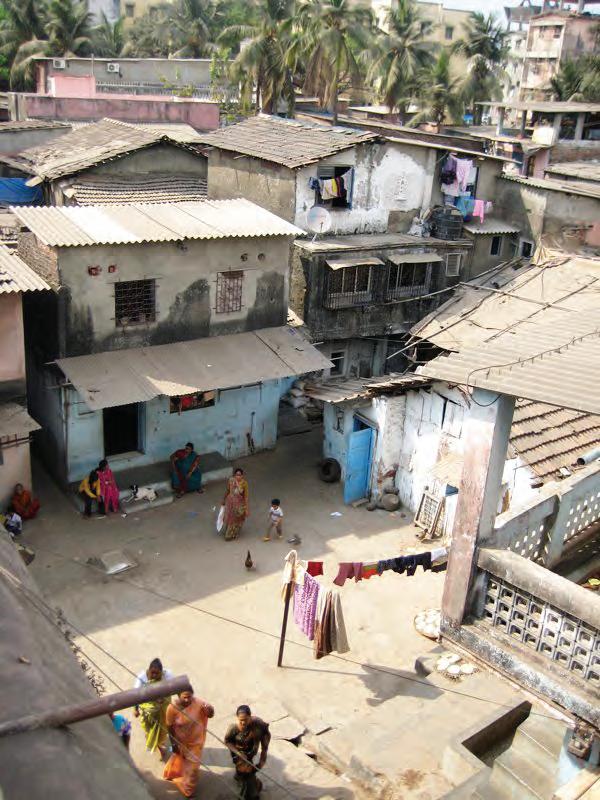

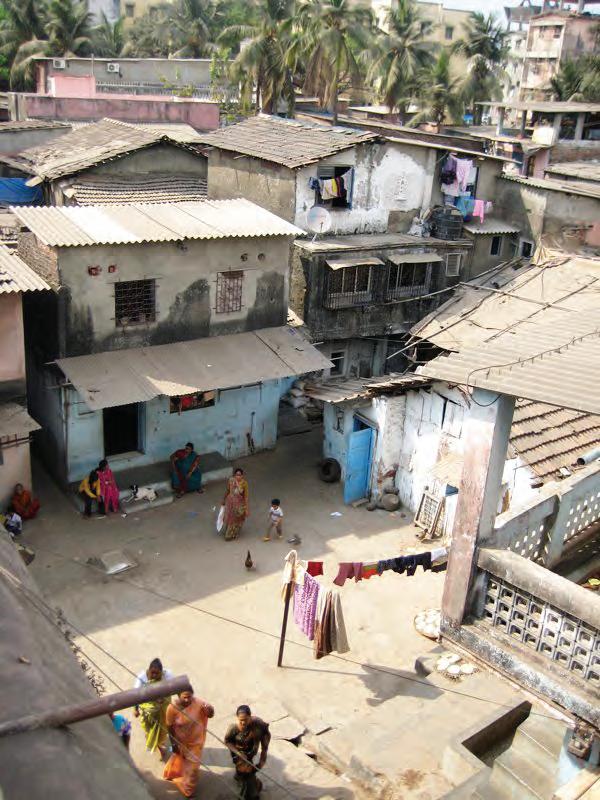

8 9 THE DOMAIN RESPONSIVE GROWTH SYSTEM 2.1 OVERVIEW a b

2.01

a. & b.

Scenes from Dharavi, one of Mumbai’s largest informal settlements.

Sources:

a. flickr.com/photos/_ spoutnik, b. commons. wikimedia.org

2.02

Total population growth in Asian regions 1950-2010, and projections for 2010-2050. Asia is the fastest growing continent and is predicted to more than double its population by 2050.

Source: UN-DESA, 2009

The majority of the global population growth at present and in the predicted near future is concentrated in urban areas of developing countries, predominantly due to rural-to-urban migration. Rapid urbanisation positively affects the economy of the country, but at the same time gives rise to an equally high demand for shelter, employment and urban infrastructure. In developing countries, cities are unable to support this growth. The divide between high demand and low supply of housing and infrastructure results in the formation of informal settlements.

As per the United Nations, 30 percent of total world population was urban in 1950, which has grown to 54 percent in 2014 and is predicted to reach 66 percent by 2050. Fastest growing urban agglomerations are medium sized cities located in Africa and Asia. The developing countries of India and China are projected to receive an additional 404 million and 292 million urban dwellers respectively between 2014 and 2050. Presently, at least one in three people (33 percent) of Asia’s urban population does not have access to basic shelter and services1 and with urbanisation, the condition will worsen adding to the population of urban poor.

Informal settlements are high density, self-built environments, usually formed on derelict vacant land. They are heterogeneous agglomerations, housing a low-income population ranging from skilled artisans and labourers to unskilled workers. The attitude or necessity of self-building allows for the flexibility required to accommodate this high influx of varied population.

The informal workforce of self-employed and wage-based workers residing and working from informal settlements, supports the formal sector and in turn positively affects the economy of a country. Anthropologist and economist Keith Hart coined the term ‘informal economy’ to refer to the same. In a lot of cases, the residence doubles up as a work place, wherein there exists a production or

retail space, sometimes overlapping with the living space. In this sense, the ‘house’ or ‘dwelling’ is an economic resource, since it is used as a production space giving them an income-earning opportunity. However, the overall income earned is low, which affects the living standards.

These settlements are unauthorised, due to which people live in fear of eviction. This is reflected in the construction quality of their self-built structures. The majority of them are temporary in nature, poorly constructed out of cheap, scavenged materials, rendering them structurally unsafe. Incremental extensions encroach on the open spaces as and when required, resulting in overcrowding and compromising on natural light and ventilation. The segregation from urban infrastructure, and lack of access to drinking water and sewage system, create an unhealthy and unhygienic environment. In many cases such settlements have a high crime rate, hence considered unsafe.

Efforts for improving these areas range from relocating the residents to housing developments (often far away from the city centre), to in-situ up-grading by retrofitting existing settlements with better infrastructure. However, the former destroys the existing economic and social networks, while the latter improves social interaction but is usually more expensive. Current interventions that involve residents in the rehabilitation process have proven to be beneficial in improving their overall living conditions.

Interventions on these settlements should therefore cater for the existing social structure and sociocultural requirements of their heterogeneous population. There is a knowledge of self-building which accommodates high population influxes however the issue of availability of resources in terms of construction materials and infrastructure provision causes problems.

2.03

Regional informal settlement population estimate 2010 for Asia. India with 109 million inhabitants is the country with the second largest informal population.

Source: UN-DESA, 2009

1950 3,000,000 2,500,000 2,000,000 1,500,000 1,000,000 500,000 South Asia East Asia South East Asia Western Asia 0 1955 1960 1965 1970 1975 1980 1985 1990 1995 2000 2005 2010 2015 2020 2025 2030 2035 2040 2045 2050 Urban population (1,000s) Year 1950 3,000,000

2,500,000

1,000,000 500,000 South Asia East Asia South East Asia Western Asia 0 1955 1960 1965 1970 1975 1980 1985 1990 1995 2000 2005 2010 2015 2020 2025 2030 2035 2040 2045 2050 Urban population (1,000s) Year 250,000 200,000 150,000 100,000 50,000 Rest of South Asia India South Asia East Asia East Asia South East Asia South East Asia Western Asia Western Asia 0 Urban Informal settlement population (1,000s) Region 10 11 THE DOMAIN RESPONSIVE GROWTH SYSTEM 2.2 INFORMAL SETTLEMENTS: VALUES AND ISSUES

2,000,000 1,500,000

RURAL-TO-URBAN MIGRATION

Supporting home-based income generating activities is one of the approaches promoted by the World Bank for the upgrading of the informal settlements. Traditional live-work communities are successful models of self-organised communities centred around work and economy generation, which makes them suitable to study in the context of informal settlements. They both successfully foster means for providing their own income, enabling them to be self-sufficient.

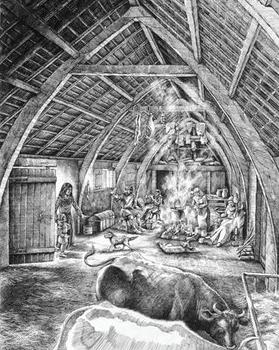

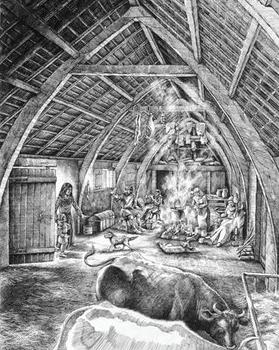

The idea of combining the work place with the dwelling has been prevalent historically, particularly before the industrial revolution. The vernacular architecture of many different cultures usually incorporated work with spaces for living, wherein a part of the residential space was used for retail or manufacturing.

In many cultures, craft-specific communities were formed with houses organised in close proximity to one another. During the medieval period, such an organisation was taken one step further wherein guilds were formed amongst similar craftsmen and traders, to regulate the quality and cost of their goods. The workshops were a part of the house, usually with all the adults of the family working. People under a guild formed a neighbourhood, sharing knowledge and resources, which brought a strong sense of community.

In this scenario, each family or a live-work household shared ties with the other households in terms of occupation, social and cultural values as well as environmental conditions. The physical spatial organisation was a resultant of these mutual relationships. Members of the community shared the same goals,

hence cooperate to reach them faster. This enabled them to take decisions collectively, with each member involved in the decision making process. Coaction was an inherently productive process, this productivity was not confined to economy, but also involved political, cultural, technological and ecological aspects.2

Like other self-organised systems, social self-organisation displays synergistic properties and emergent characteristics. Self-organisation in physical and chemical systems means the spontaneous self-structuring of matter and is temporary in nature; whereas living systems are self-structuring as well as selfmaintaining, and social systems are additionally self-creative.3

In line with this, vernacular architecture, which is self-built and organised following the social self-organised character, is proven to be efficient in responding to the sociocultural and environmental context. It is also adaptive to change and flexible in accommodating a varied population.

Similarities can be drawn between current informal urban settlements and the traditional models of craft-based communities and their physical arrangements. In informal urban settlements land is a precious commodity, due to the high-density. The overlap in functional usage of space results into the space being used throughout the day. This enables the accommodation of higher mixed-use densities and avoids the segregation that results from planned land-use zoning prevalent today. Additionally, in cultures where women predominantly take care of housework, It allows them to simultaneously mind the family and generate income.

of spinning/ weaving/ dressmaking workshop, butchery, tannery and byre in addition to kitchen, dining and bedroom

Source: © English Heritage

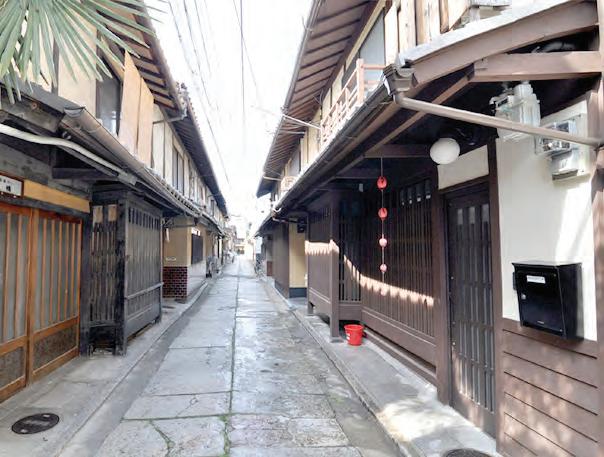

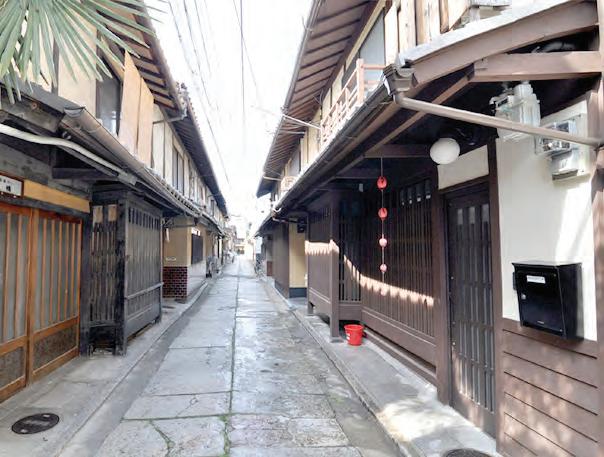

b & c. ‘Machiya’traditional Japanese merchants’ workhome. It provides a sequence of flexible spaces inclusive of the work space and private living.

Sources: b. www. maeniiya.com

c. www. theworkhome.com/

Formal entrance & shop Private entrance & garden Rear garden & services Storage Living area 12 13 THE DOMAIN RESPONSIVE GROWTH SYSTEM 2.2 INFORMAL SETTLEMENTS: VALUES AND ISSUES

a c

CRAFT-BASED AGGLOMERATIONS

2.04 a. Single storied, rectangular building inhabited by medieval peasants. The animals lived at one end and the people at the other. This single open-plan space was a combination

India: scenario

In India, 1 in 10 people lack durable housing, which creates a national housing deficit of 40 million units. Mumbai is a harbour city located on the western coast of India, and is the country’s financial capital. With a current population of 21 million it is forecast to become world’s second-largest urban agglomeration after Tokyo.4 55 percent of its current population lives in slums or slum-like conditions without access to basic necessities like clean water and decent sanitation. Hence, the challenge is not just to eliminate the existing deficit but also absorb the fast-paced growth.

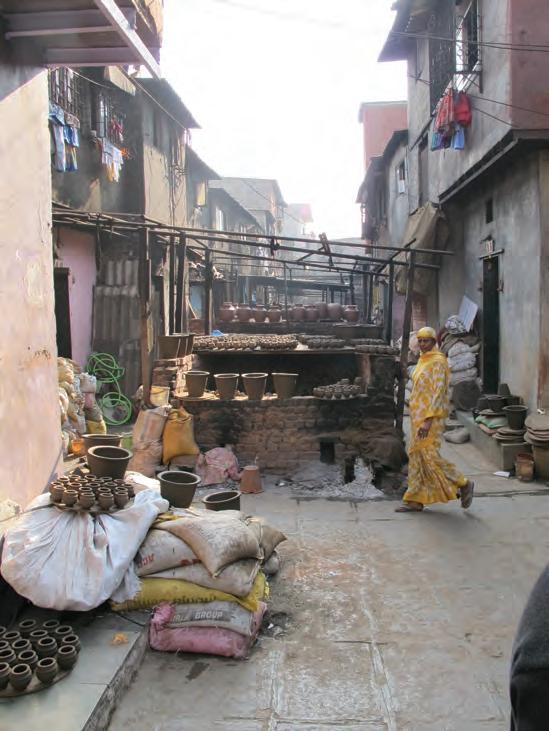

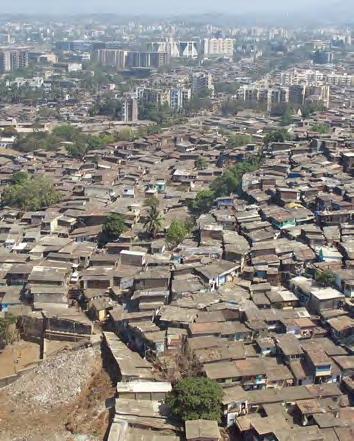

Dharavi is one of Mumbai’s oldest informal settlements and spreads over an area of 2.4 km2. During the 18th century, migrants from neighbouring states began to occupy the low-lying mudflats surrounding the Mahim creek, forming small work-communities. Over a period of time with the city sprawling northwards, Dharavi which was initially located on Mumbai’s outskirts became central.

Dharavi has a total population of 700,000 people with a striking population density of 300,000 people/km2. People now migrate from villages all over India to Dharavi in search of work. There is a high ratio of migrants from rural areas of Maharashtra as well as those of many other Indian states. According to Human Development Report, almost 66 to 75 percent of migrants in Mumbai are of rural origin.5

Dharavi comprises of five smaller sectors each with 10 to 15 neighbourhoods. The communities are formed based on similarities of work or religion; the oldest communities of potters and leather tanners being up to three generations old.

INDIA 0 2001000km Mumbai N

Mudflats Forest Mangroves Railway Rivers & Waterbodies

Bandra Sion-Bandra road link Mahim bay Bandra-Kurla complex Western railway Central railway Sion Kurla Airport Mithi River Arabian Sea Khargo Creek Navi Mumbai Mumbai Harbour Powai Lake Cshiwara River Western Railway Vihar Lake Tulsi Lake Vasai Creek Dahisar River Poisar River Mira Uttan 14 15 THE DOMAIN RESPONSIVE GROWTH SYSTEM 2.2 INFORMAL SETTLEMENTS: VALUES AND ISSUES DHARAVI

MUMBAI

Dharavi

2.05

Location of Dharavi on landfilled mudflats off the Mahim creek in Mumbai. Centrally located, it benefits from the main railway lines flanking its southern and eastern boundary.

Source: Fact Finding Committee on Mumbai Floods

2.06

Dharavi consists of smaller neighbourhoods of live-work communities sharing common household or small scale industries.

Live-work paradigm

“Dharavi embodies an efficient preindustrial live-work paradigm that is now being reinterpreted in post-industrial societies as a sustainable lifestyle option.”6

Dharavi houses a total of 4,900 production units of different scales. It is one of the most important sites of manufacturing in the city. Its central location in Mumbai makes it well connected locally as well as globally, giving it an economic impetus. In a city where rail is the most important mode of transport, Dharavi is flanked on its two sides by the central and western railway lines. Additionally, the creation of the Sion-Bandra link to the international airport makes it viable for location of export outlets.

There exists a symbiotic relationship between Mumbai and Dharavi: the city benefits from Dharavi’s small scale industries, manufacturing units and available workforce, while the informal settlement benefits from availability of resources and raw materials, connectivity and a user market spread locally as well as globally.

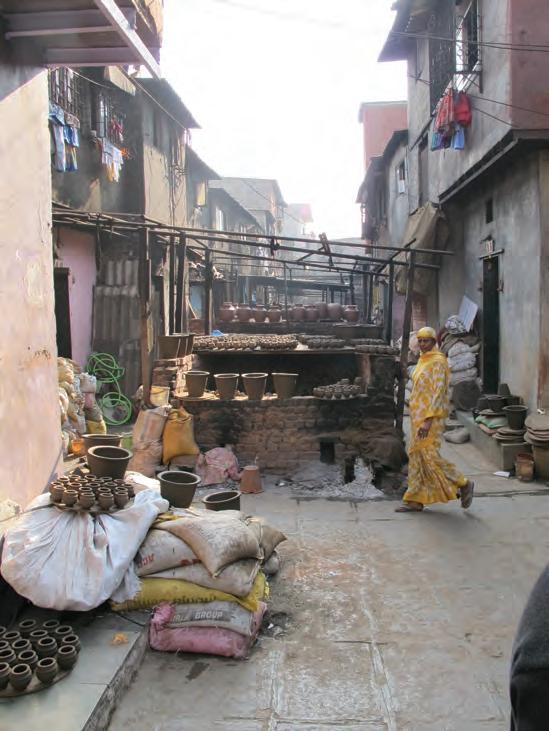

A number of household industries like pottery, broom-making and food packaging are mostly community based with families and in some cases women, working from home. This live-work environment is composed of workshops or work-spaces on the ground floor with extensions into open yards and private spaces on the upper floors.

Mumbai has a tropical climate with a distinct dry and wet season, therefore shaded open space is often used as a work space which provides comfort in high humidity. Open work spaces become important many times due to the nature of the activity, also because they are unbuilt so infrastructure cost is minimised. They are usually shared, which gives rise to work based community clustering.

Another very important industry in Dharavi is recycling, from products like plastics, rubber, cardboard and paper, to steel and electronic components. This activity is a major economy generator as it comprises around 80 percent of Mumbai’s recycling activity. In addition to this there are small manufacturing units of textile and tailoring, and leather, which mass produce garments and leather products; service industries like laundry, masonry as well as small and large retail units. Migrant workers live as tenants and work in semi-skilled labour intensive jobs.

Thus, there exist different forms of economy generation ranging from women working at home, manufacturing units (rooms for embroidery or making leather products) hiring wage-based labourers, shared open work yards between families manufacturing processed food or broom-making as well as trades involving the whole family, like potters, with a dedicated production space.

N Self-built Mangroves Railway Social amenities Government structure Major road 0100 500m Potter’s Village Muslim Nagar Dhobi Ghat (Laundry Services) BMC - Services Quarters Scrap Dealers Leather/ Zari-craft/ Textile Industry Leather/ Zari-craft/ Textile Industry Koliwada (Fishermen Colony) Recycling Industry Food - making Industry 16 17 THE DOMAIN RESPONSIVE GROWTH SYSTEM 2.2 INFORMAL SETTLEMENTS: VALUES AND ISSUES

DHARAVI

INFORMAL SETTLEMENTS

unplanned, unauthorised housing

- South-Asian developing countries

RAPID POPULATION GROWTH

housing deficit

SELF - BUILT accommodating rapid growth

CRAFT-BASED AGGLOMERATIONS

self-built, social clustering - vernacular settlements - medieval guilds

LIVE-WORK ENVIRONMENTS

flexible spacial use informal economy generation

Dharavi’s self-organised social character enables the production of a thriving informal economy of household and small-scale industries, which makes a significant contribution to Mumbai and national markets. In addition to generating their own employment through their live-work setup, the multifunctional use of space is able to accommodate a high-density population which is still rapidly growing.

This social structure is made possible by the self-built character of it’s urban fabric, which shares similarities with vernacular craftbased settlements in that the physical space is user-generated according to specific needs; in this case the need for flexibility and adaptability of space due to limited land.

However, as with other informal settlements, there are problems which arise as a result of the self-built character due to lack of resources and government support.

high density urban fabric household industries 18 19 THE DOMAIN RESPONSIVE GROWTH SYSTEM 2.2 INFORMAL SETTLEMENTS: VALUES AND ISSUES CONCLUSION

DHARAVI

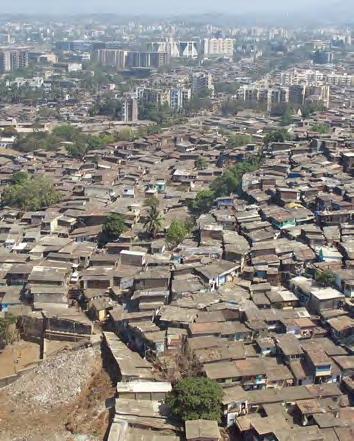

2.07

Dharavi’s residential and live-work communities are very close-knit, structured around family ties and work types. Their social values are manifested in the settlement’s physical urban characters. Migrant families generally build their first shack from scavenged sheet materials. The choice of location for where they settle is crucial for establishing themselves into the existing network of work communities, which consists of numerous household and smallscale industries.

When a suitable location is found, it becomes permanently occupied, although the dwelling will incrementally grow and its construction will become more durable over time as the family grows in number and becomes more economically stable. Once it is financially feasible, a family will resort to a permanent construction of brick and concrete, which is safer and also allows for vertical extensions to accommodate an extended family which can consist of over twenty people living under one roof.

This transition of individual dwellings in size and structure is most notable when comparing settlements of different ages. Recently formed communities, such as the Rajiv Gandhi Nagar, which have developed over the past 30 years and continue to receive newcomers, have temporary or semi-permanent dwellings which generally consist of ground floor rooms, but never exceed two floors due to their poor construction.

The fishermen’s community (Koliwada) and the potters’ quarter (Kumbharwada) are amongst the oldest in Dharavi. Their urban tissue has been consolidated over time with the result of two- to four-storey pukka (made of brick and concrete or stone) and semi-pukka (brick walls with a light-weight roof, usually corrugated metal or asbestos) dwellings and well-defined open spaces that host numerous events depending on the specific requirements at a given time: from providing space for work activities, a market, or for recreational activities and social gatherings during festivals. However, neighbourhoods like these, which are amongst the better parts of Dharavi, have reached this level of consolidation after generations of development and gradual improvement of their homes.

Therefore, although the problem of poor living conditions is true for all of Dharavi, it is most acute in the residual spaces around Dharavi’s periphery which get occupied by newcomers, and in the newer neighbourhoods, due to the poor quality of building materials and construction techniques used.

2.08

2.3 DHARAVI: EXISTING URBAN FABRIC 20 21 THE DOMAIN RESPONSIVE GROWTH SYSTEM

Dharavi’s settlements: a. Recent migrants build temporary shacks along existing settlements.

Source: Anna Phipps

b. Semi-permanent dwellings in Rajiv Gandhi Nagar, which is still undergoing population growth.

Source: Raksha Kumar

c. Pukka houses in Koliwada, Dharavi‘s oldest settlement.

a c b

Source: Camillo Boano

Incremental growth and permanency of an individual dwelling. a. Temporary stage: scavenged sheet materials for individual room construction. b. Semi-permanent stage: horizontal room additions; construction consists of brick walls and sheet material for the roof. c. Permanent stage: vertical room additions in brick and concrete a b c

INCREMENTAL GROWTH

Given the limitations of indoor space due to scarcity of land availability and building resources, communal activities in Dharavi usually take place outdoors. As with indoor spaces, which transform from bedroom to work place to kitchen according to the family’s requirements for space at different times of day, outdoor space is rarely dedicated to one single activity and its users control and transform it according to their needs.

While the development of the built fabric is characterised by incremental extensions and gradual consolidation of individual dwellings, open spaces have an emergent character which is affected by the existing surrounding buildings, and thus the type of activities that spill out onto the open spaces as a result. In this respect, open space is never privately owned, belonging to a single family, but is always shared and its character is moderated by the households and work communities which surround it.

Three principal types of emergent open spaces can be identified: main streets which usually form along commercial activities and attract high traffic; community yards which are predominantly used by a work communities as work-yards, but which can also double up as recreational space, particularly during festivities; and

residential streets which have a semi-private character because they are shared by smaller numbers of families, they are used as extensions of indoor space due to shared water taps provided by the government, but they are also spaces for social interaction and for young children to play.

The surrounding buildings also affect the open space in terms of its size and accessibility. A dwelling’s first extension will be a horizontal encroachment onto open space; however when an open space accommodates commercial activities, such as shops or markets which attract high traffic and large crowds, or is used for production, such as potter’s yards, the built encroachment is limited because these outdoor spaces are essential for people to earn their livelihood and are therefore safeguarded by their users, acting as moderators for growth.

Conversely, residential streets can become extremely narrow, due to a compromise with a need for more indoor private space. However, when open spaces become susceptible to encroachment, to the extent that they become narrow alleys or culde-sac, dwellings get poor access to adequate ventilation and light, and problems of flooding arise due to heavy monsoon rains.

2.3 DHARAVI: EXISTING URBAN FABRIC 22 23 THE DOMAIN RESPONSIVE GROWTH SYSTEM 2.09 Adams a b c

EMERGENT OPEN SPACES

The incremental growth and consolidation of individual dwellings, promoted by their self-built character, allows families the flexibility of adapting their homes according to their needs and means, however problems also emerge which lead to an unhealthy environment.

Across Dharavi, dwellings suffer from poor ventilation due to overbuilding, with little consideration for providing windows to all interior spaces. This also affects the light quality indoors. The inferior quality of scavenged materials used and inadequate construction of shacks and some semi-pukka dwellings make them prone to collapse in adverse weather.

Due to poor drainage systems and narrow streets, often littered with garbage, many areas flood. This is accentuated during the monsoon season due to proximity of the Mithi River, which is highly contaminated with heavy chemicals and oils from industries upstream, and which regularly floods Dharavi during the wet season. The stagnant and contaminated water is a source of waterborne diseases, such as cholera, which affect an estimated 4,000 people a day.

Being an unplanned informal settlement, the government provides scarce infrastructure in terms of water and electricity supply, and sanitation. Water is supplied for two hours a day through outdoor water taps usually shared by four to five households, so water is collected and stored in vessels and plastic drums, which increases the risk of water contamination. The government also provides communal toilets; however each of these is shared by 1,500 people, making them impractical for many but also particularly unsafe for women.

Incremental growth of individual households can in some cases also have a negative effect on the urban scale when community open space is put in jeopardy. Unless an open space is crucial to the community’s livelihood, it will be encroached upon to the extent that the only remaining open spaces in many areas of Dharavi are long narrow alleys. Besides their inadequacy for providing natural light and ventilation indoors, and the problems associated with flooding, there is a lack of community yards which can act as places for social interaction but which can also provide pockets of light and enhance air circulation to surrounding dwellings and alleys.

2.3 DHARAVI: EXISTING URBAN FABRIC 24 25 THE DOMAIN RESPONSIVE GROWTH SYSTEM 2.10 a b c SANITATION PROBLEM

BUILT SPACE

- temporary stage

- semi-permanent stage

- permanent stage

INCREMENTAL GROWTH AND PERMANENCY accommodates high population influx, varied population

BUILT QUALITY

- scavenged construction material - poor light, ventilation & structure

SELF-BUILDING live-work communities

customisation based on user requirements

ENCROACHMENT OF COMMUNITY OPEN SPACE

Dharavi’s pressing sanitation problem needs to be addressed in terms of safer and healthier building construction, and infrastructure providing clean water and electricity, and effective sewerage and rain water drainage systems. However the positive opportunities of a self-built settlement must also be taken into consideration, and any interventions should allow for the degree of flexibility and adaptability necessary for the self-built fabric to continue to accommodate a poor but industrious population.

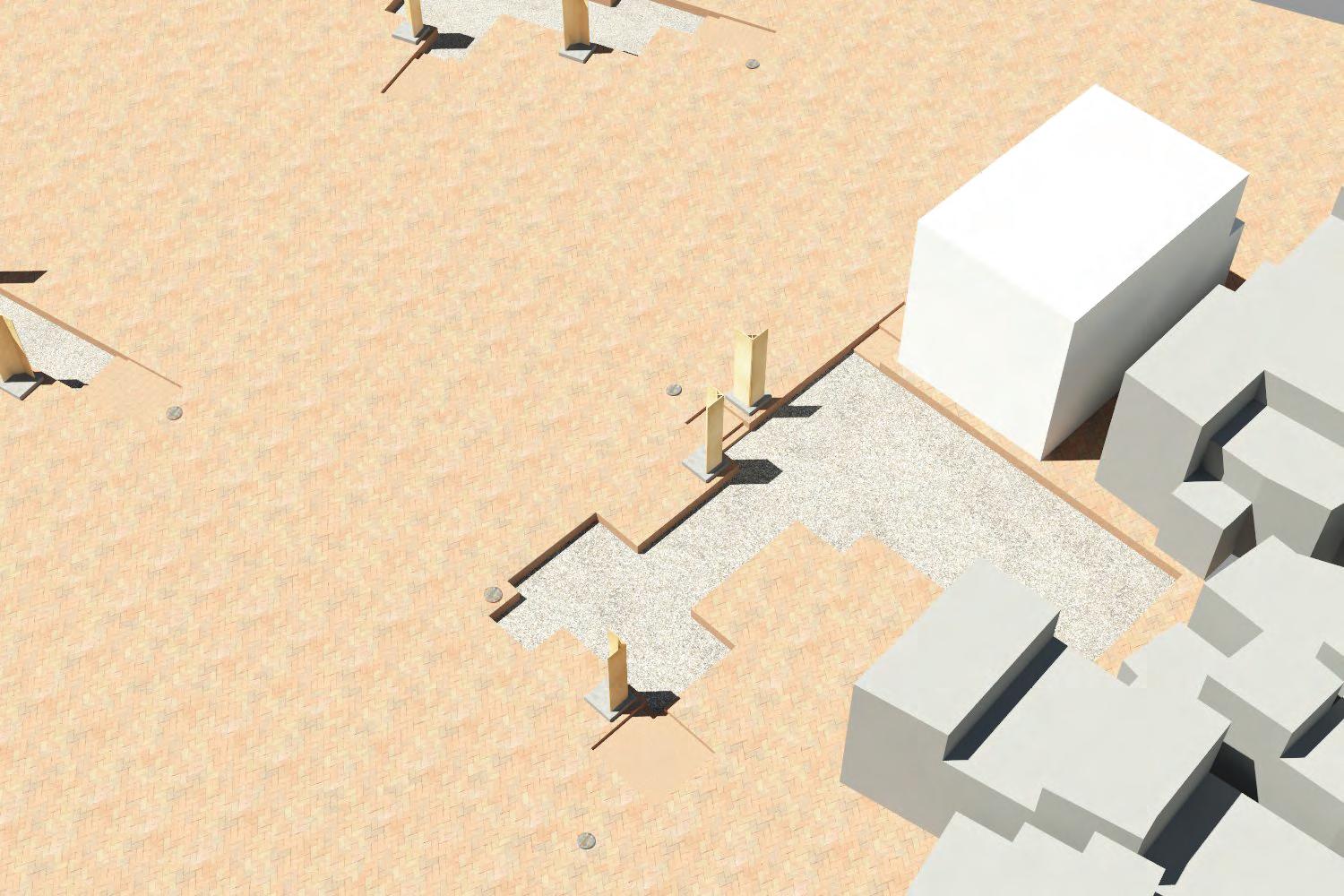

There are a number of vacant lots in Dharavi that are currently disused; they lie on the outskirts collecting garbage or were previously occupied and have been cleared out for the construction of SRA apartment buildings. These sites offer an opportunity for generating an improved self-built urban fabric, which, if successful, can also contribute to the betterment of surrounding existing neighbourhoods.

The development of an urban strategy that provides basic community amenities of infrastructure, and that complements the self-built organisation, could help with the reintegration of these vacant lots into the existing urban fabric, thus acting as generators for positive growth. There are also the available resources of cheap labour and the self-building attitude which can be banked upon to develop a strategy for the upgrading of living conditions with community involvement in order to improve the living conditions and enhance the social character.

HABITABLE URBAN ENVIRONMENT

provision

2.3 DHARAVI: EXISTING URBAN FABRIC 26 27 THE DOMAIN RESPONSIVE GROWTH SYSTEM AMBITION

durable

infrastructure

dwelling

LACK

OF SANITATION

OPEN SPACE commercial streets residential streets community open space open work space

urban fabric NEGATIVES POSITIVE

DHARAVI

OPPORTUNITIES

The construction of informal settlements should not be perceived as a problem but a solution to the housing shortage7 in the city, since they accommodate the rapid rural-urban migration and contribute to its growing urban economy. However, owing to their poor living conditions, which concern in particular health and sanitation issues, the first reaction was to clear them out of the cities. This resulted in the passing of the slum clearance policy in 1950, however, it has proved to be futile since their occurrence and growth cannot be curbed.

Since then attempts have been made by the government authorities in most developing countries to experiment appropriate strategies and policies for the improvement and upgrading of slums.

Two distinct development strategies have been explored so far – one includes rehabilitation through public housing schemes while other is an in-situ upgrading strategy through investment in infrastructure development and provision of relevant services and amenities. Each approach has its own benefits and drawbacks,

however, these schemes are generally formulated in association with the dearth of economic and limited professional resources that the authorities can allocate.

Perceived as a financial burden on the city and a depreciating public investment, the informal sector, thus, has been left with very limited options of funds, land and resources. Hence, most of the traditional schemes couple with TDR (Transferable Developmental Rights) as incentive to promote developers to invest which, in many instances like in Dharavi’s redevelopment, encourage vested commercial interests further compromising on the development of these settlements.

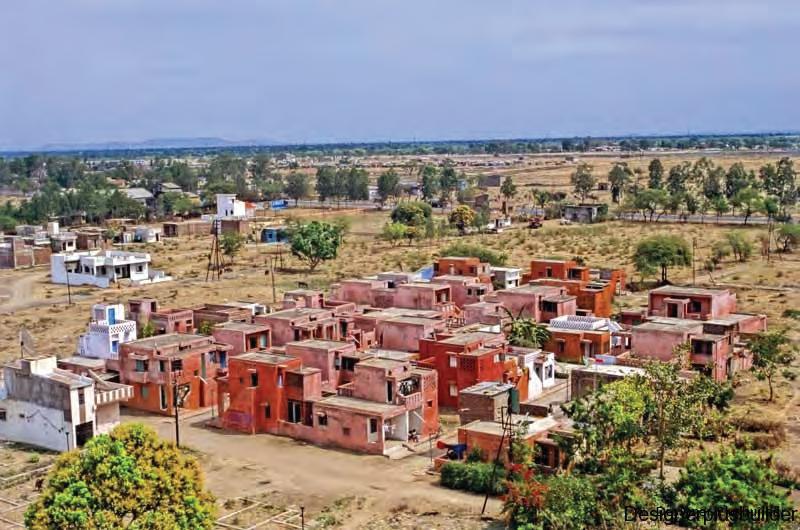

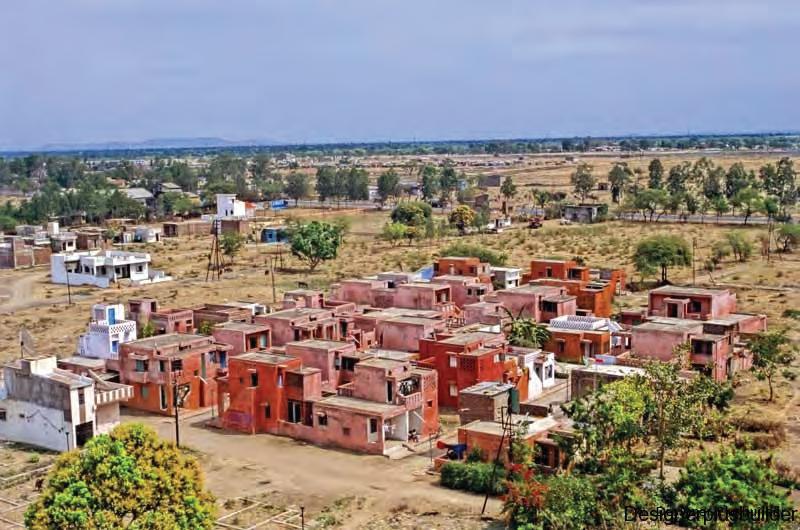

Nonetheless there are some models which have managed to effectively operate within the conventional framework of these legal and economic constraints. The current traditional public housing scheme of Dharavi’s Redevelopment plan is further discussed in the light of the successful incremental housing models of Aranya Housing Project in Indore, India and Social Housing in Quinta Monroy, Iquique Chile to arrive to some suitable conclusions.

2.4 PRECEDENTS: STRATEGIES FOR INTERVENTIONS IN INFORMAL SETTLEMENTS 28 29 THE DOMAIN RESPONSIVE GROWTH SYSTEM

2.11

Conventional public housing scheme wedged in between informal housing settlements - Slum Rehabilitation Authority (SRA) development in Dharavi, Mumbai.

Source: Sytse de Maat

b. Residents of SRA development in

2.13

a. Lack of maintenance and the narrow space between two 7-10 storeys SRA apartment blocks create dark and unpleasant gaps that collect garbage, and attract rats and breeding of mosquitoes, rather than human activity

Source: In_situMArch Dissertation of

b. SRA housing in Pune where common lobbies and corridors are ill-lit and poorly ventilated

Source: Midday News website.

The Slum Rehabilitation Authority (SRA), set up in 1995, is the planning authority responsible for designing and implementing schemes for the upgrading of the cities’ slums in India. The present scheme for redevelopment of Dharavi involves the demolition of the existing informal neighbourhoods and construction of highrise apartment blocks in their place with formalisation of major enterprises.

The Municipal Corporation for Greater Mumbai is in charge of the distribution of services and infrastructure across Mumbai and its slums. Since the prime concern is safety and upgrading of the living standards, the high-rise typology has been opted for to ensure structurally sound constructions and ease of access to safe water and sewage for healthier environment. However, this typology highly restricts the relationships households share with the community and the informal sector, leading to failure of this scheme at number of levels.

The lack of provision of live-work spaces and their segregation in the high-rise apartment blocks leads to the loss of community and social interactions that would have otherwise benefitted community well-being and proliferation of the informal enterprises within a dense horizontal fabric. It also increases the challenge for the residents to manage the house and family while they work. With only 225 sq ft apartments being provided, and no room for expansion, the problem of overcrowding is amplified. The

fundamental deficiency in the scheme is the standardization of procedures and its ‘one-size fits all’ approach in order to operate economically. By necessity this conflicts with the local variety and housing priority in such settlements8 with no allowance for their current structure of social, religious, cultural, and professional divisions.

Lack of adaption to such a drastic change in the way of living coupled with high maintenance costs for the building’s up-keeping result in neglect and inability of the residents to continue to uphold such livelihood. Narrow alleys between the apartment blocks built to maximise on the commercially developable land, turn into dump yards and lead to poorly lit and ventilated spaces. The consequence is “the creation of vertical slums which occupy a smaller ground footprint than the original informal neighbourhood”9 further worsening the quality of life.

Moreover, in the proposed master plan, only 25 percent of the current residential population is being relocated in the apartments leaving 75 percent homeless and forced to move to other slums in the city adding further to the city’s growing housing deficit rather than resolving it. The formalization and segregation of the enterprises curbs small businesses by offering fewer opportunities for their sustenance leading also to certain repercussions on the city’s economy.

2.14

Typical section and plan of the SRA apartment block typology proposed in Dharavi. Some of such blocks have already been built on the periphery of the settlement. The highlighted areas indicate an individual dwelling the typology.

Source: Study conducted by students of Sir JJ college of Architecture, Mumbai

2.4 PRECEDENTS: STRATEGIES FOR INTERVENTIONS IN INFORMAL SETTLEMENTS 30 31 THE DOMAIN RESPONSIVE GROWTH SYSTEM a b a b

Johanna Bratela and Stina Hellqvist

2.12

a. SRA apartment blocks in Dharavi

Source: Sytse de Maat

Lallubhai Compound, Mankhurd, Mumbai

have no running water access in their poorly maintained 7 storey buildings due to broken elevators and inactive water pumping system.

Sources: Akshay Mahajan

DHARAVI REDEVELOPMENT SCHEME

2.15 a.

2.16

Unlike Dharavi Redevelopment Plan, incremental housing proposals search for a middle ground between non-participatory public housing schemes that supply ready-built dwellings and slum upgrading schemes or serviced sites for new constructions which have an increased initial site investment and no cost recovery.

Aranya Township in Indore, India responds to the demands of a growing economy and harnesses the latent construction knowledge and self-building skills within the community to generate an active settlement with the capacity and means to grow. It was developed in 1983 with an initial population estimate of 40,000 people which could grow up to 60,000 people. Comprising of 6,500 housing units on plots varying between 35 to 457 m2 in size, the township proposed to accommodate a variety of income groups but predominantly EWS (economically weaker sectors), on

the 220 acres site, where basic infrastructure, including electricity, water and drainage were provided with all necessary social, welfare, economic and cultural amenities. The number of housing typologies facilitating traditional construction and modes of living were designed such that they could be added on to or adapted by inhabitants over the course of time.

While the inhabitants could buy a whole house built on a plot, there was the flexibility of purchasing only a plot with plinth to build on and a built ‘service core’ of kitchen, washroom and an additional room. This catered to different financial means and enabled the inhabitants to add to given infrastructure subsequently with gradual built accretions according to their preferences and growing needs. Though the project was located outside the city, its strength lies in its culturally appropriate design and the flexibility of space it offered that stimulated the ‘self-help’ factor to further reinforce the community way of living.

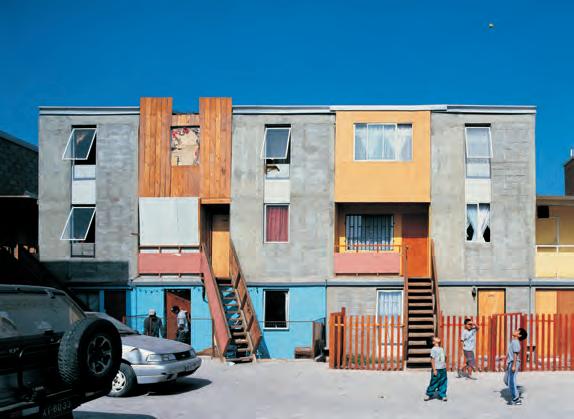

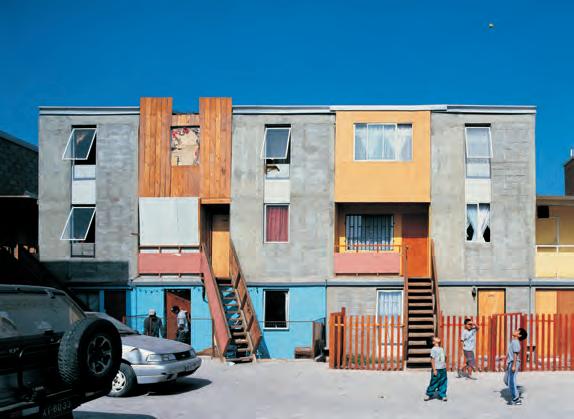

2.18

The prefabricated half house consisting of overall structure, kitchen, bathroom and stairs and its extended version by the residents.

Much like Aranya Township, the in-situ resettlement project of 100 families in Quinta Monroy, Iquique Chile developed by Elemental, also concentrates on providing the basic house nucleus including overall structure, kitchen, bathroom and stairs within the provisional 30 m2 and a standard government subsidiary of US$700 per family. The challenge was the limited land which was intended to accommodate only 30 families (one family house per plot) and the limited money left over from buying the land being enough to build only half a house for 100 families. Hence, the strategy was to build only the essentials in that half house which was otherwise a 72 m2 home, to which the residents could add or extend as per their convenience and circumstances. This incremental nature allows for customisation through occupation and financial appreciation is achieved through gradual investment.

Both Aranya Housing and Quinta Monroy Resettlement avail of legal government support and financial subsidiaries to effectively

transform informal solutions into spatial agents that generate a suitable scenario for built growth. The participative design process and the enabling of self-build facilitate an adaptive growth and also empower of sense of ownership to the inhabitants.

This, exemplifies how a social housing project can become a potential social investment by creating a framework within design where incremental physical development can take place within legal, economical and organisational needs. It is however necessary to note that both cases are in a way prescriptive to a certain limit since they are devised for predefined limited community size and variation. This is possible only if the end user is known and the growth scenarios can be precomputed. Also, although there is a level of flexibility at the individual dwelling scale, both projects introduce elements at neighbourhood and master plan scale which leave little room for adaptability and change in social character and organisation.

2.4 PRECEDENTS: STRATEGIES FOR INTERVENTIONS IN INFORMAL SETTLEMENTS 32 33 THE DOMAIN RESPONSIVE GROWTH SYSTEM Plot with plinth and built service core Initial built blocks of the house Gradual extensions over time Prefabricated structural and service core water tank structure Cores in an array of row houses Customisation and extensions on occupation a b a b

a.

2.17

& b.

Scenes from

Quinta Monroy

Social Housing of what was provided under the government scheme and what was realised on its occupation and customisation. Sources: Archdaily, csanchezreyes. wordpress.com

Source: Alejandro Aravena of Elemental in Architectural Design Vol.81 No.3

& b.

low-cost housing

prior to

occupied

built by

residents. Sources: architexturez.net, AID - Architecture in Development

Scenes from Aranya

project,

occupation and after being

and gradually

the

housing

to

adapt over time

Architect

Foundation

Model of incremental construction of traditional

typologies that inhabitants can add

or

Source:

- Vastu Shilpa

Aranya Township and Quinta Monroy Social Housing

INCREMENTAL HOUSING

2.19

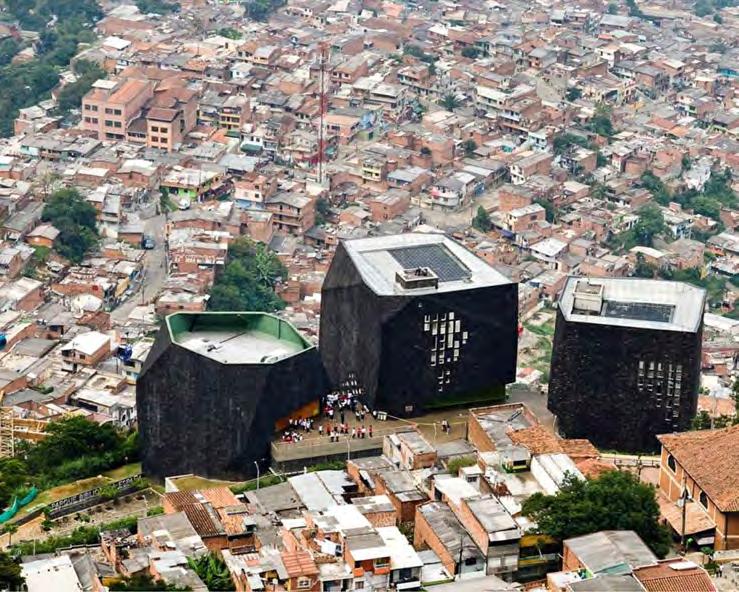

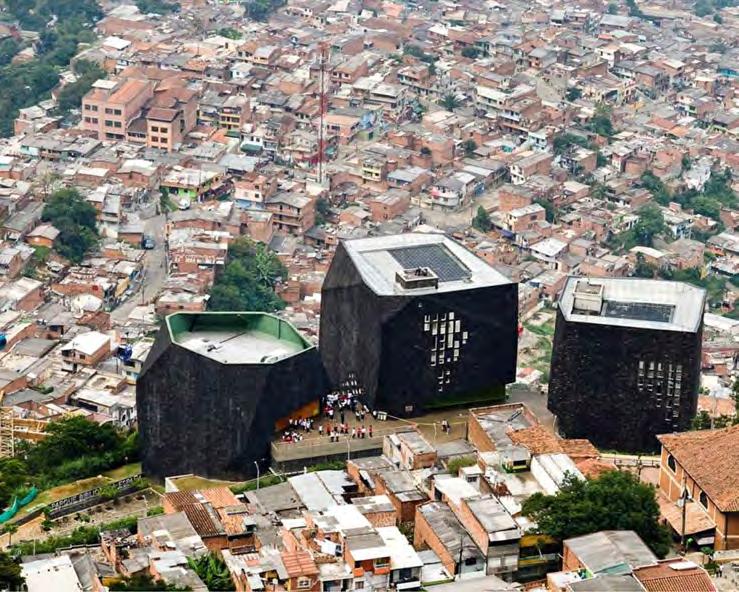

Examples of PUI interventions

a. Parque Biblioteca España in the Northeast of Medellin, b. outdoor escalators in Comuna 13, c. the metro cable running on 3 lines across the city.

Sources: Municipality of Medellin 2.20

Integral Urban Project, Medellin, Colombia

Another approach for the upgrading of informal settlements is the insertion of infrastructure and relevant services and amenities into the existing fabric, so as to “improve the spatial and social quality of area while respecting the existing spatial organisation.”10 While in cases like Integral Urban Project in Medellin, Colombia, the focus is mainly on social development by improving community access, social and cultural amenities and community activities, other projects like Slum Networking in Indore, and the Potty project in Savda Ghevra, both in India, (discussed next) capitalise on bettering infrastructure and use water and environmental sanitation as a catalyst to radically improve the settlement. This approach unlike public social housing schemes does not include large amounts of demolition and displacement but does involve a higher initial investment.

Medellin is one of Colombia’s largest cities. By the 1990s it was reputed to be the most violent city in the world, largely due to the illegal activities that flourished in its slums. In an attempt to decrease its crime rate, PRIMED was set up in 1993 for “integrated slum upgrading” in Medellin. The programme succeeded at improving public services and infrastructure and providing public parks, schools and communal facilities. However, these physical

improvements to the city’s informal settlements were not enough to improve the quality of life of their residents, who remained segregated from the rest of the city.11

Therefore, following the partial success of PRIMED, Integral Urban Project (PUI) was developed as part of the Development Plan for Medellin 2004-2007, with greater emphasis on improving slum communities’ living conditions. Rather than trying to upgrade an entire slum at once, the project focuses on implementing individual projects in specific areas of the informal urban settlements, creating a network of state-of-the-art schools, libraries, public parks and transport systems. The insertion of these services within the poorest areas of the city has helped integrate the slums with the formal city, improving the residents’ access to employment, health services and education, but also encouraging visitors into these impoverished areas creating a platform for cultural and economic exchange.

The crucial element of the programme implemented at Medellin is identification of the need of community activities and amenities specific to the social context and their strategic insertions and improved accessibility which contributes to the betterment and positive growth within the settlement. However, in some cases, a large number of insertions may be required to fully realise the

benefits of this approach which may not always be plausible.

Slum Networking and Potty Project

Slum Networking project in Indore, India was developed by engineer Himanshu Parekh in 1987, identifying lack of water and environmental sanitation as the primary concerns of informal settlements. Since most of the slums are usually located in low-lying areas, the project focused on developing an effective infrastructure network of water and sewage that takes advantage of the natural water course and connects the slums within the city. This not only helped to arrest the pollution of the underwater resources but also enabled individual houses to access the infrastructure network, improved streets by laying storm water drains and developed a buffer of green public areas in the otherwise residual parts connecting two slums. The provision of a basic framework of infrastructure at such a larger scale became a great incentive for inhabitants to invest in building private and public toilets and upgrade their living significantly.

The Potty Project developed by Julia King in Savda Ghevra, India goes a step further from a general urban master plan, and guides individual house upgrades to accommodate a new toilet and connection to the sewer system. This equitable sanitation

system enables 322 different households to add toilets to their present homes whether of pukka (permanent), semi-pukka (semipermanent) or kaccha (temporary) construction. Having private home toilets is a “safer, healthier, dignified and preferred sanitation option to public toilets, especially for women and young girls.”12

The toilets are connected through common shallow sewers running through the existing street network of the settlement to a septic tank linked to a simplified decentralised treatment system. The project succeeded in engaging the inhabitants themselves in the delivery of infrastructure with little technical guidance from the authorities.

Both the projects of Slum Networking and Potty Project, though operating at different scales succeed in improving the overall health and sanitation standards of the settlements they were implemented in without largely altering the built fabric amount of demolition or displacing residents. However, this approach does not support capacity building and enhancing the community since the solutions pertain only to the issues at hand and are not amenable to change. It involves huge monetary investment but does not support cost recovery. Also, given a high density built fabric in context, this retrofitting approach will be a slow and tedious process marking its limitations.

2.4 PRECEDENTS: STRATEGIES FOR INTERVENTIONS IN INFORMAL SETTLEMENTS 34 35 THE DOMAIN RESPONSIVE GROWTH SYSTEM a b c a b c

Examples of slum upgrading projects

a.

Buffer green public areas developed as result of Slum Networking in Indore, India.

Source: Aga Khan Awards Website b. & c. Laying of chambers and common sewers and building of the decentralised treatment system as part of the equitable sanitation system developed by Julia King in Savda Ghevra.

Sources: Archdaily and Holcim Foundation

UPGRADED INFRASTRUCTURE

GOVERNMENT REHABILITATION

high rise apartments ‘one size fits all’ structurally safe, but poor maintenance

LOSS OF GROUND CONNECTION loss of ‘informal economy’, live-work environment

INCREMENTAL GROWTH predefined plots with services expansion over time

INFRASTRUCTURE PROVISION upgrading in existing settlement with sewage and water supply provision

PHYSICAL INFRASTRUCTURE

ENABLING GROWTH

POSITIVE NEGATIVE

SYSTEM ENABLING SELF-BUILDING low-tech construction system with community involvement

GROWTH MODERATORS

Though Dharavi’s principle drawback is the problem of sanitation and unhealthy living conditions, the provision of a well-designed habitat and access to clean water and sewage does not necessarily ensure that the successful and active community character will be maintained. The network of social connections, informal work activities and amenability to change are the basic instruments inherent within the community which are essential for its survival.

Thus, in order to improve Dharavi and similar settlements, it is imperative not only to resolve housing and sanitation conditions but also ensure social empowerment, capacity building and adaptability through the process. An incremental housing approach enables this to a point but there is a necessity to allow a certain degree of freedom to respect the social organization of various economic, cultural and professional divisions prevalent in Dharavi and to accommodate the population fluctuation.

Provisions of infrastructure networks and amenity services are equally essential for better functioning of the settlement. These are also important determinants of the settlement’s urban form and influence its growth patterns. Thus, a system needs to be developed where the main infrastructure network not only facilitates individual dwelling connections to ensure minimum health and sanitation in the settlement but also mediates the settlement growth.

A strategy needs to be developed, which is informed by both the approaches of incremental housing and provisions of suitable amenities and upgraded infrastructure in conjunction, so that these two approaches negotiate with each other at different scales ensuring either of the two isn’t too prescriptive or too flexible and potentially address the problems of Dharavi.

2.4 PRECEDENTS: STRATEGIES FOR INTERVENTIONS IN INFORMAL SETTLEMENTS 36 37 THE DOMAIN RESPONSIVE GROWTH SYSTEM

CONCLUSION

Informal urban settlements provide viable models for the integration of live-work spaces and rapid urban growth. However, they also suffer from problems of low living standards and the high rise of population, due to rapid urbanization.

Dharavi’s greatest problem is the poor sanitation and infrastructure provision which affects the daily lives and safety of the community. This is brought about primarily by two factors: first an intrusive incremental growth of self-built structures which eat into open spaces that could otherwise serve the community as multifunctional social space, and which are of poor construction to the detriment of their dwellers’ health and safety; second, the insufficient provision of infrastructure delivering clean water and electricity and which addresses sanitation directly.

At the same time, the self-built character of Dharavi’s urban fabric is fundamental for the adaptive and rapid accommodation of migrant communities, and the formation of household industries which contribute to the economy. By understanding this relationship between social and physical character of Dharavi, this project aims to address the sanitation problem at three scales:

The first is the introduction of a material and construction system of cheap, temporary and semi-permanent housing, which is self-built and enables incremental growth and consolidation over time. This will provide safer structures with better ventilation and access to natural light, addressing the problems of poor habitable environment of individual dwellings and neighbourhoods.

The second is at the cluster scale with provision of community open yards. The distribution of open space respects user generated cluster formation with emergent yards where as deters over building to maintain habitability for the neighbourhood. At the neighbourhood scale, social amenities and an underground infrastructure network for drainage and water supply are provided.

The three scales of insertions will be developed as a strategy for the urban integration of residual sites in which open community yards are laid out, backed up with a skeleton of infrastructure lines of water, electricity and sewerage mains, to which households can plug-in into. The community open space will be informed by the material system in terms of its geometry as well as peripheral placement of structural elements which can initiate growth. These sites will have the potential for accommodating different scenarios of growth over time and allow for the emergence of spaces that are driven by communities’ live-work requirements.

The aim is that through a provision of demarcated open spaces, there can be a negotiation between incremental self-organised growth, informed by the proposed material system, and a pre-established provision of infrastructure and open space requirements. This will improve the urban environmental quality within and around the areas of intervention, while respecting the indeterminate character and community requirements of a fast growing, transient population whose success has been in creating a highly flexible urban fabric that is tailored to their needs.

MODERATORS

Physical infrastructure ensuring habitability Flexibility to accommodate transience & expansion

2.5 AMBITION 38 39 THE DOMAIN RESPONSIVE GROWTH SYSTEM

CRAFT BASED SETTLEMENTS

live-work spaces Flexible spatial usage

growth POOR LIVING CONDITIONS Poor construction Open space encroachment Lack of basic infrastructure SAFER DWELLING PROVISION FOR OPEN SPACE MATERIAL SYSTEM Modular, component based construction system COMMUNITY OPEN SPACE ensuring minimum built-open ratio INFRASTRUCTURE sewage, water supply, electricity PROVISION OF SANITATION DHARAVI

Integrated

Self-building accommodating rapid

1 The current urban population of the world is 3.9 million; United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2014). World Urbanization Prospects: The 2014 Revision, Highlights (ST/ESA/SER.A/352), p.1

Out of this over 750 million are urban poor; Casanova, M. (2009). Mumbai Dharavi - Scenarios for Development. 1st ed. New York: Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation of Columbia University, p.13.

2 Fuchs, C. (2003). Co-Operation and Self-Organization. [pdf] Vienna University of Technology, p.13. Available at: http://www.triple-c.at [Accessed 24 Dec. 2014].

3 I.b.i.d., p.2.

4 Majale, M., Tipple, G. and French, M. (2011). Affordable land and housing in Asia. Nairobi: United Nations, p.viii.

5 Mumbai human development report. (2009). [online] Oxford university press. p. 55. Available at: http://mhupa.gov.in/W_new/Mumbai.pdf [Accessed 24 Dec. 2014].

6 Casanova, M. (2009). Mumbai Dharavi - Scenarios for Development. 1st ed. New York: Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and

Preservation of Columbia University, p.13.

7 Turner, J. (1977). Housing by People: Towards Autonomy in Building Environments. New York: Pantheon Books,

8 I.b.i.d., p.51.

9 Casanova, M. (2009). Mumbai Dharavi - Scenarios for Development. 1st ed. New York: Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation of Columbia University, p.9.

10 Andres, C. and Arcila, C. (2008). Learning from Slum Upgrading and Participation Degree Project SoM EX 2008-18. Kungliga Tekniska Högskolan, p.25-26.

11 I.b.i.d.,p.57.

12 http://worlddesignimpact.org/projects/project2013/29/

REFERENCES 40 41 THE DOMAIN RESPONSIVE GROWTH SYSTEM

3.

METHODS

PHYSICAL EXPERIMENTS / DIGITAL SIMULATION

ANALYSIS / DIGITAL SIMULATION DIGITAL SIMULATION

ANALYSIS / DIGITAL SIMULATION

- geometrical explorations

- material properties

- fabrication process

- material surface treatment

CLUSTER COMMUNITY NEIGHBOURHOOD URBAN GROWTH AMBITION MATERIAL ‘KIT’ OPEN SPACE URBAN INFRASTRUCTURE

- aggregation logic - urban character analysis - urban growth simulation - community open space insertion - urban deployment strategy - time scale of site implementation

The potential of Dharavi lies in its social organisation which is expressed through the self-built character of the fabric. The positive aspect of self-building is absorption of a fast paced growth, negative is the resultant urban fabric which is of poor structural quality and is over built which compromises the habitability standards.

The growth is moderated at different scales of spatial organisation through specific inferences drawn from the urban fabric. The system can be categorised into inter-related parts of a material kit for unit formation, open space allocation and infrastructure access. The method for the research aims to integrate the various parts of the system through a loop of information flow where each level informs the next.

This chapter establishes the various stages of the development of the strategy to moderate urban growth in the context of informal settlements. It also discusses the various tools used in the process of the system development.

44 45 METHODS RESPONSIVE GROWTH SYSTEM 3.1 OVERVIEW UNIT

DATA

DATA

MATERIAL SYSTEM DEVELOPMENT PHYSICAL EXPERIMENTS / DIGITAL SIMULATION

Mechanical properties of cardboard as a construction material will be extracted.

Parameters related to the material behaviour for structural and climatic efficiency will be established.

Fabrication techniques for a low-tech assembly will be detailed.

Techniques will be charted for adaptation of the material system with regards to the incremental growth of the unit.

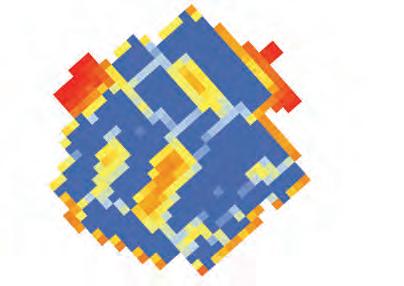

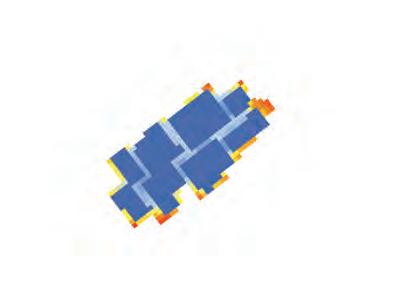

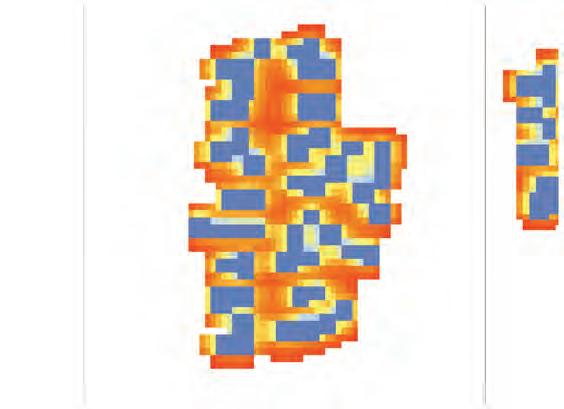

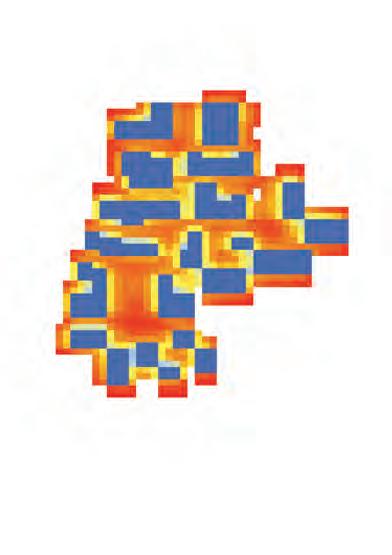

Existing urban fabric samples will be analysed to extract positive urban qualities and negative characters.

Existing urban fabric, open space hierarchy and street network will be quantified in order to extract the aggregation logic of the settlement.

The samples will be evaluated in terms of network efficiency and climatic performance.

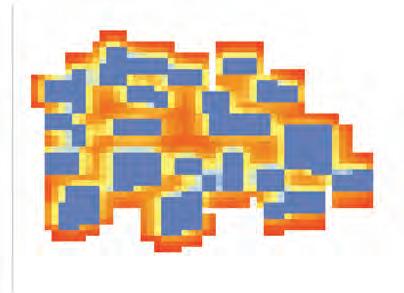

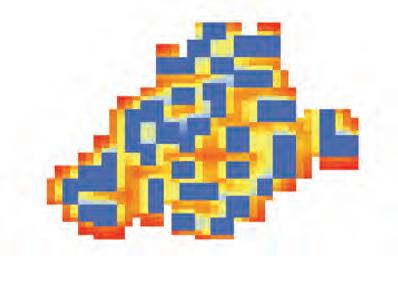

Urban growth simulation techniques like Cellular Automation (CA) and decision trees will be studied as precedent methods for growth simulation.

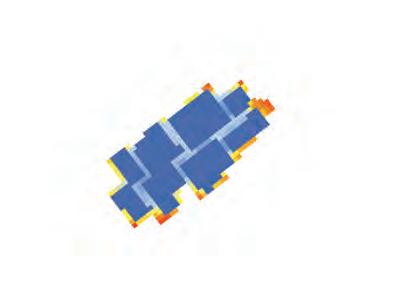

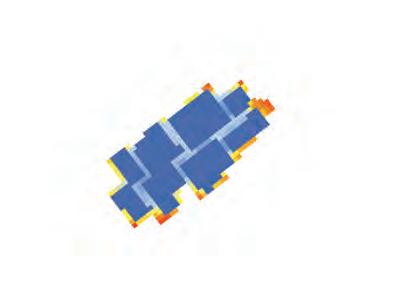

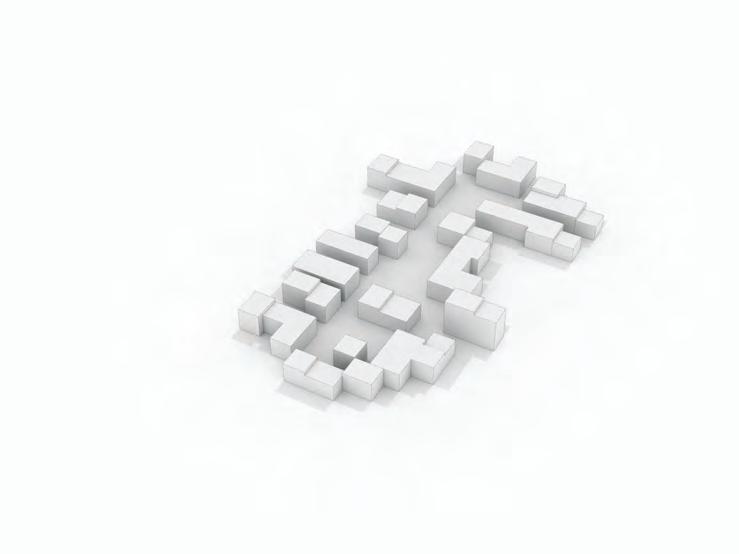

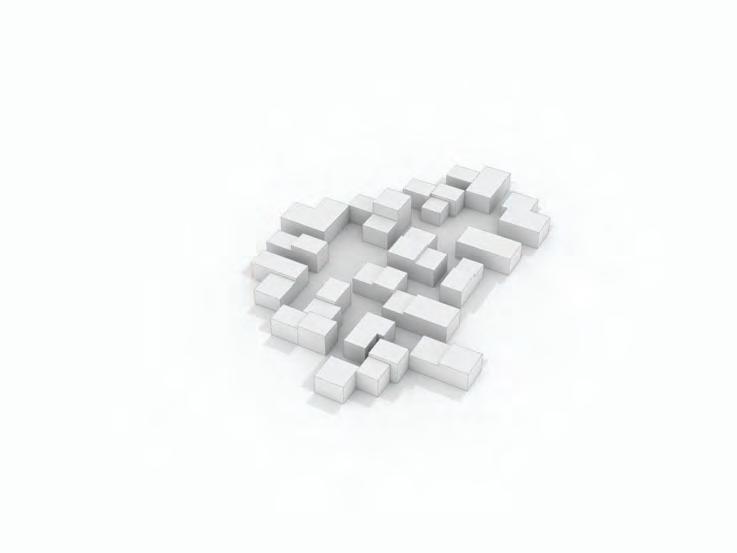

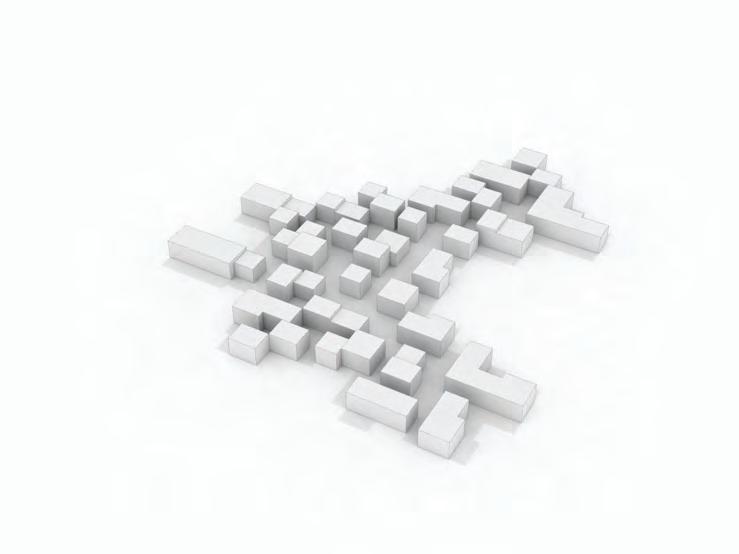

An algorithm for urban growth simulation combining the existing aggregation logic with material system constraints and habitability standards will be developed.

Experiments with growth simulation will be carried out to check the adaptability of the material system to the existing spatial organisation. These experiments will be evaluated in terms of environmental performance and will inform growth negotiation.

By analysing the social logic and open space hierarchy generated through the growth simulation, the scales for spatial organisation and programmatic drivers will be established.

Community open spaces incorporated with connections for underground infrastructure will be inserted as growth moderators.

A genetic algorithm will be used to create variation of geometries for the open space informed by material and climatic constraints. The developed geometries will be measured by the fitness criteria and categorized into variations based on the social character they can generate.

Cataloguing of residual patches in terms of peripheral context condition quantification will inform the initiation of urban growth.

A multi-phase strategy informed by the programme, spatial organisation and community structure will be developed for distribution of growth moderators. Context specific attractor-based and grid-based rules for distribution of open spaces will be developed to test the strategy on different site scenarios.

The strategy will be detailed at the patch scale (site preparation for an instance) in terms of specificity of community open space variation.

A hierarchical infrastructure network of primary, secondary and tertiary branches will be delineated.

The established strategy will be tested on site by simulating a scenario of urban growth. The potential of the parts of the system in terms of their flexibility and adaptability will be critically analysed.

Additionally, the design will be evaluated with the existing urban fabric and the rehabilitation typology of highrise, in order to compare and contrast the positives and negatives.

47 METHODS

UNIT

DATA COLLECTION DIGITAL

DIGITAL SIMULATION DIGITAL SIMULATION DATA COLLECTION / DIGITAL SIMULATION DIGITAL SIMULATION

DATA ANALYSIS

GROWTH

URBAN

URBAN

SYSTEM IMPLEMENTATION & EVALUATION

RESEARCH DEVELOPMENT SYSTEM DEVELOPMENT COMMUNITY NEIGHBOURHOOD 46 RESPONSIVE GROWTH SYSTEM 3.2 TECHNIQUES

SIMULATION

/

URBAN CHARACTER ANALYSIS

SIMULATION

GROWTH NEGOTIATORS

GROWTH DEPLOYMENT

CLUSTER

MATERIAL TECTONICS STRUCTURAL PERFORMANCE

ENVIRONMENTAL PERFORMANCE

DIGITAL SIMULATION / PHYSICAL EXPERIMENTS

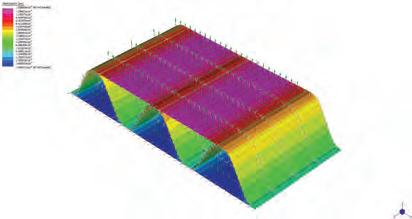

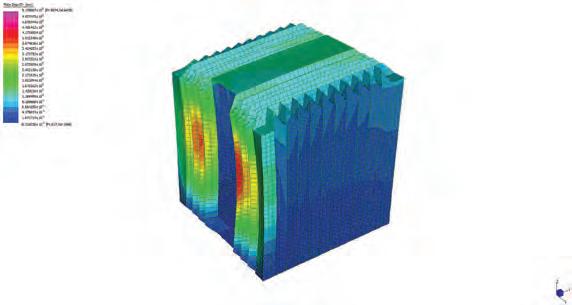

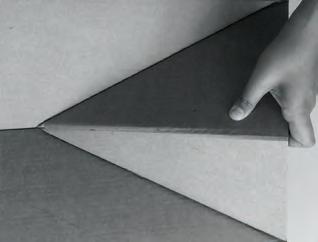

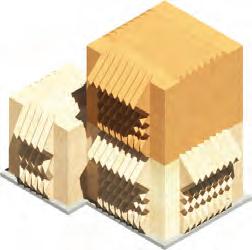

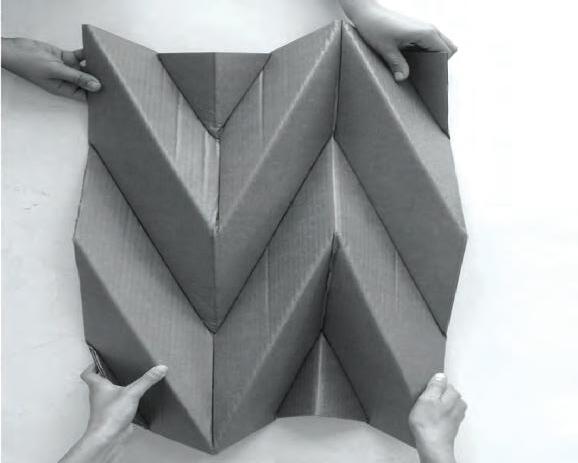

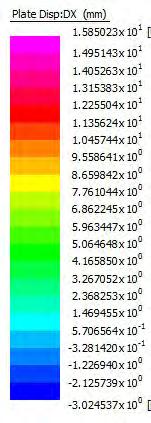

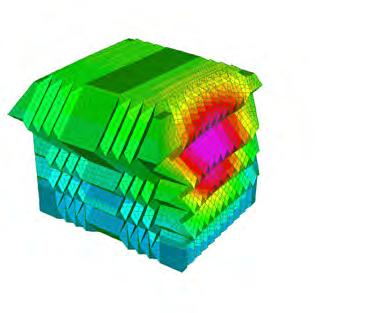

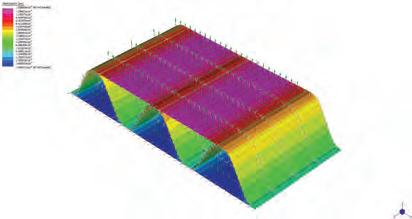

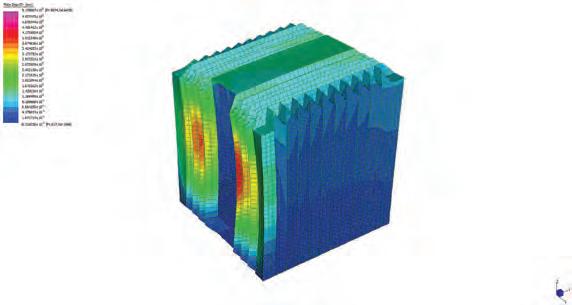

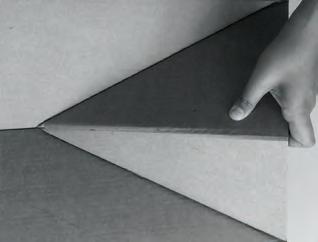

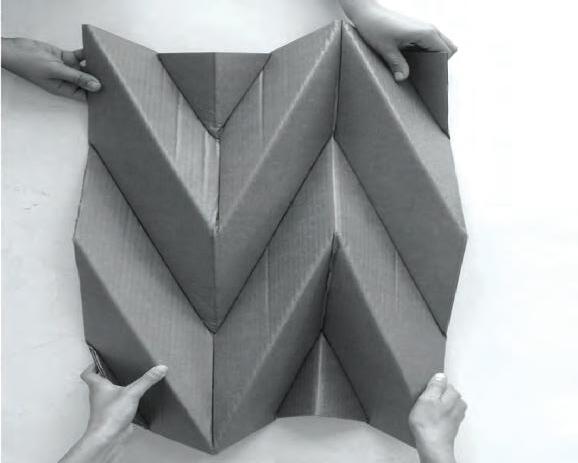

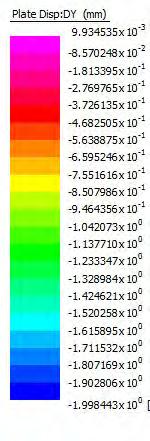

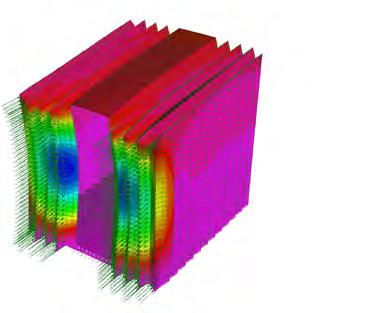

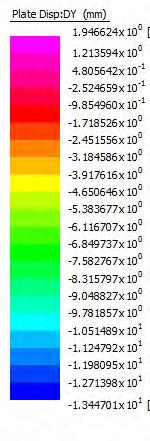

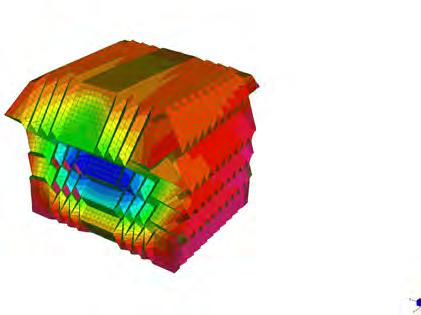

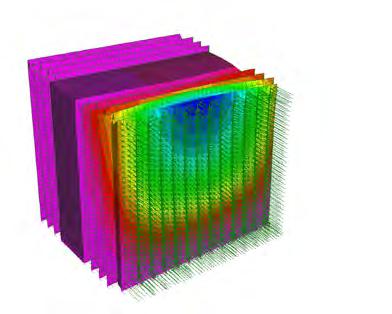

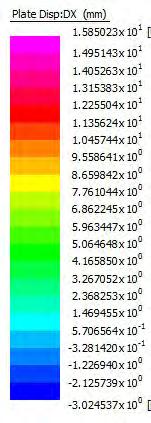

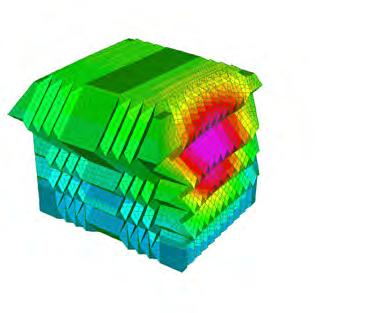

The material’s geometry will be modelled digitally using finite element analysis (FEA) to extract the structural properties of cardboard. This will facilitate the finite element analysis of folded cardboard geometries, by using plane surfaces with attributed thickness and assigned material properties. Digital tools such as Strand 7 shall be used to conduct structural analysis.

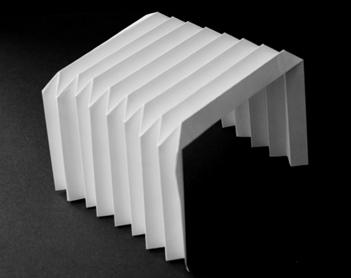

Physical models of corrugated cardboard will help evaluate the ease and time efficiency in folding. At the same time, this shall provide information on the actual effect that the values attributed to the geometrical parameters have.

DIGITAL SIMULATION

In order to perform structurally, the cardboard needs to withstand both the live load, as well as the lateral pressure applied on its vertical surfaces by the wind. These loads will be applied digitally with the finite elements method on folded geometry to which cardboard properties have been assigned.

The results will allow for the comparison of the deformation with an allowable range of values. It will help establish the final folding patterns and the range of allowable variations. The differentiated stress of the material in the local parts of the structure is analysed to delineate the parts that require further treatment and support.

DIGITAL SIMULATION

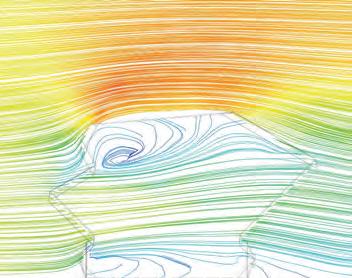

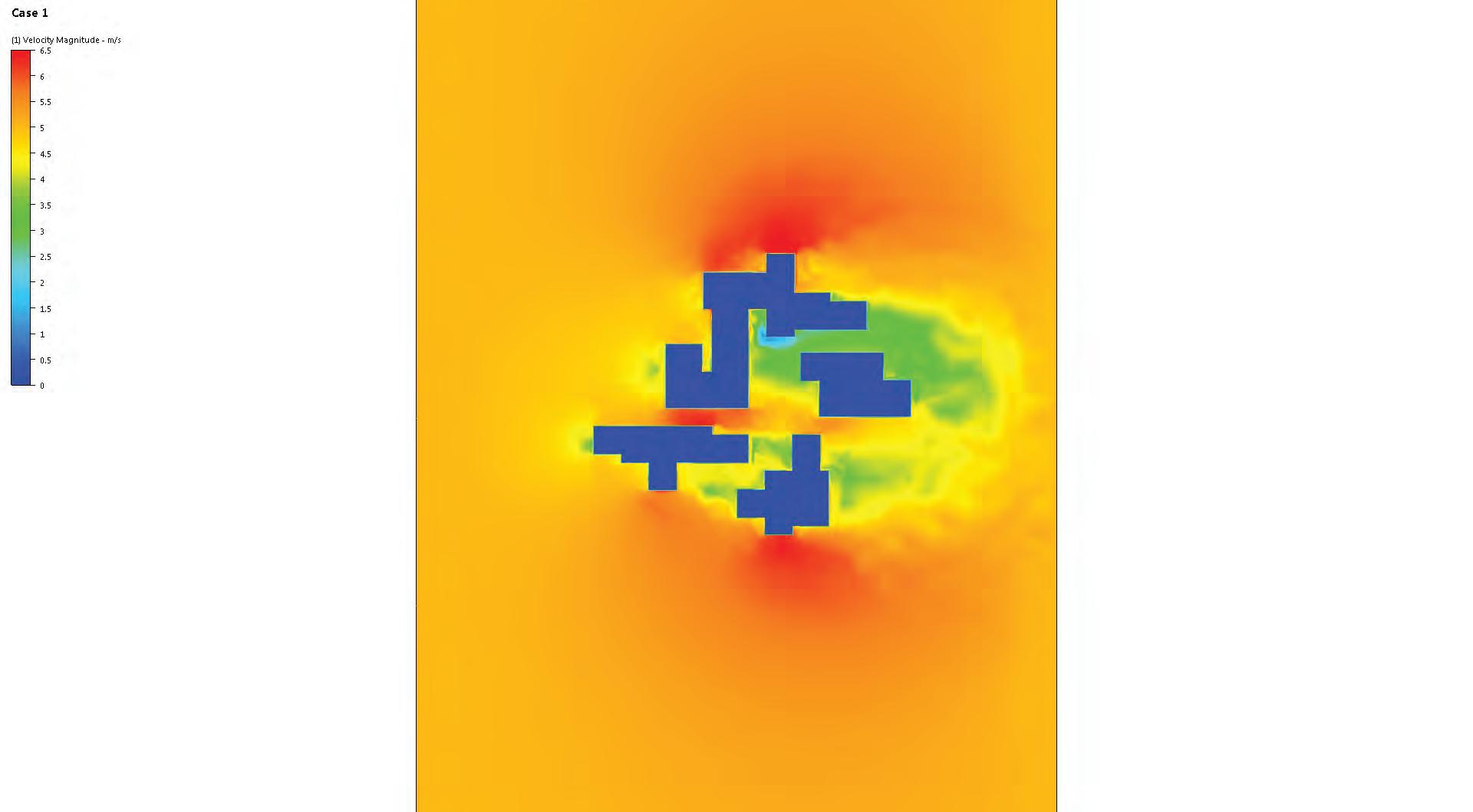

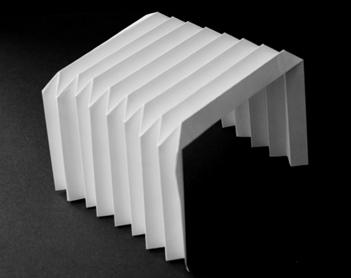

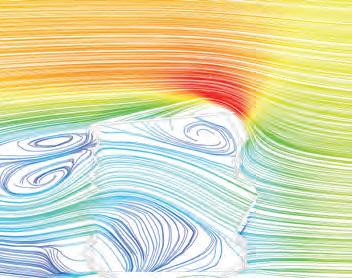

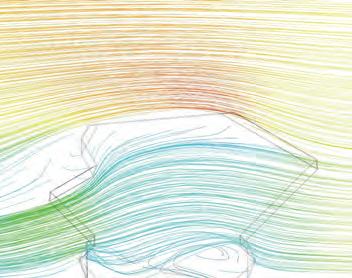

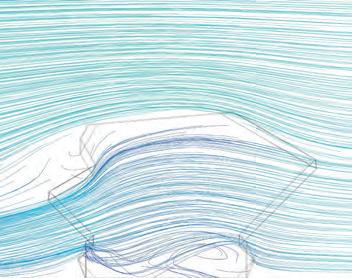

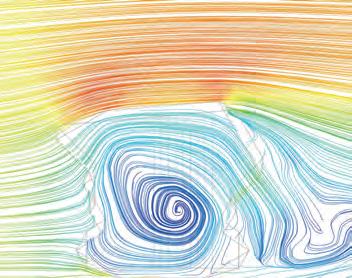

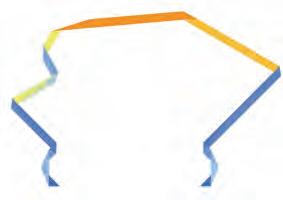

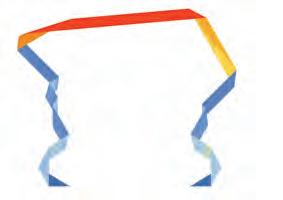

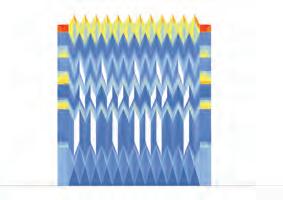

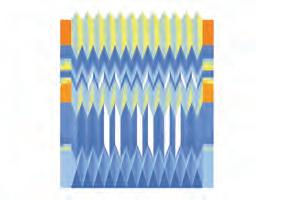

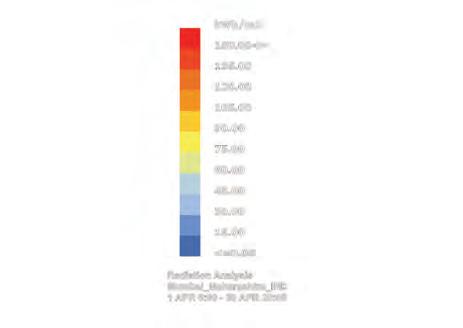

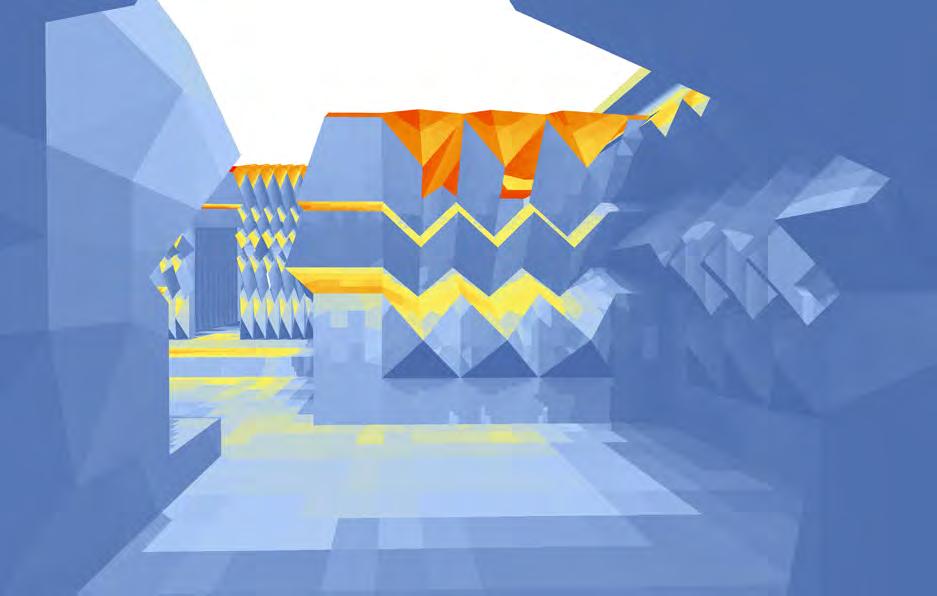

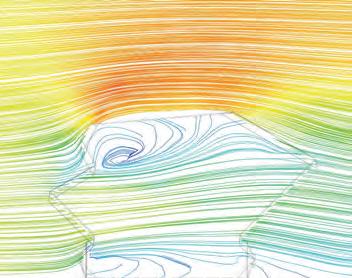

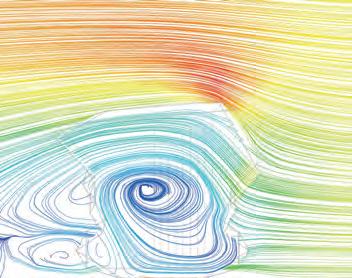

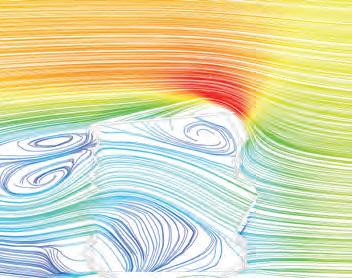

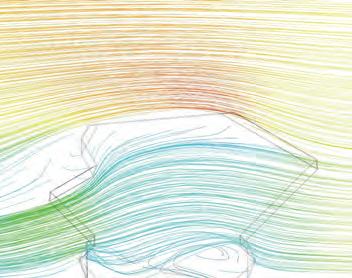

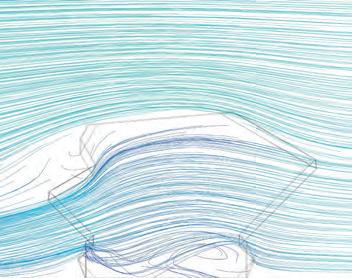

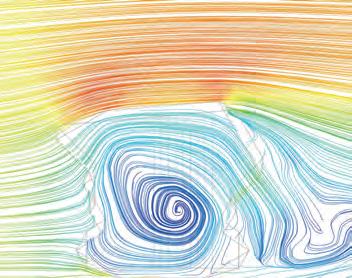

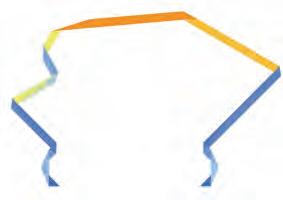

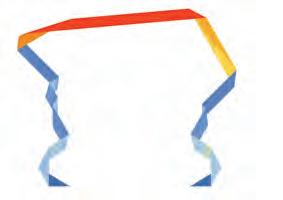

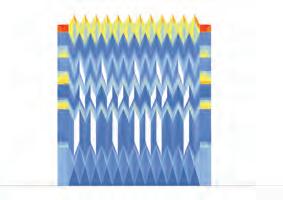

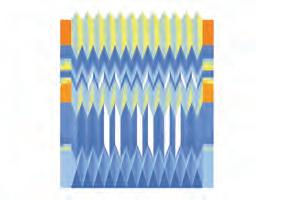

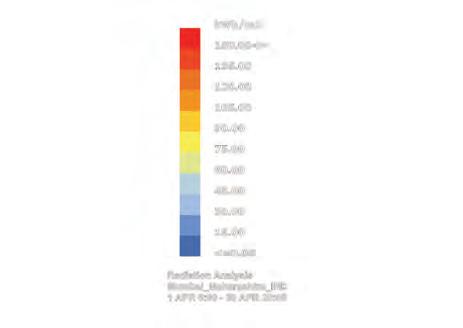

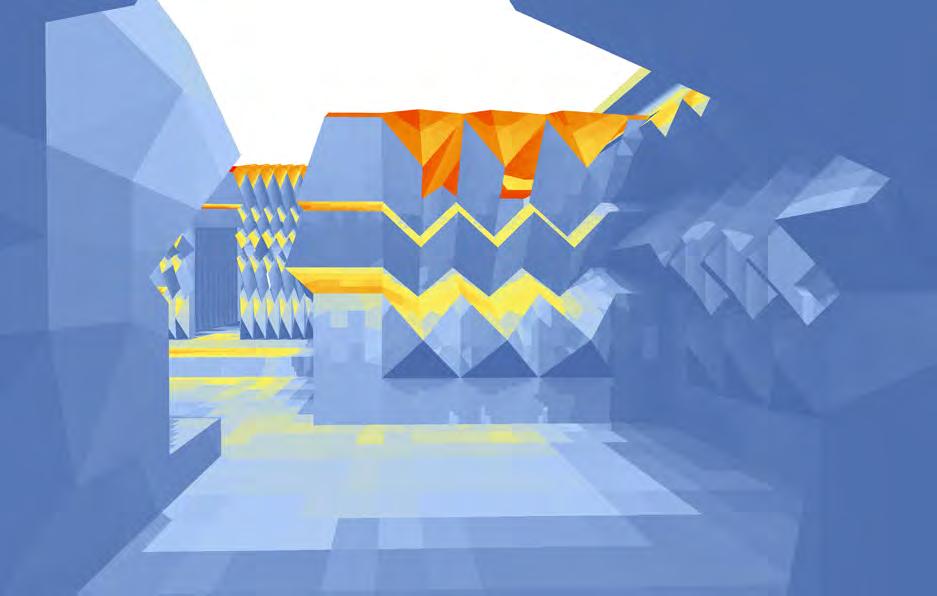

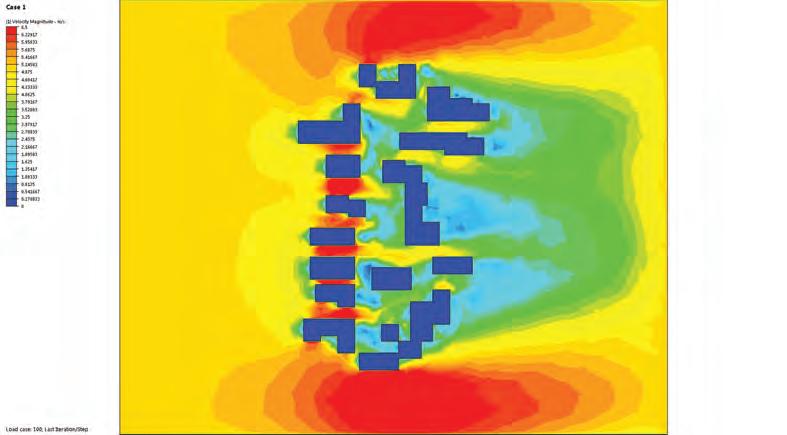

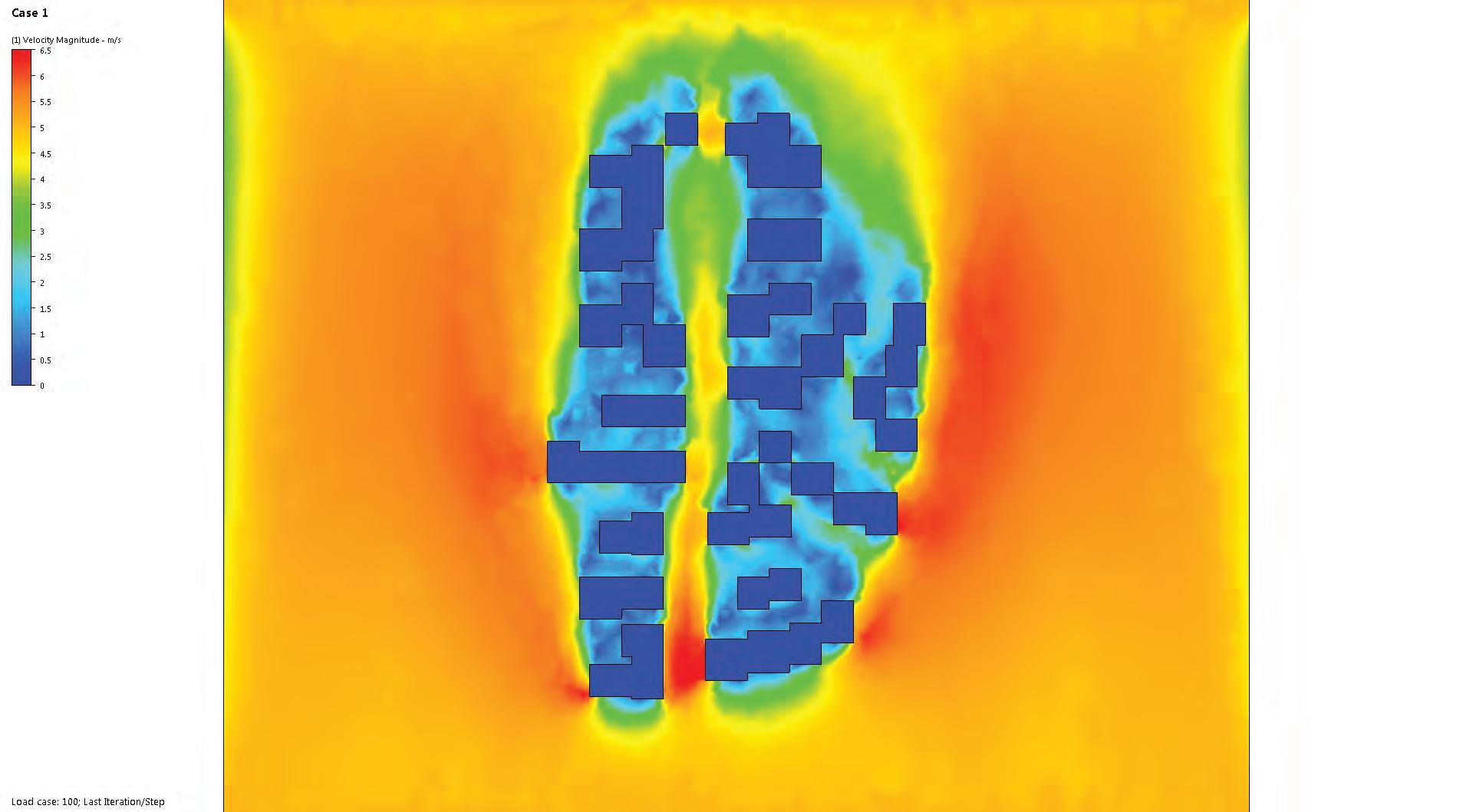

After ensuring a surface’s structural performance, its response to environmental inputs is studied. The manipulation of the pattern’s geometrical parameters and its effect on comfort levels is studied in terms of the levels of natural lighting in the interior, the effect of self-shading on its surface and its response to wind.

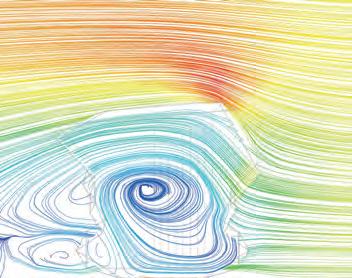

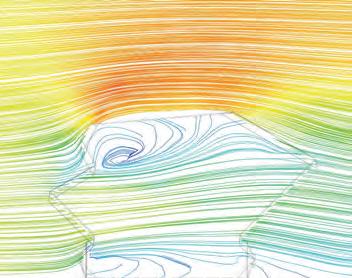

The tools that will be used are computational fluid dynamics analysis (CFD) for the response to wind, a daylight analysis to calculate the daylight factor for an overcast sky and the environmental plug-in LadyBug for Grasshopper which runs in Rhino to study self-shading.

ENVIRONMENTAL PERFORMANCE

FABRICATION FOR LOW-TECH ASSEMBLY MATERIAL SYSTEM POTENTIAL

DIGITAL SIMULATION PHYSICAL EXPERIMENTS PRECEDENT EXAMPLES

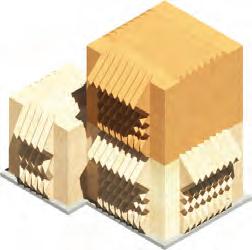

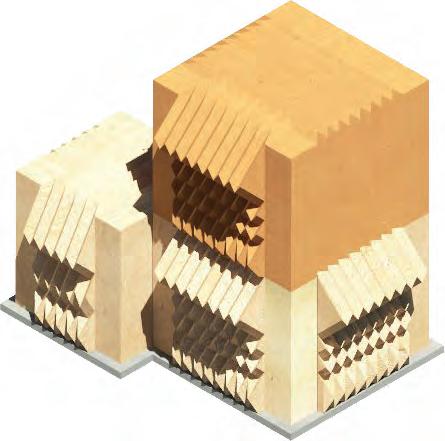

At this stage the surfaces will be studied in combinations within a range of habitable room dimensions. The environmental performance of these will be evaluated in terms of their response to wind, the daylight factor and the self-shading effect to establish a combinatorial logic. The surface combinations will be correlated with the spatial effects produced.

A unit will be developed with inputs from the social structure of Dharavi and structural and environmental limits set. An evaluation for environmental factors for a unit will reveal the extent to which it’s behaviour corresponds to the target values set and provide inputs for revisions.

A kit of modular components consisting of specialised surfaces like structural and ventilation faces with a range of variations for spatial effects, with a system of standardised connections will be established which will allow for an efficient assembly of a unit.

The production line for the fabrication of the material system components will be established clearly defining the industrial and manual processes involved.

Variations of cardboard treatment for different lifespans of material system will be established through a review of the precedent techniques for construction using corrugated cardboard. This will enable an incremental growth and expansion of the unit with respect to the user needs.

3.3 TOOLS 48 RESPONSIVE GROWTH SYSTEM UNIT

49 METHODS

CLUSTER

URBAN CHARACTER ANALYSIS

PHYSICAL ORGANISATION NETWORK ANALYSIS

DATA ANALYSIS

DIGITAL SIMULATION

Three distinct fabrics will be analysed to extract the principles of spatial organisation at three scales: unit, cluster and neighbourhood. At each scale, the urban fabric is quantified in terms of built-open relationship and open space hierarchy. The dimensions, ratios and physical characters are documented in order to understand the existing diversity in the fabric.

These studies along with the existing network hierarchy for the neighbourhood and an environmental analysis of the open spaces will help identify the characters that need to be retained to inform the urban growth simulation and those which need to be changed or avoided or added to.

Analysis using graph theory will help understand the network hierarchy and its integration in the fabric, establish relatively important nodes and their relationship to the existing use of space. This analysis will be done in order to understand the efficiency of the user generated networks.

The measured quantities are closeness and betweenness centrality. Spatial analysis plug-in Decoding spaces for Grasshopper which runs in Rhino is used for network analysis.

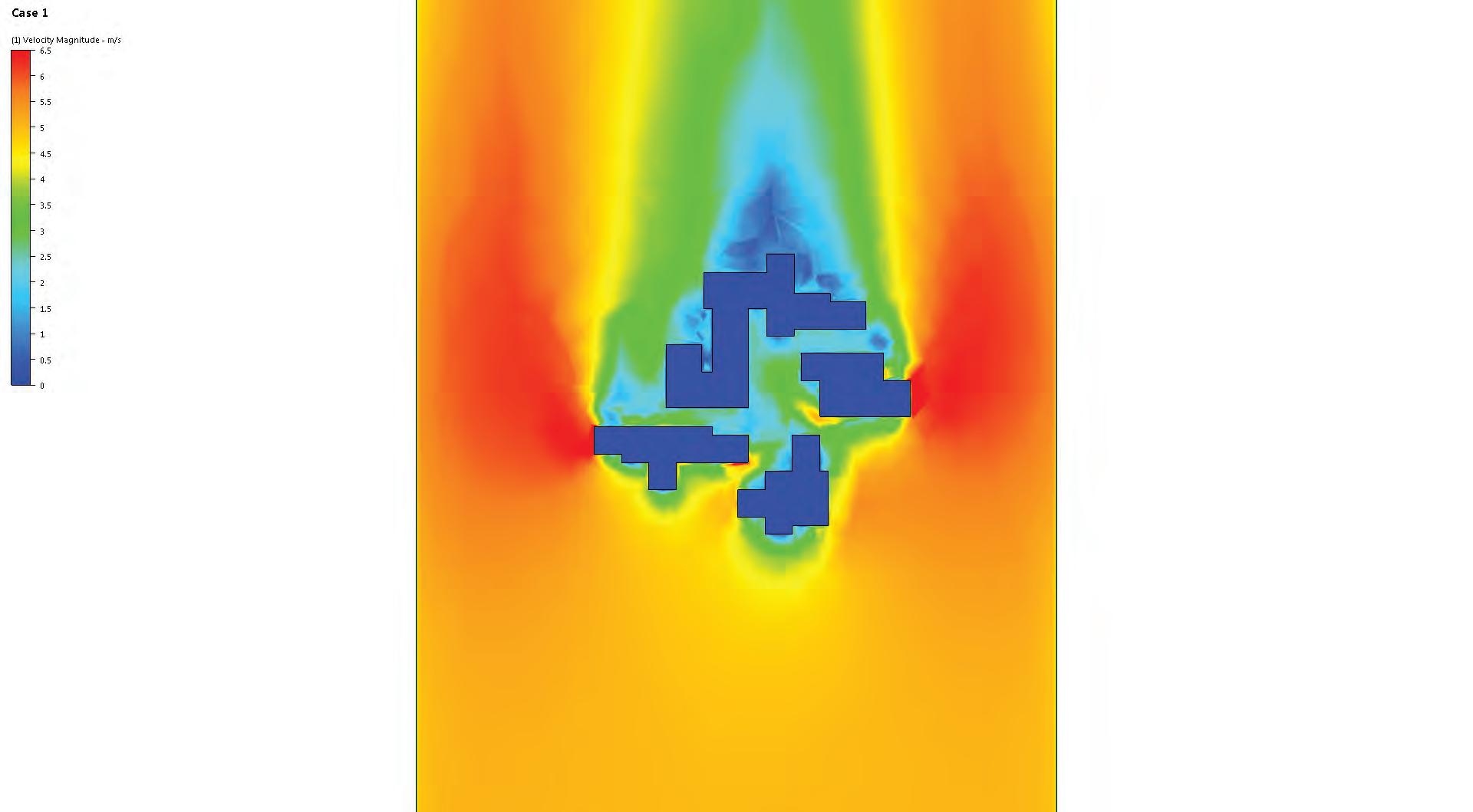

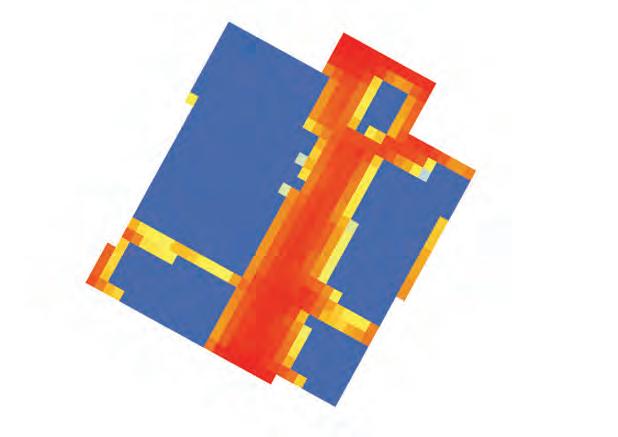

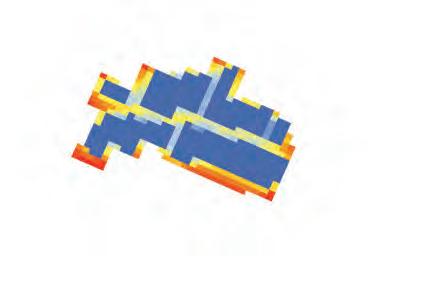

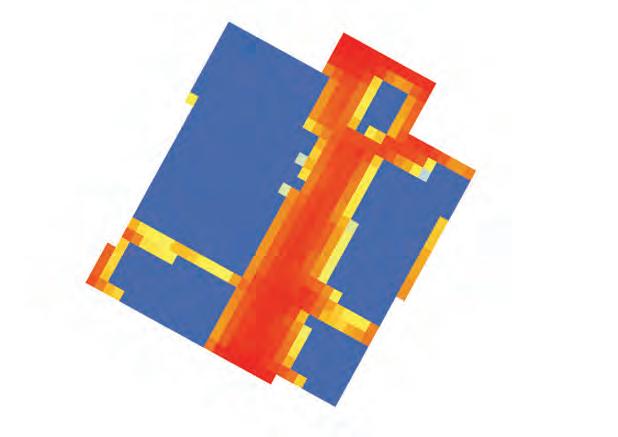

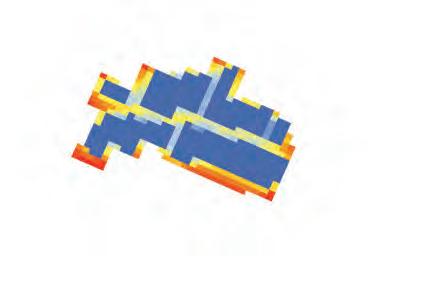

URBAN GROWTH SIMULATION

By understanding the existing aggregation rules, the urban growth will be simulated. An algorithm will be defined which will incorporate inputs from the material system and habitability constraints into the existing community’s aggregation logic. The logic is mapped out in a decision tree, with adjacency rules. Python scripting language in Rhino - Grasshopper environment will be used to write the algorithm.

This will help analyse the material system’s adaptability to generate emergent positive characters existing in the fabric. This tool will also inform the level of interventions necessary to ensure a habitability standard through the designed material system.

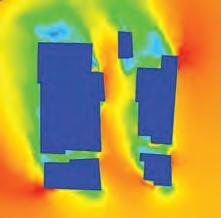

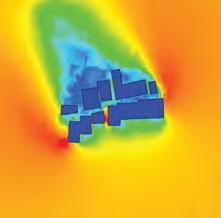

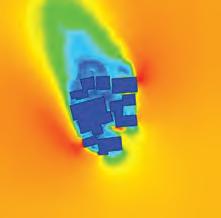

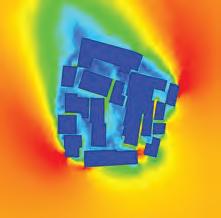

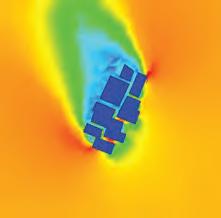

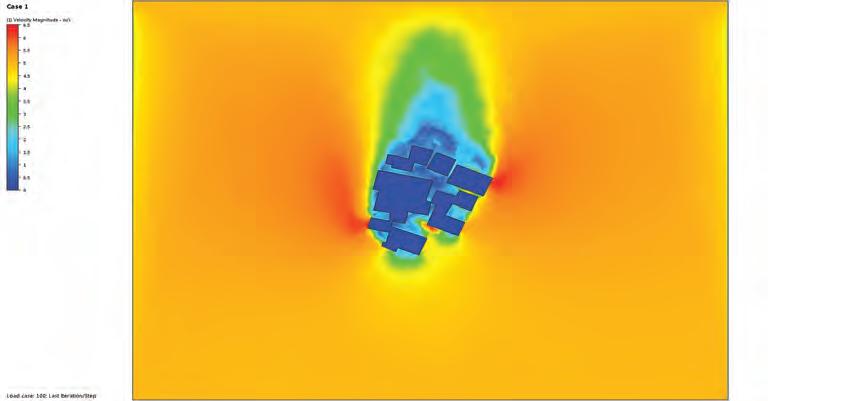

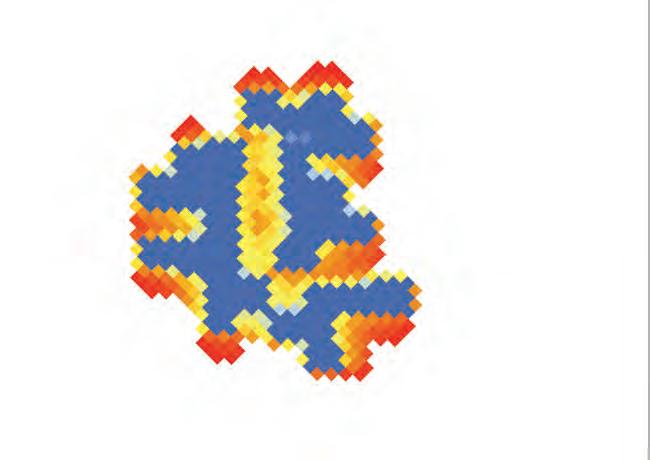

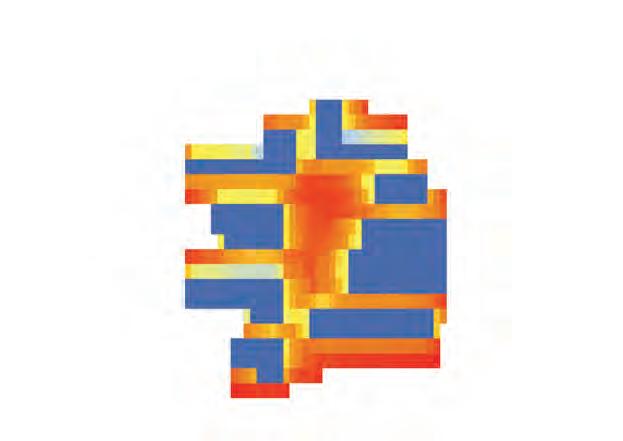

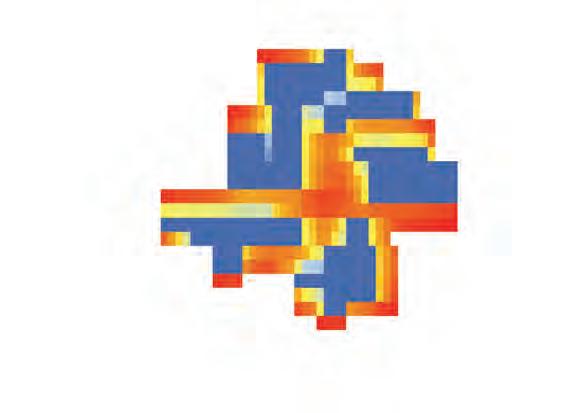

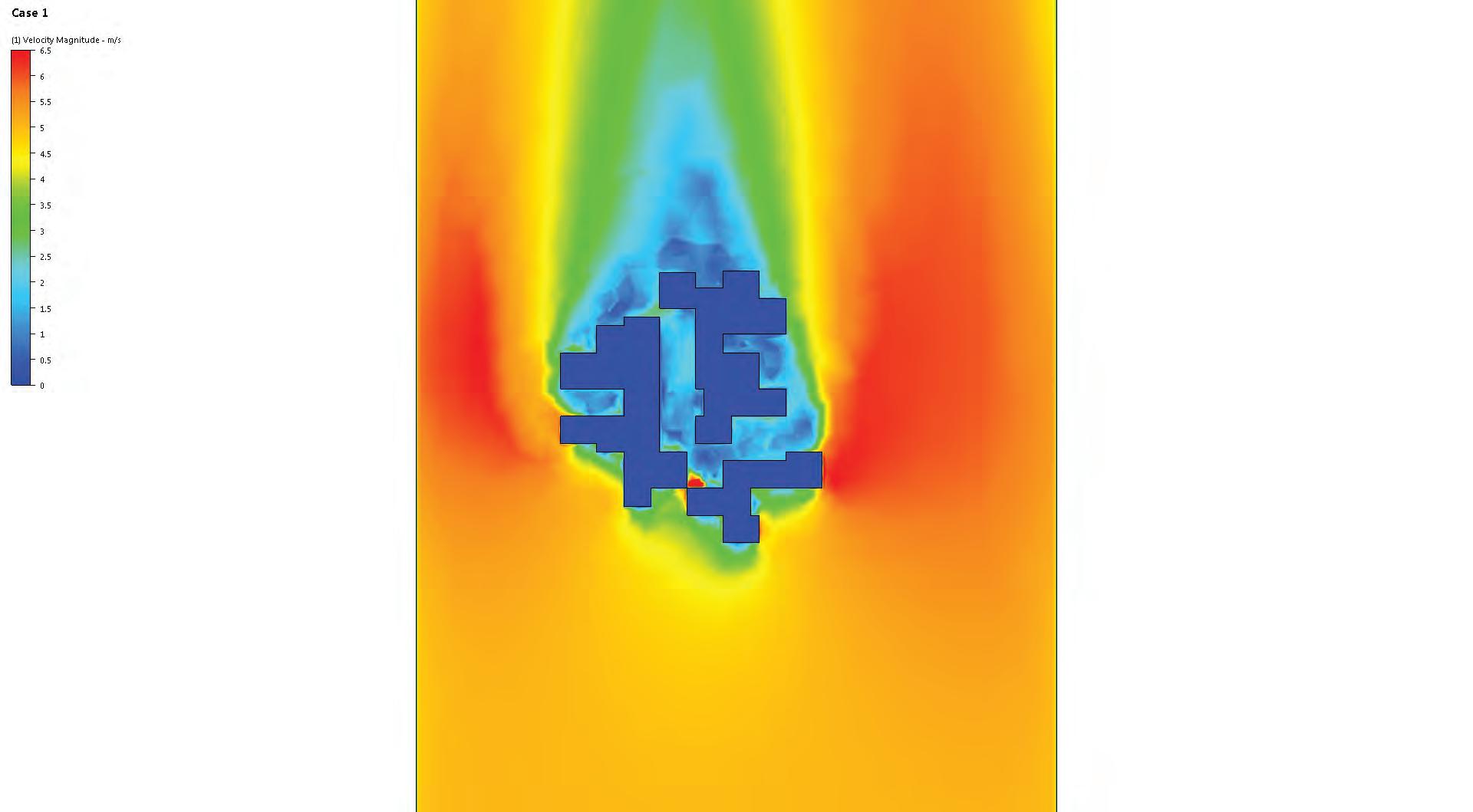

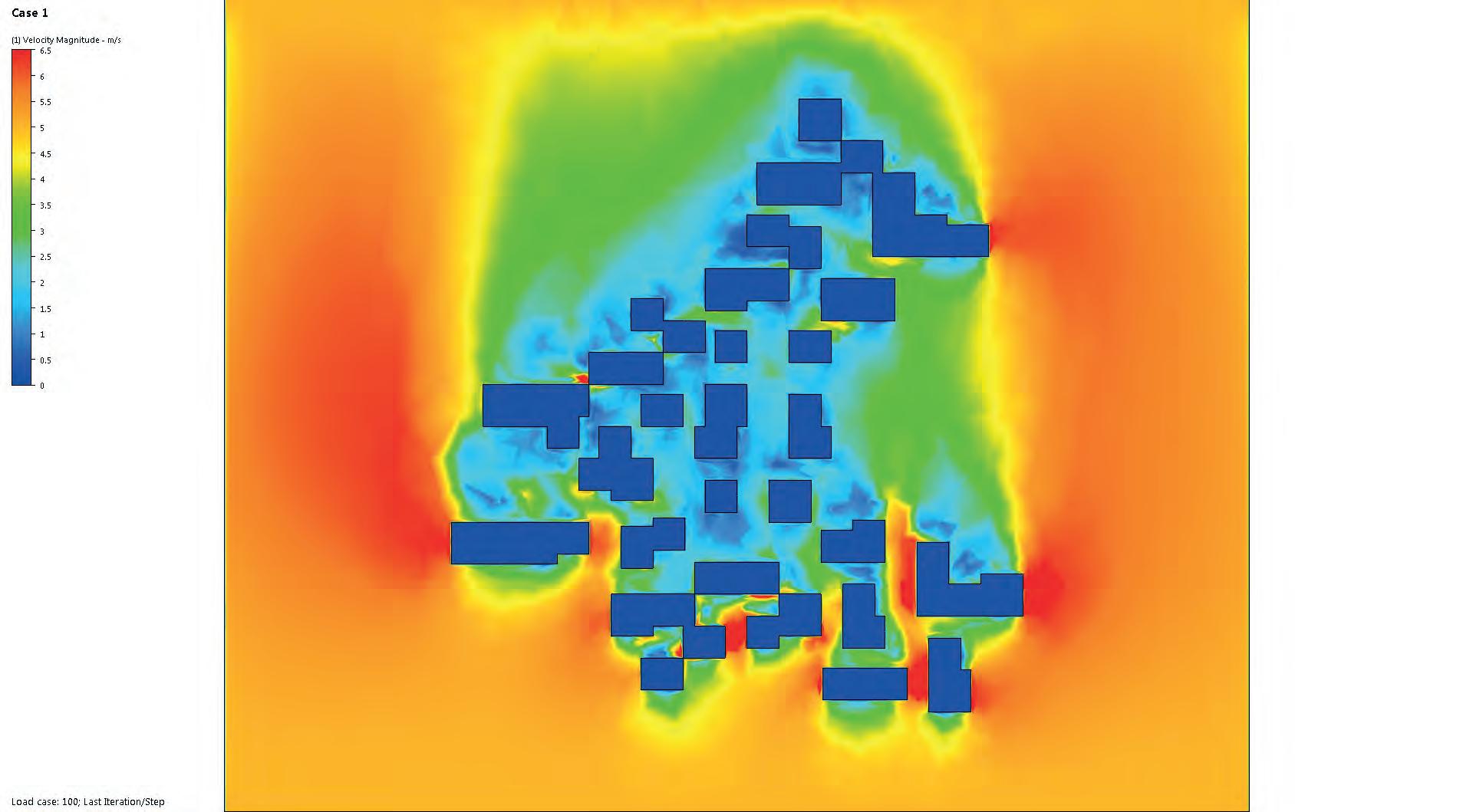

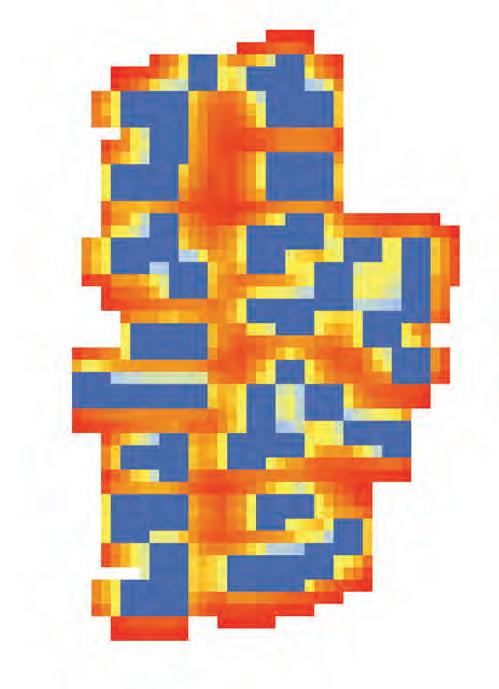

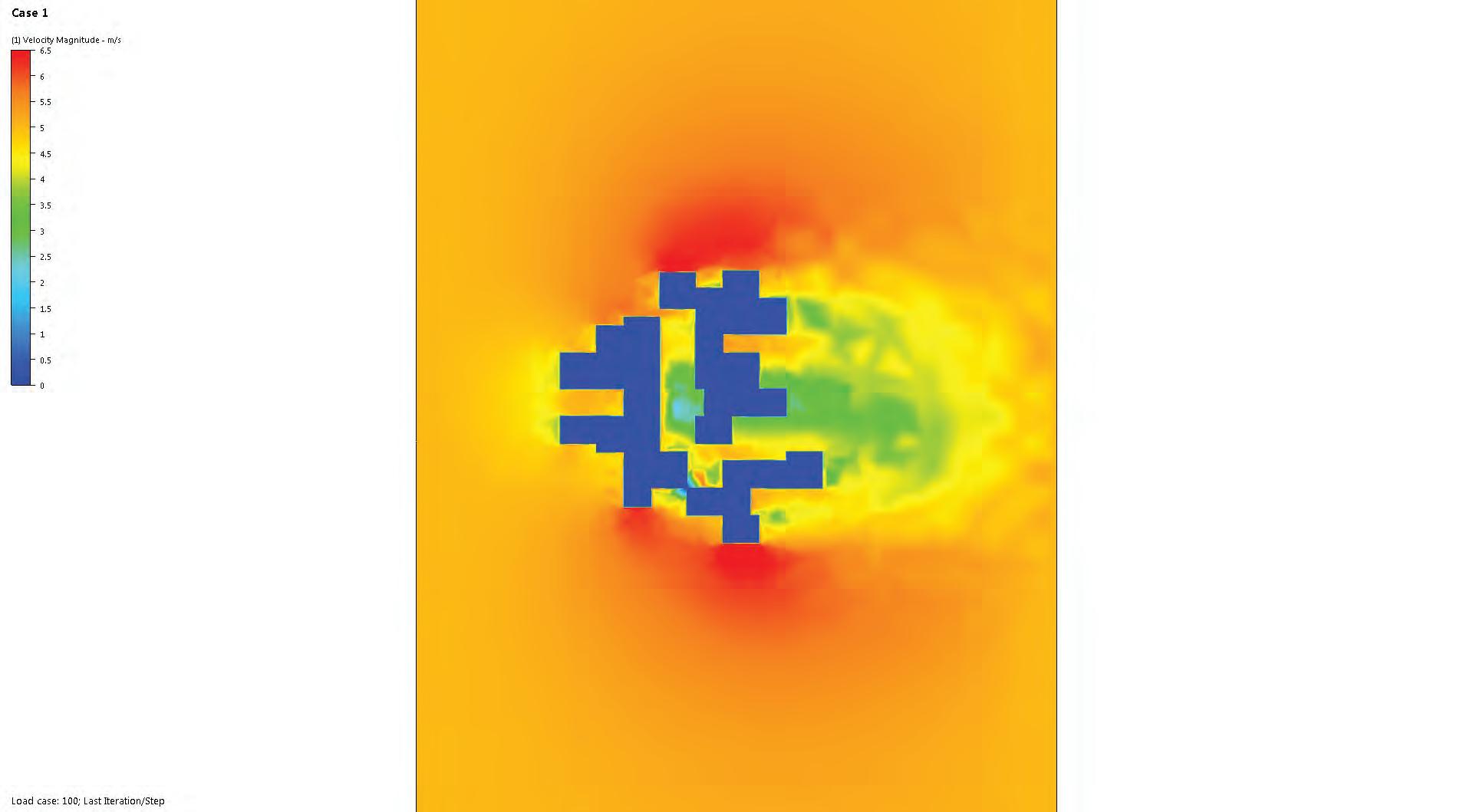

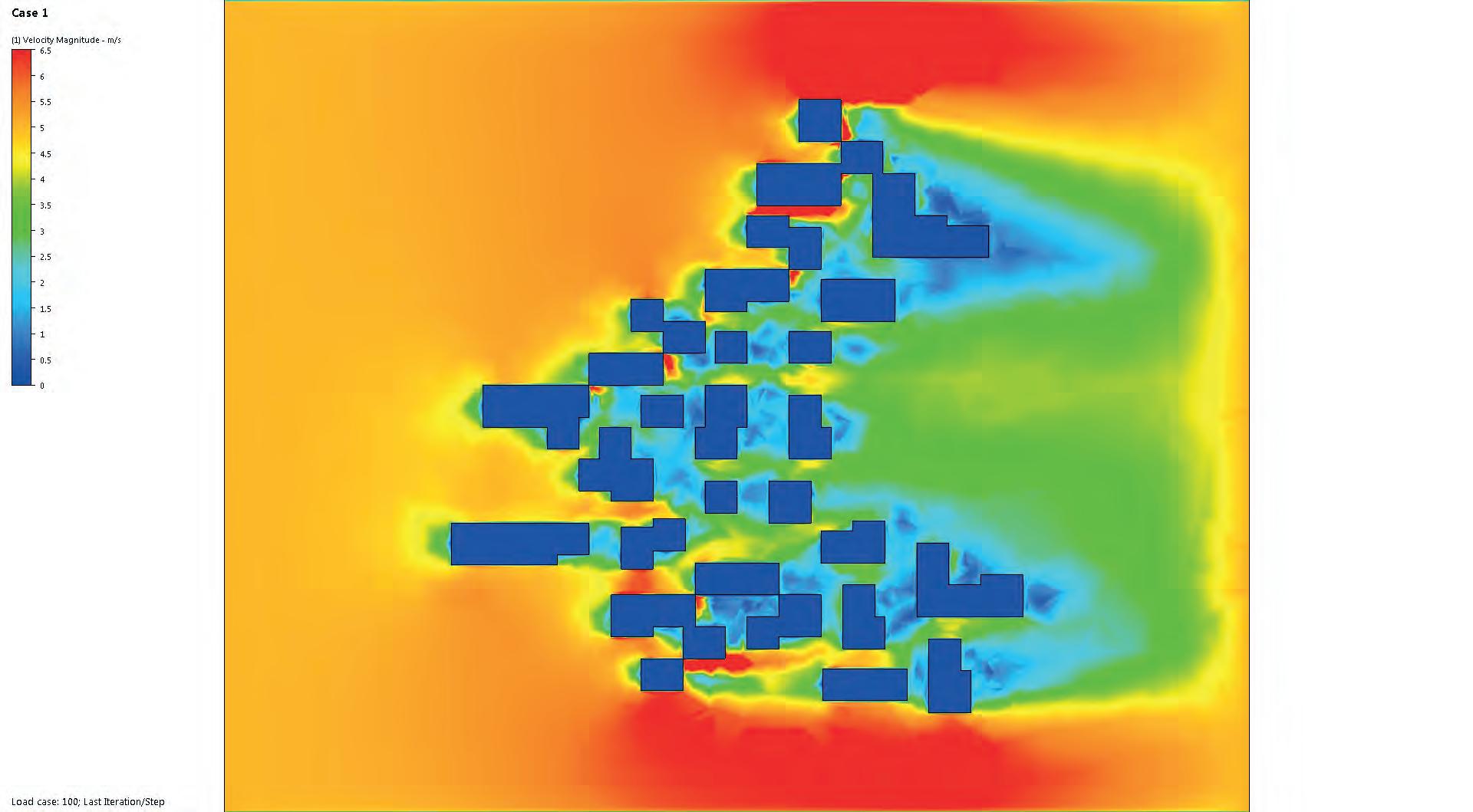

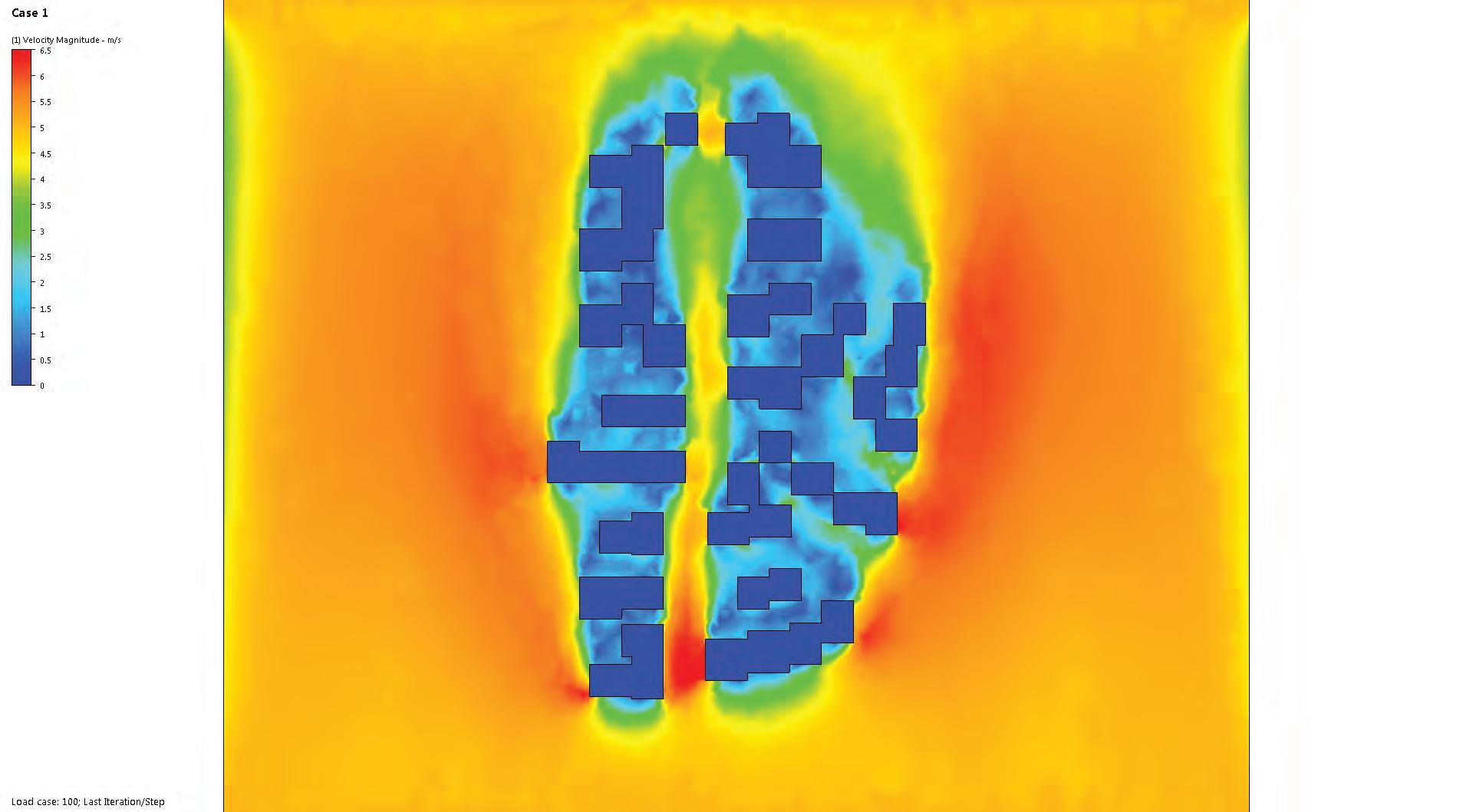

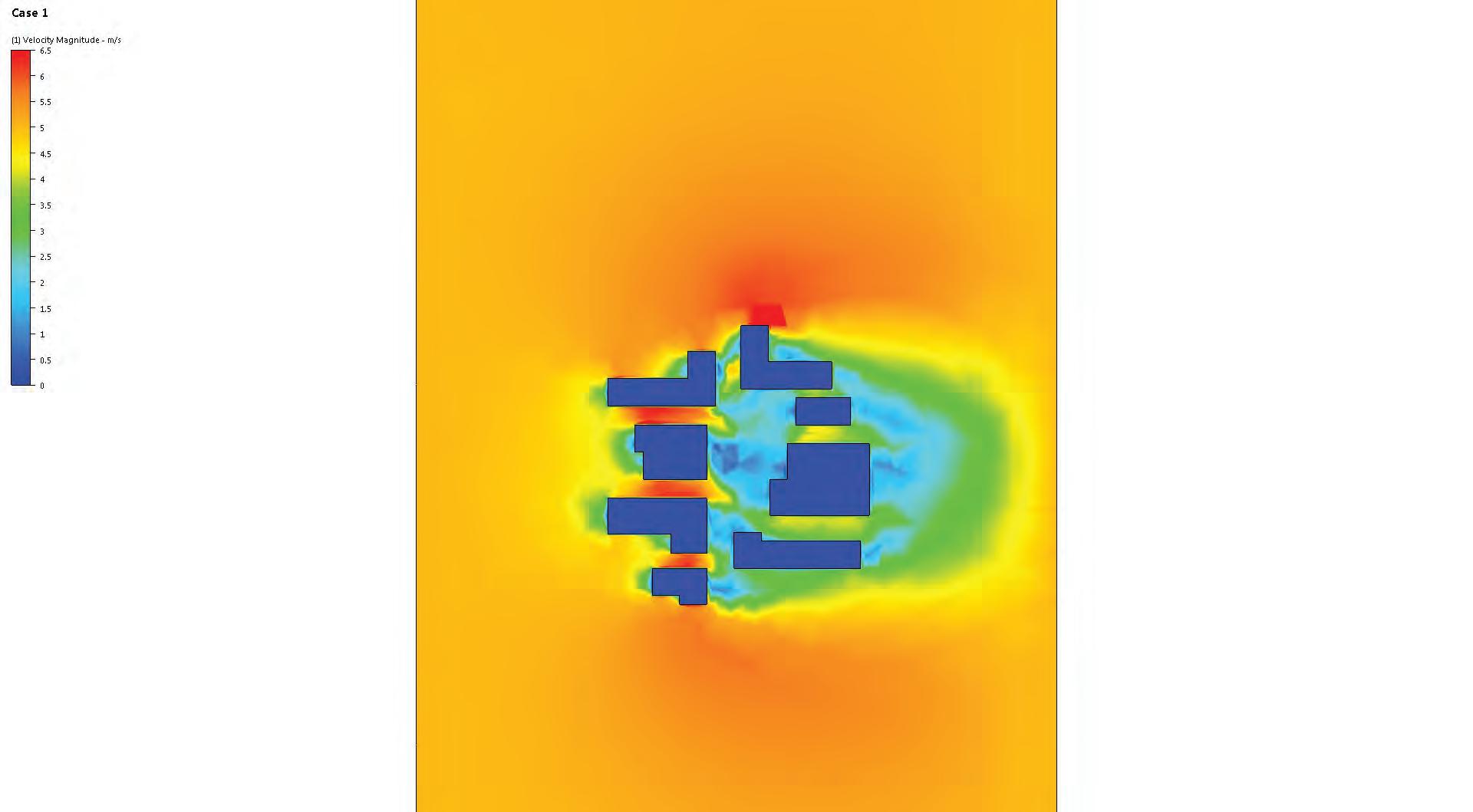

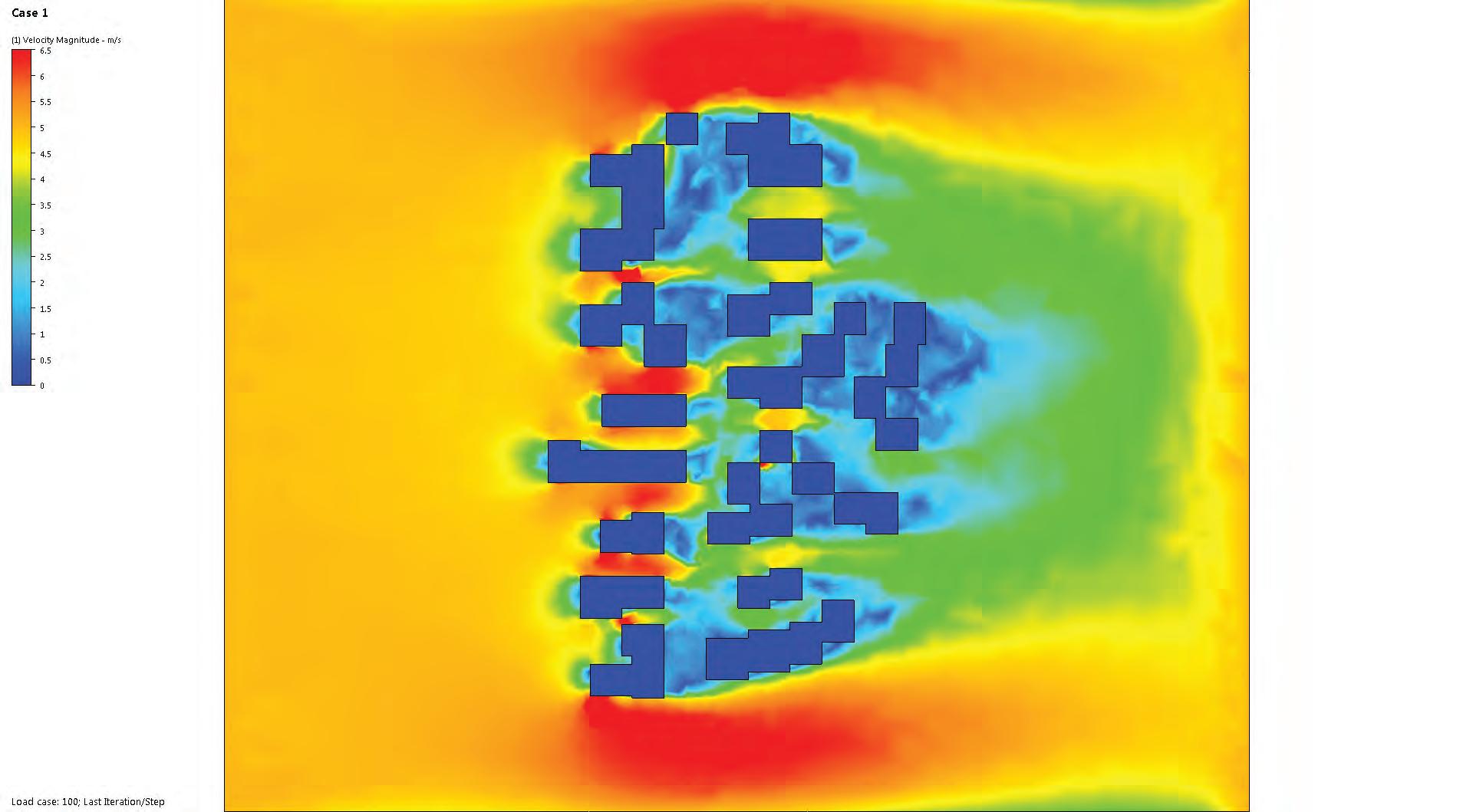

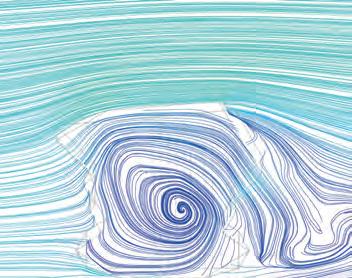

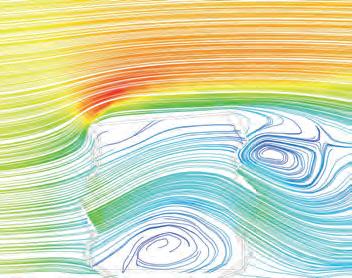

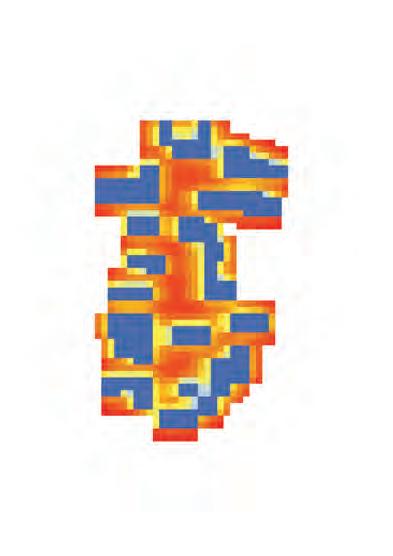

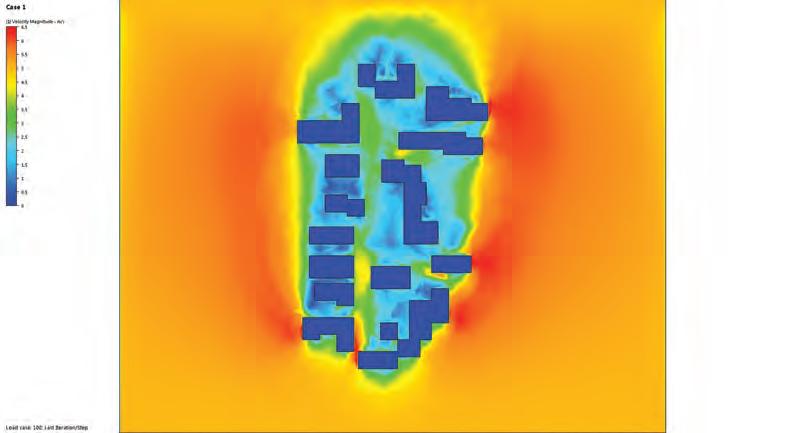

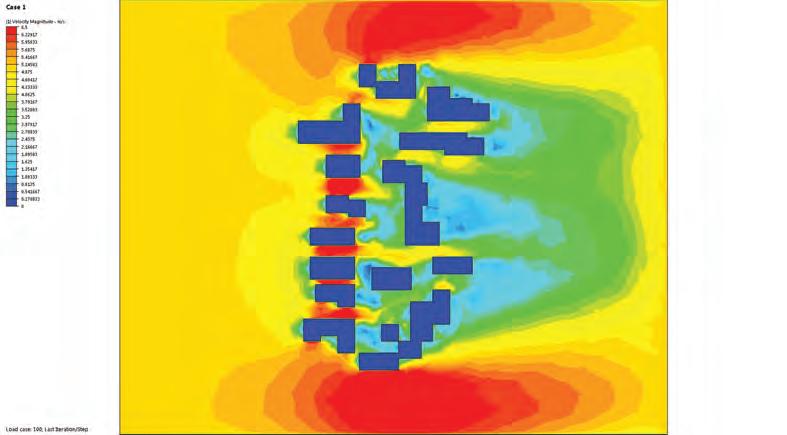

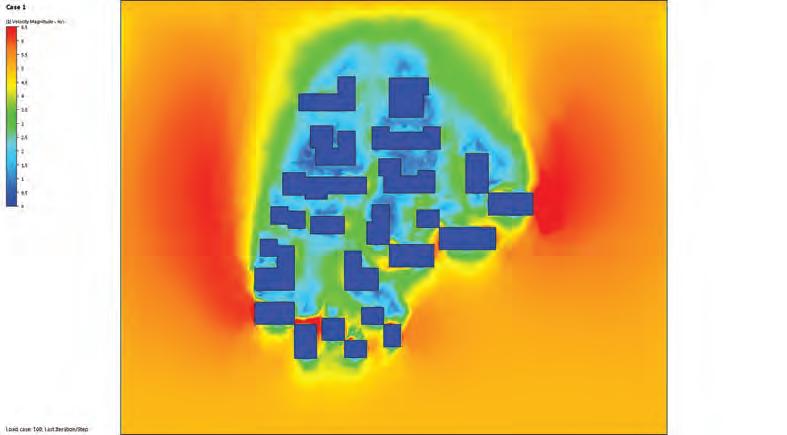

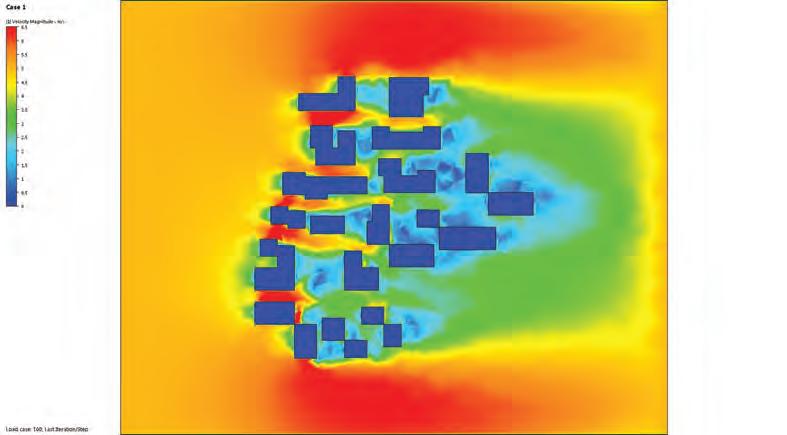

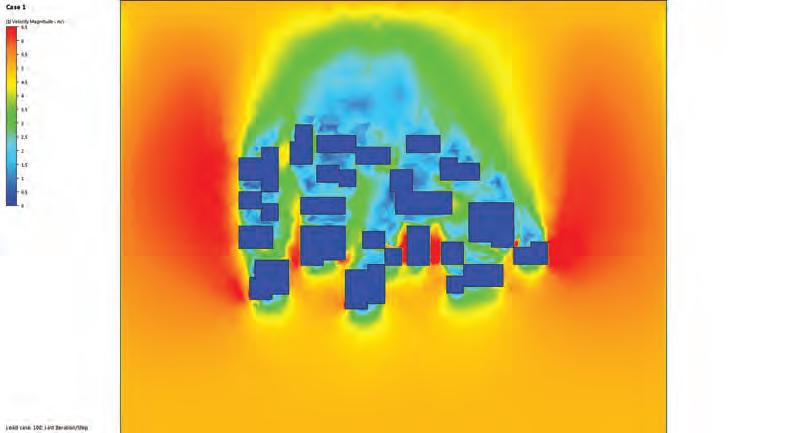

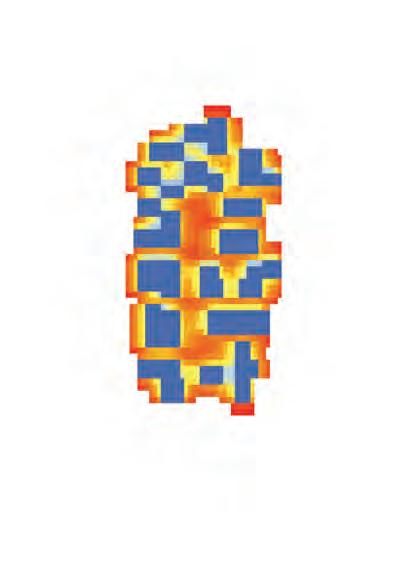

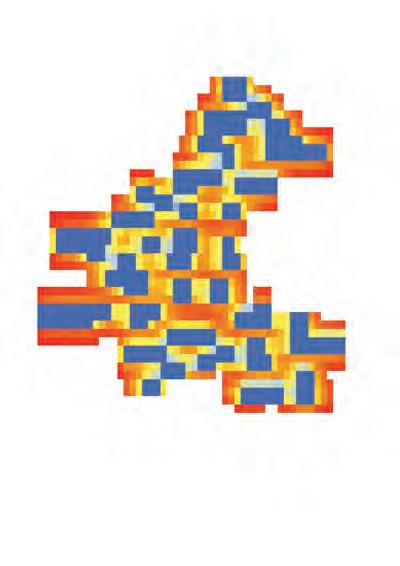

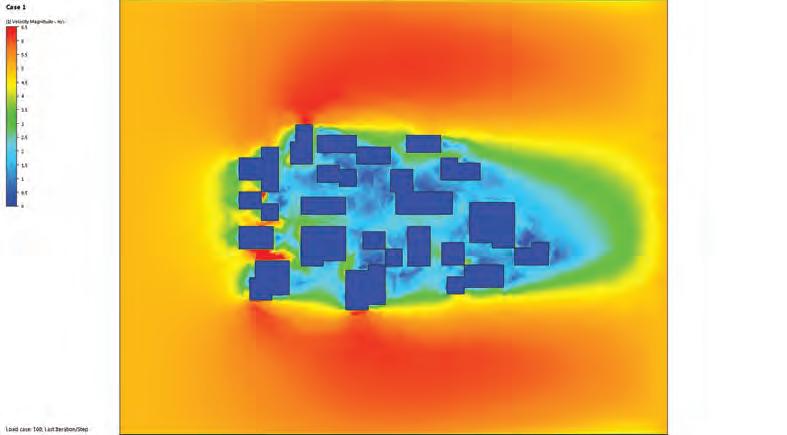

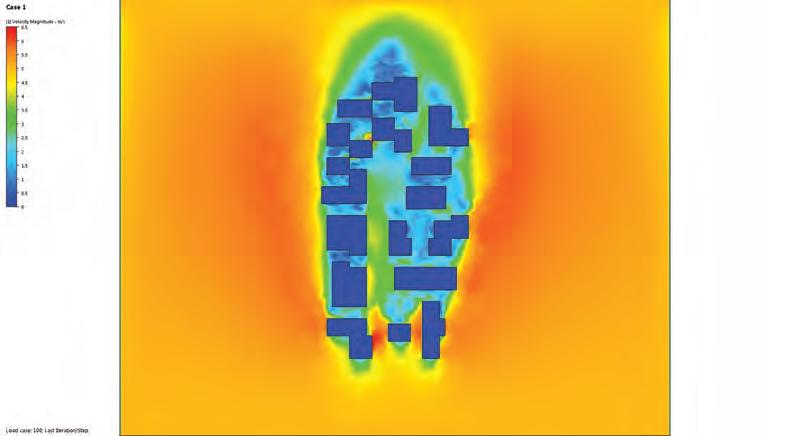

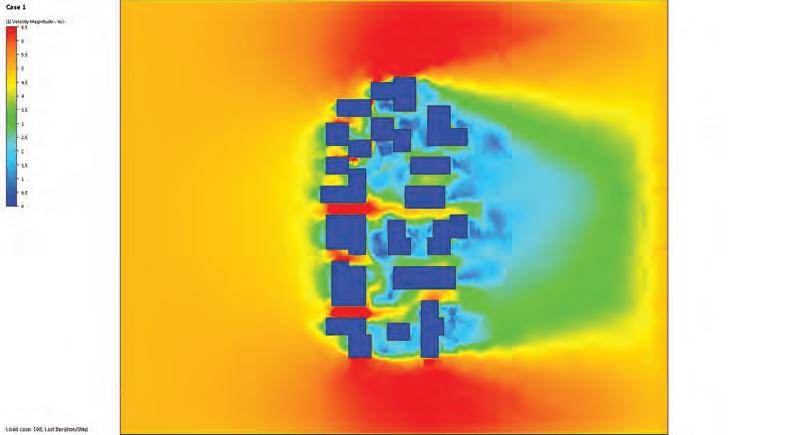

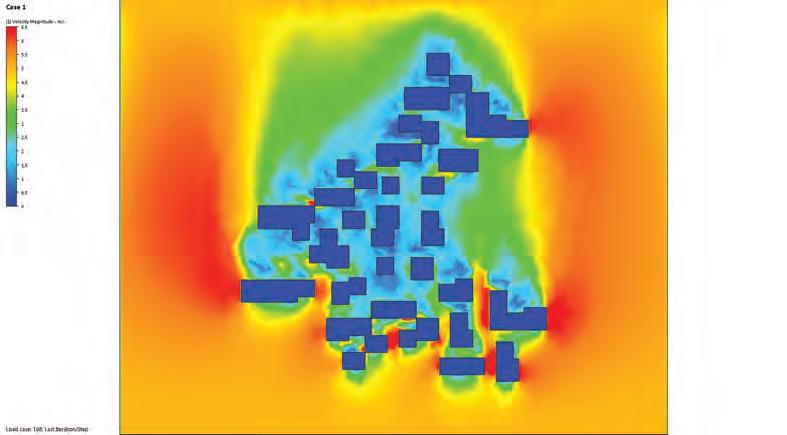

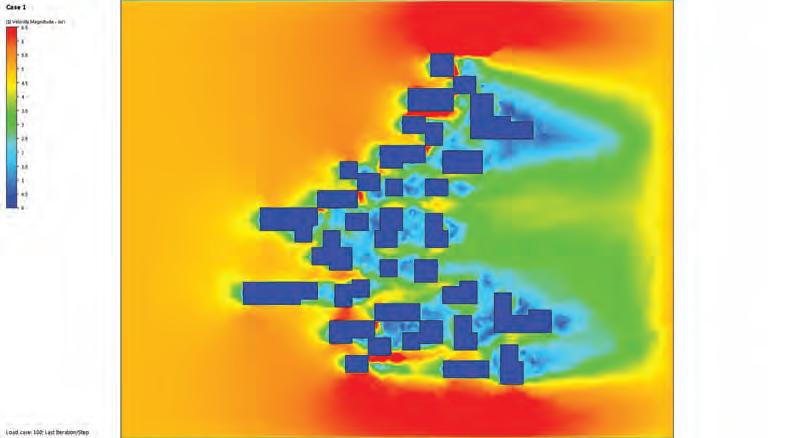

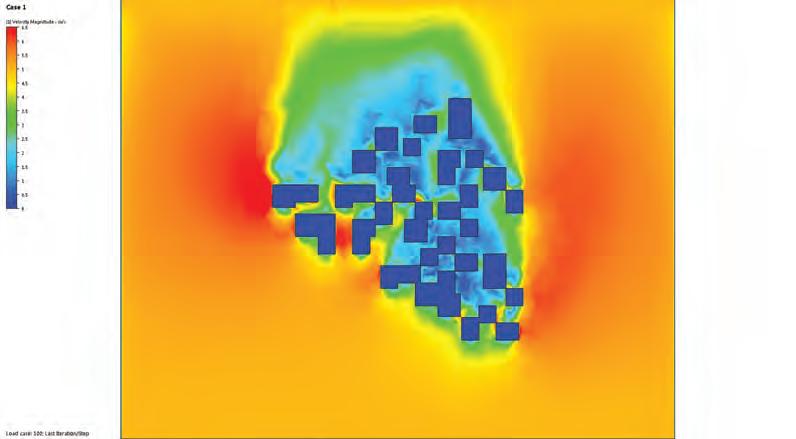

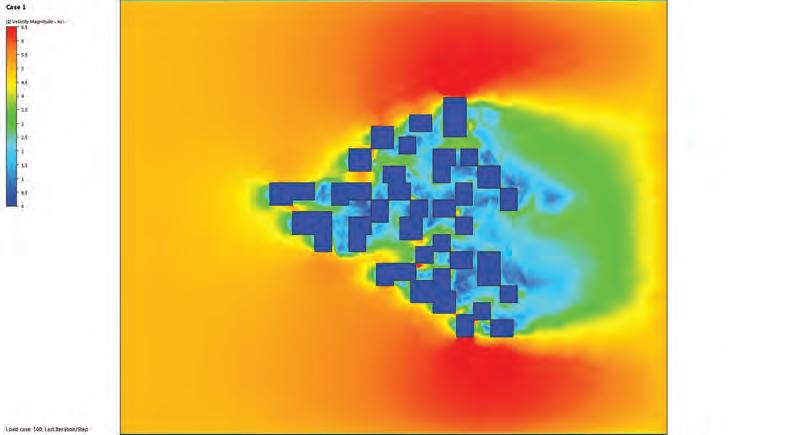

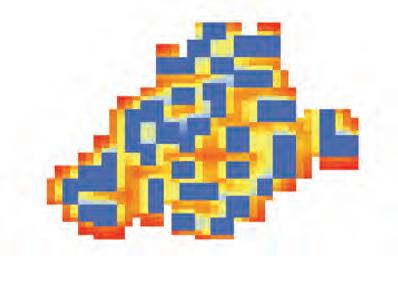

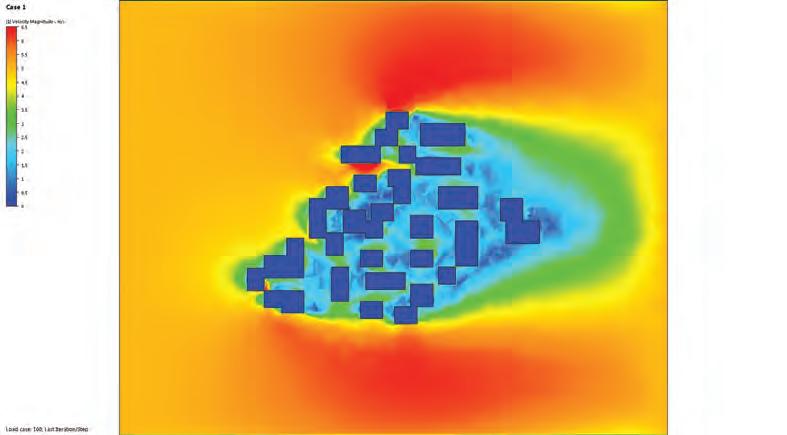

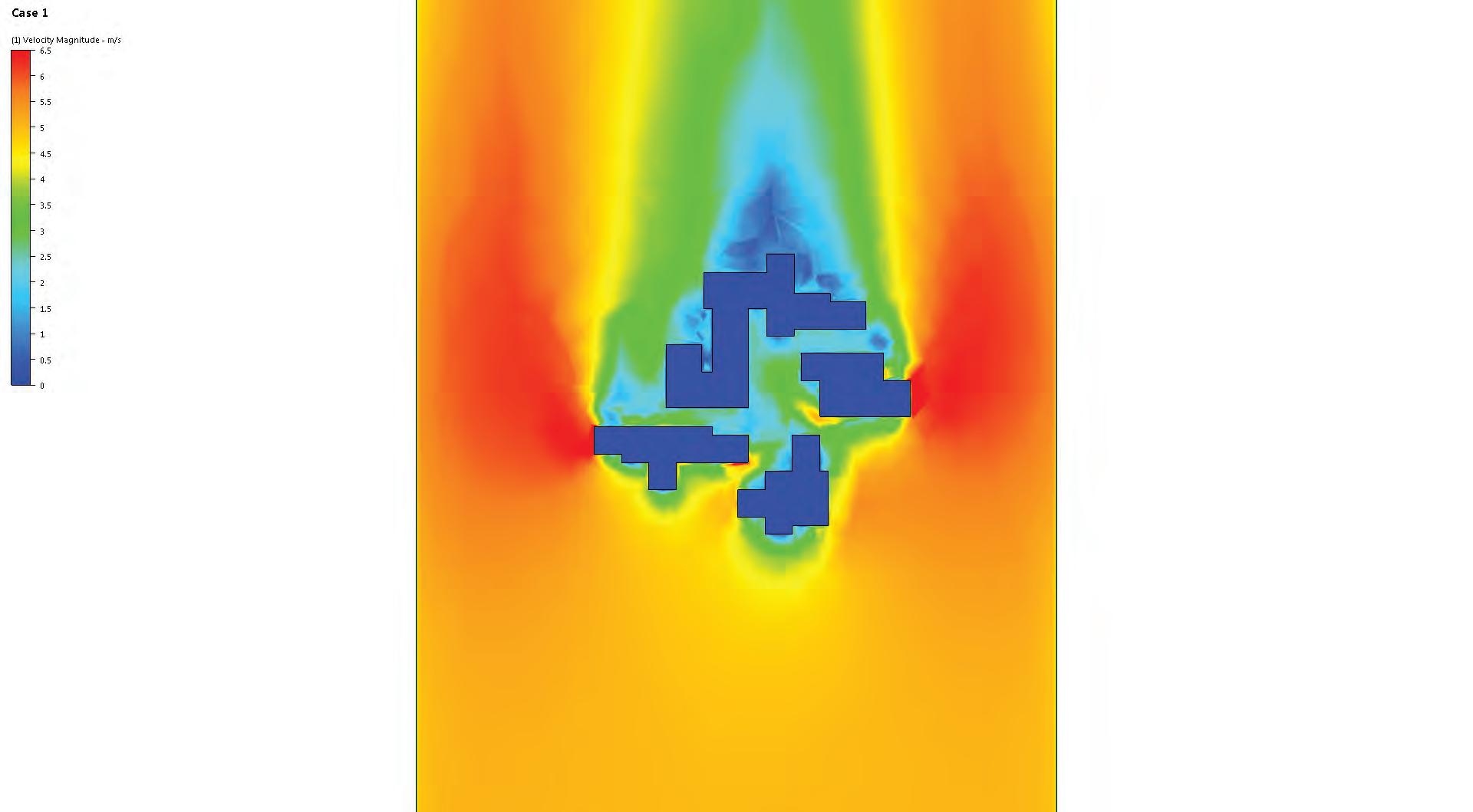

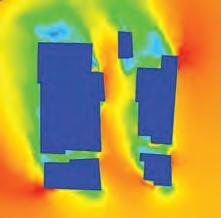

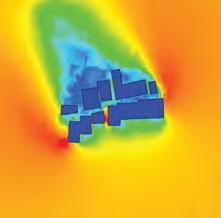

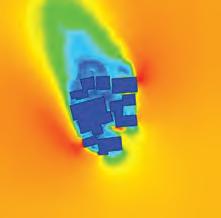

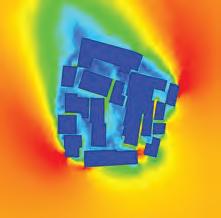

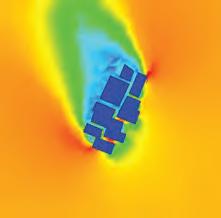

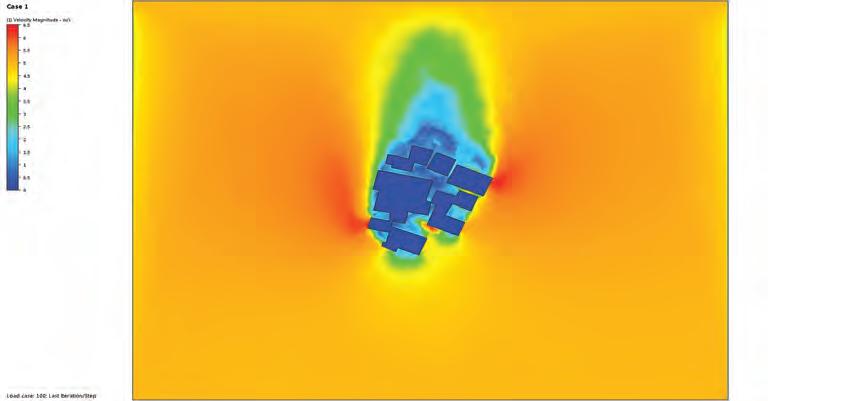

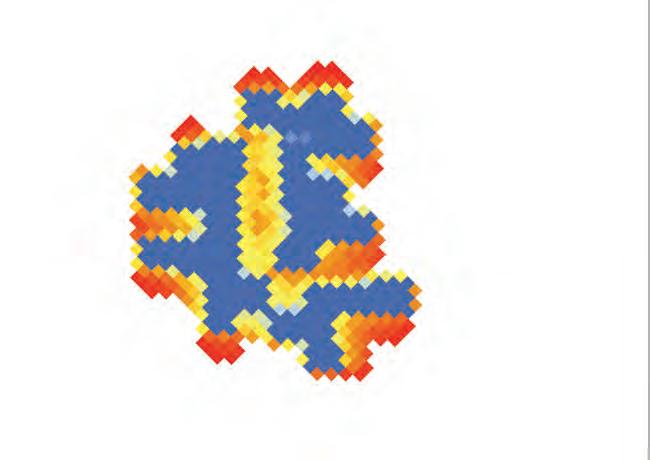

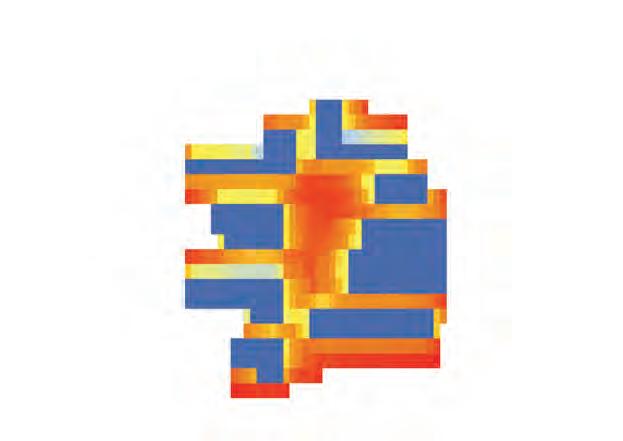

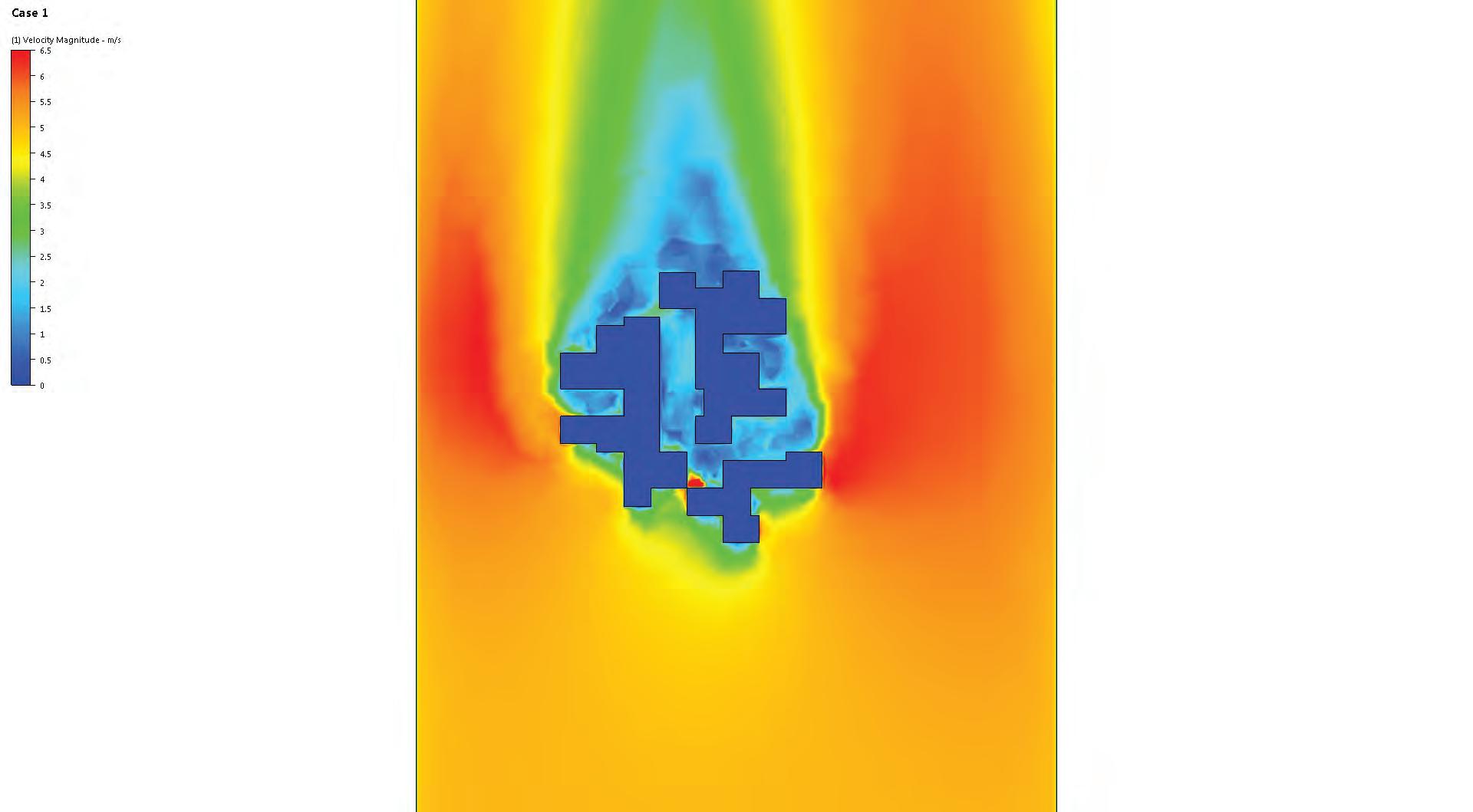

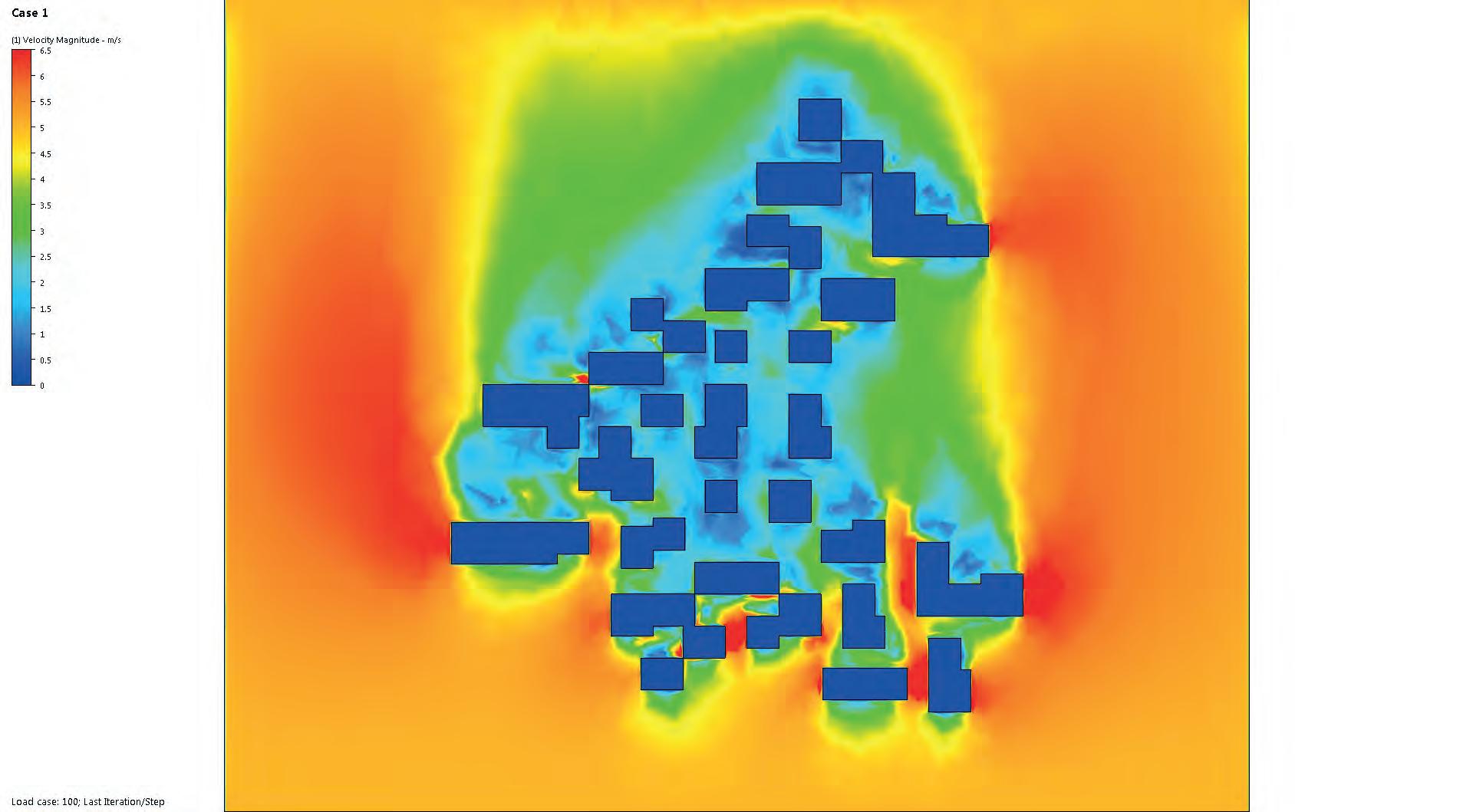

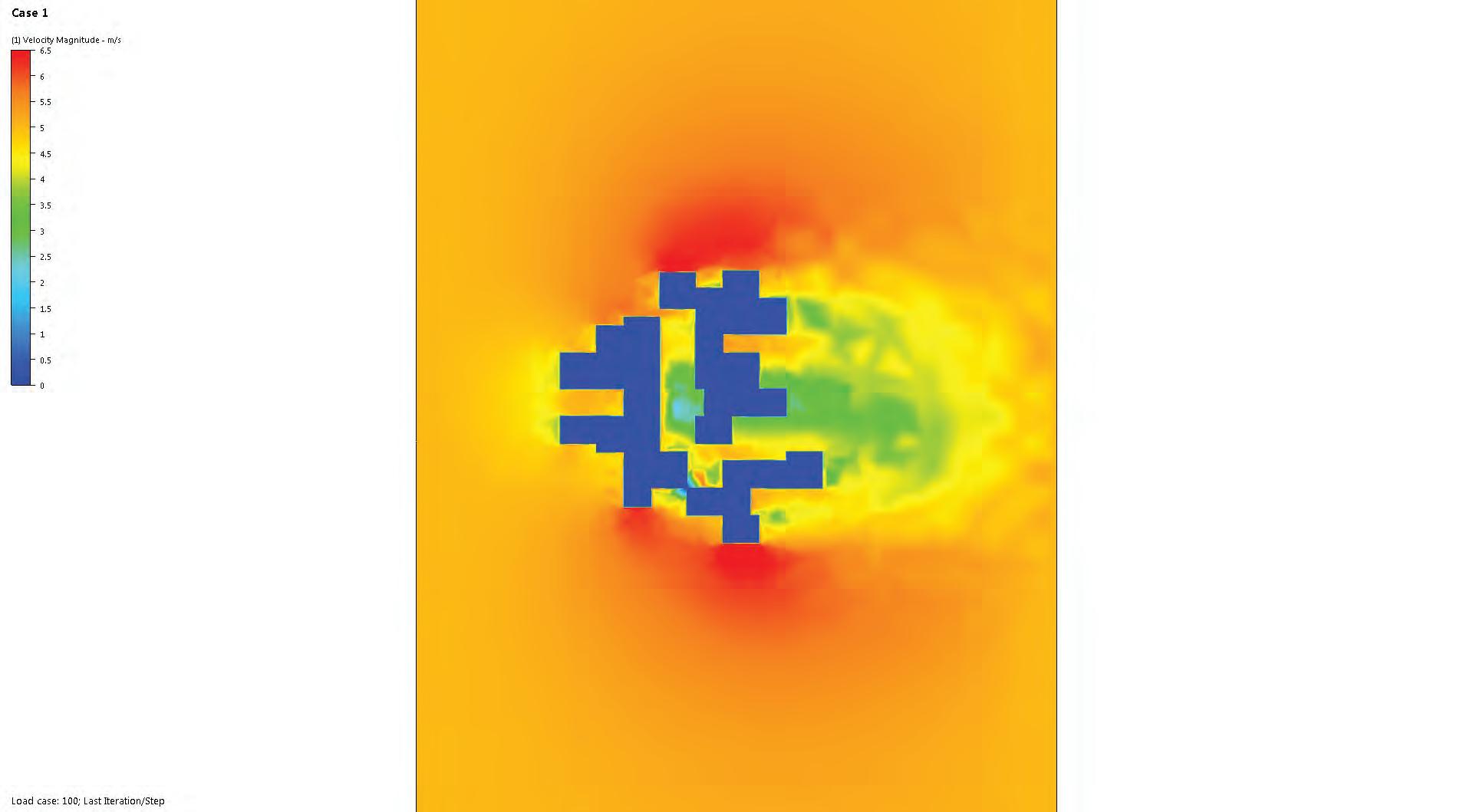

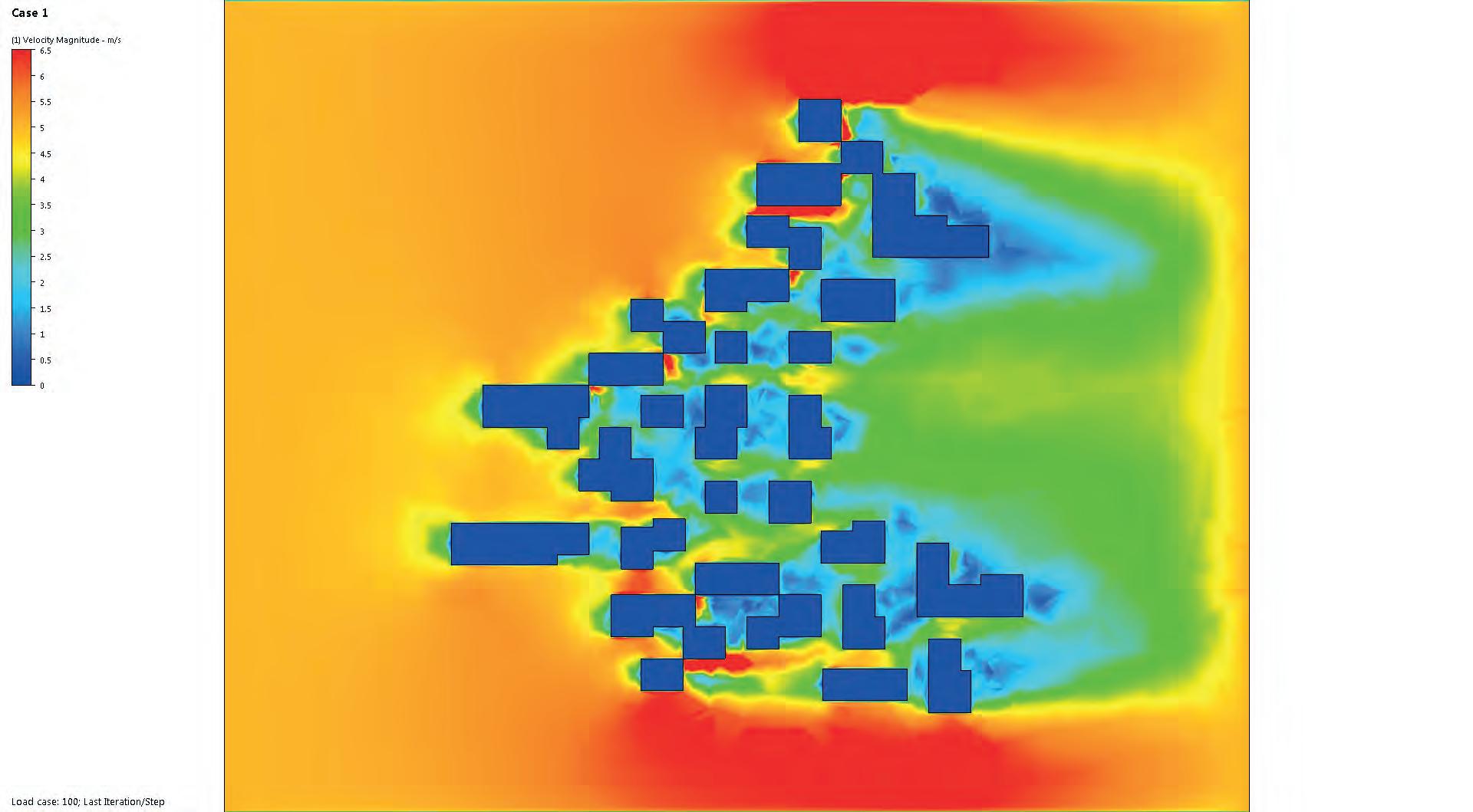

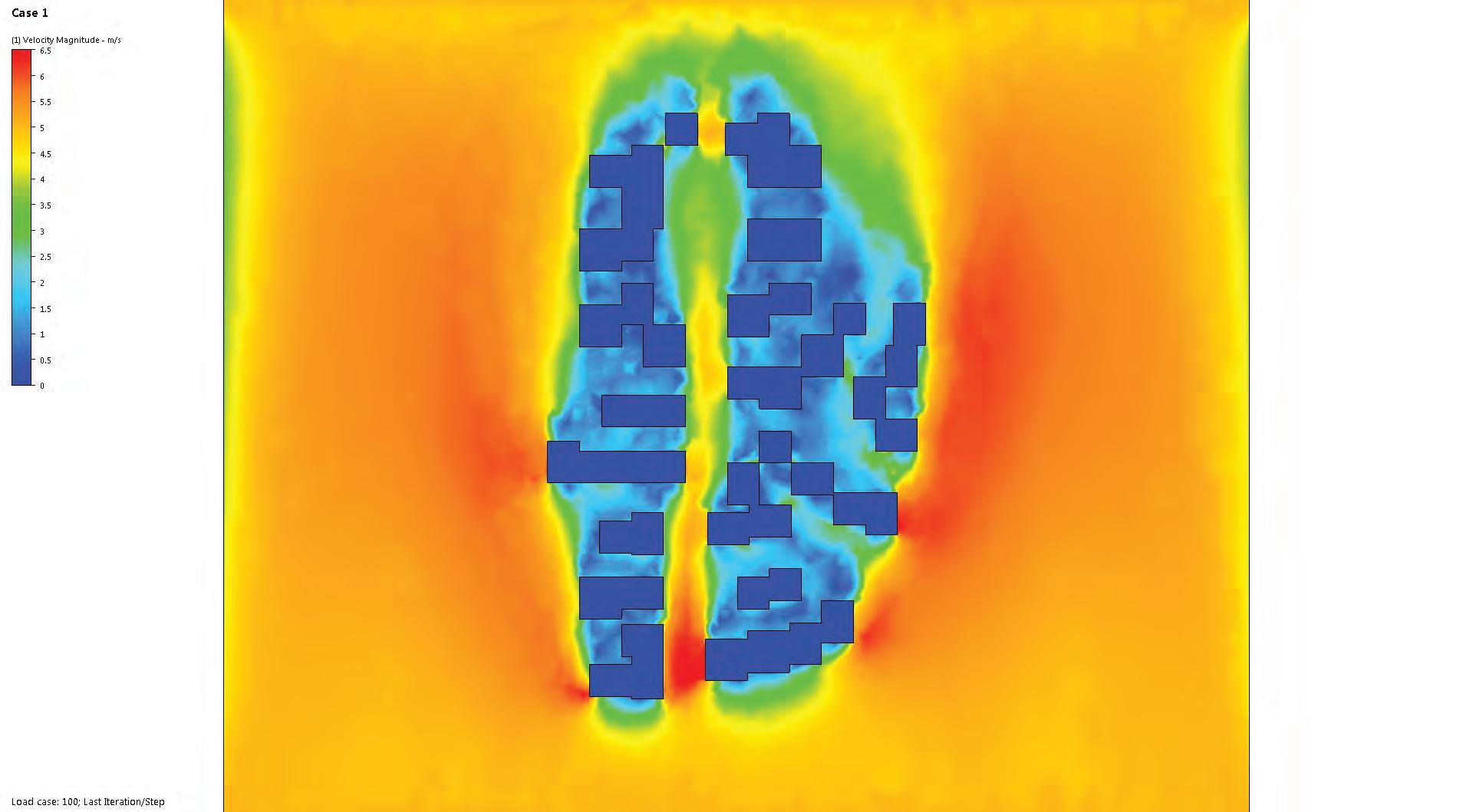

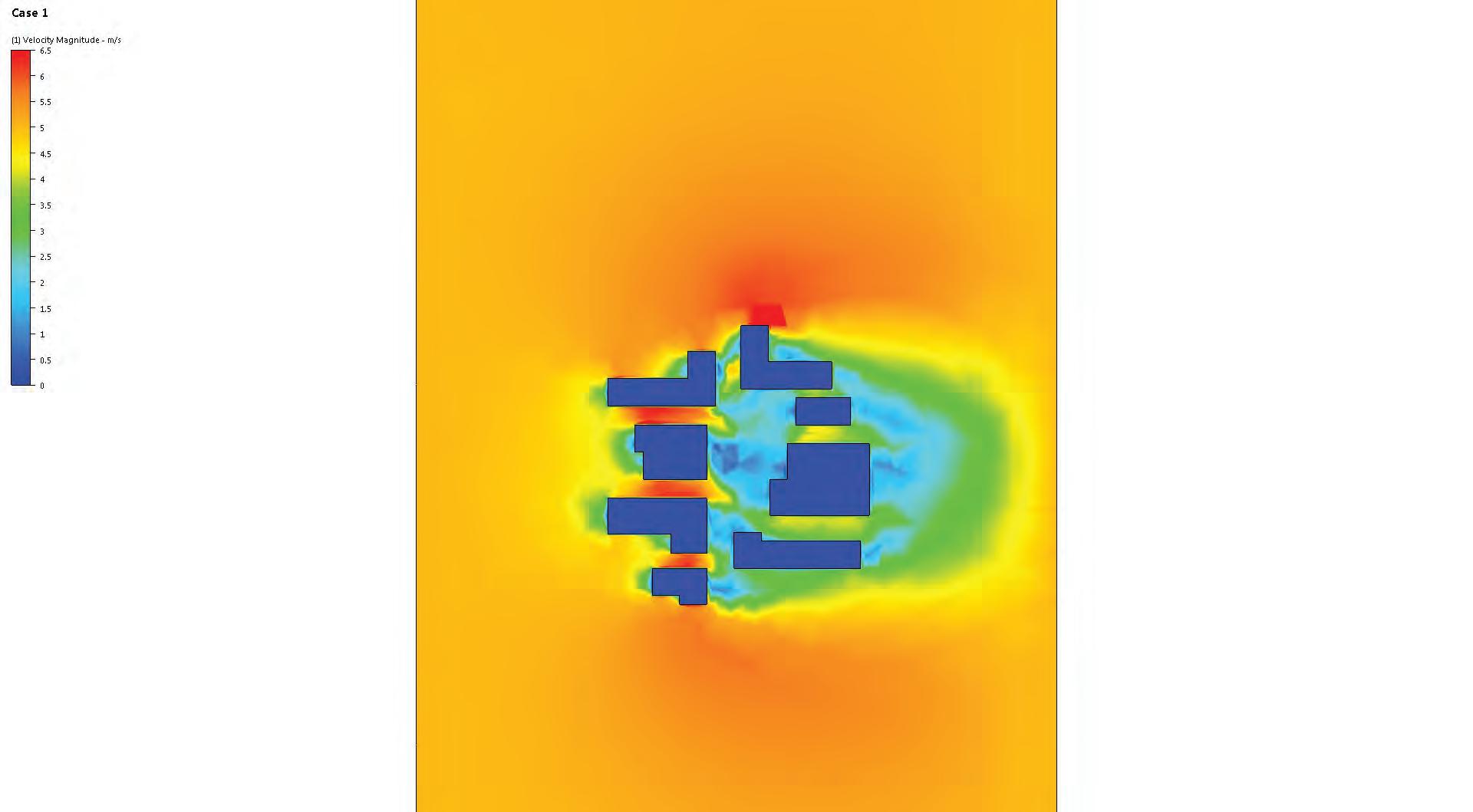

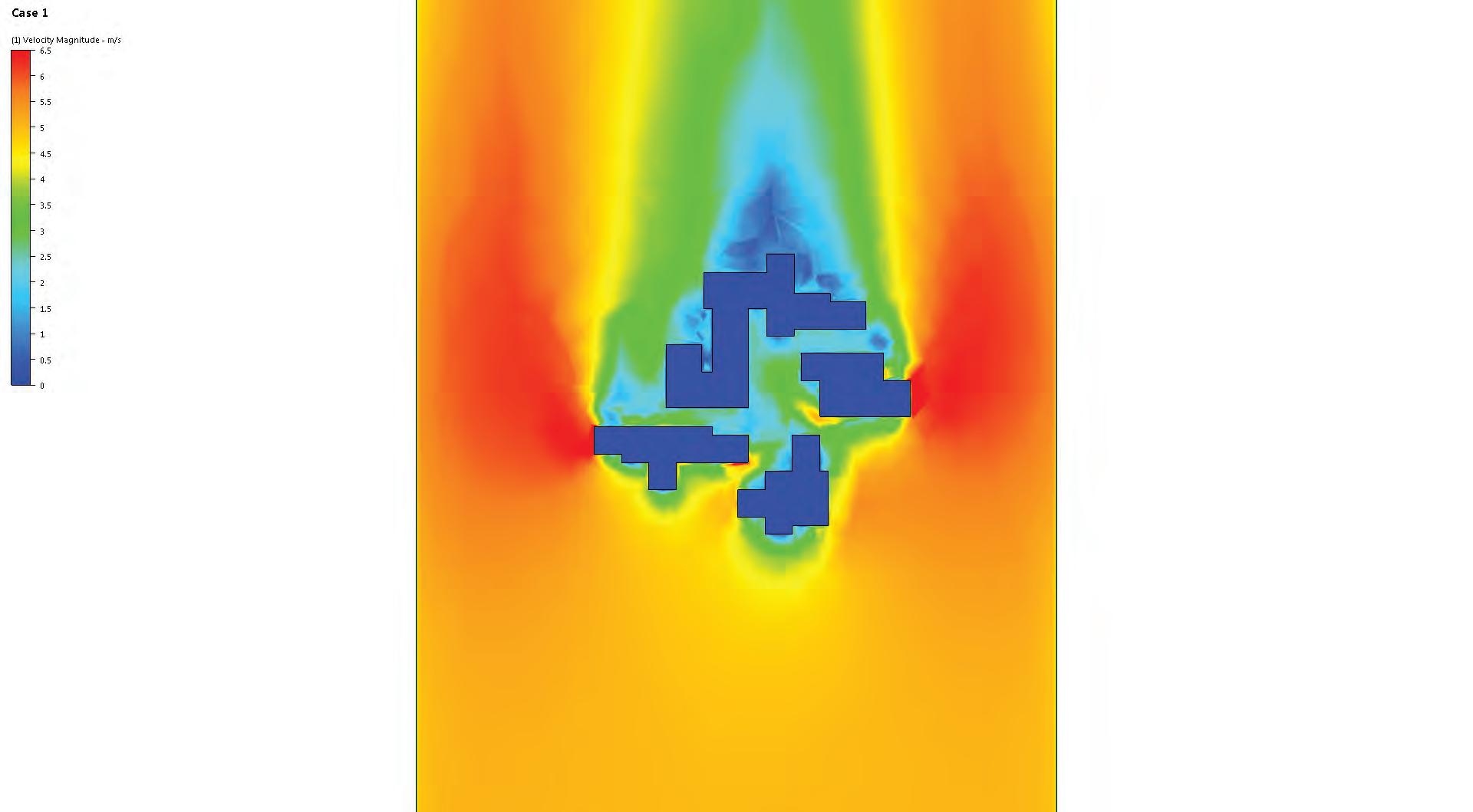

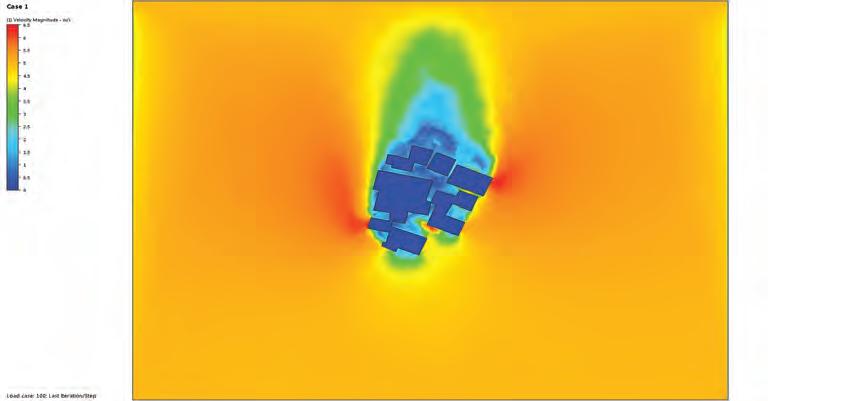

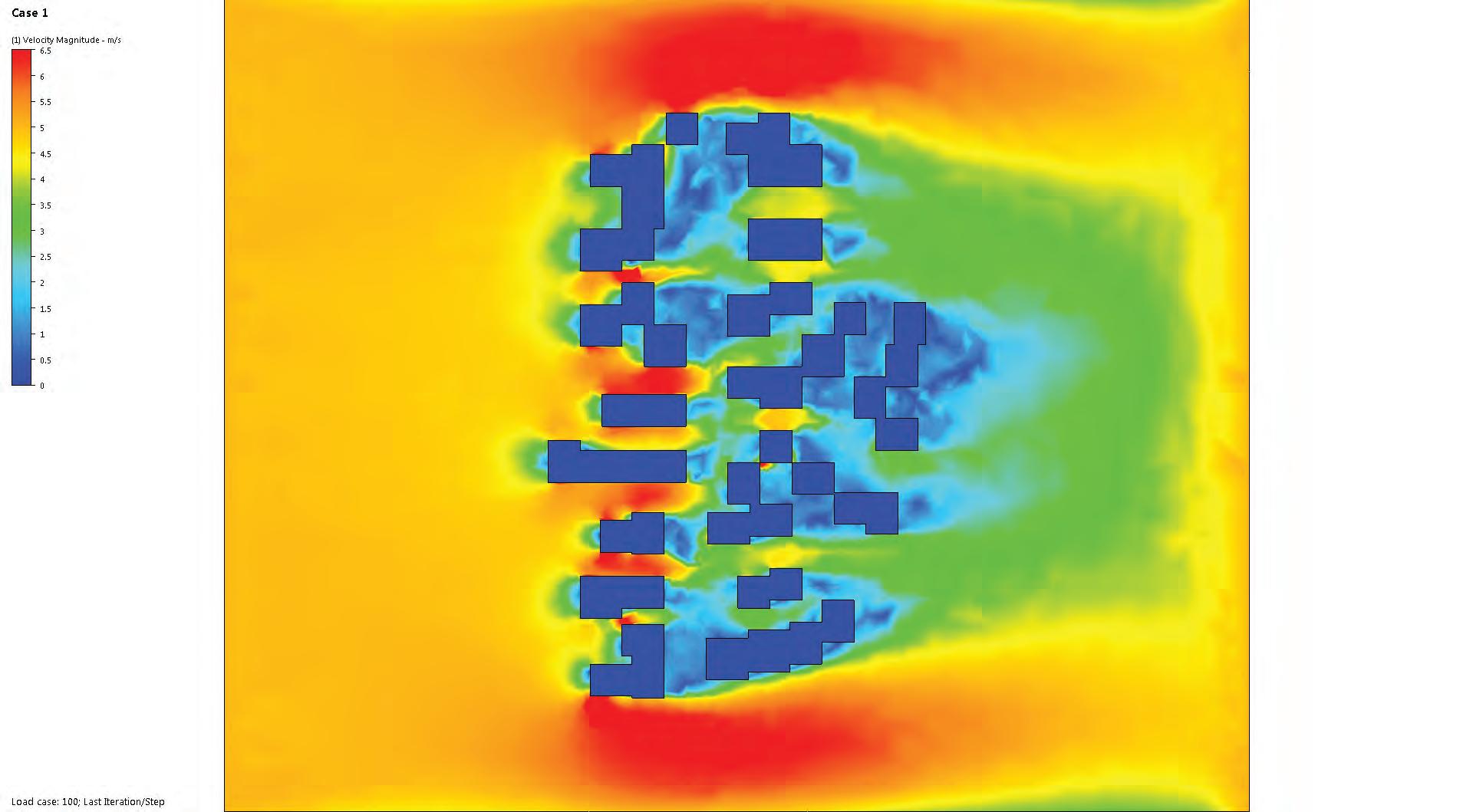

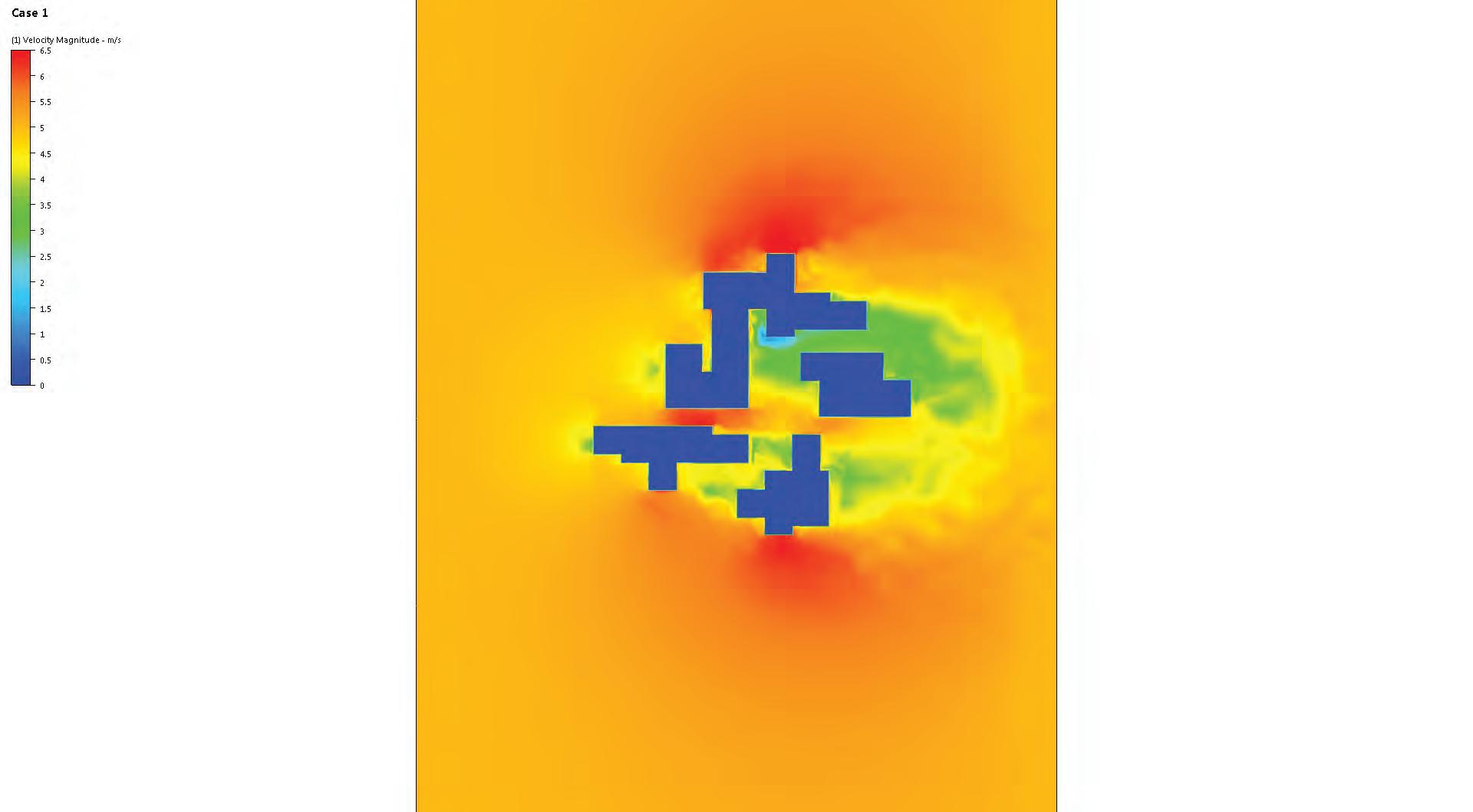

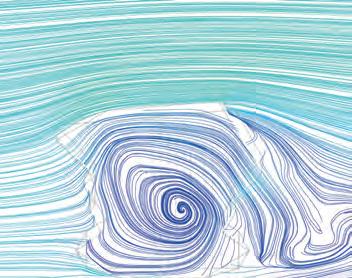

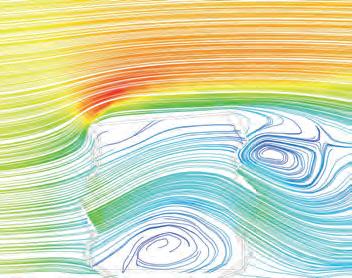

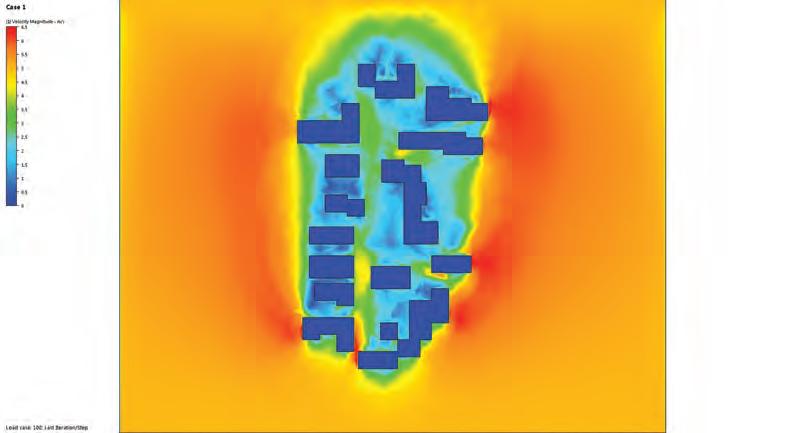

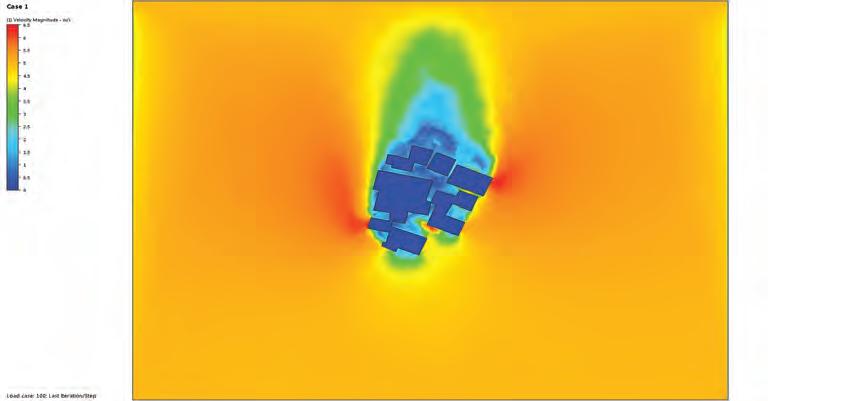

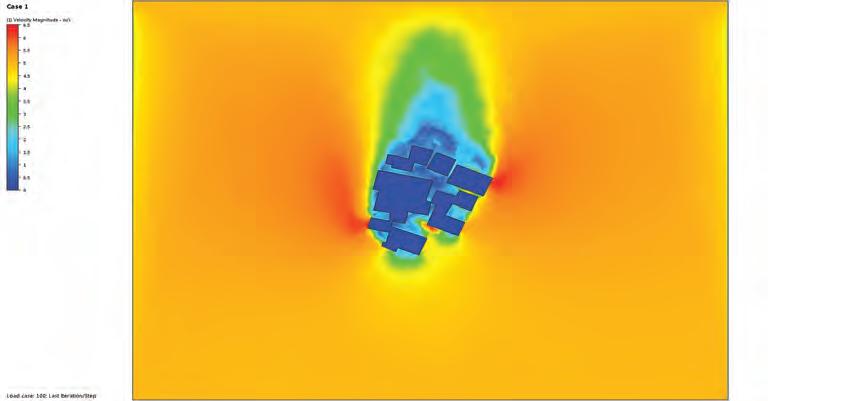

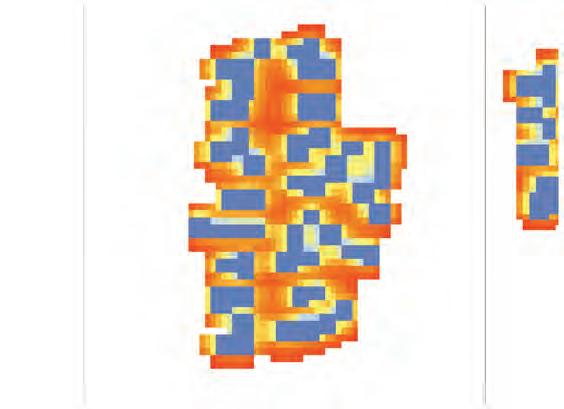

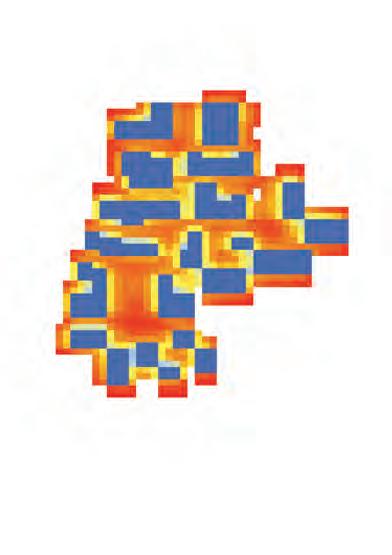

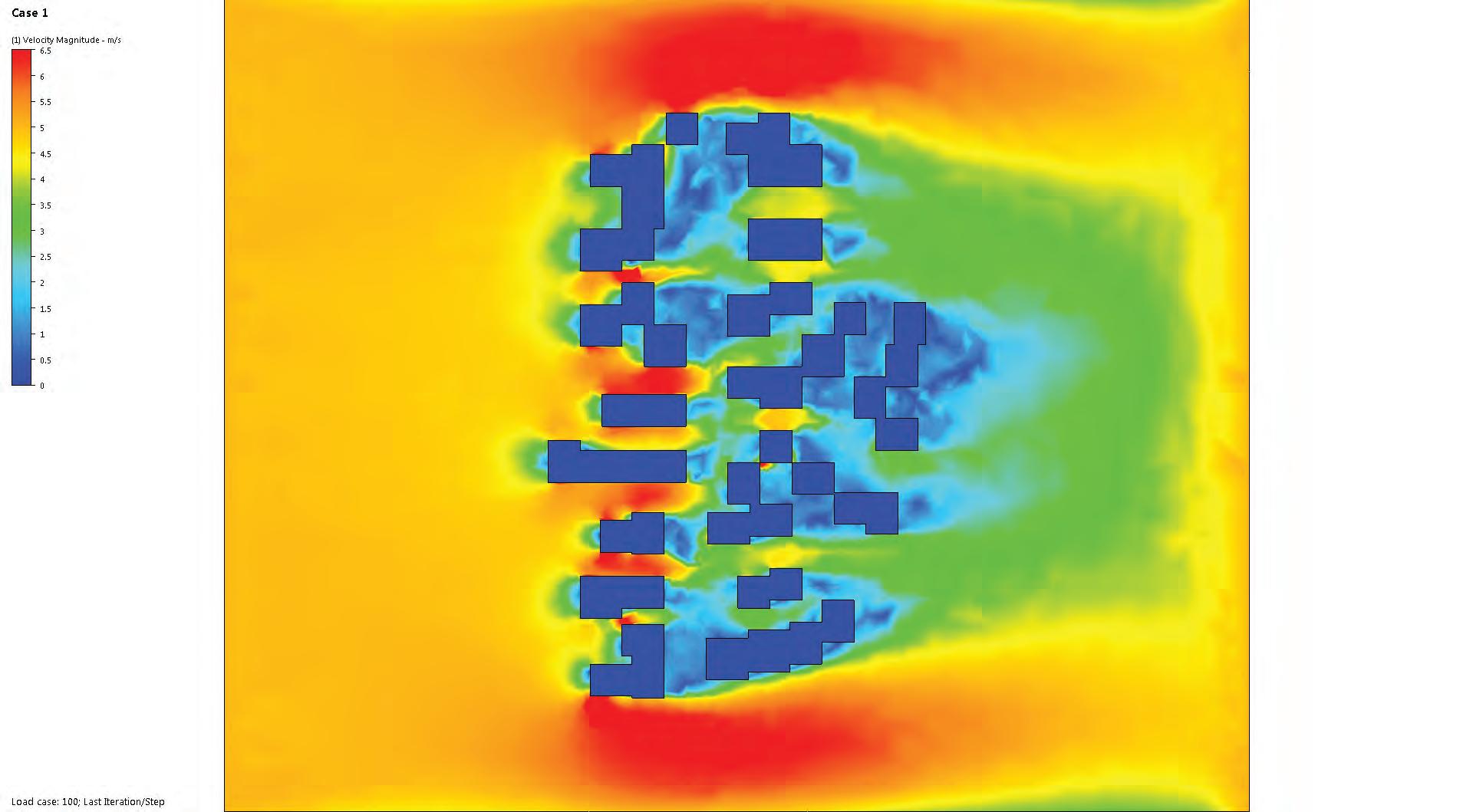

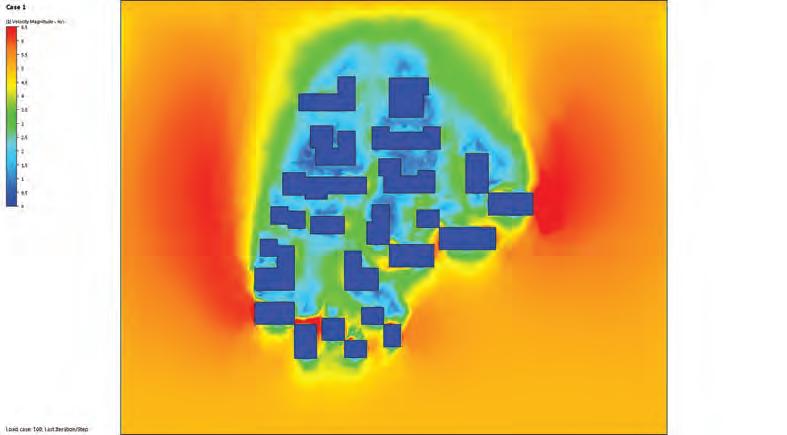

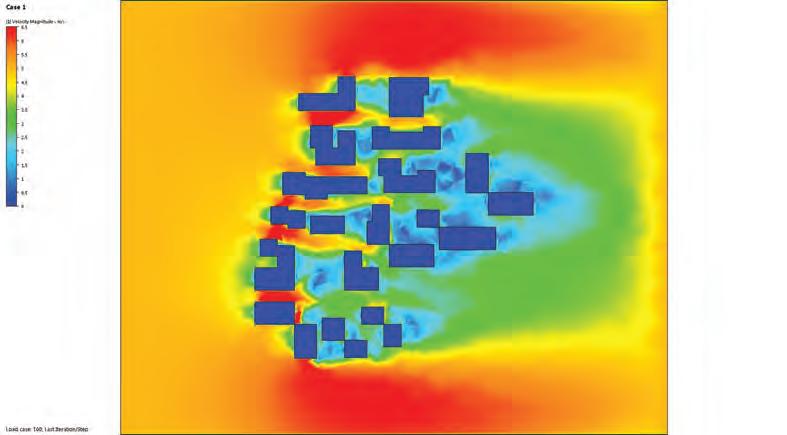

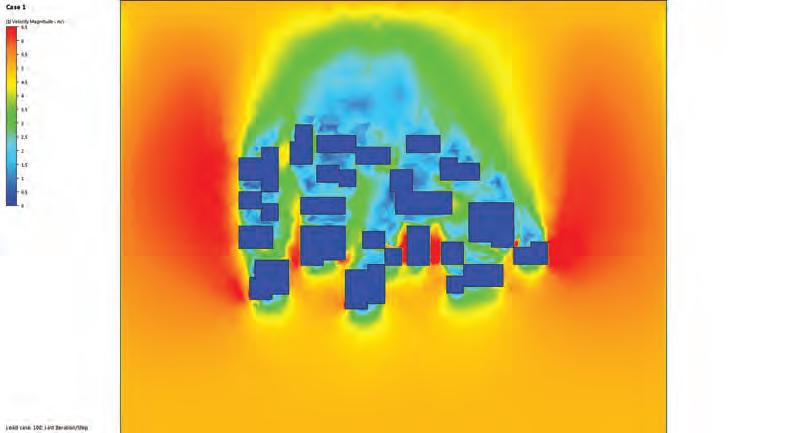

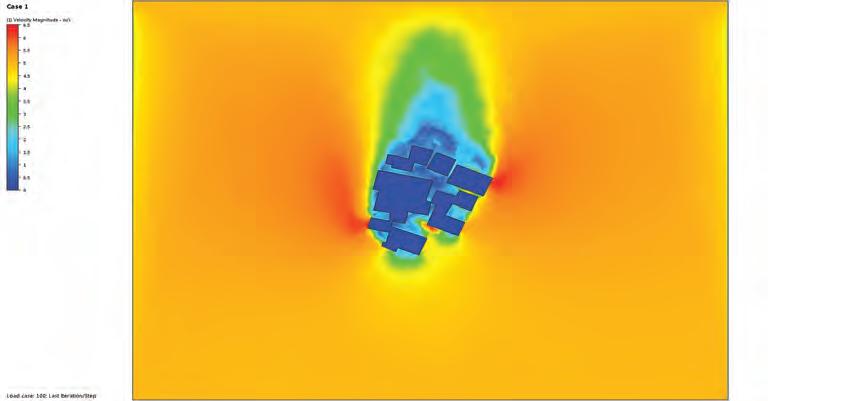

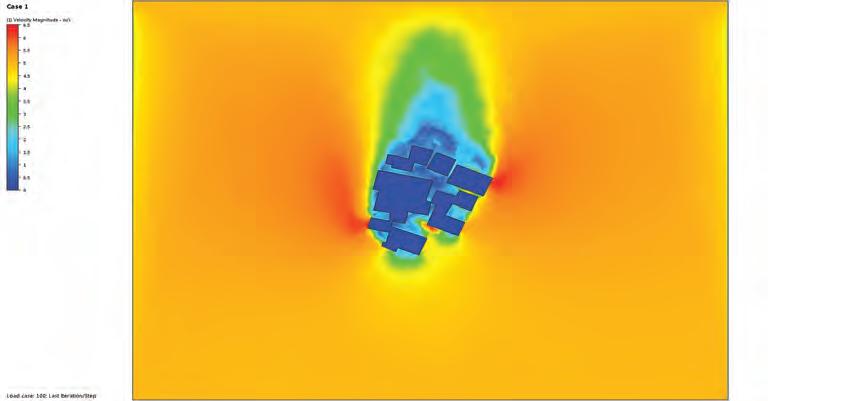

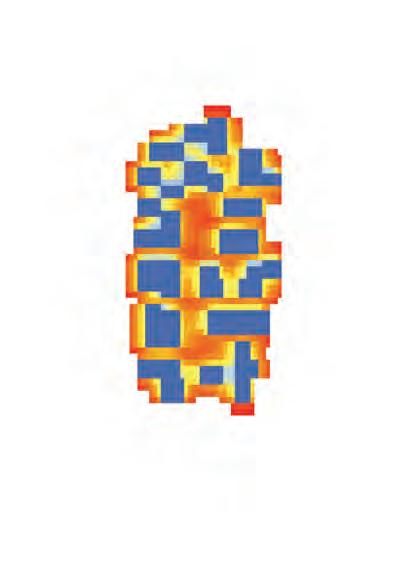

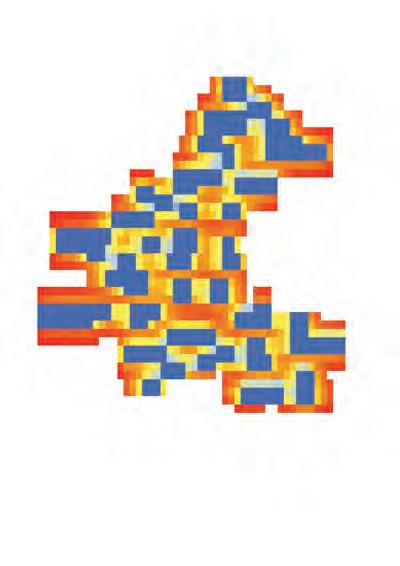

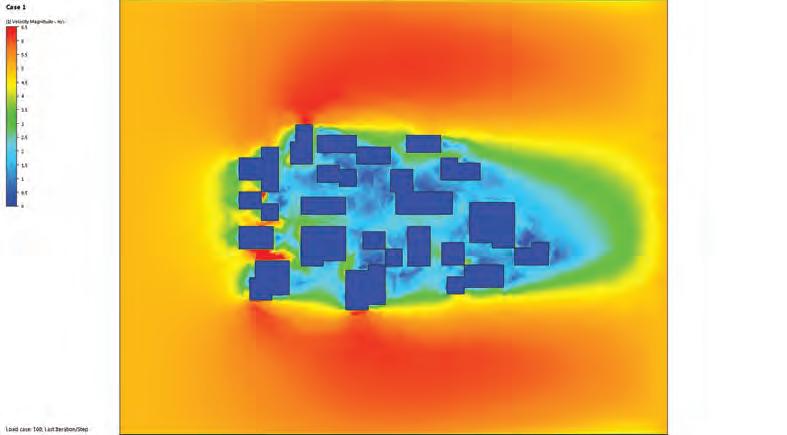

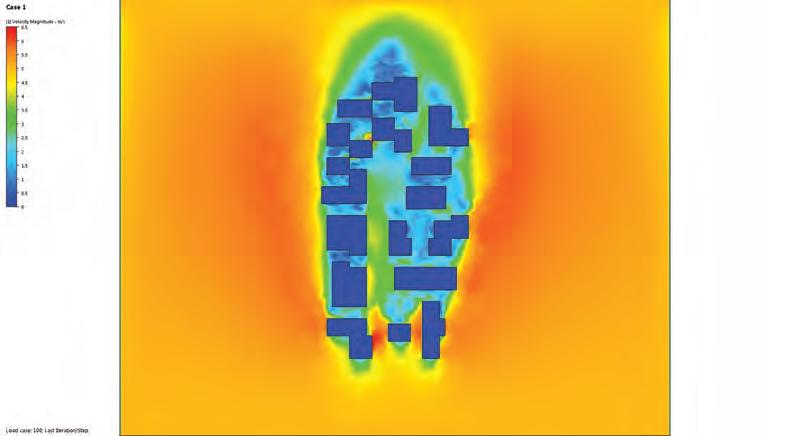

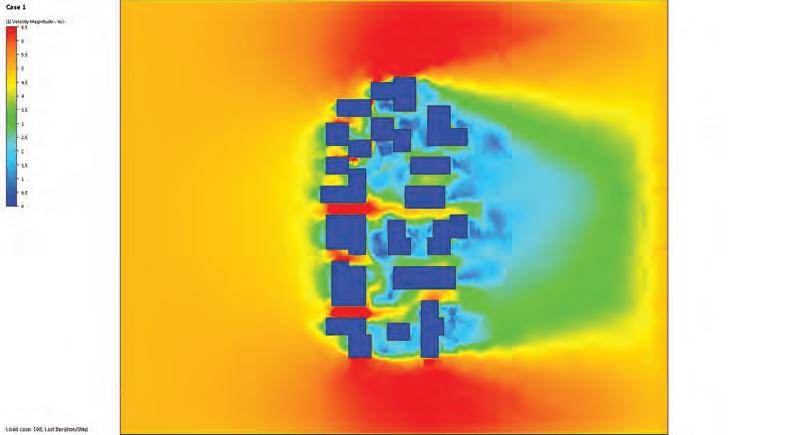

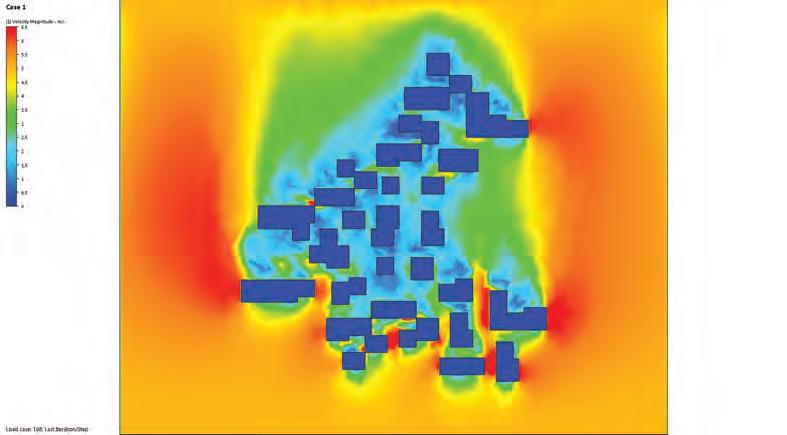

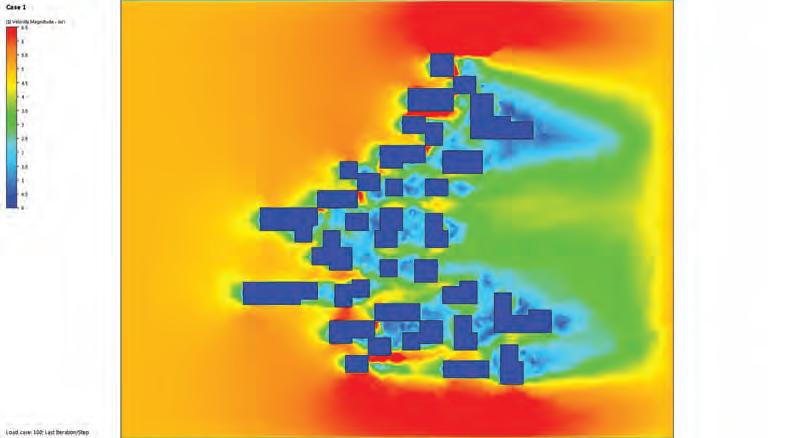

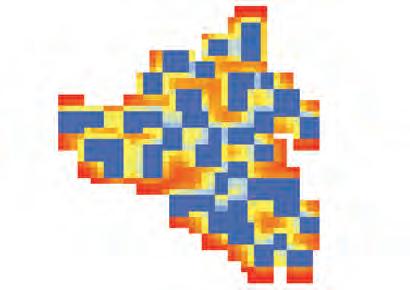

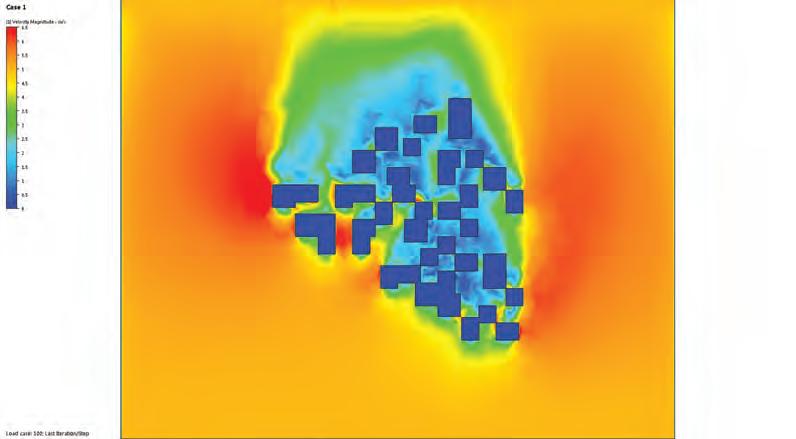

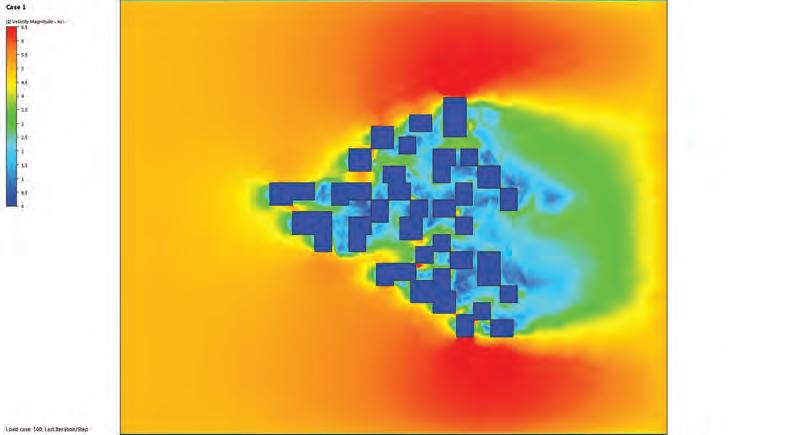

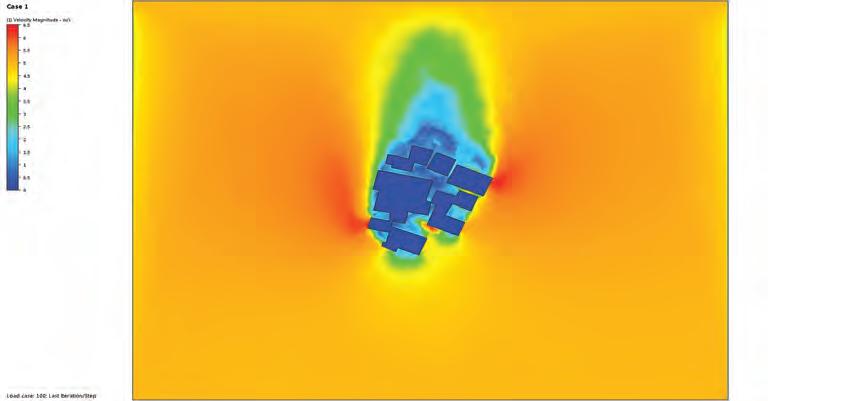

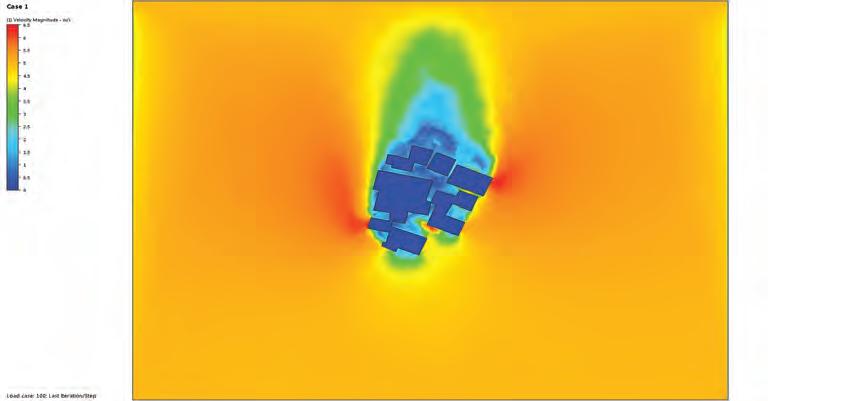

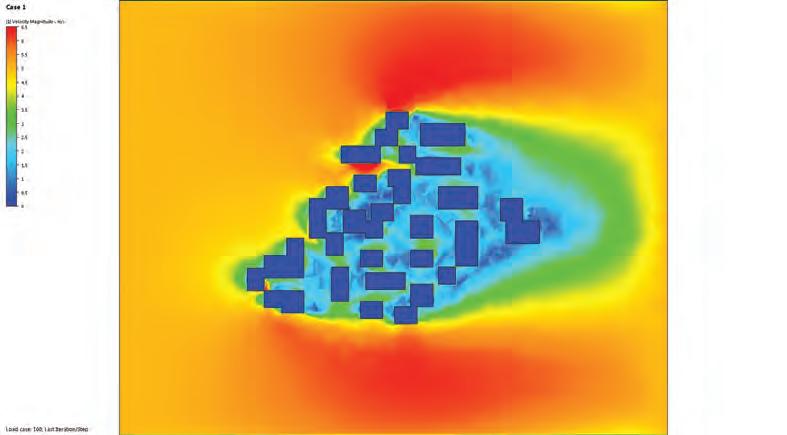

The urban growth generated will be analysed for the climatic performance of the open space agglomerations (yards).

This will include outdoor wind flow analysis through computational fluid dynamics using Simulation CFD and the study of selfshading with an environmental plug-in for Grasshopper.

The physical characters of yards in terms of their proportions and geometry along with the inlet and outlet and access points in terms of their widths and distribution will be analysed for their influence on the overall ventilation and the thermal comfort of the outdoor environment.

These analyses will help establish parameters for community open space in terms of their size, access points and extents for cluster formations around them.

3.3 TOOLS 50 51 METHODS RESPONSIVE GROWTH SYSTEM

COMMUNITY

URBAN GROWTH NEGOTIATORS

OPEN SPACE + INFRASTRUCTURE

RESIDUAL SITE STUDY

NEIGHBOURHOOD

DIGITAL SIMULATION

From the parameters established for achieving environmental comfort for open space, a variation of geometries for the community yards will be established.

A genetic algorithm will be used to create this variation within parameters defining the material system and climatic inputs. The produced geometries will be analysed in order to categorise them into variations based on the form generated and their social performance. This will inform their placement relative to the existing context.

A strategy will be developed for an infrastructure network to mediate municipal main line and individual dwellings.

DATA MAPPING

Distinct context conditions will be measured for the existing residual sites in Dharavi to identify their potential of engaging with the existing growth. This will inform new growth initiation in terms of adjacency rules.

The site periphery will be measured in terms of adjacent residential communities and pedestrian routes, amenities and open spaces, accessibility to major roads in order to inform the strategy for distribution of open space and infrastructure.

URBAN GROWTH DEPLOYMENT

STRATEGY FOR DISTRIBUTION

DIGITAL SIMULATION

A multi-level strategy for urban deployment of growth moderators will be defined. This will include preparation of the ground with distribution of the community yards and laying of infrastructure lines and.

The program drivers will be identified with respect to the scales of spatial organisation which will inform the sequential growth logic for large sites.

3.3 TOOLS 52 53 METHODS RESPONSIVE GROWTH SYSTEM

MATERIAL SYSTEM

4.

SOCIOCULTURAL CONTEXT PRECEDENTS CARDBOARD BUILDINGS

MATERIAL PROPERTIES OF CARDBOARD

ADVANTAGES OF FOLDING

CORRUGATED CARDBOARD SHEETS

-Potential building material

-Cheap, low skill and locally available

- Structural durability

- Environmental performance

Sociocultural Context

MATERIAL SYSTEM

EVALUATION

- Habitability

- Spatial variation

SELF-SHADING DAY-LIGHTINGCROSS VENTILATION

DEVELOPMENT OF KIT

-Local production

-Self building

ASSEMBLY LOGICFABRICATIONSURFACE TREATMENT

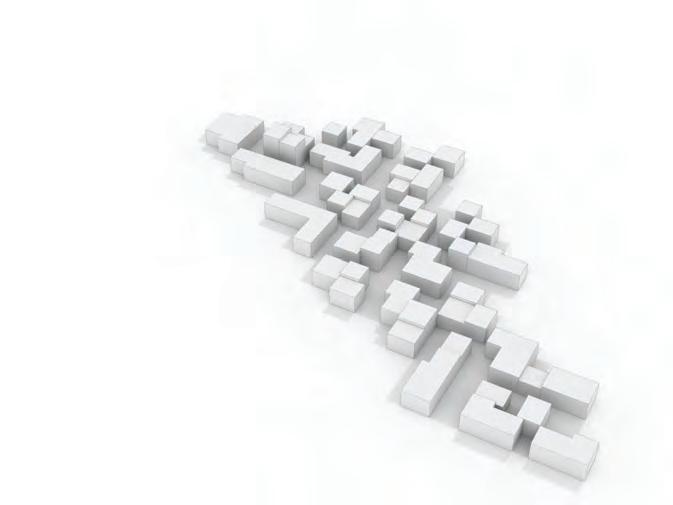

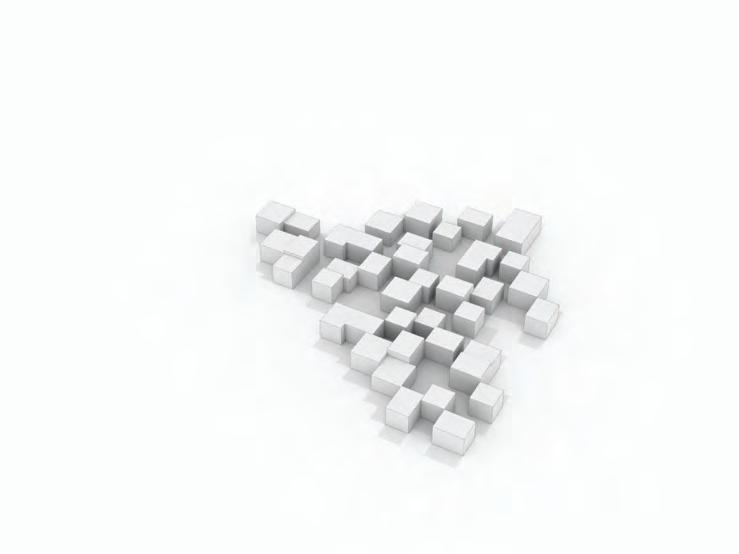

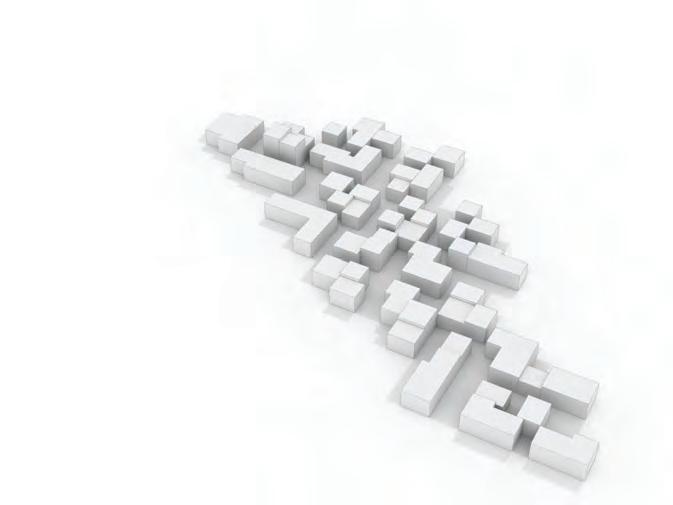

The material system is intended for a user group consisting predominantly of people who have just migrated to Dharavi in search of work. These migrants arrive with little-to-no money and few belongings; and due to their precarious situation, they prefer to set up their own shelter from cheap scavenged materials. The temporary nature of their dwellings reflects their transient lifestyle, and only if and once they find a foothold in Dharavi do they begin to make more permanent and durable dwellings. It is important to understand this social context in order to develop the material system so that it can be integrated into this scenario and appropriately improve these people’s standard of living. Therefore the material system is developed as a temporary system, but with the potential of an extended lifespan.

For the context of Dharavi, the material system needs to satisfy different requirements. Climatically, it must withstand the heavy monsoon rains. Its fabrication, including any treatments to the cardboard must be cheap and low-tech. For the given social context, the components should be fast to assemble and easy to replace or modify according to the needs of the rapid growing and changing population.