[AA Landscape Urbanism 23/24]

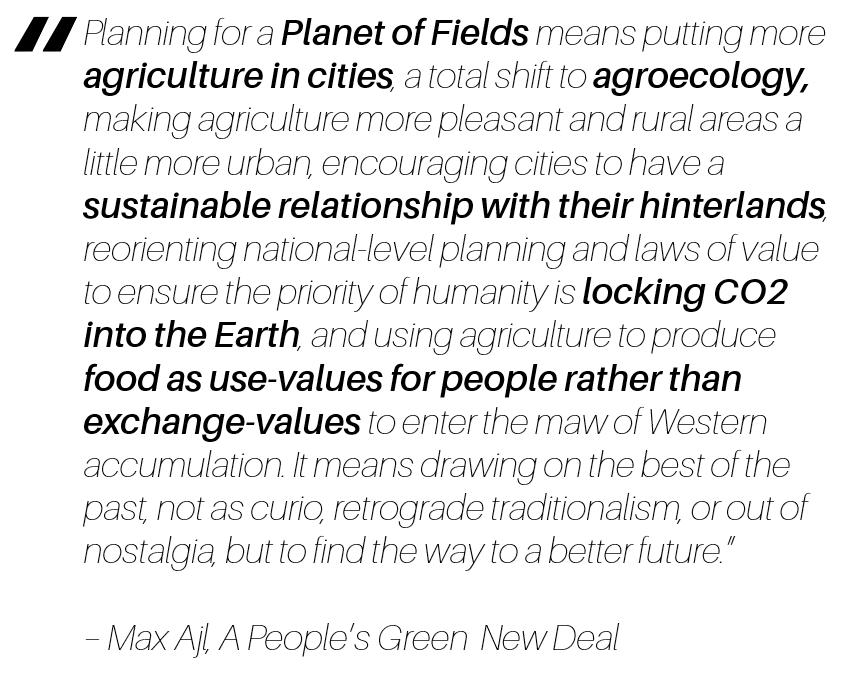

(Ajl 2021)

Abstract

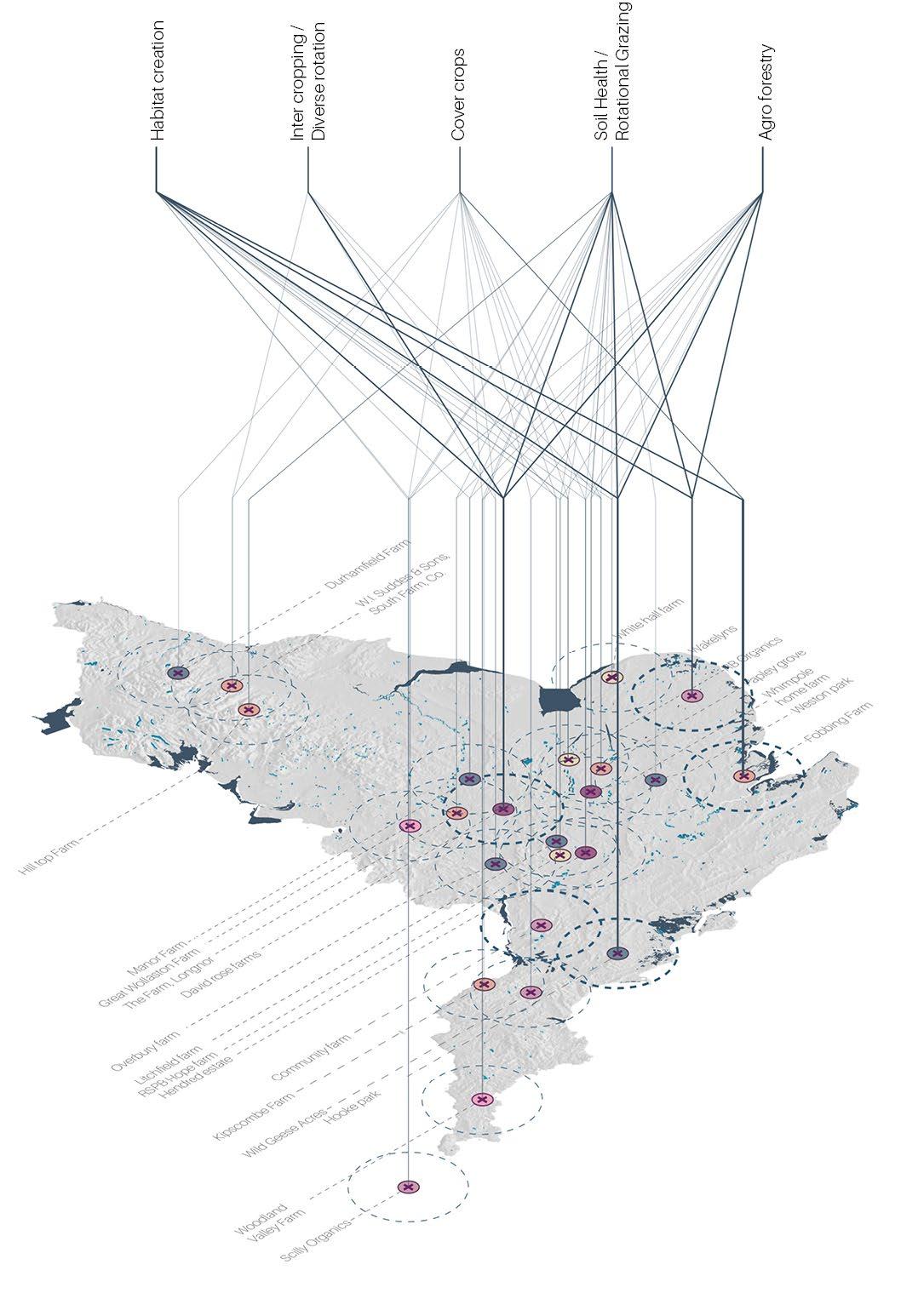

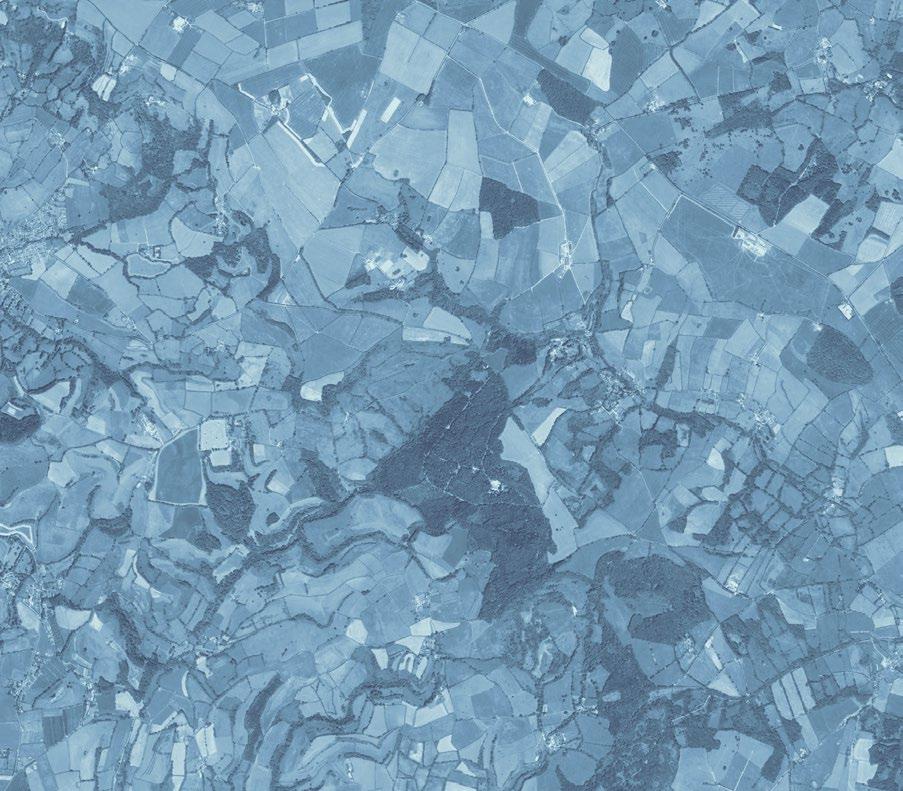

In the UK, approximately 70% of the land is destined for agriculture, with conventional monoculture dominating being the dominant form. Despite such a large proportion of agricultural land, the UK is heavily dependent on international food imports. This reliance on monoculture and international imports contributes to a considerable global footprint and also generates ecological disruptions, such as loss of biodiversity.

Greenbelts, due to their strategic location adjacent to cities—the primary drivers of demand—, are uniquely positioned to address these challenges. This thesis aims to investigate how existing policies can be modified to generate an agroecological transition, placing greenbelts at the centre. This will, in the process, strengthen the bond between urban centres and the surrounding rural areas, as well as redefining “intensification” within the context of sustainable agriculture. This transition promises the advantage of shortened supply chains and creating closer connections between local businesses and the land.

First, selected precedents that have shaped the proposal will be explained. Subsequently, we will examine the prevailing circumstances causing the disconnect between cities and greenbelts. An exploration into the current policies and their implications on agroecology will follow. Finally, we will explain our proposal for potential policy modifications, with a specific focus on the context of the Bristol Green Belt and its relevance to cereal crops.

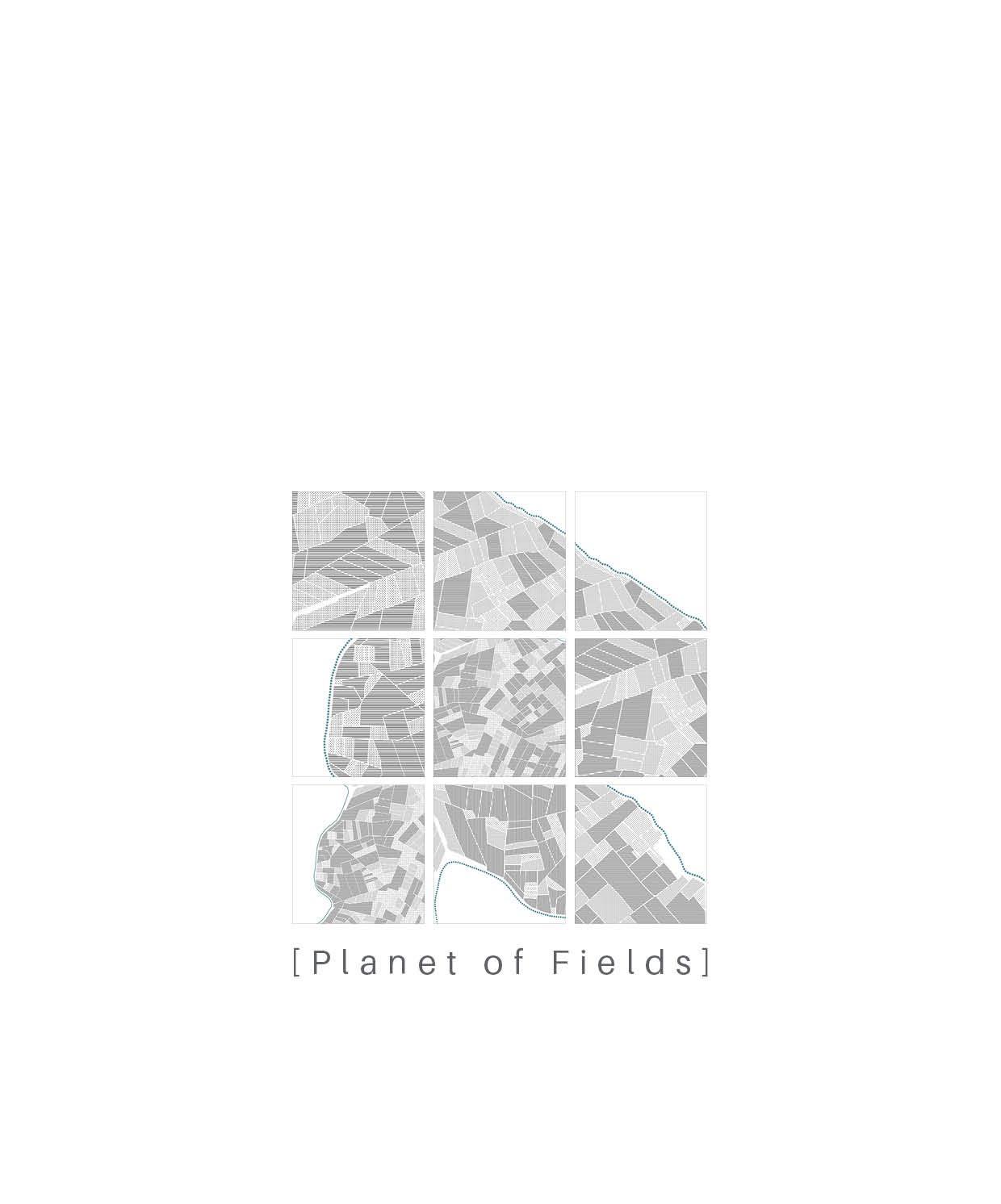

1 2 [AA Landscape Urbanism 23/24] [AA Landscape Urbanism 23/24] Planet of Fields

Monoculture fields of UK Fig .1 Https://www.istockphoto.com/photos/uk-farm-aerial Contents [01] 6 Precedents 6 Reactions to the Industrial City 7 Sebastién Marot - Taking the Country’s Side 9 Cuban peri-urban farming revolution 11 [02] 14 UK Context 14 Green Belts in the UK 15 Soil Grading and Land use 21 UK Food System 25 UK Land Ownership 31 [03] 36 The Agricultural Transition 36 Introduction 37 The 7 Year Plan 37 Visualizing ELM Schemes 39 [04] 44 Agroecology 44 Overview 45 Case Studies 49 [05] 66 The Site: Avon Green Belt 66 Soil 67 Types of green in the Green Belt 69 Mapping Bristol’s Corridors 71 [06] 76 Policy Proposal 76 Overview 77 Farm Succession 79 Council Farms and Community Ownership 81 Farm Clusters 83 [07] 92 The Case of Cereals 92 Perennial Grains 93 Regenerative Beer - Case Study 95 Proposal Implementation in the Bristol Greenbelt ����������� 99 [08] 110 Acknowledgements 110 [09] 112 References 112 4 [AA Landscape Urbanism 23/24] 3 [AA Landscape Urbanism 23/24] Planet of Fields

[01] Reactions to the Industrial City Sebastién Marot - Taking the Country’s Side Cuban peri-urban farming revolution Precedents Urban Farming in La Havana Fig 2 Https://www.architectural-review.com/essays/cubas-urban-farming-revolution-how-to-create-self-sufficient-cities 5 6 [AA Landscape Urbanism 23/24] Planet of Fields

https://www.behance.net/gallery/15865643/

Reactions to the Industrial City

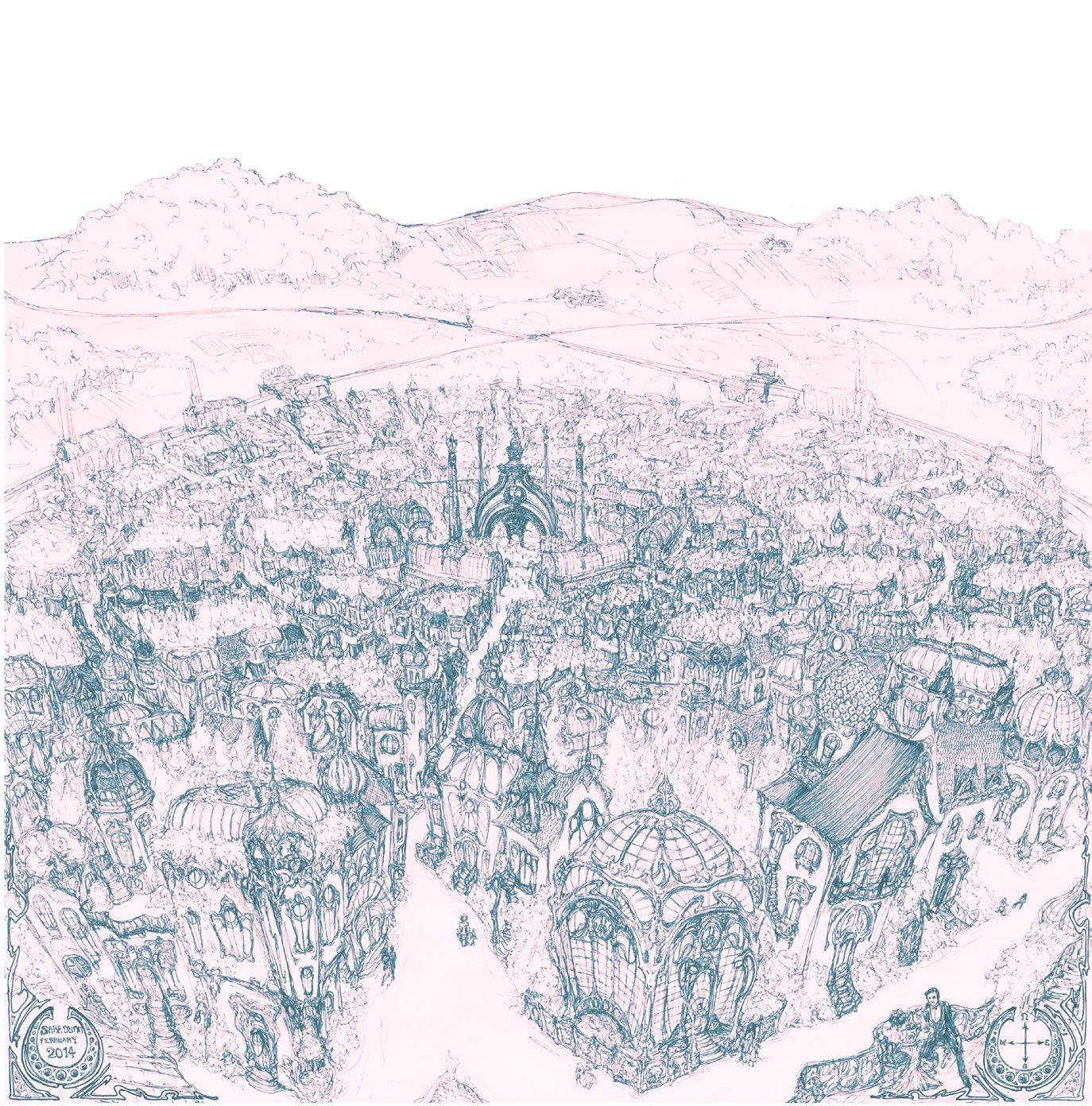

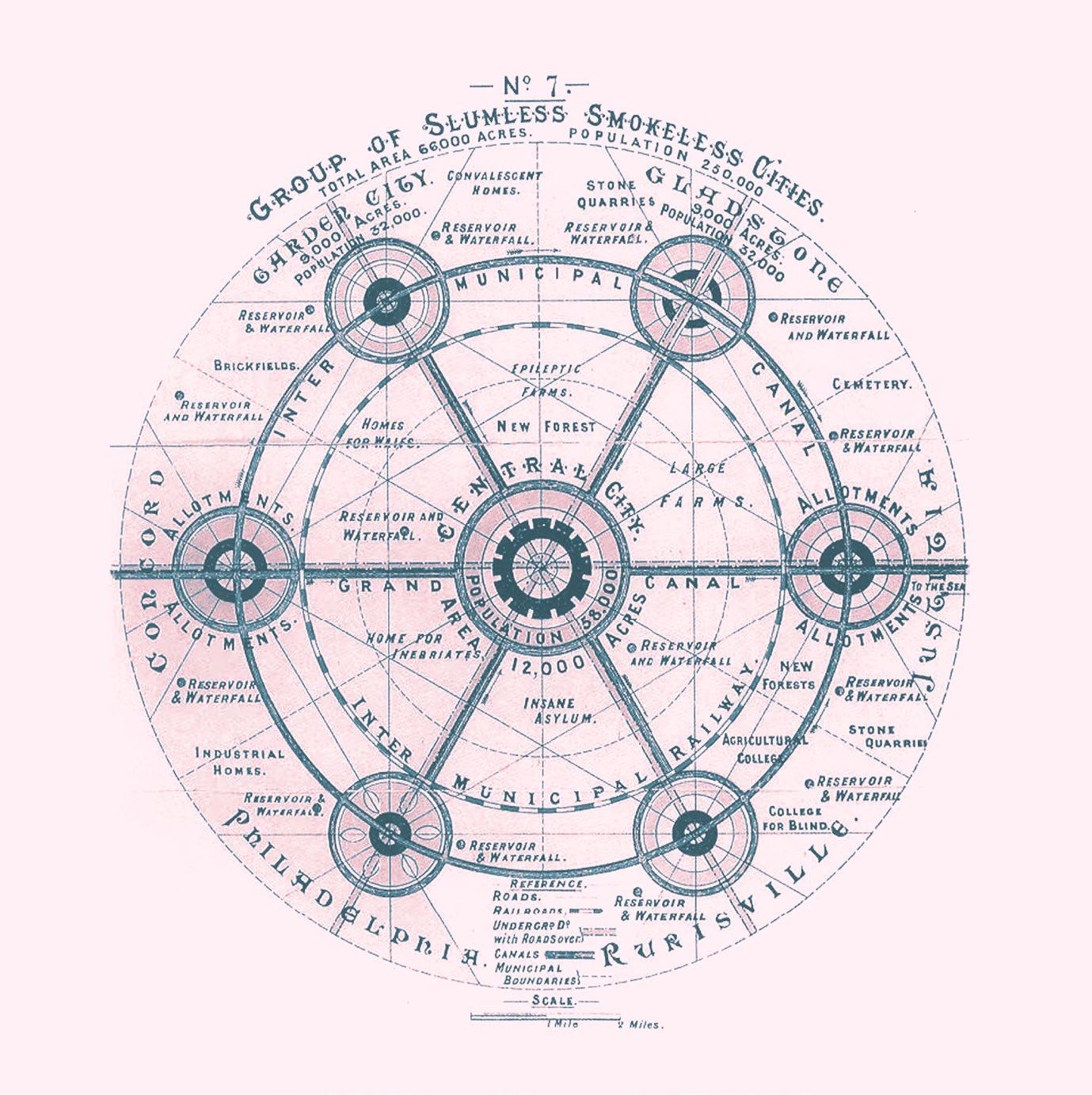

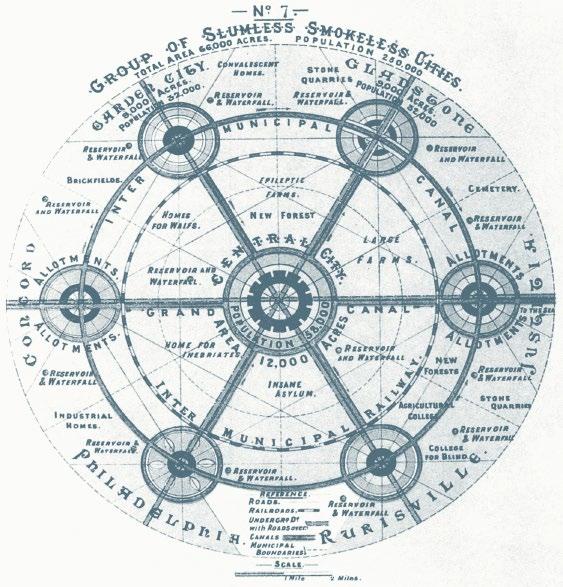

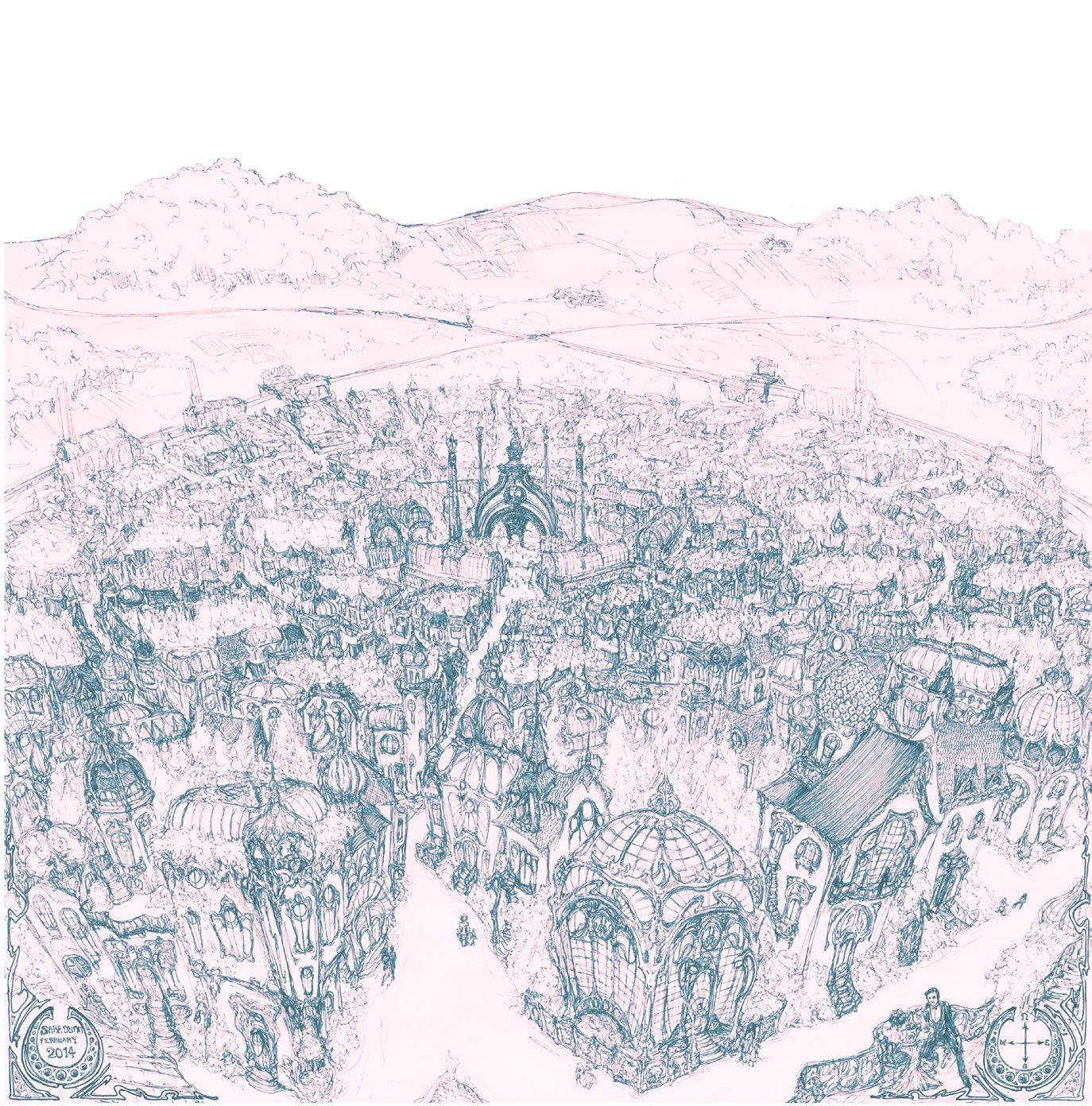

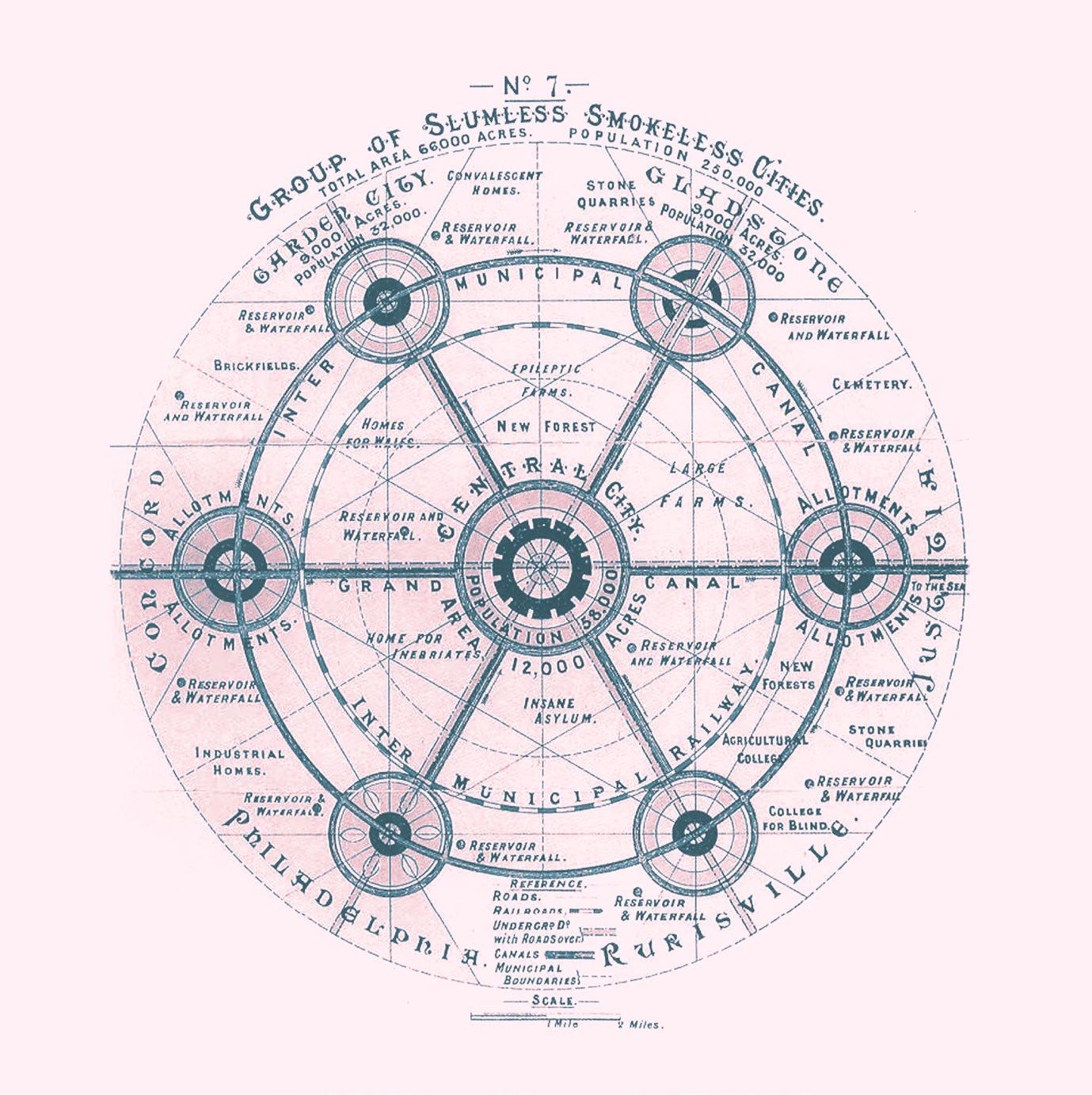

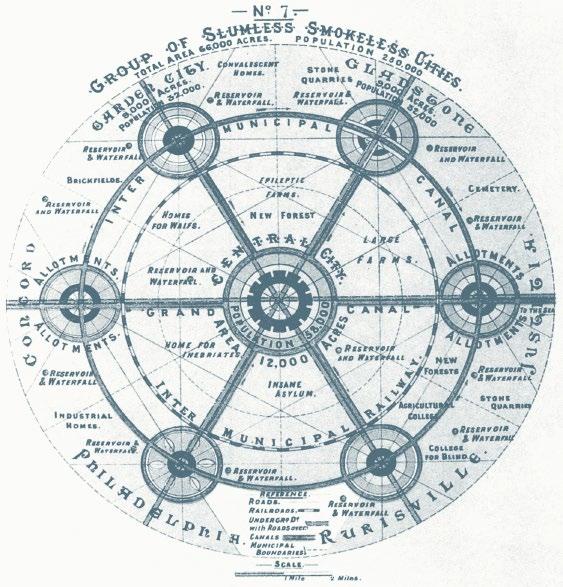

Both The Garden City and Broadacre City came about as reactions to the industrial city, depicting ideal cities but combining aspects of urban and rural living in different ways.

With the Garden City in 1898, Ebenezer Howard proposed highly planned, self-contained communities that combined the best elements of town and country. His approach was highly influenced by the idea of decentralization and polycentricity, proposing a “radial distribution of small cities around a larger central city, with each city separated by a form of proto-Green Belt.” (Bishop et al. 2020). This distribution was aimed at striking a balance between residence, industry, and agriculture and the concentric design prioritized efficient transportation and preservation of the natural landscape (Kapoor 2022).

Within this model the green belt prioritized local agriculture, serving the dual purpose of preventing urban sprawl and also providing a space for farming. However, the vision of a fully self-sustaining garden city was not realized. This was in large part due to the heavily planned topdown approach that it inherently had and that implied financial challenges, changes to housing policy, and vast urban migration (Miller 2005). Furthermore, the concept came about at a time

when housing and access to open space were of prime importance and, although those are still relevant, policymakers today have a very different context to which they must respond.

“While decent housing and access to open space are still important, other issues such as social inequality, the exclusion of sectors of society from the opportunities of their neighbours, poor employment prospects, poor quality housing, disparities in health and life expectancy, obesity, air quality, and sustainability are the new ‘wicked issues’ facing urban policymakers.” (Bishop et al. 2020)

Frank Lloyd Wright’s concept for Broadacre City, meanwhile, was introduced in 1932. His approach was, in contrast, highly decentralized, emphasizing individualism and the importance of the automobile. In Broadacre City, every family owns an acre or more of land allowing them to cultivate their plots. This combination favoured a horizontal sprawl of roads and highways which, potentially, exacerbates environmental degradation (Fishman 2016).

Broadacre city plan

Fig 5 Frank Lloyd Wright

Garden city, Territorial map

Garden city, Artist impression by Sara Dunn

Broadacre City Perspective

Fig 3

Fig 4

Fig 6

Ebenezer Howard

The-Garden-City-Utopia

Frank Lloyd Wright

Broadacre city plan

Fig 5 Frank Lloyd Wright

Garden city, Territorial map

Garden city, Artist impression by Sara Dunn

Broadacre City Perspective

Fig 3

Fig 4

Fig 6

Ebenezer Howard

The-Garden-City-Utopia

Frank Lloyd Wright

8 [AA Landscape Urbanism 23/24] 7 [AA Landscape Urbanism 23/24] Planet of Fields |

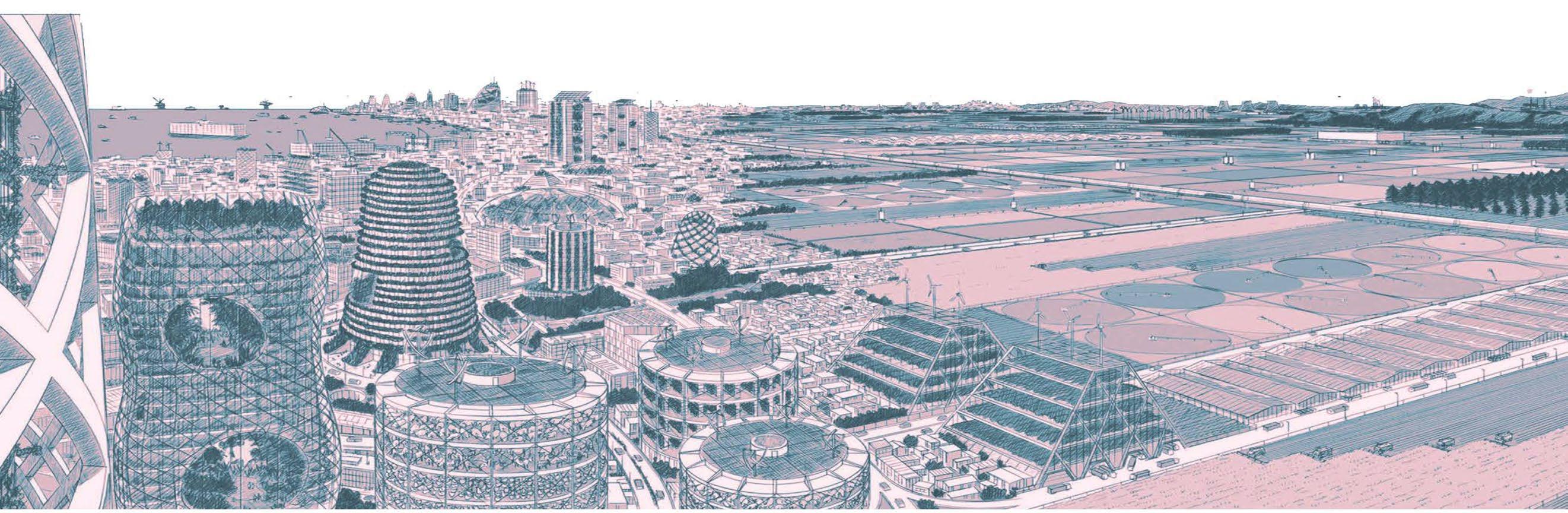

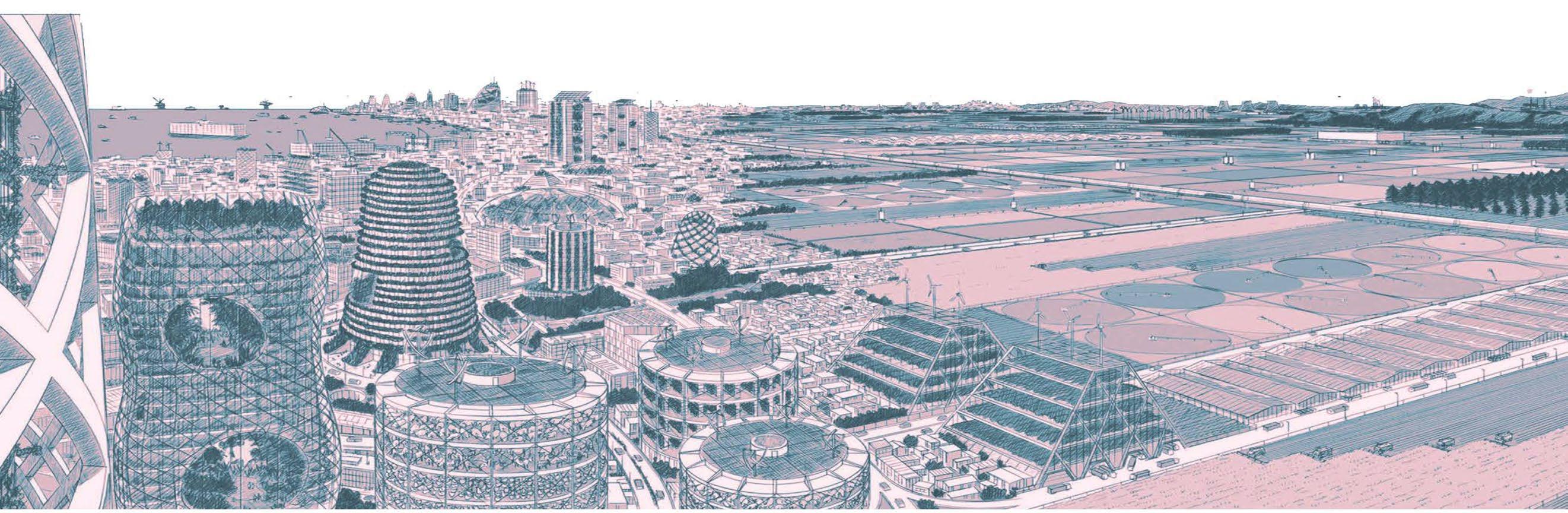

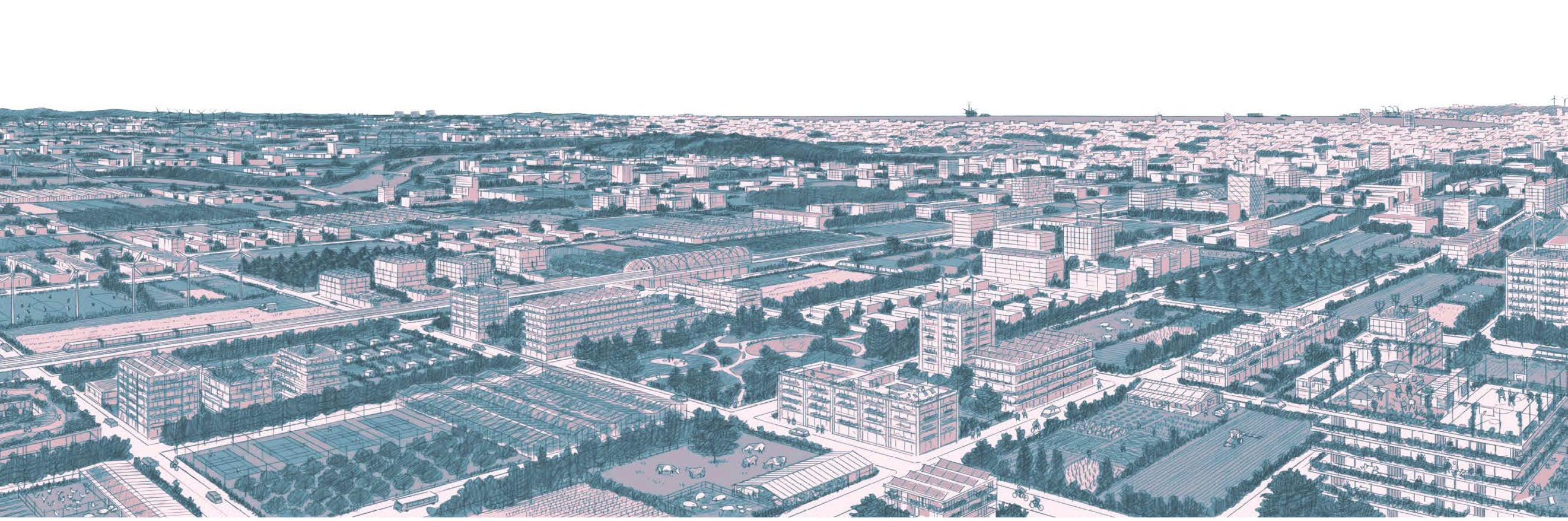

In 2019, Sebastién Marot and his team opened an exhibition titled “taking the Country’s Side”. In it, they propose four possible urban scenarios for a future relationship between city and countryside, with each one fundamentally differing in its attitude towards growth. (Catsaros 2020)

The remaining sections of this thesis will work towards similar visions, but specifically doing so in relation to greenbelt and agricultural policy.

Taking the Country’s Side Fig 7, 8, 9, 10 Sebastien Marot, https://archis.org/ volume/taking-the-countrys-side-sebastien-marot-christophe-catsaros/

Infiltration: “This is the approach, engaged in the many ‘urban agriculture’ initiatives, which invests the surplus or neglected surfaces of existing conurbations: wastelands, rooftops, parks, embankments, etc. Without questioning the logic and realities of the current urban condition, these initiatives take hold of food production, supply and consumption in order to initiate collectives and solidarity practices in the uprooted territories of metropolises.” (Catsaros 2020)

Negotiation: “Agricultural areas are thought of as integral components of cities, which in turn are designed from the territories that feed them. In this perspective of ‘agricultural urbanism’, the approaches of town planning and agriculture renegotiate their respective jurisprudence and renew them in order to reinvent each other.” (Catsaros 2020)

Incorporation: “This is the orientation of those who believe that the solution lies in pursuing urban concentration and the intensification of the technological path. Super greenhouses, vertical farms, GMOs, above-ground production, hydroponics. In this futuristic scenario, metropolises become the control towers of a countryside emptied of its inhabitants.” (Catsaros 2020)

Secession: “This is the more radical and willingly agrarian approach of those who question the hegemony of the metropolis. Leaving the city in search of autonomy. To this nebula of initiatives can be attached a whole series of movements of emancipation and/or community rooting of a political nature, such as the ‘Zones to Defend’ or the groupings of voluntary communes.” (Catsaros 2020)

Sebastién Marot - Taking

Side 9 | 10 [AA Landscape Urbanism 23/24] [AA Landscape Urbanism 23/24] Planet of Fields

the Country’s

https://www.nytimes.com/2016/06/22/dining/cuba-us-organic-farming.html

Cuban periurban farming revolution

In 1989, Cuba became disconnected from the soviet bloc, facing food and oil shortages which unravelled its green revolution system of agriculture. The machinery, pesticide production, and transportation networks that were so important to Cuba’s agricultural sector, were effectively paralyzed. Prioritizing organic farming, an emphasis on edible crops, and leverage of peasant labour, The Cuban Government, together with grassroots citizen participation achieved a transformation from conventional farming to what is now posited as the “world’s largest working model of a semi-sustainable agriculture”, with over 35,000 hectares for urban farming (Clouse 2014). In the years following the crisis, the government subsidized and backed facilities that supported urban farming and organic methods, such as agricultural stores, compost production sites, and urban veterinary clinics.

The Cuban model came about from necessity and has demonstrated proven success, whereas the agricultural philosophies of the Garden City and Broadacre City have remained largely theoretical. While the Garden City envisioned self-contained cities it fails to integrate localized agriculture at the scale of Cuba, and the concept of Broadacre City relied heavily on the automobile, contrasting with Cuba’s reduced dependence on mechanized transportation.

The Cuban model thrived, in large part, because it combined community participation, organic farming practices within urban contexts, and governmental support for industries that these first two rely on, making it more resilient to rapid socioeconomic changes.

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2017/ oct/28/organic-or-starve-can-cubas-new-farming-model-provide-food-security

Peri-Urban Farms in La Havana

Peri-Urban Farms in La Havana

Fig 11

Fig 12

Peri-Urban Farms in La Havana

Peri-Urban Farms in La Havana

Fig 11

Fig 12

11 | 12 [AA Landscape Urbanism 23/24] [AA Landscape Urbanism 23/24] Planet of Fields

UK Context

[02] Green Belts in the UK Soil Grading and Land use UK Food System UK Land Ownership

Mega-farm in the UK Fig 13 Https://ecostorm.tv/portfolio/therise-of-the-megafarm/ 13 14 [AA Landscape Urbanism 23/24] Planet of Fields

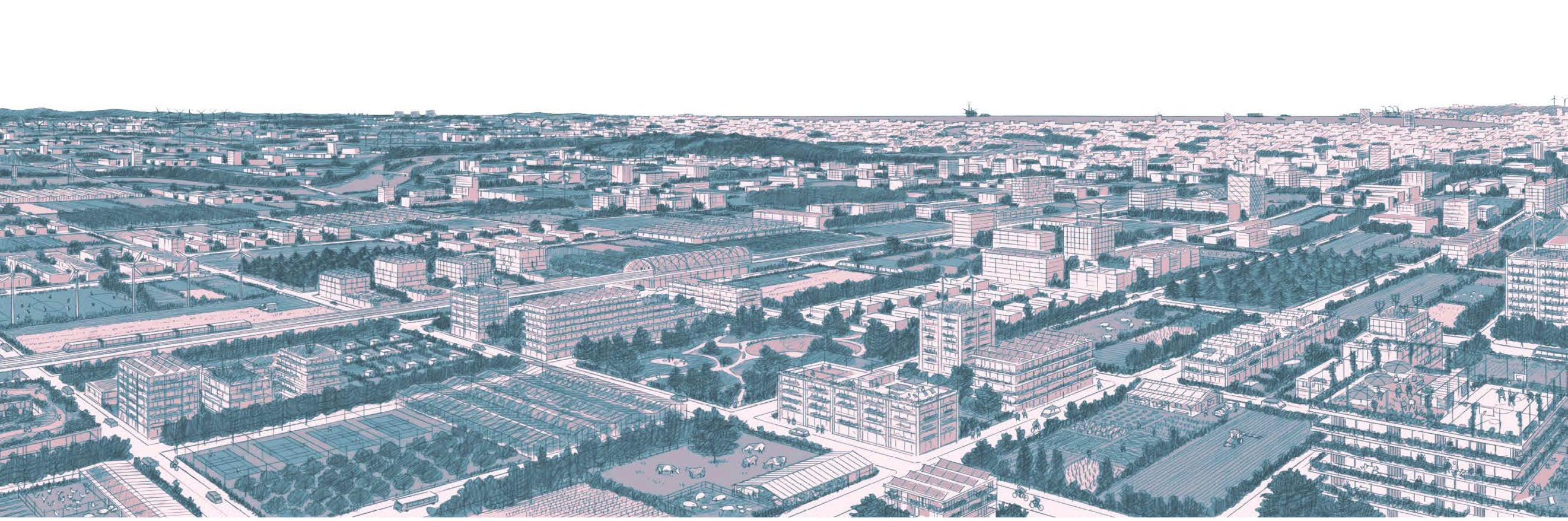

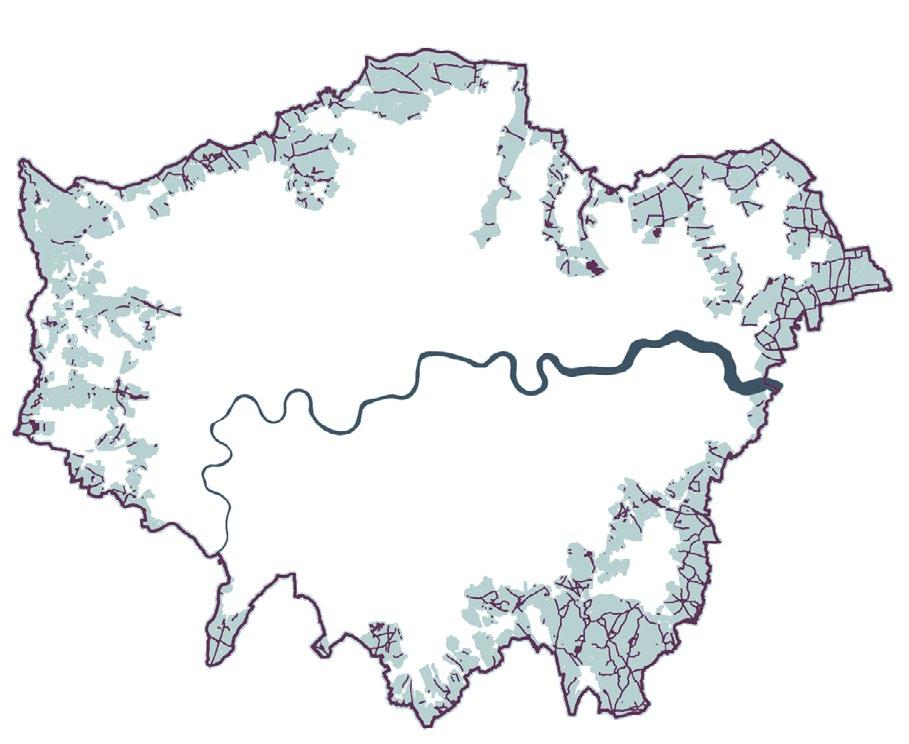

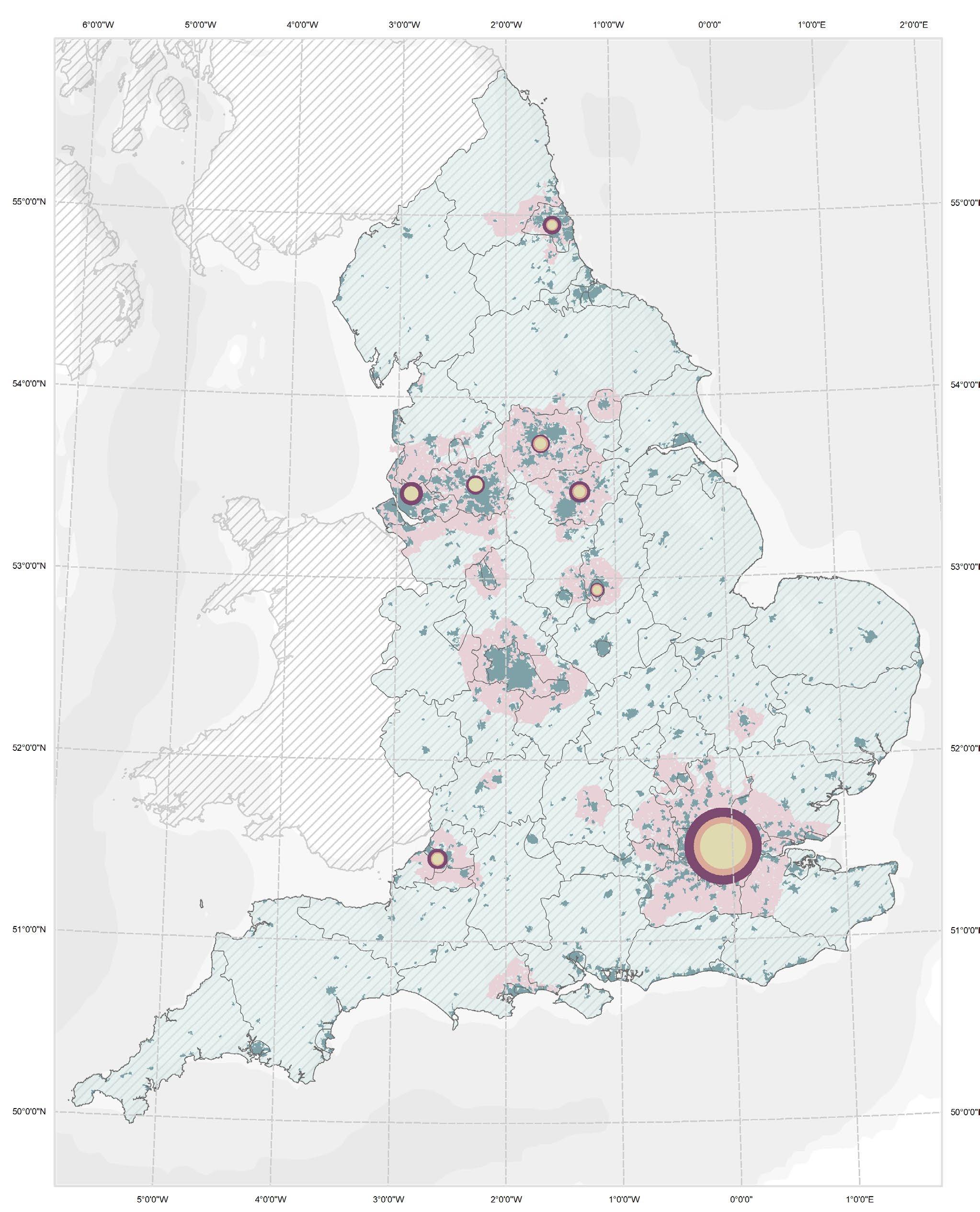

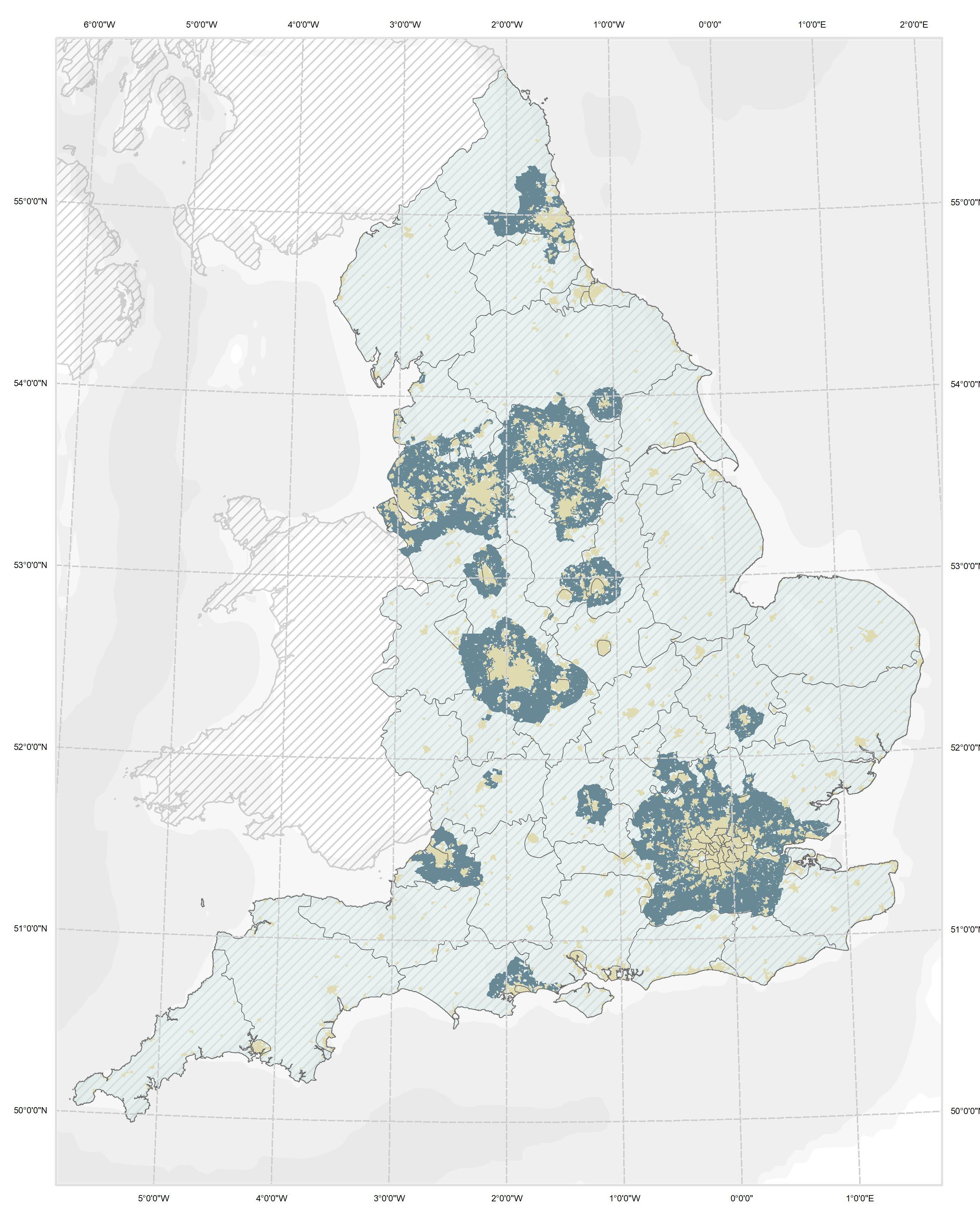

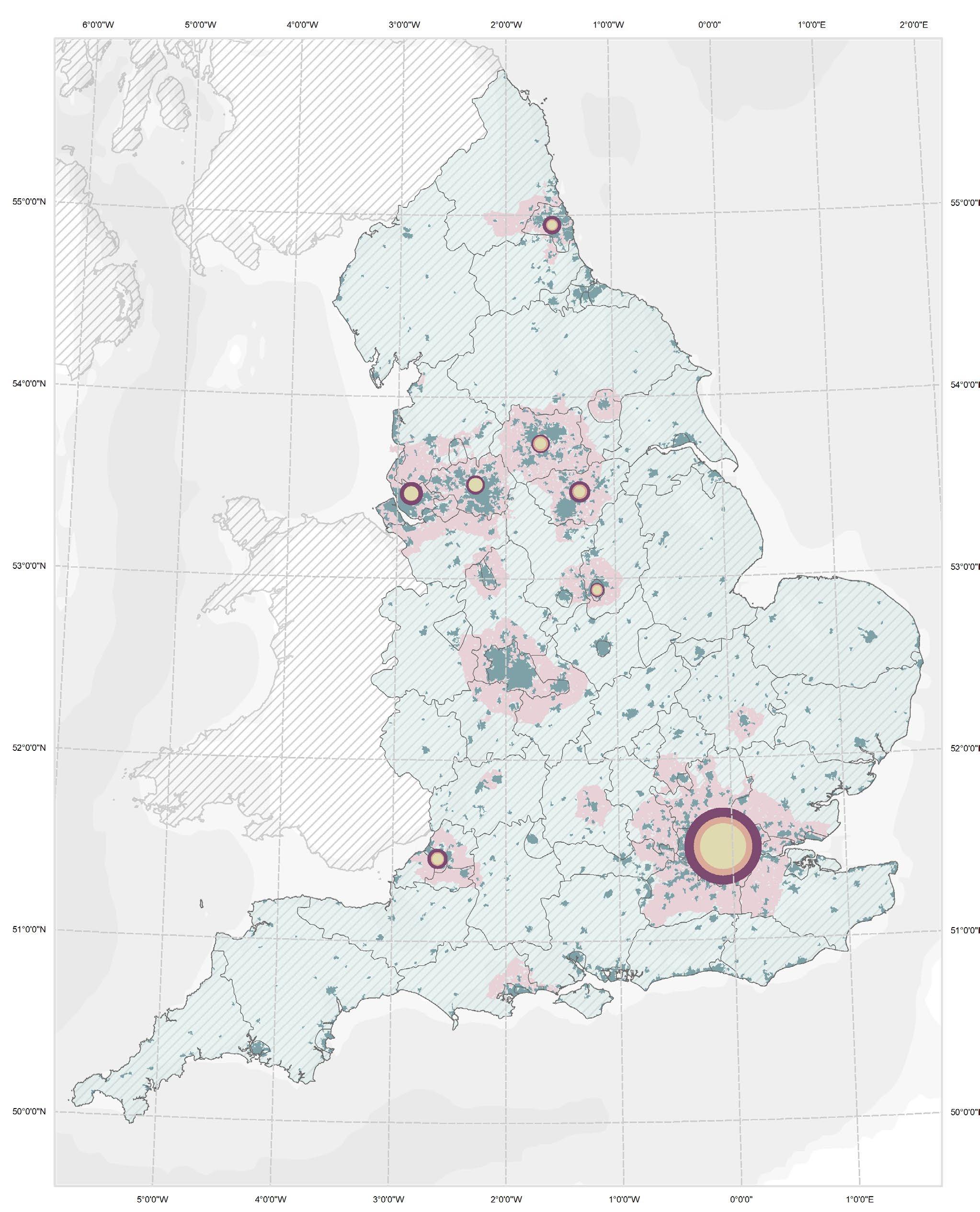

Green Belts in the UK

In the UK the Green Belt is a land use designation that surrounds urban centres. Its main purpose is to maintain open green spaces and prevent the city’s uncontrolled outward expansion, but has other tangent effects, such as promoting urban regeneration and helping to reduce demand for local service infrastructure.

In practice, areas that have been designated as part of the “Green Belt” have strict restrictions as to the type of developments that are allowed within them. In general, new developments in these areas are not permitted unless exceptional criteria have been met. However, the area that the green belt covers is subject to revision and can change in response to local council objectives (Great Britain. Ministry Of Justice 2021), with demand for housing being one of the key drivers in recent times.

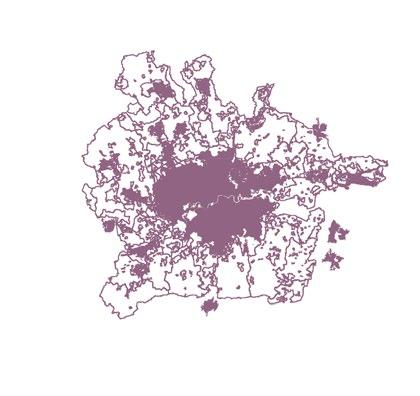

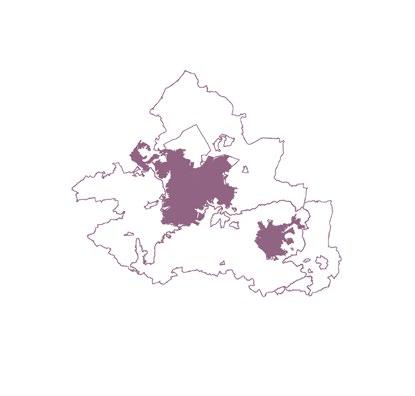

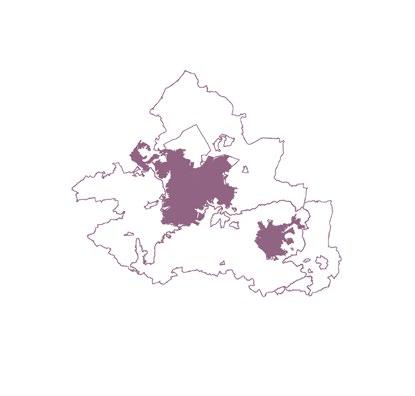

Cities & Green belts

By Khusbhoo Prashant

Fig 14

15 | 16 [AA Landscape Urbanism 23/24] [AA Landscape Urbanism 23/24] Planet of Fields

Origins

of the Green Belt Green Belts as an urban containers

Greenbelt policy emerged as an important part of UK urban planning after the Second World War. Its popularity and acceptance amongst the public were centred around a worry of losing natural green spaces for recreation, as well as the growing importance of sustainability.

However, popular perception has evolved since the policy’s original conception. What was initially conceived as a ring of the countryside that was resistant to urbanization has, with time, come to be seen by some as an urban container, setting aside its ecological relationships and quality as an area of resource management for the city. This change in perception can be traced to the ideals of the “Garden City” by Ebenezer Howard, towards the beginning of the 20th century, where he emphasized the physical limit of the city, as well as the physical limit of agricultural space. (Bishop et al. 2020)

Despite its achievements, such as the conservation of small villages around the city and the containment of urban sprawl, some argue that Green Belts contribute to today’s housing crisis. Recent political visions suggest an uncertain future for greenbelts, with tendencies to see peri-urban land as potential development areas rather than areas for ecological safe-keeping.

Garden City movement – Ebenezer Howard proposes Garden Cities surrounded by Green Belts.

Formation of CPRE, one of whose earliest campaigns was against urban sprawl

First Green Belt proposed in an official planning policy by the Greater London Regional Planning Committee “to provide a reserve supply of public open space and of recreational areas and to establish a Green Belt or girdle of open space.”

Government policy on Green Belts is contained in Planning Policy Guidance 2 (PPG2) which is the current responsibility of the department of Levelling up, Housing and Communities. (Great Britain. Ministry Of Justice 2021) The five purposes of Green Belts, set out in PPG2, are:

1. To check the unrestricted sprawl of large built up areas,

2. To prevent neighbouring towns from merging with one another,

3. To assist in safeguarding the countryside from encroachment,

4. To preserve the setting and special character of historic towns, and

5. To assist with urban regeneration, by encouraging the recycling of derelict and other urban land.

40% increase in England’s population

Car ownership increases 14 fold.

Income increases 3 fold.

Increase in housing demand

Sheffield Green Belt designated by local government.

Sheffield Green Belt designated by local government.

Town and Country Planning Act, allowed local authorities to control changes in the use of land from undeveloped to developed uses.

Green Belt policy for England was set out in Ministry of Housing and Local Government Circular 42/55 which invited local planning authorities to consider the establishment of Green Belts in their area.

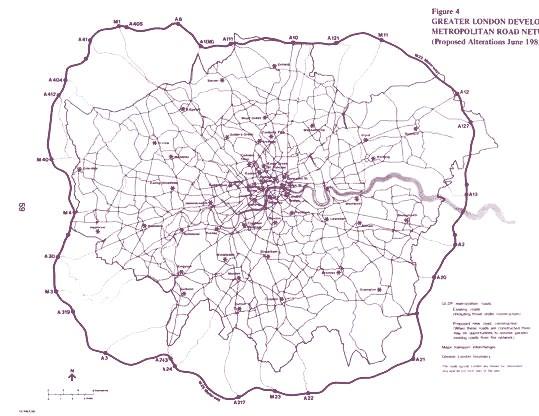

Metropolitan Green Belt fully designated in local plans.

Completion of M25 motorway, running largely through the Metropolitan Green Belt.

PPG2 amended to add positive objectives for Green Belt land.

Current version of PPG2 issued.

1926 1947

1951 1938

1935

1898

1955

1959 1986 1995 2001

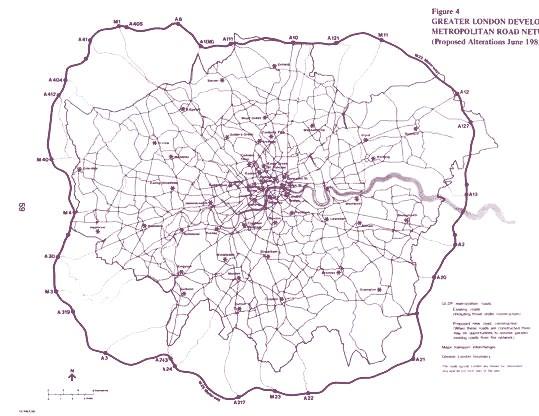

Metropolitan

Fig 15 A.Paolo

Road network map

masucci.

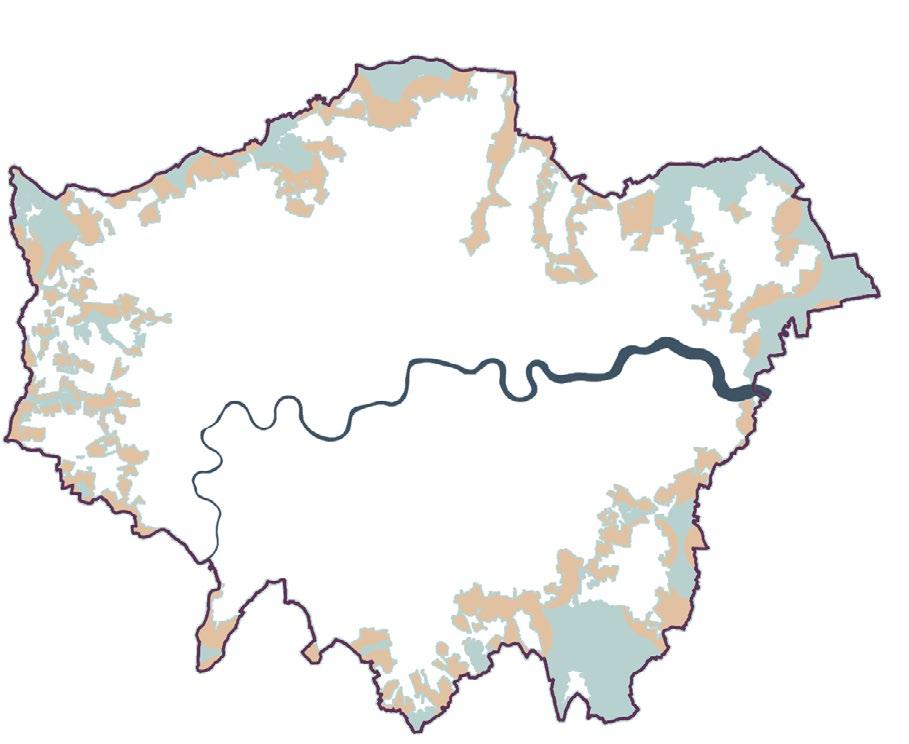

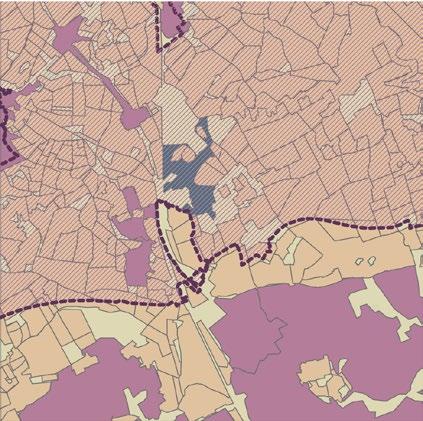

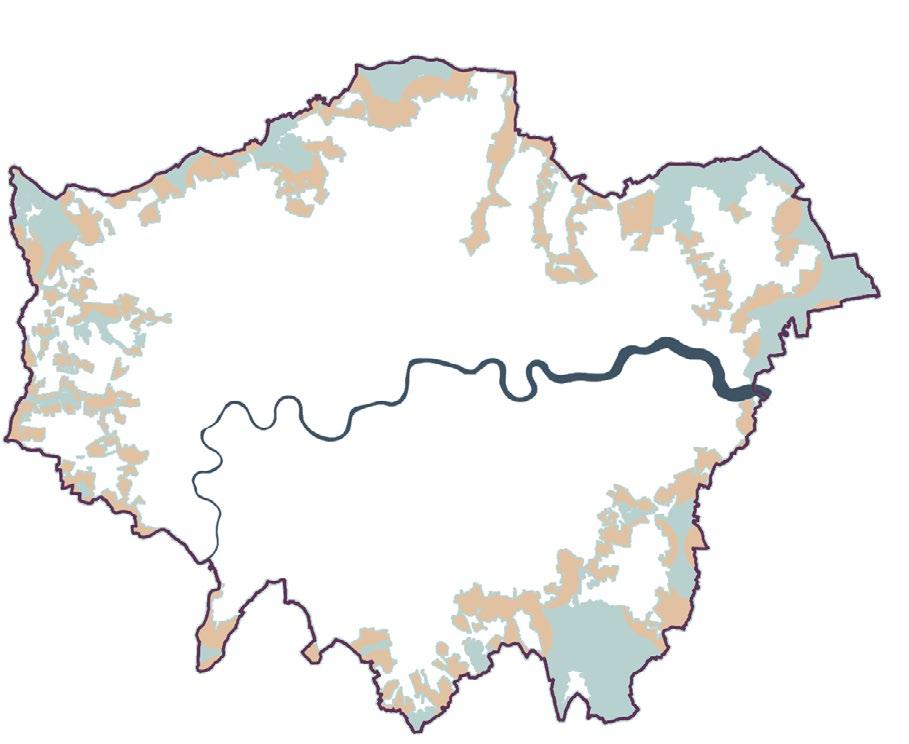

Environmental designation Within 2 km of rail stations Parks and public access Roadways and buildings Agriculture Golf course Green belt Urban centres London Greenbelt Profile Fig 16 By

17 | 18 [AA Landscape Urbanism 23/24] [AA Landscape Urbanism 23/24] Planet of Fields

Khusbhoo Prashant

Green Belts as Urban Containers

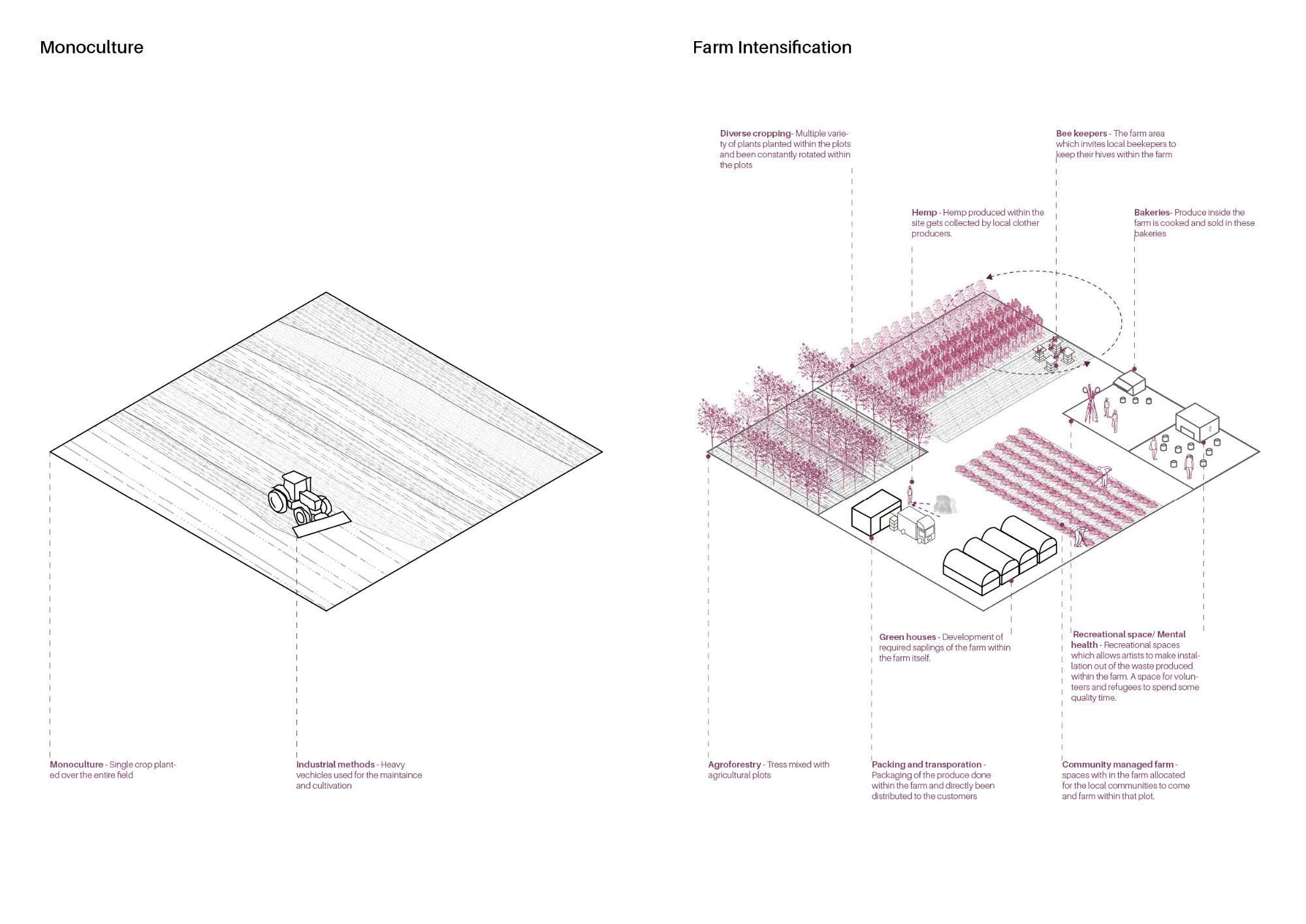

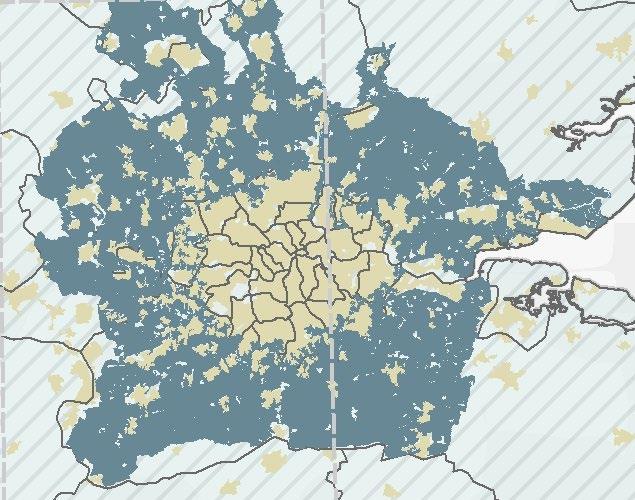

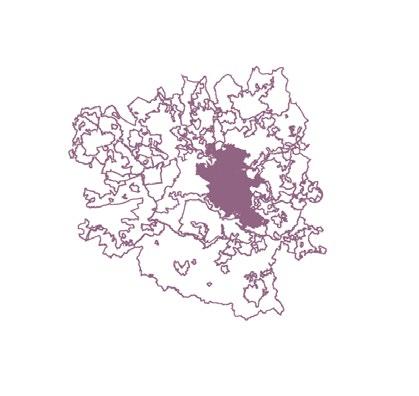

According to CPRE, the majority of the area within green belts have mainly been used for agriculture. In principle, this is a use that, not only preserves the green and “open” character of these areas, but it also facilitates the production of food in close proximity to urban centres (Campaign To Protect Rural England and Natural England (Agency 2010). However, as we will see in coming chapters, due to the nature of the UK’s food system this is not necessarily the case at present.

Alongside agricultural land the greenbelts are also host to water bodies and to woodland, (both recent and historical) which play integral roles, not only in terms of biodiversity and carbon capture but also as areas for recreation and management of resources to the city (e.g.. water reservoirs). Lastly, the greenbelt is also made up of villages and similar small urban agglomerations, most of which have a historical character of preservation associated to them.

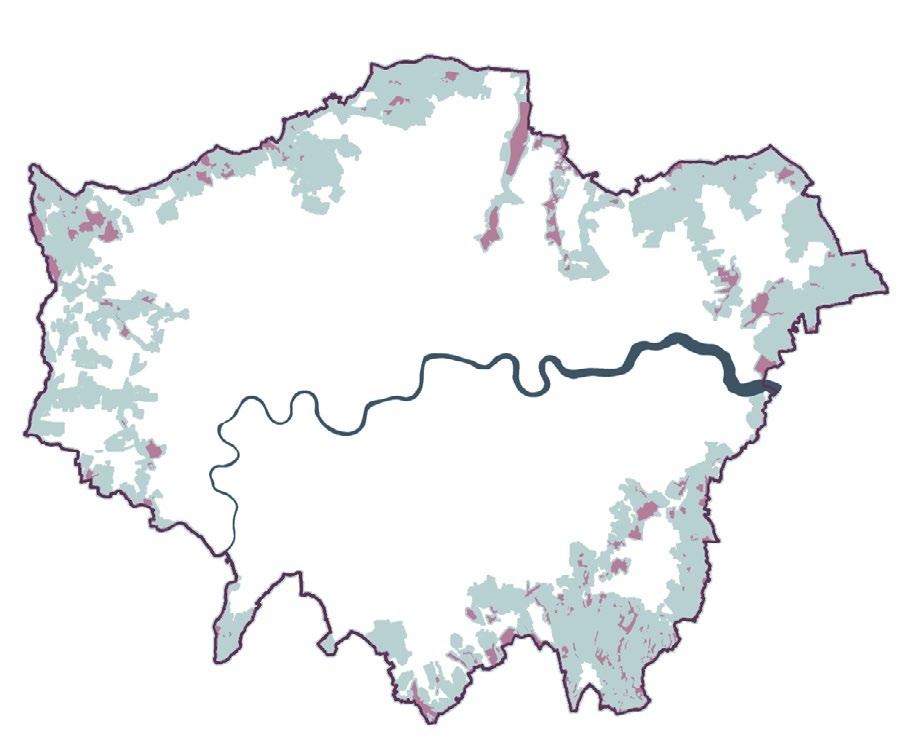

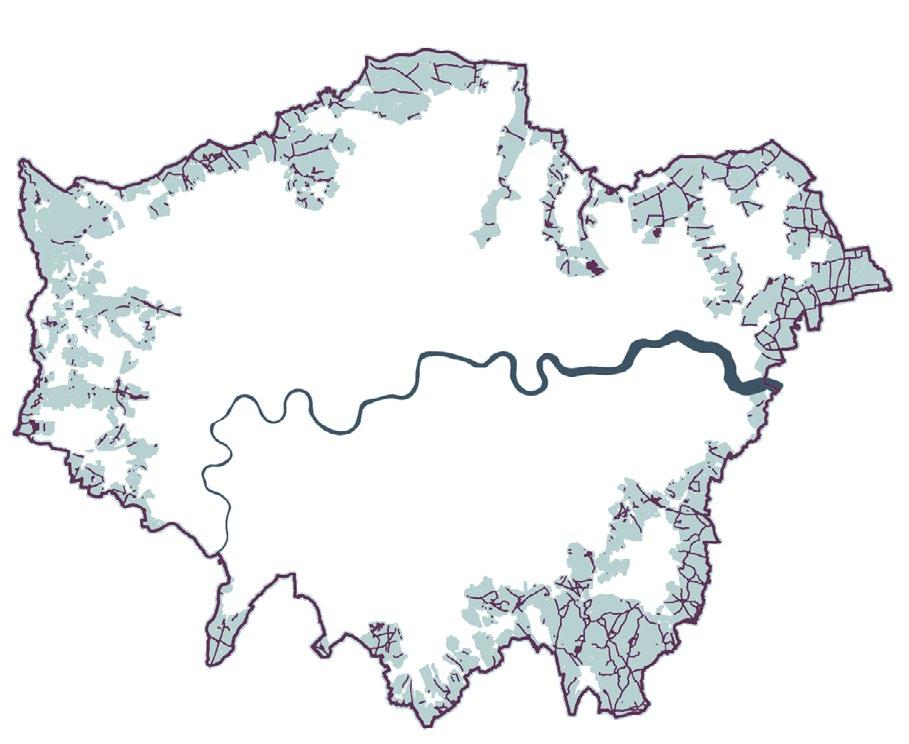

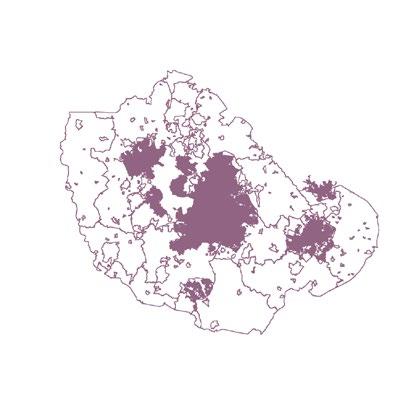

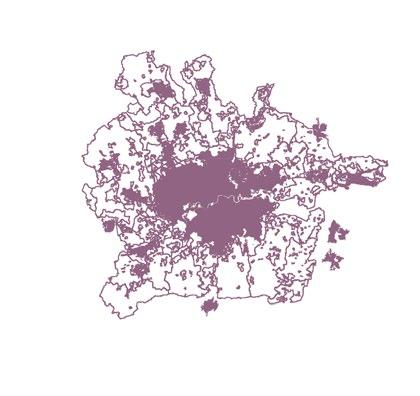

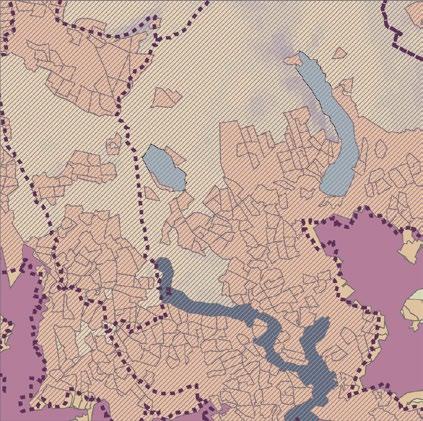

London & It’s Greenbelts Fig 17,18,19,20,21

Urban areas

Forests

Agricultural areas

Green belt boundary

Water bodies

By Jegan Muralidharan

By Jegan Muralidharan By Jegan Muralidharan

By Jegan Muralidharan

Bristol London Manchester Birmingham Bristol & Its Green belts

Manchester & Its green belts Birmingham & Its Green belts Fig

22,23,24,25,26

Fig 27,28,29,30 Fig 31,32,33,34

19 | 20 [AA Landscape Urbanism 23/24] [AA Landscape Urbanism 23/24] Planet of Fields

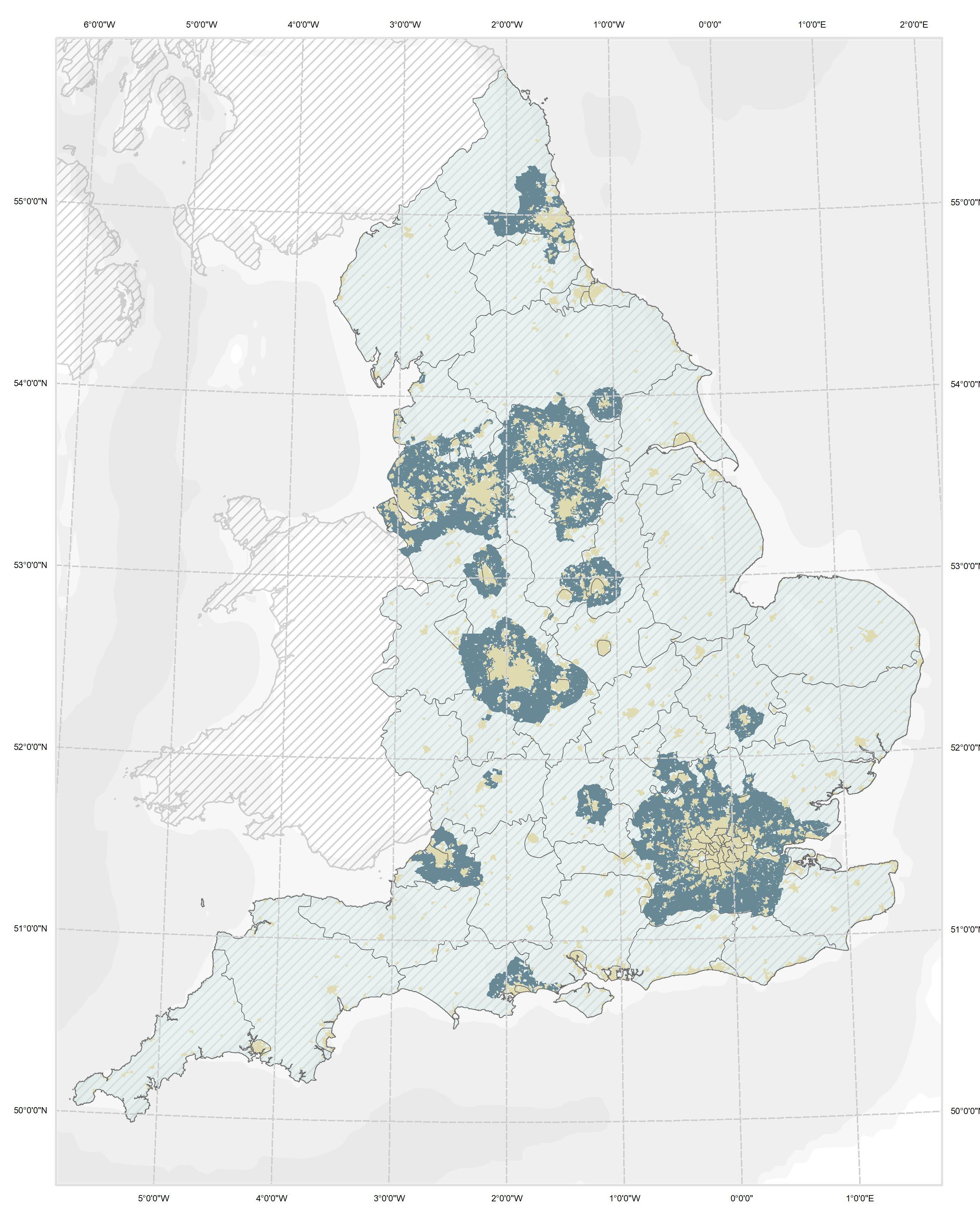

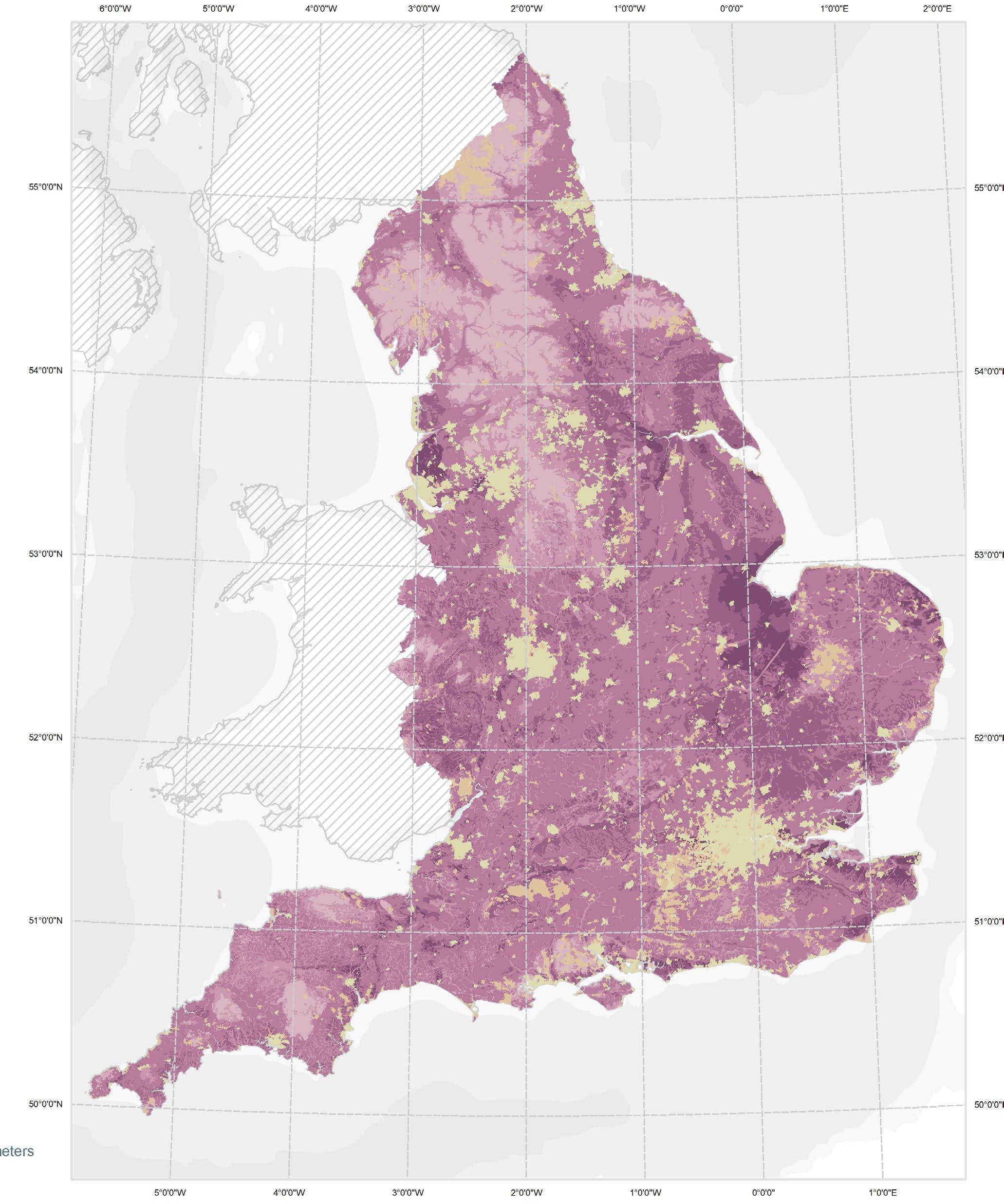

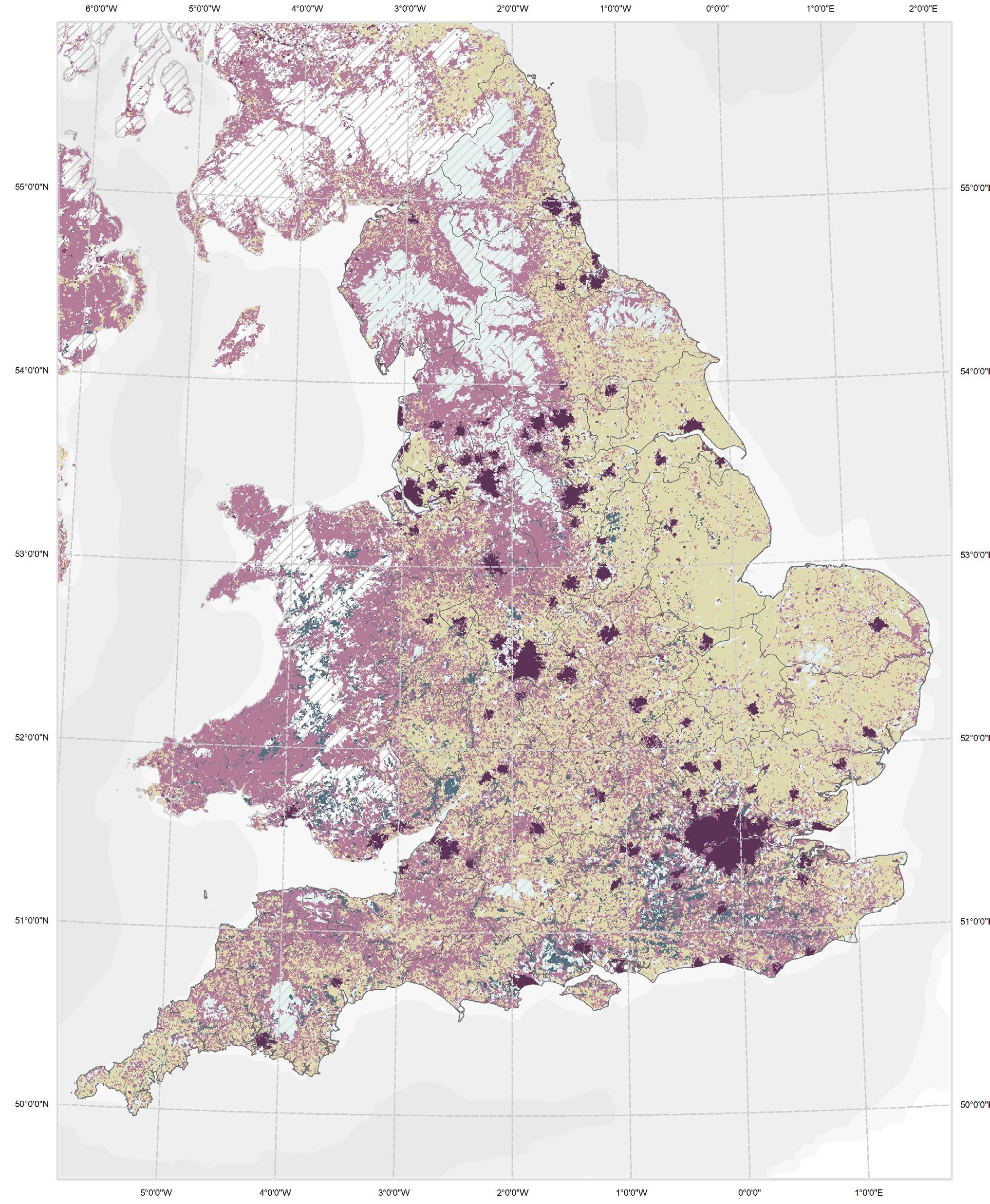

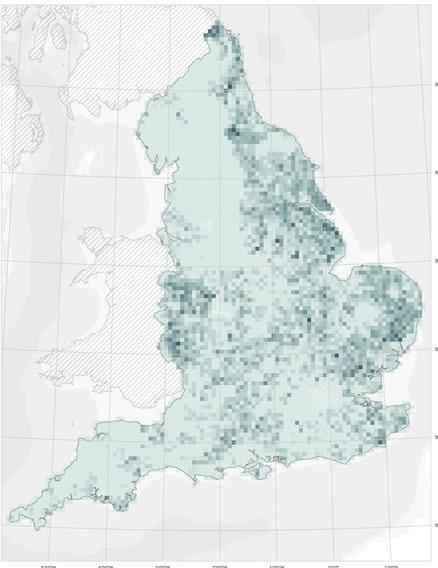

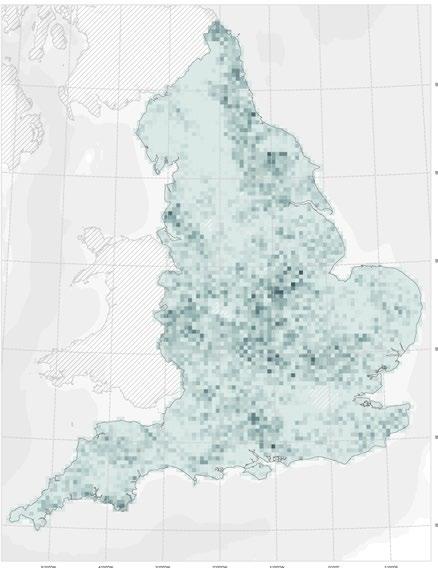

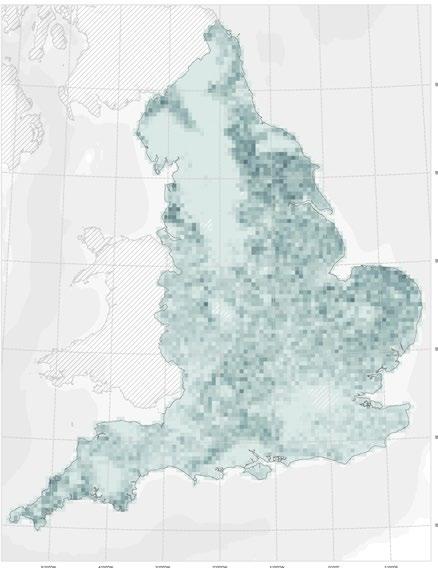

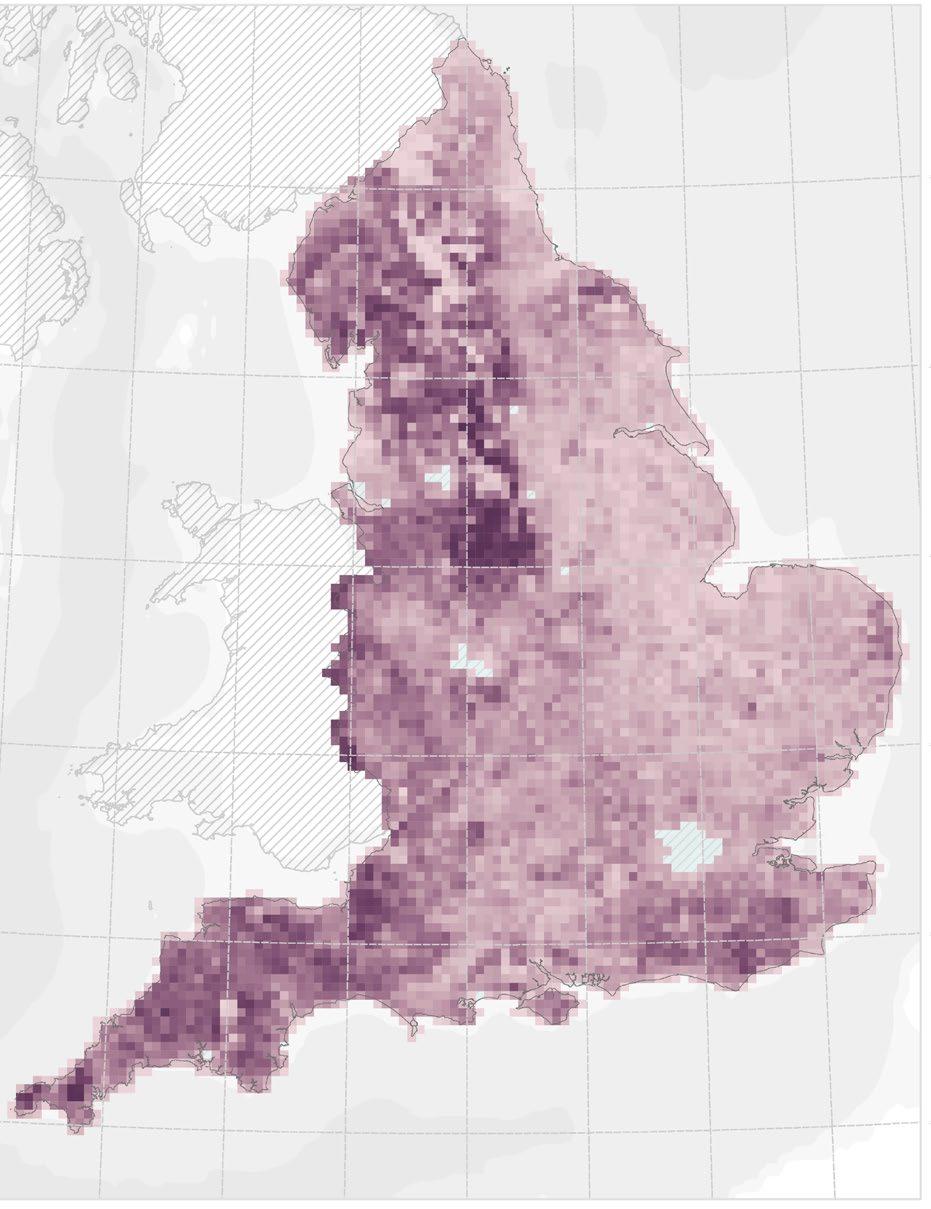

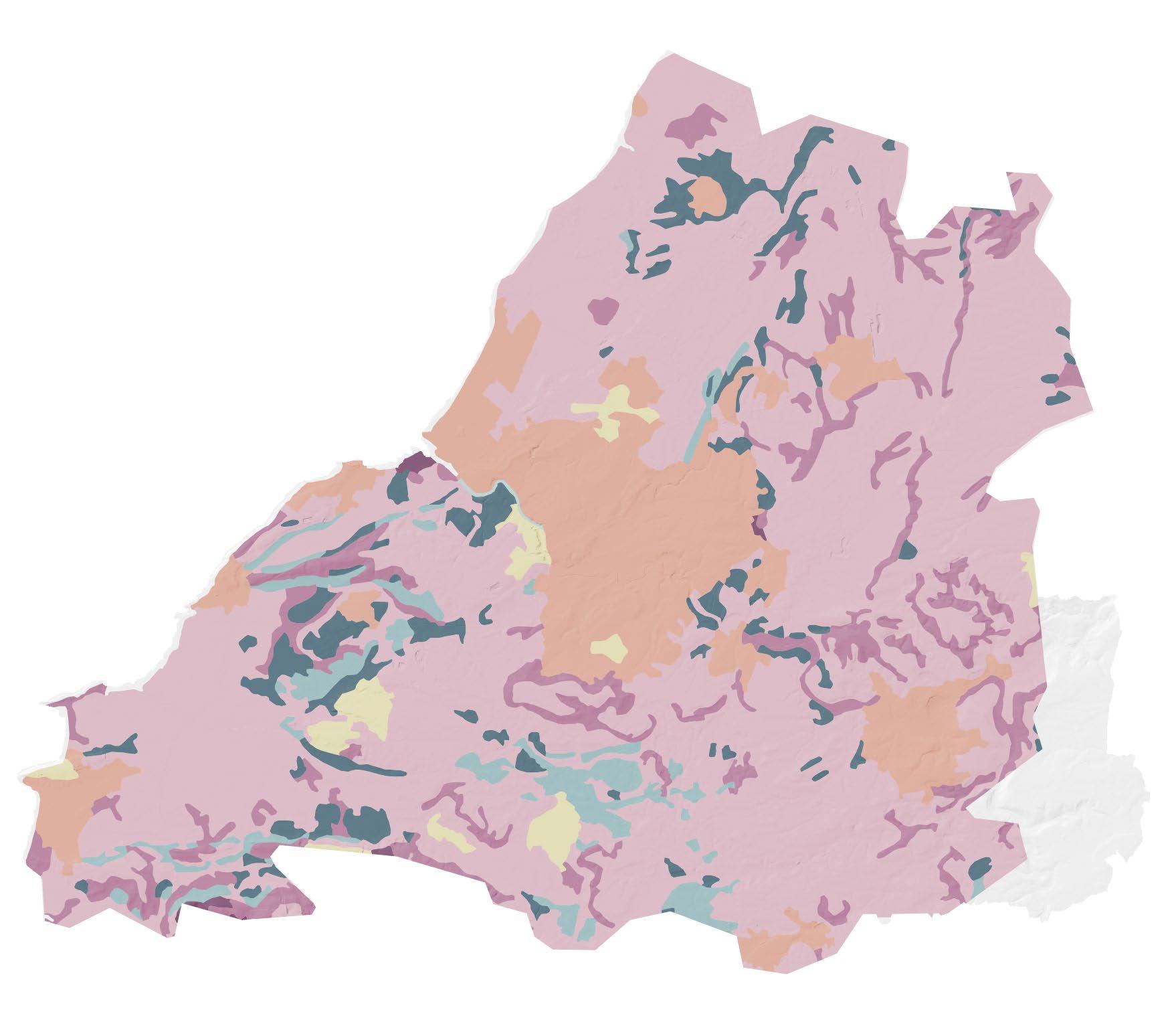

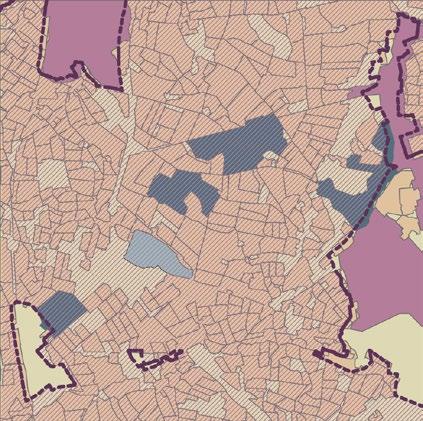

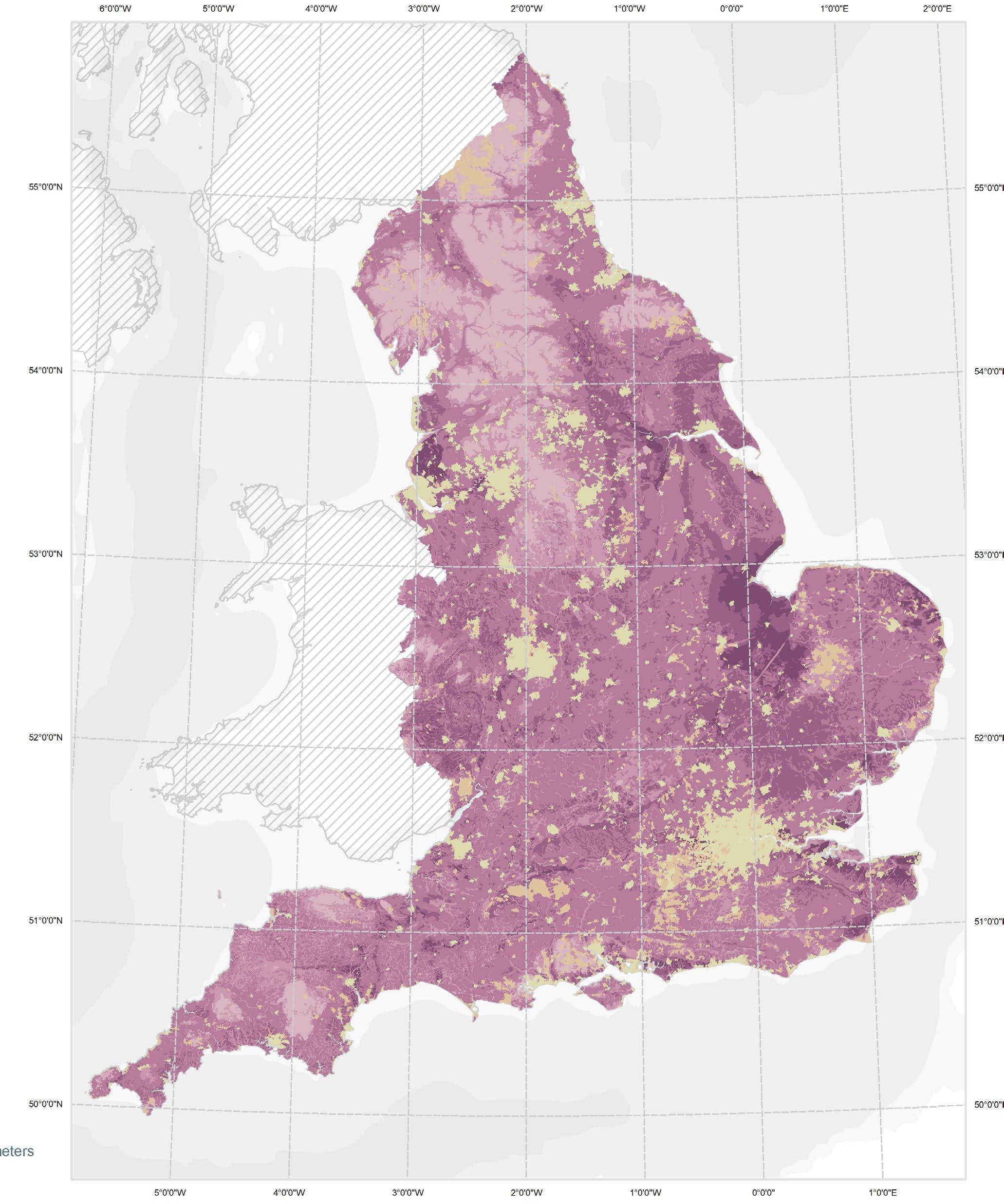

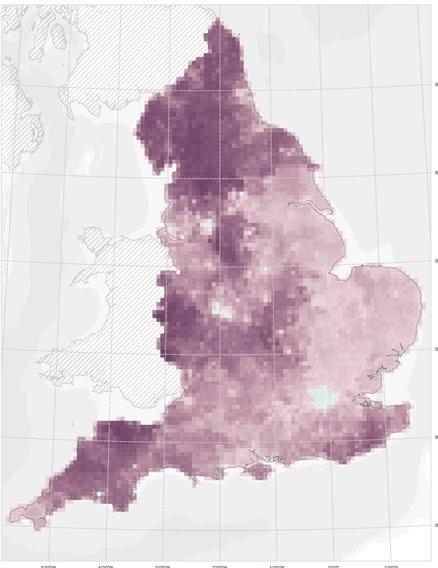

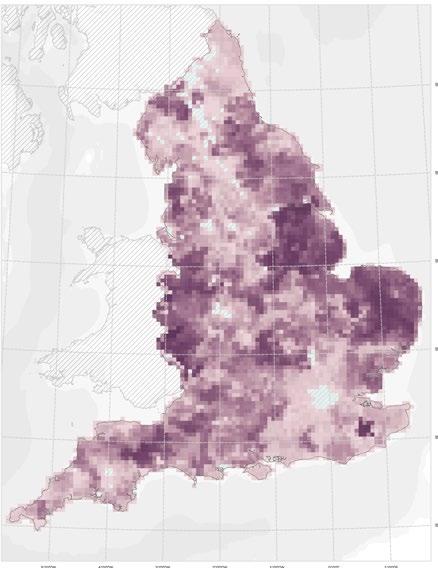

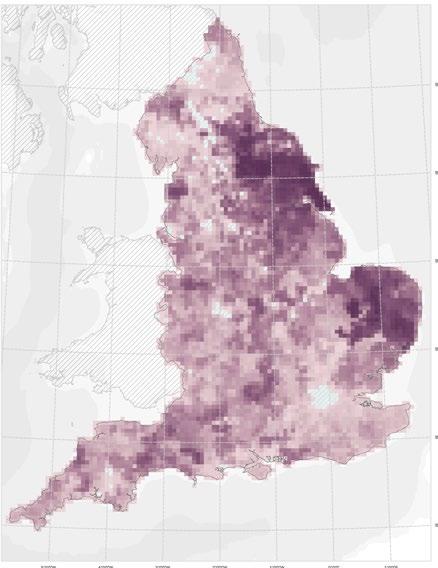

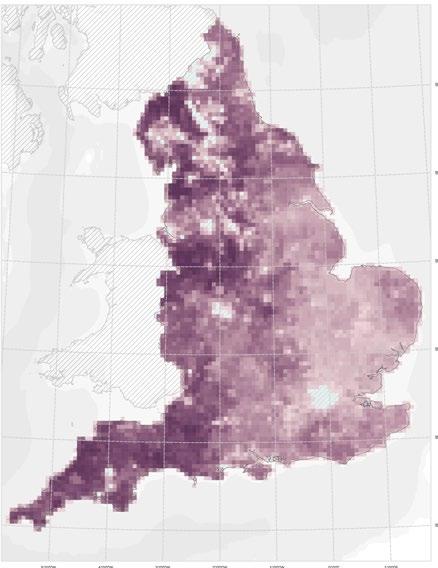

Soil Grading and Land use

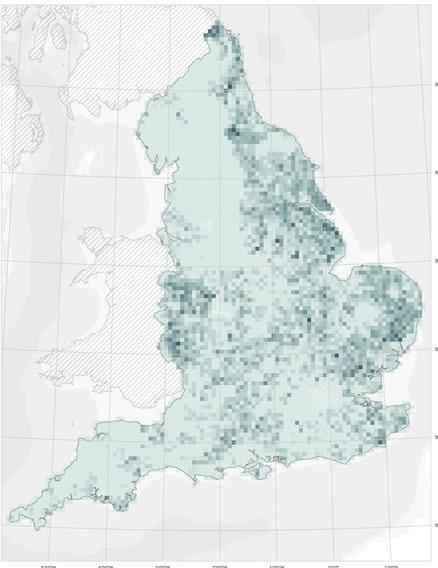

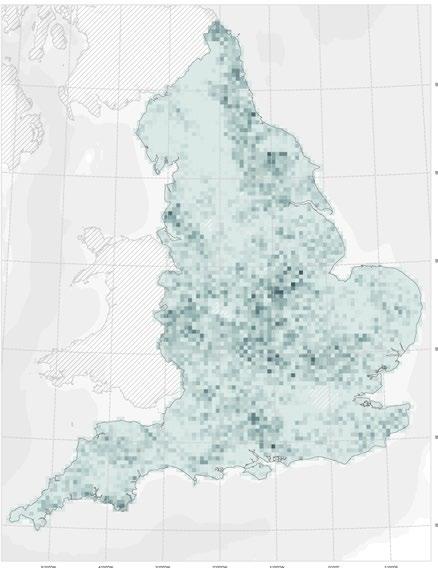

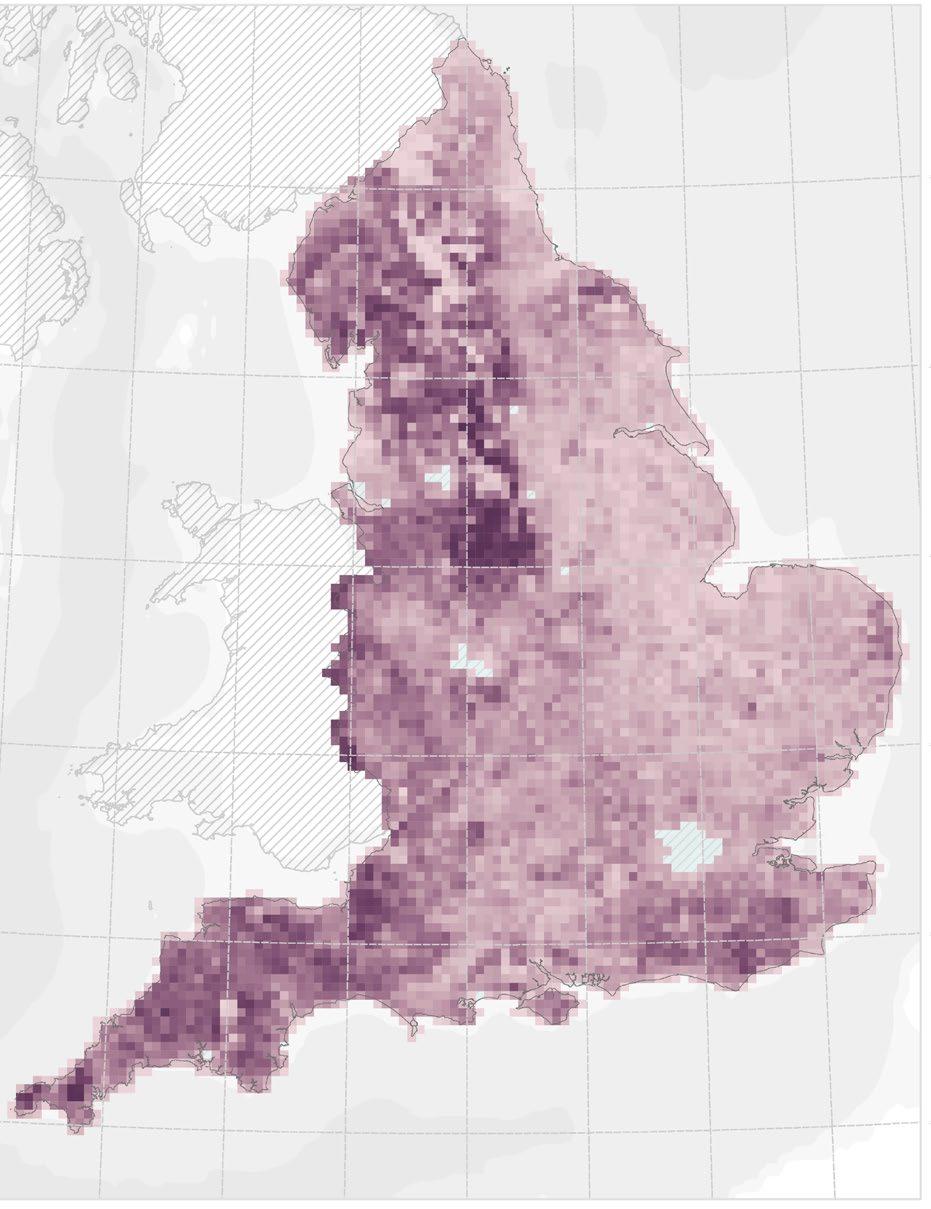

In terms of elevation, England is divided into highland, midland and lowland areas. Lowland being more suitable for agriculture and covering the majority of South eastern UK.

The cropping pattern is also influenced by soil, where Agricultural land grading is an important figure.

ALC Grade

The Agricultural Land Classification (ALC) is a system employed within England and Wales, and used to grade the quality of farmland. It revolves around the long-term limitations imposed by either physical or chemical characteristics, considering factors such as climate, soil characteristics, and flood susceptibility. (LRA, n.d.) It is a system that becomes instrumental in deliberating planning decisions because the National Planning Policy Framework mandates authorities recognize the benefits of prime agricultural land during development proposal evaluations. The ALC categorizes land into five distinct grades with and that is graded 1 considered to be the most adaptable and able to support a wider variety of crops requiring the lowest input to produce a higher yield:

Grade 1: Premium land of impeccable quality, virtually free from limitations.

Grade 2: High-quality land with minor impediments, potentially influencing crop yield and cultivation processes.

Sub-grade 3a: Respectable quality land, presenting moderate constraints that can guide crop choices and their respective yields.

Sub-grade 3b: Moderately quality-stricken land, grappling with pronounced limitations that dictate both crop choices and yields.

Grade 4: Sub-par land plagued by profound limitations, severely capping the range and yield of crops.

Grade 5: Inferior land, besieged with extreme constraints, relegating its use primarily to perennial pastures or rudimentary grazing, bar occasional pioneer forage crops.

Prashant

Grade 1

Grade 2

Grade 3

Grade 4

Grade

ALC Soil grading Fig 35 By Khusboo

Non - Agricultural 21 | UK Food System 22 [AA Landscape Urbanism 23/24] [AA Landscape Urbanism 23/24] Planet of Fields

5 Urban Exclusion

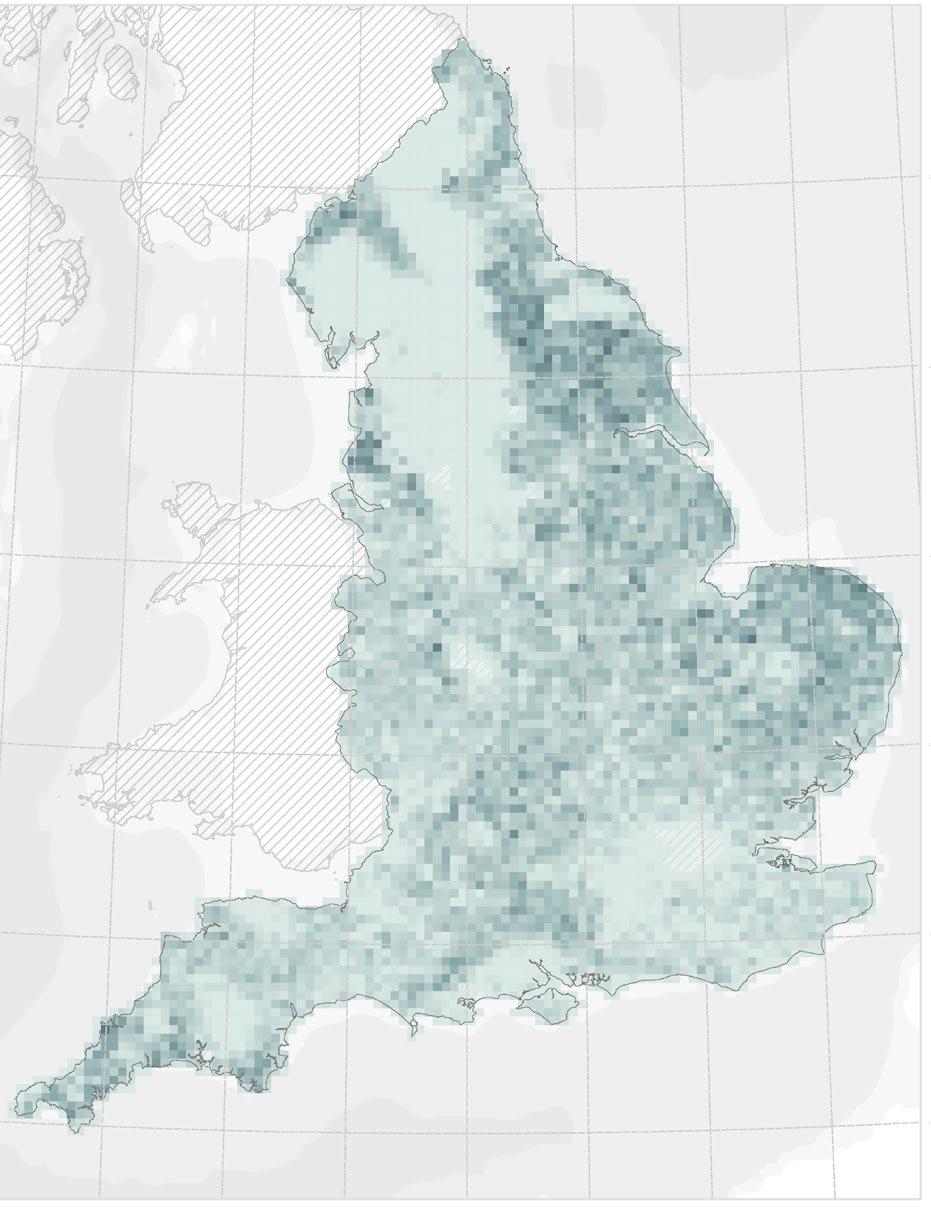

Land-use

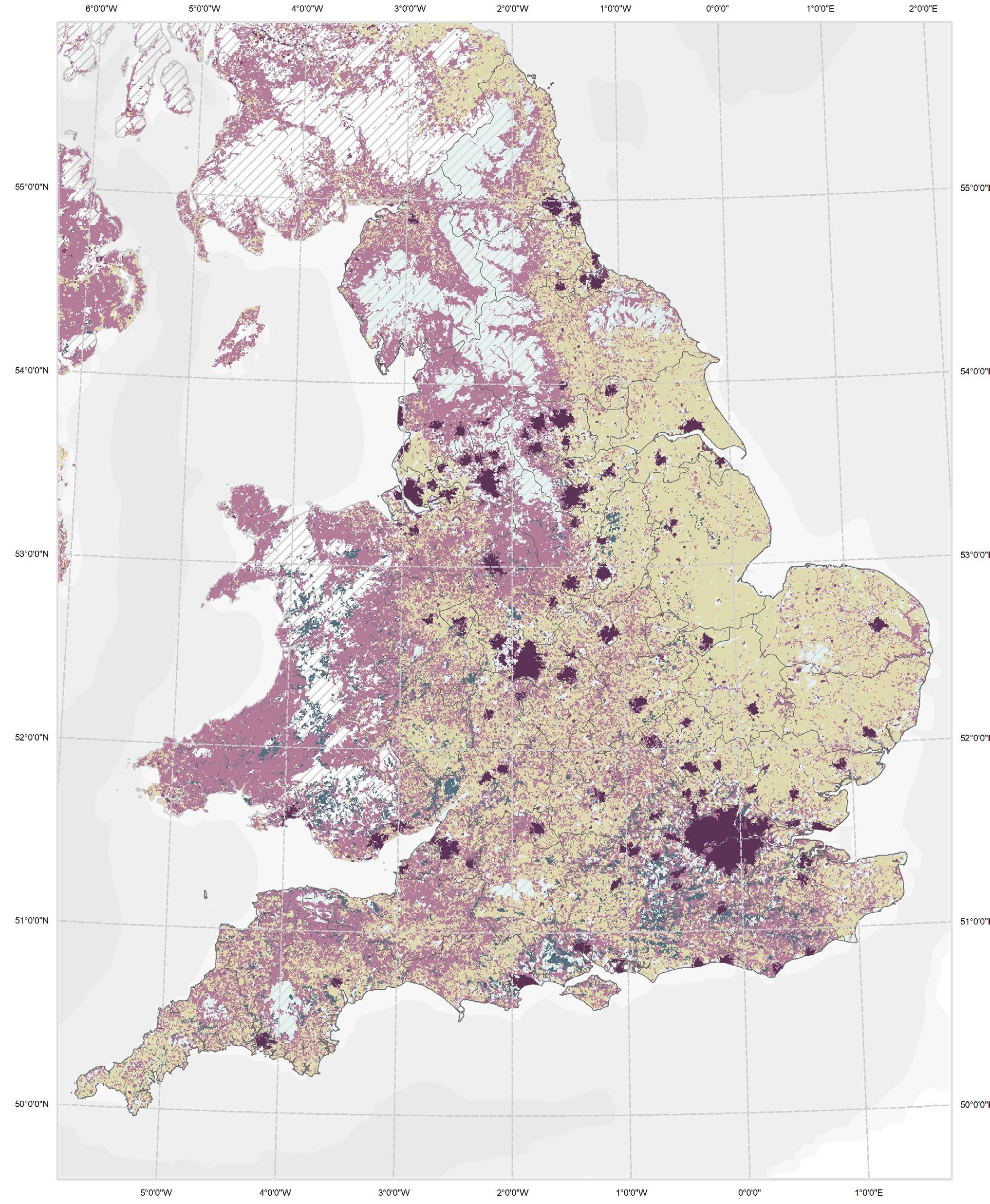

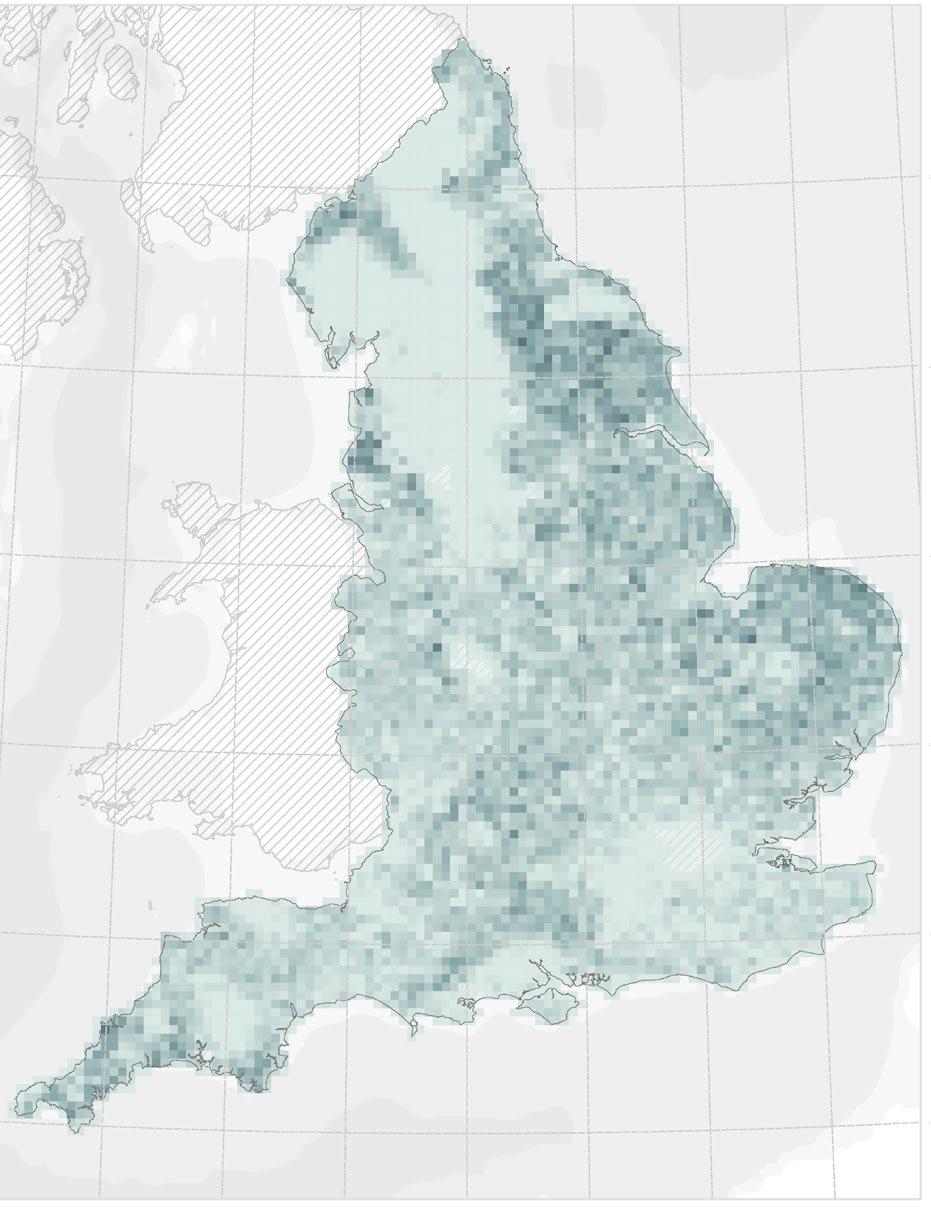

Urban areas, which include buildings, roads, and other infrastructure, cover about 6-7% of the UK and these areas are home to a significant majority of the population. With regards to forests and woodlands, they cover about 13% of the land area in the UK, as the island’s large forested areas were cleared over centuries. This percentage accounts for both commercial forestry and conservation efforts.

As mentioned previously, more than half of the UK’s total land is classified as being for agricultural use. This includes both pasture land for livestock and arable farmland. Considering that the ALC grading locates the highest graded land towards the east it stands to reason that most of the arable farmland is also in this area while most of the grazing land is located in the west where there is a generally lower ALC grading. This leads us to the topic of the UK’s food system and looking with more detail at the composition of this agricultural land, as well as its relationship to its immediate context and the rest of the world.

By Khusboo Prashant

Major cities in England

Permanent crops/ Arable/ Heterog. Agricultural land

Pastures

Industrial/ Commercial/ Transport Forests

Land Cover

Fig 36

England 23 | UK Food System 24 [AA Landscape Urbanism 23/24] [AA Landscape Urbanism 23/24] Planet of Fields

UK Food System

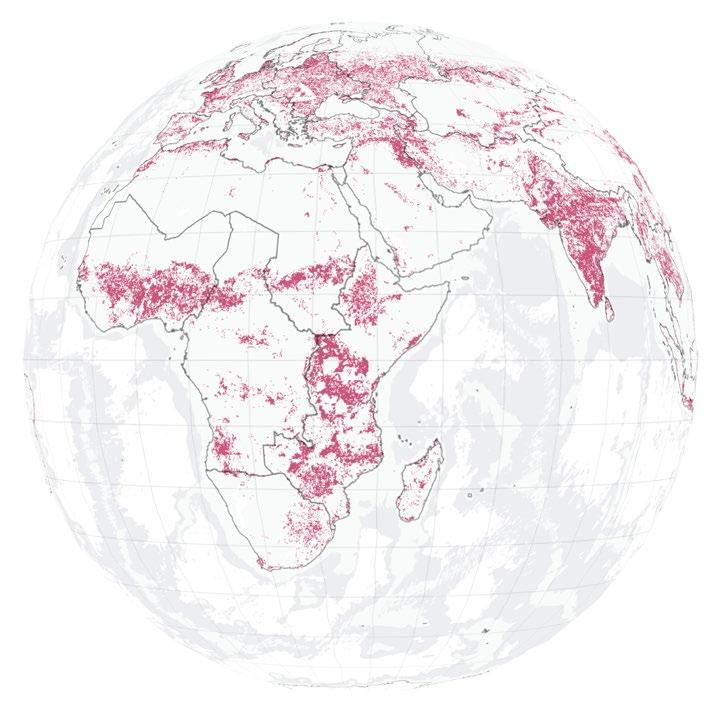

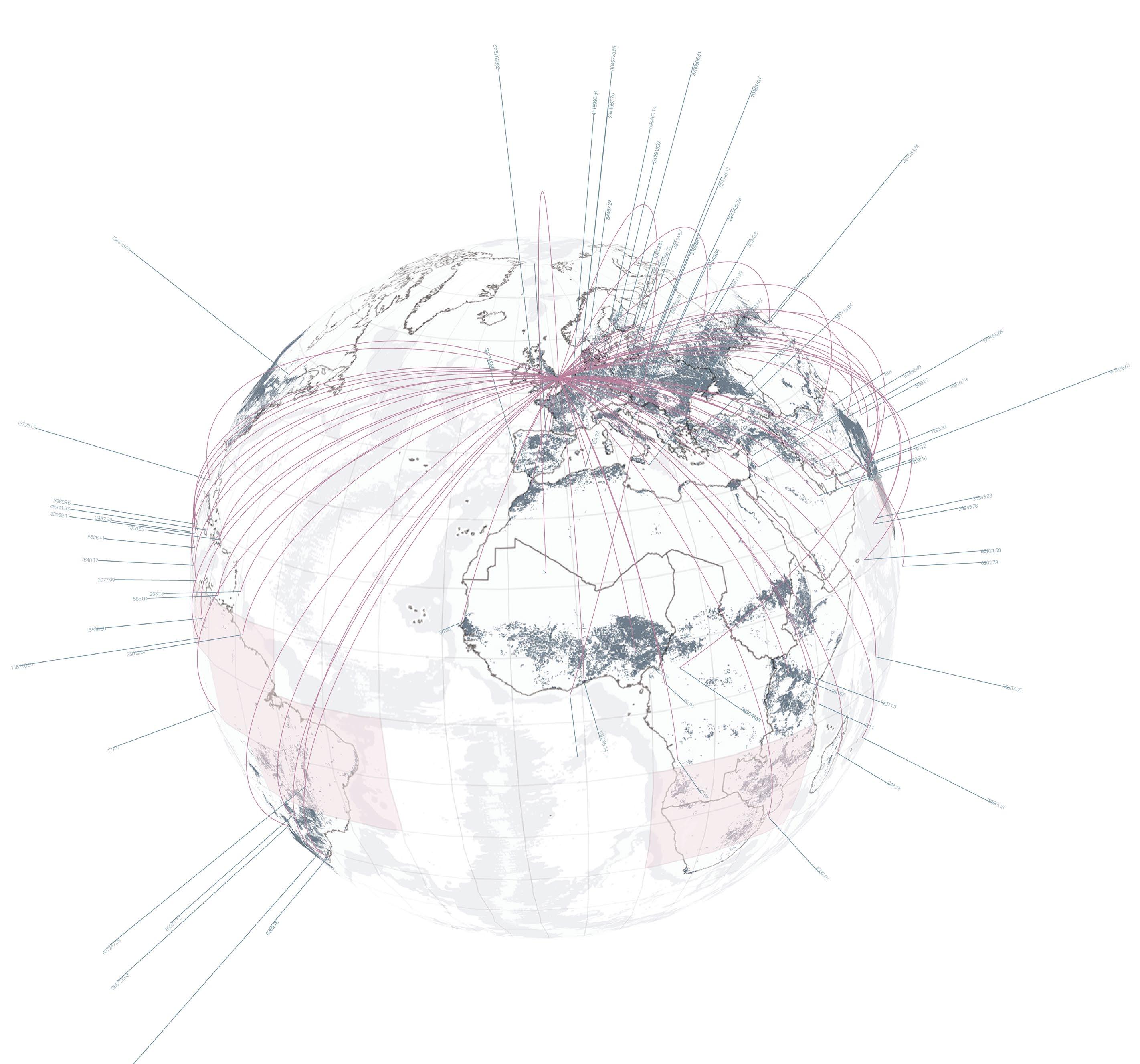

“The United Kingdom’s heavy reliance on food imports from far-flung corners of the world is not only unsustainable, but it also disconnects us from the land, the people who cultivate it, and the seasons that govern its bounty.” (DEFRA 2020)

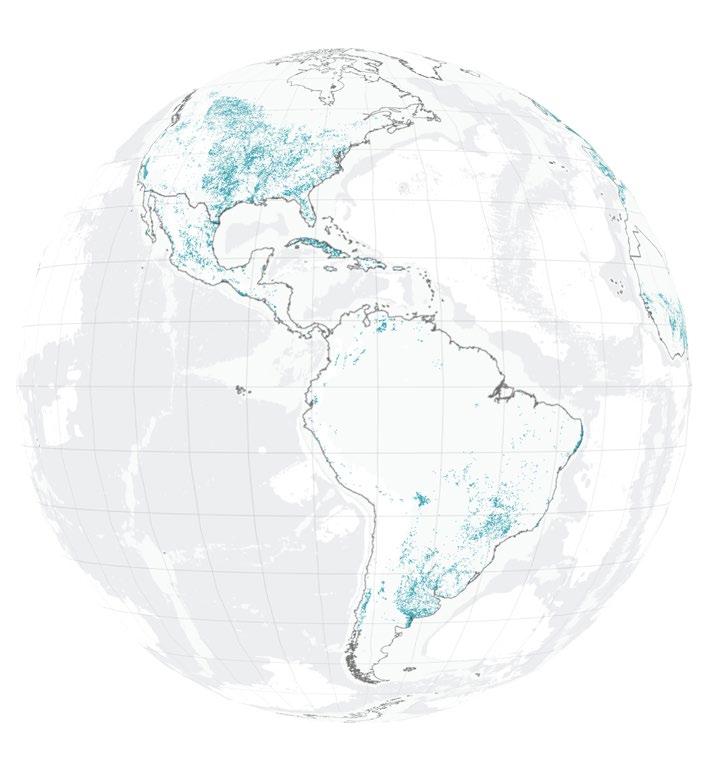

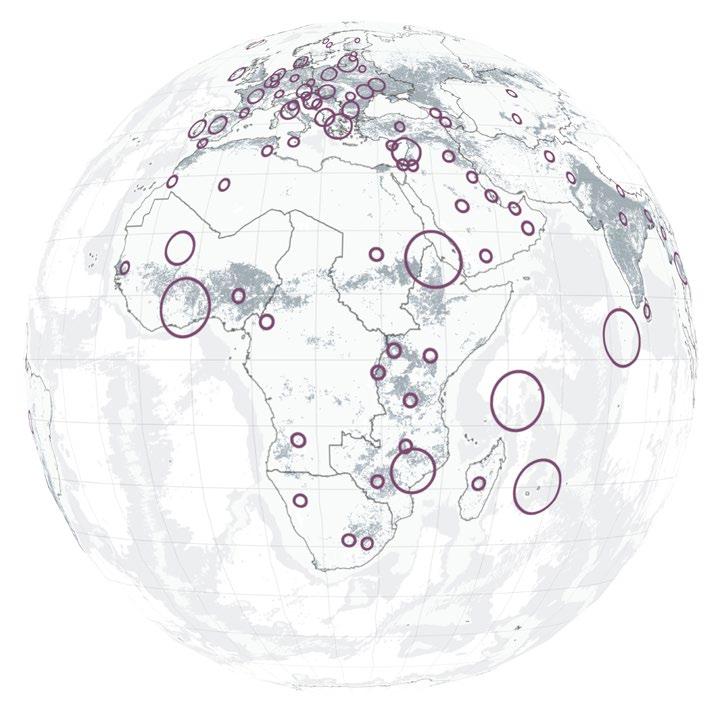

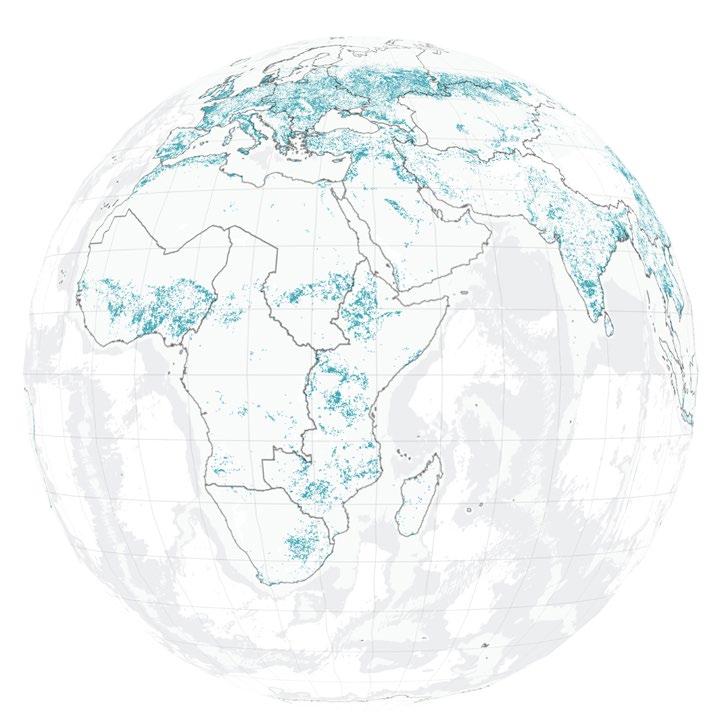

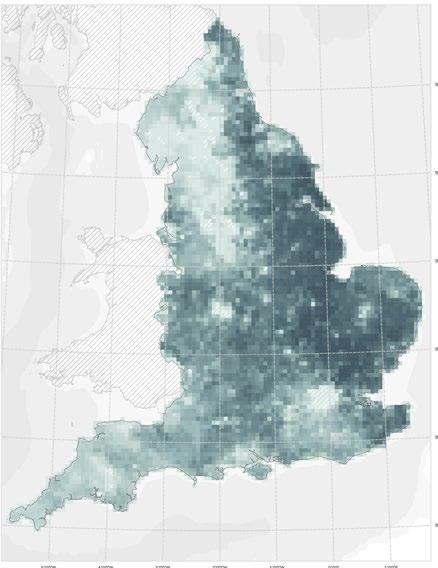

As is made evident by the National food Strategy, A large part of the Uk’s agricultural land is used to produce animal feed and almost half of the land required to feed the UK is located overseas. The latter is referred to as an “Extended Footprint.” This leads to a heavy dependence on international imports, relying on imports especially for out-ofseason produce, certain staples, and specialty products. (DEFRA 2020)

Because the cost of farming is outsourced, nationally grown food is very dependant on government subsidies in order to compete, and it ends up being sold at supermarkets with prices that don’t reflect its real cost of production. Along with the environmental impact that these globalized supply chains have, all this puts the Uk in a challenging situation with regards to long term food security.

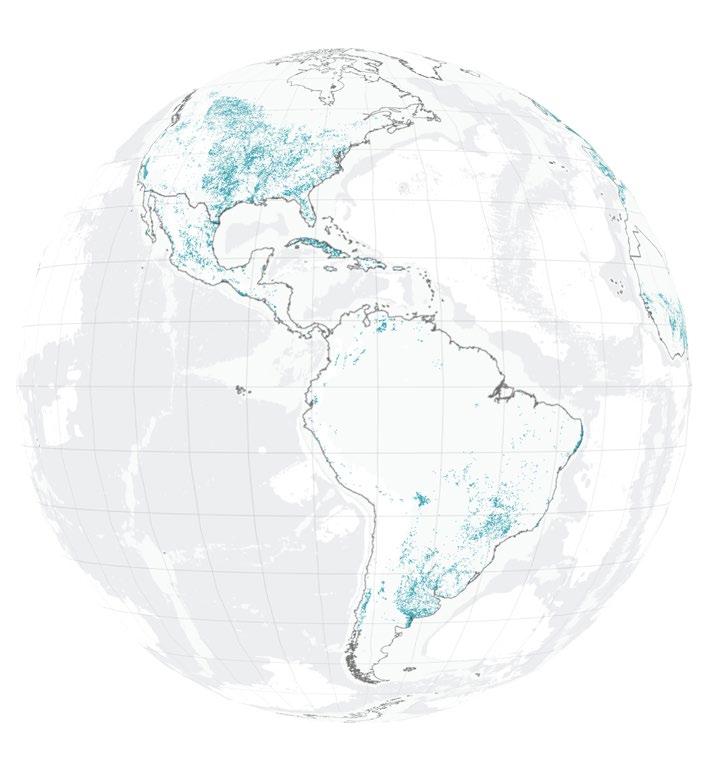

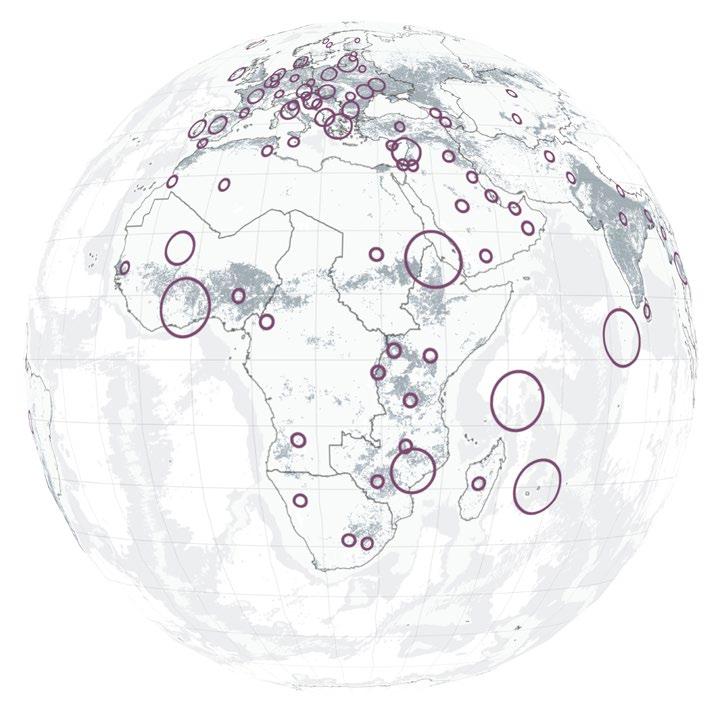

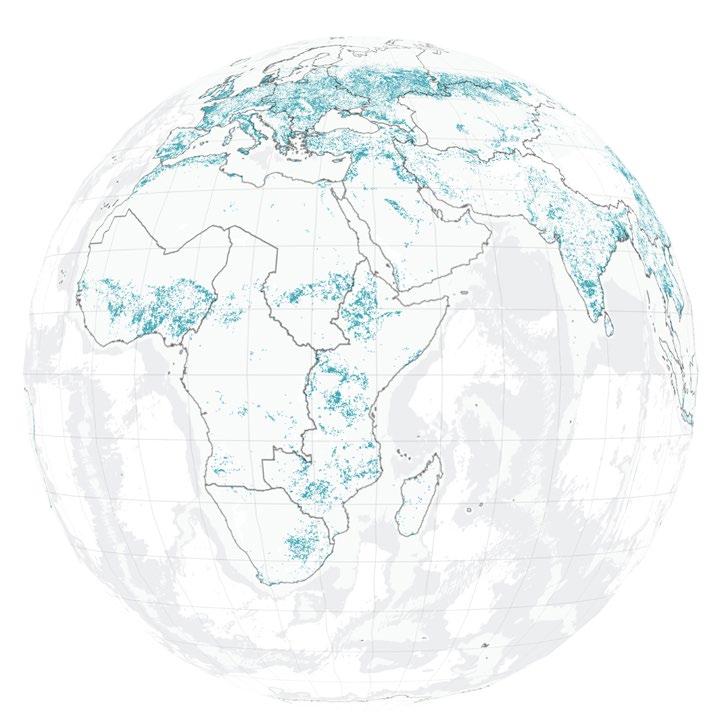

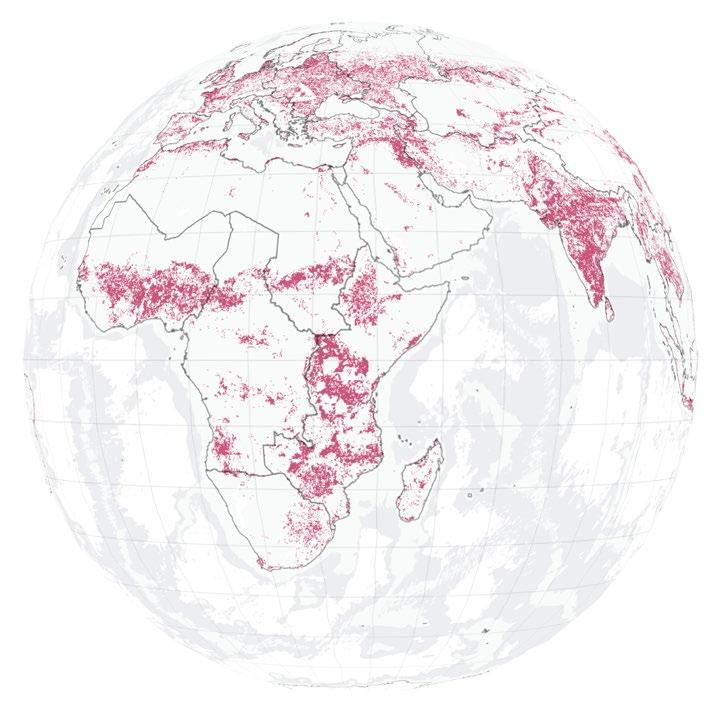

Food and Land Use

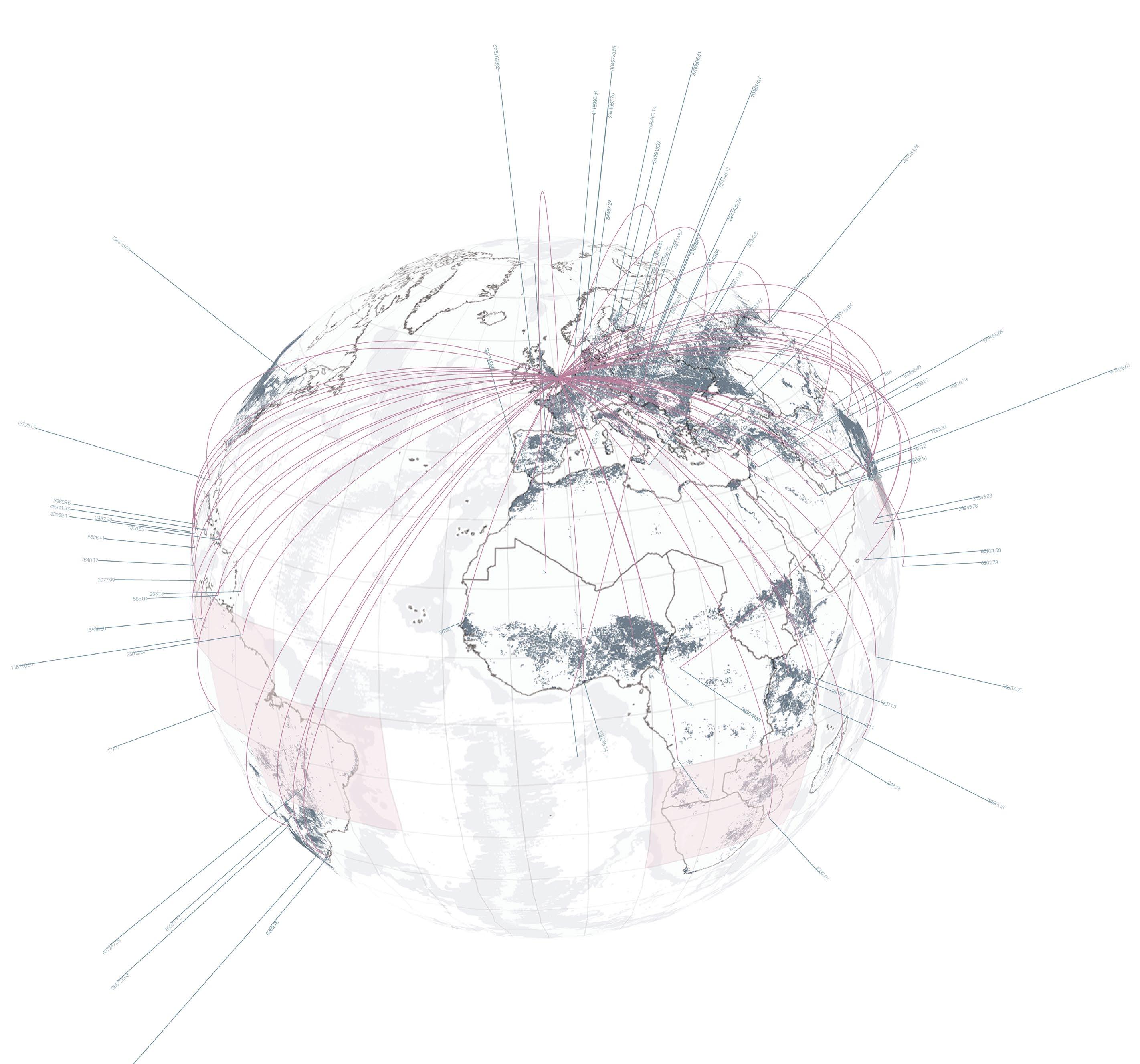

Global crop-land loss 2010-2022 Global crop land gain 2010-2022 UK Import percentages compared to a country’s overall export Routes and impact of UK’s food Area required for UK’s Food Fig 38 Fig 37 By Jegan Muralidharan National Food Strategy, Part 1

25 | UK Food System 26 [AA Landscape Urbanism 23/24] [AA Landscape Urbanism 23/24] Planet of Fields

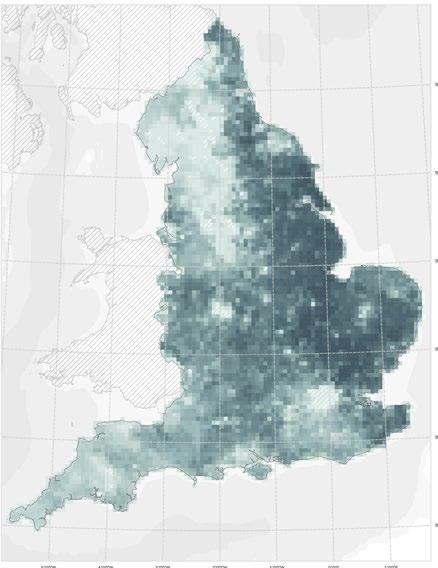

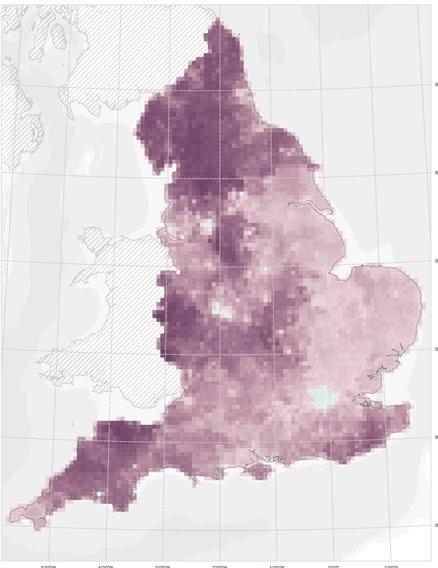

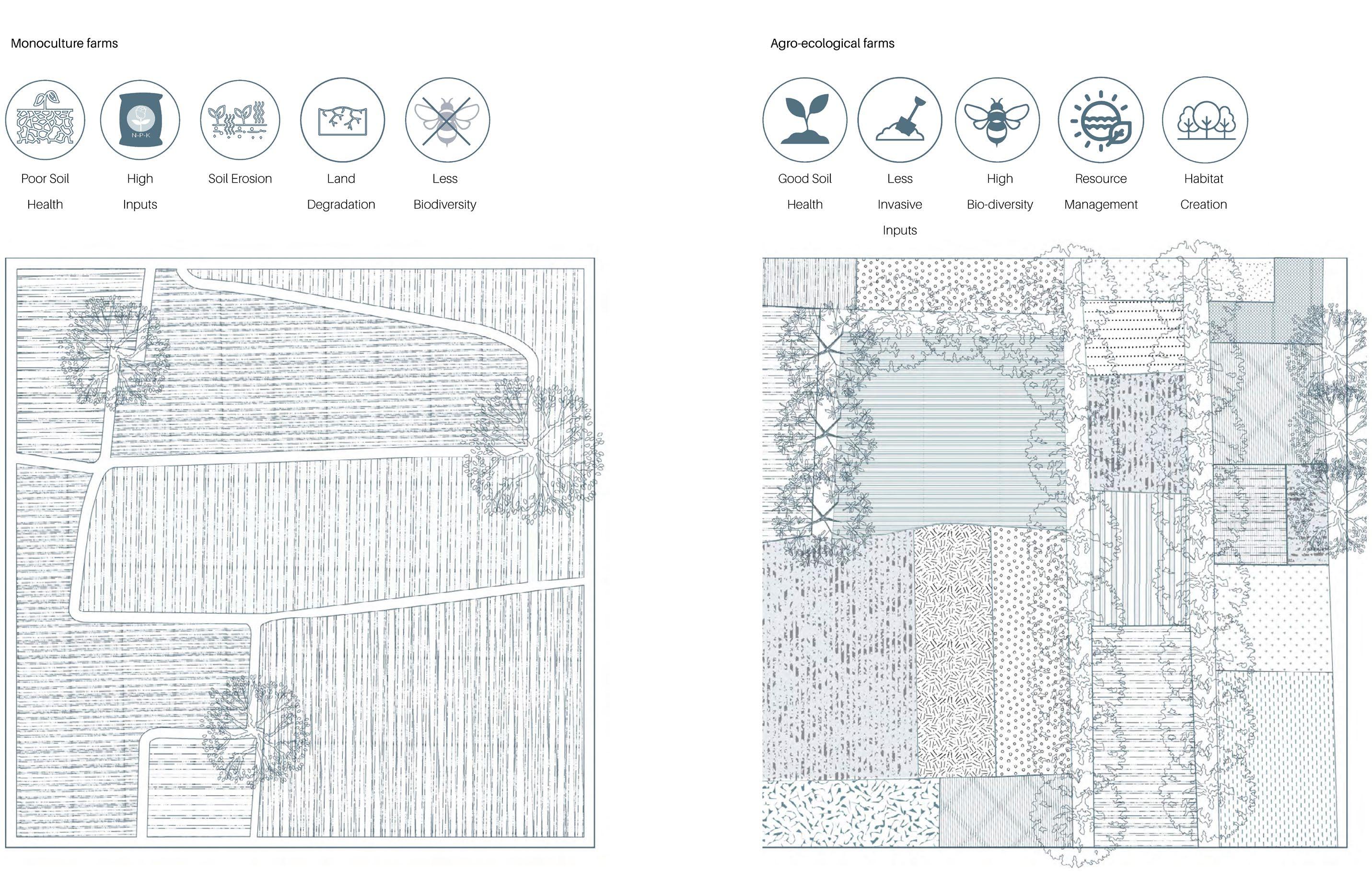

Arable land, Grassland and Mono-culture

Beyond the globalized supply chains, there is another concern: These supply chains, guided by market dynamics, predominantly favor the mono-culture of crops that promise the highest profitability. Such an approach is highly detrimental to soil health, it accelerates waterway pollution, and precipitates a notable loss in biodiversity especially. While the most conducive opportunities for diverse agriculture reside in the east of England (based on the ALC grading), it’s alarming to note that a significant part of this versatile land is allocated to the mono-culture cultivation of specific crops. Predominantly, these are oilseed, wheat, oats, and barley, which collectively represent the most part of the UK’s cultivated produce.

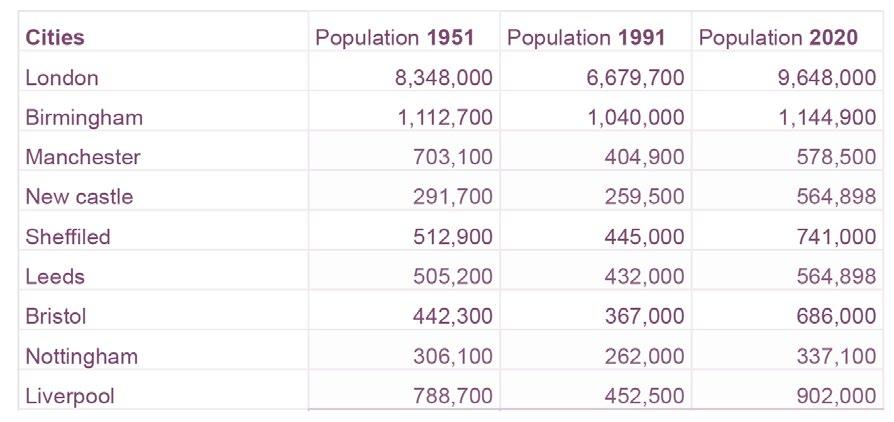

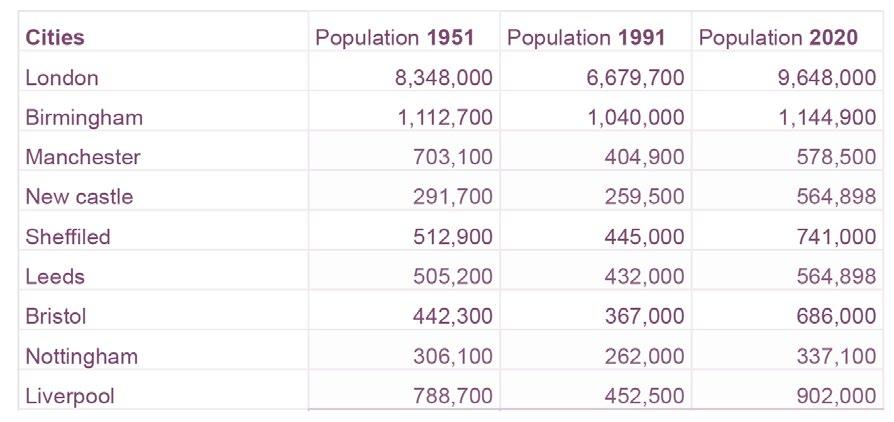

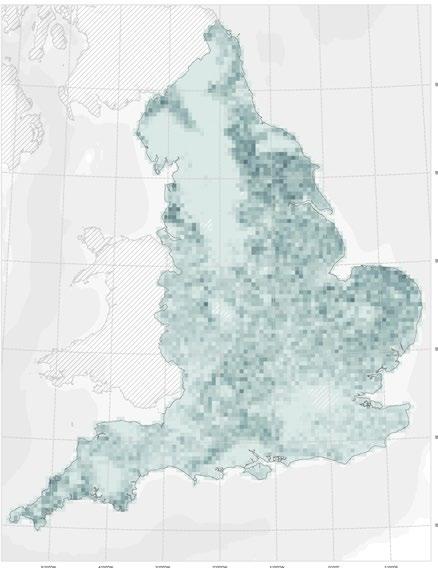

Population Growth

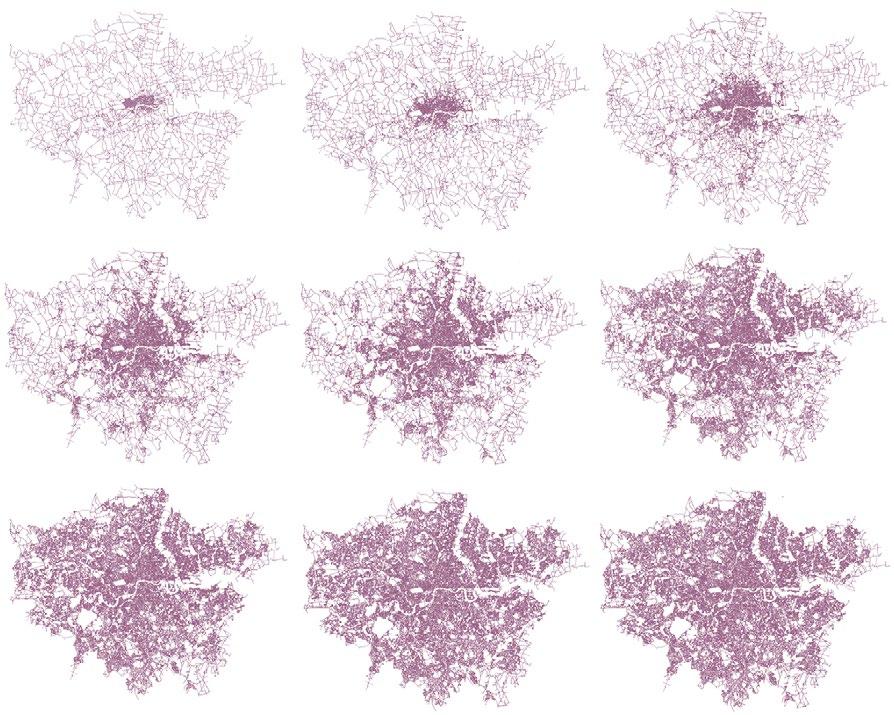

Since the industrial revolution, England has had a distinct concentration of the population in cities and urban areas and, today, the population of England grows exponentially with a rise of 0.34% every year.

The Greater London area alone is home to over 8 million residents, making it not only the most populous city in the UK but also one of the most populated in Europe (Greater London Authority 2021). The chart below shows population of England’s 8 largest cities.

Because of this population density, most of the demand that drives the UK food system is coming from cities. This puts greenbelts are in a unique position to play a role in addressing the problems associated to a globalization food system and leads us to explore the relationship between cities and their hinterlands.

By Antonio Garaycochea

By Antonio Garaycochea

Fig 40,41,42,43

Oats, Oilseed, Barley, Wheat

By Antonio Garaycochea

By Antonio Garaycochea

Poultry,

By Antonio Garaycochea

Population growth and Greenbelts

Khusboo Prashant

Grasslands Arable/ Horticulture

Cattle, Sheep, Pigs

Fig 44

Fig 39

Fig 45,46,47,48

Grasslands Poultry Oats Sheep Barley Cattle Oil seed Pigs Wheat

Arable/ Horticulture

Sheffield Liverpool Birmingham Bristol

Newcastle Leeds

London

Fig 50

27 | UK Food System 28 [AA Landscape Urbanism 23/24] [AA Landscape Urbanism 23/24] Planet of Fields

By

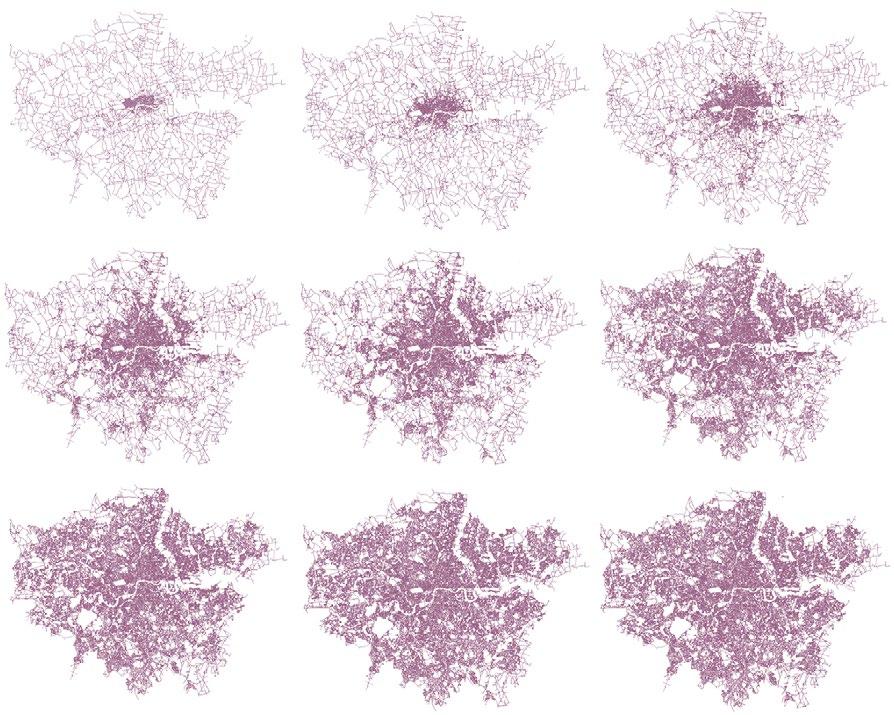

London city growth Fig 49 A.Paolo masucci.

Food Zones Proposal

Exactly how much of the food consumed in cities could we aim to produce in the Greenbelt? In response to this question, Growing Communities puts forward a proposal called “The food zones” aimed at addressing the challenges of a sustainable food and farming system. The objectives of the model are to minimize the energy, fossil fuel, and resource requirements intrinsic to the current food system while simultaneously bolstering community and job creation in both urban and rural locations.

The model functions as a spatial hierarchy that differentiates where and how different types of food should be sourced. It begins in urban centres, emphasizing the need to cultivate foods best suited for close proximity growth, and then incrementally expands outward with 17.5% of production allocated to the peri-urban. Seasonal and regional variations give way to the growing of prioritized food items ensuring minimal waste and processing, as well as optimal food distribution (Greater London Authority 2021).

The envisioned farms within this model prioritize:

A) Minimal input, verging on organic methodologies.

B) Predominantly human-scaled operations, encapsulating small to medium farms.

C) A diversity in farming practices, integrating various crop and livestock systems.

D) A focus on human labour, complemented by judiciously chosen technological and machine assistance, all anchored in robust scientific principles.

1: URBAN Salads, leafy, greens, Fruit

2: PERI-URBAN

Fruit and veg: horticulture, some field scale

3: RURAL HINTERLAND

Mainly Field-scale (inc. N fixing legumes). Some arable, livestock, agroforesty, orchards

4: REST OF THE UK

Mainly arable, livestock, agroforestry

5: REST OF EUROPE

Fruit and hungry-gap veg

6: FURTHER AFIELD

Coffee, chocolate, spices, tropical fruit

Growing Communities Food Zones Diagram

By Antonio Garaycochea

1: URBAN Salads, leafy, greens, Fruit

2: PERI-URBAN Fruit and veg: horticulture, some field scale

3: RURAL HINTERLAND

Mainly Field-scale (inc. N fixing legumes). Some arable, livestock, agroforesty, orchards

4: REST OF THE UK

Mainly arable, livestock, agroforestry

5: REST OF EUROPE

Fruit and hungry-gap veg

6: FURTHER AFIELD Coffee, chocolate, spices, tropical fruit

1: URBAN Salads, leafy, greens, Fruit

2: PERI-URBAN Fruit and veg: horticulture, some field scale

3: RURAL HINTERLAND Mainly Field-scale (inc. N fixing legumes). Some arable, livestock, agroforesty, orchards

4: REST OF THE UK Mainly arable, livestock, agroforestry

5: REST OF EUROPE Fruit and hungry-gap veg

6: FURTHER AFIELD Coffee, chocolate, spices, tropical fruit

Fig 51

7.5% 17.5% 35% 20% 15% 5% 7.5% 17.5% 35% 15% 5% 7.5% 17.5% 35% 15% 5% 7.5% 17.5% 35% 15% 5% 7.5% 17.5% 35% 15% 5% 7.5% 17.5% 35% 15% 5% 7.5% 17.5% 35% 15% 5% 0% 10% 20% 7.5% 17.5% 35% 20% 15% 5% 2 4 3 1 5 6

1: URBAN 2: PERI-URBAN 3: RURAL HINTERLAND (Within 100 miles) 4: REST OF THE UK 5: REST OF EUROPE 6: FURTHER AFIELD 20% 15% 1000km 200km 5% 7.5% 17.5% 35% 20% 15% 5% 7.5% 17.5% 35% 20% 15% 5% 7.5% 17.5% 35% 20% 15% 5%

4: REST OF THE UK 5: REST OF EUROPE 6: FURTHER AFIELD 7.5% 17.5% 35% 20% 15% 1000km 200km 25km 25km 200km 5% 7.5% 17.5% 20% 15% 5% 7.5% 17.5% 20% 15% 5% 7.5% 17.5% 20% 15% 5% 7.5% 17.5% 20% 15% 5% 7.5% 17.5% 20% 15% 5% 7.5% 17.5% 20% 15% 5% 0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 7.5% 17.5% 35% 20% 15% 5% 2 4 3 1 5 6

1: URBAN 2: PERI-URBAN 3: RURAL HINTERLAND (Within 100 miles) 4: REST OF THE UK 5: REST OF EUROPE 6: FURTHER AFIELD 29 | UK Food System 30 [AA Landscape Urbanism 23/24] [AA Landscape Urbanism 23/24] Planet of Fields

By Jegan Muralidharan

UK Land Ownership

As demand dynamics push larger landowners towards intensive farming, the issue of how the UK obtains it’s food becomes related to the issue of concentrated land ownership.

According to who owns England half of the country is owned by 1% of the population and the details of said ownership are prohibitively expensive to obtain (Evans 2019). However, Recent Investigations by “Who Owns England” have allowed to shed light on the issue.

1

Fig 52

Rise

MegaFarms article

https://www.theguardian.com/ environment/2017/jul/18/rise-ofmega-farms-how-the-us-modelof-intensive-farming-is-invadingthe-world

99 % 25000 owners 55 Million 30 % Aristocrasy and gentry 18 % Corporations 17 % Oligarchs/ City Bankers 17 % Unaccounted 8.5 % Public Sector 5 % Home owners 4.5 % Royal family/ Conservation charity / Church of england 1 % 99 % 25000 owners 55 Million England Ownership

%

Fig 53.

of

31 | UK Food System 32 [AA Landscape Urbanism 23/24] [AA Landscape Urbanism 23/24] Planet of Fields

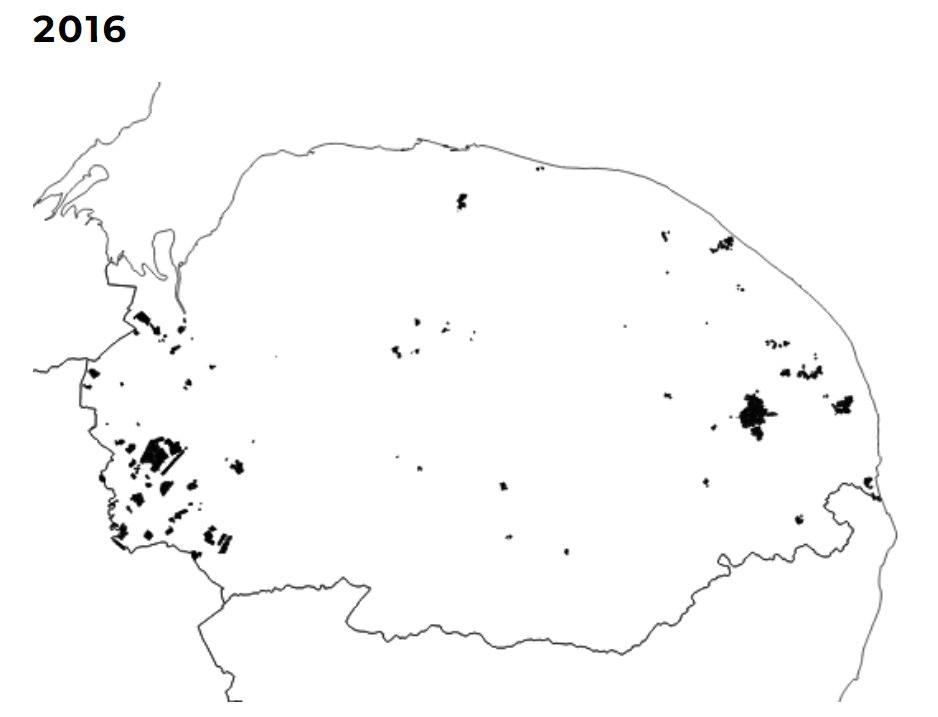

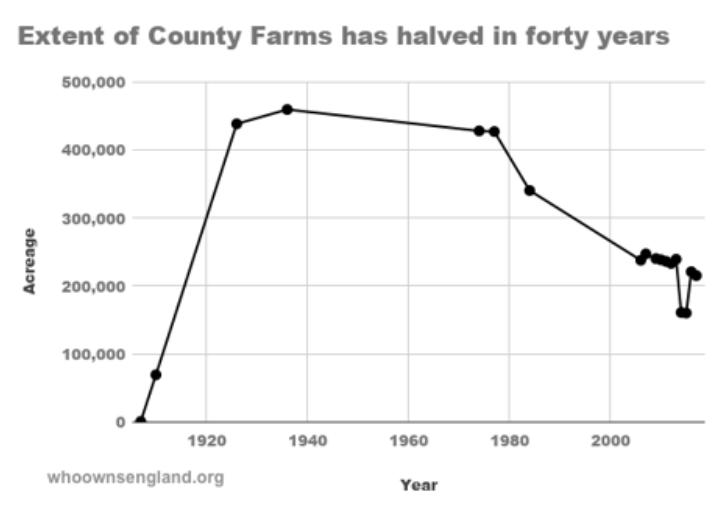

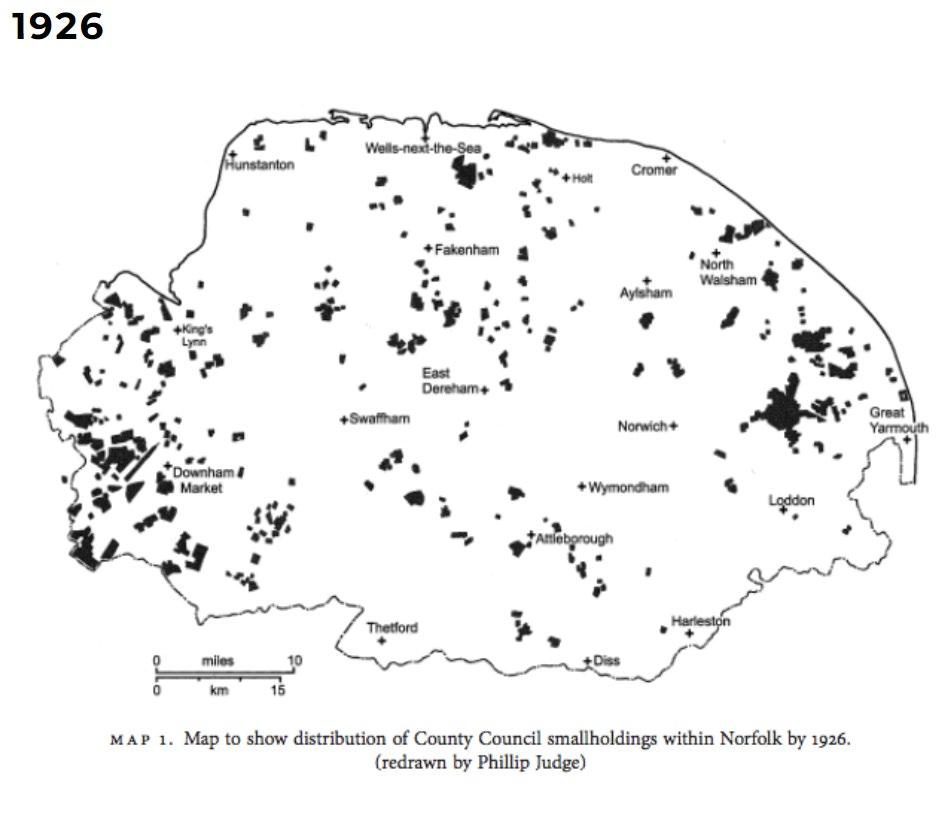

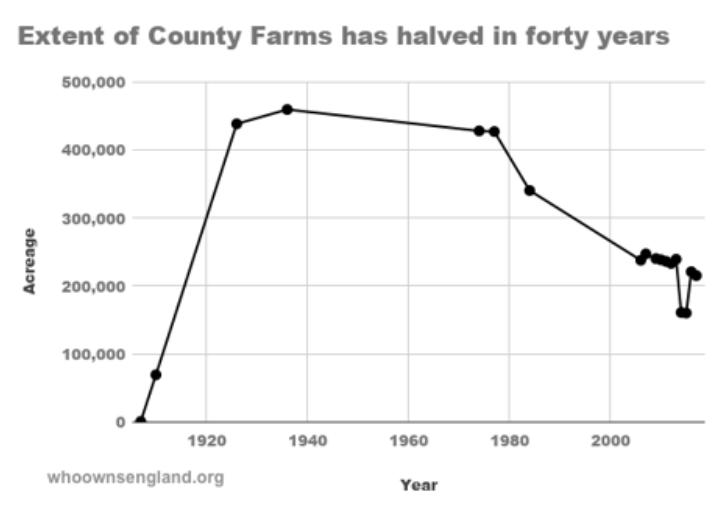

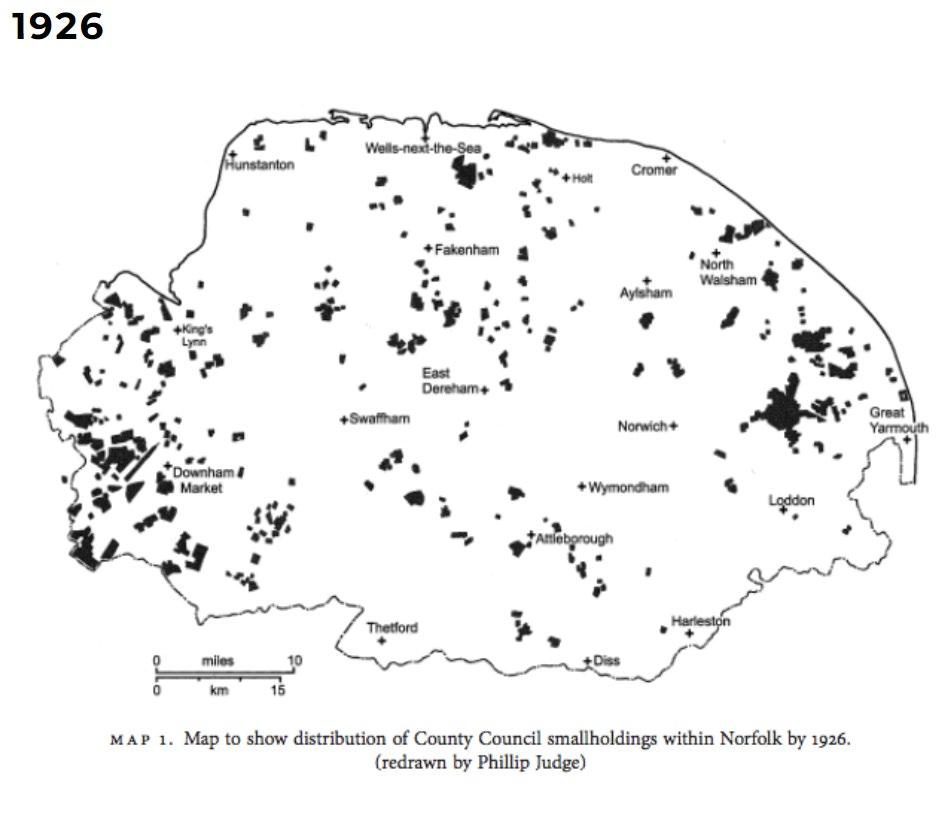

Council Farms

County Farms were historically devised to facilitate the entry of young farmers into a capital-intensive agricultural sector. This was achieved by offering them lands and infrastructure, occasionally even at submarket rental rates. These farms were perceived as the ‘initial step’ into and industry where the mean age of farmers is roughly 60 years (Who Owns England 2018).

Although the proliferation of council farms was especially pronounced from the 20th century’s commencement until World War II, the post-1970s period witnessed a pronounced reversal, with substantial tracts of these council-owned smallholdings being sold. As we’ve seen, this is characteristic of broader shifts in English agriculture over recent decades; the disappearance of smaller private farms and their integration into larger industrial agricultural entities. Between 1977 and 2017, the area of council farms has gone from 426,695 acres to only 215,155 acres.

Who Owns England indicates that the decline of County Farms can be attributed to fiscal cuts to local authority budgets by the central government. There exists a correlation between the selling of these farms and policy measures initiated by Margaret Thatcher in the 1980s, and there is currently an urgent need to alter the trajectory of the current trend, ceasing further sales.

The Uk is at a significant moment in time in relation to all the issues mentioned because the country is currently going through what has been described as an agricultural transition.

Decline of council Farms

Https://whoownsengland.org/2018/06/08/how-the-extentof-county-farms-has-halved-in-40-years/

Fig 55

Decline of Council Farms in Norfolk

Https://whoownsengland.org/2018/06/08/how-the-extentof-county-farms-has-halved-in-40-years/

Fig 54

Fig 54

33 | UK Food System 34 [AA Landscape Urbanism 23/24] [AA Landscape Urbanism 23/24] Planet of Fields

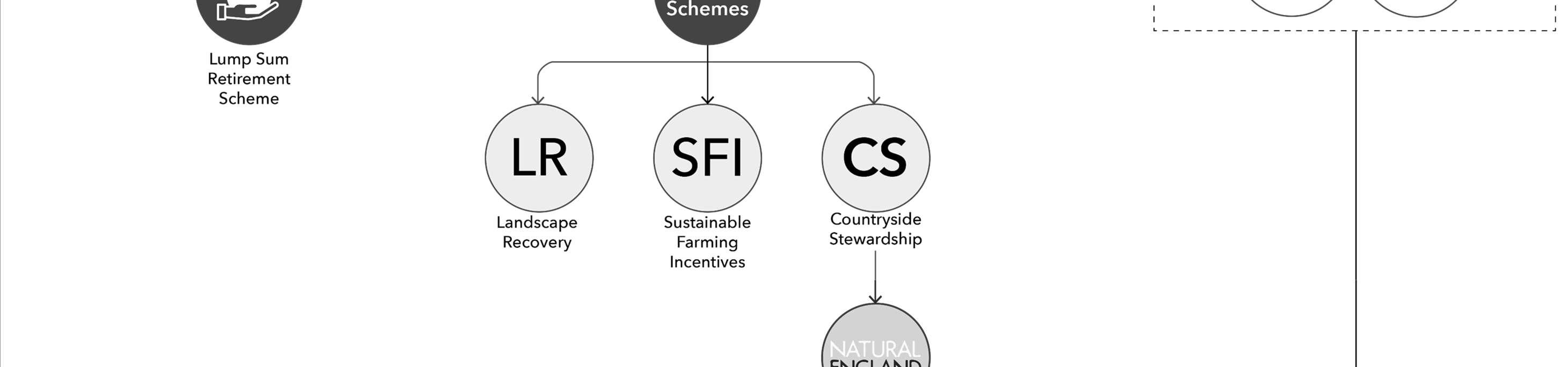

Introduction The 7-year plan Visualizing ELM schemes The Agricultural Transition [03] Agricultural Transition Plan announcement Fig. 56 Https://www.edwinthompson.co.uk/agricultural-transition-plan-2021-2024-announcement/ 35 36 [AA Landscape Urbanism 23/24] Planet of Fields

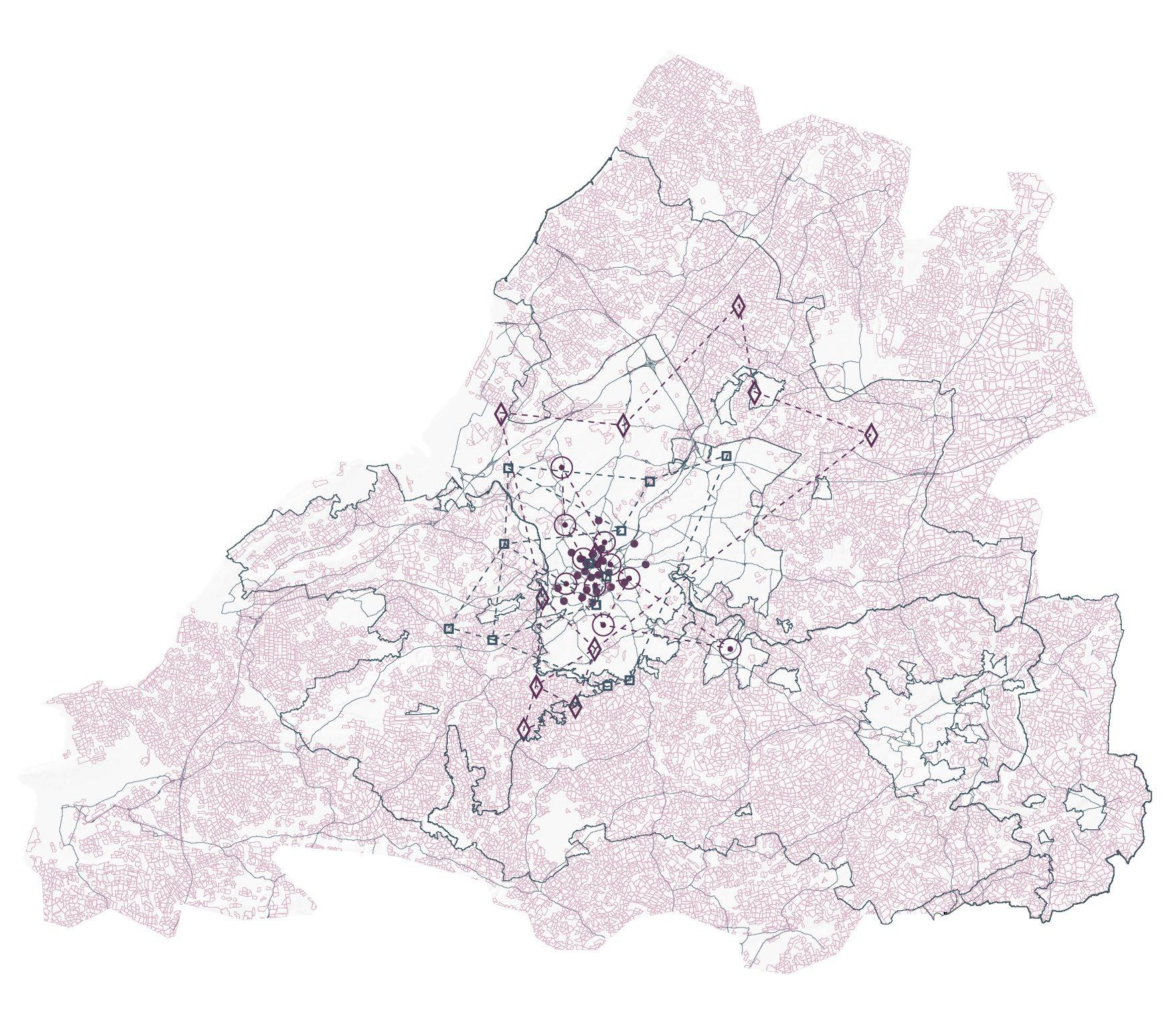

2021 Launch of the Agricultural Transition Plan

2022

Introduction of ELM Scheme

Consisting of three components: Sustainable Farming Incentive (SFI), Countryside Stewardship (CS), and Landscape Recovery.

Introduction

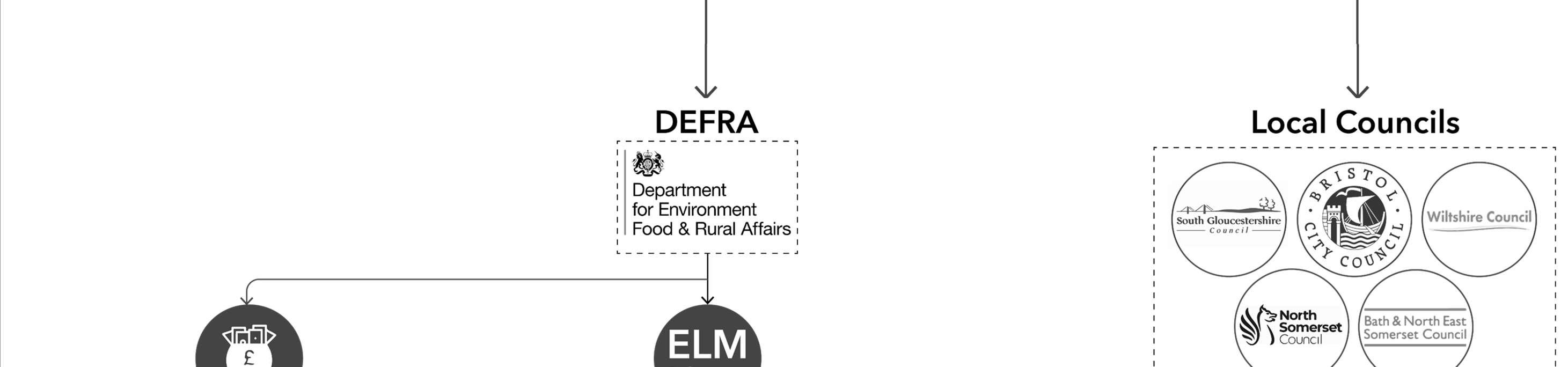

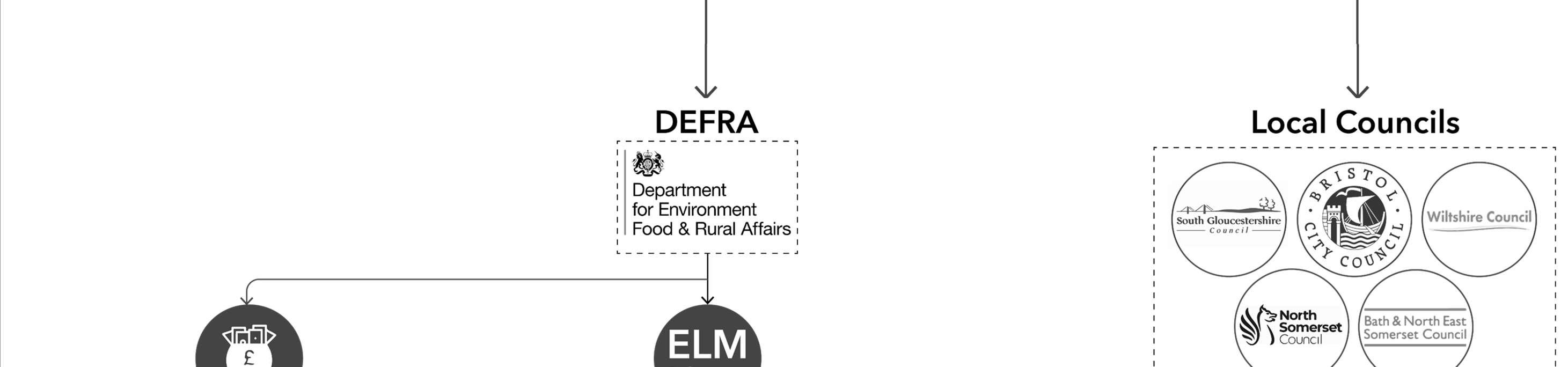

The 7 Year Plan

As part of the post-Brexit era, the department of environmental, food and rural affairs has introduced a series of new agriculture policies, which include Environmental Land Management schemes. Although these represent a step in the right direction, they may be fall short of supporting localized food systems and the idea of food sovereignty. This section will attempt to visualize the functioning of ELM schemes as of the most recent proposals, and then present an evaluation of how effective these schemes are; especially at fostering food sovereignty and local food systems, their possible impacts and the gaps that remain to be addressed in order to promote a more sustainable and equitable food future.

The concepts of food sovereignty and local food systems are complimentary. Both emphasize the importance of sustainable agricultural practices and equitable access to resources. They are part of alternative approaches to the dominant industrial and globalized food system. It could be thought of as one concept being a means to the other.

On one hand, the concept of Food Sovereignty refers to the right of communities to control their food and agriculture systems. This involves localized food systems and promotes equal access to resources like land, water and seeds through democratic decision making. (Patel 2009)

Meanwhile, a local food system is the network through which food is produced, distributed and consumed within a local or regional area, shortening supply chains between producer and consumer. The objective of this is to create resilient networks that include diversified agricultural production and contribute to local economic and social development. (Feenstra 1997)

Following Brexit, the Department for Environment, Agriculture and Rural Affairs (Defra) has been working towards rolling out a set of agricultural policies to replace the Eu’s Common Agriculture Policy (CAP). The first part of this is the “7-year agricultural transition plan”, which is closely related to the “25-year environmental plan” and the 2050 net zero commitments. This entails gradually phasing out direct payment schemes (BPS), which were part of the CAP, and replacing them with a new set of payment schemes called ELM schemes.

While payment sums under CAP were largely based on the size of farmland, ELM schemes aim to move towards linking them to certain agroecological farming practices, seeing farmers as stewards of the landscape rather than food producers, therefore theoretically moving away from favouring large scale industrial farming operations. (DEFRA 2020)

“We know that the move away from Direct Payments will be a big change for some farmers, so we are going to make the changes over a 7-year transition period to give everyone time to plan and adjust. We will be offering help to those who need it to plan and manage their businesses through the transition. (…) We will make the money we save from Direct Payment reductions available through schemes, grants and other types of support for farmers to manage land and their businesses more sustainably.” (DEFRA 2020)

By Antonio Garaycochea

2025 - 2027

Full policy Implementation

New agricultural policy expected to be fully implemented, with the focus on environmental outcomes and public goods. Direct payments continue to be phased out.

DEFRA introduced the 7-year plan, outlining the future of agriculture in the UK, post-Brexit.

Direct payments to farmers, began to be phased out

2023-2024

Expansion of ELM Scheme and Other Grant Programs

Expansion of programme with more farmers and more options available.

DEFRA investment planned in productivity grants, skills development, and pilot programs to support innovation and technology adoption in agriculture.

2027

Transitions completion

Direct payments completely phased out, and replaced with the new support system.

Timeline of the 7 year plan

Fig 57

Timeline of the 7 year plan

Fig 57

37 | UK Food System 38 [AA Landscape Urbanism 23/24] [AA Landscape Urbanism 23/24] Planet of Fields

Reports and Evaluation

Despite ELM being a step forward from BPS, farms need to have a minimum area of 5 ha in order to participate in the schemes; a detail that causes the exclusion of several small holdings. Furthermore, the interactions between the actions, as well as the way in which they are classified can be troublesome.

CS and LR are geared towards land managers while SFI agreements are directed mainly at farmers. This creates a separation between food production and the management of nature, drawing on a debate of land sparing vs land sharing. While both CS and SFI provide farmers with a list of actions to chose from, there is a lack of support for farming in a way that integrates it into nature, regenerating local ecosystems through food production and habitation of the landscape.

In terms of its effect on the farming business, a study conducted by AHBD concluded that “While the net payments for most of the standards in the SFI standards were positive, the overall impact on the farms’ net profit levels was negative once land taken out of production was considered.”

(Agriculture and Horticulture Development Board 2022). The report goes on to mention that, with their current SFI payment rates, it is unlikely to be financially beneficial to farmers to participate in certain standards unless they are already undertaking at least some of the actions required. This is mainly due to the up front costs that many actions require.

A report by Rob Booth, titled “Farming the Future” can provide key points about the future of farming with which to begin making some inferences as to how ELMs relate to the concepts of Food sovereignty and local food systems. The report puts forward 3 key processes for food systems change:

Research and development (R&D) for new agricultural methods, Production, analysis, and ownership of agricultural data, and Agricultural Knowledge and Information Systems (AKIS).

Booth suggests that there are two pathways for agriculture moving forward. In the first, existing concentrated corporate ownership is maintained, as are the inequalities driven by it. In the second, agroecology acts as a driver for social change, where producers and citizens are put in control of food systems through the democratization of local economies and alternative models of ownership such as co-operatives and community land trusts. According to Booth, within the latter, community knowledge exchange and open, publicly facilitated data are central to driving shorter supply chains in regional food systems, as well as creating jobs and reducing emissions. (Booth 2021)

From this standpoint, it’s possible to point out that, because CS and SFI standards are so specific, it seems that they might be overly prescriptive and action oriented instead of results oriented. By taking such an approach R/D for agricultural methods is disincentivized regardless of ownership. Secondly, there is no emphasis on actions to help drive regional economies (such as farmer knowledge exchange and participatory politics), thereby

limiting the development of local networks and supply chains necessary for a sustainable and equitable food system.

In the case of LR, the scheme is competition based instead of action based which avoids the prescriptive nature of SFI and CS. However, in order to participate, one needs to already be an actor with capital (Heron 2023), a fact which could potentially continue to consolidate land in the hands of multinationals that look to become net zero through their landscape recovery schemes.

Lastly, within the current schemes, there is a lack of land reform and access, with the closest being “lump sum exit grant”. Through this grant, farmers surrender their entitlement to subsidies in exchange for a lump sum payment which aims to act as a retirement incentive for farmers. This could potentially be an instrument to motivate the sale or gifting of land into community forms of ownership.

(Farming UK 2022)

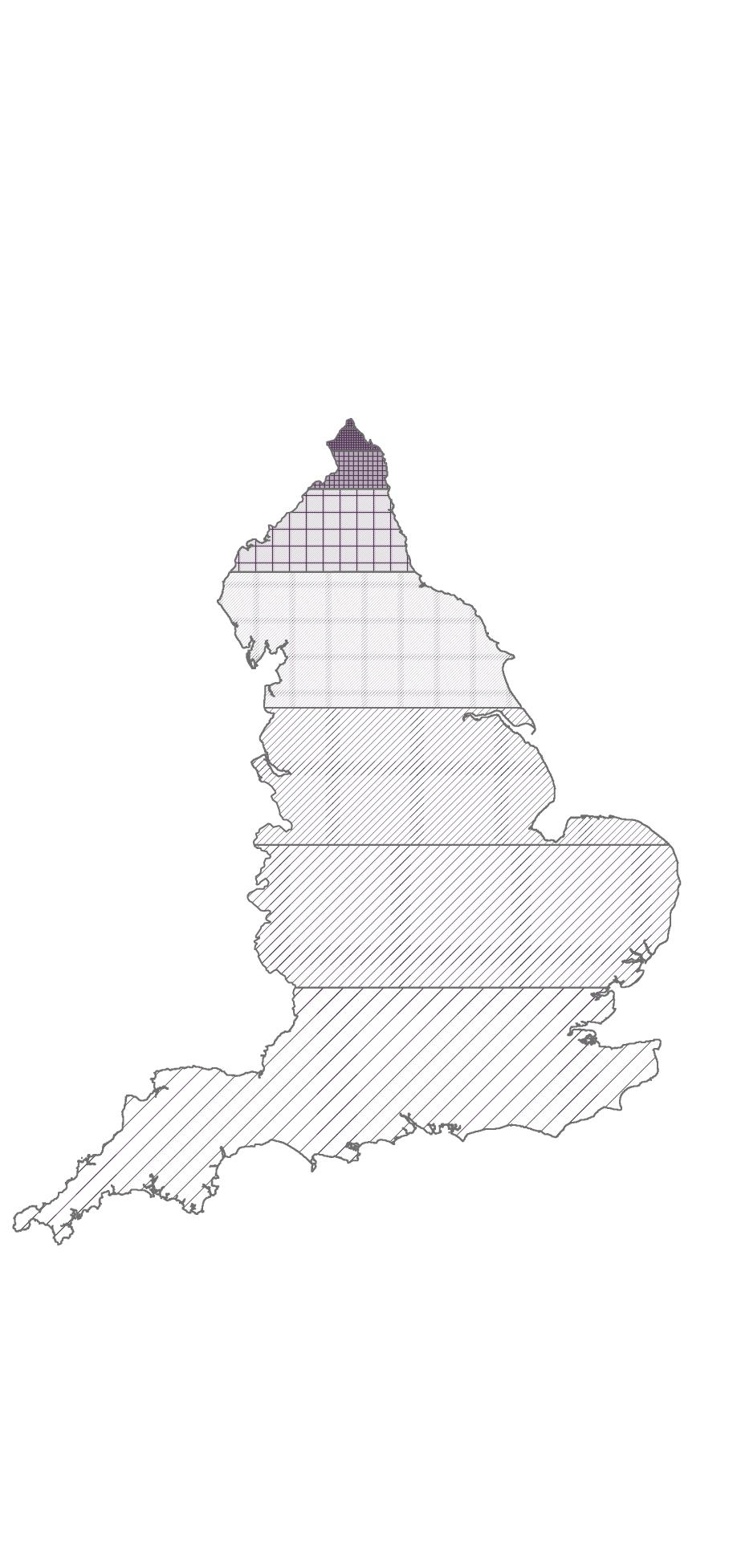

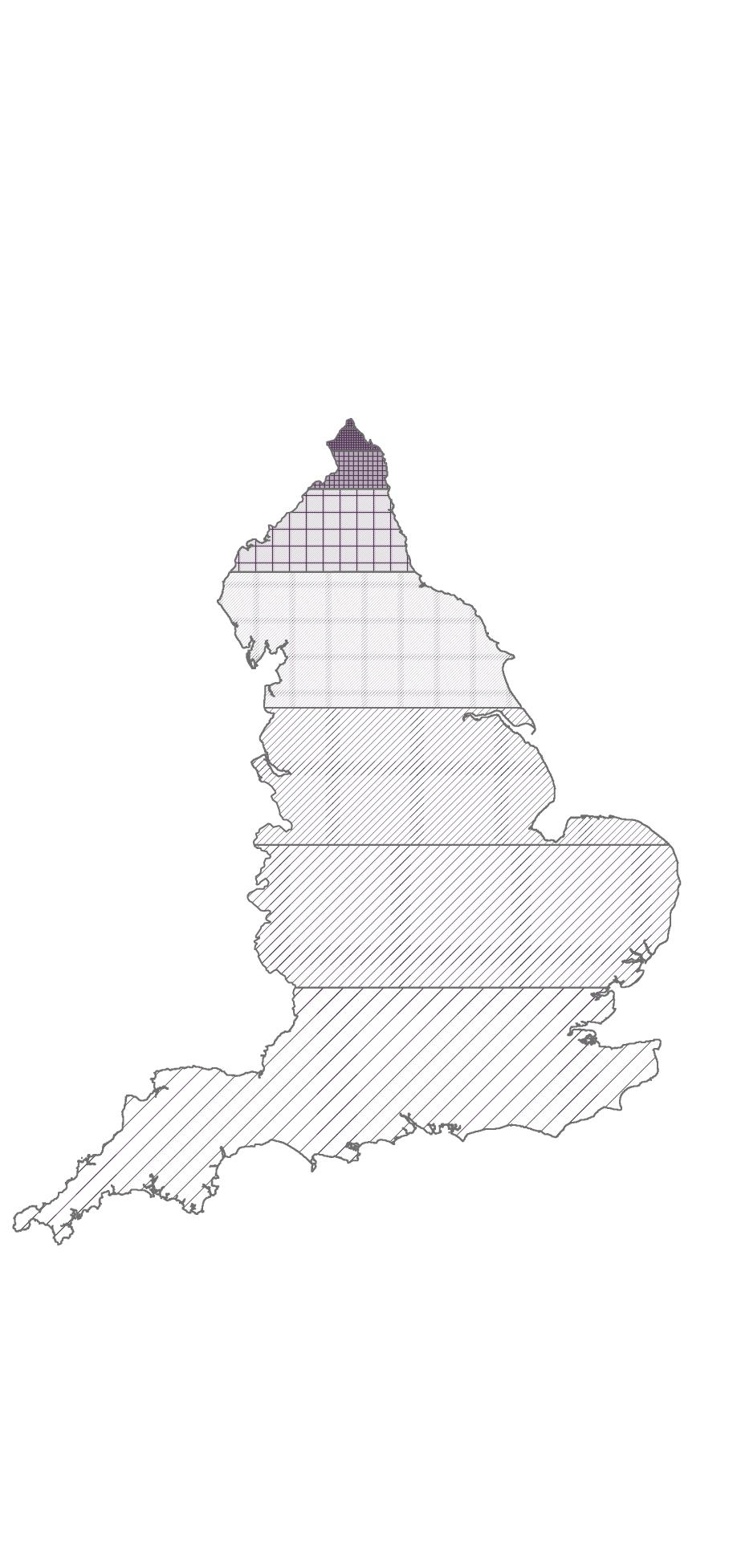

An independent review of the UK’s food sector titled “The National Food Strategy”, suggests the creation of a mixed rural land use framework – the “three compartment model” which equally divides high yield farmland, low yield (agroecological farmland) and semi-natural land in order to strike a balance between food yield and benefits to the greatest number of animal species. In this view agroecological farming and mechanized farming are not viewed as mutually exclusive provided the mechanization takes advantage of technology as well as crop mixing in order to make it less destructive. (The National Food Strategy 2021).

CONCLUSIONS

While the UK’s ELM schemes mark a move away from the EU’s CAP and towards more sustainable practices, there are still areas that need improvement. There is a lack of emphasis on developing regional economies and local networks, as well as insufficient support for land reform and access.

The approach to land use provided by the National food strategy could serve as a starting point to help reconcile the need for sustainable intensification alongside agroecology in order to meet local demand and serve as a transition strategy. However, it is also necessary to find new ways for democratic access land by part of communities.

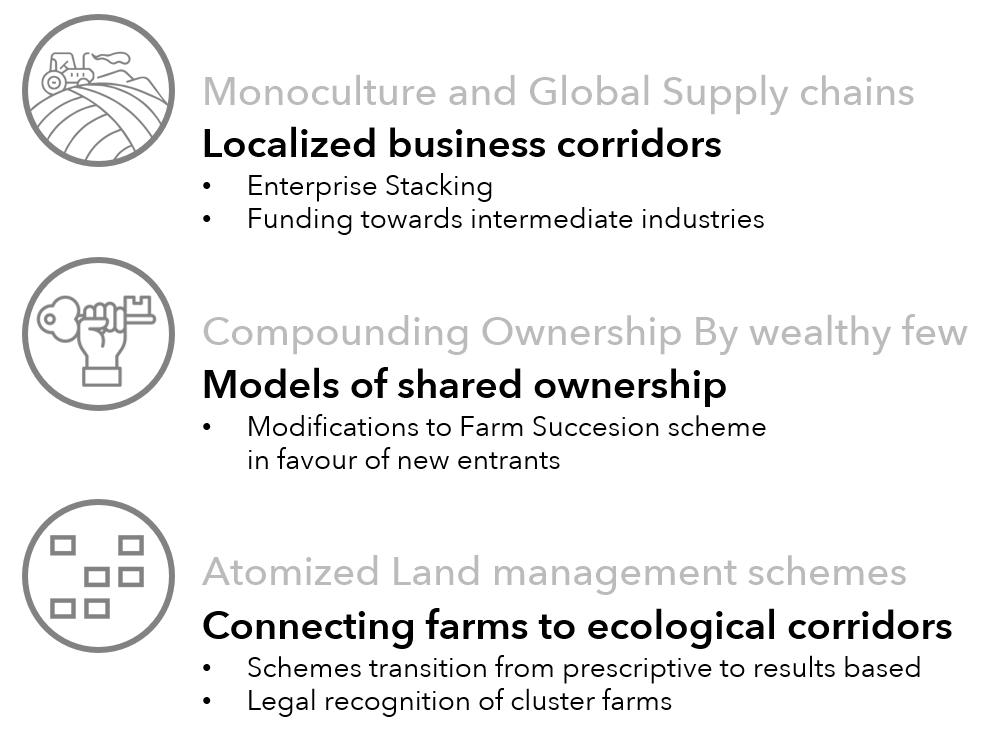

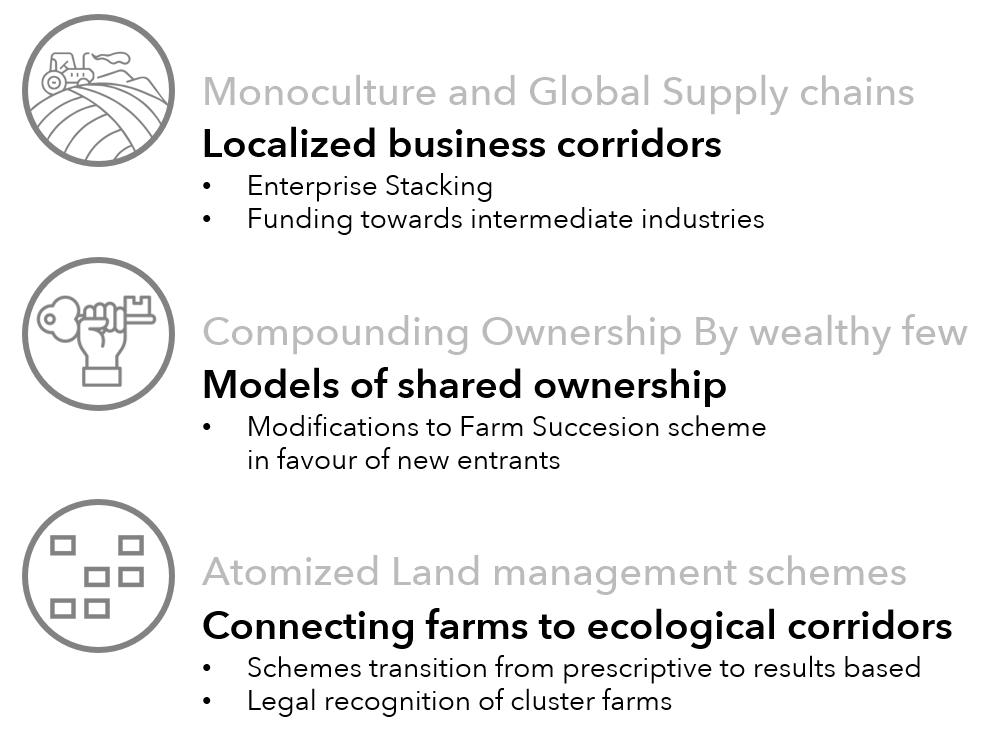

As we’ve seen up to this point, the disconnect between cities and their peri-urban land revolves around 3 main issues:

1. Concentration of ownership

2. Fragmented land management schemes and

3. Industrial farming leading to global supply chains.

Agroecology has numerously been mentioned as a key element of this ongoing transition, which leads to posit the question “What is Agroecology”?

Example CS actions

Example SFI actions

Fig 59

Fig 60

By Jegan Muralidharan By Jegan Muralidharan

42 [AA Landscape Urbanism 23/24] 41 | UK Food System [AA Landscape Urbanism 23/24] Planet of Fields

Agroecological Farm Fig 61 Https://www.arc2020.eu/comparing-organic-agroecological-and-regenerative-farming-part-2-agroecology/

[04] Agroecology

Overview Case Studies

43 44 [AA Landscape Urbanism 23/24] Planet of Fields

By Jegan Muralidharan

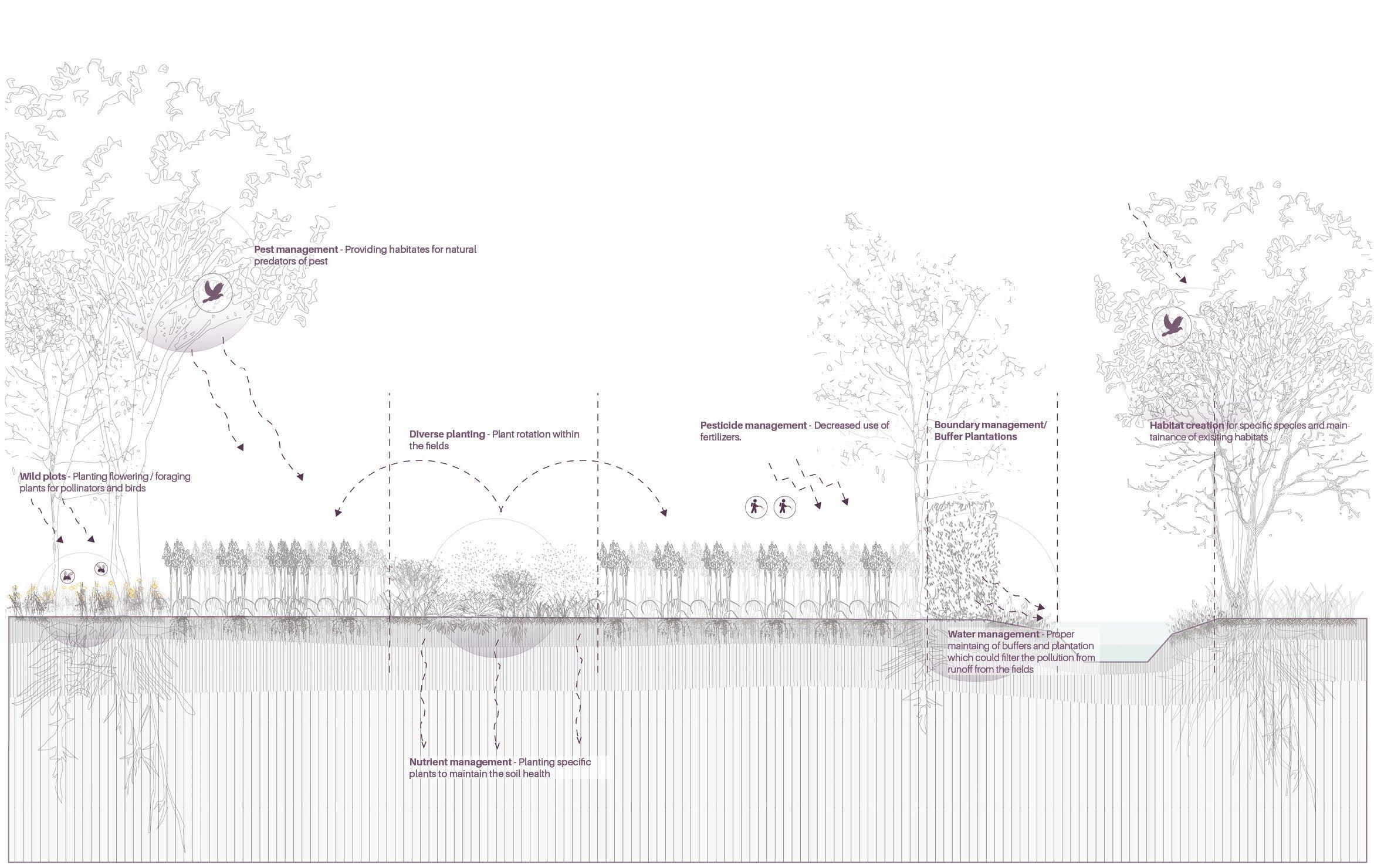

Key Principles of Agroecology

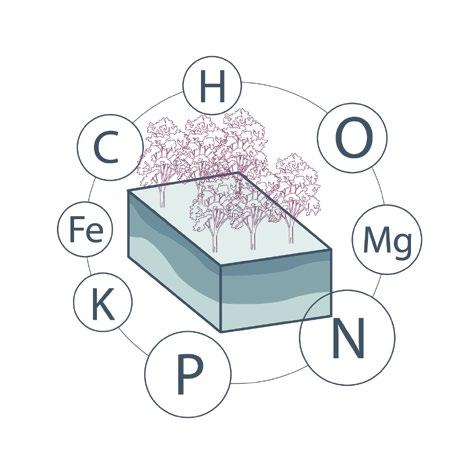

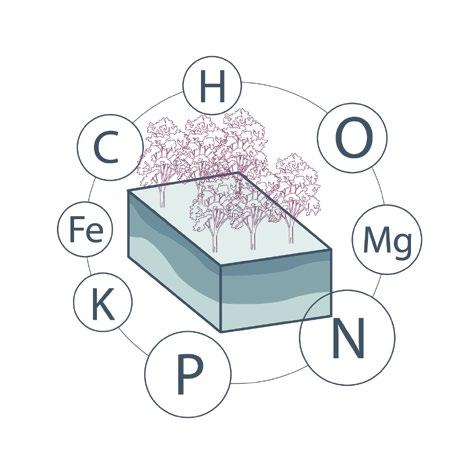

Overview

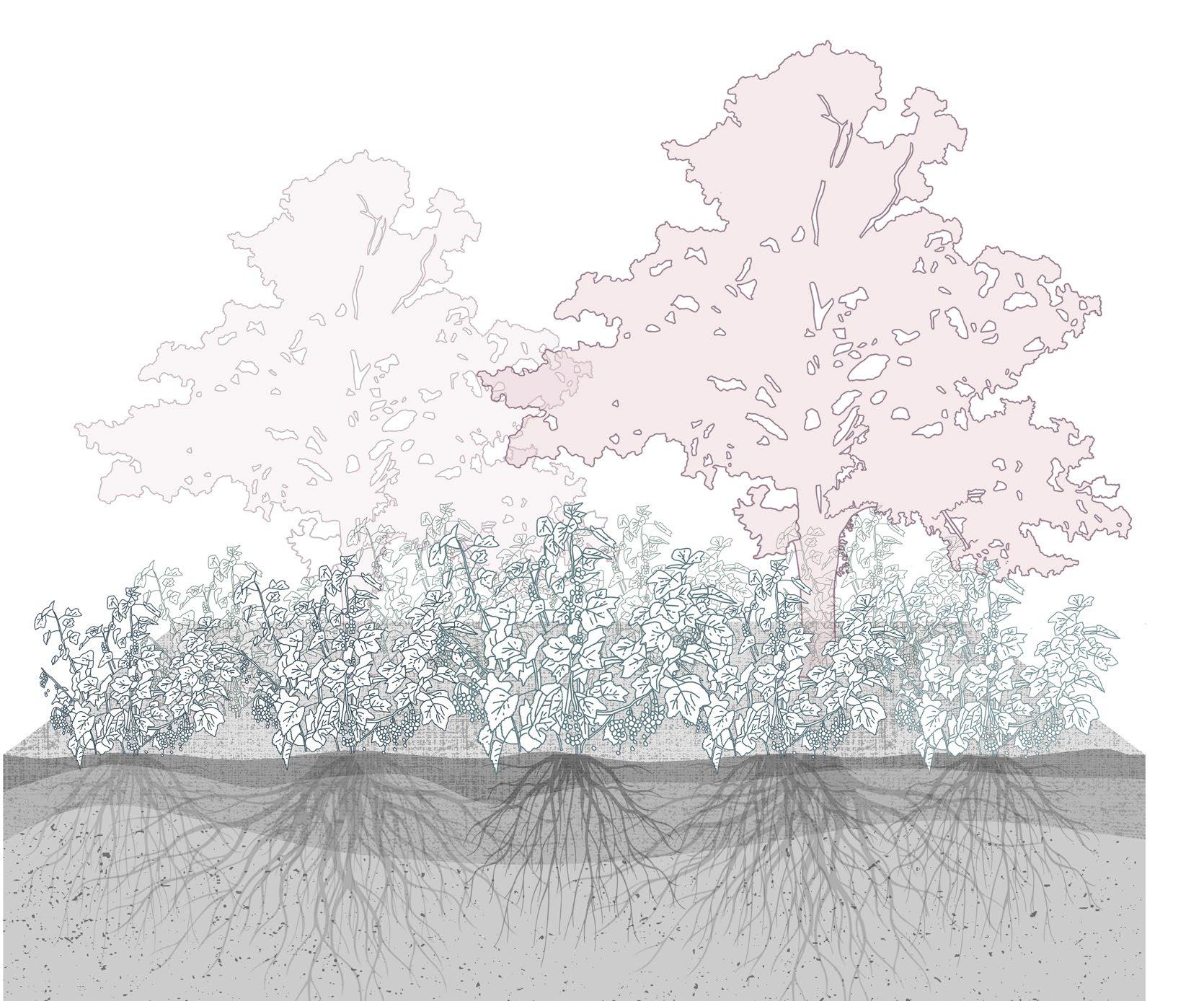

In preceding chapters, we have consistently encountered agroecology as an important part of the solution to food system challenges. This is evident not only in the Cuban farming revolution but also in aspects of the methods endorsed by the new ELMs. Building on this perspective, the forthcoming proposal in this thesis aims to use agroecology as a guide for sustainable growth and food production within the green belt.

But what precisely is agroecology? At its core, it’s an expansive term that encompasses a myriad of techniques. Each technique, however, adheres to a fundamental principle: producing food in harmony with, and complementary to, natural systems.

“Agroecology is a holistic and integrated approach that simultaneously applies ecological and social concepts and principles to the design and management of sustainable agriculture and food systems. It seeks to optimize interactions between plants, animals, humans and the environment while addressing the need for socially equitable food systems within which people can exercise choice over what they eat and how and where it is produced” (FAO, n.d.)

By Jegan Muralidharan

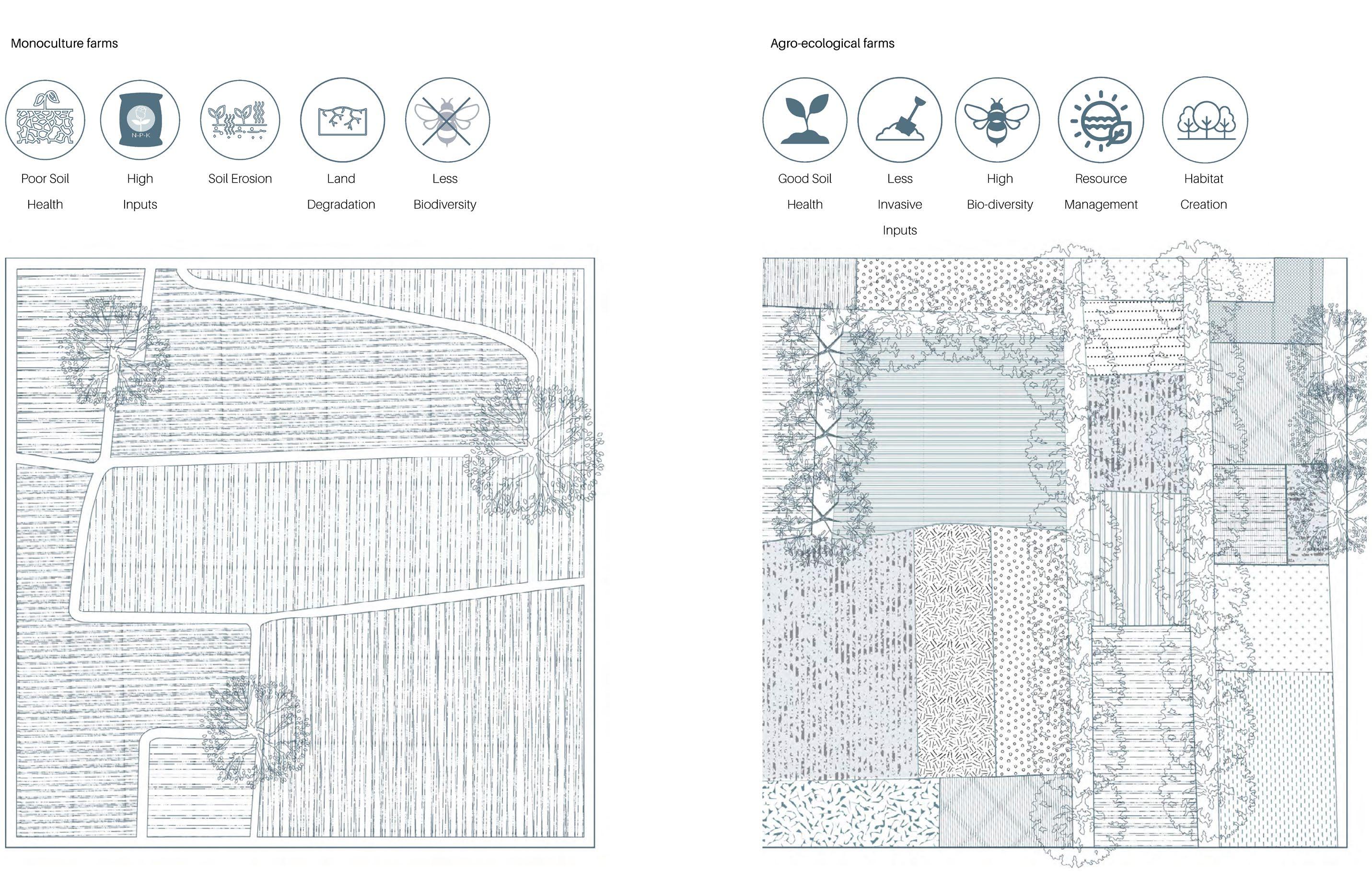

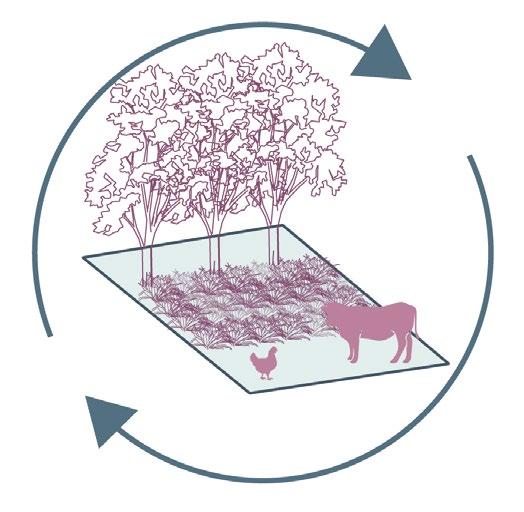

Mono-culture vs Agroecological farm

Bio Diversity & Recycling Synergy Land & Resource governance Reduced input Economic diversification Connectivity Soil Health Co-Creation of Knowledge Animal Health Social Value & Fairness

Key Principles of Agroecology Mono-culture vs Agroecological farm Fig 62 Fig 63

45 | UK Food System 46 [AA Landscape Urbanism 23/24] [AA Landscape Urbanism 23/24] Planet of Fields

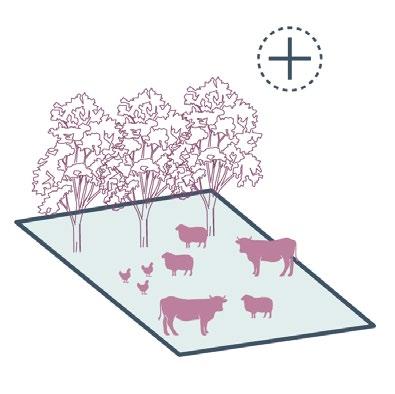

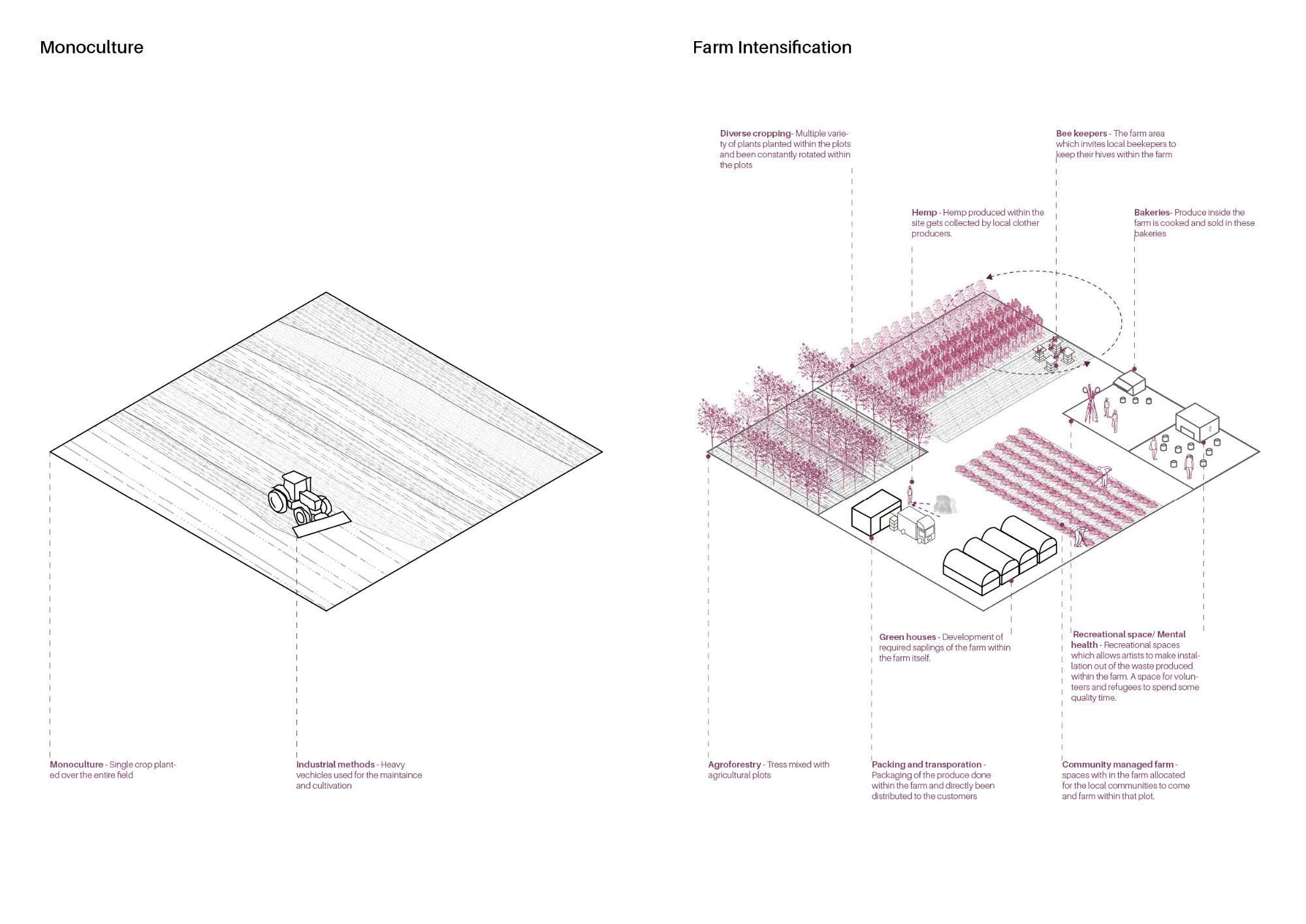

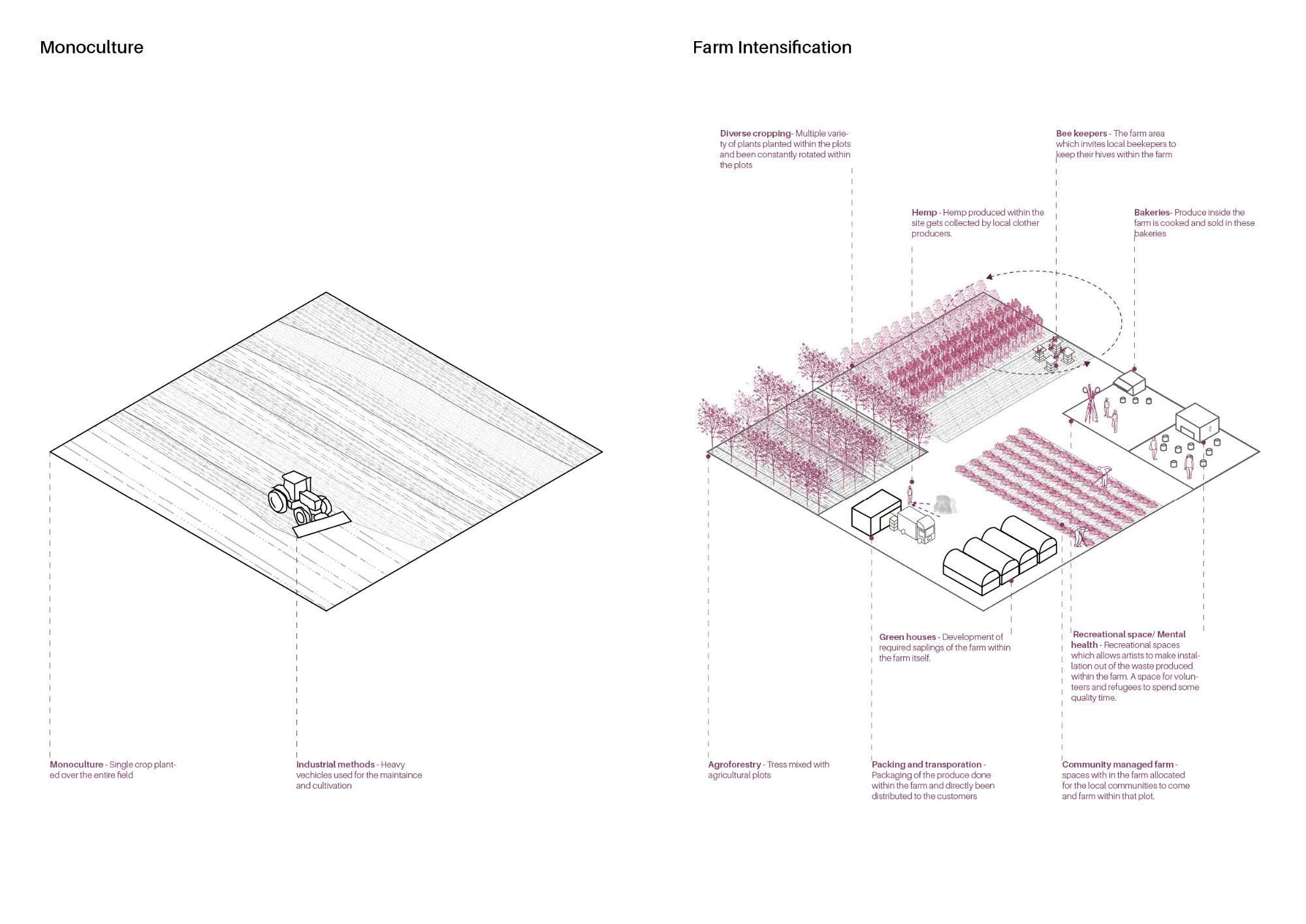

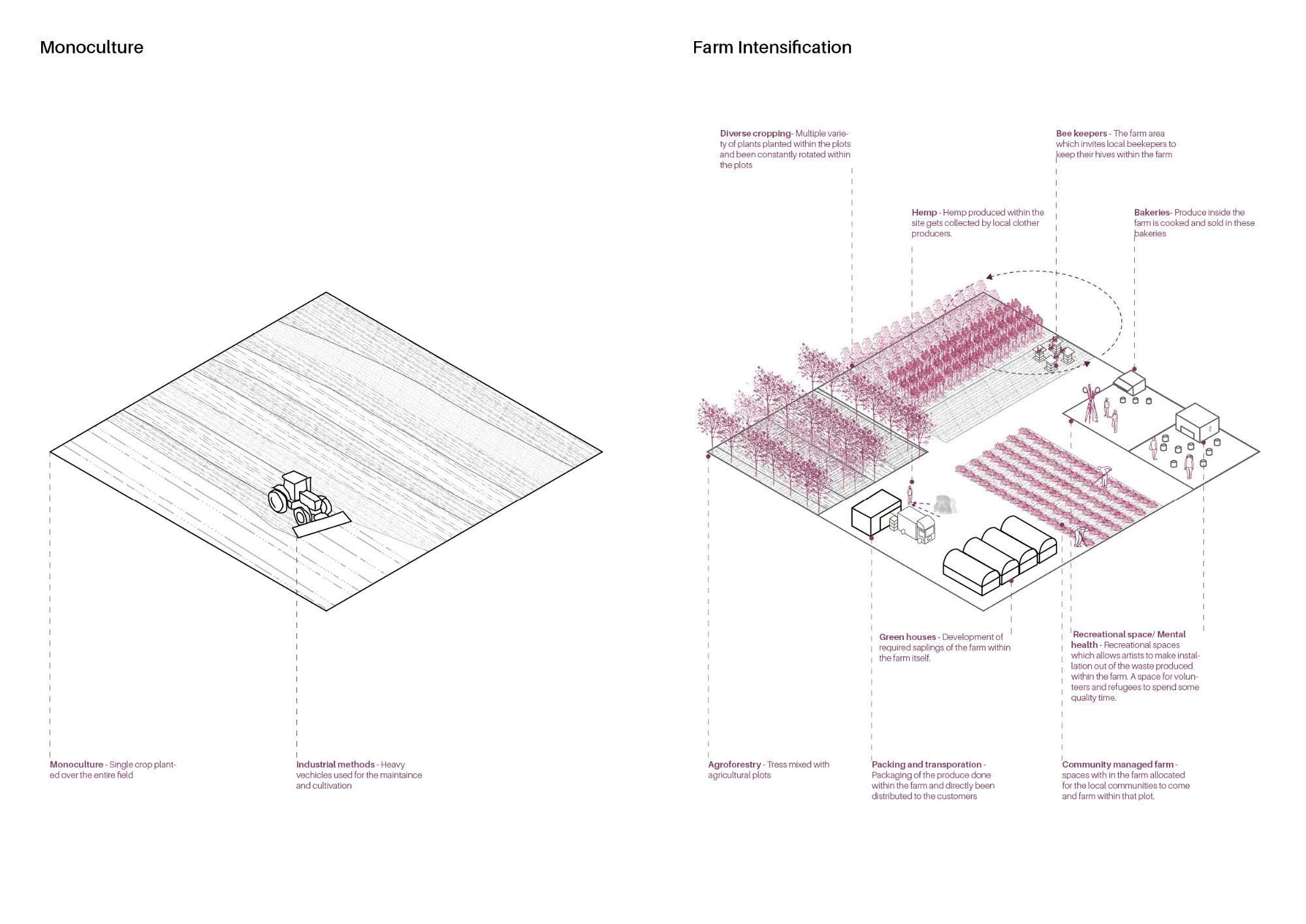

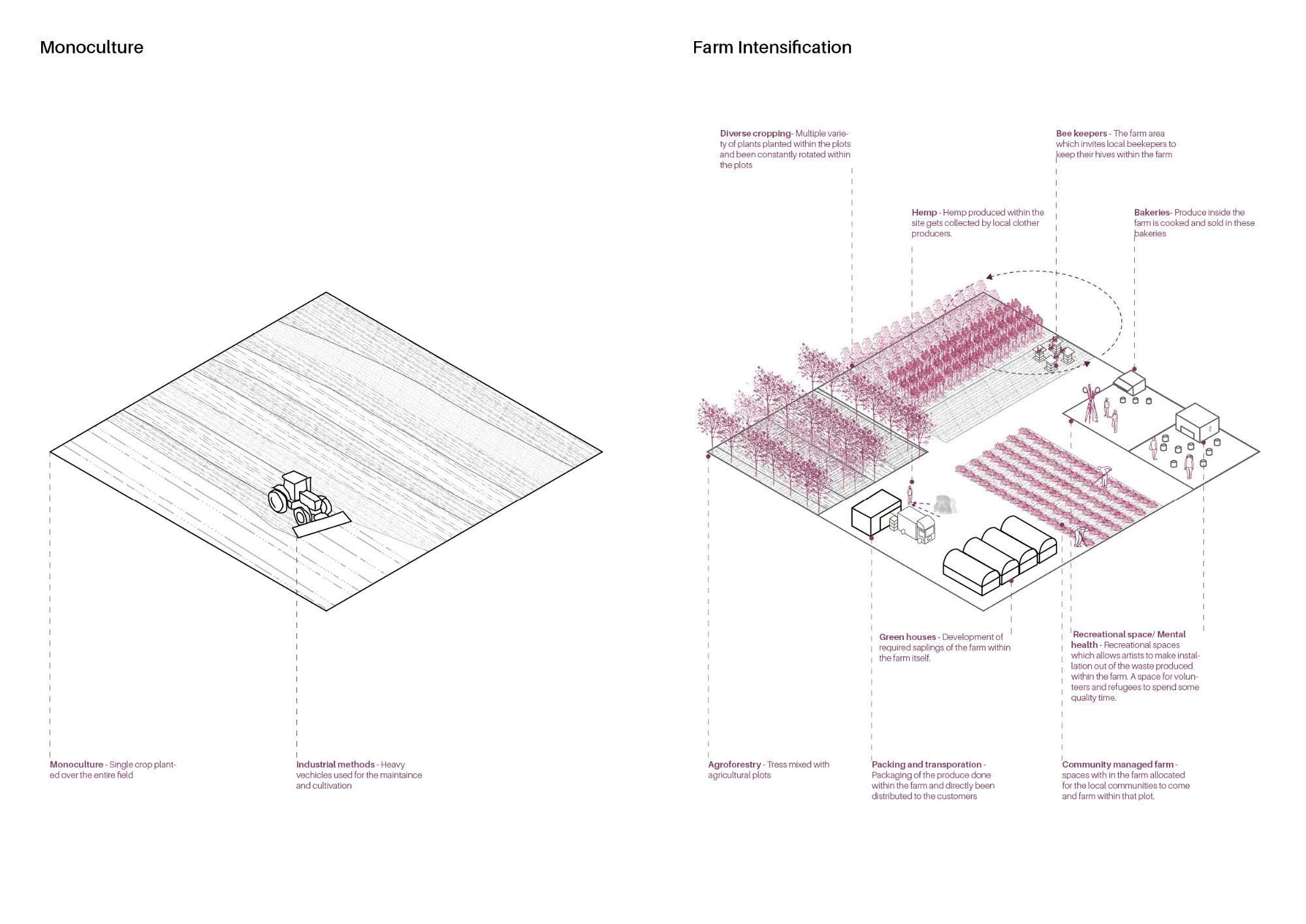

Intensification

The term “intensified farming” is commonly associated with factory farming, pointing towards farming methods that demand greater inputs and outputs per unit of agricultural land. ”In an industrialized society this typically means the use of pesticides, fertilizers, and other chemicals that boost yield, and the acquisition and use of machinery to aid planting, chemical application, and picking” (FFAC 2021).

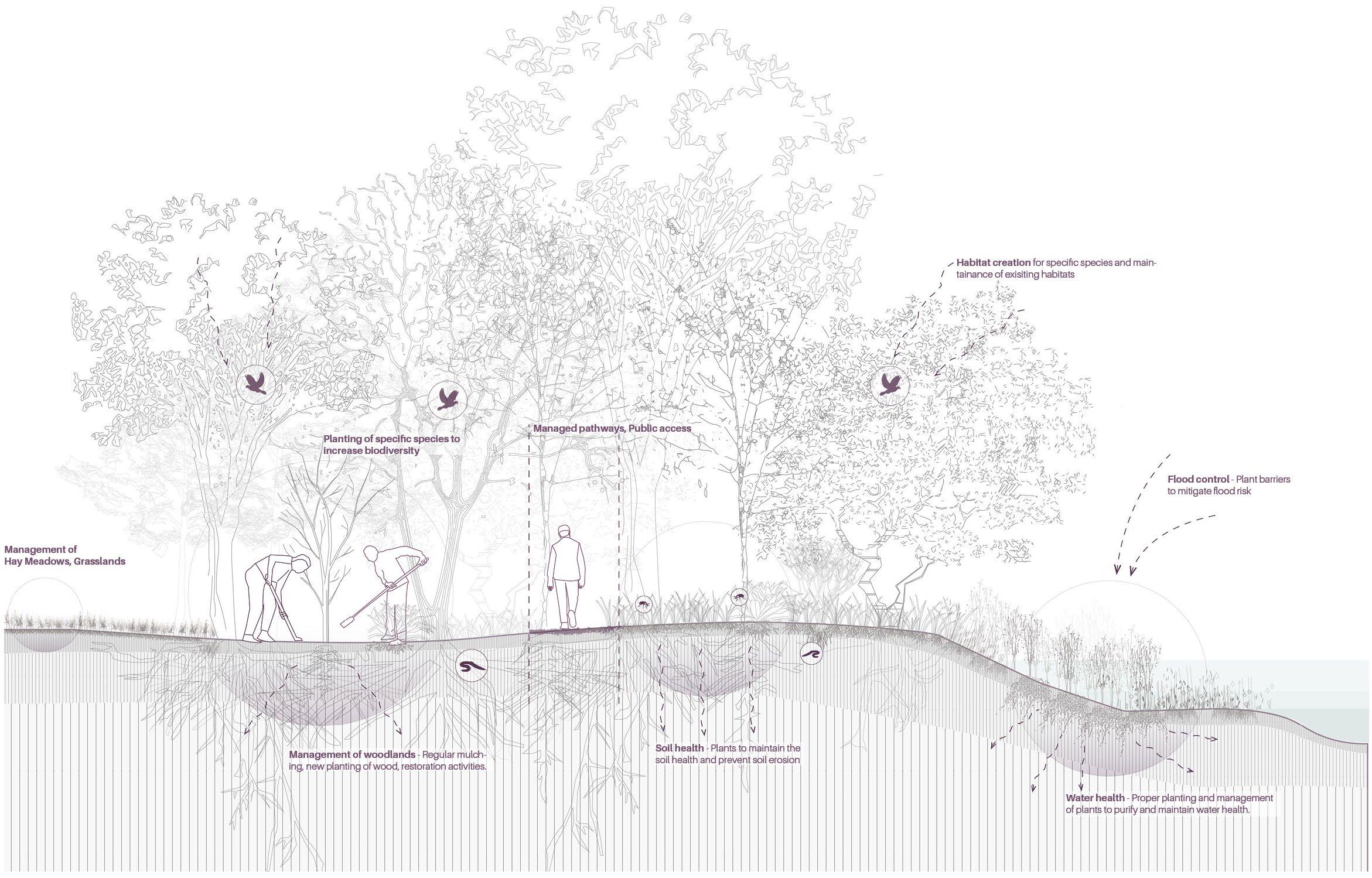

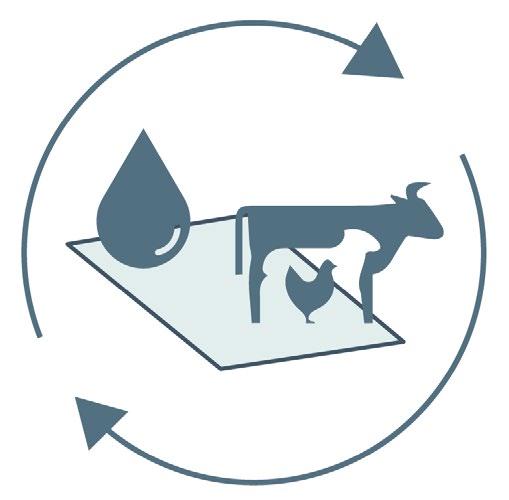

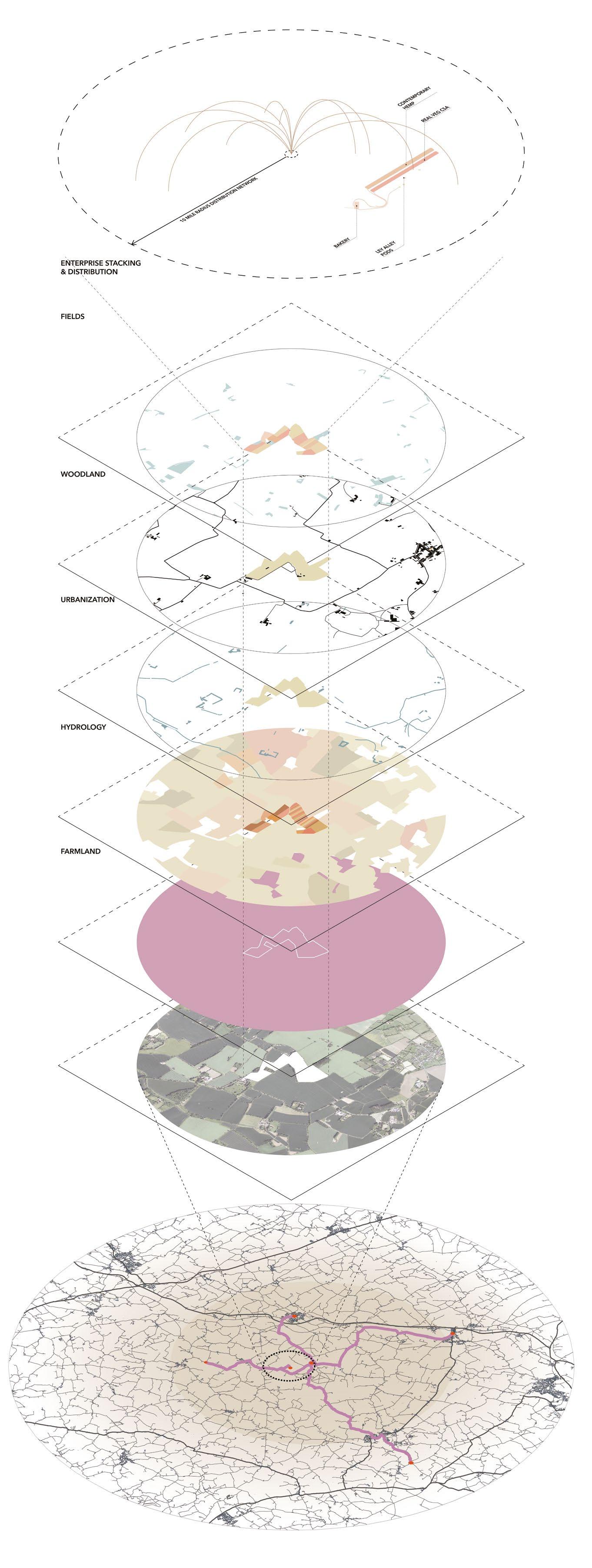

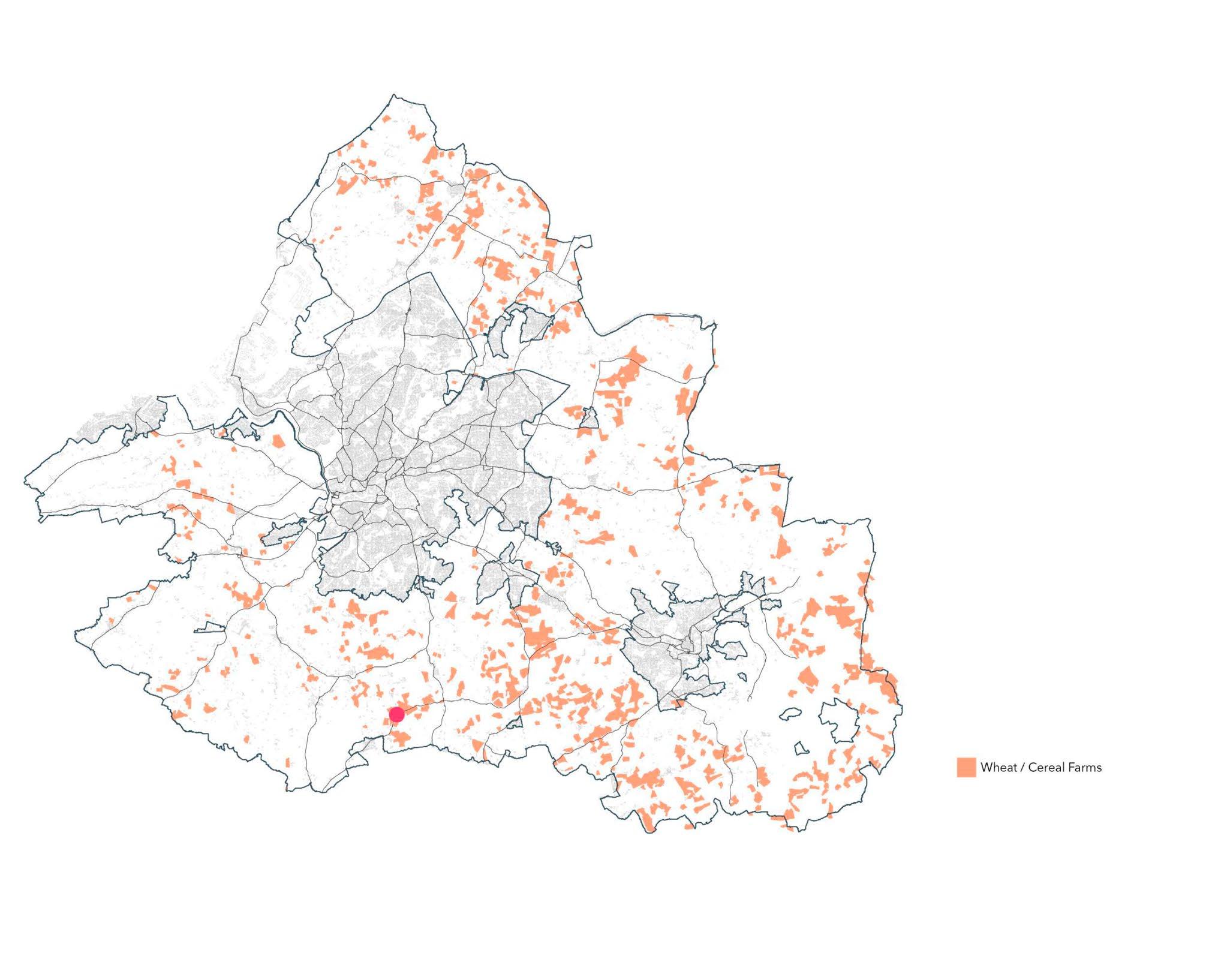

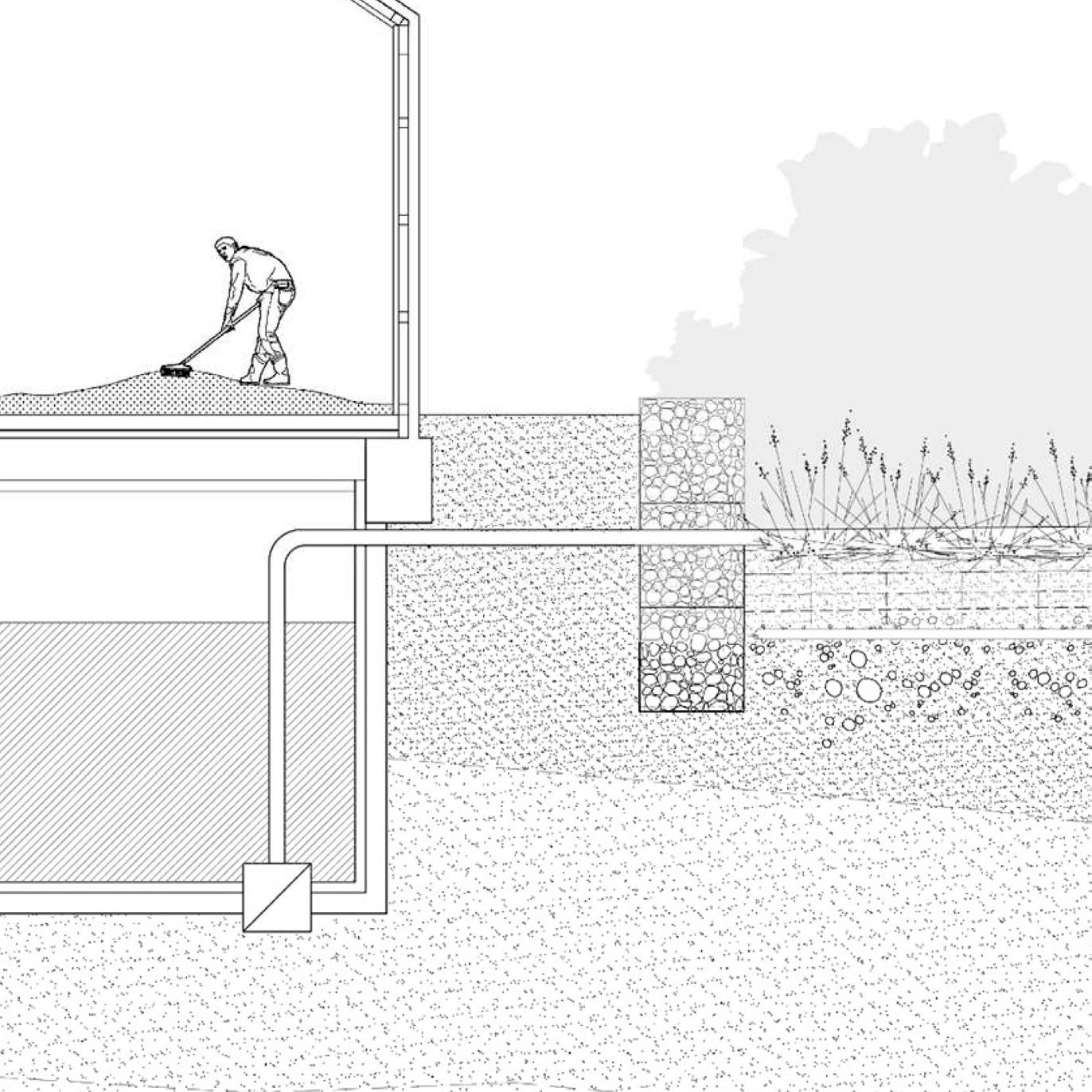

However, in the context of agroecology, this thesis re-frames the term. What if “intensifying” agriculture shifted its focus from heavy mechanization to profound human input? And instead of evaluating a farm’s success by its crop yield, what if it was assessed by the social value it produces? Under this paradigm, when “intensification” aligns with agroecological principles and is considered in relation to the peri-urban character of the green belt, it could be characterized by the following three criteria:

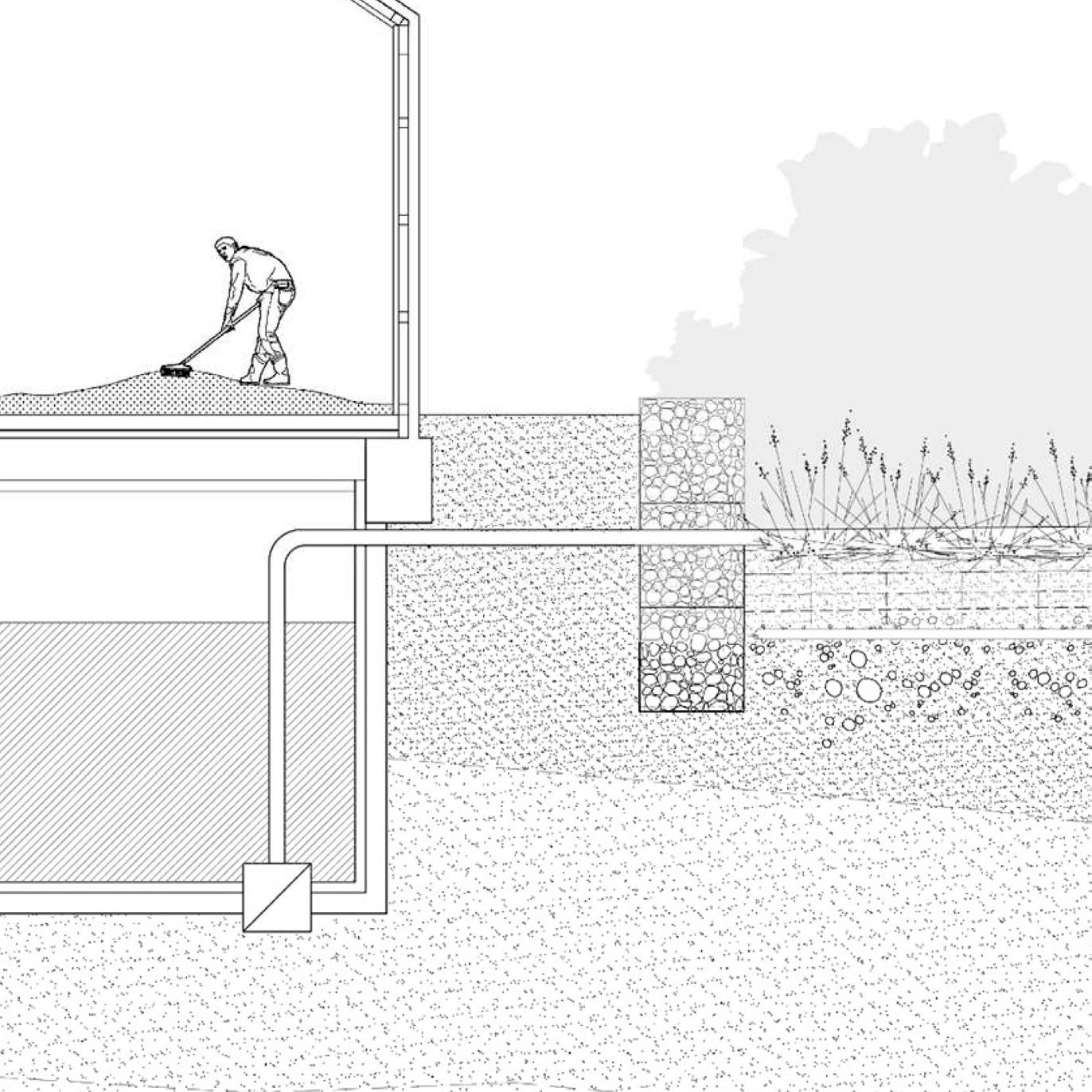

Community and Urban Infrastructure: This involves rethinking models of land ownership, water and waste management, energy generation, public transport, Sustainable Urban Drainage Systems (SUDs), and other nature-based solutions.

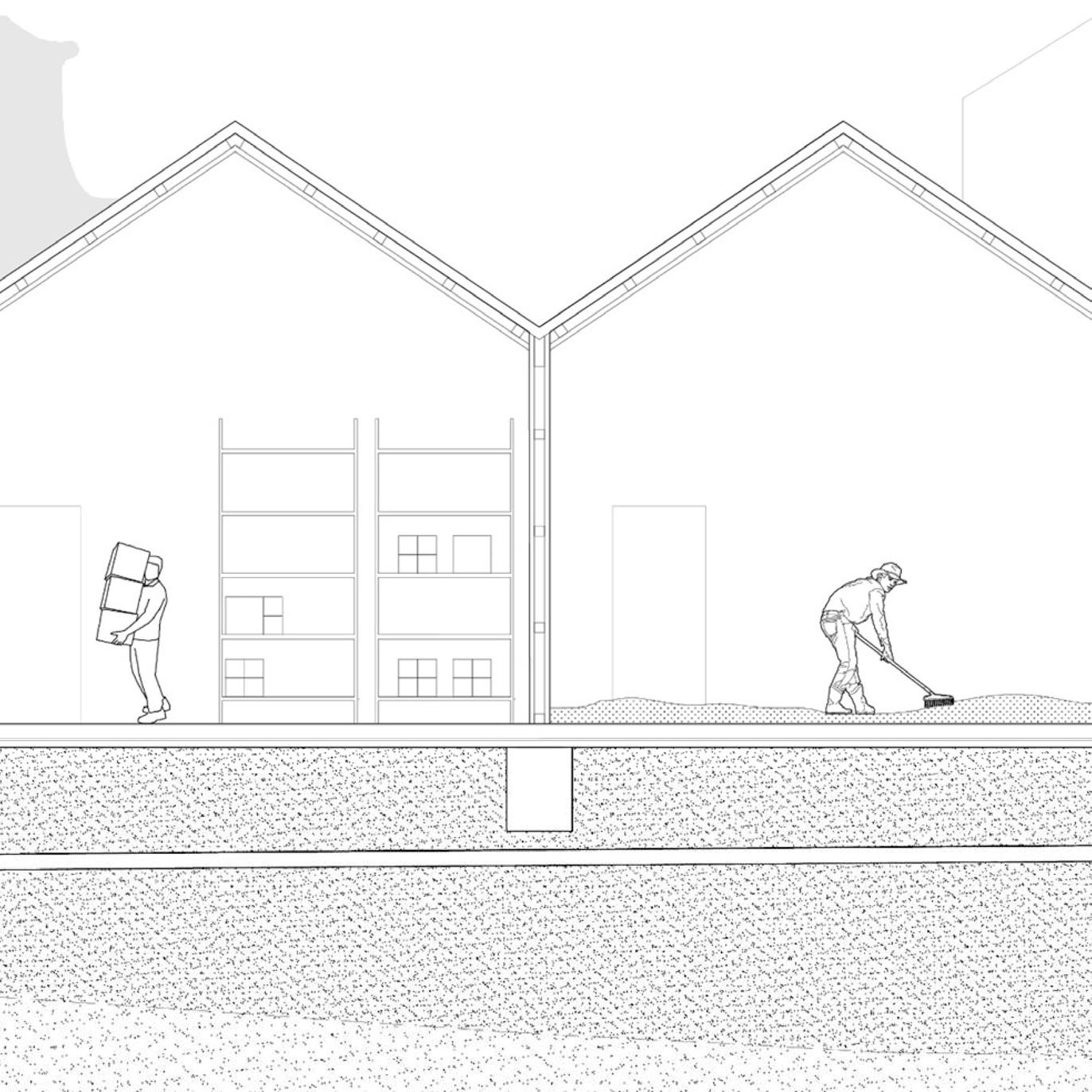

Enterprise Stacking: A concept where multiple activities coexist on a single farm, often referred to as mixed farming. It implies shorter supply chains and the re-purposing of agricultural by-products across varied industries and businesses.

Agroecological Techniques: This includes methods such as permaculture, vertical farming, agroforestry, organic farming, and circular systems, among others.

By Jegan Muralidharan & Antonio Garaycochea

Sustainable intensification

Fig 64

47 | UK Food System 48 [AA Landscape Urbanism 23/24] [AA Landscape Urbanism 23/24] Planet of Fields

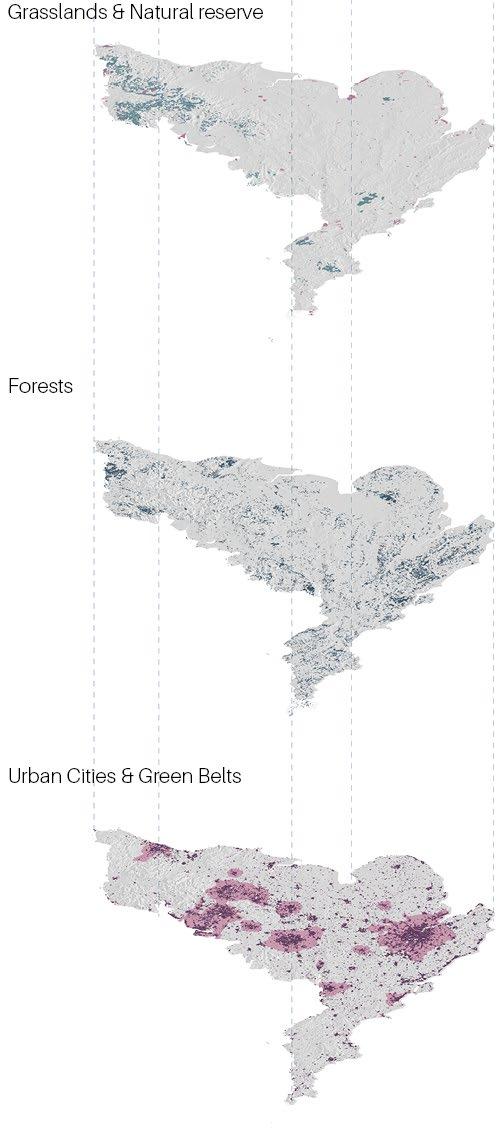

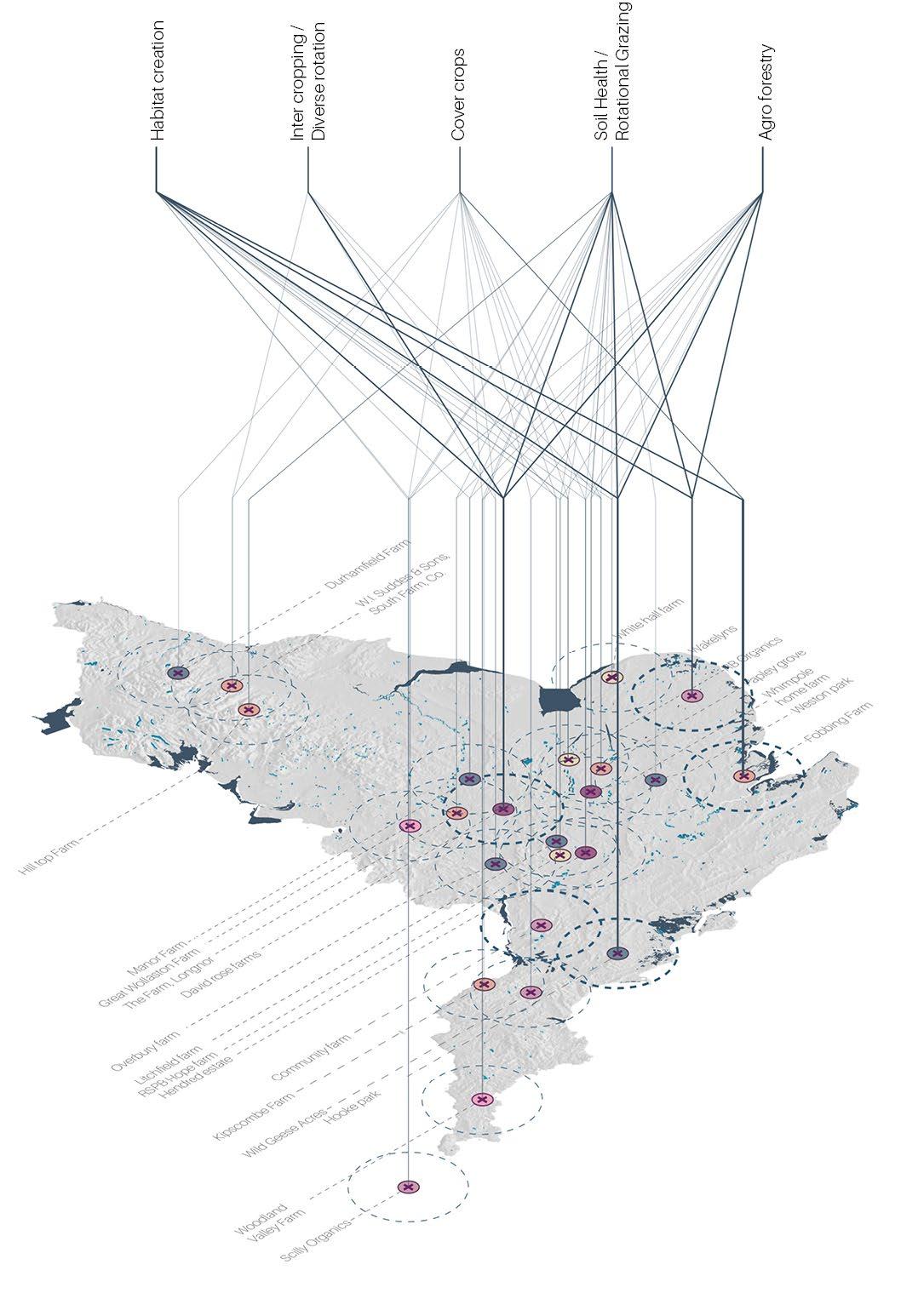

Case Studies

To gain a deeper understanding of these techniques and inform our proposal, we have compiled a catalogue of case studies. The remainder of this chapter will go on to further detail these examples.

Case study locations

65

49 | UK Food System 50 [AA Landscape Urbanism 23/24] [AA Landscape Urbanism 23/24] Planet of Fields

Fig

By Jegan Muralidharan

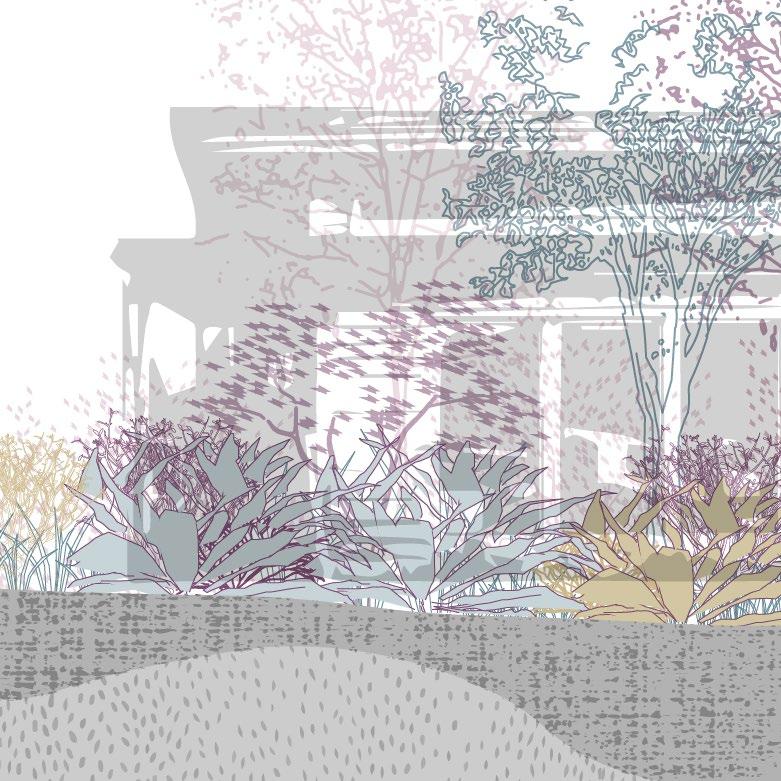

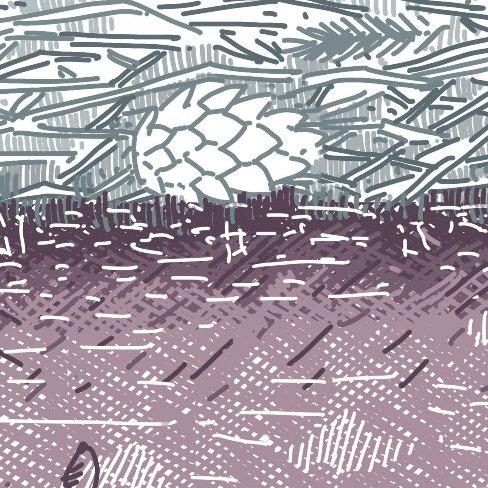

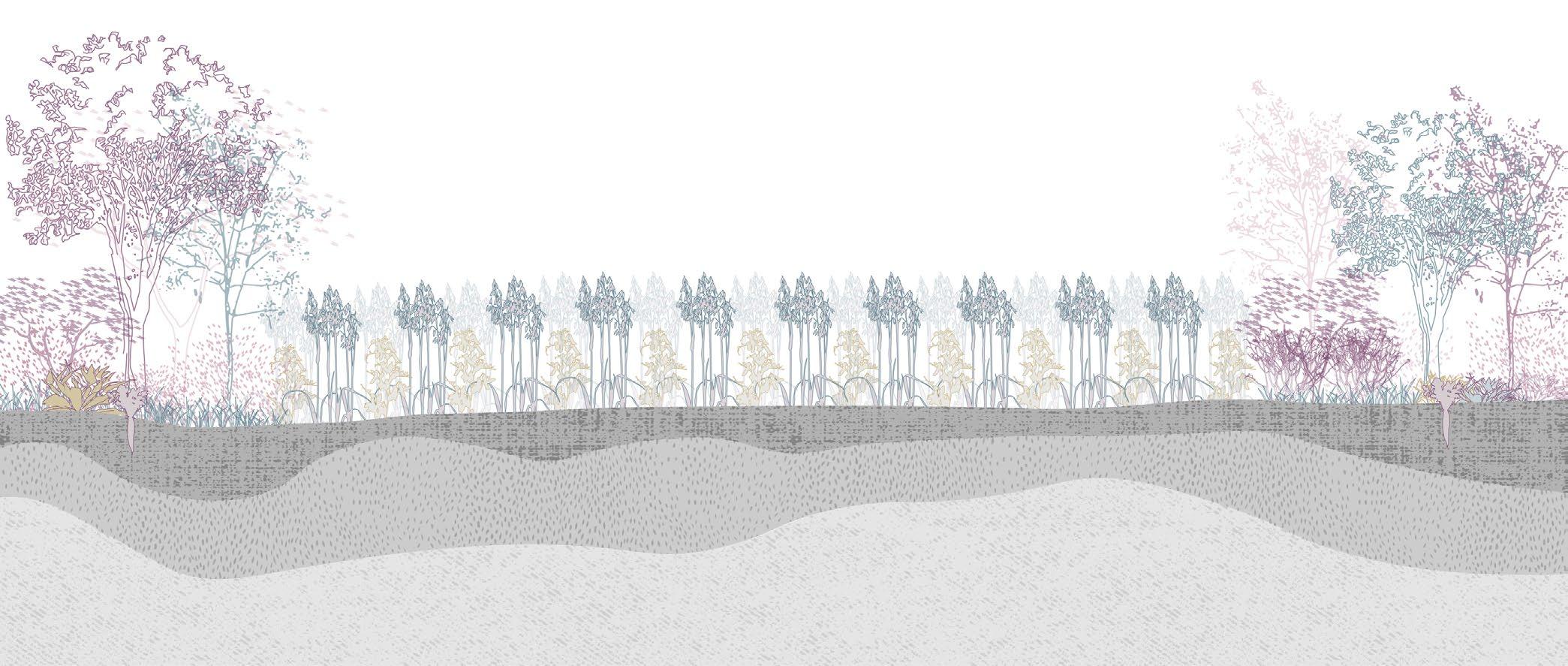

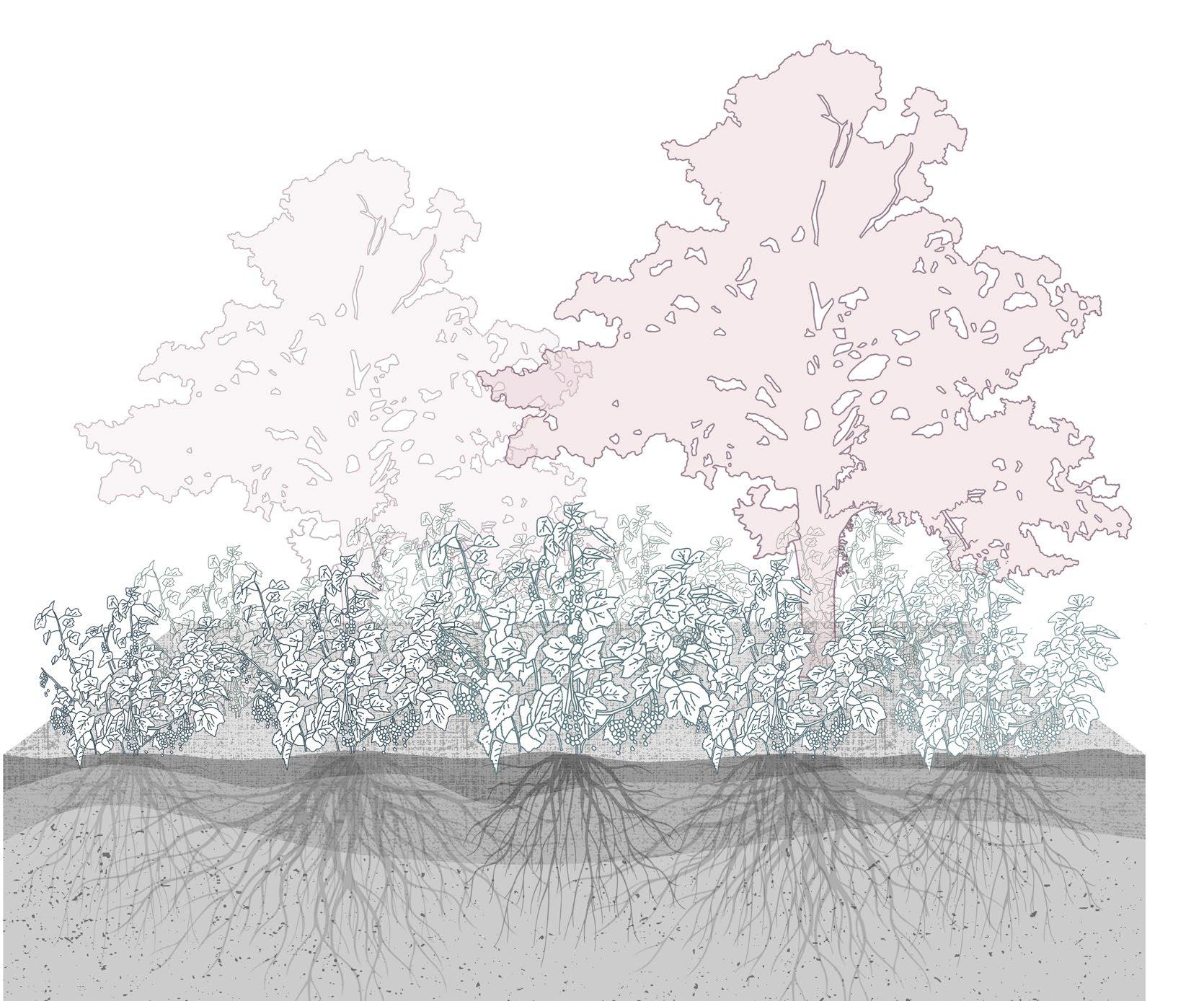

Fobbing Farm

Fobbing Farm is a 1,200 acre (485 hectare) zero tillage and zero insecticide arable and livestock farm in south Essex. They have introduced linseed, beans, heritage cereals, buckwheat, lentils, hemp, and are experimenting with sunflowers, millet, heritage corn and tiger nuts. They have also established 20% of the farm into herbal lays, and are currently investigating whith a dual purpose beef and dairy herd.

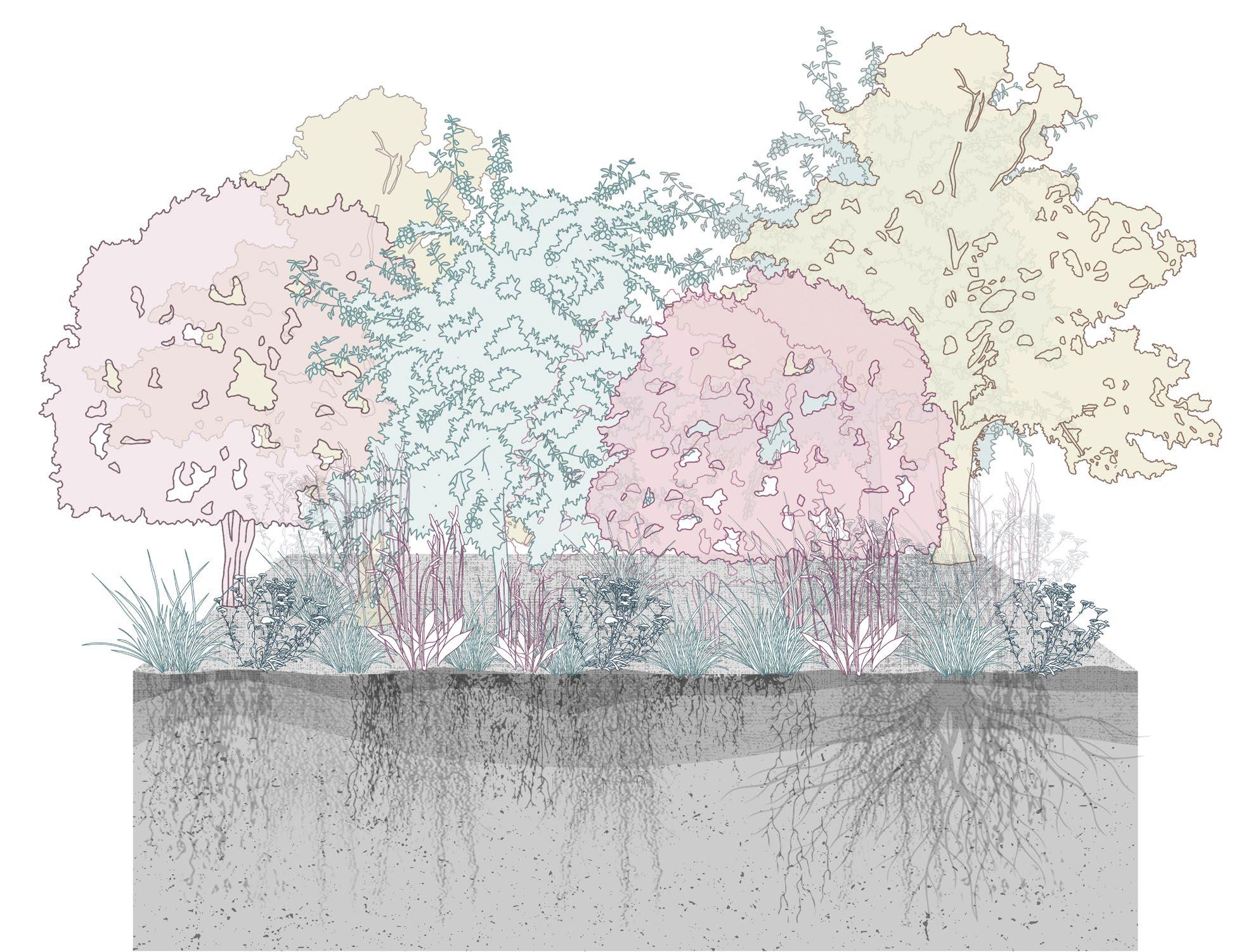

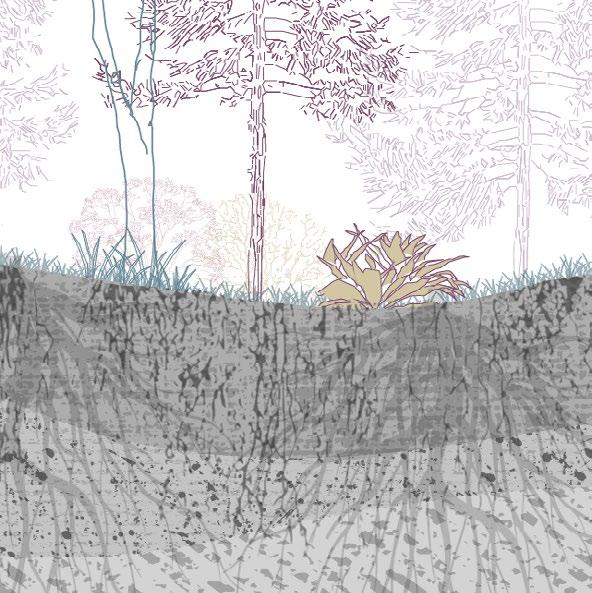

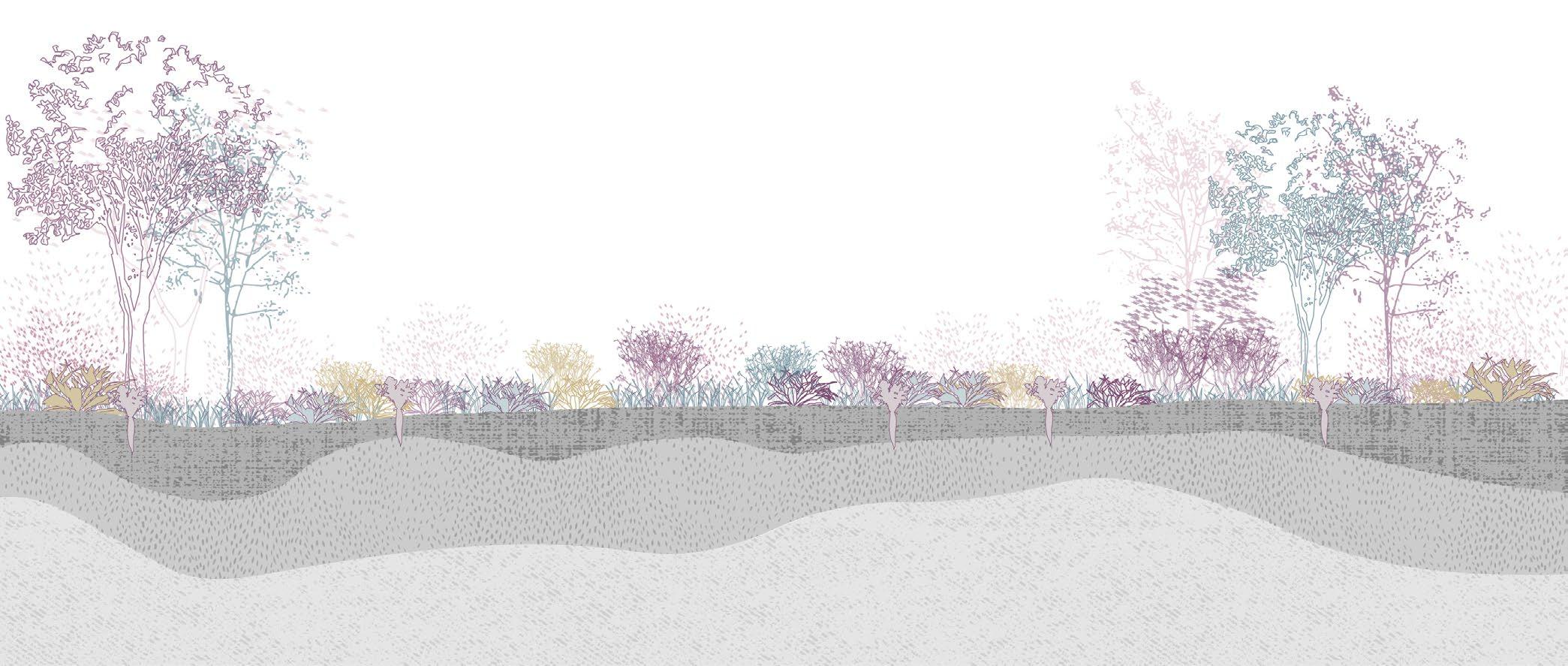

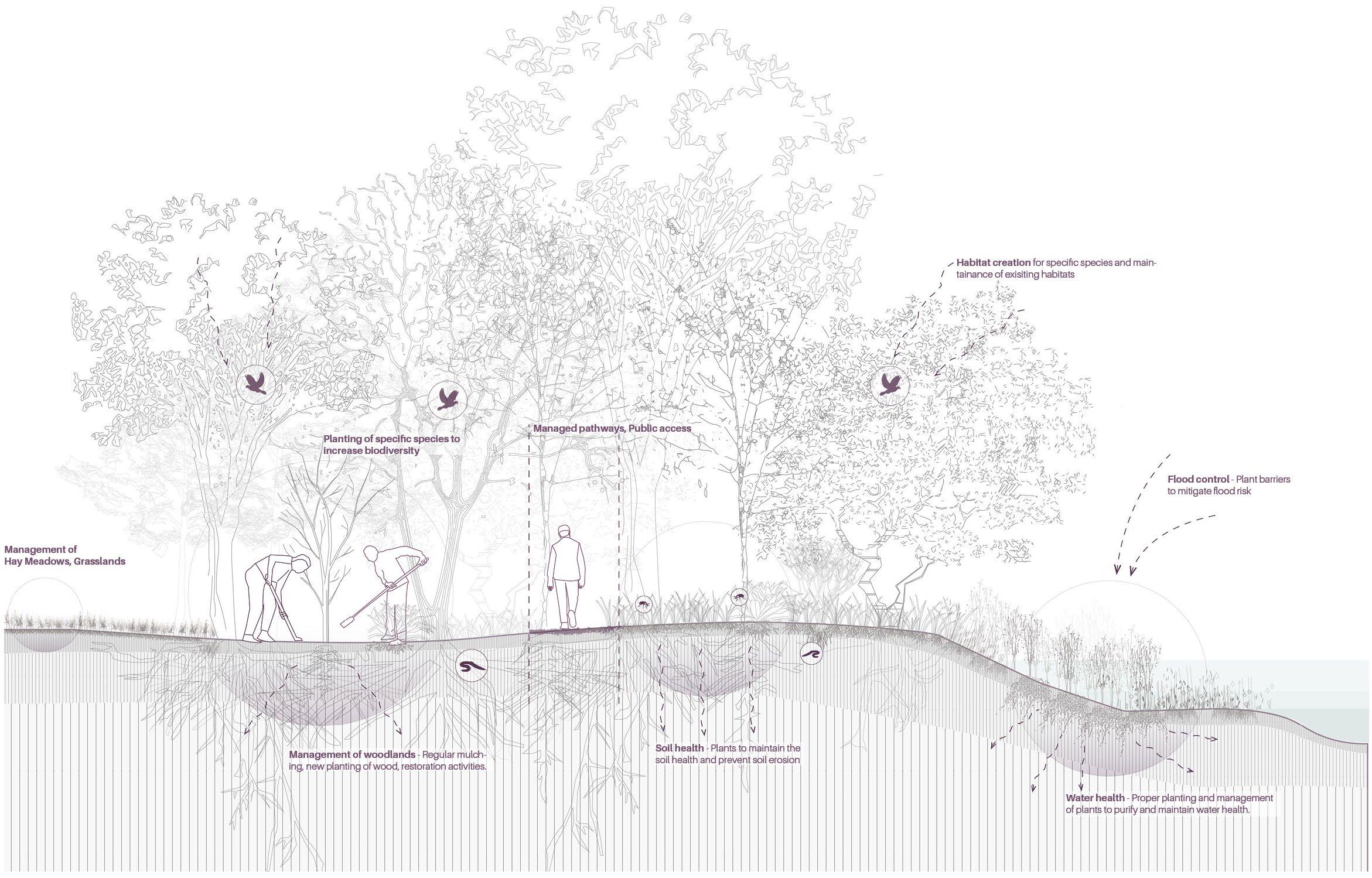

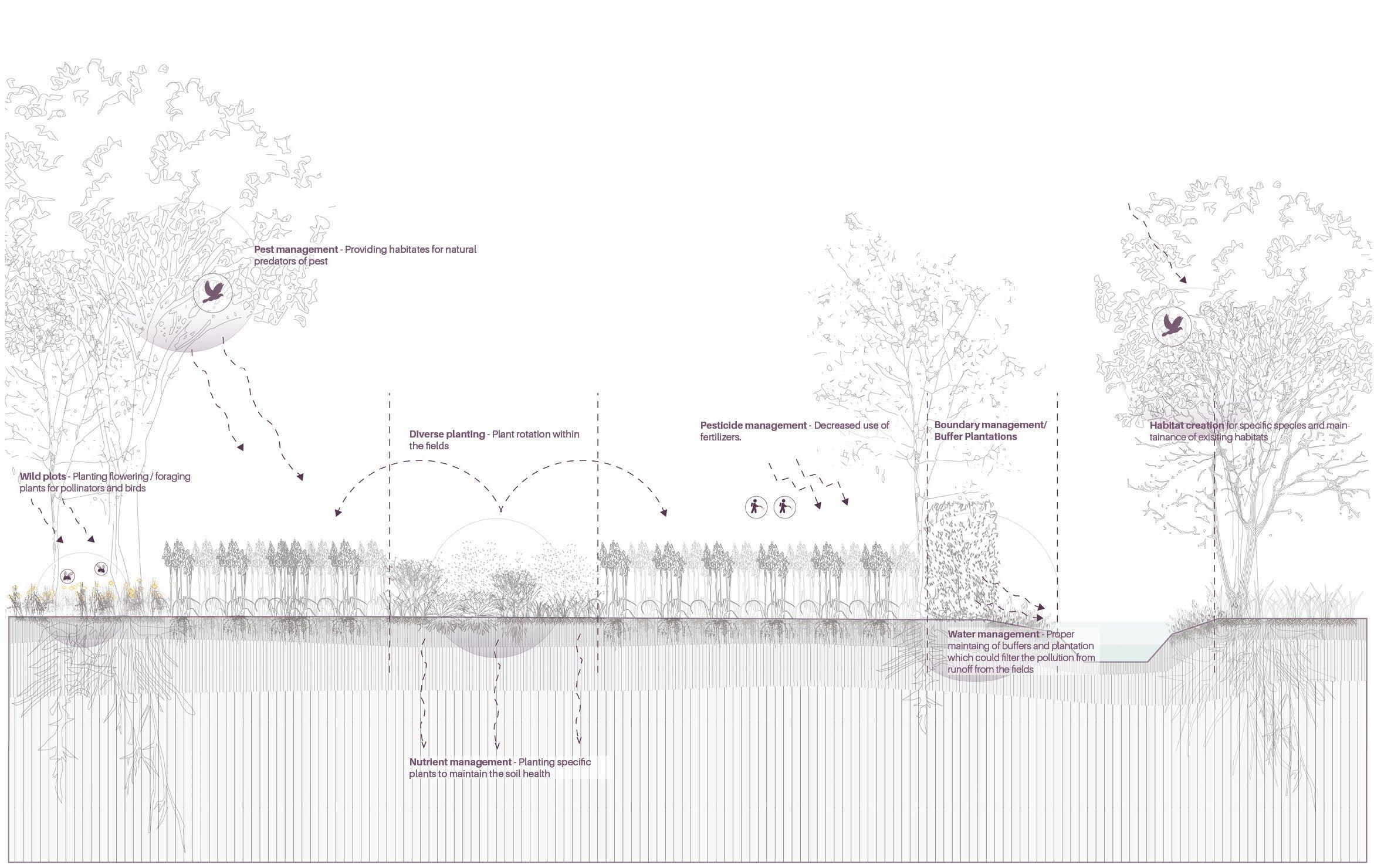

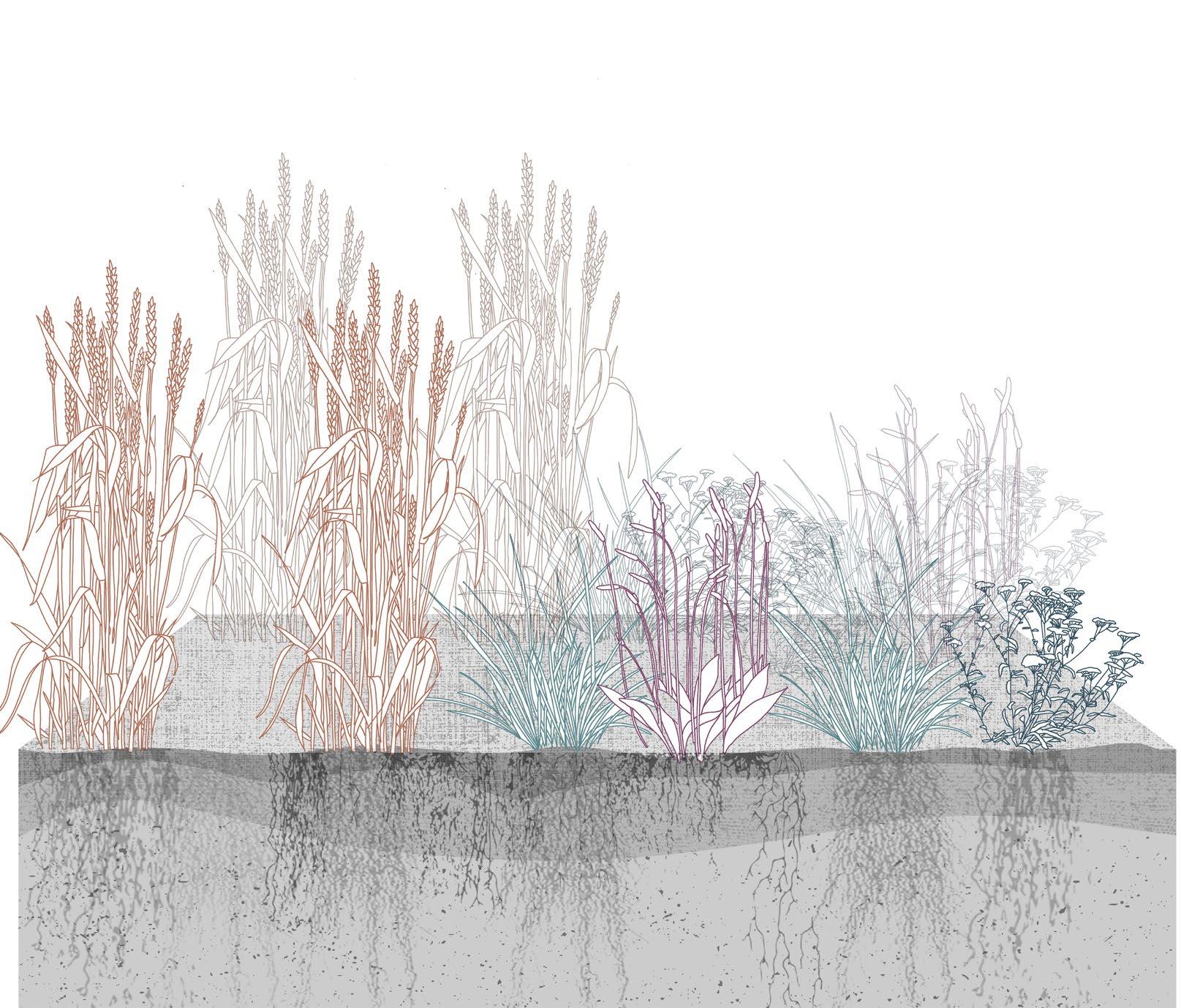

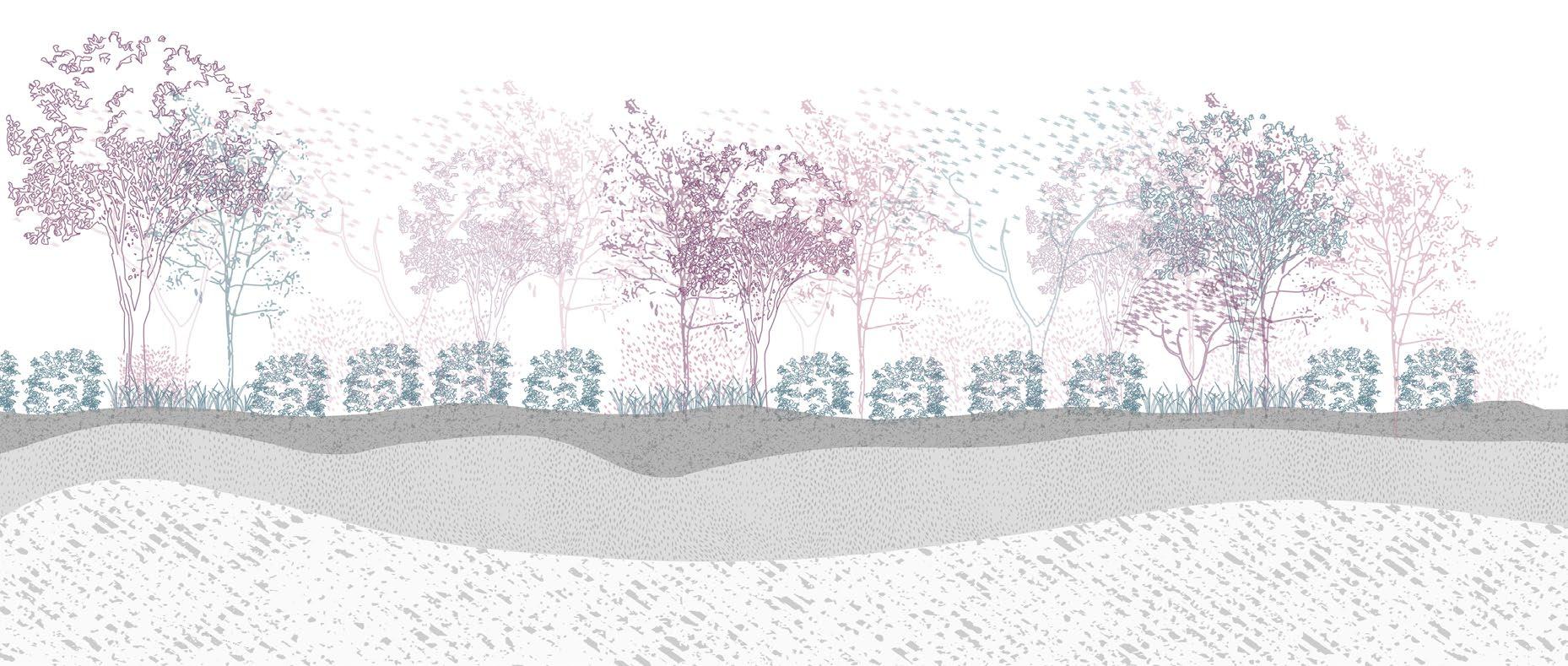

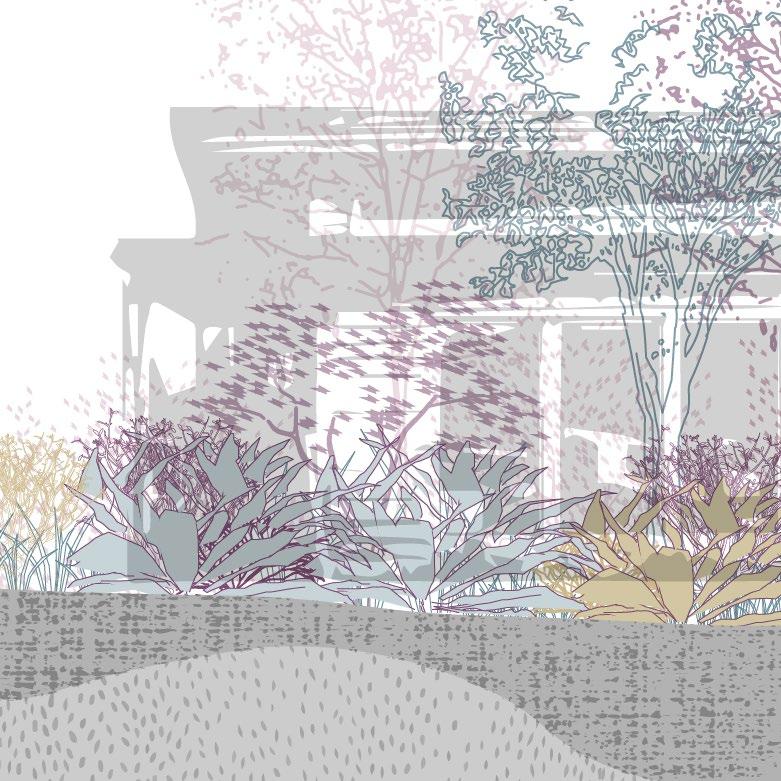

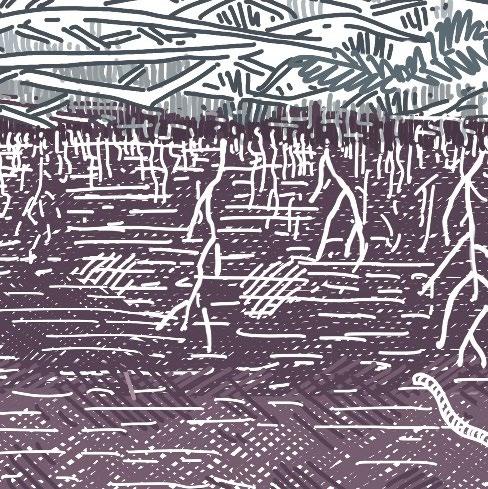

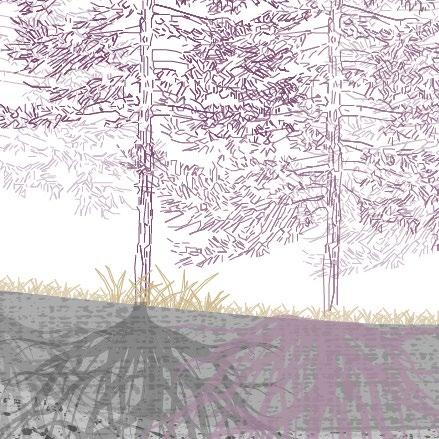

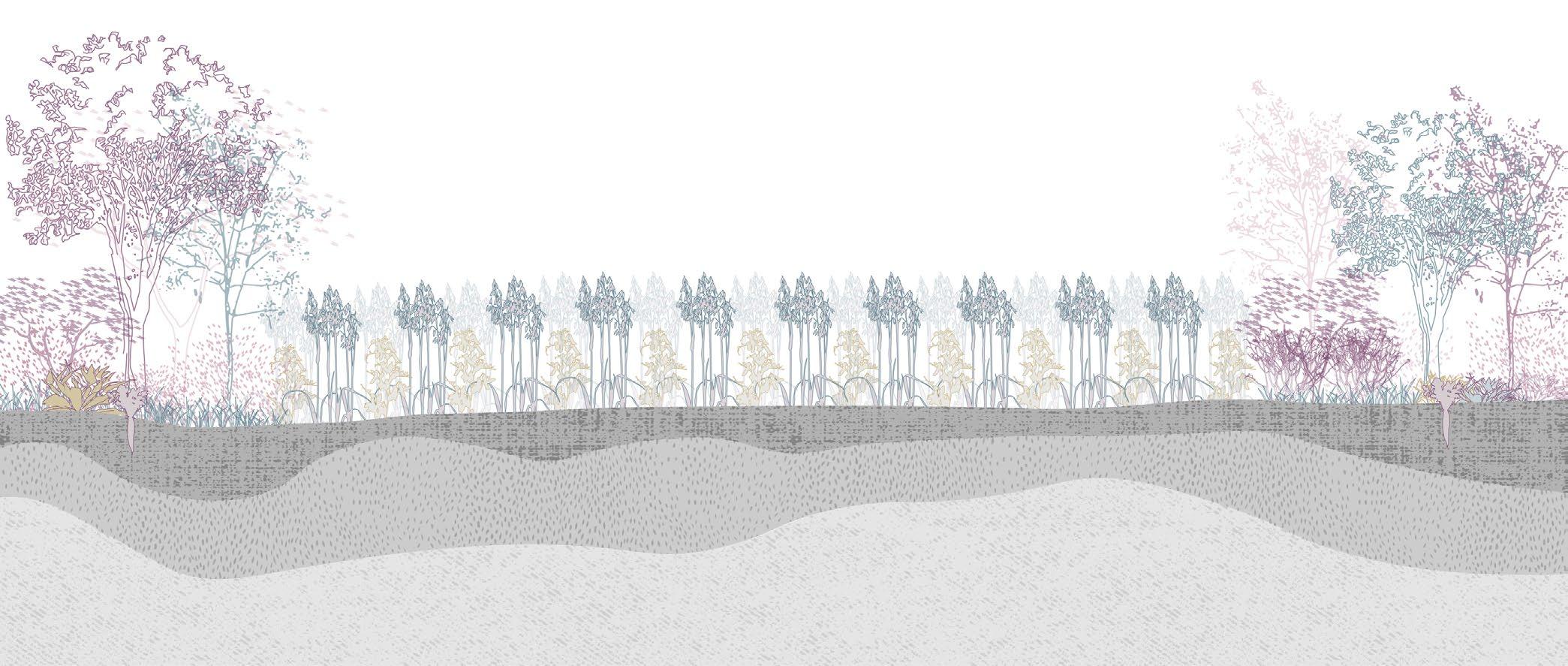

Section through Fobbing farm

By Khusbhoo

Wild Seam

Wild seam carving through the middle of the farm, which interconnects each field together. This area will be planted with sporadic trees and shrubs, and under-sown with local grasses from the Fobbing marshes.

Section through Fobbing farm

By Khusbhoo

Wild Margin

This edge is planted with native trees and fruitbushes, which over a ten to fifteen year period should become wild, and the farmers will harvest less of the fruit. These wild margins connect to the wild seam, ensuring permanent organic cover and plenty of permanent dense habitat for the animals on the farm.

Section through Fobbing farm

By Khusbhoo

By Khusbhoo

Belts

Entomologist state that insects only venture out around 20m from the margin of any field into the unknown. Due to this, the farmers decided to divide the field into agroforestry belts: 6m wide belts for trees, and 36m wide alleys for arable cropping,

Fig 67

Fig 68

Fig 69

Fig 67

Fig 68

Fig 69

Wild seam attracting pollinators and other essentials elements to maintain biodiversity Woodlands with dominant undergrowth Maintained soil health Fruit bushes like black current and red currant growing in the wild margins

Wheat plantation along to the herbal leys

Pollinators getting attracted to the agroecology belts Strengthening of the soil to prevent soil erosion

Physical layers of Fobbing Farm

Fig 66

51 | UK Food System 52 [AA Landscape Urbanism 23/24] [AA Landscape Urbanism 23/24] Planet of Fields

By Antonio Garaycochea

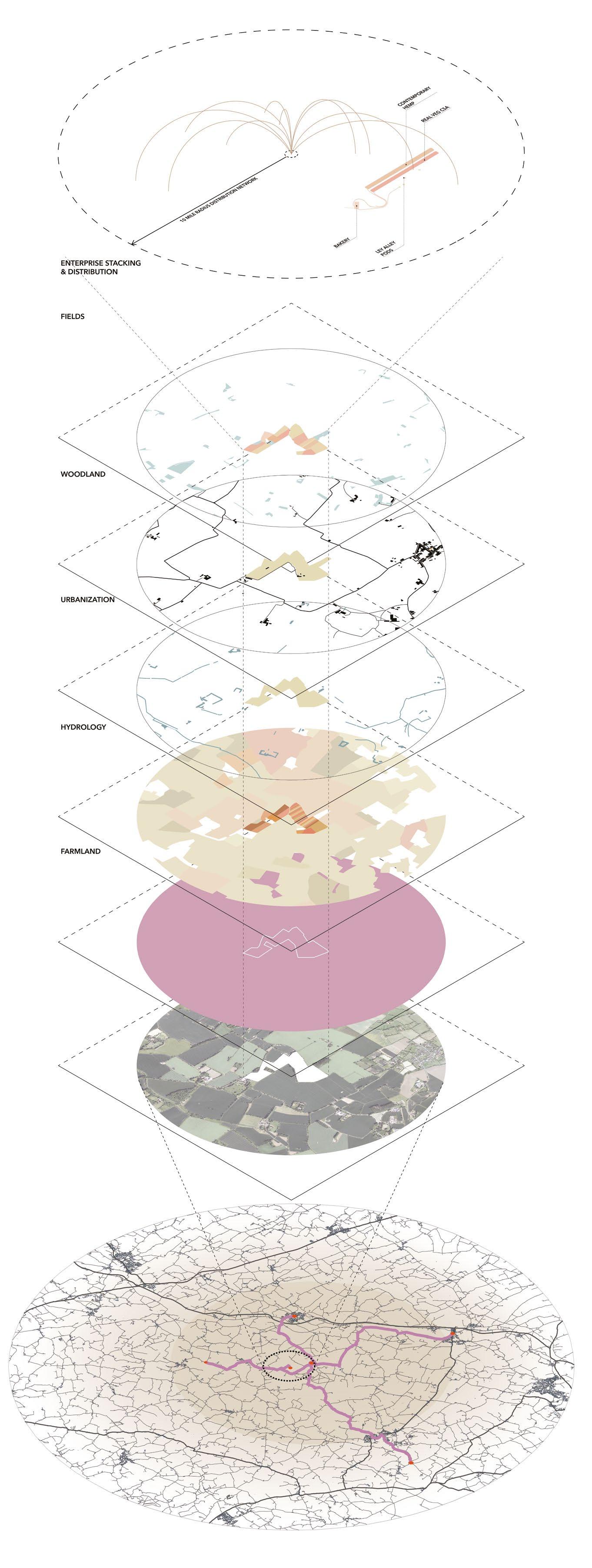

ALCGrade Croptypes Canals Urbanization Woodland

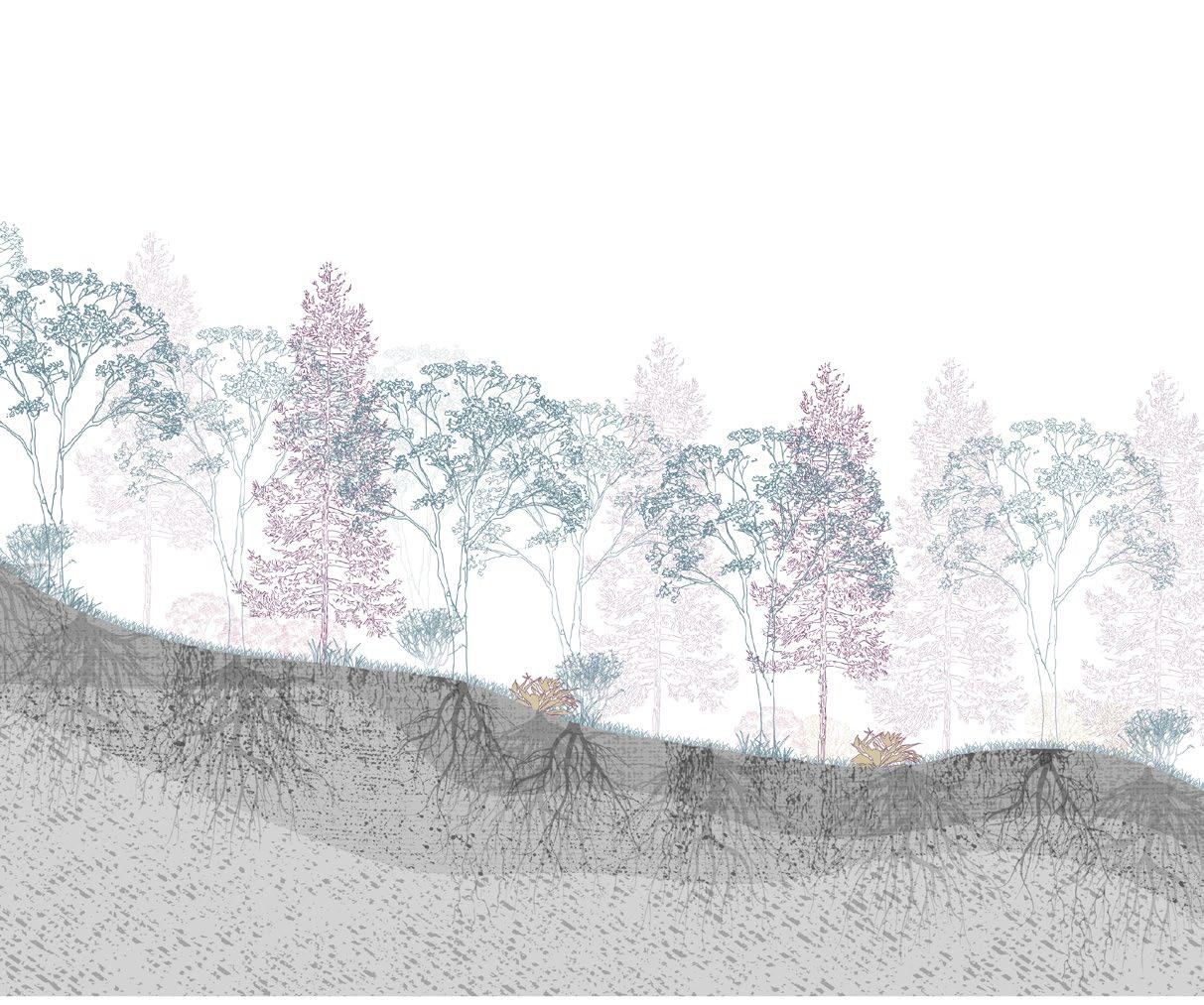

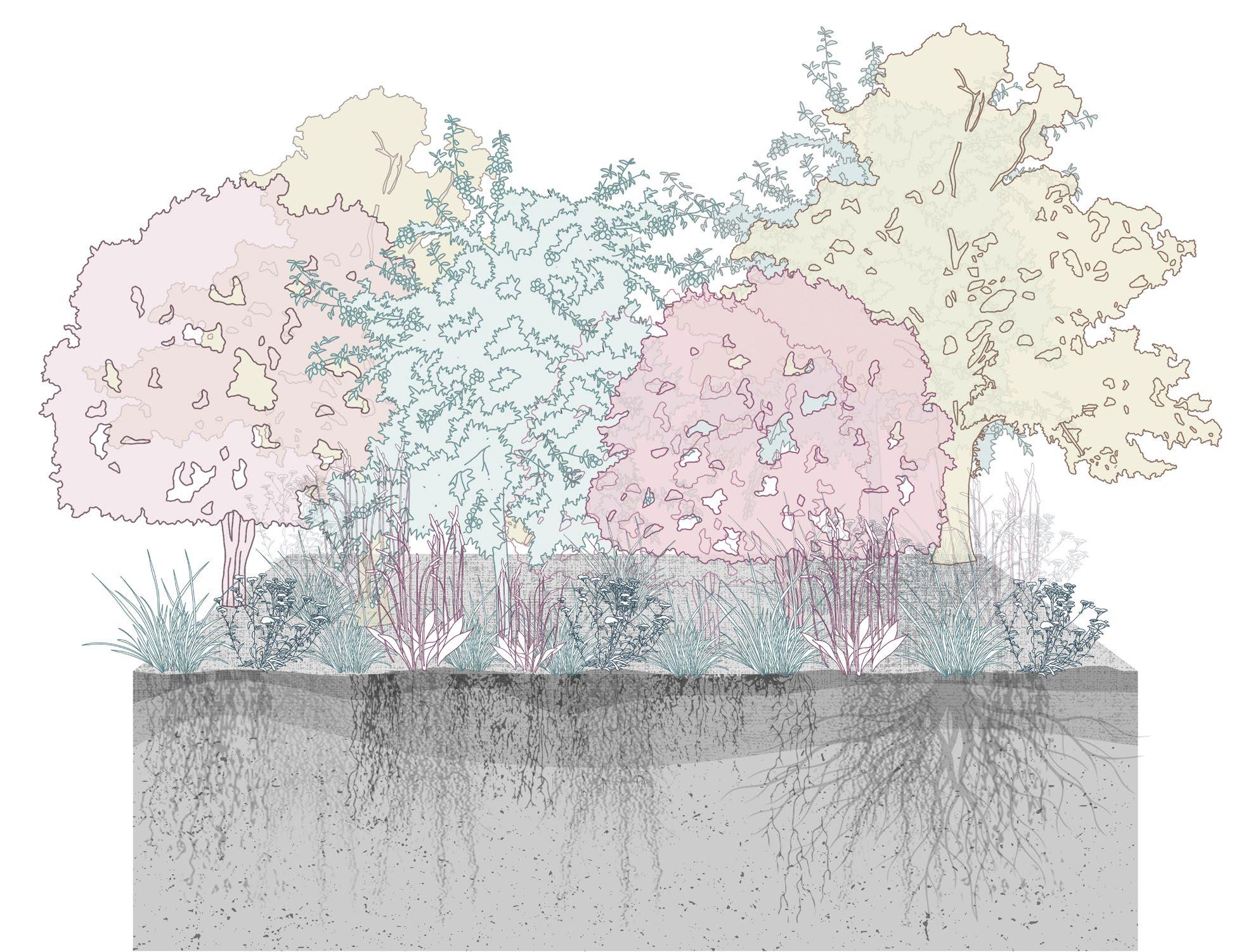

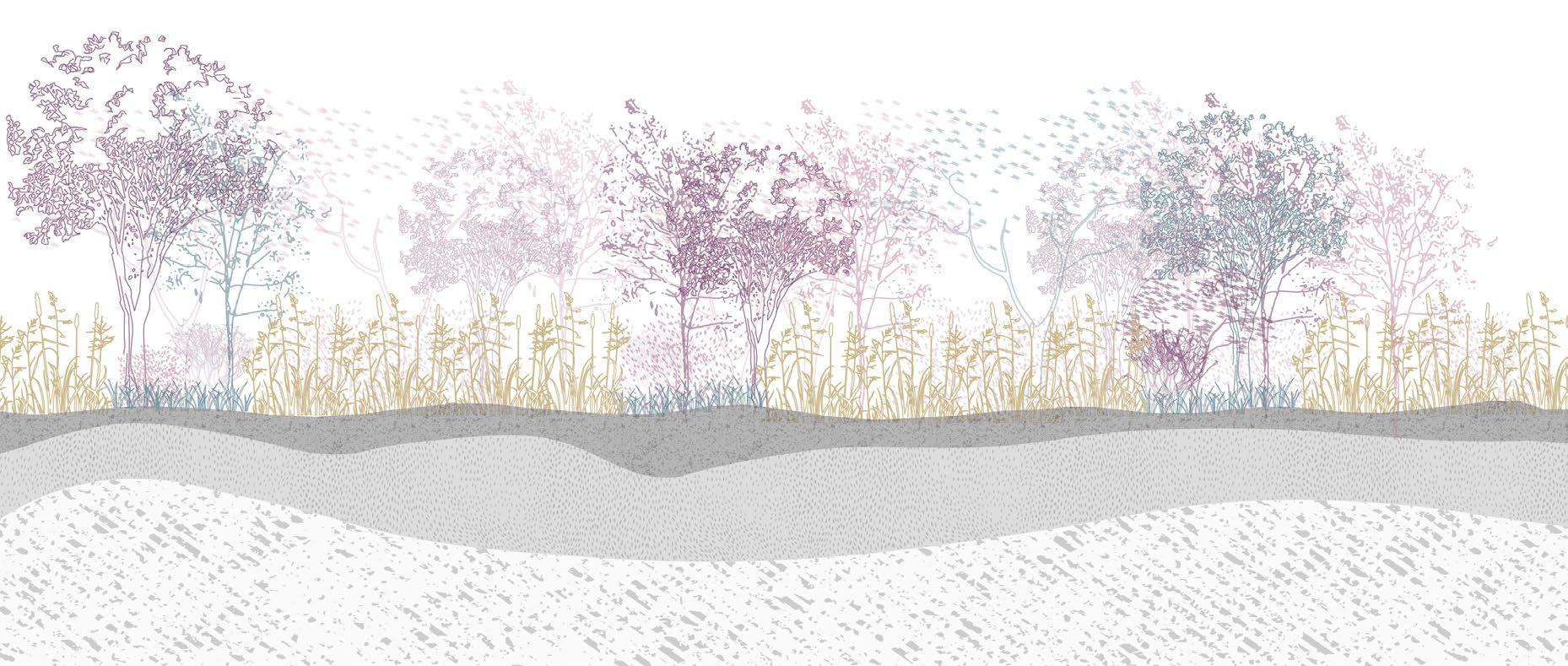

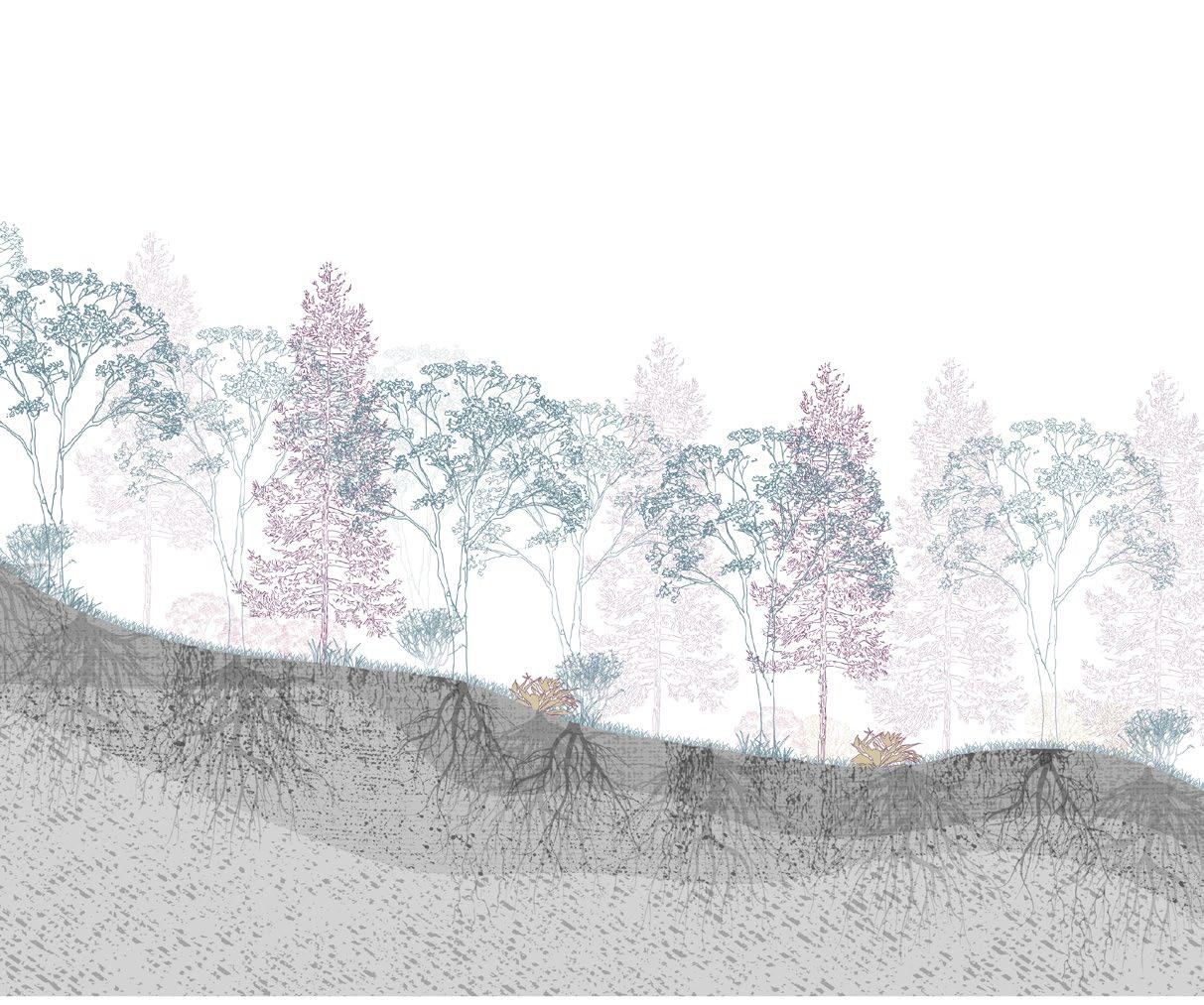

Wakelyns Farm

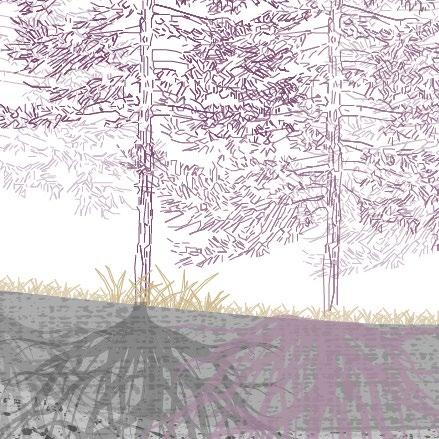

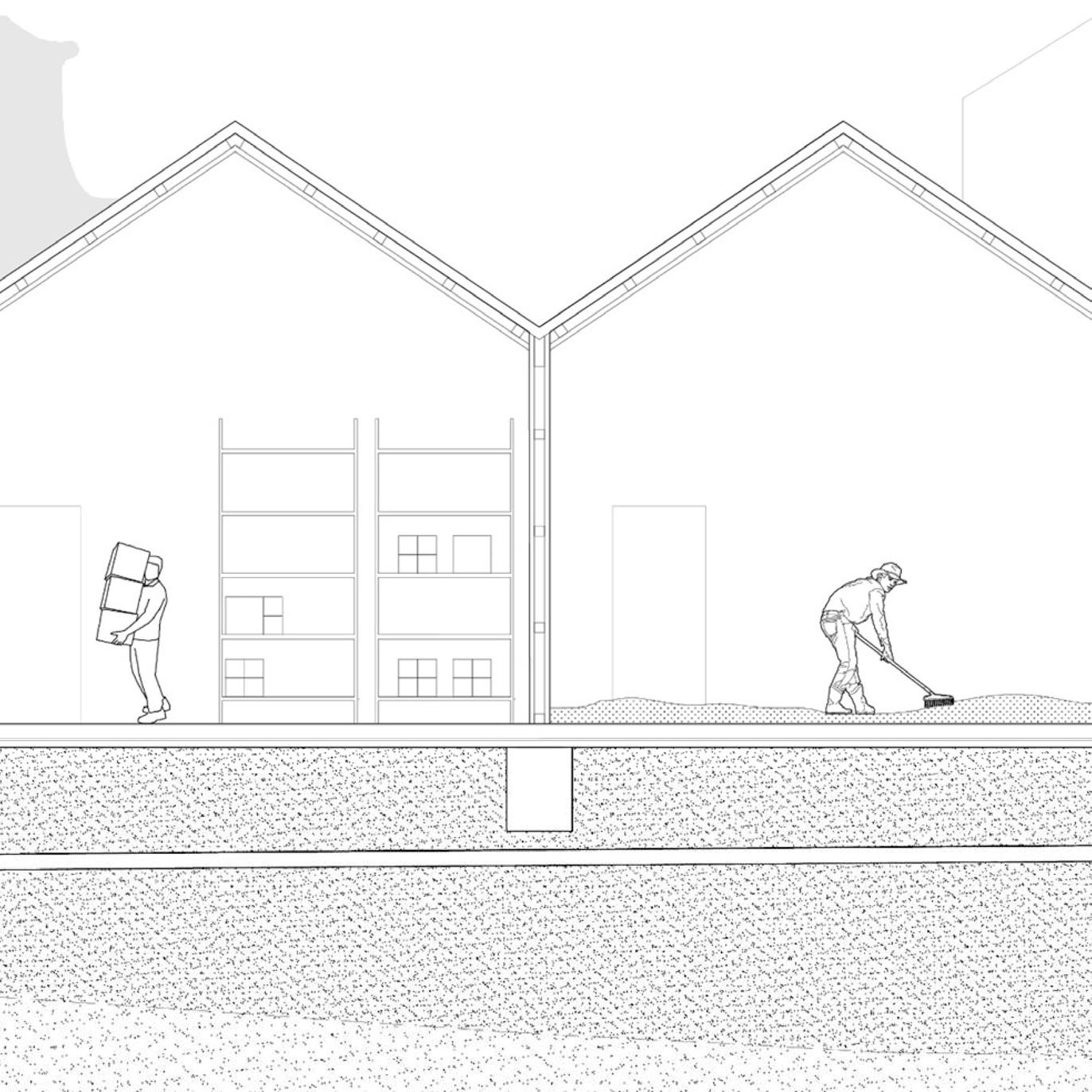

Wakelyns is a 22.5-hectare progressive farm, founded by the esteemed plant pathologist Prof. Martin Wolfe. The farm incorporates trees for timber, energy, and fruit into an organic crop rotation. For over two decades, Wakelyns has been at the forefront of research in organic crop production and agroforestry. In addition to its pioneering agroforestry methods, the farm utilizes business stacking and collaborates with various enterprises, including a bakery and bee-keeping operation. Wakelyns maintains a localized distribution system, ensuring its produce is consumed within a 10-mile radius. They follow a four year cycle; on the first year they grow wheat, which is replaced by lentil on another year and, afterwards, a herbal lay for two years.

Physical layers of Wakelyns

Section through Wakelyns

Section Through Wakelyns

Fig 70

Fig 72

Fig 71

By Antonio Garaycochea

Physical layers of Wakelyns

Section through Wakelyns

Section Through Wakelyns

Fig 70

Fig 72

Fig 71

By Antonio Garaycochea

Wheat Lentil Herbal lay 1 year 1 year Agroforesty belts Wheat 2 year Agroforesty belts Agroforesty belts Wheat Wheat Wheat Lentil Herbal lay 1 year 1 year 2 year Agroforesty belts Lentil Agroforesty belts Agroforesty belts Lentil Lentil ALCGrade CropType Canals Urbanization Woodland Distribution 53 | UK Food System 54 [AA Landscape Urbanism 23/24] [AA Landscape Urbanism 23/24] Planet of Fields

By Khushboo Prashant By Khushboo Prashant

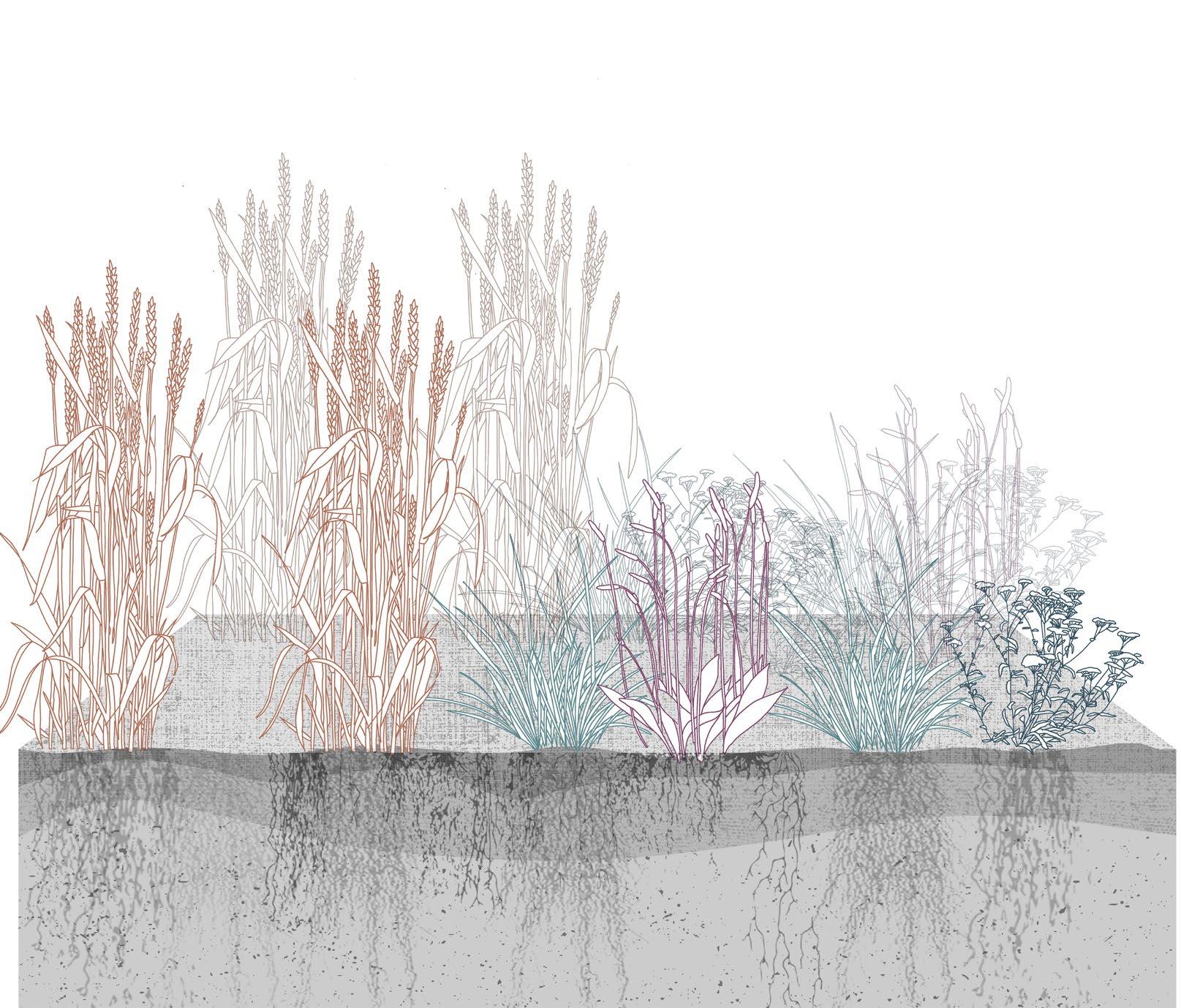

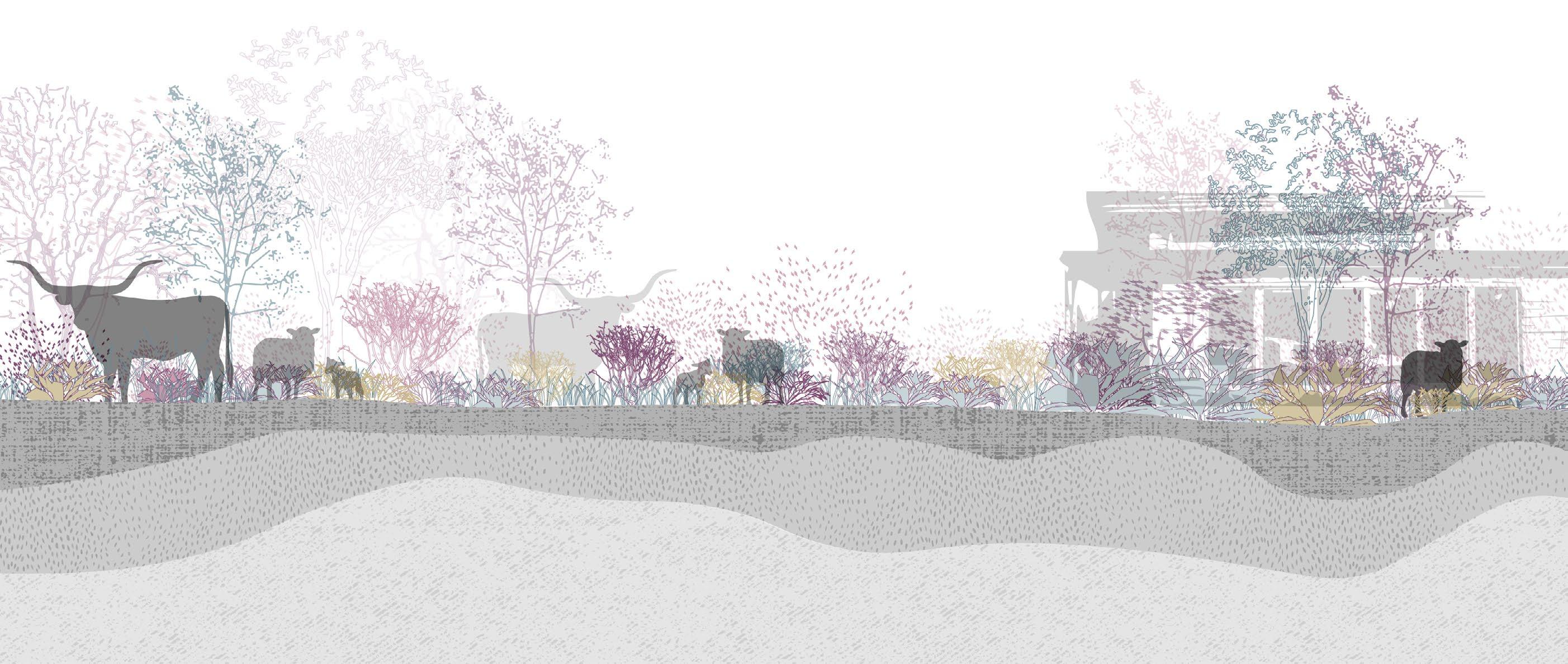

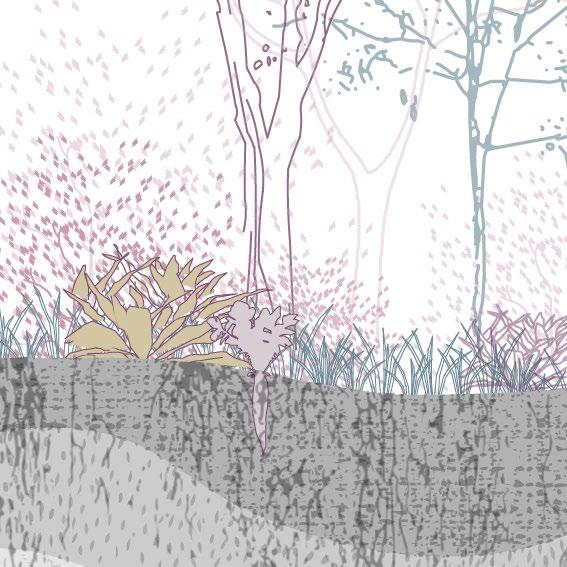

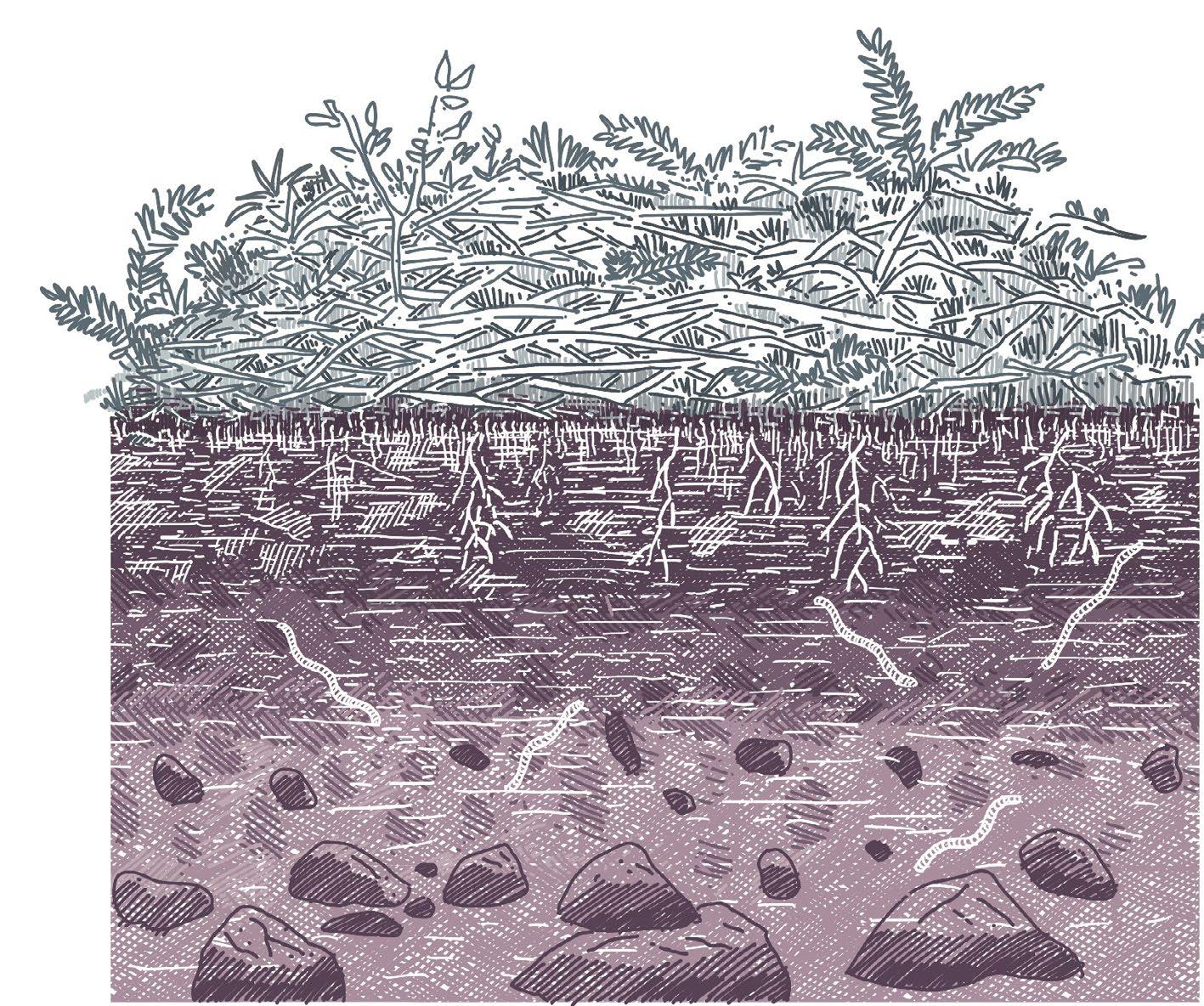

Eco-Farm Nottingham

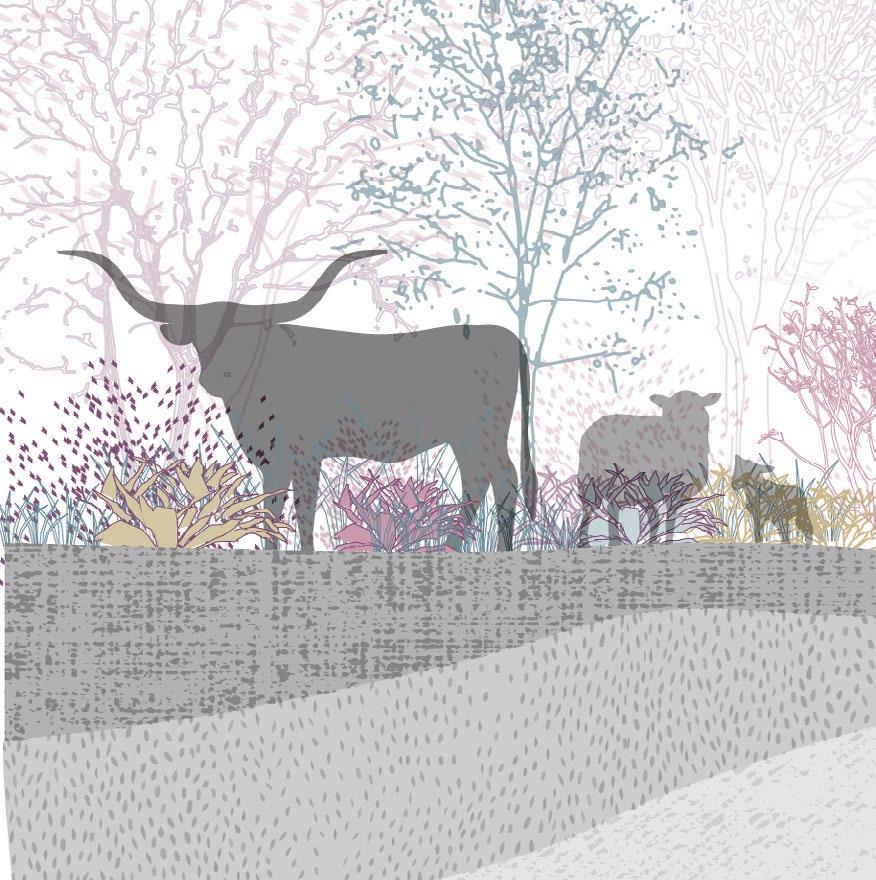

The farm spans for 450 acre in East of Trent valley. After looking for ways to diversify the business, the farm began to transition into a mixed enterprise with cereals and sheep, as well as the creation of an edible woodland for the local community (Caldbeck 2021). They are Woodland Trust Ambassador and host agroforestry research on the farm there are two main trial areas on the farm:

1. silvoarable - apple trees and elderflower within a block of arable land

2. silvopastoral sheep grazing within an edible woodland area.

Physical layers of Nottingham

Section through Nottingham

Fig 73

Fig 74

By Antonio Garaycochea

Physical layers of Nottingham

Section through Nottingham

Fig 73

Fig 74

By Antonio Garaycochea

Rotational grazing Soil monitoring Minimum Tillage Undersowing Mixed farming Agroforestry Companion crops Direct drilling Diversified rotation Habitat creation Integrated Pest Management Key Practices Urbanization Woodland Canals Croptype ALCGrade 55 | UK Food System 56 [AA Landscape Urbanism 23/24] [AA Landscape Urbanism 23/24] Planet of Fields

By Khushboo Prashant

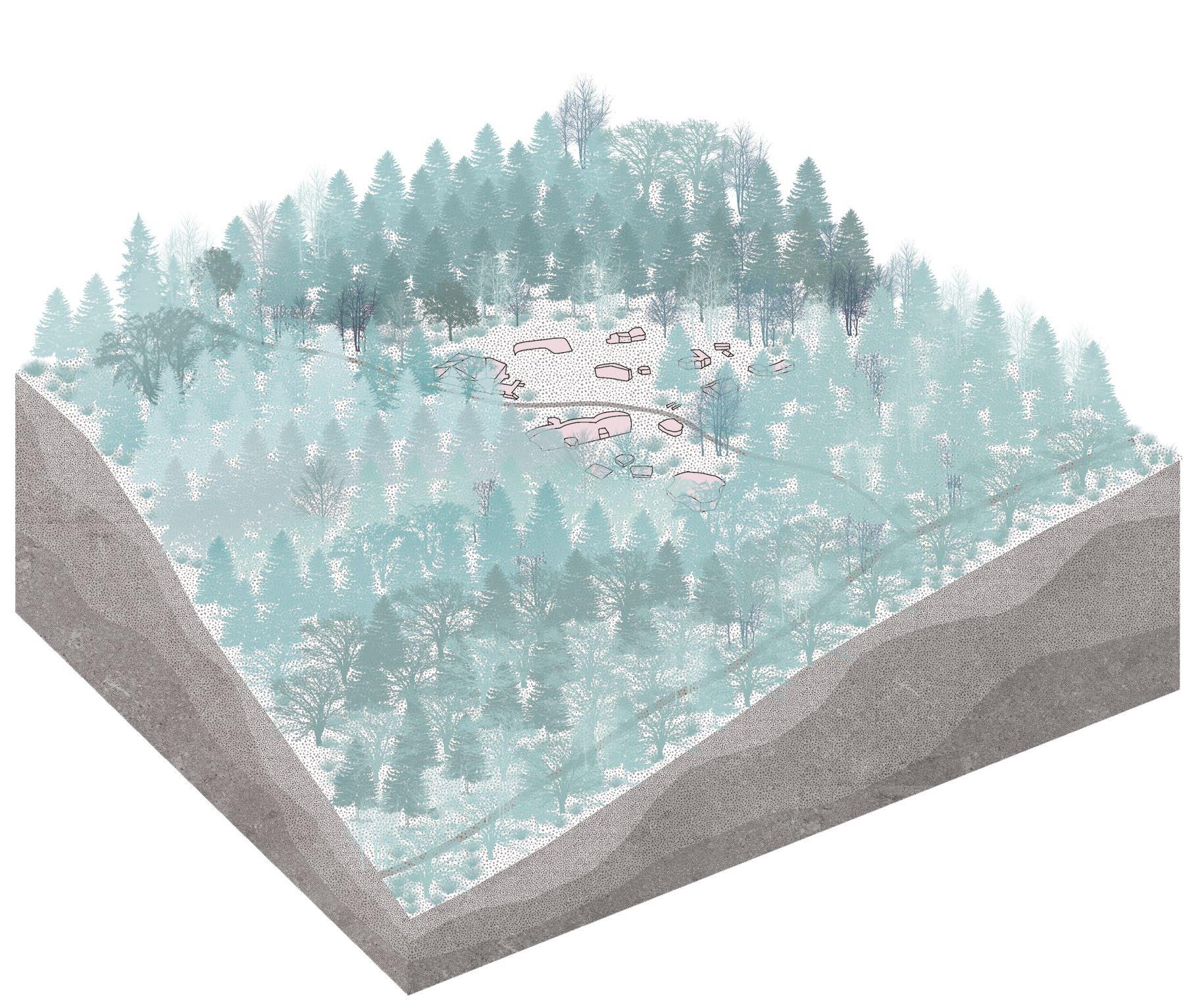

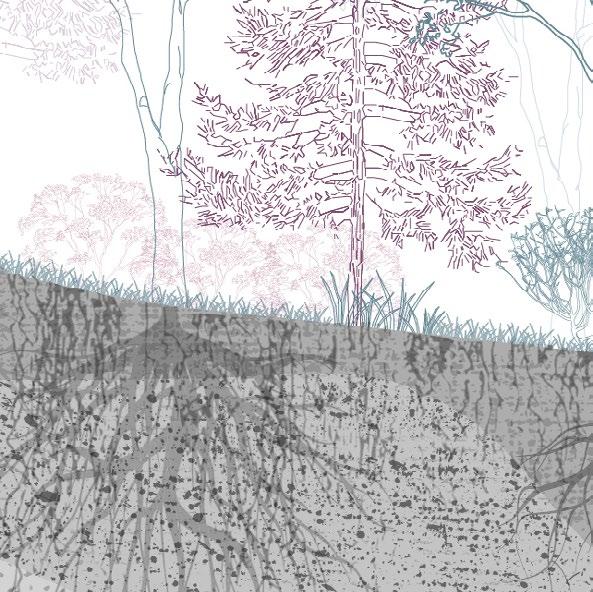

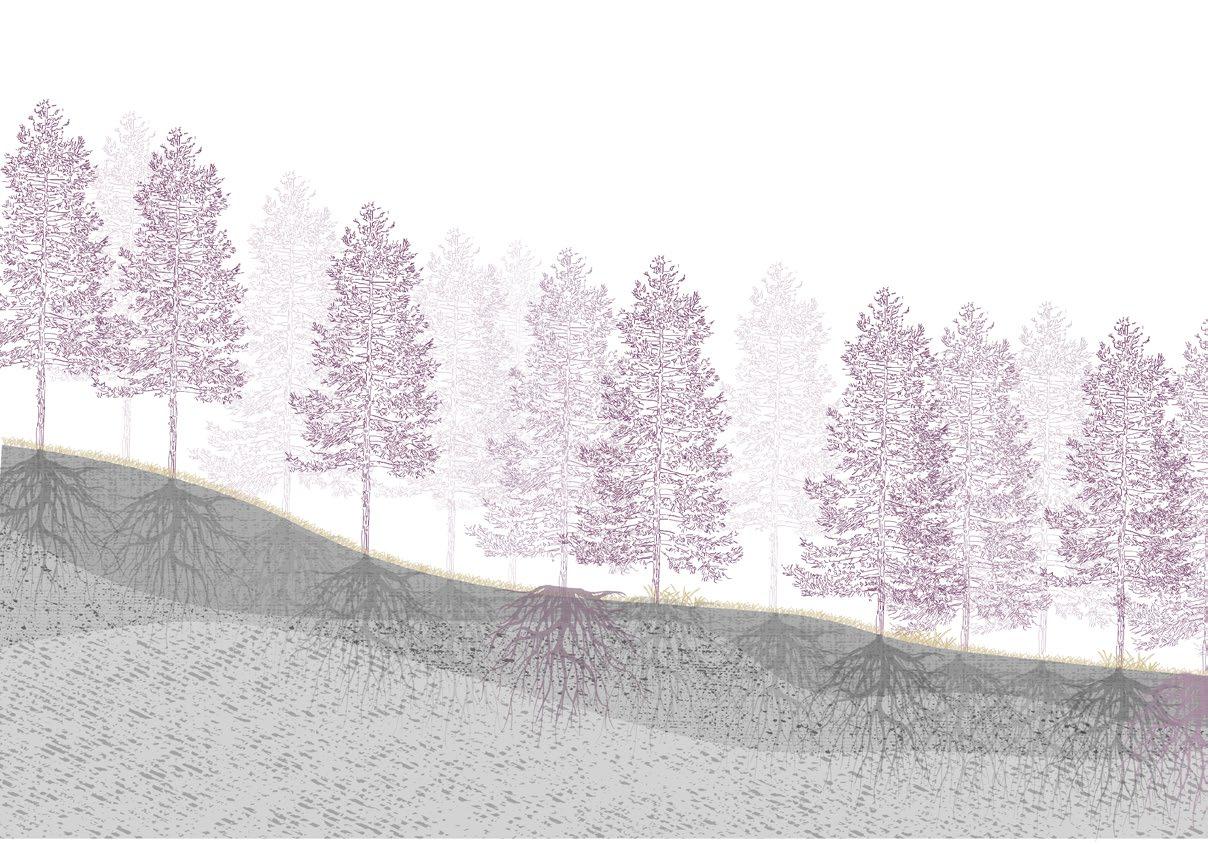

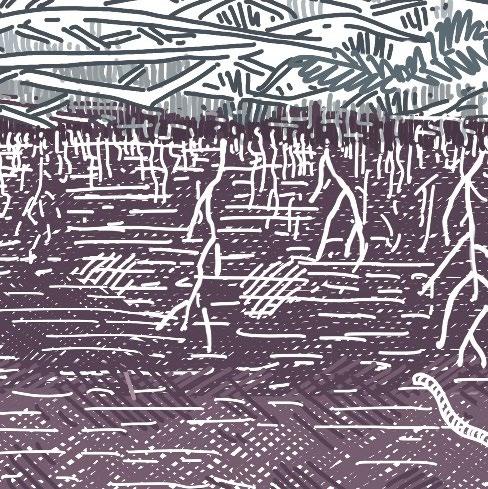

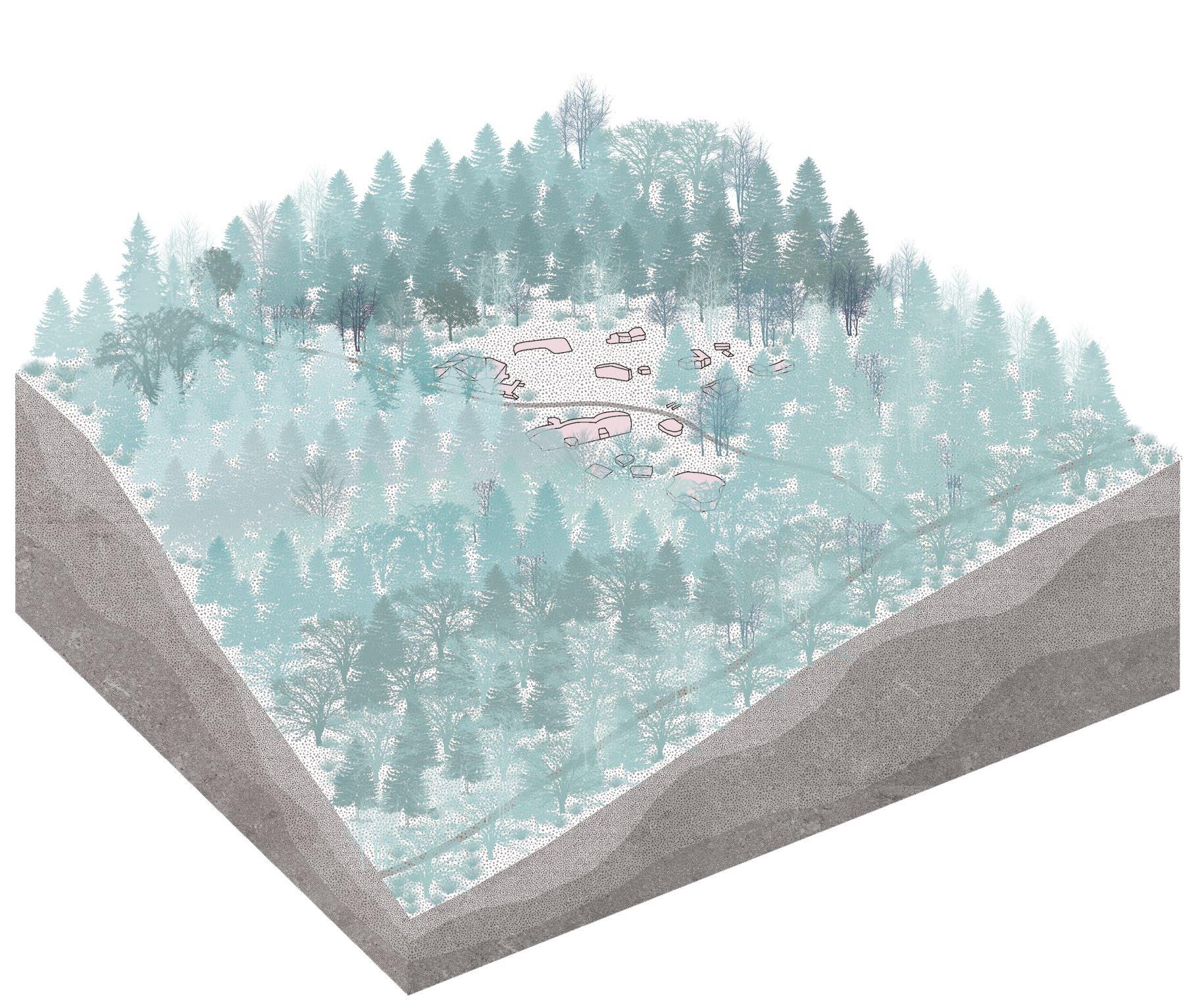

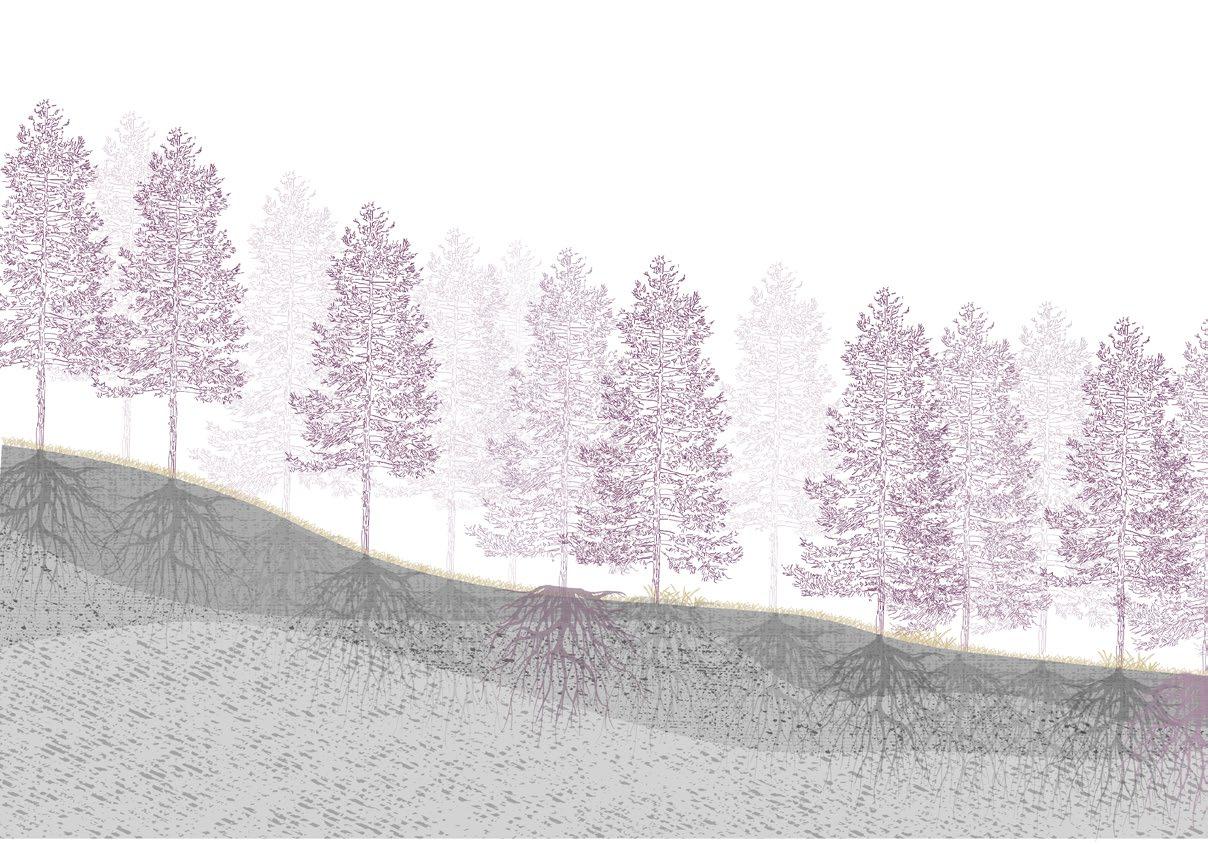

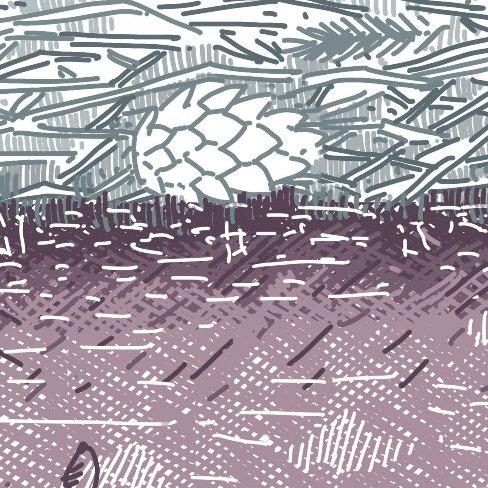

Hooke Park

Hooke Park is a 142 hectare woodland in Dorset, South West England located near the town of Beaminster and within the Dorset Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty. The site is designated as ancient woodland and historically comprised a deer hunting estate. An educational campus is located at Hooke Park that was developed by the Parnham Trust following its purchase of the site in 1983.

The park emphasizes the use of circular systems wherever feasible. It features a small-scale horticultural farm that provides a portion of the food consumed by the students. Seasonal wood is dried and processed, allowing students to work with it and, finally, the wood chips that result as a by-product are incinerated to heat the facility’s water.

Wood chipping unit Woodburningforheating Seasoned wood for construction Seasoninganddryingofwood Woods from the forest Mix forest, board leaf and pine tree

Supply cycle of Hooke Park

Fig 76

By Khusbhoo Prashant

Physical layers of Hooke Park

Fig 75

Woodland Urbanization Canals Croptypes ALCGrade 57 | UK Food System 58 [AA Landscape Urbanism 23/24] [AA Landscape Urbanism 23/24] Planet of Fields

By Antonio Garaycochea

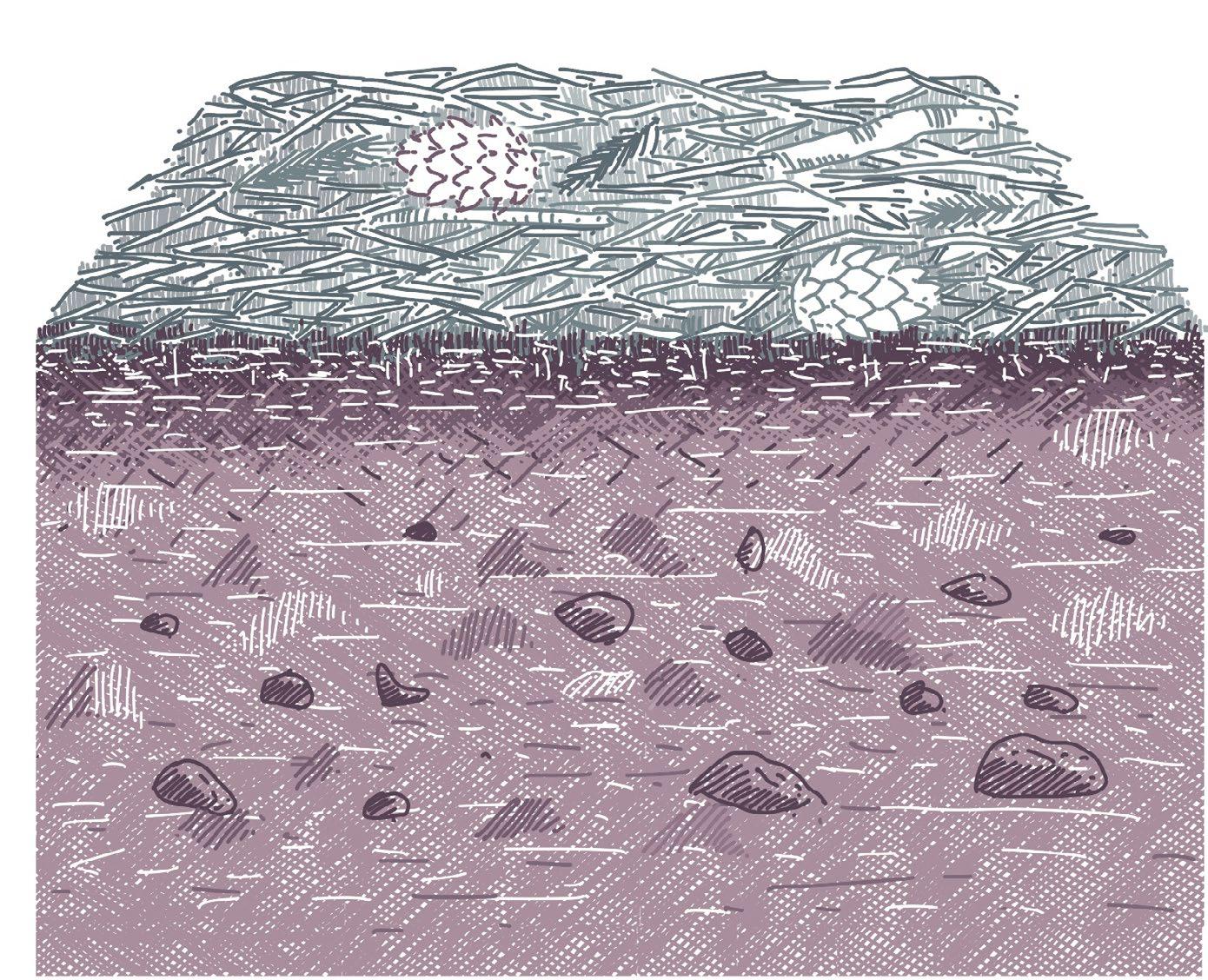

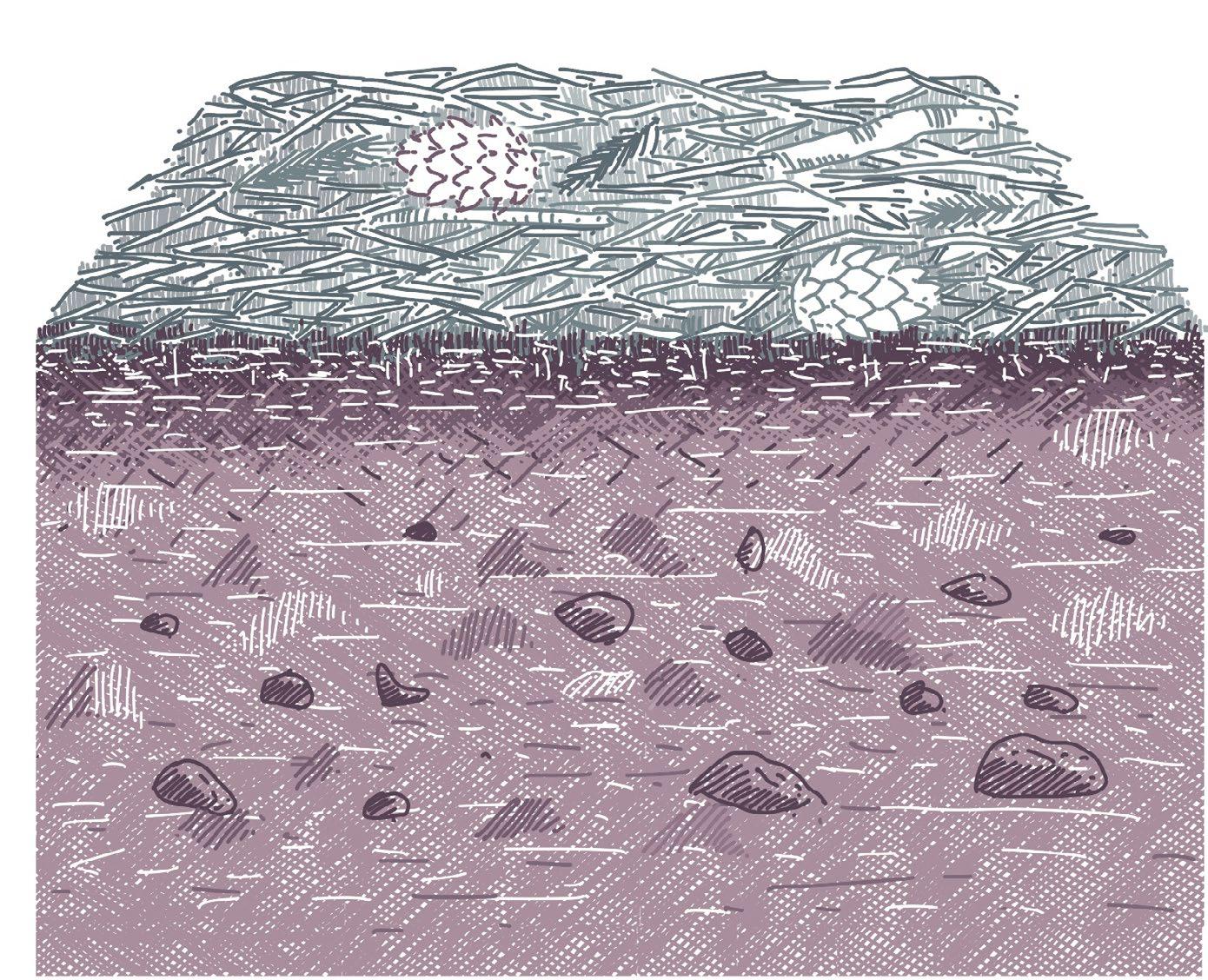

Hooke Park

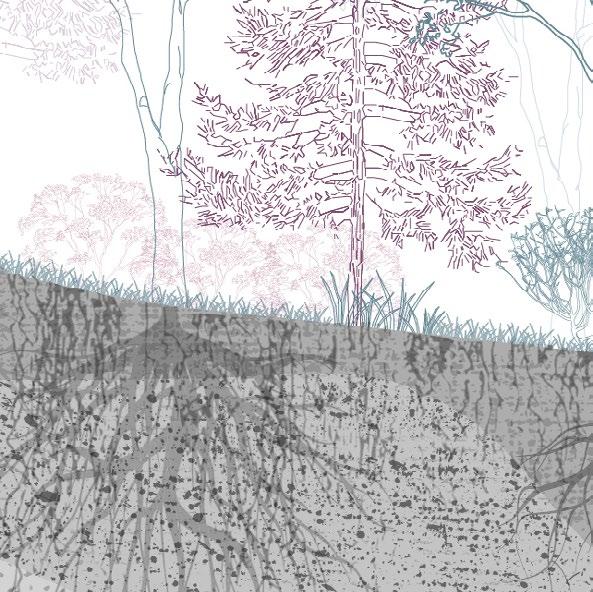

Pine Plantation Mixed Forest

Pine plantations create a thick mulch on the ground and the dense upper foliage does not allow light to penetrate as deeply.

In this section, the introduction of various broad-leaf species creates a diverse ground environment. This promotes healthy soil, supports micro-organisms, prevents soil erosion, and fosters the growth of other shrubs and under-brush species.

Horizon C with minimal or no microbiological activities

Thanks to a variety in grasses, shrubs, and sunlight permeation, there is a noticeable difference in soil health compared to the earlier example. The mulch is composed of leaves, shrubs, pine, and other organic materials, leading to considerably thicker A and B soil horizons.

Roots structure of shrubs

And grass holding soil Earth worms and other microbiological activity within soil

Section through Hooke Park Section through Hookepark

Fig 77

Fig 78 By Khusbhoo Prashant By Khusbhoo Prashant

Section through Hooke Park Section through Hookepark

Fig 77

Fig 78 By Khusbhoo Prashant By Khusbhoo Prashant

A B C

Horizon A with thick pine leaves mulch

The soil section for this area depicts reduced soil biodiversity. Horizon A is a combination of pine leaves while horizon B is only narrow band.

Sunlight penetrating through broad leaf deciduous species enhancing the soil biodiversity.

A B C

Soil section under pine plantations Soil section under mixed forest

Fig 79

Fig 80

59 | UK Food System 60 [AA Landscape Urbanism 23/24] [AA Landscape Urbanism 23/24] Planet of Fields

By Khusboo Prashant By Khusboo Prashant

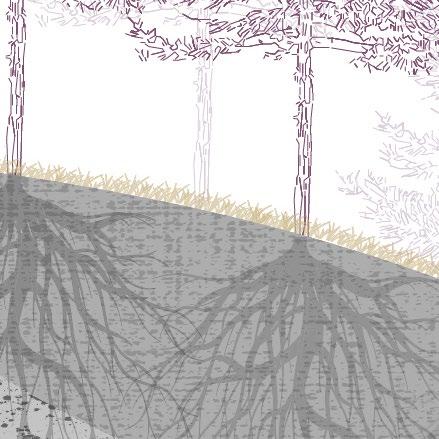

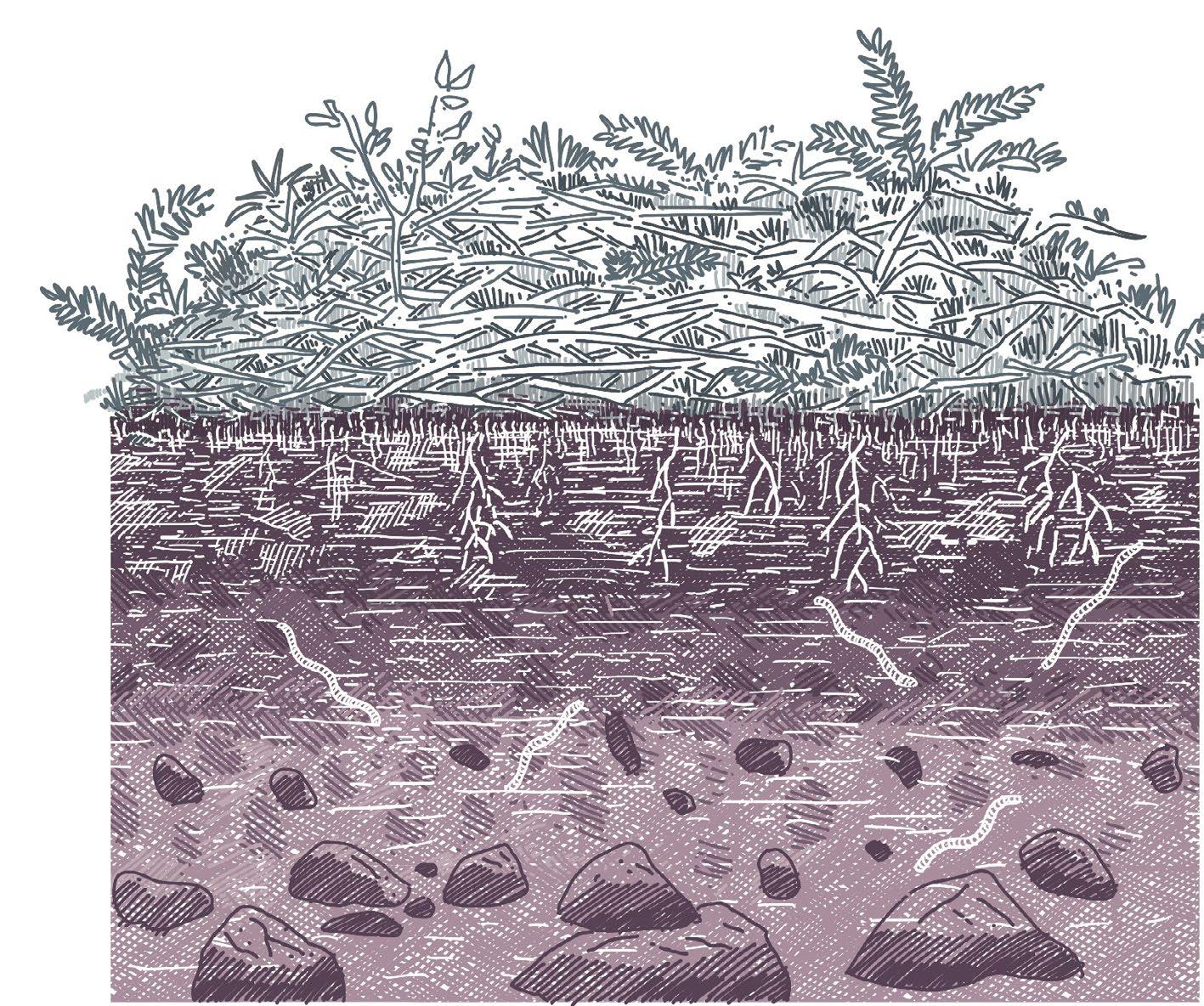

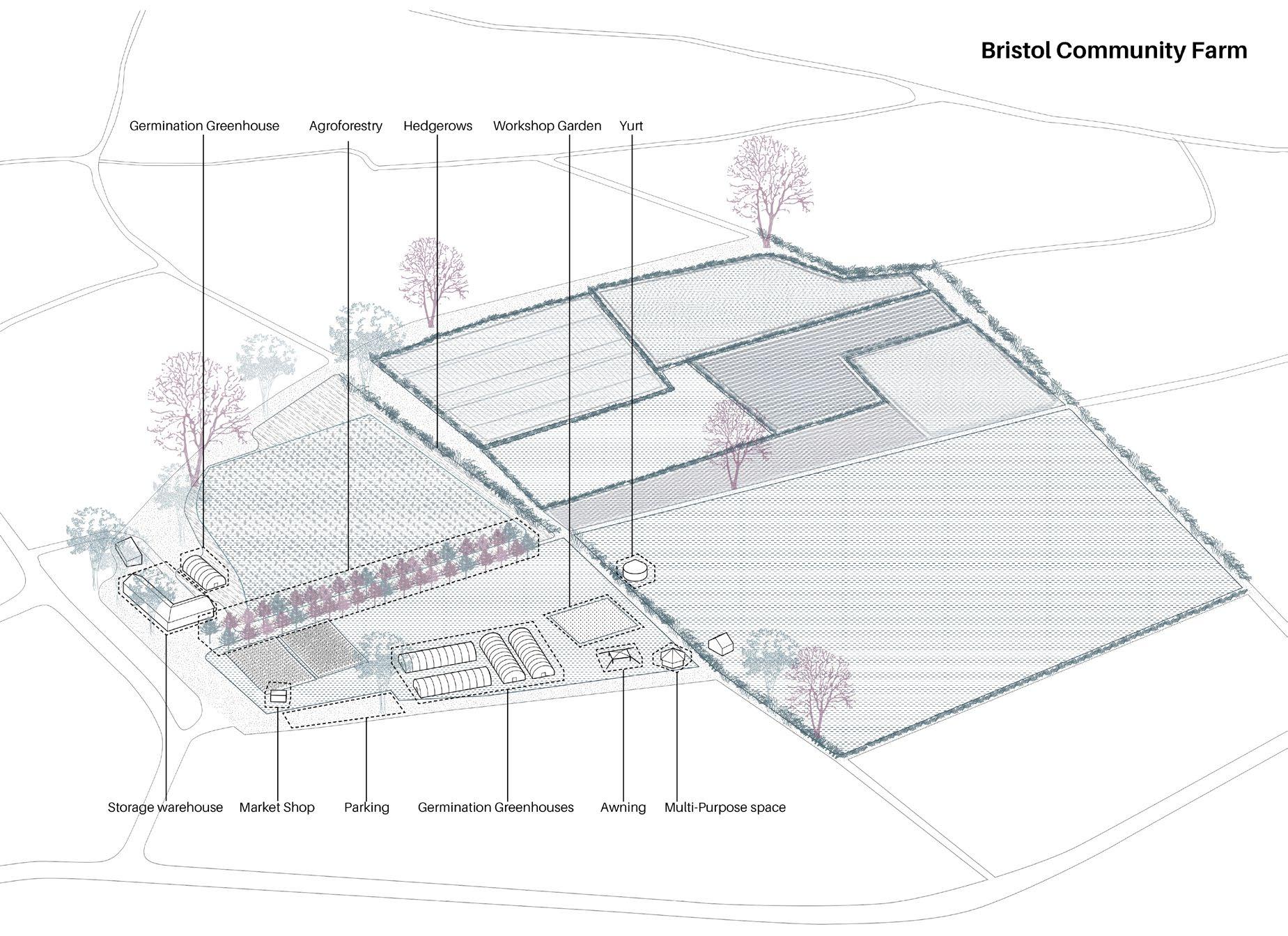

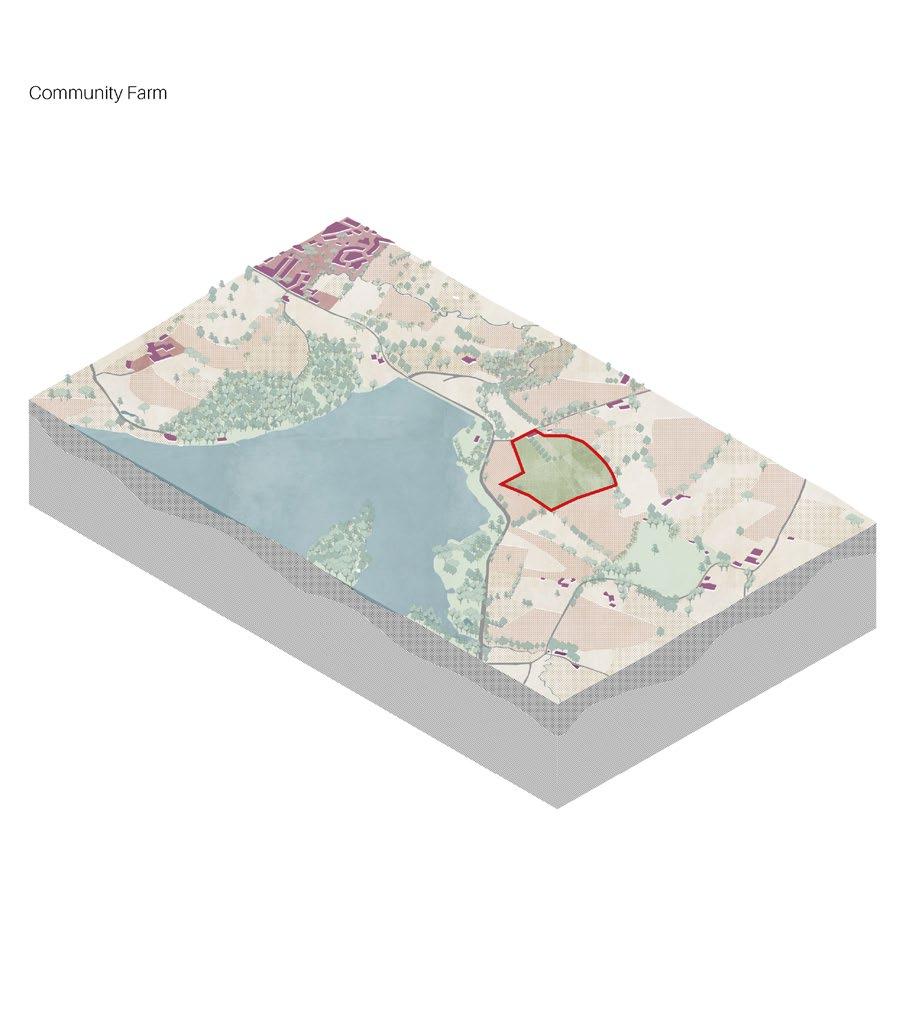

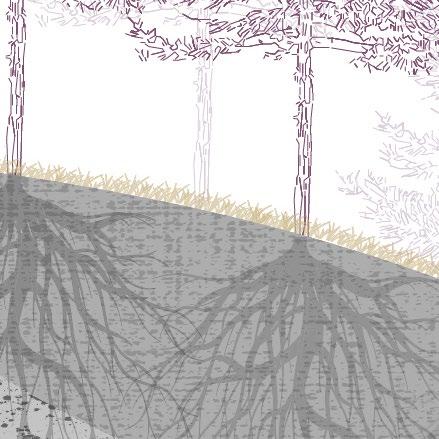

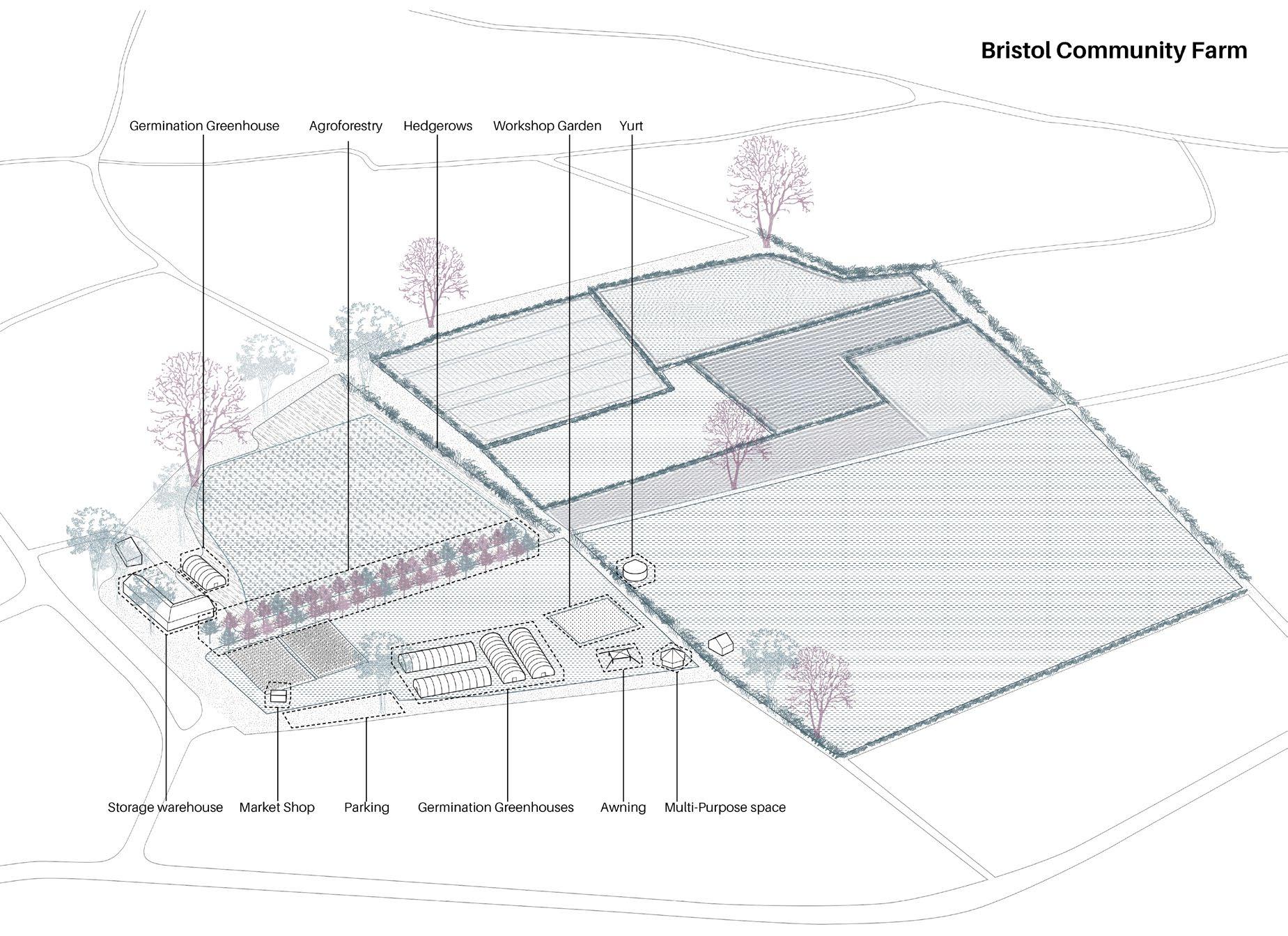

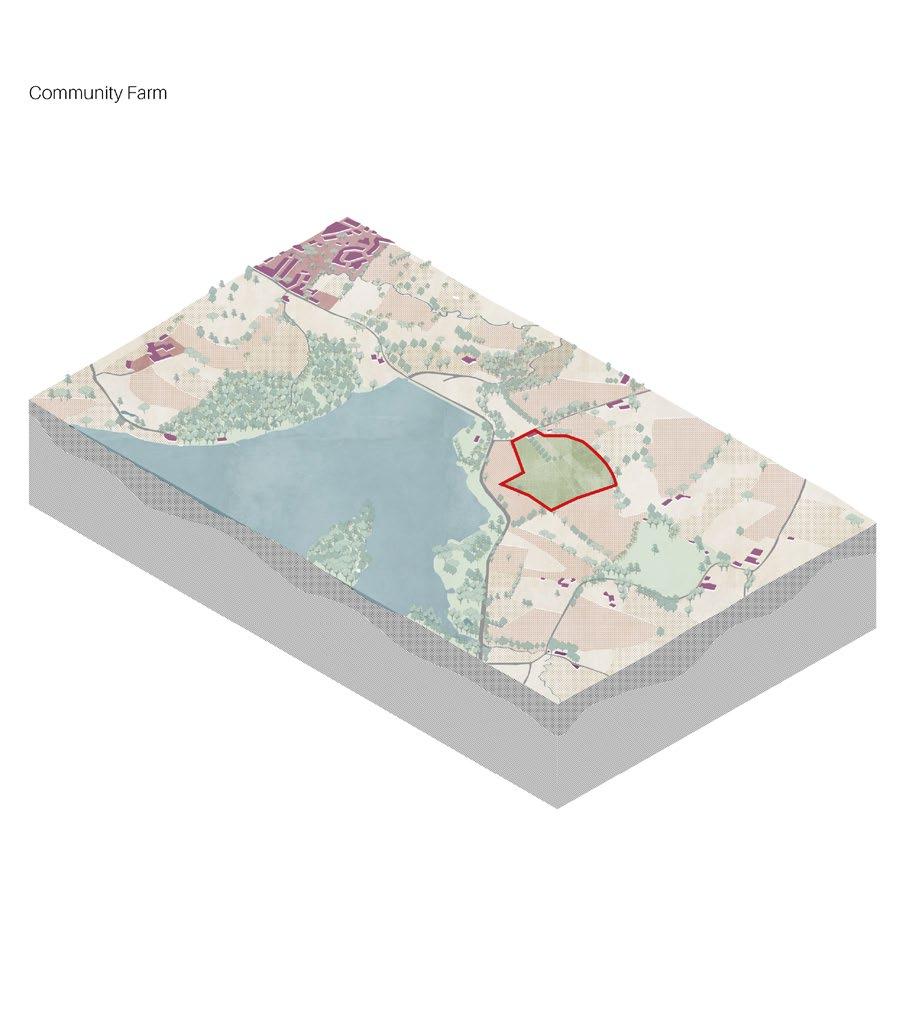

The Community Farm, Bristol

The Community Farm is a non-profit, organic farm located in the Bristol Greenbelt (also known as the Avon Green Belt). The farm cultivates and obtains food for delivery within Bristol via their acclaimed veg box programme. The farm receives over 1,000 people each year for well-being courses, social gatherings, and volunteer opportunities. It is also worth noting that it is registered as a community benefit society, which is also the legal structure under which many Community land trusts are registered.

The farm has made use of companion cropping, cultivating complementary species side by side in the same field. This method harnesses the interactions between species to yield a robust crop. Trials with Oats, Peas, and Barley have shown promising results.

Peas, being legumes, have the ability to fix nitrogen in the soil, a vital nutrient for plants and the combination of oats and peas offers structural advantages as

Section 1 Section 2

By incorporating herbal leys into their practices, the farm has been able to draw in pollinators, augmenting soil nitrogen, and enriching soil biodiversity. The farm cultivates 12 varieties of herbal leys, with the tillage radish standing out. As the tillage radish withers in the autumn, it leaves a void in the soil, which creates air circulation through the soil

Chew manga lake

Physical layers of Community farm Fig 81 By Antonio Garaycochea

Important road network connections with Bristol and Bath

Tillage radish 12 different species of herbal lays

Section through Community farm

Section through Community farm

Fig 82 Fig 83 ALCGrade

By Khusbhoo Prashant By Khusbhoo Prashant Croptype

Canals

Urbanization

Woodland 62 [AA Landscape Urbanism 23/24]

61

| UK Food System [AA Landscape Urbanism 23/24]

Planet of Fields

The Community Farm, Bristol

Distribution Diversity

The Community Farm, Bristol Social Value Index

In the comparative analysis, The Community Farm distinguishes itself from the other case studies. Beyond cultivating their own produce, they act as a hub for the distribution of goods from various neighbouring smallholdings to consumers in Bristol and Bath. A significant portion of the farm’s revenue is derived from the sale of vegetable boxes which are delivered on a subscription scheme. In addition to catering to individual buyers, they maintain partnerships with 14 local restaurants in Bristol and Bath. While their primary distribution remains within the Bristol green belt, it’s worth noting that they source most produce from farms located as far as 45 kilometres away.

By Antonio Garaycochea Khushboo Prashant Jegan Muralidharan

By Antonio Garaycochea Khushboo Prashant Jegan Muralidharan

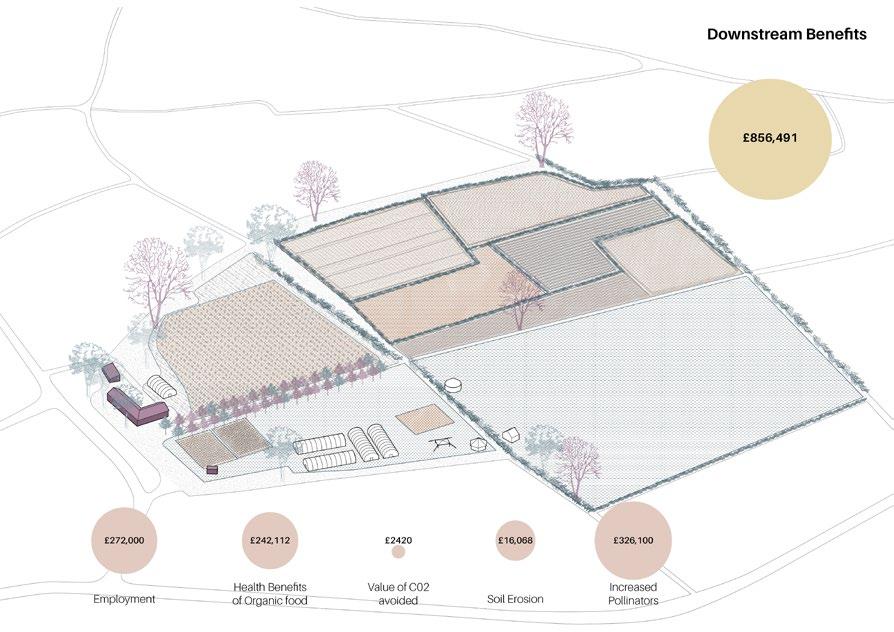

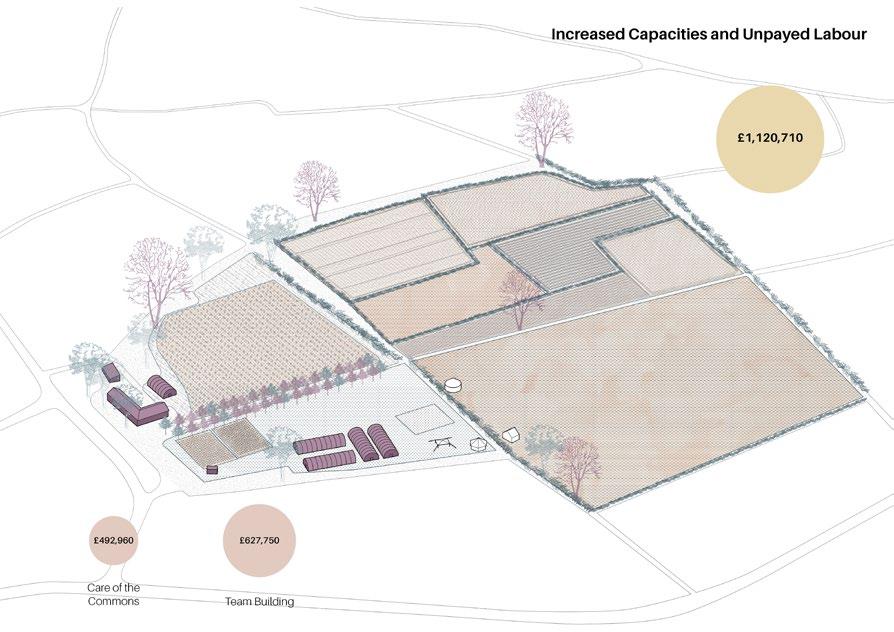

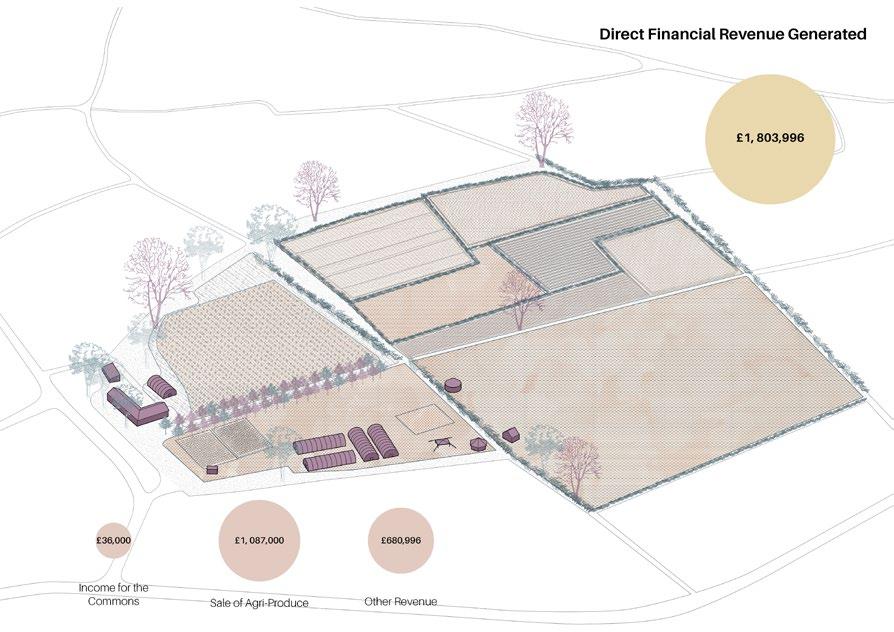

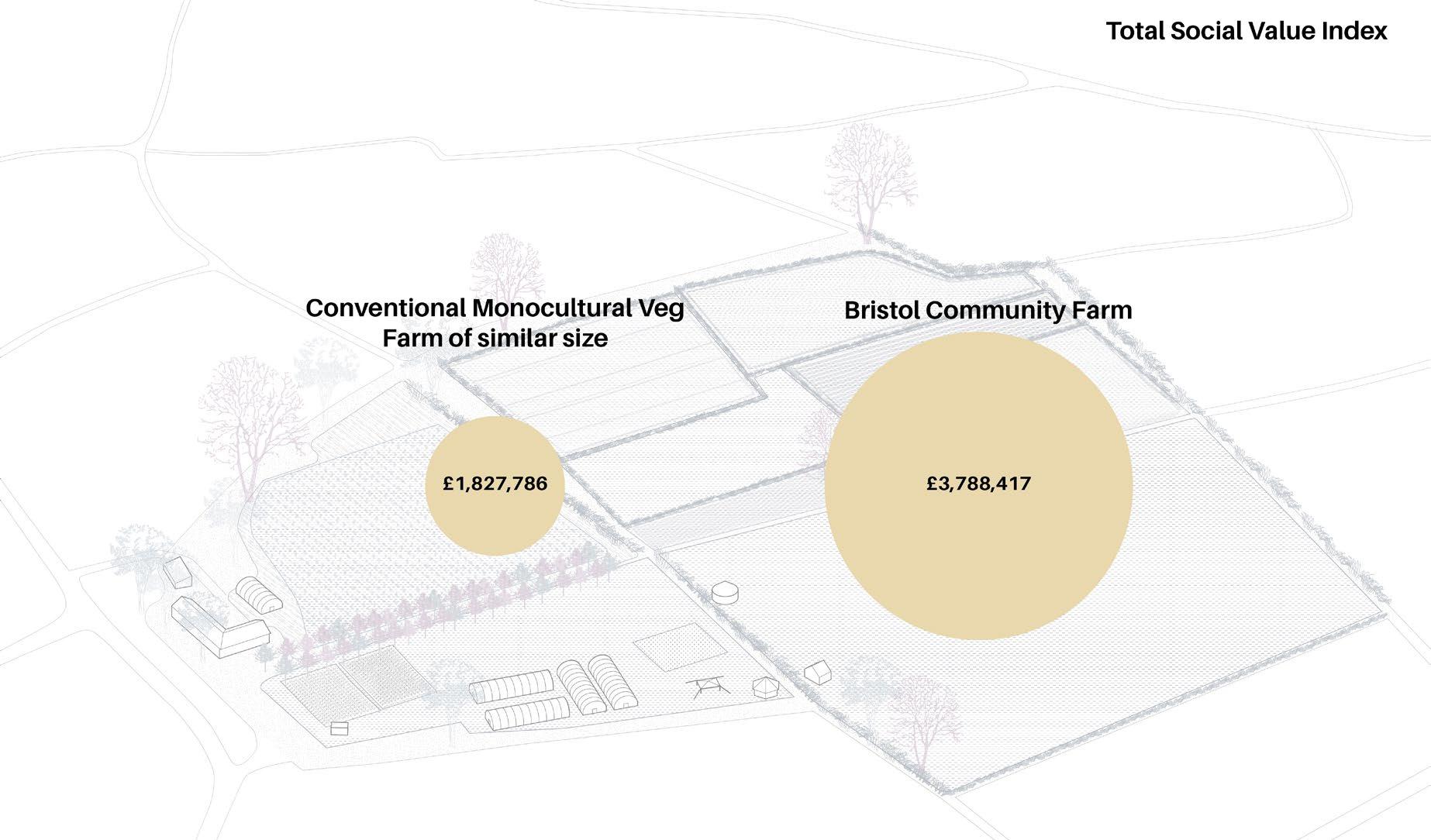

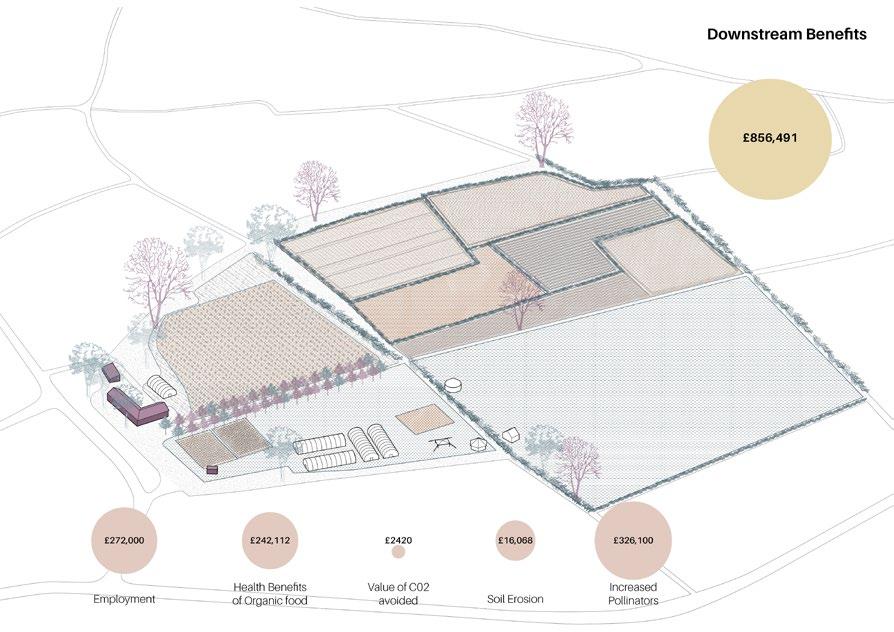

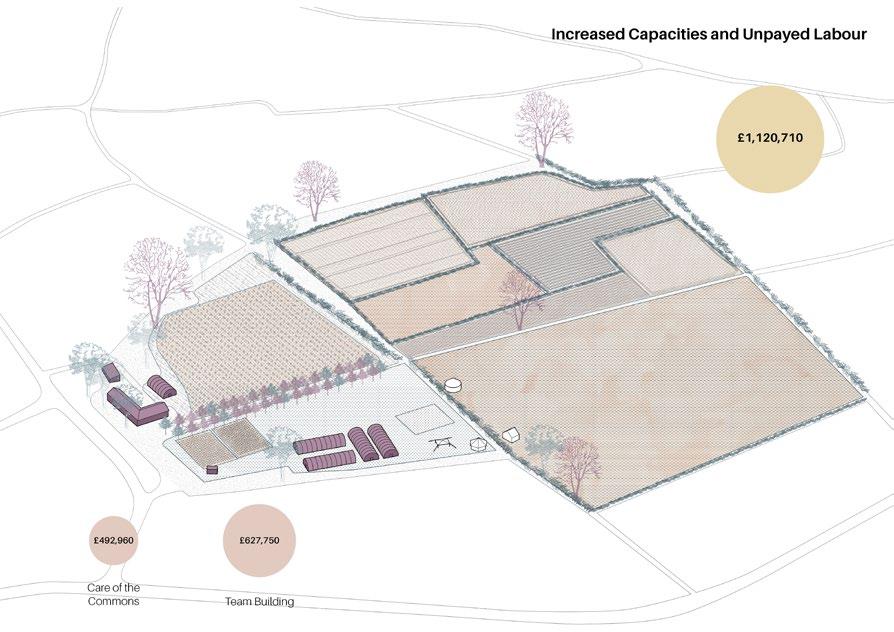

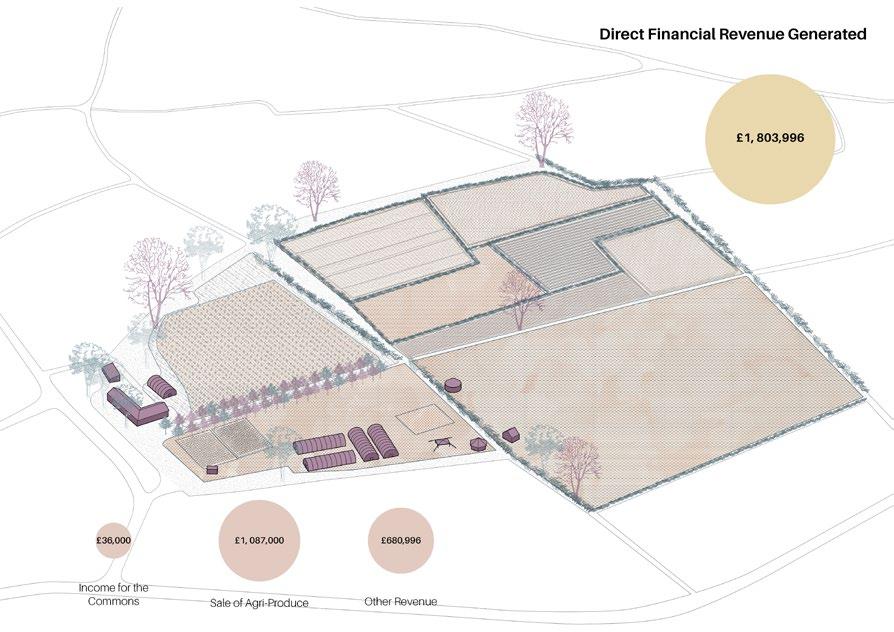

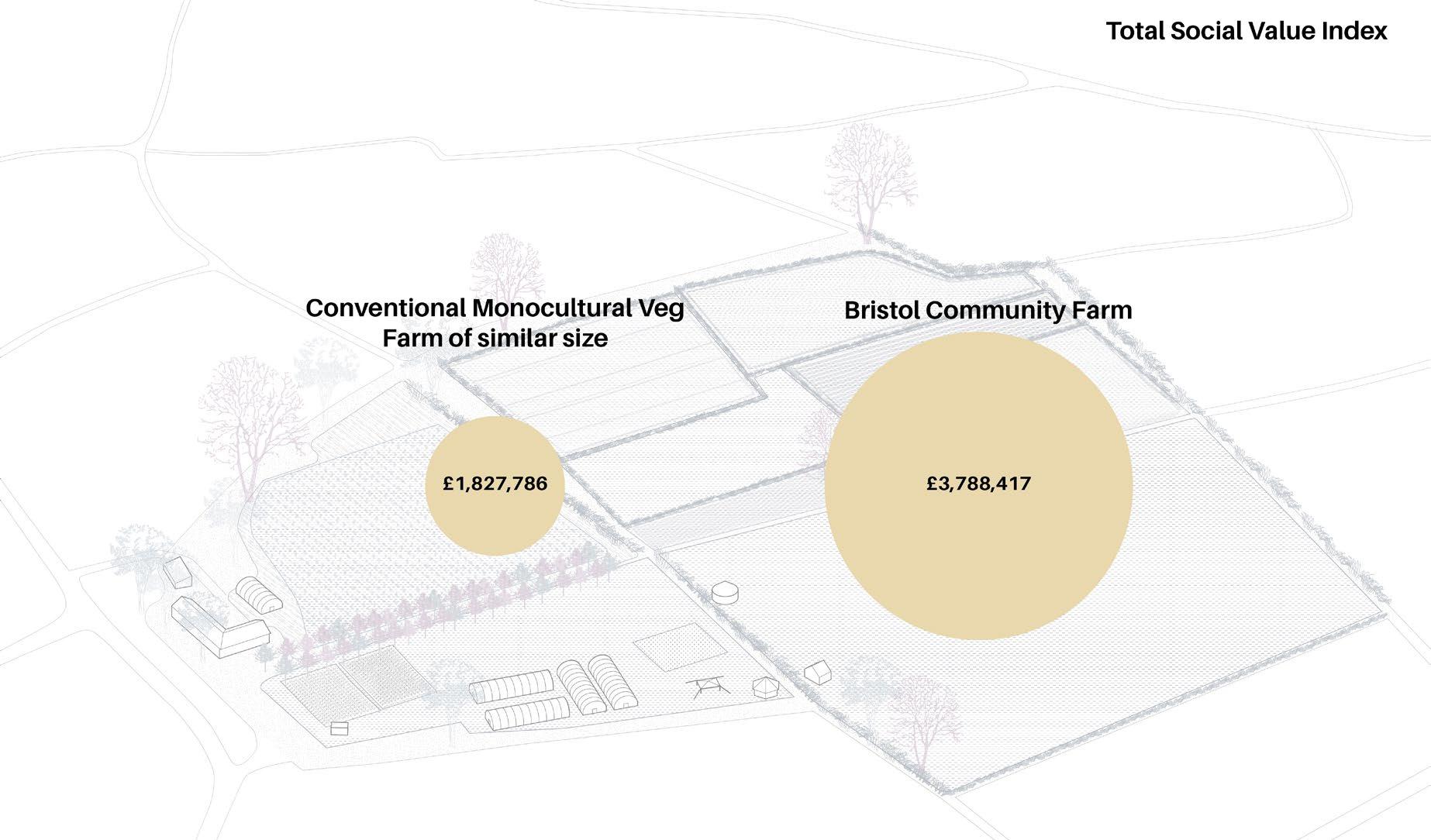

The concept of “Social Value” is used to gauge forms of value that go beyond conventional financial metrics, offering a more nuanced understanding of the effects of specific policies or developments. In order to appraise the wider benefits derived from thee multifaceted activities of the community farm— relative to standard farming practices—a Social Value Index was calculated. This was done by using a variation of the methodology previously employed in the case of a public-commons partnership at Wards Corner, London, also known as the Latin Village. This methodology itself was in turn inspired by a 2020 research paper wherein the authors examined an urban farm near Paris, and translated its social activities and benefits into tangible economic metrics (Almeida 2023).

The analysis carried out on the community farm evaluated the social value generated in 4 different categories: Direct Financial revenue, Increased capacity and labour, provision of social needs and downstream benefits. The aggregated social value for the community farm was found to be more than double when compared to a traditional vegetable farm of a comparable size. In spite of this, the community farm grapples with financial constraints and is heavily dependent on volunteer labour. An additional lies in the fact that the farm’s land area falls short of the 5-hectare threshold required for eligibility in the Environmental Land Management (ELM) scheme. Moreover, even if the farm were enrolled in ELM schemes, many of its valuable contributions are not considered within the ELM’s predetermined actions.

This analysis leads into the question: What modifications are necessary in order to make this model both feasible and prevalent within the greenbelt? To answer this, it is necessary to first study the composition of Bristol’s greenbelt.

The farm’s diversity extends beyond its agroecological practices. It embraces a number of activities, some only tangentially related to agriculture and others entirely independent of it by capitalizing on its proximity to Bristol and its innate attraction of the sites natural beauty. For instance, each summer, the farm becomes the venue for a music festival. Additionally, it offers team-building workshops tailored for local businesses and conducts gardening workshops. Most significantly, the farm is equipped to facilitate psychological retreats, which have recently emerged as an valuable resource in providing support to refugees.

Antonio Garaycochea

Community Farm Video

Location of the community farm, Near to one of Bristol’s main water reservoirs: Chew Lake Community Farm Isometric Social value calculation Social Value Index in Tottenham Community Farm location and network Fig 85 Fig 87 Fig 86 Fig 84

social-value-index-building-the-case-for-thedemocratic-commons-in-tottenham

By Antonio Garaycochea By

Https://www.common-wealth.org/publications/

63 | UK Food System 64 [AA Landscape Urbanism 23/24] [AA Landscape Urbanism 23/24] Planet of Fields

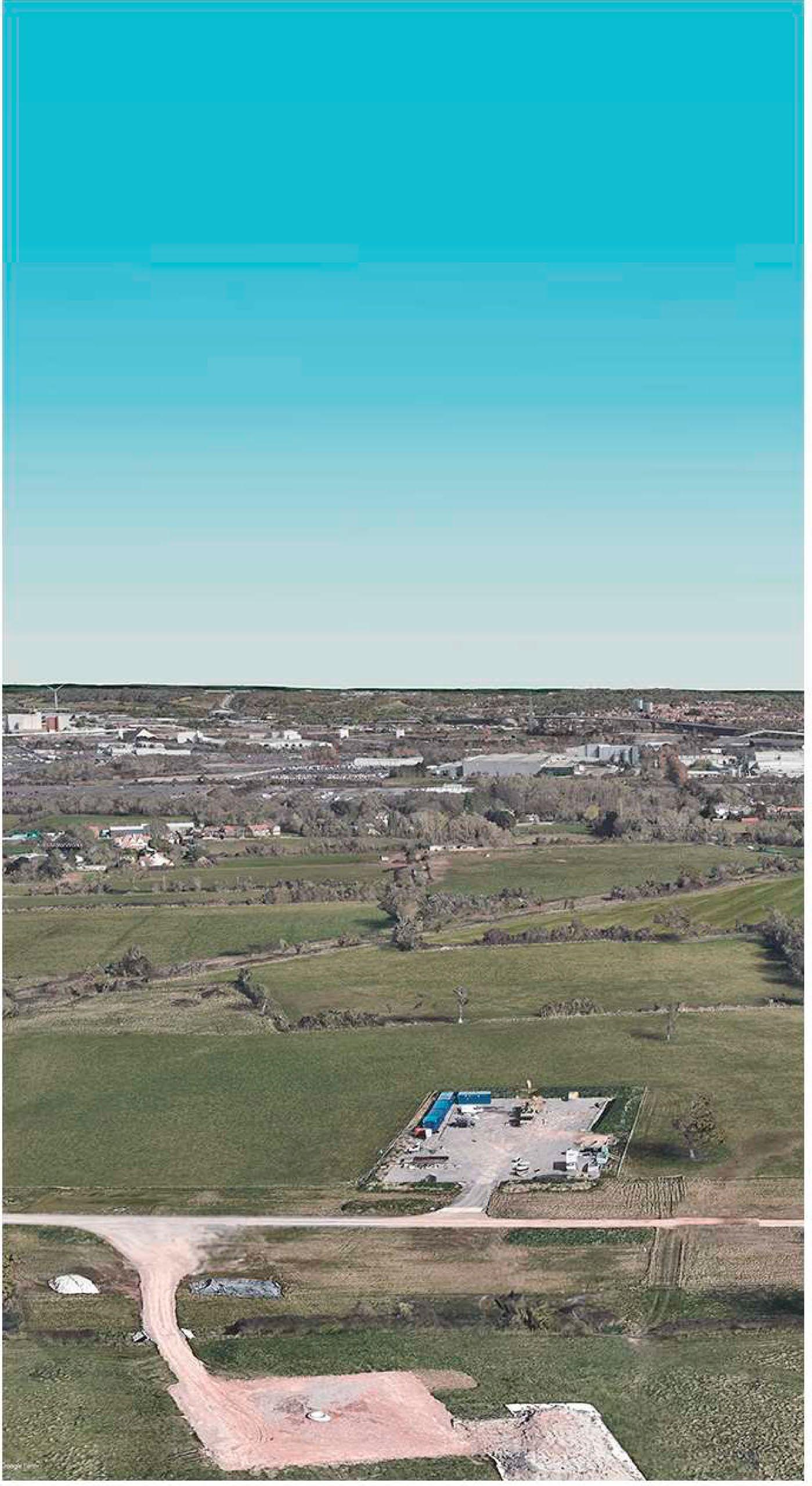

The Site: Avon Green Belt

Photo mosaic of Bristol Green Belt

Fig 88 By Khushboo Prashant Soil Types of green in the Green Belt Mapping Bristol’s corridors

Photo mosaic of Bristol Green Belt

Fig 88 By Khushboo Prashant Soil Types of green in the Green Belt Mapping Bristol’s corridors

[05] 66 [AA Landscape Urbanism 23/24] 65 Planet of Fields

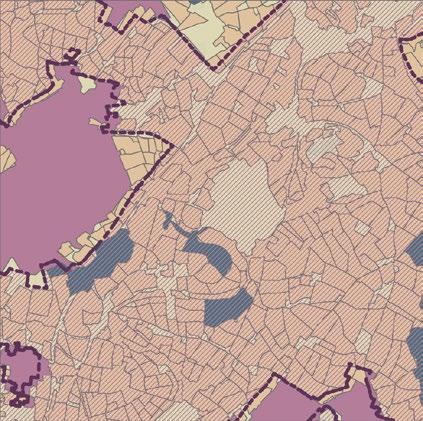

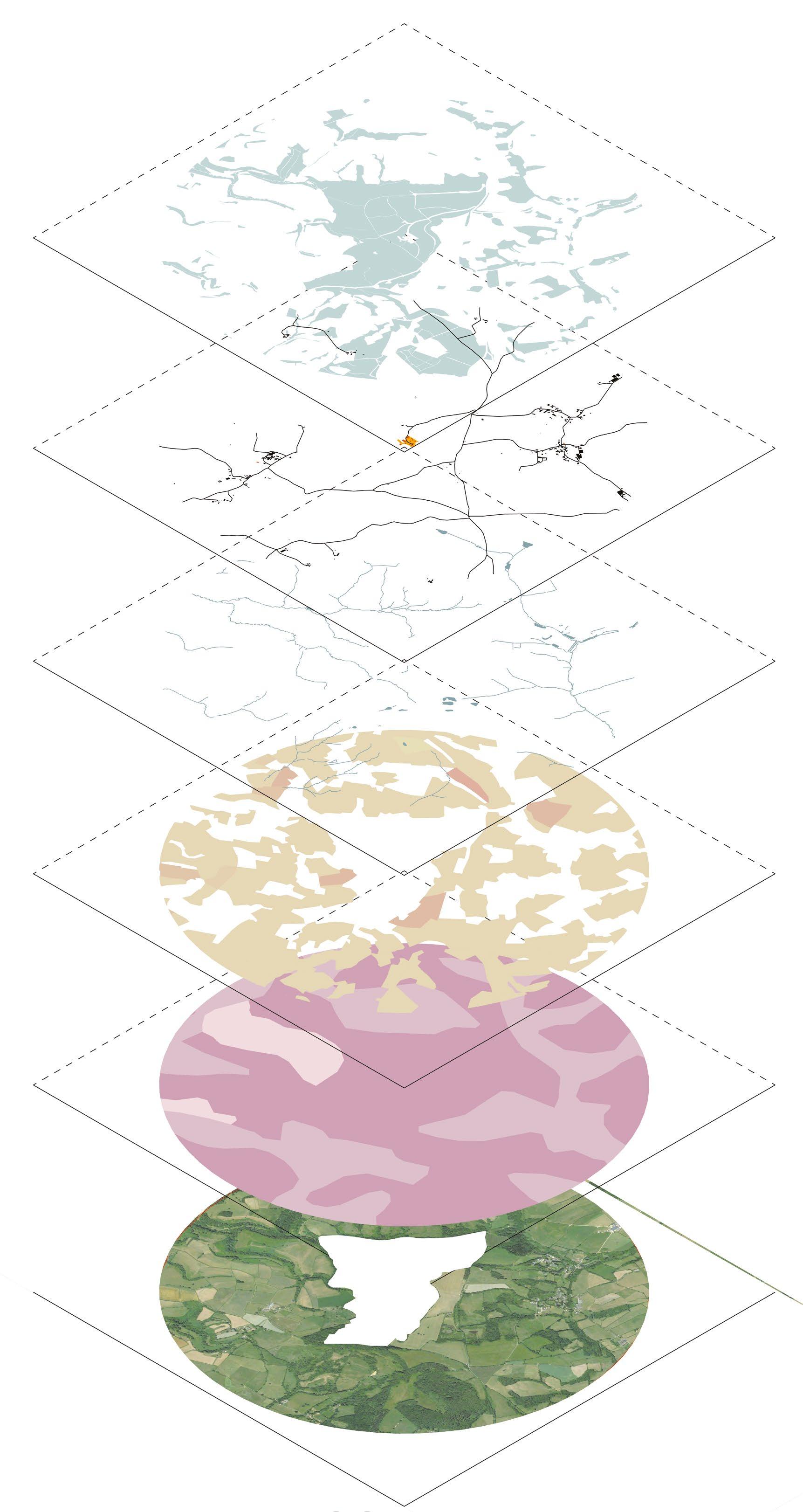

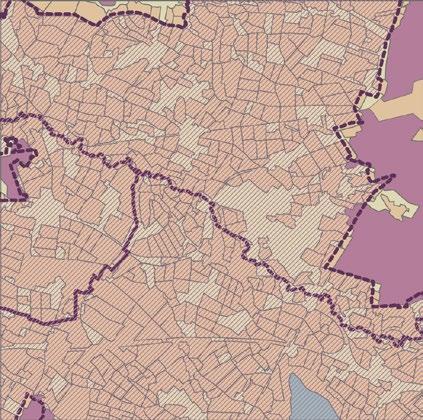

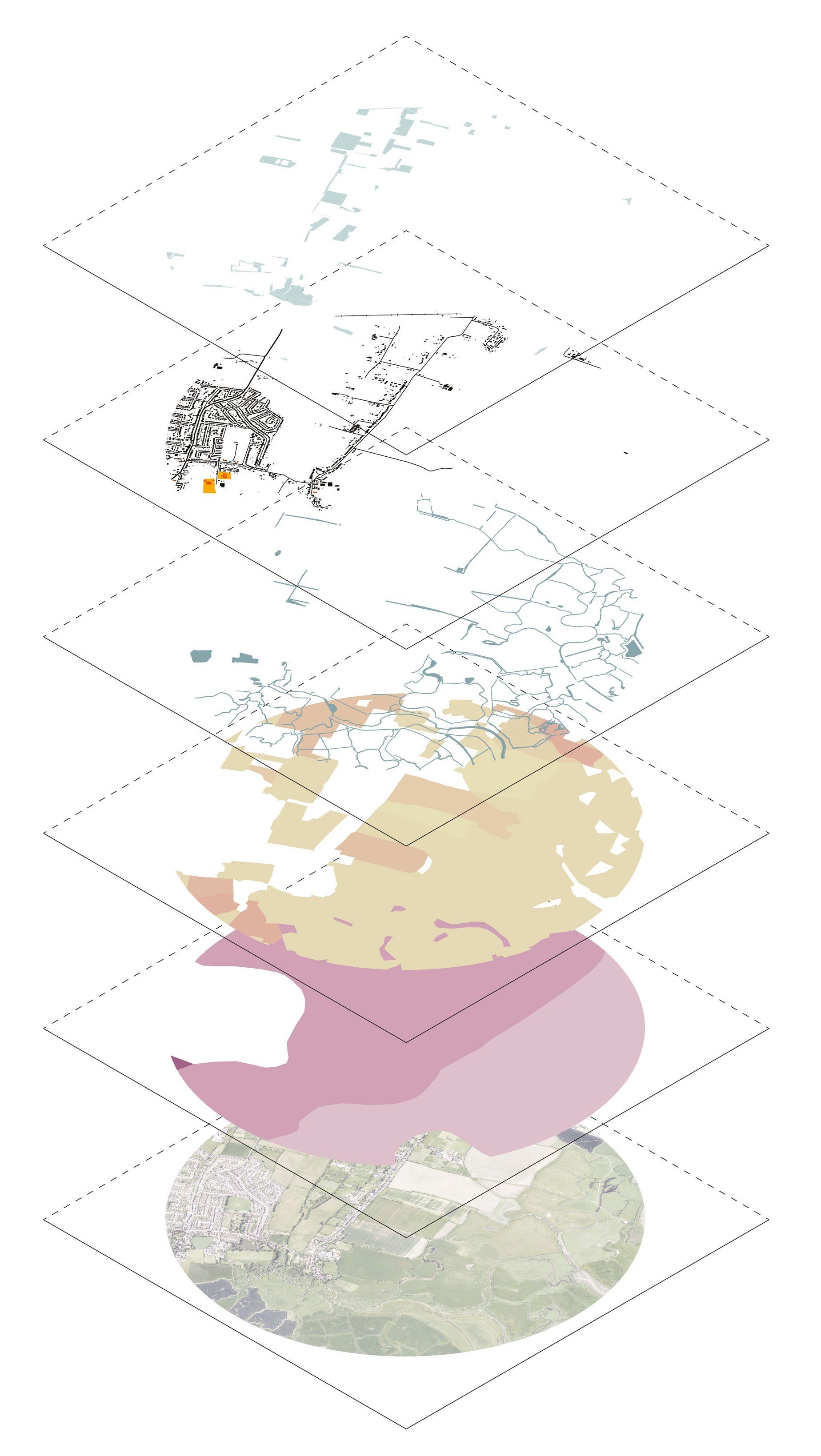

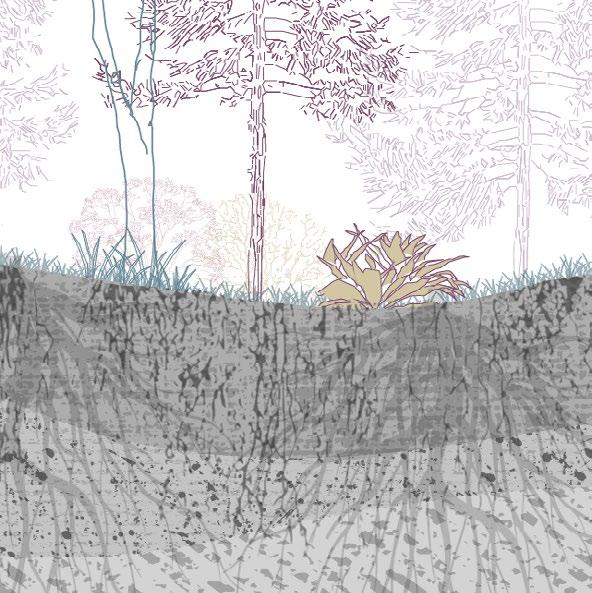

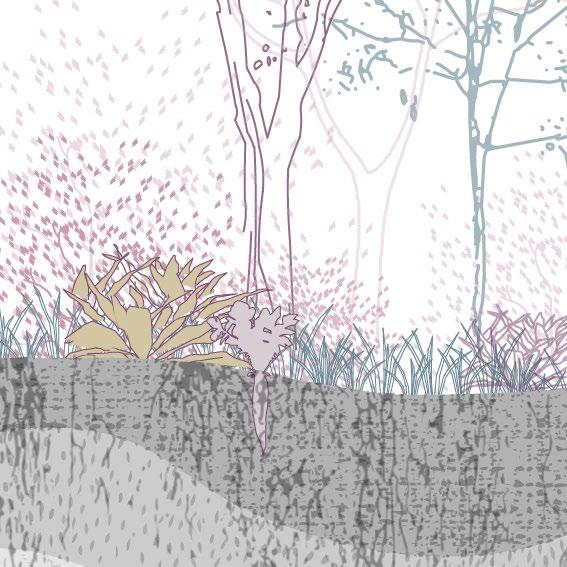

Soil

“From the red clay soils of the south to the sandy loams of the north, Bristol’s diverse range of soil types plays a vital role in supporting the city’s unique ecosystems and agricultural heritage.” (BathNES Council, n.d.)

Due to Bristol’s presence near the coast it has soils ranging from clay, loam, and sandy soils. This wide range of soil supports the wide range of natural systems, ecology and wildlife. The clay soils, prevalent in some parts of the greenbelt, retain water well but can become compacted, requiring careful management to maintain soil structure suitable for crop growth. The loamy soils offer a balanced mixture of sand, silt, and clay, making them versatile for a variety of crops (RHS 2023).

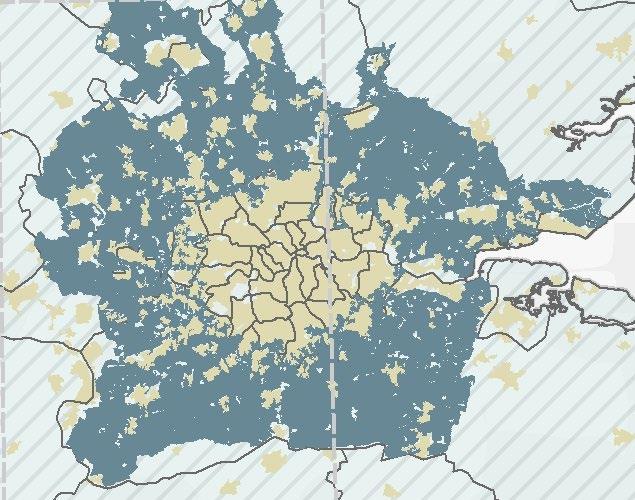

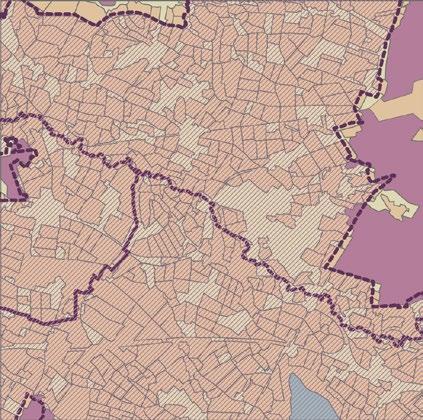

Most of the area within the greenbelt has an assigned ALC grade of 3. However, some areas with 1 and 2 grades are also present.

Fen Peat soils

Freely draining lime-rich loam

Freely draining slightly acidic

Lime rich loamy

Loamy and clayey flood plain

Loamy and sandy soil

Non - Agricultural

Salt marsh soil

Sand dune soil

Slowly permeable seasonally

Water

Bristol Soil types

0 5km 10km

Fig 90 By Khusboo Prashant

Soil Grades within Bristol Green Belt

Fig 89

Grade

Grade

Grade

Grade

Grade

Urban 0 5km 10km 67 | UK Food System 68 [AA Landscape Urbanism 23/24] [AA Landscape Urbanism 23/24] Planet of Fields

By Khusboo Prashant

5

2 Non Agricultural

3

4

1

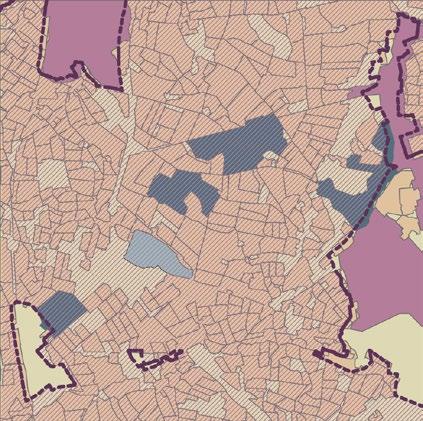

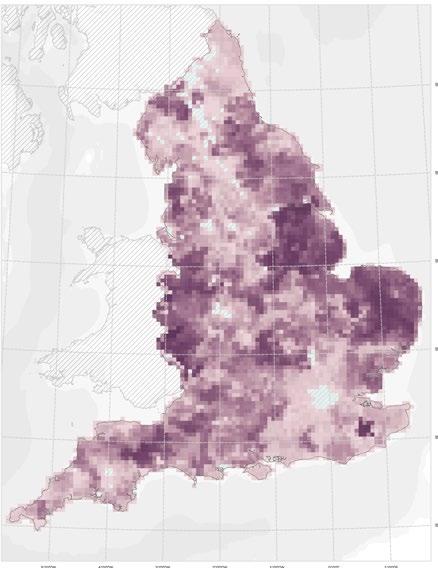

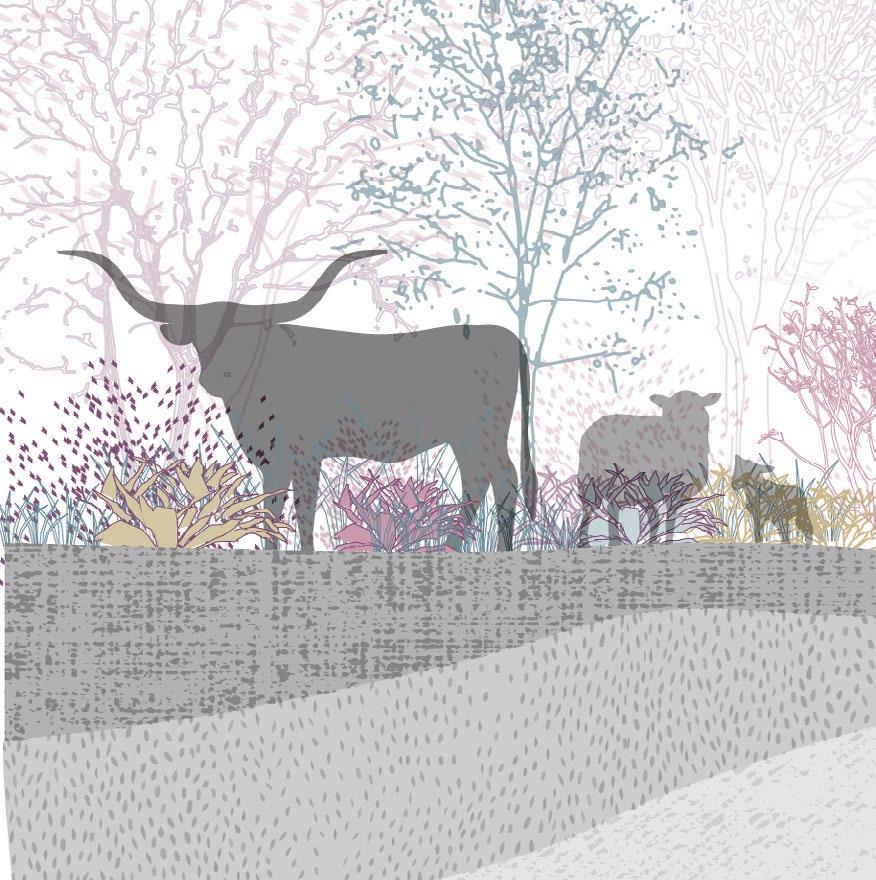

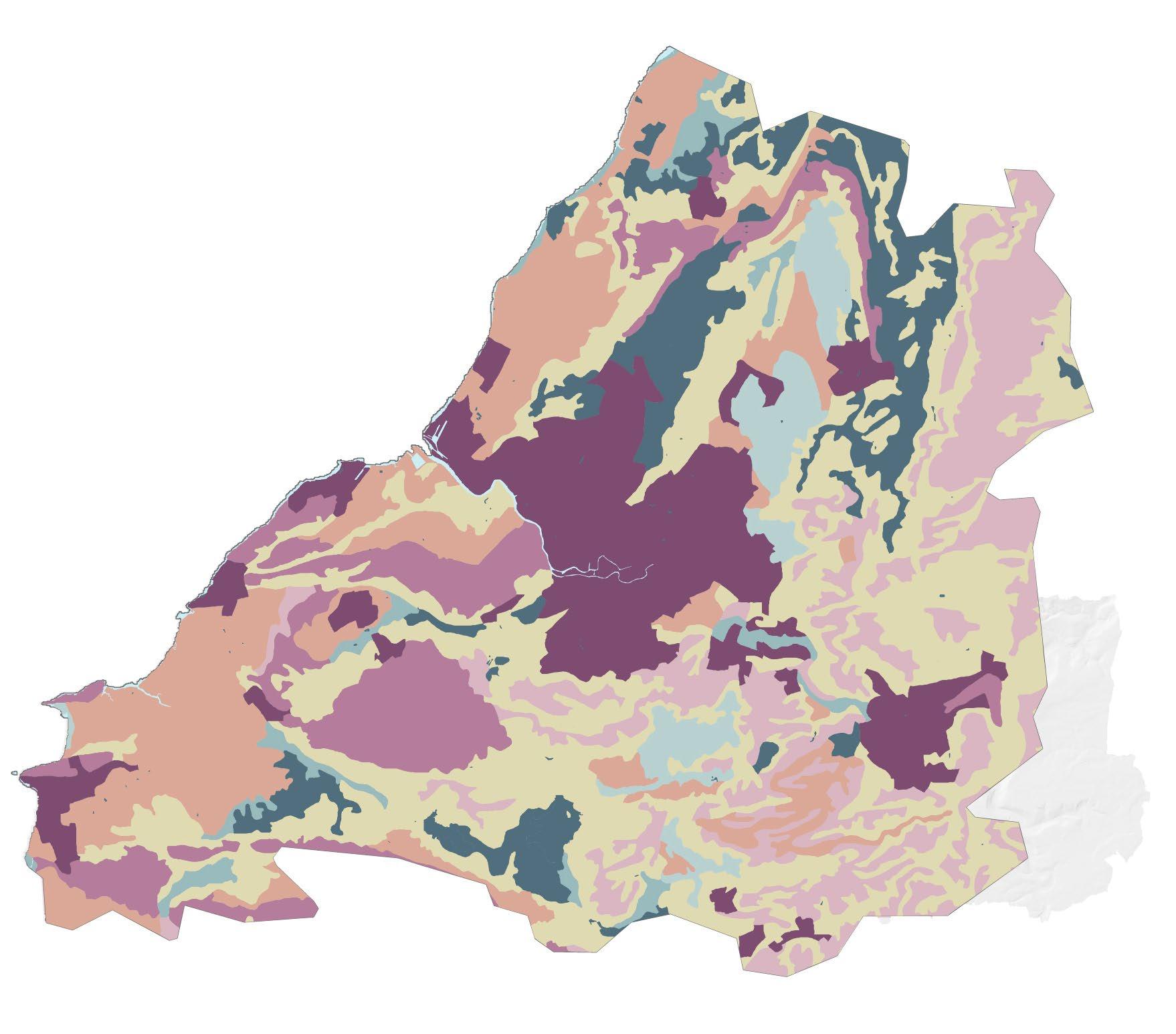

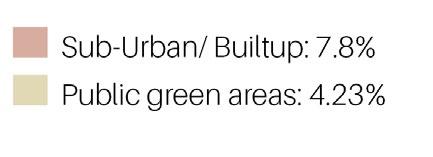

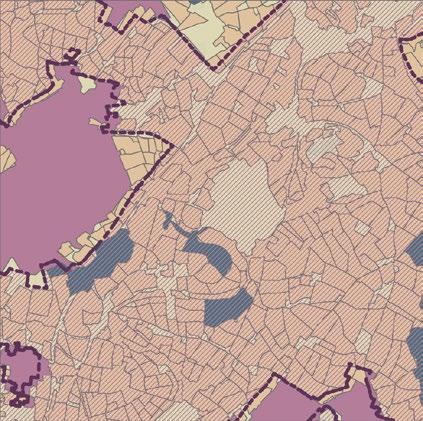

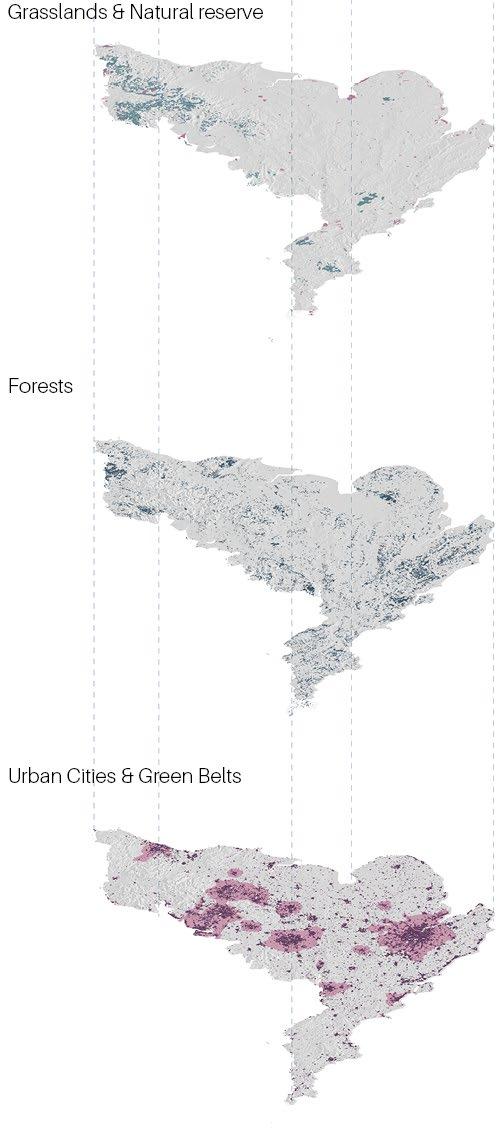

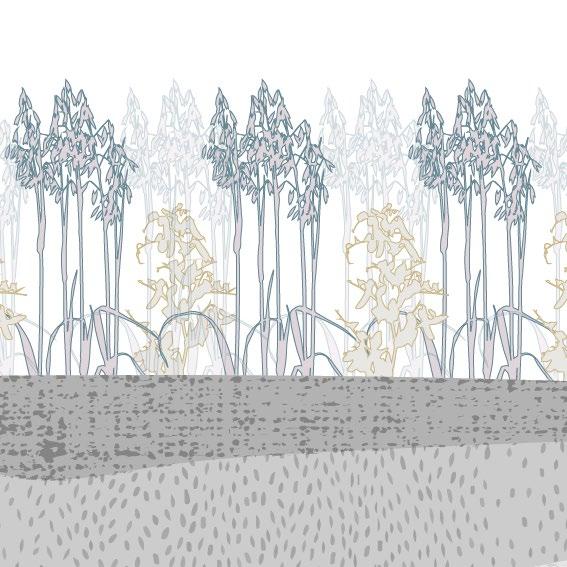

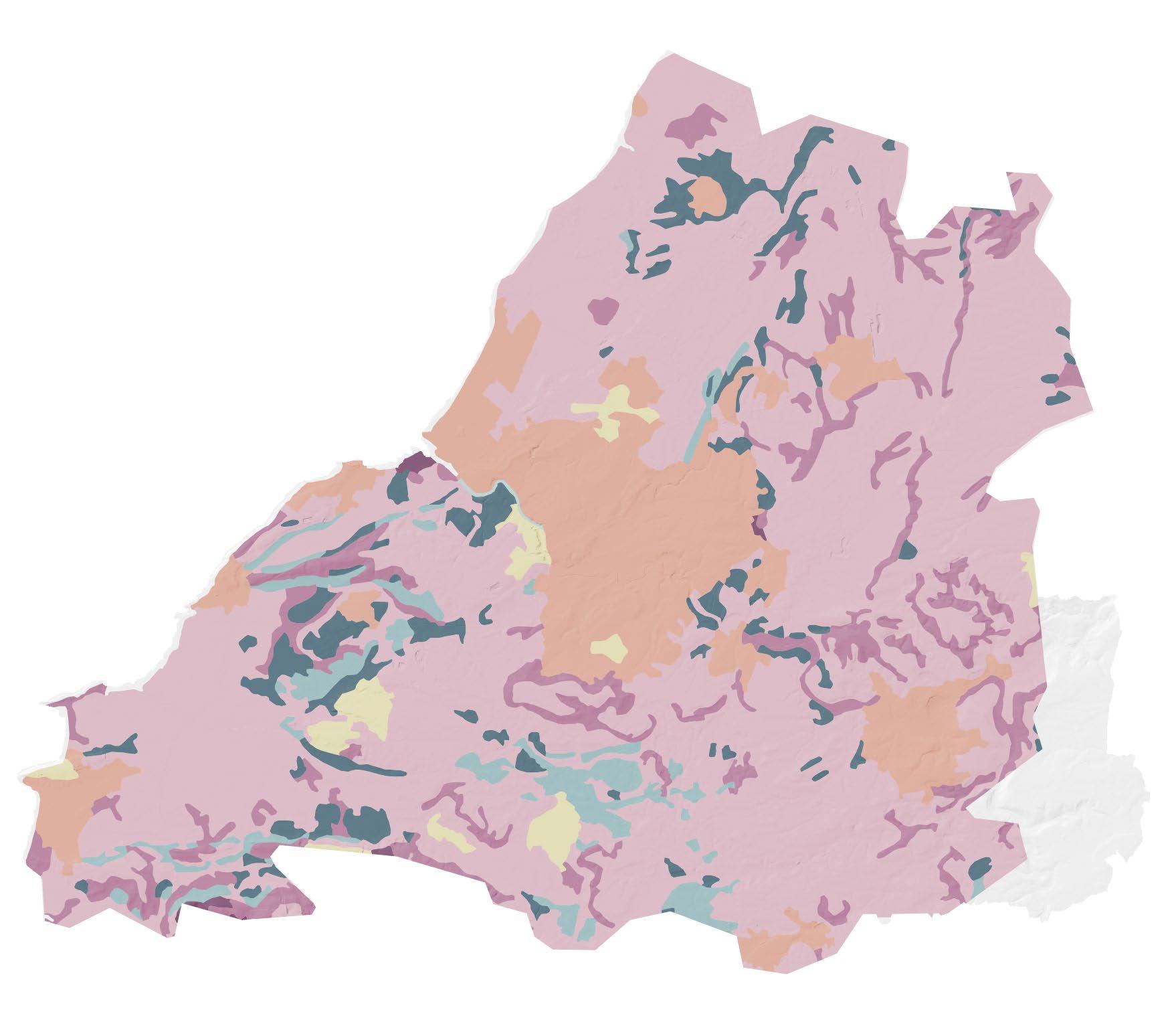

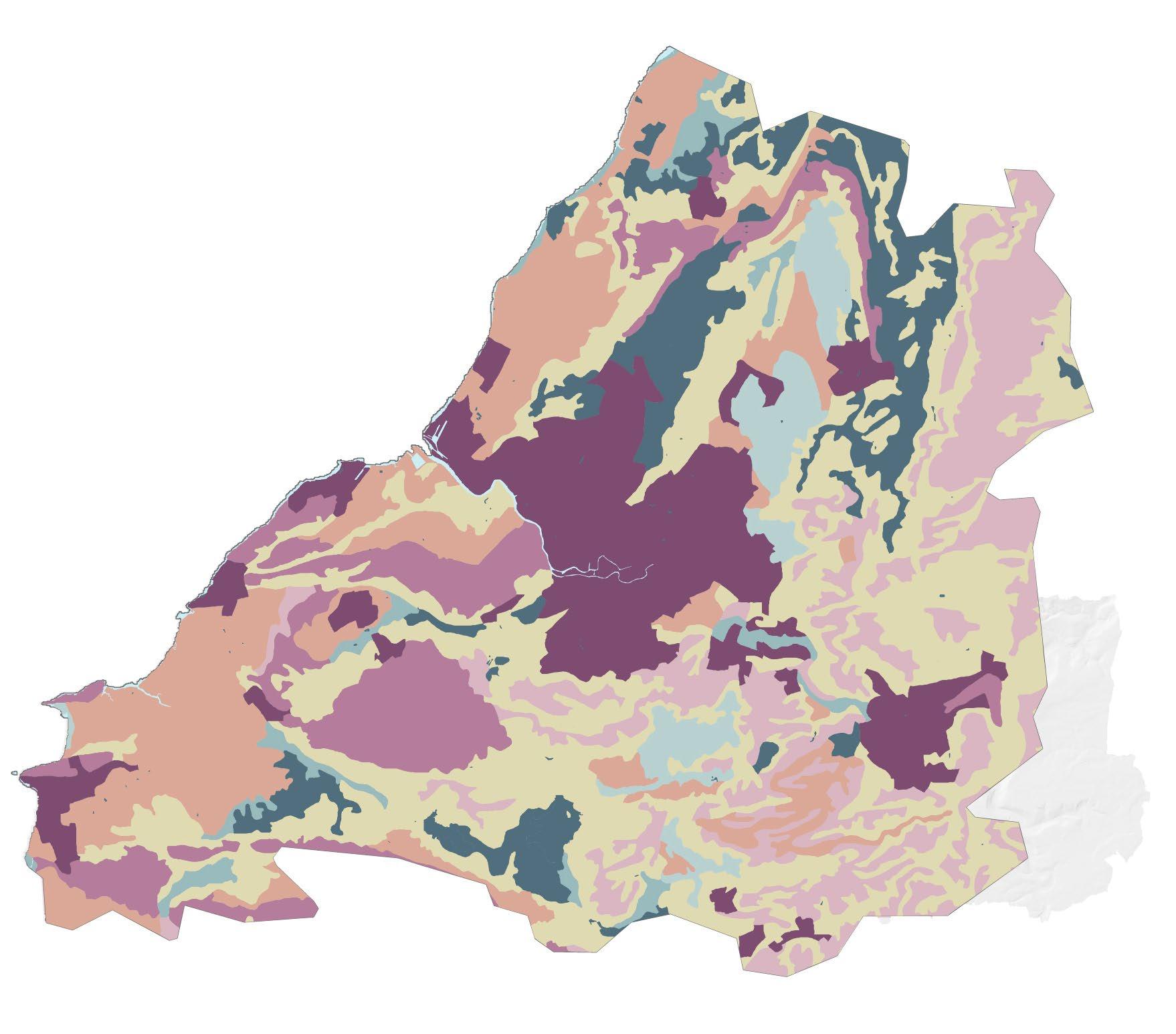

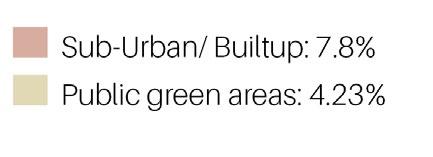

Types of green in the Green Belt

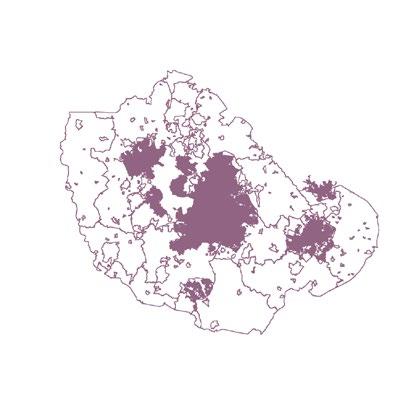

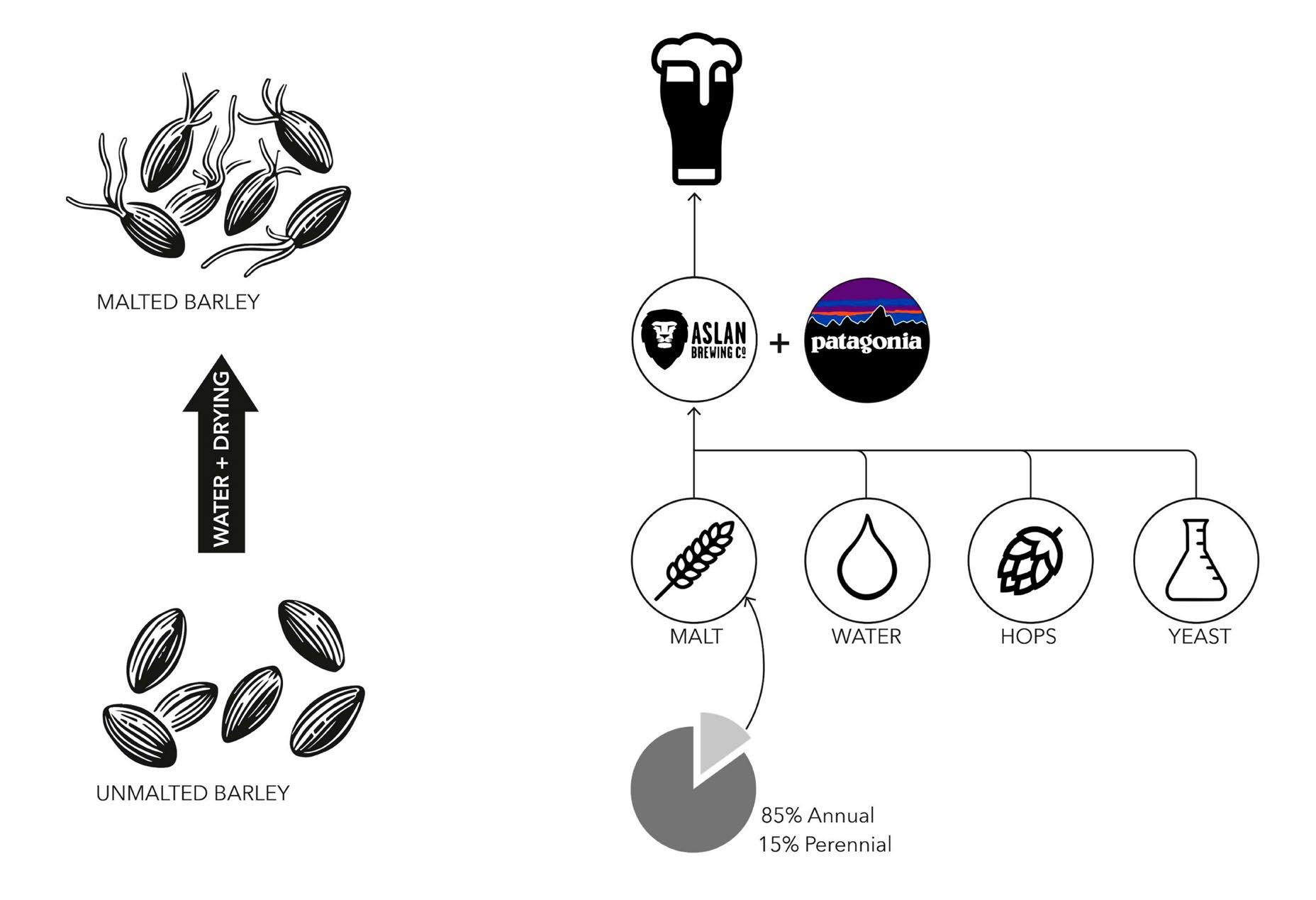

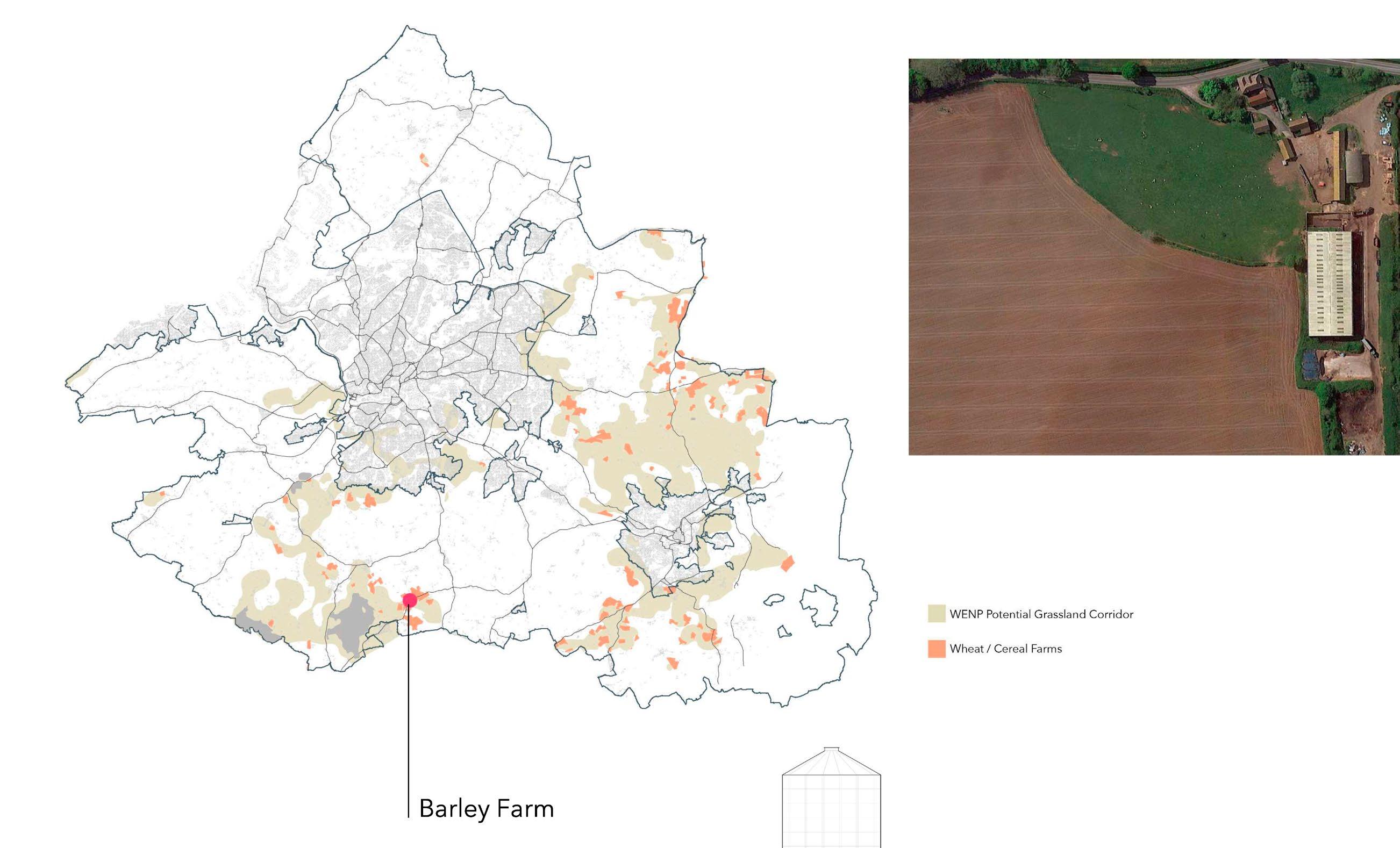

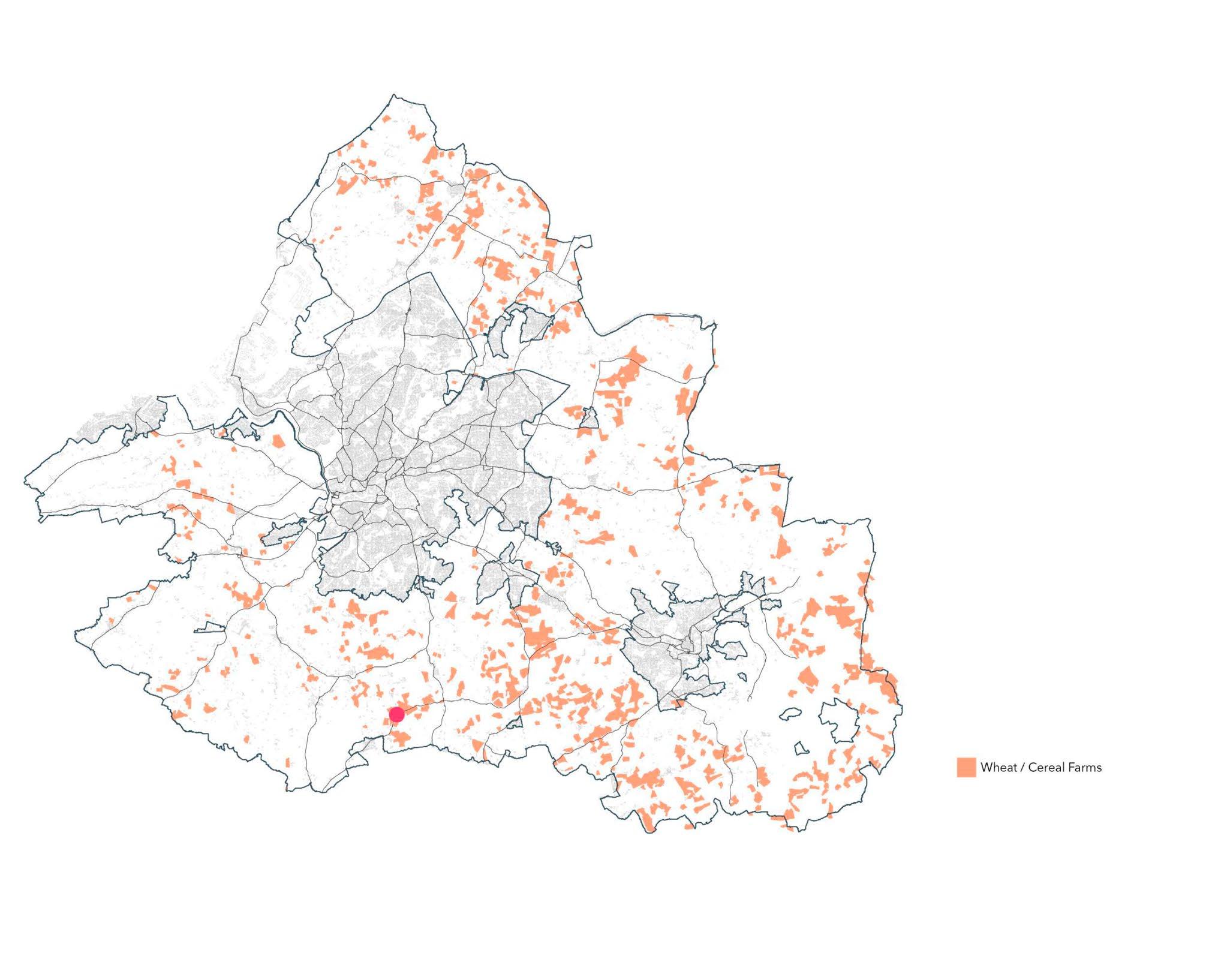

The Bristol greenbelt historically stands out in the national context for its horticultural activity. However, since 1985, suburban horticulture in the region has seen a decline by 30% (Carey 2011). Additionally, there is a significant demand for land among new farmers.

When analysing the land composition of the greenbelt, it’s evident that built-up areas and parks are limited, with approximately 60% of the total area catalogued as agricultural land. This statistic positions the Bristol greenbelt slightly above the national average in terms of agricultural land distribution. However, this statistic could be somewhat deceptive, as nearly 40% of this agricultural space is grassland that is used for grazing.

Examining the crops within the arable categories, the Bristol greenbelt appears to mirror national tendencies. Cereal farms dominate the scene, with primary cultivation of wheat and barley.

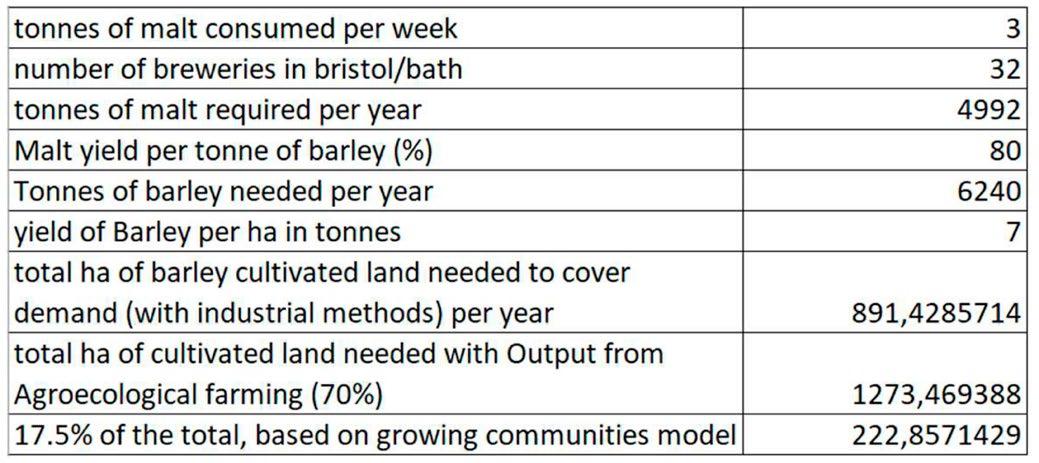

Maize 3% Oilseed Rape 1% Peas Potatoes <1% UK Bristol GB UK Grass 46% Beet Grass 73% Wheat 23% Wheat 10% Barley 7% Barley 11% Oats 2% Beet 1% Field Beans 3% Oats 1% Field Beans 2% Solar Panels 1% Maize 3% Oilseed Rape 4% Other Crops 5% Potatoes 1% Solar Panels <1% Other Crops 2% Peas 1% 20km 57% Bristol GB 25km 62% Maize 3% Oilseed Rape 1% Peas + Potatoes <1% UK Bristol GB UK Grass 46% Grass Wheat Barley Maize Oilseed Rape Other Crops Peas Potato Solar Panels Field Beans Oats Maize Oilseed Rape Other Crops Peas Potato Solar Panels Field Beans Oats Beet Grass Barley Wheat Grass 73% Wheat 23% Wheat 10% Barley 7% Barley 11% Oats 2% Beet 1% Field Beans 3% Oats 1% Field Beans 2% Solar Panels 1% Maize 3% Oilseed Rape 4% Other Crops 5% Potatoes 1% Solar Panels <1% Other Crops 2% Peas 1% 25km 20km 20km 57% Bristol GB 25km 62% Maize 3% Oilseed Rape 1% Peas + Potatoes <1% UK Bristol GB UK Grass 46% Grass Wheat Barley Maize Oilseed Rape Other Crops Peas Potato Solar Panels Field Beans Oats Maize Oilseed Rape Other Crops Peas Potato Solar Panels Field Beans Oats Beet Grass Barley Wheat Grass 73% Wheat 23% Wheat 10% Barley 7% Barley 11% Oats 2% Beet 1% Field Beans 3% Oats 1% Field Beans 2% Solar Panels 1% Maize 3% Oilseed Rape 4% Other Crops 5% Potatoes 1% Solar Panels <1% Other Crops 2% Peas 1% 25km 20km 20km 57% Bristol GB 25km 62% Maize 3% Oilseed Rape 1% Peas Potatoes <1% UK Bristol GB UK Grass 46% Grass Wheat Barley Maize Oilseed Rape Other Crops Peas Potato Solar Panels Field Beans Oats Maize Oilseed Rape Other Crops Peas Potato Solar Panels Field Beans Oats Beet Grass Barley Wheat Grass 73% Wheat 23% Wheat 10% Barley 7% Barley 11% Oats 2% Beet 1% Field Beans 3% Oats 1% Field Beans 2% Solar Panels 1% Maize 3% Oilseed Rape 4% Other Crops 5% Potatoes 1% Solar Panels <1% Other Crops 2% Peas 1% 25km 20km 20km 57% Bristol GB 25km 62% Maize 3% Oilseed Rape 1% Peas + Potatoes <1% UK Bristol GB UK Grass 46% Grass Wheat Barley Maize Oilseed Rape Other Crops Peas Potato Solar Panels Field Beans Oats Maize Oilseed Rape Other Crops Peas Potato Solar Panels Field Beans Oats Beet Grass Barley Wheat Grass 73% Wheat 23% Wheat 10% Barley 7% Barley 11% Oats 2% Beet 1% Field Beans 3% Oats 1% Field Beans 2% Solar Panels 1% Maize 3% Oilseed Rape 4% Other Crops 5% Potatoes 1% Solar Panels <1% Other Crops 2% Peas 1% 20km 57% Bristol GB 25km 62% Maize 3% Oilseed Rape 1% Peas + Potatoes <1% Bristol GB Grass Wheat Barley Maize Oilseed Rape Other Crops Peas Potato Solar Panels Field Beans Oats Grass 73% Wheat 10% Barley 7% Oats 1% Field Beans 2% Solar Panels 1% Other Crops 2% 25km 25km 62% Maize 3% Oilseed Rape 1% Peas + Potatoes <1% Bristol GB Grass Wheat Barley Maize Oilseed Rape Other Crops Peas Potato Solar Panels Field Beans Oats Grass Barley Wheat Grass 73% Wheat 10% Barley 7% Oats 1% Field Beans 2% Solar Panels 1% Other Crops 2% 25km 20km Maize 3% Oilseed Rape 1% Peas + Potatoes <1% Bristol GB Grass Wheat Barley Maize Oilseed Rape Other Crops Peas Potato Solar Panels Field Beans Oats Grass Barley Wheat Grass 73% Wheat 10% Barley 7% Oats 1% Field Beans 2% Solar Panels 1% Other Crops 2% 25km 20km Types of Green in the Green Belt Fig 91 by Antonio Garaycochea 69 70 [AA Landscape Urbanism 23/24] [AA Landscape Urbanism 23/24] | UK Food System Planet of Fields

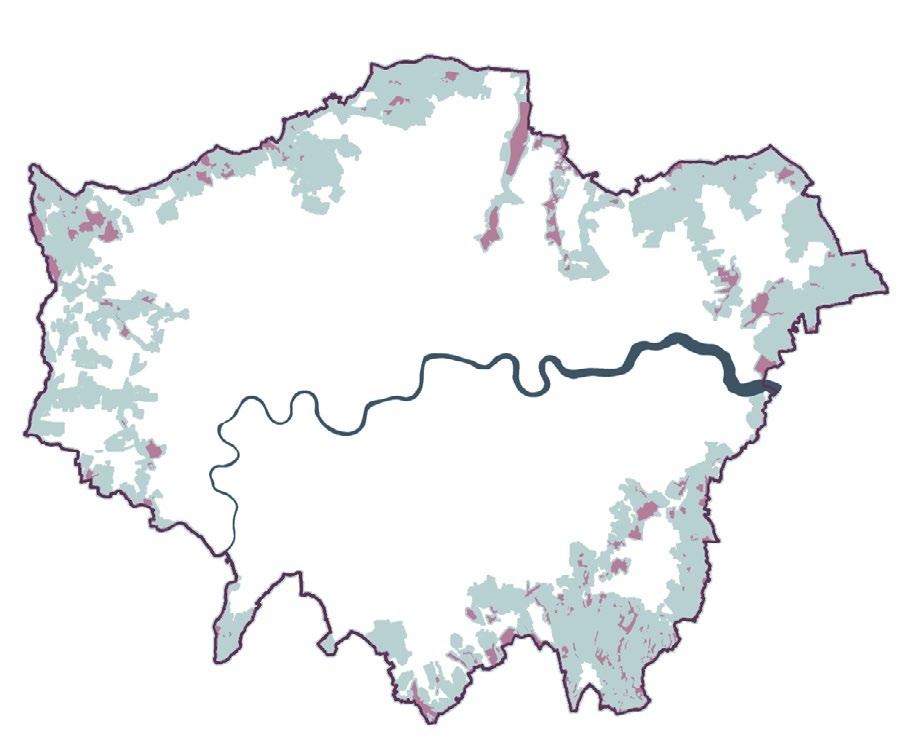

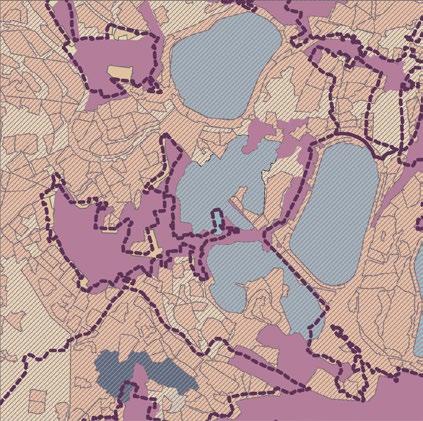

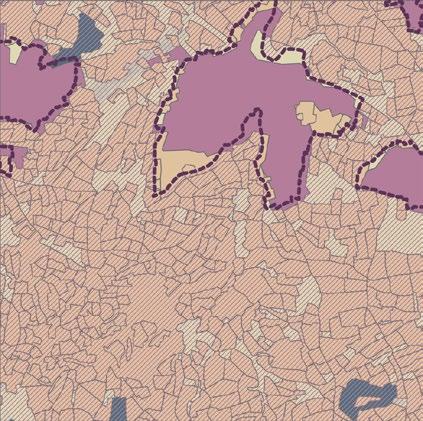

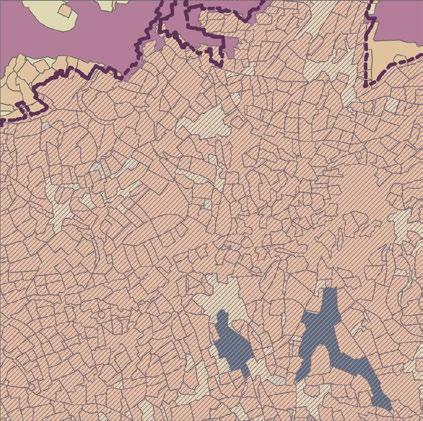

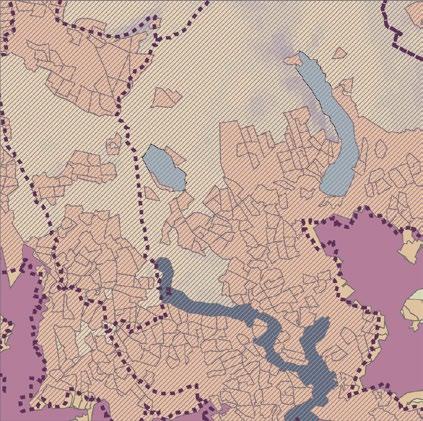

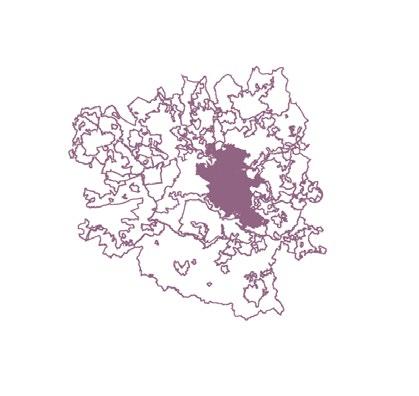

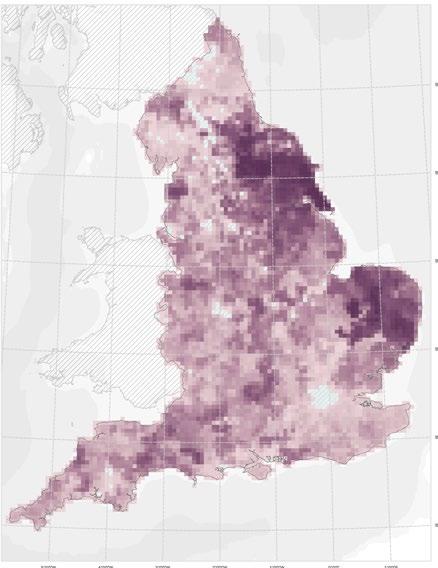

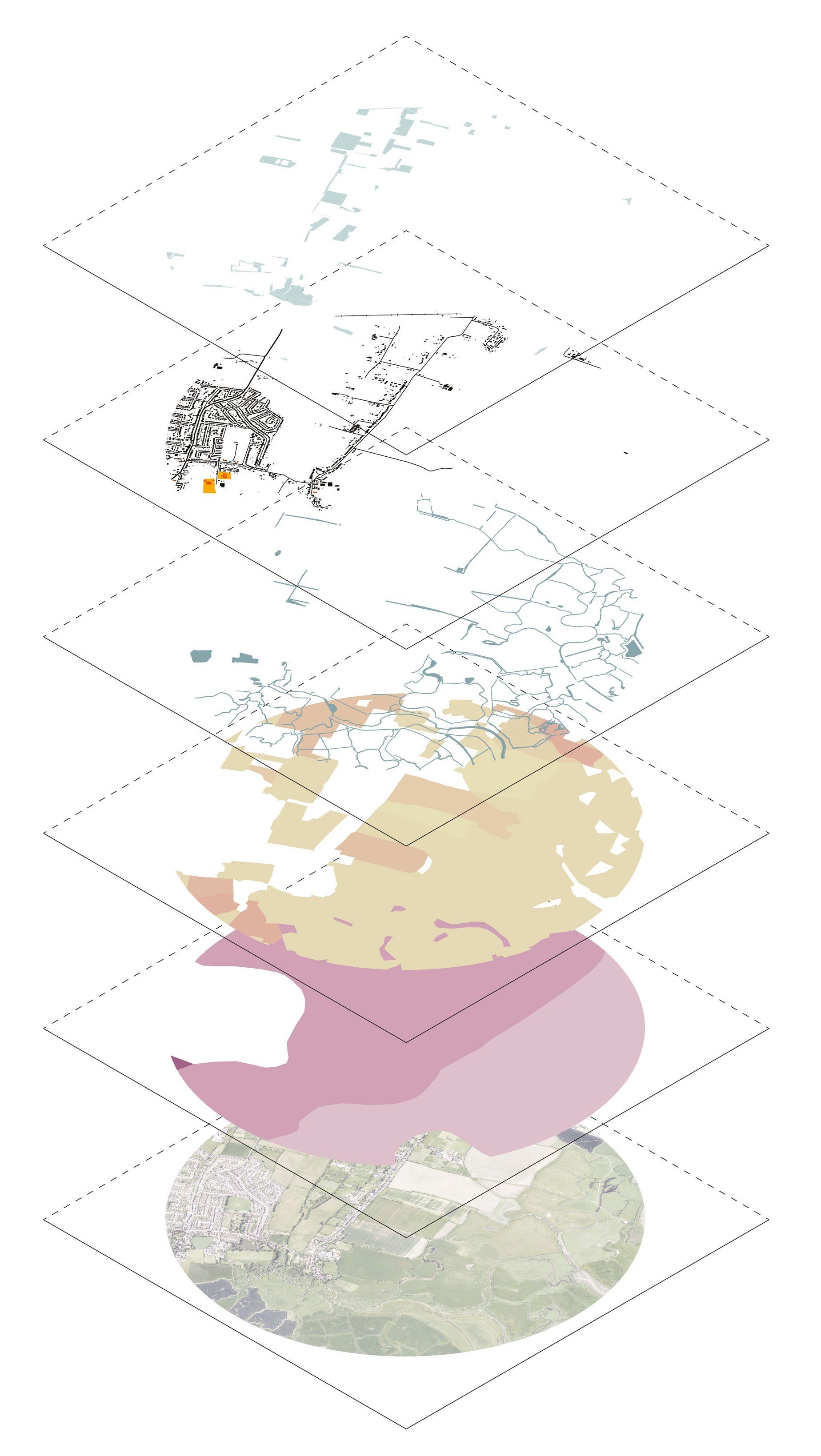

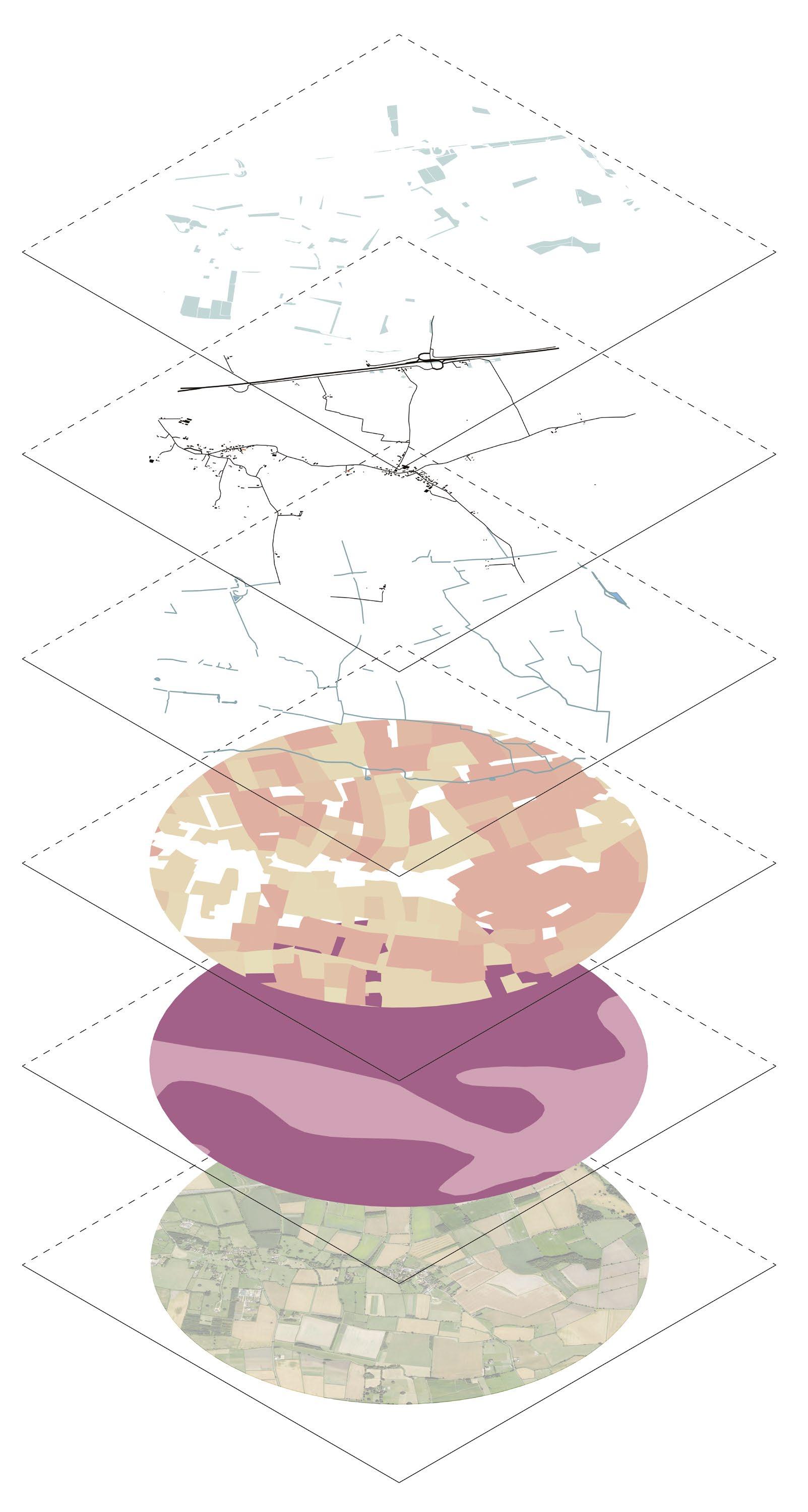

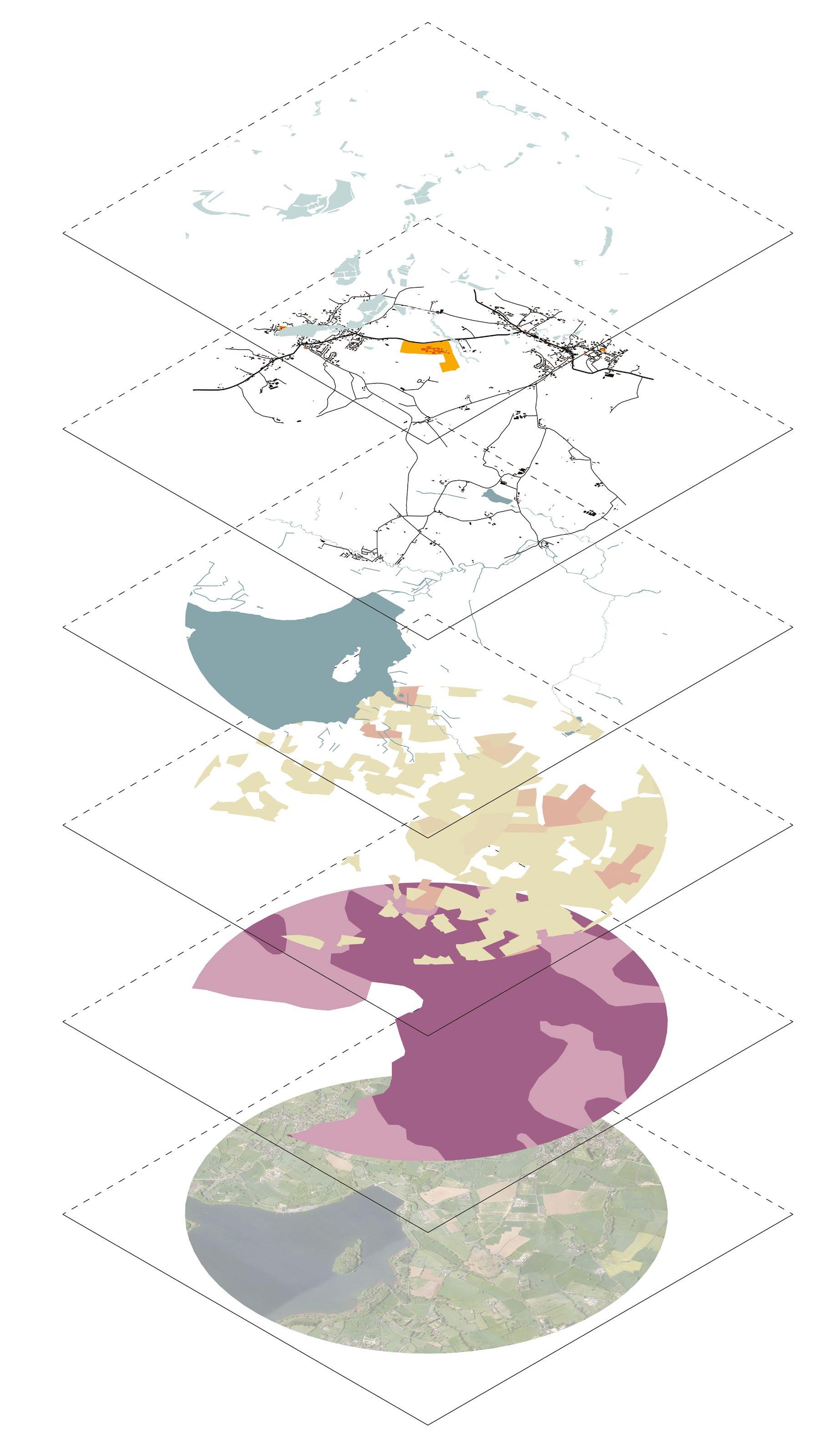

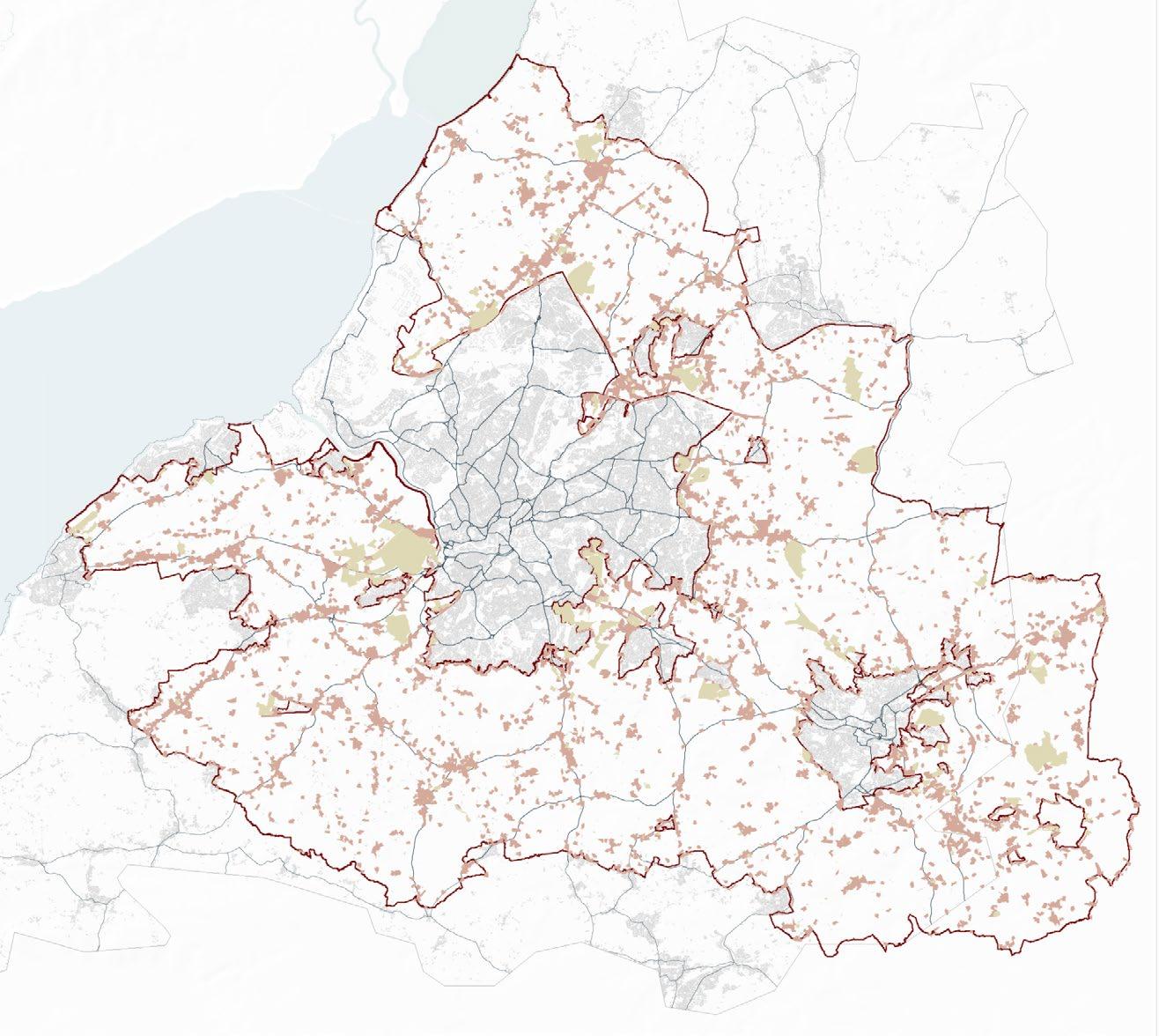

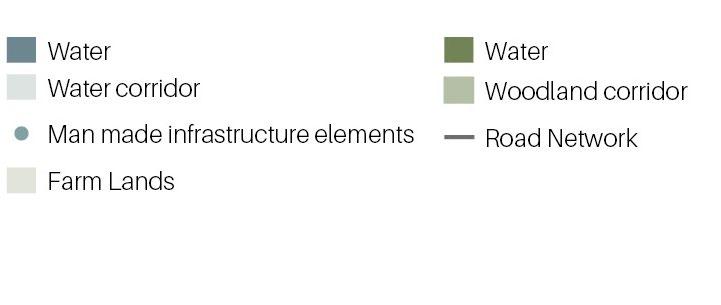

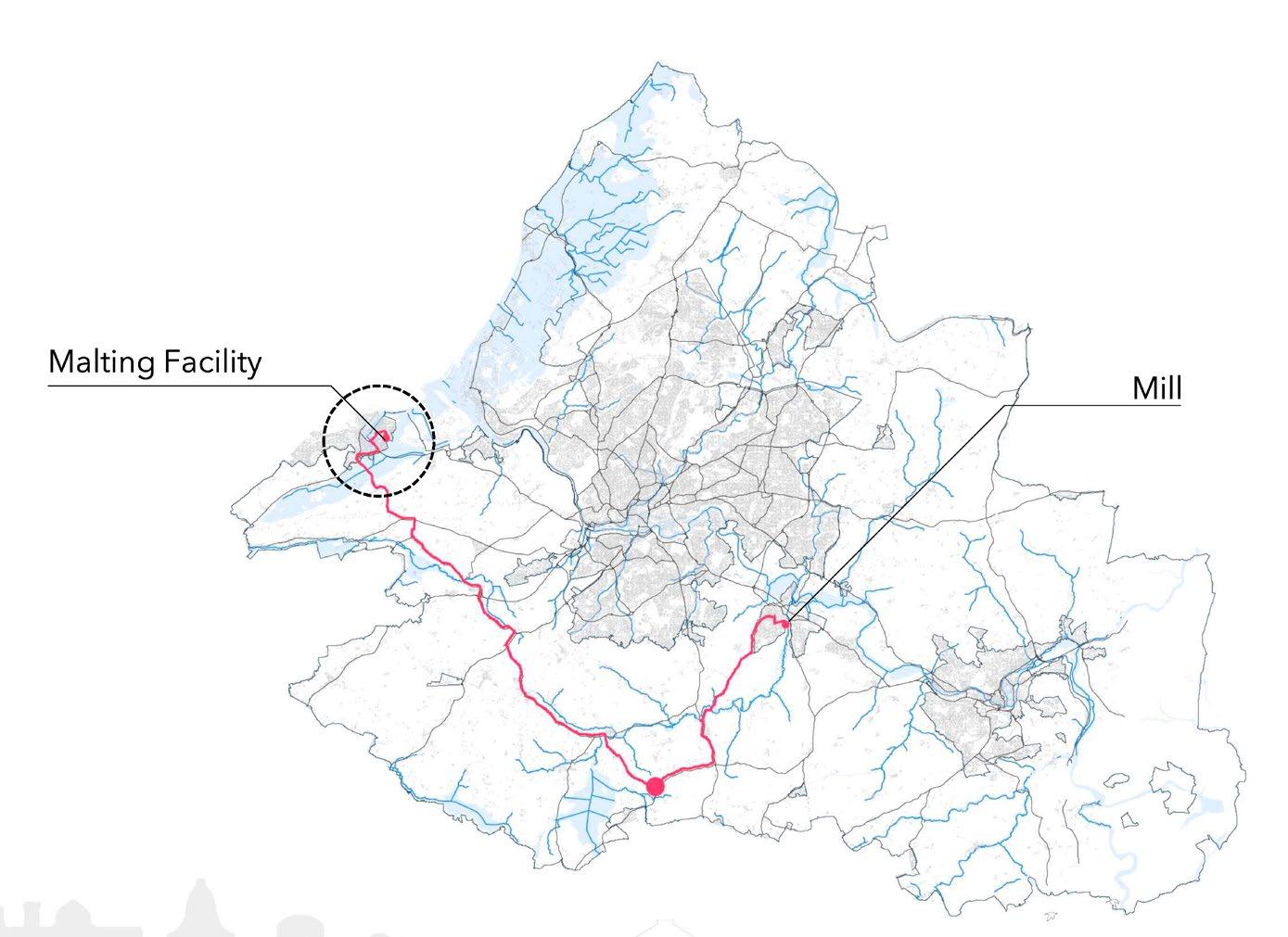

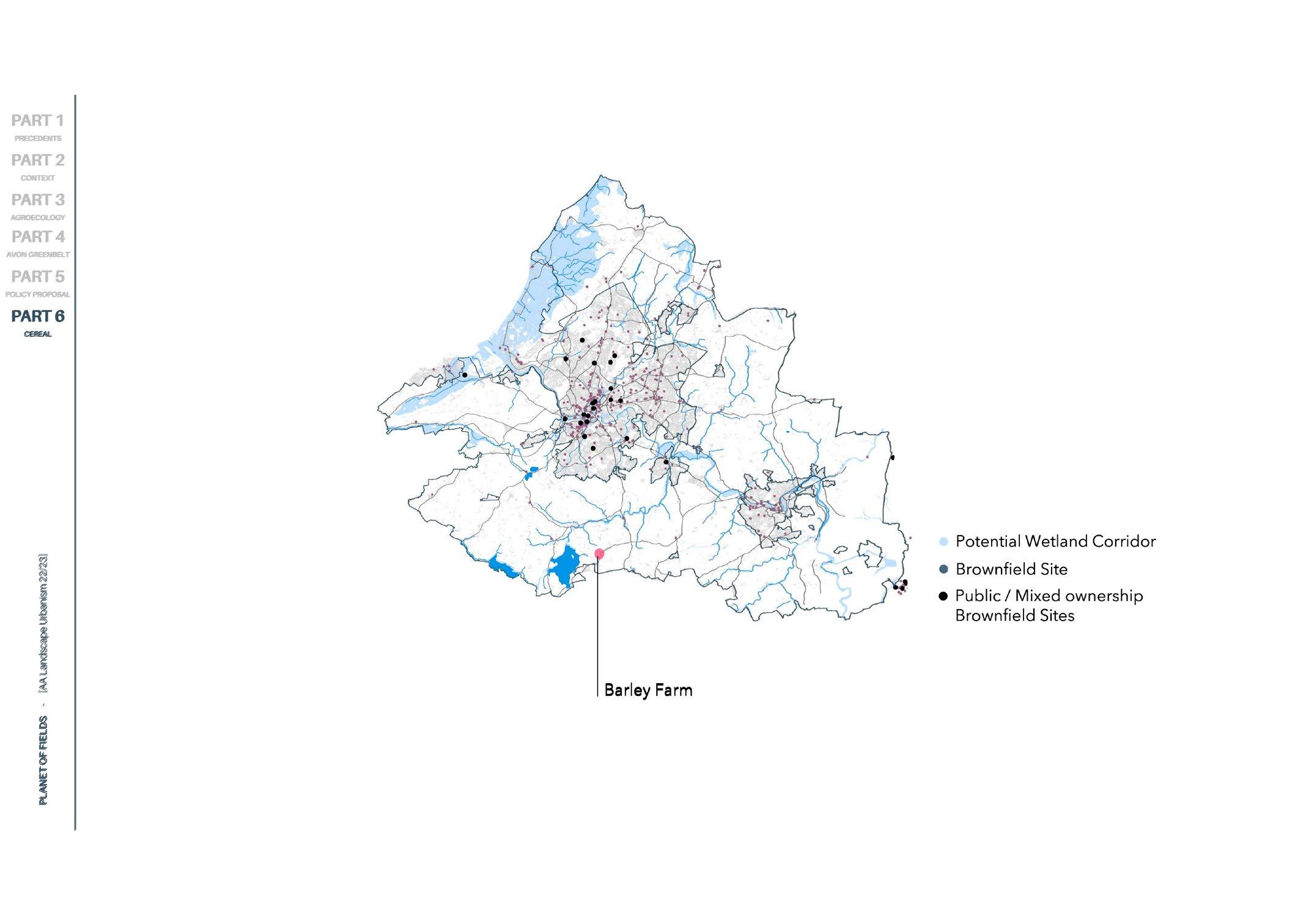

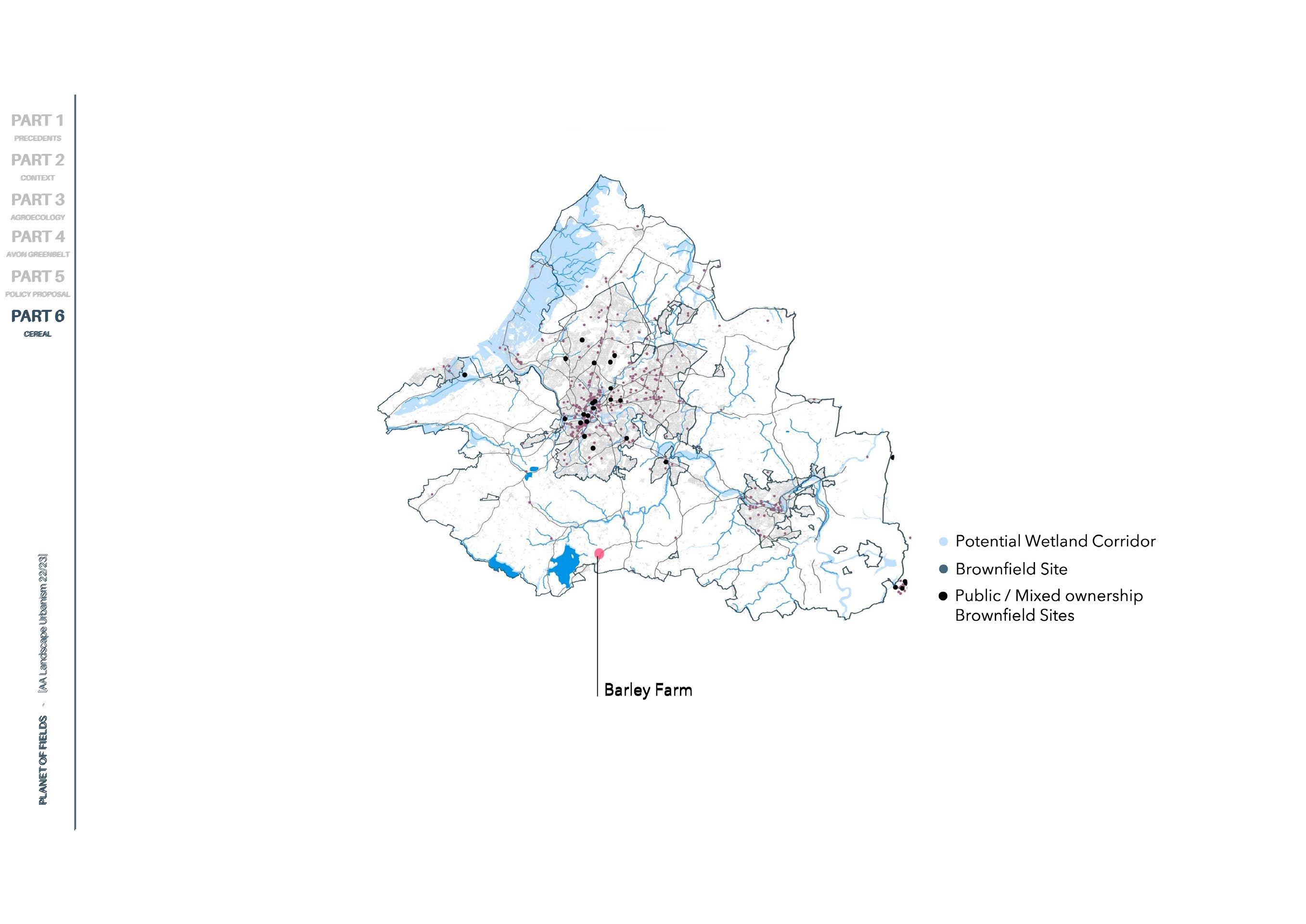

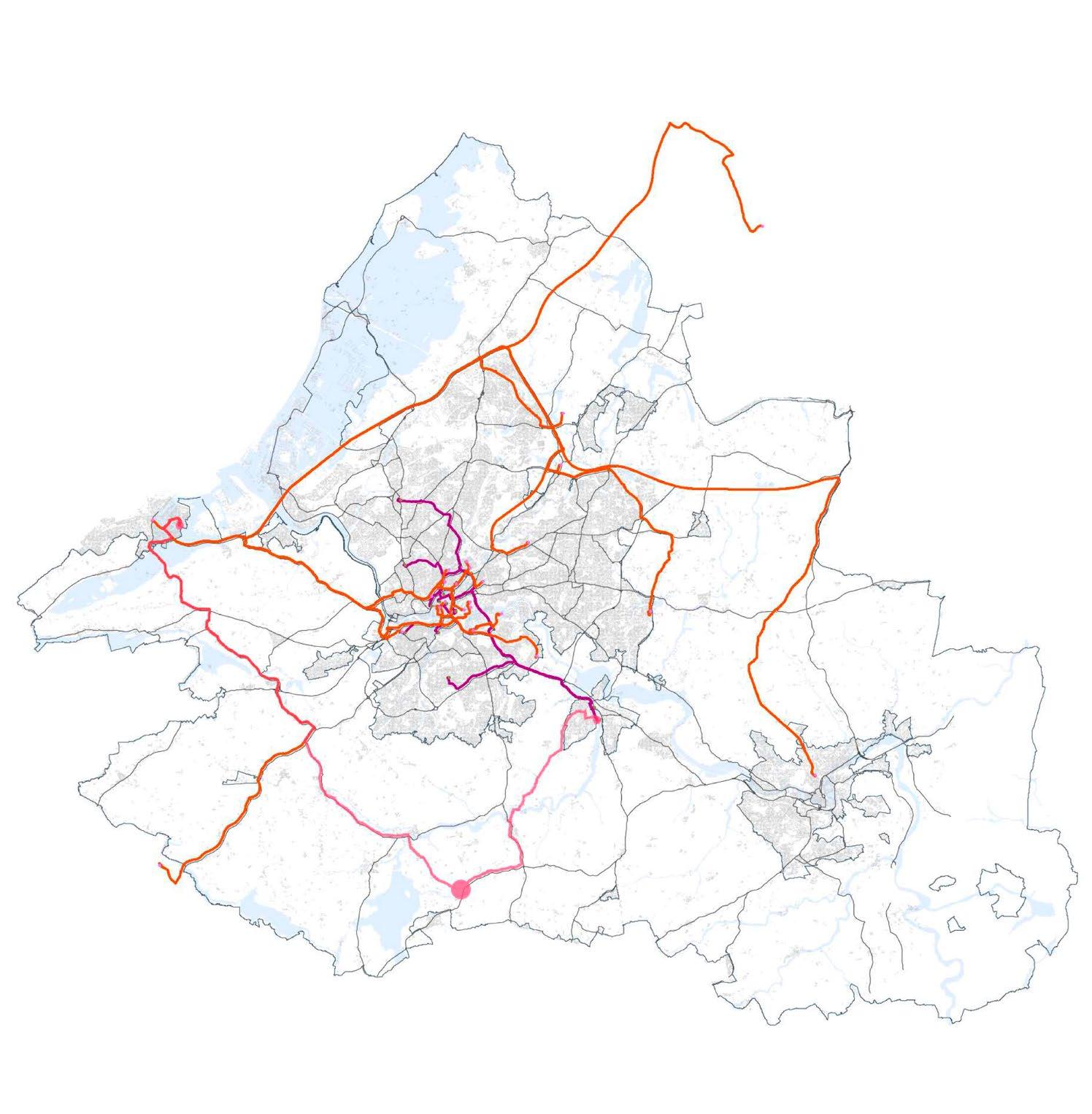

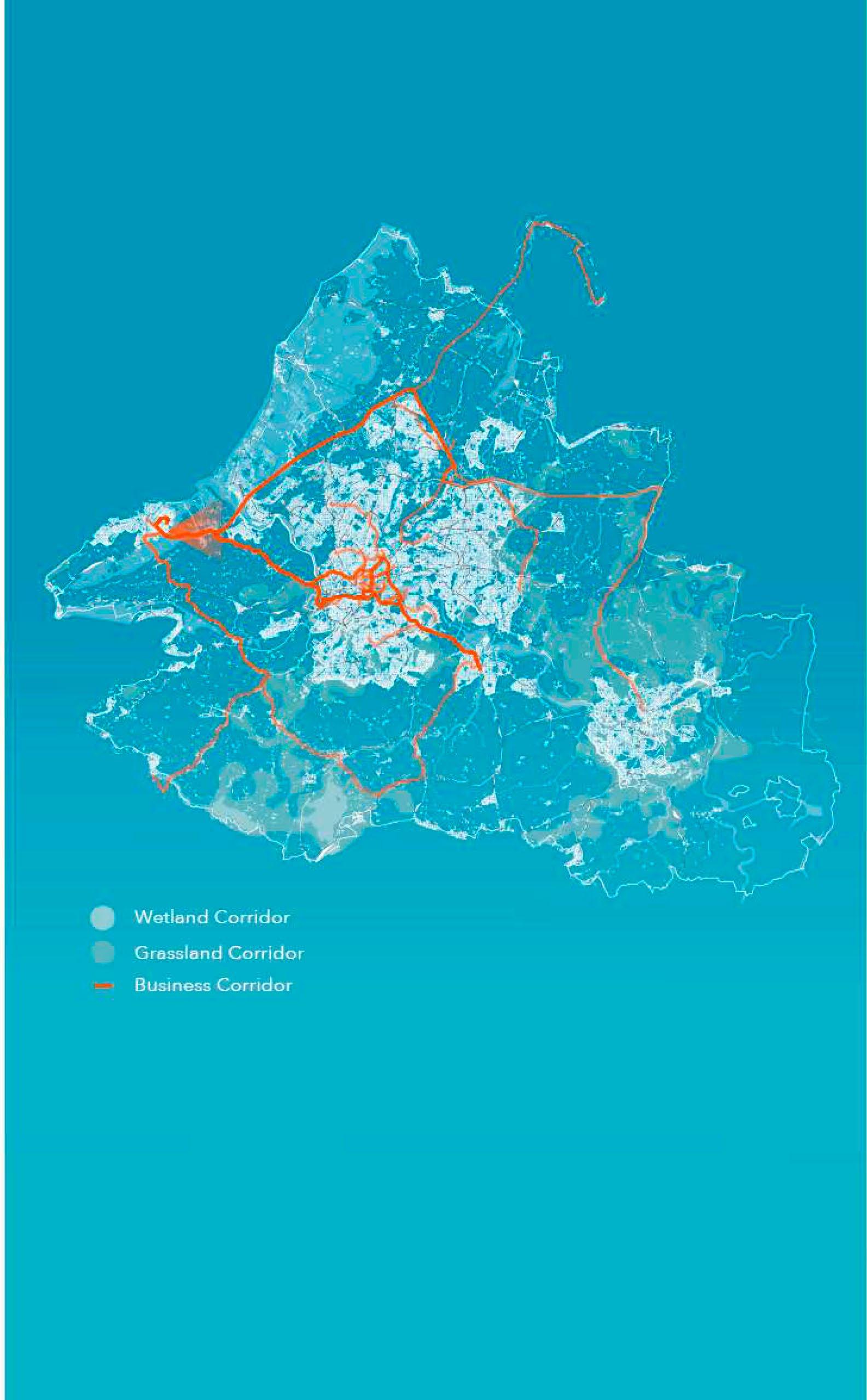

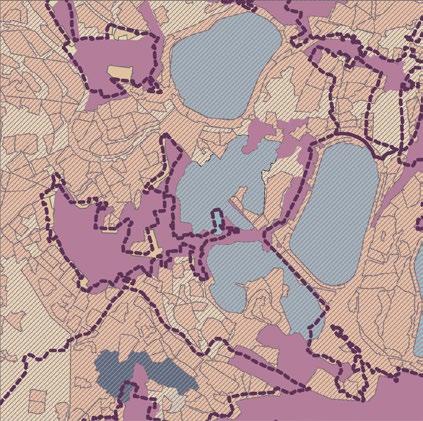

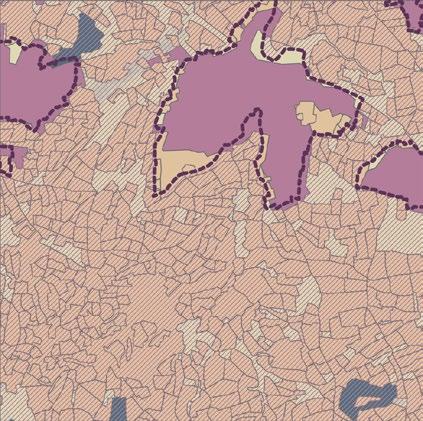

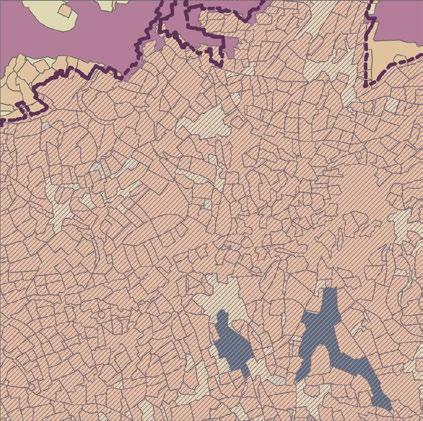

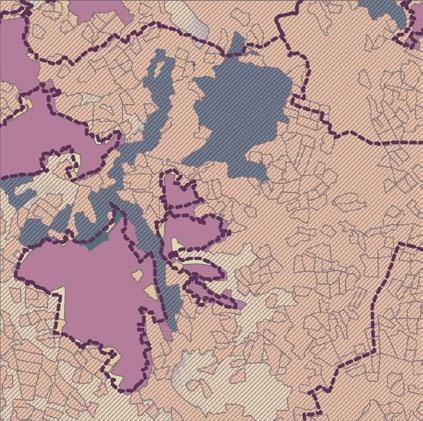

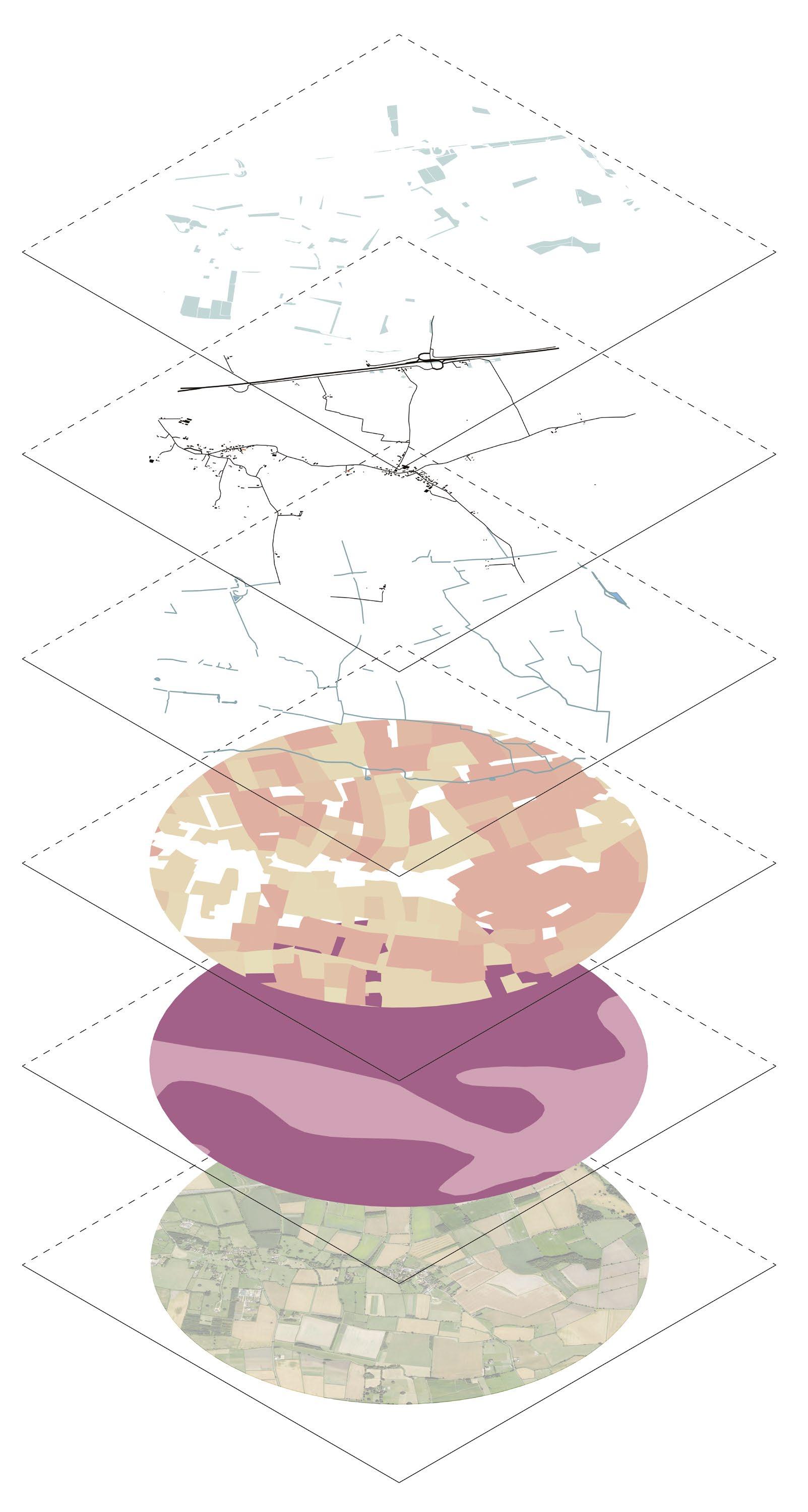

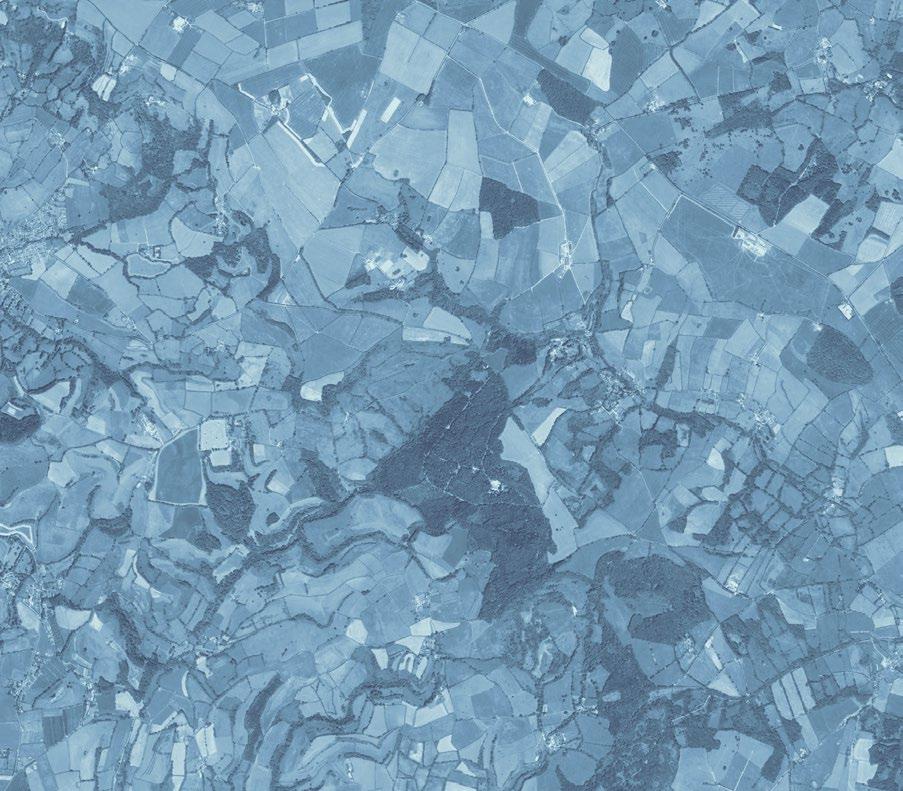

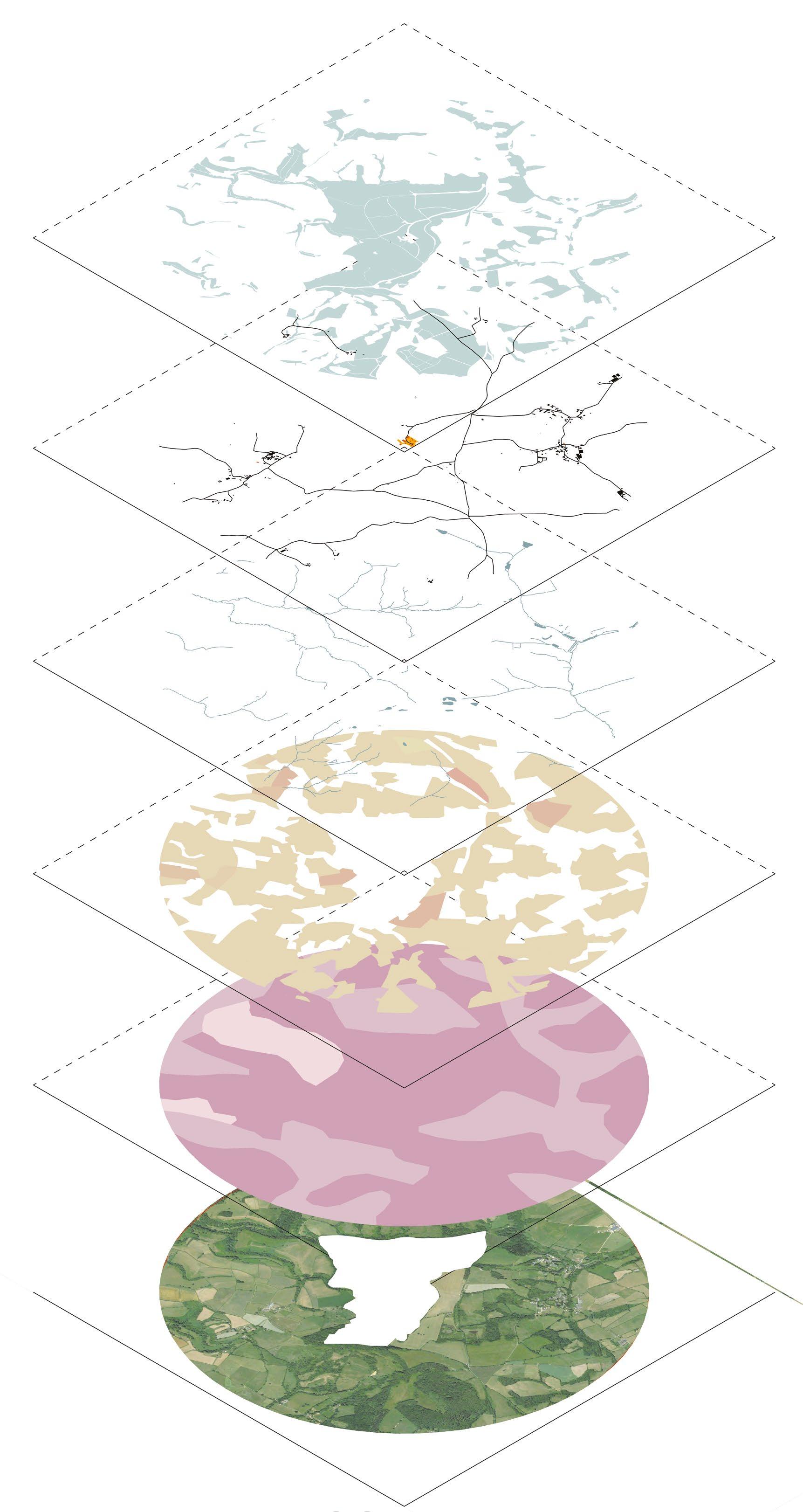

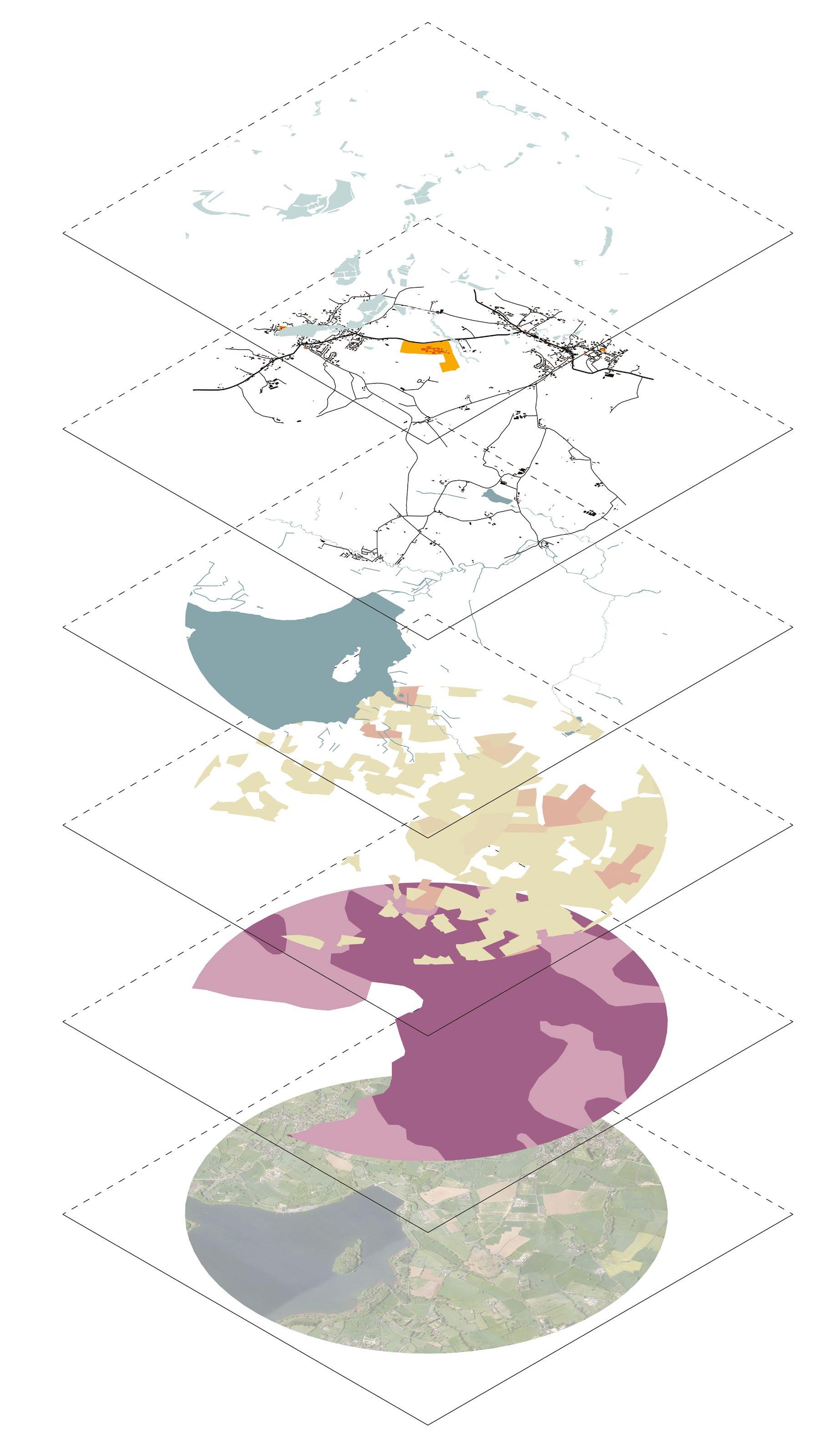

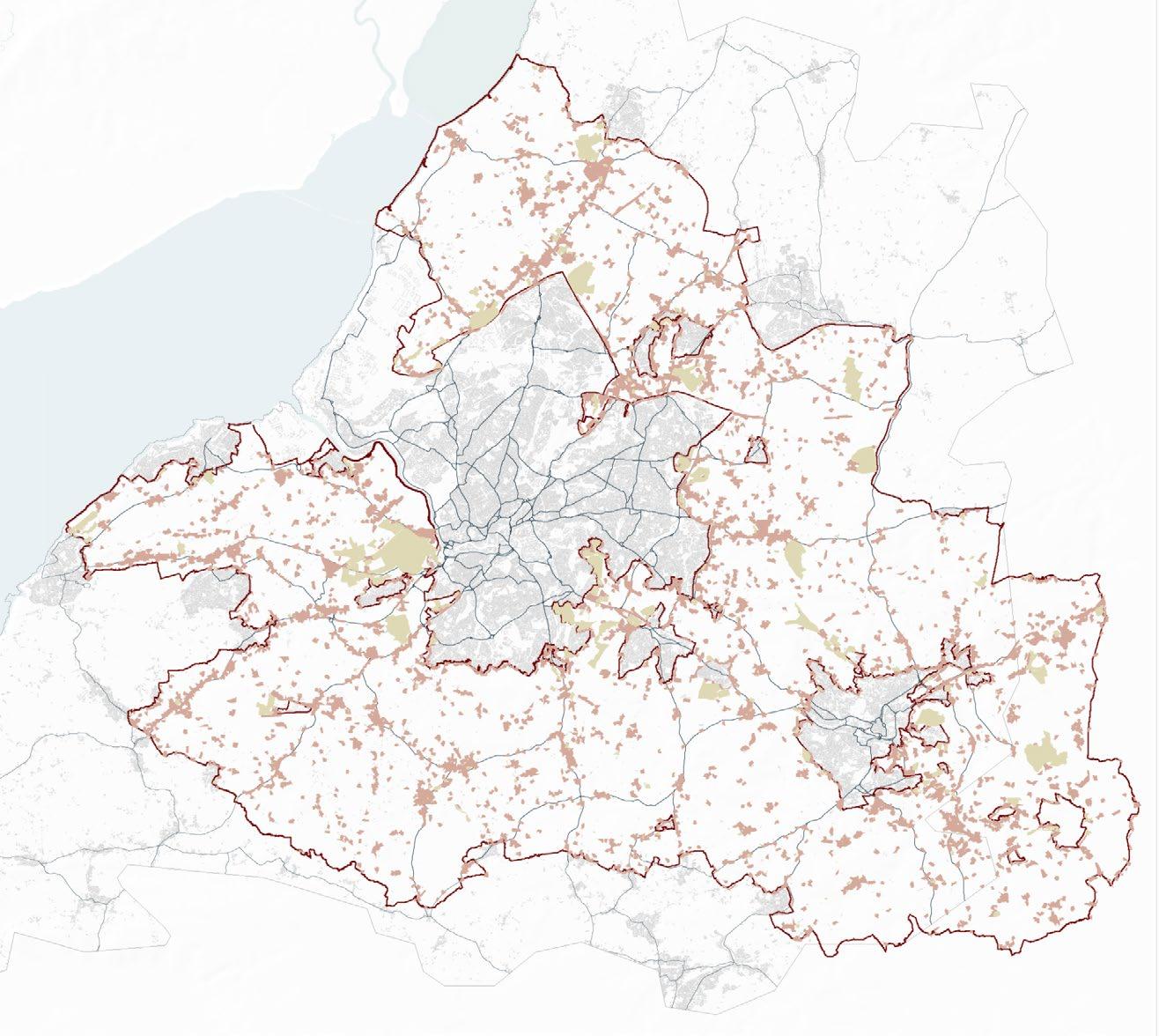

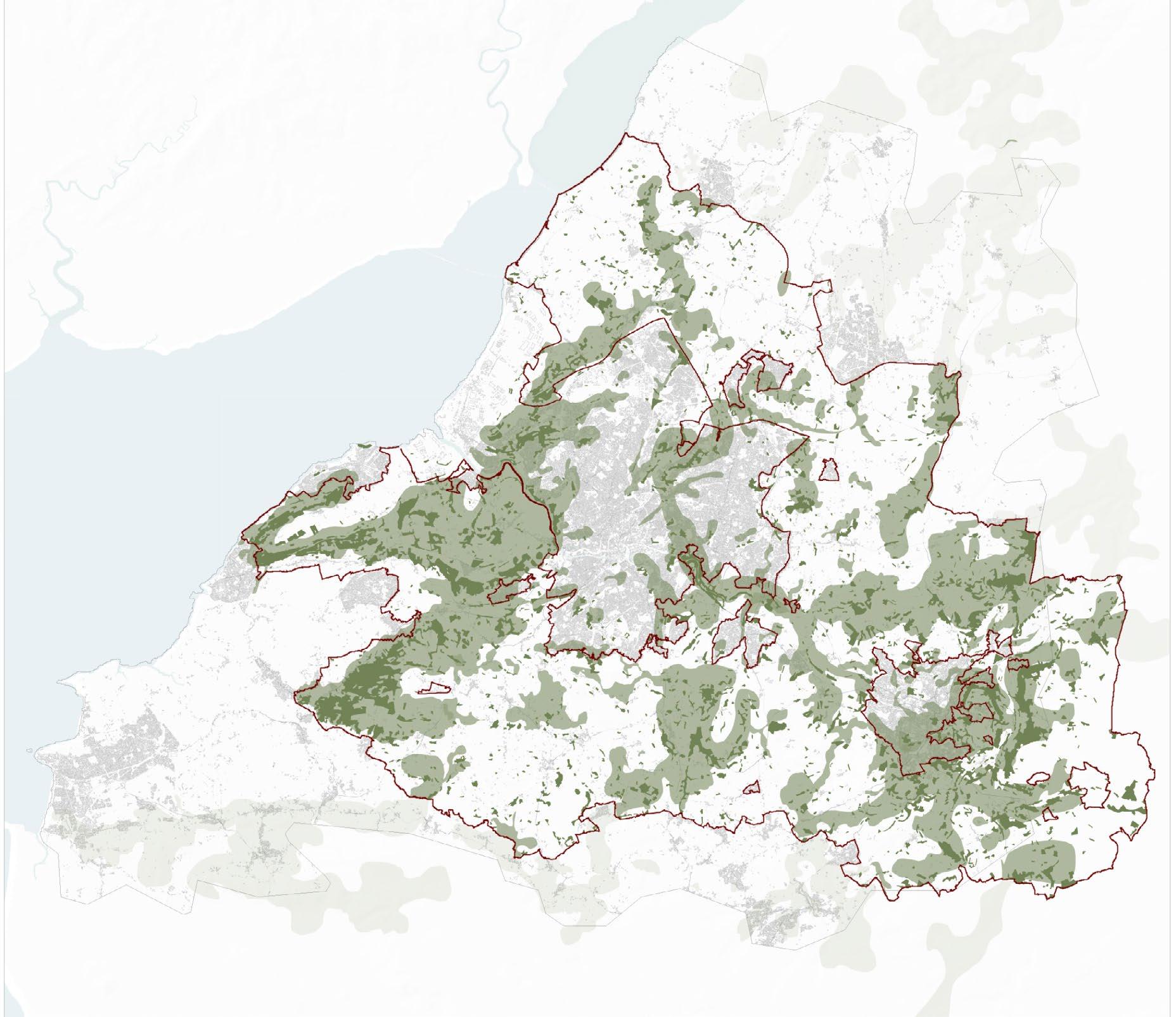

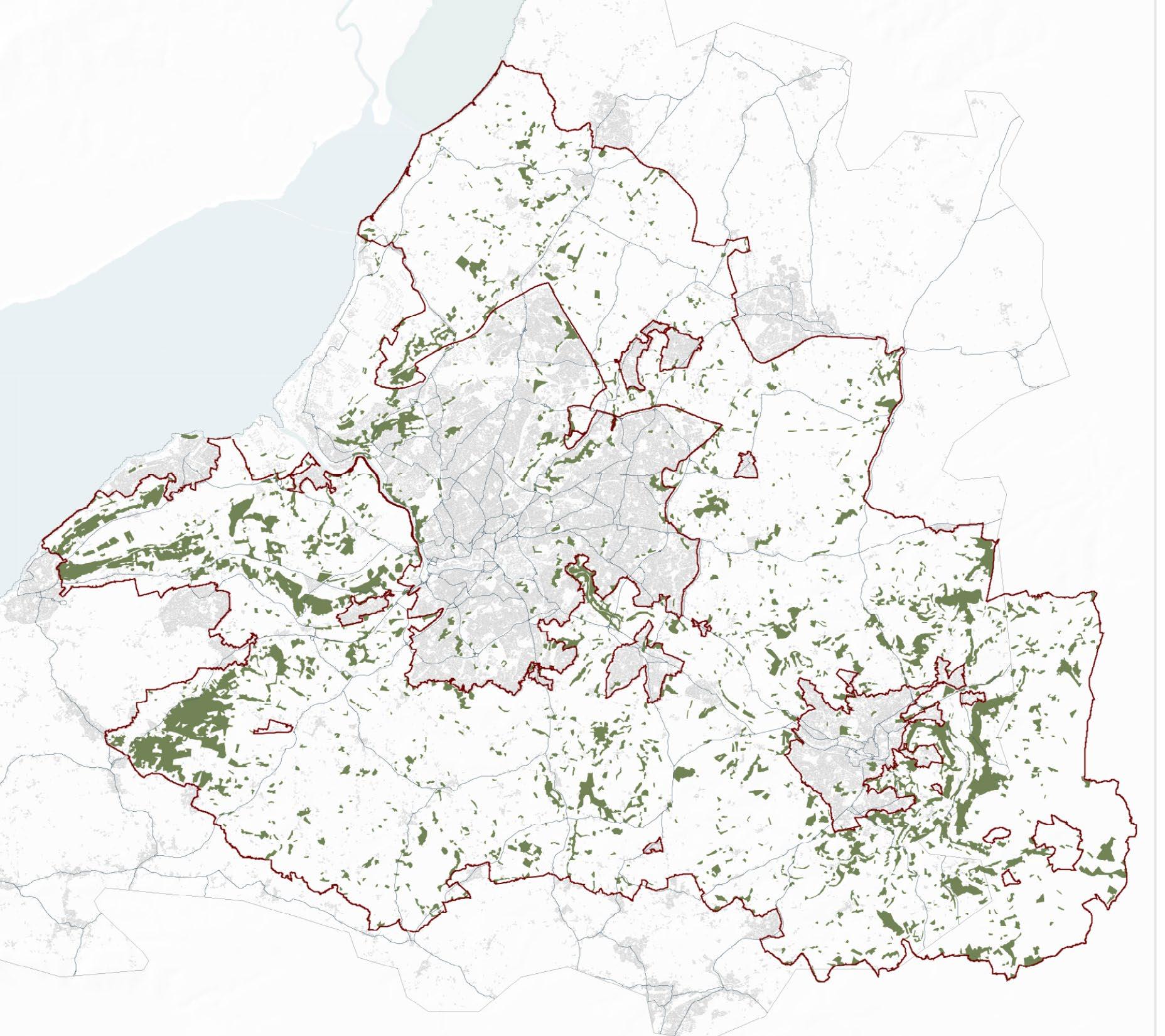

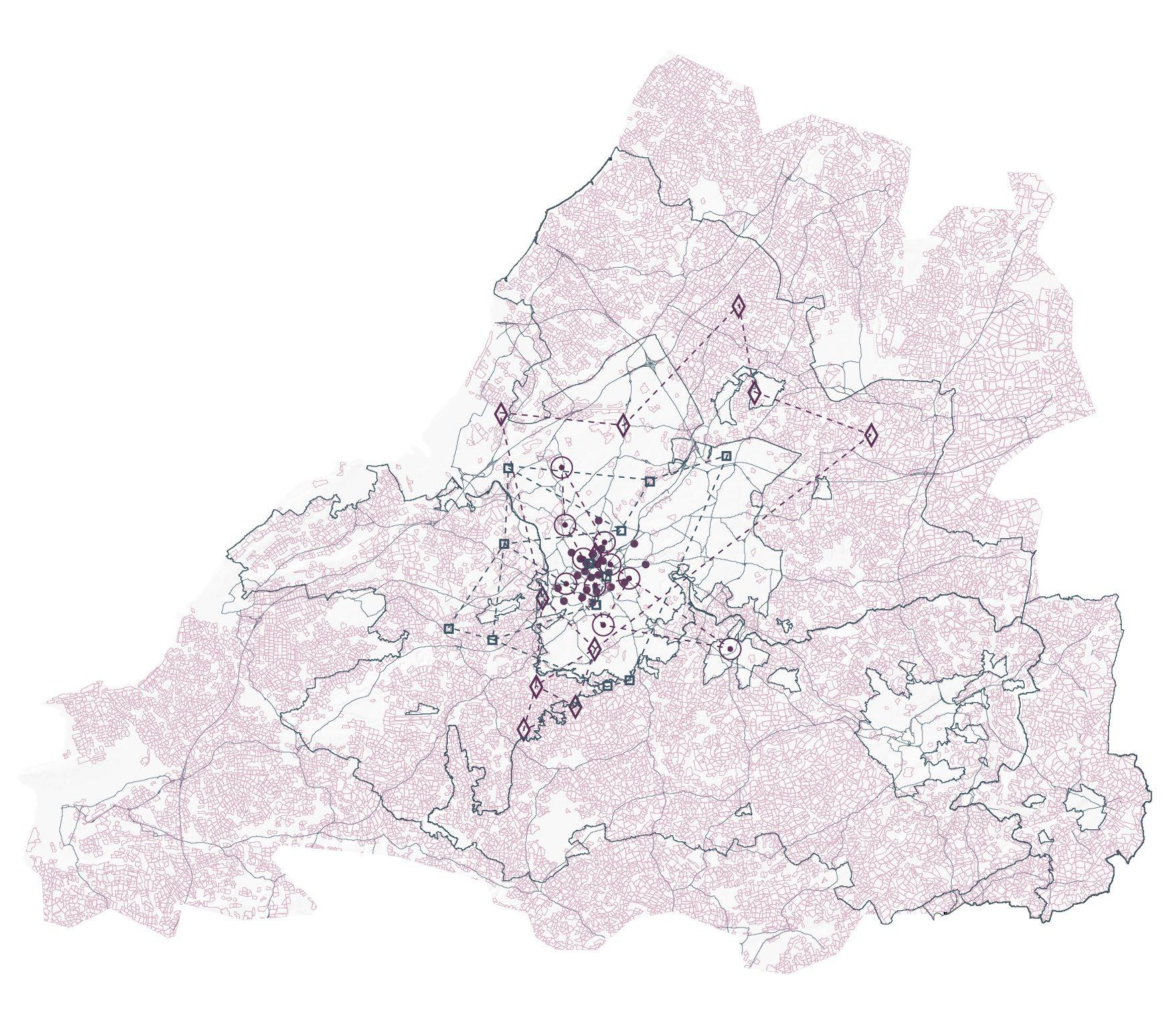

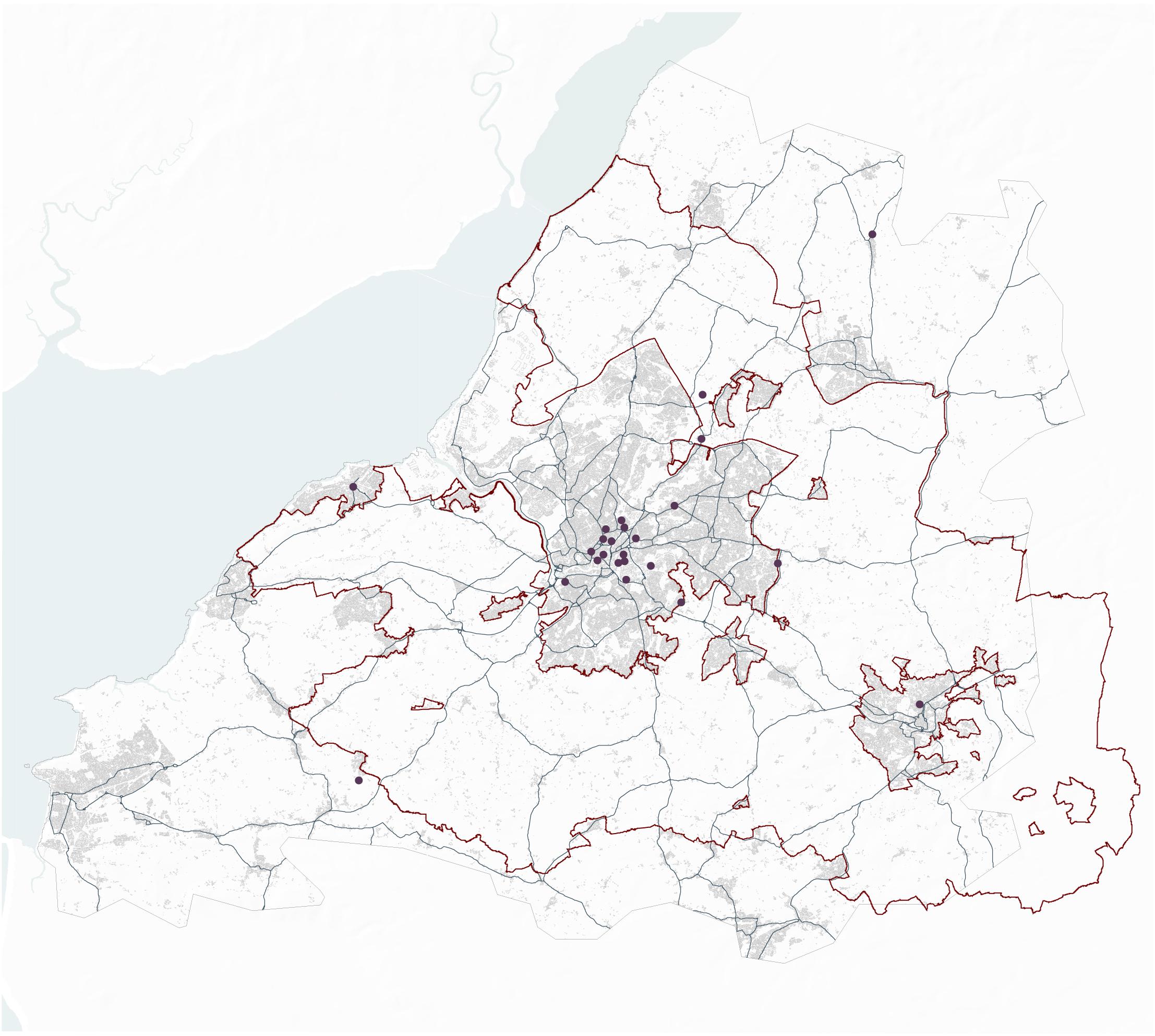

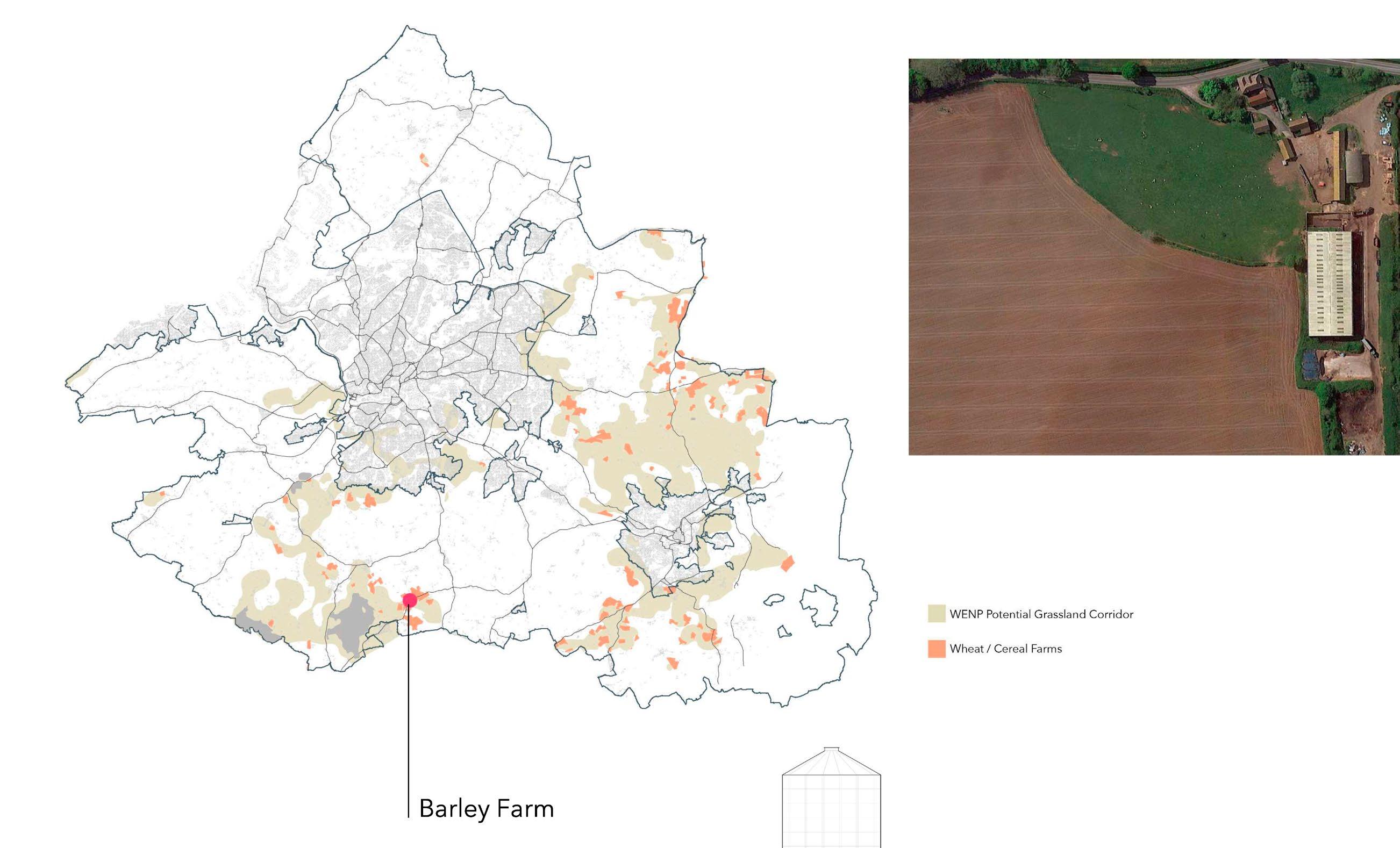

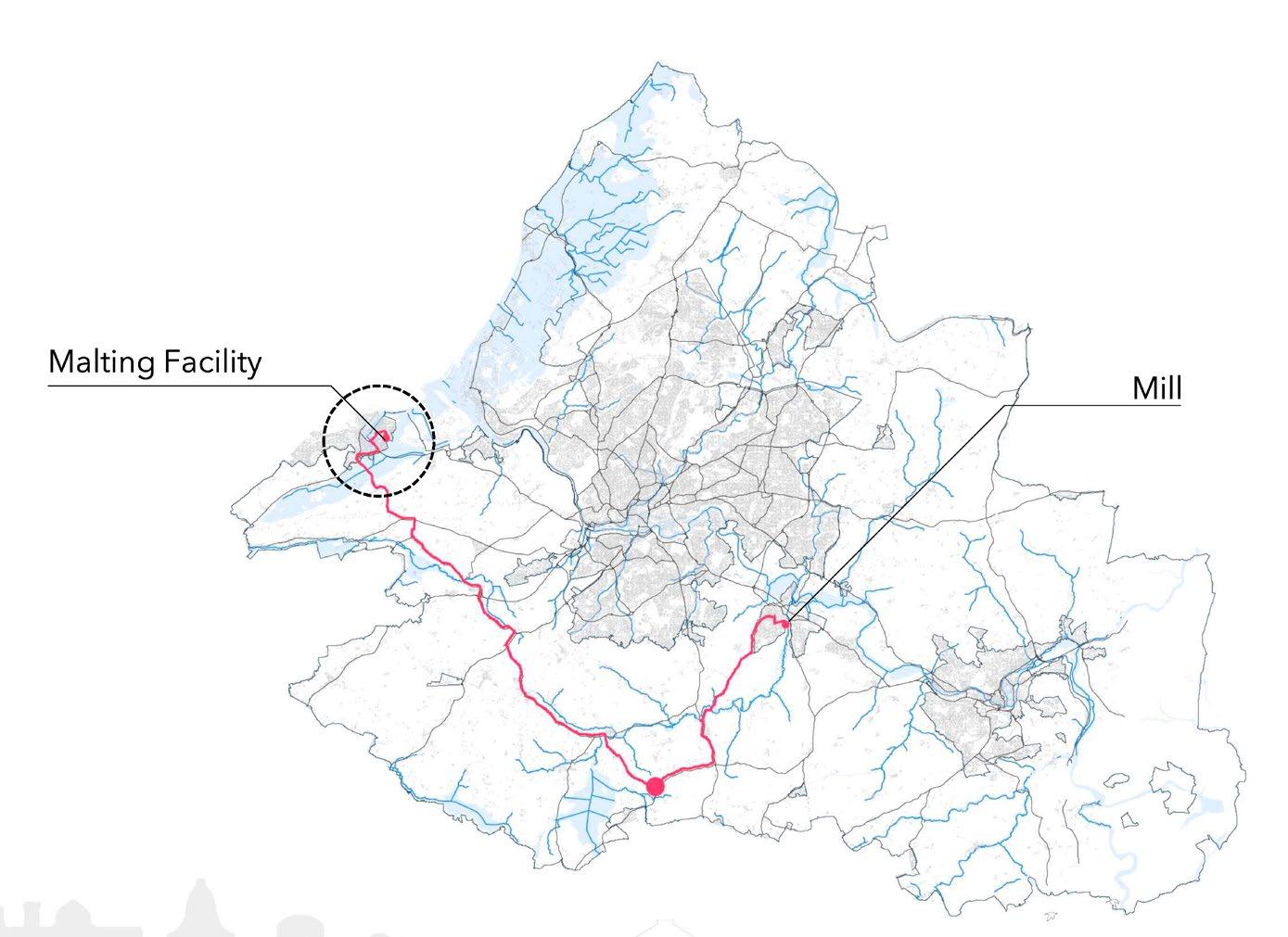

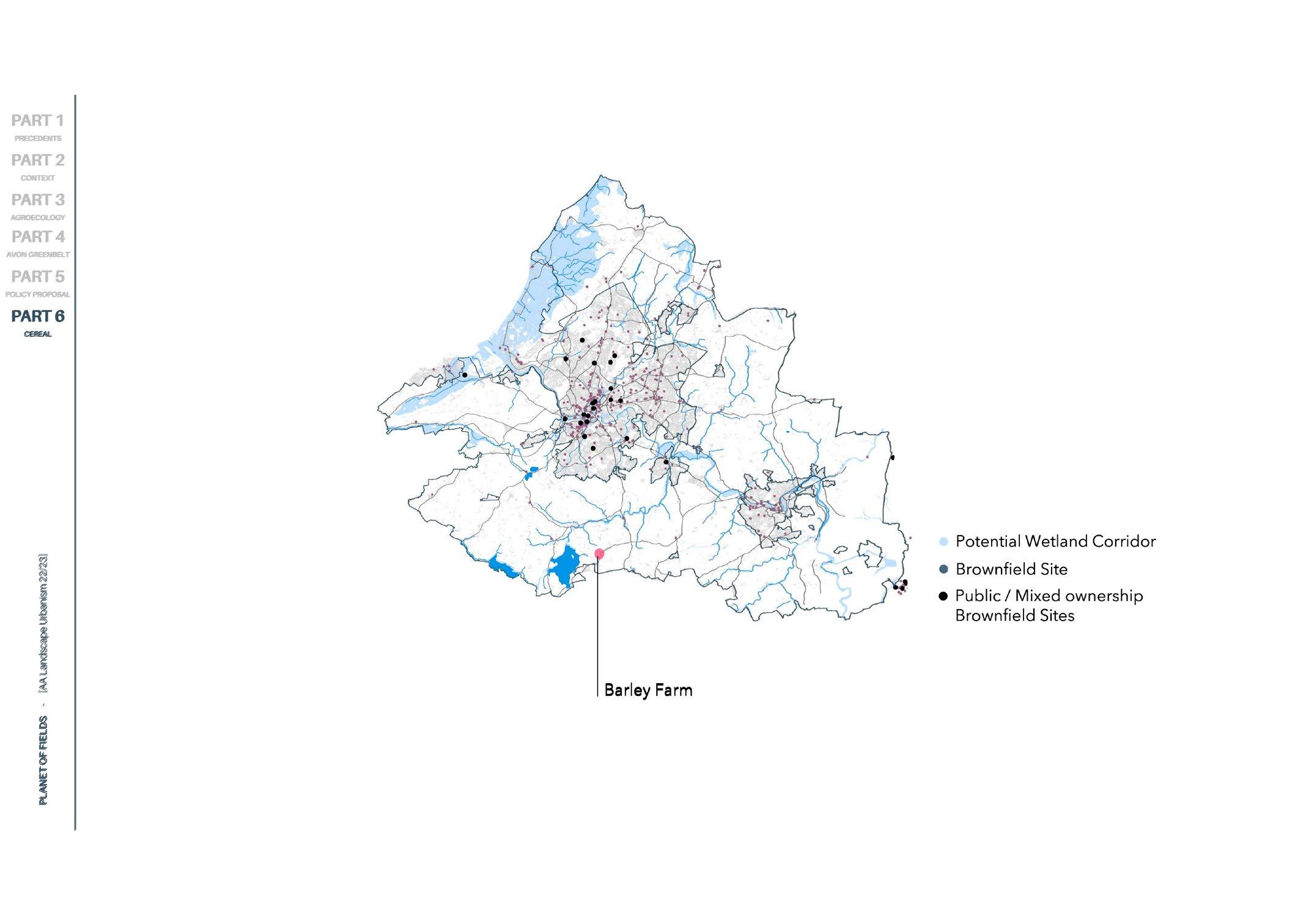

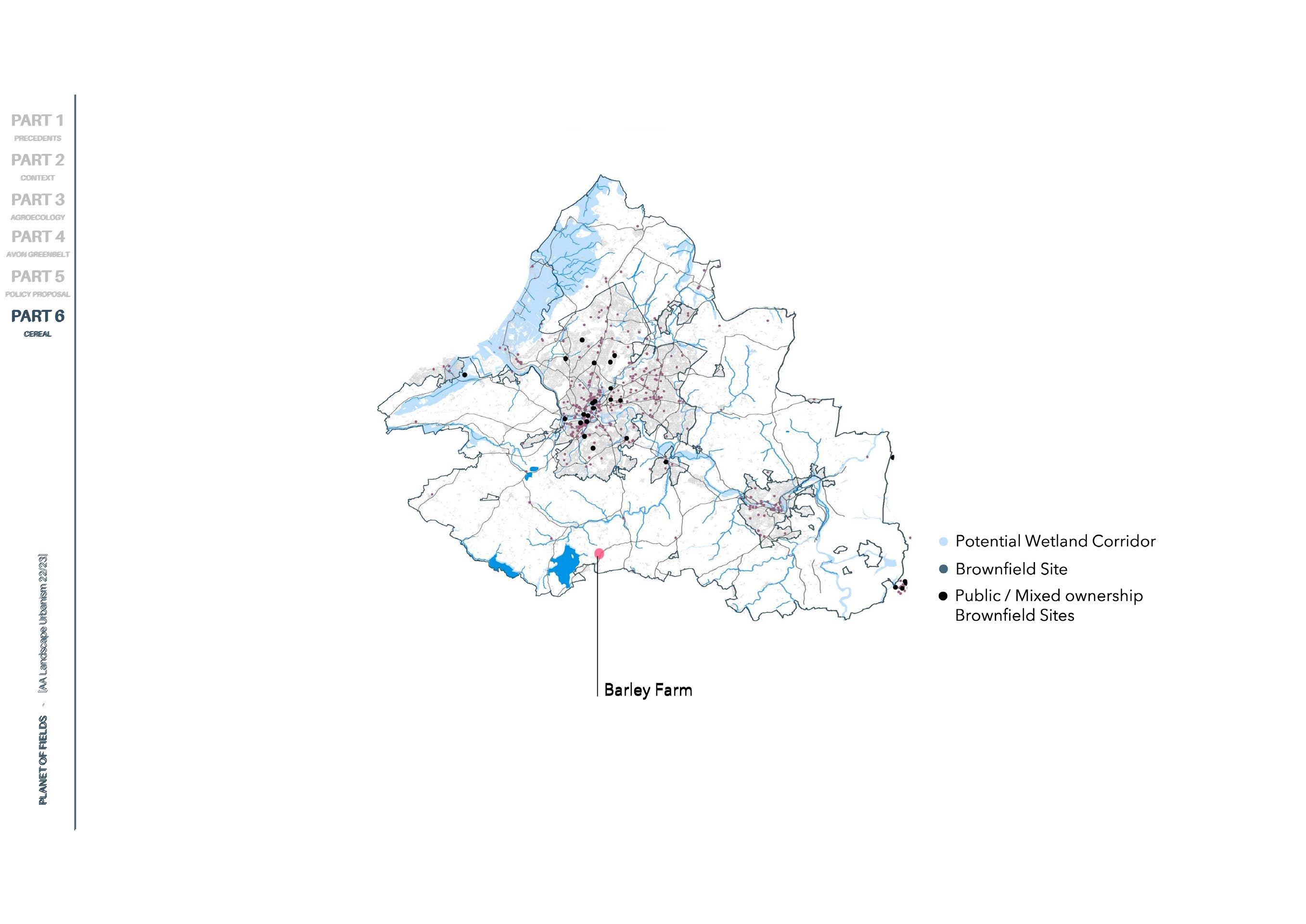

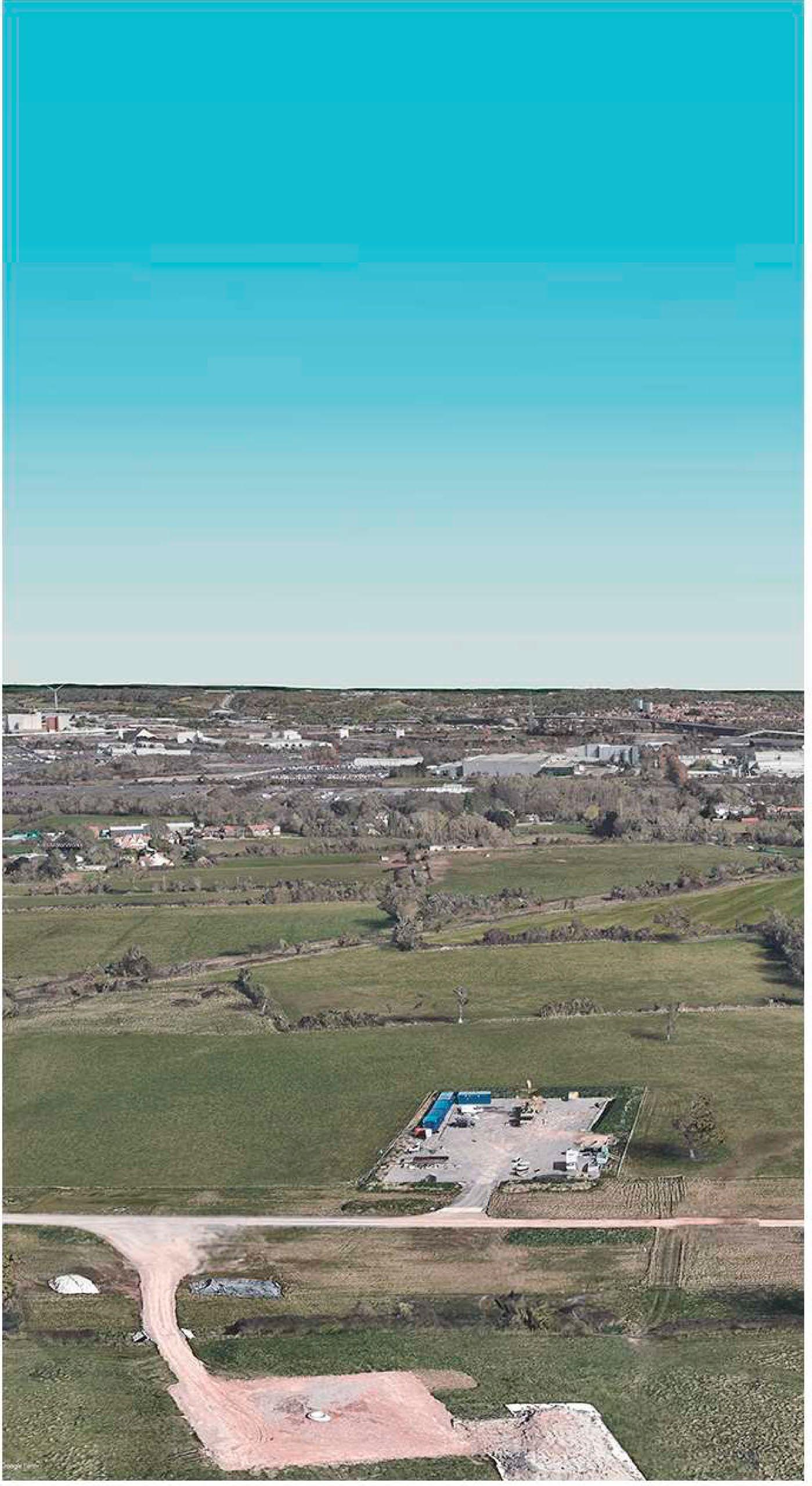

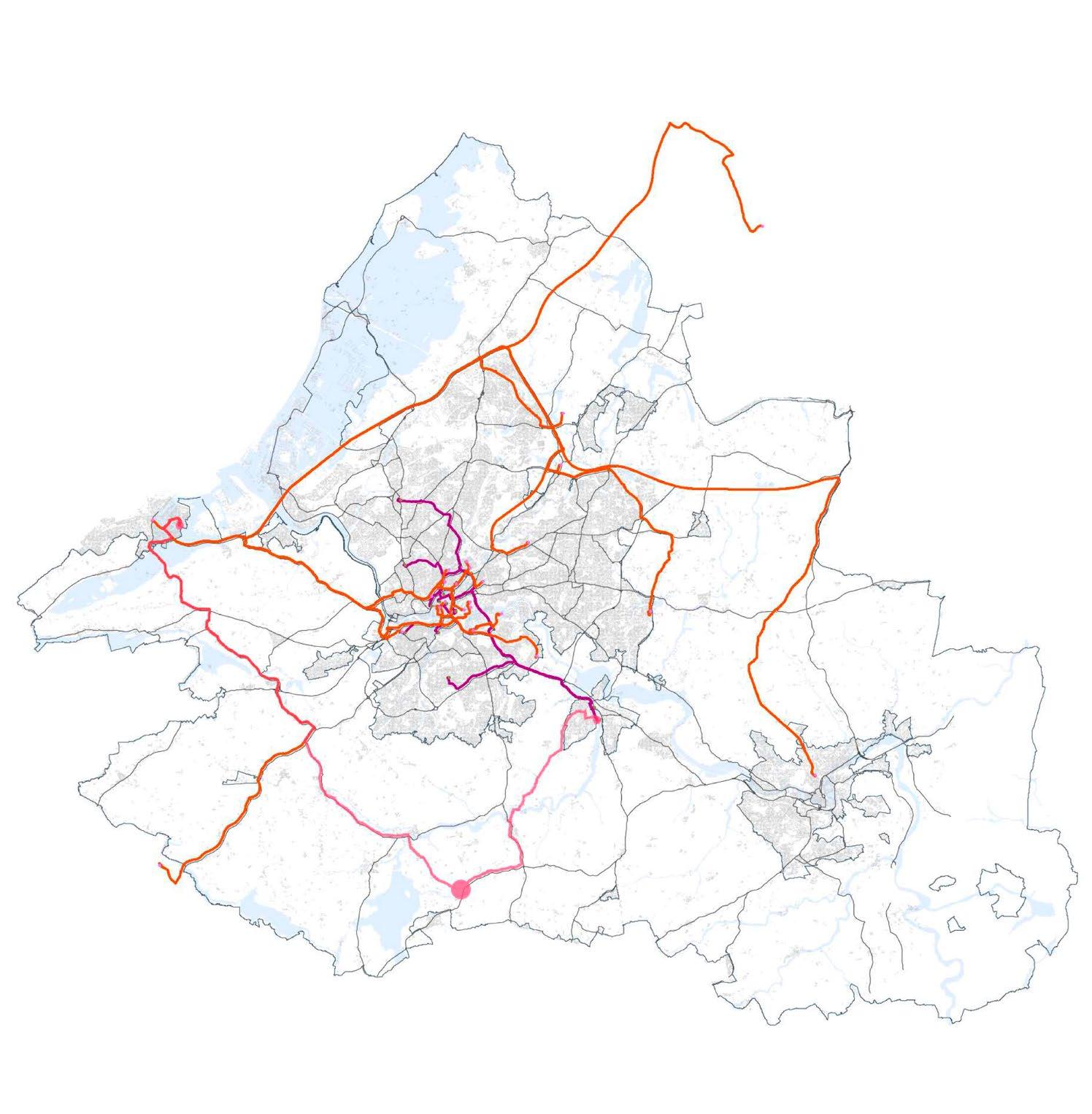

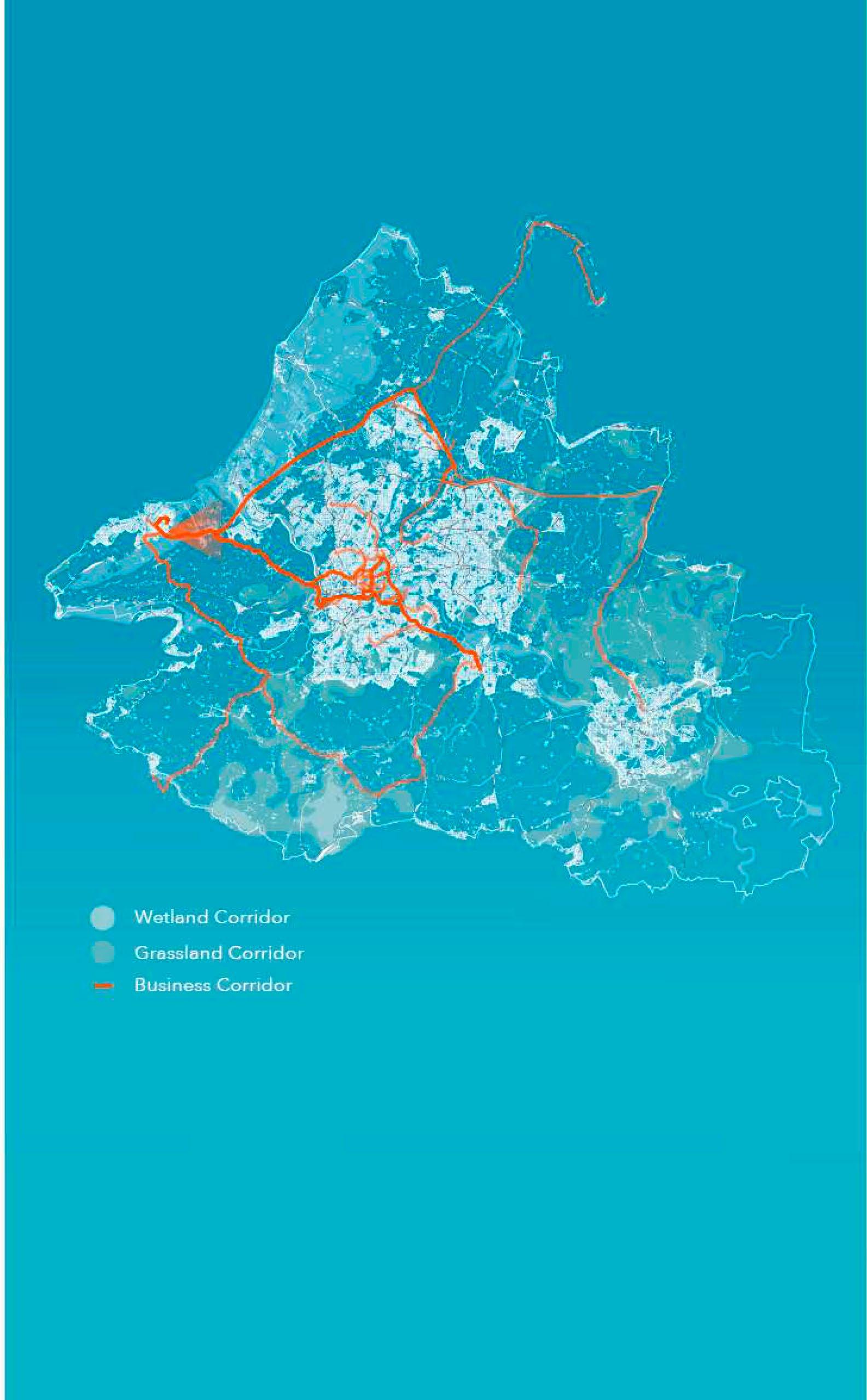

Mapping Bristol’s Corridors

Approximately 13% of the green belt region consists of woodlands. The West England Nature Partnership has identified specific areas within these woodlands that hold potential for the consolidation of woodland corridors. Similarly, they have pinpointed areas for the development of grassland and wetland corridors, collectively naming this initiative the “Nature Recovery Network”.

“WENP is a cross-sector partnership hosted by Avon Wildlife Trust and funded by North Somerset Council, Bristol City Council, South Gloucestershire Council, Bath & North East Somerset Council, Wessex Water and Bristol Water.” (West of England Nature Partnership n.d.)

The strategy outlined by the WENP offers a framework for guiding investment towards the restoration of ecological corridors, taking into account the area’s inherent geography.

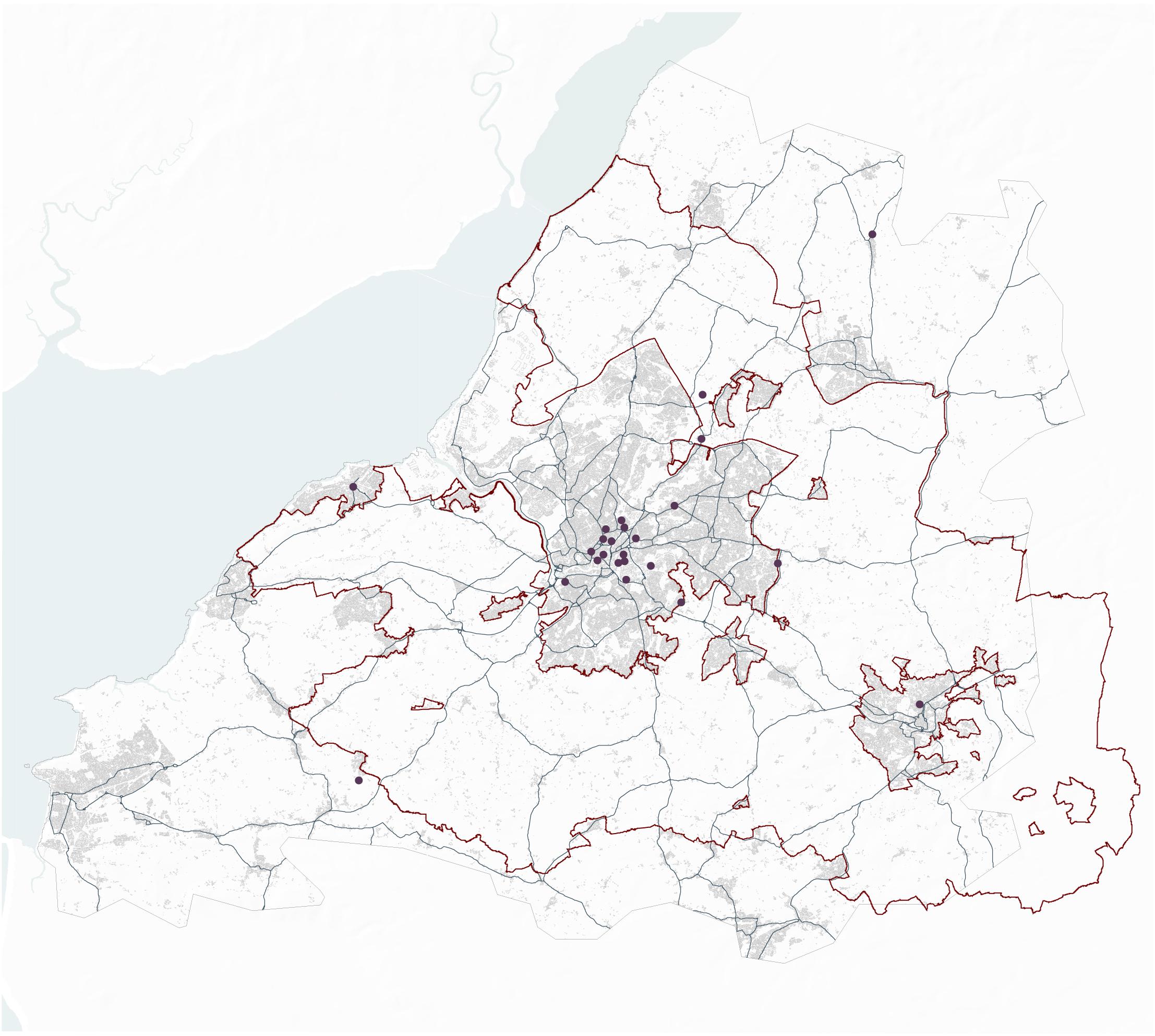

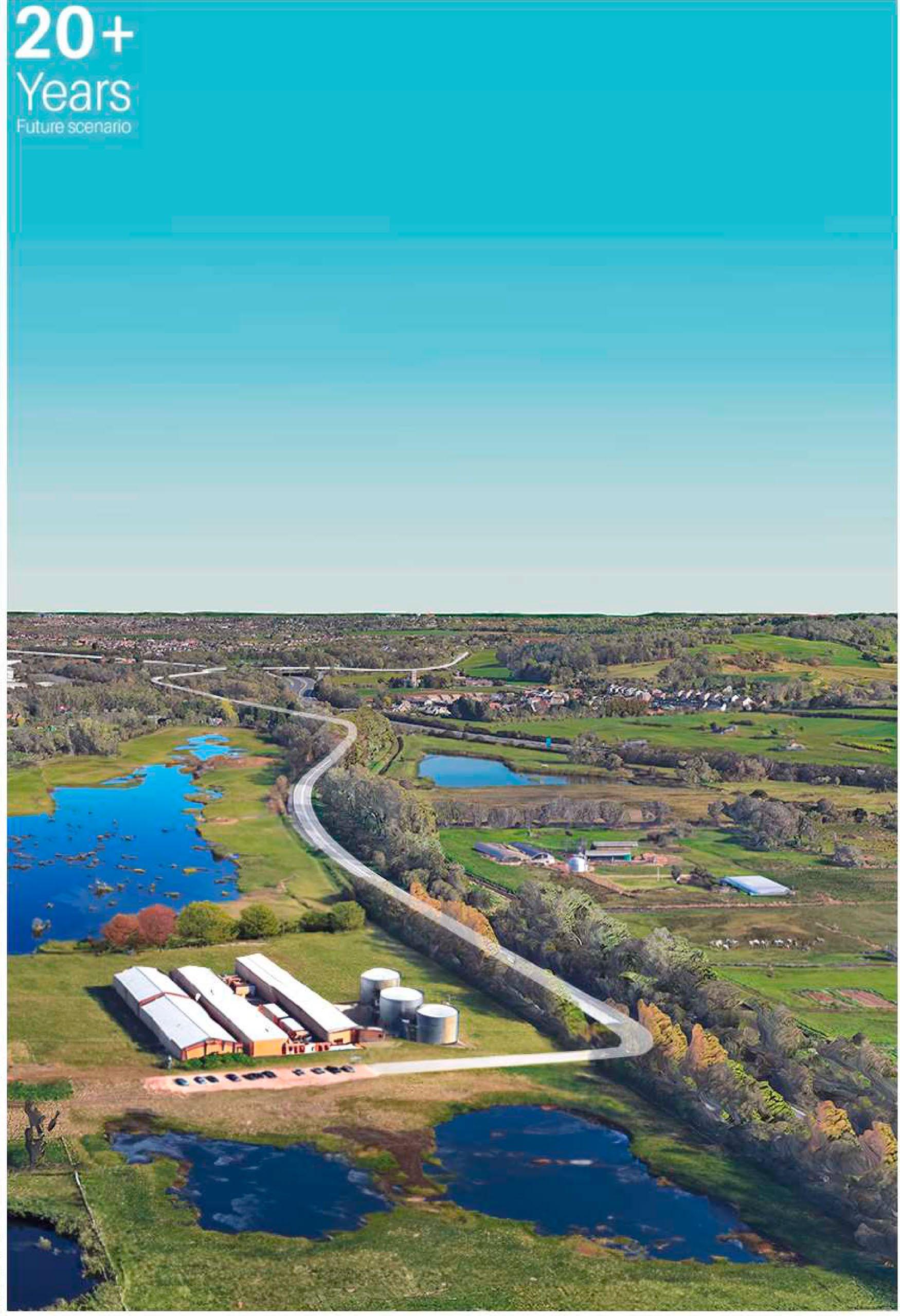

Following the examination of ecological corridors’ potential, the study explored the possibility of conceptualizing businesses within a similar corridor framework.

To start this exploration, a representative selection of businesses from diverse industries was mapped with the aim of providing insights into the spatial dynamics that might exist within a localized business corridor for the city. Each business category was linked to potential activities that could occur on a farm.

Bristol Woodland Strategic Network

Bristol Wetland Strategic Network

Woodland Strategic Corridor Ancient woodlands Greenbelt boundary Bristol Woodland Strategic Network Bristol Wetland Strategic Network Fig 93 Fig 94 By Jegan Muralidharan by Antonio Garaycochea 0 0 5km 5km 10km 10km Source West of England nature partnership Source West of England nature partnership

Wetland Strategic Corridor Greenbelt boundary

Bristol

Peri-urban Woodlands Fig 92 by Jegan Muralidharan

71 | UK Food System 72 [AA Landscape Urbanism 23/24] [AA Landscape Urbanism 23/24] Planet of Fields

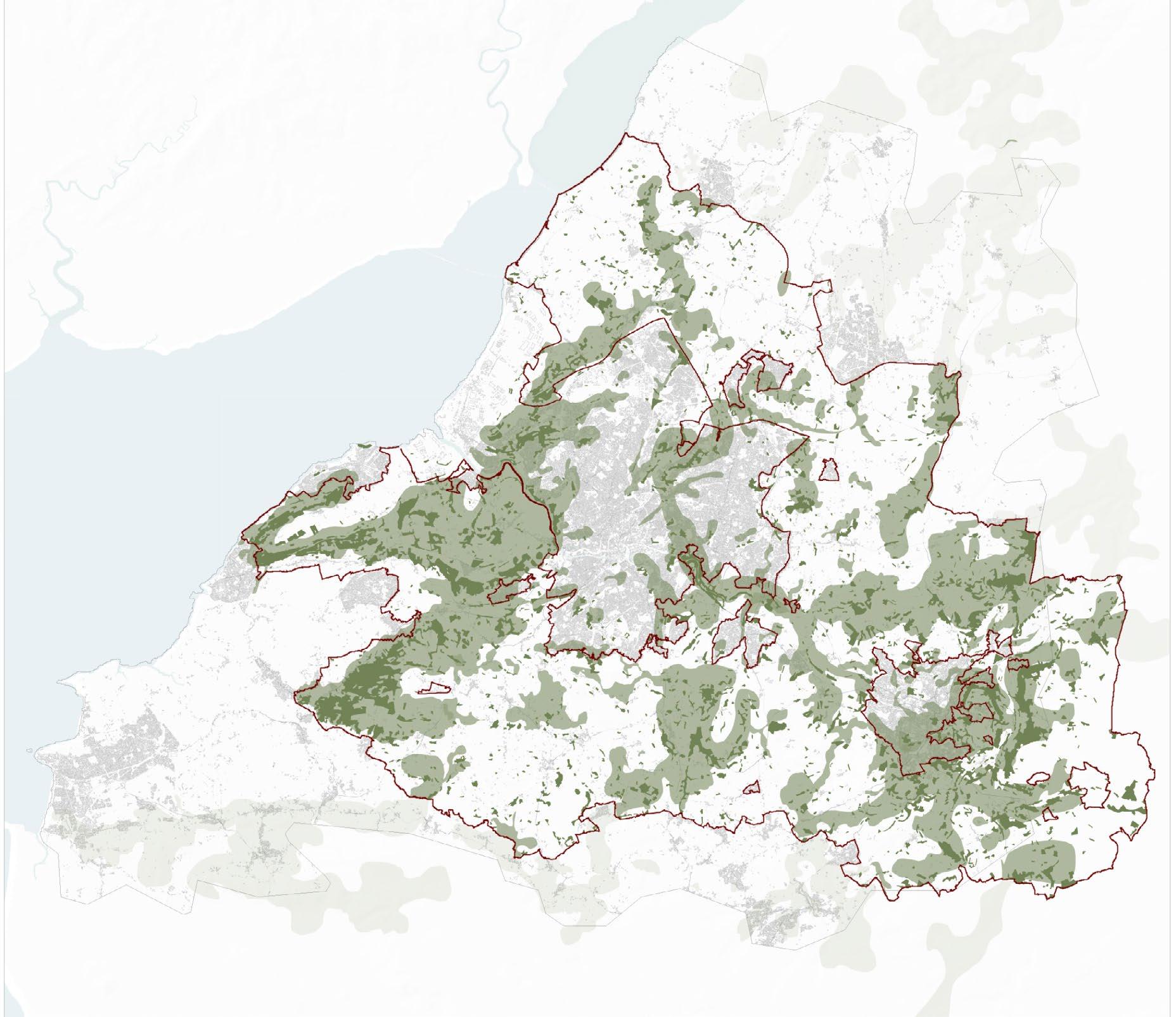

Bristol Grassland Strategic Network

Businesses Related to Food

Agri-schemes and woodland strategic network in the

Businesses related to food in Bristol

Dairy based business Food Markets

Grassland

Bristol

corridor

0 5km 10km

West

nature partnership

strategic corridor Greenbelt boundary

Grassland Strategic

Fig 95 By Antonio Garaycochea

Source

of England

Educational institutions working with Agro-ecology Eateries vicini-

ty of Community Farm

Fig 96

Fig 96

By Jegan Muralidharan

by Jegan Muralidharan

0 5km 10km

73 | UK Food System 74 [AA Landscape Urbanism 23/24] [AA Landscape Urbanism 23/24] Planet of Fields

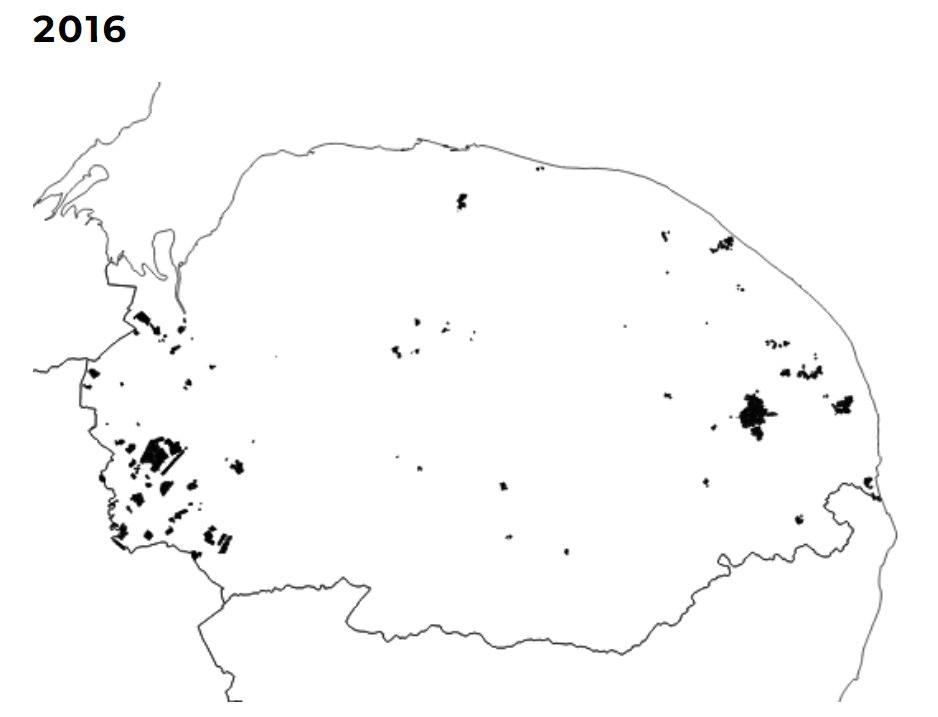

Despite the existence of these strategic networks for ecological corridors, the map below demonstrates that the areas with potential for woodland corridors don’t align with the plots entering woodland agreements. This disparity highlights the scarcity of a systematic approach in the current ELM schemes.

Village in Green Belt Fig 98 Https://www.istockphoto.com/ photos/aerial-view-uk Overview Farm Succession Council farms & community ownership Farm Clusters Policy Proposal [06] 75 76 Planet of Fields

Overview

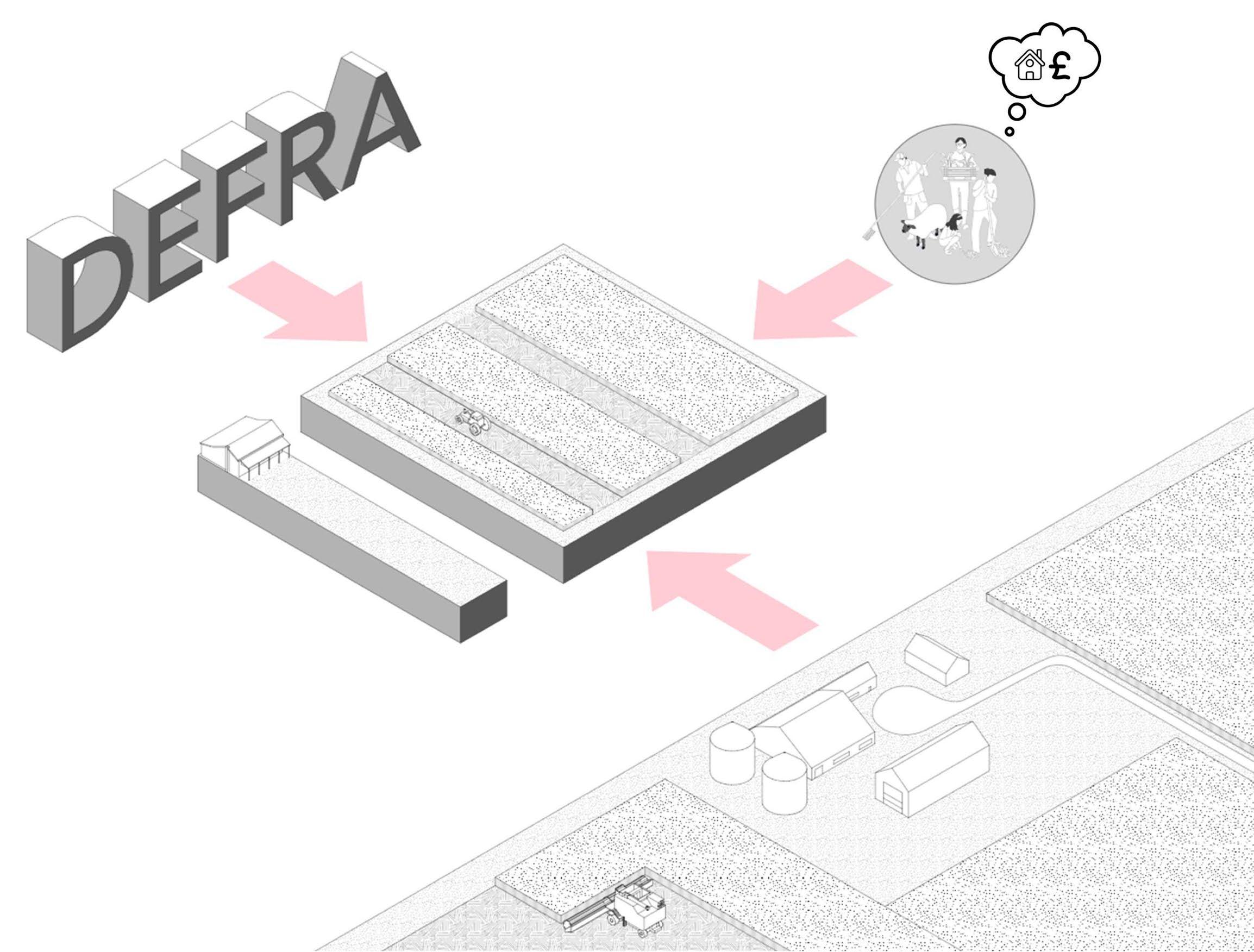

In response to the 3 issues that were previously mentioned, the specific objectives of the policy proposal are:

1. Creating localized business corridors: This will be achieved through enterprise stacking and funding of intermediate industries

2. Promoting models of shared ownership: Changes to the farm succession scheme will facilitate models of shared ownership.

3. Strengthening farm clusters: Empower farm clusters will facilitate their integration to the city’s ecological corridors.

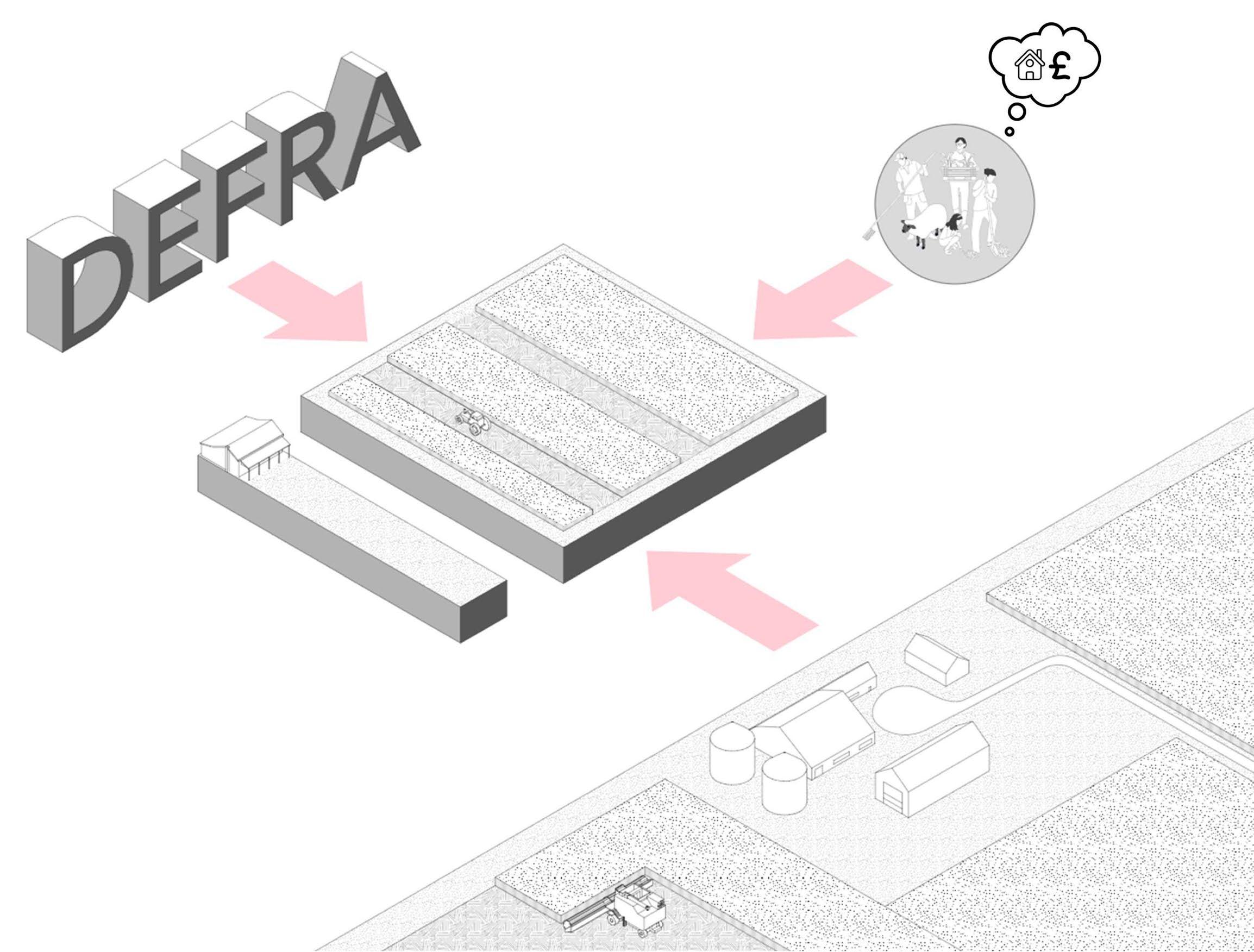

To achieve these, the proposal’s strategy impacts both top-down and bottom-up structures. From a top-down perspective, modifications will be made to the Lump Sum Retirement Scheme and council farms. Meanwhile, from a bottom-up viewpoint, the proposal impacts Community Land Trusts (CLTs) and farm clusters.

The over-arching aim of the proposed modifications, which will be detailed in the subsequent pages, is to incentivize farmers to sell their land into community ownership. Once these farms transition into community ownership, the policy will further encourage them to establish farm clusters. These clusters will then integrate with the city’s ecological corridors, at the same time fostering relationships with local businesses.

By Antonio Garaycochea

By Antonio Garaycochea

Policy proposal overview Fig 99

PLANET OF FIELDS -[AA Landscape Urbanism 22/23] PART 1 PRECEDENTS PART 2 CONTEXT PART 3 AGROECOLOGY PART 4 AVON GREENBELT PART 5 POLICY PROPOSAL PART 6 CEREAL PLANET OF FIELDS -[AA Landscape Urbanism 22/23] PART 1 PRECEDENTS PART 2 PART 3 PART 4 PART 5 PART 6 CEREAL

Ownership Modified instruments 77 | UK Food System [AA Landscape Urbanism 23/24] Planet of Fields

Current Structure Proposal Structure

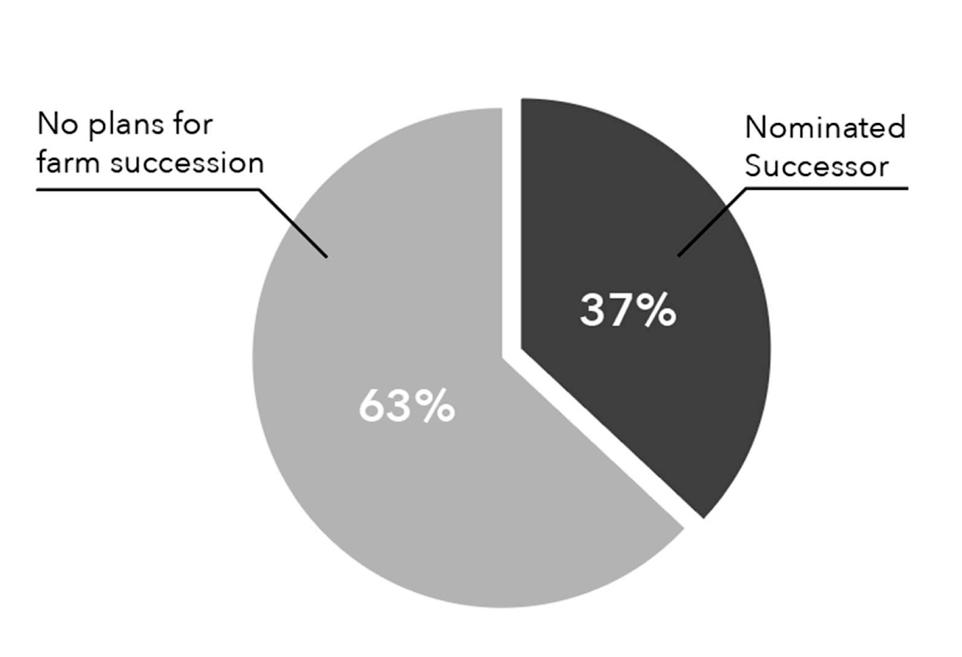

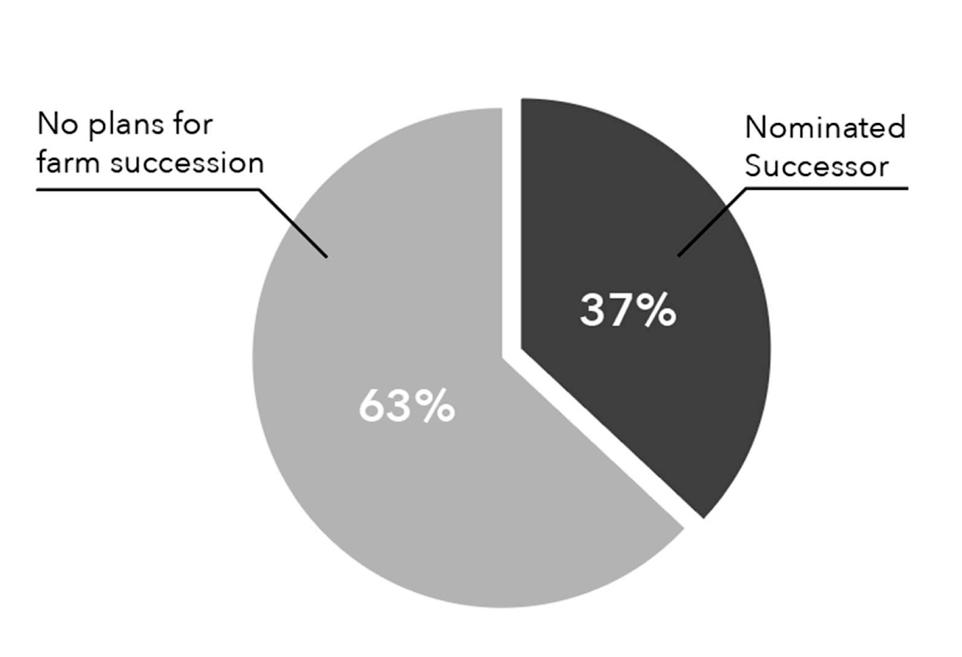

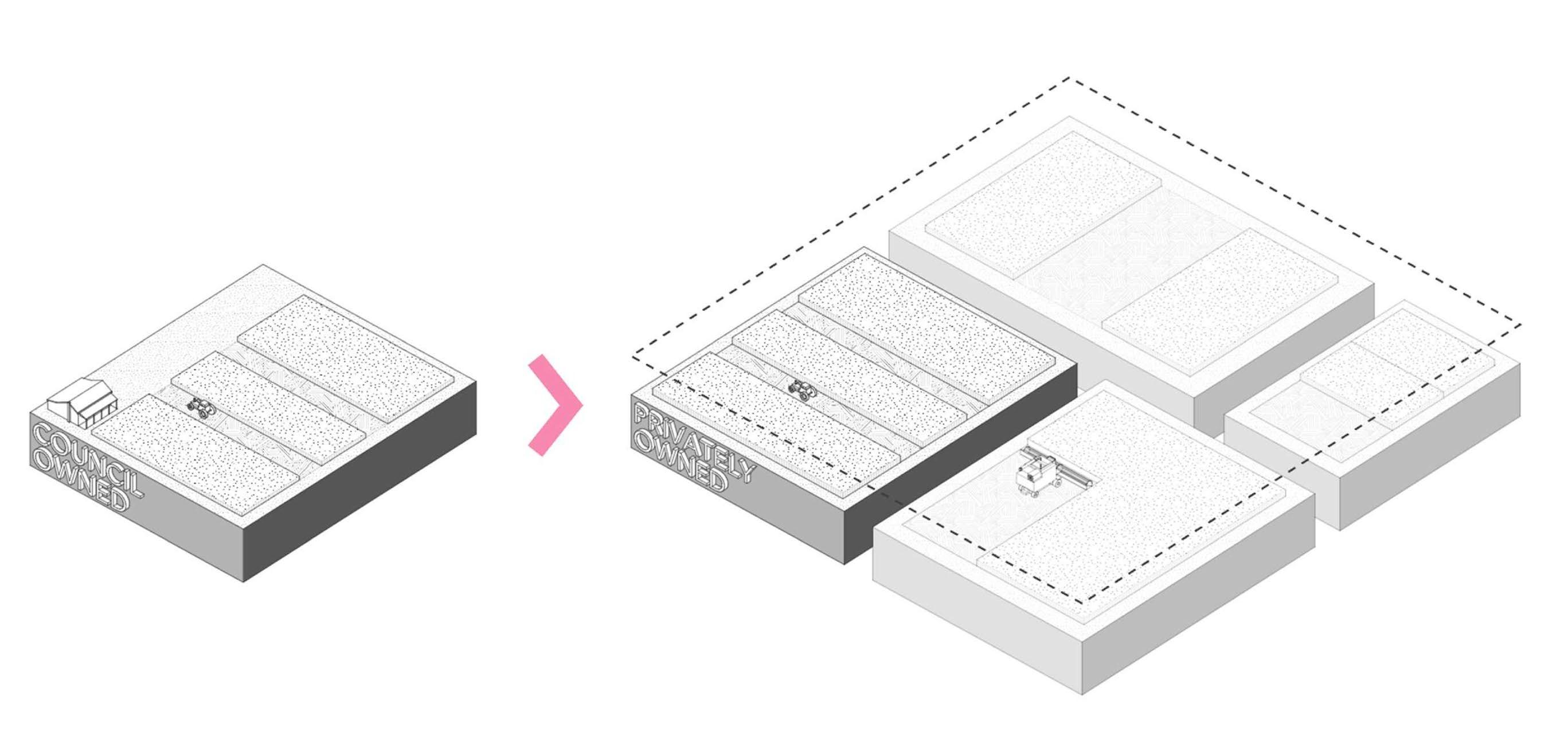

Farm Succession

According to the Office for National Statistics (ONS), two-thirds of farmers who are retiring do not have a succession plan (Oldham n.d.). Under the current retirement scheme, these farmers have the option to either sell or gift their land in exchange for a lump sum payment based on a portion of what they would have received from BPS payments in the following years. Additionally, they are allowed to retain ownership of the farmhouse and up to 15% of the land that it is on (DEFRA 2022). The latter is a measure taken to address housing concerns for the outgoing farmer.

There are some issues to take into account with this current scenario. Firstly, The present scheme appears to be more beneficial to wellestablished farmers aiming to expand rather than accommodating new entrants. New farmers not only need land but also require housing, which the current scheme doesn’t effectively provide for. Furthermore, there is a competitive disadvantage for new entrants during the purchase of the land. If retiring farmers opt to sell their land to the highest bidder, larger corporations often have greater financial capacities.

To address these concerns, this thesis’ proposal recommends the following modifications:

A) Landowners would only be eligible for the lump sum retirement payment if they sell to communitybased buyers – whether it be a Community Land Trust (CLT), a new entrant farmer, or the council.

B) In scenarios where the landowner is in a hurry to finalize the sale, the council will purchase the land at market value. If the seller decides to retain ownership of the farmhouse, they would be obligated to participate in a mentorship program for a set duration.

By Antonio Garaycochea

By Antonio Garaycochea

Planned farm succession

Current and proposed structure of farm succession

Fig 100

Fig 101

Succession scheme favours larger land owners

By Antonio Garaycochea

By Antonio Garaycochea

Planned farm succession

Current and proposed structure of farm succession

Fig 100

Fig 101

Succession scheme favours larger land owners

79 | UK Food System 80 [AA Landscape Urbanism 23/24] [AA Landscape Urbanism 23/24] Planet of Fields

Farm succession favours sale of land to local owners and exiting farmers enter a mentorship scheme

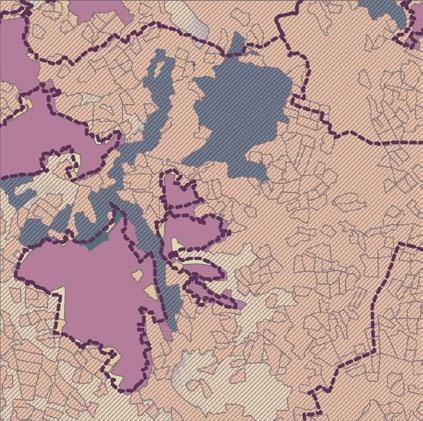

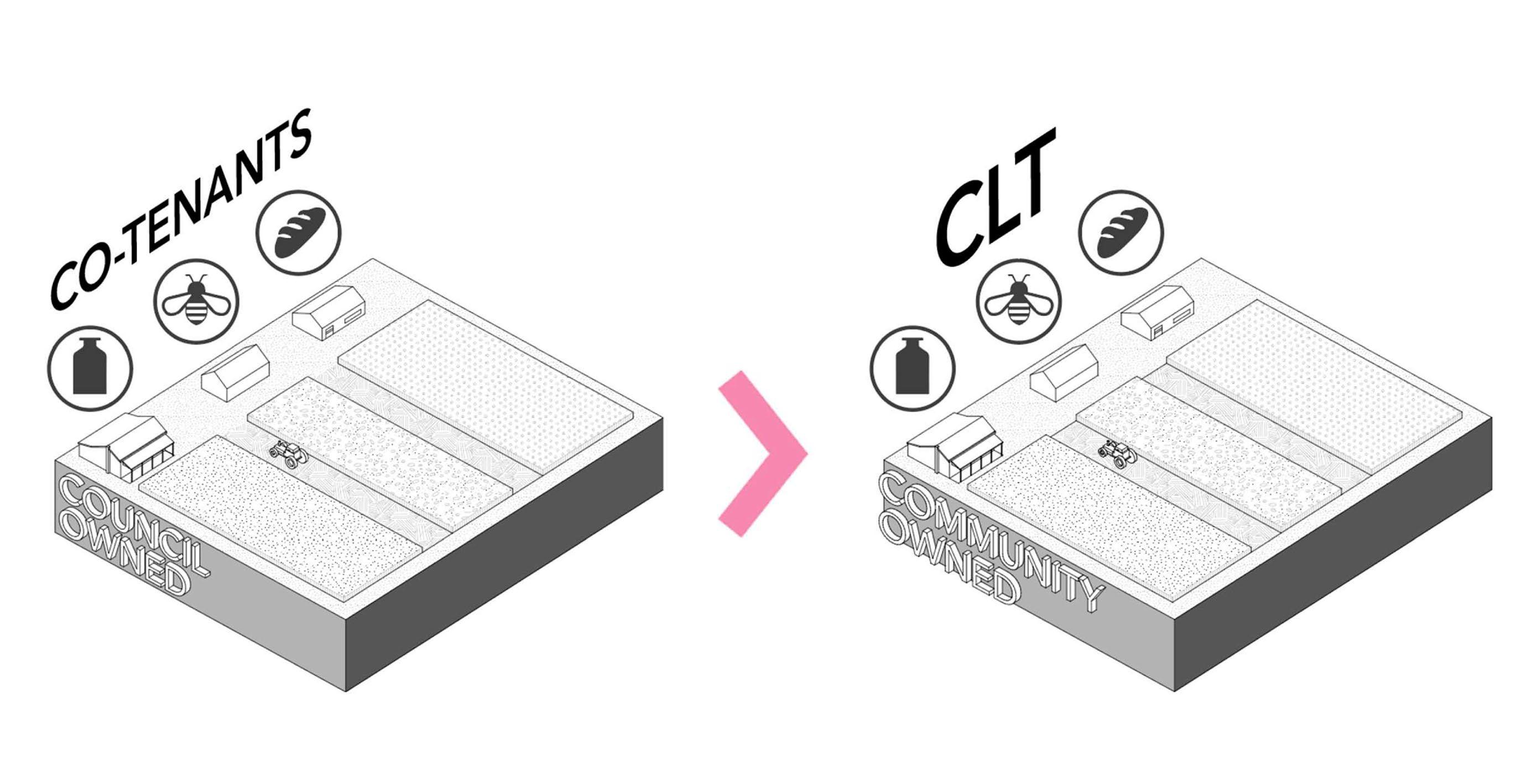

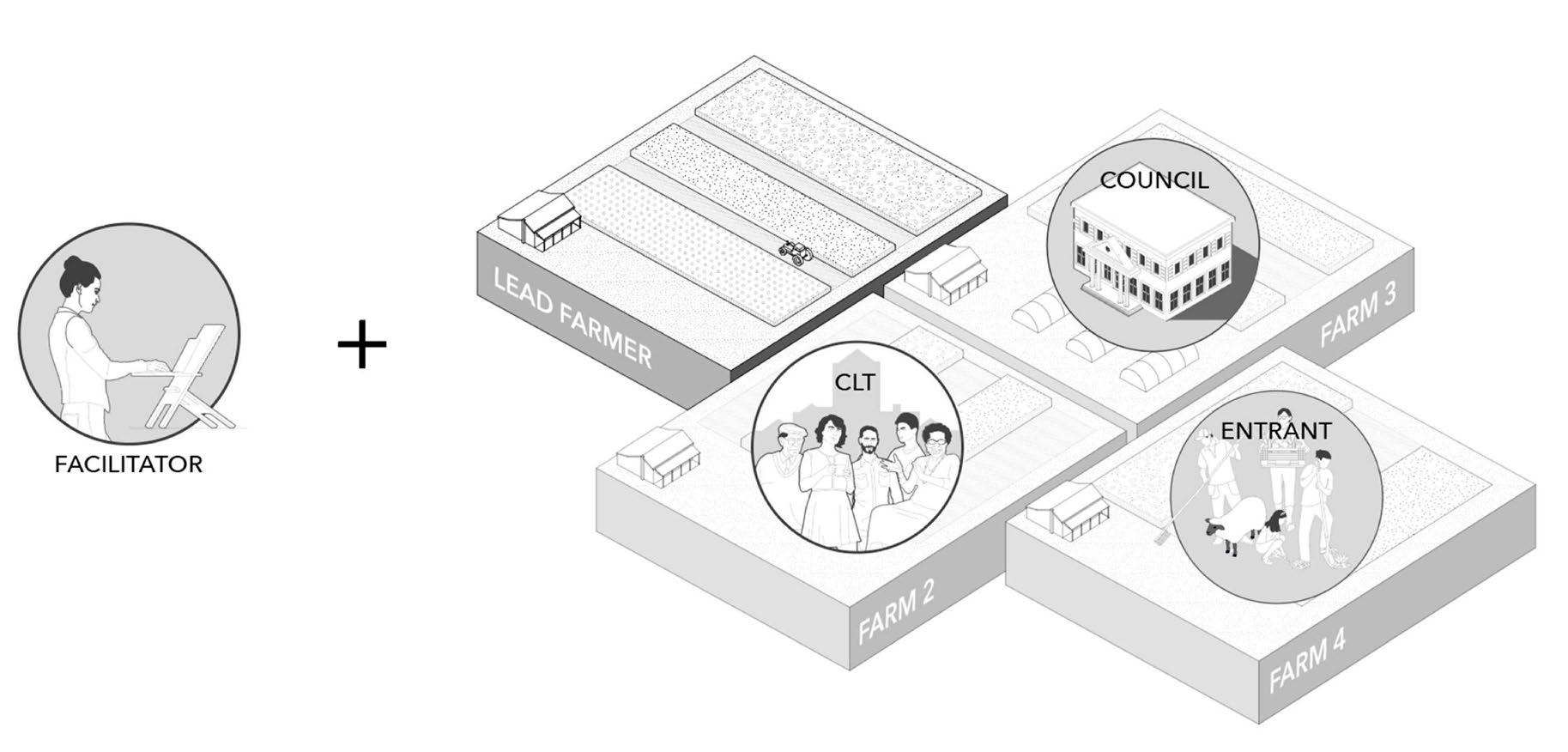

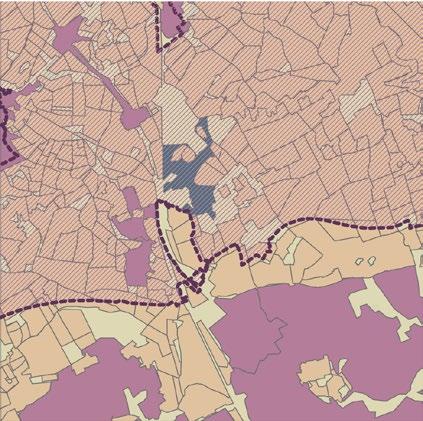

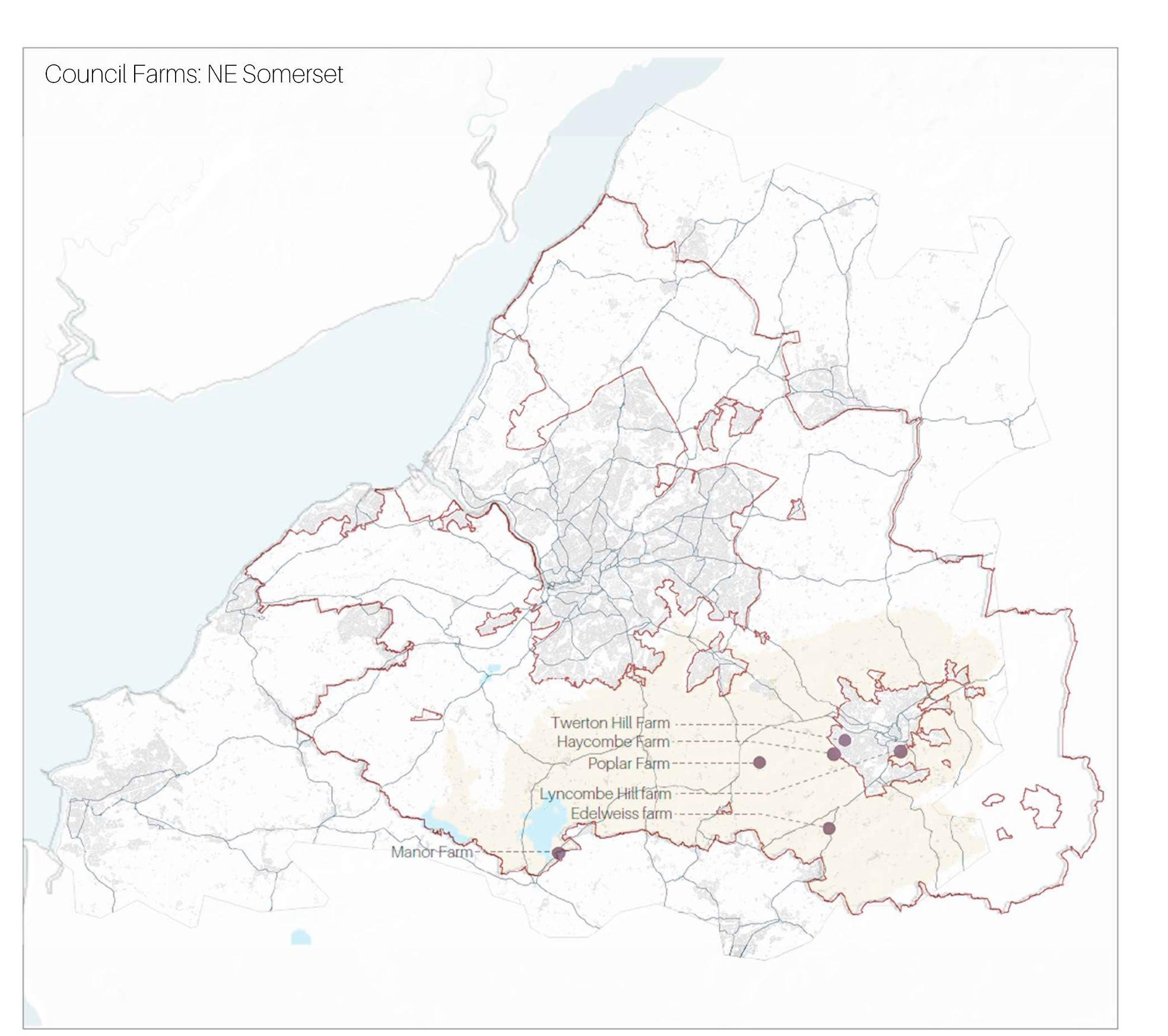

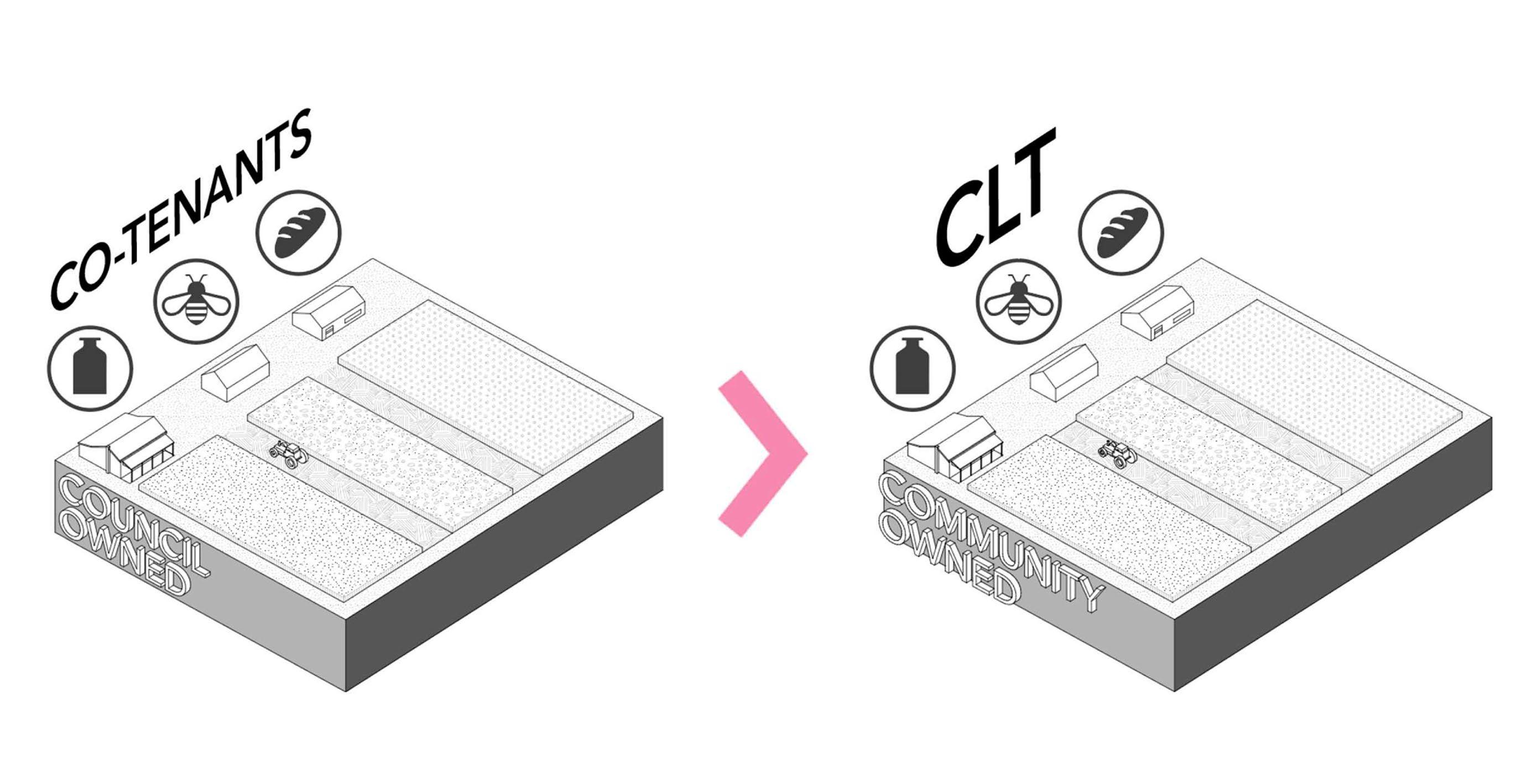

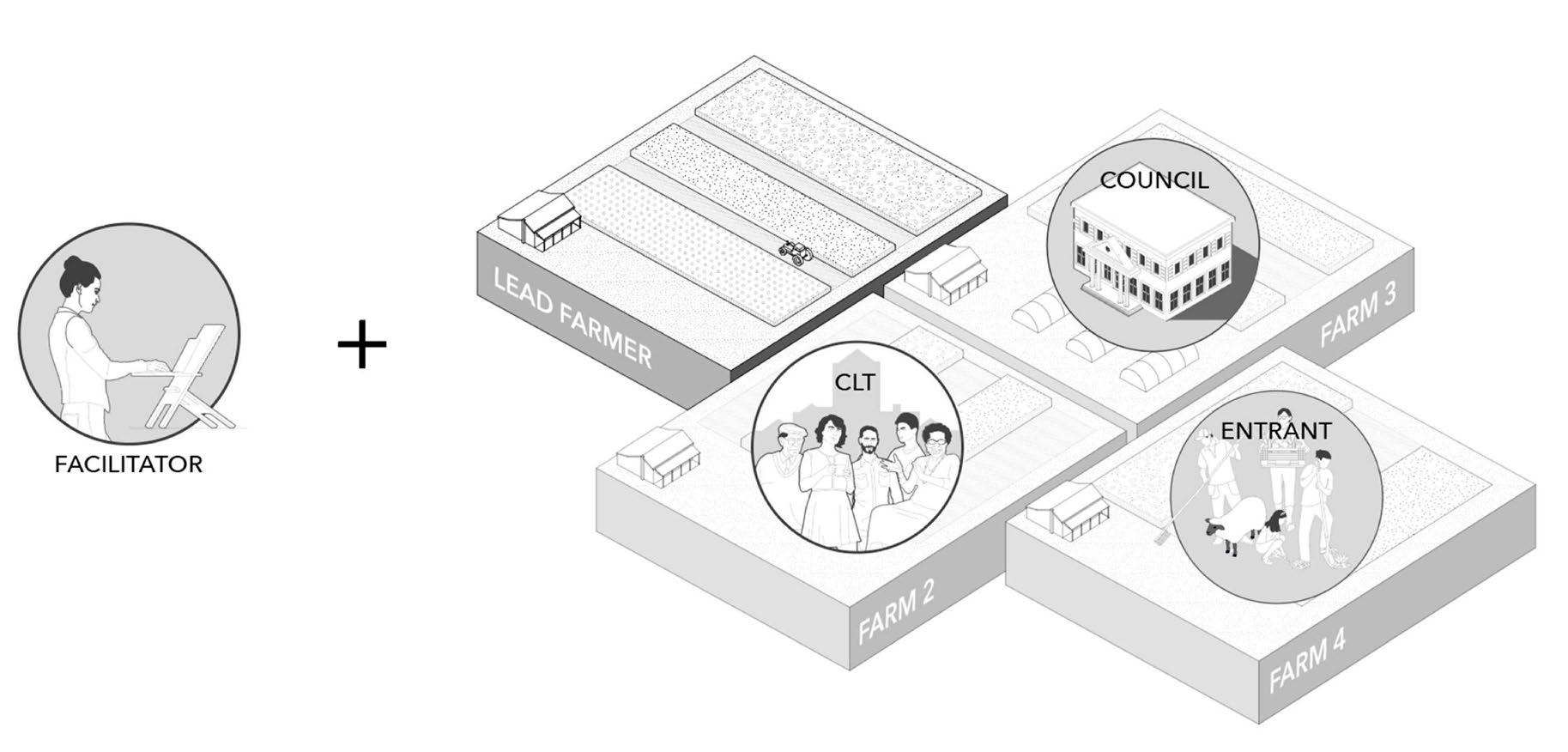

Council Farms and Community Ownership

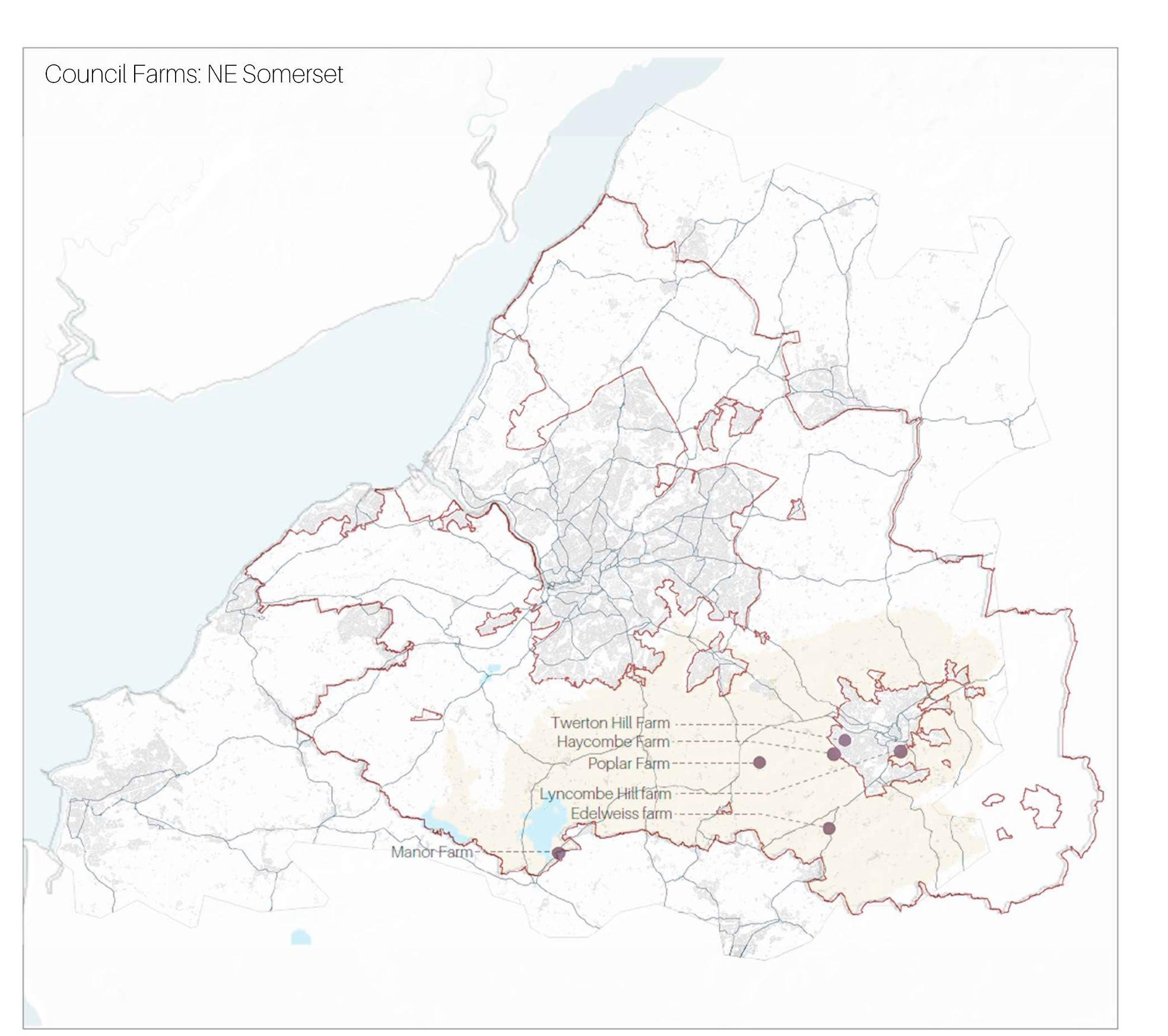

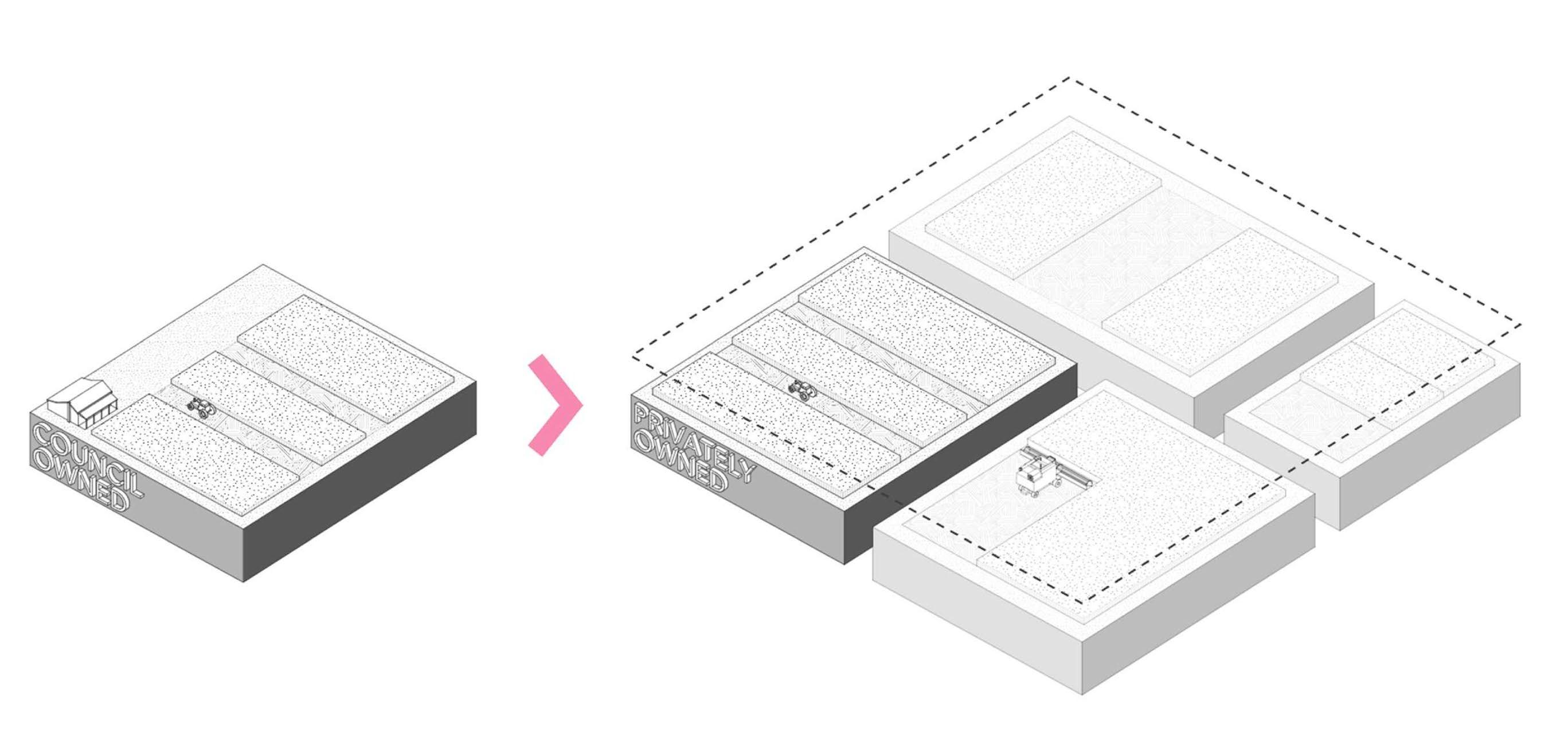

By implementing the measures previously described, there could be an increase in the number of farms acquired by councils. Data available from the North East Somerset council was extrapolated to the rest of the green belt area and it suggests that there are approximately 18 council-owned farms within the entire Bristol green belt.

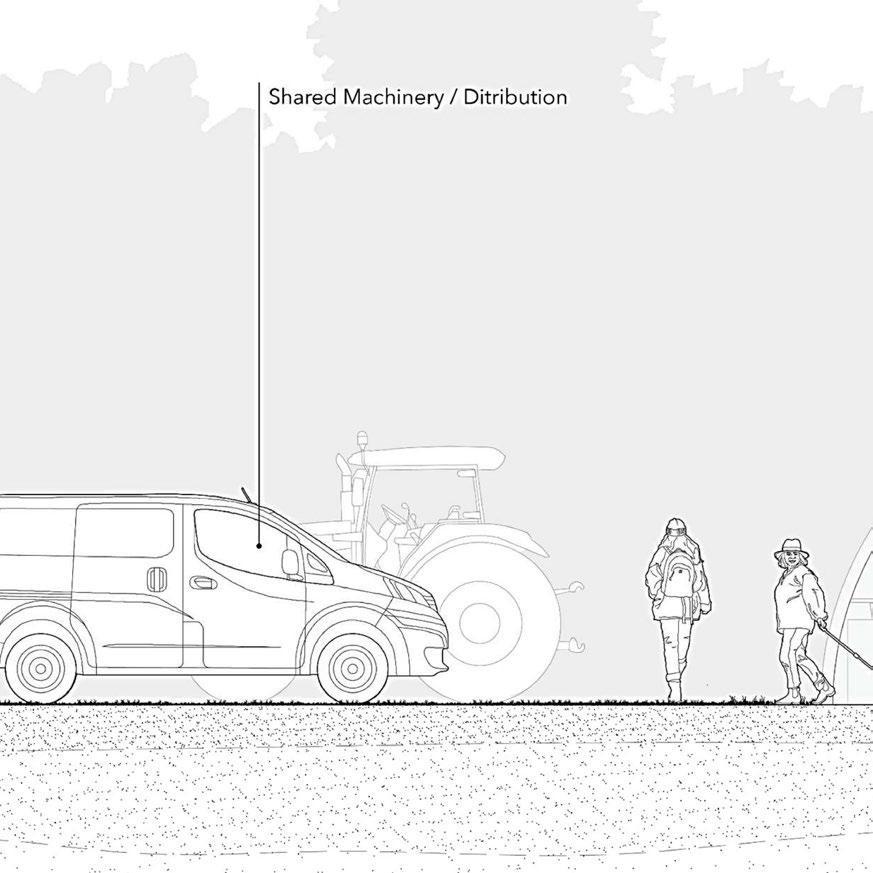

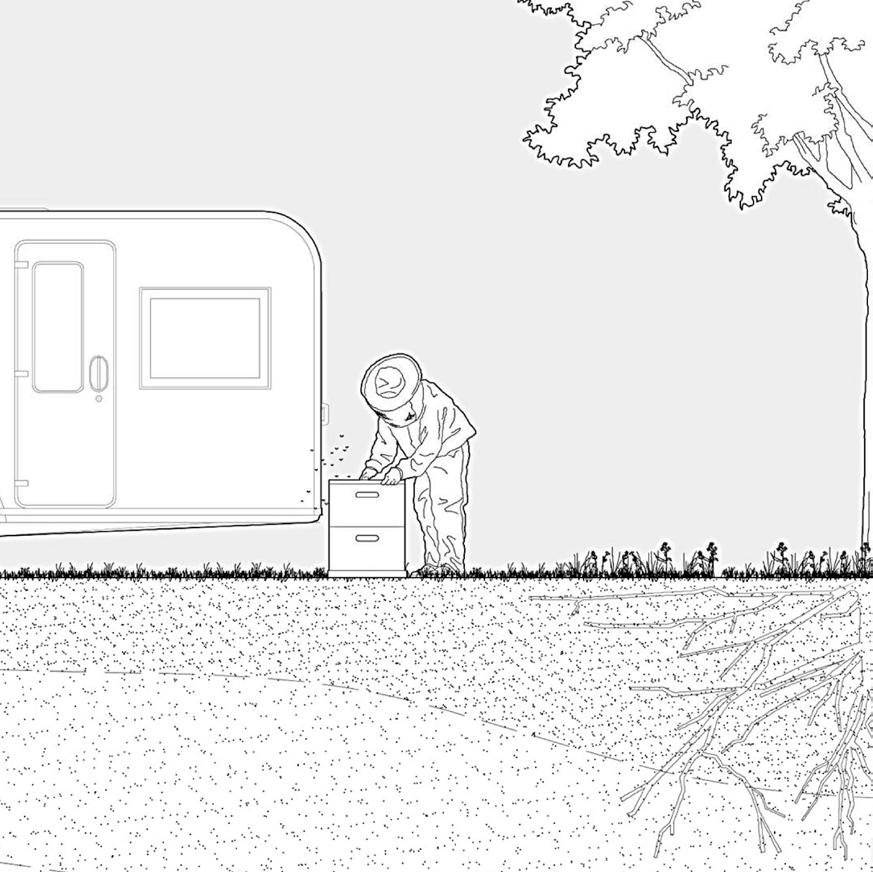

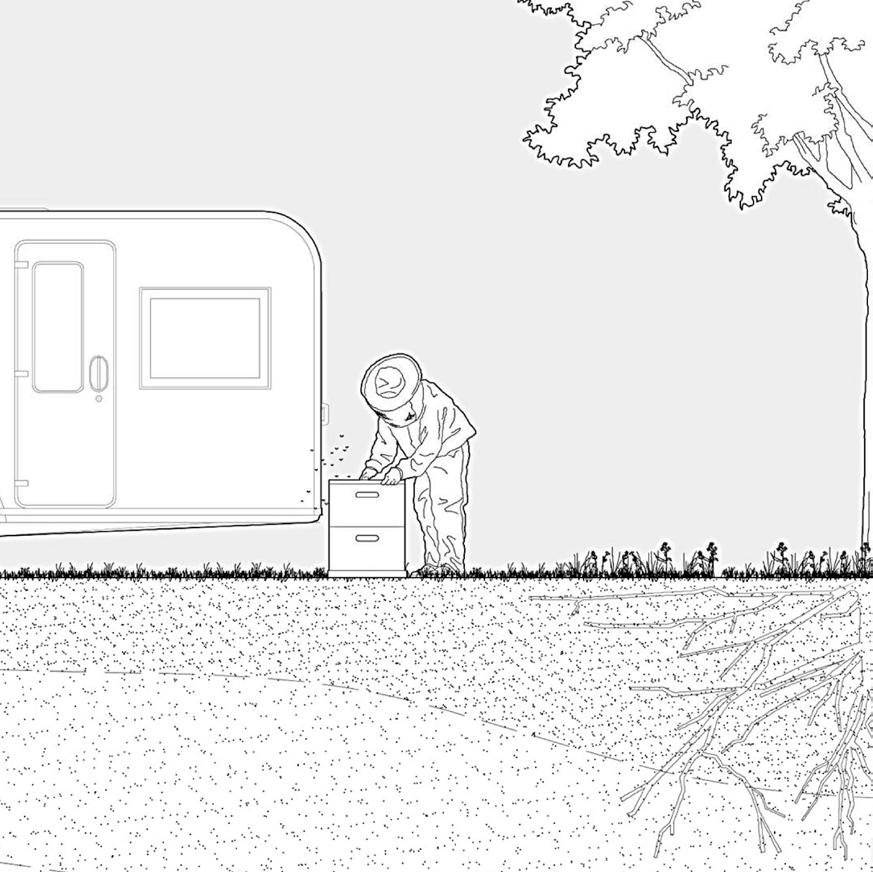

As has been mentioned in previous sections, there has been a notable trend in councils selling off their farm properties. In the majority of these cases, the land often ends up consolidated under large landowners (Who Owns England 2018). The alternative offered by this thesis allows entrant farmers to co-lease farms with local businesses. This approach makes leases more attainable for newcomers but also ensures that councils do not need to reduce their leasing revenues. In this context, the type of businesses likely to co-lease council farms are those that would benefit from the land use, such as small scale honey producers or artisanal juicers.

In addition, we suggest expanding the “Right to Buy Scheme”, which presently only applies to council housing, so that it also includes council farms. The idea behind this is to empower tenants with the ability to purchase the farm after fulfilling a specific tenancy duration. This purchase could be done independently or in collaboration with their co-leasers.

This cyclical system – where the council acquires land, leases it for a period, then sells it for collective ownership – not only enables the council to recover its initial investment but also allows it to purchase additional farms. Incrementally, this strategy would transition more land parcels into community ownership.

Current Structure

Council farms to larger land owners

Current and proposed structure of council farms

By Antonio Garaycochea

By Antonio Garaycochea

Proposal Structure

Local businesses hold shared tenancy of council farms and have access to a right to buy scheme after a predetermined number of years

Fig 103

NE Somerset council owned farms within Avon greenbelt

Fig 102

Fig 103

NE Somerset council owned farms within Avon greenbelt

Fig 102

81 | UK Food System 82 [AA Landscape Urbanism 23/24] [AA Landscape Urbanism 23/24] Planet of Fields

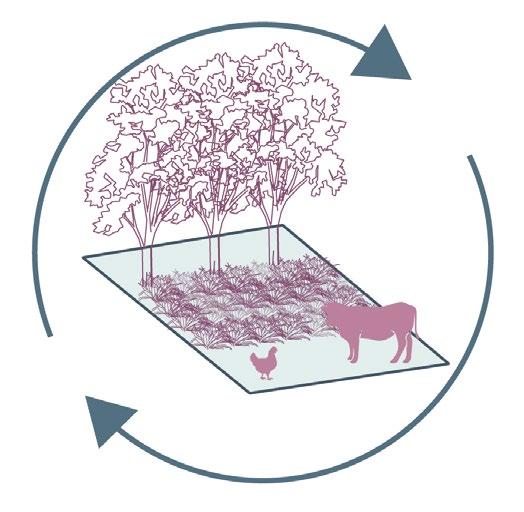

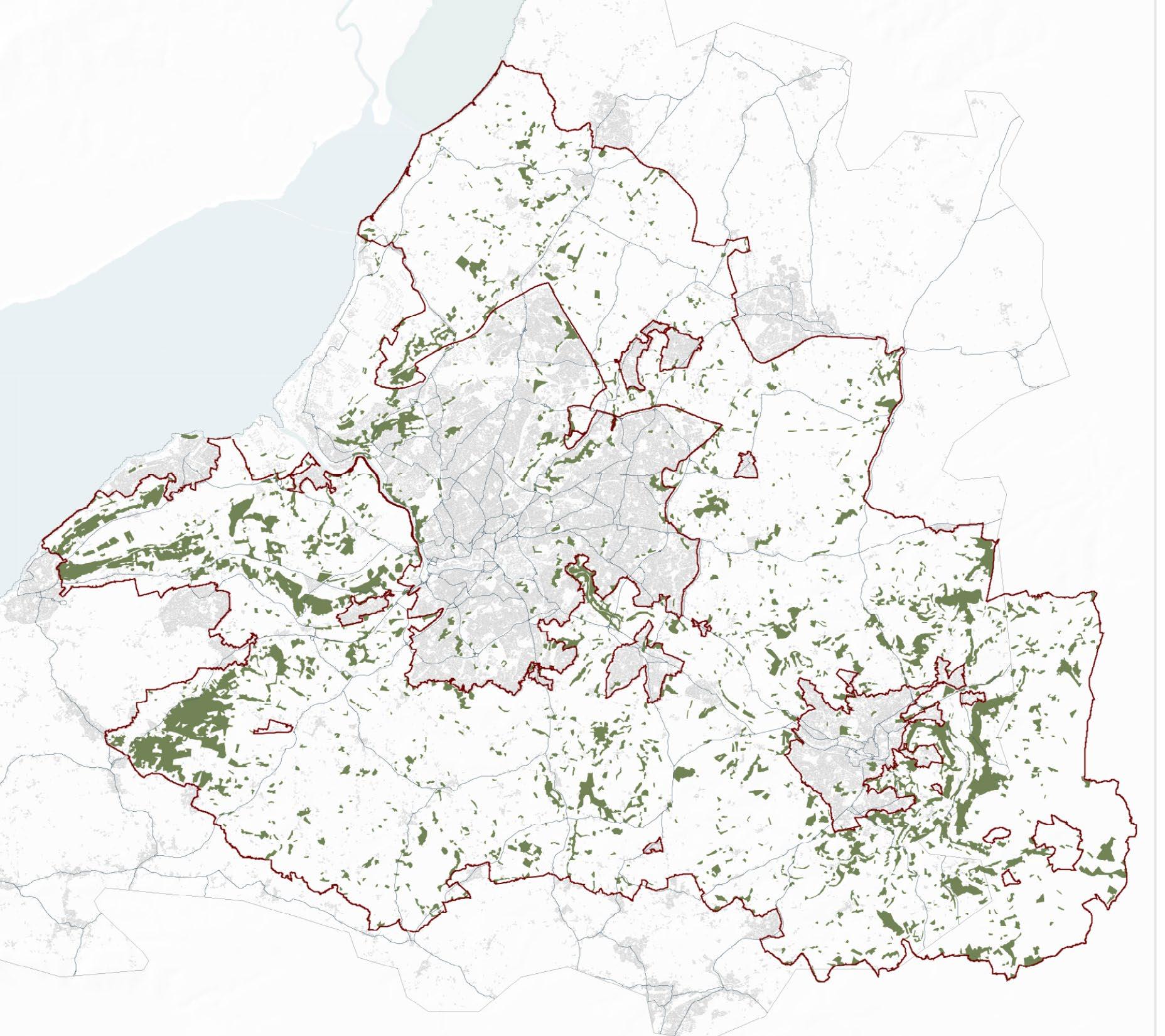

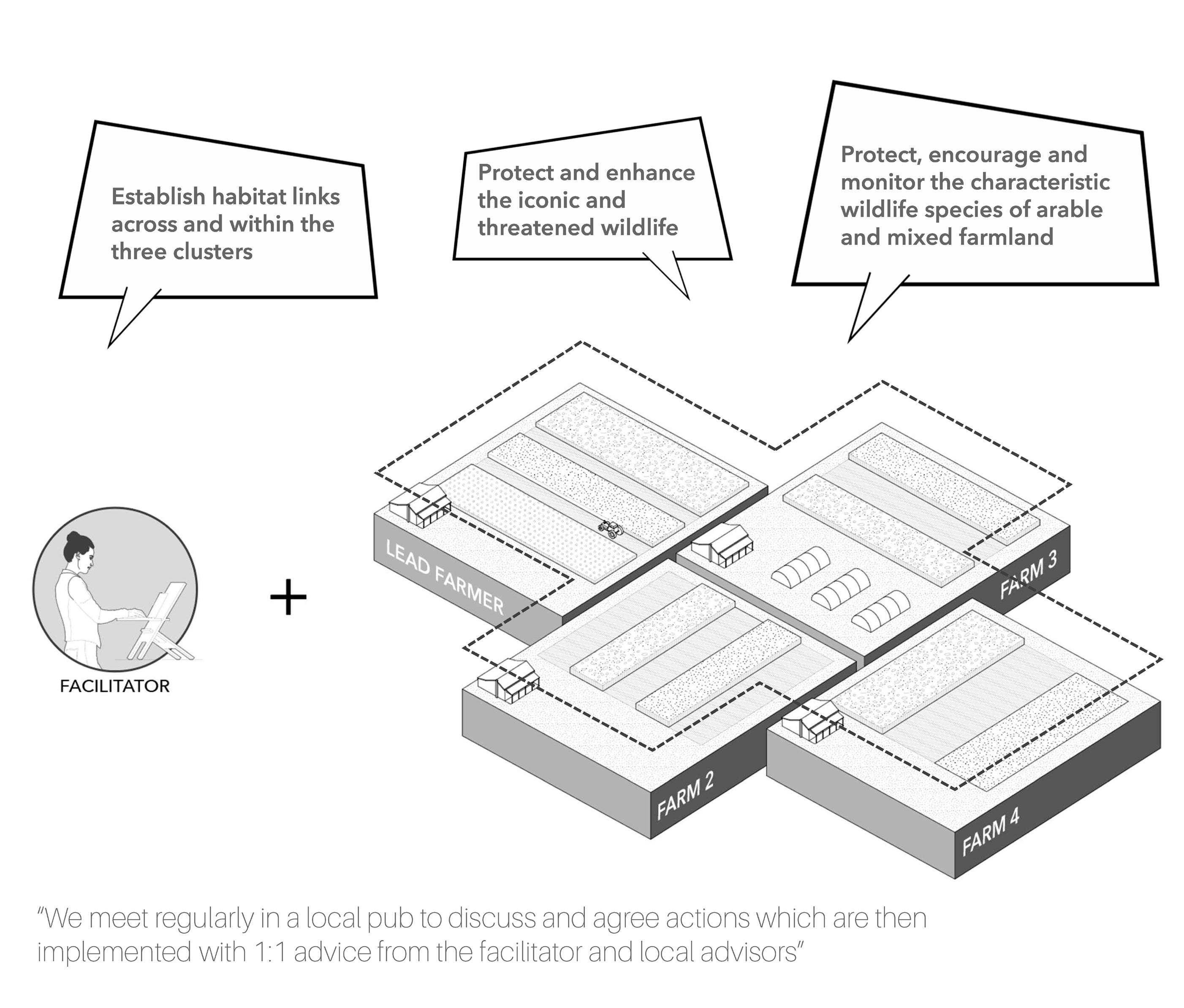

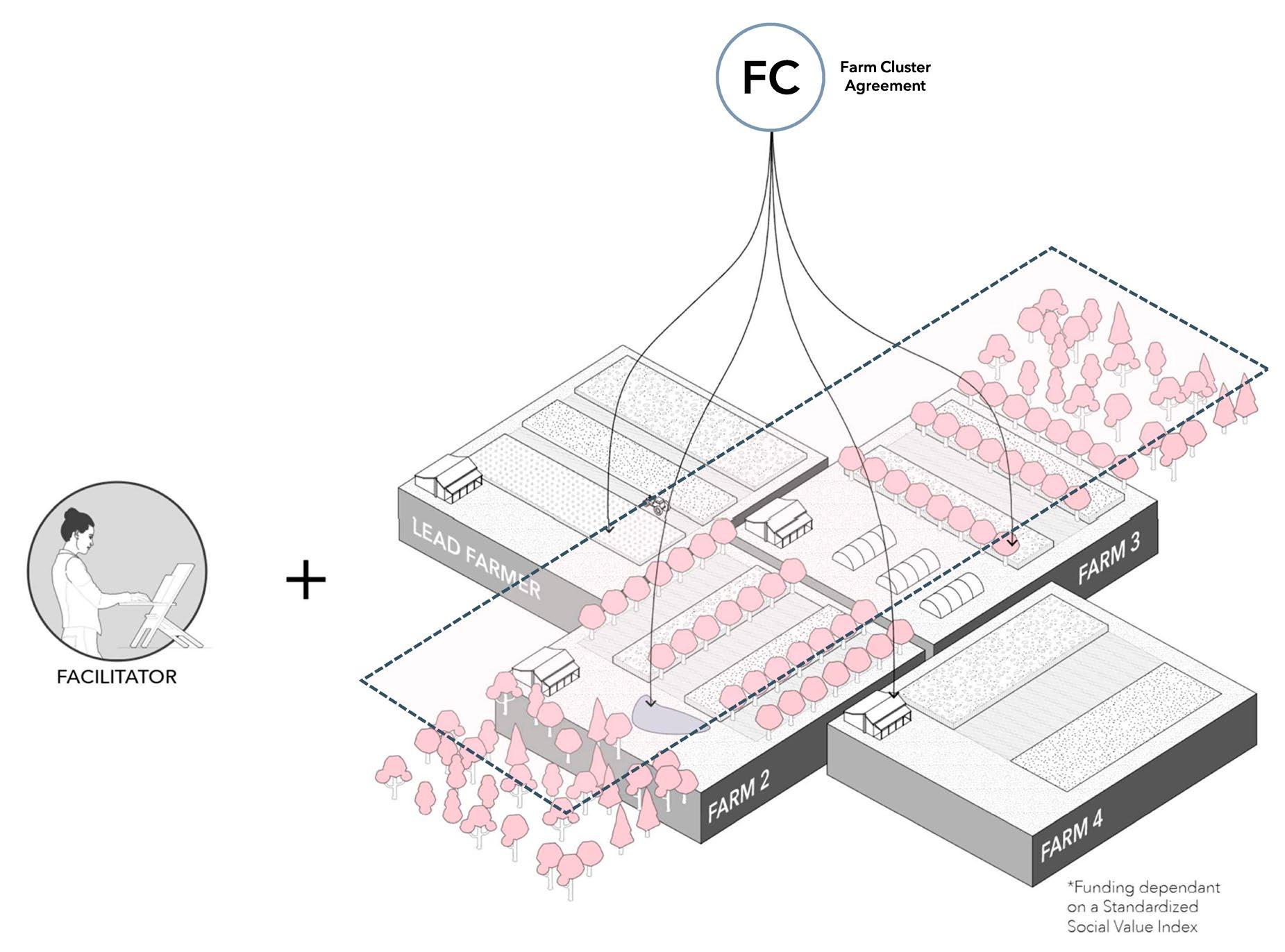

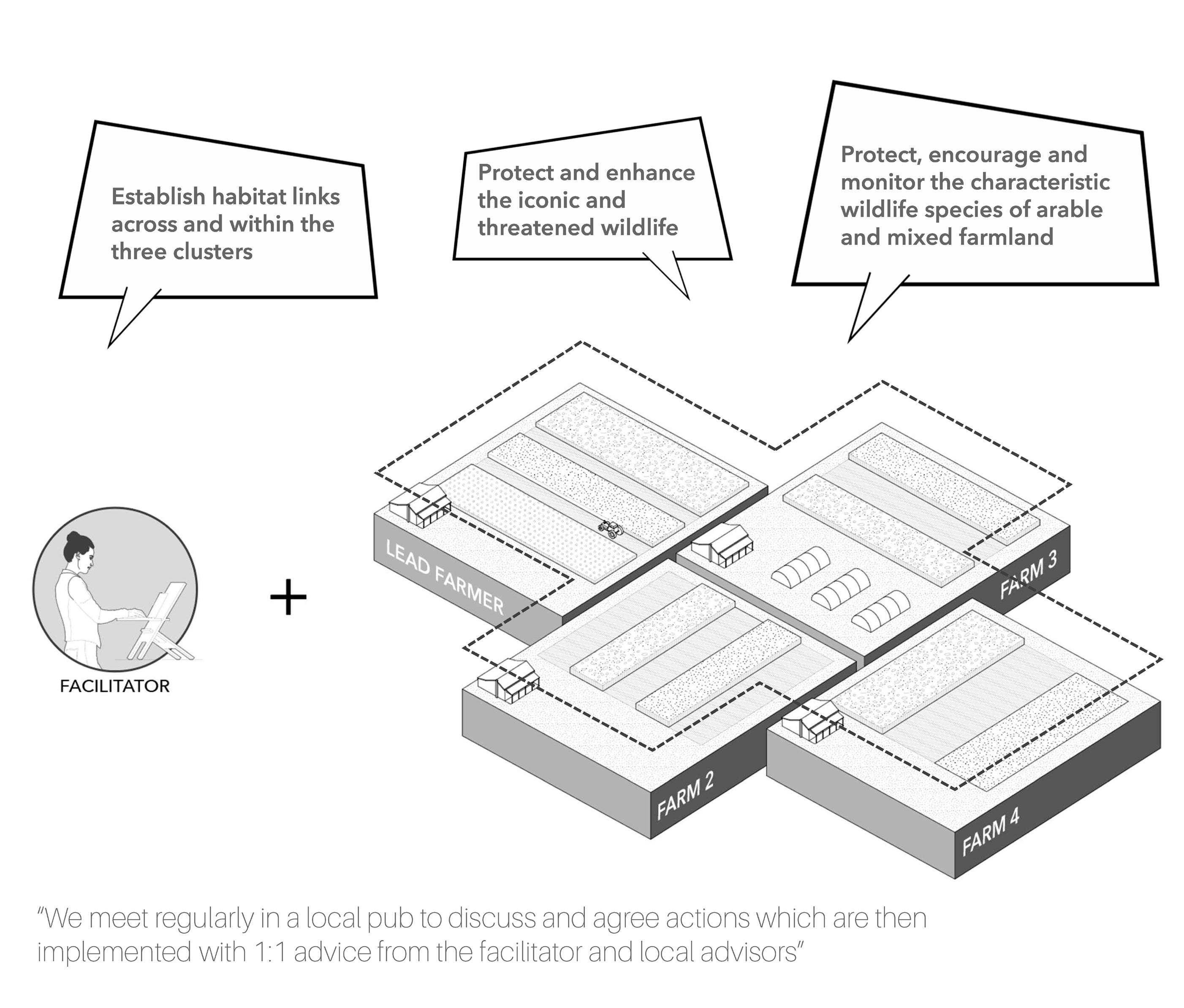

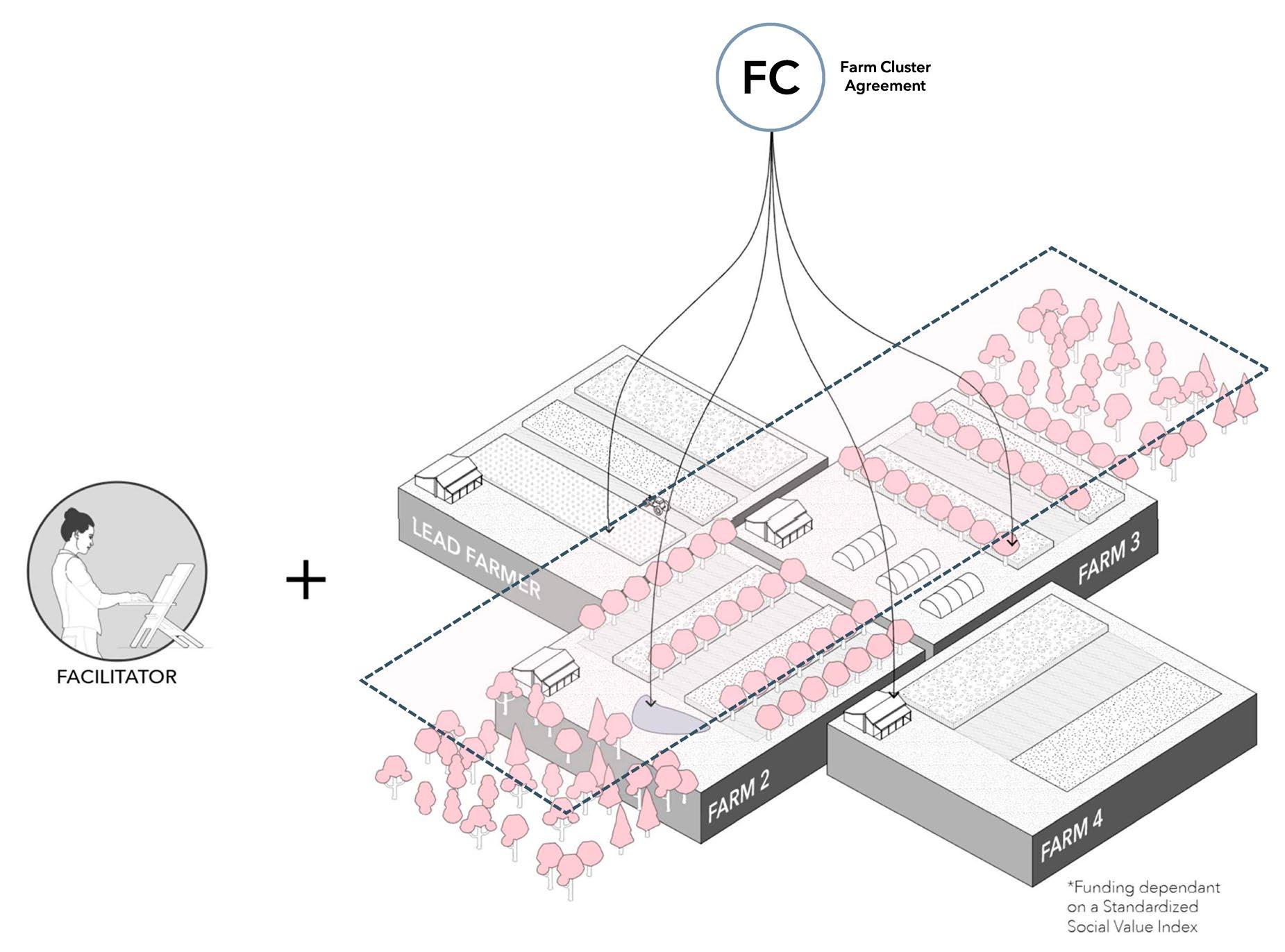

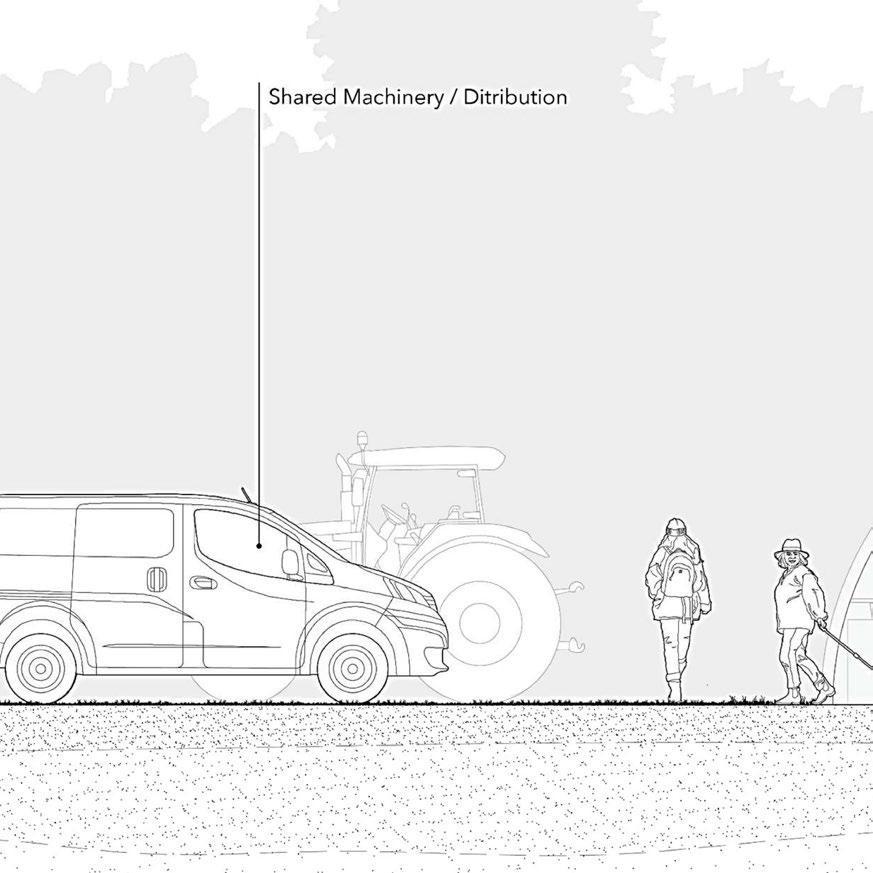

Farm Clusters

The last stage of this proposal is centred on the formation of farm clusters. Because of their larger scale and cooperative nature, farm clusters have great potential in creating sustainable and democratic agriculture. Currently, clusters are conformed by a group of farmers, with one taking the role of the lead farmer. This group then collaborates with a facilitator, who becomes responsible for guiding them towards accomplishing their self-determined objectives for the cluster (“Starting a Farmer Cluster” 2018).

Although there are others, the main source of funding for clusters is the natural England facilitation fund. It operates on a competitive basis, wherein clusters submit proposals for funding consideration (“Funding Information” 2020). The intervals between each selection process can be inconsistent, sometimes spanning up to a year. Extended and unpredictable time-frames for funding can pose challenges for the formation of clusters and the delivery of their goals.

Current Structure

Current structure of farm clusters

Current structure of farm clusters

83 | UK Food System 84 [AA Landscape Urbanism 23/24] [AA Landscape Urbanism 23/24] Planet of Fields

Fig 104 By Antonio Garaycochea

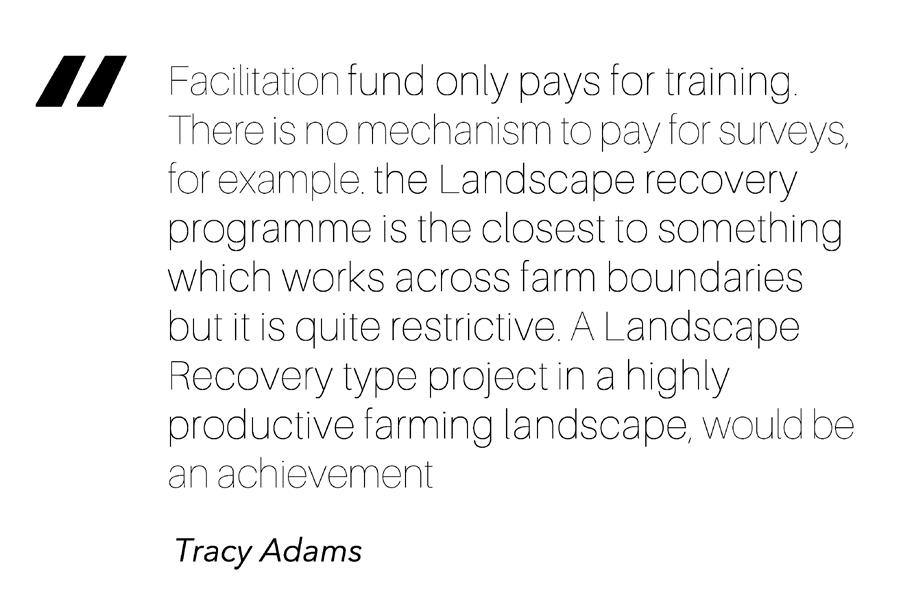

Current Structure

Based on interviews we conducted with facilitators, we noticed some problems in the way facilitation funds are structured. At the moment, these funds only cover training-related expenses, for example workshops. This does not address the funding needed for other associated actions such as tree planting or land surveying. Consequently, facilitators and farmers are compelled to resort to additional funding channels, like local councils. This chain causes inefficiencies by introducing unnecessary intermediaries and extending the time-line of projects.

Proposed Structure

In the proposed scheme, farm clusters receive legal recognition. This enables the democratic management of government funding within the cluster, similar to the way it is done in community benefit societies. With this system, clusters can directly apply for funds that are specifically directed towards their planned actions.

Another issue that became evident through these interviews is the fact that, even though farmers come together to form a cluster with shared goals, it is normal for them to independently enter Environmental Land Management (ELM) agreements. Keeping this in mind, one of the main challenges with farm clusters is being able to achieve consensus among a diverse group of farmers. A structure where every farmer has distinct ELM agreements, exacerbates the challenge because farmers will have differing priorities, resulting in a more convoluted decision-making process.

Instead of tying funding to particular prescribed tasks, the amount allocated is determined through a standardized social value index that values both ecological and social criteria. This approach would hopefully help cluster farms to integrate ecological corridors and promote shared resources, such as machinery and labour.

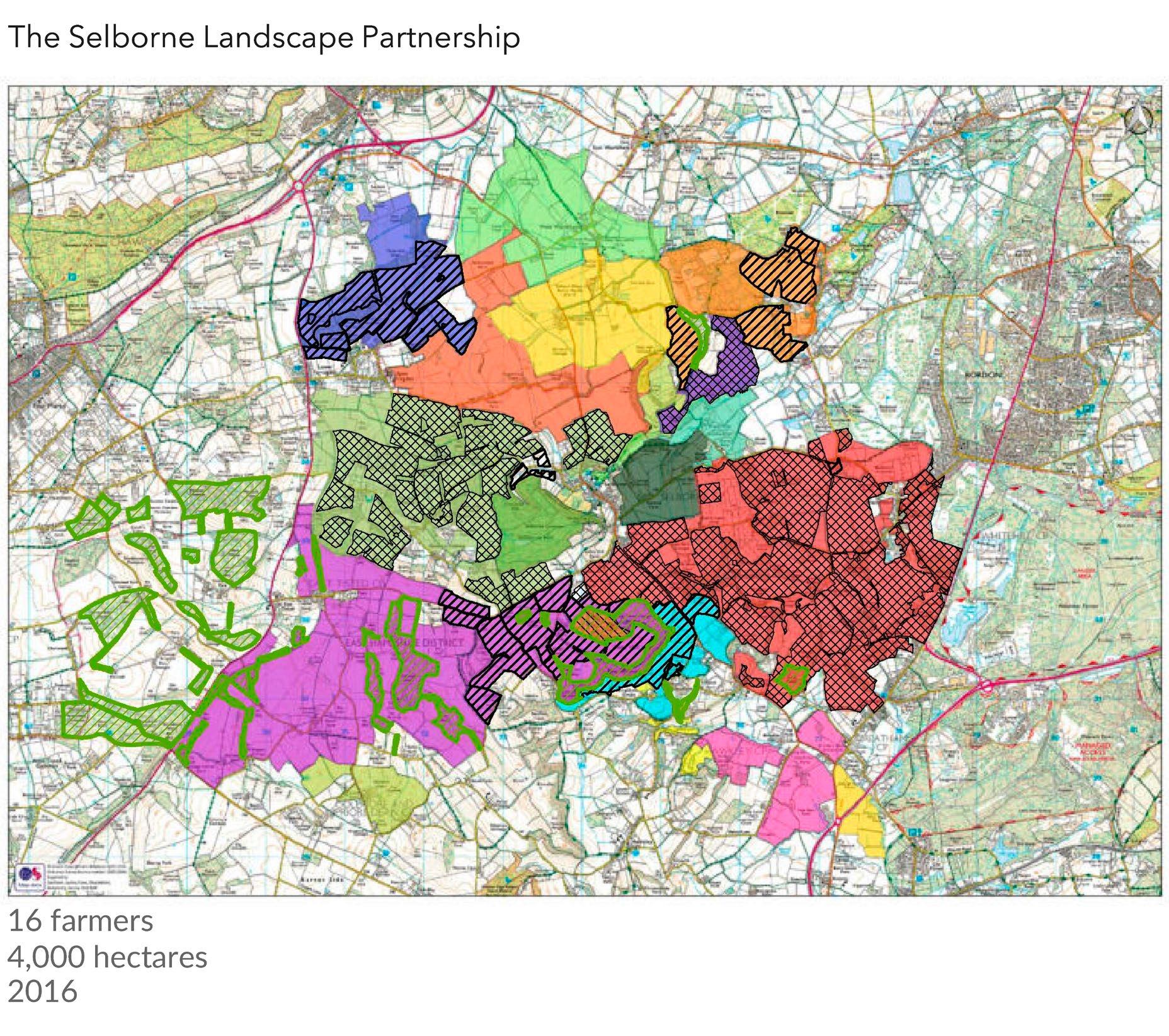

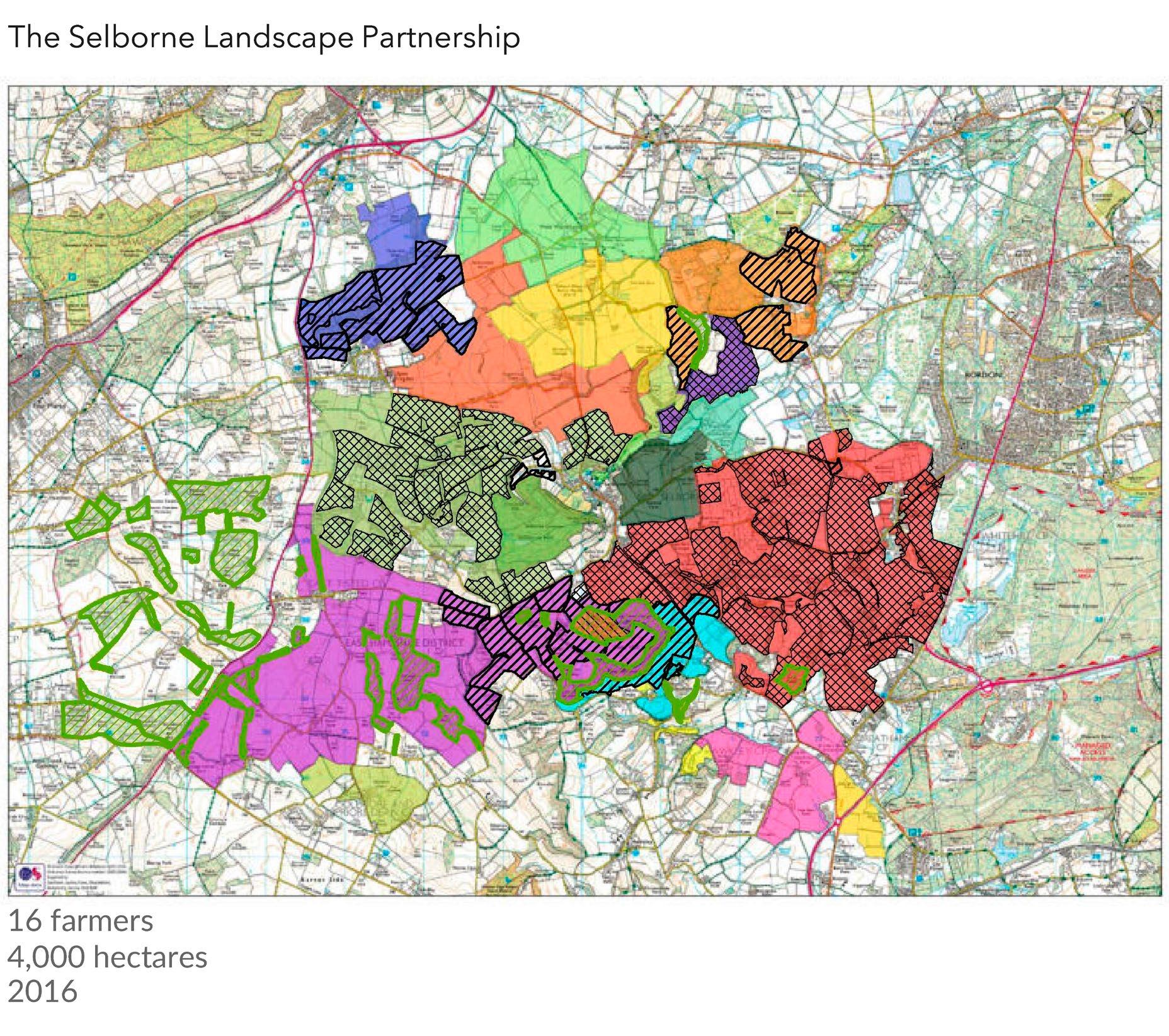

Plots subscribed to CS agreements

The Selborne Landscape Partnership and agri- schemes

Farm Clusters connecting woodland corridors

Proposed participants of cluster farms

Fig 104

Fig 106

Fig 105

By Antonio Garaycochea By Antonio Garaycochea

85 | UK Food System 86 [AA Landscape Urbanism 23/24] [AA Landscape Urbanism 23/24] Planet of Fields

By Antonio Garaycochea

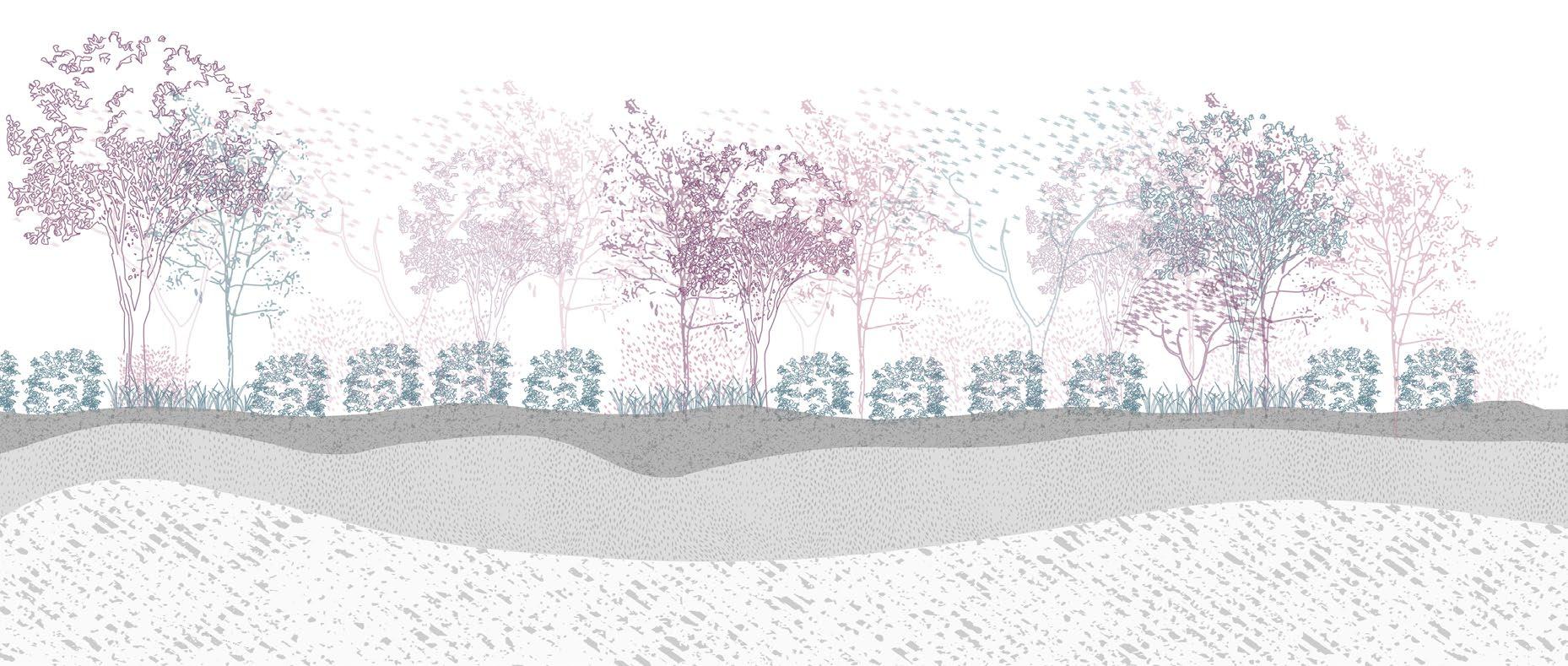

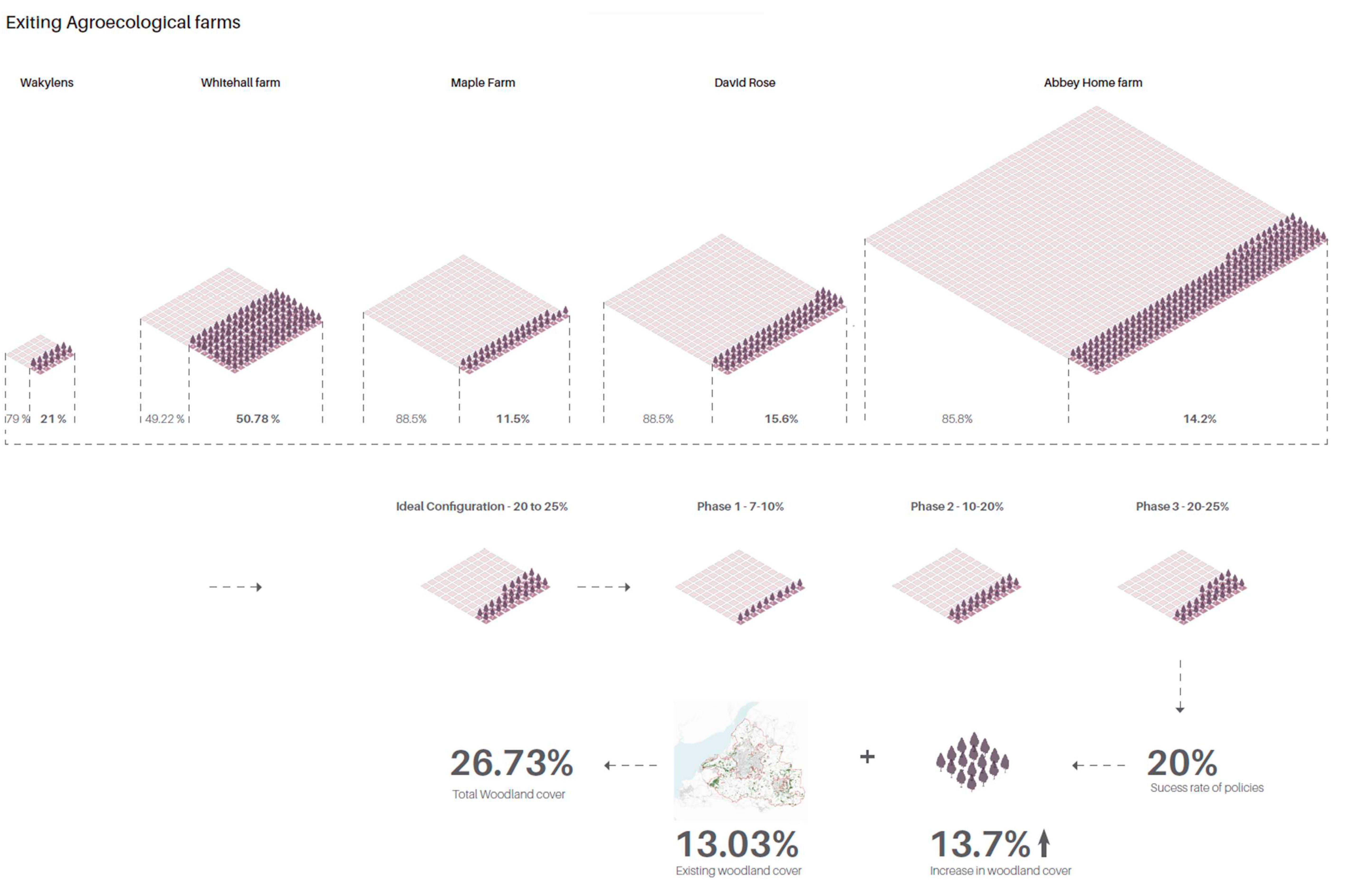

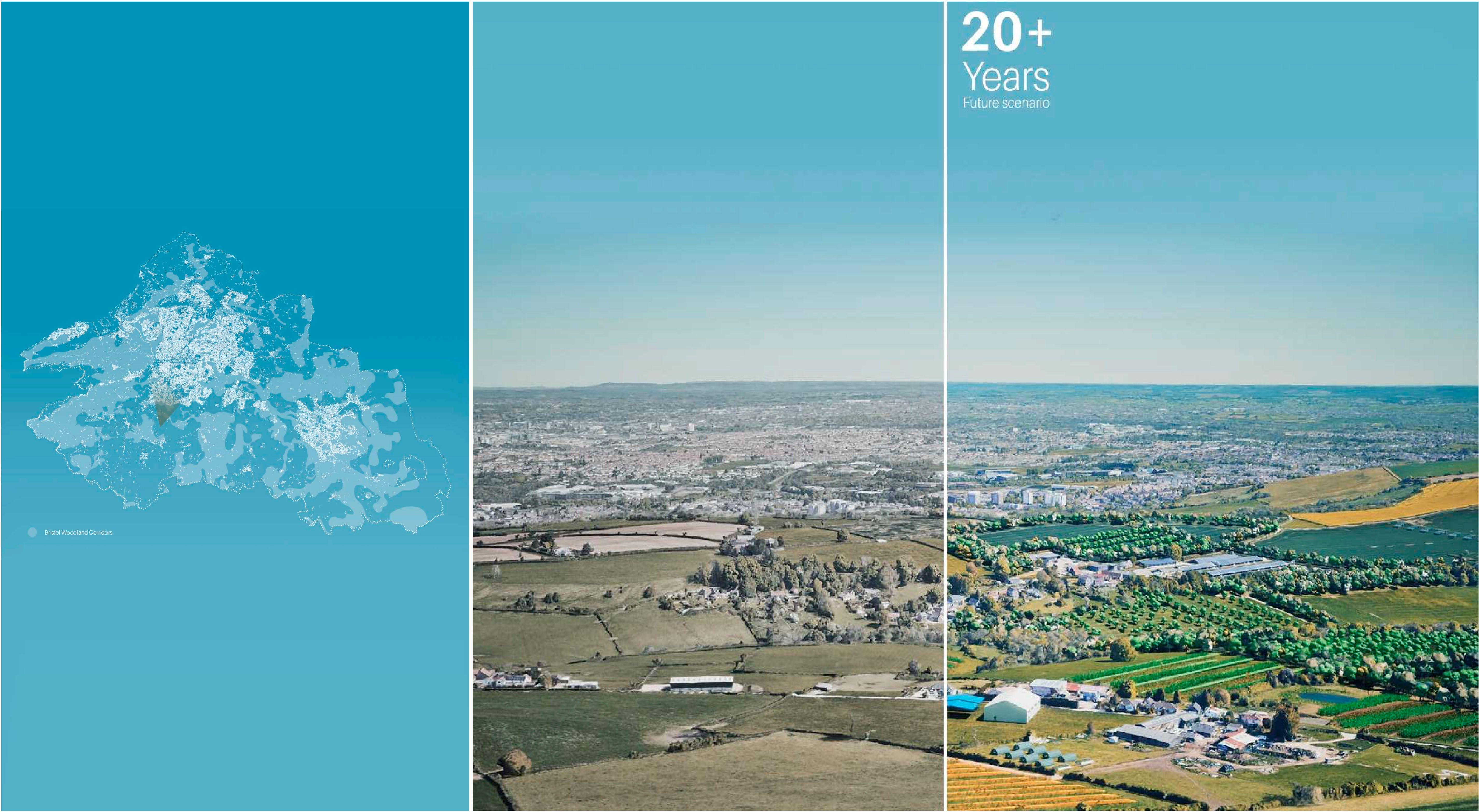

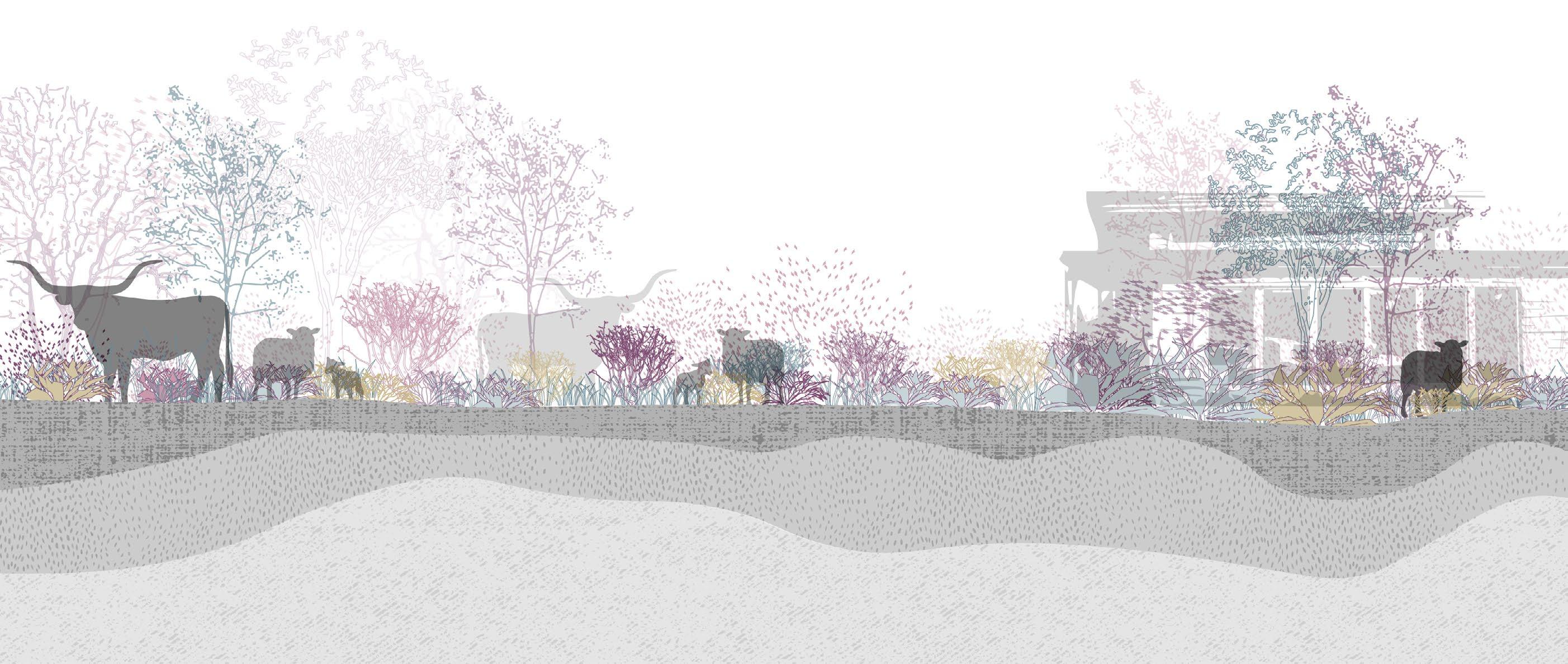

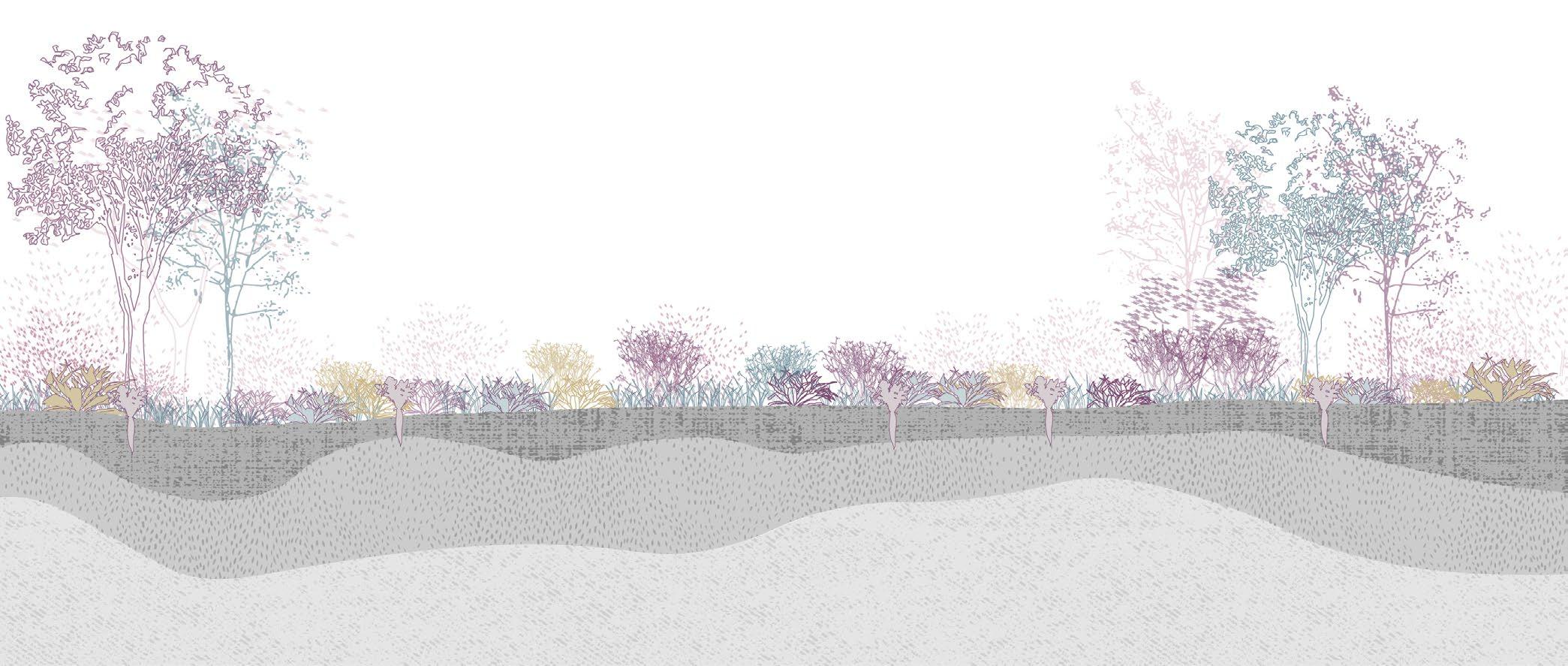

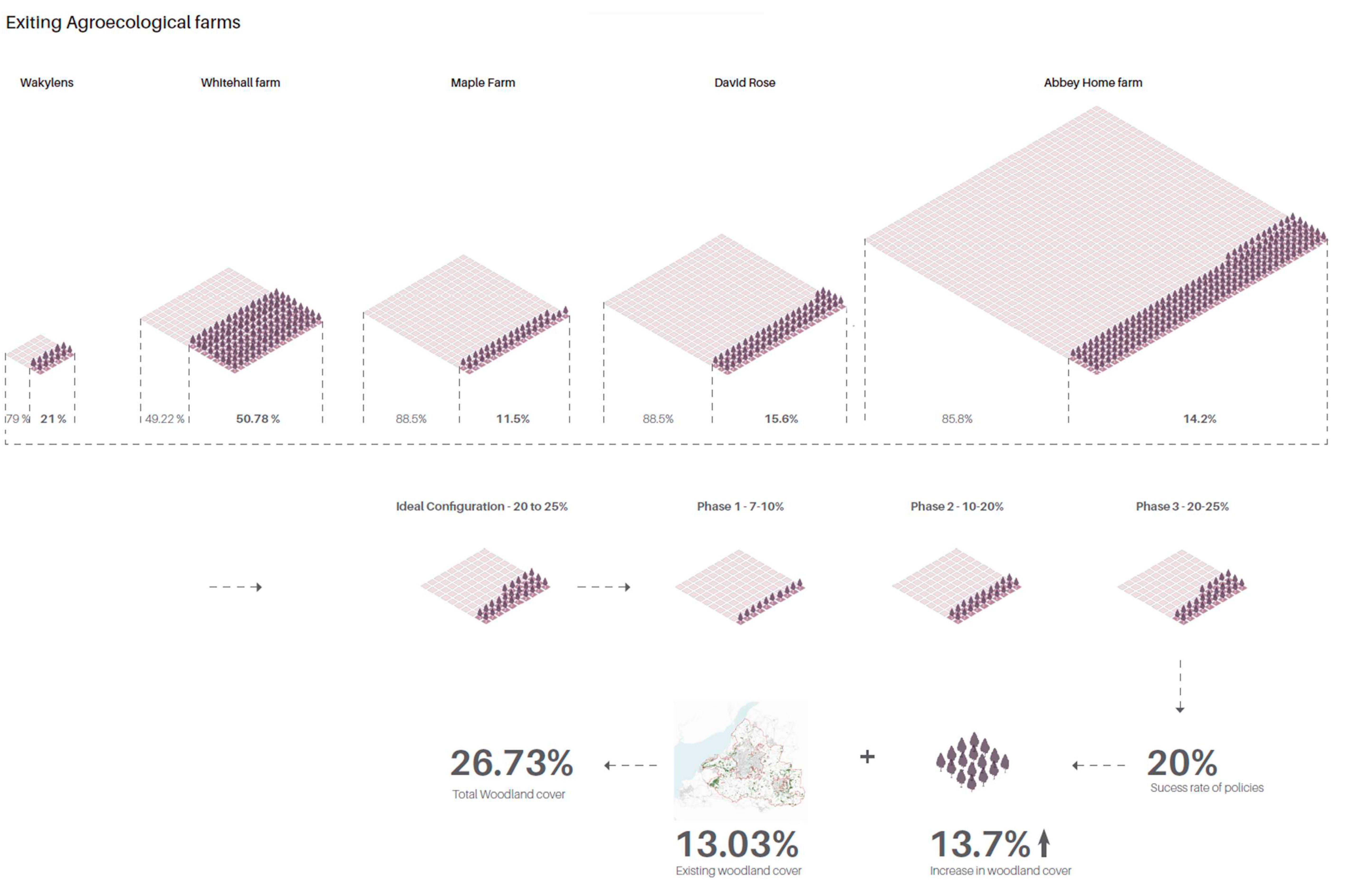

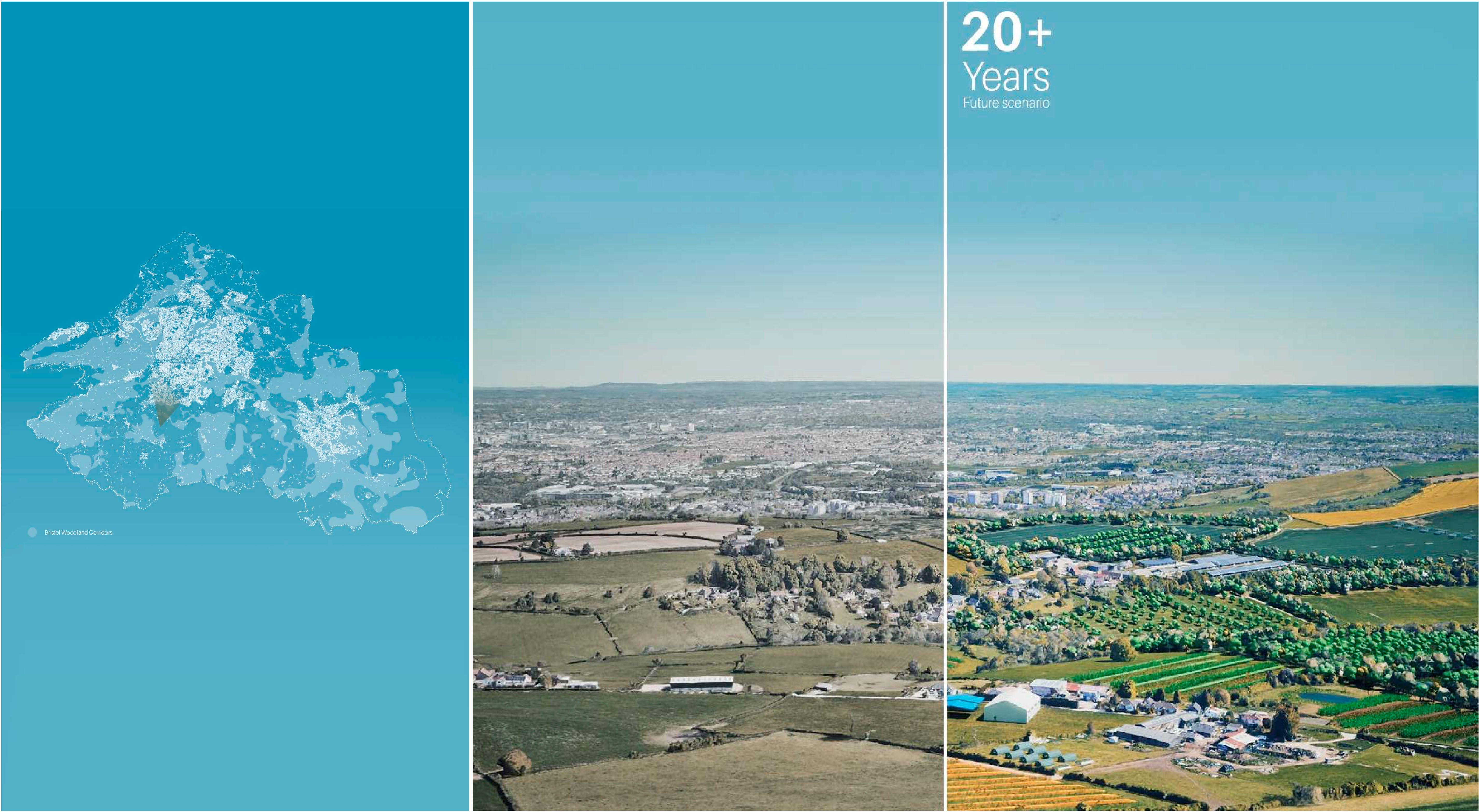

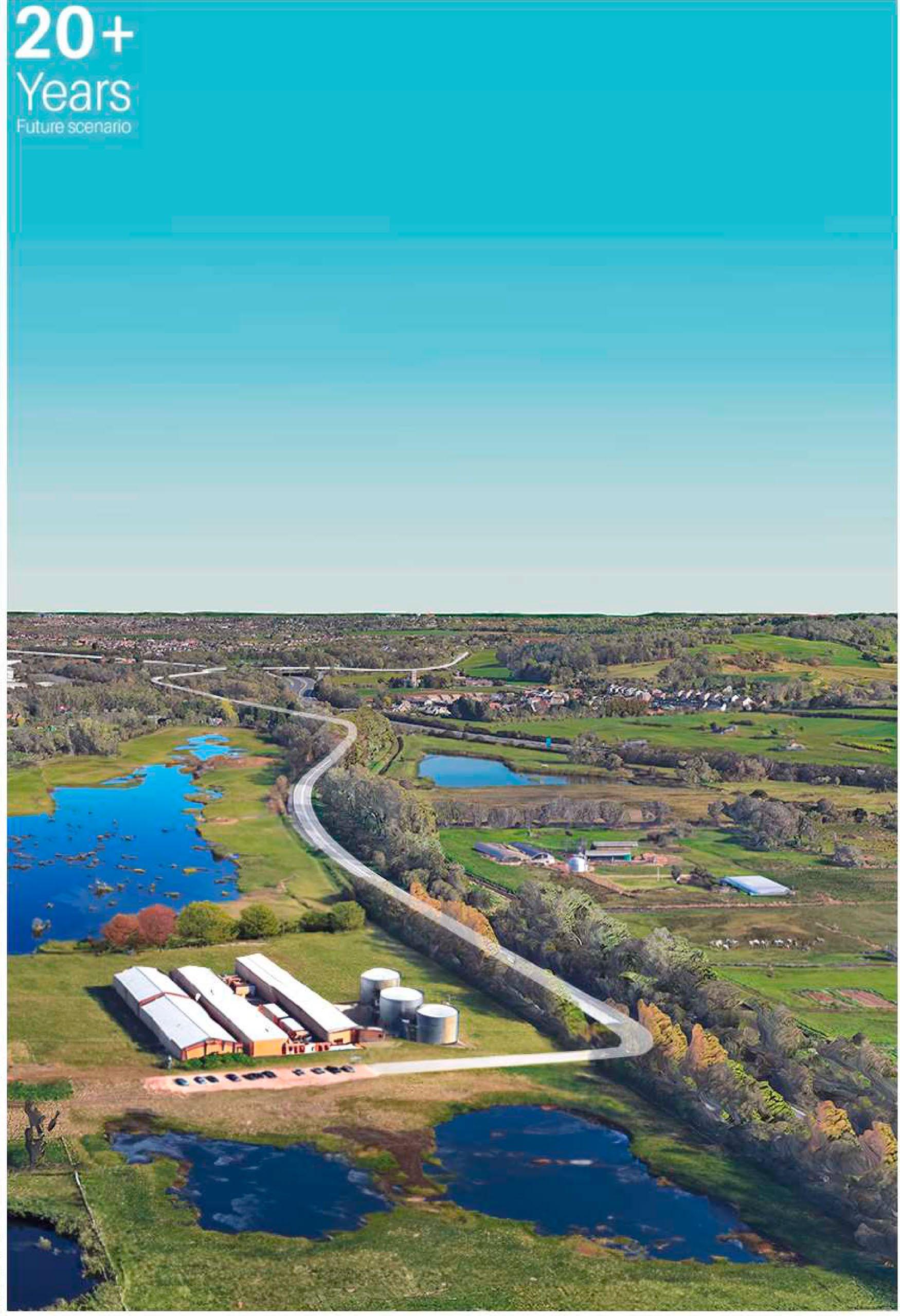

We can project and visualize the future landscape that results from applying these dynamics to woodland corridors within the greenbelt. Using our agroecological farm case studies as a starting point, we can estimate an approximate 26% increase in tree cover within the WENP woodland strategic corridor.

Calculation of resulting woodland increase

Calculation of resulting woodland increase

87 | UK Food System 88 [AA Landscape Urbanism 23/24] [AA Landscape Urbanism 23/24] Planet of Fields

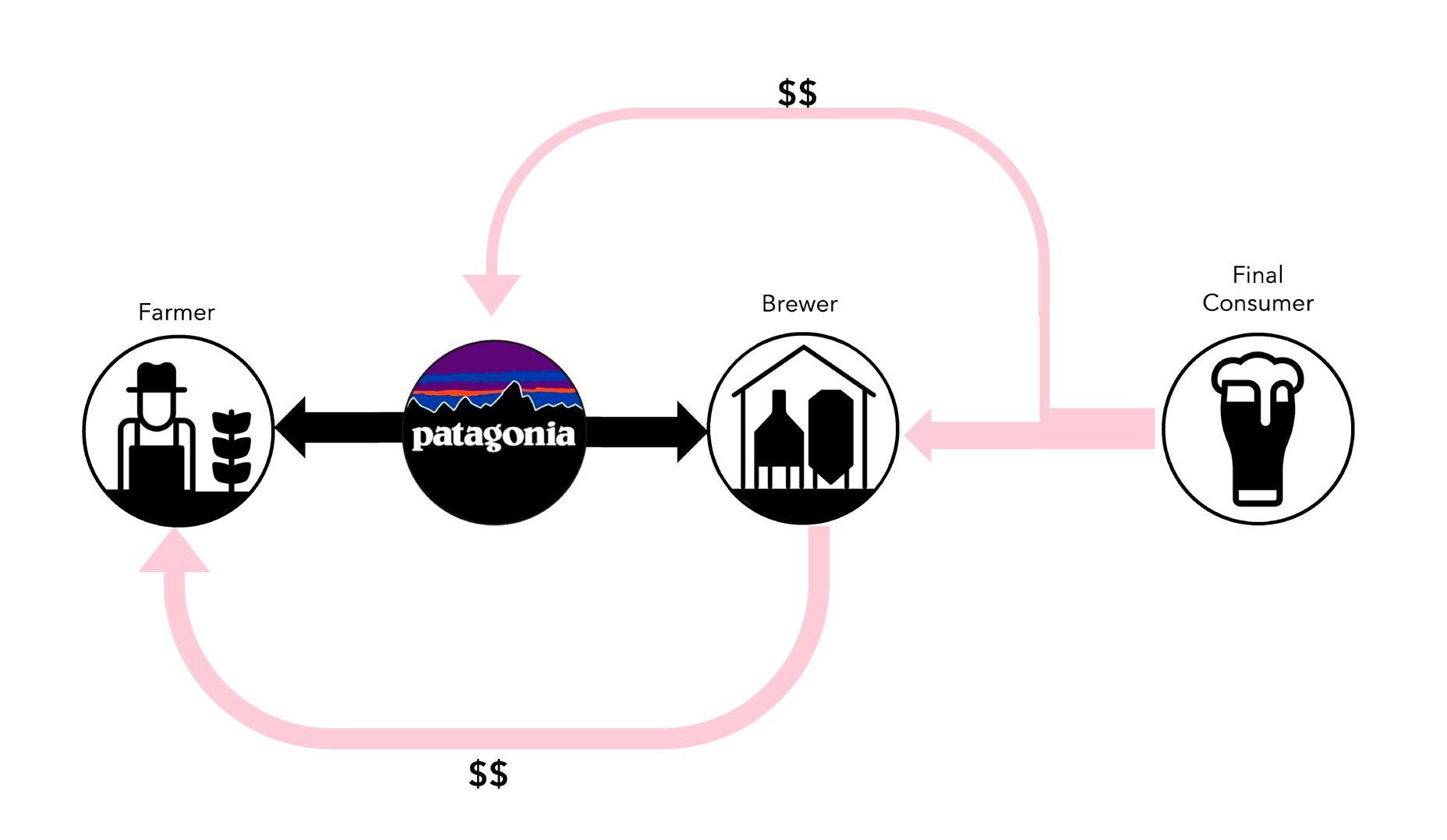

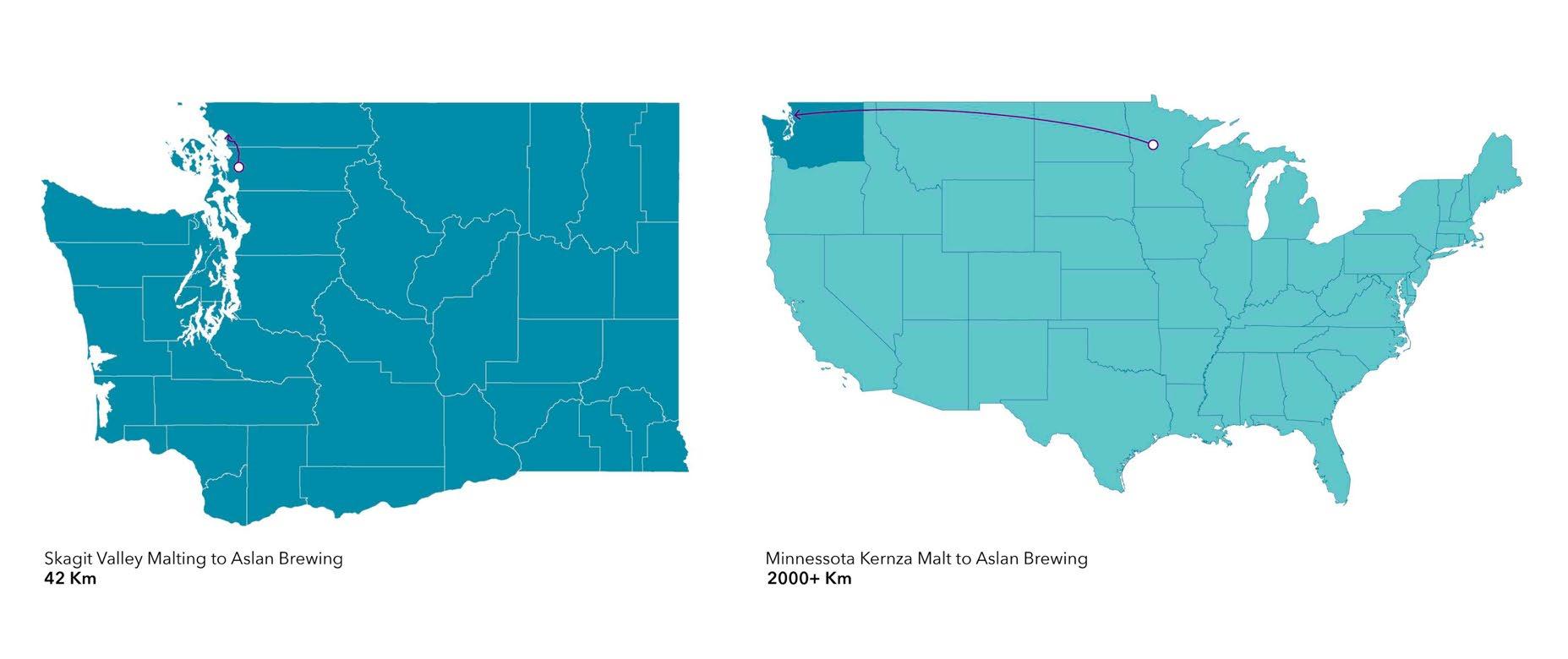

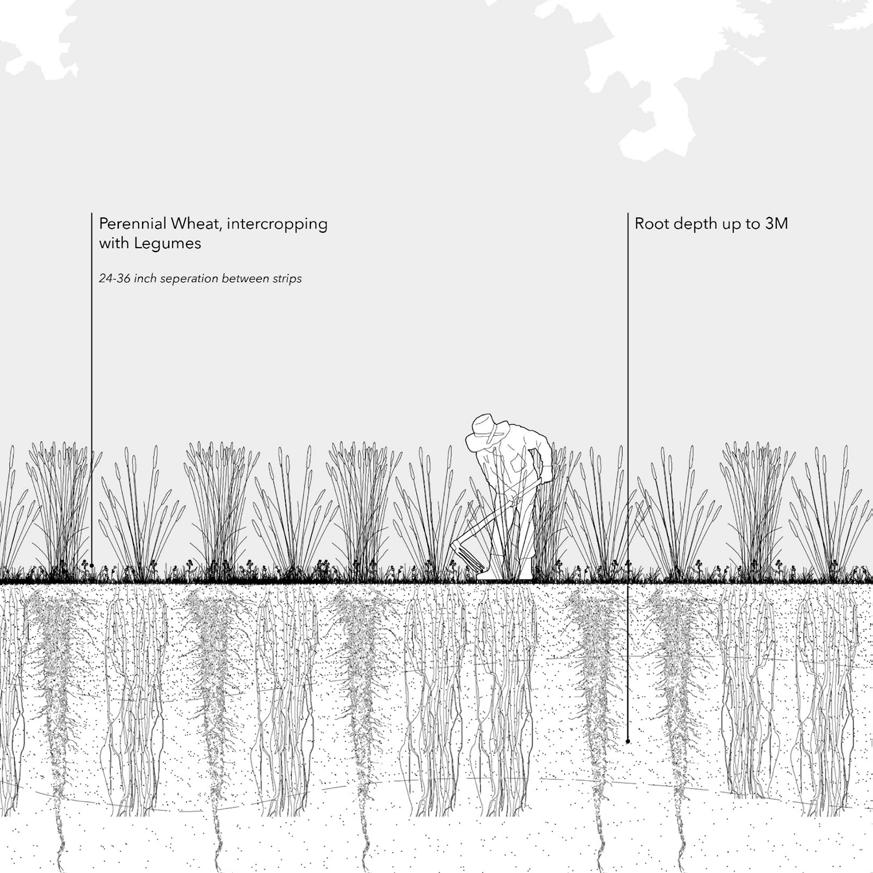

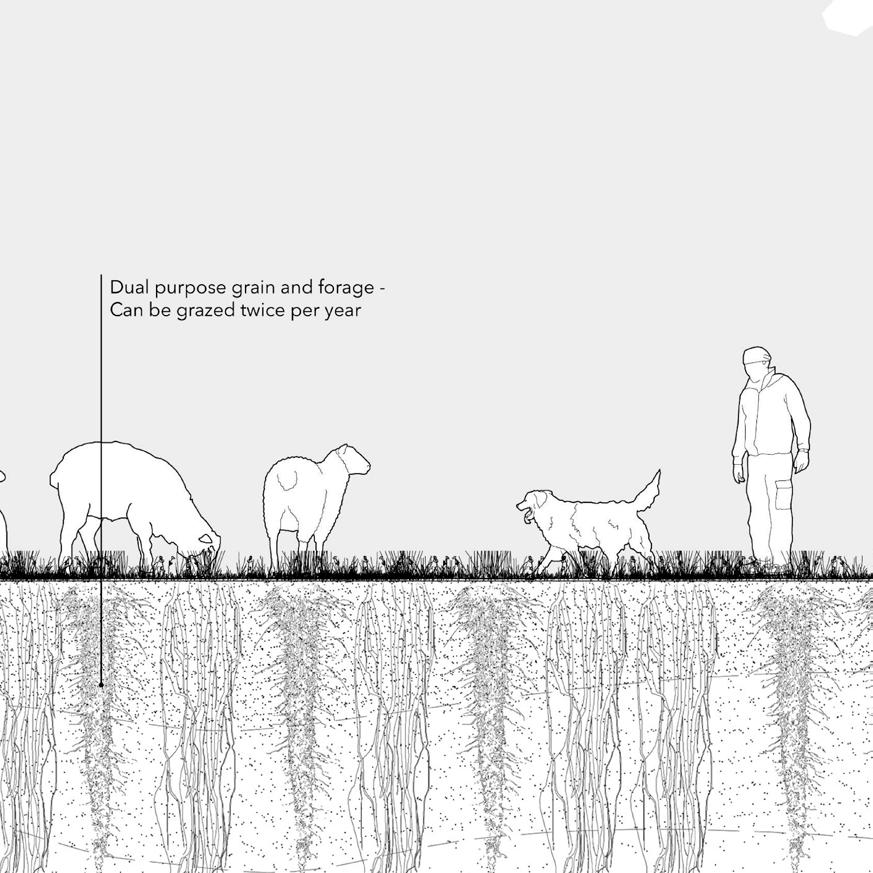

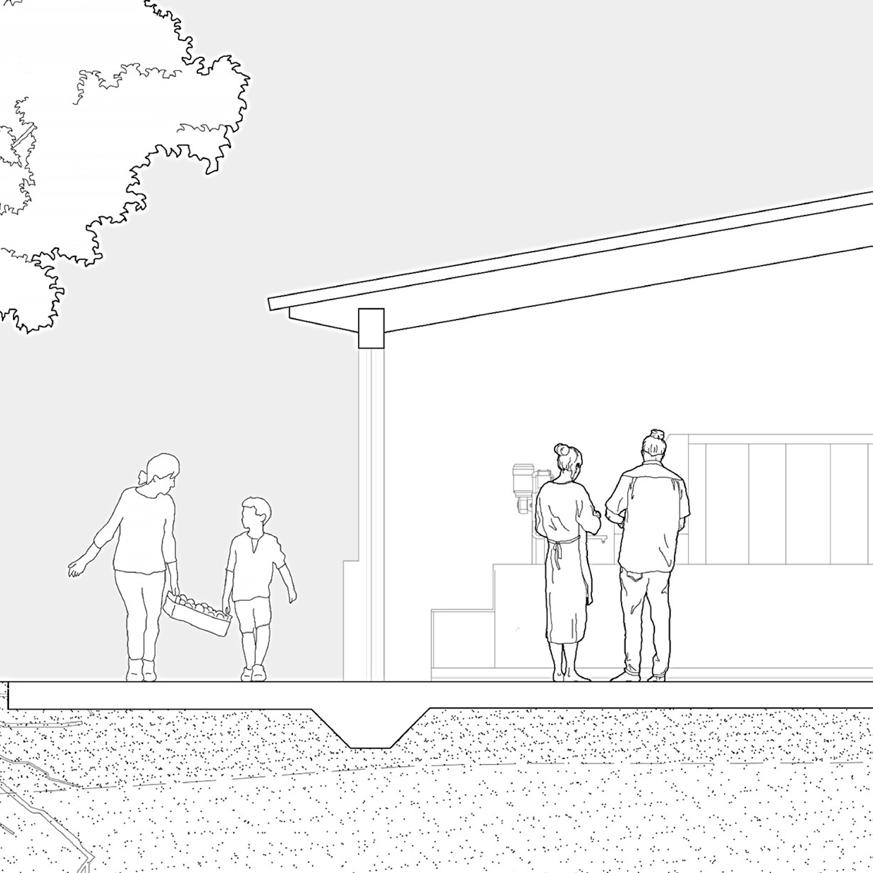

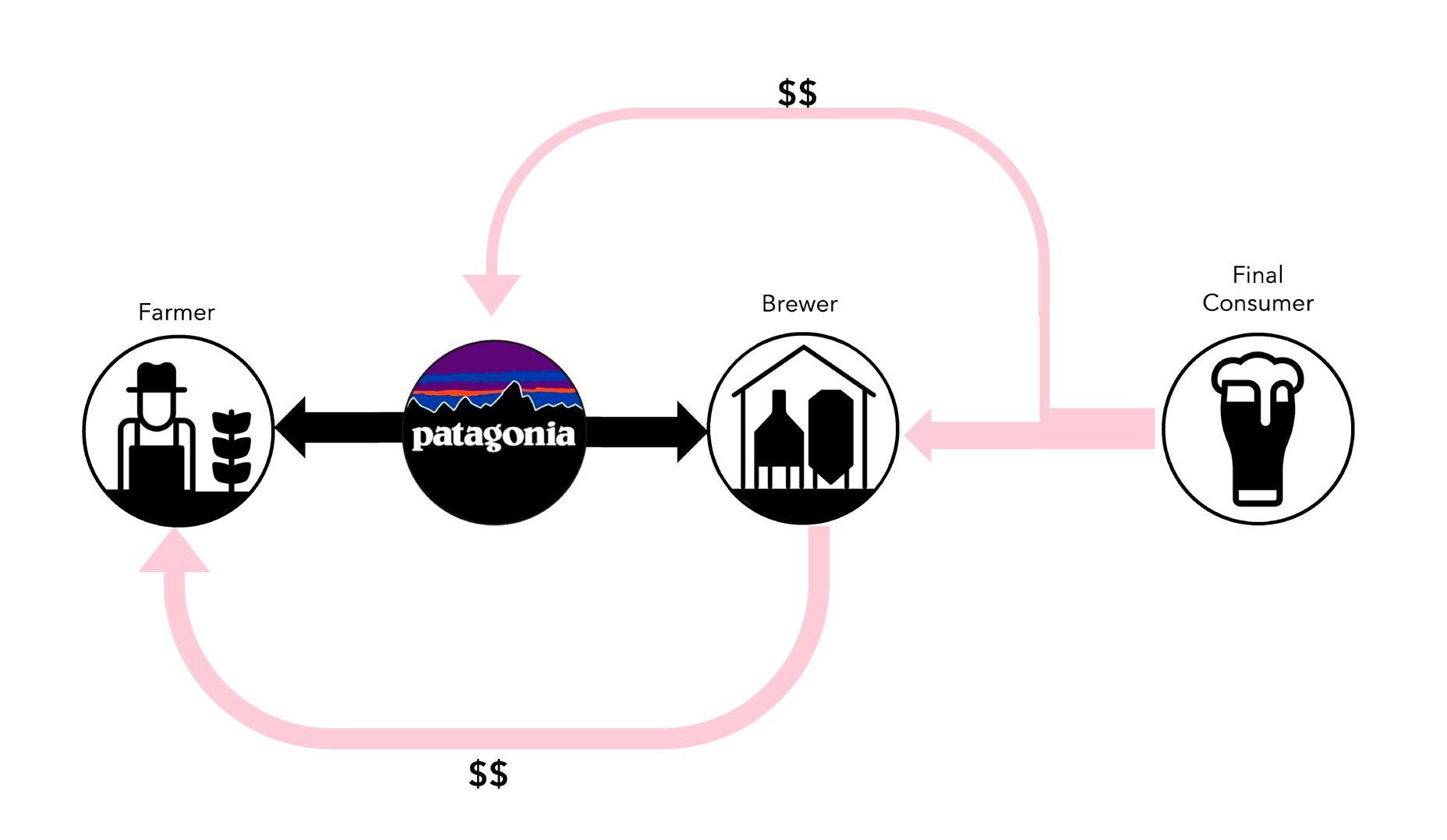

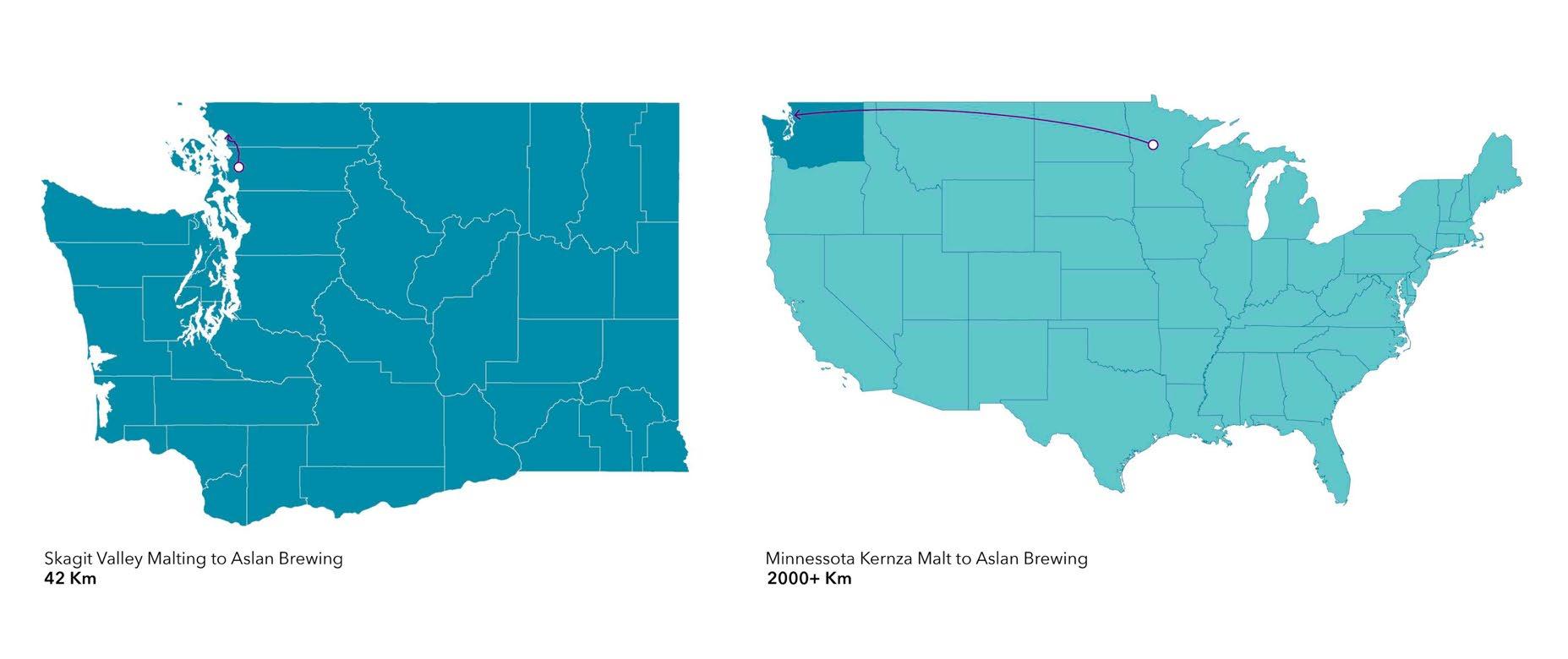

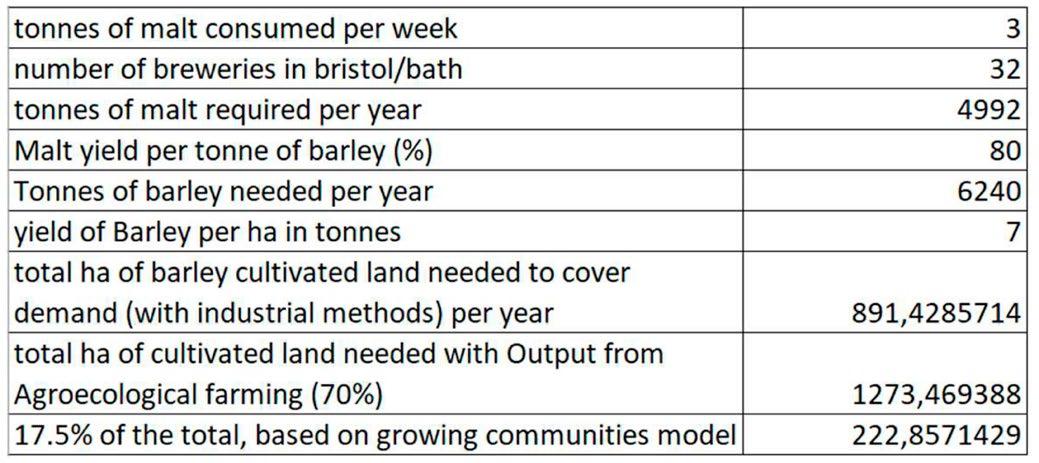

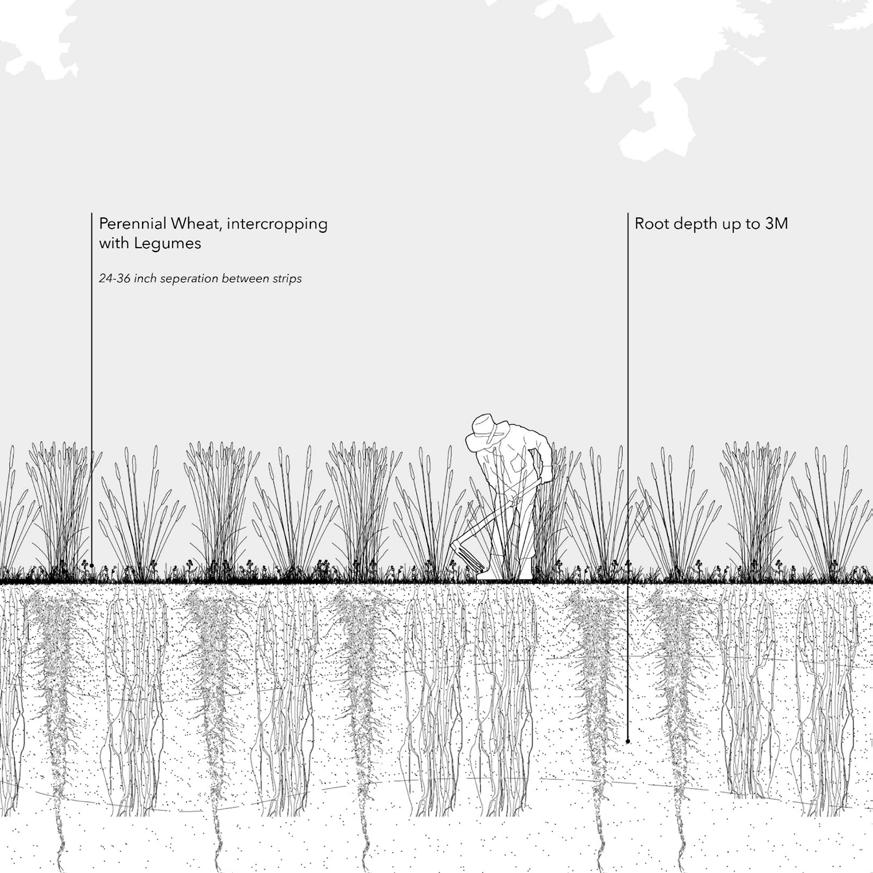

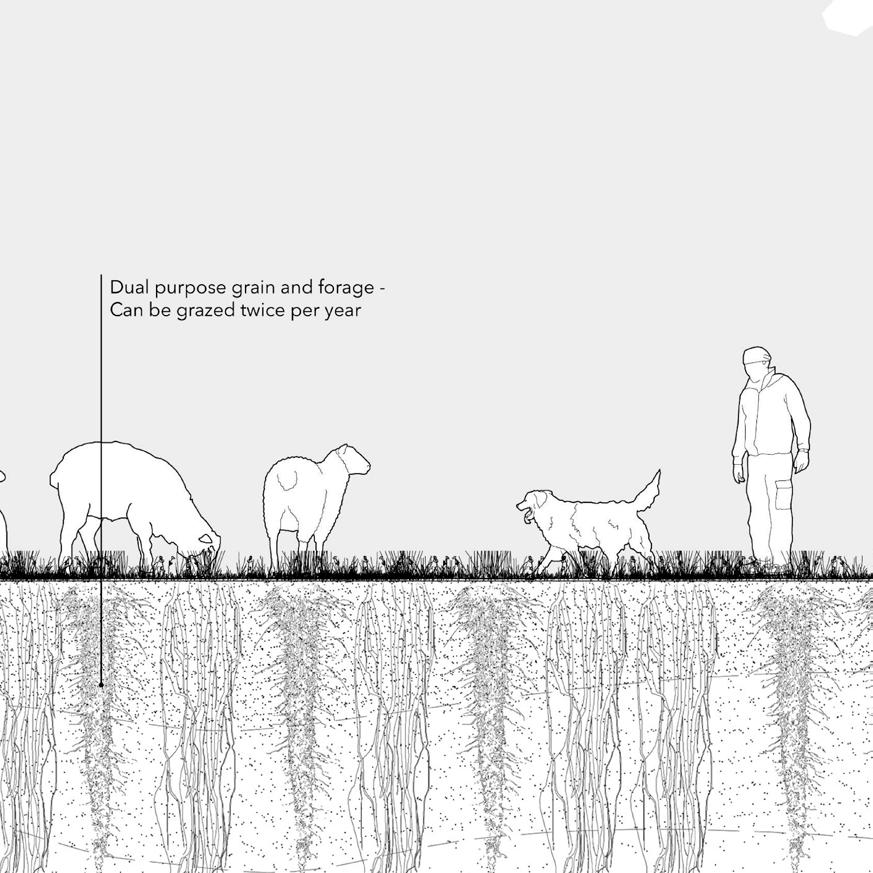

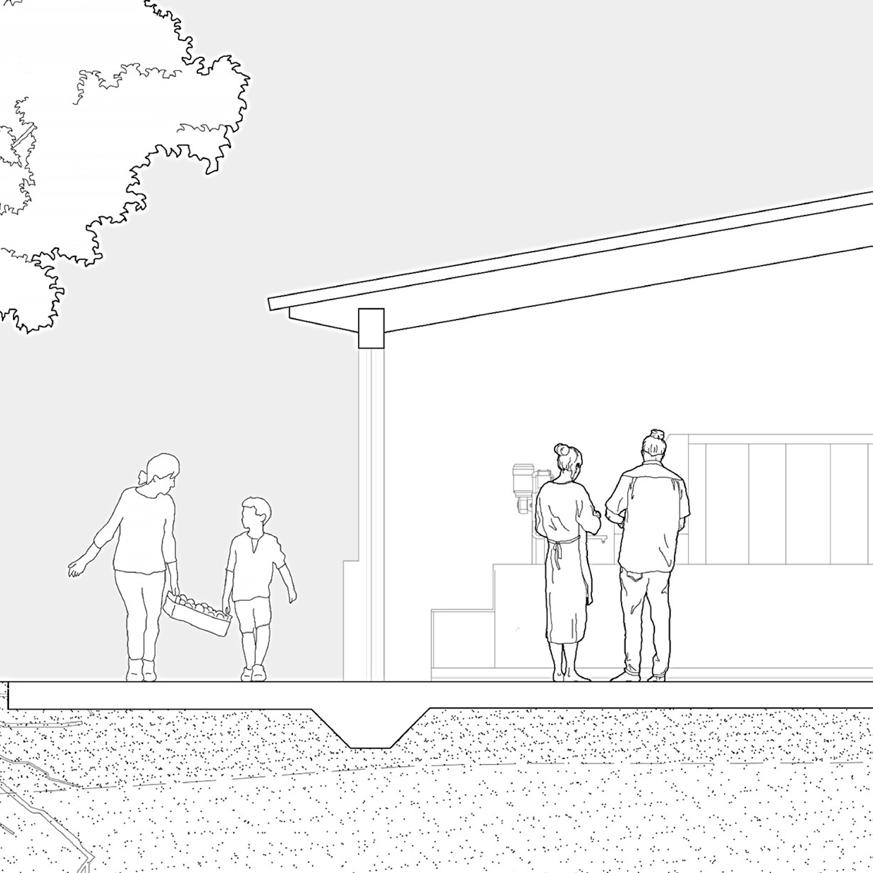

Fig 107 by Jegan Muralidharan