edited by SÉRGIO PADRÃO FERNANDES, PEDRO RODRIGUES

The space to live together: a new cartography of

SETÚBAL

urban-ground

LAB

SÉRGIO PADRÃO FERNANDES, PEDRO RODRIGUES

edited by The space to live together: a new cartography of urban-ground

SETÚBAL LAB

The space to live together: a new cartography of urban-ground ISBN 979-12-5953-030-1 (printed version)

edited by Sérgio Padrão Fernandes and Pedro Rodrigues

scientific coordinators

Sergio Padrão Fernandes, Pedro Rodrigues scientific board

Sérgio Padrão Fernandes, Pedro Rodrigues, Carlos Dias Coelho, Stefanos Antoniadis

editorial board

Sérgio Padrão Fernandes, Carlota Gala, Gonçalo Pirrolas, Rui Justo, Stefanos Antoniadis related laboratories and research programmes

The workshop and the book – The Space to Live Together: A New Cartography of Urban-Ground – has been framed in the research laboratory formaurbis LAB, CIAUD – FA.ULisboa under the Project “BUILDINGS” – Building Typology, Morphological Inventory of the Portuguese City. This book is financed by national funds through FCT – Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, I.P., under the Project with the reference PTDC/ART-DAQ/30110/2017

drawings by pags: 54, 55, 57, 59, 65, 67, 69, 75, 77, 79, 85, 87, 89, 95, 97, 99, 105, 109, 111 Rui Justo, Gonçalo Pirrolas

translation by Stefanos Antoniadis book design

Margherita Ferrari

publisher Anteferma Edizioni Srl via Asolo 12, Conegliano, TV edizioni@anteferma.it

First Edition: September 2022

Copyright

This work is distributed under Creative Commons License Attribution - Non-commercial - Share-alike 4.0 International

Workshop series

Sérgio Padrão Fernandes and Pedro Rodrigues

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Leonel Fadigas

_FOREWORDS

Stefanos Antoniadis and Gonçalo Pirrolas

Sérgio Padrão Fernandes, Rui Justo and Carlota Gala

_DESIGN STUDIO: BRIEF

THE SPACE TO LIVE TOGETHER: A NEW CARTOGRAPHY OF URBAN-GROUND

_THEORETICAL FRAME

URBANISM AND NATURE: LANDSCAPE DYNAMICS AND TERRITORIAL ORGANIZATION

THE SCAPE TO READ TOGETHER: A NEW ATLAS OF URBAN-GROUND

TOWARDS AN ARCHITECTURE FOR PUBLIC USE: A CONVERSATION WITH SAMI-ARQUITECTOS

6 10 12 21 22 32 42

_DESIGN STUDIO: THEMES

RUINS AND FRAGMENTS: VESTIGES

Sérgio Padrão Fernandes, Alessia Allegri, Pedro Rodrigues Danilo Tavares, Fernanda Costa, Mariana Reis, Roberto Lorenzon

HOUSING TOGETHER

João Leite, Maria Manuela da Fonte Ana Oliveira, Beatriz Cabral, Henrique Nunes, Mariana Frade

THRESHOLD: HYBRID SPACE

José Miguel Silva, Luís Carvalho Alessandra Pace, Carolina Martins, Filipa Lopes, Margherita Maggioni, Mattia Muresu

DISPLACEMENT: TRANSPORT / EXHIBITION

Sérgio Barreiros Proença, Filipa Serpa Cândido do Rosário, Francisco Janeiro, Paolo Richelli, Sara Alfonso, Sara Ribeiro

WALLS AND DOORS: TRANSITIONS

João Rafael Santos, Pedro Bento Elcio Djata, Francisco Manuel, Julianna Costa, Michela Stefanoni, Sara Faedda

_REPORTING FROM SETÚBAL _BIBLIOGRAPHY 53 56 66 76 86 96 107 116

FOREWORDS

The outputs that are now disseminated correspond to the result of a workshop organized in September 2021 by the Lisbon School of Architecture – Universi dade de Lisboa, in the framework of the International Master PPCEL - Planning & Policies for Cities, Environment and Landscape, advanced education course shared with the University of Girona, the University of Barcelona, the Universi ty of Sassari, and the Università Iuav di Venezia.

The workshop, with the topic “The Space to Live Together: a new cartography of urban-ground”, was attended by 25 students from the different participating institutions. For ten days, they approached the territory of the city of Setúbal, whose urban richness allowed the development of reflections and works on an increasingly important theme in the organization and experience of our urban ground: public space.

Coinciding with the period of the COVID-19 pandemic, the meeting was carried out by the commitment of FA.U Lisboa teachers, among which the Co ordinators, Professors Pedro Rodrigues and Sérgio Fernandes stand out.

However, the realization of this workshop would not have been possible without the logistical, human and documentary support of the Municipality of Setúbal, which from the beginning was essential for the assembly of an event in such an exceptional period.

The reflection and high level of the work produced, which these pages so well illustrate, reveal the capacity that our cities have to be reinterpreted, but also the energy and confidence of the new generations of architecture students, who very soon will be part of the ensemble of the actors responsible for these urban processes.

7

The President of Lisbon School of Architecture Carlos Dias Coelho

The Universities, in general, and especially the University of Lisbon, continue to contribute to the expansion of knowledge around concrete urban problems by carrying out important initiatives. The workshop “The Space to Live Together: a new cartography of urban-ground” is another example of this good practice and, also, for this reason it is imperative to congratulate the organizers of this action to promote knowledge about cities, the way they work, the way we would like them to work.

Mayors have special responsibilities in defining policies and practices for bet ter urban development and, for this reason, we saw this training action in our city as another important opportunity to reflect on our daily options on these urban matters.

It is important to highlight that the Lisbon School of Architecture chose the city of Setúbal as the theme to focus its activities which, naturally, is the reason of our enthusiasm, deserving our support. It is of the utmost importance that students of a Schools that teach what being architect means, as well as the re spective teachers and researchers, were all together investigating and looking into concrete themes of a real city.

A better knowledge of the history and of the urban form will decisively con tribute to having better equipped professionals to intervene in urban layouts, built contexts and public spaces in the future, whether they become technicians working on private projects, or technicians working at any level in the public administration offices. Also for us, as mayors and technicians of the local admin istration, the elements collected in these investigation processes can provide useful tools for our daily task.

As Mayor of Setúbal, I express my satisfaction that our city and our county are such an inspiration for the universities’ investigation and didactic activity.

9

The Mayor of Setúbal André Martins

DESIGN STUDIO: BRIEF

THE SPACE TO LIVE TOGETHER: A NEW CARTOGRAPHY OF URBAN-GROUND

Pedro Rodrigues, professor, architect, CIAUD, Research Centre for Architecture, Urbanism and Design, Lisbon School of Architecture, Universidade de Lisboa

“Of all the architectural elements, the wall comes first. The primary purpose of a wall is to establish a relationship. Association comes before separation.”1

Hamed Khosravi

12 SETÚBAL LAB

Sérgio Padrão Fernandes, professor, architect, CIAUD, Research Centre for Archi tecture, Urbanism and Design, Lisbon School of Architecture, Universidade de Lisboa

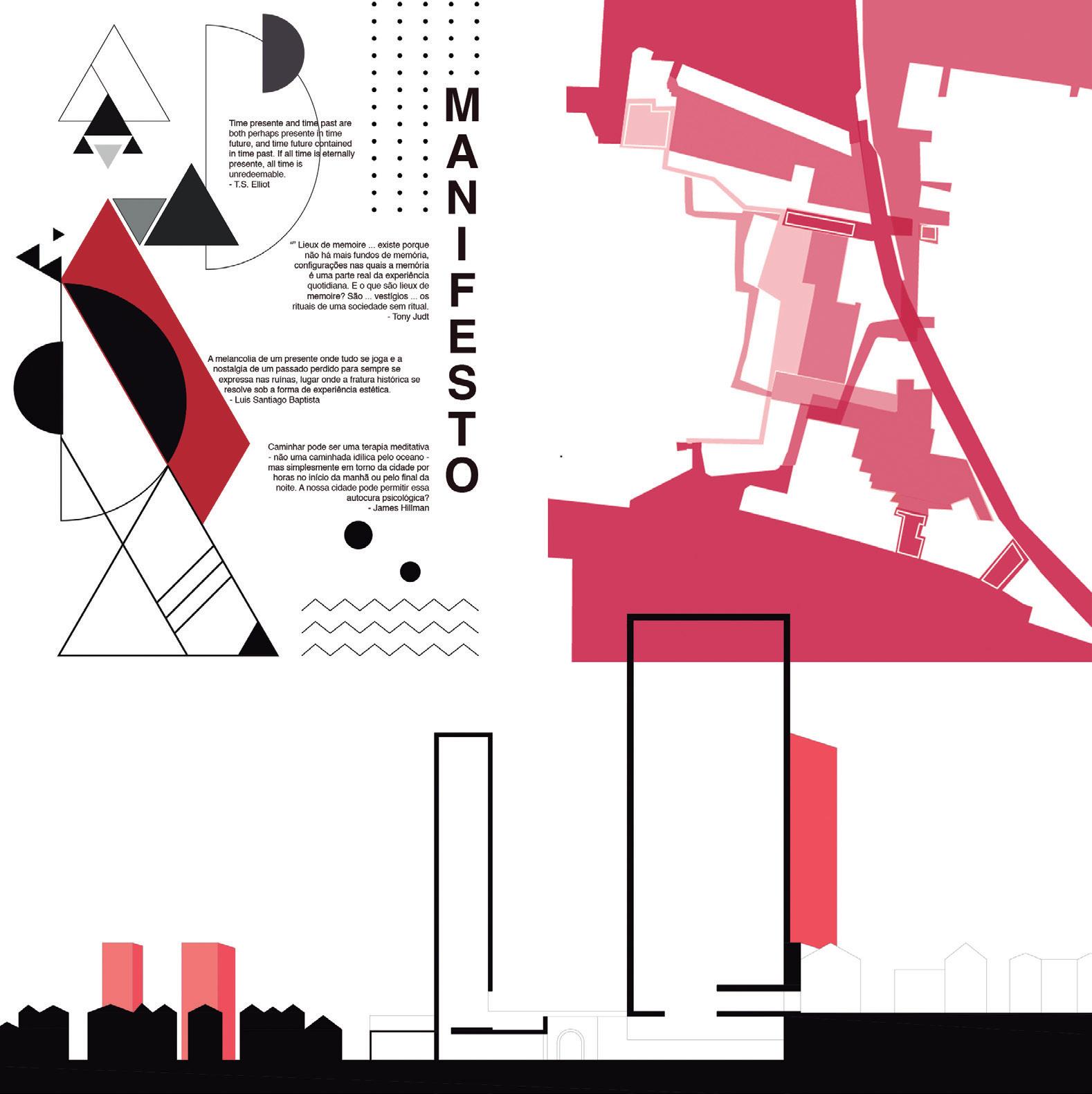

The theme “The Space to Live Together: a new cartography of urban-ground” questions ¿what spaces we need tomorrow? and uses as reference the call for reflection of the Biennale Architettura 2021 in Venice “How will we live togeth er”, proposed by Hashim Sarkis.

¿ which public spaces we will need tomorrow?

Public space can be the answer for the challenge launched by the Biennale. The public space is what unify us in the city and, therefore, we propose as a working hypothesis the formulation of a new cartography of urban-ground and a new equilibrium to explore the potential of spaces within the intersection between public and private domains…new equilibrium !

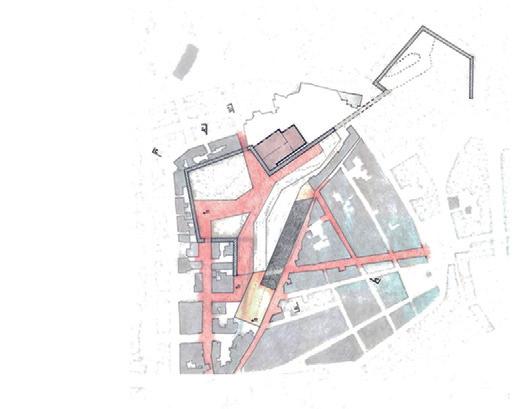

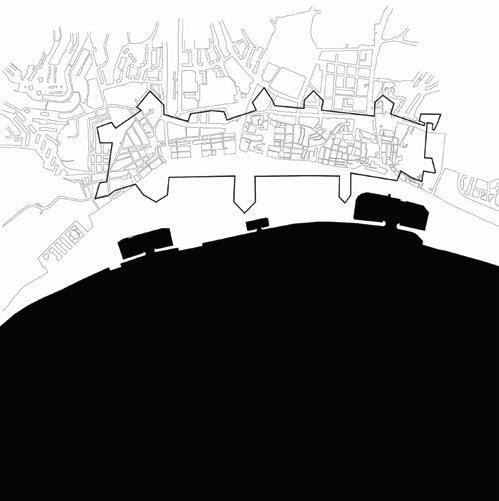

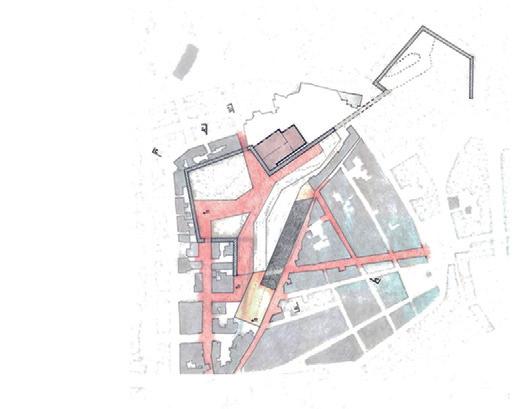

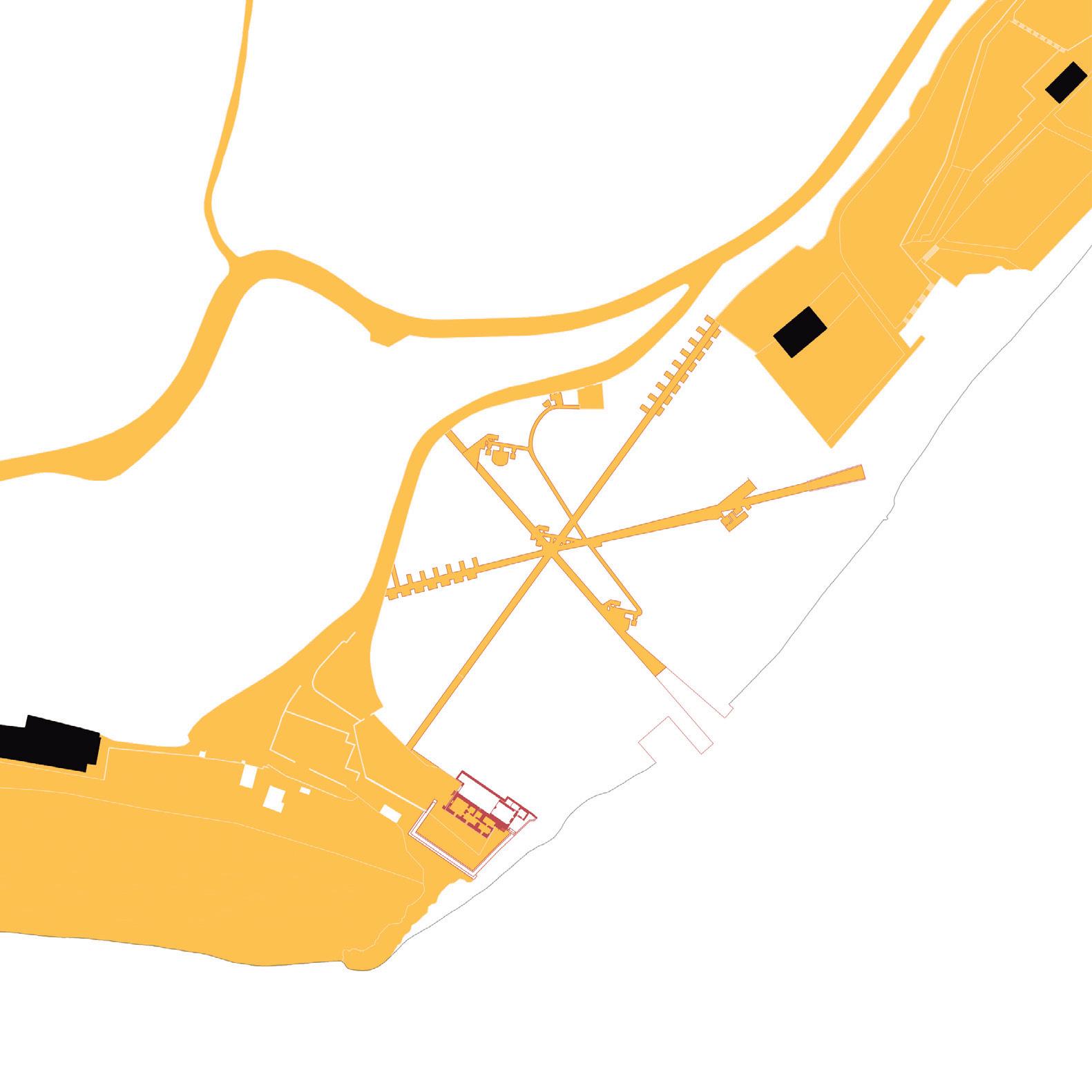

The workshop proposes to re-imagining the public space and uses the city of Setúbal as case study, focus in five fragments of urban fabric with the physical and spatial qualities of a historic city, with a natural harbour vocation and a spe cial topographic context. However, the radical changes that are taking place all over the world will lead to a major transformation of what Setúbal is today. For example, the COVID-19 pandemic or the international economy is changing real estate, property and also the uses and activities that take place in the city. The city is always in transformation, under construction and in decay, in use and transgression. It is a constant process of appropriation and reinterpretation. Inspired on graphic method of Giambattista Nolli, we propose to investigate the public form of the city in order to develop urban projects that seek the possibility of transforming abandoned historical structures into contemporary places that respond to the new demands of a public life. We intend to continue imagining the city! But we also want to find a balance between the existing city, that we inherited from the past, and the need to transforming it in order to con tinue living together.

13

14 SETÚBAL LAB

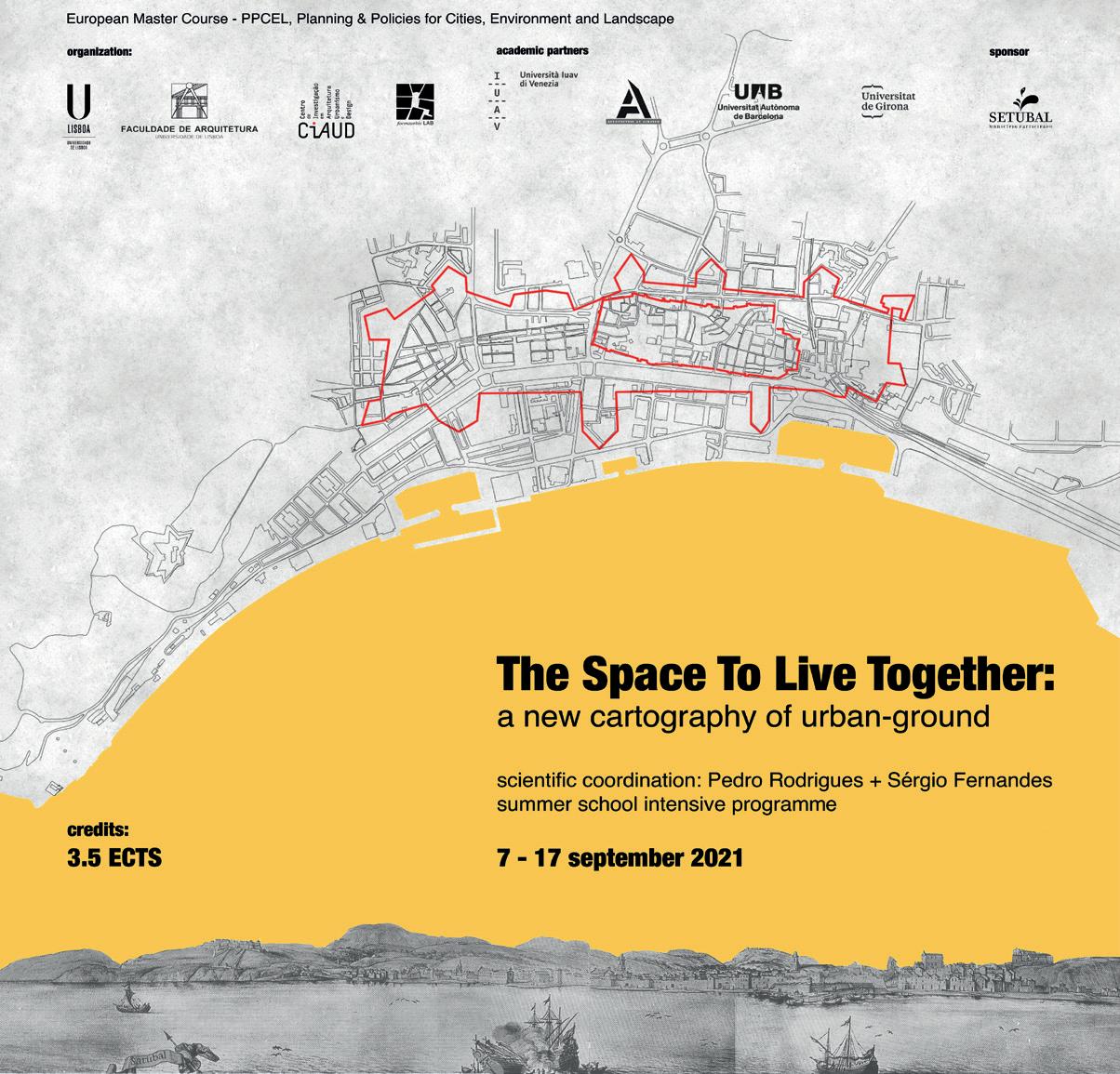

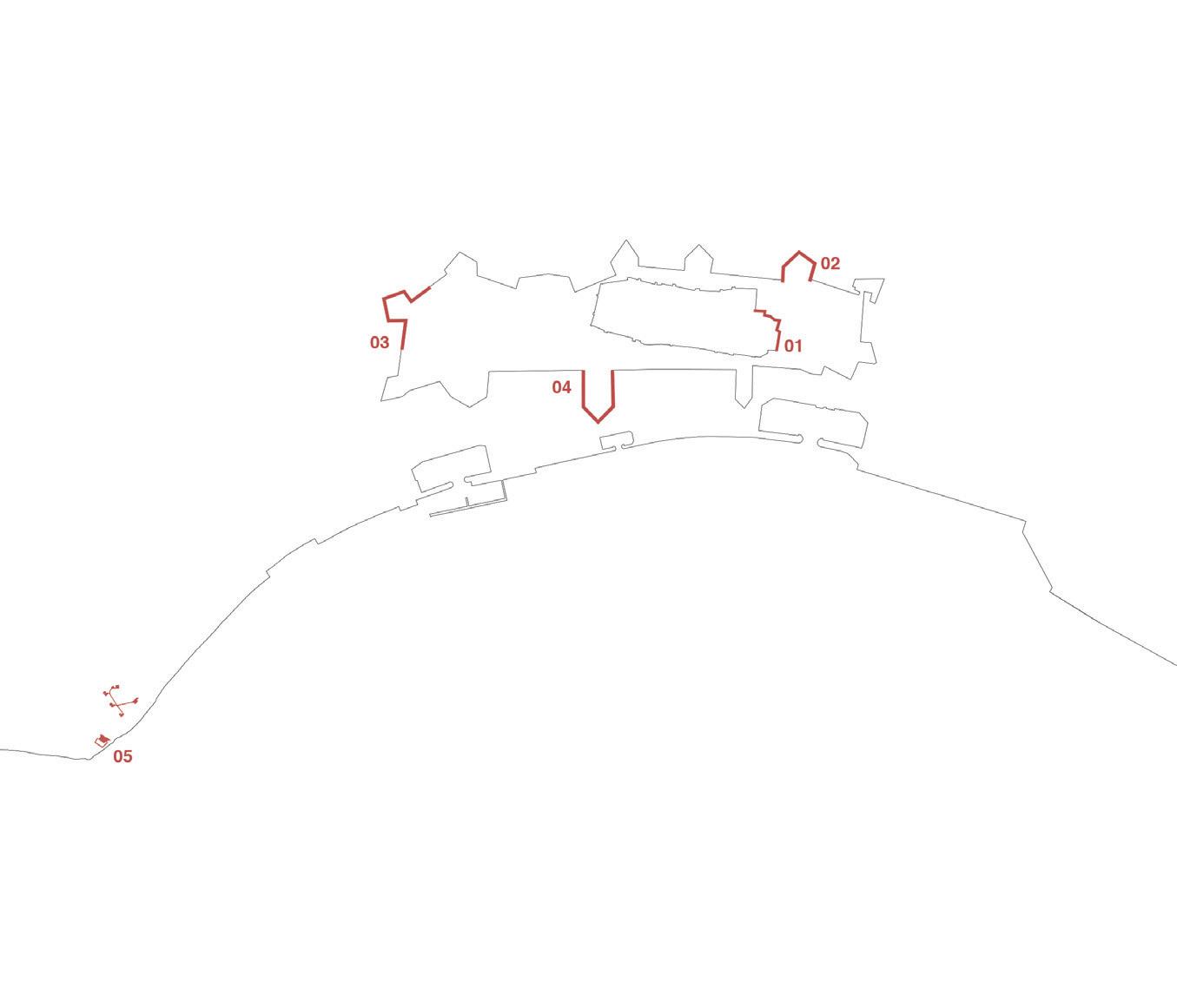

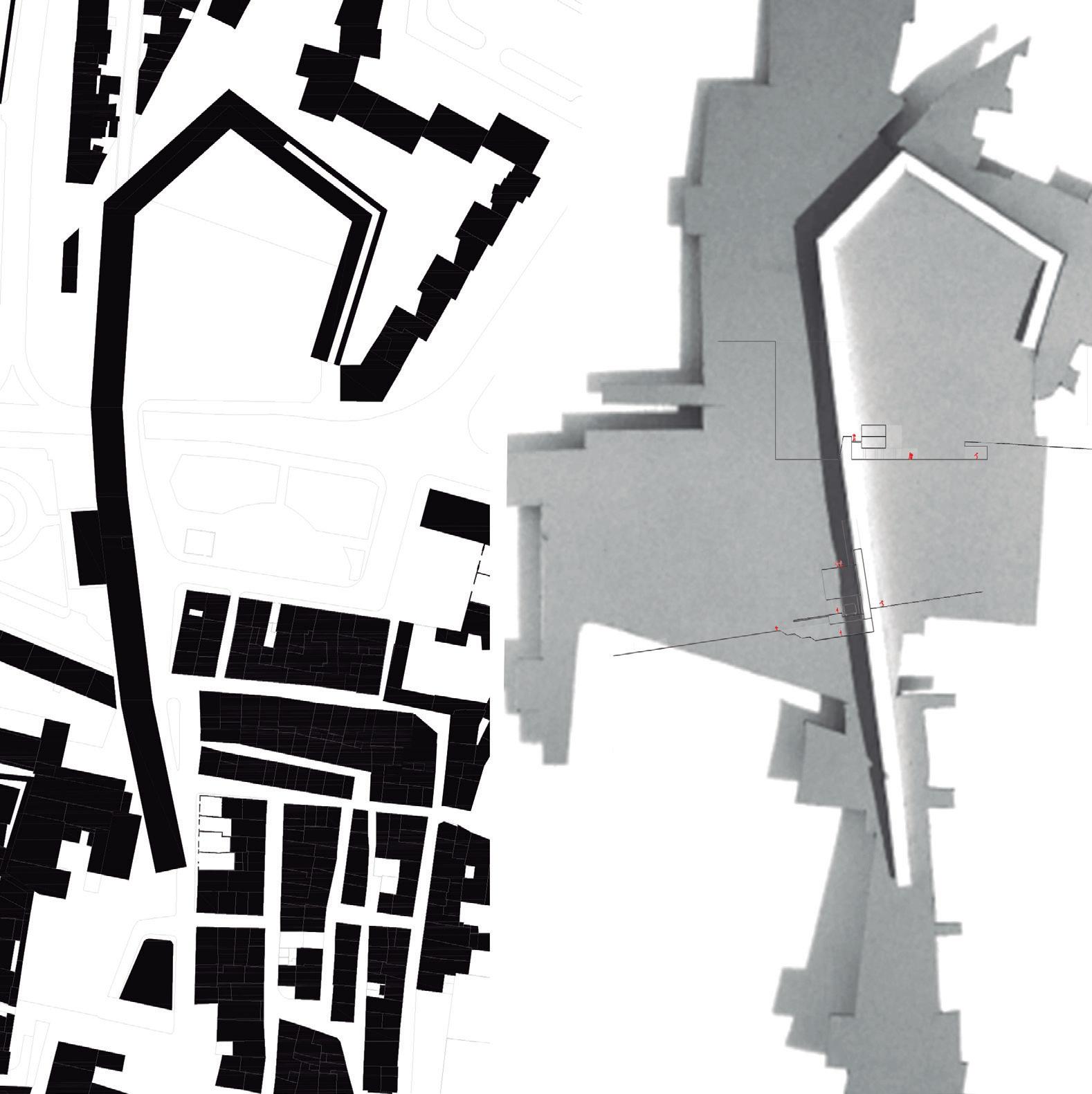

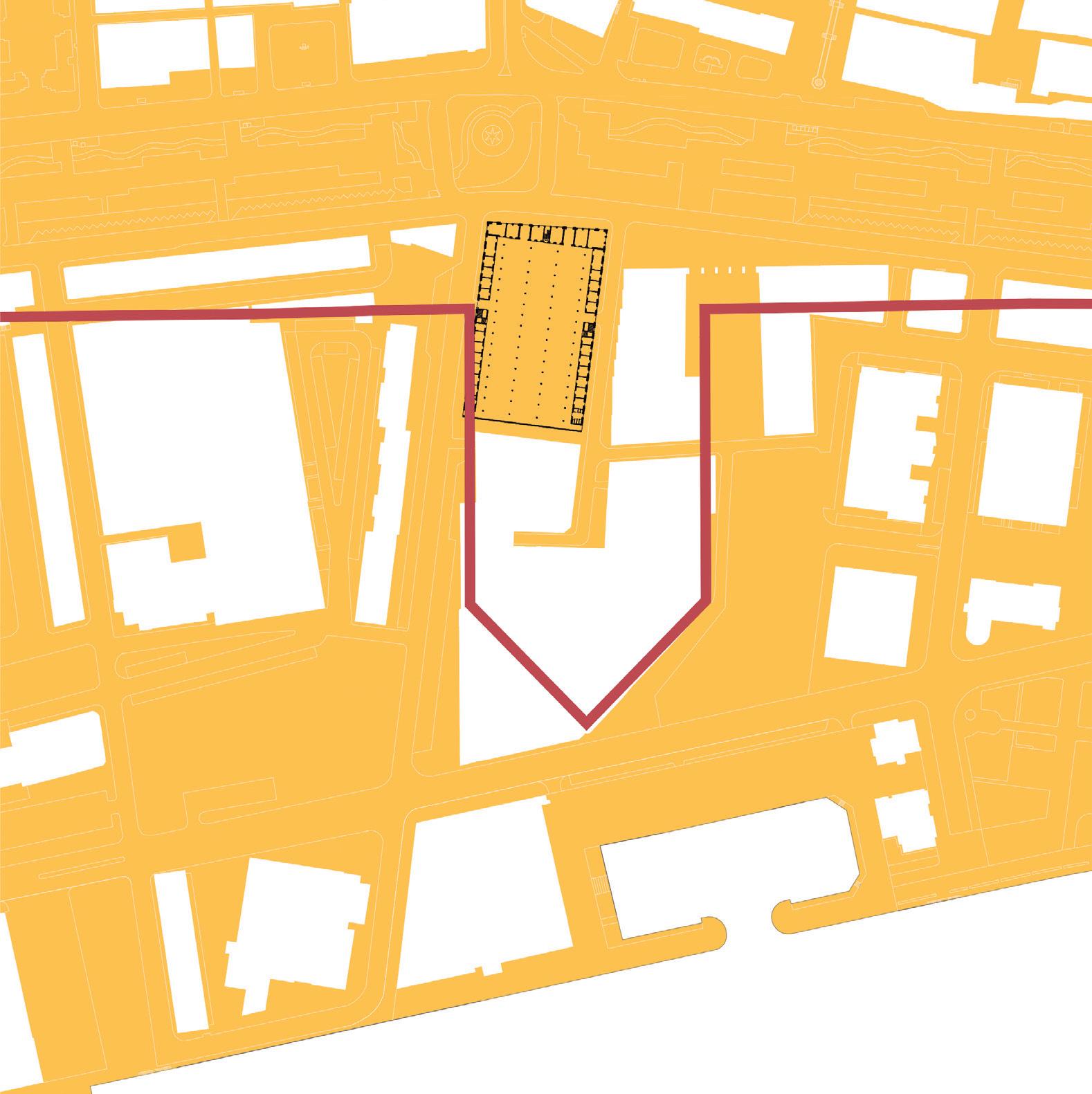

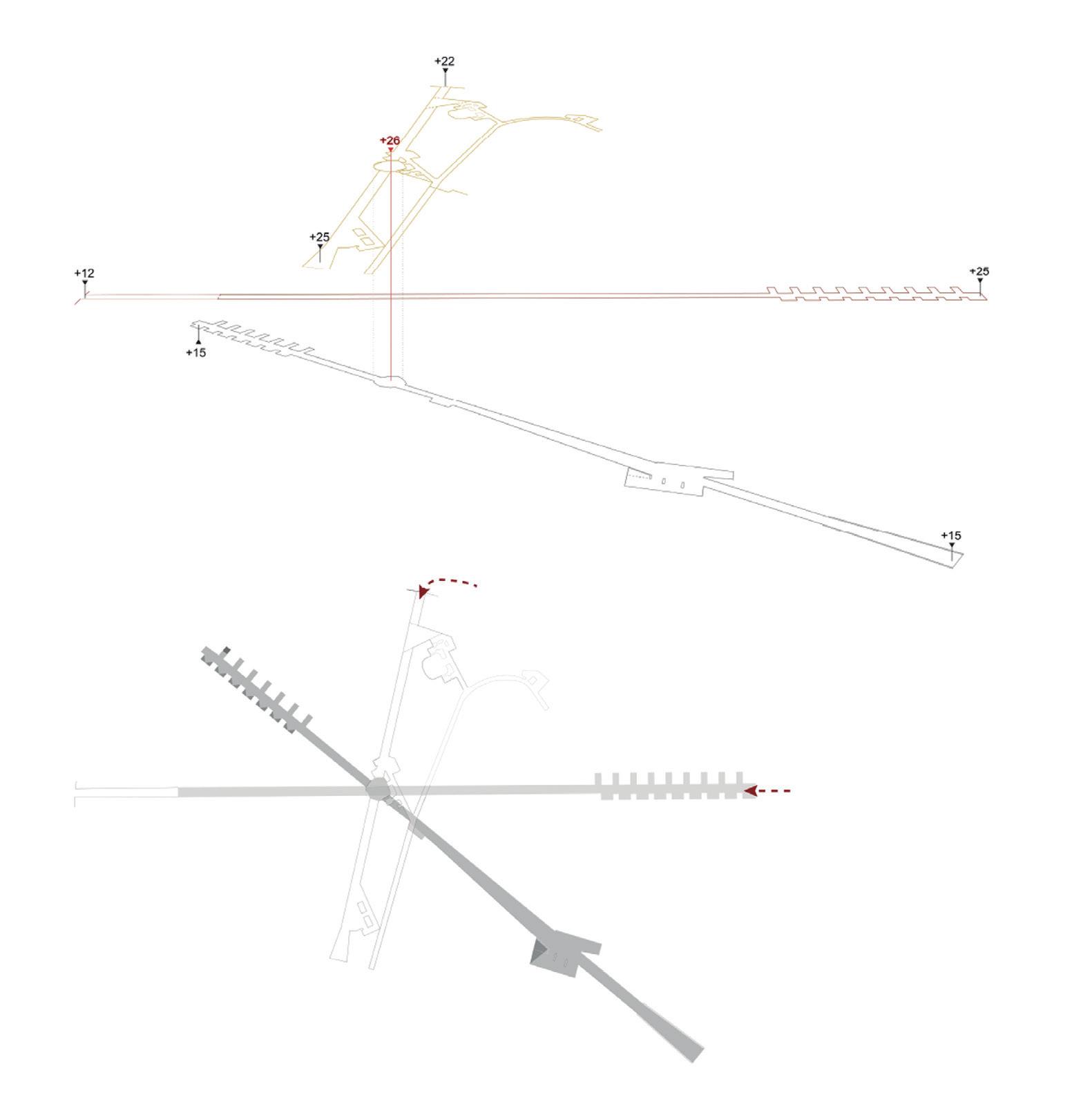

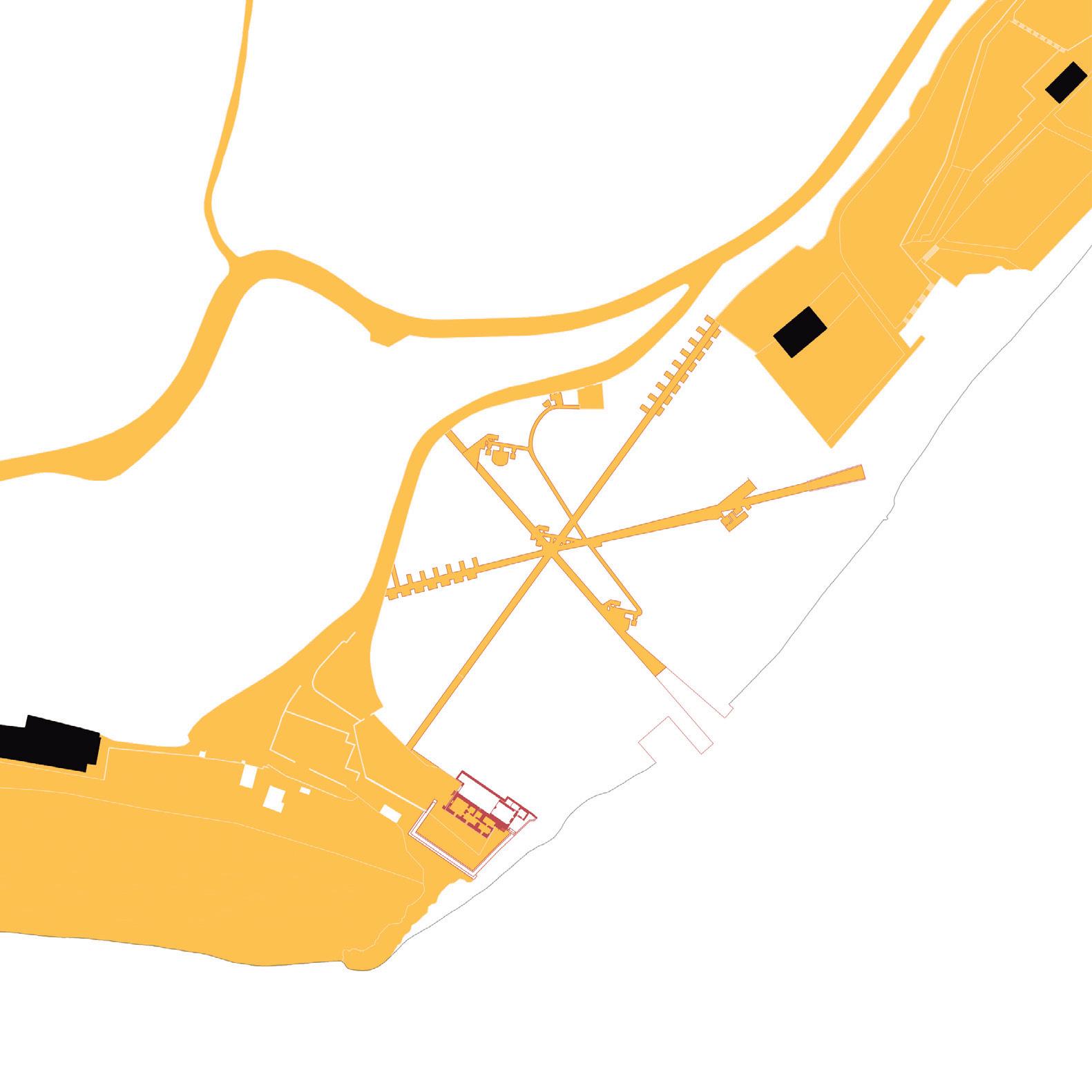

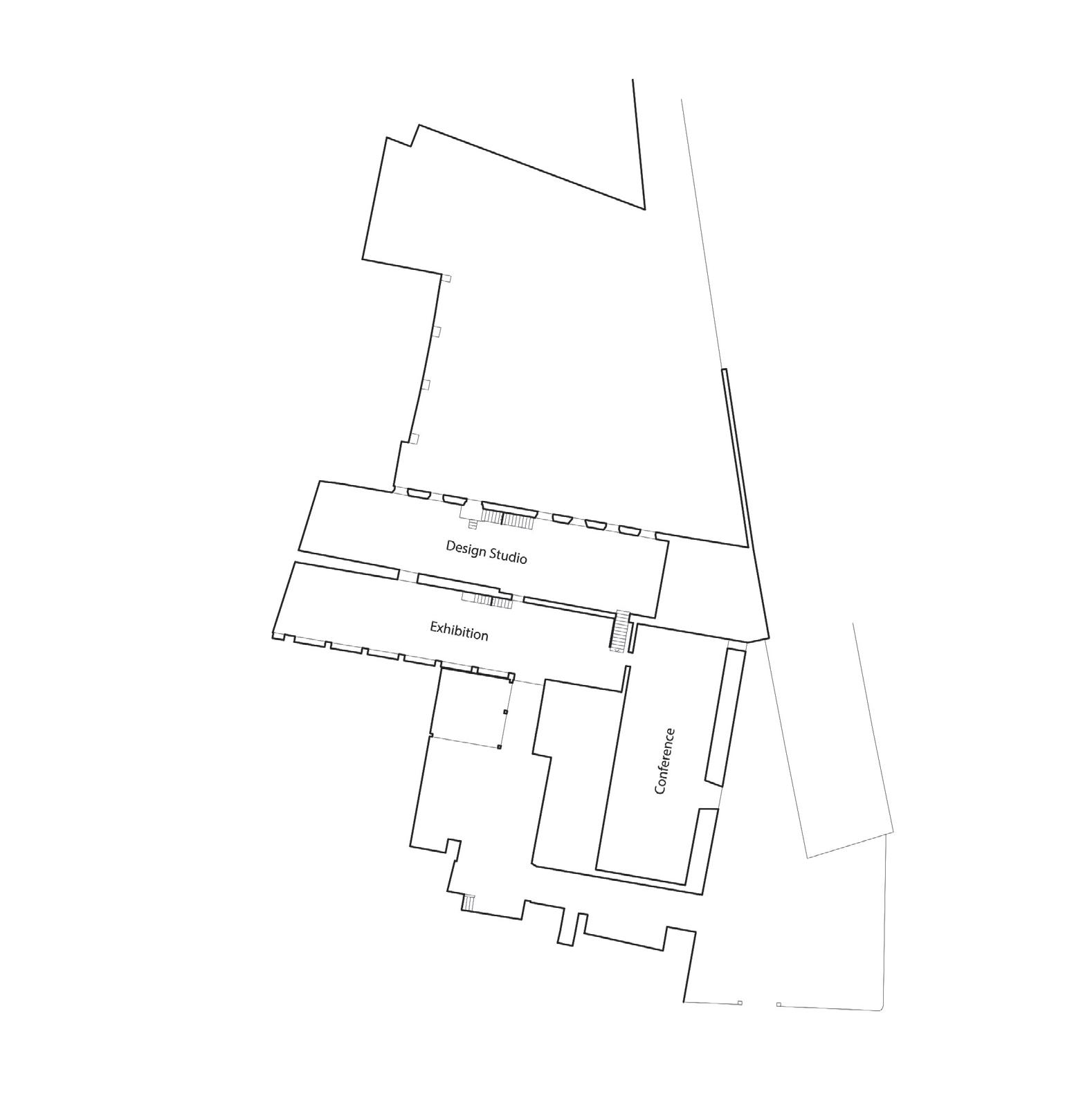

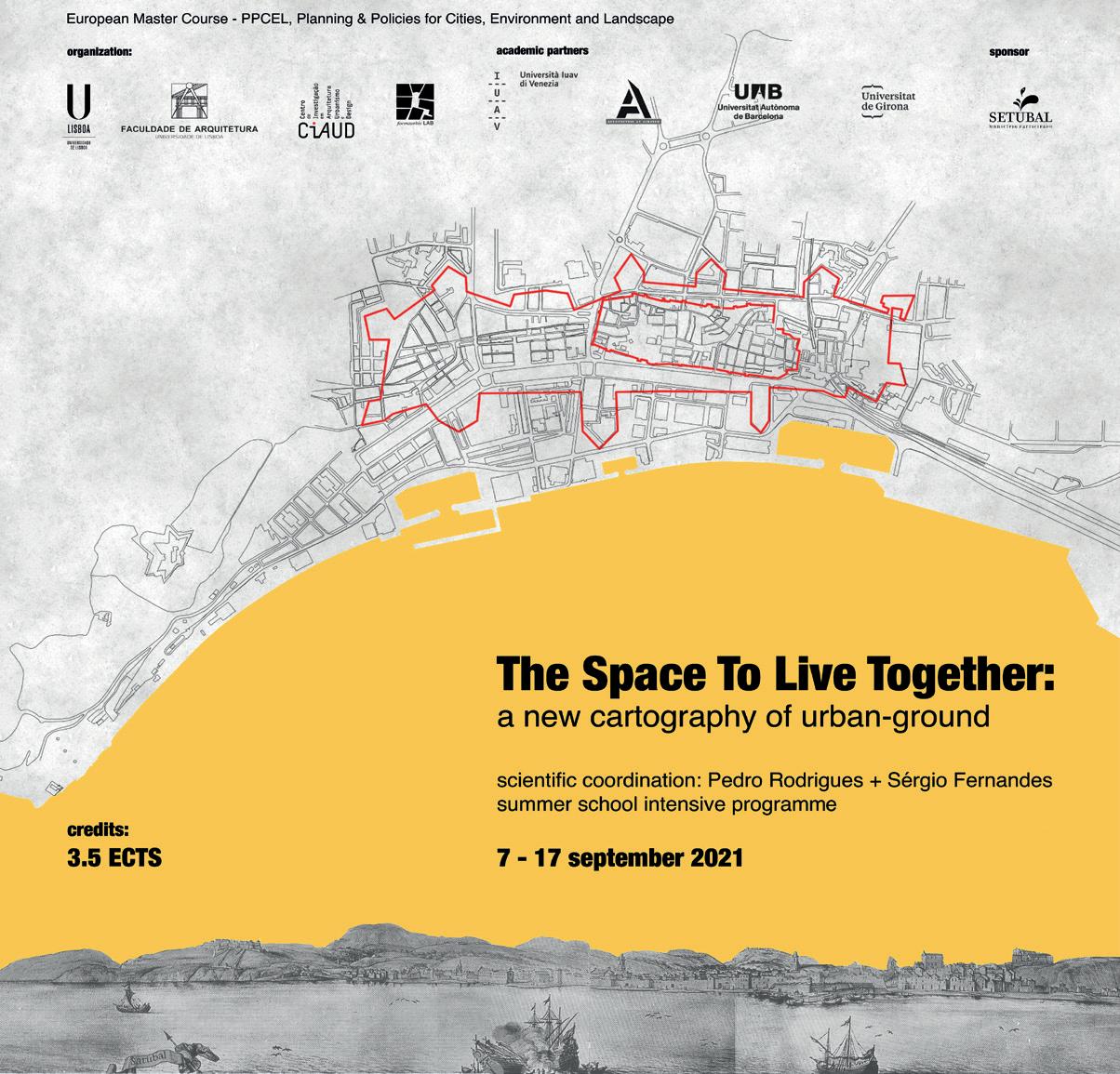

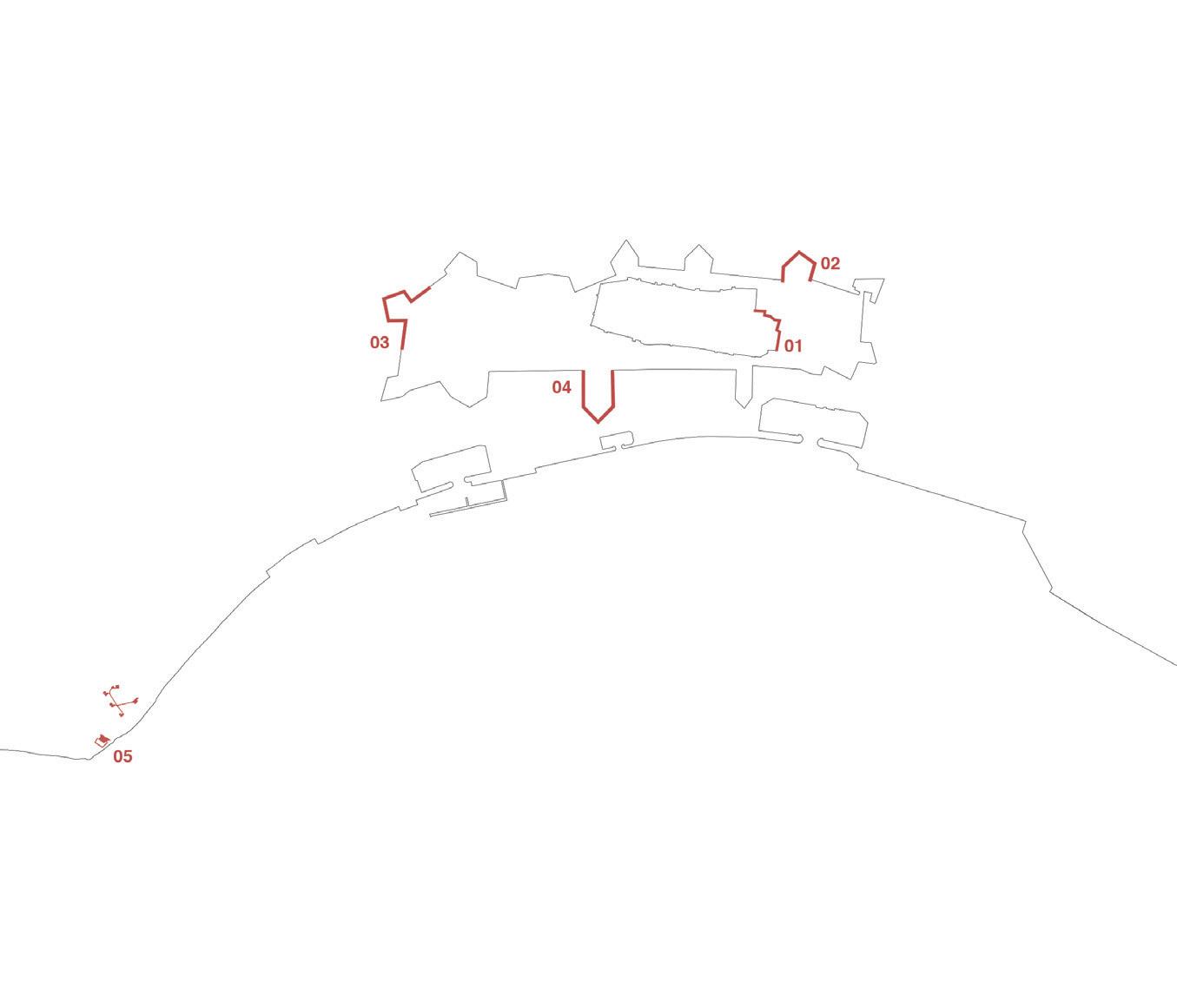

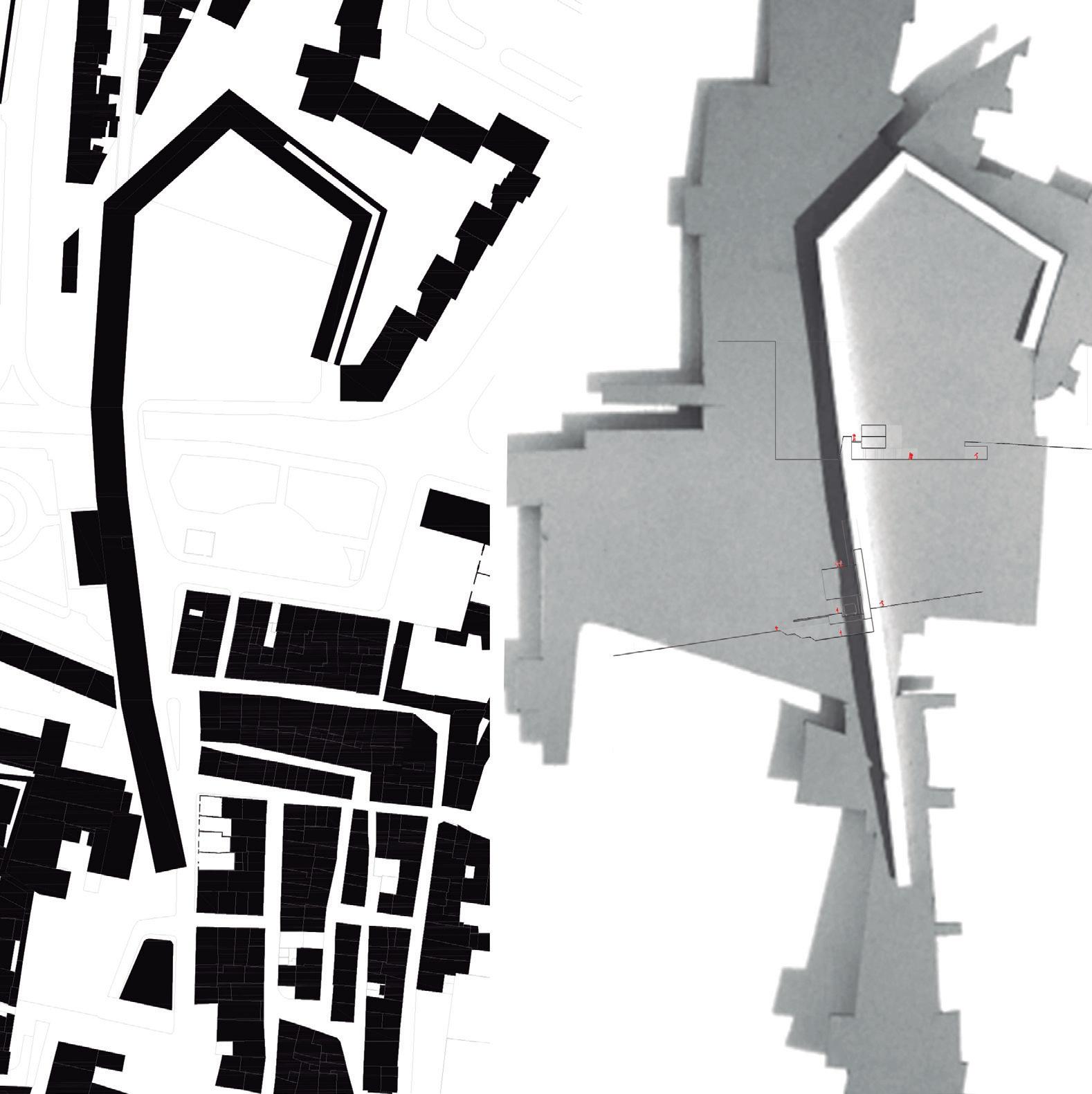

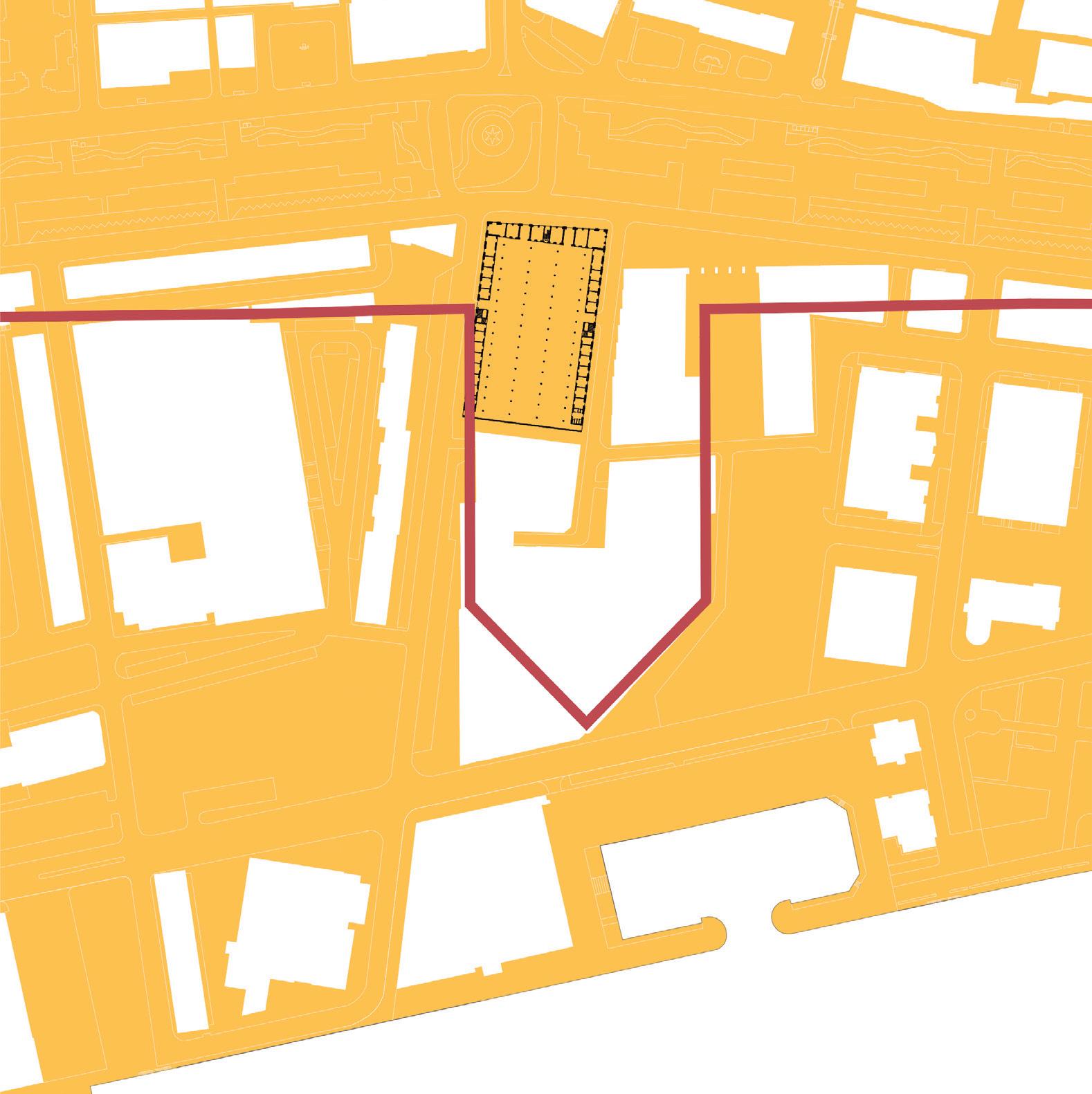

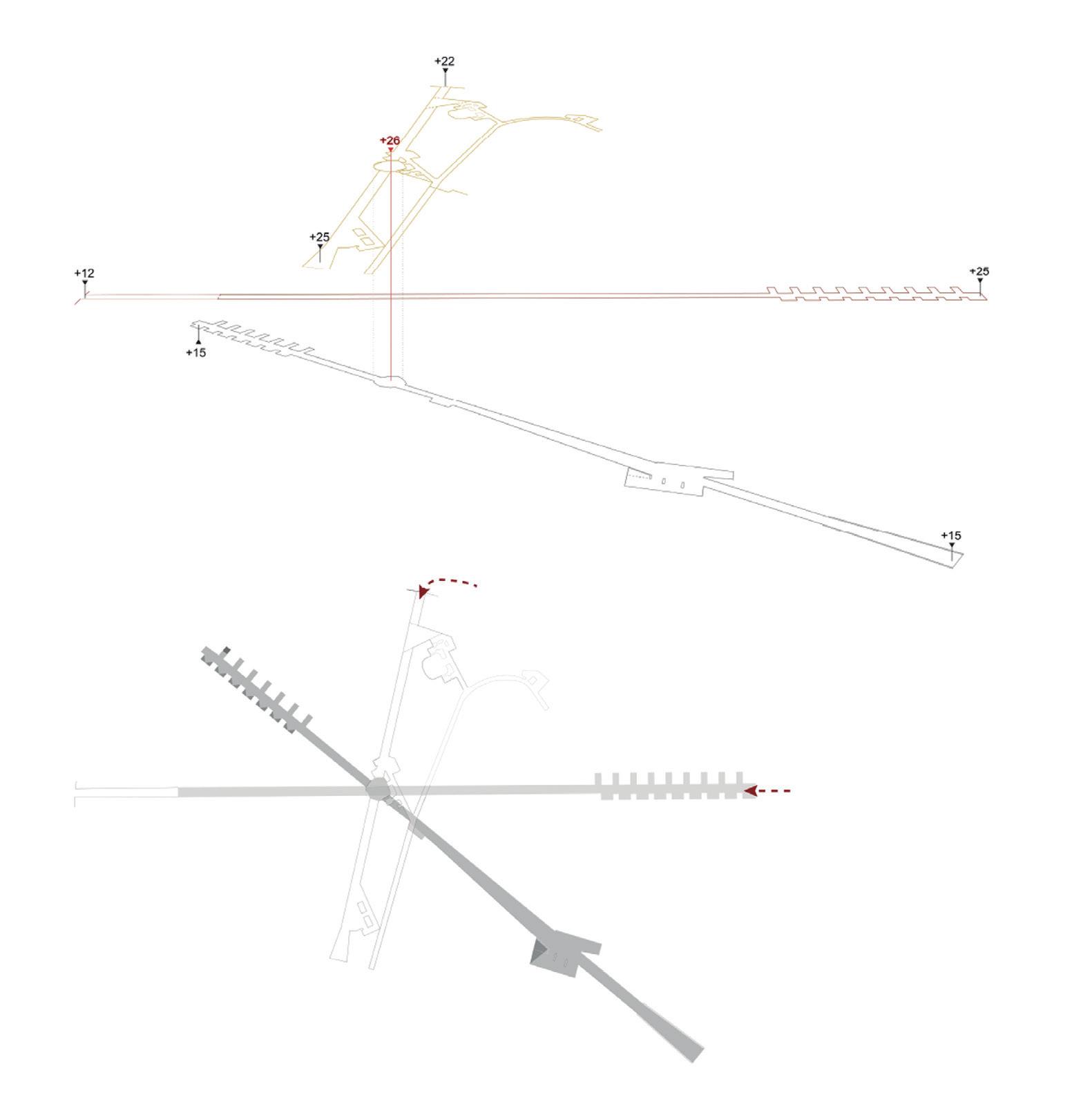

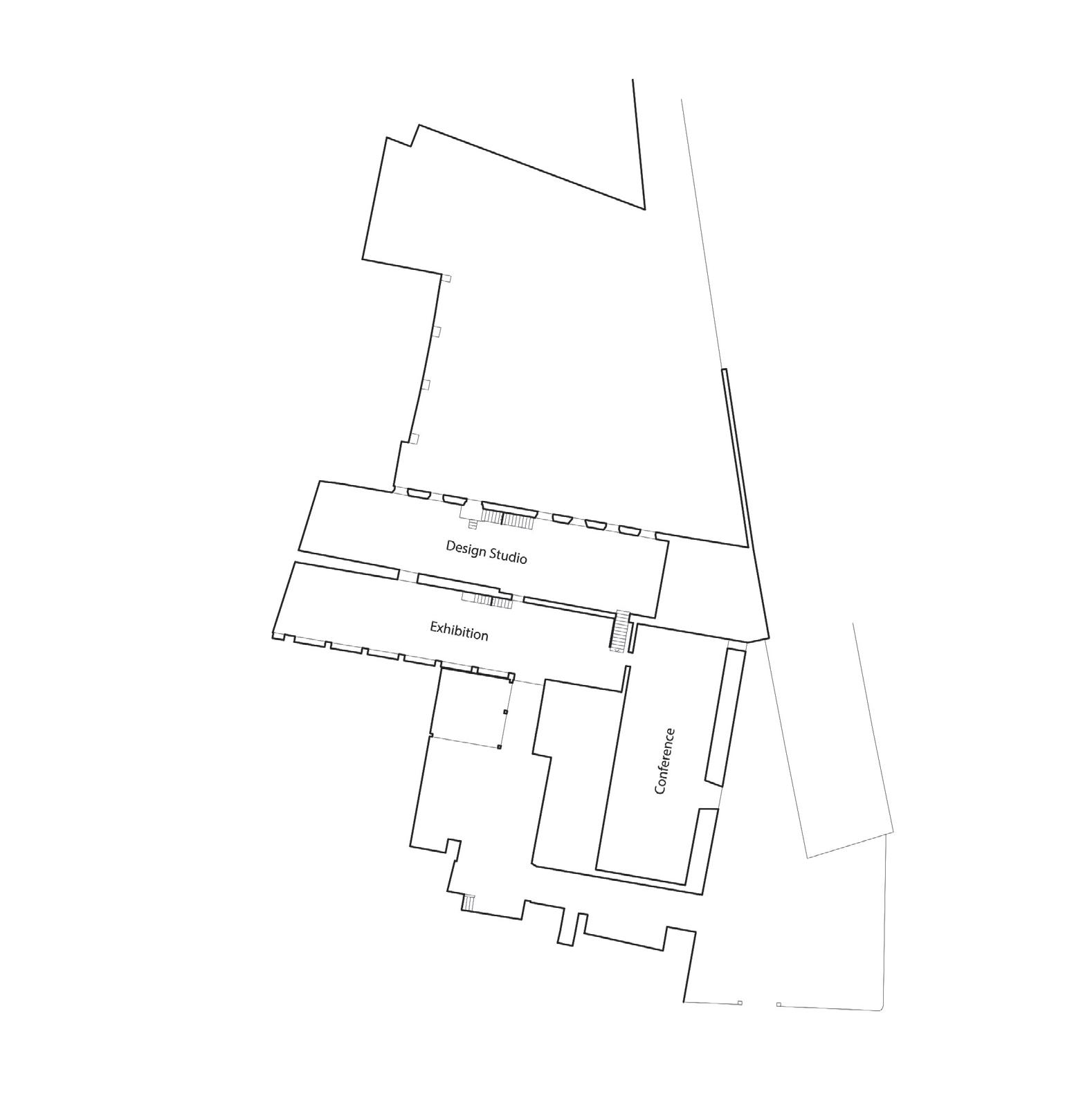

Setúbal, a city in 3 lines and case studies identification.

15

Case Study

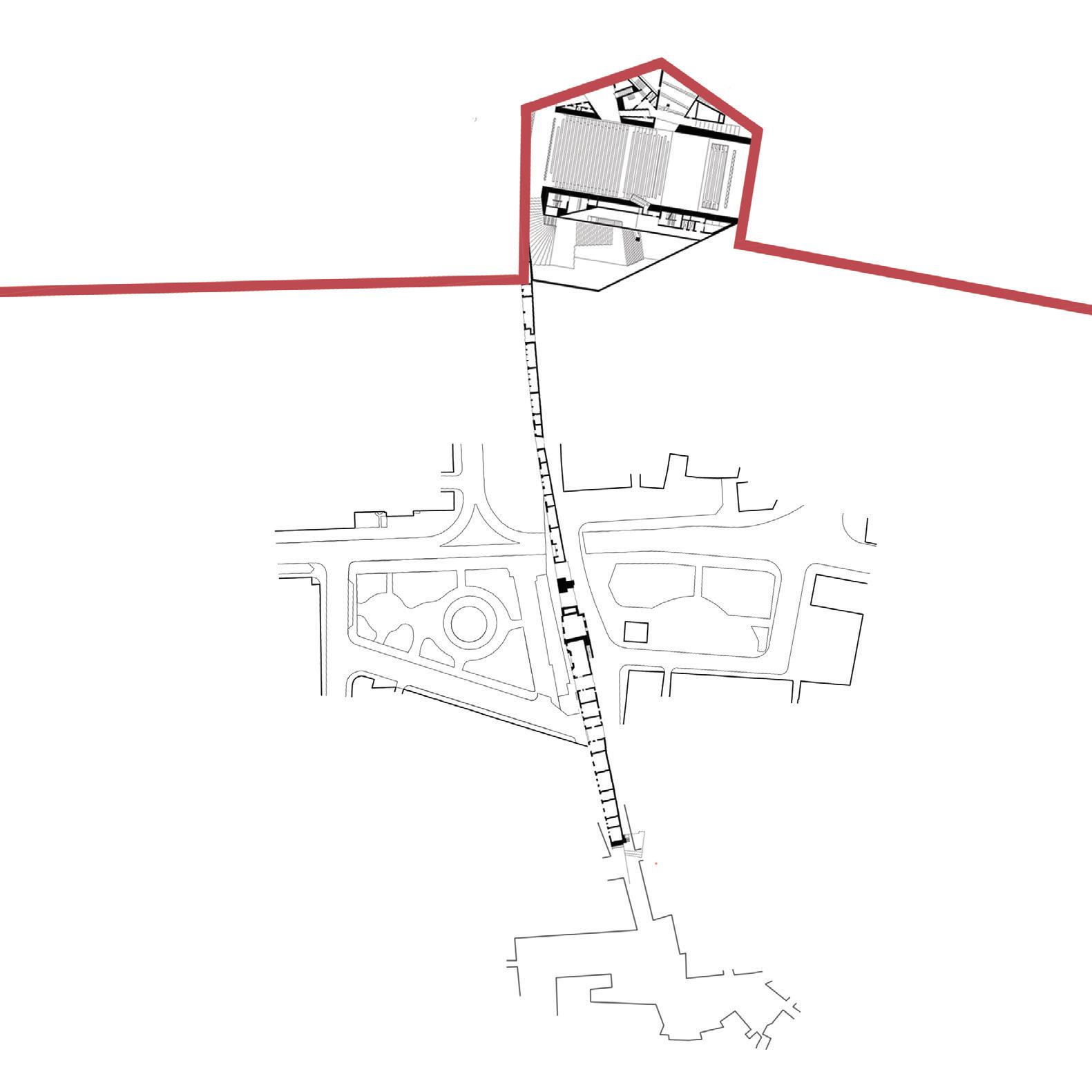

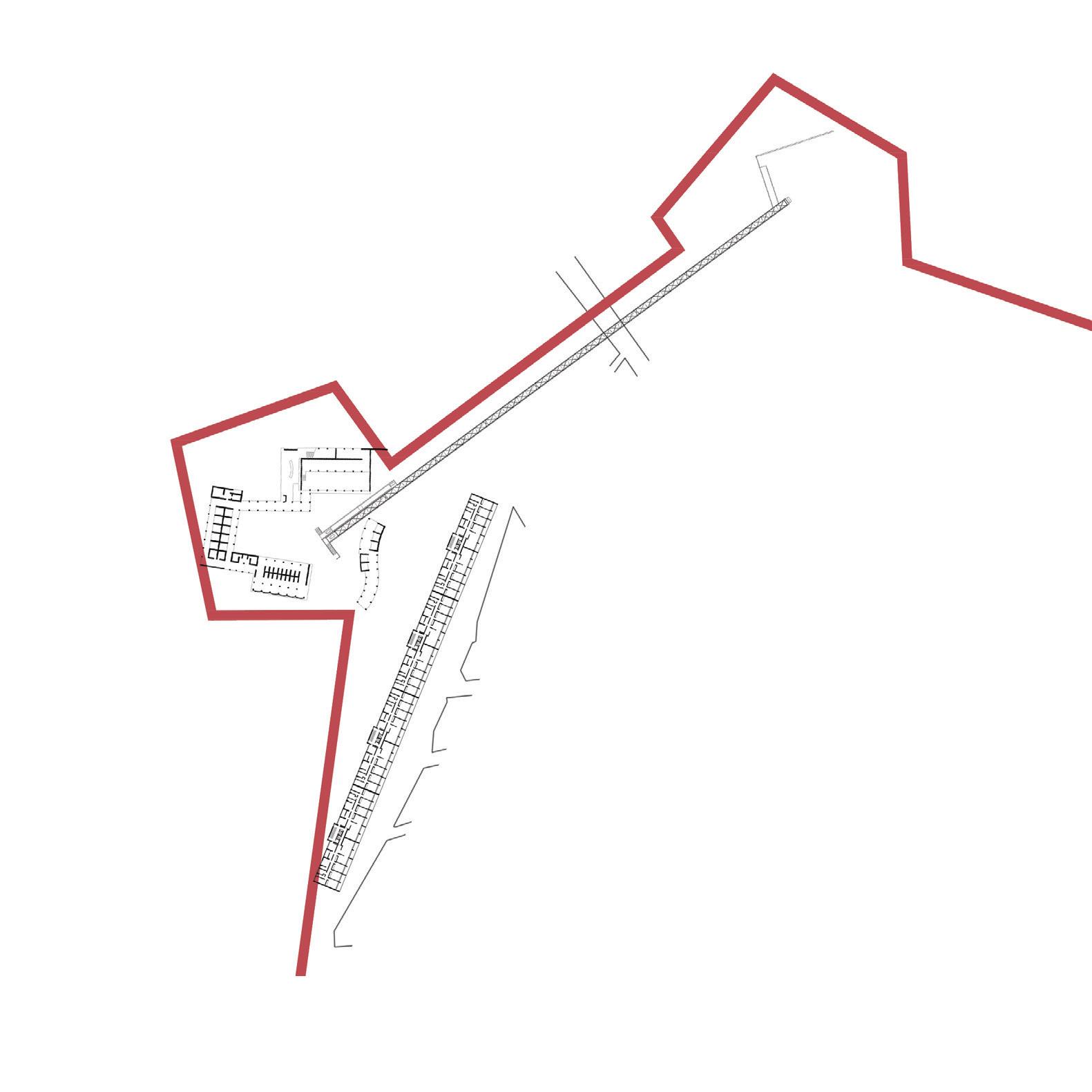

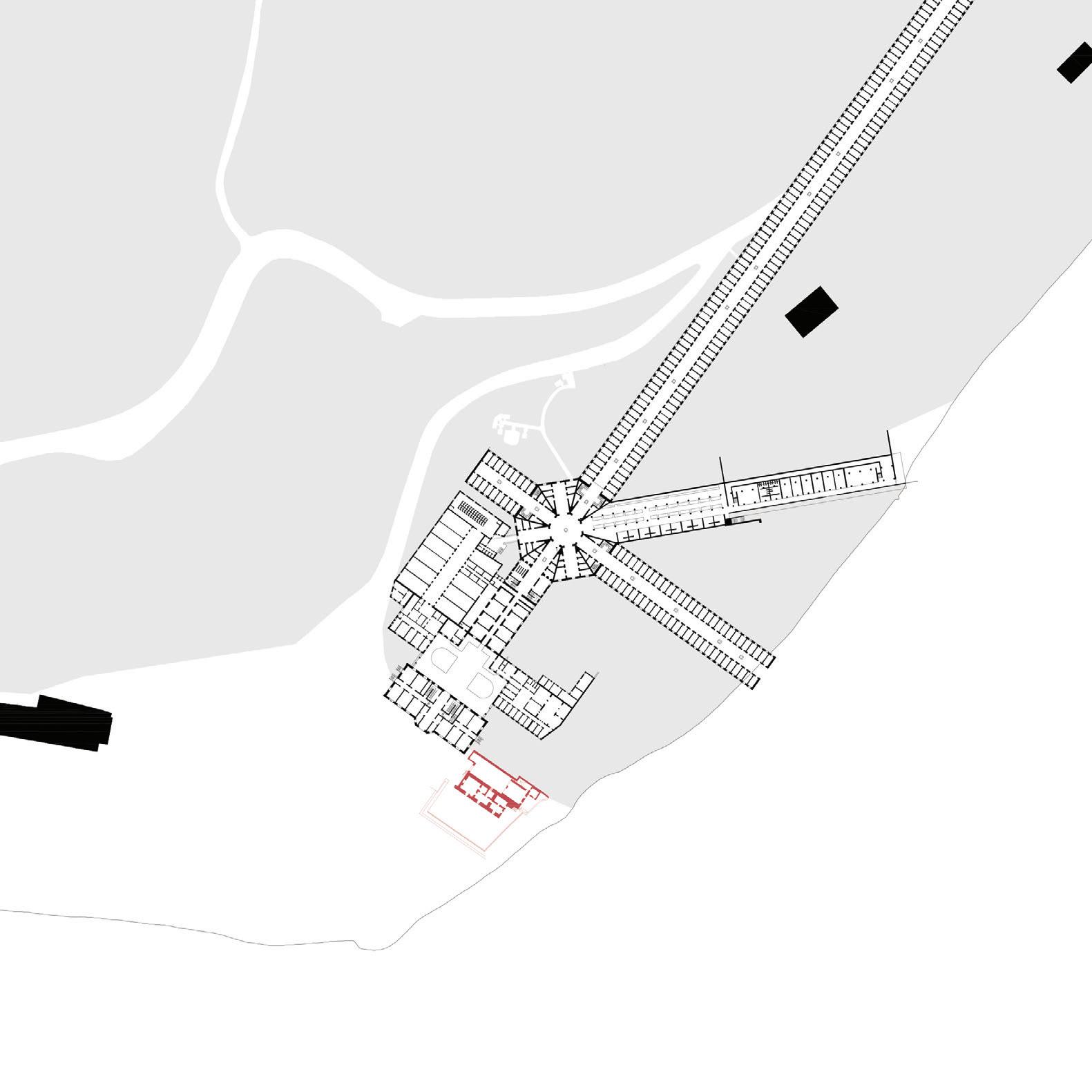

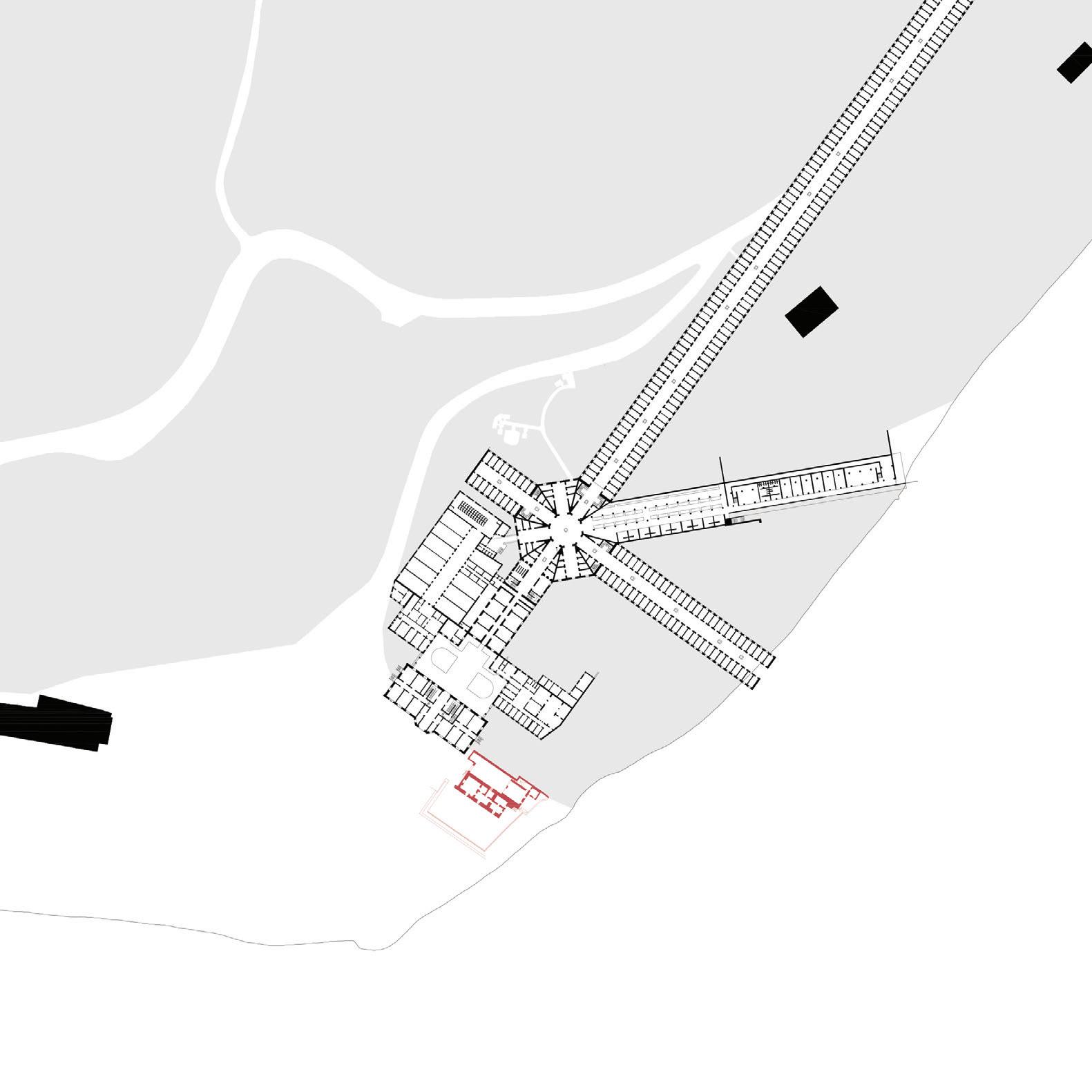

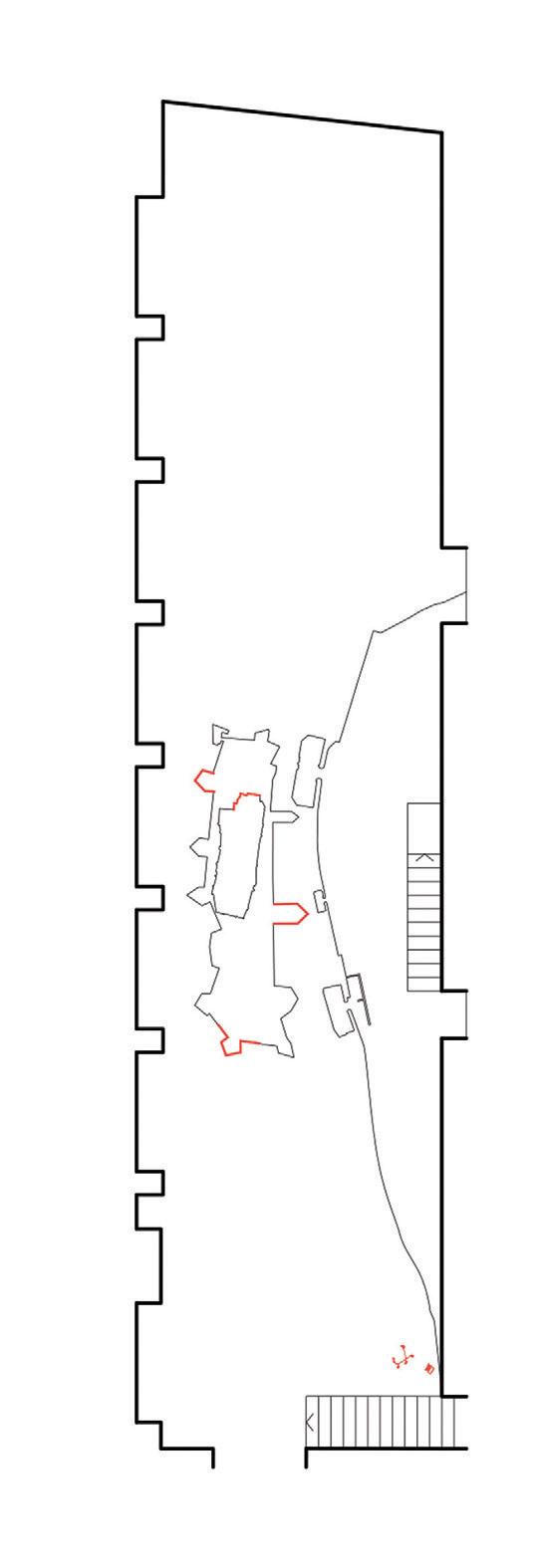

We will take the city walls of Setúbal and its surrounding buildings as our area of study, in broad sense. Within this framework we found 4 forgotten fragments of urban fabric where the wall still persists in time. Another case study, the fifth fragment, is a deactivated battery and an old small fort from the fortified Portu guese coastal line, that controlled the city entrance by the sea.

[case study 01] – medieval wall + old warehouse “a gráfica” + “pátio do Quebedo” [case study 02] – fortress of Sto. António + Quebedo square [case study 03] – fortress of Santo Amaro [case study 04] – fortress of Livramento + market [case study 05] – fortress of Albarquel + Battery of Albarquel + Arrábida

Process

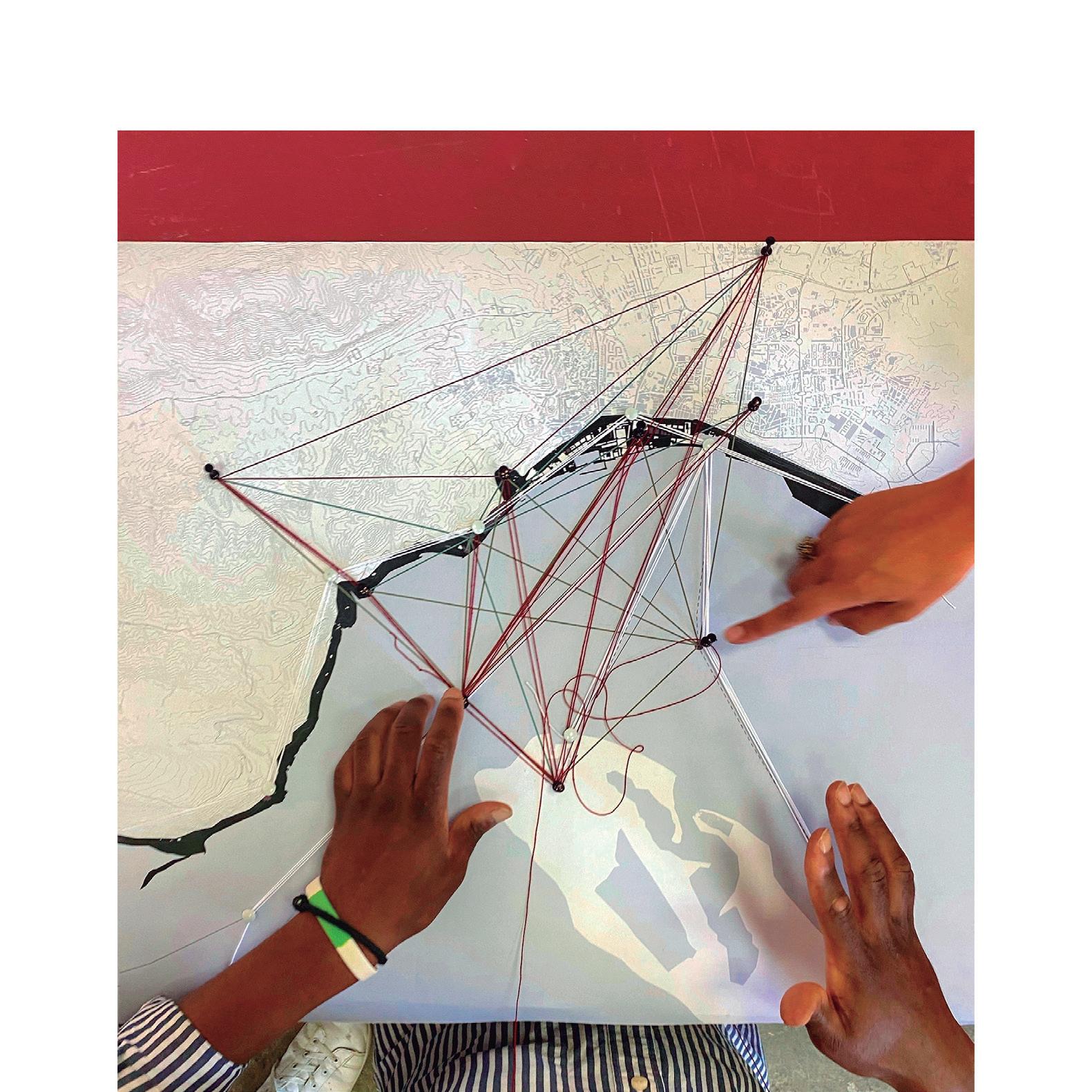

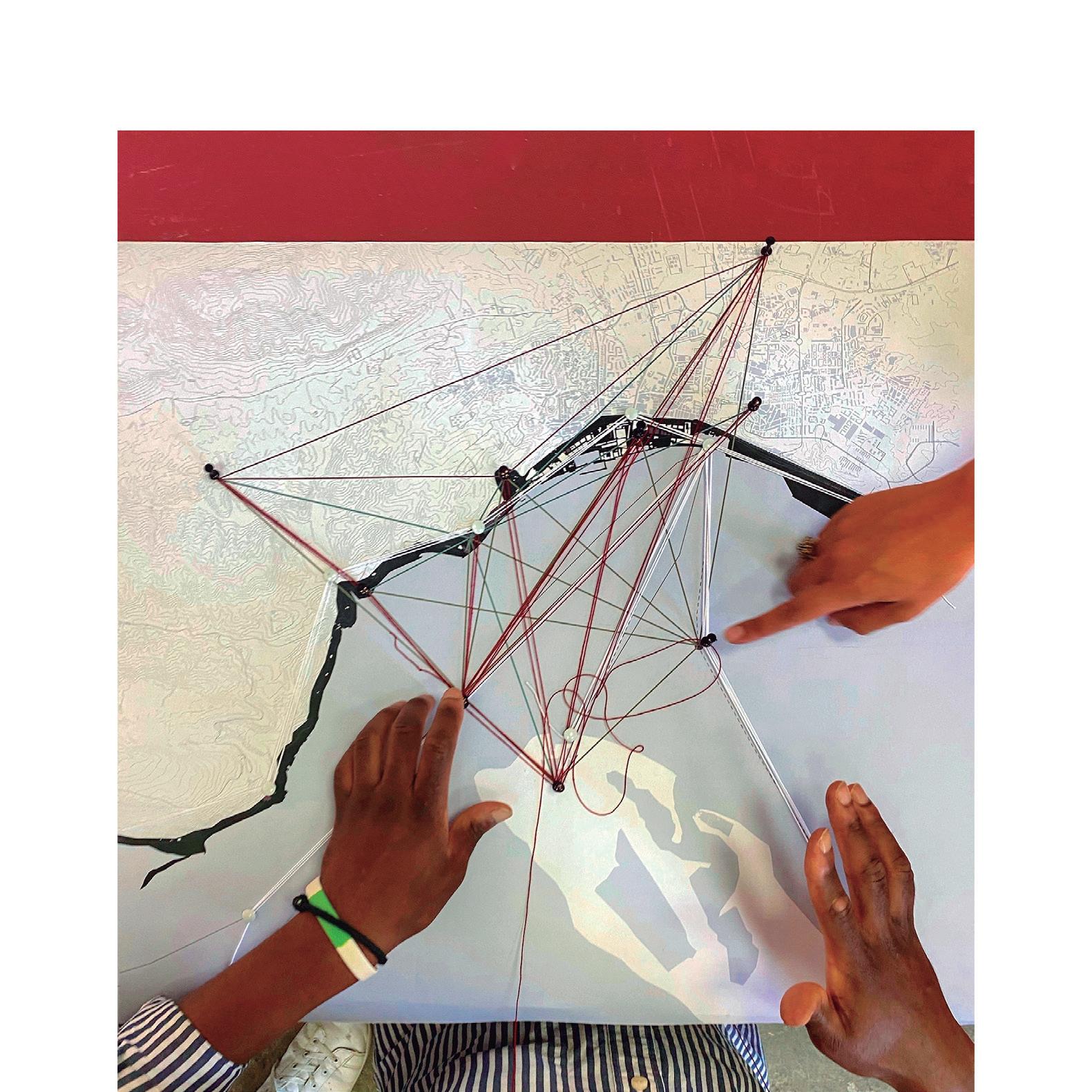

The design studio is organized according to two main tasks: [tasks 01] – reading and concept

In the first task, each team is invited to look and think about the city form, its history, memory and shape. From the recognition of territory, the urban fabric is interpreted/decoded. Furthermore, from a selection/collection of images, new conceptual references to design are formulated.

Start reading the city form:

• public spaces: as squares, streets and alleys;

• accessible spaces: as shops, stores, markets, theaters, restaurants;

• invisible spaces: as rooms offered through the internet, secret courtyards, underground restaurants, hidden urban voids, lost unbuild plots, etc.

In the first task each studio analyzes the city and its existing reality to raise an interpretative and critical point of view in relation to the actual condition of the urban space and its public use through the relation between public-spaces, common-spaces and collective spaces. Select those spaces accurately and es tablish a nexus to relate them.

Deliverables. Synthesis board – containing the following information: 1. short concept text;

16 SETÚBAL LAB

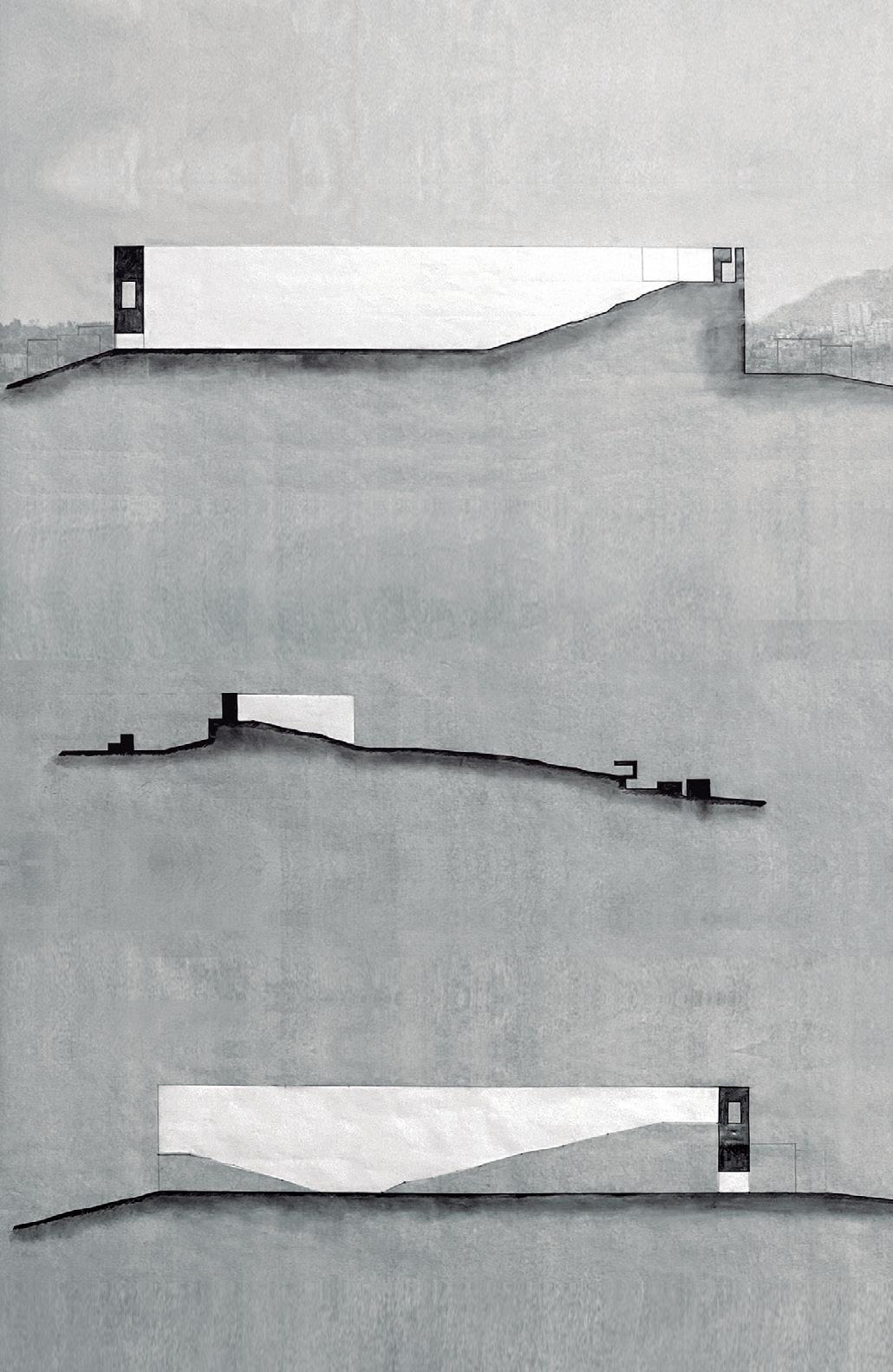

2. interpretative cartography 01 – geral plan of the city walls; interpretative cartography 02 – the footprint plan of the case study; interpretative section – one section of the case study;

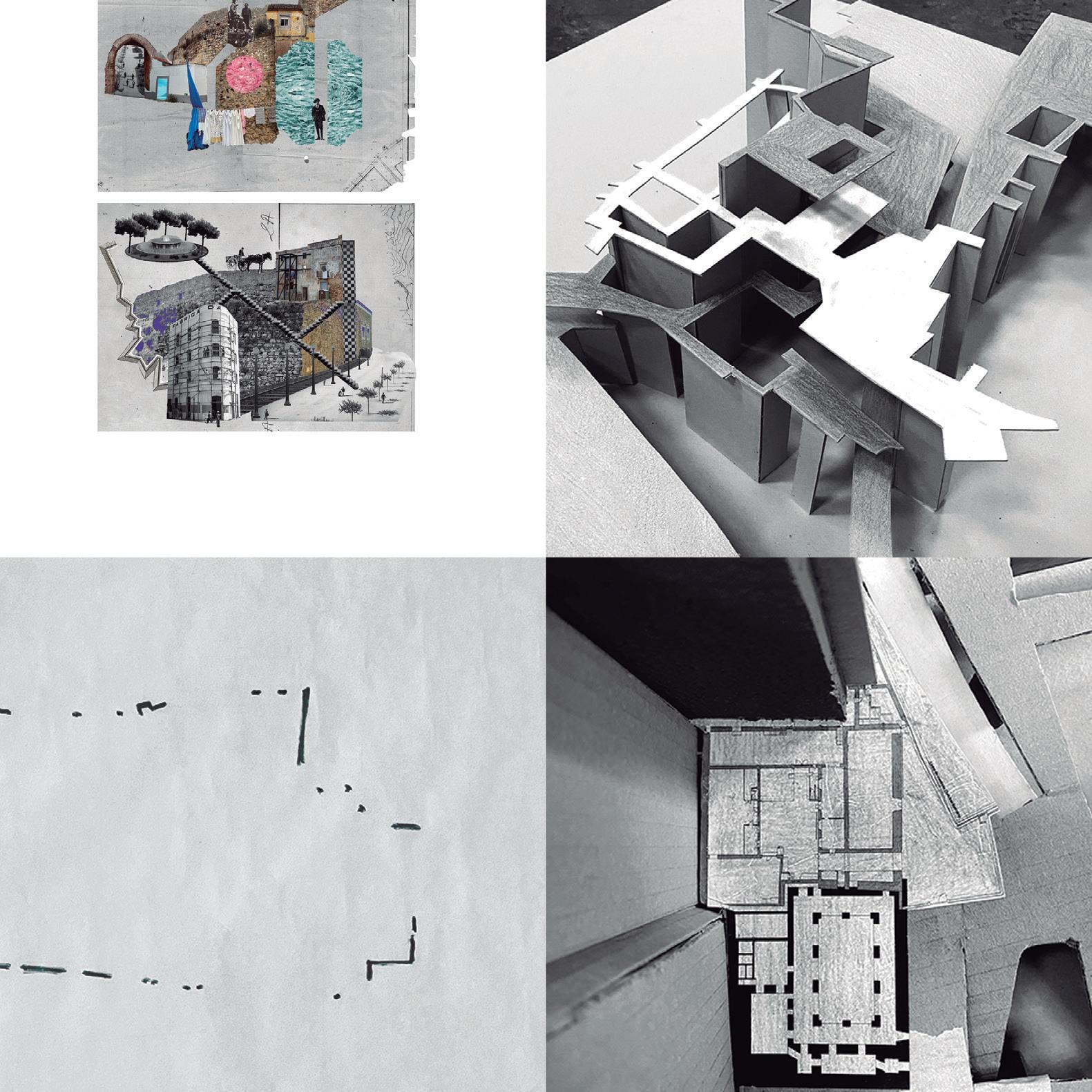

3. images – thinking in images / atlas of images that give a conceptual frame to the project;

4. conceptual diagrams – design strategies.

[tasks 02] – design

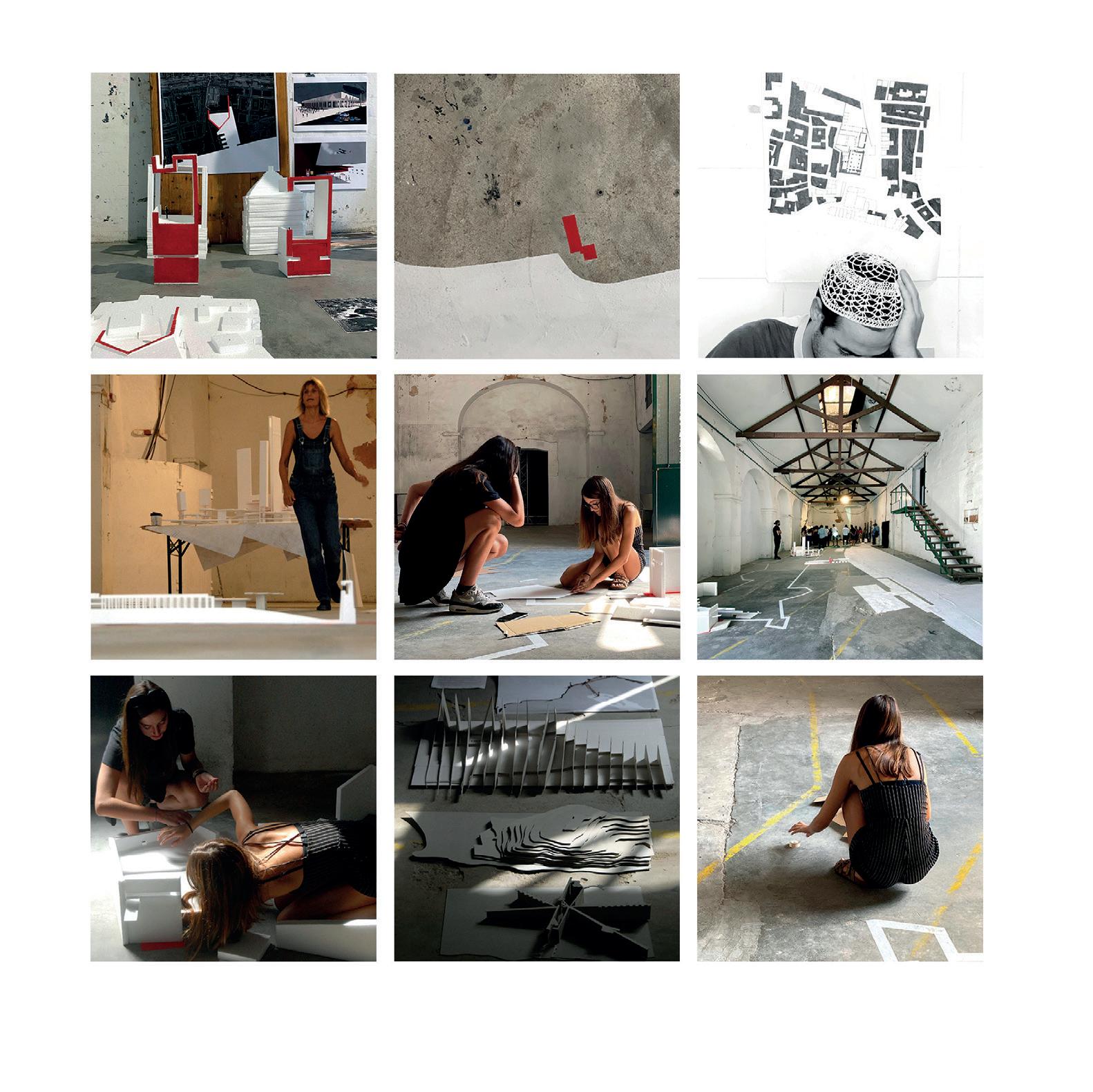

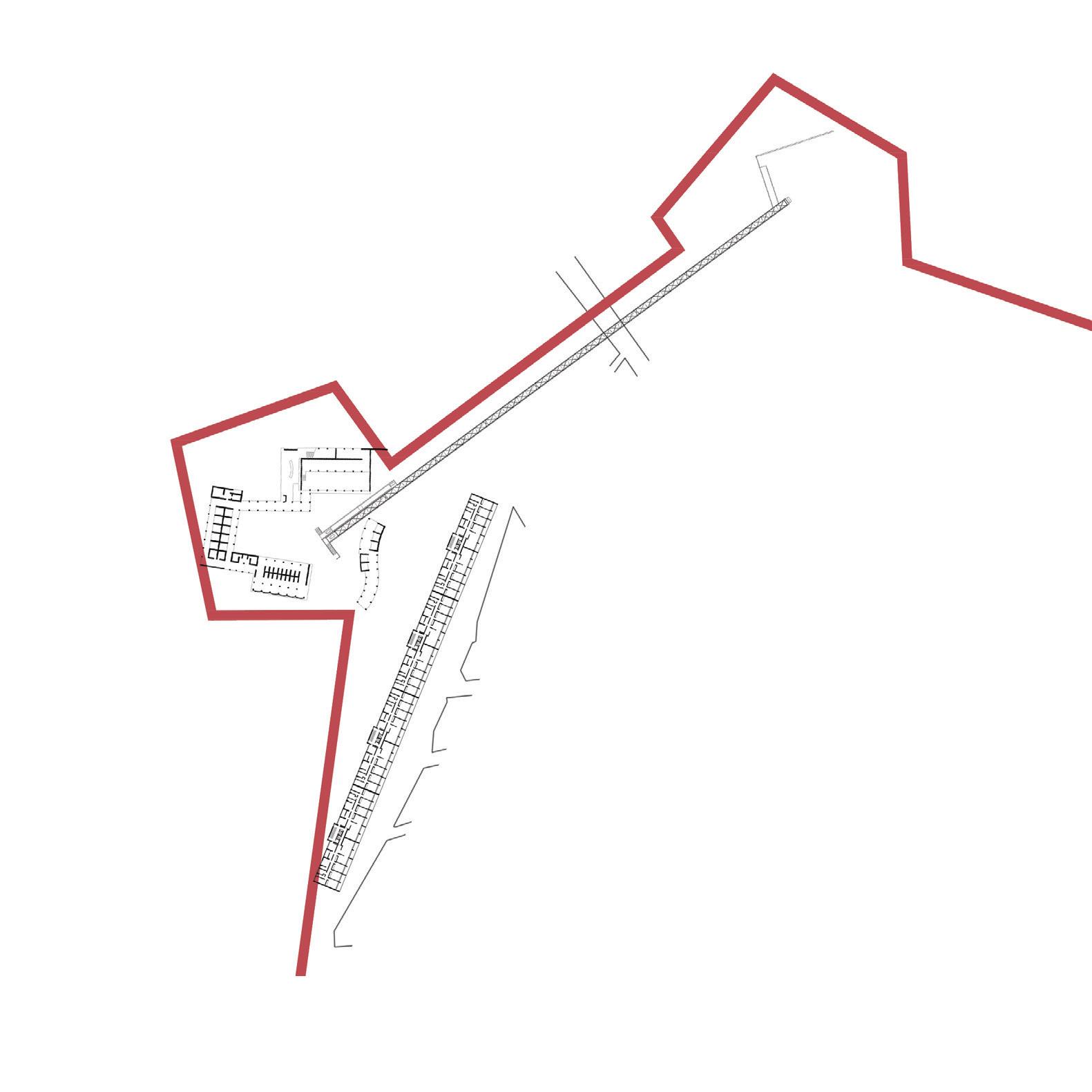

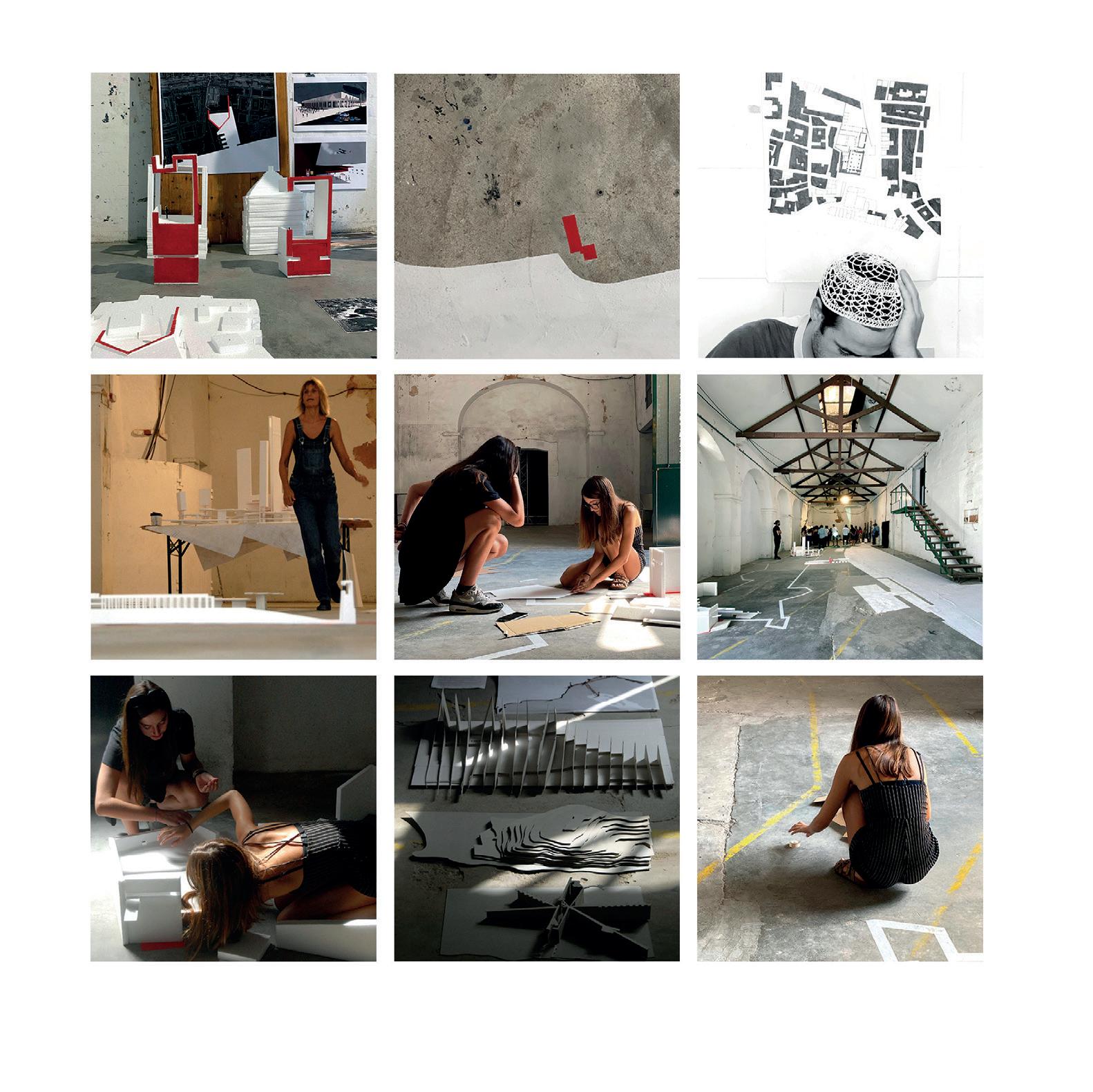

The second task of the workshop invites the students to reinvent the public urban ground of Setúbal from each fragment - case study. Each team develops an integrated design process using drawings and physical models, to reflect on the urban form surroundings and architectural spaces, exploring different scales of resolution and creative uses of public space.

The second task is based on the urban reading and its findings. Each studio is asked to design an urban system, composed by a set of public/ common/ collec tive spaces that can operate together as part of a network.

Each team is invited to establish an intersection between a site – case study –and a given topic of research – concept – that frames the design process.

Deliverables. Synthesis board – containing the following information:

1. short concept text;

2. new cartography 01 – geral strategy “collage plan” for city walls; new cartography 02 – the footprint plan of the project; new section – one section of the project; axonometric view of the project;

3. collages – proposed urban atmospheres;

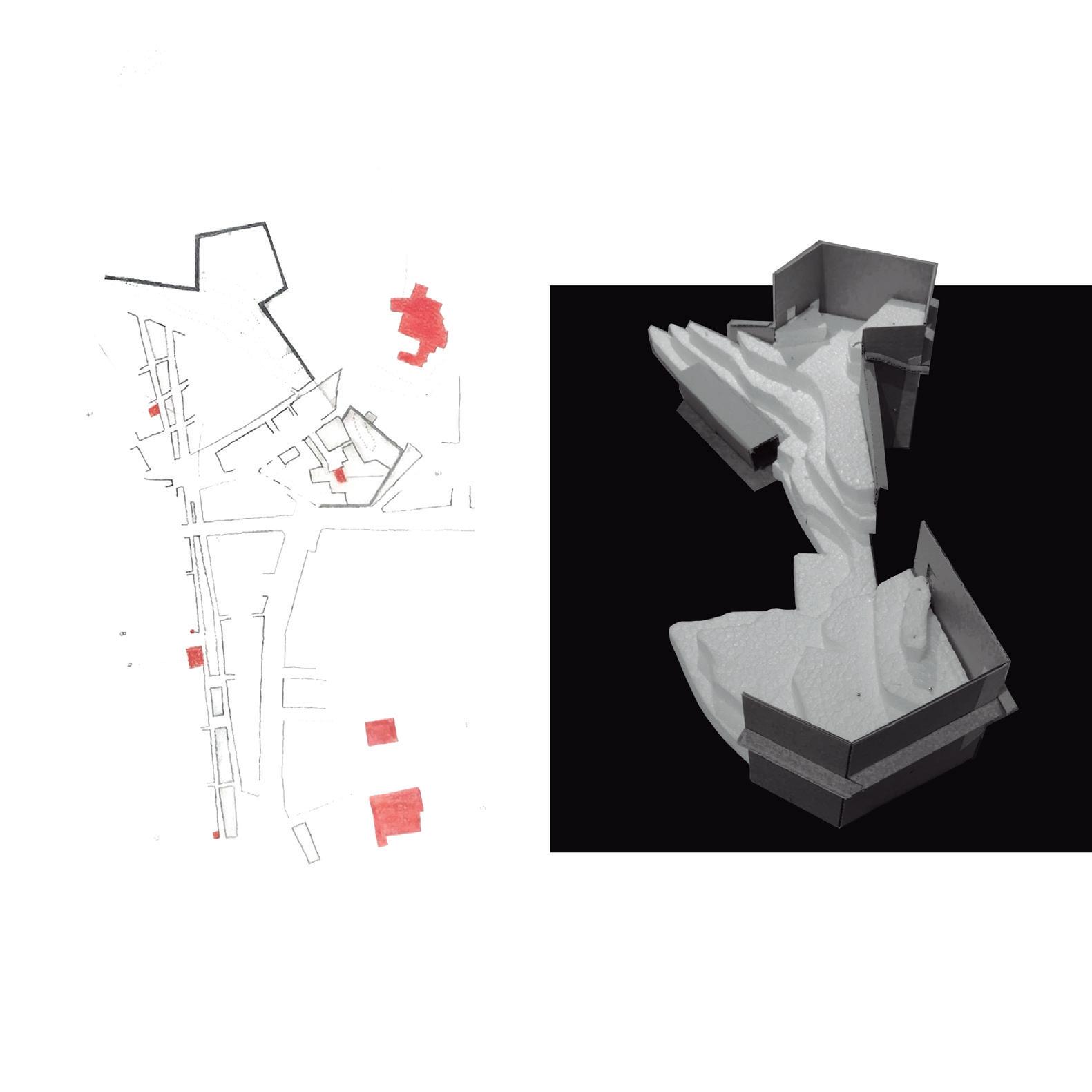

4. physical model of the project [conceptual].

Strategy

The workshop activities are organized with a balance between the design studios work and parallel events that intersect the design thoughts and ac tions: a series of field trips [walks] and lectures [talks] that give the frame to the design studios work, mainly the theoretical support and the acknowledge of the city case study.

17

WALKS:

[walk 1] – Setúbal Historical City Jesus Convent, project by Carrilho da Graça architects

[walk 2] – Arrábida, where the natural landscape meets the city Arrábida convent and Arrábida tracks

[walk 3] – Public Buildings and Public Space School of Education, project by Siza Vieira architect Bela Vista neighborhood, project by Charters Monteiro architect

[walk 4] – Public Buildings and Public Space Parish Chapel of Coração de Maria, project by SAMI – architects

TALKS:

[talk 1] – about SETÚBAL place: Setúbal town-hall topic: Setúbal. historical framing lecturer: Isabel Pratas (CMS) topic: Setúbal, the new challenges of the city lecturer: Fernando Travassos (CMS) / Rita Carvalho (CMS)

[talk 2] – about PUBLIC SPACE place: Jesus Convent topic: Public Space and Temporary Use. The New Challenges for Design of Public Space lecturers: Alessia Allegri + João Rafael Santos + Sérgio Barreiros Proença

[talk 3] – about URBANISM and NATURE place: Arrábida Convent topic: Urbanism and Nature lecturer: Leonel Fadigas

[talk 4] – about ARCHITECTURAL DESIGN: Space for Public Use place: Parish Chapel of Coração de Maria topic: The City and the Architectural Design of Public Places lecturer: SAMI – architects, Inês Vieira da Silva e Miguel Vieira

18 SETÚBAL LAB

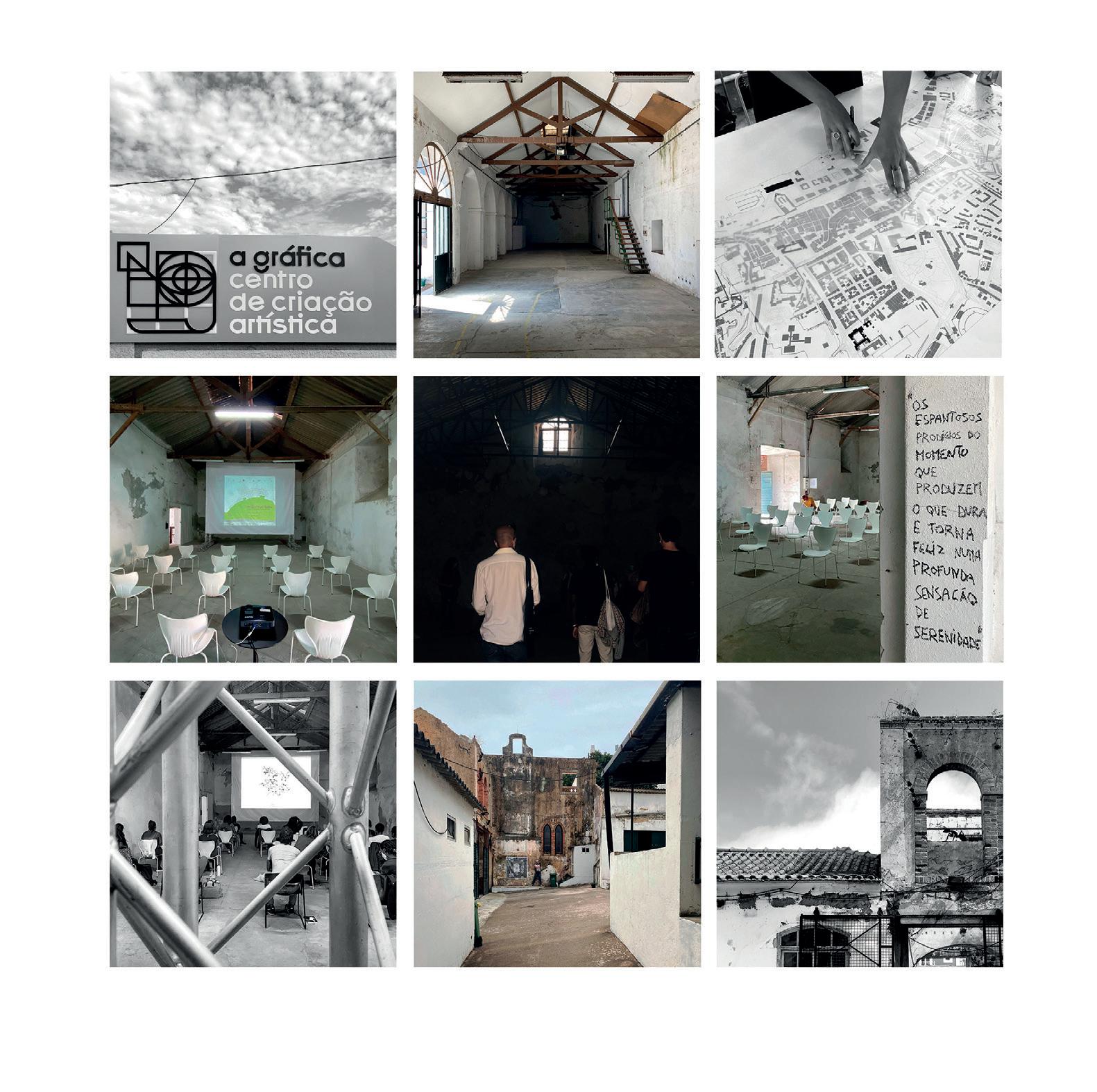

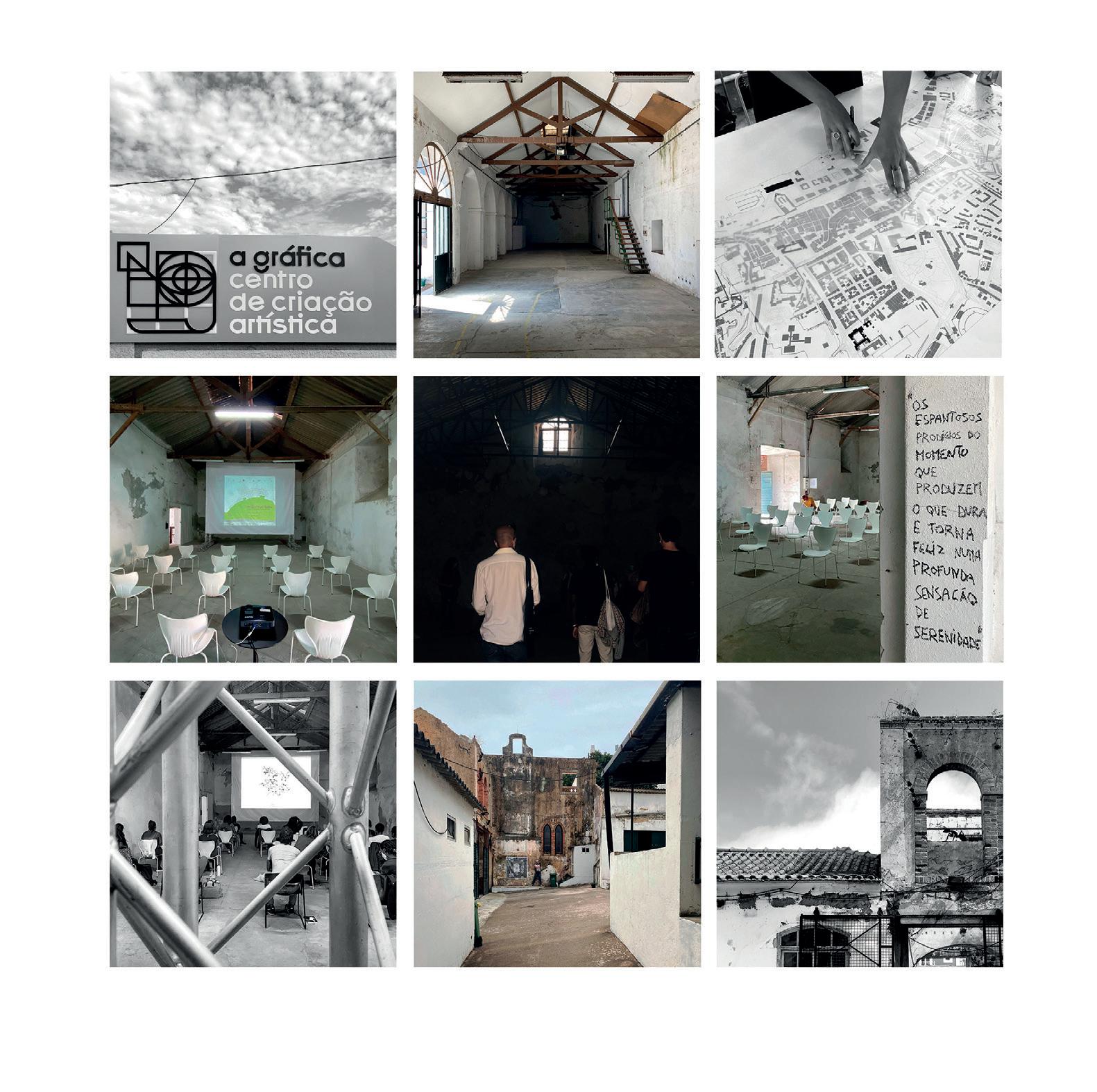

The “students talks” are a set of short presentations of academic works, mas ter thesis of FA.ULisboa, which use the city of Setúbal as case study and address similar issues of this workshop. All the “students talks” takes place at “A Gráfica, centro de criação artística”.

Results

The workshop addresses a pedagogical experience based on a fundamental issue ¿which spaces we will need tomorrow? The approach advises an operative reading that should be understood as a process of conceptual transfer. Thus, the knowledge extracted from the analysis of built city may be used to define new concepts for designing the urban fabric or can be converted into design principles, whereby it may inform an active position on the way of thinking and shaping tomorrow’s cities.

The result was an exhibition that gave the city a new critical view of itself based on a fragmented model of Setúbal composed by 5 design studio projects and a set of collages. Each team built a model of their project for their case study. Each model represents one project with an integrated vision of the city but also represents an articulated relationship with the other design studio projects. In this sense, the models of each design studio became a project for the city and an exhibition that the workshop group, students and advisors, built in the main space of the artistic creation center “A Gráfica”.

Notes

Hamed Khosravi, Walls of association: Paradise in Hashim Sarkis, Ala Tanir (eds), Expansion: Responses to How will we live together? Venezia: La Biennale di Venezia, 2021.

19

THEORETICAL FRAME

URBANISM AND NATURE: LANDSCAPE DYNAMICS AND TERRITORIAL ORGANIZATION

Leonel Fadigas, professor, landscape architect, CIAUD, Research Centre for Archi tecture, Urbanism and Design, Lisbon School of Architecture, Universidade de Lisboa

Urbanism

Urbanism is a science and a technique for organizing inhabited space. It shapes the territory, a complex system that integrates urbanized, rural spaces and natural spaces where human life is organized. It sets up the formal and or ganizational relationships between open and built space and incorporates the intangible issues that make inhabited territories more sustainable and more comfortably livable. It shapes cities and their peripheries, while considering that the city is made by the continuous and balanced management of the territory that surrounds it and by the appropriation that people make of it. Making a city and modeling territories is the result of a process, sometimes long, of managing realities, constraints and incompatibilities where urbanism is the active instru ment of concertation of interests in which the plan, as a conceptual element, is the guide and reference.

Form, function and management are parts of a whole; they do not dispense with the coherence of governance that allows their integration into urban and territorial networks, in a sustainable, socially just manner, and in balance with the past and the future.

This is why urbanism is not limited to the design it appears to be.

SETÚBAL LAB 22

Contemporary urbanism must therefore be an instrument for creating condi tions to remake and keep environmental balances in transforming the territory and organizing inhabited spaces, that is, it is a key factor of sustainability. The urban reality of our days shows us, in the complexity of its different forms and consequences, how urbanization processes determined the structuring of the territory and the organization of inhabited spaces.

The new urban realities show diversified modes of social organization that reflect the way in which human relationships are set up and kept and the way in which the spatial organization of territories is processed. Making the effects of globalization and the social phenomena associated with it clearer and the greater dimension and visibility of migratory phenomena and the fact that, in more developed societies, demographic dynamics do not result only from the biological growth of populations. Contemporary urbanism handles providing in a sustainable, socially and environmentally just way, the answers that make it more livable in urban areas and rural territories. In a framework of balance in which the new realities resulting from it led not only to the production of urban land but also to the organization and sustainable structuring of territories and landscapes.

Landscape

Landscape is a diverse set of vegetation and buildings organized in such a way that it can be associated with an identity representative of human action in the territory. In fact, the landscape is an ecological, aesthetic, geographical and cultural unit resulting from the action of man and the reaction of nature to his actions. It is an ecological unit, because it supports life; it is an aesthetic unit, because the light, the color, the sky, the movement, the textures that life and land use, rural or urban, express, give it a scenic and visual dimension; it is a geographical unit because it represents a territory and its physical dimension. But it is culture that best names the landscape as a product and expression of human presence and action in the territory.

Landscape is a reality that only exists when, as a visual, aesthetic and cultural reality, there is someone to see and interpret it. As a cultural reality, the land scape expresses the diversity of relationships, over time, between men and the environment in which they live and their contemplation and interpretation of the physical and geographical reality that surround them. In its diversity, the landscape is sets of interconnected realities in which each set of distinct real ities contributes to a coherent organizational matrix that gives it identity and allows its reading and understanding.

23

From an ecological or systemic point of view, landscapes are heterogeneous territorial realities, composed of a set of interacting ecosystems, which evolve together, and whose organizational and functional pattern is similarly repeat ed. The existence of similar morphological and functional units, organized in patterns of identical visual expression, makes it possible to form the mosaics with which the identity image of landscapes is formed. A unity made of many diversities (Forman, Godron, 1986; Naveh, Liberman, 1994).

The actions resulting from geological, physical, climatic or other phenomena and the set of human actions in the territory contribute to the creation of land scapes and to their transformation, depending on their intensity and the time they take. With what landscapes become expressions of natural dynamics and the affirmation of various times and cultures.

Landscapes, however, do not exist in isolation from the physical and geographic conditions that support them; but it is the territory that gives it its dimension and organizes its limits. The territory is a condition without which the landscape does not exist because, in addition to it, it is its cultural part that runs through and goes beyond the physical, geological and geographical reality from which it is structured. Without human presence there is no landscape but only a territorial extension with vegetation cover, fauna and geological and geographical features.

The appearance of man on earth meant that the transformation and evolution of the territory ceased to depend only on natural factors. Human action, char acterized by the ability to transform habitats in an intelligent and programmed way, adapting them to the needs of the specie, has had, since its start, a modeling action of inhabited territories. This was accentuated with the sedentarization of populations and the progressive use of agriculture as the basis for organizing the food system. This new reality clearly marks the moment from which we can consider that there are landscapes, that is, extensions of territory shaped by human action and subject to nature’s reaction to this action.

With the technological development of societies, nature, as a factor and agent for the transformation of the territory, was thus progressively replaced by hu man intervention, in a harmonious way, maintaining the ecological balances on which the environmental sustainability of inhabited spaces depends, in some cases, in a conflictive and intrusive way. In cases where nature was violently thwarted, the environmental consequences were always very strong: droughts, floods, soil erosion and landslides, reductions in available water levels, fires, loss of biodiversity and impoverishment of the productive capacity of the soil with the consequent reduction of the population’s food subsistence capacity. A re ality known throughout history, and which explains the disappearance of cities and civilizations or their population, economic and cultural weakening.

SETÚBAL LAB 24

Ermida da Memória, Santuário de Nossa Senhora do Cabo Espichel, Setúbal, photo by S. Antoniadis, 2016.

Convento de Nossa Senhora da Arrábida, Setúbal, photo by S. Antoniadis, 2016.

25

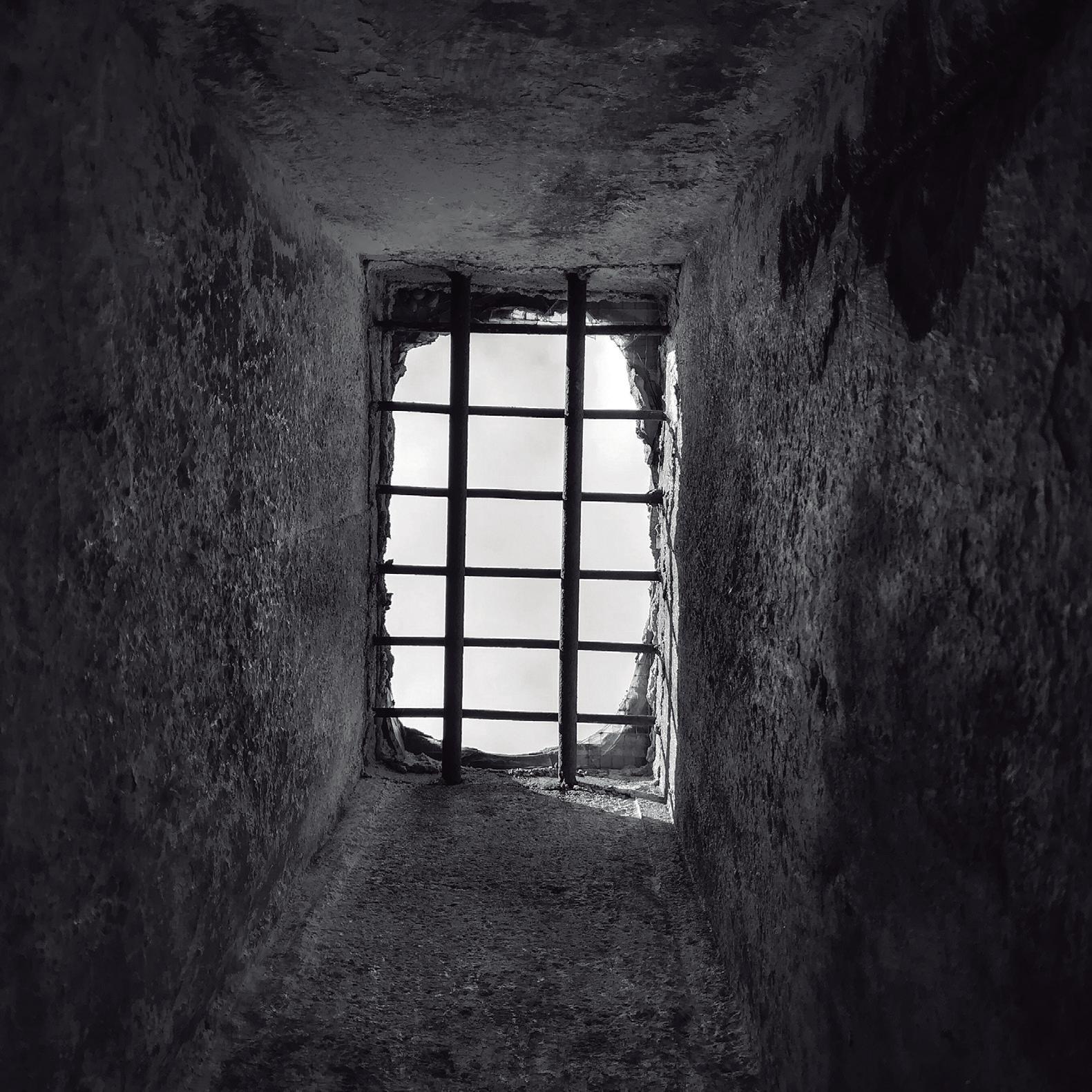

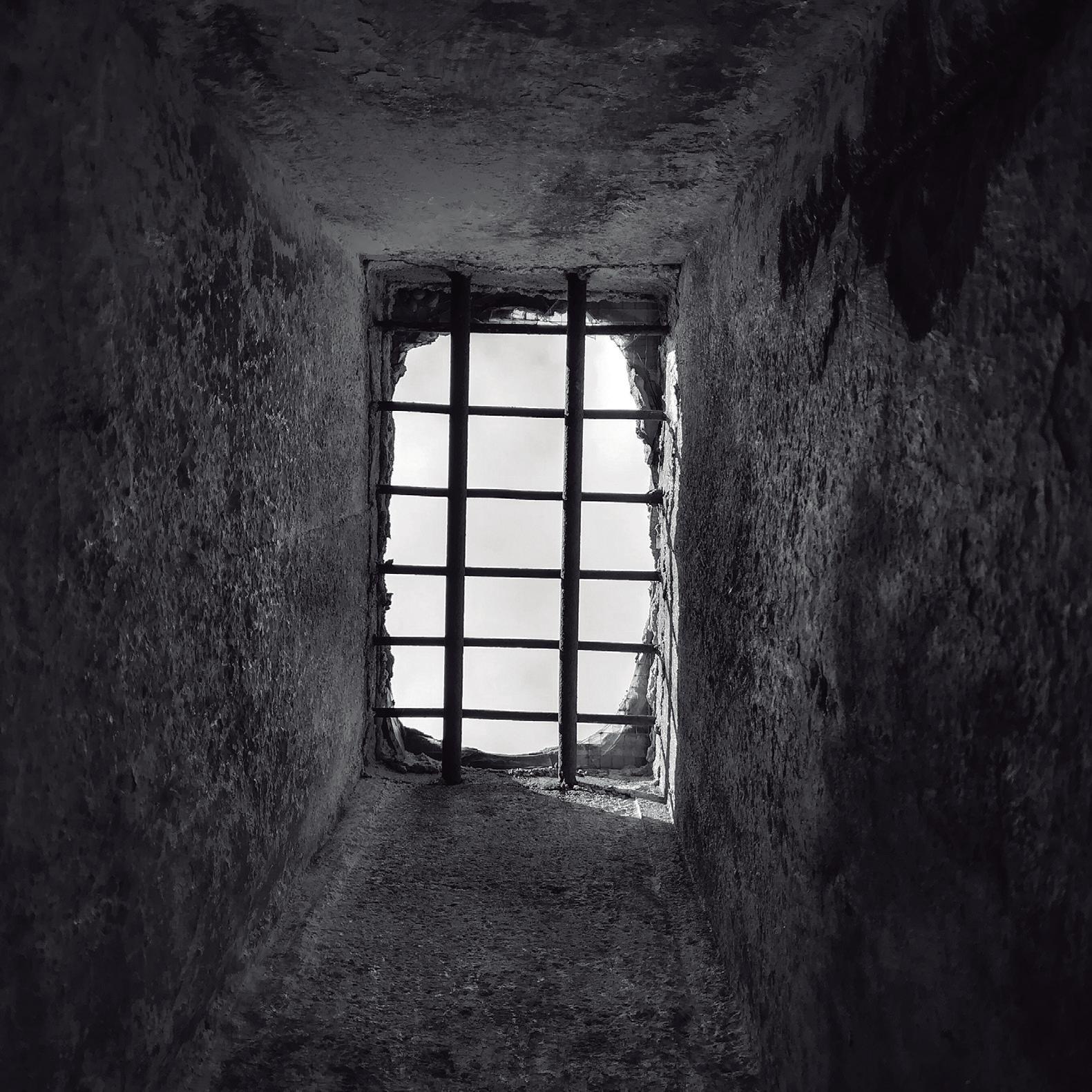

Forte Velho do Outão, remains, Setúbal, photo by S. Antoniadis, 2021.

SETÚBAL LAB 26

In this dynamic process of interaction between human action and nature’s re action, landscapes change and evolve, gain and lose complexity and functional ity through the joint action of man and nature. In their diversity, landscapes are nothing more than the result of a human history resulting from the cultivation and appropriation of the land, the construction of the habitat, and its registra tion, which expresses affective and economic relationships between men and the environment in which they live.

The basic structure of the landscape is, in its diverse geological origin, the relief, in permanent modification by the action of water, geomorphological processes, vegetation, fauna and human action. Which shows that the transformation of landscapes is part of their nature. As has always happened since the dawn of humanity, the intensity of landscape transformations being proportional to the level of technological development of society. The study of the evolution of landscapes therefore requires knowledge of their human and social history, that is, of the social, economic and cultural processes that mark times and cir cumstances and express the identity of human communities.

Territory and landscape dynamics

The territory is a complex system that integrates urbanized areas, rural areas and natural spaces and in which, in a dynamic and interactive way, human life is organized. In addition to its geographical reality, it corresponds to an area of influ ence and a space defined by power relations, and which defines power relations.

In it, the networks that format and combine it, guaranteeing the persistence of brands and symbolic values, contribute to the structuring of the landscapes that find it.

As a physical support for human activities, in its different complexity, the terri tory is organized according to the mode and intensity of the actions that occur in it. Its sustainable use therefore depends on the way in which its resources are ex ploited, and the rationality and efficiency of the processes and technologies used.

Regarding its intervention in a territorial dimension, urbanism organizes the processes of adapting the needs of current and future populations to the carrying ability of the territory and its biophysical determinants and socio-eco nomic demand. Thus, configuring the spatial distribution of human activities, the organization and formatting of urban spaces and the relationships between built-up areas, infrastructure networks and natural, agricultural, forestry and recreational spaces. From a perspective of organizing human habitats within a framework of better living conditions from an environmental, social and eco nomic point of view.

27

The territorial planning process, of which urbanism is an instrument, is, in this context, the spatial translation of the economic, social, cultural and eco logical policies of society that establishes the mode and form of the spatial distribution of activities and the exploitation of natural resources. In the set of actions that integrate it, the territorial planning process “includes urban planning and transport and communication systems; the planning and inte grated development of rural areas and the restructuring or reconversion of the productive base of rural areas; the rational management of natural, heritage and historical resources; the protection and enhancement of pro tected and ecologically sensitive areas; strategic planning of the territory, urbanism and urban projects and urban and environmental regeneration” (Fadigas, 2007, p.12).

The spatial distribution of land use, in its different forms, reflects the culture and technologies of the societies that occupy and have occupied it, the rela tionship between environmental conditions and human activity, the form and intensity of possession and use of the territory and defines the organizational matrix and characterization of the landscape. It is a brand that marks the nature of the processes, spontaneous and programmed, that shape the territory and give it conditions of continuity of use. Which depends on many factors.

The uses and forms of ownership contribute to the establishment of set tlement patterns that contribute to the territorial fragmentation that is an essential constituent of the textures with which the landscape patterns that characterize and find the different scenic and visual expressions of the terri tory are formed. The territorial dynamics, which contribute to the dynamics of the landscape in association with the occurrence of natural phenomena, can be, when they occur with great intensity in a brief period, be deciding factors of the fragmentation of the territory. Which, almost always, has consequenc es for the environmental conditions of the territory and its sustainability. Territorial fragmentation resulting from the densification of road networks and passage channels for large infrastructures, accentuated by urbanization processes, and by its consequences in terms of specialization of uses, which is felt in both urban and rural areas. In urban areas, the strong appreciation of the soil, compared to rural areas, leads to a fragmentation of uses that pro duce very fragmented urban fabrics, very striking in the definition of urban landscapes; in rural areas, especially in small properties, territorial fragmen tation results from the geometric irregularity of the plots and the variations in relief create unique textures.

The framing of these issues within the scope of environmental concerns that must be present in spatial planning and in the implementation of the pro

SETÚBAL LAB 28

Escola Superior de Educação by Alvaro Siza, Setúbal, photo by S. Antoniadis, 2021.

Cement Factory Secil-Outão, Setúbal, photo by S. Antoniadis, 2022.

29

posals that urbanism can support sustainable urban development is therefore essential. The transformation of landscapes that results from the urbanization process does not always happen with violent ruptures with the surrounding reality or with the anthropological references that link populations to their origins and the territories they occupy.

Contemporary demands

Contemporary societies have been seeing a change in social and functional paradigms with strong impacts on the shape and modes of appropriation of urban space. This accelerated the intensity of use of urban fabrics, namely the most central ones - where the loss of residents did not imply, in most cas es, loss of activities and functional importance - and a clear abandonment of those that lost importance, activities and features. The resulting functional and spatial marginality turns out to be also social and this is one of the most serious problems facing contemporary urbanism. The rapid transformations of the urban landscape, creating new identity references in urban icons, eras es memories and weakens individualities, not least because they happen in parallel with the expulsion to other areas of the city or the outskirts of a large part of the population that lived there.

At the same time, similar phenomena are found in rural areas, with a strong environmental and landscape impact. The change in agricultural production priorities, the reduction of cultivated areas and the reorganization of the dis tribution and consumption systems, generated the emergence of extensive areas of soil awaiting new uses and functions. What is not strange is the dif ference between the value of land for agricultural use and the value of land for urban use. As a result, environmental risk factors (fires, erosion, floods) have worsened and the sustainability conditions of the natural environment have been reduced, favoring physical desertification, the ecological simplification of the territory, the reduction of biodiversity and the impoverishment of hu man communities in it. with the consequent migration of the population to the existing urban areas, thus contributing to the expansion of their peripheries.

Which shows how the economy behaves as a modeler of landscapes, di rectly and indirectly. Its impacts can be factors of environmental and visual degradation or essential instruments for the environmental requalification and for the preservation of the territory’s resources. This depends on how one understands the role and importance of the economy in the context of the organization of society and its relations with the search for sustainable life models and environmentally balanced territories.

SETÚBAL LAB 30

Contemporary urbanism is thus confronted with the challenge and respon sibility of responding to the new demands of urban life and the need to create and organize sustainable and environmentally balanced territories. Territories capable of creating landscapes where the rural and the urban, the natural and the built, are interconnected in a harmonious and environmentally balanced way. Because it is that the landscape must be understood; and the territory, as such, must be organized.

It is up to each one, with intelligence, knowledge, balance and creativity, to contribute to this being so.

References

Leonel Fadigas, Fundamentos ambientais do ordenamento do território e da paisagem. Lisboa: Edições Sílabo, 2007.

31

THE SCAPE TO READ TOGETHER. A NEW ATLAS OF URBAN-GROUND

Stefanos Antoniadis, professor, architect, Lisbon School of Architecture, Universi dade de Lisboa

Gonçalo Pirrolas, research fellow, Lisbon School of Architecture, Universidade de Lisboa

Beyond the consolidated vocabulary

Whether we like it or not, the territory in which we live is not made up only by the elements of the historical and consolidated vocabulary. The elements that compose it seem no longer to agree with the grammar of the past. The vo cabulary of objects scattered throughout the territory has been considerably enriched. Nowadays territories are dotted with large production volumes and commercial malls, sport facilities and stadiums, intermodal hubs, infrastructural junctions, waterways, power lines, pylons, antennas, construction cranes, quar ries, landfills, smoking stacks, piezometric towers, hanging water deposits, silos, freight yards and villages covered by thousands of containers, immense docks, extensive car parks, shipyards, airports, power stations…

These results represent a considerable part – we could say the vast majority of the territory – of contemporary landscape which constitutes a ground of the oretical speculation, of didactic experimentation and of professional chances for designers, being ever more forced to manipulate, both with the gaze and inter ventions, the complexity of these common but unacknowledged artificial stuffs. Therefore, it is evident how important it is to baste a reading of the contem porary landscape as a fundamental means to reassess the objects and the layers

SETÚBAL LAB 32

of the territory, with the goal of facing more appropriately the complexity of the managing that the present entails.

If once conventional drawings and layouts, attributable almost exclusively to cylindrical and conical projections, were sufficient to confer form and order, harmonizing human limbs, urban and territorial elements and relate them to “the whole” – from the thought by Leon Battista Alberti to the basis of the Ge staltpsychologie of the early 20th century – now the manipulation of the scat tered landscape (Rasmussen, 1974) presupposes different engaging methods and techniques of reading.

The strategies for bringing back into play the vast contemporary urban and suburban areas, often declared Non-Places, disordered, without specific voca tion, cannot follow obsolete and past practices, based on a few known elements and operations. Rather, they must draw inspiration from investigation practices such as those typical of the nautical discipline, represented by the historical and event more recent pilot books, based on experience and observation, contain ing information relating to the regions to explore: preliminary and forerunner practices that transcended pre-established categorizations. A portolano, that’s the name for this kind of chart, reports useful information for the recognition of coastal landscapes by hybridizing different kinds of representation, keeping together textual descriptions, geographical maps and drawings of coastal sil houettes; it contains information on dangers and obstacles to navigation such as shoals or wrecks; it counts indications to recognize the entrance of ports, for anchoring and any other information deemed useful for navigation and safety. In it, a medieval watchtower, a hanging water deposit and a spur of bare rock, seen from the water, have the same dignity as elements useful for navigation. However, transcending the mere utilitarian aspect in the nautical field, we can’t ignore the forerunner look on landscape treating all those natural objects and artificial elements by their most basic and true characteristic: they’re forms contributing to the construction of a recognizable and transmissible landscape, identity and knowledge. A common ground for the for the pursuit of a shared, public and political habitat, in the noblest sense of the term.

Reading the urban ground

This approach holds true even more so for a riverside city, Setúbal, observed by the water still today. The large water basins of the estuaries of rivers such as the Tejo and the Sado, recreate a sort of measurable landscape, similar to the Medi terranean ones, close to the incommensurability of the Atlantic Ocean. The water basin works as a “contact interface between different cultures and knowledge,

33

Dieses ist lange her / Ora questo è perduto, drawing by A. Rossi, 1974.

Postcard from (contemporary) Setúbal, photo by S. Antoniadis, 2021.

SETÚBAL LAB 34

an access to heterogeneous products and techniques; a space in which the sea represents the broad interface of contact, abundantly crossed, like a large square, a public space […] between peoples who settle permanently and in an increasingly significant way on its shores.”1 It is no coincidence that the Romans already organ ized the territory of Setúbal in a polycentric way around the estuary of the Sado River (Blot, 2003).

Even a small town, such as Setúbal, actually collects an enormous abacus of the mentioned above unacknowledged elements of the contemporary vocabulary as water towers, dock cranes, port warehouses, commercial malls, silos, antennas, a huge logistic roll-on/roll-off terminal, and there would also have been the for mer thermoelectric power station high smoking stacks (unfortunately recently demolished, which represented a strong landmark for the area).

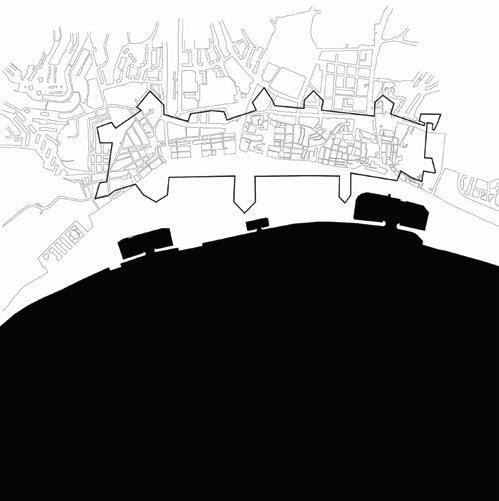

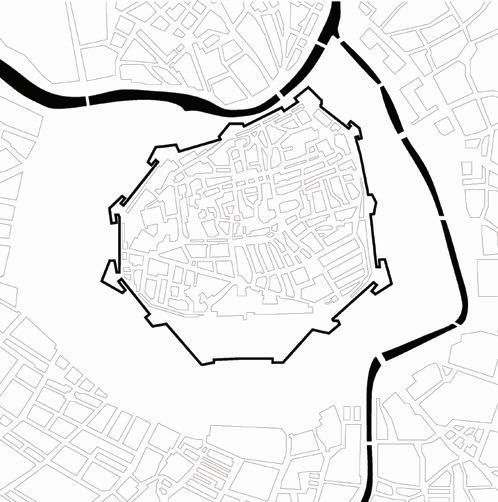

Around the tiny historic centre – increasingly at risk of becoming a sort of fake “wedding favour” for tourists and prod-users in general – whose walled edges are now almost unrecognizable and fragmented, a land of cranes, infrastructure, car parks, warehouses, ruins and decommissioned areas extends especially towards the Sado River and awaits redemption.

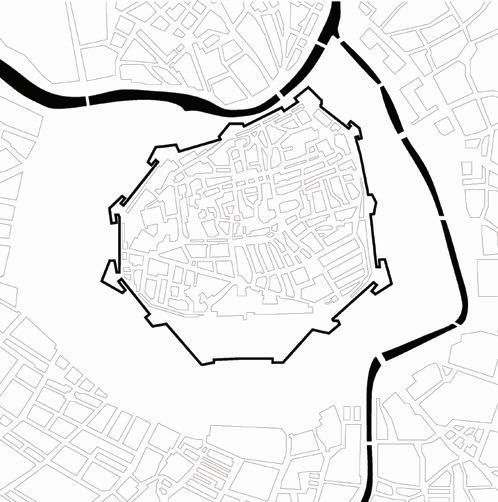

A situation not so distant, in some ways, from that of the 19th century urban dynamic in Vienna, considered paradigmatic for the history of architecture and urbanism. The known grand boulevard, the Ring, was built to replace the city walls, which had been built during medieval period. The walls and all the sur rounded fortification system were about 450 metres wide, where buildings and vegetation were prohibited for military defensive reason. By the late 18th century these fortifications had become obsolete, and the urban development was required to trigger a more significant change. The Ringstrasse plan was, in fact, the regeneration of an urban underused area by the dismantling of the city walls, open-air workshops, facilities and stalls to fill this large obsolete urban void with new public interventions of great importance to the city: palaces, museums, theatres, gardens.

Therefore, these intellectual approaches belonging to our European experi ence can still offer valid help today in the interpretation and resolution of urban landscape issues. It is a question of thinking of a new paradigm, however in con tinuity with our epistemic prerogative and with the same transformative force, for a more contemporary landscape. The challenge is played once again outside the consolidated city, beyond the walls, and beyond the unacknowledged lines2. Once again a rather desolate and underutilized dross-scape about 450 metres wide of ramparts mostly dismantled or incorporated by workshops, warehouses, uncovered areas, port support roads without any hierarchy, obsolete docks and pier close to the old city walls await acknowledging and reconfiguration.

35

Vienna urban void and Setúbal urban void, drawings by G. Pirro las, 2021.

Setúbal dock-land, orthophoto from Google Earth, 2021.

SETÚBAL LAB 36

Acknowledging Setúbal urban stuff

Today, facing the new forms of the contemporary landscape, we have once again a sensational and epochal opportunity to propose new visions. Visions that can be investigated and conveyed through some integrated photographic tools, rather than through the construction of nineteenth century romantic pictorial postcards (still too similar to the pictures that intend to build a fake, picturesque, and attrac tive image of many today cities) for a more authentic and profound sharing of the places we live together. Photos, collages, formal analogies and homologies light up the transformation attitude of the object itself – or objects if a plurality – in new and many possible ways functional to the landscape assessment, the collective space, the shapes of contemporaneity in an up-to-date architectural portolano.

Hybridization and multiplicity of techniques are characteristics on the same wave length as the mixing of urban palimpsest, as well as the coexistence of diversified identities, typical of the contemporary city. In other words, contemporary systems of architectural representation seem to intrinsically possess the qualities of the land scape3 (Moraitis, 2013). Searching the applicative possibilities in the field of reading and re-writing the landscape can make it possible to better address the complexity of the architectural demand at the scale of the building, the city, and the territory.

Since the formal structures of the contemporary landscape live and change ac cording to the multi-cultural and multi-identity gazes of the communities of our time, photography, multi-vision and image processing, understood as a systematic and compositional reading apparatus, help to conduct and weave possible relationships between parts and fragments, to “reposition, without being able to move them, the existing forms along logical, thematic, spatial sequences by means of ordering devic es” (Stendardo, 2013) as new Alberti’s lineamenta4. It is about a real post-production operation – not surprisingly a term already in use for some time in the field of photo graphic technique but still viewed with distrust in architecture – and not of make-up or falsification through which architects and urban planners can manipulate areas of contemporary cities, especially the less measurable and digestible ones.

Setúbal upgraded common scape

Combining a Greek temple of the classical era with a skeleton of port ware house, or a sacred cella of the Parthenon with the atrium of a social housing, or a silos with the volume of a tower or a bulwark is not a logical artifice of reductio ad absurdum, it is not an extreme and hostile provocation, it is not an improper and unscrupulous expedient. It is an attempt to enrich and integrate the abacus of letters and words that form the landscape in which we live.

37

La Città Analoga, drawing by A. Rossi, 1990.

Setúbal Analoga, photo by S. Antoniadis, 2021.

SETÚBAL LAB 38

The Sacred Tree of Bela Vista, photo by S. Antoniadis, 2021.

The Sacred Statue of Athena, Parthenon, reconstructive draw ing by Candace Smith, 1990.

39

Setúbal upgraded abacus of the dignity of the elements, set of orthophoto from Google Earth (from the top-left: Livramento Bulwark, Municipal Pavilion “João dos Santos”, Auditorium “José Afonso”, Conceição Bulwark, São Filipe Fortress, St. Amaro Bulwark, Alegro Shopping Mall, Bullring “Carlos Relvas”, Purifiers Wastewater Treatment Station of São Sebastião, Bela Vista Water Tanks, constructions site in Nossa Senhora da Anunciada, Old Convent of Our Lady of Arrábida chapel), image by Sara Alfonso, 2022.

Exercising gathering and matching fragments of contemporaneity, the abstrac tion of the forms that constitute our geography, the systematic comparing of com mensurable objects of the present and cases of the past for which exists an estab lished and universal awarding of quality, the unveiling of a formal dialogue between elements, may represent a healthy training in order to overcome the dichotomy old vs new, uniqueness vs uniformity and appreciated vs unacknowledged.

Focusing on the mechanisms of acknowledgement may ward off the rhetoric between the bad and the good parts of the city – but reading in its forms, as an inexhaustible condenser of meanings –, may converse, discuss and produce sig nificant improvements towards the digestion of the territory.

Updating and upgrading the atlas of urban vocabulary could represent at the same time the disciplinary grounds for structuring evaluation models for creative proposals, for the issuing of a new generation of territory laws and regulation dedicated to distinctive areas, and the communities’ common ground for devel oping possible landscapes, our scape to read and re-signify together.

SETÚBAL LAB 40

Notes

1. João Nunes, Paesaggi costieri, in Antoniadis, S., Sulla Costa. La forma del costruito mediterraneo non accredita to. Conegliano: Anteferma, 2019, p. 7.

2. The expression constitutes the keyword and semantic basis of the urban and architectural research activities made in UniPD. Among these: Beyond Unacknowledged Lines - Landscape, Infrastructure, Urban Regeneration, cycle of seminars held at the School of Engineering of the University of Padua (2013) on the up-cycling of the existing city and especially its peri-urban areas (Scientific Board: Luigi Stendardo, Stefanos Antoniadis and Luigi Siviero). The formula mimics the movie Behind Enemy Lines (directed by John Moore, USA, 2001), in which an American fighter pilot was forced to wander in hostile zone, after his aircraft was shot down during the Bosnia- Herzegovina war, discovering territories, infrastructures and abandoned factories in the Srebrenica Region, before reaching the extraction point.

3. “Using a provocative assertion we may insist on the fact that contemporary electronic aided design ap pears to possess inherent «landscape qualities»” in Konstantinos Moraitis, Landscape Interpretation through Schematism: Schematism as a theory concept, and its correlation to Landscape Aesthetics and Landscape Design, p. 217; essay presented at the XXIII World Congress of Philosophy (Athens, Greece, 2013) “Philosophy as Inquiry and way of Life”, Session n.1: Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art (August 6th 2013).

4. The set of condition generated by the encounter between drawing (and now digital photography tech niques) and architecture.

References

Stefanos Antoniadis, Sulla Costa. La forma del costruito mediterraneo non accreditato . Conegliano: Antefer ma, 2019.

Luigi Stendardo, La stratificazione di forma e materia tra coltivato e costruito, in Stefanos Antoniadis, Alice Braggion, Alessandro Carabini, Enrico Lain (a cura di), BE CITY SMART! Scenari & progetti per un’urbanità 2.0 Padova: Overview Editore, 2013, p. 93; Konstantinos Moraitis, Landscape Interpretation through Schematism: Schematism as a theory concept, and its correlation to Landscape Aesthetics and Landscape Design, in XXIII World Congress of Philosophy proceedings, Athens, 2013, p. 217.

Maria Luísa Pinheiro Blot, Trabalhos de Arqueologia 28. Os portos na origem dos centros urbanos. Contributo para a arqueologia das cidades marítimas e flúvio-marítimas em Portugal. Lisboa: Gráfica Maiadouro, 2003, pp. 259-269.

Steen Eiler Rasmussen, London: The Unique City. Boston: The M.I.T. Press, 1974, chap. 1.

41

TOWARDS AN ARCHITECTURE FOR PUBLIC USE: A CONVERSATION WITH SAMI-ARQUITECTOS

an interview by

Sérgio Padrão Fernandes, professor, architect, CIAUD, Research Centre for Architec ture, Urbanism and Design, Lisbon School of Architecture, Universidade de Lisboa

Rui Justo, researcher, architect, CIAUD, Research Centre for Architecture, Urban ism and Design, Lisbon School of Architecture, Universidade de Lisboa

Carlota Gala, research fellow, Lisbon School of Architecture, Universidade de Lisboa

Inês Vieira da Silva and Miguel Vieira founded their practice SAMI-arquitectos in 2005, in the city of Setúbal, having gained international notoriety for their first work, the Visitors Center at Gruta das Torres, on the island of Pico, in the Azores.

Among other activities, the studio develops multidisciplinary projects at different scales and fields that have been recognized with several awards, such as the AICA de Artes Visuais e Arquitectura (2015 and 2017), awarded by the International Asso ciation of Art Critics, National Secretary for Culture, and Millennium BCP Founda tion; the BIAU Prize - Bienal Ibero-Americana de Arquitectura y Urbanismo (2014 and 2016); the AADIPA - European Award for Architectural Heritage Intervention (2015); the National Tektónica/OA Award for Emergent Architecture (2009).

SAMI were invited to participate in several international exhibitions too: in 2017 they were part of the 2nd Chicago Architecture Biennale, they participat ed in the 14th International Architecture Exhibition Biennale Architettura 2014 in Venice; in 2011 they were part of the Official Portuguese Representation at the 9th International Architecture Biennale of São Paulo.

They were selected for the Wallpaper* Architects Directory 2011, which dis tinguished the 20 most promising young architects internationally and in 2007 they were included in the short list, recommended by Herzog & de Meuron, of the 100 young architects invited to develop the Villa Ordos 100 project

SETÚBAL LAB 42

The conference that SAMI held at the Igreja Paroquial do Imaculado Coração de Maria in Setúbal, on September 13th, 2021, in the frame of the workshop “The Space to Live Together” was the opportunity for a conversation around the theme “architectural design and space for public use”. The interview is divided into three parts and explores three essential issues of the work of the studio that seek to reveal the attitude of this duo of architects towards the responsi bility of the act of architectural design and the public role of architecture.

Part 1: Questions about the idea of intimacy

The Map of Places of Intimacy is a poetic look at reality and an interpretive reading of the territory. It was prepared as part of a response to the challenge launched by the architect Pedro Campos Costa, curator of the Portuguese Pavilion “Homeland: News from Portugal” (Allegri and Costa, 2014) at the 14th Biennale Architettura in Venice, for the design of an isolated single-family house. The Map of Places of Intimacy proposes a reconnaissance of the territory from your very particular point of view, which is also a first approximation to the answer on what ideally is a detached house. Is it possible to generalize and say that the idea of intimacy and/or degrees of intimacy is a transversal idea in the work of the SAMI? And, going a little deeper into your creative sphere, is it possible to say that the notion of intimacy is, for the SAMI, the basis of a definition of Architecture?

Inês and Miguel: The “Map of Places of Intimacy” was the result of work de veloped with the architect Susana Ventura for the 14th Biennale Architettura in Venice, in response to the invitation of the curator Pedro Campos Costa, who proposed to us “to think and design an isolated single-family house, in a natu ral context, for a client that we should ideally find”. In view of this statement, it seemed interesting to identify our object of study by asking the following ques tion: “Is there a place in cities for detached houses, permanent housing, with a strong relationship with the landscape, designed by an architect in a connection of proximity with a specific customer?” It seemed much more interesting to us to bring the detached single-family house issue into an urban context, than to decline the theme of the isolated house in a natural place. We chose the city of Setúbal because of its relationship with the surroundings: the Serra da Arrábi da, the River Sado and its estuary. So, we went looking for land, within the city limits, on which it was possible to design a single-family house and we found sites still vacant, because of the difficulty of access, the pre-existence – many of them military – or the accentuated topography. We identified these places and tried to register them through a “Map of Places of Intimacy”, designed with the

43

SAMI-arquitectos with Bar bara Macaes. Map of Places of Intimacy.

Paulo Catrica, Map of Places of Intimacy, photo of Santo Amaro fortress.

SETÚBAL LAB 44

architect Bárbara Maçães, and registered through the eyes of the photogra pher Paulo Catrica”.

The idea of the “Map of Places of Intimacy” allowed us to synthesize, at that moment, our way of thinking and doing architecture. We found that our atten tion to the specifics of each place, the close relationship with the client and our approach to each project was similar, regardless of the scale of each project, its program, and the fact that it is a building for public or private. From that mo ment on, the idea of intimacy became clear in our exercise of discipline.

Intimacy is a quality usually attributed to rooms in the house hosting the most reserved life activities and which, therefore, constitute the very center of the private sphere. SAMI’s Map of Places of Intimacy transports this attribute to another reality, we can even speak of a transfer from the domestic scale to the city scale. Thus, Intimacy be comes a condition for questioning the territory in a bold and original approach! Is it possible to investigate the urban public space from this notion of intimacy? How can (your) notion of intimacy explain the diversity of collective spaces for public use that are proposed in the houses in Fontainhas project?

Inês and Miguel: The Fontainhas project represents the full realization of the challenge launched by the curator Pedro Campos Costa, three years after the 14th Biennale Architettura, when one of the lands we chose for the Map of Plac es of Intimacy became a project to be developed for a private client. In one of the five places we chose, together with the architect Susana Ventura, to reflect on the role that a single-family house could play in the regeneration of the city, we were asked to think and design 46 apartments. The land is characterized by a very accentuated topography, located at the eastern end of the Historic Center of Setúbal, precisely on a hinge street between the city and its industrial expansion, to the east. A land with a privileged view over the river Sado and with the 17th century city wall at its highest level, to the north. The diversity of typologies that we proposed, as well as the diversity of the outdoor spaces that we designed, are a reflection of the desire to redesign a significant part of the urban fabric similar to the historic center in which it is located. The various scales of exterior stairs, streets and squares that we created along the plot were intended to explore the particularities of the terrain and create spaces suitable for each place.

In this sense, we transcribe the words written by the architect Susana Ventu ra when the first issue of “Homeland” was published: “SAMI embarked in anoth er exercise starting, exactly, at this relationship of intimacy that the detached house builds with the landscape. If in a natural and idyllic landscape, like the

45

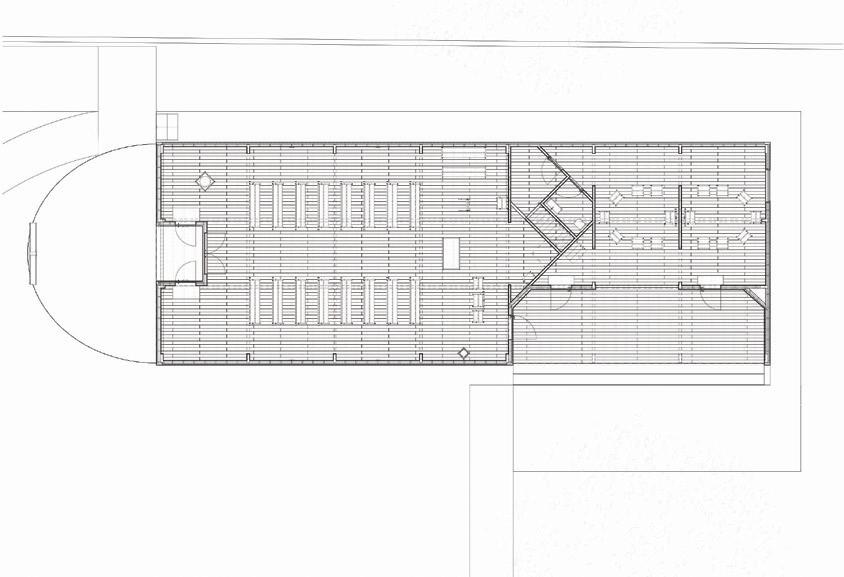

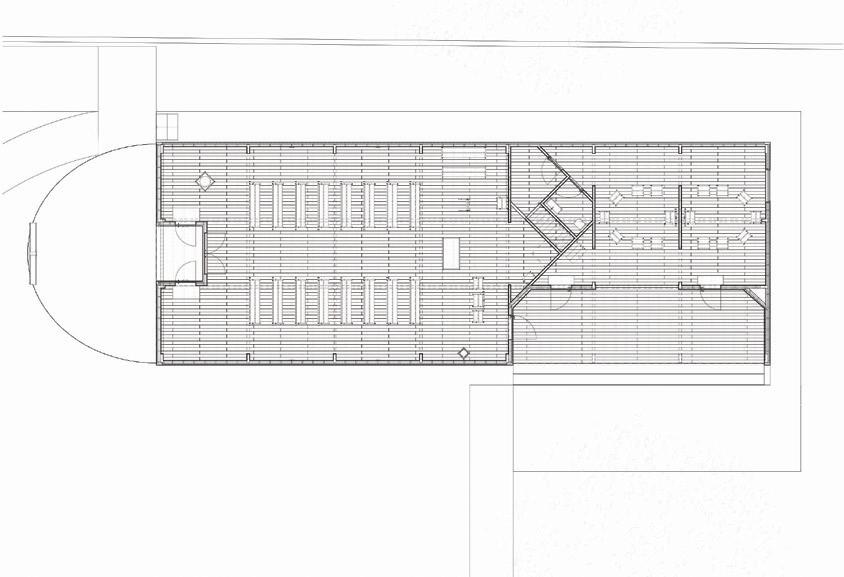

SAMI-arquitectos. Fontaínhas, floor 3 plan.

SETÚBAL LAB 46

places where some of their houses in the Azores were built, this relationship is clear, how does one create this similar space of intimacy on empty plots in the centre of a dense city? Taking as an example the city of Setúbal, where they work, they created, after several conversations and debate with the local authority urban planning teams, a “Map of Spaces of Intimacy” as an answer to that extremely difficult question posed of today’s cities and which seems to remit to the eternal question that Le Corbusier, facing the Acropolis, once asked: Why these temples? Why here? Sometimes, it is in unusual places, like the ones shown here, that architecture seems to provide another meaning to the landscape and makes it its home” (Ventura, 2014, p.126).

Somehow, the reading of the architect Susana Ventura anticipated what would later be our work when we developed 46 rooms for the same location that, without having a client, we aspired to design with the same degree of inti macy that we imagined in the Map of Places of Intimacy.

Part 2: Questions about reading and design

When I was attending the first year in the School of Architecture, I discovered a text where Álvaro Siza wrote that the idea is in the “place”, more than in the head of each one, but only for those who know how to see it (Siza, 1996, p. 60). At the time, this idea dazzled me and even today fascinates me the consequent meaning of reading the terri tory and the very understanding that the acknowledge, reading the site, can be the first act of the project. On this subject, I would like to return to the Map of Places of Intimacy which, in fact, is the representation of the territory, filtered through a very personal lens. At the same time, it reveals also a desire to question the territory, and to search in the careful reading of the context a strategy for the project. Why is it important for SAMI to explore the “reading-design” dichotomy in the creative process and architectural composition?

Inês and Miguel: Reading is the first phase of the design process, the first step on the path that each project will trace. Reading the physical territory is essential, along with reading its history, the socio-economic fabric in which the project is located or even its cultural context. The client we work for is also an important as pect to “read” from the beginning. However, also throughout the entire process, we would say that in our practice of architecture, the attention and reading of what surrounds us, of the “context” of the project, has to be constantly checked. And today, at the precise moment we are going through, it is impossible for us to work without these various readings validating the project, meaning that the project only finds its place at the intersection of all these readings.

47

SETÚBAL LAB 48

SAMI-arquitectos. Igreja do Coração de Maria, main façade west, elevation north, ground floor plan and detail of the head light lantern.

49

Supported by this constant process of understanding, composition is un doubtedly one of the fundamental points of the practice of Architecture, espe cially if we assume that architectural composition also includes the amalgam of a coherent whole that seeks to bring to the context in which we are working an attentive and revealing look. The architectural composition is one of the funda mental points that persists in any project, regardless of its constraints.

Part 3: Questions about space for public use

In this workshop, inspired by the call of the Biennale Architettura 2021 in Venice “How will we live together” (Sarkis and Tannir, 2021), we set out to re-imagine the cartogra phy of the city of Setúbal starting from the public space. The reason is that we continue to believe that the space that we collectively use and that is common to us will continue to have this power to keep us together in the future. How do you look to the future, how do you imagine that we will be able to live together again? And in this sense, what have we learned from the pandemic? What are the chal lenges for architecture and cities in this post COVID-19 era? Or, in a more personal field, what are the challenges facing SAMI and Setúbal, the city where you live and work?

Inês and Miguel: The pandemic came to remind us how much sharing, social izing outdoor is fundamental to the balance of each one. Awareness of public space as a collective asset was gained. In Setúbal, in particular, due to its unique natural surroundings – the mountains, the estuary, the bay, the beaches – we are invited to use this common space and to realize how crucial it is for every one’s future that this space is preserved and cared for. Here, too, we assume this role of responsibility whenever we have the opportunity to intervene in this context; whether through public projects or private projects, it is always through our understanding that we can add something to this common space.

A few years ago, in connection with the European Prize for Urban Public Space promoted by the Centre de Cultura Contemporània de Barcelona – CCCB, the architect Manuel Solà-Morales proposed in a short text the idea of “material urbanity” (Solà-Morales, 2013) as an attribute that refers us to the need for physical expression of the urbanity. And the urbanity as the quality of places reveal themselves through the physical form of public space with a collective meaning and content. In this sense, how do you imagine the contribution of the Igreja Paroquial do Imaculado Coração de Maria and of the entire project where the church is inserted, in the construc tion of a new cartography of public space in an area of growth of Setúbal that lacks the material condition of urbanity that we were talking about?

SETÚBAL LAB 50

Inês and Miguel: The church was born because there is a large and active Catholic community, which justifies it. Viewed in this way, it responds to a natu ral need to create a space for meeting and communion, both inside the church and outside, as a representative space for a celebration open to the community. Churches have always been, throughout history, elements of reference in the urban fabric of cities that often grew from this generating pole. This church comes in the opposite direction, filling an existing void. It is located on a plot of land surrounded by several huge-volume residential buildings, a primary and secondary school, and a large commercial area. An exposed place, almost bare, where only a large eucalyptus tree accompanied by an olive tree, at the highest point of the land, gave us some sense of implantation for the project.

We thought of the church as if it were a hermitage, as if we could think of this building detached from the urban fabric and emphasizing its relationship with the topography and existing vegetation. The exteriors were designed in the sense of making a route, a deambulation, an almost pilgrimage, to the churchyard.

This was a custom-made project for the community. All the «details» have been collectively achieved: the furniture (which we designed with the designer and friend Rui Alves), the lamps, carefully chosen and acquired as the commu nity manages to raise money for it. Also the exteriors will be made in this way.

In conclusion, almost as we started, we realize that this church is, after all, another place on our “Map of Places of Intimacy”.

References

Álvaro Siza, Um arquitecto foi chamado in Pedro de Llano and Carlos Castanheira (eds.) Álvaro Siza. Obras e Projectos. Milano: Electa, 1996, pp. 60-61.

Manuel de Solà-Morales, The impossible project of public space, 2013. Available at: https://www.publicspace. org/multimedia/-/post/the-impossible-project-of-public-space (accessed on May 2022).

Pedro Campos Costa, Alessia Allegri, (eds.), Homeland–News from Portugal. Lisboa: Note, 2014. Susana Ventura, How do we think and create intimacy in architecture?, in Pedro Campos Costa, Alessia Allegri, (eds.), Homeland–News from Portugal. Lisboa: Note, 2014, pp. 125-142.

51

DESIGN STUDIO: THEMES

RUINS AND FRAGMENTS: VESTIGES

Sérgio Padrão Fernandes, Alessia Allegri, Pedro Rodrigues, Danilo Tavares, Fernanda Costa, Mariana Reis, Roberto Lorenzon

HOUSING TOGETHER

João Leite, Maria Manuela da Fonte, Ana Oliveira, Beatriz Cabral, Henrique Nunes, Mariana David Frade

THRESHOLD: HYBRID SPACE

José Miguel Silva, Luís Carvalho, Alessandra Pace, Carolina Martins, Filipa Lopes, Margherita Maggioni, Mattia Muresu

DISPLACEMENT: TRANSPORT / EXHIBITION

Sérgio Barreiros Proença, Filipa Serpa, Cândido do Rosário, Francisco Janeiro, Paolo Richelli, Sara Alfonso, Sara Ribeiro

WALLS AND DOORS: TRANSITION

João Rafael Santos, Pedro Bento, Elcio Djata, Francisco Manuel, Julianna Costa, Michela Stefanoni, Sara Faedda

SETÚBAL LAB 54

55

Ruins and fragments: vestiges

“I am made from the ruins of the unfinished and it is a landscape of giving up that would define my being”

Fernando Pessoa, 1982

Case study 01

A Gráfica: Centro de Criação Artísica

A Gráfica: wrecks from time

Advisors

Sérgio Padrão Fernandes Alessia Allegri and Pedro Rodrigues

Students

Danilo Tavares

Fernanda Costa

Mariana Reis

Roberto Lorenzon

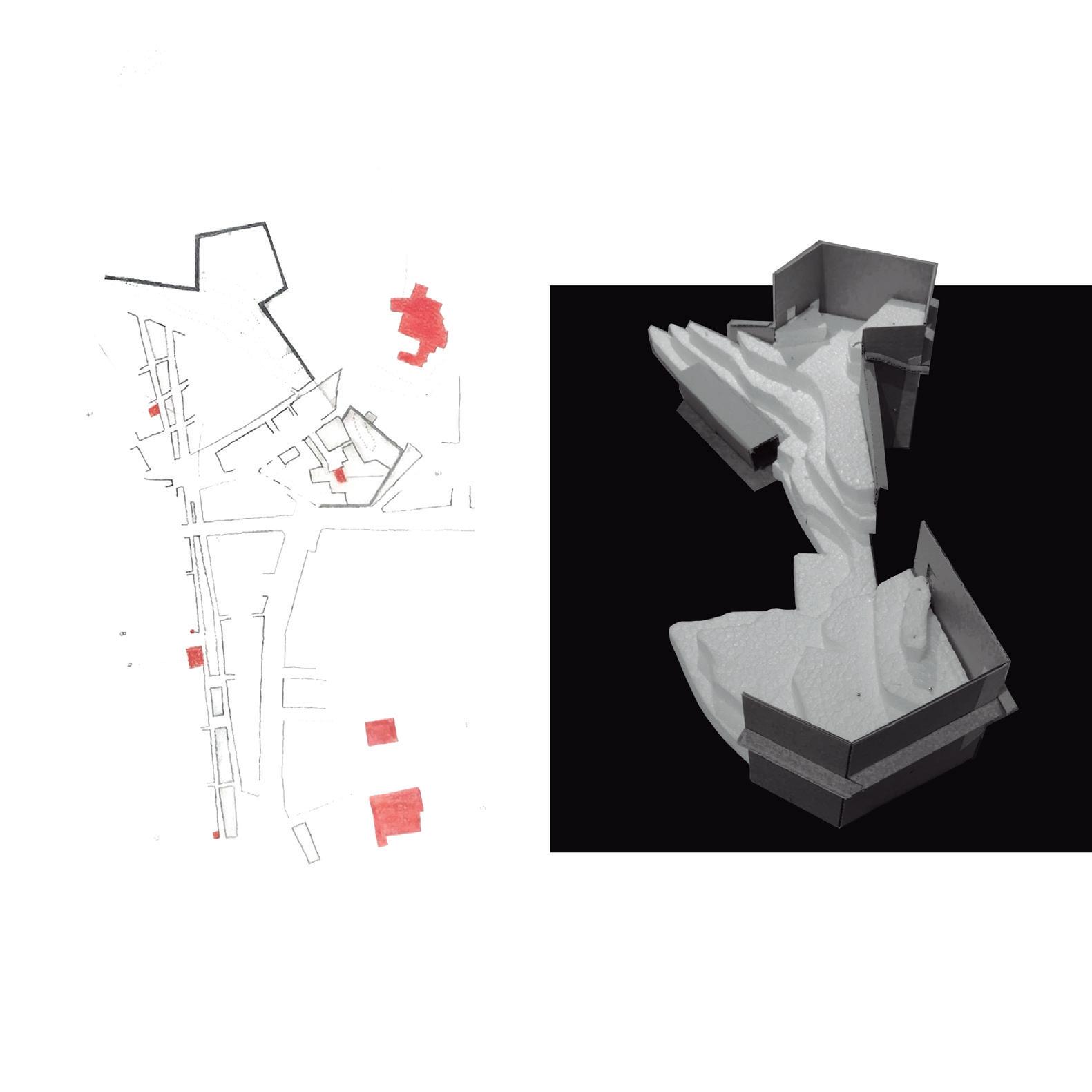

Within the scope of the workshop – that takes the walls of the city of Setúbal and the surrounding buildings as a pretext to reflect on the changes of the urban fabric over time, in order to develop urban projects that seek to transform abandoned histori cal structures into contemporary places capable of responding to the new demands of public life – our intervention area is the “A Gráfica”, in the old Sado Paper Warehouse, on the Ladeira da Ponte de São Sebastião, now transformed into an Artistic Crea tion Center by the Municipal Council of Setúbal. The built complex that houses “A Gráfica” is attached outside the oldest walls of the city of Setubal, built during the Middle Ages to protect the flourishing fishing village. The built fabric adjacent to the São Sebastião city gate, has undergone, more than once, transformations and changes in a constant process

56

57

of appropriation and reinterpretation. Today, it is a useless palace built with part of an old monastery and vestiges of a warehouse attached to an aban doned Patio with housing for factory workers. Each transformation has left traces of a complex history which, in addition to be the fascinating witnesses of the past, we want them to be ele ments and interpretative tools for designing the future. Among other fragments that tell us about the vicissitudes of this place we find parts of the medieval wall, which is a symbolic element, but which is currently hidden and forgotten, adjacent spaces for public use, such as the workers Patio and the Quebedo Square, as well as the belvedere of São Sebastião. There is no spatial continuity between these places, worsened by the different topographical dimensions and, even more, by gross overlapping and juxtapositions of built structures, public and private, that do not consider preexist ing remains. The railway, that in early 20 th century was built to facilitate the transport of goods from the port towards the interior of the region, it is a clear example of this: it divides the city and the case-study territory into two distinct parts almost without connection.

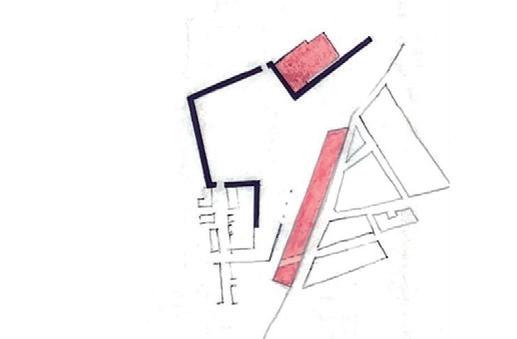

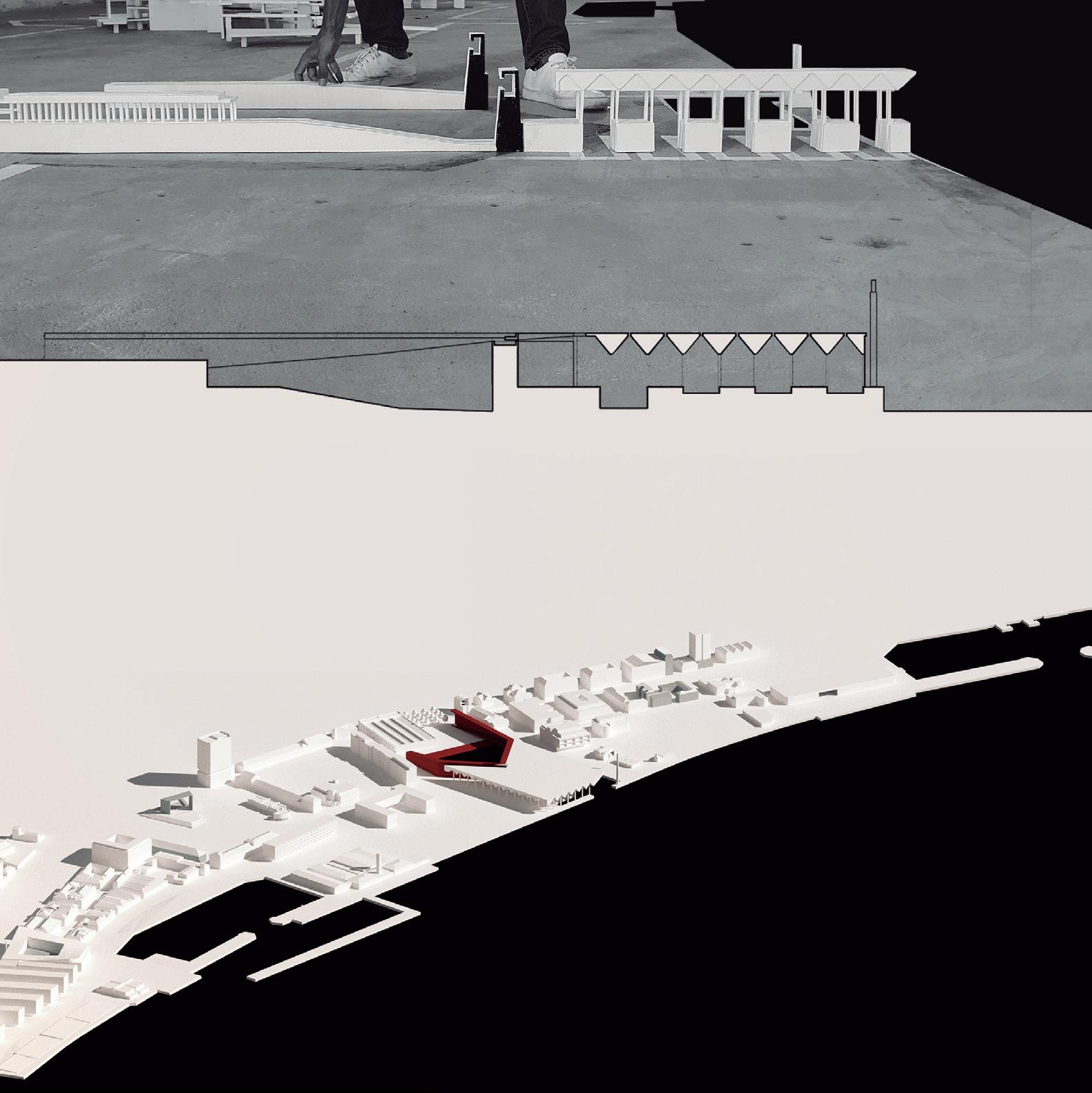

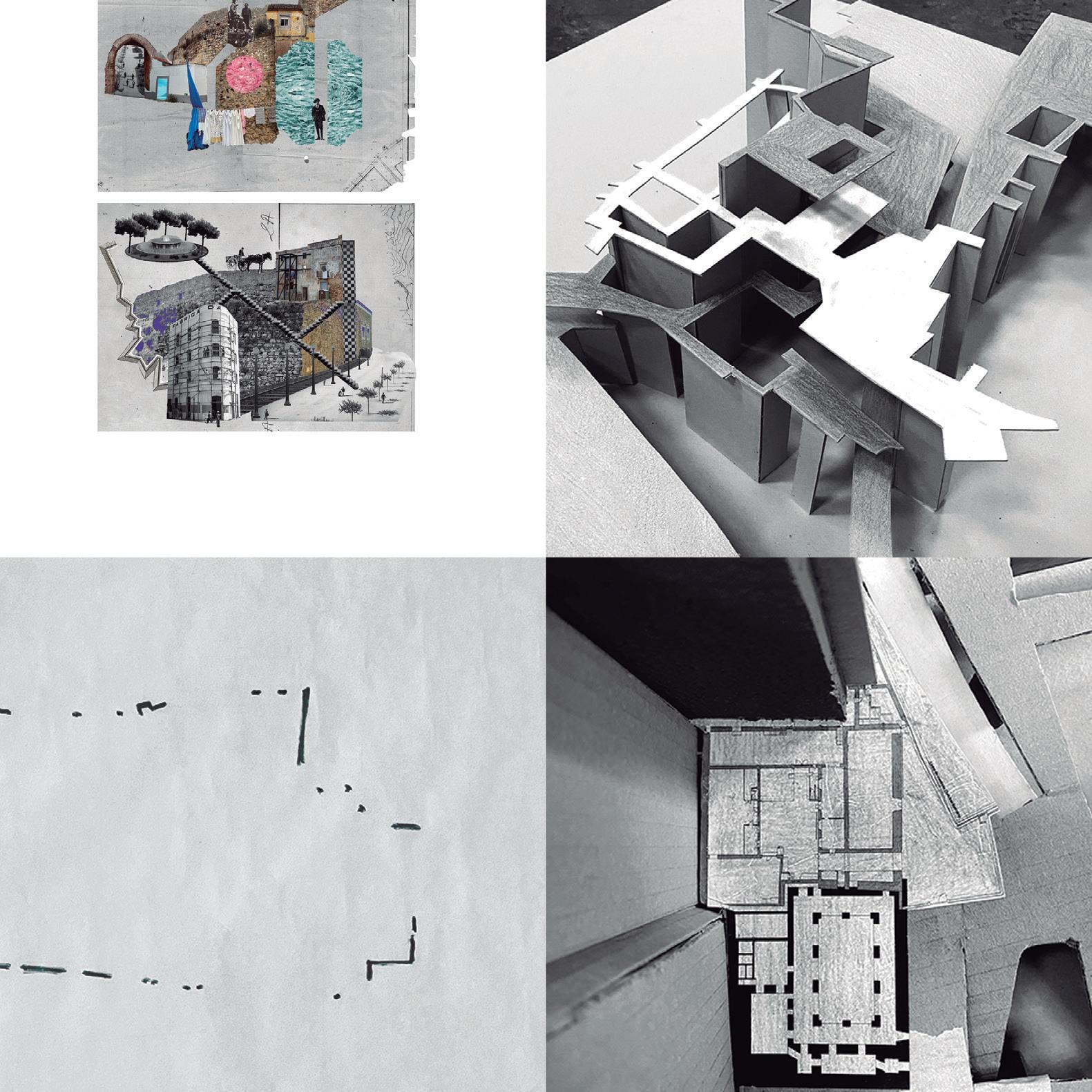

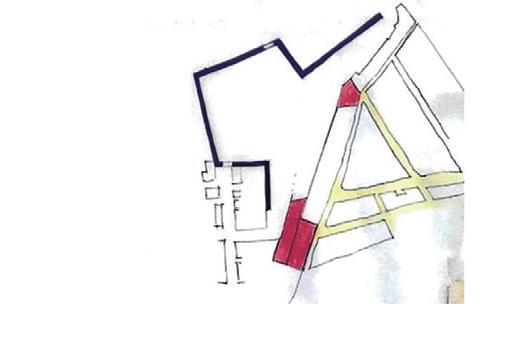

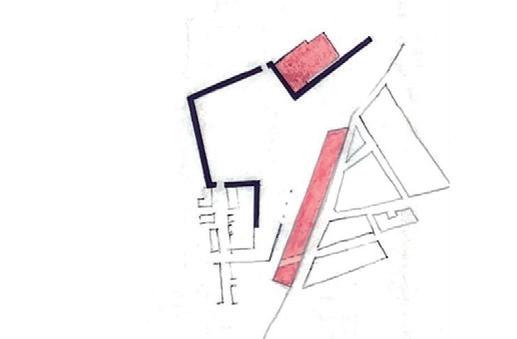

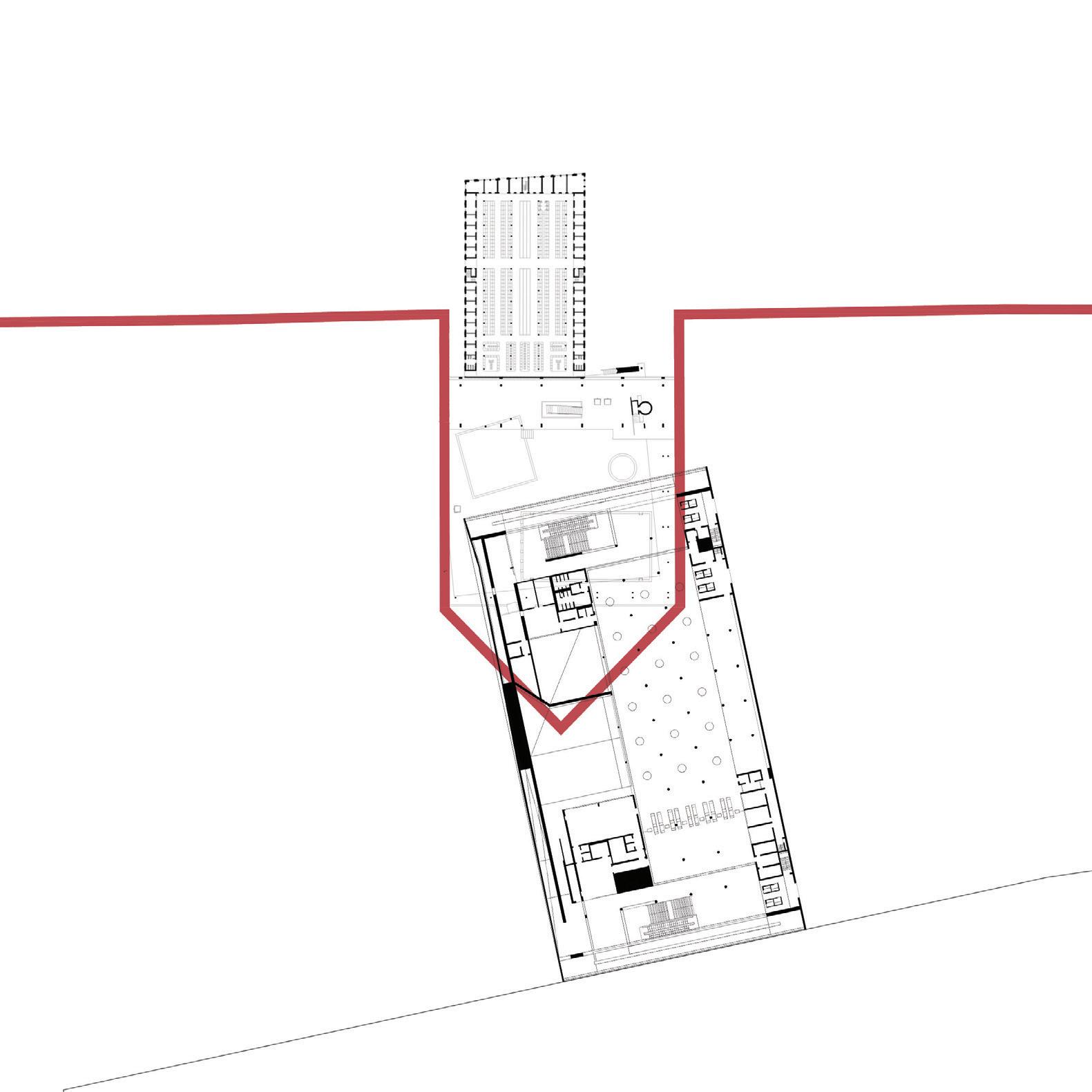

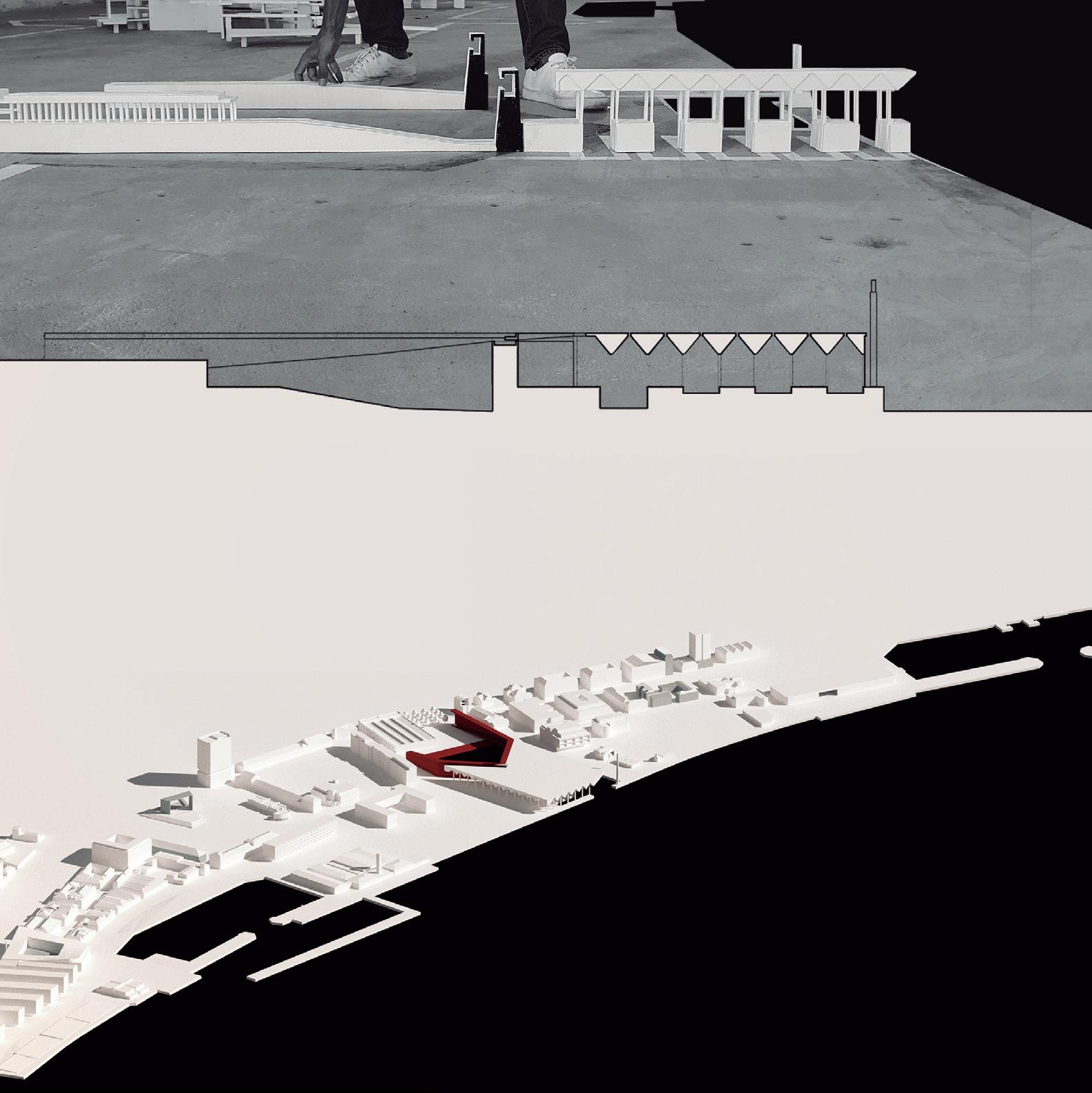

Seamless Ruins

Considering the previous reflections, supported by a careful interpretative analysis of the cartography the project visualizes “A Gráfica” as the articulating element of all the surroundings. Central – and fun damental – point of the proposed intervention, it functions as a public interface that allows to reach and connect the different parts next to it with dif ferent ground levels and different functions. A kind of a multi-level platform that turns into a facilitator of urban connectivity, transforming the whole area into a network of public paths that “cling” to the fragments and vestiges of the past.

But public space is not only about mobility. It is a common living space, the integrated functioning of which determines the extent of social cohe sion and the quality of the living environment. To advance in the knowledge of public space, it is necessary to integrate tangible but also intangi ble aspects, to include the morphological basis of public space, but also reflect about the dynamics of use that unfold in it and the layers of meaning that are condensed there. The premise of the project concept is therefore the understanding of what public space is, in this spe cific context and in each concrete moment, and the interpretation of its specificities as an essential part of a process. The project proposes a place where openness prevails over enclosure and porosity is valued over rigor and rigidity. The project relies on city’s capacity to use the ruins to deconstruct, disas semble, reconfigure and reverse the public spaces.

Designing an inhabited urban ground

The work begins with a reflection on the public space as a space of connectivity, inclusiveness and as a space continuously built on its own history, evident in its morphological patterns and in the still recognizable fragments and vestiges of the past. Next, it is shown how the contemporary public space expands beyond the canonical urban typologies and contexts, leading to greater flexibility and hybridity of its forms and functions.

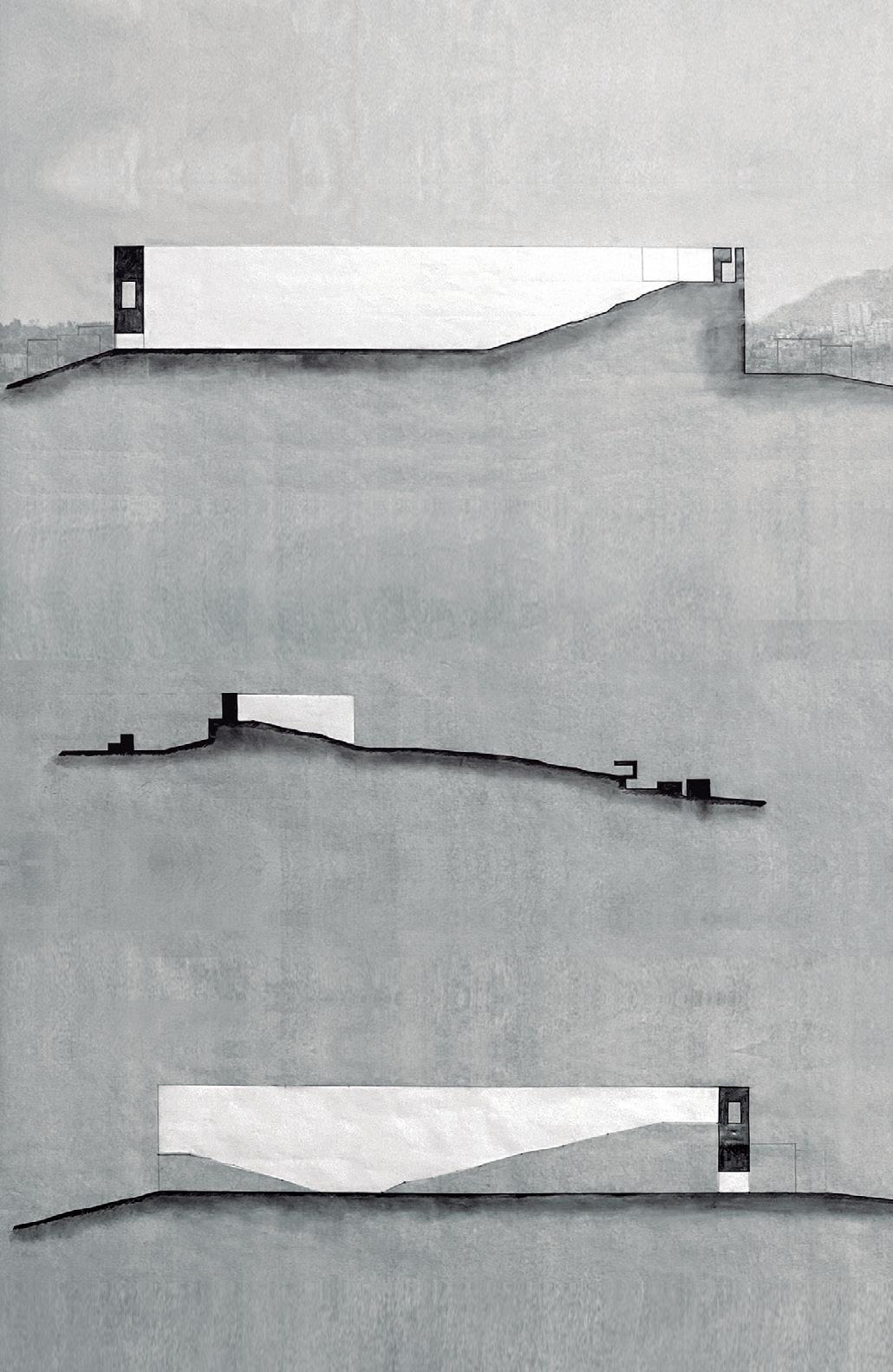

A reflection on the meaning of the ruins closes the analytical part. However, the entire design process is carried out through the construction of a series of conceptual models. The first model is an emotional object build without any scale. It is mainly a contin uous horizontal plane that represents the public space, supported by a vertical plane, which repre sented the medieval wall. This construction results from the interpretative analysis of the intervention

SETÚBAL LAB 60

area, allowing the identification of the medieval wall within the urban fabric and its powerful relationship with the surrounding public space.

A second model, at 1:500 scale, shows the different topographic levels as theoretical platforms that affect the intervention area, as well as emphasizing the existing urban fragmentation. The platforms +5m, +10m, +20m and +30m are defined as the reference levels of the public space in this area, the lowest level being the railway tunnel and the high est level being the medieval wall. The project gives to the city wall the role of reference in the land scape and gives it a new public role as a walkway/ promenade/belvedere. The singular and symbolic buildings that exist on the site – Fryxell Palace, the Graphic – become a new continuous building to host public programs. The railroad tunnel that cuts the Quebedo square becomes a new urban and pedestrian boulevard/promenade that connects the inner city with the waterfront. And, finally, the potential of the abandoned buildings that are scat tered throughout the site is used to propose public buildings that articulate different levels and become references of the urban landscape.

A final model, at 1:200 scale, summarizes the project proposal and highlights the intersection between the horizontal and vertical planes, understood as a continuous and permeable system. The very high vertical planes are purposely exaggerated and out of scale to highlight the connecting points of the entire project. These elements guarantee the continuity of the urban space and rescue the existing vestiges, ru ins and fragments, making them no longer forgotten and becoming an integral part of the city.

SETÚBAL LAB 64

Housing together

Case study 02

Santo António fortress

The inhabited wall of Santo António fortress

Advisors

João Leite

Maria Manuela da Fonte

Students

Ana Oliveira

Beatriz Cabral Henrique Nunes Mariana Frade

The public space represents in the city the place of sharing, relationship and democratic freedom. Therefore, the public space assumes a structuring role in the urban form: defines space (Montaner, 2001), supports the plots, its built fabric (Dias Coel ho, 2013) and constituted itself as a place where people interact. The theme “The space to living together: a new cartography of urban-ground” chal lenges us to think of public space as a structure that (re)defines ways of inhabiting the city, emphasizing the relevance of the ground floor of the building as an interface between public and private sphere of the urban space. Through certain commercial and work activities, the public space extends into the built, widening the collective appropriation and reconfiguring the notions of limits and modes of permanence (Monteys, 2010). The importance of

66

“The relationship between man and space is none other than dwelling, strictly thought and spoken”

Heidegger, 1971

67

this porosity is already particularly revealed in the plan of Rome, by Giambattista Nolli in 1748, where buildings with a public vocation such as atriums, galleries, courtyards and churches are considerate “public spaces”. In this way, the link between built typology, architectural element, and public space is consolidated in a spatial ambiguity that encourages a collective, diverse and free use.

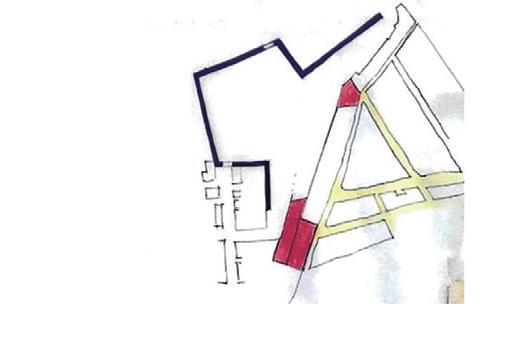

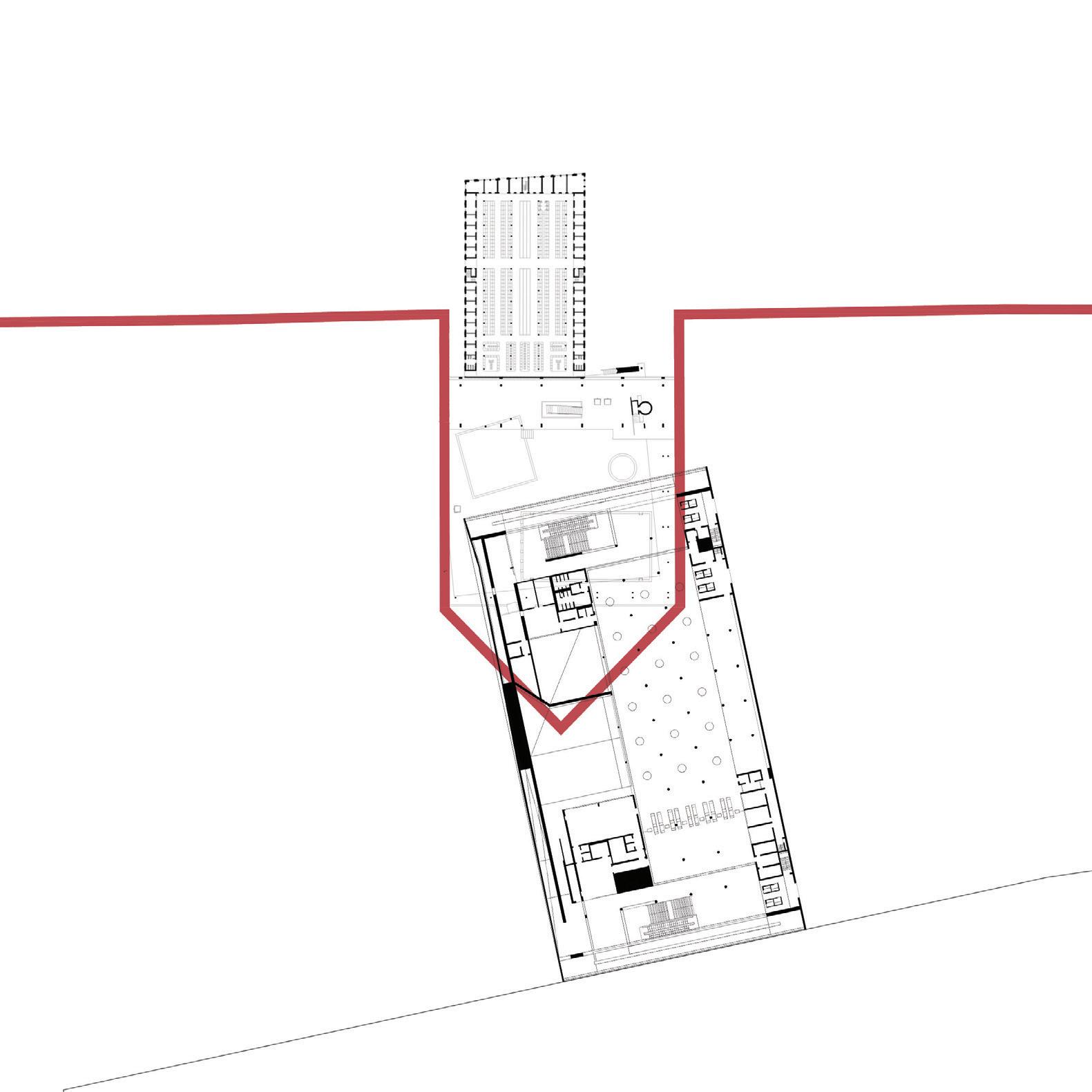

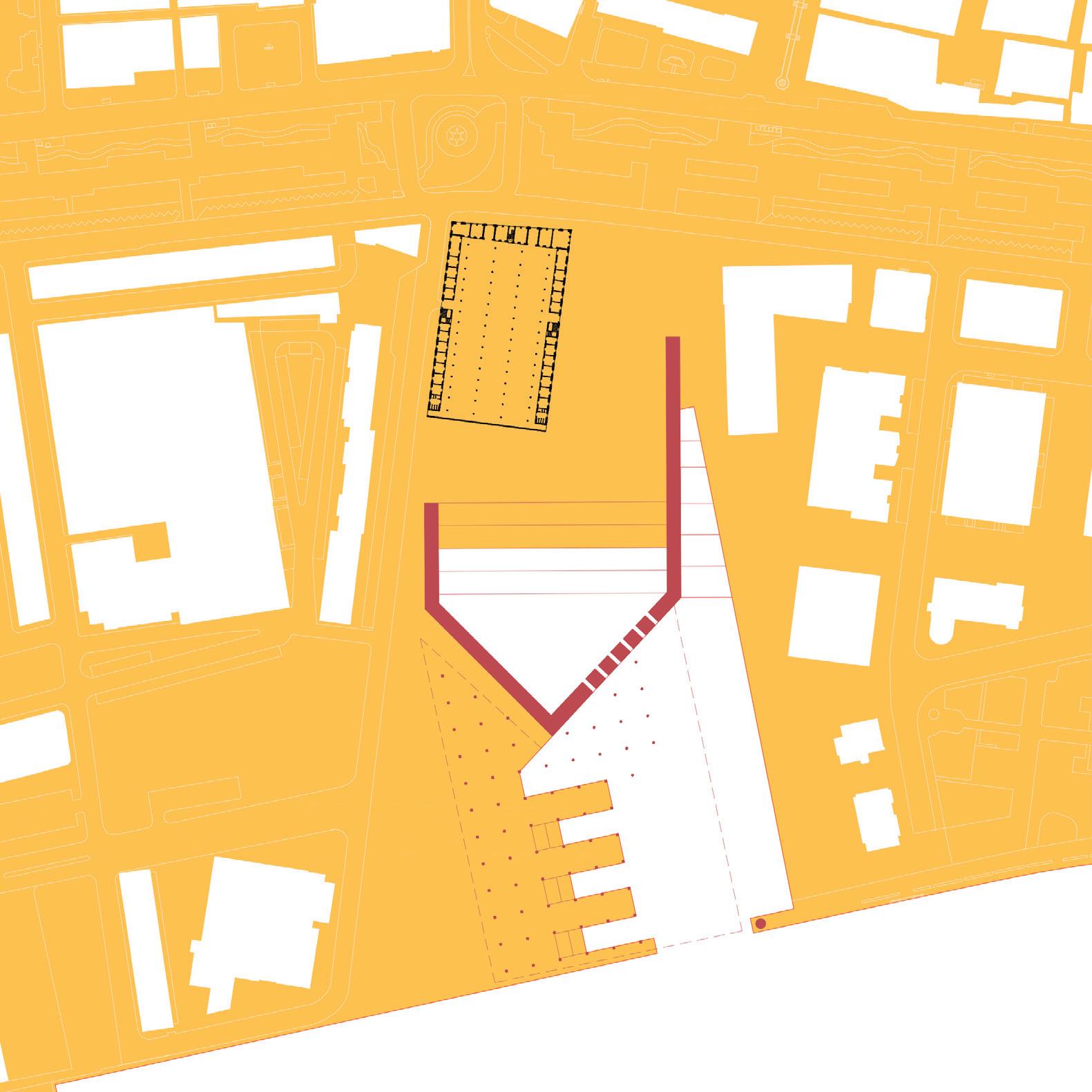

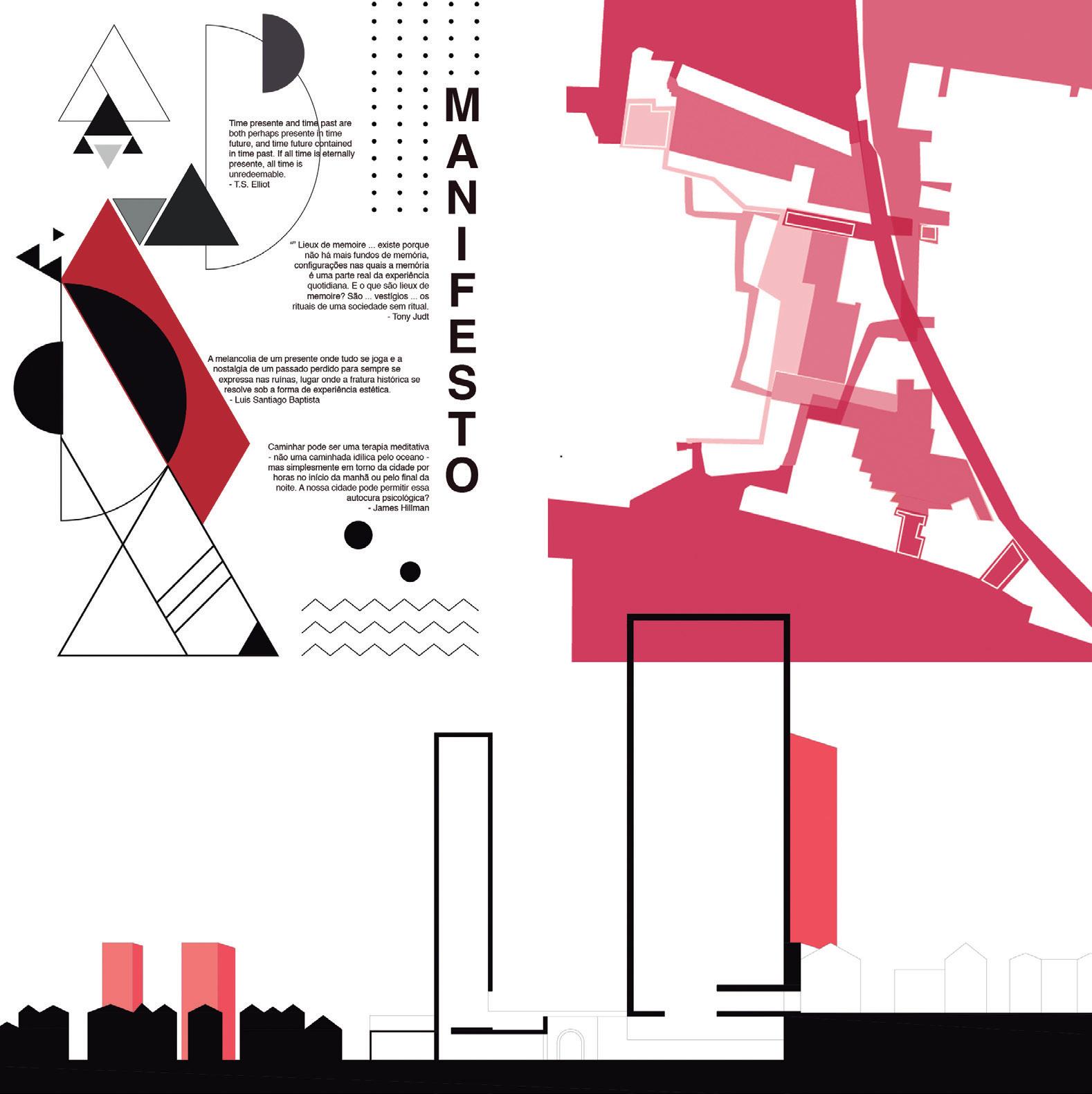

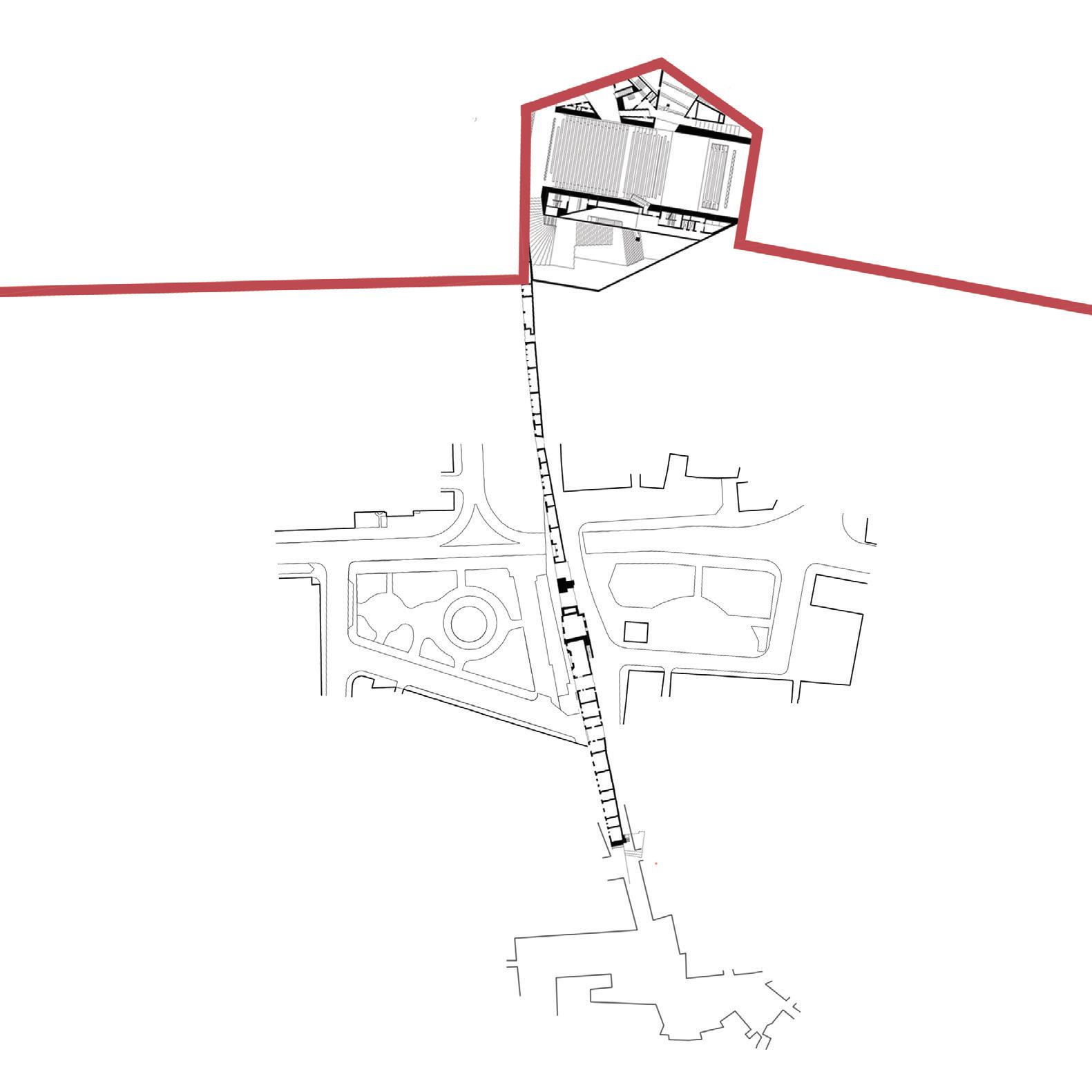

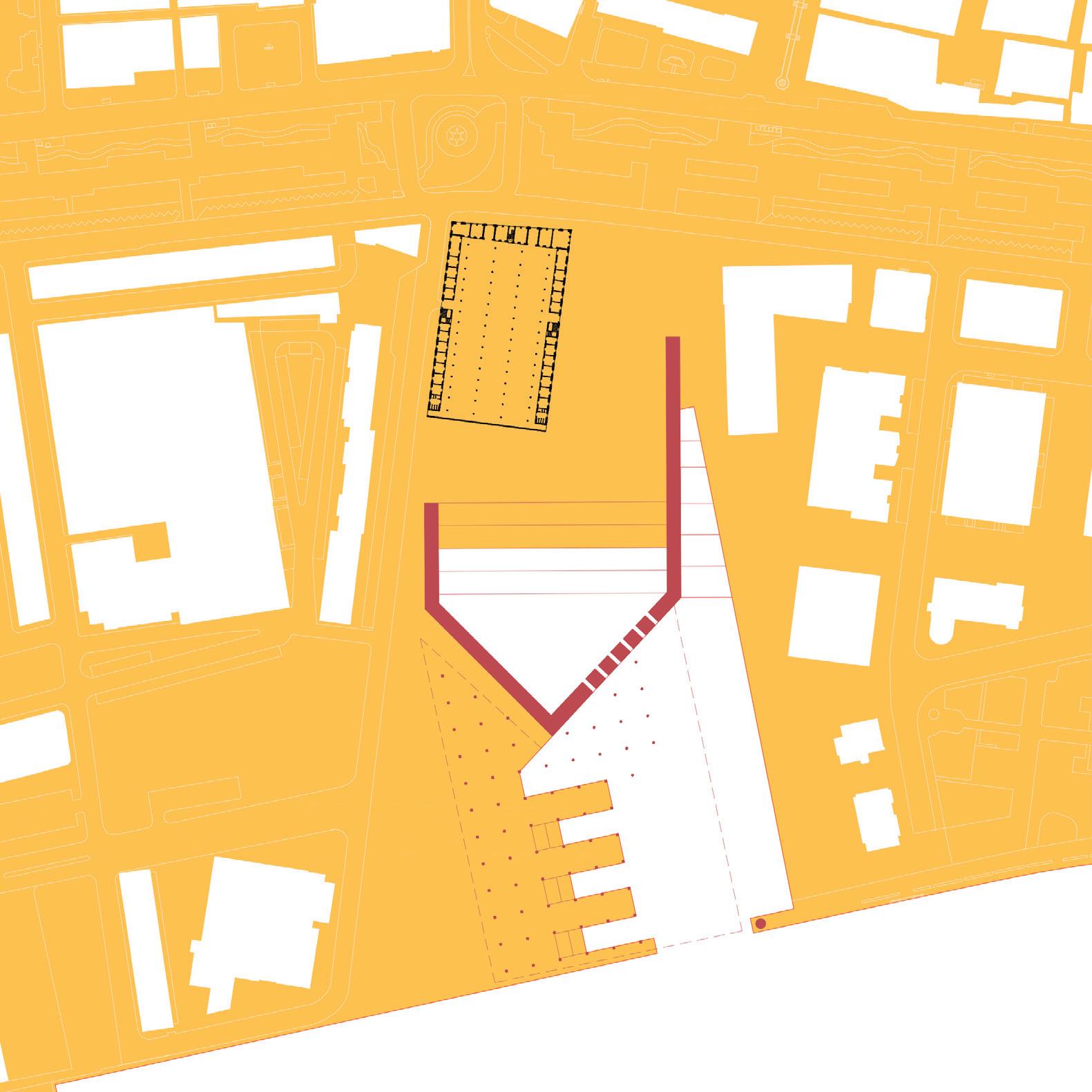

In the area surrounding Praça do Quebedo and Forte de Santo António, this theme of public space as a support for urban life, but also as an aggregat ing element, appears with special relevance. The disconnection from the urban fabric, brought about by the railway line, gives rise to an urgent need to (re)think public space as a device of connection and aggregation. In addition, the space for reflection also had as its specific theme “Housing Together” as a way of intervention and a way of questioning the current reality.

The space with a collective meaning thus emerges as a tool for articulating the two themes, at the same time that it expands spatial understandings and in terconnects public and private space. The threshold space (Boettger, 2014) acquired a greater thickness combining systems of transition and permanence, in an ambivalence structure that dissolves rigid limits and builds continuities between interior and exterior. The theme “Housing Together” finds echo through out the history of architecture and different inter pretations. However, it is important to highlight the working class inhabiting of the 19th century, beginning of the 20th century, in Portugal, with the labor villas. Typologically, the housing space extends to an outdoor space of a collective nature that, in turn, gives continuity to the public structure of the city. Later, the Modern Movement and its “dwelling machines” will configure these places of collective sharing along the horizontal distribution galleries and access to the housing units, but also in the spa

tial continuity of the hollowed ground floors; see the paradigmatic examples of the Unité d’Habitation in 1952, by Le Corbusier, in Marseille, or the various experiments carried out in cities such as São Paulo or Berlin, such as the Hansaviertel neighborhood. Even so, it was already in the 1960s that collective housing developed more intense formal links with the city’s public structure. Through the theoretical and experimental reflections of the Team 10 group, the public space finds logics of continuity within the built fabric, breaking boundaries and unifying circu lation systems and the urban layout.

In the first moment of observation of the interven tion area, Quebedo Square and Santo António For tress, there was early interest in the fact that in this land there is a clear and disturbing “wound” in the connection between communities and urban spac es, caused by the railway line. The particularity of the inhabitants of the area having little knowledge or awareness of the existence of part of the original structure of the fortress, even those who lived on it, was another important aspect observed during the workhop.

Establishing a visual and physical barrier between two very close communities (the one that inhabits the old wall inside the fort and the new wall created by the housing complex), it was one of the main ob jectives to take into account, favoring the inclusion of these two realities, through a building that served as an interface between the them.

After analyzing the place under study, the key con cepts and objectives were pointed out as a starting point for the project:

• Re-invent the concept of “Walls”, making it a habitable body and not a barrier or defense element;

• The idea of “Memory”, when the “new walls” is established, a forgotten past is reactivated, taking on a new expression and, above all, a

SETÚBAL LAB 70

new identity, proposing a new way of inhabiting;

• The idea of “Wound”, caused by the railway line, in which the way to “heal” it involves em phasizing the scar. To this end, the proposed building absorbs the infrastructure, incorpo rating it and transforming the previous bar rier into an element of connection between communities.

Thus the solution, based on these principles, in volves the creation of a large body that develops horizontally along the length of the railway line (corresponding to the section of Quebedo Square station), integrating at the highest elevation next to the São Sebastião belvedere.

In this way, the urban disruption created by the railway infrastructure is dissipated and, at the same time, a monumental character is imposed, in order to mark the urban landscape and developing a symbol ic meaning for the place: a spatial reference object to be inhabited by all arise from the urban layout. This huge sculptural arm will have housing, commer cial areas, services, various programs and activities, polarizing a large part of daily life towards the new built structure and, with this, promoting an inter connection of ways of life and ease of access and flows between the different parts, Quebedo Square and Santo António Fortress. Along with this large body comes the extension of the Quebedo Park, where a subtraction of the ter rain was made, creating a duality of spaces, implying a “natural” fruition between levels. Thus, an “unleve led square” is created with studios and commercial spaces, encouraging the passage and permanence of people. This space, at a lower level, will have ramps and stairs that will allow access to the upper level and to the wall structure indeed, providing a diversity of paths and possible links between the different parts of the urban fabric.