GHANA DECIDES

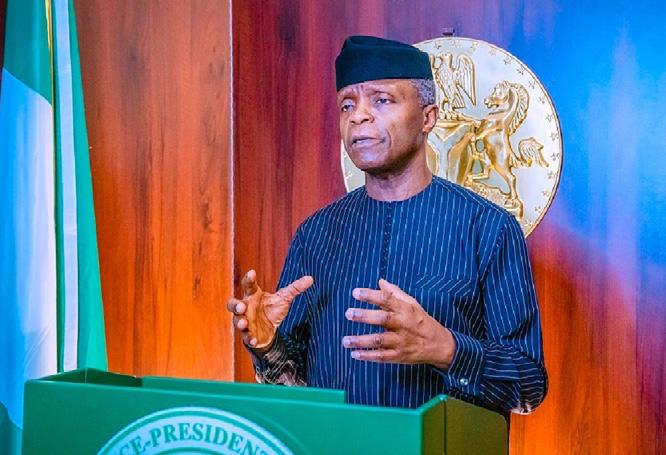

FORMER Nigerian Vice President Yemi Osinbajo's insightful presentation at the 6th African Union mid-year coordination meeting earlier this year highlights Africa’s growing prominence in global development. His reflections outline a forward-thinking narrative that moves beyond the stereotypes of resource dependency, positioning the continent as a hub for innovation, sustainable growth, and a solution provider in the climate crisis. However, achieving this vision demands global cooperation, African unity, and transformative leadership.

From resource extraction to value addition Osinbajo astutely notes the paradigm shift in Africa’s resource policies. Nearly half of subSaharan African countries now mandate value addition before exporting raw materials. This is a significant departure from the colonial model of resource exploitation, which historically left African nations impoverished despite their wealth of natural resources.

The emerging focus on green hydrogen production exemplifies this transformation. Countries like Namibia, Angola, and South Africa are advancing clean energy projects that will position Africa as a global leader in renewable energy. Namibia’s $10 billion investment in green hydrogen and Angola’s plan to export green ammonia to Germany by 2025 are testament to the continent's ambition. These projects not only signal Africa's role in combating climate change but also its ability to integrate into high-value global supply chains.

Publisher Jon Offei-Ansah

Editor Desmond Davies

Contributing

Editors

Prof. Toyin Falola

Tikum Mbah Azonga

Prof. Ojo Emmanuel Ademola (Technology)

Valerie Msoka (Special Projects)

Contributors

Justice Lee Adoboe

Chief Chuks Iloegbunam

Joseph Kayira

Zachary Ochieng

Olu Ojewale

Oladipo Okubanjo

Corinne Soar

Kennedy Olilo

Gorata Chepete

The power of youth and innovation

In 2018, six of the 10 fastest-growing economies in the world were in Africa, according to the World Bank, with Ghana leading the pack. With GDP growth for the continent projected to accelerate to four per cent in 2019 and 4.1 per cent in 2020, Africa’s economic growth story continues apace. Meanwhile, the World Bank’s 2019 Doing Business Index reveals that five of the 10 most-improved countries are in Africa, and one-third of all reforms recorded globally were in sub-Saharan Africa.

Jon Offei-Ansah Publisher

However, the real challenge lies in ensuring that these initiatives deliver broad-based benefits. African governments must create regulatory frameworks that prevent foreign investors from monopolising the value chain while excluding local communities. As Osinbajo emphasises, climate-positive growth requires a “grand bargain” with the Global North—one that prioritises fair trade rules, access to carbon markets, and investments in renewable energy.

Desmond Davies Editor

Designer

Simon Blemadzie

Africa’s demographic advantage, with a rapidly growing youthful population, offers immense potential. Osinbajo points to the rise of tech hubs and startups, such as the six unicorns in Nigeria, as evidence of African ingenuity. Platforms like the UNDP-backed $1 billion Africa Innovation Foundation further underscore the continent’s capacity for transformative change. Yet, the opportunities presented by this youthful workforce depend on sustained investment in education, digital skills, and infrastructure. Bridging the digital divide will enable African innovators to compete globally, while fostering a culture of collaboration will address the fragmented nature of the continent’s innovation ecosystem.

Angela Cobbinah Deputy Editor

Stephen Williams Contributing Editor

Director, Special Projects

Michael Orji

Country Representatives

South Africa

Edward Walter Byerley

What makes the story more impressive and heartening is that the growth – projected to be broad-based – is being achieved in a challenging global environment, bucking the trend.

Contributors

Climate-positive growth: a global imperative

Top Dog Media, 5 Ascot Knights 47 Grand National Boulevard Royal Ascot, Milnerton 7441, South Africa

In the Cover Story of this edition, Dr. Hippolyte Fofack, Chief Economist at the African Export-Import Bank (Afreximbank), analyses the factors underpinning this performance. Two factors, in my opinion, stand out in Dr. Hippolyte’s analysis: trade between Africa and China and the intra-African cross-border investment and infrastructure development.

Much has been said and written about China’s ever-deepening economic foray into Africa, especially by Western analysts and commentators who have been sounding alarm bells about re-colonisation of Africa, this time by the Chinese. But empirical evidence paints a different picture.

Justice Lee Adoboe

Chuks Iloegbunam

Joseph Kayira

One of Osinbajo’s most compelling arguments is Africa's central role in achieving global climate goals. If Africa adopts a carbon-intensive development model, the repercussions for global emissions would be catastrophic. Conversely, a climate-positive growth trajectory, leveraging renewable energy, could make Africa a global leader in sustainability.

Zachary Ochieng

Olu Ojewale

Tel: +27 (0) 21 555 0096

Cell: +27 (0) 81 331 4887 Email: ed@topdog-media.net

Oladipo Okubanjo

Corinne Soar

Designer

The African Union’s endorsement of this paradigm reflects growing continental commitment. However, the success of such a strategy hinges on international support. The Global North must not only acknowledge Africa’s sequestration capacity but also compensate the continent for preserving its carbon sinks. A reformed financial architecture that reduces borrowing costs and incentivises green investments is critical.

Collaboration is key

Despite the decelerating global growth environment, trade between Africa and China increased by 14.5 per cent in the first three quarters of 2018, surpassing the growth rate of world trade (11.6 per cent), reflecting the deepening economic dependency between the two major trading partners.

Gloria Ansah

Country Representatives

Osinbajo’s call for intra-African collaboration is timely. The African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) presents an unprecedented opportunity to unify the continent economically.

South Africa

Ghana

Nana Asiama Bekoe

Kingdom Concept Co. Tel: +233 243 393 943 / +233 303 967 470 kingsconceptsltd@gmail.com

Empirical evidence shows that China’s domestic investment has become highly linked with economic expansion in Africa. A one percentage point increase in China’s domestic investment growth is associated with an average of 0.6 percentage point increase in overall African exports. And, the expected economic development and trade impact of expanding Chinese investment on resource-rich African countries, especially oil-exporting countries, is even more important.

Edward Walter Byerley

Increased intra-African trade, coupled with coordinated trade negotiations with global blocs, could enhance Africa’s bargaining power on the world stage.

Top Dog Media, 5 Ascot Knights 47 Grand National Boulevard Royal Ascot, Milnerton 7441, South Africa

However, achieving unity requires strong leadership and an alignment of national interests with collective goals. The continent must overcome political fragmentation and address infrastructural gaps that hinder trade and economic integration.

Towards statesmanship

Nigeria

The resilience of African economies can also be attributed to growing intra-African cross-border investment and infrastructure development. A combination of the two factors is accelerating the process of structural transformation in a continent where industrial output and services account for a growing share of GDP. African corporations and industrialists which are expanding their industrial footprint across Africa and globally are leading the diversification from agriculture into higher value goods in manufacturing and service sectors. These industrial champions are carrying out transcontinental operations, with investment holdings around the globe, with a strong presence in Europe and Pacific Asia, together account for more than 75 per cent of their combined activities outside Africa.

Tel: +27 (0) 21 555 0096 Cell: +27 (0) 81 331 4887 Email: ed@topdog-media.net

Ghana

Ultimately, Osinbajo argues that Africa’s transformation requires both African and global statesmanship. Leaders must prioritise long-term goals over short-term political gains. This includes fostering regional cooperation, rethinking global financial systems, and ensuring that Africa’s natural and human resources are optimally harnessed for global progress.

Nana Asiama Bekoe

Kingdom Concept Co. Tel: +233 243 393 943 / +233 303 967 470 kingsconceptsltd@gmail.com

Nigeria

For the Global North, recognising Africa’s pivotal role in achieving net-zero emissions and global economic stability is not just a moral obligation—it is a pragmatic necessity. For Africa, the path forward lies in bold, unified action, where collaboration drives progress.

A vision worth pursuing

A survey of 30 leading emerging African corporations with global footprints and combined revenue of more than $118 billion shows that they are active in several industries, including manufacturing (e.g., Dangote Industries), basic materials, telecommunications (e.g., Econet, Safaricom), finance (e.g., Ecobank) and oil and gas. In addition to mitigating risks highly correlated with African economies, these emerging African global corporations are accelerating the diversification of sources of growth and reducing the exposure of countries to adverse commodity terms of trade.

This makes me very bullish about Africa!

Osinbajo’s presentation serves as a call to action for Africa and the world. The continent’s dynamism, youthful energy, and natural wealth position it as a cornerstone of global development. However, realising this potential requires systemic changes, both within Africa and globally. Only through mutual collaboration and visionary leadership can Africa’s promise as a driver of global prosperity be fulfilled.

Taiwo Adedoyin MV Noble, Press House, 3rd Floor 27 Acme Road, Ogba, Ikeja, Lagos Tel: +234 806 291 7100 taiadedoyin52@gmail.com

Kenya

Naima Farah Room 22, 2nd Floor West Wing Royal Square, Ngong Road, Nairobi Tel: +254 729 381 561 naimafarah_m@yahoo.com

Africa Briefing Ltd 2 Redruth Close, London N22 8RN United Kingdom

Tel: +44 (0) 208 888 6693 publisher@africabriefing.org

Nnenna Ogbu #4 Babatunde Oduse crescent Isheri Olowora - Isheri Berger, Lagos Tel: +234 803 670 4879 getnnenna.ogbu@gmail.com

Kenya Patrick Mwangi Aquarius Media Ltd, PO Box 10668-11000

Nairobi, Kenya

Tel: 0720 391 546/0773 35 41

Email: mwangi@aquariusmedia.co.ke

©Africa Briefing Ltd

2 Redruth Close, London N22 8RN

United Kingdom

Tel: +44 (0) 208 888 6693 publisher@africabriefing.org

People power must now prevail

America elects its own ‘strongman’ president

Changing demographics hold key to outcome of Ghana elections

A noticeable shift among first-time voters toward the political centre, with nearly 10 per cent identifying as non-aligned despite targeted government policies, shows that traditional strongholds no longer guarantee electoral success, writes Seth Doe

Economic crisis and galamsey debate

With inflation, youth unemployment, and environmental issues at the forefront, Ghana's December 7 election promises to be a turning point, writes Jon Offei-Ansah

The world needs a dynamic Africa

Of the many stereotypes that we have to deal with in our quest to tell the full story of the continent, none are as grating as the ones that seek to portray it as stagnant, unchanging and predictable, argues Yemi Osinbajo

Elusive peace in Mozambique

Of the many stereotypes that we have to deal with in our quest to tell the full story of the continent, none are as grating as the ones that seek to portray it as stagnant, unchanging and predictable, argues Yemi Osinbajo

Africa’s debt dilemma: pathways to economic independence

Agnes Gitau addresses Africa's escalating debt crisis, calling on the IMF, World Bank, and G20 to shift from cyclical relief to lasting reforms that would liberate African nations from dependence on high-cost, highinterest loans

Western aid: a blessing or a curse?

Despite $150 billion in annual aid, Africa remains trapped in poverty and underdevelopment. Jon Offei-Ansah critically examines why systemic issues persist and whether Western aid is truly benefiting the continent

West Africa’s $855m power project to boost regional energy trade

West Africa's ambitious $855 million energy initiative aims to boost regional electricity trade, increase renewable energy production, and enhance power accessibility in Mauritania and Mali with AfDB support

Established in 2002, Shanghai Grand International Co., Ltd. offers a variety of shipping and transportation options via air, sea and ground. Our company is based in Shanghai, China, with branches across the nation. Ranging from customs declaration, warehouse storage, containers and consolidated cargo shipping we have a large array of options to meet your needs.

In addition to being approved and designated by the Ministry of Transportation of China as a First Class cargo service provider, we have also established excellent business relations with major shipping companies including Maersk, CMA, ONE, SM line, and

C.E.O President.

Mr, Felix Ji

EMC over the past 15 years. In addition we have also built long term business relations with major airline cargo departments. In order to expand our global operation, we are looking for international partnerships to work together in this industry. Should you ever import any goods from Peoples Republic of China please ask your exporter and shipper to contact us. We will provide our best service to you.

Room 814, 578 Tian Bao Lu, Shanghai, Peoples Republic of China

E-Mail: felix@grand-log.net phone: 86-13501786280

ASEISMIC change is taking place across the political landscape in Africa. In October, the Botswana Democratic Party, which had been in power since the country gained independence from Britain in 1966, was turfed out of power by the electorate. The election ushered in the Umbrella for Democratic Change, whose presidential candidate, 54-year-old Duma Boko, replaced the BDP’s Mokgsweeti Masisi.

The BDP ended up with only four seats, out of 61, in a parliament that it had controlled for 58 years. Unlike previous trends on the continent, however, Masisi accepted the electorate’s decision and promised a smooth transition of power.

It was all the more special because he had served only one term, something that is uncommon in politics in Africa. But we must not forget George Weah of Liberia, who also served one term when he lost last year’s presidential election. This might be catching on.

In South Africa in May, the African National Congress, the liberation movement that took over the reins of power in 1994, lost its parliamentary majority, and is now in a coalition with the Democratic Alliance and Inkatha Freedom Party. It was the ANC’s worst performance in the 30 years that it had been in control of the country.

This November, the opposition Alliance for Change coalition ousted the government of the Militant Socialist Movement coalition in an election that saw the latter fail to win any of the 62 seats that are directly elected to parliament. This means that Navin Ramgoolam will return as the country’s prime minister, a position he held from 1995 to 2000 and again from 2005 to 2014.

Outgoing Prime Minister Pravind Jugnauth conceded defeat before all results were announced, saying his coalition was headed for a huge defeat as it became clear that the opposition was winning. Jugnauth, who had been in office since 2017 and seeking another five-year term, said: “The population has decided to choose another team. I wish good luck to the country.”

What do all these results portend for

the democratic process and rule of law in Africa? For one thing, it is clear that voters are not going to buy the cant that their political leaders routinely dispense at election time. For another, the electorate is getting younger. Figures show that young people constitute 60 per cent of the continent’s population under the age of 25.

And they are the ones who will hold the balance of power in Africa for generations to come. They now have a different worldview. They are not going to stand for corruption or the mismanagement of their countries as those before them did.

Young Africans are going to now take robust action against electoral fraud and the failure of the rule of law. We are seeing this currently in Mozambique where FRELIMO is trying to hang on to power since the election on October 9.

Young Mozambicans have taken on the security forces who have been opening fire against demonstrators challenging the result of the presidential election. Again, a liberation movement is under pressure but, unlike the ANC in South Africa, FRELIMO wants to stay put after 49 years in control.

The problem here for FRELIMO is that young Mozambicans do not have a clue about its liberation struggle. What they care about are bread and butter issues

independence. It has pushed its first ever elections to 2026 from December this year. But young Sudanese know that their country could do a lot better if their leader put their backs into it.

Young Africans, as we have seen in Botswana, South Africa and Mauritius, now know that they can make a difference through the ballot box. This is why the December 7 presidential and parliamentary elections in Ghana are so crucial.

By all accounts the governing New Patriotic Party (NPP) of outgoing President Nana Akufo-Addo wants to hold on to power at all costs, even though the indicators show that the government has woefully failed Ghanaians. There have been rumblings throughout this year that could explode if attempts are made to subvert the will of the people.

Since Ghana returned to democratic rule in 1992, the two main parties, the NPP and the National Democratic Congress, have been changed after two terms. The NPP has done its two terms, and Ghanaians are now expecting the party to be voted out of power.

It is high time that young people in Africa are given the respect and opportunities that they deserve. After all, they are the ones who are going to be around to work towards the continent

‘ ’

make a difference

that will give them a better a quality of life. They cannot survive on stories about the liberation struggle.

Meanwhile, another liberation movement, the Sudanese People’s Liberation Army/Movement, is hanging on to transitional power 13 years after

achieving the African Union’s Agenda 2063 that is aimed at “transforming Africa into the global powerhouse of the future”.

In it therefore imperative that people power should now be allowed to finally flourish on the continent. If not, Agenda 2063 will be a shattered dream for young Africans AB

YOU’VE got to hand it to Donald Trump. He has done it again – winning the US presidential election on November 5 emphatically, much to the chagrin of his opponents. But the Republican knows his people well, and he got his message through in a manner they quite understood.

Trump’s patter on the hustings was akin to the spiel of the archetypal American snake oil salesman of yore. He rambled on about Haitian immigrants eating “dawgs and cyats”. Give me strength!

Then we got an inane comment from Tony Hinchcliffe, a comedian (yes, indeed, a real comedian this time), about Puerto Rico being a “floating island of garbage”. Beware Puerto Ricans, the Trump administration might be eyeing your homeland to dump toxic waste from mainland America.

Gullible supporters lapped up this garbage from the Republicans with gusto. Not surprisingly, Vice President Kamala

according to partisan leanings? Whatever happened to America’s vaunted judicial independence? Justice, as we are told, must be seen to be done – meaning that any semblance of bias must make any judicial decision invalid.

It is not surprising that Trump has been reported as saying that he will be a dictator once he is sworn in on January 20, 2025. Indeed, dictatorship is not far from Trump’s demeanour, and he seems to like dictators.

He has called Egyptian President Abdul Fattah el-Sisi “my favourite dictator”. Although he is about to lock horns with China over tariffs, he adores Xi Jinping. “He controls 1.4 billion people with an iron fist. He’s a brilliant guy, whether you like him or not,” he says of the Chinese leader.

Trump regularly shoots from the hip. Many will remember the ire that he evoked among Africans when he made disparaging remarks about their continent during his first presidency. For me, by traducing

Trump’s patter was akin to the spiel of the archetypal American snake oil salesman of yore ‘ ’

Harris’ campaign floundered, leaving Trump to win the Electoral College, and along the way garnering 75,518,895 votes (50.2%) as against 72,372,332 (48.1%) for the Democratic candidate. It was the first time since 2004 that a Republican won the popular vote for the presidency.

Trump is thus primed to become all powerful running the US with his appointed “loyalists” and Republican cronies who are in control of Congress, knowing full well that challenging him will be a problem for those who want to try and rein him in. He will also have the support of the Republican Supreme Court judges, who outnumber Democratic judges by six to three.

Why should judges interpret the law

African countries, Trump was exposing his vainglorious nature.

What irked him most was that he wanted to be like some of Africa’s strongmen, but Americans would not allow him to get his way. He was reacting like a playground bully who sees others doing things that he would like to do, but he could not.

And he did try. Take the January 6, 2021 attempt to overthrow the constitutional order after he had lost the November 2020 presidential election. Like some African strongmen, he urged his militia groups, the Proud Boys and the Oath Keepers, to stage a coup, and they assaulted the Capitol.

They failed woefully. When the macho

members of the Proud Boys were sent to jail, some of them started weeping.

This was unlike the West Side Boys, during the turbulent years in Sierra Leone, who gave UN peacekeepers, Nigerian and British troops a run for their money. Of course, they were renegades who did not mean well for Sierra Leone and – just like the Proud Boys – they eventually succumbed to more superior and principled forces.

There was much equivocation by the US media about how to describe the actions of Trump’s militia, calling them “riots”. That is not how an attempted coup in an African country would have been reported by American journalists. They would have been regurgitating lazy, negative stereotypes about democracy and the rule of law on the continent.

Trump himself was there on Pennsylvania Avenue in Washington DC, exhorting his militia to be violent. “We fight. We fight like hell and if you don’t fight like hell, you’re not going to have a country anymore.”

One thing for sure is that US diplomats in Africa are going to have their work cut out under a Trump administration. How will they explain the actions of their president who makes decisions on the hoof? They will find it difficult to call out African leaders who are not on the right track while the US president himself is behaving irrationally.

Just a week after Trump’s victory, the US ambassador to Kenya, Meg Whitman, submitted her resignation to outgoing President Joe Biden. She had worked closely with Kenyan President William Ruto, and which led to his state visit to Washington in May – the first by an African leader to the US in 16 years.

So, now that Trump has ultimate power, will he try to cosy up to his fellow strongmen in Africa? Or will he upset the apple cart yet again?

Many African leaders are already trying to fathom out how to deal with an erratic American president over the next four years. AB

A noticeable shift among first-time voters toward the political centre, with nearly 10 per cent identifying as non-aligned despite targeted government policies, shows that traditional strongholds no longer guarantee electoral success, writes Seth Doe

GHANA, a beacon of democracy in West Africa, has successfully transitioned power four times under its Fourth Republican Constitution. As the nation prepares for its fifth democratic elections on December 7, President Nana AkufoAddo's New Patriotic Party (NPP) administration will conclude its second term.

The government’s 2024 manifesto outlines 72 major achievements across various sectors, including free secondary education and improvements in road and hospital infrastructure.

However, these successes are overshadowed by significant tests and public discontent.

The Ghanaian voter faces growing challenges that considerably affect livelihoods, including rampant food inflation and failed agricultural policies, alongside erratic rain patterns driving up the cost of living. Housing utility costs have reached their highest levels in two decades, adding further pressure on household finances.

The government's flagship free senior high school (SHS) programme has been central to the food supply crisis, resulting in constant food shortages in schools with pressure coming from suppliers demanding overdue payments. Economic mismanagement and a growing debt burden, despite an IMF programme intended to restore fiscal discipline, have fuelled public frustration.

This is compounded by the collapse of indigenous banks and a controversial domestic debt exchange programme, which have further strained financial stability. Pensioners, including Ghana's former Chief Justice, have staged protests against the severe impact of the debt exchange on

their meagre incomes.

Systemic corruption and environmental degradation, due to illegal mining (galamsey), have intensified voter discontent, leading to weekly demonstrations and advocacy from civil society groups, faith-based organisations and media coalitions. These issues erode trust in governance and degrade natural resources essential for community wellbeing.

This combination of hardships has resulted in widespread dissatisfaction with the country's leadership, as citizens grapple with weakened economic structures and increasingly compromised livelihoods. Notable voices, including university lecturers, business executives and respected religious leaders, who once gave the government a chance to perform, have now joined the call for a new leadership.

Several international and domestic researchers, including Fitch Solutions and Accra-based Global InfoAnalytics, have been tracking Ghana’s electoral landscape, predicting a straight win for former

President John Mahama, the presidential candidate of the opposition National Democratic Congress (NDC). These polls provide valuable insights into voting behaviour and electoral trends ahead of the elections.

Key emerging issues include a noticeable shift among first-time voters toward the political centre, with nearly 10 per cent identifying as non-aligned despite targeted government policies. Traditional strongholds no longer guarantee electoral success due to shifting population dynamics and unreliable voter density advantages.

Groups such as women, the middle class, youth, trade unions, religious bodies and labour organisations are becoming increasingly influential in shaping electoral outcomes, representing a potential “third force”.

While businessman Dr Paa Kwesi Nduom attempted to mobilise nongeographical constituencies in 2016, he failed to create a formidable “third force”. In 2024, the Butterfly Party, led by

former NPP presidential contender Alan Kyerematen, is expected to draw more votes from the geopolitical space rather than non-geopolitical constituencies.

Mahama’s NDC has crafted a 2024 campaign message targeting intersectional constituencies alongside traditional strongholds. The manifesto addresses key economic, social and governance challenges while appealing to international investors. Highlights include the establishment of a Women’s Development Bank, membership of the Islamic Development Bank, eliminating fee stress for undergraduate education, expanding accommodation for tertiary students and sustainable funding for the free SHS policy. Added to these are proposed land banks to encourage youth participation in agriculture, tax incentives for youth entrepreneurs, the elimination of various taxes, provision of free sanitary pads for schoolgirls and a strong anticorruption initiative aimed at recovering misappropriated public funds.

Polls show Mahama, among all 13 presidential contenders, as the most competent candidate who is trusted to unite Ghana and address citizens’ needs. The NPP on the other hand, represented by Vice President Dr Mahamudu Bawumia, is distancing itself from the policy failures

THE processes leading to the parliamentary and presidential elections in Ghana in December are at a deadlock, with widespread calls for a forensic audit of the voters register. This has been triggered by validation and audit queries raised by the opposition National Democratic Congress; findings that the Electoral Commission has been unable to refute.

The NDC employed structured queries to audit and validate the electronic copies of the Provisional Voters Register (PVR) it received from the EC as required by law. The NDC's audit methodologies revealed the following outcomes:

• About 243,540 cases of 2023 voter transfers were illegally added to 2024 transfers, with duplication of the illegally transferred names across the national voter roll.

• Over 15,000 cases of unidentifiable

of the Akufo-Addo administration while proposing new economic and social initiatives.

Proposals include the abolition of the E-Levy and other taxes, the creation of an SME Bank – though this faces criticism given the collapse of indigenous banks –and promises of a Miners Bank despite the environmental devastation caused by illegal mining.

Both the NDC and NPP manifestos prioritise similar themes: economic reform, social sector development, governance, gender inclusion, infrastructure and environmental protection. However, their delivery of these promises diverges based on each party’s philosophy,

voter transfer paths, implying "fraudulent registration" of voters who could not be traced to their original polling stations.

• 3,957 cases of voters present in the 2023 Final Voters Register (FVRused for District Level Elections) but missing from the 2024 PVR.

• 2,094 voters were transferred to different polling stations but not found on the corresponding counter checklist, called the "Absent Voter List," as required by electoral law.

• Corrupt electronic files, not bearing names and photos of the registered voters, were found on the PVR, without the knowledge of the public.

To address the widespread irregularities, detect problems, prevent mass disenfranchisement, block election rigging, avoid a third election petition and assure the global community of readiness for a new government, the NDC has engaged the EC with

governance history, leadership character and the prevailing local and international context. Both parties will face pressure to restore fiscal discipline while delivering on development promises, leveraging alternative financing methods. The NDC continues to propose Islamic finance frameworks, including the issuance of Islamic bonds for underserved sectors like agriculture, infrastructure and healthcare. This proposal could mark a significant shift in public finance should Mahama win.

The hung parliament (2021-2025) has been marked by intense competition, with both the NPP and NDC holding nearly equal power. The 2024 election could slightly tip the balance in favour of one party. Speaker of Parliament Alban Bagbin (NDC) has played a significant role in shaping the legislative agenda, especially as four MPs have vacated their seats due to party and constitutional dynamics.

As Ghana approaches its 2024 elections, voters face a clear choice between the NDC's emphasis on economic reform, social inclusion and anti-corruption, and the NPP's promises of policy reversals and new initiatives under Bawumia. The outcome will shape the country’s future, with key issues such as fiscal discipline, infrastructure and corruption playing decisive roles.

stakeholder audit requests, but without success.

The EC, in a press conference, admitted that its IT systems had been infiltrated by unauthorised persons who made changes to voter statuses.

Similar audit calls were made by the ruling New Patriotic Party under the "Let My Vote Count" campaign prior to the 2016 elections. The call was granted, leading to the commissioning of the Justice Crabbe Committee, which investigated and made findings related to deceased names on the voter roll.

Charlotte Osei, the previous EC Chair, recommended periodic stakeholder audits and communicated this to the Interparty Advisory Committee, which is composed of major political parties. Dr Kwadwo Afari-Gyan, the longest-serving EC Chair, also called for auditable election technologies during a national conference, the Accra Dialogue, six years ago. AB

With inflation, youth unemployment, and environmental issues at the forefront, Ghana's December 7 election promises to be a turning point, writes Jon Offei-Ansah

WITH just days to go until Ghana’s general elections on December 7, 2024, the political climate in the country has reached a boiling point. The two main political parties, the incumbent New Patriotic Party (NPP) and the opposition National Democratic Congress (NDC), are locked in a fierce battle, each promising to fix the nation’s most pressing issues. Economic hardship, rising unemployment, and environmental crises have become the focal points of the campaigns as voters prepare to make a critical decision about the country’s future. As Ghana heads to the polls, the next government will face mounting pressure to resolve these issues that are leaving citizens frustrated and concerned about their futures.

One of the key issues on voters’ minds is the country’s economic struggles, which have worsened since the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic. By the end of 2022, inflation had skyrocketed to an astonishing 54 percent, plunging the cost of living to unbearable levels. Prices for everyday goods and services continue to rise, affecting millions of Ghanaians, especially those already struggling to make ends meet. Despite slight improvements in inflation, the pain is still very real for many citizens who are grappling with a lack of affordable essentials.

The World Bank has warned that up to 850,000 Ghanaians were pushed into poverty in 2022 due to the surge in prices. This surge in poverty adds to the six million Ghanaians already living below the poverty line. The “new poor” represent a group of people who were once financially stable but are now facing hardships due to inflation, the devaluation of the currency, and the country’s mounting debt crisis. Ghana’s public debt reached over $50 billion by 2023, with little left in government coffers to support vital sectors, prompting the country to seek assistance from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) for

financial stability.

For many, the NPP’s claims that the country is “on the cusp of transformation” ring hollow. While government officials, including President Nana Akufo-Addo, argue that Ghana’s economic woes are part of a necessary transition, critics of the ruling party contend that the pace of recovery is far too slow. The NPP’s track record of addressing the economic crisis is under heavy scrutiny, and the party faces mounting criticism for its handling of public debt, inflation, and job creation. On the other hand, the NDC sees this economic turmoil as the result of poor governance and management by the NPP. The opposition party has pointed to the record levels of inflation and increasing

poverty as evidence of the government’s failure to deliver on its promises. The NDC has pledged to reset the economy if elected, offering policies that they believe will alleviate the financial burden on Ghanaians and stabilize the nation’s finances.

However, the NPP has countered these claims by arguing that their policies have already set Ghana on the path to recovery. The ruling party insists that reforms in areas like education, infrastructure, and energy will pay off in the long run, even if the effects have not yet been fully realised. Unemployment remains another pressing issue, particularly among young people. Ghana has one of the highest youth unemployment rates in sub-Saharan Africa, with an estimated 12 percent of

young people unable to find work. This has contributed to a widespread sense of disillusionment, with many young Ghanaians feeling that they have little to look forward to within the country’s borders. As a result, there has been a marked increase in emigration, with many young people seeking better opportunities abroad.

The NDC has used the unemployment crisis to fuel its election campaign, labelling the current government’s efforts as “abysmal” in terms of job creation. Party leaders are

advocating for large-scale job creation initiatives, focusing on sectors such as agriculture, technology, and the creative industries. The NDC has also promised to improve vocational training to better equip young people with the skills needed for today’s job market.

The NPP, meanwhile, points to its efforts to provide employment opportunities through the “Nation Builders Corps” and other job creation schemes aimed at addressing the unemployment crisis. While these initiatives have employed thousands, critics argue that they have not been enough to significantly reduce the youth unemployment rate.

As the elections draw nearer, the youth vote has become a crucial battleground. Many young Ghanaians are expressing frustration with the lack of job opportunities, and their votes will likely be decisive in the outcome of the election.

In addition to economic and employment challenges, environmental issues have taken centre stage in Ghana’s 2024 elections. The illegal mining industry, known as “galamsey,” has become a major source of concern. The practice involves the extraction of gold from unregulated and illegal mines, often using harmful chemicals like mercury and cyanide that pollute water sources and damage the surrounding environment. Rivers across the country, including major water sources such as the Ankobra, Tano, and Pra rivers, have been heavily polluted, making it difficult for communities to access clean water.

Protests and public demonstrations against galamsey operations have been widespread in the lead-up to the elections, with citizens demanding stronger government intervention. The issue has become a political flashpoint, with both the NPP and

NDC pledging to take action.

The NPP has maintained that the smallscale mining sector should not be shut down entirely but rather regulated to prevent environmental damage. While the government has taken steps to combat illegal mining, critics argue that not enough has been done to address the environmental degradation caused by the practice.

The NDC has taken a more hardline stance, calling for a complete ban on new mining licences and stricter regulations on existing mining operations. Party leaders have pledged to close illegal mining operations that fail to meet environmental and safety standards, aiming to protect the country’s natural resources.

The galamsey debate is especially contentious because of its economic implications. Small-scale miners provide jobs and support many local economies, and shutting down galamsey operations could lead to significant economic hardship in certain regions. Nevertheless, the environmental damage caused by illegal mining is undeniable, and the next government will need to strike a balance between economic opportunity and environmental protection.

As the election approaches, Ghana’s voters face a crucial decision. On one hand, the NPP argues that the country’s economy is on the brink of recovery, with ongoing reforms and policies that will ultimately lead to long-term growth. On the other hand, the NDC believes that a fundamental change in leadership is necessary to reset the economy, reduce poverty, and create jobs for the country’s growing youth population.

While both parties agree that galamsey and the environmental crisis must be addressed, their proposed solutions diverge significantly, further highlighting the different approaches to governance. For many Ghanaians, these divisions are not just political but a reflection of the broader struggles they face in their daily lives.

The 2024 Ghanaian elections are more than just a political contest; they represent a pivotal moment in the country’s history. With an economy in crisis, a generation of young people facing bleak job prospects, and an environmental disaster unfolding, Ghana’s future is at stake. The choices made on December 7 will determine the direction the country takes in the coming years. Will voters opt for the continuity offered by the NPP or the change promised by the NDC? As Ghana stands at a crossroads, the outcome of this election could shape the nation’s future for decades to come.

John Dramani Mahama pledges IMF renegotiation, tax cuts, and debt restructuring to ease Ghana’s economic crisis, offering a business-friendly approach if he wins December's election, writes Jon Offei-Ansah

WITH Ghana’s elections approaching, the main opposition candidate, former president John Dramani Mahama, has announced plans to renegotiate the terms of Ghana’s $3 billion International Monetary Fund (IMF) programme. Mahama, leader of the National Democratic Congress (NDC), asserts that changes are necessary to reduce taxes, restructure loan repayments, and ultimately, create a stable and growth-oriented economic environment in Ghana.

Mahama has outlined his vision to tackle what he sees as crippling financial policies introduced under the current IMF programme, implemented by President Nana Akufo-Addo’s administration last year. “We must look at rationalising the issue of tax revenues to help the economy as it emerges from a debt crisis,” Mahama says. “Under the current IMF programme, the government is not doing much to reduce expenditure, but is doing everything to increase taxes, and it’s making Ghana an unfavourable destination for business.”

The current IMF bailout came into effect in 2022 as a response to Ghana’s debt crisis. Ghana’s debt ballooned to more than 100 percent of gross domestic product (GDP), leading the government to default on its debts. The programme, which expires in May 2026, included tax hikes, such as a 2.5 percentage point increase in the valueadded tax (VAT), which rose to 15 percent, and a growth and sustainability levy on pretax profit, capped at 5 percent. These measures, Mahama claims, have placed

undue strain on Ghanaians and Ghanaian businesses.

“The current measures are unsustainable,” Mahama says. “We’re going to need a new approach that allows Ghana to find fiscal space while pursuing stable economic growth. This IMF programme was the administration’s quick fix for a long-term problem.”

Mahama’s economic proposals have gained traction among voters, as Ghana struggles to recover from a cost-of-living crisis exacerbated by debt and inflation. Inflation, which peaked at 54.1 percent in December 2022, has eased to 22.1 percent, but economic recovery remains fragile. Mahama plans to introduce significant tax

reforms that will relieve both consumers and businesses from the burdensome rates introduced under Akufo-Addo’s administration.

‘We have to make Ghana a competitive place to do business again,” Mahama says, adding that his goal is to boost investment and economic growth. “It’s about stabilising the macro environment and creating the right conditions for Ghanaians and investors alike.”

Economic analysts argue that while Mahama’s vision is ambitious, a renegotiation of the IMF programme could pose challenges. Professor Godfred Bokpin, an economist at the University of Ghana Business School, highlights the

importance of policy adjustments under the IMF framework. “Whichever party wins the election will have to review the IMF programme,” Bokpin says. “Adjustments are crucial to increase fiscal space and implement some of the reforms that Mahama and other candidates are advocating. Without flexibility, Ghana risks stalling its economic recovery.”

Another pillar of Mahama’s economic plan is to restructure Ghana’s domestic debt, worth 182 billion cedis ($11.1 billion) maturing in 2026, along with a significant commercial loan payment due before 2028. “We need to look at how we can refinance some of these debts so that we can smoothen out the debt repayment trajectory,” Mahama explains. “Our aim now is stability. How do we bring down inflation, stabilise the macro environment, and protect the value of our currency?”

The former president emphasises that debt restructuring would be a central part of his discussions with the IMF, should he secure victory on December 7. He is also open to extending the fund arrangement, if necessary, to accommodate the policy changes he envisions. "We won’t rule out an extension of the IMF programme if that’s what it takes to stabilise our economy,” he says.

Polling data suggests that Mahama is the favourite heading into the elections, with an Accra-based Global InfoAnalytics Ltd. survey showing him at 51.1 percent against Vice President Mahamudu Bawumia’s 37.3 percent. These figures reflect growing discontent with the ruling New Patriotic Party (NPP), whose austerity

measures have drawn criticism from citizens burdened by rising costs and slow economic growth.

The IMF-backed reforms have faced mixed reactions. While the programme has contributed to recent debt restructuring, critics argue that it disproportionately impacts ordinary Ghanaians. Many point to rising taxes and inflation as proof that the current administration’s economic policies are insufficient in addressing the challenges facing the population. “The people are suffering, businesses are closing down, and it seems there’s no end in sight,” Ama Osei, a local shop owner in Accra told Bloomberg. “Mahama is speaking about reducing taxes and making life easier. We need that.”

Beyond tax cuts and debt restructuring, Mahama also unveiled his “Big Push” initiative, which includes plans to create a “24-hour economy” to stimulate job growth and raise productivity. The plan advocates for three eight-hour shifts, enabling Ghana’s workforce to operate round-theclock, thereby attracting investment and enhancing economic efficiency. Mahama also aims to channel $10 billion into infrastructure projects in key sectors such as petrochemicals, mining, and transport.

“These are not just ideas but part of a structured plan to revitalise Ghana’s economy,” he has stated. “We’ll be investing in areas with high growth potential, and this will require publicprivate partnerships and foreign investment. We’re going to make Ghana a good and pleasant environment for investors again.”

Industry leaders and analysts are cautiously optimistic about Mahama’s “Big Push” strategy, although some wonder about the feasibility of such an ambitious project given Ghana’s economic constraints. Joseph Nartey, an investment consultant based in Accra, comments that, “The ‘Big Push’ is a visionary plan. If implemented effectively, it could transform Ghana’s economy, but it will depend heavily on securing reliable private sector and foreign investment. Mahama’s administration would need to reassure investors of political and economic stability to make this vision a reality.”

As Mahama campaigns on the promise of economic revival and debt relief, challenges remain. Ghana’s recovery process under the IMF programme is

delicate, and any policy shifts may need careful negotiation to avoid destabilising gains made thus far. While the IMF programme has managed to stabilise the currency and slow inflation, many argue that its heavy-handed approach is stifling growth and innovation within the private sector.

Critics of Mahama’s campaign argue that while his policies could offer shortterm relief, they may not fully address Ghana’s structural economic challenges. “A lot of these promises sound good in theory, but Ghana’s economic troubles run deeper,” says Kwame Mensah, a political analyst at the University of Cape Coast. “A fundamental rethinking of fiscal policy, beyond renegotiating IMF terms, will be necessary for Ghana to see lasting improvement.”

Nonetheless, Mahama’s support appears strong. Voters are signalling their readiness for a change from the current administration’s policies, which they argue are not yielding the expected benefits. For many Ghanaians, Mahama’s promise to renegotiate the IMF programme and introduce growth-friendly reforms resonates amid rising prices and limited opportunities.

As Ghanaians prepare to vote in December, the election is shaping up to be a critical juncture for the country’s future. The IMF programme represents both a lifeline and a constraint for Ghana’s economy. While it has provided a path out of debt default, the austerity measures it entails have left citizens bearing a heavy burden. Mahama’s proposed policies, including tax relief, debt refinancing, and infrastructure investment, have the potential to alter Ghana’s economic course.

“This election is about the future of Ghana’s economy,” Mahama says. “Our people need relief, our businesses need support, and our future requires a stable and supportive environment for growth. We are ready to make that happen.”

If elected, Mahama’s renegotiation of the IMF programme will not only be closely watched by international financial institutions but will also serve as a litmus test for other African nations grappling with similar debt challenges. For Ghana, this election offers a chance to choose between continuity under the NPP or a potentially transformative agenda under Mahama’s leadership.

AS Ghana prepares for its 2024 presidential and parliamentary elections on December 7, the United States has announced a new visa restriction policy aimed at individuals undermining the country's democratic processes. This initiative underscores the US’s ongoing commitment to ensuring free, fair, and transparent elections in Ghana, a nation known for its stability and democratic legacy in Africa.

The US Department of State made the announcement on October 28, emphasising that these restrictions will apply to individuals who are involved in activities such as electoral manipulation, vote tampering, voter intimidation, or suppressing political opposition and media. The policy targets specific individuals and, in some cases, their family members, but it is not aimed at the Ghanaian people or government. The focus is solely on those attempting to interfere with Ghana’s democratic process.

Ghana has long been celebrated for its peaceful transitions of power and its standing as one of Africa’s most stable democracies. With three decades of uninterrupted democratic practices, it serves as a model for other African nations. The United States, recognising this track record, has praised Ghana’s political achievements, calling its democracy “a model to cherish.”

In its statement, the US Department of State underscored that its decision to impose visa restrictions, if necessary, is a reflection of its commitment to the will of the Ghanaian people and its support for a peaceful, transparent, and credible electoral process. The US emphasized that the policy is designed to ensure that Ghana’s upcoming elections reflect the aspirations of the electorate.

The new policy is implemented under Section 212(a)(3)(C) of the US Immigration and Nationality Act, which grants the State Department the authority to deny visas to individuals believed to be responsible for undermining democratic processes. This includes acts such as manipulating the electoral process, using violence to intimidate voters, or suppressing political opposition and civil society.

The policy also targets actions that could interfere with the media’s ability to report freely and with the rights of citizens to assemble and express their views. By targeting these specific actions, the US aims to ensure that the electoral process is not undermined, and that all Ghanaians are able to participate in a fair and open election.

The visa ban policy will apply to actions both before and after the election, intending to

prevent any interference in Ghana’s democratic processes. The US has warned that individuals involved in electoral misconduct, whether by intimidating voters, engaging in violence, or coercing citizens into voting a particular way, will be subject to the restrictions.

In addition, the policy considers those who attempt to silence political opposition, civil society, or the media. Any efforts to prevent political party representatives, voters, or media personnel from expressing their views or engaging in activities aimed at manipulating the election will also be subject to visa sanctions.

The US stance reflects its strong commitment to ensuring that Ghana’s elections are conducted in a manner that is free from interference and in line with democratic principles. This policy provides important international backing to Ghana’s longstanding democratic values.

While the US visa restriction policy sends a clear message about the importance of maintaining democratic integrity, there are questions about its potential impact on electionrelated misconduct. While it targets individuals directly involved in electoral manipulation, its overall effectiveness in curbing election-related abuses could be limited.

The visa ban is unlikely to be a comprehensive solution to the challenges of ensuring a free and fair election in Ghana. The restrictions mainly target those on the ground who might attempt to manipulate the voting process, but they may not fully address potential systemic issues. If electoral interference is coordinated by high-ranking officials or institutions, the policy may not reach those ultimately responsible for rigging the elections. For individuals involved in such actions, the inconvenience of a visa ban may not outweigh the perceived benefits of manipulating the election process.

Additionally, senior officials in Ghana may not be as affected by the visa ban, particularly if they have limited reliance on the US for business or travel. This could mean that the policy has more symbolic value than practical consequences for the political elite.

However, the US’s position is likely to attract increased international scrutiny on Ghana’s electoral process, potentially putting pressure on local political players to ensure a fair vote. The presence of international observers and diplomatic oversight could help reduce the likelihood of electoral fraud or misconduct.

For Ghana’s opposition National Democratic Congress (NDC) and many concerned citizens, the US policy offers some reassurance of international oversight. The NDC has expressed concerns over potential electoral manipulation by the ruling New Patriotic Party (NPP) and alleged biases within the Electoral Commission. While the US policy may help bolster confidence in the electoral process, the effectiveness of such measures in actually deterring misconduct will depend on whether voters believe the electoral system is truly free from manipulation.

If voters perceive that the risk of electoral rigging remains, despite international attention, this could impact voter turnout or stability in the post-election period. The policy may help in the short term by providing a sense of global support for Ghana’s democratic process, but its long-term impact will depend on how well Ghana can uphold its electoral integrity.

The US visa restrictions are an important step in ensuring Ghana’s elections remain free from external influence and interference. However, their effectiveness in preventing election manipulation remains to be seen. While the policy targets individuals directly involved in tampering with the election process, it may not be sufficient to address larger, systemic issues, especially those driven by high-ranking officials or powerful institutions.

For the policy to be fully effective, it would need to be complemented by other measures, such as proactive monitoring by credible, independent observers and an enhanced commitment to transparent electoral processes within Ghana. While the US’s stance provides reassurance of international oversight, the real safeguard against electoral manipulation will come from within Ghana itself, with the active participation of all political actors, civil society, and the electorate in ensuring a fair and free vote.

Ultimately, the US visa restriction policy, while symbolically important, may only partially deter election-related misconduct. For the NDC and those concerned about electoral transparency, this move from the US could offer some reassurance. But for true electoral integrity, it will be the efforts of Ghana’s institutions and people that will ensure a credible and transparent election.

For in-depth analysis on developments in a fast-changing continent

Testimonials from some of our online subscribers:

We wish to compliment the Africa Briefing Magazine for its insight and value added stories from the Last Frontier. From a Scandanavian view the quality of material presented on time gives us the edge for investment and business purposes. Keep up the good work. Jon Marius Hoensi MD Marex Group, Norway.

I write in conjunction with JIC Holdings and its CEO, Mark Anthony Johnson, to commend Africa Briefing on its coverage of the important political, economic and social news and events in Africa. Its coverage of a wide range of topics is very impressive. I look forward to future editions. David W Gouldman, Consultant, JIC Holdings, United Kingdom.

News, analysis and forecast

Africa Briefing is an interesting new project. The publication helps fill the gap in business and economyfocused African journalism. Africa Briefing combines a good news sense with crisp copy to the reader rapid immersion into what is important in economies across the continent. James Schneider, Editorial Director, New African Magazine, London, UK

2 Redruth Close, London N22 8RN, United Kingdom

Phone: +44 (0) 208 888 6693

Of the many stereotypes that we have to deal with in our quest to tell the full story of the continent, none are as grating as the ones that seek to portray it as stagnant, unchanging and predictable, argues Yemi Osinbajo

THAT Africa has historically been the commodity extraction destination for its colonisers in the industrialised world for generations, is commonplace. But it is perhaps more important to know that today, over 42 per cent of African countries outside of North Africa have laws and policies banning raw export of ores, and insisting on some processing or beneficiation before exports.

Or that in the area of green sources of energy, in the past five years, there has been tremendous growth in the blue and green hydrogen industry, with many green hydrogen projects in Africa reaching Final Investment Decision (FID). Angola, Namibia and South Africa have already invested in this.

Namibia in May last year signed a $10 billion deal with Hyphen Hydrogen Energy to continue with advanced feasibility studies towards the development of its green hydrogen plant which, when done, will produce 300,000 tons of green energy annually using wind and solar.

Angola is set to become the first exporter of green ammonia to Germany by 2025. The full capacity of its green hydrogen plant is planned to produce 280,000 tons annually, and South Africa is planning to produce five million tons of green hydrogen annually by 2040. Other countries such as Egypt, Kenya, Morrocco

and Mauritania have green hydrogen production goals.

Again, knowing that Africa’s share of global aviation has stayed at two per cent or that its share of global tourism receipts hasn’t risen much from three per cent is not as useful as knowing that between 2022 and 2023, quarter-by-quarter growth in South African domestic tourism exceeded 30 per cent. Or that in a growth spurt between 2005 and 2013, international tourist arrivals in sub-Saharan Africa saw an upsurge of nearly 55 per cent, outperforming every other region.

This is the kind of knowledge about dynamic shifts in a continent that better prepares the mind for the real opportunities that Africa holds for trade, investment and global growth. Real insight about Africa’s ongoing transformation lies in learning to discern the patterns within the patterns, the shift from one lens to another, the powerful undercurrents bubbling beneath the surface. The dynamism that matters.

As the world itself confronts unprecedented turbulence in the coming years, from climate change to artificial intelligence and from the social blowback of a rapidly ageing workforce to novel zoonotic pandemics, the time has come for Africa’s unique role to be better appreciated.

It is already stale news that by 2050, as much as one-quarter of the planet’s workforce is likely to be of African origin. Of the youthful workforce, in particular, as much as 42 per cent may be in Africa. On this score, both history and present trends amply bear testimony. What many have not fully appreciated however is that rigorous research has shown that merely leveraging on the current pace of development gains could translate that demographic dividend into an additional 15 per cent in GDP volume growth.

An energetic pool of youthful talent, fortified with fast advancing artificial intelligence and the geo-engineering edge of a world desperately in need of a new economic growth paradigm, is an edge that the rest of the world ignores at great risk.

In Nigeria between 2015 and 2019, and between two recessions, we saw the emergence of six unicorns, tech or tech-enabled companies valued at over a billion dollars. All of those companies were founded by entrepreneurs under the age of 35.

Today, there are nearly 500 active tech hubs all over Africa. Just this year, the UNDP supported $1biillon Africa Innovation Foundation was launched. This is the largest facility in the world for supporting the African innovation ecosystem.

Timbuktu currently has eight sector specific hubs, which are designed to be pan-African Centres of Excellence in their respective verticals; a global African virtual innovation hub is a vital part of the ecosystem.

The major mandate of this panAfrican effort is to fix the fragmented innovation ecosystem, and to enable African innovators to benefit from existing and future synergies. It is also true that Africa alone has the biodiversity reserves and scale of natural capital to reverse the centuries of ecological erosion that the unbridled carbon-laden industrialisation of yesteryears has inflicted on this fragile planet.

But two issues emerge from this: the first is that Africa’s role as either the solution to the climate crisis or its nemesis must be recognised. What does this mean? Some of the best research we are seeing suggest that if Africa were to pursue the same carbon intensive trajectory of wealthier countries to attain middle to high

income status, it will pump 9.6 million gigatonnes of CO2e into the atmosphere and by 2050, will be responsible for 75 per cent of global emissions; ultimately making it impossible for the world to attain its net zero objectives by 2050.

So, the only way the world can achieve net zero by 2050 is if Africa pursues a climate positive growth plan. Happily, the African Union endorsed this new paradigm last September in Nairobi at the Africa Climate Summit.

The Climate Positive Growth paradigm means, for example, that by using renewable energy for the on-shore processing of 110 million tons of bauxite to aluminium, currently exported as raw bauxite from Africa to Europe and Asia, between 1.3 to 1.5 gigatonnes of CO2e emissions can be avoided annually.

In fact, by aggressively deploying its renewable energy resources, Africa can provide clean energy to all Africans, 600 million of whom currently do not have access to energy and 150 million of whom have unreliable access to energy, at a 30 per cent lower cost and with over 90 per cent lower emissions per kWh, compared to the current stated policy.

But to achieve the goal of climatepositive growth, we need a grand bargain with the Global North. What are the terms of this bargain? African countries on our part will formulate clear science-based national strategies for climate-positive growth.

Professor

correction that may well save this planet. But how do we get there? Statesmanship is what we badly need. Both the wealthier world and Africa require statesmen and women. It is statesmanship that will enable leaders of the wealthier world to see that the self-interest of nations and regions to the exclusion or disadvantage of others will simply not work. Our world is now far too interconnected.

It is global statesmanship that will enable the recognition that Africa holds the key to global development and must be resourced to do so. We cannot have long arguments about the obvious need for a rethink of the international financial architecture.

The strategies will be linked to specific targets for net negative contributions to global emissions. We must create enabling legal and policy environments for investment. The international community on its part will undertake to make the required investments in Africa’s renewable energy and work out trade rules that would give access to favour low emissions production and facilitate the rapid development of fair and equitable carbon markets. This is the realistic win-win pathway to net zero by 2050.

Clearly, then, the world needs a strong, dynamic and green industrial Africa. Africa is possibly the only region that is free of the vested interests and sunkcost mentality that has locked this planet

A system that currently makes borrowing by Africa eight times costlier than countries of other regions is untenable. Also, how can you fairly value Africa’s GDP today without factoring in the sequestration capacity of our carbon sinks which we are being told to preserve in the interest of global environmental safety?

Who pays for the opportunity cost of not exploiting these resources in the interest of all? For Africa, we need African economic statesmen. Champions of African economic cooperation, prepared to make the selfless sacrifices that individual nations must make to be able to eat from a much bigger and more lasting pie.

Then in addition, for Africa, three things are required: Collaboration. Collaboration. Collaboration. Our strength lies in our ability to work together. IntraAfrican trade, intra-African infrastructure. We must work together on trade

there are nearly 500 active tech hubs all over Africa

into an ever-accelerating death spiral of climate disaster, poisoned oceans, nuclear cataclysms and geopolitical deadlocks.

Only an Africa freed from its historic marginalisation can afford to lead the world down the path of genuine course

negotiations with the regional blocs of the world.

A fragmented Africa is of little benefit to Africa and surely cannot benefit the world. Certainly, the world needs a dynamic and united Africa.

of Nigeria from 2015 to 2023. The above are excerpts from his presentation at the Boma of Africa event held on the sidelines of the 6th African Union mid-year coordination meeting in Accra on July 21, 2024.

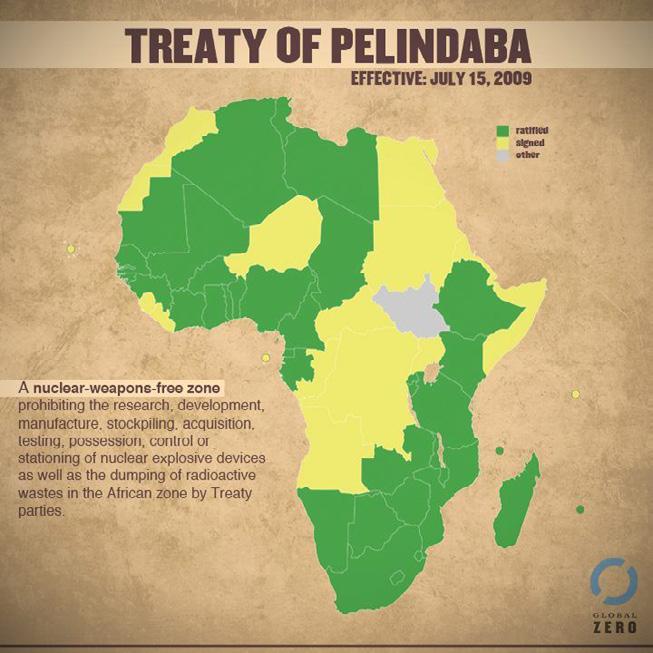

It is essential that all countries, all regions and indeed all peoples, are engaged, and play a role in efforts to bring about the elimination of weapons of mass destruction, and Africa therefore has a responsibility in this regard, as a critical building block of multilateral disarmament, argues Adedeji Ebo

GEOPOLTICAL divides have only deepened over the past few years, and cracks in the global disarmament and non-proliferation architecture have become more visible. As at 2023, global military expenditure reached $2.44 trillion while violence cost the global economy nearly $20 trillion, 13.5 per cent of global GDP.

We are in the midst of an ever-evolving nuclear landscape, characterised by the unravelling of global norms against the use, spread and testing of nuclear weapons, as well as dangerous nuclear rhetoric. Nuclear weapons are featuring more increasingly in national security strategies. At the same time, the risk of a nuclear weapon being used – whether intentionally, accidentally or by miscalculation – is at the highest point in decades.

States possessing nuclear weapons are avoiding diplomacy, opting rather for armament. Arms spending is at historic levels but there is no commensurate investment in dialogue. All nuclear-weapon states are modernising their arsenals in ways that will make their weapons smarter, more accurate, faster and stealthier.

As the High Representative for Disarmament Affairs has consistently warned, we are already in the midst of a qualitative nuclear arms race. Perhaps more worryingly, we may also be on the edge of a quantitative arms race.

To be clear, therefore, we are in a precarious state; of heightened tensions, extremism, nativism. The ever-increasing levels of military expenditure point more to a culture of war, rather than a culture of peace which is our common goal.

And yet the very first resolution of the UN General Assembly was to call for the elimination of nuclear weapons. It is a tragedy that, nearly 80 years later, some 12,500 nuclear weapons still remain in our world, and it is a world that seems to be driving towards the Bomb rather than away

from it.

When it comes to nuclear weapons, its use would have global ramifications. A single nuclear bomb can destroy a whole city, not to mention jeopardise the natural environment and lives of future generations through its long-term catastrophic effects.

It is therefore essential that all countries, all regions and indeed all peoples, are engaged, and play a role in efforts to bring about their elimination. Africa therefore has a responsibility in this regard, as a critical building block of multilateral disarmament.

As nuclear weapons threaten everyone, it is too important to be left to nuclear weapon states (NWS) alone. It is incumbent on all of us to work towards this goal, including by calling for NWS to maintain and accelerate the implementation of their disarmament commitments.

The world needs to hear – and would benefit from hearing – Africa’s voice on these issues. It is however worth emphasising that while the nuclear threat is global, regional contexts differ. It is important to locate regional particularities within the global context.

Africa’s proactive stance against the Bomb is encapsulated in, and embodied

by the Treaty of Pelindaba of 1996, which established the African nuclear- weaponfree zone. Speaking in 2005, then-UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan – a great African – recalled “the strategic and moral value of nuclear-weapon-free zones”.

The deep roots of Pelindaba are worth recalling. They go all the way back to 1964 and the call by the Organisation of African Unity for a treaty to ensure the denuclearisation of Africa. The Treaty of Pelindaba is a testament to Africa’s leadership and commitment to a world free of nuclear weapons.

But we are no longer in 1964, and it is not enough to recall glory of past leadership. We must sustain, consolidate and enhance Africa’s capacity and capability to fully live up to its impactful potential in the future.

In this regard, while the Treaty for the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW) has emerged as a major instrument for Africa’s contributions to the disarmament, non- proliferation and arms control agenda – and its legitimacy is beyond doubt – it is still in its early stages. The Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) remains the main pillar of multilateralism in this area. It means, practically therefore, that critics and supporters of the TPNW need to find a way of coexisting, in which they can acknowledge their differences but continue to work on the search for common ground.

The Pelindaba treaty should not be the final destination at which we have permanently and definitively arrived, but rather a significant milestone that set the basis for further action in Africa’s stance against the Bomb. A decade ago, the African Group called for meaningful progress towards a nuclear weapon-free world at the 2014 Vienna Conference on the Humanitarian Impact of Nuclear Weapons. That conference was instrumental in building momentum and support for convening TPNW negotiations.

Less than one year after the TPNW was adopted in 2017, the further Ordinary Session of the Conference of States Parties to the Treaty of Pelindaba called upon AU Member States “to speedily sign and ratify the [TPNW]”. A year later, the AU Peace and Security Council adopted a communiqué reiterating this call.

Today, well over 60 per cent of African states have signed or ratified the TPNW. This is commendable but we can do even better. We must remain constantly reminded of the sanctity of the three pillars of the NPT as the foundation of the nuclear non-proliferation regime: non- proliferation, disarmament and the peaceful use of nuclear energy.

The future of the planet literally belongs to the youth. We must support African youth to engage on this issue, especially bearing in mind that 60 per cent

Nuclear arsenals continue to grow

THE Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) launched its annual assessment of the state of armaments, disarmament and international security in June this year. Key findings are that the number and types of nuclear weapons in development have increased as states deepen their reliance on nuclear deterrence.

The nine nuclear-armed states – the US, Russia, the UK, France, China, India, Pakistan, the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (North Korea) and Israel – continued to modernise their nuclear arsenals and several deployed new nuclear-armed or nuclear-capable weapon systems in 2023.

Of the total global inventory of an estimated 12,121 warheads

of Africa’s population are under the age of 25, the youngest population in the world.

We should support and promote the role of the youth in disarmament and non-proliferation, including through disarmament education, professional networks and talent pipelines. By so doing, we ensure that African voices are heard, and that Africans are part of decisionmaking at the highest levels.

It is encouraging that African youth are eager and invested in global efforts to advocate for the elimination of weapons of mass destruction. Youth-led and youth-inclusive organisations, such as Youth4TPNW, provide a platform for young people from Africa to learn about nuclear disarmament and acquire tools and knowledge to contribute to the field.

African youth also participate actively in the Office for Disarmament Affairs’ youth engagement programmes, providing unique regional perspectives to strengthen approaches to build a safer world for everyone, everywhere, and enriching networks developed as part of the Youth Champions for Disarmament Training Programme and the Youth Leader Fund for a World Without Nuclear Weapons.

Africa, as we know, occupies a marginalised role in the global political economy, with implications for the weight the continent brings to multilateralism.

in January this year, 9,585 were in military stockpiles for potential use. An estimated 3,904 of those warheads were deployed with missiles and aircraft – 60 more than in January 2023 – and the rest were in central storage.

Around 2,100 of the deployed warheads were kept in a state of high operational alert on ballistic missiles. Nearly all of these warheads belonged to Russia or the US, but for the first time China is believed to have some warheads on high operational alert.

Africans against the bomb

HISTORICALLY, global nuclear discourse has been dominated by Western-centric perspectives. However, Africa’s contributions and experiences have significantly influenced the evolution of nuclear disarmament efforts.

It is therefore important to emphasise that the effectiveness of Africa’s stance against the bomb will depend, to a large extent, on the cohesion, the collectiveness, the togetherness of Africa’s agency in multilateral discourses. Africa needs a common voice.

Disarmament is about people coming together to take action. It is about Africans coming together to take action against the Bomb. The impact of such action would be most effective when Africa has a common cause and a common agenda. Without a common front on this issue, the result would be dissipated agency that is not impactful which would leave the continent further marginalised.

While we can create positive change, we must bear in mind that reinforcing such change requires adherence by states to agreed international norms, treaties and other forms of cooperation which ultimately depend on trust, solidarity and universality between states. Trust, solidary and universality represent the oxygen of multilateralism without which a culture of peace is not attainable.

Yet, the UN Secretary-General has remined us in his New Agenda for Peace that this oxygen is increasingly in short supply. We must therefore collectively do all we can to enhance the prospects for building trust, solidarity and universality.

This conference brought to light Africa’s historical and ongoing leadership in the pursuit of a nuclearfree world, while also examining the continent’s position within the emerging Third Nuclear Age. It underscored Africa’s historical and ongoing contributions to global nuclear disarmament.