edited by

SÉRGIO

Building collective livingMARVILA LAB

PADRÃO FERNANDES, JOÃO SILVA LEITE, STEFANOS ANTONIADIS, CARLOS DIAS COELHO

SÉRGIO PADRÃO FERNANDES, JOÃO SILVA LEITE, STEFANOS ANTONIADIS, CARLOS DIAS COELHO

edited by Building collective living

MARVILA LAB

MARVILA LAB

Building collective living

ISBN 979-12-5953-039-4 (printed version)

ISBN 979-12-5953-084-4 (digital version)

edited by Sérgio Padrão Fernandes, João Silva Leite, Stefanos Antoniadis, Carlos Dias Coelho

scientific coordinators

Carlos Dias Coelho, Sérgio Padrão Fernandes

related laboratories and research programmes

The workshop and the book – MARVILA LAB: building collective living – has been framed in the research laboratory formaurbis LAB, CIAUD – FA.ULisboa under the Project “BUILDINGS” –Building Typology, Morphological Inventory of the Portuguese City.

This book is financed by national funds, through the FCT – Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology, P.I., under the Project with the reference PTDC/ART-DAQ/30110/2017

translation by Stefanos Antoniadis

book design

Margherita Ferrari

social media (buildings mais): www.instagram.com/buildings_mais

publisher Anteferma Edizioni Srl via Asolo 12, Conegliano, TV edizioni@anteferma.it

First Edition: April 2024

Copyright

This work is distributed under Creative Commons License

Attribution - Non-commercial - Share-alike 4.0 International

Workshop series

3 TABLE OF CONTENT _FOREWORDS DESIGN STUDIO: BRIEF MARVILA LAB: BUILDING THE COLLECTIVE LIVING _THEORETICAL FRAME MARVELLOUS MARVILA. A POST-INDUSTRIAL INVENTORY FOR AN AMAZING CITY HABITAR MARVILA : 5 STRATEGIES TO [RE]THINK THE WAY WE LIVE 6 8 10 24 26 36 Sérgio Padrão Fernandes, Pablo Villalonga, Stefanos Antoniadis and João Silva Leite Stefanos Antoniadis João Silva Leite, Sérgio Padrão Fernandes and Rui Justo

_DESIGN STUDIO: THEMES

COMMON HOUSE: ENCUENTRO

Sérgio Padrão Fernandes and Alessia Allegri

Joana Leite, Maria do Carmo Valadares, Pedro Robles, Raquel Cruz Barbosa, Rita Baptista, Rui Raivel

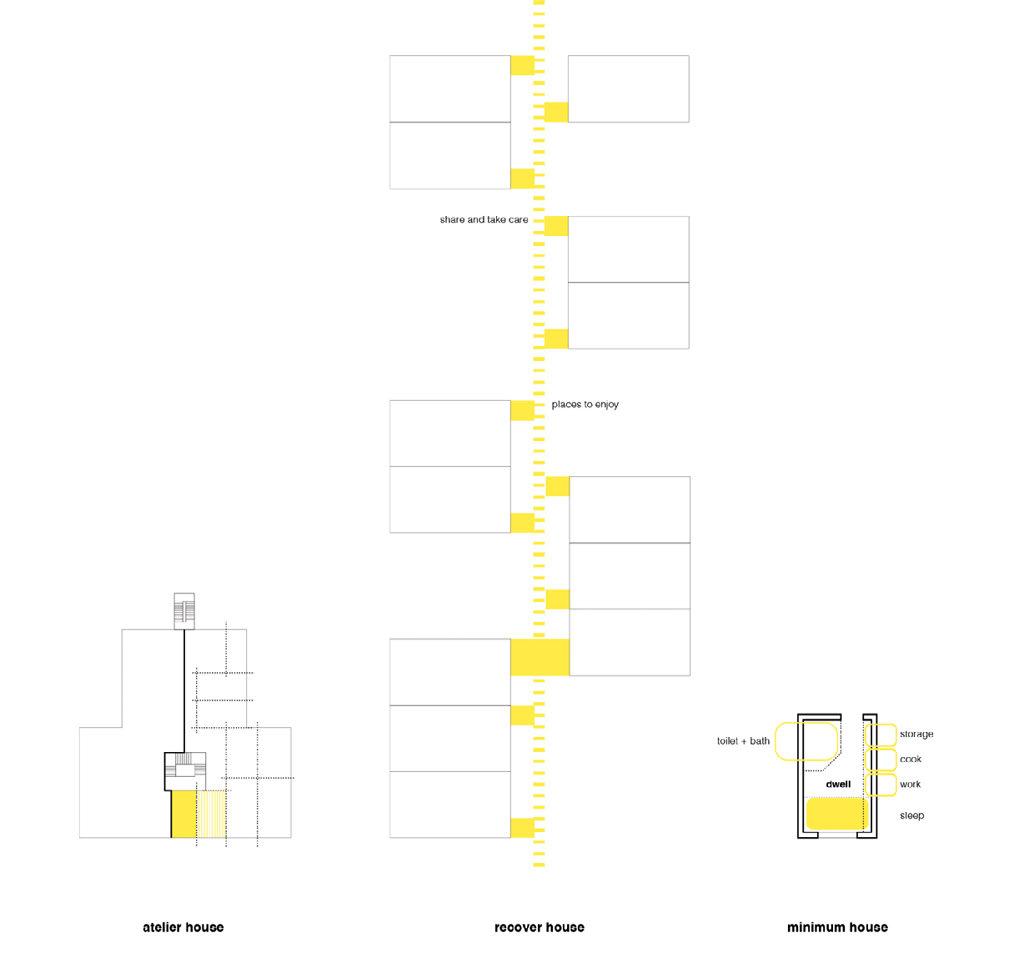

ATELIER HOUSE: LIVING UNDER A COMMON ROOF

João Silva Leite and Sérgio Barreiros Proença

Joana Henriques, Leonor dos Santos, Margarita Catalina, Mariana Vieira da Silva, Patrícia

Francisco, Pedro Leitão

RECOVER HOUSE: PLAT-EAU-FORM

Pablo Villalonga Munar and Stefanos Antoniadis

Adèle Roullet, Juliana Balage, Mafalda Soares, Marta Dias, Ona Badia, Tiago Verdasca

MINIMUM HOUSE: FROM COMPACTNESS TO TRANSFORMATION

Júlia Beltran Borràs and Tiago Mota Saraiva

Vitoria Jerónimo, Silvia Sierra, Gonçalo Mota, Ana Catarina Niza, Cláudia Vicente, Aidden Monteiro

DISPERSE HOUSE: ALONG THE VALLEY

José Miguel Silva, Rui Justo and Filipa Serpa

Beatriz Ferreira, Carlos Menacho, Cláudio Borges, Margarida Alexandre, Mariana Frade

_REPORTING FROM MARVILA

5

48 50 62 74 86 98 110 122

_BIBLIOGRAPHY

FOREWORDS

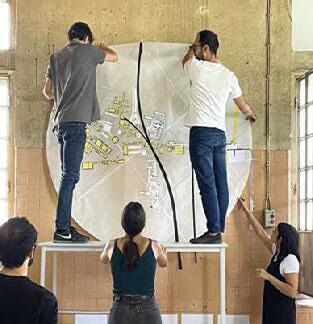

The outputs published here correspond to the results of a workshop organized in September 2022 by formaurbis LAB, a research group from the Lisbon School of Architecture, Universidade de Lisboa in the framework of the B+ event. This event provided an opportunity to present the conclusions of the research project funded by FCT - Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, focusing on the topic of Building Typology - Morphological Inventory of Portuguese City. The summer school took place simultaneously with the exhibition of the aforementioned research outputs, along with a seminar where a cluster of current and relevant topics, as well as the peculiarity of the Marvila district, were debated. This pedagogical exercise was carried out under the theme “Marvila LAB. Building Collective Living”, with 28 students from various academic institutions participating, including the Lisbon School of Architecture, Universidade de Lisboa; Escuela Técnica Superior de Arquitectura de Barcelona, Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya; and students in Erasmus mobility in our city.

An intense eleven days work allowed an approach to the theme in the particular context of Lisbon’s Oriental zone, where experimental solutions of enormous richness were materialized, pointing new ways to address the regeneration and the role of housing in that process.

However, the realization of the event was only possible due to the commitment of professors Sérgio Fernandes, João Silva Leite, José Miguel Silva, Júlia Beltran, Pablo Villalonga, Rui Justo, and Stefanos Antoniadis in the organization, as well as the close relationship with Lisbon City Hall through the town councils of Urbanism and Housing, Local Development and Startup Lisboa.

The high level of reflections produced, which can be found within the pages of this well-illustrated publication, reveals not only the sites’ capacity for reinterpretation but also the talent and quality of our architecture students who will soon enter the job market as transformative agents of our built space.

The Dean of Lisbon School of Architecture

Carlos Dias Coelho

7

DESIGN STUDIO: BRIEF

MARVILA LAB: BUILDING COLLECTIVE LIVING

Sérgio Padrão Fernandes, professor, architect, CIAUD, Research Centre for Architecture, Urbanism and Design, Lisbon School of Architecture, Universidade de Lisboa

Pablo Villalonga, professor, architect, CIAUD, Research Centre for Architecture, Urbanism and Design, Lisbon School of Architecture, Universidade de Lisboa and ETSAB, Escola Tècnica Superior d’Arquitectura de Barcelona, UPC, Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya

Stefanos Antoniadis, professor, architect, Lisbon School of Architecture, Universidade de Lisboa

João Silva Leite, professor, architect, CIAUD, Research Centre for Architecture, Urbanism and Design, Lisbon School of Architecture, Universidade de Lisboa

“utopia as metaphor and Collage City as prescription: these opposites, involving the guarantees of both law and freedom, should surely constitute the dialectic of the future rather than any total surrender either to scientific ‘certainties’ or the simple vagaries of the ad hoc.”

Colin Rowe in Collage City, Cambridge, MA: MIT press, 1978, p. 181.

10 MARVILA LAB

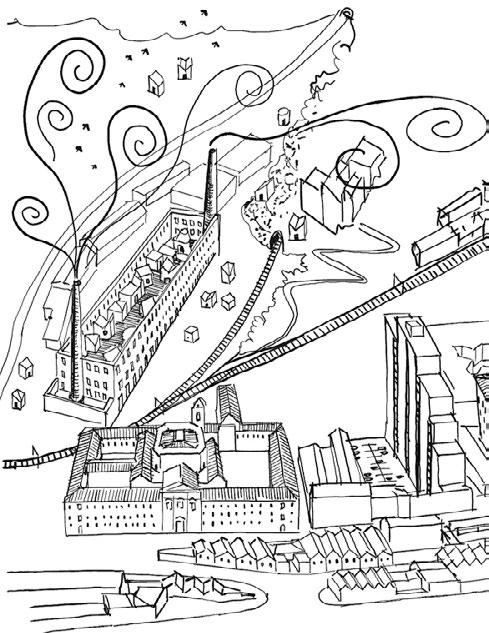

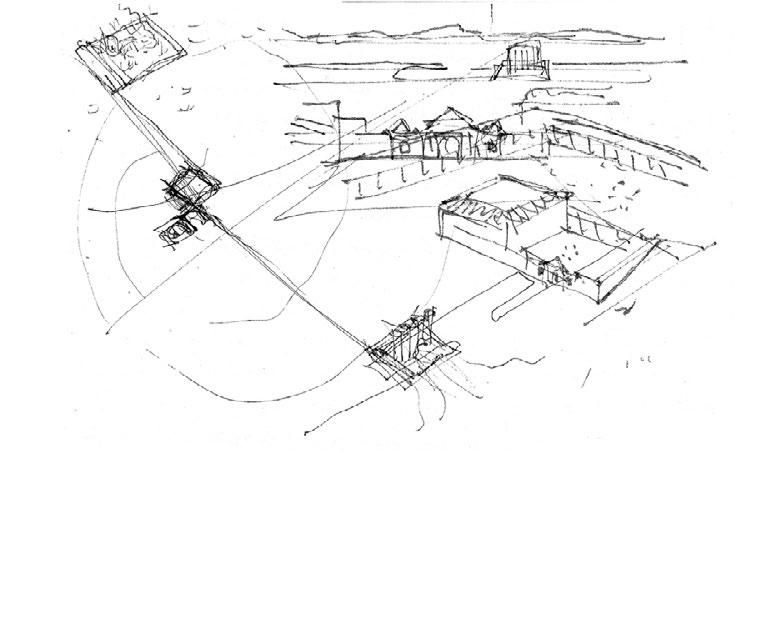

Farms, factories, grain elevators, cranes, old warehouses, convents, roads, paths, passages, small squares... from large infrastructure to detached houses, the mix of objects that make up the Marvila district is extremely heterogeneous. The neighbourhood, composed of layers in a sedimentation process whose complex relationships increase with the passage of time, constitutes a heterotopic landscape of links between different periods, whose functional variation depends on successive cultures.

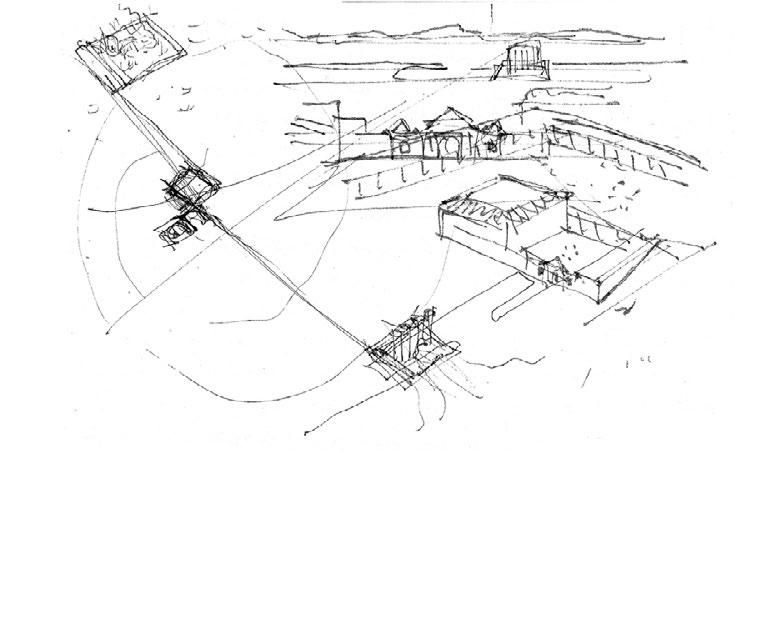

Faced with the need to prevent the dismemberment and irreversible discontinuity between fabrics, memories, and elements that constitute the place, this workshop proposes to investigate possible futures by updating and enhancing pre-existences. Through urban and architectural strategies of recycling, reuse, and refurbishment, the intensive design studio will suggest the reactivation of spaces and the reconnection of deactivated relationships.

From case studies of collective housing buildings, students will be challenged to design clusters to live in, combined with other uses that address the conflict of the transition between public ground and private space. This will be linked in a transversal way to environmental issues such as water management, green infrastructure, energy, and waste management. In any case, the starting point of the architect’s urban design process is always the surroundings, considering the immediate public space and its relationship with the territory.

In this workshop, Marvila becomes a laboratory for experimentation, building collective living, thinking and designing through different approaches and manners. The overall objective is to obtain sustainable urban and architectural devices through building’s forms, integrating the pre-existences, the relationships and the cultural background.

11

12 MARVILA LAB

Case Study

This workshop proposes a reflection through the project on a current challenge of the city of Lisbon, which allows for the articulation of the research project – inventory of buildings – with the strategic planning of the city, particularly within its most dynamic sectors such as the eastern area.

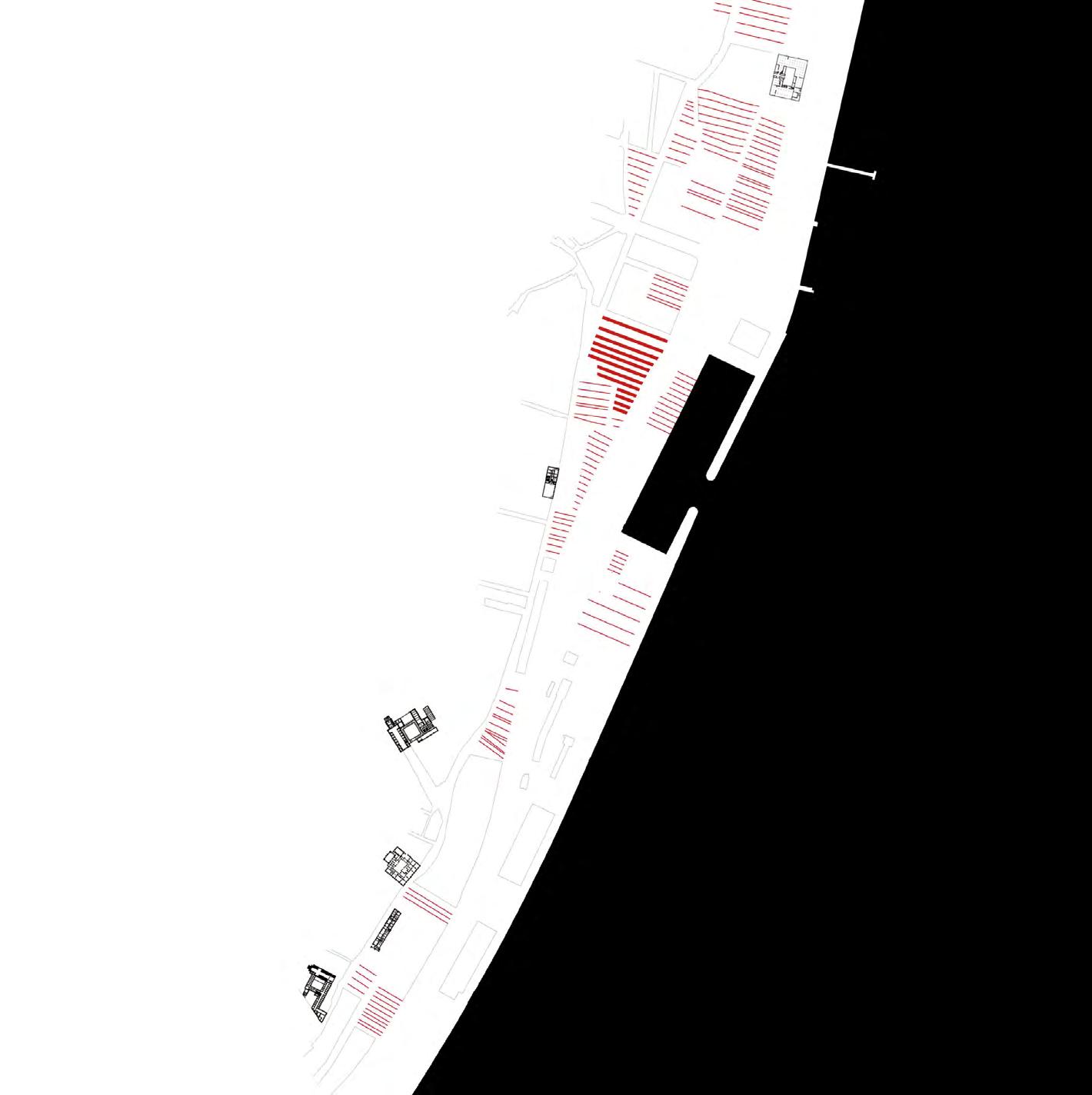

The eastern part of Lisbon – Xabregas, Beato, Marvila, Braço de Prata – is currently undergoing significant transformation. Here, the historical city coexists with heavy infrastructures, and innovative and technological programs coexist with fragments of old built structures (convents, barracks, and factories), some in ruins, others abandoned.

We propose to rethink the eastern area of Lisbon starting from some of its great buildings, currently awaiting or abandoned, which, despite being in a state of obsolescence, possess architectural significance and serve diverse urban roles.

From the case studies, it is proposed that each of the working groups, namely the Design Studio, focuses on studying the possibilities of reactivating these old structures. This involves intersecting (1) the need to create housing in the city of Lisbon based on alternative and innovative programs, and (2) the opportunity to recycle the pre-existing buildings, leveraging the monumentality of some structures to establish new public and collective spaces that are rooted in the city’s history.

[case study 01] – Tabaqueira old factory

[case study 02] – Abel Pereira da Fonseca warehouse

[case study 03] – Palácio Marquês de Abrantes

[case study 04] – Convento dos Grilos

[case study 05] – Samaritana old factory

Strategy

The workshop activities are organized with a balance between the design studio’s work and parallel events that intersect design thoughts and actions: a series of lectures [talks] and field trips [walks] that provide the framework for the design studio’s work, mainly offering theoretical support and knowledge of the city and each case study.

Given the collection of urban and architectural fragments found in the Marvila neighbourhood, the collage condition is transversal in the work methodology

13

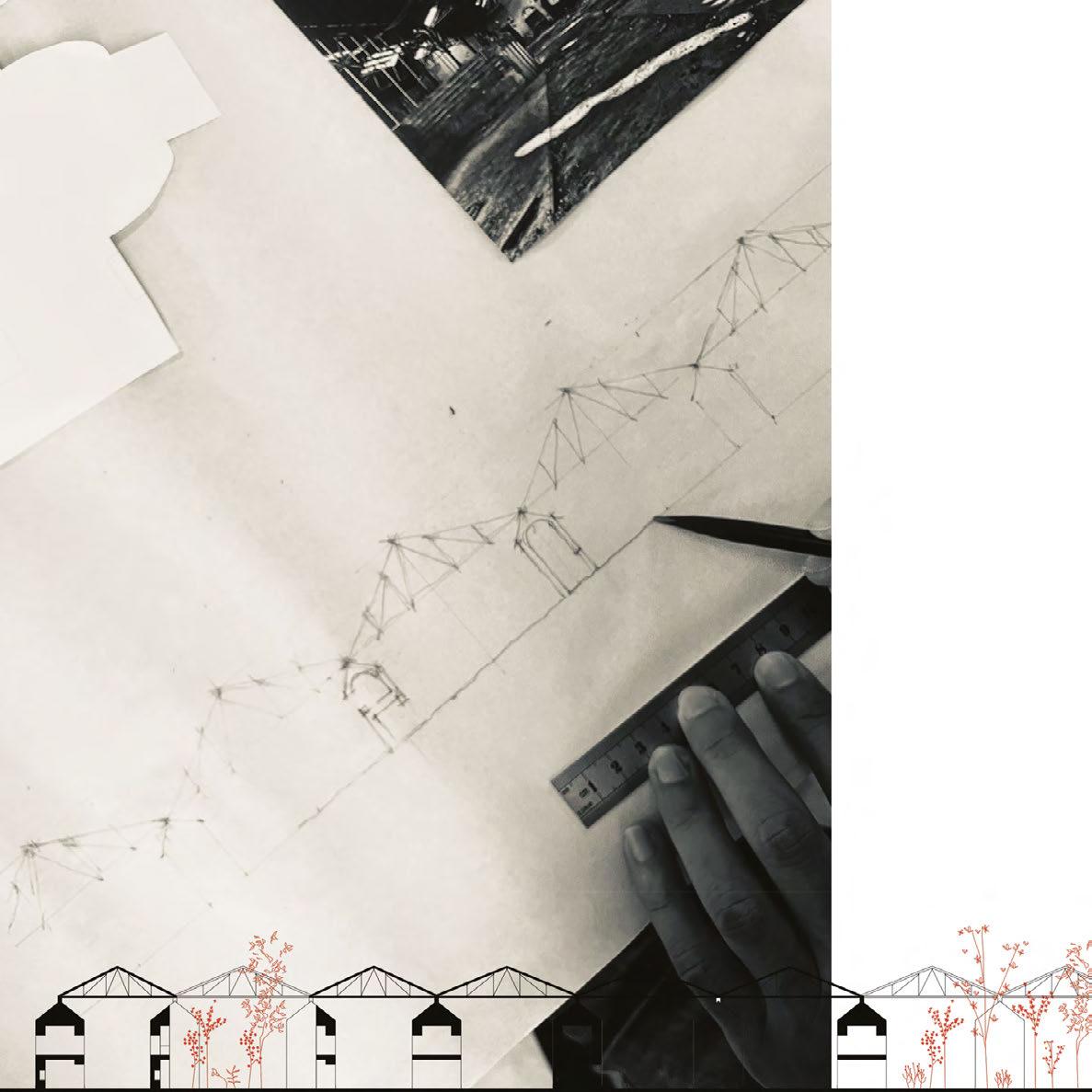

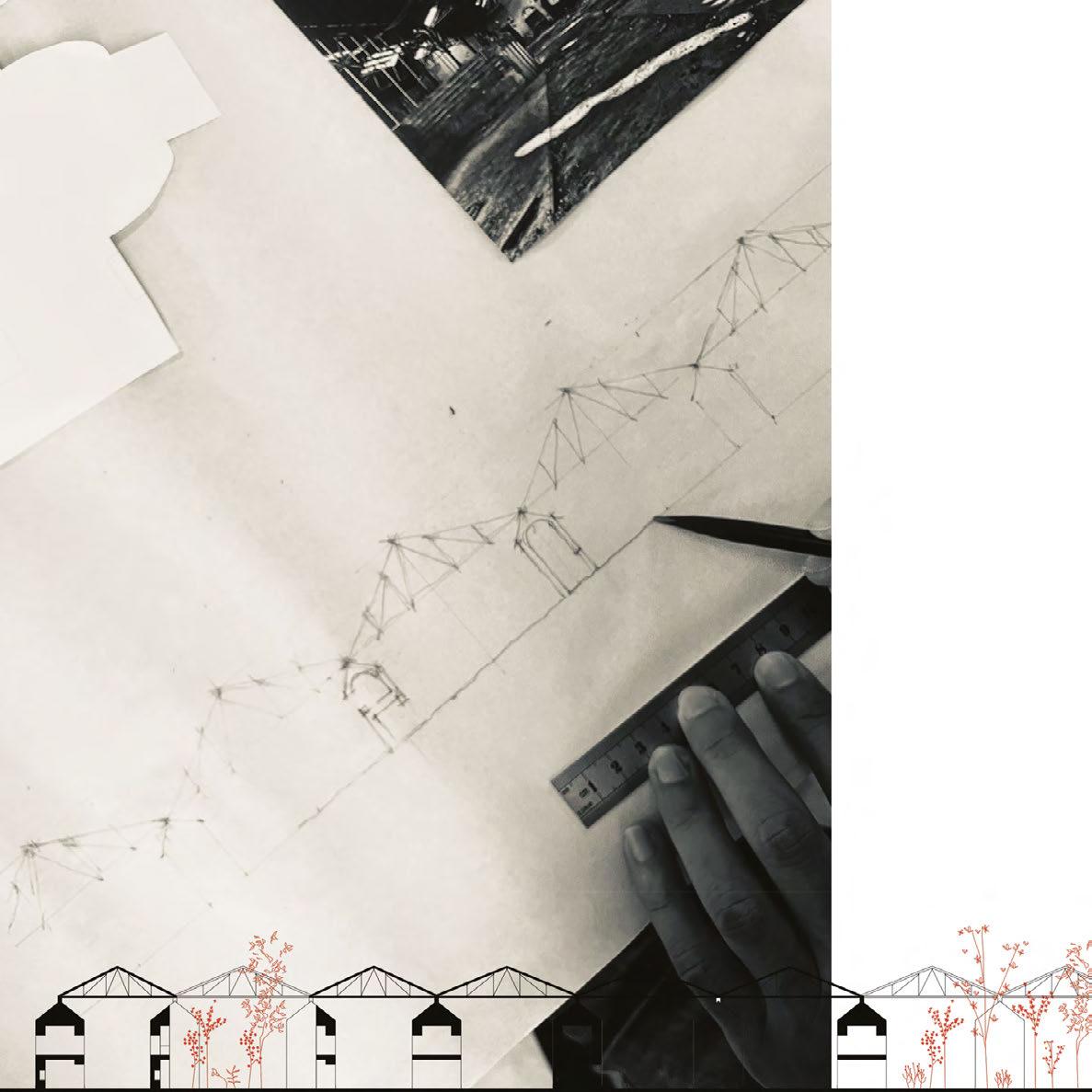

proposed in this workshop. Experimentation and project transitions will be enhanced through manual, physical, and digital work, promoting surprise in the act of joining, mixing, and combining fragments from different case studies. Starting with references from the Atlas of Forma Urbis Lab , students will be immersed in a series of enclaves chosen for their complexity and future potential as places of intersection between existing fabrics, times, buildings or infrastructures to be transformed.

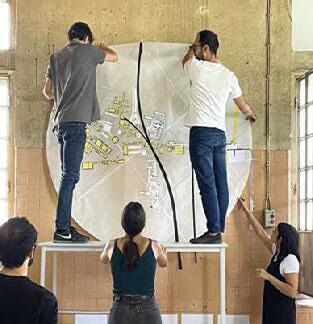

The work strategies proposed are based on the free use of references, both Portuguese and international, of representative value at the level of their configurative scheme. For this purpose, experimental work is promoted at multiple scales and formats, crossing manual collage with digital techniques in 2D, 3D, 4D, or Xd... The objective is to produce communicative material of architectural and urban ideas reflecting on Collective Living both in its materialization as an abstract object and its insertion in the place or the creation of atmospheres designed for habitation.

The workshop will consist of a collective workspace in which students and tutors will share the project experience. The space of the creative HUB of Beato, a former bread factory, is especially laden with history for this purpose. Furthermore, project work and thinking will go beyond the confines of an enclosed building, promoting the experience of visiting the city.

Walks are fundamental acts of discovery, establishing a leisurely pace capable of framing a field of awareness of the place, allowing the inclusion of consolidated knowledge with spontaneous intuitions. In this sense, the workshop walks have both a guide or host linked to the place and capable of providing a tone to each visit, as well as providing space for the student to approach the place from their own free experience. The walks will traverse spaces in the Marvila neighbourhood and others in Lisbon to understand the different tunes and rhythms that make up an explicit heterogeneity.

On the other hand, talks should be understood as a conceptual and theoretical framework to support the workshop from which to build a global view on the role of the building in the city in current urban, programmatic, and architectural situations. The views of figures linked to both academia and the profession frame a series of issues relevant to collective housing that will be useful for the design approach in Marvila. Their talks, held in the morning, will complement the project work in the afternoons. The presence of different lecturers will be a great opportunity for the students to debate and create a critical position on contemporary issues of the city.

14 MARVILA LAB

The research seminar is made up of national and international academic specialists linked to the research project Building Typology. Morphological Inventory of the Portuguese City developed by the formaurbis LAB research group.

The debates and presentations are a sample of the knowledge derived from this immense work, as well as cross reflections from which to enrich an open collection. The workshop is fed by the resources provided by this work both as information and knowledge. The crossing of international case studies with others from Portugal in the proposed workshop is another milestone in this work, as is project experimentation in the use and free manipulation of the material produced.

The 5 th of September is a meeting point for an intertwined reflection on various topics distilled from the research work. The presentations and talks of the different researchers are intended to be a starting point for the workshop as well as a sample of the wide range of possibilities that awaken and drive the research project linked to this workshop.

15

16 MARVILA LAB

17

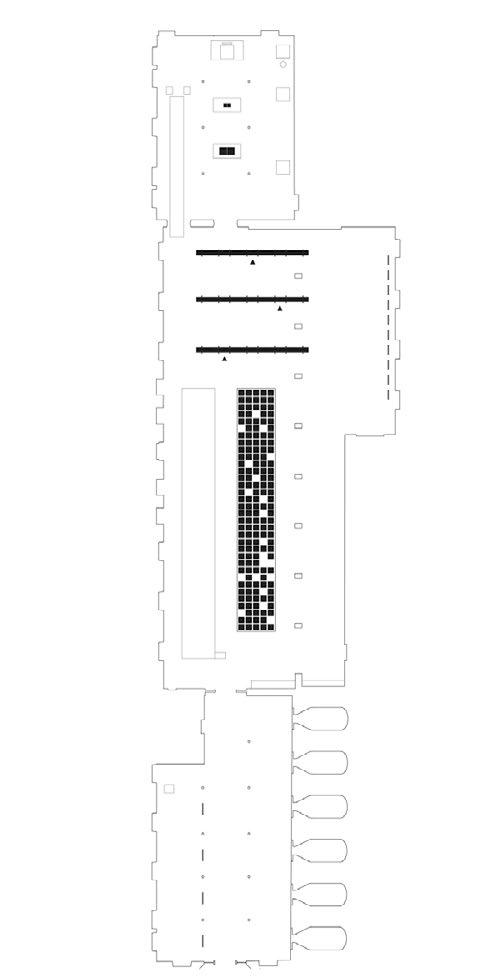

SEMINAR - about City & Buildings

Hub Criativo do Beato, Fábrica do Pão

09h30 > opening

Buildings +

Institutional greetings with FA.ULisboa

10h00 - 11h00 > research talk

Building typology: morphological inventory of the Portuguese City

Carlos Dias Coelho, FA.ULisboa, Sérgio Padrão Fernandes, FA.ULisboa

11h00 > coffee break

11h30 - 13h00 > lab talks

Passage buildings

João Silva Leite, FA.ULisboa

Jointed buildings

Rui Justo, FA.ULisboa

Buildings!...when infrastructure meets the city

Pablo Villalonga, ETSAB-UPC

Industrial Wrecks

Stefanos Antoniadis, FA.ULisboa + DICEA UniNA Federico II

Rehabit Convents in Lisbon

José Miguel Silva, FA.ULisboa

Imperfect Buildings

Pedro Vasco Martins, FA.ULisboa

13h00 > lunch time

14h30 - 17h00 >keynote talks

Llegar e instalarse. El uso contra la función

Xavier Monteys, ETSAB-UPC

Metamorfoses indiferenciadas

Fernando Salvador, FSSMGN architects + FA.ULisboa

Os desafios para a reconversão da Zona Oriental de Lisboa

Paulo Pardelha, Arquiteto e Diretor do Departamento de Planeamento Urbano, CML

17h00 - 17h30 > Round table > moderate by Jorge Spencer

Carlos Dias Coelho, FA.ULisboa, Fernando Salvador, FSSMGN architects + FA.ULisboa, Paulo Pardelha, CML, Xavier Monteys, ETSAB-UPC

18 MARVILA LAB

TALKS: lectures

about LISBON oriental

date: September 06 (morning) place: Palácio da Mitra

[talk 1] – Marvila: Buildings, Spaces, Metabolism lecturer: Paulo Pereira (FA.ULisboa)

[talk 2] – Challenges of HOUSING in oriental Lisbon lecturer: CML – housing council member, Filipa Roseta

about BUILDINGS IN TERRITORY

date: September 06 (afternoon)

place: Largo do Martim Moniz, Capela de N.S. Saúde

[talk 3] – Building from the ground lecturer: João Favila (Atelier Bugio + FA.ULisboa)

about BUILDINGS IN TIME

date: September 07 (morning) place: atelier Inês Lobo, casa-atelier na Calçada Duque Lafões

[talk 4] – Re-Use: architecture and adaptive city lecturer: Inês Lobo (Inês Lobo architects)

about CO-LIVING BUILDINGS

date: September 09 (morning)

place: Palácio Abrantes, Sociedade Musical 3 de Agosto

[talk 5] – When vacant public buildings became community led urban renovations lecturers: Tiago Mota Saraiva (ateliermob / working with 99% + FA.ULisboa)

about URBAN HOUSING

date: September 12 (morning) place: HCB – HUB Criativo do Beato, fábrica de pastelaria

[talk 6] – Urban Housing: Innovation and Flexibility lecturers: Hugo Farias (FA.ULisboa)

19

WALKS: field trips

[walk 1] – Lisbon Castle Hill date: September 06 - with João Favila (atelier Bugio)

[walk 2] –Buildings in Time: Casa e Atelier Inês Lobo, architects date: September 07 - with Inês Lobo (Inês Lobo. architects)

[walk 3] – Marvila: Lisboa Oriental date: September 09 - with Miguel Batista-Bastos, FA.ULisboa

[walk 4] – Hub Criativo do Beato date: September 13 - with José Mota Leal (Startup Lisbon CML)

Process

Students will be divided into work groups that will focus on different case studies in Marvila. Furthermore, the objective is for each group to approach their project from various topics, exploring their limits and possible formal materialization in relation to collective housing. These themes will be as follows, one for each group:

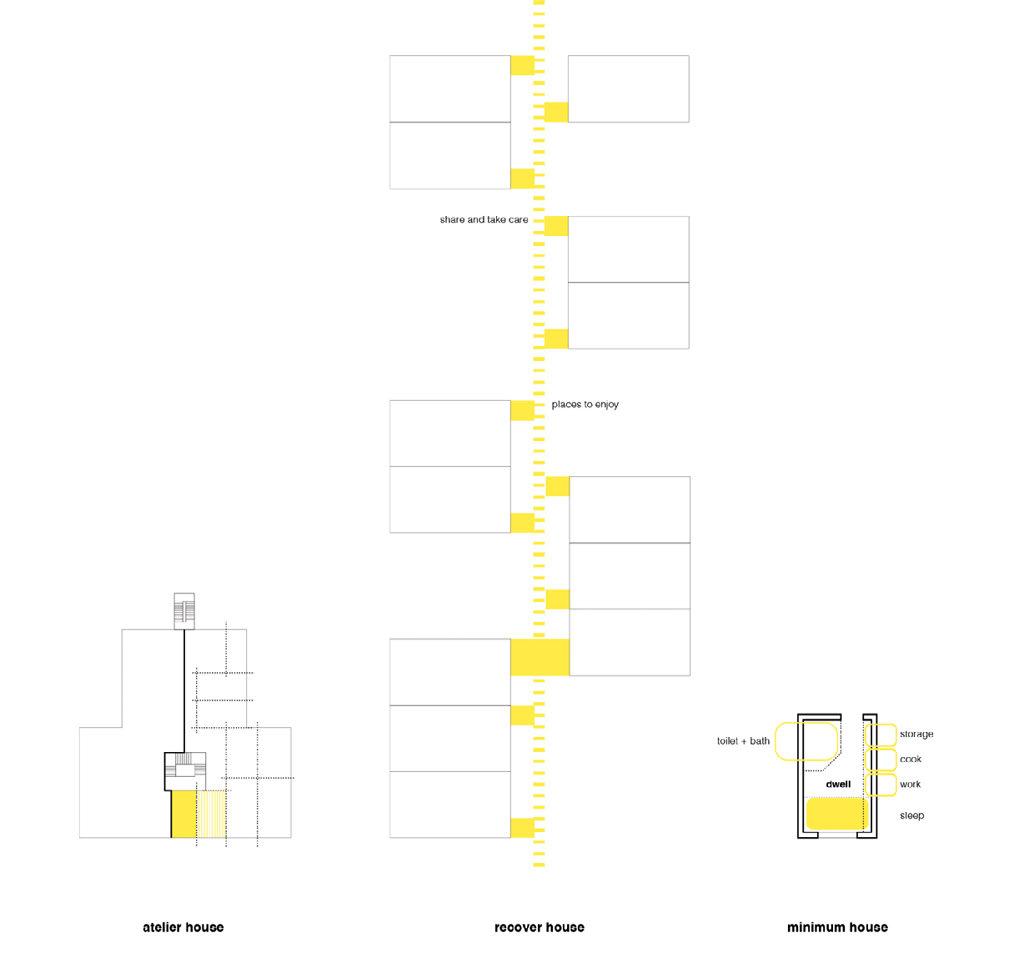

[T01] – Atelier House [to work]

[T02] – Recover House [to heal]

[T03] – Minimum House [to compact]

[T04] – Disperse House [to atomize]

[T05] – Common House [to share]

Workshop Design Studio submissions calendar

The proposed work consists of the elaboration of the following delivery material, according two main deadlines and daily submissions:

1st deadline – Intermediate Submission

The objective of this intermediate submission is to use the Buildings database as a useful resource for architectural experimentation. In this phase, there will be a strong test of different formal relationships as well as a first approach to the site condition. There will be also a description of the intentions about the place and the topic of each group.

20 MARVILA LAB

[Submission S1] – Reading and projecting the city

In S1 each team is invited to take two photos and write a text. These documents have to reflect the site from a personal point of view, showing the opportunities and site’s features of what It is like or could be to live in Marvila. They will be focused in the spaces of relationship between public and private spaces of the city.

- The photos can show questions, formal and urban relationships or any other issue that could trigger the project design (public spaces, building’s contrasts, etc.).

- The text, written in present tense, has to explain the experience of the recognition of the territory and its conditions, focusing on how urban and architectural form condition inhabiting Marvila. Both documents together will build team’s impressions to be reflected in project design.

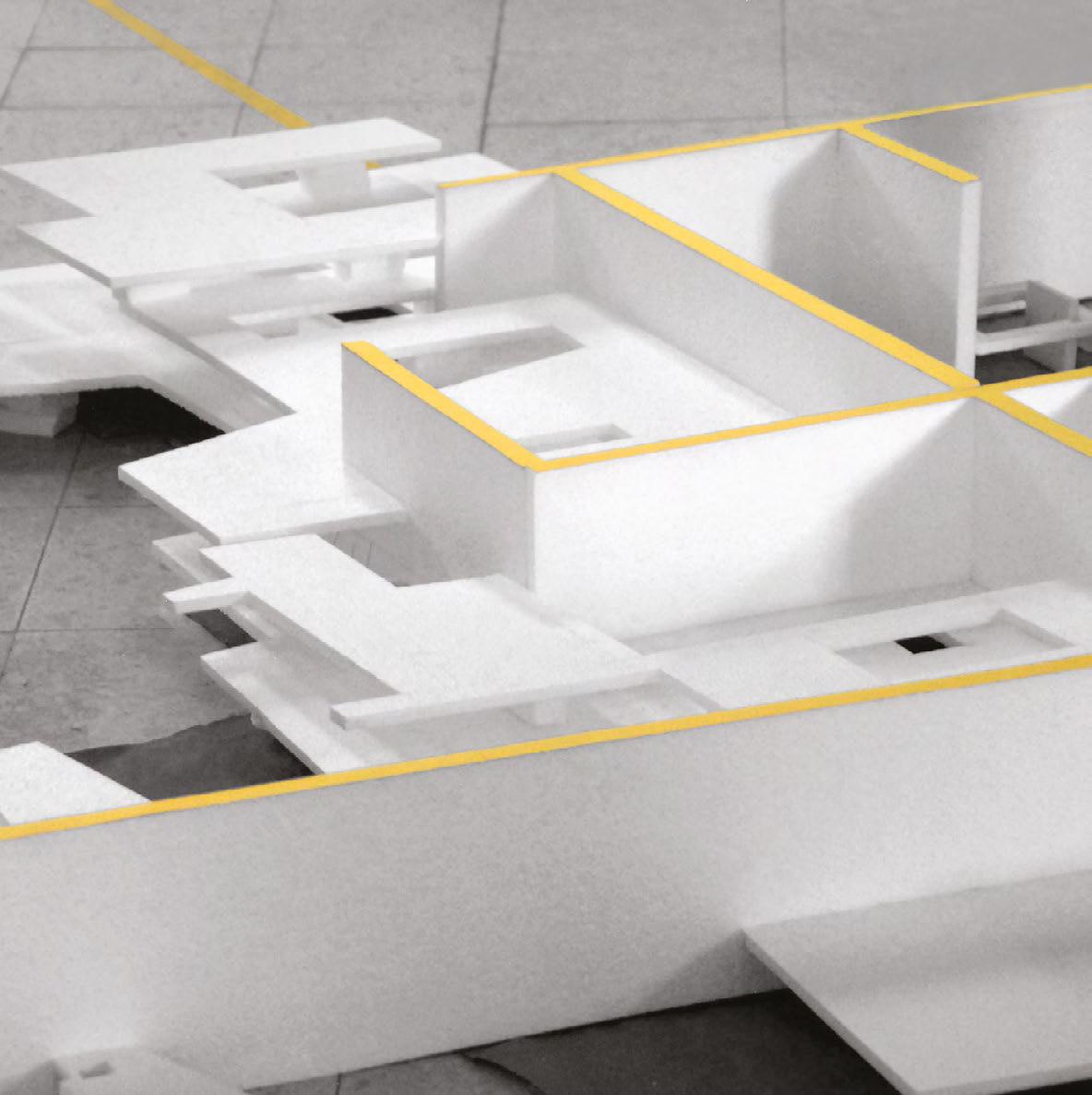

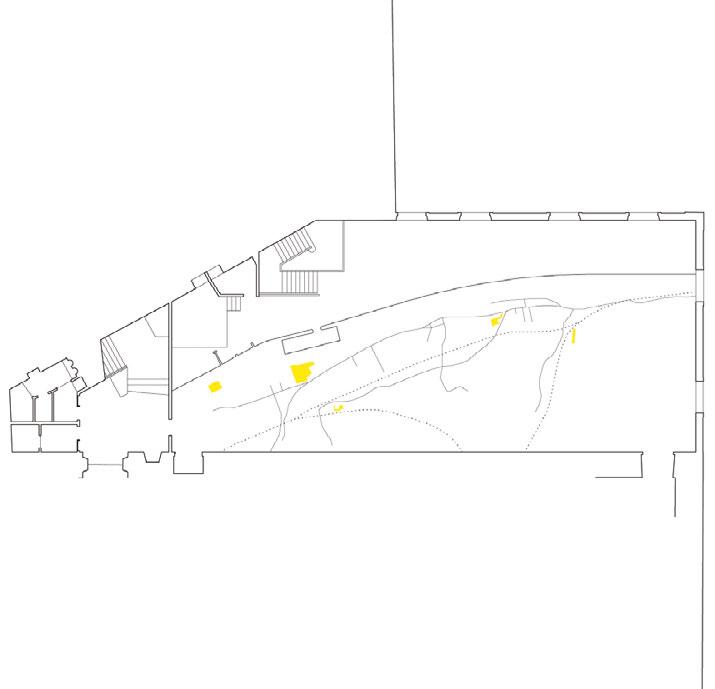

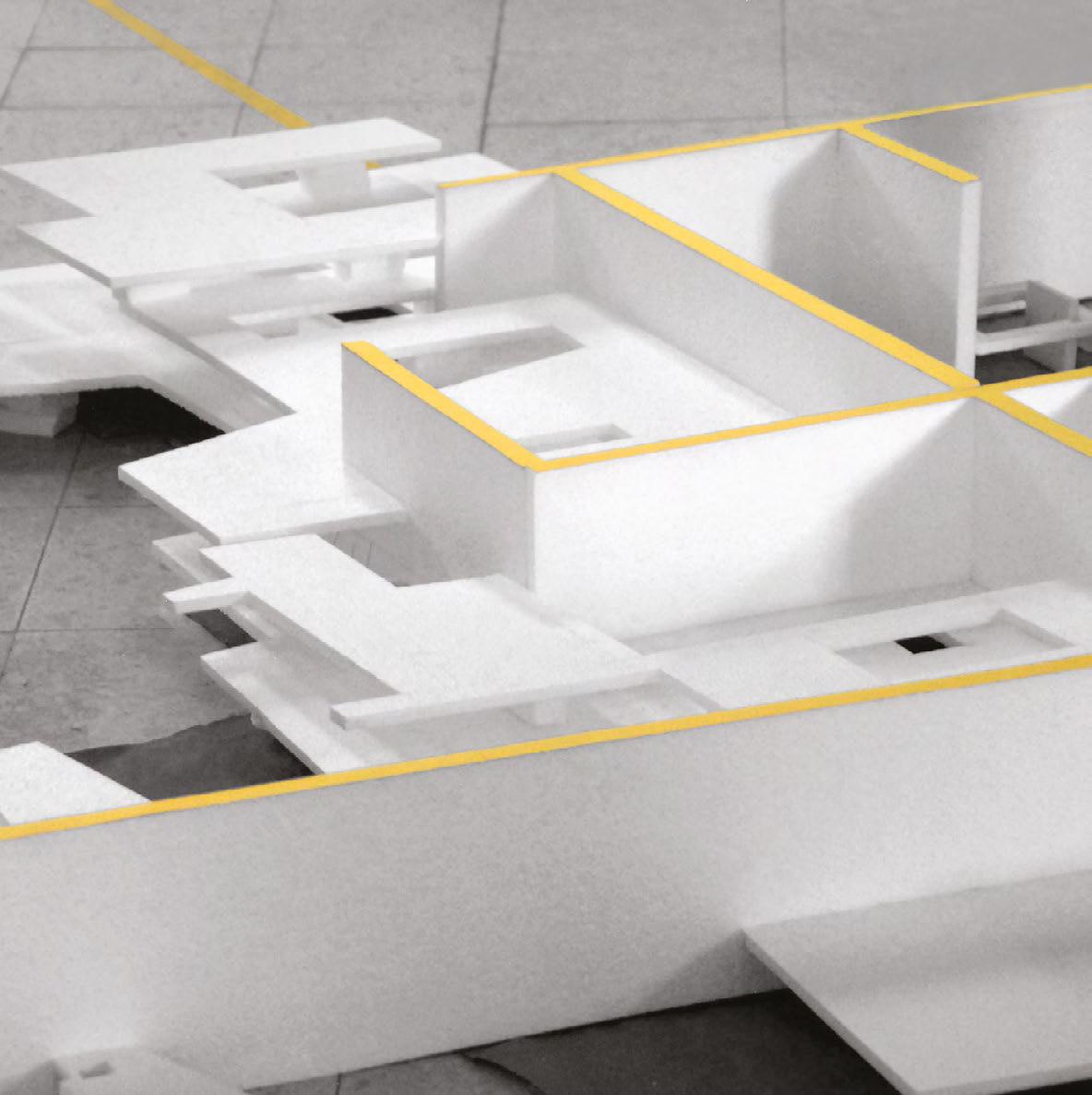

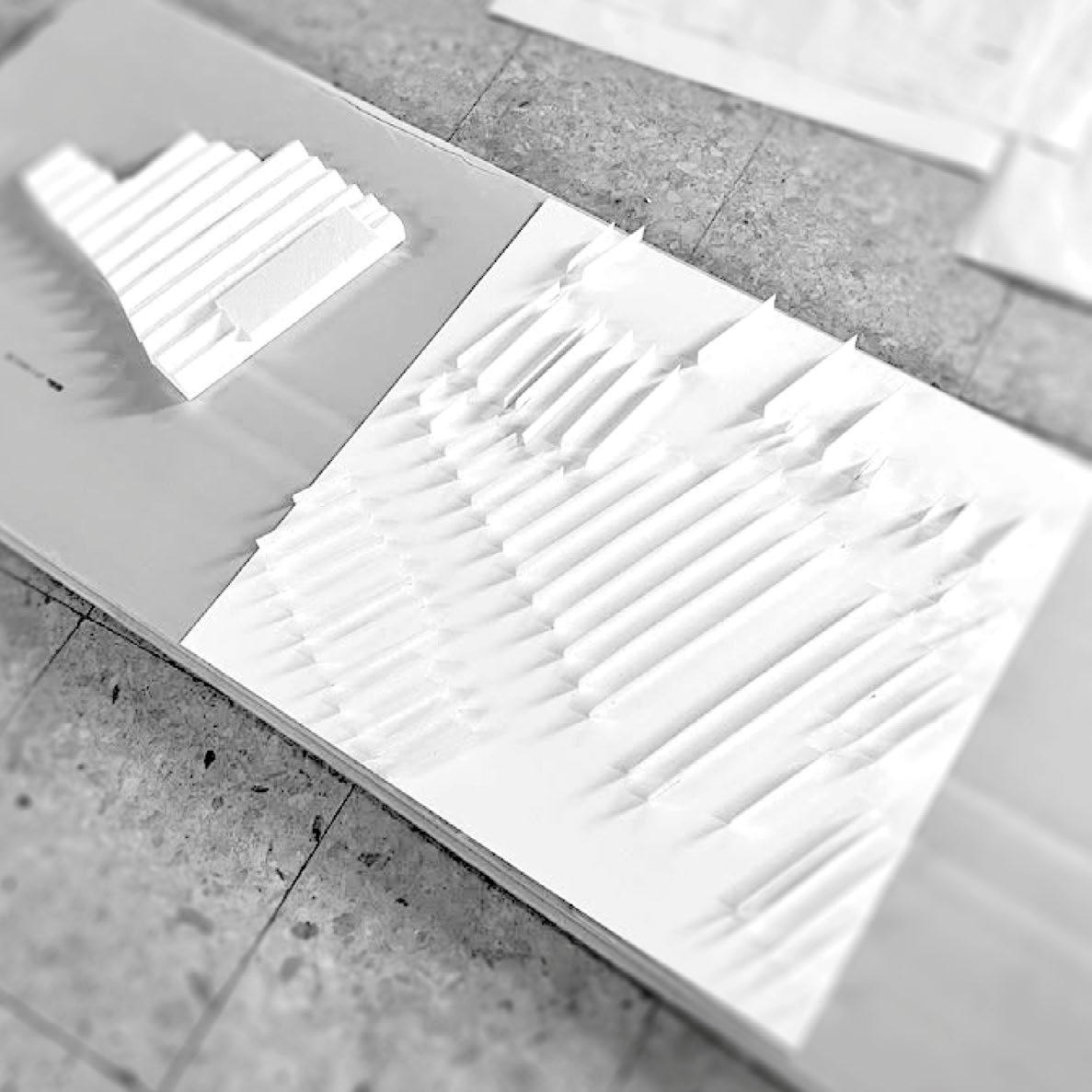

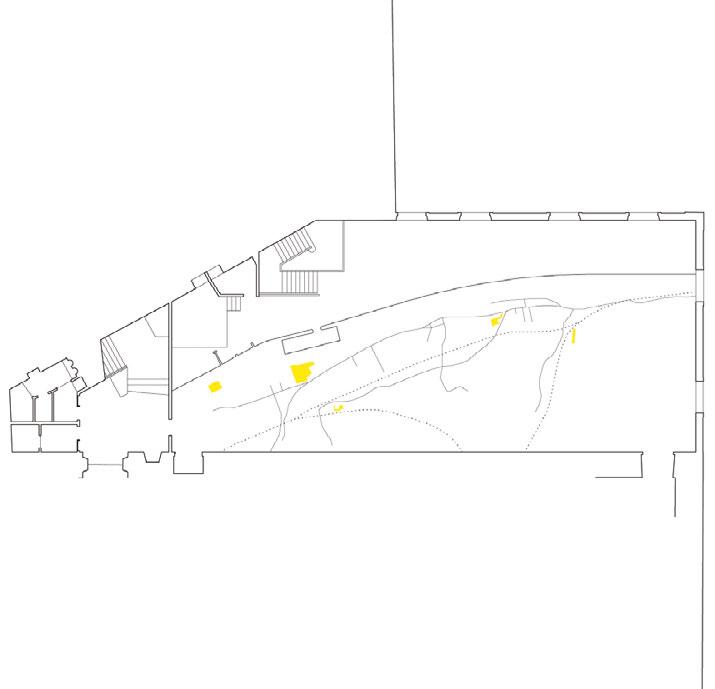

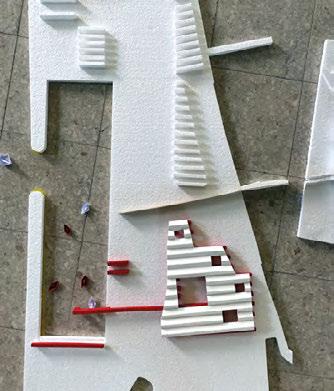

[Submission S2] – Collage plan and section

In S2, each team is invited to freely work and manipulate different architectural samples with plans. The objective is to generate systems of collective housing in an abstract manner that will be implemented at each site. Documents to produce will include plan and section collages indicating the differences between public, common, and private spaces of the system.

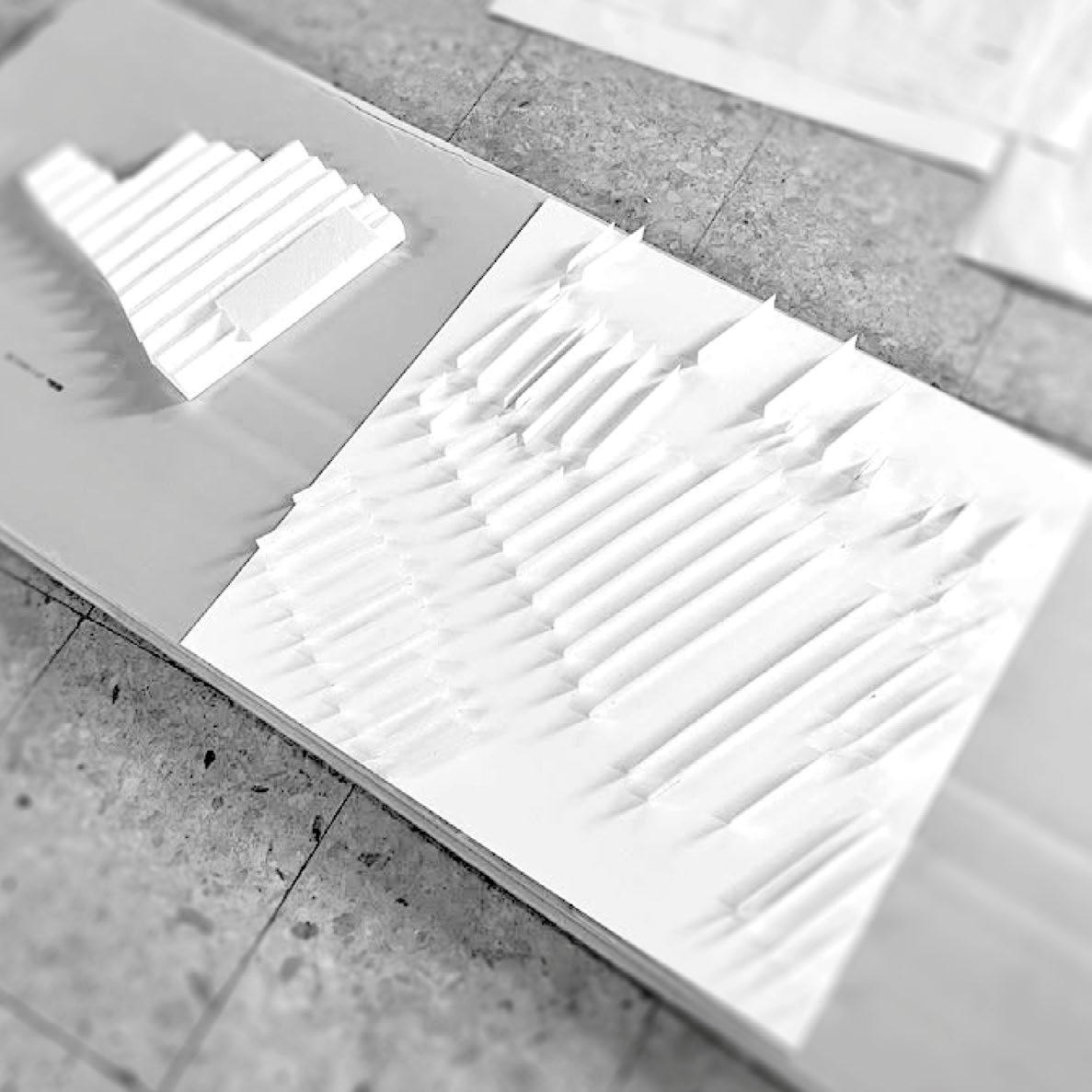

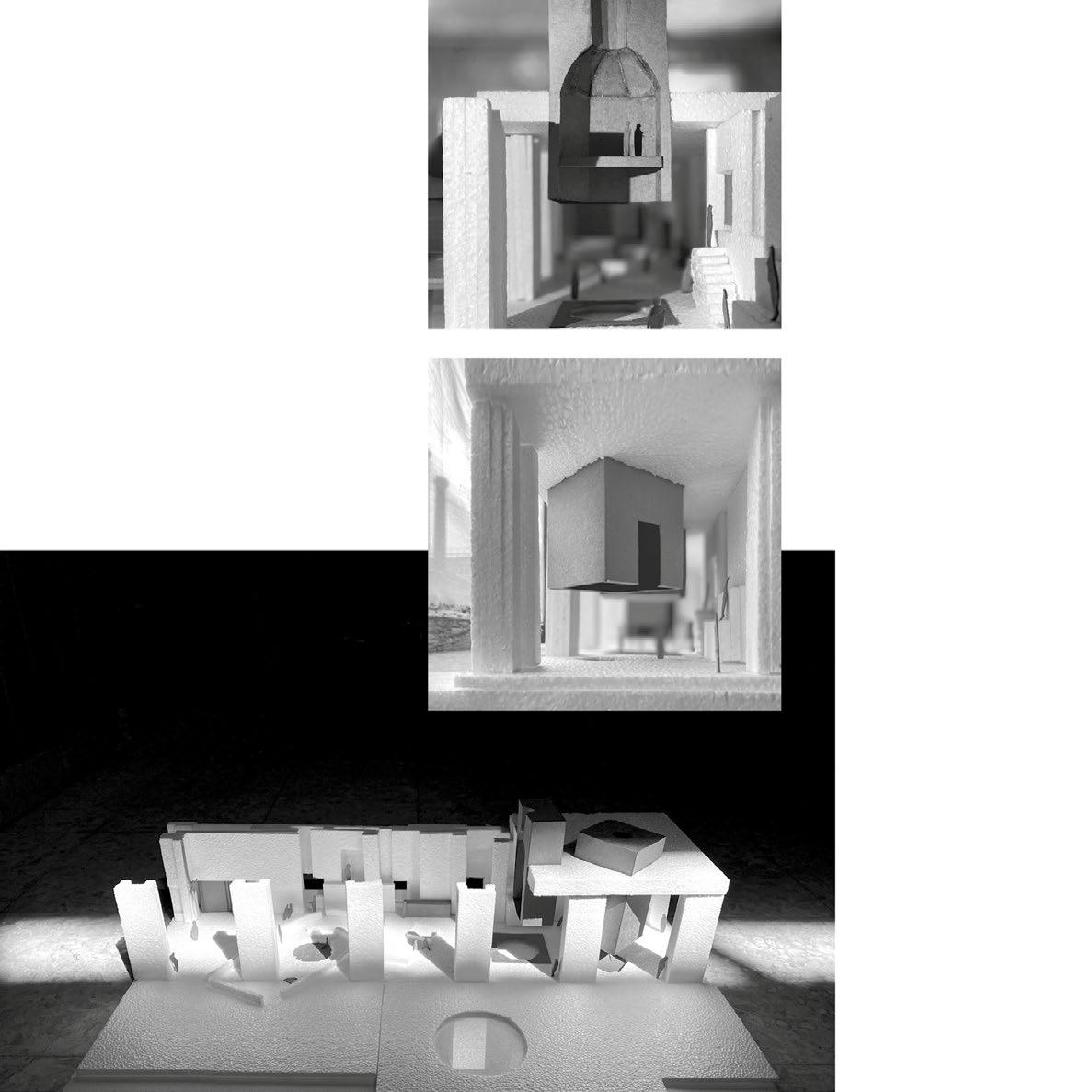

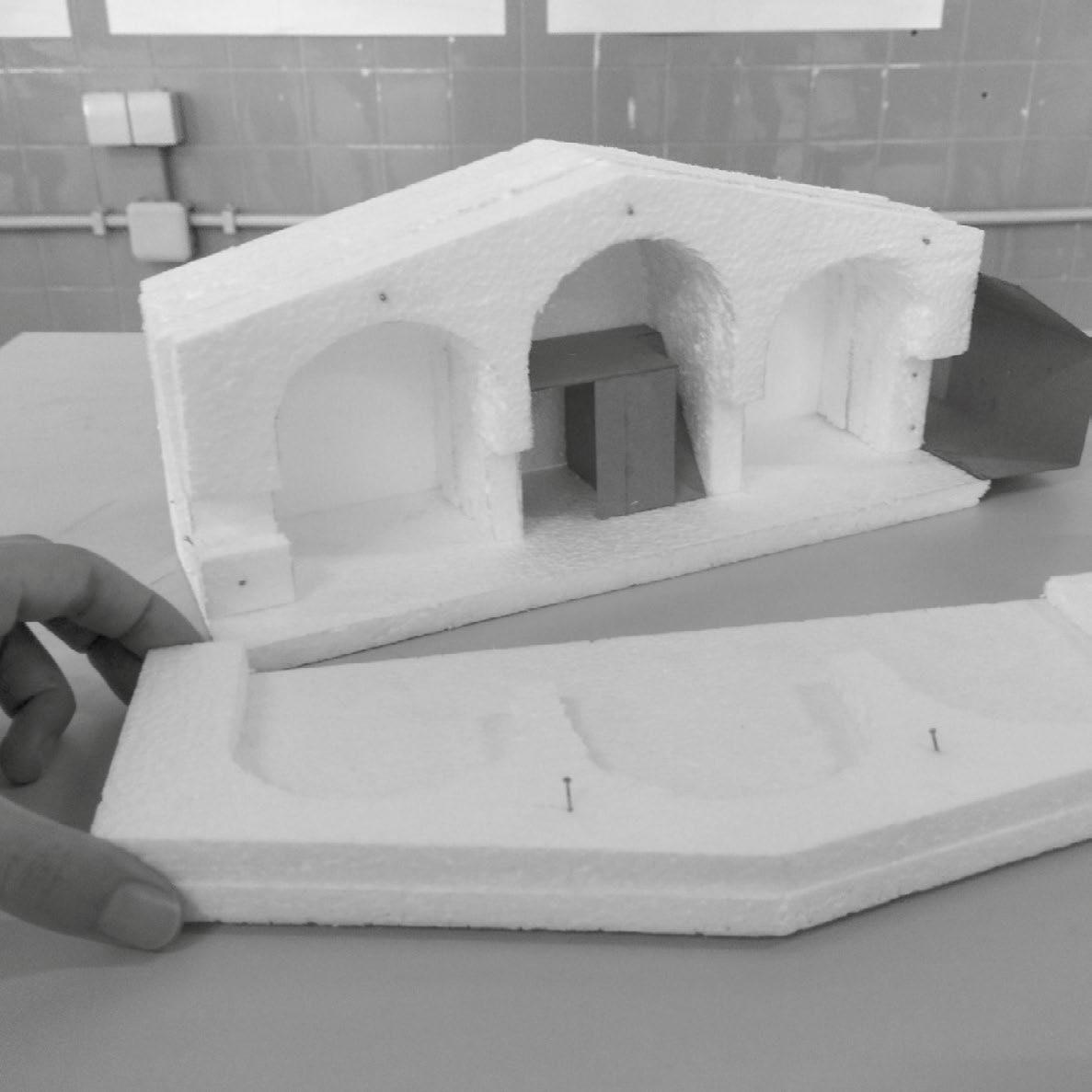

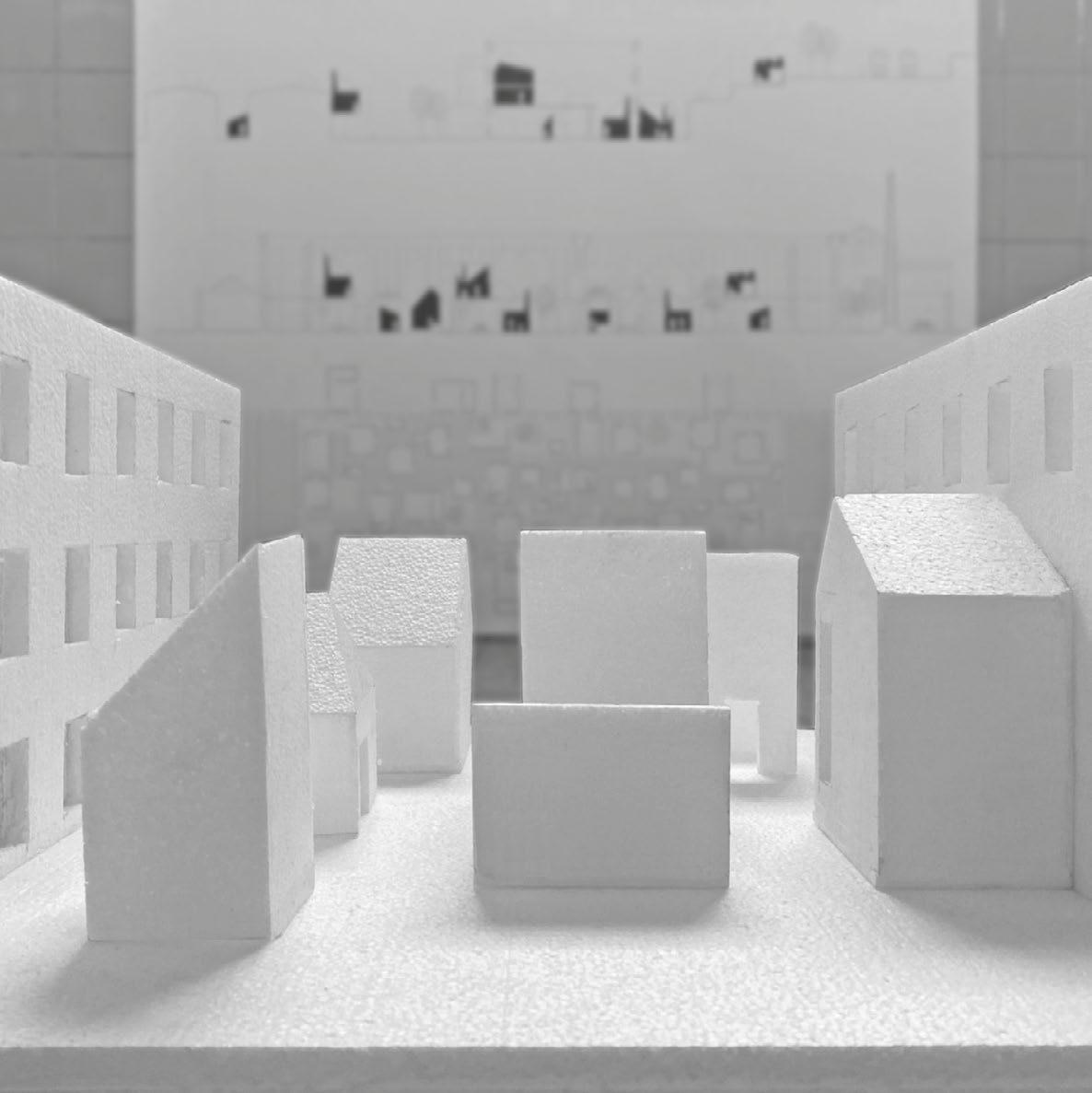

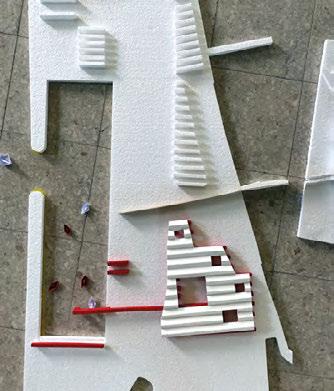

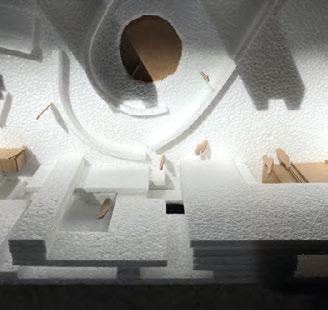

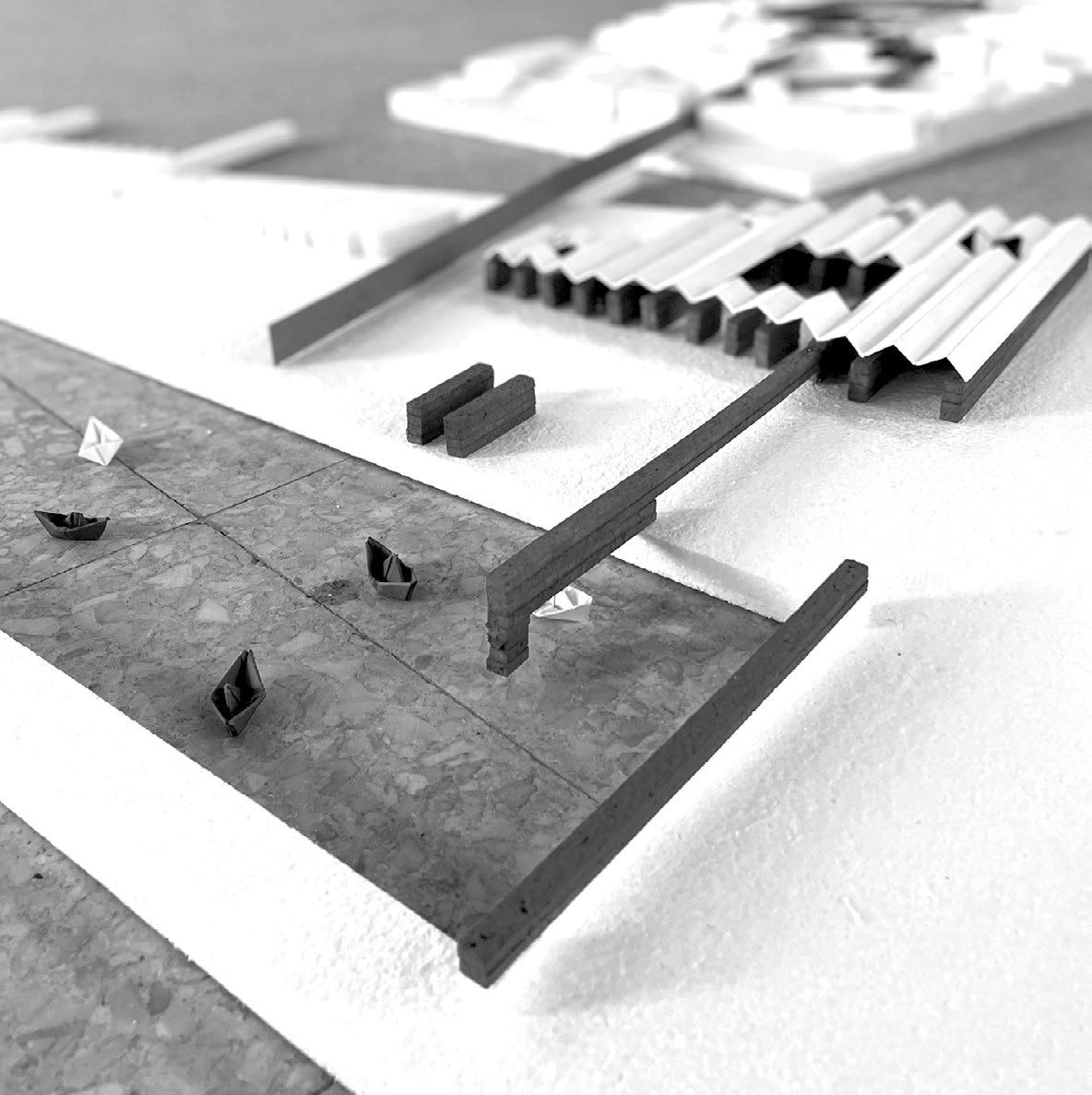

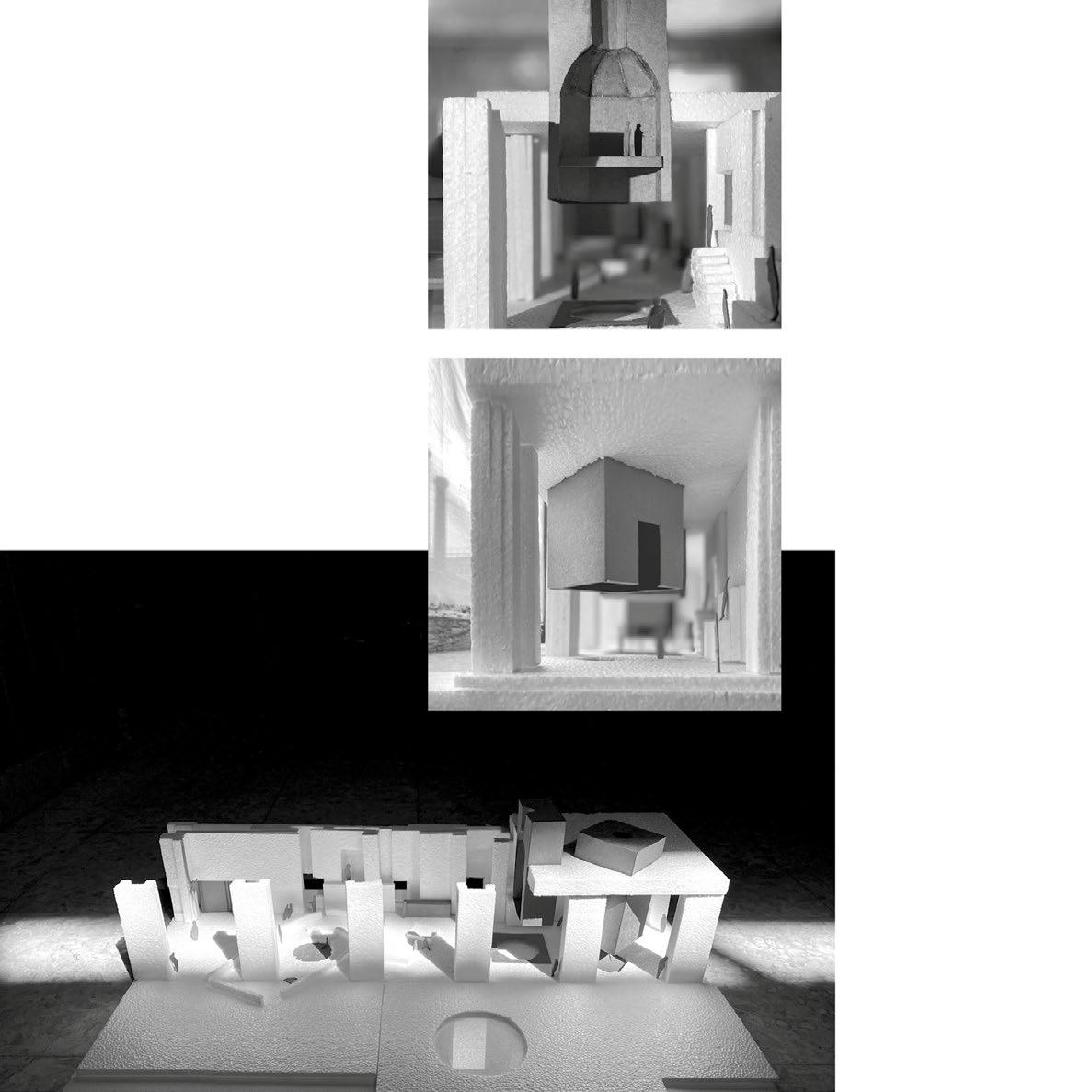

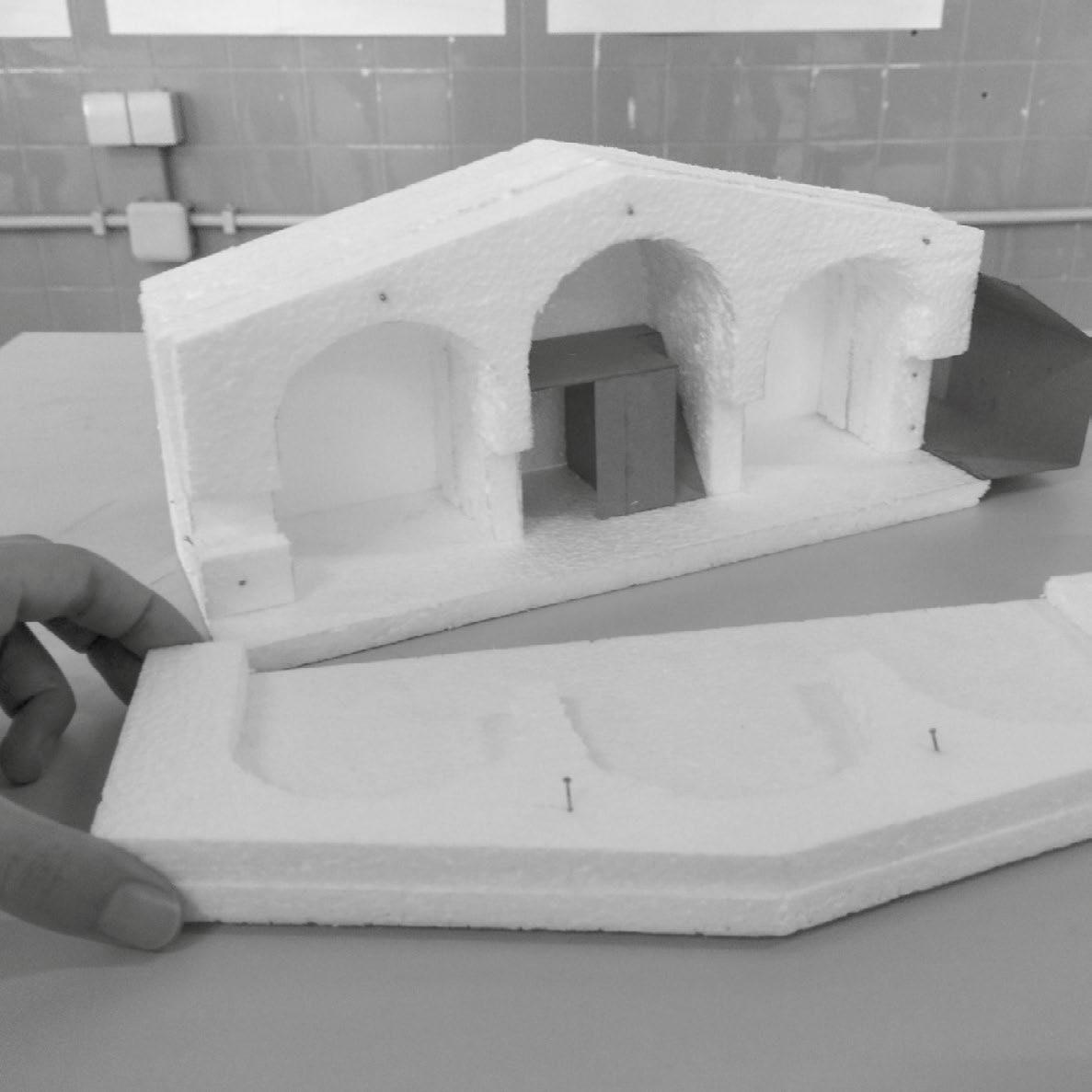

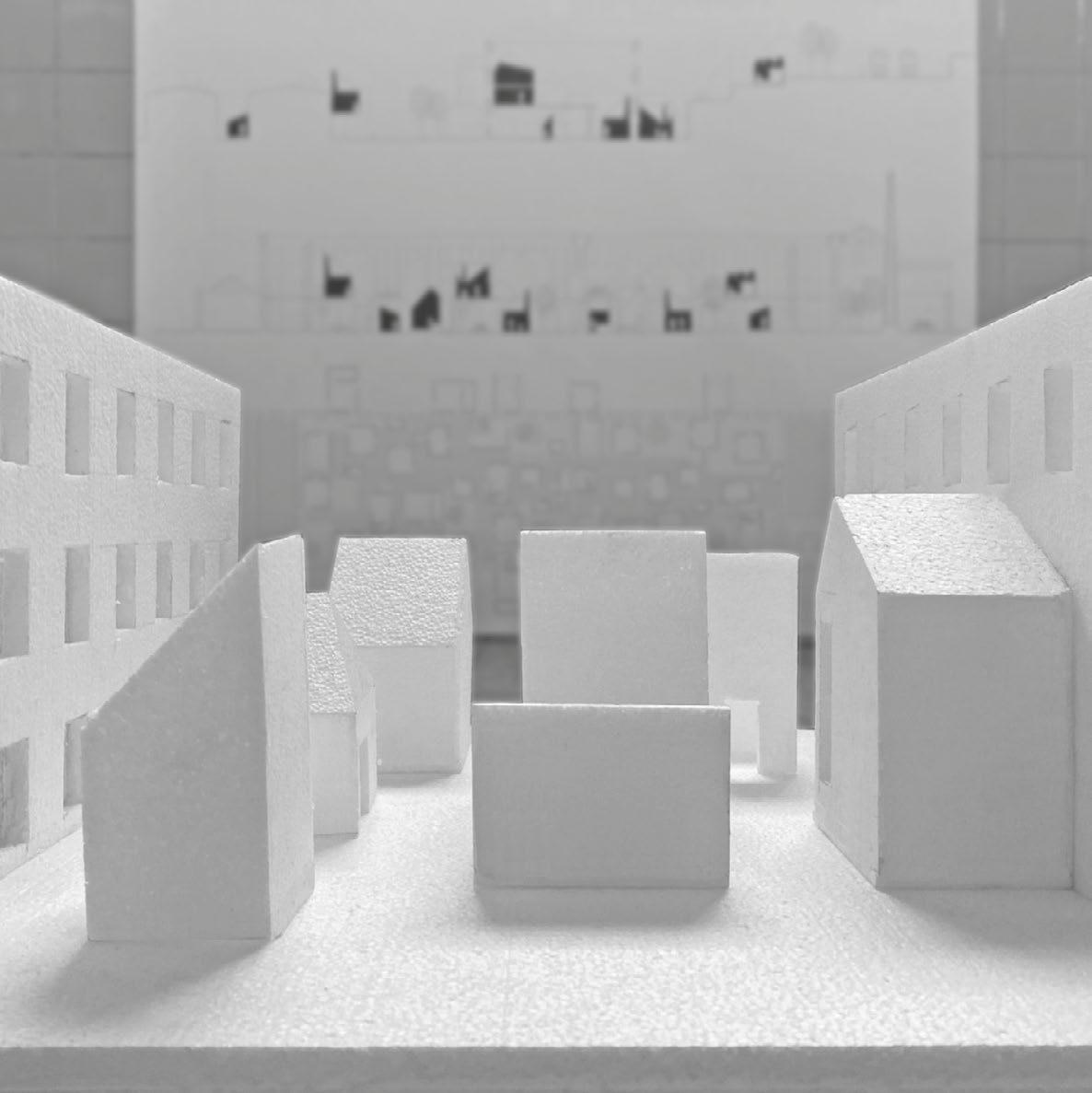

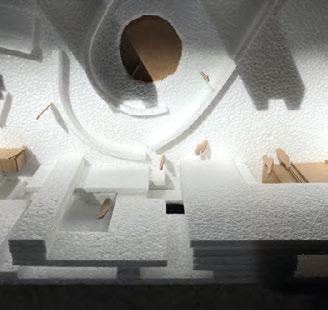

[Submission S3] – Collage model

In S3, each team is invited to create a tangible model of the plan and section collage of the project. This model will serve as an improvement and variation of the drawings, and also attending to Marvila’s case study site conditions. In this case, the model could be only a representative part of that explored in S2.

2nd deadline – Final Submission

The objective of the final submissions is to approach the concrete existing reality of Marvila from the abstract project proposals. The overall results will foster an interpretative and critical point of view regarding the current condition of the urban space and its public use by examining the relationship between public spaces, common spaces, and collective spaces. Projects will propose approaches to different topics for each group.

21

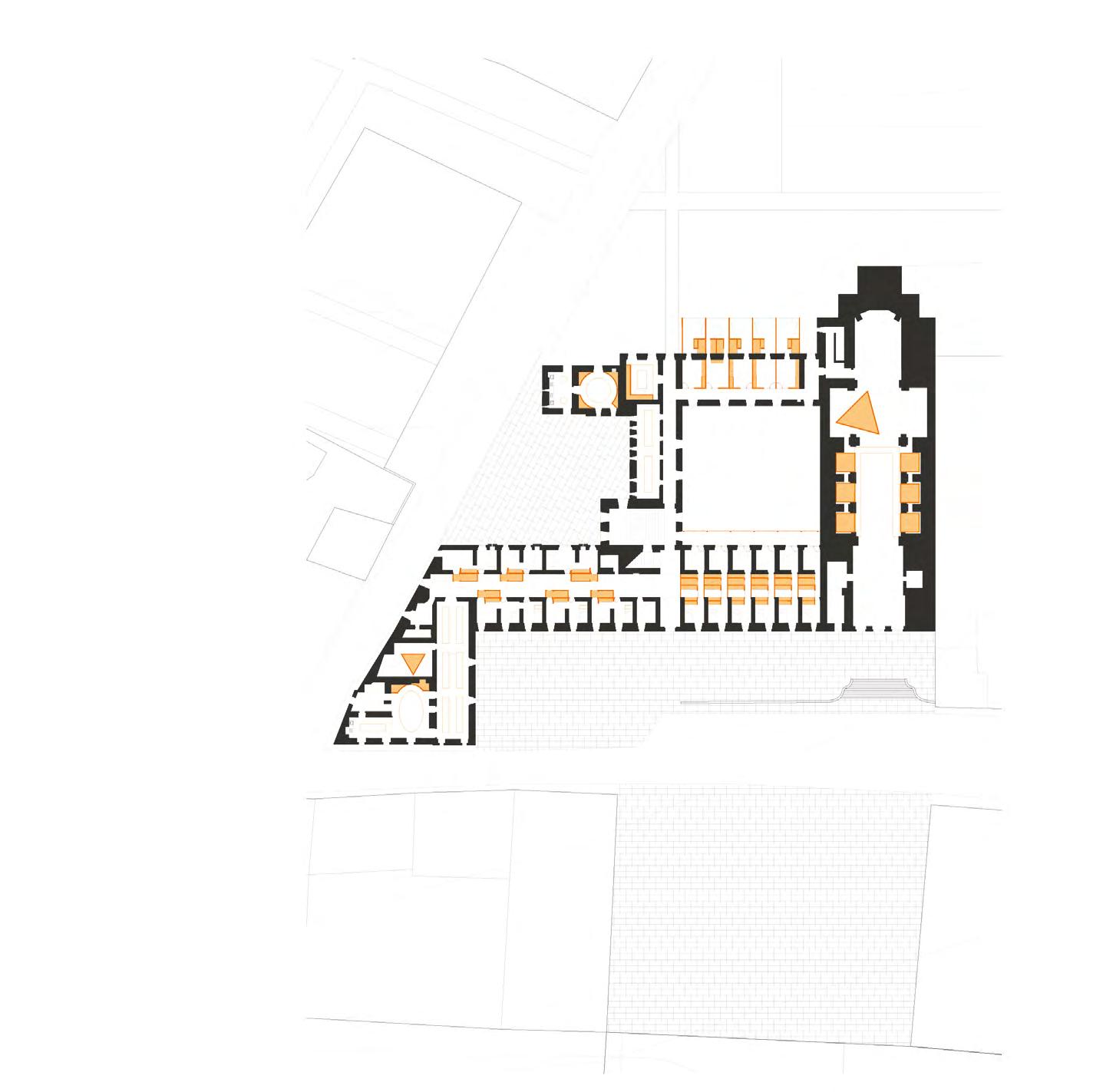

[Submission S4] – Plan+section Project on SITE

Ground floor, private-common-public space sequence contact with other buildings and public space

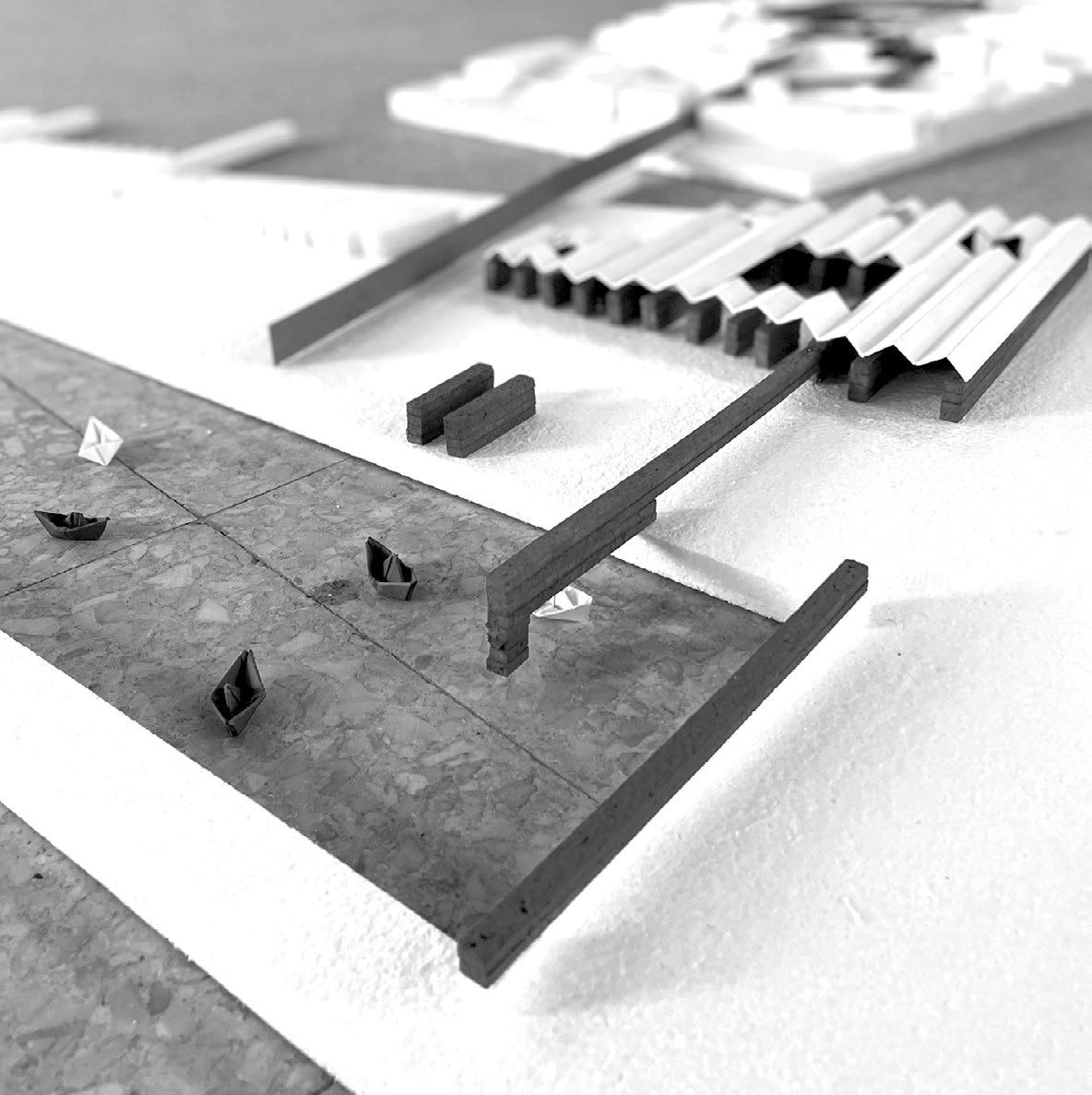

[Submission S5] – Model Collage Project on SITE

Ground floor, private-common-public space sequence contact with other buildings and public space

[Submission S6] – Atmosphere image

Private and common place: Specific place, small scale, materials, atmosphere, people

Results

The Marvila Lab workshop aims to work with a pedagogical and experimental approach in order to thinking about emerging forms of housing and anticipate future scenarios more adapted to the needs of the 21 st century. Through an analytical and operational approach, students begin with knowledge produced by a research project, Building Typology - Morphological Inventory of Portuguese City, developed by formaurbis LAB. This approach aims to transfer knowledge between research, pedagogy, and design. Through this combination, students are challenged to consider the dwelling of tomorrow and its potential role as an agent of transformation in the built city.

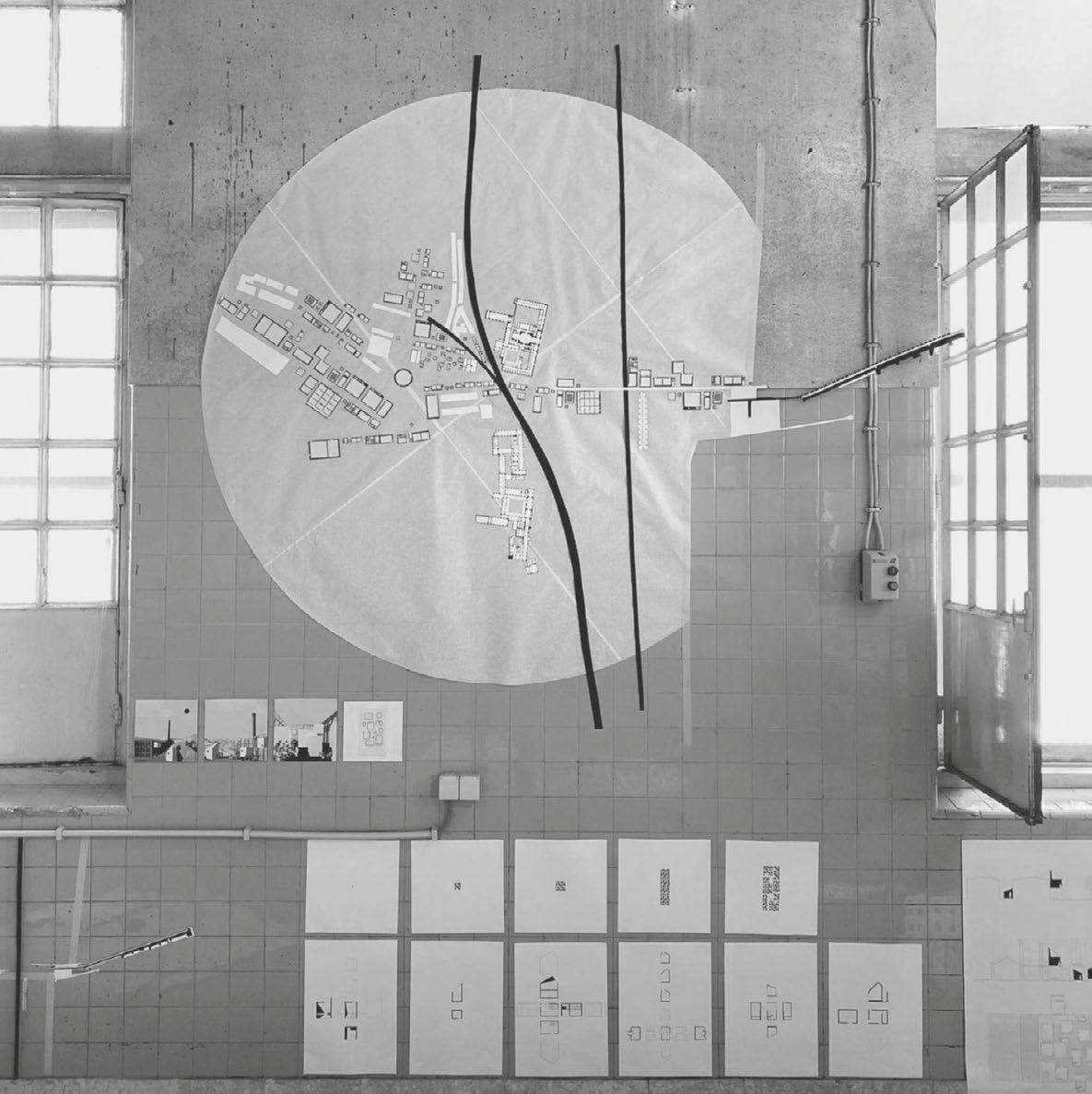

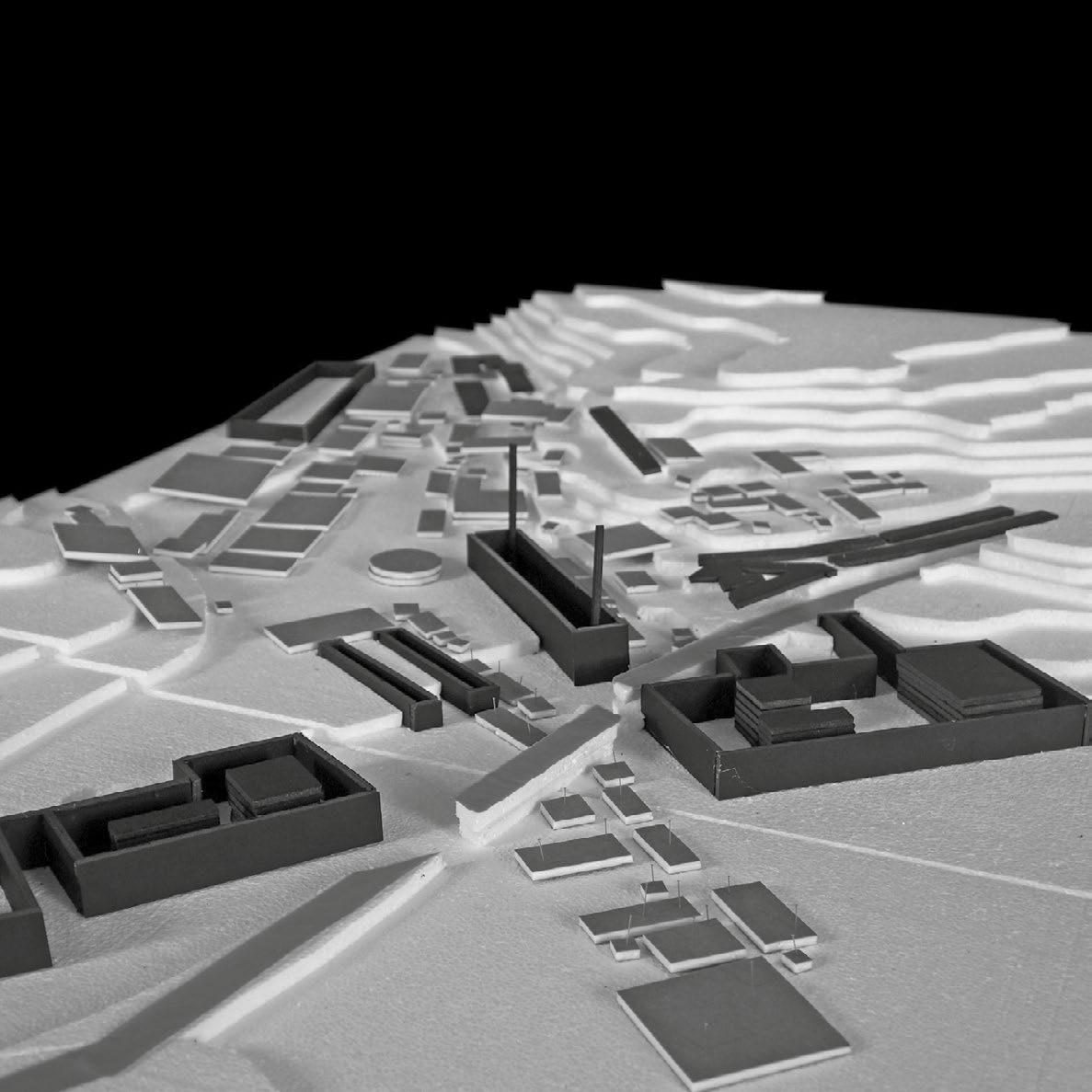

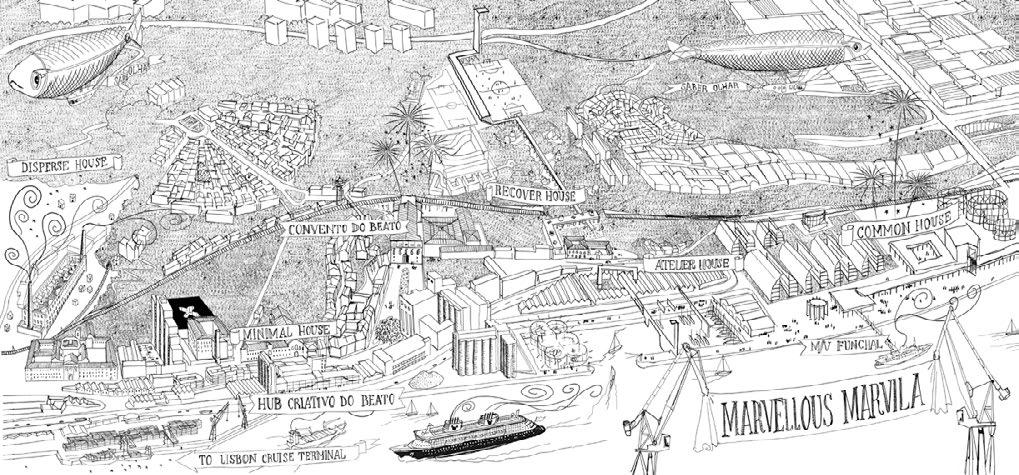

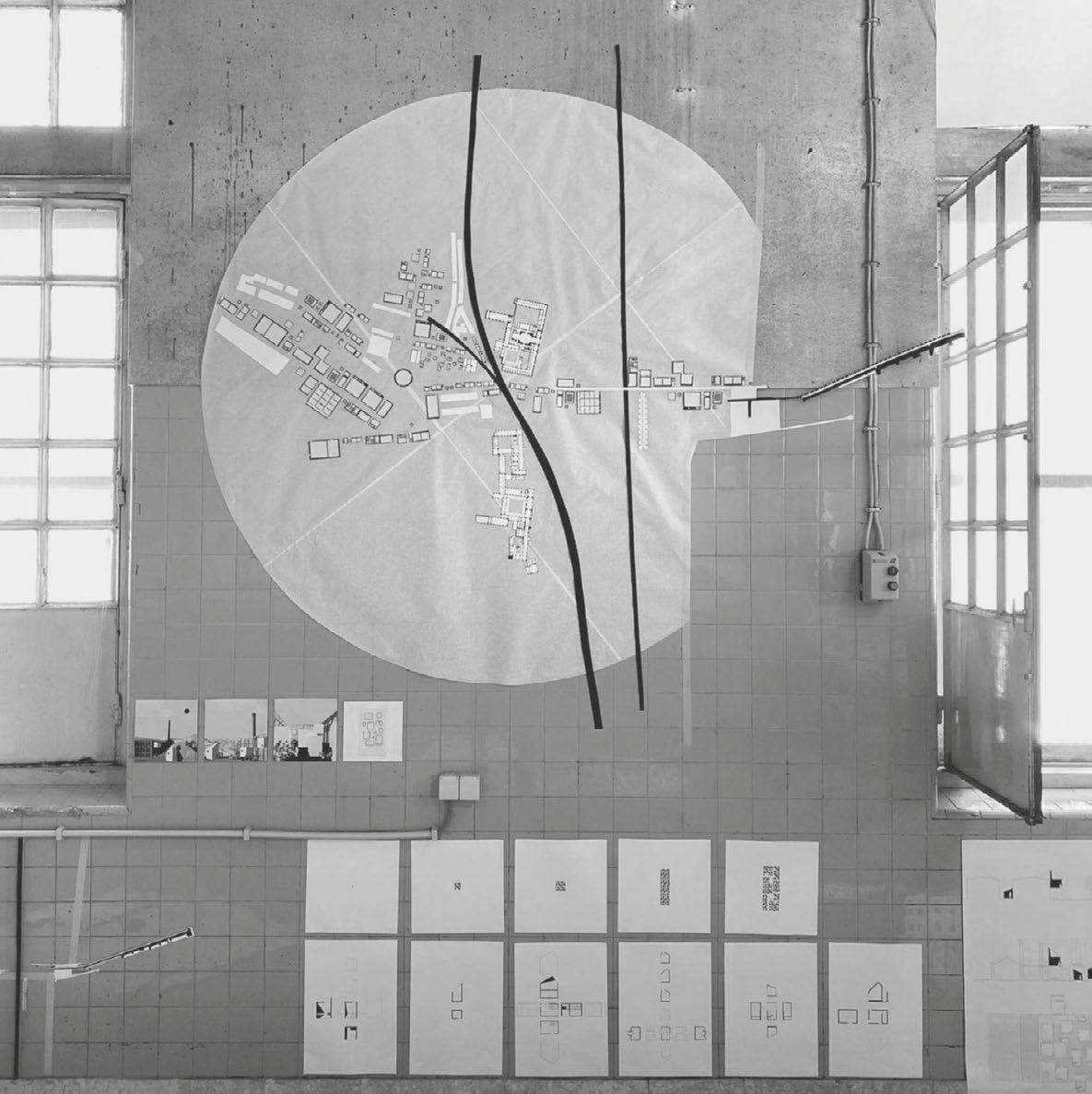

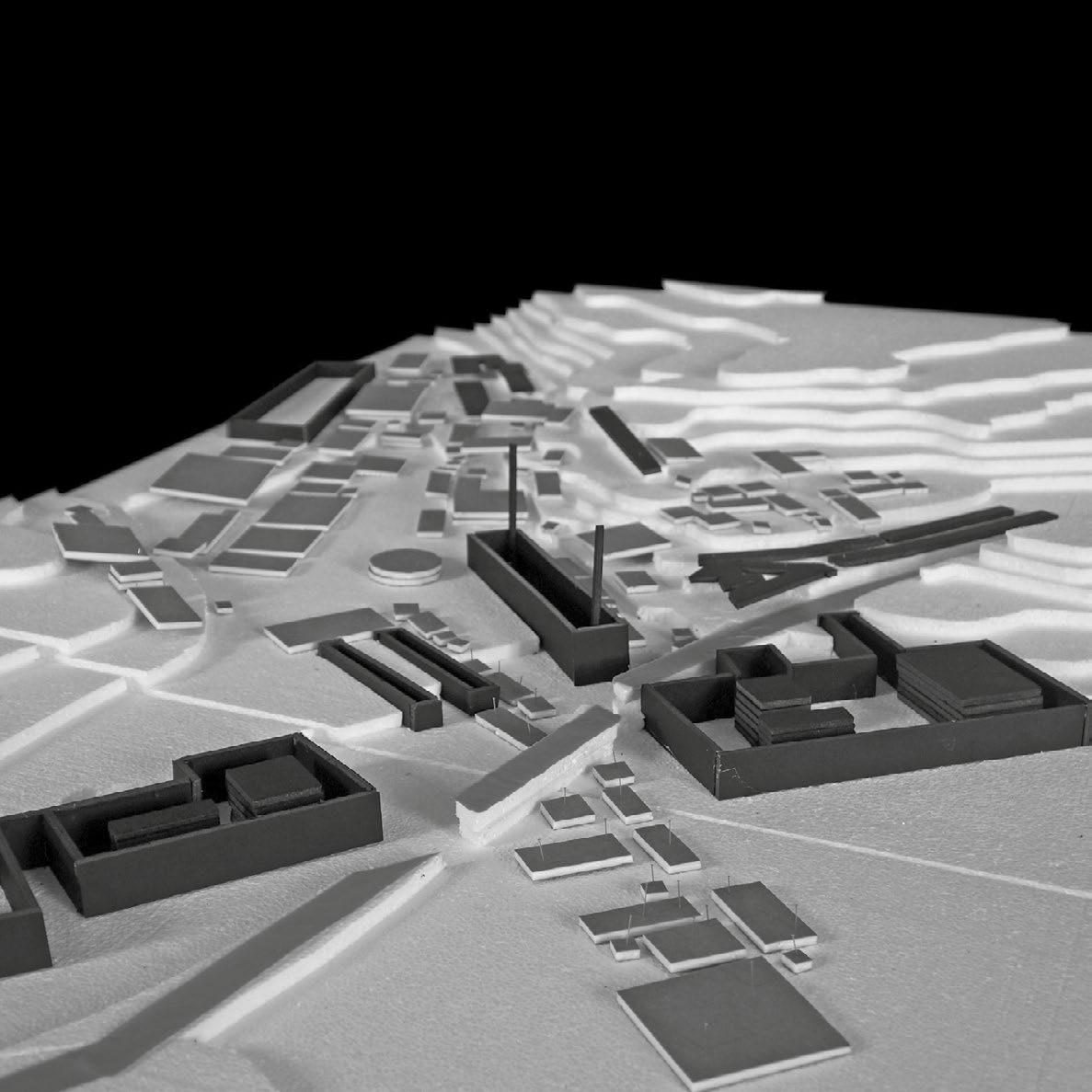

As a result, an exhibition was held that presented the proposals developed by five design studios, each associated with a specific case study (an abandoned building, typologically distinct from each other) and one of the five previously defined themes: Atelier House, Recover House, Minimum House, Disperse House, Common House. Through models, synthesis panels, or collages, each work group developed project approaches that covered several conceptual dimensions and scales of detail. Based on the built inventory produced by the investigation, the housing models start from a critical reading of the spatial qualities of the building under study to be transformed. Through collage exercises, strategies and structuring principles are defined that establish the conceptual approach both at the architectural and urban levels.

It is also noteworthy that despite the diversity of the five proposed themes of living, the five design studios idealize approaches where housing actively participates in the production of urban space. Transitional spaces with ambiguous atmospheres, where the collective sense overlaps the rigid limits of public and private, appear as links between domestic and urban spaces.

22 MARVILA LAB

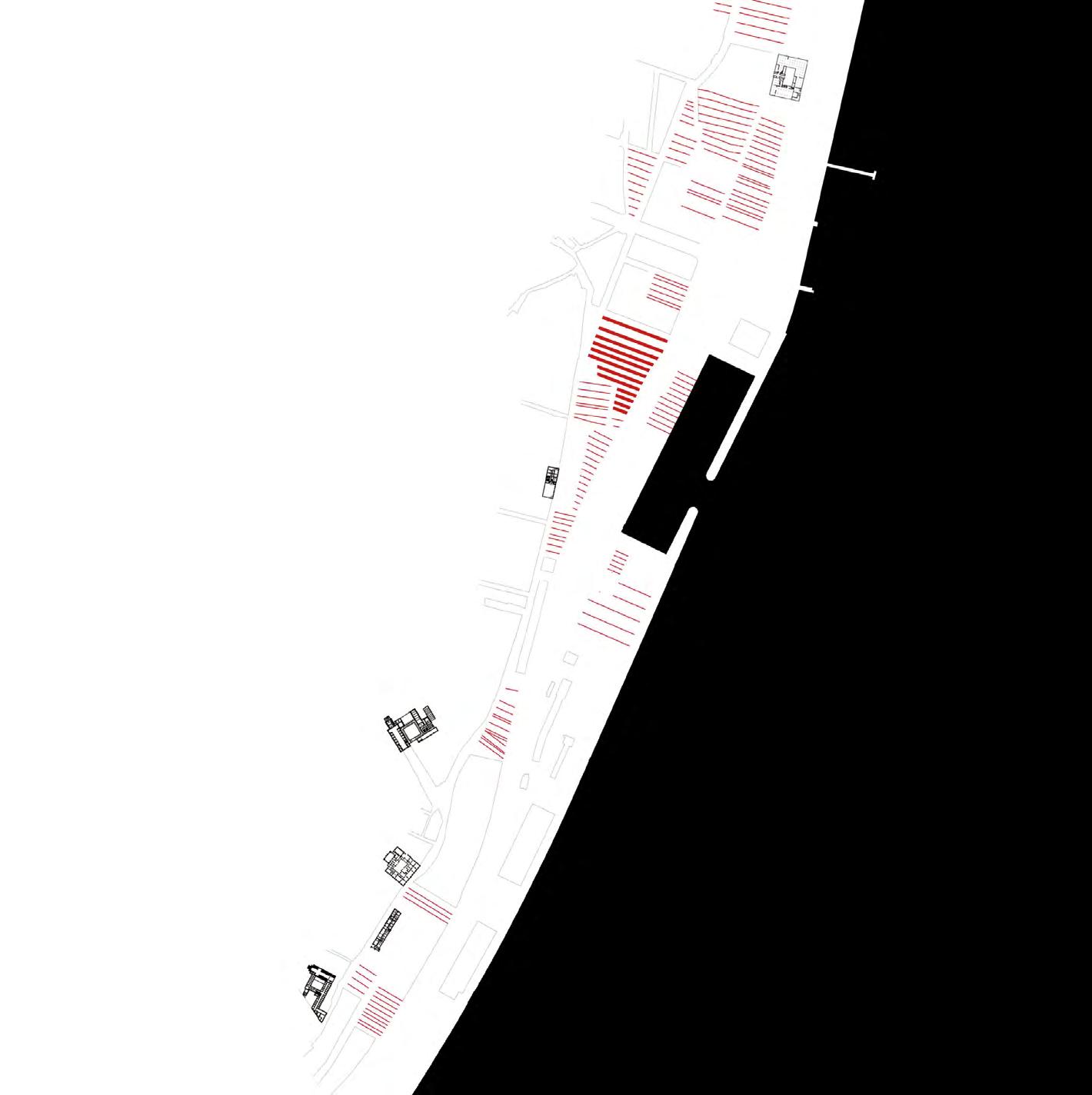

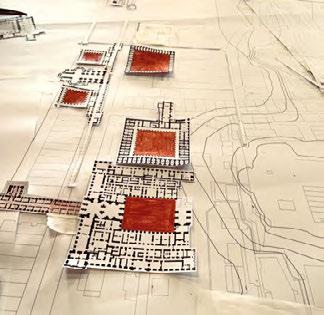

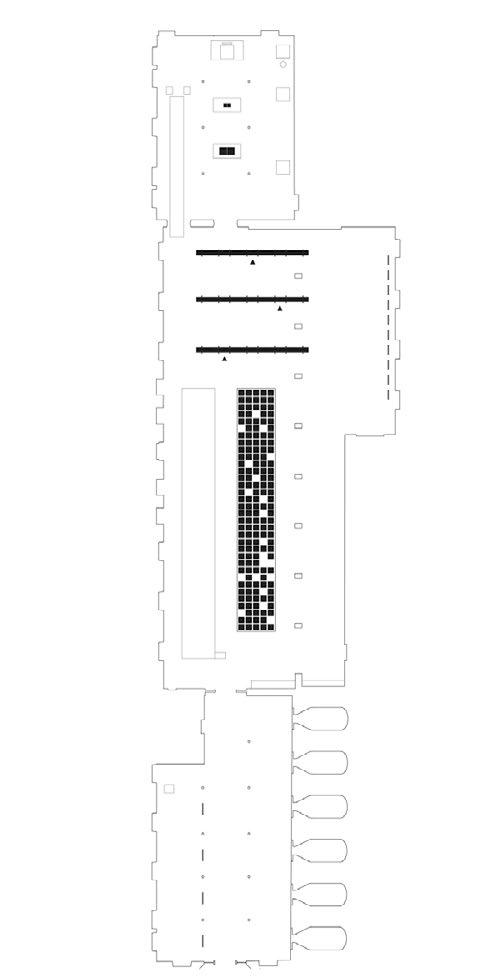

In the final layout of the exhibition and works discussion, the coastline of the eastern part of Lisbon was reconstituted, each model constituting an integrated and articulated vision in a set, which made it possible to verify the transforming look proposed by each group, reinforcing the role of housing as a place of urban reactivation.

23

THEORETICAL FRAME

A POST-INDUSTRIAL INVENTORY FOR AN AMAZING CITY

Stefanos Antoniadis, professor, architect, Lisbon School of Architecture, Universidade de Lisboa

Transurban areas and industrial buildings in the post-development era

Crossing the urban transects at the edges of the consolidated built fabric, it is easy to experience the contemporary metropolitan landscape, now recognizable and almost trendy, but still difficult to pigeon-hole and read. It is characterized by the presence of heterogeneous functions and forms, of infrastructures but also of agricultural lacerations and “voids” seemingly deprived of any vocation. These are complex trans-urban areas, in which those dyads and contradictions, still difficult to digest by the observer belonging to the domain of public conversation materialize, even though the potential of these spaces has been exploited for some years now. Artifice-nature, large-small built objects, city-countryside, active-decommissioned productive enclaves in support of urban metabolism.

Marvila’s case fits perfectly into these descriptions. Lisbon is a capital city with large industrial and shipbuilding areas now in strong disuse, especially on the south bank of the River Tagus and the eastern district.

Hence, the legislature’s desire to bring order to the land by recovering those availabilities and qualities (including formal ones) deemed reassuring, conciliatory, and opportune such as ecological balance and soil resources through new generation regulatory instruments. In recent years, laws on the containment of

MARVILA LAB 26

MARVELLOUS MARVILA.

land consumption, and corollaries on the temporary use of abandoned industrial buildings, have been produced with the aim of reordering the layout of such densely anthropic territories and redefining more clearly the edges of the built versus the unbuilt.

As much as the initiatives, according to most insiders, definitively mark the collapse of traditional town planning made up of implementation plans lowered from above in favour of a more contracted and liquid activity, which is better able to cope with contemporary transitional dynamics, urban planning tools still draw their strength from visions that are not new: the city-countryside opposition, the centrality of the functional programmes, the branded archistars’ solution as luxury estate speculation often ignoring a context still lacking in services and lagging behind in transformation. Furthermore, they contemplate the demolition of volumes considered improper, the migration elsewhere of “building credit” – i.e. cubage – and the zero balance of the used land1 not exempt from economic, environmental, and perhaps cultural costs.

In spite, then, of the evolution of procedures inherent in the way urban planning is done, there remains the risk, typical of regulatory proliferation, of diverting attention away from the investigation of the form of the contemporary city, but of the city in general, which is “the real focus of the matter [...]: a real object that we

27

Marvila, Lisbon, photo by Stefanos Antoniadis, 2022.

inhabit and experience through all our senses and that probably constitutes the most complex sediment of civilization” (Dias Coelho, Fernandes, 2022, pp. 95-96).

The city, like it or not, through successive formal and identity reconfigurations, continues to enjoy good health; the changing urban, economic, demographic, and social dynamics at work, on the other hand, highlight the increasingly limited validity and effectiveness of the tools of reading and intervention (both normative, provided by legislators, and of the arts, distilled from various disciplinary thoughts).

Urban metabolism, enclaves and wrecks

Boar forums, cattle markets, barracks, railway parks, gazometers, sewage treatment plants, landfills, commercial docks, and logistics hubs (though there are other types of specialized districts) have always functioned as closed systems serving the city. The comparison with the “thermal machines” dear to physics, capable of producing utilizable work, is an effective exemplification: the more distinct and separate these devices were from the life of the city, even though they were indisputably part of it in the economy of urban metabolism, the greater their degree of efficiency. When, with changing boundary conditions, these “machines” on the one hand become engulfed by urbanization and on the other hand lose their raison d’être, there is a transition from a closed system regime to one that will inevitably have to be open. These enclaves therefore enter into a process that, formally (through decommissioning, post-management, and alienation) or informally (phenomena of occupation and squatting), sees them increasingly as “permeable rooms” of a more open and broader urban system, a succession of remarkable areas in a larger pattern of territorial connections. All this, however, must be accompanied by avoiding the typical risk that a thermal machine, the refrigerator at home for example, runs when it is left with its door open, or when, due to failure or programmatic obsolescence, it ceases to function: to become a mere scrap to be disposed of.

The second French edition of Marc-Antoine Laugier’s (1713-1769) successful Essai sur l’architecture (Laugier, 1755) contains a rather well-known allegorical engraving by Charles-Dominique-Joseph Eisen (1720-1778). Besides giving a more visible explanation of his known theoretical approach (nature is the origin of everything), the illustration, featuring Architecture as the goddess seated on the ruins of a destroyed building showing the genius of reason (a Cupid) a primitive hut – i.e. the archetypal industrial shed, in Italy called “capannone”, big hut – talks about landscape, nature, and wrecks: three extraordinarily up-todate items production-related debates still focus on.

MARVILA LAB 28

La storia di quando Frascati divenne New York: favola figurata, Manfredi Nicoletti (drawing, 1930).

Fábrica Samaritana, Disperse House by Workshop Group #03, Stefanos Antoniadis (drawing, 2023).

29

The picture is made up of closely-standing uncut trees supporting slightly-tamed branches that provide a roof among their partially-preserved boughs as a model for a possibly obsolescence-proof building. The illustration features an ambiguously anthropised landscape where nature blends with fragments resulting from the collapse of an arrogant (irrespective of an “according to nature” praxis) building. Venturing a bold shortcut, we might subscribe to Laugier’s tenet “nature generating artifice” as still enjoying large approval. It is a successful interpretative paradigm followed throughout the centuries, in various branches and scales, in keeping with present-day results and applications both in tecno-ecological fields, in the production of architecture and land management.

The urban setting we live in is no longer the former one, and above all, we must admit that the presence of those remains merely occupying the bottom right corner of the French engraving has become much more cumbersome nowadays. Whereas in the abbot’s mind that pile of ruins belonging to a decayed building has a merely symbolic meaning, our eyes and our awareness turn it into a real everyday experience. In the illustration, the ruins are placed almost nicely at one side of a meadow, in our reality, litter is massively present even in the inner space of our Earth. The increasing degree of obsolescence of (even architectural) products, the larger and larger amounts of abandoned areas and buildings, and the recent resort to laying out untidy clusters of buildings dotting the country reveal the scattered nature of our contemporary landscape.

We live in an era strongly marked by the phenomenon of obsolescence, a dynamic that we are much more familiar with at the scale of our minor technological devices (cars, household appliances, computers, laptops, smart devices...), which concerns machines and, coherently, also all those urban and territorial machines that dot our geography.

In many fields of the human sciences, cures and antidotes to obsolescence have been envisaged, sometimes even programmatic, which for analytical convenience we could bring together under the heading of so-called “degrowth” (sometimes happy2, sometimes less so...).

While it is partly true that producing fewer objects (and buildings) somehow counteracts the frantic rush to consume, the need for an up-to-date model of everything, and reduces hypertrophic metabolism, it doesn’t really work that way with the city. A decreasing city is actually not decreasing: it is a city with an increasing ruin park. History is not new to these phenomena; immense cities have seen exponential moments and phases of almost total abandonment. Think of Rome, the city par excellence, which from the 5th century underwent a vertiginous decline until it was a rural borough of a few thousand inhabitants, but an endless artificial expanse of ruins.

MARVILA LAB 30

This circumstance, which is by no means insignificant, together with the question of the scale of these objects (they are not a few centimetres smartphones) should prompt us to think about the concepts of wreck, ruin, and form. A wreck often has a negative meaning, therefore, it is worth taking a different look at the wrecks potentially much more capable of supporting ecosystems and metabolism, or even generating new ones, than we are led to believe (Antoniadis, 2018). It’s proved with simple – yet extraordinary – evidence when dealing with sea wreckage. Sometimes, immense chunks of wreck on the bottom of the sea are at first seen as seriously impairing the natural environment, yet later they prove to be the vital triggers of lush oases evincing a high degree of biodiversity. It would be wrong to interpret such evolution as the re-appropriation of nature, as it’s winning back what has been stolen: biofouling operates in much more fascinating ways; not only does it restore, it upgrades.

On the Earth’s surface, the same practice might be resorted to, involving even more discarded materials. Segments of viaducts, portions of water-carrying infrastructures, frames of unfinished buildings, left-behind building yards, and temporary cranes are all wreckage impacting on man and landscape awaiting public opinion deliverance.

The power of the wreck is not only a matter of environmental opportunity; it is actually a matter of culture according to its widest meaning, and can be successfully dealt with from the point of view of architectural, urban, and landscape design.

Beyond architecture (in the narrowest sense), all kinds of construction may be considered part of this reservoir of formal and cultural resources, as long as their form is capable of overcoming their obsolescence, which stands as their inescapable destiny.

One basic difference between architecture and ordinary construction, and one that may actually be held as a conceptual divide between what is architecture and what is not, is that the former is never obsolescent: even when architecture is no longer able to cope with neither its original use nor its eventual ones, when it is mutilated and dismembered, even when it eventually transforms into ruins, it still remains architecture (Stendardo, 2014).

While dismissed, decommissioned, or abandoned architecture becomes a ruin, obsolescent ordinary construction is headed to turn into debris. Ordinary construction – especially infrastructure and machines – is always obsolescent. When a machine or infrastructure becomes obsolescent and broken into pieces, it becomes waste, scraps that may be recycled or, at best, exhibited as a relic in a museum, if it is worthy. This is why an ancient Roman aqueduct, even when it ceases to supply water to a town, is not considered debris, and no one would

31

La storia di quando Frascati divenne

New York: favola figurata, Manfredi Nicoletti (drawing, 1930).

think of it as a waste management problem to cope with, but everybody would recognize it as an extraordinary landmark across the landscape.

On the contrary, a technologically advanced contemporary oil pipeline, a highly specialized device, is not likely to play such a significant role in the future. The smarter machines or infrastructure are, the more technologically advanced a device is, the more rapidly obsolescent it becomes. This is clear enough since planned obsolescence policies, along with the disposable smart devices and machinery market, allowing no possibility to fix broken hardware, are actually flourishing, while the production of hazardous waste is increasingly over, although we all eager to flaunt our environmental care worries.

Work on form as an antidote to obsolescence

Actually, the aptitude of a wreck to be acknowledged as architecture depends on its formal features; or rather, we should say, on our skill to recognize its potential as formal and spatial material for architecture. It appears that this potential acknowledgment implies the complementarity of the human mind and the wreck, showing some relevant similarity with the concept of affordance as defined in environmental psychology by James J. Gibson (1966-1979).

MARVILA LAB 32

According to this acknowledgment the power of ruins, which is bound to the widely accepted concept of architecture, may be successfully shifted onto wrecks, thus allowing not only the rehabilitation and reuse of decayed built environments through new functions but also a broader recreation of architecture and space with strong cultural impacts.

These reflections can be implemented both in the recycling of built waste, such as infrastructural and built debris and scraps, and in a more aware attitude in architectural, urban, and landscape design. An attitude that is not actually new, if we just recall that one of the most powerful images of the project for the Bank of England, designed by Sir John Soane (1830), was represented by its author as an imagined view of the building in ruins. Although nowadays, the trend of architecture and civil engineering is to make artefacts based on concepts such as fitness and smartness while ignoring any long-term anti-obsolescence resilience, trying to imagine one’s project as ruins should be a must for today’s architects as well.

The importance of form in the dichotomy between ruins and debris should finally be taken into account both for good design practices of new buildings, and for the acknowledgment of the wide asset of existing built objects that are spread throughout today’s landscape.

33

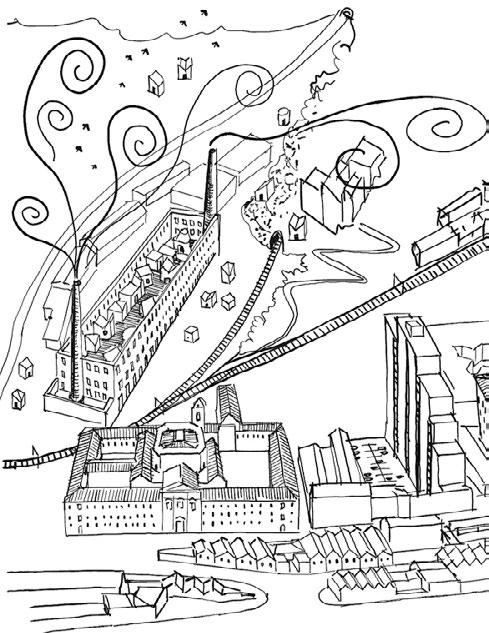

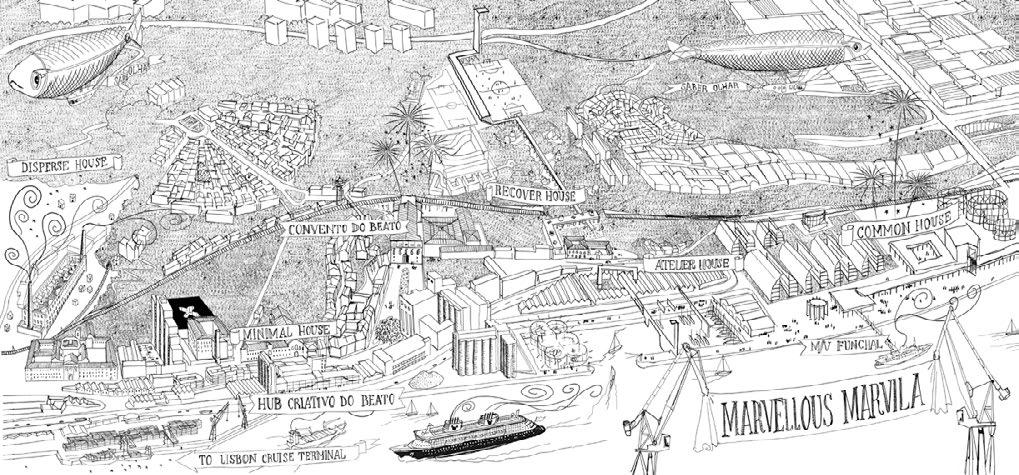

Marvelous Marvila, Stefanos Antoniadis (drawing, 2023).

Any effort in this direction is a step forward in the enlargement of our architectural and imaginative dictionary and possibly a step forward towards a world that is richer in culture, health, and, why not, happiness.

In order to hope for and initiate a change in assessment and outlook (which is where projects begin when approaching unused or partially-used, end-of-life industrial and manufacturing buildings in suburban areas of modern towns), it is useful to construct (or rather, deconstruct) some broader arguments. Such arguments involve the perception and awareness of shapes and relate to the cognitive abilities of people in general, not just insiders or architects.

The first “bad habit” to deconstruct is the trend of resorting to the “former” prefix (a kind of blocking syndrome that also affects relationships with ex-partners). Actually, it sounds odd to refer to the pyramids of Giza as “former tombs”, or to the Coliseum as a “former amphitheatre”, or to the Eiffel Tower together with the wide mall stretching at its feet as a “former Expo area” (whereas immediately after the 2015 Milan Expo it was deemed necessary to set up the “Expo after Expo”3 nation-wide team of experts, heavens know why).

Marvila is also lucky to have structures, large and small, that correspond to pure forms (silos, gazometers...), landmarks (harbour cranes, chimneys), places to be re-habit (convents, vocational schools), etc. that can work in the same way if we stop thinking of them as ex-whatever.

This unwillingness to overcome the function and abstract the form of things, which end up being defined according to their functional call, leads to a corresponding inability of the buildings themselves to adapt to new features and new lives. In this strange – though easily understandable – hypothesis formulated by Sapir-Whorf 4 applied even to urban organisms, the destiny of buildings seems to be unsplittable from the language describing them, piling up cognitive and manipulative staples that condition any possible future repurposing. Naming a decommissioned industrial building as the “formerplus the name of what it produced” accumulates inertia among the building stones, betrayed by this established cliché of naming, which affects any eventual and subsequent reuse or rethink.

Repurposing becomes, in fact, the typical solution for buildings and slices of urban areas no longer performing before the inescapable moment of rethinking.

An alternative hypothesis in the method might instead contemplate the possibility of renaming – or re-signifying – a building, or set of buildings, with respect to formal rather than functional categorizations. In order to facilitate this process, the industrial sheds will have to gradually lose their rigid plant as silhouettes against a background, in order to undergo re-significations and contaminations from the surroundings. Therefore, the theme of how to pulver-

MARVILA LAB 34

ise the limits, whether they are constituted by the sharp caesuras of the linear infrastructural bundles or by the hard edges of these specific enclaves subtracted from the city, in order to favour the reuse of abandoned areas, acquires significant importance. Fragmentation, subtraction, excavation, bending, erosion, breaking of the perimeter (and even within certain rigidity of layout), dismantling, and relocation of prefabricated elements typical of industrial construction are just some of the compositional techniques capable of transforming a figure into matter to be reacted with the context, now an active and varied support.

And so it is that in this research and design experience, with its large theoretical component, we looked at this interesting district of Lisbon as a post-industrial inventory for an amazing city. A place where “life would pulsate [...] and each citizen would find in it the answer to his every desire: tranquillity and the most overwhelming activity, the metropolis and the rural landscape, the slowness of the vernacular and the rapidity of the machine, collective life and meditative isolation” (Nicoletti, 1930, p. 56).

Notes

1. Veneto Regional Law n. 14/2017, Disposizioni per il contenimento del consumo di suolo e modifiche della Legge Regionale n. 11/2004 Norme per il governo del territorio e in materia di paesaggio

2. On the subject of degrowth, a complex of ideas has developed that is supported by alternative, anti-consumerist, anti-capitalist and ecologist cultural movements. The term degrowth is sometimes accompanied by adjectives, in expressions such as “sustainable degrowth” or “happy degrowth” (i.e. Sérge Latouche).

3. An initiative triggered by Oxway and Corriere della Sera, and accepted by numerous Italian universities, research and professional groups, with the aim of preventing the site of the Milan 2013 Universal Exhibition from becoming just a huge brownfield site.

4. The Sapir-Whorf hypothesis holds that human thought is shaped by language, leading speakers of different languages to think differently. This hypothesis has sparked both enthusiasm and controversy, but despite its prominence it has only occasionally been addressed in computational terms.

35

HABITAR MARVILA: 5 STRATEGIES TO [RE]DESIGN

THE WAY WE LIVE

João Silva Leite, professor, architect, CIAUD, Research Centre for Architecture, Urbanism and Design, Lisbon School of Architecture, Universidade de Lisboa

Sérgio Padrão Fernandes, professor, architect, CIAUD, Research Centre for Architecture, Urbanism and Design, Lisbon School of Architecture, Universidade de Lisboa

Rui Justo, researcher, architect, CIAUD, Research Centre for Architecture, Urbanism and Design, Lisbon School of Architecture, Universidade de Lisboa

Habitar

“[...] man is an animal that not only takes refuge, but also makes a home [...]” Steen Elier Rasmussen, 1974

The problem of dwelling is one of the central issues in the theory and practice of architecture and urbanism, encompassing both the object dimension of the house and human agglomeration. The disciplines of architecture and urbanism have sought to develop spatial and constructive responses that constitute habitats capable of serving humanity, addressing the needs and paradigms of each moment. The debate on the forms of dwelling is therefore part of a highly relevant theme that constantly seeks to test new solutions, hypotheses, or models capable of responding to the demands and challenges of contemporary life.

Inhabiting, as Juhani Pallasmaa (2017) states, “constitutes the most basic act of the individual relating to the world” and therefore, thinking about inhabiting and the way we live the territory continues to be a fundamental and current problem. It is, on the other hand, a promoter of direct actions that transform the surrounding environment. The architectural object acts upon the human being

MARVILA LAB 36

as a generator of a place where he builds a significant and symbolic relationship, but also on the territory as a support that changes and adapts.

Therefore, thinking of dwelling in the sense of refuge or shelter space directs us to the house, to a domestic space, a place of intimacy (Pallasmaa, 2017), and permanence that offers conditions of serenity, capable of contributing to the balance and inner peace (Bachelard, 1957) of individuals. On the other hand, its reproduction has impacts on the forms of human aggregation, particularly evident in the shape of the city and in the way we inhabit urban space. Perhaps for this reason, housing models have incorporated successive mutations and variations over time, engaging in a constant dialogue between social paradigms, formal solutions, and human desires.

In this sense, the theme of collective housing finds greater relevance in the dialogue that is established between built typology and the shape of the city and the way we live in it. Collective housing, addressed with particular attention in the Marvila Lab workshop, is therefore a very relevant subject of study. In it, the dwelling finds an urban dimension that interests us to debate and reflect.

At the beginning of the 20th century, with the emergence of the first vanguard movements such as the Bauhaus school, and then with the Modern Movement, concepts such as standardization, family type, the rationalization of space, and functionalist typological models emerged as responses to the multiple housing needs of the European city. Conceptually developed and preliminarily rehearsed in the period between the two great wars, the theories of Modern Architecture and Urbanism found in the cities destroyed by World War II had a chance to respond and implement. Technological advances to support the daily activity of housing redefine the way we use domestic space. The house model is based on spatial strategies that privilege functional efficiency, with the dimensioning of compartments and circulation areas adjusted to the pre-established function or mode of use. It is the key house model (Monteys, 2013). The house consists of a set of spaces, some serving and others served, with specialized compartments for fixed, standardized use, both during the day and at night.

In reaction to the functionalist principles of Modern Architecture, more flexible and versatile logics of space organization were developed. The excessive functional predetermination of the various compartments of the house produced rigid living spaces with a single logic of appropriation (Monteys & Fuertes, 2001). Nowadays, solutions are sought where the compartment and its relationship with others go beyond an excessive predestination of use. A bedroom can become a living room, and a living room can become a bedroom without this undifferentiated space affecting the relationships of intimacy or more collective living.

37

In this sense, there has been an increase in research on the flexibility of living spaces as a reaction to a more functionalist approach to architecture. Some are more conceptual or experimental in nature, while others have a more objective and concrete dimension, seeking to re-imagine the urban dwelling as a collective, able to interpret other ways of living in domestic spaces and more adapted to current circumstances. Issues such as changes in family models, the length of time we spend at home, and the activities we carry out within it have brought about significant changes in domestic spaces. Gender equality changes in the notion of intimacy, sharing, and family have brought changes to homes, which entail questioning standardization and encouraging a diversity of solutions. New spatial relationships within the house are sought, or old typological models are recovered, which are more versatile and allow for a greater multiplicity of appropriations. The vision of Modern Urbanism, based on the fragmentation of human activities – Home, Work, and Leisure – is reflected in the organization of the city and also in the domestic space of the house, and is, in recent times, confronted with dynamics of overlapping functions and activities. Work or leisure now takes place at certain times in the intimate space of the home. The kitchen, living room, bedroom, entrance hall, or even other transitional/distribution spaces of the house are transfigured beyond their domestic functions and are increasingly assumed to have the potential to accommodate temporary uses, work, play, or rest. Variations in employment relationships, ways of working, as well as developments in robotics, electronics, and the digitalization of society have reconfigured and diversified ways of living and inhabiting houses.

“When work is no longer confined within the nine-to- five schedule, it seems difficult to maintain the illusion that the domestic sphere is a refuge from the reality of production.”

DOGMA, 2022, p. 6

The home becomes another space, another support for working or for any leisure or entertainment activity. Faced with these changes, themes such as flexibility, adaptability, or spatial de-serialization emerge as hypotheses of response to the complexity of today’s society. The house, once composed of rooms with equivalent size or proportion and with a certain indetermination of function, emerges today as a conceptual memory of a more multifaceted living space for the different contemporary ways of life.

MARVILA LAB 38

Five design strategies

Several essays have been carried out, seeking to test collective housing solutions that combine several activities simultaneously or in different parts of the house. These solutions explore differentiating hypotheses in the common housing fabric and therefore seek to add other spatial offers that enrich the urban fabric and provide a direct response to emerging needs. Work, health, compactness, atomization or sharing emerge as themes increasingly combined with the house, instilling on housing, isolated or collective influences that question the most crystallized typological models. The experiences already realized or simply pointed out in theoretical frameworks do not necessarily mean closed architectural facts or new housing models but rather opportunities for reflection and expansion of the debate around housing and how it can present new arguments for future challenges.

The five strategies reflected here are not intended to constitute closed models, but rather to understand emerging phenomena that often start from ancestral or historical typological models and seek to re-imagine new ways of dwelling. The fundamental spatial qualities are re-interpreted and found to echo in new proposals that explore solutions that are more adjusted to the present time.

Atelier House

Working in the domestic space is something that has recurrently found space for coexistence throughout the history of housing. Exercises of intellectual reflection, such as writing or experimentation, but also other activities linked to craft production and its commercialization, introduced into the space of the house characteristics that interconnected living and working, as well as emphasized the relationship of the house with the street. The idea of the Atelier House seeks to recover, or reinvent, a close communion between domesticity and production that once coexisted and that in the 20th century was tried to be separated (DOGMA, 2022).

More than a concrete definition of a work space, the Atelier House must seek to create supports. Sometimes the support is realized through an architectural device that opens the way for the development of a work activity, let us remember the painting by Antonello da Messina, San Girolamo nello studio (St Jerome in His Study) where the studio is revealed using a piece of furniture, slightly raised from the floor and surrounding a seating area, defining a sub-space within a larger room. Exercises such as Allan Wexler’s Crate House (1990) lead us to question rigid and watertight models, demonstrating the versatility of use that a simple architectural device can introduce into a domestic space.

39

MARVILA LAB 40

41

On the other hand, situations such as the inclusion in the house typology of a hybrid compartment (which opens to the internal structure of the dwelling but also to the outside) allow providing the space with an extra room that increases the level of versatility of the house. In Lisbon, the so-called “independent room” is represented, in several typologies, as an opportunity to add to the spatial structure of the house a place of greater connection with the street (Monteys, 2013).

Through a direct opening with the staircase landing, this room assumes an additional function to the house. On the one hand, it is the continuity of the succession of rooms that constitute the front of the house and, on the other hand, a spatial room that opens to the outside constituting a small office.

More recent situations, such as the proposal of the DOGMA studio, Communal Villa, of 2015, are in turn rehearsed solutions where work and living share the same space trying to systematize spatial options of greater ambiguity. Through the design of an inhabited wall, a spatial thickness is developed that supports a common area which, depending on the time of day, serves for work or becomes an extension of the more intimate space.

The Atelier House aims to reopen the debate on the relationship between work and home, and how we can conceive housing spaces prepared for multifaceted urban dynamics that change at different rates. Additionally, the Atelier House is designed as a mediation interface between the city and the private living space. Work emerges as a moment of suture and transition between a more collective responsibility and the space of greater individuality.

Recover House

The themes of health and housing also emerge as one of the most prominent relationships in contemporary thinking. In a consolidated trend of growth of the elderly population, especially in Western urban contexts, it is essential to understand ways of living that can make domestic space and care space compatible. The Recover House emerges associated with the idea of a place of refuge, a space that offers peace, tranquillity, and balance between mind and body.

The Recover House emerges as an alternative to tendencies explored in recent decades that have focused on buildings developed according to specialized programs for the elderly, which have generally led to processes of progressive deterioration of the residents’ physical and mental health. A certain feeling of uprooting between the individual and the space raises the question of how to create housing spaces that respond to the specific needs of ageing while creating conditions for personal identification with the place and quality of life.

Some experiments, such as WoZoCo, from the 1990s, a project by the Dutch

MARVILA LAB 42

studio MRDV, aim to create housing blocks dedicated to an older population, but which also incorporate typologies for young university students, recent graduates, or young couples. This promotes synergies of mutual support that develop feelings of security and usefulness in older people.

In another sense, more recent proposals such as Torre Júlia in 2011, Barcelona, or the housing complex Bedre Billigere Boliger in 2008, Koge, Denmark, focus on the creation of outdoor collective spaces that promote daily interactions. In the first case, the tower holds 3 distinct communities, each with a large double-floor meeting space, which, together with the vertical communication system, is the main place for collective activities. In the second solution, the focus is on the system of galleries that interconnect the several houses and at strategic points of the complex generate small socializing spaces with small vertical gardens. In this case, the idea of refuge is revealed in the vertical garden which, to a certain extent, recreates the idea of the small pavilion next to a garden or a small cabin that hides in the landscape to contemplate it.

The Recover House introduces the theme of integrating the elderly into the debate on the house, highlighting the urgency of designing domestic typologies that are better prepared for the senior population and their ways of living. The Recover House points to a caring sense of living space that can become broader and embrace other age groups such as children. The home space must find complementary dynamics with other places of support and help, that is, collective spaces of social, educational, and intellectual stimulation (Espegel, Cánovas, Lapuerta, 2022), while knowing how to introduce small moments of introspection and deep intimacy or peace into the space.

Minimum House

The minimal, or compact, house has been a recurring theme throughout the 20th century. However, in the 21st century, it takes on a new guise, a new meaning, and emerges as a hypothesis of an answer to diverse themes ranging from individual housing in highly dense urban contexts to minimum survival units related to events of natural or social disasters (wars, migrations or refugees). However, it is important to recall the role of elementary shelters, ancestrally built in rocks to protect shepherds or even hermit monks, as conceptual and archetypal references. These primitive structures as well as small wooden huts, remind us of fundamental principles of rationalization and versatility of the use of space.

In a more recent time, to the functionalist and parametric principles led by the Modern Movement, issues such as space efficiency, flexibility, recycling or sustainability are added as fundamental concerns in the imagination of the minimum house. The modular sense and the intrinsic relationship with the human body are

43

determining aspects. Examples such as Diogene (2013) by Renzo Piano or the “classic” capsule of Nagakin Capsule Tower (1972) by Kisho Kurokawa, with 8 m2 and 10 m2 respectively, refer us to spatial approaches deeply designed according to the human being and the flexibility of use of the mobile devices that make up the dwelling. On the other hand, both cases present themselves as totally self-sufficient despite diverging in the underlying principles of aggregation. The Diogene as an isolated unit, the Nagakin Capsule in aggregation as several replicas.

In another sense, proposals emerge where the habitable elements refer to elementary units that, in articulation with a set of common areas, make up a system of spaces that complement each other. However, the dwelling is centered on a minimal unit. In projects such as the Casa de Azeitão by the architects Manuel and Francisco Aires Mateus, 2003, the house space is composed of the combination of several intimate and autonomous spaces that are suspended in a collective meeting area. To a certain extent, this conceptual model reminds us of the conventual systems where the cell constitutes the minimum unit of habitation, while being supported by a system of other spaces of common use.

The exhibition Still Cabanon proposes a reflection on the construction of a refuge, with an enormous load of intimacy, in order to point out a set of visions on the living space of the 21st century. Starting from the shelter designed by Le Corbusier, Le Cabanon, several authors from different artistic areas were invited to think about a dwelling that operated on themes such as polyvalence and its different uses.

The Minimum House is, therefore, a spatial exercise that aims to intervene in the thought of the house as an elementary space of extension to the individual. The idea of refuge underlies the conception of a home as it merges with the individual, their needs, intimacy, and ways of living.

Disperse House

The Dispersed House, on the other hand, refers to an idea of fragmentation, an atomization of the various living spaces where the compartments are formally disaggregated, taking advantage of particular circumstances of the territory. The Dispersed House tests solutions where the individual can inhabit several spaces located in different places depending on the needs of a particular activity: leisure, work, rest, or simply for a search for greater privacy and isolation in a given time space.

The Moriyama House project, by SANAA in 2011, is probably one of the most paradigmatic examples. The proposal involves the development of a set of dwelling units, disaggregating the house into several volumes, making autonomous part of the domestic activities while valuing the intermediate space between volumes as a place of the collective.

MARVILA LAB 44

On the other hand, there are situations where the Dispersed House, as an open unit, is realized through the sum of different rooms located in the same building. In this way the house acquires a capacity for expansion or contraction depending on the useful life or needs of the users. The cooperative housing building Kalkbreite, in Zurich, 2014, presents a wide combination of typologies where a set of small housing modules of generic character are provided as complementary compartments. Accessible to both residents and people outside the building, the generic rooms introduce a diversity of use that enriches the housing complex and instills a sense of great urbanity in common areas.

These two examples, among others, point to ways of thinking and building the space of the house, not as a closed and complete unit, but as something that can contain complementary parts located in different points of the territory or building. This hypothesis put in a subliminal way allows us to think of the house as a more complex object composed of several parts or modules that are located in strategic points of the city according to the interests and lifestyles of each individual.

Common House

The Common House is understood as a place that welcomes a community of individuals. It embodies the idea of collective living that recognizes the experiences traditionally invoked by the monastery, convent, or even the palace.

Over the last decade, a varied set of projects has sought to follow up on this principle of living in community, re-interpreting some of these classic dwelling typologies in contemporary housing essays where the shared space emerges as the main protagonist. The collective sharing space is a structuring element of the building, but it is also a main actor in the discussion of models of interaction with the city, both in its use (more or less comprehensive) and in the management of the spaces themselves. The introduction of this kind of sharing areas seeks to provide the building with places to support or complement the house (Espegel, Cánovas, Lapuerta, 2022), while fostering the creation of a small community that supports each other but also opens up to the urban space. In this way, the building represents a social role: it asserts itself as a device of articulation between the collective and the individual. The building as a whole is consolidated as a single system where the living units find extension spaces for collective use. The living room, kitchen, or laundry spaces are some of the situations that are recalibrated within the domestic space according to a generalized offer of these services near the common areas of the building. The building becomes a large house.

In 2018, the experience of the cooperative project La Borda, by the Lacol studio, is a clear commitment to the structuring of a residential building according to a

45

system of common spaces for sharing. Around an inner courtyard, like a cloister, and on the different levels, residents are offered generous living areas duly articulated with the distribution galleries and access to the houses and also to a group of server spaces such as: a common kitchen, a laundry, a dining room, or even a multipurpose space. The concepts of home are questioned and updated while designing living spaces for different family models. La Borda also has an interesting feature that goes through the spatial narrative it builds with the city. At ground level, next to the patio, a wide public passage is designed that connects the street to an urban park/garden on the opposite side of the lot. In this way, the architectural object itself plays an urban role that takes on greater value when the courtyard opens to the city, making itself available to a wider community and not just restricted to the members of the cooperative.

This feature reinforces the collective sense that certain common areas can play a role in the integration between a building and a city. The courtyard emerges as a transitional space that connects the intimate space to the large collective one. Through the creation of these collective spaces, it becomes possible to imagine transition systems that progressively constitute privacy filters. The ambiguous meaning of some of these spaces opens up the possibility of operating on different modes of relationship between public and private space, between the house and the city.

Between house and city

“Since public-private boundaries must be continually explored and renegotiated according to social developments such as changing lifestyles, household types, modes of work, and mobility, the polarity is constantly in motion. Gradations between public and private are created, and degrees of public access can be decided upon”.

Schimd, 2019

Thinking of the house and the city as a continuous spatial structure emerges in current times as a chance to rethink the space of inhabiting. The mistakes of the past have been seen as an opportunity to rediscover new forms of integration and relationships between domesticity and public or collective space. The house and the public space of the city are the privileged places of habitat for Man and, in this sense, must be understood in a relationship of continuity and complementarity, between intimacy and public life.

The urban context should then not be understood as a structure that conditions and limits the housing project, but rather as a complement (Espegel, Cánovas, Lapuerta, 2022). The space of the house and the city must in this sense establish a

MARVILA LAB 46

broader and more versatile dialogue where the public and private boundaries are not reduced to unquestionable rigidity. The development of transitional spaces or spatial systems can represent fundamental design strategies for the construction of privacy filters articulating the public and the private. Different degrees of intimacy are established in ambivalent logics of appropriation that reinforce the collective sense as an identity that mediates the most private space, the house or even the room, and the city, the public space.

The consolidation of this dialogue, house-city, challenges us to think of typological solutions where a certain functional hybridity in the way of living, and a certain versatility of space end up being relevant themes in the process of conception and creation. It is important to remember the influence that the built typology itself plays shaping of the urban space (Muratori, 1959). The formal characteristics of the building, its aggregation processes (isolated, infill, or ensemble), condition in a symbiotic way the manner in which we use the space of the house and how it articulates with the space of the city. Therefore, it can be said that although the house is only one component of the urban organism, it has a decisive influence on urban life. It is perhaps this relevance of the common urban fabric, made up of houses that fill the space between singular buildings, that should be transposed to urban areas such as Marvila, in Lisbon. Parts of the city where the urban fabric is very specialized and is in a process of obsolescence, the result of successive paradigm shifts, but at the same time stimulating and full of opportunities to re-imagine the ways of inhabiting the city.

The urban fabric of Marvila, structured along three main lines – the coastline, the railway, and the old main street of Marvila – is characterized by a fragmentation of the fabric and heterogeneity of scales and typologies. Marvila is a collage that displays working-class neighborhoods, industrial areas, mobility infrastructures, social housing blocks, or new complexes of creative activities, intermediated by large architectural pieces of historical reference such as convents, churches, factories, or warehouses. Between decay, abandonment, or requalification for startups, Marvila emerges in remarkable effervescence becoming the ideal stage to rehearse housing models to meet the challenges of the 21st century.

47

DESIGN STUDIO: THEMES

COMMON HOUSE: ENCUENTRO

Sérgio Padrão Fernandes and Alessia Allegri

Joana Leite, Maria do Carmo Valadares, Pedro Robles, Raquel Cruz Barbosa, Rita Baptista, Rui Raivel

ATELIER HOUSE: LIVING UNDER A COMMON ROOF

João Silva Leite and Sérgio Barreiros Proença

Joana Henriques, Leonor dos Santos, Margarita Catalina, Mariana Vieira da Silva, Patrícia Francisco, Pedro Leitão

RECOVER HOUSE: PLAT-EAU-FORM

Pablo Villalonga Munar and Stefanos Antoniadis

Adèle Roullet, Juliana Balage, Mafalda Soares, Marta Dias, Ona Badia, Tiago Verdasca

MINIMUM HOUSE: FROM COMPACTNESS TO TRANSFORMATION

Júlia Beltran Borràs and Tiago Mota Saraiva

Vitoria Jerónimo, Silvia Sierra, Gonçalo Mota, Ana Catarina Niza, Cláudia Vicente, Aidden Monteiro

DISPERSE HOUSE: ALONG THE VALLEY

José Miguel Silva, Rui Justo and Filipa Serpa

Beatriz Ferreira, Carlos Menacho, Cláudio Borges, Margarida Alexandre, Mariana Frade

Common House: Encuentro

“By this method paranoiac-critical activity discovers new and objective “significances” in the irrational; it makes the world of delirium pass tangibly onto the plane of reality.”

Salvador Dalì, 1935

Case study 01

Tabaqueira old factory

Cadavre Exquís

A corpse is the reminiscence of a life.

Advisors

Sérgio Padrão Fernandes

Alessia Allegri

Students

Joana Leite, Maria do Carmo Valadares, Pedro Robles, Raquel Cruz Barbosa, Rita Baptista, Rui Raivel

When something dies, physical existence is reduced to the deterioration of a body, with the most durable elements, the bones, remaining. Still, it is incredible how simple bones can convey to us the space and time of existence of any being, as if telling us a story. By joining several bones of several corpses in a sadistic game, a kind of unique puzzle is created, which, however strange it may seem, tells a story composed of several pieces of other stories.

The cadavre exquísis a surrealist game that consists of creating a collective composition, which can be literary or graphic. A piece of paper is used and folded as many times as the number of participants. Each participant writes or draws something on one fold, and the next participant continues on another fold without seeing what the previous one had represented, and so on.

50

“...Há muita gente que vai almoçar pregos à rulote, no entanto, o espaço era tanto mais agradável se não limitasse a uma frágil tenda e a um reboque com rodas...”

“...Tudo tem dois estados: estático e móvel. É engraçado como uma coisa móvel como uma rulote consegue adquirir um estado estático num lugar se permanece estático é porque tem uma força exterior aplicada para que no lugar permaneça, o homem...”

“...Este espaço vazio, junto ao rio, mostra a necessidade de ser preenchido com movimento de maneira a trazer algo em comum aos habitantes e trabalhadores da zona. É então assim, a rulote um espaço comum e de interação...”

“...La pieza mínima, en el lugar donde lo pide, genera comodidad entre las personas.

“La pieza móvil, flexible, adaptable y reciclable permite al usuario tener libertad y expresividad en el lugar sin dejar una huella física...”

“...Esta imagem tem como objetivo ilustrar a relação simples entre parte da comunidade de Marvila. E, por simples, quer se dizer que não é necessário muito para as pessoas se sentirem bem, como uma simples rulote, um elemento estático à beira rio, já com um certo sentido de permanência pode juntar uma comunidade que por lá passa, trabalha, habita, etc...”

“...A rulote apresenta-se como a personificação do sentido de comunidade e ajuda que se pretende atribuir à fundação. O ponto de encontro que resulta num catalisador de conexões, uma vez que, o ato de comer, aproxima as pessoas e desencadeia uma vivência mais duradoura e equilibrada que é fundamental para o funcionamento do habitar em comunidade...”

At the end, the sheet is unfolded, revealing a surprising form – a narrative or a drawing – with an unexpected relationship between the contributions of the different authors of a collective work. We used this game as a conceptual reference for the construction of a collective project. We began by explaining two photographs (Rulote and Mirror) that synthesise our perception of the intervention site. We folded a sheet of paper to write a text that, in addition to the photographs, expressed the point of view of the Design Studio 1 working group, on the former Tabaqueira factory and the particular urban context in which it is integrated. The result was a peculiar compilation of texts, as it brings together similar and disparate opinions in a deliberate lack of coherence of the whole.

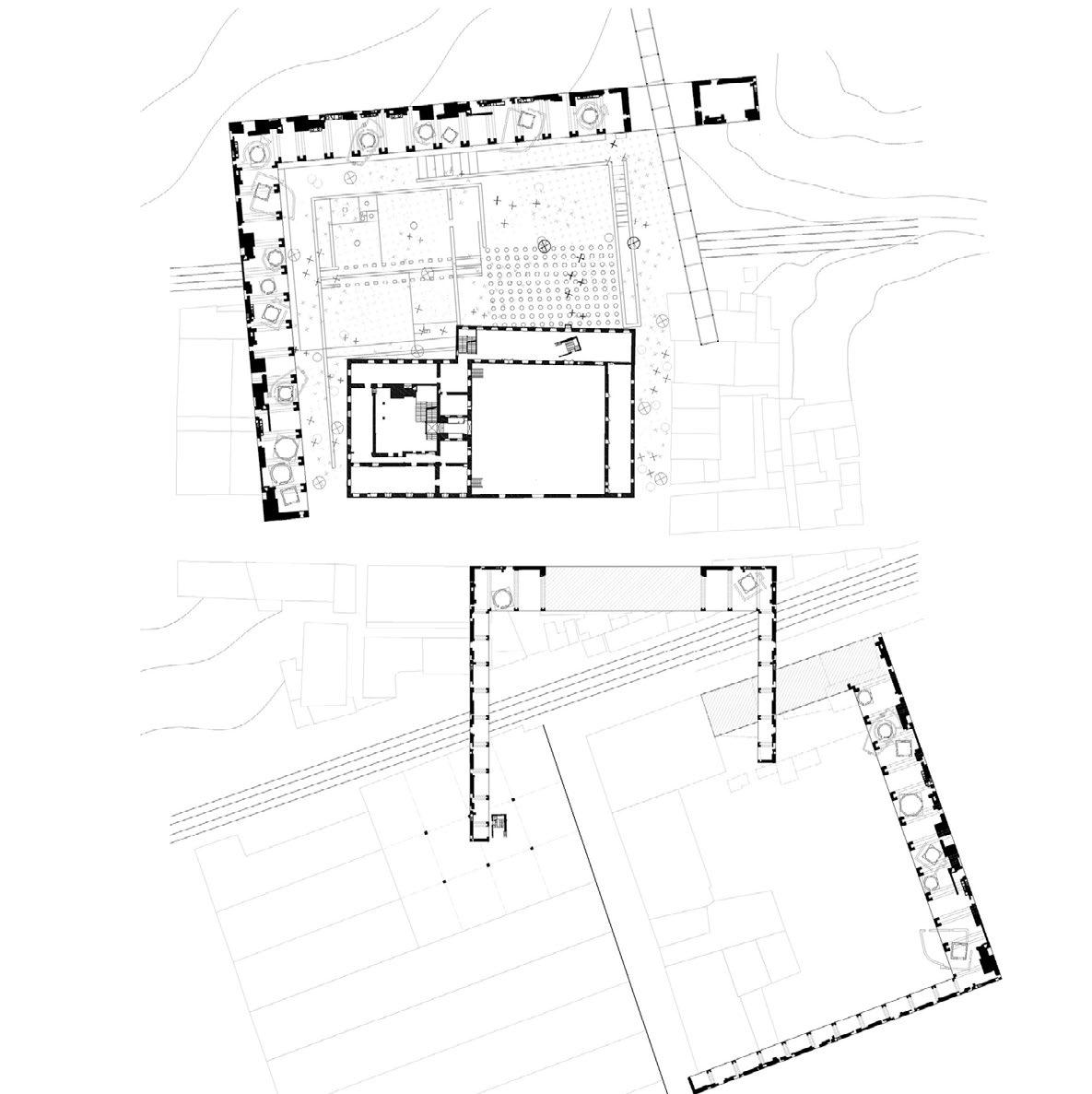

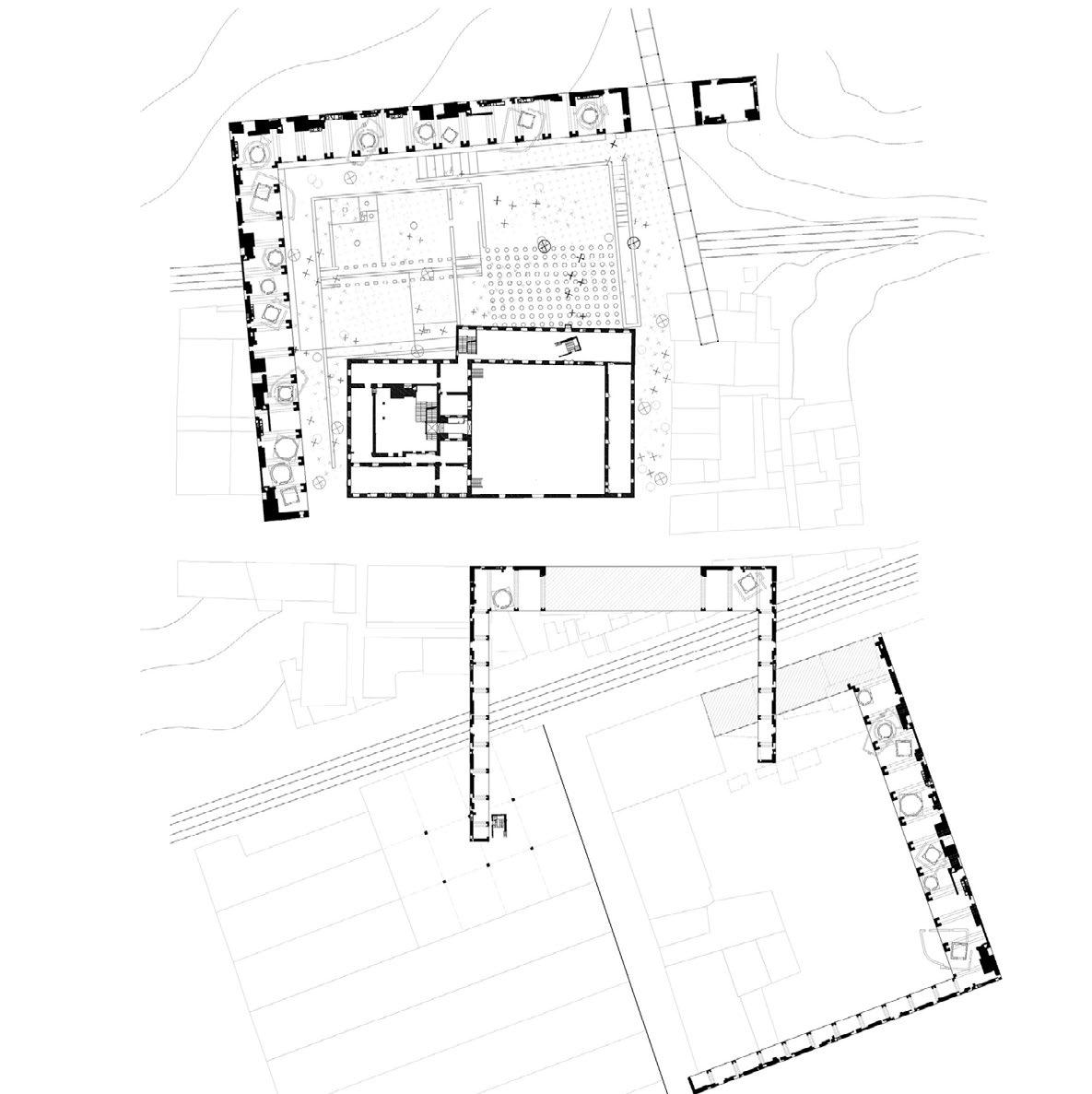

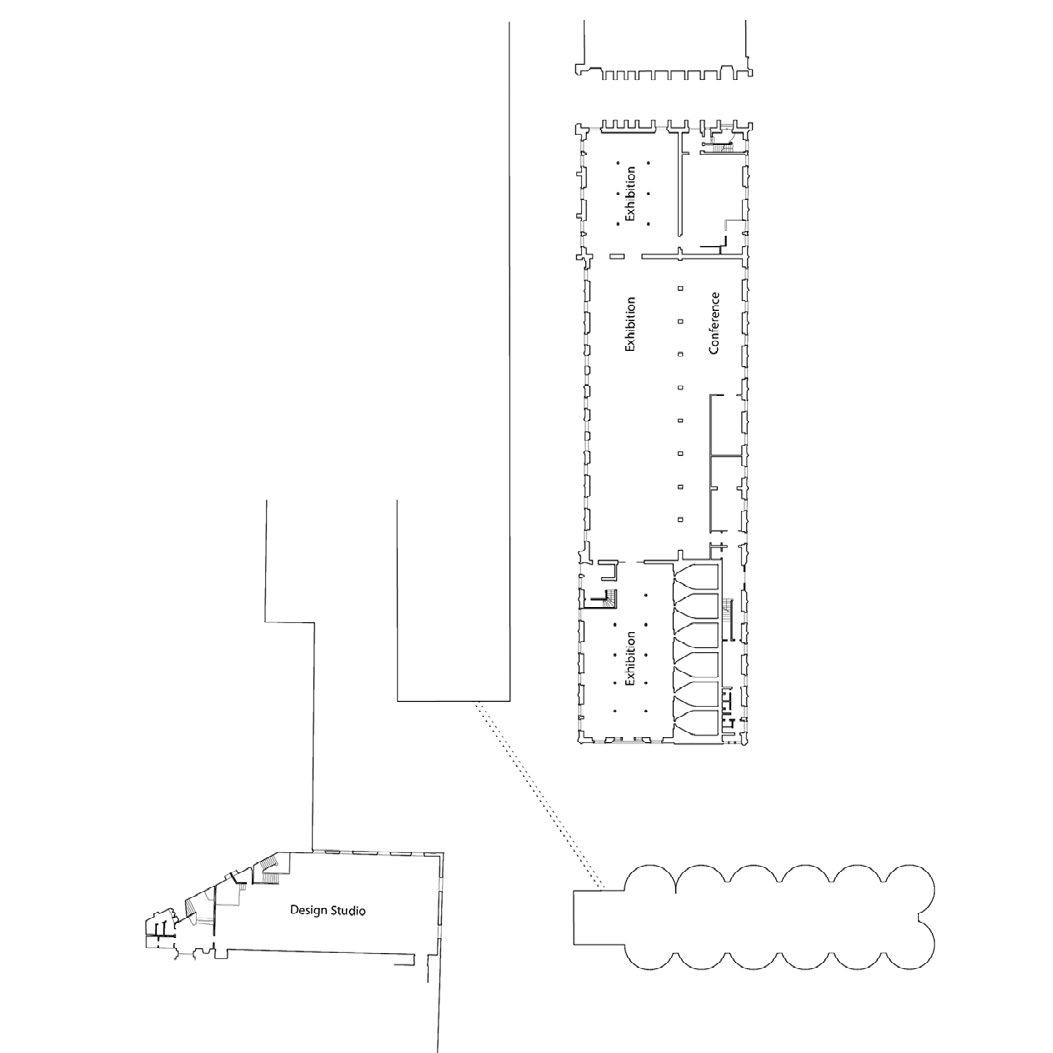

Tabaqueira

The former Fábrica da Tabaqueira is defined by its large courtyard, the huge gate, and the symmetrical composition that aligns the void of the courtyard with the prominent volume of the main entrance on the transversal axis of the rectangular plan. This building was constructed for the 1888 Industrial Exhibition, which took place on Avenida da Liberdade in Lisbon. It was later moved to its current location, next to the Matinha Quay, to accommodate the operation of a tobacco industry that extended the structure of the original pavilion. The main materials used in the complex are iron and brick, and the façade is characterised by neoclassical ornamentation with wrought iron work on metal sheets. The Tabaqueira factory was transferred to another location in the mid-1960s, and the building was gradually abandoned. In addition to a presence strongly rooted in the working-class memory of this area of the city, this building has not been able to find over time a vocation that justifies its existence.

Today, the former factory is a ruin. The advanced degradation of the building and the spontaneous appropriation of the vegetation create a surprising, seductive atmosphere that allows us to imagine the exploration of a very free and flexible appropriation of the pavilion structure of this building. It also suggests the exploration of relationships of continuity between the interior and exterior, as well as the coexistence between the built structures and the imaginary of a leafy garden of a forgotten paradise.

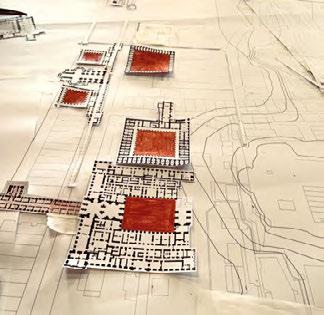

Common Living

We recognise in the architectural element – patio –the materialisation of the idea of a meeting space, the main support of collective life, and the very architectural expression of the theme “common living”. In this sense, the Tabaqueira patio became the reference to imagine the transformation of a fragment of the landfill of the eastern riverside front of Lisbon, between the Marvila Dock and the Matinha Pier. We were interested in some famous courtyards that we recognised in the inventory of buildings of the “Building Typology” research project, namely the cloisters of the great conventual structures –the Convent of Mafra, the Convent of Christ, the Carthusian Monastery of Évora and, among others, the monasteries of Alcobaça and Batalha. However, from the research project’s database, we also selected urban infrastructures such as the ÁguasLivres Aqueduct in Lisbon or the Infrastructural Conduit of the Malagueira neighbourhood in Évora, which design routes and play an important structural role in the composition of the urban layouts in which they are located.

In our wandering through the historical references of ambiguous buildings and urban megastructures, we decontextualised courtyards and courtyard sys-

MARVILA LAB 54

tems, as well as aqueducts and conduits, passages, and arcades. We transfer these architectural elements to the composition of the urban fabric. We attribute the polarising role of collective life to a system of urban courtyards that are structured by arcades/ porticoes. These draw a network of main routes that connect the different places of permanence.

The proposal of a new urban fabric composed of courtyards suggests the radical transformation of the embankment of Lisbon’s eastern riverfront with voids that subtract themselves from the matter of the pre-existing context. Complementary to the courtyards, which were understood here as part of a continuous building system that, by densifying the embankment, absorbs and integrates the traces of the pre-existing built structures.

The idea of subtraction was explored through a full/empty model, where red was used to represent the subtracted matter – the patios – in contrast to the dominant matter – the full – which represents the context.

In another model we rehearsed the logic of urban/ architectural composition by exploring the ideas of addition and juxtaposition of layers. Here we were interested in developing the idea of a continuous building – mat-building – with different levels and layers, but also as an ambiguous and naturally complex building. We used as a thematic reference the idea of the Mediterranean city, dense and compact, and particularly the urban megastructures of the bazaars such as Istanbul, Isfahan or Aleppo.

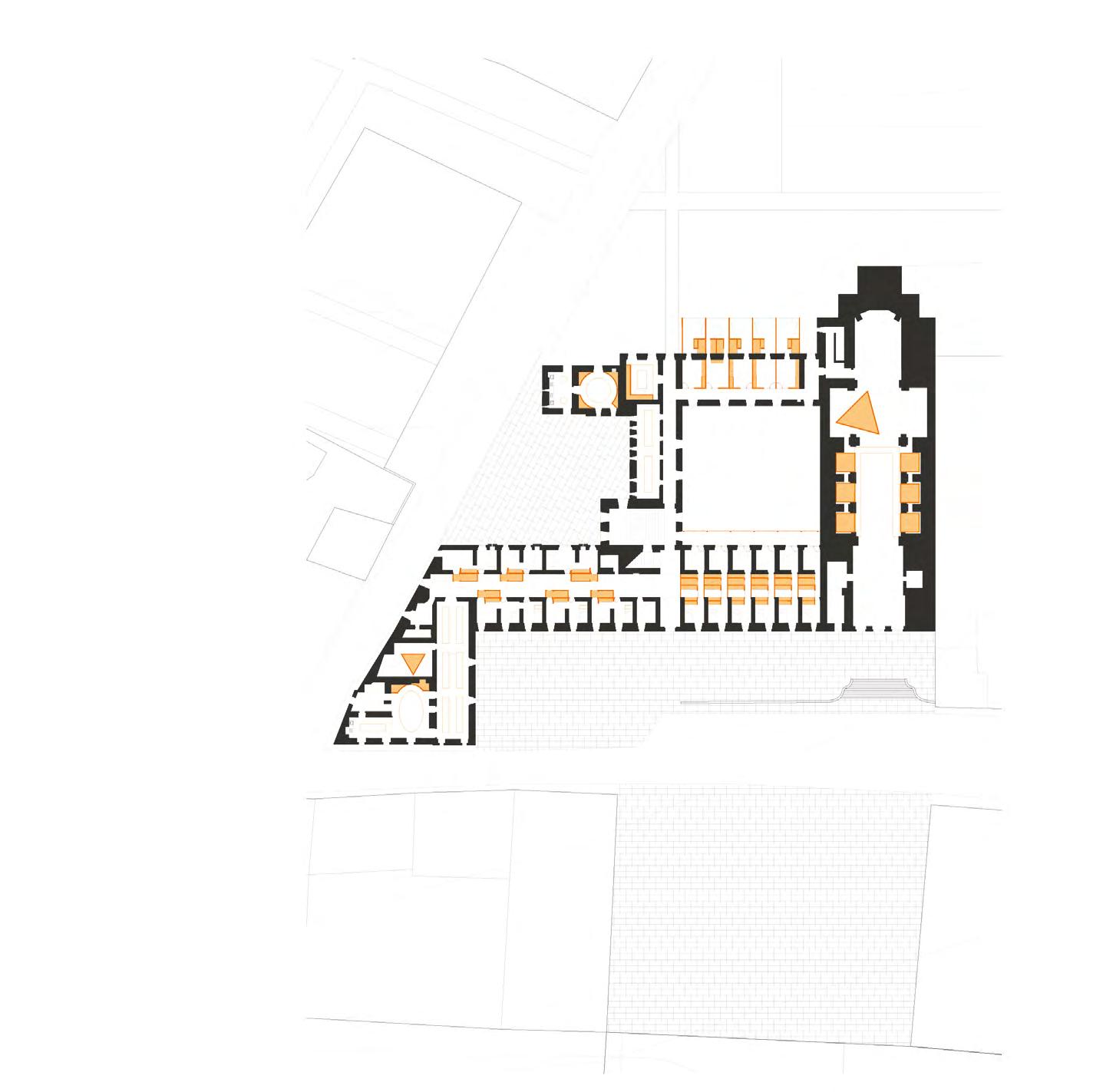

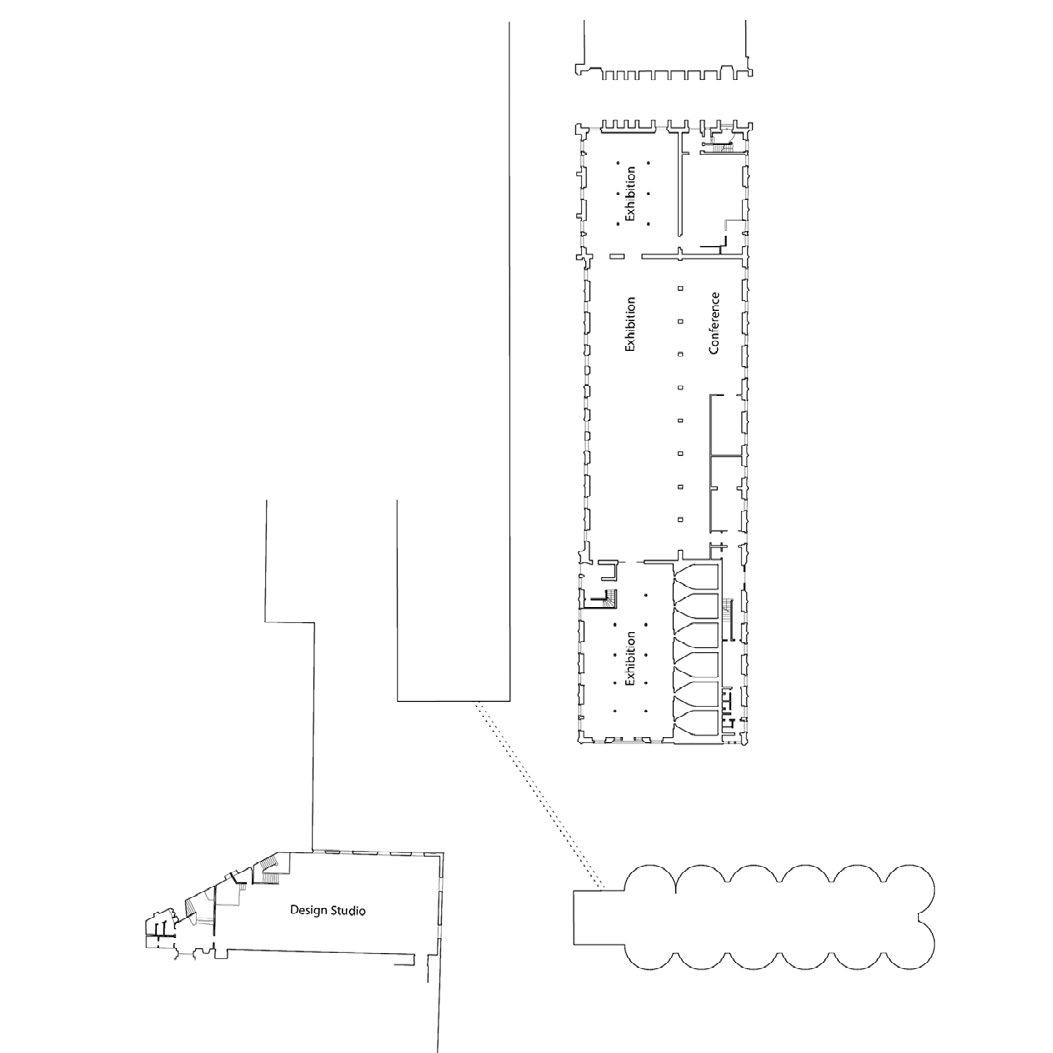

Encuentro

The common house is a system of meetings and spaces polarised around a collective courtyard. In this way, we propose the activation of the old tobacco factory with a new urban role and vocation, based on the concept of “common living” and