FOOD -PRINTS

TRANSLATING LANDSCAPE PRODUCTIVITY TOWARDS LOCAL FOOD PRODUCTION

By Parth Mehta & Reshma Susan Mathew

FOOD- PRINTS

Translating landscape productivity towards local food production

BY Parth Mehta Reshma Susan Mathew

for M.Arch. in Landscape Urbanism at Architectural Association

Acknowledgments

We extend out heartfelt gratitude to all those who took time to speak with us and teach us all that we learnt.

Clo Carbon Cymru

Richard Edwards ‘the Stickfarmer’ Cai Matthews

One Planet Council

Marc Scale

One Planet Developement Sites

Dr. Chris Vernon & Dr. Erica Thompson, Dan Y Berllan

Tao Wimbush, Llammas Eco-village

Sylvie Michielon & Wycliffe Tippins, Ty Gwennol

One Planet Centre

David Thorpe

James Shorten

Who Owns Cymru

Sioned Haf

Alex Heffron

Sam Hollick

Gleebelands

Adam

Hari Byles

Credits

Thesis Guide : Clara Oloriz

Program Tutors : Jose Alfredo Ramìrez Eduardo Rico

Technical Tutors :

Daniel Kiss

Carlotta Olivari

Elena Luciano Suastegui

William Huang-Shen Yuan

Project Partners : Runqi Ye Wenxue Hu

Copyright note:

Images: The external graphics have been sourced and duly credited. All other drawings are works of the authors unless specified otherwise.

It challenges the prevailing norms of food production, land management and climate action that all fail to prioritise ecological sustenance over economic greed.

ABSTRACT

The climate crisis that has gripped the planet has led to a variety of responses from global governments. This thesis began by looking at one such policy for climate action in Wales, UK. The One Planet Development (OPD) Policy introduced in 2011 was aimed at leading climate action by reducing the individual Ecological Footprints (EF) of residents. A close examination of the policy led the project to explore what role landscapes play in mitigating the climate crisis for a small country like Wales.

Wales is a small, proud country with a population of 4 million people living in a magnificently scenic landscape. One would then assume that they would not have such a heavy impact on the planet’s resources, but this was not true. Seeing this country rack up an ecological footprint that rivals many of the top contenders, forced us to question the nature of global climate action. We found that at best, global climate action is a misguided attempt to place responsibility of change on the individual rather than envision much needed new forms of governance.

We began to explore the nature of landscapes in Wales and came to understand that a vast majority (roughly 80%) of the landscape was used for agriculture (Welsh Parliament, 2022). But with supply chains that span across the globe, Wales is far from reaching food sovereignty. Through engagements with local climate activists and farmers, the project sought to build a more resilient and efficient food system for the locals. By changing the way food is produced, the project goes further to suggest how this food can reach the people. Knowing where your food comes from is a luxury in the modern age and this project imagines what that might mean for the Welsh landscape. The project revises the current relationship people share with their lands and also makes proposals to encourage methods of land conservation that not only preserve the ecosystems but also help capture the carbon emissions more effectively.

It challenges the prevailing norms of food production, land management and climate action that all fail to prioritise ecological sustenance over economic greed. As the onslaught of climate change gets more severe, it becomes almost impossible for countries like Wales to rely on increasingly volatile external sources for support. It is critical that they regenerate depleted resources and build up resilience through collective action as envisioned by this thesis.

CONTENTS

1 Climate Emergency

1.1. Climate Crisis

1.1.1. Global Climate action

1.1.2. Pitfalls of Global Climate Action

1.1.3. UK Climate action Plans

1.2. Climate & Carbon

1.2.1. Ecological Footprints

1.2.2. Contributors to Ecologcal Footprints

1.2.3. Agricultural Emissions

A1. A New Land Deal: Essay

1.3. Lessons from a Small Country

1.3.1. Historical Background

1.3.2. Welsh Climate Action

1.3.3. One Planet Development Policy

A2. Need of Sustainable Agriculture Business Models in Wales: Essay

2 Analysing the OPD Policy

2.1. Details of the Policy

2.1.1. Application Procedure

2.1.2. Calculating the EF in the Policy

A3. Interview with Marc Scale

A4. Interview with David Thorpe

A5. Interview James Shorten

2.1.3. Multi-unit OPD

2.2. First Hand Discoveries

2.2.1. Mapping the OPD Policy

2.2.2. Four Primary Case Studies

A6. Interview with Rhiw Las OPD Applicants

A6. Interview with Lammas Ecovillage OPD Applicants

A7. Interview with Clo Carbon Cymru

2.2.3. The OPD Storyline

2.3. Under the microscope

2.3.1. Samples from Wales

2.3.2. Samples from OPD Sites

2.3.3. Case 01: Samples from Hooke Park

2.3.4. Case 02: Samples from Wakelyns Farm

2.4. What is the OPD now?

2.4.1. Overlaying the many layers

2.4.2. Loopholes in data sets

2.4.3. Challenges and Potentials

3 Understanding Food Landscapes

3.1. Building on the OPD

3.1.1. Revising the goals

3.1.2. Conceptal Strategy

3.2. Agriculture in Wales

3.2.1. Food Trade

3.2.2. Livestock Farming

3.2.3. Dietary patterns

3.2.4. Farmers and Language

A8. Conversation with Owen

A9. Conversation with Richard

3.2.5. Housing

3.2.6. Wildlife Tourism

A10. Conversation with Alex Heffron

A11. Conversation with Sam Hollick

3.2.7. Proposed Agriculture Model

3.3. Un Cymru Policy

3.3.1. Phasing the policy

3.3.2. Phase 01: Land Aquisition and Local Collaboration

3.3.3. Phase 02: Logistics and Services

3.3.4. Phase 03: Infrastructure

4 A New Food Policy

4.1. Zooming In

4.1.1. Case of Pembrokeshire

4.2. Feeding Wales

4.2.1. Agroforestry and Wales

4.2.2. How much food do we need?

4.2.3. Market Garden Renaissance

4.2.4. Spatialising the Food Zones

4.3. Designing the Food Zones

4.3.1. The algorithm development

4.3.2. Visualising the Food Zones

4.3.3. Uplands and Lowlands

4.3.4. Food Zones

4.3.5. Lowlands

4.3.6. Uplands

4.3.7. The Expansion Strategy

5 A Food Renaissance

METHODOLOGY

The project was developed over a year’s time as a joint effort. The study was conducted through a variety of methods and skillsets brought forward by every member. A summary of our methodology is listed below.

A. Site Visits

There were several site visits conducted to dig into the subject (literally). The visits made it possible to get a first-hand experience of the site conditions and gauge the impacts of different land management strategies. Samples of soil and field work along with the concerned stakeholders were also arranged over these visits.

B. Interviews

The most crucial insights and revisions made in the project were based on data collated from numerous conversations with people. Interviews were arranged with people from all roles ranging from policy makers to local farmers. Grassroots inputs were critical in rooting the project as proposal that addressed their concerns primarily.

C. Drawing Methods

As a collaborative effort, many different methods of drawing were used to illustrate the ideas. Digital means were used to process large data sets and further design and model the large scale proposals. More analogue methods were used when the drawings were used to study and represent the human and microscopic scales. This distinction in the language of representation keeps the visualisation distinct and comprehensible to all those who may need it.

D. Project Development

The project has constantly dealt with multiple scales, from questioning the planetary networks to studying impacts on soil structure under the microscope. The analysis has been condensed with expert assistance and multiple reviews. The initial study of looking at one policy in detail was used to cross over to several other areas of enquiry. Once the policy was dissected thoroughly, future areas of enquiry were identified. Six months in, the project had crystallised into an effort to feed the Welsh people with locally grown food. The project ends by spatially demonstrating the feasibility and visualising various aspects of this proposal.

Season

Interviews

SiteVisits

Project Development

DOWN TO EARTH : SWATCHES FROM WALES

UP IN THE SKY : SWATCHES FROM WALES

CLIMATE EMERGENCY

Climate Crisis

Over the last many decades, we have seen a change in our climate and evolve into a full-blown global crisis. What has now become a global concern has been a topic of continuous deliberation and policy reform for the last several decades. There have been countless movements and initiatives by local governments and community groups to mitigate the environmental damage within their own borders however, international efforts are naturally far more complex and far less efficient.The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) established in 1992, called for action against human interference in the climate and curbing greenhouse gas emissions. It also called for more scientific research and regular negotiations to enforce climate action policies. Since then, we have seen numerous treaties signed, the most recent being the 2015 Paris Agreement, which sought to keep the planet from warming over 1.5 °C.

However, seven years and seven conferences later, we are yet to make tangible progress with regards to our consumption habits and carbon emissions. In the last COP28, there was still no tangible commitment made by the world leaders for radical reform or transitioning out of fossil fuels. A disaster fund was set up to provide financial aid to the countries that are facing the brunt of the climate crisis and at the UN General Assembly in September 2023, an adjacent Climate Ambition Summit was held to highlight the efforts of the most ambitious countries when it came to combating the crisis. The world’s largest emitters namely USA and China were not among them.

Fig. 1.2 | KEY FACTORS OF AVERAGE TEMPERATURE RISE DrawingbyWenxueHu

2. Fig1.1DataSource-UNFCC.(n.d.).Processand Meetings.RetrievedfromUnitedNationsClimateChange: https://unfccc.int/kyoto_protocol

3. Fig1.2DataSource-OurWorldinData, Surfacetemperatureanomaly,2017.OurWorldnData, Contributiontoglobalmeansurfacetemperature1851 to 2021.

In order to facilitate international cooperation and effectively mitigate the crisis, we need to end half-hearted greenwashing efforts and set firm goals for regional action against the climate crisis

As the discussions surrounding climate action and global cooperation progressed, it became imperative to quantify environmental destruction to uniformly chart the course of action across the globe. Several standards have been developed and utilised to build cases for climate action. Ecological Footprint has been the most recent and evolved standard of measurement so far, however there are limits to this method and while nations continued to evade responsibility, the climate crisis evolved into a catastrophe.

The UK currently has several such policies in place for when it comes to tackling climate change, the British government does not lack awareness. As home to many climate scientists, activists, and grassroots movements against fossil fuels, they have all the means to lead global community on climate action. However, the current government led by PM Rishi Sunak has backtracked on all major climate promises made thus far, plunging the faith of the international community. In addition to backing out of the government’s commitment to achieving net zero goals from the Paris Agreement, by 2050, the government has also sanctioned several environmentally hazardous projects causing more harm than revival. Ecological

Ecological

Ecological

Fig. 1.4 | GLOBAL DIPARITY BETWEEN EF IN NORTH AND SOUTH

Fig. 1.5 | GLOBAL CARBON EMISSION source/credits DrawingbyWenxueHu

Fig. 1.6 | GLOBAL BIO CAPACITY DrawingbyWenxueHu

5. Fig.1.5&Fig.1.6 DataSource-Footprint DataFoundation,YorkUniversityEcologicalFootprint Initiative,andGlobalFootprintNetwork:NationalFootprint andBiocapacityAccounts,2023edition.Downloaded [22/01/2024]fromhttps://data.footprintnetwork.org

2.6M MT

3.9B MT

<10M GH

>1B GH

The environmental systems continue to breakdown in record speed and anyone with knowledge of ecology can identify that these slews of never-ending disasters are not normal

Climate & Carbon

Ecological Footprints

While the ecological footprint (EF) as a metric accounted for the disparity in consumption and production between nations, it remains a fictional entity that needs reconsideration. Attempts to reduce EF without tackling issues of capitalism i.e. over consumption and relentless extraction, fails to address the root cause of climate breakdown. EF as a metric created a uniform system of evaluation globally. This derived number essentially allocates an imaginary ecological budget to every nation based on its own resources. However, to treat this number without comprehending its nuance is a grave mistake. When countries overshoot their ecological budgets, without reducing emissions they break the natural cycle of regeneration and rob future generations of its resources. It also leads to fragmented proposals that fail to restore the natural carbon cycles.

Fig. 1.7

1.8 | CYCLE OF REGENERATION AND CONSUMPTION

The nature we have (Supply)

The nature we use (Demand)

Total carbon deficit (+ve / -ve)

Natural regeneration of resources Human Consumption

Productive assets of the world

Consumption needs extracted as ecosystem services

1.9 | ECOLOGICAL FOOTPRINT CALCULATION

7. Fig.1.9DataSource-FootprintDataFoundation, YorkUniversityEcologicalFootprintInitiative,andGlobal FootprintNetwork:NationalFootprintandBiocapacity Accounts,2023edition.Downloaded[22/01/2024]from https://data.footprintnetwork.org

Rate of carbon extraction

Fig.

Fig.

01.2.2

Contributors to Ecological Footprints

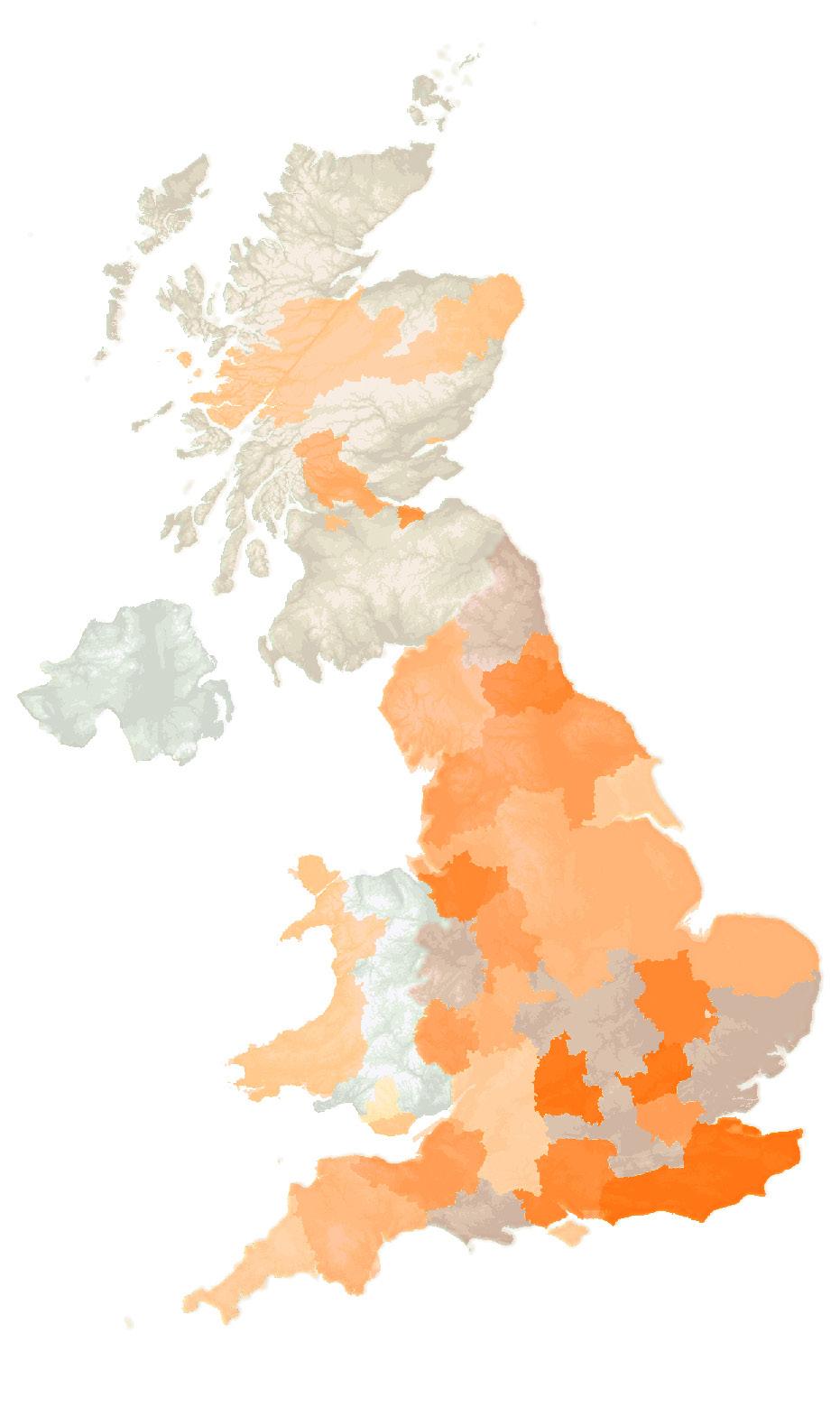

According to the latest data available [8], the ecological footprint of the United Kingdom was estimated to be 3.57 global hectares (gHa) per person in 2022. This projection also implies that, if everyone on the planet consumed as a resident in the UK did, then we would need 2.36 earths to support everyone. Although a relatively small island, the inequalities of consumption patterns and global supply chains make the UK raise alarming figures of carbon emissions. The UK relies heavily on the import of several goods and the material footprint generated by these heavy imports combined with the loss of ecological systems within the country inflate the UK’s ecological footprint.

It is worth noting that these numbers are an attempt to quantify productivity of all landscapes. This is done by engineering all forms of landscapes into comparable quantities with sweeping generalisations. Croplands, forests, mines, fossil fuel beds, polar caps are all forced to the same baseline of productivity to measure the rate at which they are being consumed and regenerated. As a result, It becomes more apparent that these numbers cannot be used blindly as landscapes are more complex systems than that represented by these statistics. While EF can measure the nation’s consumption alongside its natural resources, it is not a reliable figure when it comes to accessing the health of the ecosystems. What appears as a lush green countryside is a landscape that is fast losing biodiversity from its soil to its forests and is in desperate need of sitespecific regeneration methods; developed not with the aim to reduce EF but to restore the landscape’s resilience and natural capacity. Many of these benefits may not be quantifiable by the metrics developed today, but they will mitigate climate change far better than the misguided efforts slapped on currently.

5.2-5.3

8. WWF-UK.(2006).UK:Countingconsumption: CO2emissions,materialflowsandEcologicalFootprintof theUKbyregionanddevolvedcountry.Surrey:Arrowhead Printing.

9. FootprintDataFoundation,YorkUniversity EcologicalFootprintInitiative,andGlobalFootprint Network:NationalFootprintandBiocapacityAccounts, 2023 edition. Downloaded 12 December 2024 from https://data.footprintnetwork.org.

Fig. 1.10 | UK ECOLOGICAL FOOTPRINT DrawingbyWenxueHu

10. Fig.1.10DataSource-WelshGovernment,Survey ofagricultureandhorticulture,June2020

11. Fig1.11DataSource-OfficeForNational Statistics,UKTradeCensus,December2018

12. Fig1.12 DataSource-OfficeForNational Statistics,UKTradeCensus,December2018

Fig. 1.12

Fig. 1.11 | UK IMPORT ACROSS GLOBE

Livestock feed supply chains have wreaked havoc across the globe with swathes of rainforests cleared for growing soyabean to plump up livestock on the far side of the earth

Global estimates place the agriculture industry as one of the largest carbon emitters, particularly the livestock rearing which releases record amounts of methane. Even as agricultural yield per acre rises in historic proportions, the areas cultivated have also exponentially increased. This superproduction of food cannot be accounted for by the human population alone. These areas are also feeding the excessive numbers of livestock reared indiscriminately. Livestock feed supply chains have wreaked havoc across the globe with swathes of rain forests cleared for growing soya bean to plump up livestock on the far side of the earth. The UK is not exempt from this network. Wales supports a livestock population of over 10 million while home to only about 4 million people. Producing food for people and animals to eat should never have become such a bane to the planet’s survival. 01.2.3

Land-Use Change Supply Chain

1.13 | GREENHOUSE GAS EMISSION PER KILO-GRAM OF FOOD PRODUCT

1.14 | GREENHOUSE GAS EMISSION FROM FOOD SUPPLY CHAIN

13. Fig1.13DataSource:-Poore,J.,&Nemecek,T. (2018).Reducingfood’senvironmentalimpactsthrough producersandconsumers.Science.–ProcessedbyOur World in Data

14. Fig1.14DataSource-Poore,J.,&Nemecek,T. (2018).Reducingfood’senvironmentalimpactsthrough producersandconsumers.Science.–ProcessedbyOur World in Data

Fig.

Fig.

15. Fig1.15DataSource-FoodandAgriculture OrganizationoftheUnitedNations(viaWorldBank)–processedbyOurWorldinData

16. Fig1.16DataSource-LandUseData-HYDE (2017)–processedbyOurWorldinData

Fig. 1.16 | AGRICULTURAL LAND AREA

Fig. 1.15 | ARABLE LAND NEEDED TO PRODUCE FOOD

A1 A NEW LAND DEAL

Translating land from estate to ecology

By Reshma Susan Mathew

Green New Deal based seminars_ April 2023

Abstract Who possesses this landscape?

The man who bought it or I who am possessed by it?

– Norman MacCaig (Shrubsole, 2019)

This essay explores the role of land ownership in the global carbon economy and its implicationsfor climate action. Land has been deemed as worthless or profitable “real estate or property,” but in the era of the carbon economy, the value of land acquires an additional quality as an absorber of carbon. Therefore, addressing the disparity in land ownership and reversing it through community action is becoming critical in the Green New Deal mission. In order to effectively sequester sufficient carbon from the atmosphere, we must hold those with the resources to do accountable. In the pursuit of environmentally sustainable and economically feasible solutions to the climate crisis, the essay argues that access to the knowledge of who owns the land and how it is being used is paramount. A primary demand that can be incorporated into the Green New Deal should be that for transparency in land records, their ownerships and use.

Drawing on the idea of a “gift economy” of land management and stewardship, from Robin Wall Kimmerer’s work, one can argue that it is necessary to reimagine land

ownership as a bundle of responsibilities, serving the common good of all life forms. Landowners must either be held accountable for their ecological responsibility towards ownership of a piece of the environment or alternatively, the land must be managed towards restoring and rejuvenating the crumbling natural systems. The essay argues that this applies to all types of landowners within the 10% bracket, be it aristocracy, corporations, industries, or public sector departments.

The reading ends by looking at the work of the many other organisation that have commenced on the mission of land reforms and justice. There is a need to decolonize and restore the land to all the disenfranchised people, where land-to-the-tiller agrarian reforms schemes could initiate the decline of large-scale industrial agriculture, which has caused significant harm to the environment. By holding landowners accountable for fulfilling their ecological responsibility of ‘ownership’, we can build a new world that prioritizes the restoration of ecosystems, the revitalization of communities, and the creation of a sustainable future.

What is the role of land in the years to come? What is the future of land under the GND?

As our climate breaks down due to the

17. Adams,T.(2019,April28).WhoOwnsEngland? byGuyShrubsolereview–whythislandisn’tyourland. RetrievedfromTheGaurdian:https://www.theguardian. com/books/2019/apr/28/who-owns-england-guyshrubsole-review-land-ownership

18. Ajl,M.(2021).PlanetofFields.InM.Ajl,APeople’s GreenNewDeal(pp.117-145).PlutoPress. 19. .BakerMcKenzie.(2023).China-RealEstate Law.RetrievedfromGlobalCorporateRealEstateGuide: https://resourcehub.bakermckenzie.com/en/resources/ global-corporate-real-estate-guide/asia-pacific/china/ topics/real-estate-law

carbon we have pumped out and released into the world, we have all come to realize one fundamental truth. If we do not urgently re-capture and trap all this carbon that swells to burst, we do not stand a chance. Governments are scurrying to build their carbon economies to monetise this new order of transactions hoping to capitalize on the last vestiges of natural resources that have been spared erasure. (Pandey, 2023) After centuries of environmental degradation and alienation, we are now aiming to reverse the havoc wrecked by the destabilising activities of humans in the carbon cycles of the environment. In this new order, the value of land acquires an additional quality as an absorber of carbon and not just real property. Land has always been a valuable resource, even before we enclosed it for ourselves and began measuring it in our local unit of currency. It has been the provider of all our basic necessities.

Following the spread of the capitalist world

order, through enclosure policies and the like; land came to be deemed as worthless or profitable ‘real estate or property’. It would provide returns on your investment and prove its worth. And other aspects of the land were rendered as mere anecdotes. The real property once purchased gave its owner the “usage rights” over the physical parcel of land and appendages.

With the active burgeoning of a carbon economy worldwide, we will soon be forced to re-evaluate what is our money’s worth.

As land becomes the most critical cog in that mission to sequester carbon from the atmosphere effectively, we must have a conversation on how that can be facilitated in line with the tenets of the global Green New Deal movement.

What are the necessary steps to be undertaken?

In the absence of constraints on urban

20. Christophers,B.(2018).TheNewEnclosure-The AppropriationofPublicLandinNeoliberalBritain.London: Verso.

21. .Cwmpas.(n.d.).Cwmpas-Foreconomicand SocialChange.RetrievedfromCwmpas:https://cwmpas. coop/

22. Evans,R.(2019,April19).HalfofEnglandis ownedbylessthan1%ofthepopulation.Retrieved fromTheGaurdian:https://www.theguardian.com/ money/2019/apr/17/who-owns-england-thousandsecret-landowners-author

Fig. 1.17 | PUBLIC COASTLINE WALK ON THE WEST COAST OF WALES

economic practices, land ownership in the UK has remained skewed grossly in favour of a handful of rich and powerful2. The figures almost portray the sense that feudalism never died. Several studies have poked to the point of numbness at the alarming inequality that is prevalent. In England, half of the land is owned by a meagre 25,000 people and unsurprisingly, several of these 25,000 people sit in parliamentary offices determining the future of all their landless constituents. (Adams, 2019) In Wales, there is a stark disparity between land use and land value. Residential area land contributes to 70% of the land prices even though they occupy only 5% of the actual land area. Inversely, while agricultural land occupies almost half (50%) the land area, its value is only 5.4% of the net value of land in Wales (Haf, Gwerth Tir Cymru | The Value of Land in Wales, 2021).

The landowners have retained their property rights for decades and impacted the country more than the combined citizens that have lived in it. This impact has driven environmentally destructive developments, promoted longer supply chains, degraded local landscapes, destabilised small farm holdings, decreased internal food security and a host of other social and economic pitfalls.

To begin developing environmentally sustainable (and economically feasible) solutions to the climate crisis, we first need to gauge who has the most responsibility and power towards climate action. Access to the knowledge of who owns the land we stand on and how is it being used is paramount. This information should be public and accessible, not shrouded in secrecy as it is now. As a very basic step towards land reform, it is important to demand the publishing of the data sets of ownership. This information remains opaque and guarded by the very instruments elected to protect the people’s best interests. It is estimated that accessing

records of land ownership in England would cost an individual up to £72 million in fees paid to the land registry (Adams, 2019). As cries for just transition and land redistribution ring louder every day, agencies that work towards imagining that future need access to that knowledge.

What after gaining access to land records?

In her book Braiding Sweetgrass, Robin Wall Kimmerer talks of how indigenous communities live in a ‘gift economy’. She says that “goods and services” were not purchased but received as gifts from the earth and the land was a gift for all. In her poignant book, she describes how her Native American tribal community saw land not as a bundle of usage rights but instead as a bundle of responsibilities. These were the responsibilities of serving the common good of all life forms – creatures small and large, flora or fauna.

In modern rhetoric, it has become impossible to imagine an alternative reality to the consumer economy. A gift economy seems almost like a fairy tale, but the reality could not be any further from true. These models of land management and stewardship existed for centuries before present systems came to be and it is not impossible or impractical, in fact, it is necessary. Controversial as it may be, landowners must either be held accountable for their ecological responsibility towards ownership of a piece of the environment or alternatively, the land must be managed towards restoring and rejuvenating the crumbling natural systems.

This applies to all types of landowners within the 10% bracket, be it aristocracy, corporations, industries, or public sector departments. Having seen the disproportionate damage wrecked by the tiny elite, it would be remiss not to place the

23. GiacomoD’Alisa,GiorgosKallis,&Federico

24. Haf,S.(2021,April30).GwerthTirCymru|The Value of Land in Wales. Retrieved from Who Owns Wales ||PwyBiaCymru:https://whoownscymru.wordpress. com/2021/04/30/gwerth-tir-cymru-the-value-of-land-inwales/

sizeable responsibility of climate restoration on the same creatures.

In his book ‘A People’s Green New Deal’ Max Ajl talks of how the land must be decolonized and restored to all the disenfranchised people. In his imagination titled ‘a planet of fields’, he elaborates on the impact of introducing land-to-the-tiller agrarian reforms that could initiate the decline of capitalist markets and restore the means of production to the labour forces.

We need to translate the value of land from real estate to real ecology, its original form and function. And this transition must be chalked out for the different types of institutions that occupy the land such as the variety of industries, corporations, authorities and public agencies. Strategies for degrowth should embark on a mission for reducing national consumption and promoting more sustainable land practices. If the land has

been the most sought-after public asset in the past, those who own land also own the capacity for alternative futures. It is critical to ensure that this capacity is channelled towards the larger common good.

What is the work that is currently underway in Wales?

The task that lies ahead is daunting and by no measure a small feat. Most academics and farmers have been in consensus while advocating for a more diverse portfolio of enterprises within the farming industry. Large-scale supermarket chains and their intensive farming practices have homogenised agricultural activities with blatant disregard for socio-economic consequences. So naturally, transitioning away from these models towards ecologically restorative farming and labour practices will entail reviving more traditional relationships with the land.

25. Haf,S.(2022,February28).TheWelshAgenda. RetrievedfromWhoOwnsWales?:https://www.iwa. wales/agenda/2022/02/who-owns-wales/ 26. Kimmerer,R.W.(2013).BraidingSweetgrassIndigenousWisdom,ScientificKnowledgeandthe TeachingsofPlants.MilkweedEditions.

Fig. 1.18 | SUBTLE ENCLOSURES IN PUBLIC AREAS AT NEWLY REOPENED BATTER-SEA POWER STATION

Agroecological farming models are being explored where farms and farmers work more closely with local communities to provide them with their requirements, often building bespoke relationships with members of the community to create more dense networks of production. Agriculture can be closer to the cities and connect the urban centres to their hinterlands. There must be more government initiatives to lock carbon dioxide from the atmosphere into the ground and policies must protect and value the labour expended on ecological restoration. (Ajl, 2021)

As a Welsh farmer Rhidian Glyn said in an interview with The Guardian, ‘Agriculture is just the recycling of carbon, isn’t it? Whereas the companies that are buying carbon credits are just burning fossil fuels, aren’t they, which is just a one-way system.” (Levitt, 2021) In transitioning ahead of current models caught up in superficial greenwashing measures, adequate financial subsidies and support must be provided to boost healthy practices in the industry.

Banks must be propositioned to lend more generously towards these initiatives. With the clock ticking, it is imperative that we build collectives and learn from each other. There are a remarkable number of radical and progressive agencies working towards land justice and reform in the UK.

The LION (Land In Our Name) is an organization that works with marginalised BPOC communities to reimagine the dynamics of land stewardship – one where they cultivate a relationship with the land that “extends beyond extraction”. Through multiple projects, the organisation has curated the narrative of reparations owed to black communities centring the stories of their community’s land workers. They also conduct a variety of knowledge dissemination activities such as podcasts, talks, discussion circles and skill-sharing presentations and facilitate network building. In one project, Jumping Fences they worked to map BPOC-led land-based businesses and to discover what challenges they face and how they seek to overcome them.

Another organisation that is working towards making land more accessible is Shared Assets. They reimagine local economies, natural resources, governance and policy through land reform proposals. Towards this effort, the organisation is also working to build collective knowledge on working with land for the common good and the complex challenges it entails. Cwmpas is an organisation previously known as the Wales Co-operative Centre that works towards providing expert financial and legal assistance to support people seeking funds to develop their own businesses or to move into their own homes. By providing advice (often free of charge) they have

27. Levitt,T.(2021,December28).‘It’lltakeaway ourlivelihoods’:Welshfarmersonrewildingandcarbon markets.RetrievedfromTheGaurdian-Rewilding:https:// www.theguardian.com/environment/2021/dec/28/ agriculture-recycling-carbon-farmers-reframe-rewildingdebate

28. Pandey,K.(2023,April12).Indiapreparesfora domestic carbon market with release of a draft carbon tradingscheme.RetrievedfromMongabay: 29. https://india.mongabay.com/2023/04/ india-prepares-for-a-domestic-carbon-market-withrelease-of-a-draft-carbon-trading-scheme/?mc_ cid=346aaf1a15&mc_eid=5670febf58

Fig. 1.19 | NATIVE LAND DIGITAL INDIGENOUS MAPPING

Fig. 1.20 | WELSH LAND OWNERSHIP VS LAND VALUE

been working to empower the community through novel means of cooperation within the private sector in the form of cooperative consortia that protects the interests of their community. Their projects cover a wide range of portfolios including proposals in the housing sector, digital inclusion policies, community financing models, social enterprises and the launching of new businesses. A popular strategy adopted by them has been using Community Shares to save local businesses or starting new ones to provide services to the community. (Cwmpas, n.d.)

Resilient green spaces is a Welsh government-funded project involving multiple organisations to tackle better food systems with better quality food, better access to land, improved community farms and biodiversity. The New Economic Foundation, the Real Farming Trust, the Landworkers Alliance, the Future Narratives Lab are all many other

organisations that work towards exploring new farming techniques that are built on a sustainable model of farming that responds to the climate crisis and the pressing needs of a community that has been alienated from the landscape.

As we can see there are numerous teams and organisations working towards a more equitable and just future. These numerous examples are evidence that it is possible to imagine an alternative shared reality that works for the benefit of all. The government needs to catch up with these communitydriven initiatives and facilitate more such enterprises. With more political will, the larger systemic issues can be addressed to tackle the climate crisis. The saying goes ‘an organized people, need no state’ however the government remains responsible for serving the best interests of its people, especially when the movement has already taken shape on the ground.

30. Perkins,R.(2019,February12).Making small farms work: lessons from 59°N. Oxford Real FarmingConference2019.OxfordRealFarming. Retrieved2023,fromhttps://www.youtube.com/ watch?v=nb3jBPF7NLs&ab_channel=OxfordRealFarming

31. Shrubsole,G.(2019).WhoOwnsEngland.Great Britain: William Collins. 32. Wood,E.M.(1998,July1).TheAgrarianOrigins ofCapitalism.TheMonthlyReview,pp.1-15.

Fig. 1.21 | PRIVATISED POCKETS IN ENCLOSED PARK AT BEDFORD SQUARE IN LONDON

01.3.1 Historical Background 01.3

Lessons from a Small Country

Wales is a small proud country with a rich history. It is home to many historical cultures and has a long agrarian history. There are even entire sections of medieval Welsh poetry written on cattle and its trade (Lewis, 2013). During the Industrial Revolution, the Welsh landscapes were plundered heavily to supply coal to the factories all over the UK. Depictions of Welsh landscape from this period tends to show the picturesque landscape forming the backdrop of smoking chimneys from the coal mines. By the end of the 20th century, with transition to other fuels, the coal mines slowly shut down. The landscape now serves primarily as vast areas of livestock farming or as avenues for wildlife or adventure tourism. It has become a holiday haven for many from neighboring areas and its landscapes remain as enchanting as before. There is considerable sense of pride (and nationalism) surrounding these regions and with climate conditions getting harsher, there is movement to preserve these spaces too.

1.22 | ENVIRONMENTAL NEWS CLIPPINGS FROM WALES

33. Lewis,B.(2013).‘GwalchCywyddauGwyr’: FifteenthCenturyWales.InB.L.DFEvans,‘Apoetinthe landscape:Walesanditsregionsthroughtheeyesof Guto’rGlyn’(pp.149-76). 34. Fig23DataSource-Beaver,T.H.,Patricia.(2013, March4).LifeAfterCoal:DoesWalesPointtheWay?The DailyYonder.https://dailyyonder.com/lifafter-coal-doeswales-point-way/2013/03/04/

Fig.

Fig. 1.23 | COAL MINING AREAS IN UK

Coal Mining regions

Edinburgh

Newcastle

London

Cardiff

35. Fig1.24 &Fig1.25 -ArtisticImpressions ofNineteenthCenturyIndustrialSouthWales.(n.d.). Thomasgenweb.com.http://thomasgenweb.com/

Fig. 1.25 | DOWLAIS IRONWORKS, GEORGE CHILDS, 1840.

Fig. 1.24 | MERTHYR RIOTS, PENRY WILLIAMS, 1816.

01.3.2

Welsh Climate Action

The One Planet Development emerged under the umbrella of such Acts and is a ‘forwardthinking’ planning policy that is aimed at providing people with the means to live sustainably off their own land if they were able to reduce their ecological footprints

The Welsh government has been working towards addressing the climate crisis and building a suitable action plan towards it. Numerous attempts have been made to draft policies that tackle global warminggenerated issues in this small nation. These efforts are directed towards curbing carbon emissions, building energy-efficient buildings, and managing the waste generated to reduce the long-term shifts in temperature (Welsh Government n.d.). The earliest of such legislation was the One Wales, One Planet scheme which was introduced in 2009. This piece of legislation advocated for cutting down the country’s consumption to its fair share of the earth’s resources as per the EF. Wales also rolled out multiple legislations to prepare their climate action strategies like the Wales Climate Change Strategy (2010 revised in 2014) which aspires to create 50,000 Ha of new woodlands by 2040; the Environment (Wales) Act 2016 which further enlisted numerous supplementary policy briefs to ensure natural resources are managed sustainably. Some of them are the National Natural Resources Policy for Wales to ensure the sustained preservation of all documented natural resources through effective naturebased solutions for the prosperity of the country. Another policy is the Biodiversity and Resilient Ecosystems Duty which made the responsibility of public bodies to protect and preserve the ecological systems within their jurisdiction. A more recent one of these policies was the Well-being of Future Generations Act (2015) under which, public bodies are advised to pursue the economic, social, and environmental well-being of Welsh citizens in ways that build resilience and adaptations to the onslaught of the climate crisis (Wales 2015). It put in place necessary guidelines for sustainable development and outlined the statutory roles of public bodies. The One Planet Development emerged under the umbrella of such Acts and is a ‘forwardthinking’ planning policy that is aimed at providing people with the means to live sustainably off their own land if they were able to reduce their ecological footprints.

Lewis,B.(2013).‘GwalchCywyddauGwyr’:

2009 - One Wales One Planet

The sustainable development scheme of the Welsh assembly government

2010 - Technical Advice Note 6

Planning for sustainable rural communities

2012 - Practice Guidance Document

One Planet Development TAN 6 Planning for sustainable rural communities

2021- Review of OPD Policy

A review was conducted by the One Planet Council to identify the performance of the policy over the last 11 years

2020- Net Zero Strategic Plan

Net Zero goals in keeping with the UK targets for the Paris Agreement devised and introduced

2015- Well-being for Future Generations Act

Act introduced in Senedd promising to safeguard planetary health and create a just and equitable world for posterity

Post Brexit loss in farm subsidies

Fig. 1.26 | WELSH CLIMATE ACTION TIMELINE

01.3.3

One Planet Development Policy

The One Planet Development is a planning policy implemented under the guidelines set forth by the Welsh parliamentary legislation called the Future Generations Act. In a quest to reduce environmental impact on the planet, this policy set out to reduce individual EF by promoting avenues to a new lifestyle. The Welsh government announced this policy to encourage individuals to reduce their footprints, hoping the trend would reflect on the national figures as well.

The Welsh government announced this policy to encourage individuals to reduce their footprints, hoping the trend would reflect on the national figures as well.

Applicants who signed up to be a part of this policy were allowed to build eco-homes on their own farmlands if they were able to sustain themselves from the land on a reduced ecological footprint. The ecological footprint allowance was estimated to be 1.88 gHa per person, based on the national EF in the year the policy was drafted. Since the calculation of Welsh EF cannot be directly transferred to the individual scale, under the OPD scheme the individual EF was to be calculated based on a system designed to measure their performances over seven parameters (marked in drawing beside). The interested applicants are to submit a detailed business model to the Local Planning Authority (LPA), highlighting their strategies and five-year plan to achieve the stipulated targets under the 7 parameters. There are several clauses and conditions that must be met. These are annually monitored by the LPA for the plot be considered a successful OPD site.

Through this policy the legislators hoped to address both issues of climate change and a burgeoning rural housing crisis.

Through this policy the legislators hoped to address both issues of climate change and a burgeoning rural housing crisis. Due to the intense tourist interest in Wales, a unique condition has arisen where the purchase of second homes have driven up housing prices making housing a scarce commodity in the countryside. The OPD application provided an answer to both and encourage rural repopulation. The guidelines also created frameworks for several types of OPDs to facilitate sharing of tools and systems; such as the multi-unit, land based enterprises, small group, small planned community and the ecovillage.

Community Impact 06. Transport 05. Waste & Water

04. Energy

03. Land Management

02. Zero Carbon Building

01. Land Based Activity

Eco house built on agricultural land

Reducing Ecological Footprint to 1.88 GHa

Community Impact

39. Fig1.27LandUseConsultants;Positive DevelopmentTrust.(October2012,October).Practice Guidelines:OnePlanetDevelopment.Cardiff:Welsh Government.RetrievedJanuary26,2023,fromOne PlanetCouncil:https://www.oneplanetcouncil.org.uk/ planning-policy/

Fig. 1.27

Fig. 1.28 | VIEW OF TY GWENNOL OPD FARM

Fig. 1.29 | VEGETABLE BEDS AT DAN Y BERLLAN

Fig. 1.30 | POULTRY FARM AT DAN Y BERSHAN

Fig. 1.31 | ECO HOUSE AT THE LAMMAS ECO VILLAGE SITE

A2 NEED OF SUSTAINABLE AGRICULTURE BUSINESS MODELS IN WALES

A Path Towards One Planet Development and the Green New Deal

By Parth Mehta

Green New Deal based seminars_ April 2023

Introduction

“Industrial farming significantly contributes to climate change, releasing greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide, methane, and nitrous oxide into the atmosphere” (EPA, 2022).

These emissions have far-reaching impacts, including droughts and floods, that require immediate action. At the cost of climate change, industrial farming is also linked to the Global economy generating significant revenue and creating millions of jobs. To address this, it is crucial to change current agricultural practices (Climate Change and Land, IPCC, 2019).

Wales has implemented the one planet development policy to promote sustainable agriculture and land-use practices with low-impact living. In addition, ‘the Green New Deal provides a comprehensive vision for generating a low-carbon economy that prioritises social and environmental justice’ (H.Res, 2019-2020). By embracing sustainable agriculture practices such as agroforestry, permaculture, and regenerative agriculture, “Wales has the potential to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions, enhance biodiversity, and support local communities” (One Planet Development Wales, 2012). However, these farming methods face inevitable short-term setbacks due to the significant investment in time, resources, and knowledge. Furthermore, the current economic system has created financial barriers, including a lack of financial

incentives and support from the market and government, which limits adoption of sustainable agricultural practices.

Business models can play a crucial role in overcoming these limitations, and help farmers have a stable source of income and reduce any financial risk. This model can also build relationships between farmers and consumers by creating a sense of community and promoting more sustainable agricultural practices (Community supported agriculture, 2020).

This essay will explore different business models for sustainable agriculture and land use in Wales that support One Planet Development’s goals. I will begin by discussing the current business models used in Wales and highlighting their strengths and weaknesses. I will explore alternative business models like cooperatives, social enterprises, community-supported agriculture, and land use that can create new green jobs. The essay will conclude with ways to include these business models in the One Planet Development policy and how they can contribute to Green New Deal.

The Present

In Wales, agriculture is heavily focused on livestock farming, with sheep and cattle being the most commonly raised animals. The goal is to maximise production by keeping many animals in confined spaces. (BBC, 2020).

40. AgriculturalSourcesofGreenhouseGas Emissions,’Greenhousegasesreleasedfromagricultural practices,EPA2022,accessedApril202023,https:// www.epa.gov/ghgemissions/sources-greenhouse-gasemissions#agriculture

41. ClimateChangeandLand,”Intergovernmental PanelonClimateChange,August8,2019,https://www. ipcc.ch/srccl/chapter/summary-for-policymakers/

42. “H.R.109-RecognizingthedutyoftheFederal GovernmenttocreateaGreenNewDeal,”116thCongress (2019-2020),Congress.gov,accessedApril20,2023, https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/houseresolution/109.

This condition generates profuse animal waste in small areas, polluting soil, and water. These impacts have raised concerns about the environment and animal welfare.

Most fields in Wales are monoculture crops of wheat and barley. The reliance on synthetic fertilisers and chemical pesticides, often used with heavy machinery, has profoundly affected the environment and human health. (BBC, 2020). In Wales, synthetic fertilisers are common on crops such as potatoes and maise. The impact of agribusiness is not limited to the environment. Large business corporations have marginalized small-scale farmers, leading to a concentration of land ownership and loss of traditional farming practices and local knowledge. It has created a power imbalance, leaving small-scale farmers at the mercy of large corporations and commodity markets. (Welsh government, 2018)

These agricultural practices in Wales are

based on conventional business models of maximising productivity and profits, often at the expense of quality. Intensive farming may help to increase agricultural production, but it comes at the cost of the environment and human and animal welfare. (EPA, 2022)

For example, river Wye in Wales has been affected by nitrogen runoff due to the extensive use of synthetic fertilisers in the surrounding fields. It resulted in algal blooms and low oxygen levels in the water, affecting aquatic life and local communities that rely on the river for fishing and recreation. (Farhoud, Nada, and Tomas Malloy. 2022These conventional agricultural practices in Wales urgently need reform. The business models need to change from maximising productivity and profits gained at the expense of the environment, human health, and traditional farming practices to more sustainable alternatives that can benefit both the environment and local communities.

43. OnePlanetDevelopmentinWales,”Welsh Government,accessedApril15,2023,https://www.gov. wales/sites/default/files/publications/2020-01/practiceguidance-using-the-one-planet-development-ecologicalfootprint-calculator_0.pdf

44. CommunitySupportedAgriculture:ANew BusinessModelforSustainableAgricultureinWales,” WelshGovernment,accessedApril20,2023,https:// communitysupportedagriculture.org.uk/wp-content/ uploads/2020/07/CSA-Evaluation-Full-report-JULY-2020. pdf

Fig. 1.32 | INDUSTRIAL FARMING PRACTICE

The Alternatives

The new business model needs to operate on community involvement, shared ownership, social impact, and environmental justice principles. Various strategies can be adapted from alternative business models such as cooperatives, social enterprises, and community-supported agriculture (CSA) to address the challenges of sustainable agriculture and land use while creating new green jobs.

1. Cooperatives

These are the businesses that their members democratically control. In agriculture, it helps small farmers pool resources and share costs. This model can result in more bargaining power and tip into markets, which is otherwise impossible as an individual. (UN Food and Agriculture Organization, 2012). One such example is US-based Co-op Coffees which sources from farmer cooperatives across the globe, ensuring

fair prices for the farmers and promoting sustainable practices in coffee production (Co-Op Coffees).

2. Social enterprises

In this business model, profits are secondary; it needs to have a social or environmental mission as its core objective to develop sustainable and regenerative agriculture practices. It also creates jobs for disadvantaged communities or reduces food waste (Social Enterprise UK). This innovative model is adopted by UK-based Farm Urban, which uses hydroponic technology to grow vegetables in urban environments to reduce the carbon footprint associated with food transportation and promote access to fresh vegetables in cities. (Farm Urban)14

3. Community-supported agriculture (CSA)

In this alternative business model, consumers are connected with local farmers, providing them with fresh and seasonal

45. BBC.“Nitrogenpollution:Welshfarmersurged tocutemissions.”BBCNews,10Jan.2020,https://www. bbc.co.uk/news/uk-wales-55217228

46. SustainableAgricultureinWales:AReviewof CurrentPracticeandFutureResearchNeeds,”Welsh Government,accessedApril20,2023,https://www. gov.wales/sites/default/files/publications/2018-10/ independent-review-into-the-resilience-of-farming-inwales.pdf

Fig. 1.33 | SUSTAINABLE AGRICULTURAL PRACTICES

produce from small-scale agricultural practices. As a common practice in this model, monthly subscription fees are charged to the consumer in exchange for a share of the harvest throughout the year. It enables farmers with stable income while allowing sustainable agricultural practices, also reducing carbon emissions associated with food transportation (Soil association).

In the UK, the CSA network in Stroud, Gloucestershire, houses many CSA farms and has a thriving local food system. These farms provide weekly harvest shares to consumers who pay upfront for the season’s worth of produce. This model helps local farmers and provides fresh food to the local community while saving the environment (Stroud community agriculture)

Stacking Alternatives

The integration of these alternative models requires a multi-functional agroforestry approach. Integrating different crops,

animals, and land uses within the same farming system allows ecological and economic benefits. In Suffolk, UK, Wakelyns is a Co-op social enterprise combining agroforestry and traditional farming practices. The farm is a mixture of growing different crops, fruits and vegetables around the year while having trees, shrubs, and hedgerows. This practice has helped improve soil conditions, increasing biodiversity and sequestering carbon. The stacking model at Wakelyns creates a resilient, sustainable farming system that benefits the environment and local communities

In the context of Wales, these models, if adopted, can provide new green jobs. For example, cooperative provides the platform for farmers to share knowledge, resources, equipment, and experience of sustainable agricultural practices. It creates job opportunities like resource management that facilitates and monitors supplies or data.

47. Farhoud,Nada,andTomasMalloy.2022. “RiverWyeTurnsinto‘OpenSewer’asWatersAre Polluted.”GloucestershireLive.April6,2022.https://www. gloucestershirelive.co.uk/news/gloucester-news/riverwye-turns-open-sewer-6911722.

48. UNFoodandAgricultureOrganization. “CooperativesandRuralDevelopment.”AccessedApril20 2023,https://www.fao.org/3/ap088e/ap088e00.pdf

Fig. 1.34 | THE JOY OF COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT

Additionally, it requires an administration that monitors the coordination of farming activities.

We can create more value-added products from the social enterprise models of the farms. It enables opportunities for training and education sectors in sustainable agriculture practices. In the CSA model, direct links can be created between farmers and consumers, allowing more sustainable agriculture, and shortening the food supply chain. This model creates scope for marketing and consumer services, also for farm themselves, including farm managers, farm labourers and delivery staff. The overall integration of these models can create a range of new green jobs related to sustainable agriculture and land use practices.

Integration with One Planet Development

One Planet Development, Wales, allows lowimpact living by integrating multiple land-use activities such as forestry, horticulture, and animal husbandry. Today, this happens at an ‘individual scale’ with less than 50 single unit OPDs across Wales serving negligible/no impact on the vision of the policy (To reduce Wales’ ecological footprint while increasing the well-being of citizens). Briefly, the result of the failure of the policy is a need for more government funding, slow administration processes and an extensive application process (One Planet Development Wales, 2012). In addition, if integrated, the discussed business models can promote a more community-based approach, where groups work together to manage land and create a sustainable, resilient community.

49. SocialEnterpriseUK.“TheEnvironmentand SocialEnterprise.”AccessedApril202023,https://www. socialenterprise.org.uk

50. Soil Association. “What is CSA and How DoesitWork?”,AccessedApril202023,http://www. communitysupportedagriculture.org.uk 51. WakelynsAgroforestry.“AboutUs.”,AccessedApril 202023,https://wakelyns.co.uk

Fig. 1.35 | SPRAYING MORE FERTILISERS

Fig. 1.37 | FROM FARM TO CUP

Fig. 1.36 | IS THERE ANY CLEANUP POSSIBLE

Fig. 1.38 | THE FAR IN THE CITY

It is crucial to ensure that integrating alternative business models with OPDs remains a community approach, and a few measures must be considered.

1. OPDs should create community land trust (CLT), allowing common ownership over land and resources. It will share benefits from sustainable agriculture and land use practice within the community.

2. Community engagement and involvement must be increased in developing OPD projects. It is achievable through community consultation, workshops, and training programs. This process will ensure the active participation of community members in decision-making processes.

3. The OPD policy should priorities social enterprises and community-supported agriculture initiatives to create more sustainable agriculture and land-use practices that could benefit the community. In addition, OPD policymakers should

provide support and incentives for their implementation :for example, financial assistance, training, and equipment to integrate alternate business models can bring innovative solutions. Local authorities can also play a role by providing communityled initiatives prioritizing environmental and social justice.

Conclusion

While integrating alternative business models into One Planet development policy, we can also contribute to the Green New Deal vision; by promoting renewable energy, reducing carbon emissions, prioritising environmental protection and social justice we can create a resilient and sustainable economy (Climate Change and Land, IPCC, 2019). In short, these business models can pave the way for a more innovative and community-based approach to economic development in Wales that ensures long-term health and prosperity of planet and people

52. “CoopCoffees.”n.d.,AccessedApril20,2023. https://coopcoffees.coop.

53. GreensforGood.”n.d.FarmUrban.,Accessed April20,2023.https://www.farmurban.co.uk/greens-forgood.

54. Agriculture,CommunitySupported.n.d.“Stroud CommunityAgriculture.”AccessedApril20,2023.https:// communitysupportedagriculture.org.uk/farms/stroudcommunity-agriculture/.

Fig. 1.39 | AGROFORESTRY CONTRASTED WITH INDUSTRIAL

55. Fig1.40.GoogleEarth7.3.6.9345,(2006) Glyncorrwg51°58’0.92”N, 4°12’24.17”W,elevation280M. SatelliteImagery.[Online]Availableat:http://www.google. com/earth/index.html[Accessed15December2023]

Fig. 1.40 | 2009 SATELLITE IMAGERY OF GLYNCORRWG, AFAN VALLEY

56. Fig1.41GoogleEarth7.3.6.9345,(2021) Glyncorrwg51°58’0.92”N, 4°12’24.17”W,elevation280M. SatelliteImagery.[Online]Availableat:http://www.google. com/earth/index.html[Accessed15December2023]

Fig. 1.41 | 2020 SATELLITE IMAGERY OF GLYNCORRWG, AFAN VALLEY WITH THE PEN Y CYMOEDD WIND FARM

ANALYSING THE OPD POLICY

Details of the Policy

The EF Analysis (EFA) for the purposes of the OPD Policy is new tool developed by the policy makers specifically to measure performance across the seven parameters enlisted by the policy. EFA for the individual was designed to measure the difference “between the products and services consumed by the OPD applicants and (...) those consumed by typical UK citizens”. Practical challenges posed by the scale of the assessment made this a calculation based on economic expenses rather than ‘land productivity’ as done with EF calculations for countries. This number was instead designed to build an assessment where the low energy, low consumption lifestyle promoted by the policy would rate highly. And ‘where assumptions cannot be verified, they have not been included. The tool is therefore likely to be relatively conservative in its results.’ 02.1.1 Application Process

The application process for the OPD policy is known to be long and quite taxing. Interested candidates are required to prepare a document known as the Land Management Plan in accordance to the stipulated guidelines. The LPA is the authority that reviews, recommends modifications, and approves the project. The sanctioned projects have a five year period to set up and achieve their goals and are further monitored annually by the LPA. The process is financially quite extractive from procuring the land to hiring experts to help in preparing the document. It can also be quite circuitous with no promise of achieving a positive outcome making it an arduous process draining both time and monetary resources.

1. LandUseConsultants;PositiveDevelopment Trust.(October2012,October).PracticeGuidelines: OnePlanetDevelopment.Cardiff:WelshGovernment. RetrievedJanuary26,2023,fromOnePlanetCouncil: https://www.oneplanetcouncil.org.uk/planning-policy/

2. Fig2.1&fig2.2datasource-:LandUse Consultants;PositiveDevelopmentTrust.(October2012, October).PracticeGuidelines:OnePlanetDevelopment. Cardiff:WelshGovernment.RetrievedJanuary26,2023, fromOnePlanetCouncil:https://www.oneplanetcouncil. org.uk/planning-policy/

Fig. 2.2 | OPD ECOLOGICAL TARGETS

Fig. 2.3 | PHOTOGRAPHS OF TARGET ON SITE

01. Land Based Activity

02. Zero Carbon Building

03. Land Management

04. Energy

05. Waste & Water

06. Transport

07. Community Impact

made thus far by the British government plunging the faith of the international community. In addition to backing out of the the government’s commitment to achieving

INTERVIEW WITH MARC SCALE

Marc Scale was the head of the One Planet Council in March 2023. The One Planet Council is a collective of all approved OPD projects in Wales. The council assists new and interested parties with their applications to the LPA. They act as a knowledge sharing platform for all those interested in the policy and also act as a point of contact between OPDs to facilitate collaborations between each other. Below are a few key snippets from the conversation with Marc Scale on 22nd February 2023.

Why is land a scarce commodity in Wales?

The mountainous terrain has built a traditional history of rearing cattle. At present most farmers prefer to use their land for monoculture which has also degraded the fertility of the land. And in general people prefer not to sell their land since it is a asset inherited and passed down. The land in the North is also more expensive so everyone can mostly buy land only in the south. As a business model how much do the OPDs make? I would say perhaps on an average across the board 4000 a year.

What are the main challenges to the OPD policy right now?

A major challenge is in interpreting the planning guidelines. A lot of them are also rejected at the local council which is later overruled by the LPA. And the OPD Policy was initially going to come out with more types of OPDs but the process stopped with the Open Countryside Type. The council has tried to ease the process and share knowledge but it is taxing and it costs a lot of money to prepare and succeed. Also the OPDs need a lot more support once successful but the

LPA is no funded enough to do it. Like the winters in the eco-homes can get difficult and producing energy is difficult without sunlight then.

Why do you think the locals would rather not have OPDs?

There isa lot of misconception around the policy. When we first set up our OPD, nobody was ready to buy produce from us and there was hostility but on our Open Days, when they visited the site, many of them remarked that this was the way their grandparents used to live long ago, it wasn’t something as radical as they had perceived.

What does the OPD Council do?

We help new applicants find their feet on the ground, providing them assistance with the guidelines. The document even for measuring the Ecological Footprint Analysis is also very tedious to comprehend and nay mistake with the application can set them back unnecessarily.

How is the Ecological Footprint Analysis calculated individually?

There is an excel file with inbuilt calculations

designed to measure consumption against production. Not sure how the metrics within that works.

How does the OPD Council address challenges with the Ecological Footprint Analysis (EFA) calculation?

The OPD Council offers guidance to applicants navigating the complexities of the Ecological Footprint Analysis (EFA). We assist in interpreting the guidelines and provide support in completing the EFA accurately. Additionally, we collaborate with experts to ensure applicants understand the calculations and metrics involved. While the process can be daunting, our aim is to streamline the EFA calculation process and help applicants accurately assess their ecological impact.

What role does community engagement play in OPD initiatives?

Community engagement is fundamental to the success of OPD initiatives. We actively involve local communities through outreach programs, workshops, and open days to foster understanding and support for OPDs. long-term sustainability and positive impact on the environment and society

Fig. 2.4 | CARICATURE OF MARC SCALE

INTERVIEW WITH DAVID THORPE A4

David Thorpe is an active member of the One Planet Centre and was consulted in better understanding the inception of the One Planet concept. A conversation with him was arranged over Zoom on 19th April 2023.

David commended the OPD policy for its bold approach in tackling the climate crisis through lifestyle adjustments. He stressed the necessity of increased funding for Local Planning Authorities to effectively implement and support the policy. David proposed extending the use of Ecological Footprint Analysis (EFA) to all planning applications, beyond just those under the OPD Policy, to enhance environmental considerations across the board.

However, he expressed concerns regarding the outdated nature and complexity of the EF metric. He suggested simplifying the EF by presenting it as a pie chart or bar graph to improve comprehension and accessibility for all stakeholders involved. Additionally, David raised an important issue regarding the laborintensive nature of the lifestyle promoted by the policy, which currently excludes disabled individuals from participating as applicants.

He recommended that future iterations of the policy consider the lifespan and future health of applicants to ensure inclusivity and accessibility for all demographics. These insights underscore the potential for refining the OPD policy to not only address environmental challenges more effectively but also to promote inclusivity and sustainability in its implementation.

Fig. 2.5 | CARICATURE OF DAVID THORPE

INTERVIEW WITH JAMES SHORTEN

James Shorten was a member of the team at Land Use Consultants, the agency used by the Welsh government to draft the OPD Practice Guidelines. A conversation with him was arranged on 9th June 2023 and below is a summary from the conversation between James and the team.

The conversation primarily revolved around trying to understand the process by which the policy was conceptualised, commissioned and drafted. We came to understand that the research started in 2002 and it took a long time to finalise as it was an unconventional piece of legislature and also political shifts in the Welsh Parliament Senedd challenged the process. One year after the contract was awarded to the Land

Use Consultants by a steering committee the policy was introduced in public domain. James believed the Ecological Footprint was not an adequate measure as the work on it has stalled and the conversion factors are increasingly complicated with technological advancements. Innovations like electrical vehicles complicate the metric and he recommended the use of carbon footprints instead to measure climate action plans at that scale.

He asserted that the policy was not an alternative to housing as it was dedicated towards reducing adapting to climate emergency while ensuring access to housing, food and wellbeing. He remarked on the lack of land access and said that options of renting land out to OPDs should be considered more closely.

Fig. 2.6 | CARICATURE OF JAMES HORTEN

OPDs beyond rural areas, exploring types like multi dwellings, land-based enterprises,

Under the OPD practice guidelines published by the TAN-6: Planning for Sustainable Rural Communities in October 2012, the terms listed are assuming that all OPDs will first take shape primarily in the rural countryside. The long-term vision for this policy had sought to expand this scheme to other typologies as well. Speculations were made for OPDs to appear in other regions such as the edge of settlements and within existing settlements. Apart from variations in location, the OPD policy also envisioned a quantitative expansion by increasing the number of stakeholders involved. While these options were never explored in total capacity, the TAN-6 document has elaborated on multiple types within the open countryside. These are (1) Single Dwelling (2) Land based enterprise (3) Small group of dwellings (4) Small planned community and (5) Ecovillage. By 2023, there were very few projects that explored these varieties with the vast majority of projects applying as single units or as land-based enterprises that had small market interests. A small number of projects have explored the third type or multi-unit OPDs and an even fewer number of projects have explored the prospects of an ecovillage.

Examples

Exploring

the Dynamics of Multi-Unit OPDs: Unveiling Opportunities and Challenges

The farm known as Rhiw Las serves as an example of a multi-unit OPD. Four households collaborated, submitted an OPD application for a 21-acre farmland, now fully operational. Similarly, the Lammas eco-village, a well-known case, involves collaboration among twenty households across 120 acres. Direct conversations with these applicants unveiled the challenges and advantages of this development type. All parties agreed that alliances enhance resource management efficiency and establish vital support systems crucial in an isolated location. However, many emphasized the increased complexity associated with heightened collaboration. Despite this, the consensus remains on the positive impact, as alliances contribute to more efficient resource management and foster essential support systems in isolated areas. 7.

8. Fig2.4LandUseConsultants;Positive DevelopmentTrust.(October2012,October).Practice Guidelines:OnePlanetDevelopment.Cardiff:Welsh Government.RetrievedJanuary26,2023,fromOne PlanetCouncil:https://www.oneplanetcouncil.org.uk/ planning-policy/

Fig. 2.7 |

First Hand Discoveries

02.2.1 Mapping the OPD Policy

Upon mapping all the sanctioned OPD projects as of 2023, clear patterns begin to emerge. Between 2010 and 2021, the policy garnered 63 applications, with 39 receiving approval. Notably, a significant concentration of projects is observed in the southern regions, particularly in Pembrokeshire and Carmarthenshire counties.

All operational OPDs are established on freehold lands purchased by applicants. A closer examination of 12 of these projects reveals an average farm size of 15 acres, supporting small families consisting of approximately 2 to 4 individuals each. Aside from the main eco-house approved by the Local Planning Authority (LPA), ancillary structures such as greenhouses, polytunnels, wood sheds, and animal shelters are commonly erected. The majority opt for a grassland type with moderate Agricultural Land Classifications (ALC). These lands yield around 30% of the occupants’ food requirements, as stipulated by policy guidelines, while income generated sustains the purchase of an additional 35% of their food needs. Most OPDs are situated at least a kilometer away from the nearest town, primarily due to more affordable land prices. However, the income generated is often insufficient to cover all household expenses, prompting many residents to seek secondary employment outside the OPD. These jobs are typically pursued remotely or entail commuting to off-site locations.

The prevalence of OPDs underscores a growing trend toward sustainable living and alternative land use practices. Despite challenges such as limited self-sufficiency and the need for supplemental income, these projects contribute to local food production and rural economic diversification. As the popularity of OPDs continues to rise, policymakers may consider further support mechanisms to enhance their viability and effectiveness in fostering resilient, community-based livelihoods.

9. Banks,J.,&Clare,T.(2014).ParcyDwr.One Planet Council.

10. Bartlam,C.M.(2019).CarolynMoody,andPaul Bartlam. One Planet Council.

11. Brannoc,S.,&Hawthorn,T.(2013).BrynyrBlodau ManagementPlan.OnePlanetCouncil

12. Eames,T.(2018).CoedAlltGoch.OnePlanet Council.

2.8 | CASE STUDY OF TWELVE OPD SITES

Fig.

Fferm Pwll Lili

Baradyws

Allt Cefn Ffynnon

Perllan Herberdeg

Pencoed

Hebron Farm

Grassland Marsh

Built-up Areas

Tall Fern

Woodland & Scrub

02.2.2

Four Primary Case Studies

Cryn Fryn

This site, abutting a twenty year woodland was two fields sloping gently to the southeast. Separated by a drain ditch and hedges of hazel, hawthorn, holly and elder in the middle. The land was used for cultivating organic beef and lamb and seasonally open to camping tourists.

Golweg Gwenyn

Three fields on the boundary between cultivated land and moorland on the slopes of Carningli Mountain. A business based around eggs and honey production while being nesting grounds to valuable species of bats. A stream along the west boundary was considered for hydro electric power generation.

Alt Cyn Fynnon

High canopy ancient deciduous woodland with mixed broadleaf species. Low earth banks and hedgerows with trees form the borders with a stream to the east. Site to support business plans of timber cultivation, woodworking and charcoal production. Private holiday park to the north-west.

Perllan Herberdeg

This site on the slopes of the Gwendraeth valley, was ‘patchy’ and had areas of poor drainage however it was possible to plant ninety apple trees, grow peas, squashes, sunflowers, and chard on test beds in the first year. Priority habitat areas were conserved as wildlife habitats.

16. Murton,a.B.(2018).LandatCryn-Fryn.One Planet Council.

17. Smith,L.M.(2017).AlltCefnFfynnon.OnePlanet Council.

Fig. 2.9 | KEY MAP OF OPD SITES

Fig. 2.10 | SATELLITE IMAGERY OF OPD SITES

(Quite a Hill)

(Sight of a Bee)

(Well behind a Hill)

(Herberdeg Orchard)

Fig. 2.11 | STUDY OF CRYN FRYN

Fig. 2.12 | STUDY OF

WENYN

22. Fig2.10Smith,L.M.(2017).AlltCefnFfynnon. One Planet Council. 23. Fig2.11Moody,C.,&Bartlam,P.(2019). ManagementPlan.Carmarthenshire:OnePlanetCouncil.

Fig. 2.13 | STUDY OF ALLT CEFN FFYNNON

Fig. 2.14 | STUDY OF PERLLAN HERBERDE g

Woodland

Mosaic

Cross Inn New Quay

OPD Site

Llanarth

Charcoal

Juice Firewood Wood crafts

Acres

Acres

Llanelli Burry Port Carway

OPD Site

Pontyates

CONVERSATION WITH OPD APPLICANTS

SYLVIE AND WYCLIFF

Q: Although the OPD policy has envisioned as a very good approach, it has not managed to attract the number of required people to create an impact. So, from your perspective, as people who are already on the scheme, how you think it can be better or how it can be.

Sylvie: I think one of the biggest problems with the policy is that it’s really difficult for the planning people to enforce it. For example, you have five years within the OPD policy to kind of set up and achieve your goals; start to build your house and have a base business. But every year you submit the monitoring report, but that no one has ever gone through. We submit it every year and no one ever comes back to us. And I don’t think anyone even looks at it. I don’t know if they do, but it doesn’t seem like anyone is interested in what we’re doing to the planet, because they’re really busy and underfunded and understaffed. Since it is very new and it does attract people. I think also from our perspective, I mean, we did it. We bought land 10 years ago. But people that are now trying to get into the one planet, lots of people don’t find land. You could get farms of 100 acres. So you have to find a farmer that’s willing to split the land into a smaller parcel.

Wycliffe: Or it might be a small farmer who goes out of business, and they split into a small farm. But actually, the small farms are the ones that we kind of want to continue to exist.

And there isn’t really an overall, well, there is an overall improvement. But also, there’s a big problem with local knowledge of the policy. I think, because most people that have an OPD, frequently come from England, frequently of a certain class and education,

and they’re the people who were first interested in climate change related stuff. Whereas one of the big criticisms we get when we make an application is that such and such local farmer who wanted to build a house for their son and wasn’t allowed so, why should these newcomers be allowed? And that’s because they didn’t know the policy existed and to know that this as an available option for their children.

Sylvie: Oh, but also to put together an application. If you see our application, it’s really big. It’s a book and it’s like, we all have PhD degrees here. We know how to tackle something quite academic. But all the farmers that look at it, have to take like a big undertaking. And I think if it could be made simpler that way, then it would be more accessible to people, you know, I mean, because we did it in a group of four plots, so we kind of split the tasks as well. And Chris and Erica are really clever, so they did a lot of the numbers for us all and but it’s all quite tricky, really.

Q: From Tao we know that authority don’t follow up and they don’t check five years and things like that but have you made changes to the way you had set out from your application? And do you think there’s a way in which the planning office could make it more flexible?

Wycliffe: I don’t think it matters that what’s the plan you’ve got. One plan is what you intend to build and that obviously must stay very close to proposal. Then the other part is the business you propose to have. And really, I think this is the case of a lot of things. If you were applying for a loan or something like that, the business plan really is proving that you can plan a business.

Sylvie: Like it’s likely to change from what it