PIRACY along the Somali coast has been a persistent and multifaceted issue, affecting local communities and international shipping lanes alike.

Originating as a defence mechanism against illegal fishing by foreign vessels, Somali piracy has evolved into a significant threat to global maritime trade, driven by complex socio-economic factors and the collapse of effective governance in Somalia. Tackling this issue requires a nuanced approach that combines local empowerment with robust international support.

Piracy in Somali waters began as a desperate response to illegal fishing by foreign trawlers. For decades, Somali artisanal fishermen have faced the depletion of fish stocks and destruction of marine habitats due to the unsustainable practices of foreign vessels. Bottom trawling, a particularly harmful method, has wreaked havoc on the seafloor, further jeopardizing the livelihoods of local fishermen. With the collapse of the Somali government in the 1990s, these foreign vessels exploited the lack of maritime governance, exacerbating the problem.

PUBLISHER’S NOTE

The surge in illegal fishing activity following the fall of General Mohamed Siad Barre’s regime in 1991 left local communities vulnerable and economically desperate. The Somali Navy’s inability to patrol and protect its waters allowed foreign fishing fleets to operate with impunity, pushing local fishermen to take up arms to defend their resources. This initial defence mechanism soon morphed into a more profitable venture, with pirates targeting commercial vessels for ransom. The Gulf of Aden, a crucial route for global trade, saw a dramatic increase in piracy, disrupting shipping and causing economic repercussions worldwide.

IJon Offei-Ansah Publisher

Desmond Davies Editor

Publisher Jon Offei-Ansah

Editor Desmond Davies

Contributing

Editors

Prof. Toyin Falola

Tikum Mbah Azonga

Prof. Ojo Emmanuel Ademola (Technology)

Valerie Msoka (Special Projects)

Contributors

Justice Lee Adoboe

Chief Chuks Iloegbunam

Joseph Kayira

Zachary Ochieng

Olu Ojewale

Oladipo Okubanjo

Corinne Soar

Kennedy Olilo

Gorata Chepete

Designer

Simon Blemadzie

Country Representatives

Deputy Editor

The economic impact of Somali piracy has been substantial. Increased insurance premiums and shipping costs forced some firms to reroute around the Cape of Good Hope, significantly lengthening travel times and expenses. The sea transportation industry has borne the brunt of these costs, estimated to be around $7 billion annually, covering ransoms, security measures, and rerouting expenses. This has not only affected the global economy but also placed additional pressures on politically unstable countries.

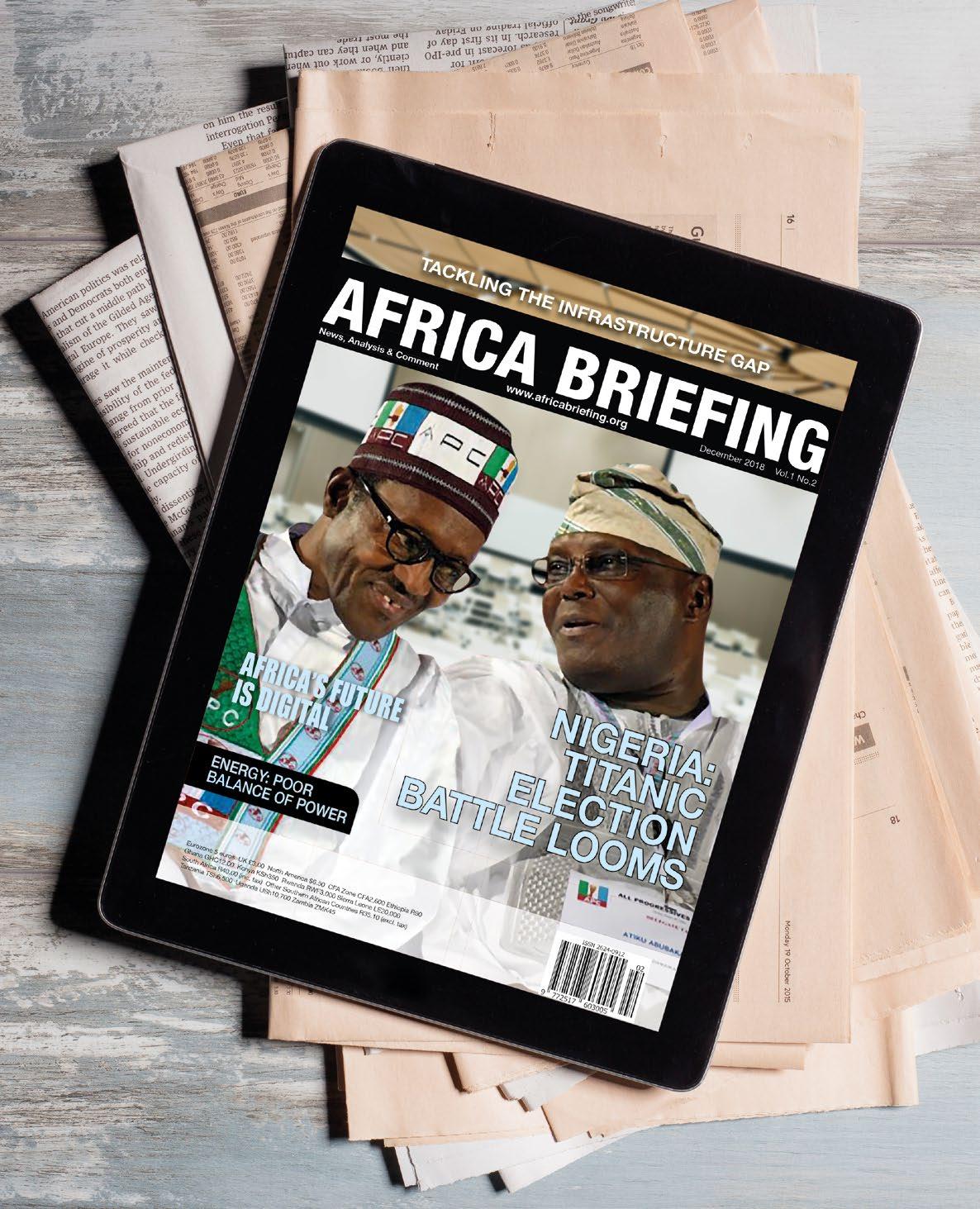

n 2018, six of the 10 fastest-growing economies in the world were in Africa, according to the World Bank, with Ghana leading the pack. With GDP growth for the continent projected to accelerate to four per cent in 2019 and 4.1 per cent in 2020, Africa’s economic growth story continues apace. Meanwhile, the World Bank’s 2019 Doing Business Index reveals that five of the 10 most-improved countries are in Africa, and one-third of all reforms recorded globally were in sub-Saharan Africa.

What makes the story more impressive and heartening is that the growth – projected to be broad-based – is being achieved in a challenging global environment, bucking the trend.

In the Cover Story of this edition, Dr. Hippolyte Fofack, Chief Economist at the African Export-Import Bank (Afreximbank), analyses the factors underpinning this performance. Two factors, in my opinion, stand out in Dr. Hippolyte’s analysis: trade between Africa and China and the intra-African cross-border investment and infrastructure development.

Angela Cobbinah

Stephen Williams Contributing Editor

Director, Special Projects

Michael Orji

South Africa

Edward Walter Byerley

Top Dog Media, 5 Ascot Knights 47 Grand National Boulevard Royal Ascot, Milnerton 7441, South Africa

Tel: +27 (0) 21 555 0096

Joseph Kayira

In response to the piracy crisis, both local and international efforts have been mobilised. One of the most effective local responses has been the establishment of the Puntland Maritime Police Force (PMPF) in 2010. With substantial support from international partners, particularly the UAE, the PMPF has played a crucial role in reducing piracy incidents. Their deployment in piracy-prone areas and effective maritime patrols have significantly enhanced security along Somalia’s coastline. The PMPF’s operations have led to a dramatic decline in piracy incidents, from a peak of 160 attacks in 2011 to virtually no recorded incidents by late 2013.

Much has been said and written about China’s ever-deepening economic foray into Africa, especially by Western analysts and commentators who have been sounding alarm bells about re-colonisation of Africa, this time by the Chinese. But empirical evidence paints a different picture.

Despite the decelerating global growth environment, trade between Africa and China increased by 14.5 per cent in the first three quarters of 2018, surpassing the growth rate of world trade (11.6 per cent), reflecting the deepening economic dependency between the two major trading partners.

Empirical evidence shows that China’s domestic investment has become highly linked with economic expansion in Africa. A one percentage point increase in China’s domestic investment growth is associated with an average of 0.6 percentage point increase in overall African exports. And, the expected economic development and trade impact of expanding Chinese investment on resource-rich African countries, especially oil-exporting countries, is even more important.

Justice Lee Adoboe Chuks Iloegbunam

Zachary Ochieng

Olu Ojewale

Oladipo Okubanjo Corinne Soar Contributors

Gloria Ansah Designer

Despite the notable success of the PMPF and other initiatives, recent incidents suggest a potential resurgence of piracy. Isolated cases of hijackings off Puntland in late 2023 highlight the need for continued vigilance and investment in maritime security. These incidents underscore the importance of accurate reporting and careful differentiation between genuine piracy and other criminal activities. Mislabelling incidents can distort the reality of piracy and undermine efforts to combat it effectively.

Country Representatives

South Africa

Edward Walter Byerley Top Dog Media, 5 Ascot Knights 47 Grand National Boulevard Royal Ascot, Milnerton 7441, South Africa

To maintain the gains made in combating piracy, ongoing investment in local security infrastructure is essential. Empowering local police and security forces, reconstructing functional courts, and modernising maritime laws are critical steps. Training prosecutors with expertise in maritime crime and establishing a robust legal framework will enhance Somalia’s capacity to address piracy comprehensively.

Cell: +27 (0) 81 331 4887 Email: ed@topdog-media.net

Ghana

Nana Asiama Bekoe

Kingdom Concept Co.

Tel: +233 243 393 943 / +233 303 967 470 kingsconceptsltd@gmail.com

Nigeria

Tel: +27 (0) 21 555 0096 Cell: +27 (0) 81 331 4887 Email: ed@topdog-media.net

Ghana

Nnenna Ogbu #4 Babatunde Oduse crescent Isheri Olowora - Isheri Berger, Lagos Tel: +234 803 670 4879 getnnenna.ogbu@gmail.com

The resilience of African economies can also be attributed to growing intra-African cross-border investment and infrastructure development. A combination of the two factors is accelerating the process of structural transformation in a continent where industrial output and services account for a growing share of GDP. African corporations and industrialists which are expanding their industrial footprint across Africa and globally are leading the diversification from agriculture into higher value goods in manufacturing and service sectors. These industrial champions are carrying out transcontinental operations, with investment holdings around the globe, with a strong presence in Europe and Pacific Asia, together account for more than 75 per cent of their combined activities outside Africa.

A survey of 30 leading emerging African corporations with global footprints and combined revenue of more than $118 billion shows that they are active in several industries, including manufacturing (e.g., Dangote Industries), basic materials, telecommunications (e.g., Econet, Safaricom), finance (e.g., Ecobank) and oil and gas. In addition to mitigating risks highly correlated with African economies, these emerging African global corporations are accelerating the diversification of sources of growth and reducing the exposure of countries to adverse commodity terms of trade.

This makes me very bullish about Africa!

Nana Asiama Bekoe

The success of the PMPF demonstrates the importance of a holistic approach that addresses both sea and land-based threats. International collaboration has been instrumental in transforming the PMPF into a professional maritime law enforcement agency. Continued international support, combined with local empowerment, is vital for sustaining maritime security and preventing the resurgence of piracy.

Kingdom Concept Co. Tel: +233 243 393 943 / +233 303 967 470 kingsconceptsltd@gmail.com

Nigeria

While significant progress has been made in reducing piracy along Somalia’s coastline, the persistent threat requires sustained efforts. Investing in local justice systems and maritime security infrastructure, along with robust international cooperation, will be crucial in ensuring long-term stability in the region and protecting global trade routes. As we move forward, it is imperative to maintain a balanced approach that addresses the root causes of piracy while enhancing the capacity of local authorities to combat this menace effectively.

Taiwo Adedoyin MV Noble, Press House, 3rd Floor 27 Acme Road, Ogba, Ikeja, Lagos Tel: +234 806 291 7100 taiadedoyin52@gmail.com

Kenya

Naima Farah Room 22, 2nd Floor West Wing Royal Square, Ngong Road, Nairobi Tel: +254 729 381 561 naimafarah_m@yahoo.com

Africa Briefing Ltd

2 Redruth Close, London N22 8RN United Kingdom Tel: +44 (0) 208 888 6693 publisher@africabriefing.org

Kenya

Patrick Mwangi Aquarius Media Ltd, PO Box 10668-11000

Nairobi, Kenya

Tel: 0720 391 546/0773 35 41

Email: mwangi@aquariusmedia.co.ke

©Africa Briefing Ltd

2 Redruth Close, London N22 8RN

United Kingdom

Tel: +44 (0) 208 888 6693 publisher@africabriefing.org

Africa’s human rights merry-go-round

Africa’s diaspora must now come to the fore for continental development Securing the Indian Ocean Threat still exists

Ahmed Ibrahim looks at the evolution of piracy along the Somali coast and, specifically, how the Puntland Maritime Police Force is combatting the resurgent sea marauders

Although the Puntland authorities are acting tough on pirates in their sphere of influence along the Somali coast, industry bodies are worried about continued acts of maritime piracy not just in the Eastern region of the continent but also in the Gulf of Guinea

World on precipice of pronounced change

Humankind is living in an unprecedented era of new, interconnected crises and elevated global uncertainty that will have profound implications for all people, the planet and the future of humanity, warns Ban Ki-moon

AGOA reauthorisation: boosting US-Africa trade in critical minerals

Experts discuss how the ongoing AGOA reauthorisation could strengthen US-Africa trade relations in critical minerals, fostering economic growth and strategic partnerships amidst the clean energy transition, Jon Offei-Ansah reports

Ghana’s minerals sector needs to be people-driven 6

Small-scale and illegal mining activities have led to the destruction of a quarter of forest cover in the south-western area of the country within the decade ending 2017 due to the absence of predictable, accountable and participatory leadership that reconciles the interests of the state and society, finds Clement Sefa-Nyarko who is proposing the use of the social licence at the disposal of members of society to reverse this trend

Embracing unity: the vision behind Africa's monument of humanity

Nestled in the picturesque seaside town of Kribi, Cameroon, a monumental project is underway, poised to rewrite history and reshape the global narrative on Africa. Spearheaded by the visionary Nijel Binns, the Mother of Humanity® Monument is set to stand tall as a beacon of unity, reflection, and hope for a shared future, writes Jon Offei-Ansah

Established in 2002, Shanghai Grand International Co., Ltd. offers a variety of shipping and transportation options via air, sea and ground. Our company is based in Shanghai, China, with branches across the nation. Ranging from customs declaration, warehouse storage, containers and consolidated cargo shipping we have a large array of options to meet your needs.

In addition to being approved and designated by the Ministry of Transportation of China as a First Class cargo service provider, we have also established excellent business relations with major shipping companies including Maersk, CMA, ONE, SM line, and

C.E.O President.

Mr, Felix Ji

EMC over the past 15 years. In addition we have also built long term business relations with major airline cargo departments. In order to expand our global operation, we are looking for international partnerships to work together in this industry. Should you ever import any goods from Peoples Republic of China please ask your exporter and shipper to contact us. We will provide our best service to you.

Room 814, 578 Tian Bao Lu, Shanghai, Peoples Republic of China

E-Mail: felix@grand-log.net phone: 86-13501786280

AS Rwandans commemorated the 30th anniversary of the genocide in their country, the Chairperson of the African Union, Moussa Faki Mahamat, rather offhandedly announced the appointment of the first AU Envoy for the Prevention of the Crime of Genocide and other Mass Atrocities. The announcement was made on X (formerly Twitter).

We say offhandedly because such an appointment warranted more than just a few lines on social media. This is a massive move and it deserved wider publicity to reassure Africans that the powers that be on the continent are concerned about changing their lax attitude to ratifying human rights treaty, dealing with conflict and, generally, reducing the tensions in African societies that are being fuelled by intense hate speech.

Faki later confirmed in a speech in Rwanda during the commemoration of the genocide that Adama Dieng, an experienced Senegalese human rights lawyer, would take up the role. We are still waiting to hear what Dieng’s terms of reference will be and how he is to go about dealing with the issues he has been charged with to tackle.

Faki is expected to step down as AU Chairperson at the beginning of 2025, and we are wondering whether the whole business was clearly thought out. Or was it just a spur of the moment idea?

This is symptomatic of the manner in which human rights, peace and security issues are dealt with in Africa. They are not given the gravity that they deserve. Is it any wonder that African civil society organisations that are focusing on these issues are frustrated with the slowness of strengthening these crucial areas on the continent?

In this edition, we have an article pointing out that the Malabo Protocol that is supposed to provide Africa with the most expansive and ambitious understanding and definition of international crime has still not entered into force 10 years after African leaders adopted the document. The reason? Although 15 countries have signed the

Protocol, only one has ratified it.

This is really not on. Indeed, the slow ratification of Africa’s ratification of human rights instrument was at the fore of the first Joint Forum of the Special Mechanisms of the African Commission and Peoples’ Rights in Dakar in April this year.

The activists reflected on the state of human rights on the continent, measured the gains, identified the key challenges, and how the African Commission “may better contribute to human rights protection and promotion on the continent, particularly within the context of the African Union’s human rights and governance agenda”. They also pointed to the “lack of sensitisation of the citizens on the human rights instruments which the state intends to ratify, and the issues which will be addressed therein”.

Crucially, the forum noted that government officials themselves did not have a clue about the instruments that had been adopted by their countries, and there were “misconceptions on the obligations of states arising from human rights instruments”.

The AU is the body that must ensure that all these treaties are in force through its Peace and Security Commission. But is the PSC up to the task?

The Egyptian ambassador to

discussing thematic issues at the expense of considering crises on our continent. The tabling of country situations should be prioritised, and appreciating that these crises ultimately involve thematic issues.”

Conflicts continue to erupt on the continent, throwing the state of peace and security in constant disarray. The latest armed conflict which blew up in Sudan last year has been most catastrophic. Some eight million Sudanese have been displaced as a result.

The Democratic Republic of Congo and Mozambique are also in the throes of violent conflict. “These realities are a reflection of the miserable state of the state during transitions and conflict in Africa,” Gad pointed out.

So, these persistent armed conflicts are causing setbacks for the implementation of human rights instruments in Africa. The upshot of these conflicts has been the negative effects they have had on populations, including the internally displaced.

The irony of all this is that the people who suffer the brunt of human rights violations and other mass atrocities are the ones who do not even know that there are legally binding mechanisms that can stop all of these happening – only if their governments would to the right thing and ensure universal

’

Ethiopia and his country’s Permanent Representative to the AU, Mohamed Gad, gave a clear insight into the failings of the PSC in an interview with the Institute for Security Studies in South Africa this May. It was talk as usual without much action to deal with peace and security issues in Africa that are linked to human rights abuses.

He said: “We have noticed an increasing trend in the Council towards

ratification and domestication of all human rights instruments and “ensure consistent reporting to the Commission, highlighting any challenges on ratification and implementation,” as the forum recommended.

This should not be a tough ask of African governments. But we wonder why they are always so reluctant to do the right thing, and continue to play games on the human rights merry-go-round. AB

THE Nigerian government recently announced the creation of a $10 billion diaspora fund aimed at harnessing remittances to fund investment in infrastructure, healthcare and education in the country. This is a splendid idea. Such a fund should make a difference in a country that received some $20 billion from its nationals living abroad in 2023, according to World Bank figures.

It should make a difference if the money goes into economically viable projects, rather than to individuals who receive the bulk of remittances. Most of this money is spent on consumption to cover daily needs of recipients. And I am not just talking about Nigeria.

Again, according to world Bank figures, in 2022, the 160 million Africans in the diaspora sent home more than $95 billion in remittances. Of this figure, $53 billion went to countries in Sub-Saharan Africa with Nigeria, Ghana, Kenya and Zimbabwe topping the list. The World Bank noted that the total figure for 2022 far outstripped the $30 billion in foreign direct investment (FDI) and just $29 billion in official development aid for SubSaharan Africa.

For the most part, complacent African governments have viewed remittances as the answer to their failure to provide a social safety net for their citizens. So, remitted funds go to cover the daily needs of over 200 million family members, according to World Bank figures.

But what about the revenue that African governments collect from individuals and companies that are involved in exploiting natural resources? Shouldn’t this be spent on social security? Fat chance. Instead, there is a drain on state funds to pay the travel expenses of entitled African leaders who go on regular foreign jaunts. Some of which are not even necessary.

There is now clearly a case for improving the management of remittances and use for a much better development effect. As the World Bank notes, when remittances are brought into the formal financial system, their impact increases.

Indeed, it is high time that such remittances go directly to productive

the devaluation of African currencies and the strengthening of external economies.”

Importing goods willy-nilly is a sure way of unnecessarily leaking money out of African economies. But the African diaspora can make a huge difference in business development in Africa. And there is a willingness to help.

Tsitsi Masiyiwa, Chair of Co-Impact and the END Fund and Founder and Chair of the Higherlife Foundation and Delta Philanthropies, notes: “Members of the African diaspora have often shared with me their desire to expand their giving beyond their immediate family or community.

“The problem, they explain, is that they do not know which local organisations they can trust. That is why credible actors should be connecting the diaspora with community-based organisations that need and deserve support.”

African diaspora funds that can directly aid local entrepreneurs must now be a priority. And there are loads of dynamic African businesses that are looking for such investment to make Africa less dependent on unnecessary imports.

It’s going to get worse on the FDI front. New data and analysis from the Organisation for Economic Development and Cooperation (OECD) show that global FDI flows dropped by seven per cent in 2023, to $1.364 billion, continuing on a declining trend and remaining below pre-pandemic levels for the second consecutive year.

This is clearly a challenge for African countries that did not even feature in the scramble for FDI. But it is a challenge that can be countered by remittances, which must now go to investments in the productive economy to make a huge difference.

businesses that are privately owned. First of all, there must be enabling regulatory frameworks that will protect such investment. Africans in the diaspora are thinking more and more these days of investing in worthwhile businesses back home that will create employment and reduce imports of goods that can be easily produced locally.

Why do African countries have to import, say, chicken, fish and turkey when they can be easily made available at home? You then get prices rising all the time because of weak local currencies.

My friend, Adedeji Ebo, aptly points out in this edition of Africa Briefing: “Africa consuming what it does not produce and producing what it does not consume is an endless path to dependency,

How We Made It in Africa is one of the best places to source credible businesses. Established in 2010, it is an award-winning online publication in Cape Town, South Africa that conducts in-depth interviews with entrepreneurs and investors in Africa to reveal how they built their companies and uncover their key investment insights.

Over the years, it has showcased an impressive array of young African entrepreneurs, many of whom are women. Now is the time for these pioneering businesspeople to be given the needed support to make a huge difference to the continent.

Africans in the diaspora do not have the vote back home. But they can call the shots through economic empowerment, and let politicians go back to being servants of the people rather than the other way round. AB

Ahmed Ibrahim looks at the evolution of piracy along the Somali coast and, specifically, how the Puntland Maritime Police Force is combatting the resurgent sea marauders

PIRACY along the coast of Somalia takes place in various locations spanning the country’s territorial waters and neighbouring areas, including the Gulf of Aden, Guardafui Channel and Somali Sea. This longstanding issue has diverse interpretations within different communities. Initially targeting international fishing vessels in the early 2000s, piracy quickly escalated to pose a significant threat to international shipping, particularly during Somalia's internal conflict.

The fishing potential in Somali waters is significant, but it faces sustainability challenges due to illegal activities by foreign vessels. While the domestic fishing sector in Somalia is limited and underdeveloped, foreign trawlers have been operating in these waters for over seven decades. Somali artisanal fishermen perceive the illegal operations of these vessels and their crews as a threat to their traditional way of life. Competition posed by these foreign factory ships has led to a decline in fish populations and damaged marine habitats, particularly through bottom trawling, a method that destroys the natural seafloor habitat.

Foreign fishing in Somali waters has experienced a significant surge, increasing enormously since 1981. The most substantial rise occurred in the 1990s following the collapse of the Somali military government under General Mohamed Siad Barre and the subsequent civil war.

Somalia was labelled a failed state due to prolonged internal conflicts and significant instability that persisted until 2012 when the Somalia Federal Government was established in exile. Despite foreign intervention and support, the Federal Government of Somalia struggled to assert full authority, facing threats from the jihadist group, al-Shabaab. Consequently, Somalia continued to be classified as a fragile state. This situation

led to ineffective government policing of Somali waters by the Somali Navy, allowing large foreign fishing vessels to exploit this weakness, posing additional threats to the livelihoods of local Somali fishing communities.

In response, local coastal communities formed armed groups to deter perceived intruders, utilising small boats such as skiffs and motorised vessels. These groups occasionally seized ships and crews for ransom, evolving into a profitable trade where substantial payments were often demanded and met. Subsequently labelled as pirates, especially after targeting nonfishing commercial vessels, these groups

operated within a context of poverty and governmental corruption, which hindered the political will to address the crisis at the local level. Many unemployed Somali youth saw piracy as a means of supporting their families. Concerns from international organisations grew over piracy's detrimental impact on global trade and the potential for profiteering by insurance companies and others. There are suggestions that certain elements within Somalia collaborated with the pirates, aiming to bolster political influence and financial gain.

The Gulf of Aden is an important link to global trade and shipments. More

than 12 per cent of world trade and 10 per cent of gas shipments pass though the Gulf. As a result, gas and oil prices have been affected, rising by approximately 30 per cent, according to reports from the United Arab Emirates (UAE) National Oil Agency. Additionally, global trade shipment prices have also risen due to increased uncertainty in the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden.

The attacks have raised concerns over potential disruptions to global supply chains. Shipping firms are reportedly weighing the difficult choice between paying significantly higher insurance premiums on the risky Red Sea route and taking the longer and costlier way around the Cape of Good Hope. This means the turbulence in the Red Sea has disrupted global trade value chains, coupled with the economic pressures imposed on the states to counter piracy. According to the Oceans Beyond Piracy project by The One Earth Future Foundation in Colorado, the sea transportation industry shouldered 80 per cent of the cost of Somali piracy’s impact on the global economy, and the remaining 20 per cent was expended on

anti-piracy efforts by countries in the region. According to the report, the total piracy cost is estimated to be around $7 billion, considering various factors, such as ransoms paid to the pirates, piracyrelated insurances, the costs of securing equipment’s and guards, as well as rerouting around the Cape of Good Hope. Such costs have had a serious impact on daily subsistence prices across the world, adding pressure on politically unstable countries

As the scourge of piracy continues to plague maritime trade routes, particularly in regions like the Gulf of Aden and the Indian Ocean, concerted efforts have been made to combat this criminal activity. One notable strategy in this ongoing battle is the option of building on-the-ground forces in areas where piracy reached alarming levels in the early 2010s, before experiencing a significant decline in the following years.

At the forefront of this reversal is the Puntland Maritime Police Force (PMPF), whose establishment and operations have played an essential role in reducing piracy activities along the Somali coastline. Since its foundation in October 2010, the PMPF has been dedicated to eradicating piracy within Somalia's territorial waters.

Headquartered in Bosaso, the force

strategically deployed forward bases in other piracy-prone towns along the Red Sea and the Indian Ocean. This deployment has provided the PMPF with the necessary operational capacity to conduct maritime patrols effectively, ensuring the safety and security of vessels navigating these perilous waters.

This has been down to international collaboration and local vigilance in maritime security.

Indeed, one of the key factors contributing to the success of the PMPF has been its regional and global connectivity. Recognising the transnational nature of piracy, Puntland's leadership sought support from international partners, most notably the UAE.

Under the leadership of then Puntland President Abdirahman Mohamud Farole, the UAE collaborated with the East African state to establish a force capable of not only patrolling the coastline but also confronting piracy on land as well as other anti-government elements. This holistic approach aimed to deny pirates a base on land and counter the threat posed by terrorist groups like Harakat al-Shabaab al-Mujahidin, and ISIS which sought to exploit Somalia's instability.

The partnership with the UAE

facilitated the recruitment and training of personnel for the PMPF, transforming it into a professional maritime law enforcement agency. Furthermore, international security training companies were engaged to provide specialised maritime training, enhancing the force's operational effectiveness. This collaboration extended to other regional and multinational stakeholders, including the European Union Capacity Building Mission, which provided training and equipment to boost the PMPF's capabilities.

The success of the PMPF is evident in the significant decline in piracy incidents along the Somali coastline. Whereas 2011 witnessed a peak in piracy attacks, with 160 reported incidents and 358 vessels targeted, the subsequent years saw a remarkable reduction in such activities. By mid-2012, following the commencement of PMPF operations, piracy incidents began to decline steadily, culminating in the eradication of piracy by late 2013, marked by the absence of recorded incidents.

However, recent events have raised concerns about a resurgence of piracy in the region. Despite the effectiveness of the PMPF and other counter-piracy measures, isolated incidents have occurred, prompting speculation about the reorganisation of pirate groups.

For instance, reports from the Atlanta Piracy Situational Report highlighted

incidents such as the hijacking of vessels off the coast of Puntland in late 2023. While these incidents are troubling, it is essential to distinguish between real piracy activities and other criminal acts masquerading as piracy.

One such example is a case reported as a piracy hijacking in December 2023 by Atlanta Piracy Situational Pirate Report. Contrary to initial assessments, investigations by the PMPF revealed that the incident resulted from a business disagreement between boat owners and crew members.

This highlights the importance of accurate reporting and careful scrutiny of incidents before labelling them as piracy-related. Misinformation not only distorts the reality of piracy activities, but also undermines efforts to combat the phenomenon effectively.

In response to reported piracy cases, local authorities, led by the PMPF, have taken swift and decisive action. The establishment of forward bases in former pirate enclaves has enabled proactive policing, which prevented the re-organisation of pirate networks by swiftly responding to any emerging threats. For instance, a recent success was a joint operation which led to the arrest of a pirate group responsible for hijacking a Bulgarian bulk carrier in December 2023. This demonstrates the effectiveness of local authorities to combat piracy and making

it difficult for the pirates to have a safe heaven on land.

Moving forward, sustaining the gains made in combating piracy requires continued investment in maritime security infrastructure on the ground. The PMPF's success underscores the importance of holistic approaches that deal with the pirates at sea and blocking them from seeking refuge on land. Additionally, efforts to address the root causes of piracy, including empowering local police and the security forces on the ground, are essential for long-term solutions.

While the eradication of piracy along the Somali coastline represents a significant achievement, recent incidents serve as a reminder of the persistent threat posed by maritime crime. The PMPF, through its professionalism and dedication, has been instrumental in combating piracy and maintaining maritime security in the region. However, sustained efforts to invest in the local justice system are still missing.

These include reconstructing functional courts, creating an attorney general’s office, training prosecutors with expertise in the maritime sector and modernising regulation by assisting the ministry of justice to develop maritime crime laws. This approach should enhance, on the ground, justice systems that alleviate pressures brought on the other states by piracy.

Although the Puntland authorities are acting tough on pirates in their sphere of influence along the Somali coast, industry bodies are worried about continued acts of maritime piracy not just in the Eastern region of the continent but also in the Gulf of Guinea

THE International Chamber of Commerce’s International Maritime Bureau (IMB) has raised concern about the continued attacks by pirates off the coast of Somalia in its first quarter report for 2024, released in April. It recorded 33 incidents of piracy and armed robbery against ships in the first three months of 2024, an increase from 27 incidents for the same period in 2023.

Of the 33 incidents reported, 24 vessels were boarded, six had attempted attacks, two were hijacked and one was fired upon. Violence towards crew continues with 35 crew members taken hostage, nine kidnapped and one threatened.

The report highlights the continued threat of Somali piracy incidents with two reported hijackings. In addition, one vessel each was fired upon, boarded and reported an attempted approach. These incidents were attributed to Somali pirates who demonstrate mounting capabilities, targeting vessels at great distances, from the Somali coast.

A Bangladesh flagged bulk carrier, MV Abdullah, was hijacked on March 12 and its 23 crew were taken hostage by over 20 Somali pirates. The vessel was underway about 550 nautical miles (nm) from Mogadishu while enroute from

Mozambique to the United Arab Emirates.

When the pirates released the hijacked ship along with its crew of 23 in April, they claimed that they were paid a ransom of $5 million ransom.

Abdirashiid Yusuf, one of the pirates, told Reuters that the ransom was delivered two nights prior, adhering to the customary procedure. “The money was brought to us two nights ago as usual… we checked whether the money was fake or not. Then we divided the money into groups and left, avoiding the government forces,” he said.

At the time of writing, the authorities in both Somalia and Puntland had failed to throw more light on the ransom issue. However, an anonymous Puntland police officer was quoted by Garowe Online as saying: “The practice of paying ransoms could potentially encourage more pirates.”

IMB says it is aware of several reported hijacked dhows and fishing vessels, which are ideal mother ships to launch attacks at distances from the Somali coastline.

ICC Secretary General John W.H. Denton noted: “The resurgence of Somali pirate activity is worrying, and now more than ever it is crucial to protect trade, safeguard routes, and the safety of seafarers who keep commerce moving. All measures to

ensure the uninterrupted free flow of goods throughout international supply chains must be taken.”

But the IMB has commended “the timely and positive actions from authorities ensuring the release and safety of the crew”. IMB Director Michael Howlett said: “We reiterate our ongoing concern on the Somali piracy incidents and urge vessel owners and Masters to follow all recommended guidelines in the latest version of the Best Management Practices.”

In the Gulf of Guinea, although the IMB reported that incidents continued to be at a reduced level, it urged caution. Six incidents were reported in the first quarter of 2024 compared to five in the same period of 2023. One such occurred in January this year when nine crew were kidnapped from a product tanker around 45nm south of Bioko Island, Equatorial Guinea.

“While we welcome the reduction of incidents, piracy and armed robbery in the Gulf of Guinea remains a threat. Continued and robust regional and international naval presence to respond to these incidents and to safeguard life at sea is crucial,” Howlett said.

Since it was established in 1991, IMB’s Piracy Reporting Centre as been serving as a crucial, 24-hour point of contact to report crimes of piracy and lend support to ships under threat. “Quick reactions and a focus on coordinating with response agencies, sending out warning broadcasts and email alerts to ships have all helped bolster security on the high seas,” the IMB noted. “The data gathered by the Centre also provides key insights on the nature and state of modern piracy.

“IMB encourages all shipmasters and owners to report all actual, attempted and suspected global piracy and armed robbery incidents to the Piracy Reporting Centre as a vital first step to ensuring adequate resources are allocated by authorities to tackle maritime piracy.”

African agency, driven and dominated by states and the elite rather than communities and societies, is, first, not African, and, second, lacking in legitimacy, argues Adedeji Ebo

AGENCY is the capacity to act intentionally and with functional organisation to produce effects. It is the capacity to influence. In the case of Africa however, such “capacity to influence” is problematic and arguably ineffectual due to a legitimacy deficit resulting from the gap and tension between the agency of African states and elite on the one hand, and the agency of citizens and communities on the other.

The net impact of the two mutually exclusive sources of agency is that Africa’s agency is conflicted. Rather than flow into each other, state/elite agency and people-centred agency are fundamentally contradictory and antagonistic to each other.

Enhancing the agency for elites is in direct tension with agency for the marginalised and disenfranchised. This tension then has a debilitating impact on the collective agency of Africa continentally.

Africa’s collective agency cannot be divorced from its political economy in a global order that is structured to sustain the continent’s marginalisation. Despite membership of the World Trade Organisation, for example, Africa’s share of global trade declined from 4.4 per cent in 1970 to 2.7 per cent in 2020, underpinning the observation that “Africa has mostly been a taker than a maker of the rules of the international system…. While developed countries often talk about the need for reform, those same countries are unwilling to cede the rules that have secured their beneficial position.”

As UN Secretary-General Antόnio Guterres has repeatedly noted, imbalance in the global political system sustains the underdevelopment of many countries, while the benefits and burdens of multilateralism are inequitably distributed.

Marginalisation in the structures and process of global production and exchange has left Africa’s agency rather feeble and spasmodic. Despite a rich body of normative pronouncements, the various

levels of agency are disconnected, both within and between them.

At best, there is a loose connection between them. Rather than being cohesive and resilient, Africa’s agency is dissipated and vulnerable to being influenced rather than wielding influence. In an environment in which dominant actors (such as the European Union) are further consolidating their political and socio-economic amalgamation, collective African agency

is essential for transforming Africa’s subaltern role in the global system of production and exchange.

Hence the call for a “renewal of African agency…that goes beyond the purview of the state, of formal actors, to include abundant manifestations of Africa’s soft power such as its creative economies, arts, theatre, innovations, some of which exist in spite of state, not because of the state”. The agency of African youth is also authentically expressed “through acts of dissent, protest and self-determination, by voting with their feet through migration across the Mediterranean”. Juxtaposed against its political economy therefore, African ownership of agency is more apparent than real, more often assumed rather than clearly conceived; merely pronounced rather than firmly constructed.

Ownership is the litmus test against which to construct and measure agency. Yet, despite and beyond the universal appeal of national and regional ownership, there is very little clarity on the implementation and operationalisation of ownership.

There is therefore the need for a distinct construct against which African ownership of agency can be clearly recognised and operationalised. In

contending that African ownership of agency is the basis for its legitimacy and without which it cannot be impactful, a framework for African ownership of agency comprises four key elements: common African vision; implementation capacity; financial resources; and a peoplecentred framework for monitoring and evaluation.

Collective action requires common purpose, otherwise Africa’s dissipated agency has the net effect of entrenching its marginalisation. Such a common vision would encapsulate and be driven by Africa’s agreed political aspirations and shared socio-economic agenda.

Africa’s agency cannot be effective (in the sense of having the capacity to influence) unless it is collective, i.e., has functional organisation driven by common purpose.

Therefore, a basic requirement for African agency is a clear African vision, which many would argue is currently rather blurry. The key question is: is there a uniquely continental “social contract” which can be said to reflect the aspirations of African stakeholders beyond the elite and governments?

Africa’s marginal role in the global political economy enforces upon it a particular and endearing urgency for the transformation (not merely tinkering) of the global system that works against and sustains its marginalisation. For Africa to define the basis of its coexistence with others, such a transformative ethos includes and must begin with the way Africans exercise agency among and within themselves.

This foundation would determine and define how Africa applies its agency to the rest of the world. A disunited Africa can neither own nor deliver impactful agency, both within Africa and between the continent and the rest of the world. Africa’s only chance of sustainable progress in a world so firmly structured against it, is one with a clear common purpose, common action, driven by collective purpose. Does the Constitutive Act of the

African Union qualify as such a capstone instrument for the synergised collective agency of Africa? Or is it merely a statutory contraption, despite its lofty PanAfricanist normative ideals?

While there admittedly is a palpable gap between aspiration and implementation, the AU Constitutive Act provides the basis for an African collective vision of agency: “Guided by our common vision of a united and strong Africa and by the need to build a partnership between governments and all segments of civil society, in particular women, youth and the private sector, in order to strengthen solidarity and cohesion among our peoples.”

To further concretise this unity of purpose, Agenda 2063 was signed in 2013 to serve as “Africa’s blueprint and master plan for transforming Africa into the global powerhouse of the future”. It is intended as “the Pan African vision of an integrated, prosperous and peaceful Africa, driven by its own citizens, representing a dynamic force in the international arena”. The complex hybridity of African governance necessitates a multistakeholder conception of agency. This recognises the important role of the states and governments behind such normative instruments while also including “various citizens formations”, as well as customary and traditional systems which are richer sources of legitimacy as they are closer to the population. This importantly includes African youth and women, not merely in the urban but also the rural parts of the continent.

In the final analysis, as legality comes from the state above, legitimacy comes from the people below. Juxtaposed against its political economy, therefore, African ownership of agency is more apparent than real, more often assumed rather than clearly conceived, merely pronounced rather than firmly constructed. A viable African vision must include both people and state and must be able to bridge the gaps and address the tensions between them.

African capacity is another critical element of viable African ownership

and collective agency. African states, communities and peoples need to not only participate, but also lead in the implementation and actualisation of their collective aspirations.

Whether in the field of engineering, science, legal affairs and whatever else, such must also include the African diaspora which remains still a marginally incorporated component. Implementation capacity is a function of the human, institutional and collective energies of African actors, be they community, state, elite or citizen.

An important dimension of capacity is psychological, i.e., the African “state of mind” and its conditioning. The departure point, and the destination of collective agency, is the conviction that Africa and Africans are unstoppable by anyone or anything, inferior to no one, and welcoming to everyone. African ownership therefore requires that Africa is first and foremost the responsibility of Africans; external actors are secondary, though welcome.

This “can do”’ and “must do” spirit is essential to drive African implementation

capacity and enhance its impact. It can only come from African solidarity, indeed very much a normative darling of the African Union, generously effused by its Constitutive Act, as well as most key AU normative instruments.

There is a political economy of ownership through which power flows to

the “donor” and away from the “recipient”. African agency must therefore be consistently cognisant that “the hand that gives is always on top”. African ownership necessitates devoting Africa’s own resources to the implementation of agency, driven by African vision.

There can be no African ownership

when and where external “donors”, for the most part, bear financial responsibility for entire processes and projects and initiatives on the continent. For example, the inspiration evoked by the AU Constitutive Act stands in sharp contradistinction with the financial dependency of the African Peace and Security Architecture (APSA), which is reported to be two-thirds externally funded.

The list of the AU’s “partners” is a long one, and the “partnership” is typically disproportionately with external actors bearing financial responsibility for “support”. Following the money, African ownership is constrained, dependent, and African voices thus structurally muted.

For collective agency to be effective, African resources are best provided through inclusive and participatory processes that enable people and communities, beyond the state, to effectively exercise agency and, indeed, oversight. The process through which African resources are appropriated is important for agency and are best configured through transparent and participatory processes which allow agency to be directed by African voices and energies at each level.

There is need for resources that are legislatively appropriated, with open hearings in parliaments featuring active civil society and citizen groups.

In the struggle to identify African

funding and resources, African energies should focus on renewed and louder calls for reforms of the international financial system, as well as calls for reparative justice in the form of financial reparations. The continent should negotiate more favourable terms on mineral and natural resources.

Growing intra-African trade should remain a priority. The New Partnership for Africa’s Development (NEPAD) should not be implemented as acquiescence to the current economic order and giving up on the demand for a New International Economic Order (NIEO).

African resources could also be released by a concerted change in Africa’s demand patterns.

Africa consuming what it does not produce and producing what it does not consume is an endless path to dependency, the devaluation of African currencies and the strengthening of external economies.

The role of Africa and Africans in tracking political and socio-economic progress is crucial for determining how and whose “success” is being considered and measured. It is therefore a key element of African ownership.

Despite membership of the World Trade Organisation, for example, Africa’s share of global trade declined from 4.4 per cent in 1970 to 2.7 per cent in 2020

The process of review and assessment through which agency is monitored and evaluated needs not only to include but be led by African communities and states, in a participatory, inclusive and transparent manner. Success is measured as impact of agency by both states and citizens more broadly.

The challenge, therefore, is to develop a uniquely African operational framework which is horizontal, objective and effective in placing Africa squarely at the centre. In this regard, the African Peer Review Mechanism provides an encouraging basis which needs to extend statutory processes.

However, the effectiveness of Africa’s agency in contributing to the contours of a new global order would depend on a clear cohesive African component, an “African Pact” based on which Africa could speak with one voice on the most important issues. To be sure, such a common path is by no means a naïve insistence on “one of everything” (language, foreign policy, culture, etc.) for an entire continent.

On the other hand, “unity in diversity” should not be equated with the least common denominator of consensus. The key message is that Africa can least afford the “long way home”. There should be no surrender to the de-energising attitude of being “realistic”. We all are creators, through collective agency, of what is “possible”.

Collective agency is a particularly urgent imperative for both Africa’s role in the world and the role of the world in Africa. Therefore, whether for its own continental consolidation or for “projecting” the continent on the global stage through multilateral organisations, Pan-Africanism is the most viable, though challenging path to the continent’s transformation and full and optimal participation in the global political economy.

Bolstering Africa’s collective agency is imperative. Otherwise, Africa’s current, dissipated agency risks being a mere ingredient in the geo-strategic recipes of others.

Adedeji Ebo is a Visiting Professor at King’s College London (KCL). He is also the Director and Deputy to the High Representative, UN Office for Disarmament Affairs. The views expressed in the above and the following two articles are those of the author only. They do not represent the views of the UN. They are from his presentation during Africa Week organised by the African Leadership Centre, KCL in March 2024 under the theme: Is Africa’s Agency for Hire, for Sale or for Renewal?

What the continent gets out of respective multilateral organisations depends on its inputs into them, and its stake is a function of the dynamic interaction between the primacy of politics and the fundamentals of economics within such a system, says Adedeji Ebo

WHILE Africa itself is losing confidence in global multilateral arrangements such as the UN, intra-African multilateralism (the AU, ECOWAS, the Intergovernmental Authority on Development, etc.) is showing signs of distress. It is, or at least, it should be, the major focus of Africa’s agency to resist and transform the current hegemonic (dis)order which is predicated on and benefits from Africa’s marginalisation.

A collective African renewal from within, interconnected and mutually reinforcing between states and society and between communities and peoples, across regions to the continental and to the global, is a necessary condition for Africa’s agency to be impactful.

To determine whether multilateral organisations are “fit for purpose”, it is necessary first to decipher the “purpose” of Africa’s agency and whose purpose. Is it a common purpose (common “African voice”) that could form the basis for collective action, or is Africa’s agency to be found only in the quest for state survival and elite interests?

There are seismic changes taking place not only globally, but within Africa itself. Old arrangements are shaky and crumbling, while new ones are emerging. There could not have been a more opportune time for Africa to resolutely focus its agency on taking advantage of the chaotic, destabilised and declining global Western hegemony, as indeed some other regions of the world are gainfully doing, producing “new and emerging powers”. Unfortunately, however, Africa’s own dissipated and dissipating agency has rendered it more of a bystander than a beneficiary of the vulnerabilities offered to subaltern actors by the current state of anomie in global affairs. The 2024 UN Summit of the Future, at which states are to set a Pact of the Future, is an important opportunity for collective African agency, were it possible.

African multilateral organisations are essentially conduits for African agency and

connect national levels to a global level of agency. However, the record of African multilateral organisations in projecting Africa’s voice is not linear.

African multilateral organisations must be credited with major achievements, including bringing an end to colonisation, engaging boldly and creatively in peacekeeping, mediation, free movement of goods and citizens. Their record has however been spasmodic, and perhaps even retrogressive.

While African multilateral bodies tend to possess a rich body of normative frameworks and instruments, there are wide gaps between norms and practice. African multilateral organisations are typically state-centric, vaguely, and loosely connected to people and communities.

Indeed, for many communities and citizens, agency is derived necessarily from resistance to the state. This results in legality-legitimacy gaps and tensions, with contradictory and mutually antagonistic energies of Africa’s agency.

What is clearly and urgently needed is an agenda for rebooting Pan-Africanism. There is a palpable need for change in Africa’s marginalised role in the current global order. However, the transformation of Africa away from the periphery to the centre of the global political economy is an arduous and necessarily multidirectional task.

To be sure, it is possible, but only through a particular African agency that is collective, cogent, cohesive and impactful, and interconnected by a deep sense of common identity and purpose. A unity of efforts should be birthed by a unity of purpose, commonality of experience and confluence of interests.

To achieve this, Africa’s agency needs to change from being hired, sold, hijacked and dissipated to become more independent, energised, self-confident and African-owned. Systematic and systemic transformation is required rather than merely “cumulative progress”. Fundamental

changes, not mere tinkering, are needed. Such a transformation requires political and economic belt-tightening and a disciplined urgent sense of purpose at every level.

Set against the status quo, it requires a transformation in the respective elements of African ownership of agency: common African vision (African social contract); implementation capacity; African resources; and a people-centred operational framework. What needs to change is the seemingly lacklustre and dissipated African agency and what is needed to achieve this is its renewal and rebirth.

Given the wide gap between where Africa currently is and where it needs and aspires to be, all hands are required on deck, inspired by a common sense of identity, solidarity and purpose. What could move the needle is a characteristically, essentially, and necessarily Pan-Africanist agenda, as quite aptly captured in the Constitutive Act of the African Union, “a unique framework for our collective vision of Africa and in our relations with the rest of the world”.

In this regard, there is a palpable

gap between the lofty aspirations in the preamble to the Constitutive Act and the relatively cautious implementation which aims only at “the gradual attainment of the objectives of the Union”.

A reawakening of Africa is urgently needed, to narrow the gap between the aspirations of African vision (as captured by the AU) and its realisation. What is required is a reboot of Pan-Africanism that interconnects various levels of African agency from the population to the state, to the regions and up to the global levels.

We are currently at an opportune juncture to revisit the basis of Africa’s multilateral arrangements and lay a firmer basis for the reinvention of Pan-Africanism. For one, the gap between multilateral normative frameworks and their practice has been rapidly widening, both subregionally, regionally and globally.

In the sub-regional case of ECOWAS, the tensions have been existential, with three Sahelian states opting out of membership. These challenges have been driven by, but extend beyond, “unconstitutional” changes of power.

The effects have been so seismic, that the ECOWAS leadership proposed a fundamental rethink of its arrangement, with “plans to engage in deep reflection with the participation of critical stakeholders on the fate of regional integration, democracy and good governance in an era of multipolarity and an asymmetric conflict environment”.

At the continental level of the AU, the timing is no less auspicious to take stock of its achievements and continuing

challenges, with a view to sharpening its vision for collective agency. The year 2025 marks the 25th anniversary of the Constitutive Act and the entire African Peace and Security Architecture, with a new leadership expected to take the helm of the AU Commission in the first quarter.

The Constitutive Act is the singular most significant attempt at an African Pact, aspiring for an African social contract. It is the basis of collective African agency, without which it would ultimately be dissipated and ineffective for the transformation that Africa sorely and urgently needs.

The time is right and nigh for a sharpening of the African vision, through a review of normative instruments such as the Constitutive Act, the entire APSA

and similar instruments for ECOWAS and other regional economic communities, with a view to better bridging the gap between norms and practice. African states and peoples should not hesitate to revisit some basic questions and topics which are essential for common action that emanates from common purpose that interconnect both state and society.

Africa’s ability to influence global processes and initiatives is a function of the level of cohesion that exists within Africa’s own multilateralism, i.e., its continental and regional arrangements. In other words, while there is a need for “forging a new compact with external partners to prevent a new Cold War in Africa”, such new arrangements can only be viable when they are based on a cohesive and united Africa which can engage external partners from a common African position. African regional multilateral organisations need to be part of a wider Pan-Africanist rebirth that effuses confidence, purpose and firm will to direct African energies.

Hopefully, the recent (attempted?) exit from ECOWAS holds the lesson that West African states are all mutual losers in a context of divided and mutilated agency. For Africa to be able to benefit from a “new compact” with external partners, first it must renew and rebuild the basis of its collective and cohesive agency.

Charity, it is said, begins at home. Africa’s collective agency is only as strong as its roots that lie in common African ownership and common purpose. African states are, ultimately, all mutual losers on a continent seemingly divided against itself. All should be guided, inspired, and challenged by the ultimate common purpose of African unity and solidarity.

There is an urgent need to stem the waste of the human potential of the continent, which must include the positive and dynamic contributions of African youth and their “can do” originality, creativity and resilience

AS the continent with the youngest population globally, (as at 2023, about 40 per cent of Africa’s population is 15 years or younger, with a median age of 20), a new partnership compact must also include a strong generational dimension. By 2030, young Africans are expected to make up 42 per cent of the world’s youth and account for 75 per cent of those under the age of 35.

Therefore, such a compact should include a strategy to harness the demographic dividend of its youthful population. However, current signs are not encouraging: 52 per cent of African youth aged between 18 and 24 are likely to consider emigrating in the next three years due to economic strife, insecurity, political intolerance, unreliable internet and poor education systems. In Nigeria and Sudan, it is 75 per cent.

The African inter-generational partnerships must also include a bridging element, in which African youth are equipped with intergenerational knowledge and awareness through the presence of those living African heroes that are evolving to becoming “future ancestors”, manifested in all walks of life and professional disciplines. Those great Africans – Mansa Musah, Nkrumah,

Mandela, to Queen Amina of Zaria –provide inspiration and direction to African youth who are typically confronted with, and distracted by, a complex set of influences.

It is a perplexing “reality” that the African continent is, so far, incapable of communicating within itself in a common African language, or two. The gap between state-elite agency and the agency of people and communities in Africa can be partly traced to the absence of a common means of communication (language) that could narrow such a gap continent-wide. The state communicates with its population in languages that many, if not most Africans, neither speak nor understand. The lack of an agreed common continental language with which African multilateral organisations, states, elite can communicate with each other and with all African citizens is a major impediment to the construction of African ownership of agency.

Article 25 of the AU Constitutive Act is a sore reminder of this missing critical ingredient of agency, a common African language: “The working languages of the Union and all its institutions shall be, if possible, African languages, Arabic, English, French and Portuguese.” Over 60 years after the founding of the Organisation

of African Unity, and almost a quarter of a century after the founding of its successor AU, the matter of “if possible” is yet to be addressed. Africa and Africans continue to conduct affairs with each other in the languages of their colonisers. This sustains the gap between state agency and citizens’ agency, has a dissipating effect on Africa’s agency, and a structural systemic handicap to Africa’s efforts at global agency.

Music as a tool of agency is underutilised. It has served Africa well as a means of social mobilisation, advocacy and indeed agency. Apart from bridging divides and building African agency, music has been a lucrative African export which has imprinted Africa as a major entertainment capital of the world and a major influencer of global culture.

The continent should continue to create the infrastructure and support for young Africans to explore their musical talent, including across national boundaries and on the global stage.

In all this, Africa has to be careful when it comes to information technology. There is a note of caution that needs to be sounded in relation to Africa’s particular vulnerability to the negative side-effects and the weaponisation of information technology.

Through misinformation, disinformation and hate speech, Africa’s agency can be subject to manipulation, divisions and deliberate falsehoods. In addition to establishing the infrastructure to police and contain such risks, African states should ensure active advocacy and educating the public that not all information found on the internet is accurate, valid, or true.

Indeed, there are often deliberate attempts to present false and inaccurate information to an otherwise unsuspecting population, weaponized for the purpose of manipulating the audience and to (mis) guide them towards particular desired outcomes and interests.

Adedeji EboIn Abidjan recently, activists discussed the issue of a proposed Prevention and Punishment of Crimes Against Humanity accord and wondered whether there was a need for it, given the existence of the International Criminal Court’s Rome Statute, writes Elise Keppler

WITH only six months until the UN’s Sixth Committee takes a decision whether to advance the Draft Articles on Prevention and Punishment of Crimes Against Humanity to treaty negotiations, the need for greater awareness on the Draft Articles is high, especially on the African continent. Africa has the largest number of states that have yet to expressly weigh in on whether the Draft Articles should advance to negotiations.

A crimes against humanity treaty would in fact be distinct from the ICC’s Rome Statute. First and foremost, the ICC deals with individual criminal responsibility, while the hoped-for crimes against humanity treaty would concern the responsibility of states to both prevent and punish the crimes. And, it is precisely such a treaty that could open the door for states to hold other states accountable through the International Court of Justice if those obligations are not met.

While genocide and war crimes have dedicated treaties – the Convention for the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide and the Geneva Conventions –crimes against humanity exist in customary international law. Having express, delineated agreed upon provisions in a treaty is far more desirable.

Indeed, this is such an obvious gap to be filled that I have yet to meet an activist who did not wish to lend their support to the effort once appreciating its purpose. Our discussion among Ivorian human rights advocates turned quickly to how to best mobilise Cote d’Ivoire and other

African states to support negotiations for the treaty.

The UN’s Sixth Committee met in April in New York to discuss the Draft Articles and states’ views on whether it is time to move them to formal treaty negotiations. More than 70 countries spoke out in support. But achieving consensus – the customary operating procedure of this committee – to move the process to negotiations will necessitate more support.

Among African governments, several have taken a clear position. Sierra Leone has shown particular leadership, alongside South Africa and The Gambia. Ghana and Portuguese speaking African states –Angola, Mozambique, Guinea Bissau, Sao Tome and Principe, Equatorial Guinea and Capo Verde – also voiced support at the April session. A couple of others earlier expressed support, including Senegal and Tunisia.

But far too many African governments have yet to take an official position on the need to move these Draft Articles to negotiations for a crimes against humanity treaty, including those that have a history of supportive positions on matters of accountability, such as Zambia, Malawi, Lesotho, Namibia, Botswana, Benin, Liberia, Cote d’Ivoire and Uganda, among others.

Global Justice Center has disseminated a series of proposals to enhance the Draft Articles to be gender-competent and survivor-centric. The following crimes, in our view, should be expressly incorporated into the Draft Articles: forced marriage, reproductive violence, gender apartheid,

and the slave trade.

We also are advocating for language that is meaningless at best regarding national pregnancy laws to be removed, for excluding the Rome Statute’s definition of gender, and for adding a definition of victims that recognises the scope of victimhood and language that attends to victims’ needs, including reparations.

But the priority is to advance the process, which has been pending in the UN’s Sixth Committee for multiple years, to the next stage – to treaty negotiations where particular proposals can be further debated.

Advocates, activists, and experts agree. More than 400 civil society groups and individuals, many from across the African continent, have signed a joint statement calling for their governments to support entering into negotiations on a crimes against humanity treaty.

Governments – particularly the many across Africa that have yet to take a formal position in support of treaty negotiations –should heed the call.

This opinion piece first appeared in the Daily Maverick on May 12. Elise Keppler is executive director of the Global Justice Center (GJC), an organization that uses international law to fight for gender equality. She joined in January 2024, after two decades at Human Rights Watch’s International Justice Programme, where she focused on situations across Africa.

At

a time when basic rights and the rule of law are increasingly under attack by those tasked with protecting and promoting them on the continent, Adama Dieng says this is now the time to strengthen commitments, overcome obstacles and reinforce opportunities

THE situation of human rights and the rule of law in Africa is in decline. More than 20 years ago, no one would have imagined the deterioration of these rights and governance that we are currently witnessing. For example, over the past four or five years, unconstitutional changes of governments have taken place in a number of African countries, with far-reaching consequences for the protection and promotion of the human rights of our peoples. The rule of law has been deliberately suppressed, while governance no longer relies on the consent of the people, but rather on the will of the powerful. Unfortunately, we are all witnesses to what is happening, among other regions, in Sudan, South Sudan, or Libya, in Tigray where the conflict is static, in the Sahel which faces enormous challenges, in the Democratic Republic of Congo, the scene of serious atrocities and in many other situations.

Overall, the human rights situation on the African continent therefore requires more in-depth reflection, but also a new approach to the way in which we collectively approach these developments that are profoundly reshaping our societies in a context which is not so positive.

Since its creation, the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights was designed to be the voice of conscience on human rights on our continent. Yet we all recognise that the strength and effectiveness of the Commission depend largely on the support it receives from all stakeholders, including political actors who have the power and responsibility to facilitate its work and implement its decisions.

Although the Commission is an important part of our African human rights system, it is not a judicial body. It is the

recognition of this fact that has galvanised our efforts to have an independent and effective judicial body, with the aim of complementing and strengthening the protection and promotion mandate of the Commission.

For example, in 1994, during the heads of state summit in Tunisia, the Secretary General of what was then the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) was responsible for “reflecting, jointly with the Commission, on means to improve the effectiveness of the Commission by considering the creation of an African Court”. Once again, this mandate entrusted to the Secretary General of the OAU was neither accidental nor misplaced. It arose from the fact that the important work of the Commission must be complemented and strengthened by that of an independent and effective judiciary.

But this task also recognised the Commission's primary role in protecting and promoting human rights. Indeed, the Commission played a vital and indispensable role in the creation of an independent Court.

The Commission has therefore played a leading role in the development of African

standards, notably by creating important mechanisms such as the appointment of a Special Rapporteur on prisons, the promotion of better conditions of detention and the maintenance of order in Africa, as well as women's rights, support for human rights defenders, preservation of freedom of expression and access to information, to name just a few. Furthermore, recognising the important role of civil society in the development of human rights, the Commission has done impressive work in collaborating with civil society organisations across the continent.

The dynamic relationship between the Commission and regional civil society groups has led to an increase in the number of entities granted observer status with the Commission, from a few dozen in the 1990s to more than 450 today. Civil society groups draw the Commission's attention to violations of the Charter, submit communications on behalf of individuals, while working to monitor states' compliance with the Charter and help ensure that the activities of the Commission are better known by organising conferences and other activities for this purpose.

Donald Deya, Executive Director of the Pan African Lawyers Union (PALU), noted the importance of this interaction between the Commission and civil society: “The Commission has provided a pillar, a foundation where African citizens and friends of Africa meet around the NGO forum, which has made it possible to build a solid platform of African actors who talk to each other.”

Beyond case law, non-binding legislation, principles, declarations and recommendations, the fact that there is a framework where citizens come twice a year to interact is an important and invaluable advantage that has not been sufficiently taken into account.

Despite this impressive contribution to jurisprudence and human rights on the continent through a mandate of promotion and protection, the Commission could do more to improve its effectiveness and promotion of human rights, the rule of law and governance. I would like to briefly highlight a few points that the Commission should take into account in its work programme:

• Strengthen the role and engagement of youth, women and other marginalised groups. This will help the Commission harness the contribution of these essential components to strengthen human rights mechanisms and processes;

• Particularly in the digital age where

information sharing is more common, the Commission should strengthen the use of technology and investments in new technologies. It could thus contribute to investigations and the collection of information and evidence to support its work. It is a fact that the private sector is one of the main violators of human rights (social, economic and political). Thus, some of the most devastating conflicts on the African continent are fuelled by the work of this sector (for example in the extractive industry). However, it is also true that the participation of the private sector would not only allow for better dialogue, but also to further leverage its power and resources to achieve better protection of human rights, particularly with regard to social, economic, political and civil rights;

• The continuation of dialogue with member states in order to strengthen their obligations in terms of the Charter’s implementation;

• Although I am aware of the efforts being made to improve collaboration between the Commission and the Court, I would like to emphasise that closer collaboration between these two institutions will not only contribute to increasing human rights jurisprudence, but also to improve the protection of human rights and the rule of law in Africa through the principle of complementarity.