How Pricing Really Works

The many innovations corporations have devised to get you to pay more

The many innovations corporations have devised to get you to pay more

4 The Age of Recoupment

How power, technology, and opportunity have come together to gouge consumers By David Dayen and Lindsay Owens

8 One Person One Price

Digital surveillance and customer isolation are individualizing the prices we pay. By David Dayen

16 Three Algorithms in a Room

A growing number of industries are using software to fix prices. Law enforcers are beginning to fight back. By Luke Goldstein

22 Loaded Up With Junk

Extra profits are the only explanation for many fees businesses charge. By Hassan Ali Kanu

28 The Urge to Surge

Businesses are hiking prices to take advantage of consumers. They learned it from Uber. By Sarah Jaffe

34 The One-Click Economy

Digital subscriptions are here to stay. What should we do about that? By Joanna Marsh

40 What We Owe

The big banks behind the rising cost of credit By Kalena Thomhave

46 War in the Aisles

Monopolies across the grocery supply chain squeeze consumers and small-business owners alike. Big Data will only entrench those dynamics further. By Jarod Facundo

52 Fantasyland General

Hospital pricing is impenetrable to consumers and regulators alike. The result: increased costs and profits, and wasteful reliance on armies of middlemen. By Robert Kuttner

58 Taming the Pricing Beast

The government has a variety of strategies to protect the public from price-gouging and information advantages over the consumer. By Bilal Baydoun

64 Parting Shot: Interview with Lina Khan

Cover and Illustrations by Jan Buchczik

Visit prospect.org/ontheweb to read the following stories:

These states have increasingly played host to major federal lawsuits implicating national policy, primarily in the Northern District of Texas, where certain divisions have just one or two judges, appointed by Republican presidents.

— Hassan Ali Kanu, on the Fifth Circuit problem

Chuck Schumer is behind a convoluted scheme to help the crypto industry avoid regulation of stablecoins, crypto tokens that are pegged to a reliable currency, like the U.S. dollar or a commodity like gold, and are used for payments, often the purchase of digital assets. Schumer is poised to tie that bill to unrelated legislation that allows cannabis businesses to get bank accounts. Yes, you read that right.

Robert Kuttner, on the majority leader’s support for crypto

Lawyer Jared Pettinato argues that Section 2 of the 14th Amendment, ratified in 1868, requires the number of representatives be reallotted from states that burden the franchise, say with ID laws or other restrictions, whether or not they impact only minority voters.— Michael Meltsner, on a challenge to voting restrictions

The deep antipathy of the Confederacy to any form of worker power—which in the antebellum South meant Black power—has persisted to the current day.

— Harold Meyerson, on the UAW’s Chattanooga victory

“John is very knowledgeable almost to a fault, as it gets in the way at times when issues arise.”

Maureen Tkacik, quoting deceased Boeing whistleblower and quality manager John Barnett’s performance review, in her ongoing coverage of the Boeing debacle

But the electoral fallout cannot be contained. Neither party has such an advantage in the House that even one seat can be sacrificed in November. Democrats saddled with an indicted congressman in TX-28 can easily be the margin of victory.— David Dayen, writing on Henry Cuellar’s undeserved support among House leadership

The Federal Trade Commission uncovered another underlying cause [for exploding gas prices]: an orchestrated plot between OPEC and American fracking tycoon Scott Sheffield to exploit the inflationary period to push prices even higher.— Luke Goldstein, writing on Pioneer Natural Resources’ CEO, and his subsequent banning from the board of ExxonMobil

EXECUTIVE EDITOR David Dayen

FOUNDING CO-EDITORS Robert Kuttner, Paul Starr

CO-FOUNDER Robert B. Reich

EDITOR AT LARGE Harold Meyerson

SENIOR EDITOR Gabrielle Gurley

MANAGING EDITOR Ryan Cooper

ART DIRECTOR Jandos Rothstein

ASSOCIATE EDITOR Susanna Beiser

STAFF WRITER Hassan Kanu

WRITING FELLOW Luke Goldstein

INTERNS Thomas Balmat, Lia Chien, Gerard Edic, Katie Farthing

CONTRIBUTING EDITORS Austin Ahlman, Marcia Angell, Gabriel Arana, David Bacon, Jamelle Bouie, Jonathan Cohn, Ann Crittenden, Garrett Epps, Jeff Faux, Francesca Fiorentini, Michelle Goldberg, Gershom Gorenberg, E.J. Graff, Jonathan Guyer, Bob Herbert, Arlie Hochschild, Christopher Jencks, John B. Judis, Randall Kennedy, Bob Moser, Karen Paget, Sarah Posner, Jedediah Purdy, Robert D. Putnam, Richard Rothstein, Adele M. Stan, Deborah A. Stone, Maureen Tkacik, Michael Tomasky, Paul Waldman, Sam Wang, William Julius Wilson, Matthew Yglesias, Julian Zelizer

PUBLISHER Ellen J. Meany

PUBLIC RELATIONS SPECIALIST Tisya Mavuram

ADMINISTRATIVE COORDINATOR Lauren Pfeil

BOARD OF DIRECTORS David Dayen, Rebecca Dixon, Shanti Fry, Stanley B. Greenberg, Jacob S. Hacker, Amy Hanauer, Jonathan Hart, Derrick Jackson, Randall Kennedy, Robert Kuttner, Ellen J. Meany, Javier Morillo, Miles Rapoport, Janet Shenk, Adele Simmons, Ganesh Sitaraman, Paul Starr, Michael Stern, Valerie Wilson

PRINT SUBSCRIPTION RATES $60 (U.S. ONLY) $72 (CANADA AND OTHER INTERNATIONAL)

CUSTOMER SERVICE 202-776-0730 OR info@prospect.org

MEMBERSHIPS prospect.org/membership

REPRINTS prospect.org/permissions

Vol. 35, No. 3. The American Prospect (ISSN 1049 -7285) Published bimonthly by American Prospect, Inc., 1225 Eye Street NW, Suite 600, Washington, D.C. 20005. Periodicals postage paid at Washington, D.C., and additional mailing offices. Copyright ©2024 by American Prospect, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this periodical may be reproduced without consent. The American Prospect ® is a registered trademark of American Prospect, Inc. POSTMASTER: Please send address changes to American Prospect, 1225 Eye St. NW, Ste. 600, Washington, D.C. 20005. PRINTED IN THE U.S.A.

Every digital membership level includes the option to receive our print magazine by mail, or a renewal of your current print subscription. Plus, you’ll have your choice of newsletters, discounts on Prospect merchandise, access to Prospect events, and much more.

out more at prospect.org/membership

You may log in to your account to renew, or for a change of address, to give a gift or purchase back issues, or to manage your payments. You will need your account number and zip-code from the label:

ACCOUNT NUMBER ZIP-CODE

EXPIRATION DATE & MEMBER LEVEL, IF APPLICABLE

To renew your subscription by mail, please send your mailing address along with a check or money order for $60 (U.S. only) or $72 (Canada and other international) to: The American Prospect 1225 Eye Street NW, Suite 600, Washington, D.C. 20005

info@prospect.org | 1-202-776-0730

How power, technology, and opportunity have come together to gouge consumersBy David Dayen and

Lindsay Owens

The Federal Reserve chair’s semiannual monetary report to the Senate Banking Committee is not typically of great interest to the average American. Committee members usually lob a predictable set of questions: when the Fed will raise or lower interest rates, whether they expect the economy to grow or slow, and maybe whether the central bank is fulfilling its supervisory duties in overseeing large banks. But Jerome Powell got a bit of a surprise this year when Sen. Sherrod Brown (D-OH), the Banking Committee chair, launched into his opening statement.

“The biggest corporations are always finding new ways to charge people more to increase their profits,” Brown said. “Fast-food restaurants and big stores are experimenting with electronic price tags, so they can change prices constantly, making it easier to sneak prices up little by little.” He called for legislative measures “to take on corporate price-gouging,” which, he argued, had “nothing to do with higher interest rates.”

Later, Brown confronted Powell directly over the increasing use of algorithms that analyze price information acquired across a whole market. If a business knows what

its competitor charges, it can adjust prices upward in real time, maximizing what it can earn. “Are you concerned that the wide adoption of these price-gouging strategies, these pricing schemes if you will, will contribute to inflation?” Brown asked.

Powell stammered through a response, keying in on Brown’s use of the term “dynamic pricing,” only one of the pricing strategies cited during the hearing. Dynamic pricing means that prices rise and fall based on how many people want the product at a given time. “I think it works both ways,”

Powell said, offering an Econ 101 theory of dynamic pricing: If there’s nobody in the store, prices would go down, and if the store is packed with customers, prices would go up. Smart shoppers would adjust, and it would all even out in the end, as long as customers were “informed,” Powell said.

“You think that this kind of surge pricing might lower prices overall?” Brown replied incredulously. “These are sophisticated economists working for these big companies. They’re not going to do things to lower their profits.”

This did not seem like an argument Powell wanted to have. “I think the price mechanism is incredibly important in our economy,” he said. “I think we need to give

companies the freedom to do that, as long as they’re not fixing prices or failing to disclose the nature of the price changes to the public.”

Jay Powell is correct; the setting of prices is one of the most critical functions in a capitalist economy. Introductory economics textbooks are filled with explanations of this process, where price is precisely plotted on a curve that takes into account supply and demand. But something is missing from Powell’s faith in what he sees as an excessively mathematical process. It ignores a central variable influencing how the economy works right now: power.

Today, everywhere consumers turn, whether they are shopping for groceries at the local Kroger or for plane tickets online, they are being gouged. Landlords are quietly utilizing new software to band together and raise rents. Uber has been accused of raising the price of rides when a customer’s phone battery is drained. Ticketmaster layers on additional fees as you move through the process of securing seats to your favorite artist’s upcoming show. Amazon’s secret pricing algorithm, code-named “Project Nessie,” was designed to identify products where it could raise prices, on the expectation that

competitors would follow suit. Companies are forcing you into monthly subscriptions for a tube of toothpaste. Banks have crept up the price of credit, so customers who cannot afford price-gouging in their everyday transactions get a second round of pricegouging when they put purchases on credit. Expedia is using demographic and purchase history data to set hotel pricing for an audience of one: you.

For those who look at this and see the normal process of for-profit companies wanting to push their earnings to the absolute peak, the numbers suggest otherwise. In the 40 years from 1979 to 2019, nonfinancial corporate profits cumulatively drove about 11.4 percent of price growth. From April to September of last year, that number was 53 percent. And in the final quarter of 2023, the Bureau of Economic Analysis showed corporate profits at a new all-time historic high, rising by $136.5 billion, compared to $90.8 billion in the previous quarter. Indeed, corporate profits surged during the pandemic years, and remain affixed at that new, higher level, all the way to the present day.

So something has changed in our economy. Companies are laser-focused on wringing as much out of Americans as possible, unleashing new schemes and building information advantages to either confuse, outsmart, or simply gouge the consumer.

The question is, why now?

For decades, the most ruthless form of American capitalism centered on cost-cutting. Beginning in the late 1970s, institutional investors—not just the hedge funds and private equity firms often caricatured as standard-issue predators but the majority of traders and analysts on Wall Street— started demanding that companies cut costs to boost profits for shareholders. Whereas mass layoffs before this period were seen as unthinkable, the result of a corporation letting down the community, the Reagan era practically promoted a race to the bottom: One out of every four employees at General Electric was laid off between 1980 and 1985. Unions were busted. Jobs and manufacturing were shipped overseas. Supply chains were outsourced. Zero-based budgeting studied every sheaf of paper, every thumbtack, and slashed budgets annually. This was seen as an unavoidable strategy to become “competitive” in corporate America.

Even after the Great Recession, companies didn’t try to make up for lower overall

demand by raising prices, instead viciously suppressing wages. Between 2009 and 2012, labor costs fell, and corporations maintained their margins by reducing workers’ share of the profits.

The results can be seen in ruined industrial ghost towns across the Midwest, and businesses strip-mined by leveraged buyouts. But there is a tipping point to all this cost-cutting. There’s only so much fat to cut before you hit bone. The strategy eventually had diminishing returns, and without a new strategy, profits would hit a plateau. That wouldn’t cut it on Wall Street.

Enter the age of recoupment. Instead of cutting costs, the new mantra is raising prices.

Price hikes are old as dirt. But today’s companies have reinvented them. They’re using a dizzying array of sophisticated and deceitful tricks to do something pretty darn simple: rip you off.

The new tricks have fancy new names. Charging you more for less is a corporate practice known as “shrinkflation.” Revealing part of the total price up front, only to tack on all manner of ridiculous-sounding fees and service charges: Industry insiders call that one “drip pricing.” Stealing your online shopping data to predict the maximum price you would be willing to pay for your next e-commerce purchase: That’s personalized pricing. Using software to coordinate pricing with other companies to make sure they don’t undercut each other: That’s algorithmic price-fixing (or plain old-fashioned collusion). And charging you more for an item when supply is limited: That’s Jay Powell’s favorite, dynamic pricing.

Three critical factors have come together to make recoupment work. None of them are necessarily new, but they have become more finely honed, more ubiquitous, and importantly more interconnected, achieving what you might call a perfect storm for pricing.

First, companies got bigger. Over the past few decades, about three-quarters of domestic industries became more concentrated. In many markets, there simply is no competition; even where an illusion of competition is perceived, companies have become adept at robbing their customers of choices. This grants the remaining corporate giants the freedom to hike prices without fear of being undercut by the competition. If the consumer has nowhere else to go, they’ll pay whatever price is available. Second, pricing went high-tech. It used to be a process where companies made some

Corporate profits surged during the pandemic years, and remain affixed at that new, higher level.

rudimentary queries about their competitors and balanced what made them a profit with what could attract customers. It’s now a highly engineered science. Technological innovations such as cloud computing, artificial intelligence, and surveillance targeting have enabled companies to collect reams of personal information on consumers. Your identity graph tells a company when you’re most likely to purchase something, where that product is in proximity to you, and how much you can afford. Website designers can construct techniques to compel you to buy products, even making it seem like you’re getting a deal when you’re actually getting ripped off. Technology, in short, has hypercharged the time-honored tactics of gouging, hidden fees, and price-fixing. Finally, market power and technological advances came together in the shadow of the pandemic, when logistics delays, broken supply chains, manpower shortages, and later geopolitical tensions created scarcity throughout the economy. The first extended bout of inflation since the early 1980s created the quintessential laboratory for companies to try out pricing strategies they’ve dreamed of implementing for decades. Any concerns CEOs may have had over damaging reputations and losing market share by executing their most egregious experiments evaporated. As a bonus, more people were shopping online than ever before, providing more data and more opportunity to tie prices to a customer’s personal habits. With prices rising everywhere they turned, nobody could discern which were justified by companies’ own rising costs, and which were truly excessive. Highly engineered “dark patterns,” where people are tricked into signing up or paying more, were chalked up to the way things are now, rather than something more insidious. If a price surges, if a fee is tacked onto the bill,

Federal Reserve chair Jerome Powell’s capacity to stem inflation is more limited in the face of novel pricing strategies.

the culprit is the economy, not the company shoving their hands into your wallet. CEOs hardly contain their delight on calls with investors. From the CFO of the international conglomerate 3M patting their team on the back for doing a “marvelous job in driving price,” to the CFO of the largest beer importer in the United States, Constellation Brands, who promised investors the company would “make sure we’re not leaving any pricing on the table” and “take as much as we can,” to the tech CEO who copped to “praying for inflation” and doing his “inflation dance,” these corporate executives were clear on one thing: Inflation was very good for business.

This perfect storm ushered in a new regime where prices are becoming increasingly unmoored from the fundamentals, like the cost of labor or materials. In its place, a new corporate credo on pricing has emerged: The best price is the one consumers are willing to pay. A fair price for everyone is increasingly becoming a thing of the past.

What does this mean for central-bank policymakers, who limit their studies of prices to how much they are rising, not the ways in which the increases are happening or the reasons why? What if prices in the economy, as Sherrod Brown suggested, have a little bit less to do with supply and demand, and a little bit more to do with corporate schemes aimed at parting consumers from their money? What if the Fed’s capacity to stem inflation is simply more limited now? What if inflation is increasingly a problem of data privacy and technological

surveillance, not aggregate demand? What if the almighty power of America’s vaunted central bank is no match for the pricing power of corporate America?

Powell may not be able to tame the last mile of inflation, but we’ve faced these problems before, and there are a host of laws duly passed by Congress, designed to prevent price-fixing, collusion, and unfair or deceptive practices. Implementation and enforcement of these laws reside not with the Fed, but in agencies across the executive branch. Government needs to be active enough to spot these strategies—even if they appear in new forms—and crack down on the companies that institute them.

Fortunately, the Biden administration is rising to this occasion in many respects. Law enforcers have brought lawsuits against algorithmic price-fixing. Regulators are working to ban junk fees, increase price transparency, and outlaw certain types of price increases seen as unfair. They’re also trying to tear down the monopolies in our economy, companies with the confidence and the power to price-gouge relentlessly.

But there’s so much more to be done. We are not at the end but the beginning of a cycle of recoupment. Computing power will be able to much more finely discern your personalized price in the future. Experiences that have habitually been associated with pricegouging—buying a car, for example, or going to a hospital where the prices are completely unknown—are adding more tricks and traps with each passing day. The grocery store, one of the more unavoidable transaction points in American life, is where so many of

these pricing schemes come together, and not surprisingly where some of the biggest cost increases have been seen. Without a wholeof-government strategy, companies will seek out unregulated corners and deploy the full weight of their superiority over consumers to take advantage of them.

In this special issue of the Prospect , you will learn about these emerging pricing strategies, and discover examples of them in everyday life. You will see the role that pricing power plays in our economy, and the technologies that no longer make it necessary for CEO s to gather in a room together to collude. You will see how price shifts have accelerated faster than consumers can adjust, and how inexplicable fees nickel-and-dime people to the tune of billions of dollars. You will see how it’s harder to figure out these days what you’re even paying for, or whether the price you pay for something is the same as everyone else. And you will hear from public servants at the state and federal level who are trying to crack down on this high-tech form of a thousand tiny thefts per day.

In this election year, we have seen how inflation can break the bonds of trust between people and their government. It has been at the top level of voter concerns for two election cycles, and across the world, incumbents have been hobbled by rising prices. Over the years, countries have outsourced too much inflation-fighting capacity to their central banks, leaving them weakened when prices soar.

You may think that a couple extra bucks in credit card interest, or a “convenience fee” on your hotel bill, or the price of a soda that’s a little bit more today than yesterday is too trivial for public policy, and too difficult to combat. You may even think it violates some sacred barrier between government and private enterprise. But the public expects elected officials to look out for them, to make sure they aren’t being treated unfairly. The outcome in 2024 will be determined at least in part by whether Joe Biden can convince the country that he’s on the side of the people against the powerful. In that sense, the stakes for understanding and reacting to the age of recoupment are nothing less than the future of the country. n

Lindsay Owens is the executive director of Groundwork Collaborative and the author of the forthcoming book Gouged: The End of a Fair Price.

Six years ago, I was at a conference at the University of Chicago, the intellectual heart of corporate-friendly capitalism, when my eyes found the cover of the Chicago Booth Review, the business school’s flagship publication. “Are You Ready for Personalized Pricing?” the headline asked. I wasn’t, so I started reading.

The story looked at how online shopping, persistent data collection, and machinelearning algorithms could combine to generate the stuff of economist dreams: individual prices for each customer. It even recounted an experiment in 2015, where

online employment website ZipRecruiter essentially outsourced its pricing strategy to two U of Chicago economists, Sanjog Misra and Jean-Pierre Dubé.

ZipRecruiter had previously charged businesses one fixed monthly price for its jobscreening services. Misra and Dubé took the information ZipRecruiter asked prospective clients on an introductory registration screen about their location, industry, and employee benefits. In the initial part of the experiment, ZipRecruiter assigned a random price to each business. The researchers could then see which attributes correlated with a willingness to pay higher prices. “There

were enough things that people involved had disclosed at the registration stage that were associated with their price sensitivities that we could build a pricing algorithm around it,” Dubé told me in an interview.

Sure enough, when ZipRecruiter deployed the algorithm, to deliver tailored prices based on the questions customers answered, profits went up 84 percent over the old system. Misra became an adviser to ZipRecruiter. The algorithm isn’t used today, but remnants of the pricing strategy remain: ZipRecruiter’s FAQ page promises to “customize” what it charges based on particular attributes.

Businesses have always wanted to maximize what they can induce people to pay, trying to walk right up to the limit before a customer says no. But everyone has a different pain point, and companies were deterred from purely individualizing what they charge, because of publicly posted prices and consumer anger over the unfairness of being charged differently for the same product.

Today, the fine-graining of data and the isolation of consumers has changed the game. The old idiom is that every man has his price. But that’s literally true now, much more than you know, and it’s certainly the plan for the future.

“The idea of being able to charge every individual person based on their individual willingness to pay has for the most part been a thought experiment,” said Lina Khan, chairwoman of the Federal Trade Commission. “And now … through the enormous amount of behavioral and individualized data that these data brokers and other firms have been collecting, we’re now in an environment that technologically it actually is much more possible to be serving every individual person an individual price based on everything they know about you.”

Economists soft-pedal this emerging trend by calling it “personalized” pricing, which reflects their view that tying price to individual characteristics adds value for consumers. But Zephyr Teachout, who helped write anti-price-gouging rules in the New York attorney general’s office, has a different name for it: surveillance pricing.

“I think public pricing is foundational to economic liberty,” said Teachout, now a law professor at Fordham University. “Now we need to lock it down with rules.”

“

How much?” is a question shoppers ask at yard sales and flea markets across the country. Vendors size them up and try to find the sweet spot: a price both sides will accept, one that tips customers to saying yes while making the transaction profitable. In the 1800s, this was the process behind virtually every retail sale. Without fixed prices, sales clerks would haggle with shoppers, aiming for that sweet spot. Some would get a discount; others would overpay.

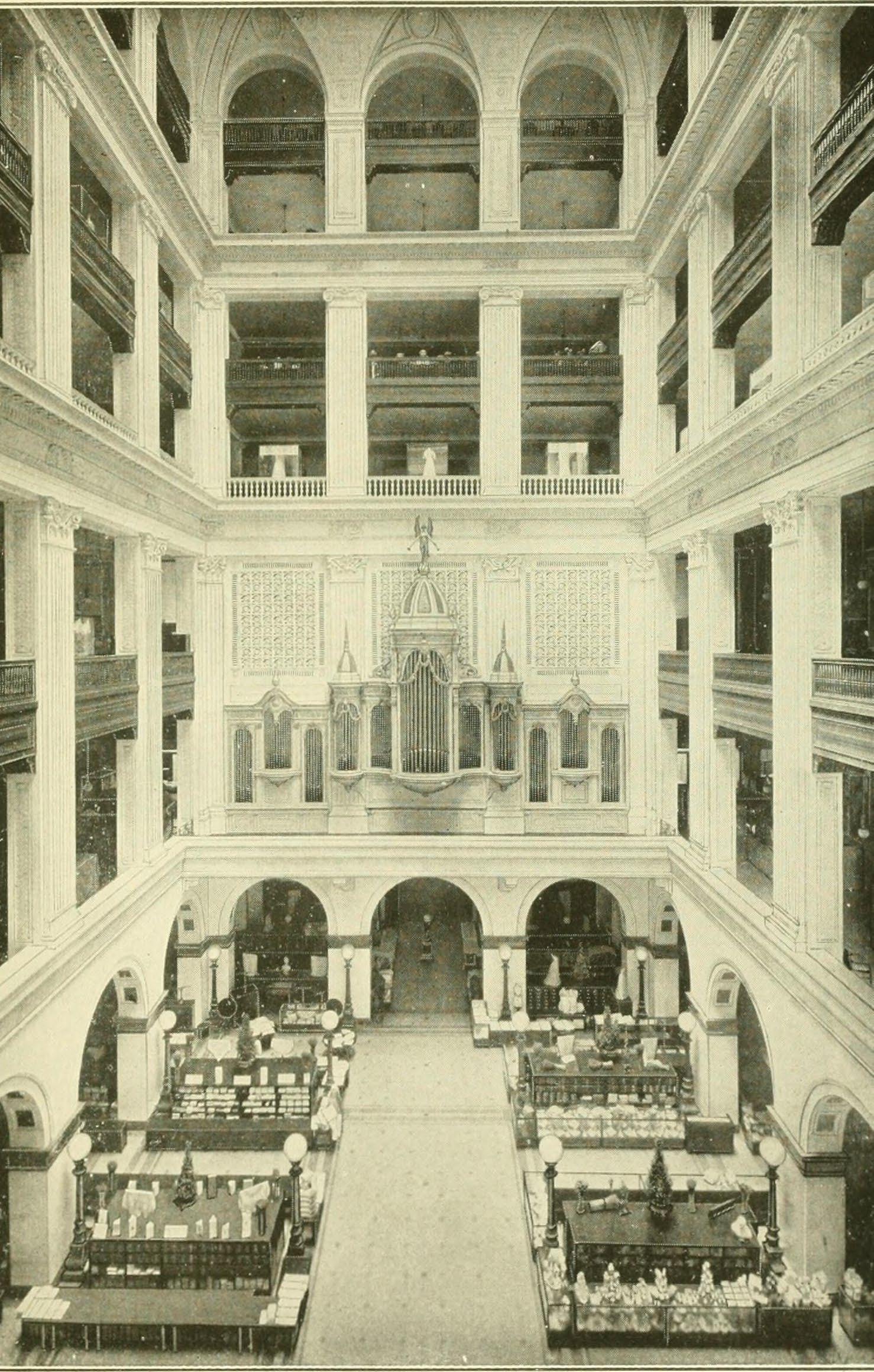

John Wanamaker opened his flagship department store in an abandoned railroad depot in Philadelphia in 1876 with a novel idea: affixing a price tag to each item. It was a big step in a nation that was fed up with differential pricing. One of the reasons railroad

monopolies inspired such Progressive Era fury had to do with the rates they charged for transport and storage of crops. Large shippers got volume discounts, and yeoman farmers were stuck paying more, which they condemned as price discrimination.

The populist Granger Movement farmers established led to the “just and reasonable” rate regulation in the Interstate Commerce Act of 1887, which prohibited any special rates, rebates, or preferential treatment for any shipper, product, or destination. “When you read Ida Tarbell, she says on the railroads everyone is talking about price discrimination … allowing companies to pick a different private price for each person,” Teachout said.

But public prices didn’t extinguish the dream for private ones, and businesses innovated. Some industries set expectations for differential prices, like airlines after deregulation. Airfares primarily hinged on the supply of available tickets, but midweek trips—likely for business on the company’s dime—cost more. Negotiations at car dealerships followed the flea market model, where salespeople could pick up clues from customers, like how someone’s residence could provide an approximation of household income.

Eventually, companies longed for real information to inform prices. Catalina Marketing used a shopper’s basket of purchases to generate real-time coupons attached to the checkout receipt. Catalina would later combine knowledge from purchases with information gathered from the credit card used to pay. Then, loyalty cards gave retailers a graph of a customer’s full shopping history, along with crude demographic characteristics like addresses and phone numbers. That allowed grocery stores to make even smarter offers.

The results were surprisingly robust. A 1996 paper by three economists and statisticians found that “rather short purchase histories can produce a net gain in revenue from target couponing which is 2.5 times the gain from blanket couponing,” the authors wrote. Even a single purchase history improved revenue on coupons by 50 percent, according to the study.

Business school academics who study personalized pricing have seemed ebullient about its possibilities. And there are many academics to choose from. There are courses taught at MIT on using data to “improve” pricing, complete with a moviestyle trailer; Harvard has an entire depart-

The old idiom is that every man has his price. That’s literally true now.

ment called the Pricing Lab, which analyzes data and conducts experiments, like the Billion Prices Project.

Their theory is that an individualized price is better for the consumer. The ZipRecruiter experiment found that 60 percent of businesses in the sample paid less with personalized prices. But making things cheaper isn’t really what economists mean by “better for the consumer.”

“Using personalized pricing,” Dubé explained, “while it’s true some people are going to pay higher prices, I could vastly increase the set of people who are actually going to be able to buy.” In other words, someone who really wants that snazzy handbag will be charged $300, and someone who wants it less will get it offered to them for $200 or even $150. In the end, more people get a handbag.

This is about the willingness to pay, not the ability to pay. If you really want or need something, and the seller knows it, with personalized pricing you will pay more. Some might call exploiting the human impulse of desire unfair; Dubé and other economists call it an efficient allocation of resources.

“Theory is a playground for the mind but not reflective of public-policy preferences,” said Lee Hepner, legal counsel with the American Economic Liberties Project. He thinks that economists often deflect from the true purpose of this type of pricing. “The literature even acknowledges that personalized pricing is a transfer of wealth from consumer to the seller. Writ large, the goal and endgame is to maximize revenue.”

There have been two binding constraints for true personalization: the quality and quantity of data collected, and the mechanism for giving individual prices to people who shop where price tags are publicly displayed. Step by step, these

constraints are being defeated, and a new frontier on pricing is becoming available. E-commerce really served both ends. Instead of being out in the world, people shop from home, unaware of any uniform

price. And data that can be grabbed over the internet dwarfs what’s available on a loyalty card. It includes your IP address, the devices you use, your phone number, email, pinpoint demographics, and a comprehensive graph of

everything you’ve ever done on the internet, from purchases to searches to websites visited to emails to social media posts and much, much more. And if the retailer doesn’t get all that information, they could always buy it.

The biggest online retailer and hoarder of purchasing data immediately tried to exploit this circumstance. In 2000, Amazon varied its prices randomly for top DVDs and MP3 players, as a blind experiment to see what price points worked. But users compared notes in chat rooms and figured it out. One shopper deleted browser cookies and got served lower prices. Jeff Bezos had to apologize and Amazon actually sent out thousands of refunds. The company claims to this day that they never differentiate prices.

Other companies have been caught. In 2012, travel site Orbitz steered Mac users to pricier hotels, after learning that they tended to spend $20 to $30 more per night. The Wall Street Journal found out and Orbitz stopped. The Princeton Review was charging more for SAT prep to ZIP codes that contained a high percentage of Asians; the company stopped asking for ZIP codes. (It now appears to get the information it needs for differential pricing from a user’s IP address.)

But it’s a big internet, with billions of prices. The same year as the Orbitz article, the Journal also found the same Swingline stapler charged somewhat differently on Staples.com on two computers just a few miles apart. Forbes found similar results in 2014. The largest restaurant franchise operator in America, Flynn Restaurant Group, employs data scientists to develop pricing models that correspond to individual locations.

Perhaps the main reason to suspect that there are thousands of examples of surveillance pricing that haven’t been caught is the explosion of so-called “pricing consultants,” who nudge everyone who sells a widget online to sign up for AI-powered services to extract data, analyze it for insights, and deploy prices that are contoured to particular customers.

Ninetailed helpfully explains “why you should use personalized pricing,” arguing that “it can help you build rapport with your customers” by giving them a customized experience. Catala Consulting focuses on hotels, also praising personalization’s ability to build loyalty and increase profitability. And yes, uber-consultant McKinsey is circling around this concept too, probably winning an euphemism award by calling price discrimination “digital pricing transformations.”

slide presentation from mobile app maker Plexure shows the data used to personalize offers to users, including their “pay day.”

The most detailed of these I found comes from a business-to-business consultant called Cortado Group, which calls personalized pricing “a cornerstone of modern business strategy.” It offered a “compelling real-world example” of an unnamed “e-commerce powerhouse” that used browsing and purchasing history and even the amount of time spent on product pages to “craft pricing models” that “rewrite the growth curve.” Cortado says that offers from the e-commerce company were “tailored for customers with a history of consistent purchases,” and that prices for occasional shoppers were “adjusted” to boost sales. There is a hint of caution: “Striking the right balance between personalization and customer privacy is an ongoing challenge.”

I asked Cortado who this e-commerce powerhouse was. They never got back to me.

Overblown hype is endemic to digital marketing, of course. But there can’t be this many consultants going on about surveillance pricing if none of it was happen-

ing. And while the standard justification of increasing access and value works in a lab, in the real world it plays out in ways that would probably offend people, if they knew what was happening.

In the story about Staples offering different prices for estimated geolocations, the Journal wrote: “Areas that tended to see the discounted prices had a higher average income than areas that tended to see higher prices.” In the consumer loan context, reduced ability to pay—a lower creditworthiness—is correlated with higher prices. A study of broadband internet offers to 1.1 million residential addresses showed the worst deals given to the poorest people.

In America, it’s always been expensive to be poor. The classic study of the subject, The Poor Pay More, published by the sociologist David Caplovitz in 1963, recounted how sellers took advantage of the limited knowledge, limited options, and limited time of lowerincome consumers to price-gouge on every-

thing. What’s new is that personalized price algorithms now reduce this process to a science, not just for the poor but for everyone.

Dubé, the University of Chicago economist, suggested to me that advances in privacy laws, particularly from the General Data Protection Regulation in Europe and copycat legislation in a dozen countries, make it harder to collect enough data to truly personalize price. He did concede that the algorithms have gotten better, but he insisted that Google’s elimination of cookies and Apple’s Ask App Not to Track standard for the iPhone make persistent tracking less available.

Jeff Chester begs to differ. “The system is in place to deliver personalized pricing,” said Chester, who runs the Center for Digital Democracy.

The digital surveillance we know about comes from platform companies like Meta, Google, and Amazon, which have built

colossal advertising business lines out of social media, search, and e-commerce. But what’s emerging is even more invasive, and more primed to find customers in unusual places, where they will have no idea what the common price might be.

You might be aware that fast-food companies like McDonald’s have begun pushing customers to their app. Deals on the app are extremely good, at least for now: $1 breakfast sandwiches, 20 percent off any purchase above $5. That’s because McDonald’s, whose CEO has talked on earnings calls recently about a “street-fighting mentality” in winning customers, wants to burrow into phones, where they can access more personal data and get people hooked on an app where specific prices can be customized to the user.

What McDonald’s is doing is almost a throwback, kind of a high-tech loyalty card for the digital age. Worldwide, 150 million active members are now on the McDonald’s app, which is run by a company called Plexure that specializes in “personalized mobile engagement.” McDonald’s has a nearly 10 percent stake in Plexure, which also works with IKEA, 7-Eleven, White Castle, and more.

A Plexure slide presentation viewed by the Prospect stresses the power of customized engagement. It starts with using a cheap offer to entice users to purchase though the mobile app. After that, various factors go into the process of “deep personalization”: Time of day, food preferences, ordering habits, financial behaviors, location, weather, social interactions, and “relevance to key moments i.e. pay day.”

It doesn’t take much brainpower to devise

ways to exploit this data. If the app knows you get paid every other Friday, it can make your meal deal $4.59 instead of $3.99 when you have more money in your pocket. If it knows you usually grab an Egg McMuffin before class on Wednesday, or that you always only have an hour to eat dinner between your first and second job, it can increase the price on that promotion. If it knows it’s cold out, it can raise the price of hot coffee; on a scorcher, it can up the price of a McFlurry. And the app gets smarter as you agree to or turn down those offers in real time.

It doesn’t sound like much, but with 300 million customer interactions across its range of apps every day, Plexure can magnify tiny price shifts into real money. The company promises that using its app strategy will increase frequency of orders by 30 percent and the size of orders by 35 percent. Domino’s just attributed its strong firstquarter earnings, with income increasing by 20 percent over last year, to its loyalty program. Grocery stores like Walmart and Kroger have also gotten into this, leveraging purchasing history with digital targeting. And improving artificial intelligence can just make this all move faster.

Like everything else on the internet, the goal is to addict the user. Plexure and other digital marketers talk openly about the “dopamine rush” that getting a targeted deal can release. And the reason those deals are so smart about their subjects has to do not only with Plexure’s tracking of data from within the app, but the agglomeration of that with everything else in your digital, and even non-digital, life.

McDonald’s uses an “identity graph” provided by a company called LiveRamp, which combines multiple levels of data associated with an individual. That includes email, social media, and browser activity; behavior on streaming video sites or other smart devices; your subscriptions and app downloads; and histories from travel, retail, financial, auto, and even medical partners.

Dubé conceded that digital retail advertising is “exploding,” but he sees it as nothing more than a bargain between retailers and consumers. “[The retailer] says, I’m going to pay you. How am I going to pay you, I’m going to give you discounts,” he told me. “But in exchange for those discounts, I’m allowed to track you.” He considers it “a fair and equitable form of consent.”

But to Chester, the point is that companies are setting up the architecture to use rampant spying to set prices. The framework gets around data privacy protections because so much of it is “first-party” data collected directly by companies, which as Dubé argues, provides the consent needed for online promotions.

“They want [customers] to say, ‘Of course I want the discount and loyalty points.’ So you’re consenting,” Chester explained. “And not only do they have geolocation and other information. But because they have consent, they’re able to leverage that data … They want your permission to freely continue to target you.”

Your phone apps are not public storefronts. Nobody else sees the offers you’re getting. The coupons may not be the same as someone else’s, and may change depending on your behaviors and habits. That’s how businesses can personalize price.

Another method is through a smart TV, a prospect that has taken streaming companies, television manufacturers, and advertisers by storm.

In January at the Consumer Electronics Show in Las Vegas, Disney announced the “future of entertainment and advertising” with a variety of new technologies, including one that reads scenes in Disney’s vast online library and allows companies to match the mood with ads. One of the most powerful features, Gateway Shop, “allows consumers to access personalized offers for purchase from a retailer without leaving the viewing environment.” In other words, viewers will be able to see an individualized offer for a product they just saw in a program, and can send it to their computer or phone for seamless purchase.

Amazon has a similar concept: “dynamic ad insertion.” At specific markers in a streaming broadcast, Amazon Web Services can place personalized ads tailored to a household, with special offers. With this in place, you could get served an ad with a different Worldwide, 150 million active members are now on the McDonald’s app, which stresses the power of customized engagement.

It’s hard to put into words how powerful this can be: an app with predictive capabilities that far exceed your own brain. “Individualized pricing is certainly one expression of surveillance capitalism’s information asymmetries,” said Shoshana Zuboff, author of the 2019 book The Age of Surveillance Capitalism . “You can easily see that the companies have a nearly infinite inferential opportunity to know and predict their customers.”

flavor of soda than the house down the street, one predicted to be more to your liking.

Most streaming media and tech companies have bought into these experiments. Walmart and NBCUniversal’s Peacock streaming platform made a deal to display “shoppable ads,” where you can buy items featured in the Bravo show Below Deck Mediterranean through your remote or with a QR code. Roku has a similar deal with Shopify for ads that enable purchases through a smart TV.

Kroger and other grocers, which have huge pipelines of first-party data, have inked deals with streaming companies. 84.51°, a media company Kroger acquired in 2015 (Kroger renamed it based on the coordinates of its corporate headquarters in Cincinnati), boasts of “leveraging data

from over 62 million households in the U.S.”

Albertsons has similar data reach and partnerships with tech firms. It’s for this reason that Chester opposes the Kroger and Albertsons merger, which would combine the data of what are really two media companies, bringing their datasets to a new, narrow marketplace where they don’t have to be concerned with posted prices.

The proposed merger between Walmart and Vizio, a smart-TV manufacturer, makes a ton more sense in the context of being able to deliver targeted ads that people can buy direct from the television. Vizio’s SmartCast system has the features of a streaming media site; it serves advertising to viewers based on their data profiles. Vizio is under a federal consent decree right now for collecting user viewing histories without consent.

It’s very clear that Walmart wants to link up Vizio’s capabilities with its retail media arm, Walmart Connect, for the purposes of direct-to-consumer advertising over the smart TV. A letter from 19 groups opposing the merger notes, “Acquiring Vizio will enable Walmart to further grow its business lines that rely on extracting, monetizing, and exploiting consumer data.”

If you thought prices on an app were shrouded in secrecy, prices paid in the home, through your TV set, through your Alexa speaker, through your smart refrigerator, will be even more inscrutable. “We’re talking about a seamless link between platforms, brands, ad agencies, and retailers,” Chester explained. “People have underestimated the role advertising and marketing plays in the media system. It’s the key underpinning.”

Surveillance pricing is done in the dark because companies know there would be some degree of anger if a product with one price suddenly had 330 million. Any kind of discrimination only works well in secret, before too many people understand the implications. “What people fundamentally want as a public-policy goal is predictable pricing,” Hepner said. “If people were aware that they were paying differently, they would be upset.”

Dubé thinks the concern over advertising promotions is misplaced. “If I literally tell you, the price of a six-pack is $1.99, and then I tell someone else the price of a six-pack for them is $3.99, this would be deemed very unfair if there was too much transparency on it,” he said. “But if instead I say, the price of a six-pack is $3.99 for everyone, and that’s fair. But then I give you a coupon for $2 off but I don’t give the coupon to the other person, somehow that’s not as unfair as if I just targeted a different price.”

But the fact that one person can get that coupon and the other cannot is the point. If people understood that, they would see it as a form of discrimination. One way to stop companies from engaging in that discrimination is to simply reveal it out in the open. Several academic papers warn companies of going too far with personalization, of causing backlash. The problem with a sunlight-only approach, however, is that companies have listened, and learned how to shroud pricing strategies in neutral or even consumer-friendly language, and to keep them far from any public sphere.

Zephyr Teachout believes that corpo -

Companies have learned how to shroud pricing strategies in consumerfriendly language, and keep them far from any public sphere.

rate hesitancy to roll out surveillance pricing in a widespread fashion gives policymakers an opportunity. “This turns the public open market into private fiefdoms, and puts people at the whim of algorithms,” she said. “It’ll be a major battle for what the Ubers of the next generation will call the right to price. But now’s the time to do it before it’s embedded in every price interaction.”

One question that raises is how you actually prohibit surveillance pricing, which has two elements: the collection of personal information, and the exploitation of that information to set differential prices. Protecting against the former would involve data privacy rules; protecting against the latter is more standard price regulation. Teachout sees the need for a mix of both.

Some targeted advertising is banned, particularly to children; the FTC is in the midst of a case against Meta on that. And some privacy rules, like on personal health information, are in place. There are disclosure regimes where companies must tell consumers how their personal data is being used; those could be extended to price discrimination.

But policy decision-making thus far has been uneven. The bipartisan deal on a federal data privacy standard announced last month specifically exempts first-party advertising, the very process that is being exploited to deliver personalized prices. On the other hand, the Department of Transportation has announced a privacy review of major U.S. airlines, another industry with access to significant data that it could sell or monetize. If an airline is planning to insert ads or offers based on an identity graph into the seatback video screen of a passenger, the review should catch that.

FTC chair Khan has pursued innovative efforts to label data broker collection and sales as an unfair practice. The data broker is of course only one of the many entities sharing data with one another, but it’s a crack of the window, an opening to manage, limit, or even ban the identity graph on fairness grounds.

“The FTC under Lina Khan understands the system that has emerged,” said Chester. “The fact that it is trying to regulate commercial surveillance shows it understands the potential for consumer harm.” But he thinks it will take more than just regulating data flows. “You have to say no, NBC and Kroger and Walmart can’t work together to

do offers and services and tools that allow you to manipulate the consumer.”

There’s something almost existential about the prospect of surveillance pricing. If sellers know when your wages increase, it’s almost not worth it to get a better job; the money will be extracted away by smart pricing. If every purchasing decision comes with doubt about whether you paid more than your friends and relatives, or more because of the time of day or a personal routine picked up on by the seller, you may spend a lot of time second-guessing your life choices. And if your every habit is intuited so well by marketers, it calls into question what agency you have in the matter.

We already have a unique identifier that follows you around as you try to navigate your financial life. It’s called the credit score, the distillation of a life of purchase histories. The origins date to the 19th century as a high-level form of gossip: A company called the Mercantile Agency hired a network of correspondents, who compiled markedly subjective, often biased information on people seeking credit, which was eventually distilled into a number and used by lenders. The credit score’s transformation of rumor into fact mirrors the transformation of someone’s mindless web scrolling and social media likes into an identity graph that can determine the prices they pay.

The feeling behind that, the humiliation attached to your financial picture with a scarlet FICO score, is perhaps best expressed in fiction. Gary Shteyngart’s Super Sad True Love Story, set in a New York City of the near future, envisions a world with Credit Poles, lamppost-like structures that display the financial worthiness of everyone who walks by. It is a depiction of a repressive government merged entirely with big business, and also an expression of the power dynamics inherent in exposing people’s deepest secrets, in public, for all to see.

Shteyngart gets a lot of this right, and the technology underpinning the Credit Pole may be coming to a phone or TV set near you. But Super Sad True Love Story ends in revolution. Corporate America has figured out that not everything should be on display. If they have their way, only their algorithms get to see the Credit Pole scores; only they know what goes into your personal price. Whether this becomes reality depends on whether policymakers open the backroom door, and reveal the whirlwind of activity going on inside. n

A growing number of industries are using software to fix prices. Law enforcers are beginning to fight back.By Luke Goldstein

It’s uncanny how most of the modern ills plaguing our economy today can be traced back to airlines. The industry is a petri dish of contaminants, from deregulation to market consolidation to financialization, that metastasized into other sectors in the 20th century.

We can add to that list the rise of algorithmic pricing, an emerging economic configuration where all competitors in a market outsource their price-setting functions to the same third-party software, in a notthat-innocent plot to fix prices.

It all began with the new world of aviation that followed the Airline Deregulation Act, signed into law in 1978 by President Jimmy Carter. By gutting the Civil Aeronautics Board, which had tightly managed airlines, Carter did away with a slew of regulations, including price controls capping airfares.

What followed was a brief window of expanded competition as new airlines entered the market. More airlines led to reduced airfares as competitors tried to

gain market share and take over particular routes. To prevent these price wars, the largest airlines got together to come up with a solution.

The airlines reorganized an existing quasi-independent service they owned called the Airline Tariff Publishing Company (ATPCO), headquartered near Dulles Airport outside of Washington, D.C. By today’s standards, ATPCO wasn’t especially hightech, but it essentially functioned as a clearinghouse to share information across the industry and set airfares. Weeks in advance, airlines would send ATPCO scheduled airfares along with detailed route information, seat numbers, and discount loyalty offers. None of this was public information. ATPCO in turn compiled this data and made it available to other airlines, so they could respond accordingly.

In the 1980s and 1990s, this information was digitized, making it available to member airlines on a moment’s notice. Today, ATPCO boasts of processing 18 million fare changes every day in its database, working

with 447 member airlines around the world.

As fares rose, ATPCO caught the attention of the Department of Justice (DOJ), which filed a lawsuit in the early 1990s. The complaint alleged that by telegraphing competitors’ scheduled airfares, ATPCO allowed airlines to identify when their prices were comparatively low and preemptively raise them to meet a higher benchmark. The DOJ concluded that ATPCO was merely a craftier, more tacit form of traditional collusion outlawed by the Sherman Act. Instead of a handshake agreement in clandestine meetings, airlines just decided to create a third party to do it for them.

That case could have been the end of the road for ATPCO. But inexplicably, it never went to trial. The DOJ opted to settle with ATPCO, a decision that was paradigmatic of the weak, ham-fisted approach that defined antitrust enforcement at the time. In the settlement, ATPCO had to make some light modifications to slow down the pace at which airfare increases could be implemented. The theory was that these mea -

sures would provide travel agents, who can also access ATPCO, enough time to make more informed decisions about the best price options for consumers.

Airfares have only risen since that settlement.

In hindsight, by not enforcing major penalties or banning ATPCO entirely, the DOJ effectively greenlit conduct that its own legal team deemed unlawful. Other actors across the economy took the hint and a proliferation of third-party price-fixing schemes sprung up, now seen in housing, agriculture, hospitality, and even health care.

These new pricing intermediaries are similar to ATPCO , but don’t just act as information exchanges between competitors. They actually set the prices for an entire industry by using machine-learn -

ing algorithms and artificial intelligence, which are programmed to maximize profits. To arrive at optimal prices, these software applications aggregate vast amounts of relevant market data, some of which is public and much of which is competitively sensitive information given to them by their clients.

Each algorithmic scheme has its own distinct features, but they all share the same underlying philosophy: Competing on price in an open market is a race to the bottom, so why not instead coordinate together to grow industry’s profits? In other words, it’s another version of the notorious Peter Thiel adage that “competition is for losers.”

These business arrangements are coming under fire from a new crop of antitrust regulators who are far more aggressive than their predecessors. Both the DOJ and the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) are

intervening to help in numerous lawsuits making their way through courts that target algorithmic price-fixing. The DOJ has even returned to the arena with its own collusion case against an agricultural information hub called Agri Stats. The outcomes could have major ramifications for this field, and rectify the lax enforcement of ATPCO in the 1990s.

Both enforcement agencies have issued statements firmly establishing that pricefixing via new technologies instead of human agents must not escape the antitrust laws.

“The idea that we don’t have a video of executives getting together and making their secret deal … does not automatically defeat a price-fixing claim in this new technological environment,” FTC chair Lina Khan told the Prospect. “We just need to be clear-eyed about that fact and update

the application of the law to match the new technological and business realities.”

It’s not yet clear whether this view will hold sway in courts, with judges entrenched in more conventional understandings of collusion through a handshake agreement. Some plaintiff cases are already meeting snags for that reason. This intensifies the threat that judges may put an exceptionally high bar on evidence of tacit collusion, which would implicitly legalize price-fixing via algorithms.

The dueling schools of antitrust don’t agree on much these days. The neoBrandeisians at the helm of the Biden administration have overturned the consumer welfare standard in favor of broader anti-competitive considerations. The Chicago school theory of consumer welfare, which reigned supreme for decades, held that prices should be the sole indicator for assessing the harms posed by monopolies.

Algorithmic price-fixing has been alleged in (clockwise from top right) Las Vegas hotels, pharmaceuticals, rental housing, and airfares.

But even during the Chicago school’s reign, collusion was the one prong of enforcement that transcended these divisions, because cartels both subvert the very underpinnings of market competition and typically result in higher prices for consumers.

Richard Posner, one of the architects of the Chicago school, argued in an influential piece from 1968 that enforcers don’t always need direct transcripts from meetings where participants explicitly agree to collude. Regulators could use “circumstantial evidence” to infer tacit collusion if, for example, all the major players in an industry were raising prices in a coordinated fashion with no clear rationale like increases in input costs.

Posner, who was effectively pro-monopoly in every other respect, believed that going after aboveground oligopolies fixing prices should be the primary function of antitrust. His position proved to be self-

defeating, since his fondness for mergers set the conditions for cartels to form among fewer players. Plus, as antitrust was deemphasized, cuts to enforcement agency funding left meager resources to identify only the most clear-cut, winnable cases against price-fixing schemes.

Regulators might have been overly cautious, but enforcement against collusion generally remained constant, even as antitrust actions dwindled in every other area.

Oligopolies, however, found new ways to innovate their way out of this regulatory burden. They turned to a burgeoning field at the time called “revenue management.” Its leaders described the work as not only designed to benefit individual firms, but to grow profits for the entire industry writ large.

Information exchanges also became easier to facilitate in the 1990s, when regulators instituted “safe harbor” laws. These were essentially carve-outs for legalized

With market power, RealPage could extract higher rents than any one landlord acting unilaterally would be able to pull off.

information-sharing between competitors, as long as companies could meet certain criteria to justify it. Though specifically targeted for health care, it became common practice for other industries to exploit safe harbors for their own purposes. The DOJ withdrew these safe harbors last year as part of its crackdown.

ATPCO was born out of this new revenue management style of thinking, and its founder, a former Alaska Airlines executive named Jeffrey Roper, was a major adherent. Roper left the country following the DOJ ’s investigation into ATPCO’s practices. He later returned in the early 2000s as a “principal scientist” for a new startup venture called RealPage.

Roper’s new company had the objective to revolutionize pricing in real estate by fixing the same problem that he helped the airlines address post-deregulation: to head off price wars by conspiring together. “A rising tide will lift all boats,” as one real estate executive whom RealPage worked with put it.

Roper took a very unsentimental approach to the business of property management, where he saw irrational human behavior driving inefficiencies. According to Roper, landlords had “too much empathy,” which prevented them from raising rent as high as they could. As Roper once put it, “If you have idiots undervaluing, it costs the whole system.”

He went about rectifying that by deposing the human agents who controlled pricing, and instead introducing algorithms that could make less emotional decisions. In its own words, RealPage promises

to “maximize profits” with the ability to “achieve … revenue lift between 3 percent to 7 percent,” even in economic downturns. There should be no doubt that RealPage does so by consistently pushing rent increases, according to testimony from clients in several recent lawsuits. RealPage, according to one lawsuit, told clients that the data they shared would never be used “to undercut RealPage’s higher prices—doing so for too long would mean losing access to RealPage.”

By virtually guaranteeing higher revenue, the service quickly spread across real estate markets and achieved extraordinary market power in several major cities.

In Seattle, for example, one of the most expensive cities for rent in the country, ten property managers control 70 percent of apartment units in one highly sought-after neighborhood. They all use RealPage.

The company became even more powerful after a major merger in 2017 with another software company called Lease Rent Options, which the Trump administration waved through after opening an investigation.

With market power, RealPage could extract higher rents than any one landlord acting unilaterally would be able to pull off in a competitive market. Without RealPage, customers could just look elsewhere for bargains, and landlords might risk not being able to fill vacancies. But when property managers are assured that virtually all surrounding residential buildings use the same service, then rent increases become more possible. Double-digit rent hikes among RealPage clients are common, according to an ongoing lawsuit.

In order to make these rent hikes stick, Roper and RealPage had to upend the conventional wisdom of the industry, called the “heads in beds” strategy. Usually, landlords want to maintain the highest occupancy rates possible, so they’re not wasting space. That means if landlords set their prices too high and can’t get any takers, they’ll usually drop the price to fill the apartment.

RealPage persuaded property managers that this was an arbitrary constraint. Since using their prices, landlords now report that they frequently operate well below 97 percent occupancy, holding out until they get tenants willing to match their higher rents. Housing prices have soared across every major market RealPage has infiltrated. With government officials looking to bring down rising housing costs, RealPage is now

coming under scrutiny, especially after a ProPublica investigation in 2022 into its business practices.

The company is facing a major class action lawsuit for price-fixing, and two others filed last year by attorneys general in Arizona and the District of Columbia. The lawsuits together paint a damning portrait of RealPage as a collusive enterprise, based on rental pricing evidence and scores of interviews with former employees and clients. The DOJ filed a statement of interest in the plaintiff lawsuit, and has its own criminal investigation into the company.

“It just doesn’t really take a leap of faith to see why it might be that rents keep going up in these dense metropolitan areas where RealPage operates,” said a senior official in the D.C. attorney general’s office. In the Washington-Arlington-Alexandria metropolitan area, over 90 percent of units in large buildings are priced using RealPage’s software, and rents have skyrocketed.

The D.C. lawsuit first explains that RealPage demanded its clients hand over highly competitive sensitive information, such as occupancy rates, rents charged for each unit and each floor plan, lease terms, amenities, move-in dates, and move-out dates.

RealPage’s clients give up this information because they know that their competitors will as well. In fact, many of them encouraged competitors to do so, as former employees allege in the lawsuit. That appears to be the “agreement” between competitors, which is a core part of any legal case for collusion.

This vast scale of information obtained by RealPage gives its algorithm a bird’seye view into the housing supply in a given market, which it can optimize meticulously and raise prices accordingly at each property. By instituting this regime, RealPage has managed to subvert an ordinarily competitive market for housing and centralize command over pricing.

One of RealPage’s subsidiaries acquired in the 2017 merger, known as Rainmaker, is also facing legal troubles for facilitating a similar form of price-fixing in the hospitality sector, promising its clients that it can boost revenues by 15 percent.

One lawsuit was brought last year against Rainmaker for fixing prices in the Las Vegas metro area, where the software is used by virtually every major hotel and casino on the Strip.

The lawsuit shows that Rainmaker employs an identical strategy as RealPage to dissuade hotel operators from focusing on occupancy rates at the cost of profits. Casinos in Vegas have historically treated their hotel accommodations as a side business, just to get customers on the gaming floor where the big money is made. They’re willing to offer somewhat cheaper prices just to fill beds and get people in the door.

Rainmaker upended that. According to the lawsuit, their team told clients that “revenue managers must recognize the ultimate goal is not chasing after occupancy growth,” and urged clients to “avoid the infamous ‘race to the bottom’ when competition inevitably becomes fierce within a market.”

This dynamic has held beyond casino hotels. Indeed, overall hotel prices remain at or near their pandemic peak, at odds with other services even within the travel industry. A class action suit filed in February against a separate hotel datasharing company called CoStar, which helped luxury hotels in 15 cities set prices, quotes the company telling clients that “total revenue grows higher when hotels understand the maximum amount a customer is willing to pay.”

But despite the evidence, the Las Vegas lawsuit against Rainmaker has seen the first setback for proponents of more active enforcement against tacit collusion by algorithms. Judge Miranda Du dismissed the case last October, citing a lack of evidence, even though the case had only reached the pleading stage, before discovery and depositions take place. Du, who claimed that she wasn’t an expert in the technology, was not convinced that there was proof of an agreement to collude, since each hotel separately accepted the pricing suggestions from Rainmaker.

RealPage is likely to use this defense as well, arguing that it merely makes “recommendations” for prices that are not binding and purely voluntary. The lawsuits say that this argument is a total ruse. Clients accept the RealPage recommendations over 80 percent of the time, and the company includes provisions in its contracts to ensure rent hikes. It heavily pushes adoption to new clients of an “auto-accept” feature that forces price increases automatically. Landlords who deviate from RealPage’s suggestions at too high a rate are subject to “discipline” and potentially even termination of their contract. “You should be compliant,” one

RealPage training document uncovered in a lawsuit stated very clearly.

Rainmaker’s success with an early version of this defense is an ominous circumstance for enforcers and plaintiff lawyers, especially since the company advertises that clients accept its recommendations 90 percent of the time. But Rainmaker isn’t out of the woods. In Atlantic City, where it controls over 70 percent market share, another lawsuit is making its way through the courts. The pleading in that case appears to have a better chance of overcoming dismissal. Plaintiffs are also getting help from the DOJ and FTC, which filed a joint statement of interest.

Asimilar arrangement has also taken hold in agriculture markets, with a third-party information exchange called Agri Stats.

Agri Stats has actually been around for a number of years, founded in the 1980s around the same time as ATPCO, when revenue management theory was on the rise.

When the service first emerged, most farmers didn’t think much of it, as Joe Maxwell remembers. He was a farmer in Missouri at the time, who later became the state’s lieutenant governor. The reason it didn’t set off alarm bells for him was in part that monopolization of the

industry by dominant middlemen was only just getting under way. Once the Big Four meatpackers gained market share, the anti-competitive impact of Agri Stats would become clearer.

Farmers at the time were accustomed to using their own information service called DTN, which compiled and organized prices in a giant tome the size of a phone book. But DTN just assembled scores of publicly available data. Agriculture is a more coordinated sector than most because it’s prone to booms and busts from annual harvests, which skews production levels and prices for the entire market. For this reason, the USDA requires substantial reporting from every market participant and publishes that information.

Agri Stats is a different beast. It works with each of the Big Four meat processors and requires detailed information about their operations. That includes prices, production schedules, and practices; information about suppliers; and full costs, including how much they pay workers and what benefits are offered. The data that meatpackers hand over entails virtually their entire balance sheet.

Agri Stats then synthesizes that data into granular analysis, which it sends out to its clients in extensive reports. It also consults with individual meatpackers several times a year, giving advice on when to raise prices

Potentially the biggest example of algorithmic price-fixing was uncovered in the FTC’s

or cut back supply. As former president Blair Snyder described it, “it’s like Agri Stats is doing the accounting for the whole industry.”

The listings are technically semi-anonymized, but easily identifiable in such a consolidated market. Each of the participants is listed in Agri Stats reports, and industry participation covers at least 80 percent and usually over 90 percent of the various market segments. Several of the meatpackers, notably Tyson, only agreed to participate because they were promised by Agri Stats that their competitor JBS would spill their secrets as well.

Agri Stats, which had to pause its turkey and pork reports due to private antitrust lawsuits, even encourages processors to move in a coordinated direction. According to a Justice Department lawsuit filed last year, one executive at the pork giant Smithfield “summarized Agri Stats’ consulting advice in four words: ‘Just raise your price.’”

“It raises red flags when we see the sharing of competitively sensitive information among rivals, whether directly or through an intermediary,” said Doha Mekki, the principal deputy assistant attorney general at the DOJ ’s Antitrust Division. “Corporations ordinarily work hard to safeguard that kind of information precisely because it helps them compete to win business.”

The department believes that Agri Stats’ price-fixing scheme is a quiet driver of high meat prices, which went up after the pandemic and have remained high.

The lawsuit argues that Agri Stats’ extensive reports allow meatpackers to easily identify when their products are priced low compared to their competitors and raise prices accordingly, which has occurred routinely. They can alter production levels to keep supply lower than they otherwise would,

because they know they can get away with it. Competition for high rankings in Agri Stats’ pricing books is intense; according to the lawsuit, some processors give bonuses to staff for finishing at or near the top.

As Joe Maxwell explains, if this behavior were exchanged between executives in a secret meeting, there would be no question it’s collusion. “The meatpackers just got a third party to do it under another roof, it’s like they all hired the same economist,” said Maxwell.

Both the Department of Justice and the Federal Trade Commission are also monitoring how algorithmic pricing may be impacting the health care sector, where prices continue to increase. Ending the safe harbor laws for information exchanges in health care was part of those efforts.

One potential target is GoodRx, a common coordinator of reimbursement rates on behalf of pharmacy benefit managers, as an investigation by the investigative website The Capitol Forum revealed. Initially, GoodRx was just a consumer-focused service to help patients search for the cheapest prescription drugs. But on the back end, GoodRx teamed up with each of the largest PBMs to squeeze independent pharmacies. By striking deals with the same intermediary, the PBMs pool their claims through GoodRx, which then calculates the lowest possible reimbursements they have to pay out. Because of the market power PBMs have accrued, most independent pharmacists can’t refuse to work with them.

“If this isn’t algorithmic price fixing, I don’t know what is,” Luke Slindee, a pharmacy consultant at Myers and Stauffer who advocates for anti-monopoly policies, told The Capitol Forum.

Potentially the biggest example of algorithmic price-fixing was uncovered in the FTC’s lawsuit against Amazon. An algorithm called “Project Nessie” would test price increases to see if competitors would follow by hiking prices as well. If they did, the price would stay at its new, higher level. This added an additional $1 billion in revenue for Amazon, to say nothing of its competitors across the internet.

Project Nessie represents an even more arm’s-length version of unilateral pricefixing, entirely done by algorithm and the feedback loops it triggers. Amazon says it ended Project Nessie in 2019, but the technological capability to restart it again is as easy as flicking a switch.

Today, there’s a bipartisan consensus emerging that enforcers need to establish a bright-line standard that algorithms can facilitate collusion, especially with the rise of more sophisticated models through artificial intelligence. It’s getting more attention in academia too. A recent paper from Harvard and Penn State researchers found that “[AI] pricing agents autonomously collude in oligopoly settings to the detriment of consumers.”

The current position of the Biden Justice Department on this front in many ways mirrors a speech delivered in 2017 by Maureen Ohlhausen, the former Republican FTC chair under Trump and a Chicago schooler in every respect. She stated very clearly that when it comes to collusion cases, “[e]verywhere the word ‘algorithm’ appears, please just insert the words ‘a guy named Bob.’ Is it OK for a guy named Bob to collect confidential price strategy information from all the participants in a market, and then tell everybody how they should price?” Her answer was affirmatively no.

The only remaining defenders of algorithmic pricing are economists who mostly operate from the theoretical premise of perfect market conditions. In a perfectly competitive market, individual firms using in-house pricing software might be incentivized to lower prices to gain market share. But that’s a figment of the economist’s imaginary models.

“They miss that market power skews the logic of competition,” said University of Tennessee law professor Maurice Stucke, who began investigating new pricing technologies early on.

The only real constraints on the Biden team’s actions are the limited resources they’re allocated to go after practices that appear unlawful. Then, there’s also the task of convincing the judiciary that pricefixing remotely by algorithm is indeed the same as price-fixing in person by humans. But enforcers believe this is an important issue to prioritize before pricing algorithms become completely embedded across the economy.

In previous eras, Doha Mekki explained, “a bad actor might have needed to work harder to facilitate an illegal information-sharing scheme. Today, instantaneous communication, the availability of data at scale, and increasingly widespread use of algorithms, machine learning, and artificial intelligence may have solved those speedbumps.” n