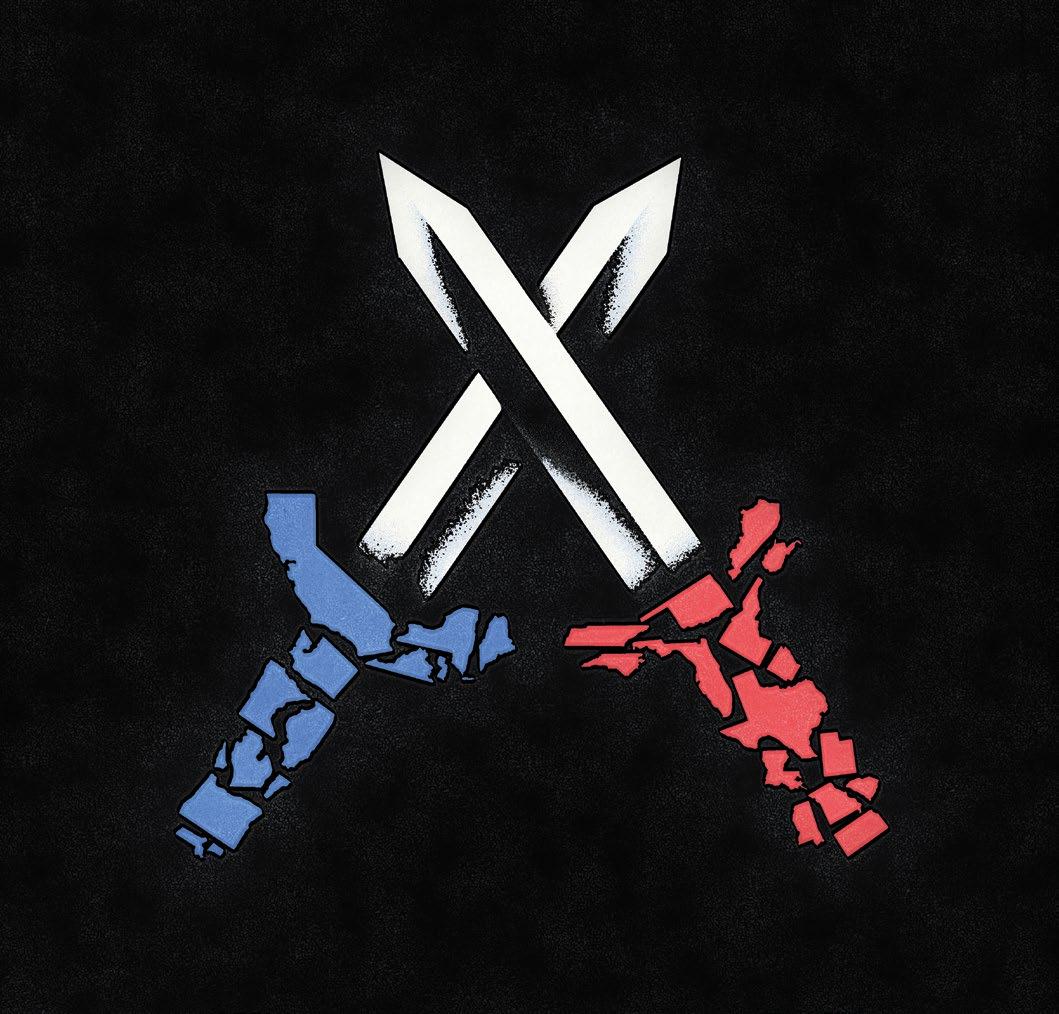

The Cold Civil War

Red and blue states are locked in a power struggle. How will it end?

The Cold Civil War

04 Introduction By David Dayen

06 The Chasm Between Oklahoma and Connecticut

Stark differences color red- and blue-state lawmakers’ policy choices—which makes all the difference in residents’ well-being. By Kalena Thomhave

12 Texas Will Mess With You

The state is a national incubator for bad ideas, which it then seeks to project across the nation. By Christopher Hooks

18 Red-State Abortion Tactics Push Into Deep-Blue Illinois

How pro-choice advocates in two cities moved to take on anti-abortion lawmakers By Emma Janssen

24 Breaking the Public Schools

Red states are enacting universal education vouchers, threatening budget calamity and potentially degrading student achievement. By Jennifer C. Berkshire

30 The Political Violence Spilling Out of Red States

Red America is imposing its vision on the rest of the country through intimidation, and in some cases even more. By Jon D. Michaels and David L. Noll

36 America’s Judicial Divisions

Every major policy issue is now also a courtroom battle, decided in increasingly partisan settings. And there’s no end in sight. By Hassan Ali Kanu

44 Falling Into Climate Disaster

Red and blue states look past each other on issues like carbon emissions, power generation. By Gabrielle Gurley

48 The Truth About the Parties and Labor

You need only look at the state level to understand who supports workers and who doesn’t. By Sharon Block and Benjamin Sachs

52 Leveraging the Money Power

Progressive state and city officials are pushing back against the right’s war on “woke capitalism.” They could be doing even more with trillions of dollars in pension funds. By Robert Kuttner

58 Playing Hardball

Rebalancing conflicts over state policy will require that blue states wield power differently. By Arkadi Gerney and Sarah Knight

63 Housing Blues By Rachael Dziaba

64 Parting Shot: An interview with Keith Ellison, Minnesota’s attorney general

Cover and interior illustrations by Alex Nabaum

Why am I getting this magazine now? Didn’t I just get one? These are among the questions you probably had when you saw this magazine in your mailbox. Here’s the answer.

The United States has a bad case of presidentialism. There’s a formal meaning of that term, describing the form of government with an elected leader of the executive branch that is separate from the legislature. There’s a more exaggerated meaning of that term, which refers to the way the media and most of the public treats the president as the government itself, and treats all things that happen in the country as referenda on the president’s ability. And there is a third meaning of the term that I put to you now, which is the mass forgetting many of us political observers have about the 50 state governments across the country that have tremendous power to shape the lives of their citizens. We may have a national legislature, but your experience with the government, with the economy, with the education and health care systems, with the quality of the air you breathe and the water you drink, and over the last couple of years, with the autonomy you have over your own body, has a lot to do with the state in which you live.

Too often this gets disregarded, especially during a presidential election when billions of dollars are spent on national politics. Only 11 of the 50 states have gubernatorial elections in presidential election years, with the vast majority of the rest, including nearly all such elections in the major swing states, happening in the lower-turnout midterms. And state legislatures are generally overlooked in the best of times. Local news deserts have grown, bringing even less attention to a transformation in how the states are wielding their power.

This special issue of the magazine tries to return some focus. The general thesis of this issue is that state policy has diverged, becoming more rigidly differentiated between red and blue. More than that, states are no longer content to see their policy stop at their borders. You will read explanations for why this is happening and examples across a number of issue areas, but I think the untold story is about the consequences for personal health, economic well-being, and even life expectancy. If your state government is taking years off your life, you’d think that would be a bigger story!

We also in this issue track the novel tactics states are using to force adoption of their policy preferences. And this is an asymmetrical game, with conservatives using these tactics far more than their liberal counterparts. While the tactics may shift depending on who wins the presidential election, the dynamic is unlikely to change. But we include prescriptions for blue-state governments to better address this aggression, through tactics that could counteract it.

I want to thank GABRIELLE GURLEY for being my co-lead editor on this project. At the Prospect, we believe in elevating critical issues that sit just off the radar screen, and we can’t think of a more important one than what’s happening at the state level. I hope you enjoy it. —David Dayen

EXECUTIVE EDITOR DAVID DAYEN

FOUNDING CO-EDITORS

ROBERT KUTTNER, PAUL STARR

CO-FOUNDER ROBERT B. REICH

EDITOR AT LARGE HAROLD MEYERSON

EXECUTIVE EDITOR David Dayen

SENIOR EDITOR GABRIELLE GURLEY

MANAGING EDITOR RYAN COOPER

FOUNDING CO-EDITORS Robert Kuttner, Paul Starr

ART DIRECTOR JANDOS ROTHSTEIN

CO-FOUNDER Robert B. Reich

ASSOCIATE EDITOR SUSANNA BEISER

EDITOR AT LARGE Harold Meyerson

STAFF WRITER HASSAN KANU

SENIOR EDITOR Gabrielle Gurley

MANAGING EDITOR Ryan Cooper

WRITING FELLOWS JANIE EKERE, LUKE GOLDSTEIN, EMMA JANSSEN

ART DIRECTOR Jandos Rothstein

INTERNS RACHAEL DZIABA, YUNIOR RIVAS GARCIA, K SLADE, MACY STACHER

ASSOCIATE EDITOR Susanna Beiser

STAFF WRITER Hassan Kanu

WRITING FELLOW Luke Goldstein

INTERNS Thomas Balmat, Lia Chien, Gerard Edic, Katie Farthing

CONTRIBUTING EDITORS AUSTIN AHLMAN, MARCIA ANGELL, GABRIEL ARANA, DAVID BACON, JAMELLE BOUIE, JONATHAN COHN, ANN CRITTENDEN, GARRETT EPPS, JEFF FAUX, FRANCESCA FIORENTINI, MICHELLE GOLDBERG, GERSHOM GORENBERG, E.J. GRAFF, JONATHAN GUYER, BOB HERBERT, ARLIE HOCHSCHILD, CHRISTOPHER JENCKS, JOHN B. JUDIS, RANDALL KENNEDY, BOB MOSER, KAREN PAGET, SARAH POSNER, JEDEDIAH PURDY, ROBERT D. PUTNAM, RICHARD ROTHSTEIN, ADELE M. STAN, DEBORAH A. STONE, MAUREEN TKACIK, MICHAEL TOMASKY, PAUL WALDMAN, SAM WANG, WILLIAM JULIUS WILSON, MATTHEW YGLESIAS, JULIAN ZELIZER

PUBLISHER MITCHELL GRUMMON

PUBLIC RELATIONS SPECIALIST

TISYA MAVURAM

CONTRIBUTING EDITORS Austin Ahlman, Marcia Angell, Gabriel Arana, David Bacon, Jamelle Bouie, Jonathan Cohn, Ann Crittenden, Garrett Epps, Jeff Faux, Francesca Fiorentini, Michelle Goldberg, Gershom Gorenberg, E.J. Graff, Jonathan Guyer, Bob Herbert, Arlie Hochschild, Christopher Jencks, John B. Judis, Randall Kennedy, Bob Moser, Karen Paget, Sarah Posner, Jedediah Purdy, Robert D. Putnam, Richard Rothstein, Adele M. Stan, Deborah A. Stone, Maureen Tkacik, Michael Tomasky, Paul Waldman, Sam Wang, William Julius Wilson, Matthew Yglesias, Julian Zelizer

ADMINISTRATIVE COORDINATOR

PUBLISHER Ellen J. Meany

LAUREN PFEIL

PUBLIC RELATIONS SPECIALIST Tisya Mavuram

Thank You, Reader, for Your Support!

BOARD OF DIRECTORS DAVID DAYEN, REBECCA DIXON, SHANTI FRY, STANLEY B. GREENBERG, MITCHELL GRUMMON, JACOB S. HACKER, AMY HANAUER, JONATHAN HART, DERRICK JACKSON, RANDALL KENNEDY, ROBERT KUTTNER, JAVIER MORILLO, MILES RAPOPORT, JANET SHENK, ADELE SIMMONS, GANESH SITARAMAN, PAUL STARR, MICHAEL STERN, VALERIE WILSON

ADMINISTRATIVE COORDINATOR Lauren Pfeil

BOARD OF DIRECTORS David Dayen, Rebecca Dixon, Shanti Fry, Stanley B. Greenberg, Jacob S. Hacker, Amy Hanauer, Jonathan Hart, Derrick Jackson, Randall Kennedy, Robert Kuttner, Ellen J. Meany, Javier Morillo, Miles Rapoport, Janet Shenk, Adele Simmons, Ganesh Sitaraman, Paul Starr, Michael Stern, Valerie Wilson

PRINT SUBSCRIPTION RATES $60 (U.S. ONLY) $72 (CANADA AND OTHER INTERNATIONAL)

PRINT SUBSCRIPTION RATES $60 (U.S. ONLY) $72 (CANADA AND OTHER INTERNATIONAL)

Every digital membership level includes the option to receive our print magazine by mail, or a renewal of your current print subscription. Plus, you’ll have your choice of newsletters, discounts on Prospect merchandise, access to Prospect events, and much more. Find out more at prospect.org/membership Update Your Current Print Subscription prospect.org/my-TAP

You may log in to your account to renew, or for a change of address, to give a gift or purchase back issues, or to manage your payments. You will need your account number and zip-code from the label:

CUSTOMER SERVICE 202-776-0730 OR INFO@PROSPECT.ORG MEMBERSHIPS PROSPECT.ORG/ MEMBERSHIP

CUSTOMER SERVICE 202-776-0730 OR info@prospect.org

MEMBERSHIPS prospect.org/membership

REPRINTS prospect.org/permissions

REPRINTS PROSPECT.ORG/PERMISSIONS

VOL. 35, NO. 6. The American Prospect (ISSN 1049 -7285) Published bimonthly by American Prospect, Inc., 1225 Eye Street NW, Suite 600, Washington, D.C. 20005. Periodicals postage paid at Washington, D.C., and additional mailing offices. Copyright ©2024 by American Prospect, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this periodical may be reproduced without consent. The American Prospect® is a registered trademark of American Prospect, Inc. POSTMASTER: Please send address changes to American Prospect, 1225 Eye St. NW, Ste. 600, Washington, D.C. 20005. PRINTED IN THE U.S.A.

Vol. 35, No. 3. The American Prospect (ISSN 1049 -7285) Published bimonthly by American Prospect, Inc., 1225 Eye Street NW, Suite 600, Washington, D.C. 20005. Periodicals postage paid at Washington, D.C., and additional mailing offices. Copyright ©2024 by American Prospect, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this periodical may be reproduced without consent. The American Prospect ® is a registered trademark of American Prospect, Inc. POSTMASTER: Please send address changes to American Prospect, 1225 Eye St. NW, Ste. 600, Washington, D.C. 20005. PRINTED IN THE U.S.A.

ACCOUNT NUMBER ZIP-CODE

EXPIRATION DATE & MEMBER LEVEL, IF APPLICABLE

To renew your subscription by mail, please send your mailing address along with a check or money order for $60 (U.S. only) or $72 (Canada and other international) to: The American Prospect

1225 Eye Street NW, Suite 600, Washington, D.C. 20005 info@prospect.org | 1-202-776-0730

The Cold Civil

States have always diverged on policies, but it’s grown more intense. And for red states, that’s not enough.

By David Dayen

Deep into the grimmest months of the COVID -19 pandemic, Medicaid officials devised a stopgap plan that proved to be one of the federal government’s most consequential decisions. To slow the spread of the deadly and contagious disease and ease up on paperwork during the public-health emergency, the feds ordered states to maintain coverage for Medicaid recipients. As a result, Medicaid rolls grew by over 23 million beneficiaries during this period, swelling to around 95 million Americans.

But in March 2023, with the virus more or less contained, Medicaid eliminated this “continuous enrollment” provision. States could manage their Medicaid rolls any way they saw fit. And the results of this experiment were revealing.

Net Medicaid enrollment across the country has fallen by 14.1 million since last March, compromising the health of millions of very poor people. At one end of the spectrum, Montana, Utah, Idaho, Oklahoma, Texas, and South Dakota each shed at least half of their enrollees who were on Medicaid when continuous enrollment was in effect. At the other, North Carolina, Oregon, Maine, California, Connecticut, and Illinois each have disenrolled 20 percent or less. (North Carolina is an outlier, because it expanded Medicaid when this all started last year.)

Florida cut short postpartum care for poor mothers due to a “computer error”; Arkansas dropped 427,000 recipients in the first six months, often for procedural reasons like not returning a renewal form. South Dakota, Montana, and Idaho led ten states that “disenrolled so many children in 2023 that they had fewer children enrolled at the end of the year than prior to the pandemic,” according to Georgetown University.

As one consumer advocate told NPR , “We have seen some amazing coverage expan-

sion in places like Oregon and California. But if you live in Texas, Florida, and Georgia, since the pandemic your health coverage has been disrupted in ways that were preventable by state leaders.”

By now you may have figured out the pattern. In the vast majority of cases, states controlled by Republicans moved quickly to cull the Medicaid rolls, and states controlled by Democrats kept them on much longer. And this holds across nearly every policy area. Red states have the most oppressive abortion restrictions; blue states have more realistic reproductive policies. If you can carry a concealed weapon without a permit, you are likely in a Republican state; if you need to pass a background check to purchase a firearm, you are in a Democratic state. Republican states have the weakest LGBTQ+ protections; Democratic states have the strongest. The 13 states with paid parental leave are all Democratic. Of the 20 states with a $7.25 minimum wage, 15 are Republican trifecta states and three have Republican legislatures.

In 1967 in a speech at Stanford University, Martin Luther King described “two Americas”: One with all the “material necessities for their bodies” and the other “perishing on a lonely island of poverty.” Nearly 60 years later, King perfectly captures the two Americas that we’re dealing with right now, bounded by a geographical reality: The laws that you live under are determined by the policymakers in the state where you live.

From the beginning, America struggled over the institution of slavery, leading to the epic clash between North and South 160 years ago. Partisans have eyed each other warily ever since. The postReconstruction era saw states splitting along the virulent racial, social, and economic prejudices that survived the Civil War. Yet as the

federal government asserted itself during the New Deal, using incentives like highway funding to force standardization, interstate economic variation began to narrow. But a nearly all-white, largely Southern Republican Party took hold only after Ronald Reagan secured the White House, and state policy started diverging wildly once again.

Over the last 30 years, a state government’s partisan orientation is the overwhelming predictor of the policies it will adopt. One University of Chicago study shows that the effects of party control on state policies have doubled since the early 1990s. Divergent ideas and beliefs have always been with us, but divergent outcomes at the state level are new, and growing.

One reason for this is that there are fewer institutional brakes on policy disagreements. In 1980, 26 states split control of the legislature and the governor’s office, and each branch checked the other. But today, only ten states have split control; a whopping 40 states have unitary Republican or Democratic governance. With state lawmakers often responsible for gerrymandering state Senate and House districts beyond recognition, they cement one party’s control well into the future by picking their own voters, even if their overall electorates are closely divided.

A federal government mired in gridlock and dysfunction also has set the stage for partisan disrupters to surge into states. Legislative meddling has become a cottage industry for corporate bill mills like the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC), which produces ready-made legislation for conservative lawmakers. While states have long produced models for national policies, encouraging the federal government to catch up to better ways of doing the people’s business, today policy extremism in the states has become an end in itself.

Policy extremism has eroded quality of

Warlife in America. As much as half of the gap between the states in life expectancy is due to geographic variation. A 2023 study found that more liberal policies on tobacco, labor, immigration, civil rights, and the environment correspond to a one-year increase in how long a state’s residents live. (In this special issue, Kalena Thomhave takes a closer look at Oklahoma and Connecticut, which had the same life expectancy in 1959 and a 4.7-year spread as of 2019.)

Of the ten states with the highest rates

obesity levels show this correlation: Ten of the 12 states with the highest percentage of obese residents have Republican trifectas. Where you live, in short, can determine how long you live.

This wide gulf between healthy and ailing America is bad enough. But red states in particular want their policy preferences to be reflected across the nation, and have engaged in numerous aggressive tactics to make that a reality.

Texas and Idaho have enabled private citizens to sue anyone providing assistance to help their residents obtain an abortion, even if another state provides the care. Cities and counties throughout Texas have barred the use of their roads for abortion travel. Texas Gov. Greg Abbott has sent over 120,000 migrants by bus into other states and dumped them there. Red-state attorneys general have issued subpoenas to force health facilities in other states to release information about genderaffirming care sought by their own residents. Anti-ESG laws require businesses and financial institutions to change corporate governance practices in order to operate in red states. Companies and conservative advocates seek out red-state courts with conservative judges to obtain nationwide injunctions on regulatory policies affecting all of us. Red-state lawmakers have even seized the tools that cities use to set their own laws (see Texas and Austin, or Tennessee and Nashville).

of uninsured residents, seven are controlled fully by Republicans. Of the ten with the fewest uninsured, seven are controlled fully by Democrats. The ten worst health systems in the country, according to the Commonwealth Fund, are all in red states. Eight of the ten states with the most COVID-19 deaths are Republican-led; so are ten of the 12 states with the highest rates of smoking-related cancer deaths. Firearm deaths are lower in blue states and higher in red states. Even

Democrats have notched victories in states they control as well, but by and large they have not adopted draconian measures to force other states to accept their ways of operating. Red states, by contrast, aren’t interested in peaceful coexistence; they appear determined to carry on their battle for national political dominance. Just enough terror has been unleashed to signal that the state of the union is not strong. The melting pot threatens to boil over, a once savory recipe spoiled beyond recognition. You can call it a cold civil war.

There needs to be a better, more nuanced understanding of this historical moment. Developments at the state level are too often ignored in the

corridors of power in Washington, where Congress and the executive branch intend to set policy for the whole country. But the likelihood that this push and pull will grow stronger as the years go on forces us to pay attention, regardless of national electoral outcomes. If Donald Trump wins, he has already signaled the willingness to use federal leverage to force changes to bluestate policies, such as withholding funding for vital needs like firefighting. If Kamala Harris wins, conservatives will retreat to their power centers, use partisan courts to their advantage, and continue to develop pernicious strategies to make other states bend to their will.

This special issue of the Prospec t lays out interstate divergence on anti-poverty programs, education, climate and energy, jurisprudence, labor rights, and more. We profile Texas, the intellectual and emotional center of this strategy of policy maximalism and interstate hostility. We look at the ways in which red states aren’t settling for dominion within their own borders, and seek control over others. And we lay out how blue states can fight back against red-state incursions into their policy territory, build power across the country, and advance critical policy objectives that preserve hard-fought rights.

Some may fear that a strategy of calibrated counteraggression could launch the country into a series of damaging reciprocal exchanges, much like the various skirmishes between free and slave states that sparked civil war. But there’s another path that doesn’t signal endless internecine strife, with strategic actions that can also lower the temperature, by proving to conservatives that their adversaries in the blue states will not be run over.

Democracy in the United States depends on state governments to safeguard basic human rights for their citizens no matter what far-flung corner of the nation they find themselves in. The circumstances of our country’s origin and its peculiar constitutional framework opened up vast ideological, political, and cultural divides over what those basic human rights are. Conscientious leaders who believe that federalism, or more likely a reconstructed federalism, is the way forward will need to step in to calm the waters and mediate these seemingly intractable political conflicts. This special issue offers a few road maps to bring the country back from the edge. n

The Chasm Between Oklahoma and Connecticut

Stark differences color red- and blue-state lawmakers’ policy choices—which makes all the difference in residents’ well-being.

By Kalena Thomhave

In a conference room with harsh fluorescent lights, several bins sit on a large table, each one overflowing with returned mail. On the floor, there are even more bins for the staff at Hunger Free Oklahoma in Tulsa to sort through. The organization’s executive assistant sits me down on a sofa outside the conference room and cheerily asks me about myself—Oklahomans like to “visit,” as they say. And with a rueful smile, she apologizes for the “mess” of mail bins that trickle out into the hall. These hundreds of letters spotlight the massive attempt by the statewide commu-

nity group to connect kids who aren’t receiving the free meals that they expect during the school year with the additional funds for food during the summer. Also known as SUN Bucks, the federal Summer EBT program provides benefits to families of children eligible for free or reduced-price school lunches during the summer months. Children receive $120 on electronic benefit transfer (EBT) cards—$40 for each summer month.

In Oklahoma, nearly a quarter of children live in food-insecure households, one of the highest rates in the country. The Annie E. Casey Foundation’s KIDS COUNT,

its annual compilation of child well-being data, ranked Oklahoma 46th in the nation overall—as well as 49th in education and 45th in health.

Yet Oklahoma’s Republican Gov. Kevin Stitt rejected the roughly $48 million of funding for the 2024 Summer EBT program and announced in August the state would also not participate in the program next summer. Oklahoma was one of 13 Republican-led states that declined this year’s summer grocery benefit. “Oklahomans don’t look to the government for answers, we look to our communities,” a spokesperson for the

governor said in a statement regarding the decision to decline the funding, which they referred to as a “handout.”

Halfway across the country, KIDS COUNT ranked Connecticut 8th overall, 3rd in education, and 11th in health. But the state, which also participated in Summer EBT this year, faces a hunger problem as well—more than 15 percent of children live in food-insecure households. In fact, Connecticut was one of the first states in the country to pilot its own program in 2011.

The two states weren’t always such polar opposites. For instance, in 1959, Oklahoma and Connecticut residents had roughly the same life expectancy. But fast-forward 60 years, and the numbers have significantly

diverged. Connecticut now ranks among the top ten states in average lifespan, with an average life expectancy at birth of 80.8 years in 2019. That same year in Oklahoma, the average lifespan at birth was more than four years lower at 76.1 years, among the bottom ten states in life expectancy. The national average life expectancy in 2019 was roughly 79 years.

Gun control policy is another key indicator of life expectancy. But Connecticut has passed background checks, permit policies, and secure storage requirements, while Oklahoma has few gun control laws on the books. In fact, in 2019, the state passed a law allowing open carry without a permit or license in most public places. In 2022,

Oklahoma had the 13th-worst rate of gun violence in the U.S., while Connecticut had the 45th-worst rate.

Jennifer Montez, professor of sociology at Syracuse University, has considered how the polarization of politics and policy contributes to health differences among state populations. Life expectancy in particular may have precipitously declined nationwide in 2015, but it had been stagnating much longer before that. And in the U.S., there are profound differences in residents’ lifespans across place—gaps that have been growing for decades.

In fact, Montez and her research team found that Connecticut passed the most progressive policies between 1970 and 2014,

while Oklahoma passed the most conservative ones. Connecticut has passed a refundable Earned Income Tax Credit, while Oklahoma cut income taxes and refused to expand Medicaid until voters passed a ballot initiative and forced the state to do so. Meanwhile, life expectancy in both states did get better, but in Connecticut it increased by 9.7 years and in Oklahoma it grew by just 5.0 years, as of 2019.

“You have two states that [we]re the same, were pretty middle-of-the-road in terms of life expectancy, but they take opposite trajectories,” says Montez. Some states, she says, took action to “invest in [the state] population’s overall economic well-being and health.” Connecticut is one of them. “And you had other states that took a much more”—she pauses, as if searching for a diplomatic way to describe it—“they took a very different approach.”

As the political parties nationalized, there were only two approaches that most state governments would take. Policies “polarized between and bundled within” states, as Montez has described them, were tied to the governing party’s ideology, creating more homogenous state policy landscapes based on whether a state was led by Democrats or Republicans.

As differences in state policy choices have widened, so have the differences in outcomes among state residents. State government, after all, plunges into the day-to-day minutiae of our lives through decisions about health, education, social services, criminal justice, and more. For example, families in some states get money to keep their kids fed during the summer; in other states, they don’t. Oklahoma leaves it up to communities—and sometimes separate governments—to fill the gaps.

On the Cherokee reservation in northeastern Oklahoma, the Woody Hair Community Center appears suddenly amidst lush trees on a single-lane highway, the building’s sleek new construction juxtaposed against the deep-green foothills of the Ozarks. The $21

million center in tiny Kenwood (population 904) is home to early-childhood facilities, a nutrition center where seniors enjoy lunches, a large softball field, two playgrounds, a rooftop garden, a large gym, and even concession stands.

In the Head Start area, children lie on napping mats; we tiptoe around their sleeping forms to view one of the playgrounds and its shiny, new plastic equipment.

Even the smallest rural community won’t be left behind by the government—the Cherokee Nation government, that is. “These are our people,” says Kim Chuculate, senior director of Cherokee Nation Public Health, her arms extending to gesture around her in the lobby of the center. The community center is meant to “be what it needs to be for the community,” she says, which can be many things at once. For example, while the facility can serve as a basketball court for high school games with concession stands where school clubs can fundraise by selling food, the community center is also outfitted to serve as a tornado shelter. And each night of the week, different sports are offered in the gym—sometimes it’s the popular new game pickleball and sometimes it’s stickball, a traditional Cherokee game.

The bumpy route back to Tahlequah, capital of the Cherokee Nation, includes other hints of the investment taking place

Life Expectancy at Birth

across Cherokee Nation lands. Construction is under way at Tahlequah’s own medical center, a massive campus where a visitor can see Cherokee art—paintings, ceramics, and more—through the windows of most of the buildings. (Building construction rules mandate that 1 percent of every project’s budget goes toward purchasing Cherokee art for display.)

More than 1 in 8 people in Oklahoma are Native American; there are 38 different federally recognized tribes in the state. The U.S. government force-marched the Cherokee and other Southeastern tribes from their homelands to Oklahoma during the ignominious 19th-century period known as the Trail of Tears. This episode set in motion the Native communities’ disproportionate rates of poverty and chronic health issues like diabetes and high blood pressure that many tribal members suffer from today.

Health care, as a result, is a major focus of the Cherokee Nation, which has spent millions constructing hospitals, clinics, and community centers in remote rural areas.

Many of the Oklahoma state government’s own public-health investments pale in comparison to tribal-run hospitals and clinics that are coordinated by tribal governments in the eastern part of Oklahoma. It’s the tribal communities that have stepped up to the challenge of feeding Okla-

As state policy choices widen, so have the differences in state residents’ health outcomes.

homa children in the summer—whether or not they are Native.

With assistance from Hunger Free Oklahoma, the Cherokee and Chickasaw Nations coordinate the federal SUN Bucks program that serves children living within Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Muscogee (Creek), and Seminole Nations. Any child on these tribal lands can receive benefits, and as tribal lands are vast and include the state’s second-largest city of Tulsa, roughly 105,000 children were eligible for benefits this summer.

But even though tribal governments are indeed helping to fill the gaps in areas like health care, it’s not their responsibility— nor can it be: Unlike the eastern part of the state, most of western Oklahoma is not tribal land. And usually, only members of federally recognized tribes can use tribalrun facilities. When COVID -19 vaccines were scarce, however, the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Citizen Potawatomi, and Osage Nations provided vaccines to any member of the public.

Meanwhile, dozens of rural hospitals in the state have closed in the past 15 years, and according to a 2024 report, 22 rural hospitals in Oklahoma are at risk of shuttering—roughly a third of those currently operating.

“Sometimes it feels like we’re filling a gap that shouldn’t be there,” says Chief Chuck Hoskin Jr., the principal chief of the Cherokee Nation. The investments across the reservation are “visual evidence that our priorities are [in] health care,” he says, mak-

ing sure someone “is as healthy as they can be before they even step in a hospital.”

Shiloh Kantz, a Cherokee citizen and executive director of the Oklahoma Policy Institute (OK Policy), says that her tribe is “not a business or corporate-centered government, [but instead] we are a peoplecentered nation.” That’s “how we’re doing policy,” she says.

Other tribes have also invested heavily in health care. Darita Huckabee, who was previously a lobbyist for the Indian Nations Council of Governments in Tulsa, is a Choctaw citizen and has fond memories of the treatment her father received in tribal facilities. She describes how he’d get an asthma diagnosis in Denver, but the Chickasaw-run hospital in the small town of Ada, open to any tribal citizen, would administer treatment. It was “the best health care I’ve ever seen,” she says, adding that the tribe’s investments in preventative health care are “going to change our world.”

In 2019, the economic impact of tribal investments in business, health, education, and jobs in Oklahoma was a remarkable $15.6 billion, according to a 2022 Oklahoma City University report.

In contrast to the tribes’ significant investments, many miles and one sovereign government away, Oklahoma City embraced the conservative preference for shifting policy responsibilities from the federal government to the states. Beginning in the 1980s, Washington gradually embarked on devolution—the transfer of governing power to the states as Congress converted program funding to fixed block grants. State lawmakers had greater flexibility: They could either cut services or increase them.

Many states have also controlled city policies by preempting localities, often but not always Democratic cities in Republican states, from passing their own policies, keeping city residents from receiving benefits like paid sick leave, higher minimum wages, or tenant protections. Moreover, today many states prioritize electing parttime, “citizen” lawmakers who have other jobs (and other priorities). Since the lawmakers don’t always have legislative staff to assist with research on these topics— Oklahoma actually has fewer staff than it did in 1979—they rely on industry lobbyists and groups that promote model bills, like the conservative American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC), that have stepped in to fill those gaps. ALEC, in particular, has

had notable successes in Oklahoma, especially with proposals to cut or ban health care services and other programs.

“We [are] governments moving in two different directions,” says Hoskin, referring to Oklahoma and the Cherokee Nation. “The state of Oklahoma has retreated from the public sphere,” he says, while “[we have] spent the last two decades with our foot on the gas, pouring hundreds of millions of dollars into the public good.”

The state of Connecticut, however, has accelerated its pace of life-changing investments. In recent years, state lawmakers have raised the minimum wage and passed paid family leave policies and a state EITC. Last year, the state started the country’s first Baby Bonds program: Any child covered by Medicaid also receives a $3,200 trust fund at birth, which the state treasurer monitors and invests. When a child reaches adulthood, they can use the funds to buy a house, further their education, save for retirement, or start a business.

“In Connecticut, there’s a sense of civic pride about passing progressive legislation—and trying to be the first state to pass certain legislation,” says Mark Abraham, executive director of DataHaven, a New Haven–based local and state statistics hub.

Indeed, Connecticut was the first state to expand Medicaid after the passage of the Affordable Care Act. It was also the first to pass paid sick leave requirements for private employers. These “bundles” of progressive policies reflect policy choices that are “internally consistent,” says Montez of Syracuse University. “You don’t see Connecticut implementing a generous EITC but not raising the minimum wage.”

Some of this work in Connecticut was inspired directly by the White House. For example, when Connecticut raised the state minimum wage to $10.10 in 2014, that number matched the Obama administration’s recommendation for a minimum-wage hike (and the raise the president gave to federal contract workers).

Policy bundles are also, of course, seen in Oklahoma and other conservative-led states, where legislation championed by groups like ALEC tends to follow other pieces of recommended proposals.

Carly Putnam, an analyst at OK Policy, is more than ready to talk to me about Oklahoma’s policy shortcom-

ings, telling me that her notes for our conversation are nine pages long.

“We have not prioritized investing in state services,” she says bluntly, referring to her state government. “We have repeatedly chosen to disinvest from systems that are proven to help Oklahoma children, families, and communities, and we’re reaping the products of that harvest now.”

The shift is even starker between 2000 and 2024; according to OK Policy, the state’s budget for the 2024 fiscal year is 12 percent smaller than the budget for the 2000 fiscal year, adjusted for population and inflation. As in many Republican states, Oklahoma legislators are quite interested in cutting taxes. During this year’s state legislative session, Republican House Speaker Charles McCall told reporters that “the people of the state of Oklahoma need to get a pay raise through a tax cut,” and that “we need to first address that before we address some other spending matters of the state.”

Darita Huckabee, a retired lobbyist, remembers the “tax-cutting frenzy” the legislature went on beginning in the mid-2000s, with repeated cuts to the state income tax. And because Oklahoma requires a threefourths majority in the legislature for any bill that raises revenue, once a tax is cut, it will be very difficult to reverse those cuts. The goal, she says, was to attract businesses that usually preferred Texas, a supposed competitor. Texas, of course, does not have a state income tax. Moreover, Oklahoma can’t begin to match what Texas, the eighthlargest economy in the world, has to offer.

Still, Oklahoma is tied for the second-lowest corporate income tax rate in the country. Yet for all politicians’ talk of attracting businesses, Oklahoma has instead served as a pawn for tax incentive schemes. When it tried to encourage Panasonic and Tesla to open facilities in the state, Oklahoma offered hundreds of millions in tax subsidies, which likely boosted the offers from Kansas, where Panasonic landed, and Texas, where Tesla ended up. Tulsa, looking to woo Tesla to Oklahoma, even altered a local statue to look like Tesla CEO Elon Musk. “When talking to key members of the team that would need to move … Austin was their top pick to be totally frank,” Musk said—as if he hadn’t known that previously.

Oklahoma has “chosen to prioritize business rather than people, but actually investing in people is what attracts business,” says Kantz of OK Policy.

Though Oklahoma may be trying to diversify its economy with bids for tech and manufacturing workers, the state still largely relies on resource extraction, with oil and gas extraction making up approximately 12 percent of the state’s GDP in 2022. With fossil fuel extraction following a boom-andbust cycle, the state’s revenue—and accompanying state investment—often does too.

Instead of state investment, when transformation does occur in Oklahoma it’s often thanks to generous funding from local organizations. About a decade ago, Oklahoma was regarded as a leader in earlychildhood education, largely championed by nonprofits and philanthropies. Still, in 1998, it was Oklahoma, and not a blue state, that was the first state to implement publicly funded, universal preschool for all four-year-olds.

“We have seen progress here and there,” said David Blatt, director of research and strategic impact at Oklahoma Appleseed, a public-interest law firm. “But the overall feeling is like you’re bailing a leaking boat with a teaspoon.”

Oklahoma’s K-12 education system is not exactly among the country’s innovators. The state has some of the worst rates for per-pupil spending and teacher pay. Its state superintendent of public instruction, Ryan Walters, has focused much of his time on touting his mandate that public schools teach the Bible (even though they seem unlikely to do so). Education funding relies in part on the state’s volatile gross production tax levied on the oil and gas industry. This severance tax is the state’s third-biggest source of revenue after the personal income tax and sales tax.

When Oklahoma does adopt more progressive policies—like Medicaid expansion—it’s often because people have demanded change. In 2020, Oklahoma voters approved a ballot measure to expand Medicaid to low-income adults without children, making an additional 215,000 people eligible for the health insurance program.

Residents are also set to vote on a minimum-wage ballot measure in November. The current minimum wage in Oklahoma matches the federal minimum of $7.25, so any increase could be big for low-wage workers—and judging by the success of previous ballot measures on raising wages, minimum-wage ballot measures are unlikely to lose.

When Oklahoma does adopt more progressive policies like Medicaid expansion, it’s often because people have demanded change.

But the spectacle of voters flexing their direct-democracy muscles unnerves Republicans. State lawmakers have moved to restrict ballot measures. This year, the governor signed two bills that will require ballot initiative sponsors to pay filing fees; one measure also requires that a petition signer include several pieces of information that exactly match their voter data on file, likely making it harder for organizing groups to get issues on the ballot.

Connecticut is not immune from poverty, inequality, and health disparities. The state has one of the most regressive tax systems in the country. According to a 2023 United Way report on cost-of-living indicators, 39 percent of Connecticut residents struggle to afford their basic needs. While Connecticut has the second-highest per capita income in the country, unsurprisingly, it also has some of the highest rates of income inequality and racial segregation.

But health care is one of Connecticut’s bright spots: Just 5.1 percent of the state population is uninsured, making Connecticut one of the best states for health care access in the country, which is reflected in its health outcomes. Still, there are widespread racial disparities in health care: While Connecticut has the lowest infant mortality rate in the country (4.8 deaths

per 1,000 births), its infant mortality rate for Black mothers is more than twice as high—11.7 deaths per 1,000 births.

Oklahoma has opted to rely on “communities” to bridge widening chasms in hunger, health, education, and a host of other social sectors, producing outcomes that are worse across the board, with limited access to health care as well as a shortage of health providers. Kantz, the state health care expert, has a teenage daughter with a rare disease. Since the beginning of the year, she says her daughter has gone through four pediatric neurologists as doctors have left the state.

Her family was originally driving three hours round trip from Tulsa to Oklahoma City to reach one, but now they must drive eight hours round trip to Dallas. Another specialist is a plane ride away in Pittsburgh. Once her daughter graduates from high school, Kantz says, it might be time for her family to leave the state.

The policy differences between states that provide robust services and states that eliminated them, or never offered them in the first place, have impacts that reverberate across people’s lives. Daily existence becomes more difficult than it would be in a place that prioritizes

improving public services and easing residents’ hardships.

The divergence between Connecticut and Oklahoma is an extreme example of what’s occurring across the country as Republican states cut taxes and services and create environments where residents are beholden to the policy whims of corporations, interest groups, and wealthy donors, all who have a vested interest in low taxes and limited social spending. n

Kalena Thomhave is a freelance journalist and researcher based in Pittsburgh. She is a former Prospect writing fellow.

To help lure Tesla to Oklahoma, Tulsa painted the face of CEO Elon Musk on a local statue.

Texas Will Mess With You

The state is a national incubator for bad ideas, which it then seeks to project across the nation.

By Christopher Hooks

Goliad County, Texas, is a pleasant jurisdiction of about 7,000 people nestled in the state’s coastal plain, on an indirect driving route from San Antonio to Corpus Christi. It is generally unremarkable except for its historical sites, which recount centuries of resistance to central, and federal, authority. Goliad exem-

plifies a certain bullheaded tendency that Texans have traditionally cherished above all other qualities.

During the Mexican War of Independence, the opponents of New Spain hid here. When Texans chose to revolt, the Mexican army massacred some 425 prisoners of war here, causing Anglo soldiers to cry Goliad’s name for the rest of the war. After Goliad

voted in favor of secession in 1861, it prospered as a stop on the Cotton Road, by which planters would smuggle their crops to Mexico past that tyrant Abraham Lincoln’s dreaded navy. When the federal army attempted to reconstruct Goliad, the courthouse burned in suspicious circumstances, destroying postwar land deeds. Generations of the state’s schoolchil -

dren have been taken to the site of the massacre, the Presidio La Bahía, and told about the crimes of the Mexican dictator Antonio López de Santa Anna and his centralists. In Texas, it is in the blood: Resistance to tyranny—or bureaucracy, or the White House—is obedience to God, though what party is the tyrant and what

party is the tyrannized is, as always, in the eye of the beholder.

That mindset makes it perhaps a little easier to understand what happened on August 28, 2023, in the Goliad County Courthouse—the one built to replace the building that burned. The County Commissioners Court, the Texas form of a

county council, passed a measure that at first glance resembled the kind of toothless resolution local governments often pass to comment on national issues. “The Goliad County Commissioners’ Court finds that abortion is a murderous act of violence,” the ordinance read. Abortion and abortion-inducing drugs would now

be banned in the unincorporated parts of the county.

Standard stuff. Because by this point abortion had already been banned for more than a year under Texas law, this meant little. But then, in the text, a legal theory emerged that may as well have come from Mars. With immediate effect, the county government created a new offense of “abortion trafficking.” Any individual who assists a pregnant woman in procuring an abortion—a woman who drives her friend, say, from Baltimore to a clinic in Los Angeles, both jurisdictions where abortion is legal— would commit an offense if their route clipped through any of the unincorporated parts of Goliad.

Stranger still was the relief prescribed in the ordinance, which mimicked a novel legal device used by the Texas state legislature in Senate Bill 8, the so-called “abortion bounty” law. “Any person”

other than a member of county government could sue someone who facilitated an abortion in some way connected to the county roads, and potentially receive injunctive relief from the Goliad courts, damages for emotional distress, statutory damages of “not less than $10,000,” and attorney’s fees.

Goliad was the second Texas county to pass such a law, which slowly spread around the state from small counties to larger cities like Lubbock in West Texas. They are questionably constitutional, and difficult to imagine being enforced, and thus may be easy to dismiss. But they’re backed by powerful forces in the state— especially the right-wing legal activist Jonathan Mitchell, who earlier this year began attempting to question women under oath who have had abortions beyond Texas’s borders. The goal is intimidation: to create a patchwork of counties and municipalities

where seeking legal abortions, even outside of Texas, creates legal risk.

And the goal is, in turn, to create pressure on the Republican legislature to act, even beyond what they’ve already done in the name of the right to life. The state of Texas, with its expansive police forces and activist attorney general, would have the actual resources to pursue those who use Texas roads to seek abortions across state lines.

There’s precedent for this. Nearly a third of Texas counties have declared themselves “Second Amendment sanctuaries,” where federal gun regulations the locals perceive to be unconstitutional are declared to have no force of law. A good idea, said state lawmakers. Pressure built, and eventually Gov. Greg Abbott signed the Second Amendment Sanctuary State Act, which barred state agencies and police from assisting in the enforcement of any federal gun control law passed after January 19, 2021.

In January, Gov. Greg Abbott evicted federal Border Patrol from a park in Eagle Pass and fenced it off with concertina wire.

The legislature and elected leadership of Texas, in its infinite wisdom, has taken it upon itself to exert its influence abroad.

But most of all, it’s the legal reasoning in the travel bans that is most worth paying attention to. In a way, Goliad was offering an inversion of the interstate commerce clause, the constitutional provision that gives Congress broad powers to regulate the economy. Because Congress regulates trade between the states and its cities, its regulations must also apply to states and cities. Goliad reasons in reverse. Because it has jurisdiction over short stretches of highway that in turn connect to every road in the nation, Goliad claims a kind of national jurisdiction.

This may seem nonsensical, but it is an increasingly important part of how politics works in Texas. The Lone Star State has been subject to one-party rule since 2003, when Republicans finally took control of the Texas House. For most of the next 20 years—even as the state’s voters drifted slowly back to the Democratic Party—the Republican Party has moved sharply to the right. Texas Republicans have been efficient and unnervingly extreme, leaving little for the GOP to run on come election time.

But because Texas sits at the crossroads of so many nationally contested issues, the same way that the city of Goliad sits at the

crossroads of state highways 59 and 183, the legislature and elected leadership of Texas, in its infinite wisdom, has taken it upon itself to exert its influence abroad. Standing up to tyrannical outsiders, after all, plays well at the ballot box. You may not be interested in messing with Texas, as the saying goes, but Texas will mess with you.

Texas leaders and lawmakers have taken so many aggressive actions against other governments and private citizens in other states in the last five years that it is difficult to organize them into coherent categories. They run the gamut from the silly and venal to the deadly serious.

With increasing regularity, Texas is launching direct challenges to the constitutional order. This January, Abbott ordered state troops and police to seize control of Shelby Park in the border town of Eagle Pass. He evicted the federal Border Patrol from the park, which contained the one usable boat ramp in the area. He fenced off the park with concertina wire and dared President Biden to send in his own troops. The Biden administration sued, and the Supreme Court ordered that federal officials could cut the wire, but Texas refused to let them in. (Amid this posturing, at least three migrants drowned in the Rio Grande.) The crisis only abated when the Mexican government began applying heavy coercive pressure to steer migrants away from Eagle Pass. In a sense, Abbott’s brinkmanship worked—though he would surely have preferred to extend the crisis.

On the other hand, you have cases like state Attorney General Ken Paxton’s 2020 crusade against the Gunnison County, Colorado, Department of Health and Human Services. In the early days of the pandemic, Gunnison tried to kick out nonresidents who were potentially bringing COVID to its many vacation homes. This included Robert McCarter, a Dallas businessman who owned a lake house in the county and had given Paxton more than $250,000 in campaign donations. Paxton’s office leapt into action, demanding a change of course and threatening to bring the state’s full might to the Rockies—until the county gave McCarter a waiver and allowed him to stay.

In between challenging long-standing federal immigration law and the health system of a county with a population of around 17,000 runs the full spectrum of

Texas-sized hostility. Many of the most successful bids to exert the state’s will on others have come from the governor’s office. Abbott has access to substantial discretionary funds and men with guns. He proved in Eagle Pass he could convert those two resources into political capital. Defying the federal government was only the first step. The Department of Public Safety, which administers the state police, was run by a longtime Abbott crony: It maintained a public relations division that was effectively an arm of the Abbott campaign.

With endless footage of lethal obstacles in the river and state military equipment built up at the border, Abbott was able to put himself in the news more frequently than he ever had in his nine years in office. At a press conference on the river in February, 14 Republican governors made the pilgrimage to give their support to Abbott—paying fealty to a man who had never before, despite his long tenure, been considered a first-rank Republican governor or contender for higher office.

By far the most successful of Abbott’s stunts has been his migrant busing program. Texas has spent $230 million and counting on running charter buses with at least 120,000 border-crossers to blue cities and blue states. For the governor, it has been worth every penny. He derives political capital not only from the perception that he is ridding the state of undesirables—many of whom appreciate the free bus ticket—but also in creating chaos in blue cities. The anguished complaints of New York City Mayor Eric Adams are among the greatest political gifts Abbott has received.

But the success of these measures goes beyond the direct policy impact and the elevation of Abbott’s profile—and even the manner in which it centered core Republican issues in an election year. Abbott was offering policy innovations, drawing in other red states to take a harder line. Some states may be “laboratories of democracy,” as Justice Louis Brandeis said. But Texas, as the political writer Molly Ivins declared, is the “national laboratory for bad government.”

Republican governors who wanted their own political capital emulated his example. Multiple states sent their own troops to bolster the Texans in Eagle Pass. Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis tried to one-up Abbott by flying migrants to Martha’s Vineyard. But it’s never enough. As press attention declined,

Abbott was asked by right-wing gadfly Dana Loesch what else the state could do to up the stakes. The governor declared, almost regretfully, that Texas had done everything they could besides open fire. It was hard not to wonder if that might be coming next.

Other Texas politicians wring political capital out of measures that aren’t successful at all. In 2021, the state legislature banned California tech companies from discriminating against conservatives by censoring their social media posts. In testimony before committees, tech representatives mostly seemed confused. (The law is currently blocked in the courts.) Paxton sued in federal court to overturn the 2020 election. This was as poorly executed as it was reprehensible, a hallmark of Paxton’s efforts more generally. In November, alleging that a Seattle children’s hospital was providing care to transgender Texans remotely, Paxton sued to obtain their patient records. Five months later, he quietly dropped the case.

Another set of initiatives relies on the economic power of the state to coerce private companies. While Paxton has done some work on this, the key actor is most often Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick, who as the president of the Texas Senate lacks Abbott’s firepower but has a fine control over policy and a keen understanding of the needs of the donor class. On several occasions—most notably, a strange, slightly manic tirade against Fort Worth–based American Airlines in 2021— Patrick has pressured large companies in Texas to keep quiet on social issues if they want to be heard in his Senate.

But Patrick’s strongest interventions have involved so-called ESG (environmental, social, and governance) investing strategies. For several years, large New York financial institutions like JPMorgan Chase and BlackRock have proclaimed their desire to shift their investment portfolios in the direction of environmental sustainability and social responsibility. Even if this was window dressing, it was taken by the Texas oil and gas industry, which still controls much of the legislature, as an existential threat.

Texas could not pass a law mandating that BlackRock subsidize carbon production, though it surely would have liked to. But it had some leverage: its enormous state investment and pension funds. The Texas Permanent School Fund, which subsidizes public schools, controls some $56 billion in

assets: The 347 retirement funds overseen by the Texas Pension Review Board total some $394 billion in assets. In 2021 and 2023, Patrick led Texas to pass laws that barred state money from being invested with firms the state judged insufficiently invested in the carbon economy.

The state did this despite protests from pension fund managers that it would lose them money, which would ultimately have to instead be extracted from employees or expended by the state. During last year’s legislative session, Amy Bishop, executive director of the $42 billion Texas County and District Retirement System, testified that she anticipated a $6 billion shortfall over the next decade from not being able

dling amount for BlackRock, which reports more than $10 trillion in assets. But a week after the state began pulling out, the firm’s CEO Larry Fink issued his annual chairman’s letter, which seemed to confirm at least a tonal shift at the company as a result of increasing political pressure. He now spoke of “energy pragmatism.” Instead of decarbonization, the company aimed to support a responsible energy “transition.”

At a potentially significant cost to its own employees and taxpayers, the legislature appeared to be bending the direction of some of the world’s largest companies.

It was a strange echo of another period in Texas history, where the legislature attempted to hold Northeastern financiers

Gov. Greg Abbott

• Set lethal obstacles in the Rio Grande to obstruct migrant crossings

• Bused nearly 120,000 border-crossers to other states

to work with a widening set of state-proscribed investment firms. The state tightened the restrictions anyway. On March 20, the Permanent School Fund announced that it was withdrawing $8.5 billion from BlackRock management.

That’s a lot of money for Texas, yet a pid-

to account. At the end of the 19th century, a very poor Texas tried to shield its mostly agrarian population from predatory lending and business practices. The Railroad Commission, founded in 1891, regulated interstate shipping rates. It was soon given oversight of the nascent oil industry, and enacted rules to keep the money flowing from the gushers at home. In 1905, the legislature created a state banking system, complete with its own predecessor of the FDIC,

intended to cater to the needs of those with no access to the national lenders. Then, as now, state financiers understood that their role was to counteract national economic forces for the good of the state. But where the impetus in 1890 was to marshal state resources to broaden the economic base, it is now to consume state resources to maintain the pools of capital claimed by

Attorney Gen. Ken Paxton

• Threatened a small Colorado resort town that tried to keep a donor out during COVID

• Sued to overturn the 2020 election

• Alleged that a Seattle children’s hospital was providing transgender care to Texans remotely

Texans said, because they could no longer win elections at the federal level. Texas was part of a “hopeless minority.” The opposition—the “controlling majority” of the federal government, backstopped by stupid do-gooders in “Massachusetts, New York, Pennsylvania”—was inimical to core Texas values, and wholly committed to destroying them from within, spreading seditious ideas and sending money to sway minds.

Worse still, the knaves running the federal government had failed in their most basic duty: to secure the border. The Beltway class had “failed to protect the lives and property of the people of Texas … against the murderous forays of banditti from the neighboring territory of Mexico.” The state

the very richest people in the state—who are, of course, well represented among the political donor class.

In some ways, we’ve come full circle. An earlier collection of the state’s most important leaders—with the blessing of the legislature—once issued a proclamation to explain why Texas needed to take new and unorthodox measures to maintain its rights. Those measures were necessary, the

Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick

• Pressured large companies to stay silent on social issues

• Championed laws to bar state money from being invested in banks that wouldn’t do business with oil companies

loudest complaint in the declaration is that Northern states had failed to enforce the Fugitive Slave Act. Texas didn’t just want to preserve slavery—it wanted Vermont to enforce slavery. Having been denied the right to extend Texas to the Canadian border, it seceded at the urging of the state’s wealthiest planters and least responsible politicians, knocking off its own elected governor by a coup d’état.

Goliad County’s effort to effectively make legal abortion in other jurisdictions illegal bears echoes of this, and it is hard not to hear those historical echoes elsewhere. This isn’t the 1860s, of course. Abbott and company are playing a dangerous game, riling up the most extreme factions in the state and stirring memories of taking up arms against federal power. Bluster or not, it would be quite easy for it to tip into conflagration.

But this constitutional tightrope walk is embedded into the structure of Texas politics. The state’s most hard-right politicians, the ones responsible for the dumbest and most unwise provocations, belong to a rump minority of the Republican caucus that is able to exercise controlling power over the majority party. It is a very particular kind of polarization that is unique to Texas. Some 3 percent of the state votes in the Republican primary, and that 3 percent has effective control of the ninth-largest economy in the world.

That control can feel like a permanent feature of Texas politics, and it may live for a while yet. But it will end someday. In the 2020 presidential election, Donald Trump won the state by just 5.6 points, a tighter margin than Ohio. In 2018, Sen. Ted Cruz won re-election by just 2.6 points. Both Cruz and Trump are in single-digit fights this year. Polls have shown at least a plurality of Texans thinking the state is on the wrong track for a long time, while a strong majority support abortion rights. (They also support busing migrants out of state, but with less of a dominant majority—52 percent—than you might think.)

had long had to expend its own funds to do so, and Congress wouldn’t pay them back.

Maybe this sounds like it came out last week, but I’m talking about Texas’s 1861 secession declaration. Banditti aside, the

When general elections become competitive again, Texas may become less of a hothouse for stupid ideas. And Gunnison County, Colorado, Seattle, and the banditti of Mexico will be able to breathe a little easier. n

Christopher Hooks is a freelance journalist based in Austin, Texas, and New York.

Red-State Abortion Tactics Push Into Deep- Blue Illinois

How pro-choice advocates in two cities moved to take on anti-abortion lawmakers

By Emma Janssen

Danville, Illinois, has all the trappings of Midwestern postindustrial decline: brick buildings, old Victorian houses, and a downtown that has seen better days. At the turn of the 20th century, the city was a major coal mining, manufacturing, and rail hub. By the beginning of the 21st, most of the mines had been transformed into lakes and the manufacturing plants shuttered. Today, 1 in 4 of Danville’s 30,000 residents live in poverty. Now, the city is working to rebuild and revitalize

by attracting tourists to the area’s museums, parks, and recreational offerings, along with new tax incentives encouraging businesses to set up shop downtown.

Last May, the Danville City Council considered an ordinance that would declare the community a “sanctuary city for the unborn” and ban abortion care within the city’s borders. It included a ban on the shipping and mailing of abortion pills to and within the city. At the time, access to the abortion pill mifepristone was on shaky ground after a series of contradictory rul-

ings from U.S. district court judges across the country. After an hours-long discussion and strongly worded letters from the state and the ACLU of Illinois, the council defied them both and passed the ordinance with a tie-breaking vote from Mayor Rickey Williams, who’s served since 2018.

If Danville had been in one of the neighboring red states—Missouri, Iowa, Kentucky, or Indiana—where abortion is effectively banned, the decision would not have been unexpected. In 2020, President Biden won the city but not overwhelming-

ly, with 51 percent of the vote to Trump’s 47 percent. But abortion has been legal in Illinois since 1973. The state enshrined the right to abortion in state law in 2019 and has gone even further, enacting shield laws to protect abortion providers who perform treatments on out-of-state patients.

Abortion care providers like LaDonna Prince, the owner of Indianapolis’s Clinic for Women, the 46-year-old facility that closed last year, planned to step in to provide care in Illinois for women traveling from prohibition states like Indiana. She had scouted out Danville as a potential location for her new clinic. Prince told Illinois Public Media that she was specifically interested in Danville due to its proximity to Indiana. “We do want to be able to continue to serve women of Indiana, if and when we lose the right to perform abortions here,” she said in 2023.

Danville, however, also happens to be just five miles from Indiana, where abortion

is effectively banned. The state legislature was the first to pass new legislation to prohibit abortion after the high court struck down Roe v. Wade. The ban contains limited exceptions with strict provisions that make care all but inaccessible: Abortions may only be provided in a hospital setting, and if there is a serious risk to the health or life of the pregnant person, a diagnosis of a “lethal fetal anomaly,” or rape and incest, before 12 weeks of pregnancy.

A week after the state ban went into effect, the courts blocked it while a lawsuit was being considered. In June 2023, the Indiana Supreme Court allowed the ban to stand once again. In April 2024, the ACLU of Indiana brought another lawsuit against the state, claiming that the ban violates the state’s Religious Freedom Restoration Act; however, as of now abortion is still illegal. Health care providers in blue states have tried to fill the gaps left by extreme anti-abortion policymakers in neighboring

states. But Prince and other reproductive rights advocates hadn’t reckoned with landing in the middle of the post-Roe minefield: blue-state, pro-life supporters embracing aggressive red-state tactics designed to prevent interstate abortion access.

When the Dobbs decision came down, trigger laws immediately came into effect in 13 states to place restrictions on abortion care, prompting a surge in interstate travel for abortion care. Today, 13 states have total abortion bans and 27 states have abortion bans based on gestational duration.

Illinois—which borders one state (Iowa) with a six-week ban and three states (Indiana, Kentucky, and Missouri) with total abortion bans—has seen the largest increase in out-of-state patients seeking abortion care in the country. In the first six months of 2023, just under 19,000 of those patients obtained care in the state. That’s an increase

of 13,300 out-of-state patients since 2020.

This massive surge is also a result of the state’s years-long effort to become an island of reproductive freedom in the Midwest.

Christina Chang, executive director of the Reproductive Freedom Alliance, a coalition of 23 pro-choice governors, explains that since the group has limited means to challenge anti-abortion legislation in rightwing states, local activists, abortion funds, and legal organizations in red areas must take up the fight against restrictive policies instead. “But what we can do,” Chang says, “is think about what the implications are [for] people who might be seeking care in alliance states.” Those efforts include shield laws that protect providers, patients, and groups that help facilitate abortion travel, as well as data protection regulations that guard the personal information of everyone involved in abortion care.

Shield laws provide legal protections against the threat of extradition, but they

have not been tested in the courts yet—and those challenges are likely on tap. Connecticut’s shield law, for example, which is one of the strongest in the nation, doesn’t require extradition requests to provide a detailed description of the alleged illegal conduct, thus making it difficult to know whether the shield law actually applies to the circumstances at hand.

Midwest Access Coalition (MAC) coordinates a practical support fund that helps provide funding for costs like travel, lodging, food, and child care that could otherwise be barriers to abortion access for patients in the region. MAC ’s director of strategic partnerships, Alison Dreith, says that in the wake of Dobbs, pro-choice policymakers and grassroots groups have learned to exist symbiotically: “I trust policymakers to know … their constituents, their fellow lawmakers, their process better than I know it, and it’s my job to know what abortion seekers need and what’s going to

help clinics succeed in supporting those health care patients,” she says.

This convoluted situation originated with red-state anti-choice activists and legal advocates who have promoted cross-state restrictions to stir up more opposition. In 2021, Senate Bill 8 went into effect in Texas. Also known as the Texas Heartbeat Act, the law prohibits physicians from performing abortions after a “fetal heartbeat” has been detected (unless it is a medical emergency). The restriction is not shocking, when compared to similar draconian anti-choice measures across the country.

What is uniquely dangerous about SB 8, though, is a provision that allows regular citizens to file civil lawsuits against anyone who performs or “aids and abets” an abortion in violation of the law. The law doesn’t specify what constitutes aiding or abetting, leaving interpretations up to the courts. However, the provision has been used against abortion and practical

Danville (left) and Quincy, Illinois, have been caught up in the national debate after Dobbs, despite the state’s abortion protections.

Red states export tactics to blue states, which in turn try to fill care gaps left by red-state bans.

support funds, which has a chilling effect on donors and recipients of those funds. Already precarious relationships can also take on chilling new dimensions. In one

Texas case, an abusive husband attempted to sue his wife’s friends for allegedly helping her seek an abortion.

In his Dobbs concurrence, conservative Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh surmised that laws restricting interstate travel for abortion would likely be unconstitutional, arguing that the Constitution carves out a fundamental right to free movement across state lines.

Despite Kavanaugh’s signal, abortion travel bans have been enacted in states across the country. After passing a near-total ban on abortions, Idaho also passed HB 242, which restricts out-ofstate travel for abortion care by criminalizing planning actions within state lines before the travel occurs.

In 2023, Alabama Attorney General Steve Marshall threatened health care providers, telling them that they could face felony charges for supporting patients who sought

out-of-state care in states where abortion is legal. A group of health care providers filed suit, and in November 2023, the Justice Department filed a statement of interest in the case, explaining that the Constitution protects the right to travel across state lines and that states cannot prevent anyone, including health care workers, from helping others exercise that right.

In Texas, two extreme anti-abortion activists—pastor and anti-abortion activist Mark Lee Dickson and former Solicitor General of Texas Jonathan Mitchell— brought the abortion travel fight to municipalities. The effort started in four Texas counties: Goliad, Mitchell, Cochran, and Lubbock. In each county, commissioners voted for ordinances that would bar pregnant Texans from traveling through the counties to seek abortions in another state. The ordinances are only enforceable with the legal power of SB 8 that allows individual citizens to act as vigilantes.

Abortion Division

Governors from 22 states and one territory have formed the Reproductive Freedom Alliance, a coalition to expand reproductive rights.

Dickson had come up with another nefarious strategy that goes hand in hand with travel bans: the so-called “sanctuary cities for the unborn” movement. Texas Monthly reported that he first met with Mitchell on a conference call to seek guidance for his plans. In June 2019, Dickson and Mitchell’s sanctuary cities strategy earned its first success in Waskom, Texas, a city of fewer than 2,000 residents with an all-male city council. As of September, there are 69 cities and eight counties that have passed sanctuary cities–style ordinances attempting to outlaw abortions and related care within their borders.

According to the ACLU of Illinois, these sanctuary city ordinances often operate by attempting to restrict the availability of medications necessary for abortion care, block the functioning of local abortion clinics, and restrict abortion-related travel in or through the community.

The strategy is a clear example of interstate aggression. The cities that have been targets of these anti-abortion legal offensives are often border cities that see a high volume of interstate travel for reproductive health treatments, such as picking up

pills in a pharmacy or receiving care in a brick-and-mortar clinic.

Chang argues that the expansion of anti-abortion policies across state lines is a strategy as old as the anti-abortion movement itself. “They’re sharing that language, and this bounty hunter law in Texas is no different,” she explains, citing SB 8. After a policy success in one state, anti-abortion activists “replicate that in all these other states,” Chang adds. SB 8 opened the floodgates for travel bans that have spread to cities thousands of miles away—like Danville.

From the moment the Danville city councilors signed off on the ordinance on May 2, 2023, it conflicted with the Illinois Reproductive Health Act, which Gov. JB Pritzker had signed into law in 2019. The law states that reproductive health care, including abortion care, is a fundamental right and ensures that local governments cannot infringe on those rights.

City officials, of course, had been warned. The day before the vote, Illinois Attorney General Kwame Raoul sent a letter to Danville Mayor Williams, reminding

him that the ordinance would be in direct violation of the Reproductive Health Act and that his office “stands ready to take appropriate action to ensure that Danville and its elected officials adhere to Illinois law, including the Reproductive Health Act.” The ACLU of Illinois also sent a letter to members of the Danville City Council’s public services committee, urging them to vote down the ordinance: “Voting yes on the proposed ordinance will only cause confusion and fear in our communities, all while exposing Danville to significant legal liability,” the organization wrote.

The legal threats from the attorney general and the ACLU of Illinois had a chilling effect on the city councilors. They backed down and amended the ordinance, adding that it would take effect only “when the city of Danville obtains a declaratory judgment from a court that it may enact and enforce” the ordinance. Until that day, the ordinance is not in effect, and Danville is not a “sanctuary city for the unborn.”

Some weeks after the Danville city councilors passed their muzzled anti-abortion ordinance, an anti-abortion extremist named Philip Buyno drove to Affirma -

tive Care Solutions, Prince’s new clinic in Danville. When he arrived at the yet-tobe-opened facility, he rammed his maroon Volkswagen Passat into the building, attempting to set fire to the clinic. FBI agents later found gasoline, road flares, tires, a pack of matches, and a hatchet in the car.

At Buyno’s criminal hearing, Prince testified that the violence would significantly delay the clinic’s opening. “This terrorist attack was intentionally timed to prohibit us from opening our doors,” she told the court. “It delayed our opening by at least a year, perhaps more.”

Three months after the vote in Danville, Carrie Bross, an organizer with the pro-choice group Voices for Choice and a resident of Quincy, Illinois, caught wind of an abortion-related issue on the city council’s agenda. Much like Danville, Quincy is a border city of 40,000 that sits just across the Mississippi River from Missouri. Two bridges, one sleek and modern built in 1987 and the other approaching the century mark, connect the two states.