School districts are prime targets for security threats such as hackers, DDoS attacks, ransomware, and more. For the IT administrators challenged with protecting sensitive data and maintaining connectivity, it’s critical to find a technology partner who can build and deliver the robust, cost-effective solutions school districts require.

The education professionals at Alaska Communications have a strong history of building customized IT environments that provide superior security and performance, with a keen understanding of government funding and a focus on optimizing every budget dollar.

907-777-4362

Local and traditional inspiration for architectural detail

By Richard PerryThere are many bridges in Alaska, the natural consequence of our many waterways (and other geographic features, notably Hurricane Gulch at mile 139.7 of the Parks Highway). Many are beautiful, but most are better described as functional.

Not so for the John O’Connell Memorial Bridge that spans the Sitka Channel, the subject of this month’s cover. The American Society of Civil Engineers Alaska Section designated the cable-stayed bridge as an Alaska Historic Civil Engineering Landmark in September 2022. According to guest author Aaron Unterreiner of PND Engineers, “It’s a beautiful bridge, but it’s not boastful. It’s a practical piece of thoughtfully designed infrastructure that has seamlessly woven itself into Sitka’s fabric. In many ways, the O’Connell Bridge represents the zeitgeist of Alaska’s economic development over the last fifty years.”

Answer “Yes” to contribute half of a PFD to an Alaska 529 account. Simply log in to pfd.alaska.gov and update your application prior to the PFD distribution, and you’ll automatically be entered to win a $25,OOO scholarship account.* 202212-2619126

Agood friend of mine had an oven/cooktop that decided it would rather not cook things anymore. After much pleading and attempts to compromise, it remained uncooperative. She and her husband took the opportunity buy their dream oven unit, which required them to order it from out of state. While they waited for the new, willing-to-doits-actual-job oven to arrive, they needed some kind of cooking option to feed her family of six and purchased a counter-top air fryer. When the new oven arrived, she asked if I wanted the air fryer, as she didn’t really have the counterspace for it. I don’t either, at home, but I keep a cooking appliance in my office at work.

I’ve never owned an air fryer, and if this one ever had a manual, it was lost shortly after its unpacking. So after I took it into work and plugged it into the wall, successfully cooking my bagel was between me and the machine.

This particular model has a few buttons and a knob, and after a few minutes of tinkering with them, I was confident I could put a thing in it and the thing would come out toasty. I was, in fact, successful.

That, in and of itself, is a testament to the marvels of engineering. Engineering an item requires taking into consideration endless details, from safety requirements to energy efficiency to ensuring the user can interact with the item so it can fulfill its purpose.

In this issue’s Architecture & Engineering special section, “Top Shelf” is an excellent example of engineering and architecture in action. Anchorage eatery Whisky & Ramen renovated a historic building with a high-end, comfortable restaurant in mind. Guests in the restaurant can observe and appreciate many of the design choices; they will be completely unaware of thousands of other decisions made that transformed the old building into one of Anchorage’s dining hotspots.

Some of the best engineering we ever experience is the engineering we don’t notice at all. Interior design or lighting choices that we don’t consciously notice that put us at ease or build up our energy, or user interfaces executed so well it doesn’t occur to us to question them.

Modern life is an engineered life. We live surrounded by infrastructure, equipment, and other items engineered to solve our problems and suit our needs. And they do such a good job that we notice them most when the tools and infrastructure we enjoy don’t work as expected—when the oven goes on strike over cooking a casserole.

VOLUME 39, #2

EDITORIAL STAFF

Managing Editor Tasha Anderson 907-257-2907 tanderson@akbizmag.com

Editor/Staff Writer Scott Rhode 907-257-2902 srhode@akbizmag.com

Editorial Assistant Emily Olsen 907-257-2914 emily@akbizmag.com

PRODUCTION STAFF

Art Director Monica Sterchi-Lowman 907-257-2916 design@akbizmag.com

Design & Art Production Fulvia Caldei Lowe production@akbizmag.com

Website Manager Taylor Sanders webmanager@akbizmag.com

BUSINESS STAFF

President Billie Martin

VP & General Manager Jason Martin 907-257-2905 jason@akbizmag.com

VP Sales & Marketing Charles Bell 907-257-2909 cbell@akbizmag.com

Senior Account Manager Janis J. Plume 907-257-2917 janis@akbizmag.com

Tasha Anderson Managing Editor, Alaska Business

Tasha Anderson Managing Editor, Alaska Business

Senior Account Manager Christine Merki 907-257-2911 cmerki@akbizmag.com

Accounting Manager James Barnhill 907-257-2901 accounts@akbizmag.com

CONTACT

Press releases: press@akbizmag.com

Postmaster:

Send address changes to Alaska Business 501 W. Northern Lights Blvd. #100 Anchorage, AK 99503

AKBusinessMonth alaska-business-monthly

AKBusinessMonth akbizmag

Businesses today are coping with the cumulative effects of a slew of issues, including supply chain disruptions, labor shortages, inflation, rising interest rates, the RussiaUkraine war, and the lingering effects of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“The pandemic has drastically changed many businesses,” says Wells Fargo Alaska Commercial Banking Leader Sam Mazzeo. “The labor market tightness, excessive inflation, real estate market changes, and material supply chain issues linked to COVID are ongoing and evolving. Nobody has navigated anything like what we experienced the past three years. Banks and borrowers are forced to reconcile the risks and opportunities related to all of these things.”

The US Federal Reserve (the Fed) raised interest rates dramatically in the past twelve months, up to

their highest points in more than ten years. Mazzeo says most economists are projecting further interest rate increases, as the Fed continues to battle inflation.

Wells Fargo is working closely with its clients to ensure they maintain adequate cash flow and strong liquidity positions. “Working with your commercial banking relationship manager early and often can help you avoid unwanted surprises and offer you flexibility,” Mazzeo says. “It’s a great time to conduct a thorough financial review, including cash flow projections, and have frank conversations to make any necessary adjustments to loan structures and working capital lines of credit.”

While the rising interest rate environment is disconcerting, one of the primary issues for

commercial banking and all industries now is labor, says Jason Criqui, commercial lending manager at Northrim Bank. Finding qualified employees, developing people internally, and finding programs to bring young people in to replace retiring Baby Boomers will be the biggest challenge. “We’re all going to have to be creative in the way we move forward, including leveraging technology to do more with less,” he says.

All these challenges place more pressure on managers, particularly at small companies, says Northrim President and Chief Lending Officer Mike Huston. From the banking side, it created a challenge—and opportunity— for Northrim to support companies’ management with its advice and expertise.

Sam Mazzeo Wells Fargo

Sam Mazzeo Wells Fargo

However, relationship banking means different things to different people, Huston says. “For us, it means having a banker that understands the market that the business engages in and being responsive to that business,” he says. “We always want to have the opportunity to engage with people.”

Huston has noticed that national banks have been looking to be more efficient with delivering services to Alaska. “Generally, that means reducing the number of people who are based in Alaska,” he explains. “They are working with regional customer service centers that manage relationships for fairly large geographical areas. Community banks are also looking for ways to be more efficient, but our approach is different. We are looking to maintain responsive, supportive, experienced people who are based in Alaska.”

For Northrim, this trend has fostered valuable opportunities for growth.

The bank recently opened a branch in Soldotna, loan production offices in Kodiak and Nome, and a branch in East Anchorage. Northrim is also opening new branches in Kodiak and Nome, bringing its total number of branches in the state to nineteen. “We’re investing in the communities that are within our economic footprint,” Criqui says. “We’re trying to service the whole state.”

Northrim’s expansion efforts are, in part, supported by the success of Alaska Native village and regional corporations. Many of these entities have diversified their workforces across the country, which creates a buffer for economic cycles in Alaska.

“We are up 12 percent on our core loan portfolio; a lot of that has come from developing strong relationships with those entities,” Criqui says.

Many financial institutions in Alaska have seen unusually high deposits over the last two years. Bank deposits are at record high levels for businesses as well as consumers, says Steve Lundgren, president of Fairbanks-based Denali State Bank. The economic shutdown during the pandemic combined with supply chain disruptions stifled spending and, in turn, enabled businesses to save more money. “Banking has been a kind of safe haven the last couple of years with all the volatility in the markets as well as the uncertainty around the world,” he says. “Until those uncertainties and instabilities kind of normalize, I think bank deposits will stay high—at least in the short term.”

Business banking clients at Wells Fargo are also in a strong capital position. Cash balances of commercial customers are higher than at any time in the past five years. “Most of our clients are very well capitalized and

Mike Huston Northrim Bank

Mike Huston Northrim Bank

"Many businesses have held more significant balances in the past two years related to federal funding from pandemic recovery,” says Elaine Kroll of First National Bank Alaska. “With interest rates rising, customers are looking for options to use or invest that money."

FNBA

positioned for growth or a downturn,” Mazzeo says.

First National Bank Alaska (FNBA) reports a similar situation. “Many businesses have strategically held capital for unseen future events,” says Chad Steadman, corporate lending director at FNBA. “While some businesses invested this capital, others continue to hold onto it.”

Steadman is seeing an increasing number of businesses transitioning ownership—selling to another company, or more commonly, selling to internal employees. “When a business sells to its employees, it is exciting to welcome a new generation of owners in Alaska,” he says.

He also sees businesses buying property they were leasing, thanks to a program of the US Small Business Administration (SBA). “Because many of these businesses are young or the properties are expensive, the SBA 504 program is ideal and offers a low down payment of 10 percent and long-term rates,” Steadman says.

FNBA’s customers continue to look for efficiencies, such as improving workflows and eliminating repetitive tasks. Over the last few years, the bank has seen businesses integrate their accounting systems with their payables and invoicing processes, according to FNBA Senior Vice President, Treasury Management and Anchorage Branch Administration Director Elaine Kroll. “Many businesses have held more significant balances in the past two years related to federal funding from pandemic recovery,” Kroll says. “With interest rates rising, customers are looking for options to use or invest that money. We are working with customers to consider which option is best for them.”

The number of commercial loans has decreased at FNBA, but the dollar volume has increased. Many customers have

opted to use their liquidity to meet small-dollar investment needs, while borrowing for larger investment needs. “These larger loans are typically for asset purchases, which is a good investment for the company long term,” Steadman explains.

At Northrim, commercial loan growth is up over last year, and demand remains strong. Criqui attributes the demand, in part, to the bank’s proactive efforts to reach out to customers to see if their needs are being met.

For Mazzeo’s team at Wells Fargo, the commercial loan pipeline is larger today than it has been in three years. However, Mazzeo notes that businesses are borrowing for defined needs, and opportunistically, as they acquire other businesses or fund capital expenditures. “Interest rates are higher, and debt is more expensive, so businesses are borrowing judiciously, and not just borrowing to put cash on the balance sheet,” he says. “Credit facilities are being extended proactively to reduce uncertainty around the economy and maturities in the near term.”

More specifically, Wells Fargo is seeing more commercial loan demand around business acquisitions and consolidation. Baby Boomers have been selling successful businesses built over their lifetimes, and Alaska Native corporations and private equity groups are acquiring them. In addition, Alaska’s tourism and oil field companies are rebounding from COVID-19 shocks.

“Alaska business leaders know that standing still is not an option for them,” Mazzeo says. “We work with them to help ensure they can operate successfully and continue contributing to the Alaska economy. Throughout it all, our goal for our clients remains the same: ensure that their financial future is deliberate, not reactive based on current market variables.”

At Denali State Bank, Lundgren is seeing some businesses delay expansion plans due to higher interest rates, larger monthly payments, and higher costs. Other businesses are pushing ahead, though. “They think that prices will never be lower, and they think that rates won’t come down for

Ihave a little secret to share with you. Alaska Business has developed a bit of a fan base—outside our office.

Whether it’s the industry leaders who help drive our economy, readers who want to be in the know, or dedicated clients who have been appearing on our pages and website for years, we’re feeling a buzz in the air and want to share some of that positive energy.

Dylan Webb, owner of Ideal Health, explains why he’s signing up for another year of sponsored content in our weekly e-newsletter, the Monitor. “The Monitor was an inexpensive and very effective way of getting my company’s name in front of the business community. I received two leads pretty quickly, which more than paid for it! It was a great investment, and I will definitely be doing it again soon.”

Teresa Thompson, Corporate Enrollment Liaison at the University of Alaska Fairbanks eCampus, is a great ambassador for our Spotlight Digital Profile saying, “Alaska Business’ Spotlight Digital Profile has really helped UAF eCampus spread the word about our Corporate Initiative. The designers were great and the staff worked closely with me to ensure the content I developed was the best for the audience. I would highly suggest working

with Alaska Business on a SDP and in their award winning magazine!”

Alaska Business has evolved into much more than a print magazine. We offer print, digital, and website advertising opportunities to target the Alaska business community. We also have sponsorship opportunities at our annual Top 49ers event, which recognizes Alaska’s largest local companies, ranked by gross revenue.

Call me to find out how we can get your business in front of our audience.

Christine Merki 907-257-2911cmerki@akbizmag.com

Christine is a sales and marketing professional with over fifteen years of local media experience. Her marketing knowledge includes creative, media planning, strategy, and market research and in her spare time she enjoys hot yoga, pilates, gardening, and reading.

“Banking has been a kind of safe haven the last couple of years with all the volatility in the markets as well as the uncertainty around the world…

Until those uncertainties and instabilities kind of normalize, I think bank deposits will stay high—at least in the short term.”

Steve Lundgren, President, Denali State Bank

the next couple of years,” Lundgren says. “We think rates are going to continue going up next year and the next year. So if a borrower waits for two or three years, it pushes out their project.”

For the most part, smaller businesses and those with optional projects are postponing their plans while many larger enterprises are deciding to move forward. “I think some of the larger businesses perhaps received more government COVID stimulus money, and maybe they were better able to restructure their business during COVID and were able to conserve cash,” Lundgren says.

Because of the supply chain and labor issues, many businesses are redefining their scope, cutting back services or operating hours. “To some, this may be liberating; to others, lost opportunity,” says Kroll. This pivot to efficiency explains the interest in digital services.

“More access to online and mobile services gives our customers the flexibility and security they need to manage their business finances while also adapting to the challenges associated with a smaller workforce and increased cyber risks,” Steadman says.

Stretching the capabilities and attention of workers and supervisors can increase the risk of losses from cybersecurity breaches, so Steadman says FNBA is responding. “We offer our customers a variety of tools to combat fraud and protect their assets so they can focus on running their businesses,” Steadman says.

Northrim also invested in its technology platform to reduce processing costs. “We can automate many repetitive, manual tasks, so that people can do things that are less routine,” Huston says. “So it [the technology investment] is targeted at not just the sophisticated customers but a broad array of small businesses that are looking to become more efficient.”

Denali State Bank is also adopting processes that allow people to conduct business remotely, yet a large segment of its customers prefers to bank in person. “Interestingly, our foot traffic is up this year,” Lundgren says. “It’s up considerably compared to the last two years and even before COVID.”

Since Fairbanks is a relatively small town, it only takes customers about five minutes to reach one of Denali’s four branches in the city. “So it’s convenient to bank in person,” Lundgren says. “Plus, Fairbanks has long, cold winters that keep people inside, so many of our customers enjoy coming in and interacting in person.”

Despite the rising interest rate environment, labor shortage, and inflation, the outlook for Alaska has never been stronger, Steadman says. Alaska has a resilient business environment that will continue to adapt and grow to the market’s needs. “While economic indicators have shown that Alaska has lagged in coming out of the pandemic,” he says, “I anticipate the Alaska market will continue to grow and be strong in the coming years.”

Homeowners’ associations (HOAs) are, in a way, the smallest unit of government. Neighbors follow a charter that defines their rights and responsibilities. Alaskans, being famously individualistic, might perceive this arrangement as a nuisance.

For example, “If you leave your trash can and your HOA has a rule about how long you can leave it on the sidewalk, your HOA is the city in that instance, and they will fine you $25 or whatever the rules are,” explains Chris Hoke, president and founding lawyer of HOA Legal Services in Anchorage. “It really is another little government that you agree to live in and abide by the rules.”

Annoying as it might be, some Alaskans do agree to those rules. “The reason people choose to live in these communities is to retain property values and also to get the services that the HOA is obligated to provide by their declaration and rules,” says Sarah Badten, an attorney with Birch Horton Bittner & Cherot. “I too live in an HOA, and I love my HOA. I’ve donated many hours to my own personal HOA. It’s a little community within a community.”

Badten pays association dues on top of housing expenses for a property she already owns. The service may be costly, but she says members get what they pay for.

Hoke agrees. “The magic of HOAs is that you share common expenses,

so in your parking lot instead of having twenty different snow plows come through when we get a dusting, we all agree that we’re going to have one company do it, and we all pay,” he says.

Community associations—the broader term for HOAs, whether for detached homes or connected condos—are nominally not-for-profit business entities governed by corporate law, yet the comparison to a tiny hamlet is unavoidable.

surely as the contractor that changes the light bulbs or picks up the trash.

Although subordinate to the board, a property manager wields enormous power. Managers handle day-to-day business, while resident members interact with management on a monthto-month basis, if at all. Relying on a manager’s expertise is exactly why the board pays them.

It shouldn’t be that way, says Dannielle Mellor with Association Management of Alaska (AMA). “My job is to facilitate the governing body to run their community,” she says. “I am not there to make those decisions for them.”

Mellor oversees twenty-one associations in the Anchorage area in tandem with an AMA colleague. She solves problems touching on people’s most valuable assets. “Money, health, and homes: those three things are so personal, and when you do this kind of job, you are inherently working with somebody on at least two of those components,” Mellor says.

In the mini government of an HOA, the board of directors is the legislative branch, setting policies and priorities. It is also the executive branch, in theory, yet that authority is often delegated to a property manager. As the board’s agent, the manager is hired help, as

Property management is “my jam,” according to Mellor. “I can’t even explain why. I’ve always loved community, so it’s absolutely my passion beyond just being my job.”

In Alaska, management firms must be overseen by a licensed realtor, but the individual managers don’t require special certification. Mellor sought some anyway, becoming a CMCA

“The homeowners are the HOA, which is lost when people are saying, ‘Oh, the HOA told me to do this.’”

Chris Hoke, President, HOA Legal Services

(certified manager of community associations) and AMS (association management specialist). “I know it’s not necessary in the field,” she says, “but when I’m working with clients, when I’m working with communities, it’s letting them know, ‘Yes, I’m taking the time to make sure you’re taken care of, too.’”

Her certifications also demonstrate that she is dedicated to best practices. “We should have, as managers, a code of ethics that we abide by when serving communities,” Mellor says.

Through ongoing education, Mellor has learned about building maintenance, housing regulations, and the logistics of governing documents. “People always say I’m a property manager, and I get kind of funny with them because I don’t manage property,” she says. “I manage communities; it’s more than just the property. It’s so all encompassing.”

Variety is what keeps Badten interested in HOA law. “It always is throwing something new at me,” Badten says. “Probably other than criminal law and maybe employment law—which tend to be the sexier legal areas, people behaving badly—HOAs have a little bit of everything. We have corporate law, bankruptcy law, UCIOA [Uniform Common Interest Ownership Act], Nonprofit Act… A little bit of all areas end up coming into play in the community associations legal area.”

Hoke had his first exposure to HOA law in 2014, when a client called about a foreclosure dispute with an association. By 2020, Hoke established HOA Legal Services to work with associations exclusively, even though it’s an uncommon specialty. “Not many law schools in the country do an entire course on HOA law, so it’s not anything I specifically took course work in, in law school,” Hoke says.

Associations always have vendor contracts or insurance policies that a lawyer must interpret and explain, as well as bylaws, declarations, and house rules. “Often the rules are decades old, depending on the HOA. And worse than that, sometimes they’re actually drafted by the development company,” Hoke says, “and banks require certain language in their HOAs and declarations. Literally,

there are HOAs in this town that have bylaws that are written by entities that have no stake in the membership or actual homeownership.”

Litigation against an association’s vendors is the biggest lift for an HOA lawyer, Hoke says, but fortunately it’s also his least frequent job. He’d rather keep busy answering board member questions, drafting documents, or collecting overdue bills.

When HOAs sue their own management, the mess compounds. Hoke notes that housing markets in Florida and Nevada have been devastated by rampant corruption among condo managers. Mellor adds that her colleague, AJ Arevalo, witnessed the rot in Las Vegas firsthand.

“A lot of management companies wield a lot of power, and they start to do things for communities and make decisions,” Mellor says. Managers are more liable to make those decisions if the board relaxes its oversight.

Fortunately, Florida has since enacted legislation ensuring managers work with communities on reserve studies, and Las Vegas has added more regulation, too.

Nevada already requires property managers to be specially licensed. In fact, Mellor says, “A lot of the Lower 48 is much more highly regulated than Alaska is, in terms of management.”

A new regulation in Alaska gives HOAs a tool to shore up their finances when dues payments are late. Thanks to Senate Bill 143, which took effect in October, “All associations in Alaska are

In her office at Association Management of Alaska, Dannielle Mellor keeps track of the twenty-one properties in her portfolio (not including the yellow pins).now entitled to what’s called the ‘super priority lien,’” Badten explains. “That is a lien that jumps ahead of the mortgage lender for six months’ worth of dues. The bank will pay that lien in order to protect its security interest in the property.”

Badten was personally involved in the legislation. “That bill was a lot of blood, sweat, and time. I’ve been trying to get that amendment passed since 2015,” she says.

The bill passed with no opposition. Mortgage lenders don’t mind deferring to associations when it comes to collecting on delinquencies. “These banks need the HOAs to be strong in order to lend into them,” Badten says, “and they want the HOAs to be taking care of the property, which is their secured interest. They have real skin in the game for keeping these HOAs strong.”

To keep HOAs strong, Mellor recommends that managers follow some best practices.

First, managers should be proactive rather than react to emergencies. Beyond the “ounce of prevention” for building maintenance, Mellor anticipates residents’ demands based on trends that emerge every year. “Chicken year was maybe two years ago; it seemed like this overarching theme that everybody wanted to get chickens. Most homeowners’ associations are not keen on the chickens,” she says. “This last year, the overarching theme has been solar panels. Everybody wants solar panels because energy is costing more.”

It also goes without saying that the best managers are honest. Mellor explains, “When you, as a manager, aren’t abiding by that code of ethics—in terms of you doing your due diligence to provide education, communication, and transparency to a community—then you’re not being a successful

Hoke agrees that transparency is key. “Nothing should happen in a nonprofit organization that it’s impossible for some homeowner to figure out,” he says.

Mellor believes successful HOAs are those where managers and boards understand their roles. “A board of directors has a very specific set of duties in what they do for their community, and as a manager, I feel, your job is to help educate them as to what those duties are and then try to help them understand and find the resources available to them to be able to do those duties,” she says.

Managers must educate board members because there’s so much to learn. “There’s not a requirement in this state for board member education in any way,” says Hoke. “There are in other states. I’ve offered this to board members, but it’s not something that, without being forced, people are often saying, ‘I’ll take you up on this two-hour training.’”

Mellor says boards can observe best practices for themselves, such as obtaining a statement from the HOA’s bank, independent of the manager’s accounting. She adds, “It’s really important that a community or board of directors adopt a code of ethics for themselves and honor their obligation of duty of loyalty, duty of care, and duty to act within their scope of authority as a board.”

The most basic practice for board members, according to Badten, is to follow the governing documents. The board must also treat neighbors fairly and act reasonably. “We do have some great cases in Alaska regarding reasonableness, and all of them have upheld the HOAs’ decisions as being reasonable under the circumstances,” she says. “It’s very difficult to find that a board acted unreasonably;

“Chicken year was maybe two years ago; it seemed like this overarching theme that everybody wanted to get chickens. Most homeowners’ associations are not keen on the chickens.”Dannielle Mellor Association Manager Association Management of Alaska Chris Hoke HOA Legal Services Alaska Business Dannielle Mellor Association Management of Alaska Alaska Business

just because an owner disagrees with what a board did or a rule it made does not make it unreasonable.”

Badten also recommends that boards stay on top of delinquent dues payments. “Never let an account get four months behind before you have sent that to an attorney or collection,” she advises. “The reason is you want to send a thirty-day notice to the owner. Then you have to have that thirty days pass. If they fail to pay, if you choose that you want to enforce the lien, the first thing we have to do is order a title report; that takes time.” All the while, the clock is ticking on the six months for a super priority lien.

Likewise, “If people are not following the rules, whether that’s not paying or any other rule, the association really should be taking action to enforce its rules,” Badten suggests. “Or, if it doesn’t like the rule and that’s why it's not enforcing it, it should amend its documents to take that rule out.”

We the Homeowners

Board member or not, every owner must read the HOA governing documents, at a minimum. “The responsibility is something that every homeowner should know by virtue of having purchased the place and having read that inch-and-a-half stack of documents that you sign when you buy a property,” says Hoke. “However, my general take on that is that most people don’t read 3-page contracts, let alone 100page contracts.”

When residents join an HOA, they not only agree to follow its rules but they acquire the power to change the rules. “The homeowners are the HOA,” Hoke says, “which is lost when people are saying, ‘Oh, the HOA told me to do this.’ If you don’t want to live in an association that says you have to get a yellow mailbox, well, get a majority of your neighbors to agree we don’t need that rule anymore.”

Hoke says it never hurts for HOA members to ask questions. And, he suggests, remember that neighbors are human, too. “To effectively communicate and work with people, it helps sometimes to be nice,” he says.

Members are never powerless in an HOA. Rules which sometimes feel confining also provide remedies.

www.akbizmag.com

At the University of Alaska, we are on a mission to empower Alaska. From drone piloting to vital climate research to critical mining solutions, our three universities and their community campuses shape the jobs and careers that fuel the economy. Through affordable, quality education and job training, we empower Alaska’s future — together. Learn more at empower.alaska.edu

By Dimitra Lavrakas

By Dimitra Lavrakas

President Joe Biden signed the $369 billion Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) last August, in part to invest in climate change solutions. It holds substantial significance for Alaska.

The World Bank estimates that more than 3 billion tons of minerals and metals will be needed to deploy wind, solar, and geothermal power and energy storage to hold global warming below 2°C above pre-industrial levels—the goal of the 2015 Paris Agreement. Readmitting the United States into the climate accords, after the Trump administration gave notice of withdrawal in 2017, was one of President Joe Biden’s first acts as president in 2021.

US industries developing green energy technologies must import critical minerals unless and until domestic sources are available. To that end, the IRA offers tax credits and direct funding for mining companies across the country. Some of those provisions hold the potential to bring Alaska a new mineral rush.

The IRA includes a tax credit for the domestic manufacture of “eligible components.” This includes the elements neodymium, dysprosium, and praseodymium—rare earth elements (REE) that are essential for the energy transition because of their use in permanent magnets for wind turbines and electric vehicles (EVs).

The tax credit covers up to 10 percent of manufacturers’ cost of production as an incentive to attract companies to start mining. For established mines it could boost their productivity.

For example, the United States has significant lithium resources; the US Geological Survey (USGS) estimates 3.6 percent of global reserves. However, the only domestic lithium producer is in Nevada, so the country imports most of its lithium.

USGS also reported that in 2021 the United States imported 78 percent of its REE from China. The IRA aims to change that.

One provision of the IRA steers $500 million authorized by the Defense Production Act. In June 2022, Biden invoked the Defense Production Act to boost manufacturing of certain technologies essential for

decarbonization of energy, such as solar panels, heat pumps, and transformers for the electrical grid, as well as the minerals needed to make them, particularly large-scale batteries.

A press release from the US Department of Energy explained, “Demand for clean energy technologies such as solar panels, heat pumps, and electrolyzers for hydrogen has increased significantly as the costs of these technologies have plummeted over the last decade.”

“As the world transitions to a clean energy economy, global demand for these essential products and components is set to skyrocket by 400 to 600 percent over the next several decades,” says a White House press statement. “Unless the United States expands new manufacturing, processing, and installation capacity, we will be forced to continue to rely on clean energy imports—exposing the nation to supply chain vulnerabilities, while simultaneously missing out on the enormous job opportunities

associated with the energy transition.”

An additional $40 million in loan guarantees is authorized in the IRA for projects that increase domestic production of critical minerals.

Alaska’s vast terrain holds forty-nine of the fifty critical minerals identified as necessary for the energy transition.

The most promising prospect for rare earth mining in Alaska is on Prince of Wales Island, just west of Ketchikan, where the Canadian company Ucore Rare Metals is developing the BokanDotson Ridge Zone.

“Ucore continues to advance its Bokan project as a long-range

heavy rare earth source to eventually complement the planned Western feedstock sources for its near-term Strategic Metals Complexes,” Ucore Vice President and COO Michael Schrider stated in an October news release. “North America desperately needs independent mineral resources to transition to a green energy future centered on electric vehicles and renewable energy sources—both of which are more achievable with the heavy rare earth elements provided at Bokan Mountain.”

In 2020, the Alaska Legislature authorized the Alaska Industrial Development and Export Authority (AIDEA) to issue bonds for up to $125

million to finance the infrastructure and construction costs of the Bokan REE project.

Ucore has scaled back its Alaska ambitions, postponing a processing facility that was to be built in Ketchikan, instead locating its first commercial-scale plant in Louisiana. But the company still has its eye on the mineral resource across Clarence Strait.

The company says 2022 field summer work, coupled with previous years’ successful drill programs, now positions the Bokan property closer to a feasibility study and allows Ucore to upgrade approximately 20 percent of the currently “indicated” mineral

“North America desperately needs independent mineral resources to transition to a green energy future centered on electric vehicles and renewable energy sources—both of which are more achievable with the heavy rare earth elements provided at Bokan Mountain.”

Michael Schrider, VP and COO, UcoreTrucks at Coldfoot head north on the Dalton highway. The Ambler Access project would connect the Ambler Mining District to the Dalton Highway via a 211-mile industrial haul road.

resource to a “measured” resource classification.

Farther north in the MatanuskaSusitna Borough, Australia-based Discovery Alaska Limited announced that its Chulitna Project shows a strong presence of lithium mineralization, based on examination of cores drilled by previous exploration. Its 2022 the historic drill core re-sampling program from the Coal Creek Lithium Prospect was part of Chulitna project.

A detailed work program of core logging, core cutting, core photography, core sampling, and laboratory analysis indicated significant broad intercepts of lithium-rich areas.

“The company is excited with the first-stage laboratory analysis results confirming significant broad zones of lithium mineralization at our Coal Creek prospect, with potential for strike and depth extensions,” Discovery Alaska Director Jerko Zuvela stated in an October news release. “These initial results provide encouragement for continued exploration works. We look forward to realizing the lithium potential.” Zuvela noted that the Coal

Creek prospect is strategically close to the Parks Highway and Alaska Railroad.

The Coal Creek Lithium Prospect is at the exploration stage, not at a feasibility or production level opportunity, according to the company. Discovery Alaska is not in a position now to consider the direct effect of the IRA on its decision to develop lithium in Alaska, but the company says it is considering additional potential project opportunities in the state.

No amount of incentives, in the IRA or otherwise, could make a mineral project affordable if the resource is stranded far from the market. Access is key, which is the reasoning behind major mining roads proposed in Alaska.

The Ambler Access project would connect a mining district east of Kotzebue with the Dalton Highway with a 211-mile industrial haul road. The district is a large prospective copper/ zinc mineral belt with extensive deposits of critical minerals and other elements

essential to meet lower emissions outlined in the IRA.

“Because of the Inflation Reduction Act’s investments, America is on track to decrease greenhouse gas emissions by about 40 percent below 2005 levels in 2030—positioning America to meet President Biden’s climate goals of cutting greenhouse gasses at least in half in 2030 and reaching net zero by no later than 2050,” says Associate Director for Climate, Energy, Environment, and Science Candace Vahlsing with the US Office of Management and Budget.

But as these projects move along, some in the industry and those who advise mining companies and government agencies express frustration with the Biden administration over the permitting process. To wit, the US Department of Interior reversed course last March, suspending a right-of-way for the Ambler Access Project through Gates of the Arctic National Park.

Drue Pearce, a former president of the Alaska Senate and now director of government affairs for the law firm Holland & Hart in its Washington, DC

office, called the reversal bewildering. The administration had already agreed in 2021 to a fifty-year right-of-way through a 25-mile corridor that would let AIDEA develop the road.

Furthermore, the Biden administration did not streamline the permitting process, Pearce says, pointing out that while the IRA holds out the promise of financial incentives for mining, it is difficult for some projects to reach final approval.

The right of way was granted based on a record of decision from the year before issued by the US Bureau of Land Management (BLM) and US Army Corps of Engineers following an exhaustive seven-year review process initiated under the Obama administration.

In the suspension notice, the Department of Interior determined that BLM did not appropriately evaluate the effects on subsistence uses along the route and did not adequately

consult with Alaska Natives. However, the suspension does not identify any specific deficiencies or corrective action.

“There’s significant compliance for these projects,” says Holland & Hart partner Kyle Parker. “The real problem with investors is the years of delay.”

The IRA provides $7,500 tax credits against the purchase of a new allelectric vehicle, starting next year, but only for vehicles with batteries that contain at least 40 percent lithium, nickel, manganese, cobalt, or graphite produced domestically or from friendly countries. By 2027, the requirement rises to 80 percent.

Most cobalt used in the United States is imported from the Democratic Republic of Congo and would not meet the qualification for the EV tax credit.

The Ambler Mining District, though, could become a reliable domestic

source of cobalt. Ambler Metals, a joint venture of South32 Limited and Trilogy Metals, is working to develop the district’s zinc and copper first, but cobalt could follow from the Bornite Deposit later in this decade.

Ambler Metals President and CEO Ramzi Fawaz says the IRA provision that lets mining companies write off 10 percent of operating costs for producing a single critical mineral is one factor in the decision. Whether the Ambler Access project is ever built is another.

The question is not whether Alaska contains the minerals to satisfy the IRA’s lofty goals for energy development but whether those minerals can be extracted.

“Alaska is one-fifth the size of the United States, with extensive mining. We are the mineral reserve for the United States,” says Parker. “Alaska can fill the need.”

“The company is excited with the first-stage laboratory analysis results confirming significant broad zones of lithium mineralization at our Coal Creek prospect, with potential for strike and depth extensions… These initial results provide encouragement for continued exploration works.”

Discovery AlaskaA truck drives over the Yukon River Bridge at Mile 56 on the Dalton Highway, passing by the Trans Alaska Pipeline System; without similar infrastructure for mining projects, Alaska’s metal and mineral resources may remain stranded. Dimitra Lavrakas A channel sample location within a rare earth mineralized vein outcrop at Ucore's Bokan-Dotson Ridge Zone mineral resource on Prince of Wales Island.

February is the perfect month to contemplate the twin arts of architecture and engineering. The chill of winter inspires gratitude for shelter and the utilities that keep buildings cozy. This also happens to be the month for National Engineers Week. On that occasion, a banquet is being held February 25 in Anchorage to honor the field’s great contributors, such as Olga Stewart of Geosyntec Consultants, who was named Alaska Engineer of the Year in 2022.

The load-bearing core of this month’s architecture and engineering special section is, as usual, the new nominees for Engineer of the Year and the Engineering Excellence Awards. Six individuals received nominations from their professional organizations, while a bridge, a water supply, and two buildings are vying for recognition, as well.

Engineers who specialize in corrosion control get special attention in “Rust Never Sleeps.” Pros from Coffman Engineers and Michael Baker International contribute insights into the challenges of protecting Alaska pipelines and marine infrastructure from wasting away. In “Harp Across the Channel,” guest author Aaron Unterreiner of PND Engineers highlights a marvel designed by his firm’s co-founder. The O’Connell Bridge in Sitka, arguably the first cable-stayed bridge in the United States, was designated a historic civil landmark last fall.

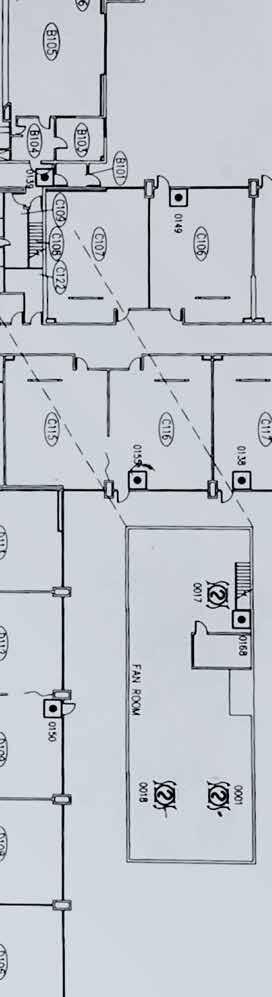

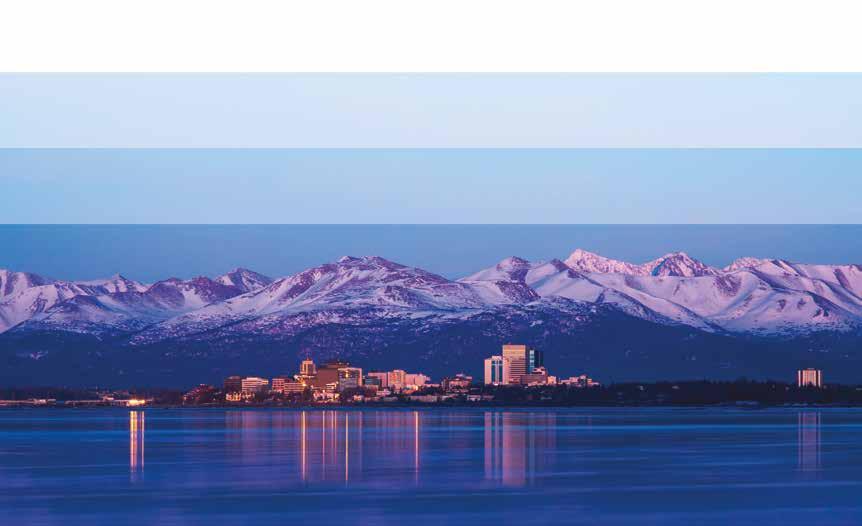

Architects shine in “Top Shelf,” which lays the foundation for how an aging storefront in Downtown Anchorage was renovated into the buzzy restaurant Whisky & Ramen, a uniquely challenging project according to Determine Design. “The Usual Schematics” looks at why some floor plans seem to pop up all over the place, while “Designing for Place” reveals how uniqueness comes from attention to local and traditional inspirations.

Summer is when Alaskans appreciate nature, and winter is for appreciating the built environment and its designers. Even those who enjoy frolicking in the snow must retreat to a structure to warm up, so these pages are for those dreamers who thought up the structures in the first place.

It’s difficult to distinguish the O’Connell Bridge from the Sitka Harbor shoreline, which is remarkable considering the bridge is 1,255 feet long and towers more than 150 feet over the Sitka Channel. Among the vast commercial fishing fleet and hundreds of charter and recreational vessels berthed on the east side of the strait, the iconic cable-stayed bridge comfortably blends into its idyllic surroundings.

The bridge’s harp design features a trio of cables suspended to the deck in each direction from high atop two sets of 100-foot twin towers. Running parallel to each other at an angle as they cut across the Sitka skyline, the bridge’s stayed cables can easily be mistaken at a distance for yet another series of stays hanging from the mast of a docked trawler.

That’s partly what makes this bridge so appealing. It’s a beautiful bridge, but it’s not boastful. It’s a practical piece of thoughtfully designed infrastructure that

has seamlessly woven itself into Sitka’s fabric. In many ways, the O’Connell Bridge represents the zeitgeist of Alaska’s economic development over the last fifty years. On Sunday, September 11, 2022—slightly more than a half-century after the bridge opened to vehicular traffic—the American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE) Alaska Section designated the John O’Connell Memorial Bridge an Alaska Historic Civil Engineering Landmark.

“We always seek through the national historic civil engineering landmark program to honor these projects and the engineers who make them happen for their skills as innovators and risktakers,” presenter Larry Magura, the ASCE Region 8 Director, said during the dedication in Sitka.

“That’s honestly what it comes down to—no risk, no reward. Engineers don’t do a particularly good job of blowing their own horn and acknowledging their accomplishments, and that’s really one of the reasons we’re here

today. This is a beautiful bridge. It’s very iconic, very aesthetically pleasing. And we’re delighted to be here today to participate in putting a state historic landmark designation on the O’Connell Bridge.”

While some recognize the O’Connell Bridge as the first cable-stayed vehicular crossing in the United States, the Historic American Engineering Record among them, the bridge at the very least is the first of its kind in Alaska, “and that is a significant achievement,” said Magura, who cited a number of other cable-stayed crossings with close if not entirely discernible start dates, hence the ASCE’s hesitation toward christening the bridge a nationally historic landmark.

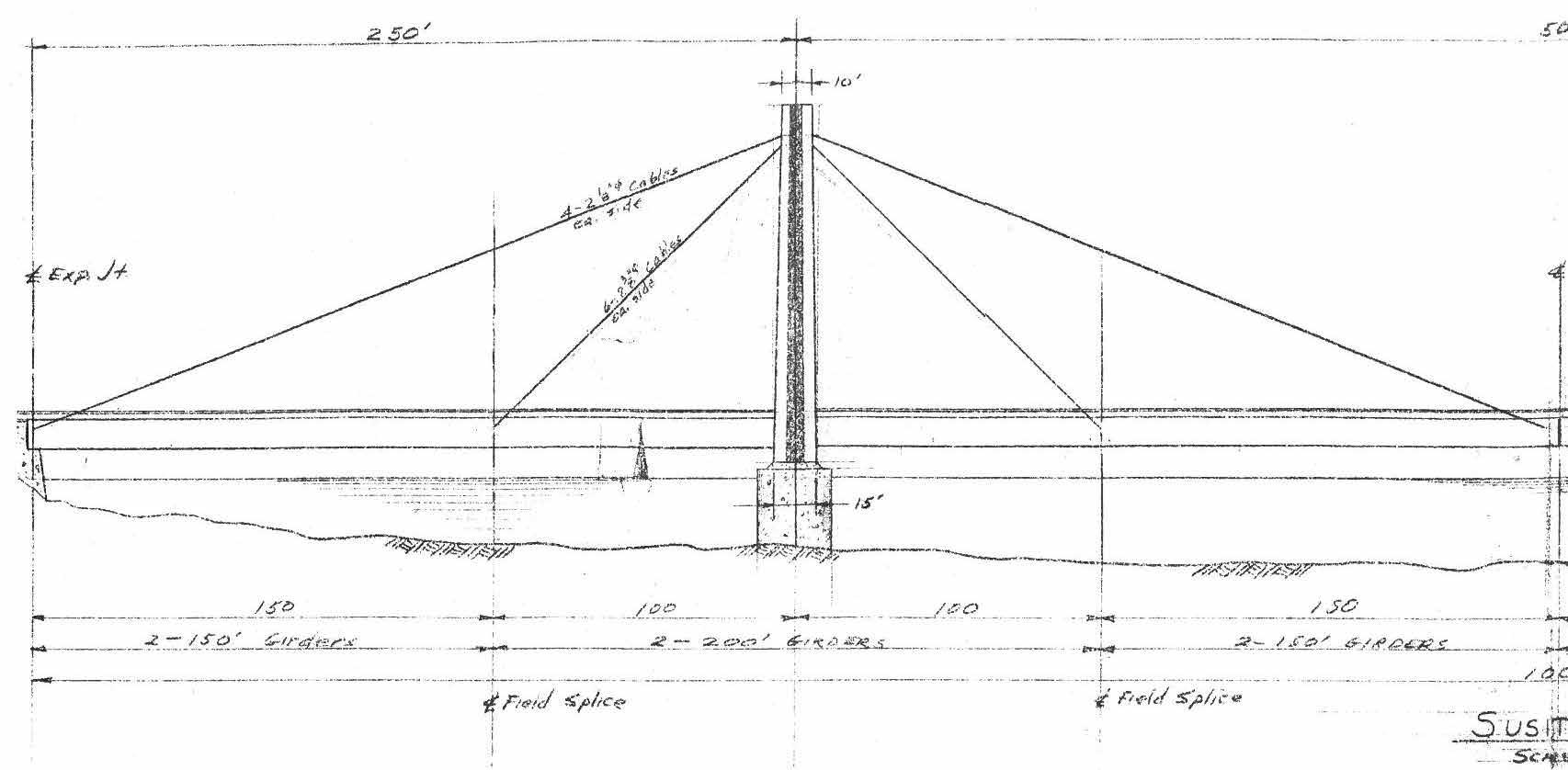

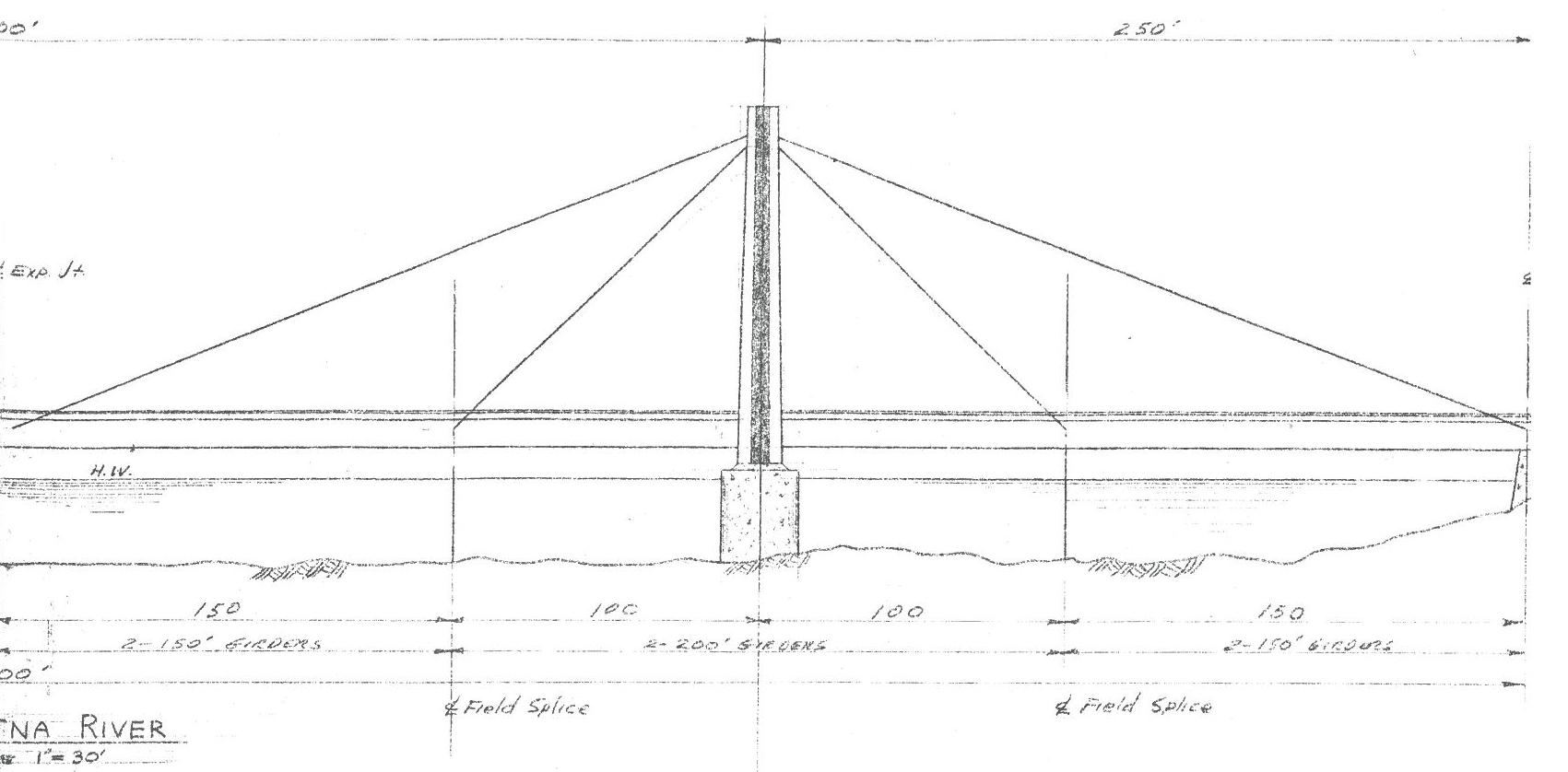

If the Alaska Department of Highways bridge designers had their way in the ‘60s, the “first” would’ve been undisputed. Roy Peratrovich Jr. and Dennis Nottingham, the co-founders

of PND Engineers, Inc. and key members of the O’Connell’s bridge design team, pitched the idea of cablestayed crossings years earlier for both the Susitna River and Copper River crossings.

“I had proposed the first one in 1962 when I had just come back to Juneau in ’61,” said Peratrovich, who was born in Southeast Alaska and earned his civil engineering degree in Washington State in the late ‘50s. “That’s when I submitted the drawing of the Susitna River Bridge—1,000 feet across, two twin towers, a 500-foot middle span. It would’ve worked, but it was way too early. My chief bridge engineer… he was sitting down at his table working over something. I came in with my drawing of the cable-stayed, and he looked at that and started shaking his head, looked up at me over his glasses and said, ‘Roy, it’s too early.’”

Peratrovich stowed the cable-stayed bridge idea in his back pocket. He was eventually promoted from Department

From left to right: Bill Gute, Roy Peratrovich, Dennis Nottingham, and Department of Highways Commissioner Robert Beardsley— key members of the ‘60s bridge design team.

Alaska Department of Transportation & Public Facilities

From left to right: Bill Gute, Roy Peratrovich, Dennis Nottingham, and Department of Highways Commissioner Robert Beardsley— key members of the ‘60s bridge design team.

Alaska Department of Transportation & Public Facilities

of Highways Bridge Design Section squad leader to section head in 1969.

“Back in ’69, when we started looking at alternate crossings for Sitka—what type to use, where to put it, how would it fit in with existing situations and future improvement to harbor work and all that—I had this cable-stayed, and I said, ‘That would be ideal there.’”

Peratrovich finally got his wish. As design squad chief, his bridge design team included Bill Gute as the design and plan preparation lead and Nottingham on design check and final structural analysis. Fred Kohls was the computer section lead, assisting Nottingham with one of the first computer-aided structural engineering designs in Alaska history.

“We didn’t have the computer programs yet,” said Peratrovich, who deferred to Kohls, Nottingham, and the Department of Highways’ new IBM 1130 Computing System unfortunately titled STRESS: an acronym for its Structural Engineering System Solver software.

“We had this paper-fed thing; you get this pile of responses and answers in this thing on folded paper that you’d pull out and spread all the way down to Seattle if you let it,” Peratrovich said. “It was just so much paperwork that you gotta go through; it just didn’t have the capabilities for doing structural work that was needed on this job. There was so much deflection analysis that had to be made because you had different deflection capabilities at different points where the cable was attached. It was pretty complicated, but Dennis figured out a way to do it.

“Later on, when the improvements were made on structural analysis, we went back and checked it again,” Peratrovich said, “and, sure enough, it was still working.”

The project was overseen by Department of Highways Commissioner Robert Beardsley. The winning bid for the project was $3.2 million in 1970; construction was completed in 1971. Beardsley was succeeded in 1972 by Commissioner Bruce Campbell, who presided over the O’Connell Bridge’s grand opening on August 19, 1972. None of the bridge design team members were present at September’s dedication. Peratrovich, who founded PND with Nottingham in 1979, spoke to PND about the O’Connell Bridge design

in 2019 during the company’s 40th anniversary celebration.

“I’ve been with the department for twenty-two years, and I love these kinds of projects,” current Alaska Department of Transportation & Public Facilities (formerly known as the Department of Highways) Commissioner Ryan Anderson said at the ceremony. “There are so many stories. Whenever you work in the transportation industry, you look around at everything that was built, there are stories everywhere. This project in particular—with the innovative design and the way that people thought about this in 1972 when they built it— really is an example for us as a state, as the Department of Transportation, of how we want to move forward.”

Alaska State Senator Bert Stedman, who has represented Southeast Alaska in the state legislature since 2003, graduated from Sitka High School in 1974. He was 16 years old when the bridge opened.

“When they built the bridge, it was pretty exciting in town,” Stedman recalled during the ceremony. “I happened to have [spent] that summer fishing out of Petersburg and bought a car when I got home. So, once it got shipped up here and I got to drive over this bridge—that was a couple of months after it was built, of course—but it was a big thing for the kids at the time to be able to drive over to Edgecumbe [on Japonski Island] and back. I think the police stayed over here [on Baranof Island], so we kind of enjoyed that until they figured it out.”

The resulting benefits of the bridge, however, were no laughing matter; its presence remains a boon to the City & Borough of Sitka today.

“When we look at this economic development, once the bridge was done, there’s been construction over on Japonski for almost fifty years straight, and you can really see it today with the hospital going on and the expansion of the Coast Guard,” Stedman said. “Without the bridge, my guess is Mount Edgecumbe High School wouldn’t be there; the hospital would probably be in Juneau. The Coast Guard would probably still be there because they like the seclusion and the location, but it was really an anchor point in the

“Back in ’69, when we started looking at alternate crossings for Sitka—what type to use, where to put it, how would it fit in with existing situations and future improvement to harbor work and all that—I had this cablestayed [drawing], and I said, ‘That would be ideal there.’”

Roy Peratrovich Jr. Co-founder PND Engineers Roy Peratrovich

Although many attribute skilled labor and trade shortages in Alaska and the United States to the Great Resignation following COVID-19, it has unfortunately been an industry topic for over a decade. Across all fifty states, money for infrastructure projects is left on the table because of the skilled labor shortage, and in Alaska, the lack of skilled labor is critical, as infrastructure funding is crucial in a state that lacks modern necessities, like roads and sanitation in rural communities.

Understanding younger generations will help industry leaders develop a long-term approach to attracting future laborers. While Millennials and Generation Z get a bad rap for their lack of what other generations label work ethic, the truth is that they have a work ethic. They just value their contribution to the workforce differently. Research indicates that the younger generations entering the workforce value a sense of meaning over the size of their salary.

Step one is engaging with the younger generation on why they should consider a career as a laborer. Industry leaders should consider developing campaigns to encourage the next generation to consider this career path by developing strategies to reach the future workforce by targeting them on platforms they regularly utilize with short, powerful stories highlighting the work’s importance.

But that can’t be the only step. Growing the next-generation laborer workforce will require a long-term plan. This plan will require overcoming several misconceptions about careers as laborers. It begins by celebrating industry successes and illustrating the history of building Alaska rather than just telling the “now” story. Alaskans are known to have grit. They are rugged and hard-working and both brilliant and resilient. From Alaska’s first people to those who have chosen to make Alaska home, we build roads, structures, and communities. The history of Alaska is very much the history of skilled labor, which evokes pride. To attract the next generation, that pride must be felt and celebrated.

What are some of the misconceptions about a career as a laborer?

Lack of advancement opportunities: FALSE. Many of our current leaders started as a laborer.

Physically demanding: TRUE and FALSE. This depends on the field and technology utilized.

Not for women: FALSE. More women are seeking careers in construction and trade, recognizing the balance afforded them when managing careers and families.

Low paying: FALSE. Skilled tradespeople have earning potential exceeding six figures.

Unrewarding: FALSE. Taking part in connecting communities and building infrastructure is highly rewarding.

After you have dispelled these misconceptions, the industry needs to create programs that introduce youth to skilled labor since schools no longer offer introductions to shop, woodworking, and other trades. It is now up to industry leaders to introduce skilled trades. Leaders and workers must volunteer in schools and youth camps and be willing to create mentorship and internship programs. Advocate for our future!

Recruitment for skilled workers must include a campaign celebrating the work’s intrinsic value, not just the monetary benefits. During a recent engagement, a client faced a shortage of workers that resulted in delayed or canceled services. To help this client, we developed a campaign that leveraged current employees to share their experiences and to function as ambassadors to generate genuine interest, resulting in new applicants. Gone are the days of standard recruiting. Recruiting today is about campaigning for action.

more information about People AK, please visit peopleak.com. or call 907-276-5707. For

For

economy to get this bridge built, and we’re reaping the benefits now.”

Sitka Mayor Steven Eisenbeisz echoed Stedman’s remarks: “We heard earlier about all of the economic activity that can happen on Japonski Island because of it, and that is on both sides of the island,” he said, referring to Baranof Island where the town center resides. “I don’t think it would be possible without this landmark here in Sitka.”

The dedication was two years overdue. Wheels were in motion for a 2020 dedication until the COVID-19 pandemic canceled all plans, travel and otherwise. The bridge’s merits were brought forth to the ASCE

Alaska Section by Nottingham, who unfortunately didn’t live long enough to see the dedication come to fruition; Nottingham died March 6, 2022.

“I’m happy to be here to bring this recognition on his behalf,” said David Gamez, the event’s emcee and a past president of the ASCE Alaska Section.

The ceremony was held beneath the bridge’s composite steel reinforced concrete superstructure, between the substructure’s piers on the east side of the bridge. While the traffic busied itself at its usual pace overhead, the O’Connell Bridge Dock gently creaked and swayed in the background, rolling with the ocean waves. It was a gorgeous day—60°F, sunny, a light breeze. The roughly two dozen folding chairs set up for the event didn’t come close

to accommodating the attendance, which numbered around fifty people. Over the crowd’s right shoulder was Crescent Bay; to the left, Castle Hill. It was fitting the ceremony took place in the shadow of the Baranof Castle State Historic Site, the national historic landmark where Russian Alaska was formally handed over to the United States in 1867.

Gamez was ticking off a number of the challenges the bridge design team faced in successfully completing this project—the high seismicity, climactic conditions, the technology at hand, and the bridge’s proximity to Castle Hill not the least among them. “In my opinion, it didn’t hurt Castle Hill,” Stedman said. “It’s just part of the community. The bridge blends in very well; the designers

On September 11, 2022, the American Society of Civil Engineers Alaska Section designated the John O’Connell Memorial Bridge in Sitka as an Alaska Historic Civil Engineering Landmark.did an excellent job.”

The bridge is a bit of an enigma. Approach it from Japonski Island in the west, and the bridge presents itself as an imposing figure in front of its Sitka Harbor and Mount Verstovia backdrop. It’s one of the first things visitors see, a striking landmark welcoming them to Sitka. Approach it from Baranof Island in the east, and the bridge humbly defers to Castle Hill and Sitka’s rich history, content to rest in the shadows. The road slowly climbs and winds its way out of town, as the bridge says “thank you for coming”. It’s a hard phenomenon to explain, even for the locals.

“A couple things come to mind when I think of this bridge, one of them is obvious and one of them

is not necessarily so obvious,” said Mayor Eisenbeisz, who spoke last with impromptu remarks. “The obvious one is this bridge is in just about everybody’s pictures. It’s in one or more drawings that you’ve done in the past. This bridge really is a landmark to Sitka, and Sitkans really do gather around the image of this bridge. So, I want to thank the people who spent the time designing it and thinking of the aesthetics of this, as well, because it does blend in so well with our community. In fact, it’s a focal point on our new city seal, which was recently redesigned. So, that’s how important this bridge is to Sitkans, whether or not they think about it every day.

“Which is my other less obvious point. I don’t know how many times

a day you drive across this bridge, but you just really don’t think about it. It’s just there. It just happens to be there— you drive to the hospital, you drive to the airport, you drive to the harbor, whatever your business on the other side of the island, you just cross the bridge. No big deal.”

An enigma.

“I’m going to think about that a little bit more every time I drive across this bridge now,” he said, “what a convenience and what an asset it really is to Sitka.”

“This bridge really is a landmark to Sitka, and Sitkans really do gather around the image of this bridge. So, I want to thank the people who spent the time designing it and thinking of the aesthetics of this, as well, because it does blend in so well with our community.”

Steven Eisenbeisz Mayor City and Borough of Sitka

By Vanessa Orr

By Vanessa Orr

Just as the wood siding on a house will deteriorate if it is not painted or treated, the steel used in pipelines, buildings, machinery, and more will corrode if not protected from the elements. The most common cause is electrochemical reactions. Galvanic corrosion is when different kinds of metal are in contact with one another; electrolytic corrosion occurs most commonly when water becomes trapped between two conductors that have an electrical voltage between them, creating an electrolytic cell.

“There are four elements to a corrosion cell: anode, cathode, electrolyte, and a metallic path. The goal is to try to reduce or eliminate one of the four items that makes up that cell,” explains Cynthia Cacy, corrosion control engineering principal at Coffman Engineers. “Applying a coating, for example,

removes the metal from contact with the electrolyte, or you can change the corrosion cell by introducing a cathodic protection system.”

For the latter case, Cacy gives the example of a water tank in someone’s home that has an anode screwed into the top of the tank. Because the anode is more reactive than the steel of the tank, it will corrode preferentially instead of the tank corroding.

“A cathodic protection system can be applied to any metallic structure, including pipelines, docks, offshore platforms, and tanks," she explains. “Boats have cathodic protection systems, and there are companies that specialize in designing cathodic protection systems for bridges.”

Depending on the object that needs to be protected, there are different corrosion control methods or

approaches. In some cases, corrosion can even be prevented by choosing a noncorrosive material during the design stage.

“In older homes with copper piping, homeowners may experience pinhole leaks, which can become a nightmare,” says Cacy. “Newer construction uses various forms of plastic pipe that aren’t susceptible to corrosion.”

Knowing what kind of systems can help prevent corrosion is a specialty of Coffman Engineers, which provides cathodic protection system design, commissioning, monitoring, and maintenance for new and existing structures for the oil and gas industry, water/wastewater, federal, utility, and commercial markets.

“We do this as part of the design process,” says Cacy, adding that each client may also have its own specific

guidelines or regulations that are required for corrosion control.

“The types of coatings recommended can depend on where you are putting the structure and how compatible the coating is with the environment it will be in,” says Cacy. “Some coatings don’t cure and adhere at really cold temperatures, so if you’re putting it on in the field, you wouldn’t use it in Alaska. For this and many other reasons, when possible, coatings are shop-applied, though there may be some touch-up work done later once the structure is in place.”

Engineering firm Michael Baker International also specifies the types of corrosion products and methods that should be used on everything from the pipelines on the North Slope to marine

and dock structures at the Port of Alaska in Anchorage.

“The pipelines that we specialize in are unique compared to those in the rest of the country, so we may use some of the same coatings but for different purposes,” explains mechanical engineer David Stamp. “In the Lower 48, most pipelines are buried in the ground, which creates one set of corrosion problems. On Alaska’s North Slope, ours are above ground, which presents another set of corrosion challenges that requires a different approach to corrosion protection and coatings.”

Historically, pipelines were insulated with polyurethane sprayed between the sheet metal jacket and the pipe.

Shane Hadaller, President, Mericka GroupWhile this was at first thought to be adequate to protect it from corrosion, over time the polyurethane would fail and allow water to get through the insulation and create CUI, or corrosion under insulation.

“The modern approach is to apply fusion-bonded epoxy to the pipe before it is insulated, which provides a protective barrier when the polyurethane fails, protecting the pipe from any water that could penetrate the insulation,” says Stamp. “This is typically applied in the shop environment, as this type of epoxy requires specific temperature and cleanliness requirements that need to be controlled.”

While Stamp says that modern pipe doesn’t require much maintenance,

PROVIDING A FULL CONTINUUM OF INNOVATIVE SERVICES TO RESTORE AND ENHANCE OUR NATION’S INFRASTRUCTURE

“People sometimes think that corrosion control is just painting over a surface and don’t understand what an intricate industry it is.”

pipes on the North Slope that have not been treated this way require a lot more effort to maintain.

“North Slope operators spend tens of millions every year removing existing polyurethane to expose corrosion,” Stamp says. “This is a huge problem for all lines built before the ‘90s.”

While operators do have to replace old lines that are too far gone, the more economical choice is to strip the pipes of old insulation and apply a coating to mitigate damage to that location. “CUI is an aggressive corrosion mechanism that can lead to pipe failure in three to five years, which is why most operators go through their inventory of lines that are susceptible, inspecting most if not all on a three- to five-year cycle,” says Stamp.

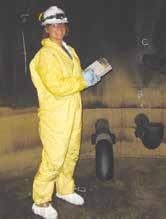

“People sometimes think that corrosion control is just painting over a surface and don’t understand what an intricate industry it is,” says Shane Hadaller, president of Mericka Group in Kenai. “You need to have very knowledgeable people who have experience working with paints and abrasives—who understand the different chemical components, the pot life, product data, mixing hazards, how to spray with PSI, and more.”

Mericka Group provides preservation and insulating services for a number of industries, such as corrosion control on fuel tanks, ships, bridges, oil platforms, military installations, and more.

“It’s not just something you spend a couple thousand dollars to hire people to do,” Hadaller adds. “It’s an expensive process that requires specialized equipment, like a $100,000 blast pot that contains sand for blasting.”

He notes that training in this field is very rigorous, and only two or three companies in Alaska, including the Mericka Group, are qualified to do QP1 and QP2, the highest painting and blasting industry standard used for asset integrity in the military.

According to Hadaller, 90 percent of corrosion control is preparation, which includes making sure that items that can corrode are thoroughly treated before they head to the field. When steel comes out of the factory, for example, it has a black sheen that

needs to be blasted away to create a porous surface on which to apply corrosion treatment.

“We blast the black sheen that covers the pipe to SP7 or SP10 [surface preparation standards in mils, or thousandths of an inch], and then apply a three-coat paint process over the surface,” says Hadaller. “Each paint— the primer, mid-coat, and topcoat—will have specific specifications for mils, with a total overall thickness of 12 to 18 mils. Painting can take anywhere from eight to twenty-four hours, depending on drying time.”

While most corrosion paints are specified to have a fifteen- to twentyyear lifespan, durability depends on where the products are used. While water, salt, and wind shorten a paint’s lifespan, Hadaller says that ultraviolet sunlight is actually one of the biggest problems.

“Alaska is a very harsh environment, and most of our work is done on industrial infrastructure that is constantly being used and abused,” says Hadaller. “On a scale of one to ten, I would rate Alaska an eight. A ten would be something like a Navy ship, or tanks in the middle of an Arizona desert in 110°F temperatures.”

For this reason, he adds, the US Navy has one of the biggest corrosion programs in the world, spending $3 billion each year to protect its ships, which are repainted every five years.

While calculations can help forecast when corrosion might occur, many factors affect the rate, including the environment, whether a coating was applied in the field or the shop, and whether there is already something wrong with the structure, such as a bad weld. There are industry, state, and federal regulations that provide guidance and regulation, including the Association for Materials Protection and Performance, the Alaska Department of Environmental Conservation, and the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration, which provides federal oversight for the oil and gas industry.

Because controlling corrosion is a constant battle, companies are always trying to find new methods, products, and technologies to make identifying and mitigating corrosion easier.

“Coatings are improving every day, as improved chemistry and a better understanding of corrosion problems enables companies to make better coatings for specific applications… Many of the advances made have also been focused on the inspection technology side, helping operators find and address corrosion.”

David Stamp

Mechanical Engineer

Michael Baker International

“Coatings are improving every day, as improved chemistry and a better understanding of corrosion problems enables companies to make better coatings for specific applications,” says Stamp. “Many of the advances made have also been focused on the inspection technology side, helping operators find and address corrosion.”

While operators have historically used X-ray technology to see through pipes to determine where corrosion has started—a process that is done by hand—robotic "crawlers" are now being used to search for problem areas.

“Inspectors used to have to set up an X-ray source and detector every foot or two along the pipeline, which

was a time-consuming and expensive process,” says Stamp. “This led to the development of robotic crawlers that move along the top of the pipe, taking X-rays as they go. In some cases, you can actually see where the insulation has gotten wet but not yet corroded the pipe, which allows operators to prioritize that area for additional inspection or to remove the insulation before the pipe is damaged.”

Monitoring has also been simplified through remote data collection capabilities that allow companies like Coffman Engineers to make sure that cathodic protection systems remain operational. “Remote monitoring has really been embraced in Alaska because,

instead of investing a lot of time to travel to remote cathodic protection sites, you can review data more frequently from data transmitted remotely,” says Cacy.

Companies have also become more proactive in preventing corrosion by incorporating corrosion mitigation methods into new construction designs. “If you are constructing a new structure or pipeline, it is much more cost effective to add cathodic protection at that time instead of pushing it to the back burner and worrying about it later,” says Cacy. “It’s like spending money now to paint a house or waiting several years to buy new siding; investing in corrosion control early can make an asset’s lifespan much longer.”

By Vanessa Orr

By Vanessa Orr

When Jon McNeil and Nicole Cusack decided to bring a ramen restaurant to Anchorage, they pictured a small, cozy place where they could share their love of phenomenal food and high-level craft cocktails. Instead, they fell in love with a historic three-story, 6,000-squarefoot building downtown that provided more than enough room for a growing restaurant—but also enough design challenges to match the space.

Now one of Anchorage’s hot spots with a two-month or more waiting list, Whisky & Ramen was a labor of love that McNeil, a dentist, and Cusack, a lawyer, can look back on with pride. But renovating the space took a lot of effort as well as innovative design solutions.

“We had no idea how big it was when we first saw it; it was just a great old concrete building that had a ton of history, including surviving the 1964 earthquake,” says McNeil. “Instead of seeing it destroyed like a lot of old buildings are, we decided to buy it so it didn’t get wasted.”

Once they started exploring their new purchase, the couple realized that much of its unique architecture had been hidden by older finishes. While the front part of the building had been built more than a century ago, the back part of the building had been added in the ‘60s. In its many iterations, it has served as a photo studio for famed Alaska painter Sydney Laurence, the home of Stoltz Electric Co., an antique store, and later a mercantile.

The back part of the building was made of board formed concrete, which the couple were able to preserve in the modern renovation. “There aren’t a lot of concrete buildings like this anymore,” says McNeil, noting that it can be cost-prohibitive to use this type of construction method in modern facilities.

It took them a couple of years to strip the building, in part because the entire façade had to be seismically upgraded to meet modern earthquake codes. Steel beams were installed behind the brick façade, which was reattached to the original concrete back of the building that was already up to code.

“While most historical buildings are grandfathered in, because we went from mercantile use to restaurant use, our project fell under current codes, which made the renovation even more difficult,” says McNeil, adding that, in addition to meeting municipal codes, the entire building is now ADA-compliant.

Because a lot of the building is below grade, the renovation had to utilize the existing sewer line and plumbing lines, incorporating their path into the design of the restaurant. McNeil and Cusack were also able to maintain the original elevator shaft and expand it, though at one point that meant hand-digging to get it to the right depth.

“One of the biggest challenges in the renovation is that every inch counted. For example, when we worked on the bathrooms downstairs, it was originally framed three inches in the wrong direction, which threw off the entire layout,” says Cusack. “We ended up flip-flopping the men’s and women’s rooms.”

Upstairs also was a squeeze. “In order to meet codes in the bar, we had to custom-build the faucets into the vertical columns of the bar to make them fit,” she continues. “The tolerances were within inches.”

In addition to keeping the concrete shell, the couple was also able to reuse the brick in the building. However, that commitment to sustainability involved spending an entire summer cleaning the concrete. “It was definitely a labor of love,” says McNeil.

Because the original building had not been designed to house a restaurant, the renovation involved more specific issues to comply with health standards and increased efficiency.