ERWIN CHEMERINSKY ON TRUMP AND THE SUPREME COURT

PRESIDENT JOE BIDEN ON HIS ECONOMIC AGENDA

ERWIN CHEMERINSKY ON TRUMP AND THE SUPREME COURT

PRESIDENT JOE BIDEN ON HIS ECONOMIC AGENDA

It’s not who Elon Musk says is responsible

By David Dayen

The American Prospect needs champions who believe in an optimistic future for America and the world, and in TAP’s mission to connect progressive policy with viable majority politics.

You can provide enduring financial support in the form of bequests, stock donations, retirement account distributions and other instruments, many with immediate tax benefits.

Is this right for you? To learn more about ways to share your wealth with The American Prospect, check out Prospect.org/LegacySociety

Your support will help us make a difference long into the future

16 We Found the $2 Trillion

Elon Musk wants to cut government spending. But the waste in the system goes to elites like him. Here’s a better way to bring down deficits. By David Dayen

26 Will the Courts Enforce the Constitution Against President Trump?

If they don’t, the checks and balances that have defined our government since its inception will give way to one-man authoritarian rule. By

Erwin Chemerinsky

The Biden administration wanted to restore the domestic semiconductor industry. The results have disappointed. By

Susannah Glickman and Madhumita Dutta

44 From the Middle Out and Bottom Up

The 46th president of the United States outlines his economic principles, and his record. By Joe Biden

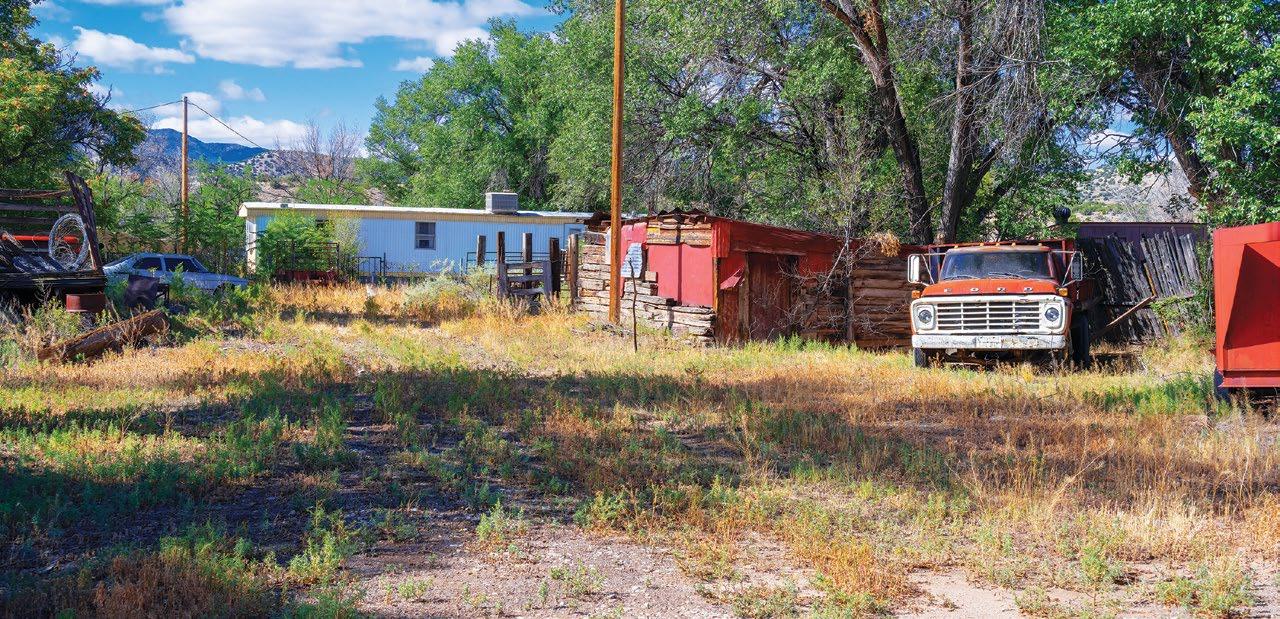

The Onion of Kensington

The American dream collides with tragedy in a historic, largely immigrant community in Philadelphia that’s one of the epicenters of the nation’s fentanyl crisis.

Guadalupe Correa-Cabrera and Sergio Chapa

I write this a week before the inauguration of Donald Trump to be the 47th president of the United States. Democrats have spent the transition period falling all over themselves to figure out the best way to work with him and the Republicans. It wasn’t all that long ago that Democrats were an opposition party, doing the kinds of things an opposition party does, like “offering a contrast” and “trying to make the ruling party pay a political price for their unpopular beliefs.” But it feels like all of that has been forgotten in the run-up to Trump’s re-coronation.

This was actually true of Trump’s first term, too. I remember Chuck Schumer trying to work together with Trump on an infrastructure plan, and a lot of Democrats on Capitol Hill believing that Trump could be nudged in their direction; wasn’t he a Democrat most of his life, after all? Core to this tendency for Democrats to kneejerk collaborate when they lose power is that they have internalized a critique Republicans have beaten into the media, that “real Americans” hate liberals and their ideas. This leads to Democrats positioning themselves as kinder, gentler Republicans for a spell. Republicans, on the other hand, lose power and mull over whether to change their approach for about six nanoseconds before doubling down, combined these days with claiming they didn’t actually lose.

Democrats are neurotic; Republicans are pathological. The party responses to defeat proceed from there.

Typically, it takes some precipitating event for Democrats to realize that they stand for something. In the first term, it was the Muslim ban; I was actually getting off a plane in Los Angeles at precisely the moment that the

protests started in the adjacent terminal, and was the only person in the protest trailing baggage behind me. We don’t know what the precipitating event will be this time; maybe mass deportations (Emma Janssen has a good piece in this issue about advocates and individuals preparing for that), maybe an unconstitutional power grab (UC Berkeley law school dean Erwin Chemerinsky highlights the major possibilities there), maybe the bid to revoke worker voices on the job (Harold Meyerson writes about the attack on the nation’s labor laws), or maybe the imperial conquest of Greenland (see our back page). But there is likely to be something that the public sours on, that makes Democrats realize they can actually fight the descent into conservative authoritarianism. Let’s hope it arrives soon.

My story for this issue begins to envision what an opposition party might say on the plan to slash social spending to pay for tax cuts, a rather unpopular initiative where Democrats have a good story to tell as an alternative: Budget giveaways to the rich and powerful make up practically all the “waste,” so let’s attack those areas instead. When the shock of the election loss wears off, this is a potential starting point for the days ahead.

I would be remiss if I didn’t mention the terrible loss our Prospect family suffered at the end of last year. Our John Lewis Writing Fellow Janie Ekere passed away; she was only 25. There’s a tribute in this issue that highlights her work uplifting marginalized voices and fighting for a better world. We remember her and vow to do the same. —David Dayen

EXECUTIVE EDITOR DAVID DAYEN

FOUNDING CO-EDITORS

ROBERT KUTTNER, PAUL STARR

CO-FOUNDER ROBERT B. REICH

EDITOR AT LARGE HAROLD MEYERSON

EXECUTIVE EDITOR David Dayen

SENIOR EDITOR GABRIELLE GURLEY

MANAGING EDITOR RYAN COOPER

FOUNDING CO-EDITORS Robert Kuttner, Paul Starr

ART DIRECTOR JANDOS ROTHSTEIN

CO-FOUNDER Robert B. Reich

ASSOCIATE EDITOR SUSANNA BEISER

EDITOR AT LARGE Harold Meyerson

STAFF WRITER HASSAN KANU

SENIOR EDITOR Gabrielle Gurley

MANAGING EDITOR Ryan Cooper

WRITING FELLOWS LUKE GOLDSTEIN, EMMA JANSSEN

ART DIRECTOR Jandos Rothstein

INTERNS K. SLADE, BROCK HREHOR, NIC SUAREZ

ASSOCIATE EDITOR Susanna Beiser

STAFF WRITER Hassan Kanu

WRITING FELLOW Luke Goldstein

INTERNS Thomas Balmat, Lia Chien, Gerard Edic, Katie Farthing

CONTRIBUTING EDITORS AUSTIN AHLMAN, MARCIA ANGELL, GABRIEL ARANA, DAVID BACON, JAMELLE BOUIE, JONATHAN COHN, ANN CRITTENDEN, GARRETT EPPS, JEFF FAUX, FRANCESCA FIORENTINI, MICHELLE GOLDBERG, GERSHOM GORENBERG, E.J. GRAFF, JONATHAN GUYER, BOB HERBERT, ARLIE HOCHSCHILD, CHRISTOPHER JENCKS, JOHN B. JUDIS, RANDALL KENNEDY, BOB MOSER, KAREN PAGET, SARAH POSNER, JEDEDIAH PURDY, ROBERT D. PUTNAM, RICHARD ROTHSTEIN, ADELE M. STAN, DEBORAH A. STONE, MAUREEN TKACIK, MICHAEL TOMASKY, PAUL WALDMAN, SAM WANG, WILLIAM JULIUS WILSON, JULIAN ZELIZER

PUBLISHER MITCHELL GRUMMON

ADMINISTRATIVE COORDINATOR LAUREN PFEIL

CONTRIBUTING EDITORS Austin Ahlman, Marcia Angell, Gabriel Arana, David Bacon, Jamelle Bouie, Jonathan Cohn, Ann Crittenden, Garrett Epps, Jeff Faux, Francesca Fiorentini, Michelle Goldberg, Gershom Gorenberg, E.J. Graff, Jonathan Guyer, Bob Herbert, Arlie Hochschild, Christopher Jencks, John B. Judis, Randall Kennedy, Bob Moser, Karen Paget, Sarah Posner, Jedediah Purdy, Robert D. Putnam, Richard Rothstein, Adele M. Stan, Deborah A. Stone, Maureen Tkacik, Michael Tomasky, Paul Waldman, Sam Wang, William Julius Wilson, Matthew Yglesias, Julian Zelizer

PUBLISHER Ellen J. Meany

Every digital membership level includes the option to receive our print magazine by mail, or a renewal of your current print subscription. Plus, you’ll have your choice of newsletters, discounts on Prospect merchandise, access to Prospect events, and much more. Find out more at prospect.org/membership

PUBLIC RELATIONS SPECIALIST Tisya Mavuram

ADMINISTRATIVE COORDINATOR Lauren Pfeil

BOARD OF DIRECTORS DAVID DAYEN, REBECCA DIXON, SHANTI FRY, STANLEY B. GREENBERG, MITCHELL GRUMMON, JACOB S. HACKER, AMY HANAUER, JONATHAN HART, DERRICK JACKSON, RANDALL KENNEDY, ROBERT KUTTNER, JAVIER MORILLO, MILES RAPOPORT, JANET SHENK, ADELE SIMMONS, GANESH SITARAMAN, PAUL STARR, MICHAEL STERN, VALERIE WILSON

PRINT SUBSCRIPTION RATES $60 (U.S. ONLY) $72 (CANADA AND OTHER INTERNATIONAL)

BOARD OF DIRECTORS David Dayen, Rebecca Dixon, Shanti Fry, Stanley B. Greenberg, Jacob S. Hacker, Amy Hanauer, Jonathan Hart, Derrick Jackson, Randall Kennedy, Robert Kuttner, Ellen J. Meany, Javier Morillo, Miles Rapoport, Janet Shenk, Adele Simmons, Ganesh Sitaraman, Paul Starr, Michael Stern, Valerie Wilson

PRINT SUBSCRIPTION RATES $60 (U.S. ONLY)

CUSTOMER SERVICE 202-776-0730 OR INFO@PROSPECT.ORG MEMBERSHIPS PROSPECT.ORG/MEMBERSHIP REPRINTS PROSPECT.ORG/PERMISSIONS

$72 (CANADA AND OTHER INTERNATIONAL)

CUSTOMER SERVICE 202-776-0730 OR info@prospect.org

MEMBERSHIPS prospect.org/membership REPRINTS prospect.org/permissions

VOL. 36, NO. 1. The American Prospect (ISSN 1049 -7285) Published bimonthly by American Prospect, Inc., 1225 Eye Street NW, Suite 600, Washington, D.C. 20005. Periodicals postage paid at Washington, D.C., and additional mailing offices. Copyright ©2025 by American Prospect, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this periodical may be reproduced without consent. The American Prospect ® is a registered trademark of American Prospect, Inc. POSTMASTER: Please send address changes to American Prospect, 1225 Eye St. NW, Ste. 600, Washington, D.C. 20005. PRINTED IN THE U.S.A.

Vol. 35, No. 3. The American Prospect (ISSN 1049 -7285) Published bimonthly by American Prospect, Inc., 1225 Eye Street NW, Suite 600, Washington, D.C. 20005. Periodicals postage paid at Washington, D.C., and additional mailing offices. Copyright ©2024 by American Prospect, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this periodical may be reproduced without consent. The American Prospect ® is a registered trademark of American Prospect, Inc. POSTMASTER: Please send address changes to American Prospect, 1225 Eye St. NW, Ste. 600, Washington, D.C. 20005. PRINTED IN THE U.S.A.

You may log in to your account to renew, or for a change of address, to give a gift or purchase back issues, or to manage your payments.

You will need your account number and zip-code from the label:

ACCOUNT NUMBER ZIP-CODE

EXPIRATION DATE & MEMBER LEVEL, IF APPLICABLE

To renew your subscription by mail, please send your mailing address along with a check or money order for $60 (U.S. only) or $72 (Canada and other international) to: The American Prospect 1225 Eye Street NW, Suite 600, Washington, D.C. 20005

info@prospect.org | 1-202-776-0730

ROBERT KUTTNER

ades, American capitalism has become more concentrated, more corrupt, and more opaque. This is true of banking, insurance, telephone and cable companies, electric utilities, airlines, railroads, tech platforms, the drug industry, and of course hospitals and health systems. The trend is also infecting smaller industries that were traditionally locally owned, such as veterinary practices, tree services, pest control companies, nursing homes, and many more, all of which are being bought up by private equity companies.

Wall Street has a cynical term for this strategy: rollups. They frustrate the competition that makes capitalism tolerably efficient, raise profits, further enrich the rich, and take advantage of consumers and workers. Orchestrating mergers and acquisitions also enriches investment bankers, so the system feeds on itself.

This has occurred despite the heroic efforts of two of President Biden’s best appointees, FTC Chair Lina Khan and Jonathan Kanter of the Justice Department’s Antitrust Division, who made a dent in extreme concentration by reviving longmoribund antitrust enforcement.

But without a clear ideology and narra

tive, voters don’t connect the dots between corporate concentration and their own daily frustrations. Instead, voters vaguely blame a corrupted system. Voters perceive, all too accurately, that neither party is addressing their frustrations and that both are part of an establishment that someone called the swamp. And they’re right.

Donald Trump got elected a second time because Democrats failed to use the Biden interlude to articulate a general critique of corrupted capitalism and its impact on ordinary people. Instead, a talented demagogue deflected inchoate grievances against predatory capitalism onto immigrants, trans people, and condescending metro liberals.

Trump and his corrupt crony, the world’s richest man Elon Musk, epitomize the marriage of fauxpopulist rhetoric and personal grifting. Too many people admire the sheer nerve of Trump and Musk, and imagine that it will somehow spill over and benefit them.

Democrats can try to point out Trump’s hypocrisy, and they have. But that’s not sufficient. And the reason why Democrats have failed to tell their own compelling story is all too obvious: Democrats are part of the corruption. Not all Democrats,

but enough Democrats to blur a coherent opposition narrative.

What concentration and corruption have in common is that they are blindingly complicated and largely opaque to ordinary people. To grasp why health care is such a nightmare, you need to know something about the consolidation of insurers, providers, and pharmacy benefit managers by conglomerates like UnitedHealthcare; the systematic upcoding of bills; other pricing games that hospitals play; the deliberate crowding out of primary care doctors by more profitable specialists; the proliferation of other middlemen in the health system; and a lot more.

Only occasionally does the abuse break through to popular consciousness and popular anger, as after the murder of UnitedHealthcare CEO Brian Thompson, or in the popular revolt against the airline cartel during delays in 2022, which finally roused Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg to issue some pro consumer rules.

But a political analysis on the part of the electorate is not self executing. The spotlight on UnitedHealth was a rare teachable moment. The Democrats did not use it to teach.

Private equity’s takeover of more and more industries is another instance of abuses that are largely invisible to the general public. Only occasionally, as in the case of the takeover of a group of Catholic hospitals by Cerberus Capital, which rebranded the chain Steward Health and extracted over a billion dollars needed for patient care, is the abuse so flagrant that it becomes palpable.

But for the most part, the executioner’s face is well hidden. Ordinary people notice that nursing homes are deteriorating in quality, or that it has become far more expensive to take your dog to the vet, or that retailers keep going out of business. They don’t track changes in corporate ownership. The press simply reports that another iconic retailer went broke.

Much of what we do at the Prospect is investigative and explanatory pieces on the deepening corruption of American capitalism and how it affects regular Americans in their roles of workers, consumers, parents, patients. The story of how corrupted capitalism undermines the living standards and life chances of ordinary people adds up to a narrative and an ideology. But it doesn’t create a politics. That’s the job of an opposition party.

Some Democrats grasp this. The work of

Elizabeth Warren, for example, provides a rough draft of what the opposition would be espousing if they were a Democratic Party worthy of the name.

For instance, Warren’s Accountable Capitalism Act, first introduced in 2018, would require any company with gross receipts over $1 billion to obtain a federal charter. For these companies, employees would elect at least 40 percent of the board of directors. A 75 percent vote of shareholders and directors would be required to approve any political spending over $10,000. The act would give directors a duty of “creating a general public benefit” with regard to a corporation’s stakeholders, including shareholders, employees, and the environment, and the interests of the enterprise in the long term.

The idea of requiring federal chartering of large corporations has been around since the Progressive Era, as an antidote to the weak system of state chartering that has created a classic race to the bottom. Warren is willing to name the problem right in the bill’s title: accountable capitalism . National Review called Warren’s proposal “the most radical proposal advanced by a mainstream Democratic lawmaker to date.” That’s precisely the point. A proposal that ought to be at the heart of the Democratic Party program is at the fringe.

A second Warren bill, the Stop Wall Street Looting Act, seeks to end the enterprise as we know it. Private equity operators make their fortunes by looting the assets of the portfolio companies they acquire. Warren would curb the use of acquiring companies via debt, end “special compensation payments” to private equity owners, put those owners on the hook for operating losses, and restrict abuse of the bankruptcy laws. The 2024 version of the bill was expanded to prohibit private equity companies from selling hospital properties to real estate investment trusts.

Private equity exists only because of a huge loophole in the securities laws that should never have been created. It is at the heart of corrupted capitalism. It is also central to the screwing of workers, since private equity owners invariably cut wages and loot pension plans.

But Warren’s bill has just six Senate cosponsors. Why? Because private equity operators include Democrats as well as Republicans, and they spread their political money around. The perception on the part of so many Trump voters that the supposed

mainstream of both parties is corrupt turns out to be all too accurate.

The Democratic Party should be explaining and narrating all of this. Instead, in the aftermath of the defeat of Kamala Harris, Democrats are all over the place in their diagnosis of what went wrong and how to fix it.

A related obstacle is that fixing a system as convoluted as health care is genuinely hard. Even if Democrats had the votes to replace the entire mess with national health insurance, the transitional challenges would be immense.

But partial policies can open the door to more transformative policies. When I was young, practical lefties were reading a French theorist named André Gorz, who came up with the concept of “nonreformist reform.” By that, Gorz meant policy changes or political demands that seemed merely incremental but that had the potential to lead to more transformative strategies. By contrast, many seemingly reformist policies have the perverse effect of reinforcing existing structures. My colleague Paul Starr, in a classic article cowritten several decades ago with Gøsta EspingAndersen, called this policy trap “passive intervention.” When progressives lack either the votes or the imagination to achieve transformative policies, they settle for inefficient half measures that reinforce existing structures of private power and make the government look bad.

The two classic areas where this occurs, Paul and Gøsta wrote (in 1979!), are health care and housing. Their critique anticipated the flaws in the Affordable Care Act, which further entrenches the private health insurance system instead of supplanting it with true social insurance.

During the ACA debate, progressives pressed President Obama to allow people to opt for a Medicare type “public option” for insurance. But Obama didn’t expend political capital on assembling the votes, even though the Democrats controlled both houses of Congress. Too many Democrats were in bed with the insurance industry.

In the case of housing, the government spends tens of billions subsidizing private developers to provide affordable housing, which is reversed as soon as the developer finds it expedient to convert to marketrate housing. Permanent social housing would be more efficient and more just, but government even under Democrats lacks the ideological nerve and the votes.

The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, another Warren invention, is a splendid example of nonreformist reform. In protecting consumers from a variety of corporate abuses, the CFPB shines an educational light on just how predatory capitalism works.

I was personally involved in one epic case of non reformist reform, the 1977 Community Reinvestment Act, which requires banks to affirmatively extend credit to underserved communities if they want regulatory approval for various activities. For four decades, the CRA energized community organizing around reinvestment goals and compelled banks to reverse redlining. This progress came to an abrupt halt after bipartisan collusion on extreme banking deregulation led to the 2008 financial collapse, wiping out several decades of progress.

A related problem for Democrats is a vacuum of leadership. I cannot recall a time when there were so few Democrats who are plausible as national leaders or possible candidates for president.

Last December, Jon Stewart interviewed the very talented and eloquent Ben Wikler, the chair of the Wisconsin Democratic Party and a leading candidate for chair of the Democratic National Committee. So compelling was Wikler that Stewart was utterly smitten. He ended the segment by saying that Wikler should not be running to head the DNC, he should be running for president. Wikler is great, but what does it say about the state of the Democratic Party that someone who has never held public office seems more attractive as a presidential contender than any elected official?

Then again, it worked for Trump.

As my Prospect colleagues and I keep writing in different ways, this era of American politics will be a populist era. Either it will be the fake populism of billionaires scapegoating various categories of “other” while they use the power of the state to further enrich themselves and further debase democracy with the power of money. Or it will be authentic economic populism.

It’s too much to expect the Democratic Party to be reborn as an anti capitalist party. But Democrats should at least be narrating the impact of concentrated capitalism on ordinary voters. If 2024 demonstrated anything, it was that a medley of left positions on social issues and modest economic measures are no match for Trumpism. n

From the church to the schoolyard to the legislature, Americans are making plans to protect themselves and their loved ones from deportation.

By Emma Janssen

Across the country, some Americans are steeling themselves for the moment when agents of the federal government, whether from the military or Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), storm into their communities and deport anyone suspected of lacking legal documentation. These preparations are happening across a wide scale, with nonprofits and legal organizations dusting off strategies from the first Trump administration, teachers discussing plans in break rooms, and mixed status couples marrying to get their documents in order.

During the 2024 campaign, President Trump promised to enact the largest mass deportation effort in U.S. history. Such an act would take an immense coordination of federal, state, and local law enforcement entities, including the National Guard and local police departments. Democratic governed states would almost certainly throw sand in the gears, as some are already planning to do.

Trump’s soonto be “border czar,” Tom Homan, has said that any immigrants who pose “public safety and national security threats” will be targeted for deportation first. Rhetoric that paints America’s 45 million immigrants as “threats” to public safety is a key Republican strategy to drum up support for mass deportations. One of the first bills passed by the Republican House in the new Congress was the Laken Riley Act, after the 22year old nursing student who was killed in February 2024 by a Venezuelan man who had entered the country illegally.

The bill would require any undocumented person or DACA recipient arrested for burglary, theft, larceny, or shopliftingrelated offenses to be detained, even if they are ultimately never charged with a crime.

The criminal justice system has long been a mechanism for deportations. Since 2015, 82 percent of ICE arrests have occurred within a local, state, or federal jail, according to Immigration Impact. During the second Trump administration, this connection between ICE and the prison system may be strengthened, with local sheriffs empowered to detain those suspected of being undocumented during even routine stops. Though much of their rhetoric has focused on immigrants already involved with the criminal justice system, Trump, Homan, and other advisers have given no indication that they’d stop there.

Some experts suggest that mass deportations of the sort Trump and his advisers have promised are improbable if not impossible. Despite that, the administration might enact a number of deportation efforts that, though far short of a full scale mass deportation, would jeopardize the perceived security of immigrant communities, forcing undocumented people into the shadows and out of public life. Rumors have been floated of a highprofile workplace raid in the D.C. area, to instill just this level of fear.

Now, Americans everywhere are preparing for the worst, whether within their families, in the halls of state legislatures, or at nonprofit and legal organizations that work in immigrant communities.

Priscilla Monico Marín, the executive director of the New Jersey Consortium for Immigrant Children (NJCIC), told the Prospect that the group is deep in contingency planning, taking the lessons learned from the first Trump term to hit the ground running on day one of the second. NJCIC represents unaccompanied children and other youth in need of immigration legal help across New Jersey. Founded in 2015 to respond to the 80 percent increase in unaccompanied children in New Jersey over just one year, NJCIC weathered the family separation crisis and operated under both Republican and Democratic administrations.

“Immigration law can and does greatly change and shift from one administration to the next and immigration practitioners must be trained, nimble, and unified,” Monico Marín said. In the leadup to Trump’s inauguration, NJCIC has been broadening the scope of its legal services, now including rapid response efforts. “This means increased onthe ground lawyering for young immigrants facing immediate and dangerous consequences stemming from the ripple effect of federal administration policies designed to disenfranchise, detain, and deport,” she explained.

In the coming months, Monico Marín says that the group will set up Know Your Rights trainings and mobile legal services to support families facing immediate danger of detention or separation. When asked what community groups can do to protect their undocumented members, she emphasized the importance of “sensitive location” designations. “Churches, schools, funeral homes, hospitals, and the like are designated as sensitive locations where, as per current policy, ICE enforcement will not take place. The incoming administration has plans to scrap these designations, which could be catastrophic for immigrant communities as they seek critical and necessary community services,” she said. If these designations are rescinded, Monico Marín recommends that community groups designate certain areas of buildings as “private” and receive training on how to respond to warrants.

For his part, California Gov. Gavin Newsom, who called a special legislative session after Trump was elected to plan the state’s resistance strategies, has crafted a rough draft of how the state could respond to

Donald Trump is expected to carry out mass deportations in part to instill fear among immigrant communities.

mass deportations. The Los Angeles Times reported on a fact sheet titled “Immigrant Support Network Concept,” which describes Newsom’s plan to mobilize California state resources. If the plan goes into action, the California Department of Social Services will create regional hubs to connect “atrisk individuals, their families and communities” with legal services, local government assistance, and other resources. The fact sheet also says that the Social Services Department would direct funding toward nonprofits that can

aid in community outreach and legal services.

“While there is a robust network of immigrantserving organizations and other community supports, there is no centralized coordination mechanism, which limits the ability of providers to effectively leverage available resources; share critical information and expertise; and identify (and adopt) best practices,” the fact sheet states.

Some Americans don’t feel comfortable relying on their state or local governments

to protect them in case of mass deportation. John and Maria (names changed to protect their identities) are high school sweethearts, now 23 and living together in New Jersey. Maria was born in Brazil but came to the United States with her family when she was 14. The family—Maria, her parents, and her younger sister—overstayed a tourist visa, making them officially undocumented residents in the country.

Growing up, Maria’s family and close friends knew her immigration status, but

she rarely told anyone outside of that tight circle, fearing that her family would be vulnerable if word got out. When she and John began dating in their senior year of high school, she waited four months to tell him that she was undocumented.

“I actually didn’t want to tell him,” she said. “My grandmother was here at the time, and she just wanted me to be completely honest, but I was very nervous and scared.”

John laughed as he told his side of the story: “You know, we were in the car, and she’s just crying, and I’m thinking, ‘Oh no, is she moving?’ And then she was like, ‘I’m undocumented.’ And I was like, ‘Oh thank God. That is the least of my worries!’”

Trump’s rise to power has coincided with Maria and John’s biggest milestones. Maria had just moved to the U.S. when he came into office for the first time. John voted for the first time in 2020 after years of being opposed to Trump’s policies and rhetoric. “Before he even won his first election, when

he was campaigning, he’s calling Mexicans rapists and criminals and doing the Muslim ban and all this stuff. So I was completely disgusted by everything [he] and his supporters stood for at that point,” he said.

Less than two weeks after Trump won the 2024 election, John and Maria got married. “We got engaged in August, and up until the day of the election, at 9 p.m., we were confident Kamala supporters,” John said. “And frankly, we knew it could happen, but we didn’t think it would. And then reality set in, and we had our marriage date set already by that point.”

Trump’s rhetoric and conservative immigration policy throughout the country had the couple on edge. “We knew there had been talks of that judge in Texas in the Federal Circuit that was shutting down parole in place for green cards and things like that,” said John, referring to a ruling that vacated the Biden administration’s “Keeping Families Together” policy two days after

For everyone who manages to find safety and status over the next four years, there will be someone else without the same security.

the 2024 election. The policy was created to let the spouses and stepchildren of U.S. citizens remain in the country while applying for permanent status. “We just knew that it would be good to [get married] as soon as possible, just in case. But we were going to do it no matter what.”

Steered by an immigration lawyer, John and Maria are on their way to securing a green card, and eventually citizenship, for Maria. Once Maria gets her green card, she said, she can apply for her parents and younger sister, allowing them to live in the country legally as well. A successful outcome would grant Maria and her family a sense of security that they haven’t had since their move to the U.S. But the process is difficult and often lonely. “People at Maria’s church have … gone through [the process], but nobody really close in age, or anyone that we talk to. So in a way, it does kind of feel like we’re doing it ourselves. There’s nobody to really help us walk through this other than the immigration lawyer,” said John.

Maria mentioned that some of the other immigrants who attend her church voted for Trump in 2024. “They didn’t experience what me and my family experienced,” she said. “It’s upsetting to see that they don’t really care about the people like their friends that are in different situations.”

For now, the couple will continue their careers and the legal process. Maria works as a nursing assistant while going to grad school for nursing, and John teaches third grade. His school has over 250 bilingual students, nearly all of whom are immigrants who have arrived within the last year. “There’s talk amongst other teachers like, what if all our students get deported, or what if they start leaving because they’re scared of getting deported?” John said. For everyone who manages to find safety and status over the next four years, there will be someone else without the same security. n

Making vouchers universal in D.C. would be universally unpopular, but there’s nothing to stop the GOP.

By Hassan Ali Kanu

The push to replace existing public school systems with government subsidized private and religious schools suffered a major blow on Election Day 2024, as voters rejected ballot measures to implement universal voucher schemes in Kentucky, Nebraska, and Colorado.

Those votes offered more data that universal voucher proposals lack popular support, even among the same populations and demographics that voted for a Republican president and for a rightwing Republican majority in both chambers of Congress.

Still, the “school choice,” or voucher, movement, which has been steered for several decades by a handful of ultraconservative billionaires, is in the midst of a watershed moment, buoyed by the aftereffects of a global pandemic and the so called culture wars attendant to the rise of Trumpism.

“School choice” programs generally reroute public money to private and religious schools via vouchers, education savings accounts, tuition tax credits, and other mechanisms. Proponents say they compel schools to improve through free market–style competition, and offer better opportunities to underprivileged families.

Opponents have generally opposed them as destabilizing to public schools.

But the issue is also clearly ideological: Leaders of the movement, like billionaire philanthropist and former Trump education secretary Betsy DeVos, have said candidly that one of their primary goals is to transform the existing public education system into a religious Christian public education system. And proponents are plainly opposed to education about nontraditional gender and sexuality, as well as historical and systemic racism.

In 2023, 18 states enacted or expanded “universal” voucher programs that allowed public money to flow to private schools, according to EdChoice. At least eight of those programs are available to nearly all students, regardless of income. The number of students who actually use a category of vouchers called “education savings accounts” nearly tripled from 2022 to 2023, rising from 33,000 students to 93,000, according to EdChoice, the leading advocacy group promoting vouchers.

Now, as Donald Trump re enters the White House, private school vouchers are poised to have another banner year. That includes the distinct possibility that advocates could effectively and fully voucherize the whole public school system in the only

jurisdiction with an existing, federally funded voucher program, which is also the only one subject to direct control by Congress: deep blue Washington, D.C.

Lindsey Burke, director of the Center for Education Policy at the Heritage Foundation, told me that the “time is right” to expand D.C.’s program into a universal one that gives students federal money regardless of family income or background, and allows families to spend that money on private schools, charter schools, tutoring, and even other kinds of educational expenses. Burke is the primary author of the education section in the conservative manifesto Project 2025, which calls for Congress to enact “universal school choice” in the District, among other changes.

“The D.C. program has always been a marker of where Congress stands on the issue of school choice,” Burke said. “This is the best opportunity we’ve had probably since the beginning of the program to expand it.”

Along with eliminating the Department of Education, “universal school choice” is a big piece of the conservative movement’s current education policy agenda. Besides Project 2025, it was laid out in the Republican Party’s official 2024 platform, as well as in “Agenda 47,” the Trump campaign’s own set of presidential policy plans.

When Trump announced his nomination of former professional wrestling executive Linda McMahon for the secretary of education post, he touted her previous work to help “achieve Universal School Choice in 12 States,” saying she “will fight tirelessly to expand ‘Choice’ to every State in America.” McMahon herself is a longtime supporter.

“One of the issues most important to me is the question of school choice,” she wrote in 2015, adding that she believes further privatization and deregulation does not “take anything away from traditional public schools … as some have feared.”

Project 2025 specifically wants Congress “to provide an example to state lawmakers” via the “K12 districts under federal jurisdiction, including Washington, D.C., public schools. (The federal government also oversees certain military schools and has authority over public schools on reservations and tribal lands.) In other words, Project 2025 aims to make D.C.’s existing public school system a sort of “laboratory of democracy,” where conservative politi

cians—from other states—can experiment with education policy ideas.

Specifically, Project 2025 includes a subsection on the city’s Opportunity Scholarship Program that calls for some fairly straightforward, yet radical, reforms: expanding voucher access universally, and deregulating the program entirely.

“Congress should expand [voucher] eligibility to all students, regardless of income or background, and raise the scholarship amount closer to the funding students receive in D.C. Public Schools,” Burke and her colleagues wrote.

Josh Cowen, education policy professor at Michigan State University, wrote the 2024 book The Privateers: How Billionaires Created a Culture War and Sold School Vouchers , and has studied voucher programs for about two decades, including research funded by conservative organizations. He notes that the Opportunity Scholarship Program was a federal creation of a prior rightwing government. “The federal government has always tinkered with the D.C. public school system to try and create what they want,” Cowen said. “It wasn’t an accident that when they couldn’t get vouchers nationally, in No Child Left Behind [in 2002], that they then did it in D.C.”

The D.C. Public Schools (DCPS) use a combination of federal and local funding, with more than 80 percent of the budget coming from local revenue sources like property

Linda McMahon, Trump’s pick for education secretary, is a loud supporter of school choice.

taxes, according to the DC Fiscal Policy Institute. The Opportunity Scholarship is uniquely designed to provide equal federal funding to the city’s traditional school system, charter schools, and the voucher program. Each program received roughly $17.5 million in each of the last five fiscal years, according to a 2023 report by K12 Dive and data from the Department of Education. It funds scholarships for lowincome students whose families earn less than 185 percent of the federal poverty level, which comes out to about $57,000 for a family of four. Scholarships for 20242025 were between $10,000 and $15,000.

“Congress should additionally deregulate the program by removing the requirement of private schools to administer the D.C. Public Schools assessment and allowing private schools” even more control and freedom in their admissions processes, according to Project 2025. The document also urges the Trump administration to implement policies in DCPS that would bar acknowledgment of or education about transgenderism, as well as teaching about contemporary or historical racial discrimination, among other policy changes.

Research by Cowen and other education experts over the years has shown that vouchers don’t necessarily accomplish advocates’ stated goals. Studies have shown that students participating in school choice

programs in Indiana, Ohio, and Louisiana actually saw their academic achievement and performance decline relative to their peers, partly due to the dearth of participating, high quality private schools.

In 2019, the Department of Education’s Institute of Education Sciences published a comprehensive comparative analysis of outcomes for D.C. students and parents between 2012 and 2014. The study found no statistically significant differences in reading or math, three years after students had applied to the program. Students who used the scholarships tested 2.1 percentile points lower in reading, and 0.2 percentile points higher in math, compared to the control group.

Studies have also shown that the programs tend to actually benefit higherincome students who are already enrolled in private schools.

The “school choice” movement’s other arguments—including the push for religious education, and to exclude LGBTQ or other nonconforming children—are obviously divisive. Indeed, since the late 1970s, voucher programs have been rejected virtually every single time that they have actually been put to a vote by state residents.

Yet proponents, who have seen some major successes through other political channels, say the programs work, and are continuing to push for national expansion. Trump himself praised and defended the D.C. voucher program during his first term, just days after another study by the National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance found that the program had a negative impact on reading and math scores.

And the latest GOP platform promises to “reassert greater Federal Control over Washington, DC”; while Trump has threatened to “take over” the city and its government during his second administration.

In short, Republican politicians have made clear that they would like to exert

more control over D.C.’s government; and conservatives, more broadly, are advocating for transforming the city’s existing public schools into a universal voucher system, applicable to students and parents at all income levels, and without much effective oversight—simply because they can.

D.C. Mayor Muriel Bowser’s office didn’t respond to requests for comment.

To put it simply, there just isn’t much that the D.C. government can do about this.

The Constitution gives Congress exclusive jurisdiction over Washington, D.C. An act of Congress, the D.C. Home Rule Act, allowed the District its own locally elected mayor and city council for the first time in the 1970s. By the same token, Congress could revoke local governance, or change local laws and policy, including via its control of federal purse strings.

Indeed, Congress originally imposed the existing voucher program on D.C. residents in 2003 by forcing it into an appropriations bill that had to be enacted in order to avoid a government shutdown, according to reports that November by The Washington Post , Education Week, and Baptist News Global.

The city’s voucher program could also be revamped via similar maneuvers, even if partisan Republican support cannot overcome a Senate filibuster.

Nonetheless, Republicans are nearly certain to face a number of challenges, including, most obviously, a lack of consensus on the issue. In some conservative led states, for example, Republican representatives from lowincome or rural areas that lack quality private school options have become holdouts against their colleagues’ bills to expand or implement private school vouchers. Voucher expansion legislation failed in Georgia, Texas, Idaho, Virginia, Kentucky, and South Dakota in 2023, according to a report by the Economic Policy Institute in April that year.

And, of course, average parents and other voters in red states like Kentucky and Nebraska rejected voucher expansion when it was put to a ballot this past November.

about other than focusing on D.C.,” Henderson, a former staffer for Sen. Chuck Schumer (D-NY), said.

Burke told me she can’t disagree on that end. “That’s not incorrect,” she said. “It’s definitely going to be a challenge to reinvigorate interest in this, and we need a concerted effort among coalition groups and other interested parties, but this is the best opportunity” we’ve had so far.

Henderson ticked off a number of other factors that might complicate an attempt to implement universal vouchers in DCPS, including that both program and private school administrators have been advocating primarily for more voucher money, rather than to expand eligibility to a broader pool of students. That’s partly a result of the relatively high cost of living in D.C., which drives up teachers’ salaries, as well as the availability of high quality and exclusive private schools and specialized charters.

Still, those challenges that Republicans might face in trying to prioritize items within a broad legislative agenda, or garnering votes for an unpopular policy, are totally outside of the control of D.C.’s government. Republicans might indeed be very busy with other issues, or may be wary of imposing an unpopular policy on people who didn’t vote for it, or fearful that an expanded voucher program might not actually improve academic performance. But these are undoubtedly not preventative measures for the large majority of D.C. residents and elected officials who oppose the GOP’s proposals.

Henderson, for her part, told me the council is prepared “as much as we can be,” and “to the extent that we have control,” to counter impositions on D.C.’s public schools.

She added that officials were prepared “to explain to the many members of Congress who may not have worked in state or local government, and don’t understand balancing a budget, implementing programs,” or “the impact of some of the things” they have proposed.

Republican politicians have made it clear that they would like to exert more control over D.C.’s government.

Christina Henderson, an atlarge member of the D.C. City Council, told me she is “just not convinced” that Republicans will successfully achieve Project 2025’s goals for DCPS, or even make a serious attempt.

“In terms of their education agenda, at the top of which is getting rid of the Department of Education, they have a lot to worry

D.C. residents can hold on to hope that the policy and facts onthe ground arguments will prove convincing to Republicans. At any rate, whether or not the GOP actually pulls off the broadest and most politically significant expansion of a school voucher program remains, for now, largely a matter of chance. What is certain is that many conservatives want to do so, and, in terms of politics and the law, there’s nothing truly in their way. n

When Biden’s NLRB began to restore workers’ rights, the world’s richest men moved to shut down the NLRB altogether.

By Harold Meyerson

On Wednesday, January 8th, even as firestorms wreaked havoc around Los Angeles, attorneys representing Amazon came to the federal courthouse in downtown L.A. to make clear that their client was still insisting on dismantling the only agency of government that enables private sector workers to join unions and bargain collectively with their employers.

During Joe Biden’s presidency, his appointees to the National Labor Relations Board—a majority of the Board’s members and the agency’s general counsel—had strengthened workers’ rights to form unions and sought to penalize employers who illegally thwarted those rights, in a manner not seen since the presidencies of Franklin Roosevelt and Harry Truman. Vexed by the Board’s determination to resurrect the letter and

spirit of the original pro worker National Labor Relations Act, Amazon, as well as SpaceX and Starbucks, had all brought lawsuits during the past year arguing that the NLRB’s power to charge unions and employers for labor law violations and have administrative courts hold hearings and rule on those charges had suddenly become unconstitutional. This is a power upheld by the Supreme Court in 1937 that had gone unchallenged ever since.

Not coincidentally, beginning in 2022, both Amazon and Starbucks had seen workers at a number of their facilities vote to go union, the first time either company had experienced such an affront to their hitherto unchallenged power. (Though no major organizing campaign was under way at SpaceX, the Board did charge the company with two labor law violations over illegal firings, which was all it took to prompt CEO Elon Musk to file suit against the NLRB as well.) As is the norm for American employers, both Amazon and Starbucks have yet to sign contracts with any of their workers who voted to go union.

Amazon argues that its now threeyear refusal to bargain with Staten Island warehouse workers who voted to unionize in early 2022 doesn’t violate the nation’s labor law. It also argues that its California, New York, Illinois, and Georgia delivery drivers who’ve voted to join the Teamsters—who deliver packages from Amazon warehouses, driving Amazon trucks, wearing Amazon uniforms, obeying Amazon’s productivity standards, and who are surveilled by Amazon cameras in their Amazon cabs—aren’t really Amazon employees, since Amazon franchises out its driving operations to thirdparty contracting companies.

The January 8th Los Angeles hearing was notable in that it was the first proceeding challenging the NLRB’s existence since the Senate had failed in December to confirm the renomination of Biden appointee Lauren McFerran to her post as NLRB chair. McFerran’s defeat meant that incoming president Donald Trump could immediately nominate McFerran’s successor, who would surely win confirmation in the newly Republican controlled Senate and thereby give Republican and pro employer members an NLRB majority.

This means that the new Board will surely reverse several Biden Board rulings in short order. Like the one that had held the mega companies that franchise out their work to contractors jointly responsible for labor law violations at those contractors, and for refusing to enter into bargaining with those franchised workers. Like the Cemex ruling, which compelled employers to begin bargaining with their workers when those employers had been found to have violated labor law and when a majority of those workers had affiliated with a union. Like the one that instructed Amazon

to bargain with drivers at its Palmdale facility in northern L.A. County, who’d voted to join the Teamsters, to which Amazon had responded by dropping its contract with the contractor (who was the drivers’ nominal employer) and claiming it had no obligation to bargain with those workers.

But despite the impending 180 degree shift in the composition and posture of the NLRB, Amazon’s attorneys weren’t content to let the new Trump Board reverse its ruling on joint employers, or undo the increase in penalties employers face for their allbutroutine violations of labor law. In federal district court in Los Angeles (where the Palmdale case is being litigated), and in federal district court in Texas (where the Staten Island case is dubiously being litigated), the lawyers for the companies founded by the world’s two richest men—Jeff Bezos and Elon Musk—have persisted in their efforts to effectively abolish the only federal agency with the power to enable workers to have some say in their compensation and their conditions of work.

A word on the Texas lawsuit: Despite the fact that none of the Amazon warehouses whose workers and drivers have voted to go union are in or even near Texas, Amazon’s lawyers filed their suit in federal court there on the microscopically thin premise that of the roughly 8,000 workers at the Staten Island warehouse at the time they voted to go union, precisely four of them now reside in Texas. Of course, they really filed in Texas because federal district courts there, and in particular the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals there, are famously Neanderthalstyle rightwing. The NLRB has filed to move the case to Washington, D.C.

Even though the combined wealth of Bezos and Musk now exceeds an almost incomprehensible half a trillion dollars, they have glimpsed spotty clouds on their earnings horizon. In 2024, Gallup put unions’ approval rating at 71 percent, while the share of Americans who had a “great deal” of confidence in big business stood at a bare 6 percent. Worse yet, the Biden NLRB was imposing actual penalties—like being compelled to enter bargaining—on employers who illegally threatened or fired workers seeking unionization. For years, the only penalty imposed on employers had been to reinstate the workers they’d illegally fired, fork over their back pay, and post a notice in the workplace saying they’d violated the NLRA , which is small potatoes

when compared to having workers with whom they are actually compelled to bargain. And when Republicans controlled the NLRB, employers could often avoid even those mini sanctions.

In federal court in San Antonio, Amazon’s attorneys have not contented themselves with simply contesting the constitutionality of the NLRB. They’ve also sought an injunction immediately forbidding the NLRB from issuing a final ruling on the cases brought against it, arguing that to do so suddenly constitutes “irreparable harm” against the company, despite the fact that NLRB rulings are not self enforcing and that Amazon can appeal that ruling or any such ruling in federal courts, a process that can take months or even years.

Julie Gutman Dickinson, the attorney who represents the Teamsters in these proceedings, notes that Amazon had “brought 43 charges against the Teamsters and Amazon Labor Union [the union of the Staten Island warehouse workers, who later voted to affiliate with the Teamsters] before the Board. They consistently availed themselves of process”—until, apparently, they decided the one way they could ensure they’d prevail was to shut down the NLRB altogether. After almost 90 years during which the Board has ruled for and against employers and for and against workers, it suddenly became a matter of immediate urgency to shut the Board down through a court injunction.

Attorneys for both Bezos and Musk have likely calculated that the ferociously antiunion Sam Alito may be able to assemble enough of his Supreme Court colleagues to curtail at least some of the NLRB’s fundamental powers. They are doubtless also encouraged by the Court’s 63 decision last year to curtail the regulatory powers of federal agencies and leave it to the courts to determine which rules and regulations pass muster.

Whether or not Amazon gets its injunction, it can still press its case against the NLRB, just as SpaceX and Starbucks can press theirs. It’s not clear that Trump’s NLRB will continue to oppose those companies in court; if it chooses not to, the Teamsters (for the Amazon workers) and Workers United (for the Starbucks baristas) will continue to try to keep the NLRB up and running. As there’s no union involvement at SpaceX, however, Musk’s lawyers could continue unopposed if President Trump (or de facto President Musk) tells the NLRB to drop the case, and effectively, to drop out of sight. n

Janie Ekere, our John Lewis Writing Fellow since May 2024, died on December 10, just a couple of weeks shy of her 26th birthday. She was exactly the type of person those of us in journalism need to welcome into our industry. She was born into an immigrant Nigerian family in Greensboro, North Carolina, graduated from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill two years ago this month, and interned with The Daily Yonder, lifting up the struggles of the working poor in rural America, before coming to the Prospect . She had a passion for telling stories about underrepresented and marginalized communities, in part because she lived that experience.

Jessica Vega, senior policy analyst at Rhode Island Kids Count, has personal experience being caught in the payday loan debt cycle. As a college graduate living on her own for the first time, she needed cash to pay for her mounting living expenses. So, after seeing ads for payday loans and consulting a friend, she visited a payday loan center.

“I borrowed, I think it was whatever the max was at the time, which is $400, or $450,” Vega said. “They give you two weeks roughly to pay it back. So when those two weeks came, I realized I didn’t have that money. So I asked for an extension … I was constantly paying back the money because I was getting paid biweekly. So I’d pay the money, and then borrow the money again.”

Vega’s story is common among payday loan borrowers both in Rhode Island and across the country. According to a fact sheet published by

the Rhode Island Coalition for Payday Reform, three out of four payday loans are a result of “churning,” or taking out a loan to repay an existing loan that’s due. The payday loan business

model depends on longterm use, with over 60 percent of their business generated by borrowers with 12 or more loans a year.

We are a small organization, and something like this has a much greater impact on our family at the Prospect . We wanted to devote some space in this issue for Janie’s writing, to give you a sense of what she focused on and what she cared about. In the first essay in his short volume The Message , Ta-Nehisi Coates imparts to young journalists the task of “nothing less than doing their part to save the world.” Janie was doing her part: learning the rhythms and meters of journalism, learning how to elevate people in pain and grant them power. We will miss her terribly.

The high costs associated with campaigning often lead to wealthier candidates running for office, according to reporting from Carolina Public Press. These individuals have more resources to selffund their campaigns, and often attend prestigious schools and work in highpaying jobs like law, giving them additional opportunities to network with wealthy potential donors. Candidates who aren’t wealthy often lack access to large donor networks and support from their parties, and are more likely to have to rely on small individual donations.

It’s also personally expensive for candidates to run for office. Poorer candidates may still need to work their regular jobs simultaneously. They can take a salary from the campaign, a provision that was expanded last year after a working class candi

date named Nabilah Islam took her case to the Federal Election Commission. Now, nonincumbent federal candidates can pay themselves up to 50 percent of a congressional salary (which is currently $174,000), or pay equivalent to their own average annual income over the previous five years, whichever is smaller.

But that still may not be enough to manage the increased personal costs of running a campaign. As the Prospect has reported, Dan Osborn, a union steamfitter apprentice and independent candidate running for U.S. Senate in Nebraska, didn’t own a suit before a trip to Washington to meet with advocates and donors. His campaign didn’t want to pay for one out of its coffers because the law prohibits using campaign expenditures on expensive clothing.

With the possibility of another Trump presidency, Democrats have directed much media attention toward Project 2025, the 922page document laying out a farright conservative governing agenda. The policies proposed under Project 2025 range from slashing social programs to banning abortion nationwide to eliminating corporate regulations.

People in rural areas are generally

Project 2025 also calls for the elimination of the Public Service Loan Forgiveness program, which offers complete debt forgiveness for borrowers who have worked for the government or a nonprofit organization for at least ten years. The authors of the document argue that PSLF unfairly favors public sector over private sector employment.

PSLF , signed into law in 2007, was dysfunctional prior to the Biden administration, with Trump’s firstterm education secretary Betsy DeVos approving just a tiny sliver of those who applied for debt forgiveness. The Biden administration fixed the program, and by

more likely to live in poverty and lack access to important social services than their urban and suburban counterparts. So as disastrous as these policies would be for most Americans, they would hit rural communities hardest. In fact, many similar policies have already been enacted in rural parts of the country, resulting in higher poverty rates, weaker infrastructure, and poorer health outcomes.

The beliefs expressed by Robinson are part of a particular brand of Black conservatism, one that holds Black people responsible for rising above racial oppression rather than opposing it through protests or direct action. It ultimately shifts the blame for antiBlack racism from a wider system to Black individuals. And, crucially, it offers validation to white conservatives who hold similar beliefs.

this October, over one million borrowers had PSLF loans canceled.

But Trump’s return could mean that promises made on PSLF could simply be broken, with government or nonprofit workers who played by the rules on the expectation of debt relief denied cancellation and thrown into chaos. Meanwhile, Congress and the White House could attempt to end PSLF for new entrants.

“Teachers, firefighters, nurses, social workers and other public servants who are just a few months away from earning cancellation through PSLF already face enough barriers to earning the relief they’re entitled to, and a Trump presidency will work to walk back every gain debtors have made in the past four years,” said Braxton Brewington, spokesperson for the Debt Collective, a union of debtors.

Robinson’s ability to rise inside the party is interesting. It’s become increasingly common for Republican politicians to gain party prominence for controversy … Before the ascendance of the Tea Party, North Carolina Republicans tried to walk a tightrope between pushing conservative policies while still appearing more moderate, which helped them succeed against Democrats. But that strategy is difficult to maintain with candidates like Robinson, who, perhaps to capture the magic of Trump, double down on incendiary rhetoric.

Maybe the pipeline from viral comments at city council meetings to running for the highest office in a swing state will be closed for people like Robinson in the future. But given the dynamics in the Republican Party, maybe not.

Sometime between the 2024 election and the 2025 inauguration, Americans discovered that they had actually voted for Elon Musk for president. Since the election, Donald Trump has faded into the background, while center stage has been taken by the South African–born billionaire with the Twitter addiction of an adolescent, whose frenetic posts are often being treated like official government statements.

Musk and Vivek Ramaswamy have been named co chairs of the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE), which sounds like a federal agency but is actually an outside agitator, tasked with devising recommendations to reduce the size and scope of government. During the campaign, Musk

Elon Musk wants to cut government spending. But the waste in the system goes to elites like him. Here’s a better way to bring down deficits.

By David Dayen ILLUSTRATIONS

BY HUGH D’ANDRADE

said he was confident he could remove $2 trillion in unnecessary waste from the budget. If he meant annually, that’s nearly onethird of total federal expenditures.

Skepticism is heavily warranted. Presidents going back to Ronald Reagan have impaneled blue ribbon commissions to hack away at deficits, with minimal success. Nongovernmental advisers carry no formal power, and Congress holds the purse strings tightly. “One person’s waste is another person’s vital congressional jobs program,” said Michael Linden, a former official with the White House Office of Management and Budget.

There are signals that DOGE will be even more useless than its predecessors, with

early proposals consisting primarily of things that sound funny but serve valuable functions, or things that are far too minuscule to make a meaningful dent in the budget. Hilariously, Musk gave up on his $2 trillion goal before the Trump presidency even started, calling the number a “best case outcome” in an interview on his social media site and declining to identify specific cuts.

Many Republicans, however, are dead serious about slashing social spending and obliterating the administrative state. House leaders have been passing around a menu of $5.7 trillion in cuts over ten years, including a large chunk from health care and food assistance for the poor. Musk’s following

among the rank and file could provide ballast for these longheld conservative wishes, while catering to his own pocketbook in the process.

federal contractors, isn’t likely to touch any of this.

How Democrats should deal with DOGE has become a top level conversation. One school of thought argues for calling out Musk and Ramaswamy’s game of using spending cuts to make room for their own tax cuts. Others draw red lines on cherished, popular programs like Social Security and Medicare, or highlight serial conflicts of interest. Still others counsel constructive engagement.

But the focus on federal spending could also teach Americans how their government really works. I’ve tallied up the savings from redesigning a handful of policies to improve effectiveness, and you really could find $2 trillion in net annual federal outlays, with no direct impact on the most vulnerable. The key lies in knowing where to look: profithungry contractors, privatized boondoggles, systemic overpayments, and a mountain of tax avoidance.

The world’s richest man, himself a serial tax evader and one of the nation’s biggest

This article should come with a warning label: We should not cancel the equivalent of 7 percent in annual GDP all at once, which would trigger a deep recession. But identifying the real sources of inefficiency in our government—the trillions funneled to elites—can preserve resources for programs to help those in need. And it can display the values of an opposition party that has strayed from its core purpose of fighting for the little guy.

Too often, Democrats have leapt to defend institutions that most Americans look upon with scorn. Now it’s the Republicans who control all branches of government; they are the establishment in every sense of the word. The Musk/DOGE plan is one of self enrichment and outward punishment. Someone should outline a different path.

It’s hard to critique DOGE because it’s hard to divine its actual intentions. Making government more responsive can sit in tension

with cutting spending. Smaller government may be ideologically satisfying but also fantastically wasteful. And when billionaires are making the decisions, selfaggrandizement is sure to follow.

Take the preoccupation with labor costs. Ramaswamy has called for a 75 percent personnel reduction across federal agencies. This would hardly save anything. According to the Congressional Budget Office, there are about 2.3 million federal employees with total compensation in 2023 of $271 billion; that’s 4 percent of the U.S. budget. Federal employees were roughly 4.3 percent of all workers in 1960 and 1.4 percent today. As a result, we’ve seen an explosion in contractors undertaking tasks that government workers used to perform. Nearly three times as much money is spent on contractors than federal workers.

Slashing the federal workforce, almost two thirds of which is at the Departments of Defense, Veterans Affairs, and Homeland Security, would likely lead to more expensive contractors, and also increase the $247 billion in improper payments the government makes every year. “When you talk about

cutting people in the Pentagon, these are people overseeing military contracts,” said economist Dean Baker. “There’s already fraud and there would be a lot more.”

Another chunk of the bureaucracy is devoted to processing federal benefits. Social Security’s administrative costs are legendarily low, down to 0.5 percent. Cutting 75 percent of its staff would delay benefit claims, make checks more difficult to process, and invite fraudulent scams. That’s the opposite of the alleged efficiency goal. Or take what Public Citizen co president Rob Weissman calls “policymaking by anecdote.” Musk’s brainpoisoned antipathy to anything that sounds woke led him recently to attack the “fake job” of Ashley Thomas, the U.S. International Development Finance Corporation’s director of climate diversification. But Thomas has nothing to do with diversity, equity, and inclusion; she works with farmers to diversify crops, to deal with changing weather patterns. So is efficiency the goal, or merely reverse political correctness and slipshod wordpolicing?

At times, DOGE ’s goals collide with ignorance over governmental procedures. Ramaswamy claims that $516 billion could be excised by ending programs that are “unauthorized” by Congress. But in every case, lawmakers have allocated funding and therefore inherently authorized those programs, which include things like health care for nine million veterans. Congress can and should reauthorize and improve programs, but any savings would be far lower than throwing out the entire Veterans Health Administration, the Justice Department, or NASA (where Musk has had $11.8 billion in contracts over the past decade).

The closest thing to an official vision for DOGE was laid out in a Wall Street Journal

op ed with Musk and Ramaswamy’s byline. The only named programs slated for cuts are the Corporation for Public Broadcasting and Planned Parenthood, which total about .012 percent of federal expenditures. And there’s a legally suspect claim that the president can nullify congressionally appropriated spending, which would be an enormous grab at Congress’s power of the purse that would trigger a constitutional crisis.

But the main target of the op ed is regulations written by “unelected bureaucrats.” (I’m straining to understand who elected Musk or Ramaswamy.) Supreme Court rulings, the DOGE duo claim, prohibit agency discretion on rulemaking, and therefore allow the president to simply pause any regulation that he imagines exceeds congressional authority, and subsequently fire the workers overseeing them.

This isn’t what the Supreme Court said; Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo specifically protected past regulations devised under the older framework of deference to agency interpretation. And a president cannot pause regulations without going through administrative procedure, nor fire employees with civil service protections. But these halftruths do serve the goal of rolling back or curtailing enforcement of regulations, which happens to benefit companies that are habitually under regulatory scrutiny, like, oh, I don’t know, Tesla and SpaceX.

Guided by this vision, Musk will pick the lists of regulations the president can instavanish. You can see how the incentives would run. “Every regulation has net positive savings for the country,” said Weissman. “They may cost corporations, they may cost billionaires, but they do not cost the country.”

have to go because they impede the free flow of capital, or because the Securities and Exchange Commission has been fighting with Musk for seven years?

Maybe it seems too parochial to suggest that the “government efficiency” effort is simply cover for defunding Elon Musk’s regulatory police, steering more contracts his way, depriving rivals of the same treatment he gets, and building oligarchy in America. Maybe Musk is a real efficiency expert who wants to bring his style of business cuts to government as a public service. Maybe he’s truly concerned about burdens being left to his children and grandchildren. Maybe he will nobly share in the sacrifice.

Color me unconvinced. And let me submit as evidence a litany of items that DOGE is likely to leave mostly untouched in its drive for austerity.

The federal government is often described as a health insurance company with an army. About 75 percent of all spending is concentrated in four buckets: Social Security payments, health care programs (e.g., Medicare and Medicaid), veterans’ benefits, and the Department of Defense. If you’re not touching them, to cut $2 trillion you’d have to eliminate everything else government does, in total.

But health care in particular is lousy with private sector profiteering, providing several options for savings.

Nearly 33 million seniors are enrolled in Medicare Advantage, a private insurance substitute for traditional Medicare. It’s heavily advertised to seniors as offering better benefits (including gym memberships and wellness programs) at a lower cost. And it’s true that MA plans typically include dental, hearing, and vision coverage, which is not part of traditional Medicare, as well as reduced premiums.

In this sense, DOGE intends to rewire government for personal use. Ramaswamy has taken unusual interest in a $6.6 billion Department of Energy loan to electric truck manufacturer Rivian. Which electricvehicle maker do you suppose would like to cancel government support for a rival? Musk has also targeted the bipartisan infrastructure law’s program to build out rural broadband; might he be mad about how his own broadband service, Starlink, was excluded from the grant process, and want to reverse that? Is high speed rail development truly a “wasteful” program, or an old vendetta from a car manufacturer who opposes mass transit? Do bank regulators

But Medicare Advantage has been criticized heavily for overbilling the government, not just by liberal activists but also by goldstandard independent auditors. The Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (Med PAC), a congressionally established expert panel, calculated that Medicare Advantage overpayments came to $83 billion in 2024 alone.

There are two reasons for these overpayments. First, Medicare reimbursement is weighted depending on the health of the patient. Insurers are compensated at higher THE MUSK/DOGE PLAN IS ONE OF SELFENRICHMENT AND

levels for enrolling sicker patients with more diagnostic codes that correspond to ailments. Insurers have exploited this in Medicare Advantage by “upcoding” patients to make them appear sicker, regardless of the actual care they receive. The Wall Street Journal recently found that UnitedHealth, the leading MA plan sponsor and also the largest employer of doctors in the U.S., routinely encouraged its doctors to add codes to their patients.

Physicians for a National Health Program (PNHP), which advocates for a singlepayer system, noticed even greater savings potential in the MedPAC report. Traditional Medicare sets a “benchmark” for spending on the average beneficiary. Several studies have shown that MA plans spend between 11 and 14 percent less, because they cherrypick healthier patients, even after accounting for upcoding to make them look sicker. Increasing denials of care allows MA plans to rake in even more profit.

In all, PNHP found that MA plans charge the government at rates $140 billion per year higher than traditional Medicare. Dr. Ed Weisbart, national board secretary with PNHP, estimated that Congress could use savings from MA overpayments to add an out ofpocket spending cap, a public drug benefit, and dental, hearing, and vision benefits to traditional Medicare, and have tens of billions left over.

“If you’re serious about DOGE , here’s something you can do,” said Weisbart. “At least let’s agree that Medicare Advantage is being outrageously subsidized.” But with the incoming administrator of Medicare and Medicaid, Dr. Oz, a longtime booster of Medicare Advantage, that’s an unlikely avenue for DOGE

Reforming physician pay schedules for Medicare could yield more savings. As my colleague Robert Kuttner has written, pay rates are determined mostly by a secretive advisory committee mostly made up of specialists, who give themselves higher reimbursements at the expense of primary care. The government rubberstamps the recommendations, and private insurers typically use them as a benchmark. Lowering these rates, which incoming Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. has expressed interest in, would not only slash specialist pay but properly value primary care, reducing health expenditures over time by finding medical problems before they fester.

Dean Baker estimates that bringing U.S.

doctor pay (now at $350,000 per year on average) to the level of physicians in Germany or Canada would reduce national health expenditures by around $200 billion per year. Some of that could be done through reductions in the federal pay schedule, but allowing qualified doctors in other countries to practice in the U.S. could also constrain costs through competition. “We have free trade in manufactured goods but we don’t do anything in services,” Baker said. “It would still be a wellpaid profession, just not as much as it is now.”

Federal health programs like Medicare (which serves 68 million enrollees) and Medicaid (72 million) account for roughly half of all national health expenditures. So a good estimate for federal savings would be $100 billion per year.

The government also spends massive amounts of money on prescription drugs. In 2022, U.S. drug prices were 178 percent higher than in 33 other industrialized nations, according to a report funded by the Department of Health and Human Services. Some of these drugs are sold at 20 to 30 times the cost of production and distribution; pharmaceutical profit margins are significantly higher than private sector counterparts.

Democrats did take some action in 2022 by allowing Medicare to negotiate drug prices with manufacturers for the first time; new prices on ten drugs will begin to come online in 2026. But more can be done. “It’s not all drugs right away negotiated to the best price possible. Anyone would look at that deal and say you should get the best deal right away,” said pharma activist Alex Lawson of Social Security Works.