DAVID DAYEN: THE SUPREME COURT HOBBLES CONGRESS

PAUL STARR: CAN DEMOCRATS WIN BACK YOUNG MEN?

DAVID DAYEN: THE SUPREME COURT HOBBLES CONGRESS

PAUL STARR: CAN DEMOCRATS WIN BACK YOUNG MEN?

Election 2024 Where Kamala Harris and Donald Trump stand on the issues

$49.99 hardcover | 326 pages | 6 x 9

ISBN 978-1-4813-2241-6

THE LONG- AWAITED ACCOUNT OF THE MAKING OF GARY DORRIEN

“Gary Dorrien is the greatest Christian ethicist since the legendary Reinhold Niebuhr. Yet his working class origins, deep philosophical probing, and especially his genuine roots in the Black prophetic tradition take him beyond Niebuhr in serious and substantive ways. What a great intellectual and spiritual gift his life and book are to us in these grim times!”

—CORNEL WEST, DietrichBonhoefferProfessorofPhilosophyandChristianPractice, UnionTheologicalSeminary

“Dorrien artfully weaves his life story together with an intellectual history of twentieth-century progressive political movements (secular and religious) and their interface with socially engaged theologies. He takes us on a dazzling tour!”

—CYNTHIA MOE-LOBEDA, ProfessorofTheologicalandSocialEthics, PacificLutheranTheologicalSeminaryandGraduateTheologicalUnionCoreDoctoralFaculty

“This riveting and beautiful book is the remarkable story of how Gary Dorrien became Gary Dorrien, how a shy athlete from rural Michigan became the foremost religious historian and theological ethicist of our time.”

—DEMIAN WHEELER, SophiaAssociateProfessorofReligiousandTheologicalStudies, UnitedTheologicalSeminaryoftheTwinCities

24 How Congress Gets Its Groove Back

The Supreme Court’s recent rulings will change how Congress writes laws. It may even force the legislative branch to take a hard look at its own dysfunctions. By David

Dayen

34 An Epic Dystopia

How a near-monopoly gained control of most of the nation’s electronic medical records, to the detriment of medical practice and doctor morale.

By Robert Kuttner

42 A Ponzi Scheme of Promises

Five years after the Business Roundtable ‘redefined’ the purpose of the corporation, has anything changed?

By Adam M. Lowenstein

I’m writing this with weeks to go in one of the stranger election seasons of my lifetime, which started with the two oldest candidates in American history and the first presidential rematch since 1892, saw one tag out after a debate collapse, then saw the other have a rather similar debate collapse at the hands of his new opponent. But the oddity is just as much about what we’re spending our time discussing, despite all the nation’s challenges at home and abroad.

With every topic Republicans hoped to exploit—Mexican border crossings, inflation, crime rates—suddenly no longer statistical liabilities, a multiday news cycle was instead invented about the presence of Haitian immigrants in a relatively small city in a non-swing state. Accusing migrants of eating pets has a tragically long and racist history, intended to demonize outsiders and drive tribal divisions. It’s disgraceful, and even though Donald Trump is exactly who you would expect to say it, it’s also a sign that his political movement is truly incapable of pursuing anything else.

Brazen nativism demands a forceful response; anyway, that’s how it feels in the moment. But of course, that’s just what nativists want. They want to play on fears and insecurities and blot out the concerns of the American people with a face they can call a savage. Instead of lunging at where the nihilists want to lead us, we can pull back and look at what they don’t want you to see.

So in this pre-election issue, we have a series of comparative studies between the candidates, on issues that don’t always get elevated to the front lines of national politics: RYAN COOPER on climate and energy, JANIE EKERE on rural America, LUKE GOLDSTEIN on corporate power and market structure, SUZANNE GORDON and STEVE EARLY on veterans’ health care, ERIK LOOMIS on the stewardship of public lands, and SARAH LEAH WHITSON on geopolitics in the Middle East.

There are of course many other areas that matter in this election: abortion rights, the future of Medicare and Social Security, the war in Ukraine, and a tax fight that will dominate headlines throughout 2025 regardless of who wins. But at the Prospect, we try to fill the gaps in coverage on the progressive left, and bring you information that you might not get elsewhere.

We’re doing the same thing throughout the election, with our reporters visiting the battlegrounds, walking along on the voter canvasses, taking in the rallies, talking to the voters, and getting to the truth. If you visit prospect.org throughout the election, we will have Election 2024 coverage from across the country that you can use to be more informed about what really matters.

And if you’re a subscriber, I have some other surprise news for you: This is not the only magazine you’ll be getting from us this October! Keep checking your mailbox for a special issue that I think you’re really going to enjoy.

Politicians, operatives, and hangers-on want to distract you. We don’t have to let them. We find stories about ideas, politics, and power, and shine a bright light for all to see. Thank you for joining us in that collective journey of understanding. –David Dayen

EXECUTIVE EDITOR DAVID DAYEN

FOUNDING CO-EDITORS

ROBERT KUTTNER, PAUL STARR CO-FOUNDER ROBERT B. REICH

EDITOR AT LARGE HAROLD MEYERSON

EXECUTIVE EDITOR David Dayen

SENIOR EDITOR GABRIELLE GURLEY

MANAGING EDITOR RYAN COOPER

FOUNDING CO-EDITORS Robert Kuttner, Paul Starr

ART DIRECTOR JANDOS ROTHSTEIN

CO-FOUNDER Robert B. Reich

ASSOCIATE EDITOR SUSANNA BEISER

EDITOR AT LARGE Harold Meyerson

STAFF WRITER HASSAN KANU

SENIOR EDITOR Gabrielle Gurley

MANAGING EDITOR Ryan Cooper

WRITING FELLOWS JANIE EKERE, LUKE GOLDSTEIN, EMMA JANSSEN

ART DIRECTOR Jandos Rothstein

ASSOCIATE EDITOR Susanna Beiser

INTERNS RACHAEL DZIABA, YUNIOR RIVAS GARCIA, K SLADE, MACY STACHER

STAFF WRITER Hassan Kanu

WRITING FELLOW Luke Goldstein

INTERNS Thomas Balmat, Lia Chien, Gerard Edic, Katie Farthing

CONTRIBUTING EDITORS AUSTIN AHLMAN, MARCIA ANGELL, GABRIEL ARANA, DAVID BACON, JAMELLE BOUIE, JONATHAN COHN, ANN CRITTENDEN, GARRETT EPPS, JEFF FAUX, FRANCESCA FIORENTINI, MICHELLE GOLDBERG, GERSHOM GORENBERG, E.J. GRAFF, JONATHAN GUYER, BOB HERBERT, ARLIE HOCHSCHILD, CHRISTOPHER JENCKS, JOHN B. JUDIS, RANDALL KENNEDY, BOB MOSER, KAREN PAGET, SARAH POSNER, JEDEDIAH PURDY, ROBERT D. PUTNAM, RICHARD ROTHSTEIN, ADELE M. STAN, DEBORAH A. STONE, MAUREEN TKACIK, MICHAEL TOMASKY, PAUL WALDMAN, SAM WANG, WILLIAM JULIUS WILSON, MATTHEW YGLESIAS, JULIAN ZELIZER

PUBLISHER MITCHELL GRUMMON

PUBLIC RELATIONS SPECIALIST TISYA MAVURAM

CONTRIBUTING EDITORS Austin Ahlman, Marcia Angell, Gabriel Arana, David Bacon, Jamelle Bouie, Jonathan Cohn, Ann Crittenden, Garrett Epps, Jeff Faux, Francesca Fiorentini, Michelle Goldberg, Gershom Gorenberg, E.J. Graff, Jonathan Guyer, Bob Herbert, Arlie Hochschild, Christopher Jencks, John B. Judis, Randall Kennedy, Bob Moser, Karen Paget, Sarah Posner, Jedediah Purdy, Robert D. Putnam, Richard Rothstein, Adele M. Stan, Deborah A. Stone, Maureen Tkacik, Michael Tomasky, Paul Waldman, Sam Wang, William Julius Wilson, Matthew Yglesias, Julian Zelizer

PUBLISHER Ellen J. Meany

ADMINISTRATIVE COORDINATOR LAUREN PFEIL

PUBLIC RELATIONS SPECIALIST Tisya Mavuram

ADMINISTRATIVE COORDINATOR Lauren Pfeil

BOARD OF DIRECTORS DAVID DAYEN, REBECCA DIXON, SHANTI FRY, STANLEY B. GREENBERG, MITCHELL GRUMMON, JACOB S. HACKER, AMY HANAUER, JONATHAN HART, DERRICK JACKSON, RANDALL KENNEDY, ROBERT KUTTNER, JAVIER MORILLO, MILES RAPOPORT, JANET SHENK, ADELE SIMMONS, GANESH SITARAMAN, PAUL STARR, MICHAEL STERN, VALERIE WILSON

BOARD OF DIRECTORS David Dayen, Rebecca Dixon, Shanti Fry, Stanley B. Greenberg, Jacob S. Hacker, Amy Hanauer, Jonathan Hart, Derrick Jackson, Randall Kennedy, Robert Kuttner, Ellen J. Meany, Javier Morillo, Miles Rapoport, Janet Shenk, Adele Simmons, Ganesh Sitaraman, Paul Starr, Michael Stern, Valerie Wilson

PRINT SUBSCRIPTION RATES $60 (U.S. ONLY) $72 (CANADA AND OTHER INTERNATIONAL) CUSTOMER SERVICE 202-776-0730 OR info@prospect.org

PRINT SUBSCRIPTION RATES $60 (U.S. ONLY) $72 (CANADA AND OTHER INTERNATIONAL) CUSTOMER SERVICE 202-776-0730 OR INFO@PROSPECT.ORG MEMBERSHIPS PROSPECT.ORG/MEMBERSHIP REPRINTS PROSPECT.ORG/PERMISSIONS

MEMBERSHIPS prospect.org/membership REPRINTS prospect.org/permissions

VOL. 35, NO. 5. The American Prospect (ISSN 1049 -7285) Published bimonthly by American Prospect, Inc., 1225 Eye Street NW, Suite 600, Washington, D.C. 20005. Periodicals postage paid at Washington, D.C., and additional mailing offices. Copyright ©2024 by American Prospect, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this periodical may be reproduced without consent. The American Prospect ® is a registered trademark of American Prospect, Inc. POSTMASTER: Please send address changes to American Prospect, 1225 Eye St. NW, Ste. 600, Washington, D.C. 20005. PRINTED IN THE U.S.A.

Vol. 35, No. 3. The American Prospect (ISSN 1049 -7285) Published bimonthly by American Prospect, Inc., 1225 Eye Street NW, Suite 600, Washington, D.C. 20005. Periodicals postage paid at Washington, D.C., and additional mailing offices. Copyright ©2024 by American Prospect, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this periodical may be reproduced without consent. The American Prospect ® is a registered trademark of American Prospect, Inc. POSTMASTER: Please send address changes to American Prospect, 1225 Eye St. NW, Ste. 600, Washington, D.C. 20005. PRINTED IN THE U.S.A.

Every digital membership level includes the option to receive our print magazine by mail, or a renewal of your current print subscription. Plus, you’ll have your choice of newsletters, discounts on Prospect merchandise, access to Prospect events, and much more. Find out more at prospect.org/membership

Update Your Current Print Subscription prospect.org/my-TAP

You may log in to your account to renew, or for a change of address, to give a gift or purchase back issues, or to manage your payments. You will need your account number and zip-code from the label:

ACCOUNT NUMBER ZIP-CODE

EXPIRATION DATE & MEMBER LEVEL, IF APPLICABLE

To renew your subscription by mail, please send your mailing address along with a check or money order for $60 (U.S. only) or $72 (Canada and other international) to: The American Prospect

1225 Eye Street NW, Suite 600, Washington, D.C. 20005 info@prospect.org | 1-202-776-0730

Franklin D. Roosevelt traveled to Yalta to meet with Winston Churchill and Joseph Stalin to make decisions on the war’s endgame and the shape of the postwar world. FDR had met repeatedly with Churchill and his entourage during the war, and once, in Tehran in 1943, with Stalin and his aides. Looking across the table at Stalin’s advisers, however, he saw one he hadn’t met before.

“Who’s that?” Roosevelt asked Stalin.

“That’s Beria,” Stalin replied, then adding helpfully, “my Himmler.”

I cite this exchange as a way of describing, as this issue of the Prospect endeavors to do, the stakes in the upcoming presidential election. And I can think of no better way to begin that discussion by noting that Donald Trump has his own Himmler: Stephen Miller.

I hasten to explain that I don’t mean Miller plans or desires to kill anyone; by all available evidence, his is not an agenda of extermination. But anyone who remembers Trump’s war on undocumented immigrants during his previous go-round as president can have little doubt that it will be Miller who will be charged with carrying out one of the few specific pledges that Trump has made repeatedly in the course of this year’s campaigning: forcibly rounding up all 12 million undocumented immigrants (in the ABC debate, Trump put the “real” number at 21 million), placing them in concentration camps along the border, and expelling them to their nations of origin, even if they’ve

lived and worked in the United States for many decades, even if they’re the parents of children who are U.S. citizens.

It was Miller, after all, who ran Trump’s war on immigrants when Trump was in the White House previously. It was Miller who devised and championed the shortlived policy of banning all immigration from seven Muslim countries. It was Miller who devised and championed the practice of separating children, even infants, from their parents at the border, with utter indifference to how and whether these families could ever be reunited. It was Miller who capitalized on the pandemic to lock out all immigrants at the border on the basis of public health. And it was Miller who ran roughshod over administration officials who lacked sufficient zeal to expedite the arrests and expulsions of the undocumented.

Unlike many Trump administration functionaries, Miller was a hard-working and diligent channeler of Trump’s most brutal instincts. He made clear those were his instincts, too, and dealt harshly with colleagues whose cruelty he found lacking. (One such insufficiently zealous figure was Homeland Security Secretary Kirstjen Nielsen, whose resignation Miller effectively forced.)

I dwell on Miller because it’s clear he will be the anti-immigrant czar of a second Trump administration, almost certain to prompt Trump to call out the National Guard when big-city police fall short in arresting immigrants, and to use the threat of force, and

force itself, when both immigrants and citizens resist the mass arrests, the concentration camps, and the deportations. Nor will his portfolio be limited to immigration: During Trump’s term as president, his title was senior adviser, in which capacity he was—and surely would be in a second Trump term—the most avid proponent of a top-down civil war on the media and other elements of our civil society opposed to autocracy and the right-wing politicization of the administration of justice.

I also dwell on Miller because if Trump prevails at the polls, Miller will not be the odd man in this time around. In 2017, Miller was more of a freelancer. There was not yet a full cadre of dedicated Trumpians with whom Trump could fill his administration.

From James “Mad Dog” Mattis to William Barr (a zealous right-winger but not an election denier), there were powerful appointees who hadn’t drunk all of Trump’s Kool-Aid. Miller, by contrast, wasn’t merely the dedicated delivery boy of Trump’s furies; he brought furies of his own to the fray.

This time around, the entire Trump administration will be staffed by the fury-filled. This will be the Stephen Miller presidency.

Much of the discussion of a second Trump term has focused on economics and foreign policy: what across-the-board high tariffs would do to Americans’ cost of living, what the renewal of Trump’s expiring tax cuts would do to our already stratospheric levels of inequality, and what Trump’s affinity for foreign autocrats would mean for defenders, both foreign and domestic, of democracy. Despite the lip service that both Trump and J.D. Vance have given to the cause of American workers, their policy toward organized labor will surely be that of Trump’s designated “efficiency czar” Elon Musk, whose call for the immediate firing of striking workers who seek a voice on the job was echoed by Trump in their two-hour meandering discourse on X.

Despite Trump’s drumbeating for economic nationalism, the tariffs he slapped on Chinese and other imported products during his presidency did nothing to jump-start a return of American manufacturing. To the contrary, it was President Biden’s turn to industrial policy that prompted the first measurable increase in factory construction that the nation has seen in decades. The tax credits going to companies that mean to build electric vehicles or computer chips or other elements of a green economy

increased domestic factory construction by more than 70 percent over previous years. Likewise with infrastructure. Despite Trump’s annual proclamations of “infrastructure weeks,” the dollar amounts he asked Congress to provide for rebuilding roads, bridges, airports, and the digital infrastructure were so meager that Congress could never construct a plausible program with them. Biden, by contrast, won sizable bipartisan support for the massive repair job that the nation needs, and without which a renewed industrial sector (or any economic sector, for that matter) cannot flourish.

Trump’s personal stake in the quiet movement of money across borders may also stand at odds with his vows of economic nationalism. It’s unimaginable that Trump would do anything to impede the characteristically concealed and laundered shifting of vast sums of money from country to country, autocrat to autocrat, that has become a regular feature of global capitalism. Indeed, it’s a good deal more imaginable that Trump might personal-

the funds needed to rebuild industry and infrastructure were instead showered on corporations, whose taxes were cut from 35 percent to 21 percent. Now Trump is proposing to lower those tax rates even more. By contrast, industrial-policy investments have become a hallmark of today’s Democratic Party, and would surely be prominent in a Kamala Harris administration.

Harris has made clear that if elected, she’ll augment Biden’s signature investments in the industrial and transportation sectors with major investments in what she terms “the care economy”: helping working- and middle-class families find affordable child care and elder care, permanently expanding the Child Tax Credit, and enacting paid family and medical leave. She’s also broadened her economic agenda to include tax breaks for small businesses. Like her care economy package, this is a cross-class pitch that Latinos and Asian Americans in particular (both groups that have high levels of smallbusiness formation) might welcome.

ly benefit from such movements of money. The insufficiently explored allegation that Trump was offered $10 million in cash from the government of Egypt five days before he became president suggests that, well, he might.

Trump’s version of economic nationalism focuses, like his immigration policy, on walling off the country to outsiders. But he is too existentially bound to his personalized version of laissez-faire capitalism—namely, tax cuts and deregulation—to do what’s required for a more vibrant and egalitarian domestic economy. During his presidency,

This economic stool, however, still needs a third leg: a commitment to a “build economy” that surpasses Harris’s vow to have the government aid in the construction of three million new homes over the next decade. To address the anxieties of working-class men—a demographic where Democrats desperately need to do better—she should pledge to create an outreach agency funneling willing workers into the construction unions’ apprenticeship programs, with appropriations to enlarge those programs, and tax credits and other funding to raise the homebuilding target well above three million. That would be both good long-term policy and good long-term and short-term politics.

Though the funding for all these longoverdue investments in working- and middle-class America will come from higher taxes on the rich and corporations, my colleague David Dayen has pointed out that some leading Democrats have already com-

mitted themselves to tax cuts of their own. Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer, for instance, has called for ending the limit on the federal income tax deduction for state and local taxes based on property assessments. Such cuts would constrict Harris’s ability to fund her expansions of assistance to working- and middle-class Americans. As president, Harris would have to rein in some of her colleagues to deliver on her promises. And should she win, it’s those promises that will have been a clear factor in her victory.

But other factors will be in play as well.

Perhaps the strongest card in Harris’s hand is the 21st-century version of Warren Harding’s 1920 Republican presidential campaign: Her election would mark a return to “normalcy.” To be sure, for Trump and the MAGA faithful, the presidency of a BlackAsian woman who is also a mainstream Democrat has nothing “normal” about it. To them, it signals the further fall of America into something new, unsettling, and subversive of the white and patriarchal America of whose restoration they dream.

But both non- MAGA Americans and swing voters alike know that a second Trump stint inescapably brings with it a loud and unending war on enemies both real and imagined, a constant disruption of the civic order through his lashings out at those against whom he harbors a raging fury for political and personal affronts. That’s why Joe Biden used this normalcy frame successfully in 2020: He called it a battle for the soul of America.

Harris similarly offers the prospect of a White House not wrapped up in the private hatreds of a wounded narcissist or the public hatreds of a casual bigot. Her claim to normalcy is that she’ll do the public’s business minus the obsessive personal insecurities that structure everything Trump does.

Trump’s enemies list is both dangerous and ridiculous; his inability to keep his daily rants from sounding ridiculous can lead a wearied public to discount the dangers they present. But in a second Trump term, the danger will be far greater than it was in the first. A second Trump administration will be almost uniformly staffed with aides who share his bigotries and hatreds, and have no hesitation wielding the power of the state, as untrammeled as the Trumpian courts will allow, against these “enemies.” One of those aides will be Stephen Miller. Trump’s Himmler. That’s what’s at stake in this election. n

The Biden-Harris administration sowed the seeds of a green American economy. A second Trump term would poison them.

By Ryan Cooper

The Biden administration undoubtedly has the best climate policy record of any president in history. Even granting that almost no other presidents even tried, President Biden and the Democratic Congress in 2021-2022

got a shocking amount done, especially given their razor-thin margin in the Senate.

The three principal laws Biden signed are the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), by far the largest climate policy package in history, at roughly between $800 billion and $1.2 trillion in size (depending on who you ask); the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA), a more traditional bill with about $500 billion for transit, passenger and freight rail, EV chargers, and

upgrades to the electric grid (as well as more for highways and such); and the CHIPS and Science Act, which authorizes about $280 billion to stand up a domestic advanced manufacturing industry for semiconductors and other high-tech industries, as well as funding more scientific research and much else. In addition, the administration has put through a blizzard of new regulations and standards to reduce carbon pollution, some independently and some as part of these new laws.

The basic goal here is to decarbonize electricity generation and electrify everything. Simultaneously, policymakers would replace all the fossil fuel–powered power plants—already in progress with the explosion in wind and solar power— while replacing all the fossil fuel–powered transportation, cement and steel production, manufacturing, agriculture, and so forth with electric versions. Technologies to do this are either already in wide use (EVs), being rolled out (green steel), in the prototype stage (industrial heat), or on the drawing board (carbon capture).

Overall, the 2024 edition of Princeton’s REPEAT Project report estimates that these laws got us about halfway to America’s stated climate goal of a 50 percent reduction in emissions (from the peak in 2005) by 2030 and thence to net zero by 2050.

Yet all those accomplishments are under threat. Should Donald Trump win another term, he would likely do serious damage to this climate policy framework, and potentially engender so much economic chaos that the entire planet’s climate efforts would be greatly set back. On the other hand, if Kamala Harris wins, she at least will have another four years to cement her predecessor’s legacy—and should the Democrats win control of Congress at some point during her presidency, she would get a chance to build on Biden’s foundation.

Let me start with the bad.

Trump has at various points promised to repeal the IRA ; re-withdraw from the Paris climate accords that Biden rejoined; revoke Biden’s regulations on power plant pollution, vehicle emissions, and fuel efficiency; revoke his limitations on oil and gas drilling; and much else. The Heritage Foundation’s Project 2025 blueprint for a second Trump term, overwhelmingly written by former Trump staffers and associates, is much more specific and extreme, essentially arguing for a wholesale gutting of the government’s capacity to protect the environment in any way.

As usual with Trump, it’s anybody’s guess what he would actually do in office. In April, he openly attempted to shake down a group of oil executives for a $1 billion campaign contribution, promising just about everything on the Big Oil wish list in return. Trump has long nurtured a bizarre prejudice against renewable energy, especially windmills, which he has claimed produce

Should Donald Trump win another term, he would likely do serious damage to Joe Biden’s climate policy framework.

“tremendous fumes” and kill whales, without evidence. (Apparently, this goes back to a wind farm built near Trump’s golf course in Aberdeen, Scotland; he thought it ruined the view.)

On the other hand, Trump recently made an abrupt about-face on electric cars “because Elon endorsed me,” and many Republican districts have benefited disproportionately from IRA spending. Several House Republican lawmakers have warned against eliminating IRA tax credits because of the impact on jobs in their districts. We all remember the last time Republicans had a trifecta in 2017-2018; they failed to repeal their previous bugbear—Obamacare— though only by one vote in the Senate.

On balance, I judge that it is highly likely that under a GOP trifecta, Trump would sign at least a partial repeal of the IRA . The pressure to inflict pain on liberals by ripping out Biden’s biggest legislative achievement would be overwhelming. And unlike repealing Obamacare, which would have thrown something like 24 million people off their health insurance, the damage from tearing up the IRA would be somewhat contained initially. It would only be later, when the American economy fell into backwardness and stagnation, that the true damage would be felt. America’s climate progress as well as its toehold on the industries of the future would be set back, possibly permanently. Whatever happens in Congress, the threat to Biden’s regulatory agenda on climate is clear. Despite Trump’s duplicitous disavowals of Project 2025, if his first term is any indication his laziness and incuriosity will give the lunatic rank and file in the conservative movement great latitude to do whatever they want.

But perhaps the greatest danger is Trump’s personality itself. In his first term, he started innumerable deranged trade fights with China, Europe, and anyone else who drew his random ire. In his second term, not only would he be even more erratic

as his obvious mental decline gathers pace, he would also have few or no institutional restraints. Virtually all Republicans who challenged or tried to contain Trump’s spiteful outbursts in his first term (with modest success) have been driven out of the party. The court system is full of his own appointees ready to rule in his favor—most importantly the Supreme Court, which has already assured him that he would be for all practical purposes immune from prosecution for any crime committed in office.

It’s impossible to say with any certainty what would happen if Trump carries out his plan to get rid of the income tax and replace it with tariffs—which if you do the math would have to be something like 133 percent—or his promise to put a 60 percent tariff on every Chinese import and a 10 percent one on everything else. At a minimum, it would start the biggest trade war in world history, with America against every country in the world.

The United States, as the global hegemon, is the keystone of the world economic system. It controls the pipelines of international finance (in part through its alliances), its dollar is the global reserve currency, its central bank serves as the lender of last resort for half the planet, and most importantly for our purposes, it has long been the global consumer of last resort through its enormous trade deficit.

There are many critics of the American economic order, including lots of Americans. But simply dropping a cluster bomb in the middle of the global economic system, without so much as a napkin sketch for what might replace it, would be unimaginable. Potentially most of the vast network of global supply chains—which as the pandemic revealed, are quite delicate—would be damaged or shattered. A tidal wave of bankruptcies, unemployment, and a deep global recession would be likely. And that would come at the worst possible time, amid the ongoing process of restructuring the global economy around green energy. This would be thrown into utter chaos, sending global temperatures soaring.

Trump might blink at this prospect, but the man was a loose cannon even before his brain started falling apart. Eliminating that risk would be worth paying almost any price.

If we look on the bright side, we can do much better than continuing the status quo. A

Harris administration could improve on her predecessor’s record, especially if her party manages to regain total control of Congress.

Even without Congress, Harris would be able to preserve the structure of Biden’s climate policy. One central goal of the IRA was to provide a full decade of policy certainty around subsidies for clean-energy installation and production, which had been previously yanked up and down willy-nilly, causing repeated chaos in the industry. Just having a Democrat in the White House (absent some debt ceiling showdown at least) would keep the current exponential growth of green energy and industry going.

Second, Harris could continue moving implementation forward. Despite heroic efforts from the federal bureaucracy,

door as of this April. More has been done since then, but much more remains.

Third and most promisingly, if the Democrats maintain control of Congress, a Harris administration would have an opportunity to pass new legislation. The nonprofit Evergreen Action, founded by a group of Washington Gov. Jay Inslee’s former presidential campaign staffers and an influential player in the design of the IRA , has identified several policy arenas that need legislative attention, including the electric grid, industry, transportation, building efficiency, and international diplomacy. “With the Harris administration, we have a fighting chance to achieve our climate goals and usher in the future she is running on: growing the middle class through clean-energy jobs, decreasing pollution and creating health-

a tremendous pile of paperwork remains before these laws can be developed to their full potential. Requirements, standards, rules, and much else must be written and put through the grinding administrative process before subsidies can flow. Under Biden, only about 17 percent of the $1.6 trillion authorized in his climate bills and the American Rescue Plan had gotten out the

ier communities, and a growing economy based on clean-energy technology,” Lena Moffitt, executive director of Evergreen, told the Prospect in an interview.

Again, much progress has been made. But for all the components of Biden’s incipient strategy to reach the required scale in time, the transition to renewable energy must be greatly accelerated. More subsidies are

needed for green industrial technology and agriculture, as well as more research into zero-carbon aviation and carbon capture. Probably the biggest general goal should be to speed up the pace of government. From the local up to the federal level, climate projects of all kinds have been caught up in America’s Kafkaesque and glacially slow bureaucratic process—especially by how long things can be tied up in the courts. At the national level, a high-voltage transmission line between what will be the largest wind farm in the Western Hemisphere and Phoenix, Arizona, has been stuck in legal limbo for more than 18 years, with no end in sight. About 1,400 gigawatts of renewableenergy proposals—or more than five times as much as exists at present—are stuck in the “interconnection queue” waiting for approval to connect to the grid. At the household level, a major reason why American rooftop solar installations cost roughly three times as much as they do in Australia is the elaborate permitting process here, which often varies dramatically between locations.

A recent analysis from the Energy Innovation think tank put some numbers on the possibilities here. They examined a bestcase scenario for Harris versus the Project 2025 plan for Trump. For Harris, they estimated that by 2030, she would actually beat the 50 percent emissions reduction target slightly (and hit net zero by 2050), add 2.2 million jobs, save $7.7 billion in yearly household energy costs, increase GDP by $450 billion per year, and prevent 3,900 early deaths from air pollution.

For Trump, they estimated that by 2030, he would stall out emission cuts (meaning an increase relative to Harris by 1.75 billion metric tons per year), destroy 1.7 million jobs, increase household energy spending by $32 billion, decrease GDP by $320 billion per year, and increase early deaths caused by air pollution by 2,100.

In sum, a second Trump administration would mean major job losses, reduced growth, a loss of the 21st century’s cuttingedge industries, great harm to the climate, and possibly a global economic crisis. A Harris administration would mean more jobs, more growth, and advances in America’s technological edge. And should the Democrats win control of Congress during her term, America may just possibly do our entire part to fight climate change for the first time. Let’s call it lose-lose-lose-lose versus win-win-win-win. n

Trump is promising major disruptions for small-town communities. Yet residents still favor him over Kamala Harris’s development and investment approach.

By Janie Ekere

With the possibility of another Trump presidency, Democrats have directed much media attention toward Project 2025, the 922-page document laying out a far-right conservative governing agenda. The policies proposed under Project 2025 range from slashing social programs to banning abortion nationwide to eliminating corporate regulations.

People in rural areas are generally more likely to live in poverty and lack access to important social services than their urban and suburban counterparts. So as disastrous as these policies would be for most Americans, they would hit rural communi-

trade policy, corporate concentration, and climate change.

Consolidation affects various parts of the rural economy, but it’s especially prominent in agriculture. Large companies like Tyson and Smithfield receive the bulk of government agricultural subsidies and can use their economic and political power to control various aspects of agricultural production. Small farmers—especially young, female, and minority farmers—struggle to compete, often going into debt or being forced to sell their land. Even the inputs for farming, like seeds and equipment, are dominated by big players like Bayer and John Deere.

ties hardest. In fact, many similar policies have already been enacted in rural parts of the country, resulting in higher poverty rates, weaker infrastructure, and poorer health outcomes.

The Biden administration has received praise for its work in breaking up corporate monopolies, revitalizing infrastructure, and funding social programs for low-income households. These policies have played an outsize role in strengthening America’s rural communities, from improving health outcomes to increasing economic participation. But questions remain about whether these rural revitalization efforts will continue under either a Harris or Trump presidency.

Agriculture sits at the intersection of many, though not all, aspects of rural policymaking. Not only does it concern America’s food system, but it’s also relevant to issues like

There are laws in place to ensure fair prices and markets for smaller farmers, like the Packers and Stockyards Act of 1921, which governs livestock and poultry production. But the Trump administration weakened those laws on behalf of big agricultural companies. They even eliminated the division of the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) meant to enforce the Packers and Stockyards Act, and folded its duties into the Agricultural Marketing Service.

The Biden-Harris administration’s pursuit of antitrust legislation has started to level the playing field for small farmers. For example, the USDA has enacted clearer standards under the Packers and Stockyards Act to prevent discrimination, retaliation, and deceptive practices against livestock producers. The Federal Trade Commission and the Department of Justice have halted multiple mergers, stemming corporate monopolization in industries like food and shipping. And the DOJ filed suit against Agri Stats, a middleman that gathered comprehensive data about poultry and other meat markets and enabled large farming interests to effectively collude to raise prices.

“When you start taking on big corporations, you help workers and small businesses everywhere, but especially in rural communities. Because in rural places, the economies are much less diverse, so one or two big corporations can run the show,” said Anthony Flaccavento, co-founder and executive director of the Rural Urban Bridge Initiative.

A Trump presidency could end these regulatory efforts. Project 2025 specifically states that departments like the USDA “should play a limited role” in agricultural markets, focusing on removing “governmental barriers that hinder food production.” One of those so-called “barriers” is sustainable agriculture.

Through the Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP), the Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) offers food producers technical and financial assistance to engage in climate-friendly agricultural practices. But much of the money going toward EQIP has been funneled to corporations whose practices are damaging the environment, said Sean Carroll with Land Stewardship Action.

“When this program was created, part of the program said, we’re not going to use any of this for confined animal feeding operations,” Carroll said. “And then the industry lobbied and removed that protection.”

Project 2025 also includes the elimination of any policy that protects certain communities from discrimination. This could mean, for example, that the USDA’s standards on discrimination against farmers could be nullified. BIPOC farmers and growers would face more difficulties entering or staying in agriculture.

Protectionist trade policies are often touted as a way to maintain fairness between domestic farmers and foreign markets, but farmers and consumers often shoulder the costs of these policies. After the Trump administration imposed tariffs on Chinese imports in 2018, China retaliated by imposing its own tariffs on agricultural products. The resulting trade war raised the price of food and burdened people living in agricultural areas.

Despite this, the use of tariffs against China is still politically popular across party lines. Biden has left most targeted tariffs in place, and Harris is likely to do the same as president, said Matt Barron, a political consultant with MLB Research Associates. Trump is reportedly planning to increase

People in rural areas are generally more likely to live in poverty, and are hurt more by policies that roll back social services.

these tariffs and impose them across the board, despite the negative effects increased tariffs could have on the economy.

Agriculture is just one aspect of rural policymaking. One that is at times overlooked is health care. People living in rural communities are less likely to have private or employer-sponsored health insurance, so Medicaid coverage is often the only way they can afford medical treatment. People in rural areas, especially children, disproportionately rely on it for low-cost insurance, said Edwin Park, a research professor at Georgetown University’s Center for Children and Families.

Hospitals serving large numbers of Medicaid recipients and low-income uninsured patients also receive increased Medicaid funding through disproportionate share hospital (DSH) payments, intended to off-

set uncompensated care. Rural hospitals and health clinics rely on DSH payments as a source of revenue. And this makes an especially huge difference in reproductive care.

According to a 2024 report from the University of Minnesota’s Rural Health Research Center, over 58 percent of rural counties did not provide hospital-based obstetrics care. People in these areas who need reproductive care usually have to drive long distances to more metropolitan areas to access services, meaning they are less likely to receive needed prenatal or postnatal care. For states that have not yet expanded Medicaid, more rural hospitals have closed or stopped providing ob/gyn care due to lack of funding.

The Biden administration’s investments helped close crucial gaps in health care in rural communities. The American Rescue Plan of 2021 allowed states

to extend pregnancy-related Medicaid coverage from the federally mandated 60 days to 12 months. As of August, 47 states have implemented the extension. In 2023, the Department of Health and Human Services announced over $100 million in awards to train nurses, midwives, and other nurse faculty. While not directly related to Medicaid, this will help address the disproportionate shortage of ob/gyn care in rural areas.

There are multiple proposals within Project 2025 to cut Medicaid funding, from capping federal funding for state programs, to moving toward individual high-deductible plans, to “voucherizing” Medicaid.

“Medicaid would be cashed out instead of providing a comprehensive array of benefits,” Park said. “You would receive as an individual some amount of funding to purchase coverage on your own in the individ-

The Democrats have a lot of catching up to do when it comes to building rural support.

ual market, and presumably an individual market that looks more like an individual market before the Affordable Care Act than the individual market we have today with the marketplaces.”

These proposals would make health care more expensive, which would deter people from seeking medical treatment. It could also lead to interruptions in care due to the addition of red tape, Park said. This is particularly dangerous, as it means rural people would be more likely to delay prenatal or postnatal care.

Another social program with major implications for rural health is the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program. SNAP allows primarily low-income families to purchase fresh and healthy food. In 48 states, the SNAP benefits are fixed, meaning those living in lower-cost areas have more purchasing power. A 2019 study from the Journal of Health Economics found that children in SNAP-recipient households in areas with lower food costs not only improve their health through their diet, but they are also slightly more likely to receive medical care.

One complication with this is that many rural areas aren’t located close to a grocery store. This means that even if a household receives SNAP benefits, their only nearby food source is a local dollar store. Some dollar stores may have a limited stock of fresh fruits and vegetables, but they primarily sell unhealthy, overly processed foods. These stores have been replacing independent grocery stores primarily in rural, low-income, or predominantly Black communities since the 1990s, leading independent grocers to exit these communities. And when compared to urban areas, the resulting loss of stores and employment decline lasts longer.

Through the bipartisan infrastructure law, the Department of Transportation provides billions of dollars in grants to support the development of public transit in rural areas. This could help people in rural communities travel more easily to

grocery stores. But SNAP and DOT grants may both be on the chopping block under a Trump presidency, making fresh groceries less affordable and less accessible for rural communities.

One of the few policies that would likely remain in place under either administration is the Child Tax Credit (CTC). The CTC currently allows households making under $200,000 (or $400,000 for those filing jointly) to claim a tax benefit of up to $2,000 for each qualifying child. As a fixed benefit that does not vary by state, the CTC has more impact in areas with a lower cost of living, which is often true for rural areas.

Both the Trump and Biden administrations have supported expanding the CTC. Trump first increased it in the 2017 tax bill from $1,000 per child to $2,000 and raised the phaseout threshold. Those measures expire in 2025. In 2021, Biden increased the credit from $2,000 to up to $3,600 for younger children, but the policy expired at the end of that year and was not renewed.

This time around, both parties are talking about a permanent expansion, and the upcoming tax fight in 2025 provides an opportunity. Trump and J.D. Vance have mused about a $5,000 CTC , though they have provided few details; Harris has endorsed bringing the CTC back to where it was in 2021, with an additional bump for newborns to a total of $6,000 in the first year.

“What we would like to see is it made fully refundable in whatever tax bill that we see in 2025 so that the families with the lowest incomes can continue to receive it,” said Elizabeth Lower-Basch, deputy executive director of policy at the Center for Law and Social Policy. Refundability means that poorer families without any tax liability can still claim the credit. “That was the change that caused child poverty to be cut almost in half in 2021,” Lower-Basch said.

In addition to funding social programs for all working-class Americans, the Biden administration has enacted several initiatives specifically targeted toward rural development. The aforementioned bipartisan infrastructure law has invested billions of dollars toward clean water, broadband connectivity, wildfire protection, and other services.

The Democrats have a lot of catching up to do when it comes to building rural support. In many rural districts, Republicans

have run unopposed for decades, leaving few electoral options for progressive voters. At the same time, Democrats running in these areas have historically struggled to gain party support or funding at the federal or state level, instead being left to run campaigns largely on their own.

Additionally, past Democratic administrations under Bill Clinton and Barack Obama made concessions to corporations at the expense of the rural working class. This has contributed to mistrust among voters.

“People felt let down by Obama,” Barron said, referring to an initiative to crack down on consolidation and anti-competitive treatment in the agricultural industry. “Obama had taken some baby steps. He’d held some hearings, and then his people at the Justice Department left for corporate jobs, big law firms, and Wall Street, and nothing happened, and people felt burned.”

With corporate donors still courting Democrats this election, there are questions about Harris’s commitment to uplifting the rural working class. In that regard, her VP pick, Minnesota Gov. Tim Walz, helps add some credibility.

“I’ve been a little bit nervous about Harris, because she’s surrounded herself with some people that are trying to push her back towards a Clintonian kind of Democratic politics,” Flaccavento said. “Easing up on the corporations, giving them a break, cutting them some slack. And I think that selection of Walz will help solidify her stance on anti-corporate and pro-rural, pro-farmer, pro-worker.”

There have also been growing efforts to support rural progressive candidates and reach out to voters in these areas, much of which came after Trump won the 2016 presidential election. An August call hosted by Rural Americans for Harris-Walz brought together politicians, celebrities, and activists from across the country. Attendees spoke about the importance of approaching rural issues with nuance and empathy. Harris also recently hired Matt Hildreth from RuralOrganizing.org, a powerhouse in organizing in small-town America, as her rural engagement director in the swing states.

Trump had four years to uplift rural America. He did little, but maintained rural support. Biden did more but received little goodwill to show for it. Harris will likely carry on Biden’s efforts; whether she’ll get more out of it remains to be seen. n

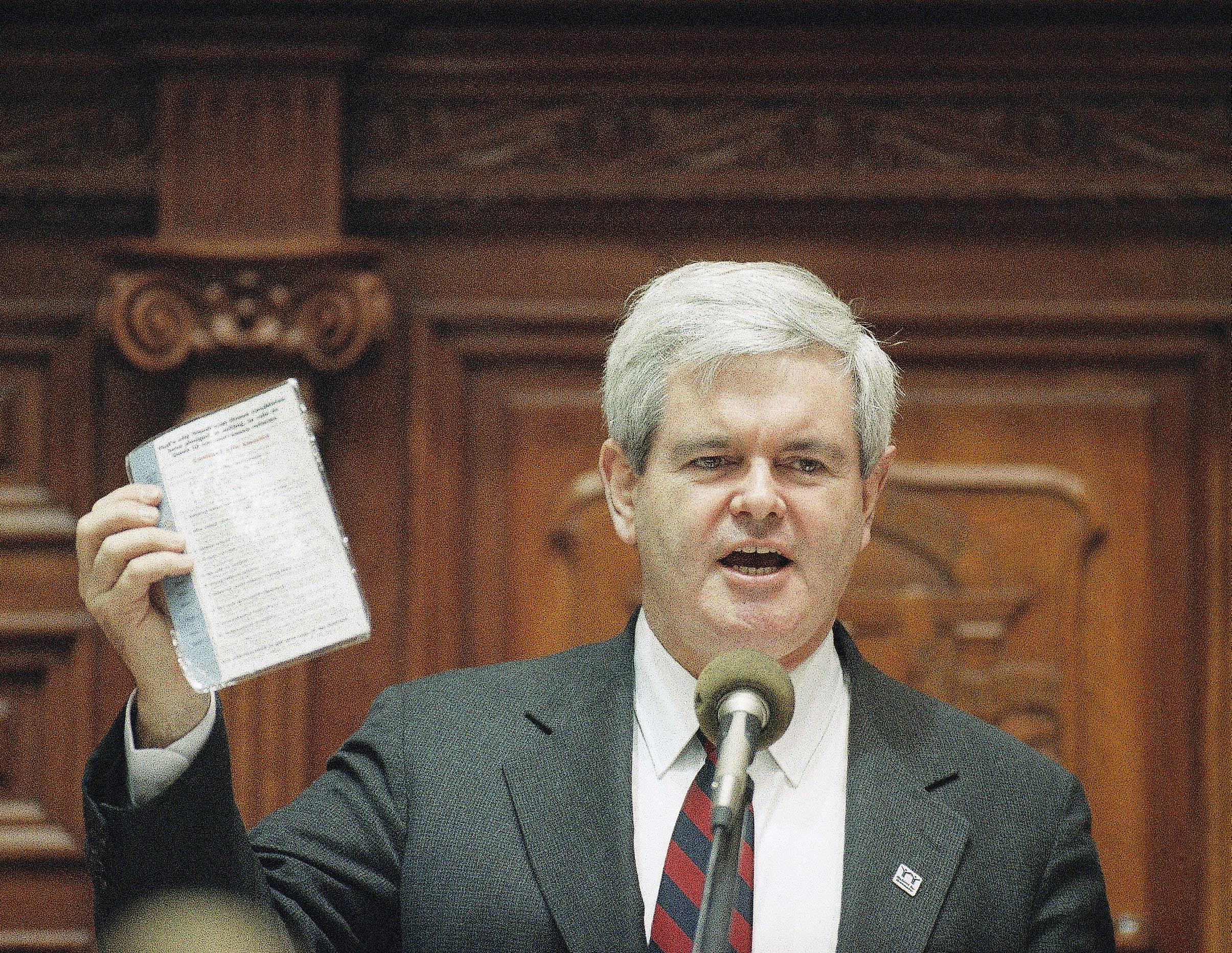

By Luke Goldstein

For 40 years, untrammeled monopoly power has been the defining characteristic of the American economy. In the 1980s, after a laissez-faire approach to antitrust laws originating with the Chicago school took hold in the Reagan administration, wealth inequality soared and new innovators struggled to break through an incumbency advantage favored by Wall Street.

Only during the Biden administration have those trend lines begun to change, thanks to a new crop of antitrust regulators: Federal Trade Commission chair Lina Khan, Jonathan Kanter at the Department of Justice Antitrust Division, and Consumer Financial Protection Bureau director Rohit Chopra have sent a clear message that the full body of anti-monopoly laws will be enforced to ensure open, competitive markets for consumers, businesses, and workers.

The presidential election will decide whether this brief window of opportunity to radically reshape economic liberty in this country can fully take root as a more permanent policy structure. But the stakes for corporate power are uniquely multifaceted.

Trump has shed the economic populist instincts he tapped into during the 2016 campaign, and cozied up to segments of the business world that previously viewed him with suspicion. Kamala Harris, on the other hand, resisted articulating a full policy vision until early September, when her campaign finally launched an issues page on her website. The economic platform gestures at giving new powers to antitrust enforcers under the overall framing of going after “bad actors,” a vague designation that leaves a lot of questions up to interpretation.

Despite Harris’s coy attitude toward policy, the political incentives are more aligned in the Democratic coalition for her to inherit the strongest administration on corporate power in decades, and give them four more years.

Based on recent polling, a majority of voters blame corporate price-gouging for inflation and support breaking up monopolies as a tool against it. The C-suite executive class also views antitrust and competition policy as one of the top issues on the ballot this November, but for entirely different reasons.

It’s one of the rare policy areas where a baseline consensus has emerged, in large part because of a massive political shift since the 2008 financial crisis.

On both the left and right, populist factions are battling it out with a more corporatist political establishment for the soul of their respective parties. But when it comes to the actual governing record, Democrats have been far more willing to challenge monopoly dominance than Republicans.

Notoriously erratic and fickle, Donald

For months now, companies have been selectively timing the announcement of new acquisition targets, in the hopes of a more businessfriendly administration with a more relaxed merger policy to wave deals through. Behind the scenes—and sometimes in public— Wall Street has also been waging an allout pressure campaign to urge the next Democratic administration to remove Lina Khan from the FTC

Those efforts didn’t really stand a chance with Biden as the nominee. But corporate leaders saw an opening when Harris, a Californian close to Silicon Valley, stepped in as the party’s new nominee. Her close advisers include the general counsel of Uber (who is also her brother-in-law) and a lawyer rep -

resenting Google against an active Department of Justice antitrust lawsuit.

When Harris took over, a procession of CEOs and business leaders, led by Democratic mega-donor and LinkedIn co-founder Reid Hoffman, went on cable shows to demand Harris oust Khan. Maryland’s governor, former investment banker and Harris ally Wes Moore, echoed this on CNBC. When asked directly about Hoffman’s proposition to move on from Khan, he said, “I think we will and I think we have to … There are going to be different dynamics that are going to require different philosophies.”

The remarks from donors came off as a thinly veiled quid pro quo and sparked widespread backlash. Even more centrist lawmakers in tough re-election races, like Sen. Jacky Rosen (D-NV), scrambled to post pictures in a room with Khan to show support. Hoffman was forced to recant during a later CNN interview, claiming he was merely speaking about Khan as an “expert,” not a donor.

Harris has never commented on the incident, nor has she committed to keeping Khan if she wins, despite championing several of the policies of Khan’s agency on the campaign trail. However, she put some progressives’ concerns to rest with her economic-policy rollout in August. It included a federal ban on price-gouging for groceries, a crackdown on algorithmic price-fixing in housing, and reforms for pharmacy benefit managers driving up drug costs. Within weeks, DOJ sued RealPage over rental pricefixing, buttressing Harris’s message.

Undeterred, monopolists continue to pressure Harris’s campaign. They aren’t wrong to view the election in such consequential terms.

It took Reagan two terms, and really a third under George H.W. Bush, for the Chicago school consumer welfare standard to become fully ingrained. If the neo-Brandeisians get another four years with a Harris administration, they will be able to more fully institutionalize one of the most far-reaching policy revolutions since the New Deal.

In the first year of his administration, President Biden issued an extensive executive order laying out a whole-of-government approach to competition. The document all but dethroned the old enforcement model of the Chicago school and gave his new-guard antitrust regulators a green light to move forward with their agenda.

That agenda has resulted in a sweeping policy overhaul. Several of America’s largest Fortune 500 companies are facing antitrust lawsuits. Agencies have gone after scam robocall farms and initiated rules to make it easier for people to cancel digital subscriptions, limit credit card late fees, or ensure medical debt doesn’t appear on credit reports. The most significant new rule, the FTC ’s ban on restrictive noncompete agreements in employment contracts, will ultimately be determined by the Supreme Court, and along with it whether the FTC has authority to create new rules through its unfair methods of competition powers.

The new merger guidelines, finalized by the FTC and DOJ last year, amount to a new corporate charter for how business can grow, and establishes that companies must innovate rather than acquire com-

petitors for market share. While there have been some setbacks operationalizing this approach to corporate power, by the FTC’s count they’ve won in court or otherwise stopped roughly 90 percent of their merger challenges. DOJ has tallied notable victories, such as blocking the Spirit-JetBlue airline merger, and publisher Simon & Schuster’s proposed combination with Penguin Random House. In August, Google was found guilty of monopolizing search markets, the first major monopolization verdict in a quarter-century. These victories have shown that neo-Brandeisian legal theories can hold up in court.

The Google search ruling in particular could prove a major precedent for other monopolization cases the FTC and DOJ have filed, including Big Tech cases against Apple, Amazon, Meta, and a separate case against Google for monopolizing

adtech markets being heard now. DOJ also has the RealPage lawsuit, and a monopolization case against Live Nation for rolling up the concert venue, promotion, and ticketing businesses.

“Once a few more of these cases win in the courts, you’re going to witness a sea change in how businesspeople operate,” said Matt Stoller, policy director of the American Economic Liberties Project.

The fate of this project to fight economic concentration depends on the next administration’s appointments and continued support.

Anti-monopoly policy still relies heavily on the inexorably slow litigation process. It usually takes more than one presidential term to initiate an investigation into a company, file a monopolization case, argue it in court, and then hash out a remedy if the government wins. That’s a near-Herculean

task for chronically understaffed enforcers whose funding is continuously put at risk in congressional appropriations.

By its very nature, this process requires more than four years to accomplish. Some antitrust experts believe this predicament necessitates some degree of bipartisan consensus, given how frequently the White House swings between party control in our current political era.

On this front, Trump has not exactly instilled confidence this election cycle. It’s hard to imagine that on the trail in 2016 he pledged to break up a giant telecom merger, calling it “too much concentration of power in the hands of too few.” Granted, the merger was between AT&T and Time Warner, the owner of CNN, a media organ hated by Trump. But it was a legitimate competition issue; his DOJ followed through on filing the merger challenge, but lost (only for AT&T to voluntarily sell off Time Warner in 2022).

During the current campaign, Trump has been more eager to court the Business Roundtable and Silicon Valley oligarchs. The latter have been core to his support and are influencing his agenda. His current platform says nothing about monopolies, but does promise light-touch regulation for crypto and essentially no government interference with the development of artificial intelligence. That’s a stark contrast with the current FTC and DOJ, which are probing the OpenAI-Microsoft partnership and AI chipmaker Nvidia.

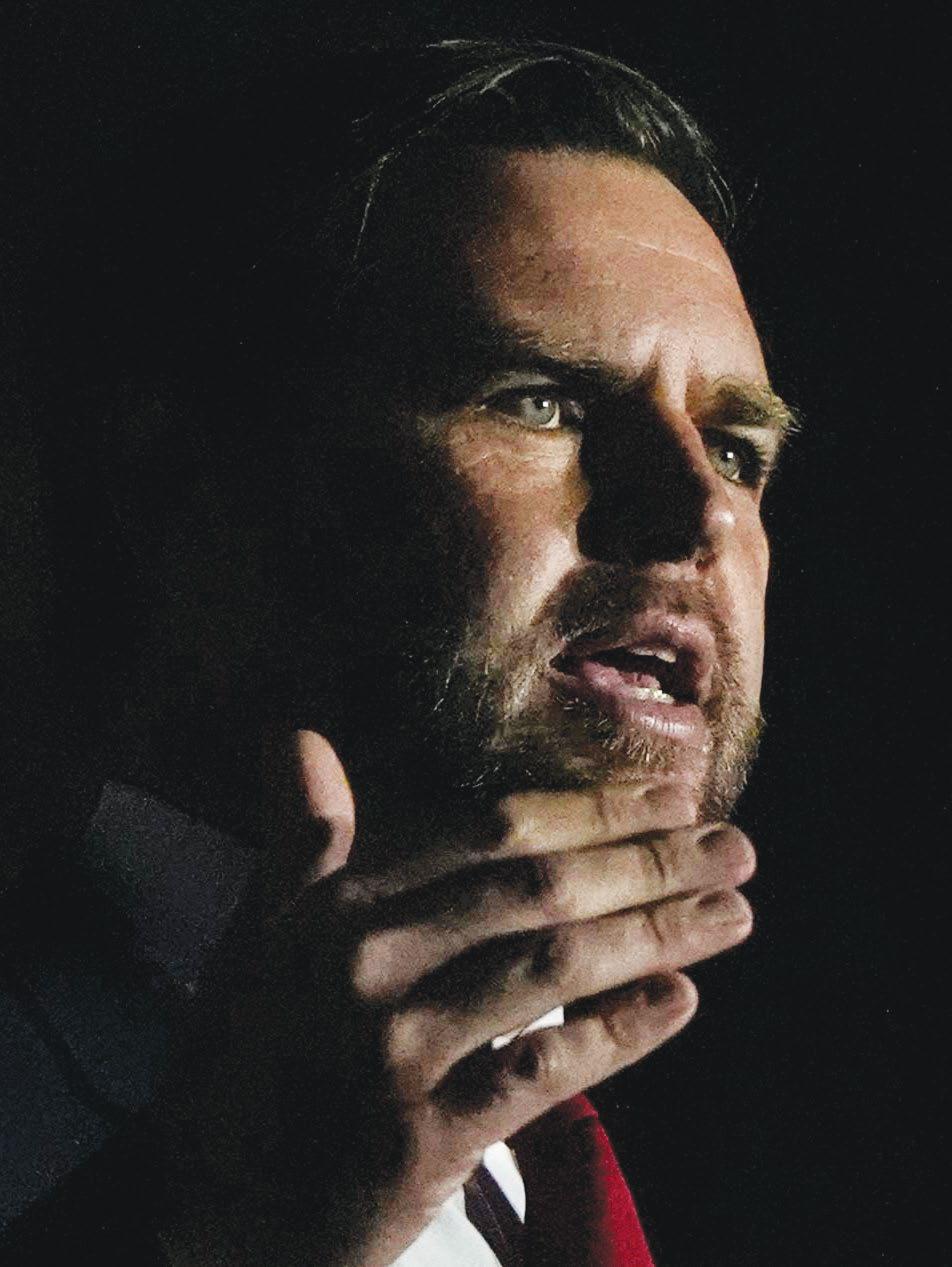

Despite his more business-friendly posture, Trump did pick as his running mate J.D. Vance, a bête noire of the GOP’s old guard, who comes from the populist wing of the party. On several occasions, Vance has openly praised Lina Khan, one of the few Biden regulators he thinks is doing a “pretty good job.” Some antitrust proponents on the right believe that Vance will steer the policy direction of their administration.

“We’re certainly a minority in our party but the energy is on our side … we expect that to carry through to appointments,” said Jon Schweppe, policy director at the American Principles Project, who worked on the antitrust sections in Project 2025 as part of the broad coalition assembled by the Heritage Foundation.

The Project 2025 antitrust section is internally conflicting, but there’s consistency in one respect: calling for dismantling the CFPB, whose constitutionality has

The real risk is that Trump will use antitrust law as a blunt political tool to go after his enemies.

been under legal threat since its origination. Many of the Bureau’s current rules, yet to be finalized, would likely be gutted under Trump, based on his first administration’s CFPB.

But there is reasonable optimism for a modicum of continuity on antitrust, even if Trump wins. Khan and Kanter have been far more coherent and bold about their policy direction, but in key respects they inherited some of the previous administration’s work on corporate power, which began the initial break from neoliberal orthodoxy.

The Biden DOJ gets credit for winning the Google search case, but it was first filed by Trump’s DOJ Antitrust Division head Makan Delrahim. The Republican-chaired FTC under Trump also filed an antitrust case against Facebook, targeting its acquisition of Instagram and WhatsApp. That case is being pursued by the current FTC.

Delrahim’s DOJ even brought some unexpected cases in labor markets, targeting no-poach agreements where competitive employers conspire not to hire each other’s employees. That was a rough precursor to the noncompete ban.

The next Trump administration would likely continue the cases against Big Tech, which conservatives view as harboring liberal bias. There could be overlap on some health care policies too. Republicans have started to rally behind cracking down on pharmacy benefit manager middlemen that drive up drug costs. Republican FTC commissioner Andrew Ferguson voted with the Democrats this July to issue a damning interim study of the industry. Pharma patent abuse is another area of convergence. “Institutional heft at the agency to take on bogus patent listings is pretty well solidified at this point,” said Spencer Waller, a law professor at Loyola University Chicago, who mostly recently served as senior adviser to the FTC

The real risk is that Trump will install loyalists at the antitrust agencies to use the

law as a blunt political tool to go after his enemies, and not pick particularly impactful legal cases. This was the legacy of Delrahim. Trump certainly won’t touch industries dominated by GOP donors, such as oil companies, or anything tech-related that harms his new Silicon Valley cronies.

Selective enforcement is also a concern for a future Harris administration. Her framing of taking on “bad actors” does not establish clear principles for what is and isn’t fair competition. Is Google, for example, a bad-actor monopolist? Harris doesn’t specify, despite a court ruling that the company violated the Sherman Act. It’s a far cry from the Biden executive order on competition, which diagnosed America’s monopoly problem as a widespread, systemic issue.

Politically, though, Harris is well positioned to continue the Biden administration’s legacy, albeit perhaps under some modified directives.

Her campaign’s rollout is especially focused on the consumer protection side. It makes sense to highlight those actions in an election year when inflation is still a major concern for voters. But it also hints at a quiet return to the consumer welfare standard, which could bleed into the policies that enforcers are pressured to target under her administration. “I see a lot more room for crackdowns on junk fees across numerous sectors. Both Biden and Harris have made that a priority,” said Waller. If Harris keeps Khan and Kanter—and there will be significant grassroots pressure to do so—their agencies will be able to finish the work they’ve already initiated and focus on clear-cut remedies to the monopolization cases. Existing litigation will take up much of their allocated budgets, but a handful of other cases could be pursued. There are active investigations into OpenAI, Nvidia, and the health care giant UnitedHealth.

There’s also hope within the anti-monopoly movement that agencies will fully resuscitate a dormant prong of antitrust law, the Robinson-Patman Act, which targets pricing discrimination.

These ambitious policy efforts require a lot of time and resources, as well as the luck of the draw in the courts. But the transformational power of this work is already playing a major role in this year’s election. It could reshape our country’s politics for decades to come, if the revolution under way can coalesce. n

By Suzanne Gordon and Steve Early

Amid the rhetorical fog of their gamechanging presidential debate on June 27, Donald Trump and his then-opponent dealt with the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) only in passing.

Trump claimed that, after he vacated the White House, “crazy Joe Biden” simply abandoned his policies of giving eligible

The results were “incredible,” and earned his administration “the highest approval rating in the history of the VA.”

veterans the “choice” to remain inside the VA health care system or seek treatment outside it. According to Trump, VA patients were able to “get themselves fixed up” in private hospitals and medical practices, rather than waiting “three months to see a doctor.”

Amid his general befuddlement, Biden didn’t point out two things. One, outsourcing has been a disastrous experiment that has led to out-of-control spending on private care and left the VHA with a projected $12 billion budget shortfall for fiscal year 2025. And two, Biden didn’t abandon these policies at all: There has been more privatization of veterans’ care under his administration than Trump’s.

Biden instead pivoted to talk about the PACT Act of 2022, which enabled many more post-9/11 vets to file successful disability claims based on their past exposure to burn pits in Iraq and Afghanistan. Over the next decade, the PACT Act authorizes hundreds of billions of dollars in additional spending for

these claims; military veterans are “a hell of a lot better off” as a result, Biden said.

This brief, typically unilluminating exchange left unaddressed the rather dire position of the Veterans Health Administration (VHA), which operates the nation’s largest public health care system and provides highquality and specialized care for nine million former service members. As a “Red Team” review committee of experts warned VA Secretary Denis McDonough in a report leaked to the Prospect last spring, “the increasing number of Veterans referred to [outside] providers … threaten to materially erode the VA’s direct care system,” leading to mass closures of VA clinics or certain services and “eliminating choice for the millions of Veterans who prefer to use the VHA direct care system for all or part of their healthcare needs.”

The dramatic and energizing midsummer switch at the top of the Democratic tick-

et has made it possible to imagine a more substantive debate about the past, present, and future of VA care. Particularly since both parties are now fielding, as their vicepresidential candidates, military veterans who have personally used VA-dispensed benefits to attend college.

If Kamala Harris and Tim Walz win in November, there will be a major opening for “not going back” to what Harris has called the “failed policies” of Trump’s first term, which have been reworked by the Heritage Foundation in its infamous Project 2025. The tough part for Harris, if not Walz, will be acknowledging that this also means curbing, not continuing, the disastrous bipartisan experiment with VHA outsourcing embraced by the Obama, Trump, and Biden administrations.

Any optimism about addressing what the Red Team called an “existential threat” is based on the personal bio—and, hopefully, postJanuary portfolio—of Harris’s running mate.

Before becoming governor of Minnesota, Tim Walz was an Army National Guard member for 24 years who used GI Bill benefits to attend a state college, and then become a public-school teacher and union member.

Walz ran for Congress in 2006 after Vietnam veteran John Kerry’s failed bid for the presidency two years earlier. After winning the first of six House races, he joined the House Veterans’ Affairs Committee (HVAC)—a low-status committee assignment spurned by many aspiring politicians.

Walz was well positioned to advocate for fellow veterans with service-related conditions because of the hearing damage he suffered due to repeated exposure to artillery blasts during National Guard training exercises. He also won applause for co-sponsoring a bill named after a Marine veteran who killed himself in 2011 after long struggles with PTSD and depression. The Clay Hunt Suicide Prevention for American Veterans Act, signed into law in 2015, kept the VA focused on the challenge of reducing suicide rates among former service members.

Walz eventually rose to become ranking Democrat on the Veterans’ Affairs Committee. In 2018, he joined just 69 other House Democrats in opposing the VA MISSION Act, one of Donald Trump’s proudest legislative achievements and the basis for his 2024 campaign pledge to make VA “patient choice” more widely available.

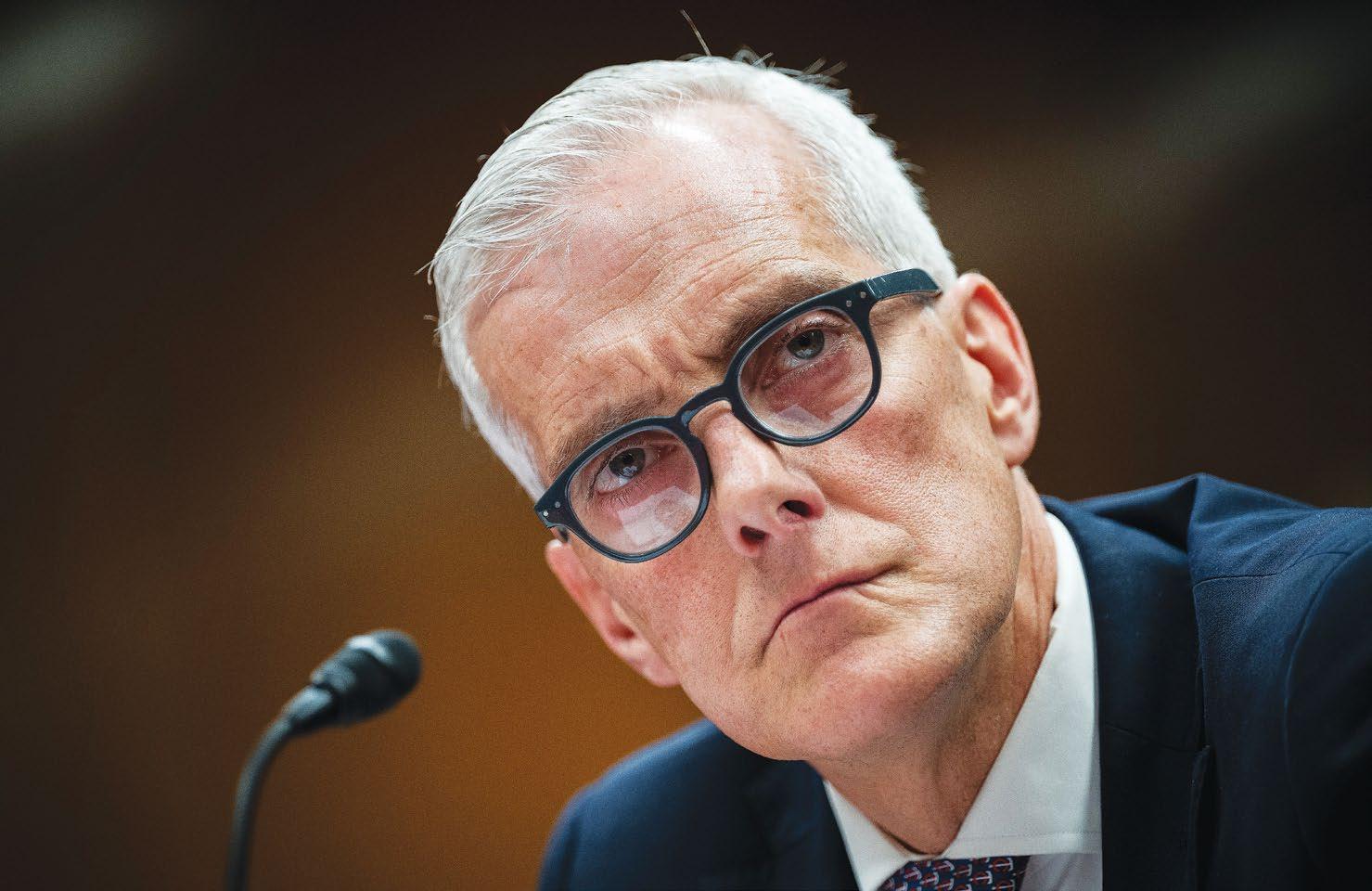

Denis McDonough plans to step down as VA secretary in 2025. He continued much of Trump’s privatization of veterans’ health care.

Walz warned, accurately, that MISSION Act outsourcing would force the VA to “cannibalize itself” by diverting billions of dollars from direct care delivery to reimbursement of private-sector providers. This incremental defunding of VHA hospitals and clinics now threatens to leave them in what Walz called a “can’t function situation.”

This is exactly what has transpired, with serious manpower shortages and red ink throughout the VHA . Walz was absolutely right, and he should take that good judgment into office if he wins.

In contrast, a campaign spokesman for Sen. J.D. Vance recently hailed the MISSION Act as bipartisan legislation that “expanded veterans’ access to quality care and cut needless red tape.” Walz’s opposition to it was “not the kind of leadership veterans need in Washington,” the spokesman said.

Walz’s role as ranking Democrat on a then Republican-led HVAC is fondly recalled by the American Federation of Government Employees (AFGE), which represents VA employees in his home state. During his first run for Congress, Walz reached out to then-AFGE vice president Jane Nygaard, who discovered that “he’s not someone who just says something to make you happy, he actually takes action.”

According to Nygaard, “when we had issues with the St. Paul VA, which had bad management and low staffing, Congressman Walz listened to the union. He got the Federal Mediation and Conciliation Service

involved and we ended up having a threeday retreat with upper management. Eventually, upper leadership retired and labor relations improved.”

The one bad mark on Walz’s union report card is his vote in favor of the VA Accountability and Whistleblower Protection Act of 2017. This Trump-era effort to strip VA workers of their due process rights in disciplinary cases was challenged in court by AFGE. To his credit, VA Secretary Denis McDonough ended a five-year legal battle over implementation of the act by reaching a deal with the union last year. Thousands of unfairly fired workers became eligible for reinstatement or back pay, at a total cost estimated to be hundreds of millions of dollars, according to the Federal News Network.

Other workers or managers terminated for “grievous misconduct” were not covered by the settlement. On the campaign trail, Trump has promised to “fire every corrupt VA bureaucrat who Joe Biden outrageously refused to remove from the job.” He has also threatened to arrest any Harris-Walz supporters in the VA, which would include many of the nation’s veterans.

If the VA does become part of Walz’s vicepresidential portfolio—and his biography is prominently mentioned on the veteran policy section of Harris’s issues page—he could help engineer much-needed personnel and policy changes. That first requires finding suitable replacements for McDonough, now scheduled to leave in January, and his undersecretary for health, Dr. Shereef Elnahal.

If the VA becomes part of Walz’s vice-presidential portfolio, he could help engineer much-needed personnel and policy changes.

As chronicled in the Prospect since 2021, McDonough has spent his term in office placating privatization fans in Congress, downplaying the disastrous impact of outsourcing, and refusing to reverse Trumpera patient referral rules, despite having administrative authority to do so. Meanwhile, his deputy, Elnahal, did not provide strong or innovative leadership at the VHA , while making mistakes that gave Republicans an easy political target.

If they win, Harris-Walz transition planners need to recruit a better team at the top. During the Clinton administration, Marine veteran Jesse Brown, the first African American VA secretary, was tasked with undoing 12 years of Reagan-Bush damage to the agency. Brown hired and empowered fellow veteran and public-health expert Dr. Kenneth W. Kizer as undersecretary for health, to lead what the Harvard Business School called the largest and most successful “turnaround” in U.S. health care history. (Kizer came to the aid of the VHA again recently as chair of the Red Team, whose urgent recommendations to McDonough have been largely ignored since last spring.)

On the website’s policy section, Harris and Walz promise “end[ing] veteran homelessness, investing in mental health and suicide prevention efforts,” and “expanding economic opportunity for military and veteran families.”

Any new administration must also tackle mounting problems at the Veterans Benefits Administration. VBA critics say this part of the agency still suffers from serious understaffing and lack of training for those who assess veterans’ service-related conditions to determine their benefit eligibility. “Because claims raters aren’t given sufficient time to understand veterans’ complex disability claims,” one Gulf War veteran explains, “this results in mistakes, which in turn creates long delays and a tsunami of appeals.”

To do anything different at the VA than Biden did, or Trump before him, Harris and Walz first have to win in November. They can help boost veteran voter turnout, particularly in battleground states, by zeroing in on the skimpiness of the GOP’s plan to “Take Care of Our Veterans”—all 48 words of it!

This lone paragraph, buried in the Republican platform adopted in Milwaukee, leads off with immigrant bashing. The party pledges to “end luxury housing and Taxpayer benefits” for border-crossers and “use those savings to shelter and treat homeless Veterans.” In addition, a second Trump administration will “expand Veterans’ Healthcare Choices, protect Whistleblowers, and hold accountable poorly performing employees not giving our Veterans the care they deserve.”

The equivalent Democratic Party platform statement is far more substantive. It covers veteran homelessness and suicide, PACT Act implementation, improving mental health programs, new services for female veterans, support for family members caring for VA patients, and cracking down on scams targeting veterans who file disability claims over their toxic exposures.

“Going forward,” the Democrats declare, “we will strengthen VA care by fully funding inpatient and outpatient care and long-term care, and by upgrading medical facility infrastructure.” The adverse impact of Biden administration outsourcing on funding for all of the above is not mentioned. The platform also reminds voters that, as president, Trump “pushed to cut funding for veterans’ benefits.”

The best way to drive this last point home is by tying Trump to the VA-related recommendations of Project 2025. As Iraq War veteran and Pennsylvania Rep. Chris Deluzio points out, that Republican playbook “takes dead aim at veterans’ health and disability benefits.”

In August, Deluzio warned readers of Military.com that his Republican colleagues on the HVAC have often “sided with corporate interests to outsource care” for VA patients. And now their presidential transition planners at the business-backed Heritage Foundation want to refer even more vets to “costly private facilities, a fiscally reckless move that … has ballooned costs for the VA.”

According to Deluzio, the “ultimate

endgame of these plans—to dismantle the VA’s clinical care mission—should send shivers down the spines of America’s veterans and those who want them to have the best care.”

On the campaign trail, Republicans are, per usual, diverting attention from that “endgame” by positioning themselves as defenders of “patient choice.” At a mid-August event at a VFW hall in Western Pennsylvania, J.D. Vance referenced the very real health care access problems of “our veterans living in rural areas.” He assured his invitation-only crowd that if “those who put on a uniform and serve our country … need to see a doctor, we got to give them veteran’s choice to give them that ability to see a doctor.”

On Capitol Hill, conservative Republicans in the House and Senate have been laying down their own cover fire for Trump and Vance by pressuring McDonough to stay the course on “community care”—the preferred congressional euphemism for privatization—until their team takes over again in January.

In less coherent fashion, Trump made similar points during an August 26 speech to a Detroit convention of the National Guard Association. The former president accused the Biden-Harris administration of gutting his many “VA reforms” related to “choice” and “accountability,” and hailed VA outsourcing as a great system of “rapid service,” in which patients “go to an outside doctor … get themselves fixed up and we pay the bill.”

According to these MISSION Act defenders, “community care is more cost-effective than VA’s direct care system”—despite all evidence to the contrary. It also doesn’t provide care that is suited to the particular needs of veterans.

Between now and Election Day, it will take a lot more truth-telling and plainspokenness by people like Walz and Deluzio to counter the steady drumbeat of disinformation directed at veterans. And it will take the commitment to a new way forward to roll back the bipartisan damage of privatization. n

Suzanne Gordon is a senior policy analyst at the Veterans Healthcare Policy Institute. Steve Early is a longtime journalist and health care reform advocate. They are co-authors, along with Jasper Craven, of Our Veterans: Winners, Losers, Friends, and Enemies on the New Terrain of Veterans Affairs (Duke University Press).

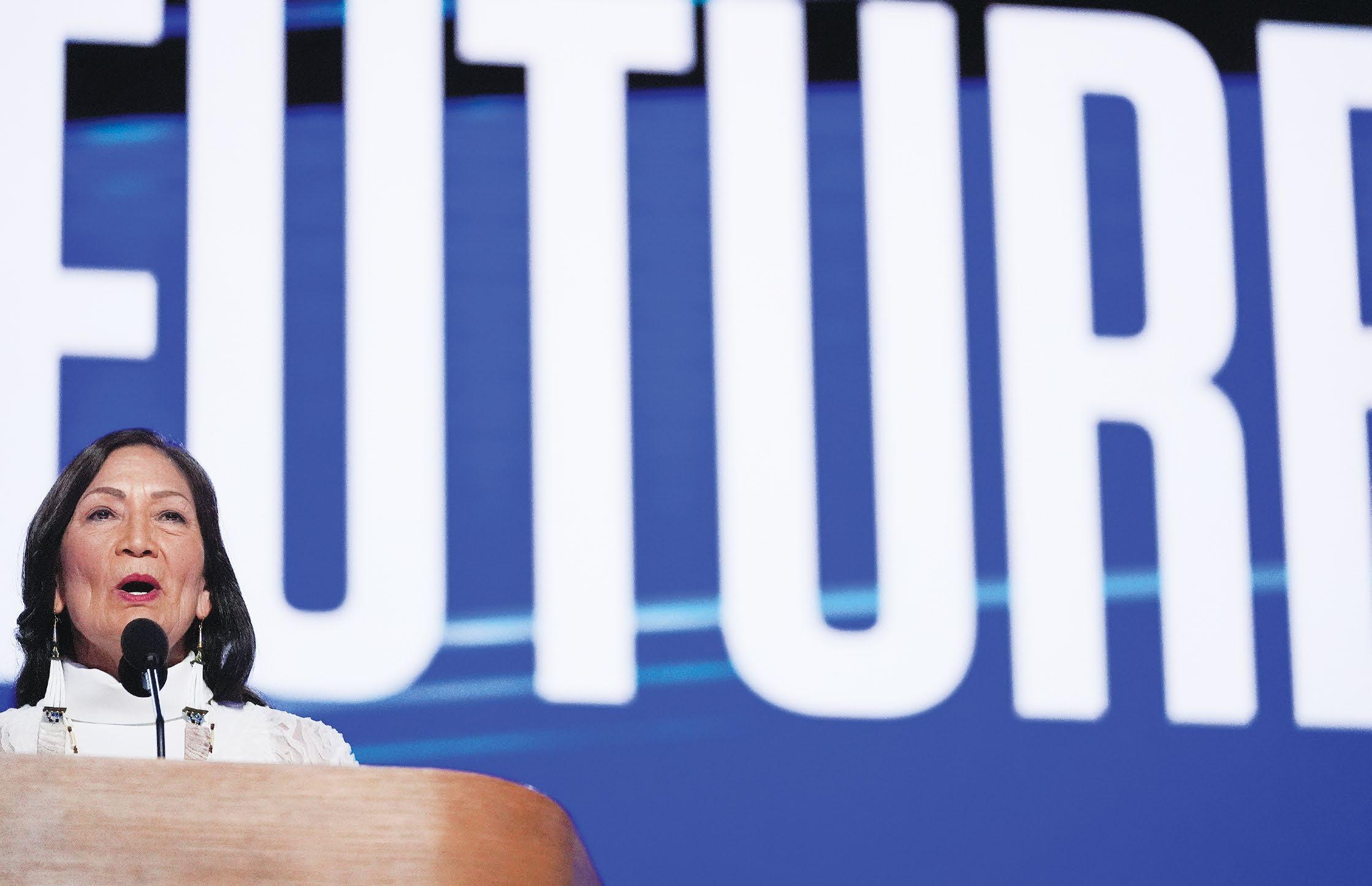

Deb Haaland has been a remarkable secretary of the interior. But the future is about funding in Congress.

By Erik Loomis